Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Hybrid Approach to Software Testing Efficiency: Stacked Ensembles and Deep Q-Learning for Test Case Prioritization and Ranking

1 School of Computer Science, University of Birmingham, Dubai, 73000, United Arab Emirates

2 School of Computer Science, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

3 Computing and Information Systems Division, Higher Colleges Technology, Abu Dhabi, 20015, United Arab Emirates

* Corresponding Author: Jaber Jemai. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Powered Software Engineering)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 74 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072768

Received 03 September 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Test case prioritization and ranking play a crucial role in software testing by improving fault detection efficiency and ensuring software reliability. While prioritization selects the most relevant test cases for optimal coverage, ranking further refines their execution order to detect critical faults earlier. This study investigates machine learning techniques to enhance both prioritization and ranking, contributing to more effective and efficient testing processes. We first employ advanced feature engineering alongside ensemble models, including Gradient Boosted, Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, and Naive Bayes classifiers to optimize test case prioritization, achieving an accuracy score ofKeywords

In today’s digital age, software covers almost every aspect of daily life, having a significant impact on industries such as communication, entertainment, healthcare, and finance. As software is increasingly integrated into these key domains, the importance of ensuring its quality and stability grows [1]. To maintain a competitive edge in the dynamic and frequently changing market landscape, software companies ranging from small-scale application developers to large-scale industrial software manufacturers must constantly innovate. This innovation aims to improve the quality and stability of their software products, which are increasingly becoming the foundation of their value proposition. This paper delves into the exploration of strategies and methodologies specifically designed to augment the ranking and prioritization of test cases. Test case ranking refers to assigning scores or relative importance values to test cases based on criteria such as risk, fault proneness, or criticality. By contrast, test case prioritization uses this information to determine the execution order of test cases, aiming to maximize early fault detection or optimize limited testing resources. In short, ranking is about evaluation, while prioritization is about action. In the context of this study, we develop and implement a hybrid approach to software testing using stacked ensemble learners and deep Q-learning models for test case prioritization and ranking. The overarching objective is to streamline testing processes, thereby catalyzing the delivery of superior-quality software solutions to end-users. This focus underscores the commitment to continuous improvement and the pursuit of excellence in software development, reflecting the industry’s response to the escalating demands of the digital age.

Software development teams frequently face time and financial restrictions [2,3]. To ensure that software systems continue to function after each modification, a complete set of tests is required. However, not all tests are equally successful at detecting errors early in the process [4]. As a result, it is critical to develop and run tests that have the best chance of detecting errors early on. Effective test case selection can considerably improve testing process efficiency and efficacy by prioritising key tests from the start. Research in software testing has explored various aspects of test case prioritization and defect detection. Studies have investigated techniques such as regression testing minimization, selection, and prioritization [5], defect prioritization [6], and the impact of test ownership and team structure on test reliability and effectiveness [7]. Furthermore, recent studies have addressed various aspects of test case prioritization in software engineering. These include prioritization methodologies tailored for object-oriented software systems [8], strategies for continuous regression testing [9], and prioritization frameworks that incorporate requirements and risk analysis. Moreover, there has been notable investigation into the application of machine learning techniques to enhance test case prioritization strategies [10].

Effective test case prioritization provides tremendous benefits. Prioritizing and performing essential tests early can enhance fault detection, decrease the likelihood of major issues later in the development cycle, and expedite issue resolution [11]. This approach optimizes resource allocation, provides early feedback on potential problems, and improves overall test coverage. Kajo Meçe et al. [10] explore the use of machine learning (ML) approaches for test case prioritization (TCP) in software testing. The review provides a comprehensive survey, highlighting the various ML techniques that have been employed to enhance TCP’s efficiency and effectiveness. Clearly, the effectiveness of machine learning based TCP heavily depends on the quality and relevance of the data used to train the models. Inaccurate or biased data can negatively impact the prioritization process, potentially causing essential test cases to be overlooked [12]. To address these limitations, we incorporate a smart feature engineering approach that significantly enhances the robustness and accuracy of ML-based TCP. Additionally, we employ ensemble learning methods, including voting, to refine the models, making them more resilient to data quality issues and better at identifying high-risk areas. This proposed approach increases the models’ predictive performance as well as their capacity to generalise across different and complicated testing contexts, resulting in more reliable and efficient software testing processes.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has recently emerged as a powerful technique in the context of ranking items. Studies such as [13] have demonstrated the feasibility of deep reinforcement learning in solving combinatorial optimization problems, showcasing the algorithm’s potential in addressing complex ranking tasks. Additionally, research by [14] has highlighted the application of RL in interactive recommender systems, emphasizing its ability to learn from dynamic interactions and plan for long-term performance. These studies collectively underscore the growing significance of RL in enhancing item ranking processes, particularly in dynamic and interactive settings. Inspired by initial efforts to apply reinforcement learning (RL) to various ranking scenarios, we conducted a comprehensive investigation into RL-based test case ranking. We approached test case prioritization as a ranking problem, modeling the sequential interactions between cycles and a test case prioritization agent as an RL problem. Our investigation was guided by three ranking models from information retrieval: listwise, pairwise, and pairwise verdict. To enhance the ranking accuracy, we also deployed a genetic algorithm, which optimizes the parameters and selection process through evolutionary techniques. The state represents the test case chosen by the RL model to have the highest priority. A reward is given if the selected test case has a verdict of 1 or if the selected test case has a shorter duration in cases where both tests have the same verdict. We combine our proposed RL model with genetic algorithms to continually adapt and enhance the ranking strategy, ensuring that critical test cases are identified and executed efficiently. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both techniques to optimize test case ranking and improve overall testing effectiveness. The key contributions of this work include:

• Hybrid methodology: Introduces a novel integration of stacked-ensemble learning for test case ranking with Deep Q-Learning for dynamic prioritization, combining predictive accuracy with adaptive decision-making.

• Comprehensive evaluation: Demonstrates the effectiveness of the approach on a benchmark dataset through comparative experiments, showing improvements in early fault detection and cost-aware efficiency metrics.

• Actionable framework: Provides a scalable and practical testing framework that can be adapted to continuous integration environments, bridging the gap between research prototypes and industrial applications.

Prioritizing and ranking test cases is vital in software testing since these actions are essential for ensuring software system quality and dependability. Developers can significantly enhance testing productivity by carefully prioritizing and sequencing test cases based on certain factors, resulting in the early detection and rectification of faults. The works discussed in this section are classified into two main streams: test case prioritization and test case ranking.

The pioneering work in software testing [15] suggests that testing code before deployment via test selection, test case minimization, and test case prioritization is advantageous for the quality of the tested software. However, these techniques are largely similar, and there is a trend towards the use of test case prioritization over other techniques. Numerous works have detailed various test case prioritization techniques, such risk-based prioritization and code coverage-based prioritization [16] and average faults per minute [9]. They conclude that test case prioritization significantly enhances fault detection compared to a retest-all approach and improves fault detection rate, budget adherence, and time effectiveness. This is further validated by the findings of [10], and [11]. Further dimensions in test case prioritization have been highlighted, such as time budgets [17] and the size of the test suite [18].

Adaptive prioritization involves dynamic methods, requiring significant computational resources and time. In [19], the authors proposed an approach focusing on prioritizing test cases based on requirements and risk factors, showcasing the relevance of context-specific prioritization methodologies. To overcome this computation time limitation, the authors in [20] presented a cost-cognizant combinatorial test case prioritization technique, contributing to the Pure Prioritization Strategy in software testing. Similarly, reference [21] presented ensemble methodologies for prioritizing test cases in UI testing. As stated in [22], the use of value-based test case prioritization techniques has been shown to outperform other regression test optimization methods. Additionally, dynamic environments like continuous integration require adaptive test case prioritization approaches that can adjust to changing test budgets and frequent additions or removals of test cases [23].

In later work, the use of machine learning models increased the efficiency and enabled the automation of test case prioritization systems [10,24,25]. Several ML models have been implemented, including genetic algorithms, support vector machines, Bayesian networks, and decision trees. Despite this, these methods require a large dataset to train effectively and achieve the desired accurate results. ML techniques with gradient boosted methods showed superior results compared to non-ML approaches and untreated data. Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms have been also developed for test case prioritization [26,27]. They exhibit a Time to First Prioritization (TTFP) of 0, as they can immediately begin predicting, unlike non-RL methods, which require training to be completed. They are also proposed to be more adaptive to change than other non-RL techniques.

On the other hand, genetic algorithms have demonstrated significant improvements in test case prioritization performance, although they typically incur higher computational costs due to the incorporation of specialized variation operators [28,29]. This highlights the importance of exploring hybrid approaches that combine multiple machine learning algorithms to enhance both the speed and effectiveness of test case prioritization. These techniques aim to accelerate software testing processes and improve defect detection rates. Elbaum et al. [11] conducted seminal empirical research on test case prioritization, demonstrating the effectiveness of a greedy algorithm to optimize test case ordering, thereby maximizing early fault detection and enhancing overall software quality.

Test case ranking is essential in software testing as it allows for the optimization of the test case sequence, thereby increasing fault detection rates and improving product quality. Test case ranking ensures that critical tests are executed early in the testing process, leading to the early detection of issues and prompt resolution. In this section, we review the recent advancements in the field, focusing on various methodologies and their impact on test case ranking. This success extends to software engineering, where reference [30] introduced the application of Markov Chain Monte Carlo Random Testing (MCMCRT) for test case ranking in regression testing. The effectiveness of MCMCRT is examined against ordinary random testing and adaptive random testing and shows a competitive advantage. In [31], the authors proposed a learn-to-rank technique to prioritize test cases. This technique uses the multidimensional features of an Extended Finite State Machine (EFSM) to improve the fault detection rate. The performance evaluation of the proposed method in terms of the APFD reached 0.884 for five subject EFSMs.

The authors in [32] developed a technique named DeepOrder to rank test cases based on historical test execution records. This method leverages past data to make informed decisions on the order of test cases. Similarly, reference [21] focused on ranking test cases as a critical practice in software engineering using some existing techniques that are time and resource-intensive, making them unsuitable for use within CI cycles. Reference [33] proposed RL for the online learn-to-rank model for test case ranking. This approach aims to minimize testing overhead and continuously adapt to the changing environment as new code and new test cases are added in each CI cycle. Similarly, in [23], the authors evaluated two learning-based approaches: RETECS (based on Reinforcement Learning) and COLEMAN (based on Multi-Armed Bandit). The study found that these approaches are applicable in real scenarios and produce near-optimal solutions. However, they have some limitations to generalize on large test case set when learning from small sets.

These studies collectively underscore the critical role of test case ranking in software testing. They demonstrate the application of diverse machine learning algorithms and genetic algorithms to optimize test case ranking, ensuring that the most crucial tests are executed early, leading to quicker detection and resolution of issues. Several related works fail to address the scalability of ranking-to-learn approaches for large-scale software systems. Many approaches depend on the comprehensiveness and representativeness of historical data. If the historical data does not accurately reflect future test cases, the performance and effectiveness of these approaches may be compromised. Additionally, these methods may require significant computational resources and time. This oversight could significantly impact the effectiveness of these methods in prioritizing test cases within complex and extensive software applications.

The integration of diverse methodologies, such as ensemble approaches, learn-to-rank methods, and time-aware prioritization techniques, showcases the evolution of test case prioritization and ranking towards more efficient and effective software testing processes.

3 Proposed Approach for Test Case Prioritization

Our proposed approach utilizes advanced machine learning techniques and sophisticated feature engineering methods to streamline and enhance the testing process. By integrating these diverse methodologies, we aim to add additional significance to our dataset and record the dynamic behavior of test cases, significantly improving software quality and reducing the risk of critical issues emerging in the later stages of development.

3.1 Dataset and Feature Engineering

The initial data used for this paper includes results from a year-long testing process, during which 89 individual test cases were utilized, resulting in a total of 25,594 tests being conducted. The dataset [26] contains the execution logs of 352 CI cycles, each comprising at least six test cases. The features of each test set are ID, Name, Duration, CalcPrio, Last Run, Last Results, Verdict, Cycle, Quarter, and Month.

We employed advanced feature engineering techniques to significantly enrich our dataset. This included the incorporation of methods such as temporal aggregation and interaction terms, which are designed to capture non-linear relationships. Specifically, we introduced the following features as defined in [10]:

• Gap in Run Time: This feature calculates the time difference between the last two runs of each test case, using the ‘last run’ feature.

• Gap Cats: This feature calculates the difference in days, capped at a maximum value of 3, between the most recent and the second-most recent executions of a test case.

• Same Cycle Run: This feature assigns a value of 1 if the previous execution of a test case occurred within the same cycle as the current test case record. If the previous execution took place in a different cycle, it assigns a value of 0.

• cycle_Run: This feature tracks the cumulative count of a test case’s executions within the same cycle.

• Last Run This feature captures the results of the most recent execution of the previous test case in the dataset.

• Failure Percentage FP: The array of last results cannot be directly utilized by the algorithm, as it only accepts numeric inputs. When determining whether a test case will fail or not, the historical failure rate becomes an invaluable indicator.

• Test Case Maturity: Test case maturity refers to the degree of evolution and refinement a test case has undergone through successive testing cycles. After conducting over 50 trials of test maturity feature combinations and measuring their mutual information, the contributing features to test case maturity were identified.

This section delves into the test case prioritization process employed in this study, with a particular emphasis on the training of the ensemble and the voting approach.

3.2.1 Ensemble Models Training

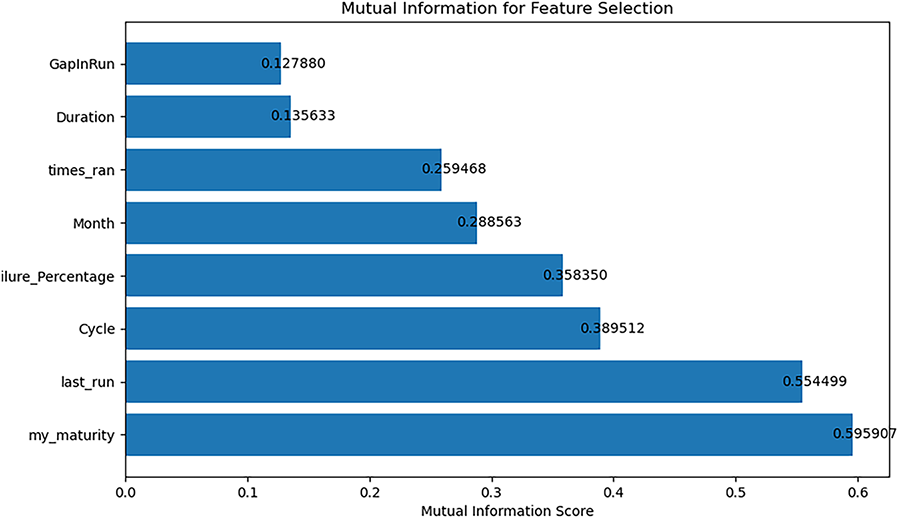

We employed a variety of supervised learning techniques to classify test cases into three distinct categories. After engineering the features as discussed in the previous section, we identified the top six features to be used in the classification algorithm. These features were selected based on their relevance and impact on the classification outcome. The selected features are as follows: my_maturity, last_run, Cycle, failure_percentage, Month, times_ran. Fig. 1 presents the mutual information after the application of advanced feature engineering techniques to enhance the dataset. Features in Fig. 1 exhibit significantly higher mutual information values, signifying a more robust and informative correlation between the features and the target variable.

Figure 1: Final feature selection with labeled mutual information

The models chosen for test case prioritization were selected based on their unique strengths and suitability for the task. Our selection includes Random Forest classifier (RF), Bayesian Networks (BN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Gradient Boosted regression model (GB). Lastly, the Voting Classifier was chosen based on the conclusion from ensemble methods in TCP, which states that ensemble-based methods can outperform their base algorithms in test case prioritization [21].

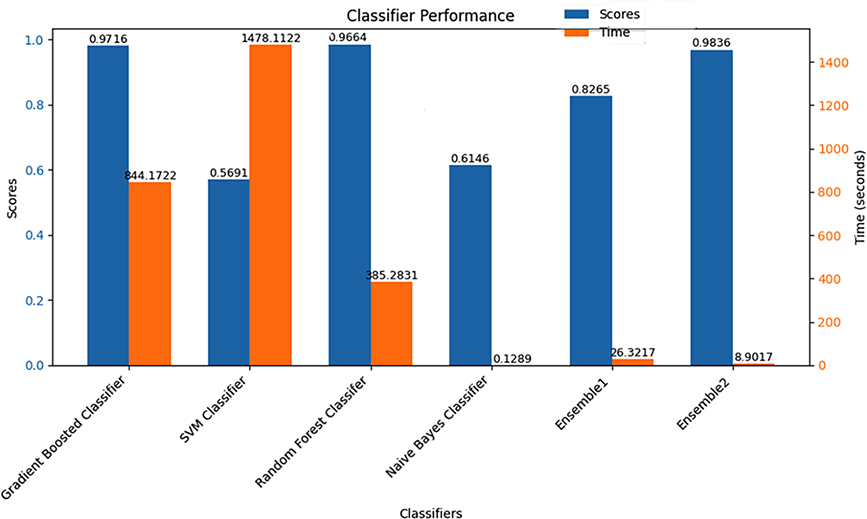

The evaluation of these models is based on two performance metrics: running time and prediction accuracy. Fig. 2 displays the accuracy scores and running times, measured in seconds. The GB regression model and the RF classifier have exhibited notable improvement in performance. In contrast, the SVM and NB classifiers have consistently demonstrated stable performance levels.

Figure 2: Classification using feature engineering

It’s crucial to note that our framework employs two voting classifiers. During the evaluation phase, we observed that the ensemble classifier, which combines all models, performed less effectively than some of the individual “child” classifiers. Therefore, we conducted a comparison of two ensembles within our proposed voting approach. Ensemble 1 combines Gradient Boosted, SVM, Random Forest, and Naive Bayes classifiers. Ensemble 2 comprises gradient boosted, random forest, and naive bayes classifiers

As shown in Fig. 2, the voting approach with three models outperforms the voting approach that includes all models. This improvement is likely due to the inclusion of models that are more complementary and less correlated in Ensemble 2, which enhances the overall decision-making process.

3.2.3 Performance Evaluation of Ensemble Models

Among the individual classifiers, the GB and RF classifiers demonstrate high accuracy with scores of 0.9716 and 0.9664, respectively, though they differ significantly in computation time, with the GB taking 844.1722 s and the RF taking 385.2831 s. The SVM Classifier, despite its long computation time of 1478.1122 s, has the lowest score of 0.5691, indicating poor performance. In contrast, the NB classifier, while having a moderate score of 0.6146, excels in computational efficiency with a time of just 0.1289 s. The ensemble methods, which utilize the voting technique to combine the strengths of individual classifiers, show notable improvements. Ensemble 1 achieves a balanced score of 0.8265 with a significantly reduced computation time of 26.3217 s. Ensemble 2 outperforms all others with the highest score of 0.9836 and an impressively low computation time of 8.9017 s. This highlights the importance of the voting technique in ensemble methods, as it effectively leverages the diverse strengths of individual classifiers to enhance overall performance while maintaining computational efficiency. By excluding the underperforming SVM classifier, Ensemble 2 demonstrates that careful selection of classifiers within an ensemble can lead to superior accuracy and efficiency, making it highly suitable for real-time applications where both accuracy and speed are critical. Using fewer but more reliable classifiers, Ensemble 2 likely reduces noise and bias in the predictions. The inclusion of only high-performing models ensures that the ensemble’s decisions are based on consistently strong.

The outcomes yielded by this approach were notably promising. The accuracy of our test case prioritization exhibited a significant improvement, averaging around 98%. This marks a considerable enhancement over our initial baseline accuracy without feature engineering, which was approximately 80%. The substantial improvement in accuracy underscores the effectiveness of combining strong machine learning approaches with feature engineering. By employing a voting mechanism among multiple ML models, we capitalized on the strengths of each algorithm to achieve enhanced predictive performance.

Importantly, there is no evidence of overfitting in our results. This conclusion is supported by consistent performance across both training and validation datasets, indicating that the model generalizes well to unseen data. The use of robust cross-validation techniques and regularization methods helped ensure that the model did not simply memorize the training data, but rather learned to identify and prioritize test cases effectively. This balanced approach allowed us to harness the power of feature engineering and ensemble learning without compromising the model’s ability to perform reliably on new data.

Furthermore, the proposed model was evaluated against the APFD metric defined below, a standard for measuring the effectiveness of test case prioritization. APFD is calculated by taking the weighted average of the number of faults detected during the run of the test suite. This comprehensive evaluation allowed us to assess the practical impact of our approach on real-world software testing scenarios.

where T is the test suite in evaluation,

The average APFD across all priority levels was 91%, compared to 89% as reported in previous studies [34]. An important observation to mention is that our model, particularly for high-priority test cases (level 3), we achieved an optimal value of APFD equal to 83%, which is significantly higher than the 74% reported in the same studies [34] using the same Paint-Control dataset. This advancement not only elevates the overall quality of the software but also streamlines resource allocation during the testing phase, thereby reducing the time and costs associated with defect identification and resolution.

In this section, we introduce our methodology for ranking test cases to optimize the efficiency and effectiveness of software testing. Our approach leverages a combination of reinforcement learning with genetic algorithms to rank test cases based on their predicted likelihood of uncovering defects.

In this work, we used the Deep Q-Network (DQN) as the RL algorithm. As the dimensionality of the problem increases, storing the Q values of all possible states and actions will quickly become infeasible. However, as a neural network is a universal function approximator, here we use a neural network to predict the Q function. A Q value is defined as the Q value of the next state plus the reward achieved in the current state. The components of the DQN are defined below:

• Temporal difference learning

We can specify the error used in the loss function for gradient descent in the neural network as follows:

This is referred to as the Temporal Difference (TD) error, as cited in [21]. The TD error is a crucial concept in Reinforcement Learning (RL), particularly in Q-Learning, where it serves as the driving force behind the learning process. The TD error represents the difference between the estimated value of a state-action pair (Q value) and the updated estimate obtained after observing a new reward and the next state.

• Loss function

The Huber loss function [23] exhibits high robustness to noise. It combines favorable characteristics of L1 and L2 loss functions by being less sensitive to outliers in data than Mean Squared Error loss. To the Huber loss function, we add a protective layer to our network against the adverse effects of noisy data. This choice ensures that the network learns efficiently and effectively even in the presence of noise.

• Algorithm

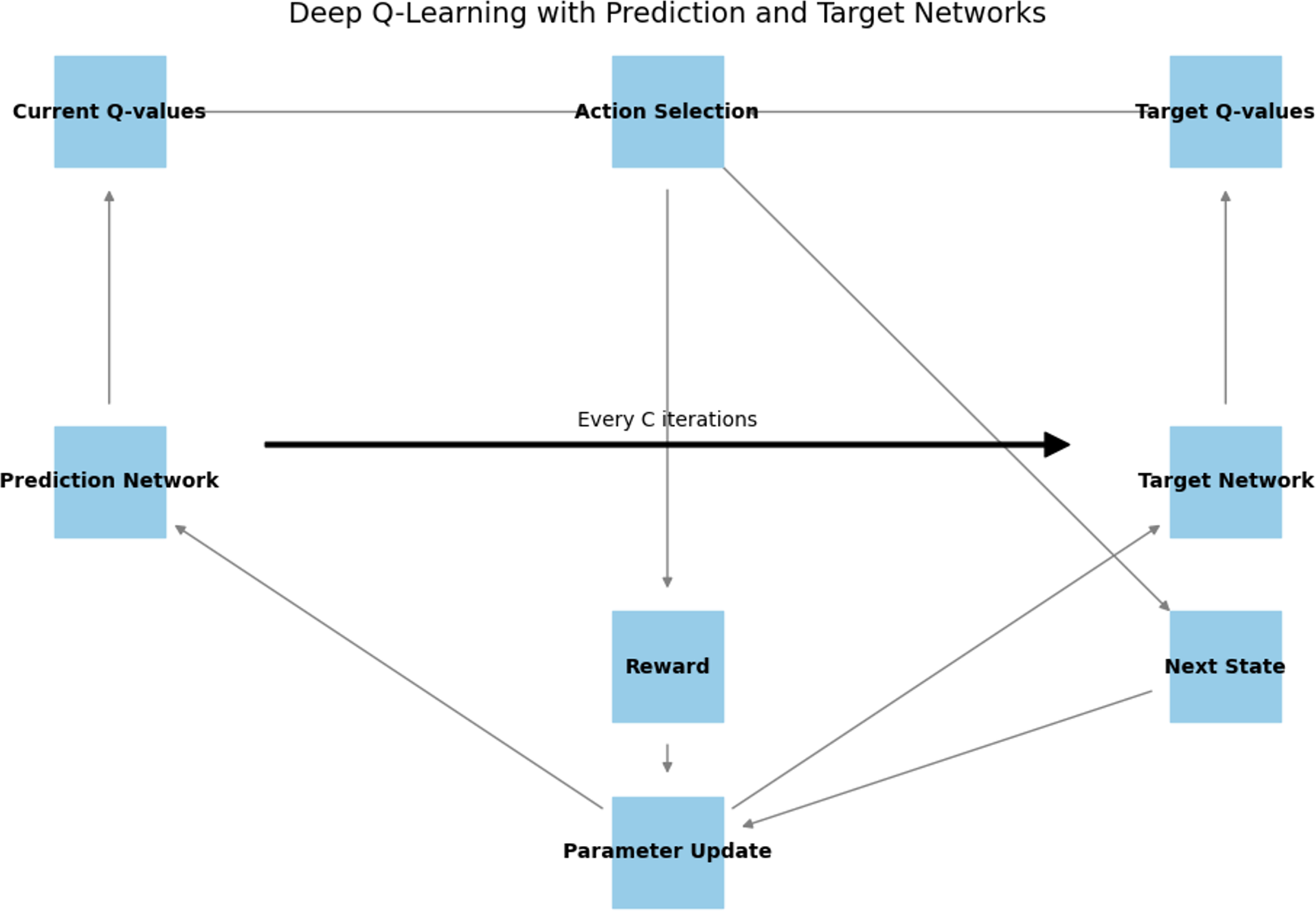

The Deep Q-Learning technique used in this paper is described, with an overview shown in Fig. 3. In our technique, we strengthen the stability of the training process by deploying two neural networks.

Every C iterations (a hyperparameter), the parameters of the Prediction Network are copied to the Target Network. This method ensures steadier training, as the target function remains fixed for a certain period.

Figure 3: Deep Q learning networks flow

We used reinforcement learning to dynamically adjust the ranking strategy based on continuous feedback from the testing process. This adaptive approach allows the model to learn from new data and improve its ranking criteria over time.

An RL environment E dictates how an agent learns as it contains these three concepts: action space A, reward space R and state space S. Three learning environments applied in this paper utilise the below methods as in [34].

The listwise environment can see the entire test case execution history at once. The algorithm will predict the highest rank element from that list and place it in a final ranked array

• State Space. As the listwise ranking predicts rank, the input features will be the features engineered.

Let

• Action Space. The agent selects one record F from L each step to place in the output list:

• Reward Space. The optimal ranking of L is known:

4.2.2 Pairwise Verdict Environment

The pairwise environment’s aim is to directly compare two test case execution records and perform a sorting procedure on which test case is more likely to fail, with the verdict estimated by the deep Q network utilising the input features discussed below. The components of this environment are defined below:

• State Space. An overview of the state space is as follows: Features of record1, Features of record2. Let

Let

The state space is then

• Action Space. Action

• Reward Space. The reward space is designed with the intention to reward the agent if the decision is to swap the test case with the predicted failing verdict; or if the verdicts are the same, then predict the test case with the shortest duration. Hence:

let

let

let

Very similar to the pairwise verdict approach as mentioned above, but this environment predicts and directly compares the ranks of two test case execution records. The records are sorted in order of lowest rank. This Environment was included as a potential supplement to the listwise ranking approach, due to results discussed below.

State Space

As the Pairwise Ranking approach is also predicting the rank of test case execution record, the state space is the very similar to listwise. The feature names are thus as follows

Action Space

Action

Reward Space

In the pairwise environment, the reward space is designed to reward the agent agent if, after the swapping has taken place, the test case execution records are ordered correctly in ascending order of ranks Hence:

let

let

let

To ensure that the models received enough training time, each appearance of a training instance must have at least 50 training episodes for pairwise, corresponding to

To enhance test case ranking, a genetic algorithm is used in conjunction with reinforcement learning. The proposed solution uses a genetic algorithm to evolve a population of policy networks utilized in the RL algorithm. The networks are evaluated based on their average reward return on a shared input. Depending on their return, they will be selected by the genetic algorithm to produce offspring and be included in the next generation of solutions.

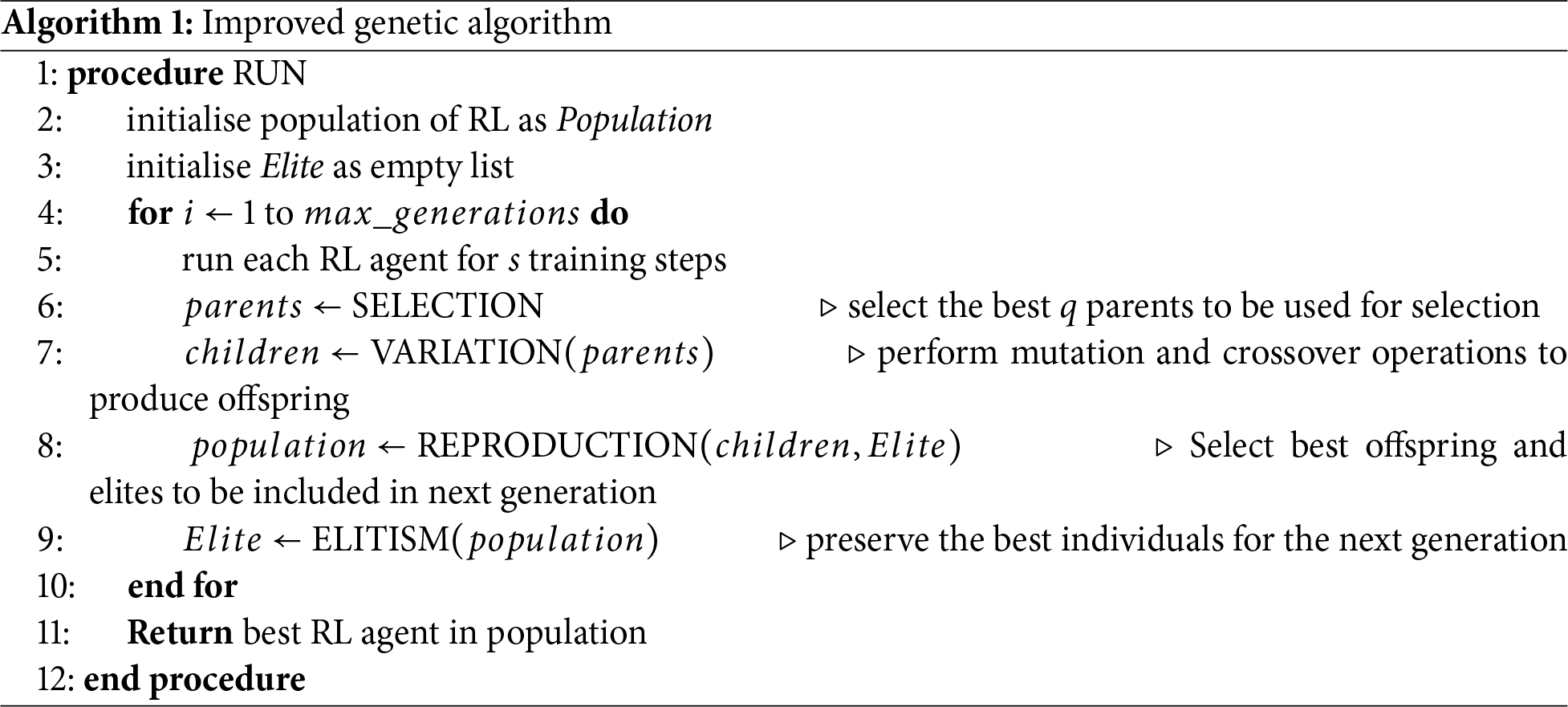

The genetic algorithm (Algorithm 1) implemented in this paper uses an elitist strategy to preserve the best individuals from each generation. The reproduction function is modified to include the elites in the next generation, and a new elitism function is added to select the elites from the current population. The components of the GA are detailed below:

• Initial Population

First the population of RL agents is initialised which consists of randomly initialising the networks weights and biases. Next the population is to be sorted in terms of how “good” each solution agent is.

• Fitness Function

In this paper we use the average test reward after a set input of shared training states in order to gauge the fitness. The proposed fitness calculation is a costly one

• Selection

The tournament selection scheme, with a configurable tournament size, is chosen for selecting models for genetic variation. In the literature, strategies such as Fitness Proportion Selection, Linear Ranking, Truncation Selection,

• Mutation

In our investigation, we use the simple random mutation and the availability mutation, a straightforward yet effective methods for introducing random changes to the weights and biases in the RL agent’s policy network.

• Crossover

Crossover is fundamental to the evolution of the population in genetic algorithms, as it allows for the exploration of new points in the solution space. In the algorithm proposed in this work, an individual in the population is represented as a Reinforcement Learning (RL) agent. Each RL agent comprises two neural networks, which encapsulate the agent’s policy and value functions. These networks are the “traits” that are subject to crossover. We employed three different types of crossover methods in our work:

1. Naive Cut Crossover: This is a simple form of crossover where one point on the parent chromosomes is selected. All data beyond that point in the two parental chromosomes is swapped between the two parents. The resulting chromosomes are the offspring.

2. Arithmetic Crossover: This method generates offspring by taking a weighted average of the parent chromosomes. It allows for a smoother transition between generations and can help in fine-tuning solutions.

Each of these crossover methods brings a unique approach to the generation of new offspring and contributes to the diversity and evolution of the population. By using these methods, we aim to enhance the performance of the RL agents and achieve more effective solutions in our genetic algorithm framework.

The computational complexity of the improved genetic algorithm (Algorithm 1) is determined by the population size

6 Results, Evaluation, and Insights

In this section, we will answer the main research question: Can a hybrid approach that combines stacked-ensemble supervised learning for test-case ranking with a Deep Q-Learning agent for run-time prioritization produce statistically and practically significant improvements in testing efficiency? To do so, we implemented first a feature selection process on the dataset as detailed in Section 3.1 to choose the main training attributes of the test cases. Then, we fitted ensemble models (see Section 3.2.1) with a voting mechanism for test case prioritization. Test cases ranking is next completed using deep Q-Learning system optimized with a genetic algorithm, as reported respectively in Sections 4.1 and 5.

Firstly, we analyze the results of our proposed reinforcement learning approach designed for ranking test cases. Subsequently, we examine the results of integrating genetic algorithms as an enhancement strategy on top of reinforcement learning. This analysis aims to assess the combined effectiveness of these approaches in optimizing test case ranking.

6.1 Reinforcement Learning Performance

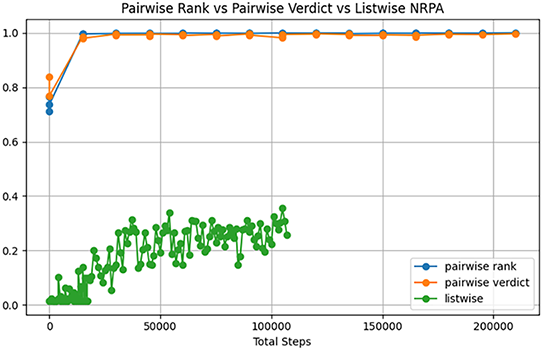

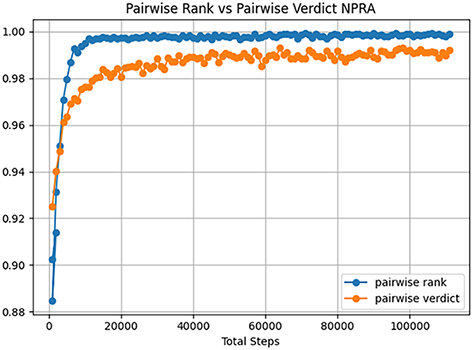

NRPA score is used to predict how closely the predicted rank of

The APFD metric measures the area under the curve of a plot of the percentage of total faults detected vs. the percentage of total test cases executed. A higher APFD value indicates a more effective test case prioritization, as it means that a larger percentage of faults are detected early in the testing process. On the other hand, NRPA is a measure of how well a prioritization algorithm ranks test cases compared to an ideal ranking. While NRPA is certainly useful, it does not directly measure the effectiveness of the prioritization in terms of fault detection, which is the primary goal of test case prioritization.

When running the listwise environment with a large number of input features, the model’s performance deteriorates. Training time, improvement in NRPA, APFD, and average reward return are notably poorer compared to other models and benchmarks.

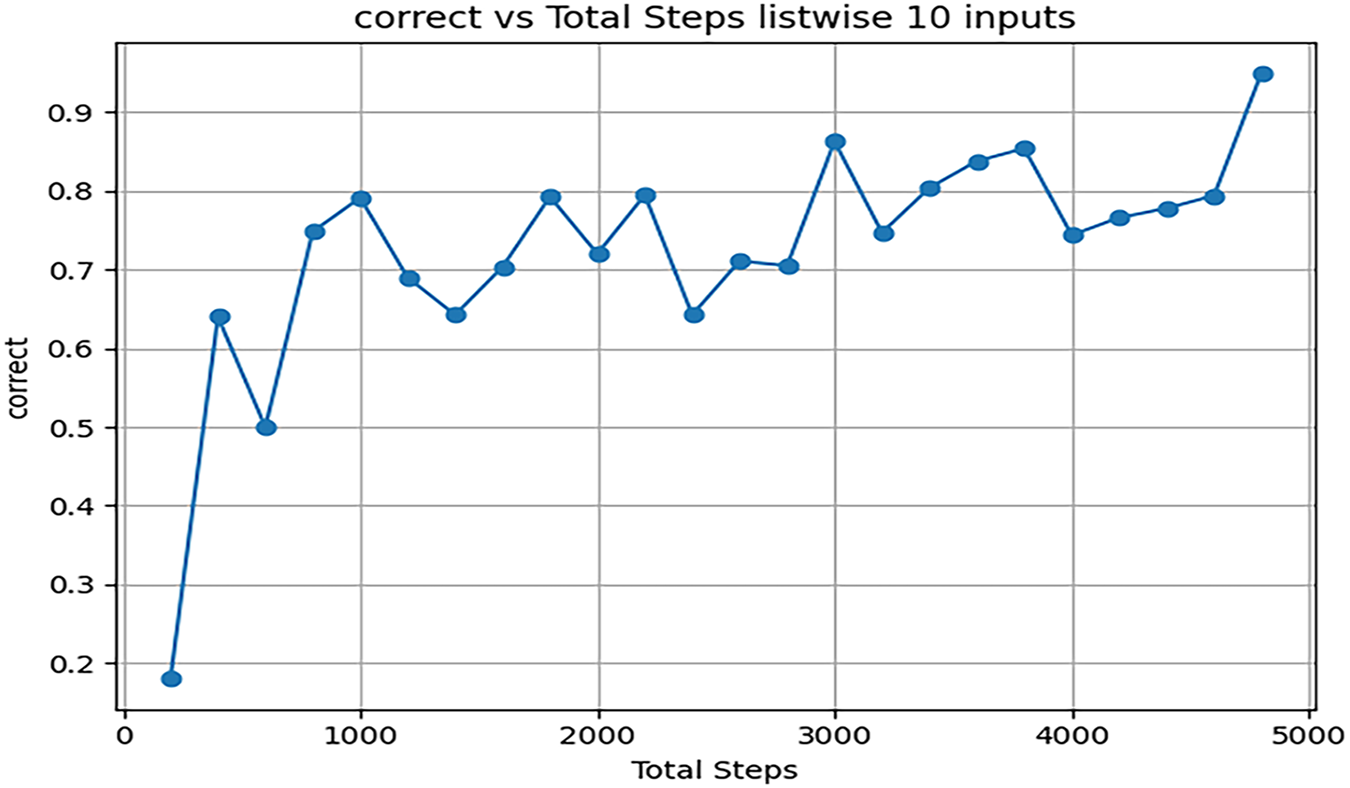

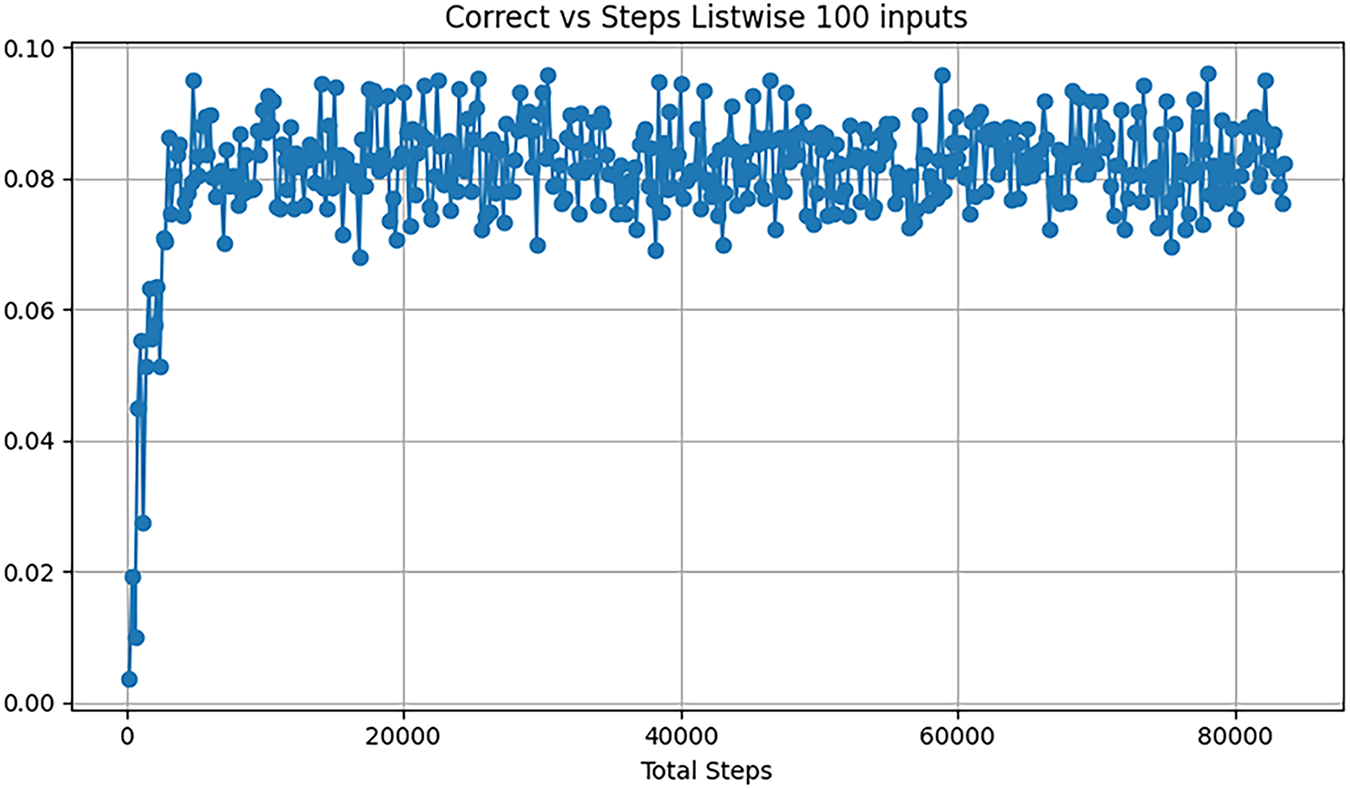

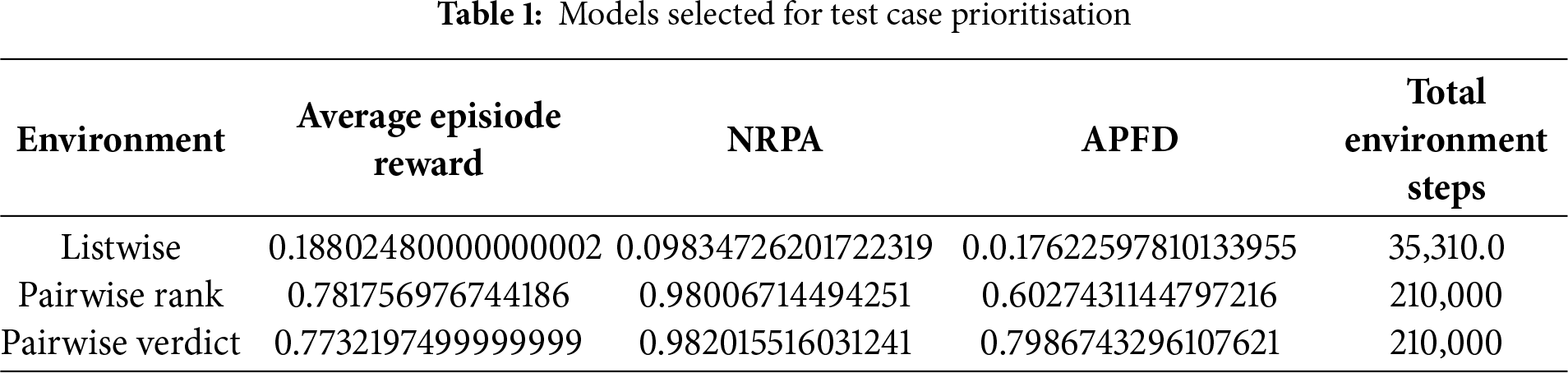

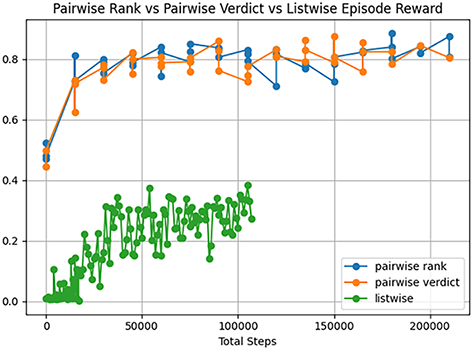

From Fig. 4, it is evident that the listwise approach performs well with an input size of 10, achieving a high average episode reward of 0.95 after only 500 steps or 40 s. The model’s performance is comparable to NRPA and APFD; however, with such a small input size, this high performance is not particularly advantageous. Fig. 5 illustrates the average performance of the listwise environment with an input size of 100. Here, the environment performs poorly across all metrics. As the model is applied to larger learning spaces, such as with an increased number of inputs, the problem becomes more pronounced, resulting in an average reward of only 0.091 after 83,600 steps.

Figure 4: Listwise steps for 10 inputs

Figure 5: Listwise steps for 100 inputs

Table 1 directly compares all environments with an input size of 100, with performance visualized in the graphs above.

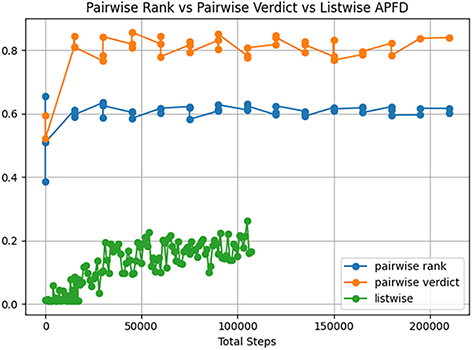

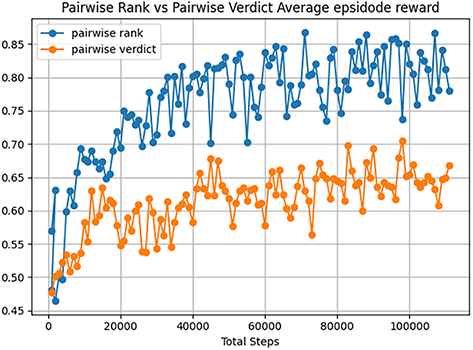

The difference between the models is a stark one. Firstly there is a gulf in performance accuracy between listwise and pairwise for the use case of 100 inputs as shown in Figs. 6–8. Taking the average episode reward each test as a metric for the speed of learning of the model, the listwise agent begins with a random initialisation, and a correctness of 0.12, and progresses only by 0.08 points. The listwise agent has the worst metric scores in all categories. As of the original RL algorithm, a listwise approach is not recommended; however, the genetic improvement may boost the performance and will be analyzed in the next section.

Figure 6: Reward comparison

Figure 7: APFD comparison

Figure 8: NRPA comparison

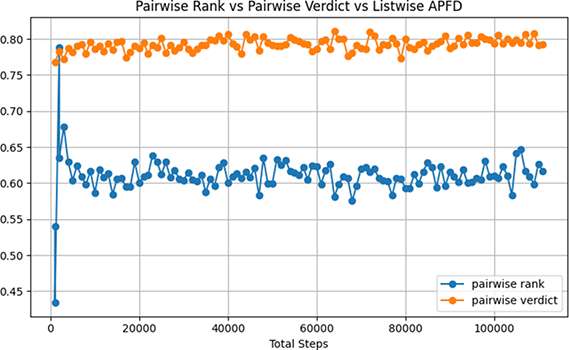

Below is the performance of both pairwise approaches for an input dataset of 1000.

Over 125,000 environment steps, pairwise rank performs considerably better in all metrics, in which the models can be directly compared. The average reward can serve as a metric for how quickly the agent can train in comparison to its opponent, with an average reward of 7.723 and a final value of 0.780. In comparison, The pairwise verdicts reward is converges at an average of 0.614 and a final value of 0.618 (see Fig. 9). Unsurprisingly, the verdict agent received a higher score for APFD (0.627, compared to 0.7910) due to the failure-focused learning characteristic as shown in Fig. 10. However, this is a an impressive result, [34] achieved an average of 0.53

Figure 9: Pairwise rank and pairwise verdict rewards for 1000 inputs

Figure 10: Pairwise rank and pairwise verdict APFD for 1000 inputs

Figure 11: Pairwise rank and pairwise verdict NRPA for 1000 inputs

Our experimental results demonstrate the advantages of applying reinforcement learning to temporal datasets. The approach proved effective in optimizing sequential decision-making, as it consistently improved long-term fault detection outcomes compared to static methods. We observed that the RL agent adapted dynamically to evolving test states, maintained a balanced strategy between re-executing historically effective tests and exploring new ones, and successfully learned from delayed rewards across the testing process. These strengths translated into measurable gains in efficiency, as reflected in temporal metrics such as higher APFD values over time and improved NRPA. Together, these findings confirm that reinforcement learning leverages temporal structure in ways that traditional ranking and supervised models cannot.

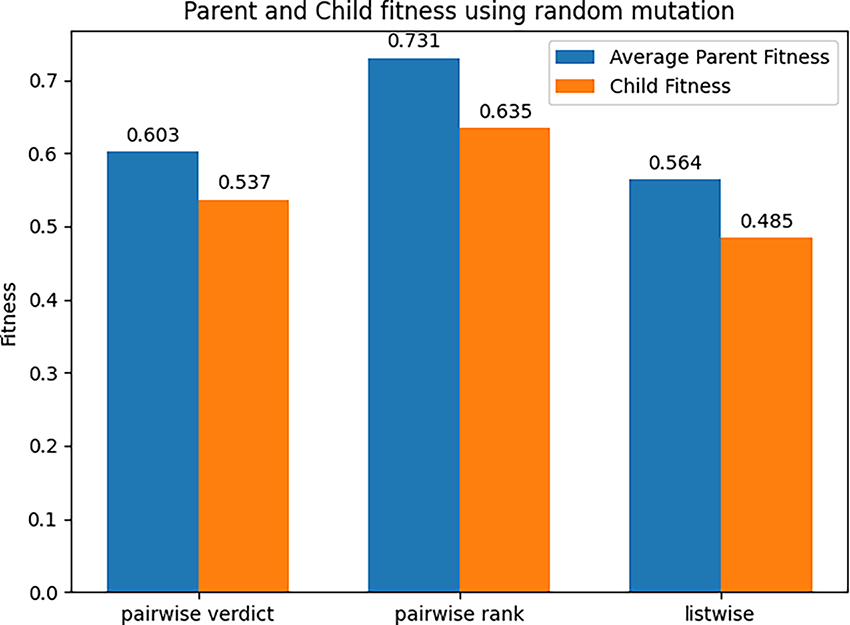

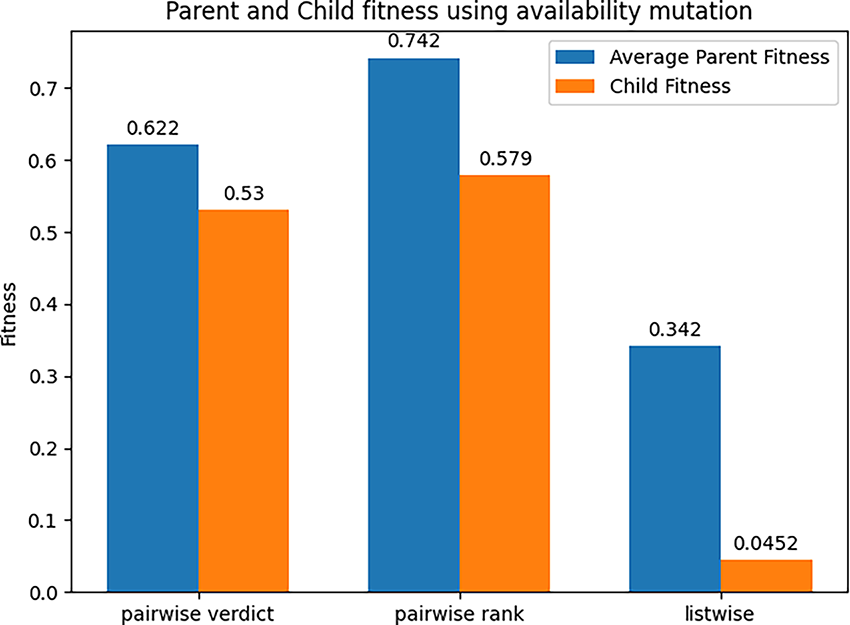

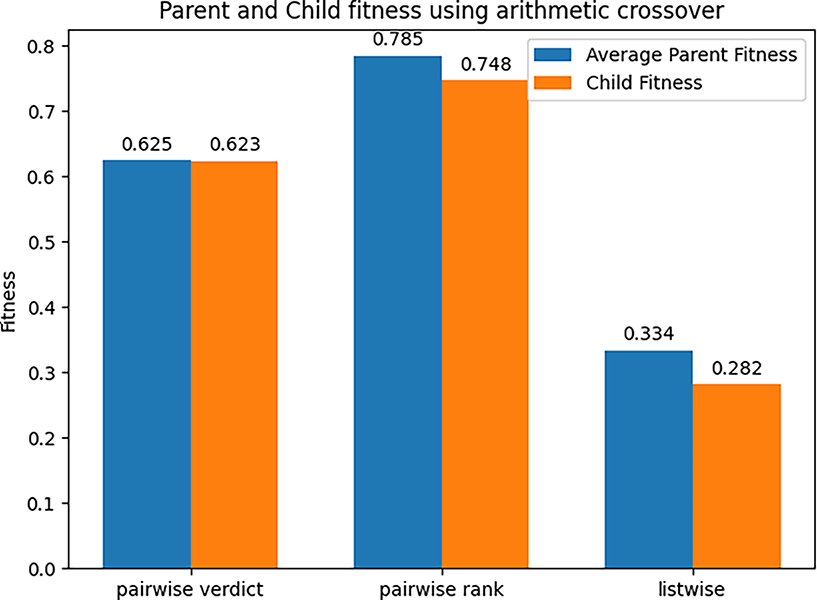

6.2 Evolutionary Improvement Performance

For each test, we will run a total of 100 generations. During these runs, we will keep track of key metrics for every individual in the population. These metrics include the running fitness, which gives us an indication of the suitability of each solution, as well as the APFD and the NRPA, which provide insights into the effectiveness of our test case ranking strategy. By monitoring these metrics, we can gain a deeper understanding of the performance and evolution of our population over time.

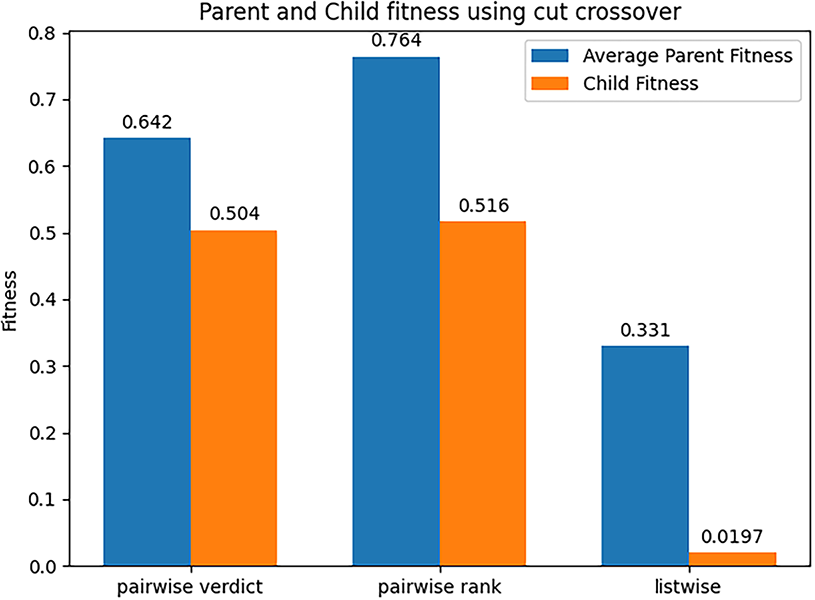

As discussed, the issue of competing conventions needed to be addressed. The concept of naive crossover is explored and will be analysed here for comparative purposes. This analysis will provide insights into the effectiveness of naive crossover in mitigating the problem of competing conventions and enhancing the performance of the evolutionary algorithm.

The next model here is the Availability Mutation. The children produced are on average much worse than their parents and are rarely better, as shown in Figs. 12 and 13. This is speculated to do with the unstable “best” individual in the population. Due to training time being minimal at the start of the learning process, the “best” individual is put there based on pure stochasticity, forming a flawed architecture target that the other agents are aiming towards. However, the variability of the availability mutation is to be noted. For example, for there to be 3 better children with an average of just under a 0.2 fitness units, the children that are improving on the solution must have a very large fitness value. This variation suggests that the operator can achieve these performances more often with the correct tuning. For future work, an approach with differing probability functions or varying hyperparameters can be trialled to attempt to offset this problem to yield stronger results.

Figure 12: Parents and child fitness using random mutation

Figure 13: Parents and child fitness using availability mutation

Figs. 14 and 15 display the results from the use of the cut crossover. It is interesting to note that the cut crossover performs much worse than its arithmetical counterpart, as discussed below. As above, the produced children are much weaker individuals than their parents. Arithmetic crossover performing better at this stage indicates that the operator is less destructive. The PCC correlation is likely to correlate some nodes that are less similar to each other as a result of the stochastic nature of the training process, and the competing conventions process, and the operator can be concluded to be much less compliant with error.

Figure 14: Parents and child fitness using cut crossover

Figure 15: Parents and child fitness using arithmetic crossover

Other results, such as the similar performance of the naive cut and the cut operator, suggest that current attempts to improve crossover using PCC have failed. Authors in [35] presented another form of correlation metric, CCA, which performs well with noisy data, suggesting a potential direction for future work. PCC does not report such an ability. The models that produced viable children are then analyzed in terms of their performance in the prioritization and ranking context.

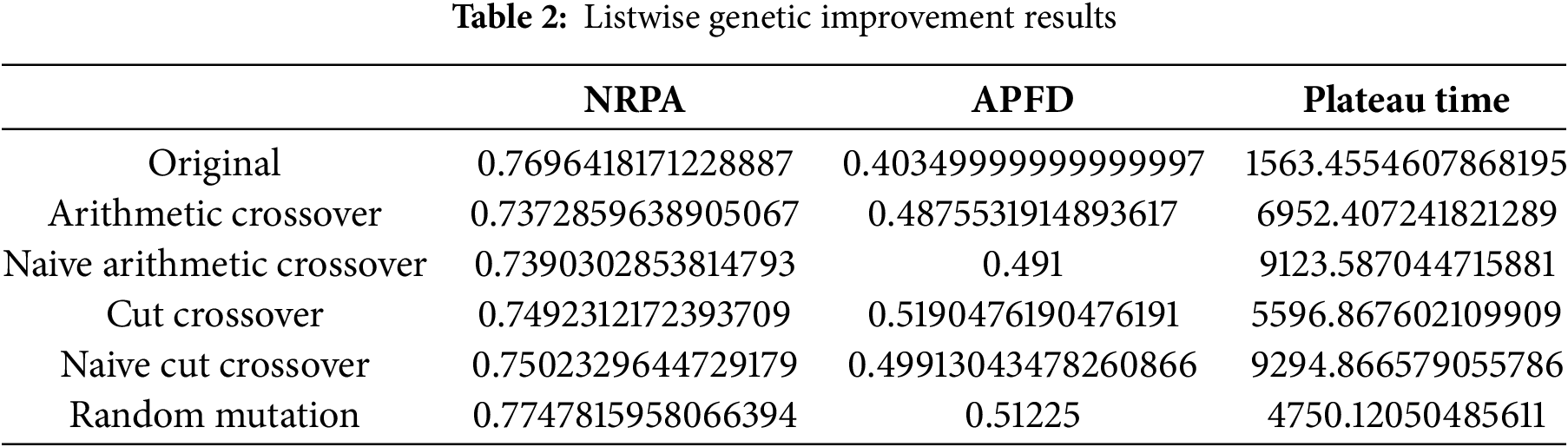

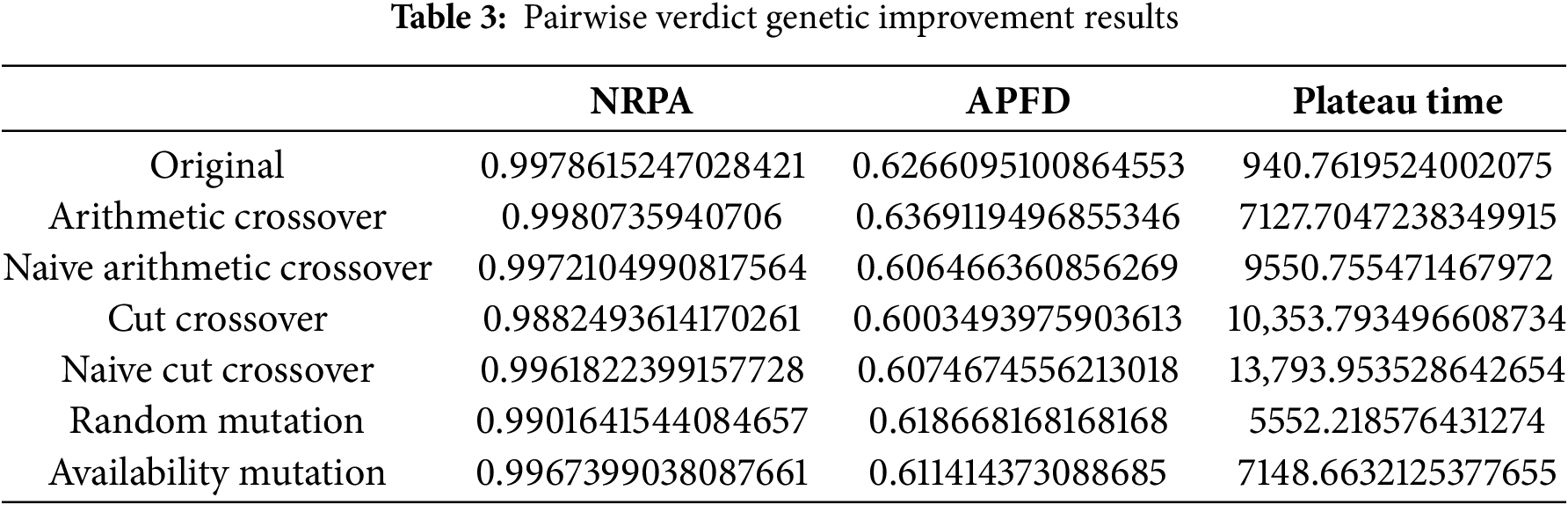

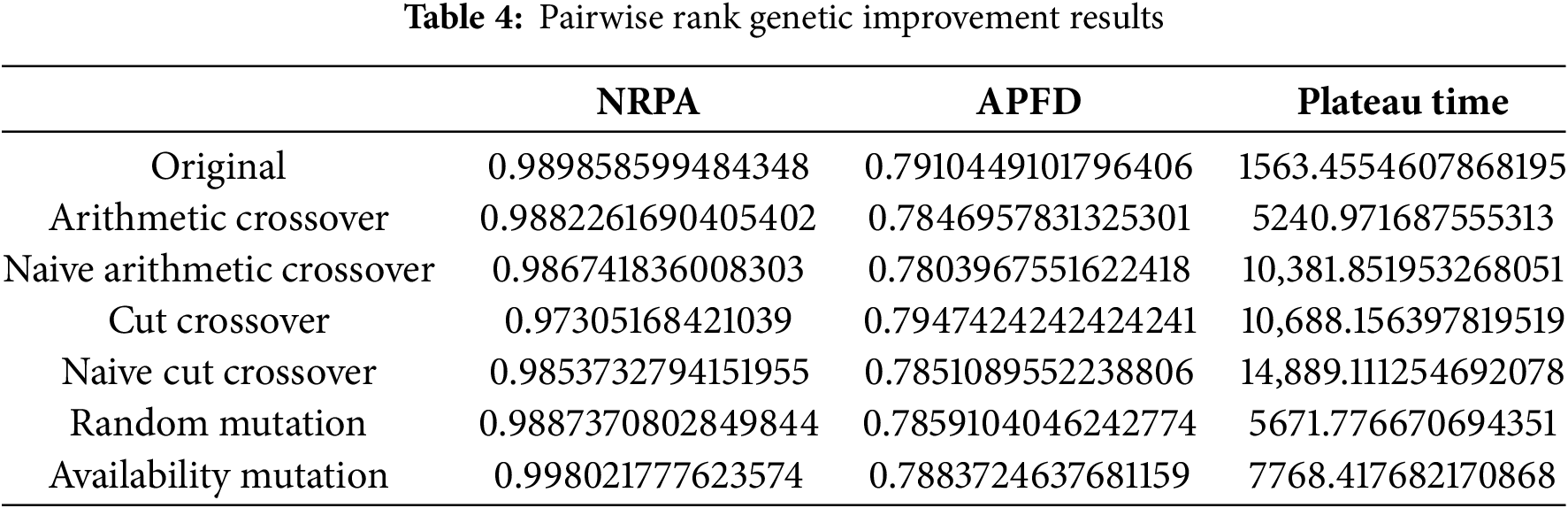

Tables 2–4 contain the evaluation of each evolutionary model for each RL environment. Each table includes the original RL agent performance metrics, as well as the performance when a genetic algorithm is applied. The values in the tables are collected from the point at which each agent terminates, either when reaching the maximum number of steps or when the agent plateaus, when the fittest individual shows no improvement in fitness values for 10 generations. For genetic agents, the minimum execution time is 100 generations.

Listwise Rank Data

Pairwise Rank Data

Pairwise Verdict Data

The listwise agent, as observed in Table 2, benefits from the genetic algorithm, experiencing an enhancement in the APFD. The NRPA also improves with the application of random mutation across all genetic algorithms. Concurrently, the pairwise agent demonstrates some improvement in both the NRPA and APFD metrics when using the arithmetic crossover (Table 4). Furthermore, Table 3 shows that pairwise verdict sees an improvement in NRPA when employing cut crossover and availability mutation. Notably, cut crossover emerges as the sole source of improvement in the APFD metric.

Upon analyzing the data, it becomes evident that there is no single superior genetic operator. However, both metrics (APFD and NRPA) show improvements with the availability mutation and cut crossover. This can be attributed to the fact that even with low-performing variation operators, offspring with better fitness are being produced, which in turn boosts the agent’s performance. The plateau time, despite indicating the superior complexity of the genetic improvement algorithm, suggests that the agent continues to learn for a longer duration than the base reinforcement learning agent. This observation presents an interesting topic for future exploration.

However, it’s important to note that despite these improvements, the running time of all the genetic improvement agents is significantly longer—339%, 850%, and 680% respectively compared to the base RL agent. This implies that a substantial cost must be incurred to achieve higher performance. When applying test case prioritization to a set of test suites, the goal is to optimize the time and budget of the testing process. If the ranking process consumes a significant portion of the budget, the solution may not be viable. Therefore, a balance must be struck between performance improvement and computational cost, making this a key consideration in the design and implementation of the genetic improvement agents.

7 Conclusions and Research Perspectives

Given the paramount importance of software testing in development, reducing the time and resource requirements for regression testing is a critical area of research.

In this paper, we investigated the application of reinforcement learning to test case prioritization and ranking, incorporating genetic improvements. Initially, we analyzed the dataset for mutual information, selecting features most correlated with the target values: prioritization group, rank, and verdict features. Classification was performed using machine learning techniques, with the dataset distributed into three priority groups. The random forest classifier emerged as the top-performing algorithm for classification, achieving an accuracy score of 0.98847.

For test case ranking, we proposed an RL approach using a Deep Q-Network. After researching this novel paradigm, we applied it to three well-known test environments: listwise, pairwise verdict, and pairwise applied for ranking. The pairwise ranking algorithm demonstrated the highest effectiveness, with an NRPA score of 0.9989902373076025 on a test size of 1000 test cases. To enhance these results, we combined RL with a genetic algorithm, creating a novel integration of GA and RL in this context. Adapted variation operators from previous works were integrated into the DQN environment. Although the genetic operators provided slight improvements in NRPA and APFD, they resulted in a substantial increase in runtime, up to 850%.

While the proposed hybrid approach demonstrates promising improvements in test case prioritization and ranking, several avenues remain open for future research. Future research should extend evaluation to larger and more diverse datasets to test the robustness of the models, benchmark the approach against techniques such as MCMCRT for deeper comparative insights, and validate its practical applicability within real-world continuous integration pipelines. This would strengthen both the generalizability and the industrial relevance of the proposed method.

In conclusion, the combination of the random forest classifier and the pairwise ranking approach proved most effective for test case prioritization and ranking compared to other methods. However, while genetic improvement shows potential for further enhancement, it requires significantly greater processing power. As such, the current implementation of genetic operators cannot be recommended for industrial environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: No funding.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Anis Zarrad and Jaber Jemai; methodology, Anis Zarrad; software, Thomas Armstrong; validation, Anis Zarrad and Jaber Jemai; formal analysis, Thomas Armstrong; investigation, Thomas Armstrong; data curation, Thomas Armstrong; writing—original draft preparation, Thomas Armstrong; writing—review and editing, Jaber Jemai; visualization, Thomas Armstrong; supervision, Anis Zarrad; project administration, Anis Zarrad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pressman RS, Maxim BR. Software engineering: a practitioner’s approach. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

2. Cohen MB, Colbourn CJ, Ling ACH. Constructing strength three covering arrays with v = 3 and v = 4. Discrete Math. 1997;175(1–3):37–47. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2006.06.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yoo S, Harman M. Regression testing minimization, selection and prioritization: a survey. Softw Test Verif Rel. 2012;22(2):67–120. doi:10.1002/stv.430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Herzig K, Just S, Zeller A. The impact of tangled code changes on defect prediction. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE ’14); 2014 May 31–Jun 7; Hyderabad, India. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2014. p. 119–30. doi:10.1145/2568225.2568263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen X, Hierons RM, Harman M. Test case prioritization for software product lines using regression test selection and prioritization techniques. Softw Test Verif Rel. 2018;28(3):e1635. doi:10.1002/stvr.1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kaushik N, Amoui M, Tahvildari L, Liu WN, Li SM. Defect prioritization in the software industry: challenges and opportunities. In: Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation; 2013 Mar 18–22; Luxembourg, Luxembourg. doi:10.1109/ICST.2013.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Padmanabhan D, Holmes R, Walker RJ. The effect of test ownership and team structure on the reliability and effectiveness of unit tests. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE 2017); 2017 May 20–28; Buenos Aires, Argentina. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 401–11. doi:10.1109/ICSE.2017.44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Arafeen MJ, Do H. Test case prioritization using requirements-based clustering. In: 2013 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation; 2013 Mar 18–22; Luxembourg, Luxembourg. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 312–21. [Google Scholar]

9. Srivastava P. Test case prioritization. J Theor Appl Inf Technol. 2008;4:178–81. [Google Scholar]

10. Kajo Meçe E, Binjaku K, Paci H. The application of machine learning in test case prioritization—a review. Euro J Elect Eng Comput Sci. 2020;4(1):1–9. doi:10.24018/ejece.2020.4.1.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Elbaum S, Malishevsky A, Rothermel G. Test case prioritization: a family of empirical studies. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2002;28(2):159–82. doi:10.1109/32.988497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Busjaeger B, Xie T. Learning for test prioritization: an industrial case study. In: Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA 2016); 2016 Nov 13–18; Seattle WA USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 339–50. doi:10.1145/2931037.2931070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Woo H, Lee H, Cho S. An efficient combinatorial optimization model using learning-to-rank distillation. In: The Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-22). Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2022. p. 8666–74. [Google Scholar]

14. Chen H, Dai X, Cai H, Zhang W, Wang X, Tang R, et al. Large-scale interactive recommendation with tree-structured policy gradient. In: The Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-19). Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2019. p. 3312–20. [Google Scholar]

15. Mäkinen S, Münch J. Effects of test-driven development: a comparative analysis of empirical studies. In: Software quality. Model-based approaches for advanced software and systems engineering (SWQD 2014). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. p. 155–69. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-03602-1_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rothermel G, Untch RH, Chu C, Harrold MJ. Test case prioritization: an empirical study. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Maintenance; 1999 Aug 30–Sep 3; Oxford, UK. p. 179–88. [Google Scholar]

17. Walcott K, Soffa M, Kapfhammer G, Roos R. Timeaware test suite prioritization. In: Proceedings of the ACM/SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, ISSTA 2006; 2006 Jul 17–20; Portland, ME, USA. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

18. Qu X, Cohen M, Woolf K. Combinatorial interaction regression testing: a study of test case generation and prioritization. In: Proceedings of the 2007 International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA); 2007 Jul 9–12; London, UK. p. 255–65. [Google Scholar]

19. Srivastva P, Kumar K, Raghurama G. Test case prioritization based on requirements and risk factors. ACM SIGSOFT Softw Eng Notes. 2008;33(4):1–5. doi:10.1145/1384139.1384146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Z, Chen L, Huang Y. Cost-cognizant combinatorial test case prioritization. Int J Softw Eng Knowl Eng. 2011;21(6):829–54. doi:10.1142/s0218194011005499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cao T, Vu T, Le H, Nguyen V. Ensemble approaches for test case prioritization in UI testing. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Software Engineering and Knowledge Engineering; 2022 Jul 1–10; Online. doi:10.18293/SEKE2022-148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ahmed F, Majeed A, Khan T. Value-based test case prioritization for regression testing using genetic algorithms. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;74(1):2211–38. [Google Scholar]

23. Lima J, Vergilio S. An evaluation of ranking-to-learn approaches for test case prioritization in continuous integration. J Softw Eng Res Dev. 2023;11:4. doi:10.5753/jserd.2023.2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pan R. Test case selection and prioritization using machine learning: a systematic literature review. Empir Softw Eng. 2022;27(2):29. doi:10.1007/s10664-021-10066-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Marijan D. Comparative study of machine learning test case prioritization for continuous integration testing. arXiv:2204.10899. 2022. [Google Scholar]

26. Bertolino A, Guerriero A, Miranda B, Pietrantuono R, Russo S. Learning-to-rank vs ranking-to-learn: strategies for regression testing in continuous integration. In: Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering; 2020 Jun 27–Jul 19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

27. Rosenbauer L, Stein A, Pätzel D, Hähner J. XCSF for automatic test case prioritization. In: Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence (IJCCI 2020); 2020 Nov 2–4; Budapest, Hungary. p. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

28. Bajaj M, Sangwan OP. An adaptive genetic algorithm-based approach for test case prioritization. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Applications and Information Security (ICCAIS 2019). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CAIS.2019.8769536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Matinnejad R, Briand L, Nejati S, Panesar-Walawege R. Automated test case selection and prioritization for model testing in adaptive systems. IEEE Trans Software Eng. 2019;45(6):553–84. doi:10.1109/TSE.2017.2762683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou B, Okamura H. Application of markov chain monte carlo random testing to test case prioritization in regression testing. IEICE Trans Inf Syst. 2012;E95(D(9)):2219–26. doi:10.1587/transinf.e95.d.2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Huang Y, Shu T, Ding Z. A learn-to-rank method for model-based regression test case prioritization. IEEE Access. 2021;9:16365–82. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3053163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sharif A, Marijan D, Liaaen M. Deeporder: deep learning for test case prioritization in continuous integration testing. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME); 2021 Sep 27–Oct 1; Luxembourg. p. 525–34. [Google Scholar]

33. Omri S, Sinz C. Learning to rank for test case prioritization. In: 2022 IEEE/ACM 15th International Workshop on Search-Based Software Testing (SBST); 2022 May 9; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

34. Bagherzadeh M, Kahani N, Briand L. Reinforcement learning for test case prioritization. arXiv:2011.01834. 2021. [Google Scholar]

35. Dragoni M, Azzini A, Tettamanzi AGB. A novel similarity-based crossover for artificial neural network evolution. In: Parallel problem solving from nature, PPSN XI (PPSN 2010). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. p. 344–53. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15844-5_35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools