Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid Malware Detection Model for Internet of Things Environment

1 Department of Documents and Archive, Center of Documents and Administrative Communication, King Faisal University, P.O. Box 400, Al-Ahsa, Hofuf, 31982, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science, Shaqra University, Shaqra, 11961, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 81 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072481

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 09 December 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Malware poses a significant threat to the Internet of Things (IoT). It enables unauthorized access to devices in the IoT environment. The lack of unique architectural standards causes challenges in developing robust malware detection (MD) models. The existing models demand substantial computational resources. This study intends to build a lightweight MD model to detect anomalies in IoT networks. The authors develop a transformation technique, converting the malware binaries into images. MobileNet V2 is fine-tuned using improved grey wolf optimization (IGWO) to extract crucial features of malicious and benign samples. The ResNeXt model is combined with the Linformer’s attention mechanism to identify Malware features. A fully connected layer is integrated with gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) in order to facilitate an interpretable classification model. The proposed model is evaluated using the IoT malware and the IoT-23 datasets. The model performs well on the two datasets with an accuracy of 98.94%, precision of 98.46%, recall of 98.11%, and F1-score of 98.28% on the IoT malware dataset, and an accuracy of 98.23%, precision of 96.80%, recall of 96.64%, and F1-score of 96.71% on the IoT-23 dataset, respectively. The findings indicate that the model has a high standard of classification. The lightweight architecture enables efficient deployment with an inference time of 1.42 s. Inference time has no direct impact on accuracy, precision, recall, or F1-score. However, the inference speed would warrant timely detection in latency-sensitive IoT applications. By achieving a remarkable result, the proposed study offers a comprehensive solution: a scalable, interpretable, and computationally efficient MD model for the evolving IoT landscape.Keywords

In recent years, hackers have been using malware to access crucial logs and sensitive information of an Internet of Things (IoT) network [1–3]. IoT architecture enables users to access their smart devices from any location. It is widely utilized in healthcare, home automation, vehicular networks, smart grids, smart cities, and other sectors [4]. The recent malware originates in a variety of forms, which cannot be detected using traditional malware detection (MD) techniques [4,5]. Malware remains a global threat to computer networks [6]. Unlike conventional computer networks, IoT networks cannot perform intrusion detection methods on individual devices due to limited processing power and memory constraints [7,8]. Due to memory constraints, IoT devices encounter challenges in storing instances of malware signatures [9]. The lack of standard security features in IoT devices leads to malware attacks in IoT infrastructure [10]. To overcome these limitations, strengthening the MD techniques is essential.

Traditional machine learning approaches, including Naïve Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF), are commonly used for classifying Malicious and Benign files [10,11]. However, these approaches demand a larger training time to produce an outcome in a real-time environment. These limitations can be addressed with the use of deep learning (DL) approaches [11,12]. Recently, DL-based techniques produced a significant outcome in identifying malware. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are widely used in developing DL applications [13]. CNNs extract the crucial features from an image. A pre-trained CNNs model can be applied for multiple image recognition tasks [14]. In addition, the trained weights can be used to build a new model. The highly balanced dataset can improve the performance of the DL-based MD framework [15]. The successful integration of DL algorithms with visualization methods witnessed widespread implementation in malware detection. DL techniques improve the process of detecting anomalies in the IoT network.

The emergence of Software-defined networking (SDN) and IoT devices has revolutionized the modern digital landscape. SDN architecture manages the complexities and enhances the dynamic nature of IoT devices [16–18]. SDN offers an opportunity for developers to build a protective environment for IoT devices. However, this paradigm shift enables unprecedented connectivity and control across a broad spectrum of applications [18]. It makes IoT and SDN environments highly attractive targets for sophisticated malware attacks. By spreading rapidly through SDN-controlled architectures, malware can exploit vulnerabilities in IoT devices, posing significant risks to critical infrastructures and industries [19].

CNNs and Vision Transformers (ViTs) present promising outcomes in image classification. These architectures treat malware as static images, neglecting contextual dependencies, feature selection, and real-world deployment considerations. DL-based MD framework can facilitate an extremely scalable, adaptable, cost-effective platform for detecting malware in IoT/SDN environments [20]. A lightweight MD framework introduces an automated feature engineering process and identifies malware signatures in IoT networks [20]. The limited scope of components in a single-layer design prevents it from delivering optimal performance [21]. There is a demand for a multi-layered distributive strategy for detecting malware in IoT environments due to the unique architecture of the smart devices [21,22]. A multi-layered architecture handles data generation and transmission in smart devices, making the system more reliable.

The existing MD models report highly accurate results. However, they lack the interpretability and potential to meet the demands of IoT/SDN environments. To overcome these limitations, there is a need for a robust, lightweight, and interpretable MD model, balancing high classification accuracy with computational efficiency and generalizability. The hybrid CNNs-ViTs architecture with an effective hyperparameter optimization approach can capture local and global dependencies in malware patterns. Additionally, incorporating Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) overlays can support analysts in visualizing the crucial malware regions. Thus, this study aims to build an explainable integrated MD framework for classifying malware into malicious and benign classes.

The scope of this study covers the detection of cyber-induced anomalies in IoT networks, which are generated explicitly by malware activities that affect device integrity, data privacy, and communication reliability. IoT ecosystems are producing vast amounts of heterogeneous data from smart sensors, wearables, cameras, and industrial control systems, which are prone to malicious attacks like botnets, ransomware, Trojans, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks. However, these anomalies are fundamentally different from the non-security problems, such as sensor drift, hardware malfunction, or network latency. This study focuses on cyber-induced anomalies that can be observed in behaviors at the binary level (executable and linkable format (ELF) executables) or network traffic level (packet capture (Pcap) flows). Therefore, data related to the anomaly management domain, including fault detection, optimization of power consumption, device authentication, and encrypted data inspection, are excluded from the study.

Within this scope, the study builds an automated, scalable, and interpretable malware detection framework that can operate in resource-constrained IoT edge environments. It focuses on supervised learning–based binary classification of benign and malicious IoT activities.

The contributions of this study are listed below:

1. A lightweight feature representation architecture that integrates MobileNet V2 and ResNeXt-Linformer.

The novel hybrid feature representation and classification architecture allows the efficient extraction of the local and global malicious signatures from the images, achieving low-latency and high detection accuracy without relying on handcrafted features or computationally expensive cloud computations.

2. Grad-CAM visualization and improved Grey Wolf optimization (IGWO)-powered model’s explainability and interpretability, making the proposed MD framework unique from the existing models.

The integration of Grad-CAM visualization provides a transparent MD mechanism that highlights the specific malicious regions in the images, enabling security analysts to validate the model’s decisions. This is a significant improvement over current IoT malware detectors, which are primarily black box systems with no actionable knowledge. Concurrently, the use of IGWO assists the proposed MD model to achieve maximum performance in the resource-constrained environment. Collectively, the suggested explainability and interpretability approach improves detection accuracy and reduces false alarms, enabling real-time deployment in resource-limited IoT environments.

The remaining part of the study is organized as follows: Section 2 reveals the features and limitations of the existing MD approaches, underscoring the research gaps. Section 3 highlights the proposed research methodology for detecting malware in the IoT environment. It presents the importance of feature representation in MD frameworks. Section 4 outlines the performance analysis using the benchmark metrics. The study’s findings are discussed in Section 5. Finally, the study’s future direction is presented in Section 6.

The performance of DL applications is based on an extensive training procedure to produce a reasonable outcome. During training, DL models learn patterns associated with malicious and benign samples [23]. In addition, dataset bias can influence DL models, leading to an inaccurate outcome [24]. Recent studies [25] transform malware binaries to grayscale or colored images in order to detect anomalies in the IoT network. However, meaningful information may be lost during conversion [26]. Thus, effective image transformation techniques are required to convert the IoT network log files into images. A number of malware visualization techniques make use of opcode n-grams recovered from Windows Portable Executable (PE) files as the basis for the pixels in the development of malware images [26]. These approaches utilize the frequency of consecutive opcodes to identify the malware.

MD research has evolved significantly, especially with the introduction of image-based learning frameworks. SDN supports MD by identifying threats rapidly and effectively with limited computational resources. It comprises an application plane, control plane, data plane, and associated south and north-bound application programming interfaces. In this architecture, the data plane is decoupled from the control plane [27]. In order to manage the control logic effectively, the SDN architecture offers a centralized control plane. The control plane decides data transmission among the multiple layers. Consequently, the intelligence and capabilities of an SDN reside in its regulated architecture. The SDN controller receives data from the south-bound protocol components [28]. IoT and SDN provide precise network surveillance to detect threats and suspicious activity [28]. Existing methods demonstrate the feasibility of identifying visual patterns at the byte level to distinguish between malicious and benign samples. These methods relied on handcrafted features and lacked scalability. With the advent of deep learning, CNNs have become prominent because they learn hierarchical textures that can automatically represent byte-distributions, entropy regions and structural artifacts. These models are capable of achieving high accuracy on image-based malware data. However, they were highly reliant on large architectures that are computationally expensive, which are not feasible to use in low-resource IoT environments.

In the feature extraction or selection process, a wide range of image processing approaches were utilized. Traditional machine learning approaches face challenges in inferring the high-level characteristics from images [25]. Recently, multiple visualization approaches have been proposed to identify malware in IoT networks. The pre-trained image classification models face challenges in propagating gradient information in order to learn the key features of malware images [29,30].

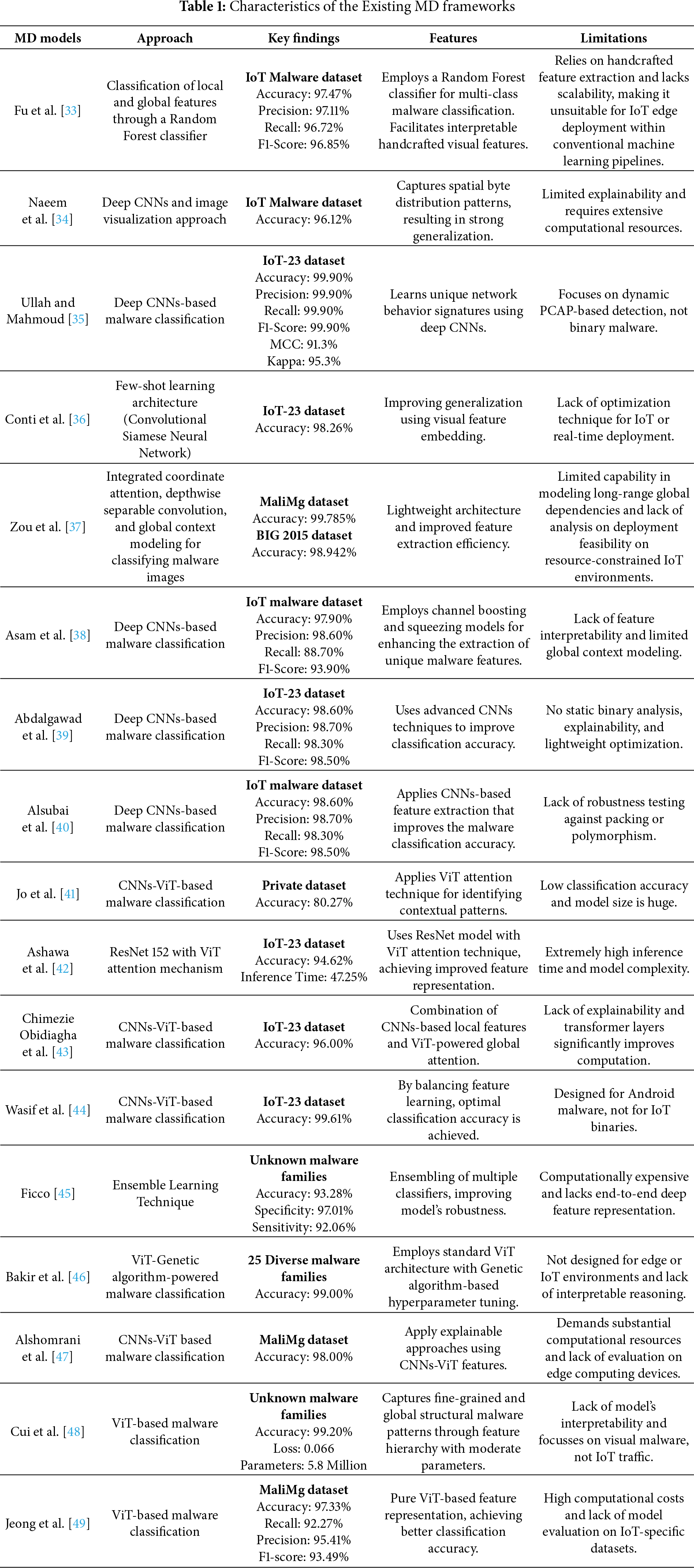

The introduction of ViTs has increased the capabilities of MD models by enabling them to capture long-range dependencies and global structural patterns across the malware images [31]. Hybrid CNN-ViT models achieve robustness and classification accuracy across different malware visualizations, including the Android and IoT datasets [32]. Nevertheless, these transformer-based architectures were usually composed of millions of parameters with high FLOPs and are not feasible for real-time detection implementation on IoT gateways, embedded systems, or SDR controllers. Some models included some genetic optimization or attention mechanism to improve feature extraction, while others included explainability modules such as Grad-CAM or SHAP. Although these developments led to higher levels of transparency and accuracy, there is a lack of trade-off between computational efficiency and robust multimodal detection. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the existing MD frameworks, including their approach, features, and limitations.

The analysis of existing studies of malware detection reveals multiple critical research gaps. The majority of the MD models rely on heavyweight CNNS or VITs with a substantial number of parameters, which are not suitable for deployment on resource-constrained IoT devices. Furthermore, the methodologies lack explainability and offer limited information about the features that underpin their decisions, limiting their application in real-time environments. The existing studies are targeted to specific domains and focus on binaries of ELF attacks or network flows, respectively, which leads to MD pipelines without generalizability across different attacks. In addition, robustness against evasion techniques such as packing and polymorphism is hardly measured, thus creating uncertainty about the true efficacy in the real world. Finally, few studies provide detailed computational measures, such as inference time, computational speed, memory utilization, and detection latency, which are essential for integrating IoT devices into practical applications.

The proposed framework addresses these shortcomings by providing a lightweight, system-resource-efficient architecture that has been optimized using IGWO to enable its deployment in a resource-constrained environment. It offers unified image-based processing that covers static and dynamic malware behaviours. By including the functionality of Grad CAM explainability, the model becomes interpretable, and malicious regions in the images can be highlighted, which leads to increased trust and robust decision validation. Furthermore, the localized-global feature-extraction hybrid design is effective against packed and polymorphic malware. In addition, the high-level computation and deployment metrics are used to evaluate the model’s performance, which makes it suitable for real-time, edge-level IoT environments.

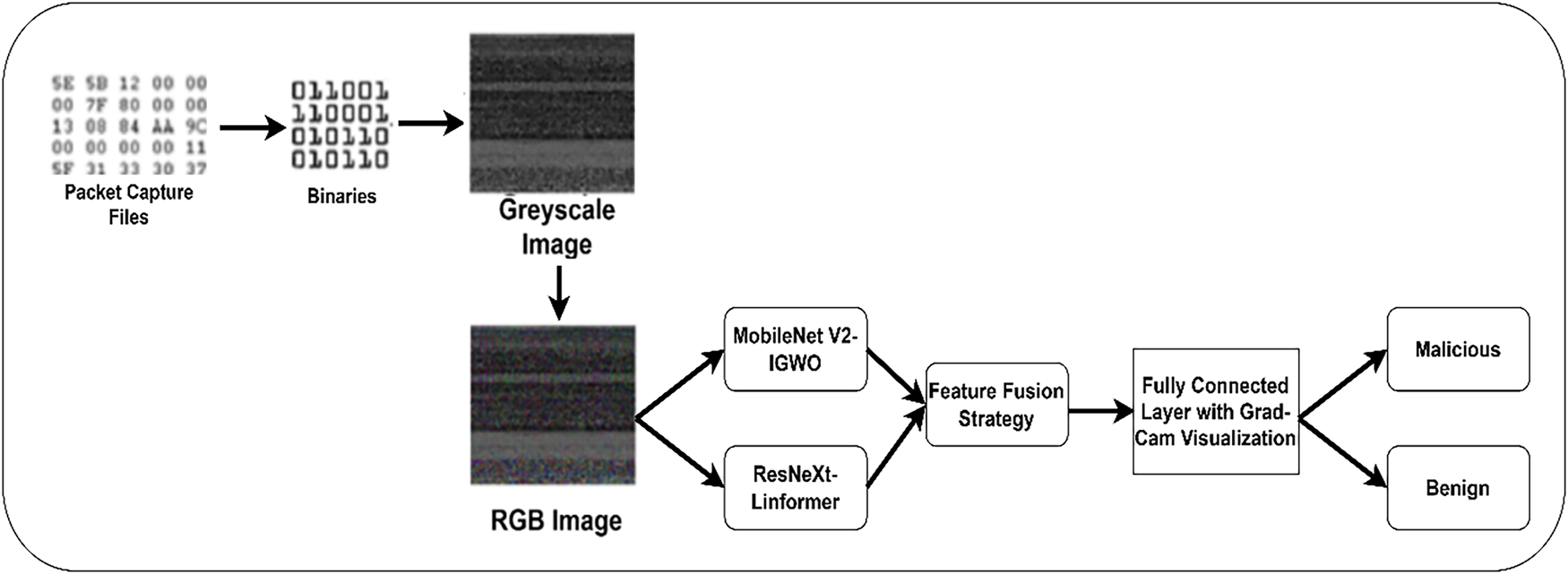

The researchers proposed an MD framework using a DL-based image classification technique. Fig. 1 outlines the processes of the proposed MD framework. In order to achieve a superior outcome with limited computing resources, they introduced an image generation approach using malware binaries and system call traces. The generated grayscale images are converted to an RGB image. In addition, the image quality is enhanced using contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) and median filtering techniques. The IGWO algorithm with MobileNet V2 and ResNeXt -Linformer model is used for feature extraction and image classification.

Figure 1: Proposed MD framework

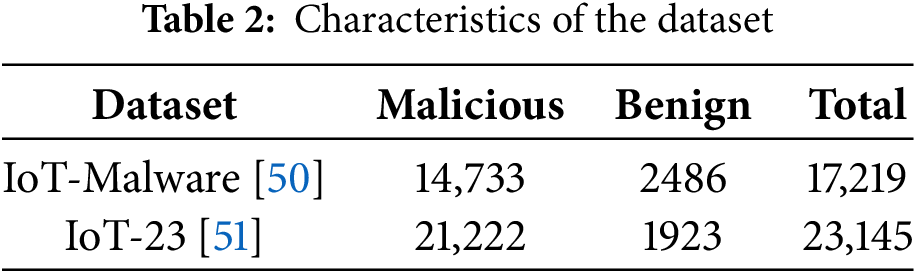

In this study, two public datasets are used to evaluate the model’s classification accuracy, robustness, and real-world applicability. The IoT-Malware dataset [50] includes 17,219 ELF-based samples. These samples are further classified into 2486 benign and 14,733 malicious binaries related to Linux-based IoT devices. They represent a broader spectrum of IoT-targeted attack behavior, including distributed denial-of-service, command-and-control, botnet propagation, and remote code execution, and maintain a balanced representation of malware families, reducing model bias towards dominant malware families. Moreover, this dataset includes packed and unpacked variants of malicious binaries, enabling evaluation of the framework’s robustness against packing-based evasion. The malware families in this dataset exhibit polymorphic behavior, in which each infection cycle alters opcodes and adds dummy instruction sequences. The IoT-23 dataset [51] includes 23,145 Pcap files (21,222 malicious and 1923 benign), complementing the static ELF dataset with a dynamic, network-level perspective on IoT threats. The IoT network activities are captured between 2018 and 2019. Table 2 highlights the details of the datasets, outlining the malicious and benign samples.

The authors utilize this dataset to evaluate the model’s generalization to unseen data. This dataset encompasses 15 malicious and 5 benign scenarios, which represent attack families, such as Mirai, Hajime, Okiru, Torii, and Mozi. Each malicious sample introduces significant polymorphism in packet sequences, payload sizes, and timing intervals. Collectively, these datasets cover static- and dynamic-level manifestations of IoT malware. The inclusion of packed binaries and polymorphic traffic flows reflects realistic adversarial conditions, supporting the validation phase to test the model’s resilience against code obfuscation, behavioral mutations, and evasion techniques.

3.2 Image Transformation and Preprocessing

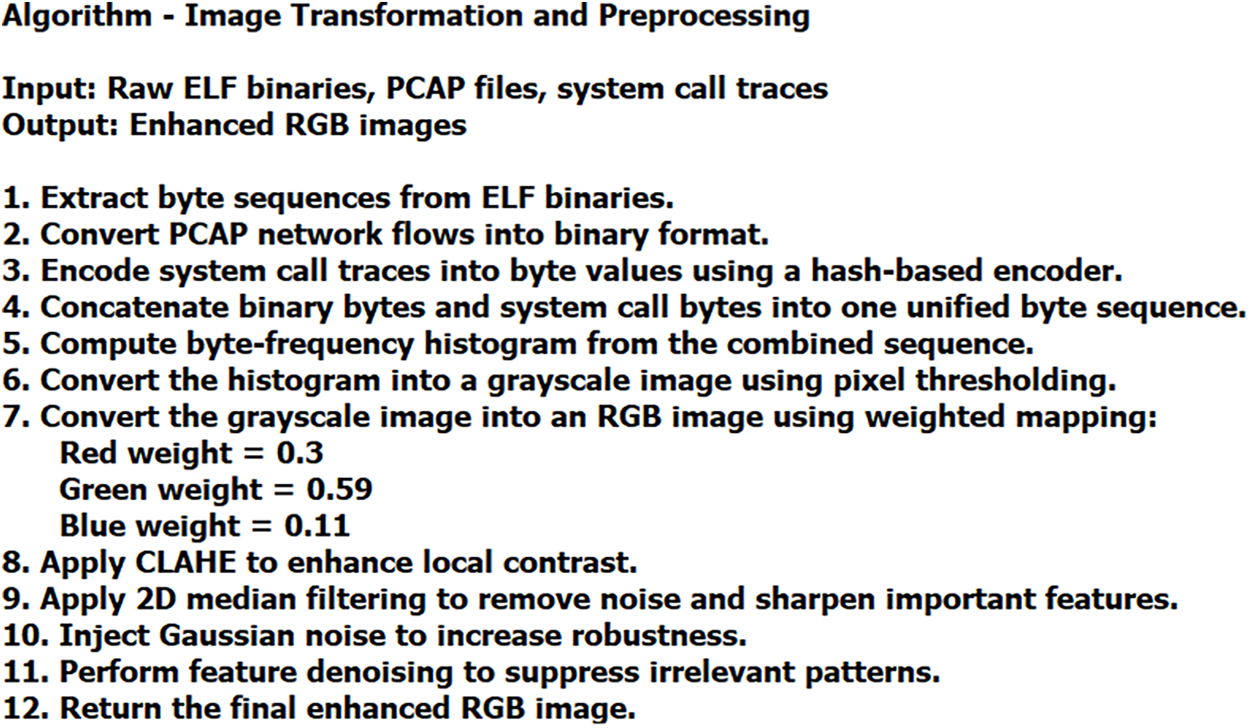

In order to facilitate a comprehensive malware representation, a unified data transformation approach is proposed. Using this approach, the raw binary sequences extracted from ELF or Pcap files and the corresponding system call traces captured during execution are combined. A lightweight hash-based encoding is used to map system call traces to byte values. This process preserves the structural entropy of the original executable traces and the temporal behavior semantics encoded in the system call transitions. Fig. 2 shows the algorithm of image transformation and Preprocessing.

Figure 2: Algorithm—Image transformation and preprocessing

By concatenating the behavioral bytes and the original binary stream, a byte sequence is generated. Through the computation of frequency distributions across the combined byte space, a compact histogram image is produced. The Pcap files are normalized to a binary format to generate the malware image. Let B be a set of binaries

where His ( ) is the histogram generation function using B.

An information abstraction process transforms the binaries into an image. A pixel thresholding operation converts the histogram into a greyscale image. Eq. (2) outlines the process of generating the greyscale image using the histogram image.

where

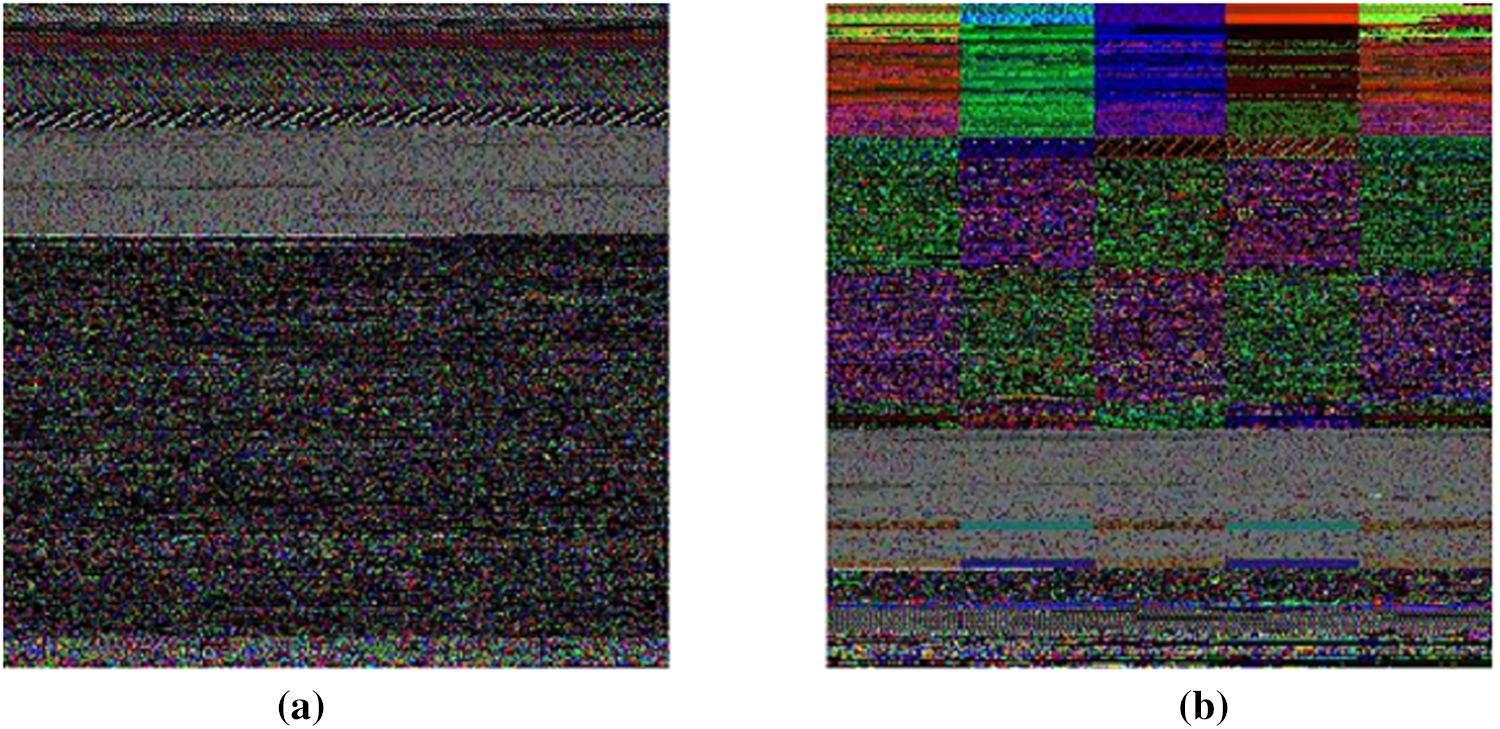

Figure 3: (a) Malicious image and (b) Benign image

The weighted method is applied for converting the greyscale images (

where i = 1 to n is the total number of images.

Unlike traditional global histogram equalization, CLAHE computes histograms with contextual regions and limits the noise amplification. Luminance-based weighting and CLAHE transform the images into enhanced RGB images. Finally, a 2D median filtering is applied to remove noise and pressure sharp edges, representing subtle malware variations. CLAHE and median filtering suppress irrelevant noises, reinforcing meaningful features rather than erasing them. In the data preprocessing pipeline, Gaussian noise injection and feature denoising blocks are implemented to improve the model’s learning capability. This approach supports the model to withstand adversarial perturbations during inference.

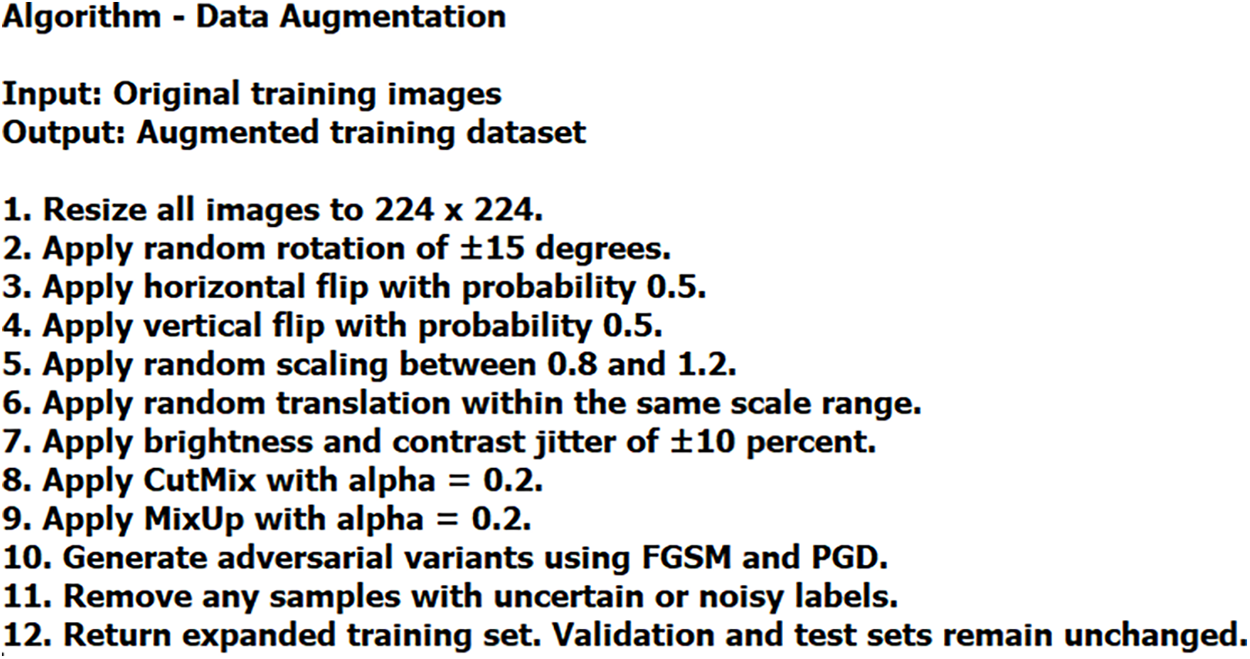

The authors implemented a comprehensive data augmentation strategy to mitigate potential issues of class imbalance and label noise. They partitioned the primary dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) in order to preserve class distributions. As a result, 10,313 malicious and 1740 benign images were in the training set, and 2210 malicious and 373 benign images were in each of the validation and test sets. In order to avoid overfitting risk, data augmentation was performed only on the training set to improve model generalization. Initially, each instance of malware/benign image is normalized to a resolution of 224 × 224 pixels, and subsequently, a series of stochastic transformations is applied to increase sample diversity. The random access procedure includes a

Figure 4: Algorithm—Data augmentation

These augmentation strategies increase the size of the training set, which contributes positively to balanced training across diverse malware types. The validation and testing dataset was intentionally left unchanged in order to maintain the integrity of the original samples and to allow an unbiased performance evaluation.

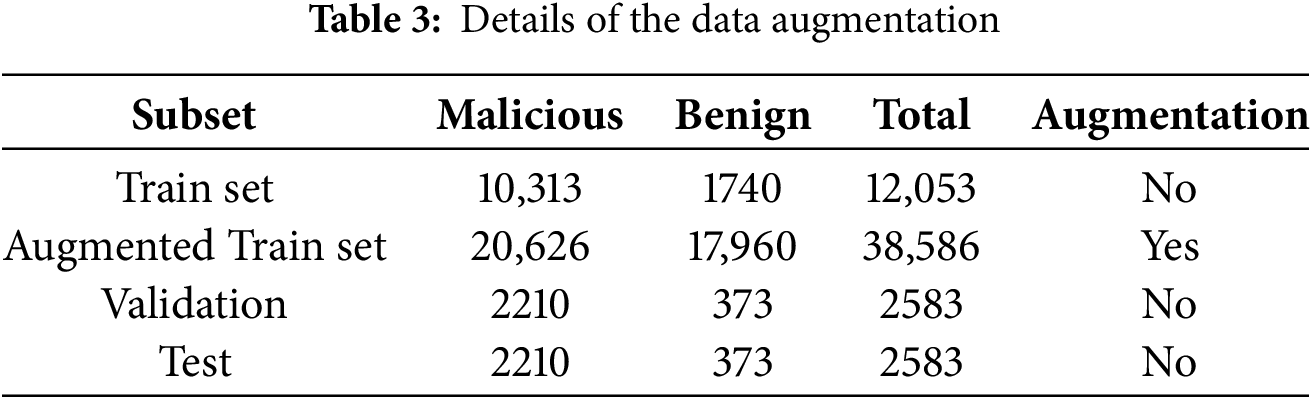

Furthermore, the authors enhanced the data augmentation pipeline in order to strengthen model’s robustness against adversarial attacks. They generated perturbed images using fast gradient sign and projected gradient descent approaches. To ensure unbiased performance evaluation, no augmentation is applied to the validation and test sets. To reduce potential label noise and ensure quality supervision, any samples with questionable annotations are excluded. Table 3 reflects the details of the training set after augmentation, validation, and test sets.

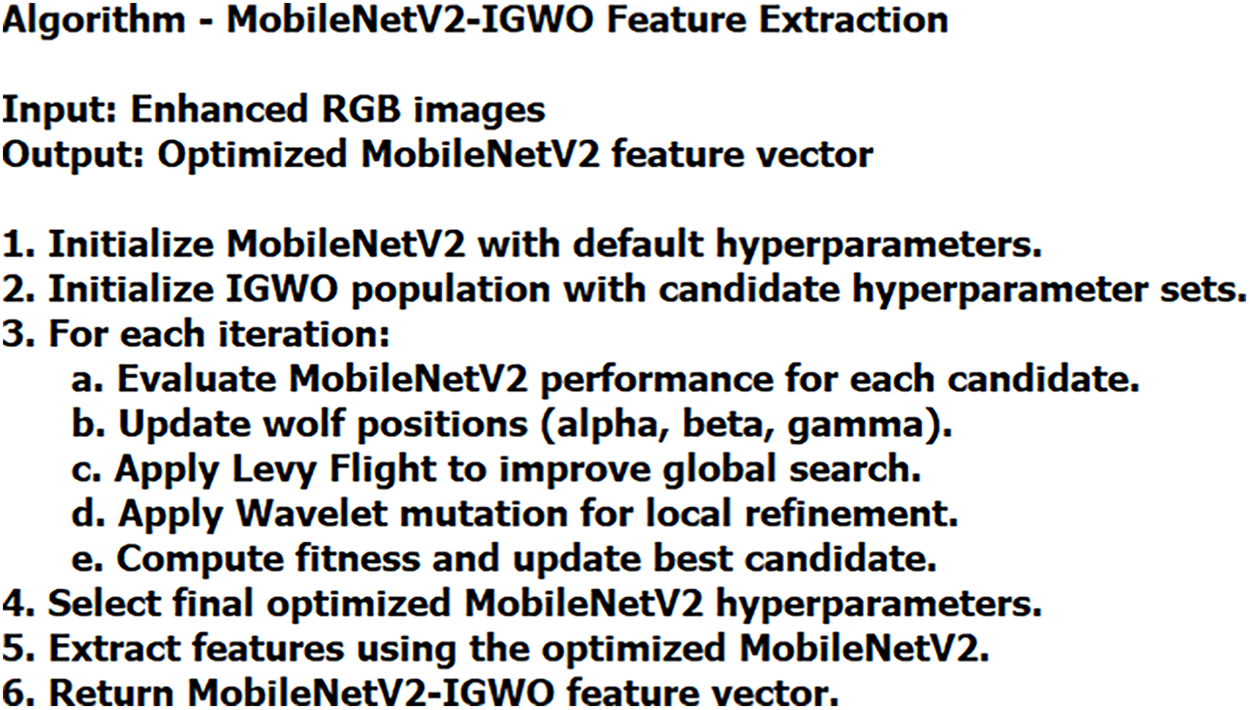

3.4 MobileNet V2-IGWO-Based Feature Extraction

In this study, the authors utilize MobileNet V2 as the base architecture to extract features from malware images. Among the MobileNet variants, MobileNet V2 preserves essential information in low-dimensional embedding with limited computational costs. This strategy ensures efficient gradient flow in shallow networks and reduces the number of parameters compared to the MobileNet V1 architecture. MobileNet higher variants are primarily used for mobile applications that may introduce architectural complexities in the context of MD using images. The linear bottleneck of the MobileNet V2 architecture is robust to post-training quantization that minimizes the computational loss, making MobileNet V2 suitable for the proposed hybrid feature extraction. Fig. 5 showcases the process of feature extraction through the proposed algorithm.

Figure 5: Algorithm—MobileNet V2-IGWO feature extraction

To improve the MobileNet V2’s performance, effective hyperparameter tuning is essential. GWO [52] mimics the leadership hierarchy and hunting strategy of grey wolves. Compared to genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization, GWO’s update mechanism effectively balances exploration and exploitation. This approach is useful in tuning the MobileNet V2 model’s hyperparameters. The GWO’s implementation requires fewer evaluations to converge, rendering it ideal for edge-aware or lightweight model tuning. The sub-optimal and third-optimal levels are combined into a single sub-optimal level. Therefore, the initial level is used to make decisions with α wolf. β wolf represents the sub-optimal level, and γ wolf provides the optimal features for the image classification process using α and β wolves. Eq. (4) shows the computation of the distance between α, β, and γ wolves, respectively.

where

where

However, the standard GWO suffers from premature convergence and may become trapped in local optima in high-dimensional complex feature space. In order to overcome this limitation, the authors enhance the GW’s behavior using Levy Flight and Wavelet mutation. The introduction of Levy Flight [53] produces long-distance jumps in the solution space, enhancing exploration and enabling the model to identify optimal feature subsets. In addition, the Wavelet mutation improves the exploitation process by performing localized fine-tuning of promising candidates. Eq. (7) presents the integrated position update mechanism.

where

where f

Eq. (9) represents the final updated position after mutation.

where

The mutation strategy determines that the IGWO maintains a trade-off between global exploration and local refinement, enabling the MobileNet V2 model to extract and prioritize malware-specific patterns. By suppressing irrelevant or redundant features, this strategy boosts classification accuracy with limited computational costs, aligning with the constraints of real-time IoT and SDN environments. Eq. (10) presents the proposed feature extraction using the IGWO algorithm.

where

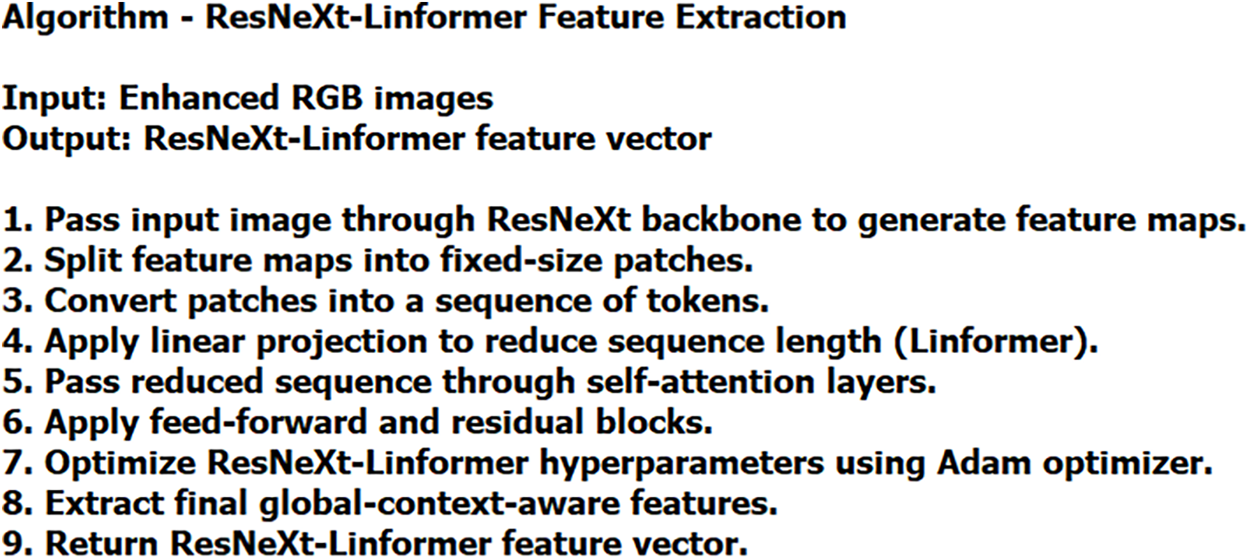

3.5 ResNeXt-Linformer-Based Feature Extraction

To extract diverse features, the authors introduce ResNext-Linformer-based feature extraction in malware detection pipeline. The ResNeXt model contains a few hyper-parameters for image classification. It applies the cardinality function to control the set of image transformations. It uses the same set of hyper-parameters to produce spatial maps of the same size. The spatial maps are downsampled by a factor of 2 at each iteration. Floating point operations per second (FLOPS) are used to evaluate the computational complexity of the model. Fig. 6 outlines the functionalities of the feature extraction using ResNeXt-Linformer.

Figure 6: Algorithm—ResNeXt-Linformer-Feature extraction

The ResNeXt model modifies the existing ResNet model to identify the key features in classifying the images. It relies on the grouped convolutions in order to achieve effective feature extraction with limited resources. This approach allows this model to learn diverse representations, leading to better generalization. The author employs the ResNeXt backbone, containing a standard 7 × 7 convolution with stride and pooling to downsample the image. Eq. (11) presents the aggregation of image transformations using cardinality.

where Decision is the classification decision, C is the cardinality of the features, and

Linformer offers a unique attention mechanism approach, handling the computational complexities of standard ViT architectures. It uses low-rank projections, enabling efficient global context modeling. Moreover, it captures long-range dependencies across the malware image. The integration of ResNeXt [54] and Linformer leads to accurate and computationally scalable image analysis. The ResNeXt features are converted into a sequence of tokens (patches). A learnable linear mapping projects the more extended sequence patches into a lower dimension. Attention blocks are added to provide a significant gain in global context modeling. Residual and feed-forward layers with skip connections are used for the feature extraction.

To fine-tune the ResNeXt-Linformer hyperparameters, Adam optimization is employed. It is based on the stochastic gradient descent algorithm. It demands fewer computational resources and configures the parameters of image classification models according to the specific problem. A random set of features are used to calculate the gradient to optimize the ResNeXt model. Eqs. (12) and (13) represent the expressions for calculating the exponentially weighted averages.

where

A total of two momentum vectors (WM and RMP) are initialized to optimize the ResNeXt model’s hyper-parameters. Eq. (14) is used to compute the moving average for WM. Eq. (13) presents the mathematical expression for calculating the RMP vector.

where

where

Using the final set of hyperparameters, the author extracts the malware features. Eq. (16) presents the feature extraction process based on ResNeXt-Linformer.

where

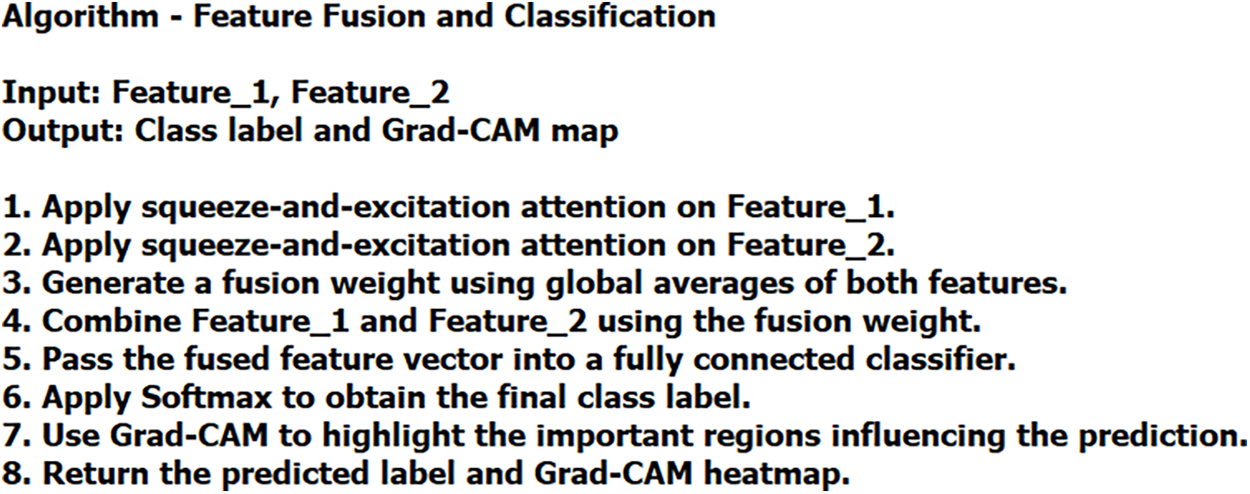

3.6 Feature Fusion and Classification

A dynamic attention-based module is introduced to effectively learn the relative importance of the extracted features. It integrates squeeze and excitation (SE) and a learnable fusion gate. By adopting this approach, adaptive channel-wise weights are generated for each feature stream. Let

Figure 7: Algorithm—Feature fusion and classification

Eq. (17) outlines the computation of channel-wise significance of the features.

where

Eq. (18) presents the mathematical form of the attention weights to recalibrate the feature maps.

where

A fusion gate mechanism is introduced to maintain a balance between recalibrated features using a scalar coefficient as shown in Eq. (19).

where

Eq. (20) presents the process of feature fusion.

Using the feature fusion approach, the proposed model identifies fine-grained features, leading to optimized classification performance and robustness.

A fully connected (dense) layer with Softmax function is used to classify the fused feature maps. The Softmax function transforms the high-dimensional semantic representation into a class prediction (Malicious or Benign). Grad-CAM is integrated into the classification pipeline, enhancing model transparency and supporting interpretability. This integration highlights the regions in the malware image that influence the model’s decision. Eq. (21) offers the process of a class-discriminative localization map.

where

By visualizing the original malware image with Grad-CAM, the influential regions of Malicious and Benign images are highlighted. Using this strategy, model’s transparency is improved, allowing cybersecurity experts to comprehend the model’s decision.

The authors follow the benchmark metrics for evaluating the performance of the proposed MD framework. The accuracy metric is used to measure the number of correct predictions generated by the MD frameworks. The images in the datasets are used as the parameter for computing the accuracy score. In binary classification, precision, recall, and F1-measure are applied to ensure the significance of the model’s performance. Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Cohen’s Kappa are crucial metrics to evaluate the capability of the proposed MD framework in handling the complexities of malware images. Standard deviation (SD) and confidence interval (CI) are computed to determine the statistical significance and variability of the outcomes. Furthermore, the area under the receiver operating characteristics (AUROC) and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) are employed to evaluate the effectiveness of the MD frameworks using true positive and false positive rates.

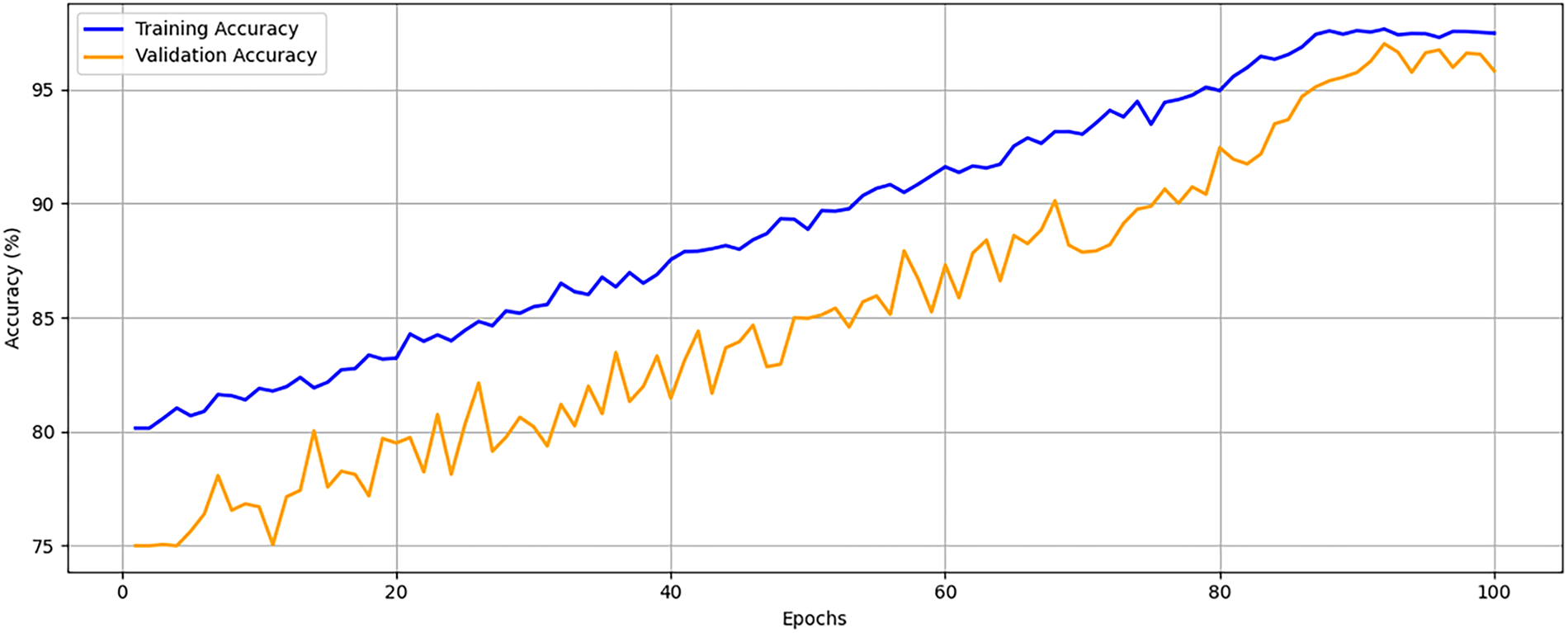

The authors evaluate the model’s performance in a resource-constrained environment. They utilize Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (4 GB RAM) running Raspbian OS with a 1.5 GHz Quad-core ARM Cortex-A72 processor. Using TensorFlow Lite, the proposed model is compressed and optimized. The authors quantize the trained model using post-training dynamic range quantization. This strategy reduces the model’s size by approximately 60% with negligible accuracy loss (<0.3%). Fig. 8 demonstrates the performance of the proposed model during the training and validation phases. It shows a steadily increasing learning curve with convergence behavior. The training accuracy increases from 80% to over 98%, plateauing smoothly after the 75th epoch. Likewise, the validation accuracy reaches 97%, reflecting strong generalization capabilities.

Figure 8: Training and validation accuracy

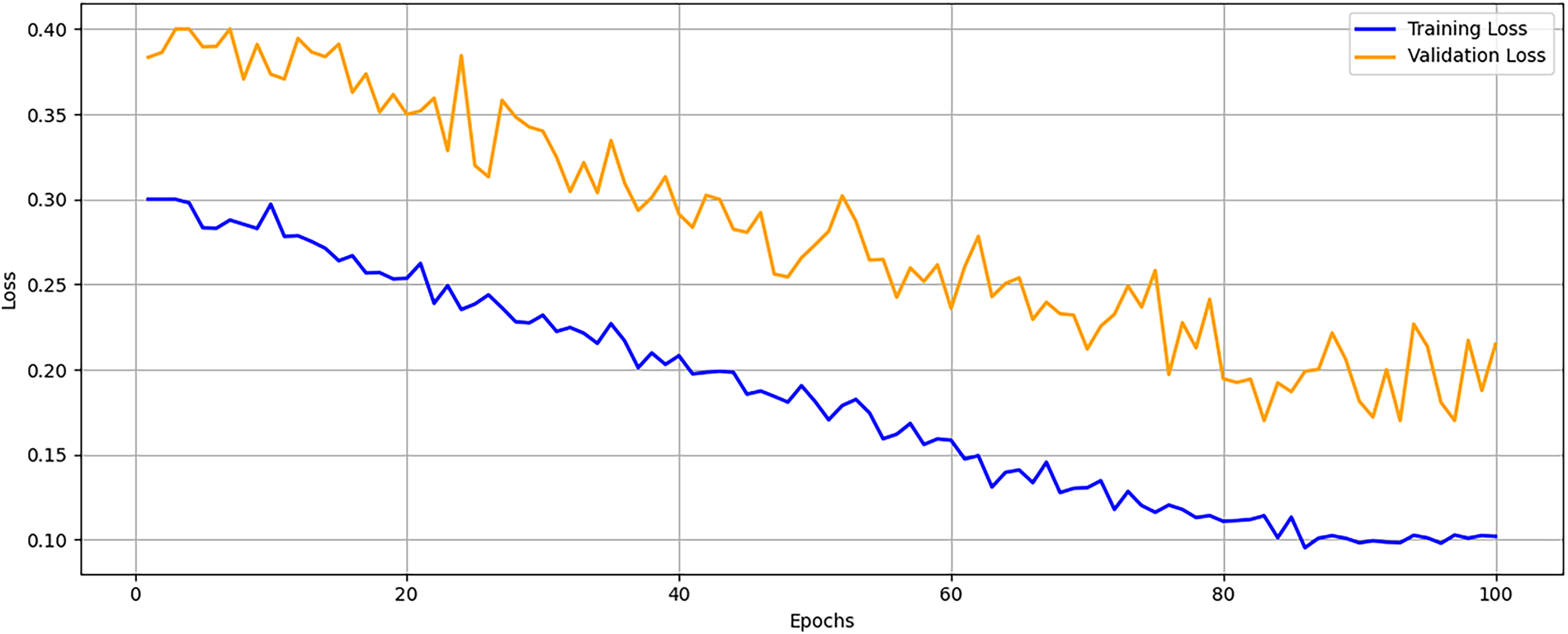

Fig. 9 illustrates a consistent and steady decline in training and validation loss. The training loss drops from 0.30 to below 0.10, while the validation loss decreases from 0.40 to 0.18. The decline in training loss demonstrates stable optimization, achieving convergence without unnecessary epochs or overfitting. The controlled generalization gap between training and validation loss reflects the proposed model’s generalization ability to unseen malware samples, which is crucial for maintaining accuracy in real-time SDN/IoT scenarios. Achieving convergence within 100 epochs suggests that the training process is computationally economical.

Figure 9: Training and validation loss

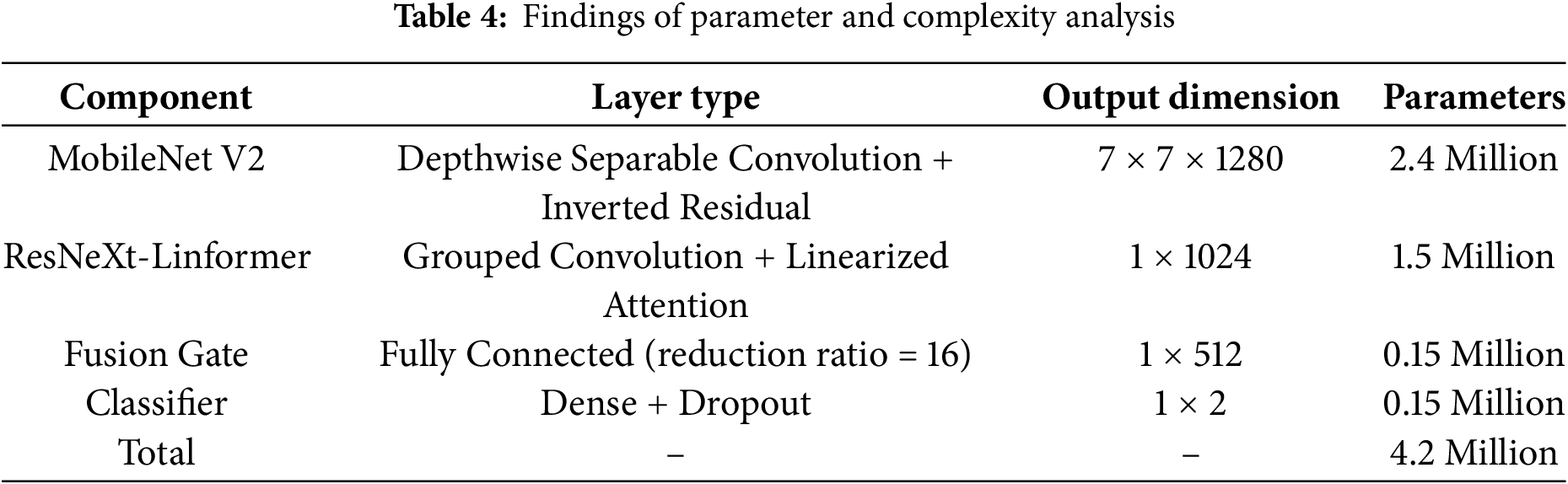

The proposed model’s architecture includes four major modules: local feature extraction (MobileNet V2), global context extraction (ResNeXt-Linformer), feature fusion, and classification head. Table 4 outlines the number of parameters required for each module. To minimize parameter counts, the local feature extraction employs inverted residual blocks with linear bottlenecks. The model contains parameters of 4.2 Million and GFlops of 0.85 per forward pass for a 224 × 224 input. The hybrid ResNeXt-Linformer reduces the complexity from O

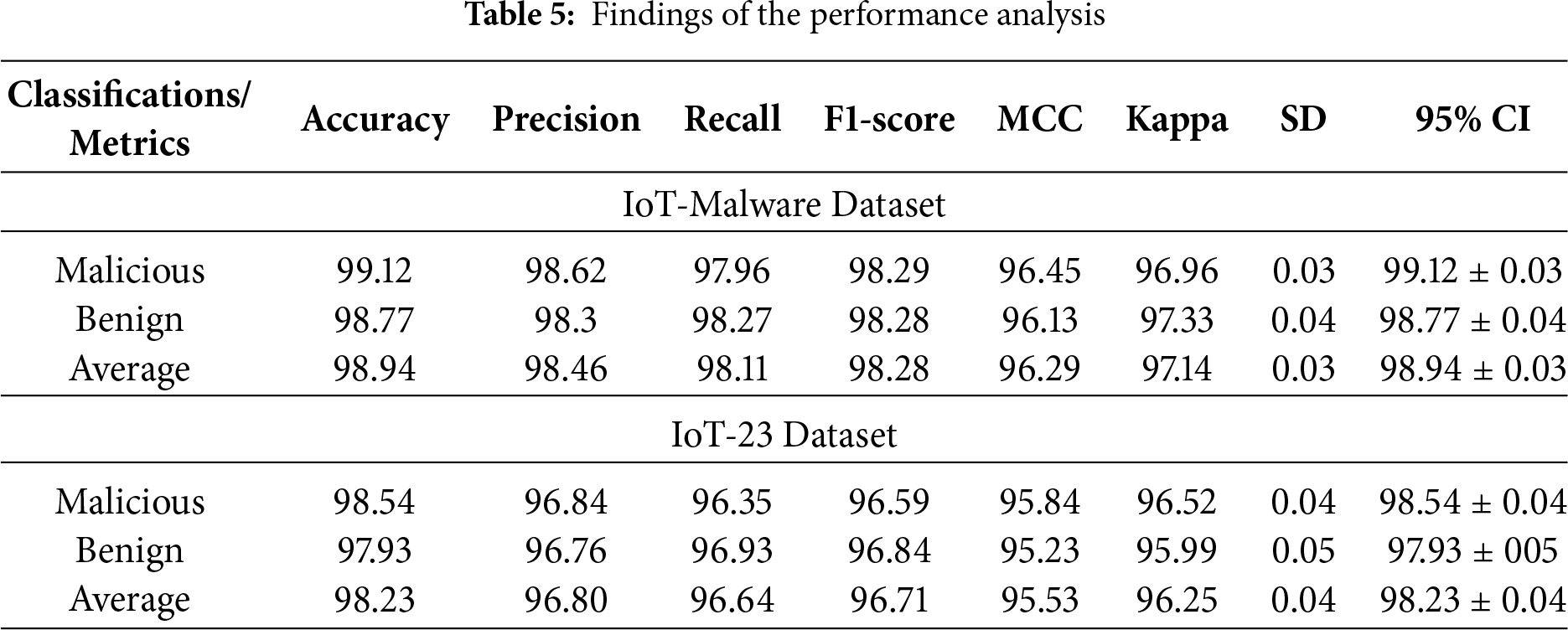

Table 5 highlights the performance of the proposed model on the IoT-malware and IoT-23 datasets, respectively. The model achieved an average accuracy of 98.94% (SD = 0.03, 95% CI = 98.94 ± 0.03) on the IoT malware dataset and 98.23% (SD= 0.04, 95% CI = 98.23 ± 0.04) on the IoT-23 dataset. The findings underscore the proposed model’s robustness and consistency across diverse data. The low SD values and CI of 95% indicate the model’s reliability to variations in the dataset and initialization conditions. The image-based representation adopted in this study is a strong countermeasure to popular evasion techniques such as packing and polymorphism, which are employed by hackers in order to obfuscate the appearance of code while maintaining its functional semantics. Traditional Byte-Sequence-based or Signature-based approaches are based on static features—opcodes, S-header descriptors, and entropic measures, which are easily compromised by packers. On the other hand, the mapping of both binaries and Pcap traffic into RGB histogram images maintains the global distribution of byte frequencies and regularities in textures, and correlations between channels. Even when a packer rearranges parts of the codes, the global properties are partially preserved. Consequently, the convolutional filters used by MobileNetV2 are responsible for separating localized intensity patterns, while the ResNeXt-Linformer branch models long-range dependencies between these spatial regions. Using this hybrid feature representation approach, the proposed model learns abstract spatial-spectral signatures that are consistent across the variants in the same malware, offering resistance to the proposed framework to identify the anomalies in the IoT network.

Although polymorphic malware continues to reorganize its network payload or code for each generation, it consistently exhibits macro-level behavioral patterns, including periodic bursts of communication, repetitive byte-density rhythms, and distinctive packet timing across multiple executions. By extending these features into the visual space, polymorphic variation is interpreted by the proposed model as minor texture noise rather than a novel class of pattern in order to maintain the stability of classification. In addition, Grad-CAM saliency visualizations suggest that the framework focuses on high entropy and control flow dense regions, instead of superficial byte sequences, thereby indicating that detection is based on an intrinsic malicious structure as opposed to potential surface signatures.

The selection of the IoT-Malware and IoT-23 datasets was carefully considered to reflect the diverse range of obfuscation and behaviors. The IoT-Malware repository includes ELF binaries from a range of different architectures, which are either packed or header-stripped, presenting an effective testbed to determine resilience to code-level disguise. These datasets complement this by offering access to the real Pcap traces of botnets, command-and-control traffic, and benign IoT communications for the model validation under realistic polymorphic networking conditions. Assessment on both corpora shows the image-based framework to generalize across anomaly levels (binary- and traffic-level), confirming its robustness, interpretability, and suitability for deployment in the heterogeneous and resource-constrained IoT and edge ecosystems.

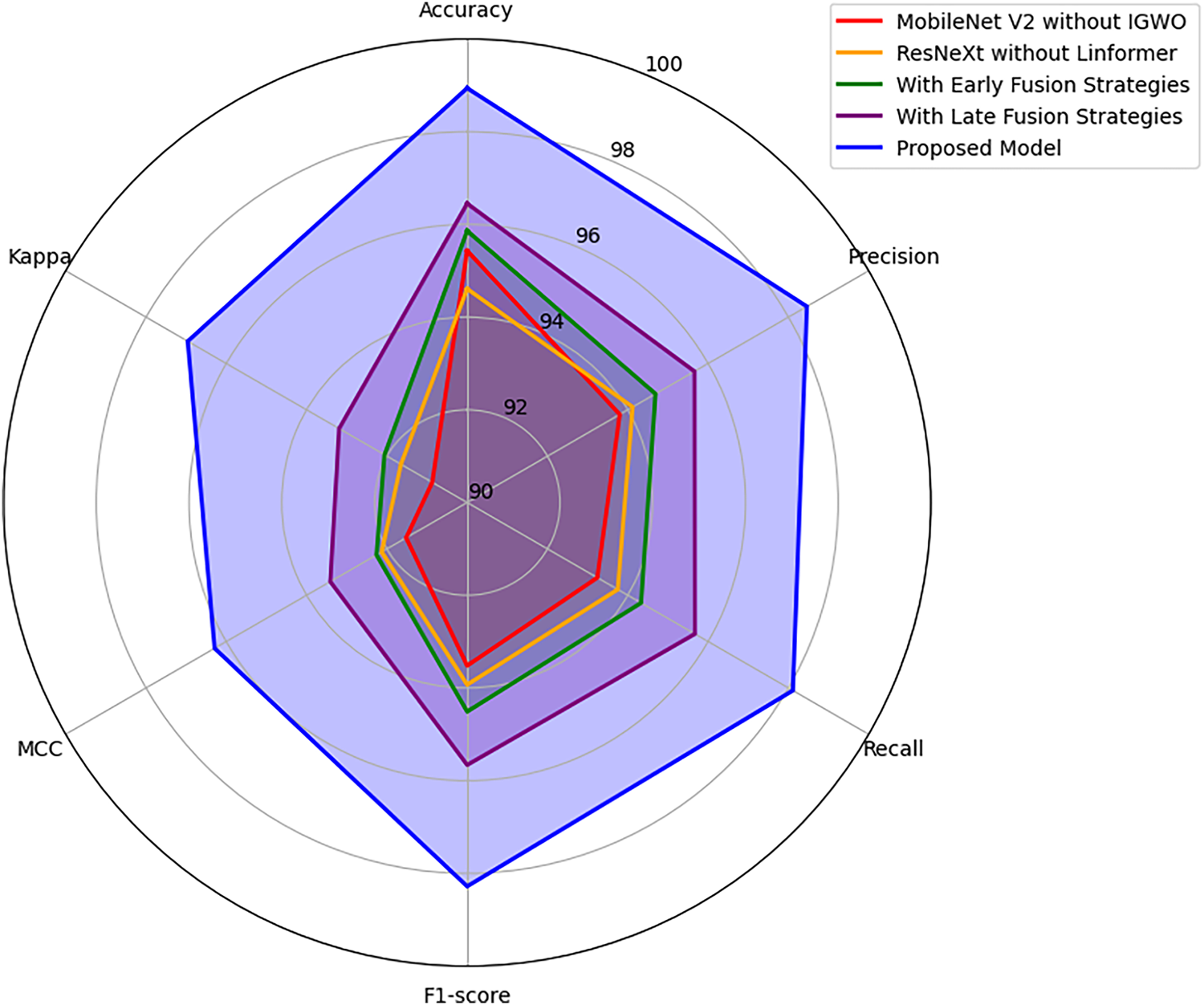

Fig. 10 presents the findings of the ablation study. Without IGWO, the performance of the MobileNet V2 model is limited on the IoT malware dataset. Similarly, the standalone ResNeXt struggles to deliver a better performance due to the lack of an effective attention mechanism. Compared to the proposed model, the early and late fusion strategies are unable to identify crucial features associated with malicious and benign classes. The use of IGWO-fined-tuned MobileNet V2, ResNeXt-Linformer, and adaptive fusion strategies supports the proposed model, outperforming the baseline architectures.

Figure 10: Ablation study: Performance comparison of model variants (IoT malware dataset)

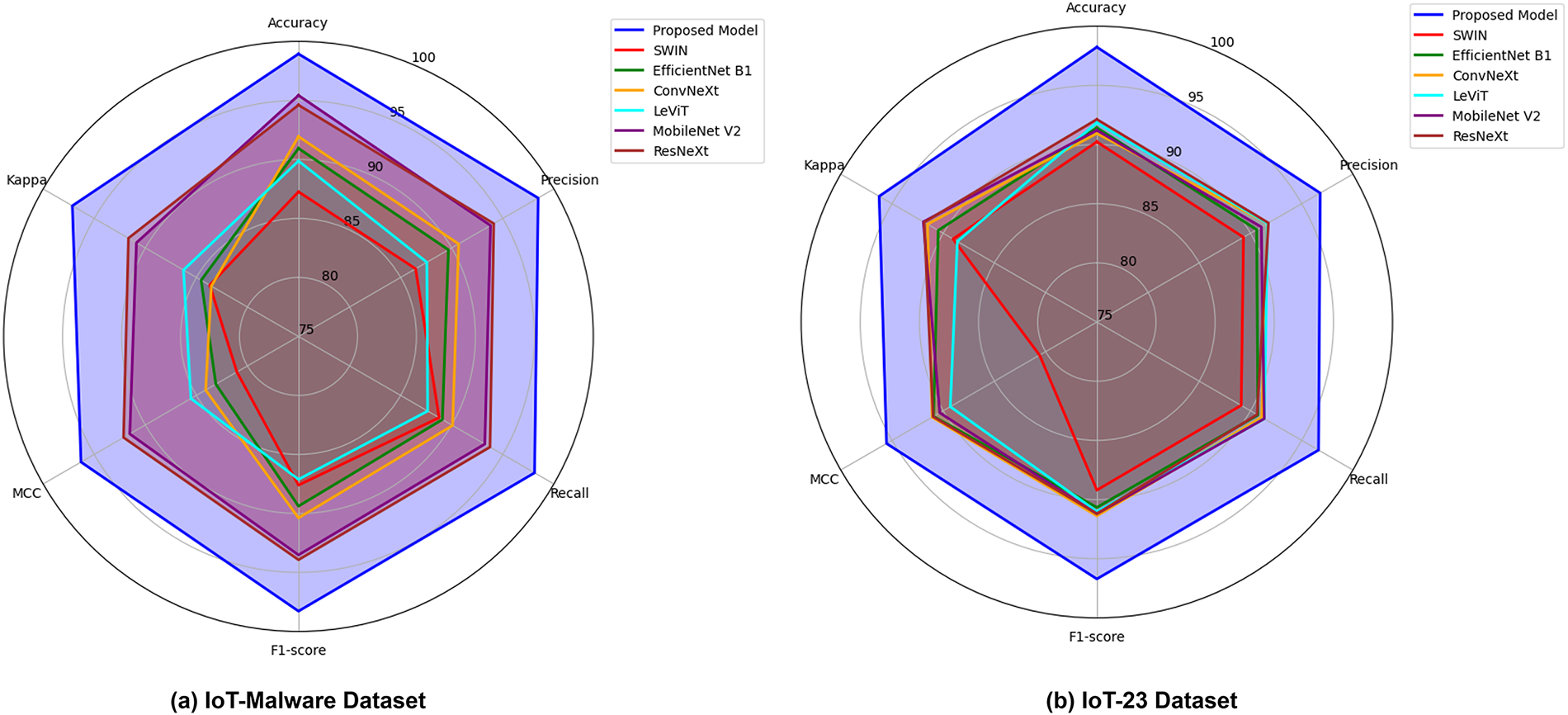

Fig. 11a,b demonstrates the effectiveness of the model on the IoT malware and IoT-23 datasets. The proposed model surpasses the baseline models across the key performance indicators. The proposed model’s highest scores reinforce its superior classification capabilities. The findings highlight the model’s balanced performance on the unseen data. Achieving state-of-the-art accuracy while maintaining stability and robustness affirms the model’s deployment in the IoT/SDN environment. The authors conduct a paired t-test to statistically validate the model’s performance against the baseline architectures. For each metric, the null hypothesis assumed no significant difference between the proposed MD classification and baseline models. The resulting p-values were consistently less than 0.5. It guarantees that the performance improvements of the proposed model were statistically significant, indicating the model’s reliability in the presence of data variability.

Figure 11: Findings of the comparative analysis (Baseline models)

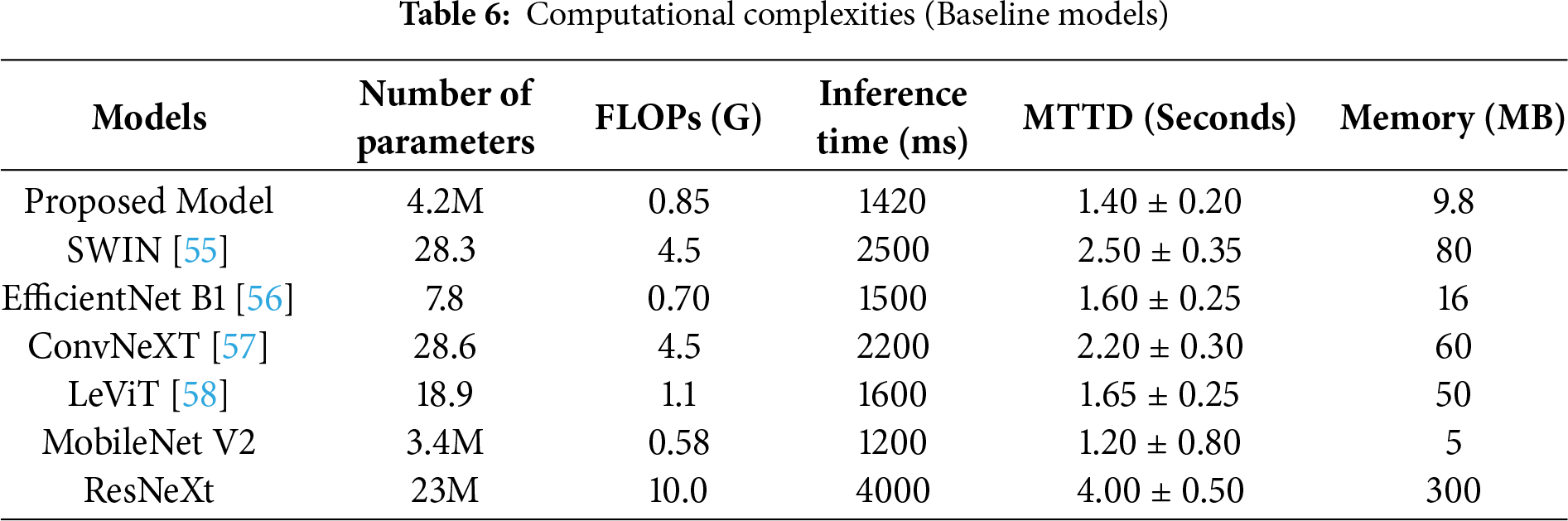

Table 6 summarizes the computational complexities of the MD models. It reinforces the advantages of the proposed MD classification model in real-world IoT/SDN deployment scenarios. With 4.2 million parameters and 0.85 G FLOPs, the model achieves an exceptional performance in 1.42 s. Compared to the heavier backbones, such as SWIN and EfficientNet, it achieves a mean time to detect (MTTD) of 1.40 ± 0.20 with lower parameter counts and a modest memory footprint of 9.8 MB. Standalone MobileNet V2 has limited computational requirement. However, the limitations, such as a lack of effective feature extraction and limited global contextual modeling, reduce its capabilities in the context of MD classification. The authors apply IGWO and enhance its feature extraction performance, achieving remarkable performance in resource-constrained environment. The findings of the comparative analysis indicated that the proposed MD framework offers an approximately 80% reduction in parameters and 75% faster inference in the context of MD.

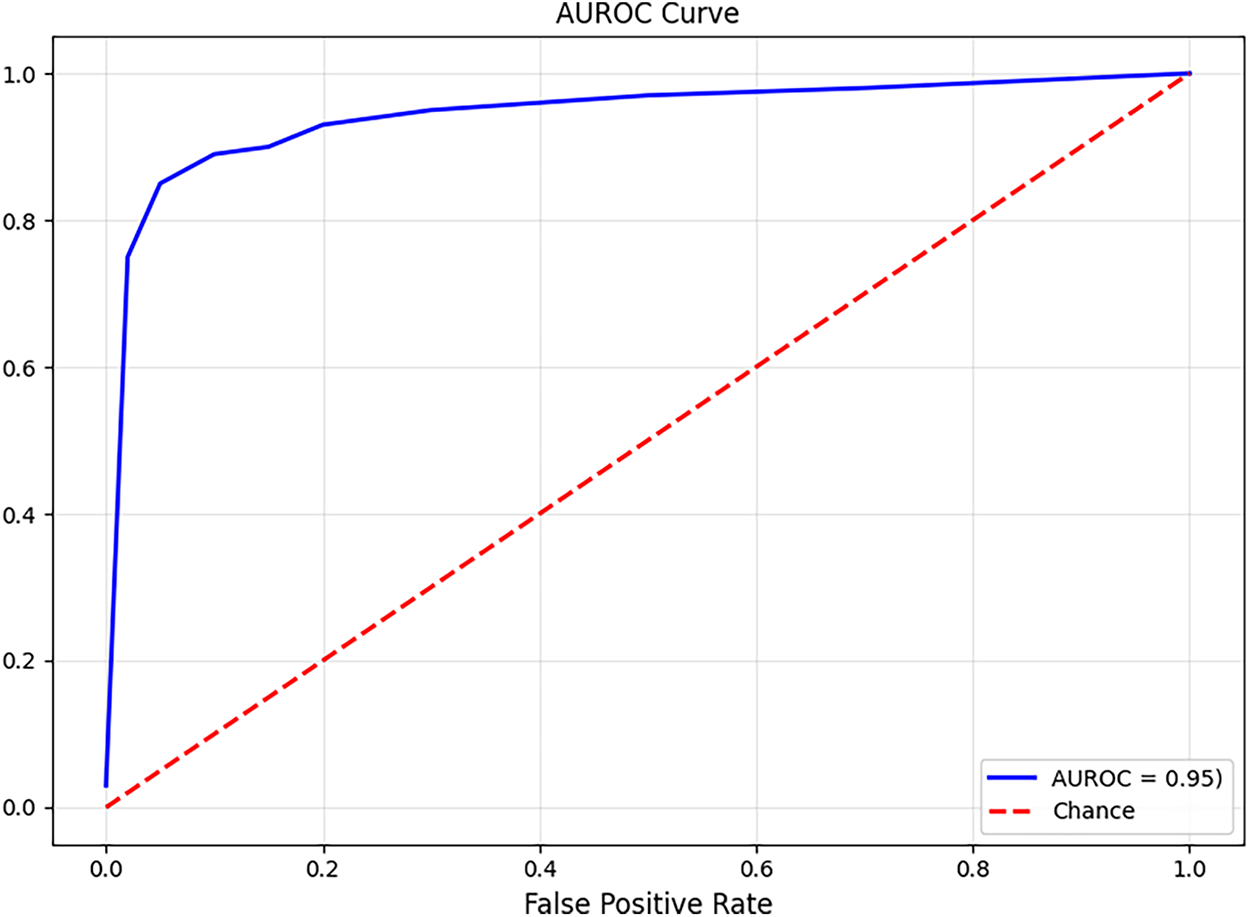

Fig. 12 shows the AUROC curve validating the effectiveness of the proposed model in differentiating malicious and benign samples. The AUROC value of 0.95 indicates the model’s effective discriminative capability. This robust performance is essential in an IoT/SDN environment, where false positives and negatives can disrupt normal operations. The high AUROC value with the consistent accuracy underscores the model’s ability to maintain reliable detection performance across different thresholds, confirming the model’s potential for real-world deployment.

Figure 12: Finding of AUROC analysis

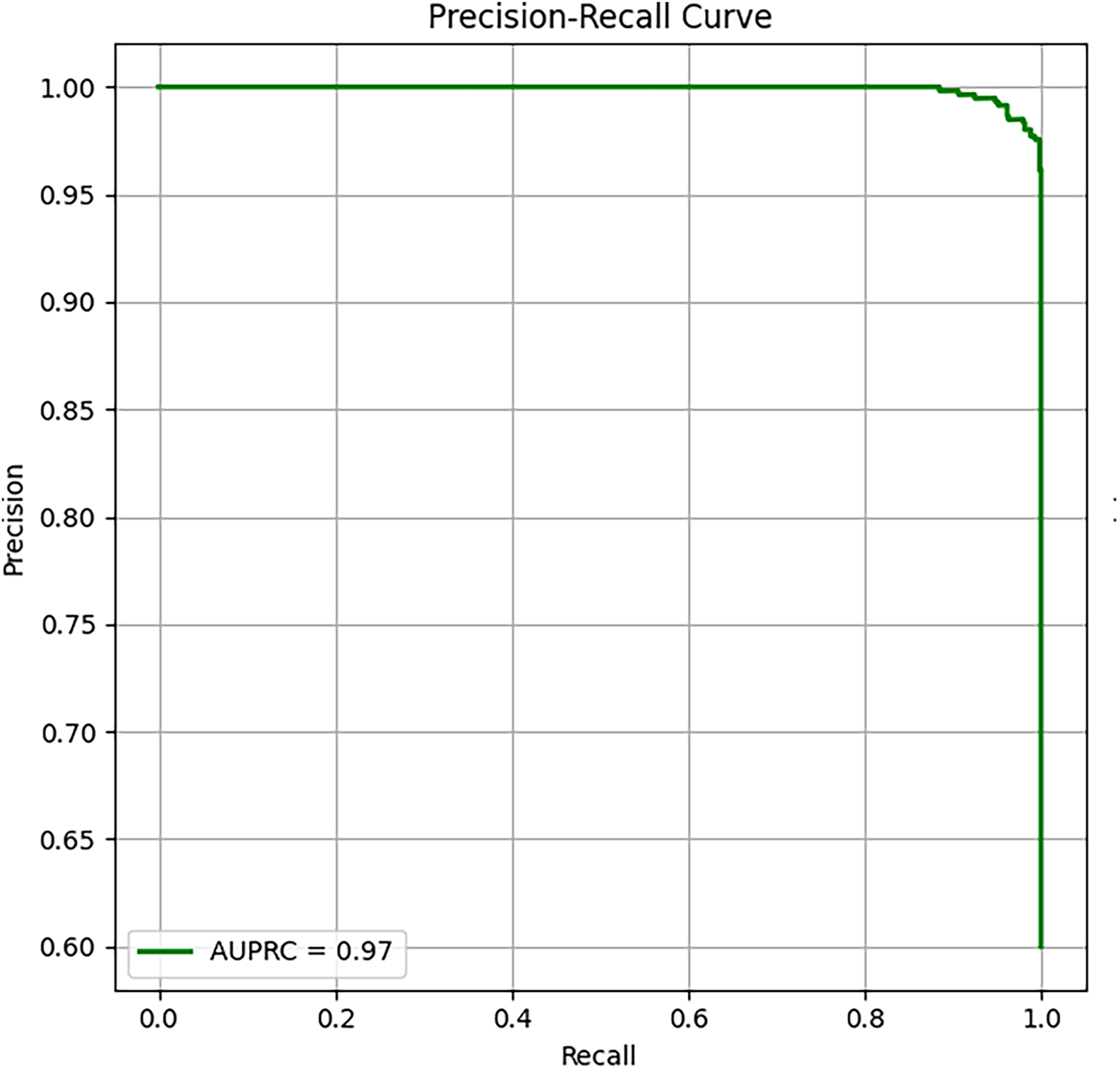

Fig. 13 provides insight into the classification performance of the proposed model. The AUPRC value of 0.97 represents the model’s capability in maintaining high precision and recall levels. The curve remains close to the maximum precision across the entire recall range, demonstrating the proposed model’s robustness and stability across different decision thresholds. The findings affirm the model’s readiness for deployment in dynamic real-time IoT/SDN applications.

Figure 13: Finding of AUPRC analysis

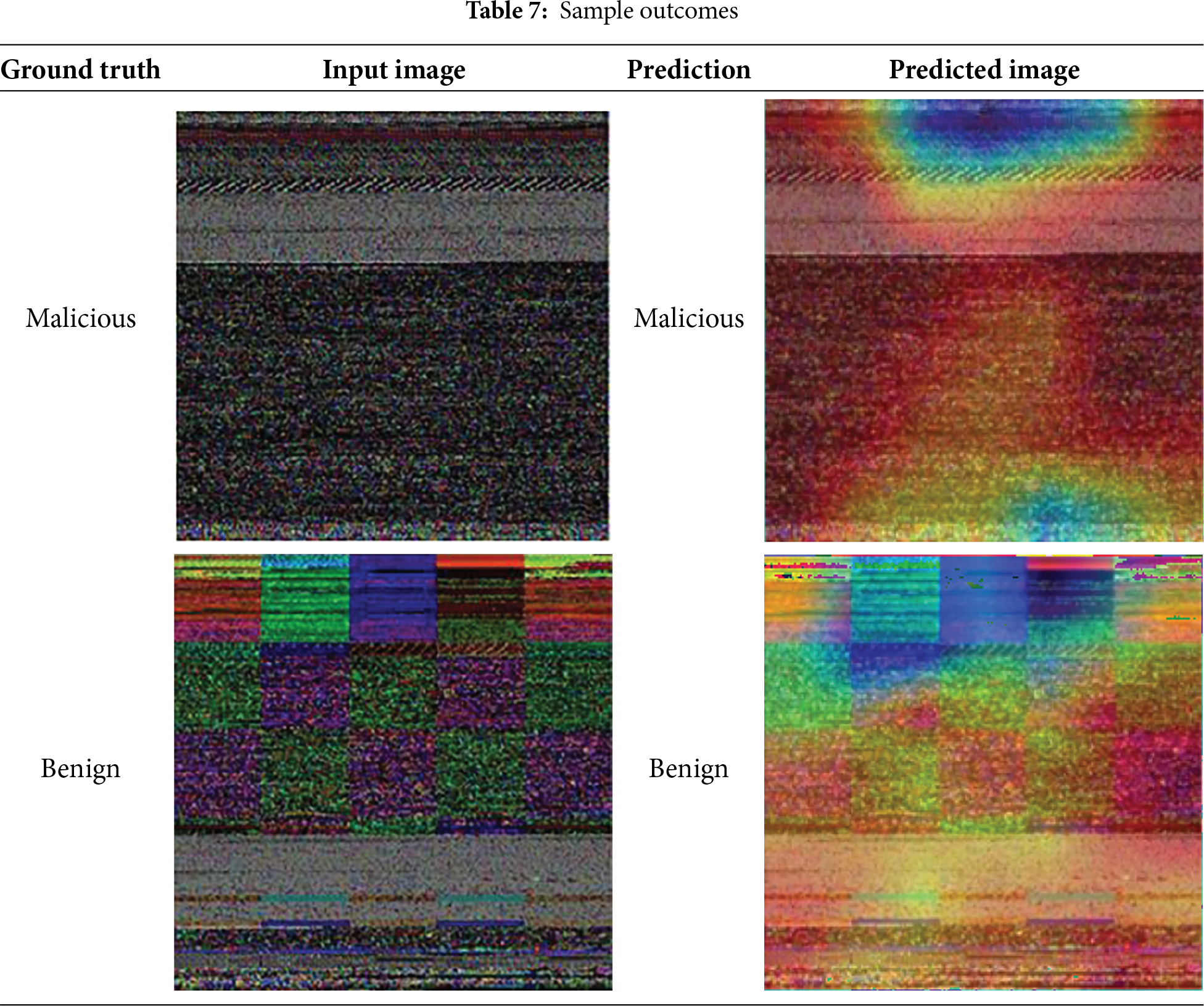

Table 7 highlights the model’s potential in explaining its decision, visualizing the discriminative regions influencing the model’s decisions. In the malicious sample, the intense red and yellow regions aligned with specific image segments, influencing the model in identifying malicious images. Similarly, in the benign samples, the heatmaps reveal a dispersed pattern of activations, indicating the model’s ability to differentiate benign and malicious patterns. These visualizations validate the model’s classification outcomes, enhancing its transparency and trustworthiness. It builds confidence that the model’s decisions are grounded in meaningful features.

A novel hybrid framework for detecting malware in the IoT environment is introduced in this study. An image transformation technique is used to convert Pcap files into an RGB image. Initially, the Pcap files were normalized to binary form. The histogram images were generated from the binaries. A threshold value was employed to generate the malware images. The authors introduce a dual feature extraction approach using MobileNet V2-IGWO and ResNeXt-Linformer models. Finally, a fully connected layer with Grad-CAM is used to classify the extracted features. MobileNet V2-IGWO and ResNeXt-Linformer reduce the demand for dedicated temporal convolutional modeling, identifying local (system call order) and global (file structure) patterns across channels. This streamlined feature extraction approach minimizes computational complexity, supporting high interpretability and lightweight deployment in the IoT environment. The study’s findings reveal the significance of the proposed MD framework in identifying malware in the IoT network. The proposed framework outperformed the baseline models on the IoT malware and IoT-23 datasets, respectively.

This research has significant implications for the development of safe IoT ecosystems where millions of devices share sensitive data with limited computational resources. It has focused on the anomalies that are security-oriented, specifically on binary-level and network-level malicious patterns. By dealing with the highly consequential categories, the study provides an effective blueprint for increasing IoT resilience to sophisticated attacks. One of the key implications of the proposed work is to show that image-based malware detection can be a unifying paradigm for different IoT data formats. Traditional malware identification techniques are based on signature matching or hand-designed statistical features, and they are frequently incapable of detecting polymorphic and obfuscated malware samples. On the other hand, the conversion of binary executables and Pcap traffic into RGB histograms is used for extracting the structural and spatial patterns. This visual abstraction allows the proposed CNNs-ViTs models to learn discriminative representations that are robust to code obfuscation or encryption layers. In addition, the proposed method achieves a superior performance on unknown malware families, proving the superiority of image transformation methods compared to traditional byte-sequence or rule-based methods in the rapidly evolving IoT malware.

In study [33], a visualization approach is built for classifying portable executable files. A dataset of 7087 malware samples was used for the performance evaluation. A feature extraction method was introduced to acquire crucial features from the images. The techniques, including RF, SVM, and K-Nearest Neighbor classifiers, are employed for malware classification. RF obtained an average accuracy of 97.47%. However, the performance of RF was limited by non-portable executable files.

The study [34] developed an MD system for the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). A sniffer gateway is used to track network data. The model obtained a detection accuracy of 97.81% on the IIOT dataset and 98.47% on the Windows dataset. The model performance was limited to specific malware attacks. On the other hand, the proposed framework is capable of identifying malicious files in the network. It can be extended to detect multiple forms of malware. In study [35], an anomaly detection model is proposed for IoT devices. They employed the CNNs technique to process the features and gated recurrent units to detect the anomalies. The framework achieved an average accuracy of 99.9% for binary classification. On the other hand, the proposed MD framework achieved a similar accuracy with limited resources. The lightweight nature of the proposed framework can support the recent IoT network architecture. The studies [36,37] introduced CNNs-based malware classification. These models employ few-shot learning and global context modeling for identifying subtle malware patterns. However, the performance of these models is limited in comparison with the proposed model.

An MD framework [38] is developed using a channel-squeezed and boosted CNNs technique. Edge exploration and smoothing techniques are used to improve the feature selection process. The split transformation merging block supported the framework for identifying the malware patterns. The channel squeezing and boosting were employed at multiple granular levels to obtain the key features for detecting the malware. Similarly, the proposed MD framework applied IGWO to select crucial malware patterns. The ResNeXt model was employed to reduce the computation time for classifying the images. In addition, the proposed framework addressed the limitations of malware detection.

The generative deep learning technique is employed in the study [39] for finding the anomalies in the IoT network. They analyzed data using adversarial auto-encoders and bidirectional generative adversarial networks (GAN). They achieved an accuracy of 99.9% on the IOT-23 dataset. The implementation of GAN-based MD model demands additional training time to learn the malware environment. In contrast, the proposed MD framework applied the IGWO and the ResNext model to reduce the execution time for image classification. In study [40], an MD framework is proposed using the CNNs technique. They used a feature extraction technique to identify the key features. The DenseNet model was applied to classify the images. In contrast, the proposed MD framework followed the feature selection approach for generating the features. The findings revealed that the feature selection technique provided valuable features for the CNNs model to predict the existence of the malware.

Similarly, the existing methods [41–49] provide remarkable results. Nevertheless, these models have a number of limitations that hinder their application in real-world malware detection environments. The most widely used CNN or CNN-ViT architectures fail to reveal the malware’s salient regions, and most of the models report the models’ accuracy without considering the computational costs, such as the number of parameters, FLOPs, and memory usage. Without these essential performance indicators, it is challenging to determine the feasibility of deploying such models in real-time environments.

Furthermore, many feature extraction techniques treat features of equal information, leading to noise and redundancy in the final classification. In contrast, the current model uses an innovative feature-extraction and classification strategy to overcome the limitations of the previous works. With only 4.2 million parameters and an inference time of 1.42 s on the IoT-Malware dataset and 2.08 s on the IoT-23 dataset, the model achieves an exceptional result. The integration of the IGWO assists the proposed model in identifying and prioritizing the discriminative features to mitigate the adverse effects of noise and redundancy. Additionally, in the existing approaches, computational efficiency is frequently overlooked in model deployment, rendering them impractical for the intended deployment scenarios.

The inclusion of SD and 95% CI in the evaluation metrics reinforces the stability of the proposed model’s performance. In contrast to the traditional CNNs-ViTs-based malware detection methods, the proposed hybrid and explainable MD framework integrates local spatial texture extraction using MobileNet V2 and ResNeXt-Linformer for capturing global contextual dependencies, yielding a trade-off between efficiency and discriminative capability. Using Grad-CAM, the proposed MD framework allows security analysts to comprehend the logic behind each prediction. The model performance enhancement through IGWO and quantization enables the framework to achieve better classification accuracy with limited computational costs, addressing the deployment barriers confronted by the existing MD frameworks.

The findings highlight the study’s alignment with its scope and the critical challenges of IoT security. Modern IoT infrastructures require scalable and autonomous threat-detection capabilities, which are independent of continuous network connectivity. The proposed model addresses this demand by achieving a trade-off between computational efficiency, interpretability, and adaptability. Its IGWO-driven hyperparameter optimisation can help the proposed model in maintaining its reliability while operating within the latency and size limits of an IIoT gateway. Therefore, this study represents a tangible step towards self-defending architectures for the Internet of Things that can detect threats locally before they spread to larger networks.

From an operational perspective, the study’s outcomes are relevant to edge and IIoT ecosystems. The lightweight architecture can be embedded in microcontrollers, gateways, or SDN controllers, thereby increasing its applicability across academic benchmarks to production systems. When combined with edge-computing infrastructure, the model acts as a distributed security sensor, continuously analyzing binary updates or traffic logs at each node. This decentralized deployment significantly lowers response time to attacks and minimizes the bandwidth needed for centralized threat analysis. Moreover, as the model is quantized, it can leverage the standard industrial hardware accelerators, guaranteeing scalability in real-world applications on smart-city infrastructures.

The findings are significant to data privacy and sustainability. By processing data at the device level, rather than sending it to external servers, the model reduces the risk of data leakage and adheres to data privacy principles that are becoming mandatory in IoT-based industrial and healthcare fields. Simultaneously, local inference minimizes network congestion and energy usage, promoting greener and sustainable IoT infrastructures. The achieved trade-off between a high accuracy level (~99%), a low memory footprint (~10 MB), and interpretability renders the model a perfect building block in next-generation secure-by-design IoT applications.

The proposed MD framework is based on the transformation of the malware binaries to RGB images. Substantial computational resources are required to convert Pcap and ELF files into an appropriate image representation. The image generation procedure used here produces images of malware with high quality that are suitable for the framework. However, real-time implementation may require a long image transformation technique that can accommodate diverse IoT device file formats. The framework achieves a commendable performance on the external dataset. However, it would benefit from an integration of additional fully connected and dropout layers to handle larger datasets. Future work should focus on enhancing the model’s classification performance with limited computational costs.

This research introduces a lightweight, explainable, and hybrid malware detection framework for IoT environments. By incorporating an IGWO-optimized MobileNetV2 model with a ResNeXt-Linformer attention mechanism, the proposed model achieves exceptional detection performance on the IoT malware and IoT-23 datasets. The efficient architecture, low inference time, and reduced parameter footprint highlight the suitability of the framework for real-time deployment on IoT gateways, smart edge devices, and industrial controllers where latency and memory availability are critical operational parameters. Moreover, the use of Grad-CAM visualizations improves interpretability, enabling security practitioners to validate the model’s decisions and leading to transparent malware analysis. Despite these promising results, the study acknowledges certain limitations. The proposed model’s evaluation is based on two well-known datasets. However, these datasets may not fully reflect comprehensive IoT malware, particularly extremely obfuscated or protocol-specific malware. Additionally, while the model is significantly lighter than many transformer-based approaches, further reductions may be required to deploy it in environments with minimal resources. The robustness assessment focuses on perturbations in the images and cannot account for advanced adversarial evasion techniques used by advanced IoT malware. Finally, as the framework is applied to static binary images and network traffic images, further multimodal integration may produce richer behavioral insights. Future work can overcome these limitations. Evaluating the proposed model using diverse malware repositories can increase its generalizability to unseen variants. Incorporating model compression techniques such as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation could enhance deployability on low-power IoT devices. Robustness can be improved by incorporating adversarial learning schemes to address obfuscation, packing, and protocol manipulation. Moreover, combining complementary data sources such as execution logs, system-call graphs, and temporal flow patterns can yield a holistic, resilient multimodal detection pipeline. Advancing in these directions will ensure that the proposed framework can be evolved into a scalable, production-ready solution to secure future IoT ecosystems.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank King Faisal University’s Deanship of Scientific Research for its financial support [Grant No. KFU253774]. The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU253774].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait and Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Methodology, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait and Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Software, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait and Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Validation, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait and Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Formal analysis, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait and Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Investigation, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait; Resources, Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Writing—original draft, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait; Writing—review & editing, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait and Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Visualization, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait; Project administration, Yazeed Alkhurayyif; Funding acquisition, Abdul Rahaman Wahab Sait. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: IoT Malware Dataset, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/anaselmasry/iot-malware (accessed on 01 December 2025). IoT-23 Dataset, https://mcfp.felk.cvut.cz/publicDatasets/IoT-23-Dataset/iot_23_datasets_full.tar.gz (accessed on 01 December 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Anand A, Rani S, Anand D, Aljahdali HM, Kerr D. An efficient CNN-based deep learning model to detect malware attacks (CNN-DMA) in 5G-IoT healthcare applications. Sensors. 2021;21(19):6346. doi:10.3390/s21196346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Rabbani M, Wang YL, Khoshkangini R, Jelodar H, Zhao R, Hu P. A hybrid machine learning approach for malicious behaviour detection and recognition in cloud computing. J Netw Comput Appl. 2020;151(4):102507. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2019.102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu K, Xu S, Xu G, Zhang M, Sun D, Liu H. A review of Android malware detection approaches based on machine learning. IEEE Access. 2020;8:124579–607. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3006143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Awan MJ, Masood OA, Abed Mohammed M, Yasin A, Zain AM, Damaševičius R, et al. Image-based malware classification using VGG19 network and spatial convolutional attention. Electronics. 2021;10(19):2444. doi:10.3390/electronics10192444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Vignau B, Khoury R, Hallé S, Hamou-Lhadj A. The evolution of IoT malwares, from 2008 to 2019: survey, taxonomy, process simulator and perspectives. J Syst Archit. 2021;116(5):102143. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2021.102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Karanja EM, Masupe S, Jeffrey MG. Analysis of Internet of Things malware using image texture features and machine learning techniques. Internet Things. 2020;9(6):100153. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2019.100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Al Razib M, Javeed D, Khan MT, Alkanhel R, Ali Muthanna MS. Cyber threats detection in smart environments using SDN-enabled DNN-LSTM hybrid framework. IEEE Access. 2022;10:53015–26. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3172304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Vasan D, Alazab M, Wassan S, Naeem H, Safaei B, Zheng Q. IMCFN: image-based malware classification using fine-tuned convolutional neural network architecture. Comput Netw. 2020;171(1):107138. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kumar S, Janet B, Neelakantan S. Identification of malware families using stacking of textural features and machine learning. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;208(11):118073. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ben Atitallah S, Driss M, Almomani I. A novel detection and multi-classification approach for IoT-malware using random forest voting of fine-tuning convolutional neural networks. Sensors. 2022;22(11):4302. doi:10.3390/s22114302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Panda P, C.U. OK, Marappan S, Ma S, S. M, Veesani Nandi D. Transfer learning for image-based malware detection for IoT. Sensors. 2023;23(6):3253. doi:10.3390/s23063253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Shaukat K, Luo S, Varadharajan V. A novel deep learning-based approach for malware detection. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;122(4):106030. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rustam F, Ashraf I, Jurcut AD, Bashir AK, Zikria YB. Malware detection using image representation of malware data and transfer learning. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2023;172(3):32–50. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2022.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Al-Ghaili A, Kasim H, Hassan Z, Al-Hada N, Othman M, Kasmani R, et al. A review: image processing techniques’ roles towards energy-efficient and secure IoT. Appl Sci. 2098 2023;13(4):2098. doi:10.3390/app13042098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Saridou B, Moulas I, Shiaeles S, Papadopoulos B. Image-based malware detection using α-cuts and binary visualisation. Appl Sci. 2023;13(7):4624. doi:10.3390/app13074624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Asam M, Hussain SJ, Mohatram M, Khan SH, Jamal T, Zafar A, et al. Detection of exceptional malware variants using deep boosted feature spaces and machine learning. Appl Sci. 2021;11(21):10464. doi:10.3390/app112110464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Falana OJ, Sodiya AS, Onashoga SA, Badmus BS. Mal-Detect: an intelligent visualization approach for malware detection. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(5):1968–83. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2022.02.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Emil Selvan GSR, Azees M, Rayala Vinodkumar C, Parthasarathy G. Hybrid optimization enabled deep learning technique for multi-level intrusion detection. Adv Eng Softw. 2022;173(2):103197. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2022.103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chaganti R, Ravi V, Pham TD. Deep learning based cross architecture Internet of Things malware detection and classification. Comput Secur. 2022;120(5):102779. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ambili KN, Jose J. A secure software defined networking based framework for IoT networks. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2020;1129:1–19. [Google Scholar]

21. Javeed D, Gao T, Khan MT, Ahmad I. A hybrid deep learning-driven SDN enabled mechanism for secure communication in Internet of Things (IoT). Sensors. 2021;21(14):4884. doi:10.3390/s21144884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Alam I, Samiullah M, Asaduzzaman SM, Kabir U, Aahad AM, Woo SS. MIRACLE: malware image recognition and classification by layered extraction. Data Min Knowl Discov. 2024;39(1):10. doi:10.1007/s10618-024-01078-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Berrios S, Leiva D, Olivares B, Allende-Cid H, Hermosilla P. Systematic review: malware detection and classification in cybersecurity. Appl Sci. 2025;15(14):7747. doi:10.3390/app15147747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kumar S, Janet B. DTMIC: deep transfer learning for malware image classification. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;64(12):103063. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bensaoud A, Kalita J. Deep multi-task learning for malware image classification. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;64(1):103057. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alshoulie M, Mehmood A. Deep learning approaches for malware detection: a comprehensive review of techniques, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access. 2025;13(3):118652–77. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3582875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rahman A, Chakraborty C, Anwar A, Karim MR, Islam MJ, Kundu D, et al. SDN-IoT empowered intelligent framework for industry 4.0 applications during COVID-19 pandemic. Cluster Comput. 2022;25(4):2351–68. doi:10.1007/s10586-021-03367-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Smmarwar SK, Gupta GP, Kumar S. Deep malware detection framework for IoT-based smart agriculture. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;104(1):108410. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jian Y, Kuang H, Ren C, Ma Z, Wang H. A novel framework for image-based malware detection with a deep neural network. Comput Secur. 2021;109(3):102400. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sharma O, Sharma A, Kalia A. Windows and IoT malware visualization and classification with deep CNN and Xception CNN using Markov images. J Intell Inf Syst. 2023;60(2):349–75. doi:10.1007/s10844-022-00734-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu X, Lin Y, Li H, Zhang J. A novel method for malware detection on ML-based visualization technique. Comput Secur. 2020;89(1):101682. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2019.101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kesharwani S, Kamaldeep, Malik M. From behavior to pixels: a vision transformer approach for Android ransomware detection. In: Proceedings of Data Analytics and Management; Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2025. p. 132–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-032-03072-6_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fu J, Xue J, Wang Y, Liu Z, Shan C. Malware visualization for fine-grained classification. IEEE Access. 2018;6:14510–23. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2805301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Naeem H, Ullah F, Naeem MR, Khalid S, Vasan D, Jabbar S, et al. Malware detection in industrial Internet of Things based on hybrid image visualization and deep learning model. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020;105(1):102154. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2020.102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ullah I, Mahmoud QH. Design and development of a deep learning-based model for anomaly detection in IoT networks. IEEE Access. 2021;9:103906–26. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3094024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Conti M, Khandhar S, Vinod P. A few-shot malware classification approach for unknown family recognition using malware feature visualization. Comput Secur. 2022;122(2):102887. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zou B, Cao C, Tao F, Wang L. IMCLNet: a lightweight deep neural network for Image-based Malware Classification. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;70(10):103313. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2022.103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Asam M, Khan SH, Akbar A, Bibi S, Jamal T, Khan A, et al. IoT malware detection architecture using a novel channel boosted and squeezed CNN. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):15498. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-18936-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Abdalgawad N, Sajun A, Kaddoura Y, Zualkernan IA, Aloul F. Generative deep learning to detect cyberattacks for the IoT-23 dataset. IEEE Access. 2021;10:6430–41. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3140015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Alsubai S, Dutta AK, Alnajim AM, Sait ARW, Ayub R, AlShehri AM, et al. Artificial intelligence-driven malware detection framework for Internet of Things environment. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2023;9(19):e1366. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Jo J, Cho J, Moon J. A malware detection and extraction method for the related information using the ViT attention mechanism on Android operating system. Appl Sci. 2023;13(11):6839. doi:10.3390/app13116839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ashawa M, Owoh N, Hosseinzadeh S, Osamor J. Enhanced image-based malware classification using transformer-based convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Electronics. 2024;13(20):4081. doi:10.3390/electronics13204081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Chimezie Obidiagha C, Rahouti M, Hayajneh T. DeepImageDroid: a hybrid framework leveraging visual transformers and convolutional neural networks for robust Android malware detection. IEEE Access. 2024;12:156285–306. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3485593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wasif MS, Miah MP, Hossain MS, Alenazi MJF, Atiquzzaman M. CNN-ViT synergy: an efficient Android malware detection approach through deep learning. Comput Electr Eng. 2025;123(6):110039. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.110039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ficco M. Malware analysis by combining multiple detectors and observation windows. IEEE Trans Comput. 2021;71(6):1276–90. doi:10.1109/TC.2021.3082002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bakır H, Bakır R, Alkhaldi T, Darem AA, Alhashmi AA, Alqhatani A. ViTGuard: a synergistic approach to malware detection using vision transformers and genetic algorithms optimization. Pattern Anal Appl. 2025;28(4):155. doi:10.1007/s10044-025-01516-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Alshomrani M, Albeshri A, Alsulami AA, Alturki B. An explainable hybrid CNN-transformer architecture for visual malware classification. Sensors. 2025;25(15):4581. doi:10.3390/s25154581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Cui B, Wang H, Qi Y, Chen H, Yuan Q, Liu D, et al. HERL-ViT: a hybrid enhanced vision transformer based on regional-local attention for malware detection. Comput Mater Continua. 2025;85(3):5531–53. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.070101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Jeong IW, Lee HJ, Kim GN, Choi SH. MalFormer: a novel vision transformer model for robust malware analysis. IEEE Access. 2025;13(86):122671–83. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3588232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. IoT Malware [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/anaselmasry/iot-malware. [Google Scholar]

51. Garcia S, Parmisano A, Erquiaga MJ. IoT-23 [Software]. [cited 2025 Dec 1]. Available from: https://mcfp.felk.cvut.cz/publicDatasets/IoT-23-Dataset/iot_23_datasets_full.tar.gz. [Google Scholar]

52. Li K, Li S, Huang Z, Zhang M, Xu Z. Grey Wolf Optimization algorithm based on Cauchy-Gaussian mutation and improved search strategy. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):18961. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-23713-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Gao Y, Zhang H, Duan Y, Zhang H. A novel hybrid PSO based on levy flight and wavelet mutation for global optimization. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0279572. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0279572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Xie S, Girshick R, Dollár P, Tu Z, He K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5987–95. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 9992–10002. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Acharya V, Ravi V, Mohammad N. EfficientNet-based convolutional neural networks for malware classification. In: 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2021 Jul 6–8; Kharagpur, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/icccnt51525.2021.9579750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Liu Z, Mao H, Wu CY, Feichtenhofer C, Darrell T, Xie S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 11966–76. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Graham B, El-Nouby A, Touvron H, Stock P, Joulin A, Jegou H, et al. LeViT: a vision transformer in ConvNet’s clothing for faster inference. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 12239–49. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.01204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools