Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on the Classification of Digital Cultural Texts Based on ASSC-TextRCNN Algorithm

1 Asia-Europe Institute, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Ludong University, Yantai, 264025, China

3 Faculty of Business and Economics, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Sameer Kumar. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 91 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072064

Received 18 August 2025; Accepted 02 December 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the rapid development of digital culture, a large number of cultural texts are presented in the form of digital and network. These texts have significant characteristics such as sparsity, real-time and non-standard expression, which bring serious challenges to traditional classification methods. In order to cope with the above problems, this paper proposes a new ASSC (ALBERT, SVD, Self-Attention and Cross-Entropy)-TextRCNN digital cultural text classification model. Based on the framework of TextRCNN, the Albert pre-training language model is introduced to improve the depth and accuracy of semantic embedding. Combined with the dual attention mechanism, the model’s ability to capture and model potential key information in short texts is strengthened. The Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) was used to replace the traditional Max pooling operation, which effectively reduced the feature loss rate and retained more key semantic information. The cross-entropy loss function was used to optimize the prediction results, making the model more robust in class distribution learning. The experimental results indicate that, in the digital cultural text classification task, as compared to the baseline model, the proposed ASSC-TextRCNN method achieves an 11.85% relative improvement in accuracy and an 11.97% relative increase in the F1 score. Meanwhile, the relative error rate decreases by 53.18%. This achievement not only validates the effectiveness and advanced nature of the proposed approach but also offers a novel technical route and methodological underpinnings for the intelligent analysis and dissemination of digital cultural texts. It holds great significance for promoting the in-depth exploration and value realization of digital culture.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of information technology and the accelerating pace of digital transformation, the digitization of cultural resources has emerged as a global trend [1]. As vital carriers of cultural information, digital cultural texts are widely distributed across news media, social networks, digital archives, online publications, and various cultural dissemination platforms, exhibiting exponential growth in volume [2]. This trend not only drives profound transformations in the production and dissemination of culture but also opens up new avenues for cultural preservation and value creation. However, how to efficiently and accurately classify and analyze massive volumes of digital cultural texts—and quickly retrieve the desired information—has become a key research focus [3]. The explosive increase and disordered distribution of textual data, including vast amounts of short cultural texts such as microblogs, news headlines, and product reviews, have significantly impacted the efficiency and effectiveness of information retrieval, thereby attracting growing attention to digital cultural text classification [4].

As a foundational task in text mining, the performance of text classification directly influences the quality and efficiency of downstream applications. In the context of digital culture, text classification faces unique challenges distinct from those in traditional domains [5]. Digital cultural texts often exhibit high sparsity and real-time generation, with imbalanced information distribution and dispersed semantic features [6]. Short texts dominate in digital media environments, and due to their brevity, they often suffer from incomplete semantic expression and insufficient information content. Moreover, the networked nature of expression introduces linguistic informality and diversity, further complicating feature extraction and semantic modeling [7].

Against this backdrop, recent methods—ranging from classical bag-of-words pipelines to transformer-based classifiers—still struggle with several practical and methodological constraints in digital-culture scenarios: short texts amplify sparsity and out-of-vocabulary issues; rapidly evolving vernacular and topic drift degrade model calibration; class imbalance and noisy labels hinder stable optimization; and common architectural choices such as max-pooling or shallow context windows often discard subtle but decisive cues. Moreover, many state-of-the-art transformers exact substantial computational cost yet provide limited gains on brevity-dominated corpora where contextualization, feature preservation, and salient-token selection must be jointly optimized. To address these limitations, we propose ASSC-TextRCNN, which augments the TextRCNN backbone with ALBERT for parameter-efficient deep semantic embeddings, enhancing generalization under data sparsity; a dual self-attention mechanism that adaptively reweights contextual signals to surface lexically sparse but semantically pivotal tokens; and Singular Value Decomposition in lieu of max-pooling to retain low-rank but information-bearing structures and mitigate feature loss, while optimizing with standard cross-entropy for stable class-distribution learning. Empirically, ASSC-TextRCNN delivers substantial gains on digital cultural text classification, achieving an 11.85% relative improvement in accuracy and an 11.97% relative increase in F1 with a 53.18% reduction in error rate over strong baselines, and exhibits a more compact, well-separated confusion structure—underscoring that the proposed integration of pre-trained representations, attention, and SVD-based feature preservation provides an effective and efficient solution for short-text classification in modern digital media environments.

As one of the foundational tasks in natural language processing, text classification has long been a central research focus in both academia and industry. Its core objective is to leverage algorithms and models to automatically assign large volumes of unstructured text to predefined categories, thereby enabling efficient information organization and precise retrieval [8]. With the explosive growth of text under the digital-culture paradigm and the escalating breadth of application demands, text classification has assumed an increasingly prominent role in domains such as information filtering, opinion mining, intelligent recommendation, digital archive management, and cultural resource discovery [9]. Continuous advances and innovation in text classification methods thus carry not only methodological significance, but also practical import for upgrading the cultural industry and advancing data-driven social governance.

Common approaches to text classification can be broadly grouped into three categories: rule-based systems, machine-learning-based systems, and deep-learning-based systems [10]. Rule-based systems are essentially akin to decision trees; while they can achieve high accuracy, they typically rely on small test sets and generalize poorly [11]. Compared with rule-based methods, machine-learning-based systems offer stronger generalization, but they require manual feature engineering, and their performance can be biased by the composition of the training data [12]. With the advent of the AI era, deep learning has been widely applied across computer vision, automatic speech recognition (ASR), and natural language processing (NLP) [13]. Deep learning obviates manual feature design and can exploit much larger training sets, albeit at the cost of reduced model interpretability [14]. Given that our task targets fine-grained classification of news texts, interpretability is not a stringent requirement. Although Chinese is among the most widely used languages globally, research on Chinese text classification remains relatively scarce [15]. This is due in part to the greater linguistic complexity of Chinese compared with English and, in part, to the limited availability of large-scale Chinese corpora—both of which constrain progress in Chinese text classification.

2.1 Traditional Text Classification Methods

Early research primarily relied on statistical approaches and hybrids of rule-based and traditional machine learning methods. Naithani proposed an analytical framework that combines natural language processing (NLP) with a support vector machine (SVM) classifier to extract events from messages [16]. However, the model’s performance was limited by substantial noise in the data. Sarker and Gonzalez trained on a combined corpus drawn from three different sources, extracting a rich set of features to train an SVM [17], experiments showed that leveraging features compatible across multiple corpora can significantly improve classification performance. In the PSB social media mining shared task, Chen et al. enhanced model expressiveness and robustness by incorporating multimodal information such as text, images, and knowledge bases [18]. Alizadeh et al. trained SVM and logistic regression classifiers using a rich feature space—including lexicon-based, sentiment, semantic features, and word embeddings—and reported higher accuracy than convolutional neural networks, with sentiment and embedding features contributing most [19]. Bashiri et al. trained an SVM with extensive textual, sentiment, and domain-specific features, demonstrating that the most influential features were general-domain word embeddings, domain-specific embeddings, and domain terminology [20]. To address issues such as feature sparsity and weak semantic signals, Zheng et al. have used topic vectors from the LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) topic–word distribution matrix to reduce dimensionality for short-text classification, while others fused lexical category features with semantics [21]. Although these approaches outperform traditional baselines, they rely on the LDA topic model—an unsupervised method that is relatively slow and sensitive to the choice of the number of topics, thus requiring continual tuning. Another line of work extracts document keywords as text features and achieves competitive results [22]; yet the keyword set grows with the number of documents, inflating the dimensionality of the vector-space matrix and increasing computation. Despite steady gains, these lines of work share constraints that are acute in digital-culture corpora: they depend heavily on hand-crafted or corpus-specific features that are brittle under vernacular drift and platform noise; SVM/logistic pipelines struggle to capture long-range context and compositional semantics, while LDA-based representations are slow, topic-number-sensitive, and require continual retuning; keyword and feature inventories expand with data scale, inflating dimensionality and computation yet still discarding subtle cues via coarse pooling or sparse vectors; and multimodal add-ons often improve coverage but at the cost of complex feature fusion and limited generalization.

2.2 Machine Learning and Neural Network Classification Methods

In recent years, a wide range of machine learning methods has been applied to text classification. Machine learning, a subfield of artificial intelligence, aims to enable computer systems to process data through automatic learning and performance improvement without explicit programming instructions [23]. Nevertheless, text exhibits weaker regularity, greater arbitrariness, and high complexity, leading to diverse forms and structures; compared with vision, deep learning in the text domain remains relatively less mature [24]. With large-scale data and modern GPU clusters, however, theoretical and computational advances have greatly strengthened the foundation for applying deep learning to text [25].

Within neural architectures, TextCNN, TextRNN, and TextRCNN are widely used models in NLP, each built on distinct neural backbones—convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), or their combinations—to suit different task requirements [26]. Soni et al. proposed a CNN-based text classifier that uses pre-trained word embeddings as input and applies one-dimensional convolutions to capture word-order information, thereby enriching sentence-level representations [27]. However, CNNs are relatively weak at modeling long-range dependencies, and pooling may discard positional information, risking information loss. Akpatsa et al. first explored joint learning with a hybrid CNN–LSTM architecture for text classification [28], subsequent work by Zhang et al. also fused CNNs and RNNs for short-text classification, leveraging CNNs for local feature extraction and RNNs for long-distance dependencies [29]. To address limitations of pure CNNs and RNNs, Long et al. introduced TextRCNN, which uses a recurrent structure to capture bidirectional context and a max-pooling layer to distill salient features—effectively combining the strengths of RNNs and CNNs while mitigating their respective weaknesses [30]. Despite their progress, these CNN/RNN hybrids still face gaps salient in short, noisy digital-cultural texts: CNNs under-capture long-range semantics; RNNs incur gradient and efficiency costs; and TextRCNN’s max-pooling can discard position- and context-sensitive cues. Many variants also depend on static or task-specific features and grow parameters when stacking or ensembling, which hampers robustness under slang, topic drift, and sparsity.

2.3 Improvement Directions for Text Classification

The introduction of attention mechanisms enables neural networks to focus selectively on salient features, yielding more faithful language modeling. Consequently, attention has been widely adopted across neural architectures. After its first use in NLP by Bhadauria et al. for machine translation, increasing numbers of studies incorporated attention to strengthen feature extraction in diverse models [31]. Sahu et al. proposed a sentence-modeling approach that combines a three-level attention mechanism with CNNs for text classification, achieving strong results [32]. Sherin et al. added bidirectional attention to GRUs for sentiment analysis, enhancing GRU-based classification [33]. Kamyab et al. introduced a bidirectional CNN–RNN architecture fused with attention, where joint learning across deep models improved accuracy [34]. Beyond network hybrids and attention, other improvements have also been explored. Mars et al. introduced BERT, a bidirectional Transformer-based language model trained on large corpora that produces context-dependent word representations [35]. Du et al. integrated logical rules into deep neural networks to mitigate opacity and leverage prior knowledge [36]. Liu et al. proposed ACNN (Attention Convolutional Neural Network), which first uses CNNs for feature extraction and then feeds the features into a self-attention encoder and a context encoder [37]; their outputs are merged and passed to a fully connected layer and a softmax classifier. Chen et al. adapted neural machine translation–style models to text classification by replacing recurrent units in a Seq2Seq framework with Transformer blocks and introducing multi-head attention, thereby better handling long sequences and capturing semantic relations [38]. Wang et al. proposed a model termed B_f that builds on FastText and employs bagging for ensembling [39]. While attention and Transformer-based advances have markedly improved text modeling, many methods remain over-parameterized, compute-intensive, and sensitive to domain drift and short-text sparsity; attention layers can overfit to noisy cues, hierarchical schemes add fusion complexity, and common pooling steps still lose fine-grained, position-aware signals. Moreover, gains from large pretrained encoders can taper off on brevity-dominated, slang-heavy corpora without tailored mechanisms for salient-token selection and feature preservation.

In the broader landscape of text feature augmentation, recent work has moved beyond raw TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) toward schemes that explicitly enrich or restructure document representations to better align with category semantics. Attieh et al. introduce a category-driven feature engineering (CFE) framework—grounded in a TF-ICF variant—that learns term–category weight matrices and augments documents with synthetic, category-informative features, yielding higher accuracy on five benchmarks with markedly lower compute than deep models [40]. Complementing these supervised augmentations, Rathi et al. survey the mathematical underpinnings and taxonomy of term-weighting, contrasting supervised and statistical families and highlighting how Vector Space Model variants serve as the scaffolding on which many augmentation strategies are built [41]. At the level of weighting functions themselves, Li et al. propose TF-ERF, replacing the logarithmic global component of TF-RF with an exponential relevance frequency to better balance local/global contributions, improving robustness and classification quality on standard corpora [42]. Together, these efforts illustrate a continuum of augmentation—from principled reweighting to category-aware projection and feature synthesis—that improves downstream classifiers while controlling model complexity and training cost.

NLP plays a pivotal role in textual information retrieval. However, most existing classifiers are designed for balanced datasets, making model performance highly sensitive to the size and quality of training data. For Chinese, the relative scarcity and imbalance of corpora substantially degrade precision on positive classes, falling short of practical requirements [43]. Data augmentation is therefore widely used to alleviate these issues by transforming existing samples into novel ones—commonly via synonym replacement or back-translation. Wei et al. introduced EDA (Easy Data Augmentation), which applies four simple edits—random deletion, replacement, swapping, and insertion—to improve text-classification performance and reduce overfitting [44], owing to its randomness, however, EDA can discard information, ignore context, and alter original meanings [45]. With advances in neural machine translation, back-translation has become a popular augmentation technique: text is translated from the source language to an intermediate language and then back to the source to create augmented samples [46]. Xie et al. proposed Unsupervised Data Augmentation (UDA), which augments manually labeled data with distantly supervised signals to construct a larger, more diverse training set and thereby improve generalization and performance across relation-extraction tasks [47]. Zheng et al. further introduced an unsupervised augmentation method that imposes a consistency loss so the model produces stable predictions across differently augmented views [48], experiments on multiple semi-supervised tasks demonstrated significant gains and broad applicability across domains and datasets. Liang et al. proposed a multi-channel neural text classification model that fuses ALBERT embeddings with CNN (local features), GCN and BiLSTM (global spatial–temporal features), then applies softmax, achieving superior accuracy and recall to single-channel and other hybrid baselines on THUCNews [49]. Gao et al. introduced ALBERT-TextCNN-Attention (PATA), which dynamically fuses intermediate ALBERT layers via two channels, adds TextCNN for local sentiment cues and an attention mechanism for richer features, yielding a compact model (≈19.72% of BERT’s parameters) that attains 90.63% accuracy on waimai-10k and outperforms recent ALBERT-based methods [50].

3.1.1 ALBERT Pretrained Language Model

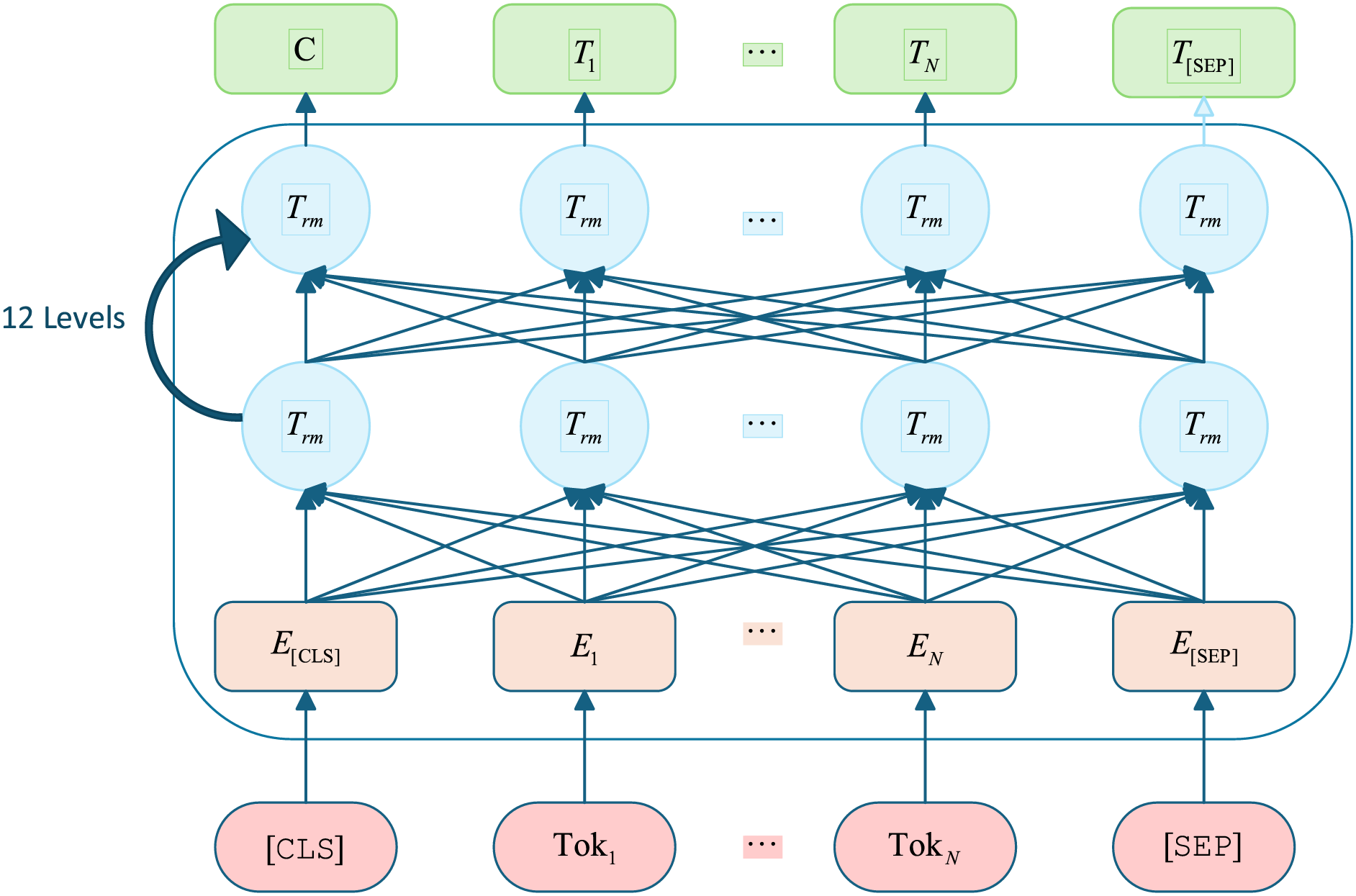

We adopt the Chinese ALBERT pretrained language model, which encodes text features using a bidirectional Transformer encoder in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: ALBERT model architecture

ALBERT addresses BERT’s parameter and training-time overhead through architectural and objective modifications: factorized embedding parameterization decouples the word-embedding dimension

As a BERT variant, ALBERT inherits BERT’s strengths while mitigating its drawbacks. In vanilla BERT,

3.1.2 Dual Attention Mechanism

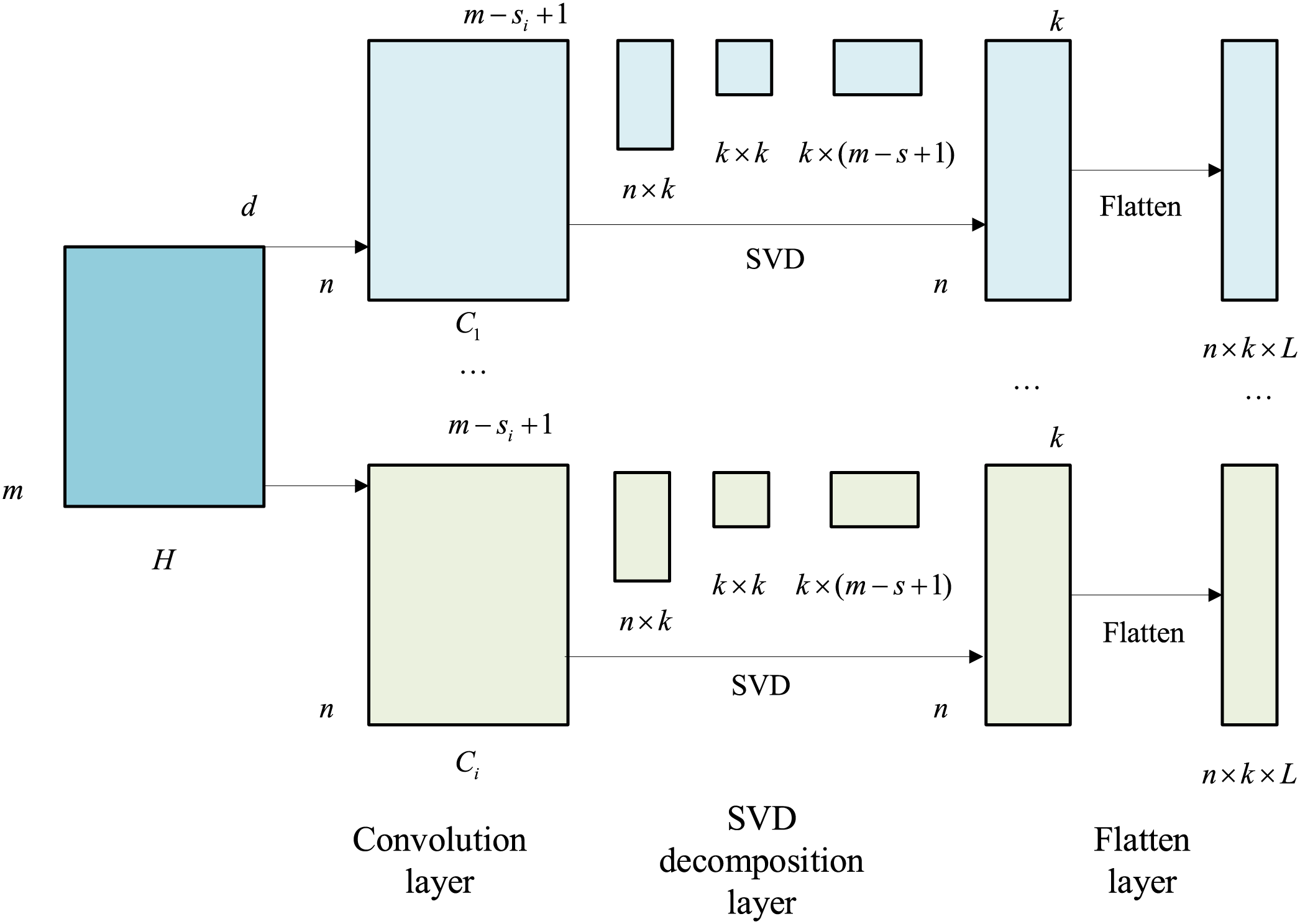

Attention was first introduced in vision and later adapted to text to extract word-level salient information, mimicking human selective focus while reading [52]. Readers naturally concentrate on informative spans to grasp a topic quickly. Formally, the attention module can be viewed as a single-layer neural network with a softmax output: its input is the preprocessed short-text word embeddings, and its output estimates each token’s contribution to every class label.

Let an input sequence be

where

where

with

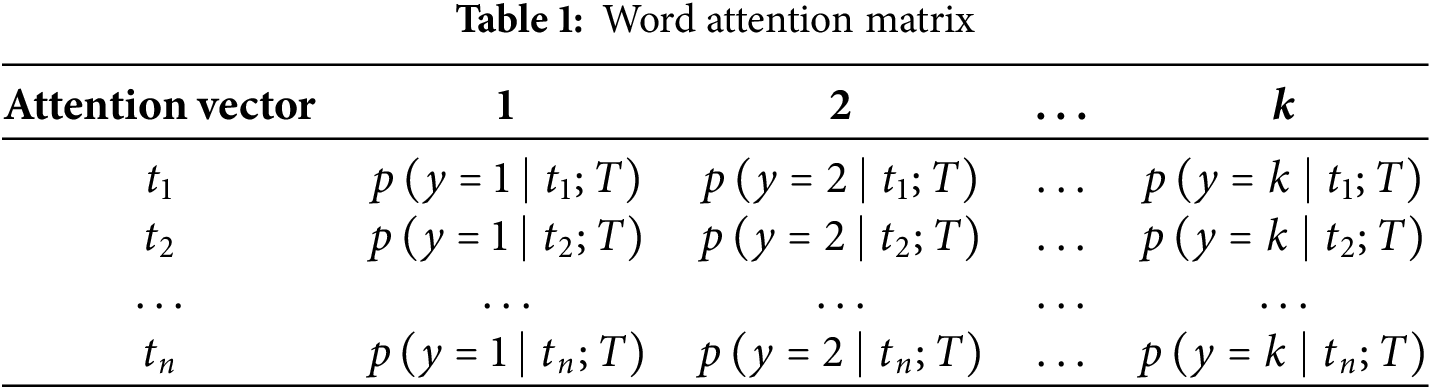

To mitigate the loss of semantic and positional information caused by max pooling in TextRCNN, we replace the conventional pooling layer with singular value decomposition (SVD). This modification performs dimensionality reduction via low-rank matrix approximation, retaining principal components while preserving global semantic relations. Unlike max pooling—which keeps only local extrema—SVD captures the global structure of the feature matrix through spectral factorization, suppressing redundancy and reducing information loss [53]. As a result, the model attains stronger representations of deep semantic cues in text.

Singular value decomposition is a matrix factorization technique that expresses a matrix as the product of three matrices. For a nonzero real matrix

A standard procedure isEigen-decompose

Eigen-decompose

yielding orthonormal eigenvectors

and the singular values are

With

Low-rank approximation. The singular-value spectrum typically decays rapidly; in practice, the top

Thus, for

Figure 2: Singular value decomposition algorithm for dimensionality reduction

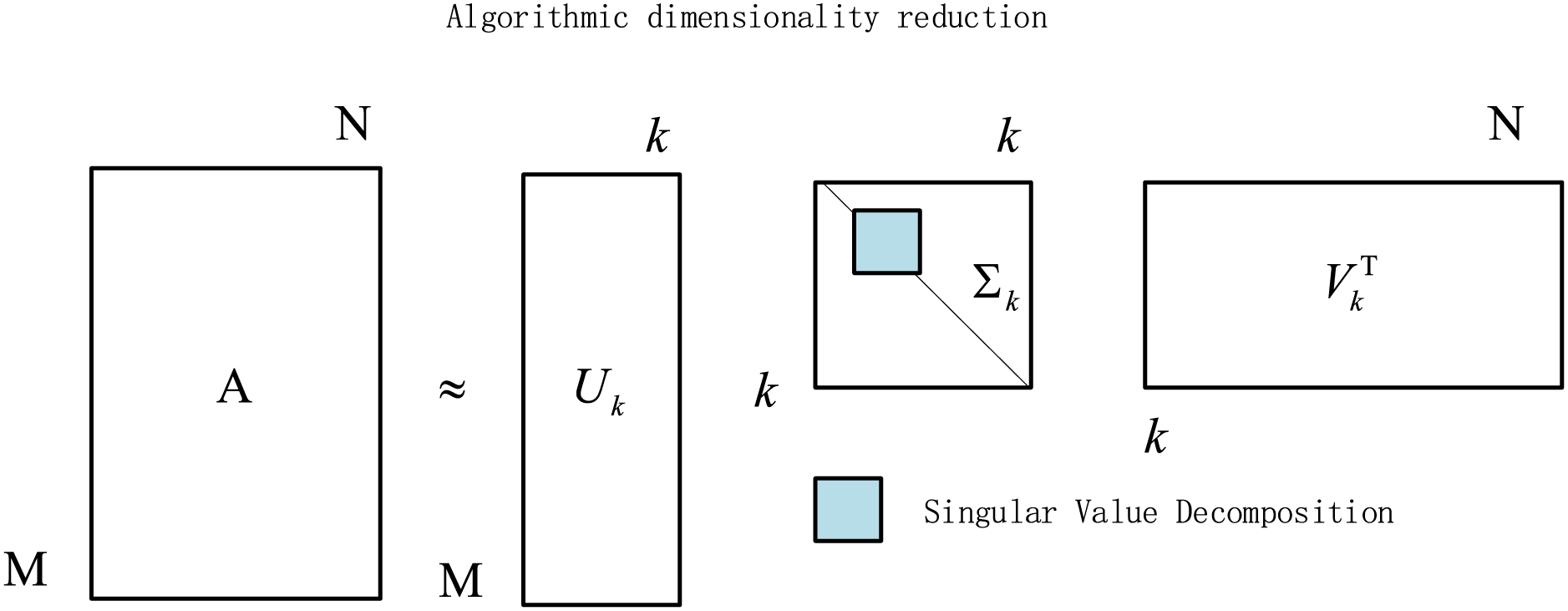

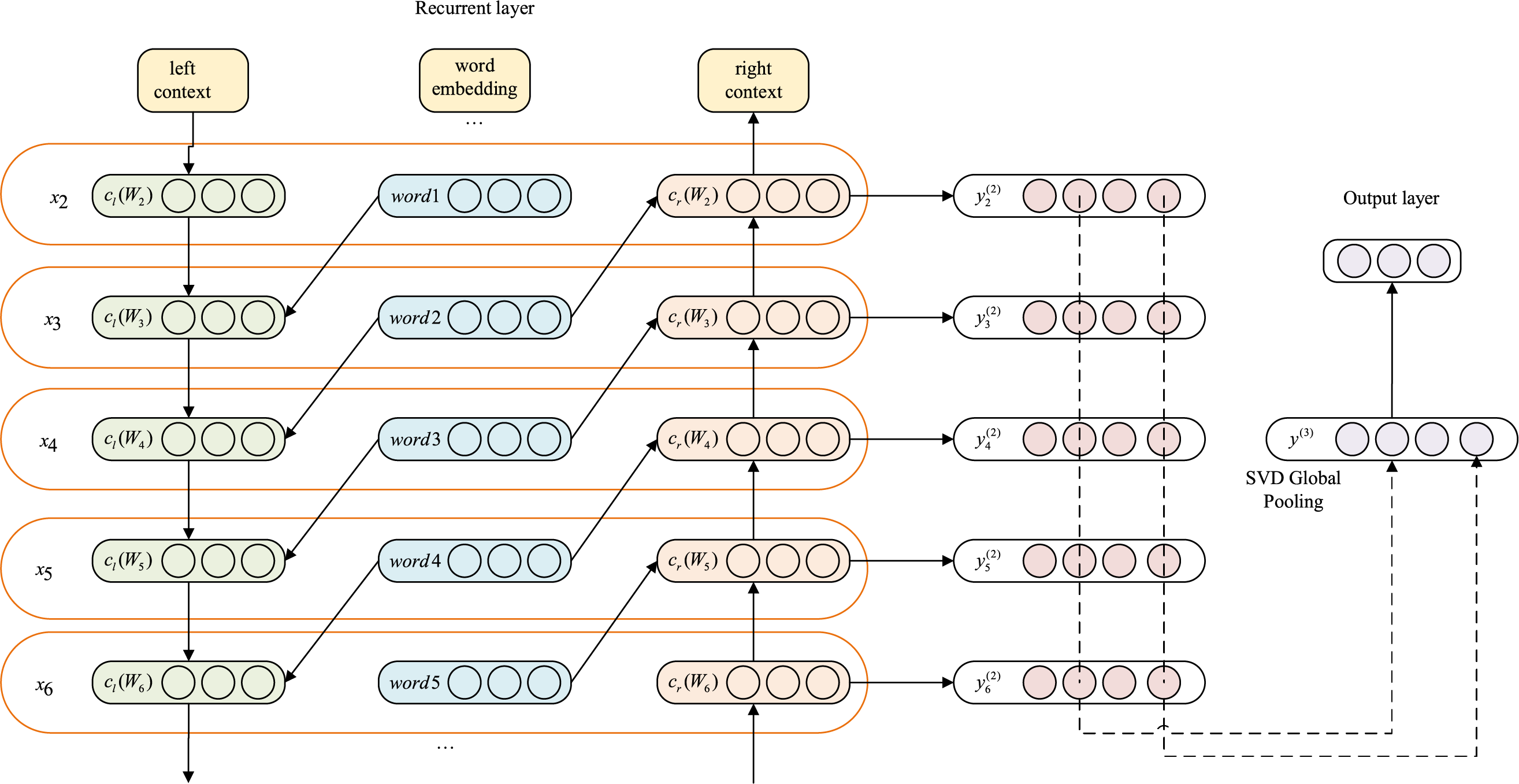

Figure 3: TextRCNN-SVD network structure diagram

3.1.4 Cross-Entropy Loss Function

In this study, we adopt the cross-entropy loss function (CrossEntropyLoss) as the objective function for model training [54]. PyTorch provides a convenient implementation, nn.CrossEntropyLoss(), to compute this loss. Cross-entropy is a widely used loss function, particularly suited for classification tasks. It measures the discrepancy between two probability distributions and is extensively applied in deep learning for model optimization.

The principle of cross-entropy is grounded in two fundamental concepts from information theory: information content and entropy. Information content quantifies the uncertainty associated with an event, representing how much information is gained when the event occurs. This is commonly defined using a logarithmic function. We train with the standard cross-entropy loss—implemented via PyTorch’s nn.CrossEntropyLoss (which combines LogSoftmax and NLLLoss)—to align the predicted class distribution with the ground-truth labels.

To overcome the limitations of both RNNs and CNNs, the TextRCNN architecture was proposed. It leverages a bidirectional recurrent structure to capture both preceding and succeeding context, enabling the model to preserve word order over a broader range compared to CNNs. Additionally, it applies a max-pooling layer to extract the most important semantic features and automatically determine which parts of the text are most relevant for classification [55]. The architecture of the TextRCNN classification model is shown in Fig. 4. The model consists of three components: (1) a recurrent structure, (2) a max-pooling layer, and (3) an output layer. First, each input word is mapped to its corresponding word embedding through the input layer, resulting in a word embedding matrix for the sentence. The size of each sentence matrix is

Figure 4: TextRCNN model architecture

The word embeddings are then fed into a bidirectional recurrent network to obtain both forward and backward contextual representations for each word:

here,

By concatenating the contextual vectors with the original word embedding, the complete representation of word

Next, a non-linear transformation is applied to compute the hidden semantic representation of each word:

To identify the most salient semantic information across the entire sentence, a max-pooling operation is applied:

Finally,

3.2.1 Improvement of the ALBERT Pre-Trained Model

In this work we use albert_tiny_zh, pretrained on a large-scale Chinese corpus of roughly two billion samples [56]. Compared with BERT base, it retains comparable accuracy while using only about

Given a preprocessed input sequence

ALBERT produces contextualized embeddings

where

Using the base version of the ALBERT model as an example, this study proposes an adaptive method to generate a semantic representation vector that best captures the meaning of each input text. Specifically, instead of relying solely on the [CLS] vector from the final Transformer layer-as done in the original ALBERT architecture-we extract the [CLS] vectors from all 12 Transformer encoder layers. We then compute dynamic weights to quantify the contribution of each layer’s [CLS] vector to the final representation. These weights are applied via an attention mechanism, producing a fused [CLS] vector that integrates semantic information from all Transformer layers. This enhancement significantly improves the expressiveness and accuracy of the resulting text representation. Since each Transformer layer in ALBERT’s pre-trained model consists only of an encoder block, we denote the [CLS] output from the

To enable the model to dynamically assign weights to each of these vectors based on the input text, we design a recurrent module based on fully connected layers. For each classification vector in the encoder_CLS group, a corresponding output is produced via a linear transformation, capturing the information strength that layer contributes to the current classification task. After all layers are processed, their outputs are concatenated and passed through a softmax normalization to produce a probability distribution over the 12 layers, representing the learned importance (dynamic weight) of each layer’s [CLS] vector. This adaptive fusion mechanism allows the model to focus on the most informative layers per input instance, yielding a richer and more context-sensitive representation than static, single-layer approaches.

3.2.2 Improvement of the Aggregation Mechanism of the Dual Attention Mechanism

We adopt a dual attention design, injecting attention at both the input layer and the bidirectional recurrent layer: Before final classification, we estimate each token’s contribution to each class to enable token filtering. The goal is to allocate higher attention to semantically meaningful parts of speech-primarily nouns and verbs-while assigning little or no attention to function words such as prepositions, particles, or colloquialisms. This increases the weight of tokens that carry precise semantics in the downstream classifier.

We introduce a class-conditional hierarchical aggregation mechanism following the acquisition of contextual representations

To enhance robustness, we apply temperature normalization and thresholding (or Top-

3.2.3 SVD Enhanced Pooling Improvement

In the TextRCNN module, the contextual token encodings from ALBERT

We then apply SVD to

Using

For

For a feature matrix

3.2.4 Improvement of the cross Entropy Loss Function

From the definitions of entropy, KL divergence, and cross-entropy, the following relationships can be derived:

Substituting into the definition of KL divergence yields:

here,

Given the prevalence of long-tail categories in news corpora, we assign a class weight

4.1 Experimental Data and Environment

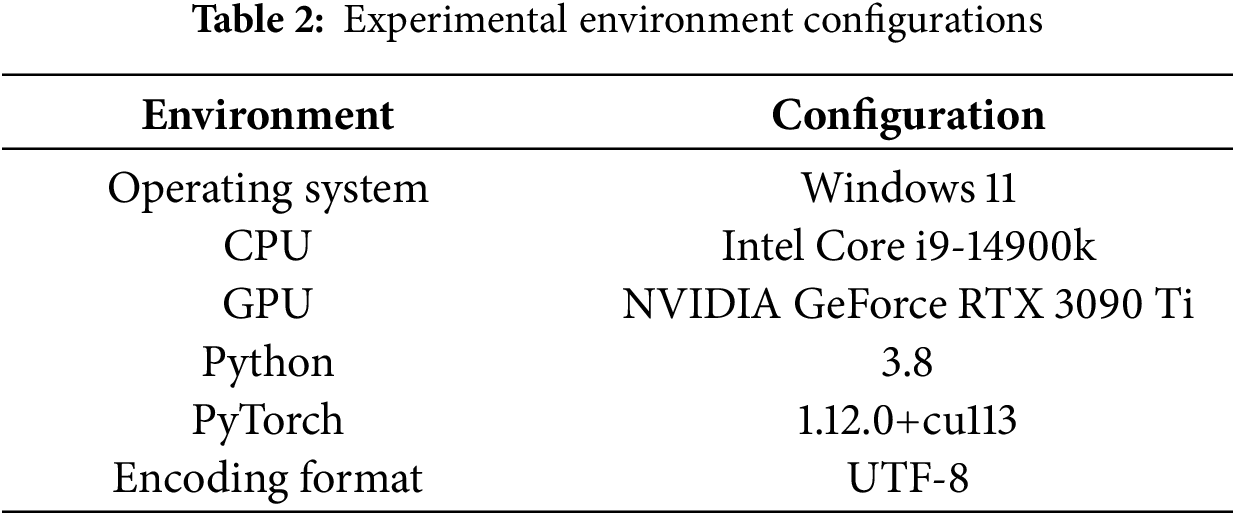

The experimental dataset is a text classification dataset selected from THUCNews (URL: https://github.com/jinmuxige0816/THUCNews/tree/main, accessed on 01 December 2025). It contains a total of 200,000 news headlines, each with a text length between 10 and 30 characters. The dataset covers ten categories: finance, real estate, stock, education, technology, society, current affairs, sports, games, and entertainment. Each category consists of 20,000 text samples, labeled with digits 0–9. In the experiments, 180,000 samples were randomly selected as the training set, 10,000 as the test set, and another 10,000 as the validation set. The experimental environment configurations are shown in Table 2.

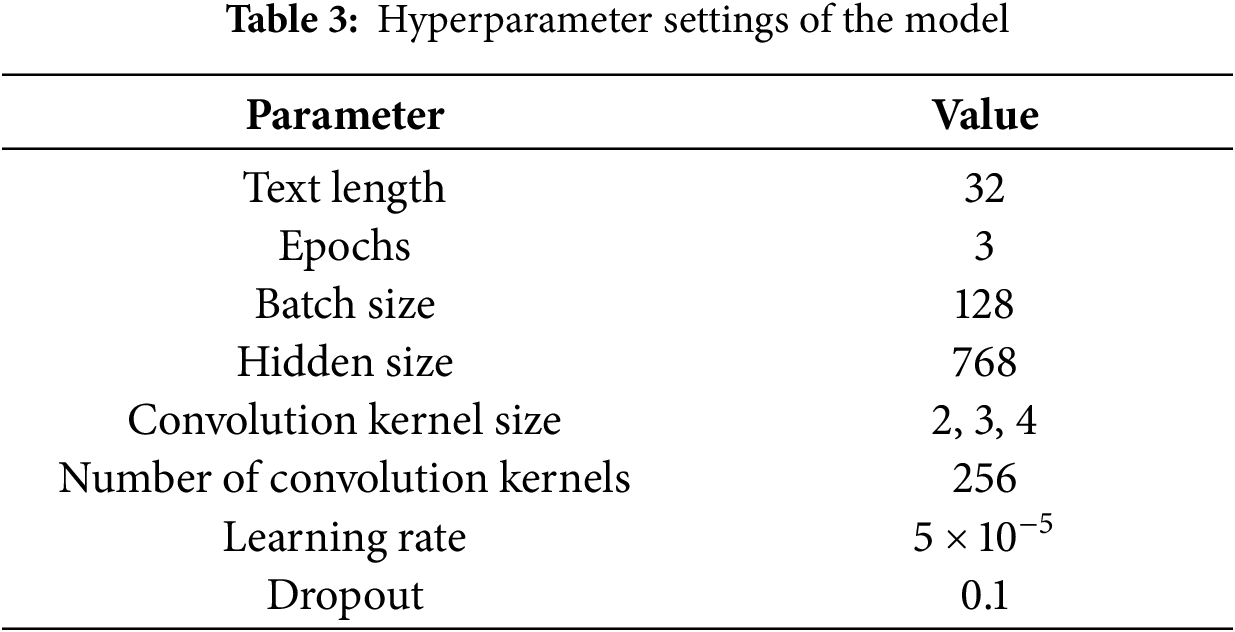

4.2 Hyperparameter Comparison Experiments

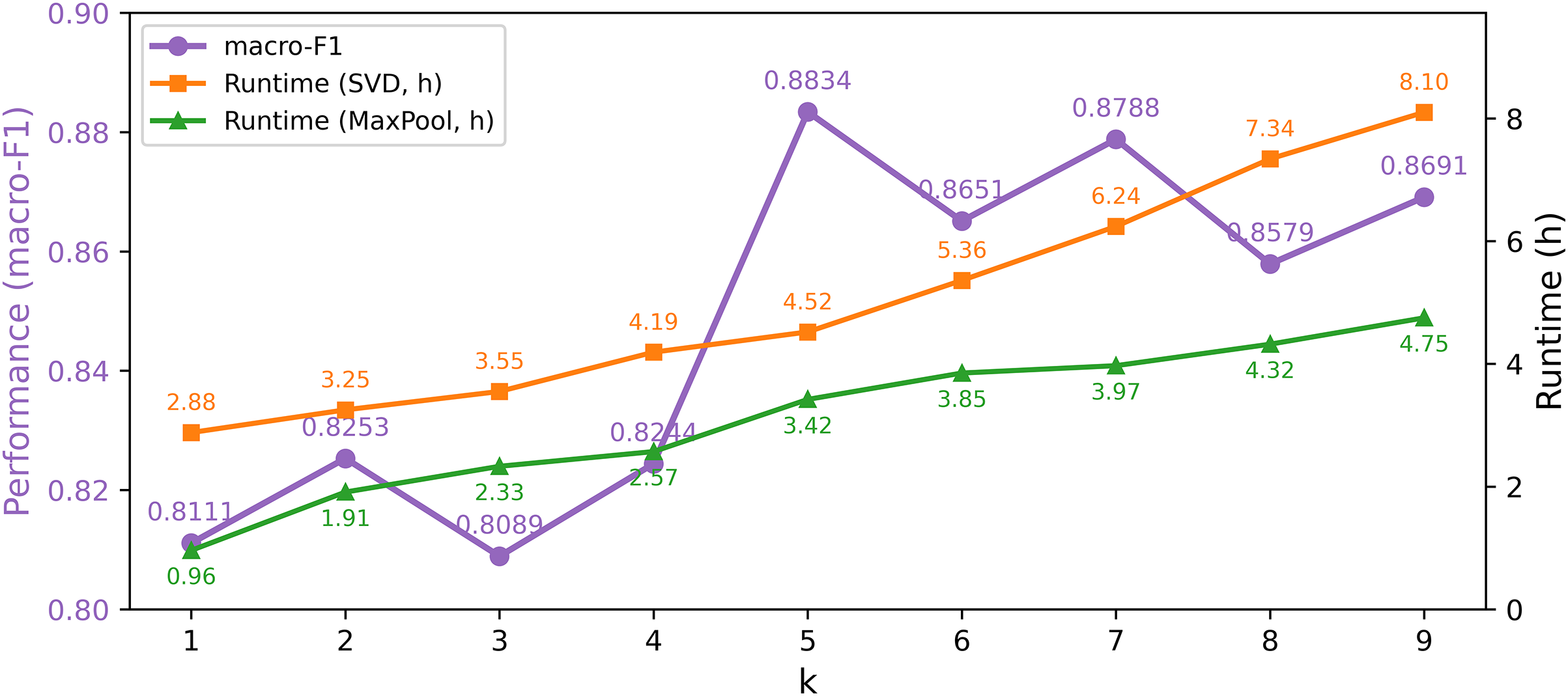

In this section, a series of comparative experiments are conducted on three hyperparameters—namely the value of k in the SVD algorithm, the convolution kernel size, and the number of convolution kernels—in order to examine their impact on the classification performance of the proposed model and to determine their optimal settings.

For the SVD algorithm, dimensionality reduction is achieved by retaining the top

Figure 5: Model performance and time under different k values in the SVD algorithm

The feature dimension retention parameter

Model parameters are internal configuration variables, and different parameter settings can significantly affect model performance. Compared with traditional machine learning, deep learning involves larger-scale data and requires a broader range of parameter choices. The hyperparameter settings used in this study are summarized in Table 3.

To ensure efficiency, we first conducted a small-scale hyperparameter search on a fixed validation set and determined the final configuration based on a trade-off between macro-averaged F1 (macro-F1) and training time. Specifically, the learning rate was fine-tuned over

4.3 Effect Experiment of Algorithm Module

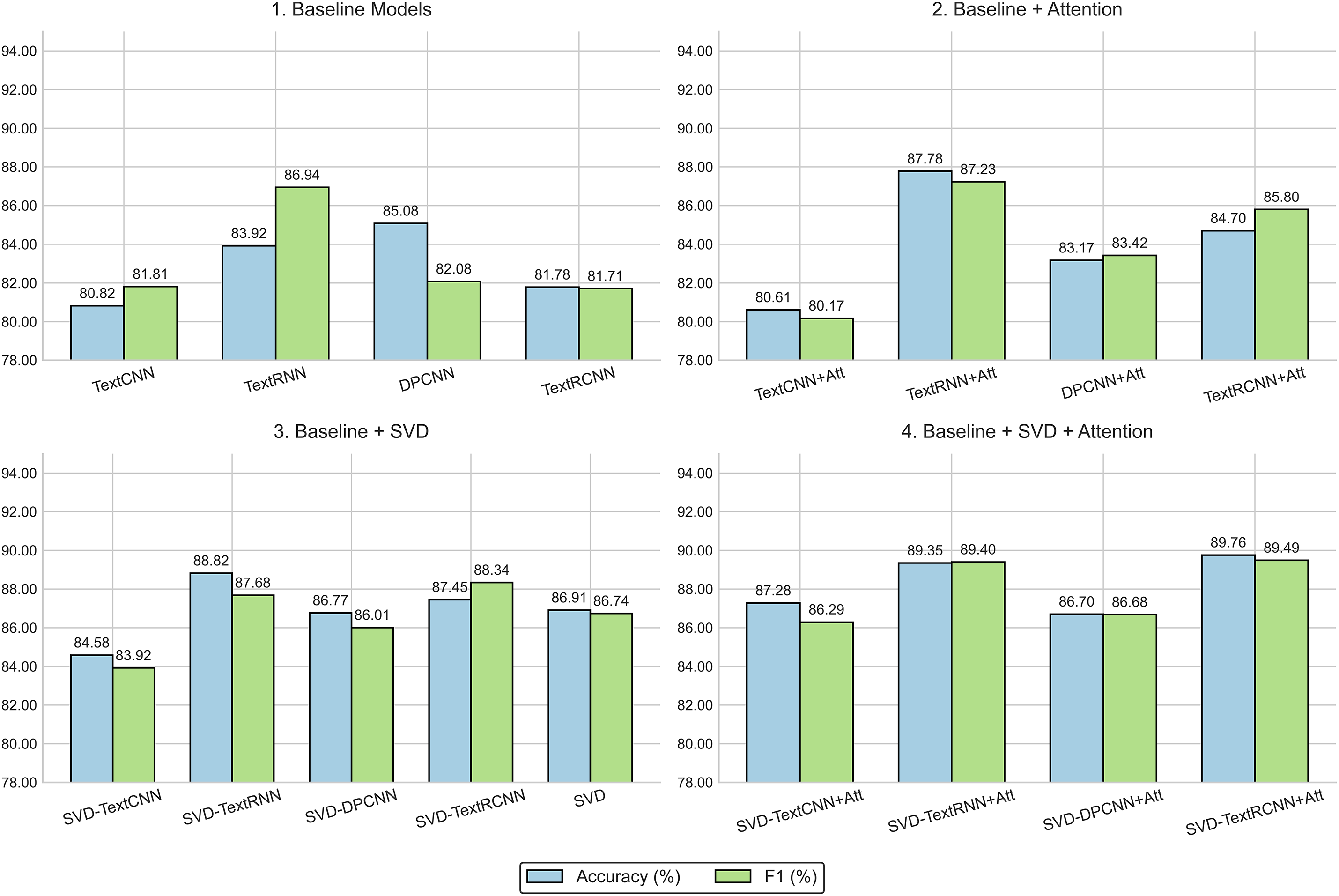

To further illustrate the impact of different architectural enhancements, Fig. 6 compares the performance of baseline models with their variants augmented by attention mechanisms, singular value decomposition (SVD), and the combination of both. The y-axis represents the performance metrics of the evaluated text classification models. Specifically, it shows the Accuracy (%) and F1-score (%), both expressed as percentages.

Figure 6: Evaluation results of classical text classification models. All models share identical data splits, hyperparameter configurations, and early-stopping criteria to ensure fair comparison. The reported metrics—classification accuracy and macro-averaged F1—are averaged over five random seeds, with standard deviations below 0.5% omitted for clarity. (1) Baseline Models: trained without attention or singular value decomposition (SVD) modules. (2) Baseline + Attention: models augmented with token-level attention to highlight salient contextual information. (3) Baseline + SVD: models enhanced with truncated SVD pooling for global structural representation. (4) Baseline + SVD + Attention: combined attention–SVD variants integrating both local focus and global semantic compression

When evaluating the constructed dataset with classical text classification models, we select four deep learning approaches without BERT or attention—TextCNN, TextRNN, DPCNN, and TextRCNN—and compare performance using accuracy and F1 score. The accuracies of the four models on this dataset are 80.82%, 83.92%, 85.08%, and 81.78%, respectively. Overall, DPCNN performs best in terms of accuracy, reaching 85.08%; its stacked deep convolutional blocks effectively enhance contextual modeling, conferring advantages in capturing long-range dependencies and extracting deep semantic features. In contrast, TextRNN achieves the highest F1 score (86.94%), indicating a better balance of precision and recall for this task. Owing to its recurrent architecture, TextRNN models sequential dependencies particularly well, leading to superior class balance in predictions. Despite the computational efficiency and simplicity of TextCNN’s local convolutional feature extraction, its accuracy (80.82%) and F1 score (81.81%) are lower than those of the other models, reflecting limitations in modeling long texts on this dataset. TextRCNN attains intermediate-to-lower performance, with an accuracy of 81.78% and an F1 score of 81.71%. Although its hybrid convolution–recurrent design captures both local and global features, it does not deliver a marked advantage at larger experimental scales.

After introducing a dual attention mechanism on this dataset, TextRNN_Att stands out, with accuracy rising to 87.78% and F1 to 87.23%, improvements of 3.86 and 0.29 percentage points over the baseline, respectively. TextRCNN_Att also improves noticeably, with accuracy increasing from 81.78% to 84.70% and F1 from 81.71% to 85.80% (gains of 2.92 and 4.09 percentage points), yet its absolute performance still lags behind TextRNN_Att by 3.08 points in accuracy and 1.43 points in F1. For DPCNN, the dual attention mechanism yields a mixed effect—accuracy decreases from 85.08% to 83.17% (−1.91 points) while F1 increases from 82.08% to 83.42% (+1.34 points)—suggesting that dual attention helps balance precision and recall but its global reweighting may partially interfere with DPCNN’s stable extraction of hierarchical n-gram structures. TextCNN_Att attains an accuracy of 80.61% and an F1 of 80.17%, both slightly below the baseline (−0.21 and −1.64 points), indicating that in shallow architectures dominated by local convolutions, dual attention provides limited benefit and may introduce minor performance fluctuations due to increased variance in weight distributions.

Building on the original models, further integrating singular value decomposition (SVD) for feature processing yields substantial gains across all four model types. SVD_TextRCNN exhibits the largest improvement, with accuracy rising from 81.78% to 87.45% (+5.67 points) and achieving the best F1 overall. The dual attention mechanism, through two levels of weighting at the token and sentence levels, both highlights salient information and suppresses irrelevant features, while globally refining the semantic distribution of sentence representations—thereby granting RNN/RCNN-type models stronger advantages in recall and F1. SVD, by performing low-rank matrix factorization for dimensionality reduction and denoising, preserves principal semantic directions and removes high-dimensional redundancy, simultaneously reducing model complexity and improving interclass linear separability; this effect is particularly pronounced for high-dimensional long-sequence representations.

Taken together merely introducing the dual attention mechanism improves F1 for some models but does not fundamentally alter TextRCNN’s relative disadvantage; however, augmenting the representation with SVD markedly enhances separability and generalization for all models, with TextRCNN attaining the highest F1 (88.34%). These results indicate that combining a dual attention mechanism with SVD can further unlock performance potential in the subsequent fusion model and better balance precision and recall in text classification tasks.

To further enhance these SVD-processed models, we introduce an attention mechanism; in particular, adding attention to SVD-TextRCNN yields the method proposed in this paper. After introducing a dual attention mechanism into the four classical text classification models already processed by singular value decomposition (SVD), all models achieve varying degrees of improvement. Among them, SVD_TextRCNN_Att performs the best, reaching an accuracy of 89.76% and an F1 score of 89.49%, which substantiates the significant role of dual attention in strengthening long-sequence dependency modeling and optimizing the fusion of global and local features. SVD_TextRNN_Att attains an accuracy of 89.35% and an F1 of 89.40; compared with SVD_TextRNN (88.82% accuracy, 87.68% F1), this reflects gains of 0.53 percentage points in accuracy and 1.72 points in F1. These results indicate that the dual attention mechanism can further enhance semantic weighting in recurrent architectures that already possess strong sequential modeling capabilities, yielding a more balanced trade-off between precision and recall.

At the feature-processing stage, SVD uses low-rank approximation to compress high-dimensional sparse features, remove noise, and preserve the principal semantic directions, thereby making the input features more compact and discriminative and providing a clearer semantic distribution for downstream classification. Within the model, the dual attention mechanism applies two levels of weighting—word-level and sentence-level—which both highlights the tokens most critical for classification and refines the sentence representation at the global contextual level, organically combining salient local information with global semantic structure. The fusion of these components equips the model with efficient, robust feature representations while enabling dynamic reweighting during inference, markedly improving its ability to capture complex semantic patterns.

This fusion strategy is particularly effective for SVD_TextRCNN: leveraging RCNN’s strong contextual capturing capacity, SVD’s feature compression advantages, and dual attention’s global–local weighting, it attains the highest accuracy and F1, validating the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method in text classification by balancing precision and recall and enhancing model generalization.

4.4 Experiments before and after the Improvement

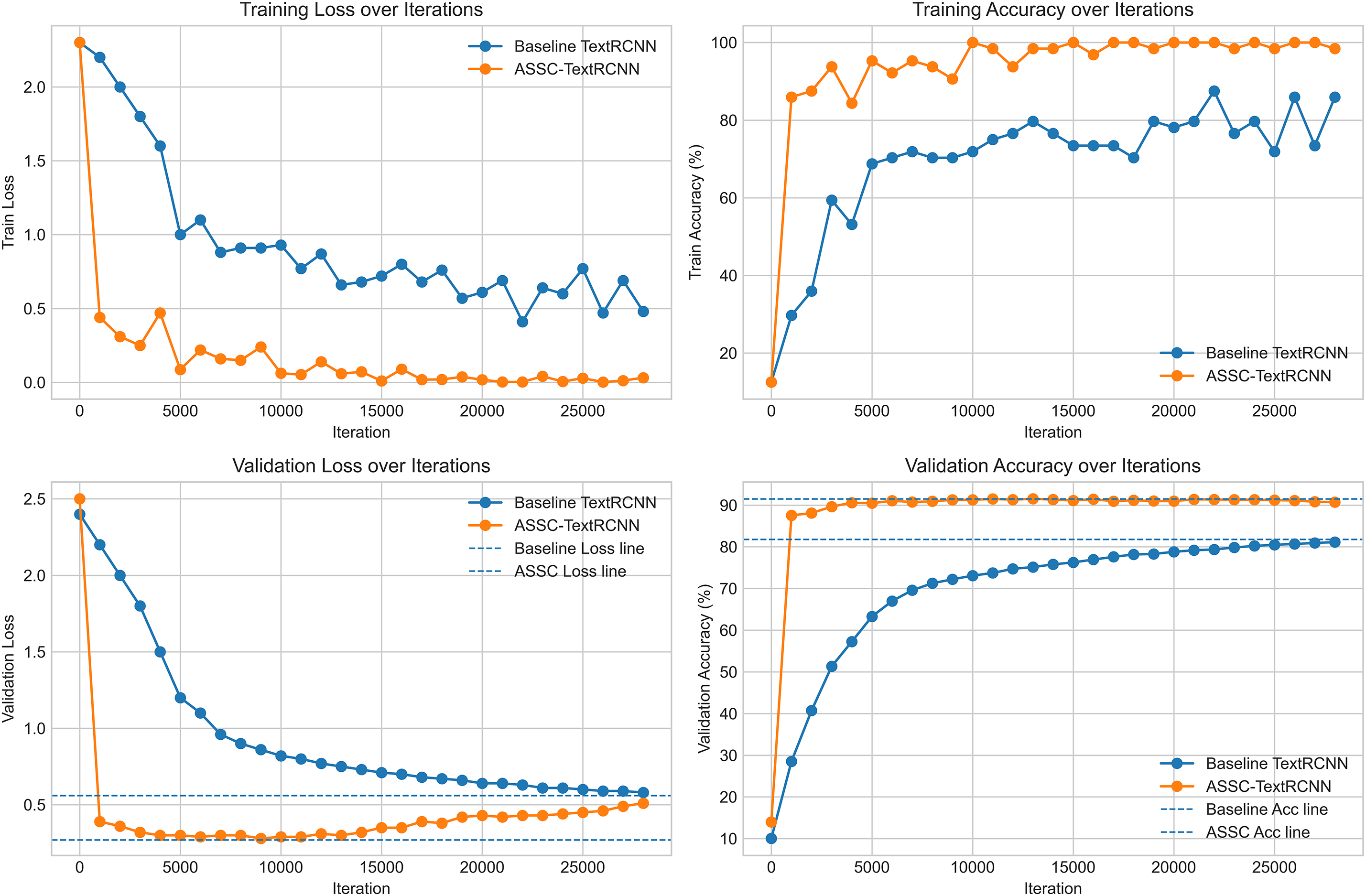

To systematically verify the effectiveness and trainability of the proposed ASSC-TextRCNN for text classification, we conduct controlled experiments using the classical TextRCNN as the baseline. The two models are trained under identical data splits and preprocessing pipelines, and they share the same optimizer, learning-rate schedule, batch size, maximum number of iterations, and regularization strategy. Except for introducing the ASSC module, all other network components and training hyperparameters remain unchanged to ensure fairness. We evaluate classification accuracy (Accuracy) and cross-entropy loss (Loss) on both the training and validation sets, recording them in sync and visualizing them against training steps, so as to examine optimization convergence, generalization behavior, and potential overfitting [57]. We compile statistics for all indicators throughout training before and after the improvement; the comparative trajectories are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Change of iteration index before and after improvement

Under the same data and training configuration, the improved ASSC-TextRCNN exhibits clear advantages over the baseline TextRCNN in convergence speed, final performance, and training stability. From the training/validation loss and accuracy curves, ASSC-TextRCNN achieves a rapid loss drop and steep accuracy rise in the early iterations (~1–3k), with training accuracy quickly surpassing 90% and entering a plateau, whereas the baseline requires more iterations to approach a lower plateau—evidence of better optimization attainability and sample efficiency. In terms of final performance, the validation accuracy of ASSC-TextRCNN stabilizes around ~90%, an absolute gain of about 10 percentage points over the ~80% baseline; meanwhile, its validation loss remains around ~0.32–0.35, markedly lower than the baseline’s ~0.55–0.60, indicating reduced generalization error. The training and validation trajectories of ASSC-TextRCNN are overall smoother with smaller oscillations, suggesting a more stable optimization process and lower sensitivity to gradient noise and hyperparameter perturbations. By strengthening contextual representations and inter-class separability, the ASSC mechanism accelerates the formation of discriminative features and smooths decision boundaries, thereby improving both convergence efficiency and generalization. Across accuracy, convergence, and robustness, ASSC-TextRCNN consistently outperforms the baseline, demonstrating clear empirical advantages and practical value.

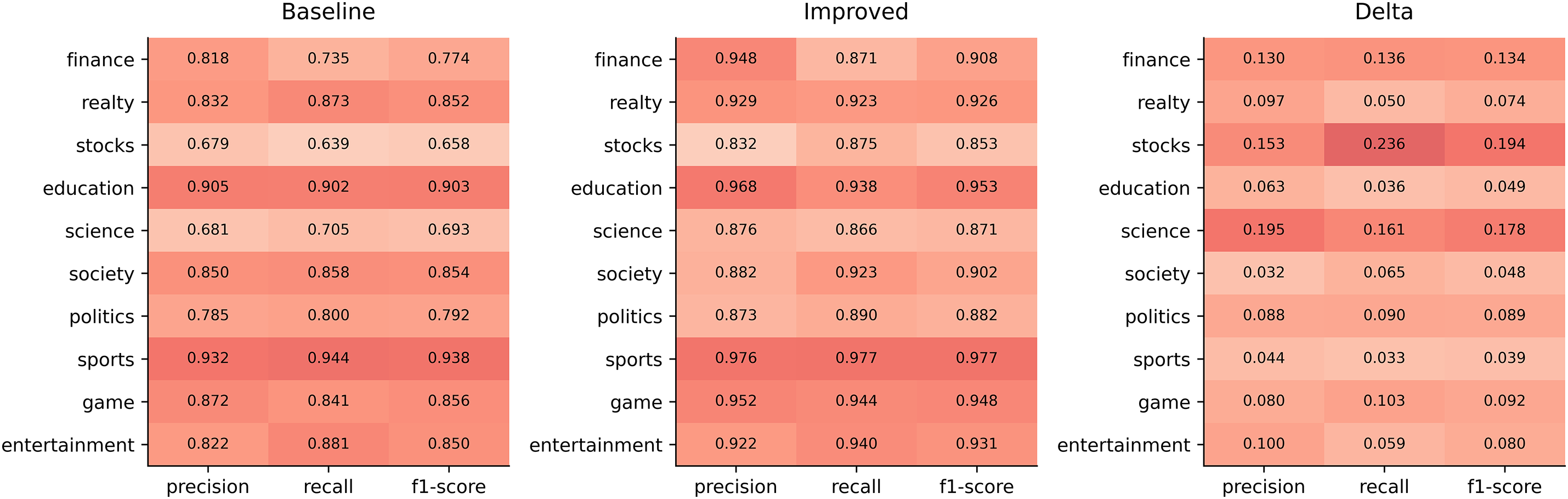

To comprehensively assess the effectiveness of ASSC-TextRCNN on a 10-class news classification task, we again adopt TextRCNN as the baseline and conduct comparable controlled experiments under identical data splits, preprocessing, and training hyperparameters. Evaluation metrics include per-class Precision, Recall, and F1, which are visualized in three heatmaps for the baseline, the improved model, and their difference, using both color intensity and cell values to encode performance magnitude and improvement.

The improved model achieves consistent and substantial gains on all three macro-averaged metrics in Fig. 8, Precision rises from 0.817 to 0.916, Recall from 0.818 to 0.915, and F1 from 0.817 to 0.915, indicating simultaneous enhancement of discriminability and coverage and a significant reduction in overall error. At the class level, improvements are broad and particularly pronounced for previously weaker categories: for example, stocks see F1 increase from 0.658 to 0.853, with Recall improving from 0.639 to 0.875 and Precision from 0.679 to 0.832; finance improves in F1 from 0.774 to 0.908, with Precision and Recall gains of 0.130 and 0.136, respectively. Even for categories that already performed well, the improved model delivers steady gains—for instance, education F1 rises from 0.903 to 0.953, and sports from 0.938 to 0.977—showing that errors can still be further reduced in high-baseline regimes.

Figure 8: Heatmap of per-class metrics

The difference heatmap exhibits a predominantly positive and continuous coloration, reflecting concurrent improvements in Precision and Recall for most categories. These gains do not stem from threshold trade-offs but from systematic enhancements in representational capacity and class separability. Coupled with the larger gains observed in semantically overlapping categories such as stocks, finance, and science, this suggests that the ASSC mechanism more effectively captures long-range context and topical cues, reduces cross-category confusion, and yields smoother, more robust decision boundaries. In summary, under a rigorously fair setting, ASSC-TextRCNN significantly outperforms the baseline at both macro and micro levels, demonstrating broad effectiveness and strong generalization, and providing solid empirical support for scaling to larger and cross-domain datasets.

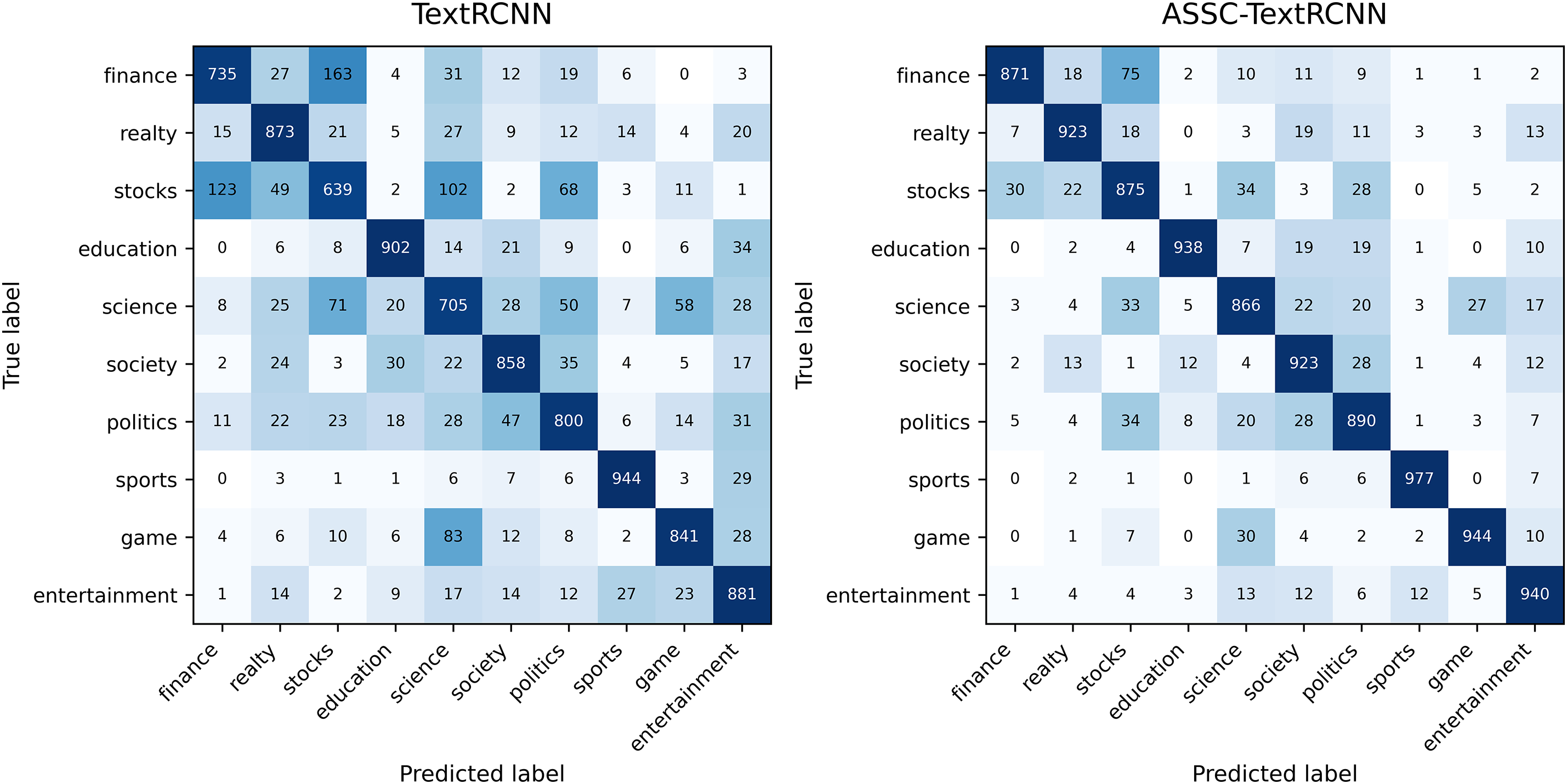

To examine the discriminative capacity and error structure of ASSC-TextRCNN on the 10-class news task, we conduct strictly comparable controlled experiments with the same data split, preprocessing, and training hyperparameters as TextRCNN, and visualize the test-set confusion matrices of both models side-by-side to characterize inter-class misclassification patterns and their trends (a LogNorm color map is used to enhance readability across different count magnitudes) in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Comparison of confusion matrix of classification task before and after improvement

The diagonal counts for ASSC-TextRCNN increase markedly across all categories, and overall accuracy improves from 81.78% to 91.47%, an absolute gain of +9.69 percentage points. This gain represents a “net improvement” driven by a substantial reduction in systematic confusions rather than a trade-off between categories. For key confusable pairs, bidirectional mistakes between finance and stocks shrink significantly: “finance-stocks” drops from 163 to 75, and “stocks-finance” from 123 to 30, with the recalls of the two classes rising from 0.735 and 0.639 to 0.871 and 0.875, respectively. Confusions due to semantic proximity between science and games also diminish notably—for instance, “games-science” falls from 83 to 30, and “science-stocks/politics/games” decrease from 71/50/58 to 33/20/27 (a total reduction of 99)—raising the science recall from 0.705 to 0.866. For high-baseline categories, the diagonal strengthening in education and sports remains evident, while residual confusions such as “education-entertainment” and “entertainment-sports/games” drop from 34 to 10 and from 27/23 to 12/5, respectively. By integrating context more effectively and shaping decision boundaries, ASSC-TextRCNN systematically reduces cross-class errors caused by topical overlap and lexical co-occurrence, improving recall for weaker classes while further lowering errors for stronger ones. The remaining few symmetric or near-symmetric confusions suggest that future work could incorporate finer-grained domain features and cross-paragraph semantic constraints to eliminate edge cases.

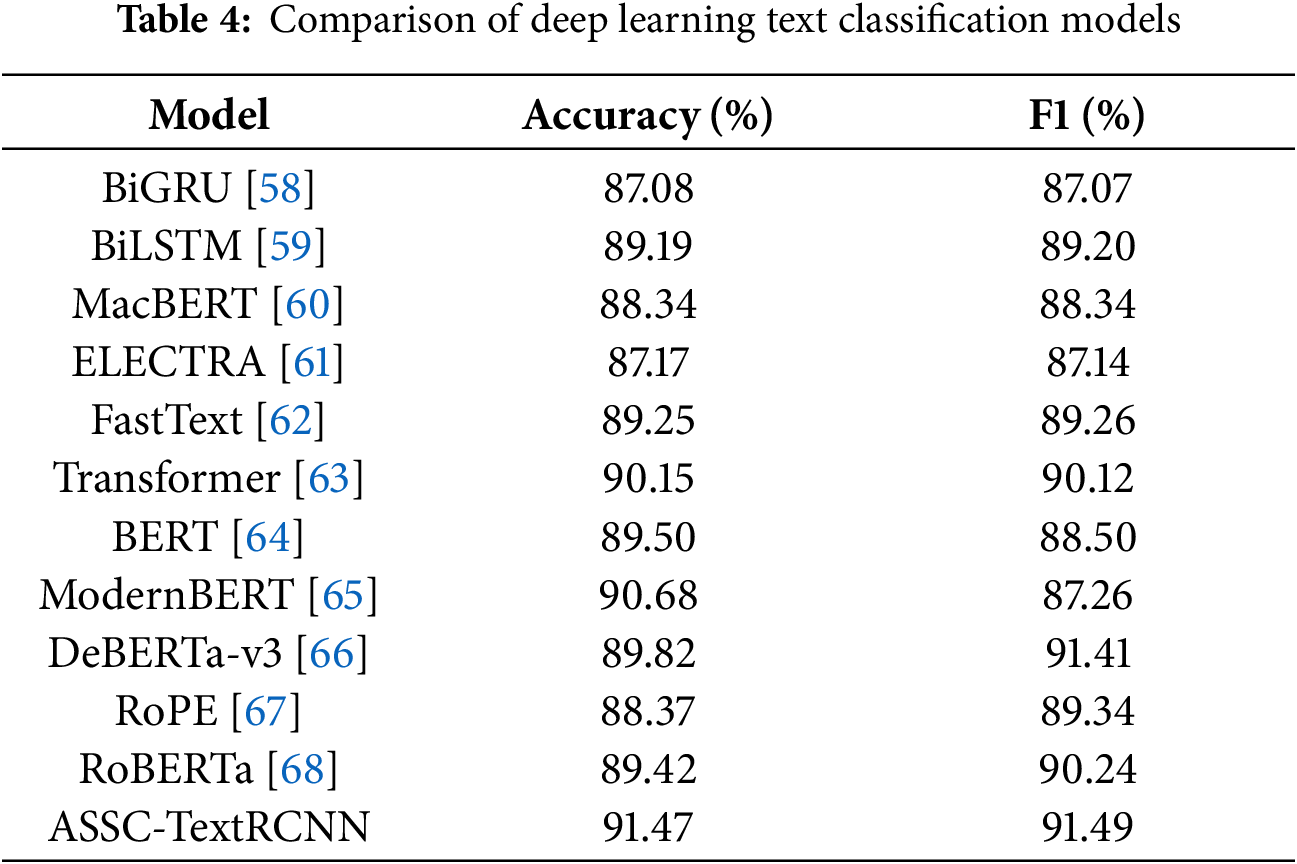

To comprehensively evaluate the overall advantages of the proposed ASSC-TextRCNN, which fuses SVD and attention, on the 10-class news classification task, we conduct comparable controlled experiments under the same data splits, preprocessing pipeline, and training settings as the competing models, and perform a horizontal comparison using accuracy and F1 as metrics across classical sequence models (BiGRU, BiLSTM, FastText), a self-attention model (Transformer), and pretrained language models (BERT, MacBERT, ELECTRA). The results are presented in Table 4. To ensure a fair comparison, all models were trained using an equivalent number of optimization steps and a unified early stopping criterion, rather than a fixed number of epochs. Specifically, we employed the AdamW optimizer with

ASSC-TextRCNN achieves the best performance on both metrics, with accuracy and F1 reaching 91.47% and 91.49%, respectively—an absolute gain of +1.32/+1.37 percentage points over the strongest current comparator, Transformer (90.15%/90.12%), corresponding to an approximate 13.4% reduction in relative error rate. Compared with FastText (89.25%/89.26%) and BERT (89.50%/88.50%), the accuracy gains are +2.22 and +1.97 points, and the F1 gains are +2.23 and +2.99 points, respectively, representing a more pronounced advantage over earlier RNN-based models and related pretrained variants. The concurrent improvements in accuracy and F1 indicate that the gains do not stem from thresholding or incidental class-distribution effects, but from systematic enhancements in representation quality and decision-boundary separability. In latent space, SVD performs low-rank compression that de-redundifies and denoises long texts and topic-mixed scenarios, highlighting sentence-level stable semantic factors; on this foundation, the attention mechanism further focuses on discriminative segments and mitigates confusions caused by cross-class lexical co-occurrence. Consequently, consistent gains are realized atop strong baselines spanning diverse architectures and training paradigms. Together with the evidence from the confusion matrices and per-class metrics, ASSC-TextRCNN substantially boosts recall for weaker classes while further reducing residual errors for stronger classes, demonstrating broad-spectrum efficacy and robust generalization.

Addressing the challenge that digital-culture texts—characterized by being sparse, short, noisy, and highly time-sensitive—are difficult to model effectively with traditional methods, this study proposes and systematically investigates a classification framework based on ASSC-TextRCNN. On top of TextRCNN’s context-aware convolution–recurrent architecture, we introduce ALBERT as a pretrained semantic encoder to enhance deep semantic alignment; we design a short-text–oriented dual-attention mechanism that adaptively focuses on latent key information along the word–context and channel–semantics dimensions; we replace traditional max pooling with singular value decomposition (SVD) to mitigate feature loss from extreme pooling and preserve discriminative subspaces; and we adopt cross-entropy loss to robustly capture class distributions. These architectural refinements strike a better balance among representation depth, information fidelity, and discriminability.

Experiments demonstrate that ASSC-TextRCNN substantially outperforms multiple mainstream deep-learning baselines on digital-culture text classification: relative to the baseline, accuracy improves by 11.85%, F1 by 11.97%, and the relative error rate decreases by 53.18%; the confusion matrix exhibits overall contraction, and class boundaries become clearer. These results indicate that deep coupling of pretrained semantics with contextual structure effectively alleviates the information scarcity of short texts; dual attention can reliably distill key cues under sparsity and noise, enhancing sensitivity to fine-grained class differences; SVD-based subspace compression and reconstruction preserve global discriminative information better than max pooling, improving robustness; and end-to-end optimization with cross-entropy enables stable decision surfaces even under class imbalance and fuzzy boundaries.

Robust understanding of short and nonstandard expressions improves automatic archiving, topic clustering, and metadata annotation for cultural materials. More accurate, fine-grained classification markedly enhances topic routing and audience targeting efficiency, reducing exposure waste from misclassification–misalignment and activating the long tail of high-quality cultural content for precise reach. The “structure-preserving + key-selection” synergy formed by dual attention and SVD effectively suppresses noise interference and semantic drift, supporting public-opinion early warning, content compliance review, and intellectual-property protection for more fine-grained governance. Stable classification signals provide quantifiable evidence for hotspot discovery, issue-evolution tracking, and curation optimization, forming a data-driven, closed-loop content-operations pipeline. ASSC-TextRCNN embodies a synergistic paradigm—from deep semantic pretraining to attention-based selection, structured compression, and robust optimization—validating the effectiveness of structure-preserving dimensionality reduction (SVD) + attention-based discrimination and furnishing core infrastructure for organized representation and at-scale distribution of digital-culture content in complex settings. With stronger semantic capacity and lower misclassification costs, the model advances a shift from experience-driven to data–algorithm co-driven cultural dissemination, accelerating value realization and the sustainable amplification of social impact.

Given the complex ecology of digital-culture texts—sparse, short, noisy, and time-critical—future work on ASSC-TextRCNN should both deepen the technical pathway and broaden cultural applications. On the technical front, we will first tackle the core issue of inadequate information in short texts by exploring a synergy of external knowledge, context modeling, and attention-based selection: atop the current ALBERT backbone, incorporate retrieval-augmented and knowledge-graph–constrained semantic completion, injecting structured relations among cultural entities into encoding and decoding; aggregate multi-granularity context across paragraphs and conversations to mitigate semantic sparsity in individual short texts. Building on dual attention, we will develop interpretable hierarchical attention, enabling causal visualization and controllable guidance of the word–context and channel–semantics foci, thus providing a traceable evidence chain for cultural concepts and narrative themes. In line with the structure-preserving idea behind replacing max pooling with SVD, we will investigate dynamic low-rank decomposition and randomized approximations to reduce latency and memory while maintaining the integrity of the discriminative space, and coordinate with parameter-efficient finetuning to ensure deployability and scalability under platform-level, high-concurrency workloads.

Digital-culture content exhibits substantial diversity in topic, style, and genre, alongside pronounced distributional drift; models must retain stable memory while updating flexibly over time: employ time-aware train/validation splits and imbalance-aware long-tail reweighting to boost recognition of emerging subcultures and niche themes; adapt across languages and dialects to build a multilingual, multi-domain shared semantic subspace, using contrastive learning to align styles across platforms and genres and thereby reduce out-of-domain performance collapse. Weak and distant supervision can rapidly expand label coverage, while active learning—via uncertainty and cost-sensitive sampling—guides human annotation to form an efficient human-in-the-loop pipeline, significantly lowering the cost of introducing new classes and topics.

For interpretability, jointly visualize the contributions of dual attention and the low-rank subspace to clarify which words/subspaces are pivotal to final decisions. Uncertainty estimation and probability calibration will help the system respond cautiously in high-risk or semantically ambiguous scenarios, reducing governance risks from misclassification. Regarding adversarial and noise robustness, systematically evaluate the impact of colloquialisms, orthographic variants, detection-evading metaphors and homophones, and machine-translation noise on decision boundaries, and reinforce with data augmentation and robust optimization to bolster resilience in real-world dissemination environments. For large-scale deployment, integrate fairness and bias auditing end-to-end, with targeted evaluations for minority-language communities, regional dialects, and youth/elderly users, preventing the technological amplification of existing discourse imbalances.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The APC was funded by China National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project Fund Innovation Training Program (202410451009).

Author Contributions: Zixuan Guo: conceptualization, methodology, writing; Houbin Wang: conceptualization, methodology, computation, analysis, visualization, writing; Yuanfang Chen: validation, writing, review, editing; Sameer Kumar: conceptualization, review, supervisor, fund acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| ASR | Automatic speech recognition |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| EDA | Easy Data Augmentation |

| UDA | Unsupervised Data Augmentation |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| ASSC | ALBERT, SVD, Self-Attention and Cross-Entropy |

References

1. Song Y. Research on innovative development strategies of cultural industry under digital transformation. In: Proceedings of 2024 6th International Conference on Economic Management and Cultural Industry (ICEMCI 2024); 2024 Nov 1–3; Chengdu, China. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Atlantis Press International BV; 2025. p. 451–8. doi:10.2991/978-94-6463-642-0_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hong N. Digital-media-based interaction and dissemination of traditional culture integrating using social media data analytics. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022:5846451. doi:10.1155/2022/5846451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Correia RA, Ladle R, Jarić I, Malhado ACM, Mittermeier JC, Roll U, et al. Digital data sources and methods for conservation culturomics. Conserv Biol. 2021;35(2):398–411. doi:10.1111/cobi.13706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. George AS, Baskar T. Leveraging big data and sentiment analysis for actionable insights: a review of data mining approaches for social media. Partn Univers Int Innov J. 2024;2(4):39–59. [Google Scholar]

5. Tao H, Wang X, Zhang K, Chen E, Wang J. Metaphors as semantic anchors: a label-constrained contrastive learning approach for Chinese text classification. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2025;12(6):5080–92. doi:10.1109/tcss.2025.3585577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou Z, Xi Y, Xing S, Chen Y. Cultural bias mitigation in vision-language models for digital heritage documentation: a comparative analysis of debiasing techniques. Artif Intell Mach Learn Rev. 2024;5(3):28–40. doi:10.69987/aimlr.2024.50303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gani Ganie A, Dadvandipour S. Exploring the impact of informal language on sentiment analysis models for social media text using convolutional neural networks. Multidiszcip Tudományok. 2023;13(1):244–54. doi:10.35925/j.multi.2023.1.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Baviskar D, Ahirrao S, Potdar V, Kotecha K. Efficient automated processing of the unstructured documents using artificial intelligence: a systematic literature review and future directions. IEEE Access. 2021;9:72894–936. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3072900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ranjgar B, Sadeghi-Niaraki A, Shakeri M, Rahimi F, Choi SM. Cultural heritage information retrieval: past, present, and future trends. IEEE Access. 2024;12:42992–3026. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3374769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Minaee S, Kalchbrenner N, Cambria E, Nikzad N, Chenaghlu M, Gao J. Deep learning—based text classification: a comprehensive review. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;54(3):1–40. doi:10.1145/3439726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chatzimparmpas A, Martins RM, Kerren A. VisRuler: visual analytics for extracting decision rules from bagged and boosted decision trees. Inf Vis. 2023;22(2):115–39. doi:10.1177/14738716221142005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hollmann N, Müller S, Hutter F. Large language models for automated data science: introducing caafe for context-aware automated feature engineering. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:44753–75. [Google Scholar]

13. Chinnaiyan B, Balasubaramanian S, Jeyabalu M, Warrier GS. AI applications-computer vision and natural language processing. In: Model optimization methods for efficient and edge AI: federated learning architectures, frameworks and applications. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2025. p. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

14. Li X, Xiong H, Li X, Wu X, Zhang X, Liu J, et al. Interpretable deep learning: interpretation, interpretability, trustworthiness, and beyond. Knowl Inf Syst. 2022;64(12):3197–234. doi:10.1007/s10115-022-01756-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sun R, He S, Zhao J, Liu K, Qiu B, Huo J, et al. Asian and low-resource language information processing. ACM Trans. 2024;23(4):3613605. [Google Scholar]

16. Naithani K, Raiwani YP. Realization of natural language processing and machine learning approaches for text-based sentiment analysis. Expert Syst. 2023;40(5):e13114. doi:10.1111/exsy.13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sarker A, O’Connor K, Ginn R, Scotch M, Smith K, Malone D, et al. Social media mining for toxicovigilance: automatic monitoring of prescription medication abuse from twitter. Drug Saf. 2016;39(3):231–40. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0379-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chen D, Zhang R. Building multimodal knowledge bases with multimodal computational sequences and generative adversarial networks. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2024;26:2027–40. doi:10.1109/TMM.2023.3291503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alizadeh M, Seilsepour A. A novel self-supervised sentiment classification approach using semantic labeling based on contextual embeddings. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(12):10195–220. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-19086-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bashiri H, Naderi H. SyntaPulse: an unsupervised framework for sentiment annotation and semantic topic extraction. Pattern Recognit. 2025;164:111593. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zheng M, Jiang K, Xu R, Qi L. An adaptive LDA optimal topic number selection method in news topic identification. IEEE Access. 2023;11:92273–84. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3308520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Huang Y, Lv T, Cui L, Lu Y, Wei F. LayoutLMv3: pre-training for document AI with unified text and image masking. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2022 Oct 10–14; Lisboa, Portugal. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 4083–91. doi:10.1145/3503161.3548112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li Q, Peng H, Li J, Xia C, Yang R, Sun L, et al. A survey on text classification: from traditional to deep learning. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2022;13(2):1–41. doi:10.1145/3495162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Breit A, Waltersdorfer L, Ekaputra FJ, Sabou M, Ekelhart A, Iana A, et al. Combining machine learning and semantic web: a systematic mapping study. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(14s):1–41. doi:10.1145/3586163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou S, Xu H, Zheng Z, Chen J, Li Z, Bu J, et al. A comprehensive survey on deep clustering: taxonomy, challenges, and future directions. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(3):1–38. doi:10.1145/3689036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sun Y, Yu Z, Sun Y, Xu Y, Song B. A novel approach for multiclass sentiment analysis on Chinese social media with ERNIE-MCBMA. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):18675. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-03875-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Soni S, Chouhan SS, Rathore SS. TextConvoNet: a convolutional neural network based architecture for text classification. Appl Intell. 2023;53(11):14249–68. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-04221-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Akpatsa SK, Li X, Lei H. A survey and future perspectives of hybrid deep learning models for text classification. In: Artificial intelligence and security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 358–69. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78609-0_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang R. Multilingual pretrained based multi-feature fusion model for English text classification. Comput Sci Inf Syst. 2025;22(1):133–52. doi:10.2298/csis240630004z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Long Q, Wang Z, Yu H. Deep learning for reddit text classification: TextCNN and TextRNN approaches. In: Proceedings of the 2024 4th Interdisciplinary Conference on Electrics and Computer (INTCEC); 2024 Jun 11–13; Chicago, IL, USA. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/intcec61833.2024.10603240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bhadauria AS, Shukla M, Kumar P, Dwivedi N. Attention-based neural machine translation for multilingual communication. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering; 2023 Nov 24–25; Kānpur, India. p. 129–42. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-1923-5_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sahu G, Vechtomova O, Bahdanau D, Laradji I. PromptMix: a class boundary augmentation method for large language model distillation. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2023 Dec 6–10; Singapore. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2023. p. 5316–27. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-main.323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sherin A, Jasmine Selvakumari Jeya I, Deepa SN. Enhanced Aquila optimizer combined ensemble Bi-LSTM-GRU with fuzzy emotion extractor for tweet sentiment analysis and classification. IEEE Access. 2024;12:141932–51. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3464091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kamyab M, Liu G, Rasool A, Adjeisah M. ACR-SA: attention-based deep model through two-channel CNN and Bi-RNN for sentiment analysis. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2022;8:e877. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Mars M. From word embeddings to pre-trained language models: a state-of-the-art walkthrough. Appl Sci. 2022;12(17):8805. doi:10.3390/app12178805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Du M, Liu N, Yang F, Hu X. Learning credible DNNs via incorporating prior knowledge and model local explanation. Knowl Inf Syst. 2021;63(2):305–32. doi:10.1007/s10115-020-01517-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu J, Yan Z, Chen S, Sun X, Luo B. Channel attention TextCNN with feature word extraction for Chinese sentiment analysis. ACM Trans Asian Low-Resour Lang Inf Process. 2023;22(4):1–23. doi:10.1145/3571716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li X, Chen W, Zhang J. Paradigm construction and improvement strategy of English long text translation based on self-attention mechanism. J Combin Math Combin Comput. 2025;127:8945–60. [Google Scholar]

39. Wang Y, Feng L. New bagging based ensemble learning algorithm distinguishing short and long texts for document classification. ACM Trans Asian Low-Resour Lang Inf Process. 2025;24(4):1–26. doi:10.1145/3718740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Attieh J, Tekli J. Supervised term-category feature weighting for improved text classification. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;261:110215. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.110215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Rathi RN, Mustafi A. The importance of Term Weighting in semantic understanding of text: a review of techniques. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(7):9761–83. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-12538-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Li C, Li W, Tang Z, Li S, Xiang H. An improved term weighting method based on relevance frequency for text classification. Soft Comput. 2023;27(7):3563–79. doi:10.1007/s00500-022-07597-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lin N, Zeng M, Liao X, Liu W, Yang A, Zhou D. Addressing class-imbalance challenges in cross-lingual aspect-based sentiment analysis: dynamic weighted loss and anti-decoupling. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;257:125059. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wei N, Zhao S, Liu J, Wang S. A novel textual data augmentation method for identifying comparative text from user-generated content. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2022;53:101143. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2022.101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Jiang Q, Sun G, Li T, Tang J, Xia W, Zhu S, et al. Qutaber: task-based exploratory data analysis with enriched context awareness. J Vis. 2024;27(3):503–20. doi:10.1007/s12650-024-00975-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Body T, Tao X, Li Y, Li L, Zhong N. Using back-and-forth translation to create artificial augmented textual data for sentiment analysis models. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;178:115033. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Xie Z, Zhang Z, Chen J, Feng Y, Pan X, Zhou Z, et al. Data-driven unsupervised anomaly detection of manufacturing processes with multi-scale prototype augmentation and multi-sensor data. J Manuf Syst. 2024;77:26–39. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2024.08.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zheng M, You S, Wang F, Qian C, Zhang C, Wang X, et al. Ressl: relational self-supervised learning with weak augmentation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:2543–55. [Google Scholar]

49. Liang K, Wang B, Yuan F. Research on multi channel text classification method based on neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME); 2024 Sep 13–15; Guiyang, China. p. 850–5. doi:10.1109/itme63426.2024.00171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Gao X, Ding G, Liu C, Xu J. Research on high precision Chinese text sentiment Classification based on ALBERT Optimization. In: Proceedings of the 2023 15th International Conference on Advanced Computational Intelligence (ICACI); 2023 May 6–9; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/icaci58115.2023.10146191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wang J, Huang JX, Tu X, Wang J, Huang AJ, Laskar MTR, et al. Utilizing BERT for information retrieval: survey, applications, resources, and challenges. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(7):1–33. doi:10.1145/3648471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ming Y, Hu N, Fan C, Feng F, Zhou J, Yu H. Visuals to text: a comprehensive review on automatic image captioning. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2022;9(8):1339–65. doi:10.1109/JAS.2022.105734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Jia W, Sun M, Lian J, Hou S. Feature dimensionality reduction: a review. Complex Intell Syst. 2022;8(3):2663–93. doi:10.1007/s40747-021-00637-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Mao A, Mohri M, Zhong Y. Cross-entropy loss functions: theoretical analysis and applications. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023 Jul 23–29; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 23803–28. [Google Scholar]

55. Jiang S, Hu J, Magee CL, Luo J. Deep learning for technical document classification. IEEE Trans Eng Manage. 2024;71:1163–79. doi:10.1109/tem.2022.3152216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Li M. Comparison of sarcasm detection models based on lightweight BERT model—differences between ALBERT-Chinese-tiny and TinyBERT in small sample scenarios. Sci Technol Eng Chem Environ Prot. 2025;1(3):1–6. doi:10.61173/6jpm4n27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Tang S, Yu Y, Wang H, Wang G, Chen W, Xu Z, et al. A survey on scheduling techniques in computing and network convergence. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials. 2024;26(1):160–95. doi:10.1109/comst.2023.3329027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Liu J, Yang Y, Lv S, Wang J, Chen H. Attention-based BiGRU-CNN for Chinese question classification. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2019;1–12. doi:10.1007/s12652-019-01344-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Joshi VM, Ghongade RB, Joshi AM, Kulkarni RV. Deep BiLSTM neural network model for emotion detection using cross-dataset approach. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2022;73:103407. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Shao D, Huang K, Ma L, Yi S. Chinese named entity recognition based on MacBERT and Joint Learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Intelligent Systems (CCIS); 2023 Aug 12–13; Dali, China. p. 1–13. doi:10.1109/ccis59572.2023.10262869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Mala JB, Anisha Angel SJ, Alex Raj SM, Rajan R. Efficacy of ELECTRA-based language model in sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Communication, IoT and Security (ICISCoIS); 2023 Feb 9–11; Coimbatore, India. p. 682–7. doi:10.1109/ICISCoIS56541.2023.10100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Yao T, Zhai Z, Gao B. Text classification model based on fastText. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Information Systems (ICAIIS); 2020 Mar 20–22; Dalian, China. p. 154–7. doi:10.1109/icaiis49377.2020.9194939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Rahali A, Akhloufi MA. End-to-end transformer-based models in textual-based NLP. AI. 2023;4(1):54–110. doi:10.3390/ai4010004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Garrido-Merchan EC, Gozalo-Brizuela R, Gonzalez-Carvajal S. Comparing BERT against traditional machine learning models in text classification. J Comput Cogn Eng. 2023;2(4):352–6. doi:10.47852/bonviewjcce3202838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Molokwu BC, Rahimi A, Molokwu RC. Fine-grained sentiment mining, at document level on big data, using a state-of-the-art representation-based transformer: ModernBERT [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 1]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5418377. [Google Scholar]

66. Li B, Qi H, Yan K. Team Bohan Li at PAN: DeBERTa-v3 with R-drop regularization for human-AI collaborative text classification. In: Proceedings of the Working Notes of the Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum (CLEF 2024); 2024 Sep 9–12; Grenoble, France. p. 2658–64. [Google Scholar]

67. Su J, Ahmed M, Lu Y, Pan S, Bo W, Liu Y. RoFormer: enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding. Neurocomputing. 2024;568:127063. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.127063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Adoma AF, Henry NM, Chen W. Comparative analyses of bert, roberta, distilbert, and xlnet for text-based emotion recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2020 17th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP); 2020 Dec 18–20; Chengdu, China. p. 117–21. doi:10.1109/iccwamtip51612.2020.9317379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools