Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

AquaTree: Deep Reinforcement Learning-Driven Monte Carlo Tree Search for Underwater Image Enhancement

1 School of Computer Science, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

2 School of Computer and Information Science, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan, 432000, China

3 Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Green Intelligent Computing Power Network, School of Computer Science, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

* Corresponding Author: Caichang Ding. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 61 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071242

Received 03 August 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Underwater images frequently suffer from chromatic distortion, blurred details, and low contrast, posing significant challenges for enhancement. This paper introduces AquaTree, a novel underwater image enhancement (UIE) method that reformulates the task as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) through the integration of Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) and deep reinforcement learning (DRL). The framework employs an action space of 25 enhancement operators, strategically grouped for basic attribute adjustment, color component balance, correction, and deblurring. Exploration within MCTS is guided by a dual-branch convolutional network, enabling intelligent sequential operator selection. Our core contributions include: (1) a multimodal state representation combining CIELab color histograms with deep perceptual features, (2) a dual-objective reward mechanism optimizing chromatic fidelity and perceptual consistency, and (3) an alternating training strategy co-optimizing enhancement sequences and network parameters. We further propose two inference schemes: an MCTS-based approach prioritizing accuracy at higher computational cost, and an efficient network policy enabling real-time processing with minimal quality loss. Comprehensive evaluations on the UIEB Dataset and Color correction and haze removal comparisons on the U45 Dataset demonstrate AquaTree’s superiority, significantly outperforming nine state-of-the-art methods across five established underwater image quality metrics.Keywords

Underwater machine vision provides a foundational capability for interpreting visual data in subaquatic settings [1], making it indispensable across various domains, including underwater robotics, marine engineering, and oceanographic exploration [2]. High-quality underwater images are highly demanded in various practical applications [3]. However, the visibility of underwater scenes is often compromised by the wavelength-dependent absorption and scattering of water [4]. Underwater images are frequently plagued by color distortion, poor contrast, and a lack of detail clarity [5], which imposes severe limitations on their practical deployment in real-world scenarios [6]. To address these limitations, this article delves into a critical aspect of underwater machine vision: underwater image enhancement (UIE). The current state of research in UIE can be broadly categorized into physical model-based methods, nonphysical model-based methods, and data-driven deep learning-based methods. Reviews of each category are provided in Sections 1.1–1.3.

1.1 Physical Model-Based Methodologies

Physical model-based methodologies restore underwater image clarity by mathematically formalizing optical physics imaging processes to estimate degradation parameters [7], achieving enhancement through inverse problem solving of the underwater imaging model [8]. Zhou et al. [9] developed an unsupervised underwater restoration method using the channel intensity prior (CIP) and adaptive dark pixels (ADP) to mitigate solid-color object artifacts and balance blue-green channels. Hou et al. [10] introduced an illumination channel sparsity prior (ICSP)-guided variational framework exploiting HSI color space characteristics to address non-uniform illumination in underwater imaging while enhancing brightness, correcting chromatic distortion, and preserving fine-scale details. Liang et al. [11] proposed a comprehensive and effective underwater image quality improvement method integrating chromatic balance, discriminant-based detail recovery, and contrast restoration to prevent transmission underestimation and minimize backscatter light while preserving base-layer details. Hsieh and Chang [12] proposed an underwater image enhancement and attenuation restoration (UIEAR) algorithm employing 3D depth-guided backscatter estimation and imaging model refinement for attenuation restoration and chromatic fidelity enhancement. Although physical model-based methodologies using simplified underwater imaging models perform effectively in specific scenarios, they tend to generalize poorly to a variety of underwater scenarios, leading to unstable and visually unimpressive results [13].

1.2 Non-Physical Model-Based Methodologies

Non-physical model-based methodologies consider UIE as an independent computer vision task without considering the inherent optical physics of underwater image formation [14]. Based on existing image processing techniques, these techniques prioritize perceptual quality by directly modifying pixel values of the degraded underwater images to enhance the visual appeal of underwater images [15]. An et al. [16] proposed a Hybrid Fusion Method (HFM) with the objective of addressing multiple underwater degradations in a unified manner. The framework incorporates perceptual fusion modules to integrate these improvements. Zhang et al. [17] proposed a weighted wavelet visual perception fusion (WWPF) method combining attenuation-map-guided color correction with maximum information entropy-optimized and fast integration-optimized contrast enhancement for integrated restoration. Wang et al. [18] proposed a discriminative underwater image enhancement method empowered by large foundation model technology, leveraging the segment anything model (SAM) for region-specific compensation and high-frequency edge fusion to avoid foreground and background regions crosstalk and restore detail clarity. Although non-physical model-based methodologies can effectively enhance the color, contrast, and details of underwater images, the reliance on empirically tuned parameters causes instability performance across various underwater scenarios, while the lack of principled guidance in the image enhancement process frequently yields inconsistent outcomes through under-enhancement or over-enhancement. Consequently, determining optimal parameter configurations for UIE models presents a notable bottleneck.

1.3 Data-Driven Deep Model-Based Methodologies

Data-driven deep model-based methodologies, comprising hierarchical nonlinear processing units, demand substantial paired training data to achieve sufficient representational power [19]. For UIE, this necessitates large-scale datasets containing degraded underwater images and their ground-truth enhanced underwater images. In this context, a data-driven deep model enhances underwater images through an end-to-end learning process that maps degraded underwater images to their corresponding clear scene without intermediate physical priors [20]. Zhou et al. [21] proposed a cross-domain enhancement network (CVE-Net) leveraging the high-efficiency feature alignment module (FAM) to adapt the temporal features and the dual-branch attention block to handle different types of information and give more weight to essential features. Zhu et al. [22] proposed an unsupervised representation disentanglement-based UIE method (URD-UIE) using adversarial disentanglement to separate content and style information for unpaired underwater image quality enhancement. Qing et al. [23] proposed a novel underwater image enhancement method (UIE-D), leveraging a global feature prior within a diffusion model framework and incorporating an underwater degradation model to learn mappings between degraded and high-quality images for stable UIE. Data-driven deep model-based methodologies primarily are trained with synthetic datasets due to the scarcity of paired real underwater images and their corresponding ground-truth non-water images [24], yet their effectiveness remains fundamentally constrained by the quality of synthetic images [25]. Furthermore, their unexplainable black-box mechanisms attract criticism.

To tackle the challenges discussed in Sections 1.1–1.3, the following four main contributions are presented:

• To the best of our knowledge, this paper presents the first application of Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) theory to the field of UIE, effectively addressing a critical theoretical gap in this domain.

• To prevent the mechanical application of uniform enhancement methods to heterogeneous underwater degradation scenarios, we formalize the Underwater Image Enhancement (UIE) task as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). This innovative deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-driven framework strategically selects and orchestrates image enhancement algorithms into optimized sequential workflows. By explicitly constructing interpretable, step-by-step enhancement procedures, the approach achieves optimal enhancement performance while ensuring full operational traceability.

• To mitigate suboptimal image enhancement, we develop a reinforcement learning reward function by integrating chromatic fidelity and perceptual consistency through multi-objective optimization. This methodology not only effectively rectifies underwater color distortions but also ensures the enhancement process aligns with human visual perception, thereby achieving simultaneous improvements in both quantitative quality metrics and qualitative subjective evaluation.

• To address the reference-dependence limitation inherent in end-to-end data-driven deep learning-based underwater image enhancement methods, this study proposes a dual-branch guidance network architecture that effectively directs the optimization search process. The framework incorporates an alternating training mechanism that dynamically orchestrates tree search strategies with network parameter optimization. By emulating the sequential decision-making rationale of professional image restoration experts, our approach transcends the quality constraints imposed by reference images while maintaining operational transparency and full traceability. This innovation yields substantial quantitative performance gains on the UIEB benchmark dataset.

2 Modeling Underwater Image Enhancement as a Markov Decision Process

This paper formalizes underwater image enhancement tasks through an MDP, establishing a mathematical representation framework for the state space, action space, and reward function. This framework provides a theoretical foundation for the global optimization of sequential enhancement operations. The MDP leverages the fourth-order Markov property to simplify decision processes: the subsequent state

2.1 Agent-Environment Interaction Modeling

In our proposed AquaTree framework, the agent, as the decision-making entity of the MDP, leverages the synergistic integration of MCTS and DRL to emulate the trial-and-error decision-making process of professional image editors. Specifically, the agent dynamically expands a tree structure guided by neural network policies, generating multi-path enhancement sequences within the action space and retrospectively selecting the optimal combination of operations via a hybrid reward mechanism. The environment, serving as the interactive counterpart to the agent, comprises both the original underwater image and intermediate processed image states during the workflow.

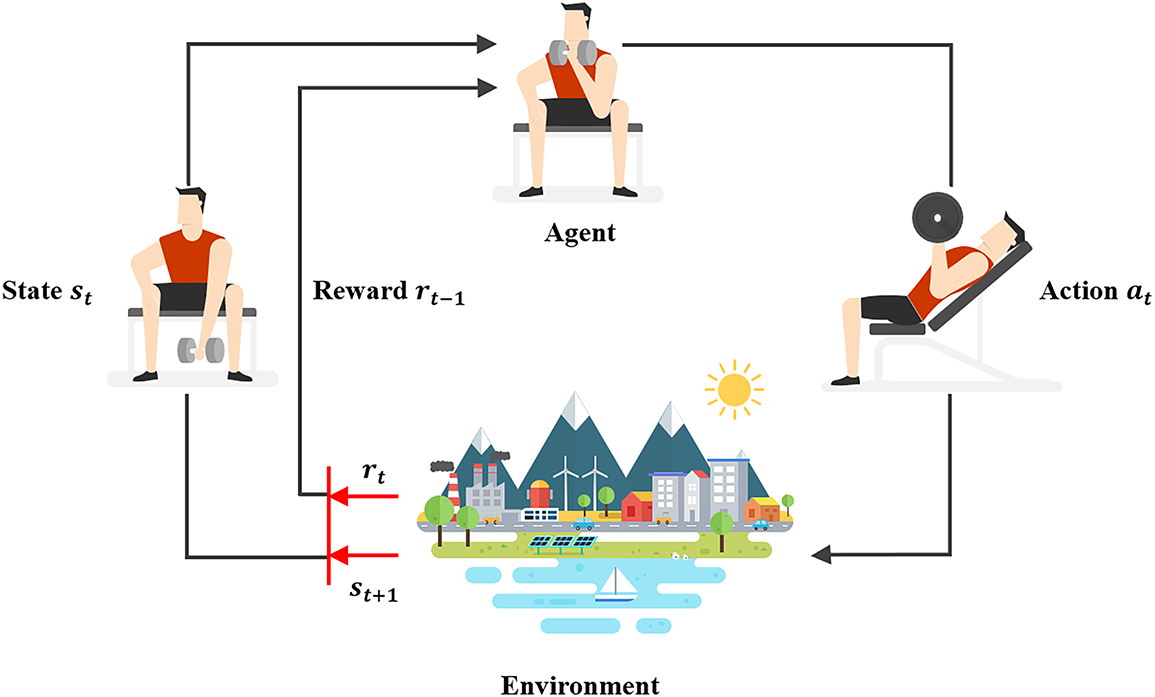

As depicted in Fig. 1, at each decision timestep t, the agent observes the current image state

Figure 1: The iterative interaction between the agent and the environment

2.2 Underwater Image Features as States

This paper constructs state space based on multi-dimensional underwater image features. Specifically, the state is jointly characterized by global chromatic features

For global chromatic features modeling, addressing the typical chromatic aberration and attenuation in underwater images, the CIELab color space is adopted as the foundation for feature extraction.

Owing to its superior color gamut coverage and perceptual uniformity compared to traditional RGB space, along with its decoupled luminance

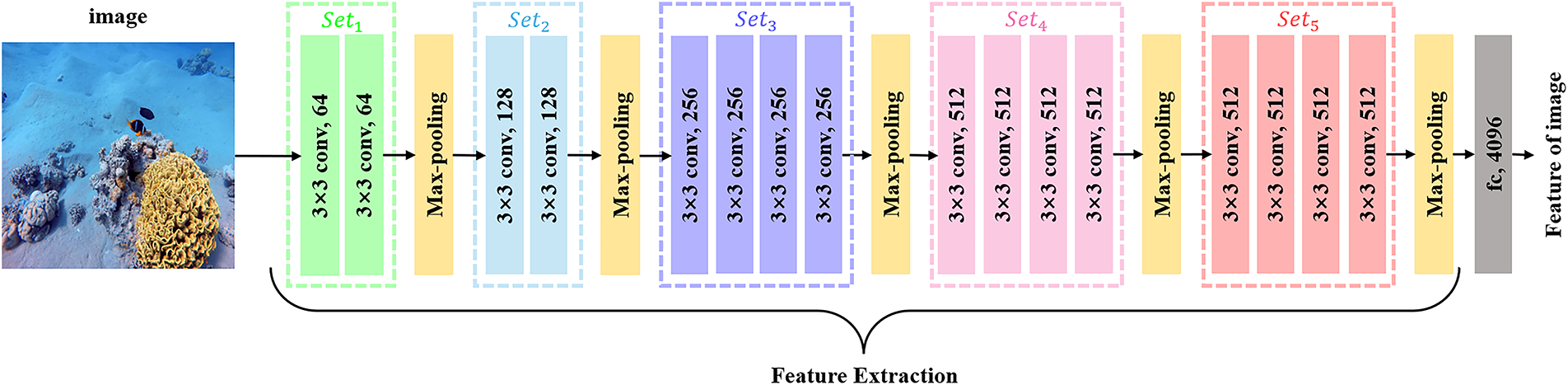

For deep perceptual features modeling, inspired by human vision, a deep CNN is introduced to extract high-level semantic information. Specifically, a transfer learning strategy employing the VGG-19 model [26] leverages its generalized representational capabilities pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. By analyzing activation patterns during image enhancement tasks, a 4096-dimensional feature vector from the fully connected layer is selected as the perceptual feature

Figure 2: Perceptual feature extraction from images leveraging the VGG-19 model

2.3 Image Enhancement Operations as Actions

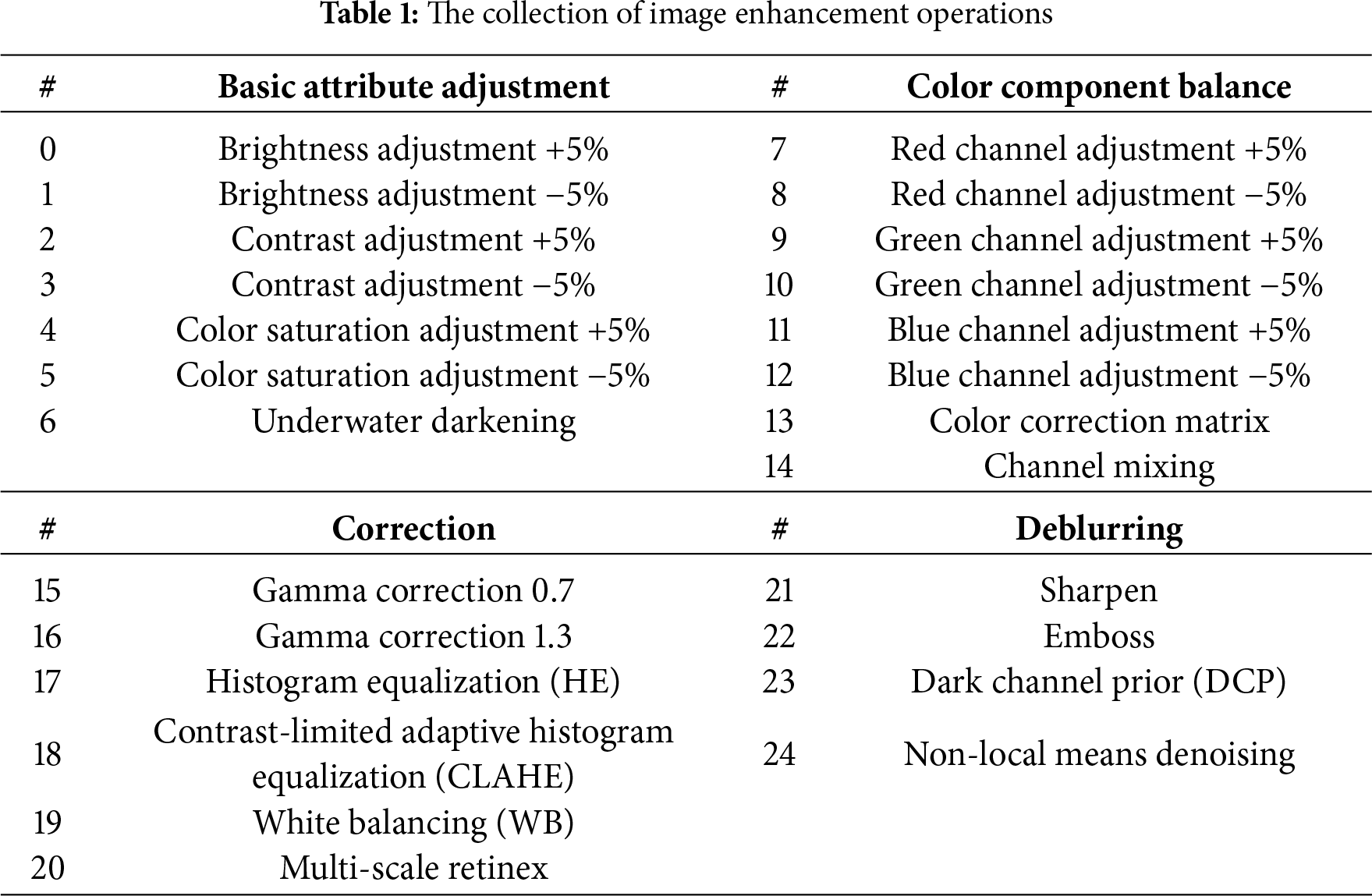

An image enhancement operation is denoted as an action a. We establish an extensible collection of actions for image enhancement operations, including 25 actions categorized into four families of operations: (1) basic attribute adjustment, (2) color component balance, (3) correction, and (4) deblurring, as displayed in Table 1.

Basic attribute adjustment operations are utilized to alter fundamental properties of an image. To prevent irreversible outcomes from single-step excessive modifications, Actions 0–5 are constrained to increase or decrease the value by no more than 5% per operation. Action 6 represents underwater dark enhancement [27], which integrates CLAHE processing in the LAB color space with blue channel compensation technology.

Color component balance operations address underwater color cast by independently adjusting the values of individual color channels. Single-channel adjustments consist of actions 7–12, employing an RGB gain adjustment model to scale each channel independently in incremental steps of 5%. Action 13 corresponds to the color correction matrix [28], which corrects nonlinear color deviations induced by complex aqueous media through a 3

Correction operations are employed to adjust the dynamic range of underwater images. Actions 15 and 16 are gamma correction, where a low gamma value primarily enhances details in dark regions while a high gamma value suppresses overexposure in bright areas. The gray histograms of underwater images typically exhibit concentration. Action 17 is the histogram equalization (HE) algorithm [30], which improves the visual quality of underwater images by expanding the gray range and achieving uniform distribution. However, its specific enhancement effects are challenging to control and may incur certain information loss. Action 18 employs the contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) [31] algorithm, which encodes image details by enhancing local contrast and edges. Action 19 is the white balancing (WB) [32] algorithm that corrects color deviations by adjusting the color temperature of images. Action 20 implements multi-scale retinex enhancement [33], constructing multi-scale Gaussian kernels and estimating illumination components to achieve detail enhancement through logarithmic domain differencing and normalization operations.

Deblurring operations integrate morphological operations and physical priors to enhance image clarity. Action 21 sharpens the image by superimposing the sharpened result onto the original, thereby preserving intrinsic details while enhancing edge distinctness. Action 22 applies an emboss operation to underwater images to accentuate the color of target objects. Action 23 implements Dark channel prior (DCP) dehazing [34], which models underwater light attenuation through dark channel characteristics. Action 24 executes Non-local Means Denoising [35] via a fast NL-Means algorithm, which employs spatial similarity patch matching.

It is worth mentioning that our action set is scalable and replaceable, allowing for easy compatibility with new underwater image enhancement operations through reserved interfaces.

2.4 Image Quality Improvements as Rewards

To effectively guide the agent in learning the optimal enhancement policy within MDP, we employ the image quality improvement at each step of the MDP as a reward. Given an underwater image enhancement model

This paper constructs a chromatic difference metric model to address the prevalent issues of chromatic attenuation and color temperature shift in underwater images. The enhanced image

For each pixel position

where the spatial dimensions

To maintain the textural details and structural authenticity of enhanced images, this paper introduces a deep feature-based perceptual consistency metric. According to research findings on visual perception mechanisms [36], pretrained deep neural networks can effectively capture high-level semantic features of images. Specifically, the corresponding perceptual consistency reward function is defined as:

where

To balance the optimization objectives of chromatic correction and detail preservation, the final reward function adopts a weighted linear combination strategy:

where

3 Training and Implementation of Our Proposed AquaTree Framework

This section outlines the AquaTree framework by first explaining its overall architecture, followed by the MCTS-DRL synergistic training mechanism that powers it, and concluding with the implementation process for underwater image enhancement.

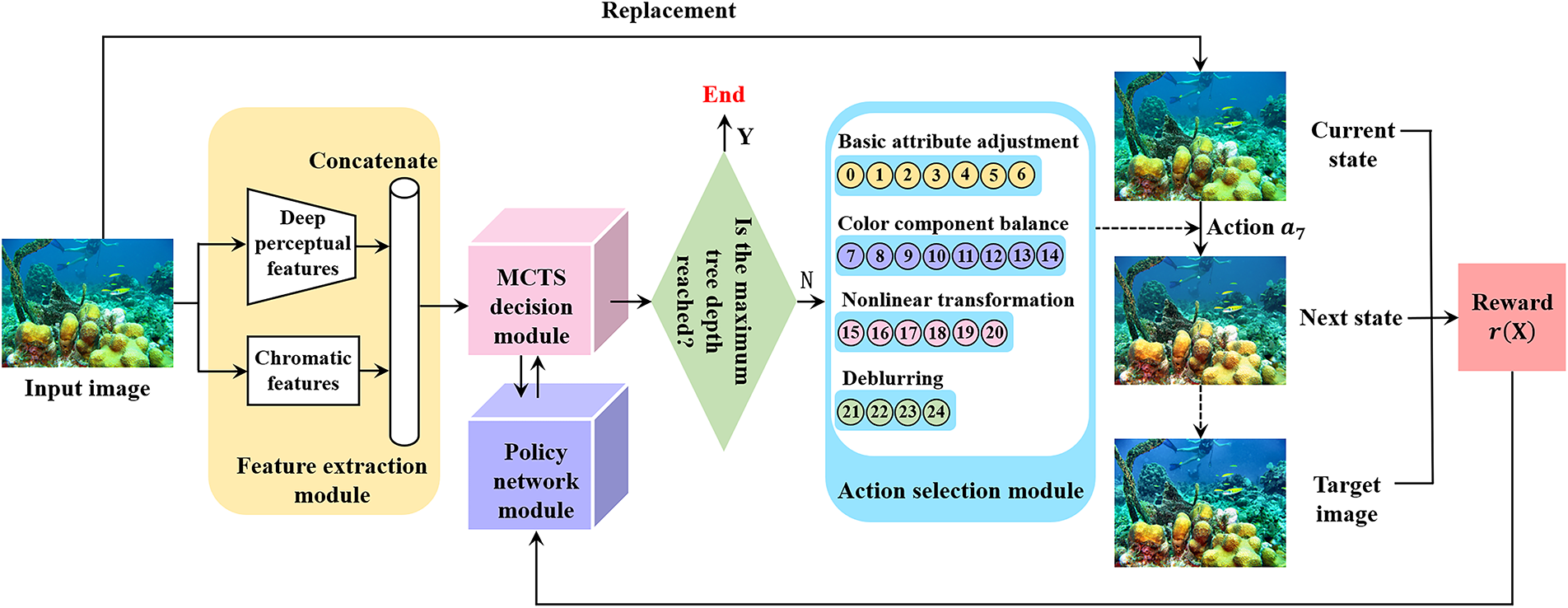

3.1 Overall Framework of AquaTree

Fig. 3 presents an overview of AquaTree, our MDP-based framework for UIE. The core concept involves modeling UIE as a sequential decision-making process, where a synergistic training mechanism integrating MCTS and DRL optimizes interpretable sequences of enhancement operations. The framework comprises five primary components. First, the feature extraction module derives chromatic features and deep perceptual features from input underwater images to jointly characterize the state representation. Second, the MCTS decision module (generative phase of the synergistic training mechanism) performs global optimization of enhancement operation sequences within the action space, leveraging an improved MCTS algorithm. Third, the policy network module (optimization phase of the synergistic training mechanism) employs a refined ResNet-18 deep learning model to guide the tree search direction and evaluate node values. Fourth, the action selection module chooses an optimal action from the candidate set based on the

Figure 3: Overview of our MDP-based AquaTree framework for UIE

3.2 MCTS-DRL Synergistic Training Mechanism

The framework receives the original underwater image X as input, conducts multi-path exploration within the predefined action set A, and yields the enhanced image

The process is implemented by constructing a dynamically growing search tree, where each node represents an intermediate image state resulting from specific editing operations. The framework employs a dual-branch neural network architecture: the policy branch predicts probability distributions over candidate operations, while the value branch estimates the expected return of the current state. The network undergoes supervised training with the objective of minimizing the perceptual discrepancy between the enhanced image X′ and the target image Y manually refined by human experts.

The training process of the framework adopts a dual-phase paradigm of alternating optimization, establishing a closed-loop learning mechanism through exploratory search in the generative phase and parameter updates in the optimization phase. The training set comprises pairs of original images and their corresponding target images, driving the framework to learn professional-grade image enhancement strategies.

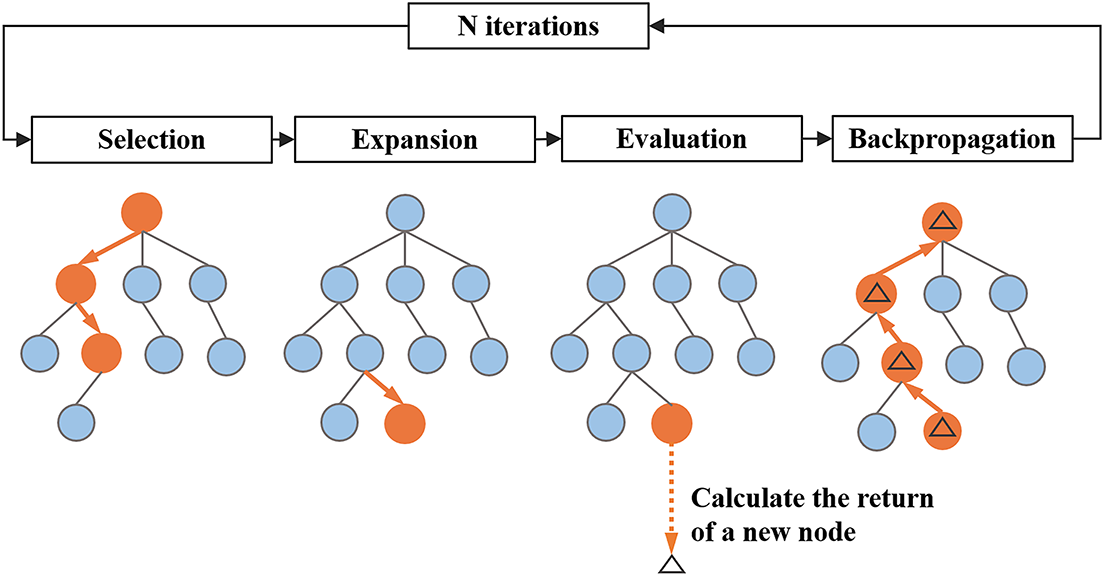

During the generative phase, a dynamically growing Monte Carlo tree is iteratively constructed via an exploration-exploitation mechanism to generate sequences of image editing operations. Initialized with the raw input image X as the root node, each iteration incorporates a new node through four core steps: selection, expansion, evaluation, and backpropagation, as detailed in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: One iteration of the modified version of MCTS

Selection: The selection phase employs a tree search strategy based on maximizing the upper confidence bound (UCB), which balances the exploration of less-visited nodes and the exploitation of those yielding high average rewards. Starting from the current root node, the framework traverses the search tree by recursively selecting the child node with the optimal UCB value until reaching a leaf node eligible for expansion. The UCB function is formally defined as:

where

Expansion: When the selected leaf node has not reached the maximum tree depth, the framework performs a full enumeration of actions within the operation space A, generating corresponding child nodes for each candidate editing operation. The newly expanded nodes inherit the state features

Evaluation: For new child nodes, the framework employs a hybrid return mechanism

Backpropagation: The return

Upon reaching the preset MCTS iteration threshold, the system generates a tree search policy

The policy serves as the probabilistic basis for action sampling in the tree search inference mode, iteratively driving the system to select optimal editing operations until a complete enhanced sequence is constructed.

During the optimization phase, the training data generated in the generation phase is constructed into triplet training samples (original image X, reward

the first term constrains the deviation between the prediction value

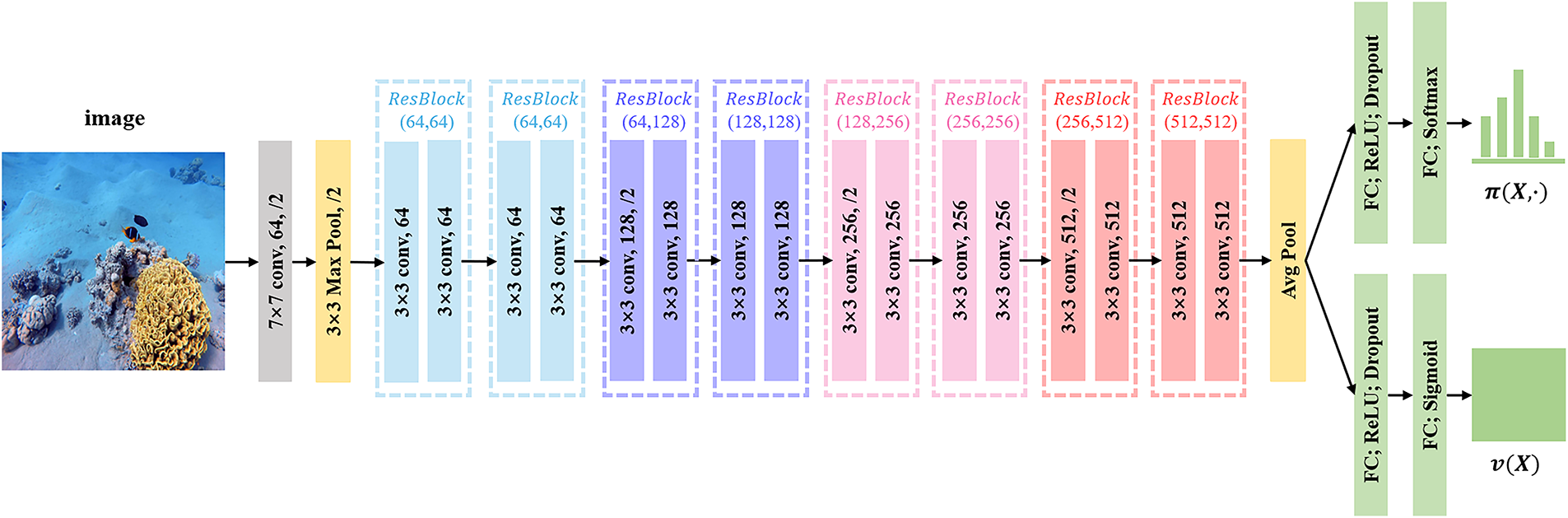

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the neural network architecture in this phase utilizes a ResNet-18 backbone with targeted modifications to adapt to the reinforcement learning framework. Key enhancements include replacing the original classification layer with a dual-branch output structure: the policy branch generates a probability distribution

Figure 5: Optimization phase based on improved ResNet-18

The trained framework provides a dual-mode inference scheme, comprising a tree search-based inference scheme and a network policy-based inference scheme, tailored for application scenarios prioritizing either enhancement quality or computational efficiency, thereby establishing a Pareto frontier between precision and efficiency.

The tree search-based inference mode extends the MCTS construction mechanism from the generation phase, exploring globally optimal solutions for enhancement operation sequences through simulated rollouts and backtracking. Due to the absence of reference images, rewards at maximum tree depth are estimated using the neural network-predicted value

Conversely, the network policy-based inference mode directly utilizes the output probability

The two modes form a complementary spectrum across the performance-efficiency trade-off, offering flexible adaptation to diverse application requirements.

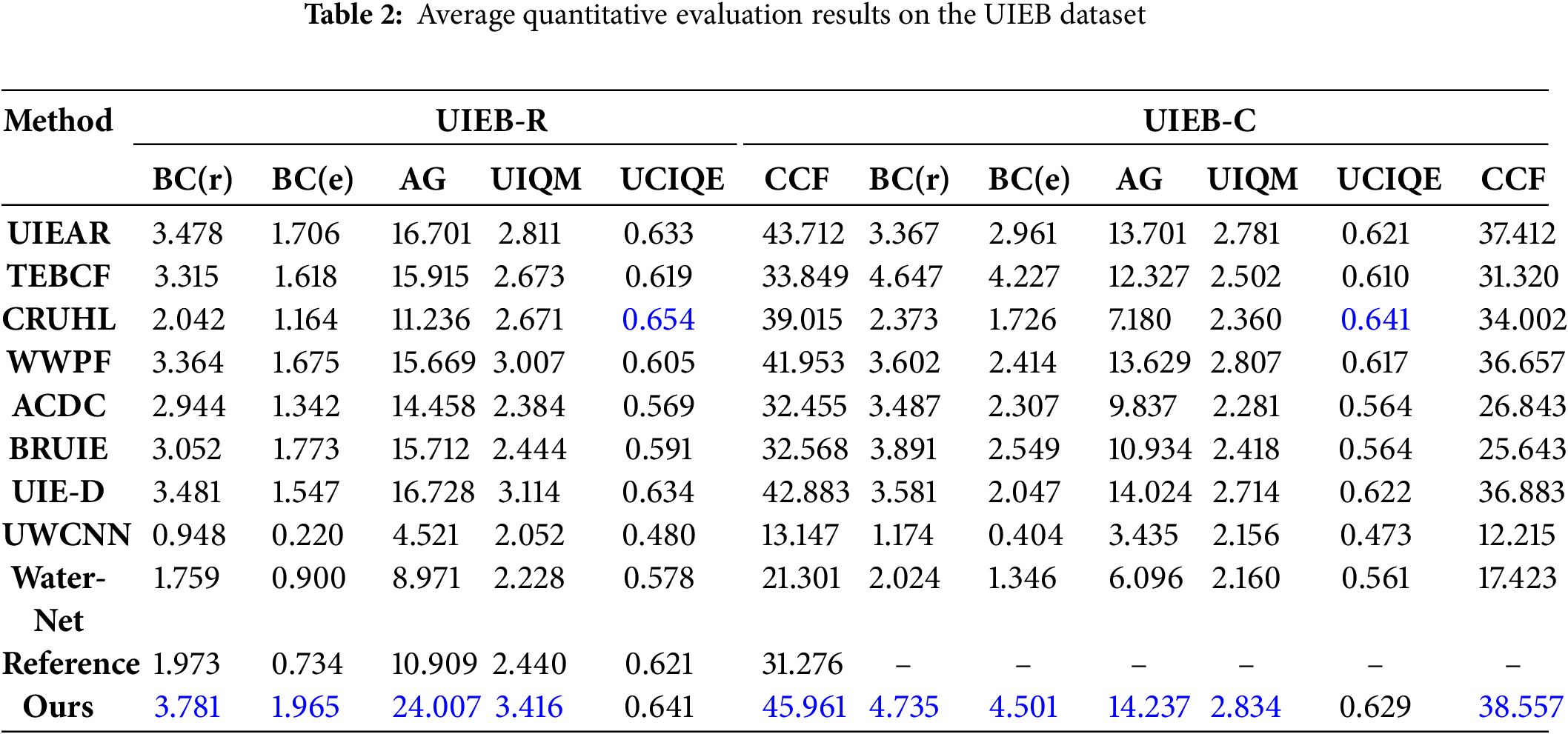

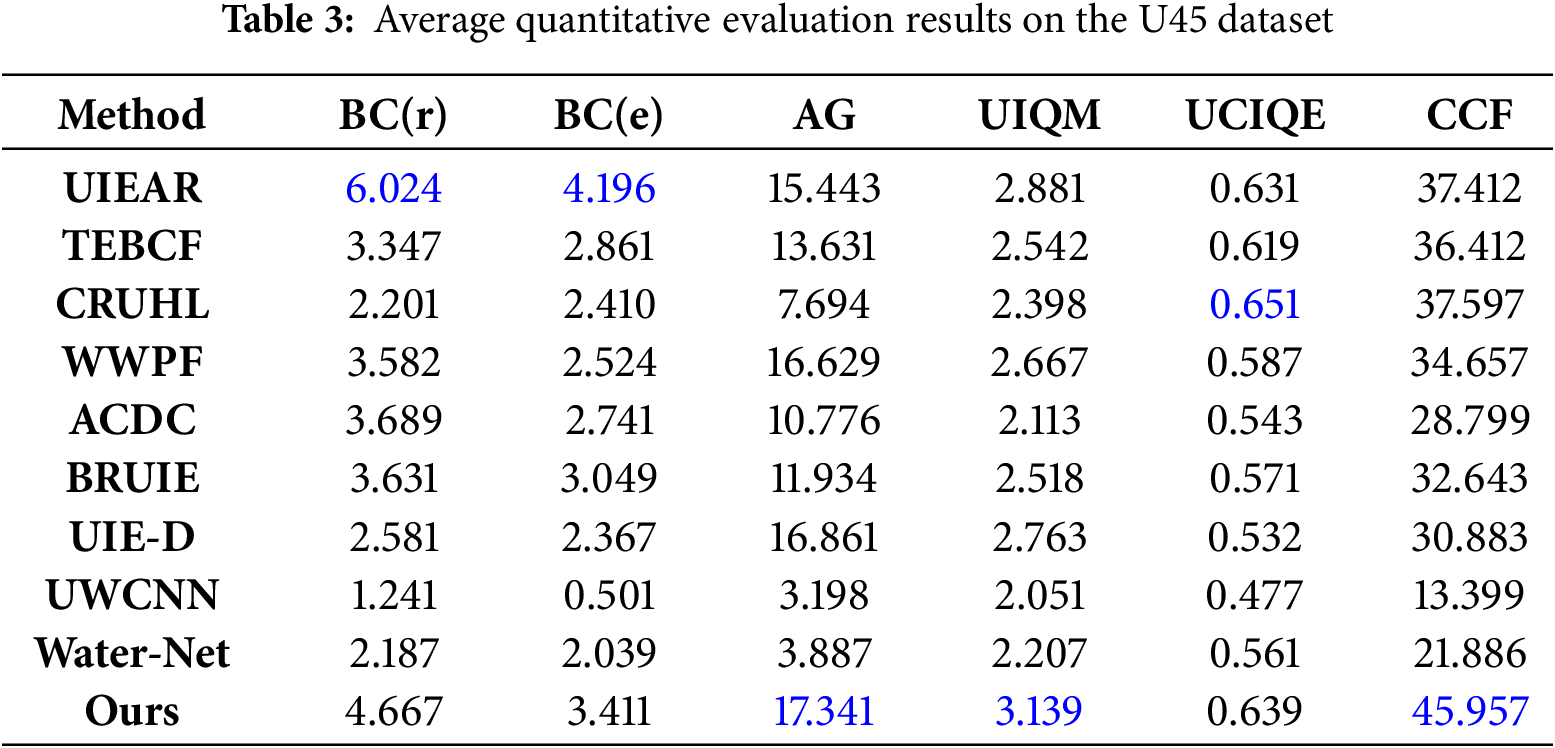

In this section, we analyze in more detail the effectiveness of our framework. In all comparative tables, the highest values for each evaluation metric are indicated in blue.

Model training was conducted on an Intel Core i7-9700KF and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 GPU workstation using PyTorch with torchvision, numpy, and kornia libraries, following Section 3.2’s alternating training protocol. During the generation phase,

For a comprehensive evaluation, nine comparative methods were employed: UIEAR [12], TEBCF [37], CRUHL [38], WWPF [17], ACDC [39], BRUIE [40], UIE-D [23], UWCNN [41], and Water-Net [42]. These methods are categorized as follows: UIEAR [12], TEBCF [37], and CRUHL [38] represent physics-based methods; WWPF [17], ACDC [39], and BRUIE [40], constitute non-physics-based methods; UIE-D [23], while UWCNN [41], and Water-Net [42] exemplify deep learning-based methods. The performance of these benchmark methods was rigorously assessed and comparatively analyzed against our proposed framework.

For performance evaluation of diverse underwater image enhancement methodologies, this paper employs two datasets: UIEB [42] and U45 [43]. Specifically, the UIEB dataset comprises two distinct subsets: UIEB-R and UIEB-C. The UIEB-R subset contains 890 real-world underwater scene images paired with corresponding reference-enhanced images, generated through a rigorous selection process involving 50 human volunteers, who chose the optimal enhancement result from 12 algorithm-generated candidates for each raw input image. The UIEB-C subset consists of 60 severely degraded images representing challenging scenarios. Collectively, this dataset facilitates rigorous robustness assessment of UIE methods across heterogeneous underwater conditions. We randomly select 790 image pairs from the UIEB-R subset as the training set and the remaining 100 pairs as the testing set 1. The UIEB-C subset serves as testing set 2. After training on the 790 pairs, experiments are conducted on testing set 1 and testing set 1. The U45 dataset comprises 45 underwater images categorized into three distinct subsets: Green, Blue, and Haze-like, each containing 15 images representing green deviation, blue deviation, and hazy veiling effects, respectively. It serves to assess the performance of different methods in color correction and haze removal under specific degradation scenarios. Finally, to evaluate the generalization capability of our framework, we employ the U45 dataset as testing set 3.

Five metrics were employed to comprehensively evaluate enhancement performance: the blind contrast restoration assessment (BCRA) [37], the average gradient (AG) [44], the underwater image quality measure (UIQM) [45], the underwater color image quality evaluation measure (UCIQE) [46], and the colorfulness contrast fog density index (CCF) [47]. Specifically, BCRA evaluates the extent of detail enhancement between pre- and post-processing states through two subcomponents: BC(r) and BC(e), where BC(r) measures gradient magnitude enhancement at edge pixels and BC(e) assesses edge visibility improvement. AG serves to quantify image sharpness and edge distinctness. Elevated BCRA and AG values correspond to superior visual quality characteristics. UIQM incorporates three elements: the underwater image colorfulness measure (UICM), the underwater image sharpness measure (UISM), and the underwater image contrast measure (UIConM). The underwater color image quality evaluation (UCIQE) is a composite metric derived from chromaticity, saturation, and contrast. Similarly, the colorfulness contrast fog density index (CCF) synthesizes colorfulness, contrast, and fog density into a single score. For all three metrics, elevated scores are directly proportional to a stronger correlation with human visual perception.

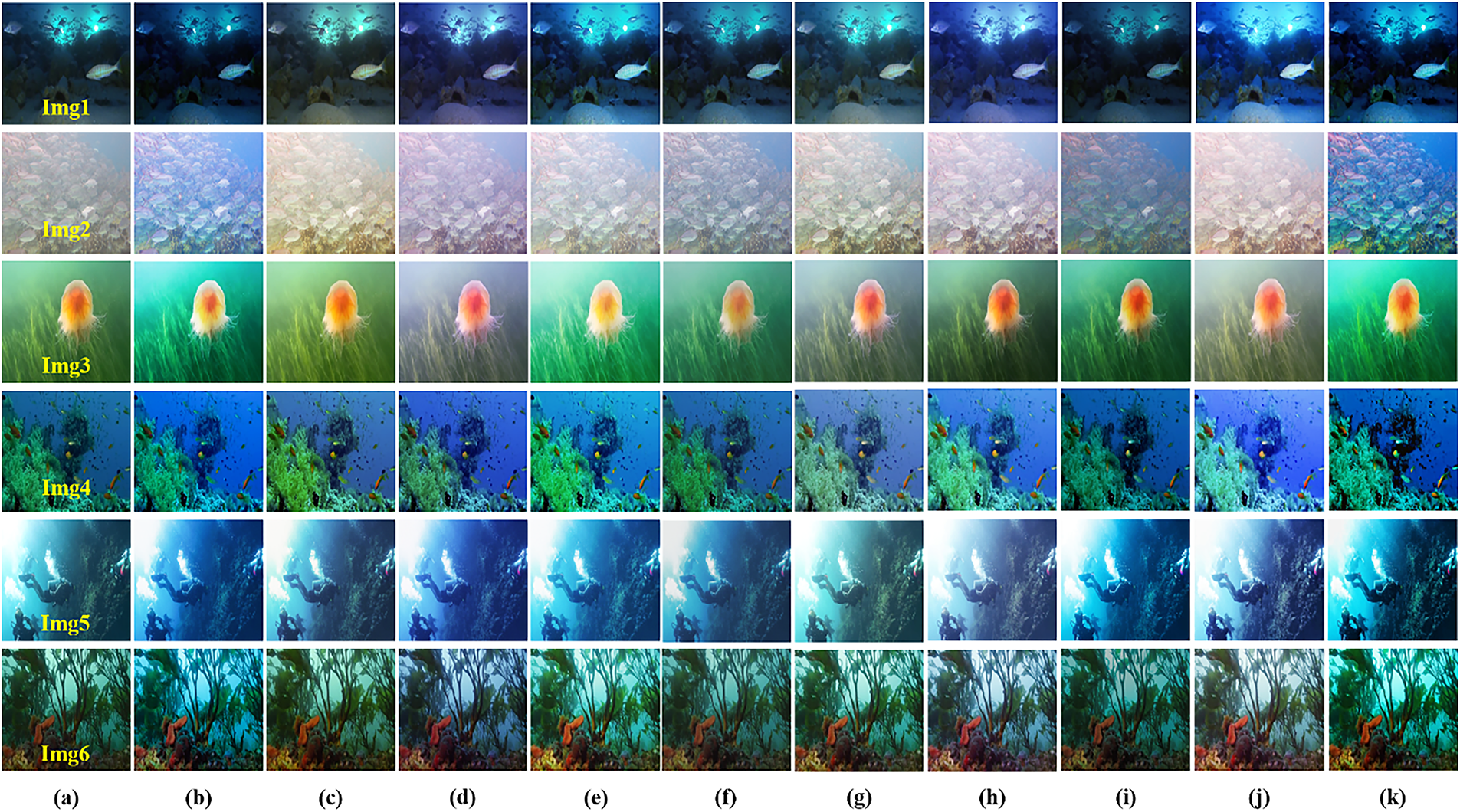

4.5 Evaluations of Comprehensive Enhancement on the UIEB Dataset

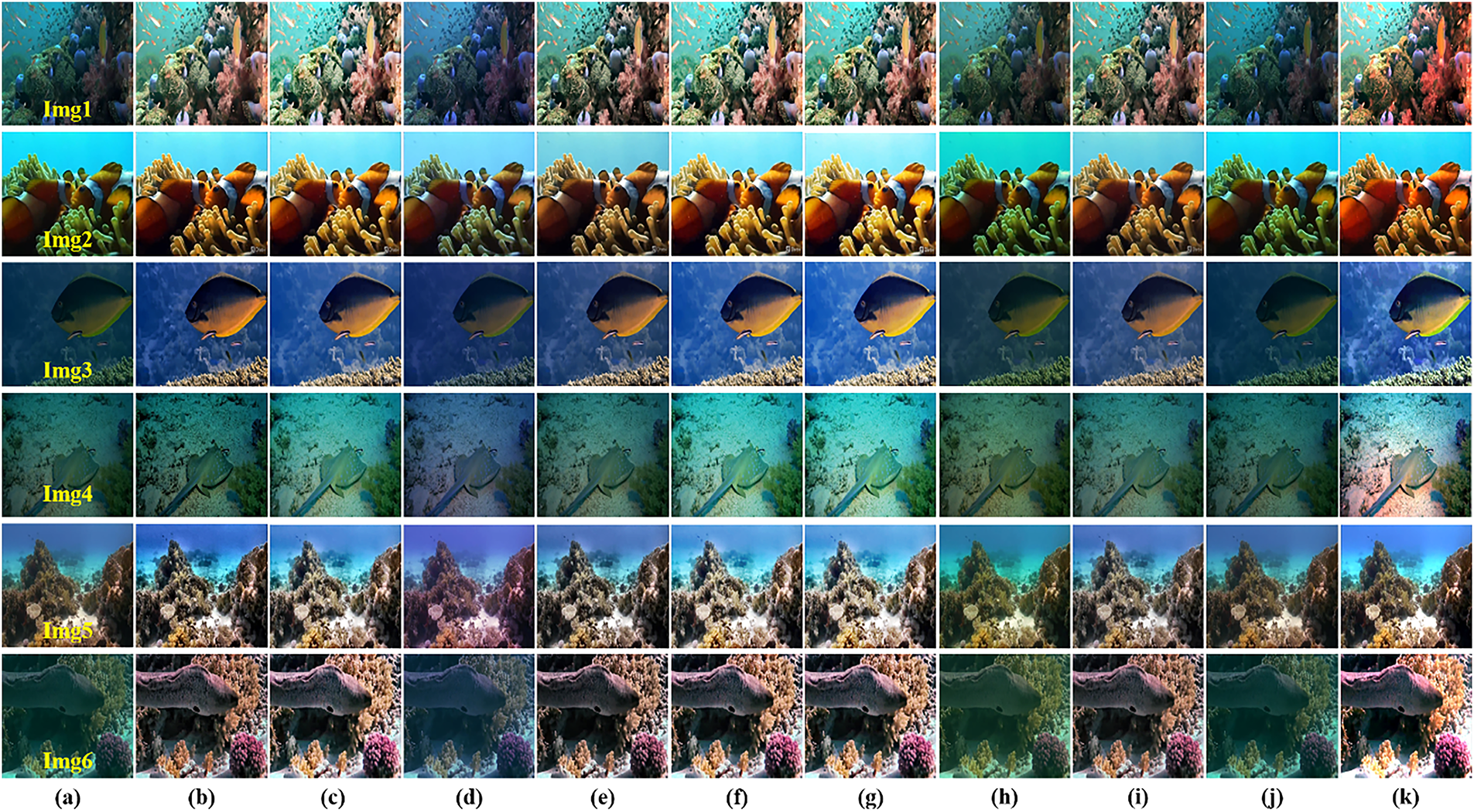

Qualitative results from Testing set 1 in Fig. 6 show that several models suffer from specific shortcomings: UIEAR, UWCNN, and UIE-D exhibit poor color cast correction, CRUHL, BRUIE, and WWPF cause overexposure, and while TEBCF, ACDC, and Water-Net handle color well, they struggle with desaturation and low contrast, respectively. Furthermore, a common failure in preserving fine details is observed across all compared methods, except for TEBCF and our proposed framework. However, TEBCF’s detail enhancement comes at the cost of amplified noise. By contrast, our method’s superior performance, which simultaneously overcomes color distortion, low contrast, and blurring, is attributed to its MCTS-DRL mechanism that intelligently sequences enhancement operations for a globally optimal output.

Figure 6: Qualitative evaluation results of the testing set 1. (a) Raw underwater images, (b) TEBCF, (c) CRUHL, (d) UIEAR, (e) ACDC, (f) BRUIE, (g) WWPF, (h) UWCNN, (i) Water-Net, (j) UIE-D, and (k) our framework

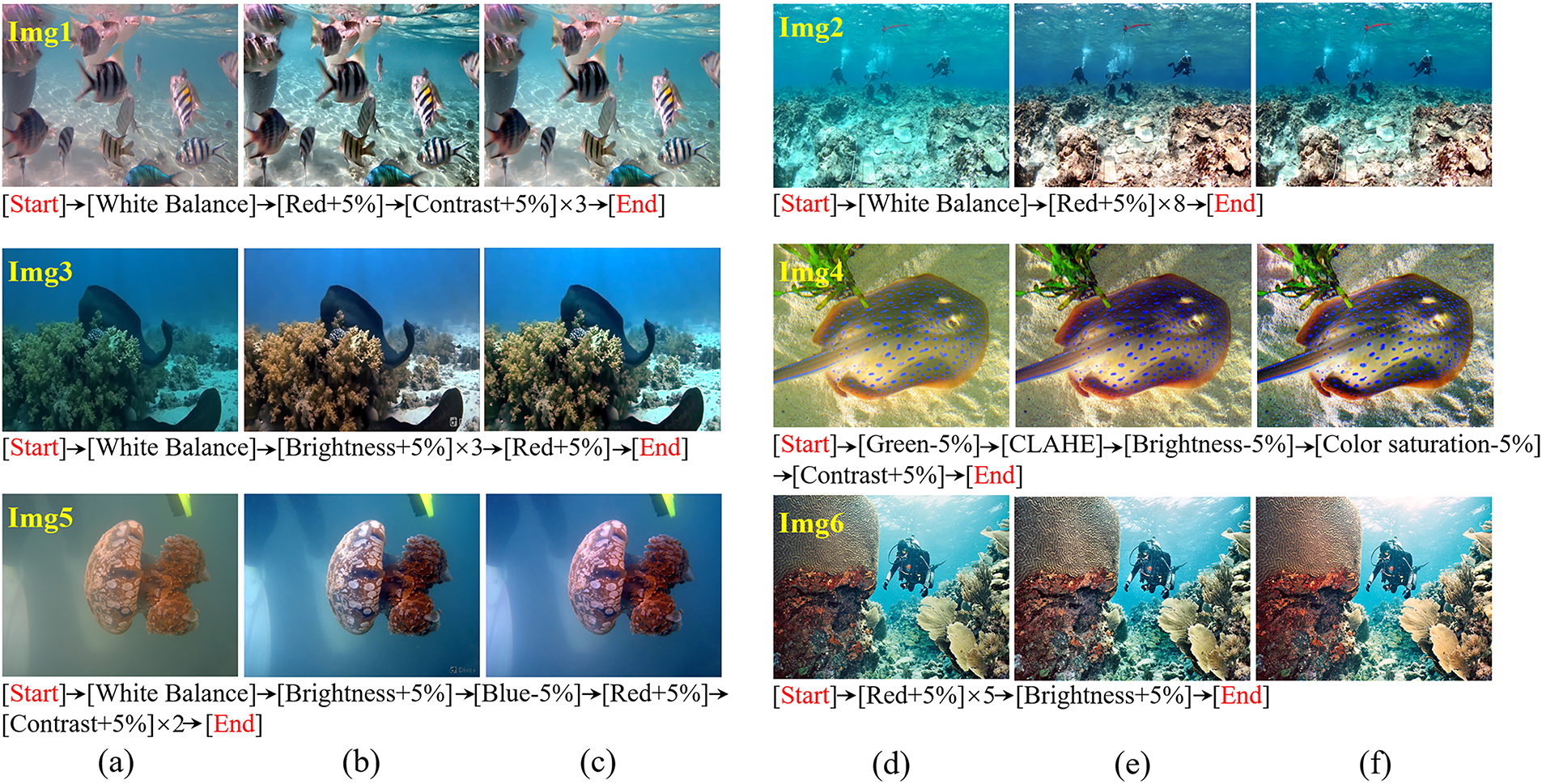

Fig. 7 presents the intermediate action sequences selected by the agent alongside visual comparisons between our enhanced results and the reference-enhanced images, demonstrating superior performance in color cast elimination (e.g., Img1 and Img2), low-contrast improvement (e.g., Img3 and Img4), and blurred detail restoration (e.g., Img5 and Img6). This enhancement efficacy stems from the global optimization capability of MCTS, which effectively circumvents suboptimal local solutions inherent in traditional single-step enhancement models. Given that reference-enhanced images are curated by 50 volunteers selecting from 12 enhancement results per raw underwater image, direct visual comparisons confirm closer alignment of our method with human visual perception.

Figure 7: Action sequences selected by the agent and qualitative evaluation results of the testing set 1. (a) Raw underwater images, (b) reference-enhanced images from the UIEB-R subset, and (c) enhanced images of our framework

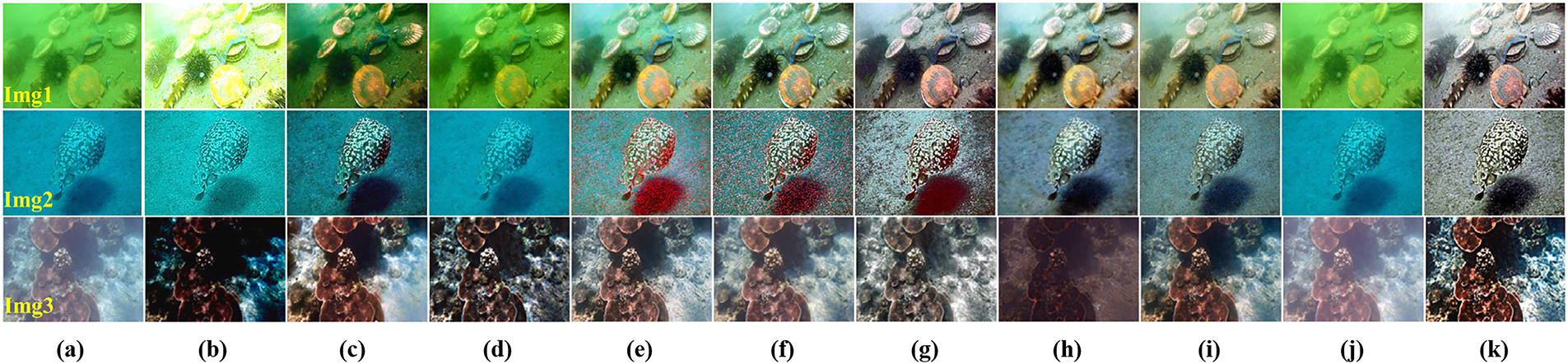

The superior generalization capability of our method is evidenced by its performance on testing set 2 in Fig. 8. Conversely, UIEAR, CRUHL, UWCNN, Water-Net, and UIE-D show limited efficacy in addressing color casts. TEBCF and ACDC, while removing unwanted tones, introduce new artifacts. Furthermore, BRUIE and WWPF only achieve partial color correction at the expense of contrast and uniform brightness. Our framework stands out by consistently producing visually pleasing results across these challenging cases.

Figure 8: Qualitative evaluation results on the testing set 2. (a) Raw underwater images, (b) TEBCF, (c) CRUHL, (d) UIEAR, (e) ACDC, (f) BRUIE, (g) WWPF, (h) UWCNN, (i) Water-Net, (j) UIE-D, and (k) our framework

Table 2 presents the average quantitative evaluation results for both UIEB subsets. On the testing set 1 and testing set 2, our method achieves the highest scores across BC(r), BC(e), AG, UIQM, and CCF metrics, while ranking second in UCIQE to CRUHL. This marginal difference stems from specialized color distribution optimization of CRUHL, whereas AquaTree prioritizes balanced enhancement across multiple degradation dimensions. Compared to state-of-the-art benchmarks including UIEAR, WWPF, and UIE-D, our reward-based optimization avoids the over-saturation typical of WWPF and the under-enhancement limitations of UIEAR, while our sequential action selection outperforms the monolithic deep learning approach UIE-D by explicitly modeling enhancement as a multi-step process. Cumulatively, these experimental results substantiate the holistic efficacy of our proposed framework in tackling the intertwined challenges of color distortion, low-contrast degradation, and detail blurring. More importantly, the enhancements it produces exhibit superior congruence with human visual perception, even when benchmarked against professionally reference-enhanced images.

4.6 Color Correction and Haze Removal Comparisons on the U45 Dataset

The U45 dataset serves as the basis for qualitative assessment of color correction and haze removal performance across multiple methods, with outcomes visualized in Fig. 9. In the case of Img1, which exhibits a pronounced green cast, Water-Net achieves partial suppression of the green cast, though residual green tones remain visible in background areas. BRUIE, CBAF, and ACDC demonstrate effective green-color correction; however, the first two yield insufficient contrast enhancement, and ACDC leads to noticeable undersaturation. When processing the blue-dominated image (e.g., Img2), while BRUIE, CBAF, and ACDC succeed in blue-color normalization, BRUIE offers no contrast improvement, CBAF attenuates image brightness, and ACDC produces a desaturated outcome. For the hazy image (e.g., Img3), dehazing is accomplished to some extent by most methods except UWCNN and UIE-D. By comparison, the proposed framework performs robustly across all three challenging conditions: it corrects color deviations effectively, removes haze competently, enhances contrast naturally, and avoids typical artifacts such as undersaturation or introduced color biases.

Figure 9: Qualitative evaluation results on the U45 dataset. (a) Raw underwater images, (b) TEBCF, (c) CRUHL, (d) UIEAR, (e) ACDC, (f) BRUIE, (g) WWPF, (h) UWCNN, (i) Water-Net, (j) UIE-D, and (k) our framework

Our framework demonstrates superior effectiveness in concurrently mitigating color deviation and haze degradation, as validated by its performance on the U45 dataset in Table 3. It obtains top rankings in three key metrics: AG, UIQM, and CCF, indicating enhanced capability in detail preservation, overall perceptual quality, and integrated color-contrast-haze restoration.

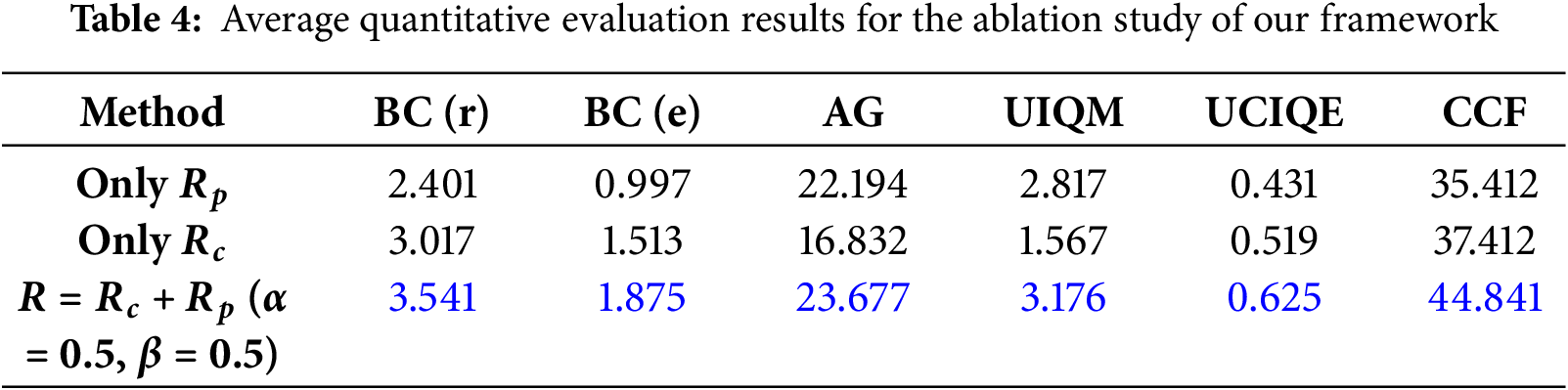

To clarify the contribution of individual components in our framework, we conducted an ablation analysis on testing set 1. The study evaluates three reward configurations: perceptual consistency reward

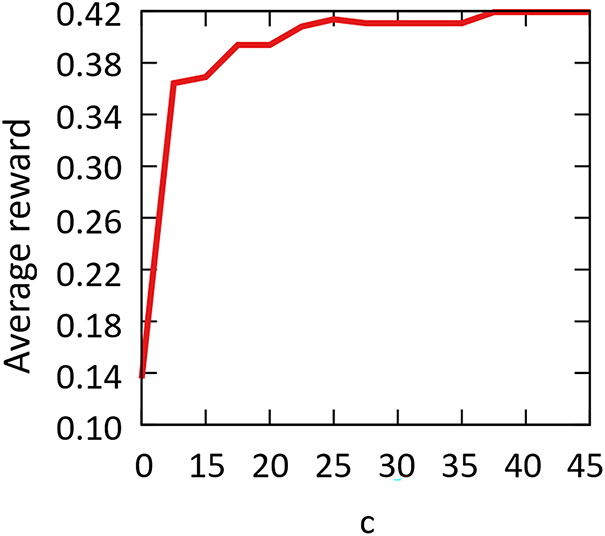

The exploration-exploitation coefficient

Figure 10: Average reward obtained on the testing set 1 varying the exploration-exploitation coefficient

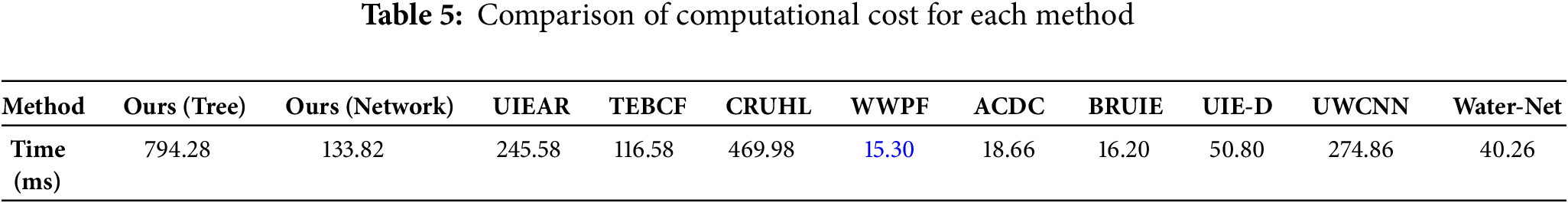

In Table 5, we evaluate the computational cost of the two inference modes on testing set 1, comparing them with baseline methods in terms of average processing time per image (at 256

This paper proposes AquaTree, the first UIE method based on the synergistic training of the MCTS algorithm and DRL. By modeling UIE as an MDP, we establish a multi-tiered action space that integrates physical priors with semantic perception, coupled with a dual-objective reward mechanism to guide policy optimization. This framework achieves simultaneous breakthroughs in interpretability and performance. Qualitative and quantitative experiments validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed framework in addressing degradation issues in underwater images, confirming the core advantage of sequential decision-making: global optimization of operation sequences avoids local optima inherent in single-step models while maintaining transparency.

Although our framework demonstrates satisfactory performance in enhancing the color, contrast, and details of underwater images, it still has the following limitations:

• If the action set needs to be expanded, the model must be retrained.

• The current framework focuses on image enhancement that aligns with human visual perception, without verifying its adaptability to different imaging devices and water quality conditions.

To address these limitations, the following solutions will be explored in the future: First, we will investigate methods to directly expand the action list on a pre-trained model, combining adaptive adjustment of operational parameters based on underwater optical characteristics to improve generalization capabilities for unknown water environments. Finally, we will optimize the network architecture and search strategies by exploring more efficient feature extractors, image enhancement algorithms, underwater image quality assessment metrics, and reinforcement learning models to further enhance the performance of the paradigm.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Hubei Provincial Technology Innovation Special Project and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province under Grants 2023BEB024, 2024AFC066, respectively.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing: Chao Li; writing—original draft, Resources, Data curation, Investigation: Jianing Wang; Visualization, Supervision, Formal analysis: Caichang Ding; Supervision: Zhiwei Ye. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cong R, Yang W, Zhang W, Li C, Guo CL, Huang Q, et al. PUGAN: physical model-guided underwater image enhancement using GAN with dual-discriminators. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2023;32:4472–85. doi:10.1109/TIP.2023.3286263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yu F, He B, Liu J, Wang Q. Dual-branch framework: AUV-based target recognition method for marine survey. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;115(12):105291. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang H, Sun S, Chang L, Li H, Zhang W, Frery AC, et al. INSPIRATION: a reinforcement learning-based human visual perception-driven image enhancement paradigm for underwater scenes. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133:108411. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qi Q, Li K, Zheng H, Gao X, Hou G, Sun K. SGUIE-Net: semantic attention guided underwater image enhancement with multi-scale perception. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2022;31:6816–30. doi:10.1109/TIP.2022.3216208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang W, Wang H, Ren P, Zhang W. Underwater image color correction via color channel transfer. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2023;21:1–5. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2023.3344630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou J, Li B, Zhang D, Yuan J, Zhang W, Cai Z, et al. UGIF-Net: an efficient fully guided information flow network for underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–17. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2023.3293912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li T, Rong S, Zhao W, Chen L, Liu Y, Zhou H, et al. Underwater image enhancement using adaptive color restoration and dehazing. Opt Express. 2022;30(4):6216–35. doi:10.1364/OE.449930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Song Y, She M, Köser K. Advanced underwater image restoration in complex illumination conditions. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2024;209:197–212. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2024.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou J, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Ren W, Lam KM, Zhang W. Underwater camera: improving visual perception via adaptive dark pixel prior and color correction. Int J Comput Vis. 2023;27:1–19. doi:10.1007/s11263-023-01853-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hou G, Li N, Zhuang P, Li K, Sun H, Li C. Non-uniform illumination underwater image restoration via illumination channel sparsity prior. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(2):799–814. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3290363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liang Z, Zhang W, Ruan R, Zhuang P, Xie X, Li C. Underwater image quality improvement via color, detail, and contrast restoration. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(3):1726–42. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3297524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hsieh YZ, Chang MC. Underwater image enhancement and attenuation restoration based on depth and backscatter estimation. IEEE Trans Comput Imaging. 2025;11:321–32. doi:10.1109/TCI.2025.3544065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xie J, Hou G, Wang G, Pan Z. A variational framework for underwater image dehazing and deblurring. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2022;32(6):3514–26. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2021.3115791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang W, Zhuang P, Sun HH, Li G, Kwong S, Li C. Underwater image enhancement via minimal color loss and locally adaptive contrast enhancement. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2022;31:3997–4010. doi:10.1109/TIP.2022.3177129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang H, Frery AC, Li M, Ren P. Underwater image enhancement via histogram similarity-oriented color compensation complemented by multiple attribute adjustment. Intell Mar Technol Syst. 2023;1:12. doi:10.1007/s44295-023-00015-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. An S, Xu L, Deng Z, Zhang H. HFM: a hybrid fusion method for underwater image enhancement. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;127:107219. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang W, Zhou L, Zhuang P, Li G, Pan X, Zhao W, et al. Underwater image enhancement via weighted wavelet visual perception fusion. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(4):2469–83. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3299314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang H, Köser K, Ren P. Large foundation model empowered discriminative underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63:1–17. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2025.3525962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ummar M, Dharejo FA, Alawode B, Mahbub T, Piran MJ, Javed S. Window-based transformer generative adversarial network for autonomous underwater image enhancement. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;126:107069. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Song H, Chang L, Wang H, Ren P. Dual-model: revised imaging network and visual perception correction for underwater image enhancement. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;125:106731. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhou J, Zhang D, Zhang W. Cross-view enhancement network for underwater images. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;121:105952. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhu P, Liu Y, Wen Y, Xu M, Fu X, Liu S. Unsupervised underwater image enhancement via content-style representation disentanglement. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;126:106866. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Qing Y, Liu S, Wang H, Wang Y. DiffUIE: learning latent global priors in diffusion models for underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2025;27:2516–29. doi:10.1109/TMM.2024.3521710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dudhane A, Hambarde P, Patil P, Murala S. Deep underwater image restoration and beyond. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2020;27:675–9. doi:10.1109/LSP.2020.2988590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li K, Wu L, Qi Q, Liu W, Gao X, Zhou L, et al. Beyond single reference for training: underwater image enhancement via comparative learning. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(6):2561–76. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3225376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2015. 10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li L, Wang H, Liu X. Underwater image enhancement based on improved dark channel prior and color correction. Acta Opt Sin. 2017;37(12):1211003. doi:10.3788/AOS201737.1211003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Song I, Kwon HJ, Kim TK, Lee SH. 3D image representation using color correction matrix according to the CCT of a display. J Korea Multimed Soc. 2019;22(1):55–61. doi:10.9717/kmms.2019.22.1.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Rehman S, Rong Y, Chen P. Designing an adaptive underwater visible light communication system. Sensors. 2025;25(6):1801. doi:10.3390/s25061801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Hummel R. Image enhancement by histogram transformation. Comput Graph Image Process. 1977;6(2):184–95. doi:10.1016/S0146-664X(77)80011-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Reza AM. Realization of the contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) for real-time image enhancement. J VLSI Signal Process Syst. 2004;38:35–44. doi:10.1023/B:VLSI.0000028532.53893.82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Akazawa T, Kinoshita Y, Shiota S, Kiya H. N-white balancing: white balancing for multiple illuminants including non-uniform illumination. IEEE Access. 2022;10:89051–62. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3200391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhou J, Yao J, Zhang W, Zhang D. Multi-scale retinex-based adaptive gray-scale transformation method for underwater image enhancement. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81:1811–31. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-11327-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. He K, Sun J, Tang X. Single image haze removal using dark channel prior. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2011;33(12):2341–53. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2010.168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Kim DY, Oh JG, Hong MC. Non-local means denoising method using weighting function based on mixed norm. J IKEEE. 2016;20(2):136–42. doi:10.7471/ikeee.2016.20.2.136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Park T, Liu MY, Wang TC, Zhu JY. Semantic image synthesis with spatially-adaptive normalization. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 2671–80. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yuan J, Cai Z, Cao W. TEBCF: real-world underwater image texture enhancement model based on blurriness and color fusion. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:4204315. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3110575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Berman D, Levy D, Avidan S, Treibitz T. Underwater single image color restoration using haze-lines and a new quantitative dataset. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43(8):2822–37. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2020.2977624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang W, Wang Y, Li C. Underwater image enhancement by attenuated color channel correction and detail preserved contrast enhancement. IEEE J Ocean Eng. 2022;47(3):718–35. doi:10.1109/JOE.2022.3140563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhuang P, Li C, Wu J. Bayesian retinex underwater image enhancement. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2021;101:104171. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2021.104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li C, Anwar S, Porikli F. Underwater scene prior inspired deep underwater image and video enhancement. Pattern Recogn. 2020;98:107038. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2019.107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Li C, Guo C, Ren W, Cong R, Hou J, Kwong S, et al. An underwater image enhancement benchmark dataset and beyond. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2020;29:4376–89. doi:10.1109/TIP.2019.2955241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Li H, Li J, Wang W. A fusion adversarial underwater image enhancement network with a public test dataset. arXiv: 1906.06819. 2019. 10.48550/arXiv.1906.06819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu R, Ma L, Zhang J, Fan X, Luo Z. Retinex-inspired unrolling with cooperative prior architecture search for low-light image enhancement. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE. p. 10561–70. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Panetta K, Gao C, Agaian S. Human-visual-system-inspired underwater image quality measures. IEEE J Ocean Eng. 2016;41(3):541–51. doi:10.1109/JOE.2015.2469915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yang M, Sowmya A. An underwater color image quality evaluation metric. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2015;24(12):6062–71. doi:10.1109/TIP.2015.2491020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wang Y, Li N, Li Z, Gu Z, Zheng H, Zheng B, et al. An imaging-inspired no-reference underwater color image quality assessment metric. Comput Electr Eng. 2018;70:904–13. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools