Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FedCCM: Communication-Efficient Federated Learning via Clustered Client Momentum in Non-IID Settings

1 Faculty of Information Engineering and Automation, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, 650500, China

2 Yunnan Key Laboratory of Computer Technologies Application, Kunming, 650500, China

* Corresponding Author: Kai Zeng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Omnipresent AI in the Cloud Era Reshaping Distributed Computation and Adaptive Systems for Modern Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 72 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072909

Received 06 September 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

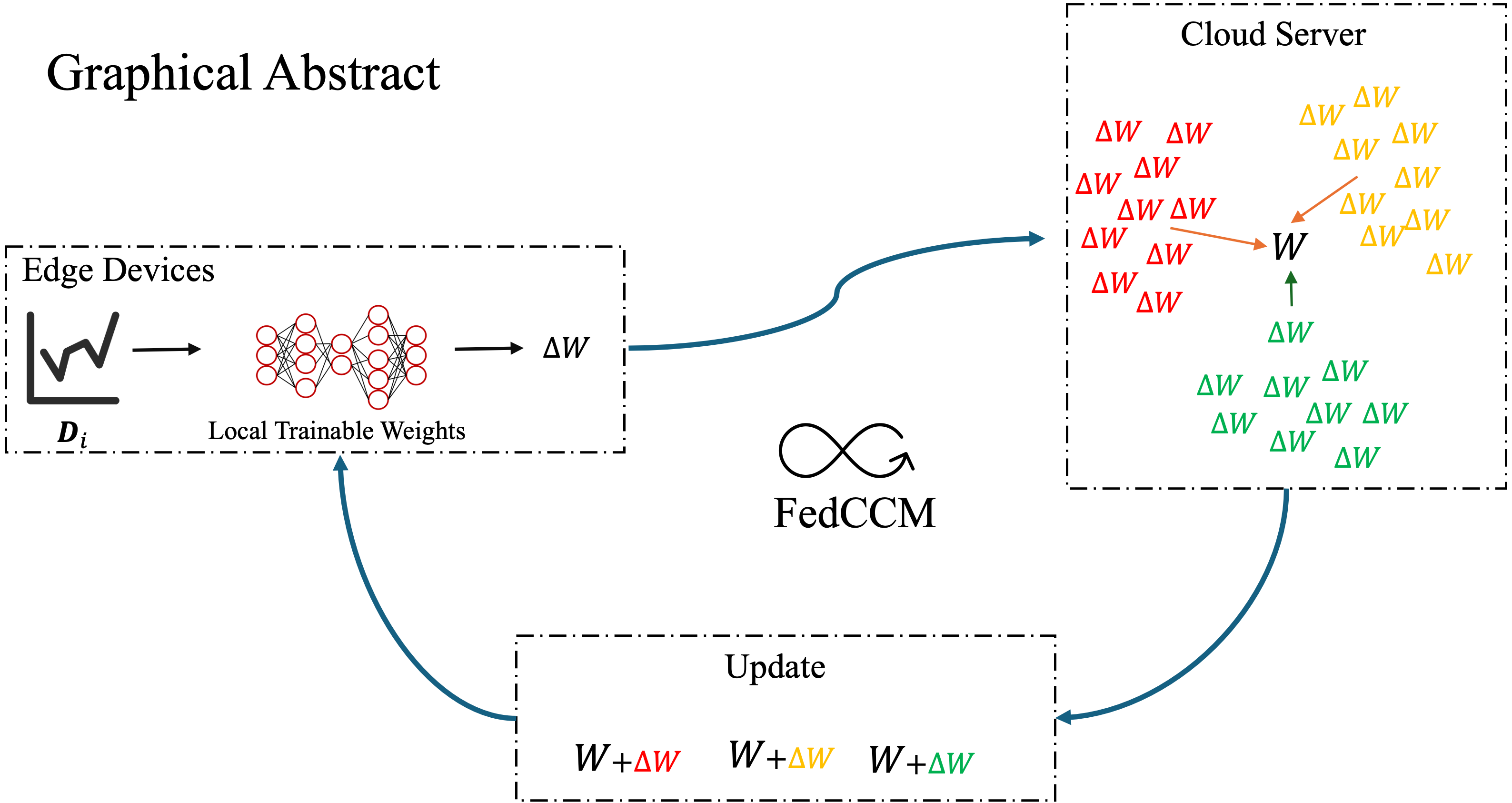

Federated learning often experiences slow and unstable convergence due to edge-side data heterogeneity. This problem becomes more severe when edge participation rate is low, as the information collected from different edge devices varies significantly. As a result, communication overhead increases, which further slows down the convergence process. To address this challenge, we propose a simple yet effective federated learning framework that improves consistency among edge devices. The core idea is clusters the lookahead gradients collected from edge devices on the cloud server to obtain personalized momentum for steering local updates. In parallel, a global momentum is applied during model aggregation, enabling faster convergence while preserving personalization. This strategy enables efficient propagation of the estimated global update direction to all participating edge devices and maintains alignment in local training, without introducing extra memory or communication overhead. We conduct extensive experiments on benchmark datasets such as Cifar100 and Tiny-ImageNet. The results confirm the effectiveness of our framework. On CIFAR-100, our method reaches 55% accuracy with 37 fewer rounds and achieves a competitive final accuracy of 65.46%. Even under extreme non-IID scenarios, it delivers significant improvements in both accuracy and communication efficiency. The implementation is publicly available at https://github.com/sjmp525/CollaborativeComputing/tree/FedCCM (accessed on 20 October 2025).Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Federated Learning (FL) [1–4] is a distributed machine learning framework [5] designed to address challenges in data privacy and security. It is particularly well-suited for Internet of Things (IoT) [6] applications or devices in hospitals and banks, where sensitive data is generated across numerous distributed devices. Unlike traditional machine learning paradigms that require centralizing data on a single cloud server, FL enables model training to be performed directly at the data source, thereby avoiding the risks of raw data transmission and leakage. The standard process typically involves a central cloud server and multiple data holders: the cloud server initializes and distributes a global model, each edge trains the model locally using its private data, and then sends the resulting parameter updates back to the cloud server. The cloud server aggregates these momentum to iteratively refine the global model until convergence. Through iterative communication rounds, FL facilitates knowledge sharing and joint model construction while preserving data privacy. This approach tackles the challenge of data isolation induced by regulatory or commercial restrictions and provides a practical pathway for large-scale collaborative machine learning in high-stakes domains such as healthcare and finance.

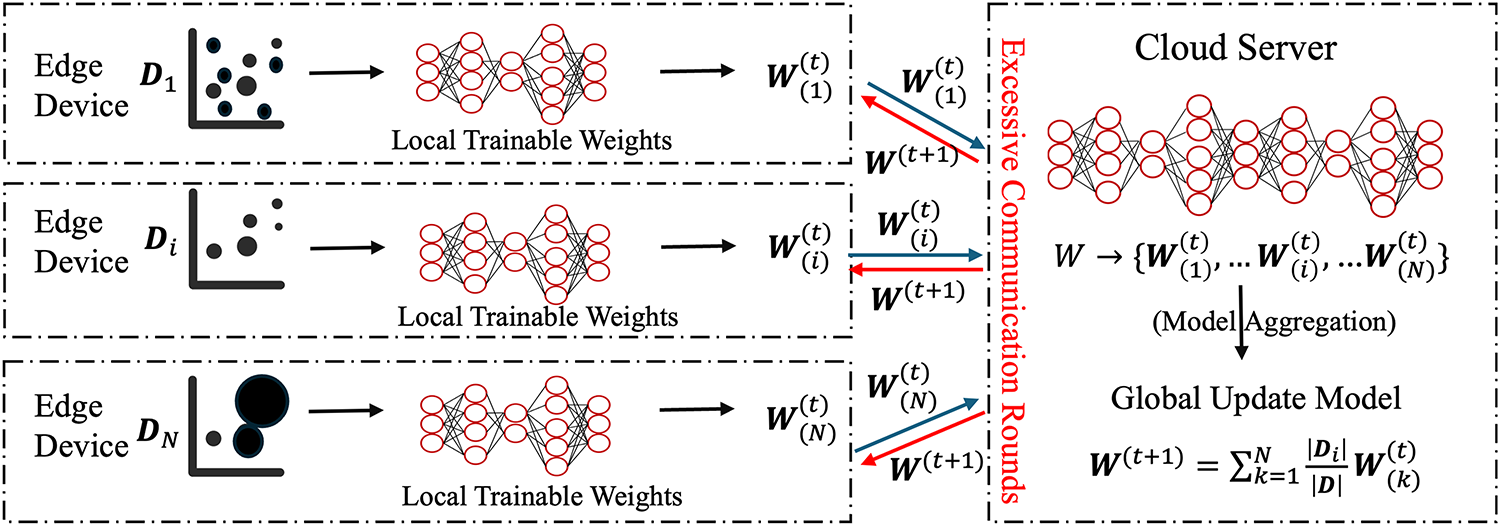

Although FL alleviates the challenges of data sharing, it still faces the critical issue of statistical heterogeneity in real-world deployments [7]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, edge data frequently display non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) characteristics. Such heterogeneity induces edge device drift during training, resulting in slower convergence, an increased number of communication rounds, and, in turn, higher communication overhead. The non-IID problem manifests in several key aspects [8–10]. First, there may be systematic differences in the feature space across edge devices, leading to feature distribution shifts. Second, label distributions are often imbalanced; for example, some edge devices may have abundant samples in certain classes but very few in others, resulting in label distribution skew. Third, the amount of data can vary significantly among edge devices, causing quantity imbalance. Finally, data distributions may evolve over time, making it difficult for historical models to adapt to emerging patterns. The combined effect of these factors violates the IID assumption that underlies traditional machine learning algorithms. This violation leads to severe issues, such as edge device drift. Edge device drift impedes both the convergence speed and the final performance of the global model. As a result, the training process experiences a significant increase in communication overhead.

Figure 1: Limitation of existing FL: non-IID data causes model drift, increasing rounds and communication overhead

To mitigate the negative impact of edge device drift, researchers have proposed a variety of strategies. Edge-side regularization methods add a proximal term to the local loss function to directly limit the deviation of local models from global model. Personalized federated learning [11–14] adopts a different perspective, arguing that under highly heterogeneous data, pursuing a single global model may be impractical. Instead, it leverages techniques such as transfer learning, or edge clustering to produce models that are better tailored to different data distributions. Cloud-side optimization methods introduce momentum or lookahead gradient prediction during the aggregation phase [15,16]. This approach mitigates noise and reduces the impact of conflicting gradients from different edge devices. These approaches mitigate edge device drift from different perspectives but still have limitations. Cloud-side optimizations often fail to fully leverage the specific data characteristics of edge devices, while personalized methods, though improving local performance, can sacrifice global model consistency. Moreover, they do not achieve good convergence while maintaining a reasonable communication load. Therefore, enhancing the global model’s convergence and accuracy, while effectively adapting to and utilizing data heterogeneity, remains a critical challenge in FL research and serves as the foundation of this work.

How to optimize momentum to further mitigate the impact of data heterogeneity and thereby enhance communication efficiency is the central question we aim to explore. Building on this insight, we propose a refined guidance framework, termed Federated Learning via Clustered Client Momentum (FedCCM). The key idea is to abandon a single global momentum and instead maintain distinct momentum vectors for different edge clusters. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

(1) We identify and highlight the limitations of existing global momentum–based FL algorithms in handling highly heterogeneous data, namely their uniform treatment of all edge devices without adaptation to data heterogeneity.

(2) We propose FedCCM, a FL framework that moves from global guidance to personalized guidance through edge clustering with group level momentum; it dynamically identifies edge groups without any additional network communication, and extra cost is confined to cloud-side computation and memory.

(3) Experimental results indicate that, compared with baselines, FedCCM mitigates edge device drift more effectively, delivering faster convergence and higher final accuracy, and on CIFAR-100 it achieves a state of the art 65.46% accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work. Section 3 introduces the preliminaries. Section 4 presents the proposed methodology. Section 5 reports the experimental results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

This study is closely related to following research areas: personalized FL and strategies for mitigating communication overload in FL.

2.1 Personalized Federated Learning

In traditional settings, each edge node is trained with a fully independent model. While this ensures local adaptability, it inevitably undermines global knowledge sharing and limits the model’s capacity for generalization. To address these limitations, Personalized Federated Learning (PFL) has been introduced, aiming to deliver customized models for individual edge devices or groups while preserving a degree of shared knowledge. Research on PFL has subsequently evolved along three primary technical directions.

Group-level personalization. IFCA [17] is a pioneering and representative work in clustered. It assumes that edge devices can be partitioned into clusters, where edge devices within same cluster share similar data distributions. The algorithm operates through an elegant alternating optimization between edge devices and cloud server: on edge side, each edge downloads all current cluster models, evaluates them locally, selects the best-performing model for local training, and sends the update back to cloud server; on cloud side, momentum corresponding to each cluster are aggregated separately to refine cluster models. Through repeated iterations, edge devices gradually affiliate with cluster that best matches their data distribution, eventually yielding K models tailored to different edge groups. This approach elegantly resolves the dilemma of whether to cluster first or to train first, enabling edge devices with similar data to collaborate effectively and mitigating challenges posed by heterogeneity.

Parameter-level personalization. pFedHN [18] opened a new direction for fine-grained personalization. Its key idea is to train a shared hypernetwork on cloud server, which is responsible for generating model parameters for each edge rather than directly solving target task. Each edge is assigned a learnable low-dimensional embedding vector representing its data characteristics. When personalization is required, edge transmits its embedding to cloud server, and hypernetwork outputs a full set of customized model weights. During training, edge devices only need to update and upload their embedding vectors, greatly reducing communication costs. Subsequent extensions broadened this framework to generate parameters for edge devices with heterogeneous architectures, enhancing its applicability in realistic federated environments.

Architecture-level personalization. PerFedRLNAS [19] pushes personalization to the architectural level. It argues that in highly heterogeneous federated settings, not only model parameters but also the model architecture itself should be personalized. To this end, it formulates the search for optimal edge-specific architectures as a reinforcement learning (RL) problem. A controller, typically an RNN, acts as the agent on cloud server. Its actions are sequences that define network layers, its states may include edge identifiers, and its rewards are validation accuracies obtained after short-term training of the generated architecture on edge. Using policy gradient methods, the controller learns to design architectures that are both performance-optimal and resource-aware for each edge. While this approach offers unprecedented flexibility for personalization, it comes at the cost of significant computational complexity.

PFL has emerged as a promising paradigm to address the heterogeneity of edge data distributions by tailoring models to individual devices or groups. However, personalization inherently increases the communication burden, since more rounds of interaction or additional model parameters are often required to achieve convergence under non-IID settings.

2.2 Communication-Efficient Federated Learning under Non-IID Data

Due to the presence of non-IID data, edge device tend to optimize in divergent directions during local training, thereby leading to the phenomenon of edge device drift. When local data distributions vary across edge devices, the local training objectives diverge from the global objective, resulting in conflicting momentum directions in local updates. The continuous accumulation of such conflicts leads to slow convergence of the aggregated global model, causing it to fluctuate near the optimum. This significantly degrades the model’s performance and increases communication overhead. To address this issue, researchers have proposed various optimization strategies designed to mitigate the impact of edge device drift on communication efficiency.

2.2.1 Update Alignment Methods for Communication-Efficient FL

Optimization in local update bias correction. One major research direction focuses on correcting bias in local updates. FedProx [20] introduces a proximal term

Data level explorations. Recognizing the limitations of optimizer-level correction alone, recent studies have explored remedies from broader perspectives. FedBSS [22] represents a data-centric innovation, starting from the assumption that edge device drift is the cumulative effect of biased local samples. Instead of adjusting gradients afterwards, FedBSS adopts a bias-aware sample selection mechanism: in early training stages, it prioritizes low-bias samples and progressively introduces high-bias samples, akin to curriculum learning. This strategy smooths local training trajectories from the root, thereby mitigating drift. From the system perspective, MTGC [23] addresses multi-level drift in hierarchical federated architectures. Extending the SCAFFOLD principle, MTGC incorporates control variates at both the device–edge and edge–cloud levels, achieving systematic correction of drift across scales.

2.2.2 Momentum Methods for Communication-Efficient FL

Incorporating momentum into has become a common approach to improving performance. Early methods primarily introduced momentum or adaptive optimizers on the cloud side to aggregate edge momentum. More recent approaches, such as FedCM and the original FedACG [16], further leverage global momentum information to guide local training on edge devices. In conventional centralized training, momentum is a well-established technique for accelerating optimization. In FL, its introduction aims to smooth global update oscillations caused by gradient conflicts across edge devices, thereby speeding up convergence. Over the past years, research on momentum in FL has evolved from simple cloud-side strategies to more sophisticated edge-cloud collaborative mechanisms.

The development of momentum methods in FL has evolved from purely cloud-side strategies to more sophisticated edge-cloud collaborative designs. The early work FedAvgM [15] represents the simplest cloud-side momentum approach. It maintains a momentum vector at cloud server, computed as the exponential moving average of past global updates. In each round, instead of directly applying the aggregated edge updates, cloud server combines them with its momentum vector to determine the global update direction. This strategy smooths the optimization trajectory of the global model, mitigating abrupt oscillations caused by edge data heterogeneity. Its strengths are simplicity and zero communication overhead, but the limitation is that momentum information remains confined to cloud server and cannot guide local edge optimization.

To address this shortcoming, more recent studies have designed edge-cloud collaborative momentum mechanisms. For instance, FedACG introduces the idea of accelerated edge gradients, embedding global momentum into the local optimization process. Specifically, cloud server maintains a momentum vector and generates an accelerated model

The application of momentum in FL has followed a clear trajectory, evolving from simple cloud-side aggregation to deeper edge-cloud collaboration. Researchers have moved beyond merely smoothing updates at cloud server, focusing instead on designing mechanisms that efficiently and effectively transmit global momentum information to influence local edge training. Alongside these algorithmic advances, stronger theoretical guarantees have also been established, reinforcing both the convergence and robustness of momentum-based methods and paving the way for their continued development in FL.

The key difference between our FedCCM and these methods lies in the fact that we maintain a unified global model shared by all edge devices. The purpose of clustering is not to partition the model, but to offer more precise training guidance. By leveraging personalized momentum to enable more efficient local training, all edge devices ultimately contribute higher-quality updates to the same global model, thereby achieving an organic integration of personalized guidance and global knowledge sharing.

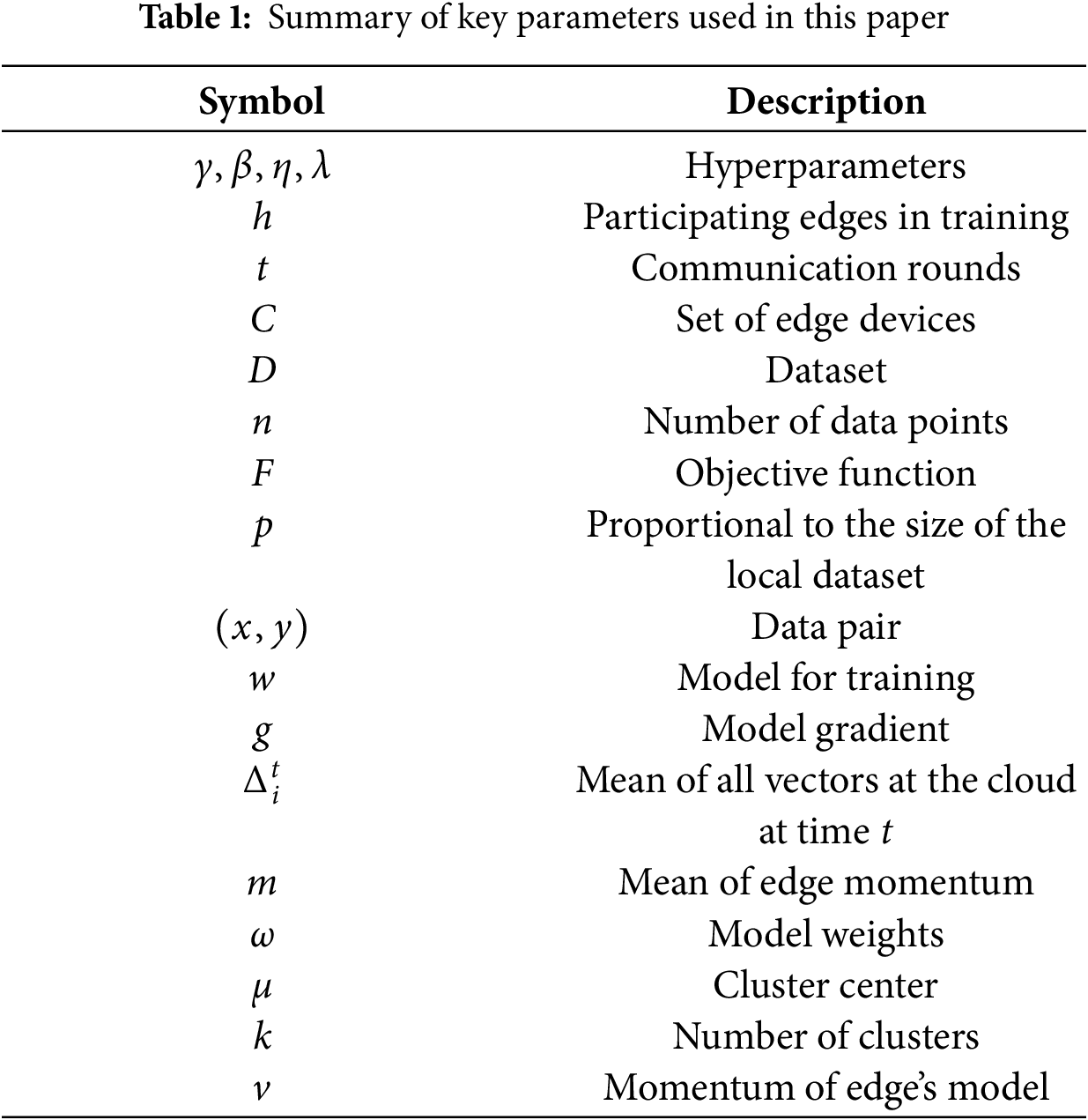

Before introducing the proposed approach, we provide a brief overview of the fundamental concepts and formulations of FL and cluster analysis. The meanings of the symbols used are shown in Table 1.

From the perspective of mathematical optimization, the fundamental goal of FL is to minimize a global objective function. This global objective is typically defined as the weighted average of the local objective functions of all participating edge devices. A local objective function measures the empirical risk, that is, the prediction loss of the current model on an edge’s local dataset. By optimizing this global function, we aim to obtain a single global model

Consider a FL system with C edge devices, indexed by

For edge

Here,

The ultimate goal of FL is to minimize the weighted average loss across all edge devices, referred to as the global objective function

By substituting the definition of the local objective function into the above equation, we obtain:

Accordingly, the optimization problem in FL can be formally stated as finding a set of optimal model parameters

The key challenge lies in the fact that the dataset

The core of FL lies in iteratively optimizing a global model by aggregating local model updates distributed across edge devices. However, when edge data exhibit non-IID characteristics, the local gradients

First, cloud server computes the averaged model update

Then, cloud server adjusts the update direction

where

Finally, instead of directly moving to the averaged model, cloud server uses the updated momentum

where

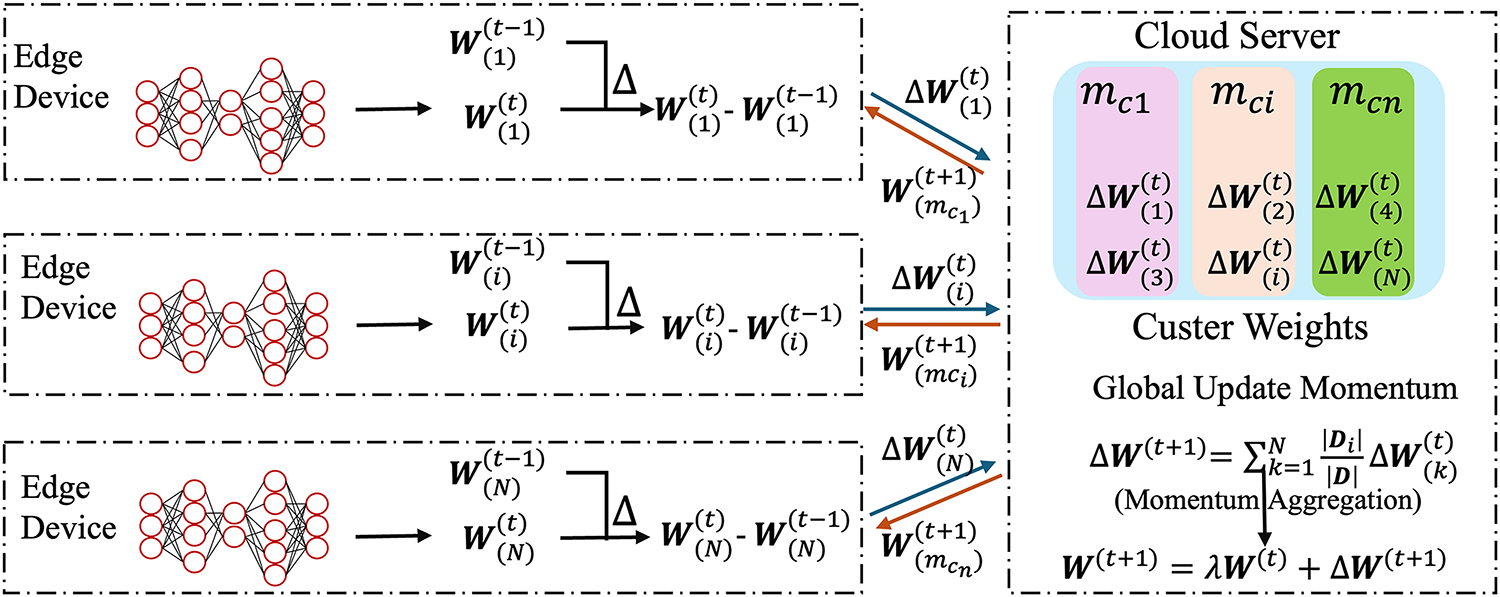

In this section, we provide a detailed description of the FedCCM framework, including the algorithm motivation and process. The detailed FedCCM framework is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Framework of FedCCM. The server maintains a momentum vector

4.1 Limitation Analysis of Existing Momentum-Based Method

The original FedACG algorithm provides forward-looking guidance to edge devices by broadcasting an accelerated model

4.2 Client Clustering Based on Model Momentum

Clustering Algorithm. Clustering is a fundamental unsupervised learning task that partitions a dataset

The most widely used algorithm for solving this clustering problem is K-means, which iteratively alternates between assigning each data point to its nearest centroid and updating the centroid positions. In the assignment step, each sample

where

where

These steps are repeated until convergence, which can be defined as the change in centroids falling below a predefined tolerance or the maximum number of iterations being reached. Convergence of K-means is guaranteed in a finite number of iterations due to the monotonic non-increasing property of the objective function.

To enable personalized guidance, cloud server must first identify the group membership of each edge device. Each edge’s model momentum

4.3 Personalized Momentum for Global Aggregation

The training process of FedCCM is similar to the original FedACG, but with key differences in momentum and model aggregation. The server maintains a separate momentum vector

While the guidance provided to edge devices is personalized, the aggregation of model updates is performed globally. After cloud server collects the momentum

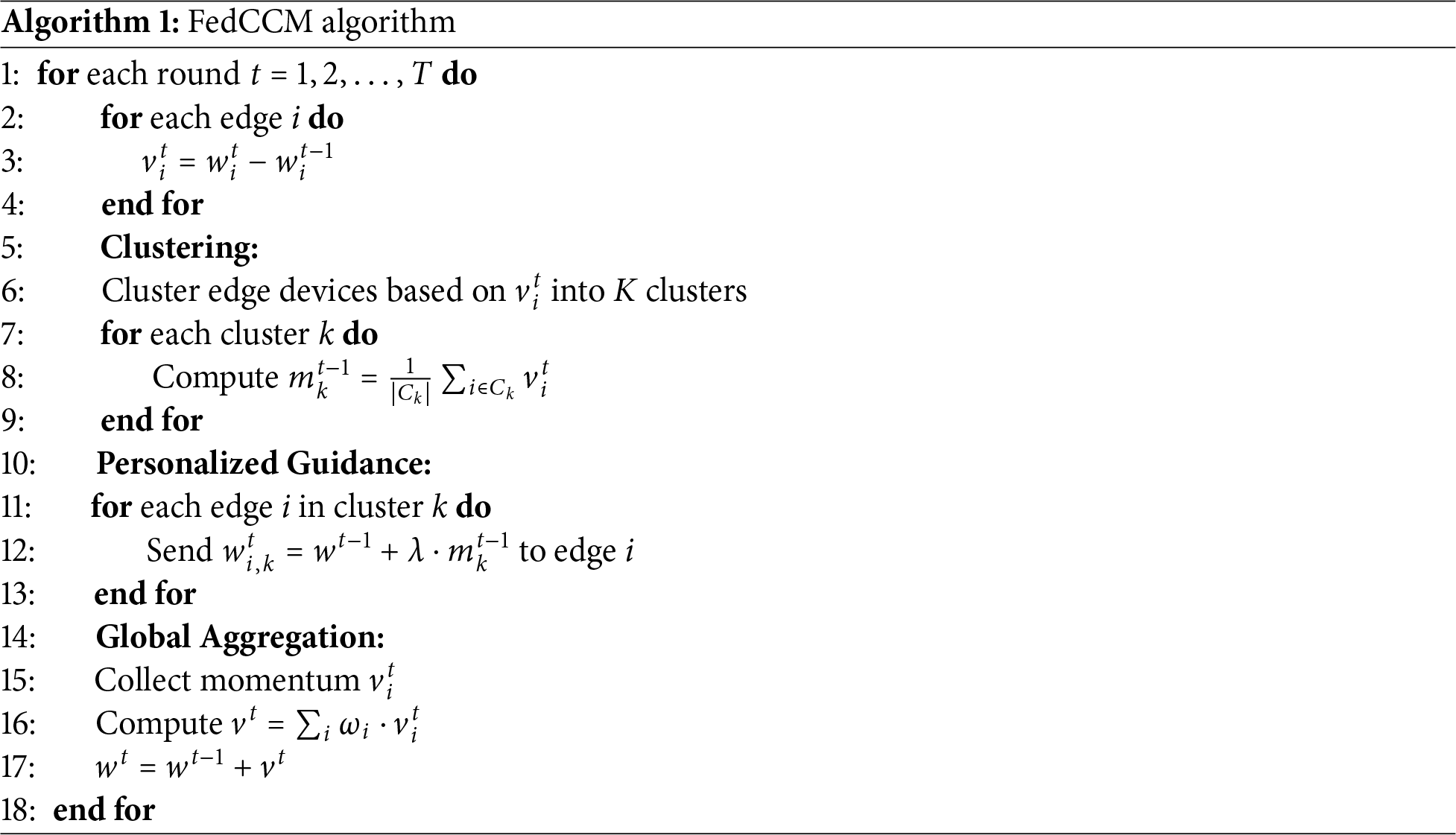

FedCCM incurs the same per-round communication cost as FedACG, each round requires uploading H client momentum and downloading one global model. This design ensures that the global model can learn from all edge devices, maintaining its generality, while the personalized momentum serves as an intermediate medium to enhance local training efficiency and accelerate global convergence. FedCCM process is outlined in Algorithm 1.

To establish the convergence analysis of FedCCM, we adopt a set of assumptions consistent with those in [16]. Specifically, we derive a simplified convergence guarantee for FedCCM under the standard theoretical conditions commonly used in federated optimization. We assume that each local objective function

Under these conditions, FedCCM decouples into K independent FedACG processes, one per cluster. Let

where

By design, FedCCM eliminates the between-cluster variance term through clustering, leading to a tighter error bound under data heterogeneity.

We conduct an experimental evaluation comparing FedCCM with a range of other FL techniques. This section includes detailed implementation descriptions, such as experimental setup, dataset configuration, comparisons with existing methods, evaluations under different environmental configurations, and the selection of hyperparameters.

Dataset. All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti GPU to ensure parallel training acceleration and system stability. The datasets used include CIFAR-10 [26], which consists of 60,000

Baselines. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed FedCCM method, we compare it against a range of FL algorithms, including FedAvg [1], FedProx [20], FedAvgM [15], FedADAM [7], FedDyn [28], MOON [29], FedCM [30], FedMLB [31], FedLC [32], Fed-NTD [33], and FedDecorr [35]. In all experiments, we adopt the standard ResNet-18 architecture as the backbone network and follow the experimental setup in [16], replacing all Batch Normalization layers with Group Normalization.

Evaluation Metrics. To evaluate the generalization performance of all methods, we conduct testing on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and TinyImageNet datasets and record their inference accuracy. In FL, both training speed and final accuracy are key indicators. Following the methodology of Kim et al. [16], we quantify performance from two perspectives: (i) the accuracy achieved by each method at a specified communication round, and (ii) the number of communication rounds required for each method to reach the target accuracy. For methods that fail to reach the target accuracy within the maximum allowed communication rounds, we append a

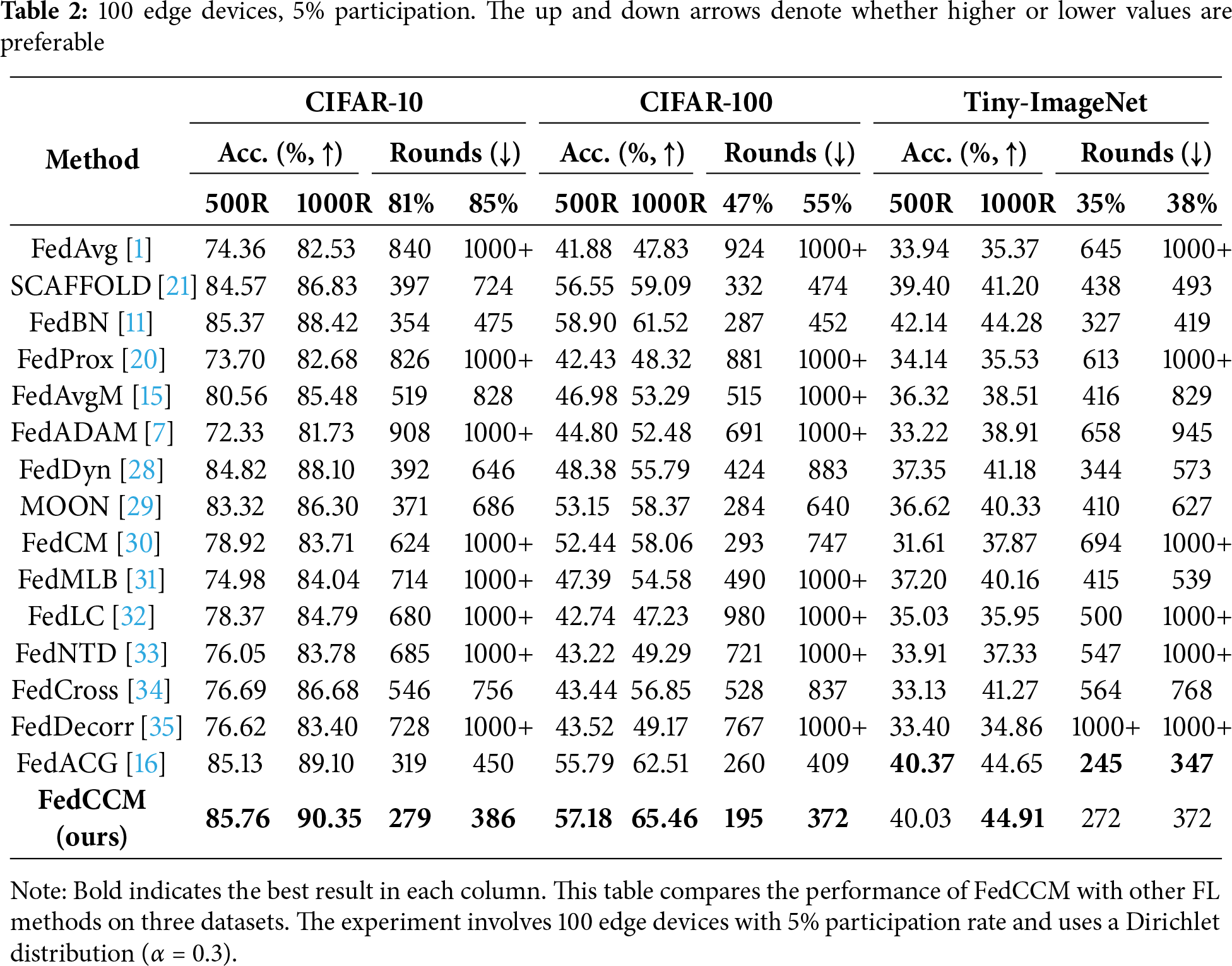

We conducted experiments on three datasets to compare our proposed FedCCM method with several existing FL approaches, such as FedProx, FedDyn and SCAFFOLD. The experimental results are shown in Table 2. The experimental setup involved 100 edge devices with a 5% participation rate, and the local data of each edge was generated using a Dirichlet distribution (

Our experimental results demonstrate that FedCCM is an effective solution for addressing the challenges of non-IID data, optimizing computational efficiency, and enhancing stability.

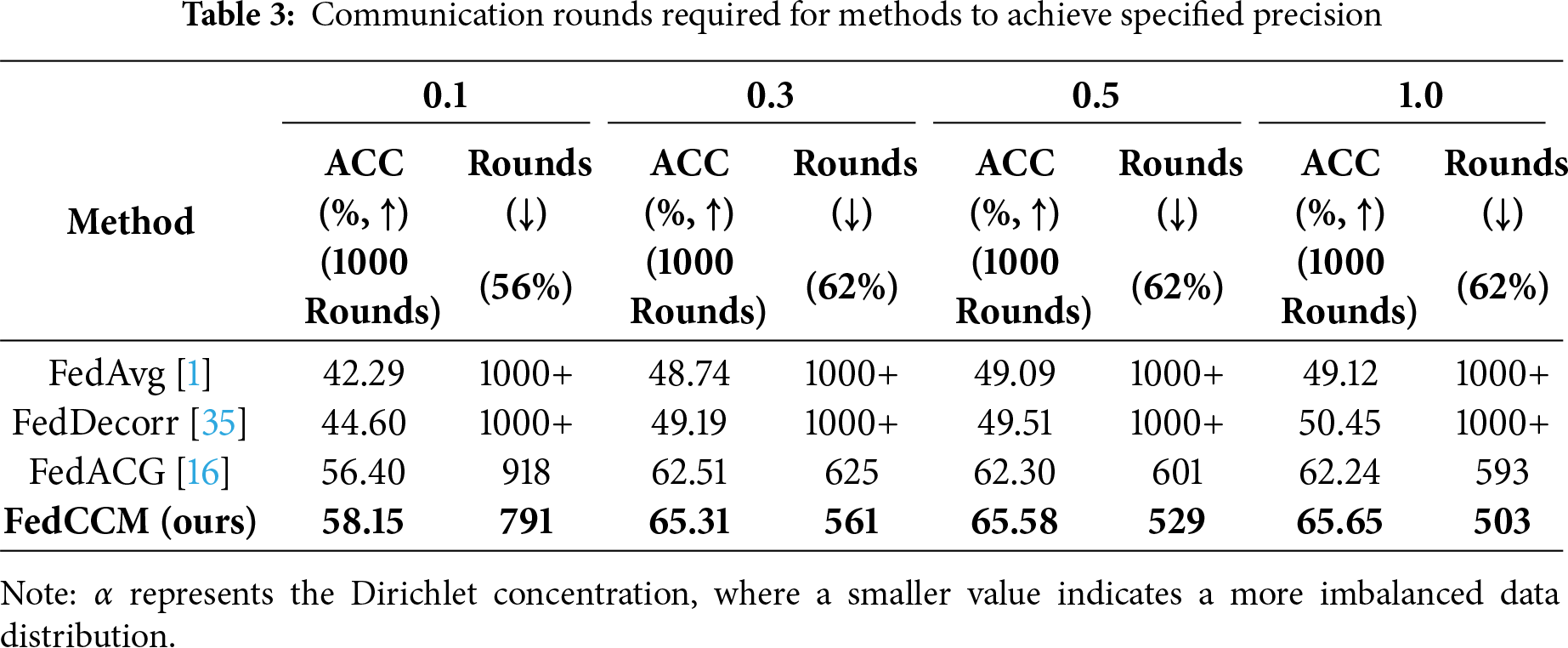

5.3 Performance Evaluation across Different Non-IID Settings

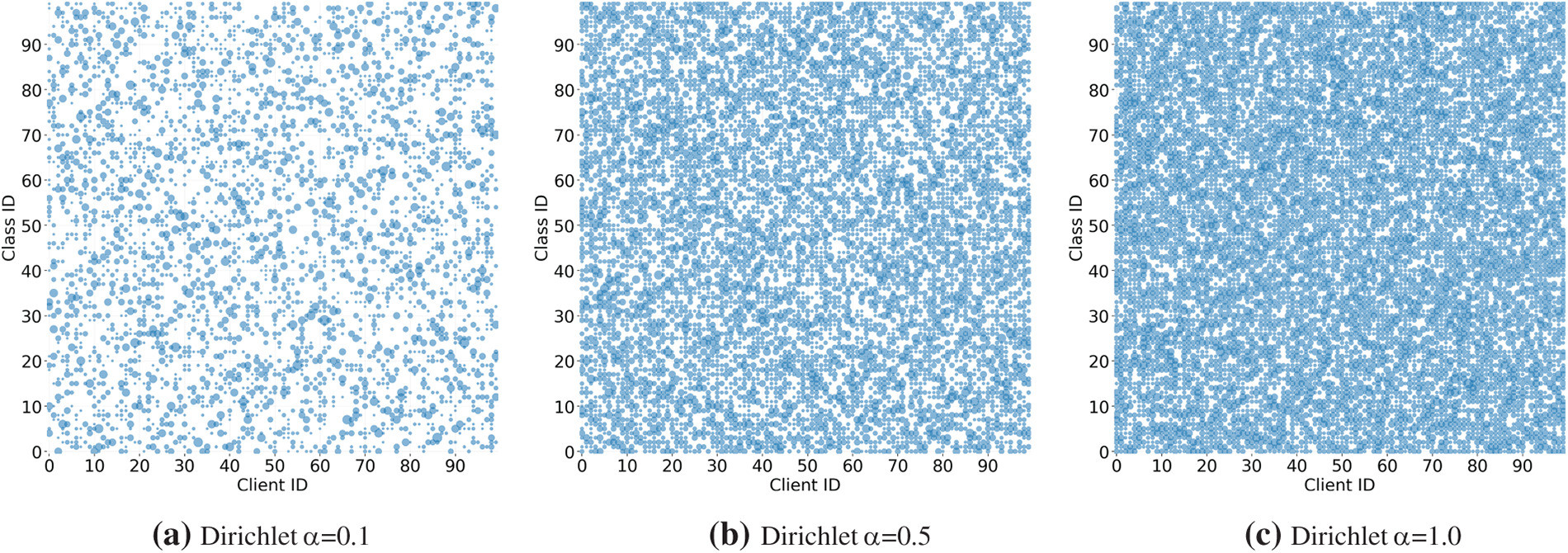

The degree of non-IID data across edge devices significantly affects both the convergence accuracy and the number of communication rounds needed to reach convergence. As shown in Fig. 3, the bubble plots illustrate edge data distributions under different degrees of non-IID. Each bubble represents the number of samples an edge has for a given class; larger bubbles indicate more samples, and the absence of a bubble means that the class is missing for that edge. The figure clearly reveals the distinct differences in edge data distributions across varying non-IID parameters. We compared and analyzed the performance of different methods under various non-IID scenarios. The experiment used the Dirichlet distribution parameter

Figure 3: Bubble plots of edge devices under varying degrees of non-IID. Denser bubbles indicate more uniform data distribution across edge devices, while sparser bubbles suggest more dispersed distributions

From the performance of the baseline methods, FedAvg performed poorly across all non-IID settings. In the most extreme data heterogeneity scenario (

FedCCM achieved the best performance across all experimental settings, showing significant superiority. In the most challenging data distribution setting (

Overall, the experimental results fully validate the effectiveness of FedCCM in addressing the challenges of data heterogeneity in FL, providing a more efficient and stable solution for communication-efficient FL in non-IID scenarios.

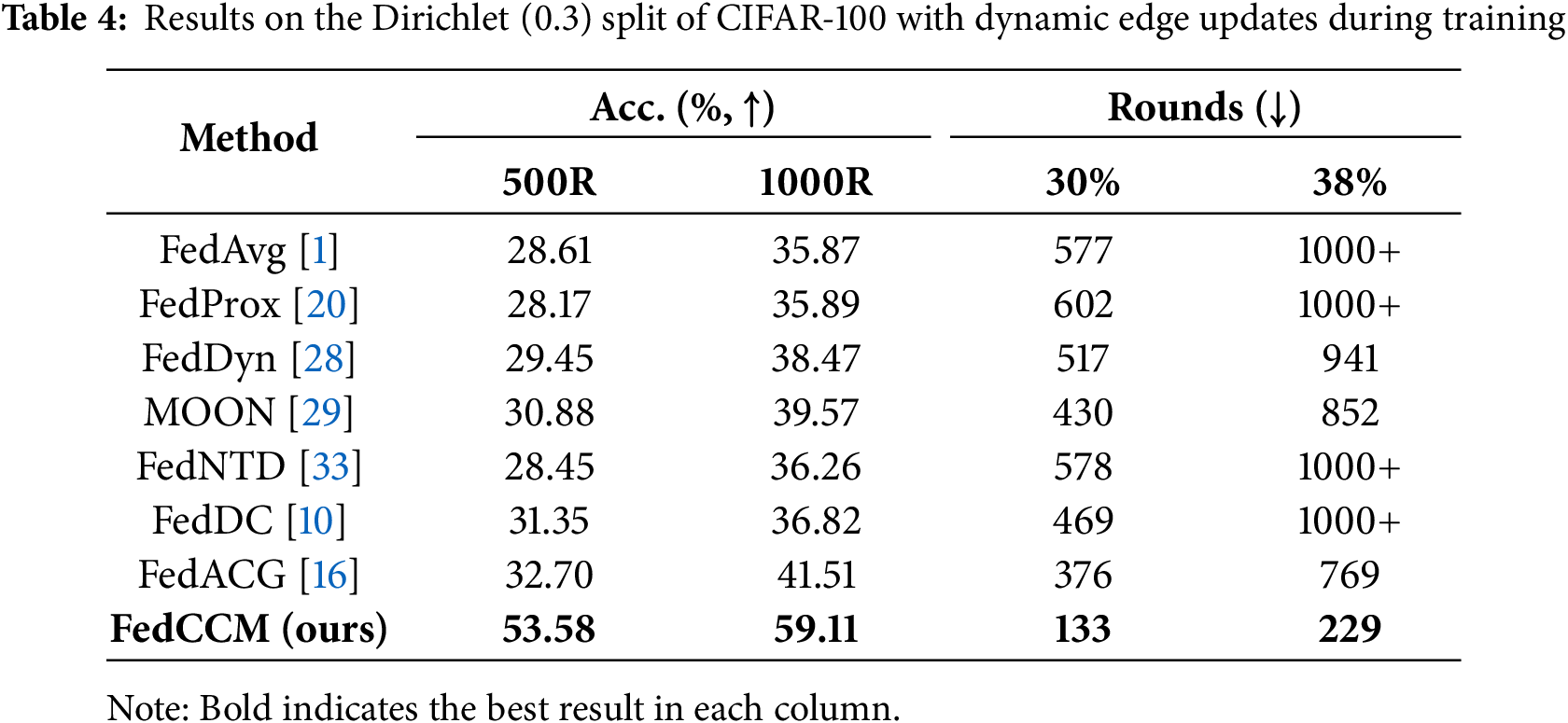

5.4 Robustness under Dynamic Client Participation

Table 4 evaluates FL methods on CIFAR-100 with Dirichlet (0.3) under a dynamic edge set: 250 edge devices are maintained, but each edge is replaced with probability 0.5 every 100 rounds; only 4% participate per round. FedCCM performs best with 53.58% at 500 rounds, 59.11% at 1000 rounds, and only 133 and 229 rounds to reach 30% and 38%. FedACG is the strongest baseline with 32.70% and 41.51%, reaching the targets in 376 and 769 rounds. Since our method caches historical momentum sets on cloud server during execution, it exhibits strong robustness against edge dropouts. Experimental results demonstrate that under this scenario, our approach still achieves outstanding performance.

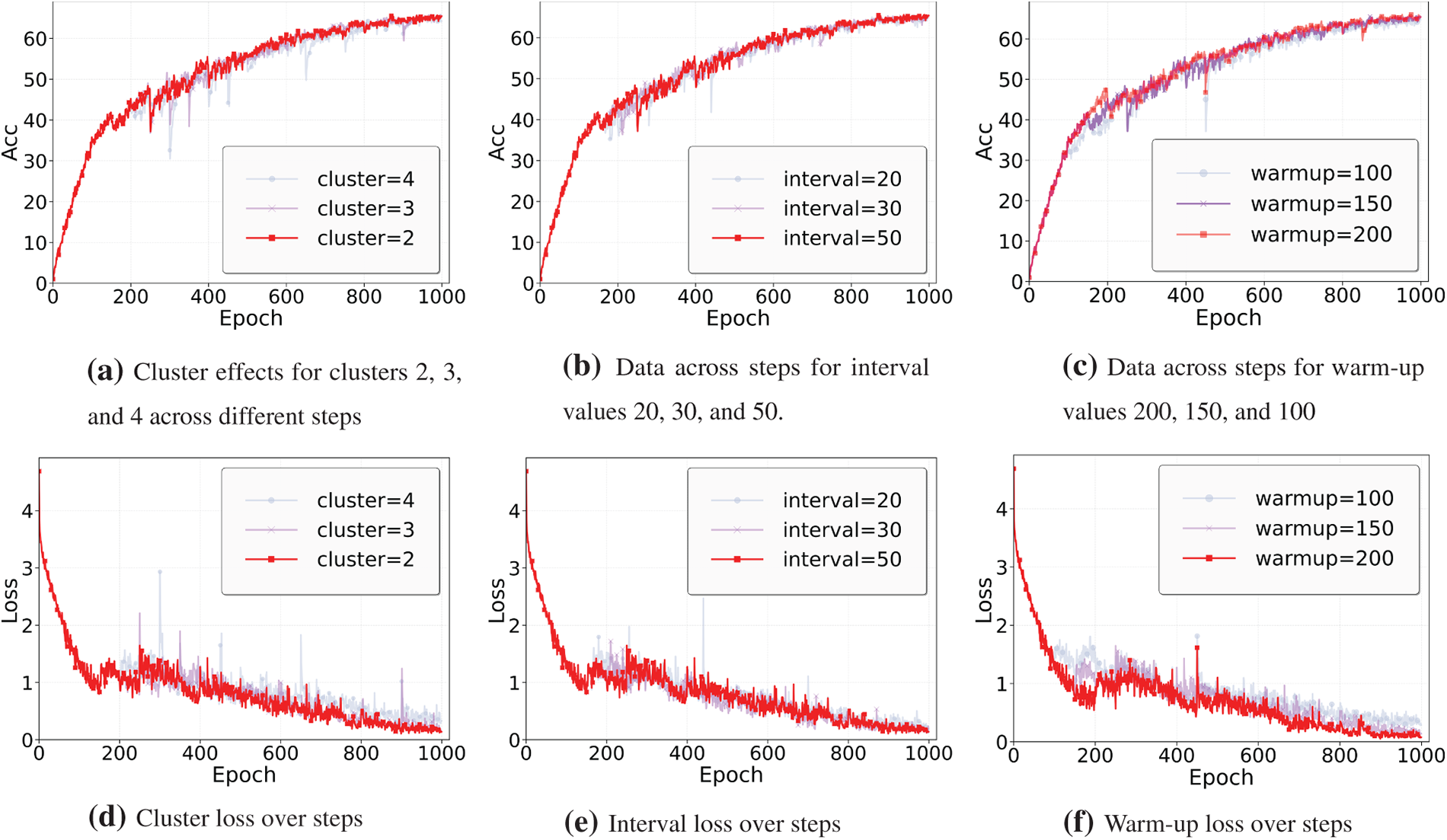

This experiment aims to investigate the impact of three key hyperparameters on model performance: the number of clusters, the aggregation interval in terms of communication rounds, and the number of warm-up rounds. The rationale behind the choice of each hyperparameter and its impact on the model will be discussed in detail below.

Number of Clusters. The number of clusters determines the number of centroids in the model, which influences both the model’s complexity and accuracy. As shown in Fig. 4a, the graph presents the data for clusters 2, 3, and 4 across different steps. In this experiment, we selected 2 clusters. This configuration allows the model to converge quickly on simpler data structures while effectively capturing the main features of the data. Fewer clusters reduce the computational burden and help avoid overfitting. While increasing the number of clusters enhance the model’s capacity to capture finer data details, it also significantly raises the computational cost and can lead to overfitting.

Figure 4: Comparison of effects for clusters, intervals, and warm-up values across steps. The first row shows the accuracy plots, and the second row shows the corresponding loss plots. Higher accuracy is better, and lower loss is preferred

Aggregation Interval in Terms of Communication Rounds. The aggregation interval controls the frequency at which clustering results are updated, directly impacting both the training efficiency and stability of the model. As shown in Fig. 4b, the trend for an interval of 50 rounds is highlighted in purple, illustrating its distinct pattern compared to other intervals. In this experiment, we set the aggregation interval to 50 rounds to balance computational efficiency while allowing the model to converge smoothly. A longer aggregation interval reduces the frequency of clustering updates, thereby lowering the computational burden and helping to avoid potential training instability that could arise from frequent updates, especially on more complex datasets. In contrast, while a shorter interval may accelerate convergence, frequent updates can cause oscillations during training, which could negatively affect the final results.

Warm-Up Rounds. The warm-up phase adjusts the initial learning rate to ensure smooth convergence of the model. As shown in Fig. 4c, we set the warm-up rounds to 200, aiming to balance training speed and stability. A shorter warm-up may cause the model to transition too quickly into the regular learning phase, resulting in training instability. Conversely, a longer warm-up can further stabilize the training process but may unnecessarily extend the training time. The choice of 200 warm-up rounds ensures a gradual increase in the initial learning rate, enhancing convergence stability while avoiding the computational redundancy that could arise from an excessively long warm-up phase.

Through experimental exploration, we chose a configuration with 2 clusters, an aggregation interval of 50 rounds, and 200 warm-up rounds. These hyperparameters were chosen based on the need to optimize model performance, while striving to balance computational efficiency and model stability.

Although FedCCM introduces additional operations on the cloud server, it imposes no extra computational or memory burden on edges, and its communication payload remains identical to FedAvg. The server maintains K cluster-level momentum vectors (each of dimension

Our results show that under non-IID conditions, the proposed method achieves superior accuracy and faster convergence while maintaining the same communication cost. It consistently yields competitive performance across diverse non-IID settings. Remarkably, in the extreme case with

These results can be attributed to our shift from a single global training guidance scheme to a personalized momentum-guided framework, in which we innovatively integrate the k-means algorithm to form momentum-based clusters. In addition, by leveraging historical momentum information on the cloud server, our method demonstrates strong robustness to highly non-IID conditions. Overall, FedCCM provides a promising solution for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of FL, particularly in large-scale and heterogeneous data scenarios.

This study presents FedCCM, a novel FL framework tailored for highly heterogeneous data environments. By shifting from a single global momentum guidance to a personalized, cluster-specific momentum paradigm, FedCCM effectively mitigates edge device drift. We introduce a momentum-driven clustering mechanism based on KMeans to adaptively capture intrinsic data structures and handle outlier edge devices, thereby significantly enhancing training stability and convergence performance. Furthermore, a warm-up mechanism is incorporated into the clustering process, ensuring robust clustering even under low edge participation rates. Experimental results show that FedCCM outperforms multiple baselines, including the original FedACG, in both convergence speed and final accuracy. FedCCM clusters only the momentum uploaded by edges, without accessing the raw data. Its privacy risk is therefore only slightly higher than that of standard FedAvg, and can be mitigated using mechanisms such as differential privacy (DP). Nevertheless, the computational overhead of cloud-side clustering and the reliance on associated hyperparameters remain notable limitations. Future work will focus on developing lightweight online clustering algorithms, integrating the framework with other federated optimization methods, and validating its applicability to broader domains such as federated graph neural networks and federated reinforcement learning.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to everyone who contributed to the completion of this work.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62462040), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202501AT070345), the Major Science and Technology Projects in Yunnan Province (202202AD080013).

Author Contributions: Hang Wen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software Implementation, Experiment Design and Execution, Data Analysis, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. Kai Zeng: Supervision, Theoretical Guidance, Formal Analysis, Writing—Review and Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials supporting the findings of this study are openly available at https://github.com/sjmp525/CollaborativeComputing/tree/FedCCM (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. McMahan HB, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Aguera y Arcas B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017;54. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

2. Yuan L, Wang Z, Sun L, Yu PS, Brinton CG. Decentralized federated learning: a survey and perspective. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(21):34617–38. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3407584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Almanifi ORA, Chow C-O, Tham M-L, Chuah JH, Kanesan J. Communication and computation efficiency in federated learning: a survey. Internet Things. 2023;22(9):100742. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2023.100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pei J, Liu W, Li J, Wang L, Liu C. A review of federated learning methods in heterogeneous scenarios. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(3):5983–99. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3385440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Y, Shen J, Vijayakumar P, Lai C-F, Sivaraman A, Sharma PK. Next-generation consumer electronics data auditing scheme toward cloud-edge distributed and resilient machine learning. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):2244–56. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3368206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tsai C-W, Lai C-F, Chiang M-C, Yang LT. Data mining for internet of things: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2014;16(1):77–97. doi:10.1109/SURV.2013.103013.00206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Reddi S, Charles Z, Zaheer M, Garrett Z, Rush K, Konečný J, et al. Adaptive federated optimization. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021 May 3–7; Virtual. p. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhang J, Guo S, Qu Z, Zeng D, Zhan Y, Liu Q, et al. Adaptive federated learning on non-IID data with resource constraint. IEEE Trans Comput. 2022;71(7):1655–67. doi:10.1109/TC.2021.3099723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Q, Diao Y, Chen Q, He B. Federated learning on non-IID data silos: an experimental study. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2022 May 9–12; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 965–78. doi:10.1109/ICDE53745.2022.00077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gao L, Fu H, Li L, Chen Y, Xu M, Xu C. FedDC: federated learning with non-IID data via local drift decoupling and correction. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 10112–21. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li X, Jiang M, Zhang X, Kamp M, Dou Q. FedBN: federated learning on non-IID features via local batch normalization. In: 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021; 2021 May 3–7; Virtual. p. 1–27. doi:10.1109/ictai52525.2021.00138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pillutla K, Malik K, Mohamed A-R, Rabbat M, Sanjabi M, Xiao L. Federated learning with partial model personalization. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning. Vol. 162. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 17716–58. [Google Scholar]

13. Jiang M, Le A, Li X, Dou Q. Heterogeneous personalized federated learning by local-global updates mixing via convergence rate. In: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024 May 7–11; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

14. Marfoq O, Neglia G, Vidal R, Kameni L. Personalized federated learning through local memorization. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning. Vol. 162. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 15070–92. [Google Scholar]

15. Hsu T-MH, Qi H, Brown M. Measuring the effects of non-identical data distribution for federated visual classification. arXiv:1909.06335. 2019. [Google Scholar]

16. Kim G, Kim J, Han B. Communication-efficient federated learning with accelerated client gradient. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–10. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ghosh A, Chung J, Yin D, Ramchandran K. An efficient framework for clustered federated learning. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Dec 6–12; Virtual. Vol. 33. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2020. p. 8329–41. doi:10.1109/TIT.2022.3192506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shamsian A, Navon A, Fetaya E, Chechik G. Personalized federated learning using hypernetworks. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning. vol. 139; Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 9489–502. [Google Scholar]

19. Yao D, Li X, Chen M, Wang Z, Liu J, Zhang H. PerFedRLNAS: one-for-all personalized federated neural architecture search. In: Proceedings of the 38th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024 Feb 20–27; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2024. p. 1–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i15.29576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li T, Sahu AK, Zaheer M, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. In: Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems; 2020 Mar 2–4; Austin, TX, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 429–50. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1812.06127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Karimireddy SP, Konečný J, Jaggi M, Stich SU. SCAFFOLD: stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In: Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning. Vol. 119. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2020. p. 5132–43. [Google Scholar]

22. Xu H, Li J, Wu W, Ren H. Federated learning with sample-level client drift mitigation. In: Proceedings of the 39th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2025 Feb 25–Mar 4; Philadelphia, PA, USA. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2025. p. 21752–60. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2501.11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fang W, Han DJ, Chen E, Wang S, Brinton CG. Hierarchical federated learning with multi-timescale gradient correction. In: NIPS ’24: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc. p. 78863–904. [Google Scholar]

24. Chen X, Li Y, Wang J, Zhang M, Liu Q, Zhao K. Federated learning with joint server-client momentum. Heliyon. 2025;11(2):e24567. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-99385-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sun J, Wu X, Huang H, Zhang A. On the role of server momentum in federated learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(13):15164–72. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i13.29439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Krizhevsky A, Hinton G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto; 2009. [Google Scholar]

27. Le Y, Yang X. Tiny imagenet visual recognition challenge. CS 231N. 2015;7(7):3. [Google Scholar]

28. Acar DA, Zhao Y, Matas R, Mattina M, Whatmough P, Saligrama V. Federated learning based on dynamic regularization. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021 May 3–7; Virtual. Vienna, Austria: ICLR; 2021. [Google Scholar]

29. Li Q, He B, Song D. Model-contrastive federated learning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 19–25; Virtual. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 10713–22. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xu J, Wang S, Wang L, Yao AC-C. FedCM: federated learning with client-level momentum. arXiv:2106.10874. 2021. [Google Scholar]

31. Kim J, Kim G, Han B. Dataset condensation via efficient synthetic-data parameterization. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning. Vol. 162. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 11058–73. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhang X, Li Y, Li W, Guo K, Shao Y. Personalized federated learning via variational Bayesian inference. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. Vol. 162. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 26293–310. [Google Scholar]

33. Lee G, Jeong M, Shin Y, Bae S, Yun S-Y. Preservation of the global knowledge by not-true distillation in federated learning. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. Vol. 35. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2022. p. 38461–74. [Google Scholar]

34. Hu M, Zhang Y, Wang H, Li J, Chen X. FedCross: towards accurate federated learning via multi-model cross-aggregation. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2024 Apr 16–20; Utrecht, Netherlands. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1234–46. doi:10.1109/ICDE60146.2024.00170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shi Y, Liang J, Zhang W, Tan VYF, Bai S. Towards understanding and mitigating dimensional collapse in heterogeneous federated learning. arXiv.2210.00226. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools