Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Anonymous Authentication and Key Exchange Protocol for UAVs in Flying Ad-Hoc Networks

1 School of Network Security, Jinling Institute of Technology, Nanjing, 211169, China

2 School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing, 210096, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yanan Liu. Email: ; Suhao Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 52 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072710

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Flying Ad-Hoc Networks (FANETs) are widely used in both civilian and military fields, but they face severe security, trust, and privacy vulnerabilities due to their high mobility, dynamic topology, and open wireless channels. Existing security protocols for Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks (MANETs) cannot be directly applied to FANETs, as FANETs require lightweight, high real-time performance, and strong anonymity. The current FANETs security protocol cannot simultaneously meet the requirements of strong anonymity, high security, and low overhead in high dynamic and resource-constrained scenarios. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an Anonymous Authentication and Key Exchange Protocol (AAKE-OWA) for UAVs in FANETs based on One-Way Accumulators (OWA). During the UAV registration phase, the Key Management Center (KMC) generates an identity ticket for each UAV using OWA and transmits it securely to the UAV’s on-board tamper-proof module. In the key exchange phase, UAVs generate temporary authentication tickets with random numbers and compute the same session key leveraging the quasi-commutativity of OWA. For mutual anonymous authentication, UAVs encrypt random numbers with the session key and verify identities by comparing computed values with authentication values. Formal analysis using the Scyther tool confirms that the protocol resists identity spoofing, man-in-the-middle, and replay attacks. Through Burrows Abadi Needham (BAN) logic proof, it achieves mutual anonymity, prevents simulation and physical capture attacks, and ensures secure connectivity of 1. Experimental comparisons with existing protocols prove that the AAKE-OWA protocol has lower computational overhead, communication overhead, and storage overhead, making it more suitable for resource-constrained FANET scenarios. Performance comparison experiments show that, compared with other schemes, this scheme only requires 8 one-way accumulator operations and 4 symmetric encryption/decryption operations, with a total computational overhead as low as 2.3504 ms, a communication overhead of merely 1216 bits, and a storage overhead of 768 bits. We have achieved a reduction in computational costs from 6.3% to 90.3%, communication costs from 5.0% to 69.1%, and overall storage costs from 33% to 68% compared to existing solutions. It can meet the performance requirements of lightweight, real-time, and anonymity for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) networks.Keywords

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have grown increasingly prevalent across both civilian and military sectors, which is attributed to their inherent advantages, including accessibility, versatility, and low operational costs. Their practical applications are wide-ranging, encompassing parcel delivery [1], crowd and traffic monitoring [2], search-and-rescue operations [3], and disaster response efforts [4]. A new type of aerial ad-hoc networks—Flying Ad Hoc Networks (FANET) have evolved from a single node operation to a group of nodes to accomplish the above specific tasks. UAVs are used in these networks to monitor the networks by using sensing and communication technologies [5].

In FANETs, a multitude of nodes achieve autonomous wireless interconnection, which effectively enhances the scalability of operational scenarios. When deployed for monitoring tasks, multi-UAV systems leverage their small radar cross-section—a key advantage over large radar cross-section platforms—to optimize mission adaptability. Additionally, these networks offer systematic node deployment, extensive coverage range, and low-cost transmission services; they also maintain reliable communication with ground-based Base Stations (BSs) [6,7]. Furthermore, UAV nodes within such networks can cover designated geographical regions, rendering them highly feasible for emergency scenarios where the deployment of conventional networks is impracticable. Leveraging ad hoc network capabilities, these systems have also enhanced traditional field operations and workflows—including defense monitoring, formation coordination, firefighting, and transportation—by optimizing task execution efficiency and adaptability [8].

However, despite their diverse advantages, FANETs are plagued by security, trust, and privacy vulnerabilities issues that can undermine and impair overall network performance [9]. The wireless channels make data transmission vulnerable and susceptible to various malicious attacks and activities, e.g., spoofing, replay attack, man-in-the-middle attack, physical capture attack, etc. [10,11]. Therefore, trust management methods, especially the authentication and key management protocols, must be adopted to evaluate the trust of UAV nodes and detect malicious nodes.

While FANETs share certain similarities with other Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks (MANETs) architectures, they possess distinct characteristics, such as higher node mobility, greater movement flexibility, three-dimensional (3D) rotational capability, dynamic network topology, and deployment in open spaces (which increases their susceptibility to detection). Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are required to complete instantaneous network formation, authentication, and key agreement in the air without fixed central infrastructure, so as to ensure mission collaboration and data security. It is not only necessary to inherit the ideas for addressing dynamic topologies in traditional mobile communication ad hoc networks, but also required that the authentication mechanism be decentralized—supporting nodes to independently complete identity verification while being capable of resisting man-in-the-middle attacks and routing spoofing [12]. Therefore, lightweight, high real-time performance, and strong anonymity constitute the core challenges in designing security protocols for UAV networks.

In this paper, an anonymous authentication and key exchange protocol based on one-way accumulators (OWA) [13] is proposed for UAVs in FANETs. By leveraging the one-way and quasi-commutative properties of OWAs, the proposal can implement mutual authentication and establish a shared key without disclosing the identities of UAVs. This design not only achieves anonymity but also enables resistance against typical malicious threats, such as impersonation attacks, re-play attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, and physical capture attacks.

To sum up, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. Unidirectional accumulator construction and authentication: A method for constructing a unidirectional accumulator based on the strong RSA assumption is proposed, which utilizes its unidirectionality to provide authentication for drones, ensuring the security and irreversibility of identity information, laying the foundation for anonymous authentication in FANETs.

2. Key negotiation mechanism: With the quasi-commutativity of a unidirectional accumulator, an efficient key negotiation mechanism has been designed to enable any two drones to calculate the same key value through the accumulation operation, thereby achieving secure key negotiation and meeting the real-time and security requirements of drone communication in FANETs.

3. Security analysis and performance optimization: Scyther tool was used for formal verification, and combined with BAN logic proof deduction, the security of the protocol was comprehensively analyzed to ensure its ability to resist various attacks; Meanwhile, the computational cost, communication cost, and storage resource cost were evaluated through experiments, verifying the efficiency and feasibility of the protocol in resource constrained FANETs environments.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the related works. Section 3 presents Definitions and Assumptions, the detailed introduction of network models and related threat models, and the definition of symbols involved in this article. Section 4 provides a detailed explanation of the mathematical derivation process of the AAKE-OWA protocol from the three stages of KMC registration, key exchange, and mutual authentication. Section 5 verifies the security of the protocol using Scyther tool and BAN logic, and quantitatively compares its overhead with five mainstream protocols. Section 6 summarizes the research results, protocol advantages, existing shortcomings, and future research directions.

2.1 Authentication and Key Management in MANETs

FANETs are a specialized subset of Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks (MANETs). Both belong to the family of ad-hoc networks, sharing core features such as decentralized architecture, dynamic topology, and multi-hop communication capabilities. These commonalities mean authentication and key management solutions in FANETs inherit basic design principles from MANETs.

Presently, many authentication and key management protocols are designed to protect for MANETs, which can be roughly categorized into the following four types.

(1) Symmetric Cryptography-Based Authentication protocols: These primarily use lightweight operations such as hash functions, message authentication codes (MACs), or symmetric encryption algorithms. For example, Nikooghadam et al. [14] proposed an ECC-based authentication protocol for the Internet of Drones (IoD) in 2021. Although this protocol achieves efficient authentication and key agreement using elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), it still fails to fully meet the requirement of non-repudiation.

(2) Public Key Infrastructure (PKI)-Based Authentication protocols: In traditional PKI technology, private keys are directly associated with user identities, making it impossible to ensure user anonymity. Khalid et al. [15] proposed the HOOPOE protocol in 2023, which combines AES and RSA algorithms to achieve efficient anonymous handover authentication for UAVs flying out of their designated zones. However, it still suffers from complex certificate management and high communication overhead. To achieve anonymity, multiple anonymous public-private key pairs and certificates must be generated for each user. Although this provides non-repudiation, chain certificate downloads and Certificate Revocation List (CRL) distribution result in excessive communication overhead, making it unsuitable for high-dynamic, intermittently connected aerial links.

(3) Identity-Based (IDB) Authentication protocols [16,17]: These avoid PKI certificate management issues but often require time-consuming bi-linear pairing operations and introduce key escrow. To implement anonymous authentication, users’ temporary identities must be dynamically changed, leading to frequent updates of public and private keys and increased system overhead. In 2017, Chen [18] constructed a two-party roaming authentication key agreement protocol and its improved version [19] with strong security and anonymity, using ECC and identity-based crypto-systems combined with the Schnorr signature algorithm. This protocol can resist temporary secret leakage attacks. However, to achieve anonymity (hiding the link between the mobile node’s public key and its real ID), temporary identities of mobile nodes must be generated as their public key certificates. While this eliminates certificate management, it relies on bi-linear pairing operations, resulting in high computational and energy overheads, as well as key escrow risks.

(4) Certificateless-Based (CLB) Authentication protocols [20]: These avoid both PKI certificate management and IDB key escrow issues but, like IDB protocols, still cannot avoid bilinear pairing operations and frequent public-private key updates. For example, Zhang et al. [21] proposed an anonymous authentication and key agreement protocol for Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) based on certificateless aggregate signatures in 2020. This protocol meets the conditional anonymity requirement of vehicles and enables cloud servers to authenticate vehicles, but it cannot guarantee mutual authentication (i.e., vehicles cannot verify the identity of cloud servers). In 2024, Huang et al. [22] proposed the BAKAS-UAV protocol, which uses blockchain and Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) to achieve secure authentication in UAV networks, providing new insights into solving key update and synchronization issues in CLB protocols. Although it balances decentralization and efficiency, it still requires frequent updates of temporary public keys, suffers from complex key synchronization, and struggles to achieve true anonymity.

However, FANETs are distinct from general MANETs due to their unique application scenario and derived technical attributes [23]. Unlike MANETs, which typically involve ground-based nodes (e.g., mobile phones, laptops) with relatively low mobility speed and two-dimensional (2D) movement constraints, FANET nodes (UAVs) exhibit higher mobility velocity, three-dimensional (3D) movement freedom, and more volatile link quality [24]. Additionally, FANETs often face stricter requirements for real-time performance and energy efficiency. Therefore, the existing security protocols designed for MANETs cannot be directly applied to FANETs due to the differences in their network characteristics and requirements. Conducting targeted research on specific security protocols for FANETs is academically and practically essential.

2.2 OWA-Based Cryptographic Protocols

A One-Way Accumulator (OWA) is a cryptographic primitive that was first proposed by Josh Benaloh and Michael de Mare in 1995 [13]. A OWA is a function with such quasi-commutativity, and it satisfies the one-way property, that is, it is easy to calculate the accumulator value from a set of elements, but it is computationally infeasible to derive the original elements from the accumulator value. In other words, a one-way accumulator can compactly aggregate a set of elements into a single “accumulator value”, and new elements can be dynamically added to the set, and the accumulator value can be updated efficiently without re-processing all existing elements. At the same time, for any element in the accumulated set, a short “witness” can be generated to verify that the element is part of the set [25].

The OWAs have wide-ranging applications in cryptography, especially in anonymous authentication. They enable users to prove membership in a trusted set without revealing their specific identity. For instance, in secure communication systems, a user can generate a witness to confirm they belong to the authorized group, allowing mutual authentication with a server while preserving anonymity.

In 2011, Liu et al. [26] proposed a new anonymous authentication protocol for trusted platforms based on one-way accumulators. This protocol uses OWA technology to accumulate ring signature member information, fixing the length of the signature ring, effectively reducing the number of hash computations and encryption/decryption operations during verification, and improving authentication efficiency. However, the signature initiator in this protocol has unconditional anonymity, which may allow the signer to frame other non-actual signers.

In 2016, Cai et al. [27] addressed the issue of sensitive information leakage caused by revoking abnormally behaving vehicles in VANETs by proposing a privacy-preserving revocation mechanism based on universal one-way accumulators. This reduced the computational complexity of authentication management and improved authentication efficiency but still relied on an “alias” mechanism—constructing multiple aliases for vehicles to achieve anonymity.

In 2020, Wang et al. [28] studied multi-factor authentication protocols for real-time data access in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). They analyzed the defects of existing protocols in security and efficiency, providing insights for optimizing authentication mechanisms by combining technologies such as accumulators. The proposed protocol leveraged the computational imbalance of the RSA cryptosystem to improve efficiency, indirectly demonstrating the application value of lightweight cryptographic technologies in resource-constrained scenarios. One-way accumulators can further reduce computational complexity in similar scenarios.

In 2023, Chen [29] proposed introducing one-way accumulators as an identity data structure in a blockchain-based Decentralized Cross-Domain Identity Management System (DCIMB) to improve authentication efficiency and protect user privacy. Although this enhanced cross-domain authentication efficiency, the authentication process across multiple trust domains still suffered from complexity and time delays, affecting the response time of practical applications.

In 2024, Zhong et al. [30] proposed a Cross-Domain Batch Authentication protocol (CD-BASA) based on blockchain and accumulators to address low efficiency and high storage overhead in cross-domain multi-vehicle authentication in VANETs. This protocol used one-way accumulators to aggregate vehicle identity information, stored witness values using the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), and designed a multi-accumulator batch proof algorithm, significantly reducing the computational and storage overheads of cross-domain batch authentication. However, when vehicles frequently enter or exit the network, continuous updates and synchronization of accumulators introduce large system overheads, affecting real-time performance in practical applications.

In 2025, Zhang et al. [31] proposed a lattice-based puncturable CP-ABE (Pt-CP-ABE) protocol for cloud-assisted IoT to address the issue that long-term user key leakage endangers the confidentiality of previously generated data. This protocol used dynamic accumulators (an extension of one-way accumulators) to achieve flexible forward security. By associating user attributes and tag information via accumulators, it supported users to independently update private keys and revoke decryption rights for specific ciphertexts. A Pt-RCP-ABE protocol was further proposed by combining a direct revocation mechanism, achieving quantum resistance, forward security, and user revocation. However, the size of the puncturable private key in this protocol grows quadratically with the number of puncturing operations, and the lattice-based cryptosystem results in a large public parameter scale.

In this paper, we employ the Benaloh-Mare OWA to propose an anonymous authentication and key exchange protocol for UAVs in FANETs. During the mutual authentication process, the UAV calculates the accumulator value to derive a temporary ticket to prove membership without revealing its identity.

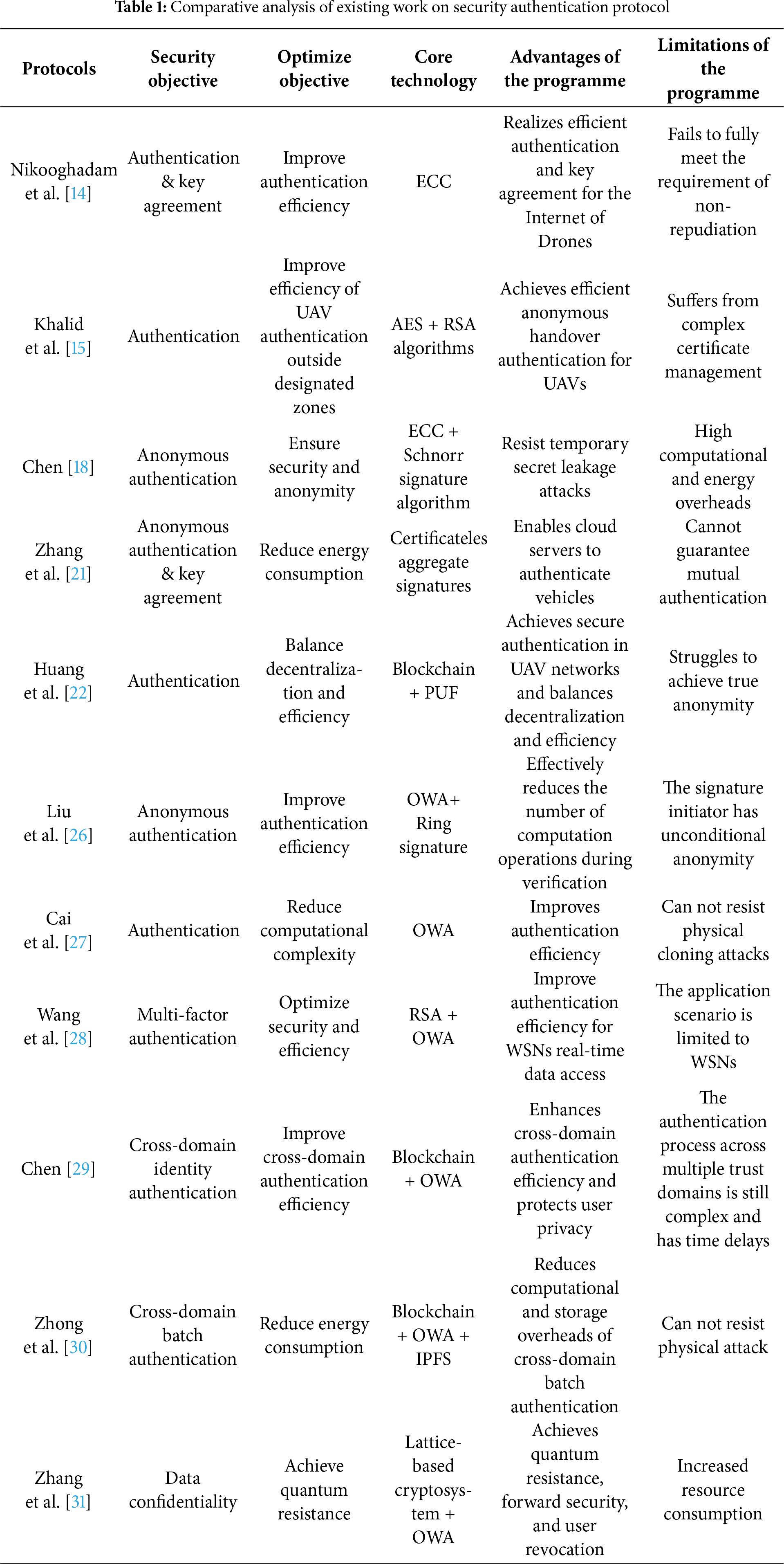

To systematically evaluate the strengths, limitations, and applicability of current research efforts in the field of security authentication. Table 1 provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of existing security authentication studies.

Through the review of research on the aforementioned security protocols, it is found that the existing solutions in current relevant studies are difficult to simultaneously meet the comprehensive requirements of FANETs for security attributes (such as non-repudiation and true anonymity), low resource overhead (storage, computation, and communication), and adaptation to highly dynamic scenarios. For instance, the protocol proposed by Nikooghadam et al. [14] lacks non-repudiation; the scheme by Huang et al. [22] struggles to achieve true anonymity and suffers from high computational overhead and complex key synchronization; and the HOOPOE protocol by Khalid et al. [15] incurs excessive storage and communication overhead due to the management of multiple sets of key certificates. All these solutions fail to balance anonymity, low overhead, and attack resistance effectively.

In contrast, the proposed Anonymous Authentication and Key Exchange Protocol (AAKE-OWA) in this paper, which is based on the Benaloh-Mare One-Way Accumulator (OWA), enables UAVs to calculate the accumulator value and generate a temporary credential to prove their group membership without disclosing their real identities during the mutual authentication process. While ensuring security and anonymity, this protocol significantly reduces various types of overhead, thereby addressing the shortcomings of existing solutions in adapting to the highly dynamic and resource-constrained environment of FANETs.

Definition 1: One-Way Accumulator. A one-way accumulator is a finite set of functions that satisfies three properties:

(1) Computational feasibility:

(2) One-way property: No polynomial P exists where a probabilistic polynomial-time algorithm

(3) Quasi-commutativity: For all

Definition 2: Benaloh-Mare OWA [25]. There are various ways to construct a one-way accumulator. In this paper, one definition is chosen:

FANETs are a specialized subset of MANETs designed for UAVs. Unlike ground-based MANETs, FANETs have distinct traits shaped by UAV operations. First, they feature high node mobility and 3D movement: UAVs move at higher speeds and in three-dimensional space, leading to rapidly changing network topologies with frequent node joins, exits, and link disruptions. Second, FANETs rely on decentralized architecture: Without fixed infrastructure (e.g., base stations in cellular networks), UAVs connect autonomously via multi-hop wireless communication, enhancing scalability for tasks like formation flight or disaster rescue. Third, they face unique link challenges: Open wireless channels make data transmission vulnerable to jamming, eavesdropping, and spoofing. Additionally, UAVs have limited battery and computing resources, demanding lightweight protocols.

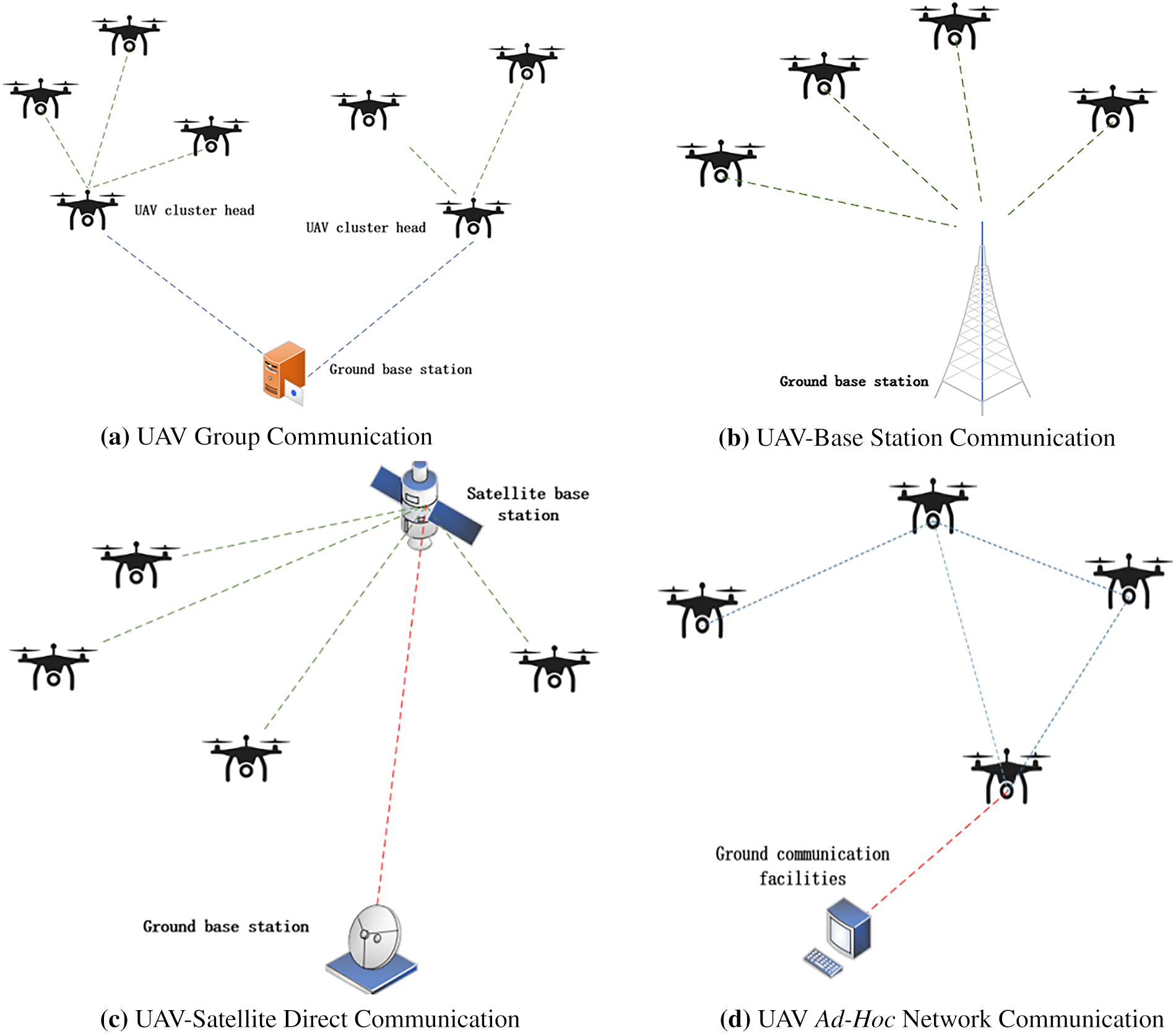

In FANETs, UAV communication scenarios exhibit high diversity and complexity, imposing more stringent requirements [32]. As shown in Fig. 1, different communication scenarios vary significantly in terms of network topology, node dynamics, communication distance, and security requirements.

Figure 1: Different UAV communication scenarios

Fig. 1a: UAV Group Communication: Multiple UAVs form a temporary group to execute collaborative tasks, requiring high-frequency interaction of task instructions and sensor data between nodes. In this scenario, the network topology dynamically changes with UAV positions, and nodes frequently join or exit. The authentication mechanism must support rapid session establishment while preventing forgery attacks from malicious nodes outside the group [33].

Fig. 1b: UAV-Base Station Communication: UAVs upload data and receive instructions via ground base stations or low-altitude communication towers. As fixed infrastructure, base stations act as bridges between UAVs and the core network. Secure mutual authentication is essential to avoid UAV identity leakage or malicious counterfeiting of base stations, while adapting to signal fluctuations caused by high-speed UAV movement [34].

Fig. 1c: UAV-Satellite Direct Communication: In remote areas or emergency scenarios, UAVs achieve beyond-line-of-sight communication via satellite links to support remote control and global collaboration. This scenario is characterized by high communication latency, limited bandwidth, and vulnerability to interference in space links. The authentication protocol must be lightweight to reduce communication overhead, while ensuring anti-interference and non-repudiation capabilities [35].

Fig. 1d: UAV Ad-Hoc Network Communication: A distributed network without a central node, where UAVs transmit information through multi-hop routing. It is suitable for scenarios without infrastructure coverage, such as post-disaster rescue and battlefield communication. Node roles in the network switch dynamically, and the topology is highly dynamic. The authentication mechanism must be decentralized to support autonomous identity verification by nodes, while resisting man-in-the-middle attacks and routing deception [36].

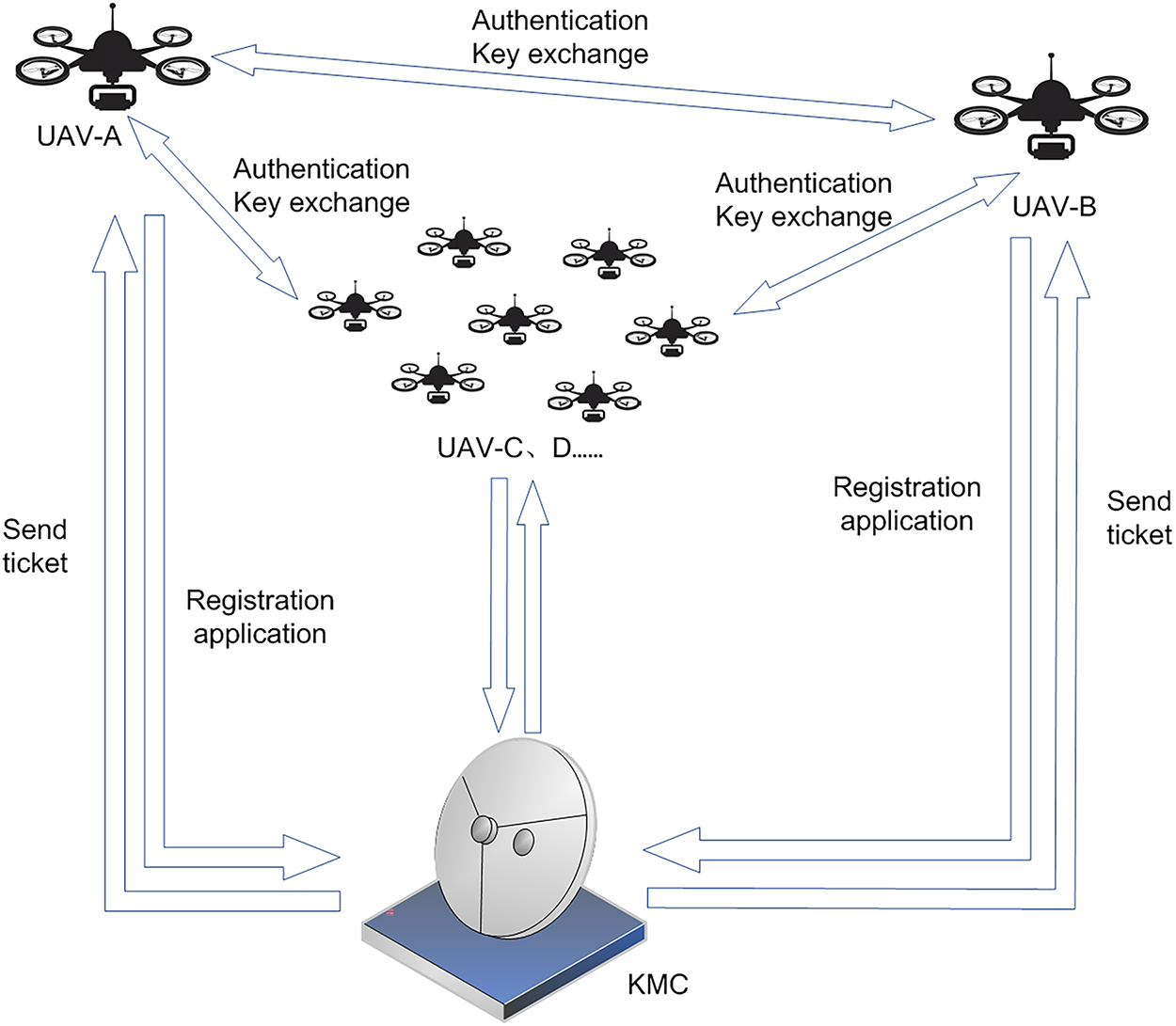

Under the STRIDE and Dolev Yao models, the core security threats of FANETs mainly include: attackers can use open channels and high-speed dynamic topologies to anonymously forge identities, tamper with or replay routes, control messages, steal/block data, and carry out man in the middle, Sybil, wormhole, denial of service attacks at any node, completely controlling the communication link. In this paper, we mainly focus on the communication among low-altitude UAVs and the grounded BS. The proposed protocol involves three entities: a Key Management Center (KMC), UAV-A, and UAV-B, as shown in Fig. 2. The KMC is deployed on a grounded control cloud platform and generates temporary identity tokens for each low-altitude UAV. UAV-A completes anonymous authentication and key exchange with UAV-B using the token distributed by the KMC.

Figure 2: Authentication and key exchange between UAV-A, and UAV-B

In the protocol proposed in this paper, KMC utilizes OWA to generate temporary identity credentials for each low-altitude UAV. These credentials are securely written into the onboard tamper-proof module through a secure channel, maintaining anonymity while serving as credentials for subsequent authentication. When two UAVs (A and B) need to establish an air-to-air secure link, they extract their temporary credentials and generate temporary authentication credentials using instant randomization. Leveraging OWA’s exchangeability, A and B can derive identical session keys within a single broadcast round, meeting the millisecond-level lifespan requirements for low-altitude communication links.

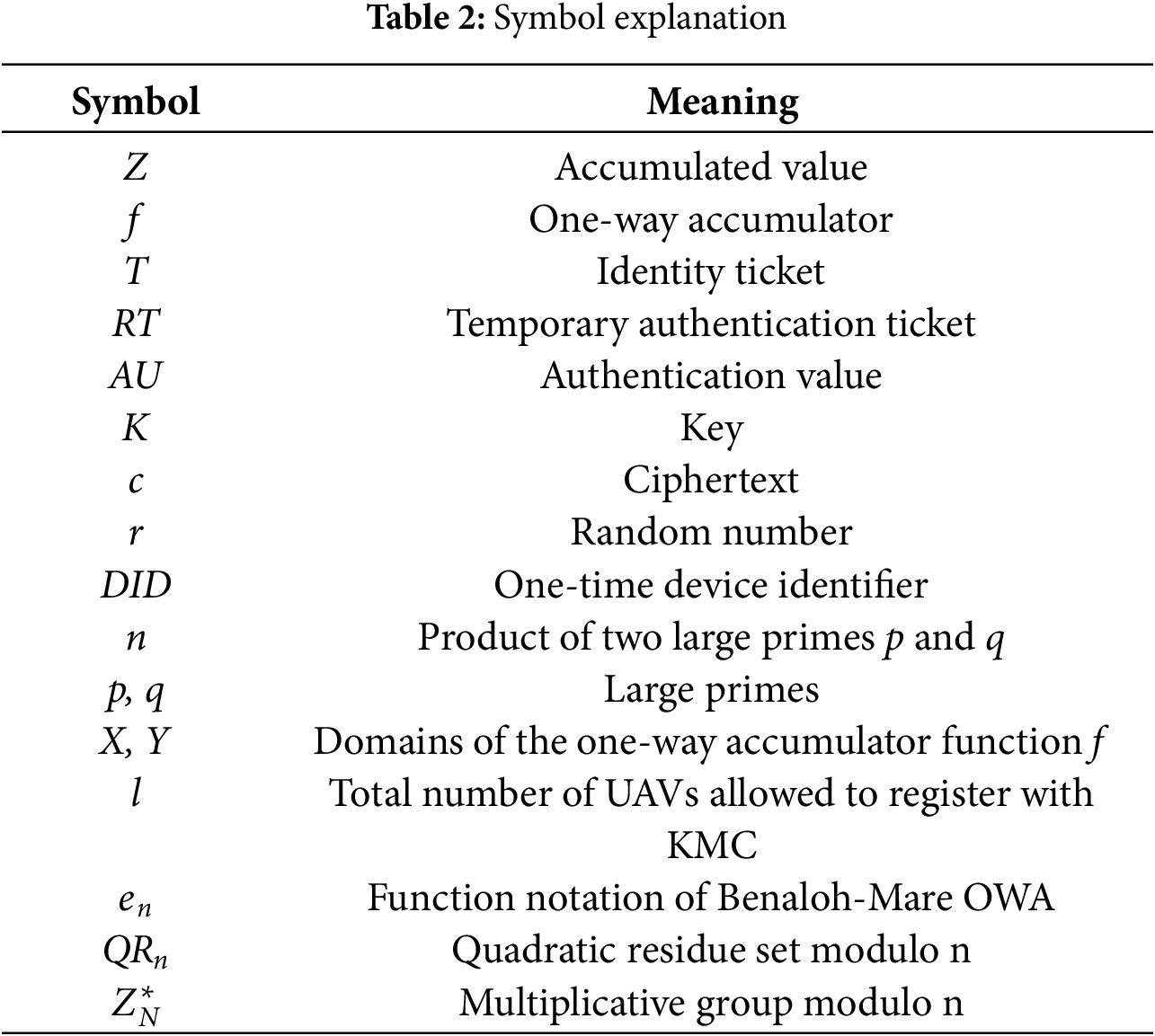

The symbols involved in this paper are explained in Table 2.

The main idea of this AAKE-OWA protocol is as follows: The Key Management Center (KMC) utilizes a one-way accumulator to generate an identity ticket for each registered Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). This ticket is then written into the UAV’s on-board tamper-proof module (TPM) via a secure channel, serving as a credential for subsequent authentication. When two UAVs (UAV-A and UAV-B) need to establish an air-to-air secure link, each extracts its own identity ticket, generates a temporary random number, and creates a temporary authentication ticket. Leveraging the quasi-commutativity of the one-way accumulator, UAV-A and UAV-B can compute the same session key within a single broadcast round, meeting the millisecond-level latency requirement for low-altitude communication links.

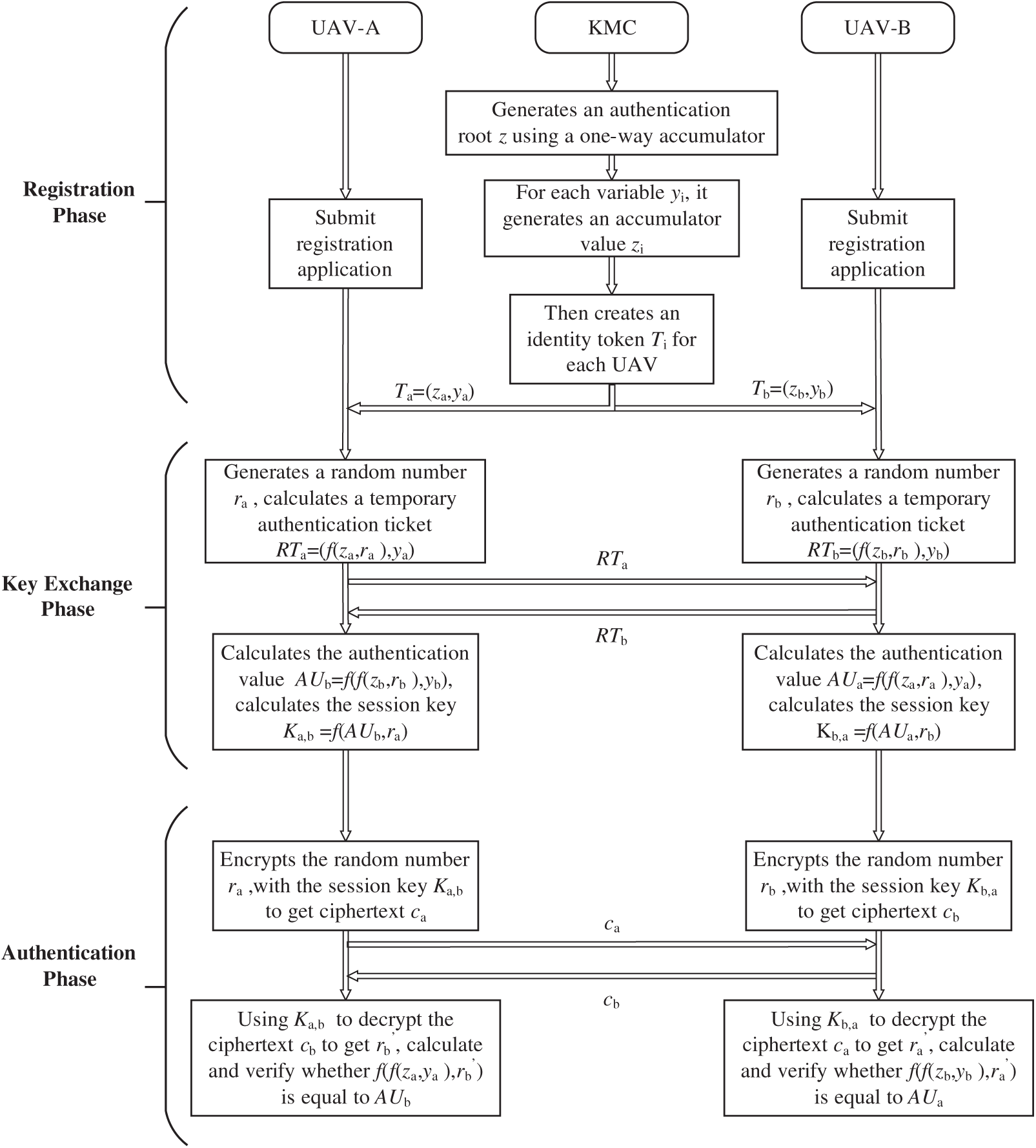

As shown in Fig. 3, the protocol process is divided into three phases: (1) UAV registration at the KMC; (2) Key exchange between UAV-A and UAV-B; (3) Mutual anonymous authentication between UAV-A and UAV-B.

Figure 3: Specific process of an anonymous authentication key exchange protocol based on the one-way accumulator

4.1 UAV Registration at the KMC

(1) UAV-A submits a registration application to the KMC, providing only a one-time Device Identifier (DID-A) without exposing real identity information.

(2) Recall that the one-way accumulator function f is defined as

(3) For each variable

(4) Using the accumulator values generated in Step 3, the KMC creates an identity token for each UAV, denoted as

(5) The KMC securely transmits the UAV’s identity token to the corresponding UAV.

4.2 Key Exchange between UAV-A and UAV-B

(1) UAV-A generates a random number ra, computes a temporary authentication ticket

(2) UAV-B generates a random number rb, computes a temporary authentication ticket

(3) UAV-A first computes the authentication value

(4) UAV-B computes the authentication value

(5) Based on the quasi-commutativity of the one-way accumulator f, it can be derived that

thereby achieving key exchange.

4.3 Mutual Anonymous Authentication between UAV-A and UAV-B

UAV-A encrypts the random number ra using the key Ka,b to generate the ciphertext

UAV-B encrypts the random number rb using the key Kb,a to generate the ciphertext

UAV-A decrypts cb using Ka,b to obtain

UAV-B decrypts ca using Kb,a to obtain

5 Analysis, Simulation, and Comparisons

The proposed AAKE-OWA protocol is experimentally analyzed using the Scyther formal analysis tool. Scyther is a formal analysis tool developed by Cass Cremers of the University of Zurich, Switzerland. It can automatically analyze protocol security and identify potential vulnerabilities and attack paths.

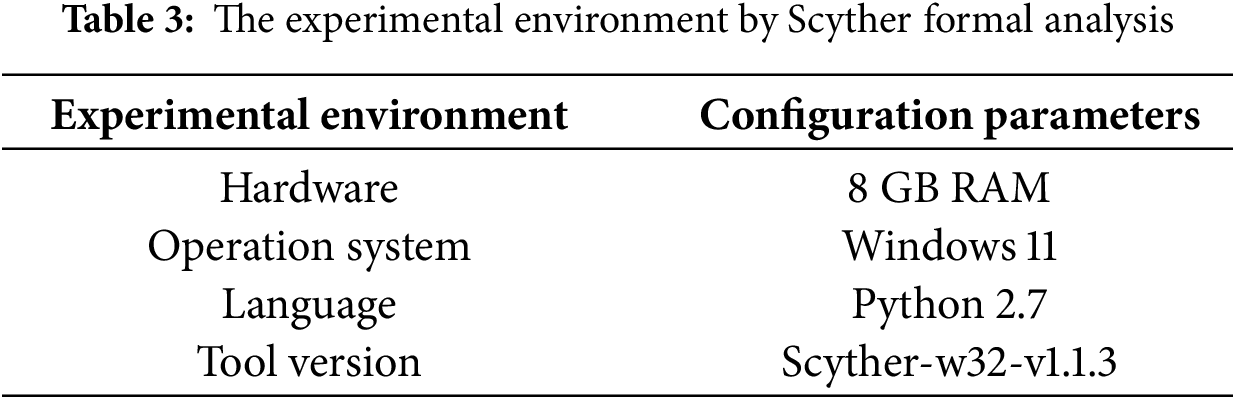

The experimental environment by Scyther is listed in Table 3.

The protocol involves four roles: UAV-A, UAV-B, and the KMC. During the analysis, the role information and message content of the protocol were converted into the input format of Scyther, which uses the Security Protocol Description Language (SPDL). After describing the protocol, its security was verified.

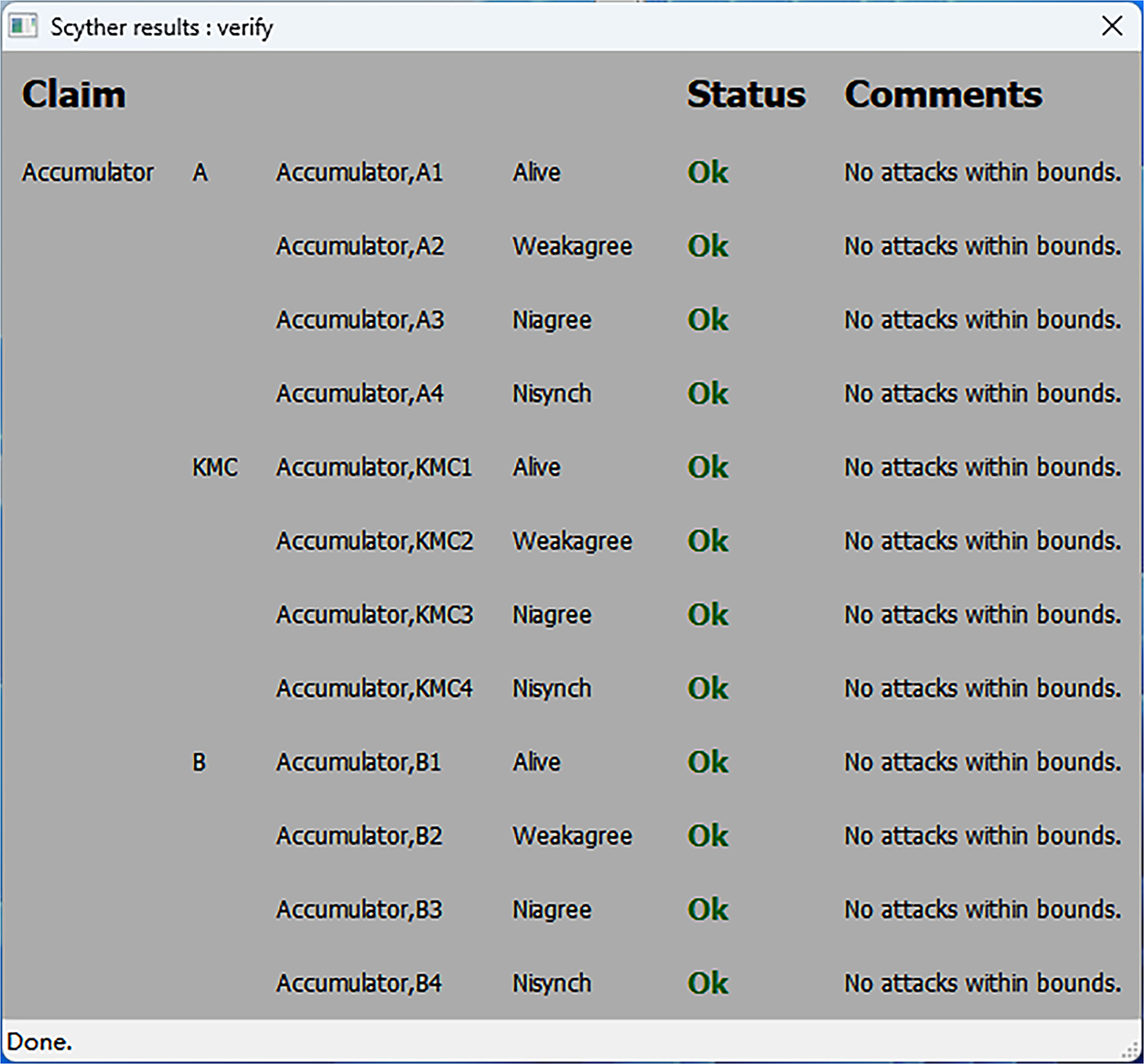

Fig. 4 shows the results of the formal analysis of the UAV identity verification protocol using Scyther. All security claims involving UAV-A, UAV-B, and the KMC—including Alive (subject liveness confirmation), Weakagree (weak agreement), Niagree (non-injective agreement), and Nisynch (non-synchronization)—are marked as “OK”.

Figure 4: Verification results of all Scyther claims

Liveness (Alive): The protocol ensures that UAV-A, UAV-B, and the KMC are correctly identified as real participants during interaction, resisting identity spoofing attacks where adversaries pretend to be legitimate roles and infiltrate communication.

Weak Agreement (Weakagree): The protocol ensures that all interacting parties reach a consistent understanding of each other’s identities, resisting identity confusion tactics commonly used in man-in-the-middle attacks.

Non-Injective Agreement (Niagree) and Non-Synchronization (Nisynch): The successful verification of these properties indicates that the protocol maintains reliable identity verification even in asynchronous communication scenarios. This means that even if an attacker attempts to disrupt communication timing by intercepting, delaying, or replaying messages, the protocol still ensures that all roles reach a consistent identity verification result, effectively resisting replay attacks, timing manipulation attacks, and other advanced threats.

The experimental results demonstrate that the protocol is designed to resist advanced attacks such as identity spoofing, man-in-the-middle attacks, replay attacks, and timing manipulation, providing a fundamental guarantee for secure communication between UAVs.

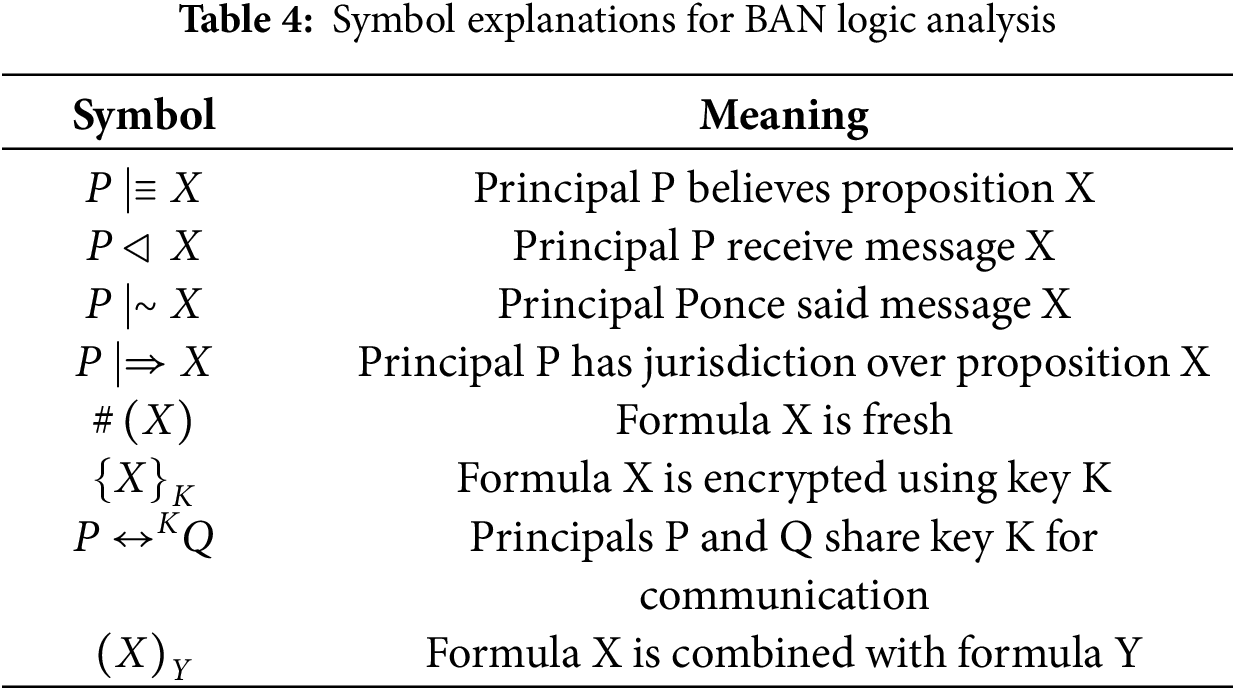

5.2 Burrows-Abadi-Needham (BAN) Logic Proof

Burrows-Abadi-Needham (BAN) logic is a formal analysis method used to verify the correctness of authentication and key agreement protocols. It models the beliefs of participating entities and the evolution of these beliefs during protocol execution, thereby demonstrating whether the protocol achieves expected security goals such as mutual authentication and key consistency. The symbols involved in the BAN logic formal analysis are explained in Table 4.

The main rules of BAN logic used in the analysis are as follows:

Rule 1: Message Meaning Rule: If

Rule 2: Freshness Rule: If

Rule 3: Belief Rule: If

Rule 4: Jurisdiction Rule: If

Using these rules, the AAKE-OWA protocol is analyzed as follows:

Theorem 1: Session Key Generation and Consistency Verification.

Proof of Theorem 1:

1. UAV-A Computes

From

UAV-A believes the relationship between its accumulator value

The session key is computed as:

2. UAV-B Computes

From

AV-B believes the relationship between its accumulator value

The session key is computed as:

3. Consistency Derivation:

From the above calculations,

Theorem 2: Mutual Authentication Derivation.

Proof of Theorem 2:

1. UAV-A Authenticates UAV-B:

UAV-A receives

Since only A and B know

Message Meaning Rule:

UAV-A believes its self-generated random number

Belief Rule:

Since

2. UAV-B Authenticates UAV-A:

UAV-B receives

Since only A and B know

Message Meaning Rule:

UAV-B believes its self-generated random number

Belief Rule:

That is, UAV-B completes the identity authentication of UAV-A. □

Theorem 3: Derivation of Anonymity.

Proof of Theorem 3:

UAV-B receives the temporary authentication token

Due to the one-way property of the one-way accumulator,

Similarly, it can be obtained that

Theorem 4: Long-Term Anonymity Derivation.

Proof of Theorem 4:

The core of long-term anonymity is cross-session identity unlinkability, meaning that even after long-term monitoring of multiple sessions, an attacker still cannot bind public parameters to the real identity of a UAV. The following verification combines the cryptographic properties of the protocol and logical deduction:

1. Structure of Public Parameters in Multiple Sessions

When UAV-A interacts with different UAVs (e.g., UAV-B, UAV-C), it generates a public parameter for each session (the i-th session):

(i)

(ii)

The attacker can intercept

2. One-Way Accumulator Blocks Reverse Derivation of

The One-Way Accumulator adopted in the protocol is based on the Discrete Logarithm Problem: Given

For any single round of

Theorem 5: Derivation of Resistance to Replay Attacks.

Proof of Theorem 5:

The session key

Theorem 6: This protocol guarantees the secure connectivity is 1.

Proof of Theorem 6: Secure connectivity is defined as the probability that two communicating parties can establish a session key. In this protocol, any two legitimate UAVs (i.e., those that have successfully registered with the KMC and obtained identity tokens) can successfully establish a session key. Therefore, the secure connectivity is 1. □

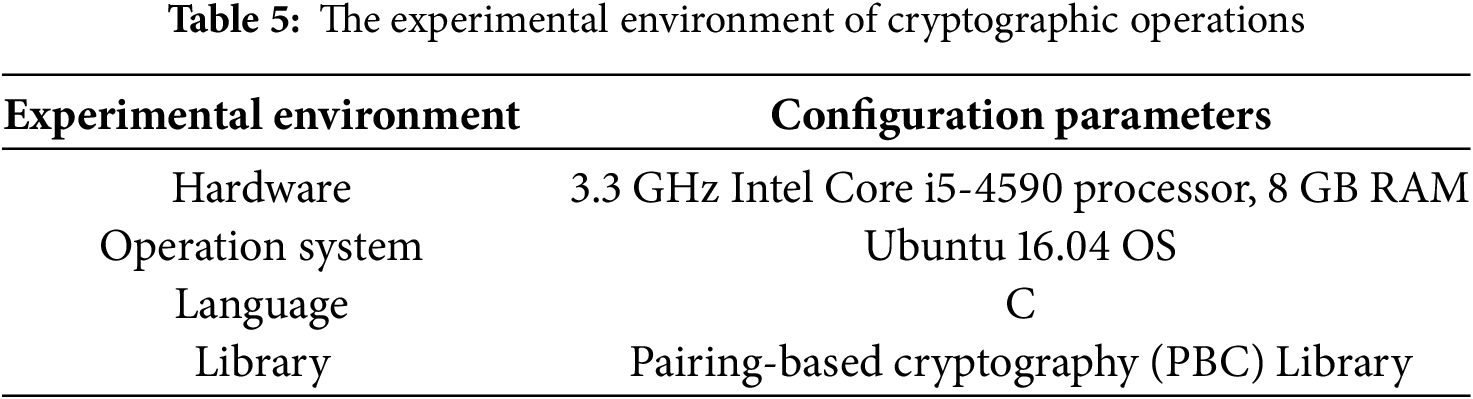

To evaluate computational overhead, the total execution time of various cryptographic operations in both the proposed and comparative protocols was experimentally measured. The experiments primarily focused on the execution efficiency of cryptographic operations. All fundamental operations were implemented using the C language and the OpenSSL library. Then, we timed each operation with the high-precision clock_gettime() function. To ensure accuracy, we ran each cryptographic operation 1000 times and took the average time. The experimental environment is listed in Table 5.

Through experiments, we obtained the single execution time of 9 cryptographic algorithms, which is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The single execution time of 9 cryptographic algorithms in our experimental environment

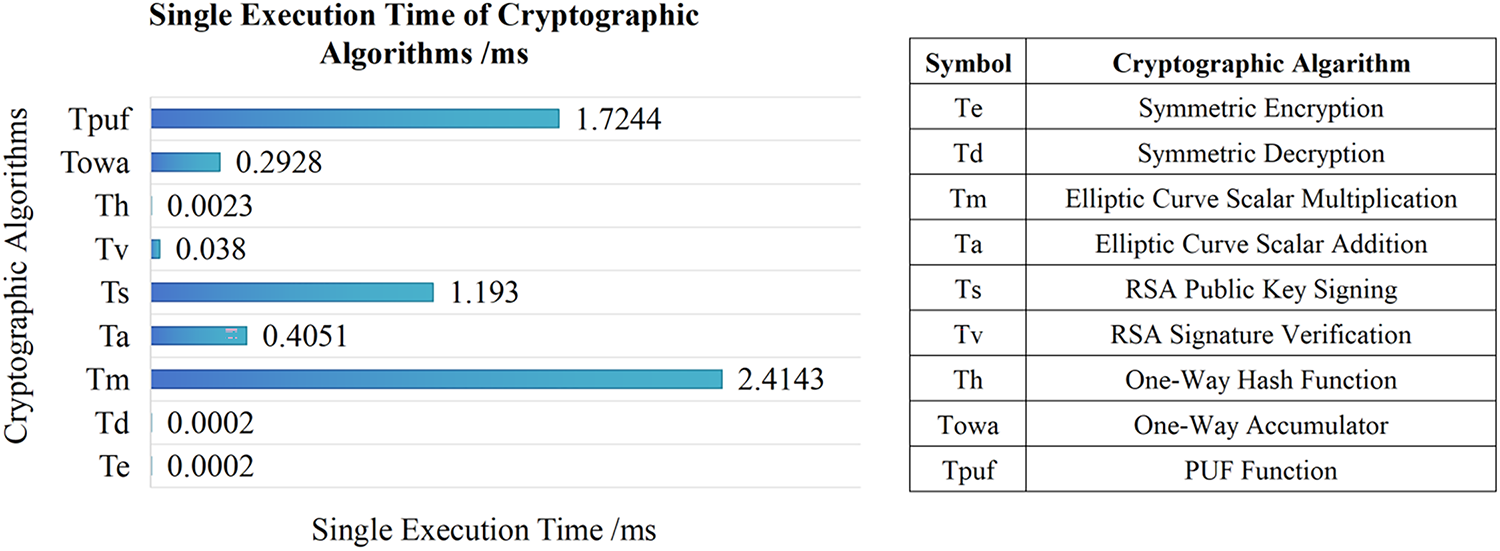

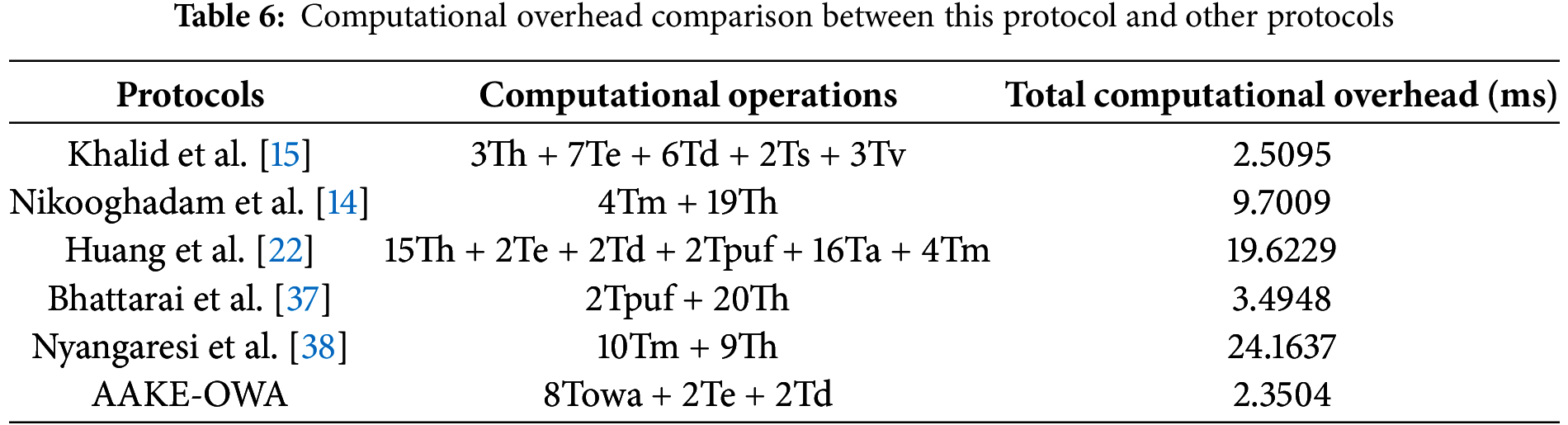

Subsequently, the total computational overheads of this protocol and other protocols were calculated experimentally, with the statistical results shown in Table 6.

As shown in Fig. 6, completing authentication between two UAVs in this protocol requires 8 one-way accumulator operations and 4 symmetric encryption/decryption operations, resulting in a total computational overhead of 2.3504 ms. This is significantly better than Khalid et al.’s protocol [15] (2.5095 ms, involving 3 hashes, 7 encryptions, 6 decryptions, 2 RSA signatures, and 3 verifications), Nikooghadam et al.’s protocol [14] (9.7009 ms, involving 4 elliptic curve multiplications and 19 hashes), and Huang et al.’s protocol [22] (19.6229 ms, involving 15 hashes, 4 symmetric enc/dec, 2 PUF operations, 16 elliptic curve additions, and 4 elliptic curve multiplications), Bhattarai et al.’s protocol [37] (3.4948 ms, involving 2 PUF operations and 20 hashes), Nyangaresi et al.’s protocol [38] (24.1637 ms, involving 10 elliptic curve multiplications and 9 hashes). The core advantage of this protocol over others lies in replacing costly elliptic curve multiplications and PUF operations with lightweight OWA operations, while simultaneously reducing the total number of operations to 12. This ultimately achieves a reduction in computational overhead ranging from 6.3% to 90.3%. However, in practical deployment, network latency and message propagation time will significantly affect its real-time performance, reliability, and task adaptability. In ideal scenarios of low-altitude, single-hop, and Line-of-Sight (LOS) communication, the impact of latency factors on performance is relatively slight, enabling the protocol to give full play to its advantages. Nevertheless, in scenarios such as multi-hop communication, Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) environments, large-scale clusters, or ultra-long-distance (satellite) communication, latency may cause performance degradation. This problem can be alleviated through measures like “pre-authentication mechanisms, routing optimization, and hardware acceleration”.

Figure 6: Comparison of computation overheads between this protocol and others [14,15,22,37,38]

In conclusion, this protocol demonstrates significant advantages in identity authentication scenarios for resource-constrained UAV networks.

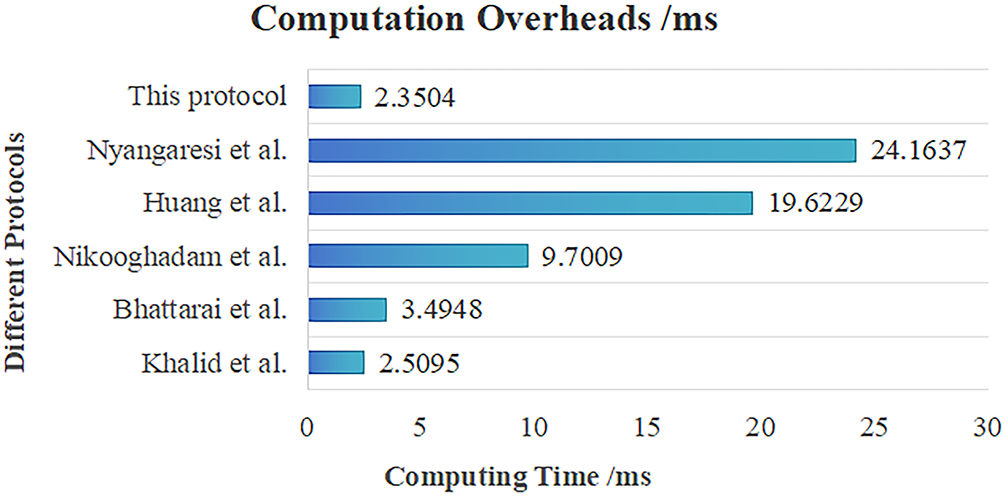

As shown in Fig. 7, for this protocol, when the selected natural number yi is 128 bits, the generated temporary authentication ticket RT has a length of 256 bits. The encrypted random number Ciphertext c has a length of 16 bits under AES encryption. In this case, the total communication overhead for anonymous authentication and key exchange is

Figure 7: Comparison of communication overheads between this protocol and others [14,15,22,37,38]

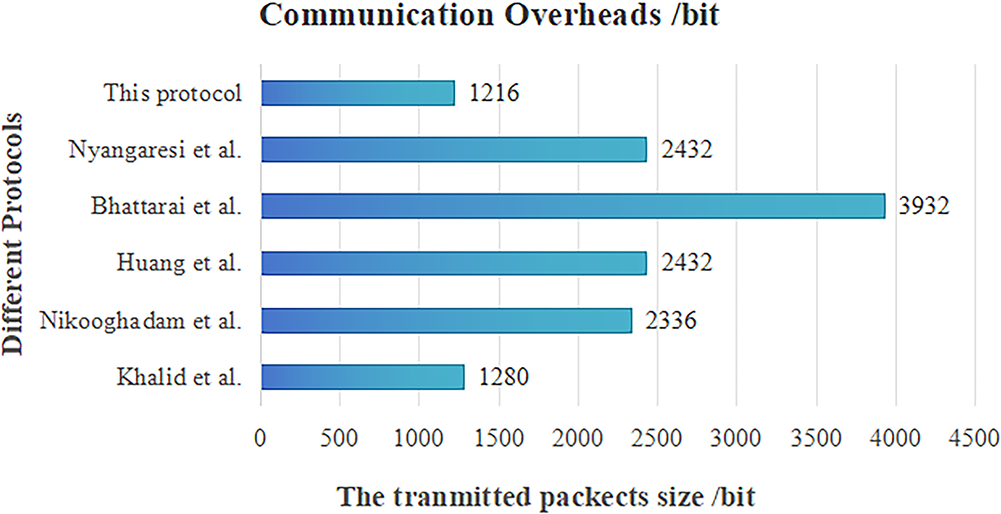

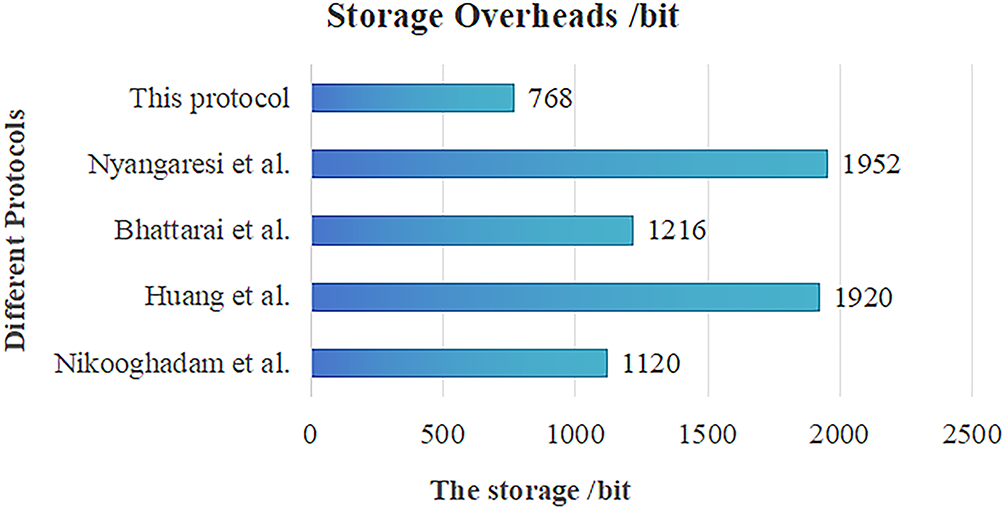

Storage overhead was analyzed by comparing the data storage sizes of this protocol and other protocols. The analysis of storage overhead relies on a theoretical calculation framework. A unified parameter standard is applied to ensure fair comparisons, and all data used are explicitly stated theoretical estimates, which helps avoid deviations that might occur in real-world environments. After UAV registration, the ground station does not participate in the communication between UAVs. Therefore, the storage overhead of this protocol primarily focuses on the UAV side during the phases of identity authentication and key agreement. In this protocol, the total length of the identity credentials stored locally on the UAV is 256 bits (including a 128-bit accumulator value and a 128-bit random number). The temporarily stored temporary authentication ticket RT and random number r during sessions are 256 bits and 128 bits, respectively, while the cached session key K has a size of 128 bits (using the AES encryption algorithm). In summary, the total storage overhead of this protocol is 768 bits. In the protocol proposed by Nikooghadam et al. [14], the length of locally stored data after user registration reaches 1120 bits (480 bits stored on the UAV node, 640 bits on the user node), related to the storage of numerous key parameters involved in its authentication process. Huang et al.’s protocol [22], due to the introduction of blockchain and Physical Unclonable Function (PUF)-related certificates and credential information, further increases storage overhead to 1920 bits. The storage overhead of the Bhattarai et al.’s protocol [37] is 1216 bits (544 bits for the UAV side and 672 bits for the ground station). The protocol of Nyangaresi et al. [38] has a slightly higher storage overhead of 1952 bits than other solutions because both the UAV and ground station need to store ECC parameters. Calculations indicate that the storage overhead of the proposed protocol is only 68.6% of that in Bhattarai et al. [37], 39.3% of Nikooghadam et al. [14], 33.3% of Nyangaresi et al. [38], and 40.0% of Huang et al. [22]. This significant storage advantage not only reduces the hardware storage pressure on UAV terminals but also minimizes energy consumption and time delays during data read/write processes as the cluster scales, providing strong support for large-scale UAV cluster deployment. The comparison of storage overheads among different protocols is shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Comparison of storage overheads between this protocol and others [14,15,22,37,38]

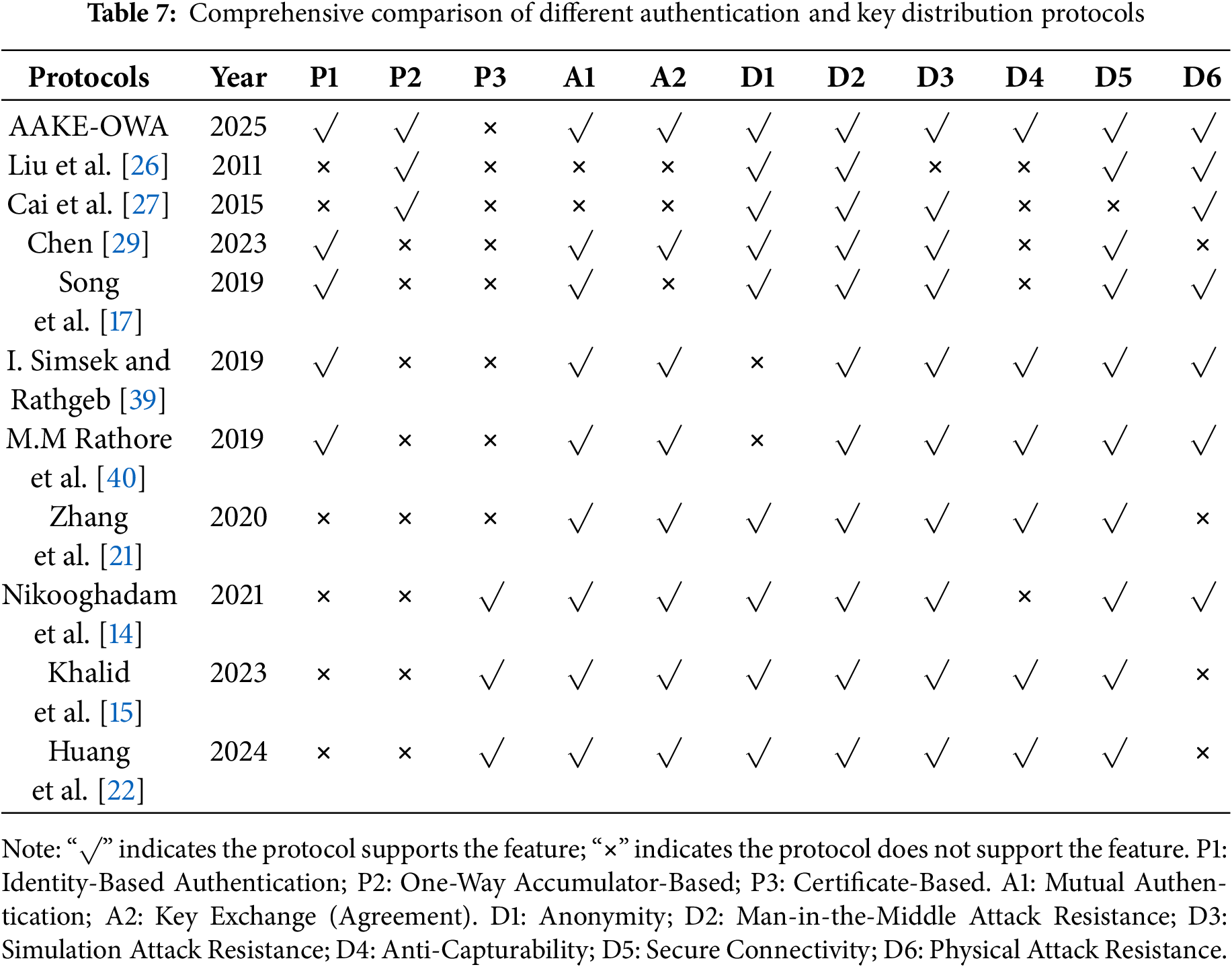

Table 7 compares the security functions of the proposed protocol with other authentication and key distribution protocols in recent years. First, a comparison is made between this protocol (which uses one-way accumulators) and the protocols proposed by Liu et al. [26] and Cai et al. [27]:

Liu et al.’s [26] protocol implements ring signature-based anonymous authentication using one-way accumulators. It only supports one-way platform-to-platform authentication and cannot resist chosen group public key attacks due to the lack of member filtering in ring signatures, resulting in security flaws. Additionally, its efficiency is limited by the construction of collision-resistant hash functions. In contrast, this protocol enables mutual authentication between UAVs, uses shared keys, and is not limited by collision-resistant hash functions in terms of efficiency. Cai et al.’s [27] protocol requires selecting appropriate witnesses for authentication, leading to uncertain secure connectivity. It also uses an alias mechanism for anonymity, which increases storage consumption due to multiple aliases.

Chen [29], Song et al. [17], and this protocol all adopt identity-based authentication. However, unlike this protocol (which uses one-way accumulators), the other two protocols typically rely on specific devices (e.g., Tamper-Proof Devices (TPDs)) to store core sensitive information such as private keys and random parameters. Although some protocols enhance physical protection through “tamper-proof” designs, they lack dynamic protection measures such as immediate key revocation and rapid identity cancellation, meaning compromised devices remain persistent security vulnerabilities in the system.

The protocols proposed by I. Simsek and Rathgeb [39] and M.M. Rathore et al. [40] lack anonymity—device IDs are directly used as public identity identifiers, allowing attackers to track device communication behavior via these explicit identifiers.

The certificate-based protocols proposed by Nikooghadam et al. [14], Khalid et al. [15], and Huang et al. [22] have obvious shortcomings in resisting physical attacks. These protocols rely on physical devices to store certificates and corresponding private keys; if a device is physically captured or compromised, the stored certificates and private keys can be easily stolen, enabling attackers to forge legitimate identities for authentication and undermine system security. Although Zhang et al.’s [21] certificateless protocol avoids the key escrow issue of identity-based systems, an attacker may use leaked temporary private keys combined with partial public information to deduce session keys if the temporary private key is leaked.

To address the challenge of conflicts among security, anonymity, and resource efficiency in UAV communication within FANETs, this paper proposed the AAKE-OWA protocol based on one-way accumulators (OWAs). By leveraging the one-wayness and quasi-commutativity of OWAs, the protocol enables UAVs to achieve mutual authentication and shared key establishment using temporary tickets instead of real identities, thereby ensuring strict anonymity without leaking identity information. In the security analysis section, verification via the Scyther tool confirms that the protocol can resist identity forgery and replay attacks; both formal and informal analyses prove its effectiveness in defending against security threats such as man-in-the-middle attacks and physical capture attacks. Performance experiments demonstrate that the protocol exhibits excellent lightweight characteristics in terms of computational overhead, communication overhead, and storage overhead. This proposal tried to balance the trade-off among anonymity, security, and efficiency in FANET authentication, providing a feasible lightweight security paradigm for FANETs. Furthermore, they offer a low-cost and high-security solution for large-scale UAV applications such as smart city surveillance and emergency rescue. However, the current design lacks the functionality to track malicious UAVs and update UAV authentication tickets. Future work will focus on three aspects: introducing a Trusted Third Party (TTP) dynamic audit module to enable the tracing of malicious UAVs, designing a lightweight ticket update mechanism for automatic credential iteration, and integrating a behavioral anomaly detection model to optimize update decisions. This will form a “tracking-update-management” closed loop, balance anonymity and security, and adapt to the needs of large-scale FANETs.

Acknowledgement: We thank the School of Network Security of Jinling Institute of Technology for their support to this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (under Grant 61902163), the Jiangsu “Qing Lan Project”, Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (Major Research Project: 23KJA520007), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (No. SJCX25_1303).

Author Contributions: The individual contributions of the authors are as follows: [Yanan Liu and Suhao Wang]: Led the research design, protocol development, and manuscript writing. [Lei Cao]: Conducted theoretical analysis and performance evaluations. [Pengfei Wang]: Provided critical revisions. [Zheng Zhang and Shuo Qiu]: Supervised the project and secured funding. [Ruchan Dong]: Provided technical validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Ethics Approval: This work involves no ethical conflicts as it focuses solely on protocol design and theoretical analysis without human/animal involvement or private data usage.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Patchou M, Sliwa B, Wietfeld C. Flying robots for safe and efficient parcel delivery within the COVID-19 pandemic. In: 2021 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon); 2021 Apr 15–May 15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/SysCon48628.2021.9447142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Huang H, Savkin AV, Huang C. Decentralized autonomous navigation of a UAV network for road traffic monitoring. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst. 2021;57(4):2558–64. doi:10.1109/TAES.2021.3053115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Scherer J, Yahyanejad S, Hayat S, Yanmaz E, Andre T, Khan A, et al. An autonomous multi-UAV system for search and rescue. In: Proceedings of the First Workshop on Micro Aerial Vehicle Networks, Systems, and Applications for Civilian Use; 2015 May 19–22; Florence, Italy. p. 33–8. doi:10.1145/2750675.2750683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Maza I, Caballero F, Capitán J, Martínez-de-Dios JR, Ollero A. Experimental results in multi-UAV coordination for disaster management and civil security applications. J Intell Rob Syst. 2011;61(1):563–85. doi:10.1007/s10846-010-9497-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Temel S, Bekmezci Ï. On the performance of Flying Ad Hoc Networks (FANETs) utilizing near space high altitude platforms (HAPs). In: 2013 6th International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies (RAST); 2013 Jun 12–14; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 461–5. doi:10.1109/RAST.2013.6581252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Saleem Y, Rehmani MH, Zeadally S. Integration of cognitive radio technology with unmanned aerial vehicles: issues, opportunities, and future research challenges. J Netw Comput Appl. 2015;50(1):15–31. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2014.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Vinci A, Brigante R, Traini C, Farinelli D. Geometrical characterization of hazelnut trees in an intensive orchard by an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for precision agriculture applications. Remote Sens. 2023;15(2):541. doi:10.3390/rs15020541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Khor JH, Sidorov M, Law SZ, Tan SY, Woon PY. Public blockchain-based data integrity protection for federated learning in UAV networks using MAVLink protocol. In: International Conference on Green Energy, Computing and Intelligent Technology; 2023 Jul 10–12; Iskandar Puteri, Malaysia. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 321–33. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-9833-3_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Singh K, Verma AK. FCTM: a novel fuzzy classification trust model for enhancing reliability in flying ad hoc networks (FANETs). Ad Hoc Sens Wirel Netw. 2018;40(1–2):23–47. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2012.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Malhotra A, Kaur S. A comprehensive review on recent advancements in routing protocols for flying ad hoc networks. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2022;33(3):e3688. doi:10.1002/ett.3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lu S, Zheng J, Cao Z, Wang Y, Gu C. A survey on cryptographic techniques for protecting big data security: present and forthcoming. Sci China Inf. 2022;65(10):1–34. doi:10.1007/s11432-021-3393-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ionescu O, Besleaga C, Dumitru V, Pricop E. UAV identification system based on memristor physical unclonable functions. In: 2020 12th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI); 2020 Jun 25–27; Bucharest, Romania. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ecai50035.2020.9223154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Benaloh J, de Mare M. One-way accumulators: a decentralized alternative to digital signatures. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT’93; 1993 May 23–27; Lofthus, Norway. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1994. p. 274–85. doi:10.1007/3-540-48285-7_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nikooghadam M, Amintoosi H, Islam SH, Moghadam MF. A provably secure and lightweight authentication scheme for Internet of Drones for smart city surveillance. J Syst Archit. 2021;115(2):101955. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2020.101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Khalid H, Hashim SJ, Hashim F, Ahamed SMS, Chaudhary MA, Altarturi HHM, et al. HOOPOE: high performance and efficient anonymous handover authentication protocol for flying out of zone UAVs. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;72(8):10906–20. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3262173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lippold G, Boyd C, Gonzalez Nieto J. Strongly secure certificateless key agreement. In: Pairing-Based Cryptography—Pairing 2009; 2009 Aug 12–14; Palo Alto, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 206–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03298-1_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Song C, Zhang MY, Peng WP, Jia ZP, Liu ZZ, Yan XX. Research on batch anonymous authentication protocol for VANET based on bilinear pairing. J Commun. 2017;38(6):49–57. (In Chinese). doi:10.11959/j.issn.1000-436x.2017112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen M. Strongly secure anonymous implicit authentication and key agreement for roaming service. J Comput Res Dev. 2017;54(12):2772–84. doi:10.7544/issn1000-1239.2017.20160485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen M. Strongly secure and anonymous two-party authenticated key agreement for mobile roaming service. Acta Electron Sin. 2019;47(1):16–24. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0372-2112.2019.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Y, Chen W, Cai Z, Fang Y. CAKA: a novel certificateless-based cross-domain authenticated key agreement protocol for wireless mesh networks. Wirel Netw. 2016;22(8):2523–35. doi:10.1007/s11276-015-1109-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang WF, Lei LT, Wang XM, Wang Y. Secure and efficient authentication and key agreement protocol using certificateless aggregate signature for cloud service oriented VANET. Acta Electron Sin. 2020;48(9):1814–23. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0372-2112.2020.09.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Huang K, Hu H, Lin C. BAKAS-UAV: a secure blockchain-assisted authentication and key agreement scheme for unmanned aerial vehicles networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(22):36858–83. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3431879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Alsamhi SH, Shvetsov AV, Kumar S, Shvetsova SV, Alhartomi MA, Hawbani A, et al. UAV computing-assisted search and rescue mission framework for disaster and harsh environment mitigation. Drones. 2022;6(7):154. doi:10.3390/drones6070154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu Y, Cai L, Xue H, Gao B, Wang X, Lu S, et al. EUAV: an enhanced blockchain-based two-factor anonymous authentication key agreement protocol for UAV networks. Comput Netw. 2025;270(10):111492. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2025.111492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Barić N, Pfitzmann B. Collision-free accumulators and fail-stop signature schemes without trees. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1997. p. 480–94. doi:10.1007/3-540-69053-0_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu DS, Tian H, Lin YL. Research on a new anonymous authentication. Microelectron Comput China. 2011;28(5):157–61. doi:10.19304/j.cnki.issn1000-7180.2011.05.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cai PF, Wang CK, Li XP. Privacy protection revocation mechanism based on universal one-way accumulator in VANET. Appl Res Comput. 2016;33(8):2396–401. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-3695.2016.08.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang D, Wang P, Wang C. Efficient multi-factor user authentication protocol with forward secrecy for real-time data access in WSNs. ACM Trans Cyber-Phys Syst. 2020;4(3):1–26. doi:10.1145/3325130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen LJ. Optimization of blockchain cross-domain identity management system. Comput Technol Dev. 2023;33(2):138–45. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-629X.2023.02.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhong Q, Zhao X, Xia Y, Liu X. CD-BASA: an efficient cross-domain batch authentication scheme based on blockchain with accumulator for VANETs. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(10):14560–71. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3386730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang T, Jiang M, Luo F, Guo Y. A lattice-based puncturable CP-ABE scheme with forward security for cloud-assisted IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(14):26538–54. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3559567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Owaid SA, Miry AH, Salman TM. A survey on UAV-assisted wireless communications: challenges, technologies, and application. In: 2024 11th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ICEEE); 2024 Apr 22–24; Marmaris, Turkiye. p. 333–40. doi:10.1109/ICEEE62185.2024.10779287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Qu Y, Sun H, Dong C, Kang J, Dai H, Wu Q, et al. Elastic collaborative edge intelligence for UAV swarm: architecture, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Commun Mag. 2024;62(1):62–8. doi:10.1109/mcom.002.2300129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mei W, Zhang R. Uplink cooperative interference cancellation for cellular-connected UAV: a quantize-and-forward approach. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2020;9(9):1567–71. doi:10.1109/LWC.2020.2997837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang C, Yang X, Du Q, Wang J. Outage performance of satellite-UAV network framework based on NOMA. In: 2021 IEEE 5th International Conference on Cryptography, Security and Privacy (CSP); 2021 Jan 8–10; Zhuhai, China. p. 171–5. doi:10.1109/CSP51677.2021.9357597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xiong R, Xiao Q, Wang Z, Xu Z, Shan F. Leveraging lightweight blockchain for secure collaborative computing in UAV Ad-Hoc Networks. Comput Netw. 2024;251:110612. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bhattarai I, Pu C, Choo KR, Korać D. A lightweight and anonymous application-aware authentication and key agreement protocol for the Internet of drones. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(11):19790–803. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3367799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Nyangaresi VO, Ahmad M, Maghrabi LA, Althaqafi T. Cost-effective PUF and ECC-based authentication protocol for secure Internet of drones communication. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(16):33844–57. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3576313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Simsek I, Rathgeb EP. Zero-knowledge and identity-based authentication and key exchange for Internet of Things. In: 2019 IEEE 5th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT); 2019 Apr 15–18; Limerick, Ireland. p. 283–8. doi:10.1109/wf-iot.2019.8767235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Rathore MM, Bentafat E, Bakiras S. Smart home security: a distributed identity-based security protocol for authentication and key exchange. In: 2019 28th International Conference on Computer Communication and Networks (ICCCN); 2019 Jul 29–Aug 1; Valencia, Spain. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/icccn.2019.8847034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools