Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

RSG-Conformer: ReLU-Based Sparse and Grouped Conformer for Audio-Visual Speech Recognition

Institute of Automation and Electronic Information, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, 411105, China

* Corresponding Author: Xin Du. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 55 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072145

Received 20 August 2025; Accepted 27 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Audio-visual speech recognition (AVSR), which integrates audio and visual modalities to improve recognition performance and robustness in noisy or adverse acoustic conditions, has attracted significant research interest. However, Conformer-based architectures remain computational expensive due to the quadratic increase in the spatial and temporal complexity of their softmax-based attention mechanisms with sequence length. In addition, Conformer-based architectures may not provide sufficient flexibility for modeling local dependencies at different granularities. To mitigate these limitations, this study introduces a novel AVSR framework based on a ReLU-based Sparse and Grouped Conformer (RSG-Conformer) architecture. Specifically, we propose a Global-enhanced Sparse Attention (GSA) module incorporating an efficient context restoration block to recover lost contextual cues. Concurrently, a Grouped-scale Convolution (GSC) module replaces the standard Conformer convolution module, providing adaptive local modeling across varying temporal resolutions. Furthermore, we integrate a Refined Intermediate Contextual CTC (RIC-CTC) supervision strategy. This approach applies progressively increasing loss weights combined with convolution-based context aggregation, thereby further relaxing the constraint of conditional independence inherent in standard CTC frameworks. Evaluations on the LRS2 and LRS3 benchmark validate the efficacy of our approach, with word error rates (WERs) reduced to 1.8% and 1.5%, respectively. These results further demonstrate and validate its state-of-the-art performance in AVSR tasks.Keywords

Recent advances in deep learning techniques, computational resources, and large-scale labeled speech datasets have substantially improved the performance of automatic speech recognition (ASR) models. Traditional frameworks based on Gaussian Mixture Models and Hidden Markov Models (GMM-HMMs) have been progressively superseded by deep neural networks (DNNs) [1–4], owing to their superior ability to integrate formerly separate modeling steps. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [5,6] demonstrate enhanced robustness against local distortions, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [7,8] and more recent transformer-based approaches [9–11] are effective at capturing long-range temporal dependencies. Despite these advances, even state-of-the-art ASR models remain susceptible to adverse acoustic conditions—such as background noise or overlapping speech. Visual speech recognition (VSR) methods [12–15], which leverage lip movement cues, offer complementary information, particularly in noisy environments. However, due to the intrinsic ambiguity and limited discriminative information of the visual modality alone, VSR models—despite advancements brought by Spatiotemporal Convolution Neural Networks (3D CNNs) [15–17] and Visual Transformer-based Architectures [18,19]—still fall short of matching the performance of audio-based systems. To overcome these challenges, AVSR has been developed as an integrated approach that leverages both modalities, enhancing recognition accuracy and robustness. Building on this foundation, various novel architectures and training strategies have been investigated to effectively learn joint representations from temporally aligned audio and visual streams. Notably, Afouras et al. [20] developed a Transformer-based encoder-decoder architecture for sequence-to-sequence learning. Petridis et al. [21] integrated Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC) with attention-based decoding to enhance multimodal sequence modeling. Makino et al. [22] established an RNN-Transducer framework for alignment-free AVSR, while Yu et al. [23] designed a dynamic modality fusion mechanism for audio-visual feature integration. Building upon advances in temporal alignment and modality fusion, Khan et al. [24] introduced the Joint Multi-Scale Multimodal Transformer (JMMT), which significantly enhances the ability to capture both inter- and intra-modal relationships of visual and audio modalities. Subsequent innovations feature Ma et al. [25] replacing RNNs with Conformer encoders [26] and incorporating Transformer language models, alongside Shi et al.’s [27] self-supervised approach employing cross-modal contrastive learning for noise-robustness processing. In addition, Khan et al. [28] designed a novel Cross-Modality Transformer (CMT), which achieves fine-grained and deep-level feature fusion across modalities. More recently, Ma et al. [29] implemented an automated labeling pipeline to scale visual speech model training, and Kim et al. [30] devised cross-modal attention modules to augment video representations with audio cues.

However, while demonstrating effectiveness, Transformer-based methods such as represented in [31–33] incur substantial computational overhead and generate high-density activation patterns. These characteristics significantly reduce training and inference efficiency, particularly during long-form sequence processing. To mitigate these limitations, researchers have primarily investigated two strategies: linearization and sparsification. Linear attention mechanisms, exemplified by Longformer [34] and Cosformer [35], alleviate computational demands through kernel-based approximations of softmax operations. This formulation achieves linear complexity relative to sequence length. Nevertheless, these methods often depend on non-negative activation functions (e.g., ReLU, ELU), which may result in substantial information loss. Furthermore, their inability to selectively emphasis critical regions may impair representation capacity. In contrast, sparsification-based approaches, such as Longformer [34] and Reformer [36], aim to reduce computational complexity by selectively attending to important tokens or regions. In addition to computational efficiency, these approaches often enhance interpretability by promoting selective connectivity and suppressing noise from irrelevant input. Although sparsification-based approaches substantially enhance computational efficiency and facilitate long-sequence modeling, their restricted connectivity patterns constrain expressive power. Specifically, fixed sparse patterns, as adopted in Longformer [34], may fail to capture critical contextual dependencies, whereas the hard truncation strategies employed in Routing Transformers [37] risk discarding valuable information, potentially degrading performance on tasks that require fine-grained or global interactions. To bridge this gap, this study proposes the ReLU-based Sparse and Grouped Conformer (RSG-conformer) architecture, which incorporates a Global-enhanced Sparse Attention (GSA) mechanism to enhance long-range dependency modeling while maintaining computational efficiency via sparse attention. As the framework’s core component, GSA integrates ReLU-based sparsity with a global context restoration module, systematically reconstructing critical global relationships often fragmented by conventional sparse attention approaches. Concurrently, Grouped-scale Convolution (GSC) module is embedded within Conformer blocks to compensate for weakened local continuity and enrich multi-scale feature representations, enabling the extraction of diverse local patterns. Furthermore, we introduce the Refined Intermediate Contextual CTC (RIC-CTC) strategy, as inspired by prior works [38,39] and the broader perspective offered in recent survey [40], to augment the model’s expressive capacity and further relax the conditional independence assumption inherent in standard CTC training. Collectively, these contributions constitute a unified framework that balances sparsity-driven efficiency with improved global and local modeling capabilities, ultimately improving performance in AVSR tasks. This work makes the following key contributions:

• RSG-Conformer architecture is proposed, which integrates a GSA module for efficient long-range dependency modeling and a GSC module to strengthen temporal representation, collectively enhancing computational efficiency and robustness.

• Introduction of a global context restoration module that mitigates limitations of ReLU-based sparse attention through depthwise convolution, reinforcing global dependency modeling and reconstructing fragmented information pathways.

• Integration of the proposed GSC module to enrich local feature representations, restore local continuity disrupted by sparse attention, and capture diverse short-term temporal patterns across multiple temporal scales.

• Adoption of an RIC-CTC supervision strategy that strengthens hierarchical representation expressiveness and further relaxes the conditional independence assumption inherent in standard CTC training.

• Demonstration of superior performance and practical applicability on LRS2 and LRS3 benchmarks, validating efficacy under diverse challenging AVSR conditions.

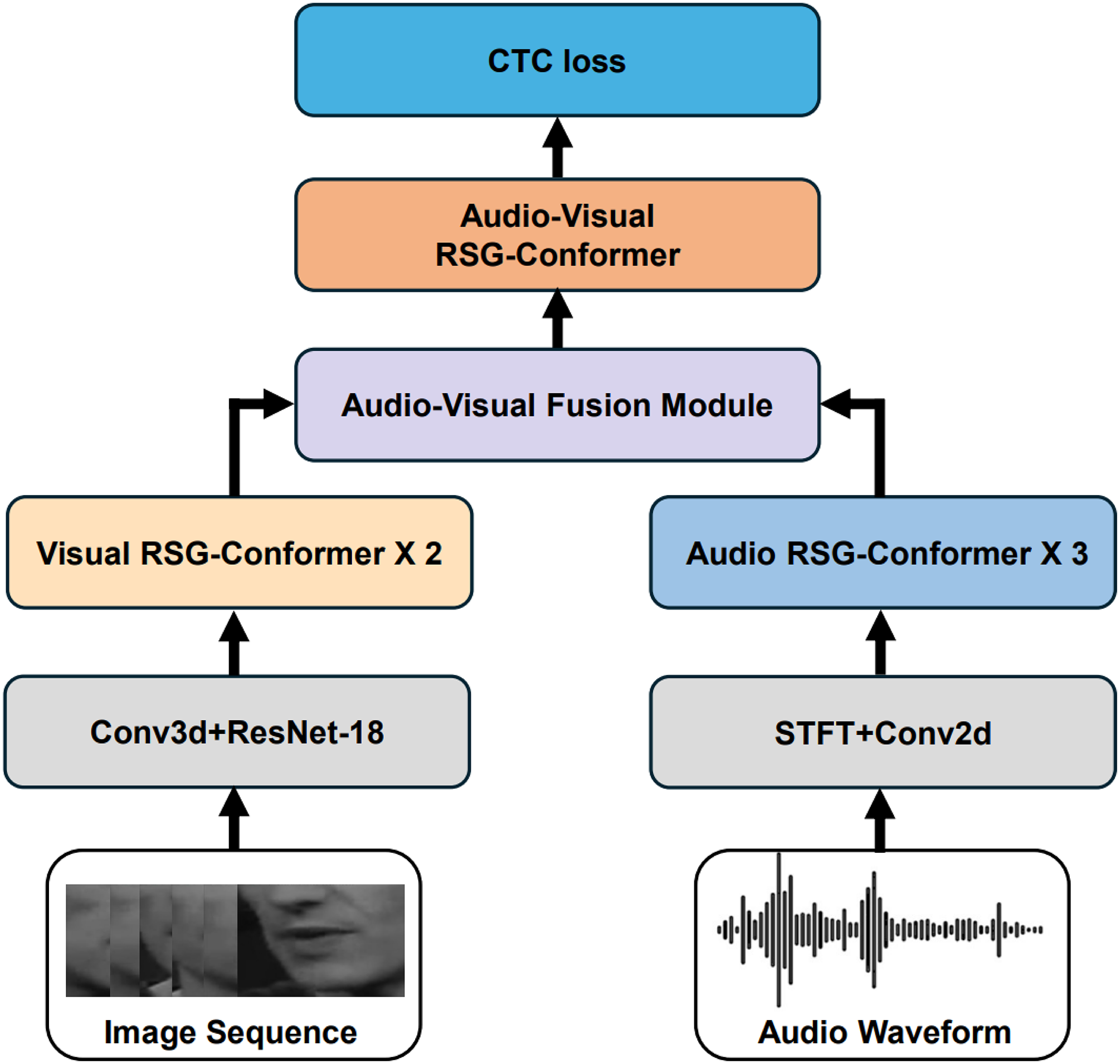

This section provides a detailed analysis of the Conformer’s components, examining their respective advantages and limitations. The proposed RSG-Conformer framework is then described in detail, comprising four primary modules: a dedicated encoder for each modality, a fusion unit to integrate cross-modal features, and a joint audio-visual encoder. The modality-specific encoders individually process raw inputs into temporal sequence. These sequences are then processed by RSG-Conformer backend networks, which concurrently capture both short-and long-range temporal dependencies. The extracted modalities undergo fusion and refinement through the dedicated audio-visual encoder to capture cross-modal synergistic interactions. The model adopts intermediate CTC loss during training and, alongside the final output layer, is optimized through end-to-end learning. An RIC-CTC strategy is introduced to further improve model performance. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall architecture.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed method, our proposed method involves modality-specific front-ends to extract audio and visual features, then independently encoded by RSG-conformer encoders. The fusion module combines both streams and passes them to a shared audio-visual RSG-conformer encoder. Finally, a CTC prediction block enables end-to-end training via the CTC loss

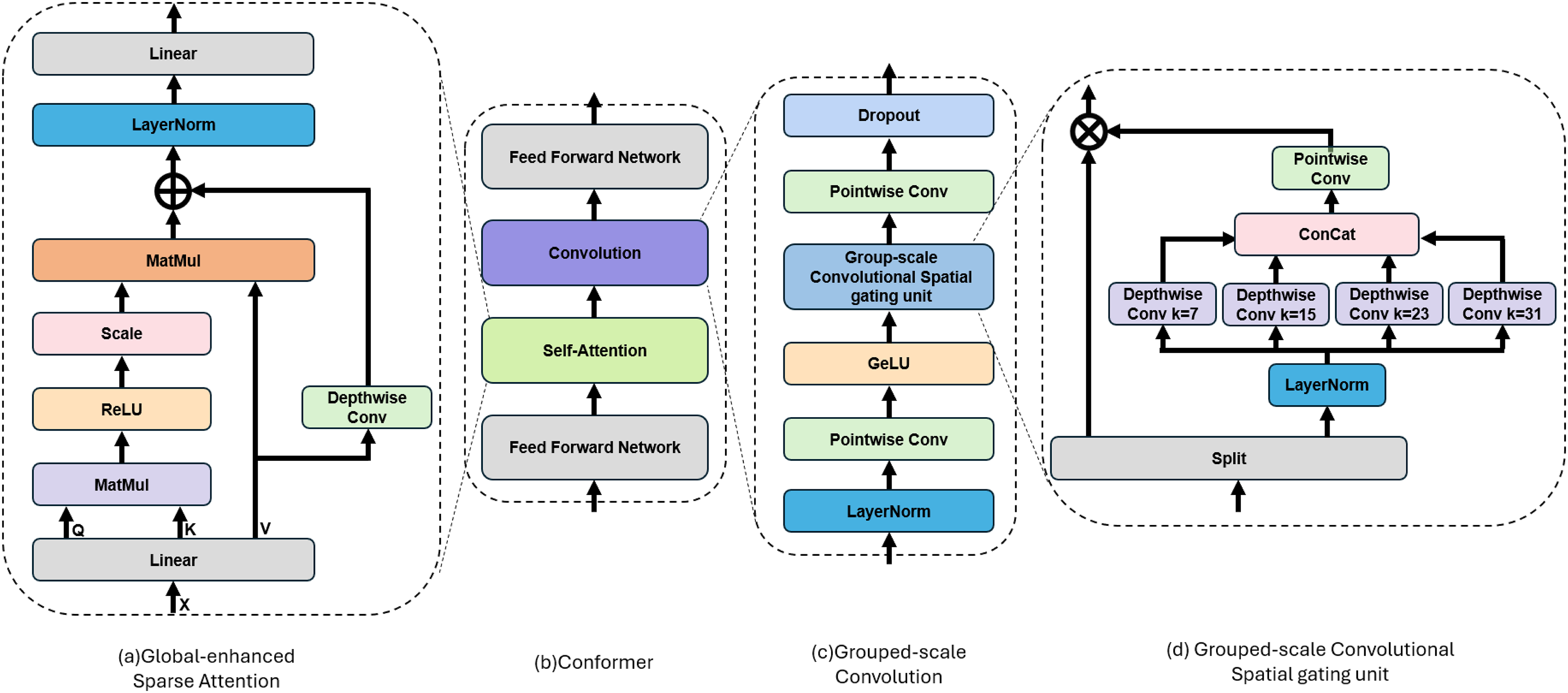

The Conformer integrates Transformer and CNN to jointly model local and global dependencies in feature sequences, addressing the limitations inherent in using either Transformer or CNN alone for sequential data processing. The overall structure of the Conformer block, illustrated in Fig. 2b, is also adopted in the proposed RSG-Conformer. A standard Conformer block consists of four sequentially arranged modules: an initial feed-forward sublayer (FFN), a multi-head self-attention mechanism (MHSA), a convolutional processing unit, and a concluding feed-forward layer. Given an input sequence S

where S′, S″, and S‴

Figure 2: Overview of our RSG-Conformer encoder layer. (a) GSA module (b) Conformer: RSG-Conformer retains the overall structure of the Conformer block, while replacing the original MHSA with the GSA module and the convolution module with GSC module. (c) GSC module. (d) Group-scale gating unit. For brevity, the residual structure is omitted

The MHSA module dynamically assigns weights to all pairwise positions in sequence (Eq. (5)), enabling flexible context-aware feature fusion. Additionally, MHSA facilitates the parallel extraction of distinct features from multiple representational sub-spaces. However, it incurs a quadratic computational complexity of O(n2) with respect to sequence length n, which limits its scalability to long sequences. In addition, the attention is broadly spread across all context elements, including those that are seemingly unrelated.

The convolution module in the Conformer block enhances local feature modeling, effectively compensating for MHSA’s limitations in short-range dependency capture and improving the modeling of localized temporal structures. However, the use of fixed-size convolutional kernels may restrict its flexibility in handling variable temporal patterns.

This section introduces the RSG-Conformer, an enhanced Conformer variant optimized for superior efficiency and modeling capabilities. As shown in Fig. 2, the framework preserves the original Conformer block structure while incorporating two novel modules. Specifically, The GSA module (Fig. 2a) replaces the conventional distribution-based attention mechanism with a linear activation function, promoting sparsity. Concurrently, the GSC module (Fig. 2c,d) enhances local dependency modeling through a multi-scale convolutional structure.

To improve computational efficiency and enhance model robustness, we propose GSA module. Unlike traditional attention mechanisms, which typically exhibit dense attention distributions, suffer from quadratic complexity O(n2) with respect to sequence length, and tend to focus on irrelevant tokens, the GSA module abandons the distribution assumption and instead employs a linear activation instead. The architectural design, illustrated in Fig. 2a, replaces the standard MHSA with a lightweight sparse variant while maintaining the ability to model global context. To address the limited connectivity commonly observed in ReLU-based sparse attention mechanisms, our approach directly enhances the value representation to retain critical contextual information. Specifically, let S

where

To avoid instability caused by large dot-product values, we first apply a scaling operation to the query matrix Q before further processing. The attention output is then obtained by applying the attention weights to the value matrix:

To alleviate the restricted connectivity inherent in sparse attention and to complement the position-sparse nature of Z, we apply a depthwise convolution layer over the value matrix V to enhance global context integration, compensating for the information flow limitations of sparse attention:

Finally, to improve training stability, Layer Normalization is applied:

Although convolution modules are effective in capturing local temporal features, their fixed-size kernels constrain adaptability to variable-length sequences. To overcome this issue, we propose the GSC module, designed to adaptively model temporal dependencies across multiple scales. Given an input tensor S

The activated tensor is then split along the channel dimension:

where A serves as the main branch, and B as the gating branch. For branch B, we first apply another LayerNorm layer, then split it into n channel groups:

Each group Bi is passed through a depthwise convolution with a distinct kernel size ki:

All group outputs are concatenated and fused via a pointwise convolution:

Unlike conventional multi-scale fusion methods that rely on direct summation or concatenation, we employ a pointwise convolution layer to enable learnable channel-wise interactions across multiple receptive fields. This design allows the model to dynamically weigh the relative contributions of each scale, which enhances the flexibility and adaptivity of the fusion process without introducing significant overhead. Element-wise multiplication is then performed between the main and gating branches, followed by a pointwise convolution for final projection and a Dropout layer for regularization:

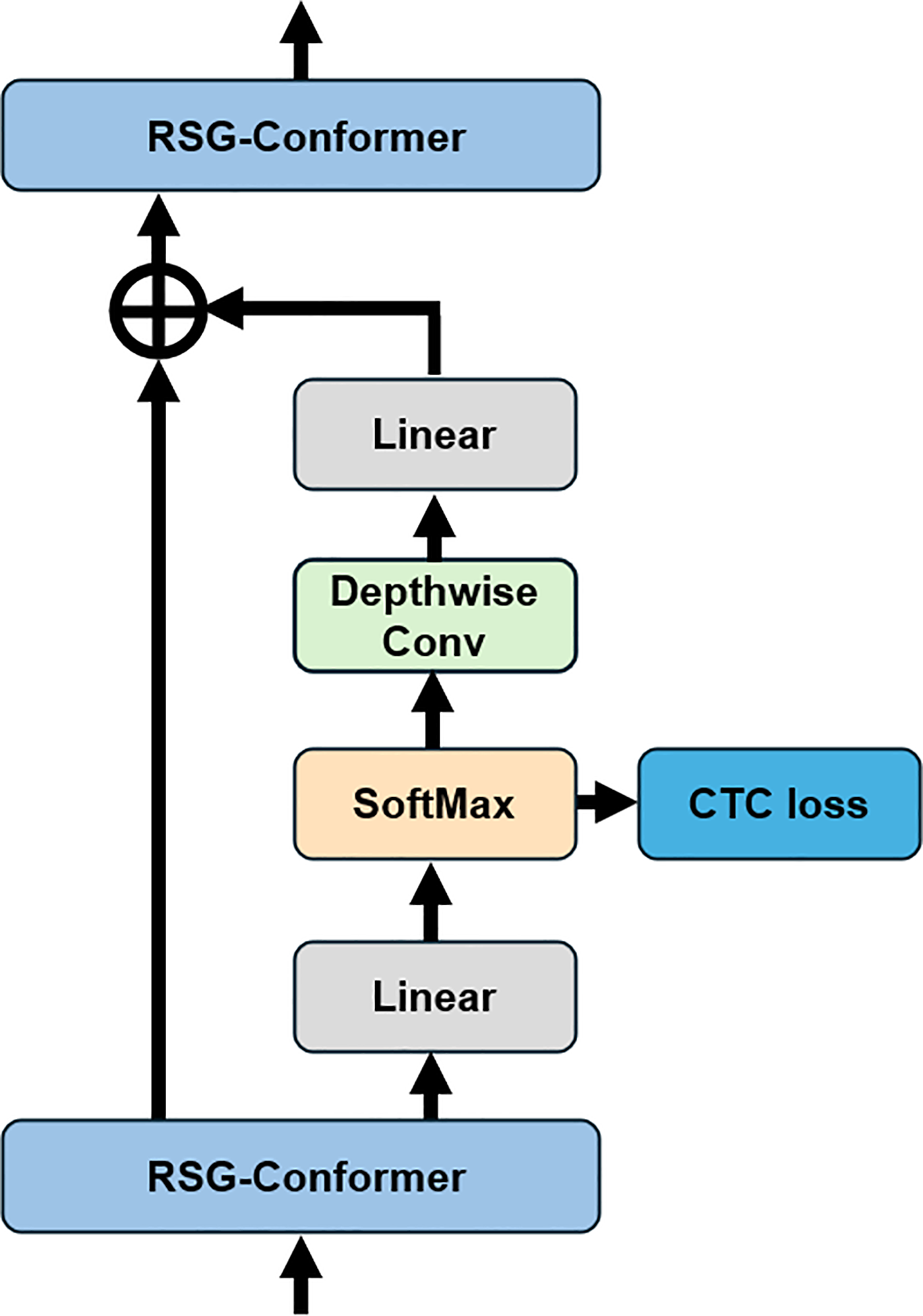

Inter CTC residual modules have been widely adopted in encoder blocks to facilitate training and to relax the conditional independence assumption inherent in conventional CTC frameworks. By inserting intermediate CTC losses, the model benefits from improved gradient flow and more effective optimization of early-layer representations. In the standard setup, the output On from the nth encoder block is first projected to the vocabulary space using a linear transformation, and a softmax is then applied to obtain a token probability distribution:

To guide representation learning, the softmax output is then projected back to the original feature dimension via a linear layer and added as a residual connection, serving as the input to the next encoder layer:

To enhance training efficiency and further relax the conditional independence assumption inherent in CTC-based models, we propose an RIC-CTC mechanism. Specifically, to aggregate local contextual information form the softmax distribution, we apply a depthwise 1D convolution with a large kernal size over the softmax output. The overall computation process is formulated as follows:

This lightweight convolutional operation facilitates the aggregation of local temporal context. Moreover, to encourage deeper layers to contribute more semantically meaningful supervision, we introduce a layer-specific weighting strategy that assigns larger loss weights to intermediate CTC outputs from deeper layers. It is expressed as:

As shown in Fig. 3, this scheme places greater emphasis on deeper encoder layers, which typically encode more abstract and semantically aligned representations, thereby promoting better convergence and overall performance. Formally, the overall loss is formulated as:

Figure 3: Refined intermediate contextual CTC

LCTC denotes the final CTC loss, with the weighting coefficient

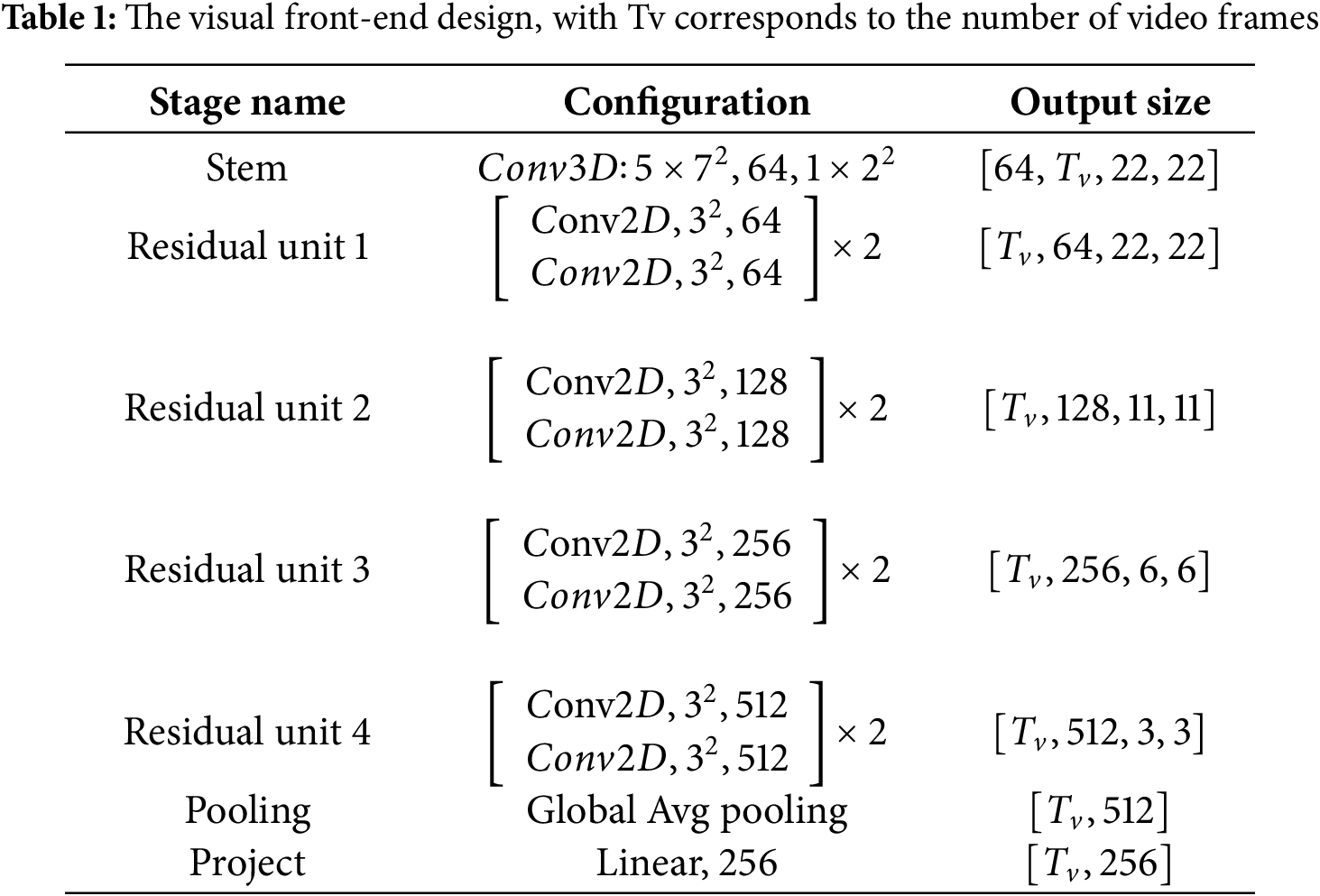

To effectively capture spatial structures and temporal variations in raw video in-put, the visual frontend begins with a 3D convolutional layer using a 5 × 7 × 7 kernel. This operation jointly encodes motion across adjacent frames and preserves rich local spatial textures. By performing early spatiotemporal fusion, it avoids treating individual frames independently and thereby enhances temporal coherence for downstream processing. The resulting feature map is then passed to a 2D ResNet-18, which extracts spatially discriminative features on a per-frame basis through its deep residual blocks. To further reduce spatial redundancy and generate compact feature embeddings, spatial average pooling is applied, yielding a temporally ordered sequence of visual representations. This sequence is then mapped via a linear layer to match the hidden dimensionality required by the backend encoder. Detailed architectural configurations are summarized in Table 1.

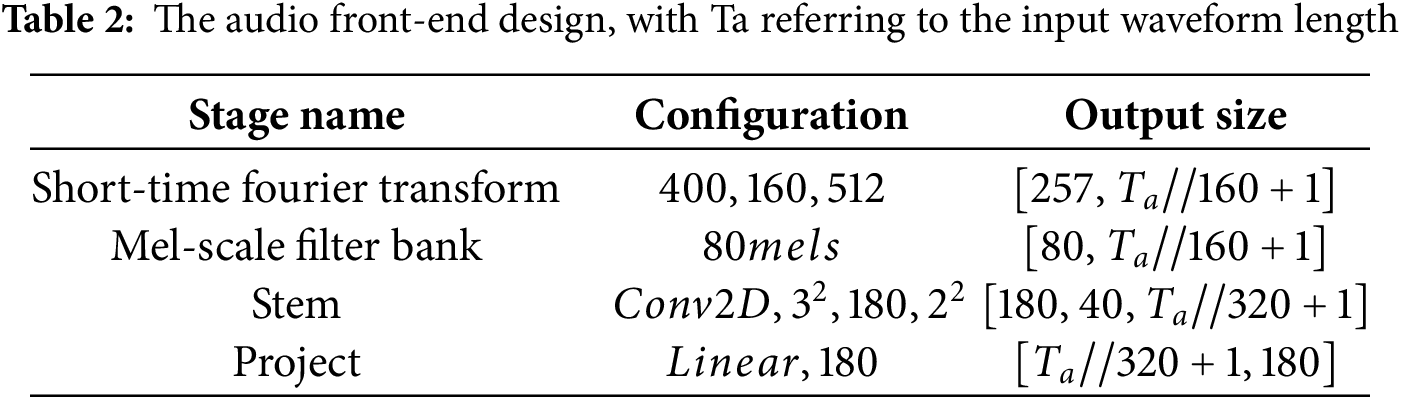

The raw audio waveform is transformed into Mel spectrograms via Short-Time Fourier Transform to extract robust and informative acoustic representations. A 20 ms window and 10 ms hop are chosen to ensure adequate temporal resolution while maintaining frequency fidelity. The resulting spectrogram is further transformed via 80-dimensional Mel-scale logarithmic filter bank, which better aligns with human auditory perception. To capture local frequency patterns and temporal dynamics, the log-Mel spectrogram is subsequently processed by a stack of 2D convolutional layers. These convolutional operations not only enhance local pattern learning but also reduce the temporal resolution, resulting in a compact sequence of acoustic feature frames at a frame rate of 20 ms. This processed sequence is then fed into the encoder network for higher-level modeling. Implementation details are summarized in Table 2.

The backend module is constructed based on the proposed RSG-Conformer framework and adopts multi-stage hierarchical architecture to progressively process and align audio-visual features. Temporal downsampling layers are strategically placed between RSG-Conformer stages to gradually reduce the sequence length while increasing the feature dimensionality. This stage-wise design enables efficient modeling of long-range dependencies while keeping computational costs manageable. The audio stream is processed through three consecutive stages, resulting in feature representations with a temporal resolution of 80 ms. In parallel, the visual stream is passed through two stages to ensure temporal alignment with the audio features.

3.4 Audio-Visual Fusion Module

The audio-visual fusion module is designed to effectively integrate multimodal features. Given temporally aligned audio and video feature sequences, the corresponding feature tensors are first concatenated across the feature dimension to produce a unified joint representation. This fused tensor is then projected into a higher-dimensional space, specifically dff = 4 × dmodel, via a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation function. This dimensional expansion enables richer cross-modal interaction and facilitates more expressive feature blending. The activated representation is subsequently projected back to the original feature dimension dmodel, ensuring compatibility with the downstream encoder. This simple yet effective fusion strategy achieves sufficient modality interaction.

Five RSG-Conformer blocks are stacked in the audio-visual encoder’s single-stage backend, with no temporal reduction applied.

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness and generalizability of the pro-posed AVSR framework across diverse conditions, we validate our method on three widely recognized benchmark datasets: LRW [12], LRS2 [20], and LRS3 [43]. The LRW dataset, comprising short, isolated word-level video clips, is used for visual pre-training to develop robust spatiotemporal visual representations. Subsequently, LRS2 and LRS3, which feature more complex sentence-level utterances, are employed for end-to-end training and evaluation of the full AVSR system.

The LRW dataset is a large-scale audio-visual corpus at the word level, built through an automated data collection process. By leveraging extensive audiovisual content from British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) television programs, it substantially expands dataset scale and speaker diversity. This corpus comprises 488,766 samples spanning 500 target words, spoken by over 1000 speakers under varied conditions. Following standard evaluation protocols, the dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and test sets to support reproducible and systematic evaluation.

The LRS2-BBC dataset is a large-scale audio-visual corpus aimed at sentence-level speech recognition, sharing its data acquisition method and source with the LRW dataset. It contains 224 h of video data comprising 144,482 utterances. Compared to LRW, LRS2 exhibits increased complexity in linguistic structures and greater variability in speaker poses, facial expressions, and lighting conditions, thus better suited for developing models handling natural unconstrained speech.

LRS3-TED, a publicly available large-scale sentence-level audio-visual corpus, contains approximately 479 h of TED and TEDx video content, yielding 151,819 annotated clips. It features greater coverage in terms of total length, speaker diversity, and offers longer, more semantically rich utterances. Its extensive content diversity and natural speaking conditions make LRS3 a challenging and realistic benchmark for developing robust AVSR systems capable of generalizing open-domain scenarios.

A standardized preprocessing pipeline is applied to each video frame to ensure consistent spatial alignment and enhance visual feature extraction. Initially, each raw video frame is cropped to a 96 × 96 pixel bounding box to address variations in rotation and scale, effectively filtering out background noise and non-facial content. These cropped regions are then refined using RetinaFace [44], which robustly detects and extracts face regions under diverse poses and lighting conditions. Subsequently, a Face Alignment Network (FAN) [45] normalizes these regions, standardizing facial geometry and orientation across frames. Following this, 68 facial landmarks are extracted per frame, providing dense structural cues that improve the model’s sensitivity to subtle lip movements. Finally, the aligned video frames are transformed into grayscale to minimize redundancy and highlight motion-related features, followed by normalization to ensure stable training.

A Byte Pair Encoding tokenizer is trained via SentencePiece [46] on the combined transcripts from LRS2 and LRS3 for text processing. The resulting vocabulary consists of 256 subword units, with the CTC blank token included. The vocabulary is designed to segment text into a sequence of tokens. This preprocessing ensures consistent representation of visual and linguistic information. It also promotes stable training con-vergence and improves robustness against speaker and content variability.

To improve the model’s generalization and robustness across diverse practical conditions, we apply a series of data augmentation techniques to both audio and visual modalities. For audio modality, widely used Spec-Augment [47] technique is adopted to the Mel spectrograms during training, which effectively prevents overfitting and encourages temporal invariance. Specifically, two frequency masks operations with a size parameter of F = 27 are employed, along with five-time masks operations with an adaptive size parameter ps = 0.05. These augmentations introduce variability in the spectral domain, simulating missing frequency bands and temporal segments that may arise in noisy or incomplete audio signals.

For the visual stream, temporal masking [48] is employed to simulate temporal disruptions such as dropped frames or occlusions. Specifically, one temporal mask is applied per second, with each mask spanning up to 0.4 s. To improve spatial robustness and increase visual variability, the training process incorporates spatial augmentations, including random crops to 88 × 88 pixels and horizontal flipping. During visual-only testing, we adopt the approach introduced by Prajwal et al. [18], employing center cropping along with horizontal flipping to enhance prediction consistency. These combined strategies bridge the gap between training and deployment environments, improving model robustness across diverse acoustic and visual conditions.

The experimental procedure follows the protocol outlined in [49]. To initialize the visual frontend, a word-level pretraining stage is conducted on the LRW dataset for 30 epochs, providing a robust foundation for visual representation learning. Subsequently, joint training of audio and visual encoders is performed on LRS2 and LRS3 to capture richer linguistic and contextual information across modalities. The Adam optimizer [50] is employed, configured with hyperparameters β1 set to 0.9 and β2 set to 0.98. To address the risk of overfitting, L2 regularization is implemented across all trainable weights, employing a regularization strength of 10−6. The learning rate is dynamically adjusted using Noam scheduling strategy [51], which incorporates an initial warm-up phase spanning 10,000 steps and achieves a maximum value of 0.001. The batch size is kept at 256 throughout the training process. The training periods vary for each model type: the audio-only (AO) model undergoes training for 200 epochs, the visual-only (VO) model is trained for 100 epochs, and the comprehensive audio-visual (AV) model completes its training in 70 epochs. Model performance is evaluated using WER. Training is conducted on NVIDIA GPUs, specifically, the VO and AV models utilize an RTX 4090 GPU to meet higher visual processing demands, while the AO model is trained on an RTX 3090. The system is implemented in Python, leveraging the PyTorch framework for modular design, efficient GPU acceleration. To ensure consistency and maintain training efficiency, video samples exceeding 450 frames (approximately 18 s) are excluded during preprocessing.

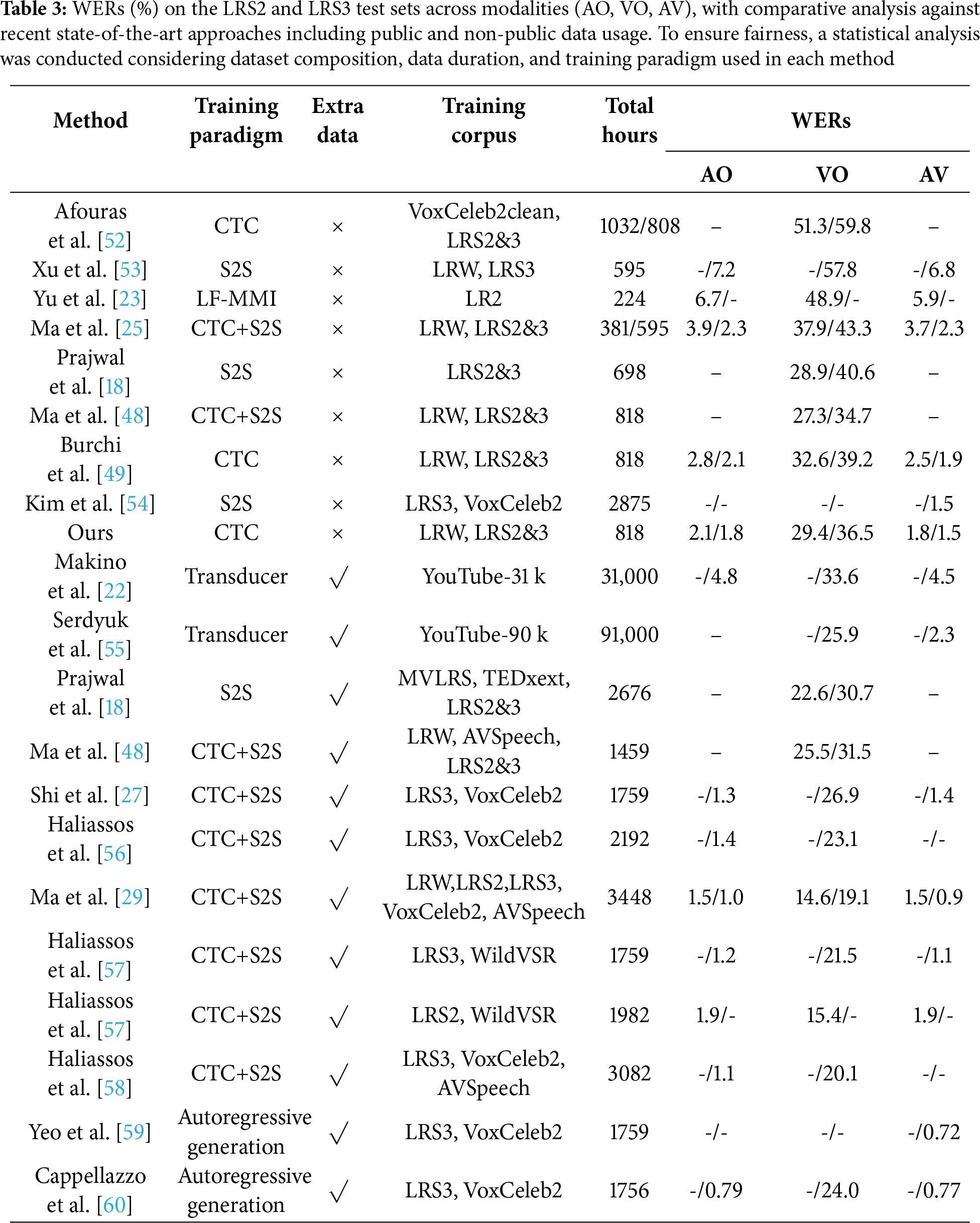

Table 3 presents a detailed performance comparison between the proposed architecture and recent state-of-the-art approaches under audio only (AO), visual only (VO) and audio visual (AV) conditions on LRS2 and LRS3 test sets. In the AO setting, the RSG Conformer encoder combined with RIC-CTC supervision demonstrates outstanding performance, attaining WERs of 2.1% on LRS2 and 1.8% on LRS3. For the VO condition, although the model does not surpass the performance reported in Ref. [45], it still achieves competitive WERs of 29.4%/36.5%, underscoring the effectiveness of our design under the standard CTC framework. The most substantial improvements are observed in the AV setting, where the full model achieves competitive performance, yielding WERs of 1.8% on LRS2 and 1.5% on LRS3, which validates the strength of the proposed audio-visual integration and joint optimization strategy.

To provide a more comprehensive evaluation, we compare our approach with semi-supervised methods [29,58] and recent Large Language Models (LLM) based models [59,60]. Semi-supervised methods achieve performance gains by leveraging large-scale unlabeled data, while LLM-based AVSR models achieve lower WERs by pretraining on massive datasets with extremely large parameter counts. However, these approaches entail substantial costs in terms of model size and computational resources. In contrast, our model relies on limited labeled training data yet still achieves competitive performance. Compared to these approaches, its main limitations are slightly higher WERs and potentially weaker generalization to unseen domains.

5.1 Attention Map Visualization

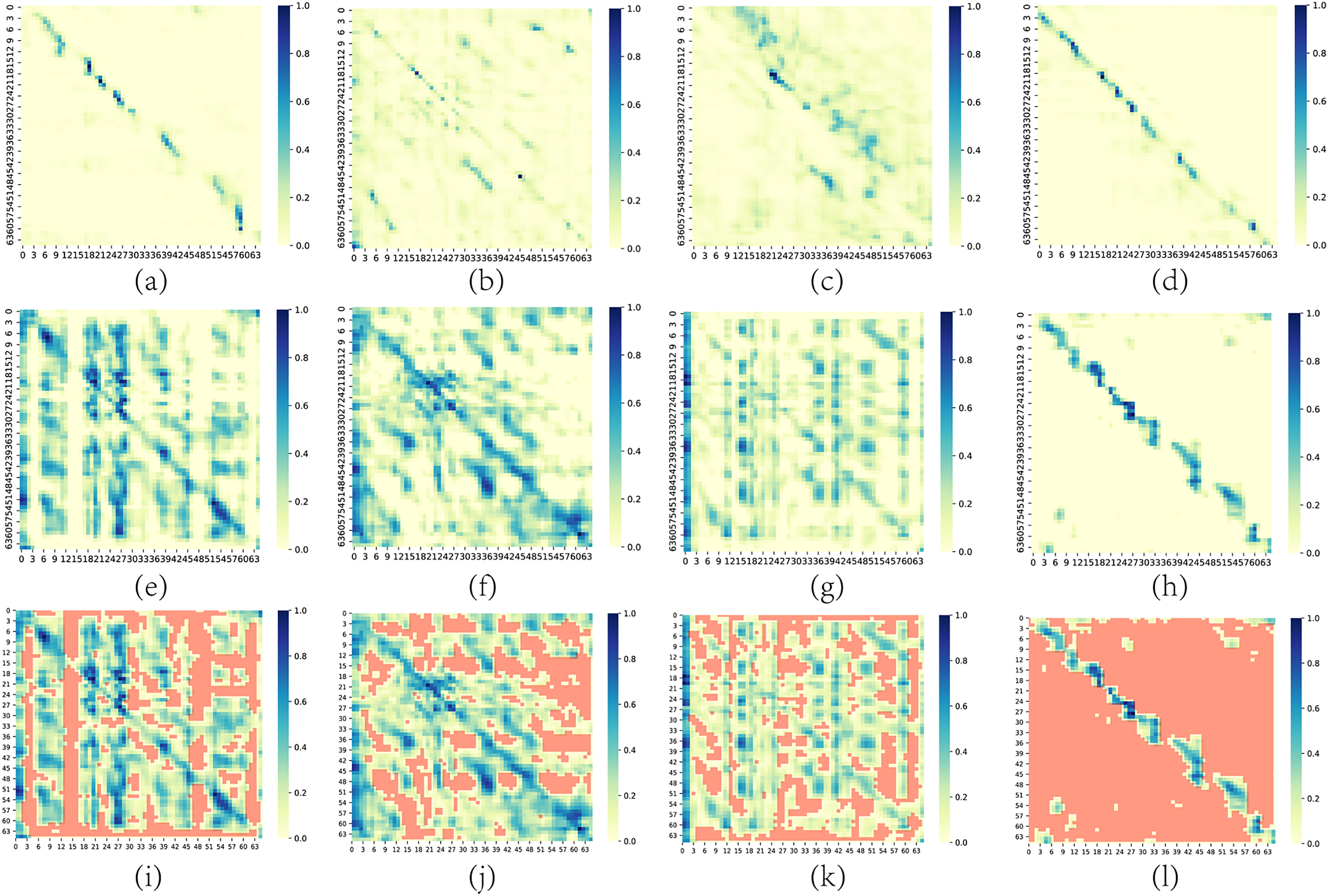

To further analyze the behavior of GSA module, we compare visualizations of multi-head attention maps from the same layer under both softmax-based and ReLU-based attention formulations. As illustrated in Fig. 4, subfigures (a–d) display the attention distributions from four heads (H0–H3) utilizing conventional softmax attention. These maps exhibit dense and smoothly varying patterns, indicating that each query attends broadly across the entire sequence, characteristic of fully connected attention. In contrast, subfigures (e–h) depict the corresponding attention heads under the ReLU-based sparse attention. These attention maps are significantly more localized and sparser, with a considerable proportion of entries explicitly set to zero. To enhance visual clarity, subfigures (i–l) highlight the zero-valued positions in red. Notably, the sparsity level across the ReLU-based attention maps approaches 50%, which contributes to a substantial reduction in computational complexity compared to the dense softmax attention. This balance between contextual expressiveness and computational efficiency positions GSA module as a compelling alternative to MHSA module, particularly for long-sequence modeling.

Figure 4: Visualization of attention maps. (a–d) show the attention distributions from the vanilla attention, while (e–h) depict those from the ReLU-based sparse attention. (i–l) further highlight the zero-valued regions in (e–h) by marking them in red for better visualization of the sparsity pattern. ‘H’ stands for ‘Head’

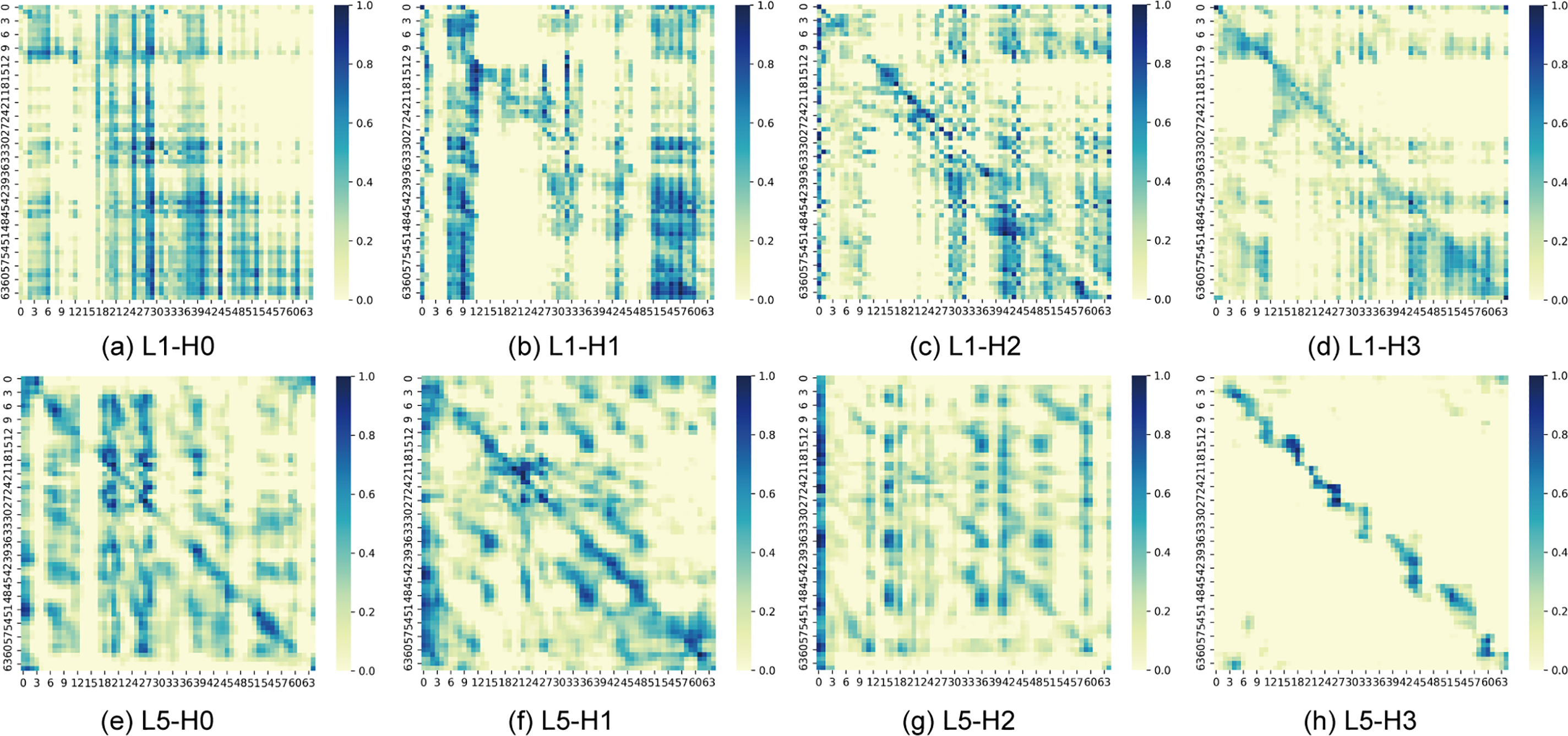

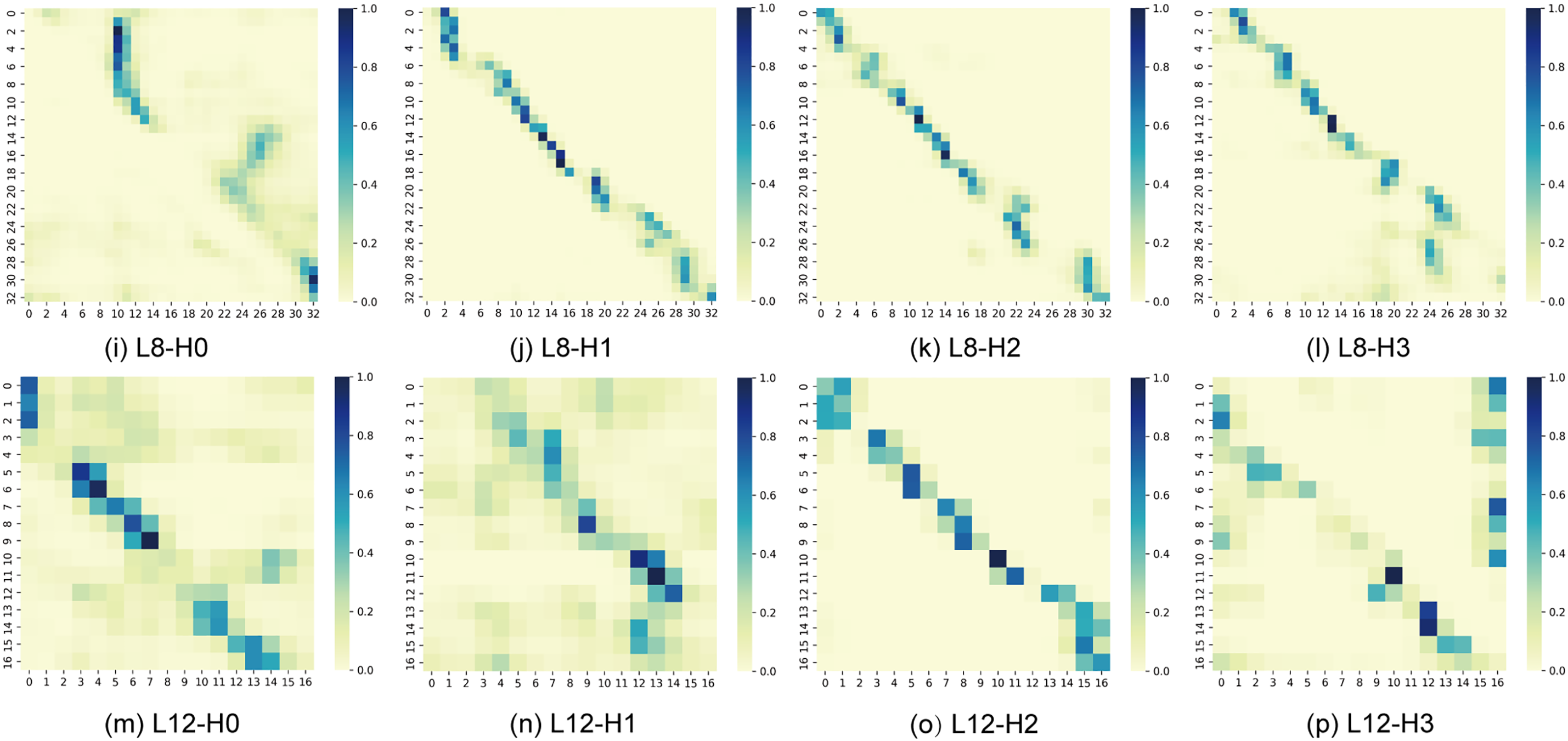

As shown in Fig. 5, the attention visualizations across layers reveal the model’s progressive learning behavior. In the early layers, the attention maps feature vertical narrow stripes, indicating that the model initially captures global dependencies, prioritizes easily generalizable low-level features, and highlights potentially important temporal segments as candidates for subsequent layers. With increasing depth, these vertical patterns become more fragmented, and clearer diagonal structures emerge, suggesting that the model gradually shifts toward local context modeling and structured temporal representation. After further downsampling, each token corresponds to a longer speech segment, enabling the model to reinforce local alignment. In deeper layers, the attention heads exhibit differentiated functions, with some maintaining weak global attention to preserve contextual coherence while emphasizing key tokens, whereas others focus more exclusively on discriminative information for final prediction. Overall, this progression reflects a hierarchical learning trajectory, evolving from global generalization to structured alignment and finally to high-level abstraction.

Figure 5: Attention visualizations from different layers. Lx-Hy denotes the y-th attention head of the x-th layer. (a–d) show the attention distributions of the first layer, (e–h) the fifth layer, (i–l) the eighth layer, and (m–p) the twelfth layer

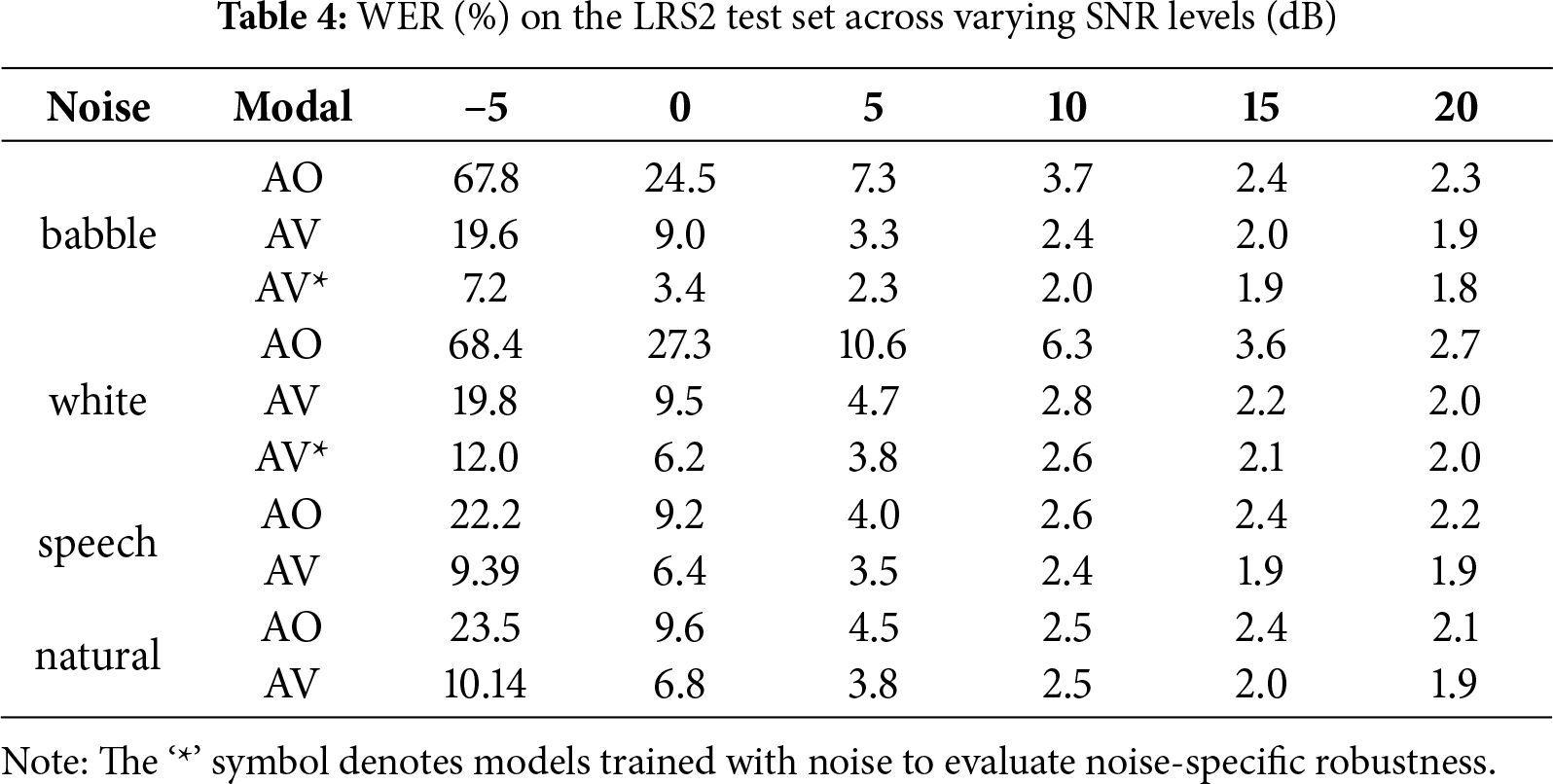

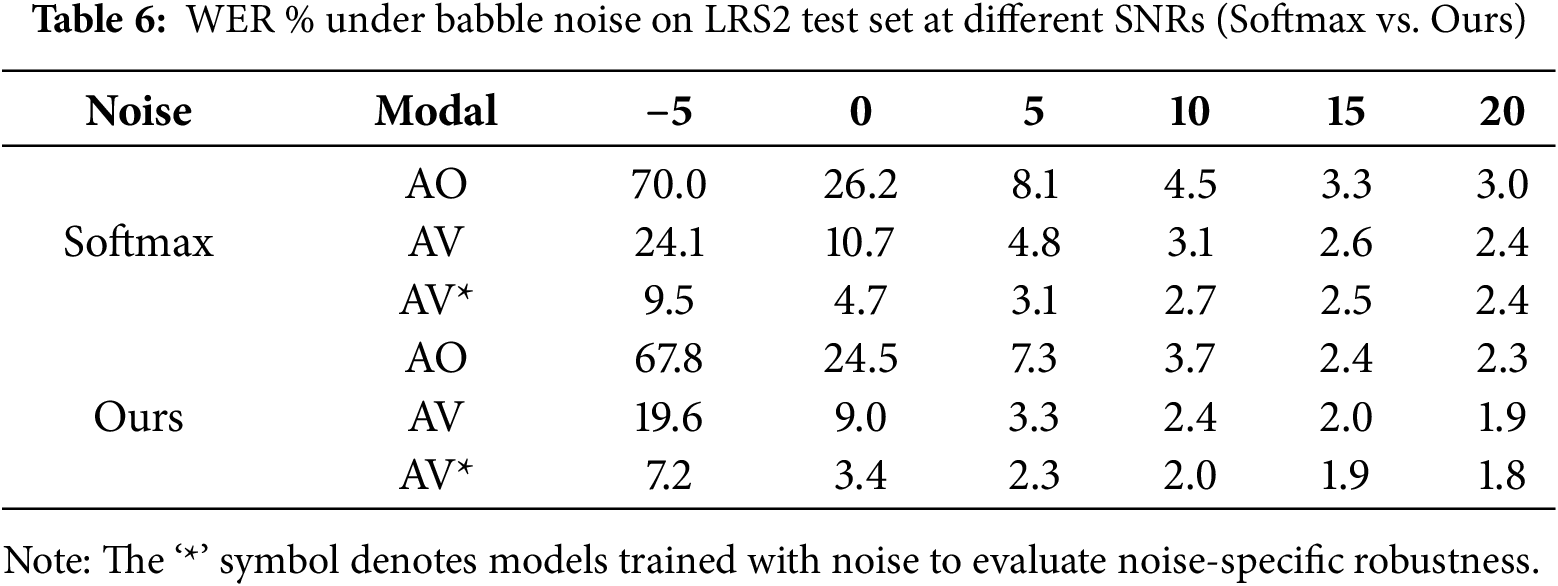

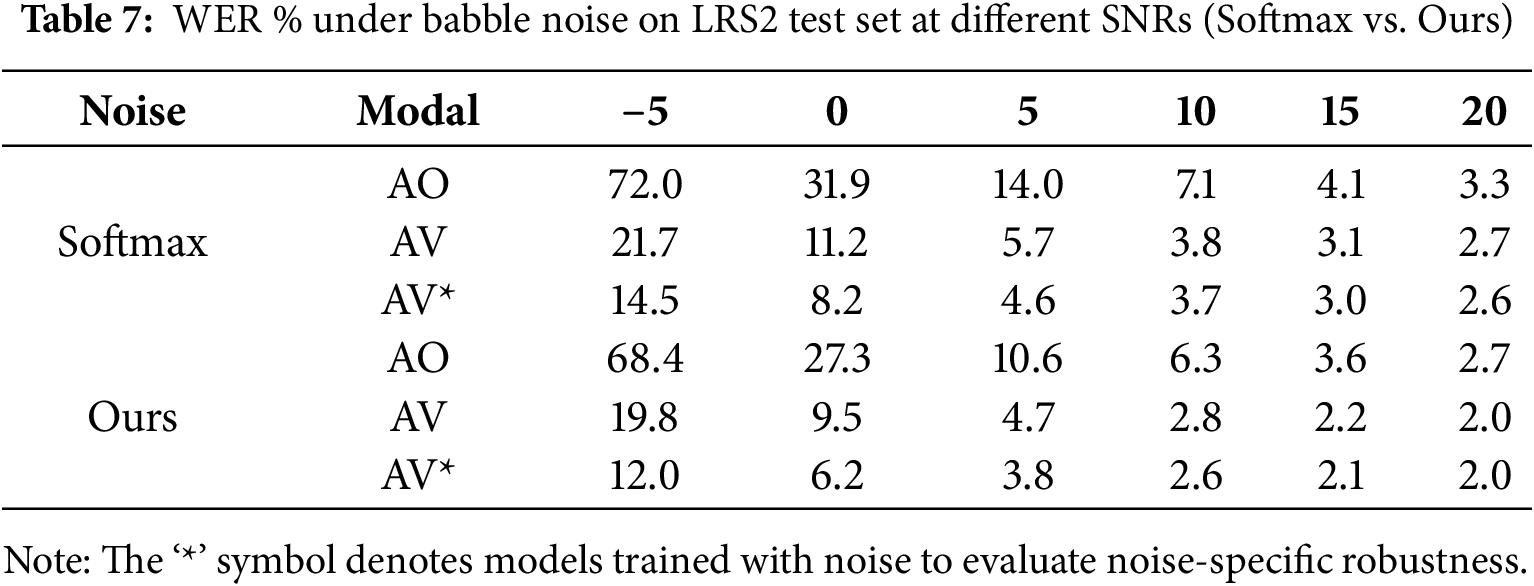

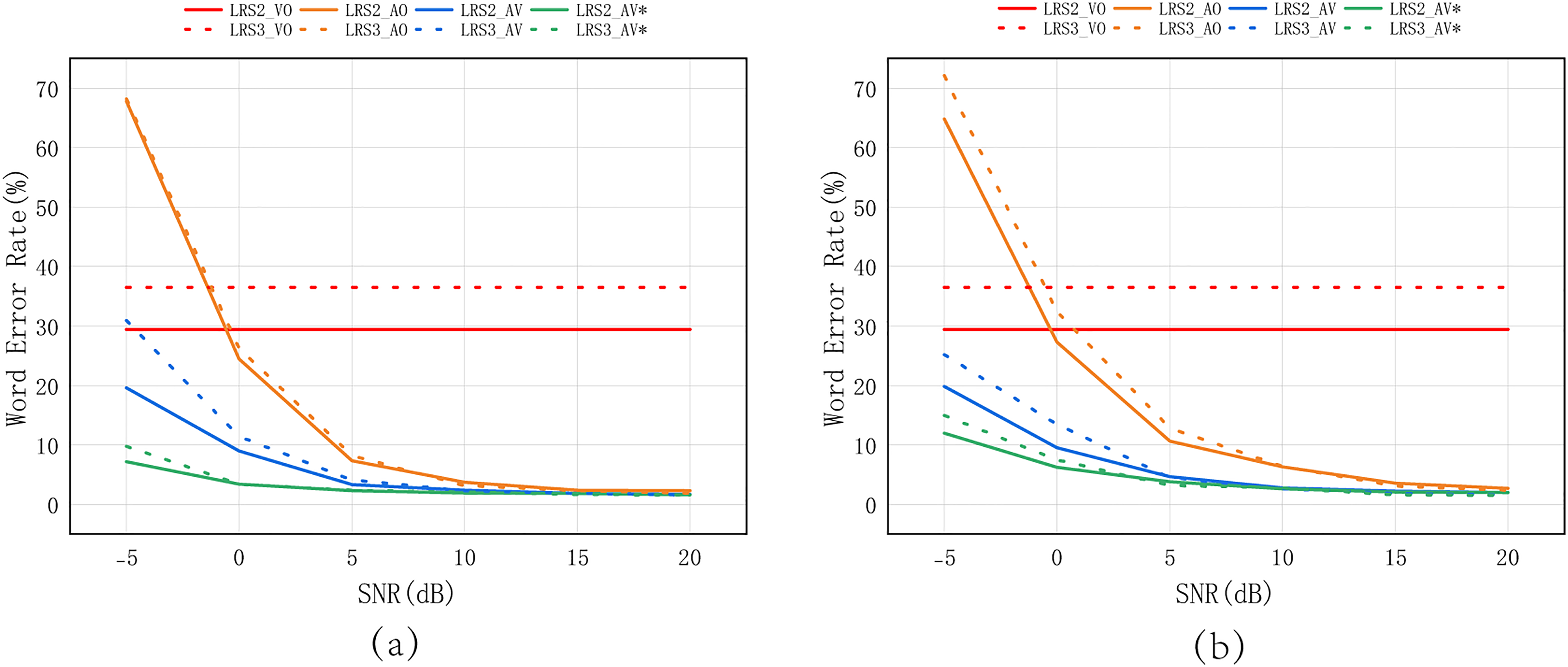

5.2 Noise Robustness Evaluation

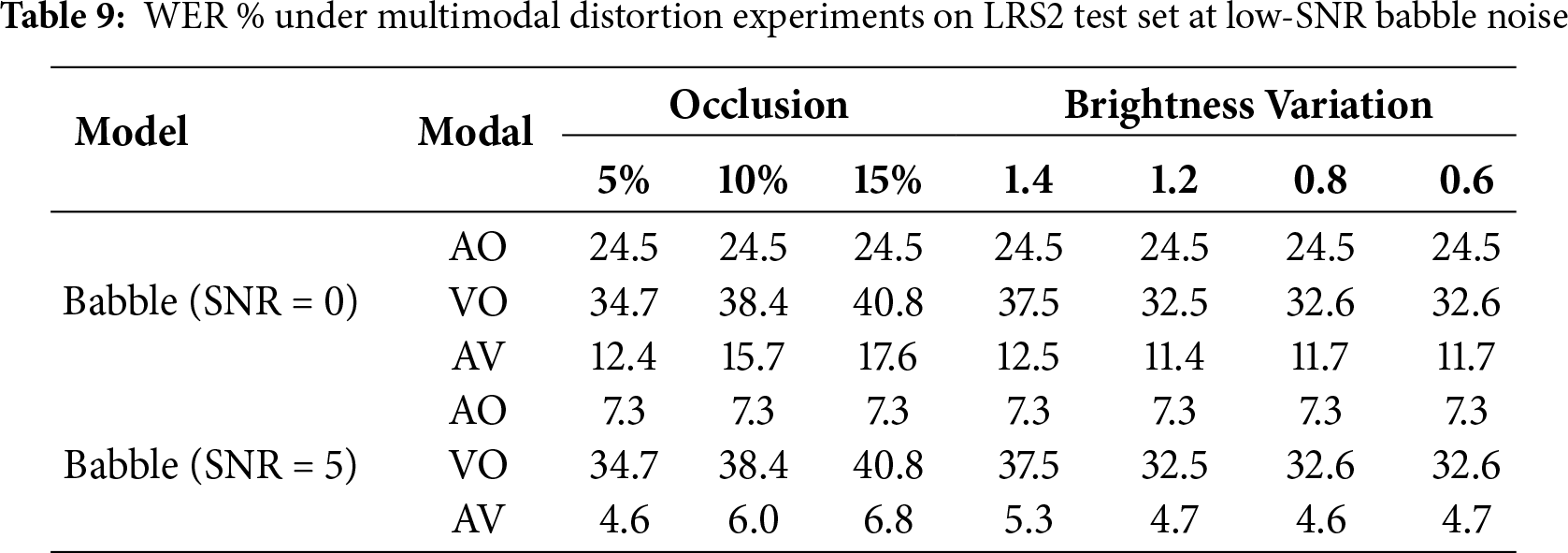

Environmental noise robustness is critical for deploying AVSR systems in real-world settings. To assess our model’s performance under noisy conditions, we conduct noise robustness experiments using babble, white, natural, and speech noises from the MUSAN corpus [61]. The evaluation is performed across a range of signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) from −5 dB to 20 dB, using WER as the evaluation metric. We also conduct visual robustness experiments, including random shape occlusion of the mouth region, in which 20% of the frames are randomly selected and three consecutive frames at each selected frame are masked with geometric shapes. The occlusion size is set to 5%, 10%, or 15% of the mouth region. In addition, global brightness variation is introduced by scaling the overall frame intensity. Finally, we design multimodal distortion experiments by combining low-SNR babble noise (0 and 5 dB) with the above visual distortions, thereby providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s resilience under multimodal distortions.

As shown in Tables 4 and 5, the AO model suffers increasing performance degradation with higher noise levels, highlighting its vulnerability to adverse acoustic conditions. In contrast, the integration of visual modality significantly enhances recognition performance under these challenging acoustic conditions, which highlights the effectiveness of multimodal fusion in enhancing robustness under adverse acoustic environments. Moreover, training the audio-visual (AVSR) model with noisy audio further improves robustness, indicating the effectiveness of noise-aware training strategies. The results also indicate that different noise types affect model performance to varying degrees. Babble and white noise induce the most severe degradation in the audio-only modality due to their broadband and overlapping spectral characteristics heavily mask speech information. In contrast, speech and natural noises cause relatively milder interference, since their spectral distributions overlap less with the target speech.

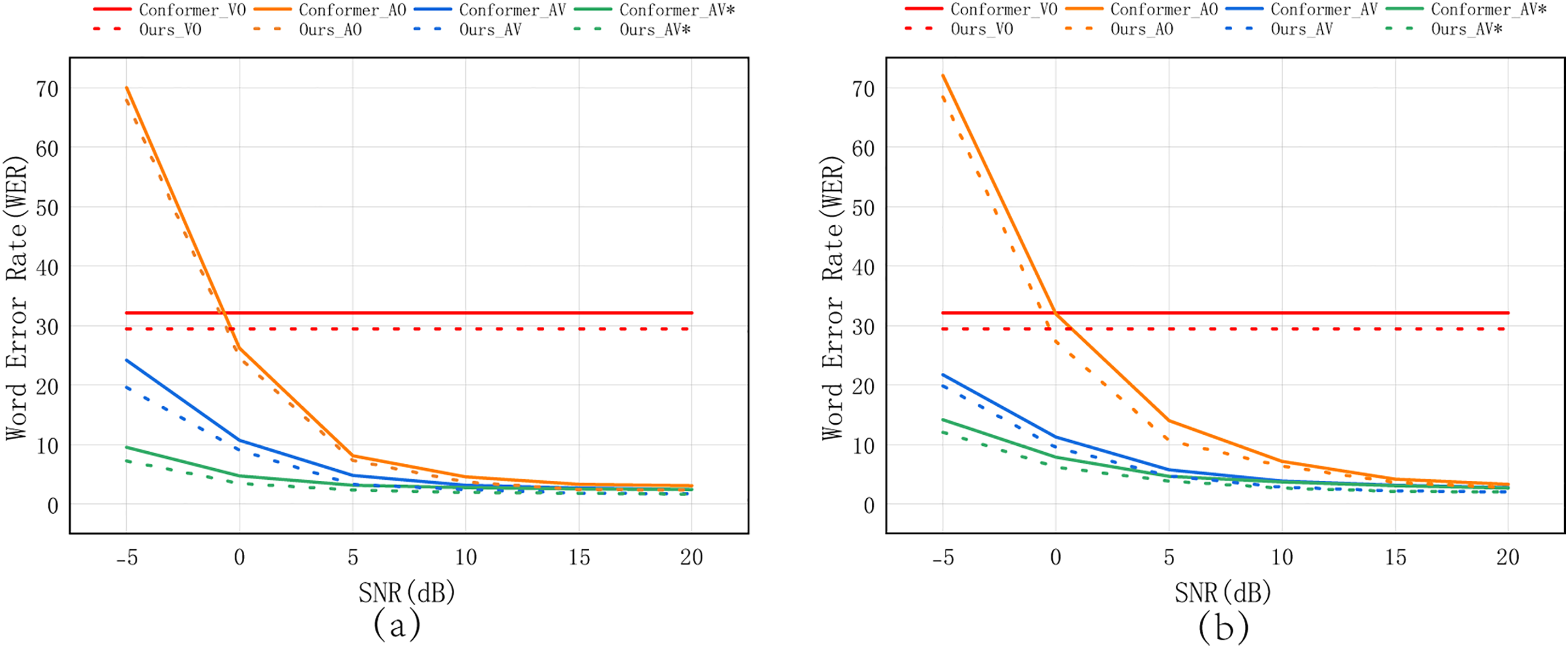

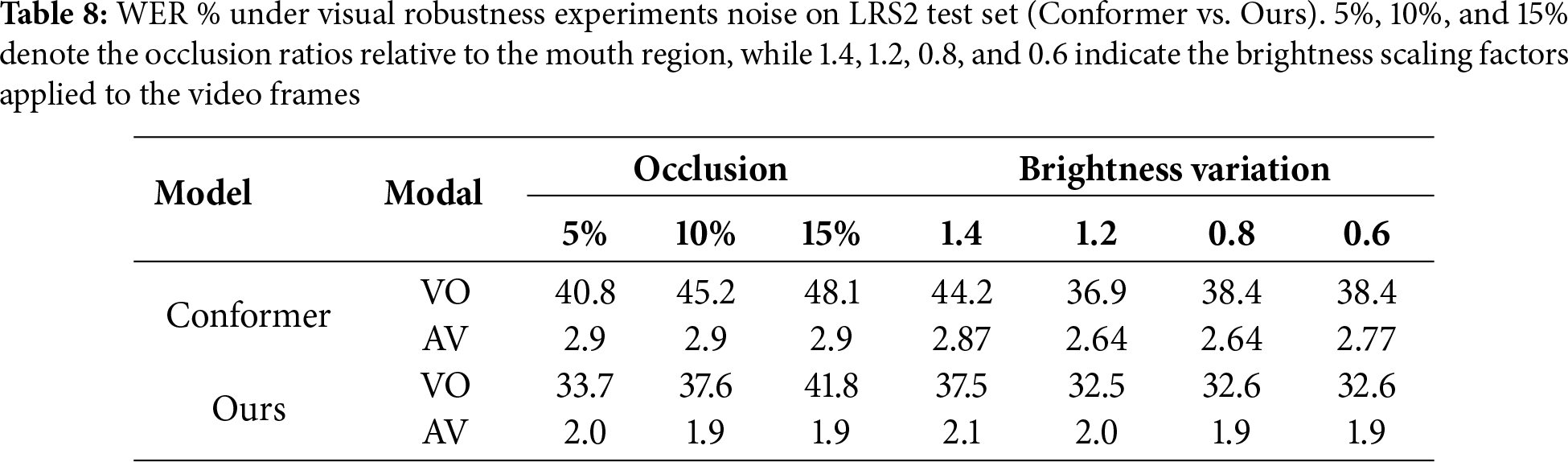

In addition, we compare our proposed model against a standard Conformer encoder-based AVSR baseline. As shown in Tables 6 and 7, our model consistently outperforms the baseline across all SNR levels and for both noise types. This performance gain underscores the noise tolerance of the proposed GSA mechanism, which effectively suppresses noisy activations and filters out irrelevant temporal frames. Figs. 6 and 7 intuitively present the performance changes shown in the tables.

Figure 6: Evaluation results of the proposed model under different signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) conditions (in decibels) on LRS2 and LRS3, tested separately in (a) babble noise and (b) white noise scenarios to assess robustness to background interference. The “*” symbol denotes models trained with noise to evaluate noise-specific robustness

Figure 7: Evaluation results comparing the proposed model with the Conformer baseline on the LRS2 dataset under varying SNRs levels, with separate assessments in (a) babble noise and (b) white noise environments. The “*” symbol denotes models trained with noise to evaluate noise-specific robustness

As shown in Tables 8 and 9, random mouth-region occlusion leads to a clear performance drop in the visual-only model, as it directly blocked critical lip cues. In contrast, when audio information is incorporated, the occlusion has little impact, as the audio-visual model could flexibly adjust its reliance on audio and visual modalities. Furthermore, brightness variation results in a smaller performance decrease, since structural information of the lips remained visible.

In the multimodal distortion experiments, where low-SNR babble noise is combined with visual distortions, the audio-visual model exhibits a further performance decline. This is because acoustic cues are largely masked by babble noise, while concurrent visual distortions reduce the reliability of lip movements, limiting the availability of clean features. Nevertheless, the model leverages stronger cross-temporal and cross-modal compensation mechanisms, achieving significantly lower WER than both audio-only and visual-only models. This demonstrates the robustness and advantage of multimodal fusion under severe environments.

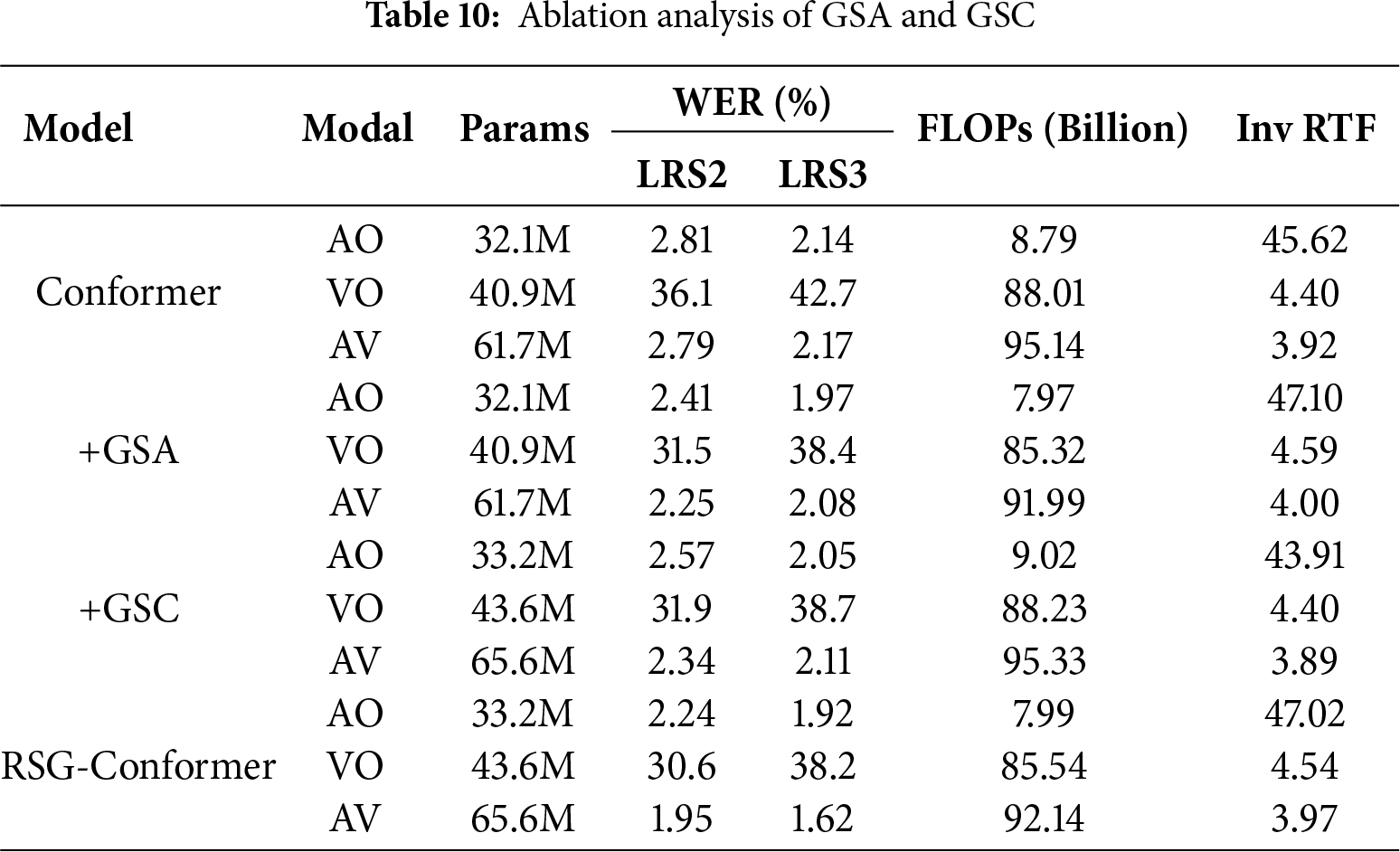

To assess the individual contributions of each proposed component, a series of ablation studies are conducted on both the LRS2 and LRS3 datasets. Specifically, we evaluate the impact of the GSA and GSC modules, where we not only compare their recognition performance, but also report computational efficiency in terms of Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) required to process a 10-s audio-visual sequence, as well as inverse real-time factor (Inv RTF). We further investigate alternative fusion strategies within the GSC design, and examine the effectiveness of depthwise convolution and the progressive weighting strategy employed in the RIC-CTC scheme. By incrementally enabling these components, we systematically analyze their respective influences on model performance in terms of WER. Under consistent training configurations, AO models are trained for 200 epochs, while both the VO and AV models undergo 50 epochs. The corresponding results of these controlled experiments are re-ported in Tables 8–10. and are further discussed in the following subsections.

Ablation experiments evaluate the individual and combined contributions of the proposed GSA and GSC modules. As shown in Table 10, incorporating the GSA alone yields a clear reduction in WERs on both LRS2 and LRS3 datasets, along with a noticeable efficiency gain, as reflected by lower FLOPs and higher Inv RTF. This improvement mainly comes from the sparse attention mechanism, which reduces redundant computation while retaining key dependencies. Independently replacing the standard convolution module in the Conformer block with GSC module also results in performance gains, though at the cost of increased FLOPs and reduced Inv RTF due to its multi-scale convolutional operations. This improvement can be attributed to its ability to adaptively model local temporal dynamics at multiple scales. When combined with GSA, the two modules complement each other, enabling the integrated model to achieve further reductions in WERs while simultaneously improving overall efficiency. These findings collectively verify the effectiveness of each proposed component and show that the redesigned back-end architecture offers significant improvements in modeling capacity.

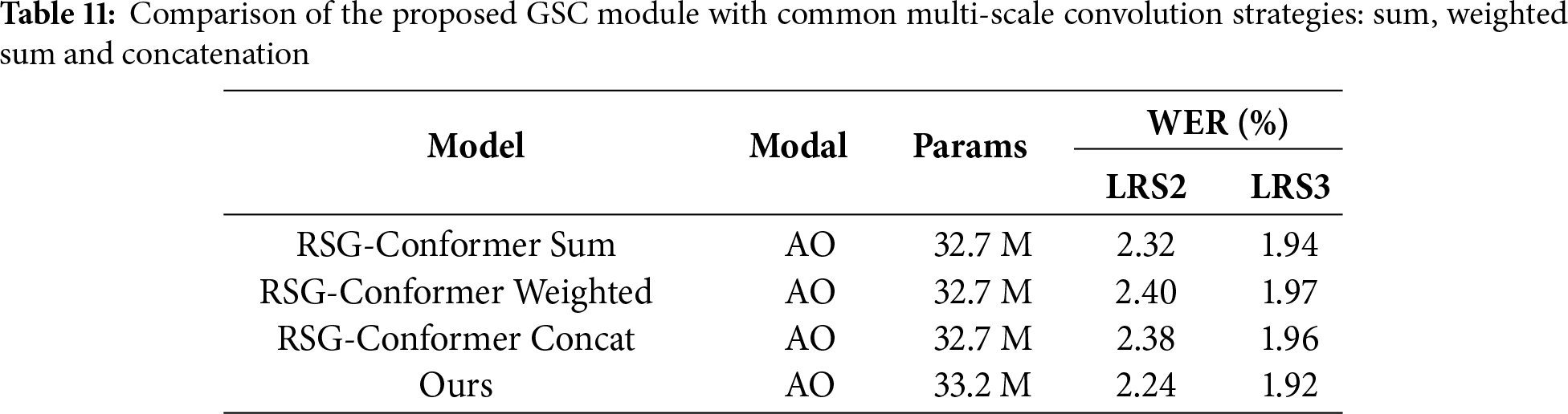

6.2 Comparison with Conventional Multi-Scale Convolution Methods

An extensive ablation analysis is carried out to compare the GSC module against several commonly used multi-scale convolution fusion strategies, including element-wise addition, learnable weighted summation, and concatenation-based integration. As shown in Table 11, although all these fusion methods lead to modest improvement in WER over the standard Conformer convolution, their gains are relatively limited when compared to the performance of GSC. These results suggest that simply increasing the receptive field diversity is insufficient for significant performance gains in the absence of effective cross-scale interaction. In contrast, our GSC module consistently achieves superior results, demonstrating its capacity to adaptively integrate information across different temporal scales in a structured and learnable manner. Overall, these findings highlight that although basic multi-scale aggregation provides some benefits, a principled and trainable fusion mechanism, as implemented in GSC, is crucial for fully exploiting temporal scale diversity in sequence modeling.

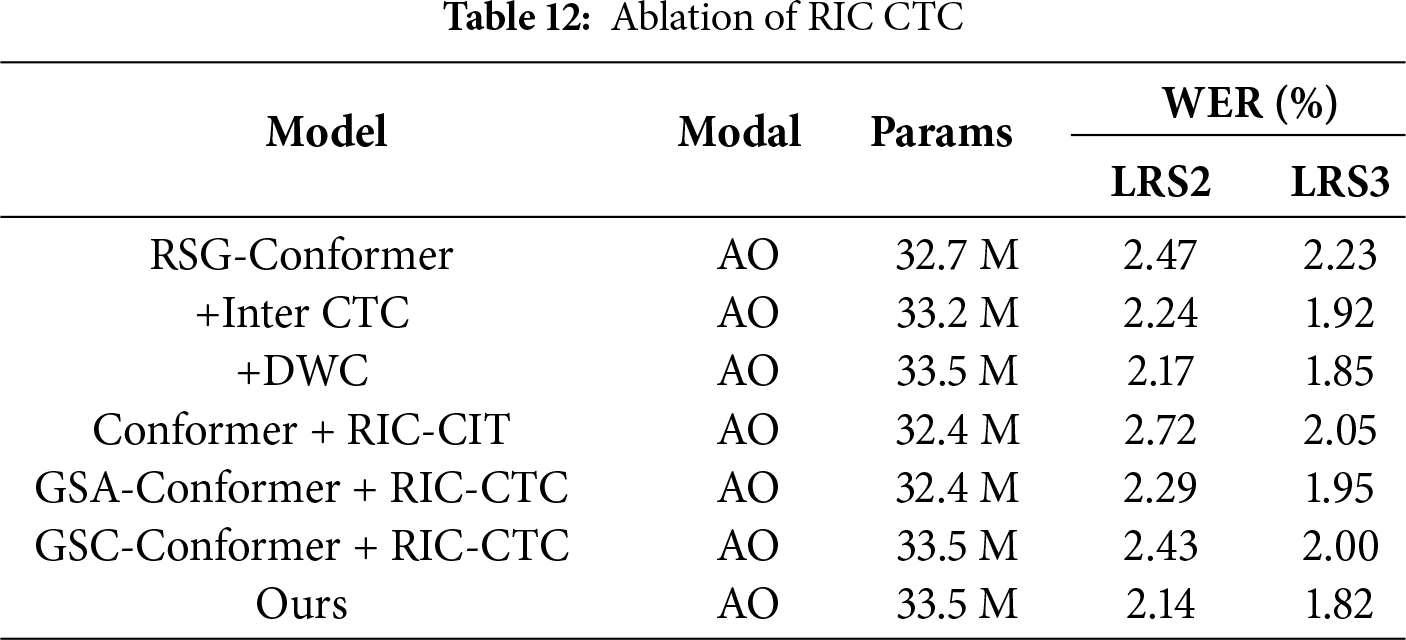

To evaluate the efficacy of our RIC-CTC design, we investigate both the impact of integrating a Depthwise Convolution (DWConv) layer and a progressive CTC weighting strategy, as well as its synergy with the proposed GSA and GSC models. As summarized in Table 12, introducing DWConv alone leads to improved performance over the standard residual InterCTC configuration. This gain can be attributed to DWConv’s capacity to alleviate the conditional independence assumption by aggregating contextual dependencies from neighboring frames. Building upon this, further improvement is observed when the uniform CTC loss weights are replaced with a progressive schedule, which assigns higher weights to deeper encoder layers that capture more abstract and discriminative representations. This strategy facilitates more effective gradient flow, encouraging the model to concentrate on higher-level semantic features that are critical for accurate prediction. Beyond these individual contributions, we also examine combinations such as Conformer + RIC-CTC, GSA-Conformer + RIC-CTC, and GSC-Conformer + RIC-CTC. The results consistently show that, while RIC-CTC alone improves performance, its integration with GSA or GSC yields further reductions in WER, highlighting the complementary and synergistic benefits of these modules.

In this work, we propose a novel RSG-Conformer framework for AVSR, which significantly enhances both the modeling capacity and applicability of AVSR systems. Specifically, an efficient GSA mechanism is introduced to promote attention sparsity and improve global context modeling, while improving computational efficiency without sacrificing performance. In parallel, the GSC module enhances the model’s flexibility in real-world scenarios. Moreover, we design an RIC-CTC strategy that relaxes the conditional independence assumption inherent in CTC frameworks, further improving model’s performance. These components are cohesively integrated to address the limitations of conventional backbones in modeling long-form and variable-length speech sequences. Extensive experiments on the LRS2 and LRS3 datasets demonstrate that our RSG-Conformer architecture consistently outperforms baseline models across audio-only, video-only, and audio-visual settings, achieving impressive WERs of 1.8% on LRS2 and 1.5% on LRS3.

Overall, this study provides a compact yet powerful AVSR framework that advances the modeling of multimodal speech signals and offers a promising foundation for developing efficient, robust, and scalable AVSR systems. While the model achieves improvements in both performance and efficiency, its FLOPs remain relatively high, posing challenges for deployment on low-resource devices. In future work, we plan to explore further model optimizations and validate the proposed framework on multilingual datasets to extend its applicability.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Xiangtan University for its strong support.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China: 61773330.

Author Contributions: Yewei Xiao: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, project administration; Xin Du: Conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization; Wei Zeng: Software, validation, formal analysis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The widely recognized LRW, LRS2, and LRS3 datasets, which are publicly available, are utilized in this study. These datasets were released with the necessary consents and licenses for research purposes, and we have strictly adhered to their terms of use. All ethical and data privacy considerations were carefully observed in our study. These datasets can be accessed via the following link: https://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/data/lip_reading/ (accessed on 01 April 2023).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Seide F, Li G, Yu D. Conversational speech transcription using context-dependent deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2011; 2011 Aug 27–31; Florence, Italy. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2011-169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bourlard HA, Morgan N. Connectionist speech recognition: a hybrid approach. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-3210-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hinton G, Deng L, Yu D, Dahl G, Mohamed AR, Jaitly N, et al. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: the shared views of four research groups. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2012;29(6):82–97. doi:10.1109/msp.2012.2205597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Feng S, Halpern BM, Kudina O, Scharenborg O. Towards inclusive automatic speech recognition. Comput Speech Lang. 2024;84(4):101567. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2023.101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Collobert R, Puhrsch C, Synnaeve G. Wav2Letter: an end-to-end ConvNet-based speech recognition system. arXiv:1609.03193. 2016. [Google Scholar]

6. Li J, Lavrukhin V, Ginsburg B, Leary R, Kuchaiev O, Cohen JM, et al. Jasper: an end-to-end convolutional neural acoustic model. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2019; 2019 Sep 15–19; Graz, Austria. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2019-1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Graves A. Sequence transduction with recurrent neural networks. arXiv:1211.3711. 2012. [Google Scholar]

8. Graves A, Mohamed AR, Hinton G. Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing; 2013 May 26–31; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 6645–9. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2013.6638947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dong L, Xu S, Xu B. Speech-transformer: a no-recurrence sequence-to-sequence model for speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2018 Apr 15–20; Calgary, AB, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 5884–8. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2018.8462506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Q, Lu H, Sak H, Tripathi A, McDermott E, Koo S, et al. Transformer transducer: a streamable speech recognition model with transformer encoders and RNN-T loss. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 7829–33. doi:10.1109/icassp40776.2020.9053896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yao Z, Guo L, Yang X, Kang W, Kuang F, Yang Y, et al. Zipformer: a faster and better encoder for automatic speech recognition. arXiv:2310.11230. 2023. [Google Scholar]

12. Chung JS, Zisserman A. Lip reading in the wild. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ACCV 2016; 2016 Nov 20–24; Taipei, Taiwan. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 87–103. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54184-6_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Assael YM, Shillingford B, Whiteson S, de Freitas N. LipNet: end-to-end sentence-level lipreading. arXiv:1611.01599. 2016. [Google Scholar]

14. Ahn YJ, Park J, Park S, Choi J, Kim KE. SyncVSR: data-efficient visual speech recognition with end-to-end crossmodal audio token synchronization. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2024; 2024 Sep 1–5; Kos, Greece. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2024-432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yeo JH, Kim M, Watanabe S, Ro YM. Visual speech recognition for languages with limited labeled data using automatic labels from whisper. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 10471–5. doi:10.1109/icassp48485.2024.10446720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Stafylakis T, Tzimiropoulos G. Combining residual networks with LSTMs for lipreading. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2017; 2017 Aug 20–24; Stockholm, Sweden. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2017-85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sheng C, Pietikäinen M, Tian Q, Liu L. Cross-modal self-supervised learning for lip reading: when contrastive learning meets adversarial training. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2021 Oct 20–24; Virtual. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 2456–64. doi:10.1145/3474085.3475415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Prajwal KR, Afouras T, Zisserman A. Sub-word level lip reading with visual attention. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 5152–62. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang C. Multi-grained spatio-temporal modeling for lip-reading. arXiv:1908.11618. 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. Afouras T, Chung JS, Senior A, Vinyals O, Zisserman A. Deep audio-visual speech recognition. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(12):8717–27. doi:10.1109/tpami.2018.2889052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Petridis S, Stafylakis T, Ma P, Tzimiropoulos G, Pantic M. Audio-visual speech recognition with a hybrid CTC/attention architecture. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT); 2018 Dec 18–21; Athens, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 513–20. doi:10.1109/slt.2018.8639643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Makino T, Liao H, Assael Y, Shillingford B, Garcia B, Braga O, et al. Recurrent neural network transducer for audio-visual speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU); 2019 Dec 14–18; Singapore. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 905–12. doi:10.1109/asru46091.2019.9004036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yu J, Zhang SX, Wu J, Ghorbani S, Wu B, Kang S, et al. Audio-visual recognition of overlapped speech for the LRS2 dataset. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 6984–8. doi:10.1109/icassp40776.2020.9054127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Khan M, Ahmad J, Gueaieb W, De Masi G, Karray F, El Saddik A. Joint multi-scale multimodal transformer for emotion using consumer devices. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(1):1092–101. doi:10.1109/TCE.2025.3532322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ma P, Petridis S, Pantic M. End-to-end audio-visual speech recognition with conformers. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021 Jun 6–11; Toronto, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 7613–7. doi:10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gulati A, Qin J, Chiu CC, Parmar N, Zhang Y, Yu J, et al. Conformer: convolution-augmented transformer for speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2020; 2020 Oct 25–29; Shanghai, China. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2020-3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shi B, Hsu WN, Mohamed A. Robust self-supervised audio-visual speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022; 2022 Sep 18–22; Incheon, Republic of Korea. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2022-99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Khan M, Tran PN, Pham NT, El Saddik A, Othmani A. MemoCMT: multimodal emotion recognition using cross-modal transformer-based feature fusion. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):5473. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-89202-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ma P, Haliassos A, Fernandez-Lopez A, Chen H, Petridis S, Pantic M. Auto-AVSR: audio-visual speech recognition with automatic labels. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Rhodes Island; 2023. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10096889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kim S, Jang K, Bae S, Kim H, Yun SY. Learning video temporal dynamics with cross-modal attention for robust audio-visual speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT); 2024 Dec 2–5; Macao, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 447–54. doi:10.1109/SLT61566.2024.10832305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Peng Y, Dalmia S, Lane I, Watanabe S. Branchformer: parallel MLP-attention architectures to capture local and global context for speech recognition and understanding. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

32. Kim K, Wu F, Peng Y, Pan J, Sridhar P, Han KJ, et al. E-branchformer: branchformer with enhanced merging for speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT); 2023 Jan 9–12; Doha, Qatar. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 84–91. doi:10.1109/slt54892.2023.10022656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li J, Li C, Wu Y, Qian Y. Unified cross-modal attention: robust audio-visual speech recognition and beyond. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2024;32:1941–53. doi:10.1109/taslp.2024.3375641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Beltagy I, Peters ME, Cohan A. Longformer: the long-document transformer. arXiv:2004.05150. 2020. [Google Scholar]

35. Qin Z, Sun W, Deng H, Li D, Wei Y, Lv B, et al. Cosformer: rethinking softmax in attention. arXiv:2202.08791. 2022. [Google Scholar]

36. Kitaev N, Kaiser Ł, Levskaya A. Reformer: the efficient transformer. arXiv:2001.04451. 2020. [Google Scholar]

37. Roy A, Saffar M, Vaswani A, Grangier D. Efficient content-based sparse attention with routing transformers. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2021;9(3):53–68. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Graves A, Fernández S, Gomez F, Schmidhuber J. Connectionist temporal classification: labelling unsegmented sequence data with recurrent neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning—ICML’06; 2006 Jun 25–29; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2006. p. 369–76. doi:10.1145/1143844.1143891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lee J, Watanabe S. Intermediate loss regularization for CTC-based speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021 Jun 6–11; Toronto, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 6224–8. doi:10.1109/icassp39728.2021.9414594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Djeffal N, Kheddar H, Addou D, Mazari AC, Himeur Y. Automatic speech recognition with BERT and CTC transformers: a review. In: Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Energy and Measurement (IC2EM); 2023 Nov 28–29; Medea, Algeria. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/IC2EM59347.2023.10419784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ramachandran P, Zoph B, Le QV. Searching for activation functions. arXiv:1710.05941. 2017. [Google Scholar]

42. Lu Y, Li Z, He D, Sun Z, Dong B, Qin T, et al. Understanding and improving transformer from a multi-particle dynamic system point of view. arXiv:1906.02762. 2019. [Google Scholar]

43. Afouras T, Chung JS, Zisserman A. LRS3-TED: a large-scale dataset for visual speech recognition. arXiv:1809.00496. 2018. [Google Scholar]

44. Deng J, Guo J, Ververas E, Kotsia I, Zafeiriou S. Retinaface: single-shot multi-level face localisation in the wild. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 5202–11. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bulat A, Tzimiropoulos G. How far are we from solving the 2D & 3D face alignment problem? (and a dataset of 230,000 3D facial landmarks). In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 1021–30. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Kudo T, Richardson J. SentencePiece: a simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for neural text processing. arXiv:1808.06226. 2018. [Google Scholar]

47. Park DS, Zhang Y, Chiu CC, Chen Y, Li B, Chan W, et al. Specaugment on large scale datasets. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 6879–83. doi:10.1109/icassp40776.2020.9053205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ma P, Petridis S, Pantic M. Visual speech recognition for multiple languages in the wild. Nat Mach Intell. 2022;4(11):930–9. doi:10.1038/s42256-022-00550-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Burchi M, Timofte R. Audio-visual efficient conformer for robust speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2023 Jan 2–7; Waikoloa, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 2258–67. doi:10.1109/wacv56688.2023.00229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2015. [Google Scholar]

51. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:1–11. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Afouras T, Chung JS, Zisserman A. ASR is all you need: cross-modal distillation for lip reading. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 2143–7. doi:10.1109/icassp40776.2020.9054253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Xu B, Lu C, Guo Y, Wang J. Discriminative multi-modality speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 14421–30. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Kim S, Jang K, Bae S, Cho S, Yun SY. MoHAVE: mixture of hierarchical audio-visual experts for robust speech recognition. arXiv:2502.10447. 2025. [Google Scholar]

55. Serdyuk D, Braga O, Siohan O. Audio-visual speech recognition is worth 32 × 32 × 8 voxels. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU); 2021 Dec 13–17; Cartagena, Colombia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 796–802. doi:10.1109/asru51503.2021.9688191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Haliassos A, Ma P, Mira R, Petridis S, Pantic M. Jointly learning visual and auditory speech representations from raw data. arXiv:2212.06246. 2022. [Google Scholar]

57. Haliassos A, Mira R, Chen H, Landgraf Z, Petridis S, Pantic M. Unified speech recognition: a single model for auditory, visual, and audiovisual inputs. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;37:1–27. [Google Scholar]

58. Haliassos A, Zinonos A, Mira R, Petridis S, Pantic M. BRAVEn: improving self-supervised pre-training for visual and auditory speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 11431–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10448473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Yeo JH, Rha H, Park SJ, Ro YM. MMS-LLaMA: efficient LLM-based audio-visual speech recognition with minimal multimodal speech tokens. In: Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025; 2025 Jul 27–Aug 1; Vienna, Austria. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2025. p. 20724–35. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.findings-acl.1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Cappellazzo U, Kim M, Chen H, Ma P, Petridis S, Falavigna D, et al. Large language models are strong audio-visual speech recognition learners. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2025 Apr 6–11; Hyderabad, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10889251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Snyder D, Chen G, Povey D. MUSAN: a music, speech, and noise corpus. arXiv:1510.08484. 2015. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools