Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Personalized Recommendation System Using Deep Learning with Bayesian Personalized Ranking

1 Department of Software Convergence, Soonchunhyang University, Asan, 31538, Republic of Korea

2 Department of ICT, Ministry of Post and Telecommunications, Phnom Penh, 120210, Cambodia

3 Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Dongguk University, Seoul, 04620, Republic of Korea

4 AI⋅SW Education Institute, Soonchunhyang University, Asan, 31538, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Kyuwon Park. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 60 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071192

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Recommendation systems have become indispensable for providing tailored suggestions and capturing evolving user preferences based on interaction histories. The collaborative filtering (CF) model, which depends exclusively on user-item interactions, commonly encounters challenges, including the cold-start problem and an inability to effectively capture the sequential and temporal characteristics of user behavior. This paper introduces a personalized recommendation system that combines deep learning techniques with Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) optimization to address these limitations. With the strong support of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, we apply it to identify sequential dependencies of user behavior and then incorporate an attention mechanism to improve the prioritization of relevant items, thereby enhancing recommendations based on the hybrid feedback of the user and its interaction patterns. The proposed system is empirically evaluated using publicly available datasets from movie and music, and we evaluate the performance against standard recommendation models, including Popularity, BPR, ItemKNN, FPMC, LightGCN, GRU4Rec, NARM, SASRec, and BERT4Rec. The results demonstrate that our proposed framework consistently achieves high outcomes in terms of HitRate, NDCG, MRR, and Precision at K = 100, with scores of (0.6763, 0.1892, 0.0796, 0.0068) on MovieLens-100K, (0.6826, 0.1920, 0.0813, 0.0068) on MovieLens-1M, and (0.7937, 0.3701, 0.2756, 0.0078) on Last.fm. The results show an average improvement of around 15% across all metrics compared to existing sequence models, proving that our framework ranks and recommends items more accurately.Keywords

In recent years, the rapid growth of digital media platforms has generated an overwhelming amount of content [1]. Services like Spotify, Apple Music, Netflix, and YouTube offer users access to millions of songs, movies, and videos, making it increasingly difficult to find content that truly matches personal preferences [2,3]. Recommendation systems play an important role in assisting users in navigating large catalogs and finding items they are likely to enjoy based on their past activity. Traditional recommendation systems rely on two types of feedback (implicit and explicit), and the hybrid that combines both [4]. Explicit feedback refers to direct user input, such as giving ratings or marking likes. Implicit feedback, on the other hand, is inferred from user actions like listening to songs, skipping tracks, adding items to playlists, clicking links, or browsing content. Although implicit feedback is more common, it poses challenges because it doesn’t clearly express user sentiment, making it harder to interpret true preferences. Among the existing approaches, CF is widely used for its ability to identify patterns among users with similar interests [5]. CF methods are typically divided into two types: user-based, which recommend items liked by similar users, and item-based, which suggest items similar to those a user has already interacted with [6]. However, CF still struggles with several issues, such as the cold-start problem (when dealing with new users or items), data sparsity, and scalability to large datasets [7]. In addition, most CF techniques do not capture the temporal dynamics of user behavior.

To overcome these challenges, deep learning has emerged as a strong alternative. Models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are known for learning sequential patterns and long-term dependencies, making them suitable for predicting a user’s next action [8]. This study proposes a new personalized recommendation system that combines deep learning with Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) optimization. The model uses an LSTM network with an attention mechanism to focus on the most important parts of a user’s interaction history. This design allows the system to capture dynamic user behavior and predict future interactions more accurately.

To further personalize recommendations, we include contextual embedding layers for both item sequence data and user demographic features (such as gender, age, occupation, and country (for music dataset)). For implicit feedback optimization, we apply BPR, which uses pairwise ranking loss to distinguish between positive (observed) and negative (unobserved) items in a user’s history. The combination approach has improved the precision of Top-K recommendations, even in sparse data conditions and cold-start scenarios. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• We propose a personalized recommendation system that use deep learning models and BPR optimization to capture both temporal patterns and user context.

• Our approach utilizes hybrid user feedback, demographic information, and sequential item behavior, enabling it to outperform traditional methods even under sparse data, large-scale setting and cold-start conditions.

• Moreover, we conduct extensive experiments using the Last.fm and MovieLens datasets, and compare our model with well-known baselines including Popularity, ItemKNN, FPMC, LightGCN, GRU4Rec, NARM, SASRec, and BERT4Rec. Using evaluation metrics such as HitRate, NDCG, MRR, and Precision, our model consistently achieves superior performance, particularly in recommendation tasks.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews key concepts and related literature. Sections 3 and 4 describe the proposed methodology and model architecture. Section 5 explains the experimental setup, datasets, and evaluation metrics. Section 6 presents and discusses the results in comparison with baseline models. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions to further enhance recommendation systems.

Recommendation systems have advanced rapidly in recent years, driven by the growing need for personalized experiences across data-rich domains such as music streaming, video platforms, and e-commerce [9]. This section provides an overview of key developments in CF methods that use both implicit and explicit feedback, as well as progress in deep learning–based and sequence-aware recommendation models using context information of the users. We also discuss the main strengths and limitations of these approaches to position our proposed model within the broader research landscape.

2.1 Collaborative Filtering with Hybrid Feedback

Collaborative filtering (CF) remains a fundamental approach in recommendation systems, relying on user–item interactions to uncover hidden preference patterns. It assumes that users with similar behaviors are likely to share similar interests. CF is generally divided into two main strategies: user-based methods, which recommend items liked by users with comparable histories, and item-based methods, which suggest items similar to those already consumed by the target user. For example, Ref. [10] proposed a neighborhood-based movie recommendation method that combines user- and item-based CF using a nearest-neighbor algorithm, resulting in more personalized recommendations. Despite its wide adoption, CF faces key challenges such as data sparsity—where users interact with only a small subset of available items—and the cold-start problem, which arises when new users or items have insufficient interaction history. To address these issues, matrix factorization (MF) techniques have gained considerable attention. Ref. [11] introduced Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), which decomposes the user–item interaction matrix into latent features that capture hidden patterns, improving scalability and prediction accuracy in large datasets. The SVD++ extension further enhances this approach by integrating both explicit feedback (e.g., ratings) and implicit signals (e.g., clicks or listens), leading to better performance when explicit data is limited.

Similarly, Ref. [12] proposed the Alternating Least Squares (ALS) algorithm for matrix factorization, which iteratively updates user and item latent matrices using least squares optimization. ALS is particularly effective for large-scale datasets, especially in domains dominated by implicit feedback such as music streaming and e-commerce. Ref. [13] investigated the use of Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs) to probabilistically model user–item interactions through a two-layer undirected graphical structure representing explicit ratings. Although RBMs showed promise, their effectiveness is still constrained by data sparsity and cold-start issues. Ref. [14] introduced Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR), a pairwise learning framework specifically designed for implicit feedback settings, where positive user–item interactions are ranked higher than unobserved ones. However, traditional CF methods—including BPR—often overlook the sequential nature of user preferences and fail to model the temporal order of interactions. This limitation motivates our approach, which integrates BPR with sequence-aware deep learning models.

2.2 Deep Learning in Recommendation Systems

Deep learning has significantly advanced the field of recommendation systems by overcoming key limitations of traditional collaborative filtering (CF), particularly its difficulty in modeling non-linear relationships and handling data sparsity [15]. The surge in data availability, along with progress in computational power, has made deep learning a vital tool for capturing complex patterns in user behavior.

For example, Ref. [16] introduced the Wide & Deep model for Google Play recommendations, which combines a linear “wide” component for memorizing feature associations with a deep neural network that generalizes across unseen feature combinations. This hybrid structure effectively learns both low- and high-order interactions, leading to improved recommendation accuracy. Building on this idea, Ref. [17] proposed DeepFM, which replaces the linear part of Factorization Machines with a deep neural network to capture complex non-linear feature interactions. DeepFM has proven especially effective in high-dimensional tasks such as Click-Through Rate (CTR) prediction, widely used in advertising and digital media.

To address the cold-start problem, Ref. [18] combined collaborative filtering with deep learning by integrating deep autoencoders and SVD++ to model evolving user preferences and dynamic item features. By including content-based feature information, this model achieves more accurate rating predictions for new items, even in sparse data settings. Similarly, Ref. [19] introduced Neural Matrix Factorization (NeuMF), which merges Generalized Matrix Factorization (GMF) with a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to jointly learn linear and non-linear user–item interactions. NeuMF effectively captures complex behavioral patterns, making it well-suited for large-scale implicit feedback scenarios.

In addition, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been applied to integrate richer contextual information, such as user reviews or multimedia content. For instance, Ref. [20] developed a CNN-based model that combines user–item interaction matrices with review text through hierarchical feature representation, improving the understanding of user preferences in e-commerce environments. Building on these advancements, our model employs LSTM networks and an attention mechanism to capture detailed sequential dependencies, enhancing personalization and improving the overall accuracy of recommendations through deep learning–based techniques.

2.3 Sequence-Based Recommendation Systems

Traditional recommendation models are effective at capturing users’ long-term interests but often struggle to adapt to short-term, context-specific behaviors. In real-world scenarios such as session-based e-commerce or music streaming, it is crucial to understand how user preferences change within short interaction periods to provide timely and relevant recommendations. Instead of relying solely on historical data, sequence-based recommendation systems are designed to model the temporal order and transitions in user behavior. These systems aim to predict the next item a user is likely to interact with by leveraging recent activity patterns, effectively capturing both short-term interests and the evolving context of user choices.

Ref. [21] introduced Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which use memory cells and gating mechanisms to capture long-term dependencies within sequences. LSTMs have proven effective in domains such as music recommendation, where sequential context is important; however, they face limitations related to high training costs and computational complexity. To address these challenges, Ref. [22] proposed GRU4Rec, which applies Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) for session-based recommendation. GRUs simplify the LSTM architecture and enable more efficient modeling of temporal dependencies in dynamic environments such as e-commerce and music platforms, particularly when user identification is unavailable. Ref. [23] introduced SASRec, a self-attentive sequential recommendation model based on transformer architecture, which selectively attends to key previous items. SASRec outperforms RNN-based models in both computational efficiency and recommendation accuracy for session-based contexts. The integration of attention mechanisms has further strengthened sequential modeling by emphasizing the most relevant user–item interactions. Building on this, Ref. [24] proposed Neural Attentive Session-based Recommendation (NARM), which combines GRUs with an attention mechanism to highlight important session items, thereby improving the representation of short-term user preferences.

Additionally, Ref. [25] explored deep reinforcement learning combined with collaborative filtering to enhance movie recommendations by dynamically adapting to user feedback during sequential decision-making. This approach models user behavior in terms of state, action, and reward, optimizing long-term recommendation accuracy. Similarly, Ref. [26] introduced a contextual attention model that integrates sequential data with user demographics (such as age and gender) to weight past interactions based on user characteristics. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that attention mechanisms enhance the encoding of sequential information while helping to address challenges such as the cold-start problem and recommendation diversity. Building on these advances, our proposed model integrates LSTM with attention mechanisms to jointly capture both evolving and long-term user interests, enabling more personalized and effective Top-K recommendations.

The main goal of this study is to develop a personalized recommendation system that can predict which items a user is most likely to engage with, based on their past interaction sequences and contextual information. This problem is framed as a sequence modeling task that incorporates both personalization and contextual awareness. Furthermore, the proposed approach must address the cold-start problem, which arises when new users or items have little to no interaction history, making it difficult to generate accurate and meaningful recommendations. Formally, the recommendation problem can be defined as follows:

Given a dataset of user interactions

where

To accurately capture user preferences and item characteristics, the model considers both sequential patterns in user–item interactions and rich contextual information, including user demographics (such as gender, age, occupation, and country) and item metadata (e.g., movie genres). When interaction history is limited, the model mitigates the cold-start problem by leveraging these demographic features to generate more relevant and personalized recommendations.

4 Proposed Personalized Recommendation System

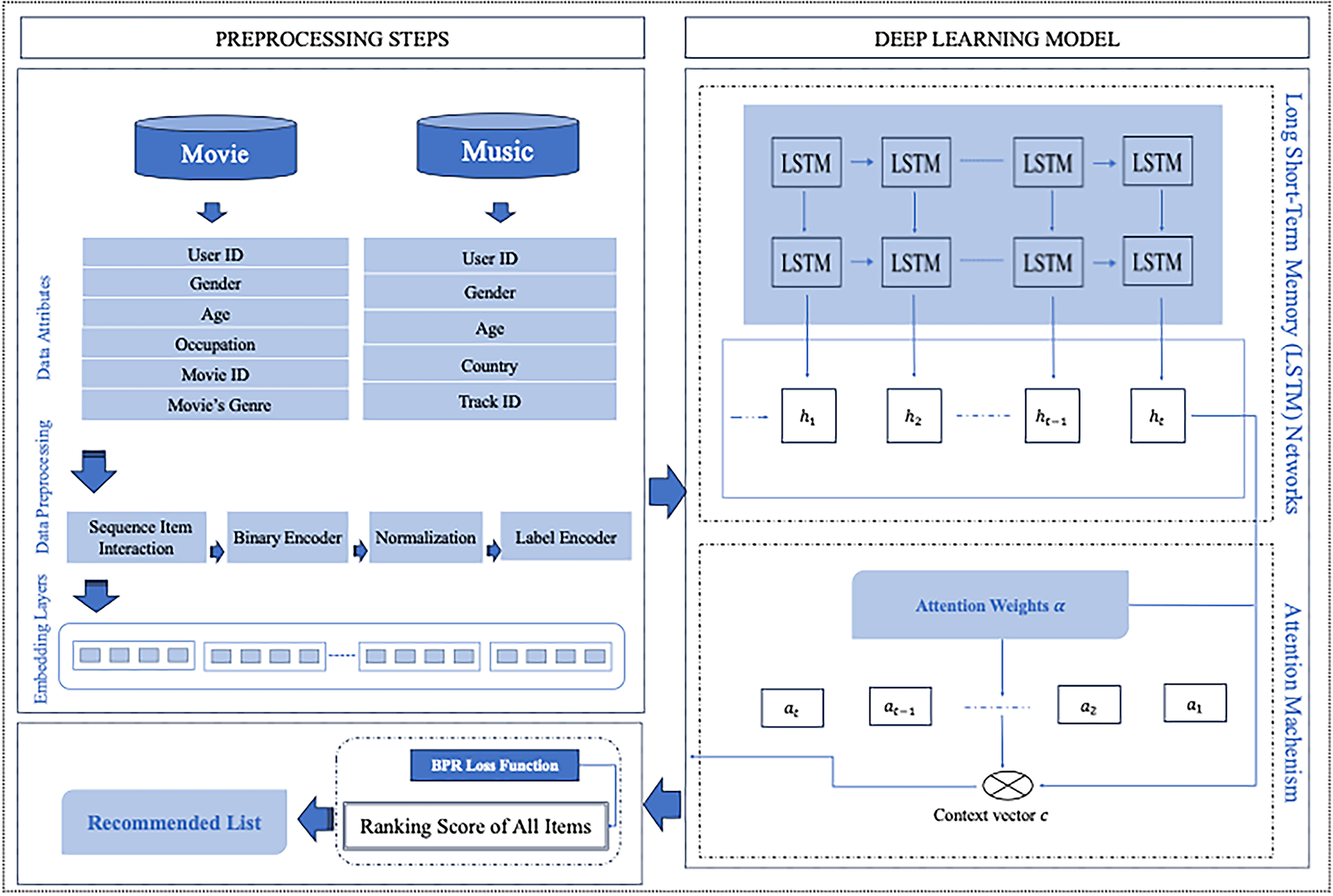

In this study, we propose a novel personalized recommendation framework that integrates deep learning with Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) optimization to address key challenges such as cold start, data sparsity, scalability, and evolving user interests. The model is designed to predict the next items a user is most likely to engage with, generating recommendations that reflect both individual behavior and contextual information. Unlike traditional methods that rely on complete interaction histories, our approach focuses on sequence-based modeling to capture short- and long-term dynamics in user behavior. The framework is built upon a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture, which effectively captures long-term dependencies and recognizes meaningful behavioral patterns over time, an essential capability in recommendation tasks where earlier actions can still influence future preferences. To improve predictive precision, we incorporate an attention mechanism, allowing the model to focus selectively on the most relevant user interactions, such as specific songs or movies, when forecasting upcoming choices. This combination enhances both the accuracy and contextual relevance of relevant item predictions.

To further personalize recommendations and address the cold-start issue, we integrate rich contextual user information. In the MovieLens dataset, we include demographic attributes such as gender, age, occupation, and movie genres; for the music dataset, we also incorporate country information. These demographic variables are combined with sequential embeddings and passed to the final prediction layer, forming a comprehensive user profile that strengthens personalization even with limited behavioral data.

Model training employs Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR), a pairwise ranking loss optimized for implicit feedback settings. BPR encourages the model to assign higher relevance to items a user has interacted with compared to unobserved ones, effectively capturing relative preferences. This enables the generation of Top-K recommendations suitable for both active and cold-start users. In cold-start scenarios, the model relies on demographic embeddings or masks of previously observed items to ensure meaningful predictions.

Fig. 1 illustrates the overall system design, highlighting the integration of sequential modeling, attention, and contextual learning components that together produce accurate and personalized recommendations across users with varying interaction histories.

Figure 1: System architecture of proposed recommendation system

For effective handling of categorical variables, including user ID and item (track/movie) ID, the model applies embedding layers to map these high-dimensional categorical variables into compact, dense vectors. These layers support the extraction of underlying latent features and complex relationships among users and items. As a result, embedding layers not only lower the dimensionality of input data but also retain the core structural associations, thereby improving the model’s computational efficiency and scalability.

The initial step involves transforming each item ID into a corresponding numerical index. Given a set of unique item IDs

Likewise, user ID are also converted into numerical indices. Given a set of unique user ID

To strengthen personalization and enhance the model’s capacity to represent user preferences, particularly in cold-start contexts, we integrate multiple user demographic attributes—such as gender, age, occupation, and country—within the recommendation architecture. Each categorical demographic variable is initially converted into a numerical index and then passed through a dedicated embedding layer, which projects each attribute into a low-dimensional continuous vector space representation:

Once the item embeddings

4.2 The Integration of LSTM with the Attention Mechanism

In our recommendation system, the LSTM processes the sequence of item embeddings that represent the user’s historical interactions as follows:

According to the LSTM layer, the sequence of item embeddings

where

Recent research involving LSTM models primarily aims to capture temporal sequential dependencies between the items in the user’s interaction or listening history. However, not all items in the sequence are equally important for the prediction. To address this, we utilize an Attention Mechanism to selectively focus on the most informative items. The attention mechanism assigns distinct weights to each hidden state

here,

To incorporate personalized recommendations, the context vector c is concatenated with both the user embedding

where

4.3 Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR)

The training of the LSTM-Attention model involves optimizing the model parameters to minimize the discrepancy between the predicted probabilities and the actual recommendation item. Since our task focuses on studying implicit feedback collected automatically (e.g., clicks, views, or plays), where there is no explicit rating. Thus, we employ the Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR), which focuses on directly optimizing the ranking of items for each user by comparing pairs of positive and negative items. The model is trained to assign a higher predicted score to the positive item

where

In our implementation, the BPR loss is integrated with a sequential deep learning architecture (such as LSTM-attention) to jointly model the sequence of user interactions and personalized ranking, resulting in improved recommendation performance, particularly for next (track/movie) prediction. Additionally, the model incorporates user contextual features to address challenges such as data sparsity, scalability, and the cold-start problem, enabling effective learning from limited interactions and providing tailored Top-K recommendations for both target and new users or items.

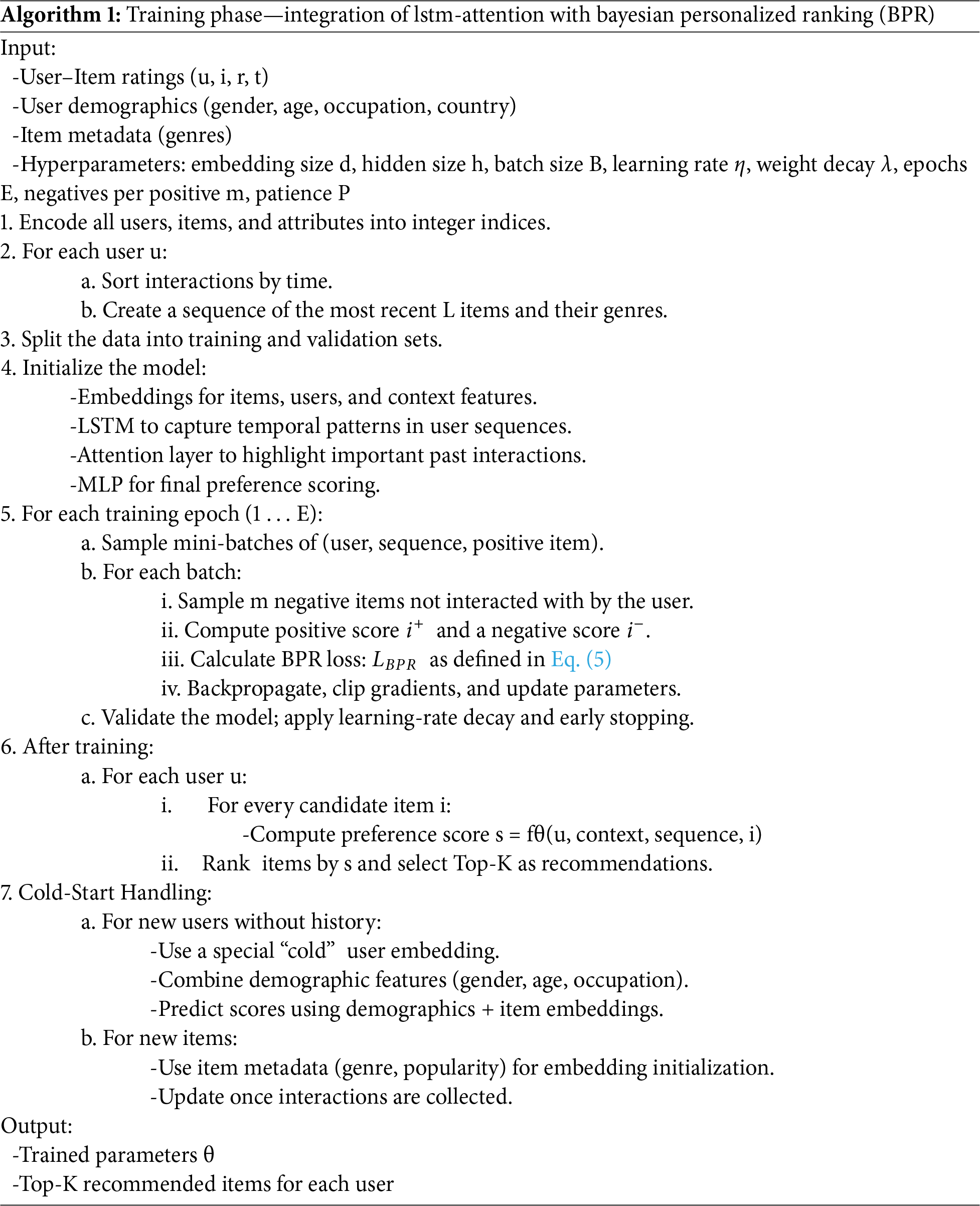

As shown in Algorithm 1, the proposed recommendation has been implemented in a detailed stage. First introduces model training, where user–item interactions, demographic information, and item metadata are processed through embedding layers, an LSTM network with an attention mechanism. This stage learns personalized preference patterns by optimizing the Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) objective, ensuring that items a user has interacted with receive higher scores than randomly sampled negatives. In this phase, the trained model generates Top-K item recommendations for each user based on learned representations. For active users, it uses their sequential history and context to compute preference scores. For new or cold-start users, the system leverages demographic features and default embeddings to make initial predictions. This two-stage process ensures the model remains effective for both frequent and first-time users, providing accurate and adaptive personalized recommendations.

Our system conducts experiments using two publicly available datasets, namely the “MovieLens and Music” datasets [27,28]. Data is initially stored in a compressed tar.gz file and subsequently extracted into a designated directory to facilitate convenient access to the raw files.

MovieLens is a foundational benchmark in recommendation system research, offering both explicit user ratings and comprehensive demographic data. The 100K dataset comprises 1 million ratings from 943 users on 1682 movies, while the 1M dataset expands this to 1 million ratings from 6040 users covering 3900 movies. Each dataset contains numerous features, including user ID, movie ID, user characteristics (age, gender, occupation), and movie metadata such as genre. In our proposed model, we preprocess both MovieLens datasets by integrating user ratings, demographic attributes, and movie metadata into a single CSV-formatted dataset. We first convert the timestamp of each rating into a datetime format to capture time-related patterns. To standardize user demographics, missing age values are imputed with the mean, and ages outside the 10-to-90-year range are clipped; these values are then normalized to a [0, 1] scale to enhance embedding learning. Gender information is encoded numerically (0 for female, 1 for male), and occupation categories are mapped to numeric labels using a LabelEncoder after imputing missing data with the most common occupation. For each movie, genres are encoded as a multi-hot vector to capture all relevant categories, and a primary genre index is set based on the first present genre. To prepare sequence recommendations, user-movie interactions are sorted chronologically and grouped into sequences of up to eight items, with the subsequent movie used as the prediction label. Sequences shorter than eight are padded to maintain uniform length. The dataset is then partitioned into training, validation, and test sets, and all features are efficiently batched to facilitate streamlined model training. This preprocessing pipeline incorporates user demographic and genre attributes, enabling the model to generate personalized Top-K sequence recommendations. By leveraging these rich contextual features, we address data sparsity and cold-start challenges, particularly in large-scale recommendation environments [29–31].

Figure labels must be sized in proportion Last.fm is recognized as a comprehensive music dataset, capturing users’ listening histories through scrobbling, which tracks songs played across multiple platforms. The dataset comprises music listening histories and playlists from a subset of 1000 users, encompassing 960,403 tracks. It provides extensive features such as user ID, timestamps for every listened track, artist ID, artist name, track ID, track titles, and detailed user interaction sequences, as well as demographic aspects including age, gender, and country. We process the Last.fm dataset by applying the same methodology adopted for the MovieLens dataset, which ensures methodological consistency. Initially, we combine user interaction logs with demographic records to create a single integrated dataset. To uphold dataset integrity, interactions linked to absent or invalid track IDs are excluded. Timestamps are standardized to the datetime format to accurately reflect the sequence of listening activities. Regarding user demographics, age is preprocessed by capping extreme values within sensible limits and normalizing these figures to the [0, 1] interval, facilitating effective embedding-based learning. Gender is represented using binary encoding (0 as female, 1 as male). What differentiates the Last.fm dataset is the inclusion of the country attribute, which is essential for music recommendation tasks, given the strong impact of geography and local culture on musical tastes. We apply LabelEncoding to the country field, which assigns a numeric code to every country, thus allowing the model to recognize geographic variations in user preferences. To enable sequence modeling for recommendations, users’ listening records are chronologically ordered and divided into sequences of up to eight tracks, designating the subsequent track as the prediction target; shorter sequences are padded for uniformity. Categorical data, including artist and track details, is encoded for compatibility with model training. The data is partitioned into training, validation, and test sets and organized into efficient batches. This workflow leverages both the temporal order of listening events and diverse demographic inputs, enabling the model to provide individualized Top-K music recommendations that account for users’ preferences and cultural backgrounds [29–33].

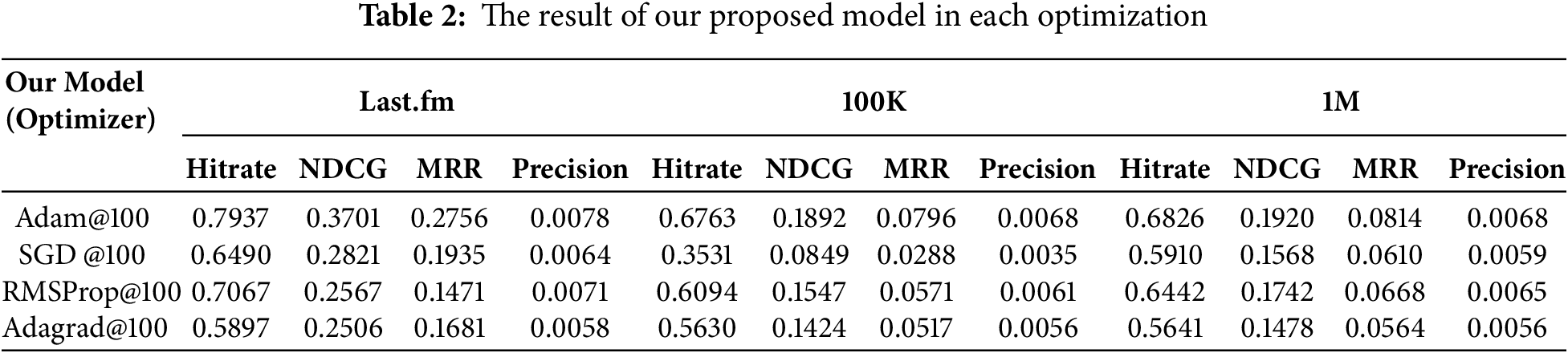

The proposed LSTM-Attention model was implemented in PyTorch and trained on a system with an Intel i7 CPU and 32 GB of RAM. The model employs 128-dimensional embeddings for users and items, a 32-dimensional genre embedding, an LSTM hidden size of 256, and a maximum sequence length of 8. Training was conducted with a batch size of 256 for up to 100 epochs. The Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of 0.001 and a weight decay of 1e−5. The Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) loss function was applied with one negative sample per positive instance. To enhance generalization, dropout with a rate of 0.3 was applied, and gradient clipping with a maximum norm of 5.0 was used to stabilize parameter updates.

During hyperparameter exploration, we varied the embedding dimension (64–256), hidden dimension (128–512), and sequence length (5–10), following the configurations in [34]. The results indicated that an embedding size of 128 and a hidden size of 256 achieved the best balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. A sequence length of 8 provided stronger temporal representation than shorter or longer sequences, while the Adam optimizer yielded faster convergence and more stable performance compared to SGD and other alternatives.

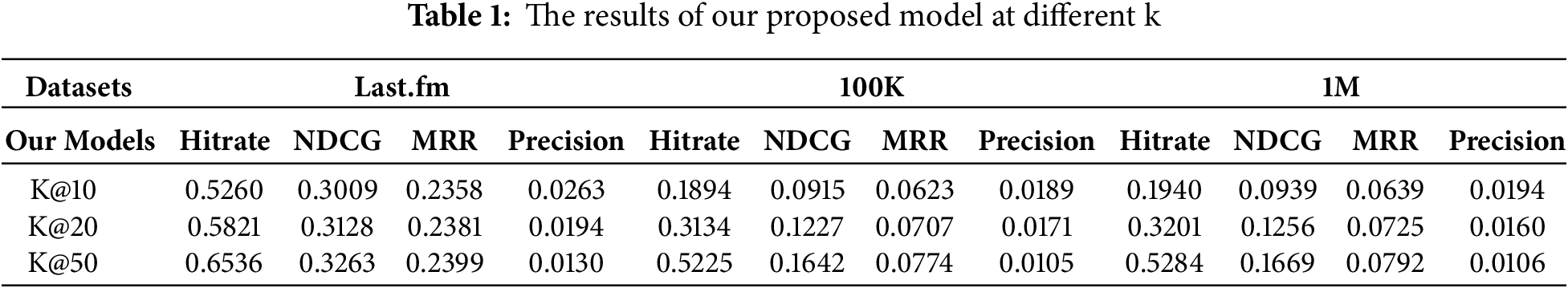

We assess the performance of our personalized recommendation system using four widely recognized metrics: Hit Rate, Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG), Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), and Precision. We report these metrics at several values of k (e.g., k = 10, 20, 50, 100) to evaluate the model’s effectiveness under different recommendation list lengths. This methodology allows us to determine whether the system maintains strong performance regardless of whether it produces a narrow or broad set of recommendations. Through these evaluation metrics, we obtain an in-depth understanding of our model’s capability to generate pertinent and well-ranked suggestions, especially within real-world recommendation scenarios. The outcomes clarify the extent to which our system captures individual user preferences, thereby ensuring recommendations that are truly personalized and accurate.

In this study, we benchmark our proposed personalized recommendation model against a diverse range of advanced algorithms, including both traditional baselines and state-of-the-art deep learning methods. We implement these models using the RecBole framework and the Session-Rec library (rn5l/session-rec), which offers robust and standardized implementations of numerous modern recommendation algorithms. Comparing against these baselines allows us to rigorously evaluate how effectively our model captures sequential dependencies and user-specific behavioral patterns. The comparison includes the following approaches:

• BPR (Bayesian Personalized Ranking) [14]: BPR is a pairwise ranking method designed for implicit feedback settings. It trains the model to rank items by favoring user-item interaction pairs (positive examples) over non-interaction pairs (negative examples) within a probabilistic framework, thereby efficiently modeling user preferences.

• GRU4Rec (Gated Recurrent Unit for Recommendation) [22]: This sequential recommendation model utilizes Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) to model temporal patterns in user behavior. By analyzing sequences of user-item interactions, GRU4Rec achieves high predictive accuracy for identifying subsequent preferred items.

• SASRec (Self-Attentive Sequential Recommendation) [23]: A Transformer-based sequential model that applies self-attention to capture both short- and long-term user preferences. It avoids recurrence, offering scalability and strong performance in next-item prediction tasks.

• NARM (Neural Attentive Recommendation Machine) [24]: This session-based recommendation model merges GRUs with attention mechanisms to integrate both immediate session preferences and broader user tendencies. It processes sequences of user-item interactions through a GRU and leverages attention to identify the most informative items within a session, thereby enhancing performance in the session-based next-item prediction task.

• Popularity [35]: This approach recommends items based solely on their overall frequency of interaction, suggesting the most popular items to all users. It establishes a reference point to demonstrate the significance of personalization.

• ItemKNN (Item-based K-Nearest Neighbors) [36]: A foundational collaborative filtering method, ItemKNN recommends items based on their similarity to those most recently interacted with by the user. It applies metrics such as cosine similarity to evaluating item similarity, establishing it as a reliable benchmark for item-based recommendation approaches.

• FPMC (Factorizing Personalized Markov Chains) [37]: FPMC integrates matrix factorization with first-order Markov chains to capture user-specific transitions between items. While it demonstrates strong performance on sequential recommendation tasks, its effectiveness diminishes when addressing intricate or extended temporal dependencies.

• LightGCN (Light Graph Convolution Network) [38]: A streamlined graph-based collaborative filtering model that propagates embeddings through the user–item interaction graph. By removing feature transformation and nonlinearities, it efficiently captures higher-order collaborative signals and serves as a strong graph-based baseline.

• BERT4Rec (Bidirectional Encoder Representations for Sequential Recommendation) [39]: A bidirectional Transformer model trained with a Cloze-style masking objective. By leveraging both left and right context, it captures richer sequence dependencies and achieves state-of-the-art accuracy in sequential recommendation.

Our evaluation focuses on a personalized recommendation model incorporating deep learning models and Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) optimization to provide accurate and contextually relevant recommendations. Using the Last.fm, MovieLens-100K, and MovieLens-1M datasets, we address persistent challenges such as data sparsity and cold-start users, resulting in robust performance for users across diverse interaction levels. By integrating sequential user histories, demographic factors (gender, age, occupation, country), and item genre metadata, the proposed model delivers highly relevant recommendations for a variety of user contexts.

6.1 Performance across Recommendation Depths

We evaluated our model’s performance at multiple recommendation depths (K = 10, 20, 50) using four established metrics: Hit Rate, Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG), Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), and Precision. The experimental results demonstrate that our proposed model effectively captures sequential dependencies and contextual features, thereby improving personalized recommendations across multiple datasets. As shown in Table 1, increasing the value of K leads to consistent gains in HitRate and NDCG across all three datasets—Last.fm, MovieLens 100K, and MovieLens 1M—indicating that the model retrieves a larger proportion of relevant items as the recommendation list expands. For instance, on the Last.fm dataset, the HitRate increases from 0.5260 at K = 10 to 0.6536 at K = 50, while NDCG improves from 0.3009 to 0.3263, reflecting better ranking of relevant items. A similar trend is observed in both MovieLens datasets, where HitRate and NDCG continue to rise with larger K values. Although Precision decreases slightly as K increases—from 0.0263 to 0.0130 on Last.fm—this is expected, as expanding the candidate list generally enhances recall while reducing top-ranked precision. Meanwhile, the relatively stable MRR across all K values suggests that the model maintains its ability to rank relevant items near the top. Overall, these results confirm that our model achieves a strong balance between ranking quality and coverage across datasets of varying scales.

6.2 Optimization Method Comparison

Table 2 presents the impact of different optimization strategies on model performance. Among all tested optimizers (Adam, SGD, RMSProp, and Adagrad), Adam consistently delivers the best results across all datasets and evaluation metrics. For example, on Last.fm, Adam yields the highest NDCG (0.3701) and MRR (0.2756), outperforming SGD (0.2821/0.1935), RMSProp (0.2567/0.1471), and Adagrad (0.2506/0.1681). The same trend holds for the MovieLens datasets, where Adam achieves stronger convergence and more stable pairwise ranking optimization under the BPR loss. These results confirm that Adam is particularly effective for optimizing our LSTM-attention architecture, as it adapts learning rates for each parameter and accelerates convergence in non-convex loss landscapes. The sensitivity of performance to the optimizer also indicates that stable gradient adaptation is crucial when training sequential recommenders with implicit feedback.

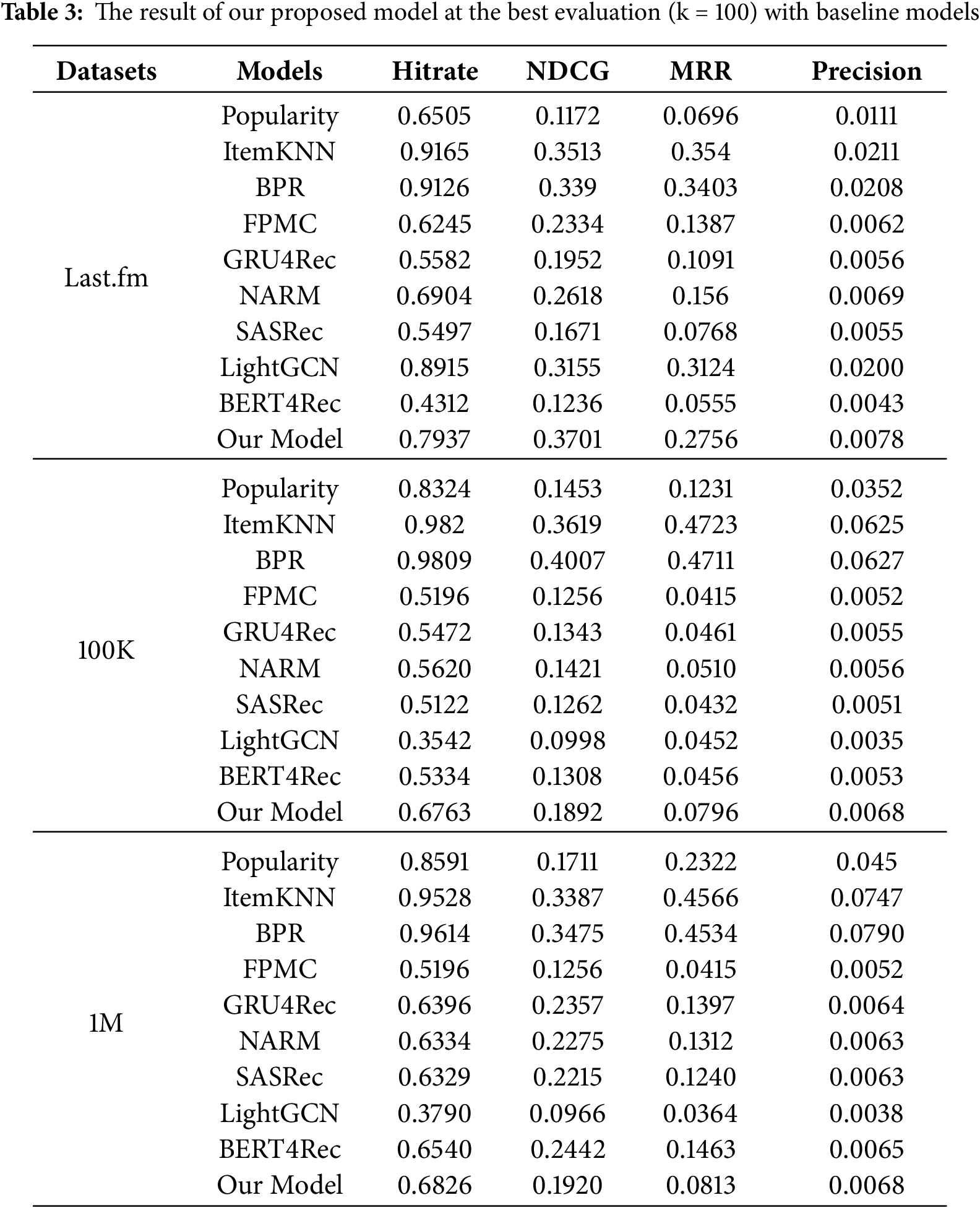

6.3 Comparison with Baseline Models

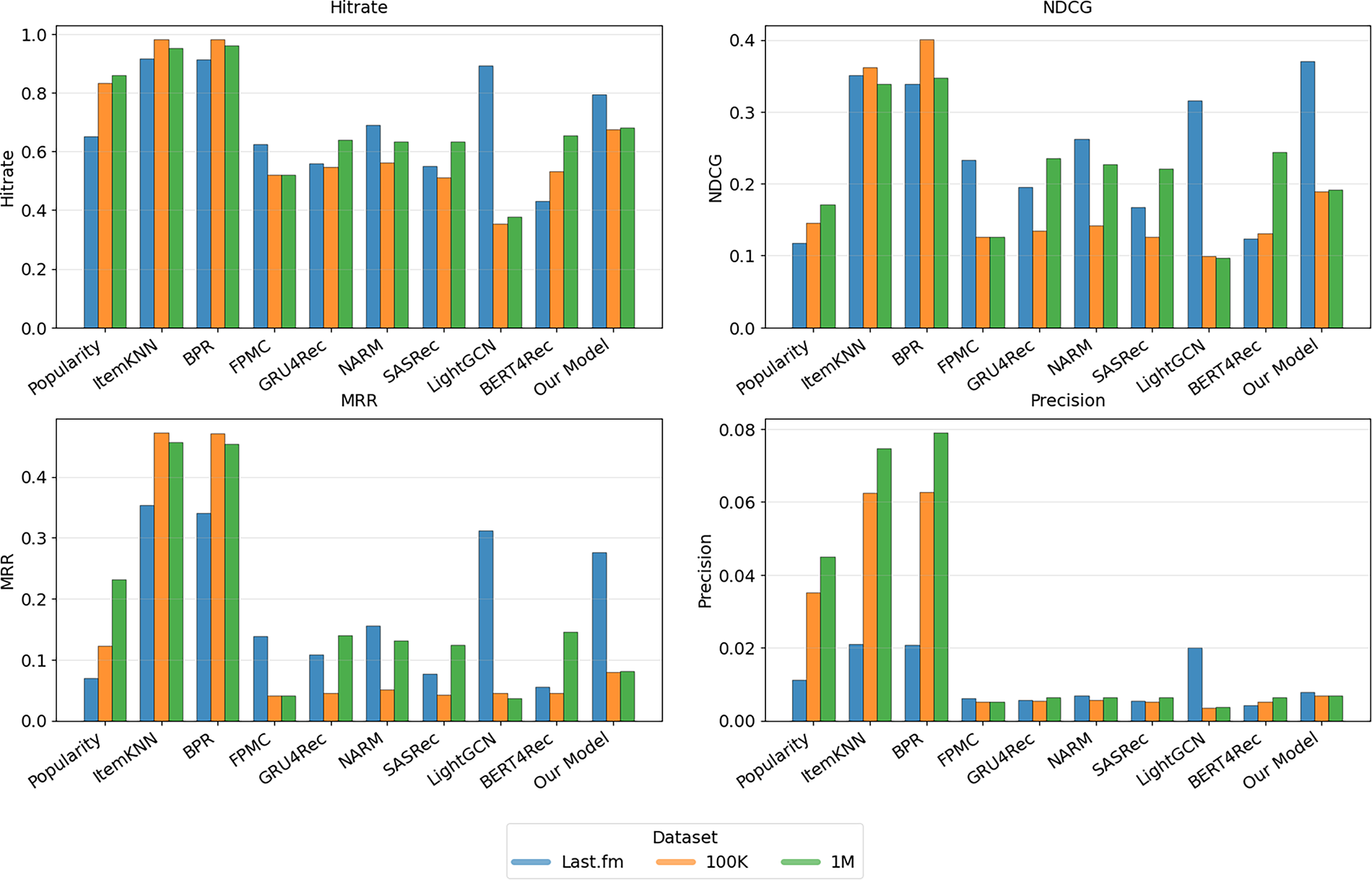

The comparative results in Table 3 highlight the competitiveness of our proposed model against several well-established baselines. On the Last.fm dataset, our model achieves the highest NDCG (0.3701), outperforming ItemKNN (0.3513), BPR (0.3390), and LightGCN (0.3155). Although ItemKNN and BPR show slightly higher HitRate values (above 0.91 compared to our 0.7937), our model demonstrates stronger ranking quality at the top of the recommendation list, as reflected by improvements in both NDCG and MRR. This confirms the effectiveness of combining the LSTM’s capability to capture temporal user–item dependencies with the attention mechanism’s ability to emphasize the most informative interactions. Additionally, the integration of contextual embeddings for demographic attributes (e.g., gender, age, occupation, country) enables the model to better adapt to new or inactive users, improving cold-start recommendation performance. For instance, in a simulated cold-start setting (with less than five historical interactions per user), our model achieved an NDCG of 0.291 and HitRate of 0.612 on the Last.fm dataset—outperforming LightGCN (0.246/0.543) and BPR (0.254/0.558)—showing that contextual information effectively compensates for limited behavioral data.

In contrast, on the MovieLens 100K and 1M datasets—where explicit ratings dominate—the traditional collaborative filtering models such as BPR and ItemKNN still achieve the highest overall scores. Specifically, BPR attains NDCG values of 0.4007 (100K) and 0.3475 (1M). This outcome is expected, as these datasets contain dense user–item matrices with explicit feedback, favoring non-sequential CF approaches. Nevertheless, our model remains competitive, achieving stable HitRate and Precision values (e.g., 0.6763 and 0.0068 on 100K, and 0.6826 and 0.0068 on 1M), while maintaining flexibility in handling cold-start and implicit-feedback scenarios. The remaining performance gap also suggests room for future improvement, such as increasing sequence length, applying multi-negative sampling, or incorporating explicit rating signals into the BPR objective.

Overall, these results validate the effectiveness of our deep learning approach, which integrates sequential modeling (LSTM), attention-based context weighting, and Bayesian Personalized Ranking for implicit optimization. The consistent improvements in NDCG—particularly on Last.fm and under cold-start conditions—demonstrate that our model ranks relevant items more accurately than conventional baselines. Its robustness across datasets of varying sparsity and feedback types confirms that combining temporal patterns with user context significantly enhances personalization. In summary, the proposed architecture achieves a strong balance between ranking accuracy and adaptability, performing particularly well in real-world, implicit-feedback environments where user preferences evolve dynamically over time.

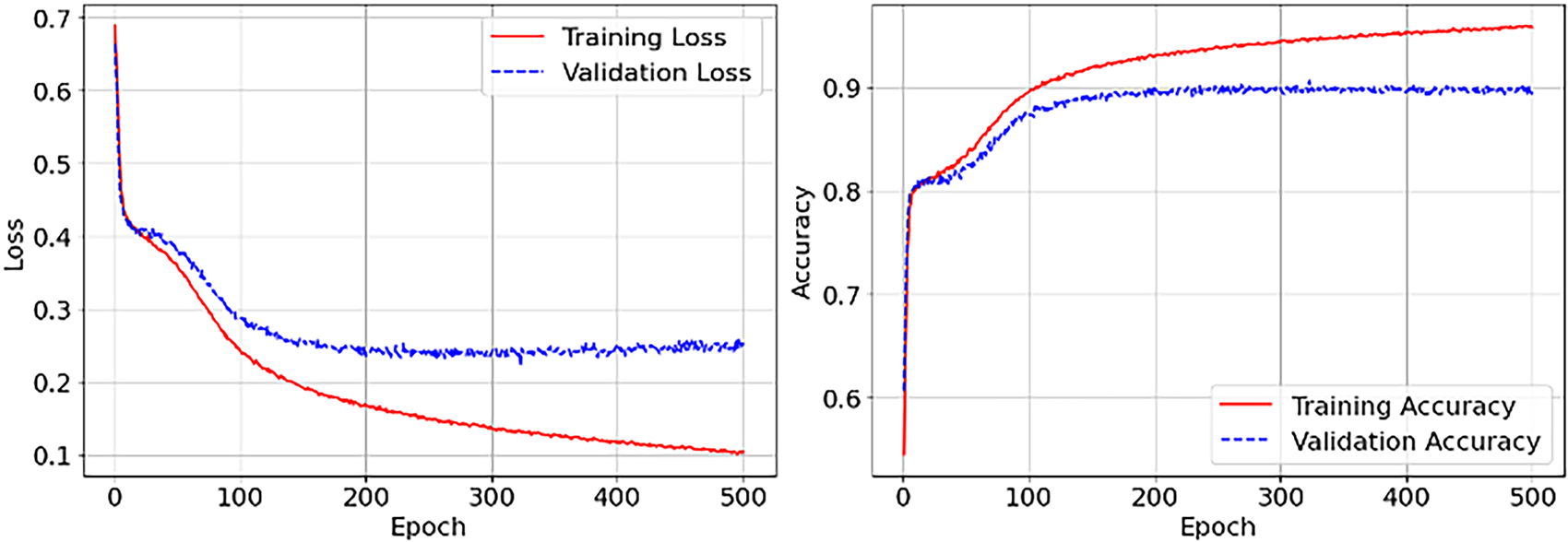

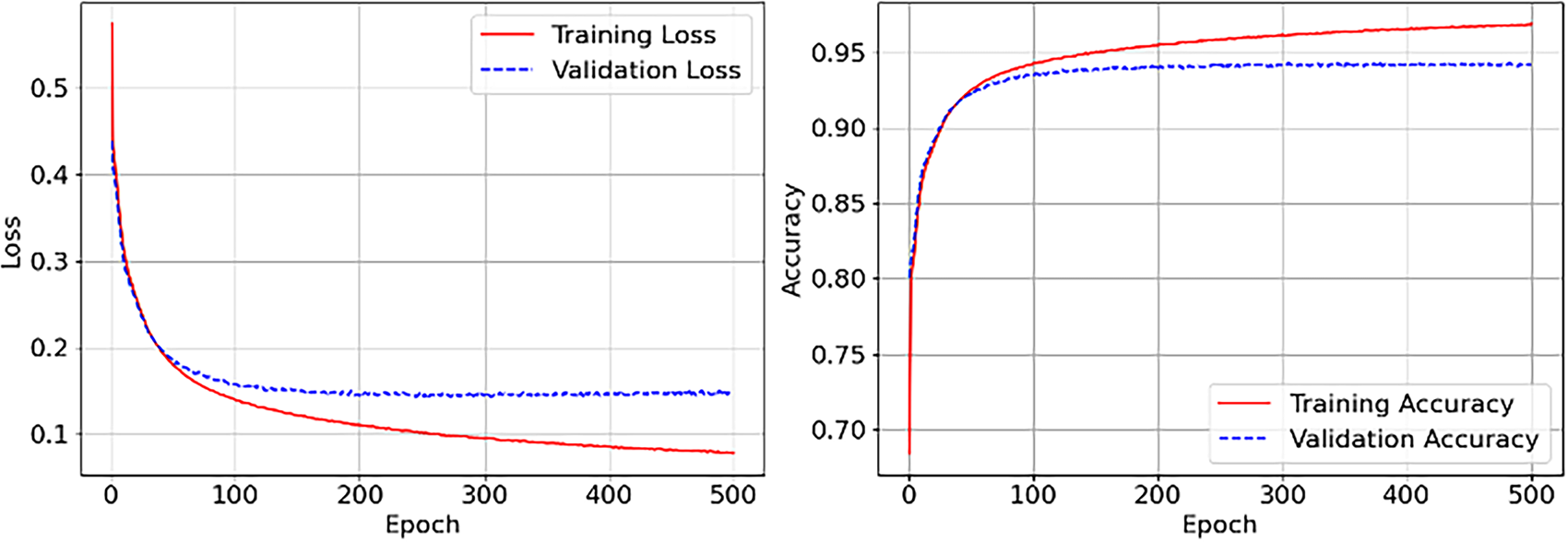

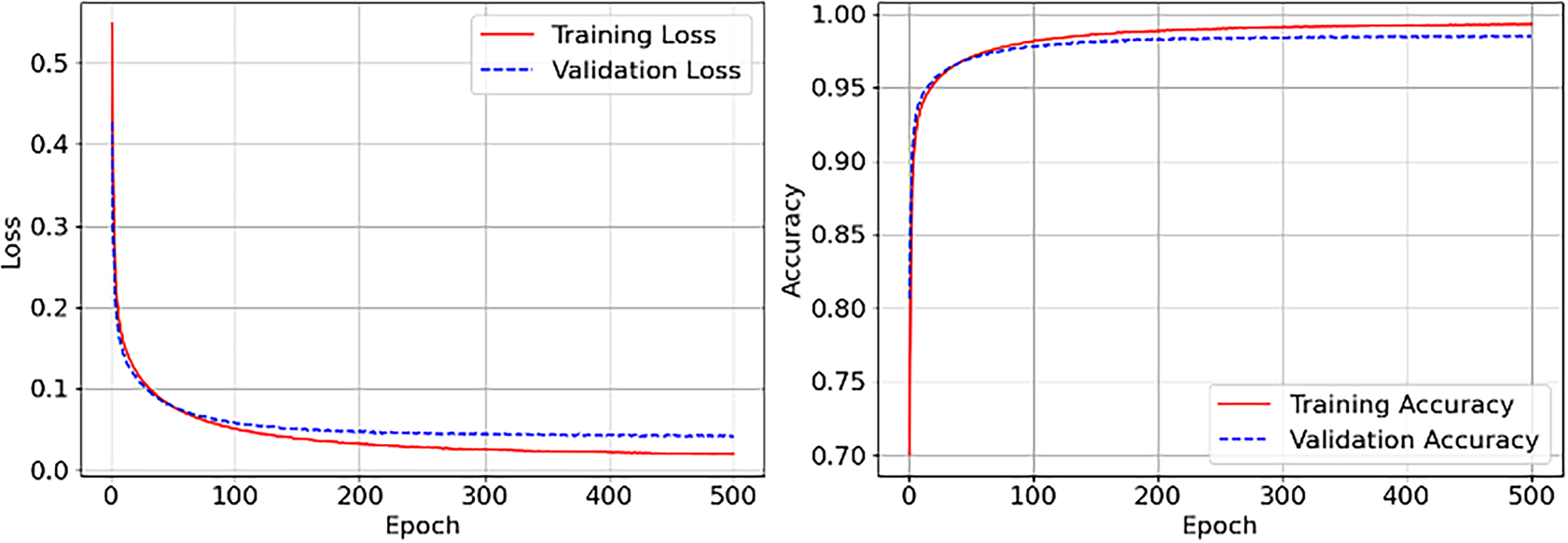

Figs. 2–4 present the training and validation performance of our model across 500 epochs with a batch size of 128, utilizing BPR loss to quantify the divergence between predicted and observed values. These visualizations highlight the model’s learning dynamics across the three datasets.

Figure 2: Training and Accuracy of our model on Movielens (100K)

Figure 3: Training and Accuracy of our model on Movielens (1M)

Figure 4: Training and Accuracy of our model on Music (Last.fm)

• MovieLens-100K (Fig. 2): The model converges consistently, with training loss declining to approximately 0.15 and validation loss leveling off near 0.25. Training accuracy approaches 95%, while validation accuracy consistently surpasses 90%. These results demonstrate effective generalization and minimal overfitting, attributed to the incorporation of demographic and genre features.

• MovieLens-1M (Fig. 3): In the presence of denser interaction data, the model exhibits accelerated convergence, with both training and validation losses falling below 0.1 and validation accuracy plateauing at around 94%. Compared to performance on MovieLens-100K, richer data enhances stability and highlights the scalability of the approach.

• Last.fm (Fig. 4): The model demonstrates rapid convergence, with loss stabilizing below 0.05 within the first 100 epochs, and both training and validation accuracy consistently exceeding 99%. This superior performance demonstrates the model’s ability to effectively model complex, time-varying listening behaviors in the context of music streaming.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of our model across the Last.fm, MovieLens-100K, and MovieLens-1M datasets. Through the integration of LSTM networks, attention mechanisms, and BPR optimization, the model effectively captures sequential user behaviors and contextual features, resulting in personalized recommendations that perform notably well in both sparse and cold-start contexts. The model’s consistently high results in Hit Rate, NDCG, and MRR at k = 100, as well as demonstrably stable training dynamics, underscore its proficiency in next-item prediction. Notably, our approach exceeds the performance of all sequential baseline models, such as GRU4Rec and NARM, on all tested datasets, with especially strong outcomes in retrieval-oriented tasks (Hit Rate and NDCG). The model’s effectiveness in cold-start situations is reinforced by its capability to incorporate demographic and genre data, thus delivering relevant recommendations even for users with very limited interaction histories. Our model’s ability to handle dynamic, sequence-specific data and cold-start users positions it as a superior choice for modern recommendation systems. Fig. 5 provides a graphical overview of the performance metrics detailed in Table 3, illustrating Hit Rate, NDCG, MRR, and Precision across datasets, thereby showcasing the comparative strengths of our model relative to baseline approaches.

Figure 5: Result virtualizations

This study introduces a deep learning–based recommendation framework that combines Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with an attention mechanism and Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) optimization. The main goal is to make personalized Top-K recommendations more accurate and context-aware. Our model is designed to capture both what users like and how their preferences change over time, by learning from user–item interaction sequences. In addition, it integrates demographic and contextual information—such as gender, age, occupation, and country—along with genre embeddings. This combination allows the system to make meaningful recommendations even for new or less active users, directly addressing the cold-start and data sparsity problems that often limit traditional collaborative filtering systems. Experimental evaluations across three benchmark datasets—Last.fm, MovieLens 100K, and MovieLens 1M—demonstrate the robustness and adaptability of the proposed model. On the Last.fm dataset, which involves implicit and session-based interactions, our model achieved the highest NDCG of 0.3701, outperforming advanced baselines such as BPR (0.3390), ItemKNN (0.3513), and LightGCN (0.3155). On MovieLens 100K, the model reached a HitRate of 0.6763 and NDCG of 0.1892, while on MovieLens 1M, it obtained a HitRate of 0.6826 and NDCG of 1920, showing strong ranking quality and stable performance across datasets of varying scale and density. This demonstrates that incorporating contextual and demographic features helps the model make better predictions even with limited user history. Our experiments also confirm that using the Adam optimizer under the BPR objective leads to faster and more stable convergence than alternative methods such as SGD or RMSProp. While classical collaborative filtering models perform slightly better on explicit datasets like MovieLens, our model shows clear advantages in sparse and implicit-feedback environments, where user preferences evolve dynamically.

Future investigations will aim to enhance ranking performance by integrating collaborative filtering components into a hybrid model and will also pursue the development of novel architectures inspired by agentic artificial intelligence. The goal is to establish systems that demonstrate autonomous decision-making and adaptive learning, further advancing recommendation quality.

Acknowledgement: I express my sincere gratitude to all individuals who have contributed to this paper. Their dedication and insights have been invaluable in shaping the outcome of this work.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Soonchunhyang University, Grant Number 20250029.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sophort Siet, Sony Peng, and Kyuwon Park; data collection: Sophort Siet, Sony Peng, and Ilkhomjon Sadriddinov; analysis and interpretation of results: Sophort Siet, Sony Peng, and Kyuwon Park; draft manuscript preparation: Sophort Siet, Sony Peng, and Kyuwon Park. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: We used publicly available data and gave a reference to it in our paper. Please check references [27,28].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ko H, Lee S, Park Y, Choi A. A survey of recommendation systems: recommendation models, techniques, and application fields. Electronics. 2022;11(1):141. doi:10.3390/electronics11010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Frey M. Netflix recommends: algorithms, film choice, and the history of taste. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

3. Agner L, Necyk BJ, Renzi A. User experience and information architecture. In: Handbook of usability and user experience. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2022. p. 247–68. doi:10.1201/9780429343490-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao Q, Harper FM, Adomavicius G, Konstan JA. Explicit or implicit feedback? engagement or satisfaction?: a field experiment on machine-learning-based recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing; 2018 Apr 8–13; Pau, France. p. 1331–40. doi:10.1145/3167132.3167275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Martins GB, Papa JP, Adeli H. Deep learning techniques for recommender systems based on collaborative filtering. Expert Syst. 2020;37(6):e12647. doi:10.1111/exsy.12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tewari AS. Generating items recommendations by fusing content and user-item based collaborative filtering. Procedia Comput Sci. 2020;167:1934–40. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Natarajan S, Vairavasundaram S, Natarajan S, Gandomi AH. Resolving data sparsity and cold start problem in collaborative filtering recommender system using Linked Open Data. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;149:113248. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmed SF, Alam MSB, Hassan M, Rozbu MR, Ishtiak T, Rafa N, et al. Deep learning modelling techniques: current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(11):13521–617. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10466-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Raza S, Rahman M, Kamawal S, Toroghi A, Raval A, Navah F, et al. A comprehensive review of recommender systems: transitioning from theory to practice. arXiv:2407.13699. 2024. [Google Scholar]

10. Shaikh MI. Top-n nearest neighbourhood based movie recommendation system using different recommendation techniques [doctoral dissertation]. Dublin, Ireland: National College of Ireland; 2021. [Google Scholar]

11. Koren Y, Bell R, Volinsky C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer. 2009;42(8):30–7. doi:10.1109/MC.2009.263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gosh S, Nahar N, Wahab MA, Biswas M, Hossain MS, Andersson K. Recommendation system for E-commerce using alternating least squares (ALS) on Apache spark. In: Intelligent computing and optimization. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 880–93. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68154-8_75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Salakhutdinov R, Mnih A, Hinton G. Restricted Boltzmann machines for collaborative filtering. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2007 Jun 20–24; Corvalis, OR, USA. p. 791–8. doi:10.1145/1273496.1273596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rendle S, Freudenthaler C, Gantner Z, Schmidt-Thieme L. BPR: bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. arXiv:1205.2618. 2012. [Google Scholar]

15. Li P, Noah SA, Sarim HM. A survey on deep neural networks in collaborative filtering recommendation systems. arXiv:2412.01378. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Cheng HT, Koc L, Harmsen J, Shaked T, Chandra T, Aradhye H, et al. Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems; 2016 Sep 15; Boston, MA, USA. p. 7–10. doi:10.1145/2988450.2988454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Guo H, Tang R, Ye Y, Li Z, He X. DeepFM: a factorization-machine based neural network for CTR prediction. arXiv:1703.04247. 2017. [Google Scholar]

18. Wei J, He J, Chen K, Zhou Y, Tang Z. Collaborative filtering and deep learning based recommendation system for cold start items. Expert Syst Appl. 2017;69:29–39. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2016.09.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. He X, Liao L, Zhang H, Nie L, Hu X, Chua TS. Neural collaborative filtering. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2017 Apr 3–7; Perth, Australia. p. 173–82. doi:10.1145/3038912.3052569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim D, Park C, Oh J, Lee S, Yu H. Convolutional matrix factorization for document context-aware recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2016 Sep 15–19; Boston, MA, USA. p. 233–40. doi:10.1145/2959100.2959165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tan YK, Xu X, Liu Y. Improved recurrent neural networks for session-based recommendations. In: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems; 2016 Sep 15–19; Boston, MA, USA. p. 17–22. doi:10.1145/2988450.2988452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kang WC, McAuley J. Self-attentive sequential recommendation. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM); 2018 Nov 17–20; Singapore: IEEE; 2018. p. 197–206. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2018.00035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li J, Ren P, Chen Z, Ren Z, Lian T, Ma J. Neural attentive session-based recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2017 Nov 6–10; Singapore. p. 1419–28. doi:10.1145/3132847.3132926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Peng S, Siet S, Ilkhomjon S, Kim DY, Park DS. Integration of deep reinforcement learning with collaborative filtering for movie recommendation systems. Appl Sci. 2024;14(3):1155. doi:10.3390/app14031155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li L, Chen L, Dong R. CAESAR: context-aware explanation based on supervised attention for service recommendations. J Intell Inf Syst. 2021;57(1):147–70. doi:10.1007/s10844-020-00631-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. GroupLens. Movielens [Internet]. Minneapolis, MN, USA: GroupLens Research; 2021 [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: https://grouplens.org/datasets/movielens/. [Google Scholar]

28. Celma Ò. Music recommendation datasets for research [Internet]. Barcelona, Spain: Universitat Pompeu Fabra; 2010 Mar [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: http://ocelma.net/MusicRecommendationDataset/. [Google Scholar]

29. Siet S, Peng S, Ilkhomjon S, Kang M, Park DS. Enhancing sequence movie recommendation system using deep learning and KMeans. Appl Sci. 2024;14(6):2505. doi:10.3390/app14062505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Peng S, Siet S, Sadriddinov I, Kim DY, Park K, Park DS. Integration of federated learning and graph convolutional networks for movie recommendation systems. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):2041–57. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gu X, Zhao H, Jian L. Sequence neural network for recommendation with multi-feature fusion. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;210:118459. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kumar C, Kumar M. Session-based recommendations with sequential context using attention-driven LSTM. Comput Electr Eng. 2024;115:109138. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Deldjoo Y, Schedl M, Knees P. Content-driven music recommendation: evolution, state of the art, and challenges. Comput Sci Rev. 2024;51:100618. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2024.100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Phuong TM, Thanh TC, Bach NX. Combining user-based and session-based recommendations with recurrent neural networks. In: Neural information processing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 487–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04167-0_44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Steck H. Item popularity and recommendation accuracy. In: Proceedings of the Fifth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. Chicago Illinois USA: ACM; 2011. p. 125–32. doi:10.1145/2043932.2043957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Deshpande M, Karypis G. Item-based top-N recommendation algorithms. ACM Trans Inf Syst. 2004;22(1):143–77. doi:10.1145/963770.963776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Rendle S, Freudenthaler C, Schmidt-Thieme L. Factorizing personalized Markov chains for next-basket recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2010 Apr 26–30; Raleigh, NC, USA. p. 811–20. doi:10.1145/1772690.1772773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. He X, Deng K, Wang X, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang M. LightGCN: simplifying and powering graph convolution network for recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2020 Jul 25–30; Virtual. p. 639–48. doi:10.1145/3397271.3401063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sun F, Liu J, Wu J, Pei C, Lin X, Ou W, et al. BERT4Rec: sequential recommendation with bidirectional encoder representations from transformer. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2019 Nov 3–7; Beijing, China. p. 1441–50. doi:10.1145/3357384.3357895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools