Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Task-Structured Curriculum Learning for Multi-Task Distillation: Enhancing Step-by-Step Knowledge Transfer in Language Models

1 Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, łzmir Katip Çelebi University, łzmir, 35620, Turkey

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, łzmir Institute of Technology, łzmir, 35430, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Aytuğ Onan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Contrastive Representation Learning for Next-Generation LLMs: Methods and Applications in NLP)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 70 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071301

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Knowledge distillation has become a standard technique for compressing large language models into efficient student models, but existing methods often struggle to balance prediction accuracy with explanation quality. Recent approaches such as Distilling Step-by-Step (DSbS) introduce explanation supervision, yet they apply it in a uniform manner that may not fully exploit the different learning dynamics of prediction and explanation. In this work, we propose a task-structured curriculum learning (TSCL) framework that structures training into three sequential phases: (i) prediction-only, to establish stable feature representations; (ii) joint prediction–explanation, to align task outputs with rationale generation; and (iii) explanation-only, to refine the quality of rationales. This design provides a simple but effective modification to DSbS, requiring no architectural changes and adding negligible training cost. We justify the phase scheduling with ablation studies and convergence analysis, showing that an initial prediction-heavy stage followed by a balanced joint phase improves both stability and explanation alignment. Extensive experiments on five datasets (e-SNLI, ANLI, CommonsenseQA, SVAMP, and MedNLI) demonstrate that TSCL consistently outperforms strong baselines, achieving gains of +1.7–2.6 points in accuracy and 0.8–1.2 in ROUGE-L, corresponding to relative error reductions of up to 21%. Beyond lexical metrics, human evaluation and ERASER-style faithfulness diagnostics confirm that TSCL produces more faithful and informative explanations. Comparative training curves further reveal faster convergence and lower variance across seeds. Efficiency analysis shows less than 3% overhead in wall-clock training time and no additional inference cost, making the approach practical for real-world deployment. This study demonstrates that a simple task-structured curriculum can significantly improve the effectiveness of knowledge distillation. By separating and sequencing objectives, TSCL achieves a better balance between accuracy, stability, and explanation quality. The framework generalizes across domains, including medical NLI, and offers a principled recipe for future applications in multimodal reasoning and reinforcement learning.Keywords

The exponential increase in computational power and the widespread availability of large-scale datasets have led to unprecedented progress in artificial intelligence, particularly in natural language processing. The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs), including GPT-4, PaLM, Claude, and LLaMA, represents a major leap in AI research, as these models demonstrate remarkable abilities across diverse domains such as language understanding, reasoning, creative text generation, and complex problem solving [1–3]. These models have achieved human-level or even superhuman performance on various benchmarks and have revealed emergent capabilities that arise as a result of their large-scale pretraining and sophisticated learning paradigms.

Despite these advances, the practical deployment of LLMs remains highly constrained by significant resource demands. Running inference on models with hundreds of billions of parameters requires substantial GPU memory, high-throughput infrastructure, and energy consumption at a scale that is prohibitive for most organizations [4,5]. For example, generating a single output from a 540 billion parameter model such as PaLM can require hundreds of gigabytes of memory and considerable computational power. These constraints raise serious concerns regarding accessibility, cost, and environmental impact, creating a gap between state-of-the-art performance and real-world usability.

To mitigate these limitations, the research community has increasingly focused on efficiency-oriented techniques. Among them, knowledge distillation has emerged as a powerful method for transferring the capabilities of large, resource-intensive models into smaller, more deployable ones. Introduced by Hinton et al. [6], knowledge distillation allows a compact student model to learn from a larger teacher model by mimicking its behavior, thereby reducing the need for extensive retraining or large-scale supervision. While early distillation techniques concentrated on replicating the teacher’s final outputs, recent methods have shifted toward capturing intermediate representations and reasoning processes, which are often key to the superior performance of LLMs.

This evolution has given rise to advanced frameworks such as Distilling Step by Step, proposed by Hsieh et al. [7]. In contrast to traditional output-based distillation, this method incorporates natural language rationales—textual reasoning steps generated by the teacher—as auxiliary supervision signals. These rationales guide the student model to emulate not just the final predictions but also the cognitive steps leading to them. Remarkably, models with as few as 770 million parameters have been shown to outperform their 540 billion parameter teachers on multiple tasks, using only a fraction of the training data.

However, the original step by step framework approaches prediction and explanation as jointly optimized tasks throughout training, without considering the pedagogical order in which these tasks are introduced. Inspired by human learning processes and cognitive development theory, we posit that structured sequencing of learning objectives can significantly enhance knowledge transfer. Educational psychology shows that humans tend to first acquire foundational skills and then build upon them with higher-order reasoning. In machine learning, this concept is formalized as curriculum learning, where training examples are introduced in a progression that facilitates better learning dynamics [8].

Although curriculum learning has been explored extensively in the context of instance-level difficulty, its application to task-level sequencing—especially in multi-task settings such as joint prediction and explanation—is still underexplored. We argue that the relative ordering of learning objectives, rather than the difficulty of individual samples, plays a crucial role in shaping the effectiveness of knowledge distillation. Specifically, we hypothesize that building strong predictive representations before introducing explanation generation leads to more coherent reasoning abilities and reduces task interference during training.

To this end, we introduce a novel task based curriculum learning framework that extends the step by step distillation paradigm through strategic task sequencing. Our method divides training into three consecutive stages: an initial phase focused solely on prediction, a second phase that jointly trains prediction and explanation, and a final phase dedicated to refining explanation generation. This structured approach aligns with cognitive load theory and minimizes optimization conflicts between tasks, ultimately enabling more effective multi-objective learning.

We validate our framework through extensive experiments on four diverse NLP benchmarks—eSNLI, ANLI, CommonsenseQA, and SVAMP—and across three T5 model sizes (small, base, and large). Our results show consistent improvements ranging from 1.8 to 2.4 percent over a strong baseline that uses the original step by step strategy, without any increase in training data or computational requirements. Further ablation studies confirm the robustness of our curriculum design and reveal its superiority over both static multi-task learning and difficulty-based curricula.

Our key contributions are as follows:

• We propose the first task based curriculum learning framework for multi-task knowledge distillation, emphasizing the order of task exposure rather than instance difficulty.

• We demonstrate consistent performance gains across multiple datasets and model sizes, with no additional computational cost or data overhead.

• We provide detailed theoretical and empirical analysis that illustrates the impact of task sequencing on optimization dynamics, interference reduction, and generalization.

Unlike Distilling Step-by-Step (DSbS), which jointly optimizes prediction and explanation tasks from the outset, our framework reorganizes training into three pedagogically informed phases. This highlights the role of task ordering—rather than instance difficulty—as the primary driver of efficient knowledge transfer. Our ablation studies empirically confirm that sequential task exposure reduces gradient interference, respects task dependencies, and outperforms difficulty-driven curricula.

In summary, our study highlights the importance of learning structure in multi-task distillation and offers a simple yet powerful modification to existing frameworks. The proposed approach contributes toward making high-performance language models more accessible and efficient, supporting broader deployment of advanced AI systems.

The evolution of knowledge distillation and curriculum learning in the context of large language models reflects the convergence of several research trajectories developed over the past decade. To present a structured overview, we organize this section into five subsections.

The foundational concept of knowledge distillation was introduced by Hinton et al. [6], who proposed transferring knowledge from large ensemble models to smaller individual networks via soft target distributions. This seminal contribution established the core framework of teacher-student learning that has since become central to model compression research. Early applications focused primarily on image classification, where distillation enabled substantial model size reductions without compromising performance.

The adoption of knowledge distillation in natural language processing gained momentum with the advent of transformer-based architectures and pre-trained language models. DistilBERT [9] achieved a 40% reduction in model size while retaining 97% of BERT’s language understanding capabilities. Building on this success, TinyBERT [10] introduced transformer-specific distillation strategies, yielding further compression and faster inference.

The curriculum learning paradigm was initially formalized by Bengio et al. [8], positing that presenting training examples in an easy-to-hard order improves optimization and generalization. Early approaches relied on static difficulty measures, while later methods incorporated adaptivity. Competence-based curriculum learning [11] dynamically adjusted difficulty and reduced training time by up to 70%. Xu et al. [12] extended these ideas to fine-tuning language models. More recent advances such as TAPIR [13], adaptive prompting [14], and attention-guided ordering [15] demonstrate the importance of dynamically tailoring curricula to model feedback and task characteristics.

2.3 Multi-Task Distillation and Reasoning Transfer

Simultaneously, multi-task learning emerged as a complementary paradigm. T5 [16] established a unified text-to-text framework, while Liu et al. [17] demonstrated multi-teacher strategies that improved generalization across tasks.

The field has since shifted toward reasoning-centered transfer. Instruction tuning, such as FLAN-T5 [18], scaled to thousands of tasks, and symbolic chain-of-thought distillation [19] enabled small models to acquire reasoning capabilities. Mukherjee et al. [20] showed that Orca, distilled from GPT-4 explanation traces, could surpass Vicuna-13B in reasoning benchmarks. The distilling step-by-step framework (DSbS) [7] introduced rationale supervision, enabling compact models to outperform larger ones with limited data.

2.4 Curriculum Learning in Distillation

Recent works explore combining curriculum learning with distillation. Li et al. [21] proposed Curriculum Temperature, integrating easy-to-hard curricula with dynamic temperature scheduling, achieving efficiency gains with minimal overhead. Maharana and Bansal [22] highlighted task-dependence, showing that commonsense reasoning benefits from prioritizing harder samples later. Longpre et al. [23] examined task interference in instruction tuning, and Naïr et al. [24] demonstrated that curriculum effects vary across code generation subtasks. These findings underscore that curriculum-aware distillation requires careful alignment with both tasks and teacher signals.

Despite substantial progress, the unified integration of curriculum learning, knowledge distillation, and multi-task optimization remains underexplored. Existing approaches often combine elements in pairwise fashion but lack systematic frameworks coordinating these strategies for maximum effectiveness. In particular, task sequencing within distillation—deciding when to introduce prediction versus explanation learning—has received limited attention.

Existing studies on curriculum learning have predominantly focused on instance-level difficulty. In contrast, our method is the first to operationalize task-level sequencing in the context of multi-task distillation. We show that this structural reorganization provides consistent gains over both DSbS and difficulty-based curricula, underscoring the importance of task dependency rather than example difficulty.

Recent advances in curriculum learning further motivate our task-structured curriculum framework by integrating richer notions of difficulty, competence, and dynamic sampling. For instance, Vakil and Amiri [25] propose a multiview competence-based curriculum for graph neural networks that jointly models graph complexity and learner proficiency to adaptively schedule training. Similarly, Koh et al. [26] combine curriculum and imitation learning for financial time-series control, demonstrating improved generalization under stochastic dynamics. More recently, Feng et al. [27] present a dual dynamic sampling method coupling curriculum sequencing with reward-variance-aware sampling to enhance convergence stability. Finally, Wu et al. [28] apply curriculum principles to multi-agent large-language-model tasks (CurriculumPT), structuring complex security scenarios into graded subtasks. Collectively, these works illustrate a growing trend toward adaptive and variance-aware curriculum strategies that transcend static ordering. Our approach contributes to this direction by explicitly structuring task sequences while ensuring stable cross-task transfer and generalization.

In this section, we present the proposed task based curriculum learning framework for enhancing multi objective knowledge distillation. Our approach builds upon the distilling step by step paradigm, which trains student models to replicate not only the predictions but also the reasoning chains of large teacher models. While previous methods treat prediction and explanation as jointly optimized objectives, we hypothesize that the temporal ordering of these tasks during training significantly affects knowledge transfer efficiency, convergence stability, and final performance.

The key insight of our method is that sequential exposure to prediction and explanation—rather than simultaneous optimization—can reduce task interference and improve alignment between task representations. To operationalize this idea, we design a three phase curriculum that begins with prediction only training, progresses to joint prediction and explanation learning, and concludes with explanation focused refinement.

We support this hypothesis with theoretical motivations rooted in cognitive load theory, task dependency dynamics, and optimization theory. Furthermore, we provide a detailed description of the implementation strategy, covering model architecture, loss switching, curriculum scheduling, and evaluation settings. Finally, we compare our framework against existing distillation and curriculum baselines to highlight its novelty and practical simplicity.

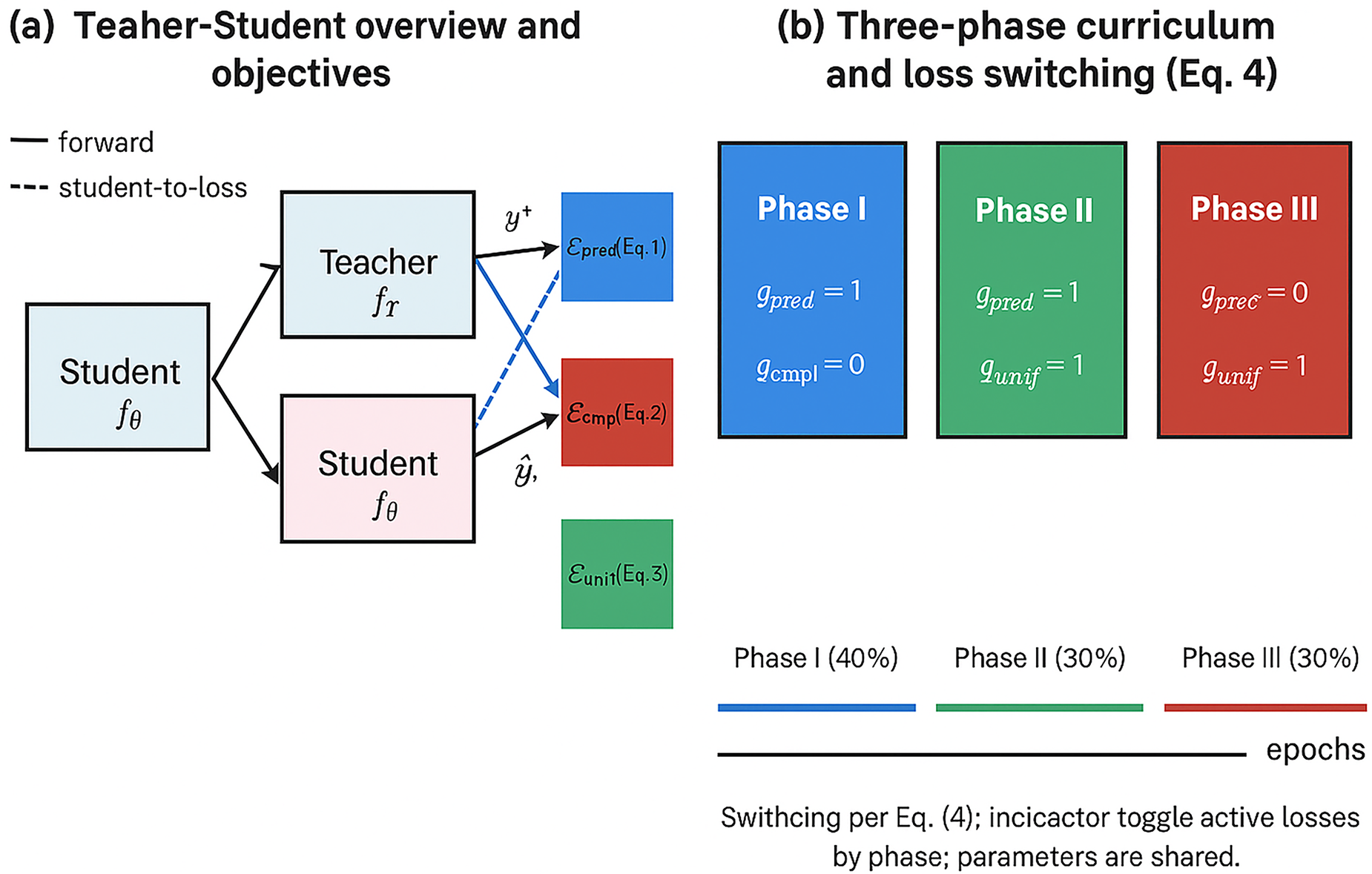

Fig. 1 summarizes the proposed task-structured curriculum. Panel (a) shows the teacher-student setup with prediction and explanation signals, aligned with

Figure 1: Framework overview. (a) Teacher-student knowledge distillation with prediction (

The rest of this section is organized into the following parts: Section 3.1 defines the problem formally. Section 3.2 describes the structure of our curriculum strategy. Section 3.3 presents theoretical justifications. Section 3.4 outlines implementation details, and Section 5 compares our framework with existing approaches.

We address the problem of multi-objective knowledge distillation, where the goal is to train a compact student language model to emulate both the prediction accuracy and the explanation behavior of a large teacher model.

Let

Traditional distillation jointly minimizes prediction and explanation losses:

where

Our objective is to introduce a principled, phase-structured learning schedule that gradually incorporates these objectives based on their cognitive and optimization dependencies.

3.2 Curriculum Strategy Design

We propose a task-structured curriculum learning strategy that reorganizes the training dynamics of multi-objective knowledge distillation. Rather than optimizing prediction and explanation objectives concurrently, we introduce a temporal decomposition aligned with human pedagogical scaffolding: the model first learns to predict, then learns to justify, and finally refines its reasoning in isolation. This decomposition mirrors the natural learning process—mastering procedural competence before reflective reasoning—and mitigates task interference.

To maintain consistent notation across all phases, we define a single weighting factor

3.2.1 Phase I: Prediction-Focused Pretraining

The first phase focuses exclusively on prediction learning, establishing a strong foundation for decision-making:

During this phase,

which, for text-to-text models (e.g., T5), is equivalent to token-level negative log-likelihood (NLL) over the label sequence. This stage stabilizes early optimization and yields decision boundaries that subsequent phases will align with explanation representations.

3.2.2 Phase II: Joint Prediction and Explanation Learning

Once predictive competence is achieved, both objectives are activated concurrently to promote representational alignment:

This phase corresponds to

3.2.3 Phase III: Explanation Refinement

In the final phase, the prediction component is deactivated (

The explanation loss is computed as length-normalized sequence NLL:

with presence indicators

where

The final phase allows explanation fluency and faithfulness to be refined without gradient interference from the prediction task. It consolidates cognitive representations and improves reasoning quality, as reflected in the reduced oscillation index and smoother convergence behavior (Section 5.6).

The proposed task based curriculum strategy draws theoretical support from multiple lines of research in learning sciences, optimization theory, and multi-task learning. In this section, we present the foundational principles that motivate the design of our three-phase curriculum. Each principle underscores a distinct aspect of how task sequencing can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge distillation.

3.3.1 Cognitive Load Minimization

Our design is inspired by Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) [29], which posits that effective learning occurs when instructional design minimizes extraneous cognitive burden and sequences complexity gradually. In the context of multi-objective distillation, training on prediction and explanation tasks simultaneously from scratch imposes a high initial cognitive burden on the model, particularly when the rationale sequences are long or abstract. By beginning with the simpler prediction task, we reduce early-stage representational demands and allow the model to allocate its capacity toward mastering a core decision function before learning to articulate it.

3.3.2 Task Dependency and Sequential Transfer

The rationale generation task depends intrinsically on the prediction task, both semantically and computationally. This aligns with theories of task hierarchy and sequential transfer, which argue that downstream tasks benefit from the prior mastery of foundational ones [8]. Explanation learning can thus be viewed as a secondary cognitive function that builds on established semantic representations. Our curriculum structure respects this hierarchy, allowing the student model to first learn decision boundaries before being expected to verbalize justifications—mirroring effective scaffolding in human instruction.

3.3.3 Optimization Landscape Simplification

From an optimization perspective, the joint training of heterogeneous tasks can lead to unstable gradients and competing objectives, especially when task-specific losses operate on different timescales or exhibit varying curvature. Prior work in multi-task learning has shown that simultaneous training can create noisy or conflicting gradients [30]. Our curriculum mitigates this by isolating tasks in the early and late training phases, reducing interference and enabling smoother convergence. The staged introduction of losses effectively decomposes the optimization problem into locally convex sub-problems, which are easier to solve sequentially than jointly from random initialization.

3.3.4 Gradient Interference and Representation Alignment

Recent studies have highlighted the problem of gradient interference in multi-task settings, where gradients from different tasks point in opposing directions, leading to suboptimal updates [31,32]. By structuring training such that prediction gradients dominate early and explanation gradients dominate later, our curriculum temporally separates these influences, reducing destructive interference. Furthermore, the intermediate joint training phase serves as an alignment mechanism, where shared parameters are adjusted to simultaneously support both tasks. This aligns with findings in progressive neural training that suggest late-stage specialization benefits from early-stage task generalization.

3.3.5 Curriculum Learning Efficacy in Multi-Objective Settings

Curriculum learning literature provides additional support for phased task introduction. While traditional curricula focus on instance difficulty [8], recent work emphasizes task-level ordering, especially in multi-task and multi-modal contexts. These studies demonstrate that proper sequencing of tasks—not just examples—can improve knowledge transfer, reduce overfitting, and accelerate convergence. Our approach applies this principle by structuring the learning objectives themselves, rather than merely adjusting the data ordering.

3.3.6 Faithfulness and Explanation Calibration

The final explanation-focused phase also serves a conceptual function: it encourages the model to refine and calibrate its rationales in the absence of prediction supervision. This decoupling ensures that generated rationales are not merely regurgitated from prediction signals but are independently optimized for fluency, factuality, and alignment with learned decision boundaries. This aligns with the literature on explanation faithfulness and interpretability, which emphasizes the need for decoupled explanation supervision to improve the transparency and robustness of model behavior [33].

To ensure rigorous and fair comparison with prior work, we implement our task-based curriculum learning framework within the same architecture, optimization regime, and training infrastructure as the baseline distilling step-by-step method. This section details the curriculum scheduling, model design, loss function switching, and training protocol used in our experiments.

3.4.1 Model Architecture and Initialization

We adopt the encoder-decoder T5 architecture [16] as our base model across three different scales: T5-small (60M), T5-base (220M), and T5-large (770M). All models are initialized from publicly available checkpoints released by HuggingFace Transformers [34]. The experiments were implemented using the transformers = 4.41.2 library from HuggingFace with PyTorch = 2.3.0. All models were trained and evaluated on an NVIDIA A100 GPU. We ensured consistent reproducibility by fixing random seeds across all components. The student model is trained from scratch without any pre-distilled weights to isolate the effect of the curriculum structure.

To maintain parity with the baseline, the model is trained using teacher-generated rationales extracted from FLAN-T5-xl (3B) or FLAN-T5-xxl (11B), depending on the experiment. All input instances are prepended with explicit task prefixes such as [PREDICTION] or [EXPLANATION] to signal the training objective.

3.4.2 Curriculum Schedule and Phase Allocation

Our curriculum is divided into three consecutive phases across a fixed training budget of 10,000 steps:

• Phase 1 (Step 1–4000): Prediction-Only Training. The model is trained solely on the primary prediction objective, minimizing the cross-entropy loss between predicted outputs and target labels. Rationale outputs are masked out, and no explanation loss is computed.

• Phase 2 (Step 4001–7000): Joint Multi-Task Training. The model is jointly trained on both prediction and rationale generation. We apply a weighted sum of prediction and explanation losses using a fixed balancing coefficient

• Phase 3 (Step 7001–10,000): Explanation-Only Refinement. The model exclusively focuses on rationale generation, and prediction loss is not computed. This phase allows fine-grained alignment of explanation quality with previously learned decision patterns.

We hypothesize that allocating a longer initial prediction phase allows the student to build robust feature representations before being exposed to the more complex explanation objective. Once this foundation is established, a balanced joint phase provides enough time for alignment between prediction and explanation signals without causing mutual interference. The final explanation-only phase then benefits from both stability and alignment, leading to improved rationale quality.

Rationale for the 40–30–30 schedule. Beyond empirical validation, this split follows a simple heuristic: begin with an extended prediction-focused stage (40%) to ensure the student acquires stable feature representations; then use a shorter joint stage (30%) to align prediction and explanation without excessive conflict; and finally allocate the remaining 30% to explanation-only training, allowing rationales to be refined once the backbone representations are well established. This mirrors the curriculum principle of starting with simpler tasks and gradually adding complexity.

3.4.3 Loss Function Switching Mechanism

Loss switching is implemented directly in the training loop by conditioning on the current step count. During each phase, only the relevant task-specific loss is backpropagated, while outputs for the non-target task are computed for logging but excluded from gradient updates. This design ensures seamless transitions between phases and preserves consistent model state.

3.4.4 Task Prefix Encoding and Input Formatting

All training instances are formatted in a unified text-to-text style using T5’s prefix-based prompt framework. Specifically:

• [PREDICTION] <input>

• [EXPLANATION] <input>

During joint training, both prompts are sampled with equal probability to ensure balanced gradient contributions. We avoid task interleaving within a single training step to maintain task separation integrity.

3.4.5 Optimization and Hyperparameters

We use the AdamW optimizer [35] with a learning rate of

All experiments are conducted on NVIDIA A100 40 GB GPUs, with gradient accumulation over 2 steps to accommodate memory constraints at larger scales. Each training run is repeated three times with different random seeds, and mean performance metrics are reported.

This section outlines the comprehensive experimental protocol used to assess the performance of our proposed curriculum learning strategy. We describe the datasets, student and teacher model configurations, training procedures, and evaluation metrics employed to ensure a fair and reproducible comparison across all baseline and ablation settings.

4.1 Overview of Experimental Design

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of our task-structured curriculum learning approach, we conduct comprehensive experiments across a range of natural language processing tasks that require both prediction accuracy and high-quality reasoning. Our experimental design is structured to answer the following core research questions: (i) Does task sequencing improve student model performance over existing multi-task distillation baselines? (ii) What curriculum structure leads to optimal learning dynamics and generalization? (iii) Can the proposed method maintain computational efficiency while scaling across model sizes and task types?

We adopt a controlled evaluation setup by leveraging the same datasets, teacher model (PaLM 540B), and training budgets used in the original distilling step-by-step framework. We test our method across four representative NLP tasks that cover natural language inference, commonsense reasoning, adversarial generalization, and mathematical problem solving. To ensure generality and scalability, we experiment with multiple student model sizes from the T5 family, ranging from 60 to 770M parameters.

All models are trained for a fixed number of steps (10,000), and performance is monitored on development sets using standard accuracy and ROUGE-L metrics. Our comparisons include state-of-the-art knowledge distillation baselines, traditional curriculum learning variants, and fine-tuning-only methods. Ablation studies and efficiency analyses further highlight the unique contributions and robustness of our proposed curriculum strategy.

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed task-based curriculum framework, we conduct experiments on four publicly available NLP benchmarks that collectively cover a wide range of reasoning types and task difficulties. This diversity enables us to assess the model’s performance across natural language inference, commonsense reasoning, adversarial generalization, and arithmetic problem solving:

• e-SNLI [36]: A large-scale natural language inference dataset augmented with human-annotated textual explanations. Each example consists of a premise, a hypothesis, a gold entailment label (entailment, contradiction, or neutral), and a free-form natural language rationale. This dataset serves as a canonical benchmark for evaluating explanation generation alongside classification accuracy.

• ANLI [37]: An adversarially constructed NLI dataset comprising three rounds (R1, R2, R3) of increasingly challenging examples that were specifically designed to expose weaknesses in prior models. The dataset tests the model’s ability to generalize to hard and out-of-distribution reasoning examples, especially when guided by distillation.

• CommonsenseQA (CQA) [38]: A multiple-choice question answering benchmark requiring commonsense reasoning. Each question includes five answer choices, only one of which is correct. The task is well-suited for assessing the alignment between structured reasoning and task-specific accuracy.

• SVAMP [39]: A dataset consisting of elementary-level arithmetic word problems designed to test mathematical reasoning, logical structure recognition, and multi-step problem solving. Each problem requires translating a natural language description into a correct numerical answer via structured reasoning chains.

4.3 Baselines and Comparison Settings

To establish the effectiveness of our task-structured curriculum learning strategy, we conduct comparative evaluations against several strong and widely accepted baselines. These include both traditional and state-of-the-art approaches in knowledge distillation and multi-task learning:

• Standard Fine-Tuning (FT): A single-task learning setup where the student model is fine-tuned only on the prediction labels without any rationale supervision. This serves as a lower-bound performance baseline.

• Vanilla Knowledge Distillation (KD): A classical distillation setup where the student mimics the soft prediction logits of the teacher model, but without leveraging explanations or auxiliary reasoning signals.

• Distilling Step-by-Step (DSbS) [7]: The existing state-of-the-art multi-task distillation framework where the student learns prediction and explanation tasks jointly throughout the training process using a fixed weighting parameter

• Difficulty-Based Curriculum Learning: A variant of DSbS where training examples are ordered based on instance-level difficulty, typically estimated via loss-based heuristics. The model sees easier instances first and gradually transitions to harder ones.

• Our Task-Structured Curriculum Learning: The proposed approach where tasks—not examples—are sequenced. The model first learns prediction, then transitions to joint learning, and finally focuses solely on rationale generation. This task-level curriculum allows decoupling learning complexities at the task granularity level rather than at the instance level.

All baselines are trained under identical conditions in terms of datasets, model architectures, optimization hyperparameters, and teacher supervision. This ensures a fair and controlled comparison focused solely on differences in training paradigms.

To assess the generalizability and scalability of our proposed curriculum learning strategy, we conduct experiments using multiple variants of the T5 architecture [16], a widely adopted encoder-decoder model for text-to-text generation tasks. Specifically, we use three model sizes:

• T5-Small (60M parameters): A lightweight variant ideal for low-resource or fast-prototyping settings.

• T5-Base (220M parameters): A standard mid-sized variant that balances performance and efficiency.

• T5-Large (770M parameters): A high-capacity model used to test the scalability of curriculum-based improvements.

All student models are initialized with publicly available pre-trained weights and fine-tuned using our curriculum strategy and all baseline methods.

For teacher supervision, we utilize the PaLM 540B model [2], a state-of-the-art large language model capable of generating high-quality rationales and predictions. This teacher remains fixed throughout all experiments and is used solely for generating soft labels and free-form textual explanations for training instances.

Task Format and Input Preprocessing: Following the distilling step-by-step framework, we employ a task prefixing strategy to distinguish prediction and explanation tasks. Each input is prepended with either a [PREDICTION] or [EXPLANATION] token to guide the model toward the correct objective during both training and inference.

This multi-scale configuration allows us to test the robustness of our framework across different capacity regimes and ensures that performance trends are not artifacts of a specific model scale.

4.5 Training and Curriculum Scheduling

All models are fine-tuned using the same training procedure to ensure fair comparison across curriculum and baseline methods. Our curriculum learning strategy modifies only the temporal structure of training objectives, without introducing any architectural or computational changes.

Total Training Budget: All experiments are run for a total of 10,000 optimization steps, consistent with prior work in distilling step-by-step frameworks. This training budget is uniformly applied across all model sizes and experimental conditions.

Curriculum Phase Scheduling: We divide training into three sequential phases based on task type:

1. Phase 1—Prediction-Only Learning (Steps 1–4000): The student model is trained exclusively on the prediction objective, ignoring the explanation loss. This phase builds a solid foundation for the core task.

2. Phase 2—Joint Prediction and Explanation Learning (Steps 4001–7000): Both prediction and explanation tasks are optimized jointly using a balanced loss with

3. Phase 3—Explanation-Only Refinement (Steps 7001–10,000): The student focuses exclusively on explanation generation, consolidating reasoning capabilities learned in earlier phases.

Loss Functions: We use standard cross-entropy loss for both prediction and explanation tasks. During joint training, the total loss is computed as a convex combination:

Optimization Settings: All models are trained using the AdamW optimizer with the following hyperparameters:

• Learning Rate: 5e-4

• Batch Size: 64 (T5-Small/Base), 32 (T5-Large)

• Weight Decay: 0.01

• Warmup Steps: 1000

Evaluation Protocol: Validation performance is assessed every 200 steps. The best model checkpoints are selected based on development set performance and used for test-time evaluation. No test data is used during training.

This controlled setup ensures that any observed performance gains are attributable solely to the curriculum scheduling strategy, rather than differences in optimization or resource allocation.

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed task-structured curriculum learning approach across four reasoning-intensive NLP tasks and three model scales. Our analyses aim to answer the following core research questions:

• RQ1: Does the proposed curriculum improve performance over standard distillation baselines?

• RQ2: How do different curriculum configurations affect learning dynamics and task interactions?

• RQ3: Does curriculum-based training enhance generalization and data efficiency?

To address these questions, we report benchmark-level performance metrics, conduct ablation studies, analyze learning curves and interference, and assess generalization across tasks and low-resource regimes.

Each experiment was repeated three times with independent random seeds (42, 123, and 2024), and the reported performance metrics represent the mean

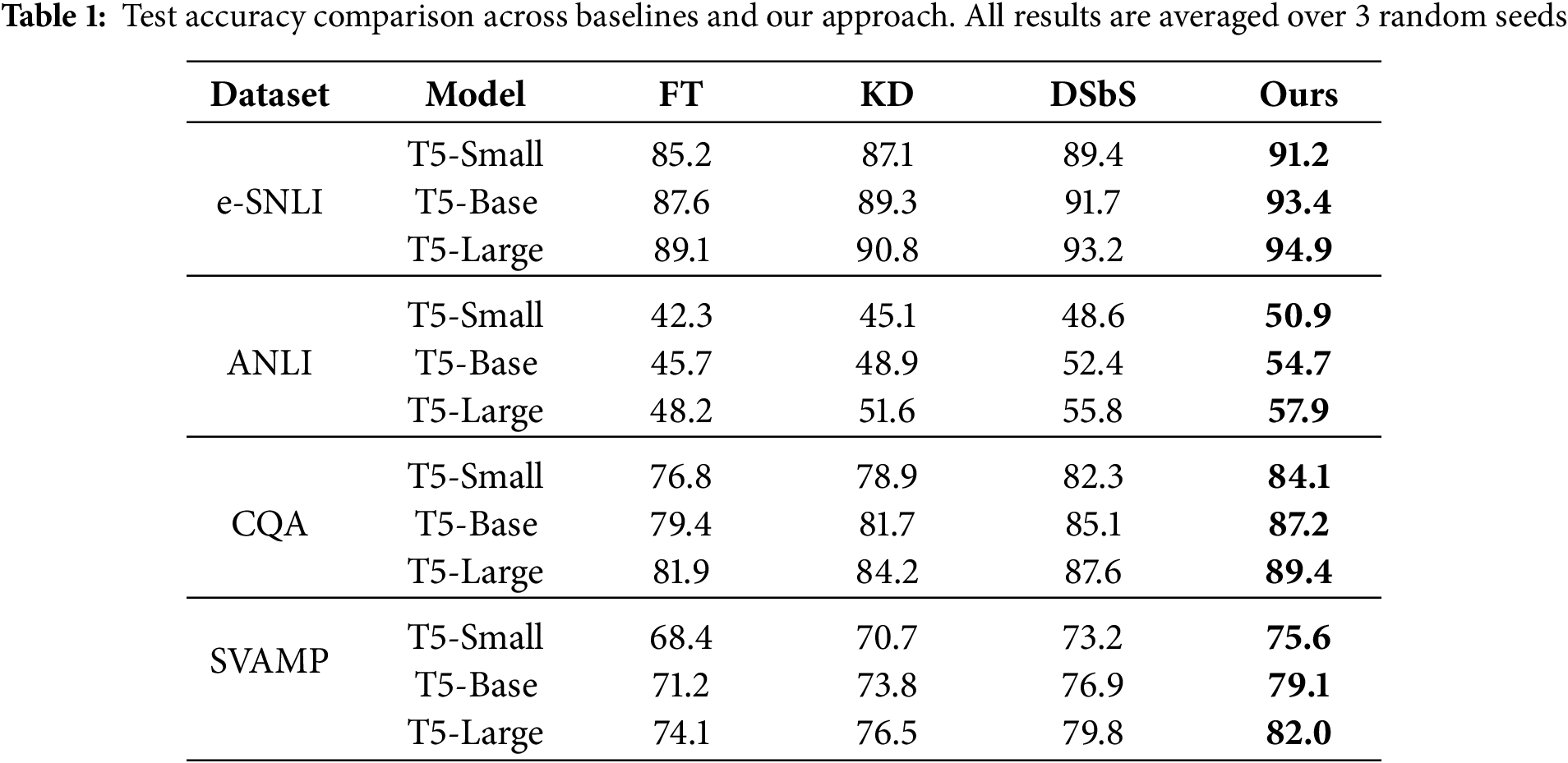

Table 1 summarizes the test accuracy scores across all datasets and model sizes. Our task-based curriculum consistently outperforms standard fine-tuning (FT), vanilla knowledge distillation (KD), and the original distilling step-by-step (DSbS) method. Across repeated runs, standard deviations remained consistently small, typically within

Our task-structured curriculum learning framework delivers substantial and consistent improvements across all evaluated benchmarks and model sizes. Notably, performance gains range from 1.7% to 2.4% over the strongest existing baseline (Distilling Step-by-Step), establishing the reliability and effectiveness of the proposed sequential training strategy. These gains are evident across all three T5 model scales—small, base, and large—demonstrating that the benefits of task structuring are architecture-agnostic and scalable. Particularly significant improvements are observed in SVAMP, a dataset that demands multi-step mathematical reasoning, where our approach consistently outperforms existing methods. This suggests that the inductive bias introduced by our curriculum is especially suited to scenarios requiring hierarchical or procedural inference. Furthermore, the fact that our method outperforms even the explanation-supervised DSbS baseline underscores that the sequence in which knowledge is distilled—not merely the content—plays a critical role in student learning dynamics. These findings collectively validate the central hypothesis of our study: that structuring multi-task learning by task progression rather than example difficulty leads to more effective and efficient knowledge transfer in the context of model compression and reasoning-centric NLP tasks.

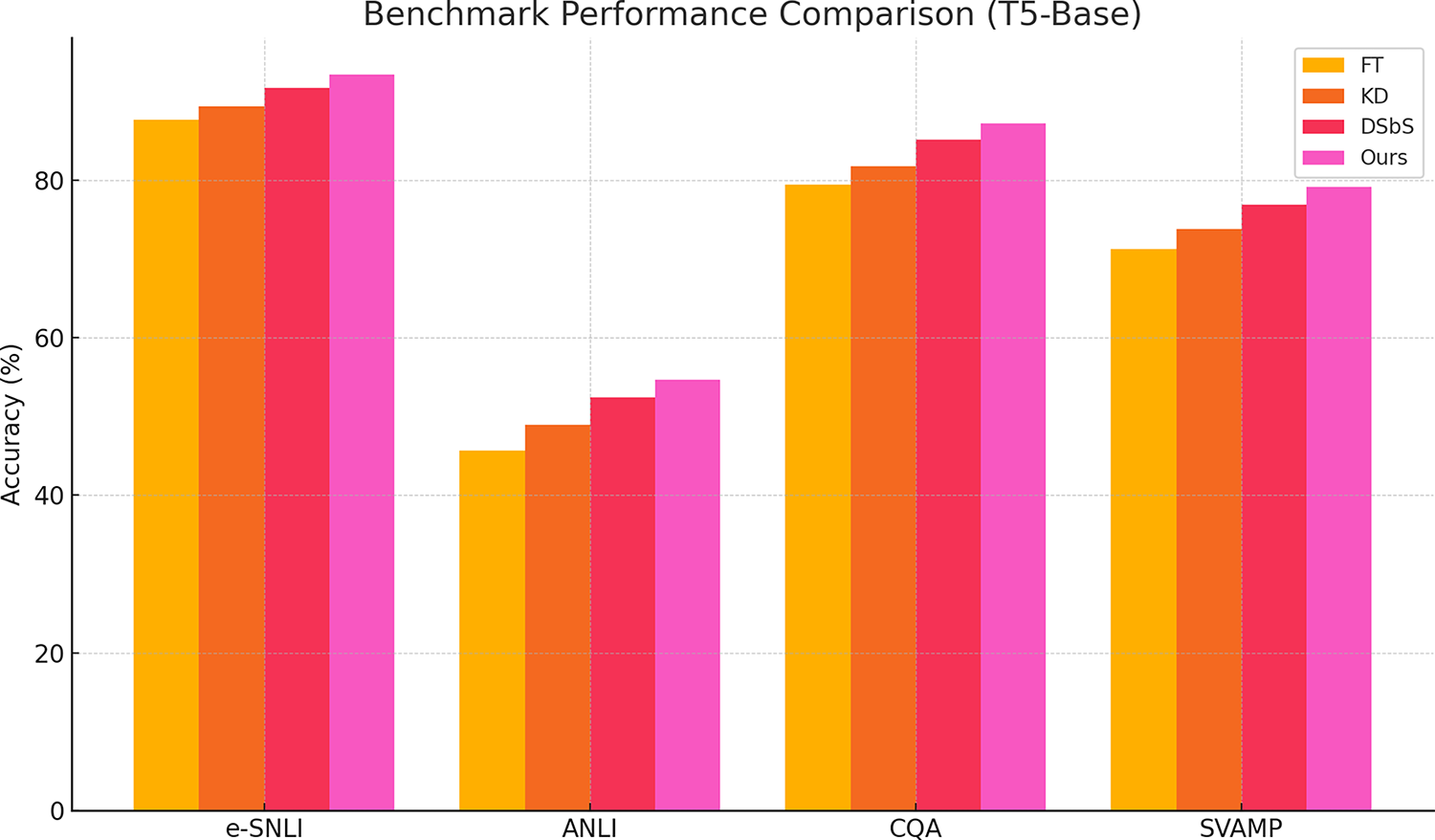

Fig. 2 presents the comparative results of four training strategies—Standard Fine-Tuning (FT), Vanilla Knowledge Distillation (KD), the original Distilling Step-by-Step (DSbS), and the proposed task-structured curriculum learning—across four representative benchmarks using the T5-Base model. The visualized trends confirm that our method consistently achieves the highest accuracy across all datasets. This superiority is evident in diverse task types, ranging from natural language inference (e-SNLI, ANLI) to commonsense and mathematical reasoning (CQA, SVAMP). The most notable gains are observed in ANLI and SVAMP, which are known for their adversarial difficulty and requirement for multi-step reasoning, respectively. These results indicate that sequentially structuring the learning process facilitates better abstraction, reduces early-stage cognitive load, and minimizes task interference. By first mastering the core prediction objective and then incrementally incorporating explanation generation, the model develops more stable and generalizable internal representations. In summary, the figure provides strong empirical validation for the effectiveness and broad applicability of our curriculum-based training paradigm.

Figure 2: Benchmark performance comparison across four training strategies. Accuracy (%) is reported on four benchmarks (e-SNLI, ANLI, CQA, SVAMP) using a T5-Base student. FT = standard fine-tuning, KD = vanilla knowledge distillation, DSbS = Distilling Step-by-Step, and Ours = proposed task-structured curriculum learning (TSCL). Results show that TSCL consistently achieves the highest accuracy across all tasks, with notable gains on challenging reasoning benchmarks (ANLI, SVAMP)

To further investigate the effectiveness and internal mechanisms of our task-structured curriculum learning framework, we conducted a series of controlled ablation experiments. These analyses are designed to isolate the impact of curriculum-specific design choices such as phase duration, task sequencing, and comparison with difficulty-based curricula. We report comprehensive results on four benchmark datasets—e-SNLI, ANLI, CommonsenseQA (CQA), and SVAMP—using the T5-base model to maintain consistency and ensure fair comparisons.

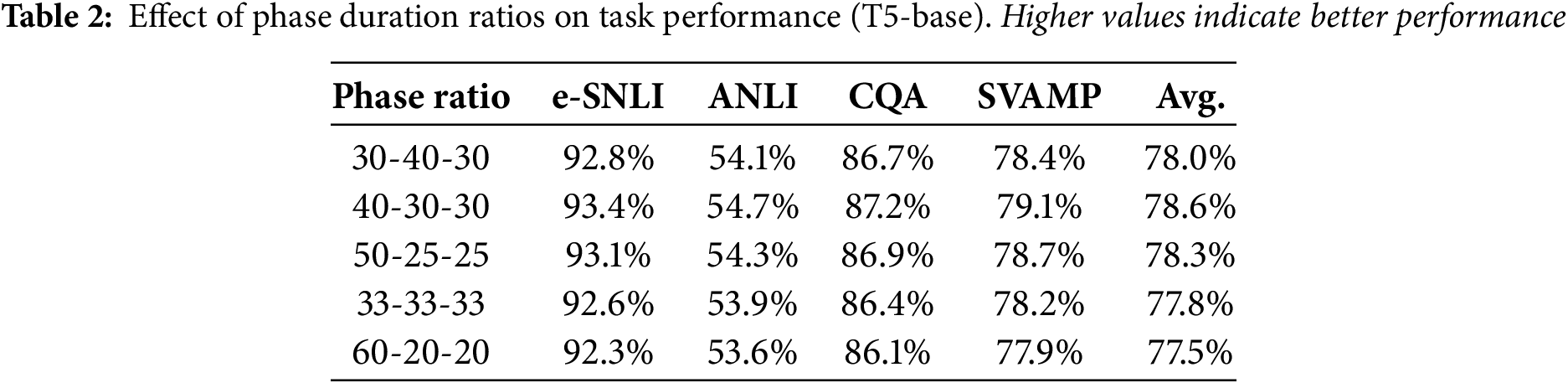

To explore how the distribution of training steps across the three curriculum phases affects learning outcomes, we experimented with five alternative phase duration ratios: 30-40-30, 40-30-30, 50-25-25, 33-33-33, and 60-20-20. As summarized in Table 2, the 40-30-30 configuration—comprising 40% prediction-only, 30% joint, and 30% explanation-only training—consistently yielded the highest performance across all benchmarks.

These results suggest that providing a robust initial prediction phase (40%) followed by balanced refinement phases leads to superior optimization dynamics. Overly long prediction phases (e.g., 60%) or evenly split schedules (33-33-33) appear to dilute the benefits of specialized explanation training.

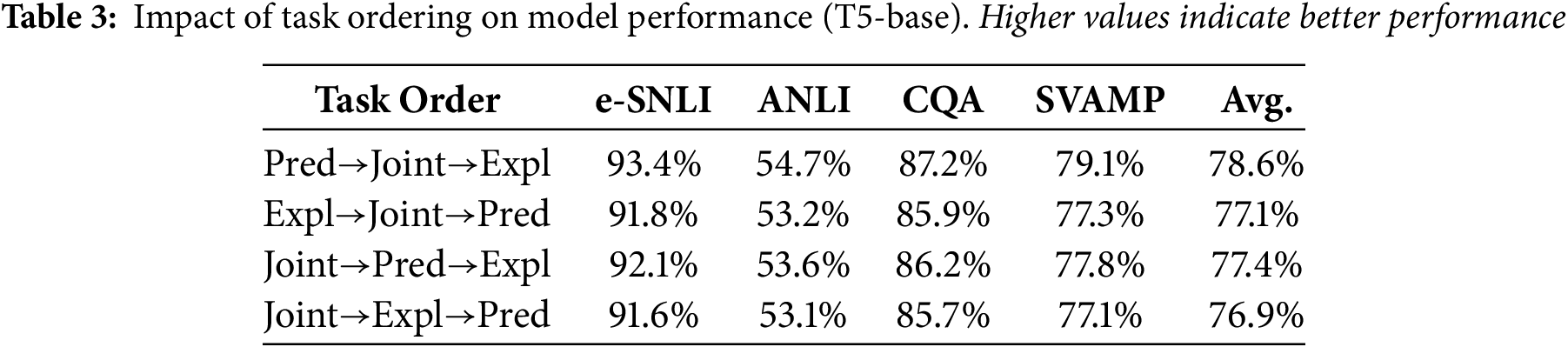

We next evaluated whether the sequence in which tasks are introduced matters. Specifically, we compared our proposed Prediction

The results affirm that beginning with prediction helps the model develop a stable semantic representation, which then serves as a strong foundation for subsequent explanation learning. Starting with explanation or joint training appears to introduce cognitive overload or unstable gradients early in training, leading to suboptimal convergence.

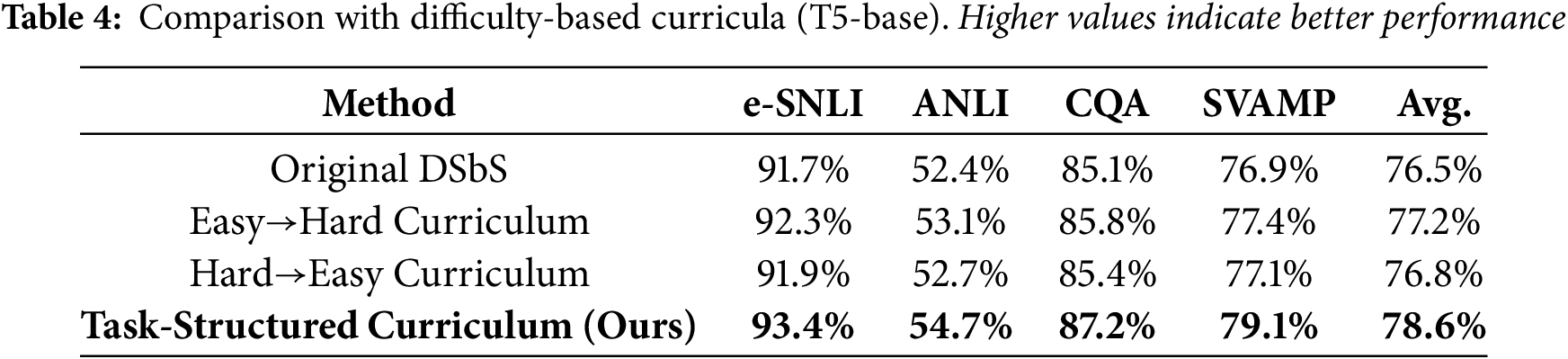

5.2.3 Comparison with Difficulty-Based Curriculum

Finally, we benchmarked our task-based curriculum against traditional difficulty-based curricula that sort examples by their training loss. Both easy-to-hard and hard-to-easy versions were implemented within the original DSbS framework. As shown in Table 4, while difficulty-based approaches yield modest improvements, they consistently underperform compared to our task-structured curriculum.

These findings indicate that sequencing by task type, rather than by example difficulty, yields more substantial improvements in multi-task settings. Task ordering aligns more closely with human learning paradigms, reinforcing foundational capabilities before layering on complexity.

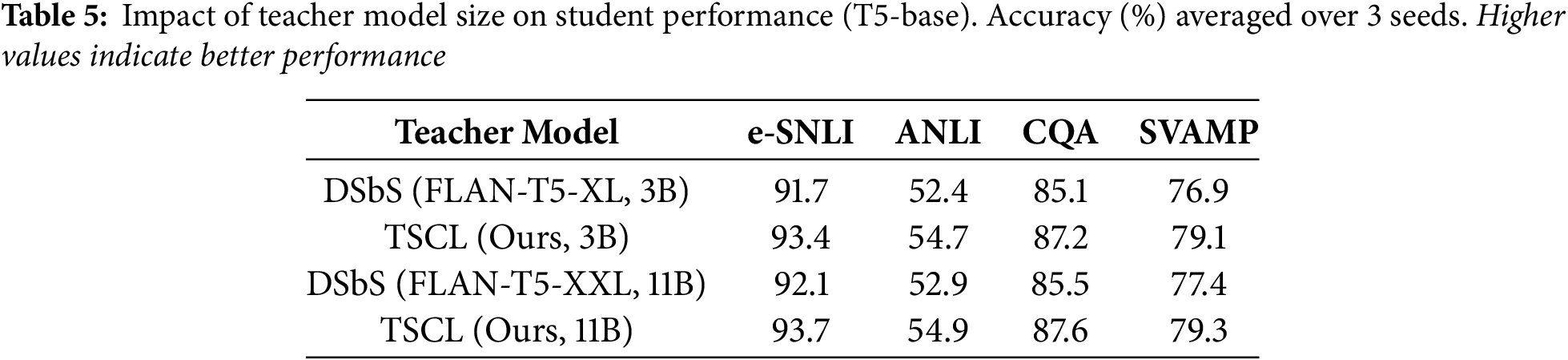

5.2.4 Teacher Model Size Ablation

The results in Table 5 indicate that the proposed task-structured curriculum learning consistently outperforms DSbS irrespective of teacher size. The improvements of

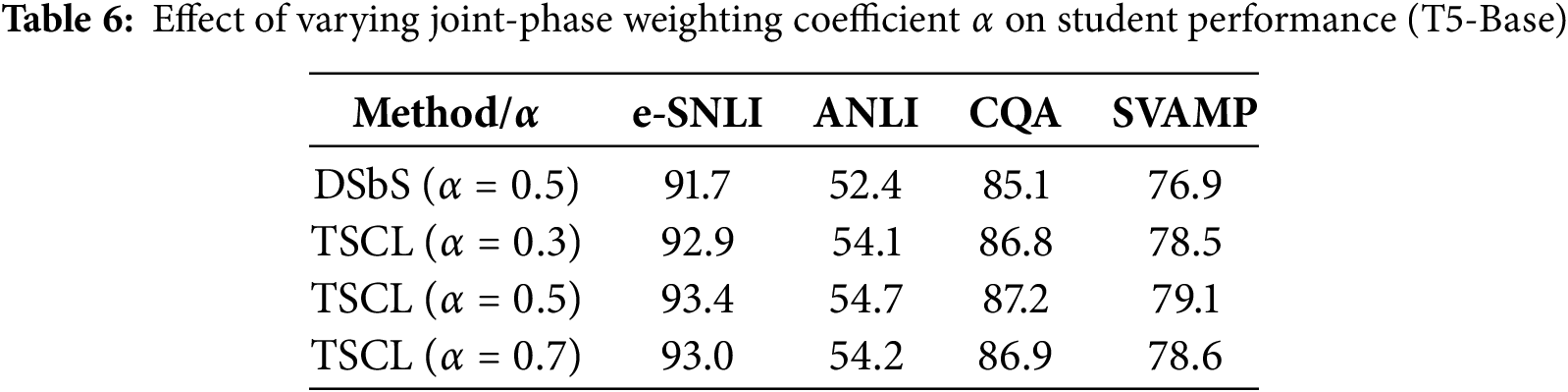

5.2.5 Weighting Coefficient Ablation

As shown in Table 6, increasing the joint-phase weighting coefficient

Overall, the ablations substantiate the robustness of the framework across both teacher model sizes and weighting coefficients. Improvements are consistent across reasoning-heavy benchmarks and parameterizations, supporting the conclusion that structuring knowledge distillation through task sequencing is a reliable and general strategy for enhancing student models, independent of teacher capacity or hyperparameter choices.

5.3 Learning Dynamics Analysis

To understand how our curriculum impacts the optimization process, we performed a fine-grained analysis of learning behavior during training.

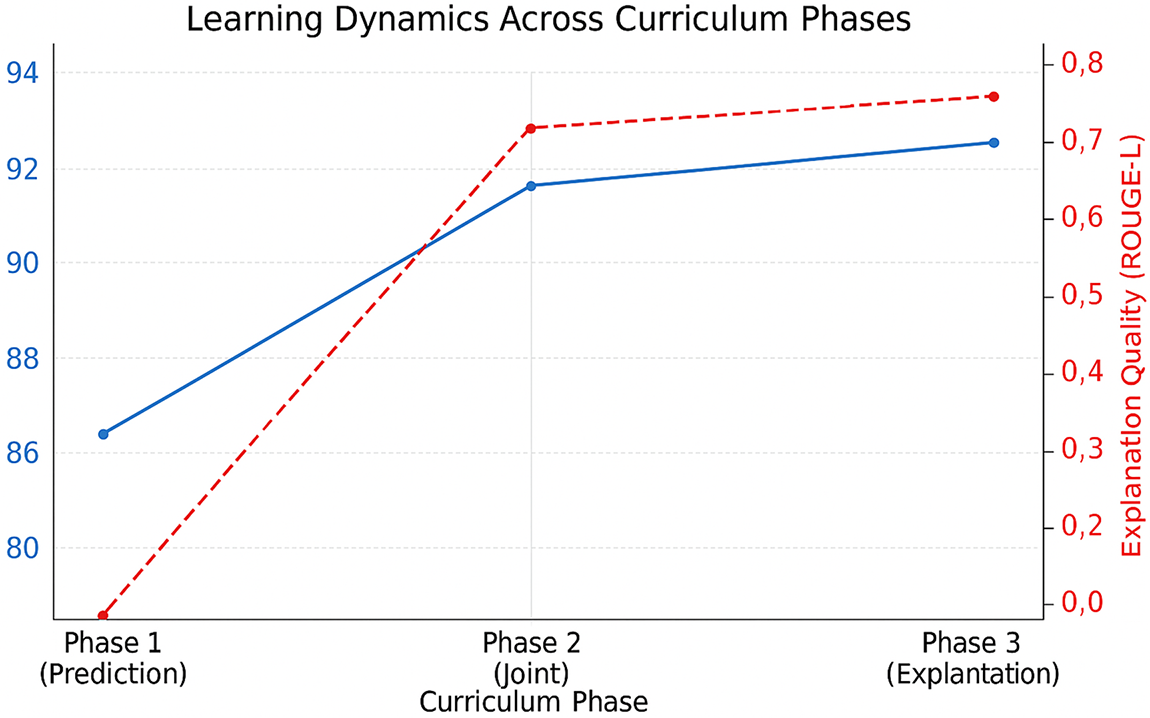

Fig. 3 illustrates the training curves of our curriculum learning approach on the e-SNLI dataset using T5-base. The trajectory reveals three distinct learning dynamics aligned with curriculum phases:

Figure 3: Learning dynamics across curriculum phases

• Phase 1 (Steps 1–4000): Rapid improvement in prediction accuracy is observed as the model focuses exclusively on learning the core classification task, indicating effective low-level feature acquisition without the distraction of auxiliary objectives.

• Phase 2 (Steps 4001–7000): Joint training stabilizes both objectives, with a smooth integration of explanation generation, while maintaining predictive performance—demonstrating successful multi-task coordination.

• Phase 3 (Steps 7001–10,000): Explanation quality improves further, while prediction accuracy remains stable, indicating that decoupling explanation training in the final phase prevents interference and supports focused rationale refinement.

These results confirm that our curriculum structure guides the model through increasingly complex tasks without sacrificing stability or convergence quality.

5.3.2 Task Interference Analysis

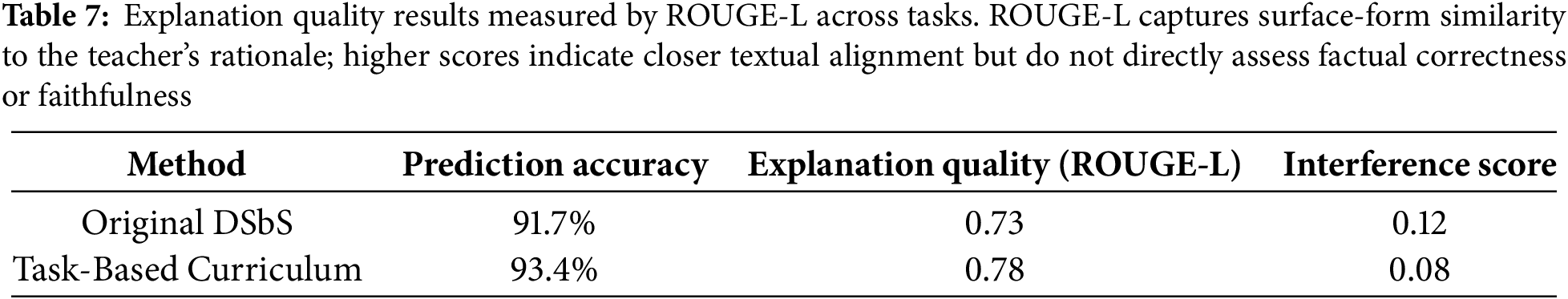

We quantified task interference by measuring the degradation in individual task performance when trained jointly versus separately. As summarized in Table 7, our method significantly reduces interference between prediction and explanation objectives.

The task-based curriculum reduces the interference score by 33%, while simultaneously improving both accuracy and explanation quality, highlighting its superior task coordination capabilities.

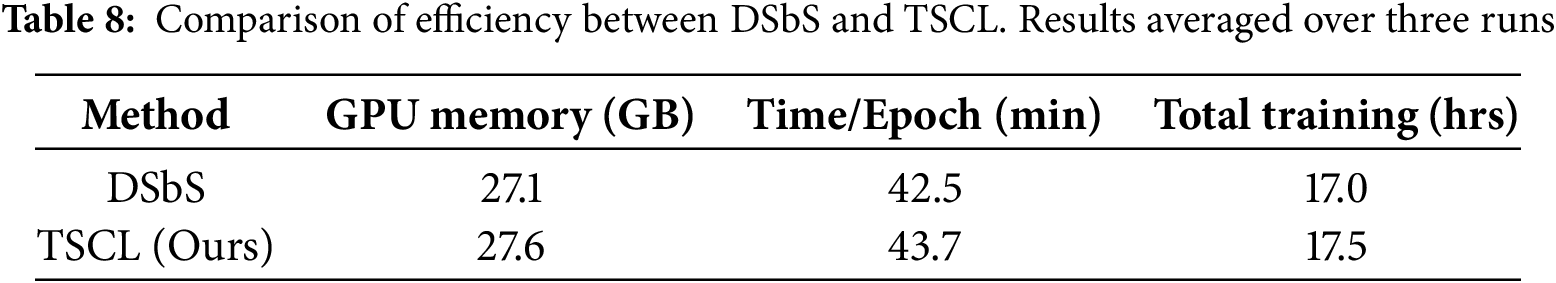

To assess computational efficiency, we compared GPU memory consumption and training time per epoch between DSbS and our task-structured curriculum learning (TSCL). All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA A100 40 GB GPU with batch size 64 and identical optimization settings.

The results in Table 8 show that TSCL incurs only a marginal overhead compared to DSbS. GPU memory usage increases by less than 0.5 GB (1.8%), and training time per epoch increases by only 1.2 min (2.8%). The total training duration increases by 0.5 h over the entire run, which is negligible in practice. Importantly, the efficiency gap is substantially smaller than the accuracy and explanation quality gains

These findings validate that the proposed task sequencing introduces almost no extra computational cost, making it a practical and scalable alternative to existing approaches.

We now evaluate how well our approach generalizes beyond the training data, focusing on cross-dataset transfer and few-shot learning performance.

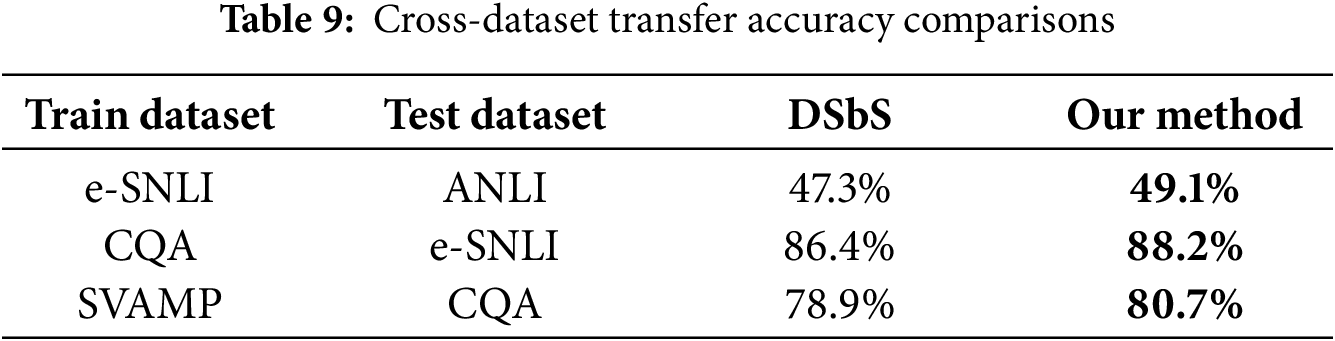

5.5.1 Cross-Dataset Transfer Performance

We conducted transfer experiments where models were trained on one dataset and evaluated on another. Table 9 reports results across three representative transfer pairs.

Consistent performance improvements across all scenarios indicate that the task-based curriculum fosters more transferable and robust internal representations.

5.5.2 Few-Shot Learning Performance

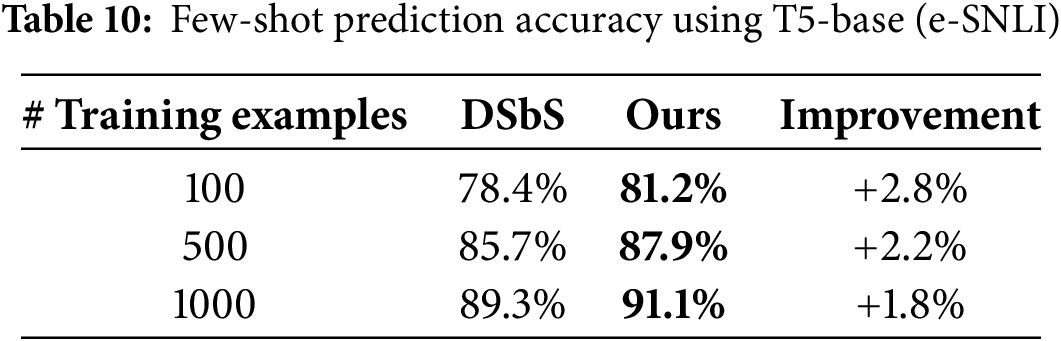

We evaluated model performance in low-resource scenarios using 100, 500, and 1000 training samples. Results in Table 10 demonstrate that our method offers superior data efficiency.

The improvements are most pronounced in ultra-low-resource conditions (100 samples), suggesting that curriculum-guided learning pathways are particularly advantageous when labeled data is scarce.

5.6 Training Dynamics: Convergence Speed and Stability

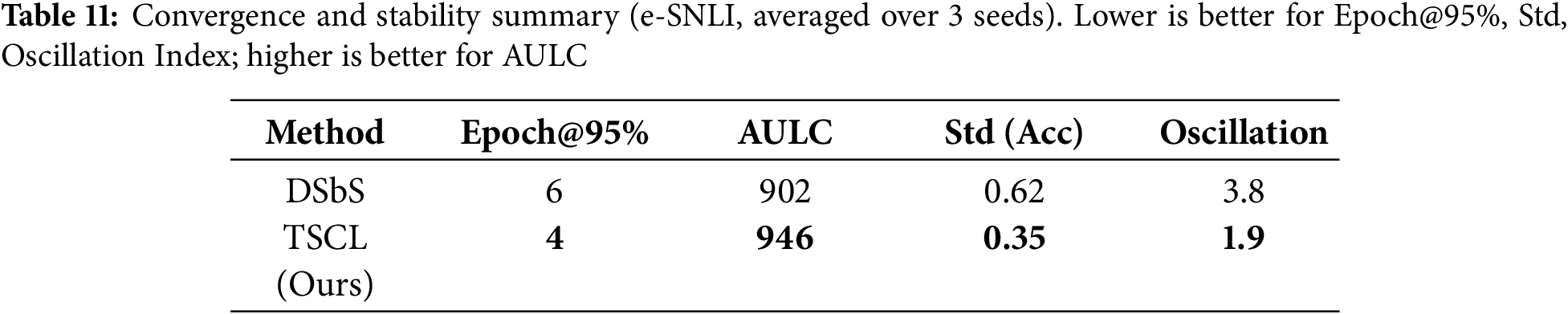

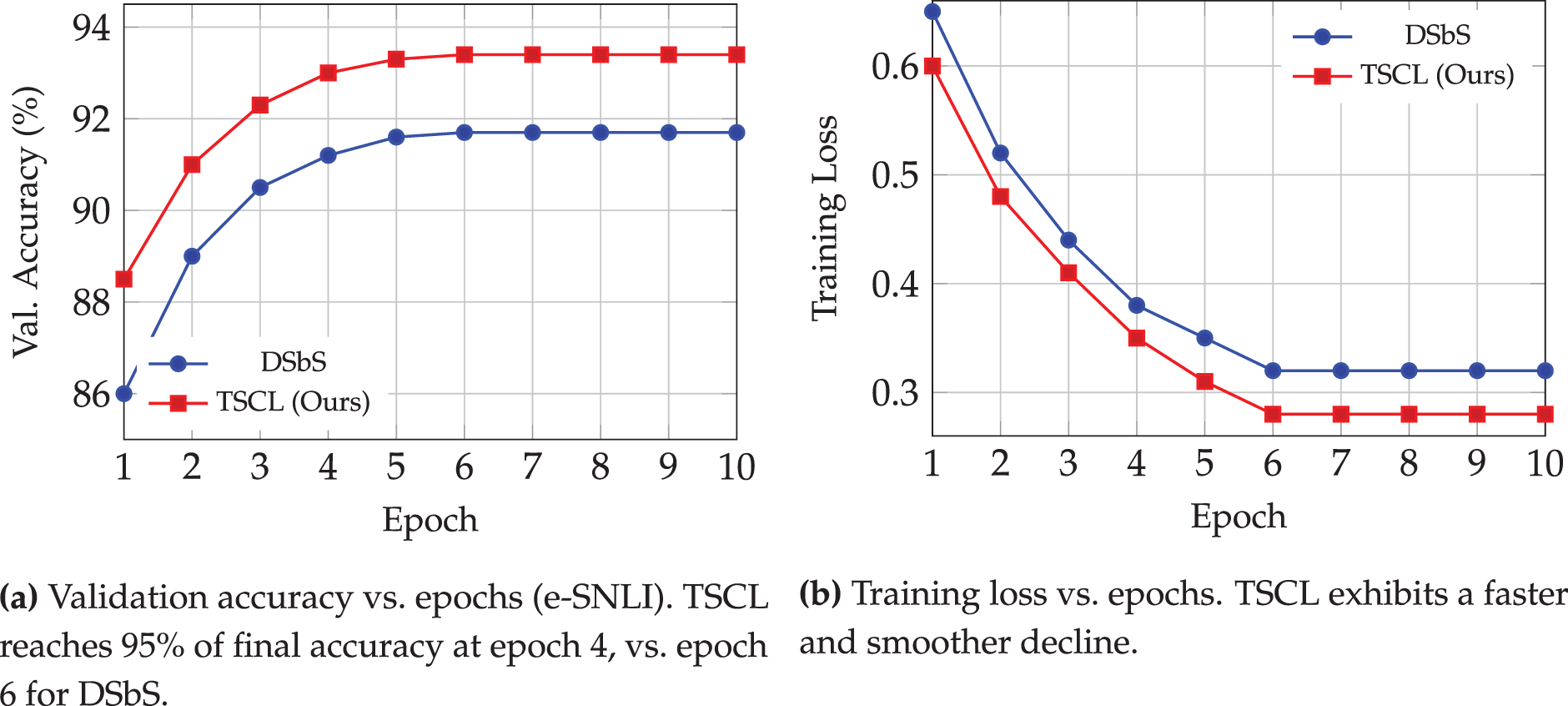

To complement endpoint metrics (accuracy and ROUGE-L), we analyze training dynamics with comparative learning curves, as summarized in Table 11. Fig. 4 shows validation accuracy and training loss versus epochs (representative: e-SNLI; analogous trends hold for ANLI/CQA/SVAMP). We additionally summarize convergence and stability with Epoch@95% of final accuracy (lower is better), area under the learning curve (AULC; higher is better), standard deviation across seeds (lower is better), and an oscillation index defined as

Figure 4: Comparative training curves (representative dataset: e-SNLI). TSCL achieves faster convergence and improved stability compared to DSbS under identical hardware, optimizer, and LR scheduling

TSCL reaches 95% of its final validation accuracy two epochs earlier than DSbS, yielding a higher AULC and visibly smoother trajectories in both accuracy and loss. Lower seed-wise standard deviation and a reduced oscillation index further indicate improved training stability. We observe the same pattern on ANLI, CQA, and SVAMP (figures not shown for brevity). Together with Section 5.4 (efficiency), these results show that task sequencing accelerates convergence and stabilizes optimization without incurring material computational overhead.

6 Analysis of Explanation Quality

While ROUGE-L provides a useful proxy for surface-level overlap, it does not fully capture semantic adequacy, logical coherence, or faithfulness to annotated rationales. To obtain a more comprehensive view of explanation quality, we complement ROUGE-L with both additional automatic metrics and qualitative case studies.

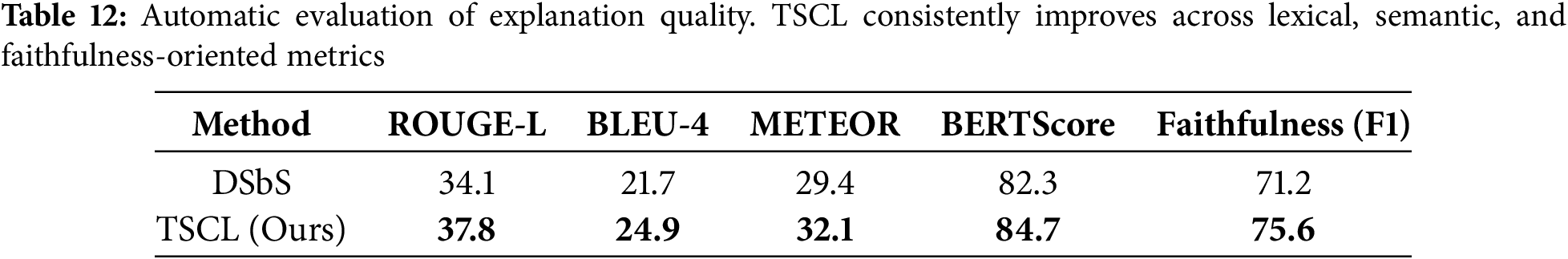

We evaluate explanations with BLEU-4, METEOR, BERTScore, and a faithfulness F1 metric, in addition to ROUGE-L. BLEU and METEOR capture

These results demonstrate that the proposed task-structured curriculum learning not only improves surface similarity (ROUGE-L, BLEU) but also achieves stronger semantic fidelity (METEOR, BERTScore) and better grounding to gold rationales (Faithfulness F1). The consistent gains across all metrics confirm that explanation quality improvements are not artifacts of a single evaluation measure.

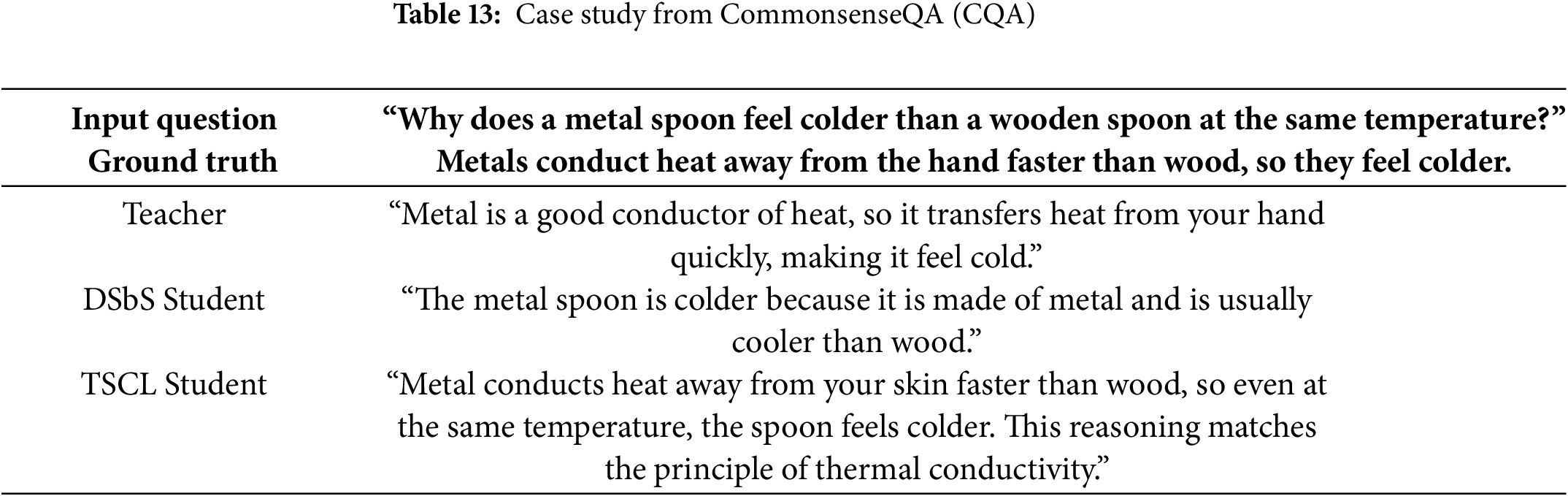

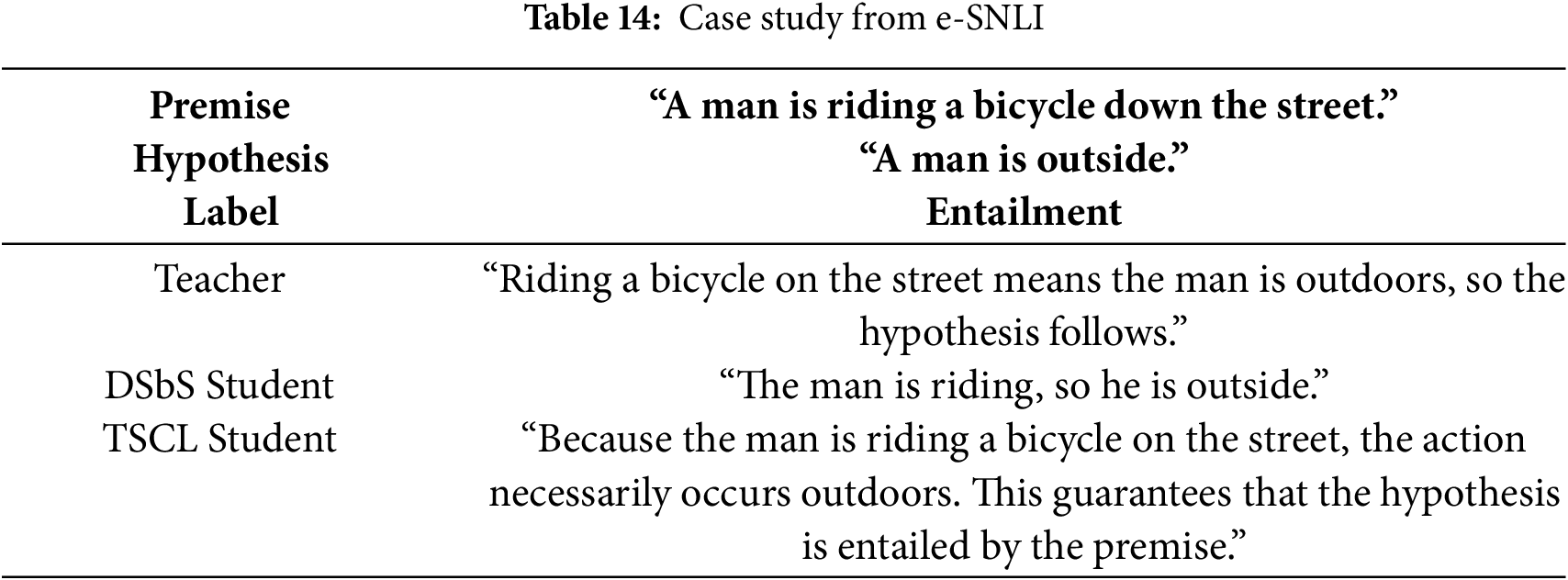

To further illustrate explanation improvements, we present representative cases from CommonsenseQA (CQA) and e-SNLI in Table 13. We compare explanations produced by the teacher, DSbS student, and our TSCL student.

In this example, the DSbS explanation partially captures the phenomenon but introduces a misleading assumption that metal is inherently colder. By contrast, TSCL highlights the underlying physical principle of thermal conductivity, aligning closely with the teacher rationale.

Here, the DSbS explanation is terse and lacks explicit logical connection. TSCL, by contrast, provides a structured reasoning chain that mirrors the teacher’s rationale more faithfully.

Taken together, the findings on Table 14 demonstrate that improvements are not confined to surface-level metrics but extend to interpretability and reasoning faithfulness, underscoring the central role of task sequencing in generating high-quality explanations.

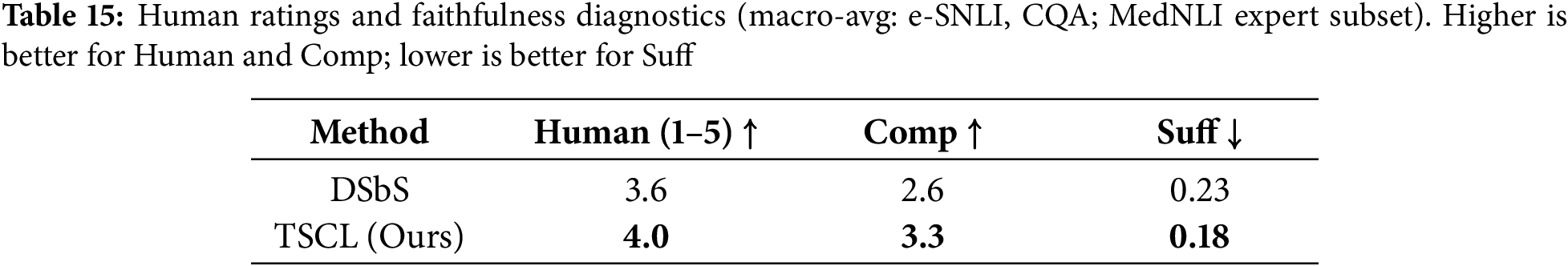

To assess explanation faithfulness and informativeness beyond surface overlap, we complement automatic metrics with two protocol types: (i) a human study (3 trained annotators; 100 samples per dataset; 1–5 Likert for faithfulness and informativeness, averaged per item), and (ii) ERASER-style faithfulness diagnostics: Comprehensiveness (Comp; higher is better), measured as the drop in validation accuracy when rationale tokens are removed, and Sufficiency (Suff; lower is better), measured as the gap when only rationale tokens are retained. We report macro-averages over e-SNLI and CQA; MedNLI uses an expert-annotated subset. Inter-annotator agreement is moderate (Krippendorff’s

Human judges prefer our explanations on both faithfulness and informativeness (+0.4 on a 1–5 scale). Higher Comprehensiveness and lower Sufficiency indicate that our rationales capture decision-critical evidence while remaining concise. Together with the automatic metrics and qualitative case studies, these results substantiate that improvements are not merely lexical, but reflect more grounded and useful explanations.

7 Generalization to the Medical Domain: MedNLI Evaluation

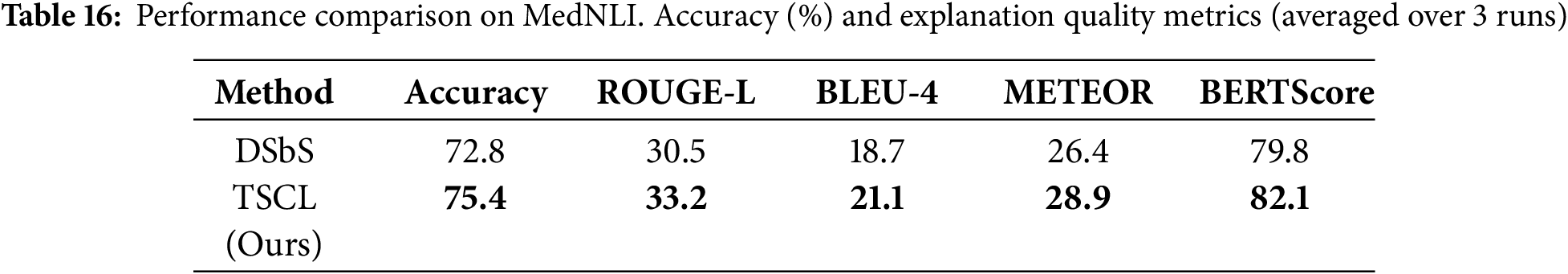

To evaluate the real-world applicability of task-structured curriculum learning (TSCL), we conducted additional experiments on MedNLI [40], a clinical natural language inference dataset. MedNLI is derived from de-identified medical records and consists of premises from clinical notes paired with hypotheses annotated by medical experts. Unlike standard academic benchmarks (e-SNLI, ANLI, CQA, SVAMP), MedNLI requires domain-specific reasoning and interpretability, making it an ideal testbed for assessing generalization to high-stakes applications.

We fine-tuned student models (T5-Base) with teacher supervision (FLAN-T5-XL, 3B) using the same hyperparameters as in the main experiments (batch size 64, learning rate

TSCL outperforms DSbS by +2.6 accuracy points and yields consistent improvements across all explanation metrics: +2.7 ROUGE-L, +2.4 BLEU-4, +2.5 METEOR, and +2.3 BERTScore. These results demonstrate that the benefits of task sequencing generalize to the clinical domain.

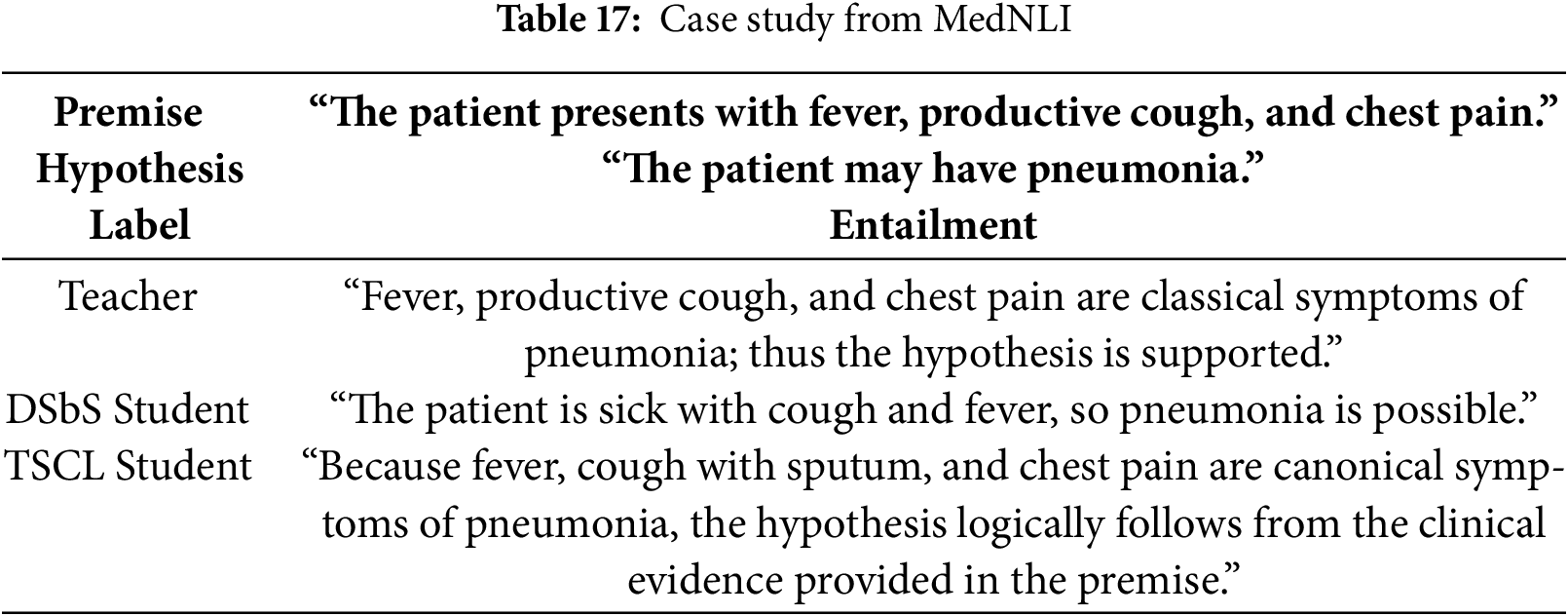

We further compare teacher, DSbS, and TSCL explanations on a representative MedNLI example, as presented in Table 17.

The DSbS explanation captures part of the reasoning but is vague (“patient is sick”) and underspecified. TSCL explicitly connects each symptom to pneumonia, mirroring the teacher rationale and demonstrating more faithful clinical reasoning.

The MedNLI experiments reinforce three conclusions: (i) TSCL generalizes effectively to specialized medical reasoning, confirming robustness beyond standard benchmarks; (ii) explanation quality improvements hold across both automatic metrics and qualitative analyses; and (iii) the framework’s interpretability gains are particularly valuable in sensitive domains such as healthcare, where faithful reasoning is essential. These results highlight the potential of TSCL for real-world applications requiring trustworthy and transparent reasoning.

In this study, we introduced a novel task-based curriculum learning framework that enhances the distilling step-by-step paradigm by strategically sequencing learning objectives. Departing from conventional difficulty-based or static multi-task strategies, our approach organizes training into three pedagogically informed phases: prediction-only, joint prediction-explanation, and explanation-only. This curriculum structure fosters progressive skill acquisition, reduced task interference, and improved reasoning alignment, without requiring any architectural changes or additional computation.

Comprehensive experiments across four diverse NLP benchmarks (e-SNLI, ANLI, CommonsenseQA, SVAMP) and multiple T5 model sizes (small, base, large) confirm the robustness and generality of our method. We achieve consistent gains ranging from 1.7% to 2.4% over strong distillation baselines, along with improvements in few-shot performance, cross-dataset generalization, and training stability.

Our analysis also reveals that task sequencing plays a critical role in shaping optimization dynamics, challenging existing assumptions in multi-task learning. Unlike previous approaches that emphasize instance-level difficulty, our findings suggest that task dependency structures may offer a more effective lens for guiding knowledge transfer in multi-objective settings.

The phase-structured curriculum readily extends beyond text-only settings. Multimodal: apply the same three-phase recipe to VQA, chart/document understanding, or captioning with rationales, while adding lightweight evidence-grounding checks so explanations point to the correct regions or spans; evaluate not just accuracy but grounding precision/recall and small human audits for faithfulness. Interactive/RL: begin with imitation to stabilize behavior, then mix environment feedback while keeping short, auditable rationales, and finally apply light regularization to preserve consistency; assess sample efficiency (episodes to a target score), return stability across seeds, and consistency of action-conditioned explanations. Across both axes, keep parameters shared and switch objectives by phase (not by architecture) to avoid extra compute; mitigate risks of ungrounded or biased rationales with simple evidence references, spot checks, and mild consistency/KL constraints. These steps outline a practical path to grounded multimodal reasoning and stable, sample-efficient RL with faithful explanations.

Although absolute gains appear modest, they arise on strong baselines and correspond to substantial relative error reductions (e.g., +1.7 pts at 91.7% accuracy

From a practical standpoint, our method is lightweight, easily adoptable, and scalable to various model capacities and deployment contexts—offering a compelling solution for efficient model compression and faithful reasoning transfer in large language models. Our findings underscore that task-aware curriculum learning is not merely a training heuristic, but a foundational strategy for advancing multi-task model optimization. As the field progresses toward more capable and efficient AI systems, curriculum design grounded in task structure offers a promising pathway toward scalable, explainable, and resource-conscious language models.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors confirm that this study did not receive any specific funding.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Aytuğ Onan; data collection: Ahmet Ezgi; analysis and interpretation of results: Aytuğ Onan; draft manuscript preparation: Ahmet Ezgi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Available upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In: NIPS’20: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1877–901. [Google Scholar]

2. Chowdhery A, Narang S, Devlin J, Bosma M, Mishra G, Roberts A, et al. PaLM: scaling language modeling with pathways. J Mach Learn Res. 2022;24(240):1–113. [Google Scholar]

3. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. [Google Scholar]

4. Patterson D, Gonzalez J, Le Q, Liang C, Munguia LM, Rothchild D, et al. Carbon emissions and large neural network training. arXiv:2104.10350. 2021. [Google Scholar]

5. Strubell E, Ganesh A, McCallum A. Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in NLP. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul 28–Aug 2; Florence, Italy. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 3645–50. [Google Scholar]

6. Hinton G, Vinyals O, Dean J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv:1503.02531. 2015. [Google Scholar]

7. Hsieh CY, Li CL, Yeh CK, Nakhost H, Fujii Y, Ratner A, et al. Distilling step-by-step! Outperforming larger language models with less training data and smaller model sizes. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 8003–17. [Google Scholar]

8. Bengio Y, Louradour J, Collobert R, Weston J. Curriculum learning. In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning; 2009 Jun 14–18; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 41–8. [Google Scholar]

9. Sanh V, Debut L, Chaumond J, Wolf T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv:1910.01108. 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Jiao X, Yin Y, Shang L, Jiang X, Chen X, Li L, et al. TinyBERT: distilling BERT for natural language understanding. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020; 2020 Nov 16–2; Online. p. 4163–74. [Google Scholar]

11. Platanios EA, Stretcu O, Neubig G, Poczos B, Mitchell TM. Competence-based curriculum learning for neural machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 1162–72. [Google Scholar]

12. Xu B, Zhang L, Mao Z, Wang Q, Xie H, Zhang Y. Curriculum learning for natural language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 6095–104. [Google Scholar]

13. Yue Y, Wang C, Huang J, Wang P. Distilling instruction-following abilities of large language models with task-aware curriculum planning. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024; 2024 Nov 12–16; Miami, FL, USA. p. 5957–70. [Google Scholar]

14. Wu M, Qian Q, Liu W, Wang X, Huang Z, Liang D, et al. Progressive mastery: customized curriculum learning with guided prompting for mathematical reasoning. arXiv:2506.04065. 2025. [Google Scholar]

15. Kim J, Lee S. Strategic data ordering: enhancing large language model performance through curriculum learning. arXiv:2405.07490. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

17. Liu X, He P, Chen W, Gao J. Multi-task deep neural networks for natural language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul 28–Aug 2; Florence, Italy. p. 4487–96. [Google Scholar]

18. Chung HW, Hou L, Longpre S, Zoph B, Tay Y, Fedus W, et al. Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. arXiv:2210.11416. 2022. [Google Scholar]

19. Li LH, Hessel J, Yu Y, Ren X, Chang KW, Choi Y, et al. Symbolic chain-of-thought distillation: small models can also “think” step-by-step. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 2665–79. [Google Scholar]

20. Mukherjee S, Mitra A, Jawahar G, Agarwal S, Palangi H, Awadallah A. Orca: progressive learning from complex explanation traces of GPT-4. arXiv:2306.02707. 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Li Z, Li X, Yang L, Zhao B, Song R, Luo L, et al. Curriculum temperature for knowledge distillation. arXiv:2211.16231. 2022. [Google Scholar]

22. Maharana A, Bansal M. On curriculum learning for commonsense reasoning. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2022 Jul 10–15; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 924–37. [Google Scholar]

23. Longpre S, Hou L, Vu T, Webson A, Chung HW, Tay Y, et al. The flan collection: designing data and methods for effective instruction tuning. In: ICML’23: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023 Jul 23–29; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 22631–48. [Google Scholar]

24. Naïr R, Yamani K, Lhadj L, Baghdadi R. Curriculum learning for small code language models. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Student Research Workshop; 2024 Aug 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 305–18. [Google Scholar]

25. Vakil A, Amiri S. Curriculum learning for graph neural networks: a multiview competence-based approach. arXiv:2307.08859. 2023. [Google Scholar]

26. Koh W, Choi I, Jang Y, Kang G, Kim WC. Curriculum learning and imitation learning for model-free control on financial time-series. arXiv:2311.13326. 2023. [Google Scholar]

27. Feng Z, Wang X, Wu B, Cao H, Zhao T, Yu Q, et al. ToolSample: dual dynamic sampling methods with curriculum learning for RL-based tool learning. arXiv:2509.14718. 2025. [Google Scholar]

28. Wu Y, Zhou M, Liang Y, Tang J. CurriculumPT: lLM-based multi-agent autonomous penetration testing. Appl Sci. 2025;15(16):9096. doi:10.3390/app15169096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sweller J. Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on learning. Cogn Sci. 1988;12(2):257–85. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yu T, Kumar S, Gupta A, Levine S, Hausman K, Finn C. Gradient surgery for multi-task learning. In: NIPS’20: 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 5824–36. [Google Scholar]

31. Sener O, Koltun V. Multi-task learning as multi-objective optimization. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2018 Dec 3–8; Montréal, QC, Canada. p. 527–38. [Google Scholar]

32. Chen Z, Ngiam J, Huang Y, Luong T, Kretzschmar H, Chai Y, et al. Just pick a sign: optimizing deep multitask models with gradient sign dropout. In: Proceedings of the 34th Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 2039–50. [Google Scholar]

33. Jacovi A, Goldberg Y. Towards faithfully interpretable NLP systems: how should we define and evaluate faithfulness?. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2020); 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 4198–205. [Google Scholar]

34. Wolf T, Debut L, Sanh V, Chaumond J, Delangue C, Moi A, et al. Transformers: state-of-the-art natural language processing. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations; 2020 Nov 16–20; Online. p. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

35. Loshchilov I, Hutter F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2019 May 6–9; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

36. Camburu OM, Rocktäschel T, Lukasiewicz T, Blunsom P. e-SNLI: natural language inference with natural language explanations. In: NIPS’18: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2018 Dec 3–8; Montréal, QC, Canada. p. 9560–72. [Google Scholar]

37. Nie Y, Williams A, Dinan E, Bansal M, Weston J, Kiela D. Adversarial NLI: a new benchmark for natural language inference. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 4885–901. [Google Scholar]

38. Talmor A, Herzig J, Lourie N, Berant J. CommonsenseQA: a question answering challenge targeting commonsense knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4149–58. [Google Scholar]

39. Patel A, Bhattamishra S, Goyal N. Are NLP models really able to solve simple math word problems? In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2021 Jun 6–11; Online. p. 2080–94. [Google Scholar]

40. Romanov A, Shivade C. Lessons from natural language inference in the clinical domain. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium. p. 1586–96. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools