Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CIT-Rec: Enhancing Sequential Recommendation System with Large Language Models

1 School of Software and Microelectronics, Peking University, Beijing, 100871, China

2 Information Application Research Center of Shanghai Municipal Administration for Market Regulation, Shanghai, 200032, China

* Corresponding Author: Tong Mo. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 100 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071994

Received 17 August 2025; Accepted 02 December 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Recommendation systems are key to boosting user engagement, satisfaction, and retention, particularly on media platforms where personalized content is vital. Sequential recommendation systems learn from user-item interactions to predict future items of interest. However, many current methods rely on unique user and item IDs, limiting their ability to represent users and items effectively, especially in zero-shot learning scenarios where training data is scarce. With the rapid development of Large Language Models (LLMs), researchers are exploring their potential to enhance recommendation systems. However, there is a semantic gap between the linguistic semantics of LLMs and the collaborative semantics of recommendation systems, where items are typically indexed by IDs. Moreover, most research focuses on item representations, neglecting personalized user modeling. To address these issues, we propose a sequential recommendation framework using LLMs, called CIT-Rec, a model that integrates Collaborative semantics for user representation and Image and Text information for item representation to enhance Recommendations. Specifically, by aligning intuitive image information with text containing semantic features, we can more accurately represent items, improving item representation quality. We focus not only on item representations but also on user representations. To more precisely capture users’ personalized preferences, we use traditional sequential recommendation models to train on users’ historical interaction data, effectively capturing behavioral patterns. Finally, by combining LLMs and traditional sequential recommendation models, we allow the LLM to understand linguistic semantics while capturing collaborative semantics. Extensive evaluations on real-world datasets show that our model outperforms baseline methods, effectively combining user interaction history with item visual and textual modalities to provide personalized recommendations.Keywords

Recommendation Systems (RS) have become an essential component of numerous application platforms, with the primary objective of recommending relevant information resources to users based on their individual preferences and needs [1]. By analyzing users’ historical behaviors, interests, and evolving requirements, recommendation systems offer personalized suggestions tailored to each user. With the rapid advancement of technology, user preferences have shifted from being static to dynamic, continuously evolving over time. This has led to an increased focus on sequential recommendation methods, which have garnered significant research attention due to their ability to capture user behavior sequences and temporal dynamics [2]. Sequential recommendation systems not only provide valuable insights into the changing patterns of user behavior but also enable the prediction of users’ future actions based on their past interactions. As a result, they offer more timely, relevant, and personalized recommendations that better align with users’ evolving needs and preferences.

Sequential Recommendation Systems (SRS) capitalize on historical interaction sequences to predict the subsequent item that holds the highest potential for capturing each user’s interest, as elucidated in [3]. A pivotal aspect of SRS is the enhancement of our understanding of user preferences derived from interaction sequences, which help to capture user behavior and improve recommendation accuracy. A plethora of technical methodologies has been crafted to address this objective, with the most notable being those based on recurrent neural networks [4], convolutional neural networks [5], and self-learning networks. Attention mechanisms [6] and multi-layer perceptrons [7] also play key roles in improving recommendation quality. As representative foundational models of advanced methodologies, BERT4Rec [3], CL4SRec [8], and SASRec [9] have made significant progress in sequential recommendation, providing valuable insights for subsequent research and applications.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have made rapid advancements, demonstrating exceptional capabilities in context understanding, reasoning, and modeling world knowledge [10]. These remarkable achievements have sparked intense interest and exploration in applying LLMs across various fields [11]. The extensive world knowledge embedded in LLMs enables them to effectively transfer existing knowledge to new tasks. In recommendation tasks, integrating LLMs with recommendation systems allows the system to go beyond traditional numerical features and simple user behavior sequences, providing a deeper understanding of users’ underlying intentions. At the same time, the vast knowledge base of LLMs helps recommendation systems better comprehend content across various industries and domains, thereby enhancing the relevance of recommendations. Additionally, LLMs can infer users’ potential needs based on contextual information. Especially in cold-start problems, the application of LLMs has shown significant advantages, particularly when generating recommendations for new users or new items [12]. By analyzing user language descriptions or natural language introductions of items, LLMs help the system better understand users’ interests, thereby improving the personalization of recommendations [13].

The integration of LLMs with recommendation systems, particularly in pioneering research, often hinges on leveraging intrinsic learning mechanisms [14]. In such approaches, LLMs are directly tasked with generating recommendations based on natural language prompts [15]. However, empirical evidence suggests that raw, unmodified LLMs struggle to provide accurate and effective recommendations. This challenge primarily arises from the absence of task-specific training, which is crucial for optimizing performance in recommendation tasks, leading to suboptimal recommendation accuracy [16]. To mitigate this issue, an increasing body of research has focused on fine-tuning LLMs by incorporating data that is specifically tailored to recommendation tasks [17]. Fine-tuning enables LLMs to adapt to the intricacies of recommendation systems and improve their ability to provide relevant suggestions. However, despite these advancements, the fine-tuned LLMs still face significant hurdles in outperforming well-established, traditional recommendation models. This is particularly evident when dealing with warm-start users or items, where the performance of fine-tuned LLMs does not consistently surpass that of conventionally trained models that have been specifically designed to address such challenges.

We argue that the limitations of existing approaches arise from a significant semantic gap between the language semantics modeled by LLMs and the inherent collaborative semantics that underpin recommendation systems. More specifically, in contemporary recommendation models, user behavior is typically represented as a sequence of item IDs, rather than as detailed textual descriptions. In essence, LLMs and traditional recommendation models utilize distinct vocabularies and methods to learn and represent their respective semantic spaces, leading to a disconnect between the two. This semantic gap presents a substantial challenge in fully exploiting the advanced capabilities of LLMs for recommendation tasks. Additionally, when researchers explore potential solutions, there is often an overemphasis on representing item-related information, with insufficient attention given to the personalized modeling of user data, which is crucial for improving the accuracy and relevance of recommendations.

To address the above issues, in this paper, we propose CIT-Rec, a model that integrates Collaborative semantics for user representation and Image and Text information for item representation to enhance Recommendations. Specifically, the CIT-Rec model consists of three modules: the User Collaboration Information Module, the Item Semantic Embedding Module, and the Fusion and Recommendation Module. To more accurately represent users and capture their personalized preferences, we design the User Collaboration Information Module. Compared to text, which can be naturally inserted into prompts and easily understood by LLMs, ID-based user representations may be incompatible with the textual nature of the prompts used by LLMs. Therefore, to bridge the modality gap, we map the ID-based user representation space into the language space of LLMs. This consistency enables LLMs to interpret and leverage behavioral knowledge from users’ interaction history. In the Item Semantic Embedding Module, to represent items more accurately, we align image information, which intuitively represents the items, with textual information containing semantic features to obtain item representations. First, we encode the item information from different modalities. Then, to effectively capture higher-order signals of the items and obtain precise representations, we use contrastive learning to extract item representations from both visual and textual modalities. Finally, in the Fusion and Recommendation Module, to enable LLMs to understand the user and item representations obtained from the two modules above, we fuse these representations into prompts. The prompts include task definitions, interaction sequences with user and item representations, and a candidate set with item representations. The model then uses Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) fine-tuning to generate recommendation results. And we evaluate the proposed model on there benchmarks.

Our contributions are as follows:

Firstly, we align intuitive image information with text information containing semantic features to more accurately represent items, thereby improving the quality of item representations.

Secondly, we not only focus on item representations but also consider user representations, training the user’s historical interaction data with traditional sequential recommendation models to capture personalized user representations.

Thirdly, we combine LLMs and traditional sequential recommendation models, enabling the LLM to understand linguistic semantics while capturing collaborative semantics. We conducted experiments on three publicly available datasets, and the results demonstrate that our method outperforms several advanced baseline methods, generating more accurate recommendation results.

In this section, we will introduce large language models, recommendation systems based on large language models, and related work on multimodal large language models.

The development of LLMs in natural language processing stems from in-depth exploration of language understanding and generation capabilities. Through pre-training, language models can capture the complex relationships between vocabulary and syntactic structures in context, enabling probabilistic modeling [18]. The introduction of the transformer architecture greatly enhanced the model’s understanding of long sequences, allowing for more efficient processing of large-scale text in parallel computing. Based on this, pre-trained models such as BERT [19], GPT [20], and T5 [21] adopt encoder, decoder, and encoder-decoder architectures, respectively, demonstrating excellent performance across different tasks. These models are pre-trained on large-scale unlabeled data and then fine-tuned for specific tasks to improve language understanding and generation capabilities, making them suitable for diverse natural language processing applications. With the increase in model parameters, training data, and computational resources, LLMs have gradually become an enhanced version of pre-trained language models, exhibiting emergent abilities to handle complex tasks. These LLMs, such as GPT-4 [22] and Llama [23], have shown significant performance improvements and demonstrated new abilities in tasks like reasoning, generation, and instruction following. In addition, domain-specific LLMs, such as those in finance [24], medicine [25], and law [26], combine domain expertise with the general commonsense knowledge of LLMs, forming capabilities tailored to specific fields. For example, BloombergGPT [24] focuses on the finance domain, supporting market analysis, prediction, and intelligent decision-making by training on vast amounts of financial data, greatly improving efficiency and accuracy in the finance industry. These advancements have inspired us to explore the potential applications of LLMs in recommendation systems.

LLMs have surged in popularity, finding broad applications across numerous fields within artificial intelligence [27]. This widespread success is largely due to their exceptional capabilities in understanding and generating nuanced language semantics. In the context of RS, researchers are increasingly exploring ways to harness the power of LLMs to boost recommendation quality. Efforts in this area generally fall into two main categories. The first category focuses on using LLMs as an enhancement for traditional recommendation systems. For example, the KAR model [28] taps into LLMs’ powerful semantic understanding to extract deep insights about user preferences and item characteristics, which are then incorporated into conventional recommendation frameworks, leading to improved recommendation performance. Similarly, ONCE [29] enhances content-based recommendation systems by integrating open-source and proprietary LLMs, drawing on the strengths of both to achieve more relevant and personalized recommendations. The second category involves the direct application of LLMs to generate recommendations by leveraging their advanced contextual understanding. TALLRec [17], for instance, employs the LoRA [30] method to fine-tune LLMs specifically for recommendation tasks, enabling the model to provide personalized suggestions. Meanwhile, A-LLMRec [31] combines collaborative filtering with static, frozen LLMs, using both collaborative and textual information to enrich recommendation quality during inference. LLaRA [32] integrates the item representations obtained from traditional sequential recommendation into the recommendation process of LLMs, using a two-stage fine-tuning approach to improve recommendation quality. In contrast to the aforementioned research, we first not only consider the item representations but also take into account the user representations, capturing personalized user embeddings through traditional sequential recommendation models. Second, we incorporate image information into the text part of the item representation, leading to more accurate item representations. Finally, by combining LLMs with traditional sequential recommendation models, we enable the LLMs to understand language semantics while capturing collaborative semantics, resulting in more accurate recommendation outcomes.

2.3 Multi-Modal Large Language Models

Despite the impressive versatility and performance of LLMs in text processing tasks, most existing LLMs are still limited to handling text inputs. However, information and knowledge do not exist solely in textual form—visual, video, audio, and other modalities also contain rich data and information. With the ongoing research, scholars have proposed Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) that effectively integrate text with these other modalities, aiming to overcome the limitations of single-modality models [33]. These models are designed to process and understand a wider range of inputs, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the world. Recent studies on MLLMs have shown that the visual space can be aligned harmoniously with the textual space, enabling models to perform language generation tasks conditioned on visual input [34]. By aligning the visual and textual spaces, MLLMs can generate descriptions or answers that are more contextually aware and rich in semantic detail. In addition to vision, other modalities such as audio have also been incorporated into LLMs, allowing them to better digest and understand information and knowledge from various modalities, thereby improving their performance in complex tasks [35]. The integration of multiple modalities enables these models to offer richer, more nuanced outputs that leverage the complementary strengths of different types of data. Building on this research progress, we incorporate item image information into the CIT-Rec model, providing a more intuitive representation of items. This not only enhances our understanding of items but also, by combining the characteristics of sequential recommendation systems, offers richer contextual information for recommendation tasks. In doing so, we enable the model to leverage both visual and sequential interaction data, which improves the accuracy and personalization of the recommendations. The incorporation of image data helps bridge the gap between visual and textual information, enriching the semantic understanding of items and ensuring that recommendations are more aligned with user preferences and behaviors. This multimodal approach significantly enhances the performance of the recommendation system, making it more robust and capable of delivering tailored, high-quality suggestions.

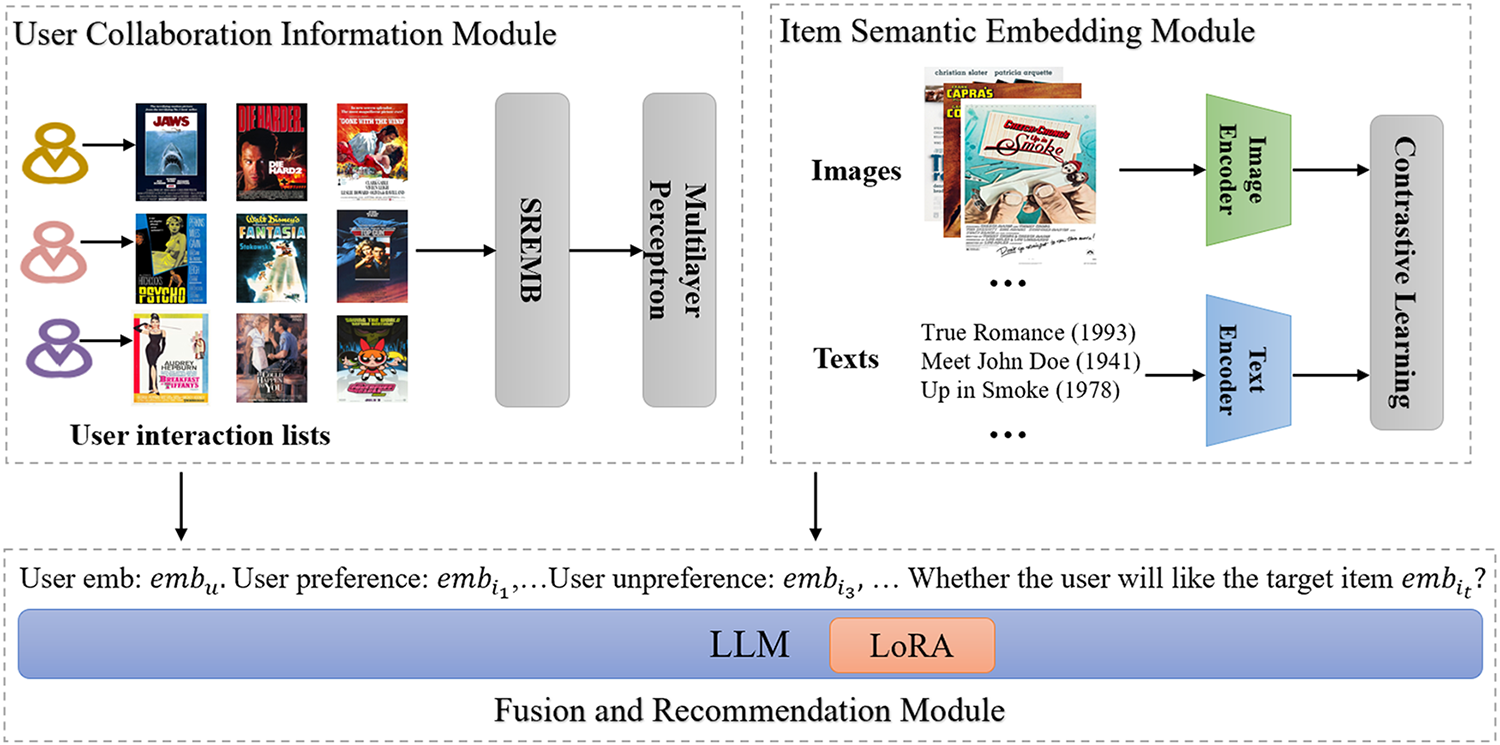

In this section, we will specifically introduce the proposed CIT-Rec method, and the overall framework of the model is shown in Fig. 1. The CIT-Rec model consists of three modules: (1) User Collaboration Information Module, (2) Item Semantic Embedding Module, and (3) Fusion and Recommendation Module. To more accurately represent users and capture their personalized preferences, we design a user collaboration information module. Compared to text-based representations that can be naturally inserted into prompts and easily understood by LLMs, ID-based user representations may be incompatible with the textual nature of the prompts used by LLMs. Therefore, to bridge the modality gap, we map the ID-based user representation space into the language space of LLMs. This consistency enables LLMs to interpret and leverage the behavioral knowledge from users’ interaction history. To implement this idea, we train the user’s historical interaction behavior data using traditional sequential recommendation models, which effectively capture ID-based behavioral patterns. In the item semantic embedding module, to represent items more accurately, we align the image information, which intuitively represents the items, with the textual information containing semantic features to obtain item representations. First, we encode the item information from different modalities. Then, to effectively capture higher-order signals of the items and obtain precise representations, we use contrastive learning to extract item representations from both visual and textual modalities. By treating matching image-text pairs as positive views and mismatched image-text pairs as negative views, this method tightens the integration of item image and text embeddings in the feature space, allowing the model to capture higher-order item signals. Finally, in the fusion and recommendation module, to enable LLMs to understand the user and item representations obtained from the above two modules, we fuse these representations into prompts. The prompts mainly contain task definitions, interaction sequences with user and item representations, and a candidate set with item representations. The model then uses LoRA fine-tuning to generate recommendation results.

Figure 1: Overall framework of the CIT-Rec. CIT-Rec consists of three modules: (1) User collaboration information module, (2) Item semantic embedding module, and (3) Fusion and recommendation module

3.1 User Collaboration Information Module

In order to more accurately represent users and capture their personalized preferences, we have designed a user collaboration information module. Specifically, compared to text that can naturally insert prompts and is easily understood by LLM, ID based user representation may not be compatible with the textual nature of LLM prompts. Therefore, in order to bridge the modal gap, we map the user’s ID based representation space to the language space of the LLM. This consistency enables LLMs to interpret and utilize behavioral knowledge of user interaction history. To achieve the above idea, we adopt the traditional sequential recommendation model SASRec [9]. After training on the user’s historical interaction behavior data, it can effectively capture the user’s ID based behavior pattern. For user

Then, we use a multi-layer perceptron to map user embeddings to the desired dimensions, as follows:

3.2 Item Semantic Embedding Module

To obtain a more accurate and comprehensive item representation, we align visual features with textual semantic information by integrating data from multiple modalities. For visual encoding, we leverage CLIP-ViT-B/16, based on the CLIP framework proposed by Radford et al. [36], which learns visual representations through large-scale supervision from raw image-text pairs. For textual encoding, we utilize Llama2-7B [23], an instruction-tuned large language model pre-trained on extensive text corpora, which enables it to effectively capture the semantic nuances of item descriptions. By combining these two modalities, we construct a unified item representation that captures both visual and textual semantics.

To effectively capture the higher-order signals of items and obtain precise representations of items, we employ a contrastive learning approach to derive item representations from both the visual modality and the textual modality. Specifically, by treating image-text pairs of matching items as positive views and non-matching image-text pairs as negative views, this approach allows the item’s image and text embeddings to become more tightly integrated in the feature space, enabling the model to capture higher-order item signals. In this process, the contrastive loss can be expressed as follows:

where

3.3 Fusion and Recommendation Module

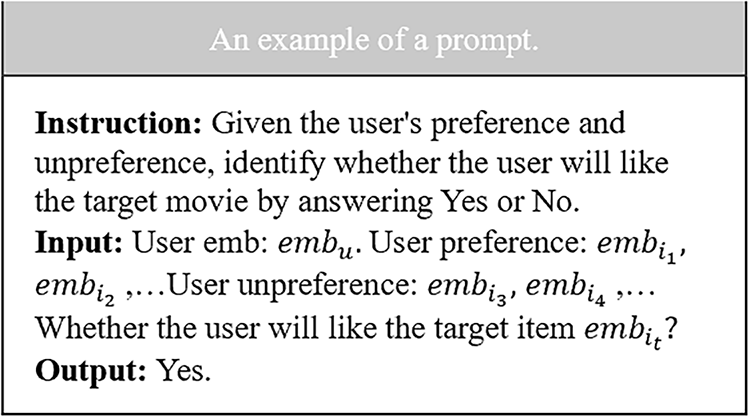

To enable the LLM to comprehend the user and item representations obtained from the aforementioned modules, we incorporate these representations into a carefully designed prompt and fine-tune the LLM using LoRA to generate recommendation results. The prompt primarily includes three components: a textual description of the recommendation task to define the objective, the user’s historical interaction sequence with items enriched by the corresponding user and item representations, and a candidate item set constructed using the item representations generated by the semantic embedding module. This integrated prompt design ensures that the LLM can effectively leverage both user preferences and item semantics for personalized recommendation.

Our prompt design captures users’ personalized preferences based on their interaction history, aligning image information that intuitively represents items with text information containing semantic features to better represent the items. This approach addresses the limitations of prompts that rely solely on IDs or text data, leading to more accurate recommendations. An example of a specific prompt is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: An example of a prompt. It includes task definitions, the user’s historical interaction lists and candidate item in the input, as well as the output

Then, we use LoRA fine-tuning on the LLM to obtain recommendation results, with the objective of seamlessly and efficaciously integrating the employed LLM with the specific nuances of the recommendation task. Regarding the process of instruction tuning, we follow the conventional supervised fine-tuning methodology, endeavoring to minimize the autoregressive loss derived from the discrepancy between the actual values and the outputs generated by the LLM. In our approach, we obscure the absent positions within the prompt. Nonetheless, directly fine-tuning the entire model poses a significant computational burden and can be exceedingly time-consuming. To surmount this challenge, we introduce a streamlined fine-tuning strategy employing the LoRA technique. This method entails immobilizing the parameters of the pre-trained model while integrating trainable, rank-decomposed matrices into the fabric of each layer within the Transformer architecture. This approach enables a more nimble tuning process, concurrently curtailing the consumption of GPU memory. The ultimate learning objective can be articulated as follows:

where

In this section, we first introduce the datasets and evaluation metrics, followed by a discussion of the implementation details. Next, we present the baseline for this experiment. Then, we provide the experimental results and compare them with the baseline. After that, we conduct an ablation study to analyze the components of the model. Finally, we present a specific example of a recommendation made by the model.

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metric

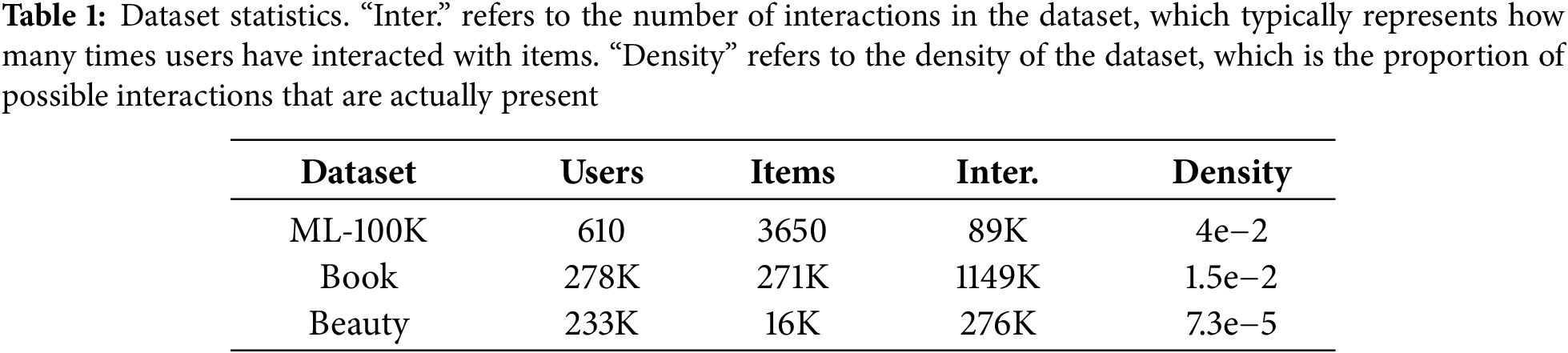

Three benchmark datasets were used in the experiments, with their statistics shown in Table 1. The Movie dataset is derived from MovieLens100K [37]. Due to training time constraints, the dataset was then split into a training set and a test set, with 80% allocated for training and 20% for testing. The Book dataset is based on Book Crossing [38], which includes user ratings (on a scale of 1 to 10) and item descriptions. For each user, we randomly selected one previously interacted item as the prediction target and extracted ten items to represent the user’s historical interactions. The Beauty dataset is from Amazon [9] and includes beauty and personal care product information, along with associated images and user ratings.

We evaluate the task’s performance employing a conventional metric: the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC). We eschew rank-based metrics in our assessment, as the fine-tuning phase of the LLMs’ text sequence generation necessitates an understanding of the item sequence order’s fundamental truths, an aspect that, in practice, is non-existent.

In the user collaboration information module, for the generation of user representations, we use the SASRec [9] model as a traditional sequential recommendation model for the experiment. In the item semantic embedding module, for the generation of item representations, we harness the functionalities of CLIP-VIT-B/16 [36] to encode image information. Additionally, we utilize Llama2-7B [23] for encoding text information. In the fusion and recommendation module, we apply LoRA fine-tuning on the Llama2-7B model to obtain recommendation results. For the experimental dataset setup, we select 80% as the training set and 20% as the test set. Regarding hyperparameter settings, for LoRA, r is set to 8, α to 32, dropout to 0.1, learning rate to 3e−4, and weight decay to 1e−4. We use the AdamW optimizer, set early stopping to 50, train for 500 epochs, and use a random seed of 0. For contrastive learning, the temperature τ is set to 0.07. All experiments are conducted on a GPU: NVIDIA A800 Tensor Core GPU (80 GB).

We categorize the baseline models into three types: traditional sequential recommendation models, graph-based recommendation models, and LLM-based recommendation models. These algorithms are then compared with the proposed method.

Traditional sequential recommendation models include:

• BERT4Rec [3]: BERT4Rec uses bidirectional self-attention to model user behavior sequences. To avoid information leakage and effectively train the bidirectional model, it adopts a Cloze objective for sequence recommendation, where the context of items on both sides is jointly used to predict randomly masked items in the sequence. In this way, a bidirectional representation model is learned, allowing each item in the user’s historical behavior to integrate information from both sides for making recommendations.

• CL4SRec [8]: CL4SRec is a sequential recommendation contrastive model that not only leverages the traditional next-item prediction task but also utilizes a contrastive learning framework to obtain self-supervised signals from the raw user behavior sequences. As a result, it can extract more meaningful user patterns and further effectively encode user representations.

• SASRec [9]: SASRec is a sequence-based recommendation model designed to predict the next item a user is likely to be interested in, by leveraging their historical interaction data. It utilizes a self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to capture long-range dependencies and sequential patterns in user behavior, ultimately improving the accuracy of recommendations.

Graph-based recommendation models include:

• SGL [39]: SGL is a self-supervised graph learning method for recommendation, which alters the graph structure using three strategies: node dropout, edge dropout, and random walks. It trains with auxiliary self-supervised tasks to enhance node representations, thereby improving recommendation performance. This method shows good performance on long-tail items and in handling interaction noise.

• XSimGCL [40]: XSimGCL abandons traditional graph enhancement methods and instead uses noise based embedding enhancement to generate contrastive learning views. XSimGCL believes that contrast loss (InfoNCE) is the key to improving recommendation performance, while graph enhancement has a relatively small effect.

LLM-based recommendation models include:

• Zero-Shot CoT [41]: This is a method based on LLM that uses LLM for recommendation. It directly queries the original LLM for recommendations using prompts.

• TALLRec [17]: TALLRec is an efficient tuning framework designed to optimize the operational capabilities of LLMs in recommendation systems. By going through two stages of tuning, the framework enables LLMs to better adapt to recommendation tasks.

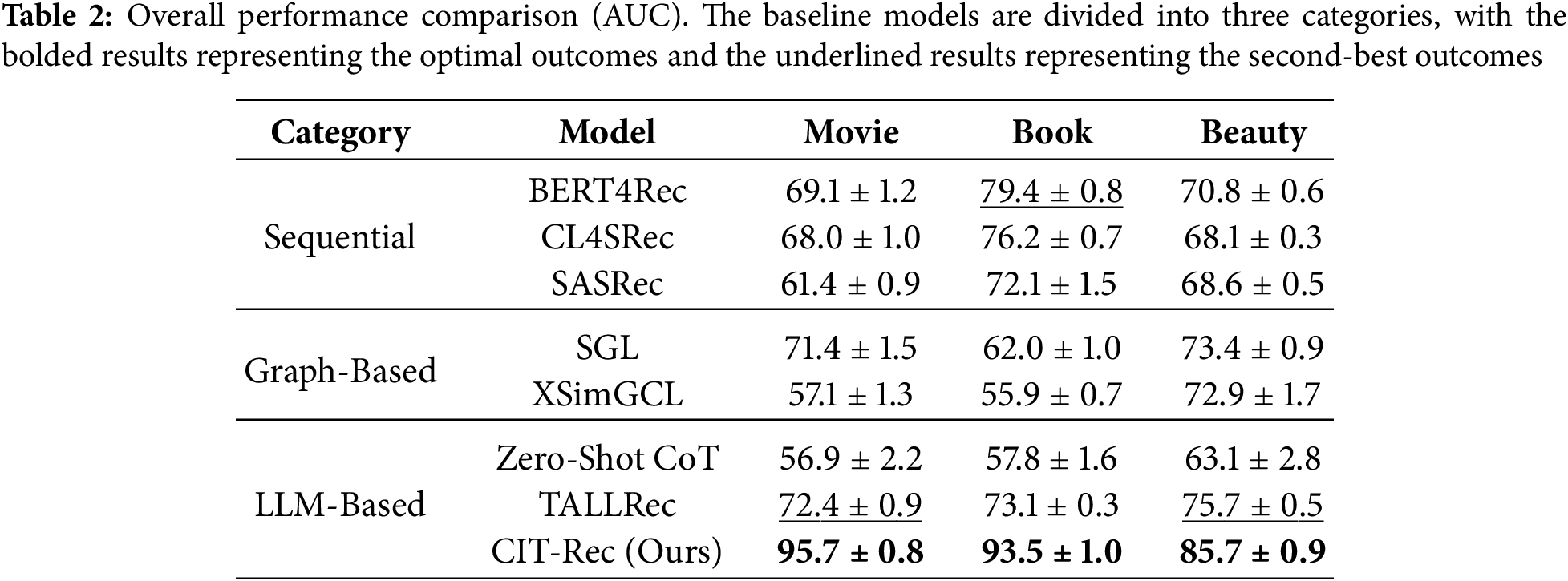

This segment is primarily dedicated to assessing the performance of the proposed approach in comparison with established benchmark methodologies. Table 2 reports the first sets of results, where the recommendation performance of all schemes are compared. In Table 2, we compare the proposed method with three categories of baseline models used for sequential recommendation. The first category consists of traditional sequential recommendation models, including BERT4Rec [3], CL4SRec [8], and SASRec [9]. These models rely on sequential data patterns to make predictions. The second category includes graph-based recommendation models. Since previous graph-based recommendation models have demonstrated excellent performance in similar tasks, we selected two representative models in this category: SGL [39] and XSimGCL [40]. These models leverage graph structures to model relationships between users and items, thus enhancing the recommendation process. The third category is composed of LLM-based recommendation models, including Zero Shot CoT [41] and TALLRec [17]. Zero Shot CoT directly uses prompts to make LLM provide recommended answers. TALLRec is an efficient fine-tuning framework designed to improve the performance of LLMs within recommendation systems. By applying a two-stage fine-tuning process, TALLRec enables LLMs to better adapt to the specific needs of recommendation tasks, improving their accuracy and relevance.

In Table 2, the optimal experimental results are bolded, while the second-best results are underlined. From a comprehensive analysis of the experimental results, it is evident that the method based on fine-tuning LLM outperforms traditional sequential recommendation techniques, graph based recommendation methods, and direct use of prompts in a wide range of evaluation metrics. Particularly noteworthy are the substantial improvements in AUC values observed on both datasets. This robust performance underscores the efficacy of utilizing LLMs to capture nuanced user interaction patterns and item semantic information, thereby facilitating the delivery of highly personalized and contextually relevant recommendations. These findings highlight the considerable advantages and versatility of this approach in various recommendation contexts.

Furthermore, our proposed method consistently surpasses all three categories of baseline models. Across the three datasets, our method exhibits marked enhancements over the next best models, underscoring its superior capability to detect and model complex patterns within users’ continuous behavior sequences. This enhanced modeling capacity leads to more relevant and accurate recommendations, significantly enhancing user satisfaction and engagement. Additionally, the consistent and strong performance demonstrated across different datasets further validates the robustness, adaptability, and generalizability of our approach. It effectively handles diverse types of data and user interaction behaviors, illustrating its broad applicability and effectiveness across a wide range of recommendation scenarios and domains.

The relatively smaller improvement in the Beauty dataset, compared to the Movie and Book datasets, can likely be attributed to its shorter interaction sequences. These shorter sequences may limit performance gains by providing less data for the model to learn from, potentially constraining its ability to capture complex user preferences and behavior patterns. Despite these limitations, our proposed method still outperforms the baseline models across all three datasets. This consistent superiority underscores its ability to deliver high-quality, effective recommendations even under varying conditions and across diverse domains. Nonetheless, overall, our proposed method outperforms the baseline models in all three datasets, demonstrating its ability to deliver high-quality and effective recommendations across diverse domains. The results highlight the robustness and versatility of our model, confirming its potential to revolutionize recommendation systems by integrating advanced techniques and information sources.

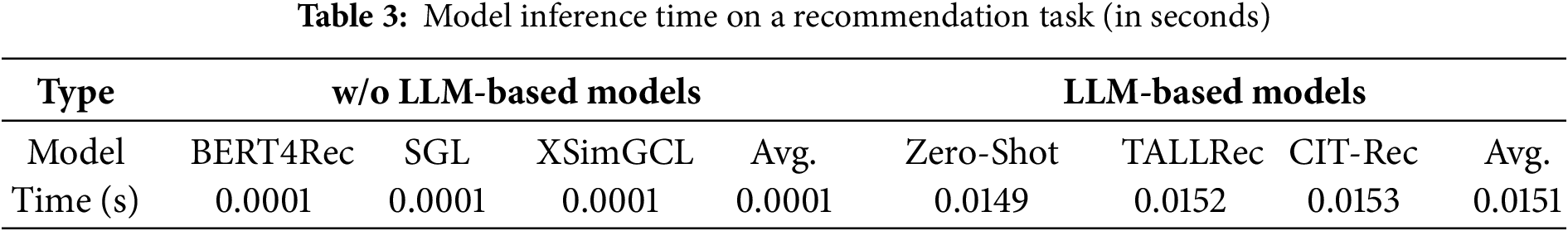

In addition, we evaluated the inference efficiency of our proposed CIT-Rec against various baselines, as summarized in Table 3. The column “Avg.” denotes the average inference time for non-LLM and LLM-based models on the Book dataset. As observed, models without LLM components yield much faster inference, while LLM-based ones consume noticeably more time. This performance gap mainly arises from the substantial number of parameters and the intricate attention operations within LLMs. Nevertheless, LLM-based methods demonstrate markedly higher AUC results in our experiments, highlighting their stronger capabilities in semantic representation and user intent comprehension. In essence, LLM-based recommenders trade a certain level of inference efficiency for a considerable gain in recommendation accuracy.

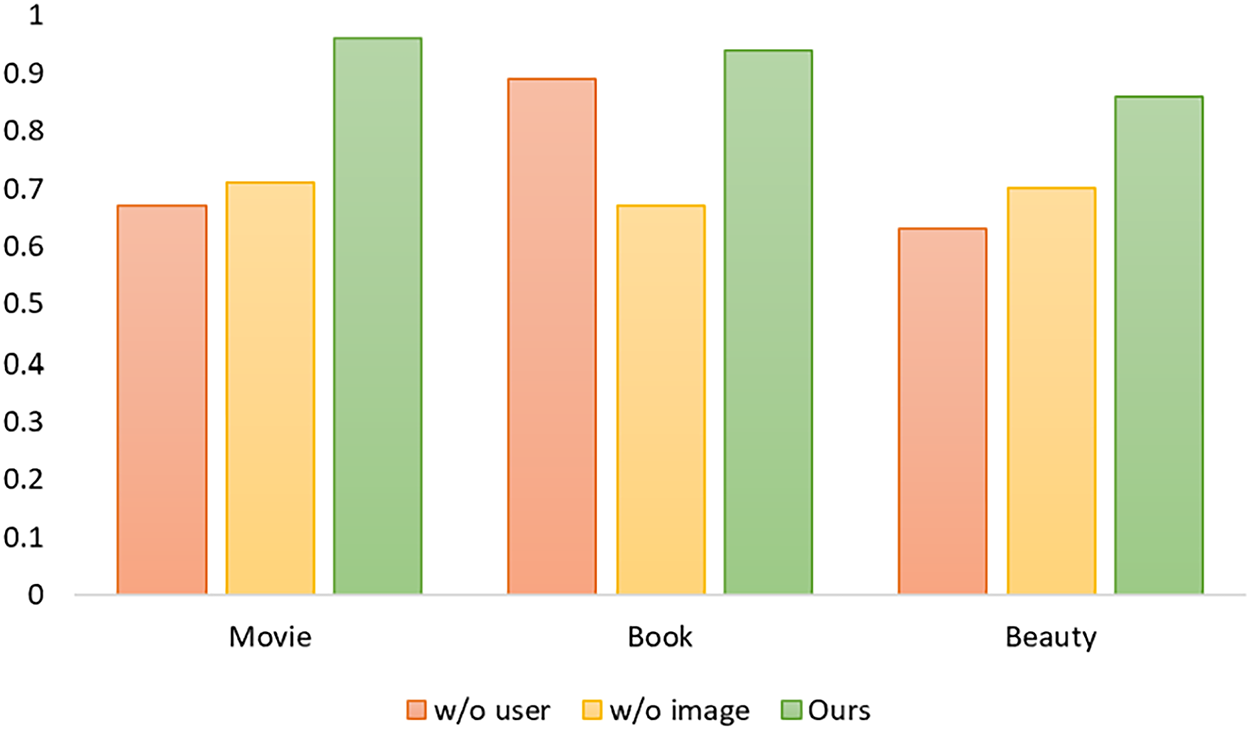

To investigate the effectiveness of the user collaboration information module and the item semantic embedding module, we designed two ablation experiments for comparison with our proposed model, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3, “w/o user” refers to the model without the user collaboration information, and “w/o image” refers to the model where the image information is removed from the item semantic embedding module, leaving only text information to represent the items. These experiments were designed to isolate and evaluate the impact of each individual module on the overall performance of the recommendation system.

Figure 3: Ablation study. “w/o user” refers to the model without the user collaboration information, and “w/o image” refers to the model where the image information is removed from the item semantic embedding module, using only text information to represent the items

Based on the experimental results, we can see that our proposed method outperforms both ablation experiment setups. Specifically, compared to the model without user information, the improvement in AUC values across three datasets indicates that the incorporation of user collaboration information significantly enhances the model’s ability to make accurate recommendations by leveraging user interaction patterns and preferences. Compared to the model without image information, the improvement in AUC values across three datasets demonstrates the critical role of image information in capturing the semantic features of items, particularly for content that benefits from visual cues such as movies and beauty products.

From this analysis, we can conclude that the user collaboration information module and item semantic embedding module in our method do indeed improve the accuracy of recommendations, validating the importance of both user-specific and item-specific information in enhancing the performance of recommendation systems. The results suggest that our approach can effectively combine multiple sources of information to generate more personalized and contextually relevant recommendations.

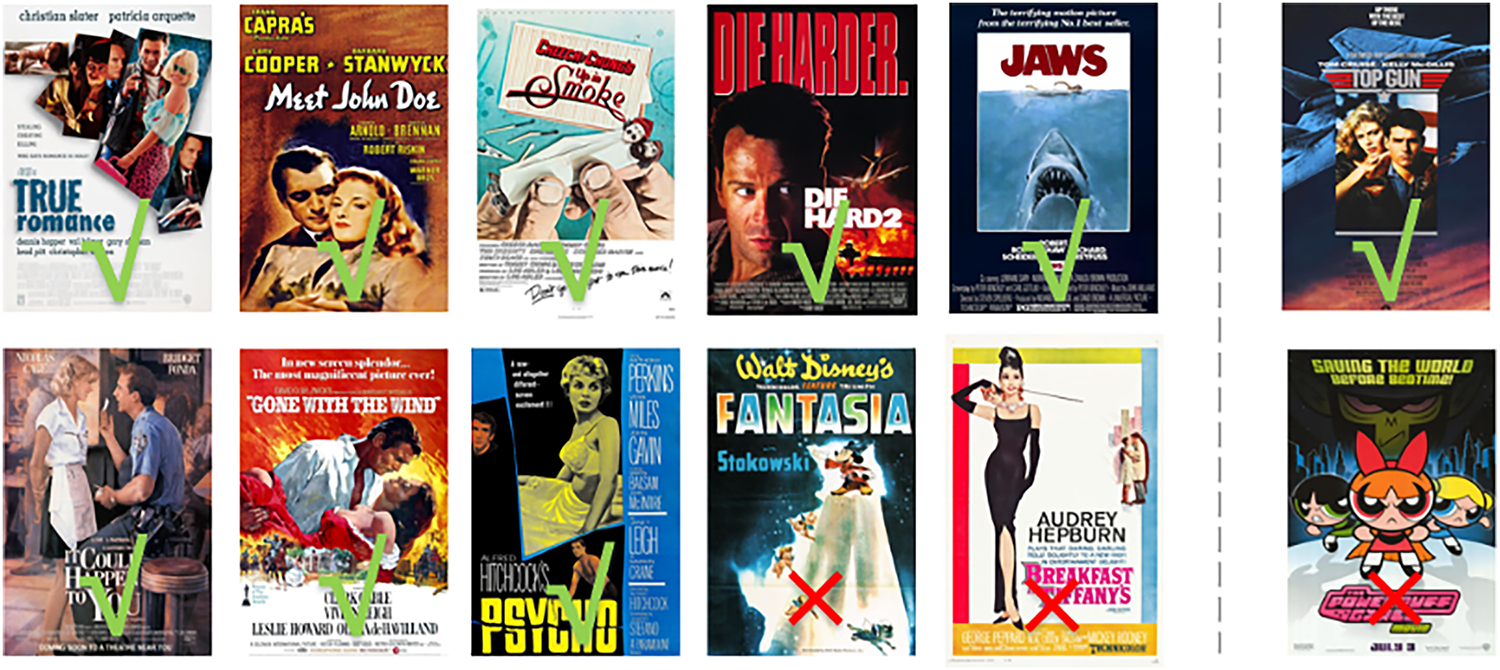

We provide a recommendation example from the proposed model, as shown in Fig. 4. On the left side is the user’s interaction history, with a check mark indicating movies the user likes and a cross mark indicating movies the user dislikes. On the right side are the recommendations made by the model.

Figure 4: A case study. On the left side is the user’s interaction history, with a check mark indicating movies the user likes and a cross mark indicating movies the user dislikes. On the right side are the recommendations made by the model

Specifically, in the user’s interaction history, the movies the user likes include “True Romance, Meet John Doe, Up in Smok, Die Hard 2, Jaws, It Could Happen to You, Gone with the Wind, and Psycho”. The movies the user dislikes include “Fantasia and Breakfast at Tiffany’s”. Based on the user’s interaction history, we can see that the user prefers emotionally rich, adventurous, suspenseful, and action-oriented movies, and dislikes animated and romantic love stories. The films that appeal to the user tend to have strong emotional depth, fast-paced action, and a sense of thrill or danger, reflecting a preference for high-energy experiences that involve intense personal or situational conflict.

Furthermore, the model’s recommendations align with our analysis. The user likes “Top Gun”, a classic action film about a pilot’s adventure and challenges, with strong suspense and action elements. The movie features high-octane action sequences, intense emotional stakes, and a focus on personal growth, all of which are likely to resonate with the user’s preferences. On the other hand, the user dislikes “The Powerpuff Girls Movie”, an animated movie. This recommendation is consistent with the user’s clear aversion to animated films, particularly those with a lighter, more fantastical tone, such as this one. The model’s ability to accurately recommend “Top Gun” and avoid “The Powerpuff Girls Movie” demonstrates its deep understanding of the user’s taste and behavior, as well as its capacity to effectively match user preferences with appropriate content.

In this paper, we propose a recommendation system framework based on LLM, named CIT-Rec, which enhances the ability of LLM to better understand users and items, leading to more accurate recommendations. Specifically, CIT-Rec utilizes a user collaboration information module to capture personalized user preferences from their interaction history and generates personalized user embeddings. It then uses an item semantic embedding module, aligning the image information that intuitively represents the items with the semantic features contained in the text to obtain precise item representations. These user and item embeddings are then fed into a fusion and recommendation module, which constructs prompts based on the embeddings from the user collaboration information module and the item semantic embedding module. The LLM is fine-tuned using LoRA to generate the final recommendation results. Extensive empirical evaluations on various real-world datasets show that the proposed model outperforms the baseline, effectively combining user historical interactions with the visual and textual modalities of items to jointly model and provide personalized recommendations. Ablation experiments also demonstrate the importance of image information in our proposed user collaboration information module and item semantic embedding module. Finally, we provide a specific example of how to use the CIT-Rec model for recommendations. Although CIT-Rec achieves promising results, it still has certain limitations, such as increased computational cost and training time introduced by multimodal fusion. Addressing these issues in future work could further enhance the efficiency and generalization capability of our framework.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China [2022YFF0902703] and the State Administration for Market Regulation Science and Technology Plan Project (2024MK033).

Author Contributions: Ziyu Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing & Review; Zhen Chen: Funding, Acquisition, Resources, Supervision; Xuejing Fu: Writing, Review & Editing; Tong Mo (Corresponding Author): Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing & Review; Weiping Li: Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Resources & Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets are public datasets.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chang J, Gao C, Zheng Y, Hui Y, Niu Y, Song Y, et al. Sequential recommendation with graph neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2021 Jul 11–15; Virtual. p. 378–87. doi:10.1145/3404835.3462968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lin X, Luo J, Pan J, Pan W, Ming Z, Liu X, et al. Multi-sequence attentive user representation learning for side-information integrated sequential recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2024 Mar 4–8; Merida, Mexico. p. 414–23. doi:10.1145/3616855.3635815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sun F, Liu J, Wu J, Pei C, Lin X, Ou W, et al. BERT4Rec: sequential recommendation with bidirectional encoder representations from transformer. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2019 Nov 3–7; Beijing, China. p. 1441–50. doi:10.1145/3357384.3357895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Donkers T, Loepp B, Ziegler J. Sequential user-based recurrent neural network recommendations. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2017 Aug 27; Como, Italy. p. 152–60. doi:10.1145/3109859.3109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yan A, Cheng S, Kang WC, Wan M, McAuley J. CosRec: 2D convolutional neural networks for sequential recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2019 Nov 3–7; Beijing, China. p. 2173–6. doi:10.1145/3357384.3358113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. He Z, Zhao H, Lin Z, Wang Z, Kale A, McAuley J. Locker: locally constrained self-attentive sequential recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2021 Nov 1–5; Virtual. p. 3088–92. doi:10.1145/3459637.3482136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li M, Zhang Z, Zhao X, Wang W, Zhao M, Wu R, et al. AutoMLP: automated MLP for sequential recommendations. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023; 2023 Apr 30–May 4; Austin, TX, USA. p. 1190–8. doi:10.1145/3543507.3583440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xie X, Sun F, Liu Z, Wu S, Gao J, Zhang J, et al. Contrastive learning for sequential recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2022 May 9–12; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. p. 1259–73. doi:10.1109/ICDE53745.2022.00099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kang WC, McAuley J. Self-attentive sequential recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM); 2018 Nov 17–20; Singapore. p. 197–206. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2018.00035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Y, Feng F, Zhang J, Bao K, Wang Q, He X. CoLLM: integrating collaborative embeddings into large language models for recommendation. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2025;37(5):2329–40. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2025.3540912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang L, Chen H, Li Z, Ding X, Wu X. Give us the facts: enhancing large language models with knowledge graphs for fact-aware language modeling. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(7):3091–110. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2024.3360454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sanner S, Balog K, Radlinski F, Wedin B, Dixon L. Large language models are competitive near cold-start recommenders for language- and item-based preferences. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2023 Sep 18–22; Singapore. p. 890–6. doi:10.1145/3604915.3608845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao Z, Fan W, Li J, Liu Y, Mei X, Wang Y, et al. Recommender systems in the era of large language models (LLMs). IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(11):6889–907. doi:10.1109/tkde.2024.3392335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:1877–1901. doi:10.5555/3495724.3495883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dai S, Shao N, Zhao H, Yu W, Si Z, Xu C, et al. Uncovering ChatGPT’s capabilities in recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2023 Sep 18–22; Singapore. p. 1126–32. doi:10.1145/3604915.3610646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang J, Xie R, Hou Y, Zhao X, Lin L, Wen JR. Recommendation as instruction following: a large language model empowered recommendation approach. ACM Trans Inf Syst. 2025;43(5):1–37. doi:10.1145/3708882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bao K, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Wang W, Feng F, He X. TALLRec: an effective and efficient tuning framework to align large language model with recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2023 Sep 18–22; Singapore. p. 1007–14. doi:10.1145/3604915.3608857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chiang WL, Li Z, Lin Z, Sheng Y, Wu Z, Zhang H, et al. Vicuna: an open-source chatbot impressing GPT-4 with 90%* Chatgpt Quality [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 1]. Available from: https://lmsys.org/blog/2023-03-30-vicuna/. [Google Scholar]

19. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Long and Short Papers); 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. Vol. 1, p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

20. Radford A, Wu J, Child R. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog. 2019;1(8):9. [Google Scholar]

21. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

22. OpenAI, Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Ahmad L, Akkaya I, et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv:2303.08774. 2023. [Google Scholar]

23. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. [Google Scholar]

24. Wu S, Irsoy O, Lu S, Dabravolski V, Dredze M, Gehrmann S, et al. Bloomberggpt: a large language model for finance. arXiv:2303.17564. 2023. [Google Scholar]

25. Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, Mahdavi SS, Wei J, Chung HW, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972):172–80. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Cui J, Li Z, Yan Y. Chatlaw: open-source legal large language model with integrated external knowledge bases. CoRR. 2023:1–11. [Google Scholar]

27. Wu L, Zheng Z, Qiu Z, Wang H, Gu H, Shen T, et al. A survey on large language models for recommendation. World Wide Web. 2024;27(5):60. doi:10.1007/s11280-024-01291-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xi Y, Liu W, Lin J, Cai X, Zhu H, Zhu J, et al. Towards open-world recommendation with knowledge augmentation from large language models. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2024 Jul 11–15; Bari, Italy. p. 12–22. doi:10.1145/3640457.3688104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu Q, Chen N, Sakai T, Wu XM. ONCE: boosting content-based recommendation with both open- and closed-source large language models. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2024 Oct 14–18; Merida, Mexico. p. 452–61. doi:10.1145/3616855.3635845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, Allen-Zhu Z, Li Y, Wang S, et al. Lora: low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR. 2022;1(2):3. [Google Scholar]

31. Kim S, Kang H, Choi S, Kim D, Yang M, Park C. Large language models meet collaborative filtering: an efficient all-round LLM-based recommender system. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2024 Aug 25–29; Barcelona, Spain. p. 1395–406. doi:10.1145/3637528.3671931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liao J, Li S, Yang Z, Wu J, Yuan Y, Wang X, et al. LLaRA: large language-recommendation assistant. In: Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2024 Jul 14–18; Washington, DC, USA. p. 1785–95. doi:10.1145/3626772.3657690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Y, Liang F, Zhao L, Cui Y, Ouyang W, Shao J, et al. Supervision exists everywhere: a data efficient contrastive language-image pre-training paradigm. arXiv:2110.05208. 2021. [Google Scholar]

34. Li J, Li D, Savarese S, Hoi S. Blip-2: bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023 Jul 23–29; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 19730–42. [Google Scholar]

35. Lyu C, Wu M, Wang L, Huang X, Liu B, Du Z, et al. Macaw-llm: multi-modal language modeling with image, audio, video, and text integration. arXiv:2306.09093. 2023. [Google Scholar]

36. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Online. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

37. Harper FM, Konstan JA. The MovieLens datasets. ACM Trans Interact Intell Syst. 2016;5(4):1–19. doi:10.1145/2827872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ziegler CN, McNee SM, Konstan JA, Lausen G. Improving recommendation lists through topic diversification. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on World Wide Web—WWW '05; 2005 May 10–14; Chiba, Japan. doi:10.1145/1060745.1060754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wu J, Wang X, Feng F, He X, Chen L, Lian J, et al. Self-supervised graph learning for recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2021 Jul 11–15; Virtual. p. 726–35. doi:10.1145/3404835.3462862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yu J, Xia X, Chen T, Cui L, Hung NQV, Yin H. XSimGCL: towards extremely simple graph contrastive learning for recommendation. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(2):913–26. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2023.3288135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wei J, Wang X, Schuurmans D, Bosma M, Xia F, Chi E, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:24824–37. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools