Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modeling Pruning as a Phase Transition: A Thermodynamic Analysis of Neural Activations

Laboratory for Social & Cognitive Informatics, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Sedova St. 55/2, Saint Petersburg, 192148, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Rayeesa Mehmood. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Deep Learning and Neural Networks: Architectures, Applications, and Challenges)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 99 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072735

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Activation pruning reduces neural network complexity by eliminating low-importance neuron activations, yet identifying the critical pruning threshold—beyond which accuracy rapidly deteriorates—remains computationally expensive and typically requires exhaustive search. We introduce a thermodynamics-inspired framework that treats activation distributions as energy-filtered physical systems and employs the free energy of activations as a principled evaluation metric. Phase-transition–like phenomena in the free-energy profile—such as extrema, inflection points, and curvature changes—yield reliable estimates of the critical pruning threshold, providing a theoretically grounded means of predicting sharp accuracy degradation. To further enhance efficiency, we propose a renormalized free energy technique that approximates full-evaluation free energy using only the activation distribution of the unpruned network. This eliminates repeated forward passes, dramatically reducing computational overhead and achieving speedups of up toKeywords

Deep neural networks (DNNs) have achieved remarkable success across computer vision, natural language processing, and reinforcement learning. However, their increasing complexity and over-parameterization raise growing concerns regarding computational efficiency, energy consumption, and deployment in resource-constrained environments. Consequently, network pruning—the process of reducing model complexity by removing redundant components—has become a key strategy for compressing models while preserving accuracy [1].

Most existing pruning approaches focus on weight magnitudes or structural heuristics, often overlooking the dynamic behavior of activations during inference. In contrast, activation pruning selectively suppresses neuron activations based on their estimated importance, offering a complementary and adaptable mechanism for runtime sparsification [2]. Despite its promise, activation pruning faces a fundamental challenge: reliably identifying the critical pruning threshold, the point at which accuracy begins to degrade sharply. Determining this threshold typically depends on exhaustive trial-and-error procedures, which are computationally costly and yield inconsistent results across architectures and datasets. The lack of a unified theoretical framework therefore limits both the practicality and widespread adoption of activation pruning.

To address this challenge, we introduce a thermodynamics-inspired framework that interprets activation distributions as physical systems subject to energy filtering. Within this formulation, we employ the free energy of activations as a principled metric for characterizing network behavior under varying pruning thresholds. Salient features of the resulting free-energy curve—such as extrema, inflection points, or curvature changes—serve as indicators of critical pruning thresholds, providing a theoretically grounded alternative to exhaustive empirical search. Moreover, we develop a renormalized free energy that approximates the full free-energy profile using only the activation statistics of the unpruned network (

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

• We introduce a thermodynamics-based theoretical framework for activation pruning, in which free energy provides a principled estimator of critical pruning thresholds and corresponding sparsity levels.

• We propose a renormalized free energy approximation that accurately tracks the full-evaluation free energy curve, eliminates repeated inference, and substantially reduces computational cost.

• We conduct an extensive experimental evaluation on both vision and text classification tasks, covering pretrained and non-pretrained models, and demonstrate the efficiency, robustness, and broad applicability of the proposed approach.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work and outlines the motivation for adopting a thermodynamic perspective. Section 3 formalizes the framework, presents the phase transition analysis, and introduces the renormalized free energy method. Section 4 describes the datasets, models, and experimental setup, while Section 5 reports the empirical results. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main findings, discusses limitations, and outlines directions for future work.

2.1 Magnitude Pruning: Weight and Activation Pruning

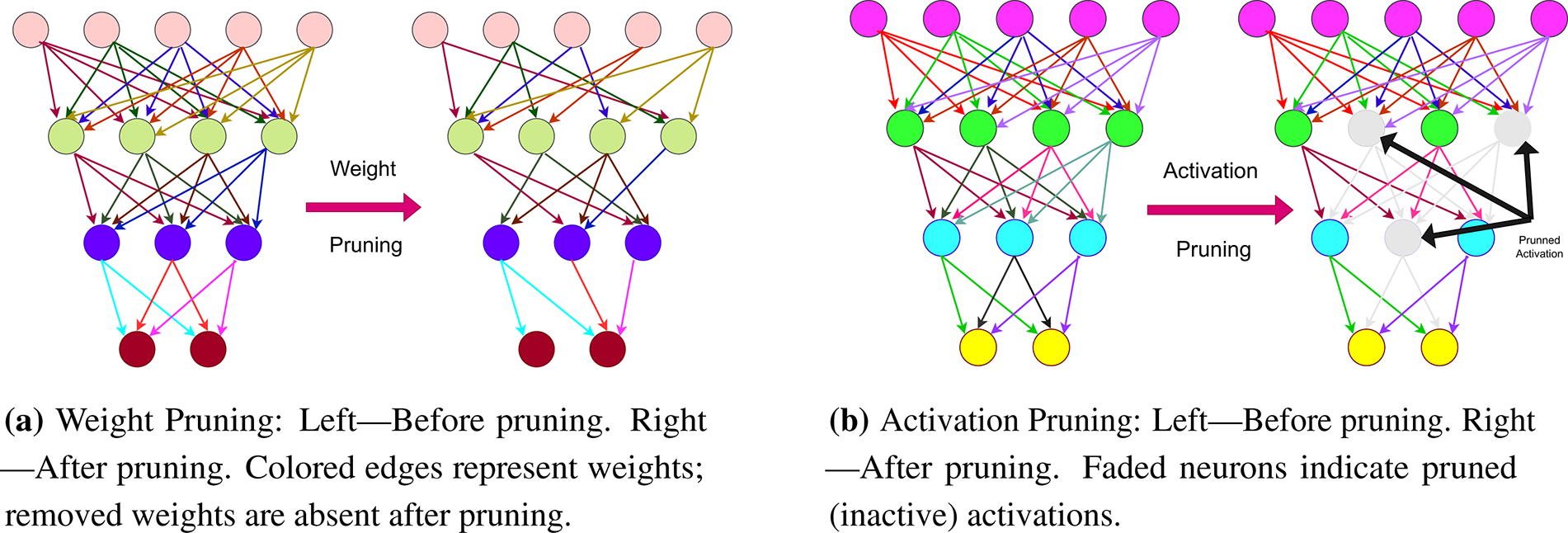

Magnitude pruning is a widely used technique for compressing deep neural networks (DNNs) by removing low-magnitude elements under the assumption that they exert minimal influence on overall performance. Existing methods largely fall into two categories: weight pruning, which operates on static model parameters, and activation pruning, which dynamically sparsifies neuron outputs during inference. Fig. 1 provides a visual comparison of these two approaches.

Figure 1: Visualization of weight and activation pruning

Weight pruning reduces model size and computational cost by removing weights deemed unimportant, typically based on their magnitudes. Han et al. [3] demonstrated that unstructured pruning can compress models such as AlexNet and VGG-16 by more than 90% with minimal loss in accuracy. While unstructured pruning, which removes individual weights, achieves high compression ratios, it yields irregular sparsity patterns that are difficult to exploit efficiently on standard hardware. In contrast, structured pruning removes entire filters, channels, or layers, resulting in more hardware-friendly sparsity. Recent advances incorporate group-wise dependency preservation, gradient-based saliency metrics, and second-order sensitivity analyses to enable more precise and reliable pruning decisions [4–6]. Despite its effectiveness across domains—including reinforcement learning and edge deployment—weight pruning remains a static, input-independent approach.

Activation pruning dynamically zeros neuron activations during inference based on a threshold

A variety of activation pruning methods have been proposed, including spatially adaptive sparsification [10], ReLU pruning [11,12], iterative pruning based on activation statistics [13], Wanda pruning [2], attention-guided structured pruning [14], and semi-structured activation sparsity [15]. Recent work [16] introduces WAS, a training-free method that computes weight-aware activation importance and uses constrained Bayesian optimization to allocate sparsity across transformer blocks. Another study [17] proposes R-Sparse, a training-free activation pruning technique for large language models that applies a rank-aware thresholding rule to eliminate low-magnitude activations and reduce unnecessary weight computations. The authors of work [18] present TEAL, a training-free magnitude-based activation pruning method that zeros low-magnitude activations across transformer blocks, achieving substantial sparsity and meaningful inference speedups with limited impact on model quality. Finally, the authors of work [19] introduce Amber Pruner, a training-free N:M activation pruning method that applies structured top-

Unlike weight pruning, activation pruning produces dynamic, input-dependent sparsity patterns, which complicates theoretical analysis. Although such techniques leverage activation behavior to improve computational efficiency, they typically depend on empirically tuned thresholds [20], and the underlying theory remains underdeveloped. Concepts such as the activation blind range provide partial insight into zero-output regions [11], yet no unified framework currently exists for predicting critical pruning thresholds or determining optimal sparsity levels.

Beyond classical structured and unstructured pruning approaches, recent years have seen the development of adaptive and one-shot methods capable of achieving high sparsity without retraining [21–23]. These techniques primarily aim to reduce computational cost and accelerate inference. In contrast, our work focuses on analyzing the thermodynamic behavior of neural representations and exploiting the free-energy profile to identify the phase-like transition at which the model begins to lose functional stability. The proposed criterion is therefore not intended to replace existing pruning strategies, but rather to complement them by offering an interpretable, architecture-agnostic means of determining reliable sparsity levels.

2.2 Thermodynamic Perspective on Activation Pruning

Given the heuristic nature of existing activation pruning approaches, a principled theoretical framework is required to estimate when pruning begins to degrade performance and to guide the selection of effective pruning thresholds. To address this need, we introduce a thermodynamics-inspired perspective in which neuron activations are treated analogously to energy states in physical systems.

Within this framework, pruning is interpreted as imposing an energy cutoff, where removing low-activation neurons corresponds to filtering out low-energy states. This analogy enables the definition of thermodynamic quantities such as entropy, internal energy, and free energy over activation distributions, providing a quantitative basis for analyzing how pruning influences model behavior. Notably, we observe that model performance remains stable over a broad range of pruning thresholds but deteriorates sharply beyond a critical point, resembling a phase transition. This transition manifests in distinct features of the free-energy curve, which serve as reliable indicators of critical thresholds without requiring exhaustive empirical tuning.

The proposed formulation offers theoretical insight into the trade-off between pruning intensity and predictive accuracy, while enhancing interpretability and robustness across architectures and datasets. In the following section, we formalize these concepts, introduce precise definitions, and derive the free-energy criterion used to approximate critical pruning thresholds.

3 Formal Thermodynamic Framework and Phase Transition Analysis

Building on the thermodynamic perspective introduced in Section 2.2, we now develop a formal framework that models activation pruning using concepts from statistical physics. Specifically, we define entropy, internal energy, and free energy over activation distributions, and show how these quantities expose critical thresholds at which model behavior undergoes abrupt transitions. This formulation establishes a unified and interpretable connection between sparsity, thresholding, and accuracy degradation.

3.1 Activation Pruning as Energy-Based Filtering

We model the neural network as a statistical system characterized by the distribution of neuron activations during inference. Activation pruning is implemented by applying a threshold

The pruning process is applied layer-wise, and for each threshold

3.2 Shannon Entropy of Activations

Let M denote the number of nonzero activations after pruning and N the total number of activations before pruning (i.e., at

As the threshold

We define an effective temperature T in terms of the pruning threshold

Here, T serves as a formal parameter that reflects system “hotness” (low

Let

This logarithmic ratio quantifies the remaining “energy” of the system and reflects how aggressively pruning suppresses the activation magnitude distribution.

The free energy F balances internal energy (E) and entropy (S), scaled by temperature (T), as given in Eq. (5):

Using the definitions above, we obtain the equivalent expression in Eq. (6):

Free energy serves as the central metric in our framework. Its extrema and curvature encode characteristic signatures of phase transitions—points at which pruning shifts from benign sparsification to rapid accuracy degradation. These dynamics and the associated critical thresholds are examined in detail in the following section.

3.6 Phase Transitions and Critical Threshold Identification via Free Energy Analysis

The free energy function

Because extrema, inflection points, and curvature changes all signal the onset of thermodynamic instability, we select the earliest such feature encountered as

This thermodynamic instability reflects a phase transition from a dense, information-rich activation regime to a sparse, degraded one. The critical threshold

The associated critical sparsity

3.7 Renormalized Free Energy for Efficient Threshold Selection

Building on the free-energy analysis used to identify critical thresholds, we now introduce a renormalization procedure that enables fast, architecture-agnostic estimation of pruning thresholds. This method operates on a fixed activation array—collected from the trained model and a representative dataset prior to pruning—and simulates the pruning process by applying magnitude thresholds directly to this array, treating activations as an unstructured distribution. Thermodynamic quantities, including density, Shannon entropy, internal energy, and free energy, are then computed using the same definitions introduced earlier, but without requiring repeated model inference. This strategy can substantially reduce computational cost while preserving the characteristic shapes and derivative patterns of the free-energy curves obtained from full evaluation.

Although the activation array depends on the specific model and dataset, the renormalized analysis abstracts away architectural details and eliminates the need for retraining, providing a general and efficient approach for approximating critical pruning thresholds. As demonstrated in Section 5, the renormalized free-energy curves closely match those derived from the full evaluation, confirming both their accuracy and reliability. This method thus elevates pruning-threshold selection from heuristic tuning to a principled, physics-inspired procedure.

Procedure for Determining the Critical Pruning Threshold

Since the renormalized free energy

The critical threshold

4.1 Datasets and Preprocessing

To evaluate our proposed method, we conducted experiments on both image and text classification tasks. For image classification, we used CIFAR-10 (50,000 training images, 10,000 test images, 10 classes) and the Oxford-102 Flowers dataset (8189 images, 102 classes; split into 1020 training, 1020 validation, and 6149 test samples). For text classification, we used AG News (120,000 training samples, 7600 test samples, 4 classes) and Yelp Review Full (650,000 training samples, 50,000 test samples, 5 sentiment categories).

CIFAR-10 images were normalized to the range

Text datasets were tokenized, padded, and truncated to fixed maximum sequence lengths determined from training-data percentiles. Transformer-based models used their pretrained subword tokenizers, whereas the LSTM employed an NLTK-based word-level tokenizer. Text was converted to lowercase when appropriate, and special tokens (padding, unknown) were inserted as required. For GPT-2, the end-of-sequence token was used as padding. Tokenized inputs (IDs and attention masks) were processed using a batch size of 32.

We evaluated a range of architectures spanning both non-pretrained and pretrained models. For image classification, the non-pretrained models include an MLP, implemented as a fully connected network with three hidden layers and pruning applied after ReLU activations, and a CNN consisting of three convolutional layers with batch normalization, ReLU, and max-pooling, followed by fully connected layers, with pruning applied after the convolutional layers and the first two fully connected layers. The pretrained models include ResNet-18 [24], with pruning applied after ReLU activations in the residual blocks; MobileNetV2 [25], which uses inverted residual blocks and pruning applied after ReLU6 activations; and a lightweight Vision Transformer (ViT) [26], with pruning applied after linear layers and GELU activations in the MLP blocks, while the last four transformer blocks and the classification head are fine-tuned.

For text classification, we evaluated one non-pretrained LSTM model and four pretrained transformer models covering encoder-only, encoder–decoder, and decoder-only architectures. The LSTM includes an embedding layer, a unidirectional LSTM, and a three-layer classifier, with pruning applied after the intermediate classifier layers. BERT [27] and ELECTRA [28] are encoder-only models, with pruning applied to the intermediate fully connected layers within the encoder blocks and to the classifier, using hooks on the encoder layers. T5 [29], an encoder–decoder model, is pruned after the fully connected layers in both encoder and decoder blocks and in the classifier, using the pooled mean of the final decoder states. GPT-2 [30], a decoder-only model, is pruned after the fully connected layers in the decoder blocks and in the classifier.

4.3 Pruning Procedure and Parameter Settings

All models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and cross-entropy loss. Dropout with a rate of 0.3 was applied to fully connected layers. Early stopping based on validation accuracy, with a patience of three epochs, was used across all models to mitigate overfitting. Training was conducted on a single GPU with CUDA support, and a fixed random seed was used to ensure reproducibility. No fine-tuning or additional optimization techniques were employed, as our objective was to analyze pruning behavior rather than to maximize accuracy.

After training, activation pruning was applied over a range of thresholds. For each threshold, test accuracy and activation statistics were recorded to compute the thermodynamic quantities (density, entropy, internal energy, and free energy) defined in Section 3. The implementation of our pruning framework, along with scripts for reproducing all experiments and free-energy analyses, is available at https://github.com/hse-scila/Activation_Pruning (accessed on 12 November 2025).

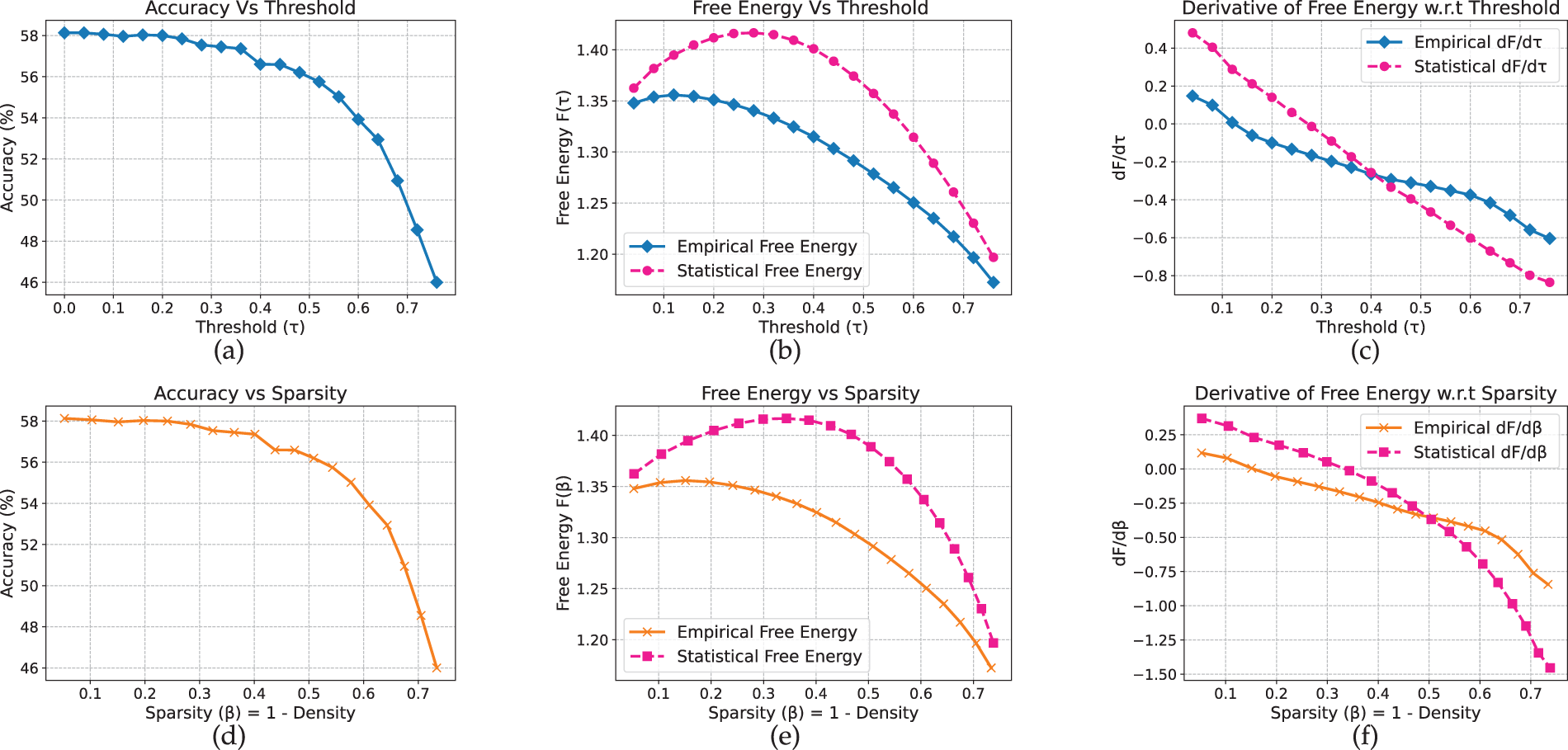

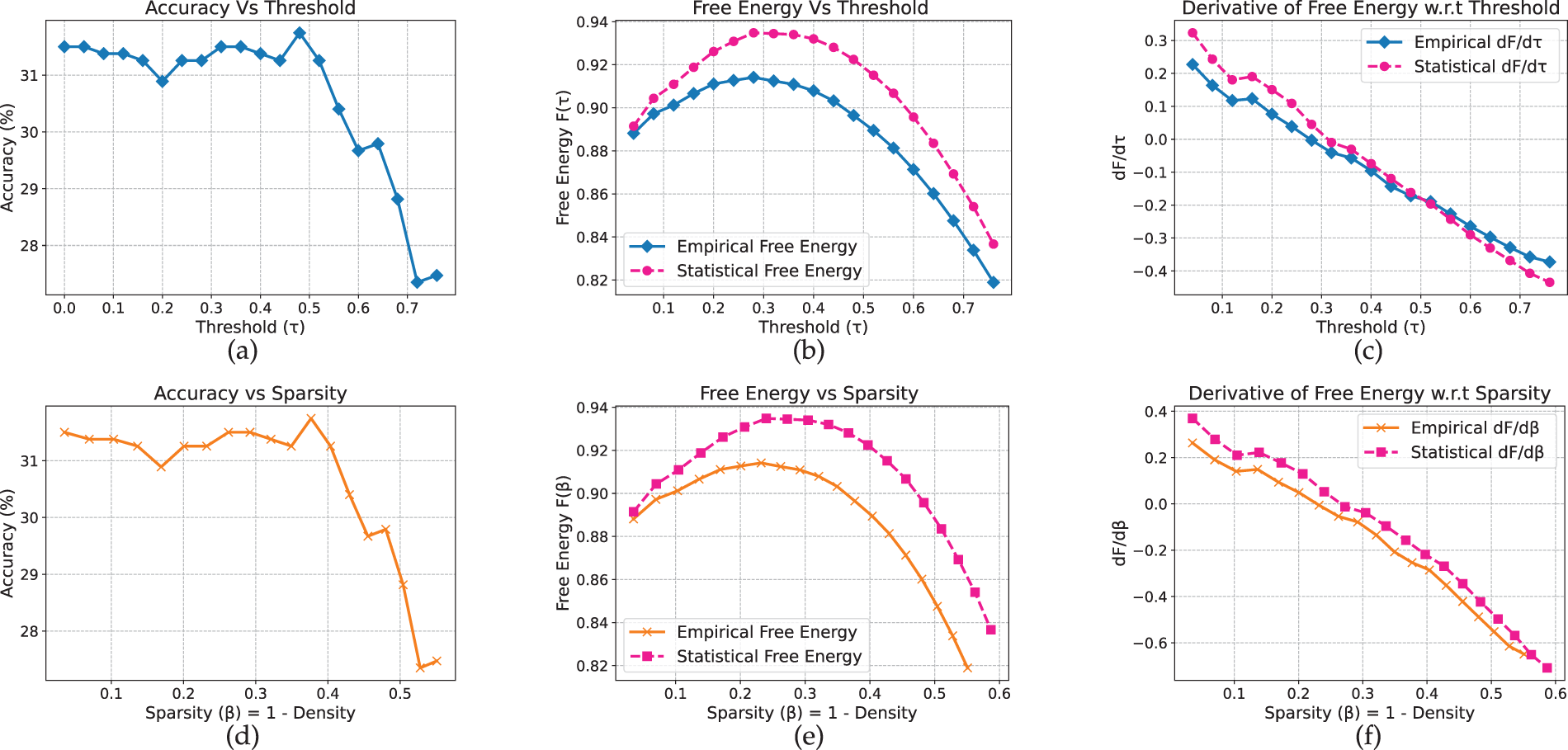

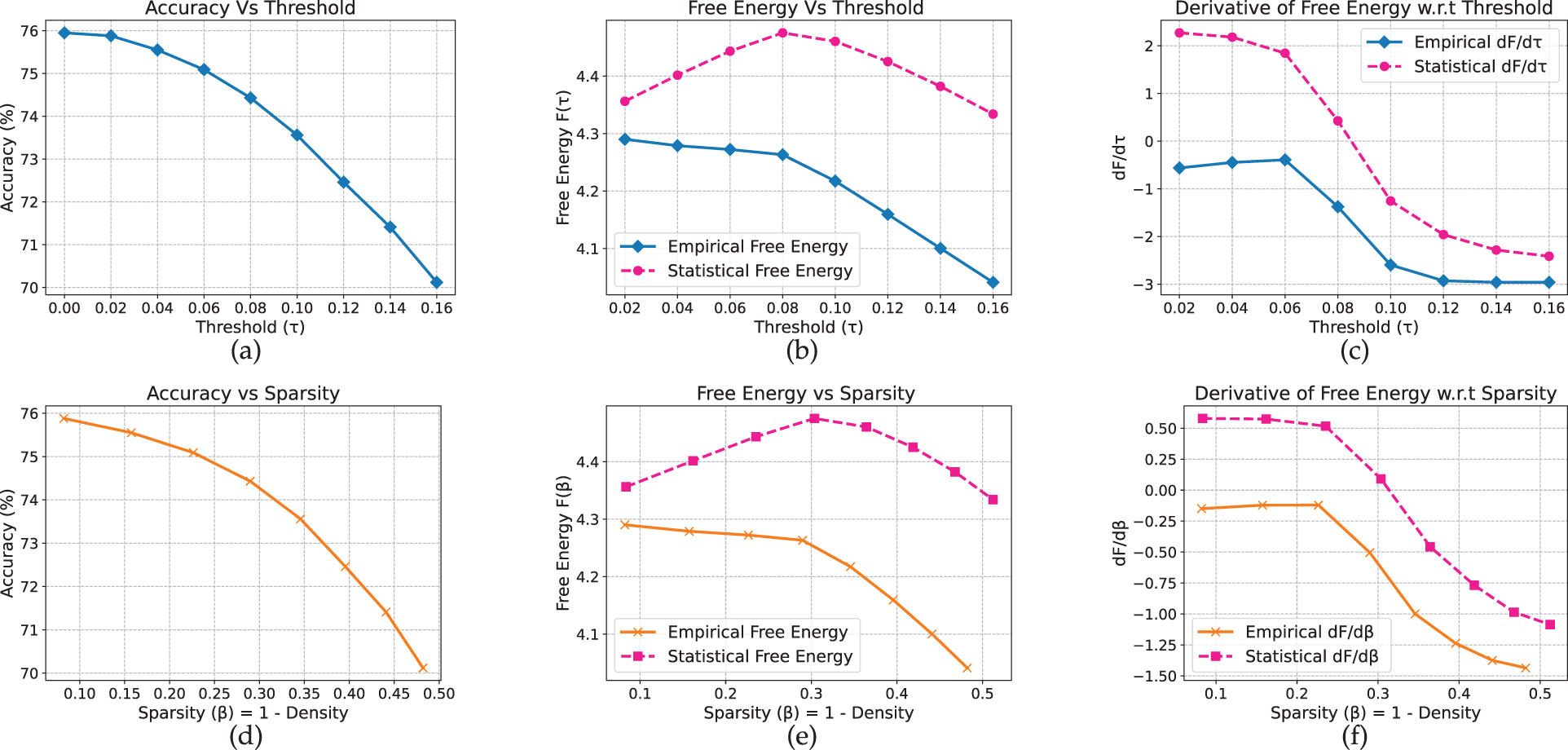

For each model–dataset pair, we present six plots that show test accuracy, free energy, and its derivative as functions of the pruning threshold (

When comparing free-energy curves across methods, we emphasize the shape of the curve rather than its absolute magnitude. Vertical shifts may arise from renormalization constants and do not influence the derivative-based transition detection. We therefore define a “match” as the agreement of the first qualitative transition (extremum or inflection point) at the same sparsity level

Furthermore, for all results reported below, the critical thresholds and sparsity levels are stable across random seeds, with variability typically within 3%–5%. Representative mean values are shown for clarity and conciseness.

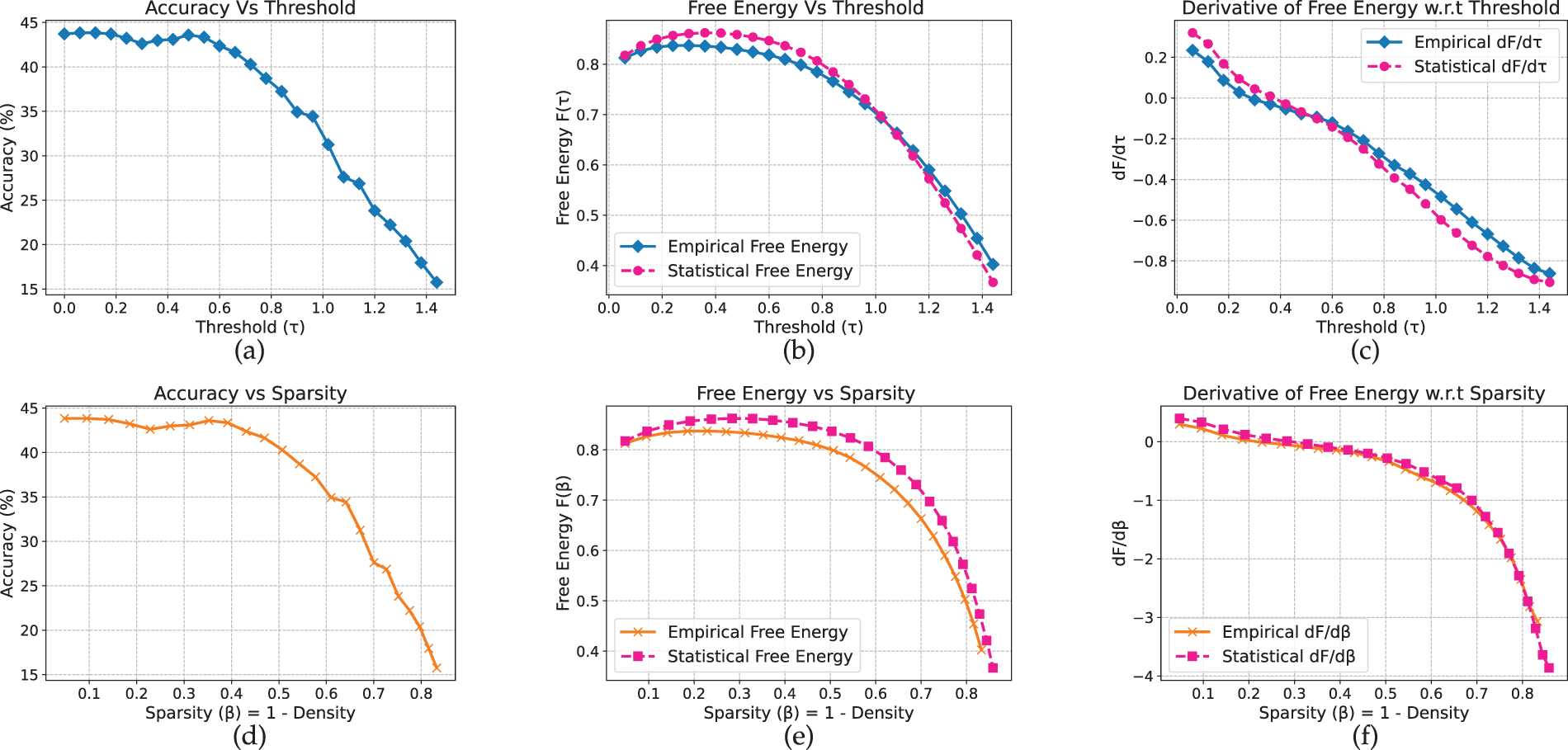

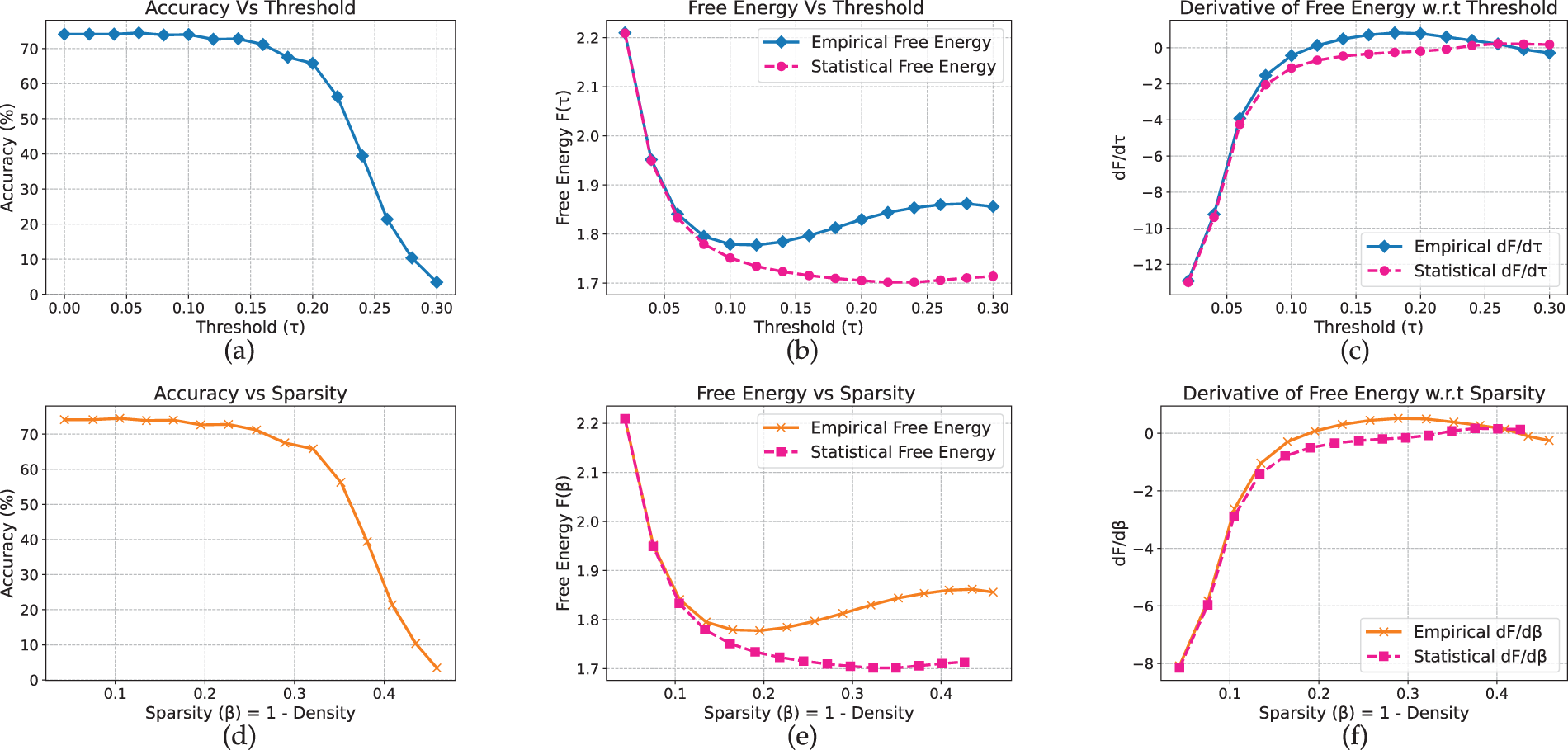

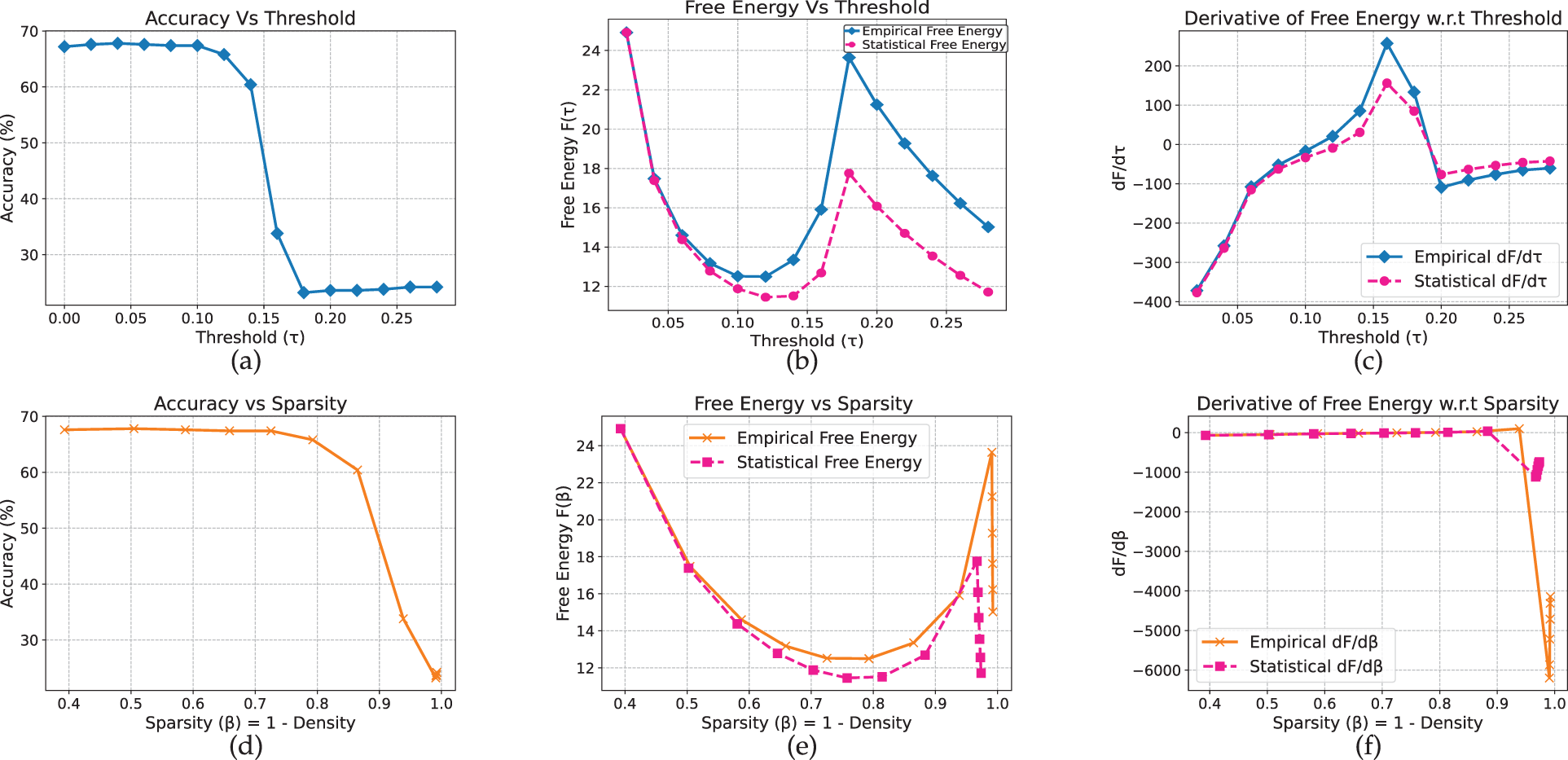

We begin by analyzing our framework on vision models and datasets. On CIFAR-10 (Fig. 2), the MLP maintains an accuracy of approximately 58% under moderate pruning thresholds (

Figure 2: MLP model on CIFAR-10 dataset

Figure 3: MLP model on Flowers-102 dataset

For the convolutional network, trends similar to those observed for the MLP arise across both datasets. On CIFAR-10 (Fig. 4), accuracy remains near 76% for moderate pruning thresholds (

Figure 4: CNN model on CIFAR-10 dataset

Figure 5: CNN model on Flower-102 dataset

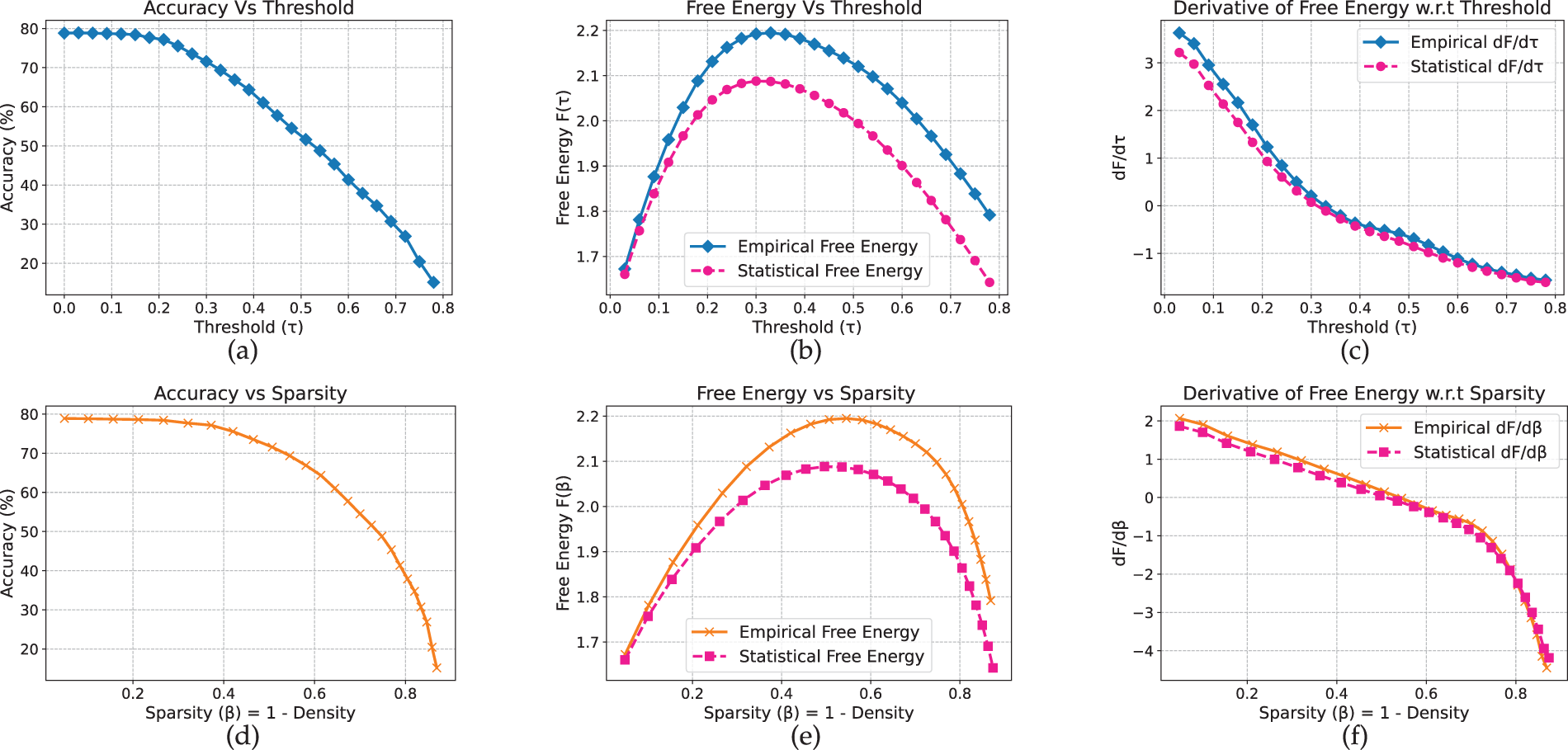

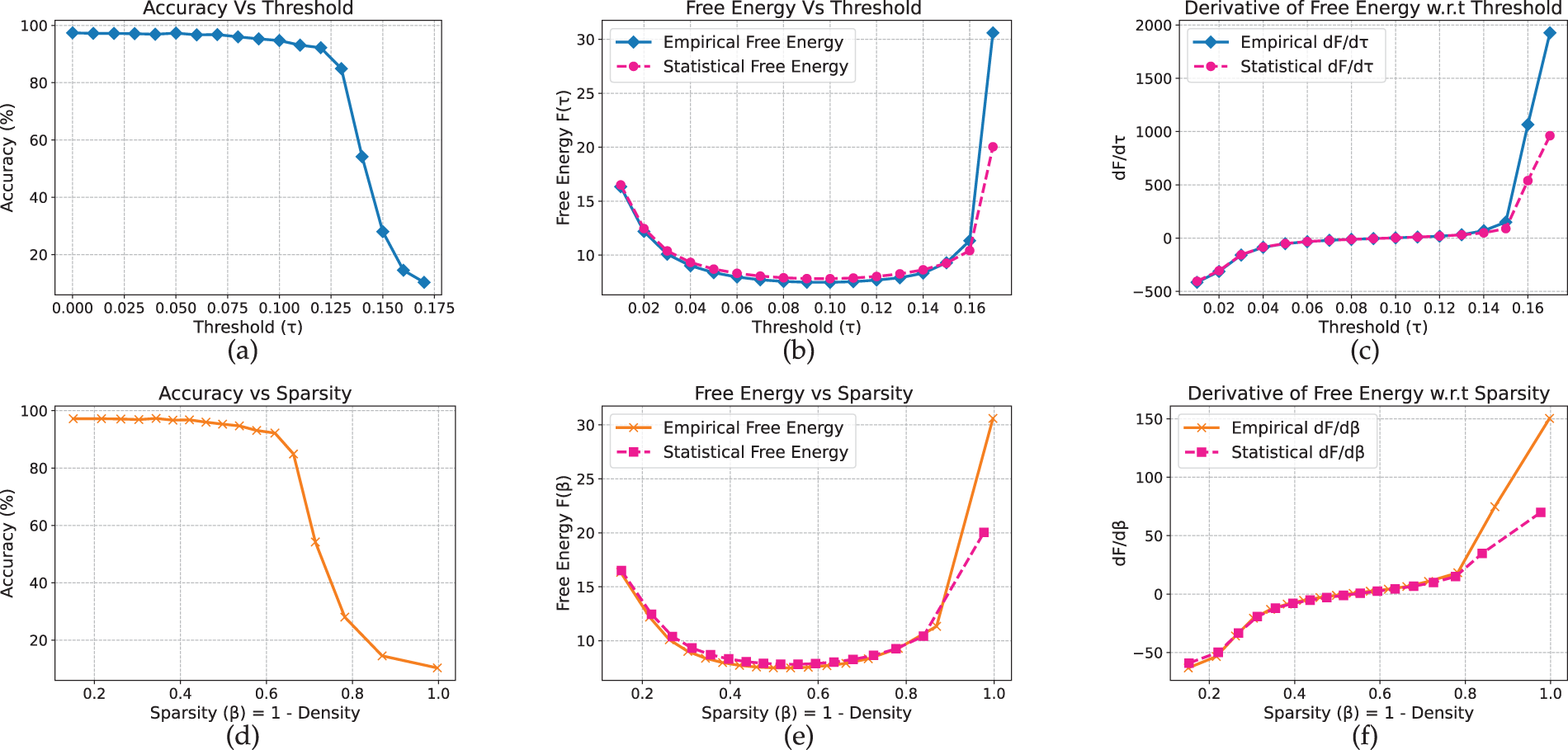

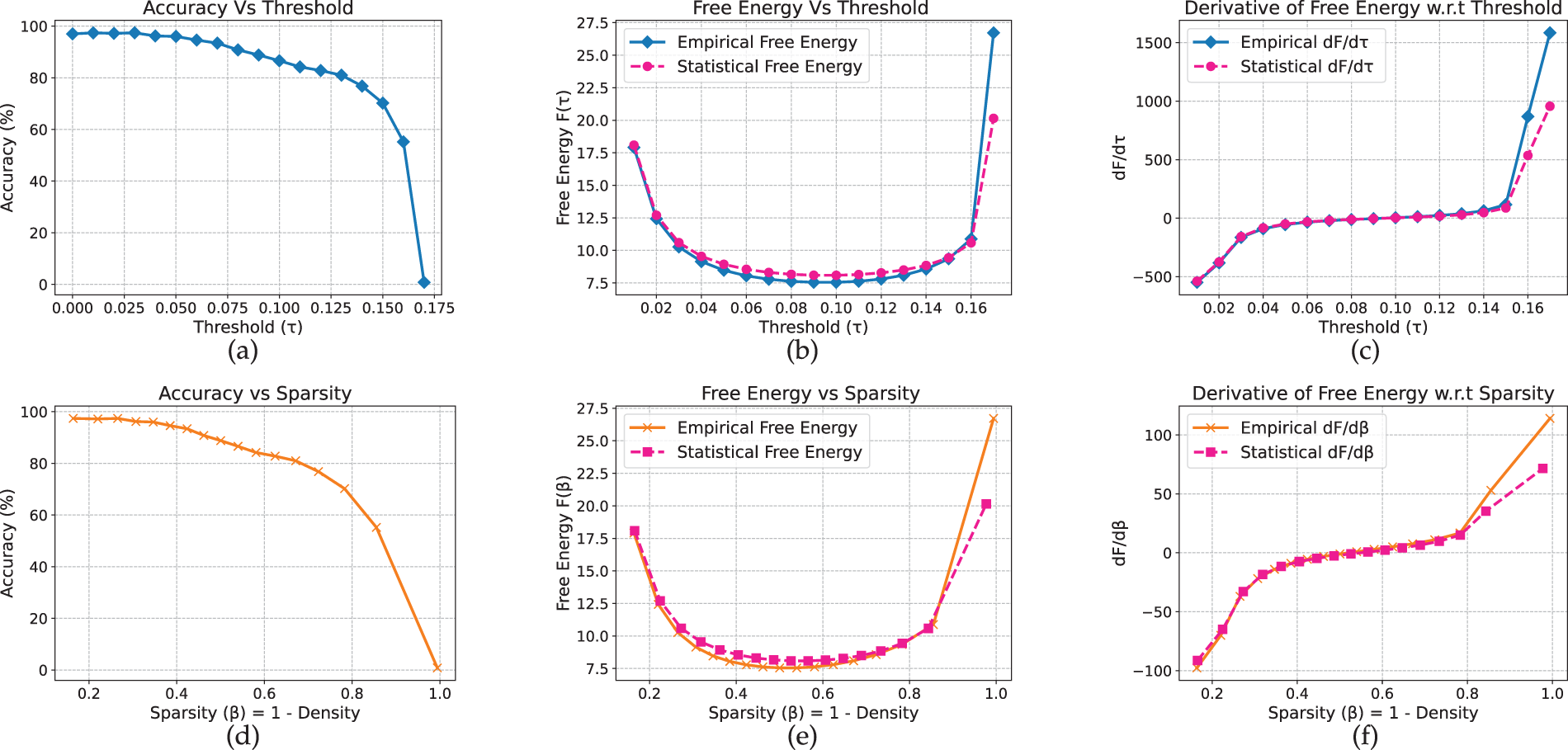

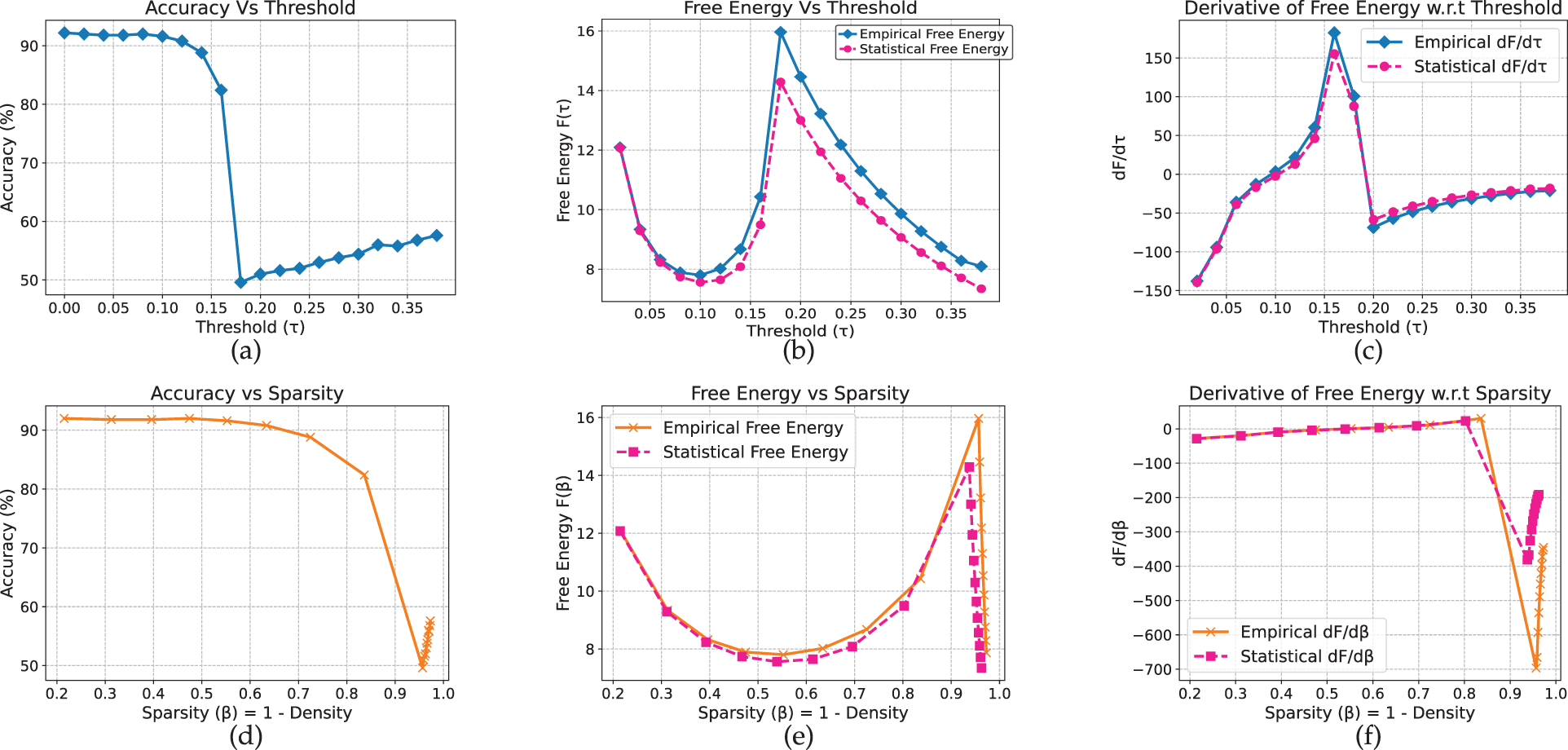

Compared to shallow MLP and CNN, ResNet-18 exhibits a noticeably sharper transition. On CIFAR-10 (Fig. 6), accuracy remains close to 79% before declining markedly between

Figure 6: Resnet-18 model on CIFAR-10 dataset

Figure 7: Resnet-18 model on Flower-102 dataset

For MobileNetV2, the results exhibit clearer dataset-dependent variation compared to the previous convolutional models. Moreover, unlike the earlier architectures that display a distinct peak in the free-energy curve, MobileNetV2 shows a bend on CIFAR-10 (Fig. 8) and a local minimum on Flowers-102 (Fig. 9). On CIFAR-10, accuracy remains near 73% at low thresholds and begins to decline around

Figure 8: MobileNet model on CIFAR-10 dataset

Figure 9: MobileNet model on Flower-102 dataset

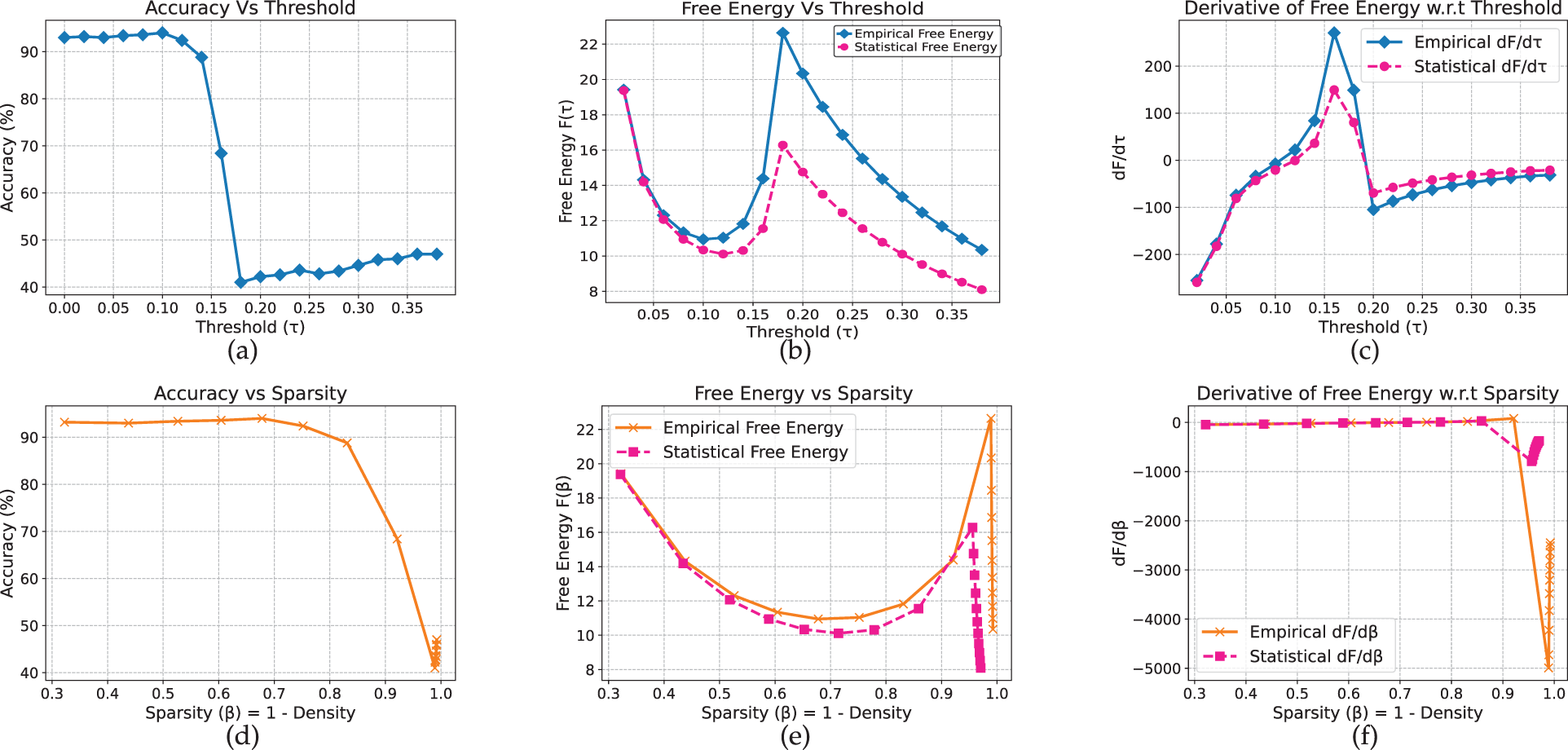

Analysis of the Vision Transformer reveals qualitatively distinct behavior, characterized by a free-energy valley rather than a peak or bend. On CIFAR-10 (Fig. 10), accuracy remains near 97% at low thresholds and begins to decline around

Figure 10: ViT model on CIFAR-10 dataset

Figure 11: ViT model on Flower-102 dataset

Across the vision models, free energy tends to precede the onset of accuracy degradation for scratch-trained architectures (MLP, CNN) and roughly coincides with it for pretrained models (ResNet-18, MobileNetV2, ViT). Transitions in pretrained models appear smoother and more predictable, whereas the MLP and CNN exhibit sharper accuracy drops and slightly noisier free-energy curves. Characteristic patterns—such as the bends in MobileNetV2 and the valley-shaped curve of the Vision Transformer—highlight the diversity of pruning dynamics across architectures. The renormalized free-energy curves generally track the full-evaluation trends, capturing the critical regions with only minor vertical offsets.

The differences in the shapes of the free-energy curves across architectures may be related to how information is distributed within each model. In CNNs and ResNets, activations within a channel tend to be spatially correlated, and a single channel often encodes a coherent local feature. Consequently, removing a channel during pruning can cause a sharp disruption in the learned representation, which manifests as a pronounced peak in the free-energy curve.

In MobileNetV2, the use of depthwise-separable convolutions and inverted residual blocks leads to more evenly distributed information and weaker inter-channel correlations. As a result, the loss of individual channels produces a smoother degradation of representation, reflected in a flatter free-energy curve.

In Vision Transformers, the self-attention mechanism enables global information flow across tokens, allowing the model to compensate for suppressed activations during the early stages of pruning. This flexibility gives rise to a broader free-energy valley that precedes the accuracy drop.

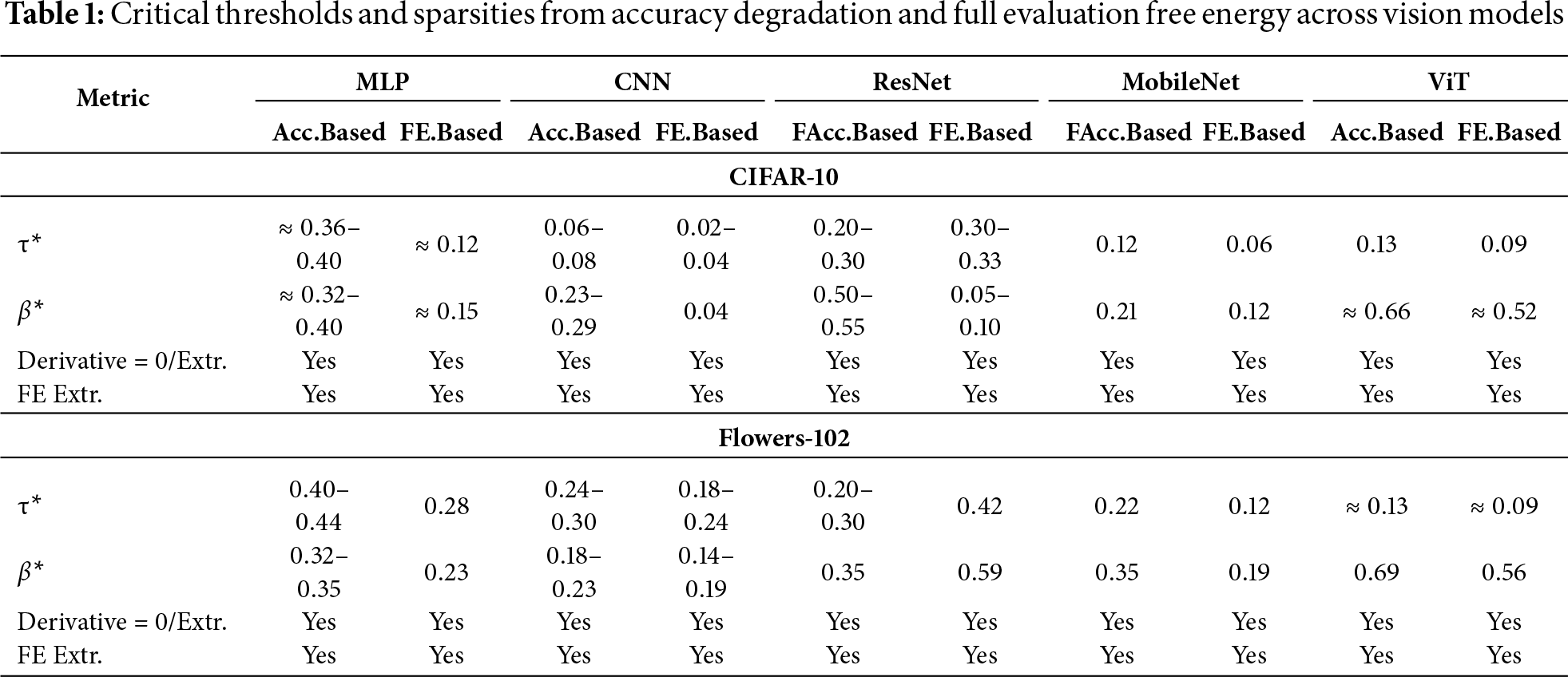

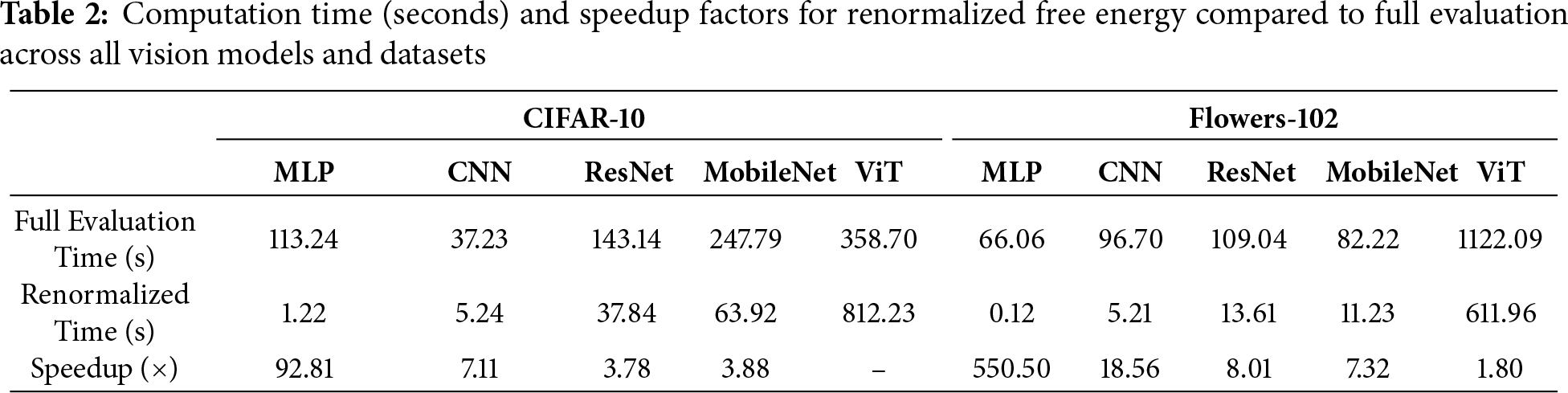

Table 1 summarizes the critical thresholds (

Time Efficiency Analysis

We evaluated the computational gains of the renormalized free energy (RFE) method relative to the full-evaluation free energy (FE) across all architectures. RFE provides substantial speedups: over 550

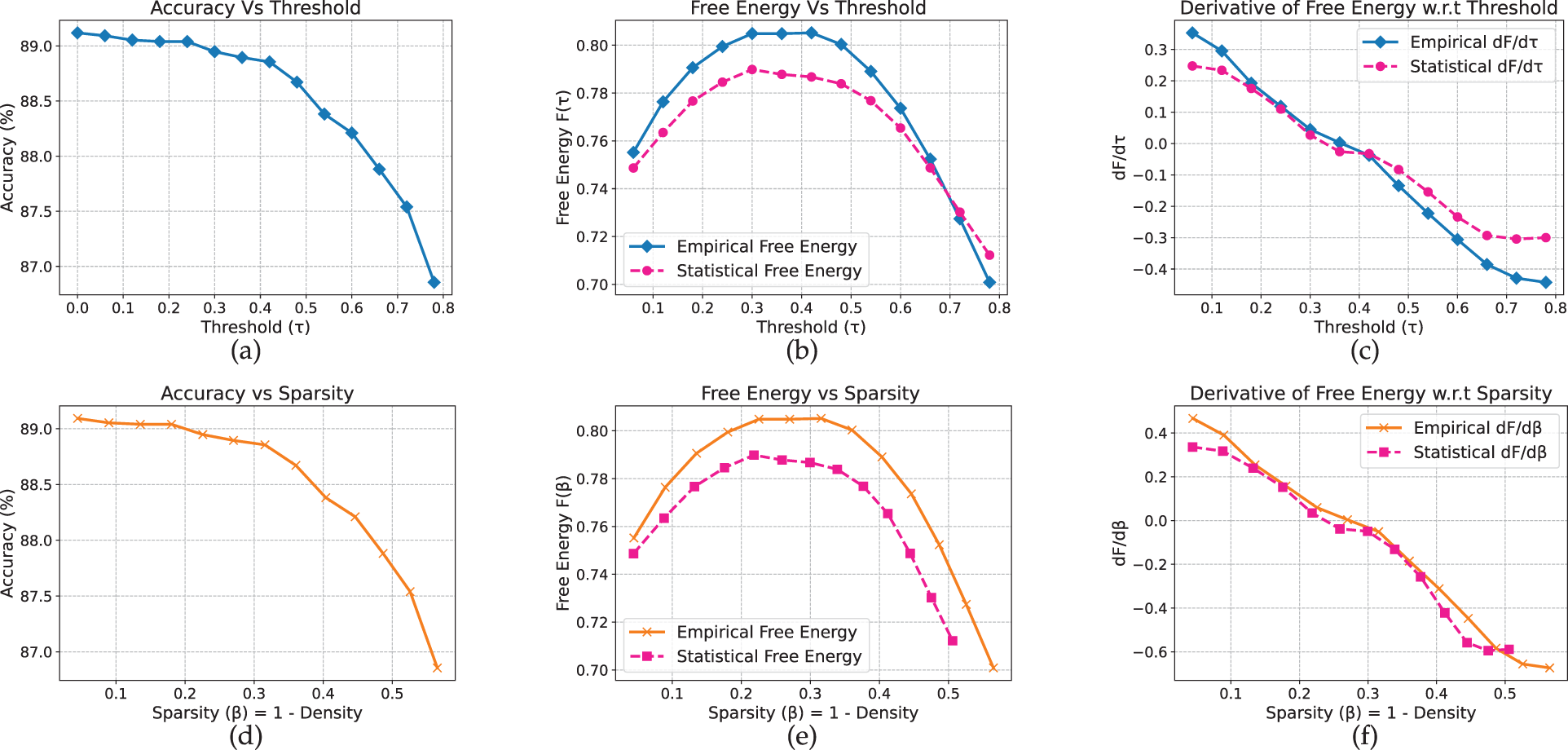

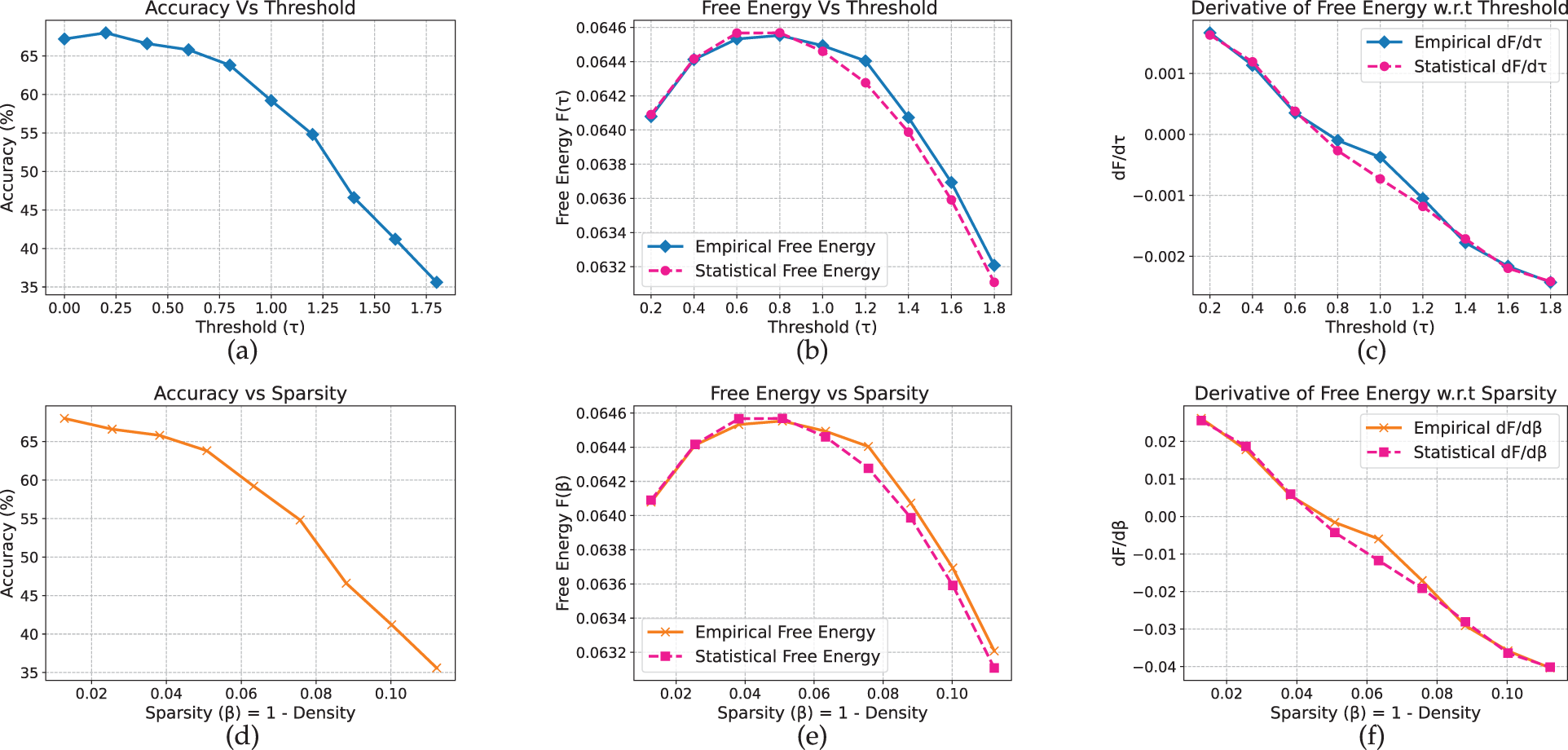

Extending our analysis to text models, we observe that for non-pretrained LSTMs, the free-energy peaks align closely with the accuracy drop, in contrast to the scratch-trained vision models where the peak typically appears earlier. On AG News (Fig. 12), accuracy remains stable up to approximately

Figure 12: LSTM model on AG_News dataset

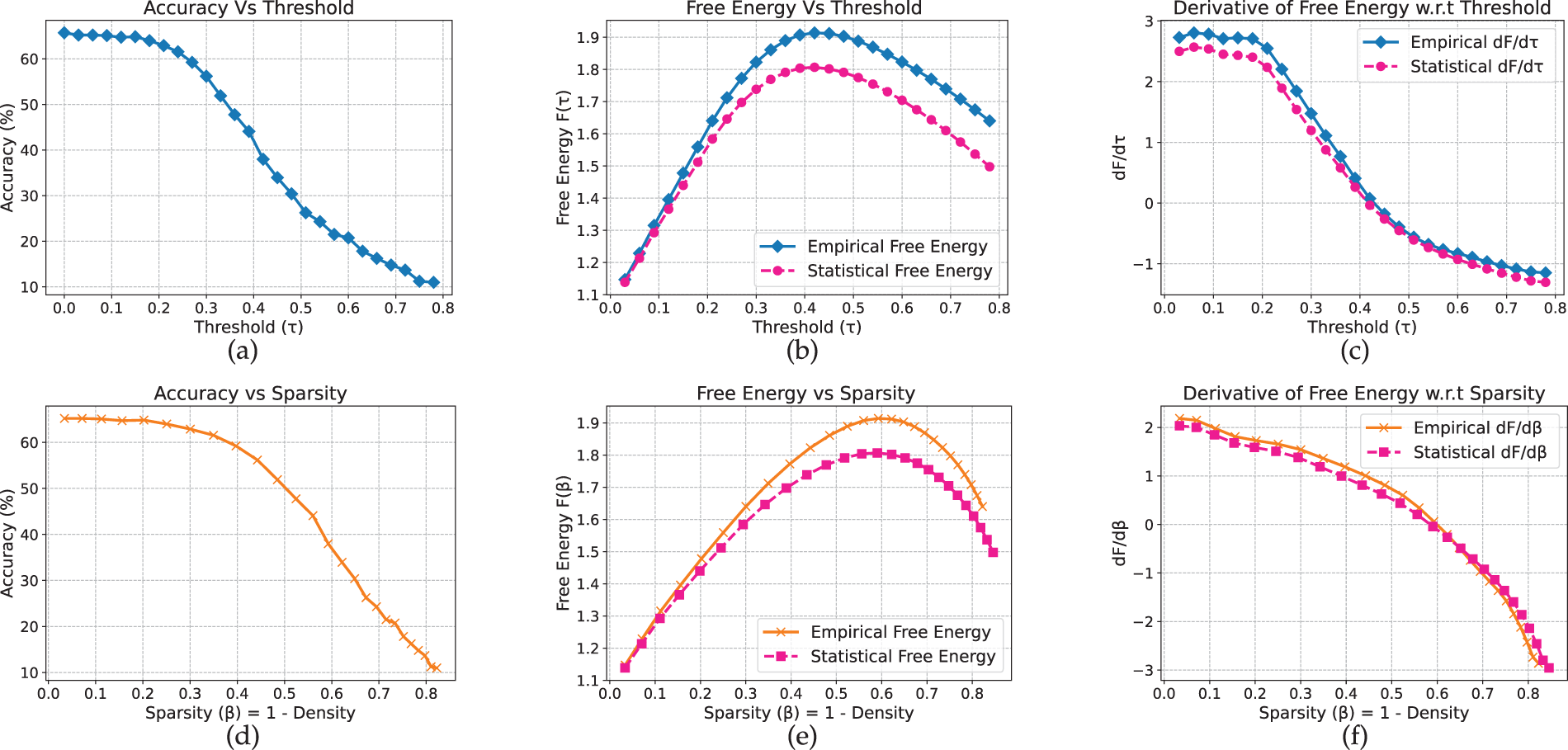

On Yelp (Fig. 13), a similarly abrupt transition is observed: accuracy remains near 62.9% before dropping between

Figure 13: LSTM model on yelp full review dataset

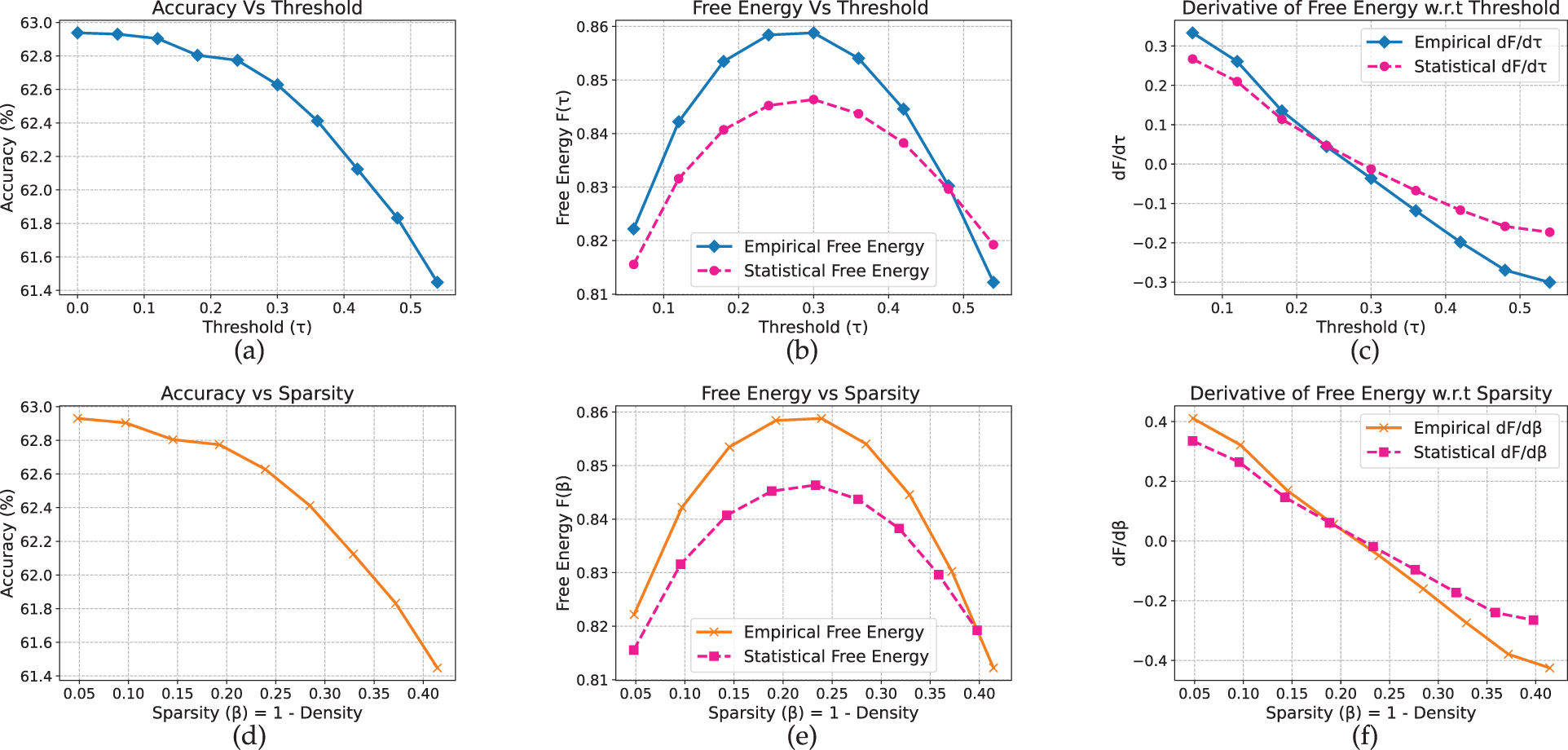

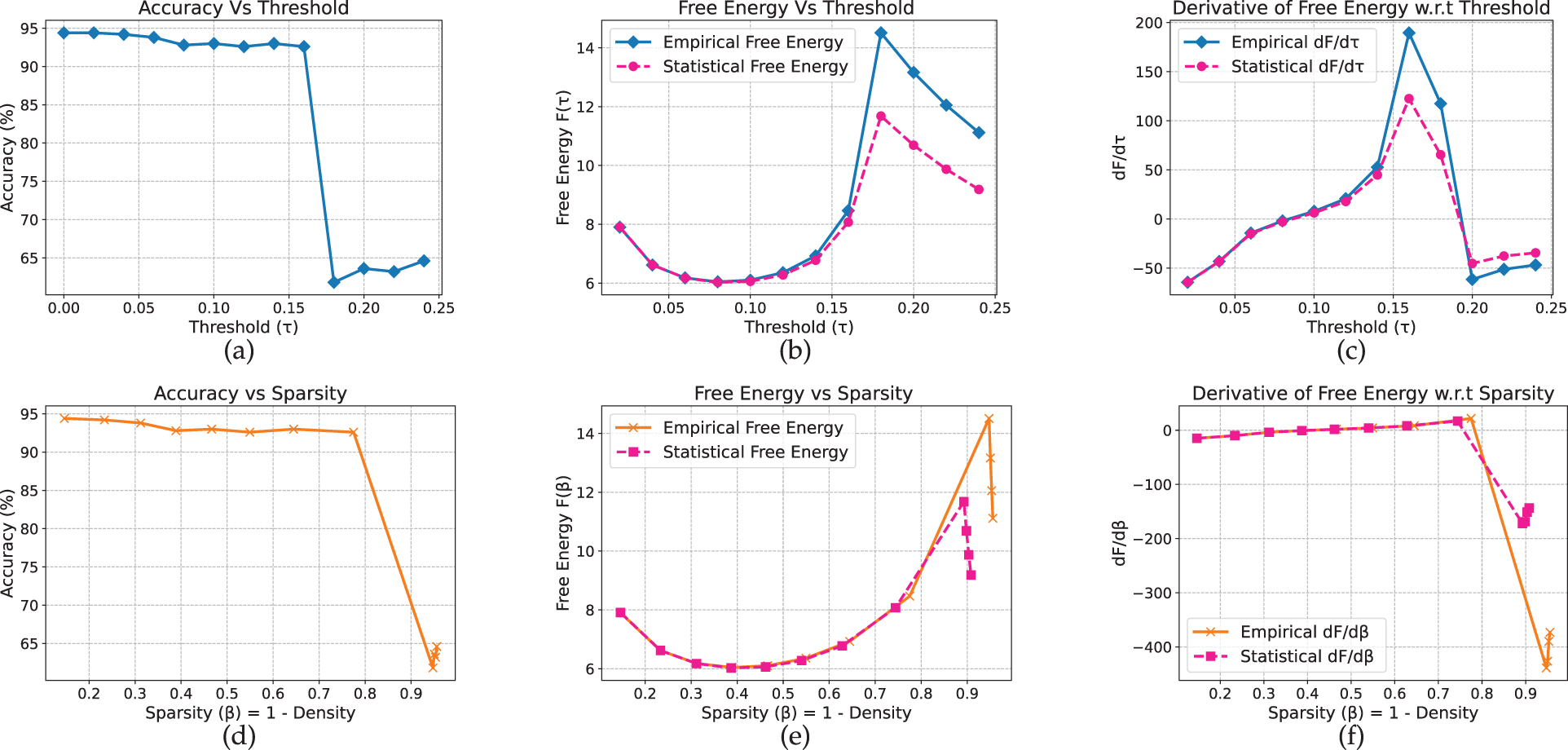

In contrast, pretrained encoder-only transformers exhibit more structured and predictable behavior. On AG News (Fig. 14), BERT maintains approximately 93%–94% accuracy up to

Figure 14: BERT model on AG_News dataset

On Yelp (Fig. 15), a similar accuracy drop occurs between

Figure 15: BERT model on yelp full review dataset

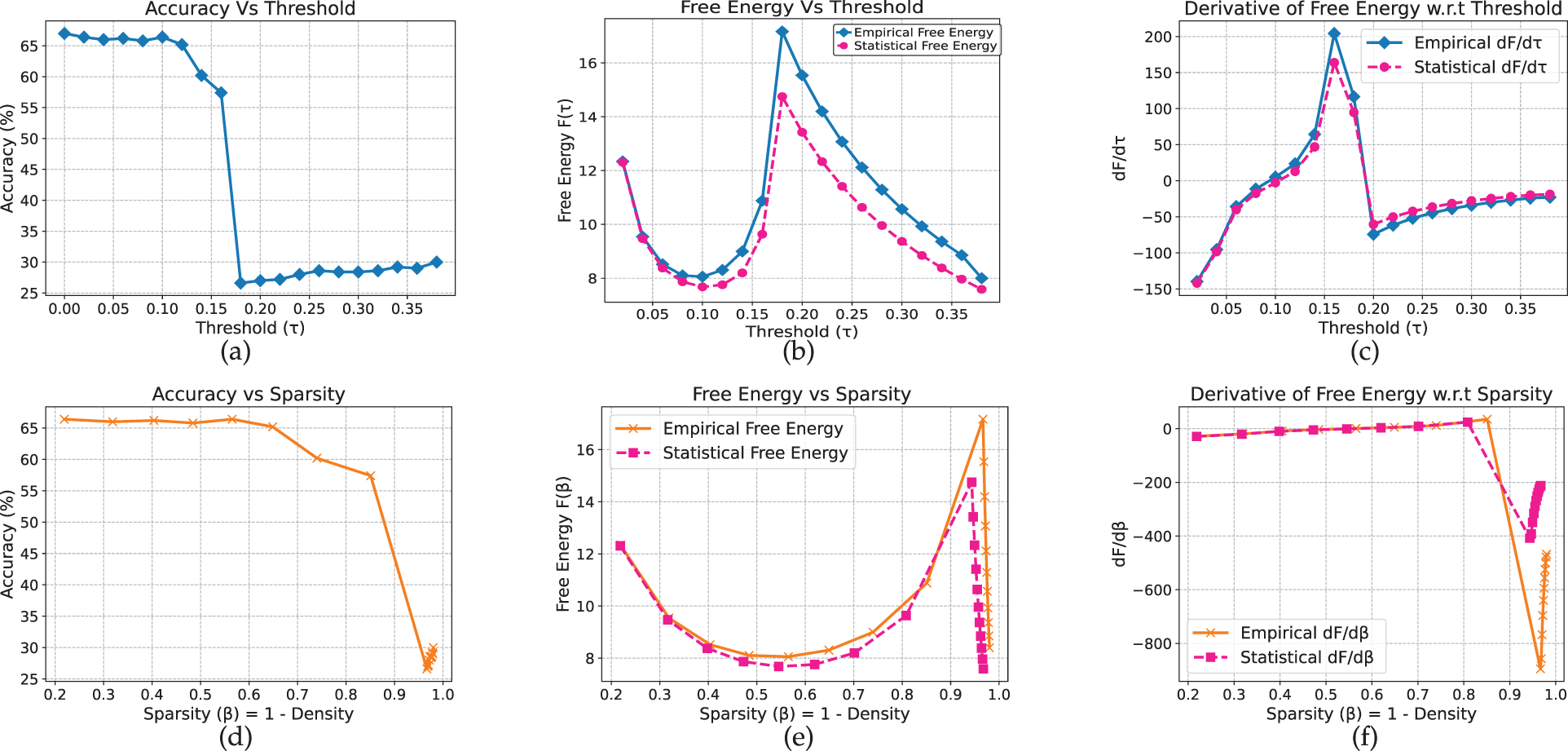

ELECTRA (Figs. 16 and 17) exhibits analogous behavior, with clear stable, transition, and collapsed regimes across both datasets. The full and renormalized free-energy curves yield consistent estimates of the critical threshold near

Figure 16: Electra model on AG_News dataset

Figure 17: Electra model on yelp full review dataset

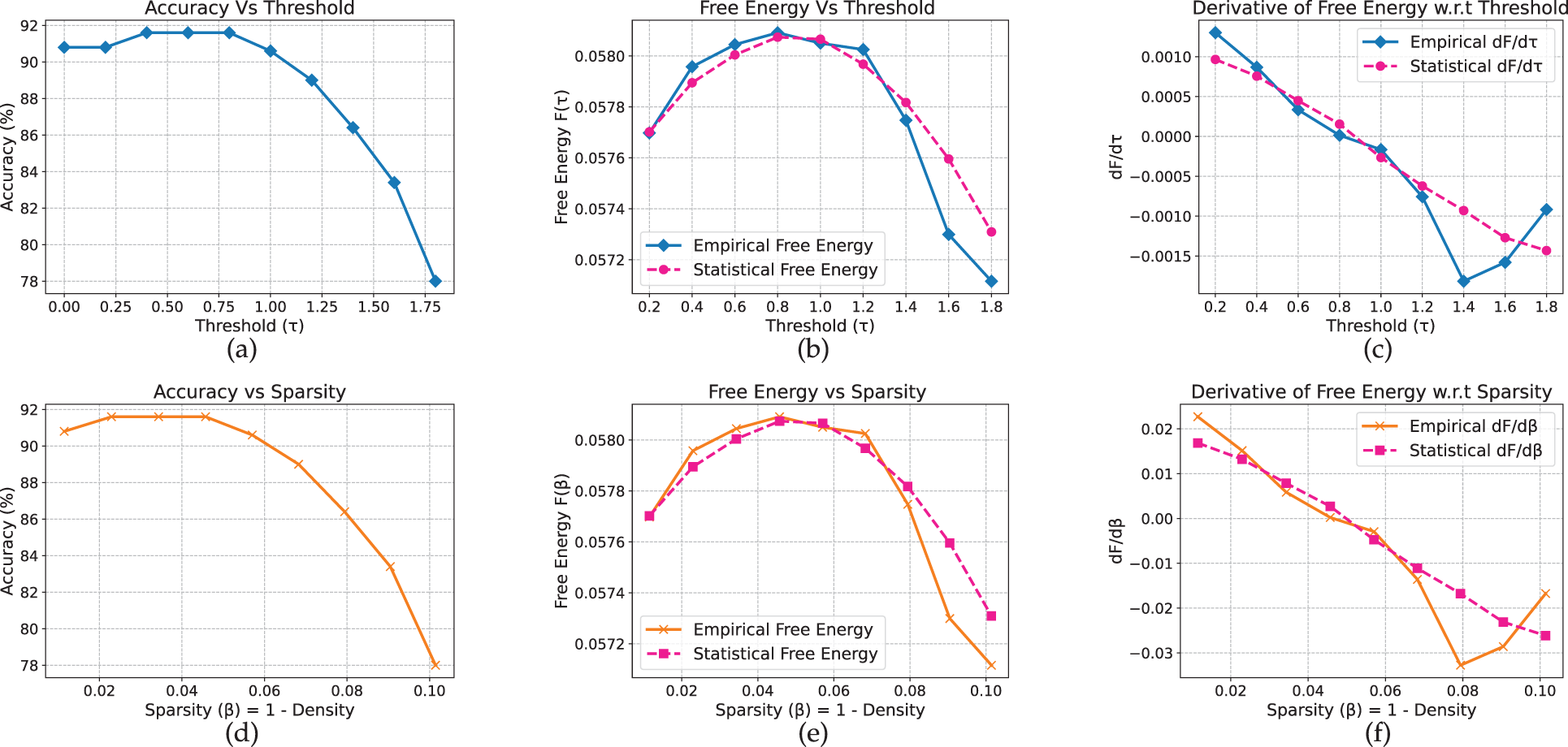

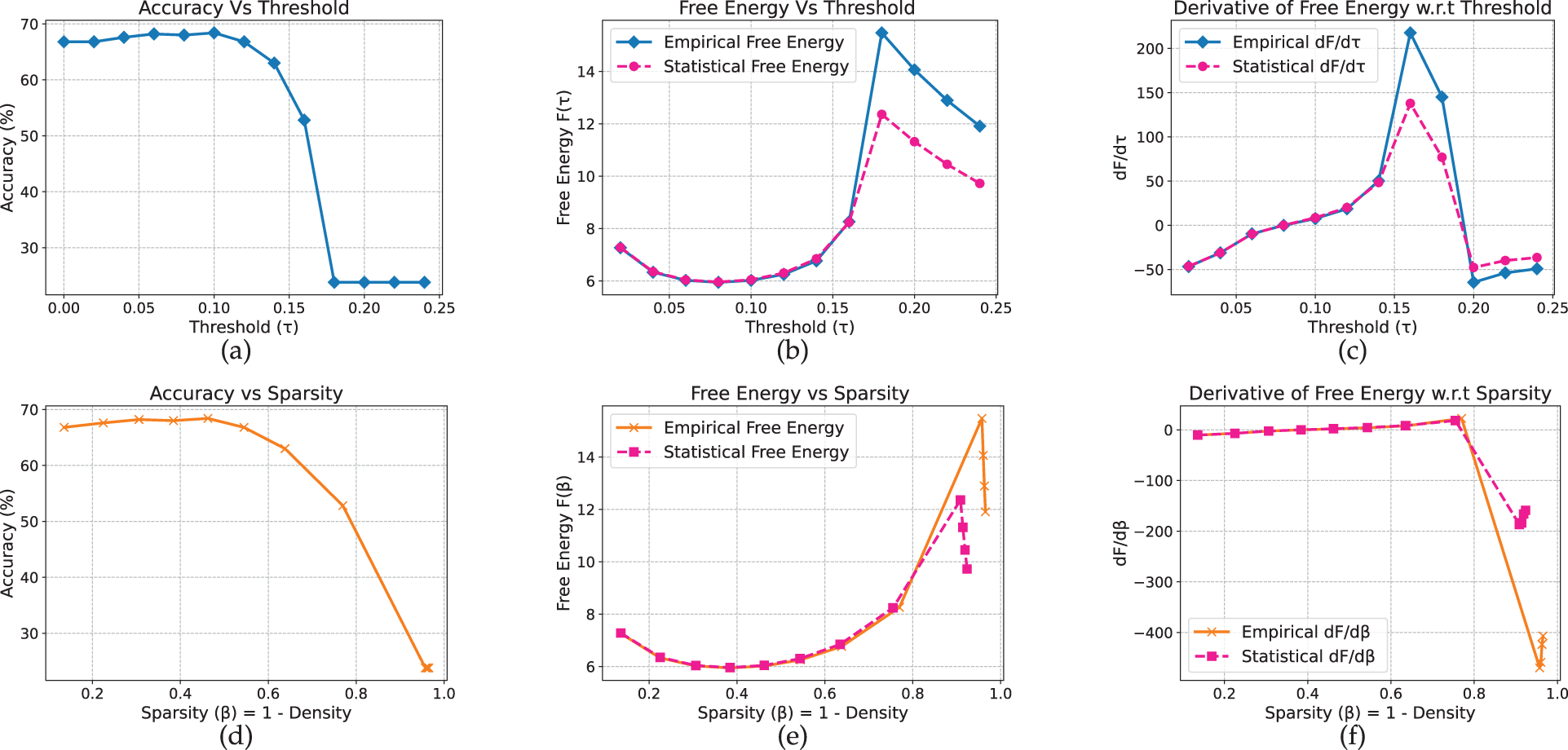

The results for T5, a sequence-to-sequence transformer, exhibit comparatively smoother pruning behavior. On AG News (Fig. 18), accuracy remains stable (approximately 91%–92%) up to

Figure 18: T5 model on AG_News dataset

Figure 19: T5 model on yelp full review dataset

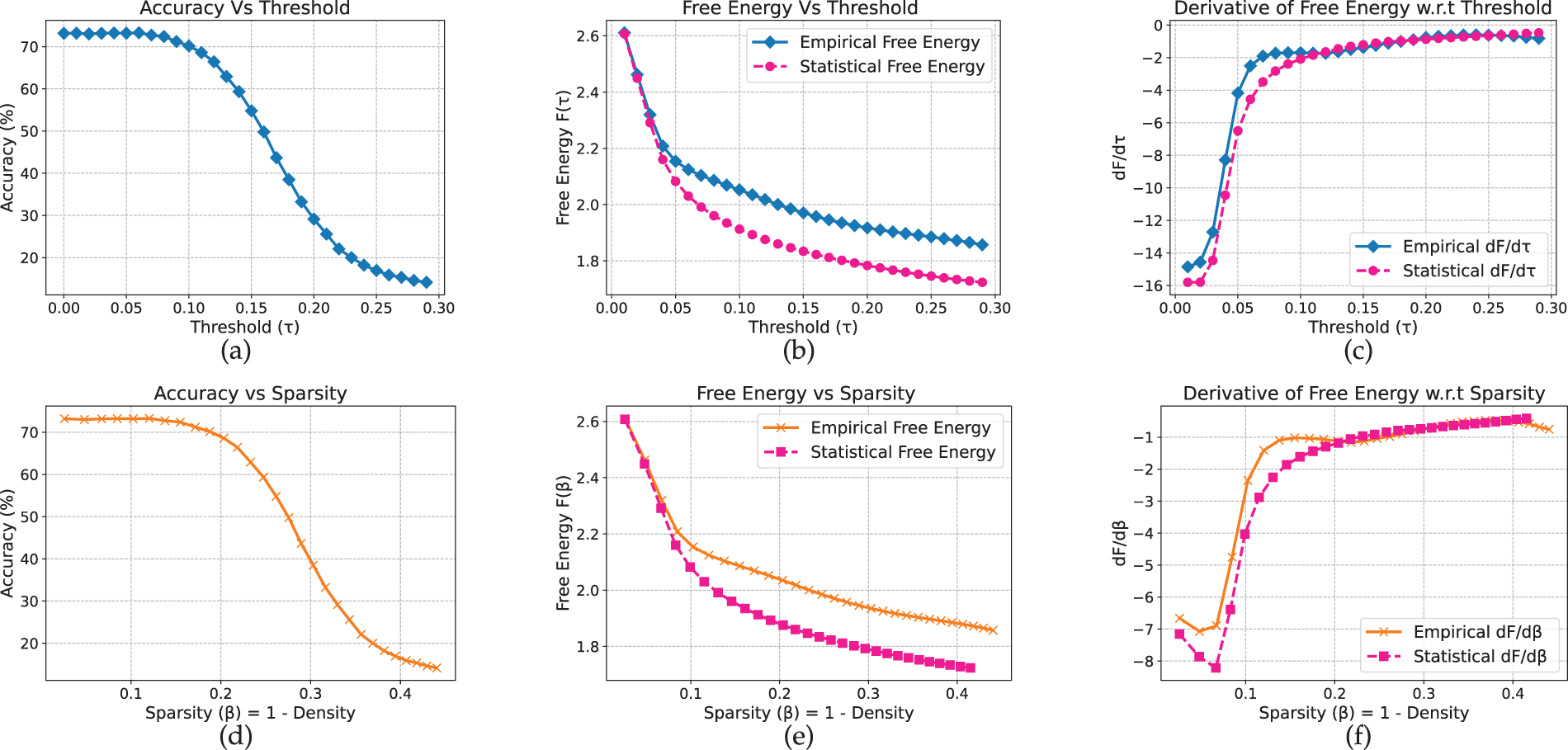

In GPT-2, the pruning dynamics vary noticeably across datasets. On AG News (Fig. 20), accuracy remains high (approximately 92%–94%) until a sharp decline at

Figure 20: GPT_2 model on AG_News dataset

On Yelp (Fig. 21), accuracy declines earlier, at

Figure 21: GPT_2 model on yelp full review dataset

Across the text models, free energy offers a reliable estimate of critical thresholds near the onset of accuracy degradation, with derivative curves marking the corresponding phase transitions. Non-pretrained LSTMs exhibit abrupt and largely dataset-independent transitions, whereas pretrained transformers display smoother and more predictable behavior. Encoder-only models (BERT, ELECTRA) show sharp minima that provide clear approximations of the critical threshold; T5 degrades gradually, forming soft critical regions; and GPT-2 demonstrates dataset-dependent extrema. In all cases, the renormalized free-energy curves closely follow the full-evaluation trends across architectures and datasets.

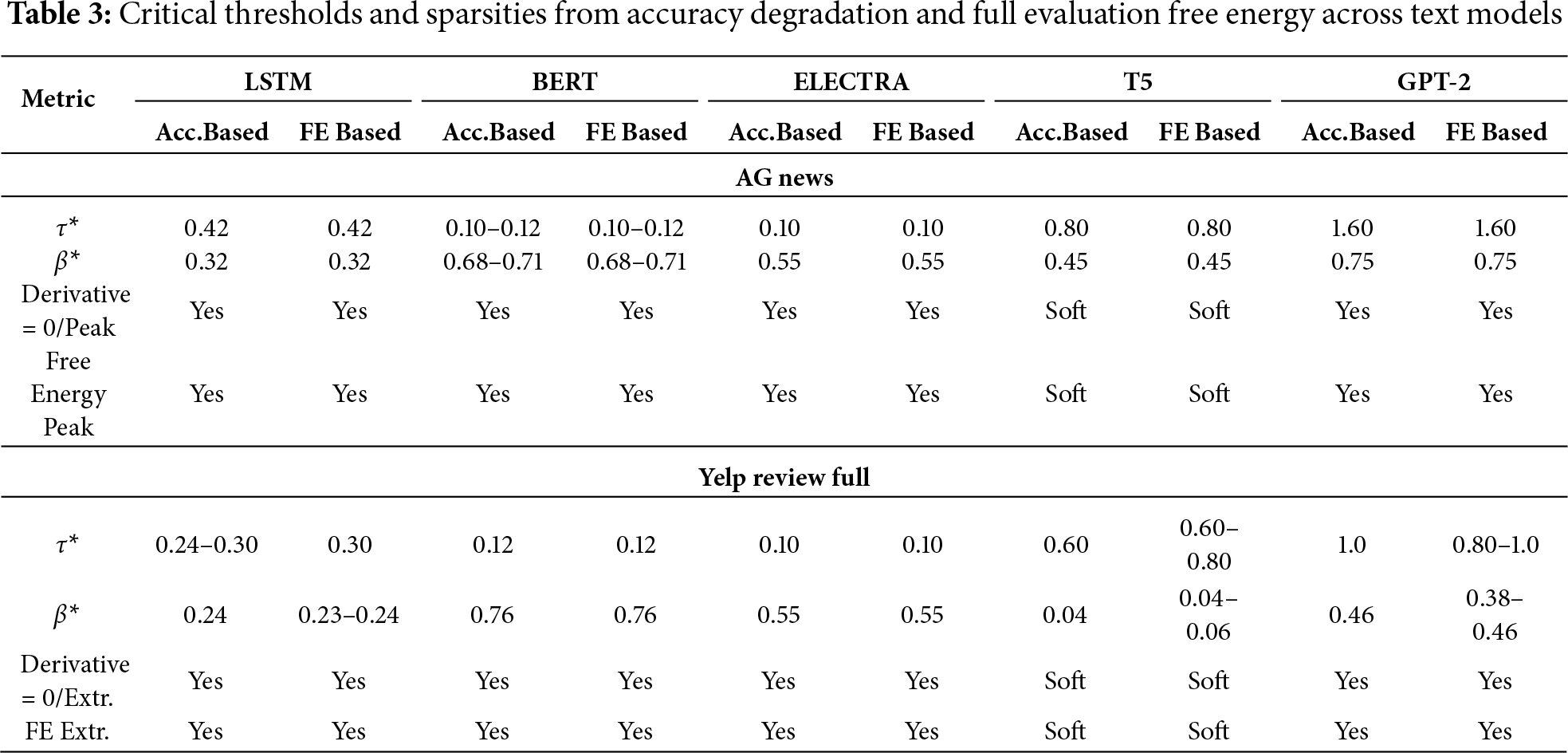

Table 3 summarizes the critical thresholds (

Empirically, we observe that accuracy remains stable before the free-energy transition, typically varying by only 3%–5%. Once this transition is crossed, however, performance drops sharply (by at least 30% in our experiments). This behavior confirms that the free-energy transition corresponds to a phase-like boundary rather than a gradual degradation.

Time Efficiency Analysis

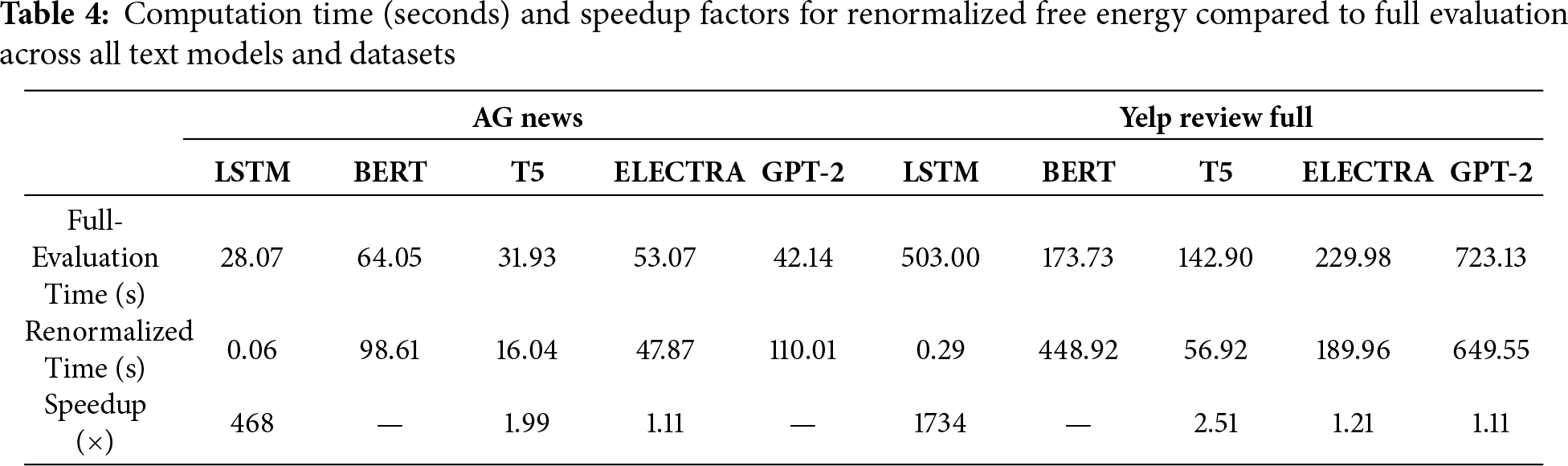

For text models as well, RFE provides substantial computational gains for simpler architectures. The LSTM achieves dramatic speedups—over 460

We presented a thermodynamics-inspired framework for activation pruning, using free-energy dynamics as a proxy for approximating critical pruning thresholds. Across both vision and language models, extrema and inflection points in the free-energy curve typically precede or closely coincide with the onset of accuracy degradation, revealing architecture- and dataset-dependent behavior: non-pretrained networks (MLP, CNN, LSTM) exhibit sharp, abrupt transitions, pretrained models such as ResNet-18, MobileNetV2, and ViT display smoother and more gradual dynamics, and transformer architectures show model- and dataset-specific extrema.

To improve efficiency, we introduced a renormalized free-energy method that reconstructs the same diagnostic curves using only unpruned activations, thereby eliminating the need for repeated inference. This renormalized evaluation yields substantial speedups for fully connected, convolutional, and residual architectures, achieving up to a 500

This work bridges theoretical insight and practical application, demonstrating that free energy offers a principled and generalizable perspective on pruning behavior. While our experiments focus on classification tasks, extending this framework to generative models, reinforcement learning settings, and finer-grained layerwise analyses represents a promising direction for future research.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported in part through computational resources of HPC facilities at HSE University.

Funding Statement: This work is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at HSE University

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Rayeesa Mehmood, Sergei Koltcov, Anton Surkov and Vera Ignatenko; methodology, Rayeesa Mehmood, Sergei Koltcov, Anton Surkov and Vera Ignatenko; software, Rayeesa Mehmood; validation, Rayeesa Mehmood, Sergei Koltcov, Anton Surkov and Vera Ignatenko; formal analysis, Rayeesa Mehmood and Sergei Koltcov; investigation, Rayeesa Mehmood, Vera Ignatenko and Anton Surkov; resources, Rayeesa Mehmood and Anton Surkov; data curation, Rayeesa Mehmood; writing—original draft preparation, Rayeesa Mehmood; writing—review and editing, Vera Ignatenko, Sergei Koltcov and Anton Surkov; visualization, Rayeesa Mehmood and Vera Ignatenko; supervision, Sergei Koltcov; project administration, Vera Ignatenko; funding acquisition, Sergei Koltcov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Github at https://github.com/hse-scila/Activation_Pruning (accessed on 12 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| MobileNet | Mobile-Optimized Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| ELECTRA | Efficiently Learning an Encoder that Classifies Token Replacements Accurately |

| T5 | Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer |

| GPT-2 | Generative Pretrained Transformer 2 |

References

1. Li H, Kadav A, Durdanovic I, Samet H, Graf HP. Pruning filters for efficient convnets. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR’17); 2017 Apr 24–26; Toulon, France. p. 1683–95. [Google Scholar]

2. Sun M, Liu Z, Bair A, Kolter JZ. 1A Simple and effective pruning approach for large language models. In: The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024 May 7–11; Vienna, Austria. p. 4640–62. [Google Scholar]

3. Han S, Pool J, Tran J, Dally W. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural network. In: Cortes C, Lawrence N, Lee D, Sugiyama M, Garnett R, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 28. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2015. p. 1135–43. [Google Scholar]

4. Neo M. A comprehensive guide to neural network model pruning [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.datature.io/blog/a-comprehensive-guide-to-neural-network-model-pruning. [Google Scholar]

5. Heyman A, Zylberberg J. Fine granularity is critical for intelligent neural network pruning. Neural Comput. 2024;36(12):2677–709. doi:10.1162/neco_a_01717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Chen E, Wang H, Shi Z, Zhang W. Channel pruning for convolutional neural networks using l0-norm constraints. Neurocomputing. 2025;636:129925. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.129925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hu H, Peng R, Tai YW, Tang CK. Network trimming: a data-driven neuron pruning approach towards efficient deep architectures. arXiv:1607.03250. 2016. [Google Scholar]

8. Foldy-Porto T, Venkatesha Y, Panda P. Activation density driven energy-efficient pruning in training. arXiv:2002.02949. 2020. [Google Scholar]

9. xiao Li Z, You C, Bhojanapalli S, Li D, Rawat AS, Reddi SJ, et al. The lazy neuron phenomenon: on emergence of activation sparsity in transformers. arXiv:2210.06313. 2022. [Google Scholar]

10. Tang C, Sun W, Yuan Z, Liu Y. Adaptive pixel-wise structured sparse network for efficient CNNs. arXiv:2010.11083. 2021. [Google Scholar]

11. Hussien M, Afifi M, Nguyen KK, Cheriet M. Small contributions, small networks: efficient neural network pruning based on relative importance. arXiv:2410.16151. 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Kurtz M, Kopinsky J, Gelashvili R, Matveev A, Carr J, Goin M, et al. Inducing and exploiting activation sparsity for fast inference on deep neural networks. In: Daumé H III, Singh A, editors. Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning. Vol. 119. London, UK: PMLR; 2020. p. 5533–43. [Google Scholar]

13. Ganguli T, Chong EK. Activation-based pruning of neural networks. Algorithms. 2024;17(1):48. doi:10.3390/a17010048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao K, Jain A, Zhao M. Adaptive activation-based structured pruning. arXiv:2201.10520. 2022. [Google Scholar]

15. Grimaldi M, Ganji DC, Lazarevich I, Deeplite SS. Accelerating deep neural networks via semi-structured activation sparsity. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1171–80. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang M, Zhang M, Liu X, Nie L. Weight-aware activation sparsity with constrained bayesian optimization scheduling for large language models. In: Christodoulopoulos C, Chakraborty T, Rose C, Peng V, editors. Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2025. p. 1086–98. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhang Z, Liu Z, Tian Y, Khaitan H, Wang Z, Li S. R-Sparse: rank-aware activation sparsity for efficient LLM inference. arXiv:2504.19449. 2025. [Google Scholar]

18. Liu J, Ponnusamy P, Cai T, Guo H, Kim Y, Athiwaratkun B. Training-free activation sparsity in large language models. arXiv:2408.14690. 2025. [Google Scholar]

19. An T, Cai R, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Chen H, Xie P, et al. Amber pruner: leveraging n:m activation sparsity for efficient prefill in large language models. arXiv:2508.02128. 2025. [Google Scholar]

20. Ding Y, Chen DR. Optimization based layer-wise pruning threshold method for accelerating convolutional neural networks. Mathematics. 2023;11(15):3311. doi:10.3390/math11153311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sanh V, Wolf T, Rush AM. Movement pruning: adaptive sparsity by fine-tuning. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS ’20. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2020. p. 20378–89. [Google Scholar]

22. Frantar E, Alistarh D. SparseGPT: massive language models can be accurately pruned in one-shot. arXiv:2301.00774. 2023. [Google Scholar]

23. Frantar E, Ashkboos S, Hoefler T, Alistarh D. GPTQ: accurate post-training quantization for generative pre-trained transformers. arXiv:2210.17323. 2023. [Google Scholar]

24. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

25. Sandler M, Howard A, Zhu M, Zhmoginov A, Chen LC. MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 4510–20. [Google Scholar]

26. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In: International Conference on Learning Representations. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2021. p. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

27. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Burstein J, Doran C, Solorio T, editors. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

28. Clark K, Luong MT, Le QV, Manning CD. ELECTRA: pre-training text encoders as discriminators rather than generators. arXiv:2003.10555. 2020. [Google Scholar]

29. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

30. Radford A, Wu J, Child R, Luan D, Amodei D, Sutskever I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners [Internet]. San Francisco, CA, USA: OpenAI; 2019 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://cdn.openai.com/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools