Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Improved PID Controller Based on Artificial Neural Networks for Cathodic Protection of Steel in Chlorinated Media

1 Centro de Investigación en Micro y Nanotecnología, Universidad Veracruzana, Bv. Adolfo Ruíz Cortines 455, Costa Verde, Boca del Río, Veracruz, 94294, Mexico

2 Instituto de Matemáticas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Blanco Viel 596, Cerro Barón, Valparaíso, 2340000, Chile

3 Instituto de Ingeniería, Universidad Veracruzana, Av. Juan Pablo II S/N, Costa Verde, Boca del Río, Veracruz, 94294, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Sebastián Ossandón. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Applications of Neural Networks in Materials)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 22 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072707

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In this study, artificial neural networks (ANNs) were implemented to determine design parameters for an impressed current cathodic protection (ICCP) prototype. An ASTM A36 steel plate was tested in 3.5% NaCl solution, seawater, and NS4 using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor the evolution of the substrate surface, which affects the current required to reach the protection potential (Keywords

Metallic structures are essential components of modern infrastructure, yet their corrosion—a natural degradation process—accounts for approximately 5 % of the world’s annual GDP. Consequently, corrosion management strategies are continually evolving to reduce the associated economic, safety, and sustainability losses. Among these strategies, cathodic protection—implemented either through sacrificial anodes (SACP) or impressed current systems (ICCP)—is one of the most effective methods for mitigating corrosion in continuous media such as soil, concrete, or seawater.

In ICCP systems, a power source supplies the electrical current required to achieve the protection potential (

Several self-regulating systems have been proposed, although most operate only within limited ranges (approximately 80 mA and 5 V) [8,9]. For instance, Ramírez-Fernández et al. (2021) developed a prototype using an Arduino-based controller that applied the necessary current to protect a steel plate through an on–off voltage regulation system. Their design also allowed switching between multiple power sources to prevent current interruptions caused by connection failures or the intermittent availability of renewable sources such as solar and wind energy [10].

Nevertheless, the absence of adaptive reference values in the control algorithm—reflecting the evolving condition of the metal surface—prevented the system from maintaining potentials close to the protection standard. Furthermore, the response was not truly real-time, since the input values did not accurately represent the actual current demand or impressed voltage.

To address these limitations, automatic control systems can be implemented to dynamically regulate the supplied current in response to variations at the electrochemical interface. In this context, artificial intelligence (AI) techniques—particularly artificial neural networks (ANNs)—have emerged as promising tools [11–14]. ANN-based models have been successfully employed to predict pipeline failure rates [15–17], predict current efficiency [18], design evaluation and prediction strategies [19], optimize anode configurations for corrosion protection [20,21], and estimate optimal current drainage based on parameters such as solution pH and system current demand [22].

Jasim et al. (2023) demonstrated that the application of neural networks can enhance the performance of cathodic protection systems while reducing the power consumption required to supply current to the anodes, thereby facilitating the integration of renewable energy sources such as solar cells [23]. Similarly, Obi et al. (2025) introduced a neural-network-based predictive controller designed to minimize voltage deviations and optimize energy costs in dynamic microgrid environments [24].

These examples highlight the potential of ANN-based approaches to capture complex electrochemical relationships and enable the development of self-regulating ICCP systems capable of maintaining optimal protection conditions with minimal human intervention.

The methodology proposed in this study for improving an ICCP system consisted of four main steps.

First, the electrochemical behavior of low-carbon steel under cathodic protection was evaluated in three different solutions. The electrochemical parameters of each system were determined through equivalent circuit simulations and subsequently used to construct a dataset. Second, the input and output variables were analyzed using statistical methods. Third, artificial neural network (ANN) models were trained to predict (a) the real and imaginary components of the impedance and (b) the electrochemical parameters. Finally, the obtained electrochemical parameters were employed to fine-tune an ANN-based proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller for the ICCP system.

2.1 Data Collection: Electrochemical Evaluation of Steel under Cathodic Protection in Saline Medium

To evaluate the electrochemical behavior of steel under ICCP in the three media, ASTM A36 steel plates were used. The samples were sanded with silicon carbide (SiC) sandpaper ranging from grade 220 to 600, followed by cleaning with distilled water and acetone.

A three-electrode electrochemical cell was employed, consisting of a saturated Ag/AgCl reference electrode (RE), a 6 mm diameter graphite rod auxiliary electrode (AE), and an ASTM A36 steel plate as the working electrode (WE) with an exposed area of 16.9

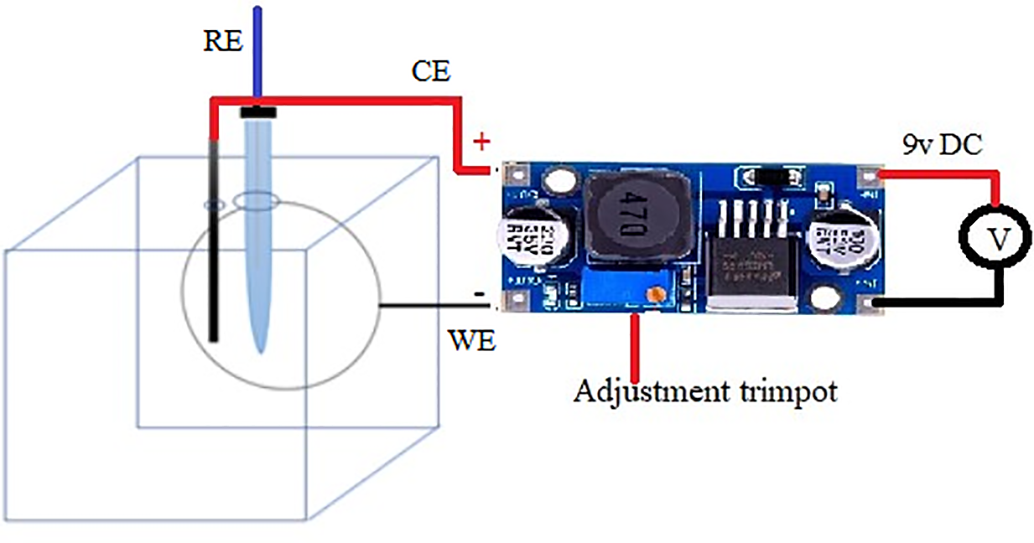

To maintain the protection potential for 30 days, the setup shown in Fig. 1 was used. A 9 V power supply was connected to a buck converter, which regulated the voltage applied to the plates. The voltage was continuously monitored using the reference electrode and a multimeter.

Figure 1: Cathodic protection setup

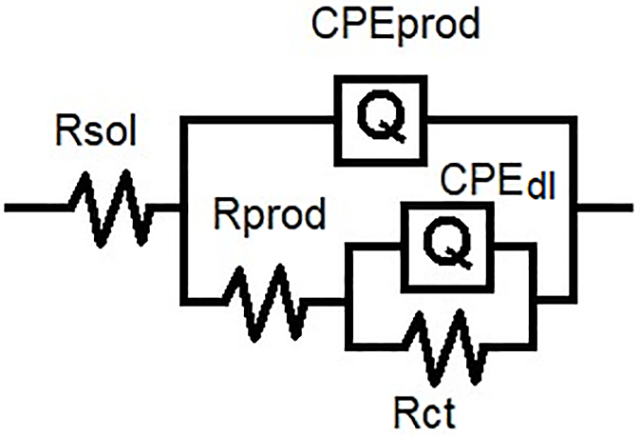

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) was applied at imposed potential, using a Buck converter, powered with a 9 V and 1.2 A source. The converter output was adjusted to impose a potential of −800 mV vs. Ag/AgCl, which was interrupted once the connections were made to the potentiostat, in which a sequence was performed to impose the protection potential, followed by the application of the EIS technique, in a frequency range of 0.10 to 100 kHz, an amplitude signal of 10 mV, and 7 points per decade of frequency. Then, Nyquist plots of 1, 5, 10, 15 and 20 days were fitted using the equivalent circuit in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Equivalent circuit for EIS data fitting

All experiments were conducted at ambient temperature and pressure in Veracruz (approximately

2.2 Artificial Neural Networks for PID Control of ICCP Systems

ICCP systems are known to be influenced by a variety of factors, including environmental conditions, corrosion rates, and structural parameters. A conventional PID controller can be described by Eq. (1).

Here,

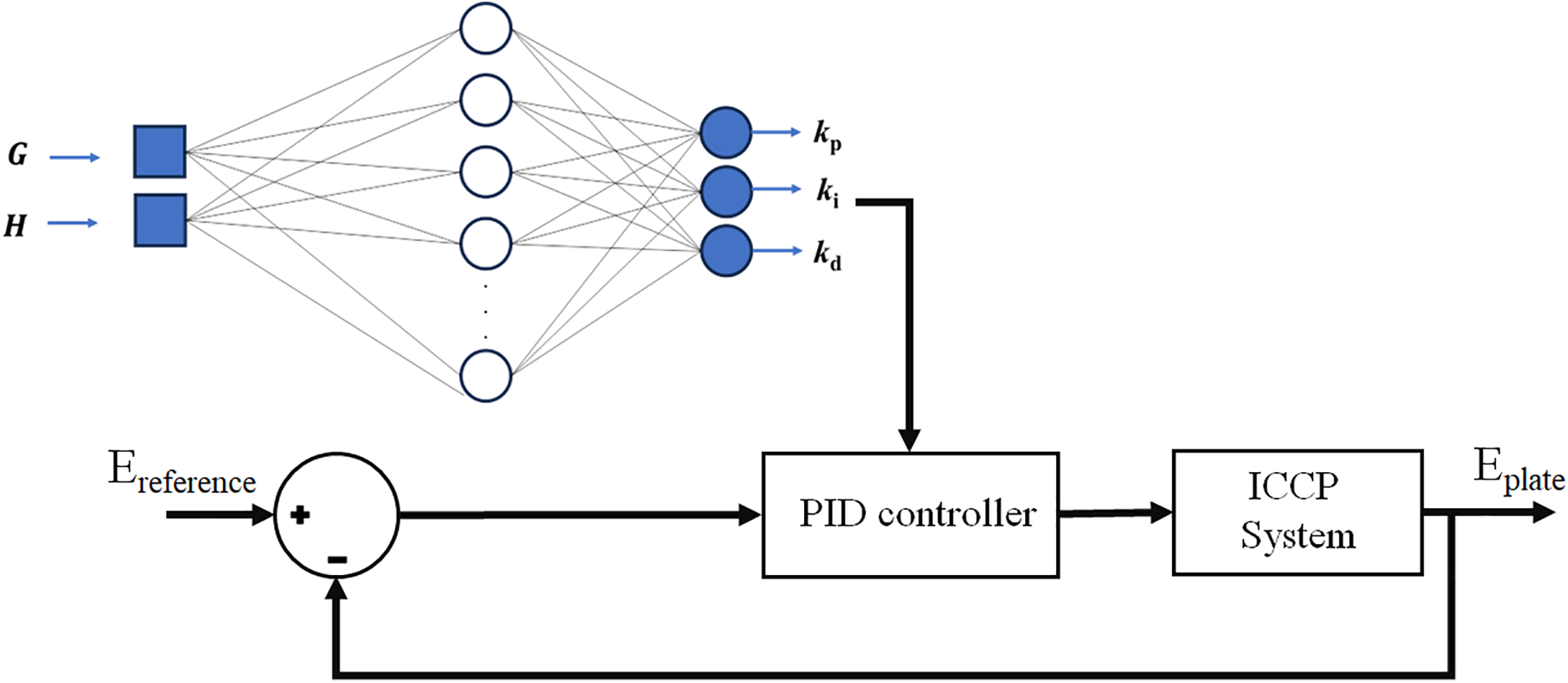

Fig. 3 shows the block diagram of the PID controller proposed to regulate the protection potential in an ICCP system for three corrosive media. The following points were considered when coding Algorithms 1 and 2 in MATLAB:

1. The electrochemical parameters of the ICCP system are associated with the equivalent circuit (Fig. 2) and represented by the plant transfer function

2. Lower and upper bounds for the PID controller gains (

3. The input-output data generated in the previous step are used to train a feedforward artificial neural network (using the fitnet function in MATLAB) with 50 neurons in the hidden layer. The network is trained to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) as the cost function.

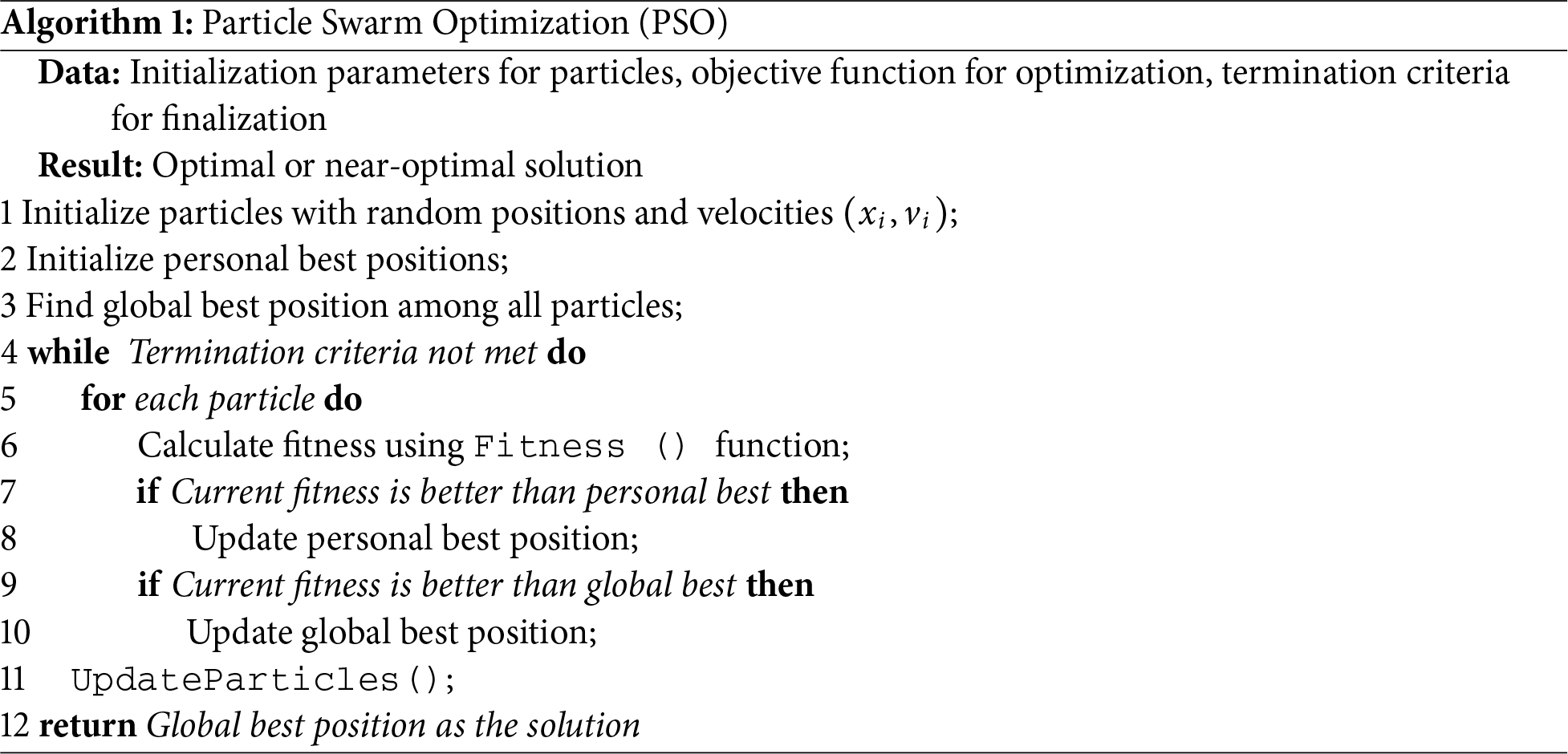

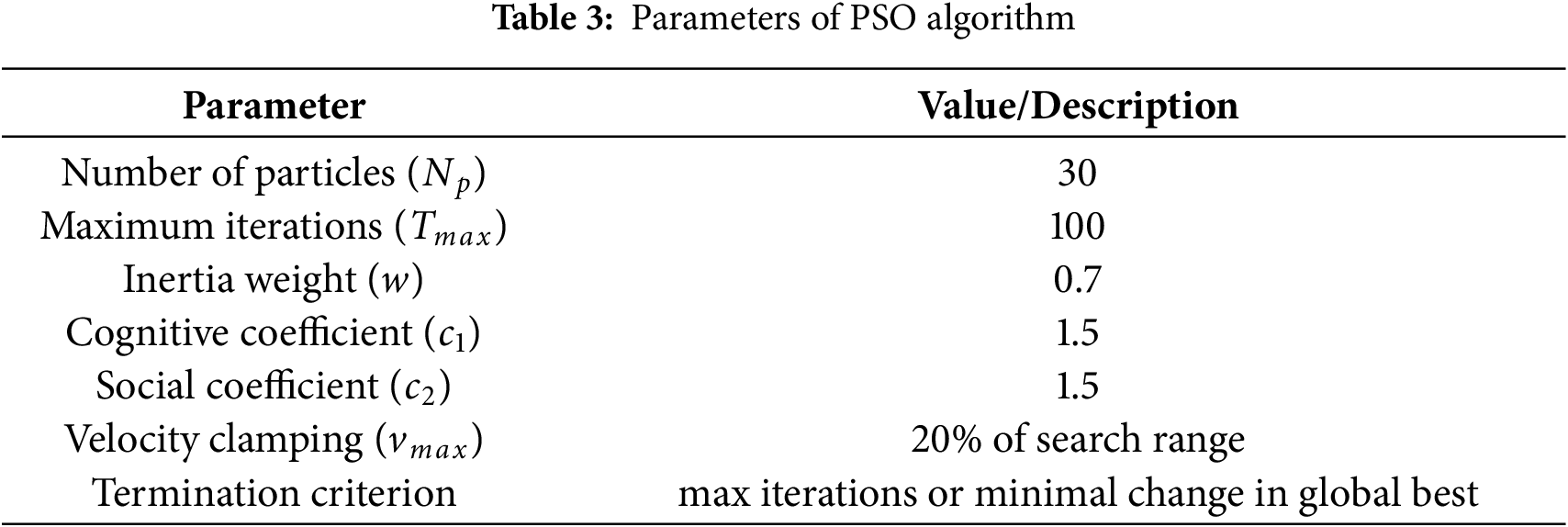

4. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is configured (see Algorithm 1 and [26]) with parameters such as swarm size and display options. PSO is employed to identify the optimal PID gains that minimize the cost function at each time step in the temporal evolution of the open-loop system (steel + medium).

5. An adaptable PID controller is implemented using the optimized gains for each time step in the evolution of the open-loop system.

Figure 3: Closed-loop system using a PID controller tuning with ANNs

Overall, the code combines PSO and an ANN to optimize the PID controller gains for the plant system. The ANN and PSO play complementary but distinct roles in the proposed hybrid PID tuning framework. The ANN acts as a nonlinear mapping tool that learns the dynamic behavior of the plant by establishing a relationship between the input excitation and the corresponding system response. Specifically, the ANN is trained using input-output data generated from the simulated transfer function

In contrast, the PSO algorithm serves as a global optimization procedure to identify the optimal PID gains

The ANN-PSO-PID controller consistently outperforms a classical fixed-gain PID in terms of adaptability, robustness, and steady-state accuracy. While a conventional PID relies on static gains tuned for a specific operating condition, its performance deteriorates when system dynamics or external disturbances change. In contrast, the ANN-PSO-PID continuously adjusts the effective control gains through the neural network’s learning mechanism, enabling real-time adaptation to nonlinearities, parameter variations, and time-varying behaviors.

Moreover, the ANN-PSO-PID achieves faster convergence and reduced overshoot during transients, demonstrating superior tracking under changing reference signals or load disturbances [26]. A fixed-gain PID, on the other hand, requires manual retuning to maintain comparable performance, making it less suitable for systems with uncertain disturbances or strong nonlinearities.

In summary, the ANN-PSO-PID provides a data-driven enhancement of classical PID control, delivering higher precision and resilience without compromising stability.

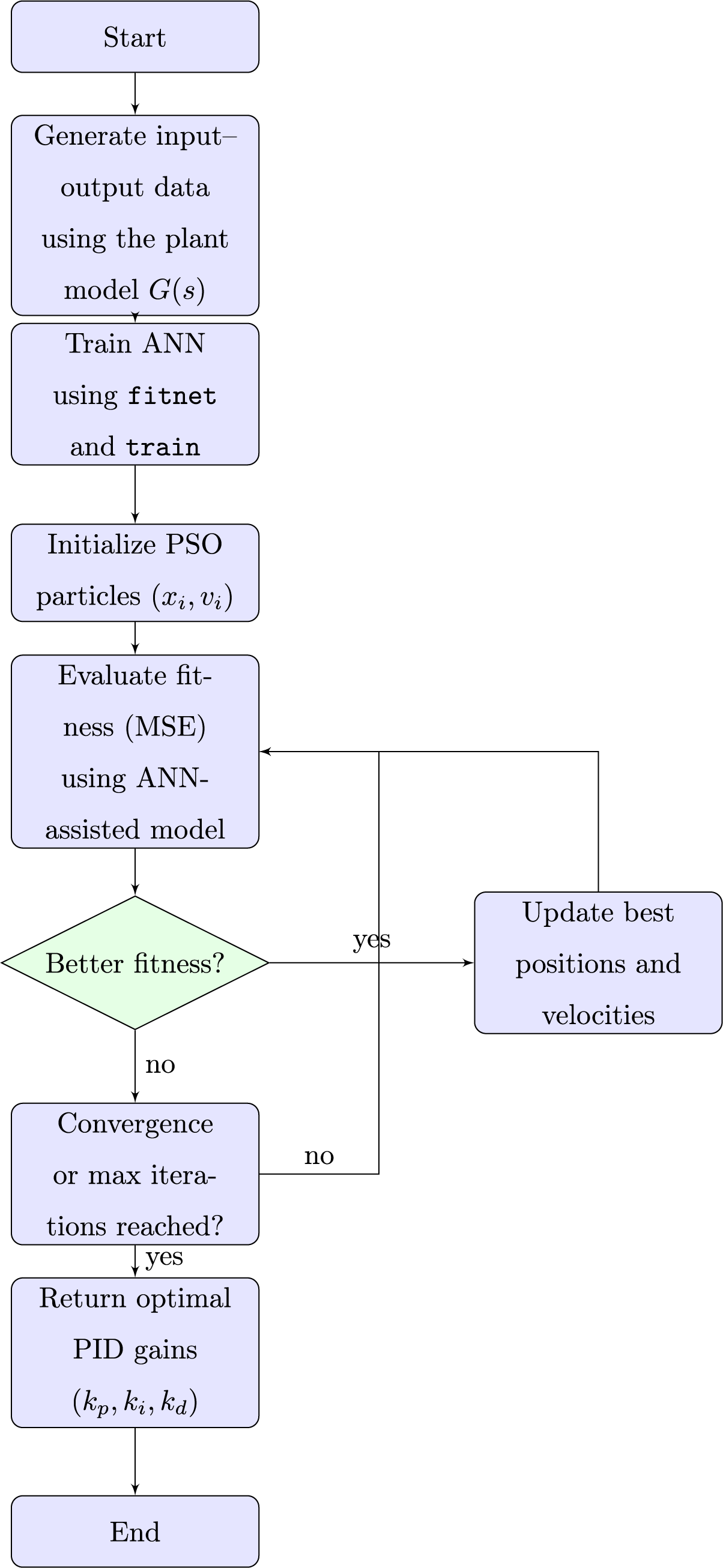

Fig. 4 shows the flowchart of the training and optimization process for the proposed ANN-PSO framework. The process begins with data generation from the simulated plant model, followed by ANN training using MATLAB’s fitnet and train functions. Next, the PSO algorithm is initialized with random particle positions and velocities. The optimization loop then iteratively evaluates the cost function, updates the individual and global best solutions, and refines the search for the optimal PID gains.

Figure 4: Flow chart of the ANN–PSO-based PID tuning process

3.1 Electrochemical Analysis of Steel with ICCP in Saline Media

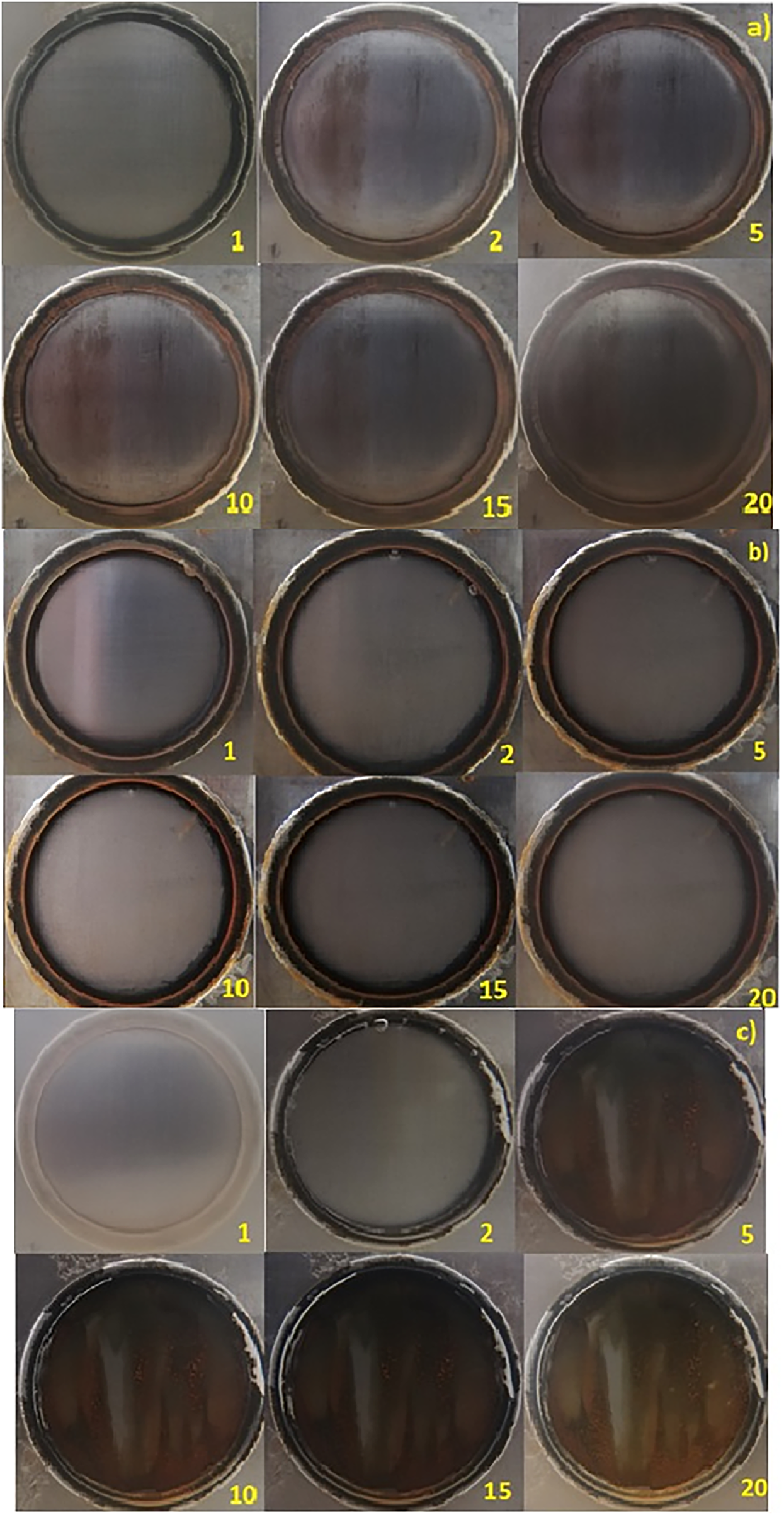

The surface evolution of the steel substrate immersed in the three solutions over 20 days is shown in Fig. 5. For the metal in 3.5% NaCl (Fig. 5a), changes in the surface are noticeable despite the protection. The metal loses its initial luster and develops black corrosion products, characteristic of magnetite [27]. From day two, when some corrosion products are first observed, no significant changes occur in subsequent days, suggesting that the sample remains close to the immunity region of the Pourbaix diagram. It is important to note that even the small amount of corrosion products formed directly affects the current required to maintain the protection condition, as these products are less electrically conductive than the bare substrate, increasing the resistance for electron transfer during the reduction reaction [28].

Figure 5: Surface evolution for A36 steel under cathodic protection inmersed in (a) NaCl 3.5%, (b) seawater and (c) NS4 solution

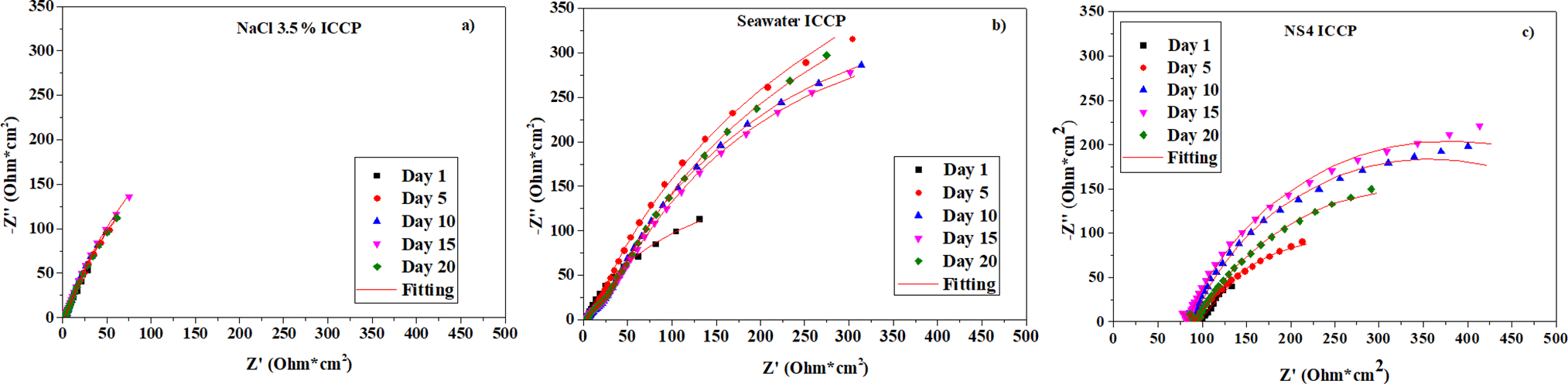

In seawater (Fig. 5b), the steel surface loses its brightness by day two and gradually develops a thin, slightly white layer over the following days. Literature suggests that this layer corresponds to calcareous deposits commonly formed in this electrolyte. No rust or black corrosion products were observed on the surface, although they may have formed beneath the calcareous layer. Interestingly, the Nyquist plot magnitude in seawater is higher than that in 3.5% NaCl. This difference can be attributed to the oxygen concentration, which influences the reduction reaction and, consequently, the impedance. Robbins et al. report that a 3.5% NaCl solution contains the maximum concentration of dissolved oxygen, which likely explains the lower impedance observed in Fig. 6a compared to seawater in Fig. 6b, where dissolved oxygen levels are variable (6–12 ppm) [29].

Figure 6: Nyquist diagrams for A36 steel under cathodic protection inmersed in (a) NaCl 3.5%, (b) seawater and (c) NS4 solution

For the steel in NS4 solution (Fig. 5c), a notable amount of corrosion products forms by day two. However, the surface does not undergo significant changes over the remaining immersion period, indicating that the cathodic protection system performed effectively. It is important to emphasize that even with a protection system, complete immunity of the metal cannot be guaranteed over the entire immersion period, as corrosion is a spontaneous process.

The results obtained from EIS measurements for the three media under impressed current cathodic protection are presented below. Fig. 6a shows the Nyquist plot for steel immersed in 3.5% NaCl under the protection potential, starting at 10 kHz. The observed changes in impedance are attributed to the evolution of the substrate surface, as magnetite forms in this medium [30,31]. The applied potential leads to minimal impedance variation over the exposure period.

For steel in seawater (Fig. 6b), two time constants are evident: the first corresponds to the double-layer capacitance, and the second to the corrosion products formed on the metal surface, including metal oxides and calcareous deposits [32,33].

In the NS4 solution (Fig. 6c), the steel exhibits higher solution resistance along with two time constants, which are associated with the formation of corrosion products [34,35]. Although cathodic protection slows this process, variations in impedance are still observed due to the ongoing evolution of the surface [36].

Fig. 6a shows the Nyquist plot for steel in 3.5% NaCl on day one. The initial segment, when fitted with the equivalent circuit of Fig. 2, forms a semicircle characteristic of a charge-transfer-controlled system. In a freely corroding system, this semicircle would represent the resistance of the substrate to electron transfer to the species being reduced, in this case, oxygen. Although steel spontaneously releases electrons during corrosion, in the ICCP system most of the current consumed by oxygen is supplied by the power source.

For day one, the resistance associated with the reduction reaction is lower than on subsequent days. This behavior can be explained by the elements through which the current flows until it reaches the oxygen reduction reaction. In this context, the main resistances are charge transfer resistance and mass transport resistance of the oxygen molecules. With the metal surface free of oxides, the initial impedance response primarily reflects the availability of oxygen at the substrate surface, which is rapidly consumed due to the cathodically favored reaction that also generates an alkaline environment.

Fig. 6b presents the Nyquist plot for steel in seawater under cathodic protection. Multiple time constants are observed in the high-to-medium frequency range, as also indicated by the Bode plot. This behavior is expected for seawater in protected conditions due to the formation of calcareous deposits on the substrate [37]. The measured capacitance is attributed both to the calcareous products and to the metal, with the semicircle corresponding to the calcareous layer appearing first. This occurs because the calcareous barrier is in direct contact with the electrolyte, while the metal interacts with the medium through pores in the deposit. On day one, the charge transfer resistance

Fig. 6c shows the Nyquist plot for steel in the NS4 soil-simulating solution. As observed in unprotected conditions, this medium exhibits higher electrolyte resistance than NaCl or seawater. Consequently, the current required to achieve the protection potential is similar to that in NaCl, despite NaCl being a more aggressive environment.

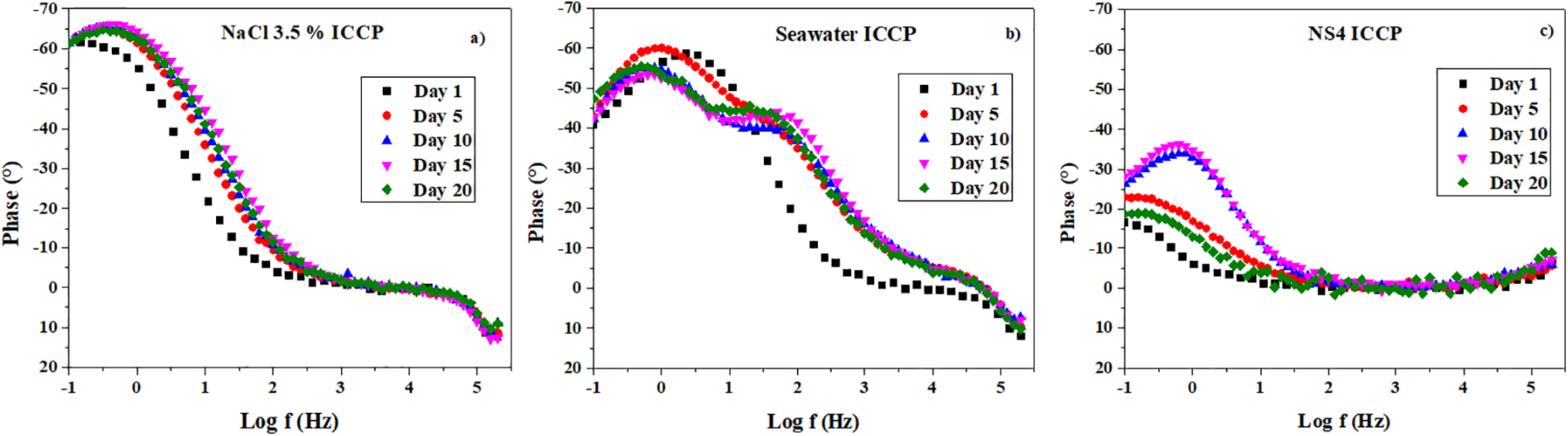

The Bode plots in Fig. 7 reveal distinct behaviors for each medium. In Fig. 7a (steel in 3.5% NaCl), two time constants are evident, corresponding to the double layer and the corrosion products, with a maximum phase shift of approximately

Figure 7: Bode plots for A36 steel under cathodic protection inmersed in (a) NaCl 3.5%, (b) seawater and (c) NS4 solution

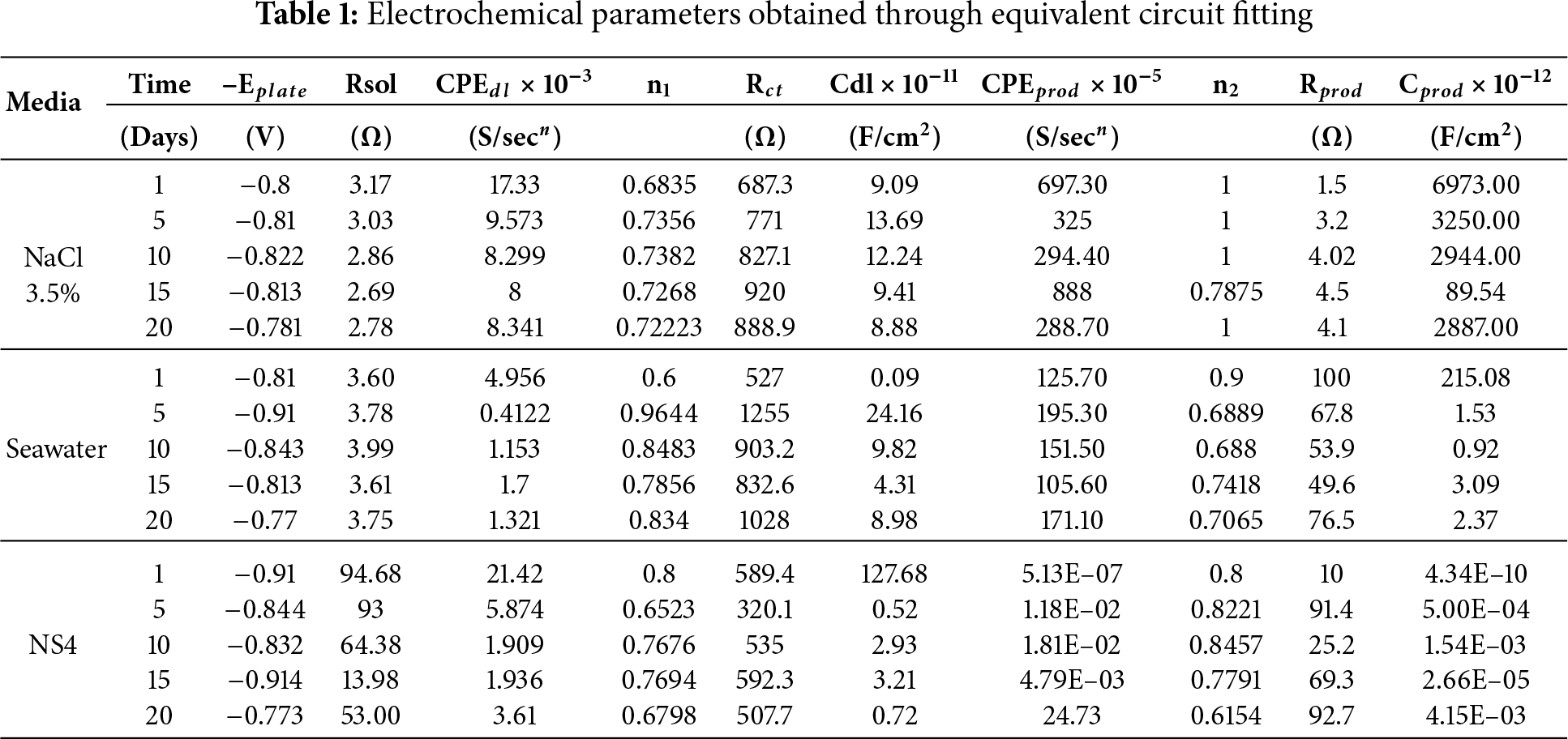

Table 1 presents the electrochemical parameters obtained by fitting the impedance data with the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 2. Brug’s equation (Eq. (3)) was used to calculate the double layer and corrosion product capacitances for the three systems. The equivalent circuit consists of a solution resistance in series with a constant phase element (CPE) representing the corrosion product capacitance, which is in parallel with a corrosion product resistance. This branch is in series with a second CPE corresponding to the double layer capacitance, along with its associated charge transfer resistance. This configuration reflects the sequence of current flow: first through the solution resistance, then through the corrosion products, and finally across the charge transfer interface.

The evolution of the double layer capacitance highlights the influence of the products forming on the metal surface in each medium. For the capacitance of the corrosion products, the highest values are observed for steel in 3.5% NaCl, consistent with the greater formation of magnetite in this medium. In contrast, in seawater, calcareous products predominate, resulting in lower capacitance due to their more porous nature. Variations in the resistances of each system also impact the current required to maintain the protection potential.

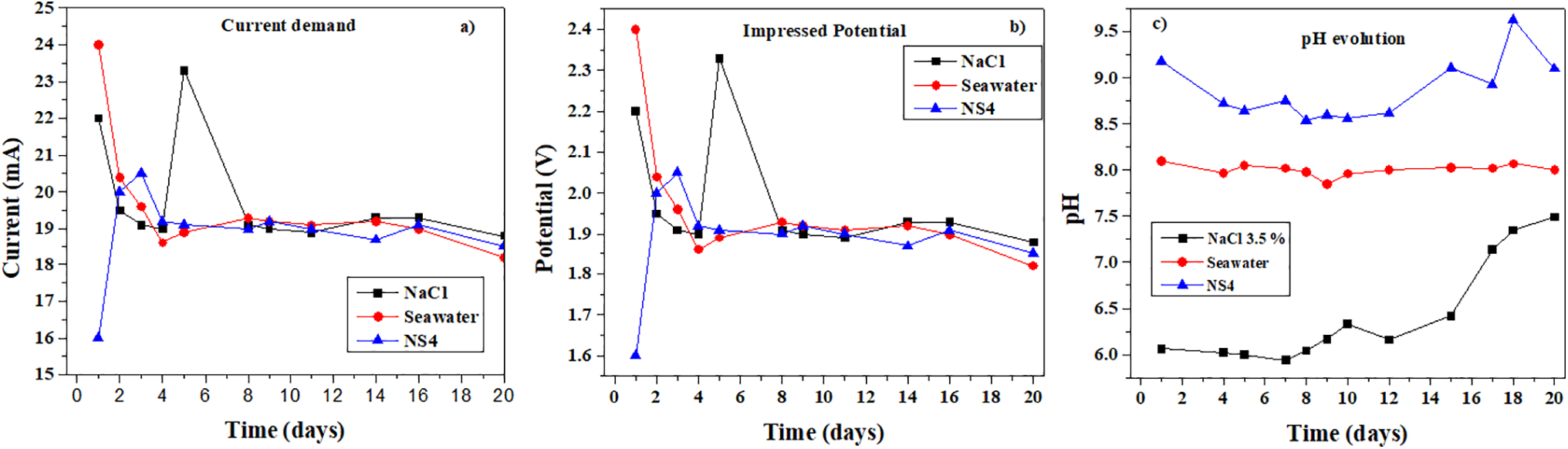

The current demand and impressed potential required to reach a protection potential of

Figure 8: Graphs of the A36 steel immersed in the chlorinated solutions for (a) current demand, (b) impressed potential and (c) pH evolution

Fig. 8a shows the current demand for each system, which varies according to the substrate evolution and the formation of calcareous and corrosion products. These products reduce the exposed steel surface, leading to a decrease in current demand. In intervals where an increase in current is observed, this is attributed to the precipitation of products at the bottom of the electrochemical cell [43,44].

Fig. 8b depicts the impressed potential of the power source. During the first days of immersion, variations in the potential required to maintain the protection criterion are observed, corresponding to rapid changes on the substrate surface [14].

Fig. 8c presents the pH evolution for the three media. Increases in pH are attributed to

3.2 Model Proposal for the Implementation of a PID Control System for Steel with ICCP in Saline Media

PID controllers have long been a cornerstone of control systems due to their simplicity and effectiveness. However, tuning them to meet specific performance criteria can be a time-consuming and expertise-dependent task. The integration of artificial neural networks (ANNs) into PID controller design provides a novel approach to streamline this process. By combining the principles of traditional control theory with the adaptive capabilities of ANNs, it becomes possible to optimize PID parameters more efficiently and accurately.

In this section, we explore how ANNs are employed to enhance PID controllers for steel under ICCP in various saline media. This approach enables the controller to adapt dynamically to changing environmental and electrochemical conditions, improving efficiency, robustness, and responsiveness to the complex behaviors observed in the system.

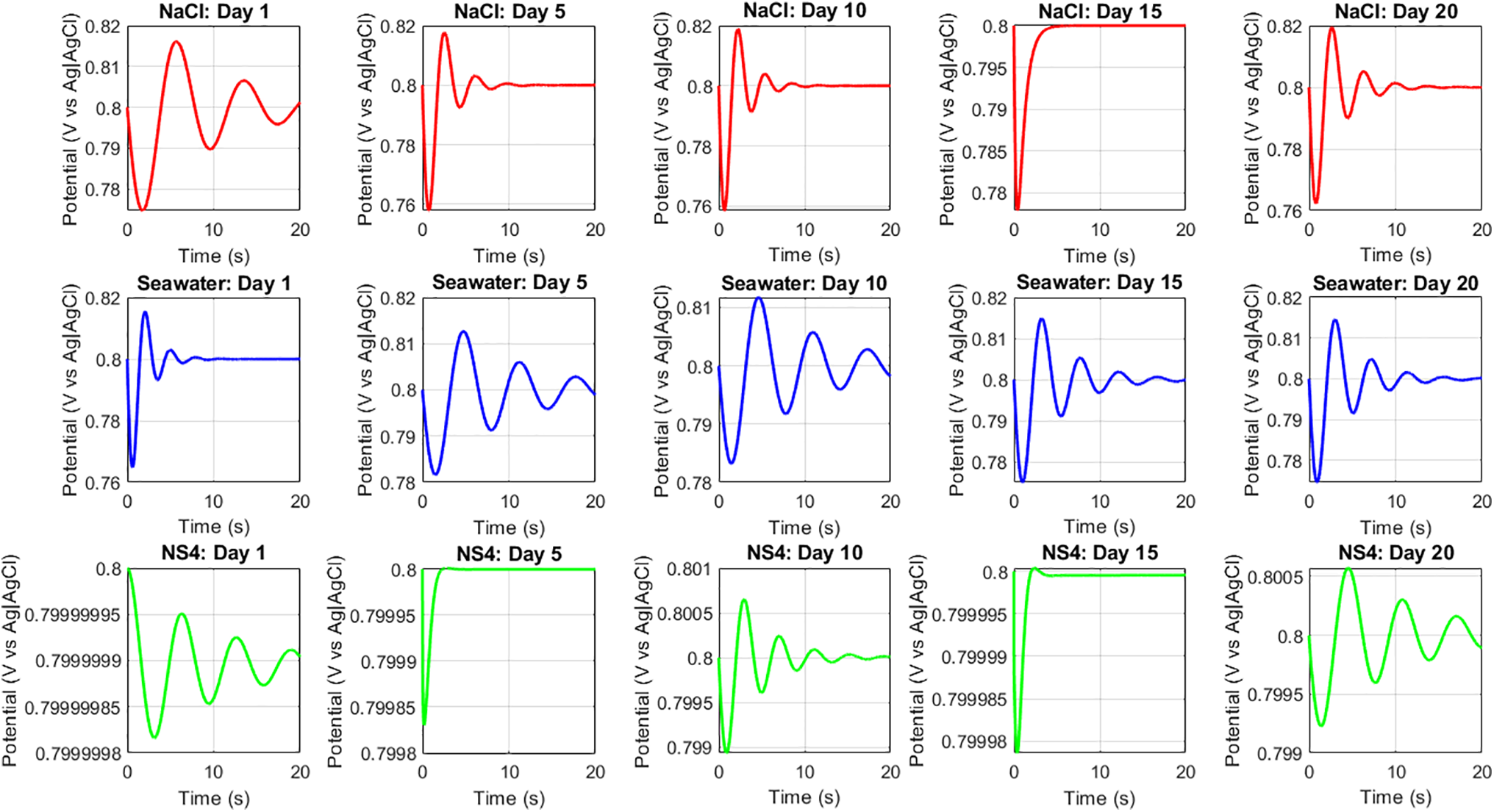

In Fig. 9, we observe the response of closed-loop systems controlled with PID controllers, considering the evolution of the substrates (steel + medium) in the open-loop system. The analysis focuses on intervals where the potential changes are relatively stable, since the metal must undergo a stabilization process after immersion. For unprotected steel, this corresponds to reaching the corrosion potential, whereas for cathodically protected steel, it corresponds to reaching a state in which the potential remains close to the protection potential. In this stabilized state, the PID controller can effectively maintain the protection potential, adjusting the control signal when minor deviations occur. Across all cases, excellent system performance is achieved in only a few seconds.

Figure 9: Closed loop system using a PID control tuning with ANNs and considering the evolution of the substrate in different chlorinated media at day 15 of immersion

Additionally, it is evident that the system adjusts dynamically at different times of immersion. As discussed in the EIS results, the properties of the metal-electrolyte interface evolve over time, leading to modifications in the PID gains. For the system with the highest initial variation, the protection potential is reached after approximately 8 seconds.

Once the system reaches a more stable state—when corrosion products have formed on the surface and potential variations are minimal—the closed-loop system stabilizes even faster, typically within 3 seconds.

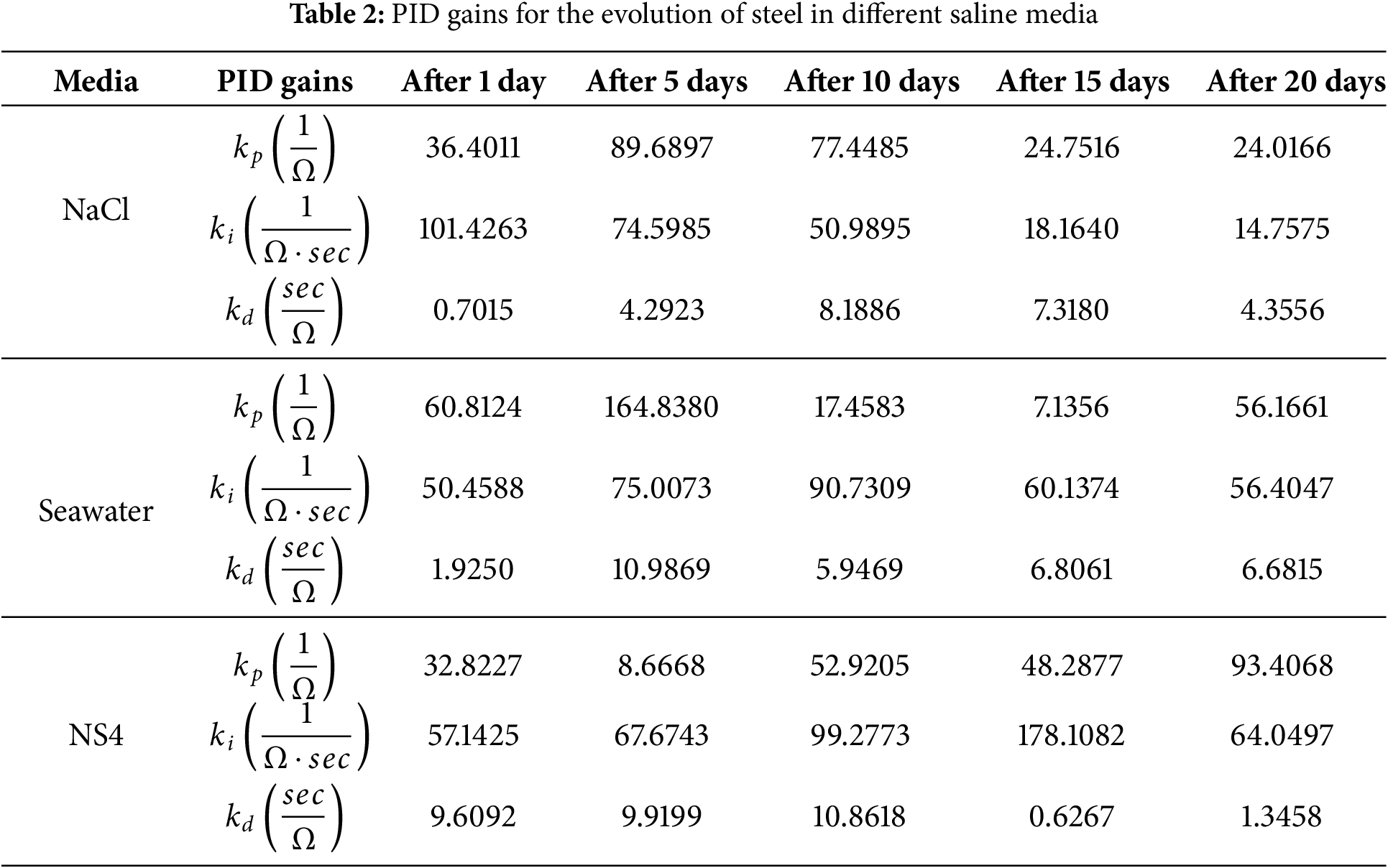

The units of the PID gains are expressed relative to the impedance response of the system:

Table 2 presents the PID gains associated with each saline medium, accounting for substrate evolution. Even under cathodic protection, some product formation occurs on the metal surface, albeit in smaller quantities than in unprotected steel. The PID gains are adjusted via the neural network according to changes in system impedance, as previously discussed. In all cases, the rapid stabilization of the closed-loop system indicates that real-time adjustments of the protection system are feasible.

Note that in this study, the control variable is the electrochemical impedance (measured in ohms,

The parameters used for the PSO algorithm are summarized in Table 3.

This configuration has been found to yield reliable convergence behavior and stable performance in control parameter tuning.

In this work, a numerical method based on artificial neural networks (ANNs) was presented to design an impressed current cathodic protection (ICCP) controller to mitigate corrosion of ASTM

A two-time-constant equivalent circuit was employed for all three systems, reflecting the presence of layers of corrosion and calcareous products. This approach allowed simulation of the combined capacitance of the surface products and the electrochemical double layer.

The ANN models were capable of accurately reproducing the impedance diagrams of ASTM A36 steel under ICCP, achieving an

An ANN-PSO-based PID control system was implemented to optimize the control parameters and improve the overall system performance. The numerical results demonstrate excellent performance in regulating the substrate potential (steel + medium) within only a few seconds. This rapid response is attributed to the adaptive nature of machine learning algorithms, enabling real-time adjustments to the protection system and ensuring that structures are consistently shielded from corrosion.

We conclude that the integration of machine learning techniques, specifically ANNs, can significantly enhance the effectiveness of ICCP systems for corrosion control. By employing PID control based on ANN-PSO optimization, it is possible to dynamically tune the control parameters and improve system performance. The proposed methodology has potential applications in offshore oil and gas platforms, pipelines, and marine structures, where it can reduce maintenance costs, increase operational efficiency, and enhance the safety and reliability of critical infrastructure. Further research and development are warranted to fully exploit the potential of machine learning in ICCP control and to address challenges associated with deploying these techniques in real-world environments.

Acknowledgement: Authors extend their gratitude to the CONAHCYT, the MICRONA center and the Instituto de Ingeniería of the Universidad Veracruza for the economic and technical support provided for this work as well as the support from the project DI INVESTIGACIÓN INNOVADORA INTERDISCIPLINARIA PUCV 2021 No 039.409/2021. Nanoiónica: Un enfoque interdisciplinario.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: Original draft: José Arturo Ramírez-Fernández, Henevith G. Méndez-Figueroa, Sebastián Ossandón. Experimentation for data acquisition: José Arturo Ramírez-Fernández. Data processing: José Arturo Ramírez-Fernández, Henevith G. Méndez-Figueroa, Sebastián Ossandón. Revision and technical support: Ricardo Galván-Martínez, Miguel Ángel Hernández-Pérez, Ricardo Orozco-Cruz. Laboratory equipment and capacitation: Ricardo Galván-Martínez, Ricardo Orozco-Cruz. Corrections: José Arturo Ramírez-Fernández, Henevith G. Méndez-Figueroa, Sebastián Ossandón, Miguel Ángel Hernández-Pérez. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Peabody AW. Peabody’s control of pipeline corrosion. 2nd ed. Houston, TX, USA: NACE International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

2. Von Baeckmann W, Schwenk W, Prinz W. Handbook of cathodic corrosion protection. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1997. [Google Scholar]

3. Quej-Aké L, Nava N, Espinosa-Medina M, Liu H, Alamilla J, Sosa E. Characterisation of soil/pipe interface at a pipeline failure after 36 years of service under impressed current cathodic protection. Corros Eng Sci Technol. 2015;50(4):311–9. doi:10.1179/1743278214y.0000000226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Brenna A, Beretta S, Uglietti R, Lazzari L, Pedeferri M, Ormellese M. Cathodic protection monitoring of buried carbon steel pipeline: measurement and interpretation of instant-off potential. Corros Eng Sci Technol. 2017;52(4):253–60. doi:10.1080/1478422x.2016.1262096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hoe K, Roy S. Current densities for cathodic protection of steel in tropical sea water. Br Corros J. 1998;33(3):206–10. [Google Scholar]

6. Mekki I, Kessar A, Mouaz R, Ahmed M, M’Naouer E, Oran A. Design of a printed circuit board for real-time monitoring and control of pipeline’s cathodic protection system via IoT and a cloud platform. Int J Eng. 2023;36(9):1667–76. [Google Scholar]

7. Dang TB, Nghiem TP. Studying and realizing the based-intelligent iot system for pipeline cathodic protection. JST Smart Syst Dev. 2023;33(3):24–32. doi:10.51316/jst.168.ssad.2023.33.3.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Khan MS, Kakar FK, Khan S, Athar SO. Efficiency and cost analysis of power sources in impressed current cathodic protection system for corrosion prevention in buried pipelines of Balochistan, Pakistan. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;414:012034. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/414/1/012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sibiya C, Kusakana K, Numbi B. Smart system for impressed current cathodic protection running on hybrid renewable energy. In: 2018 Open Innovations Conference (OI); 2018 Oct 3–5; Johannesburg, South Africa. p. 129–33. [Google Scholar]

10. Fernández JAR, Aguilar GG, Hernandez MÁ, Reyes JLR, Canto J, Cabrera-Sierra R. Corrosion study and control of an A-36 steel immersed in chloride solutions using a laboratory developed prototype. ECS Trans. 2021;101(1):301–11. doi:10.1149/10101.0301ecst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kundu A, Tuhin SI, Sani MSH, Easin MWR, Masum MAH. Analytical comparisons of the PID, ANN, and ANFIS controllers’ performance in the AVR system. Int J Innov Sci Res Technol. 2023;8:28. [Google Scholar]

12. Priya IS, Jawaharrani K, Duraibabu B, Manimekalai K, Nelson L, Gomathi S. ANN based voltage control of hybrid DC microgrid connected system. In: 2023 8th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES); 2023 Jun 1–3; Coimbatore, India. p. 231–6. [Google Scholar]

13. Kushwah B, Batool S, Gill A, Singh M. ANN and ANFIS techniques for automatic voltage regulation. In: 2023 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET); 2023 May 26–28; Belgaum, India. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

14. Hamsir H, Sutresman OS, Arsyad H, Syahid M, Widyianto A. Suppression of corrosion on stainless steel 303 with automatic impressed current cathodic protection (a-ICCP) method in simulated seawater. East-Europ J Enterprise Technol. 2022;6(12):120. doi:10.15587/1729-4061.2022.267264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ma S, Du Y, Liang Y, Wang S, Su Y. Machine learning approach to AC corrosion assessment under cathodic protection. Mater Corros. 2023;74(2):255–68. doi:10.1002/maco.202213252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li R, Wang H, Zhu Y, Mu X, Wang X. Machine learning-assisted in situ corrosion monitoring: a review. Corros Rev. 2025. doi:10.1515/corrrev-2025-0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Onuoha DO, Mgbemena CE, Godwin HC, Okeagu FN. Application of industry 4.0 technologies for effective remote monitoring of cathodic protection system of oil and gas pipelines-a systematic review. Int J Ind Prod Eng. 2022;1(2):29–50. [Google Scholar]

18. Tanjung RA, Foury MA, Rohimsyah FM. Using artificial neural networks for the prediction and optimization of electrochemical capacity in aluminum-based sacrificial anodes. Solid State Phenomena. 2025;377:3–12. doi:10.4028/p-asdq6h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Noroznia H, Gandomkar M, Nikoukar J. Pipeline failure evaluation and prediction using failure probability and neural network based on measured data. Heliyon. 2024;10(5):e26837. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kim YS, Seok S, Lee JS, Lee S, Kim JG. Optimizing anode location in impressed current cathodic protection system to minimize underwater electric field using multiple linear regression analysis and artificial neural network methods. Eng Anal Bound Elem. 2018;96:84–93. doi:10.1016/j.enganabound.2018.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hashim MS, Hamadi RNJ, Hamadi NJ. Modeling and control of impressed current cathodic protection (ICCP) system. Iraq J Elect Elect Eng. 2014;10(2):80–8. doi:10.33762/eeej.2014.95594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rezaei A. Artificial neural network modelling to predict the efficiency of aluminium sacrificial anode. Corros Eng, Sci Technol. 2023;58(8):747–54. doi:10.1080/1478422x.2023.2252258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jasim DM, Hussein EAR, Al-Libawy H. Cathodic protection systems: approaches and open challenges. Nexo Revista Científica. 2023;36(6):956–67. doi:10.5377/nexo.v36i06.17451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Obi CE, Gantassi R, Choi Y. Application of artificial intelligence in minimizing voltage deviation using neural network predictive controller. In: International Conference on Model and Data Engineering; 2024 Nov 18–20; Naples, Italy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 158–72. [Google Scholar]

25. De Sena RA, Bastos IN, Platt GM. Theoretical and experimental aspects of the corrosivity of simulated soil solutions. Int Sch Res Notices. 2012;2012(5):103715. doi:10.5402/2012/103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Bonyadi MR, Michalewicz Z. Particle swarm optimization for single objective continuous space problems: a review. Evol Comput. 2017;25(1):1–54. doi:10.1162/evco_r_00180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. H. M. The corrosion behaviour of a low carbon steel in natural and synthetic seawaters. J South Afr Inst Min Metall. 2006;106(8):585–92. [Google Scholar]

28. McCafferty E, McCafferty E. Thermodynamics of corrosion: pourbaix diagrams. In: Introduction to corrosion science. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. p. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

29. Robbins J. Ions in solution: 2. An introduction to electrochemistry. Oxford Chemistry Series. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1972. 127 p. [Google Scholar]

30. Martínez I, Andrade C. Application of EIS to cathodically protected steel: tests in sodium chloride solution and in chloride contaminated concrete. Corros Sci. 2008;50(10):2948–58. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2008.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gao ZM, Liu Y, Lin F, Dang L, Wen L. EIS characteristic under cathodic protection and effect of applied cathodic potential on surface microhardness of Q235 steel. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2013;8(8):10446–53. doi:10.1016/s1452-3981(23)13120-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Narozny M, Zakowski K, Darowicki K. Time evolution of electrochemical impedance spectra of cathodically protected steel in artificial seawater. Constr Build Mater. 2017;154:88–94. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hartt WH, Culberson CH, Smith SW. Calcareous deposits on metal surfaces in seawater—a critical review. Corrosion. 1984;40(11):609–18. doi:10.5006/1.3581927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gurrappa I. Cathodic protection of cooling water systems and selection of appropriate materials. J Mater Process Technol. 2005;166(2):256–67. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.09.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen Y, Wang Z, Wang X, Song X, Xu C. Cathodic protection of X100 pipeline steel in simulated soil solution. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2018;13(10):9642–53. doi:10.20964/2018.10.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Galván-Martínez R, Orozco-Cruz R, Carmona-Hernández A, Mejía-Sánchez E, Morales-Cabrera MA, Contreras A. Corrosion study of pipeline steel under stress at different cathodic potentials by EIS. Metals. 2019;9(12):1353. doi:10.3390/met9121353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Loto CA. Calcareous deposits and effects on steels surfaces in seawater—a review and experimental study. Orient J Chem. 2018;34(5):2332–41. doi:10.13005/ojc/340514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yang Y, Scantlebury JD, Koroleva EV. A study of calcareous deposits on cathodically protected mild steel in artificial seawater. Metals. 2015;5(1):439–56. doi:10.3390/met5010439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Googan C. The cathodic protection potential criteria: evaluation of the evidence. Mater Corros. 2021;72(3):446–64. doi:10.1002/maco.202011978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Refait P, Jeannin M, Sabot R, Antony H, Pineau S. Electrochemical formation and transformation of corrosion products on carbon steel under cathodic protection in seawater. Corros Sci. 2013;71:32–6. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2013.01.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mahlobo MG, Olubambi PA, Mjwana P, Jeannin M, Refait P. Study of overprotective-polarization of steel subjected to cathodic protection in unsaturated soil. Materials. 2021;14(15):4123. doi:10.3390/ma14154123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kim JH, Kim YS, Kim JG. Cathodic protection criteria of ship hull steel under flow condition in seawater. Ocean Eng. 2016;115:149–58. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Refait P, Jeannin M, Sabot R, Antony H, Pineau S. Corrosion and cathodic protection of carbon steel in the tidal zone: products, mechanisms and kinetics. Corrosion Science. 2015;90:375–82. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2014.10.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chung NT, Hong MS, Kim JG. Optimizing the required cathodic protection current for pre-buried pipelines using electrochemical acceleration methods. Materials. 2021;14(3):579. doi:10.3390/ma14030579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang J, Lu J, Yan L, Feng Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y. The applicability of EIS to determine the optimal polarization potential for impressed current cathodic protection. Anti-Corros Methods Mater. 2010;57(5):249–52. doi:10.1108/00035591011075896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools