Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CCLNet: An End-to-End Lightweight Network for Small-Target Forest Fire Detection in UAV Imagery

1 Hunan Automotive Engineering Vocational University, Zhuzhou, 412001, China

2 College of Forestry, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, 410004, China

* Corresponding Author: Gui Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 58 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072172

Received 21 August 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Detecting small forest fire targets in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) images is difficult, as flames typically cover only a very limited portion of the visual scene. This study proposes Context-guided Compact Lightweight Network (CCLNet), an end-to-end lightweight model designed to detect small forest fire targets while ensuring efficient inference on devices with constrained computational resources. CCLNet employs a three-stage network architecture. Its key components include three modules. C3F-Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (C3F-CGLU) performs selective local feature extraction while preserving fine-grained high-frequency flame details. Context-Guided Feature Fusion Module (CGFM) replaces plain concatenation with triplet-attention interactions to emphasize subtle flame patterns. Lightweight Shared Convolution with Separated Batch Normalization Detection (LSCSBD) reduces parameters through separated batch normalization while maintaining scale-specific statistics. We build TF-11K, an 11,139-image dataset combining 9139 self-collected UAV images from subtropical forests and 2000 re-annotated frames from the FLAME dataset. On TF-11K, CCLNet attains 85.8% mAP@0.5, 45.5% mean Average Precision (mAP)@[0.5:0.95], 87.4% precision, and 79.1% recall with 2.21 M parameters and 5.7 Giga Floating-point Operations Per Second (GFLOPs). The ablation study confirms that each module contributes to both accuracy and efficiency. Cross-dataset evaluation on DFS yields 77.5% mAP@0.5 and 42.3% mAP@[0.5:0.95], indicating good generalization to unseen scenes. These results suggest that CCLNet offers a practical balance between accuracy and speed for small-target forest fire monitoring with UAVs.Keywords

With the intensification of climate change, the frequency of forest fires is increasing, causing enormous ecological damage and economic losses. Once a forest fire occurs, it can spread rapidly when conditions are right, making early intervention crucial for effective fire suppression [1]. Detecting forest fire ignition points in their early stages, especially small-scale fires in complex forest scenes, is crucial for preventing catastrophic outbreaks [2,3].

Traditional forest fire monitoring methods, such as satellite remote sensing [4,5], fixed watchtower surveillance [6,7], and ground patrols [8], have played an important role over the past few decades. However, their performance is limited by weather conditions, spatial coverage, and operational costs, making reliable real-time monitoring difficult in complex field environments. The emergence of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has brought new possibilities for rapid and flexible fire monitoring, enabling multi-view data acquisition and timely situational awareness [9,10]. In typical UAV monitoring, especially at altitudes of 50–100 m, small-target flames may occupy less than 1% of the entire image area [8], posing a significant challenge to traditional detection frameworks.

Recent advances in deep learning have made computer vision–driven object detection a promising solution for enhancing UAV-based forest fire surveillance. Two-stage detection frameworks such as Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN) and its variants [11–13] provide high-precision and robust feature extraction capabilities, but their reliance on region proposals often incurs significant computational overhead, limiting their application in real-time aerial scenarios. In contrast, single-stage detectors such as Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [14] and You Only Look Once (YOLO)-based [15–17] can perform classification and localization in a single pass. This high efficiency has made the models based single-stage detector widely used for detection in forest fire and industrial environments [18–20]. For instance, Gonçalves et al. demonstrated that YOLO variants can reliably detect smoke and flames in both ground and aerial imagery [8]; Wang et al. proposed Fs-YOLO, an improved YOLOv7 that boosts fire-smoke detection accuracy by up to 6.4% mean Average Precision (mAP) on custom datasets [18], further emphasizing the effectiveness of end-to-end detection frameworks for UAV-based forest fire monitoring.

Recent studies have attempted to tackle the difficulty of small-target detection in aerial fire images by combining lightweight backbone networks [21], attention mechanisms [22], and multi-scale feature fusion strategies [23]. For example, network compression and attention-enhanced feature pyramids have been used to improve the detection performance of drones [21–23], while other studies have integrated optimized loss functions and specialized detection heads to enhance robustness to false positives [24]. Although these methods have achieved significant improvements in accuracy, they often increase computational complexity or fail to fully address the visual variations of small flames in complex forest fire environments [25]. These limitations highlight the need for a model that is both lightweight and capable of maintaining robustness against smoke occlusion, background clutter, and scale variation in UAV-based small-fire scenarios. Building on these objectives, our network architecture was designed with two guiding principles: first, to enhance small-target feature representation without inflating model size; second, to streamline computational flow for deployment on UAV or other resource-limited platforms.

This study proposes Context-guided Compact Lightweight Network (CCLNet), an end-to-end lightweight detection network designed specifically for early and small forest fire detection from UAV imagery. The network integrates three core innovations:

• The computationally efficient local context-aware unit C3F-Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (C3F-CGLU) reduces redundant operations while improving spatial detail preservation.

• The Context-Guided Feature Fusion Module (CGFM) enhances multi-scale feature fusion and improves the representation of small fires in visually complex scenes.

• The Lightweight Shared Convolution with Separated Batch Normalization Detection (LSCSBD) head minimizes the number of parameters without sacrificing accuracy across object sizes.

Comprehensive experiments on our self-constructed UAV forest fire dataset TF-11K, demonstrate that CCLNet achieves excellent performance in small object detection while maintaining low computational cost, making it well suited for edge deployment in real-time forest fire monitoring systems. The following section details the overall architecture and the functional role of each component.

We created a forest fire detection dataset named TF-11K for model training and evaluation, which consists of 11,139 images split into 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing. The TF-11K integrates self-collected UAV-based forest fire imagery with publicly available datasets, covering scenarios from early ignition to large-scale suppression and offering comprehensive scale coverage. All images were annotated using LabelImg with a unified “fire” label format to ensure annotation consistency.

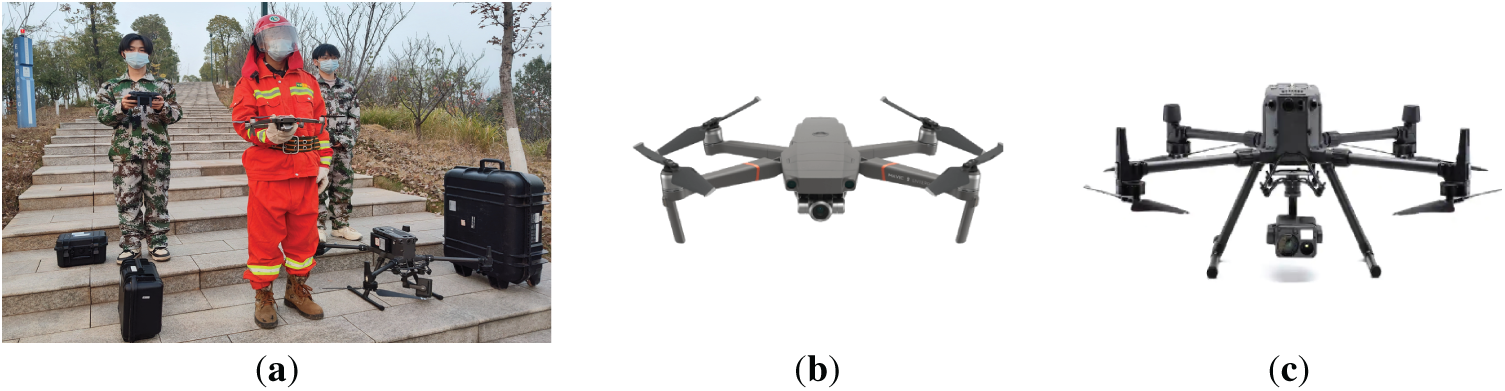

The self-collected portion includes 9139 images captured for task-specific preprocessing, emphasizing dynamic fire evolution, multi-perspective observations, small-target and medium-scale features, and complex background interference. These images document the full lifecycle of fire events—from ignition to suppression—under diverse conditions. Data collection took place in a subtropical forested area in Zhuzhou City, Hunan Province, China, representative of southern China’s hilly forest ecosystems. The data collection experiment employed an air-ground collaborative observation model commonly used in frontline firefighting operations. UAV platforms included: DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual (0–50 m altitude) and DJI Matrice 300 RTK (50–100 m altitude). Fig. 1 illustrates selected experimental scenes and custom equipment configurations used in this study.

Figure 1: Field data collection setup. Panels (a–c) show: (a) the firefighting team equipped with specialized monitoring devices; (b) the DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual UAV platform; and (c) the Matrice 300 RTK UAV equipped with an H20T camera

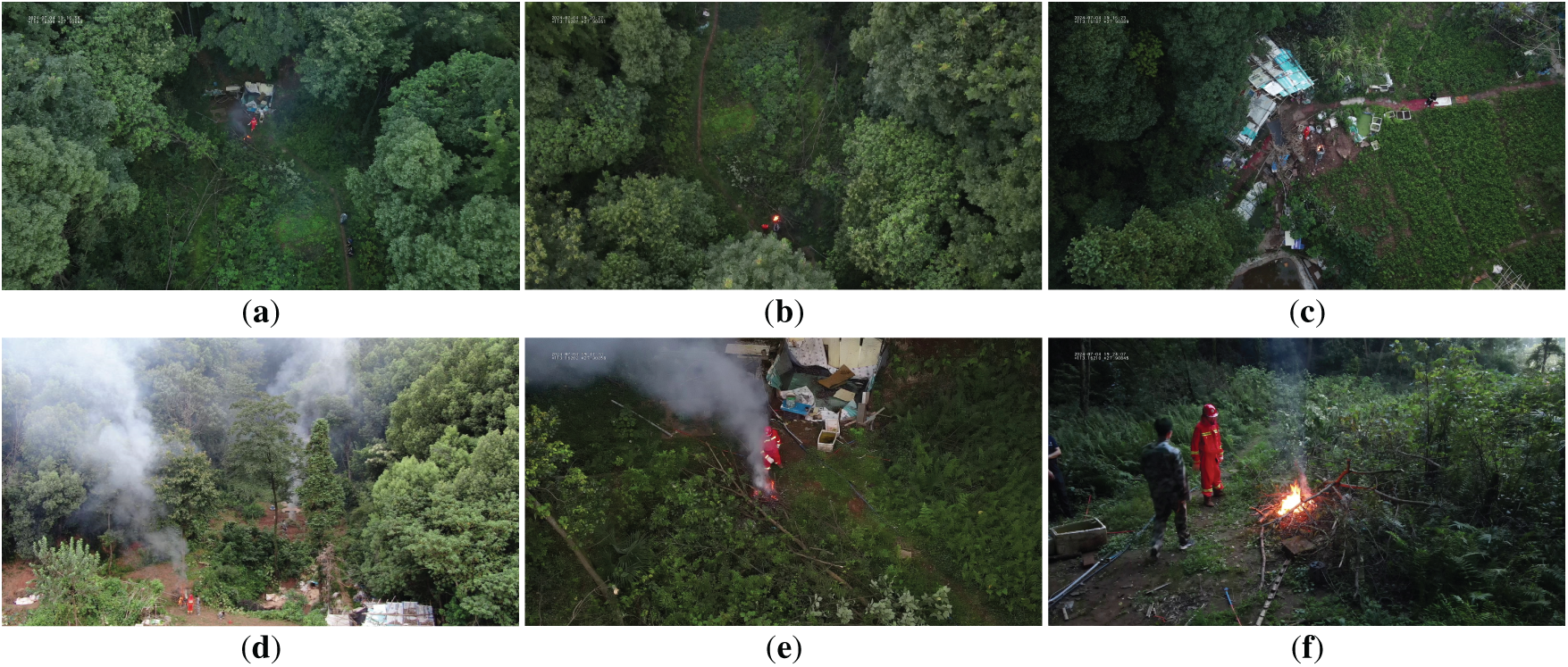

To ensure dataset diversity, the collection process covered multiple environmental conditions, including varying illumination levels, different vegetation densities, and scenarios with different degrees of smoke interference. UAVs also captured images at multiple altitudes. This diversity improves the robustness of the trained model, enabling it to better handle the challenges of real-world forest fire monitoring. Fig. 2 presents representative scenes from the self-collected dataset, where Fig. 2a–c depicts high-altitude views, while sub-Fig. 2d–f corresponds to medium-and low-altitude perspectives.

Figure 2: Representative forest fire scenes of the self-collected forest fire dataset. Panels (a–f) show fires captured from different UAV altitudes: (a–c) high-altitude imagery highlighting large-area environmental context, and (d–f) medium-and low-altitude imagery emphasizing fine-grained flame features and localized fire behavior

To further ensure annotation quality, we adopted a dual-review mechanism: each image was independently labeled by two experts using the LabelImg tool. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions, and the final inter-annotator agreement score reached 0.92. This process minimized subjectivity and ensured consistent labeling quality across the entire TF-11K dataset.

The access link for the self-collected dataset is provided in the Data Availability Statement section, and the dataset will be publicly released upon acceptance of this paper.

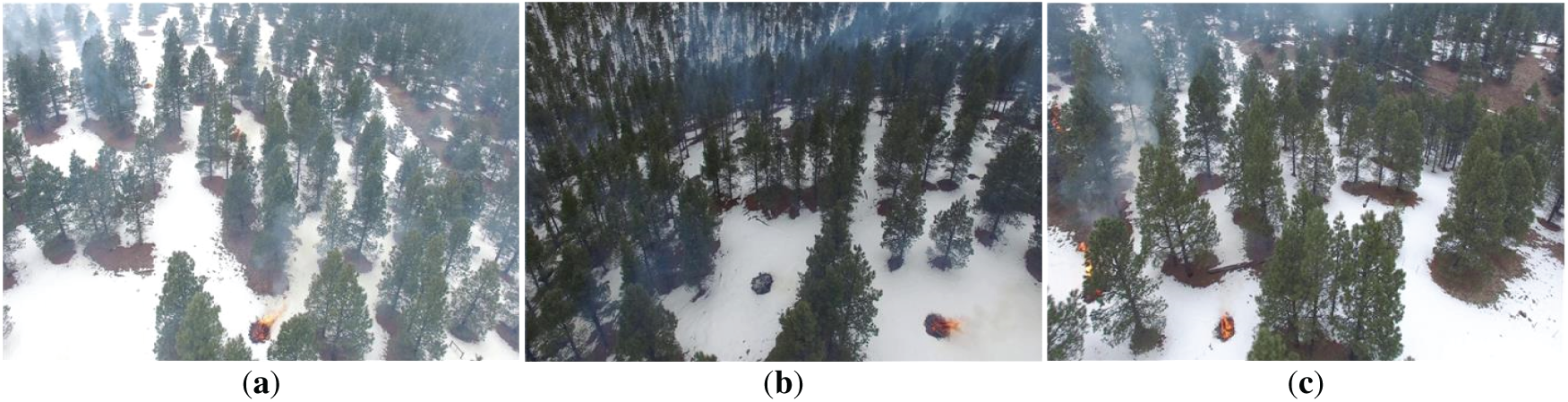

The public portion of TF-11K consists of 2000 reannotated images from the Flame dataset [26]. These data were collected using UAV platforms during controlled pile-burning operations in pine forests of Arizona. They include both visible and thermal video frames for classification and pixel-level segmentation tasks. Re-annotating and including these frames enhance the generalization capability of the trained model by introducing diverse visual patterns and complex forest backgrounds into TF-11K. Fig. 3 presents representative scenes from the Flame dataset.

Figure 3: Representative forest fire scenes of the FLAME, captured from UAV perspectives during prescribed pile burning in an Arizona pine forest. Panels (a–c) show the same fire captured from different UAV viewing angles as the drone circled over the fire site

To assess how well the proposed model generalizes across different datasets, we employed the Dataset for Fire and Smoke (DFS) [27] exclusively for cross-dataset validation. The DFS dataset contains 9462 high-quality images collected from diverse real-world scenes and annotated into three categories: ‘fire’, ‘smoke’, and ‘other’—where the latter refers to objects with fire-like color or brightness that may cause false alarms. This dataset covers a broad range of fire appearances, smoke densities, and challenging distractors, making it well suited for evaluating robustness in unseen domains. Fig. 4 presents representative scenes from the DFS dataset.

Figure 4: Typical forest fire scenes from the DFS. Panels (a–c) show the same type of fire observed under different conditions: (a) close-range view, (b) distant view with heavy smoke, and (c) nighttime wide-area fire

2.2 CCLNet Network Architecture

2.2.1 Overall Architecture Design

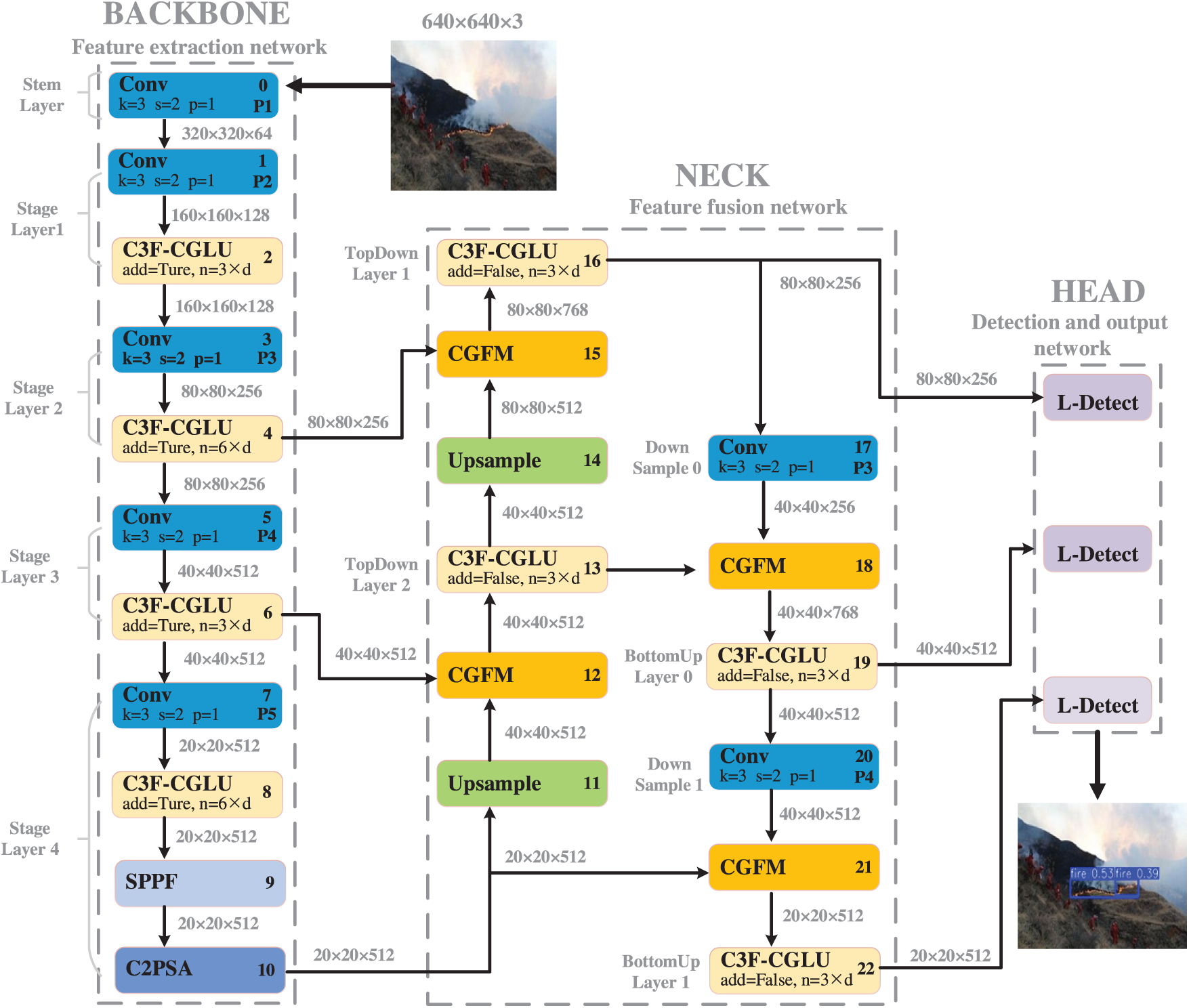

The proposed CCLNet adopts a three-stage architecture (Fig. 5). Feature extraction network (Backbone) is responsible for multi-scale feature extraction from UAV images, enhanced with the proposed C3F-CGLU module for efficient small-flame detection. Feature fusion network (Neck) is designed to integrate features from different scales using the proposed CGFM, improving the representation of subtle flame patterns in complex forest backgrounds. Detection and output network (Head) is implemented as the Lightweight Shared Convolution with LSCSBD, enabling efficient multi-scale detection with reduced parameters.

Figure 5: Network architecture of CCLNet

The parameters in Fig. 5 are as follows: k denotes the convolution kernel size, s represents the stride, and p indicates the padding size. n specifies the number of repeated modules, while d refers to the depth multiplier, which adjusts the network depth according to the model scale. These parameters collectively determine the receptive field, feature map resolution changes, and depth configuration of the convolutional operations.

In this study, we introduced three targeted design to address the challenges of small-target flame detection in UAV imagery. C3F-CGLU optimizes local feature extraction while reducing redundant computation, particularly for small-scale flames that occupy less than 1% of the image area. CGFM replaces standard concatenation with attention-guided feature fusion to amplify discriminative features while suppressing background noise. LSCSBD reduces the number of parameters through convolution sharing while preserving scale-specific statistics via independent batch normalization layers. The proposed design provides an effective trade-off among accuracy, inference speed, and model compactness, enabling practical real-time use on UAV platforms with limited computational resources.

2.2.2 The C3F-CGLU Architecture for Enhanced Flame Detection

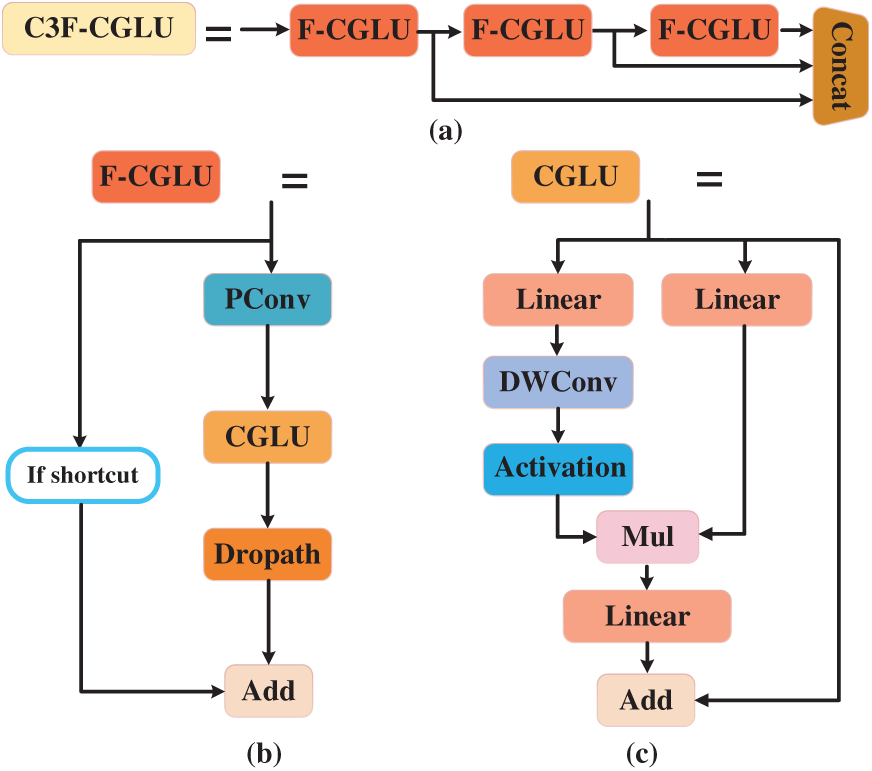

In the backbone network, we used the C3F-CGLU module (Fig. 6a), whose complete mathematical formulation is given by Formula (1). The C3F-CGLU incorporates a Faster-Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (F-CGLU) module through two synergistic innovations. The F-CGLU module is a customized design based on the Gated Linear Unit (GLU) [28] to improve the efficiency of small-target flame feature extraction. The original GLU, introduced in language modeling, employs an element-wise multiplicative gating mechanism to enhance convergence speed and gradient propagation performance.

Figure 6: Structure of C3F-CGLU. Panels (a–c) show different components of the module: (a) the overall C3F-CGLU structure, (b) the Faster Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (F-CGLU) decomposition, and (c) the Convolutional Gated Linear Unit (CGLU) decomposition

As illustrated in Fig. 6b, the F-CGLU module combines Partial Convolution (PConv) [29] and CGLU to optimize feature processing. The F-CGLU Block architecture employs an optimized feature processing pipeline that integrates several key components to achieve efficient computation while preserving feature integrity. The pipeline begins with PConv, a partial convolution operation that selectively processes input channels while maintaining spatial details. This is followed by a conditional shortcut path that preserves the original features when activated. The refined features generated through the CGLU (whose gating mechanism is detailed in Formula (3)) and DropPath [30] mechanisms are subsequently combined with the original features via residual connections. This design ensures robust gradient propagation during training while maintaining feature consistency. By incorporating selective channel processing, adaptive feature enhancement, and residual learning, the F-CGLU Block achieves an effective balance between computational efficiency and representational capacity. This structured approach facilitates stable training dynamics while minimizing information loss, making it suitable for deep neural network architectures requiring both high performance and parameter efficiency. Formula (2) provides the complete mathematical definition of this F-CGLU transformation.

The PConv improves computational efficiency by selectively processing only a subset of input channels while preserving high-frequency flame details through identity mapping of the remaining channels, thereby reducing redundant calculations without compromising spatial information about flame boundaries. Complementing PConv, the CGLU introduces dynamic feature selection via a gating mechanism, where a depthwise-separable convolutional branch (DWConv3x3) [31] generates spatially-adaptive weights through sigmoid activation. This design adaptively enhances flame-relevant features by combining linearly-transformed representations with gated local context, while suppressing background noise—particularly crucial for detecting small flames with subtle patterns against complex backgrounds. The depthwise operation ensures computational efficiency by processing each input channel independently, preserving fine-grained spatial details without cross-channel interference. The integration of PConv and CGLU forms an efficient feature processing pipeline: PConv ensures lightweight spatial feature extraction, while CGLU provides adaptive feature refinement, collectively achieving both computational efficiency and improved detection accuracy for small-target flames. This approach is suited to UAVs and other constrained edge devices. Fig. 6c presents the CGLU architecture.

Specifically, the computational process of C3F-CGLU and its sub-modules (F-CGLU and CGLU) is given in Formulas (1)–(3):

X is the input feature, W1 and W2 are weight matrices. b1, b2 are bias terms. ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication, ⨁ represents the concat. The gating branch σ denotes the Sigmoid function, generates weights between 0 and 1, selectively filtering information.

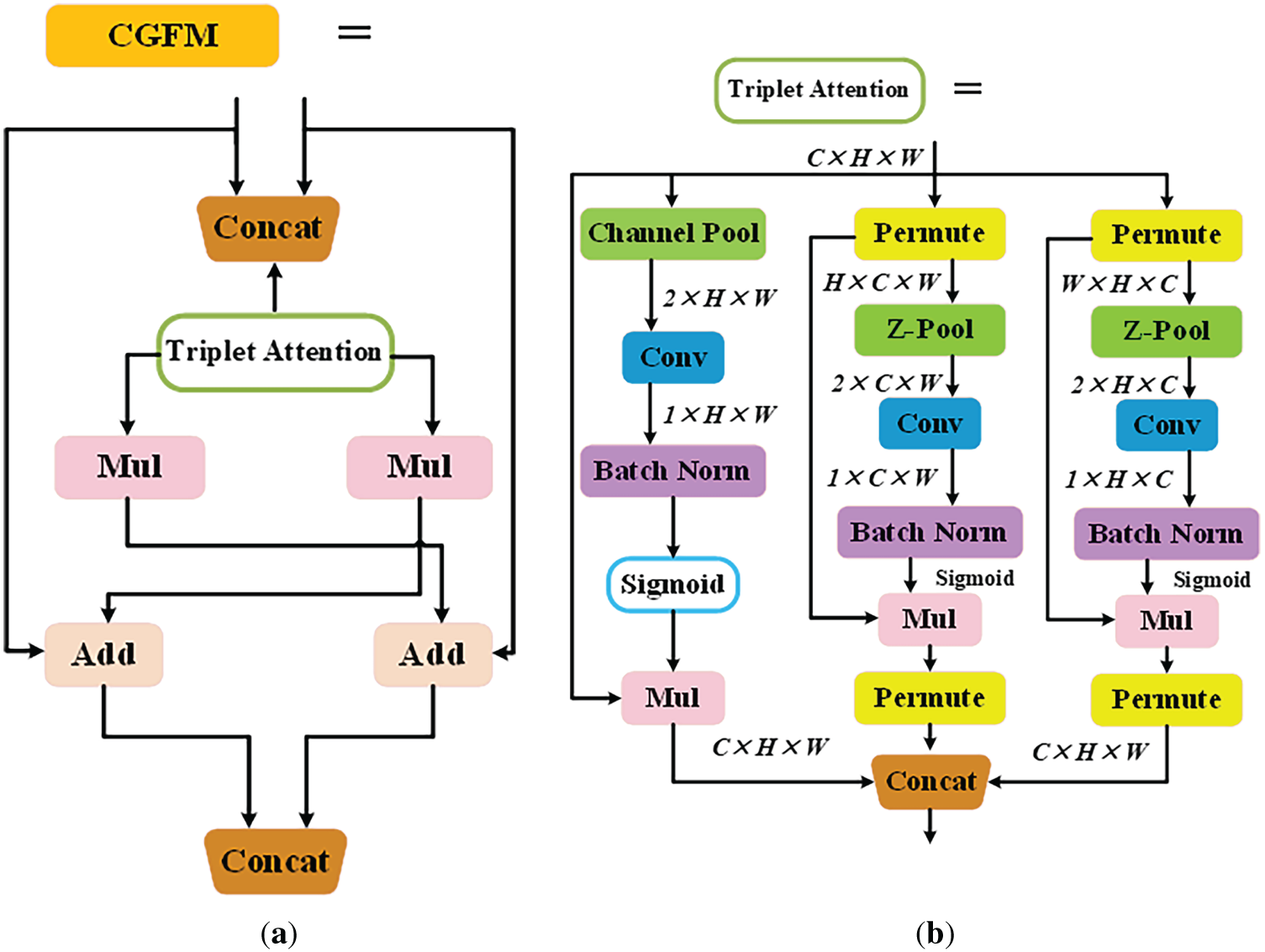

2.2.3 Context-Guided Fusion Module (CGFM) for Enhanced Feature Integration

We introduce the CGFM to optimize the intelligent feature fusion mechanism in small target flame detection. The basic structure of CGFM is shown in Fig. 7a, and its principle is as shown in Formulas (4)–(6). CGFM implements a three-stage process that actively models feature relationships: First, the aligned features are con-catenated to establish cross-feature context. Then, Triplet Attention [32] processes the concatenated tensor to generate a unified weight map, which is immediately split into two weights along the channel dimension. Finally, instead of direct element-wise multiplication, the module executes cross-enhanced fusion through residual addition.

Figure 7: Structure of the CGFM. Panel (a) shows the CGFM architecture, and panel (b) illustrates the Triplet Attention mechanism used within the module

The key advantage of CGFM over standard concatenation lies in its dynamic feature re-weighting capability. Conventional concatenation treats all features equally. This dilutes subtle flame signatures from low-resolution features during gradient propagation, since the network must manually learn feature importance through later convolutions. By contrast, the Triplet Attention mechanism in CGFM generates optimized importance weights through three specialized branches. The Channel-Height branch detects vertical flame patterns, the Channel-Width branch captures horizontal spread, and the Spatial branch preserves localized hot-spot details. The detailed architecture is illustrated in Fig. 7b. Through systematic tensor rotations and residual transformations, this architecture simultaneously captures channel-height, channel-width, and spatial interrelationships while maintaining original feature dimensions.

This approach effectively suppresses irrelevant background features that typically dominate small-target scenarios while amplifying subtle but discriminative flame characteristics through cross-feature enhancement, as mathematically characterized in Formulas (7)–(9). CGFM’s residual cross-gating strategy ensures complementary enhancement between feature streams while preserving original features through identity connections and maintaining complete feature hierarchies in the final con-catenation. The framework maintains computational efficiency comparable to standard concatenation while significantly improving feature discrimination for small targets.

X represents the input feature map. Fh(X), Fw(X), and Fs(X) denote the outputs of the horizontal, vertical, and spatial attention branches, respectively. Xtri is the final output feature map. ⊙ indicates element-wise multiplication, while σ is the sigmoid activation function. Ph(·) and Pw(·) are permutation operators. GAP(·) denotes global average pooling.

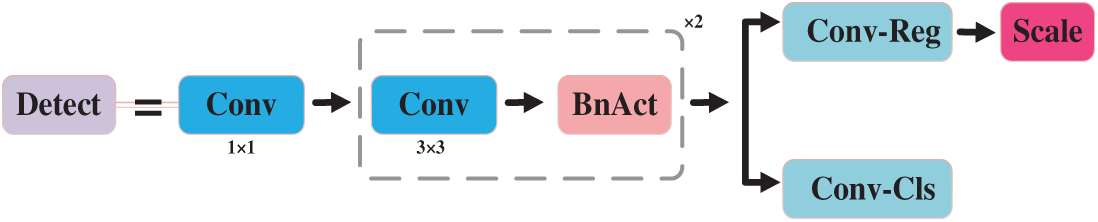

2.2.4 Lightweight Shared Convolution with Separated Batch Normalization Detection (LSCSBD) Head

An improved detection head, termed LSCSBD, is proposed to balance computational efficiency with detection accuracy in recognizing small flame targets. Building upon the foundation of shared convolutional layers. First, it employs parameter-shared convolutional layers across different detection scales to significantly reduce model complexity, while maintaining distinct Batch Normalization (BN) [33] layers for each scale to preserve the statistical characteristics unique to different feature levels. This separation of shared convolution and independent BN effectively resolves the feature distribution conflicts that would arise from complete parameter sharing. Fig. 8 shows the structure of LSCSBD. Second, it replaces of Group Normalization (GN) with BN layers, following NAS-FPN [34]’s design philosophy. While GN has demonstrated benefits for detection tasks, the high computational cost at the inference stage limits its practicality for deployment on resource-limited platforms. The LSCSBD maintains BN’s efficiency advantages while preventing feature contamination across scales through the independent BN layers. Complementing this design, the module incorporates learnable Scale layers that dynamically adjust feature magnitudes at different detection levels, addressing the inherent scale variations in multi-level feature representations without introducing significant computational burden.

Figure 8: Structure of LSCSBD

This combination of architectural choices results in a detection head that achieves parameter reduction compared to conventional designs while maintaining accuracy. The shared convolutional layers minimize redundant computations, while the separate BN layers and scale adaptation ensure proper handling of multi-scale features critical for detecting small flames across varying distances and resolutions.

3 Experimental Results and Discussion Analysis

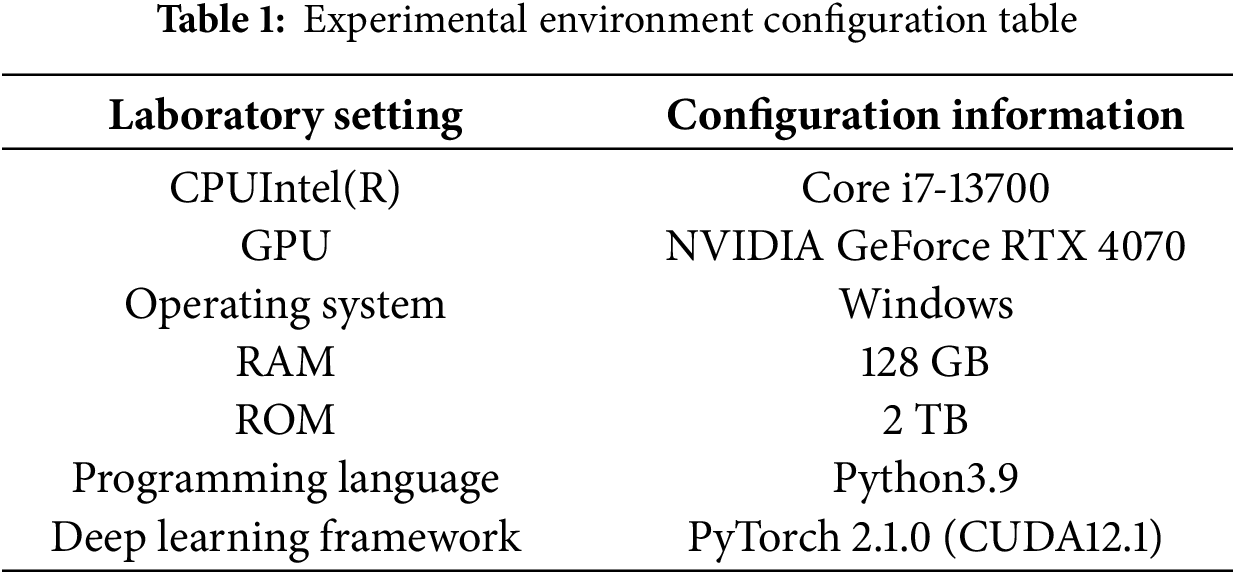

3.1 Experimental Platform and Parameters

We implemented our models in Python 3.9 using PyTorch 2.1.0 framework. The hardware and software settings used in the experiments are outlined in Table 1.

The TF-11K dataset containing 11,138 annotated flame images was processed at a fixed 640 × 640 resolution, with augmentation including random flipping, color jitter, and scaling. Training was conducted for 400 epochs with a batch size of 16, using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer (initial learning rate = 0.01) with a cosine annealing schedule. Early stopping with a patience of 20 epochs was applied based on validation mAP@0.5 to prevent overfitting. This configuration balanced computational efficiency with detection accuracy while maintaining reproducibility.

To improve the model, evaluate its performance, and compare differences between models, we employ a multi-metric approach—Precision (P), Recall (R), and Mean Average Precision (mAP)—to rigorously evaluate the model’s efficacy in small-target forest fire detection. Here, True Positives (TP) correspond to correctly identified fire regions, False Positives (FP) denote background misclassifications, and False Negatives (FN) represent missed detections. Formulas (10)–(13) definitions of these metrics are as follows:

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s lightweight optimization and real-time performance, we employ three computational efficiency metrics: the number of trainable parameters (Params, in millions) indicating model complexity, floating-point operations (FLOPs, in billions) representing computational workload, and frames per second (FPS) measuring inference speed. To ensure transparency and fairness, all FPS values reported in the subsequent experiments were measured under the unified hardware configuration described in Section 3.1. The metrics give a clear measure of how well the model can be applied in practice.

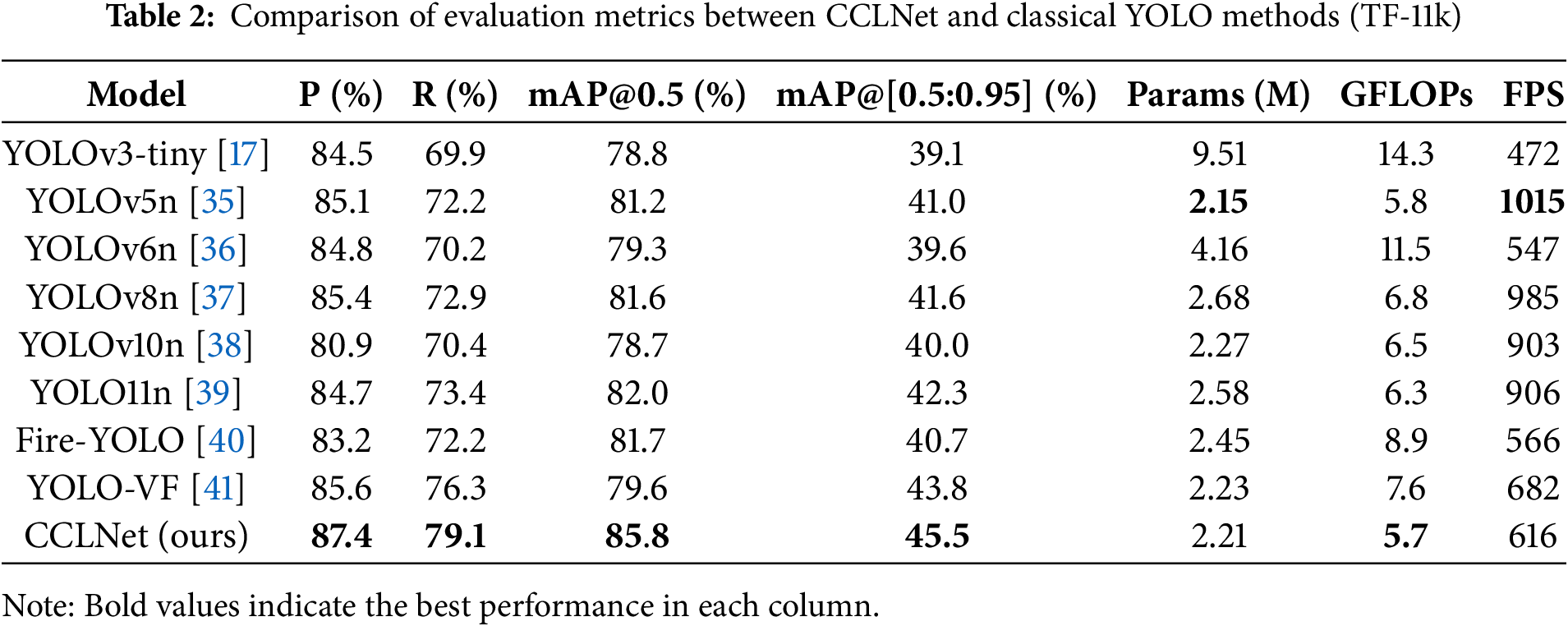

To verify the advantages of the CCLNet model for detecting small target flames, this paper conducted comparative experiments on a self-built dataset under the same experimental conditions. It also compared the CCLNet model with end-to-end models of the YOLO series. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

The Experimental results show that the CCLNet has the best comprehensive performance in small target flame detection, with comprehensive improvements across all key metrics. As shown in the comparison Table 2, CCLNet reaches 87.4% precision, 79.1% recall, 85.8% mAP@0.5, and 45.5% mAP@[0.5:0.95], outperforming all YOLO variants while maintaining excellent efficiency with only 2.21 M parameters and 5.7 GFLOPs. The 3.8% mAP@0.5 improvement over YOLO11n and 4.6% gain over YOLOv5n are particularly significant for forest fire detection tasks, where even marginal accuracy improvements can substantially enhance early warning capabilities. The model’s 616 FPS processing speed, though slightly lower than YOLOv5n, remains well within real-time operation requirements for forest monitoring systems. These advancements are achieved through our novel hybrid attention mechanism and optimized feature pyramid architecture, which specifically address the challenges of detecting small, irregular flame targets in complex forest environments. The trade-off between precision and efficiency enables CCLNet to be effectively deployed on lightweight edge platforms for forest fire monitoring, where it provides more reliable small-flame identification while maintaining practical inference speeds. The model’s enhanced recall performance (76.3%) is especially valuable for small-target fire detection scenarios, reducing the risk of missed alarms while maintaining high precision to minimize false positives. These improvements are achieved without compromising the model’s lightweight characteristics, as demonstrated by the 14.3% parameter reduction compared to YOLO11n, making it suitable for deployment on edge devices.

Fig. 9 illustrates the small target detection capabilities of different models on the TF-11K dataset. Notably, CCLNet maintains robust detection performance even for partially occluded flames, as shown in Fig. 9c demonstrating its ability to accurately identify small-scale fires obscured by vegetation, highlighting the model’s exceptional feature extraction capabilities under complex visual conditions. The architecture’s consistent performance across both visible and obscured fire scenarios confirms its practical utility for real-world forest fire monitoring applications.

Figure 9: Algorithm performance comparison on TF-11K dataset. Panels (a–e) show detection results from different data sources: (a–c) represent self-collected forest fire scenarios, while (d,e) illustrate samples from public datasets

Despite the strong overall performance of CCLNet, certain failure cases were observed. Fig. 10a–c present representative missed detections on the TF-11K dataset. Overall, the self-collected subset had a higher rate of missed detections compared with the flame public dataset, mainly because the self-collected data intentionally contained smaller fire targets. Specifically, Fig. 10a shows a missed detection caused by an extremely small flame region, while Fig. 10b shows a case where the flame was both small and partially occluded by vegetation. Fig. 10c illustrates a failure from the public dataset, where the flame color blended with the background, resulting in confusion. To analyze temporal continuity, Fig. 10d–f shows the frames immediately before and after Fig. 10a–c even when single frames exhibited missed detections, the continuity of video ensured that the fire was still captured in adjacent frames. This demonstrates that CCLNet remains robust for real-time UAV monitoring, as occasional frame-level misses do not prevent reliable fire detection at the sequence level.

Figure 10: Representative failure cases of CCLNet on the TF-11K dataset. Panels (a–c) show examples of missed detections under different challenging conditions: (a) extremely small flame size in self-collected data, (b) small flame size combined with partial occlusion in self-collected scenes, and (c) flame-background color confusion in public-dataset images, Panels (d–f) present the nearby frames corresponding to (a–c), illustrating that temporal continuity enables reliable detection even when single-frame misses occur.

To verify the robustness of these improvements, each ablation experiment was repeated three times with different random seeds. The results consistently followed the same trend, with variations of less than ±0.3% in mAP@0.5, indicating that the observed performance gains, especially those of the CGFM module compared with baseline concatenation, are stable and reliable rather than due to random variation.

To verify whether the introduction of C3F-CGLU, CGFM, and LSCSBD can improve the network architecture of CCLNet—making the model lighter while enhancing both detection accuracy and real-time performance for small-target flames in forest fires. We used YOLO11n as the baseline model and conducted ablation experiments on a self-constructed forest fire dataset. The experimental results are presented in Table 3.

The systematic ablation experiments demonstrate progressive performance improvements through our architectural innovations. The baseline model achieves 82.0% mAP@0.5 with 2.58 M parameters and 6.3 GFLOPs. The FasterCGLU-C3K2 (F) module shows remarkable efficiency gains, reducing parameters by 13.6% to 2.23 M and computational cost by 11.1% to 5.6 GFLOPs while maintaining comparable accuracy at 82.1% mAP@0.5. The CGFM (C) module exhibits exceptional precision capabilities (86.5%) and achieves the highest single-module mAP@0.5 improvement of 83.9% (+1.9%), confirming its effectiveness in multi-scale feature fusion, though with a moderate 3.9% parameter increase to 2.68 B. The LSCSBD (H) module demonstrates balanced enhancement across all metrics, delivering 83.3% mAP@0.5 with particularly strong recall (76.2%), validating its advantage in spatial relationship modeling. The complete CCLNet model integrating all three components achieves optimal performance with 85.8% mAP@0.5 (+3.8%), 87.4% precision (+5.4%), and 79.1% recall (+5.7%), while maintaining lightweight characteristics at 2.21 M parameters (14.3% reduction) and 5.7 GFLOPs (9.5% reduction). The hierarchical combination of F+C modules shows synergistic effects (84.5% mAP@0.5), while the F+H combination achieves the best efficiency-accuracy balance (85.1% mAP@0.5 at 5.5 GFLOPs). The full integration demonstrates comprehensive improvements, particularly in mAP@0.5-95 (45.2%), and addressing the critical “higher recall preferred” requirement for forest fire detection where missed detections carry greater consequences than false alarms.

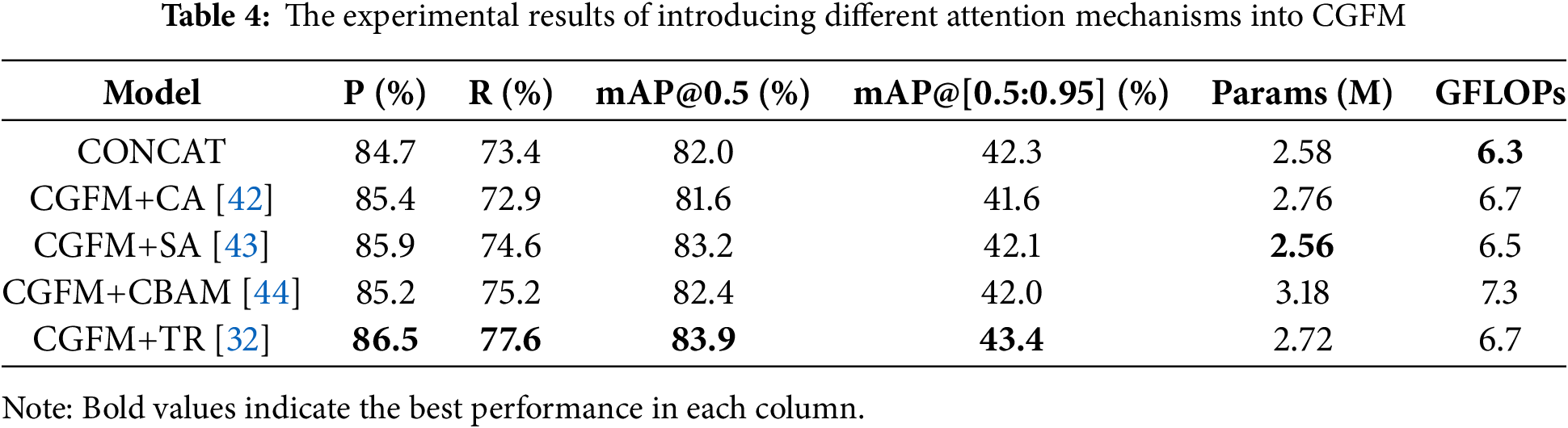

3.5 Comparison of the Performance of Different Attention Mechanisms in the CGFM Module

We replace standard concatenation with the CGFM incorporating triplet attention, demonstrating significant performance improvements as shown in Table 4. The baseline model with conventional concatenation achieves 82.0% mAP@0.5 at 2.58 M parameters, while our CGFM with triplet attention attains 83.9% mAP@0.5 (+1.9%) and 77.6% recall with comparable computational cost (6.7 vs. 6.3 GFLOPs). This enhancement stems from the triplet attention’s unique ability to simultaneously model channel-height, channel-width, and spatial relationships—particularly valuable for small flame detection, where traditional attention mechanisms show limitations. Coordinate Attention (CA) achieves higher precision (85.4%) but lower recall (72.9%), while Spatial Attention (SA) improves recall (74.6%) at the expense of precision (85.9%). The triplet attention’s balanced performance across all metrics (86.5% precision, 77.6% recall) confirms its superiority in handling complex forest fire scenarios, where it effectively suppresses background clutter while amplifying subtle flame signatures. Notably, our model maintains parameter efficiency (2.72 B) despite the added attention mechanism, representing only a 5.4% increase over baseline YOLO11n. These improvements are especially evident in mAP@0.5-95 (43.4% vs. 42.3%), demonstrating better performance on strict evaluation metrics crucial for small-target forest fire detection. The results validate that concatenation with triplet-attention-enhanced CGFM provides optimal balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency for small flame identification tasks.

Fig. 11 presents Layer-Class Activation Map (Layer-CAM) visualizations to compare attention choices inside CGFM. Each panel contains six columns: (1) Original image, (2) YOLO origin concatenation (baseline), (3) CGFM+SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation), (4) CGFM+CA (Coordinate Attention), (5) CGFM+SA (Spatial Attention), and (6) CGFM+TR (Triplet Attention). Panel (a) shows self-collected long-range scenes with small, distant flames, and panel (b) shows FLAME UAV scenes with multiple flame foci. Across both settings, CGFM+TR concentrates activations more tightly on flame regions and suppresses background responses more effectively than SE, CA, SA, and the baseline concatenation, indicating a clearer semantic focus on the fire targets under cluttered backgrounds.

Figure 11: Layer-CAM visualization of different attention modules. Panels (a,b) each contain six columns: (1) Original image, (2) YOLO origin concatenation (baseline), (3) CGFM+SE, (4) CGFM+CA, (5) CGFM+SA, and (6) CGFM+TR (Triplet Attention). Panel (a) shows self-collected long-range scenes with small, distant flames; panel (b) shows UAV images from the Fire Luminescence Aerial Multi-spectral Evaluation FLAME dataset with multiple flame foci

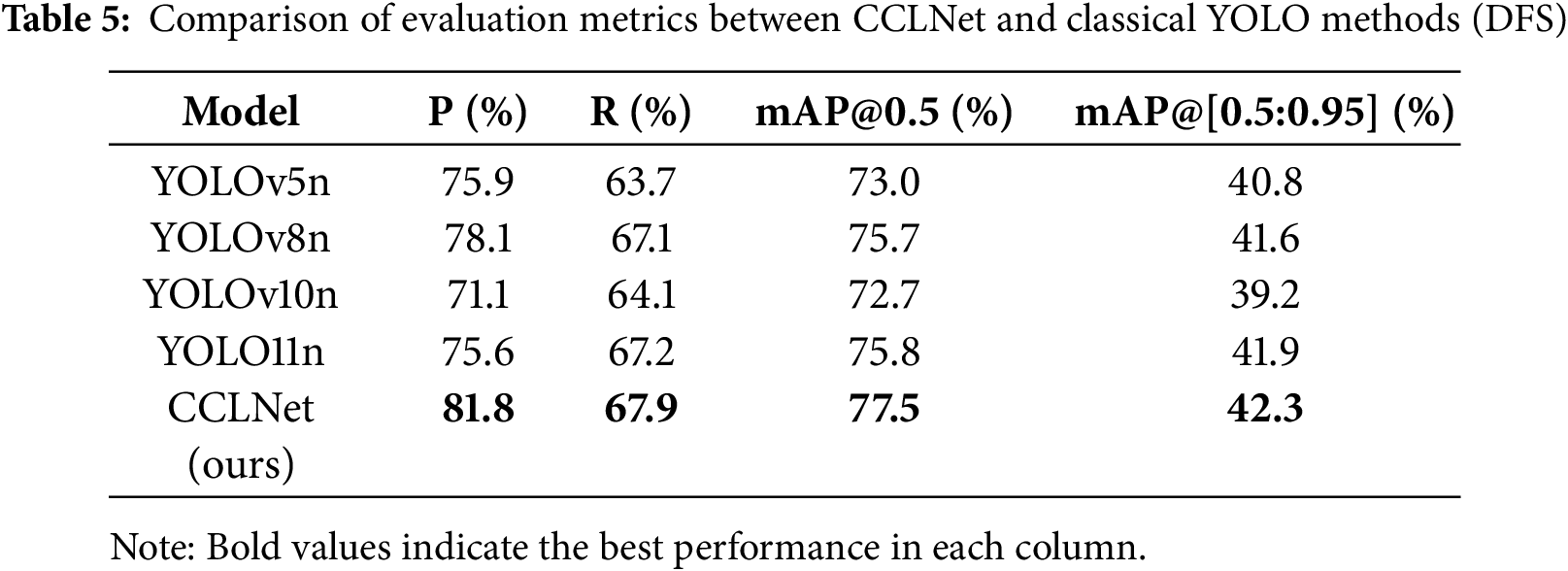

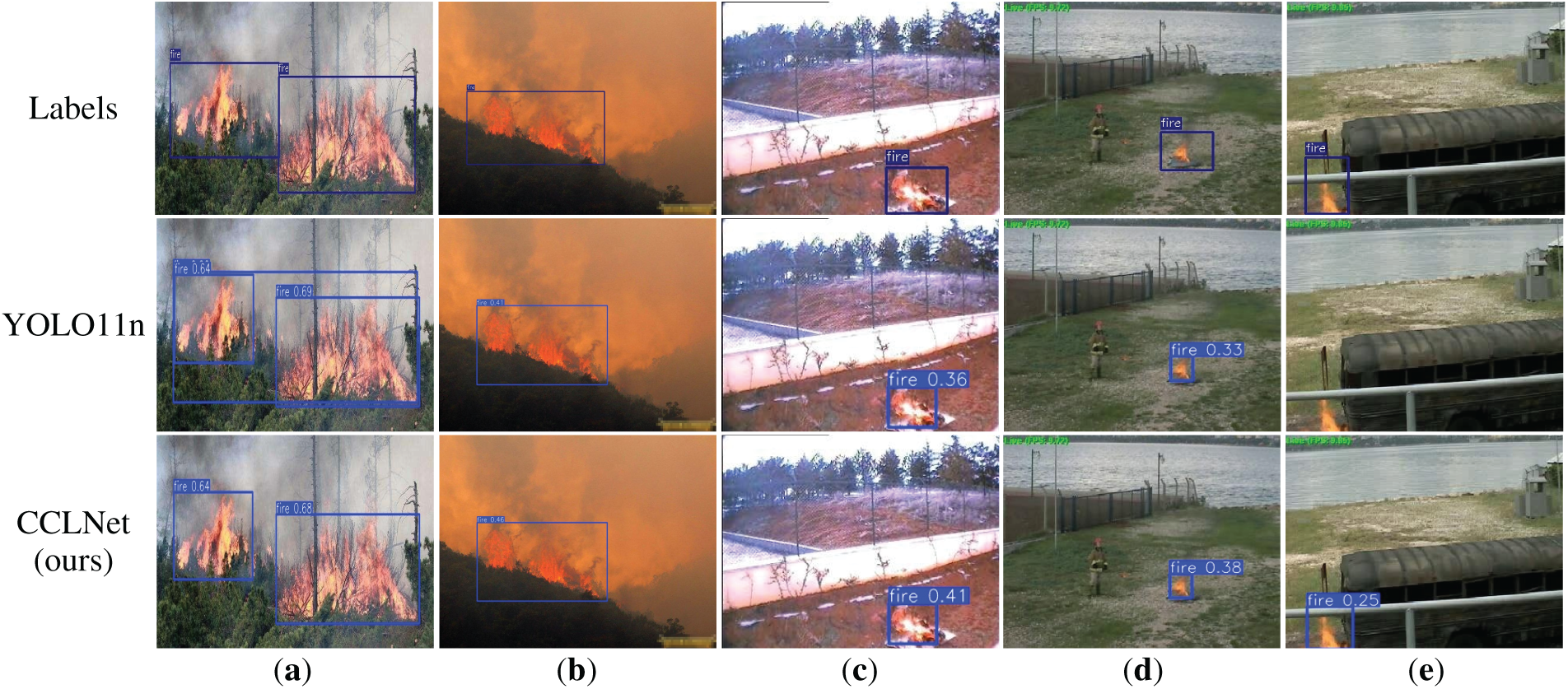

To rigorously evaluate the generalization capability of our model, we conducted cross-dataset validation on the DFS dataset. Comparative experiments were performed against the YOLO n-series models under identical experimental conditions to ensure fair comparison. The results in Table 5 show that CCLNet outperforms the compared models on every evaluation metric. It achieves a precision of 81.8%, surpassing YOLOv8n (78.1%) and YOLO11n (75.6%). At the same time, it maintains the highest recall rate of 67.9% among all models. The model shows a 1.8% improvement in mAP@0.5 (77.5%) over YOLOv8n (75.7%) and achieves 42.3% mAP@[0.5:0.95], outperforming all baseline models. These results substantiate that our architectural innovations yield generalized feature extraction benefits that effectively translate to diverse fire detection applications.

In cross-dataset detection tasks, the CCLNet model demonstrates significant performance improvements, particularly in localization accuracy and small-target detection capability. As illustrated in Fig. 12a–e, the model achieves precise detection of fire targets. For instance, in Fig. 12a, CCLNet provides more accurate spatial localization of flame regions compared with the baseline YOLO11n, validating the effectiveness of its architectural design for fine-grained feature extraction. Furthermore, CCLNet exhibits markedly improved sensitivity to small-scale targets. In Fig. 12d, it not only achieves higher detection confidence than YOLO11n but also surpasses manual annotations in localization precision. Notably, even in complex scenarios with occluded objects (Fig. 12e), the model maintains reliable detection of small targets, underscoring the advantages of the CGFM in semantic-aware feature integration.

Figure 12: Cross-dataset evaluation on DFS. Rows 1–3 show ground-truth annotations, YOLO11n predictions, and detection results of CCLNet, respectively. Panels (a–e) correspond to different observation conditions: (a) a close-range forest fire scene, (b) a distant fire scene with dense smoke and low visibility, and (c–e) flame scenes captured by fixed video-surveillance systems

CCLNet’s superior generalization on the DFS dataset is attributed to CGFM’s dynamic feature re-weighting, which adapts to varying flame morphologies and background textures. LSCSBD further stabilizes detection across scale shifts introduced by different UAV altitudes. Together, these modules enable the model to maintain high detection accuracy under diverse environmental conditions, effectively mitigating domain shifts between TF-11K and DFS.

3.7 Edge Deployment Benchmarks

To further validate the lightweight design and real-time capability of CCLNet, we deployed the model on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX platform equipped with a CSI camera (Fig. 13). Inference was performed as continuous processing of TF-11K dataset images with an input resolution of 604 × 640. The measured inference speed ranged from 32.3 FPS in complex canopy scenes to a peak of 116.7 FPS under simpler backgrounds, with an average of 89.6 FPS. These results demonstrate that CCLNet achieves stable real-time performance on embedded platforms. As expected, FPS varies with input resolution and scene complexity, but remains well above the real-time threshold (≥25 FPS), confirming the model’s suitability for UAV-based forest fire surveillance under resource-constrained conditions.

Figure 13: Edge deployment of CCLNet on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX platform

Based on comprehensive experimental evaluation, CCLNet achieved stable and reliable performance in small-target forest fire detection, maintaining a balance between detection accuracy and model compactness. Its architecture—comprising C3F-CGLU for fine-grained feature enhancement, CGFM for context-guided multi-scale fusion, and LSCSBD for stable detection—helps address common challenges such as feature sparsity, background interference, and scale variation in UAV imagery. The overall design remains computationally efficient, making the network suitable for real-time operation on resource-limited platforms.

Future work will focus on improving the robustness and adaptability of the model in complex environments. Expanding UAV-collected datasets to include more early-stage and extreme forest fire conditions will support better generalization across scenes. In parallel, integrating multi-modal sensing—such as thermal, gas, and temperature–humidity data—and refining module coordination through backbone optimization and hybrid-encoder adjustment may enhance the model’s capability to capture diverse flame characteristics and environmental cues. Further investigation into attention mechanisms and loss-function optimization could also strengthen performance on small-scale and partially occluded targets.

From an application perspective, we plan to deploy CCLNet on embedded platforms such as Raspberry Pi 4 or RISC-V-based platforms to establish autonomous early-warning systems for forest fire monitoring in remote regions. Field testing under different weather, lighting, and altitude conditions will help evaluate the model’s operational reliability. To facilitate large-scale deployment, techniques such as model pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation will be explored to reduce inference cost and improve real-time efficiency. Beyond forest fire detection, the modular design of CCLNet supports adaptation to other small-object detection tasks—such as wildlife monitoring, illegal-logging detection, and industrial-safety inspection, where lightweight and efficient vision models remain essential for real-time operation on edge devices.

Acknowledgement: We thank our families and colleagues who provided us with moral support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2025JJ80352), and the National Natural Science Foundation Project of China (Grant No. 32271879).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Qian Yu and Gui Zhang; Methodology, Qian Yu and Xin Wu; Investigation, Ying Wang and Jiangshu Xiao; Writing—original draft, Wenbing Kuang and Juan Zhang; Writing—review & editing, Gui Zhang; Funding acquisition, Gui Zhang; Supervision, Gui Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The source code, pretrained weights of CCLNet, and the self-collected UAV imagery portion of the TF-11K dataset (9139 images from subtropical forests in Zhuzhou, China) are hosted at: https://github.com/yuqian-hn/CCLNet-TF11K-ForestFireDetectionDataset (accessed on 01 January 2025). These materials will be released under open-access licenses immediately following the publication of this article. The TF-11K dataset used in this study includes 9139 UAV forest fire images collected by our team, which were combined with the FLAME public UAV dataset and re-annotated for small-target detection on UAV platforms. The same self-collected dataset has also supported our other forest fire research, such as multi-view and multi-scale flame detection, where it was combined with different public datasets to address distinct research objectives. Although part of the raw imagery overlaps, the dataset construction, algorithmic design, and application scenarios differ substantially, making these research directions complementary. This distinction will be further reflected in our subsequent studies.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Stocks BJ, Mason JA, Todd JB, Bosch EM, Wotton BM, Amiro BD, et al. Large forest fires in Canada, 1959–1997. J Geophys Res. 2002;107(D1):FFR 5-1–12. doi:10.1029/2001jd000484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mamadmurodov A, Umirzakova S, Rakhimov M, Kutlimuratov A, Temirov Z, Nasimov R, et al. A hybrid deep learning model for early forest fire detection. Forests. 2025;16(5):863. doi:10.3390/f16050863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jin P, Cheng P, Liu X, Huang Y. From smoke to fire: a forest fire early warning and risk assessment model fusing multimodal data. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;152(5):110848. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xu H, Zhang G, Chu R, Zhang J, Yang Z, Wu X, et al. Detecting forest fire omission error based on data fusion at subpixel scale. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2024;128(7):103737. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2024.103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xu H, Zhang G, Zhou Z, Zhou X, Zhou C. Forest fire monitoring and positioning improvement at subpixel level: application to himawari-8 fire products. Remote Sens. 2022;14(10):2460. doi:10.3390/rs14102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Heyns A, du Plessis W, Kosch M, Hough G. Optimisation of tower site locations for camera-based wildfire detection systems. Int J Wildland Fire. 2019;28(9):651–65. doi:10.1071/wf18196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cosgun U, Coşkun M, Toprak F, Yıldız D, Coşkun S, Taşoğlu E, et al. Visibility evaluation and suitability analysis of fire lookout towers in Mediterranean Region, southwest Anatolia/Türkiye. Fire. 2023;6(8):305. doi:10.3390/fire6080305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gonçalves LAO, Ghali R, Akhloufi MA. YOLO-based models for smoke and wildfire detection in ground and aerial images. Fire. 2024;7(4):140. doi:10.3390/fire7040140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu H. UAV forest fire early warning and inspection plan based on multiple nests. Sci Technol Eng Chem Environ Prot. 2024;1(4):1–7. doi:10.61173/def0fv86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Y, Zheng C, Liu X, Tian Y, Zhang J, Cui W. Forest fire monitoring method based on UAV visual and infrared image fusion. Remote Sens. 2023;15(12):3173. doi:10.3390/rs15123173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2014. p. 580–7. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2014.81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Girshick R. Fast R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 1440–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang QX, Lin GH, Zhang YM, Xu G, Wang JJ. Wildland forest fire smoke detection based on faster R-CNN using synthetic smoke images. Procedia Eng. 2018;211(3):441–6. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.12.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot MultiBox detector. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 6517–25. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang D, Qian Y, Lu J, Wang P, Hu Z, Chai Y. Fs-yolo: fire-smoke detection based on improved YOLOv7. Multimed Syst. 2024;30(4):215. doi:10.1007/s00530-024-01359-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yu P, Wei W, Li J, Du Q, Wang F, Zhang L, et al. Fire-PPYOLOE: an efficient forest fire detector for real-time wild forest fire monitoring. J Sens. 2024;2024(1):1–10. doi:10.1155/2024/2831905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen C, Yu J, Lin Y, Lai F, Zheng G, Lin Y. Fire detection based on improved PP-YOLO. Signal Image Video Process. 2023;17(4):1061–7. doi:10.1007/s11760-022-02312-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Huang L, Ding Z, Zhang C, Ye R, Yan B, Zhou X, et al. YOLO-ULNet: ultralightweight network for real-time detection of forest fire on embedded sensing devices. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(15):25175–85. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2024.3416548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang Y, Chen S, Wang W, Zhang W, Zhang L. Pyramid attention based early forest fire detection using UAV imagery. J Phys Conf Ser. 2022;2363(1):012021. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2363/1/012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Han Y, Duan B, Guan R, Yang G, Zhen Z. LUFFD-YOLO: a lightweight model for UAV remote sensing forest fire detection based on attention mechanism and multi-level feature fusion. Remote Sens. 2024;16(12):2177. doi:10.3390/rs16122177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang J, Wang Y, Liu L, Yin H, Ye N, Xu C. Weakly supervised forest fire segmentation in UAV imagery based on foreground-aware pooling and context-aware loss. Remote Sens. 2023;15(14):3606. doi:10.3390/rs15143606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sun H, Xu R, Luo J, Cheng H. Review of the application of UAV edge computing in fire rescue. Sensors. 2025;25(11):3304. doi:10.3390/s25113304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Shamsoshoara A, Afghah F, Razi A, Zheng L, Fulé PZ, Blasch E. Aerial imagery pile burn detection using deep learning: the FLAME dataset. Comput Netw. 2021;193(4):108001. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu S, Zhang X, Liu R, Li B. A dataset for fire and smoke object detection. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(5):6707–26. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13580-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dauphin YN, Fan A, Auli M, Grangier D. Language modeling with gated convolutional networks. arXiv:1612.08083. 2016. [Google Scholar]

29. Liu G, Reda FA, Shih KJ, Wang TC, Tao A, Catanzaro B. Image inpainting for irregular holes using partial convolutions. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 89–105. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01252-6_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Huang G, Sun Y, Liu Z, Sedra D, Weinberger KQ. Deep networks with stochastic depth. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 646–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46493-0_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1800–7. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Misra D, Nalamada T, Arasanipalai AU, Hou Q. Rotate to attend: convolutional triplet attention module. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 3138–47. doi:10.1109/WACV48630.2021.00318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. arXiv:1502.03167. 2015. [Google Scholar]

34. Ghiasi G, Lin TY, Le QV. NAS-FPN: learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 7029–38. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Huang T, Cheng M, Yang Y, Lv X, Xu J. Tiny object detection based on YOLOv5. In: Proceedings of the 2022 the 5th International Conference on Image and Graphics Processing (ICIGP); 2022 Jan 7–9; Beijing, China. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 45–50. doi:10.1145/3512388.3512395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li C, Li L, Jiang H, Weng K, Geng Y, Li L, et al. YOLOv6: a single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv:2209.02976. 2022. [Google Scholar]

37. Wu L, Chen L, Li J, Shi J, Wan J. SNW YOLOv8: improving the YOLOv8 network for real-time monitoring of lump coal. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(10):105406. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad5de1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. YOLOv10: real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;37:1–28. [Google Scholar]

39. Bakirci M, Bayraktar I. Assessment of YOLO11 for ship detection in SAR imagery under open ocean and coastal challenges. In: Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computing Science and Automatic Control (CCE); 2024 Oct 23–25; Mexico City, Mexico. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CCE62852.2024.10770926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao L, Zhi L, Zhao C, Zheng W. Fire-YOLO: a small target object detection method for fire inspection. Sustainability. 2022;14(9):4930. doi:10.3390/su14094930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang X, Chen B. Research on malaria parasite detection in thick blood smears based on YOLO-VF. In: Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST); 2023 Dec 8–10; Guangzhou, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1486–90. doi:10.1109/IAECST60924.2023.10502526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hou Q, Zhou D, Feng J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 13708–17. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhu X, Cheng D, Zhang Z, Lin S, Dai J. An empirical study of spatial attention mechanisms in deep networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 6687–96. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools