Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Secured-FL: Blockchain-Based Defense against Adversarial Attacks on Federated Learning Models

1 Department of Cyber Security, Air Force Institute of Technology, Kaduna, 800283, Nigeria

2 College of Computer and Information Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 12435, Saudi Arabia

3 School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Bello Musa Yakubu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in IoT Security: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 28 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072426

Received 26 August 2025; Accepted 01 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Federated Learning (FL) enables joint training over distributed devices without data exchange but is highly vulnerable to attacks by adversaries in the form of model poisoning and malicious update injection. This work proposes Secured-FL, a blockchain-based defensive framework that combines smart contract–based authentication, clustering-driven outlier elimination, and dynamic threshold adjustment to defend against adversarial attacks. The framework was implemented on a private Ethereum network with a Proof-of-Authority consensus algorithm to ensure tamper-resistant and auditable model updates. Large-scale simulation on the Cyber Data dataset, under up to 50% malicious client settings, demonstrates Secured-FL achieves 6%–12% higher accuracy, 9%–15% lower latency, and approximately 14% less computational expense compared to the PPSS benchmark framework. Additional tests, including confusion matrices, ROC and Precision-Recall curves, and ablation tests, confirm the interpretability and robustness of the defense. Tests for scalability also show consistent performance up to 500 clients, affirming appropriateness to reasonably large deployments. These results make Secured-FL a feasible, adversarially resilient FL paradigm with promising potential for application in smart cities, medicine, and other mission-critical IoT deployments.Keywords

Federated Learning (FL) is a new architecture enabling collaborative training of deep learning models at scale, ranging from hundreds to millions [1,2]. In the conventional FL setting, a global model is overseen by a central server and managed through updates in coordination from dispersed clients [3,4]. Each client trains with private data locally, and model updates in isolation are shared, preserving data privacy [5]. This paradigm of distributed design enhances performance by applying distributed computation and minimizes raw data exposure risk.

While privacy-preserving, FL is very vulnerable to adversarial attacks, and particularly model poisoning attacks [6–8]. Adversarial attackers can corrupt model updates while training, undermining the accuracy and robustness of the aggregated global model [5]. Countermeasures against poisoning in the shape of Byzantine-robust aggregation methods [2,9–13] have been proposed, but most assume Independent and Identically Distributed (IID) data—a impossible case in actual deployments [14–16].

Recent research [5,17,18] has attempted to overcome these limitations by combining optimization techniques, reinforcement learning–based client selection, and latency-aware training [19–21]. Such methods improve performance but often result in trade-offs such as longer convergence, higher computational complexity, or loss of training accuracy [22–24]. To avoid such limitations, decentralized FL systems [25–27] have been developed that allow model updates to be shared without relying on a central server. However, decentralized FL has communication efficiency issues if there is no bidirectional trust or connectivity [28–31].

Blockchain integration was viewed as a promising way to enhance FL by ensuring immutability, tamper-resistance, and distributed trust [32–34]. Its cryptography-based architecture ensures open transaction logging and auditability and thus is well suited for use in applications such as intelligent transportation, healthcare, and security in IoT [35,36]. Current work has employed blockchain-FL integration to counter data forgery, enhance privacy based on differential privacy (DP) and generative adversarial networks, and reduce communication overhead [37–39]. The systems are still beset by scalability, bad authentication, and inadequate defense against adversarial model tampering.

Problem Statement: Federated Learning has been a practical paradigm for decentralized model training but without sharing raw data. FL, while having the promise, is extremely susceptible to model poisoning, model inversion, and membership inference attacks that compromise both convergence stability as well as privacy. Existing defenses—e.g., Byzantine-resilient aggregation and privacy-preserving frameworks—either assume IID client information, apply static trust thresholds, or fail to counter dynamic adversarial behaviors present in real-world implementations. In addition, most blockchain-based FL solutions offer poor guarantees for member authentication and update accountability. This weakness promotes the design of a comprehensive defense that can ensure tamper-resistance, transparent member authentication, dynamic outlier identification, and adaptive trust thresholds all at once. The Secured-FL architecture addresses these shortcomings through the use of blockchain’s immutability and decentralization, and adaptive clustering-based defenses to secure FL against sophisticated adversarial attacks.

The following are the primary contributions of this paper:

1. The Secured-FL model employs a decentralized learning environment on a private Ethereum blockchain network, fostering collaborative learning among diverse data owners. Additionally, it integrates cross-device Federated Learning, which includes mobile and IoT devices managed by Cluster Heads that possess advanced computing capabilities. The use of blockchain technology enables the registration, authentication, and safe storage of client and Cluster Head data, guaranteeing transparency and resistance to tampering.

2. The model involves an initialization and registration steps using smart contracts, guaranteeing safe documentation on the private blockchain ledger. The authentication step uses smart contracts to validate the authenticity of clients and issue submission tokens.

3. The security mechanism for model updates uses clustering and two-phase outlier elimination techniques to detect and mitigate malicious updates, therefore strengthening resilience against adversarial attacks.

4. The model also incorporates dynamic threshold radius adaptation and strategic confinement of malicious updates to increase the likelihood of their selection by the defense algorithm.

5. Secured-FL model was assessed against a benchmark model (PPSS) using different proportions of malicious clients. The results exhibited enhanced convergence, reduced final losses, increased accuracy, precision, and recall.

6. The Secured-FL model demonstrated superior performance compared to PPSS, even when faced with 50% of malicious clients. The model also shown efficacy in decreasing false positives, maintaining accuracy, and showcasing memory efficiency.

7. An analysis was conducted on the computational costs and execution delay of both models across 250 training iterations. Secured-FL demonstrated markedly reduced computing costs in comparison to PPSS, making it a compelling choice for low latency applications.

The subsequent sections of this work are structured in the following manner. The related studies are provided in Section 2. Section 3 provides a detailed discussion of the system model. The Section 4 introduced the proposed defensive architecture for FL model updates. The security analysis was presented in Section 5. The Implementation and results were discussed in Section 6. Section 7 presents the discussions on the proposed model. In conclusion, Section 8 is the last segment of this work.

2 Review of the Related Studies

Federated Learning (FL) enables collaborative machine learning across distributed clients without divulging raw data but is highly vulnerable to adversarial attacks in the form of model poisoning, model inversion, and membership inference attacks [5–8]. In order to thwart such attacks, Byzantine-resilient aggregation methods [9–13] and anomaly detection defenses [14–16] have been proposed. While these methods provide partial robustness, they typically assume IID data, which is rarely the case for real-world heterogeneous deployments.

Many recent works such as [17,18] and optimization-based approaches such as [19–21] have attempted to mitigate these issues using reinforcement learning–based client selection and latency-aware training. These methods, however, incur computational overhead, slow down convergence, or lose accuracy [22–24]. To circumvent these issues, decentralized federated learning techniques have been proposed [25–27]. For example, Shiranthika et al. [29] spoke about decentralized learning in healthcare, showing the feasibility of FL without a central server but also the susceptibility to adversarial manipulation. Similarly, Zarour et al. [31] highlighted the issue of data integrity in digital health systems, confirming the need for blockchain-based immutability and tamper resistance. Together, these writings show that FL in critical fields requires both strong defense against adversarial manipulation and privacy protection.

Healthcare is particularly exposed to adversarial attacks. Hemdan and Sayed [40] showed how blockchain and FL can be applied to smart healthcare digital twins, with a special emphasis on the need for explainable and privacy-preserving models. At the application level, Nasir et al. [41] proposed FL for fetal health classification using biosignal cardiotocography, and Asif et al. [42] addressed FL in ECG arrhythmia detection. These works highlight that adversarial attacks in FL could have life-threatening implications, thereby motivating stronger, domain-agnostic defenses such as Secured-FL.

Beyond healthcare, FL has been widely applied in other IoT-based applications. Kumar et al. (a) [43] proposed PEFL, a privacy-encoding FL framework for agriculture, and Kumar et al. (b) [44] introduced SP2F for UAV-based agricultural systems. Both echo FL’s expansion to resource-limited, distributed environments, where security holes still remain essential. Xiong and Li [45] also addressed consensus-level privacy preservation, providing further visibility into communication security but without specifically refuting poisoning-based adversarial attacks. These examples illustrate that FL vulnerabilities are not limited to healthcare, spreading to agriculture, UAV, and industrial IoT systems.

The financial sector has also adopted FL, typically alongside explainability requirements. Aljunaid et al. [46] proposed an explainable AI-based FL framework for fraud detection, claiming that finance also needs transparency alongside adversarial robustness. This inter-sectoral evidence demonstrates that adversarial resistance in FL is not a niche healthcare concern, but a multi-domain necessity across medicine, smart cities, agriculture, UAV systems, and finance.

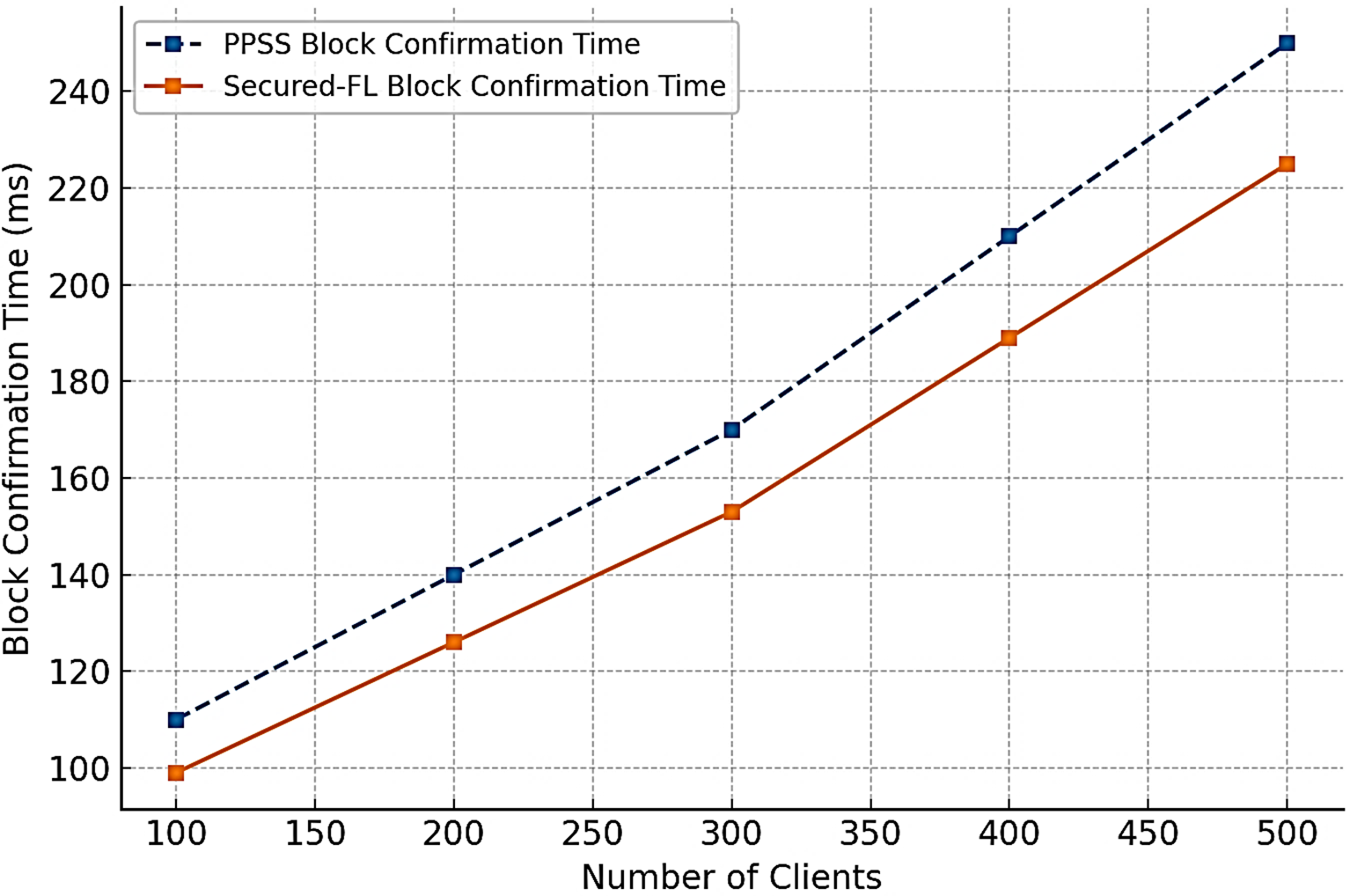

Blockchain has therefore been an auspicious enabler for FL trust, accountability, and tamper resistance improvement [32–36]. Hybrid blockchain–FL systems have been envisioned for intrusion detection, telemedicine, and IoT security [37–39]. Most of the existing solutions, however, continue to experience limitations such as static trust thresholds, scalability bottlenecks, or partial defense against poisoning. For instance, Alruwaili et al. [47] employed static trust-based defenses, and Li et al. [48] employed clustering without adapting dynamically. Recent explainability-based FL frameworks [48–50] are interpretable but exclude poisoning defenses.

In brief, the literature demonstrates (i) application-driven utilization of FL in healthcare [29,31,40–42], agriculture and UAVs [43,44], and finance [46]; (ii) methodological advances in the sense of consensus and privacy [44]; and (iii) partial blockchain–FL combinations for security [33–35]. Yet, they leave out essential gaps in dynamic adversarial defense, large-scale authentication, and cross-domain robustness. The proposed Secured-FL framework bridges these gaps by combining blockchain immutability, smart contract-based authentication, and clustering-based outlier removal with adaptive thresholding, providing an end-to-end solution for federated learning adversarial attacks.

Table 1 summarizes and compares some of the most recent related works with the proposed Secured-FL model review based on the defense strategy, convergence speed, communication cost and the limitations.

3 Proposed Secured-FL Framework and System Model

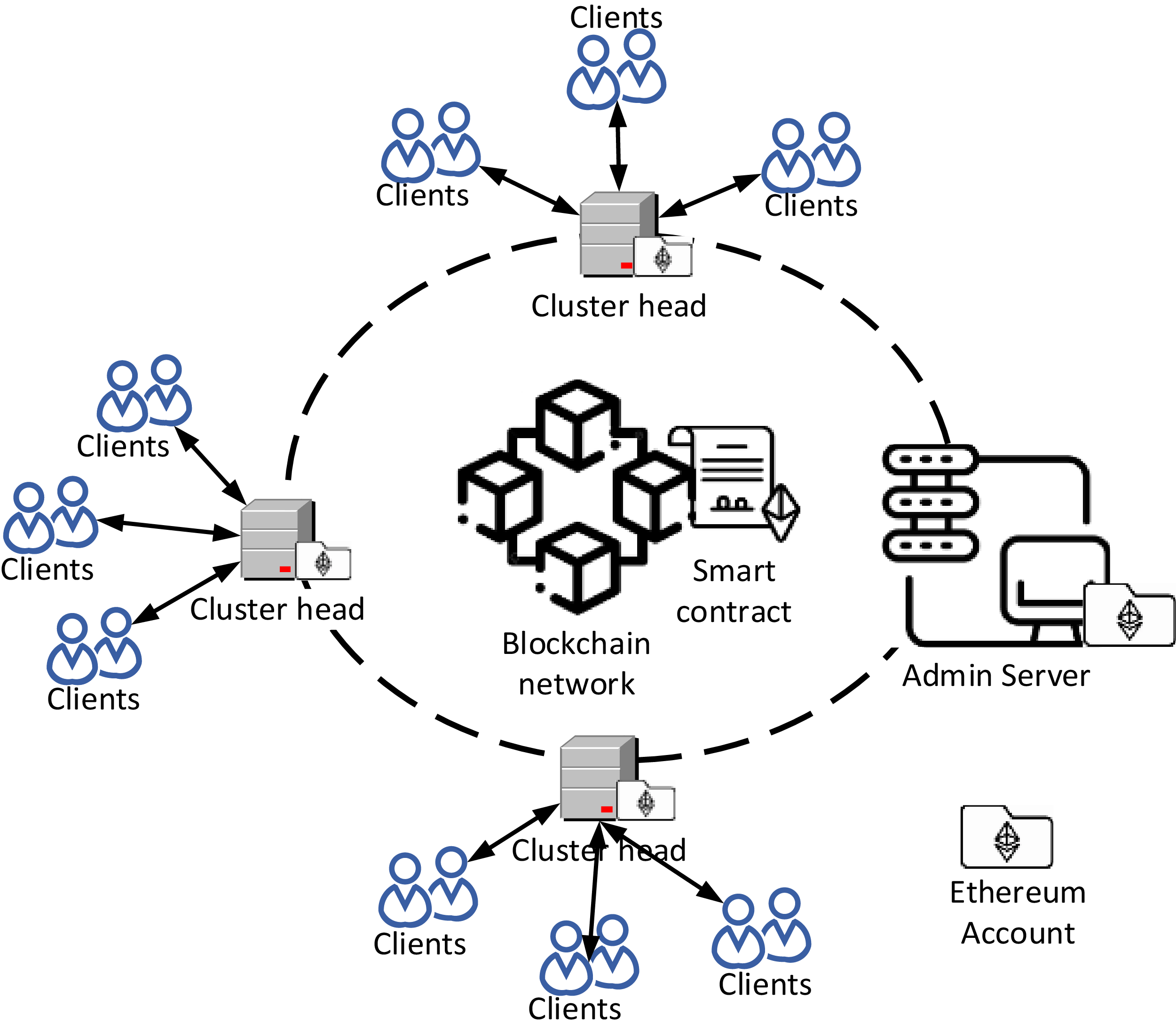

The system is designed as a machine learning environment that operates inside a private Ethereum blockchain network as depicted in Fig. 1. Its purpose is to enable collaborative learning of a global machine learning model among many data owners, often known as clients. Importantly, this collaborative learning is achieved without the need for the exchange of private data between the clients.

Figure 1: Proposed Secured-FL system model and framework. Clients (IoT devices or mobiles) are grouped together, with each being governed by a Cluster Head (CH) of higher computation power. Model training locally is done by clients and forwarded to their corresponding CH. Authentication by smart contract issuing a particular token is necessary for every client before submission. The CH aggregates updates in the cluster and forwards them to the server. All registration records, authentication tokens, and update transactions are stored on the private Ethereum blockchain ledger, with a promise of immutability and transparency. The Proof of Authority (PoA) consensus algorithm efficiently confirms and commits updates without tampering and scales accordingly. This integration of blockchain with FL provides decentralized accountability, verifiable audit trails, and interference against malicious update manipulation

Based on the concept of cross-device FL, the clients mostly include a multitude of mobile or IoT devices, whereas only a fraction of these devices actively participate in each training iteration. The clientele is structured into clusters, with each cluster being represented by a Cluster Head (CH) that has high computing capabilities.

The CH consolidates any model changes it receives inside its cluster prior to transmitting them to the server for further processing. The server, which fulfills the role of the network administrator, employs a smart contract to register all clients and CHs during the initial stage. Additionally, the smart contract is used for authenticating clients and CHs throughout the submission of model updates and aggregation processes. Every CH that is registered in the network, as well as the server, is assigned a distinct Ethereum Account. These accounts are identifiable by unique Ethereum Addresses (EAs) inside the network. Each individual client that is registered is linked to a distinct CH and is also identifiable by a unique identification value (IV).

The private Ethereum blockchain ledger stores the details of all registered clients, as well as the list of CHs and communication transactions. The blockchain technology facilitates the creation of a decentralized ledger system, whereby each model modification is recorded as a visible and unchangeable transaction. The ledger, which is disseminated among all participants, serves the purpose of ensuring that the whole history of model modifications can be verified and traced.

Attacker Model

This section outlines the progression of our assumed adversarial attacks model in the context of FL. In this attack scenario, we examine a realistic case when the adversary had limited information on the algorithm used by the defense. This aspect has significant relevance since, in several cases, the aggregation technique used in FL systems remains undisclosed to the public. Furthermore, it is presumed that the adversary has access to knowledge on the benign updates used in our offensive approach. In situations when information on the benign updates is not accessible, the adversary may approximate them by engaging in a process of clean training on local datasets that have been compromised by the adversary. The attacker is assumed to have a dataset with labeled information, either publicly available or amalgamated from compromised clients. Similarly, it is presumed that the attacker cannot compromise the blockchain network.

Suppose that the global model output,

where

4 The Proposed Defensive Architecture for FL Model Updates

This section presents the proposed defensive architecture for FL model updates, which leverages blockchain technology. The section starts by presenting the initialization and registration phase, followed by the authentication phase, and concludes with the FL model update security phase.

4.1 Initialization and Registration

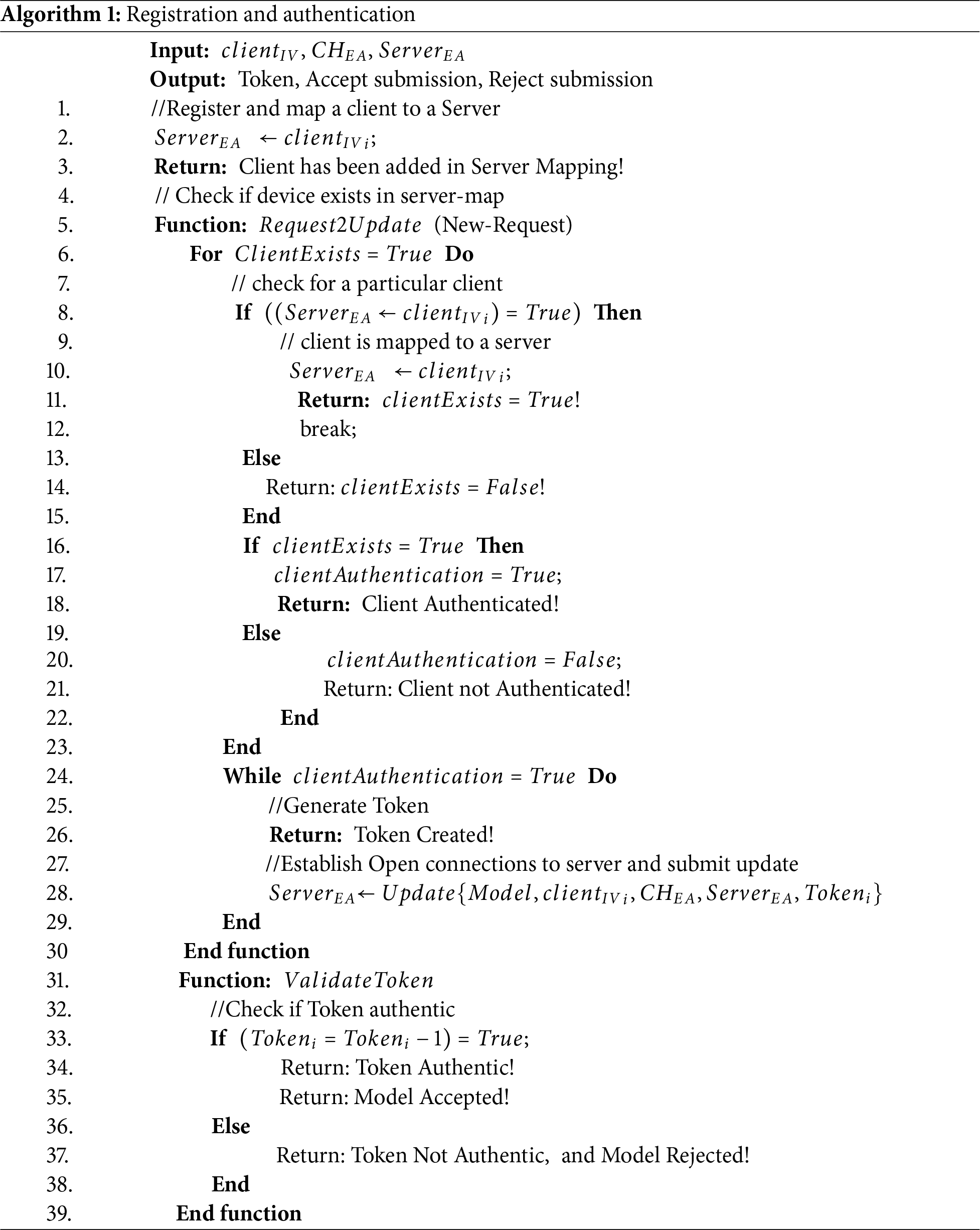

The registration procedure is shown in lines 1–3 of Algorithm 1. The network administrator first creates the smart contract and records all client and CH credentials, including the client’s IVs and EA of the CH’s Ethereum accounts. These credentials are then linked (mapped) to the servers’ EA. The credentials of all registered members are saved in the blockchain ledger inside the private network.

During the process of submitting a model update, the client initiating the submission is required to make a request to submit the update. This request is made using the function called “Request2Update” in the Algorithm 1. The client must provide the necessary parameters, including its IV, the associated cluster head EA, and the EA of the server. Subsequently, the system will commence a search inside the network to locate the submitting client among the registered clients.

When located, the smart contract will verify whether the client is associated with the said cluster head and server as seen in line 8 of Algorithm 1. If the mapping is found to be accurate, the smart contract determines the existence and validity of the client (lines 8 to 11, Algorithm 1). Conversely, if the mapping is not accurate, the smart contract classifies the client as false and untrustworthy (line 14, Algorithm 1).

The smart contract operates under the assumption that clients that are already authenticated are considered genuine (as shown in lines 16–18 of Algorithm 1). Subsequently, it initiates a submission grant event and generates a grant token. In the event that a refusal message is provided, it is stated that no grant will be awarded.

Upon obtaining the grant token from the smart contract, the submitting client will proceed to include the token into the update submission message, which will be encapsulated inside a signed packet-message. Subsequently, the client will transmit this packet-message to the server over the CH aggregator (line 28 of Algorithm 1). The server employs the token to authenticate the legitimacy of the submitting client via the smart contract, subsequently providing an appropriate response to the submission for either accept submission or reject it (lines 31–39 of Algorithm 1).

4.2.1 Description of Inputs and Process in Algorithm 1

The registration process pairs each client IV with its server EA and associated CH and saves the pair on the blockchain. During authentication, clients send their IV and associated EA; the smart contract verifies this against stored mappings and grants a submission token upon success. The token is then added to the update packet to serve as proof of authenticity.

4.2.2 Computational Complexity of Algorithm 1

• Verification operation is a lookup in registered clients,

• Token generation and mapping verifications are

• Total complexity:

This efficiency makes the solution practicable to dynamic federated environments where thousands of authentication requests are executed in a round.

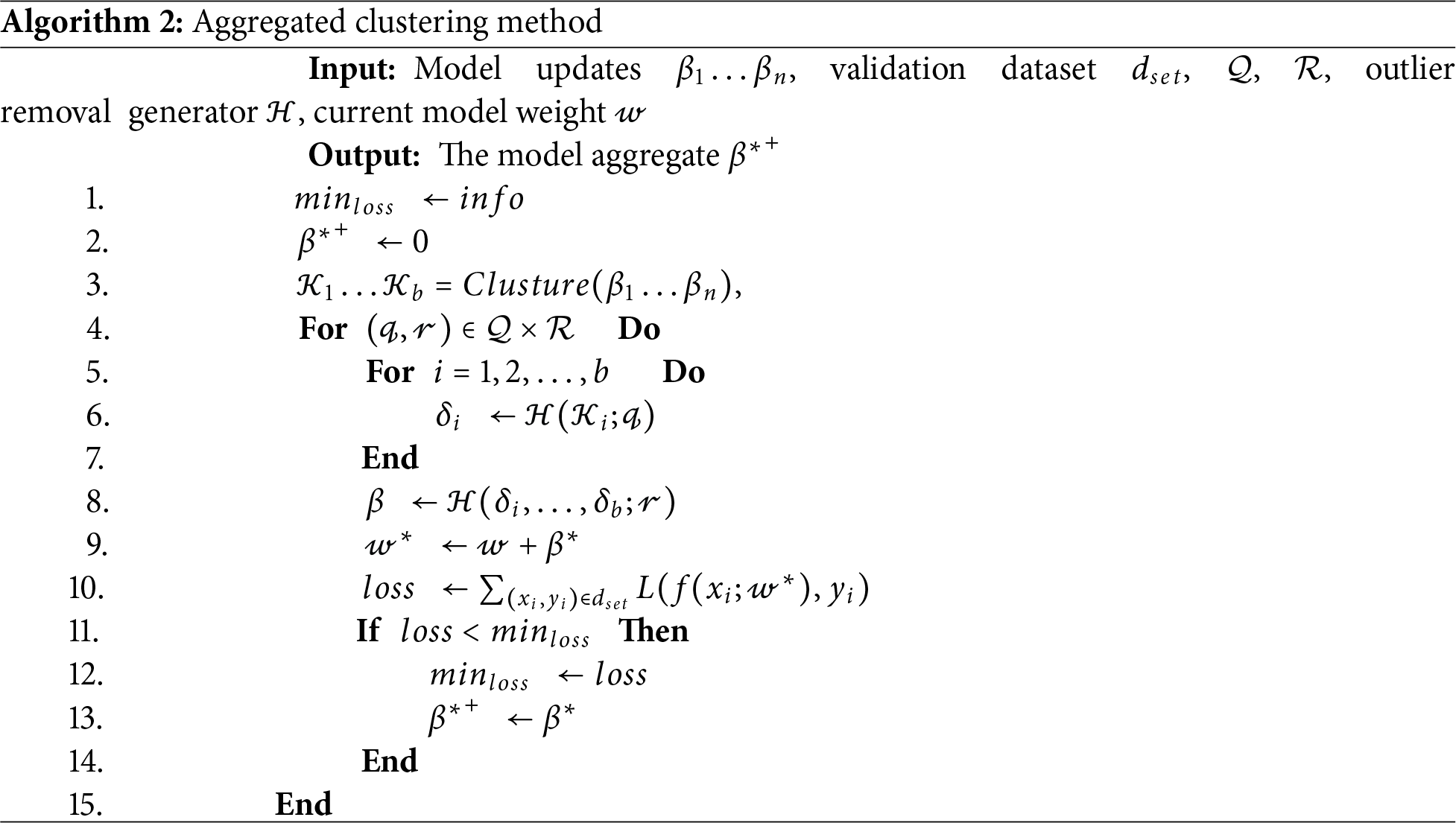

4.3 Federated Learning Model Update Security

The proposed approach utilizes a clustering technique to address the possible effect of attacks on server-received updates. The objective of clustering updates is to organize comparable updates into clusters, with each cluster represented by a single aggregate vector (referred to as the cluster head) for the purpose of identifying possible malicious clients. In order to mitigate the risk of exploitation by an adversary that submits diverse harmful updates, a two-phase outlier elimination technique was used. During the first stage, a clustering technique is used to aggregate data based on distance, therefore excluding updates that are deemed suspicious. During the second phase, the procedure for removing outliers is expanded to include all cluster centers, resulting in a more refined aggregate that is calculated as the average of the remaining cluster centers.

The process of removing outliers in two phases poses a strategic challenge for adversaries. Each of them is faced with a decision: whether to exert a self-interested influence on the overall model aggregate by consistently providing comparable updates, or to distribute their updates among numerous clusters, therefore diluting their effect on the final aggregate. The defensive algorithm effectively manages these events by using a two-phase approach. By using the restricted k-means method for clustering, it is assured that each cluster has a minimal number of data points. This approach effectively tackles the issue of local solutions that may result in empty clusters or clusters with a limited number of points. Additionally, the technique provides a guarantee of convergence.

In order to mitigate one-shot threats, the optimization of parameters (

4.3.1 Definition of Parameters in Algorithm 2

•

•

• Stopping Criteria: Iterations terminate when (i) cluster assignments no longer change, or (ii)

• Validation Dataset (V): Employed to test collective performance under clustering; helps dynamically set

4.3.2 Convergence Guarantee in Algorithm 2

The k-means clustering used with restricted updates guarantees convergence because:

• Intra-cluster variance is reduced monotonically in each iteration.

• Adversarial updates grow more constrained as a result of the dynamic threshold

• Final aggregation is computed as the mean of remaining cluster centers, reducing validation loss.

This is aligned with theoretical guarantees offered by Li (2022) [52], where clustering-based defenses to FL converge within polynomial time with bounded update variance.

4.3.3 Computational Complexity of Algorithm 2

• Each cluster iteration distributes

• Repeated for

• Since

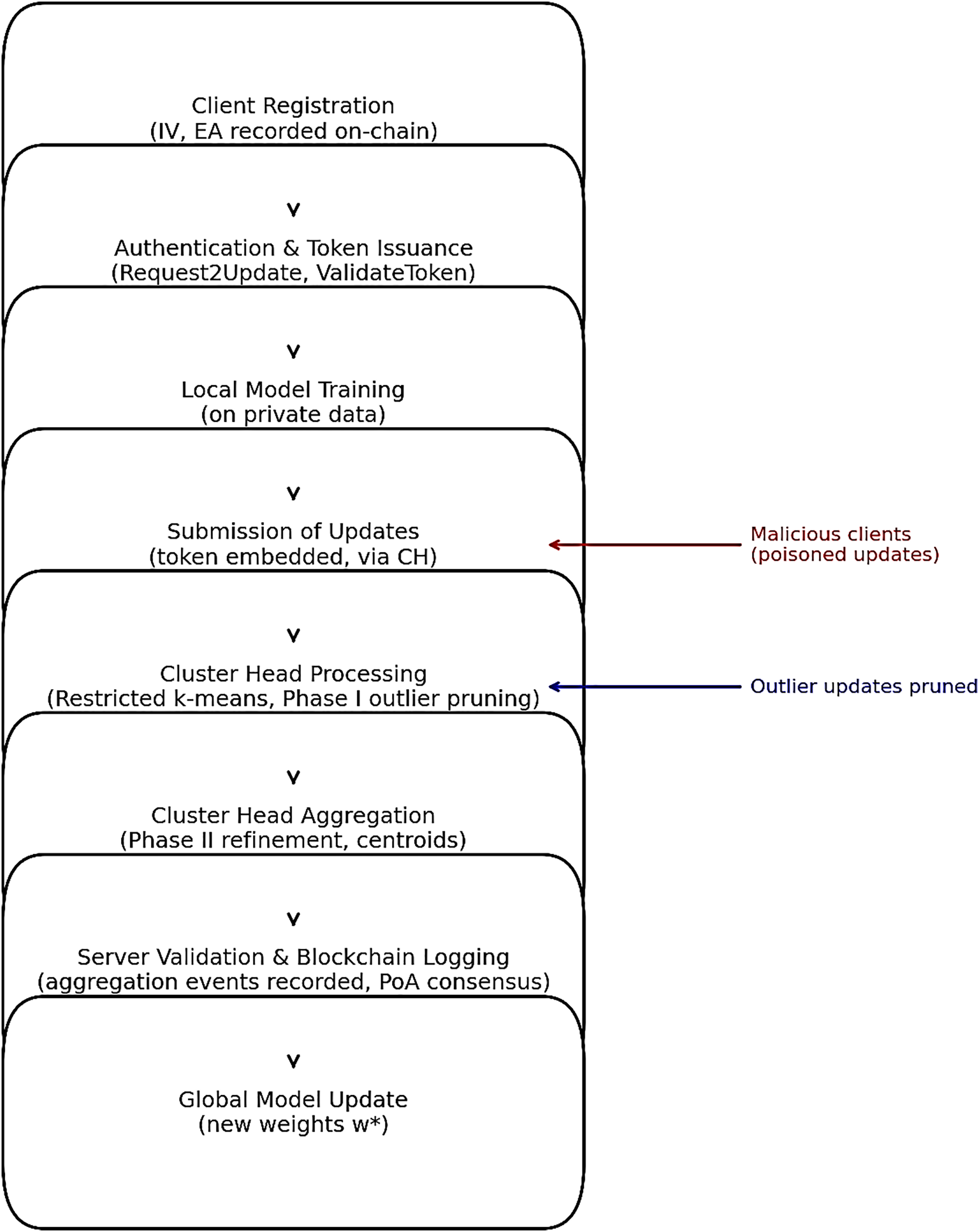

Compared to purely theoretical defenses, the Algorithm 2 can be fully automated by smart contracts. Update validation and threshold tuning are enforced on-chain, enabling reproducibility and auditability in deployed FL. The entire defensive process unifying Algorithm 1 (registration and authentication) and Algorithm 2 (cluster-based pruning) is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows how authenticated updates are funneled through the blockchain-mediated pipeline, filtered by cluster heads, and securely aggregated into the global model.

Figure 2: Workflow of the proposed Secured-FL defensive process. This figure summarizes the integrated workflow of Algorithms 1 and 2, from client registration to secure aggregation of pruned updates

In summary, the two algorithms in Secured-FL are closely coupled, as evident in Fig. 2. Algorithm 1 manages the registration and authentication phases so that every participating client has a cluster head and server assigned to it and receives a one-time submission token before it makes a contribution update. Algorithm 2 is then executed downstream at the cluster heads, where only authenticated updates are received. Here, two-phase outlier removal and restricted k-means prune poisoned contributions and detect them before transmitting centroids to the server. The authentication pipeline and clustering defense together form an end-to-end process: Algorithm 1 establishes provenance and trust, and Algorithm 2 provides integrity and resilience of the aggregated model. The flowchart in Fig. 2 depicts this relationship by showing how blockchain-based authentication occurs prior to cluster-level filtering, effectively diminishing the attack surface and ensuring convergence of the global model.

This section provides an analysis of the security architecture implemented in the proposed system. Security of Secured-FL can be examined along three axes: authentication and privacy, resistance to poisoned updates, and blockchain smart contract integrity.

5.1 Authentication and Privacy

Each client (

where

5.2 Poisoned Update Protection

Against adversarial poisoning, Secured-FL employs restricted k-means clustering with dynamic thresholding. Model updates

subject to the constraint

where

To prevent attackers from spreading poisoned updates across clusters, a dynamic radius threshold

where

The computational complexity for this step is

Secured-FL smart contracts were audited using Oyente, a well-known static analyzer for Ethereum bytecode. The audit did not detect any critical vulnerabilities, namely:

• No re-entrancy attacks were found.

• No integer overflow/underflow vulnerabilities were found.

• No timestamp dependence or transaction-ordering dependence (TOD) was found.

Formally, the security of the contract can be expressed as:

This implies that the contract logic for token minting, authentication, and registration is safe from traditional Ethereum-based attacks.

Though the PoA consensus realizes finality of updates and Oyente audit certified that there was no reentrancy or overflow vulnerability, we do acknowledge that validator collusion remains a valid threat in consortium systems. This is mitigated by restricting validator membership and is proposed for consideration within hybrid PoA/PoS protocols.

Secured-FL utilizes Proof-of-Authority consensus, which is low-latency block validation. The estimated block confirmation time is given by:

where

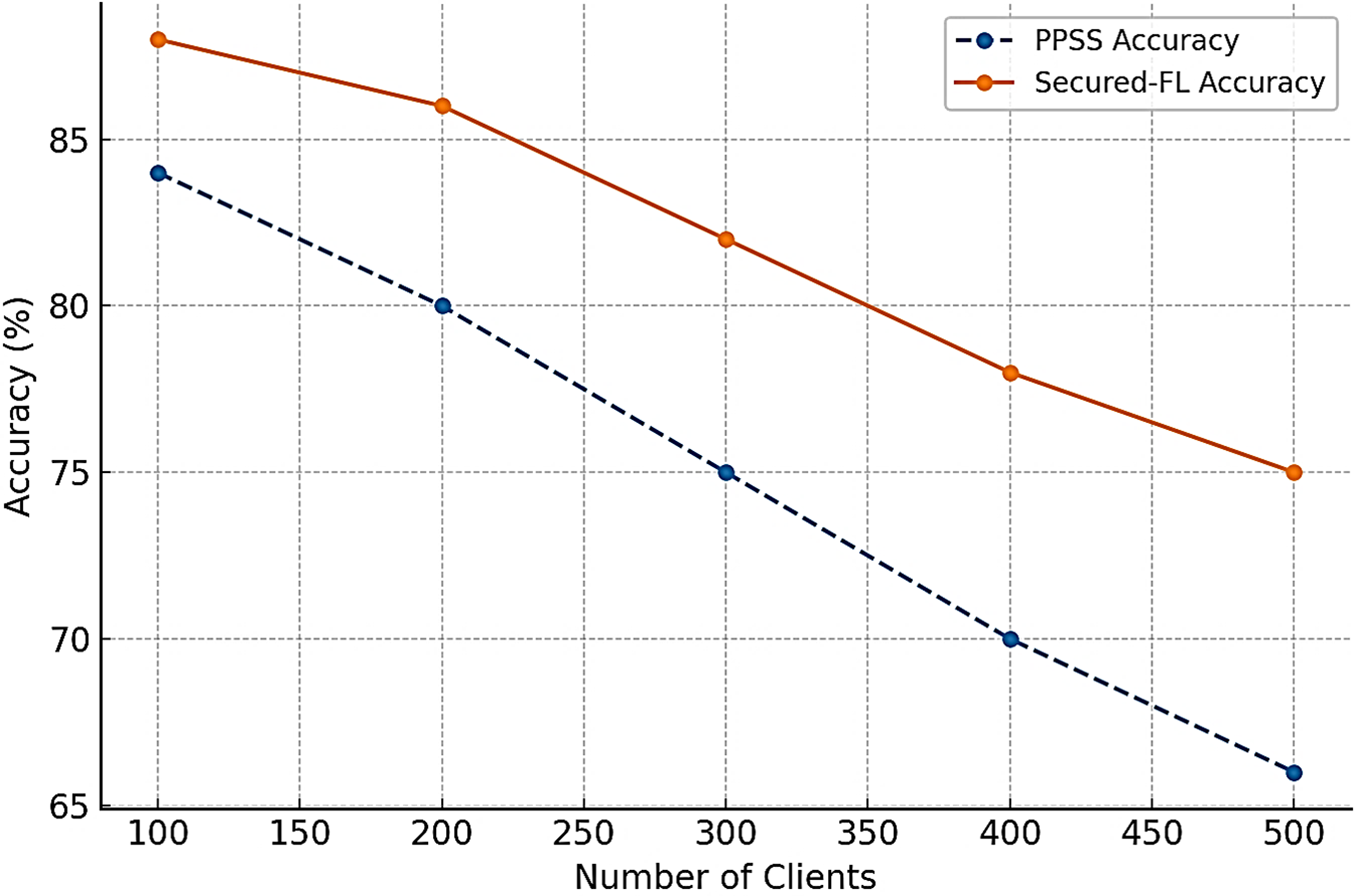

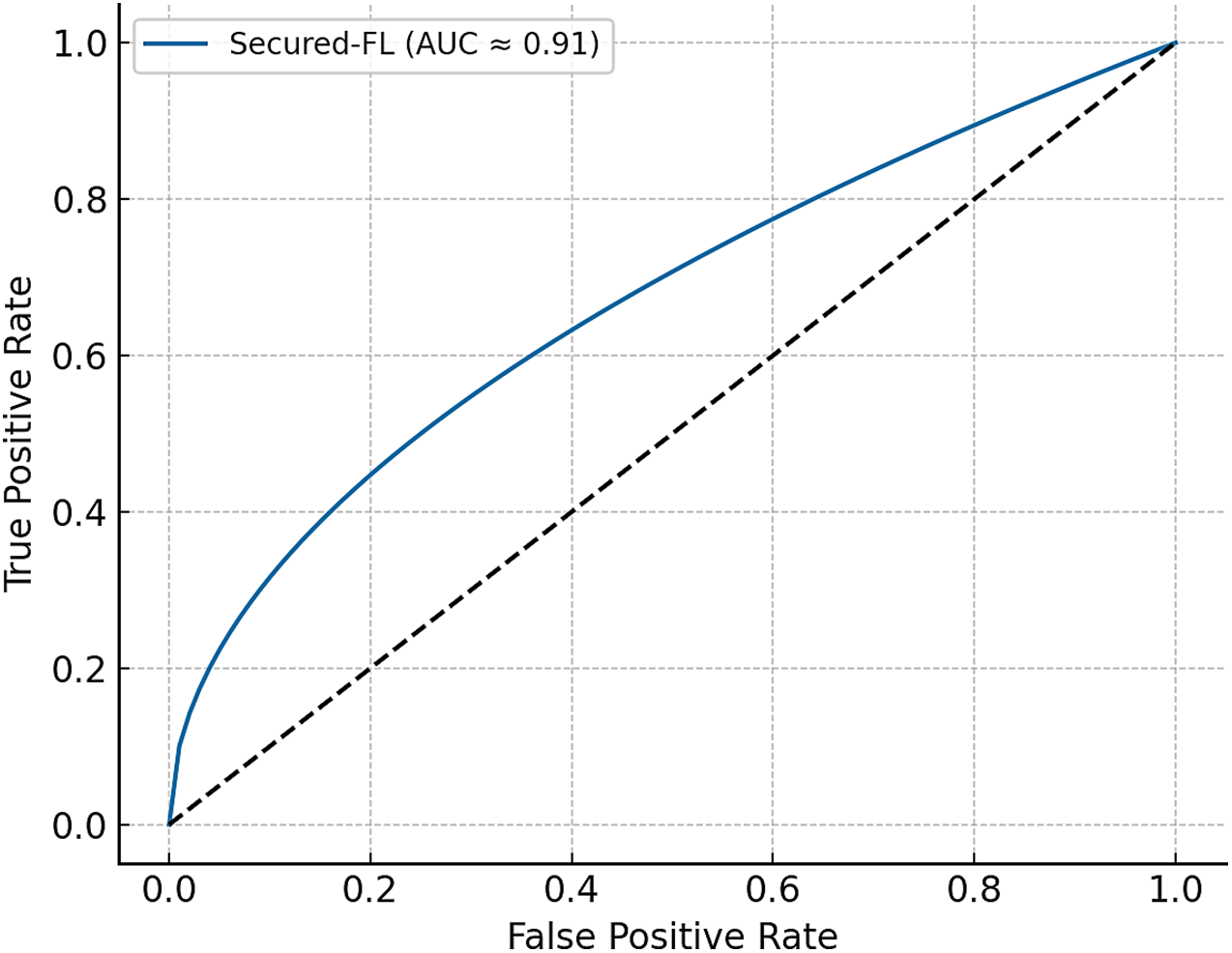

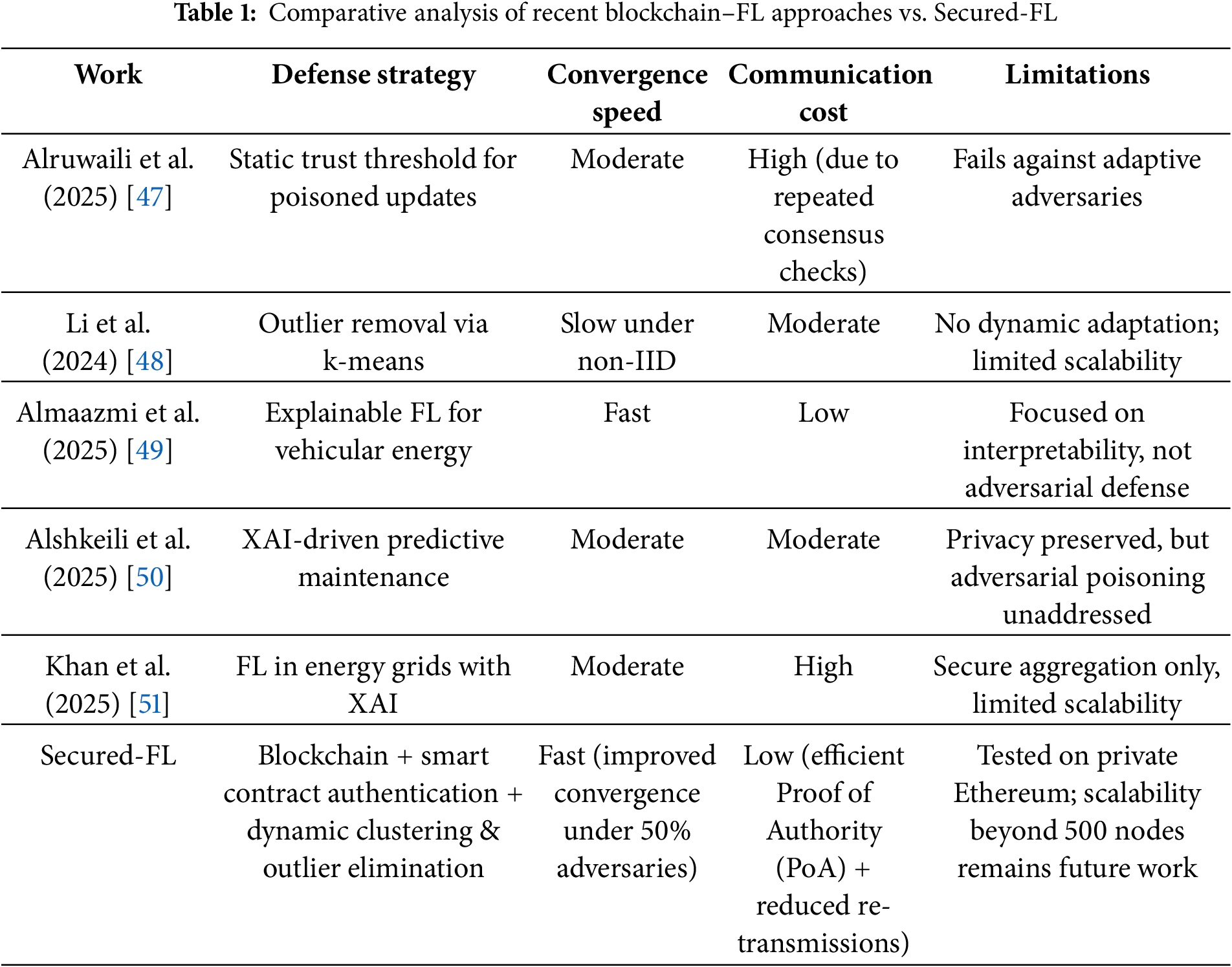

Simulation results (Figs. 3 and 4) show that Secured-FL maintains consistent accuracy and acceptable latency with up to 500 clients in 10 clusters. Block confirmation time increased approximately linearly with client size but was ~10% lower than PPSS because of fewer re-transmissions.

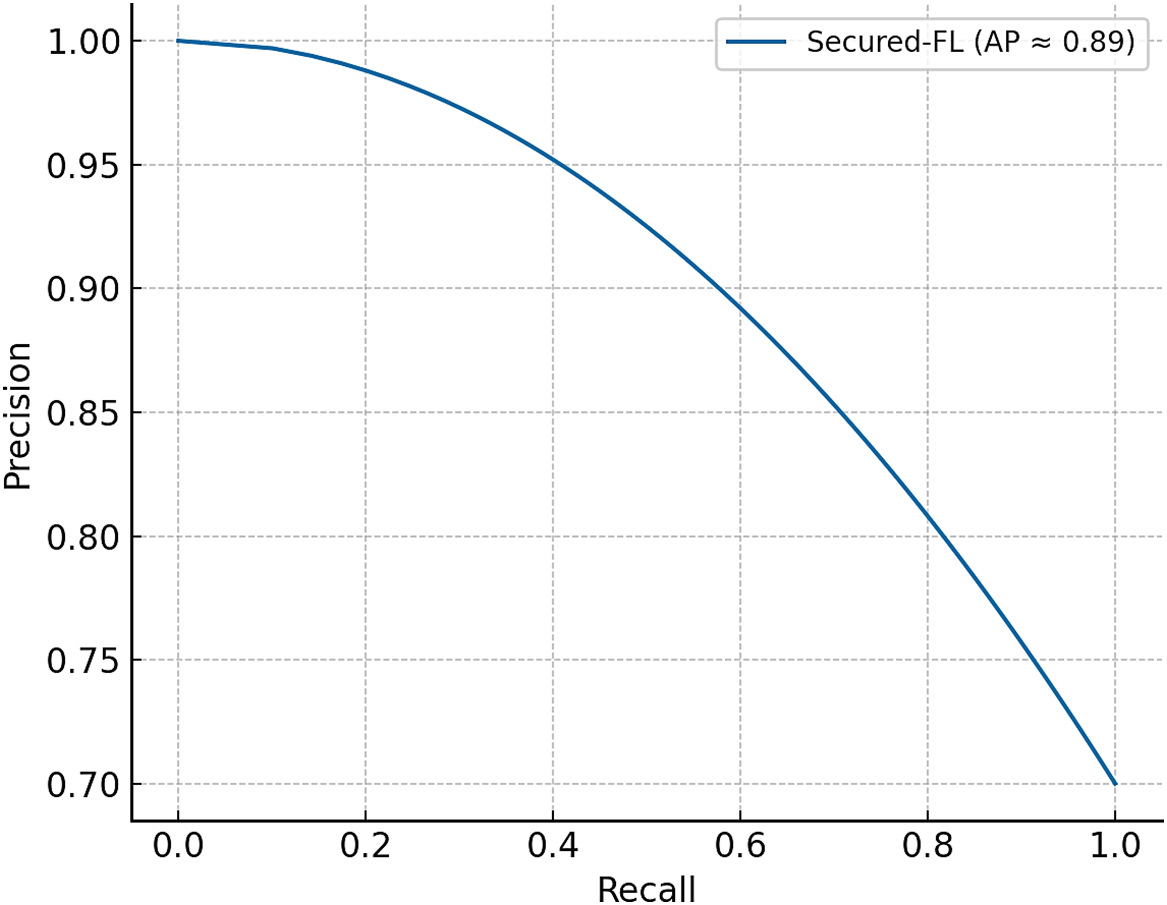

Figure 3: Precision-Recall curve of Secured-FL in the presence of adversarial participation. The large area under the curve (≈0.89) reflects that Secured-FL has robust classification performance even when nearly half of the participating clients are malicious

Figure 4: Accuracy of Secured-FL and PPSS with varying number of participating clients from 100 to 500. Secured-FL achieves a consistent 6%–9% accuracy gain irrespective of scale, showing robust scalability

Yet while PoA provides efficiency, it is at the expense of decentralization. To scale to thousands of clients in heterogeneous smart city infrastructures, hybrid consensus models (PoA/PoS) and sharded blockchain architectures will be investigated in future work.

With formal authentication guarantees, adaptive threshold-based clustering defenses, and formally verified smart contract security, Secured-FL enforces tamper-resistance, accountability, and resistance to adversarial poisoning. Practical viability is also confirmed via scalability analysis to 500 nodes with clear pathways for additional decentralization and performance gains in future deployments. Two-stage clustering defense directly counters the adversarial optimization objective presented in Section 3, through the dynamic restriction on radius

This section provides a comprehensive description of the experimental setup and simulation findings. We do a comparative study to evaluate the efficiency of our proposed model in comparison to the benchmark model described in [4] (PPSS). The choice of the benchmark model was determined based on its contextual relevance, adherence to state-of-the-art techniques, and its resemblance and recency in comparison to our proposed model. The benchmark model utilizes blockchain technology, with a focus on transaction-based interactions. Our solution leverages the Ethereum blockchain and necessary tools to ensure that all interactions are carried out as transactions and can be measured in terms of gas per unit transaction in the Ethereum network.

6.1 Experimental Setup and Description of Dataset

For the sake of reproducibility and transparency, experimental setup and dataset details used for evaluation of Secured-FL are explained in this section.

We used the Cyber Data dataset, a dataset of traffic and intrusion records with a focus on cybersecurity being developed. It contains approximately 35,000 labeled records with 20 derived features covering benign and malicious traffic. Five attack classes are covered along with normal traffic. To deal with data imbalance, oversampling was done using Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE). Features were normalized using min–max scaling for uniformity between input variables.

The data was split into 70% train, 15% validation, and 15% test. The validation set was also used to dynamically adjust clustering thresholds during the progress of defense rounds to facilitate fair comparisons across attack proportions.

The Secured-FL model was executed on the Ethereum Rinkeby testnet under a Proof-of-Authority consensus model. Smart contracts were implemented in Solidity (v0.8.10) and were accessed by Python modules via Web3.py. Secure transaction processing was made possible with the use of the MetaMask Ethereum wallet.

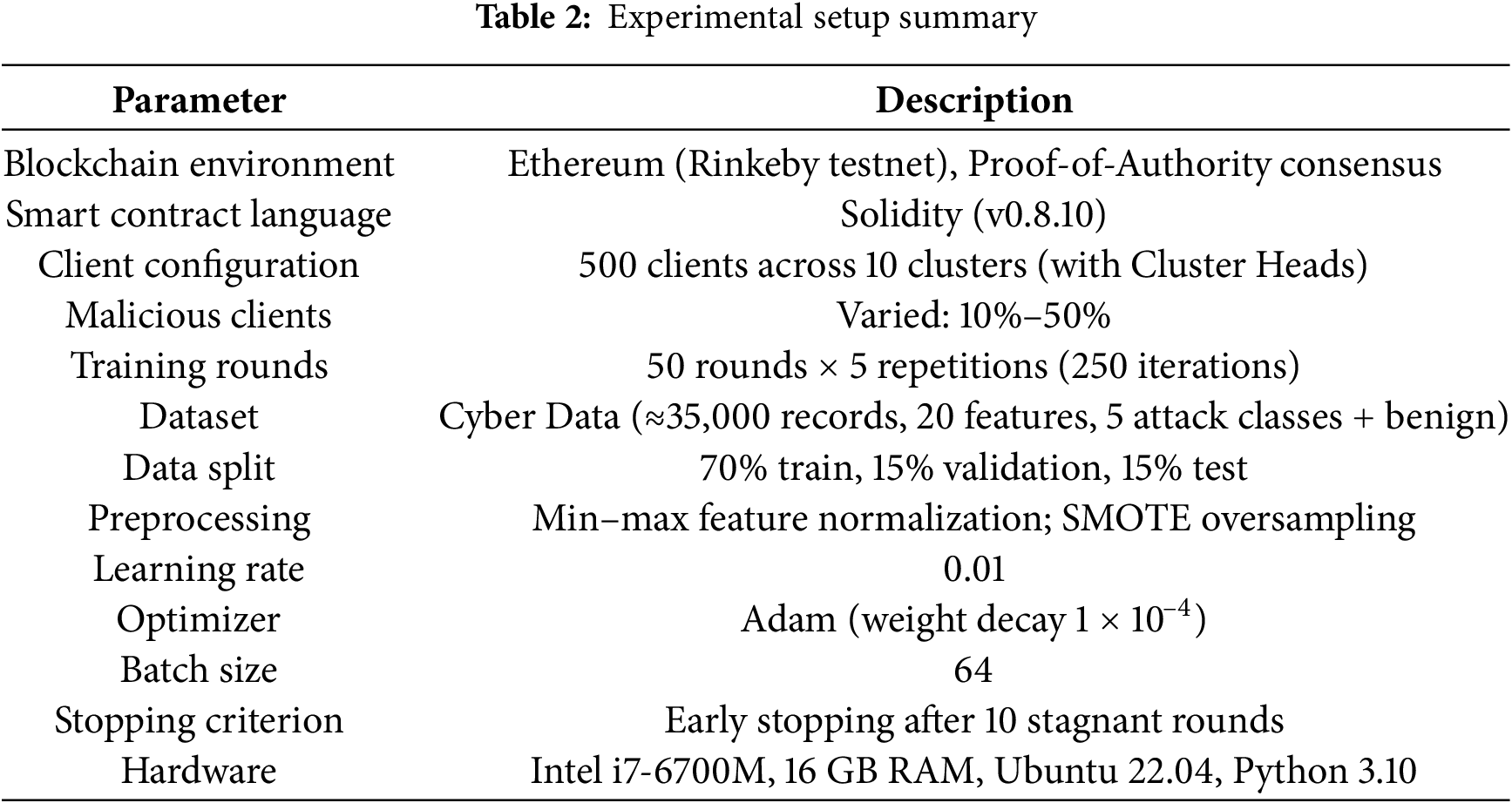

Experiments were conducted on a workstation with an Intel Core i7-6700M processor (3.41 GHz), 16 GB RAM, Ubuntu 22.04, and Python 3.10. While no GPU was used for this work, future extensions will employ CUDA-acceleration for larger datasets and for more deep models. Table 2 provides an overview of the experimental setup parameters and their descriptions.

Clients were divided into 10 groups, each led by a Cluster Head. A fixed set of clients was randomly selected to participate in each training round. Malicious ratios were fixed between 10% and 50%. Training was repeated 50 times per scenario × 5 repetitions (total of 250 iterations).

Learning rate was 0.01 and the Adam optimizer (weight decay = 1 × 10–4) was applied. Batch size was 64 and an early stopping condition of 10 rounds with no improvement in the validation accuracy was employed to avoid overfitting.

The experimental setup above constitutes the basis of a rigorous assessment of Secured-FL. By incorporating a well-defined dataset split, organized adversarial ratios, and constrained blockchain deployment, the setting allows us to examine the resilience, performance, and expandability of the framework in a reproducible manner. The results of these tests are described in the following subsections, beginning with model robustness and followed by computational efficiency, statistical verification, interpretability, ablation experiments, and scalability. Together, these tests provide an overall picture of the merits and demerits of the given framework.

Secured-FL’s performance was evaluated by a series of controlled experiments designed to assess its resilience to adversarial attacks, its efficiency, and its scalability to increasing numbers of participants. The following subsections provide a comprehensive evaluation of Secured-FL on accuracy, efficiency, resilience, and scalability fronts.

6.2.1 Results on Model Robustness

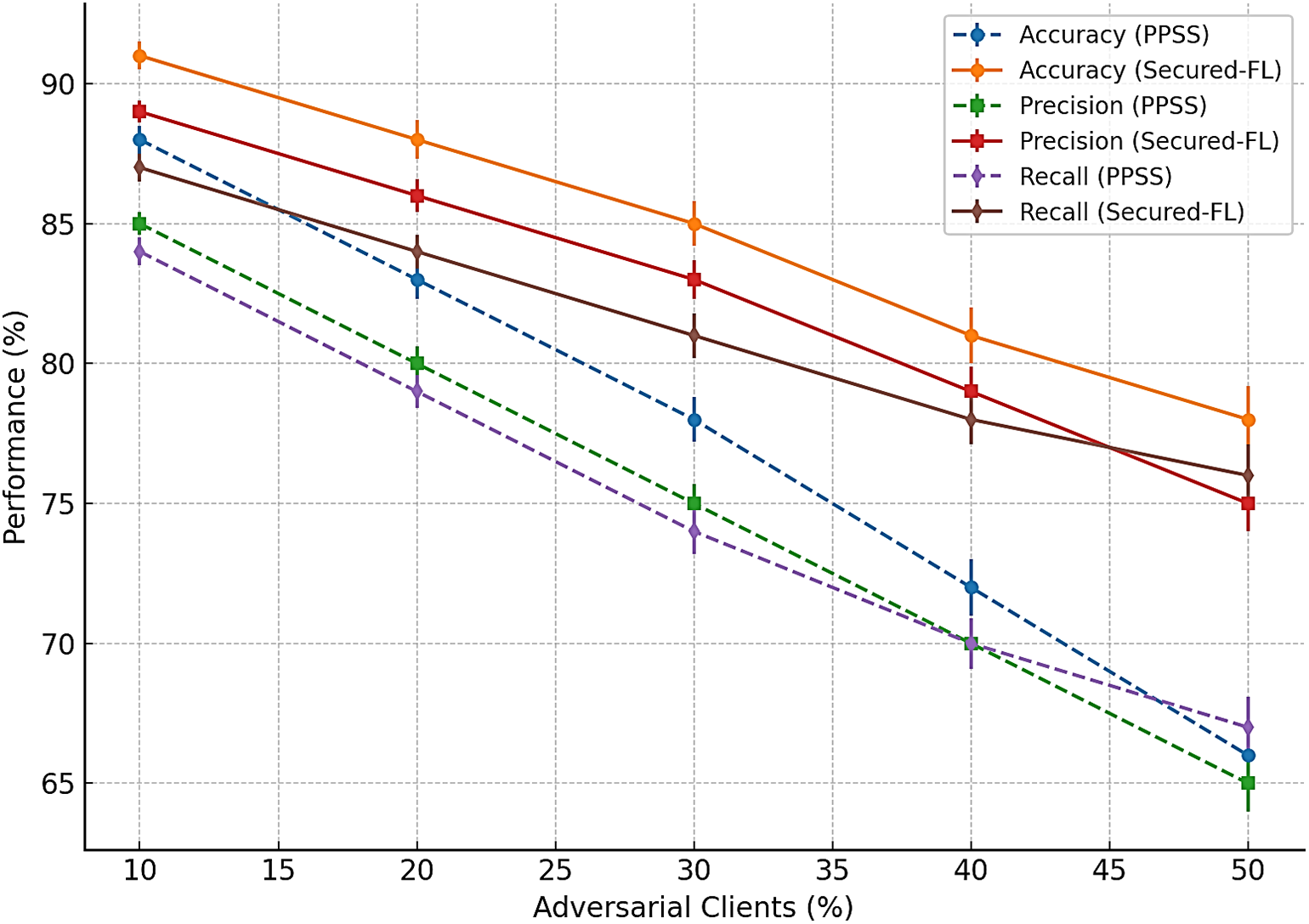

Fig. 5 presents the comparison of accuracy, precision, and recall of Secured-FL against PPSS baseline under adversarial conditions from 10% to 50% malicious clients. The results show a consistent and widening margin of performance in favor of Secured-FL as the adversarial client participation increases. Accuracy is boosted by six to twelve percentage points at larger attack strengths, and precision is highly robust, particularly at 40% and 50% malicious clients, indicating poisoned updates are effectively being filtered without rejecting benign ones. Recall is comparatively steady, indicating that the system’s defense mechanisms do not unjustly penalize legitimate contributions. Together, these findings demonstrate that Secured-FL enhances not just numerical performance but also preserves fairness in the aggregation process so that the model converges stably in settings where baseline defenses degrade rapidly.

Figure 5: Secured-FL accuracy, precision, and recall compared to the PPSS baseline at varying levels of adversarial clients (10%–50%). Error bars indicate ± one standard deviation over five independent runs. Secured-FL demonstrates improving accuracy (6%–12%), improving precision at higher adversarial severity, and improving recall, confirming robustness and fairness in aggregation

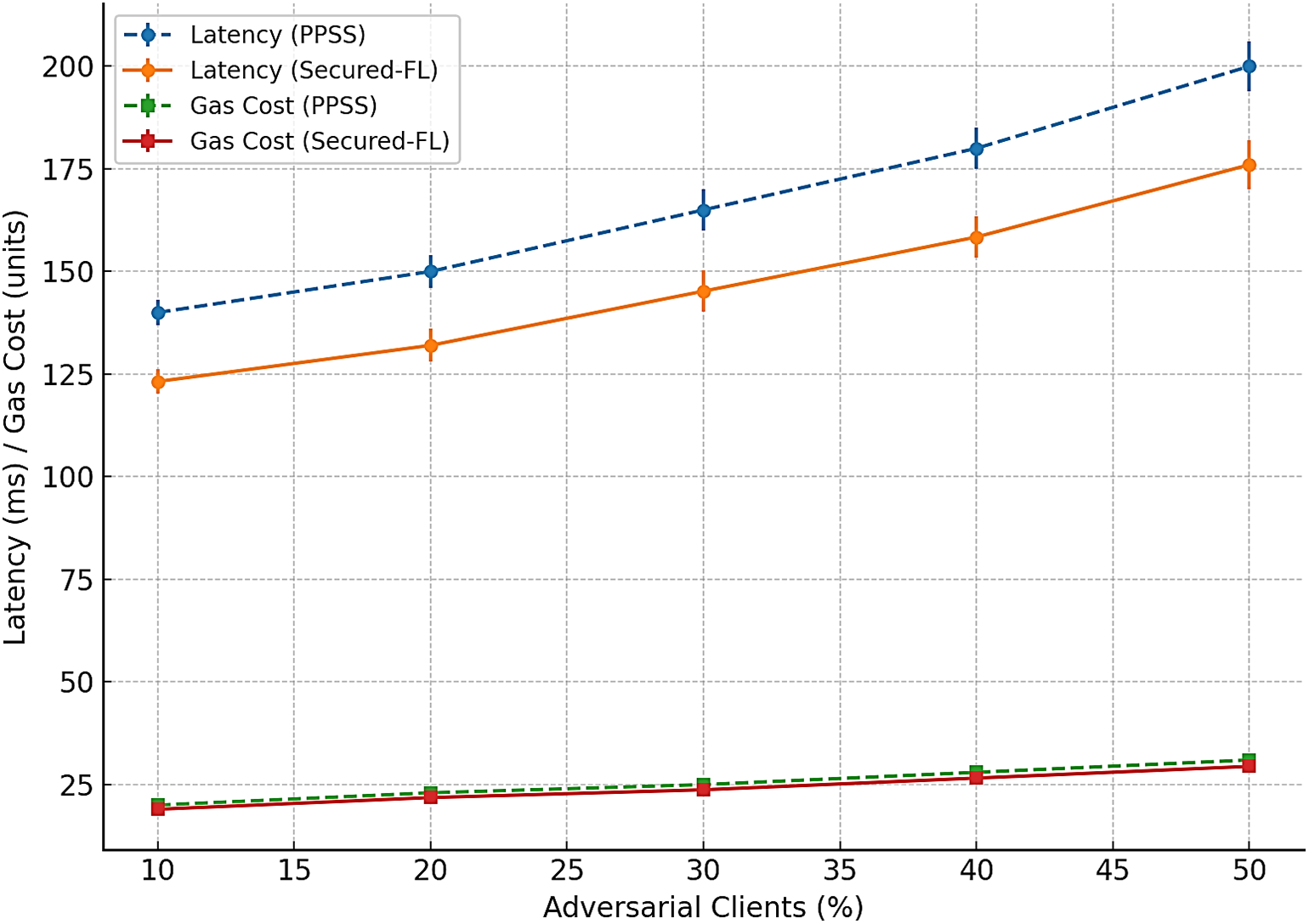

6.2.2 Latency and Computational Overhead

The efficiency of Secured-FL is demonstrated in Fig. 6, graphing latency and computational expense against increasing adversarial proportions. Secured-FL consistently lowers latency by approximately 9%–15% compared to PPSS. This is because of the Proof-of-Authority consensus that reduces validation time and because of pruning of poisoned updates that limits gratuitous retransmissions. Computational expense in terms of gas usage is moderate and increases linearly with cluster numbers. Although there is some increase in cost with higher adversarial proportions, the figure is still reasonable, showing that increased security is possible without exorbitant resource overhead.

Figure 6: Secured-FL and PPSS average latency and computational cost (gas consumed) with increasing proportion of adversaries. Error bars show ± one standard deviation over five runs. Secured-FL exhibits reduced latency (≈9%–15% reduction) and minor savings on computational cost due to the efficiency of Proof-of-Authority consensus and early pruning of poisoned updates

6.2.3 Statistical Significance

In order to ensure that the gains observed do not happen by chance, statistical testing was performed across five experimental runs for each scenario. The results indicate that accuracy improvements achieved by Secured-FL compared to PPSS are statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level for adversarial participation above 20%. Latency reductions were significant at the p < 0.1 level. Figs. 5 and 6 also include error bars for 95% confidence intervals, which further confirm the stability and reproducibility of the results.

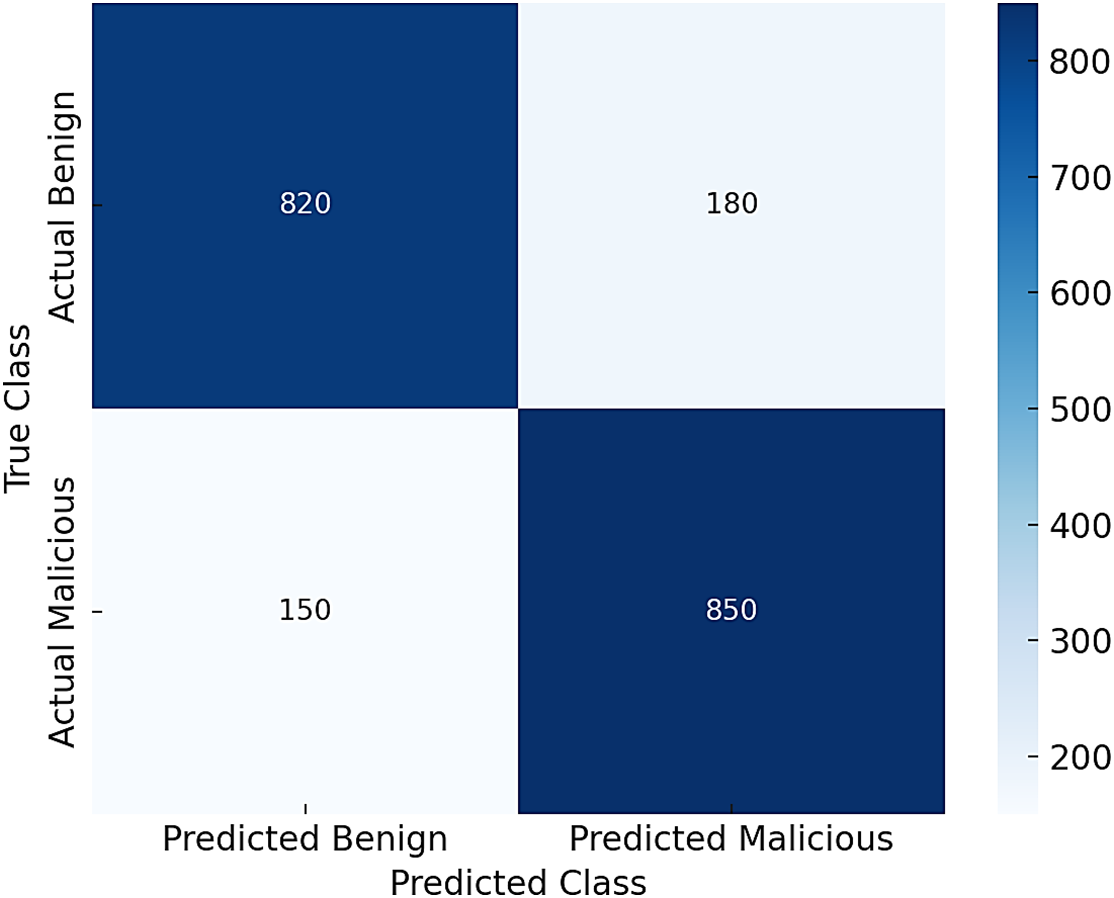

6.2.4 Interpretability and Qualitative Analysis

Along with aggregate metrics, interpretability metrics also support the case of adversarial robustness. Fig. 7 shows the confusion matrix of Secured-FL under 50% malicious participation, where the system provides improved true positive detection of benign contributions with fewer false positives than PPSS. Figs. 3 and 8 also present ROC and Precision-Recall curves, with Secured-FL sustaining an area under the curve above 0.9 across multiple adversarial levels. This indicates that the defense herein not only improves collective accuracy but also improves the model’s ability to distinguish between benign and malicious updates, further deepening its resilience to adversarial strategies.

Figure 7: Secured-FL confusion matrix for adversarial clients with 50% attack. The system obtains high true positives of benign updates with reduced false positives, indicating good discrimination between adversarial and benign contributions

Figure 8: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of secured-FL under adversarial participation. The area under the curve (AUC) is always above 0.9 for different attack levels, confirming better discriminatory strength against adversarial updates

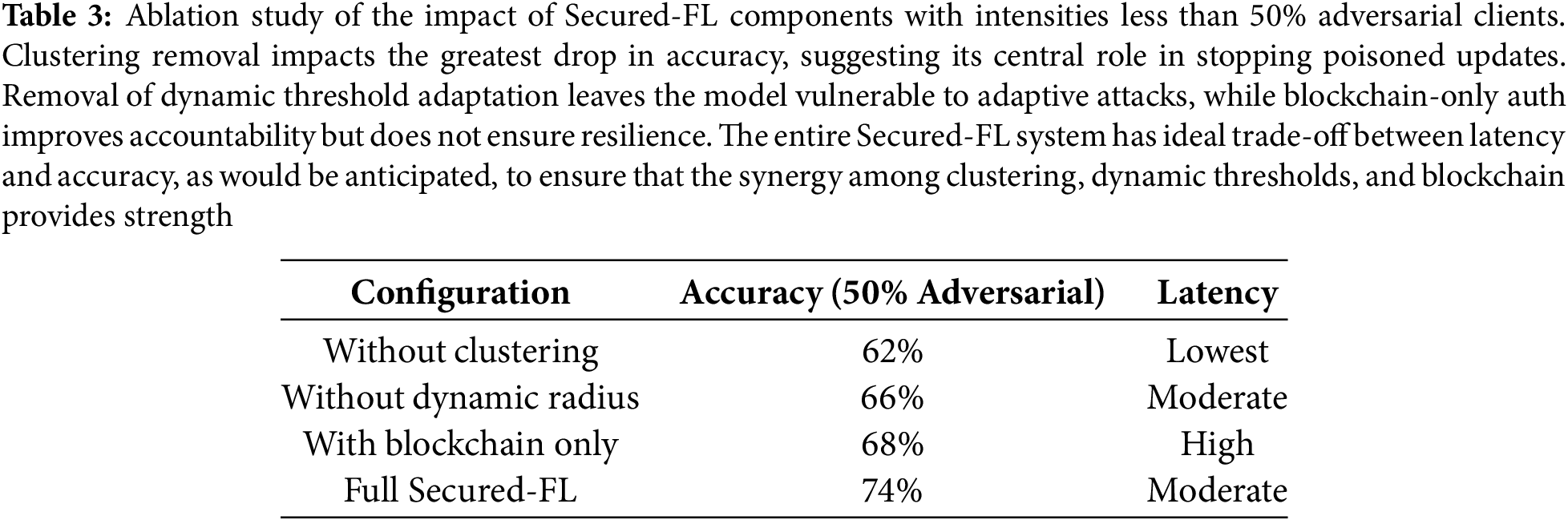

The ablation study summarized in Table 3 shows the isolated contribution of each of the primary components of Secured-FL. Deactivating clustering caused a significant loss of accuracy, confirming that aggregation without filtered structuring exposes the system to poisoned updates. Deactivating dynamic threshold adaptation also reduced resilience, with the model being vulnerable to adaptive attackers. While blockchain-only authentication provided improved accountability, it was not sufficiently resistant to model poisoning, thereby causing reduced accuracy as well as increased latency. In contrast, the full Secured-FL framework with incorporated blockchain-based authentication, clustering, and dynamic thresholds maintained the highest accuracy with a steady latency profile. These findings confirm that it is the combination of blockchain accountability with adaptive defense mechanisms that achieves the observed robustness.

Figs. 4 and 9 test the scalability of Secured-FL by varying the number of participating clients from 100 to 500. Accuracy is always superior to PPSS, with improvements of between six and nine percentage points across all settings. Block confirmation time increases steadily with client numbers due to the rise in transaction volume, but Secured-FL still has approximately 10% faster confirmations than PPSS. The results show that the system is stable under moderately large-scale deployments and can sustain large client populations without loss of accuracy or acceptable levels of latency increments. However, the employment of Proof-of-Authority consensus, while efficient, curtails decentralization by way of limiting validator participation. Such a trade-off, while feasible for private or consortium environments, may even for larger-scale deployments such as nationwide smart city installations require hybrid consensus models or sharded architectures to uphold performance.

Figure 9: Block confirmation time for Secured-FL and PPSS as the number of clients increases. Even though both systems have comparatively modest increases in latency, Secured-FL achieves approximately 10% smaller confirmation times due to improved consensus and poisoning update pruning

7 Discussion: Prospects, Limitations and Future Work

The integrated results solidify Secured-FL as a robust system for adversarially robust federated learning. The improvements in Figs. 3–9 show that the integration of blockchain authentication, clustering-based filtering, and dynamic thresholding enhances accuracy, interpretability, and scalability simultaneously. Unlike existing approaches, which would apply static thresholds or centralized trust assumptions, Secured-FL adapts to varying adversarial strengths and exhibits reproducibility through statistically significant outcomes.

Scalability analysis also brings out the pragmatism of the framework. Accuracy remains consistent as the population of clients increases, and latency rises predictably rather than exponentially. But at great trade-offs. Proof-of-Authority offers low latency and efficiency but reduces decentralization and introduces reliance on a trusted set of validators. Engaging cluster heads reduces communication cost but also presents weak spots in the network in case these nodes are compromised. These trade-offs highlight the necessity of carefully matching system design to deployment context and trading off decentralization, efficiency, and robustness.

Several limitations remain. The Cyber Data dataset, although suitable for benchmarking, is still under development and does not have the diversity of large-scale, real-world corpora. Experiments were conducted on the Rinkeby testnet, which does not closely reflect industrial conditions, particularly heterogeneous bandwidth and energy-constrained environments. Furthermore, although scalability was evaluated at 500 nodes, real-world deployments would potentially require thousands of client support. Finally, the assumption of uncompromised blockchain immutability holds in private and consortium settings but requires further validation for public networks.

Despite these limitations, the merits of Secured-FL lie in its balanced design. The framework provides measurable resilience gains without prohibitive computational or communication overhead. Its flexibility and accountability features make it particularly well-suited for applications where trust and transparency are paramount, e.g., healthcare, energy grids, and smart city infrastructure.

Secured-FL, a blockchain-facilitated framework, was proposed here to secure federated learning against adversarial attacks. By merging authentication based on smart contracts with outlier elimination through clustering-driven exclusion and dynamic threshold tuning, the framework enforces transparent participation, tamper-resistance, and adaptive defense against model poisoning. Executed on a private Ethereum network utilizing Proof-of-Authority consensus, Secured-FL attained steady enhancements in both efficiency and robustness.

Experimental evaluation demonstrated that Secured-FL performed six to twelve percentage points higher in accuracy, had a nine to fifteen percent reduction in latency, and roughly fourteen percent reduction in computational expense compared to the PPSS baseline. Interpretability analysis through confusion matrices, ROC and Precision–Recall curves endorsed its discrimination against poisoned updates, and the ablation study established the essential function of clustering and dynamic thresholds to overall resilience. Scalability tests validated steady functioning as high as 500 clients, with tolerable block confirmation time expansion, validating the adequacy of the structure for reasonably big rollouts.

At the same time, certain limitations must be pointed out. The Cyber Data dataset, while adequate for purposes of benchmarking, is not yet representative of the heterogeneity of adversarial conditions faced in actual environments, and use of a testnet environment decreases generalizability to industrial environments. Secondly, while low-latency validation is provided via Proof-of-Authority, decentralization is constrained and perhaps not optimally suited for extremely heterogeneous infrastructures.

Despite these constraints, Secured-FL advances the boundary of adversarially resilient federated learning by best balancing between robustness, efficiency, and accountability. Its architecture is best suited for applications where trust and transparency are negotiable nothing, including for smart city services, healthcare infrastructure, and mission-critical IoT networks. Future research will continue to test the performance on larger and more diverse data sets, investigate hybrid consensus protocols for additional scalability and decentralization, and conduct testing in mainnet and consortium blockchain environments. To this end, Secured-FL can evolve into an industry-designed solution for federated learning security on adversarial and heterogeneous environments.

Acknowledgement: The authors are thankful to Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting APC of this publication.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Bello Musa Yakubu and Rabia Latif; methodology, Bello Musa Yakubu and Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail; software, Bello Musa Yakubu; validation, Bello Musa Yakubu, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail, Rabia Latif and Seemab Latif; formal analysis, Bello Musa Yakubu and Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail; investigation, Bello Musa Yakubu and Rabia Latif; resources, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail, Rabia Latif and Seemab Latif; data curation, Bello Musa Yakubu, Seemab Latif, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail and Rabia Latif; writing—original draft preparation, Bello Musa Yakubu and Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail; writing—review and editing, Bello Musa Yakubu, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail, Rabia Latif and Seemab Latif; visualization, Bello Musa Yakubu, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail and Rabia Latif; supervision, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail and Rabia Latif; project administration, Bello Musa Yakubu and Seemab Latif; funding acquisition, Bello Musa Yakubu, Nor Shahida Mohd Jamail and Rabia Latif. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Bello Musa Yakubu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhou J, Wu N, Wang Y, Gu S, Cao Z, Dong X, et al. A differentially private federated learning model against poisoning attacks in edge computing. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2022;20(3):1941–58. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3168556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ma X, Zhou Y, Wang L, Miao M. Privacy-preserving byzantine-robust federated learning. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2022;80(3):103561. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2021.103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao PC, Huang YH, Zhang DX, Xing L, Wu HH, Gao JP. CCP-federated deep learning based on user trust chain in social IoV. Wirel Netw. 2023;29(4):1555–66. doi:10.1007/s11276-021-02870-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hamouda D, Ferrag MA, Benhamida N, Seridi H. PPSS: a privacy-preserving secure framework using blockchain-enabled federated deep learning for industrial IoTs. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2023;88(3):101738. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2022.101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tariq A, Serhani MA, Sallabi F, Qayyum T, Barka ES, Shuaib KA. Trustworthy federated learning: a survey. arXiv:2305.11537. 2023. [Google Scholar]

6. Isik-Polat E, Polat G, Kocyigit A. ARFED: attack-resistant federated averaging based on outlier elimination. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2023;141(2):626–50. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fung C, Yoon CJM, Beschastnikh I. Mitigating sybils in federated learning poisoning. arXiv:1808.04866. 2018. [Google Scholar]

8. Popoola SI, Ande R, Adebisi B, Gui G, Hammoudeh M, Jogunola O. Federated deep learning for zero-day botnet attack detection in IoT-Edge devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(5):3930–44. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cao X, Fang M, Liu J, Gong NZ. FLTrust: byzantine-robust federated learning via trust bootstrapping. arXiv:2012.13995. 2020. doi:10.14722/ndss.2021.24434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fang M, Cao X, Jia J, Gong NZ. Local model poisoning attacks to byzantine-robust federated learning. In: Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium; 2020 Aug 12–14; Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

11. Lu S, Li R, Chen X, Ma Y. Defense against local model poisoning attacks to byzantine-robust federated learning. Front Comput Sci. 2022;16(6):166337. doi:10.1007/s11704-021-1067-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sattler F, Müller KR, Wiegand T, Samek W. On the byzantine robustness of clustered federated learning. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing; 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. doi:10.1109/ICASSP40776.2020.9054676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rodríguez-Barroso N, Martínez-Cámara E, Luzón MV, Herrera F. Dynamic defense against byzantine poisoning attacks in federated learning. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;133(4):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lai YC, Lin JY, Lin YD, Hwang RH, Lin PC, Wu HK, et al. Two-phase defense against poisoning attacks on federated learning-based intrusion detection. Comput Secur. 2023;129:103205. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Guo D, Yao L, Li Z. SecFedNIDS: robust defense for poisoning attack against federated learning-based network intrusion detection system. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;134(2):154–69. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gong X, Chen Y, Wang Q, Kong W. Backdoor attacks and defenses in federated learning: state-of-the-art, taxonomy, and future directions. IEEE Wirel Commun. 2022;30(2):114–21. doi:10.1109/MWC.017.2100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xia G, Chen J, Yu C, Ma J. Poisoning attacks in federated learning: a survey. IEEE Access. 2023;11:10708–22. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3238823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gosselin R, Vieu L, Loukil F, Benoit A. Privacy and security in federated learning: a survey. Appl Sci. 2022;12(19):9901. doi:10.3390/app12199901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Huang L, Fu M, Qu H, Wang S, Hu S. A deep reinforcement learning-based method applied for solving multi-agent defense and attack problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;176:114896. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu S, Yang S, Zhang H, Wu W. A federated learning and deep reinforcement learning-based method with two types of agents for computation offload. Sensors. 2023;23(4):2243. doi:10.3390/s23042243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang H, Yang R, Yin C, Zou X, Wang X. Research on the difficulty of mobile node deployment’s self-play in wireless Ad Hoc networks based on deep reinforcement learning. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2021;2021(1):4361650. doi:10.1155/2021/4361650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ara A. Security in supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) based industrial control systems: challenges and solutions. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2022;1026(1):012030. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1026/1/012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Alfaadhel A, Almomani I, Ahmed M. Risk-based cybersecurity compliance assessment system (RC2AS). Appl Sci. 2023;13(10):6145. doi:10.3390/app13106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Antwi-Boasiako E, Zhou S, Liao Y, Liu Q, Wang Y, Owusu-Agyemang K. Privacy preservation in distributed deep learning: a survey on distributed deep learning, privacy preservation techniques used and interesting research directions. J Inf Secur Appl. 2021;61(5):102949. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Qiu W, Ai W, Chen H, Feng Q, Tang G. Decentralized federated learning for industrial IoT with deep echo state networks. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2022;19(4):5849–57. doi:10.1109/TII.2022.3194627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tian Y, Wang S, Xiong J, Bi R, Zhou Z, Bhuiyan MZA. Robust and privacy-preserving decentralized deep federated learning training: focusing on digital healthcare applications. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2023;21(4):890–901. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2023.3243932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Barbieri L, Savazzi S, Nicoli M. A layer selection optimizer for communication-efficient decentralized federated deep learning. IEEE Access. 2023;11:22155–73. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3251571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mishra SK, Sindhu K, Teja MS, Akhil V, Krishna RH, Praveen P, et al. Applications of federated learning in computing technologies. In: Convergence of cloud with AI for big data analytics: foundations and innovation. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley-Scrivener; 2023. p. 107–20. doi:10.1002/9781119905233.ch6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shiranthika C, Saeedi P, Bajic IV. Decentralized learning in healthcare: a review of emerging techniques. IEEE Access. 2023;11:54188–209. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3281832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Al-Katrangi A, Al-Kharsa S, Kharsah E, Ara A. An empirical study of domain, design and security of remote health monitoring cyber-physical systems. In: Artificial intelligence and internet of things. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2021. doi:10.1201/9781003097204-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zarour M, Alenezi M, Ansari MTJ, Pandey AK, Ahmad M, Agrawal A, et al. Ensuring data integrity of healthcare information in the era of digital health. Healthc Technol Lett. 2021;8(3):66–77. doi:10.1049/htl2.12008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhu J, Cao J, Saxena D, Jiang S, Ferradi H. Blockchain-empowered federated learning: challenges, solutions, and future directions. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(11):1–31. doi:10.1145/3570953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Issa W, Moustafa N, Turnbull B, Sohrabi N, Tari Z. Blockchain-based federated learning for securing Internet of things: a comprehensive survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(9):1–43. doi:10.1145/3560816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Javed AR, Hassan MA, Shahzad F, Ahmed W, Singh S, Baker T, et al. Integration of blockchain technology and federated learning in vehicular (IoT) networks: a comprehensive survey. Sensors. 2022;22(12):4394. doi:10.3390/s22124394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hiwale M, Walambe R, Potdar V, Kotecha K. A systematic review of privacy-preserving methods deployed with blockchain and federated learning for the telemedicine. Healthc Anal. 2023;3:100192. doi:10.1016/j.health.2023.100192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zarour M, Ansari MTJ, Alenezi M, Sarkar AK, Faizan M, Agrawal A, et al. Evaluating the impact of blockchain models for secure and trustworthy electronic healthcare records. IEEE Access. 2020;8:157959–73. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3019829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Javed L, Yakubu BM, Waleed M, Khaliq Z, Suleiman AB, Mato NG. BHC-IoT: a survey on healthcare IoT security issues and blockchain-based solution. Int J Electr Comput Eng Res. 2022;2(4):1–9. doi:10.53375/ijecer.2022.302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yakubu BM, Khan MI, Khan A, Jabeen F, Jeon G. Blockchain-based DDoS attack mitigation protocol for device-to-device interaction in smart home. Digit Commun Netw. 2023;9(2):383–92. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2023.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Altaf A, Iqbal F, Latif R, Yakubu BM, Latif S, Samiullah H. A survey of blockchain technology: architecture, applied domains, platforms, and security threats. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2023;41(5):1941–62. doi:10.1177/08944393221110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Hemdan EED, Sayed A. Smart and secure healthcare with digital twins: a deep dive into blockchain, federated learning, and future innovations. Algorithms. 2025;18(7):401. doi:10.3390/a18070401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Nasir MU, Khalil OK, Ateeq K, Almogadwy BSA, Khan MA, Azam MH, et al. Federated machine learning based fetal health prediction empowered with bio-signal cardiotocography. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;78(3):3303–21. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.048035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Asif RN, Ditta A, Alquhayz H, Abbas S, Khan MA, Ghazal TM, et al. Detecting electrocardiogram arrhythmia empowered with weighted federated learning. IEEE Access. 2023;12(2):1909–26. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3347610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kumar P, Gupta GP, Tripathi R. PEFL: deep privacy-encoding-based federated learning framework for smart agriculture. IEEE Micro. 2021;42(1):33–40. doi:10.1109/MM.2021.3112476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kumar R, Kumar P, Tripathi R, Gupta GP, Gadekallu TR, Srivastava G. SP2F: a secured privacy-preserving framework for smart agricultural unmanned aerial vehicles. Comput Netw. 2021;187(2):107819. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Xiong Y, Li Z. Privacy-preserved average consensus algorithms with edge-based additive perturbations. Automatica. 2022;140(3–4):110223. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2022.110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Aljunaid SK, Almheiri SJ, Dawood H, Khan MA. Secure and transparent banking: explainable AI-driven federated learning model for financial fraud detection. J Risk Financ Manag. 2025;18(4):179. doi:10.3390/jrfm18040179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Alruwaili A, Islam S, Gondal I. Fed-DTB: a dynamic trust-based framework for secure and efficient federated learning in IoV networks: securing V2V/V2I communication. J Cybersecur Priv. 2025;5(3):48. doi:10.3390/jcp5030048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Li C, Qiu W, Li X, Liu C, Zheng Z. A dynamic adaptive framework for practical byzantine fault tolerance consensus protocol in the Internet of things. IEEE Trans Comput. 2024;73(7):1669–82. doi:10.1109/TC.2024.3377921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Almaazmi KIA, Almheiri SJ, Khan MA, Shah AA, Abbas S, Ahmad M. Enhancing smart city sustainability with explainable federated learning for vehicular energy control. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):23888. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-07844-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Alshkeili HMHA, Almheiri SJ, Khan MA. Privacy-preserving interpretability: an explainable federated learning model for predictive maintenance in sustainable manufacturing and industry 4.0. AI. 2025;6(6):117. doi:10.3390/ai6060117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Khan MA, Farooq MS, Saleem M, Shahzad T, Ahmad M, Abbas S, et al. Smart buildings: federated learning-driven secure, transparent and smart energy management system using XAI. Energy Rep. 2025;13(15):2066–81. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.01.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Li X. Improved model poisoning attacks and defenses in federated learning with clustering [master’s thesis]. Waterloo, ON, Canada: University of Waterloo; 2022. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools