Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Comprehensive Survey on Blockchain-Enabled Techniques and Federated Learning for Secure 5G/6G Networks: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Directions

1 EIAS Data Science Lab, College of Computer and Information Sciences, and Center of Excellence in Quantum and Intelligent Computing, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

2 College of Computer and Information Sciences, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11432, Saudi Arabia

3 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha, 410083, China

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Asim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070684

Received 21 July 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The growing developments in 5G and 6G wireless communications have revolutionized communications technologies, providing faster speeds with reduced latency and improved connectivity to users. However, it raises significant security challenges, including impersonation threats, data manipulation, distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, and privacy breaches. Traditional security measures are inadequate due to the decentralized and dynamic nature of next-generation networks. This survey provides a comprehensive review of how Federated Learning (FL), Blockchain, and Digital Twin (DT) technologies can collectively enhance the security of 5G and 6G systems. Blockchain offers decentralized, immutable, and transparent mechanisms for securing network transactions, while FL enables privacy-preserving collaborative learning without sharing raw data. Digital Twins create virtual replicas of network components, enabling real-time monitoring, anomaly detection, and predictive threat analysis. The survey examines major security issues in emerging wireless architectures and analyzes recent advancements that integrate FL, Blockchain, and DT to mitigate these threats. Additionally, it presents practical use cases, synthesizes key lessons learned, and identifies ongoing research challenges. Finally, the survey outlines future research directions to support the development of scalable, intelligent, and robust security frameworks for next-generation wireless networks.Keywords

Wireless communication has been a vital means to enable pervasive connectivity, enabling instant information exchange between user devices and infrastructures [1,2]. Owing to the growing demand for real-time processing in wireless networks, traditional cloud computing architectures cannot meet their requirements [3,4]. To overcome the limitations of cloud computing, edge computing (EC) has been proposed, which is viewed as a groundbreaking paradigm in the field of distributed computing. It offers unmatched promise for low-latency processing, real-time data analysis, and enhanced scalability [3,5]. EC is capable of overcoming the limitations of cloud computing due to edge decentralized computation, especially in the application scenarios where response and processing are required swiftly, such as autonomous vehicles, industrial automation, and smart cities.

In spite of the EC benefits, it also poses a new range of security threats to user devices [6]. EC frameworks are more susceptible to threats like data breaches, unauthorized access, and advanced cyberattacks, because of Its decentralized nature and resource-constrained edge nodes [7]. In contrast to centralized cloud architecture, EC necessitates lightweight, distributed, and dynamic security functions in order to protect the data confidentiality, integrity, and availability [8]. With the advent of 5G and 6G networks, the deployment of EC has been pushed even further, enabling ultra-reliable, low-latency, and high-throughput communication services to a huge spectrum of intelligent systems, including the Internet of Things (IoT), autonomous mobility, and future industrial use [9]. But the same decentralized and extensive nature of these networks imposes large security and privacy threats.

Federated learning (FL) and blockchain (BC) subsequently became prominent technologies to support security and trust enhancement in 5G/6G edge-based infrastructure [10]. BC offers tamper-evident data exchange and decentralized access control [11], and FL supports cooperative model learning without raw data sharing while preserving privacy in distributed environments. This work presents a comprehensive survey of their contributions towards wireless network security enhancement. We will examine some of the security challenges that manifest in the edge environments, investigate existing solutions available, and find newer research advancements in this important field. Moreover, this paper will provide guidelines on securing EC for the future with a focus on new innovative strategies to address the evolving threat landscape. This review aims to inform an effort to improve the EC systems against future threats to security by synthesizing current evidence and highlighting gaps in the literature.

1.1 State-of-the-Art in Wireless Communication Technologies

The evolution of wireless communication has led to the development of 5G and 6G networks [12]. 5G focuses on enhanced mobile broadband (eMBB), ultra-reliable low-latency communications (URLLC), and massive machine-type communications (mMTC) [13]. In contrast, 6G introduces Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven networking and quantum-safe communication technologies to enhance network security and efficiency.

With speed, connection, and latency advances, 5G networks have completely changed the wireless communication scene [14,15]. IoT, smart grids, and real-time applications have all benefited from the quick adoption of massive machine-type communication (mMTC) and eMBB, according to recent research by Popovski et al. [16]. In terms of 6G, Yang et al. [17] and Nguyen et al. [18] forecast the arrival of AI-driven networking and terahertz communication, opening up possibilities for uses like smart healthcare and holographic communication. These networks will need strong security frameworks to safeguard sensitive data in these high-performance settings.

Ahmad et al. [19] highlight the underlying advanced threat profile encompassing 5G networks and draw attention to security vulnerability heterogeneity in the new technology paradigms underlying 5G implementation. The authors provided a structured explanation of the overriding security concerns, ranging across data privacy and authentication threats, DoS attacks, and virtualized infrastructure vulnerabilities, to emphasize the need for robust security at both architectural and operational dimensions. In tackling these obstacles, the research surveys existing mitigation strategies and recognizes proactive approaches, including the use of artificial intelligence to detect anomalies, blockchain to handle decentralized trust, and the design of next-generation cryptographic primitives.

The increasing use of EC and accepting open architectures create new cyberattack risks. Furthermore, there is a greater chance of data leakage, privacy breaches, and unauthorized access due to the vast number of linked devices. According to work by Ramezanpour and Jagannath [20] and Chen et al. [21], a move toward decentralized security procedures is necessary to secure the enormous and intricate 5G and 6G networks. These mechanisms are essential for real-time threat detection and mitigation in highly dispersed networks.

The deployment of 5G and 6G technology brings forward a variety of security issues. For example, Alnaim [22] highlight how software-defined networking (SDN) and network function virtualization (NFV) are essential components of 5G design, but they also provide vulnerabilities in the control plane. In their work, they investigated how such technologies expose networks to new attack paths like resource exhaustion and virtual network function (VNF) attacks while promoting flexibility and resource handling.

Similarly, Shehab et al. [23] had conducted an extensive analysis to examine the role of 5G networks as an enabling pillar of sustainability in the context of smart cities. Their work demonstrates how the advanced features of 5G can provide the technology backbone required to accommodate sustainable urban development. The review gives an overview of the 5G communication network architecture and characteristics, emphasizing their ability to support the wide variety of smart city applications like intelligent transport systems, energy-efficient infrastructure, and massive IoT installations. From the examination of a number of important 5G technologies, the authors demonstrate how these developments work towards optimizing resource use, lowering the energy footprint, and enhancing the efficiency and resilience of city systems as a whole, thus furthering long-term sustainability objectives.

This work attempts to investigate how FL techniques and BC technology can be adapted to address the new security issues of 5G and 6G communication. While BC offers tamper-proof and open records, FL allows distributed ML without the need for centralized storage of data, both technologies offer decentralized solutions to improving network security. The following will be the main topics of this paper:

• How BC technology may reduce risks such as DDoS assaults, illegal access, and data manipulation.

• FL’s function in intrusion detection and privacy-preserving data analysis.

• Current research has focused on integrating FL and BC technology into 5G and 6G networks to safeguard against advanced threats and provide secure communication.

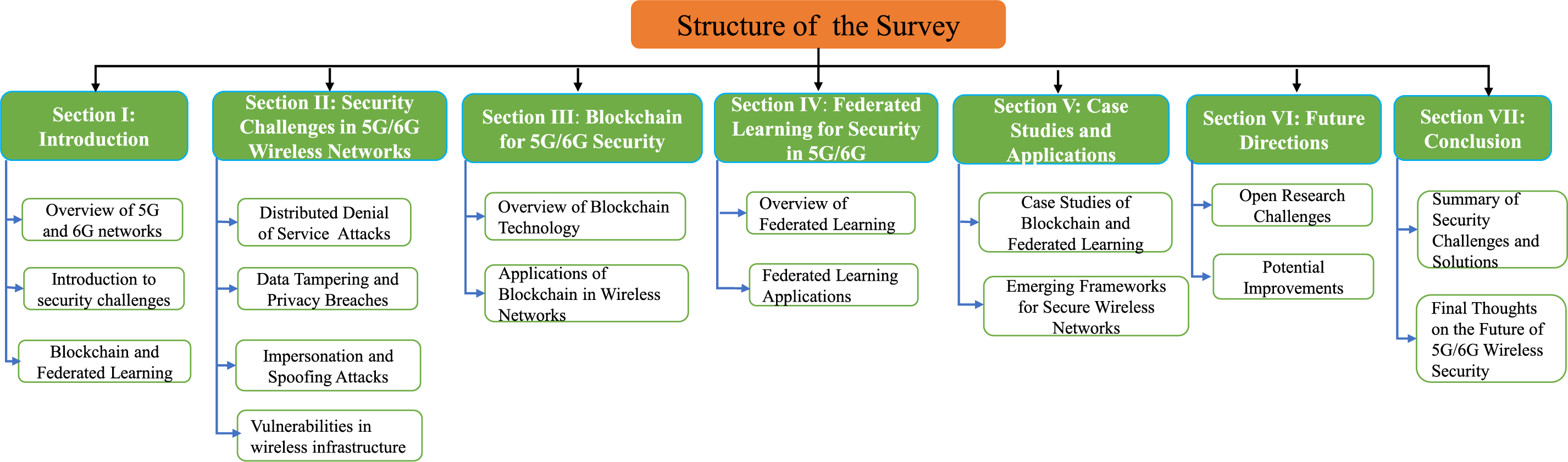

This paper systematically explores the security issues and creative solutions related to 5G and 6G wireless networks, with particular emphasis on cutting-edge methods like FL and BC. Several major components make up the paper, as seen in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Structure of the survey

This work primarily serves as a comprehensive survey of existing research on the applications of FL and BC for addressing security issues in 5G/6G. While it does not present original experimental data or case studies, the manuscript systematically reviews state-of-the-art approaches, highlights key challenges, and discusses potential future directions. Relevant experimental findings from prior studies are cited where appropriate to illustrate the potential effectiveness of these technologies. The objective is to provide a solid foundation for subsequent empirical research and practical implementations in this rapidly evolving area.

This work considers the following research questions to guide the analysis of BC and FL for secure 5G/6G networks:

1. What are the main security and privacy challenges in 5G/6G networks?

2. How can BC integration enhance trust, reliability, and incentive mechanisms in 5G/6G networks?

3. How can FL integration enhance trust, reliability, and incentive mechanisms in 5G/6G networks?

4. How to integrate digital twins (DT) for addressing security issues in 5G/6G networks?

5. What are the existing approaches based on BC and FL, trade-offs, and limitations in 5G/6G networks?

6. Which application domains, such as IoT and Internet of Vehicles (IoV), benefit most from BC and FL, and how is its effectiveness evaluated?

These questions provide a structured framework for the categorization, analysis, and discussion throughout this survey.

The use of BC technology in Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) systems has drawn considerable interest since it can improve security, privacy, and data integrity. This part consolidates information from recent review and survey papers on the application of BC technology towards securing MEC with emphasis on existing challenges, solutions, and future work.

• BC for enhancing MEC security and privacy

BC’s decentralized nature provides robust security characteristics, making it a suitable option to provide data integrity and secure communication in MEC environments. Different survey articles have explored this integration, for example, Mathur et al. [24] showcased a survey on the applications of BC for various IoT applications. Sharma et al. [25] also touched on the application of BC in green IoT and highlighted its advantages in providing secure and open data-sharing platforms. Similarly, Conti et al. [26] conducted a survey of security threats to MEC and proposed BC as an optimal choice for developing secure access control systems, citing the technology’s ability to verify devices and keep communications confidential. Furthermore, Tang et al. [27] provides a comprehensive analysis of BC-based FL, highlighting its potential to address the privacy, security, and reliability challenges inherent in traditional FL.

• Consensus mechanisms in BC-enabled MEC

The appropriate consensus mechanisms are crucial to the scalability and performance of BC-enabled MEC systems. Traditional consensus protocols like proof of work (PoW) and proof of stake (PoS) are computationally intensive and thus not best suited for MEC’s resource-constrained environments. Jain et al. [28] described a comprehensive overview of light-weight consensus protocols for MEC, namely delegated PoS (DPoS) and practical byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT), and accounted for their reduced computational requirements and decreased latency. Besides, Luo et al. [29] proposed an energy-efficient two-stage computationally efficient consensus mechanism for BC-based MEC.

• Resource management optimization

Integrating BC with MEC introduces significant challenges in resource management, particularly regarding computational power, storage, and bandwidth. Mershad [30] reviewed various BC-based resource allocation schemes that use smart contracts to automate and optimize the allocation of resources, thereby enhancing the operational efficiency of MEC networks. Additionally, Xue et al. [31] presented an in-depth survey of the integration of EC and IoT. They briefly discussed the architecture of IoT and its challenges. Adam et al. [32] provided an extensive research study on IoT security, privacy, and trust that was structured according to a three-layered IoT architectural model comprising the perception, network, and application layers. The study begins with an overview of the fundamentals of IoT security, privacy preservation, and trust building, emphasizing their essentiality in ensuring reliable and sustainable IoT applications. From this context, the authors present the systematic review of the main security requirements in each layer of the IoT architecture—such as authentication, confidentiality, integrity of data, and access control—along with the discussion of the unique vulnerabilities and threats inherent in resource-constrained IoT environments. Difficulty such as heterogeneity of devices, large-scale connectivity, lack of standardized protocols, along with the compromise between lightweight security solutions and robust protection, are highlighted by the review. Furthermore, the paper explains how privacy-enhancing mechanisms and trust models can be combined with traditional security solutions to enhance end-to-end system resilience.

• BC for secure data offloading and task scheduling:

Integrating BC technology with MEC has garnered significant attention for its potential to address security, privacy, and efficiency concerns in computation offloading and resource management. A comprehensive survey by Moghaddasi and Rajabi [33] explores BC-based offloading methods within MEC, offering a systematic review of current trends, algorithms, and techniques used to enhance the security and privacy of offloading processes. This survey also discusses future directions for BC integration in MEC, underscoring its growing importance in IoT and edge environments.

Xue et al. [34] provided another essential review on the integration of BC and EC in IoT applications. They highlighted how BC can be leveraged to improve data management, resource allocation, and security in EC systems. Their paper sheds light on the dual role of BC in enhancing both the performance and the privacy of EC by decentralizing trust and offering secure transaction mechanisms.

The role of BC in resource scheduling for EC is further discussed by Luo et al. [35], who surveyed the challenges and techniques related to resource scheduling in MEC environments. The review covers computation offloading, resource allocation, and provisioning methods, and it emphasizes the need for more efficient solutions to meet the increasing demands of real-time applications. It also highlights the potential of BC to improve fairness and transparency in scheduling decisions.

Additionally, Mach and Becvar [36] critically summarized the fundamental concepts and decision-making processes of MEC that control whether computation tasks are executed locally on mobile devices or offloaded to proximate edge servers. The survey also delves into the complexities of resource management, wherein latency limitations, energy consumption, and available bandwidth in the network affect offloading decisions. Furthermore, authors discuss mobility management issues that arise in mobile dynamic environments, particularly maintaining service continuity and QoE as users roam across heterogeneous networks. By placing these issues in the broader context of MEC system design, Mach and Becvar offer valuable insights into the potential and limitations of computation offloading and lay the foundation for future work on optimizing edge-enabled mobile applications.

Mikavica and Kostić-Ljubisavljević [37] presented a survey of BC-based solutions for security, privacy, and trust management in vehicular networks. They aimed to review, classify, and discuss a range of the proposed models in BC-based vehicular networks. They presented a comparison of the available models with their main features and objectives regarding security, privacy preservation, and trust management.

While the existing surveys provide valuable insights into the integration of BC technology with MEC for enhancing security, privacy, and trust, several critical gaps remain. Most of the reviewed papers focus on either the technical feasibility of BC in MEC or on optimizing specific aspects like consensus mechanisms, resource management, or data offloading separately. There is a lack of comprehensive research that systematically addresses the challenges of deploying BC in MEC environments across multiple dimensions, including security, scalability, energy efficiency, and real-time processing. Furthermore, existing studies often overlook the practical implementation scenarios and the interoperability challenges that arise when combining BC with diverse EC infrastructures.

This work aims to fill these gaps by providing a holistic review of BC-assisted technologies for securing MEC, examining integrated solutions that address the multifaceted challenges of MEC environments, and identifying future research directions that can facilitate the seamless adoption of BC in EC. This work will also explore novel BC-based frameworks that can enhance the reliability, efficiency, and scalability of MEC systems, laying a foundation for secure and intelligent EC networks.

2.1 Consensus Mechanisms in Blockchain-Enabled MEC

Consensus mechanisms are fundamental protocols in blockchain technology that ensure all nodes in a distributed network agree on the validity of transactions or data, maintaining the integrity and consistency of the blockchain. In the context of Mobile EC(MEC), consensus mechanisms play a crucial role in enabling secure, decentralized, and trustworthy interactions between edge devices, users, and services.

In MEC environments, where computational tasks and data processing are moved closer to the network edge [3], integrating blockchain requires efficient consensus mechanisms to ensure secure data transactions and resource sharing among edge nodes. The unique characteristics of MEC, such as low latency, high bandwidth, and real-time processing, make the selection of suitable consensus algorithms critical for maintaining performance and security.

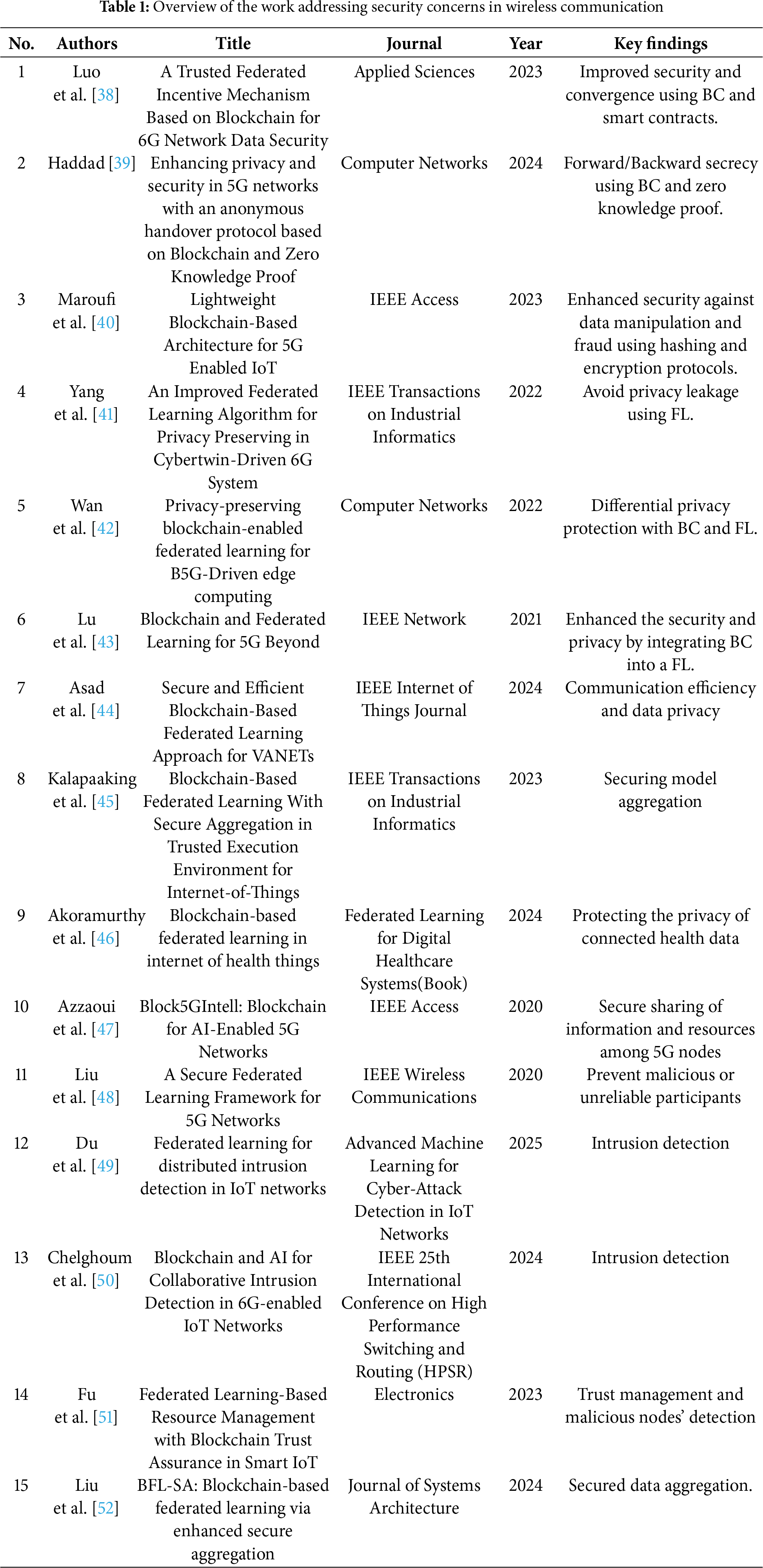

Some common consensus mechanisms in Blockchain-Enabled MEC are given in Table 1 and are discussed below:

PoW is the original consensus mechanism used by Bitcoin, which requires nodes (miners) to solve complex mathematical puzzles to validate transactions. However, due to its high computational requirements and energy consumption, PoW is generally not suitable for MEC environments where devices have limited resources.

PoS is an alternative to PoW that requires validators to own a certain amount of cryptocurrency to participate in the consensus process. Validators are chosen to create new blocks based on their stake. PoS is more energy-efficient than PoW, but it can still be challenging to implement in resource-constrained edge devices typical of MEC networks.

2.1.3 Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS)

DPoS is an extension of the initial PoS consensus algorithm that seeks to promote scalability and efficiency for distributed ledger systems. In this system, network stakeholders vote proportionally to their stake to select a small group of trusted delegates, also referred to as witnesses or validators. These voted delegates are later given the privilege to confirm transactions, generate new blocks, and also keep the overall integrity of the blockchain. DPoS significantly reduces communication overhead, accelerates the time for block confirmation, and also achieves higher throughput than the conventional PoS and PoW systems by restricting the consensus process to a smaller set of nodes. This light-weight nature renders DPoS particularly effective in low-latency and resource-constrained environments such as MEC, where immediate consensus is imperative in facilitating real-time services and applications. Furthermore, the voting mechanism ensures a degree of decentralized control since stakeholders continue to maintain the ability to replace satisfactory or malicious delegates, hence maintaining accountability and responsiveness within the system. DPoS offers scalability and efficiency, which are essential for EC scenarios.

2.1.4 Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT)

PBFT is a consensus mechanism designed to tolerate Byzantine faults (where nodes may act maliciously or fail unpredictably). It achieves consensus through a series of communication rounds among nodes, ensuring that even if some nodes are compromised, the system remains secure. PBFT is efficient in terms of resource consumption, making it well-suited for MEC environments with a smaller number of nodes.

2.1.5 Proof of Authority (PoA)

PoA relies on a limited number of pre-approved validators who are responsible for validating transactions. This approach reduces the computational load and enhances transaction speed, making it suitable for private or consortium blockchains in MEC. PoA offers a balance between decentralization and efficiency, which is crucial for edge-based applications.

2.1.6 Federated Byzantine Agreement (FBA)

FBA, used by systems like Stellar, involves a network of nodes agreeing on a set of trusted nodes to validate transactions. This consensus mechanism is lightweight and can be adjusted to suit the scalability and security needs of MEC environments, where trust relationships can be predefined based on network architecture.

2.2 State-of-the-Art Approaches in Addressing Security Issues

Recent improvements in wireless communication, particularly with 5G and 6G, have revealed the potential of BC and FL to address security concerns. Below is an overview of studies that explore these topics further. For 6G data security, Luo et al. [38] provided a trusted federated incentive mechanism that combines BC and FL. The suggested method makes use of BC and smart contracts to protect user privacy and incentivize edge nodes to engage in secure FL. When compared to conventional algorithms, this method enhances convergence and security. The use of BC technology to improve the decentralization of security protocols in 5G networks is covered by Haddad [39]. Their work focuses on developing an immutable ledger for network transactions to protect data integrity and mitigate distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. A lightweight BC-Based architecture is put out by Maroufi et al. [40] to secure 5G-enabled IoT scenarios. Their architecture outperforms conventional 5G (without BC) regarding security against data manipulation and fraud. FL is investigated by Yang et al. [41] for model training on 5G networks while maintaining privacy. Their study demonstrates how FL may be used to cooperatively discover anomalies among various IoT devices while protecting user privacy. In 6G networks, Wan et al. [42] provide BC-enabled FL for B5G-driven EC, where massive data collected from edge devices fuels AI model training. To protect sensitive data while enabling collaborative learning, they propose a hybrid framework combining BC-enabled FL and WGAN-based differential privacy.

Lu et al. [43] enhanced the security and privacy by integrating BC into a FL scheme for maintaining the trained parameters. Asad et al. [44] proposed a secure and efficient BC-based FL approach to ensure communication efficiency and data privacy in vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs). Their research minimized the long delay while avoiding possible threats and attacks using homomorphic encryption systems. Kalapaaking et al. [45] BC-based FL framework with Intel Software Guard Extension-based trusted execution environment to securely aggregate local models in Industrial IoT. BC-based FL systems are investigated by Akoramurthy et al. [46] as a means of protecting medical IoT data. Their research shows how BC protects privacy while sensitive healthcare data models are being trained federatedly.

Azzaoui et al. [47] presented a comprehensive intelligence and secure data analytics framework for 5G networks based on the convergence of BC and AI named Block5GIntell. Liu et al. [48] presented a BC-based secure FL framework to create smart contracts and prevent malicious or unreliable participants from being involved in FL.

For IoT networks, Du et al. [49] suggested an FL architecture that offers distributed, secure intrusion detection. The application of FL with BC for intrusion detection systems in 5G and 6G networks was investigated by Chelghoum et al. [50]. Their method improves the security of networked devices by identifying anomalous activity in real-time. Fu et al. [51] presented an IoT resource management framework incorporating BC and FL. They proposed a specific FL-based resource management with a BC trust assurance algorithm.

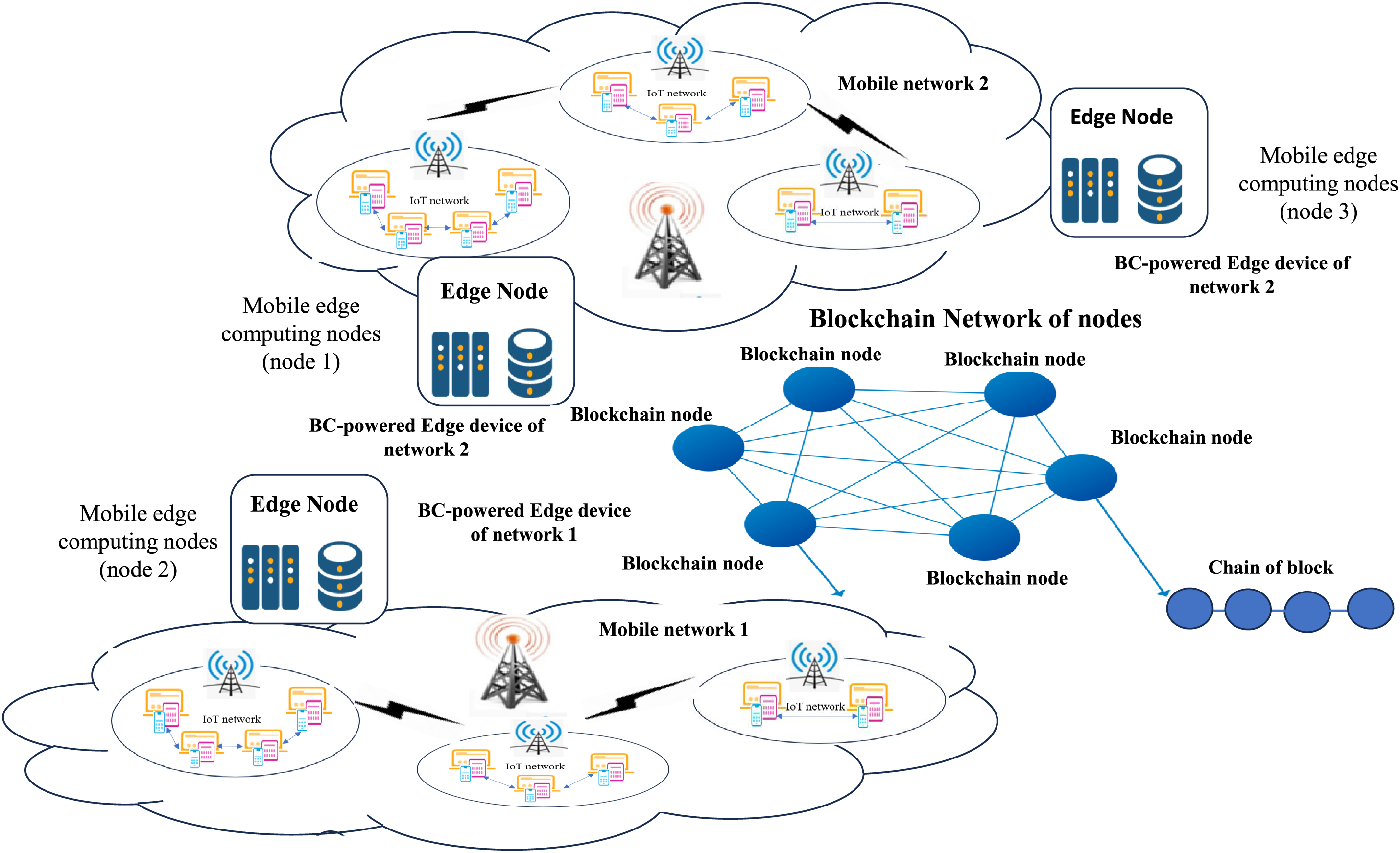

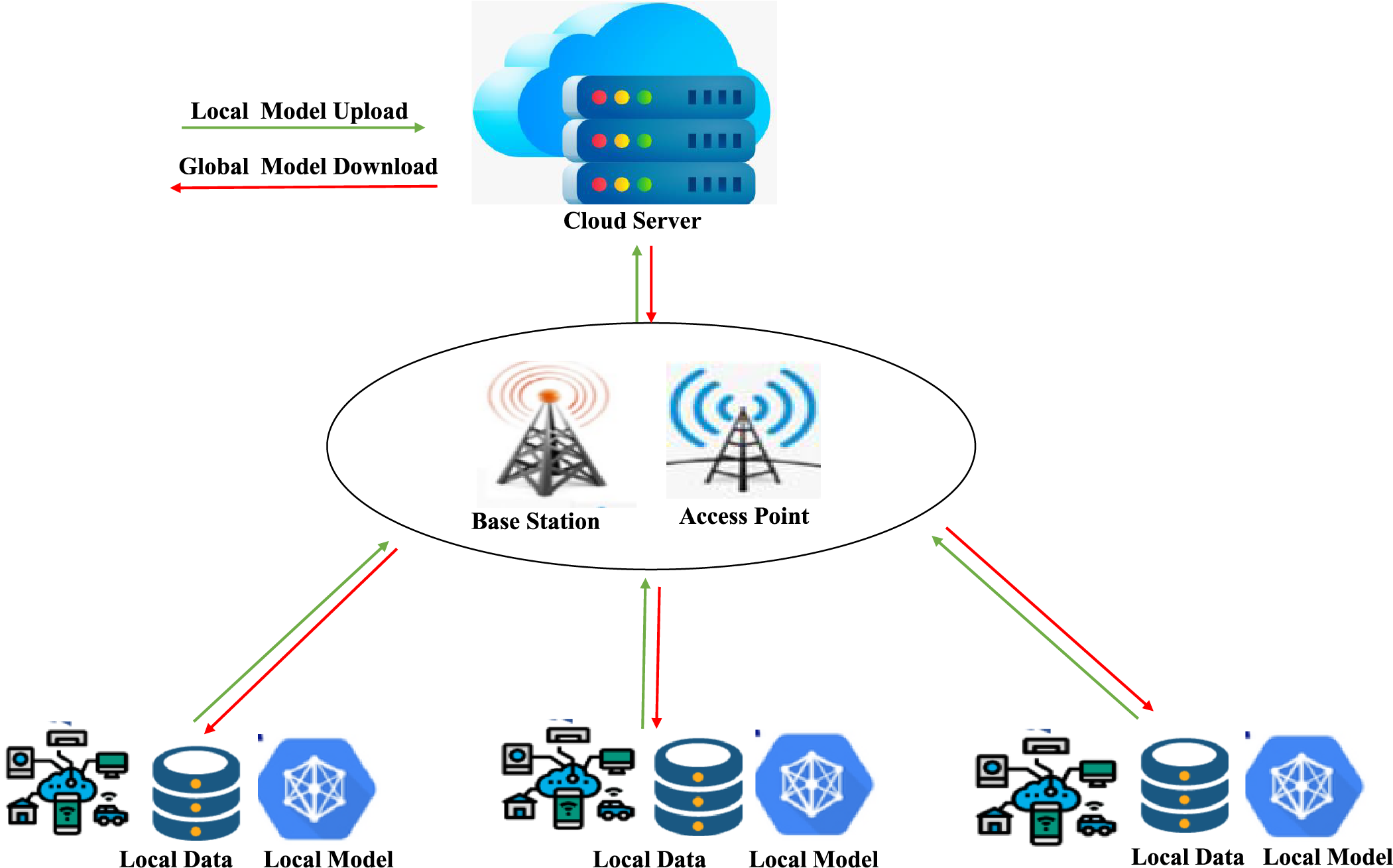

Liu et al. [52] proposed a BC-based FL via enhanced secure aggregation. Their method boosted security and fault tolerance while improving the efficiency of data utilization in the secure aggregation process. Fig. 2 illustrates how FL and BC are integrated to secure wireless networks, especially in 5G and 6G scenarios. The image demonstrates how data moves between edge devices, how FL is used for local model training, and how BC ensures safe data transfers, privacy, and authentication.

Figure 2: Generic layered architecture of BC and FL for securing wireless communication networks

2.3 Quantitative Metrics for Security and Privacy

Although this survey primarily provides a qualitative analysis of security mechanisms and privacy-preserving techniques in next-generation wireless networks, quantifiable metrics reported in the literature are included to strengthen the discussion. Prior studies provide numerical insights such as encryption and decryption latency, key size requirements, privacy leakage probabilities, and differential privacy noise parameters relevant to quantum-safe cryptography, Blockchain-based security, and federated learning frameworks [53–55]. These quantitative findings are summarized where appropriate to contextualize the performance of different techniques. Furthermore, the survey emphasizes the need for future empirical evaluations under realistic network environments to establish standardized benchmarks for assessing security and privacy effectiveness in 5G and 6G systems.

3 Notable Case Studies and Applications

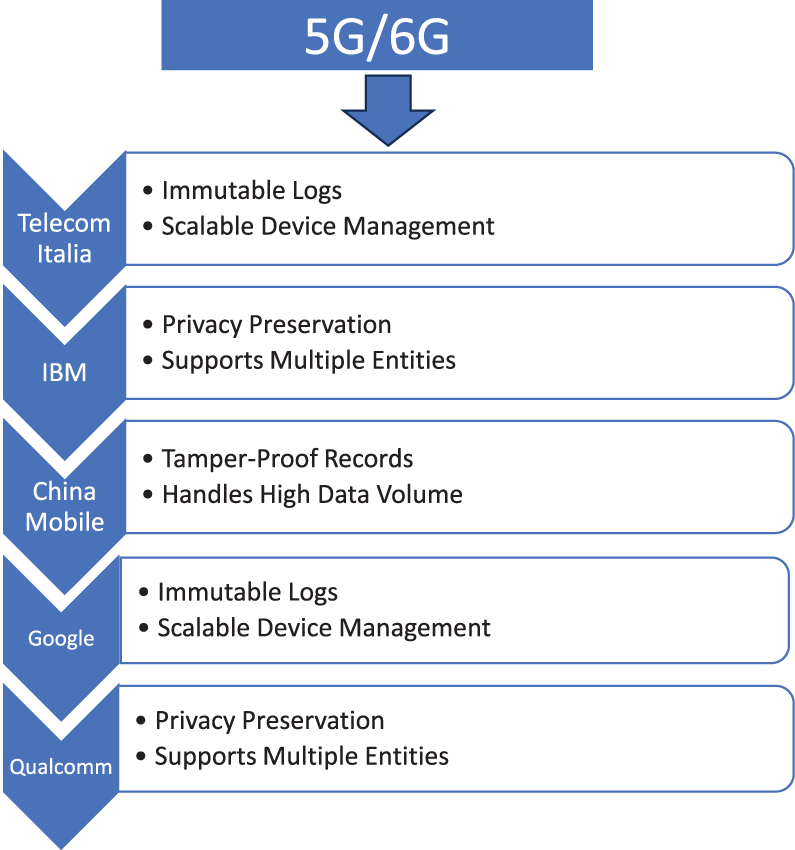

The latest advancements in technology witnessed BC and FL showing great potential for providing security in 5G and 6G networks. The section brings forth major real-world applications of the technologies, with emphasis on how they are efficient and scalable for various situations.

3.1 Telecom Italia’s BC-Based IoT Security Solution

Telecom Italia has launched a BC-based security solution to protect IoT devices on its 5G network. A decentralized ledger is utilized to record device identities and encrypt data communication. With this BC, Telecom Italia is able to provide immutable records of device interactions, restricting the spoofing and unauthorized access risk. Scalable with the large number of IoT devices, the decentralized nature of the system addresses central bottlenecks but accommodates massive deployment.

3.2 IBM’s FL for Privacy-Preserving Data Analytics

IBM uses FL to enable privacy-preserving data analytics on its 5G network. Deployment enables model training collaboratively without the exchange of raw data. FL retains sensitive information locally, thus enhancing privacy and regulatory compliance. FL can support a large number of entities to participate in model training to avoid data centralization issues and scale with the network.

Fig. 3 presents real-world applications of BC and FL in 5G/6G networks, demonstrating significant advancements in securing and scaling modern communication infrastructures. Each case study highlights unique approaches to addressing security challenges, from privacy preservation to scalable data management. The integration of these technologies offers promising solutions to enhance network security and efficiency. Future developments will continue to refine these applications and address emerging challenges in the evolving landscape of wireless communication.

Figure 3: Applications of BC and FL in 5G/6G Networks

3.3 Security Issues in Wireless Communication

Because of the growing number of applications that operate over wireless networks, wireless communication security is essential. All these challenges cover a broad range of issues, such as user privacy, network attack resilience, and confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data. Since wireless networks are broadcast in nature, they are inherently more susceptible to security attacks than wired networks. Some of the principal security concerns include the following.

• Unauthorised users are able to intercept communications over wireless channels, potentially causing data breaches. Encryption protocols must be used to avoid data interception. Current research emphasizes the role of advanced encryption methods in preventing such threats [56].

• Unauthorized attempts at access are feasible in wireless networks. Effective access control and authentication measures must be implemented to prevent access by unauthorized entities. Several techniques for improving access control and authentication in wireless networks have been shown in research [57].

• Data integrity is defined as a promise that information does not get altered during transmission. Methods like digital signatures and cryptographic hashing are utilized to ensure data integrity. Significant surveys summarize significant developments in integrity verification techniques [58].

• Overloading the network with excessive traffic can interfere with services in wireless networks using DoS attacks. Intrusion detection technology and efficient traffic management are required to counter such threats. Comprehensive research on DoS attacks and remedies could be referred to through the literature [59].

• Rogue or unauthorized access points may be installed to deceive users and plunder information. Network monitoring and management are needed to detect and remove rogue access points. Solutions for rogue access point detection and rogue access point control are discussed in recent studies [60].

3.4 Developments in Wireless Protection

Recent developments are intended to overcome these challenges.

• Data wireless transmission is made secure using enhanced encryption techniques. Comparisons of encryption technology and performance of encryption in wireless networks are useful pieces of information [61].

• AI and ML technologies are being used more and more for threat detection and response, making the network more capable of detecting and responding to any security weaknesses. Recent critiques have discussed how AI and ML are applied to improve wireless network security [62].

• BC adds an extra layer of security to wireless networks through the offering of a decentralized way of handling transaction security and access control. The potential of BC technology to improve security is highlighted in papers on its use in wireless networks [63].

Because 5G networks use a service-based architecture (SBA), which divides the control and user planes to provide scalability and flexibility, they significantly improve wireless communication. eMBB, Massive Machine Type Communications (mMTC), and URLLC are some salient characteristics. These characteristics support large numbers of linked devices, low latency, and high-speed communication. 5G’s security features include increased authentication techniques like 5G-AKA (Authentication and Key Agreement) and better encryption technologies [19].

With the integration of AI-driven network management, sophisticated network slicing, and seamless satellite network integration, 6G is anticipated to enhance the design of wireless networks significantly. It seeks to enable cutting-edge applications, including quantum and holographic communication technologies, and use Terahertz (THz) communication channels [64]. In order to handle new threats and improve privacy-preserving measures, 6G is expected to include AI-driven security protocols and quantum-safe encryption techniques [65,66].

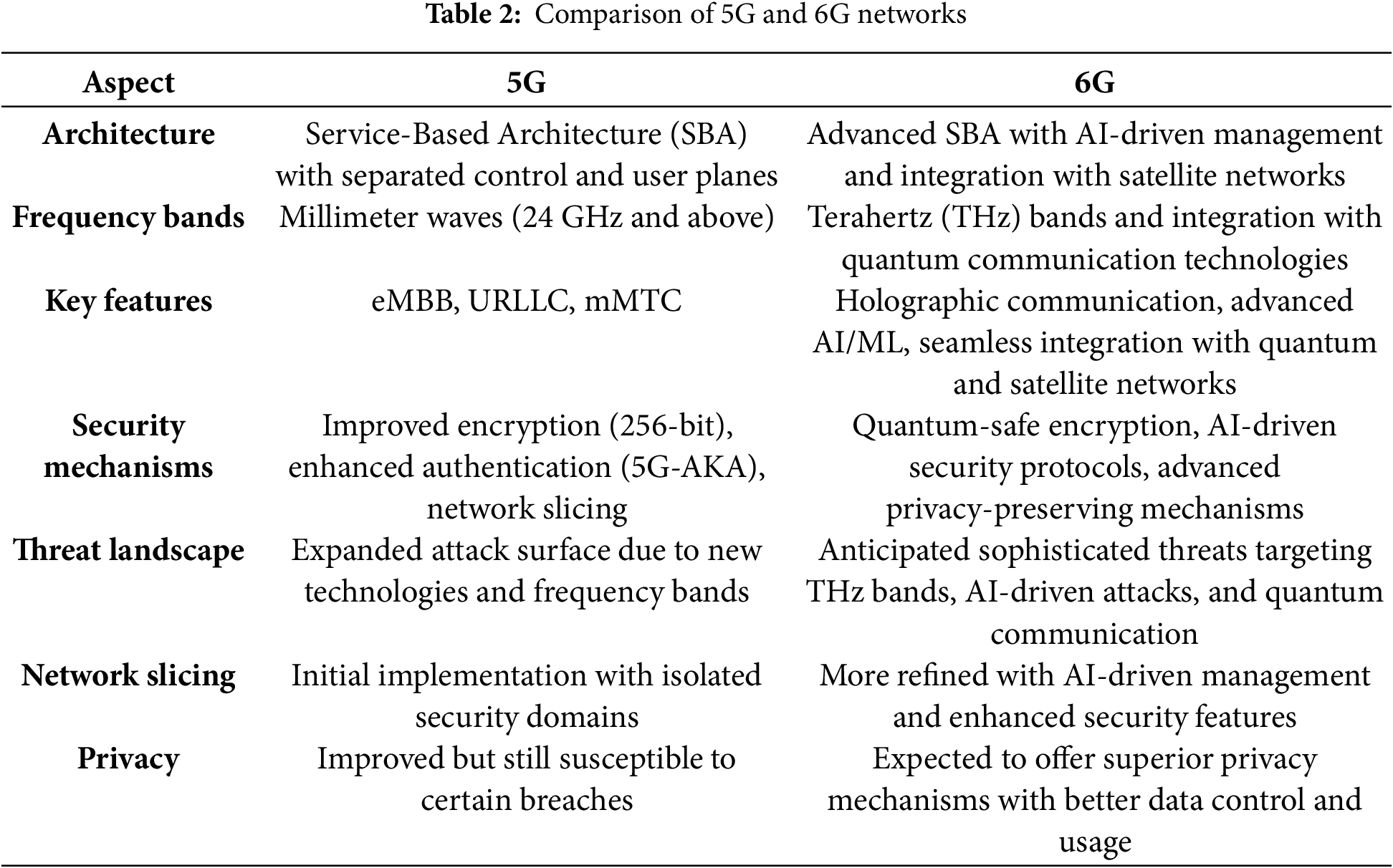

3.5 Comparison between 5G and 6G Networks

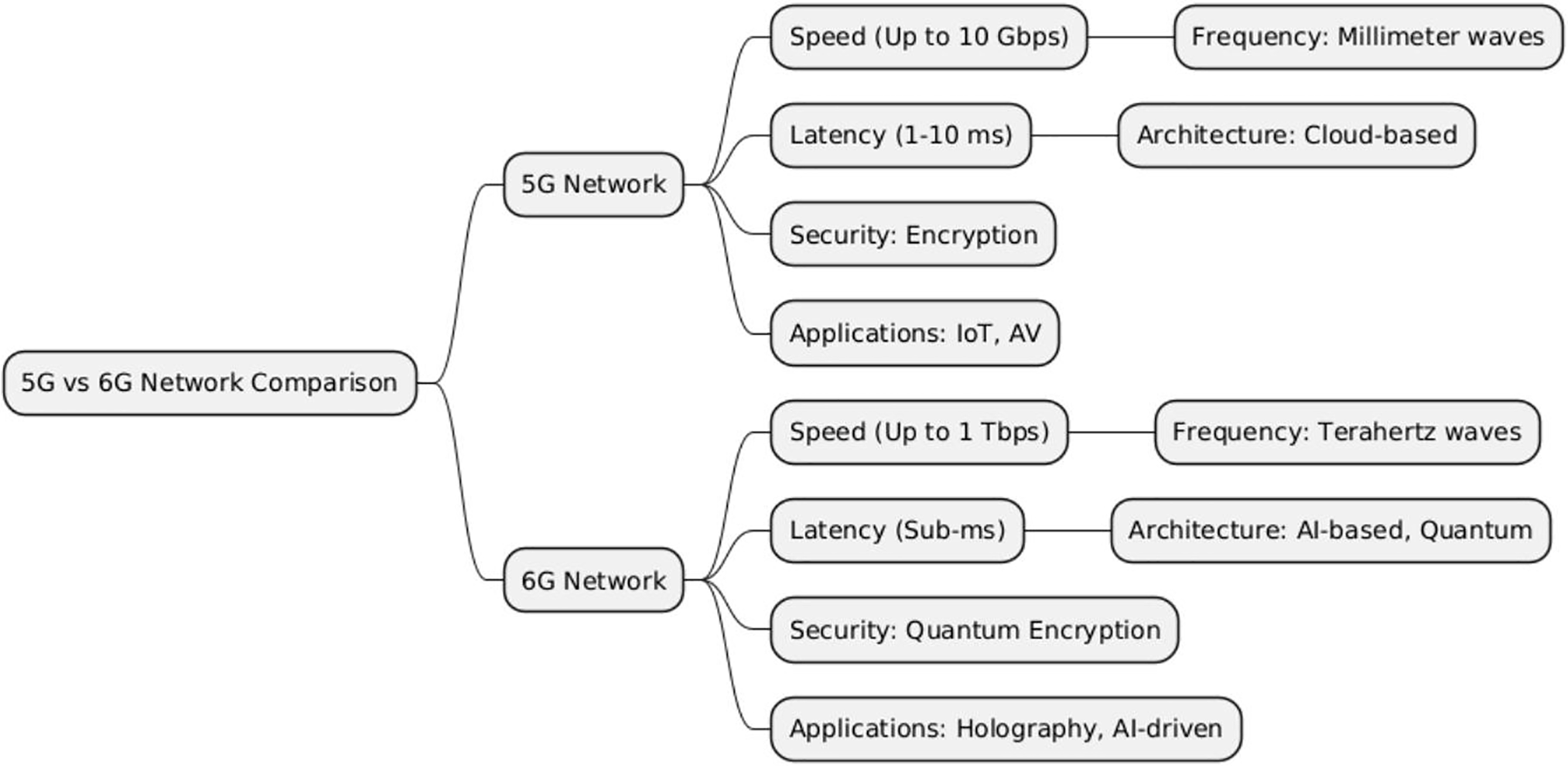

Table 2 and Fig. 4 provide comparisons of key features of 5G and 6G networks. The comparison is mainly based on the following directions.

1. Architecture: 6G builds on 5G’s SBA by adding more sophisticated integration and management features.

2. Frequency bands: 6G will use quantum technology and THz bands, whereas 5G uses millimeter waves.

3. Security: While 6G is anticipated to provide quantum-safe encryption and AI-driven security, 5G offers enhanced authentication and encryption [67,68].

4. Threat landscape: New technologies give 5G a larger attack surface, while more advanced threats are expected for 6G [69,70].

Figure 4: Comparison of key features between 5G and 6G networks

The IoT and increased connectivity in 5G and 6G networks increase the potential of privacy intrusions. Network protocol flaws can be exploited by malicious actors, particularly during network handovers. Common risks include location monitoring, unlawful access to personal information, and communication interception. Important countermeasures include methods like end-to-end encryption, pseudonymization, and privacy-preserving models like differential privacy. Humayun et al. [71] discuss various privacy-preserving techniques in IoT environments over 5G, focusing on challenges like data sharing and access control. Research by Huang et al. [72] highlights privacy-preserving schemes for 5G vehicular networks, where encryption and anonymization techniques play a critical role. Furthermore, Al Ridhawi et al. [73] outline methods to protect sensitive user data in their proposal for secure communication protocols for 5G-enabled smart cities.

3.5.2 Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks

The dispersed nature of DDoS attacks makes them a huge threat to 5G and 6G networks. Attackers can deny network availability by flooding services with spurious traffic, affecting critical applications like healthcare and autonomous vehicles. In their distributed defense against DDoS attacks in 5G, Hoque et al. [74] highlight the necessity for cooperative detection systems. With emphasis on deep learning methods, Kuadey [75] exhibit excellent results in early detection and prevention of DDoS attacks in 5G-based IoT systems. In order to avoid service interference, Patel [76] presented AI-Powered Intrusion Detection and prevention systems in 5G networks.

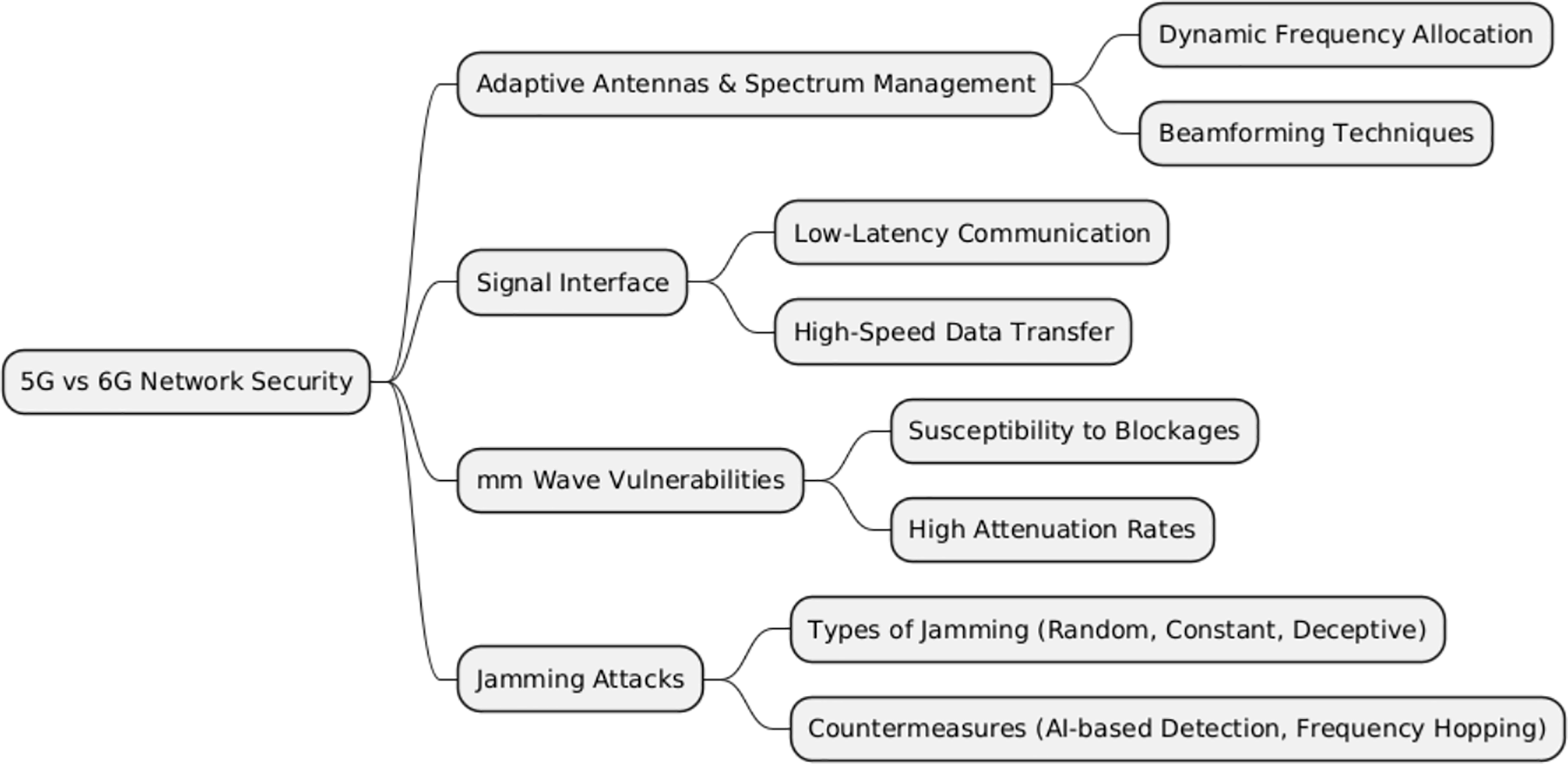

Jamming attacks seriously threaten 5G and 6G communication networks since the attackers use interfering signals to interfere. This is particularly important in mmWave networks. Pirayesh and Zeng [77] offered a comprehensive survey on Jamming Attacks and Anti-Jamming Strategies in Wireless Networks. Mpitziopoulos et al. [78] provided a general overview of the critical issue of jamming in WSNs and cover all the relevant work, providing future research directions. Chen et al. [79] provided a comprehensive survey on various multiple-antenna techniques in physical layer security, with an emphasis on transmit beamforming designs for multiple-antenna nodes.

3.5.4 Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks

In 5G and 6G networks, where attackers may intercept and control messages, MITM attacks pose a serious concern. In their study of machine learning’s application to 5G networks, Arul Stephen et al. [80] provided models for anomaly detection based on traffic patterns to identify MITM assaults. Bhushan et al. [81] provided an overview an-in-the-middle attack in wireless and computer networking. In 2022, Conti et al. [82] reviewed the literature on MITM to analyse and categorize the scope of MITM attacks, considering both a reference model, such as the open systems interconnection model.

3.5.5 Spoofing and Impersonation

In 5G and 6G networks, spoofing and impersonation attacks enable hackers to obtain unauthorized access by imitating reputable equipment or users. Babu et al. [83] presented a comprehensive analysis of spoofing. Dasgupta et al. [84] discussed a sensor fusion-based Global Navigation Satellite System spoofing attack detection framework for autonomous vehicles (AVs). Furthermore, it has been determined that certificate-based security and mutual authentication are essential methods for thwarting these kinds of assaults.

3.5.6 Vulnerabilities in Wireless Communication Infrastructure

The core network, which handles resource allocation, user authentication, and data management, acts as the foundation of 5G and 6G communication networks. The attack surface has grown dramatically since network slicing and virtualization were introduced. Some of the key security threats in 5G and 6G networks are given in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Key security threats in 5G/6G networks

• Vulnerabilities in Virtualization: Misconfigurations or vulnerabilities in Hypervisors can compromise Virtualized Network Functions (VNFs). Attackers could use these flaws to break into networks or obtain unauthorized access.

• Network Slicing: This technique presents customized networks for certain use cases (autonomous cars, IoTs, etc.). Cross-slice attacks, which enable attackers to travel laterally across slices, are a possibility if one slice is compromised.

• Signaling Storms: The likelihood of signaling storms, which may overwhelm the network and cause denial-of-service (DoS) circumstances, is increased by the high density of connected devices in 5G and 6G networks.

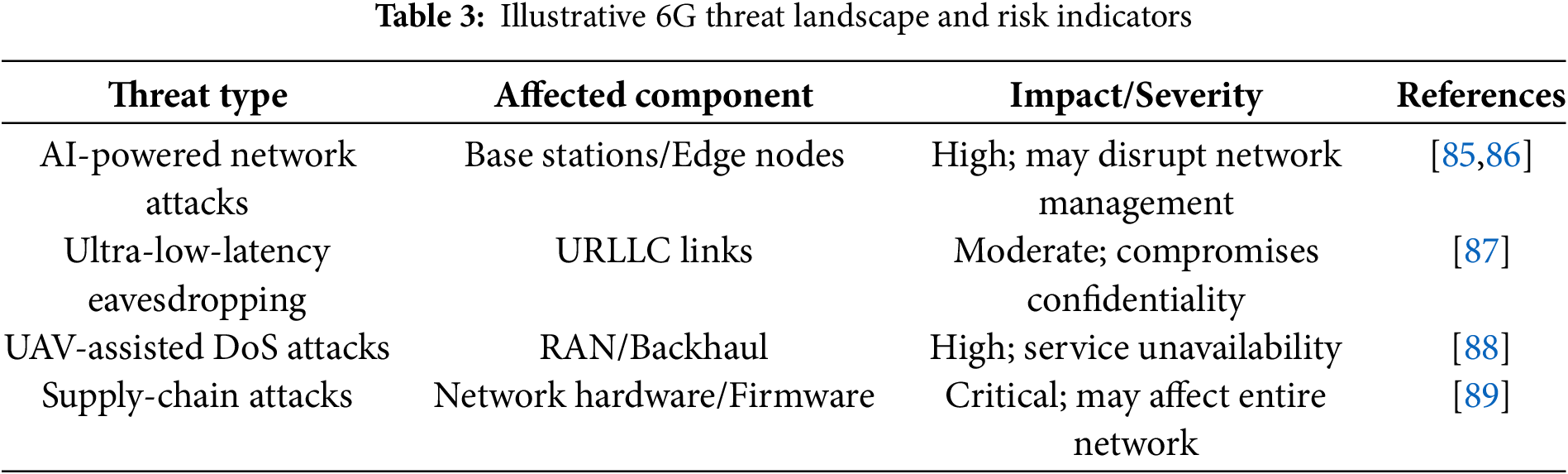

To provide a clearer and more structured understanding of the emerging 6G security landscape, this section presents specific examples of anticipated threats and their potential implications. Key risks include AI-driven automated attacks, ultra-low-latency eavesdropping enabled by enhanced sensing, UAV-assisted denial-of-service attacks, and supply-chain vulnerabilities affecting 6G hardware and software components. Where available, qualitative and quantitative indicators of threat likelihood and severity from recent studies are included to contextualize their impact. Table 3 summarizes major threat categories, the associated network elements, expected impact, and supporting references, offering a concise foundation for risk assessment in next-generation wireless networks.

3.7 Overview of BC in the Wireless Communication

Decentralized ledger technology, or BC, keeps transactions safely on a distributed network. Because it can enhance security, transparency, and data integrity, its application in wireless communication networks, particularly 5G and 6G, is gaining increasing importance. BC offers ways to protect the many devices most susceptible to hacking, data manipulation, and privacy violations in forthcoming wireless networks. BC is a distributed ledger technology (DLT) that maintains a ledger of transactions in a decentralized environment on several devices. With the ability to handle gigantic amounts of data on billions of networked devices securely, with surety, and with less overhead, it has its application in wireless communication, particularly in next-generation wireless networks like 5G and 6G. Due to its decentralized design, free from a point of failure, BC technology is an important asset in protecting wireless networks against any cyber attacks, ranging from data tampering, DDoS attacks, and privacy violations.

BC’s capability in lowering single points of failure, network integrity, and trustless interaction allows BC to be useful for wireless communications. BC is the technology that needs to be used for applications like smart cities, autonomous vehicles, and large IoT deployments because it is decentralized to process data in millions of devices securely and enables wireless networks to securely process data in millions of devices. BC-enabled MECs are particularly useful for managing network resources, encrypting data at the edge, reducing latency, and improving real-time decision-making. BC technology was also used in wireless communications to solve data privacy issues, device authentication, and spectrum control. For instance, eliminating middlemen by BC will enhance security for IoT devices and achieve optimal utilization of resources. Furthermore, it is important to manage 5G networks through network slicing because BC provides confidentiality and isolation of various virtual networks from a common shared physical infrastructure. The key features of BC include the following.

1. Decentralization: BC is immune to single-point failures due to the fact that it depends on a decentralized network. The decentralization of wireless communication enhances the security of dispersed edge devices and limits attack avenues on centralized servers. Decentralized authentication, spectrum management, and resource allocation are some of the important uses of BC in this field.

2. Immutability: Once committed to a BC, information can’t be erased or altered. This protects the network records of device identifiers, resource reservation, and transaction logs from being tampered with or deleted. It has implications for spectrum management, sensitive data protection, and network slicing compliance.

3. Transparency: BC enables data exchanges and transactions to be traceable by all members of a wireless network. Decentralization’s transparency enhances accountability and allows trust building in the management of spectrum resources, device authentication, and data consistency among multiple nodes.

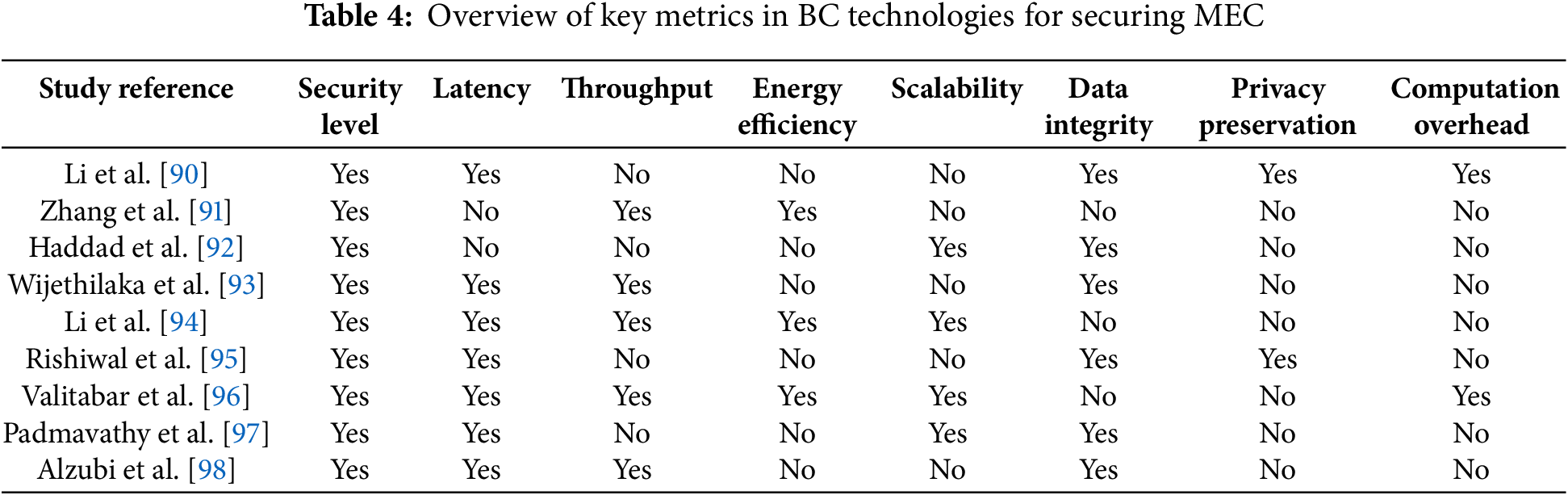

In recent years, using BC integration for wireless networks has been investigated to improve efficiency, security, and transparency. Among the pioneer works, published in 2023 and 2024, are those that describe the promises of BC technology for wireless communication. Li et al. [90] studied a BC-based privacy-preserving and accountable MEC framework for the Metaverse, termed Meta-BMEOC. Zhang et al. [91] investigated a directed acyclic graph BC-enhanced user-autonomy spectrum sharing model.

Haddad et al. [92] investigated a novel, efficient and secure authentication and key agreement protocol for 5G networks using BC. Their security analysis illustrated that the proposed scheme is secure and withstands the known attacks; DOS, DDOS, MITM, hijacking and compromising attacks.

Wijethilaka et al. [93] designed a BC-based secure authentication and authorization framework for robust 5G network slicing. Li et al. [94] investigated BC-based data security for AI applications in 6G networks.

Rishiwal et al. [95] researched a Exploring Secure vehicle-to-everything (V2X) Communication Networks for Human-Centric Security and Privacy in Smart Cities.

Furthermore, Valitabar et al. [96] investigated efficient resource allocation for BC-enabled MEC: a joint optimization approach.

In 2024, Padmavathy and Goyal [97] presented a BC based secure cross layer design for wireless sensor networks. Alzubi et al. [98] investigated BC-enabled security management framework for MEC. The study demonstrated how BC enhances data integrity and privacy protection by securing data transfers between edge devices, cloud servers, and IoT sensors. Moreover, Table 4 presents overview of some recently published works and the key metrics in BC technologies for securing MEC.

3.8 Overview of FL Techniques in Wireless Communication

FL is a machine learning paradigm that permits cooperative model training by several edge devices or dispersed data sources, all while maintaining localized data. This addresses privacy concerns and bandwidth constraints since there is no need to move big or sensitive datasets to a centralized server [90,93].

EC allows data to be stored and computed closer to the point of demand, i.e., at the network edge instead of a central data center. This aids in bandwidth optimization, real-time processing improvement, and latency reduction [91,94]. FL was intended mainly to solve privacy issues in applications with extremely sensitive user data, such as mobile devices and healthcare settings. Google first introduced it in 2016 by McMahan et al. [99]. In the context of 5G/6G networks, where vast volumes of data are created across many IoT devices, FL has become increasingly important by separating data from the core training process. FL gathers just model changes, such as gradients, on a central server, iteratively improving the model rather than centralizing data from all devices. This structure is especially appropriate for 5G and 6G networks, where a wide range of IoT devices produce copious amounts of sensitive data Kairouz et al. [100].

One of the FL’s key advantages is its privacy-preserving data analytics, which makes it extremely relevant to sensitive industries like healthcare and telecommunications. It allows collaborative training without requiring the release of raw data. Niknam et al. [101] proposed a model that makes sure that gadgets, from IoT sensors to smartphones, can improve the accuracy of the global model without running the risk of invading privacy. To improve data safety during model updates, FL systems frequently use strategies like secure multiparty computation (SMPC) and differential privacy Bonawitz et al. [102]. Furthermore, FL provides real-time threat monitoring, allowing nearby devices to monitor any threats and react quickly. These devices can detect abnormalities or assaults by continually evaluating local data; these can then be handled at the network’s edge to stop them from spreading further, Amiri and Gunduz [103]. This feature is necessary to keep security in the intricately linked world of contemporary wireless networks.

As shown in Fig. 6, the FL process begins with the FL server initializing the global model parameters and distributing the model to all connected clients through wireless networks. Each client then trains the model locally using its own dataset (e.g., text messages) and subsequently uploads the updated model parameters back to the FL server. The server aggregates these updates from all clients to create a refined global model. This process is repeated iteratively, with the server broadcasting the updated global model to clients until the model reaches convergence.

Figure 6: FL in wireless communication

3.8.1 FL in Privacy Preserving Data Analytics

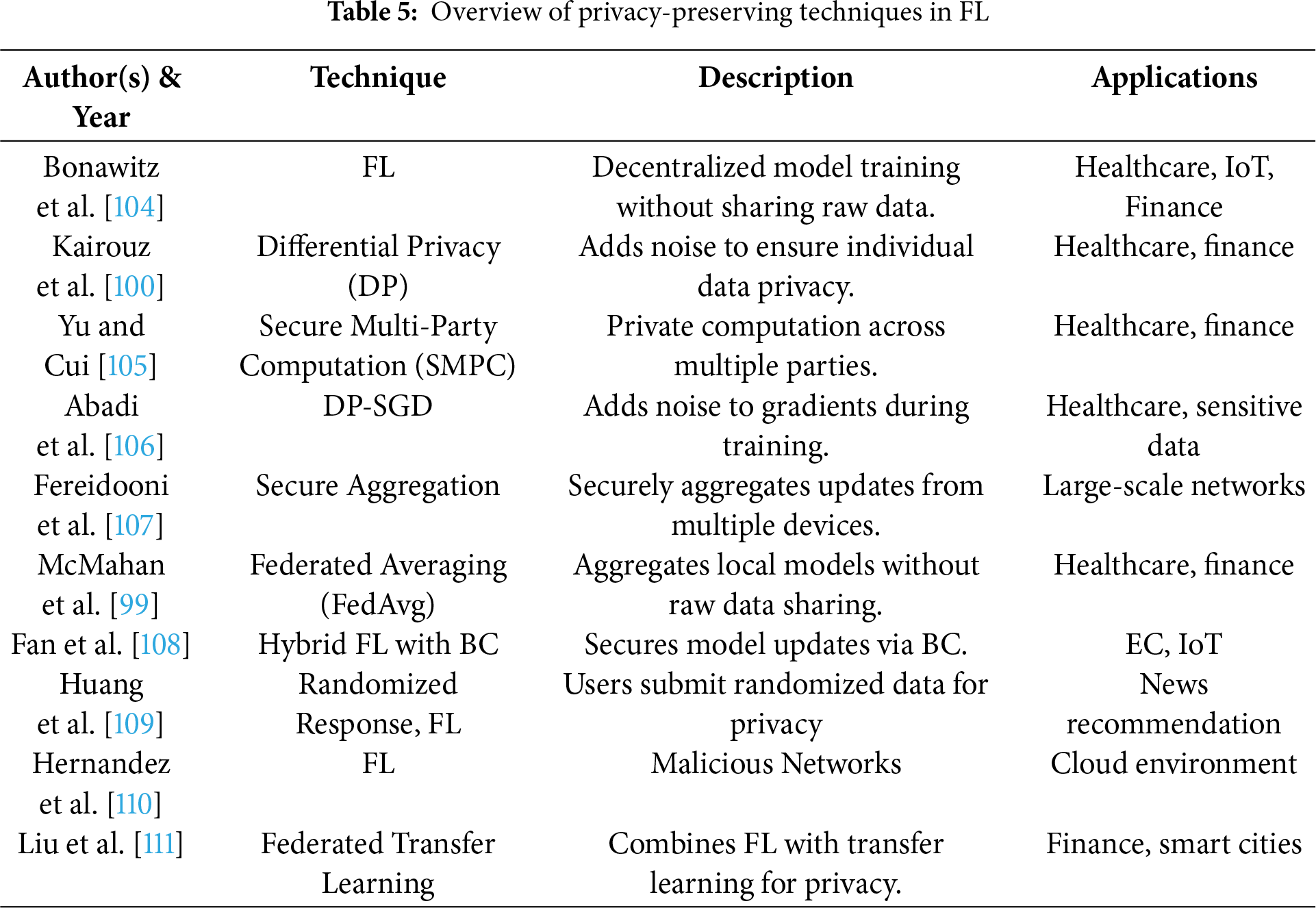

Conventional machine learning methods involve centralizing data for training, which raises significant privacy problems, especially in industries with highly sensitive data, such as healthcare, banking, and smart cities. FL significantly reduces the risk of data breaches by letting users’ data stay on their devices and only exchanging model changes or gradients. Further improvements to privacy are made possible by methods like Differential Privacy and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC), which add noise to model updates and securely compute shared functions without disclosing specific data points. FL has been used in a number of healthcare situations to safeguard private patient data. The following Table 5 summarizes various privacy-preserving techniques used in FL, highlighting the authors, methods, descriptions, and potential applications.

3.8.2 FL in Smart Healthcare Using EC or IoT

The healthcare industry has increasingly adopted cutting-edge machine learning techniques over the past few years to enhance care for patients as well as streamline treatment outcomes. FL, a technique that preserves patient privacy while supporting collaborative model training across decentralized sources of data, is one such approach that has been gaining popularity among these technologies. This is especially important in the healthcare industry because private policies that keep sensitive patient data confidential are very stringent. Patient information security is further augmented in the training process by adding privacy-preserving techniques, such as differential Privacy and secure multi-party computation.

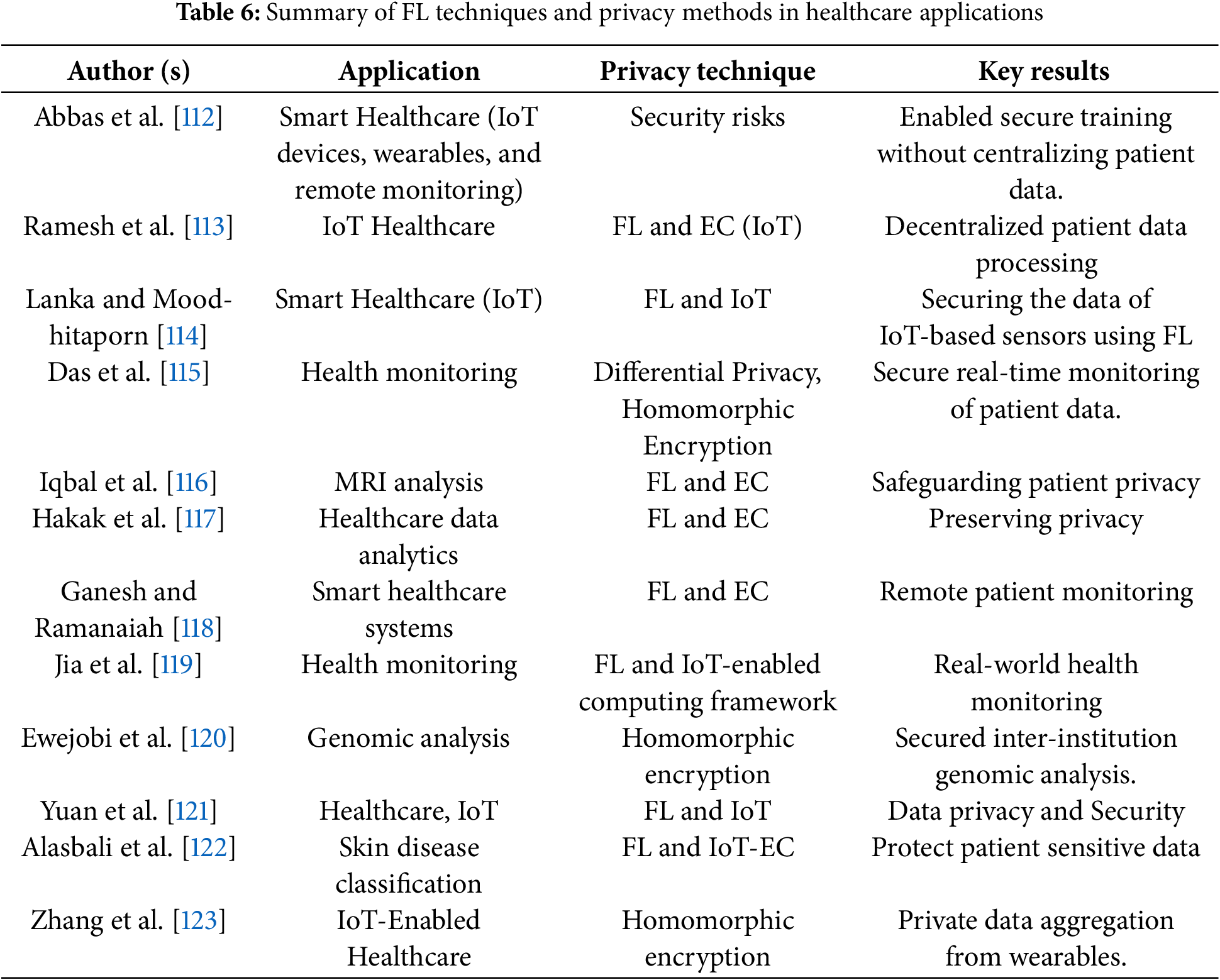

FL allows medical facilities to jointly diagnose diseases securely. For instance, Abbas et al. [112] studied the role of FL in healthcare, highlighting its ability to enable privacy-preserving collaborative model training across institutions and smart health systems using IoT and wearable devices. They discussed major challenges, including security threats, data heterogeneity, and scalability and emphasized emerging privacy-preserving techniques as essential for wider FL adoption and improved healthcare outcomes. Ramesh et al. [113] used FL with EC called as FLEC to process patient data in a decentralized manner, helping in healthcare analytics. This study applies FLEC using simulated healthcare data activating alerts for any defects to observe temperature, heart rate, and SpO2 levels. Lanka and Moodhitaporn [114] used FL and IoT to enhance the security for smart healthcare. They considered different research work for the security-enhancing process using FL in IoT enhanced smart healthcare.

FL enables privacy-preserving real-time data collection in continuous health monitoring. Differential privacy and homomorphic encryption were both used by Das et al. [115] presented a FL-based framework for wearable-enabled personalized healthcare where they addressed its guiding principles, obstacles, and possibilities, showcasing its adaptability and potential to enhance patient insights and health care systems.

To ensure patient confidentiality in remote care settings, Iqbal et al. [116] employed Domain adaptive FL for EC-enabled privacy-preserving MRI analysis. Hakak et al. [117] studied an EC-assisted data analytics framework that used FL to retrain local ML models using user-generated data. Their framework leveraged pre-trained models to extract user-customized insights while preserving privacy and Cloud resources. Ganesh and Ramanaiah [118] delved into the evolution of FL and EC, exploring their convergence in the context of smart healthcare. It examined various applications of FL and EC within healthcare, from remote patient monitoring to predictive analytics and personalized medicine. Jia et al. [119] presented the personalized meta-FL framework for personalized IoT-enabled health monitoring. Ewejobi et al. [120] provided a mini review on homomorphic encryption for Genomics data storage on a federated cloud. This provides secure collaborative genetic dataset analysis for disease research while having strong privacy protection. Yuan et al. [121] proposed an advanced FL framework to train deep neural networks, where the network is partitioned and allocated to IoT devices and a centralized server. Alasbali et al. [122] integrated FL in an IoT-enabled EC for privacy-enhanced skin disease classification. FL was shown to be useful in health monitoring systems by Zhang et al. [123]. They proposed a dropout-tolerable scheme in which the process of FL would not be terminated if the number of online clients is not less than a preset threshold.

Table 6 below summarizes some of the principal research comparing different FL techniques and related privacy measures in health applications. Such research shows how FL can provide data-driven insights without invading the privacy of private health information.

3.8.3 FL Applications in Smart Cities

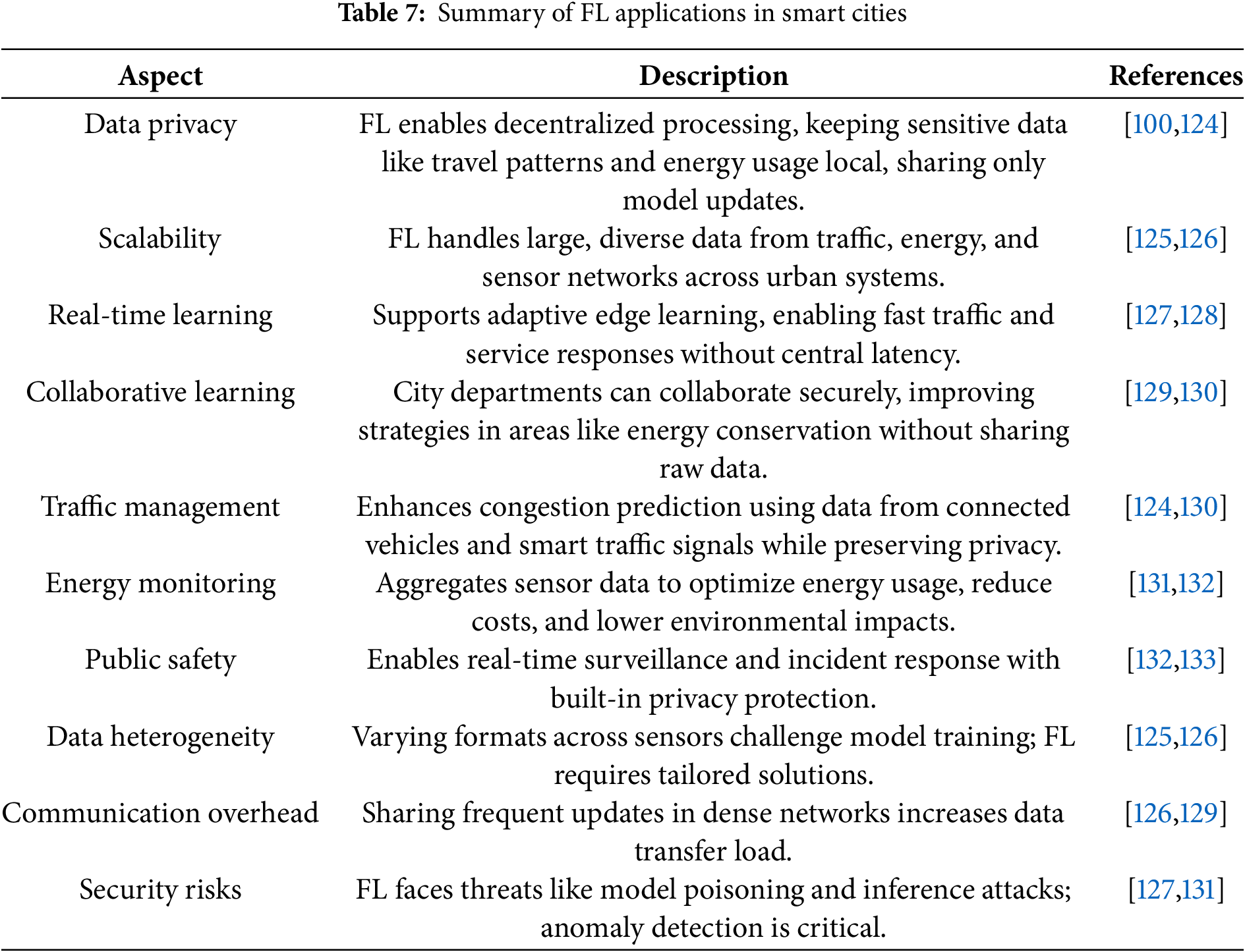

FL, which improves data privacy, scalability, and collaborative learning across urban systems, offers smart cities several advantages. Regarding data privacy, FL permits local data processing, guaranteeing the protection of sensitive data, including individual travel habits and energy use. There is less chance of privacy invasion because just the model parameters are disclosed [100,124]. Moreover, the decentralized structure of FL is scalable and capable of handling big, heterogeneous datasets produced by a variety of city systems, such as energy grids, traffic, and other sensors [125,126].

Real-time learning is essential in dynamic urban situations like traffic management, requiring prompt choices. Without the delay of central systems, FL supports adaptive learning by enabling continuous model updates directly on edge devices [127,128]. According to Zhang et al., [129] and Myakala et al. [130], FL promotes interdepartmental cooperation by enabling municipal agencies to exchange views without disclosing confidential data, strengthening group urban initiatives for traffic reduction and energy saving.

Traffic management is one of the practical uses of FL in smart cities, where information from smart traffic signals and linked cars enhances forecasts and controls congestion while protecting privacy [124,130]. By evaluating dispersed data from citywide sensors, FL facilitates effective resource distribution for energy consumption monitoring, lowering expenses and environmental impact [131]. FL facilitates rapid responses while upholding privacy requirements in public safety by supporting real-time monitoring and incident detection [132,133]. One of the difficulties is data heterogeneity, which leads to consistency problems in model convergence due to different formats from environmental devices, energy meters, and traffic sensors. This issue is being addressed by continuing research [125,126]. Because sharing model updates across several devices results in substantial data transfer costs, especially in highly populated locations, communication overhead is another issue [129,130].

The security of FL models must be improved by countermeasures such as anomaly detection in updates, even if FL increases data privacy. This is because FL is still susceptible to security risks, including model poisoning and inference assaults [127,131]. These advancements highlight how crucial FL is to facilitating safer, more effective, and cooperative smart city operations. Security issues, such as the possibility of model poisoning, further highlight the necessity for strong countermeasures to guarantee the dependability of FL applications. Table 7 outlines the main uses and difficulties of FL in the context of smart cities, showing how this technology makes collaborative, safe, and scalable urban improvements possible.

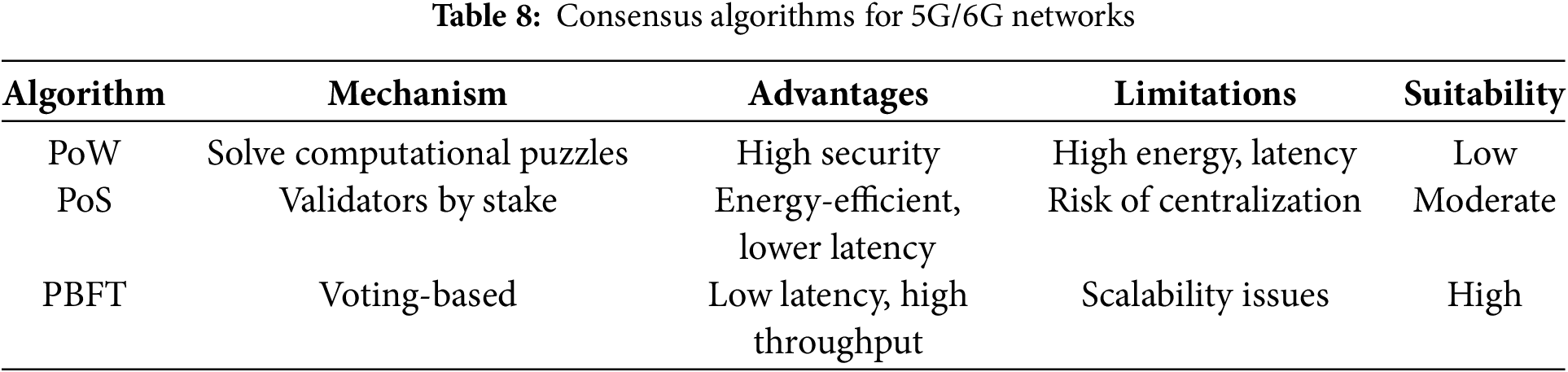

3.9 Consensus Algorithms in 5G/6G Networks

Distributed and edge-based 5G/6G networks require low-latency, secure consensus mechanisms. Table 8 summarizes commonly used algorithms.

PBFT is highly suitable for edge/fog deployments due to low-latency deterministic consensus. PoS can be applied in hybrid networks, while PoW is generally impractical [134,135].

3.10 FL Aggregation Techniques

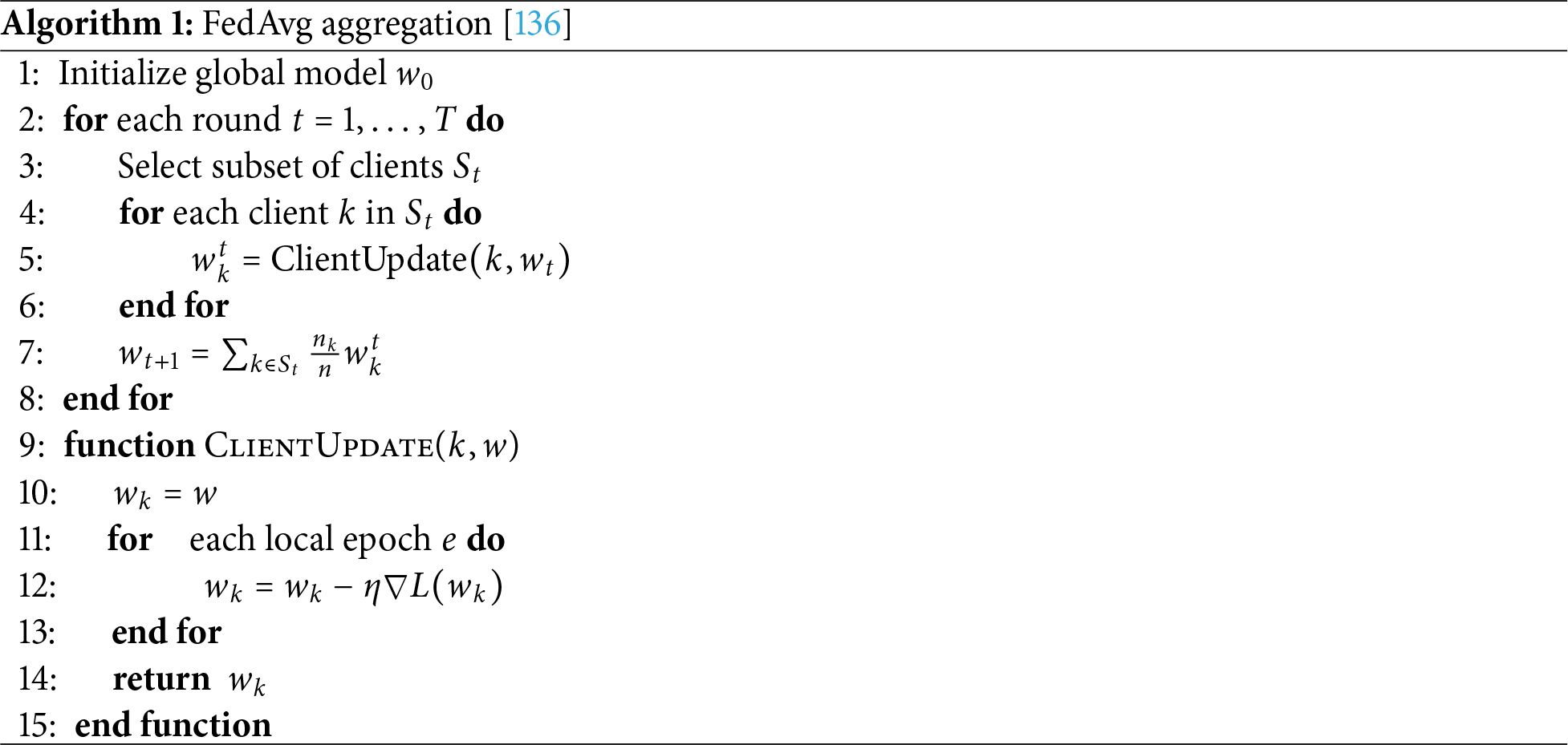

FL aggregates local updates to train a global model without sharing raw data. Two common methods are FedAvg and secure aggregation.

3.10.1 FedAvg (Federated Averaging)

In FL’s methodology, the FedAvg algorithm (presented in Algorithm 1) is the most widely adopted aggregation technique. It iteratively updates the global model by averaging locally trained client models, weighted by the proportion of local data. This ensures scalability across heterogeneous client devices while maintaining data privacy.

Secure aggregation protects client updates, revealing only the aggregated model. It is essential for privacy-sensitive 5G/6G applications [102].

3.11 Ongoing Standardization Efforts and Interoperability in 5G/6G and AI

Ensuring interoperability and standardization in 5G/6G networks and AI-enabled systems is crucial for large-scale deployment. Several ongoing initiatives aim to harmonize communication protocols, security, and AI governance.

3.11.1 Standards and Regulatory Efforts

• IEEE: IEEE 802.11 and 802.15 working groups define wireless communication protocols and interoperability guidelines. IEEE P2413 provides architectural standards for IoT systems, facilitating integration across heterogeneous devices.

• 3GPP: 3GPP Release 17 and 18 introduce 5G enhancements for URLLC, massive IoT, and AI/ML integration, promoting inter-network compatibility and edge AI support.

• NIST: The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides guidelines for AI system evaluation, including trustworthiness, robustness, and secure FL frameworks [137].

• EU AI Act: The European Union’s AI Act proposes risk-based regulatory frameworks to ensure AI transparency, accountability, and interoperability in cross-border applications [138].

3.11.2 Proposed Interoperability Framework

To achieve seamless integration between heterogeneous networks and AI systems, a three-layer interoperability framework can be considered as:

1. Communication Layer: Standardized protocols (e.g., 5G NR, IEEE 802.11/15) with secure handover and cross-network compatibility.

2. Data and AI Layer: FL and secure aggregation techniques with standardized model representation formats (e.g., ONNX, PMML) to enable cross-platform AI deployment.

3. Governance Layer: Alignment with international guidelines such as NIST AI Risk Management Framework and EU AI Act to ensure ethical, transparent, and auditable AI operations.

This framework ensures interoperability across multi-vendor networks, heterogeneous edge nodes, and AI-enabled applications in 5G/6G, supporting global scalability while adhering to emerging regulations.

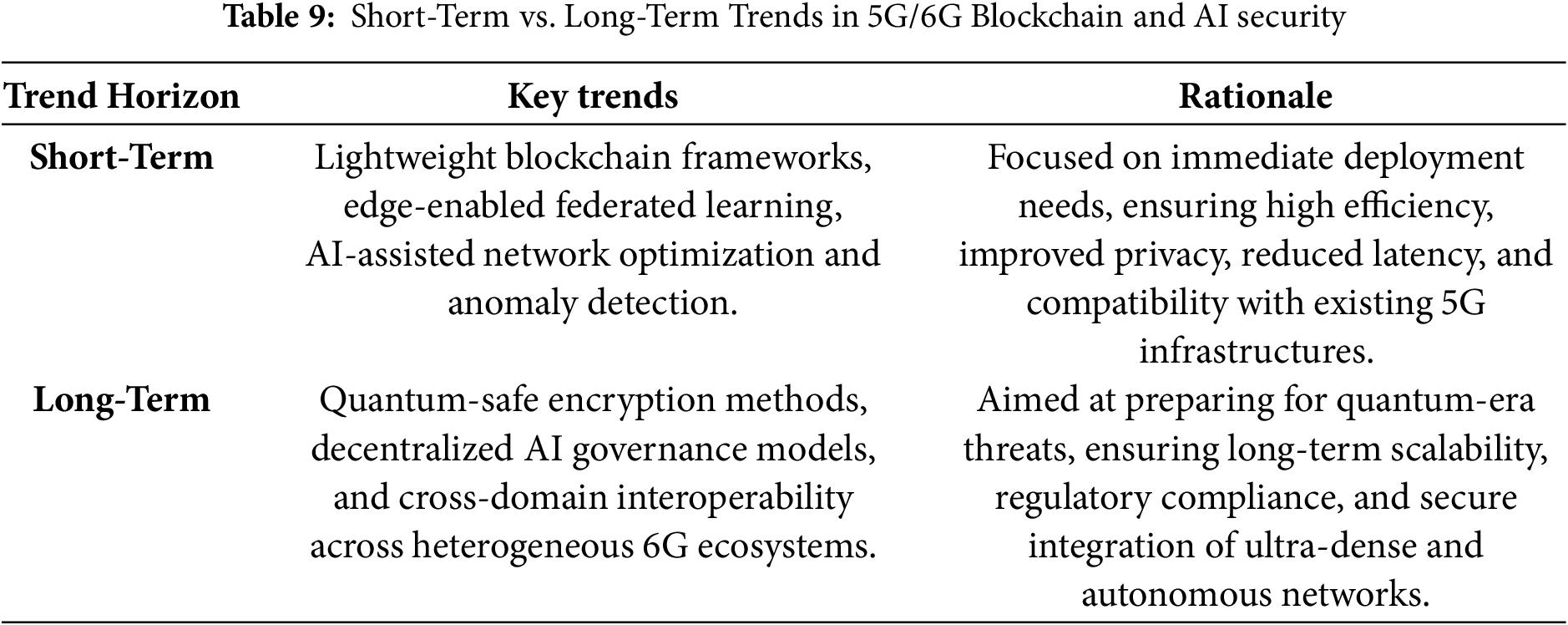

3.12 Emerging Trends in 5G/6G BC and AI Security

Emerging technologies in 5G/6G networks are evolving at different time scales. For clarity, we categorize these trends into short-term and long-term developments, along with their rationale, as shown in Table 9.

Following are some of the short-term trends:

• Lightweight BC: Optimized for low-power edge devices and constrained IoT nodes, enabling efficient consensus and data integrity without high computational overhead [139].

• Edge-Based FL: Deploying FL at the network edge reduces latency, preserves data privacy, and enables near-real-time analytics.

• AI-Assisted Network Optimization: Use of ML for traffic prediction, resource allocation, and anomaly detection in 5G/6G networks.

Rationale: These trends focus on practical deployment in the near term, leveraging existing technologies and standards to enhance efficiency, privacy, and security in edge and IoT-enabled 5G/6G networks.

Following are some of the long-term trends:

• Quantum-Safe Encryption: Preparing networks for future quantum threats by developing cryptographic algorithms resistant to quantum attacks.

• Fully Decentralized AI Governance: Integration of BC and AI to create autonomous, auditable, and trustless AI ecosystems.

• Cross-Domain Interoperability Frameworks: Standardized architectures enabling seamless integration of 5G/6G networks, IoT, and AI across multiple vendors and regulatory regimes.

Rationale: These long-term trends anticipate future technological and regulatory challenges, focusing on scalability, post-quantum security, and global interoperability to ensure sustainable, resilient 5G/6G systems.

3.13 Scalability Analysis of BC in 6G Networks

Scalability is a critical concern for BC integration in 5G/6G networks, particularly due to the massive number of connected devices and high transaction rates. Two main approaches have emerged to improve BC scalability:

• Sharding: Divides the network into smaller, parallel-processing shards, reducing the load per node and increasing overall throughput [140].

• DAG-Based Architectures: Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) structures such as IOTA or Tangle allow multiple transactions to be confirmed in parallel without requiring strict sequential block validation, improving TPS and lowering latency [141].

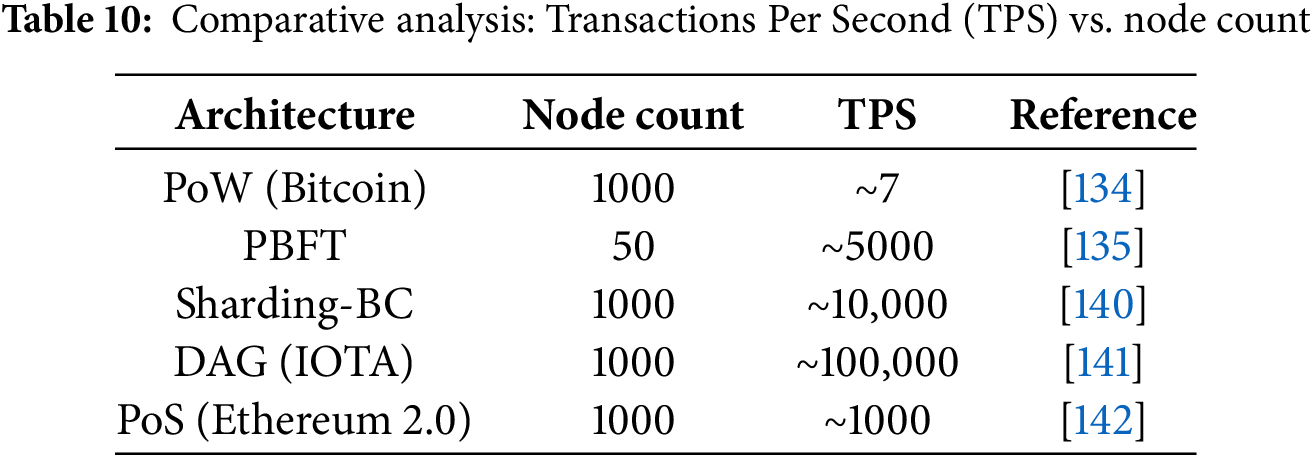

3.13.1 Transaction Throughput vs. Node Count

Table 10 compares the approximate throughput of different BC architectures with varying network sizes, based on recent studies.

As the Table 10 shows, traditional PoW BC suffer from low TPS and limited scalability, making them unsuitable for high-density 6G networks. PBFT provides higher throughput but is limited by the number of nodes due to communication overhead. Emerging solutions such as sharding-based BC and DAG-based architectures can support the massive number of nodes and high transaction rates expected in 6G.

• Sharding achieves scalability by processing transactions in parallel shards, suitable for mid-term deployment in 6G edge networks.

• DAG-Based BC offers near-linear TPS scaling with the number of nodes and is promising for long-term 6G deployments, especially in IoT-dense environments.

Overall, integrating sharding or DAG-based BC with EC and FL frameworks can ensure secure, scalable, and efficient data processing in future 6G networks.

3.14 Differential Privacy in FL for 5G/6G Networks

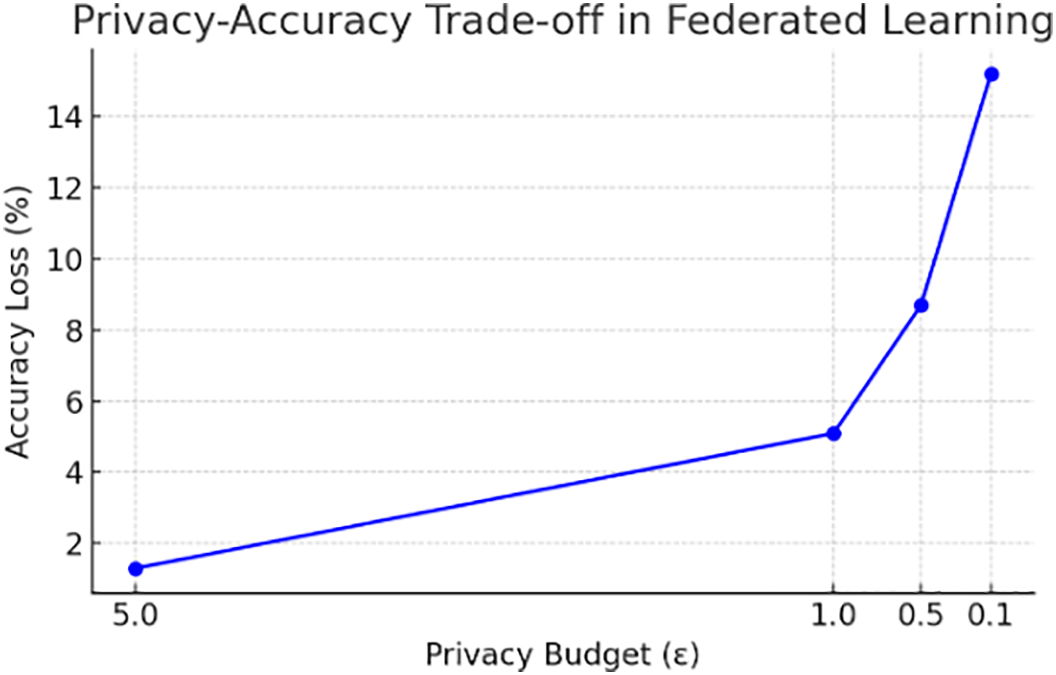

FL often requires privacy preservation when aggregating model updates across distributed devices. Differential Privacy (DP) introduces controlled noise to model updates to prevent leakage of sensitive data. However, applying DP can degrade model accuracy, and tuning the privacy budget

Studies have shown the trade-off between privacy and accuracy, as presented in Fig. 7:

• Lower

• Higher

Figure 7: Illustration of the trade-off between privacy budget (

3.14.2 Adaptive Differential Privacy

To mitigate accuracy degradation, adaptive DP techniques dynamically adjust noise levels based on: 1) Model convergence rate, 2) Importance of specific updates, and 3) Sensitivity of the data being aggregated.

This discussion highlights key insights and implications derived from our study, with a particular focus on privacy-preserving mechanisms in federated learning for 5G/6G edge scenarios.

• In 5G/6G edge scenarios, adaptive DP allows privacy-preserving FL while supporting latency-sensitive applications.

• The privacy-accuracy trade-off can be tuned per application (e.g., IoT telemetry, autonomous vehicles).

• Combining DP with secure aggregation ensures robust protection against data inference attacks, even when nodes are compromised.

Legal-Technical Co-Design for GDPR Compliance

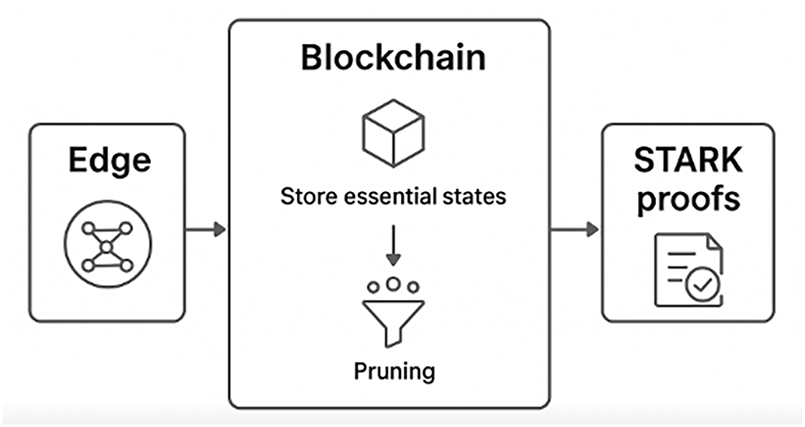

BC’s inherent immutability can conflict with GDPR’s “right to erasure” (Article 17), creating legal challenges for storing personal data on-chain. To address this, legal-technical co-design approaches can be employed. Sensitive data can be stored off-chain in encrypted form with only cryptographic hashes maintained on-chain, allowing selective deletion without compromising auditability. Pruning and compression techniques, such as Merkle tree pruning or STARK-based proofs, can reduce on-chain storage requirements while retaining verifiable state. Additionally, selective encryption with key revocation can render personal data inaccessible, effectively achieving GDPR compliance. These strategies enable a balance between regulatory adherence, system performance, and verifiability, particularly benefiting resource-constrained edge nodes [53–55].

4 Interoperability Challenges of FL and BC

While FL and BC can complement each other to enhance security and privacy in 5G/6G networks, their integration poses several interoperability challenges. BC consensus mechanisms can introduce latency that delays FL model aggregation, potentially affecting convergence rates. Lightweight consensus protocols or asynchronous aggregation strategies can mitigate this issue. Additionally, combining decentralized FL with BC can lead to significant storage and computational overhead as the number of participants or model complexity increases. Techniques such as model compression, sharding, and off-chain storage of model parameters can alleviate scalability bottlenecks. Effective co-design of FL aggregation protocols and BC architectures is thus essential to balance latency, throughput, security, and storage efficiency, enabling practical and scalable deployments.

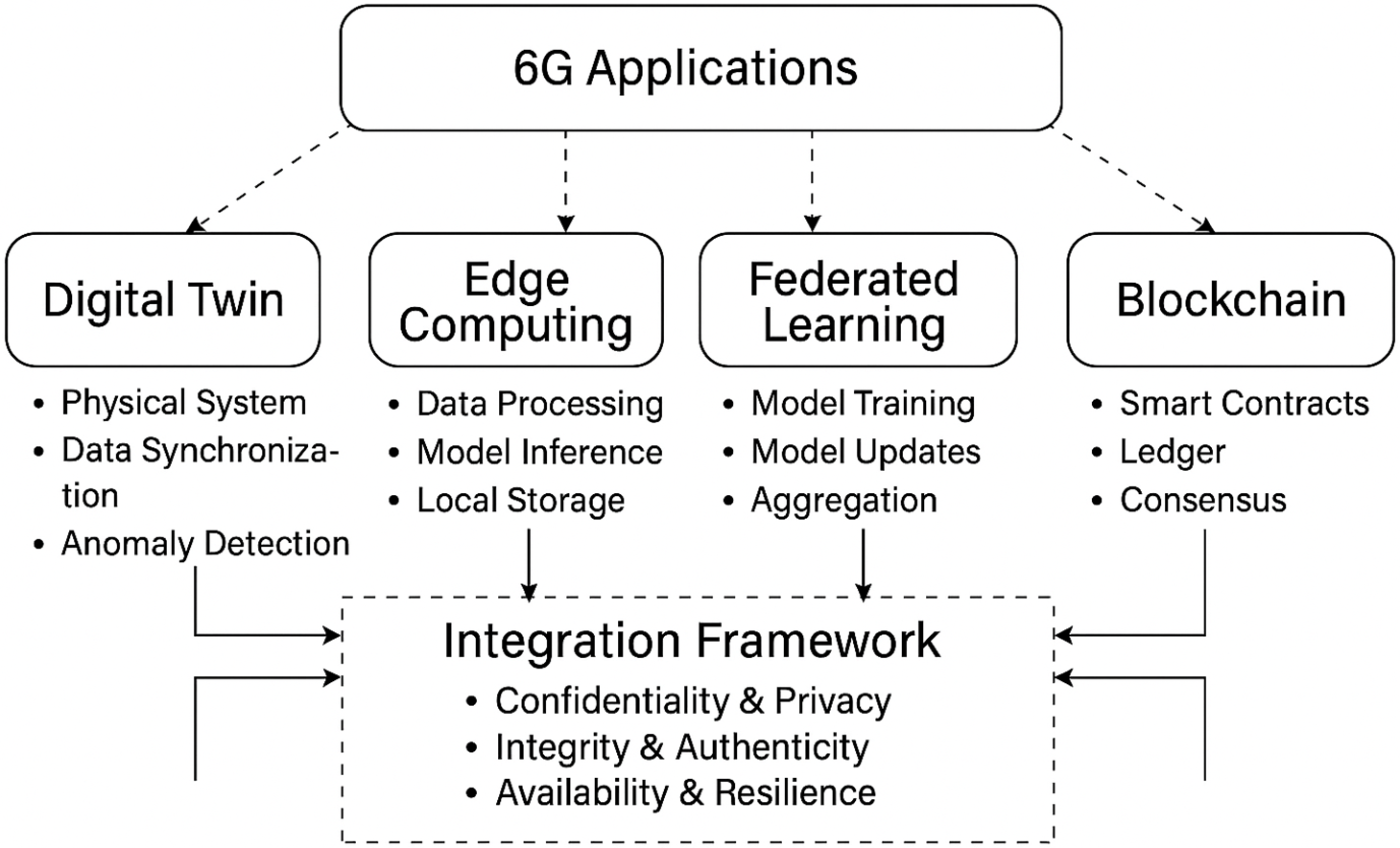

5 Integration of Digital Twins, FL, BC, and EC for Securing 6G Applications

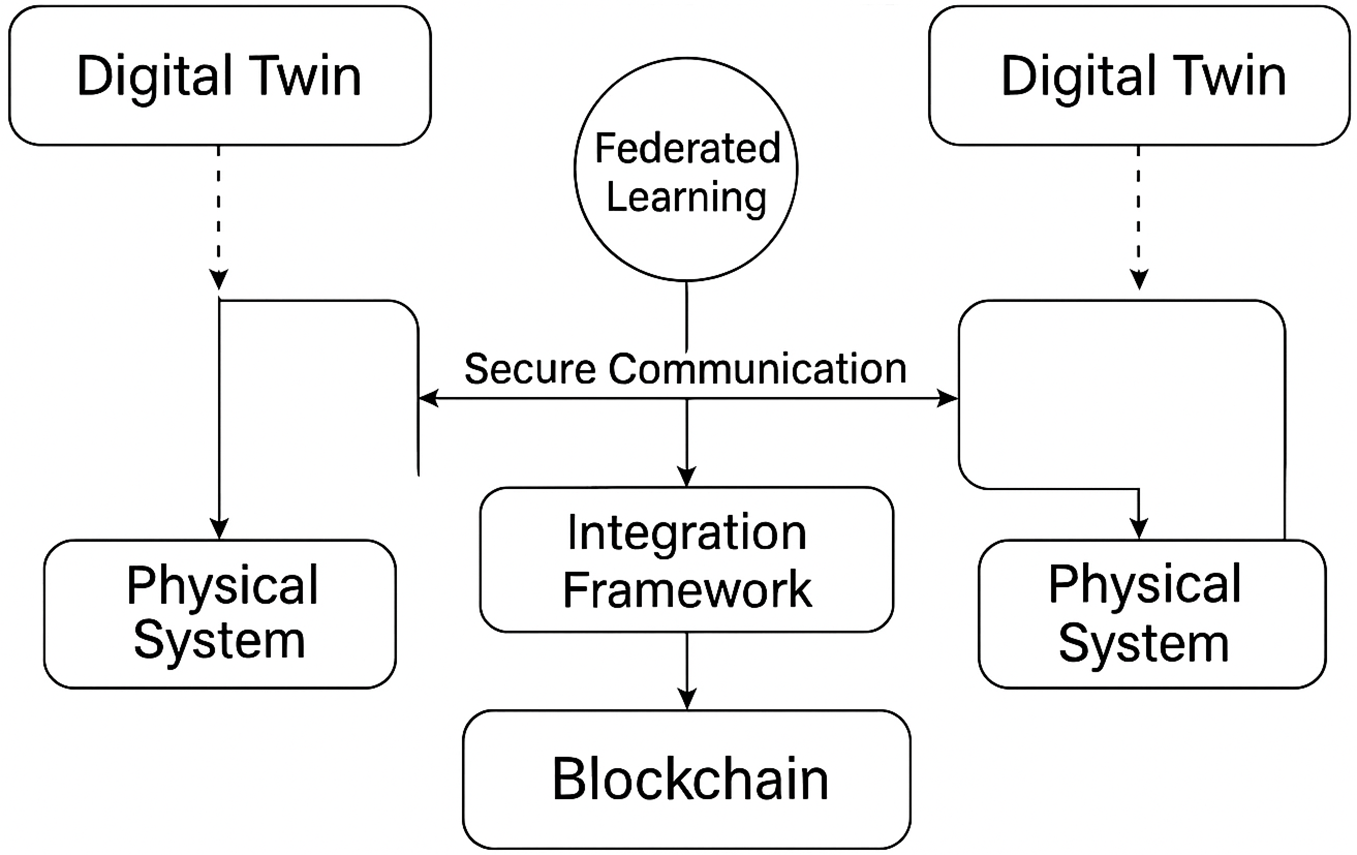

The emergence of 6G networks promises ultra-high data rates, extremely low latency, and pervasive connectivity, enabling revolutionary applications such as autonomous transportation, holographic communications, industrial automation, and intelligent healthcare. However, due to the distributed, heterogeneous, and latency-sensitive nature of 6G services, such developments introduce unprecedented security and privacy challenges. Combining emerging paradigms, including digital twins (DT), FL, BC, and MEC, can provide a synergistic platform to address these challenges. A DT is a virtual replica of a physical system that is refreshed with real-time data. DTs in 6G can model the users’ states, networks’ states, and environmental states to enable predictive analysis and decision-making in real-time [143,144].

The integration of DT, FL, BC, and MEC forms a multi-layered architecture that is well-adapted to the 6G foundation principles of responsiveness, intelligence, and trust. Fig. 8 presents a framework for this integration. The lowest layer is shrouded by EC, e.g., MEC, which enables distributed data processing near where data is being generated, relieves the burden on centralized cloud resources, and complies with the latency requirements. It is also the foundation on which FL is implemented, which leverages the distributed nature of MEC to facilitate model training without sensitive data centralization.

Figure 8: DT, MEC, FL, and BC integrated framework

DTs reside in the middle layer, tightly connected to the edge infrastructure. Each physical device (e.g., user device, intelligent car, or medical sensor) is represented by a digital twin that observes its activity, environmental data, and operational readings. Prediction models complement twins learned using FL to enable anticipatory decision-making (e.g., predicting vehicular traffic or patient deterioration) [145]. BC manages the trust and coordination layer, which secures model update exchanges and transaction history through smart contracts and consensus rules. BC provides non-repudiation, audibility, and tampering resistance. BC is significant in scenarios when edge nodes would be controlled by different administration domains (e.g., factories, traffic control, hospitals). This integration not only deals with security attacks but also enables secure collaboration among heterogeneous nodes.

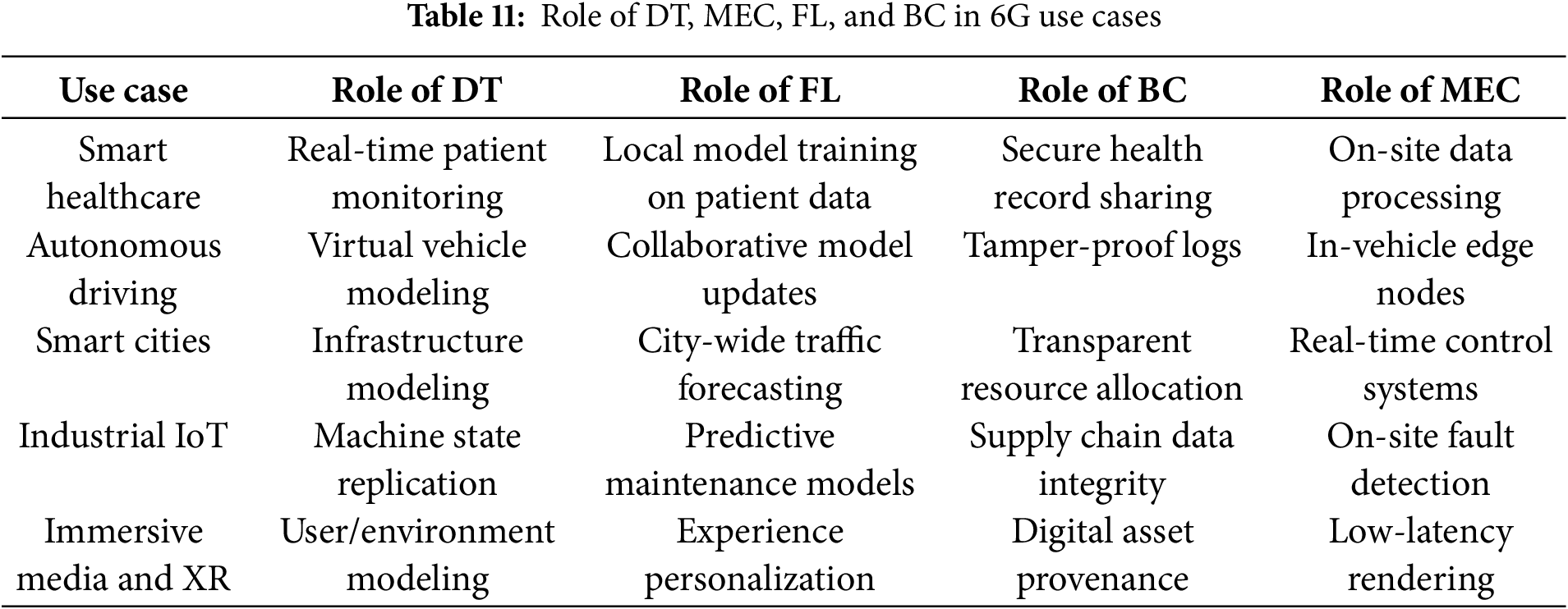

5.1 Potential Use Cases of the Proposed Integrated Framework

This integration of DT, FL, BC, and EC can be depicted via heterogeneous 6G-enabled applications. This includes the following use cases [145,146].

1. Smart healthcare (Healthcare 5.0)

DT can represent patient physiological variables such as heart rate, glucose level, and blood pressure, updated in real-time by wearable sensors. Predictive diagnosis is done using the twins. FL makes learning models shift locally in patient data, while keeping it private. BC makes sensitive health data private, grants access control to smart contracts, and audits medical data exchanges. EC performs initial processing (e.g., filtering the ECG signal) at bedside terminals, enabling fast response in case of emergencies.

2. Autonomous driving

DTs of internal system (e.g., engine, sensors) and external world (e.g., traffic environment) are fitted in vehicles. They facilitate real-time decision-making. Vehicles learn to update their driving models (e.g., path planning, obstacle detection) without sharing raw sensor data via FL. These model updates are recorded via BC for integrity verification and cooperation among several transport authorities and vehicle manufacturers. Embedded edge nodes in vehicles and roadside units supply latency-sensitive computation.

3. Smart cities

DTs model city infrastructures, including traffic lights, power grids, and water networks. FL offers city-wide prediction, e.g., predicting traffic congestion or power spikes. BC offers open data-sharing across departments (e.g., transport, energy) and verifies the source of control decisions. Edge devices, e.g., MEC servers embedded with smart meters and traffic cameras, perform local computation to provide quick feedback and control.

4. Industrial IoT (IIoT)

In manufacturing, DTs simulate production lines and the health status of machines. FL enables on-site learning from the behavior of machines for predictive maintenance and production optimization. BC offers secure supply chain logging of data, authenticity of components, and usage logs of machines. EC helps in real-time quality control and anomaly detection.

5. Immersive media and XR

DTs replicate user motions, environmental dynamics, and device interactions for applications such as holographic communication and interactive gaming. FL allows real-time personalization of immersive experiences. BC supplies ownership and traceability of virtual assets, and EC supplies ultra-low-latency rendering and media synchronization. Table 11 summarizes the key benefits of the integrated technologies for the previously mentioned applications.

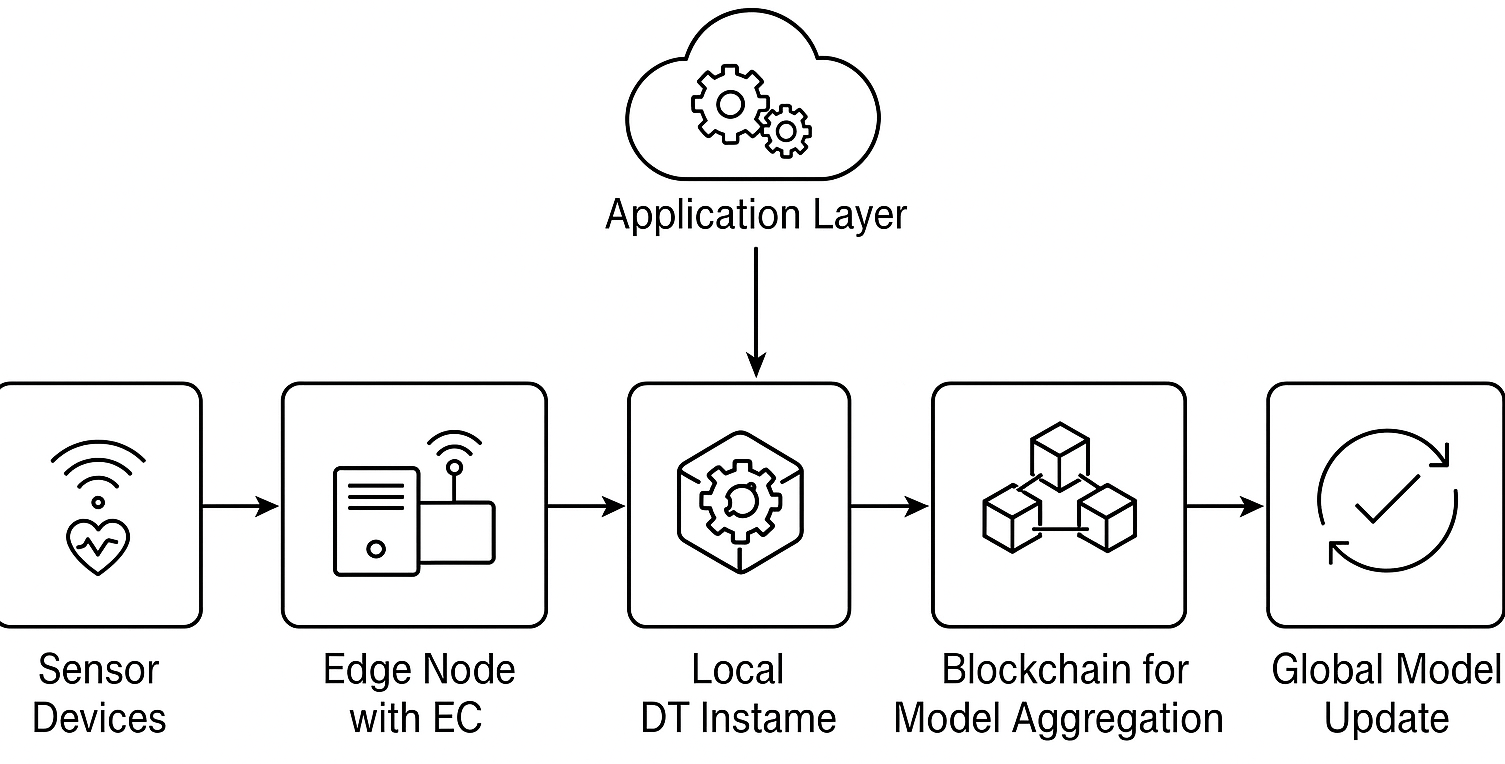

Fig. 9 presents a systematic workflow architecture of 6G application security by leveraging the integration of DT, FL, BC, and EC. The workflow describes the processing of sensor data, learning from it, securing it, and utilizing it to enhance the robustness, privacy, and intelligence of 6G systems. The proposed framework consists of the following main layers.

1. Sensor devices (Data collection layer)

In the lowest layer, smart sensor devices such as IoT sensors, wearables, and embedded systems collect real-time information from the physical world. These sensors include biomedical sensors in a healthcare environment, LiDAR, radar, and cameras in autonomous vehicles, utility meters in a smart city, and industrial sensors in a production line. Such sensors continuously send raw data in the form of temperature, movement, audio, and health parameters, which are the sensory backbone of a 6G-enabled system. Data in this layer can be spoofed, tampered with, or subjected to man-in-the-middle attacks when not treated securely.

2. Edge node with EC (Data preprocessing and filtering)

The second stage comprises edge nodes, e.g., mobile base stations, smart gateways, and vehicular edge devices, equipped with EC capabilities. These nodes filter, normalize, and preprocess raw sensor data. Also, this layer extracts useful features for downstream operations and performs latency-sensitive tasks like real-time detection, event triggering, or local control. EC avoids sending sensitive data unnecessarily across the network, reducing bandwidth usage and exposure risks. Furthermore, it enables confidentiality through local data processing and reduces reliance on centralized cloud servers.

3. Local DT instance (Real-time virtualization)

A DT is at the edge of each physical thing (e.g., patient, car, smart meter). The twins contain a real-time, synchronized digital copy of the physical system, enabling simulation of future states, predictive diagnostics (e.g., vehicle or patient anomaly detection), and context-aware responses and situational awareness. DTs are equipped with processed data from edge nodes and replicate decision outcomes based on past and current conditions. Also, DTs provide semantic consistency and are essential for anomaly detection of suspicious behaviors that indicate cyber-physical attacks.

4. Training of FL (Coordinated edge model updates)

The edge nodes and corresponding DTs contribute to FL by training local ML models on preprocessed and contextualized data, avoiding raw data exchange to maintain privacy, and generating encrypted or masked model updates (e.g., gradients or weights). This process takes place among a number of distributed edge devices concurrently, allowing each device to update a global model of intelligence without ever disclosing the user data. FL invokes data sovereignty and differential privacy and guards against model inversion attacks as well as data leakage.

5. BC for model aggregation (Trust infrastructure layer)

Model updates generated by each node are sent to a BC network that verifies each update with digital signatures, uses consensus algorithms, e.g., proof of stake, practical Byzantine fault tolerance, to validate updates, and cancels smart contracts to automate reward, access, and verification. This prevents tampering, poisoning attacks, and provides a zero-trust architecture for the FL pipeline. BC ensures integrity, traceability, and non-repudiation of model updates and enables decentralized trust management.

6. Global model update (Knowledge fusion)

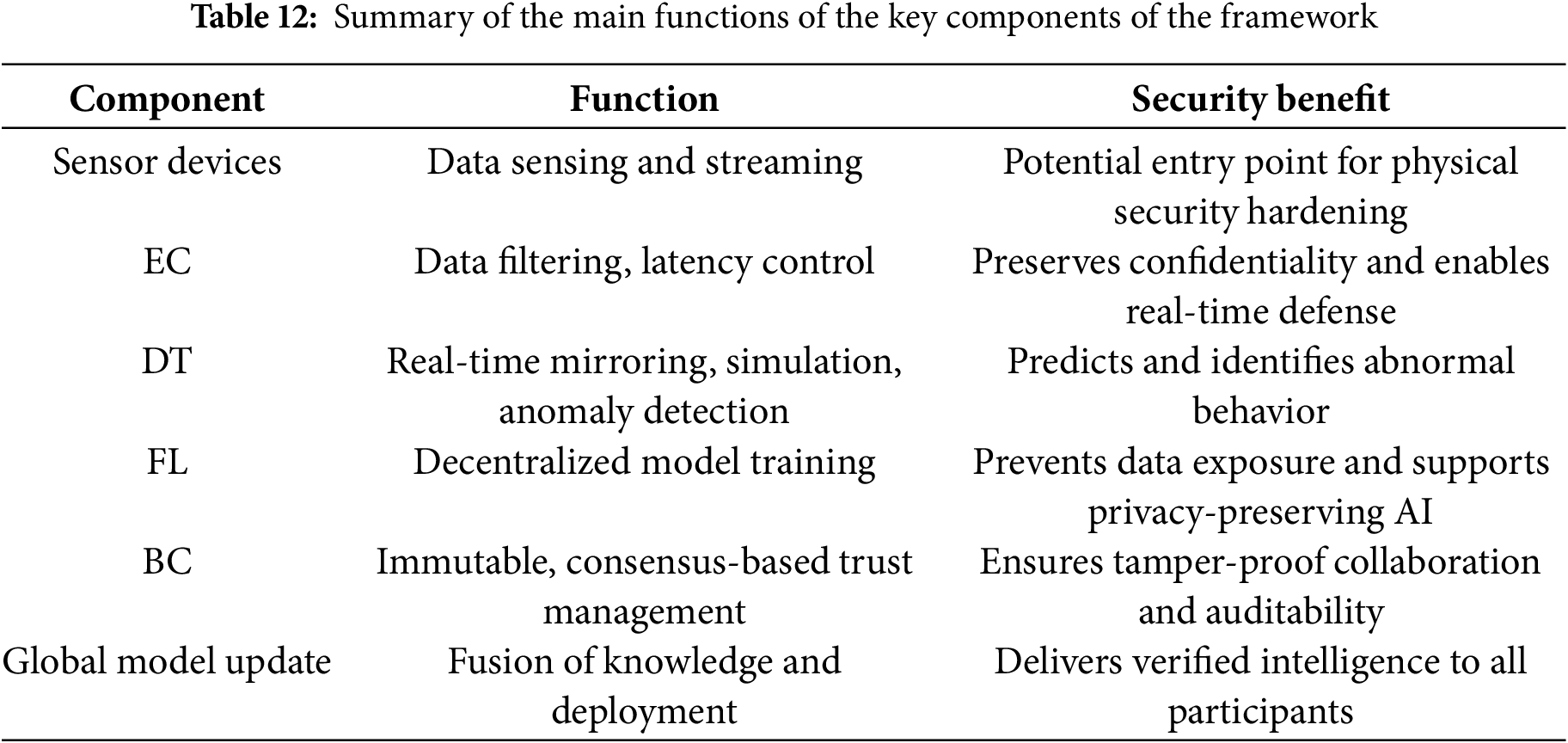

Once validated by BC consensus, the model updates are combined into a global model through secure methods, e.g., federated averaging, returned to edge nodes and DTs, and refined iteratively over time through successive rounds of learning. This global intelligence is then put to use at the application level, driving intelligent 6G applications such as autonomous control systems, immersive XR environments, or personalized health diagnostics. Furthermore, this layer facilitates uniform and secure delivery of acquired intelligence, which is crucial for collaborative action in distributed settings. Table 12 summarizes the key functions of each component of the framework.

Figure 9: Workflow of DT, MEC, FL, and BC integrated framework

5.3 Security Analysis of the Framework

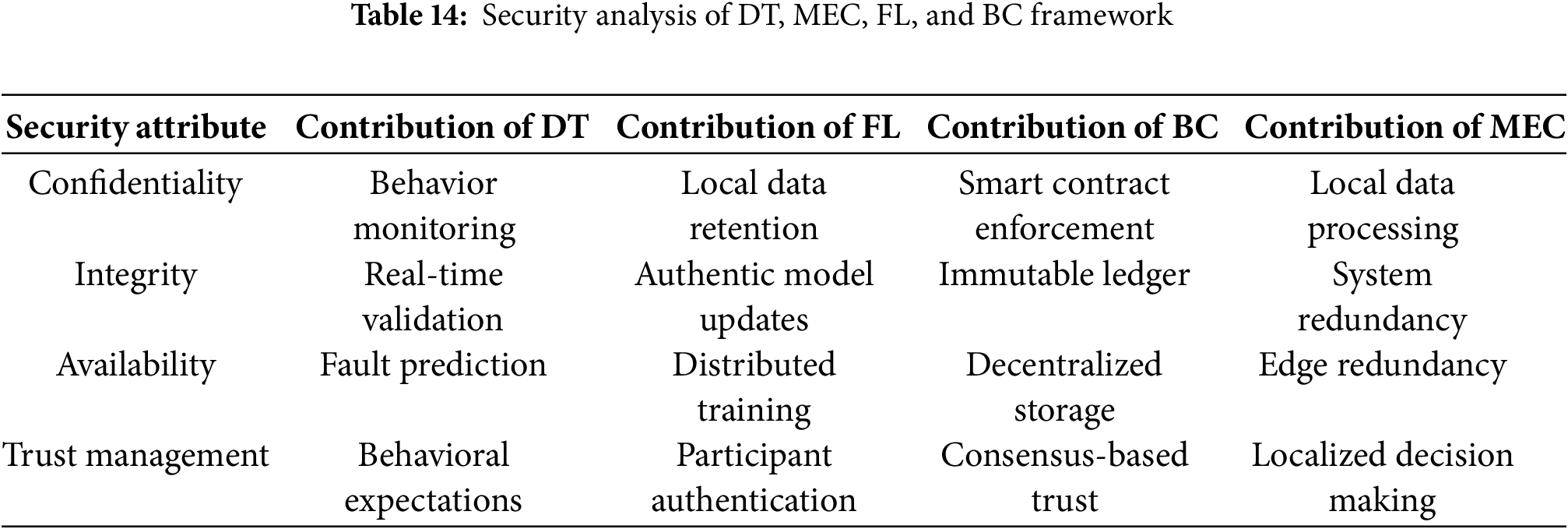

The integrated DT-FL-BC-MEC model significantly enhances security by leveraging the unique strengths of each component.

1. Confidentiality and privacy

As 6G networks become increasingly integrated into critical infrastructures such as healthcare, transportation, and smart government, the confidentiality of data and users’ privacy take center stage. The highly distributed nature of these systems implies that vast amounts of sensitive information are generated and processed at the network edge. Traditional centralized security solutions are no longer sufficient, as they expose data to the risk of interception and misuse while being transmitted to central servers.

FL in this context is a privacy-aware model that stores raw data locally, hence minimizing exposure. This is necessary in the case of privacy-concerned applications such as healthcare and personal mobility. EC also reduces privacy threats by offering localized data analysis and storage. In addition to this, BC technology also optimizes data access control by using smart contracts that apply fine-grained authorization and unalterable audit trails. Together, these technologies ensure a multi-layered defense mechanism that ensures confidentiality of the data but also maintains the usefulness of information in making intelligent decisions.

2. Integrity and authenticity

Authenticity and integrity are necessary to ensure that data, control messages, and AI models in a 6G environment remain tamper-free and authentic. In applications such as autonomous vehicles or real-time diagnosis in healthcare, a slight change in the data or an unauthorized control message can prove catastrophic. Thus, end-to-end data integrity becomes mandatory, which cannot be waived.

BC is one of the key elements of data integrity that maintains a tamper-proof record of all activity, including sensor logs, control messages, and AI model updates. Distributed verification protects against unauthorized updates and traceable entries allow auditing. In addition, attempted tampering is detectable with ease. DTs enable the monitoring of system behavior over time compared to forecast models and raise an alarm in real-time about divergence that may be a sign of data tampering or interference by an adversary. Thus, it can continuously authenticate physical system behavior, detecting anomalies that could be indicators of spoofing or tampering. Furthermore, FL enables model updates to be traced back to source and permits malicious updates to be filtered through reputation mechanisms or Byzantine-resistant aggregation protocols.

3. Availability and resilience

In future 6G systems, continuous availability of services and system fault or attack recoverability are critical to maintain user confidence and system reliability. For mission-critical use cases, e.g., industrial automation, and emergency response applications, service unavailability or reduced quality is unacceptable. Resilience, therefore, must be designed into all facets of the system.

EC naturally enhances availability by distributing processing burdens across localized nodes, minimizing the likelihood of a central point failure. Even in the event of a loss of connectivity with the central cloud, edge nodes can continue to operate independently. Additionally, DTs offer predictive analytics by predicting potential system crashes or cyberattacks ahead of time in the physical world. The distributed nature of BC architecture further strengthens resilience through the guarantee that no single node holds essential data alone. This cooperative synergy ensures that services are robust, self-healing, and can function under stress or in partial system breakdown.

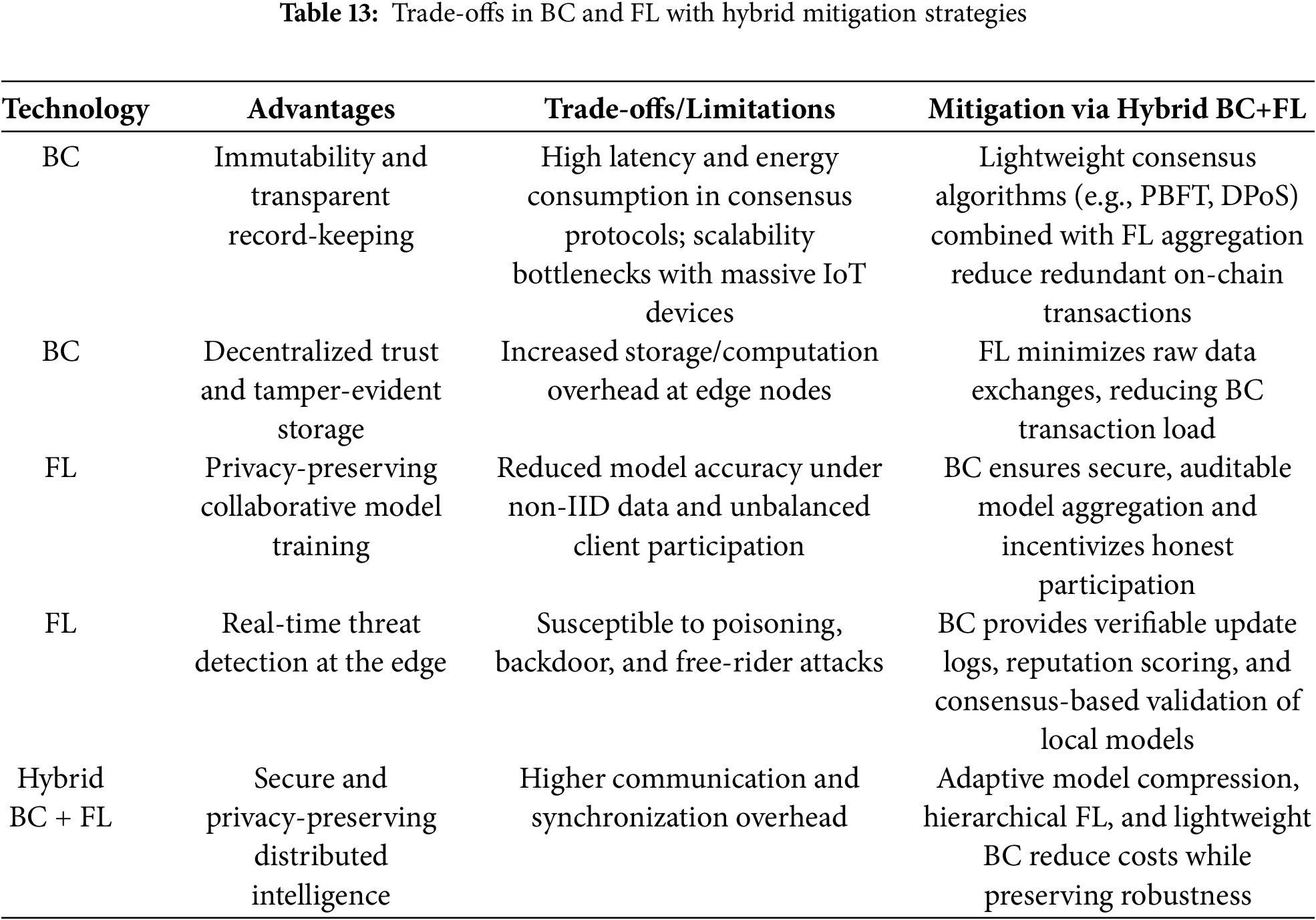

5.4 Trade-Offs in BC and FL for 5G/6G Security