Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Blockchain and Smart Contracts with Barzilai-Borwein Intelligence for Industrial Cyber-Physical System

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University), Banglore, 562112, Karnataka, India

2 Department of Information Technology, Siddhartha Academy of Higher Education-Deemed to be University, Vijayawada, 520007, India

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Dayananda Sagar University, Bengaluru, 562112, Karnataka, India

4 School of Computing, SASTRA Deemed University, Thanjavur, 613401, Tamil Nadu, India

* Corresponding Author: Manikandan Ramachandran. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 36 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071124

Received 31 July 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPSs) play a vital role in modern industries by providing an intellectual foundation for automated operations. With the increasing integration of information-driven processes, ensuring the security of Industrial Control Production Systems (ICPSs) has become a critical challenge. These systems are highly vulnerable to attacks such as denial-of-service (DoS), eclipse, and Sybil attacks, which can significantly disrupt industrial operations. This work proposes an effective protection strategy using an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled Smart Contract (SC) framework combined with the Heterogeneous Barzilai–Borwein Support Vector (HBBSV) method for industrial-based CPS environments. The approach reduces run time and minimizes the probability of attacks. Initially, secured ICPSs are achieved through a comprehensive exchange of views on production plant strategies for condition monitoring using SC and blockchain (BC) integrated within a BC network. The SC executes the HBBSV strategy to verify the security consensus. The Barzilai–Borwein Support Vectorized algorithm computes abnormal attack occurrence probabilities to ensure that components operate within acceptable production line conditions. When a component remains within these conditions, no security breach occurs. Conversely, if a component does not satisfy the condition boundaries, a security lapse is detected, and those components are isolated. The HBBSV method thus strengthens protection against DoS, eclipse, and Sybil attacks. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed HBBSV approach significantly improves security by enhancing authentication accuracy while reducing run time and authentication time compared to existing techniques.Keywords

A blockchain is an immutable distributed ledger that securely records transactions and tracks assets across industrial networks. Traditional industrial security processes are slow and labor-intensive, particularly with increased data exchange, monitoring, and automation. Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPSs) integrate cyber and physical worlds, enabling data-driven, intelligent, and collaborative industrial operations. However, ICPSs are highly vulnerable to attacks, such as DoS, eclipse, and Sybil attacks, making security a major concern.

Blockchain and Smart Contracts offer strong potential for securing [1] Industrial IoT (IIoT) data by ensuring transparency, privacy, and tamper-resistant communication. Existing blockchain-based IIoT approaches improve security and reduce delays; however, they still suffer from limitations such as unaddressed block validation time, inadequate legislative compliance, and inability to minimize runtime or attack success probability [2].

To overcome these issues, this study proposes an Barzilai (HBBSV) method. It aims to reduce runtime, enhance authentication accuracy, and minimize attack success by classifying the component features as secure or insecure. Smart Contracts verify production plant data, whereas the Barzilai–Borwein Support Vectorized algorithm strengthens detection against common attacks.

Main Contributions of HBBSV (Crisp Points)

1. Reduced runtime with lower attack success probability.

2. Smart Contract and blockchain-based verification to speed up authentication and ensure secure condition monitoring in ICPSs.

3. Barzilai–Borwein supports vectorized classification to filter secure components and eliminate insecure components to improve security.

Motivation

This study uses the HBBSV method to classify component features within a production line, thereby improving security, authentication accuracy, and authentication time. As blockchain-based smart contracts face security challenges such as DDoS attacks, this study integrates blockchain and smart contracts to ensure secure and timely access to industrial CPSs.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work, Section 3 presents the HBBSV method, Section 4 discusses experiments and results, and Section 5 concludes the study.

A review of industrial blockchain applications in [3] highlighted security and integrity issues, but many prior studies lacked adequate security and privacy considerations. Two privacy-preserving schemes, DeepPAR and DeepDPA, were introduced in [4] for ICPSs; DeepPAR protects input privacy and update secrecy, while DeepDPA ensures backward secrecy but does not reduce runtime. CPS standards and components have been summarized in [5], although attack detection was missing.

A C2P cyber-physical risk model using Bayesian networks and SHS was proposed in [6]; however, other steady-state methods were not explored. The CPS studies in [7,8] did not address latency. In [9], privacy-preserving ICPSs and blockchain applications (e-government, e-health, cryptocurrencies, smart cities, and cooperative ITS), but did not minimize execution time. IoT–blockchain challenges were reviewed in [10], and storage limitations were overlooked in.

The CPS prototype in [11] faced safety issues owing to its scale and complexity. The safety control tasks in [12] did not reduce subsystem preservation time. Blockchain-enabled Safe-aaS in [13] enhanced security but lacked a hybrid blockchain. IoT dataset sharing for ICPSs in [14] involves third-party risk. AI and Blockchain offer promising solutions to enhance cybersecurity in smart cities were proposed in [15], whereas a blockchain-IIoT framework in [16] omitted data authorization and storage rules. Digital tokens for manufacturing traceability in [17] did not reduce the runtime. A novel pattern of malware validation scheme based on blockchain technology was introduced in [18]. The POMS in [19] ignored anonymity and transparency.

The hybrid machine learning-blockchain approaches performed in [20] to ensures data integrity, secures communication. The PDI security model in [21] identified issues at the process, data, and infrastructure levels, but was not applied to trustworthy industrial AI. The Machine Learning and Blockchain Synergy in [22] for focus on smart contract (SC).

The digital twin studies in [23,24] faced limitations in terms of blockchain suitability and large-scale data handling. A several security challenges in IoT-enabled SG applications to support sustainability [25]. A blockchain-based framework [26] to leverages decentralized security, smart contracts, and edge computing, and cybersecurity in ADN [27].

A blockchain technology with privacy-preserving framework [28] to achieve the required level of security while improving system efficiency. A cyber-security trust model [29] to provides multi-risk protection for secure data transmission in cloud computing. A deepCLG hybrid learning model [30] to improve network intrusion detection systems (NIDSs). A distributed intrusion detection framework [31] based on fog computing.

The weighted and extended isolation forest algorithms [32] for the real-time detection of cyber-attack transactions. An integrated approach using Deep Neural Networks and Blockchain technology (DNNs-BCT) [33] to improve the detection and prevention in IoT environments. An investigative report based on cyber vulnerability detection [34] using AI, ML, and DL. A novel framework [35] to integrates artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and smart contracts. A fully decentralized system based on ethereum smart contracts and Interplanetary File System (IPFS) [36] for IIoT. A Hyperledger Fabric-based blockchain network [37] for EVCSs to mitigate these risks.

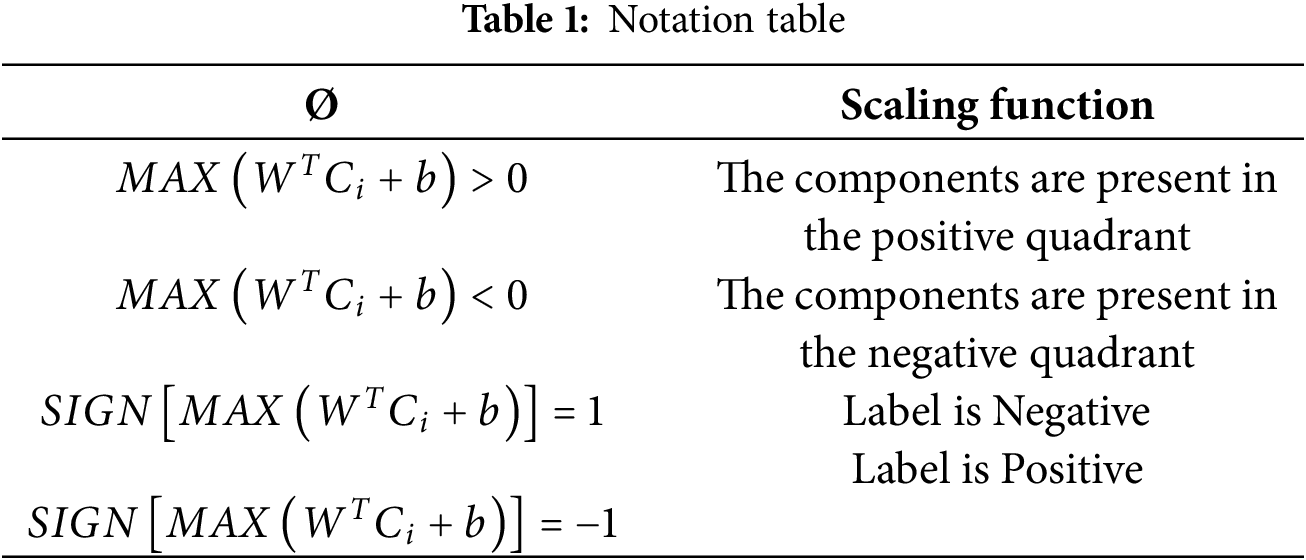

The symbols of

Smart contracts are programs deployed on a blockchain that automatically execute agreement terms when predetermined conditions are met. They remove the need for intermediaries and ensure immediate, trustworthy outcomes. A Cyber-Physical System (CPS) is a computer-controlled system integrating computation with physical processes. CPSs are core components of IIoT and Industry 4.0, enabling real-time intelligent applications through interconnected sensors, aggregators, and actuators. They monitor and manipulate physical objects to create efficient, reliable, and secure smart environments. CPS applications include smart cities, healthcare, manufacturing, transportation and grids. However, connecting cyber and physical layers introduces major security risks. To enhance security, this study proposes a blockchain–smart contract framework that enables secure, tamper-resistant transactions without third parties. The HBBSV method addresses the common attacks.

Sybil attacks: multiple fake identities

Eclipse attacks: isolating a victim node

DoS attacks: overwhelming nodes with traffic

The blockchain serves as a distributed transaction ledger that ensures data integrity. Smart contracts verify the contract execution and support secure on-chain transactions. In this study, on-chain transactions secure industrial CPS data, and the HBBSV smart contract model reduces runtime and lowers attack success probability.

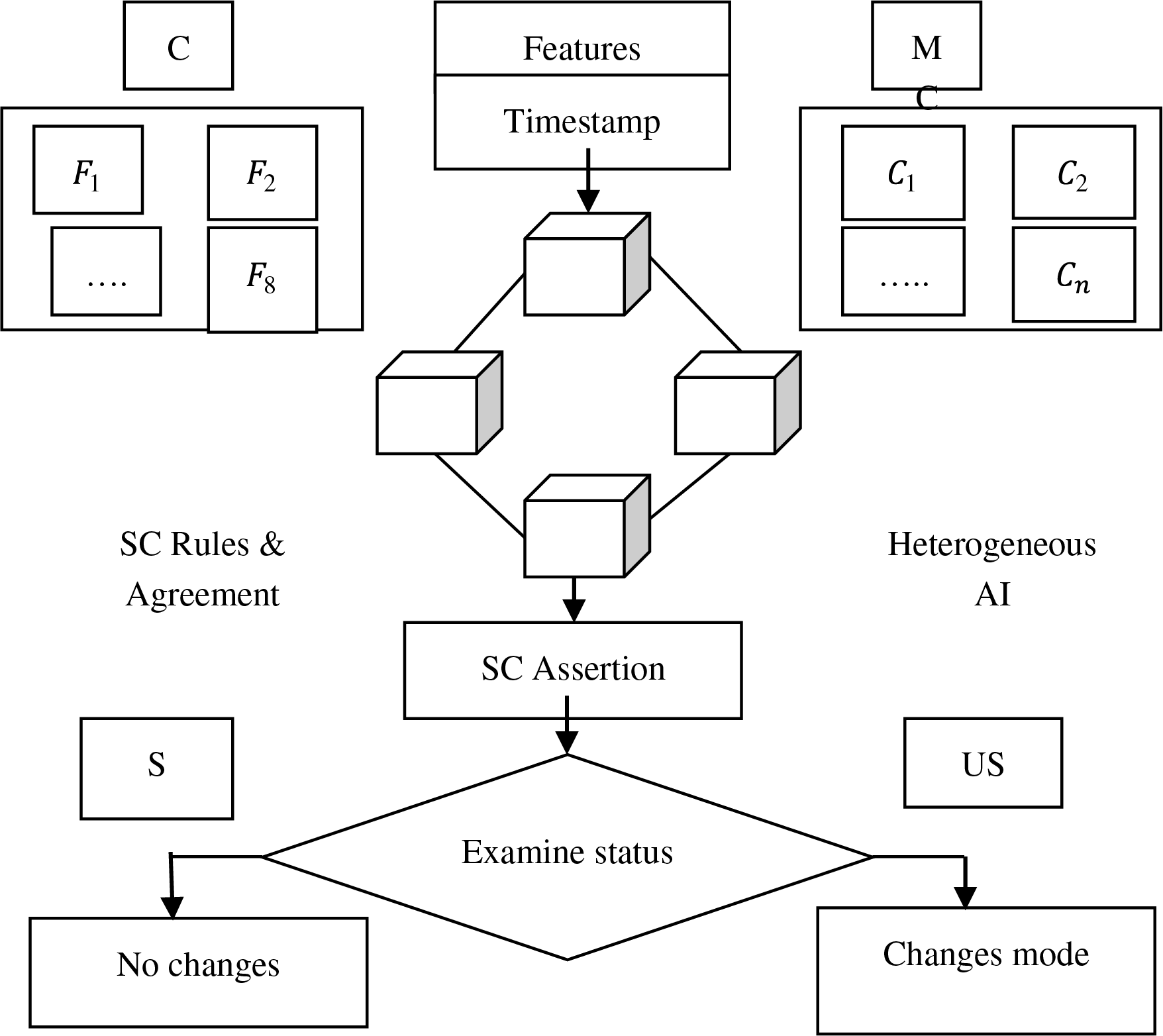

Fig. 1 illustrates HBBSV: manufacturer components (MC) send timestamps and eight predicted features to the blockchain, whereas actual component data (training data) are stored in component C for validation.

Figure 1: Block diagram of HBBSV

The proposed method was applied to two datasets. The first is the production plant data for the condition-monitoring dataset. This dataset was obtained from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/inIT-OWL/production-plant-data-for-condition-monitoring (accessed on 23 November 2025). It includes 8 features. The production plant data for the condition monitoring dataset included the conditions of an important component within the production lines, which is usually not available directly through a sensor and must be derived from a multitude of available signals.

On the other hand, the Versatile Production System dataset obtained from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/inIT-OWL/versatileproductionsystem?resource=download (accessed on 23 November 2025) comprises six features as well as a large number of instances. The number of CSV files obtained in different ways: delivery model, dosing model, Filling_ALL.module.csv, Filling_CapGrabber.module, Filling_CapScrewer.module, Filling_CornPortioning.module, Filling_Pump.module, Production.csv, Storagemodule. The dataset was mainly utilized to produce csv files in 7729 instances and ranged from 100 to 1000 components.

Let us consider the input production plant data for condition monitoring of the respective plants, concentrating on the prediction of the component condition within production lines. These components are mathematically represented as follows.

where, ‘C’ represents the components of interest for condition monitoring; the state of a component is vital for a plant to successfully function and achieve high-quality products. From the input dataset, 8 features ‘

where ‘

On the other hand, production plant data for conditional monitoring are confirmed by admin if

In this ICPS context, BC and SC refer to blockchain and smart contracts, and not social categories. The smart contract (SC) performs both the administrative and conditional checks. It contains Component Functions (CF) and Component Events (CE) at specific blockchain addresses. CF represents the code through which component Ci executes transactions Ti, while CE notifies all components of the system events.

All SC actions are governed by smart contract codes that are visible across the blockchain network, ensuring rule-based trust and transparency. In the proposed method, a single smart contract SC manages component information (SC_C). Each manufacturer interacts with SC_C to enroll the components and update theirfeatures. This unified management reduces inconsistencies and minimizes the probability of attack success.

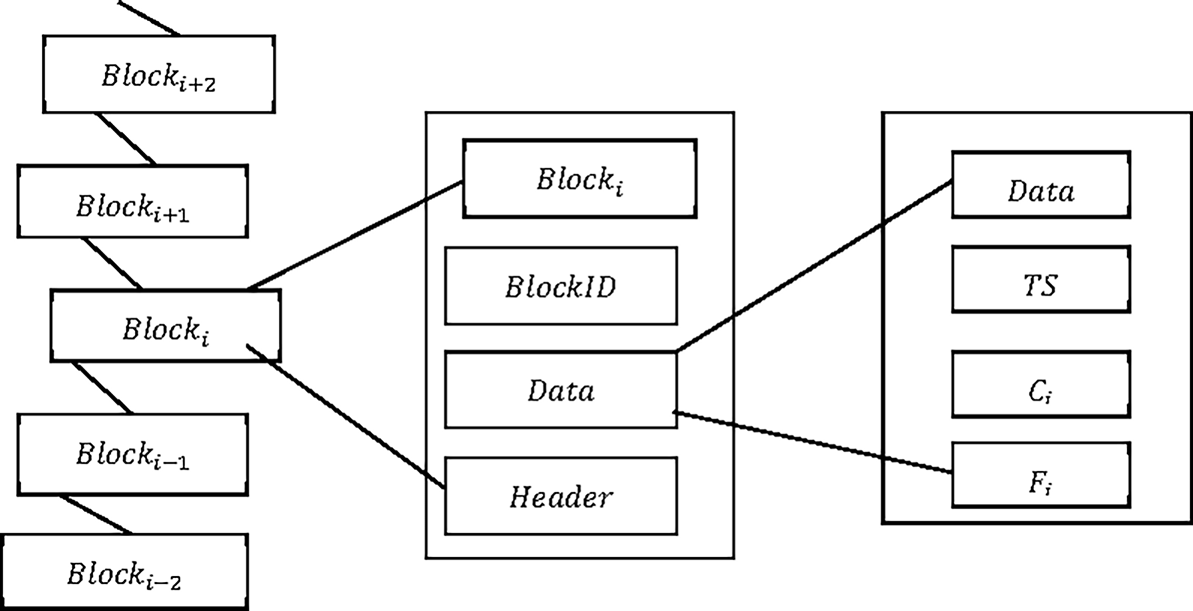

Validating individual blocks with Smart Contracts before adding them to a blockchain is complex and requires an AI-based analysis. Therefore, the Heterogeneous Barzilai–Borwein AI (HBBAI) model was introduced. Fig. 2 shows the block structure used for ICPS condition monitoring, containing data, timestamp (TS), components

Figure 2: Sample block structure for condition monitoring in industrial-based CPS

For this process, a binary-labeled training set of components is defined as

where ‘

where ‘

where the component with maximum ‘

where ‘

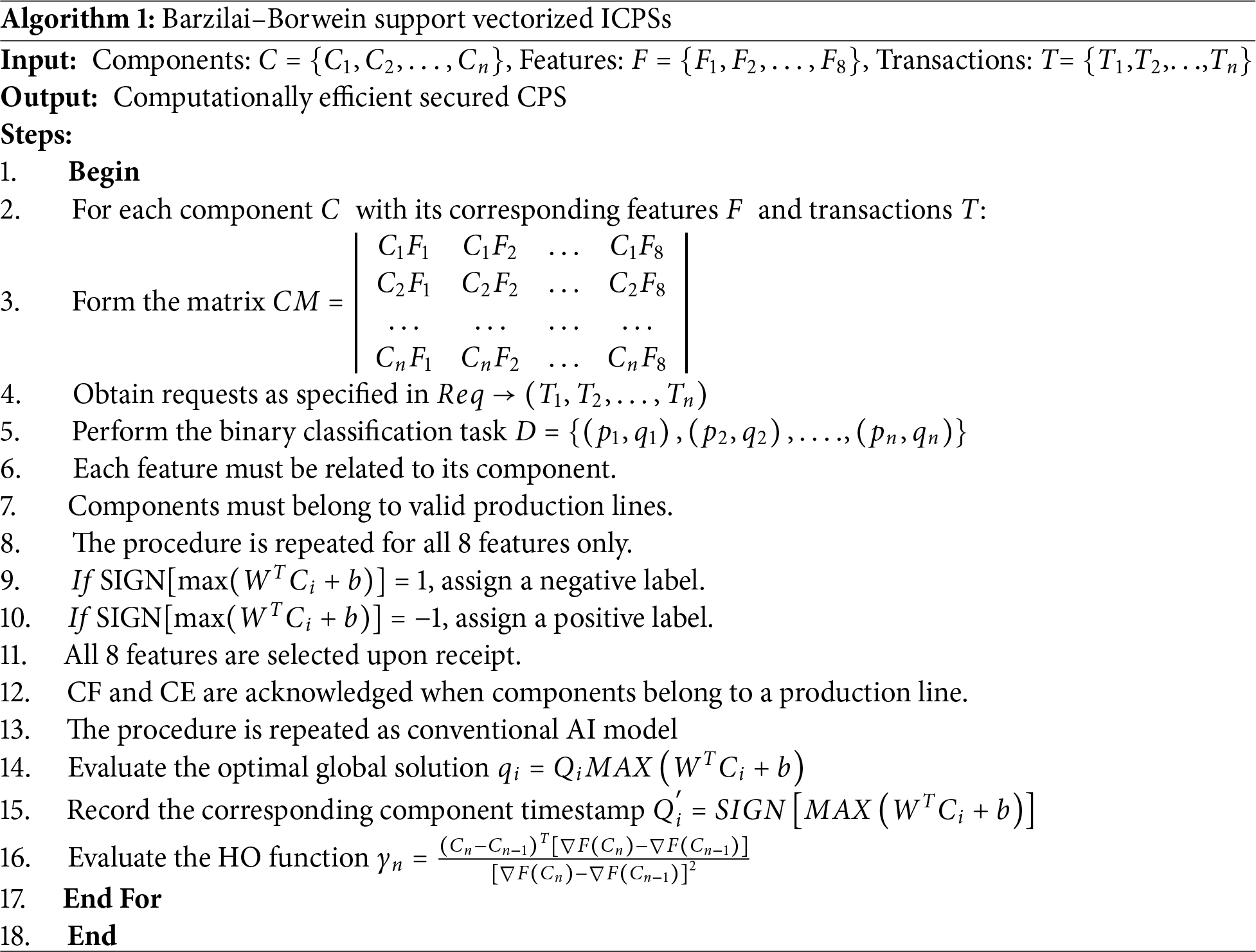

Algorithm 1 uses the Barzilai–Borwein Support Vectorized ICPS to classify components using Smart Contract rules. An iterative hyperplane separates components within and outside the production line. Discarding unsafe components reduces runtime and attack success probability.

The proposed HBBSV method was experimentally evaluated against four existing approaches: blockchain IIoT [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], an energy-efficient framework [20], and IoT-enabled active distribution networks [27]. All methods were implemented in Java and tested on a Windows 10 system with an Intel Core i3-4130 (3.40 GHz) processor, 4 GB of RAM, and 1 TB of storage.

Experiments used two datasets:

• Condition-Monitoring dataset (50–500 components)

• Versatile Production System dataset with six features and 7729 instances (100–1000 components)

The performance was assessed using run time, probability of attack success, authentication accuracy, authentication time, and security.

The results comparing HBBSV with the four baseline methods are presented in tables and graphs, showing the performance across all evaluation metrics.

The runtime is the time required to identify whether the components are within the production lines and is computed as follows:

where the run time ‘

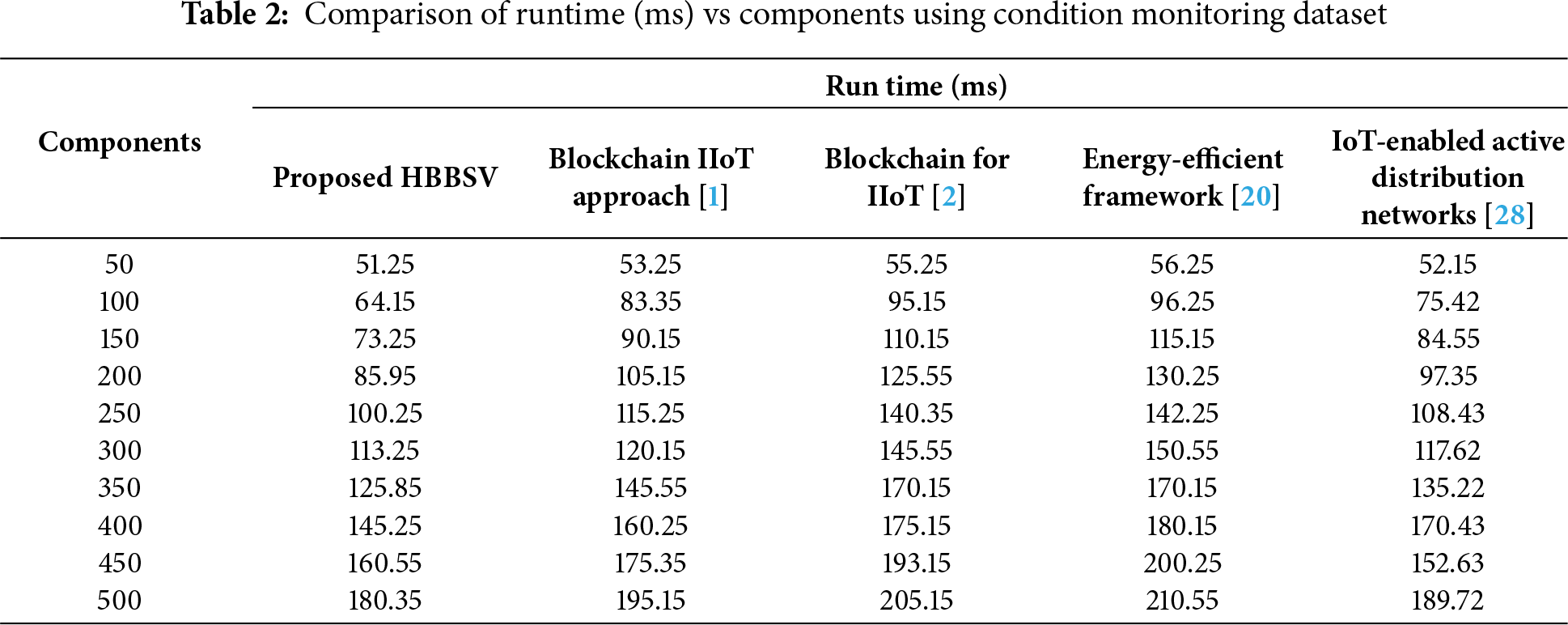

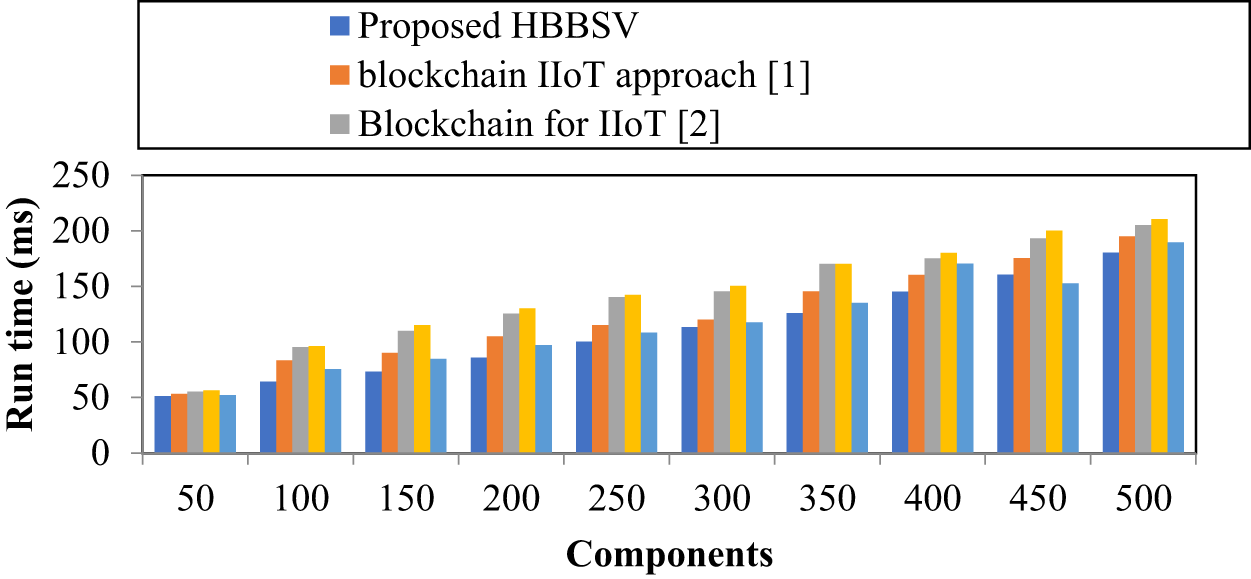

Table 2 and Fig. 3 show that the runtime increases as the number of components (50–500) increases. The proposed HBBSV method achieves a lower runtime than blockchain IIoT [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], energy-efficient framework [20], and IoT-enabled ADNs [27]. For 450 components, HBBSV records 160.55 ms, outperforming the baseline (175.35, 193.15, 200.25, and 152.63 ms). By verifying the component features through BC and SC before processing, HBBSV reduces unnecessary computations. Overall, HBBSV lowered the runtime by 12%, 22%, 17%, and 7% compared to the four existing methods.

Figure 3: Run Time Measurements for Condition Monitoring Dataset [1,2]

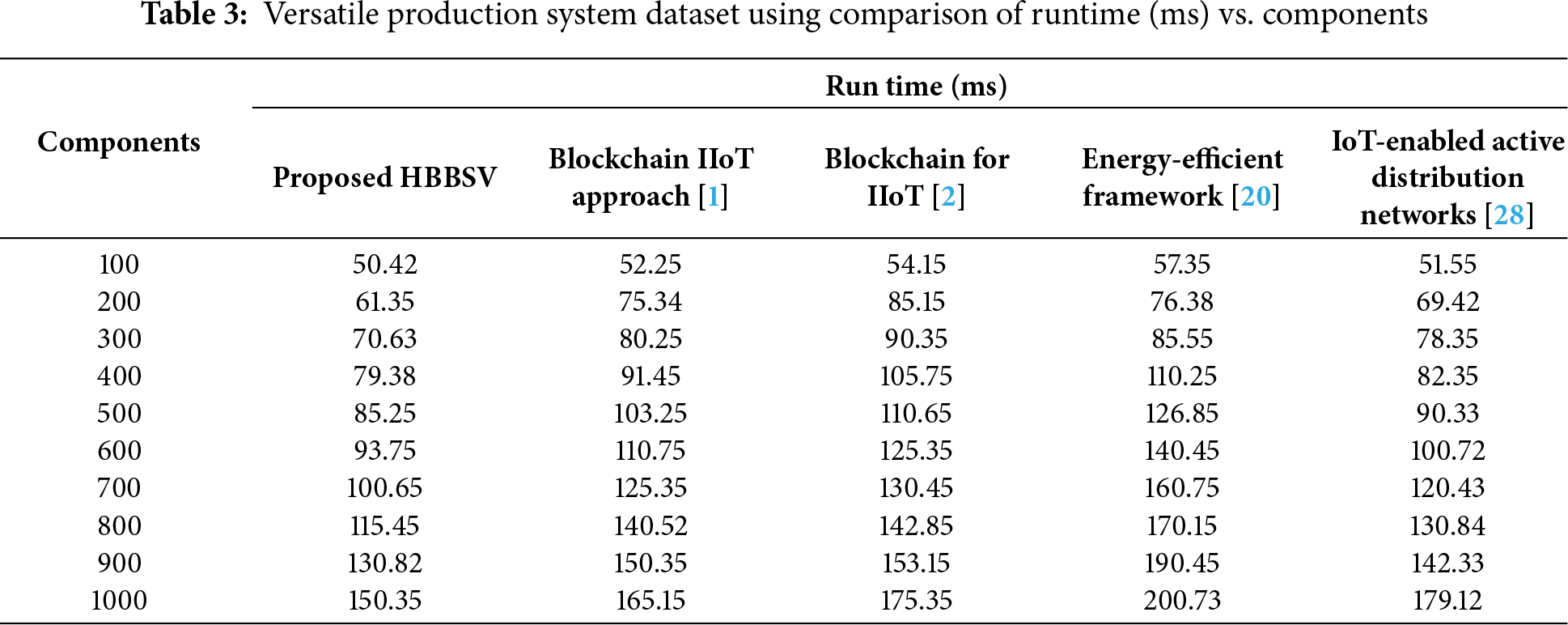

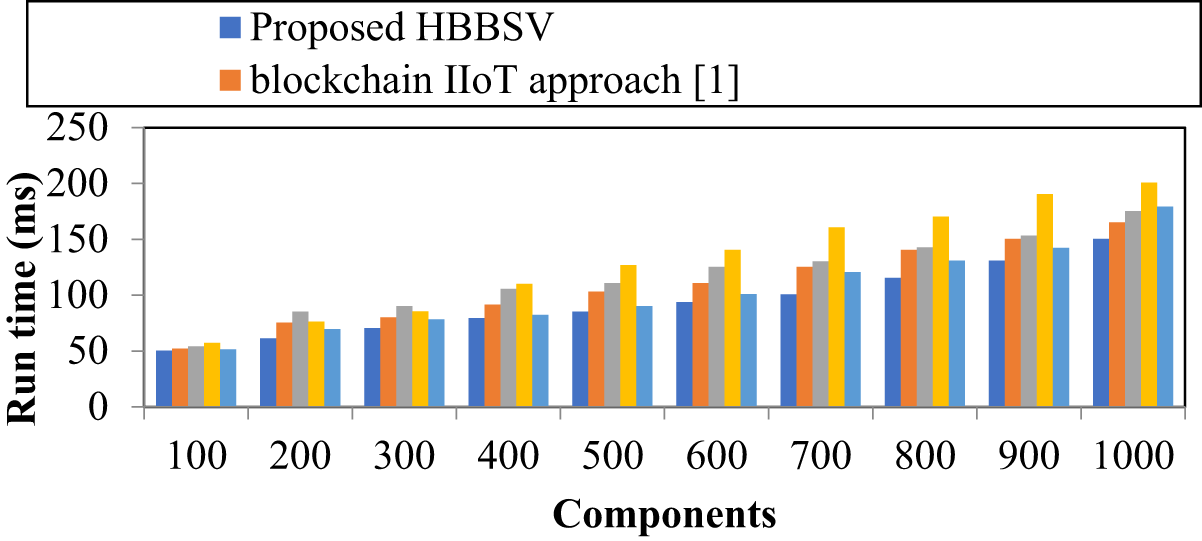

Table 3 and Fig. 4 show that the runtime increases with 100–1000 components, and HBBSV consistently outperforms blockchain IIoT [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], energy-efficient framework [20], and IoT-enabled ADNs [27]. Using BC and SC with six component features, HBBSV achieved significantly lower runtime. Overall, it reduces runtime by 14%, 20%, 26%, and 9% compared to the four existing methods.

Figure 4: Run time measurements for versatile production system dataset [1]

4.2 Probability of Attack Success

An attack is any malicious attempt to harm or access a system, such as through data theft or denial-of-service. The probability of attack success is the percentage of components whose features are compromised among the total components.

where, the probability of attack success ‘

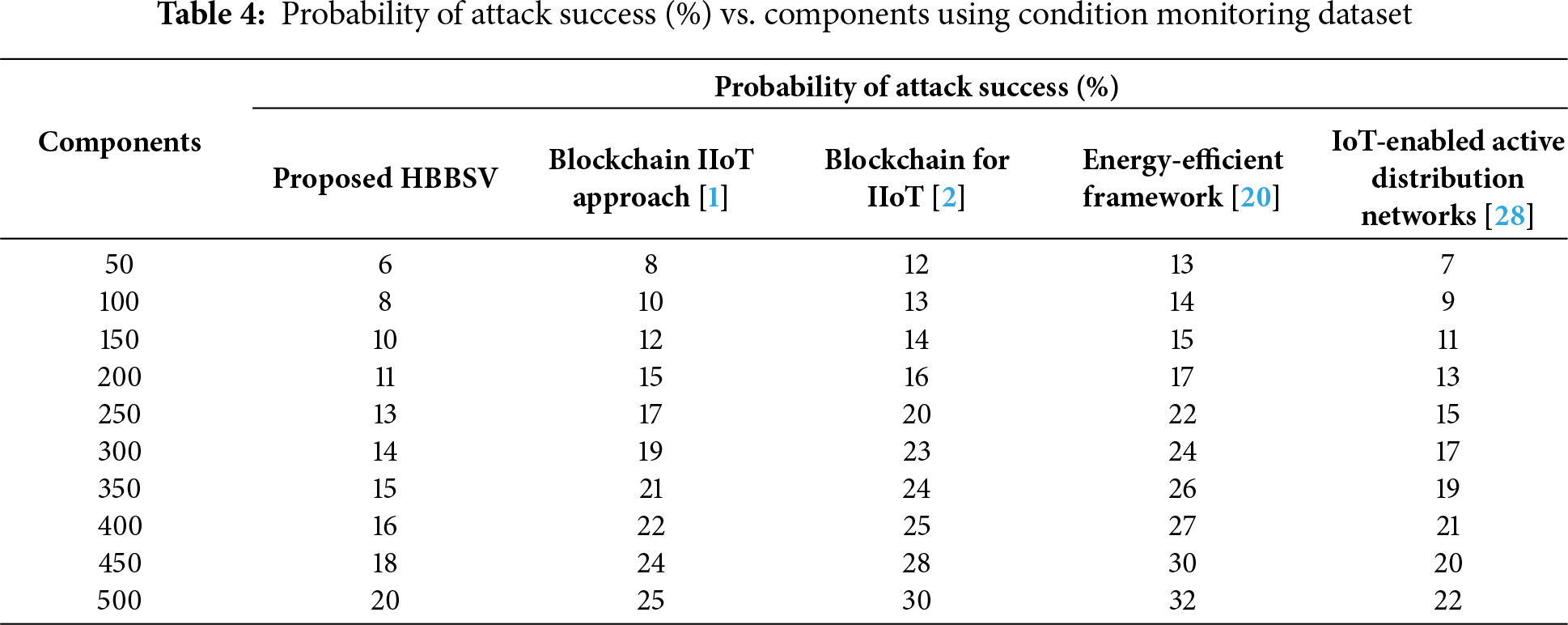

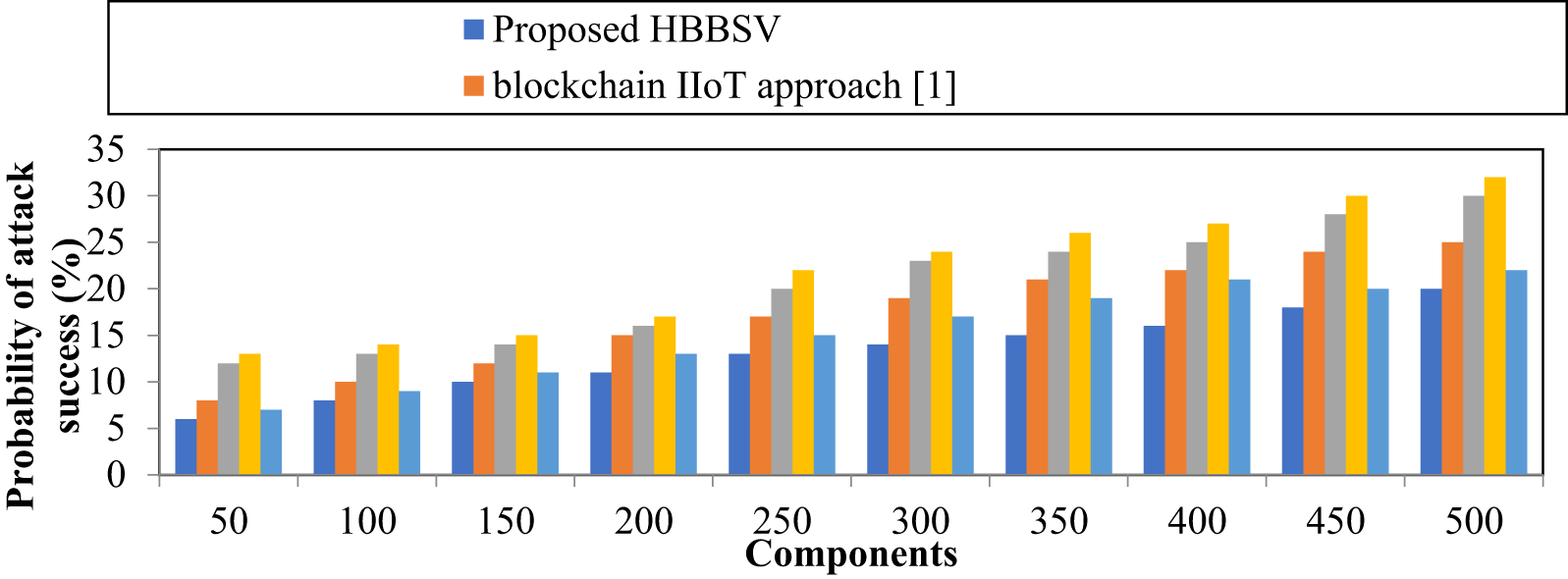

Table 4 and Fig. 5 show the probability of attack success (PAS) for 50–500 components across all methods. With 50 components, HBBSV achieved 6% PAS, which is lower than blockchain IIoT [1] (8%), blockchain for IIoT [2] (12%), energy-efficient framework [20] (13%), and IoT-enabled ADNs [27] (7%). PAS increased as the component count increased, but HBBSV consistently maintained its lowest values.

Figure 5: Probability of Attack Success Measurement for Condition Monitoring Dataset [1]

HBBSV performs better because the Barzilai–Borwein Support Vector algorithm separates compromised and uncompromised features through optimal hyperplane classification, thereby eliminating abnormal components before processing. As a result, HBBSV improves PAS by 24%, 37%, 41%, and 14% compared to methods [1,2,20,27], respectively.

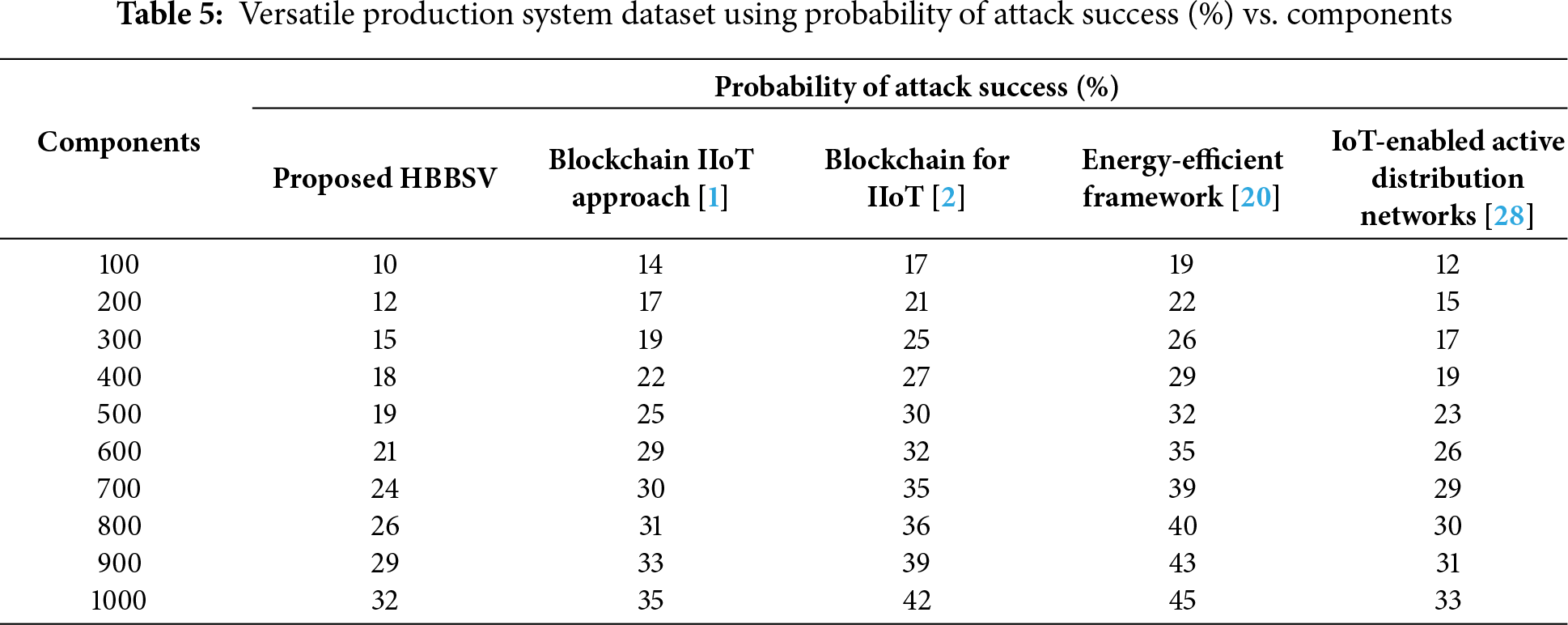

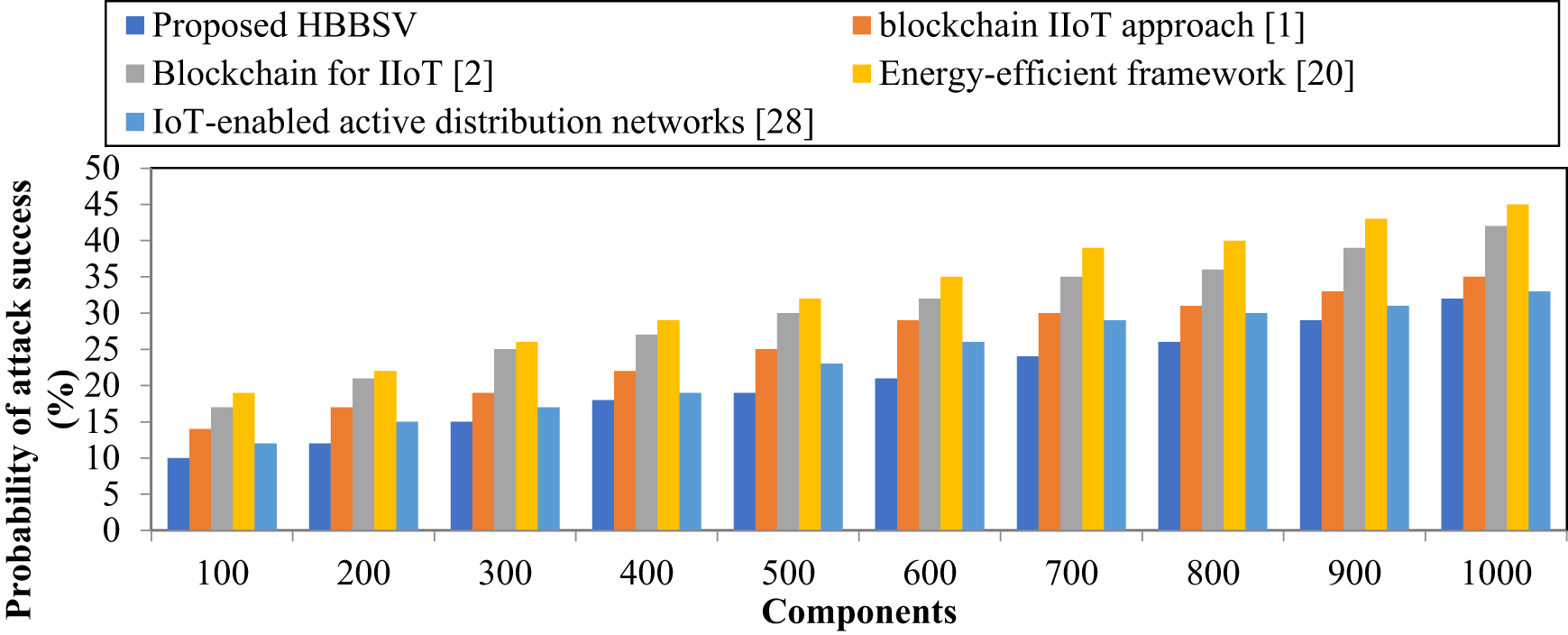

Table 5 and Fig. 6 illustrate the measured probability of attack success using Versatile Production System datasets of the four methods. The components are plotted on the horizontal axis and the probability of attack success is plotted on the vertical axis. As shown in the graphical chart, the blue, brown, green, and violet lines indicate the probability of attack success of the proposed HBBSV, existing [1,2,20,27], respectively. AS a result, the proposed HBBSV method improves the probability of attack success by 21%, 34%, 39% and 13% compared to the existing blockchain IoT approach [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], energy-efficient framework [20] and compared to [27], respectively.

Figure 6: Probability of attack success measurement for versatile production system dataset [1,2,20,28]

Authentication accuracy ‘AA’ is measured as the ratio of the number of component features correctly authorized to the total number of components. AA is expressed as follows:

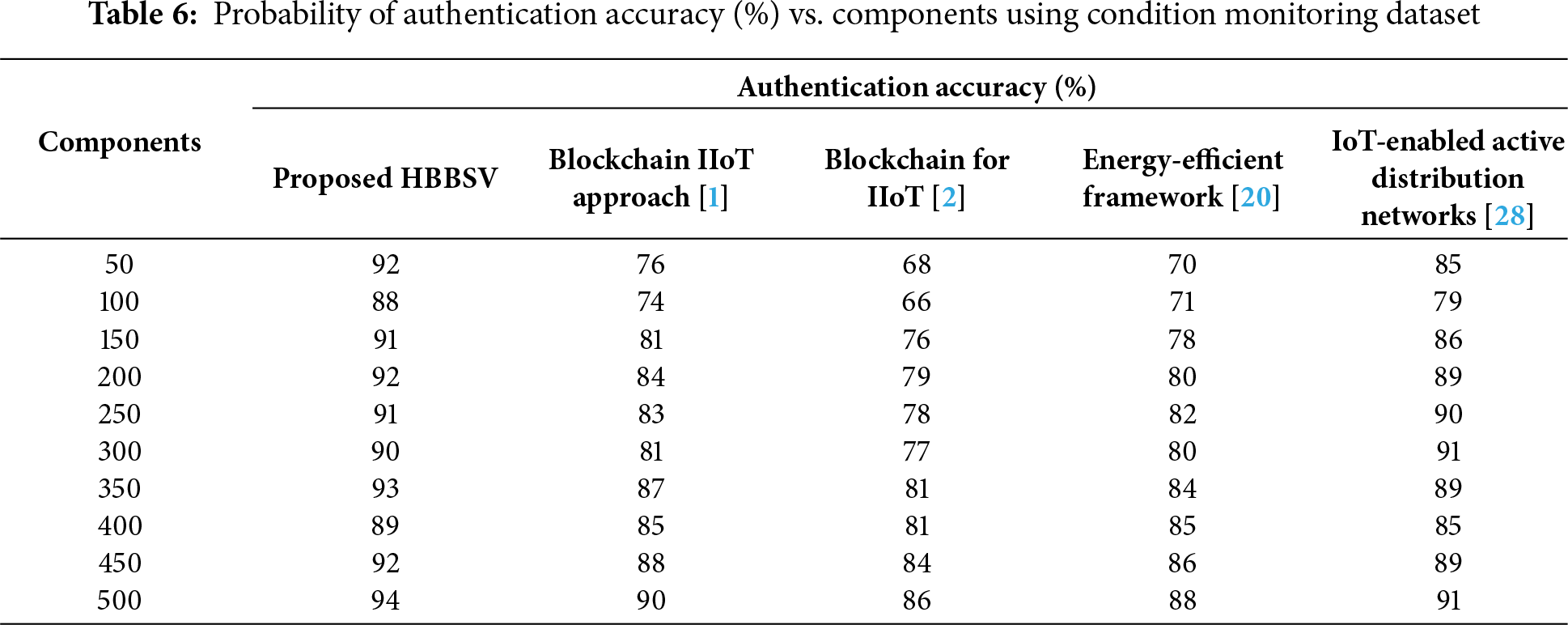

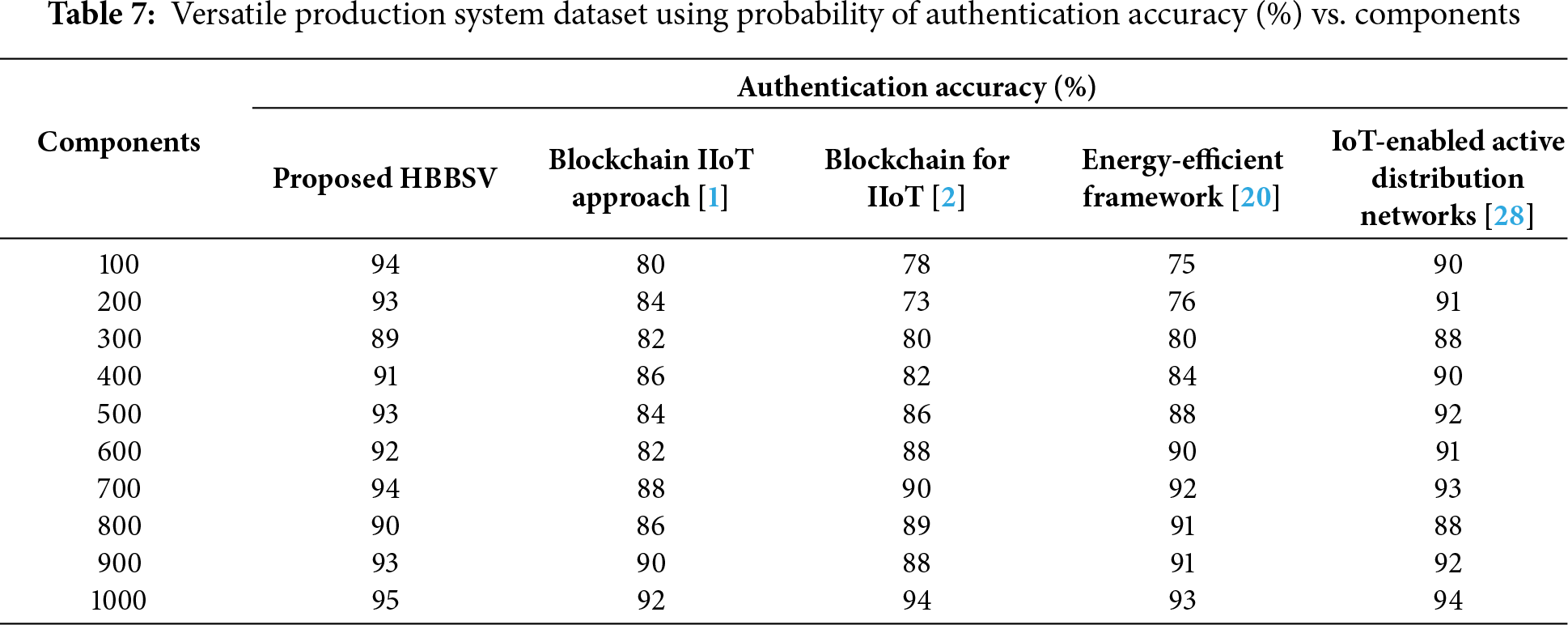

From below Table 6, represents the comparison of authentication accuracy vs. components.

Table 6 and Fig. 7 show that HBBSV consistently achieves the highest authentication accuracy across 50–500 components, outperforming blockchain IIoT [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], energy-efficient frameworks [20], and IoT-enabled ADNs [27]. For 50 components, these methods achieved 76%, 68%, 70%, and 85% accuracy, respectively, while HBBSV reached 92%.

Figure 7: Authentication accuracy measurement for condition monitoring dataset [1,2,20,28]

The Barzilai–Borwein Support Vector algorithm enhances the HBBSV by optimally separating component features through hyperplane classification, retaining valid components, and removing invalid ones. This leads to improved authentication accuracy, with HBBSV outperforming the other four methods by 10%, 18%, 14%, and 4%, respectively.

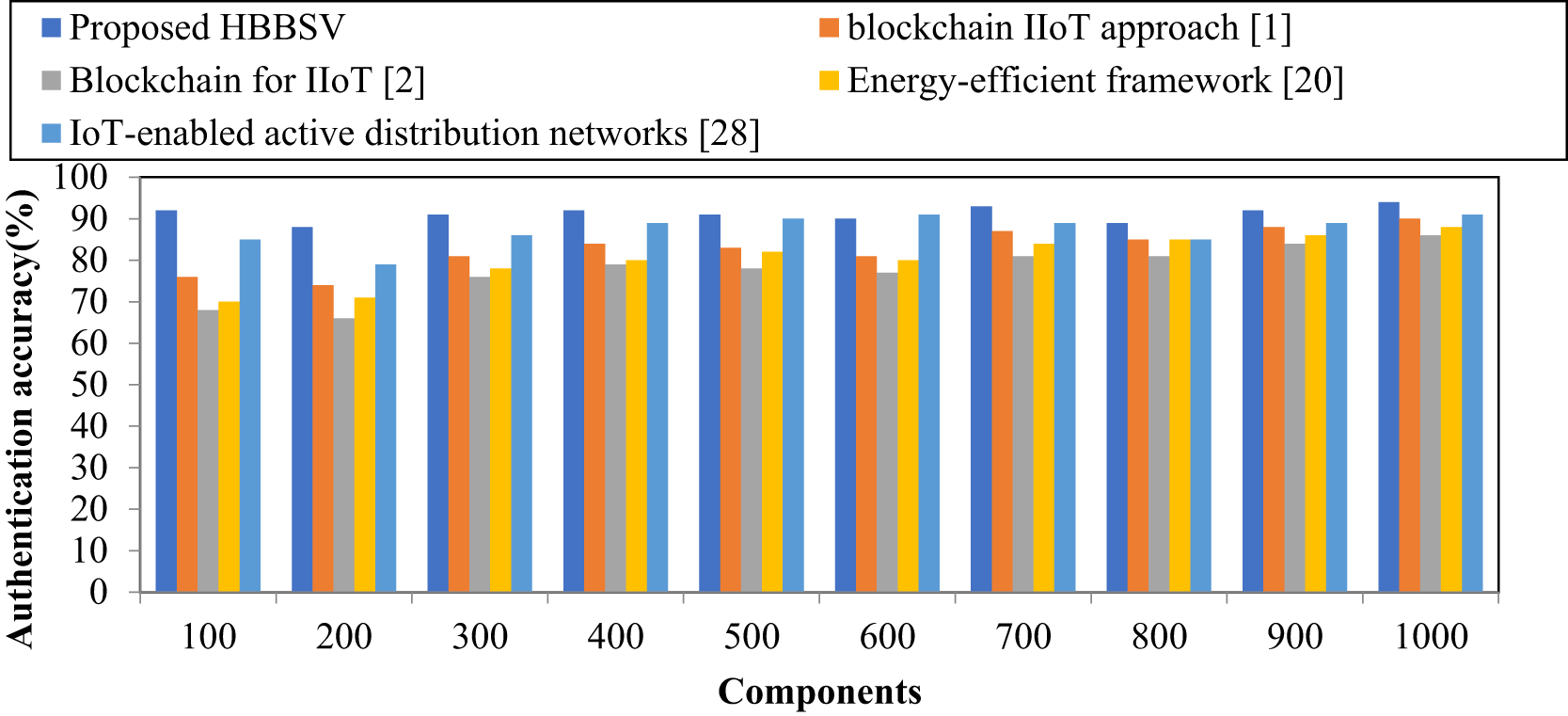

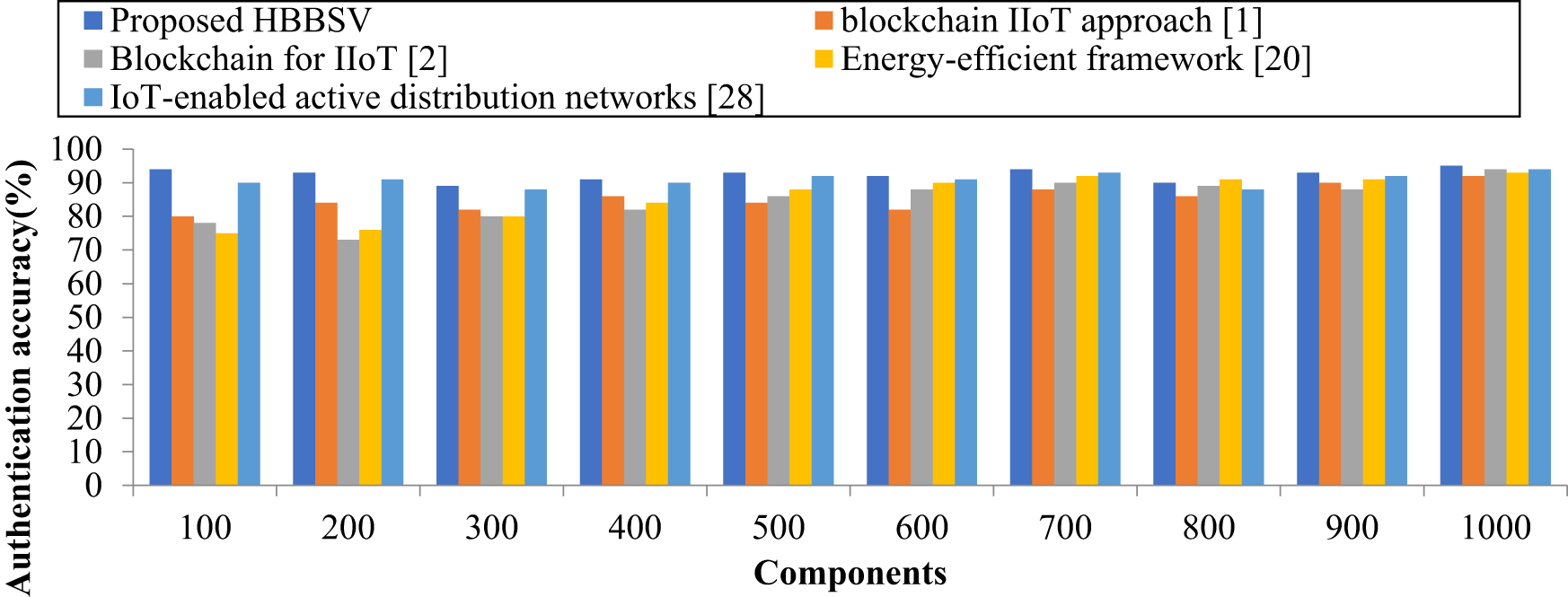

From Table 7 and Fig. 8, a comparison graph for authentication accuracy with different components was obtained. The authentication accuracy results of the proposed HBBSVmethod were compared with those of the existing blockchain IoT approach [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], energy-efficient framework [20], and IoT-enabled active distribution network [27]. Among the four methods, the proposed HBBSV method showed the greatest ability to increase authentication accuracy. To conduct the experiments, 10 iterations were measured for 100–1000 components. In the first iteration with 100 components, the authentication accuracies of [1,2,20,27] improved by 80%, 78%, 75%, and 90%, respectively. In a greater comparison, the HBBSV method further improved authentication accuracy by 94%. Fig. 7 also reveals that as the number of components increases, the proposed HBBSV method continuously produces better authentication accuracy than the other methods. Consequently, the proposed HBBSV method achieved greater authentication accuracy by 9%, 10%, 2%, and 7% compared with the existing blockchain IoT approach [1], blockchain for IIoT [2], energy-efficient framework [20], and IoT-enabled active distribution network [27], respectively.

Figure 8: Authentication accuracy measurement for versatile production system dataset [1,2,20,28]

Authentication time is defined as the amount of time required to identify the compromised component features. AT is mathematically estimated as follows:

where

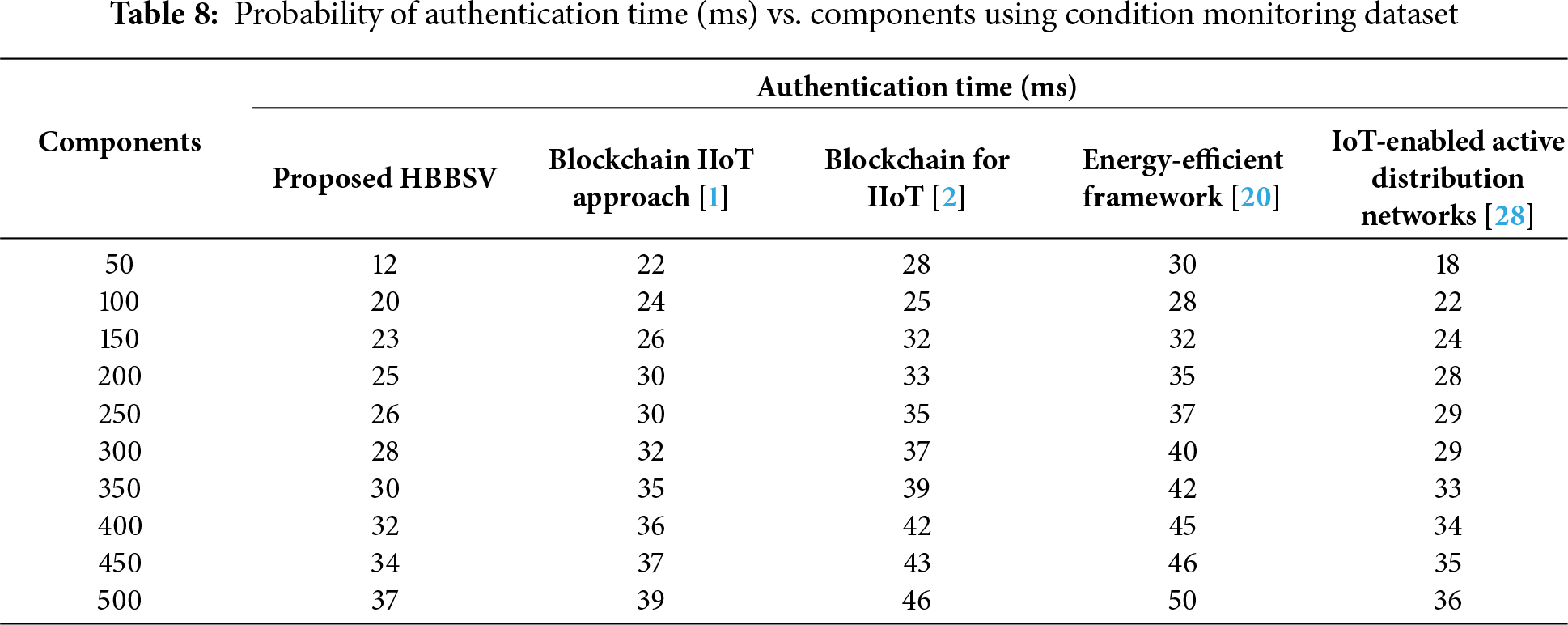

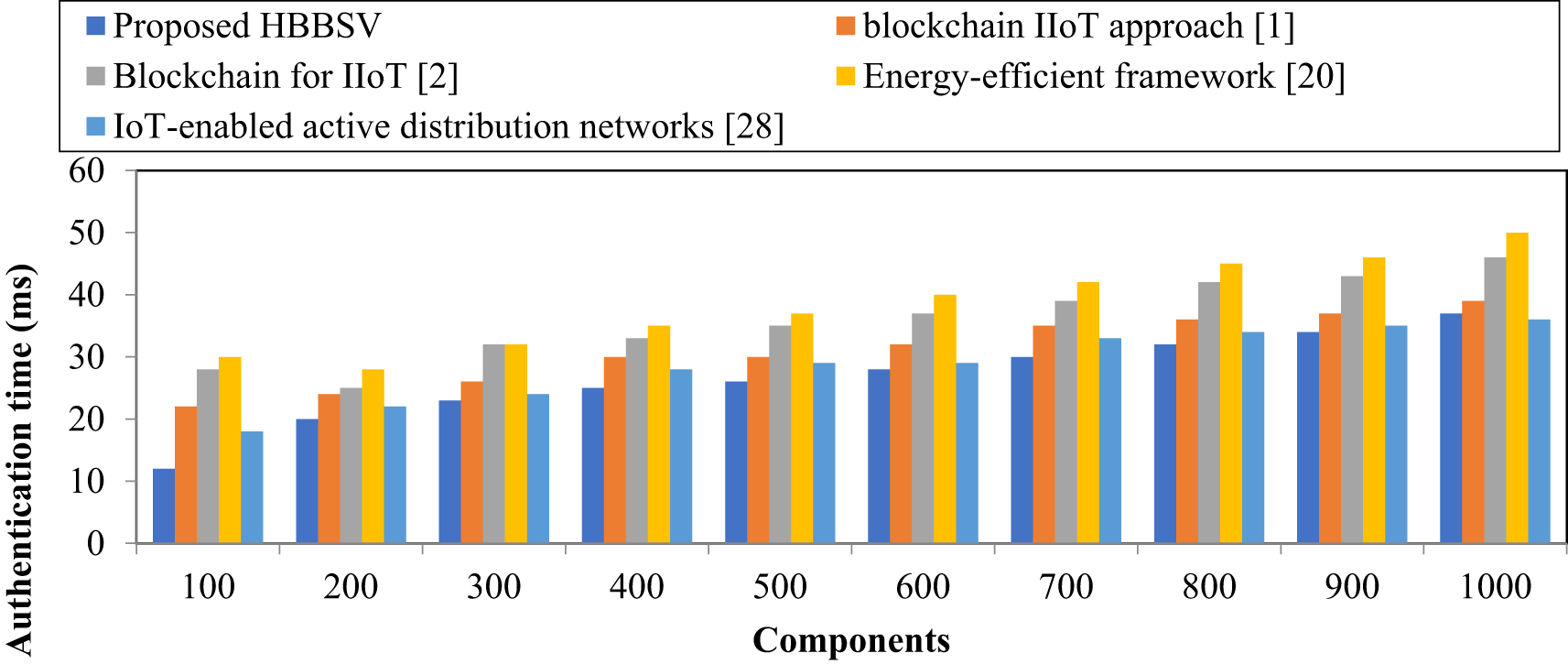

Table 8 and Fig. 9 show that with 100 components, HBBSV achieves an authentication time of 20 ms, which is faster than blockchain IIoT [1] (24 ms), blockchain for IIoT [2] (25 ms), the energy-efficient framework [20] (28 ms), and IoT-enabled ADNs [27] (22 ms). Across all runs, HBBSV remained consistently faster because BC and SC validated components directly through CF and CE, ensuring feature consistency and reducing delays. Overall, HBBSV reduces the authentication time by 16%, 26%, 32%, and 8% compared with the four existing methods.

Figure 9: Authentication time measurement for condition monitoring dataset [1,2,20,28]

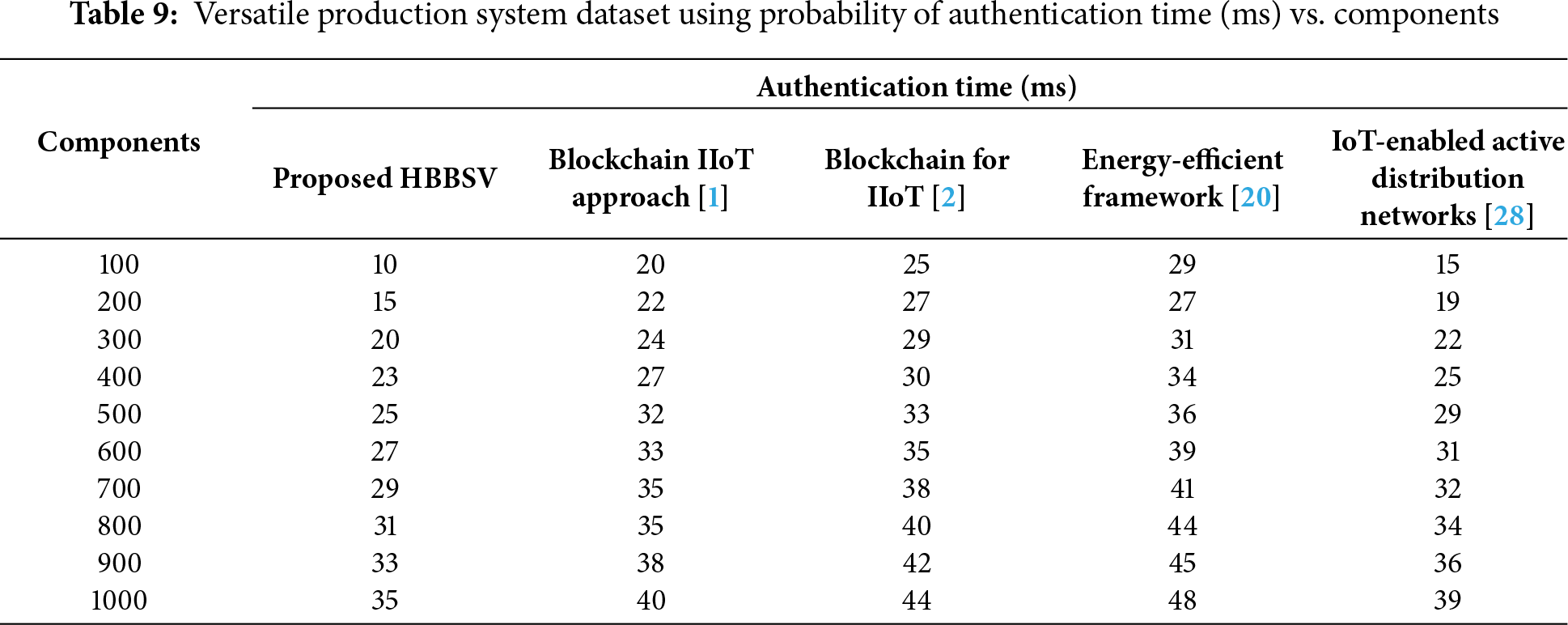

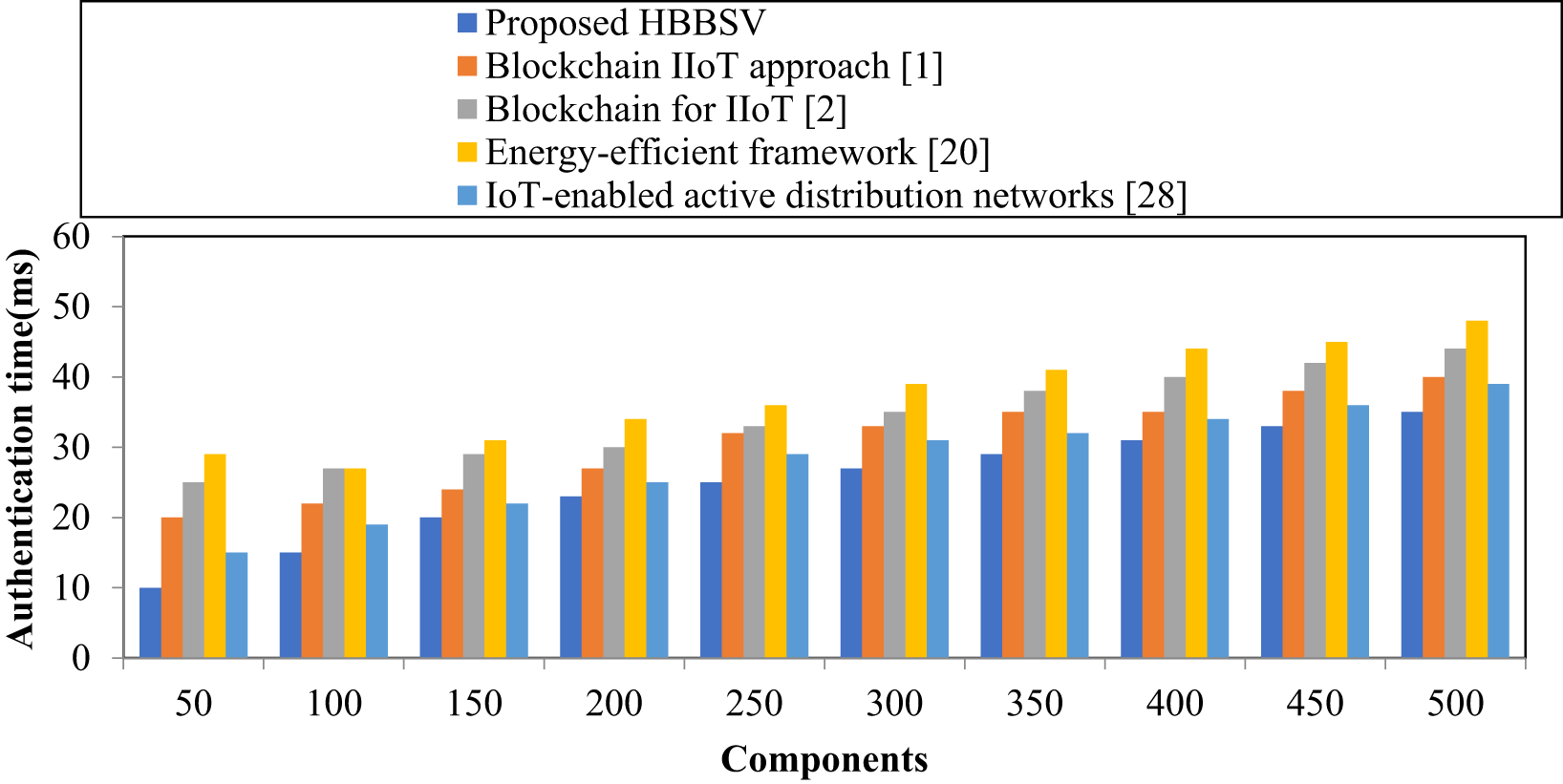

Table 9 and Fig. 10 present the performance results of authentication time for 100–1000 component features. The components are given on the x-axis and the time taken to identify the component features is represented on the y-axis. Ten different results were obtained for the four techniques, which confirms that the HBBSV method utilizes a smaller

Figure 10: Authentication time (ms) for Versatile Production System dataset [1,2,20,28]

Security is defined as the ratio of the number of component features compromised by authentic users without any modification to the total number of components and is mathematically expressed as

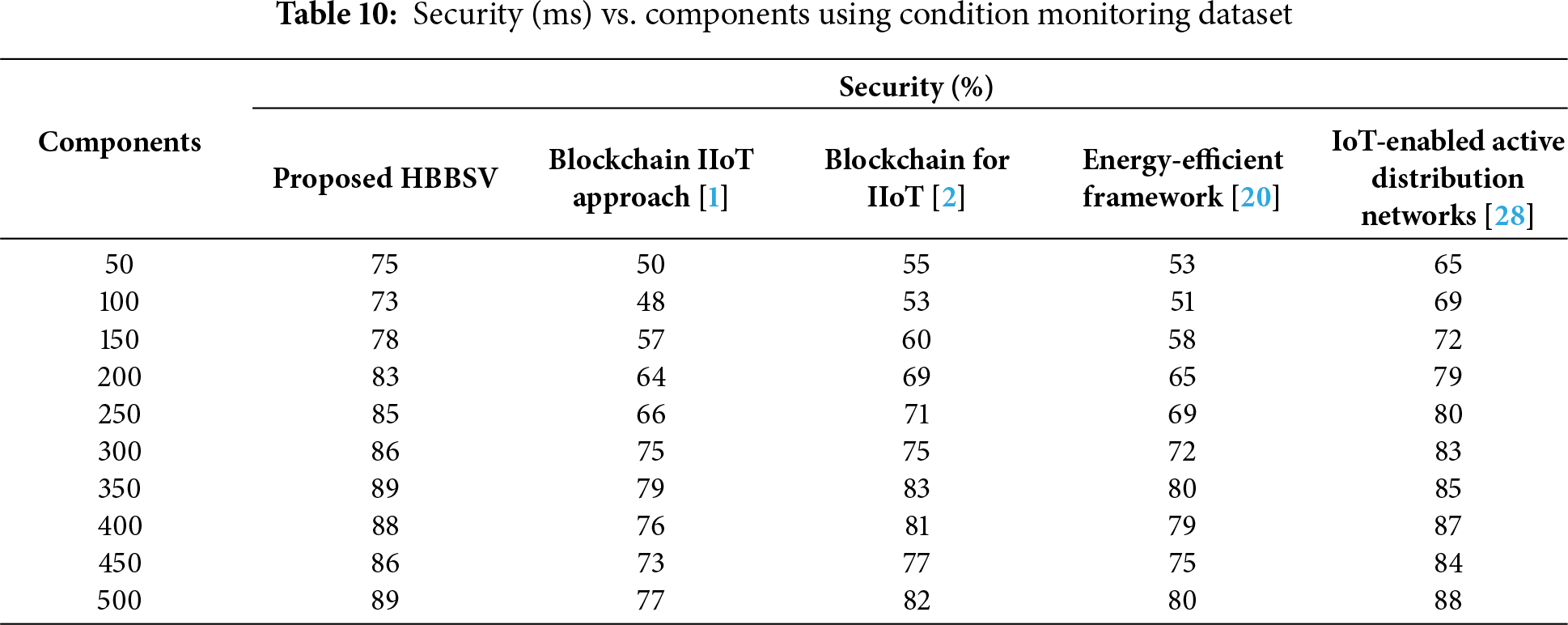

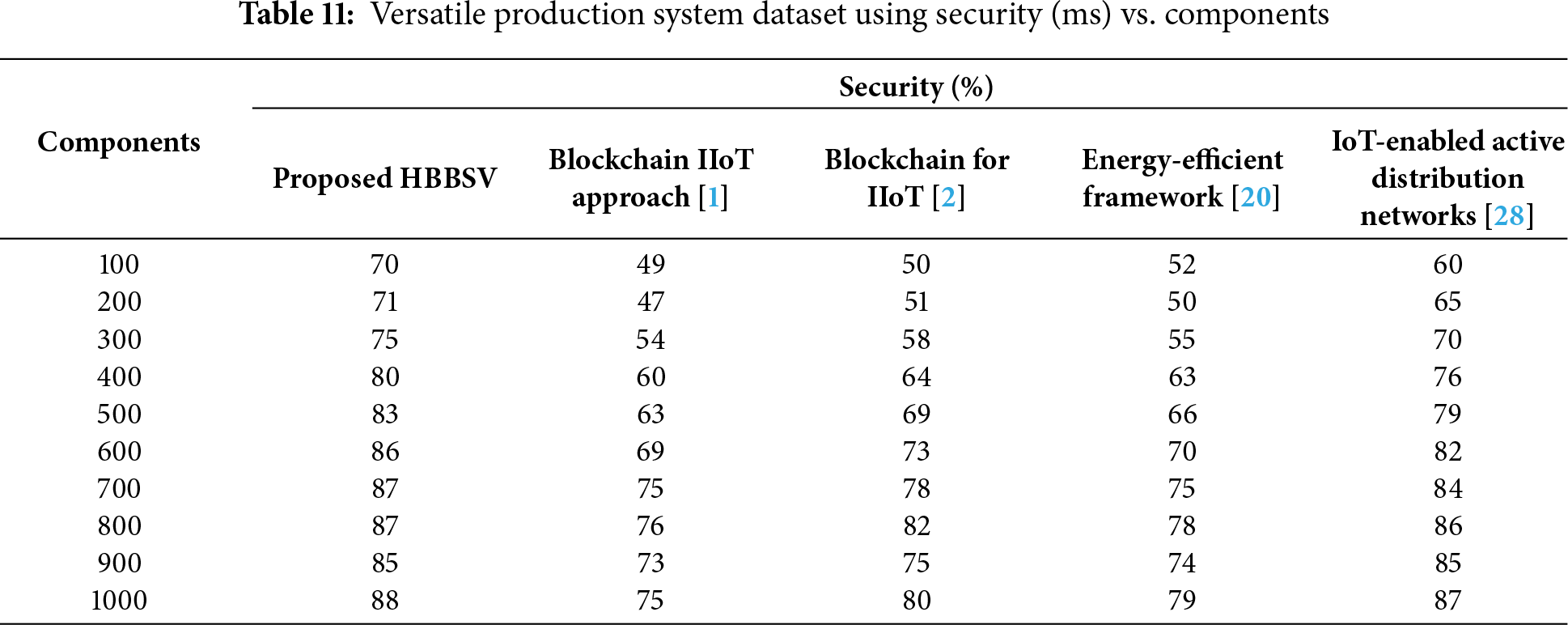

Table 10 and Fig. 11 indicate that HBBSV provides higher security than the four existing methods across 50–500 components. With 50 components, methods [1,2,20] achieved 50%, 55%, and 53% security, respectively, whereas HBBSV reached 75%. For 100 components, HBBSV again led to 73% security. The Barzilai–Borwein SVM improves security by separating the secured and unsecured component features and eliminating the latter. Overall, HBBSV achieves higher security by 28%, 19%, 24%, and 5% compared with methods [1,2,20,27], respectively.

Figure 11: Security measurements for condition monitoring dataset [1,2,20,28]

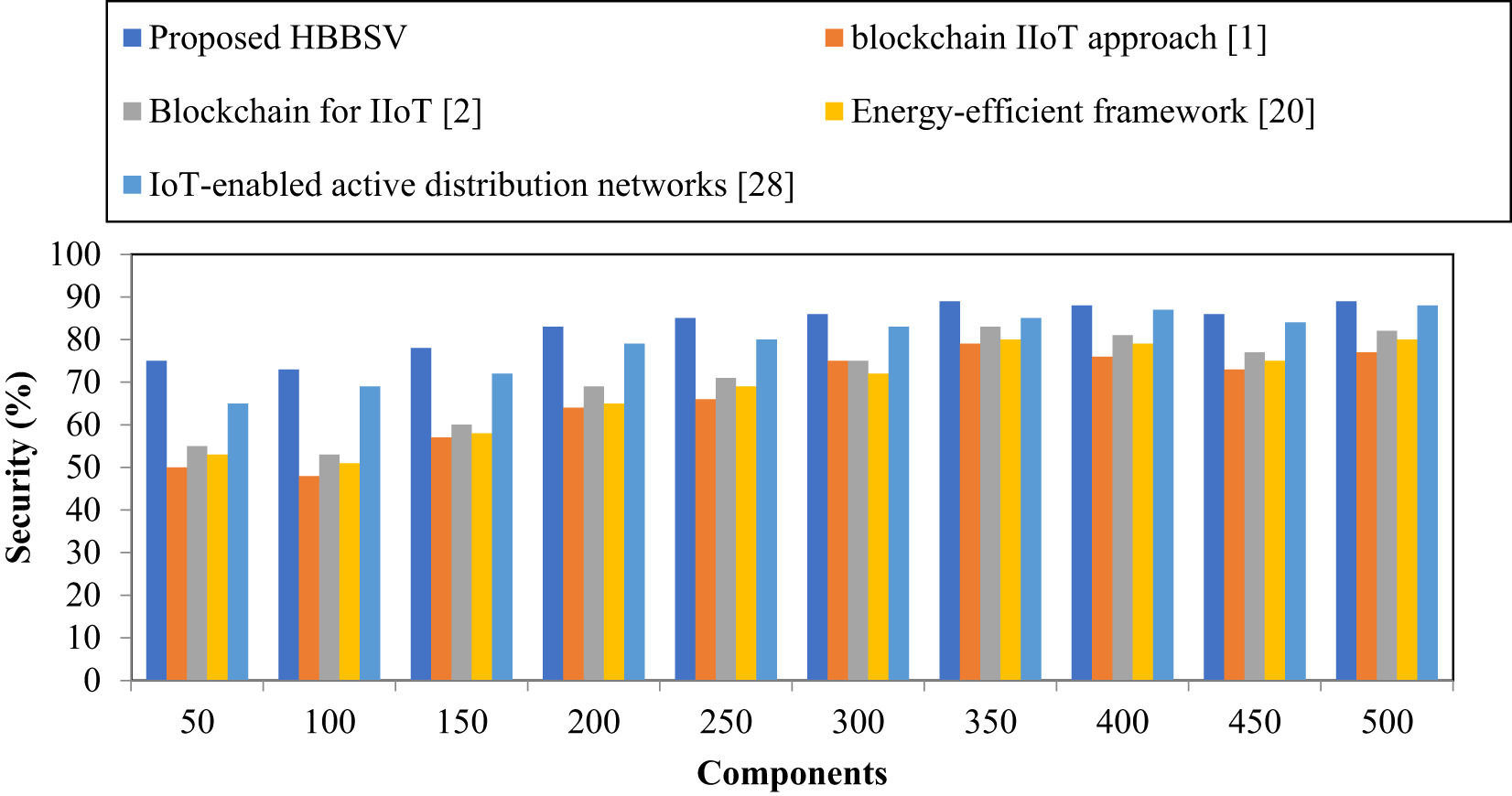

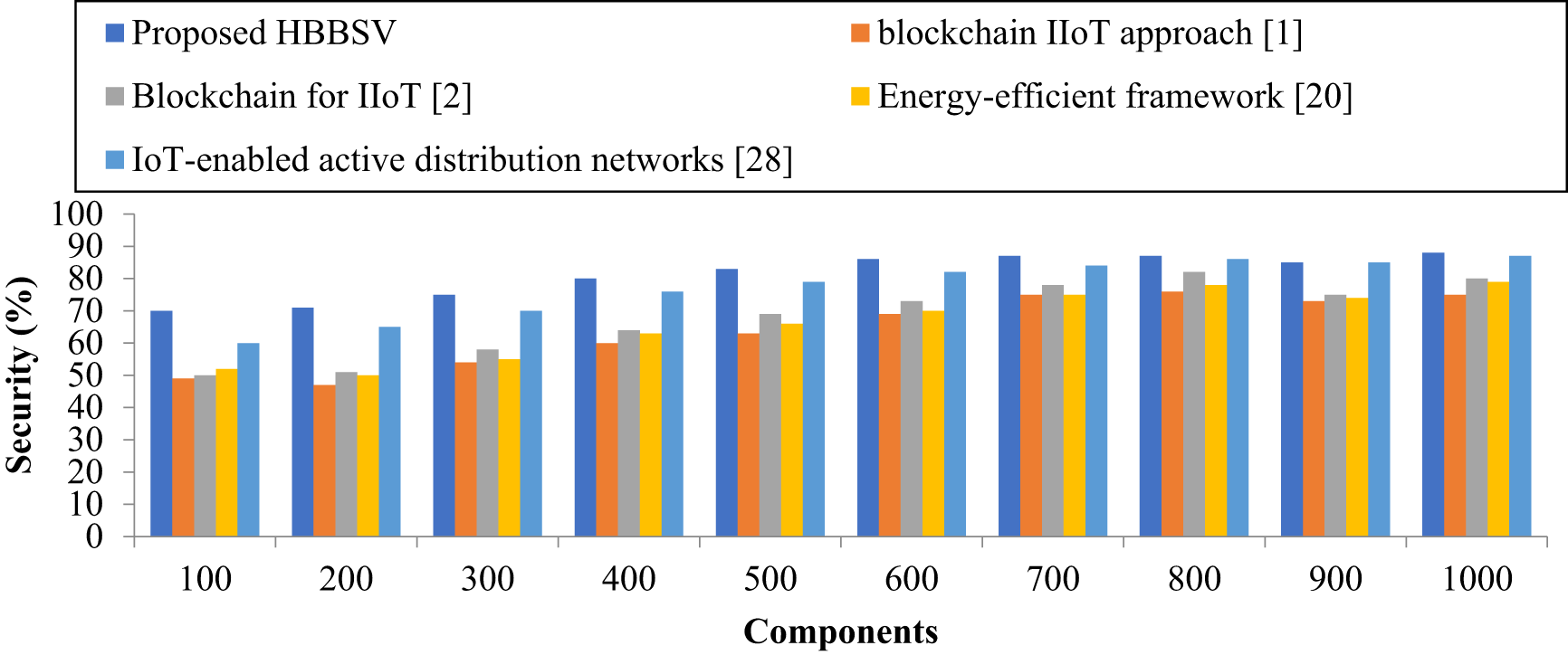

Table 11 and Fig. 12 show that HBBSV consistently provides higher security than all the four existing methods for 100–1000 components. For example, with 100 components, the baselines achieved 49%–60% security, whereas HBBSV reached 70%, and similar gains were observed across all iterations. By removing unsecured features and resisting DoS, Eclipse, and Sybil attacks, or significance tests.

Figure 12: Security measurements for versatile production system dataset [1,2,20,28]

Confidence intervals strengthen the results by showing a range of plausible values for an estimate, providing more insight than a simple yes/no significance test. They quantify precision and uncertainty, indicating the reliability of the findings and whether the effect is practically meaningful. While significance tests show that results are unlikely due to chance, confidence intervals reveal the range in which the true value likely lies.

This work proposes an AI-enabled smart-contract model, the Heterogeneous Barzilai–Borwein Support Vector (HBBSV), to secure ICPSs by reducing runtime and attack success probability. HBBSV uses blockchain and smart contracts to validate component conditions, and applies the Barzilai–Borwein SVM algorithm to detect abnormal features and enforce security rules. Its performance—evaluated through runtime, probability of attack success, authentication accuracy, authentication time, and security—shows significant improvements: with the condition-monitoring dataset, HBBSV achieved higher authentication accuracy (+14%), stronger security (+24%), lower attack success (−11%), reduced runtime (−17%), and shorter authentication time (−27%); with the second dataset, gains included +7% accuracy, +13% security, −27% attack success, −17% runtime, and −19% authentication time. Limitations include communication-based vulnerabilities, lack of unified safety–security analysis, high system complexity, smart-contract immutability, reliance on oracles, and limited legal recognition. Future work will integrate advanced AI-based smart contracts with IoT and blockchain to further enhance security and authentication performance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gowrishankar Jayaraman, Ashok Kumar Munnangi; data collection: Manikandan Ramachandran; analysis and interpretation of results: Ramesh Sekaran, Arunkumar Gopu; draft manuscript preparation: Gowrishankar Jayaraman, Ashok Kumar Munnangi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rathee G, Balasaraswathi M, Chandran KP, Gupta SD, Boopathi CS. A secure IoT sensors communication in industry 4.0 using blockchain technology. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2021;12(1):533–45. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02017-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bai L, Hu M, Liu M, Wang J. BPIIoT: a light-weighted blockchain-based platform for industrial IoT. IEEE Access. 2019;7:58381–93. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2914223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alladi T, Chamola V, Parizi RM, Choo KR. Blockchain applications for industry 4.0 and industrial IoT: a review. IEEE Access. 2019;7:176935–51. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2956748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang X, Chen X, Liu JK, Xiang Y. DeepPAR and DeepDPA: privacy preserving and asynchronous deep learning for industrial IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;16(3):2081–90. doi:10.1109/TII.2019.2941244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Colombo AW, Karnouskos S, Kaynak O, Shi Y, Yin S. Industrial cyberphysical systems: a backbone of the fourth industrial revolution. IEEE Ind Electron Mag. 2017;11(1):6–16. doi:10.1109/mie.2017.2648857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Huang K, Zhou C, Tian YC, Yang S, Qin Y. Assessing the physical impact of cyberattacks on industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2018;65(10):8153–62. doi:10.1109/TIE.2018.2798605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Casino F, Dasaklis TK, Patsakis C. A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: current status, classification and open issues. Telemat Inform. 2019;36:55–81. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2018.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bernal Bernabe J, Canovas JL, Hernandez-Ramos JL, Torres Moreno R, Skarmeta A. Privacy-preserving solutions for blockchain: review and challenges. IEEE Access. 2019;7:164908–40. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2950872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Reyna A, Martín C, Chen J, Soler E, Díaz M. On blockchain and its integration with IoT. Challenges and opportunities. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018;88(3):173–90. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.05.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fernández-Caramés TM, Fraga-Lamas P. A review on the use of blockchain for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access. 2018;6:32979–3001. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2842685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Leitão P, Colombo AW, Karnouskos S. Industrial automation based on cyber-physical systems technologies: prototype implementations and challenges. Comput Ind. 2016;81:11–25. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2015.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jiang Y, Yin S, Kaynak O. Data-driven monitoring and safety control of industrial cyber-physical systems: basics and beyond. IEEE Access. 2018;6:47374–84. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2866403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Roy C, Misra S, Pal S. Blockchain-enabled safety-as-a-service for industrial IoT applications. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2020;3(2):19–23. doi:10.1109/IOTM.0001.1900080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Banerjee M, Lee J, Choo KR. A blockchain future for Internet of Things security: a position paper. Digit Commun Netw. 2018;4(3):149–60. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2017.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Denis A, Thomas A, Robert W, Samuel A, Kabiito SP, Morish Z, et al. A survey on artificial intelligence and blockchain applications in cybersecurity for smart cities. SHIFRA. 2025;2025:1–45. doi:10.70470/shifra/2025/001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao S, Li S, Yao Y. Blockchain enabled industrial Internet of Things technology. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2019;6(6):1442–53. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2019.2924054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Westerkamp M, Victor F, Küpper A. Tracing manufacturing processes using blockchain-based token compositions. Digit Commun Netw. 2020;6(2):167–76. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2019.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abed Mohammed M, Lakhan A, Zebari DA, Ghani MKA, Marhoon HA, Abdulkareem KH, et al. Securing healthcare data in industrial cyber-physical systems using combining deep learning and blockchain technology. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;129:107612. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Production plant data for condition monitoring. [cited 2018 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/inIT-OWL/production-plant-data-for-condition-monitoring. [Google Scholar]

20. Song W, Zhu X, Ren S, Tan W, Peng Y. A hybrid blockchain and machine learning approach for intrusion detection system in industrial Internet of Things. Alex Eng J. 2025;127(1):619–27. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2025.05.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Leng J, Zhou M, Zhao JL, Huang Y, Bian Y. Blockchain security: a survey of techniques and research directions. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;15(4):2490–510. doi:10.1109/TSC.2020.3038641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sghaier R, El Hog C, Ben Djemaa R, Sliman L. Machine learning and blockchain synergy: opportunities and challenges for ML models and smart contracts. Blockchain Res Appl. 2025;2025:100411. doi:10.1016/j.bcra.2025.100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Leng J, Ruan G, Jiang P, Xu K, Liu Q, Zhou X, et al. Blockchain-empowered sustainable manufacturing and product lifecycle management in industry 4.0: a survey. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020;132:110112. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Leng J, Zhang H, Yan D, Liu Q, Chen X, Zhang D. Digital twin-driven manufacturing cyber-physical system for parallel controlling of smart workshop. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2019;10(3):1155–66. doi:10.1007/s12652-018-0881-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mohanta BK, Awad AI, Elsaka T, Kheddar H, Baraka E. Smart-contract-based blockchain-enabled decentralized scheme for improving smart-grid security. Internet Things. 2025;34:101811. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2025.101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Essaid M, Ju H. Blockchain solutions for enhancing security and privacy in industrial IoT. Appl Sci. 2025;15(12):6835. doi:10.3390/app15126835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li Z, Shahidehpour M, Liu X. Cyber-secure decentralized energy management for IoT-enabled active distribution networks. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy. 2018;6(5):900–17. doi:10.1007/s40565-018-0425-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Patil SM, Dakhare BS, Satre SM, Pawar SD. Blockchain-based privacy preservation framework for preventing cyberattacks in smart healthcare big data management systems. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(22):25547–66. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-20109-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Akbar M, Waseem MM, Mehanoor SH, Barmavatu P. Blockchain-based cyber-security trust model with multi-risk protection scheme for secure data transmission in cloud computing. Clust Comput. 2024;27(7):9091–105. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04481-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gulzar Q, Mustafa K. Enhancing network security in industrial IoT environments: a DeepCLG hybrid learning model for cyberattack detection. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2025;16(7):4797–815. doi:10.1007/s13042-025-02544-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kumar P, Kumar R, Gupta GP, Tripathi R. A distributed framework for detecting DDoS attacks in smart contract-based blockchain-IoT systems by leveraging fog computing. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2021;32(6):e4112. doi:10.1002/ett.4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Feng Z, Li Y, Ma X. Blockchain-oriented approach for detecting cyber-attack transactions. Financ Innov. 2023;9(1):81. doi:10.1186/s40854-023-00490-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sathyabama AR, Katiravan J. Enhancing anomaly detection and prevention in Internet of Things (IoT) using deep neural networks and blockchain based cyber security. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):22369. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-04164-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ali Laghari A, Khan AA, Ksibi A, Hajjej F, Kryvinska N, Almadhor A, et al. A novel and secure artificial intelligence enabled zero trust intrusion detection in industrial Internet of Things architecture. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):26843. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-11738-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Alevizos L. Automated cybersecurity compliance and threat response using AI, blockchain and smart contracts. Int J Inf Technol. 2025;17(2):767–81. doi:10.1007/s41870-024-02324-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dwivedi SK, Amin R, Vollala S. Smart contract and IPFS-based trustworthy secure data storage and device authentication scheme in fog computing environment. Peer-Peer Netw Appl. 2023;16(1):1–21. doi:10.1007/s12083-022-01376-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chowdhury A, Shafin SS, Masum S, Kamruzzaman J, Dong S. Secure electric vehicle charging infrastructure in smart cities: a blockchain-based smart contract approach. Smart Cities. 2025;8(1):33. doi:10.3390/smartcities8010033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools