Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Advanced Video Processing and Data Transmission Technology for Unmanned Ground Vehicles in the Internet of Battlefield Things (loBT)

1 School of Cyber Science and Technology, Shandong University, Qingdao, 266237, China

2 Wuhan Zhongyuan Communication Co., Ltd., China Electronics Corporation, Wuhan, 430205, China

3 System Engineering Institute, Academy of Military Sciences, Beijing, 100141, China

* Corresponding Authors: Mao Ye. Email: ; Guoyan Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Smart Roads, Smarter Cars, Safety and Security: Evolution of Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 38 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072692

Received 01 September 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the continuous advancement of unmanned technology in various application domains, the development and deployment of blind-spot-free panoramic video systems have gained increasing importance. Such systems are particularly critical in battlefield environments, where advanced panoramic video processing and wireless communication technologies are essential to enable remote control and autonomous operation of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs). However, conventional video surveillance systems suffer from several limitations, including limited field of view, high processing latency, low reliability, excessive resource consumption, and significant transmission delays. These shortcomings impede the widespread adoption of UGVs in battlefield settings. To overcome these challenges, this paper proposes a novel multi-channel video capture and stitching system designed for real-time video processing. The system integrates the Speeded-Up Robust Features (SURF) algorithm and the Fast Library for Approximate Nearest Neighbors (FLANN) algorithm to execute essential operations such as feature detection, descriptor computation, image matching, homography estimation, and seamless image fusion. The fused panoramic video is then encoded and assembled to produce a seamless output devoid of stitching artifacts and shadows. Furthermore, H.264 video compression is employed to reduce the data size of the video stream without sacrificing visual quality. Using the Real-Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP), the compressed stream is transmitted efficiently, supporting real-time remote monitoring and control of UGVs in dynamic battlefield environments. Experimental results indicate that the proposed system achieves high stability, flexibility, and low latency. With a wireless link latency of 30 ms, the end-to-end video transmission latency remains around 140 ms, enabling smooth video communication. The system can tolerate packet loss rates (PLR) of up to 20% while maintaining usable video quality (with latency around 200 ms). These properties make it well-suited for mobile communication scenarios demanding high real-time video performance.Keywords

With the rapid advancements in communication and multimedia technologies, video surveillance systems have become integral across various industries and sectors [1,2]. For instance, video surveillance systems deployed on unmanned vehicles are tasked with analyzing and processing visual data captured during operation [3]. However, traditional video surveillance systems for UGVs typically rely on single-channel video acquisition methods. These approaches are inadequate for capturing, processing, and analyzing panoramic images surrounding the vehicle. Additionally, they suffer from significant video transmission and processing latency, which severely impact real-time user experience [4]. Consequently, the development of techniques to obtain panoramic video images while minimizing processing and transmission latency has emerged as a critical area of research in recent years.

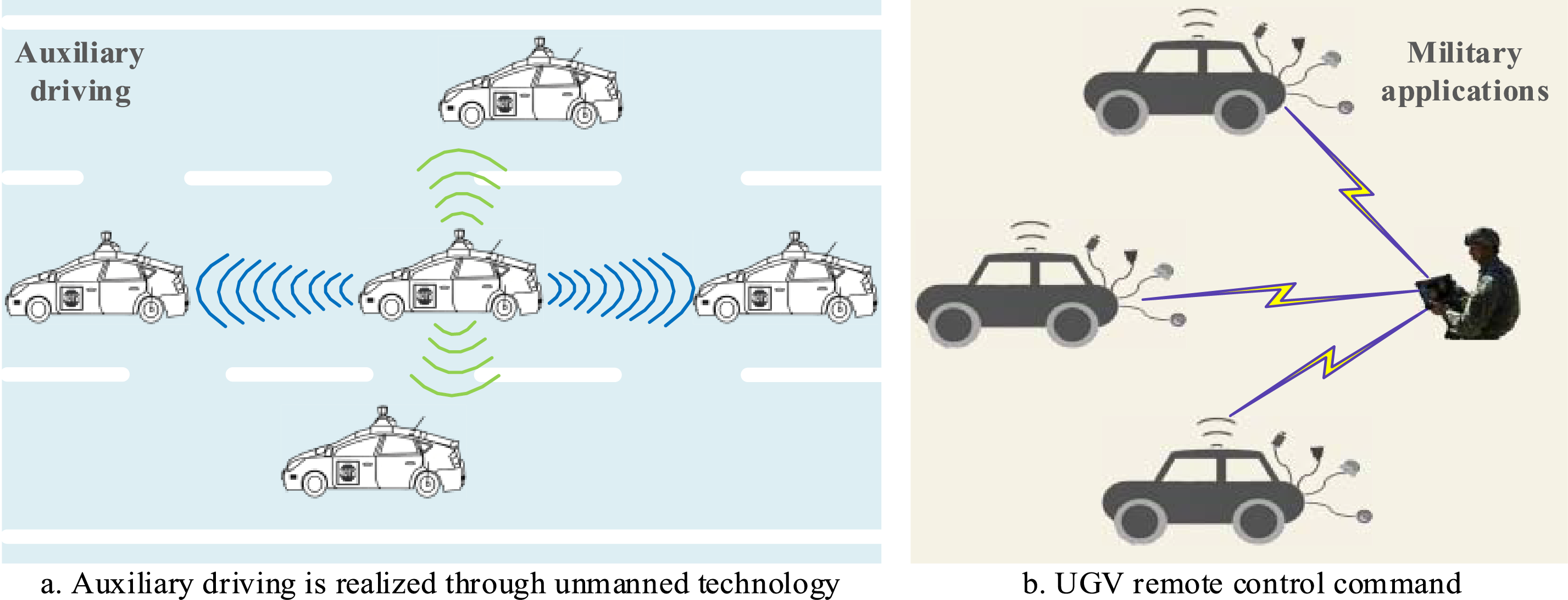

As shown in Fig. 1, the use of unmanned vehicles for video communication has been widely adopted today [5]. Unlike video processing and communication systems in the civilian domain [6], video surveillance systems in tactical scenarios must capture more comprehensive battlefield information while minimizing latency.

Figure 1: Typical communication scenarios for unmanned vehicles.

For instance, to minimize casualties during military operations, frontline troops often rely on unmanned vehicles for reconnaissance and operations over the frontline terrain. However, a single-direction video perspective fails to provide comprehensive, all-directional video coverage, making it difficult to accurately identify hostile targets, particularly when operating deep within enemy territory. Therefore, all-directional information is essential for accurate decision-making. Typically, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are used to monitor terrain and enemy formations. However, their wide field of view makes them easily detectable and identifiable [7], limiting their applicability in certain scenarios. For instance, in environments such as mountainous regions or urban warfare, the onboard video surveillance systems of UGVs offer significant advantages. Similarly, panoramic video technology plays a vital role in automotive driver-assistance systems. With the rapid growth in vehicle numbers and lagging development of urban traffic infrastructure, traffic conditions have deteriorated, contributing to a rising number of accidents annually. Many of these accidents result from blind spots and drivers’ inaccurate perception of inter-vehicle distances. A reliable real-time video transmission system can significantly enhance vehicular safety by mitigating these issues.

1.2 Motivation and Contributions

This paper investigates the performance of panoramic video stitching and compression technologies in the context of video transmission and communication for UGVs. When an unmanned vehicle operates via a wireless network, its panoramic video mosaicking system employs multiple fixed cameras to capture the same scene from various perspectives [8–11]. A critical research challenge lies not only in generating images with a broader field of view than individual images by leveraging inter-image correlations but also in ensuring low-latency video transmission over wireless communication networks. Moreover, in practical applications, the highly complex and variable communication environment often leads to high packet loss rates over wireless links, posing a persistent challenge. Ensuring uninterrupted video communication in highly dynamic battlefield environments with severe packet loss is therefore a critically important problem to address.

To address the aforementioned challenges, our paper makes several key contributions to this field, detailed as follows.

(1) Real-Time Video Stitching System: We developed a real-time video stitching system that integrates multi-channel video streams using feature extraction, matching, and fusion techniques. The system applies a homography matrix to perform a linear transformation on 3D homogeneous vectors, enabling efficient processing and filtering of spliced video data. This approach produces a seamless panoramic stitching video.

(2) Block-Based Video Encoding Method: We proposed a block-based video encoding method for video data detection, transformation, and quantification. By leveraging hardware-based encoding and implementing coding control via the Lagrangian algorithm, the system achieves high efficiency without imposing additional CPU load. Moreover, the method ensures timely recovery from data packet loss or dislocation within the sequence set, thereby improving system robustness.

(3) RTSP-Based Push Flow Server: We designed an RTSP-based streaming server to manage pre-processed video streams and optimize network transmission. This server monitors video readiness and efficiently handles streaming operations, significantly improving video transmission performance.

The structure of the paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we review related work on resource allocation. Section 3.1 describes the system architecture and its components. In Section 3.3, we explain the principles and methods of real-time video stitching. Sections 3.4 and 3.5 introduce video encoding techniques and efficient video streaming strategies. In Section 4, we present experimental results to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future directions.

With the rapid advancement of Internet technology, panoramic video coding and transmission technologies are being increasingly applied across various industries. This growth has driven researchers to explore efficient methods for video processing and transmission, which has led to the development of numerous innovative approaches.

Zhang et al. proposed an acceleration method for calculating optical flow in panoramic video stitching. Their method allows for computations to be performed independently and in parallel, significantly improving processing efficiency [12]. Li et al. introduced a novel flexible super-resolution-based video coding and uploading framework that enhances live video streaming quality under conditions of limited uplink network bandwidth [13]. To address the challenge of insufficient support for 360-degree panoramic videos, Zhao et al. developed a highly versatile 360-degree panoramic SLAM method based on the ORB-SLAM3 system framework [14]. Qiu et al. proposed a multi-azimuth reconstruction algorithm to address the distortion issues in panoramic images, by leveraging the imaging principles of dome cameras [15]. Woo Han et al. introduced a novel deep learning-based network for 360-degree panoramic image inpainting. This approach leverages the conversion of panoramic images from an equirectangular format to a cube map format, enabling inpainting with the effectiveness of single-image inpainting methods [16]. Additionally, Li et al. proposed a transmission scheme based on multi-view switching within the human eye’s field of view and demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing network bandwidth usage through a live platform implementation [17].

In the field of video encoding, Chao et al. proposed a novel rate control framework for H.264/Advanced Video Coding (H.264/AVC)-based video coding, which enhances the preservation of gradient-based features such as Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) or Speeded-Up Robust Features (SURF) [18]. Manel introduced a Distributed Video Coding (DVC) scheme that incorporates block classification at the decoder, combined with a new residual computing method based on modular arithmetic and simple entropy coding [19]. Wang et al. presented a joint optimization approach for transform and quantization in video coding [20]. Duong et al. proposed learned transforms and entropy coding, which can serve as (non-) linear drop-in replacements or enhancements for linear transforms in existing codecs. These learned transforms can be multi-rate, enabling a single model to function across the entire rate-distortion curve [21]. Ding et al. developed a high-efficiency Deep Feature Coding (DFC) framework that significantly reduces the bitrate of deep features in videos while maintaining retrieval accuracy [22].

In the area of video transmission, Chiu et al. proposed a multidimensional streaming media transmission system consisting of a control center, a client platform, and a multidimensional media producer. The system provides detailed specifications for the login, link, interaction, and logout processes [23]. Wang et al. introduced a reference-frame-cache-based surveillance video transmission system (RSVTS), which enables real-time delivery of wide-angle, high-definition surveillance video over the Internet using multiple rotatable cameras [24]. Bakirci introduced a novel system to tackle the core issues plaguing swarm UAV systems, namely constrained communication range, deficient processing capabilities for real-time tasks, network delays and failures from congestion, and limited operational endurance due to energy mismanagement. The proposed solution employs a suite of salient features, including robust communication, synergistic hardware integration, task allocation, optimized network topology, and efficient routing protocols [25]. Aloman et al. evaluated the performance of three video streaming protocols: MPEG-DASH, RTSP, and RTMP [26], results indicate that RTSP is more efficient than MPEG-DASH in initiating video playback, but at the expense of decreased QoE due to packet loss. Conversely, the longer pre-loading time intervals required by MPEG-DASH and RTMP help mitigate the impact of packet loss during transmission, which is reflected in a lower number of re-buffering events for these two protocols.

Building upon a comprehensive analysis of related work, we note that most existing studies are conducted in environments with sufficient wired bandwidth or stable wireless links. These works often do not address the challenges of video transmission in highly complex and dynamic scenarios, such as those involving network interruptions or high packet loss rates. To tackle these challenges, we approach the problem from a global perspective. First, we propose a real-time video stitching system and analyze the stitching process and image fusion algorithm. Next, we design an efficient video encoding scheme. Finally, we develop a video transmission system based on RTSP. Additionally, we investigate video transmission strategies for scenarios that poor network connectivity results in significant packet loss. This research is particularly relevant for enhancing the surveillance and data transmission capabilities of UGVs.

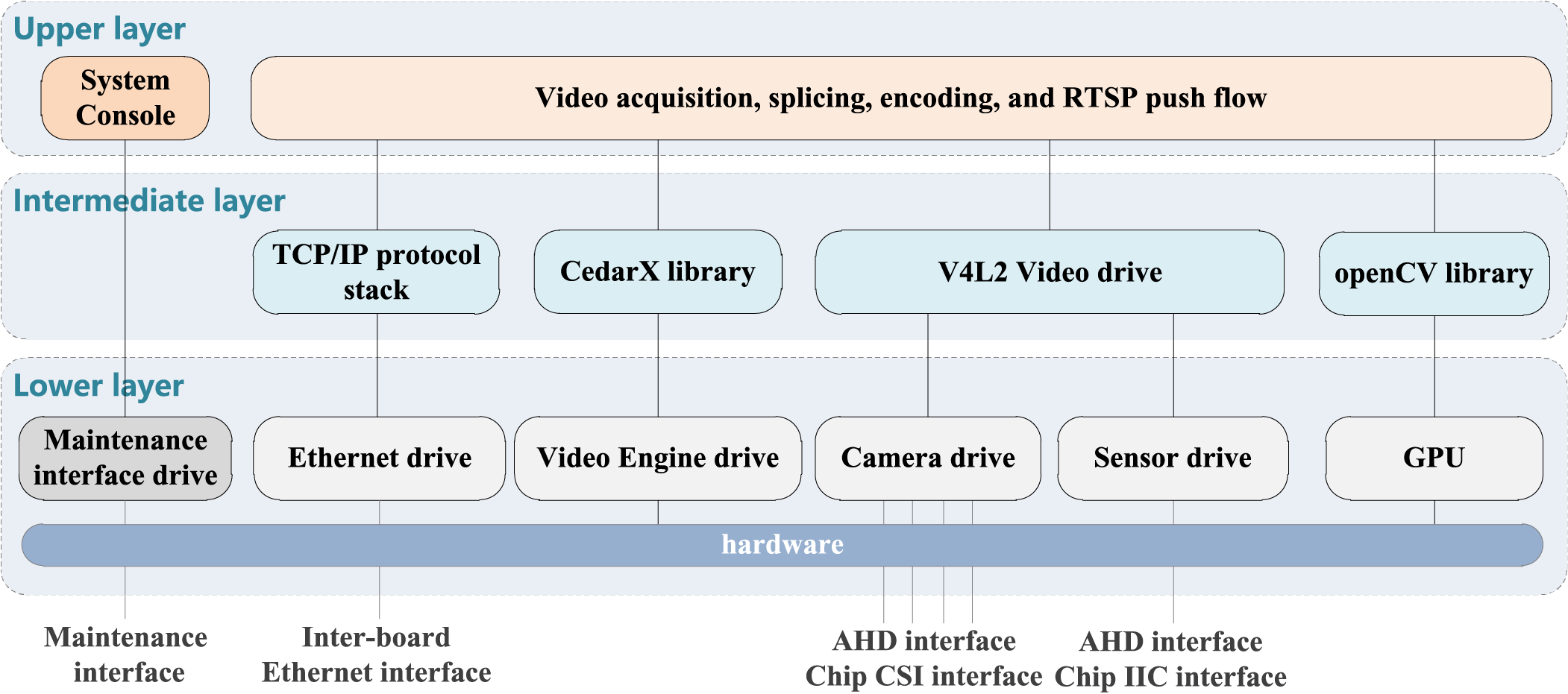

3.1 The Architecture of the System Composition

The basic operational workflow of the system involves capturing video through multiple AHD HD cameras, followed by stitching and encoding the footage, and finally pushing the stream to clients via the RTSP protocol. The video processing software is mainly composed of upper-layer software, middle-layer software, and lower-layer software. Video acquisition is performed using the V4L2 (Video for Linux 2) driver framework; the video stitching module uses the OpenCV library to stitch multiple video streams, video encoding is performed using the CedarX library; and the video streaming module is responsible for pushing the stream, leveraging the RTSP protocol. The software architecture of this hierarchical system is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Video processing software architecture.

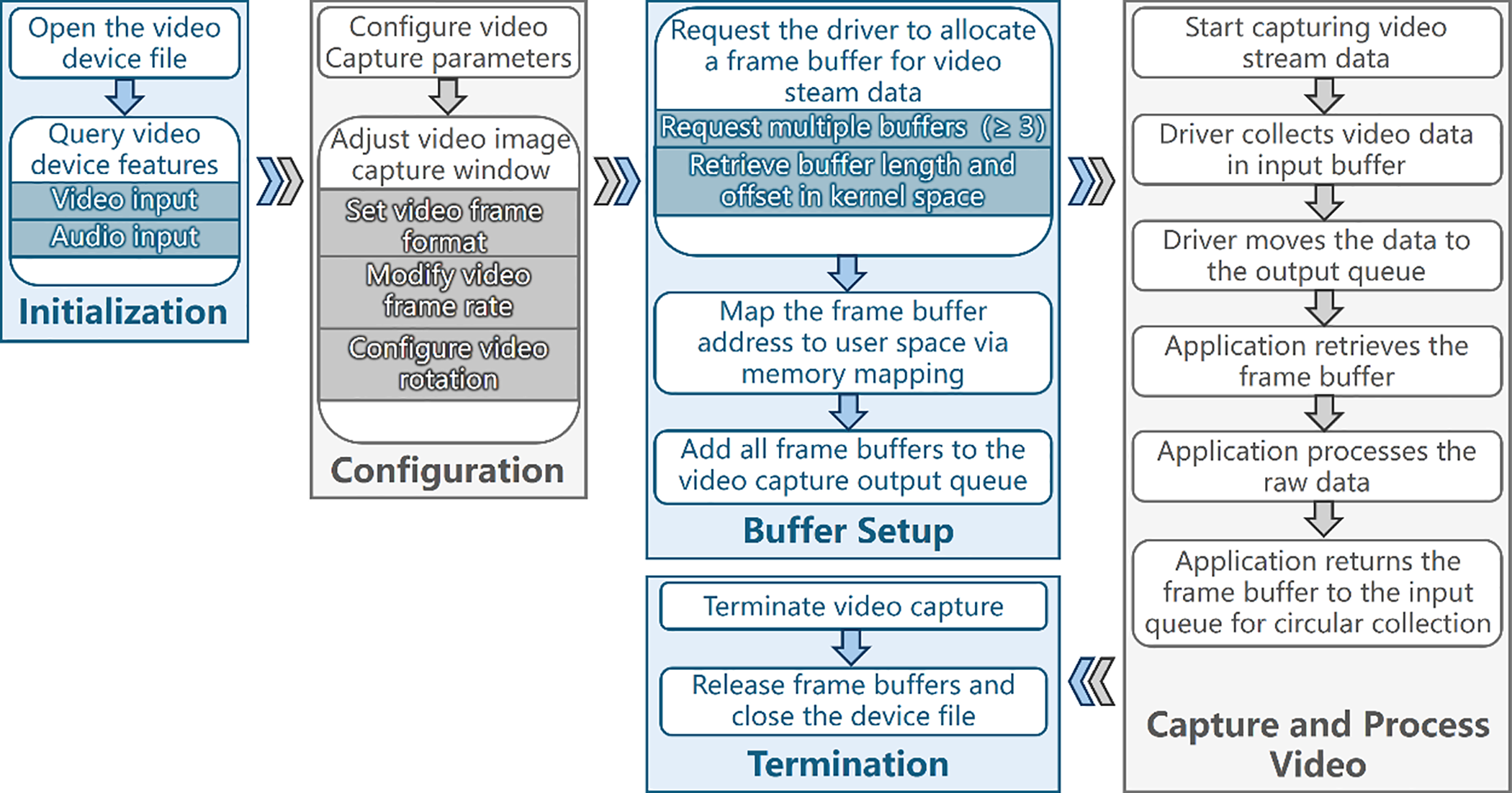

The video capture module is based on the Video for Linux 2 (V4L2) driver framework. V4L2 is a standard framework in the Linux kernel for video capture, which comprises a hardware-independent V4L2 driver core and hardware-specific components such as camera drivers, sensors, and other related elements. The V4L2 driver core handles the registration and management of specific camera drivers, providing a unified device file system interface for Linux user-mode applications to access camera data and control camera parameters. The camera driver is a platform-specific component responsible for video frame processing, while the sensor driver is a camera-specific module dedicated to controlling camera parameters. The video acquisition process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Video capture process.

As shown in Fig. 3, the video capture process consists of several key steps. First, the video device file is opened, and its capabilities (e.g., video and audio inputs) are queried. Next, video capture parameters are configured, including the capture window size, video frame format (such as pixel format, width, and height), frame rate, and rotation. Subsequently, the driver is instructed to allocate frame buffers (typically at least three) for the video stream; the buffer length and offset are retrieved in the kernel space. These frame buffers are then mapped to the user space via memory mapping, enabling direct data access without copying. All allocated buffers are enqueued into the video capture output queue to store the incoming data. Once initiated, the video capture process proceeds as follows: the driver transfers video data to the first available buffer in the input queue and then moves that buffer to the output queue. The application dequeues a buffer containing data, processes the raw video, and returns the buffer to the input queue for reuse in a circular manner. Finally, video capture is terminated, all buffers are released, and the video device is closed.

3.3 Video Real-time Stitching Module

3.3.1 Stitching Process Analysis

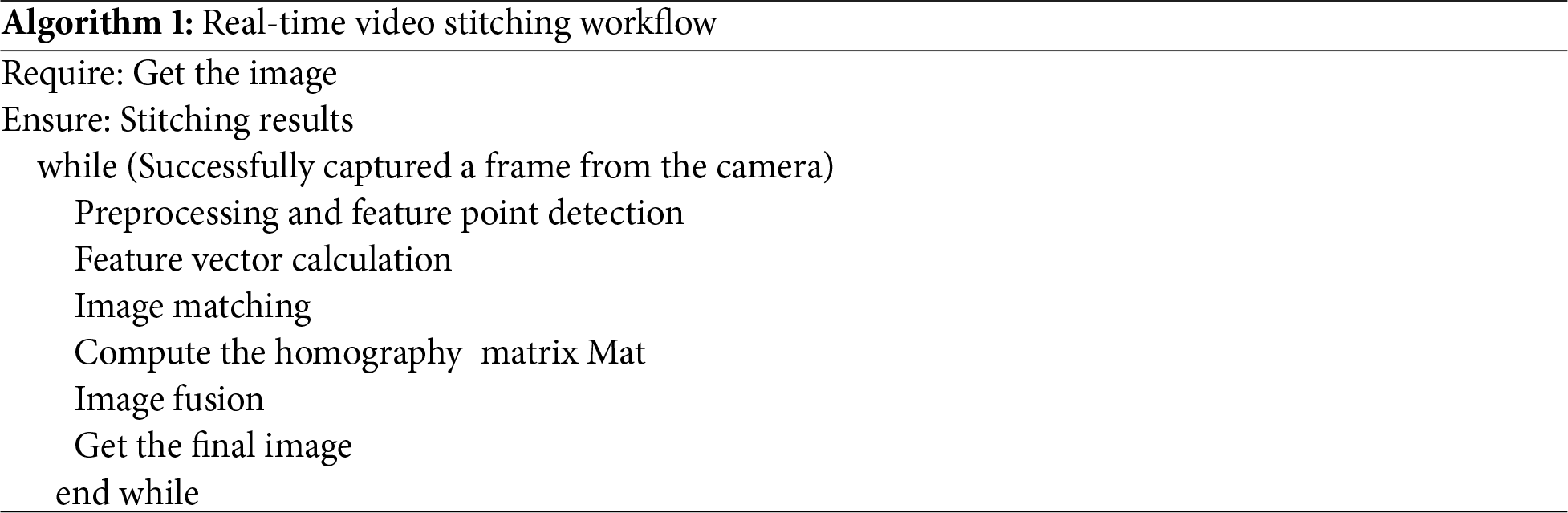

Video stitching is an extension of image stitching techniques, with image stitching serving as its fundamental prerequisite [27]. Consequently, the quality of image stitching directly determines the effectiveness of the resultant video stitching. The core principle involves first extracting individual frames from the source video stream. These frames subsequently undergo a series of image stitching operations-including feature extraction, matching, and fusion. Finally, the processed frames are encoded and compressed back into a seamless video format. This complete video stitching workflow is detailed in Algorithm 1.

In this approach, subsequent video frames requiring real-time stitching can be processed with minimal latency, as the time-consuming steps of feature extraction and registration are significantly reduced. This method relies solely on the precomputed perspective transformation matrix for image transformation, stitching, and fusion. Furthermore, the experimental setup utilizes standard cameras for synchronized video capture, which enhances computational efficiency and improves the practical applicability of the proposed system.

3.3.2 Image Homography Matrix Calculation

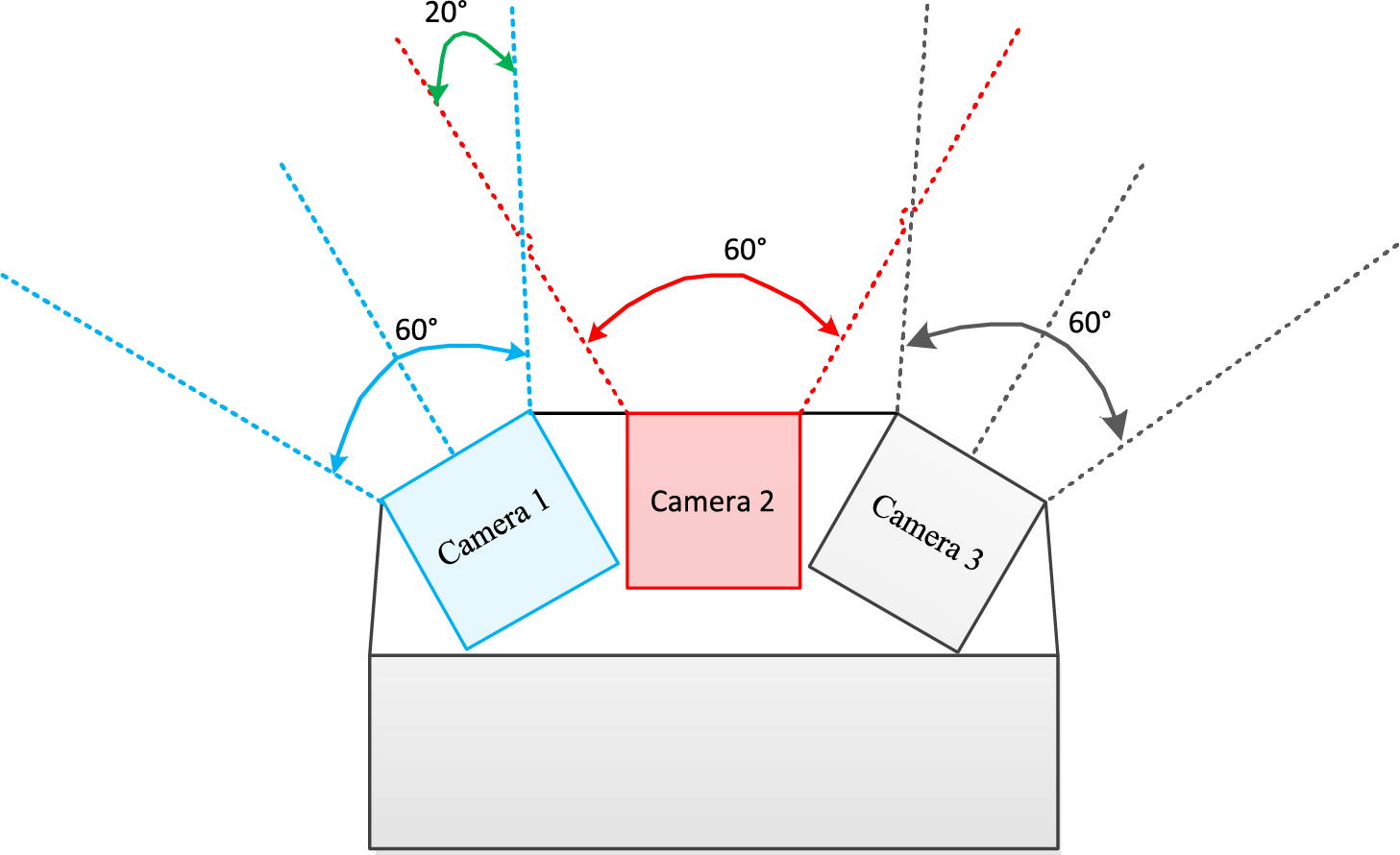

The camera is equipped with an infrared high-definition night-vision module, featuring a 6 mm lens that provides a 60-degree field of view. It supports multiple video encoding formats, including H.264, MJPEG, and YUY2 [28–30]. This configuration ensures excellent performance in both indoor and outdoor environments, with accurate color reproduction. The physical structure of the three-camera array is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Camera assembly structure.

As shown in Fig. 4, a system of three cameras is used to capture the images required for stitching. The principle of stitching two images involves first identifying the overlapping region between them and then extracting similar feature points from this area [31]. A series of subsequent processing steps are then applied to complete the stitching. Empirical results indicate that an overlap of 30% or more between images enables more reliable identification of feature points. For cameras with a 60-degree field of view (FOV), an overlapping angle of approximately 20 degrees between adjacent cameras yields optimal results. In Fig. 4, this overlapping region is represented by the intersection of the red and blue dashed lines.

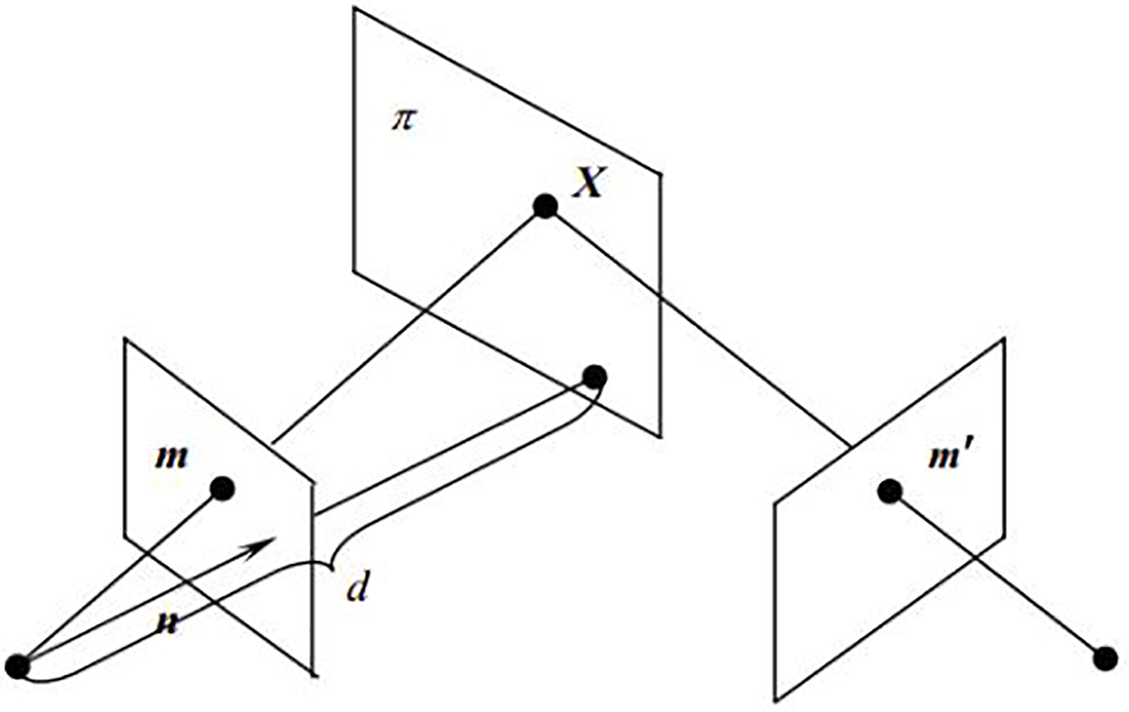

The geometric transformation for projecting a point from one image plane to another can be modeled as a linear transformation of 3D homogeneous coordinates using homography. This transformation is represented by a 3 × 3 non-singular matrix H, known as the homography matrix. As illustrated in Fig. 5, this matrix enables the projection of a point from one projective plane onto another.

Figure 5: Homography matrix transformation.

The linear transformation between two image planes is defined by the following equation.

A point in one image plane, represented in homogeneous coordinates as x1 = (u1, v1, 1)T, is mapped to a corresponding point in the other plane, x2 = (u2, v2, 1)T, by the following equation:

The homography matrix is derived through a process involving image pre-processing and registration, as detailed below.

(1) Image Preprocessing

Image preprocessing constitutes a fundamental and indispensable step in the image stitching pipeline [32]. Ye et al. proposed a systematic image preprocessing framework comprising resizing, denoising, downscaling, binarization, color inversion and morphological operations. This methodology effectively enhances image quality by suppressing noise and emphasizing salient features essential for subsequent interpretation [33,34]. Variations in image acquisition conditions—such as inconsistent illumination and differences in camera performance—often introduce artifacts including noise and low contrast in raw images. Furthermore, disparities in shooting distance and focal length may contribute to additional geometric and photometric irregularities. Preprocessing is therefore critical to improve the accuracy and efficiency of feature extraction and matching. Common preparatory operations include grayscale conversion and spatial filtering.

Feature point descriptors are largely invariant to chromatic information. Therefore, converting color images to grayscale prior to processing reduces computational complexity and expedites subsequent registration and fusion.

Images captured by cameras are inevitably corrupted by noise during acquisition, digitization, and transmission. This degradation often leads to a reduction in image quality, adversely affecting perceptual fidelity and compromising visual performance.

In general, the presence of noise degrades image quality, resulting in blurring and the obscuration of salient features. This degradation impedes subsequent image analysis and reduces overall visual fidelity, making direct analysis challenging. It is therefore essential to suppress noise-induced interference, enhance meaningful signal content, and ensure consistency across image sets under uniform constraints. Commonly used filtering methods include smoothing filters, median filters, and Gaussian filters, each offering distinct advantages and limitations. The selection of an appropriate filter depends primarily on the characteristics of the noise present. For implementation, the OpenCV library is employed for image processing tasks; notably, the cvtColor() function is used for grayscale conversion.

(2) Feature Point Detection and Descriptor Extraction

For feature extraction, we adopt the Speeded-Up Robust Feature (SURF) algorithm [35]. The OpenCV implementation of the Speeded-Up Robust Features (SURF) algorithm comprises five main steps: (a) construction of the Hessian matrix; (b) generation of a scale space using a Gaussian pyramid; (c) initial detection of candidate feature points via non-maximum suppression; (d) precise localization of extreme points; (e) assignment of a dominant orientation to each feature point; and (f) computation of the SURF descriptor. The initial step consists of constructing the Hessian matrix and a scale-space Gaussian pyramid. The Hessian threshold dynamically varies between 300 and 500 based on real-time network conditions, a higher threshold value yields faster detection speeds, and its initial value is set to 500. The upright parameter is set to true, meaning rotation invariance is not calculated. The number of scale space layers (nOctaves) is set to 4. SURF employs the determinant of the Hessian matrix for image approximation, which provides computational efficiency and accelerated feature detection [36]. The Hessian matrix H is formed from the second-order partial derivatives of a function f(z, y). For an image, the Hessian matrix at a given pixel is defined as shown in Eq. (3).

The Hessian matrix is computed for each pixel, and its determinant is provided in Eq. (4).

The determinant value serves as a scalar measure derived from the Hessian matrix H. Points can be classified according to the sign of this determinant. In the SURF algorithm, the image intensity at a pixel, denoted as L(x, y), corresponds to the function value f(x, y). The second-order partial derivatives are approximated using filters based on the second-order Gaussian derivatives. By convolving the image with these derivative kernels, the components of the Hessian matrix–Lxx, Lxy and Lyy–are efficiently computed.

To ensure scale invariance of the detected feature points, the Hessian matrix must be filtered with a Gaussian kernel prior to its construction. Thus, the filtered matrix H is computed as shown in Eq. (6).

The function L(x, t) denotes the multi-scale representation of an image, obtained by convolving the original image I(x) with a Gaussian kernel G(t), where G(t) is defined in Eq. (7).

In this context, t denotes the variance of the Gaussian function, and g(x) represents the Gaussian kernel. Using this formulation, the determinant of the Hessian matrix H can be computed for every image pixel, and this response value serves to identify feature points. To improve computational efficiency, Herbert Bay et al. proposed replacing L(x, t) with a box-filter approximation. A weight value is introduced to balance the error between the exact value and the approximate value. These weights vary across scales, and the determinant of the matrix H can then be expressed as Eq. (8).

The second step involves applying non-maximum suppression to identify candidate feature points. For each pixel, the Hessian response value is compared to those of its 26 neighbors within the three-dimensional scale-space neighborhood. The point is retained as a candidate feature point only if it represents a local extremum (either a maximum or minimum) within this region.

The third step entails the accurate localization of extremal points at sub-pixel precision. This is achieved through three-dimensional linear interpolation across the scale space. Subsequently, points exhibiting response values below a predefined threshold are discarded, retaining only the most salient features.

The fourth step involves assigning a dominant orientation to each feature point. This process begins by computing Haar wavelet responses within a circular region centered at the feature point. Specifically, for a rotating 60-degree sector window, the sums of the horizontal and vertical Haar wavelet responses are accumulated for all points within the sector. The Haar wavelet size is set to 4 s, which is the characteristic scale of the feature point, producing one vector per sector. The sector is rotated in discrete angular intervals, and the direction yielding the highest vector magnitude is selected as the dominant orientation for the feature point.

The fifth step involves constructing the SURF descriptor. A square region centered on the feature point—with side length 20 s, which is the scale of the feature point—is oriented along the dominant direction identified in Step 4. This region is subdivided into 4 × 4 = 16 sub-regions. Within each sub-region, Haar wavelet responses are computed in both the horizontal and vertical directions (aligned with the dominant orientation) for 25 sample pixels. For each sub-region, four values are collected: the sum of the horizontal Haar responses, the sum of their absolute values, the sum of the vertical responses, and the sum of their absolute values. Thus, each feature point is represented by a 64-dimensional descriptor (16 × 4). This constitutes a reduction by half compared to the SIFT descriptor [37,38], leading to improved computational efficiency and significantly accelerated feature matching.

(3) FLANN-Based Feature Matching

The Fast Library for Approximate Nearest Neighbors (FLANN) is extensively employed for efficient approximate nearest neighbor search in high-dimensional spaces [39]. It offers a suite of algorithms optimized for this task and can automatically select the most appropriate algorithm and optimal parameters for a given dataset. In computer vision, identifying nearest neighbors in high-dimensional feature spaces is often computationally expensive. FLANN provides a faster alternative to conventional matching algorithms for high-dimensional feature matching. After extracting feature points and computing their descriptors using the SURF algorithm, the FLANN matcher is applied to establish correspondences. Based on these matching results, the homography matrix representing the geometric transformation between images is computed.

The objective of image fusion is to seamlessly integrate two images into a common coordinate system. After estimating the homography matrix, the source image is warped into the target image’s coordinate system using a perspective transformation, implemented via OpenCV functions. The four corner points of the overlapping region are then computed, and its boundaries are determined. Within this overlapping area, the pixel values are fused by averaging the intensity values from both the warped source image and the target image. Denoting the final stitched image as I, the fusion relationship is given by Eq. (9).

Unlike simple averaging, the intensity values of corresponding pixels in the overlapping region are not computed as a direct average of the warped source image and the target image. Instead, a weighted average is applied to the pixels from both images. Let I denote the final fused image and let I1 and I2 represent the two images to be stitched.

In Eq. (10), w1 denotes the weight assigned to pixels from the left image within the overlapping region of the stitched result, while w2 represents the weight for the corresponding pixels from the object image, satisfying w1 + w2 = 1 with 0 < w1 < 1 and 0 < w2 < 1. To achieve a smooth transition across the overlapping area, appropriate weighting values can be selected to effectively eliminate visible seams in the fused image.

Depending on the desired fusion outcome, appropriate weighting functions w1 and w2 can be selected. In this study, a gradual transition weighting scheme was employed. The two weights are determined based on the width of the overlapping region. Let W denote the total width of the overlap. Then, w1 decreases linearly from 1 to 0 across the region, while w2 increases linearly from 0 to 1, ensuring w1 + w2 = 1 throughout. This approach results in a smooth transition between images I1 and I2 within the overlap, effectively eliminating visible seams and achieving a natural blending effect.

Furthermore, when the pixel value in either I1(x, y) or I2(x, y) is too low, that region may appear black. To mitigate this, the gradual in-out weighting method is applied alongside a threshold check. Specifically, if I1(x, y) < k, the pixel is discarded by setting w1 = 0, effectively excluding it from fusion. The threshold k can be empirically adjusted based on experimental results to achieve optimal blending performance.

To evaluate the similarity performance after image fusion, we employ the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) as the quality assessment metrics.

In Eq. (11), K denotes the original image, I represents the fused image, M is the total number of pixels in image I, and N is the total number of pixels in image K. A smaller MSE value indicates a higher degree of similarity between the images. In Eq. (12), MAX is the maximum possible pixel value of the image. A higher PSNR value indicates less distortion and better quality of the generated image.

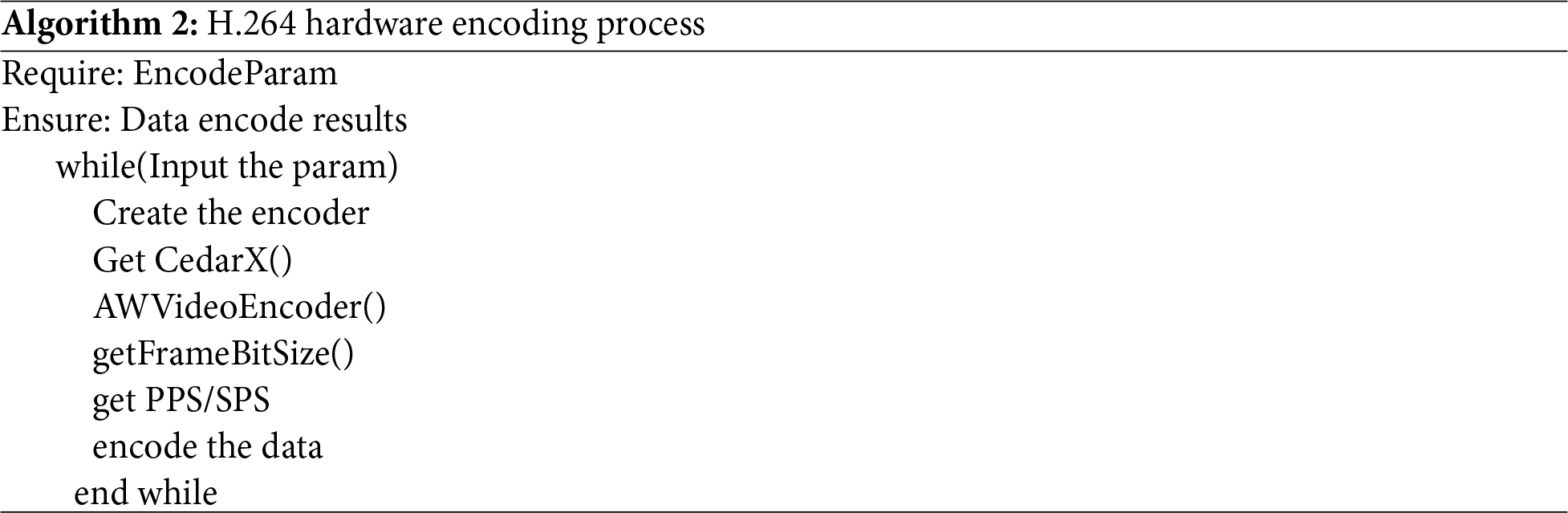

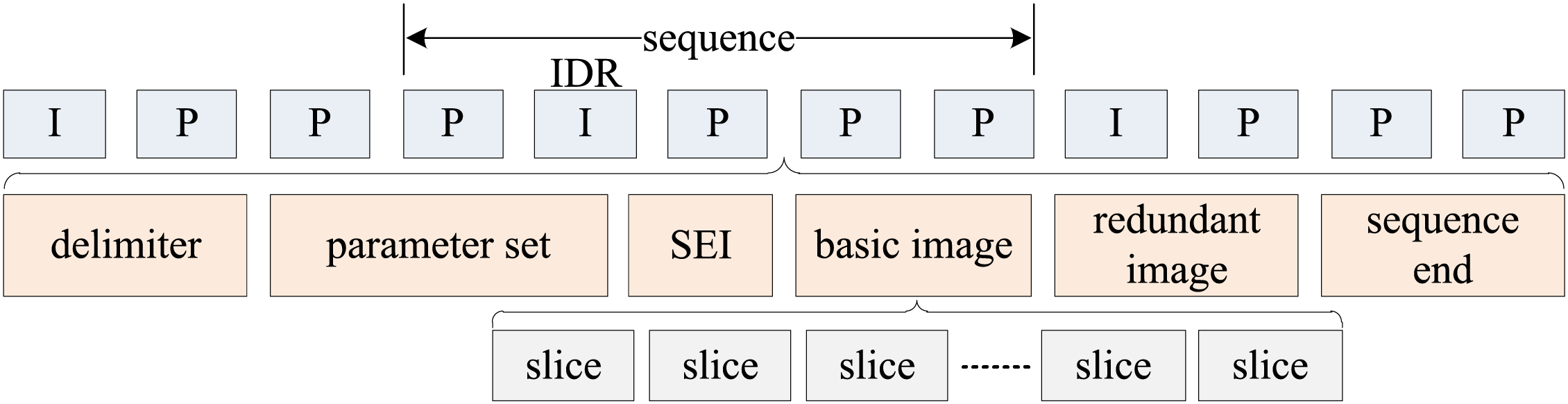

Video encoding employs H.264, a block-based compression technology that primarily involves data detection, transformation, and quantization [40]. H.264 encoding can be implemented through two primary methods: software-based and hardware-based encoding [41]. Hardware encoding offers greater efficiency without consuming additional CPU resources. The selected hardware platform utilizes the AWVideoEncoder library, which is built upon the CedarX encoding component. This library provides a simplified interface with minimal parameter configuration: only the input and output data formats need to be specified, while remaining parameters are automatically optimized to default values. The upper software layer can initiate encoding through a straightforward function call, abstracting underlying complexities such as memory management, hardware interfaces, platform specifics, and SDK version dependencies. The H.264 hardware encoding process is outlined in Algorithm 2.

To mitigate the effects of network packet loss, H.264 improves system resilience through the use of resynchronization mechanisms during decoding. This capability enables the timely recovery of lost or misordered data packets, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: H.264 decode resynchronization.

Given the complexity of the specialized vehicle’s operating environment and the presence of numerous moving objects in the video, block-based motion compensation is employed. This technique partitions each frame into multiple macroblocks. The prediction process models the translational motion of these blocks. The displacement of each block is interpolated to sub-pixel accuracy, enabling motion compensation with a precision of up to 1/4 pixel, as depicted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: H.264 motion compensation design.

Furthermore, the H.264 codec employs the Lagrangian algorithm for rate-distortion optimization within the encoding mode detailed in the following section [42].

In this formulation, I denotes the coding mode, λ represents the Lagrange multiplier, S indicates the input sample, and J(Sk, I/λ) refers to the Lagrange cost function. Here, D(S, I) and R(S, I) correspond to the distortion and the bit rate of the encoded bitstream, respectively.

The encoding mode is optimal when the Lagrangian cost function J(Sk, I/λ) is minimized. For a given sample Sk, the resulting bit rate and distortion depend solely on the chosen encoding mode Ik.

Therefore, by selecting the optimal coding mode for each sample Sk ∈ S, the minimum value of the Lagrangian cost function J(Sk, I/λ) can be achieved, thereby facilitating precise rate control.

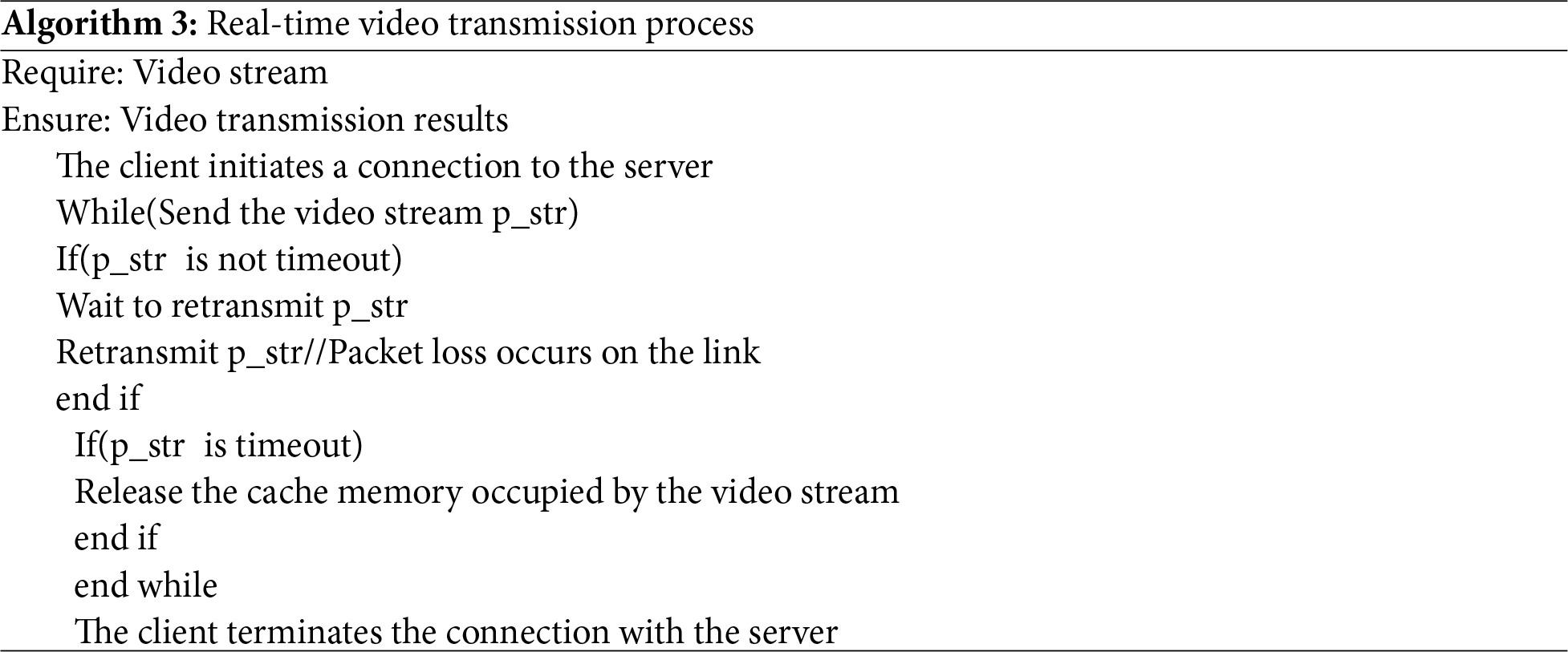

After encoding, the video is prepared for transmission. The video streaming module comprises two main components: a push server and an RTSP-based streaming component.

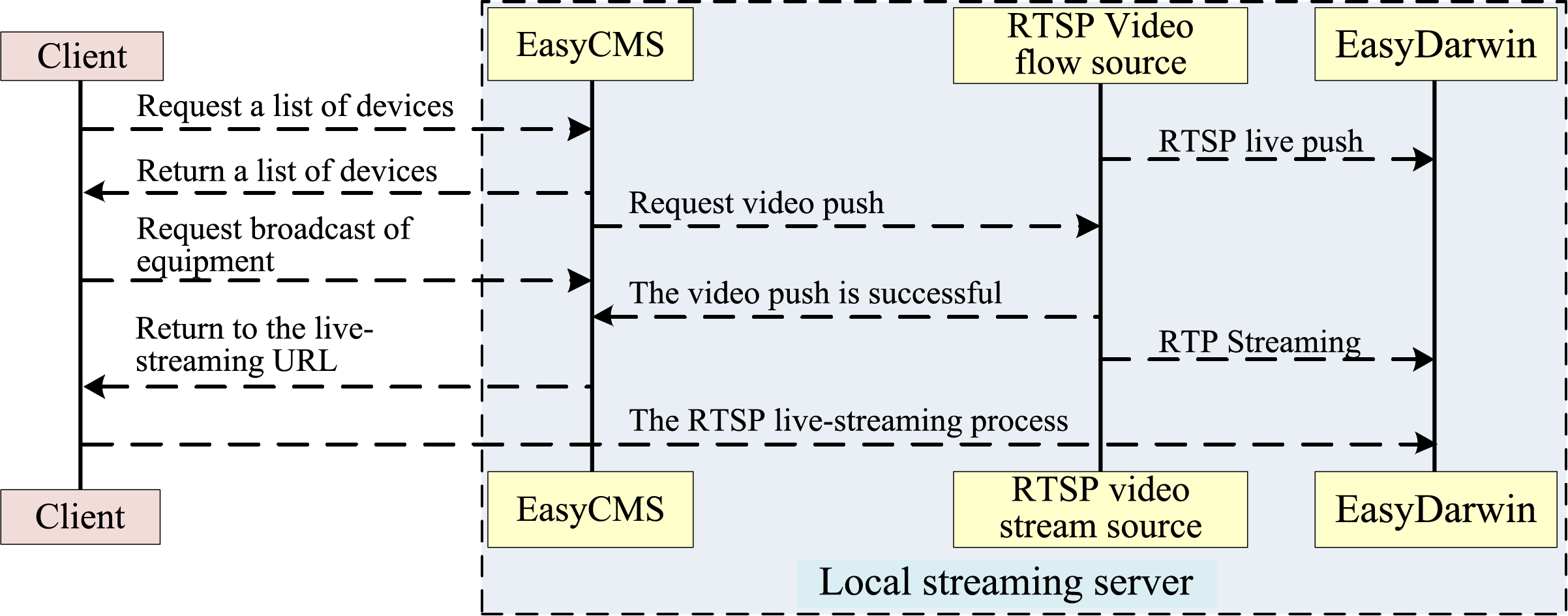

The prerequisite for streaming initiation is the deployment of a streaming media server capable of monitoring incoming video requests and pushing the video stream in real time via Ethernet. The streaming server is implemented using the open-source framework EasyDarwin, which supports protocols including RTSP, HLS, and HTTP. The overall architecture of the push-stream server is illustrated in Fig. 8, exhibiting the following characteristics.

(1) The streaming media server integrates EasyCMS and EasyDarwin to manage and distribute RTSP video streams.

(2) When a client stops playback, the streaming session is terminated, and the allocated bandwidth resources are immediately released.

Figure 8: Video streaming system architecture.

The Real-Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP) is an application-layer protocol designed for controlling the delivery of real-time multimedia data, such as audio and video streams. It supports operations such as pausing and fast-forwarding but does not encapsulate or deliver the data itself. Instead, RTSP provides remote control over the media server, which can select the transport protocol (TCP or UDP) for actual data transmission. When a wireless link connects the client and server, the measured data transmission latency is 30 ms. During video streaming, the system caches the most recently transmitted data. In the event of packet loss caused by wireless link instability, the affected data packets are retransmitted from the cache, thereby minimizing retransmission latency and ensuring continuous playback. The complete video transmission process is outlined in Algorithm 3.

4 Analysis of Experimental Results

4.1 Video Stitching Experimental Results

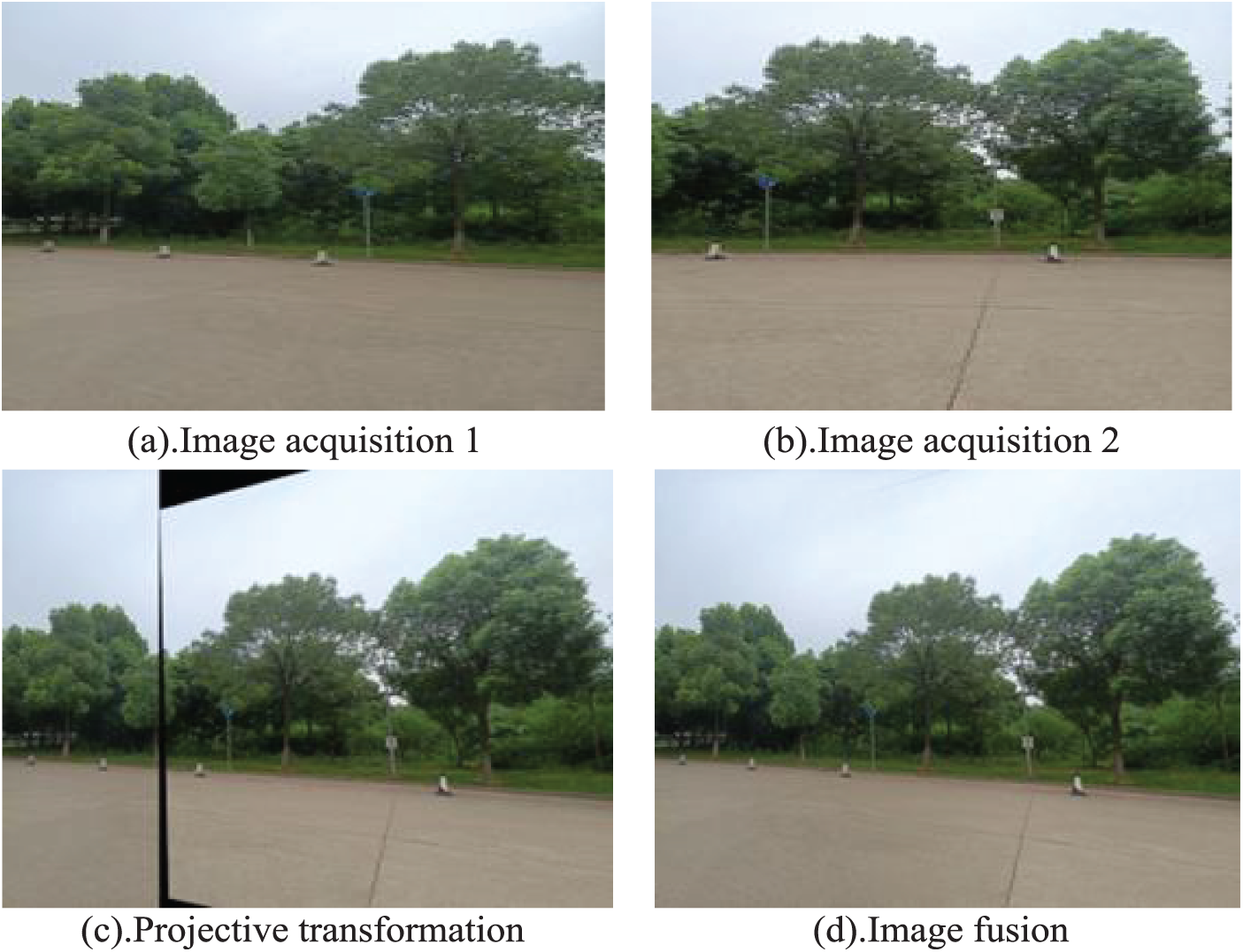

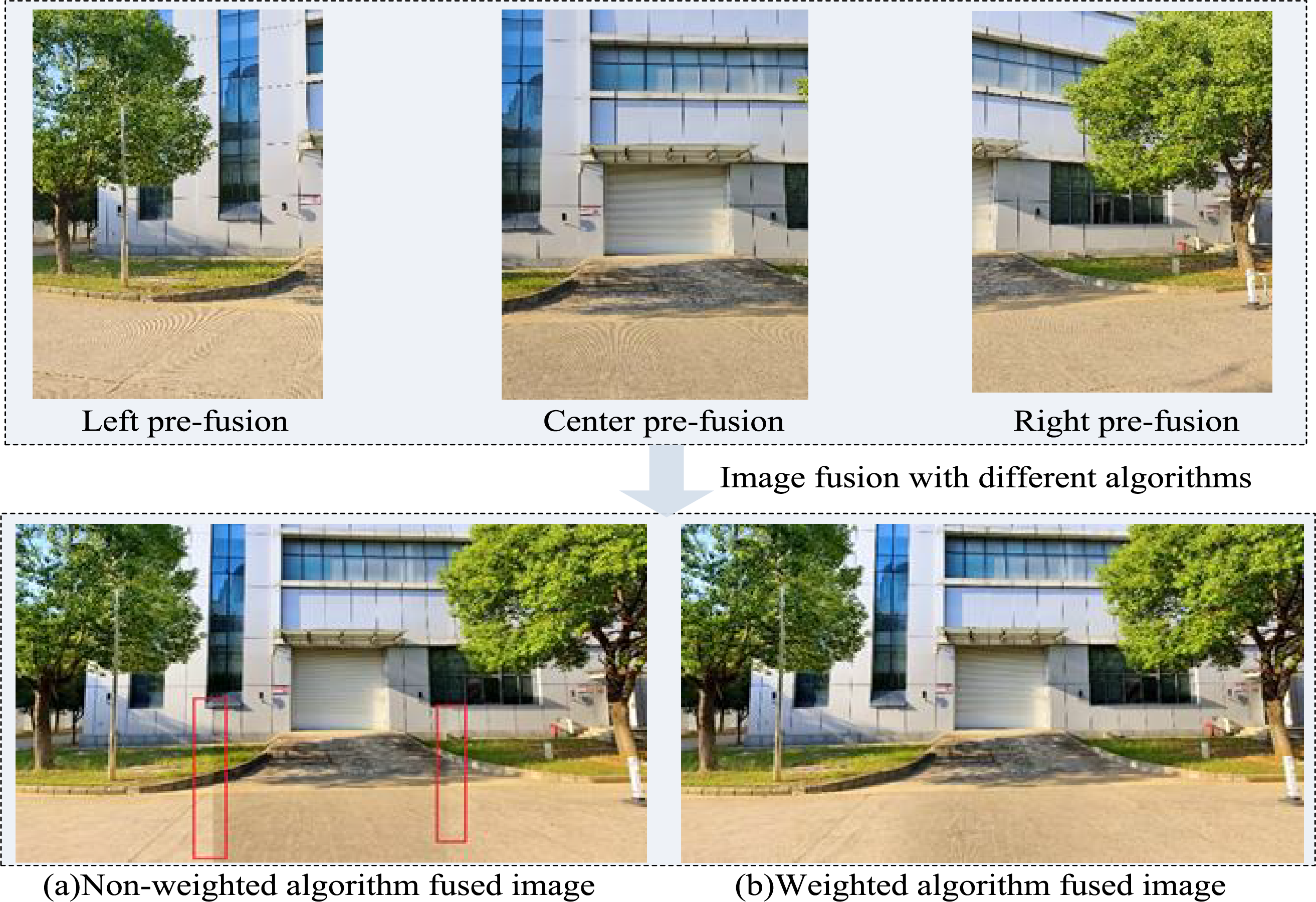

As illustrated in Fig. 9, images captured by the camera were acquired and processed using the V4L2 framework and OpenCV library functions (a). The two images were then projected onto the same plane using the computed homography matrix (b). A weighted average method was applied to merge the images (c). After projection of the right image, redundant black regions in the fused result were cropped to produce the final stitched image (d).

Figure 9: Video image acquisition.

A performance comparison was carried out between the improved weighted-average algorithm and our proposed approach.

As shown in Fig. 10, the experimental results demonstrate that the weighted average fusion algorithm effectively eliminates visible stitching seams, thereby significantly enhancing visual quality and practical utility. Prior to applying the weighted average fusion algorithm, as shown in (a), the PSNR value was 25 dB. Following its application, shown in (b), the measured PSNR value increased to 48 dB, indicating higher fidelity in the fused image.

Figure 10: Comparison of the performance of different image fusion algorithms.

4.2 Video Processing Latency Experimental Results

As shown in Fig. 11, the total latency in video transmission originates primarily from video acquisition, encoding, streaming, decoding, rendering, and display. Denote the end-to-end latency as ΔT, the initial timestamp as T1, and the timestamp after decoding as T2. The latency is computed as follows:

Figure 11: Procedure for latency testing.

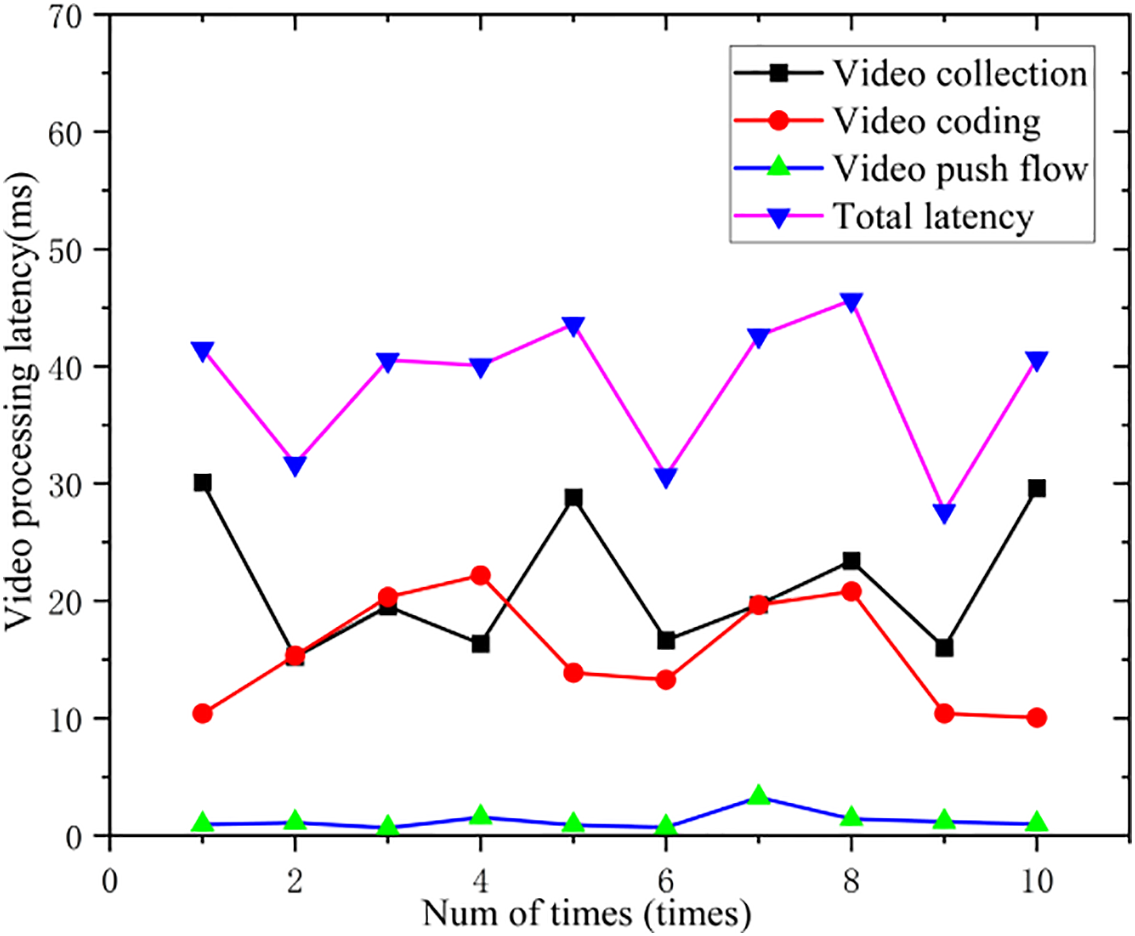

We evaluated the latency of the acquisition, encoding, and streaming processes using four video sequences at 720 p resolution and 25 fps. The measured latency for each processing stage is presented in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Video sender processing latency.

As shown in Fig. 12, video processing latency occurs predominantly during the acquisition stage, which is largely constrained by the video frame rate. We further measured the latency introduced during stream retrieval, decoding, and rendering on the client side; the corresponding results are presented in Fig. 13.

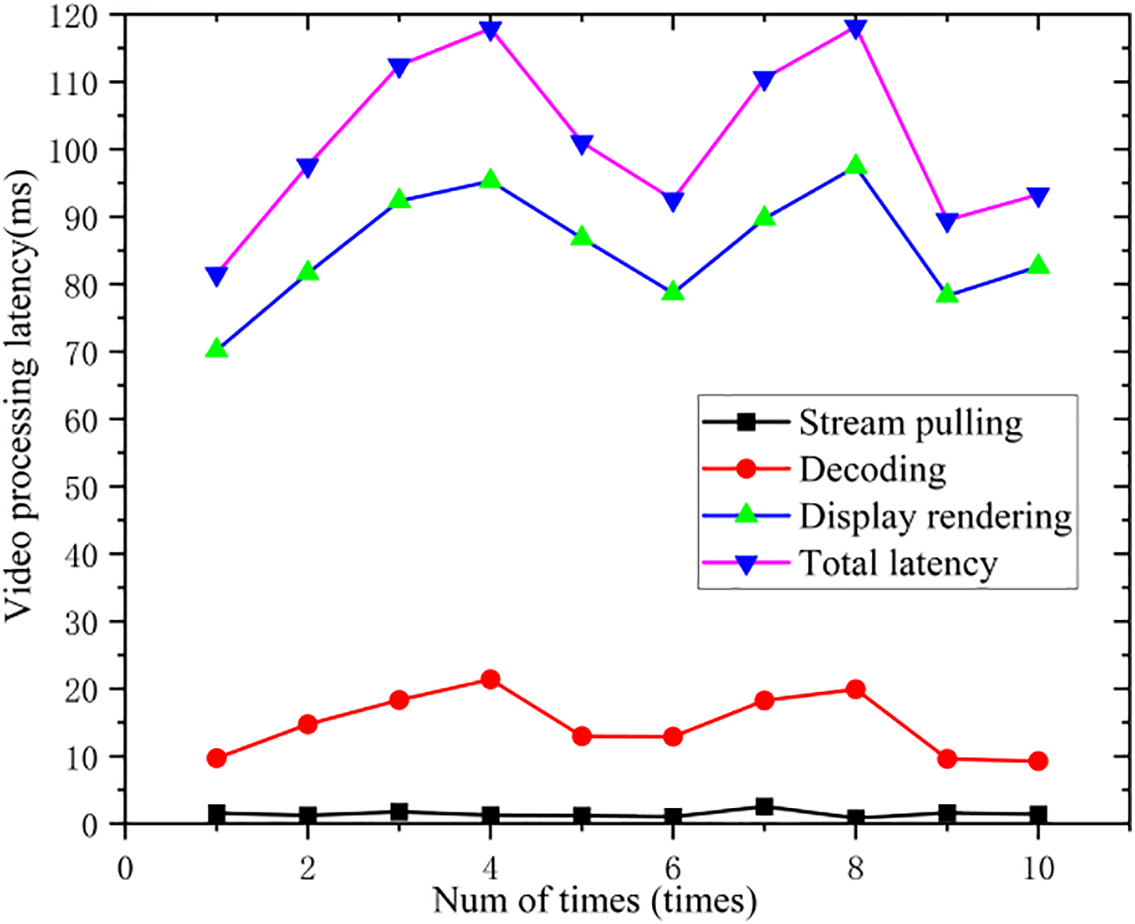

Figure 13: Video receiver processing latency.

As shown in Fig. 13, image display and rendering account for the majority of the latency at the receiver side. A comparative analysis of the video transmission and processing latency between the open-source solution and the embedded platform-optimized design was conducted, with the results presented in Fig. 14.

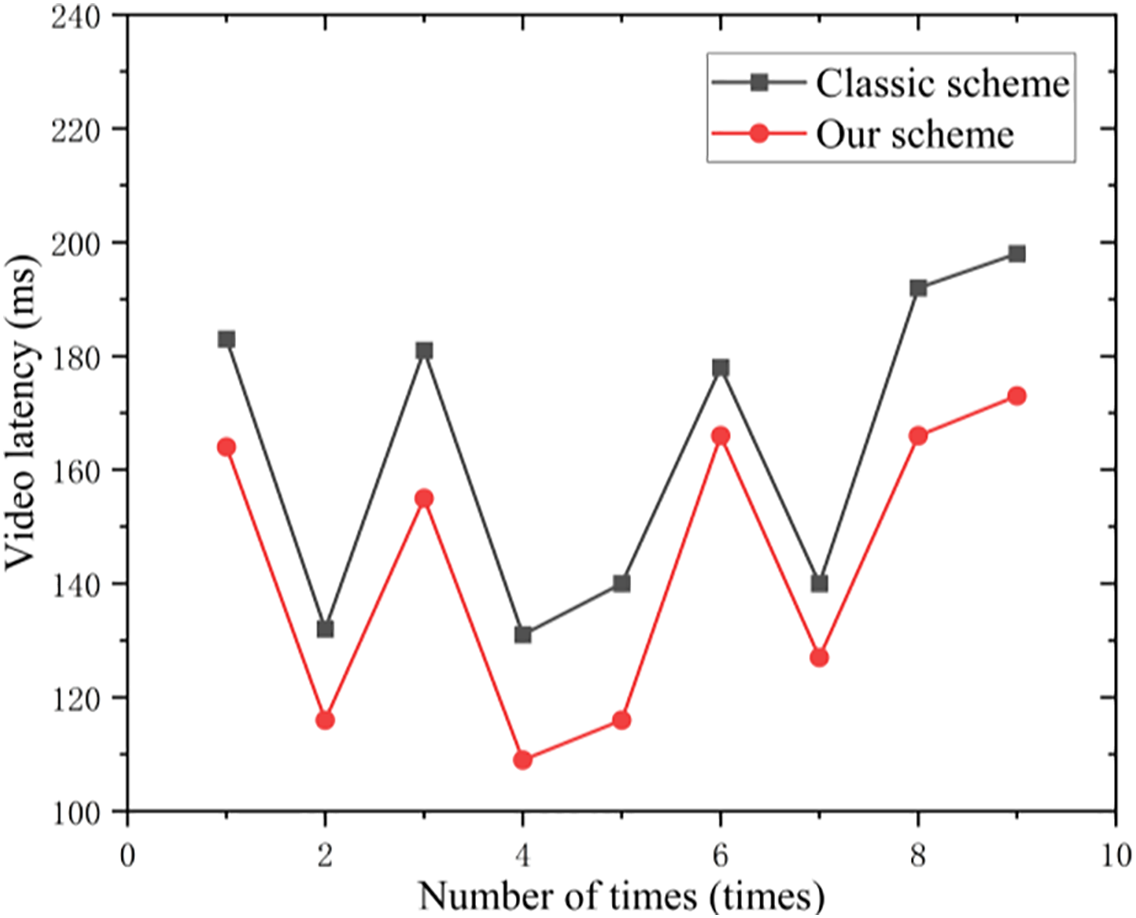

Figure 14: Latency comparison: classic vs. new schemes.

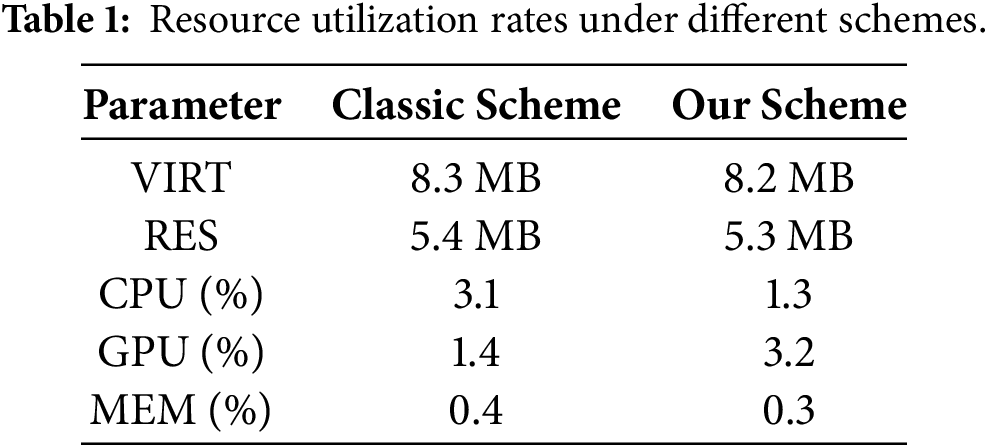

As shown in Fig. 14, the proposed optimized framework reduces end-to-end video transmission latency by an average of nearly 20 ms compared to the classic scheme. We adopted an ARM-based embedded Allwinner T5 processor. This chip integrates a quad-core Cortex-A53 CPU and GPU, supports multiple video input interfaces, and is compatible with OpenGL ES 1.0/2.0/3.2, Vulkan 1.1, and OpenCL 2.0. A comparative analysis between the classic and proposed methods was conducted in terms of memory usage, CPU utilization, and GPU utilization, with the results summarized in Table 1.

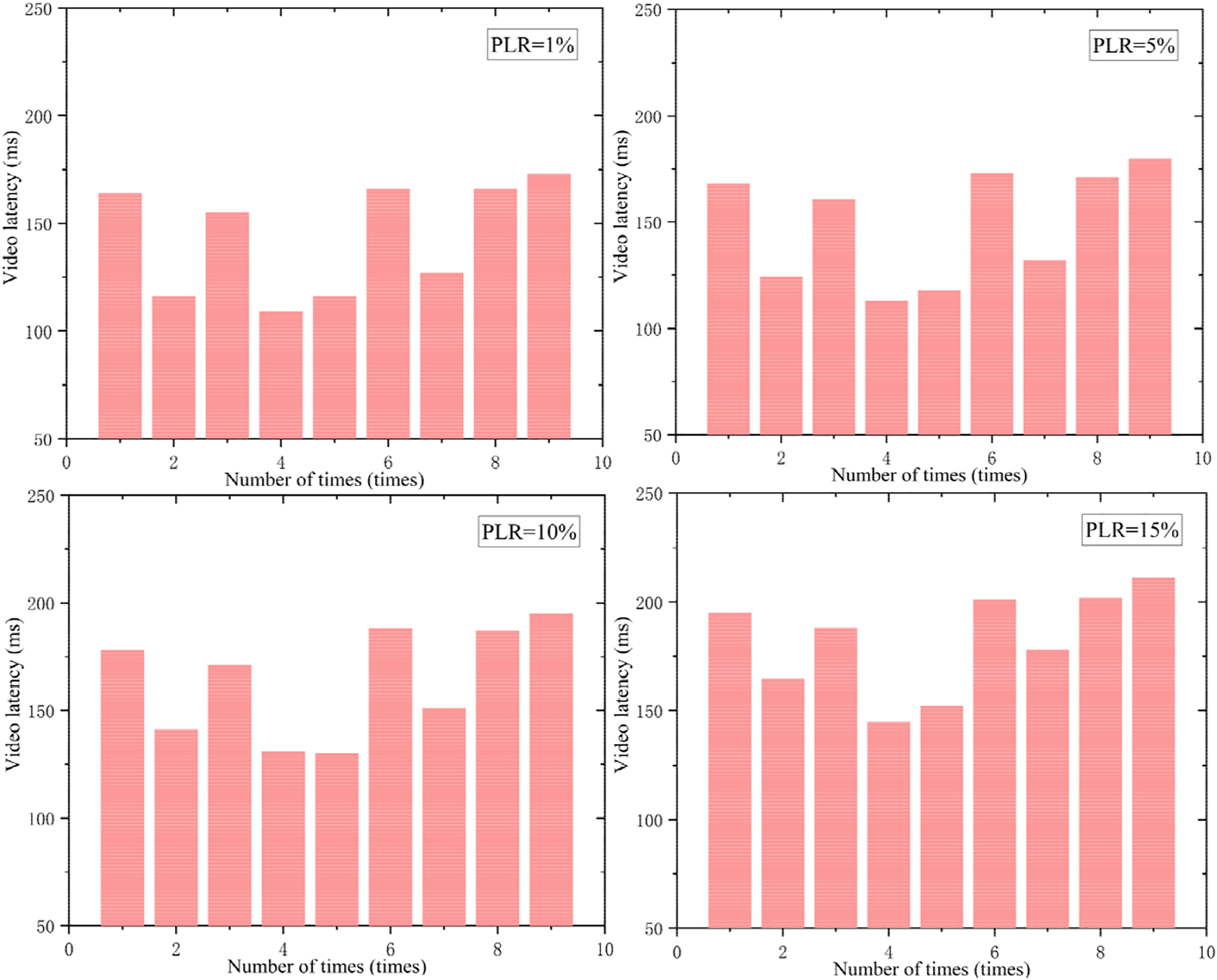

As summarized in Table 1, the proposed solution significantly reduces utilization of general-purpose processing resources on the host platform by efficiently offloading computation to the video processor’s GPU, thereby improving overall system performance. To closely emulate real-world conditions—where factors such as adverse weather, physical obstructions, and platform mobility often lead to unstable transmission channels, packet loss, and performance degradation—we conducted ten latency tests. By placing jamming devices in the wireless channel, the video transmission latency under different network packet loss rates was simulated. Under stable wireless link conditions with a transmission latency of 30 ms, the channel bandwidth is set to 20 Mbps. The system’s end-to-end latency remained consistently around 140 ms, as illustrated in Fig. 15.

Figure 15: Video latency under different packet loss rates.

As shown in Fig. 15, system latency increases with higher packet loss rates during real-time video transmission. This occurs because packet loss triggers the receiver to signal the sender to throttle the transmission rate and prioritize retransmission of lost packets. Consequently, elevated packet loss rates result in increased latency. Since the system continues to process and display successfully received packets while managing retransmissions in parallel, video playback remains uninterrupted. The correlation between packet loss rate and video transmission latency is further detailed in Fig. 16.

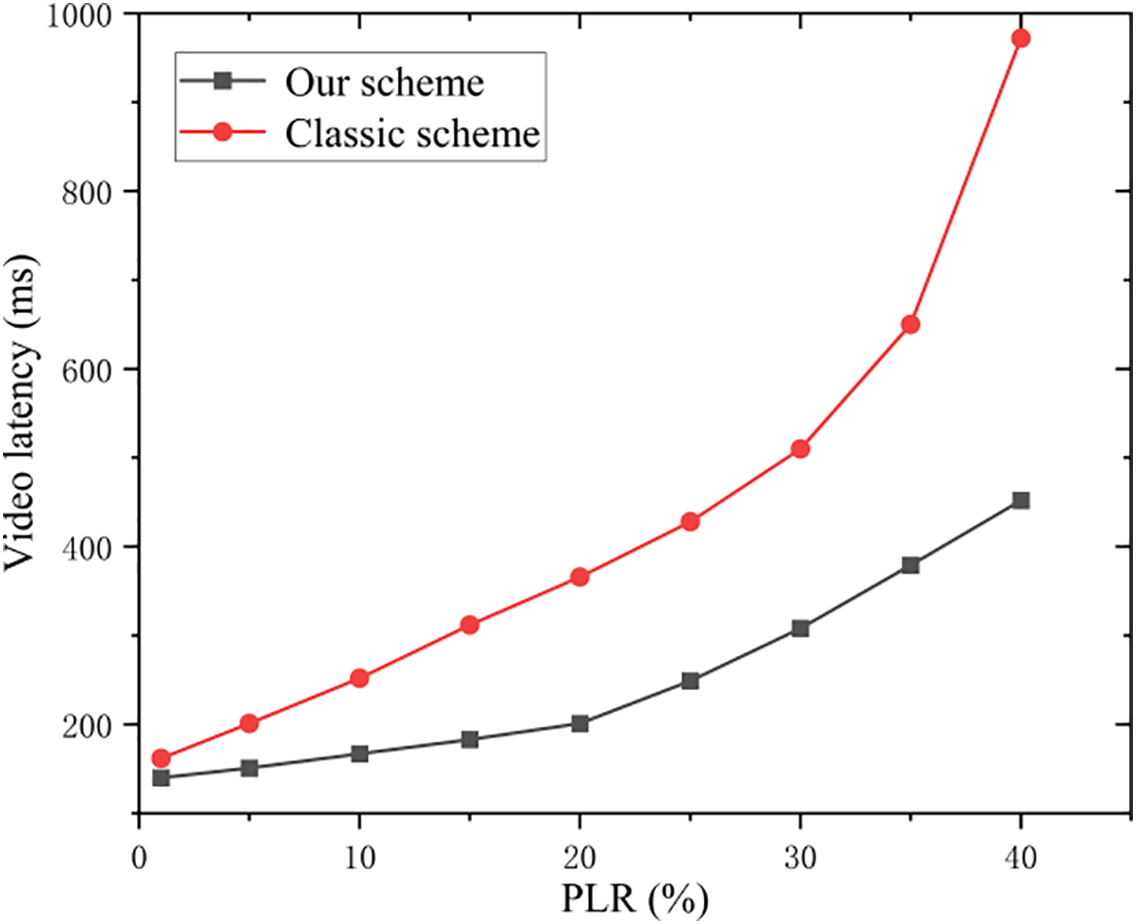

Figure 16: Packet loss vs. video transmission performance.

As shown in Fig. 16, the video transmission system maintains operational integrity at packet loss rates of up to 20%, as a result, the video transmission latency increased to nearly 200 ms. Beyond this threshold, system performance degrades significantly with further increases in packet loss. Moreover, under identical packet loss conditions, the proposed scheme achieves lower transmission latency compared to conventional methods. Based on user experience, video transmission quality is rated on a scale from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating superior quality. The relationship between packet loss, latency, and perceived user experience is further illustrated in Fig. 17.

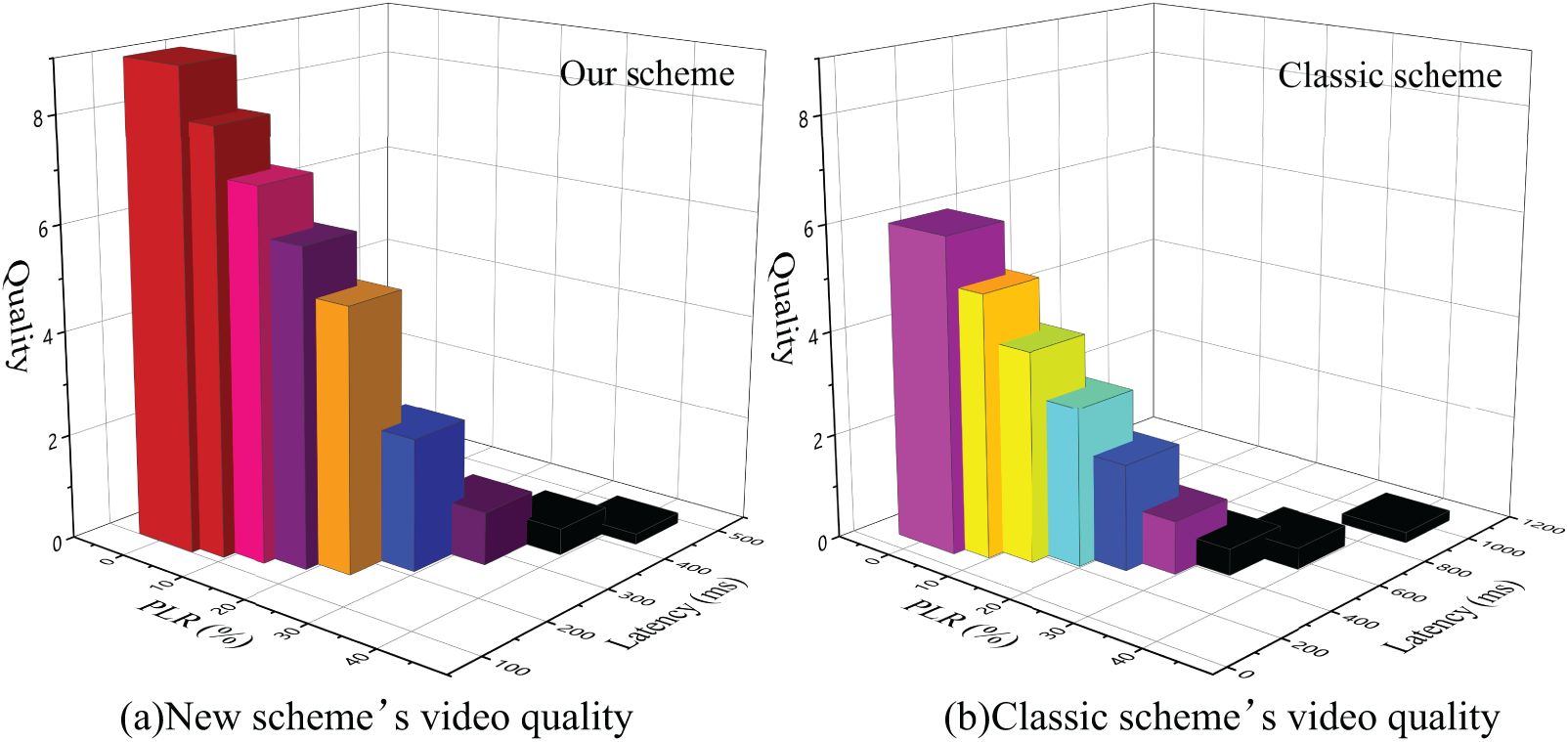

Figure 17: Video quality assessment under different latency and packet loss conditions.

As shown in Fig. 17, lower latency and reduced packet loss rates contribute to enhanced video transmission quality and improved user experience. The proposed solution achieves a video transmission latency below 200 ms and maintains satisfactory video quality (corresponding to a QoS level of 5) even under packet loss rates of up to 20%. In contrast, conventional schemes exceed 200 ms latency once packet loss surpasses 5%, failing to meet user requirements. Therefore, under identical network conditions, our approach delivers superior video quality compared to traditional methods and demonstrates robust performance in adverse network environments typical of real-world battlefield scenarios.

This paper presents an embedded processing platform designed for real-time stitching of multiple video streams. Video data captured from multiple cameras are collected and processed using OpenCV-based algorithms. The processing pipeline involves feature point extraction, homography matrix calculation, perspective transformation, and image fusion, resulting in a seamless panoramic video with an extended field of view. Through optimization of the image fusion algorithm, the stitching quality is significantly improved. The system supports concurrent video input from four Analog High Definition (AHD) cameras and enables hardware-accelerated compression and low-latency transmission of four simultaneous video streams at 720p@25fps. Experimental results show that the overall latency of the embedded surveillance system remains around 140 ms. Even under a packet loss rate of 20%, the system sustains satisfactory video transmission quality, meeting the requirements for unmanned vehicle video communication applications. The proposed system offers key advantages such as low latency, high reliability minimal distortion, and flexible deployment, making it highly suitable for onboard wireless video communication systems.

Future work will focus on further enhancing the system’s resilience to even higher packet loss rates and more dynamic network conditions, by integrating a deep learning algorithm, the system achieves real-time perception of the current network environment, capturing metrics such as communication distance, latency, link packet loss rate, vehicle speed, and channel bandwidth. These parameters are then comprehensively processed by the algorithm, and the computational results are used to dynamically adjust system parameters, including the retransmission mechanism and video pixel extraction/processing strategies, thereby improving its overall robustness and real-time performance in challenging operational environments.

Acknowledgement: The professors, experts, and students from the School of Cyber Science and Engineering at Shandong University and the Systems Engineering Research Institute of the Academy of Military Sciences provided in-depth theoretical guidance and experimental assistance for this research. Engineers from the network communication research team of China Electronics Wuhan Zhongyuan Communication Co., Ltd. offered substantial support during the construction of the physical test and verification platform. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all of them. We also extend our thanks to the experts who reviewed this paper amidst their busy schedules.

Funding Statement: The work has partly been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72334003), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFB2702804), the Shandong Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2020ZLYS09), and the Jinan Program (Grant No. 2021GXRC084-2).

Author Contributions: Tai Liu was primarily responsible for proposing the research framework, conducting algorithm simulations, and drafting the manuscript. Feng Wu focused on the design of high-dynamic application scenarios for unmanned vehicles and the analysis of user requirements. Chao Zhu led the implementation of the algorithm in practical software development. Bo Chen was chiefly engaged in the hardware development of the physical system. Mao Ye provided experimental guidance for the research plan, while Guoyan Zhang was mainly responsible for its theoretical direction. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The empirical data reported in this study are grounded in actual measurements from hardware prototypes, ensuring their validity and reliability.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dai Q, Wang K. Integration of multi-channel video and GIS based on LOD. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA); 2021 Jun 28–30; Dalian, China. p. 963–6. doi:10.1109/icaica52286.2021.9497915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. IEEE 1857.10-2021. IEEE standard for third-generation video coding. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE Standards Association; 2022. [Google Scholar]

3. Simmers E, Salman A, Day E, Oracevic A. Secure and intelligent video surveillance using unmanned aerial vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Smart Mobility (SM); 2023 Mar 19–21; Thuwal, Saudi Arabia. p. 98–103. doi:10.1109/SM57895.2023.10112347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Minopoulos G, Memos VA, Psannis KE, Ishibashi Y. Comparison of video codecs performance for real-time transmission. In: Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI); 2020 Jun 26–29; Nagoya, Japan. p. 110–4. doi:10.1109/iccci49374.2020.9145973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sharma P, Awasare D, Jaiswal B, Mohan S, Abinaya N, Darwhekar I, et al. On the latency in vehicular control using video streaming over Wi-Fi. In: Proceedings of the 2020 National Conference on Communications (NCC); 2020 Feb 21–23; Kharagpur, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ncc48643.2020.9056067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Anitha Kumari RD, Udupa N. A study of the evolution of video codec and its future research direction. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Third International Conference on Advances in Electronics, Computers and Communications (ICAECC); 2020 Dec 11–12; Bengaluru, India. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

7. Balobanov V, Balobanov A, Potashnikov A, Vlasuyk I. Low latency ONM video compression method for UAV control and communication. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Systems of Signals Generating and Processing in the Field of on Board Communications; 2018 Mar 14–15; Moscow, Russia. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/SOSG.2018.8350571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li J, Sun R, Wang G, Fan M. Panoramic video live broadcasting system based on global distribution. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC); 2019 Nov 22–24; Hangzhou, China. p. 63–7. doi:10.1109/cac48633.2019.8996293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rasch J, Warno V, Ptatt J, Tischendorf C, Marpe D, Schwarz H, et al. A signal adaptive diffusion filter for video coding using directional total variation. In: Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2018 Oct 7–10; Athens, Greece. p. 2570–4. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2018.8451579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Skupin R, Sanchez Y, Wang YK, Hannuksela MM, Boyce J, Wien M. Standardization status of 360 degree video coding and delivery. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP); 2017 Dec 10–13; St. Petersburg, FL, USA. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/VCIP.2017.8305083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang Y, Chen Z, Liu S. Equirectangular projection oriented intra prediction for 360-degree video coding. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP); 2020 Dec 1–4; Macau, China. p. 483–6. doi:10.1109/vcip49819.2020.9301871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang Y, Xue Y, Peng S. A parallel acceleration method in panoramic video mosaic system based on 5G Internet of Things. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC); 2020 Jun 15–19; Limassol, Cyprus. p. 1995–8. doi:10.1109/iwcmc48107.2020.9148230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li Q, Chen Y, Zhang A, Jiang Y, Zou L, Xu Z, et al. A super-resolution flexible video coding solution for improving live streaming quality. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25:6341–55. doi:10.1109/tmm.2022.3207580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao X, Hu Q, Zhang X, Wang H. An ORB-SLAM3 autonomous positioning and orientation approach using 360-degree panoramic video. In: Proceedings of the 2022 29th International Conference on Geoinformatics; 2022 Aug 15–18; Beijing, China. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/Geoinformatics57846.2022.9963855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Qiu S, Li B, Cheng K, Zhang X, Duan G, Li F. Multi-directional reconstruction algorithm for panoramic camera. Comput Mater Contin. 2020;65(1):433–43. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.09708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Woo Han S, Young Suh D. A 360-degree panoramic image inpainting network using a cube map. Comput Mater Contin. 2020;66(1):213–28. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.012223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li J, Xu K, Wang G. Research on a panoramic video transmission scheme based on multi-view switching within the human eye’s field of view. In: Proceedings of the 2022 34th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC); 2022 Aug 15–17; Hefei, China. p. 2286–91. doi:10.1109/CCDC55256.2022.10033652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chao J, Huitl R, Steinbach E, Schroeder D. A novel rate control framework for SIFT/SURF feature preservation in H.264/AVC video compression. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2015;25(6):958–72. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2014.2367354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Manel B. Block-based distributed video coding without channel codes. In: Proceedings of the 2015 3rd International Conference on Control, Engineering & Information Technology (CEIT); 2015 May 25–27; Tlemcen, Algeria. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/CEIT.2015.7233154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang M, Xie W, Xiong J, Wang D, Qin J. Joint optimization of transform and quantization for high efficiency video coding. IEEE Access. 2019;7:62534–44. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2917260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Duong LR, Li B, Chen C, Han J. Multi-rate adaptive transform coding for video compression. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10095879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ding L, Tian Y, Fan H, Wang Y, Huang T. Rate-performance-loss optimization for inter-frame deep feature coding from videos. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2017;26(12):5743–57. doi:10.1109/TIP.2017.2745203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chiu JC, Tseng HY, Lee ZY. Design of multidimension-media streaming protocol based on RTSP. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Computer Symposium (ICS); 2020 Dec 17–19; Tainan, Taiwan. p. 341–7. doi:10.1109/ics51289.2020.00074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang M, Cheng B, Yuen C. Joint coding-transmission optimization for a video surveillance system with multiple cameras. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2018;20(3):620–33. doi:10.1109/TMM.2017.2748459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bakirci M. A novel swarm unmanned aerial vehicle system: incorporating autonomous flight, real-time object detection, and coordinated intelligence for enhanced performance. Trait Du Signal. 2023;40(5):2063–78. doi:10.18280/ts.400524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Aloman A, Ispas AI, Ciotirnae P, Sanchez-Iborra R, Cano MD. Performance evaluation of video streaming using MPEG DASH, RTSP, and RTMP in mobile networks. In: Proceedings of the 2015 8th IFIP Wireless and Mobile Networking Conference (WMNC); 2015 Oct 5–7; Munich, Germany. p. 144–51. doi:10.1109/WMNC.2015.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mamta, Pillai A, Punj D. Image splicing detection using retinex based contrast enhancement and deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Technologies (ICACCTech); 2023 Dec 23–24; Banur, India. p. 771–8. doi:10.1109/ICACCTech61146.2023.00127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Siqueira I, Correa G, Grellert M. Complexity and coding efficiency assessment of the versatile video coding standard. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS); 2021 May 22–28; Daegu, Republic of Korea. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/iscas51556.2021.9401714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lim WQ, Schwarz H, Marpe D, Wiegand T. Post sample adaptive offset for video coding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Picture Coding Symposium (PCS); 2019 Nov 12–15; Ningbo, China. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/PCS48520.2019.8954544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shilpa KS, Narayan DG, Kotabagi S, Uma M. Suitability analysis of IEEE 802.15.4 networks for video surveillance. In: Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks; 2011 Oct 7–9; Gwalior, India. p. 702–6. doi:10.1109/CICN.2011.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen J, Shi X. Image mosaics algorithm based on feature points matching. In: Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electronics, Communications and Control (ICECC); 2011 Sep 9–11; Ningbo, China. p. 278–81. doi:10.1109/ICECC.2011.6067889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fang JT, Tu YL, Yu LP, Chang PC. Real-time complexity control for high efficiency video coding. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Information Communication and Signal Processing (ICICSP); 2018 Sep 28–30; Singapore. p. 85–9. doi:10.1109/ICICSP.2018.8549738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ye M, Chen L, Milne A, Hillier J, Sølvsten S. GAN-enabled framework for fire risk assessment and mitigation of building blueprints. In: Proceedings of the 30th EG-ICE: International Conference on Intelligent Computing in Engineering; 2023 Jul 4–7; London, UK. [Google Scholar]

34. Chen D, Chen L, Zhang Y, Lin S, Ye M, Sølvsten S. Automated fire risk assessment and mitigation in building blueprints using computer vision and deep generative models. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62(6):102614. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shinde PS, Dongre YV. Objective video quality assessment based on SURF feature matching. In: Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA); 2019 Sep 19–21; Pune, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCUBEA47591.2019.9129297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jadhav D, Bhosle U. SURF based video summarization and its optimization. In: Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP); 2017 Apr 6–8; Chennai, India. p. 1252–7. doi:10.1109/ICCSP.2017.8286581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jia Y, Sun W, Rong C, Zhu Y, Yang Y. An improvement in image registration with SIFT features and logistic regression. In: Proceedings of the 2018 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, Biomedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI); 2018 Oct 13–15; Beijing, China. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/CISP-BMEI.2018.8633020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yang J, Pei Y, Li B, Tao Q. Multivideo mosaic based on SIFT algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology; 2011 Dec 24–26; Harbin, China. p. 1497–501. doi:10.1109/ICCSNT.2011.6182249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Raheem HA, Al-Assadi TA. Video important shot detection based on ORB algorithm and FLANN technique. In: Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Engineering Conference on Sustainable Technology and Development (IEC); 2022 Feb 23–24; Erbil, Iraq. p. 113–7. doi:10.1109/IEC54822.2022.9807488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Choi K, Chen J, Park MW, Yang H, Choi W, Ikonin S, et al. Video codec using flexible block partitioning and advanced prediction, transform and loop filtering technologies. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2020;30(5):1326–45. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2020.2971268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Saleh MA, Tahir NM, Hashim H. Coding structure and performance of high efficiency video coding (HEVC) and H.264/AVC. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE); 2015 Apr 12–14; Langkawi, Malaysia. p. 53–8. doi:10.1109/ISCAIE.2015.7298327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang X, Song L, Luo Z, Xie R. Lagrangian method based rate-distortion optimization revisited for dependent video coding. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2017 Sep 17–20; Beijing, China. p. 3021–5. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools