Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Beyond Wi-Fi 7: Enhanced Decentralized Wireless Local Area Networks with Federated Reinforcement Learning

1 Department of Engineering Science, University West, Trollhattan, 46132, Sweden

2 Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

3 Future Networks and Cyber-Physical Systems (FuN-CPS)-Research Group, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Rashid Ali. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 12 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070224

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Wi-Fi technology has evolved significantly since its introduction in 1997, advancing to Wi-Fi 6 as the latest standard, with Wi-Fi 7 currently under development. Despite these advancements, integrating machine learning into Wi-Fi networks remains challenging, especially in decentralized environments with multiple access points (mAPs). This paper is a short review that summarizes the potential applications of federated reinforcement learning (FRL) across eight key areas of Wi-Fi functionality, including channel access, link adaptation, beamforming, multi-user transmissions, channel bonding, multi-link operation, spatial reuse, and multi-basic servic set (multi-BSS) coordination. FRL is highlighted as a promising framework for enabling decentralized training and decision-making while preserving data privacy. To illustrate its role in practice, we present a case study on link activation in a multi-link operation (MLO) environment with multiple APs. Through theoretical discussion and simulation results, the study demonstrates how FRL can improve performance and reliability, paving the way for more adaptive and collaborative Wi-Fi networks in the era of Wi-Fi 7 and beyond.Keywords

Over the past two decades, Wi-Fi technology has played a central role in delivering high-performance wireless networking and has driven continuous innovation across its generations. Its evolution has enabled the widespread availability of affordable user devices and access points (APs). Starting from the original 1997 IEEE 802.11 standard, which achieved peak data rates in the range of a few hundred kilobits per second (Kbps), Wi-Fi has evolved to achieve speeds in the thousands of megabits per second (Mbps) with the current Wi-Fi 6 technology (IEEE 802.11ax) [1].

Wi-Fi 7, the next generation of Wi-Fi technology [1], is designed to provide higher bandwidth and improved performance compared to Wi-Fi 6, with specific support for extended reality (XR) and metaverse applications [2]. Key features include multi-access point coordination (mAPC), advanced beamforming, and multi-link operation (MLO) [3], all aimed at enabling reliable transmission of large data volumes required by XR. MLO, in particular, allows devices to establish and use multiple wireless links with different APs simultaneously, thereby increasing bandwidth and reducing latency for real-time XR traffic. In addition, Wi-Fi 7 introduces support for high-frequency bands above 6 GHz [1], expanding the available spectrum for bandwidth-intensive applications while relieving congestion on the 2.4 and 5 GHz bands.

Machine learning (ML) plays a central role in advancing new functionalities in Wi-Fi networks [4]. According to recent surveys [4], reinforcement learning (RL) is frequently used for decision-making tasks such as channel selection, power control, and beamforming. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are applied to prediction, classification, and clustering, supporting traffic forecasting, interference management, and security. Deep learning (DL) architectures, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), are used for signal processing tasks such as beamforming and spectrum sensing. Evolutionary algorithms, such as genetic algorithms (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO), focus on optimization and parameter tuning for resource allocation and network topology design. Unsupervised learning methods, including K-means and expectation maximization, are applied to clustering and anomaly detection, for example in detecting rogue APs or abnormal network activity. Overall, ML has become a cornerstone for enabling advanced Wi-Fi functionalities, particularly for XR applications, and is expected to remain central in this domain.

However, the proliferation of decentralized and uncoordinated Wi-Fi networks introduces challenges even for advanced ML techniques [5]. In dense environments with many APs and stations, large volumes of data may be generated, yet the data available at each AP is often limited, making independent training difficult. Centralized ML could aggregate data for model training and then share predictions with APs; however, collecting geographically dispersed data introduces latency and scalability issues. Privacy is another concern, as decentralized networks involve many clients producing sensitive data, which is difficult to protect in centralized frameworks. In addition, dynamic network conditions make it challenging for ML models to adapt in real time. These challenges highlight the need for new ML approaches specifically designed for decentralized networks, including distributed and federated learning, privacy-preserving methods, and adaptive algorithms for dynamic environments.

Problem Formulation and Contributions

In this paper, we address the problem of efficient and privacy-preserving decision-making in decentralized Wi-Fi networks, where multiple networks must coordinate without centralized control. Each network acts as an intelligent agent that aims to maximize its long-term throughput while minimizing interference and preserving user privacy. The overall objective is to achieve network-wide efficiency through collaborative learning under partial observability.

To this end, we propose a federated reinforcement learning (FRL) framework in which each AP maintains a local learning model (LLM) and periodically exchanges compact reward statistics to update a global learning model (GLM). This design enables adaptive, decentralized optimization without sharing raw data.

As a short review paper, the main contributions of this study are as follows:

• We provide a concise survey of recent applications of ML and RL for MAC-layer optimization in Wi-Fi networks, emphasizing decentralized and federated approaches relevant to Wi-Fi 7 and beyond.

• We identify open challenges in applying ML to dense, multi-BSS environments and outline how FRL can address these through distributed collaboration and privacy-preserving reward aggregation.

• We present a conceptual problem formulation for decentralized link activation using FRL and demonstrate its feasibility through a case study in a MLO environment.

Dense multi-BSS deployments worsen co-channel interference; recent work therefore couples coordinated spatial reuse (CSR) with learning-based power control. Wang and Fang [6] propose a federated learning-based double deep Q-Network (FL-DDQN) for CSR power allocation, reporting enhanced throughput and latency gains over baselines while preserving data locality. At a higher level of coordination, Zhang et al. [7] design a deep RL channel-access (DLCA) protocol within a multi-AP controller architecture and show improvements in both throughput and proportional fairness in overlapping enterprise Wi-Fi networks. These approaches demonstrate the advantages of coordination (federated), yet typically assume either (i) explicit multi-AP control planes or (ii) centralized entities for aggregation, which may be impractical in uncoordinated deployments and do not target Wi-Fi 7 MLO link-activation granularity.

Some of the researchers also propose cooperative multi-agent RL (MARL) to replace heuristic contention process. Fan et al. [8] develop a selective-communication MAC with centralized training and decentralized execution, showing better throughput and latency than CSMA/CA while maintaining fairness and scalability to varying number of users. Similarly, Du et al. [9] combine FL with Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) for dense-channel access, reducing MAC delay via training-pruning and aggregation strategies in ns-3 (Network Simulator 3). These protocols validate that limited message exchange among agents can stabilize access decisions. However, they focus on contention windows (CW) or transmission decisions per slot rather than multi-link activation under concurrent multi-band operation, and they do not explicitly encode max–min fairness across neighboring BSSs. Channel bonding increases peak rates but intensifies contention. Zhong et al. [10] employ proximal policy optimization-based (PPO) deep reinforcement learnin (DRL), centralized and distributed variants, to allocate primary channels and bonding widths without prior interference models, handling hidden-terminal/channel scenarios and dynamic loads. Chen et al. [11] propose a decentralized DRL dynamic channel bonding (drlDCB) that speeds convergence by using an estimated-throughput reward and discouraging excessive bonding once demand is met. While both works advance distributed decision-making for bonding, they do not consider federated reward sharing among APs nor fairness-aware global signals; furthermore, decisions are single-link/channel-centric rather than the joint multi-link activation problem emphasized by Wi-Fi 7 MLO.

Tan et al. [12] leverage Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) with an “access opportunity” abstraction to transfer policies from single-link to multi-link networks, achieving up to 23.9% throughput gains with robustness and fairness. Wu et al. [13] optimize multi-link frame aggregation lengths via DRL, showing that aggregation must adapt to time-varying environments and is not monotonically throughput-improving. These works underscore the importance of cross-link scheduling under partial observability. Still, they either assume controlled training environments or do not articulate how to exchange learning signals among neighboring APs under the tight airtime and latency budgets of WLAN control traffic.

Beyond access control, distributed learning is being adopted for network operations. Salami et al. [14] compare FL and knowledge distillation for AP load prediction on campus traces and show up to 93% accuracy gains while reducing communication and energy overheads by

In addition to Wi-Fi-specific studies, RL has also been applied to optimize decision-making in other decentralized wireless systems. For instance, a recent work on delay-tolerant networks introduces an RL-based routing strategy that improves packet delivery ratios by learning encounter patterns and transmission histories, demonstrating the adaptability of RL in dynamic, partially connected environments [17]. Similarly, FL has shown promising results in distributed internet of things (IoT) data collection, where periodic scheduling minimizes communication overhead while improving convergence and energy efficiency [18]. These studies further reinforce the growing relevance of RL and FL paradigms for distributed and resource-constrained wireless networks, conceptually aligning with our proposed FRL-based framework for decentralized Wi-Fi systems.

At the same time, data transmission expense is a key barrier to FL at the edge. Zhang et al. [19] propose DRL-driven gradient quantization to jointly balance training time and quantization error under time-varying channels in vehicular edge computing. While not Wi-Fi-specific, such techniques motivate lightweight statistics exchange for WLANs and support our choice to share compact reward summaries in beacon-like frames instead of high-dimensional model updates.

3 Machine Learning Applications in Wi-Fi

A wide range of ML-based solutions have been developed for the PHY and MAC layers of the IEEE 802.11 standard to optimize internal parameters in both dynamic and static environments. These approaches aim to reduce collisions during channel access, improve data rates through link configuration and aggregation, determine optimal frame length using frame aggregation techniques, and mitigate interference or noise at the PHY layer. RL methods are primarily used to adjust access parameters, while supervised and unsupervised learning techniques are employed to estimate channel conditions. Together, these approaches improve overall system performance. Fig. 1 provides an overview of representative ML contributions for optimizing Wi-Fi environments.

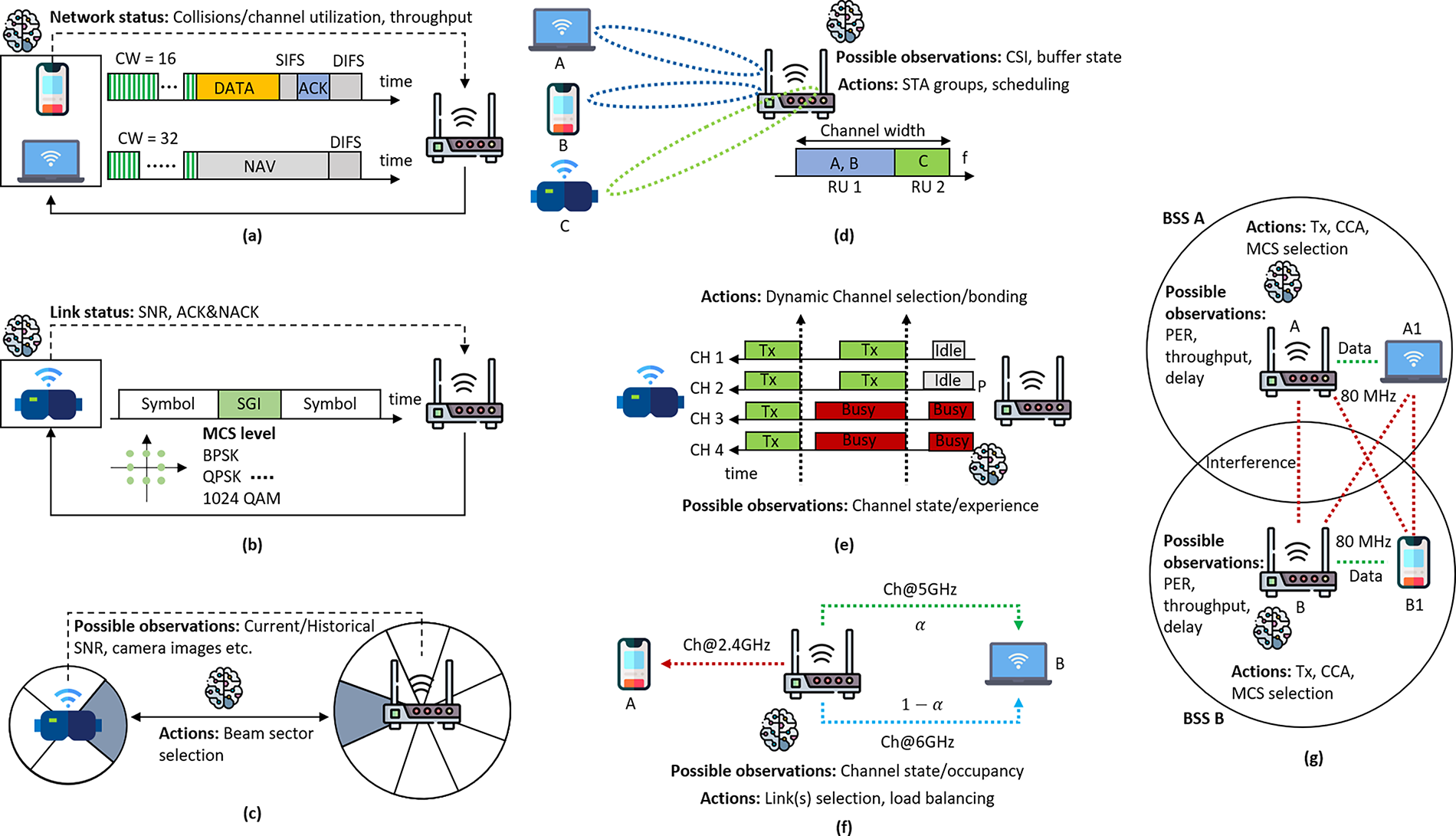

Figure 1: Machine Learning applications in Wi-Fi: (a) ML models for Wi-Fi channel access control via Distributed Coordination Function (DCF), leveraging network status observations to adjust contention window parameters. (b) ML-based adaptive link configuration, including rate selection, utilizing link status observations to adjust MCS levels. (c) Beam sector alignment within Wi-Fi networks using ML, featuring an 8-sector AP and a 4-sector station. (d) ML agent role in identifying compatible station groups and scheduling transmissions based on past experiences, such as channel or buffer state information. (e) ML technique aiding APs in selecting optimal channels based on observations like channel state information. (f) ML predicting channel occupancy for traffic balancing in multi-band APs, as shown for device B using 5 and 6 GHz bands (

3.1 ML for Channel Access in Wi-Fi Networks

ML is widely used to improve Wi-Fi performance by optimizing channel access mechanisms. A common approach is to fine-tune the CW value, a key parameter for avoiding collisions among devices sharing the same radio channel. The goal is to maximize throughput by reducing both collisions and idle periods. Different ML models—including supervised learning, RL, deep RL, and FL—have been applied to IEEE 802.11 standards and their amendments [20]. For example, RL algorithms such as Q-learning can estimate collision probabilities and dynamically adjust the CW size according to network conditions [20]. Fig. 1a illustrates an example where an RL agent optimizes CW parameters for station (STA) 1.

3.2 ML for Adaptive Link Configuration in Wi-Fi Networks

The IEEE 802.11 amendments introduced high-speed connectivity through features at both the PHY and MAC layers, such as channel bonding and adaptive link configuration. Rate adaptation is critical for achieving optimal throughput under varying channel conditions, and ML models have been applied to balance transmission errors against channel utilization in dynamic scenarios. In ML-enabled rate adaptation, an agent estimates the probability of successful transmissions for each Modulation and Coding Scheme (MCS) and selects the data rate that maximizes performance. ML models can also support the choice of Short Guard Interval (SGI) values using online learning methods such as Thompson sampling (TS), which can adapt effectively to fluctuating channel quality. These predictions are based on indicators such as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) or a cross-layer approach that incorporates acknowledgment (ACK) and negative acknowledgment (NACK) feedback. Online learning methods are therefore well-suited to handle variations caused by interference, fading, and attenuation. Fig. 1b shows an example of rate selection using ML models.

3.3 Beamforming with Machine Learning

Beamforming is a Wi-Fi technique used to direct signals toward specific receivers or areas. A major challenge is selecting the optimal beam sector pairs between the transmitter and receiver. ML addresses this problem by using historical data—such as past and current SNR values, and in some cases camera images—to predict the best sector pairs. ML can also assist with user-to-multiple-AP association in dense deployments. Once the beam sectors are selected, rate adaptation is required, which can be supported by ML algorithms such as regression and Support Vector Machines (SVM) for channel classification [21]. Fig. 1c illustrates this process. Compared with traditional exhaustive beam search methods, ML provides a more efficient solution, while RF-based techniques continue to support channel classification.

3.4 ML for Multi-User Wi-Fi Transmissions

Recent Wi-Fi standards have introduced multi-user (MU) transmissions, enabling simultaneous data transfers to multiple STAs through spatial multiplexing. IEEE 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6) extended this capability to both downlink and uplink traffic by introducing orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing access (OFDMA), which partitions bandwidth into resource units (RUs) allocated to individual users. In the forthcoming IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7), the combination of multi-user multiple-input multiple-output (MU-MIMO) and OFDMA is expected to be essential. Enhancements such as assigning multiple RUs to a single user and adopting implicit channel sounding will further improve efficiency. However, optimizing MU communications requires effective grouping of compatible stations, which remains a complex problem. ML provides a promising solution by enabling adaptive station grouping and parameter configuration under dynamic conditions. As shown in Fig. 1d, an ML agent can learn STA compatibilities and allocate larger RUs to compatible users (e.g., STA A and STA B), while assigning smaller RUs to others (e.g., STA C). For efficient operation in wireless local area networks (WLANs) with OFDMA, the AP must also schedule stations and allocate resources intelligently, a task well-suited to DRL. Overall, ML techniques show strong potential in enhancing MU communications, MU-MIMO, and OFDMA, with studies demonstrating their effectiveness for scheduling, user selection, link adaptation, reducing channel sounding overhead, and improving resource allocation [22–24].

3.5 ML-Based Channel Selection/Bonding

Broadening Wi-Fi channels can increase throughput but also raises the risk of contention in dense environments with adjacent networks. To address this, ML techniques can identify optimal channel allocation and bonding configurations for specific scenarios, enabling adaptive optimization. A learning agent, for example, can monitor channel occupancy and select appropriate actions, especially when the primary channel is idle. The optimal configuration depends on factors such as the number and location of competing devices, basic service set (BSS) load, and channel availability. RL methods, including multi-armed bandits (MAB) and predictive modeling, support online learning by allowing the agent to refine decisions based on real-time observations [25,26]. Wi-Fi 7 extends support to channels up to 320 MHz, which requires adaptive selection of both channel and width. Since MAB methods often fail to meet network or user requirements, DRL is being explored to improve key metrics such as delay and throughput. Fig. 1e illustrates an ML-based approach where an AP selects optimal transmission channels using channel state information.

3.6 ML-Enabled Multi-Link Operation

ML techniques enhance advanced Wi-Fi mechanisms, particularly in WLANs. For MLO, neural networks can predict channel state information (CSI) and select the most suitable frequency band [27]. DRL can also improve AP selection and resource distribution, thereby increasing the efficiency of distributed MIMO transmissions [28]. NN-based models are especially effective at predicting channel conditions and grouping stations for efficient full-duplex communication, outperforming traditional predefined methods for channel and resource management [29]. Probabilistic neural networks further support multi-interface utilization by forecasting interface idleness. Supervised learning has been applied to packet re-transmission strategies, where models decide whether to retransmit on the same band or switch to an alternate band. Fig. 1f illustrates such an application: ML predicts occupancy on the 5 and 6 GHz bands to distribute traffic efficiently to STA B, while assigning a legacy device (STA A) to the 2.4 GHz band.

3.7 Using ML for Wi-Fi Spatial Reuse

The IEEE 802.11ax standard introduced SR, which allows concurrent transmissions among devices from different BSSs. Although the 802.11ax SR mechanism is rule-based and conservative, it still delivers noticeable performance gains. ML techniques can further improve SR by adapting to diverse scenarios, leading to higher throughput and lower latency. Wi-Fi 7 (IEEE 802.11be) extends SR by enabling coordination between neighboring APs, and ML can enhance this coordination by identifying devices that can safely transmit concurrently using CSI from multiple devices. For example, in Fig. 1g, two APs transmit on the same 80 MHz channel at reduced power, maximizing throughput and creating SR opportunities. RL approaches, such as Q-learning [20] and multi-armed bandits (MABs) [30], have been applied to SR, where multiple agents learn transmission policies by interacting with the environment. However, convergence can be difficult when agents compete without collaboration. Supervised learning methods, including NNs, multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), and decision trees (DTs), have also been explored for selecting SR parameters based on scenario characteristics [31]. These models are typically trained offline using datasets that represent a range of configurations. In dense WLANs, interference can be reduced by jointly optimizing transmission power and channel allocation. Q-learning has been applied in this context, with training guided by event-triggered updates to reduce iterations. When network conditions change due to user mobility, the learning process is repeated to maintain optimal resource allocation [32].

3.8 ML Applications in Multi-BSS Environments

The MAC layer faces additional complexities in multi-AP environments [33]. ML algorithms can help mitigate these challenges by enabling optimal channel selection, user roaming optimization, dynamic frequency selection, and strategic AP placement [4]. For example, ML can predict channels with minimal interference and higher throughput for each AP, improving channel selection and reducing cross-interference, as shown in the spatial reuse scenario of Fig. 1g. Device transitions between APs often introduce latency due to re-association, but ML can predict roaming patterns and direct devices to APs with stronger signal quality for smoother handovers. In addition, ML can support AP deployment planning by analyzing network structure and user dynamics, helping eliminate coverage gaps and improve overall network efficiency.

4 Challenges in Applying ML to Decentralized Wi-Fi Networks

Due to the novelty, complexity, and ongoing development of many of the above mentioned features of ML for Wi-Fi networks, there are several areas that remain unexplored or have only been superficially addressed. As a result, further research is necessary in this field. Indeed ML has proven its value and importance to play a vital role in different optimization problems for Wi-Fi networks. However, ML applications in dense Wi-Fi networks with several BSS (standalone APs) can face several challenges and issues due to the nature of the decentralized management of shared spectrum with several BSSs. Here are few of the key challenges and issues a decentralized Wi-Fi network environment may face:

• Interference: In a dense Wi-Fi network environment, multiple APs can cause interference, which can negatively impact the performance of ML applications at each AP. This interference can be caused by overlapping channels, signal reflections, and other factors.

• Latency: In a decentralized Wi-Fi network, the latency varies widely depending on the location of the device and the AP it is connected to. This leads to delays in the transmission of data, which can negatively impacts the performance of ML applications due to a selfish local learning strategies at each device/AP individually.

• Security and Privacy: ML applications in dense Wi-Fi networks need to ensure that the data transmitted over the network is secure and protected from malicious attacks. This can be a challenge in a decentralized network with multiple APs, as the data can be intercepted and compromised. Therefore, in decentralized Wi-Fi networks, exchanging learning parameters among APs may expose vulnerabilities such as inference leakage, model poisoning, or denial-of-service (DoS) attacks on control messages. Although a detailed evaluation is beyond the scope of this survey, several mitigation strategies can be adopted. These include: (i) robust reward aggregation (e.g., median or trimmed minima) to resist malicious updates, (ii) lightweight authentication and integrity checks for beacon-like exchanges, and (iii) privacy-preserving mechanisms such as quantization or local noise addition when sharing rewards. Addressing these aspects is critical for practical deployment of distributed federated reinforcement learning in future Wi-Fi networks.

• Network Congestion: As more and more devices connect to a Wi-Fi network, the network becomes congested, leading to slower speeds and reduced performance. This can be a significant challenge for ML applications that require high-speed data transmission.

• Resource Allocation: In a decentralized Wi-Fi network with multiple BSSs, the allocation of resources such as bandwidth and power can be a challenge. ML applications need to be able to adapt to the changing resource availability in order to maintain their performance. For example, in outdoor environments, ML-enabled resource allocation techniques for intra-BSS and resource coordination methods for inter-BSS that are aware of beamforming needs to be thoroughly explored.

• Multi-User Communication: The field of multi-user communication requires further research to advance ML-based solutions for efficient allocation of spatial streams and resource units to active stations, especially when confronted with realistic traffic patterns and quality-of-service (QoS) demands. In order to improve Wi-Fi’s handling of sensitive traffic, future traffic projections should factor in competing devices and environmental circumstances, resulting in more satisfactory worst-case latency through resource pre-reservation. Furthermore, channel sounding can be optimized with ML techniques by selectively requesting information from stations that are likely to be scheduled, thereby improving overall performance.

• Spatial Reuse and Spectral Efficiency: As discussed in Section 3.7, the application of ML techniques in optimizing SR has been extensively investigated in decentralized BSSs, where individual nodes make decisions based on their observed inputs. However, the recent introduction of transmission opportunity (TXOP) sharing and cooperative schemes in IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7) necessitates a different approach that incorporates ML techniques to enhance their performance. More research is required to compare and assess the effectiveness of these methods. Additionally, there is considerable potential for DRL to optimize channel aggregation techniques in combination with OFDMA RU allocation.

• Decentralized Multi-Link Operation: The recently introduced new feature of Wi-Fi, called multi-link operation, brings about numerous challenges, such as selecting optimal channels and distributing various flows across multiple links. ML techniques could be advantageous in determining when to execute channel switching, detecting patterns of link occupancy that favor certain traffic types, and allocating or distributing flows across different links, especially in decentralized multi-BSSs environments.

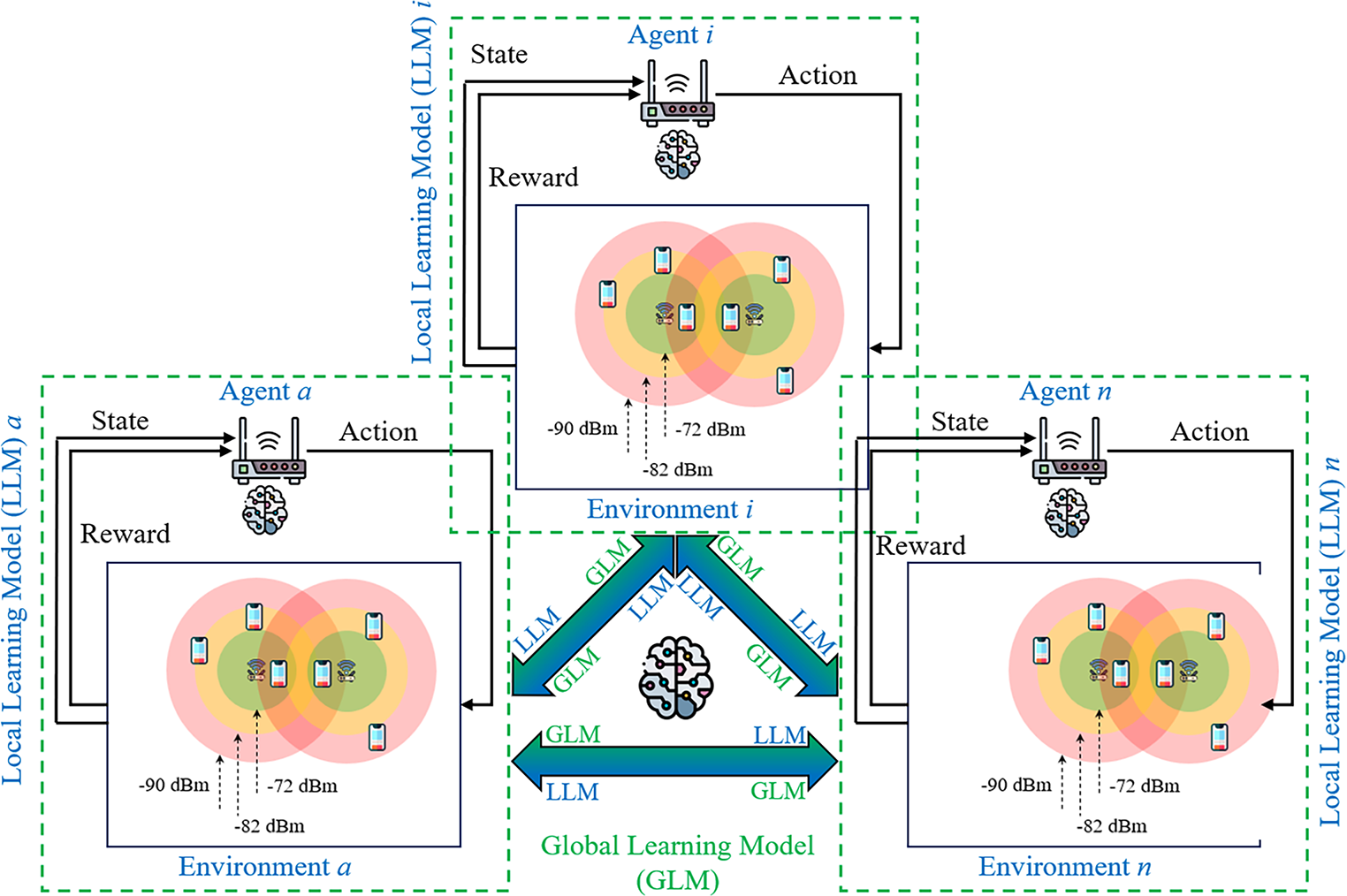

5 Distributed Federated Reinforcement Learning Model for Decentralized Wi-Fi Networks

The FRL framework integrates two key components: a local learning model (LLM) and a global learning model (GLM). Each AP operates as an autonomous agent that employs RL within its LLM to evaluate network configurations based solely on local performance metrics [34]. Although RL-based methods have achieved promising results in decentralized systems, they often struggle in multi-agent environments where agents act independently, leading to suboptimal collective performance [20]. To address this limitation, the FRL framework incorporates a GLM, in which multiple agents share their locally obtained rewards with either a centralized server or neighboring agents in a decentralized setup. The aggregated global reward is then computed from these shared experiences to guide the learning process toward a coordinated and globally optimal policy.

FRL presents a promising approach to overcoming the challenges encountered by ML in Wi-Fi networks. By combining the advantages of RL and FL, FRL enables each agent to learn from both its own experiences through the LLM and the shared experiences of other agents through the GLM. In distributed FRL (DFRL) for decentralized Wi-Fi networks, the collective intelligence of interconnected agents can effectively address many of the challenges faced by modern Wi-Fi systems, particularly in scenarios involving beamforming, MLO, and multi-BSSs environments. As illustrated in Fig. 2, each agent autonomously learns from its local environment and shares its insights with neighboring agents, contributing to the GLM. Through this collaborative exchange, agents jointly refine their policies for channel access, power control, and beamforming in response to dynamic network conditions and user demands. DFRL facilitates seamless adaptation to changing environments by leveraging the diverse experiences of distributed agents, thereby enabling network-wide optimization while minimizing interference and maximizing throughput in complex multi-BSS deployments.

Figure 2: A Distributed Federated Reinforcement Learning (DFRL) framework for resource allocation optimization in decentralized multi-BSS network environment

We consider MLO feature of upcoming Wi-Fi 7 as our case study and evaluate the potential performance of using a DFRL framework.

We assume that we have a multi-BSSs environment with four APs, each associated to a single STA. In this study, we consider a decentralized multi-link Wi-Fi network with a finite number of radio links distributed among all AP and STA pairs. These limited resources must be allocated among competing APs to maximize overall network performance. The system model consists of a set A of

We define a set L of

where each link

We adopt the channel path loss model specified for the residential scenario in the IEEE 802.11ax standard, as detailed in [35]. In this environment, the path loss (in dB) between an AP–MLD and a nonAP–MLD separated by a distance

In this model,

5.1.2 Transmission Rate Estimation

Each AP–MLD estimates its achievable data transmission rate (

Here,

5.2 Foundational Assumptions for DFRL

To develop a framework using DFRL for decentralized link activation (LA) strategies in AP-MLD contexts, we define a set of possible LA actions, O, for an AP-MLD

We focus on downlink traffic between an AP-MLD and its nonAP-MLD counterparts. The DFRL framework splits into two learning environments: local (LLM) and global (GLM). In LLM, each AP-MLD uses RL tailored to its environment. While effective for spectrum management, RL faces challenges, especially in multi-agent settings, leading to potentially unfair link activations as AP-MLDs prioritize their own benefits. To overcome this, we introduce a decentralized GLM that uses federated learning to optimize spectrum allocation collectively. AP-MLDs share learning outcomes with their neighbours to align their strategies, tackling similar challenges together. This collaborative approach helps because an AP-MLD alone might not fully explore its environment. By sharing experiences, AP-MLDs can learn faster and improve overall performance.

Given that the choices made by APs are only known to a limited extent at the allocation stage, we adapt our local learning model to a MAB framework. The MAB algorithm is employed here as a lightweight and interpretable RL baseline to demonstrate the basic interaction between local and global rewards in the proposed DFRL setup. This simplified choice supports conceptual clarity rather than exhaustive parameter analysis, which is planned for future, large-scale evaluations. In this setup, each AP operates with

To address the competitive decisions made by individual agents in the LLM, we integrate GLM on the top of LLM to enable a cooperative approach in optimizing resource allocation, specifically for link activation decisions. In the GLM framework, each AP communicates its locally determined reward to adjacent APs through periodic, beacon-like signals. For the operation of the GLM, APs employ a Minimum Achieved Reward (MAR) function. This function adopts the smallest reward value from those reported by neighboring APs as the instant global reward for each action. The MAR function effectively translates an AP’s locally calculated reward into the least satisfactory outcome linked with a given action. Consequently, the reward for an AP

In our approach, we implement a max-min fairness strategy, where a DFRL agent, specifically an AP

Max-min fairness is a principle aimed at achieving equitable distribution in network resource allocation. It strives to allocate as much bandwidth as possible to the users with lower data rates, thereby preventing the squandering of network resources. The essence of this strategy is to enhance the minimum possible data rate accessible to all network participants. In the context of a wireless network composed of links with fixed capacities and AP-STA pairs operating over these links, our objective is to activate a selection of links for each AP-STA pair, ensuring the data rate for each pair does not exceed the link capacity. A resource allocation is deemed max-min fair if increasing the data rate for one transmission necessitates the reduction of the data rate for another, less-capable transmission.

To calculate the mean global reward for a specific action

This mean global reward guides the AP in selecting its subsequent action in an exploitation phase (i.e., with probability

5.5 Exploration vs. Exploitation

It is important to know that, in RL frameworks employing MAB algorithms, agents navigate the crucial balance between exploration and exploitation. This balance dictates whether an agent should rapidly gather new information (exploration) or optimize decisions based on current knowledge (exploitation). A key mechanism for managing this trade-off is the implementation of a learning rate parameter (

6 Performance Evaluation: A Toy Scenario for DFRL Framework

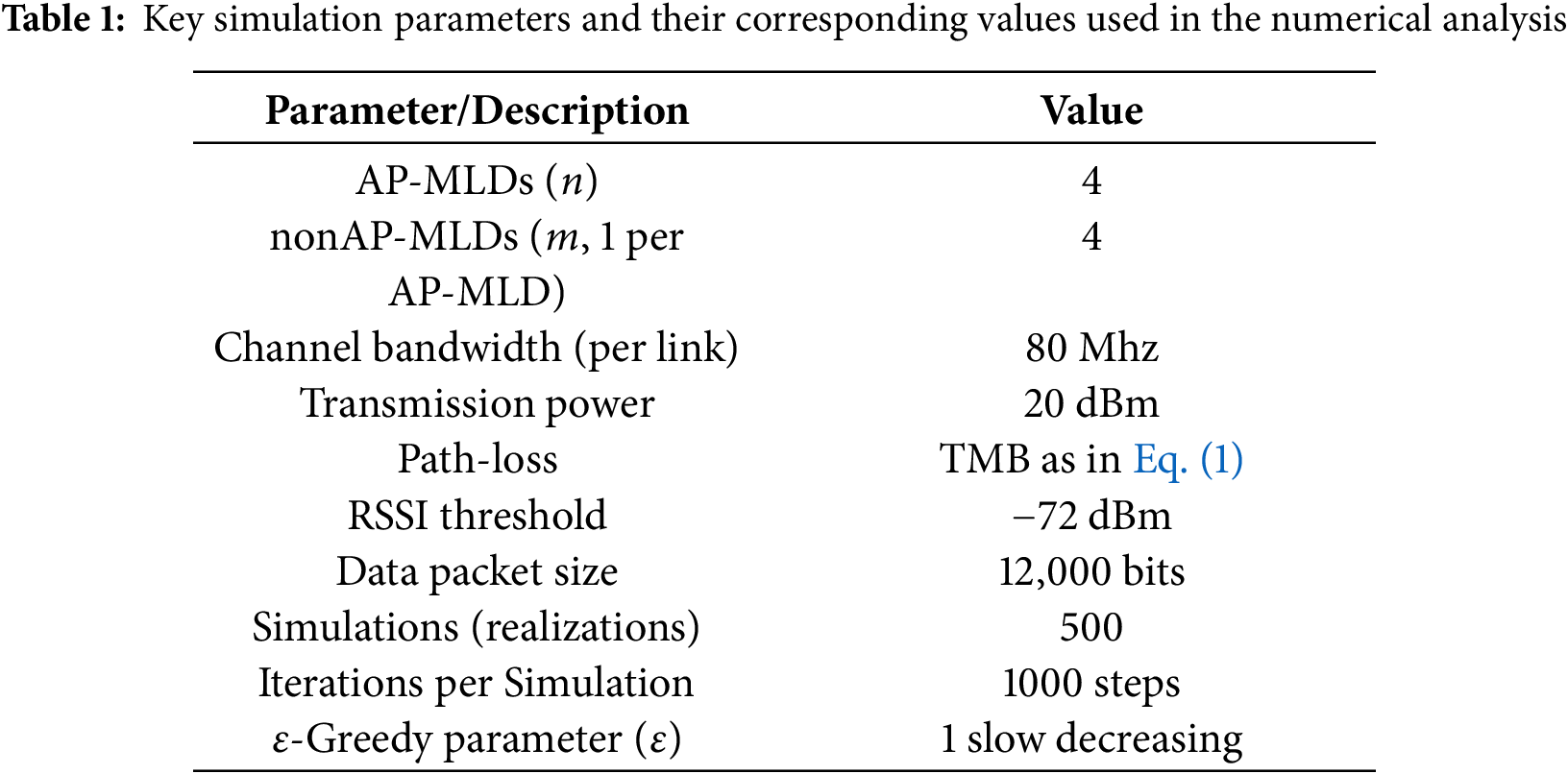

We assess the efficacy of our proposed DFRL framework for decentralized link activation (LA) by analyzing outcomes derived from a demonstrative toy scenario. Within this scenario, we deploy four AP-MLDs randomly across a

For performance assessment, we initiate our evaluation by simulating 500 randomly positioned scenarios employing a fixed LA scheme. This scheme enables all AP-MLDs to utilize two available links for transmission. Subsequently, we implement a random LA scheme [33] wherein each AP-MLD activates one or both links arbitrarily for transmission. Additionally, we conduct simulations utilizing a RL-based mechanism [37] employing MAB algorithm to learn from its local environment. This mechanism exploits actions with the highest cumulative average reward. Lastly, we employ our proposed DFRL-based mechanism, to collaboratively determine the most suitable link(s) for activation. Within this DFRL-based framework, each AP-MLD shares its locally computed loss function with neighboring AP-MLDs, as described in Eq. (4), and calculates its global regret as outlined in Eq. (5). This mechanism enables AP-MLDs to select optimal actions based on minimized global expected regret.

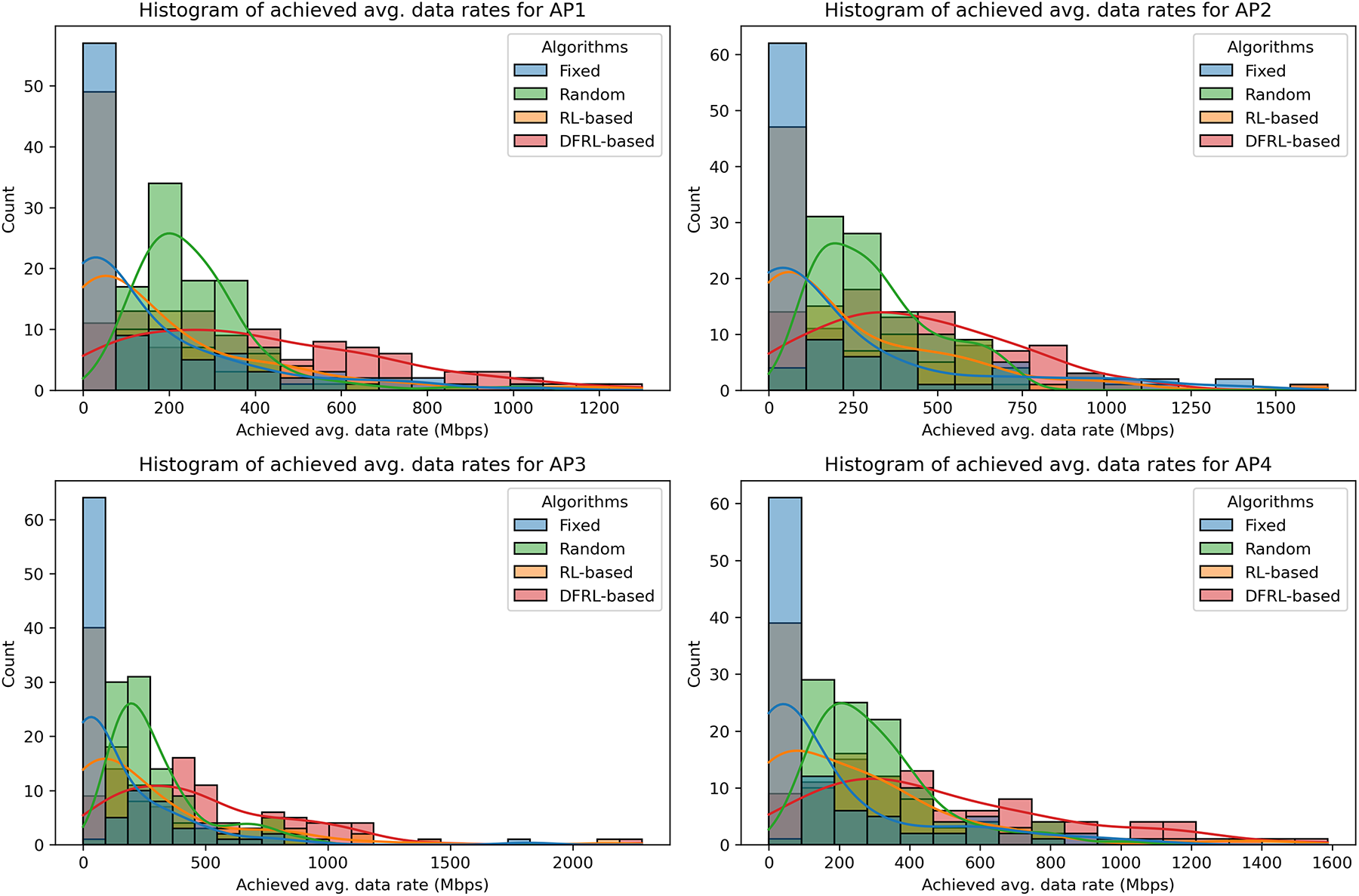

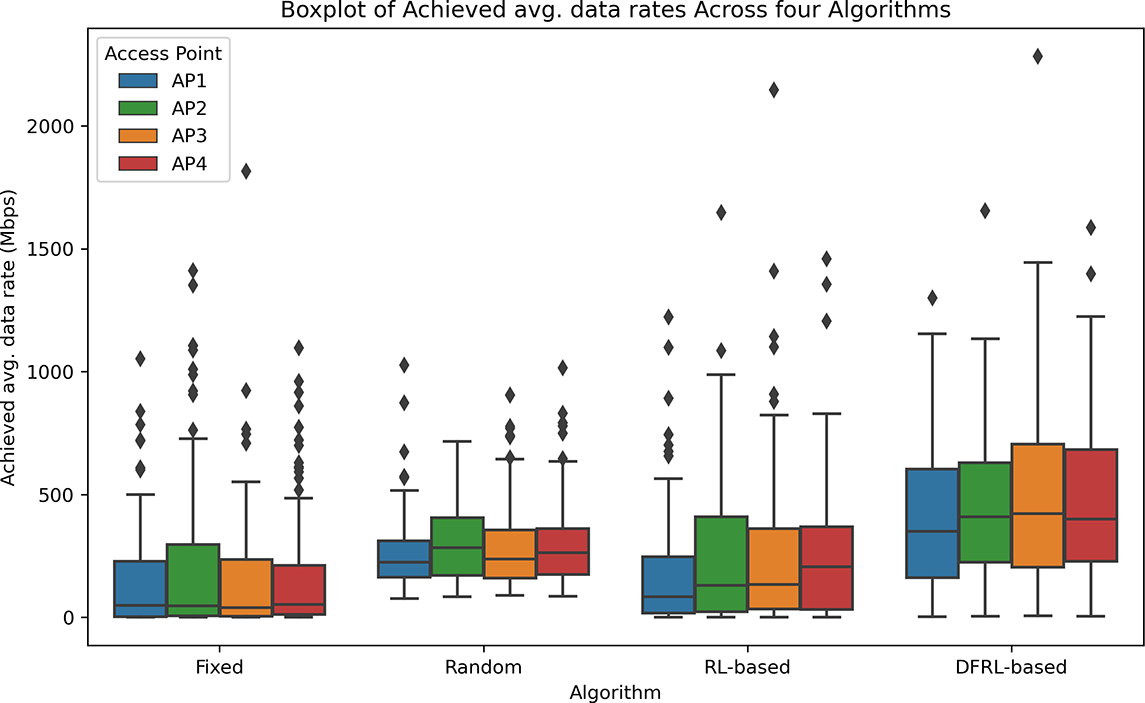

Fig. 3 compares the performance of four different LA strategies across the four access points (AP1-AP4). The Fixed and Random strategies show consistently lower data rates for all APs, indicating that they do not use the available channels efficiently. In contrast, the RL-based strategy achieves noticeably better results by adapting to network conditions and learning from experience. The proposed DFRL approach further improves performance by allowing APs to share information during learning, leading to fairer and more balanced use of network resources. The boxplot in Fig. 4 clearly illustrates these improvements. With DFRL, all APs achieve higher and more stable data rates compared to the other schemes. On average, the DFRL-based link activation increases throughput by about 28%–35% compared to the RL-based method and by more than 50% compared to the Fixed and Random baselines. These results demonstrate that collaborative reward sharing helps APs make more consistent decisions and use the available spectrum more efficiently. Overall, the DFRL approach shows strong potential for improving performance in decentralized Wi-Fi networks.

Figure 3: Comparison of achieved average data rate histograms for Fixed, Random, RL-based, and DFRL-based decentralized link activation schemes across four AP-MLDs network scenarios, based on 500 different realizations

Figure 4: Performance comparison of four LA strategies across four APs (AP1, AP2, AP3, and AP4), measured by achieved average data rates (Mbps). The boxplot highlights the efficacy of DFRL-based link activation strategy in enhancing the performance of all APs, showcasing improved data rate distribution and resource utilization efficiency

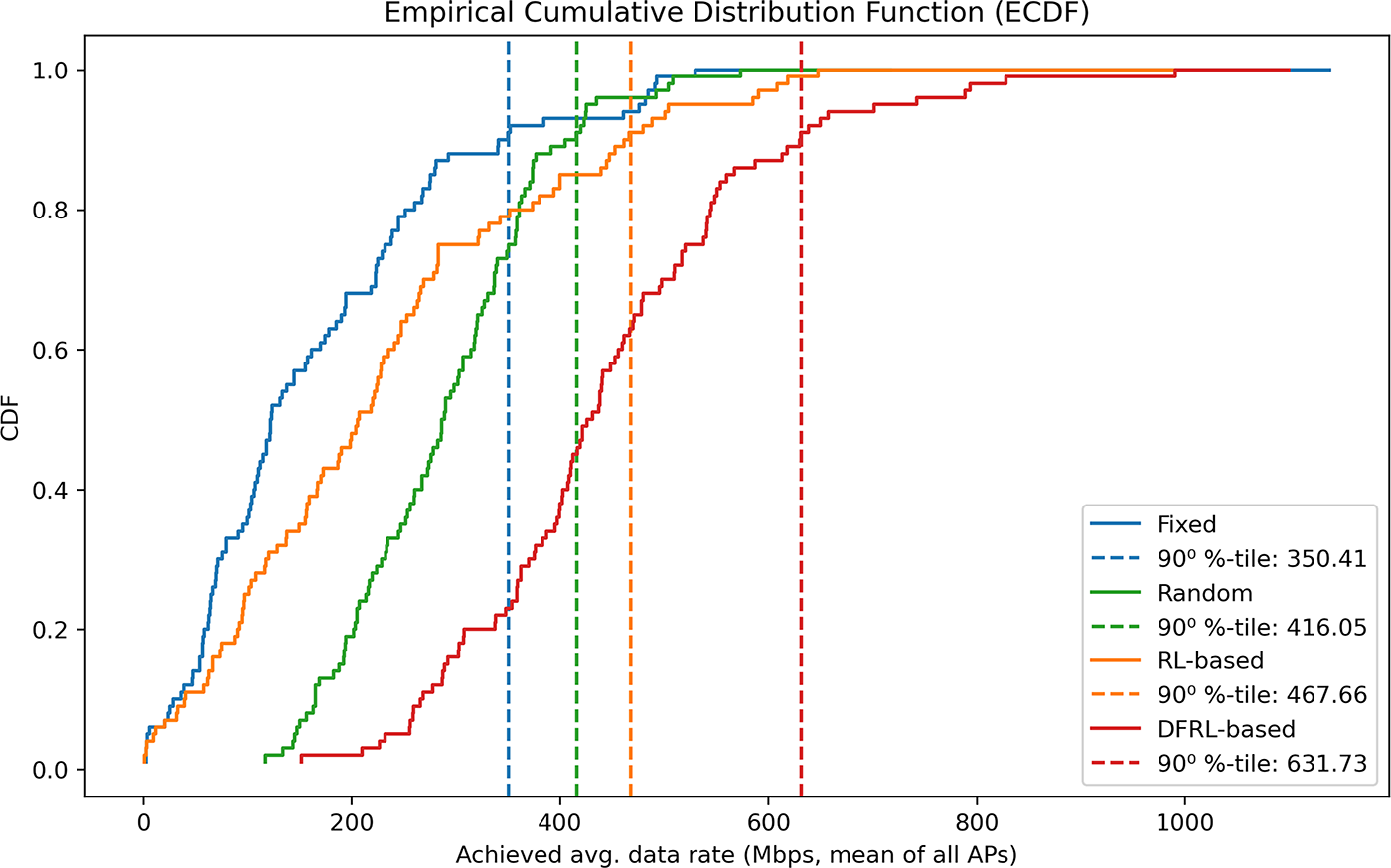

Fig. 5 presents the empirical cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the achieved average data rates for the four LA strategies. The CDF provides a broader view of performance by showing how often different data rate levels are achieved across 500 simulation runs. As expected, the Fixed strategy produces almost identical results in all realizations because every AP always uses all available links, leaving no room for adaptation. The Random strategy performs slightly better since its stochastic behavior occasionally reduces interference between APs, but the improvement is inconsistent. Both the RL-based and DFRL-based approaches show a clear rightward shift in the CDF, indicating higher and more stable throughput across the network. Among these, DFRL achieves the best overall results by combining local learning with collaborative reward sharing. This allows APs to make coordinated decisions that balance interference and maximize throughput. Quantitatively, the 90th percentile data rates confirm this advantage: DFRL reaches 631.73 Mbps, followed by RL-based (467.66 Mbps), Random (416.05 Mbps), and Fixed (305.41 Mbps). These results show that DFRL not only increases average throughput but also reduces variability across different network conditions, demonstrating its effectiveness in decentralized Wi-Fi environments.

Figure 5: A comparison of empirical CDF of the achieved average data rates (Mbps) for Fixed, Random, RL-based, and DFRL-based decentralized LA schemes in four AP-MLDs network scenarios (500 different realizations)

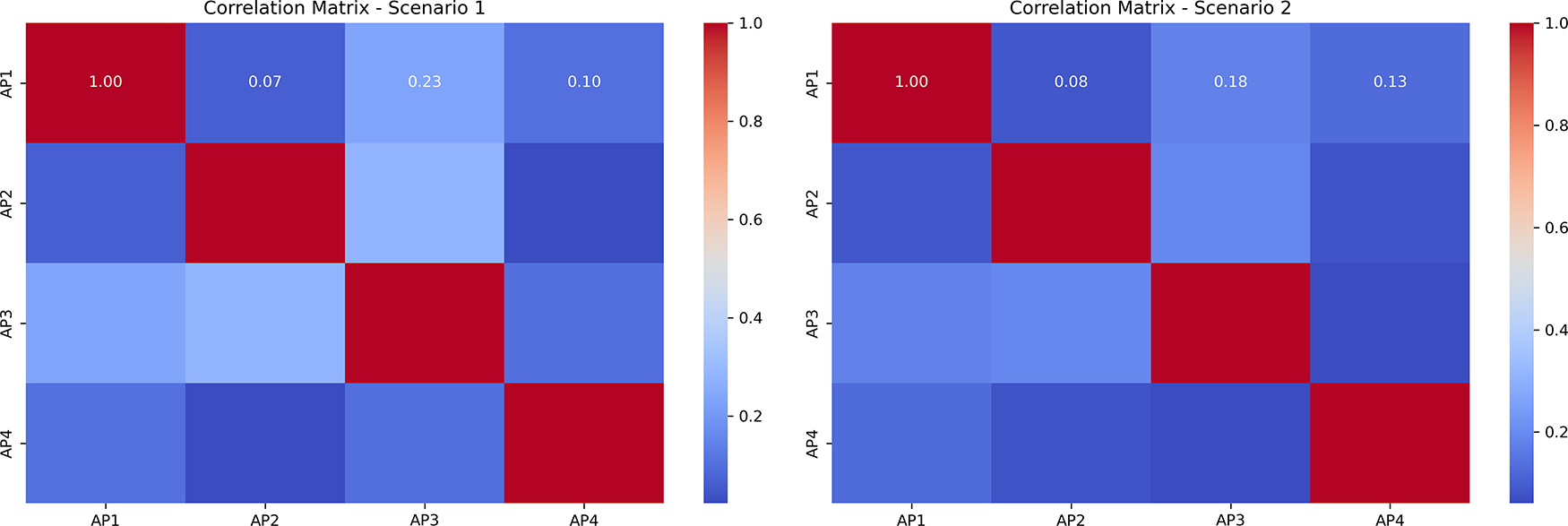

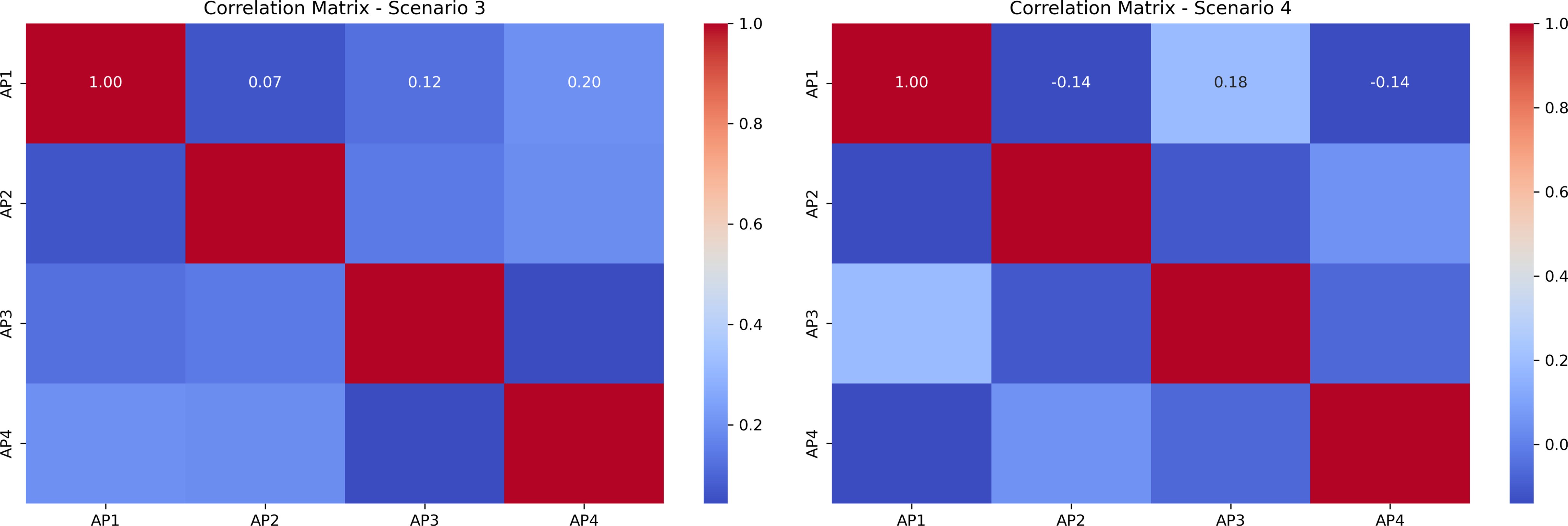

Fig. 6 presents correlation heatmaps that compare the interaction patterns among the four AP-MLDs for each LA strategy: Fixed, Random, RL-based, and DFRL-based. Each subplot represents how strongly the performance of one AP is correlated with that of the others, revealing how interference spreads across the network. In the Fixed and Random schemes, the heatmaps show high positive correlations between APs, meaning that their transmissions interfere heavily with one another, leading to lower overall throughput. The RL-based strategy reduces these correlations, showing that learning-based decisions help APs partially avoid overlapping transmissions and manage interference more effectively. The DFRL-based approach, however, shows the most favorable pattern: correlations are not only weaker but even slightly negative, indicating that APs are learning complementary behaviors rather than competing for the same spectrum. This decorrelation reflects efficient coordination and minimal interference across APs. Overall, the DFRL strategy creates a more balanced and interference-aware network environment, which directly contributes to the performance gains observed in earlier figures.

Figure 6: Heatmap comparison of correlation matrices among AP-MLDs under Fixed, Random, RL-based, and DFRL-based link activation schemes, highlighting DFRL’s effectiveness in minimizing interference and improving network performance

It is worth noting that the proposed DFRL framework is designed to maintain low computational and communication overhead. Each AP only exchanges compact scalar reward values with neighboring nodes rather than full model parameters, which minimizes bandwidth consumption and delay. This makes the approach suitable for latency-sensitive Wi-Fi environments. Furthermore, the local decision space for link activation remains small, ensuring lightweight computations that can be executed in real time without specialized hardware.

In conclusion, our investigation highlights the transformative potential of integrating FRL into Wi-Fi technology, especially with the impending adoption of Wi-Fi 7 and its successors. Our analysis, supported by the figures presented, highlights the challenges faced by decentralized Wi-Fi networks and underscores the importance of optimizing resource allocation and network performance across multiple autonomous APs. By proposing and presenting the application of FRL, we unveil a pathway towards more adaptive, efficient, and collaborative Wi-Fi networks. Our approach integrates the MAB algorithm for local learning and leverages empirical risk minimization through local and global learning models, facilitating a nuanced understanding and execution of decentralized multi-link activation and resource management.

The crux of our contribution lies in demonstrating, both theoretically and through simulation results showcased in the figures, how FRL significantly elevates network performance by enabling dynamic and intelligent link activation and resource sharing among APs. This strategy optimizes not only the immediate network environment but also enhances the overall robustness and reliability of Wi-Fi connectivity.

As we look ahead, this work shows that advanced machine learning—especially FRL—can play a key role in making future Wi-Fi networks more intelligent and adaptive. The results from our framework demonstrate how decentralized learning can improve coordination and performance even in simple network setups. While this study focuses on simulation-based validation rather than theoretical analysis, the consistent improvements observed across multiple metrics suggest that the proposed DFRL mechanism is both stable and fairness-oriented in practice. Formal proofs of convergence and stability will be explored in future work to further substantiate these findings. Also, in the next stage of our research, we plan to compare the proposed DFRL approach with other learning methods such as centralized RL, gossip learning, and actor-critic frameworks. This will help us better understand its scalability, robustness, and advantages in larger and more complex Wi-Fi environments.

Acknowledgement: This research work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, grant number RG-2-611-42 (A. O. A.).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Rashdi Ali; methodology, Rashid Ali; software, Rashid Ali; validation, Alaa Omran Almagrabi; formal analysis, Rashid Ali; investigation, Rashid Ali and Alaa Omran Almagrabi; resources, Alaa Omran Almagrabi; data curation, Rashid Ali and Alaa Omran Almagrabi; writing—original draft preparation, Rashid Ali and Alaa Omran Almagrabi; writing—review and editing, Alaa Omran Almagrabi; visualization, Rashid Ali; supervision, Alaa Omran Almagrabi; project administration, Alaa Omran Almagrabi; funding acquisition, Alaa Omran Almagrabi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable, this study does not involve humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Garcia-Rodriguez A, López-Pérez D, Galati-Giordano L, Geraci G. IEEE 802.11be: Wi-Fi 7 strikes back. IEEE Communicat Mag. 2021;59(4):102–8. doi:10.1109/MCOM.001.2000711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Schulz J, Dubslaff C, Seeling P, Li SC, Speidel S, Fitzek FHP. Negative latency in the tactile internet as enabler for global metaverse immersion. IEEE Network. 2024;38(5):167–73. doi:10.1109/MNET.2024.3375522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Carrascosa-Zamacois M, Galati-Giordano L, Jonsson A, Geraci G, Bellalta B. Performance and coexistence evaluation of IEEE 802.11be multi-link operation. arXiv:2205.15065. 2022. [Google Scholar]

4. Szott S, Kosek-Szott K, Gawłowicz P, Gómez JT, Bellalta B, Zubow A, et al. Wi-Fi Meets ML: a survey on improving IEEE 802.11 performance with machine learning. IEEE Communicat Surv Tutor. 2022;24(3):1843–93. doi:10.1109/COMST.2022.3179242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ali R, Zikria YB, Garg S, Bashir AK, Obaidat MS, Kim HS. A federated reinforcement learning framework for incumbent technologies in beyond 5G networks. IEEE Network. 2021;35(4):152–9. doi:10.1109/MNET.011.2000611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang J, Fang X. Research on next-generation Wi-Fi spatial reuse power control based on federated reinforcement learning. In: 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring); 2024 Jun 24–27; Singapore. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhang L, Yin H, Roy S, Cao L. Multiaccess point coordination for next-gen Wi-Fi networks aided by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(1):904–15. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2022.3183199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fan Y, Yu J, Ye H, Liang L, Jin S. Cooperative multi-agent reinforcement learning-based Wi-Fi multiple access. In: 2024 16th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP); 2024 Oct 24–26; Hefei, China. p. 413–8. doi:10.1109/WCSP62071.2024.10827195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Du X, Fang X, He R, Yan L, Lu L, Luo C. Federated deep reinforcement learning-based intelligent channel access in dense Wi-Fi deployments. arXiv:2409.01004. 2024. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhong Y, Chen H, Liu W, You L, Wang T, Fu L. Deep reinforcement learning based channel allocation for channel bonding Wi-Fi networks. In: 2023 19th International Conference on Mobility, Sensing and Networking (MSN); 2023 Dec 14–16; Nanjing, China. p. 113–9. doi:10.1109/MSN60784.2023.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen H, Liu P, You L, Guo Z, Luo J, Sun X, et al. Deep reinforcement learning based dynamic channel bonding for Wi-Fi networks. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Parallel & Distributed Processing with Applications, Big Data & Cloud Computing, Sustainable Computing & Communications, Social Computing & Networking (ISPA/BDCloud/SocialCom/SustainCom); 2023 Dec 21–24; Wuhan, China. p. 153–60. [Google Scholar]

12. Tan B, Gao Y, Sun X. Throughput-optimal multi-link access for Wi-Fi 7 via multi-agent reinforcement learning. In: 2025 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2025 Mar 24–27; Milan, Italy. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/WCNC61545.2025.10978161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wu J, Fang X, Min G. Deep reinforcement learning based multi-link frame aggregation length optimization in next generation Wi-Fi networks. IEEE Transact Wirel Commun. 2024;23(10):14482–97. doi:10.1109/TWC.2024.3415118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Salami D, Wilhelmi F, Galati-Giordano L, Kasslin M. Distributed learning for Wi-Fi AP load prediction. In: GLOBECOM 2024-2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2024 Dec 8–12; Cape Town, South Africa. p. 968–73. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM52923.2024.10901369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Guo J, Ho IWH, Hou Y, Li Z. FedPos: a federated transfer learning framework for CSI-based Wi-Fi indoor positioning. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(3):4579–90. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2022.3230425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kumar R, Popli R, Khullar V, Kansal I, Sharma A. Confidentiality preserved federated learning for indoor localization using Wi-Fi fingerprinting. Buildings. 2023;13(8):2048. doi:10.3390/buildings13082048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rezaei P, Derakhshanfard N. Reinforcement learning based routing in delay tolerant networks. Wirel Netw. 2025;31(3):2909–23. doi:10.1007/s11276-025-03911-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. AzharShokoufeh D, DerakhshanFard N, RashidJafari F, Ghaffari A. Optimizing IoT data collection through federated learning and periodic scheduling. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;317:113526. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang C, Zhang W, Wu Q, Fan P, Fan Q, Wang J, et al. Distributed deep reinforcement learning-based gradient quantization for federated learning enabled vehicle edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(5):4899–913. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3447036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ali R, Shahin N, Zikria YB, Kim BS, Kim SW. Deep reinforcement learning paradigm for performance optimization of channel observation-based MAC protocols in dense WLANs. IEEE Access. 2019;7:3500–11. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2886216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chang TW, Shen LH, Feng KT. Learning-based beam training algorithms for IEEE802.11ad/ay networks. In: 2019 IEEE 89th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2019-Spring); 2019 Apr 28–May 1; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/VTCSpring.2019.8746379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Balakrishnan R, Sankhe K, Somayazulu VS, Vannithamby R, Sydir J. Deep reinforcement learning based traffic- and channel-aware OFDMA resource allocation. In: 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); 2019 Dec 9–13; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM38437.2019.9014270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sangdeh PK, Pirayesh H, Mobiny A, Zeng H. LB-SciFi: online learning-based channel feedback for MU-MIMO in wireless LANs. In: 2020 IEEE 28th International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP); 2020 Oct 13–16; Madrid, Spain. p. 1–11. doi:10.1109/ICNP49622.2020.9259366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kotagiri D, Nihei K, Li T. Multi-user distributed spectrum access method for 802.11ax stations. In: 2020 29th International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); 2020 Aug 3–6; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1–2. doi:10.1109/ICCCN49398.2020.9209737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Karmakar R, Chattopadhyay S, Chakraborty S. Learning based adaptive fair QoS in IEEE 802.11ac access networks. In: 2019 11th International Conference on Communication Systems & Networks (COMSNETS); 2019 Jan 7–11; Bangalore, India. p. 22–9. doi:10.1109/COMSNETS.2019.8711461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Khan Z, Lehtomäki JJ. Interactive trial and error learning method for distributed channel bonding: model, prototype implementation, and evaluation. IEEE Transact Cognit Communicat Netw. 2019;5(2):206–23. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2019.2897695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yano K, Egashira N, Webber J, Usui M, Suzuki Y. Achievable throughput of multiband wireless LAN using simultaneous transmission over multiple primary channels assisted by idle length prediction based on PNN. In: 2019 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC); 2019 Feb 11–13; Okinawa, Japan. p. 22–7. doi:10.1109/ICAIIC.2019.8668975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nurani Krishnan N, Torkildson E, Mandayam NB, Raychaudhuri D, Rantala EH, Doppler K. Optimizing throughput performance in distributed MIMO Wi-Fi networks using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Transact Cognit Communicat Netw. 2020;6(1):135–50. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2019.2942917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang Y, Wu Q, Shikh-Bahaei M. A pointer network based deep learning algorithm for user pairing in full-duplex Wi-Fi networks. IEEE Transact Vehic Technol. 2020;69(10):12363–8. doi:10.1109/TVT.2020.3011613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Barrachina-Muñoz S, Chiumento A, Bellalta B. Multi-armed bandits for spectrum allocation in multi-agent channel bonding WLANs. IEEE Access. 2021;9:133472–90. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3114430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Timmers M, Pollin S, Dejonghe A, Van der Perre L, Catthoor F. A spatial learning algorithm for IEEE 802.11 networks. In: 2009 IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2009 Jun 14–18; Dresden, Germany. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICC.2009.5198673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yin B, Yamamoto K, Nishio T, Morikura M, Abeysekera H. Learning-based spatial reuse for WLANs with early identification of interfering transmitters. IEEE Transact Cognit Communicat Netw. 2020;6(1):151–64. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2019.2956133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Deng C, Fang X, Han X, Wang X, Yan L, He R, et al. IEEE 802.11be Wi-Fi 7: new challenges and opportunities. IEEE Communicat Surv Tutor. 2020;22(4):2136–66. doi:10.1109/COMST.2020.3012715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Qi J, Zhou Q, Lei L, Zheng K. Federated reinforcement learning: techniques, applications, and open challenges. arXiv:2108.11887. 2021. [Google Scholar]

35. Merlin S, Barriac G, Sampath H, Cariou L, Derham T, Rouzic JPL, et al. TGax simulation scenarios. IEEE 802.11 working group [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Oct 16]. Available from: https://mentor.ieee.org/802.11/dcn/14/11-14-0980-16-00ax-simulation-scenarios.docx. [Google Scholar]

36. Wilhelmi F, Bellalta B, Cano C, Jonsson A. Implications of decentralized Q-learning resource allocation in wireless networks. In: 2017 IEEE 28th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC); 2017 Oct 8–13; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/PIMRC.2017.8292321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Busoniu L, Babuska R, De Schutter B. A comprehensive survey of multiagent reinforcement learning. IEEE Transact Syst Man Cybernet Part C (Appl Rev). 2008;38(2):156–72. doi:10.1109/TSMCC.2007.913919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools