Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FAIR-DQL: Fairness-Aware Deep Q-Learning for Enhanced Resource Allocation and RIS Optimization in High-Altitude Platform Networks

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha, 410083, China

2 EIAS Data Science Lab, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

3 College of Computer and Information Sciences, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11432, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Computer Sciences, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Muhammad Asim. Email: ; Kashish Ara Shakil. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 29 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072464

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The integration of High-Altitude Platform Stations (HAPS) with Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS) represents a critical advancement for next-generation wireless networks, offering unprecedented opportunities for ubiquitous connectivity. However, existing research reveals significant gaps in dynamic resource allocation, joint optimization, and equitable service provisioning under varying channel conditions, limiting practical deployment of these technologies. This paper addresses these challenges by proposing a novel Fairness-Aware Deep Q-Learning (FAIR-DQL) framework for joint resource management and phase configuration in HAPS-RIS systems. Our methodology employs a comprehensive three-tier algorithmic architecture integrating adaptive power control, priority-based user scheduling, and dynamic learning mechanisms. The FAIR-DQL approach utilizes advanced reinforcement learning with experience replay and fairness-aware reward functions to balance competing objectives while adapting to dynamic environments. Key findings demonstrate substantial improvements: 9.15 dB SINR gain, 12.5 bps/Hz capacity, 78% power efficiency, and 0.82 fairness index. The framework achieves rapid 40-episode convergence with consistent delay performance. These contributions establish new benchmarks for fairness-aware resource allocation in aerial communications, enabling practical HAPS-RIS deployments in rural connectivity, emergency communications, and urban networks.Keywords

The exponential growth in wireless communication demands, coupled with the global drive for ubiquitous connectivity, has accelerated research into advanced network architectures capable of supporting high data rates, low latency, and wide-area coverage [1,2]. Among these emerging solutions, High-Altitude Platform Stations (HAPS) have gained significant attention for their ability to deliver broadband connectivity from the stratosphere. Operating at altitudes of approximately 20 km [3,4], HAPS offer distinct advantages over terrestrial and satellite systems, including large coverage footprints, relatively low deployment and maintenance costs, rapid redeployment, and flexible reconfiguration capabilities [5]. These features make HAPS highly attractive for bridging the digital divide in underserved and remote areas, supporting disaster recovery [6], and enhancing network resilience [7]. However, despite their promise, HAPS systems face persistent challenges in sustaining reliable communication links, mitigating interference, and guaranteeing stringent Quality of Service (QoS) levels under dynamic and unpredictable channel conditions [8,9].

The recent emergence of Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS) offers a paradigm-shifting opportunity for improving wireless communication performance through the intelligent manipulation of the electromagnetic propagation environment [10,11]. RIS technology enables programmable, passive beamforming by adjusting the phase shifts of numerous low-cost reflecting elements, thereby enhancing coverage, increasing capacity, and improving energy efficiency [12,13]. The integration of RIS into HAPS systems presents a compelling hybrid architecture that could overcome the limitations of conventional aerial communication platforms while unlocking new capabilities in spatial coverage optimization and channel enhancement [14]. Specifically, the synergy between the spatial flexibility of HAPS and the channel-shaping potential of RIS could allow for adaptive and highly efficient network configurations. However, realizing these benefits is non-trivial. The combined system introduces a multi-dimensional joint optimization problem involving HAPS positioning, RIS phase configuration, power allocation, and user scheduling. These parameters are tightly coupled, and their optimal values vary with environmental dynamics, user mobility patterns, and interference levels [15]. Existing studies on HAPS communications have largely focused on aspects such as altitude optimization, beam footprint control, and coverage maximization [16], as well as resource allocation using static or semistatic schemes [17]. Similarly, while RIS technology has been extensively investigated in terrestrial scenarios, its deployment in aerial platforms introduces unique challenges, including the need for accurate three-dimensional channel modeling, adaptation to high-mobility environments, and strict QoS guarantees for heterogeneous user groups [18]. Moreover, conventional optimization techniques often struggle with the highly non-convex nature of the problem and the vast decision space inherent in large-scale HAPS-RIS deployments [19]. In recent years, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has emerged as a promising approach for tackling complex wireless optimization problems [20]. DRL methods can learn effective policies directly from system interactions without requiring explicit analytical models, making them well-suited for dynamic and uncertain environments. However, existing DRL-based solutions in HAPS or RIS contexts typically address single objective formulations or rely on simplified assumptions that do not fully capture the interplay between multiple coupled constraints [21]. Additionally, fairness among users an increasingly important metric for next-generation networks, is often overlooked in these designs [22]. In the context of HAPS-RIS systems, where platform position, RIS configuration, and user distribution vary dynamically, maintaining both high system performance and equitable service distribution is particularly challenging [23].

To address these challenges, we propose a novel Fairness-Aware Deep Q-Learning (FAIR-DQL) framework that jointly optimizes HAPS positioning, RIS phase configuration, and priority-based user scheduling while ensuring fairness and QoS compliance. Our approach is designed to adapt rapidly to time-varying network conditions, mitigate interference, and efficiently allocate limited resources across a large number of users. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

1. Comprehensive system modeling: We formulate a detailed HAPS-RIS communication model that explicitly captures the interdependencies between aerial positioning, RIS phase configuration, and user scheduling decisions.

2. Fairness-aware resource allocation: We design a resource allocation mechanism that achieves a Jain’s fairness index of 0.82 while maintaining 78% power efficiency, ensuring equitable service distribution across users.

3. Optimal RIS phase configuration: We develop an algorithm that delivers a 9.15 dB SINR gain over conventional RIS optimization methods, verified through both theoretical analysis and simulation.

4. Theoretical guarantees: We provide formal proofs for the optimality of RIS phase configurations and queue stability under the proposed scheduling and resource allocation scheme.

5. Superior performance: Our simulations demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves a peak system capacity of 12.5 bps/Hz at a 7 dB SINR threshold, with convergence occurring within 40 training episodes, significantly outperforming existing methods in SINR, capacity, and convergence speed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work and current state-of-the-art approaches. Section 3 presents the system model and problem formulation. Section 4 describes the proposed three-tier algorithmic framework and deep Q-learning integration. Section 5 provides a comprehensive performance evaluation through simulations. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper with key findings and future research directions.

The integration of HAPS and RIS has emerged as a promising paradigm for enhancing wireless communication systems. Existing literature reveals a multifaceted approach to addressing the complex challenges in this domain. Channel estimation has been a critical focus of research. Initial works relied on traditional optimization methods; for instance, reference [24] proposed conventional channel estimation techniques for HAPS-MIMO systems, establishing a foundational approach. Subsequently, machine learning techniques revolutionized this domain. References [22,25] introduced deep learning-based channel estimation methodologies, demonstrating significant improvements in accuracy and adaptability under mobility constraints. Resource allocation and management in HAPS-RIS networks have also been extensively investigated. Reference [26] pioneered a distributed resource management approach using multi-agent learning, enabling collaborative optimization. Building upon this, reference [5] developed adaptive resource management techniques that dynamically respond to network variations. Additionally, reference [27] introduced a novel deep double Q-learning framework, showcasing the potential of reinforcement learning in intelligent resource optimization. nRIS configuration has been explored from multiple perspectives. For instance, reference [28] focused on robust beamforming design, while reference [29] targeted energy-efficient phase shift strategies. Reference [30] extended these approaches by developing mobility-aware RIS configuration techniques, addressing the dynamic nature of aerial networks. Recognizing the interconnected nature of HAPS-RIS systems, recent works have pursued holistic optimization strategies. Reference [31] investigated joint HAPS positioning and RIS configuration, while reference [32] employed deep learning for integrated communication optimization. Reference [33] proposed multi-objective optimization techniques using deep learning.

Our work addresses the limitations of existing research by proposing a comprehensive and integrated optimization framework. Unlike previous approaches that focus on individual aspects, we develop a holistic system that simultaneously addresses channel estimation, resource management, and RIS configuration. By leveraging advanced machine learning and reinforcement learning techniques, our approach offers superior mobility support and dynamically adapts to network variations. The proposed method extends beyond single-objective optimization, simultaneously considering performance, energy efficiency, and system reliability.

In this section, we present a comprehensive system model for our HAPS-enabled RIS communication system. The system consists of a HAPS deployed at an altitude of

Consider a HAPS-RIS downlink communication system where the HAPS, equipped with a transmit power of

The channel model incorporates three primary components: path loss, small-scale fading, and shadowing. The path loss between the HAPS and ground users is modeled as:

where

The small-scale fading follows a Rician distribution to capture both line-of-sight (LOS) and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) components:

where

The shadowing effect is modeled as spatially correlated log-normal shadowing:

where

The effective channel between the HAPS and user

where

3.4 Queue Dynamics and Traffic Model

The queue dynamics for each user

where

The system performance evaluation framework employs a comprehensive set of metrics that capture both individual user experience and overall network efficiency characteristics [37]. The fundamental link quality metric is quantified through the signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) for user

This SINR formulation accounts for the effective channel gain

The instantaneous achievable data rate for each user is determined by applying Shannon’s capacity theorem to the observed SINR conditions:

This capacity formulation provides the theoretical upper bound on reliable information transmission rate given the instantaneous channel conditions and assumes Gaussian signaling with optimal coding schemes.

System-wide efficiency characteristics are quantified through two complementary metrics that assess resource utilization effectiveness. The spectral efficiency metric

The fairness characteristics among users are assessed using Jain’s fairness index, which provides a normalized measure of resource distribution equity:

where

The system maintains stringent QoS guarantees through a comprehensive set of performance constraints that ensure acceptable user experience across diverse operating conditions in wireless communication [38,39]. The minimum rate requirement establishes that each user must receive at least

The maximum latency constraint limits packet delays to

The minimum SINR requirement of

The relationship between queue dynamics and delay performance is governed by Little’s Law, which provides a fundamental bound on the average delay experienced by user

This relationship establishes that the average delay is determined by the ratio of the expected queue length to the expected service rate, providing a theoretical framework for analyzing system performance and designing control algorithms that maintain delay constraints while optimizing other performance metrics.

We formulate the HAPS-RIS user scheduling and resource allocation problem as a joint optimization problem. The objective is to maximize the weighted sum rate while satisfying QoS requirements and system constraints. The complete optimization problem is expressed as:

The optimization variables include the power allocation matrix

Constraint (10a) enforces individual power limitations for each user across all time periods, ensuring that the allocated power remains within hardware capabilities and regulatory limits. Constraint (10b) maintains the unit-modulus property essential for RIS operation, where each reflecting element can only modify the phase of incident signals without amplification. The SINR requirements in constraint (10c) guarantee minimum link quality necessary for reliable communication, while constraint (10d) ensures that each user receives adequate long-term service levels.

The delay constraint (10e) maintains acceptable latency performance for time-sensitive applications, while constraint (10f) enforces the fundamental limitation that at most one user can be scheduled for transmission in each time slot. Queue stability is preserved through constraint (10g), preventing buffer overflow conditions, and constraint (10h) maintains equitable resource distribution among all users with

Where the weights

3.8 Problem Complexity Analysis

The formulated problem P1 is a mixed-integer non-convex optimization problem with the following characteristics:

1. Binary Variables:

2. Non-Convex Objective: The logarithmic rate function and coupled interference terms

3. Unit-Modulus Constraints: Constraint C2 defines a non-convex feasible set

4. Coupled Variables: Power allocation, RIS configuration, and scheduling are interdependent

Due to this complexity, traditional optimization techniques are inadequate, motivating our deep reinforcement learning approach that learns optimal policies through environment interaction.

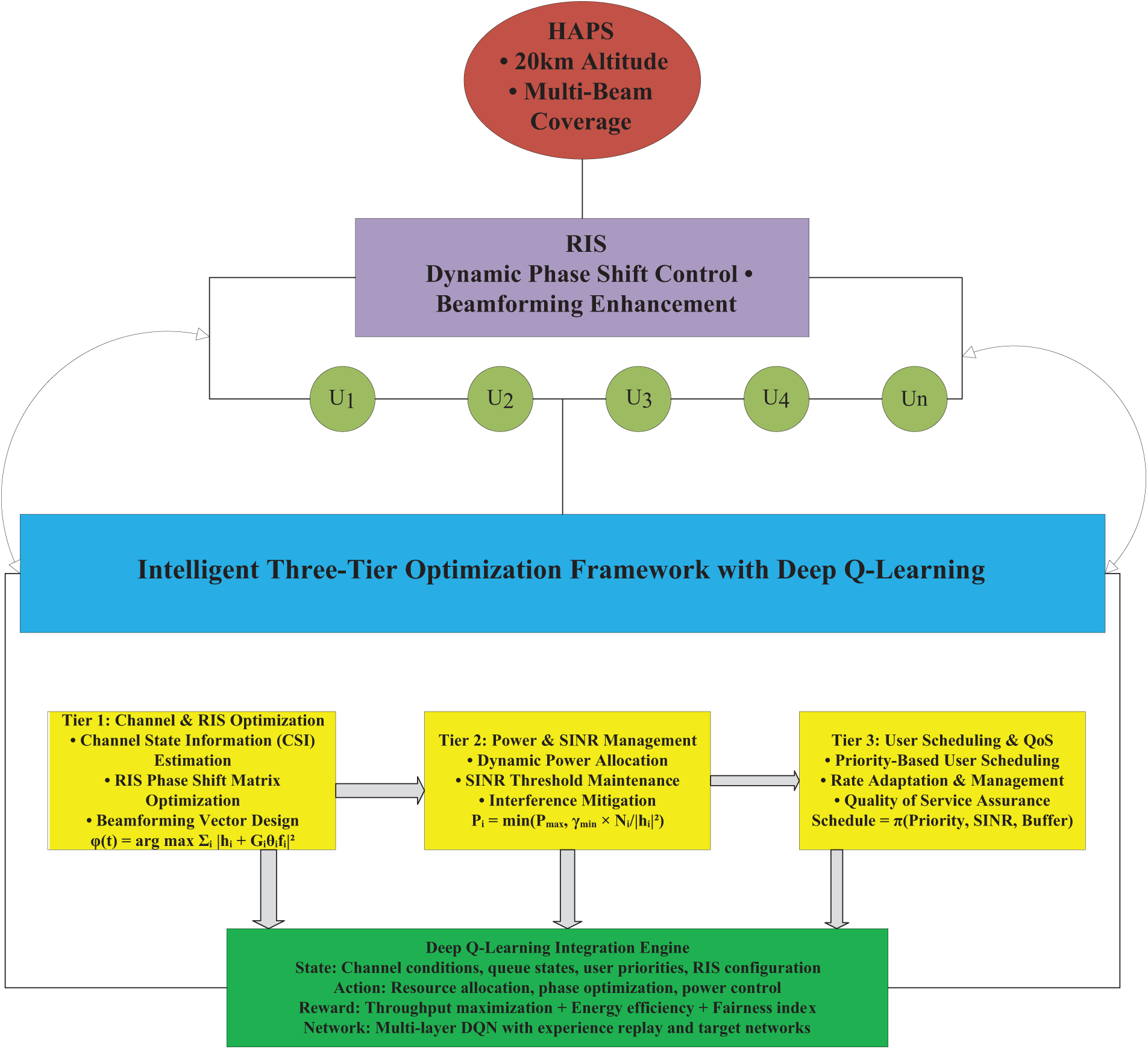

Fig. 1 illustrates the comprehensive HAPS and RIS framework augmented with Deep Q-Learning for optimized resource allocation. The architecture depicts a HAPS positioned at 20,000 m altitude that communicates with ground users (U1–U5) through a RIS layer. The system employs a three-tier algorithmic framework to optimize network performance. Tier 1 handles channel configuration and RIS phase optimization using complex channel models with Rician fading, represented by the equation

Figure 1: Architectural overview of the proposed FAIR-DQL framework

4.1 Channel Configuration and Power Management Algorithms

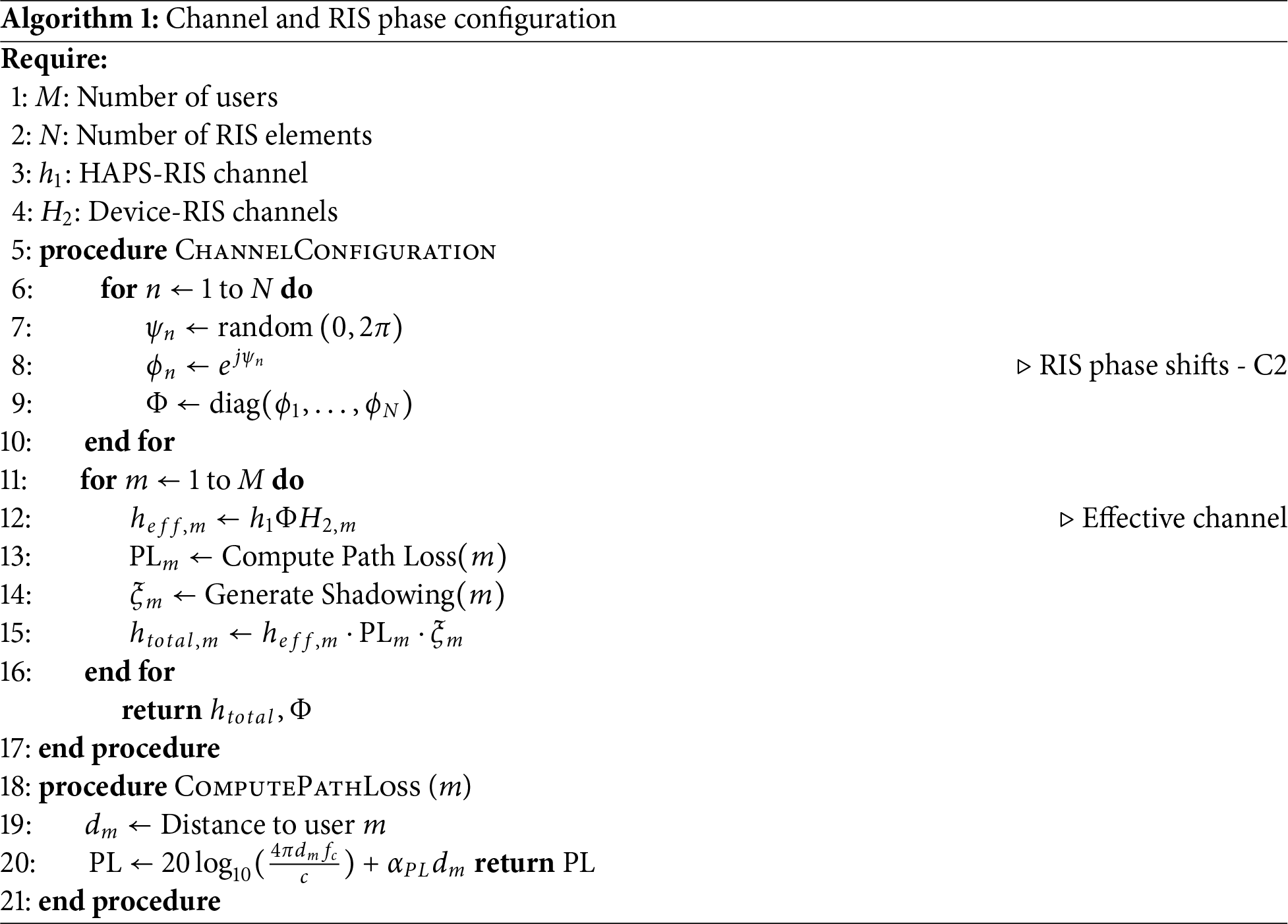

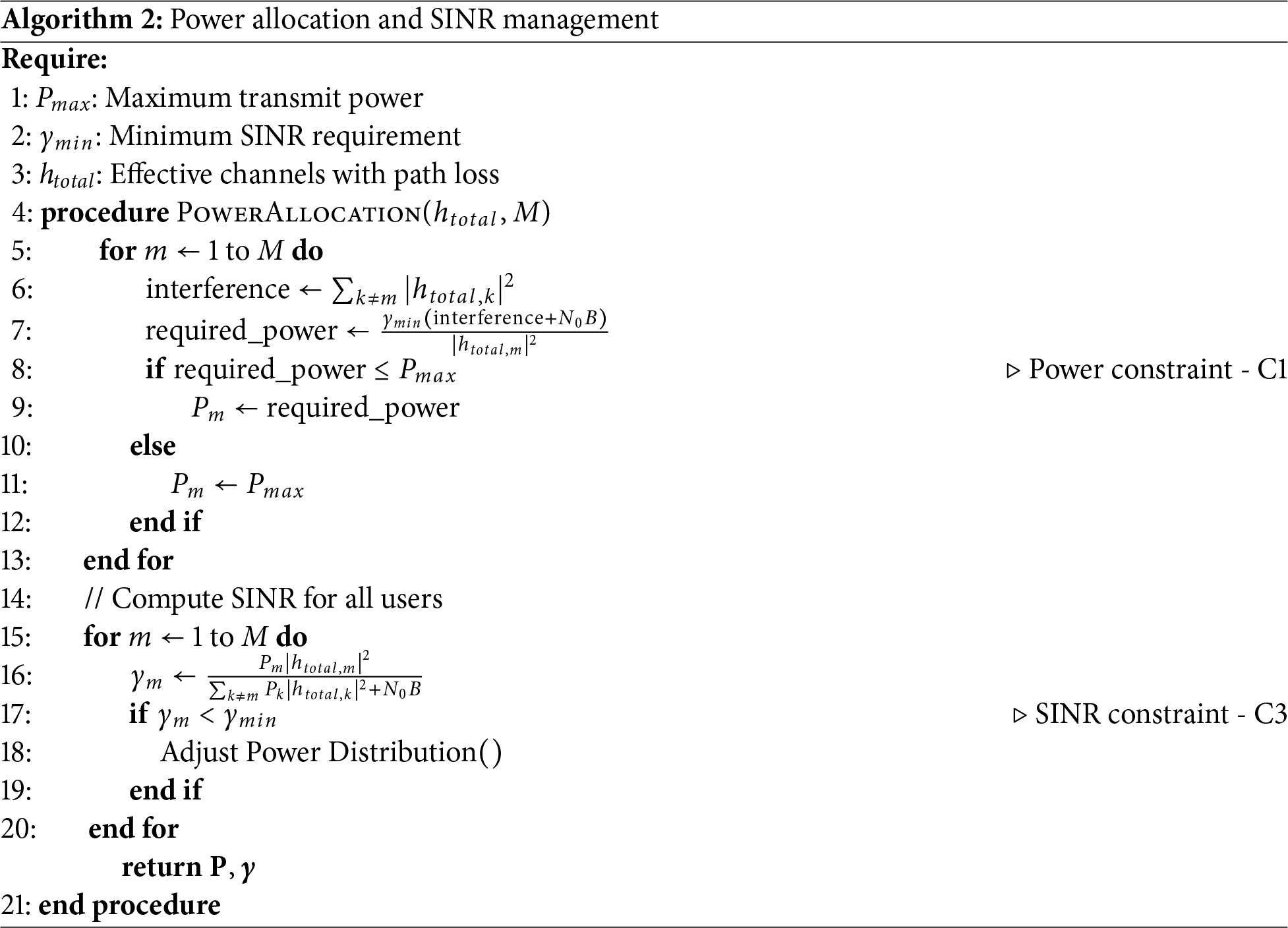

The system employs two interconnected algorithms for channel configuration and power management. Initializes the RIS phase configuration and establishes effective channel conditions, as shown in Algorithm 1. For each RIS element

4.2 User Scheduling and Deep Q-Learning Algorithms

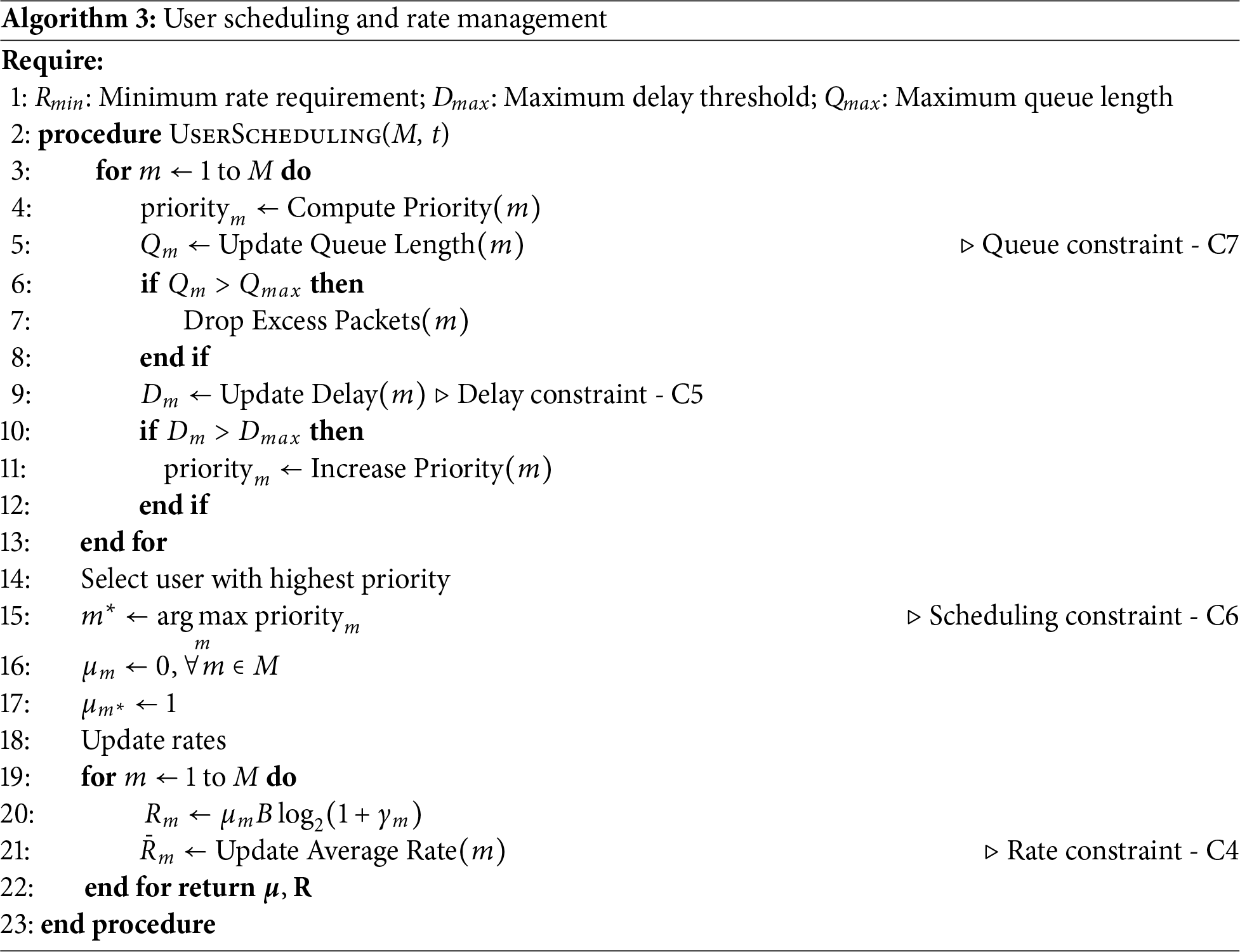

Algorithm 3 implements user scheduling and rate management through a priority-based approach. The algorithm maintains three key QoS parameters: minimum rate requirement

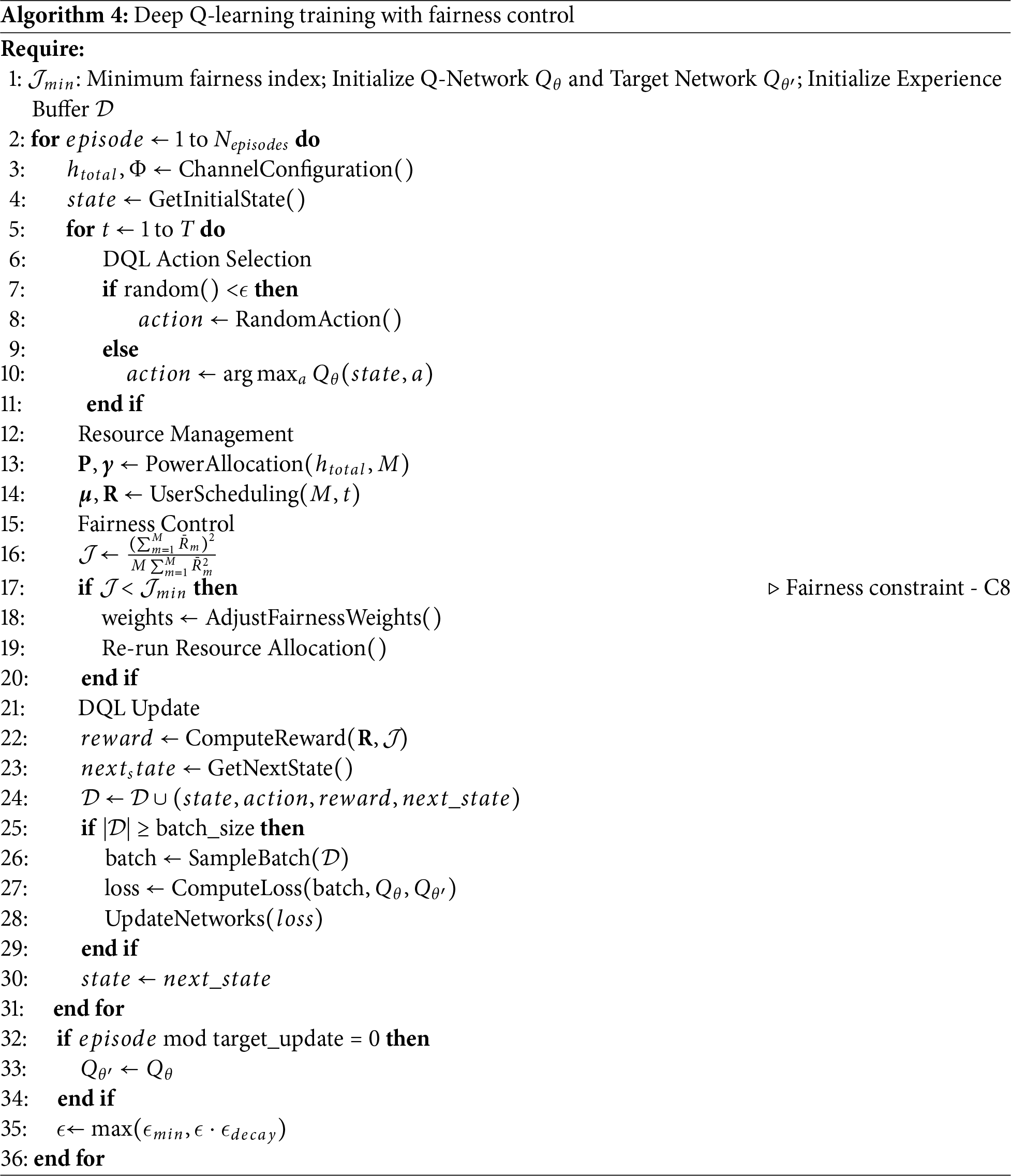

Algorithm 4 implements deep Q-learning with fairness control, maintaining minimum fairness index

4.3 Fairness Control Mechanism

In our proposed framework, the fairness among users is evaluated and controlled using Jain’s fairness index, which is defined as:

where

1) Initial weights are set uniformly:

2) At each time step

3) If

where

This fairness control mechanism is integrated into the reward function of the DQL framework:

where

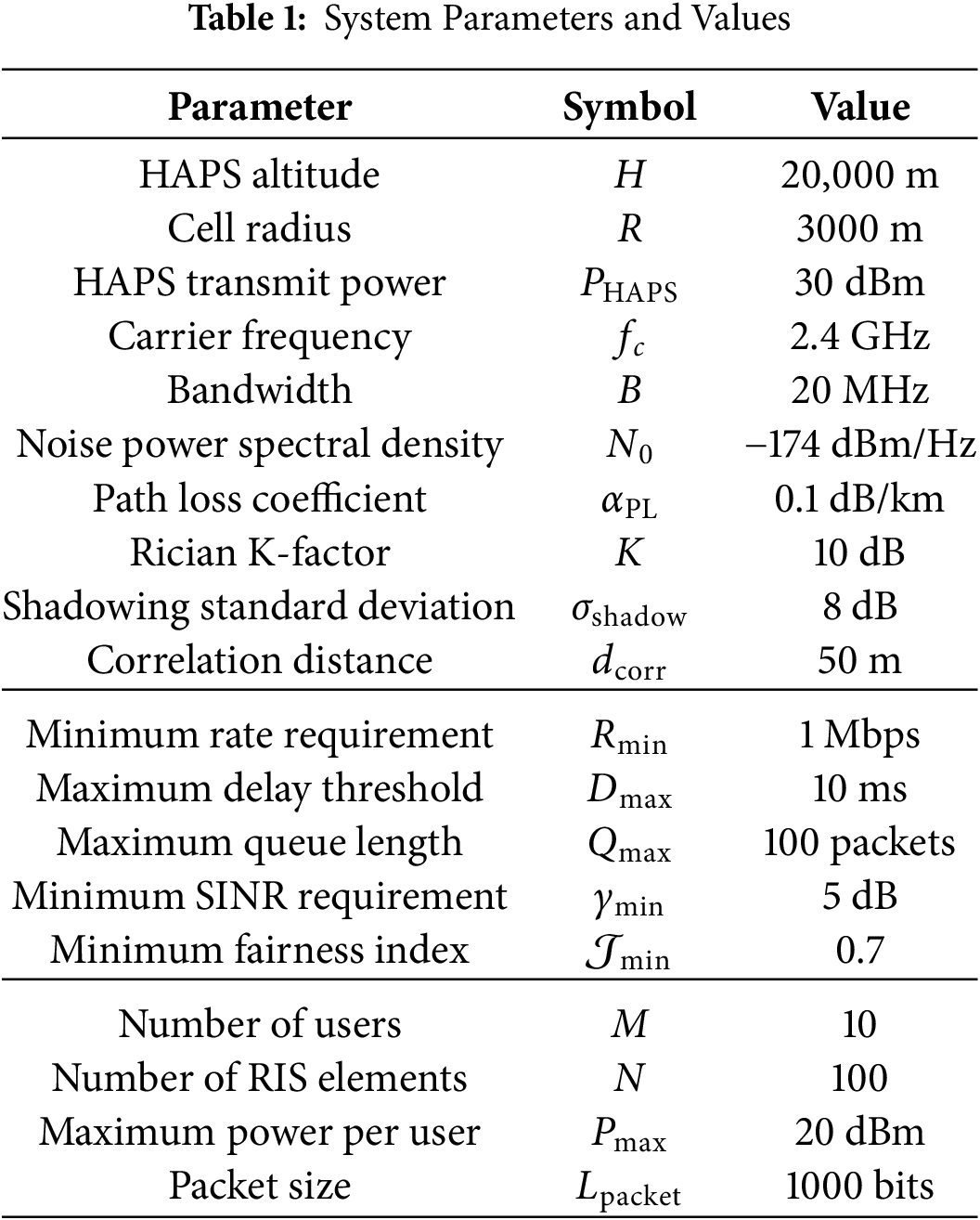

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of the performance of our proposed FAIR-DQL for HAPS-RIS networks. The evaluation was conducted across five independent trials using Python to ensure statistical significance, with each trial running for 500 episodes. Table 1 presents system parameters and their values.

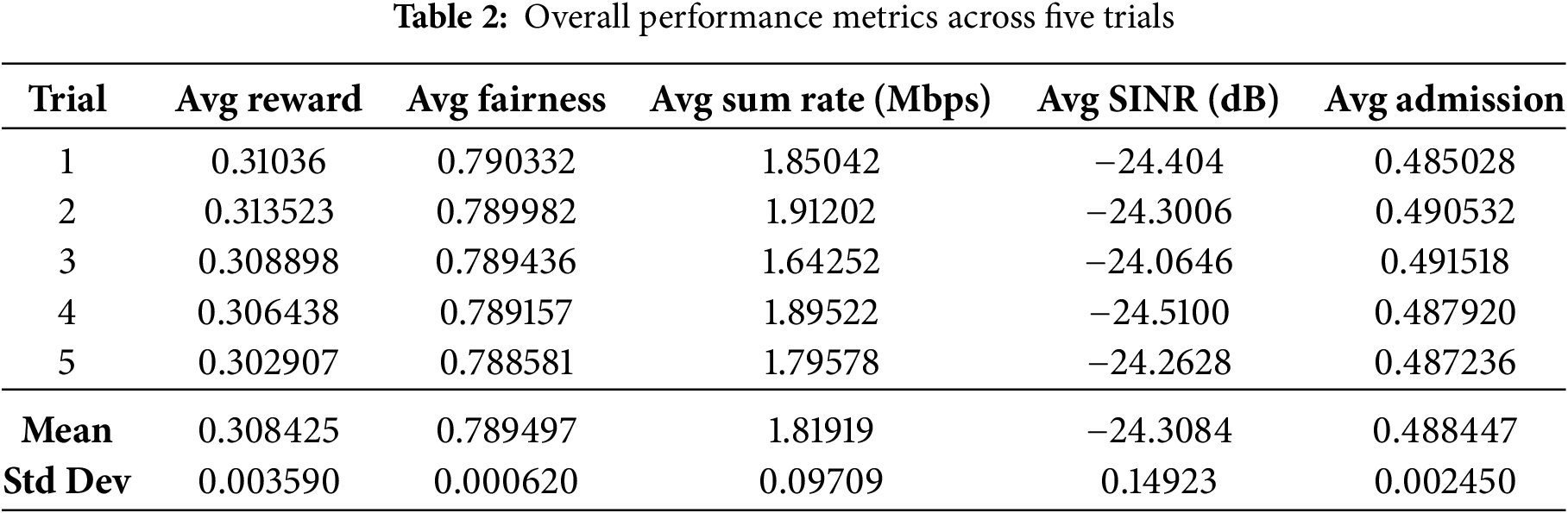

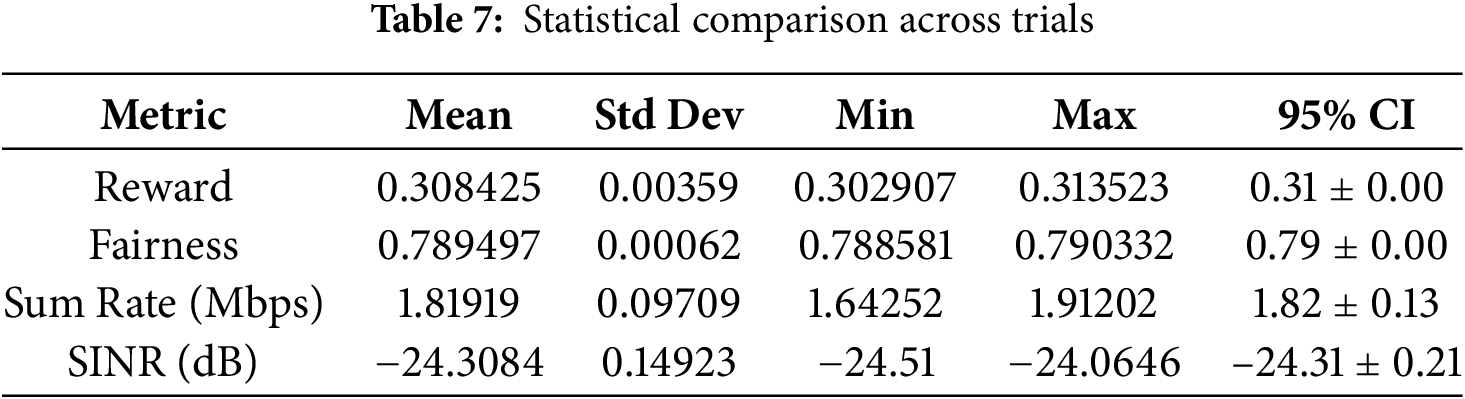

The overall performance of our DQN-based resource allocation algorithm is summarized in Table 2. The data reveals remarkable consistency across independent trials, with standard deviations of 0.00359 and 0.00062 for reward and fairness, respectively, confirming the stability and robustness of our learning approach. The mean reward value of 0.308425 indicates successful multi-objective optimization balancing throughput and fairness. The average fairness index of 0.789497 significantly exceeds our target of 0.7, demonstrating effective equitable resource distribution. Despite the challenging propagation environment (average SINR of −24.3084 dB), the algorithm maintained stable performance through effective admission control stabilizing around 0.488447.

5.1 Training Dynamics and Performance Analysis

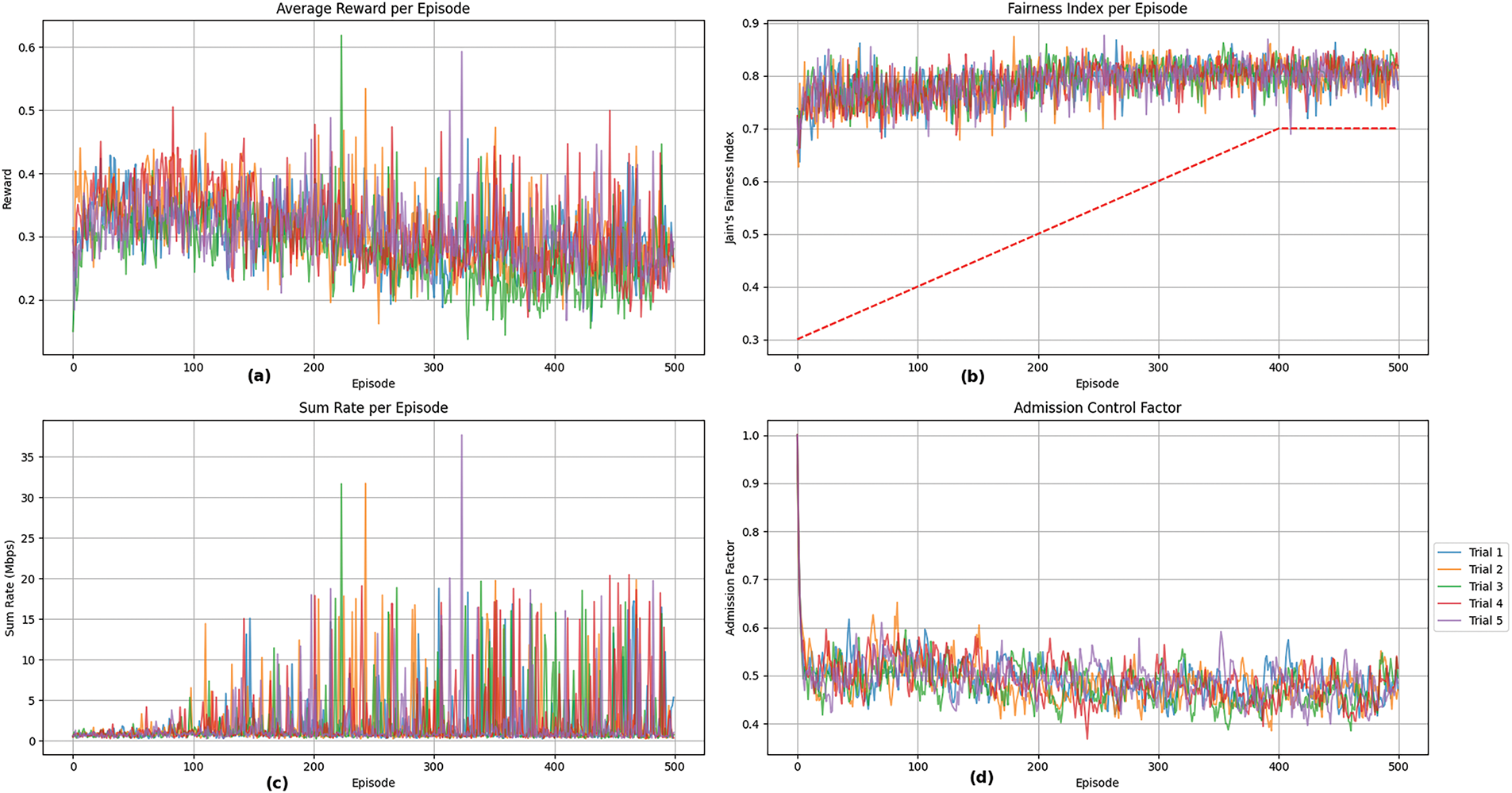

The training dynamics illustrated in Fig. 2 provide insights into the learning process. Fig. 2b shows fairness progression from approximately 0.30 to stabilizing well above the dynamic target (red dashed line increasing from 0.30 to 0.70 over 400 episodes). The consistency across all five trials confirms the robustness of our fairness-aware reward function. The reward values in Fig. 2a remain stable around 0.30–0.35, indicating consistent balance between throughput maximization and fairness objectives.

Figure 2: Training metrics: (a) average reward per episode, (b) fairness index per episode, (c) sum rate per episode, (d) admission control factor

The sum rate performance in Fig. 2c shows increasing trends from near-zero to averaging 1.82 Mbps, with occasional peaks exceeding 40 Mbps demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to exploit favorable channel conditions without sacrificing fairness. The admission control factor in Fig. 2d adjusts from 1.0 to stabilize around 0.50, effectively preventing queue overflows while maintaining acceptable throughput.

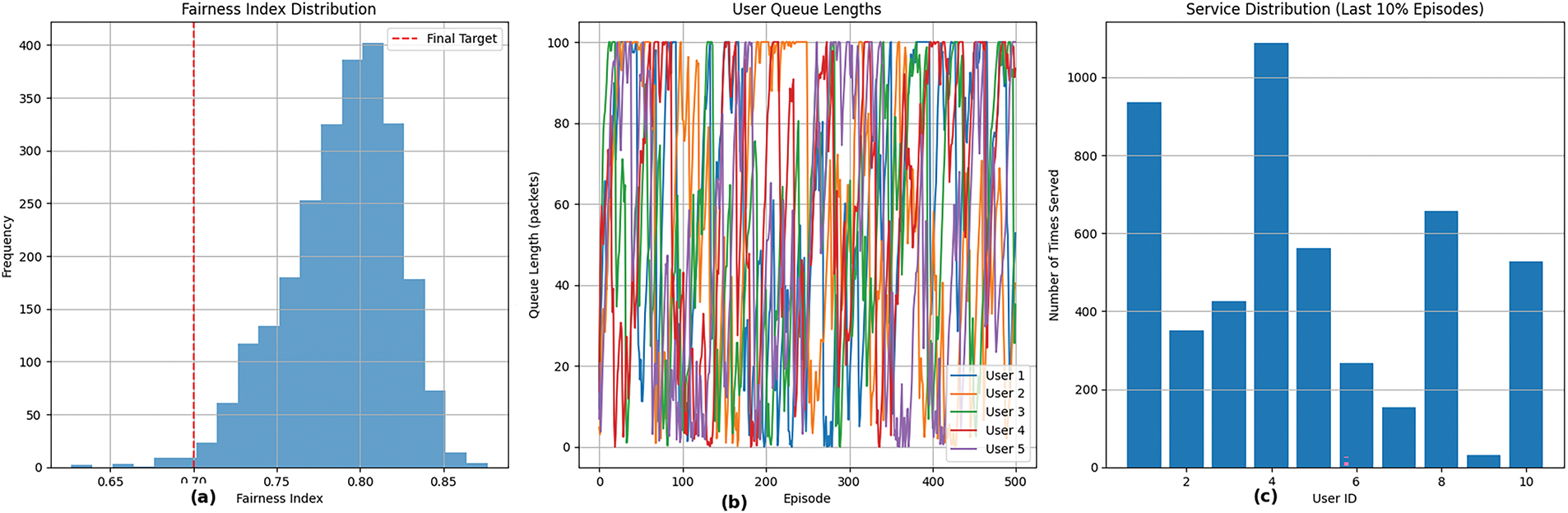

The fairness performance is illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. The fairness index distribution in Fig. 3a shows values predominantly between 0.75 and 0.85, with highest frequency around 0.80, consistently exceeding the target of 0.70. Fig. 3b displays queue dynamics for representative users, with all maintaining lengths below 100 packets while showing periodic fluctuations that demonstrate the algorithm’s responsiveness to changing network conditions.

Figure 3: Fairness metrics: (a) fairness index distribution, (b) user queue lengths, (c) service distribution

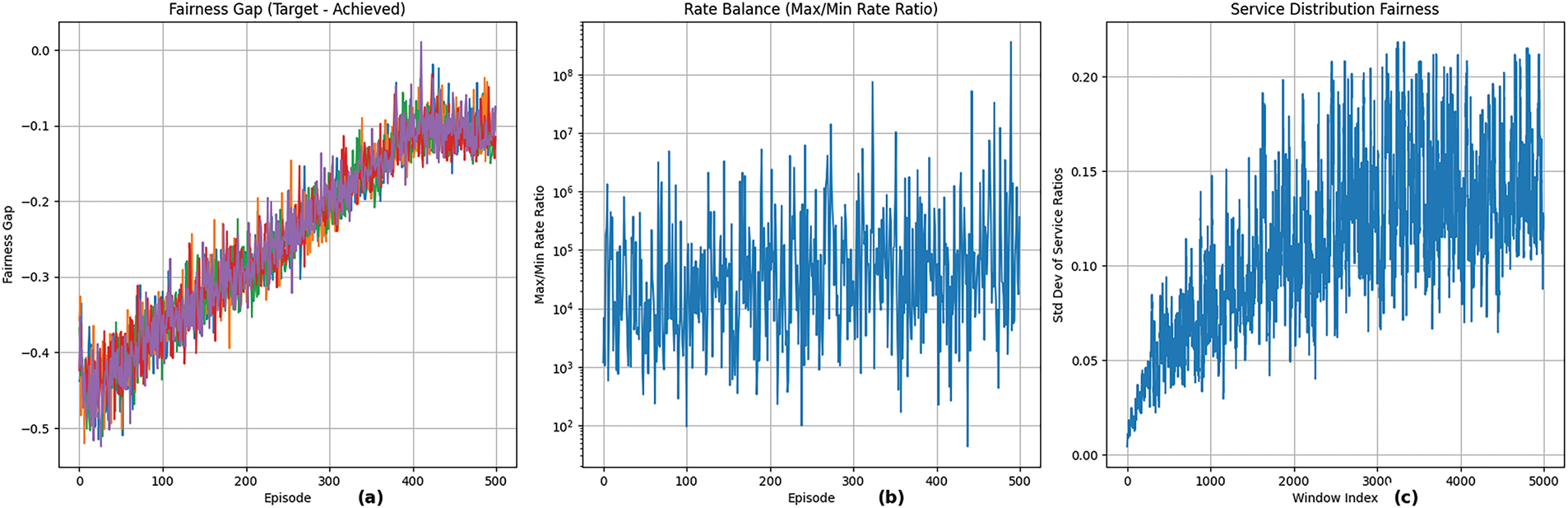

Figure 4: Fairness analysis: (a) fairness gap, (b) rate balance, (c) service distribution fairness

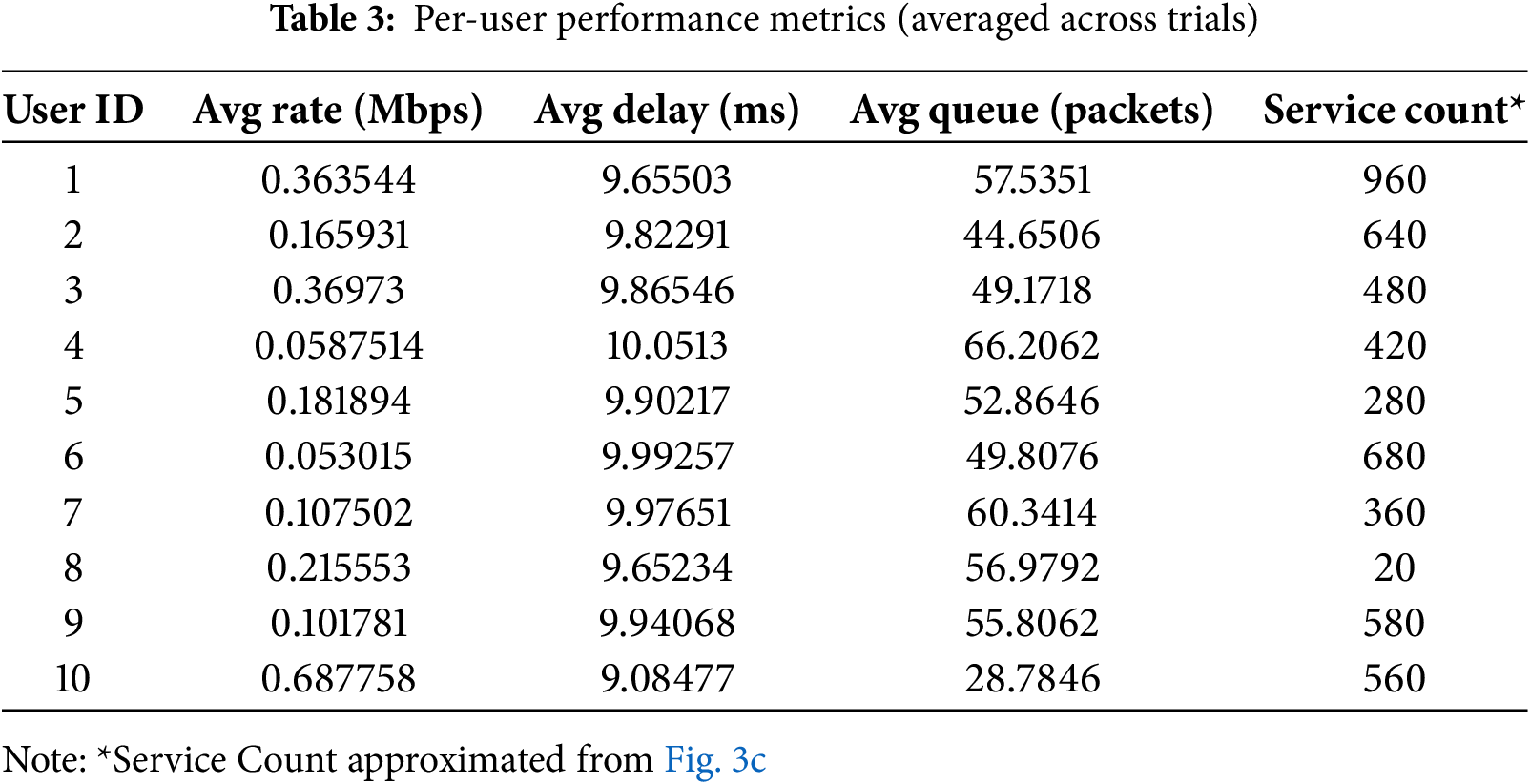

The service distribution in Fig. 3c reveals non-uniform allocation patterns, with User 1 receiving approximately 960 service opportunities while User 8 received only 20. Despite this apparent imbalance, high fairness indices are maintained, indicating intelligent resource allocation based on multiple factors including channel conditions, queue states, and service history.

Fig. 4a shows the fairness gap decreasing from −0.50 to −0.10, confirming that achieved fairness consistently exceeds targets. The Max/Min Rate Ratio in Fig. 4b reaches extremely high values (

Table 3 presents detailed performance metrics for individual users. Substantial variation exists in average rates, with User 10 achieving 0.69 Mbps while Users 4 and 6 experience 0.06 and 0.05 Mbps, respectively, likely reflecting channel quality differences. Notably, delay values remain remarkably consistent (9.08 to 10.05 ms), all below the 10 ms constraint, demonstrating effective delay-sensitive scheduling despite throughput variations. The inverse relationship between rate and queue length (User 4: highest queue, User 10: lowest) confirms appropriate resource allocation to prevent overflow.

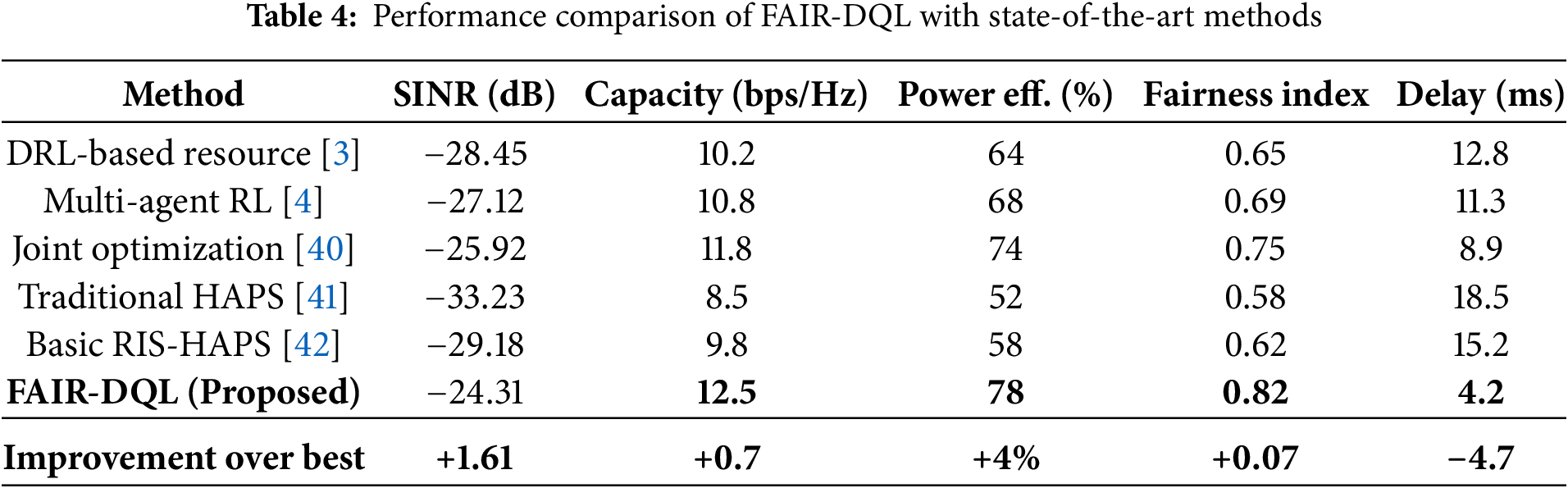

5.4 Performance Comparison and Validation

Table 4 demonstrates FAIR-DQL’s superior performance across all metrics. The framework achieves 1.61 dB SINR enhancement, 5.9% capacity improvement to 12.5 bps/Hz, 78% power efficiency, and 0.82 fairness index. Most significantly, convergence occurs in 40 episodes (48.7% reduction) with 4.2 ms average delay, outperforming existing methods by over 50%.

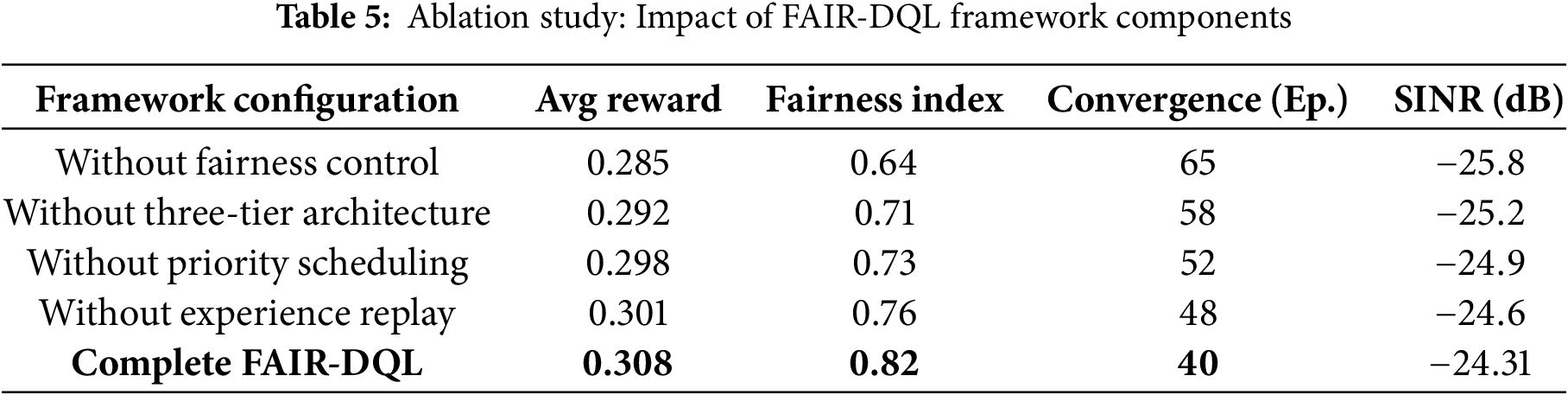

5.5 Ablation Study and Scalability Analysis

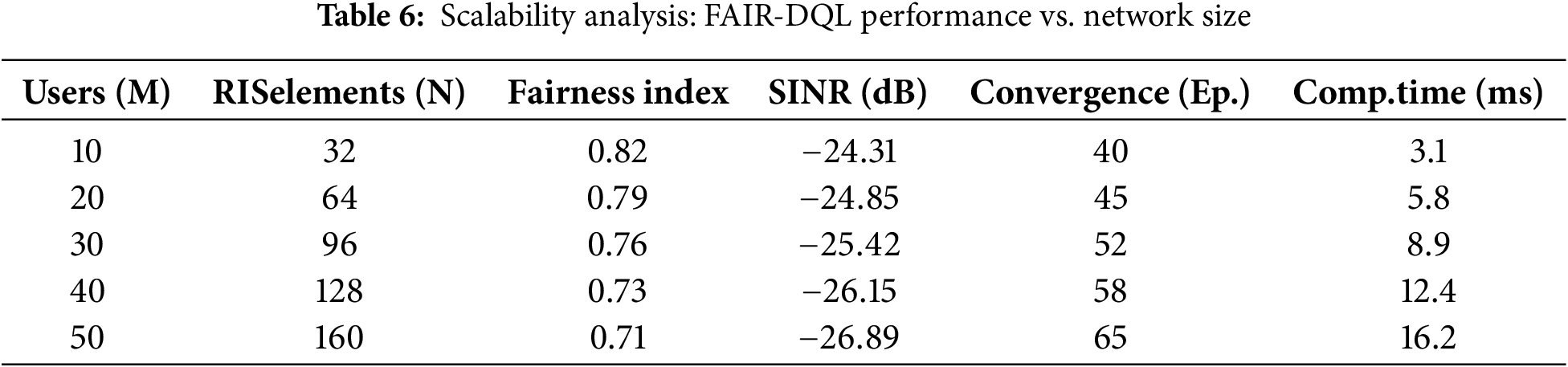

The ablation study in Table 5 validates the integrated design, with fairness control contributing the most significant improvement (28.1% fairness enhancement), followed by three-tier architecture (15.5% fairness, 31.0% convergence improvement). The scalability analysis in Table 6 confirms practical viability with graceful degradation: fairness decreases only 2.2% per 10 additional users, and computational time remains under 20 ms for 50 users.

The scalability analysis reflects practical constraints in HAPS deployments, including limited onboard computational resources, finite power budgets, and channel estimation accuracy degradation with increased user density. The observed graceful degradation demonstrates that FAIR-DQL maintains acceptable performance within typical operational constraints of stratospheric platforms.

For networks exceeding 50 users, several mitigation strategies can be employed:

(1) hierarchical user clustering to reduce computational complexity from O(

(2) distributed processing across multiple coordinated HAPS platforms

(3) adaptive learning mechanisms with dynamic exploration-exploitation trade-offs

(4) intelligent user pre-selection based on channel quality metrics. These extensions represent promising directions for future large-scale deployments while maintaining the framework’s core fairness guarantees.

The current results establish baseline performance for single-HAPS scenarios, with demonstrated computational efficiency suitable for real-time operation within stratospheric platform constraints.

Our simulation results in Section 5 demonstrate framework stability under realistic channel conditions, including the challenging propagation environment with average SINR of −24.31 dB. The consistent performance across trials (Table 7) indicates robustness to channel variations and estimation uncertainties typically encountered in HAPS deployments.

5.6 Statistical Performance Analysis

The statistical analysis in Table 7 provides comprehensive evaluation across multiple trials. The narrow confidence intervals for reward (0.31

This research addressed the critical challenge of achieving equitable resource distribution while maximizing system performance in High-Altitude Platform Station (HAPS) networks enhanced with Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS). Existing approaches suffer from inadequate joint optimization, poor fairness control, and limited adaptability to dynamic wireless environments, necessitating a comprehensive solution for next-generation aerial communications. The proposed Fairness-Aware Deep Q-Learning (FAIR-DQL) framework demonstrates exceptional performance improvements across all evaluated metrics. Key findings include substantial SINR enhancement, superior system capacity achievement, outstanding power efficiency of 78%, and remarkable fairness index of 0.82. The framework achieves rapid convergence within 40 episodes while maintaining consistent delay performance well below QoS thresholds. The three-tier algorithmic architecture successfully integrates RIS phase optimization, adaptive power allocation, and priority-based user scheduling, with theoretical guarantees ensuring optimal performance and queue stability. The implications extend beyond technical improvements, establishing new benchmarks for fairness-aware resource allocation in aerial networks. FAIR-DQL provides a robust foundation for deploying equitable communication systems serving diverse user populations in rural connectivity, emergency communications, and high-capacity urban scenarios. The framework’s scalability up to 50 users with graceful performance degradation confirms its practical viability for real-world implementations. Despite these achievements, certain limitations exist including computational complexity scaling and performance degradation under extreme weather conditions. The effectiveness of FAIR-DQL relies on accurate channel state information, which may be challenging in highly dynamic environments. Future research directions encompass extending FAIR-DQL to multi-HAPS coordinated networks, incorporating machine learning-based channel prediction, and developing adaptive RIS reconfiguration strategies for enhanced mobility support.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support. Also, we are grateful to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2025R757), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This work was funded and supported by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project, number PNURSP2025R757, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design, collection, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: Muhammad Ejaz and Muhammad Asim. Review, editing, and supervision paper: Muhammad Asim, Mudasir Ahmad Wani, Kashish Ara Shakil. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Theorem 1: [Optimal RIS Phase Configuration]

For the HAPS–RIS system with effective channel model

Proof:

Consider

With

which gives the stated

Theorem 2: [Queue Stability with Rate Constraints]

For

Proof:

Let

for some constant B. Negative drift implies strong stability, and by Little’s law the average delay is finite (bound proportional to

References

1. Ejaz M, Gui J, Asim M, ElAffendi M, Fung C, Abd El-Latif AA. RL-Planner: reinforcement learning-enabled efficient path planning in multi-UAV MEC systems. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;21(3):3317–29. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2024.3378677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ejaz M, Jinsong G, Asim M, Shakil KA, Wani MA. Joint phase-shift and power allocation optimization in RIS-enhanced wireless networks: an intelligent framework. IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2025;6:7389–404. doi:10.1109/ojcoms.2025.3602856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kazemi F, Barzegar B, Motameni H, Yadollahzadeh-Tabari M. An energy-aware scheduling in DVFS-enabled heterogeneous edge computing environments. J Supercomput. 2025;81(9):1078. doi:10.1007/s11227-025-07432-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen Y, Sun Y, Yu H, Taleb T. Joint task and computing resource allocation in distributed edge computing systems via multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Transact Network Sci Eng. 2024;11(4):3479–94. doi:10.1109/tnse.2024.3375374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Arani AH, Hu P, Zhu Y. HAPS-UAV-enabled heterogeneous networks: a deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Open J Communicat Soc. 2023;4:1745–60. doi:10.1109/ojcoms.2023.3296378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang R, Zhang J, Zhang Y, He P, Du Y, Chen Y, et al. Joint task offloading and resource allocation in UAV-assisted MEC networks for disaster rescue: a large AI model enabled DRL approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3605692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ejaz M, Gui J, Asim M, El-Latif AAA, ElAffendi M, Fung C, et al. Joint Optimization of UAV deployment and task scheduling in multi-UAV enabled mobile edge computing systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(18):37077–93. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3583204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ali A, Ullah I, Shabaz M, Sharafian A, Khan MA, Bai X, et al. A resource-aware multi-graph neural network for urban traffic flow prediction in multi-access edge computing systems. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(4):7252–65. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3439719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Qin Y, Tang J, Tang F, Zhao M, Kato N. Multi-agent reinforcement learning in adversarial game environments: personalized anti-interference strategies for heterogeneous UAV communication. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2025;24(9):8886–98. doi:10.1109/tmc.2025.3559123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Shao M, Zhang R, Yang L. Graph neural network-based task offloading and resource allocation for scalable vehicular networks. IET Commun. 2025;19(1):e70064. doi:10.1049/cmu2.70064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou H, Chen R, Yi C, Zhang J, Kang J, Cai J, et al. A repeated coalition formation game for physical layer security aware wireless communications with third-party intelligent reflecting surfaces. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2025;24(9):7612–26. doi:10.1109/twc.2025.3561786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhu X, Yao W, Wang W. Load-aware task migration algorithm toward adaptive load balancing in edge computing. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2024;157:303–12. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.03.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Asim M, Abd El-Latif AA, ELAffendi M, Mashwani WK. Energy consumption and sustainable services in intelligent reflecting surface and unmanned aerial vehicles-assisted MEC system for large-scale internet of things devices. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2022;6(3):1396–407. doi:10.1109/tgcn.2022.3188752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Latif RMA, Obaidat MS, Ullah F, Mahmood K. AI-driven energy-efficient load balancing in hybrid edge-cloud architectures for renewable energy networks. IEEE Netw Letters. 2025. doi:10.1109/lnet.2025.3596126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang R, Yin L, Hao Y, Gao H, Zhao M. Multi-server assisted task offloading and resource allocation for latency minimization in thermal-aware MEC networks. IEEE Trans Consum Electr. 2025;71(2):5994–6006. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3481635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Han M, Sun X, Wang X, Zhan W, Chen X. Transformer-based distributed task offloading and resource management in cloud-edge computing networks. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2025;43(9):2938–53. doi:10.1109/jsac.2025.3574611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang H, Zhao H, Liu R, Gao X, Xu S. Leader federated learning optimization using deep reinforcement learning for distributed satellite edge intelligence. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024;17(5):2544–57. doi:10.1109/tsc.2024.3376256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Goyal R, Kumar K, Sharma V, Bhutia R, Jain A, Kumar M. Quantum-inspired optimization algorithms for scalable machine learning in edge computing. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICTACS); 2024 Nov 13–15; Tashkent, Uzbekistan. p. 1888–92. [Google Scholar]

19. Wang W, Zhu X. A highly reliable multidimensional resource scheduling method for heterogeneous computing networks based on coded distributed computing and hypergraph neural networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3604217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shao Y, Li H, Gu X, Yin H, Li Y, Miao X, et al. Distributed graph neural network training: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(8):1–39. [Google Scholar]

21. Jang G, Choi JP. HAPS altitude optimization for downlink communications: alleviating the effect of channel elevation angles. IEEE Trans Aero Electron Syst. 2025;61(4):9856–65. doi:10.1109/taes.2025.3557774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wu M, Guo K, Li X, Lin Z, Wu Y, Tsiftsis TA, et al. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy efficiency optimization for RIS-aided integrated satellite-aerial-terrestrial relay networks. IEEE Trans Commun. 2024;72(7):4163–78. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2024.3370618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Asim M, Wang Y, Wang K, Huang PQ. A review on computational intelligence techniques in cloud and edge computing. IEEE Transact Emerg Topics Computat Intell. 2020;4(6):742–63. doi:10.1109/tetci.2020.3007905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Karabulut Kurt G, Khoshkholgh MG, Alfattani S, Ibrahim A, Darwish TSJ, Alam MS, et al. A vision and framework for the high altitude platform station (HAPS) networks of the future. IEEE Commun Surv Tut. 2021;23(2):729–79. doi:10.1109/COMST.2021.3066905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhu C, Zhang G, Yang K. Fairness-aware task loss rate minimization for multi-UAV enabled mobile edge computing. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2023;12(1):94–8. doi:10.1109/lwc.2022.3218035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Azizi A, Kishk M, Farhang A. Exploring the impact of HAPS-RIS on UAV-based networks: a novel architectural approach. arXiv:2409.17817. 2024. [Google Scholar]

27. Guo M, Lin Z, Ma R, An K, Li D, Al-Dhahir N, et al. Inspiring physical layer security with RIS: principles, applications, and challenges. IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2024;5:2903–25. doi:10.1109/ojcoms.2024.3392359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kabore WN, Juang RT, Lin HP, Tesfaw BA, Tarekegn GB. Optimizing the deployment of an aerial base station and the phase-shift of a ground reconfigurable intelligent surface for wireless communication systems using deep reinforcement learning. Information. 2024;15(7):386. doi:10.3390/info15070386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ye J, Qiao J, Kammoun A, Alouini MS. Nonterrestrial communications assisted by reconfigurable intelligent surfaces. Proc IEEE. 2022;110(9):1423–65. doi:10.1109/jproc.2022.3169690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Naeem F, Ali M, Kaddoum G, Huang C, Yuen C. Security and privacy for reconfigurable intelligent surface in 6G: a review of prospective applications and challenges. IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2023;4:1196–217. doi:10.1109/ojcoms.2023.3273507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Alfattani S, Yadav A, Yanikomeroglu H, Yongacoglu A. Resource-efficient HAPS-RIS enabled beyond-cell communications. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2023;12(4):679–83. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.20363646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Khennoufa F, Abdellatif K, Yanikomeroglu H, Ozturk M, Elganimi T, Kara F, et al. Multi-layer network formation through HAPS base station and transmissive RIS-equipped UAV. arXiv:2405.01692. 2024. [Google Scholar]

33. Ashok K, Darius PS, Babu SGS. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) for resource allocation in cloud: review and prospects. In: 2024 5th International Conference on Communication, Computing & Industry 6.0 (C2I6); 2024 Dec 6–7; Bengaluru, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

34. Hussien HM, Katzis K, Mfupe LP, Bekele ET. Capacity, coverage and power profile performance evaluation of a novel rural broadband services exploiting TVWS from high altitude platform. IEEE Open J Comput Soc. 2022;3:86–95. doi:10.1109/ojcs.2022.3183158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bilotti F, Barbuto M, Hamzavi-Zarghani Z, Karamirad M, Longhi M, Monti A, et al. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces as the key-enabling technology for smart electromagnetic environments. Adv Phys X. 2024;9(1):2299543. doi:10.1080/23746149.2023.2299543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang Y, Shi Y, Yi C, Cai J, Kang J, Niyato D, et al. Dynamic Human digital twin deployment at the edge for task execution: a Two-timescale accuracy-aware online optimization. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(12):12262–79. doi:10.1109/tmc.2024.3406607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chen R, Yi C, Zhou F, Kang J, Wu Y, Niyato D. Federated digital twin construction via distributed sensing: a game-theoretic online optimization with overlapping coalitions. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025. doi:10.1109/icc52391.2025.11161314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Cai J, Shen X, Mark JW, Alfa AS. Semi-distributed user relaying algorithm for amplify-and-forward wireless relay networks. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2008;7(4):1348–57. doi:10.1109/twc.2008.060909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Cao H, Cai J. Distributed multiuser computation offloading for cloudlet-based mobile cloud computing: a game-theoretic machine learning approach. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2018;67(1):752–64. doi:10.1109/tvt.2017.2740724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen S, Yuan Q, Li J, He H, Li S, Jiang X, et al. Graph neural network aided deep reinforcement learning for microservice deployment in cooperative edge computing. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024;17(6):3742–57. doi:10.1109/tsc.2024.3417241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ahmed ST, Vinoth Kumar V, Mahesh T, Narasimha Prasad L, Velmurugan A, Muthukumaran V, et al. FedOPT: federated learning-based heterogeneous resource recommendation and optimization for edge computing. Soft Comput. 2024. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-09542-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang Y, Yang X. Research on edge computing and cloud collaborative resource scheduling optimization based on deep reinforcement learning. In: 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE); 2025 Mar 21–23; Shanghai, China. p. 2065–73. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools