Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design of Virtual Driving Test Environment for Collecting and Validating Bad Weather SiLS Data Based on Multi-Source Images Using DCU with V2X-Car Edge Cloud

AI Graduate School, GIST, Gwangju, 61005, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Sun Park. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancing Edge-Cloud Systems with Software-Defined Networking and Intelligence-Driven Approaches)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 15 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072865

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In real-world autonomous driving tests, unexpected events such as pedestrians or wild animals suddenly entering the driving path can occur. Conducting actual test drives under various weather conditions may also lead to dangerous situations. Furthermore, autonomous vehicles may operate abnormally in bad weather due to limitations of their sensors and GPS. Driving simulators, which replicate driving conditions nearly identical to those in the real world, can drastically reduce the time and cost required for market entry validation; consequently, they have become widely used. In this paper, we design a virtual driving test environment capable of collecting and verifying SiLS data under adverse weather conditions using multi-source images. The proposed method generates a virtual testing environment that incorporates various events, including weather, time of day, and moving objects, that cannot be easily verified in real-world autonomous driving tests. By setting up scenario-based virtual environment events, multi-source image analysis and verification using real-world DCUs (Data Concentrator Units) with V2X-Car edge cloud can effectively address risk factors that may arise in real-world situations. We tested and validated the proposed method with scenarios employing V2X communication and multi-source image analysis.Keywords

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are vehicles capable of perceiving their driving environment, making decisions, and controlling their operation without a human driver. AVs utilize sensors (such as LIDAR, cameras, and radar), artificial intelligence (AI), advanced software, and network connectivity, which automate real-time environmental perception, decision-making, control, and navigation. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) categorizes levels of automation into six levels (Level 0 to Level 5), with Level 5 representing full autonomy (self-driving under all conditions). Currently, Levels 2 to 4 (partial to high automation) technologies are primarily being commercialized. To achieve Level 5 AVs, extensive performance and safety verification is still required. The best way to verify the performance and safety of AVs is through real-world road testing. However, real-world testing poses several challenges. Safety risks arise from unforeseen situations, inclement weather, and sensor or system malfunctions that may cause accidents and casualties. The verification process across vast distances and diverse conditions (including varied road, weather, and traffic scenarios) demands substantial investment and time. Reproducibility remains problematic due to difficulties in replicating rare edge cases and experiencing diverse environments such as nighttime or snowy conditions. Legal and ethical constraints further limit testing by prohibiting deliberate simulation of dangerous situations and imposing regulatory restrictions across jurisdictions. Moreover, achieving comprehensive environmental diversity that spans urban centers, suburbs, tunnels, highways, and varied weather and traffic policies presents considerable difficulty [1–3].

Driving simulators are widely used to address the challenges associated with real-world testing of AVs. Using simulators for autonomous vehicle testing offers several advantages, including enhanced safety, greater efficiency, cost reduction, improved reproducibility and repeatability, and increased diversity of test scenarios. These benefits accelerate the development and validation processes while facilitating standardization and regulatory compliance. However, despite these advantages, simulators have drawbacks such as limitations in accurately simulating reality (the simulator–real-world gap), inherent biases and restrictions, certification and reliability concerns, usability and cost issues, as well as side effects like simulator sickness [4,5]. Vehicle driving simulators are designed to enable drivers to virtually experience various driving environments encountered on the road by operating a virtual vehicle on a virtual road. Depending on the purpose, the types of vehicle simulators used include road safety simulators [6], human-machine interface simulators (HMI simulators) [7], advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) simulators [8], and vehicle dynamics simulators for research and development (R&D) [9]. Simulation methods in autonomous driving system development and verification can be categorized into Software-in-the-Loop Simulation (SiLS) [10], Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation (HiLS) [10], Vehicle-in-the-Loop Simulation (ViLS) [11], and Driver-in-the-Loop Simulation (DiLS) [12], which organize virtual and hybrid simulation environments. SiLS connects a virtual environment (simulator) with autonomous driving system software at the software level, reproducing all sensor, vehicle, and environmental information through software for verification. HiLS integrates physical hardware, such as sensors, ECUs, and controllers with the simulator to reflect real hardware performance and characteristics. ViLS connects a real vehicle to a simulator, allowing the vehicle to be driven in the real world for some time, while providing environmental and sensor information from the virtual environment. DiLS evaluates various conditions by having a driver directly operate the vehicle within a simulated environment.

V2X (Vehicle-to-Everything) is an advanced communication system that enables vehicles to exchange information with various objects on the road. V2X is a core technology for autonomous driving and future Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), and it plays various roles, including enhancing traffic safety, increasing road efficiency, and preventing accidents. Depending on the type of V2X communication, it can be categorized as V2V (Vehicle-to-Vehicle), V2I (Vehicle-to-Infrastructure), V2P (Vehicle-to-Pedestrian), V2N (Vehicle-to-Network), V2C (Vehicle-to-Cloud), V2D (Vehicle-to-Device), V2G (Vehicle-to-Grid), V2H (Vehicle-to-Home), and V2B (Vehicle-to-Building). For V2X communication, Wi-Fi-based DSRC (Dedicated Short Range Communications) technology and (4G LTE/5G) cellular-based C-V2X (Cellular V2X) technology are competing to become the standard [13–15].

The authors of this paper conducted a five-year project, from 2020 to 2024, titled ‘Development of a V2X-based Connected Platform Technology Capable of Responding to External Environments, Including Inclement Weather.’ The project focused on developing a connected platform incorporating V2X communication technologies. For the communication technology, a partner company researched and developed hybrid V2X communication modules and software capable of simultaneously utilizing C-V2X and DSRC. The research on the connected platform was divided into three areas: V2X car edge cloud [16], DCU [17], and driving simulator [18]. While the V2X car edge cloud and DCU are described in detail in related studies, this paper focuses on the driving simulator. We previously published a short paper [18] that conceptually outlined a virtual driving test environment (VDTE) related to a driving simulator. This paper is a full-length version that implements and validates the proposed method based on that earlier concept.

This paper proposes a VDTE capable of collecting and verifying SiLS data in adverse weather conditions, based on multi-source images, using the DCU and V2X-Car edge cloud. The proposed method utilizes Prescan [19,20] to build a virtual driving environment for selected roads and surrounding areas at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST). This enables the handling of various events such as weather, time of day, and moving objects that cannot be verified in a real-world autonomous driving environment. Depending on the application, the virtual driving environment can be used to collect SiLS data based on multi-source images from multiple cameras on the real-world DCU. The data is then transmitted to the V2X-Car edge cloud for storage and analysis, where it can be verified. Alternatively, the edge cloud can be integrated into the DCU (i.e., DCU with edge cloud), allowing for collection, analysis, and verification directly on the DCU. The contributions of this paper are as follows: First, we present a small-scale autonomous driving verification platform that is safe, affordable, and reliable. Second, we implement an integrated framework connecting the real world, virtual environment, and distributed computing (DCU/Edge Cloud). Finally, we improve the reliability of the architecture and simulations by enabling automated and scalable verification of complex situations based on multi-source images.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the related studies on methods of driving simulator and V2X car edge cloud; Section 3 explains the proposed virtual driving test environment; Section 4 shows the experiment results. Finally, Section 5 discusses the conclusion and future direction.

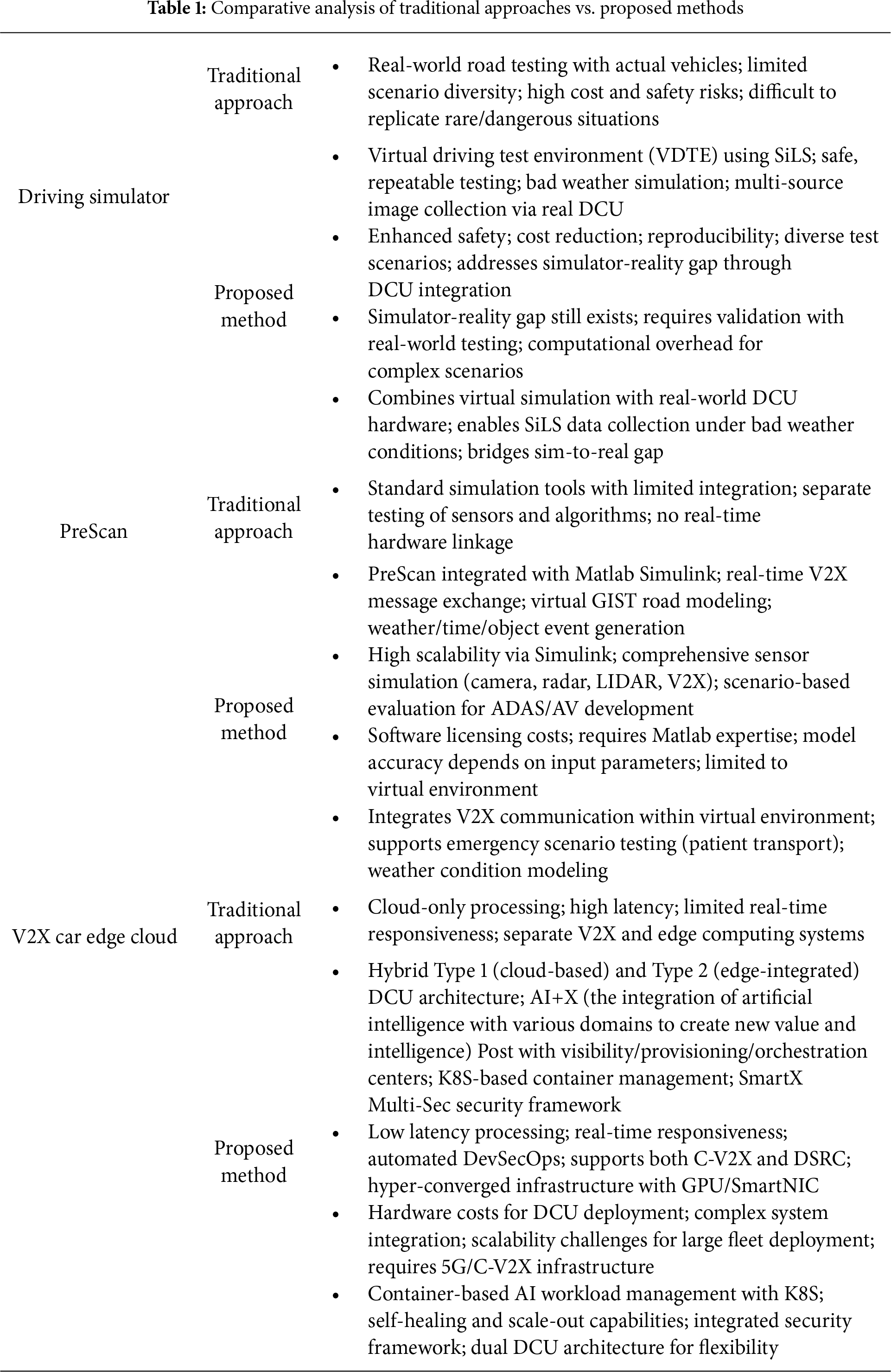

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed Virtual Driving Test Environment (VDTE) and existing approaches for three core components: Driving Simulator (Section 2.1), Prescan (Section 2.2), and V2X Car Edge Cloud (Section 2.3), in terms of key differences, advantages, limitations, and innovations.

To address the shortcomings of subjective ride and handling evaluations using actual vehicles and those based on various analytical techniques, vehicle driving simulators are being developed. Vehicle driving simulators are designed to allow drivers to indirectly experience various driving environments encountered on the road by driving a virtual vehicle on a virtual road, rather than using actual vehicles to assess driving performance. A vehicle simulator is a vehicle development tool developed to allow drivers to virtually experience driving situations by implementing the dynamic behavior of a vehicle driven by the driver in a virtual driving environment through real-time graphics and a real-time motion platform. Various types of vehicle simulators are used depending on the research purpose. The Road Safety Simulator is a cutting-edge simulation system that virtually recreates real-world roads and driving environments, enabling use in traffic safety research, education, assessment, and training. It is used for evaluating the design of high-risk traffic zones, testing advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), and conducting experiments on autonomous vehicle interactions [6]. An HMI simulator (Human-Machine Interface Simulator) is a system that virtually replicates interactions between machines, equipment, operators, or users in a digital environment, without using actual physical machines. It is used for real-time feedback, iterative experiments across various designs and situations, cost and time savings, development risk minimization, and usability evaluations combined with ergonomics and psychometrics (e.g., ECG, EDA, etc.) [7]. Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) are advanced driver assistance technologies that utilize electronic sensors and software installed in vehicles to enhance driver safety and convenience. These systems are used to prevent accidents, minimize damage to life and property, reduce driver fatigue, and improve driver behavior and road safety [8]. Vehicle dynamics R&D is a field that studies and develops the interaction between a vehicle’s movement and its environment, namely how a vehicle behaves during various operations such as driving, steering, acceleration, braking, cornering, and road surface changes. This technology is utilized in automotive development to optimize safety, drivability, ride comfort, fuel economy, and performance [9].

Drive simulation verification methods are divided into SiLS (Software-in-the-Loop Simulation), HiLS (Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation), ViLS (Vehicle-in-the-Loop Simulation), and DiLS (Driver-in-the-Loop Simulation). SiLS is a virtual testing method that runs and verifies control systems, especially embedded control software, in a software environment (e.g., a PC simulator) without actual hardware. It integrates mathematical models and control software to rapidly iterate through logic and functional verification. This method is used in early development, code verification, and algorithm testing [10]. HiLS is a simulation that verifies overall system operation by connecting actual hardware (controllers/ECUs, etc.) with software and plant models (virtual environments) in real time. HiLS is widely used in practical applications such as hardware interfacing, real-time signal feedback, hardware operation error and system interoperability evaluation, automotive and aircraft controllers, and sensor integration [10]. ViLS is an integrated testing platform that connects physical vehicles (real or partially real) with virtual environments (traffic, roads, sensors, scenario simulators, etc.) to evaluate vehicle behavior under complex road conditions and sensor signals. It is used in autonomous driving and ADAS fields to simultaneously acquire real-world vehicle responses and simulated data, ensuring the reliability of online and offline test data [11]. DiLS is a simulation environment that incorporates human drivers within the simulator to analyze driver behavior and to study collaboration strategies between drivers and autonomous driving systems [12].

Siemens’ Prescan (officially Simcenter Prescan) is software that creates a virtual traffic environment and simulates various scenarios by equipping vehicles with sensors. A virtual traffic environment includes roads, sidewalks, indicator objects such as traffic lights and signs, and multiple vehicles. Prescan’s on-vehicle sensors, such as cameras, radar, LIDAR, and V2X, can be integrated into a control vehicle model for simulation. Sensor results can be viewed through Matlab Simulink, allowing users to modify the sensor data to match real-world results or design control algorithms using the sensor data. Because the results are generated through Matlab Simulink, the system can leverage Simulink’s capabilities, offering significant scalability. In other words, this software virtually reproduces various sensors (radar, LIDAR, cameras, ultrasound, etc.) and traffic, road, and environmental elements to create a driving environment close to reality, and is used for development/verification of ADAS and autonomous driving systems, high-precision sensor simulation, and scenario-based evaluation [19].

Abdullah et al. published a review paper on the integration of V2X (Vehicle-to-Everything) communication, a key player in Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), and edge computing (EC). They discussed the synergy between edge computing and V2X communication, enabling data processing and analysis to be performed on vehicles or roadside infrastructure (edge) rather than in the cloud, thereby reducing latency, enabling real-time responsiveness, reducing network bandwidth, and enhancing security. They also introduced the latest technological trends, including the differences and characteristics of C-V2X (cellular-based) and DSRC (dedicated short-range communications), and the V2X edge computing standard established by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). Furthermore, they presented practical application studies, simulations, and a comparison of the features, performance, and pros and cons of various frameworks (e.g., mobile edge computing, cloudlets, and fog computing). Various use cases were discussed, including enhanced security combined with block chain, off-road and computing resource efficiency, low latency (VR/AR and video streaming), and vehicle platooning (platooning) [21]. Lucas et al. reviewed the latest trends and implementation cases of integrating mobile edge computing (MEC) into vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication architecture and services. They discussed how combining V2X architecture with MEC can minimize latency and enable real-time services. They reviewed how MEC can be utilized within the V2X architecture in various ways, including efficient computational offloading, traffic distribution, and local data analysis. Key application examples included real-time traffic safety systems (accident detection/alert, platooning), traffic efficiency (real-time analysis of traffic lights/road conditions), real-time high-precision map updates and navigation, infotainment, remote software updates, emergency response, and energy management. They also highlighted examples of combining block chain and private networks to enhance the security and privacy of V2X data [22]. Hawlader et al. experimentally compared and analyzed edge- and cloud-based offloading strategies to address the computational load and latency issues of real-time object recognition in AVs. They evaluated how to process large amounts of image data collected from vehicle sensors (cameras) on edge/cloud platforms via V2X networks (especially C-V2X, 5G-based), and conducted an in-depth analysis of the trade-off between object recognition accuracy and delay time according to compression (JPEG, H.265) quality during offloading [23]. Xie et al. [24] propose a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based collaborative scheduling algorithm (MADRL-CSTC) for resource allocation in digital twin Vehicular Edge Computing [VEC] networks. By analyzing delays from twin maintenance and task processing, their approach optimizes resource allocation under limited resources and outperforms alternative methods. Xu et al. [25] propose a joint optimization framework using LLM-based MOEA/D for fair access and Age of Information (AoI) optimization in 5G NR V2I Mode 2 vehicular networks. By adaptively adjusting the Semi-Persistent Scheduling (SPS) selection window, their approach addresses the unfair resource access caused by varying vehicle velocities and Road Side Unit [RSU] dwell times.

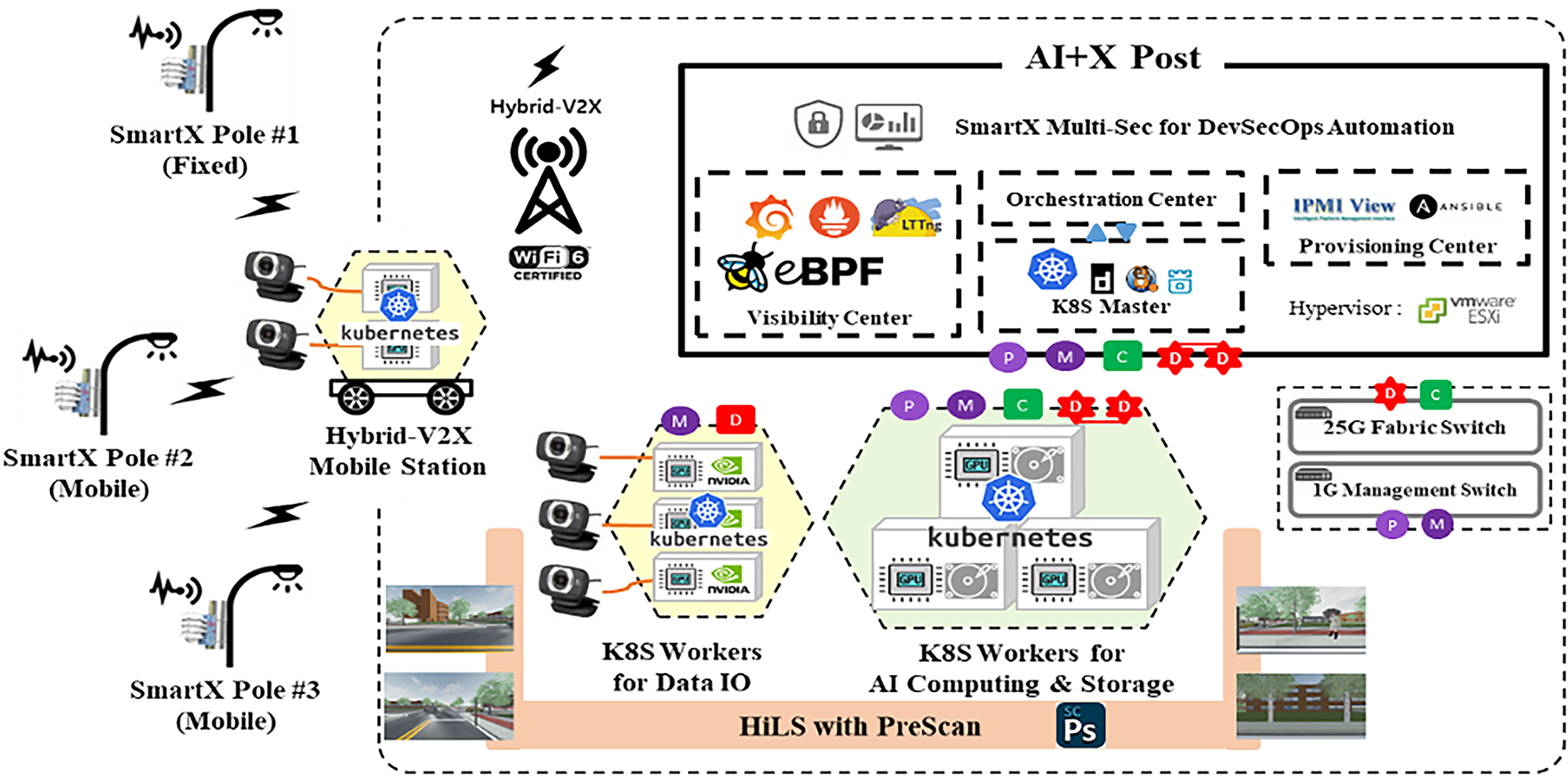

The authors of this paper propose a V2X-Car Edge Cloud concept, featuring an automated framework for efficiently managing edge clouds for V2X-Car services, capable of providing efficient cloud services based on massive amounts of V2X communication information. We designed and implemented a V2X-Car-Edge cloud prototype with enhanced cloud-based security and verified it through use cases for implementing mobility AI services. The V2X-Car Edge Cloud architecture consists of several components: AI+X Post, K8S Worker for AI Computing and Storage, K8S Worker for Data IO, Hybrid-V2X Mobile Station, SmartX Pole (an advanced smart city pole equipped with sensing, communication, and AI capabilities), and SiLS with Prescan. The basic end-edge-tower structure remains the same as before, but the AI+X Post now more strongly controls the other units within the V2X-Car Edge Cloud. Within the AI+X Post, dedicated software functions called Centers responsible for visibility, provisioning, and orchestration—are deployed. The Kubernetes master node, which coordinates the AI-DCU (AI Data Computing Unit) boxes by grouping them into resource sets, is also hosted in the AI+X Post. The Visibility Center ensures observability by using system-level monitoring tools such as eBPF or LTTng within distributed AI-DCUs and leverages visualization tools like Prometheus and Grafana for cloud overview. The Provisioning Center manages the initialization, deletion, and power control of AI-DCUs via cloud-based automated provisioning, utilizing the DsP Tool, IPMI View, and Ansible Playbook. Orchestration across the V2X-Car Edge Cloud is performed using Kubernetes, with dedicated orchestration centers coordinating AI convergence services deployed as containers and integrating with various Kubernetes masters. The SmartX Multi-Sec framework covers the entire AI+X Post to ensure secure DevSecOps for all AI-DCUs, monitoring and controlling both internal and external cloud traffic. This security layer detects and responds to abnormal network traffic as well as specific processes that generate excessive traffic within the cloud, helping to maintain a secure and efficient V2X-Car Edge Cloud environment. Fig. 1 shows a conceptual diagram of the V2X-Car Edge cloud [16–18].

Figure 1: Conceptual diagram of AI-integrated V2X-car edge cloud [16]

The differences between the proposed VDTE and existing related research are as follows. The proposed method provides the ability to safely and precisely test and evaluate the collaboration between AVs and traffic infrastructure in complex emergency situations. The proposed simulator integrates V2X communications and multiple video streams, and enables real-time data integration and analysis via the DCU, ensuring high realism and accuracy. Furthermore, the container-based scalability and high availability of AI workloads were experimentally verified in a real Type 2 DCU and multi-camera environment, supporting fault recovery capabilities to enhance system reliability.

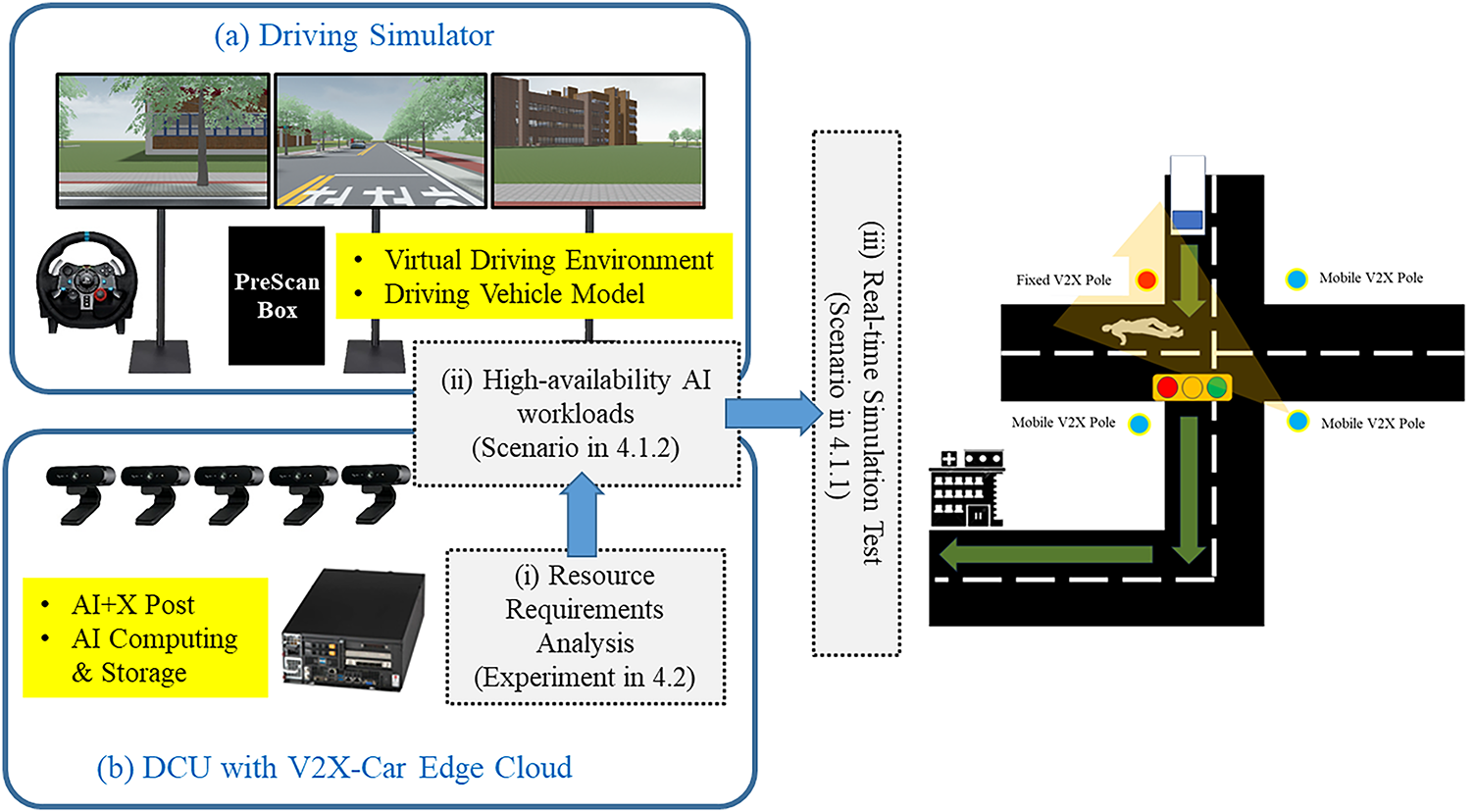

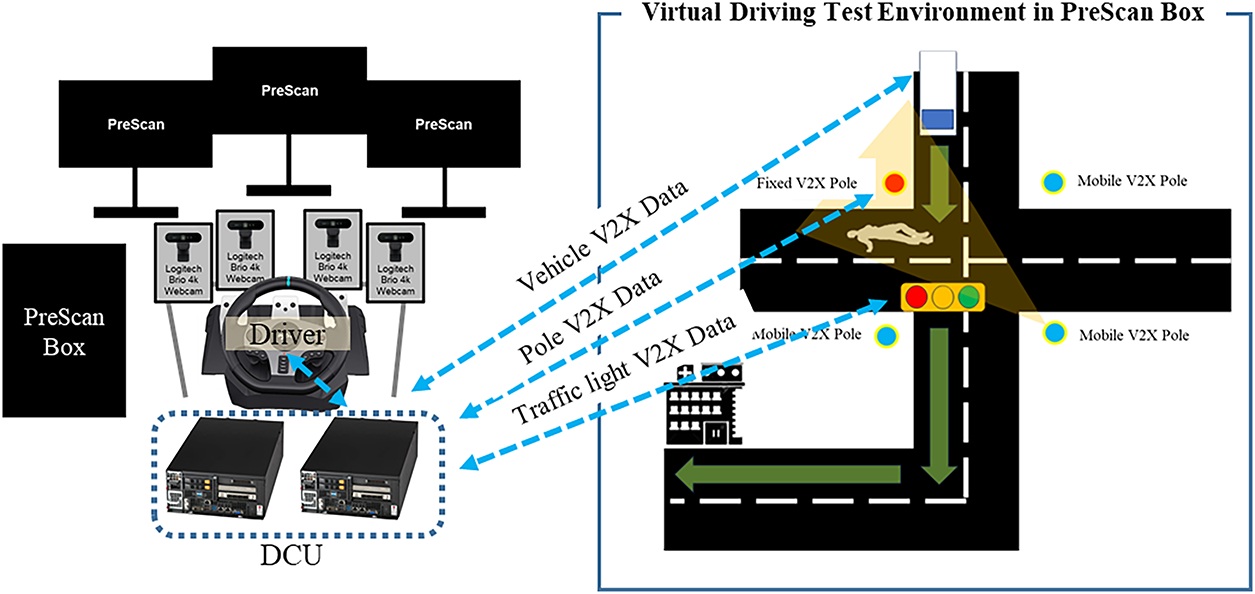

3 Virtual Driving Test Environment

The VDTE consists of a driving simulator and DCU with V2X-Car Edge Cloud [4]. The driving simulator simulates and displays a car and its surroundings on a virtual road in bad weather when a driver sitting in a real-world driving chair drives with a racing wheel. The DCU collects the virtual road environment and car driving images of the driving simulator with multiple cameras and delivers them to the V2X-Car Edge Cloud. V2X-Car Edge Cloud recognizes objects (i.e., pedestrians, bicycles, cars, …) from multiple virtual images delivered. Fig. 2 shows the implemented Virtual Road Driving Test Environment.

Figure 2: Virtual road driving test environment

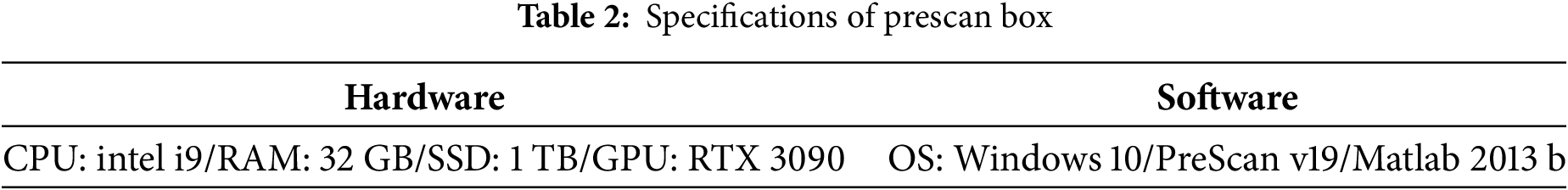

A human-operated system is required to collect and verify accurate SiLS data. In this paper, a driving simulator is built for driving in the real world and driving environment in the virtual world. The driving simulator consists of PreScan box and driver seat with racing wheel. The driver seat consists of a Playseat evolution chair and Logitech G29 wheel with pedals. A cradle for mounting the DCU boxes and cameras was added to the driving seat. Table 2 shows the hardware and software specifications of the PreScan box.

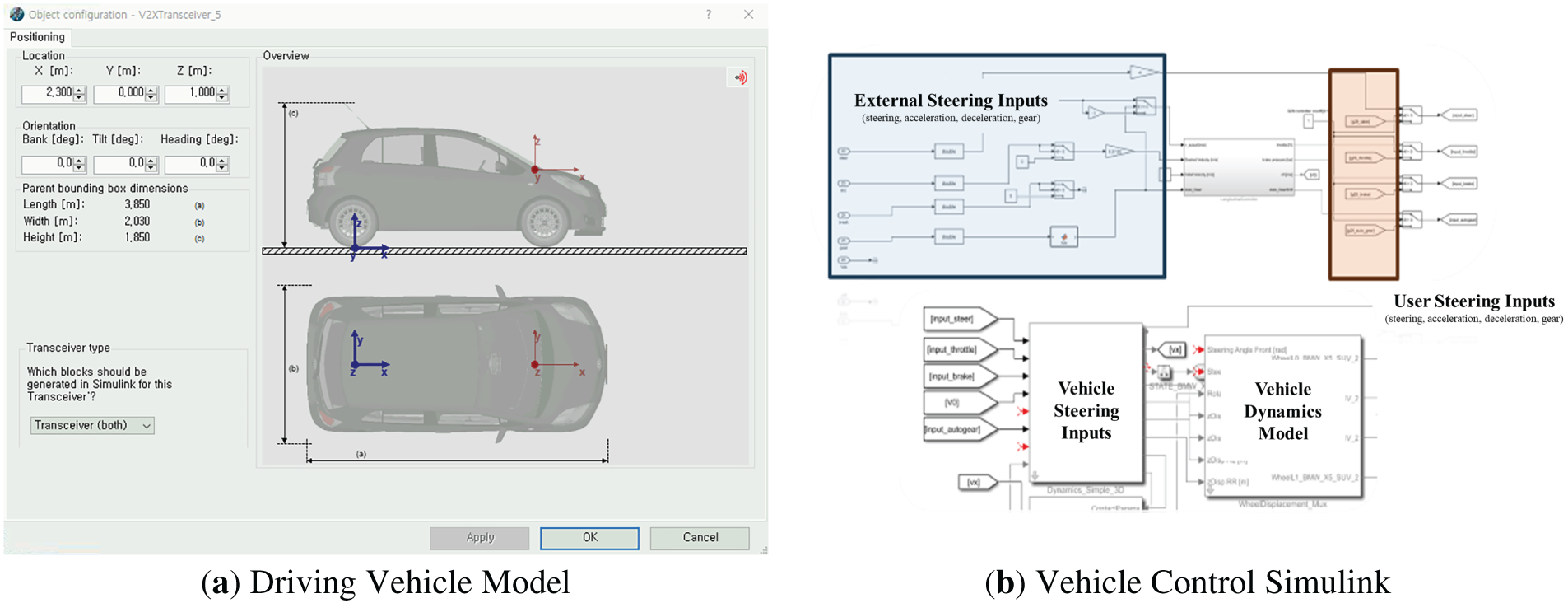

The PreScan box supports virtual driving environments and virtual driving models. PreScan GUI serves as a pre-processor that composes virtual driving environments such as roads and infrastructure. In the PreScan GUI, various infrastructures such as roads, buildings, signs, and weather conditions can be simulated like real roads. In this paper, some roads in GIST were modeled as a virtual driving environment using PreScan. Fig. 3a shows modeling of the virtual driving vehicle model for environment in bad weather using Prescan. The model built with Matlab Simulink receives messages sent from the driver seat and controls the movement of the vehicle in a virtual bad weather environment through an internal control algorithm with respect to driving. Fig. 3b shows the model of the driver’s vehicle built with the Matlab Simulink.

Figure 3: Role of prescan box with virtual driving environment and driving vehicle model. (a) Virtual driving vehicle model for environment in bad weather using prescan; (b) Matlab simulink structure of driver vehicle

3.1.2 Creating a Virtual Driving Environment

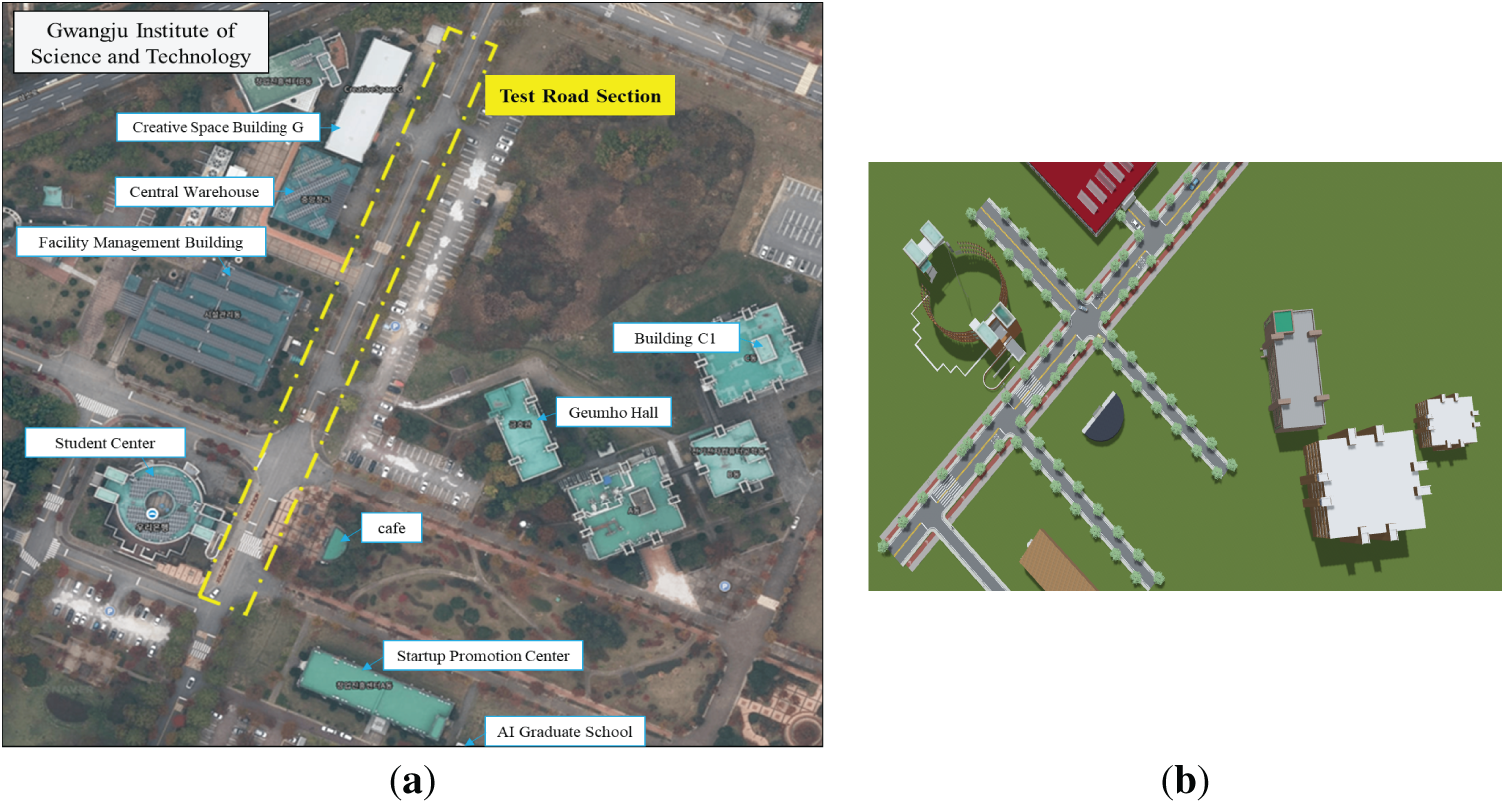

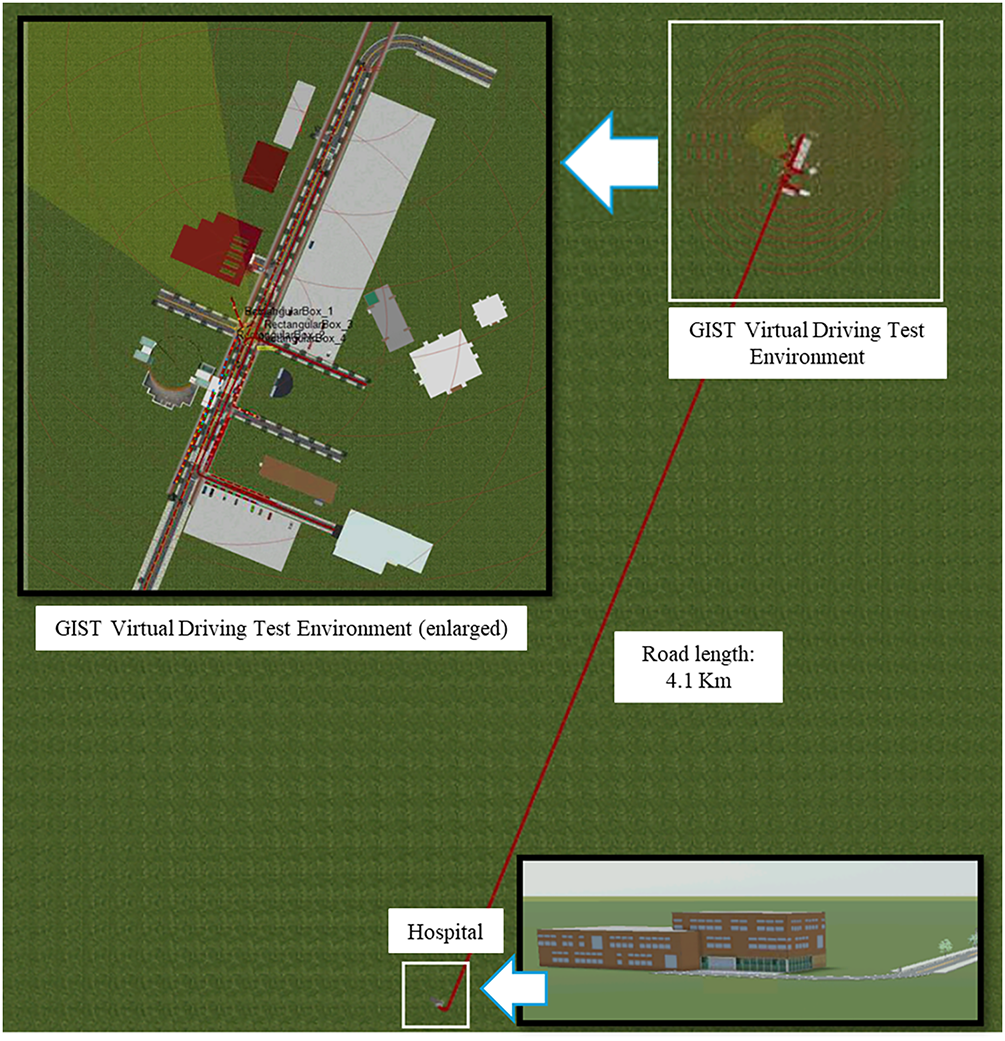

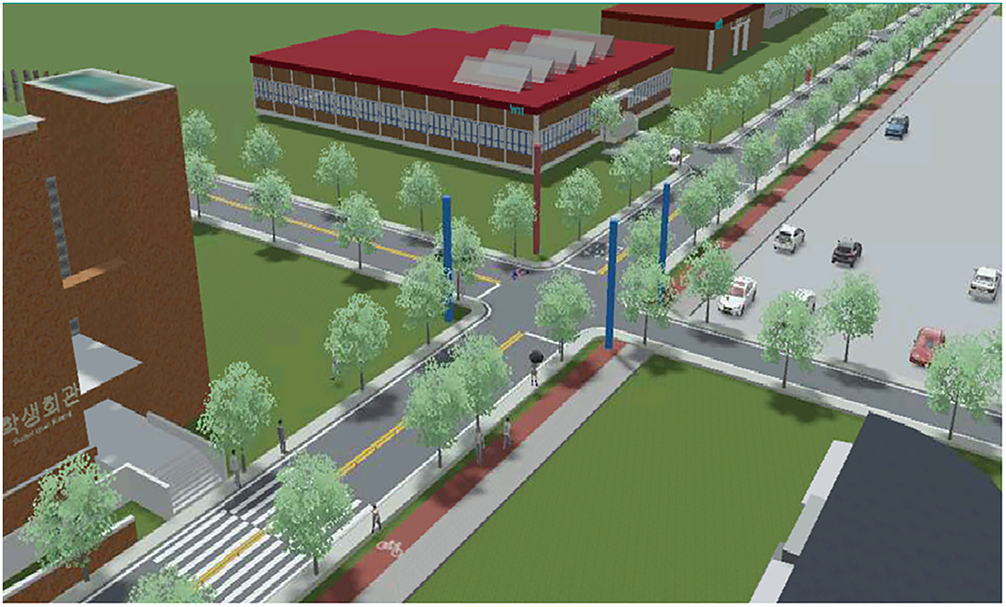

In this chapter, we create a virtual driving environment for SiLS data collection with DCU. Through software-in-the-loop simulation, we developed and verified a technology that links real vehicles (i.e., DCU) with the virtual traffic environment program Prescan to verify autonomous driving performance. A section of a road at the GIST was created as a virtual driving environment and used as a test road to verify the service developed using SiLS technology. Fig. 4a shows the test road section created as a virtual environment on an actual map.

Figure 4: The actual map location of the GIST test road section created as a virtual environment. (a) Actual location on the map; (b) Virtual driving environment scenario

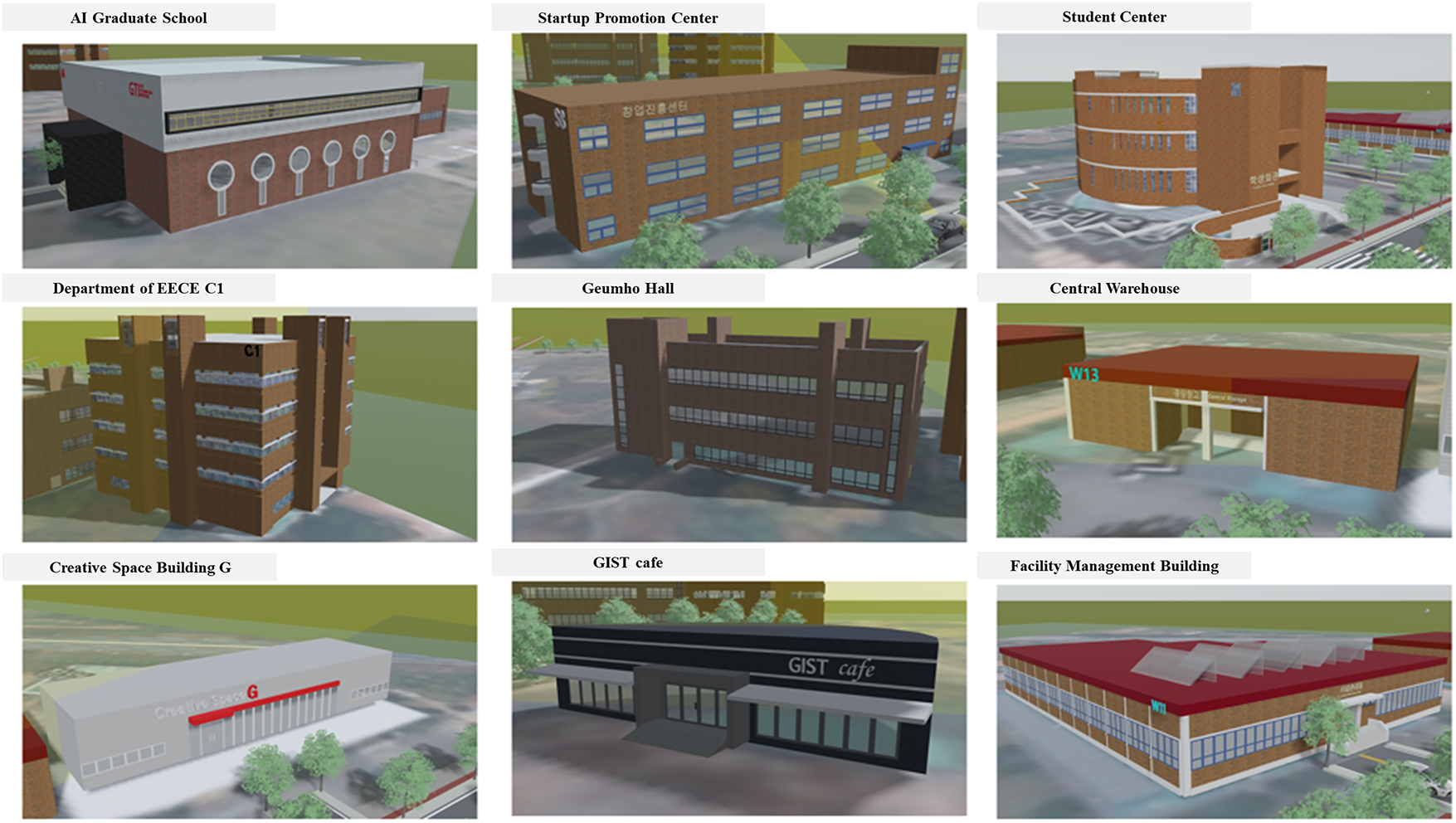

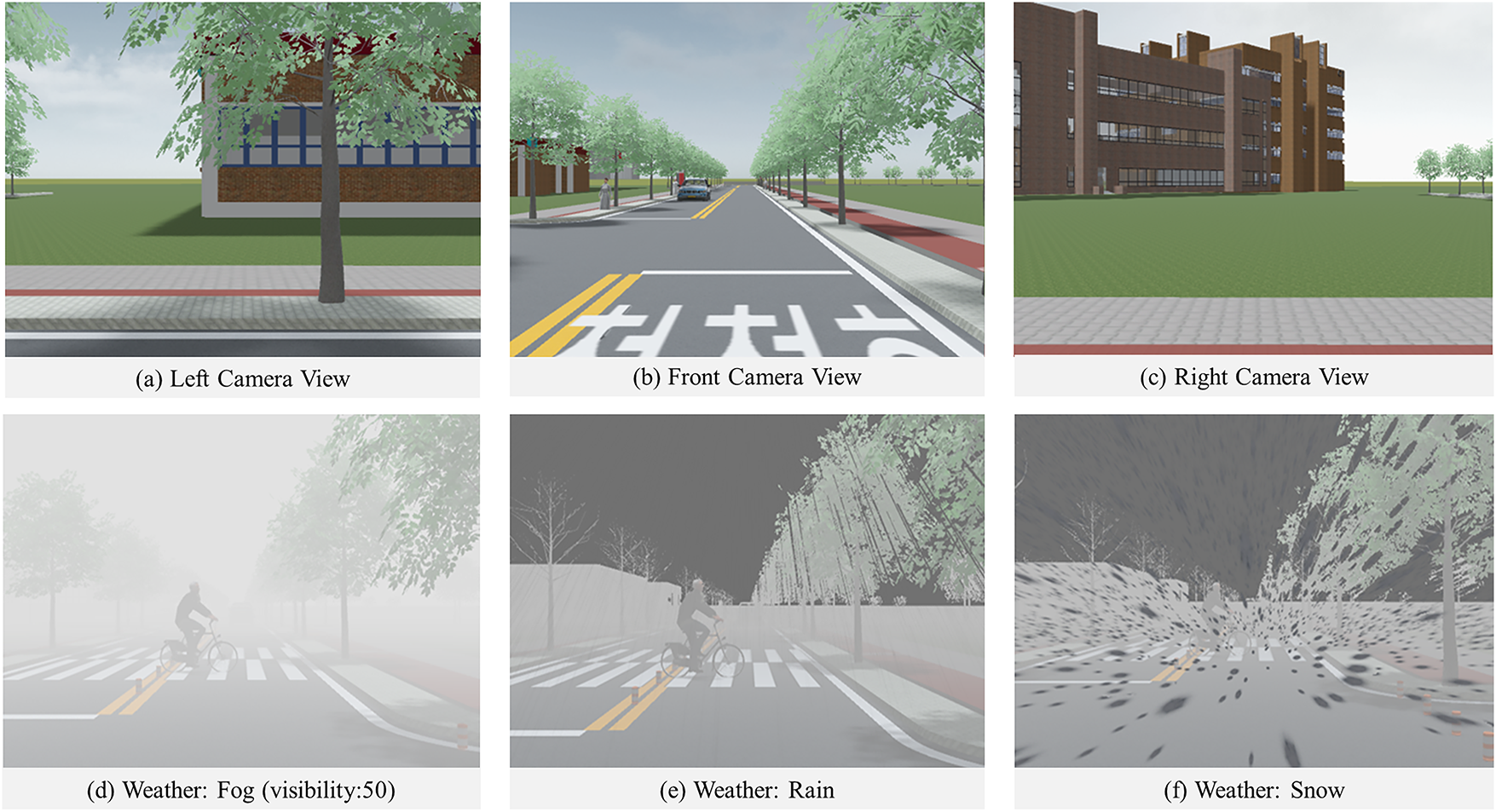

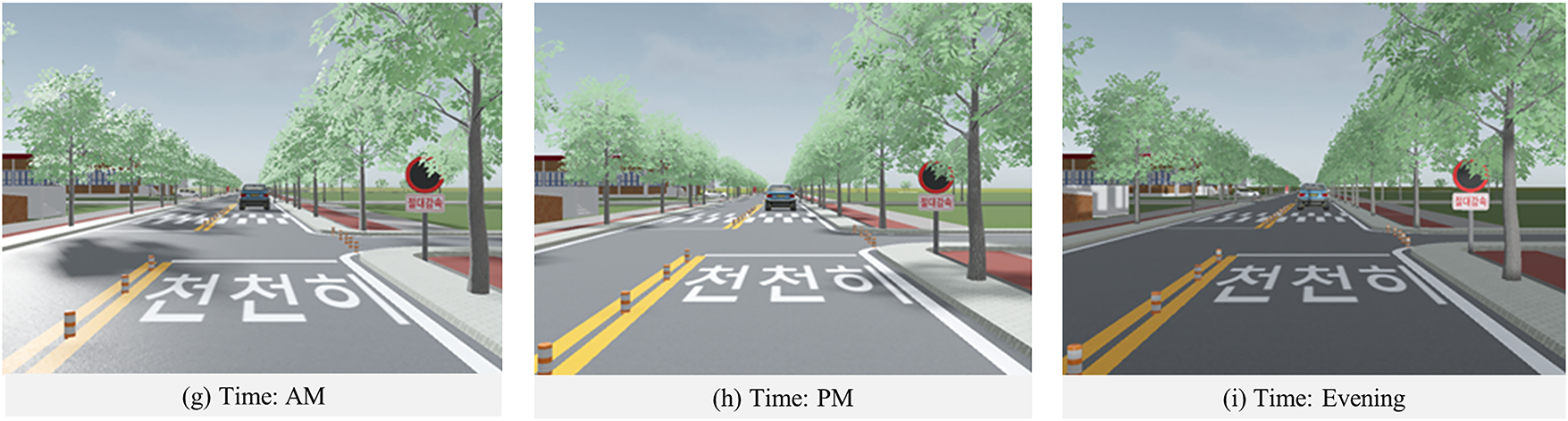

For the VDTE scenario, we used Prescan to model various infrastructure and weather conditions such as roads, buildings, and signs of the driving test section at GIST. The virtual building modeling around GIST’s driving test road was done by modeling a total of 9 buildings, including the AI Graduate School, Startup Promotion Center, Student Center, Department of Electrical and Electronic Computer Engineering Building (EECE) C1, Geumho Hall, Central Warehouse, Creative Space Building G, Cafe, and Facility Management Building, as shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 4b shows a scenario generated based on the driving test road in Fig. 4a, and the virtual building of GIST in Fig. 5. To collect data from the DCU, a virtual driving environment was simulated, as if a DCU-equipped vehicle were driving on a road for data collection. Fig. 6a–c shows the viewpoint of the virtual driving environment for the vehicle. To collect data from diverse situations, environmental conditions such as weather and climate, as well as various infrastructures similar to real-world environments, such as roads, trees, crosswalks, people, and signs, must be reflected. Fig. 6d–f shows a virtual driving environment that reflects road infrastructure, signs, pedestrians, vehicles, and weather conditions. Fig. 6g–i shows a virtual driving environment that reflects time conditions.

Figure 5: Nine GIST buildings modeled for a virtual driving environment

Figure 6: Adjusting the conditions of the virtual driving environment: (a) Driver’s left view in the virtual driving; (b) in the virtual driving; (c) Driver’s right view in the virtual driving; (d) 50% visibility fog conditions; (e) Rainy conditions; (f) Snowy conditions; (g) Morning time conditions; (h) Afternoon time conditions; (i) Evening time conditions

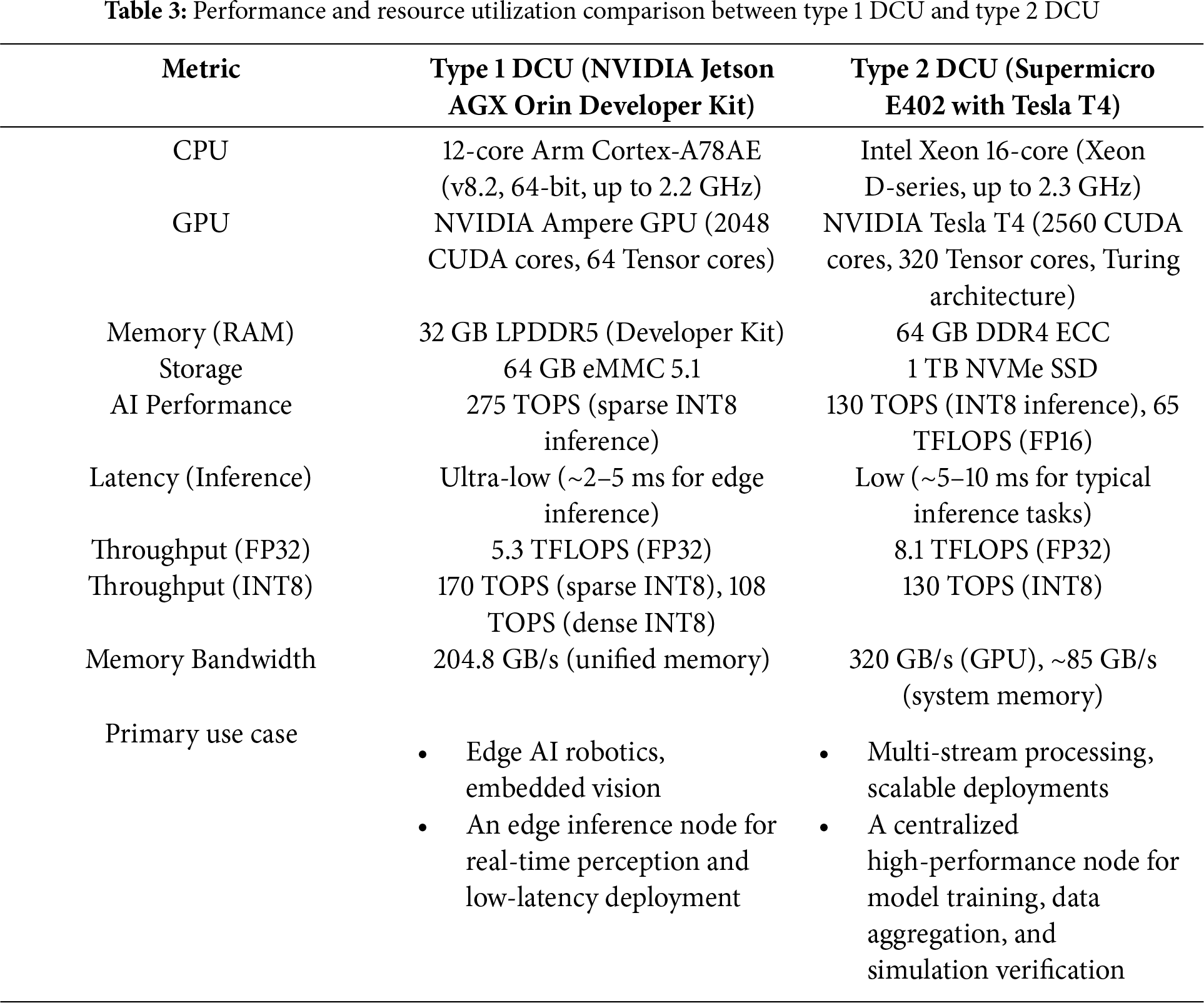

The DCUs were designed as Type 1 DCU [17] and Type 2 DCU depending on the service type. Type 1 DCU is used for services outside the cloud, where data collected through the DCU can be sent to the V2X-Car Edge cloud [18] for storage, analysis, and verification. Type 2 DCU is for services that have an integrated edge cloud, allowing for direct data collection, analysis, and verification at the edge, minimizing network latency and enabling resource-efficient usage. Table 3 compares the performance and resource utilization of Type 1 and Type 2 DCUs.

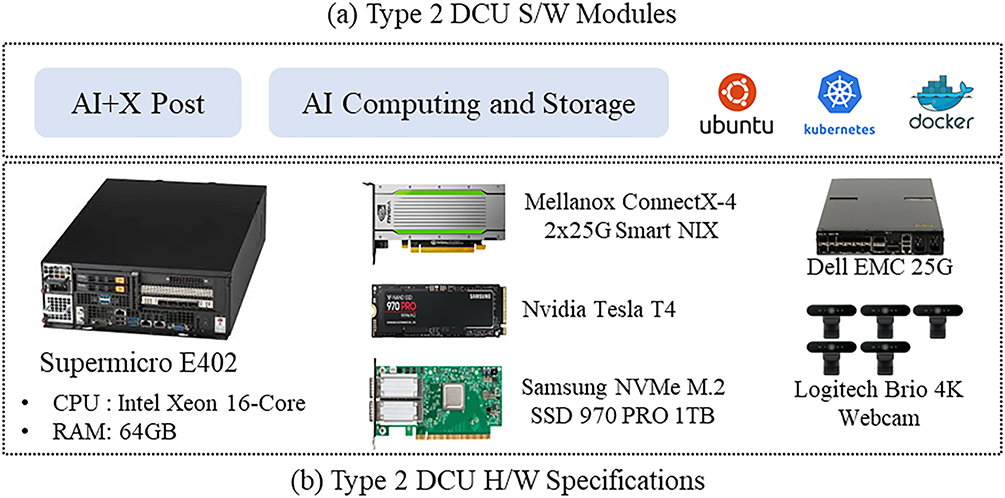

This paper focuses on the Type 2 DCU. The hardware that makes up the Type 2 DCU will be directly mounted on a mobile device for future experiments and research, so it was selected to ensure a compact form factor and an appropriate level of performance. Because the box mounted on a mobile device is difficult to access via wired connections, expandability was taken into consideration, including the addition of a Wi-Fi mesh and a V2X communication module to enable wide-ranging wireless access. The DCU is a hyper-converged system that integrates compute, storage, and networking resources, providing optimal support for CPU/GPU-based computing, all-flash storage, and SmartNIC-based networking. The Type 2 DCU hardware consists of two compact E403-9D-16C-FN13TP servers equipped with Intel Xeon CPUs (32 threads) and 64 GB memory for multi-data fusion. It integrates a Mellanox ConnectX-4 SmartNIC with dual 25G ports, an NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU based on Turing architecture for AI workloads, and a 1 TB Samsung SSD 970 PRO with high-speed NVMe storage. The two DCUs are interconnected by a 25G PowerSwitch for high-bandwidth data transfer. For real-time resource analysis, one DCU is connected to five UHD-capable Logitech Brio webcams. Fig. 7b shows the hardware specifications of the Type 2 DCU. The Type 2 DCU software is built as a hyper-converged system supporting Machine Learning (ML) workloads through Docker containers and Kubernetes. Running on Ubuntu with NVIDIA-Docker, it enables GPU integration for the Tesla T4, while Calico manages high-volume network traffic. Although Kubeflow could be used for ML pipelines, GPU scheduling conflicts limited its practicality, so Pods were configured directly for real-time multi-stream object detection. Customized container images for camera-based object recognition were obtained from Docker Hub and other registries and deployed as Pods. Fig. 7a illustrates the Type 2 DCU software module, composed of the AI+X Post and AI Computing & Storage. The AI+X Post acts as a containerized Kubernetes host, running the control plane to manage workloads, orchestrate edge nodes, and monitor network traffic with low latency using Xeon CPUs, large memory, and 25G NICs. The AI Computing & Storage component consists of worker containers for tasks such as real-time inference, object detection, and data storage. These containers share DCU resources including Tesla T4 GPUs, Xeon CPUs, and dual 25G NICs, enabling local data processing to minimize latency and improve responsiveness. High-throughput networking is achieved via 25G fabric switches, while the AI+X Post dynamically allocates resources across workloads to optimize performance in the distributed system.

Figure 7: Software and hardware concepts of Type 2 DCU: (a) Concept of DCU S/W Modules; (b) Hardware components of the DCU

In this paper, we test and validate the proposed VDTE using scenarios that incorporate V2X communication and multi-source image analysis (i.e., AI workload), as well as through analysis of DCU resources. The authors previously presented the scenario and resource analysis for Type 1 DCU; for more details, please refer to the papers Type 1 DCU [17] and V2X-Car Edge Cloud [16]. Therefore, this paper focuses on the scenario and resource analysis related to Type 2 DCU.

The scenario analysis consists of two scenarios. The first scenario simulates a complex emergency situation where AVs and transportation infrastructure closely interact, with V2X communications and data from various devices integrated and analyzed in the DCU. The second scenario verifies the scalability (scale-out) and fault recovery (self-healing) of a container-based object recognition system on the actual infrastructure (two Type 2 DCUs and multiple cameras) where the AI workload from the first scenario operates.

4.1.1 Emergency Patient Transport Scenario

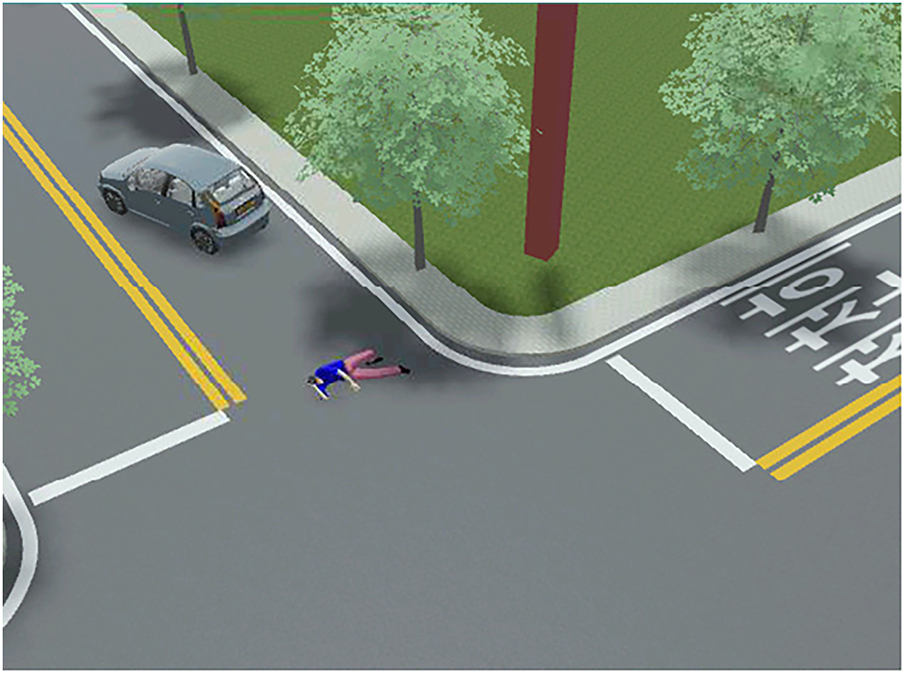

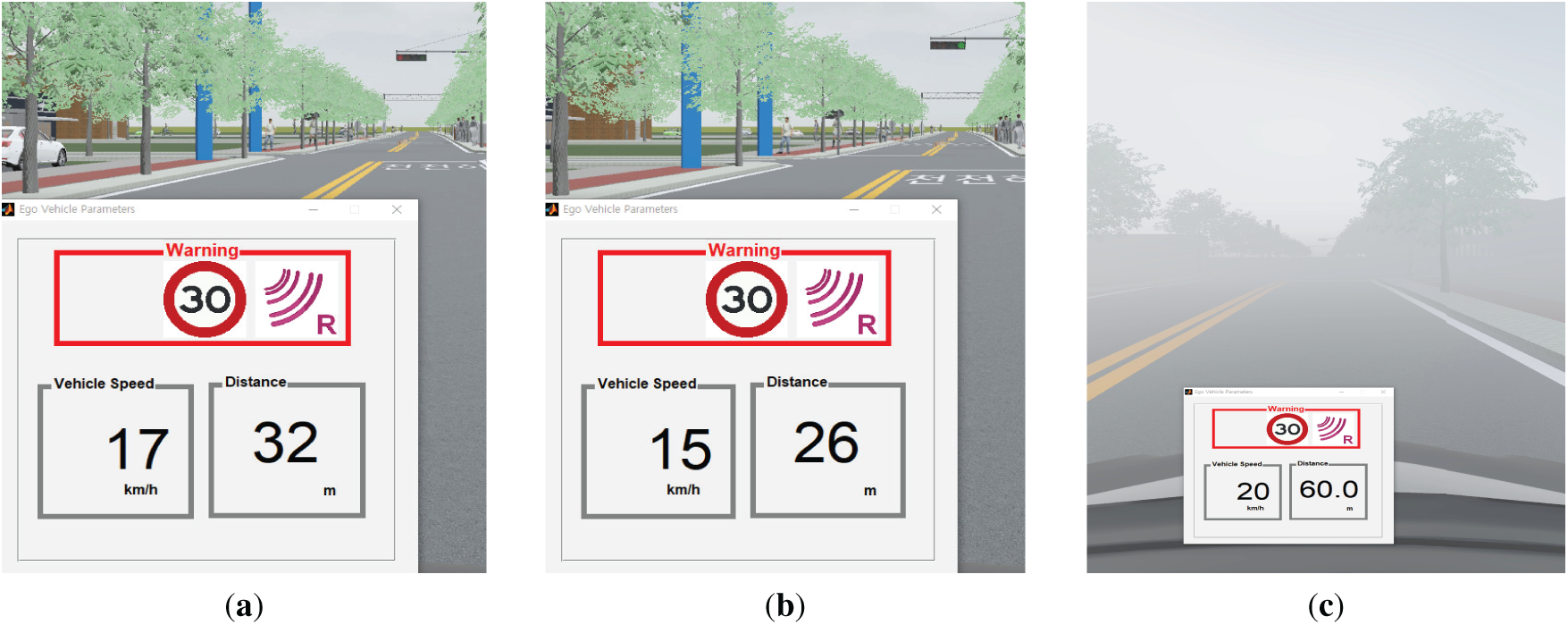

The service scenario involves a pedestrian suddenly collapsing at an intersection within the GIST. When an emergency situation occurs, a SmartX Pole equipped with V2X and a camera in the patient’s vicinity automatically recognizes the patient and transmits an emergency signal to available emergency vehicles. Upon receiving the emergency signal, an autonomous vehicle approaches the patient and uses V2X communication to control surrounding traffic lights and traffic flow. After the patient is loaded into the vehicle, it autonomously transports the patient to the hospital. During the journey, the vehicle continues to control traffic lights via V2X communication and relays its location to the hospital. The hospital receives this transmission and prepares for the patient’s arrival. All communication data are then transmitted to the DCU for collection and verification. Fig. 8 shows the VDTE for the scenario. The PreScan Box provides a virtual driving environment (a driver’s seat view) on the monitor and receives driver input signals such as steering, acceleration, and deceleration. It transmits and receives V2X messages to and from SmartX Poles within PreScan, vehicles, traffic lights, hospitals, and other entities. These messages are used to control autonomous driving and traffic lights. V2X messages from each vehicle, traffic light, and hospital (including GPS data, speed, and acceleration) are transmitted to the DCU. Fig. 9 shows the data flow between the DCU and the driving simulator.

Figure 8: Virtual driving test environment for scenarios

Figure 9: Data flow between the type 2 DCU and the driving simulator

In this scenario, four SmartX Poles were modeled, as shown in Fig. 10, and all were equipped with V2X virtual sensors. A camera was installed on only one SmartX Pole. As shown in Fig. 11, the camera mounted on the SmartX Pole can be used to monitor the patient’s condition in the event of an emergency. In addition to recognizing patients from the smart pole, we also enabled patient recognition using the actual camera of the Type 2 DCU. This scenario uses V2X communication between a transport vehicle and a traffic light to control the light, enabling quick transport of a patient to a hospital during an emergency. Using V2X communication, the light is set to automatically turn green when the vehicle is within 30 m of the traffic light. As shown in Fig. 12a, the light turns red when the vehicle is more than 30 m away and changes to green when within 30 m, as shown in Fig. 12b. To enable verification of real-time V2X-linked driving scenarios under various inclement weather conditions, the weather can be modified. Fig. 12c shows a driving scenario in inclement weather.

Figure 10: Modeled smart pole at an intersection

Figure 11: Emergency patient detection using a camera

Figure 12: Driving scenario conditions. (a) Light turns red when more than 30 m from the traffic light. (b) Light turns green when within 30 m of the traffic light. (c) Inclement weather driving scenario situation

This scenario verification demonstrates that the proposed VDTE is a powerful tool for safely and precisely testing and evaluating the collaborative capabilities of AVs and transportation infrastructure in complex emergency situations. The simulator’s experimental scenario can verify the automated response capabilities of AVs and V2X-based smart transportation infrastructure in real-world emergency situations, where they closely work together to recognize patients and control traffic signals and vehicles to support rapid emergency transport. Furthermore, it comprehensively simulates V2X message transmission and location information sharing among vehicles, traffic lights, and hospitals, testing communication stability and cooperative driving capabilities. Data collection through the PreScan virtual driving environment and DCU linkage enhances the realism and accuracy of the simulation and enables systematic analysis of driving and communication data. In other words, complex transportation and emergency response scenarios can be evaluated safely and precisely.

4.1.2 High-Availability Support Scenarios for AI Workloads

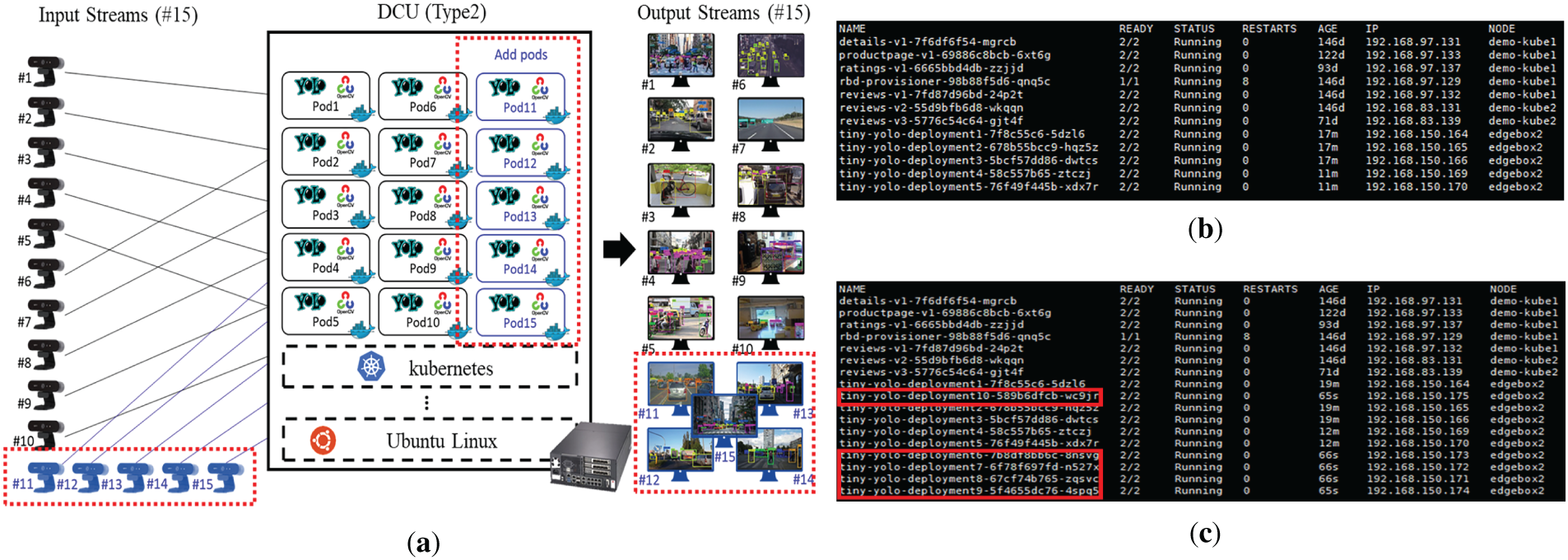

To ensure reliable AI container operation for multi-source video tasks such as object detection, a Kubernetes (K8S) orchestration environment was adopted. The system’s high availability (HA) was verified through two scenarios: first, scale-out under increased input load and second, self-healing after container failure. Two Type 2 DCUs (edgebox1 and edgebox2) were used, each connected to five cameras. The first scenario tested the system’s scalability when input video streams increased. Initially, ten YOLO (You Only Look Once) containers (five per DCU) were deployed; then, five more were requested to evaluate dynamic expansion. Fig. 13a illustrates the scaling concept, Fig. 13b shows five running containers, and Fig. 13c presents the expanded ten-container setup. Across 50 trials, all scale-out operations succeeded (100% success rate). The average provisioning latency was 21.5 ± 5.8 s (95% CI: 19.8–23.2), and per-stream FPS (Frames Per Second) changed slightly from 29.7 ± 1.1 to 29.3 ± 1.3 (p = 0.07), showing no significant performance drop. These results confirm that Kubernetes efficiently allocates new AI containers under higher workloads without degrading inference throughput.

Figure 13: Container expansion scenario due to increased distributed AI-DCU tasks. (a) Object detection container increase scenario (Scale and run 5 containers). (b) Five existing running containers. (c) Five additional containers are added to the existing five (total of ten running containers)

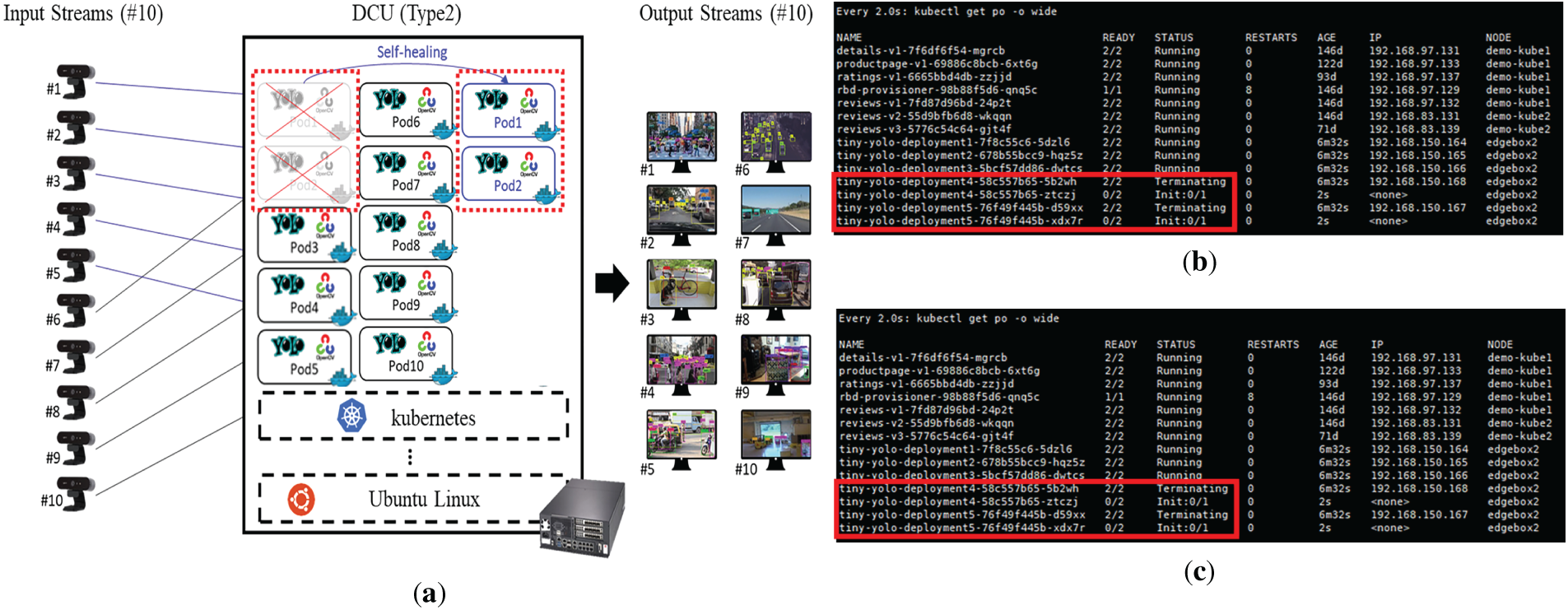

The second scenario evaluated automatic recovery from container failures caused by Pod errors or external conditions. A YOLO container was deliberately deleted to simulate a fault. Fig. 14a outlines the process; Fig. 14b shows the Terminating phase followed by new container creation; Fig. 14c confirms recovery as the new container enters Running state. Repeated 50 times, all recoveries completed within 60 s, achieving a 100% success rate. The average recovery latency was 12.8 ± 3.9 s (95% CI: 11.7–13.9), and post-recovery throughput retained ≥95% of baseline FPS (p = 0.06). This demonstrates that the K8S-based management enables fast, autonomous restoration of AI workloads without human intervention. Both scenarios (Figs. 13 and 14) confirm that the proposed Kubernetes framework provides automatic scaling and self-recovery, maintaining stable AI inference even under varying input loads and failure conditions.

Figure 14: Emergency recovery scenario for continued operation of a distributed AI-DCU. (a) Container emergency recovery scenario (Automatically restore after force-stopping 2 containers). (b) Terminating and creating a new object detection pod when a task is deleted (edgebox2). (c) After a certain amount of time, the new task status changes to Running (edgebox2)

4.2 Resource Demand Analysis of Distributed Type 2 DCU

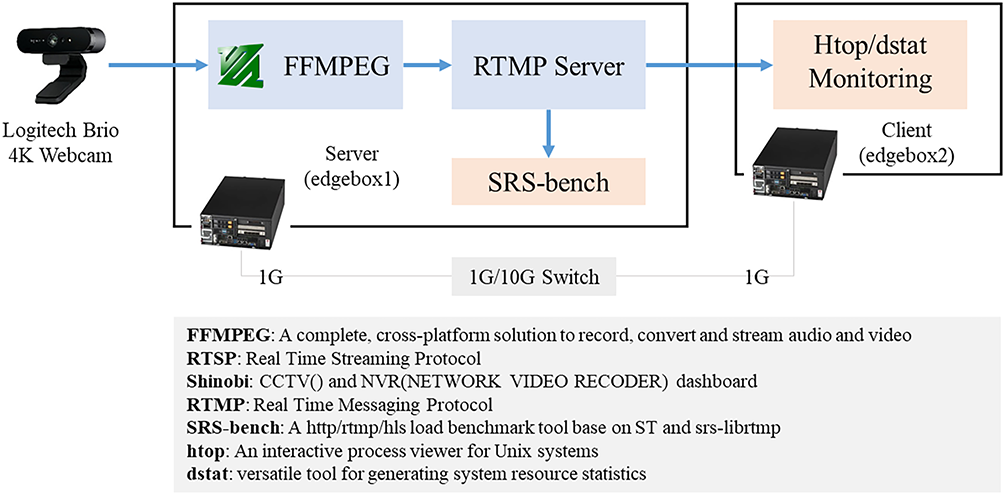

To design a distributed XAI(eXploratory Artificial Intelligence)-compliant data concentrator for multi-data fusion analysis, a comprehensive resource demand analysis was performed on distributed Type 2 DCUs. This analysis quantified computational and network utilization during real-time UHD video streaming based on an RTMP (Real-Time Messaging Protocol) architecture and compared baseline (CPU-only) and proposed (GPU-accelerated) configurations through multi-run replication statistics.

As illustrated in Fig. 15, two Type 2 DCUs (edgebox1 and edgebox2) were configured as a server-client pair. The server DCU handled UHD webcam capture and encoding using FFMPEG with optional GPU acceleration and streamed the output via an RTMP server. The client DCU requested the stream and generated variable connection loads to evaluate scalability. Both DCUs were linked through a 1 Gbit Ethernet switch. Resource utilization was monitored using htop (CPU/memory per process) and dstat (network throughput) at 1-, 3-, and 5-min intervals. Streaming bitrate was maintained at approximately 5.8 Mb/s. Two configurations were compared: Baseline: CPU-only (software FFMPEG encoding), Proposed: GPU-accelerated encoding (hardware-assisted FFMPEG). Each configuration was executed 10 times (N = 10 per load level) for reproducibility. Mean ± SD and 95% confidence intervals were calculated per metric.

Figure 15: RTMP-based video streaming benchmarking concept

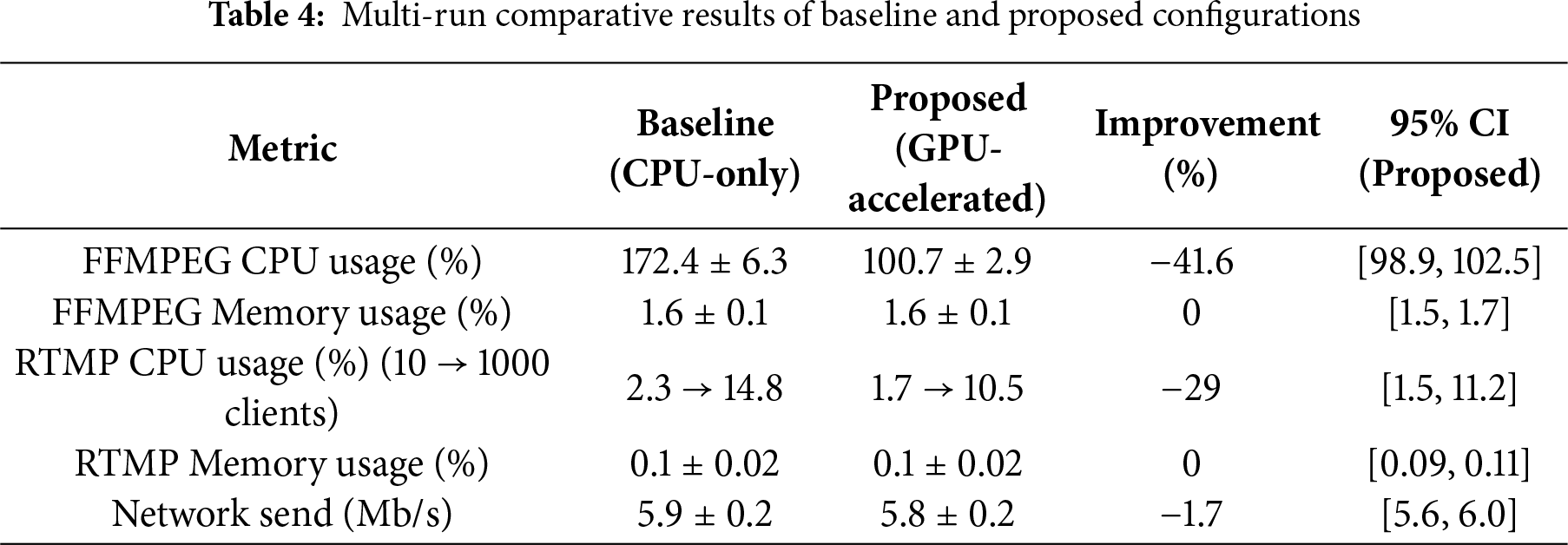

Table 4 summarizes the averaged resource utilization for both configurations, including standard deviation (SD), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and relative improvement rates. GPU acceleration substantially reduced CPU utilization while maintaining identical throughput and bitrate. Each entry represents mean ± SD computed across 10 independent repetitions per client-load condition. A paired t-test revealed significant CPU usage reduction under GPU acceleration (p < 0.01), with no significant changes in memory consumption or network throughput. Replication trials showed low variance (SD < 3%) across runs, validating reproducibility. The proposed configuration maintained consistent bitrate and streaming stability throughout all repetitions.

In this paper, we designed and implemented a VDTE utilizing a DCU and a V2X-Car edge cloud, enabling the collection, analysis, and validation of multi-source image-based Software-in-the-Loop Simulation (SiLS) data within a small-scale virtual driving environment under conditions that are difficult to replicate and verify in the real world, such as inclement weather. The proposed method has the following advantages: First, the proposed method establishes a small-scale Prescan-based virtual test environment that replicates rare and hazardous real-world scenarios, enabling controlled, repeatable, and systematic verification through rigorous comparison and validation. Second, the virtual environment’s effectiveness was enhanced by integrating real-world DCUs with multi-source imaging and leveraging the V2X-Car edge cloud for large-scale data handling, thereby improving simulation reliability and reducing the sim-to-real gap. Third, it supports flexible verification workflows by enabling cloud-based validation with external DCUs (Type 1) or direct edge-based validation with embedded DCUs (Type 2), thereby reducing latency and improving resource efficiency. Finally, it enables integrated verification between simulations, real vehicles, and infrastructure, enhancing software-hardware validation and supporting practical expansion for ITS and autonomous driving applications through the V2X-Car edge cloud. Future research will focus on minimizing the sim-to-real gap by developing advanced transfer technologies and expanding the vehicle-simulation verification framework for better reliability assessment. It will also diversify scenarios using rare and risky situation datasets from simulations and real-vehicle tests. Additionally, efforts will address challenges like computational overhead, fleet scalability, and real-world testbed integration.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the AI Graduate School at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST) and the Korean government for enabling this research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Institute of Information and Communications Technology Planning and Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2019-0-01842, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (GIST)). This work was supported by Korea Planning & Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) grant funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Republic of Korea) (RS-2025-25448249, Automotive Industry Technology Development (R&D) Program). This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education(RISE) program through the (Gwangju RISE Center), funded by the Ministry of Education(MOE) and the Gwangju Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-05-001).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization & methodology, Sun Park and JongWon Kim; writing—review and editing, Sun Park and JongWon Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. WIKIPEDIA. Vehicular automation [Internet]; 2025. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vehicular_automation. [Google Scholar]

2. Bathla G, Bhadane K, Singh RK, Kumar R, Aluvalu R, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Autonomous vehicles and intelligent automation: applications, challenges, and opportunities. Mob Inf Syst. 2022;2022(2):7632892. doi:10.1155/2022/7632892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. TaskUs. Top autonomous vehicle challenges and how to solve them [Internet]; 2025. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.taskus.com/insights/autonomous-vehicle-challenges/. [Google Scholar]

4. Kaur D, Karn AK, Singh AK, Kathuria T, Singh A, Singh AR. Autonomous driving simulation. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Optimization Techniques in the Field of Engineering (ICOFE); 2024 Oct 22–23; Tamil Nadu, India. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhang S, Zhao C, Zhang Z, Lv Y. Driving simulator validation studies: a systematic review. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2025;138:1–18. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2024.103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Meocci M, Terrosi A, Paliotto A, Torre FL, Infante I. Driving simulator for road safety design: a comparison between virtual reality tests and on-field tests. J Inf Technol Constr. 2024;29:1005–25. doi:10.36680/j.itcon.2024.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wu S, Deng M, Lyu N, Du Z. Research on intelligent connected HMI test system based on driving simulator. In: Proceedings of the 24th COTA International Conference of Transportation Professionals (CICTP); 2024 Jul 23–26; Shenzhen, China. [Google Scholar]

8. Aleksa M, Schaub A, Erdelean I, Wittmann S, Soteropoulos A, Fürdös A. Impact analysis of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) regarding road safety—computing reduction potentials. J Eur Transp Res Rev. 2024;16(39):1–13. doi:10.1186/s12544-024-00654-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lee S. Mastering vehicle dynamics in automotive R&D [Internet]. NumberAnalytics; 2025. [cited 2025 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-vehicle-dynamics-automotive-randd. [Google Scholar]

10. Kim JH, Choi YM. Study on how to increase SIL test effectiveness by comparing SIL test to HIL test. In: Proceedings of the Korean Society of Automotive Engineers Fall Conference; 2024 Nov 20–23; Jeju, Republic of Korea. p. 885–90. [Google Scholar]

11. Cheng J, Wang Z, Zhao X, Xu Z, Ding M, Takeda K. A survey on testbench-based vehicle-in-the-loop simulation testing for autonomous vehicles: architecture, principle, and equipment. Adv Intell Syst. 2024;6(6):2300778. doi:10.1002/aisy.202300778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dias CAR, Júnior JL. The use of artificial intelligence in driver-in-the-loop simulation: a literature review. Aust J Mech Eng. 2023;23(1):161–9. doi:10.1080/14484846.2023.2259709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang X, Li J, Zhou J, Zhang S, Wang J, Yuan Y, et al. Vehicle-to-everything communication in intelligent connected vehicles: a survey and taxonomy. Automot Innov. 2025;8(1):13–45. doi:10.1007/s42154-024-00310-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Clancy J, Mullins D, Deegan B, Horgan J, Ward E, Eising C, et al. Wireless access for V2X communications: research, challenges and opportunities. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2024;26(3):2082–119. doi:10.1109/COMST.2024.3384132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yusuf SA, Khan A, Souissi R. Vehicle-to-everything (V2X) in the autonomous vehicles domain—a technical review of communication, sensor, and AI technologies for road user safety. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2024;23(11):1–23. doi:10.1016/j.trip.2023.100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ku DH, Zang H, Yusupov A, Park S, Kim JW. Vehicle-to-everything-car edge cloud management with development, security, and operations automation framework. Electronics. 2025;14(3):478. doi:10.3390/electronics14030478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yusupov A, Park S, Kim JW. Synchronized delay measurement of multi-stream analysis over data concentrator units. Electronics. 2024;14(1):81. doi:10.3390/electronics14010081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Park S, Ji KH, Ku DH, Yusupov A, Kim JW. Autonomous driving test environment employing HiLS data collection and verification. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Advanced Engineering and ICT-Convergence (ICAEIC); 2024 Jul 9–12; Jeju, Republic of Korea. p. 140–50. [Google Scholar]

19. Omanakuttannair NKA. Identifying and testing the operational design domain factors of lane keeping system at horizontal curves using PreScan [master’s thesis]. Delft, The Netherlands: Delft University of Technology; 2022. 105 p. [Google Scholar]

20. Abdolhay H. Simcenter prescan 2507: revolutionizing virtual testing with dynamic lighting, smart displays, and enhanced traffic simulation [Internet]. SIEMENS; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 4]. Available from: https://blogs.sw.siemens.com/simcenter/simcenter-prescan-2507-revolutionizing-virtual-testing-with-dynamic-lighting-smart-displays-and-enhanced-traffic-simulation/. [Google Scholar]

21. Abdullah MFA, Yogarayan S, Razak SFA, Azman A, Amin AHM, Salleh M. Edge computing for vehicle to everything: a short review. F1000Research. 2023;10:1104. doi:10.12688/f1000research.73269.4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lucas BG, Kacimi R, Beylot AL. Mobile edge computing for V2X architectures and applications: a survey. Comput Netw. 2022;206(4):108797. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2022.108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hawlader F, Robinet F, Frank R. Leveraging the edge and cloud for V2X-based real-time object detection in autonomous driving. Comput Commun. 2024;213:372–81. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2023.11.0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xie Y, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Wang J, et al. Resource allocation for twin maintenance and task processing in vehicular edge computing network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(15):32008–21. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3488535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu X, Wu Q, Fan P, Wang K. Enhanced SPS velocity-adaptive scheme: access fairness in 5G NR V2I networks. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Workshop on Radio Frequency and Antenna Technologies (iWRF & AT); 2025 May 23–26; Shenzhen, China. p. 294–9. doi:10.1109/iWRFAT65352.2025.11102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools