Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review on Fault Diagnosis Methods of Gas Turbine

1 Key Laboratory of Knowledge Automation for Industrial Processes of Ministry of Education, School of Automation and Electrical Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, 100083, China

2 Systems Engineering Research Institute, China State Shipbuilding Corporation Limited, Beijing, 100094, China

* Corresponding Author: Tao Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Signal Processing for Fault Diagnosis)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072696

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The critical components of gas turbines suffer from prolonged exposure to factors such as thermal oxidation, mechanical wear, and airflow disturbances during prolonged operation. These conditions can lead to a series of issues, including mechanical faults, air path malfunctions, and combustion irregularities. Traditional model-based approaches face inherent limitations due to their inability to handle nonlinear problems, natural factors, measurement uncertainties, fault coupling, and implementation challenges. The development of artificial intelligence algorithms has provided an effective solution to these issues, sparking extensive research into data-driven fault diagnosis methodologies. The review mechanism involved searching IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science for peer-reviewed articles published between 2019 and 2025, focusing on multi-fault diagnosis techniques. A total of 220 papers were identified, with 123 meeting the inclusion criteria. This paper provides a comprehensive review of diagnostic methodologies, detailing their operational principles and distinctive features. It analyzes current research hotspots and challenges while forecasting future trends. The study systematically evaluates the strengths and limitations of various fault diagnosis techniques, revealing their practical applicability and constraints through comparative analysis. Furthermore, this paper looks forward to the future development direction of this field and provides a valuable reference for the optimization and development of gas turbine fault diagnosis technology in the future.Keywords

The expanding natural power generation capacity has become an effective solution to address the stability shortcomings of renewable energy while meeting increasingly frequent grid peak-shaving needs, under the goals of ‘carbon peak and carbon neutrality’ [1]. With mature natural gas transportation technology, these turbines require minimal space and can be flexibly deployed in urban areas with limited space. The gas turbine generators play a crucial role in grid peak-shaving operations, which are characterized by short start-stop cycles, rapid load response, and high flexibility [2]. However, frequent start-stop cycles and load fluctuations subject gas turbines to variable operating conditions, significantly increasing the risk of equipment faults over time. In recent years, the construction of digital power plants, smart power generation, and intelligent power plants has gradually become a trend in the power industry. Intelligent diagnosis serves as a vital component of smart power plants, utilizing next-generation information technologies to deeply analyze operational parameters [3]. This approach aims to identify underlying correlations, enable rapid automated diagnostics when equipment anomalies occur, provide maintenance recommendations to operators, and prevent further fault propagation that could compromise generator reliability, safety, and economic efficiency [4].

With the growing adoption of AI algorithms in industrial applications, intelligent turbine diagnostics has entered a new era. Given the inherent challenges of turbines—complex structures, intricate mechanisms, coupled faults, and dynamic excitation patterns—the selection of appropriate algorithms or models to process fragmented knowledge, identify latent fault indicators, and enable reliable predictive analysis has become a crucial approach for achieving intelligent and effective fault diagnosis [5–7]. It is imperative to carry out research on the intelligent diagnosis of gas turbines. The intelligent diagnosis system can provide expert advice for the power plant from the perspective of operation and maintenance, to ensure the reliable, safe, and efficient operation of the power plant [8,9].

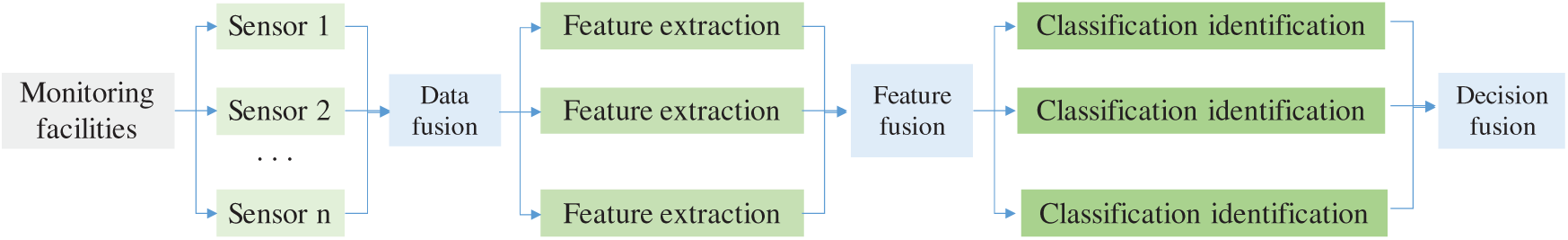

The common fault types mainly include three categories: mechanical faults, gas path faults, and combustion faults in gas turbine fault diagnosis [10–12]. Each category is further subdivided into different specific faults, which are shown in Table 1 [13,14].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the specific fault of the gas turbine, main characteristics, and primary causes were presented. Section 3 illustrated that the method of low-dimensional features with discriminative, robust, and interpretable characteristics was extracted from high-dimensional and redundant original signals. The data-based fault diagnosis, model-based fault diagnosis, and knowledge-based fault diagnosis are compared and analyzed in Section 4.

2.1 Working Principle of Gas Turbine

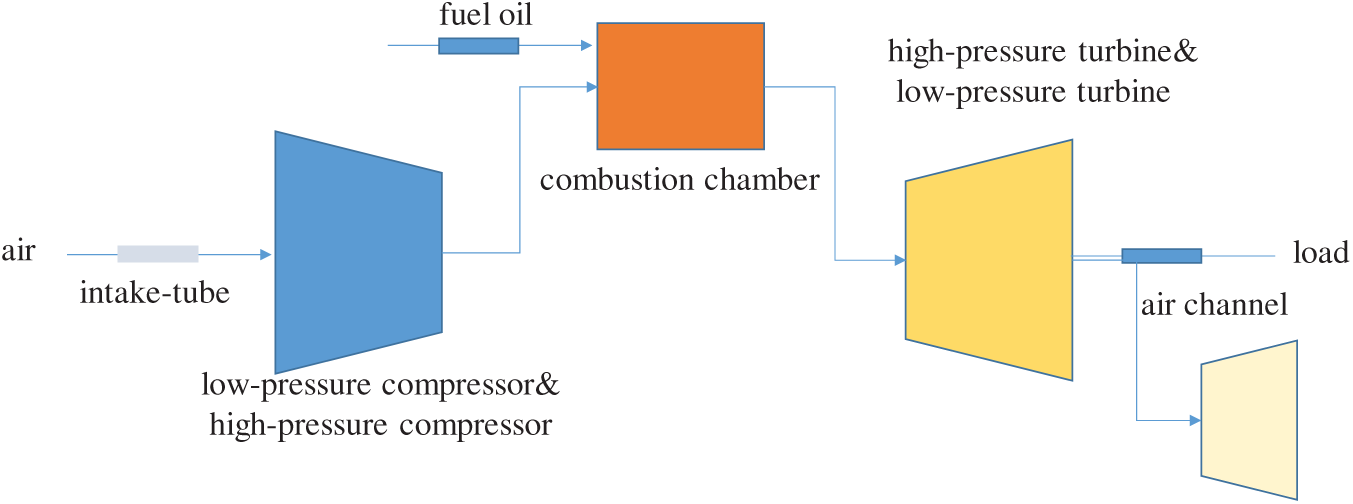

The schematic diagram of a gas turbine is shown in Fig. 1. In the atmospheric environment, air first enters the intake duct. After undergoing filtration and noise reduction treatment, the streamlined air is directed to the inlet of the low-pressure compressor. Following compression by both low-pressure and high-pressure compressors, the air enters the combustion chamber where it mixes with fuel for combustion, generating high-temperature, high-pressure gas [20,21]. Ventilation systems are installed at the outlets of both low-pressure and high-pressure compressors to cool the stationary and rotating blades of the turbines. Moreover, we analyze the fault of rotor imbalance, rotor collision, and blade crack in a gas turbine [22–24].

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of gas turbine

The compressor continuously draws air from the surrounding environment, compresses it, and delivers it to the adjacent combustion chamber. Structurally, it consists of two main components: a rotor with a rotating shaft as its core, featuring moving blades arranged in specific patterns; and a stator with stationary components mounted on the casing, containing stationary blades following identical alignment principles. The compressor’s fundamental working unit is a stage, comprising a row of adjacent moving blades and a row of stationary blades. Multiple interconnected stages form the compressor’s flow path. Within each stage, moving blades are driven by external forces to rotate continuously, imparting kinetic energy to the gas flow through increasing its absolute velocity. The stationary blades act as diffuser channels, converting the kinetic energy of high-speed gas into pressure energy to supply the combustion chamber with high-pressure gas. A set of inlet guide vanes precedes the first stage, directing airflow into it, while a set of rectifying vanes follows the last stage to regulate the exit gas flow.

The flow direction is changed to the axial direction, which is more conducive to the expansion of air flow in the annular diffuser. The combustion chamber serves three primary functions: First, it mixes compressed gas from the compressor with fuel for efficient combustion; Second, it ensures uniform mixing of compressed gas from another compressor section with combustion products, reducing the temperature from 1800°C to the turbine inlet’s initial temperature for power generation; Third, it controls nitrogen oxide emissions to meet regulatory standards. Its structure consists of key components, including the fuel injector, front cylinder, igniter, flame tube, transition section, flue gas pipe, and flow guide sleeve.

The turbine converts energy from high-temperature, high-pressure gases in the combustion chamber into mechanical energy, with most of it used for the gas turbine’s effective output power while a small portion drives the compressor. Its structure resembles that of a compressor, primarily consisting of a stator and an impeller with moving blades. In a converging-diverging flow path, the stator accelerates the high-temperature gas flow. During this process, both temperature and pressure gradually decrease, converting part of the gas’s thermal and pressure energy into kinetic energy. The kinetic energy-rich gas then rushes toward the moving blade grid in a specific direction, driving the impeller to rotate and transforming its kinetic energy into mechanical energy.

Throughout the operation of a gas turbine, the exhaust state of the compressor significantly impacts its performance. Variations in this state alter the compression ratio, which subsequently affects fuel consumption and combustion processes within the combustor. Unstable exhaust pressure and temperature levels reduce combustion efficiency, thereby compromising both the overall operational quality and energy conversion efficiency of the gas turbine. The exhaust state of the gas turbine’s turbine critically influences the performance of the entire gas-steam combined cycle. The residual heat from turbine exhaust serves as a key indicator of steam turbine efficiency in this system. When the gas path of the gas turbine deteriorates, these parameters undergo corresponding changes, which can be used to characterize the performance status of the gas turbine’s gas path.

Therefore, the prediction model will be constructed for three state parameters of compressor exhaust temperature, exhaust pressure, and turbine exhaust temperature, so as to master the health status and performance decline of the gas turbine.

Rotor imbalance, misalignment, rubbing between rotating and stationary components, and cracks are common rotor failures in gas turbines [25]. Rotor imbalance is one of the most frequent failures, primarily caused by manufacturing errors, component wear, and uneven deposits [26]. These factors exacerbate rotor vibrations, adversely affecting operational stability and safety [27]. Rotor misalignment occurs when the rotor’s axis line deviates from the bearing’s axis line, generating additional forces and torques that cause vibration, accelerate bearing wear, and shorten turbine lifespan [28]. Rotating-stationary friction arises from collisions between rotating components and stationary parts, often due to rotor warping, insufficient bearing clearance, or damaged seals [29]. This intensifies vibrations, generates noise and heat, and may ultimately damage both components. Rotor cracks manifest as surface or internal fissures, typically resulting from material fatigue, excessive stress, or manufacturing defects. Such cracks weaken rotor strength and rigidity, compromising operational safety [30,31].

Rotor Imbalance

Rotor imbalance is the most common fault in heavy-duty gas turbines, accounting for over half of all rotational faults. This imbalance can stem from various causes, including manufacturing and installation errors, foreign objects on the rotor, loose components, as well as deformation and fatigue during operation [32,33]. The additional load caused by rotor imbalance leads to gradually increasing vibration amplitude over time, significantly raising the risk of equipment damage [33–35].

Rotor imbalance can be categorized into two types: mass distribution imbalance and component defects. Mass distribution imbalance in rotors is typically caused by design flaws or improper assembly. Component defects in rotors refer to phenomena such as corrosion, material loss, and structural damage [33,36]. Rotor imbalance generates additional centrifugal forces during operation, which are transmitted to bearings and supports. This causes bearing wear and increases overall machine vibration, with the amplitude of vibrations generated by rotor imbalance superimposing on the rotor’s power frequency. Such conditions heighten equipment wear and fault risks, making timely diagnosis and correction of rotor balance status crucial for maintenance [34–36].

The differential equation of motion of the rotor axis is as follows when the rotor is unbalanced:

where, x is rotor axial displacement, y is radial displacement of rotor, M is rotor mass, m is rotor eccentricity mass, e is eccentricity,

Rotor Rubbing

Rotor rubbing is a critical mechanical fault, typically referring to unintended contact between the rotor and stator. This wear can be caused by multiple factors, including rotor dynamic instability, bearing damage, excessive axial displacement of the rotor, or mechanical imbalance [37,38]. Friction primarily manifests in radial and axial forms. Radial friction mainly affects the radial movement of heavy-duty gas turbine lever-type rotors with minimal impact. Axial friction includes full circumferential rubbing and localized friction. Such axial wear causes rotor displacement and vibration along the axis. Severe axial wear alters inter-rotor pressure distribution, disrupts normal unit operation, and significantly impacts rotor performance [39,40]. Rotor rubbing fault can lead to local wear, free vibration of the pull rod rotor, which may lead to component deformation and rotor imbalance fault, and may also change the speed of the rotor [41]. During the operation of a gas turbine, the rotation speed of the rotor is very fast, and changing the speed of the rotor is very dangerous, which may damage the entire unit [42].

The motion differential equation for rotor radial wear is as follows:

The motion differential equation for axial radial wear is as follows:

where,

Bearings wear, loosen, and lubrication failures are common issues in gas turbines. Bearing wear refers to material degradation on or within the bearing surfaces, primarily caused by inadequate lubrication, excessive loads, or material defects. This leads to increased clearance between bearings, compromising rotor rotation precision and stability. Loose bearings occur when components aren’t securely mounted on shafts, often due to improper installation, deformed bearing housings, or loose bolts. Such misalignment intensifies vibrations and negatively impacts turbine operation stability. Poor lubrication results from insufficient oil supply, substandard lubricants, or clogged filters, accelerating wear and reducing the turbine’s operational lifespan [43,44].

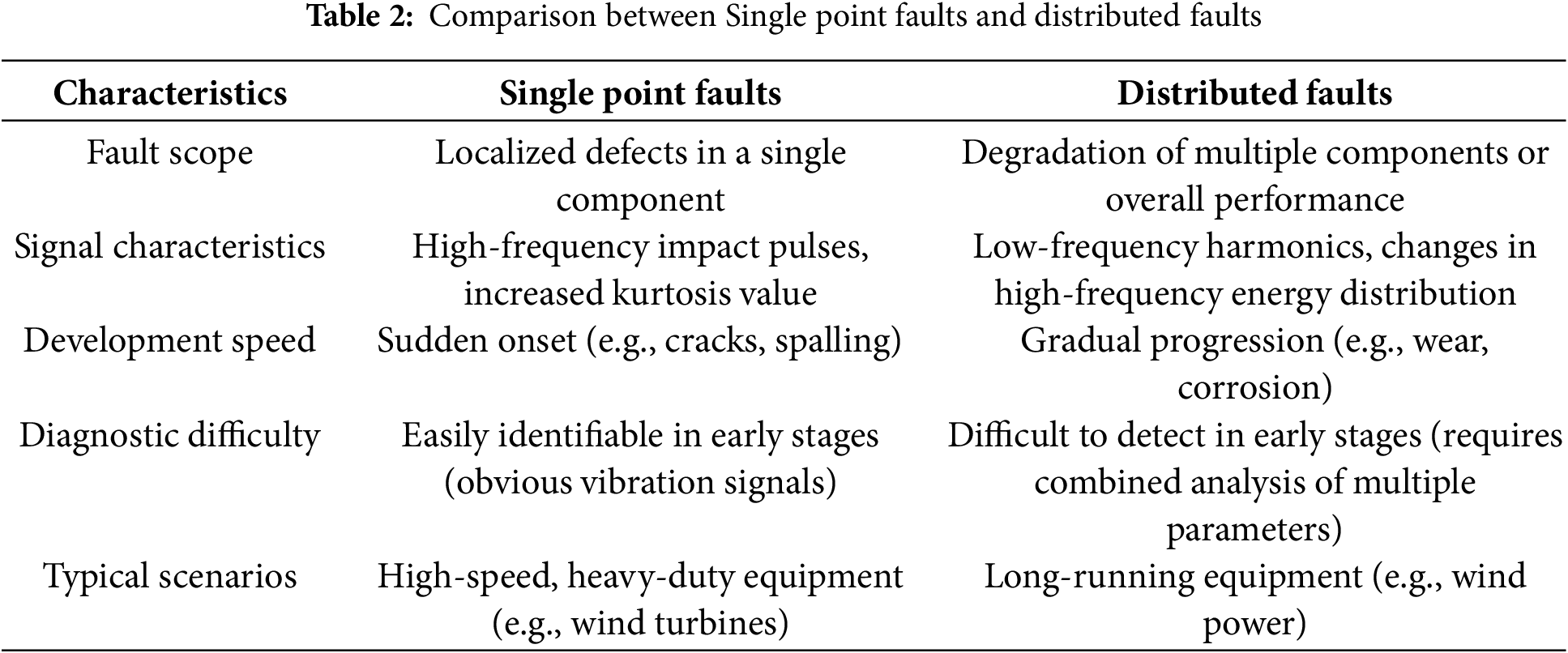

Moreover, the single point faults (e.g., cracks, spalls), distributed faults (e.g., wear, corrosion), and compound faults (e.g., a combination of single-point and distributed faults) are research hotspot. Bearing faults are a primary cause of failures in rotating machinery. Single point faults, such as cracks or spalls, often result from localized stress concentrations, while distributed faults, like wear or corrosion, develop gradually over time. Compound faults, which involve multiple fault types, pose significant challenges for diagnosis due to their complex signatures [45].

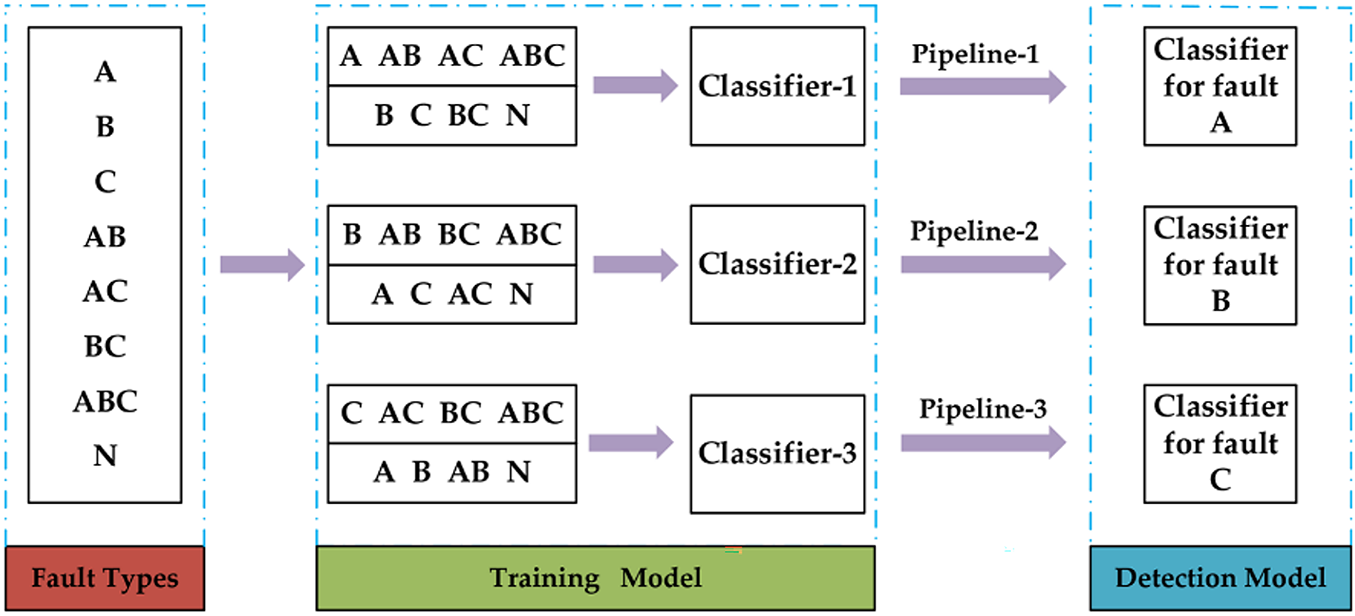

Single point faults are confined to a single component and do not spread to other parts. When rolling elements pass over the defect site, short-duration sharp impulse excitations are generated, leading to an increase in high-frequency components in the vibration signal. Time-domain parameters such as amplitude, variance, and kurtosis significantly deviate from their normal values. As shown in Fig. 2, A, B, and C represent three types of single faults, while AB, AC, BC, and ABC denote four categories of compound faults, and N stands for the normal operating condition. When detecting a specific fault type, the feature set used for training should be divided into a positive sample set that includes the fault type and a negative sample set that excludes it. By enabling the classifier to handle a binary classification problem, the complexity of the classifier can be reduced [46].

Figure 2: The principle of training for single fault classier. Reprinted with permission from reference [46]. © 2021 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

A distributed fault refers to the degradation of multiple components or the overall performance of a bearing, typically caused by manufacturing errors, improper installation, or prolonged operation. Distributed faults affect multiple components or the bearing as a whole, such as wear, corrosion, or scuffing [47]. These faults develop gradually over time and are difficult to detect in their early stages. Fault characteristic frequencies and their harmonics appear in the low-frequency band, while energy increases in the high-frequency band. The comparison between Single point faults and distributed faults is shown in Table 2.

In summary, Single point faults and distributed faults may coexist, necessitating the development of multi-feature fusion diagnostic methods. Therefore, further research on compound fault diagnosis is required. Given the massive volume of vibration data involved in compound faults, leveraging deep learning to enhance fault classification accuracy is of paramount importance.

Combustion oscillation and flame flickering are abnormal phenomena that may occur during gas turbine combustion. Combustion oscillation refers to the occurrence of oscillations in the combustion chamber, primarily caused by uneven fuel-air mixing, improper burner design, and unstable combustion control systems. These factors intensify turbine vibrations and adversely affect operational stability. Flame flickering manifests as intermittent flickering of the combustion flame in the chamber, resulting from unstable fuel-air ratios, blocked burner nozzles, or malfunctioning combustion control systems. This phenomenon reduces combustion efficiency and increases pollutant emissions.

In gas turbine combustion processes, carbon soot formation and unburned fuel emissions are critical concerns. Carbon soot accumulation occurs when carbon particles from combustion build up in the combustion chamber, primarily due to high carbon content in fuel, insufficient combustion temperatures, and inadequate burning duration. This negatively impacts thermal efficiency while increasing pollutant emissions. Unburned fuel emissions refer to residual unburned fuel expelled from the combustion chamber, mainly caused by uneven fuel-air mixing, improper burner design, and malfunctioning combustion control systems. Such emissions not only waste fuel resources but also contribute to elevated pollutant levels [48,49].

Air compressor failures primarily involve three factors: fouling, wear, and blade failure. Fouling occurs when contaminants accumulate internally, including dust and impurities from the air supply and fuel, which reduce airflow efficiency and pressure output. Wear refers to wear on components like blades and vanes, caused by erosion from airborne particles and corrosion from fuel residues, ultimately compromising performance and lifespan. Blade failures manifest as cracks, deformation, or fractures, typically resulting from material fatigue, excessive stress, or manufacturing defects that negatively impact operational reliability [50–52].

Turbine blade failures primarily involve three types: corrosion, wear, and cracks. Corrosion occurs when corrosive components in combustion gases and cooling water erode the blade surface, compromising structural integrity and reducing turbine efficiency. Wear refers to material abrasion on both surfaces and interiors, caused by dust erosion from combustion gases and impurities in fuel, which adversely affects turbine performance and service life [53,54]. Cracks manifest as fissures on blades’ surfaces or internal structures, resulting from material fatigue, excessive stress, or manufacturing defects, ultimately impairing turbine reliability and operational effectiveness [55,56].

Blades are critical components in gas turbines, and blade Cracks reduce strength, decrease efficiency and power output, which compromise durability and reliability, and may even lead to fractures [57–59]. Blade cracks severely impact turbine performance and safety, increase maintenance costs, and potentially damage internal components, thereby reducing operational efficiency and reliability while raising both running and maintenance expenses [50,60]. The primary causes of blade cracks include:

(1) Thermal Fatigue. Thermal fatigue occurs due to rapid temperature changes in the blades during the varying operating conditions of a gas turbine. It arises because different sections of the blade experience varying degrees of thermal expansion or cooling effects. These uneven thermal changes induce cyclic thermal stresses, and over extended periods of cycling, thermal cracks develop in the blade material. These cracks typically propagate along the direction of thermal stress in the blade, gradually increasing its fragility and ultimately potentially leading to fracture.

(2) Fatigue Load. The blades continuously endure vibrations and pressure variations from the engine during high-speed rotation, and these repetitive fatigue loads can cause material fatigue and the formation of cracks. Fatigue can be categorized into high-cycle fatigue, low-cycle fatigue, and thermal fatigue. High-cycle fatigue is typically associated with vibration cycles experienced by the blades at high frequencies. This type of fatigue often occurs when the blade’s vibration frequency matches the external excitation frequency, causing a sharp increase in the amplitude of blade failure and leading to material fatigue. Low-cycle fatigue is related to fatigue cycles experienced by the blades at lower frequencies, which are usually associated with large strain amplitudes, such as thermal stress variations during startup and operation.

(3) Overstress. Blades typically consist of three parts: the blade root, blade body, and blade tip (or shroud). Stress concentration tends to occur in the regions of the blade root and blade tip. Stress concentration refers to an abnormal increase in stress caused by geometric irregularities or dimensional changes in local areas, making the blades more prone to cracking in these regions and potentially leading to fracture.

(4) Creep. Creep is a critical issue faced by gas turbine blades during prolonged operation in high-temperature environments. The creep rate initially progresses slowly, but accelerates as the material’s internal structure undergoes gradual changes. This creep-induced deformation can cause blade deformation, including bending, twisting, or length variations. As plastic deformation intensifies, cracks may develop and eventually lead to fracture.

(5) Corrosion. Corrosion is a prevalent failure mode for gas turbine blades during operation, particularly when exposed to prolonged exposure to high-temperature environments containing corrosive compounds. This corrosion reduces blade mechanical strength and thermal resistance, leading to deformation, cracks, or even fracture. Persistent corrosion accelerates material degradation rates. Modern gas turbine blades typically employ anti-corrosion coatings and thermal coatings that provide physical and chemical protection against accelerated corrosion.

2.5 Analysis of Typical Fault Characteristics

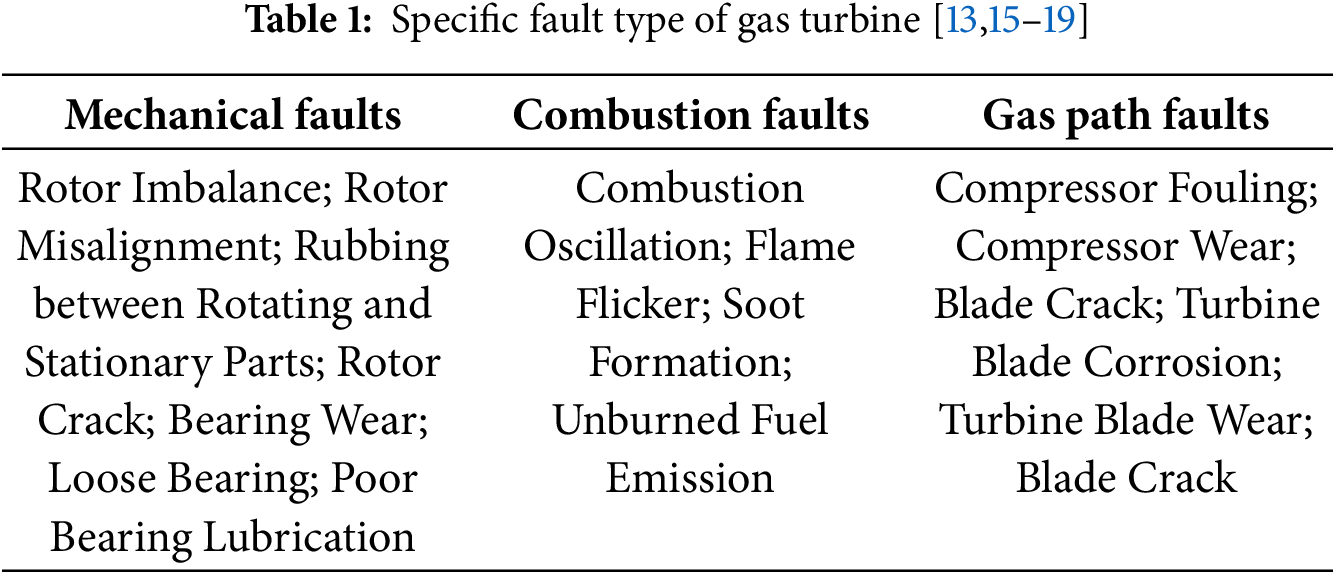

We have analyzed mechanical fault, combustion fault, and gas path fault in gas turbines, and provided detailed introductions to faults such as rotor imbalance, bearing wear, and compressor fouling. Through the analysis of these faults, the importance and necessity of gas turbine fault diagnosis have been fully demonstrated. Table 3 presents the main characteristics and causal factors of different types of faults summarized through a literature review.

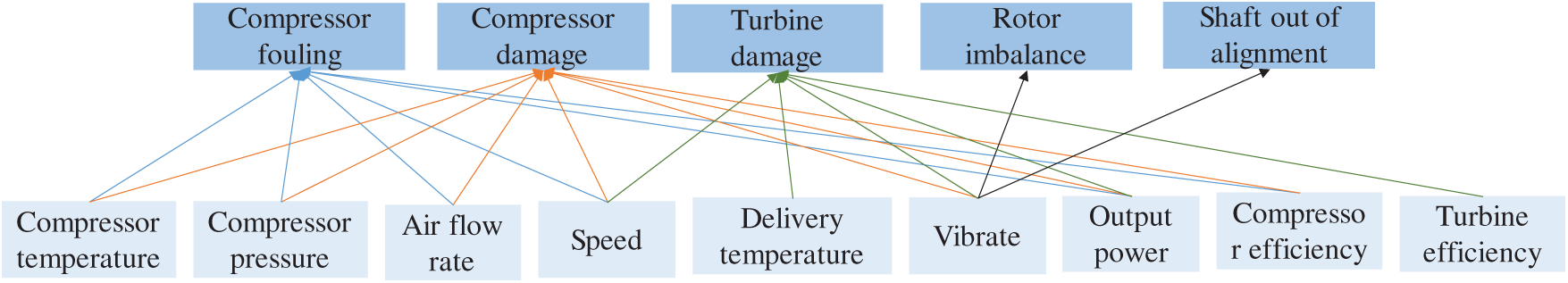

The key to gas turbine performance monitoring and fault diagnosis lies in analyzing changes in parameters related to the health status of gas circuit components, such as temperature, pressure, air, and fuel flow rates, to accurately determine whether faults have occurred. As critical power equipment, gas turbines require monitoring of multiple types of operational parameters. Common monitoring signals include mechanical, gas circuit, and combustion-related performance parameters. Mechanical parameter signals encompass vibration, rotational speed, and power output, primarily indicating mechanical failure conditions [51,54]. Gas circuit performance parameters mainly consist of pressure, temperature, flow rate, and efficiency, which reflect operational status and can detect abnormalities like gas line blockages or combustion oscillations [57]. The correlation between common faults and performance parameter changes is detailed in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Correlation between fault mode and performance parameter variation

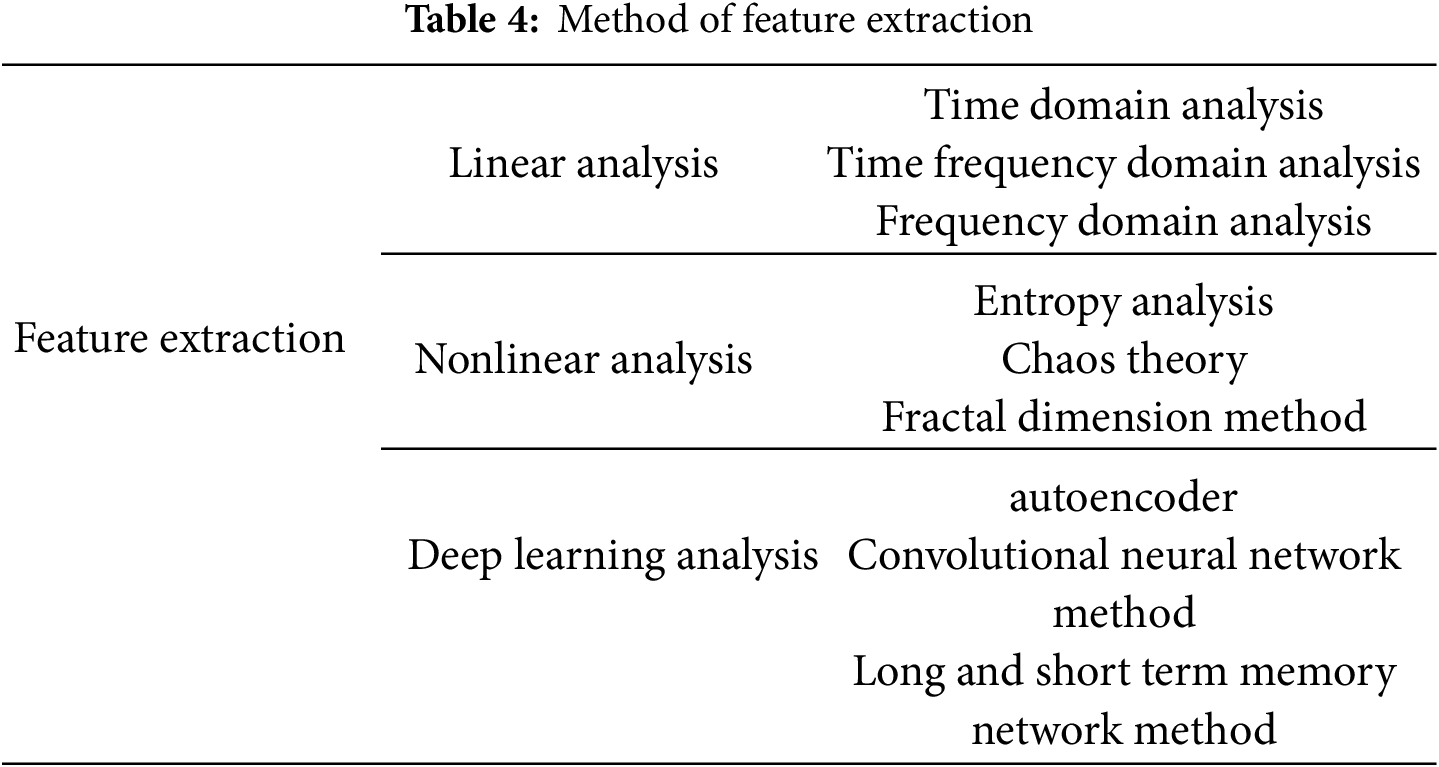

With the advancement of data acquisition technologies, data-driven fault diagnosis methods have gained widespread application. These approaches eliminate the need for precise physical models, enabling accurate health status assessment through operational data alone. As a critical component of fault diagnosis, the effectiveness of fault feature extraction directly impacts diagnostic outcomes [58,59]. Among various signal types, vibration signals-rich in fault information-are extensively utilized in feature extraction. However, noise and interference during signal acquisition often introduce deviations from ideal signals, necessitating proper signal analysis and feature extraction techniques to mitigate these errors [60,75]. Current mainstream feature extraction methodologies include linear analysis, nonlinear analysis, and deep learning approaches, as illustrated in Table 4.

Time-domain characteristics possess strong physical concepts, intuitive expressions, and computational simplicity, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis of gas turbine fault signals. These features can generally be categorized into two types [67,68,76]. Among them, dimensional characteristics demonstrate heightened sensitivity to operational condition variations in gas turbines, allowing them to better reflect the turbine’s operational status. In contrast, dimensionless characteristics remain largely unaffected by external disturbances such as turbine operating conditions and environmental factors, thus providing a more stable representation of operational status information. To enhance fault diagnosis accuracy, we typically employ a combination of dimensional and dimensionless characteristic values, achieving a balance between stability and adaptability.

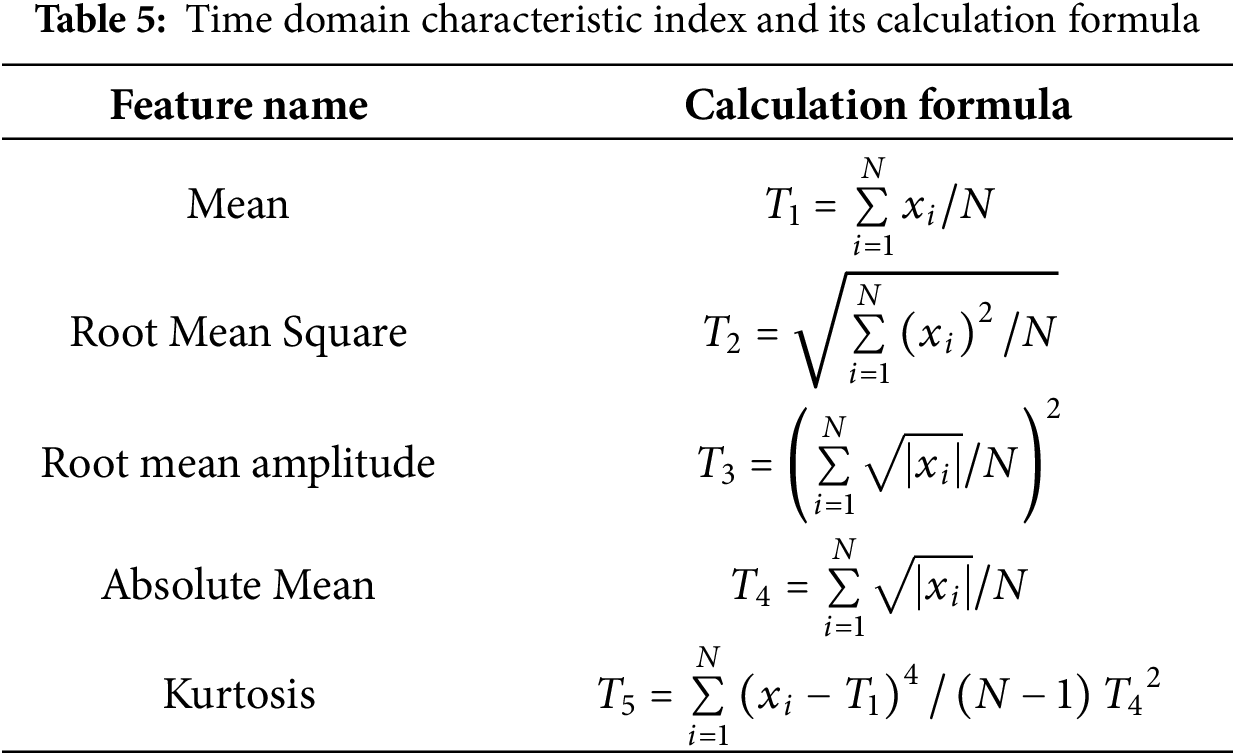

The time-domain analysis method directly examines the waveform of the original signal, utilizing its time-domain characteristics for fault detection. Commonly used time-domain features include mean, standard deviation, peak-to-peak value, kurtosis, waveform factor, and margin factor. This approach primarily employs statistical principles to characterize the relationship between signals and time [69,77]. Let a discrete-time sequence signal be defined as, where N represents the number of sampling points. The commonly used time-domain feature indicators are listed in Table 5.

3.1.2 Frequency Domain Analysis

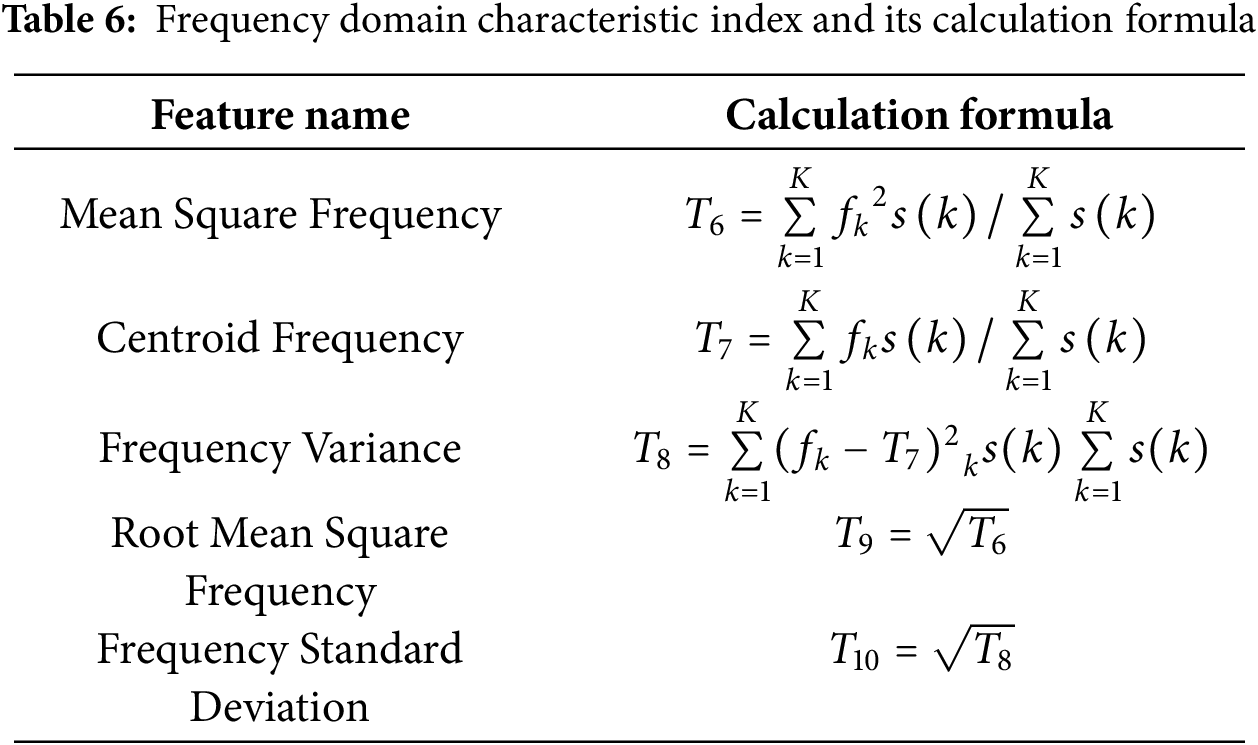

Frequency domain analysis involves examining a signal’s frequency spectrum. When equipment such as gas turbines experiences faults, their signal frequency patterns undergo changes. To extract fault information from the frequency domain, engineers can analyze spectral parameters like frequency and peak values for equipment diagnostics. Key methods in domain analysis include Fourier transform analysis, refined spectral analysis, power spectrum analysis, and Hilbert envelope spectrum analysis [62,78].

Domain analysis converts time-domain signals into the frequency domain using frequency as the reference, with the Fourier transform being the primary analytical method [79,80]. By applying the fast Fourier transform to gas turbine fault signals, we can obtain fault characteristics containing frequency-domain information. The commonly used frequency-domain feature indicators and their calculation formulas are listed in Table 6.

Traditional time-domain and frequency-domain analysis methods are inadequate for processing non-stationary signals, while conventional approaches demonstrate limitations in handling complex dynamic signals, failing to meet fault diagnosis requirements. In contrast, the time-frequency domain analysis method effectively addresses unstable and nonlinear signals, making it widely adopted in feature extraction for fault diagnosis [81,82].

Deep learning demonstrates exceptional capability in feature extraction, making it ideal for analyzing operational data from monitoring equipment [83,84]. Compared to other methods, deep learning approaches can extract deeper-level features from data, significantly boosting efficiency. Self-encoders excel at processing nonlinear data and are widely used in feature reduction applications.

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and their variants (such as LSTM, GRU), construct deep architectures by stacking multiple layers (e.g., convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers). Each layer is responsible for learning features at different levels of the data. Low-level features: These typically capture local and fundamental characteristics of the data, such as edges, textures, colors (in image processing), or temporal patterns, local dependencies (in sequence data processing). High-level features: Formed by combining low-level features, these create more abstract and global representations, capturing semantic information or complex patterns in the data.

CNNs excel in feature extraction and have been widely adopted in fault diagnosis applications. Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM) are particularly suited for classifying and predicting time-series data. Traditional feature extraction methods demonstrate limitations when handling complex coupled systems, often resulting in biased features due to human experience and subjective factors. Deep learning-based feature extraction approaches minimize human influence through hierarchical architectures, enabling direct identification of relevant features from raw data [84,85]. With advancements in computing power, deep learning models can now extract high-quality features from complex datasets, which is crucial for cutting-edge research and practical applications in feature extraction [65,86].

4 Fault Diagnosis Methods of Gas Turbine

In real-world industrial settings, turbine data are often incomplete, noisy, or unbalanced, which degrades diagnostic accuracy. To mitigate this, researchers have explored data augmentation techniques (e.g., adding synthetic noise) and semi-supervised learning approaches that leverage both labeled and unlabeled data. These methods show promise in improving model robustness under non-ideal conditions.

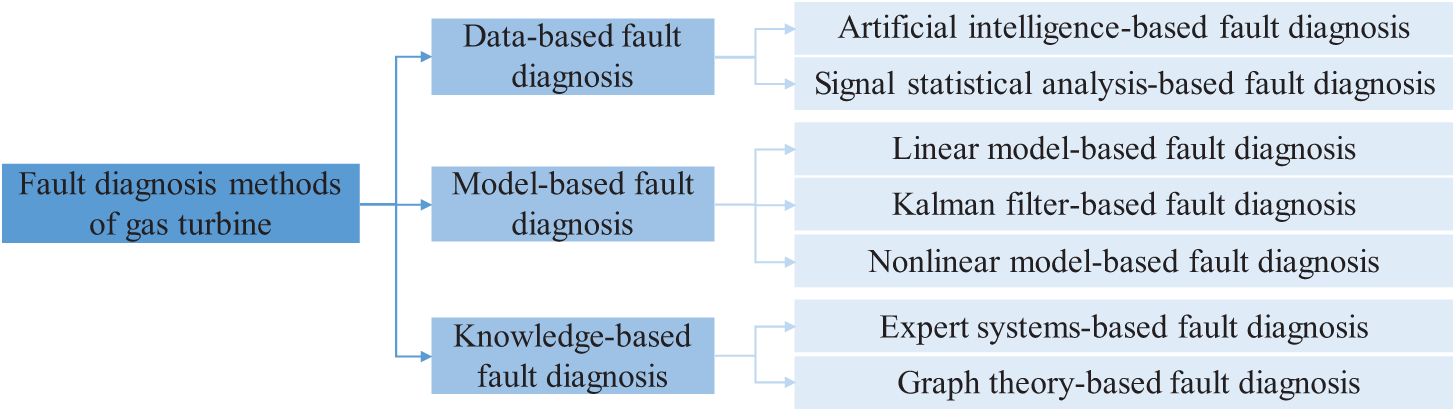

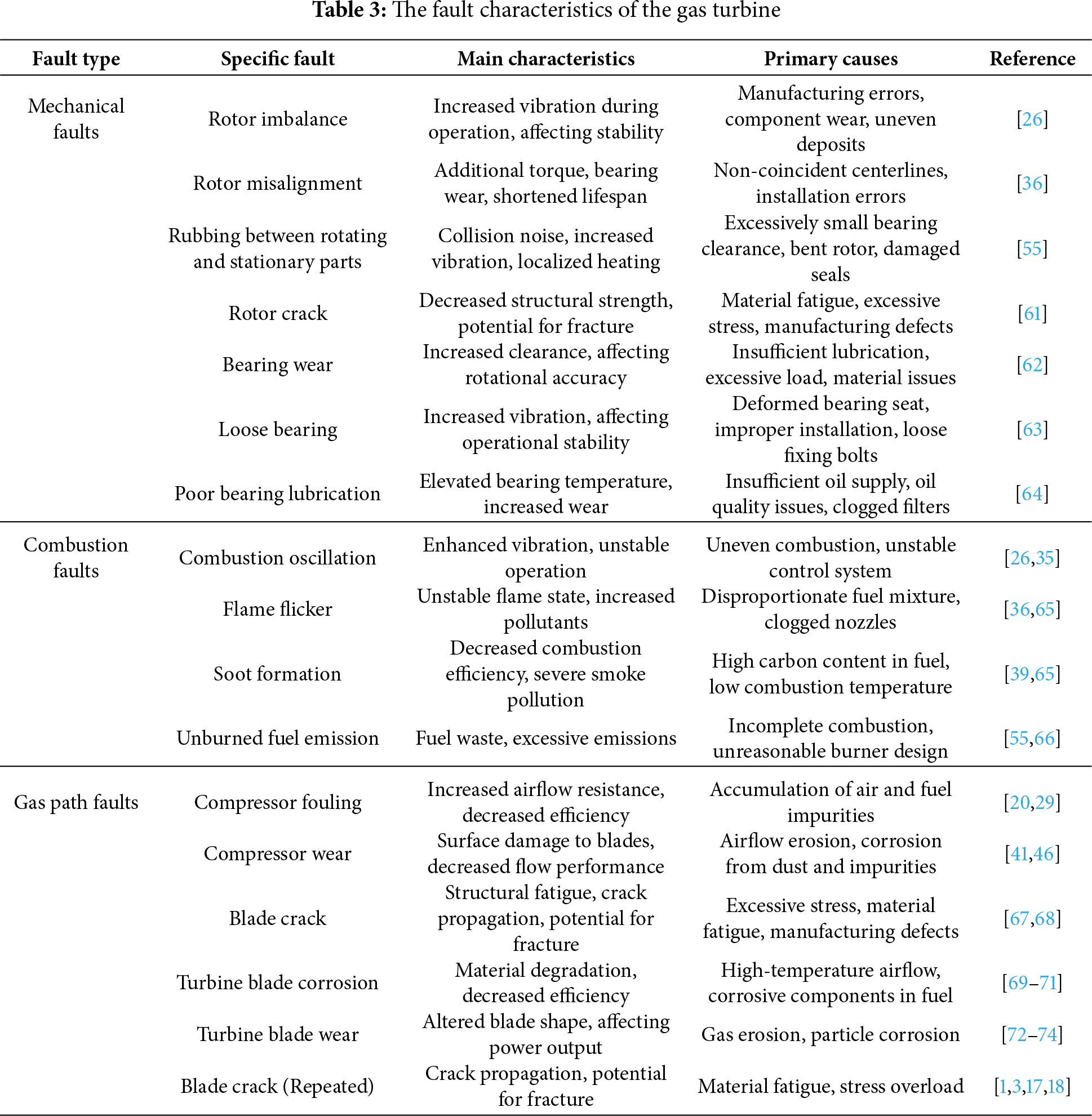

Gas turbine health status diagnosis serves as one of the most critical approaches for maintenance, while advancements in fault diagnosis technology play a vital role in enhancing operational safety and economic efficiency [87,88]. The emergence of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms has provided new perspectives for researchers worldwide in gas turbine fault diagnosis. To improve operational safety and maintenance cost-effectiveness, scholars have increasingly focused on three major component failures and airflow path degradation in gas turbines [63,66]. These diagnostic studies are categorized into three methodologies: data-based fault diagnosis, model-based fault diagnosis, and knowledge-based fault diagnosis, which are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Fault diagnosis methods of a gas turbine

4.1 Data-Based Fault Diagnosis

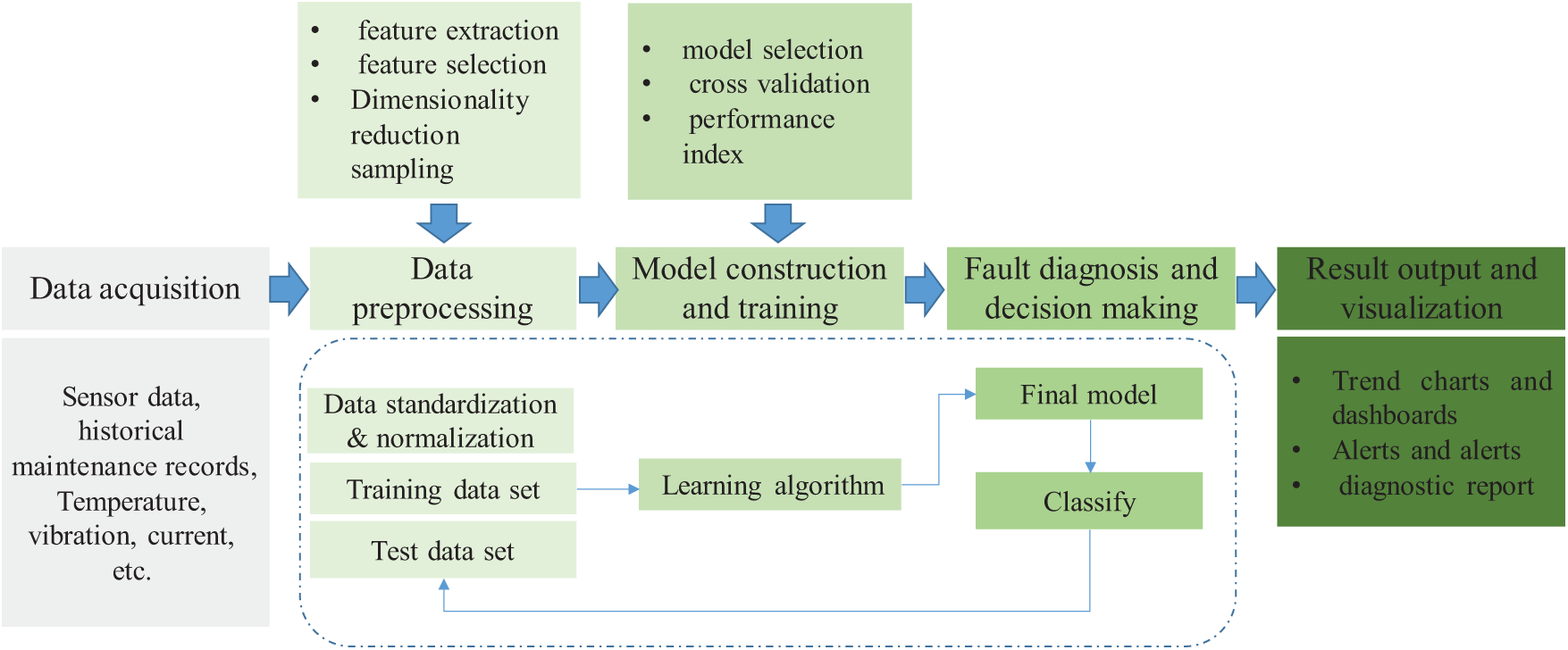

Data-based fault diagnosis employs machine learning algorithms to analyze operational data, identifying discrepancies between malfunctioning and healthy datasets. The flow chart of the data-driven fault diagnosis method of the gas turbine is shown in Fig. 5 and the standard workflow involves:

Figure 5: Flow chart of data-driven fault diagnosis method of gas turbine

1) Collecting both fault and health datasets, then proportionally dividing them into training and test sets.

2) Extracting features through preprocessing.

3) Training the model iteratively until optimal performance is achieved.

4) Conducting cross-validation using test set data [89–91].

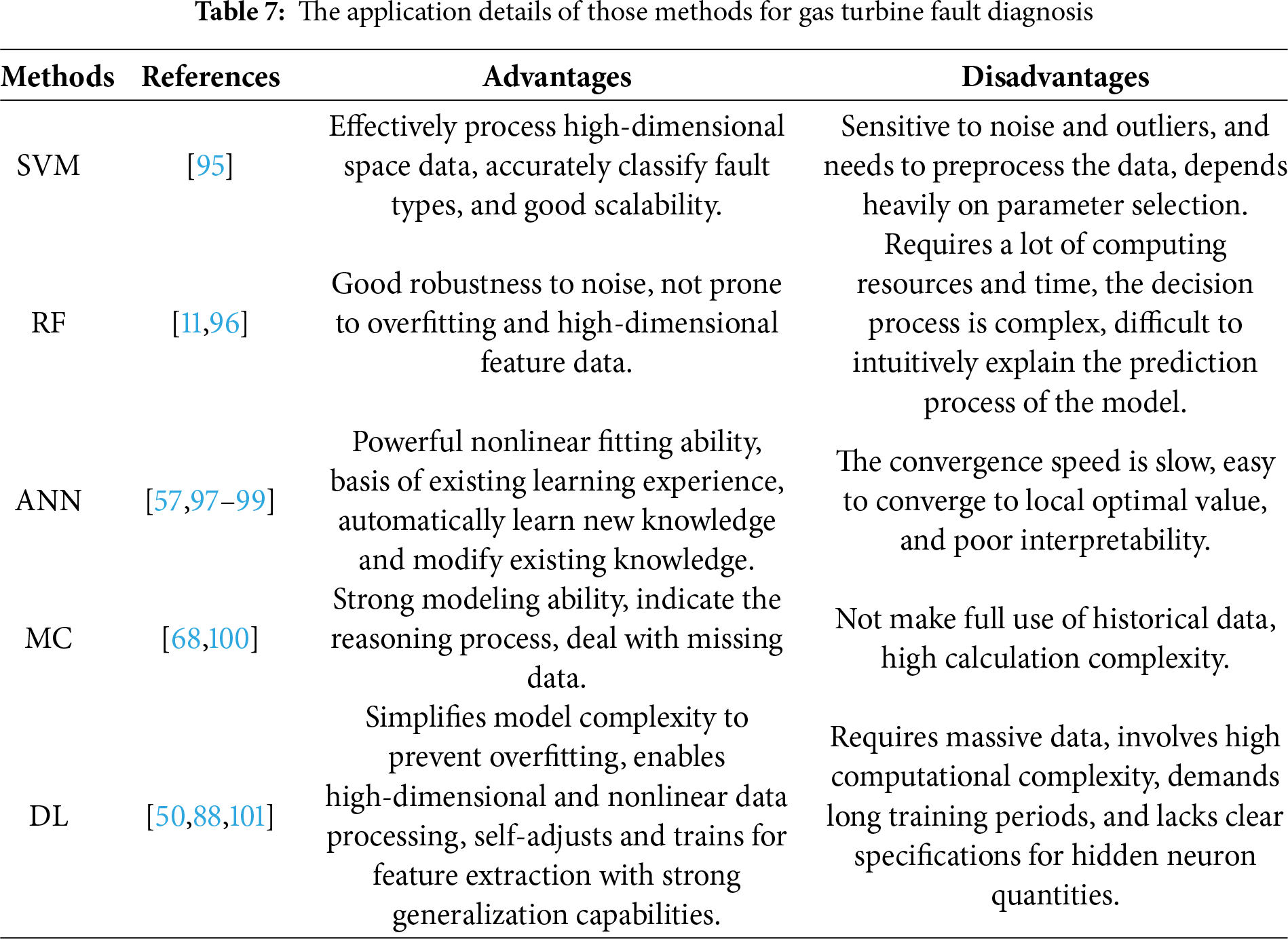

Machine learning enables computer systems to extract patterns and correlations from large datasets, allowing them to make predictions and classifications. Current machine learning approaches include Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), Markov Chains (MC), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and Deep Learning (DL) [64,70,92–94]. The application details of those methods for gas turbine fault diagnosis are summarized in Table 7.

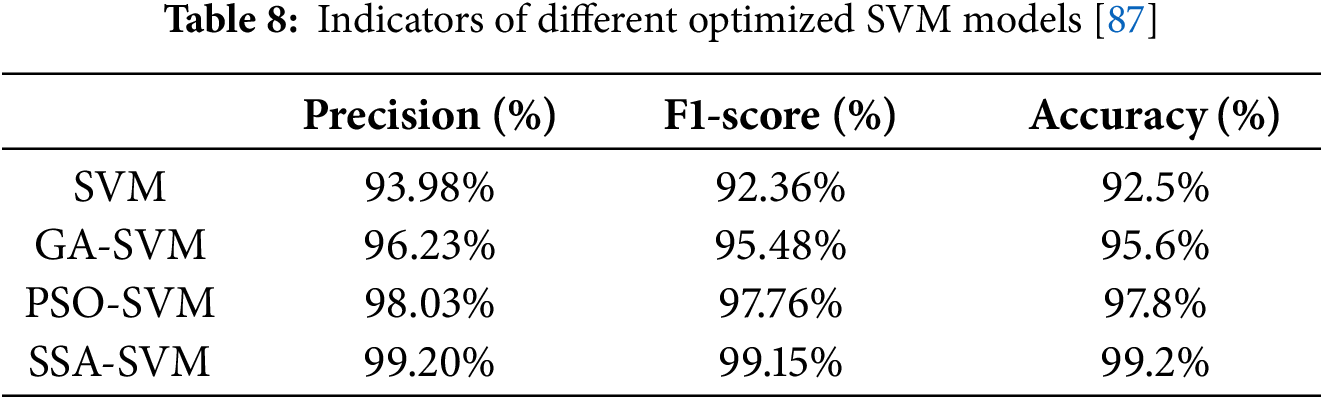

SVM is a widely-applied supervised learning algorithm primarily utilized for classification and regression analysis. SVM operates by identifying an optimal hyperplane that effectively separates samples of different classes, while simultaneously maximizing the margin between the two classes. This hyperplane is referred to as the decision boundary, and the support vectors are the sample points that are closest to this decision boundary. A newly proposed Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) was employed to optimize the SVM model, aiming to search for the optimal combination of penalty factor and kernel function parameters [87]. The comparative experimental results of different optimized SVM models are presented in Table 8 with evaluation metrics including confusion matrices, among others.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are mathematical models inspired by biological neural networks [102,103]. They simulate the brain’s neural systems and its response mechanisms to external stimuli to solve complex problems. The concept of artificial neural networks can be traced back to the 1940s when McCulloch and Pitts proposed the MCP neuron model in 1943. In the 1950s, Rosenblatt developed the perceptron model for binary classification tasks. It wasn’t until the 1980s, ANN sparked widespread interest across multiple disciplines with the advent of backpropagation algorithms [71,101,104].

Biological neurons are the fundamental functional units of biological nervous systems. Similarly, artificial neural networks are composed of artificial neurons that are extensively interconnected based on the simulation of the structure and function of biological nervous systems. Artificial neural networks can solve nonlinear, complex mathematical problems and perform operations involving complex logic by organizing and adjusting the connection relationships among artificial neurons. The connection relationships between artificial neurons can be represented by directed weighted arcs, which correspond to the axon-synapse-dendrite structure in human brain neurons. These arcs consist of two parts: direction and weight. The direction represents the path of information transmission, while the weight represents the strength of the interaction between artificial neurons, influencing the degree to which input signals activate the neurons [100,105].

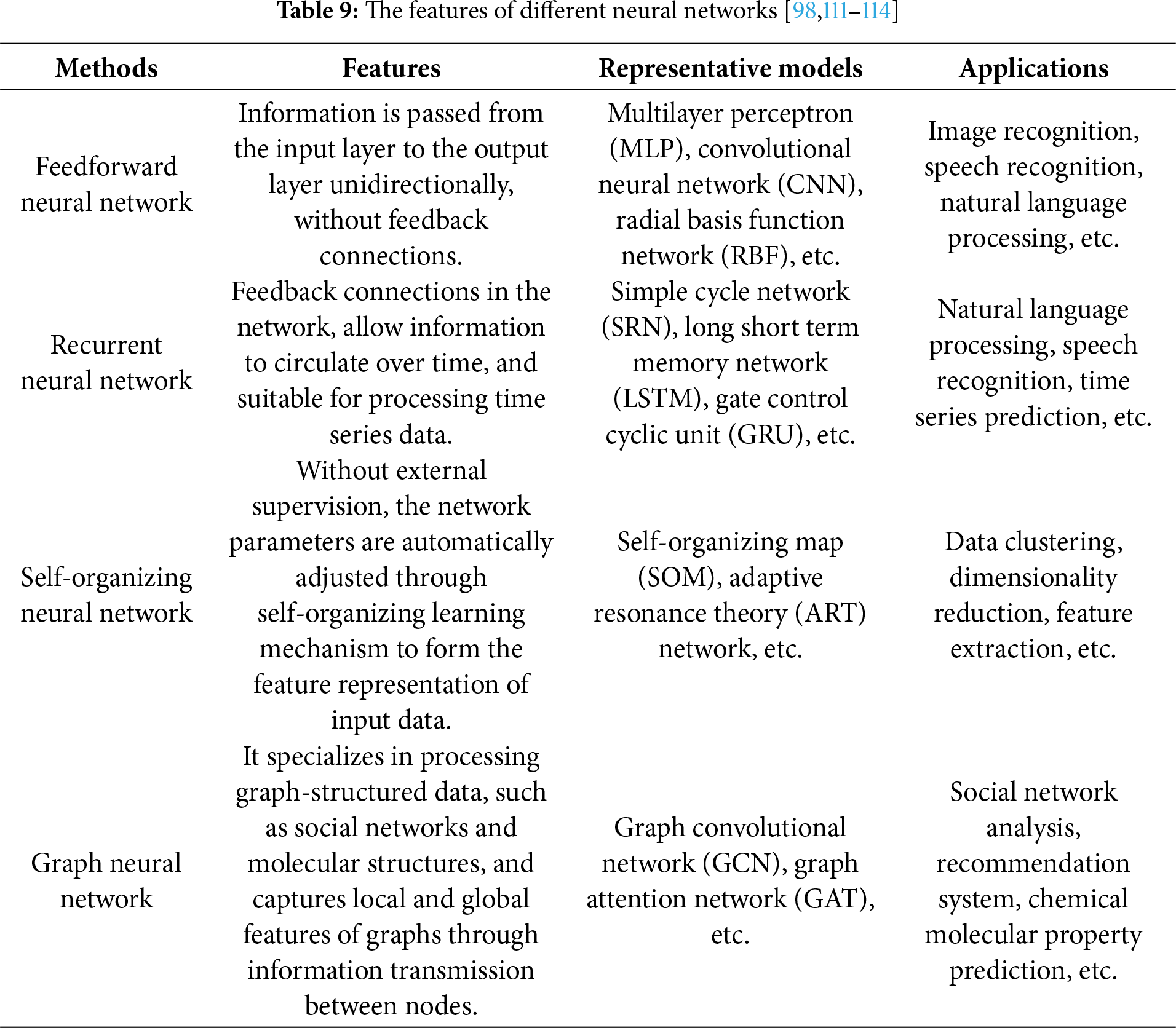

There are different neural networks, which are feedforward neural networks, recurrent neural networks, graph neural networks, and self-organizing neural networks by network structure classification [106].

In a feedforward neural network, information flows from the input layer through hidden layers for progressive processing before being output from the final layer. This process involves feature extraction and abstraction at each layer, with unidirectional propagation that excludes any recurrent connections. Each layer’s output depends solely on its preceding layer’s input, maintaining independence with subsequent layers. Common feedforward neural networks include Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Deep Feedforward Networks, and Deep Convex Networks [107–109]. These networks typically disregard temporal lag effects between inputs and outputs, focusing instead on mapping relationships that can be visualized as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs).

In recurrent neural networks (RNNs), neurons not only receive input signals from other neurons but also generate their own feedback. The feedback mechanism in RNNs operates through a unique property: the output of a neuron becomes its new input, shaping its next output based on all previous outputs. These networks typically account for temporal delays between inputs and outputs, making them ideal for processing sequential data such as time series prediction and natural language processing. Common FNN variants include Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs), Hopfield networks, and Gate-Regulated Recurrent Units (GRUs). RNNs enable internal feedback loops through recurrent connections, which can be visualized using directed circular graphs [72,95,98].

A self-organizing neural network is a self-learning neural network. It autonomously identifies essential attributes and inherent patterns in information, thereby adaptively modifying its structure and parameters. A typical self-organizing neural network architecture consists of an input layer and a competitive layer. This type of network primarily handles classification and clustering tasks [110].

We summarize the characteristics, typical models, and application scenarios of different approaches, which are shown in Table 9.

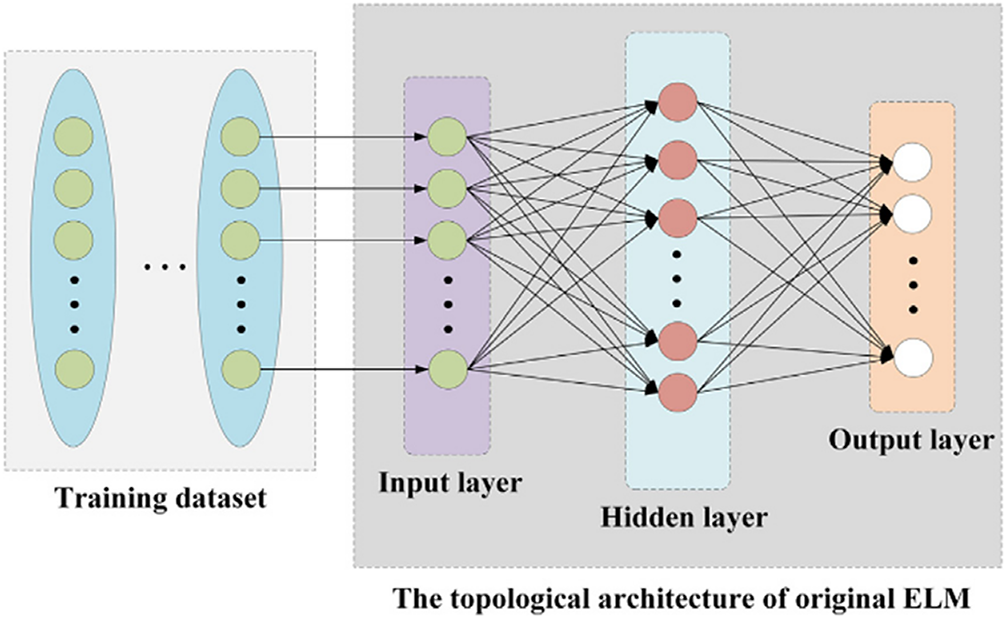

The research and application of deep learning in the field of gas turbine fault diagnosis, through automatic extraction of data features and modeling of complex nonlinear relationships, has significantly improved the accuracy, real-time, and generalization ability of fault detection [115–117]. Extreme learning machine is a single-hidden layer feedforward neural network with an input layer, hidden layer, and output layer, which is shown in Fig. 6 [46].

Figure 6: The typical architecture of an extreme learning machine

Traditional methods rely on manual extraction of time-domain and frequency-domain features (such as mean, variance, spectral peaks), whereas deep learning models like CNNs and LSTMs can directly learn multi-level features from raw data (vibration signals, images, logs, etc.), reducing dependence on expert knowledge. Industrial equipment failures typically manifest as complex nonlinear dynamic processes, where deep learning models can capture latent patterns that traditional methods struggle to model. By integrating multi-source data such as vibration signals, temperature, pressure, and acoustic signals through multimodal fusion networks, diagnostic robustness is enhanced. End-to-end deep learning models can be deployed on edge devices for real-time monitoring, while transfer learning techniques enable rapid adaptation to new equipment or operating conditions, reducing the cost of data annotation [118–120].

When the number of samples in one class in a dataset is significantly smaller than that in another class, the model may tend to predict the majority class, leading to a decline in classification performance for the minority class. SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) is a classic algorithm designed to address class imbalance in datasets. It enhances the model’s ability to recognize the minority class by generating synthetic samples to increase the quantity of minority class samples [82].

To address the ‘black box’ nature of deep learning, researchers are developing explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as SHAP values, to interpret model decisions. Additionally, incorporating physical domain knowledge into deep learning models can improve transparency and trust in safety-critical systems.

4.2.1 Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

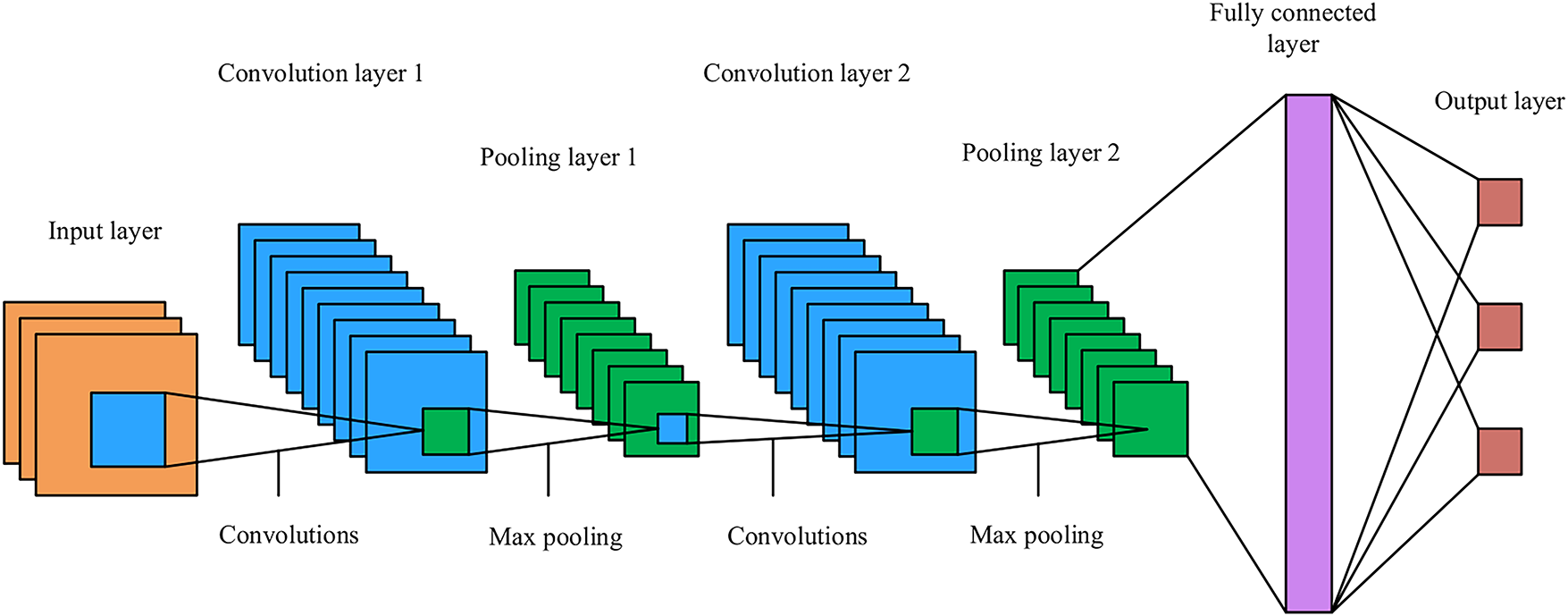

CNN is one of the representative algorithms in the field of deep learning, which can perform convolutional calculations, excel at extracting image features, and perform exceptionally well in image classification tasks. A convolutional neural network (CNN) primarily consists of an input layer, convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers with Softmax activation, and an output layer as shown in Fig. 7 [87]. The core component of CNN is the convolution-pooling layer. Convolutional layers extract features by applying convolution kernels to input images, featuring weight-sharing characteristics that reduce network parameters and prevent overfitting caused by excessive weights. Pooling layers reduce neural network parameters by compressing features extracted from convolutional layers through downsampling. Common pooling operations include maximum pooling and average pooling [97,99,121].

Figure 7: Architecture of a convolutional neural network. Reprinted with permission from reference [87]. © 2023 Production and hosting by Elsevier Ltd. on behalf of Chinese Society of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CNN, renowned for its powerful deep feature extraction capabilities that eliminate the need for tedious manual feature extraction, has been adopted by researchers worldwide to diagnose gas turbine health status. Conventional CNN models typically employ Softmax activation functions in their final layer to transform input values from previous layers into outputs. However, the Softmax function may cause gradient vanishing or explosion, which can hinder model training. Additionally, this approach increases model complexity and computational costs when handling tasks with multiple categories.

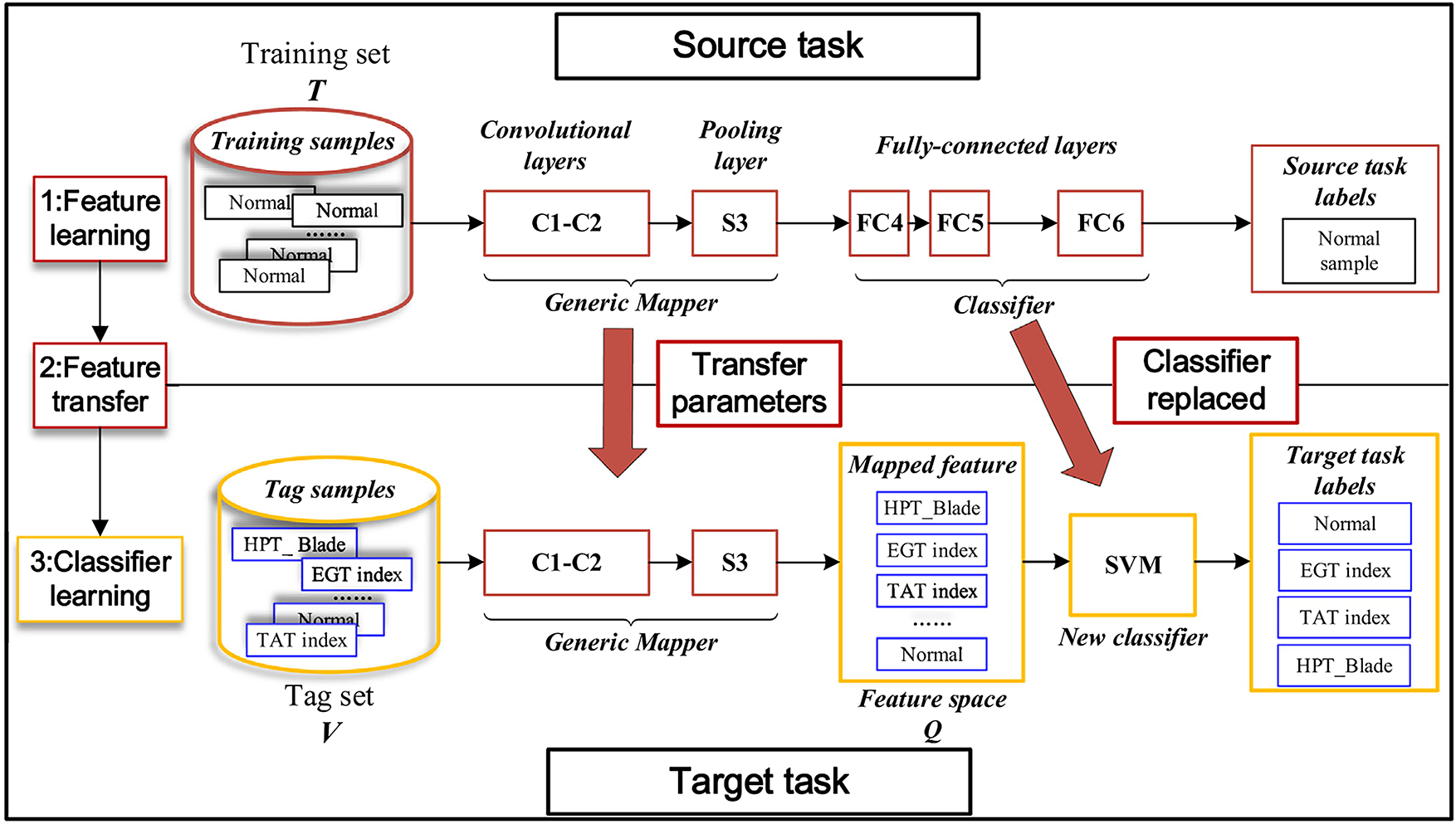

The superior classification capability of CNNs stems from their ability to learn rich feature representations from large annotated datasets. However, this characteristic currently limits CNN applications in scenarios with limited sample sizes. A transfer learning approach combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) is demonstrated to efficiently transfer the feature representations learned by CNNs on large-scale annotated normal gas turbine datasets to fault diagnosis tasks with limited data [15]. A mapping method is designed to extract fault dataset features by leveraging internal layers trained on normal datasets, while employing SVM for fault detection. Experimental results show that despite differences between the two datasets, the transferred feature representations significantly enhance fault diagnosis performance while markedly reducing individual variations and data noise effects. Moreover, the internal layer of the CNN can act as a generic mapper, which can be trained on one annotated dataset and then reused on other target tasks, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Transferring parameters of CNN. Reprinted with permission from reference [15]. © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

4.2.2 Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

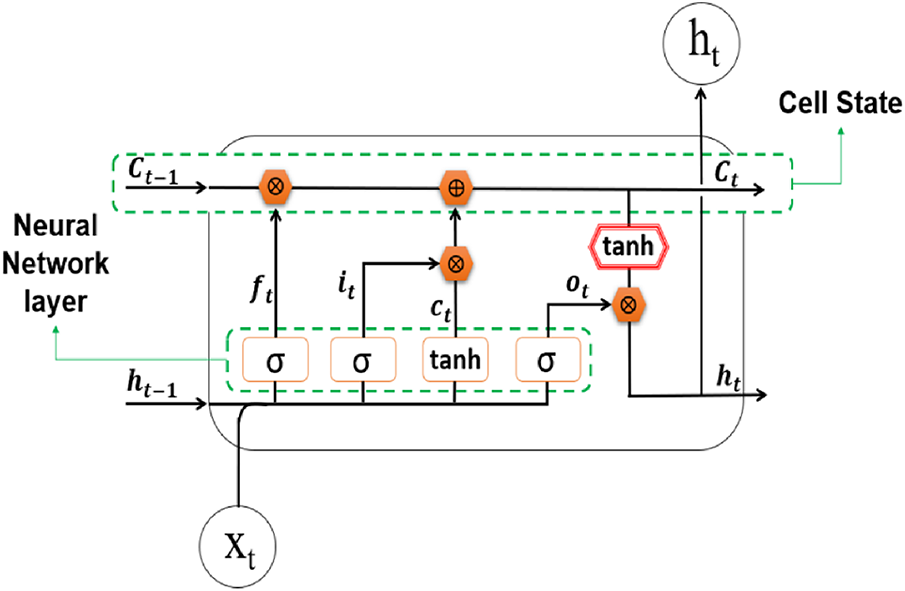

LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) is a special type of recurrent neural network (RNN) specifically designed to address the issues of gradient vanishing and gradient explosion encountered by traditional RNNs when processing long sequence data. A general view of an LSTM is shown in Fig. 9. This enables it to better capture and learn long-term dependencies within sequential data [73,122,123]. In recurrent neural networks (RNNs), the output of neurons is determined by weights, biases, and activation functions through a chain-like structure with fixed parameter settings at each time step. When processing longer sequences using gradient descent optimization for weights, the system must consider information from all preceding time points while accumulating loss function values. Additionally, the application of activation functions requires derivative calculations, which involve multiplying activation functions. This computational process makes RNNs prone to issues like gradient explosion or gradient disappearance, rendering them unsuitable for handling long sequence data [2,7,123].

Figure 9: A general view of an LSTM. Reprinted with permission from reference [50]. © 2024 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

To address the limitations of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), researchers developed LSTM by enhancing RNNs. The LSTM architecture introduces three gate mechanisms: forget gate, input gate, and output gate—to regulate information flow, along with a state transfer mechanism for storing transmission states. These gate structures enable precise control over which information to retain, forget, or update at each time step, effectively resolving long-term dependency issues in RNNs and overcoming challenges like gradient explosion and vanishing gradients in long sequence data processing.

4.3 Knowledge-Based Fault Diagnosis

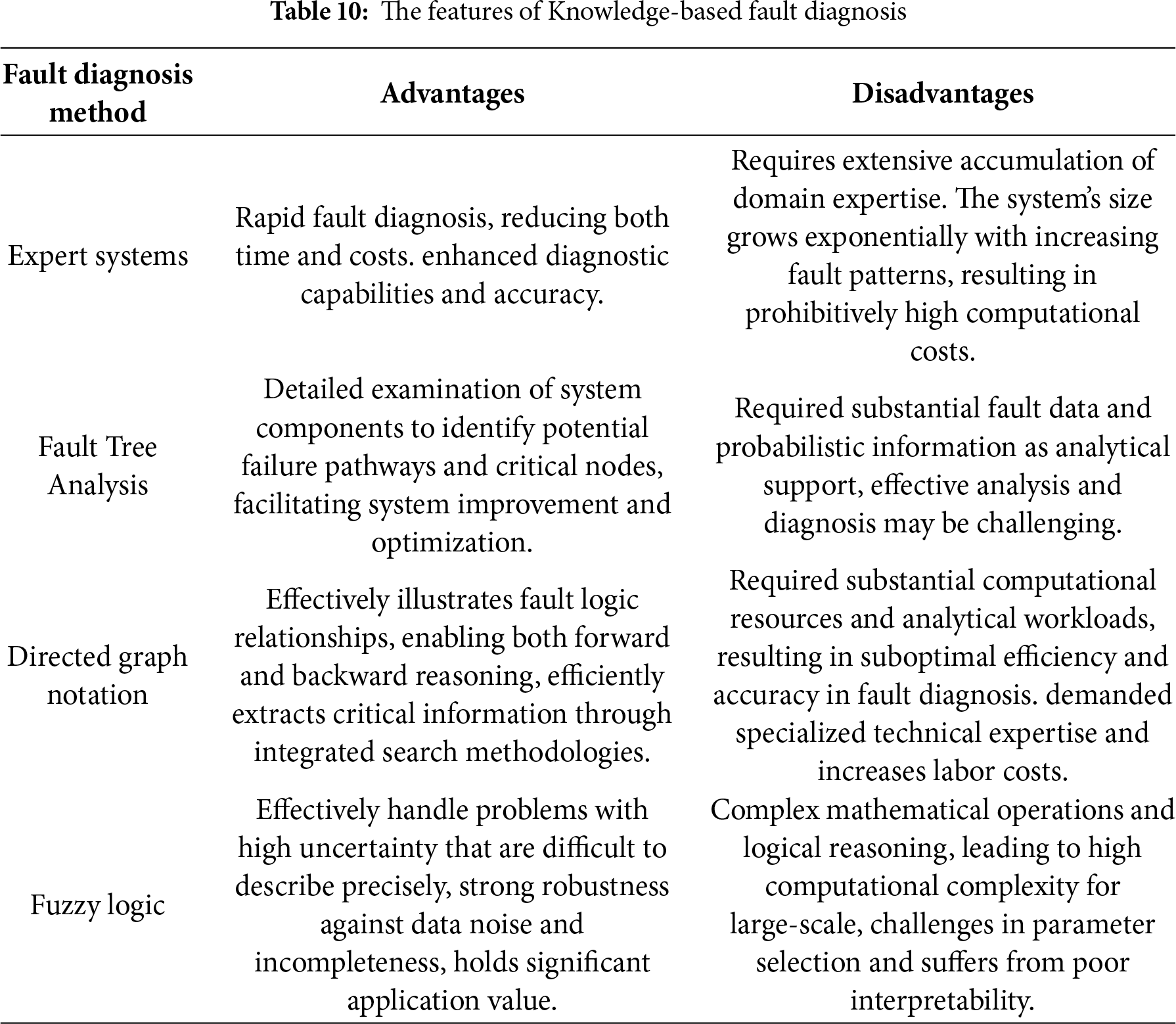

Knowledge-based fault diagnosis methods establish knowledge bases by accumulating effective experience and expertise. Through continuous monitoring of equipment status, classifiers analyze observed data to determine how closely the equipment operational conditions match predefined knowledge base entries. This matching evaluation enables accurate fault detection. Current knowledge-based approaches primarily include expert systems, fault tree analysis (FTA), signed directed graphs, and fuzzy logic.

This kind of method is highly interpretable, in line with engineering logic, has low dependence on data, adapts to structured problems, security and compliance assurance. However, the disadvantages of this approach are also obvious. The cost of knowledge acquisition and update is high, the ability to deal with unknown faults is poor, the modeling of complex systems is difficult, and the ability to recognize complex patterns is insufficient. The advantages and disadvantages of this fault diagnosis method are shown in Table 10.

Obviously, knowledge-driven approaches demonstrate significant advantages in interpretability, security, and data efficiency. However, their implementation remains constrained by knowledge acquisition costs and complex pattern processing capabilities. Looking ahead, the advancement of hybrid intelligence technologies will further expand their application scope, particularly in scenarios requiring high reliability, compliance, or human-machine collaboration, where they will continue to play a pivotal role.

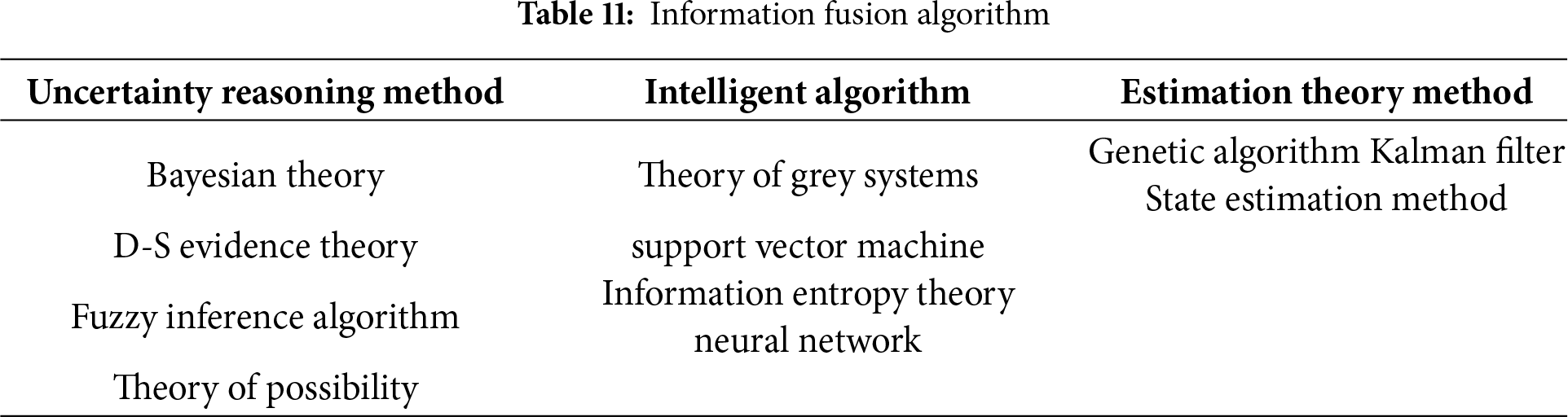

Information fusion is an information processing technology that integrates data from multiple sources through computer analysis guided by specific criteria, aiming to obtain more valuable, complete, and accurate information than any single source. The development of information fusion technology originated in the 1970s, when it was synonymous with data fusion. However, with the rapid advancement of information technology, the definition of information has expanded significantly. Consequently, information fusion now encompasses not just data integration but also multi-sensor fusion, image fusion, feature fusion, classifier fusion, and other aspects. Research in this field primarily focuses on two core areas: information fusion patterns and algorithms. The foundational models and frameworks of information fusion determine how data is organized, processed, and integrated. Meanwhile, fusion algorithms serve as the key implementation methods, utilizing various mathematical tools and techniques to comprehensively process information from different levels and sources.

Research in information fusion technology primarily focuses on two core domains: information fusion patterns and algorithms. The system’s model and framework form the foundational architecture of information fusion, determining how information is organized, processed, and integrated. Information fusion algorithms, meanwhile, serve as the key implementation mechanism. These algorithms encompass various mathematical tools and techniques designed to comprehensively process information from different levels and sources.

Among various fusion algorithms, estimation theory methods hold a significant position. These methods are primarily used for estimating and predicting target states, with the most representative being Kalman filters and their extended variants. In addition to estimation theories, uncertainty reasoning methods constitute another major category in information fusion. Such approaches focus on processing uncertain information through frameworks like fuzzy theory, probability theory, and evidence theory. They effectively address uncertainties and ambiguities in information, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of fusion outcomes. Table 11 shows the information fusion algorithm.

With the advancement of sensor technology, it has become feasible to deploy numerous sensors on target equipment to collect multidimensional operational data. The fusion diagnosis method, integrating big data and deep learning technologies, aims to enhance both the efficiency and accuracy of fault detection. By consolidating data from diverse sources, this approach provides deep learning networks with richer input data, significantly improving their capability to diagnose equipment failures. Information fusion technology proves particularly effective in managing complex industrial systems, where coordinated efforts among various sensors and data sources enable comprehensive solutions for predictive maintenance and health monitoring. This methodology can be implemented at multiple levels, with fusion diagnosis primarily applied across three tiers: data layer, feature layer, and decision-making layer in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Flow charts of three information fusions

(1) Data layer fusion

Data layer fusion represents the most fundamental integration approach, processing acquired data directly without complex analysis. It involves collecting diverse raw data types from multiple measurement points, such as sound, vibration, and stress measurements. These data are consolidated into a unified dataset, where feature extraction and fault classification enable integrated fault diagnosis. This method’s advantage lies in preserving maximum data integrity while delivering optimal diagnostic outcomes. However, it requires substantial data volume, excessive redundant information, and demands significant time investment for analysis. Moreover, this approach is limited to integrating signals of a single type.

(2) Feature layer fusion

Feature-layer fusion, as an intermediate-level integration approach, combines multi-source data by extracting individual features from each source. Through methods such as feature dimensionality reduction and the combination of feature vectors, it generates a fused feature set for fault characteristic extraction. This method significantly reduces redundant information, enabling real-time processing while integrating multiple signals. However, it inevitably loses partial information during the fusion process.

(3) Decision-making layer fusion

Decision fusion represents the highest-level integration. After each sensor acquires data and generates corresponding classification results, relevant fusion algorithms synthesize multiple diagnostic outcomes to produce a final diagnosis. This method demonstrates strong anti-interference capabilities, maintaining accurate results even when partial sensors malfunction. Common decision fusion approaches include D-S theory criteria, Bayesian inference, and fuzzy set theory. The D-S theory criteria excel in handling information uncertainty representation and comprehensive analysis, making them widely adopted in fault diagnosis applications.

While information fusion technology has been extensively researched and applied across multiple domains, a unified theoretical framework remains lacking to precisely define various fusion systems. The diagnostic framework for information fusion is not a rigid process but rather a natural reasoning mechanism that relies on rich data and enhances information quality through systematic abstraction concepts. The methodologies encompassing information fusion are remarkably diverse, spanning not only mathematical fields like category theory, uncertainty theory, and mathematical logic, but also computational domains such as ontology and algorithmic theory. Therefore, constructing a comprehensive formal framework to fully describe and analyze information fusion technologies presents significant challenges, requiring in-depth analysis and customization tailored to specific application scenarios and requirements.

Gas turbine fault diagnosis technology plays a vital role in ensuring the safe and reliable operation of gas turbines. In recent years, with the rapid development of interdisciplinary integration and automation technologies, the accuracy and real-time performance of fault detection have been significantly enhanced. This paper reviews the latest advancements in this field, particularly emphasizing the application of multidimensional data feature extraction, cluster analysis, and adaptive optimization algorithms in fault detection. The conclusions drawn are as follows:

1. Model-based methods rely on accurate mathematical modeling, but in the face of complex gas turbine systems, it is difficult to establish high-precision models that can adapt to variable working conditions, and the maintenance cost of the model is high.

2. The data-driven method excavates data features through statistical analysis and machine learning technology, which improves the flexibility of diagnosis, but it relies heavily on the integrity, quality, and comprehensiveness of data collection. Data loss or noise may affect the diagnostic effect.

3. Deep learning method has outstanding performance in gas turbine fault diagnosis due to their powerful feature extraction ability, but it has some problems, such as high demand for computing resources, long training time, and opaque decision-making process, which still need improvement in application scenarios with high safety requirements.

Future research should focus on hybrid models that integrate physical fault mechanisms with data-driven techniques to improve interpretability and robustness. Additionally, real-time multi-fault diagnosis systems and transfer learning approaches for cross-domain applications are promising directions to explore.

With the advancement of diagnostic technologies, model optimization has emerged as a critical approach to enhancing fault diagnosis performance in gas turbines. Future research should focus on integrating physical models with data-driven methodologies to improve diagnostic accuracy and applicability. The following aspects require particular attention:

1. In feature selection, automated methods like recursive feature elimination have improved diagnostic efficiency, but they may still miss critical features in complex systems. Furthermore, while deep learning models excel at feature extraction, their current lack of effective physical constraints makes some extracted features difficult to interpret physically.

2. In terms of parameter optimization, the selection of hyperparameters has a significant impact on model performance, but it still mainly relies on experience or grid search, and it is difficult to find the optimal balance between calculation efficiency and diagnostic accuracy.

3. Although the fusion model can combine the advantages of various methods, it still has some challenges in determining the weight of the model combination, and increases the calculation complexity.

Acknowledgement: The authors appreciate that this research is funded by the Science and Technology Vice President Project in Changping District, Beijing.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by the Science and Technology Vice President Project in Changping District, Beijing (Project Name: Research on multi-scale optimization and intelligent control technology of integrated energy system; Project number: 202302007013).

Author Contributions: Hailun Wang: writing draft, visualization; Tao Zhang: supervisor, conceptual, review, fund acquisition. Tianyue Wang and Tian Tian: review, fund acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang Q, Li S, Cao Y. Multiple model-based detection and estimation scheme for gas turbine sensor and gas path fault simultaneous diagnosis. J Mech Sci Technol. 2019;33(4):1959–72. doi:10.1007/s12206-019-0346-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang X, Zhao Q, Wang Y, Cheng K. Fault signal reconstruction for multi-sensors in gas turbine control systems based on prior knowledge from time series representation. Energy. 2023;262:124996. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yang X, Bai M, Liu J, Liu J, Yu D. Gas path fault diagnosis for gas turbine group based on deep transfer learning. Measurement. 2021;181(1):109631. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2021.109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yan L, Dong X, Zhang H, Chen H. A feature weighted kernel extreme learning machine ensemble method for gas turbine fault diagnosis. In: Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2020: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition; 2020 Sep 21–25; Virtual. V005T05A003. doi:10.1115/gt2020-14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yao K, Wang Y, Fan S, Fu J, Wan J, Cao Y. Improved and accurate fault diagnostic model for gas turbine based on 2D-wavelet transform and generative adversarial network. Meas Sci Technol. 2023;34(7):075104. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/acc5fe. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yazdani S, Montazeri-Gh M. A novel gas turbine fault detection and identification strategy based on hybrid dimensionality reduction and uncertain rule-based fuzzy logic. Comput Ind. 2020;115:103131. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2019.103131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yoo S, Kim M, Park GS, Oh KY. Hybrid explainable anomaly detection framework of gas turbines for feature selection and fault localization. Struct Health Monit. 2025;24(5):2689–714. doi:10.1177/14759217251333312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yu B, Cao LA, Xie D, Chen J, Zhang H. Fault diagnosis of gas turbine based on feature fusion cascade neural network. Energy. 2025;321:135439. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.135439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yue Y, Wang H, Zhang P, Gu F. An anomaly detection method for gas turbines based on single-condition training with zero-fault sample. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2025;224:112209. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.112209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zaccaria V, Fentaye AD, Kyprianidis K. Assessment of dynamic Bayesian models for gas turbine diagnostics, part 2: discrimination of gradual degradation and rapid faults. Machines. 2021;9(12):308. doi:10.3390/machines9120308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang K, Li H, Wang X, Xie D, Yang S. Enhancing gas turbine fault diagnosis using a multi-scale dilated graph variational autoencoder model. IEEE Access. 2024 Aug 24–28;12:104818–32. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3434708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao H, Lin X, Liao Z, Xu M, Yao Y, Duan B, et al. Highly fault-tolerant thrust estimation for gas turbine engines via feature-level dissimilarity design. Measurement. 2025;244:116350. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao J, Sha Y, Luan X, Tong X, Zhang Z. Method for enhancing fault feature signals of rolling bearings in gas turbine engines. J Vib Control. 2024;2024:10775463241286013. doi:10.1177/10775463241286013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao J, Li YG. Abrupt fault detection and isolation for gas turbine components based on a 1D convolutional neural network using time series data. In: AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2020 Forum; 2020; Virtual. 3675 p. doi:10.2514/6.2020-3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhong SS, Fu S, Lin L. A novel gas turbine fault diagnosis method based on transfer learning with CNN. Measurement. 2019;137:435–53. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2019.01.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou D, Huang D, Hao J, Wu H, Chang C, Zhang H. Fault diagnosis of gas turbines with thermodynamic analysis restraining the interference of boundary conditions based on STN. Int J Mech Sci. 2021;191(1):106053. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.106053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhou D, Huang D, Zhang H, Yang J. Periodic analysis on gas path fault diagnosis of gas turbines. ISA Trans. 2022;129(Pt B):429–41. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2022.01.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhou D, Wei T, Huang D, Li Y, Zhang H. A gas path fault diagnostic model of gas turbines based on changes of blade profiles. Eng Fail Anal. 2020;109:104377. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2020.104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou D, Yao Q, Wu H, Ma S, Zhang H. Fault diagnosis of gas turbine based on partly interpretable convolutional neural networks. Energy. 2020;200:117467. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhou H, Ying Y, Li J, Jin Y. Long-short term memory and gas path analysis based gas turbine fault diagnosis and prognosis. Adv Mech Eng. 2021;13(8):16878140211037767. doi:10.1177/16878140211037767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu L, Liu J, Ma Y, Zhou W, Yu D. A coupling diagnosis method for sensor faults detection, isolation and estimation of gas turbine engines. Energies. 2020;13(18):4976. doi:10.3390/en13184976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhu Y, Zhang X, Luo M. A fault early warning method based on auto-associative kernel regression and auxiliary classifier generative adversarial network (AAKR-ACGAN) of gas turbine compressor blades. Energies. 2025;18(3):461. doi:10.3390/en18030461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ahsan S, Lemma TA, Hashmi MB, Liang X. Investigation of operational settings, environmental conditions, and faults on the gas turbine performance. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(12):125902. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad678c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Akbari M, Khoshnood AM. A new feature selection-aided observer for sensor fault diagnosis of an industrial gas turbine. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(16):18047–54. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2021.3085209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Akbari M, Khoshnood AM, Irani S. Development of L1-norm sliding mode observer for sensor fault diagnosis of an industrial gas turbine. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part I J Syst Control Eng. 2021;235(8):1337–54. doi:10.1177/0959651821996173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Akbarpour S, Khosrowjerdi MJ. A multiple model-based approach for gas turbine fault diagnosis. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Electr Eng. 2025;49(1):265–78. doi:10.1007/s40998-024-00754-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Akhtar M, Ashraf WM, Hayat N, Uddin GM, Riaz F. Numerical and experimental investigation of gas turbine rotor for early fault detection. Energy Sci Eng. 2025;13(5):2546–64. doi:10.1002/ese3.70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alblawi A. Fault diagnosis of an industrial gas turbine based on the thermodynamic model coupled with a multi feedforward artificial neural networks. Energy Rep. 2020;6:1083–96. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2020.04.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Alozie O, Li YG, Pilidis P, Liu Y, Wu X, Shong X, et al. An integrated principal component analysis, artificial neural network and gas path analysis approach for multi-component fault diagnostics of gas turbine engines. In: Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2020: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition; 2020 Sep 21–25; Virtual. V005T05A023. doi:10.1115/gt2020-15740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Amiri MH, Hashjin NM, Najafabadi MK, Beheshti A, Khodadadi N. An innovative data-driven AI approach for detecting and isolating faults in gas turbines at power plants. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;263:125497. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Amirkhani S, Chaibakhsh A, Ghaffari A. Nonlinear robust fault diagnosis of power plant gas turbine using Monte Carlo-based adaptive threshold approach. ISA Trans. 2020;100:171–84. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2019.11.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Amirkhani S, Tootchi A, Chaibakhsh A. Fault detection and isolation of gas turbine using series-parallel NARX model. ISA Trans. 2022;120:205–21. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2021.03.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Bai M, Liu J, Long Z, Luo J, Yu D. A comparative study on class-imbalanced gas turbine fault diagnosis. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part G J Aerosp Eng. 2023;237(3):672–700. doi:10.1177/09544100221107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bai M, Liu J, Ma Y, Zhao X, Long Z, Yu D. Long short-term memory network-based normal pattern group for fault detection of three-shaft marine gas turbine. Energies. 2021;14(1):13. doi:10.3390/en14010013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bai M, Yang X, Liu J, Liu J, Yu D. Convolutional neural network-based deep transfer learning for fault detection of gas turbine combustion chambers. Appl Energy. 2021;302(1):117509. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Barrera JM, Reina A, Mate A, Trujillo JC. Fault detection and diagnosis for industrial processes based on clustering and autoencoders: a case of gas turbines. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2022;13(10):3113–29. doi:10.1007/s13042-022-01583-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Cao Y, Luan J, Han G, Lv X, Li S. A marine gas turbine fault diagnosis method based on endogenous irreversible loss. Energies. 2019;12(24):4677. doi:10.3390/en12244677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Cao Y, Lv X, Han G, Luan J, Li S. Research on gas-path fault-diagnosis method of marine gas turbine based on exergy loss and probabilistic neural network. Energies. 2019;12(24):4701. doi:10.3390/en12244701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen J, Xu C, Ying Y, Li J, Jin Y, Zhou H, et al. Gas-path component fault diagnosis for gas turbine engine: a review. In: 2019 Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM-Qingdao); 2019 Oct 25–27; Qingdao, China. IEEE; 2019. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/phm-qingdao46334.2019.8942819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen X, Tong Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Qing X. A hybrid multimodel-based condition monitoring and sensor fault detection method for aero gas turbine. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(20):32729–39. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2024.3450859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen Y, Xi Y, Chen J, Zhang H. A novel gas path fault diagnostic model for gas turbine based on explainable convolutional neural network with LIME method. In: Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2021: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition; 2021 Jun 7–11; Virtual. V004T05A008. doi:10.1115/gt2021-59289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chen YZ, Zhang WG, Tsoutsanis E, Zhao J, Tam ICK, Gou LF. An advanced performance-based method for soft and abrupt fault diagnosis of industrial gas turbines. Energy. 2025;321:135358. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.135358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Chen Z, Zhang Y, Gong H, Le X, Zheng Y. Fault diagnosis of gas turbine fuel systems based on improved SOM neural network. In: Advances in neural networks—ISNN 2019. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 252–65. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22808-8_26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Cheng K, Wang Y, Yang X, Zhang K, Liu F. An intelligent online fault diagnosis system for gas turbine sensors based on unsupervised learning method LOF and KELM. Sens Actuat A Phys. 2024;365:114872. doi:10.1016/j.sna.2023.114872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mishra RK, Choudhary A, Fatima S, Mohanty AR, Panigrahi BK. A systematic review on advancement and challenges in multi-fault diagnosis of rotating machines. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;156:111306. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.111306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tang X, Gu X, Rao L, Lu J. A single fault detection method of gearbox based on random forest hybrid classifier and improved Dempster-Shafer information fusion. Comput Electr Eng. 2021;92:107101. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Xia H, Meng T, Zuo Z, Ma W. Fault semantic knowledge transfer learning: cross-domain compound fault diagnosis method under limited single fault samples. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2025;260:111050. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2025.111050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Cui Y, Wang H, Wang X. Fault diagnosis for gas turbine rotor using MOMEDA-VNCMD. In: Proceedings of IncoME-VI and TEPEN 2021. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 403–16. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-99075-6_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Deriabin G, Zeng Z, Blinov V. Classification of gas turbine fault group using machine learning methods. In: The Eighteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management; 2024 Aug 5–8; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 716–25. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-5098-6_50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Khalid Fahmi AW, Reza Kashyzadeh K, Ghorbani S. Fault detection in the gas turbine of the Kirkuk power plant: an anomaly detection approach using DLSTM-Autoencoder. Eng Fail Anal. 2024;160:108213. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Fahmi AWK, Reza Kashyzadeh K, Ghorbani S. Advancements in gas turbine fault detection: a machine learning approach based on the temporal convolutional network-autoencoder model. Appl Sci. 2024;14(11):4551. doi:10.3390/app14114551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Feng K, Xiao Y, Li Z, Jiang Z, Gu F. Gas turbine blade fracturing fault diagnosis based on broadband casing vibration. Measurement. 2023;214:112718. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2023.112718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Fentaye AD, Ul-Haq Gilani SI, Baheta AT, Li YG. Performance-based fault diagnosis of a gas turbine engine using an integrated support vector machine and artificial neural network method. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part A J Power Energy. 2019;233(6):786–802. doi:10.1177/0957650918812510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Roig Greidanus MD, Heldwein ML. Model-based control strategy to reduce the fault current of a gas turbine synchronous generator under short-circuit in isolated networks. Electr Power Syst Res. 2022;204:107687. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2021.107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Hadroug N, Hafaifa A, Alili B, Iratni A, Chen X. Fuzzy diagnostic strategy implementation for gas turbine vibrations faults detection: towards a characterization of symptom-fault correlations. J Vib Eng Technol. 2022;10(1):225–51. doi:10.1007/s42417-021-00373-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hanachi H, Liu J, Kim IY, Mechefske CK. Hybrid sequential fault estimation for multi-mode diagnosis of gas turbine engines. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2019;115:255–68. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2018.05.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Hashmi MB, Mansouri M, Fentaye AD, Ahsan S, Kyprianidis K. An artificial neural network-based fault diagnostics approach for hydrogen-fueled micro gas turbines. Energies. 2024;17(3):719. doi:10.3390/en17030719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Hashmi MB, Fentaye AD, Mansouri M, Kyprianidis KG. A comparative analysis of various machine learning approaches for fault diagnostics of hydrogen fueled gas turbines. In: Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2024: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition; 2024 Jun 24–28; London, UK. Vol. 4. V004T05A050. doi:10.1115/gt2024-129279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Hu M, He Y, Lin X, Lu Z, Jiang Z, Ma B. Digital twin model of gas turbine and its application in warning of performance fault. Chin J Aeronaut. 2023;36(3):449–70. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2022.07.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Hu MH, Jin BT, Liu SP, Wang WM, Jiang ZN, Zhang XY, et al. Fault diagnosis method for blade fracture of gas turbine based on casing vibration. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2025;234:112806. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2025.112806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Hadroug N, Iratni A, Hafaifa A, Alili B, Colak I. Implementation of vibrations faults monitoring and detection on gas turbine system based on the support vector machine approach. J Vib Eng Technol. 2024;12(3):2877–902. doi:10.1007/s42417-023-01020-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Li J, Ying Y. A novel machine learning based fault diagnosis method for all gas-path components of heavy duty gas turbines with the aid of thermodynamic model. IEEE Trans Reliab. 2024;73(4):1805–18. doi:10.1109/TR.2024.3383922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Liu Y, Tian L, Li Z, Zhang W. Fault modeling of electro hydraulic actuator in gas turbine control system based on Matlab/Simulink. In: 2021 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC); 2021 May 22–24; Kunming, China; 2021. p. 2086–91. doi:10.1109/ccdc52312.2021.9602583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Ma S, Wu Y, Hua Z, Gou L. Application of fuzzy inference system in gas turbine engine fault diagnosis against measurement uncertainties. Chin J Mech Eng. 2025;38(1):2. doi:10.1186/s10033-024-01145-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Liu J, Long Z, Bai M, Zhu L, Yu D. A comparative study on fault detection methods for gas turbine combustion systems. Energies. 2021;14(2):389. doi:10.3390/en14020389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Long Z, Zhou Z, Suo P, Yao P, Bai M, Liu J, et al. Gas turbine circumferential temperature distribution model for the combustion system fault detection. Eng Fail Anal. 2024;158(1):108032. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Huang D, Ma S, Zhou D, Jia X, Peng Z, Ma Y. Gas path fault diagnosis for gas turbine engines with fully operating regions using mode identification and model matching. Meas Sci Technol. 2023;34(1):015903. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ac97b4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Jin Y, Ying Y, Li J, Zhou H. Gas path fault diagnosis of gas turbine engine based on knowledge data-driven artificial intelligence algorithm. IEEE Access. 2021;9:108932–41. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Li B, Zhao YP, Chen YB. Learning transfer feature representations for gas path fault diagnosis across gas turbine fleet. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;111:104733. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Montazeri-Gh M, Nekoonam A. Gas path component fault diagnosis of an industrial gas turbine under different load condition using online sequential extreme learning machine. Eng Fail Anal. 2022;135(1):106115. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Nekoonam A, Montazeri-Gh M. Noise-robust gas path fault detection and isolation for a power generation gas turbine based on deep residual compensation extreme learning machine. Energy Sci Eng. 2023;11(11):4001–18. doi:10.1002/ese3.1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Xia S, Chi Z, Zang S. Comparative study of two data-driven gas path fault quantification methods for a single-shaft gas turbine. In: Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition; 2022 Jun 13–17; Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Vol. 2. V002T05A014. doi:10.1115/gt2022-82406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Yan L, Zhang H, Dong X, Zhou Q, Chen H, Tan C. Unscented Kalman-filter-based simultaneous diagnostic scheme for gas-turbine gas path and sensor faults. Meas Sci Technol. 2021;32(9):095905. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/abfd67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Hu Y, Zhu J, Sun Z, Gao L. Sensor fault diagnosis of gas turbine engines using an integrated scheme based on improved least squares support vector regression. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part G J Aerosp Eng. 2020;234(3):607–23. doi:10.1177/0954410019873795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Irani FN, Soleimani M, Yadegar M, Meskin N. Deep transfer learning strategy in intelligent fault diagnosis of gas turbines based on the Koopman operator. Appl Energy. 2024;365(1):123256. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Kazemi H, Yazdizadeh A. Fault detection and isolation of gas turbine engine using inversion-based and optimal state observers. Eur J Control. 2020;56:206–17. doi:10.1016/j.ejcon.2020.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Li J, Ying Y, Ji C. Study on gas turbine gas-path fault diagnosis method based on quadratic entropy feature extraction. IEEE Access. 2019;7:89118–27. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2927306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Li J, Ying Y, Wu Z. Gas turbine gas-path fault diagnosis in power plant under transient operating condition with variable geometry compressor. Energy Sci Eng. 2022;10(9):3423–42. doi:10.1002/ese3.1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Li L, Liang Q, Liang Y. Fuzzy fault tree analysis of a gas turbine fuel system. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2019;237:022024. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/237/2/022024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Liu B, Xue Y, Li G, Yang Y. Research and application of gas turbine blade fault monitoring based on blade passing frequency analysis. In: Equipment intelligent operation and maintenance. London, UK: CRC Press; 2025. p. 52–60. doi:10.1201/9781003470076-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Liu D, Zhong S, Lin L, Zhao M, Fu X, Liu X. Highly imbalanced fault diagnosis of gas turbines via clustering-based downsampling and deep Siamese self-attention network. Adv Eng Inform. 2022;54(1):101725. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2022.101725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Liu D, Zhong S, Lin L, Zhao M, Fu X, Liu X. Feature-level SMOTE: augmenting fault samples in learnable feature space for imbalanced fault diagnosis of gas turbines. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238:122023. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Liu J, Liu J, Yu D, Wang Z, Yan W, Pecht M. Early fault detection of gas turbine hot components under different ambient and operating conditions. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part G J Aerosp Eng. 2021;235(13):1898–910. doi:10.1177/0954410020986890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Liu J, Bai M, Long Z, Liu J, Ma Y, Yu D. Early fault detection of gas turbine hot components based on exhaust gas temperature profile continuous distribution estimation. Energies. 2020;13(22):5950. doi:10.3390/en13225950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Liu S, Wang H, Tang J, Zhang X. Research on fault diagnosis of gas turbine rotor based on adversarial discriminative doma in adaption transfer learning. Measurement. 2022;196:111174. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Liu S, Wang H, Zhang X. Research on improved deep convolutional generative adversarial networks for insufficient samples of gas turbine rotor system fault diagnosis. Appl Sci. 2022;12(7):3606. doi:10.3390/app12073606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Liu X, Chen Y, Xiong L, Wang J, Luo C, Zhang L, et al. Intelligent fault diagnosis methods toward gas turbine: a review. Chin J Aeronaut. 2024;37(4):93–120. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2023.09.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]