Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DyLoRA-TAD: Dynamic Low-Rank Adapter for End-to-End Temporal Action Detection

1 School of Information Science and Technology, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

2 Yunnan Key Laboratory of Smart Education, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

3 Key Laboratory of Education Informatization for Nationalities, Ministry of Education, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

4 School of Cyber Science and Technology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510275, China

* Corresponding Author: Shu Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Action Recognition: Algorithms, Applications, and Emerging Trends)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 92 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072964

Received 08 September 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

End-to-end Temporal Action Detection (TAD) has achieved remarkable progress in recent years, driven by innovations in model architectures and the emergence of Video Foundation Models (VFMs). However, existing TAD methods that perform full fine-tuning of pretrained video models often incur substantial computational costs, which become particularly pronounced when processing long video sequences. Moreover, the need for precise temporal boundary annotations makes data labeling extremely expensive. In low-resource settings where annotated samples are scarce, direct fine-tuning tends to cause overfitting. To address these challenges, we introduce Dynamic Low-Rank Adapter (DyLoRA), a lightweight fine-tuning framework tailored specifically for the TAD task. Built upon the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) architecture, DyLoRA adapts only the key layers of the pretrained model via low-rank decomposition, reducing the number of trainable parameters to less than 5% of full fine-tuning methods. This significantly lowers memory consumption and mitigates overfitting in low-resource settings. Notably, DyLoRA enhances the temporal modeling capability of pretrained models by optimizing temporal dimension weights, thereby alleviating the representation misalignment of temporal features. Experimental results demonstrate that DyLoRA-TAD achieves impressive performance, with 73.9% mAP on THUMOS14, 39.52% on ActivityNet-1.3, and 28.2% on Charades, substantially surpassing the best traditional feature-based methods.Keywords

Temporal Action Detection (TAD) [1–3] is a fundamental yet highly challenging task in the field of video understanding [4–6]. Its core objective is to identify specific action categories and localize their start and end times within untrimmed long videos. This task holds significant practical value in various critical domains, such as surveillance and security [7], educational video analysis [8], healthcare monitoring, and autonomous driving.

In recent years, TAD models have made significant progress in architectural design. However, recent studies have highlighted two emerging trends: end-to-end training [9–11] and fine-tuning of vision foundation models [12,13]. End-to-end TAD methods [9,10,14,15] jointly train video encoders and action detectors, enabling simultaneous modeling of local spatiotemporal features and global temporal dependencies, while offering notable advantages over feature-based methods [16–18] by facilitating knowledge transfer from pretrained models. Fine-tuning pretrained vision models, either fully [19,20] or partially, has shown strong performance across various downstream vision tasks. In TAD, recent end-to-end methods incorporate such fine-tuning to further improve performance. For example, Liu et al. [14] proposed the Temporal-Informative Adapter (TIA), which partially fine-tunes models like VideoMAE-S [21] and achieves notable improvements over traditional feature-based detection methods.

It is evident that integrating the strengths of end-to-end training with the fine-tuning of large vision models can significantly enhance the generalization ability and computational efficiency of TAD models, thereby facilitating progress toward higher accuracy and real-time performance. However, current end-to-end approaches in TAD predominantly rely on computationally intensive full fine-tuning, which often leads to issues such as catastrophic forgetting and overfitting during transfer learning—particularly when applied to downstream datasets with limited annotations, a common scenario in the TAD domain.

In this work, we aim to overcome the aforementioned limitations by enhancing TAD performance through the integration of vision foundation model fine-tuning and end-to-end training. In recent years, vision foundation models such as ViT [22] and VideoMAE [21] have demonstrated remarkable transferability across various video understanding tasks. This has motivated researchers to explore more efficient fine-tuning strategies that can fully leverage the pretrained knowledge while minimizing interference with the model’s original parameters. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [23] introduces learnable low-rank matrices into pretrained models, allowing efficient adaptation to new tasks with minimal parameter overhead while mitigating overfitting.

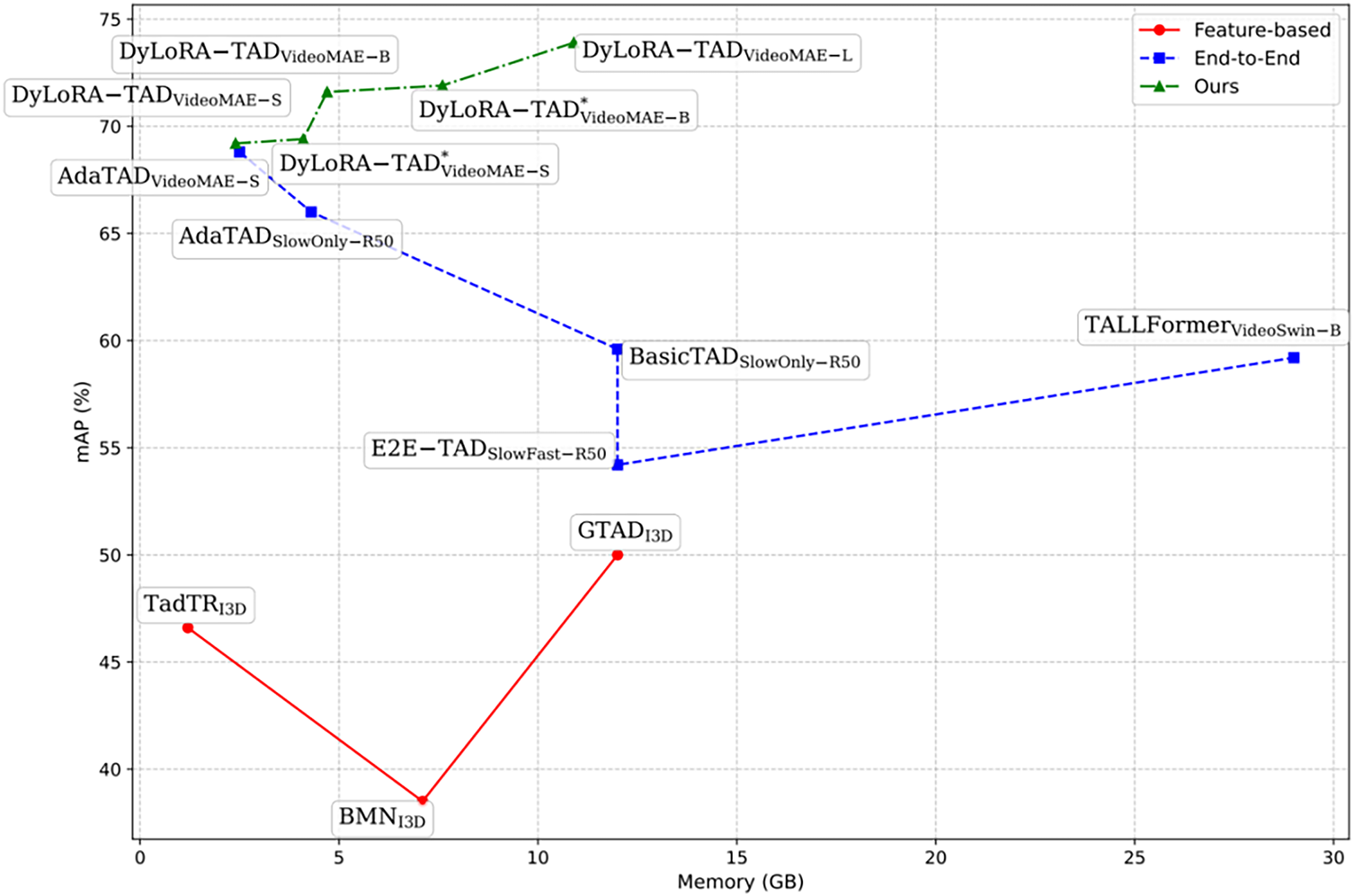

We designed the Dynamic Low-Rank Adapter (DyLoRA) and applied it to the TAD task, forming the DyLoRA-TAD method. This approach significantly enhances the end-to-end training efficiency of TAD models through a lightweight architecture design. As shown in Fig. 1, the proposed method (DyLoRA-TAD) achieves remarkable results in the TAD task by cleverly combining the strengths of end-to-end training and fine-tuning strategies.

Figure 1: Comparison of different TAD models in terms of mean Average Precision (mAP, %, y-axis) and GPU memory usage during training (GB, x-axis). In the figure, the blue line represents the performance of a series of end-to-end trained TAD models, the red line represents the performance of feature-based TAD models, and the green line corresponds to the proposed DyLoRA-TAD methods

To achieve these goals, we first constructed an end-to-end baseline based on the efficient TAD framework Actionformer [18]. Experiments revealed that full fine-tuning introduces significant computational redundancy. To address this, we propose an adaptive rank adjustment mechanism that dynamically controls the update rank of adaptation parameters, balancing parameter size and performance. Based on this, we designed DyLoRA, a novel adapter deployed as the only learnable module between backbone layers. DyLoRA is optimized for TAD tasks and incorporates a temporal dimension weight optimization, effectively mitigating the loss of temporal feature representation caused by partial fine-tuning. Validated on multiple TAD datasets, DyLoRA-TAD achieves 73.9% mAP on THUMOS14, demonstrating the effectiveness of combining end-to-end training with parameter-efficient fine-tuning in TAD.

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

1. We propose a lightweight Dynamic Low-Rank Adapter. Unlike traditional low-rank adaptation methods with static rank configuration, DyLoRA dynamically adjusts the update rank of the adaptation parameters, adaptively balancing computational resource consumption and model performance. Additionally, DyLoRA enables progressive optimization of the temporal dimension weights while freezing the pretrained spatial feature extractor, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to model complex temporal dependencies in long video sequences.

2. Based on DyLoRA, we design an efficient end-to-end TAD framework named DyLoRA-TAD. By fine-tuning only a small subset of parameters in the pretrained model, the framework requires less than 5% of the parameters compared to full fine-tuning methods, yet achieves superior performance. This parameter-efficient fine-tuning strategy not only consistently boosts performance but also highlights the significance of vision foundation model fine-tuning in TAD. Furthermore, by adopting partial fine-tuning under different application scenarios, it effectively mitigates the computational overhead of full fine-tuning and the overfitting issue in low-resource settings.

3. This paper conducts in-depth research based on the DyLoRA-TAD framework, exploring the potential value of multi-scale feature aggregation in enhancing model performance. We constructed the Temporal DyLoRA Fuser module, which fine-tunes the weight allocation between components to achieve effective integration of multi-source feature information. This strategy not only strengthens the expressive capability of the original framework but also significantly improves overall performance, leading to the evolution of a more advanced DyLoRA-TAD*.

Existing TAD methods can be mainly divided into three categories: one-stage methods [6,16,18,24], two-stage methods [22,25–28], and DETR-based methods [29,30]. One-stage methods refer to approaches that directly perform action localization and classification within a multi-scale feature pyramid framework. For example, TriDet [16] improves the pyramid structure to enhance model performance. One-stage methods are efficient for real-time processing but may lack precise localization of action boundaries in complex scenarios. Two-stage methods first use one stage for feature extraction and optimization, followed by a second stage to refine these features for improved accuracy. For instance, BMN [17] jointly optimizes boundary prediction and boundary matching processes, allowing for more precise localization of action segments and improving detection accuracy. Two-stage methods are suitable for handling complex action patterns but tend to have higher computational costs. DETR-based methods use the Transformer [31,32] architecture for end-to-end action detection. For example, TadTR [29] leverages self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies, making it particularly well-suited for multi-scale actions and complex background interference, demonstrating strong representational capabilities. MD-TAPN [16] introduces a truncated attention-aware proposal network with multi-scale dilation to improve action boundary localization and detection accuracy, especially for complex temporal patterns.

From the perspective of feature learning, TAD methods can be further divided into two categories: feature-based methods and end-to-end training methods. Feature-based methods [9,33–35] typically separate feature extraction and action detection into two distinct stages, relying on pre-extracted features such as RGB or optical flow. This results in a disconnection between feature representation and detection objectives. In contrast, end-to-end methods [9,11,14,29,36] jointly optimize feature extraction and detection tasks through deep learning models. For example, PBRNet [36] reduces redundant computation by predicting action boundaries and categories in parallel. PCL [37] proposes a prototype contrastive learning framework for point-supervised TAD, enhancing feature representation and action localization under weak supervision. ActionFormer [18] uses Transformers to encode global temporal context and directly outputs action segments; TadTR [29] introduces learnable query vectors to locate actions, simplifying the detection process. Despite the significant progress made by end-to-end methods, most still rely on full fine-tuning paradigms, which face the challenge of high computational costs, requiring further optimization of lightweight training strategies.

2.2 Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

In recent years, Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) [38–41] has emerged as a research hotspot in deep learning. Compared to full fine-tuning methods, PEFT introduces a small number of trainable parameters into the pretrained model, significantly reducing computational costs and memory usage while preserving the integrity of the pretrained knowledge. In TAD tasks, the high-dimensional spatio-temporal features of video data often lead to a sharp increase in model parameters, making PEFT particularly important for reducing computational resource consumption.

Existing studies have explored a variety of PEFT strategies. For example, the early Adapter Tuning [42] inserts lightweight adaptation modules between Transformer layers to enable parameter-efficient updates. Subsequent methods like Prompt Tuning [43] and Prefix Tuning [44] introduce learnable prompt tokens to adapt models to specific scenarios, though their effectiveness is limited in long-sequence tasks. LoRA perturbs pretrained weights using low-rank decomposition of weight increments, enabling zero inference latency while preserving the original computational graph structure, offering a new perspective for joint visual-temporal modeling.

Although PEFT significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters, tasks such as video understanding, which are both data-intensive and computationally demanding, still require more efficient fine-tuning solutions. Our work builds on PEFT methods, particularly drawing inspiration from the LoRA mechanism, to explore its potential in TAD tasks for the first time, and adopts a more efficient design framework to enhance performance.

In this section, we will progressively introduce DyLoRA-TAD. First, we will define some symbols and explore end-to-end TAD methods to establish an end-to-end baseline model. Next, we will introduce DyLoRA, a dynamic low-rank adapter designed specifically for efficient TAD. Finally, we propose the Temporal DyLoRA Fuser module, aimed at enhancing DyLoRA’s ability to model temporal features across different dimensions, resulting in the formation of DyLoRA-TAD*.

The task definition of TAD is as follows:

The proposed end-to-end TAD architecture consists of two main components: feature extraction and action detection. To enable the model to better understand and distinguish action transitions in videos, we adopt ActionFormer as the action detection module.

In the feature extraction stage, Snippet Representation and Frame Representation are two common approaches for encoding raw video frames. The snippet representation method divides a video into multiple short segments (e.g., 16 frames each), with each snippet processed by a backbone network to extract segment-level features. In contrast, the frame representation method treats the entire video as a single snippet and feeds it directly into the network, extracting only spatially pooled features. This approach is particularly suitable for attention-based models, as it effectively reduces the complexity of temporal attention computation. According to previous studies [14], frame representation not only outperforms snippet representation in terms of performance but also consumes less memory. Therefore, we adopt frame representation to encode videos in our experiments.

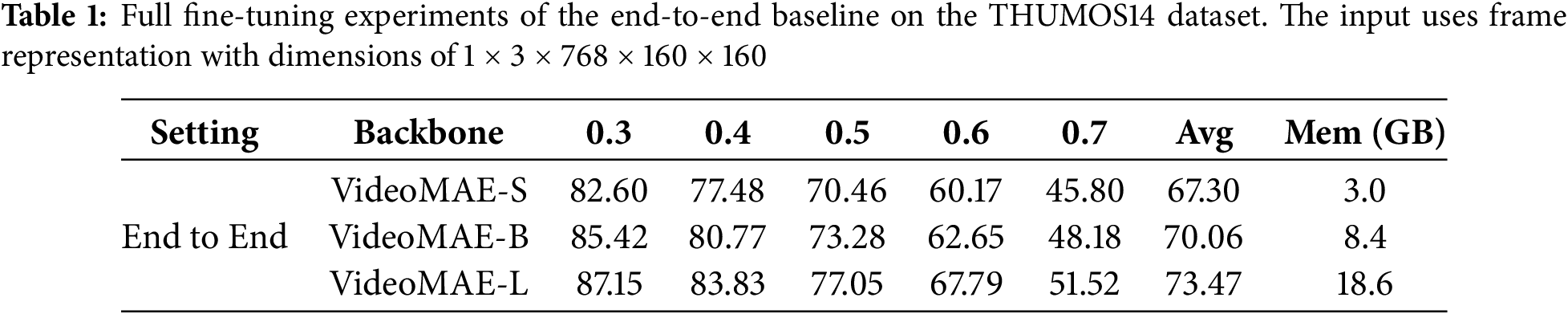

In Table 1, when extending from the smaller video backbone network VideoMAE-S [21] to a larger-scale model, the simple end-to-end baseline we constructed experiences a significant surge in computational resource consumption during training. More importantly, this baseline employs the full fine-tuning approach, resulting in insufficient transfer learning capability. Furthermore, in low-resource settings, full fine-tuning is prone to overfitting or catastrophic forgetting. If the downstream task’s dataset lacks sufficient diversity, it can even undermine the powerful feature representations learned from the pre-trained model.

To address the issues of the end-to-end baseline, this paper adopts a parameter-efficient fine-tuning mechanism and proposes a fine-tuning module called DyLoRA to achieve efficient transfer learning for end-to-end TAD.

First, let’s review the structure of the LoRA, which was proposed in research [23]. For a standard pre-trained Transformer model, its linear transformation is typically represented as:

here,

To avoid directly updating the original weight matrix

here, matrix

Finally, the low-rank adjustment term

In LoRA, a scaling factor

While LoRA enhances efficiency by fine-tuning low-rank decomposed weights, its fixed-rank constraint hinders the modeling of task-specific complexities, thus limiting adaptability to diverse scenarios. To overcome this limitation, we propose the DyLoRA, as shown in Fig. 2b.

Figure 2: Architecture of (a) LoRA Adapter and our (b) Dynamic Low-Rank Adapter (DyLoRA). We design a Rank Estimator to enable dynamic rank adjustment

DyLoRA retains the residual design of LoRA, where the input data

where

Then, the DyLoRA layer is used for model parameter updates and low-rank adaptation. In the DyLoRA layer, we design a rank estimator. The rank estimator consists of three linear layers and ReLU activation functions, with the final layer using the Sigmoid activation function

here,

Following this, in DyLoRA, the low-rank matrix operation continues, where the rank

here,

Finally, the two branches are fused to obtain

here,

DyLoRA introduces a dynamic rank adjustment mechanism that adaptively tunes the rank of low-rank matrices and other key hyperparameters based on the characteristics of the input data. This allows the model to effectively address varying task demands and complexity. By leveraging the benefits of adaptive parameter modulation, DyLoRA flexibly optimizes the model during training to fully unleash the potential of large-scale pre-trained models, while overcoming the performance bottlenecks encountered by traditional LoRA in handling highly complex tasks. In particular, DyLoRA mitigates performance degradation caused by increasing rank through optimized update scaling, ensuring efficient and stable fine-tuning across diverse application scenarios. As a result, DyLoRA is especially well-suited for applications that seek optimal performance in resource-constrained environments, enhancing both model efficiency and expressiveness.

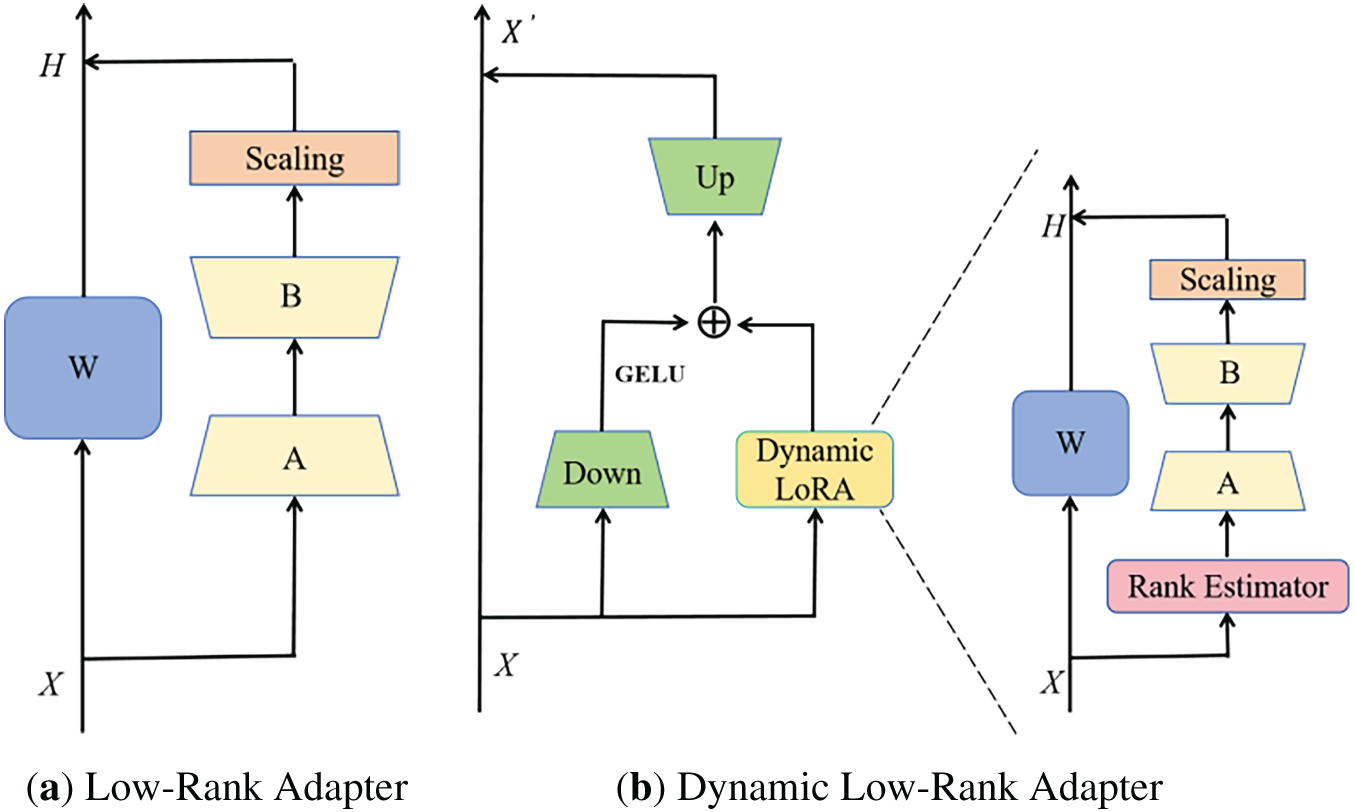

The overall architecture of our end-to-end training model is shown in Fig. 3. The architecture mainly consists of four parts: First, the feature embedding layer, which converts the input video into feature vectors; Next, the frozen Transformer layers, which use pre-trained parameters and remain fixed during training, aimed at leveraging their powerful feature extraction capabilities to provide stable foundational feature representations; Then, the Dynamic Low-Rank Adapter module, which fine-tunes and adapts to different application scenarios; Finally, the detection head, which detects and locates action instances in the video from the refined feature representations.

Figure 3: The overall architecture of DyLoRA-TAD for temporal action detection, including the feature embedding layer, frozen Transformer layers, learnable DyLoRA layers, and detection head

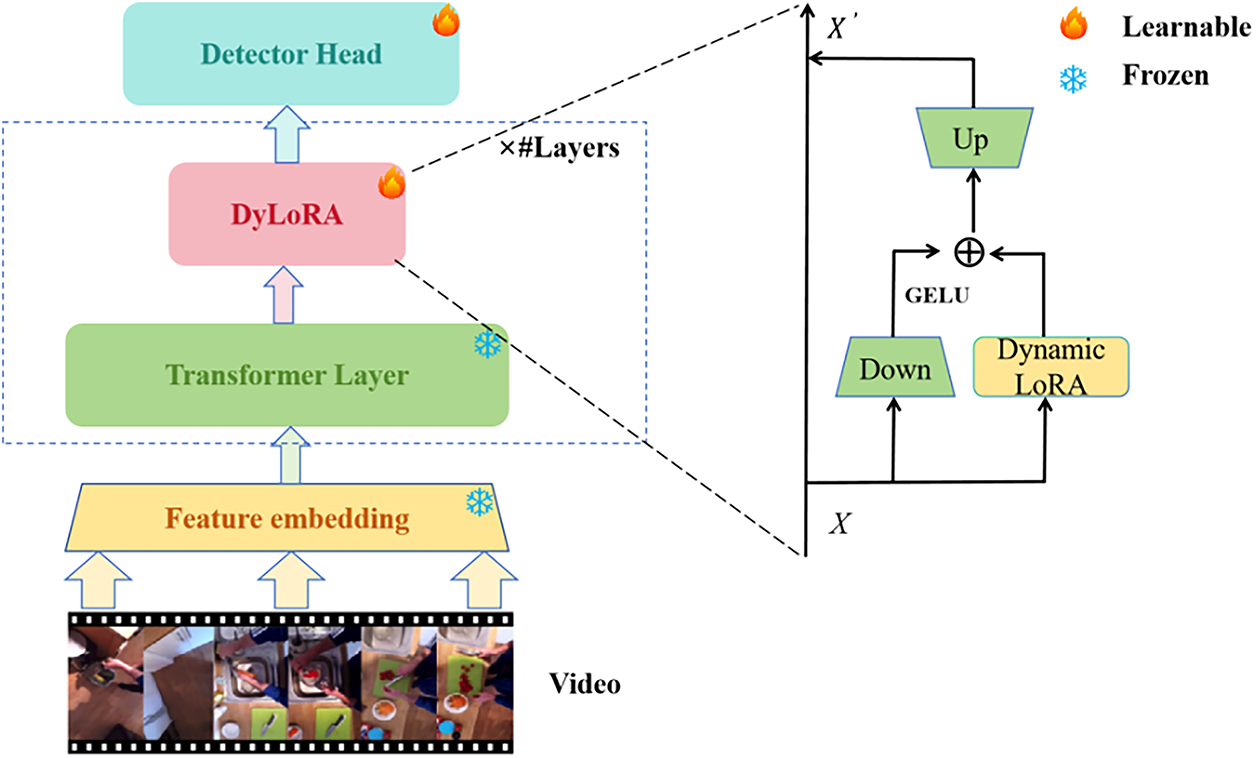

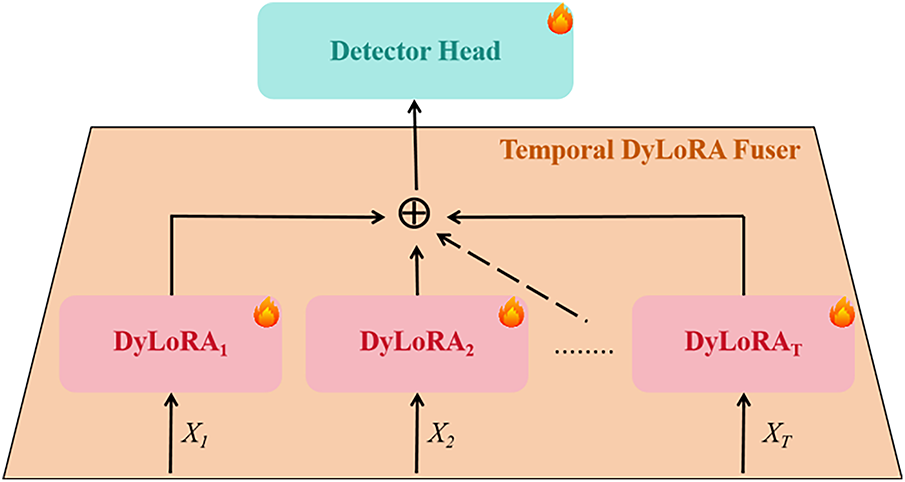

To further investigate the impact of multi-scale temporal feature fusion [45] on the optimization of the DyLoRA-TAD, we designed a simple yet effective module named Temporal DyLoRA Fuser. As illustrated in Fig. 4, this module is primarily integrated between each DyLoRA layer and the detection head, serving to enhance temporal feature representation across different scales.

Figure 4: The Temporal DyLoRA Fuser. This module processes multi-scale temporal features through multiple DyLoRA layers and enhances the DyLoRA-TAD model’s capability to understand and handle complex temporal sequences by fusing the outputs of these layers

First, we initialize a weight vector matrix

Finally, a weighted summation is applied to fuse the temporal features extracted from different adapters, resulting in the fused representation

In this process, we introduce the concept of multi-scale temporal feature fusion, which captures dynamic changes in video sequences across different temporal scales. This approach not only enables the model to better understand the video content but also improves the accuracy of complex action recognition. Moreover, by applying the Softmax function to the weight vector, the relative importance of each adapter is effectively quantified, thus guiding the subsequent feature fusion process more precisely. Ultimately, the fused features generated through this method provide the detection head with richer and more representative information, contributing to the overall performance improvement of the model.

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

To validate the effectiveness of our proposed method, we conduct experiments on three widely used action detection datasets: THUMOS14 [46], ActivityNet-1.3 [47], and Charades [48]. THUMOS14 consists of 20 action categories and 413 untrimmed third-person videos, and it is widely adopted in action detection tasks. ActivityNet-1.3 covers a diverse range of daily activity categories, containing over 10,000 YouTube videos, making it a large-scale benchmark for video understanding. Charades focuses on multi-label action detection in everyday indoor scenarios and is particularly suitable for studying complex video understanding and action interaction.

Based on common evaluation standards, we use mean average precision (mAP) at different Temporal Intersection over Union (tIoU) thresholds and the average mAP as performance evaluation metrics. Specifically, for the ActivityNet-1.3 dataset, the tIoU thresholds are {0.5, 0.75, 0.95}; for the THUMOS14 dataset, the tIoU thresholds are {0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7}; and for the Charades dataset, we primarily evaluate the average mAP at different tIoU thresholds.

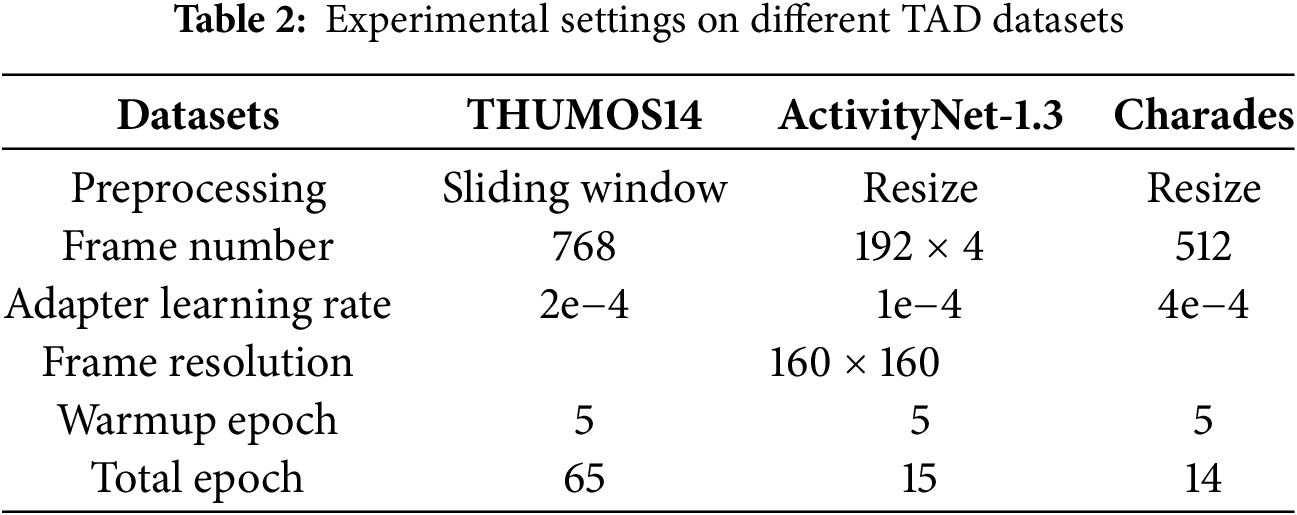

The experiments were conducted using PyTorch 2.0 [49] and the MMAction2 [50] framework, with training performed on two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs. The model’s detection head utilizes the Actionformer architecture, and only the adapter parameters in the backbone network are trained, while the other parameters are frozen. The hyperparameter configurations for different datasets are detailed in Table 2. For data preprocessing, we followed previous research [14]. Considering the variation in action durations in the ActivityNet-1.3 dataset, we resized the videos to a fixed length of 768 frames. For the THUMOS14 and Charades datasets, as the videos are generally longer, we randomly cropped fixed-length segments for processing. To demonstrate the statistical reliability of the experimental results, we report the average and standard deviation (mean ± std) over three independent runs under the same settings.

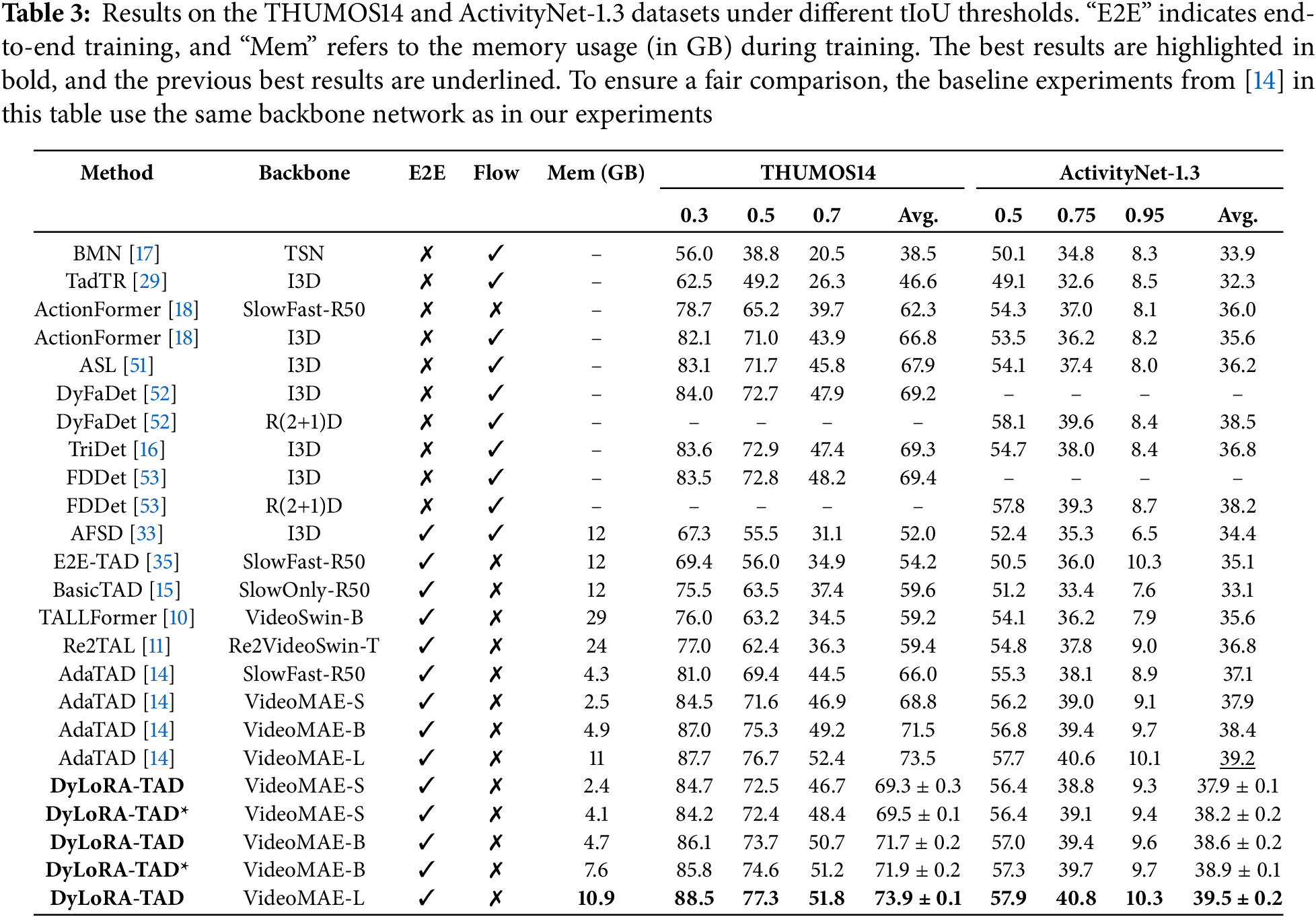

4.3 Comparison and Analysis with State-of-the-Art Methods

Table 3 shows a performance comparison of our proposed DyLoRA-TAD with other state-of-the-art methods on the THUMOS14 dataset. In the preliminary experiments, we used the VideoMAE-S version as the backbone network, which was previously applied in [14]. In contrast, our DyLoRA adapter outperforms its design based on deep convolution TIA adapters, achieving better performance with lower memory consumption. This comparison further highlights the advantages of LoRA fine-tuning and end-to-end training. The experimental results show that after applying DyLoRA for low-rank adaptation, the DyLoRA-TAD model achieves a 73.9% performance improvement on the THUMOS14 dataset.

In addition, we conducted exploratory experiments with the DyLoRA-TAD* variant on the THUMOS14 dataset. The results show that, whether using VideoMAE-S [21] or VideoMAE-B [21] as the backbone network, DyLoRA-TAD* consistently outperforms the original DyLoRA-TAD model. However, when training the DyLoRA-TAD* model with the VideoMAE-L [21] backbone in an end-to-end manner, we encountered GPU memory overflow due to the large model size and limited GPU resources. To mitigate memory limitations, future work could adopt gradient checkpointing, mixed-precision training, or smaller backbone variants. Experiments with smaller VideoMAE backbones show that DyLoRA significantly reduces memory usage and remains scalable for long videos under standard hardware. Nevertheless, based on the completed experimental results, we can confirm that the Temporal DyLoRA Fuser module provides a clear performance boost to the DyLoRA-TAD.

Meanwhile, Table 3 presents the mAP performance of different methods on the ActivityNet-1.3 dataset under various tIoU thresholds. The experimental results demonstrate that our proposed DyLoRA-TAD method significantly outperforms other approaches across all evaluation metrics. As the scale of the backbone network increases, DyLoRA-TAD shows a clear upward trend in performance. Notably, DyLoRA-TAD excels under higher tIoU thresholds, highlighting its strong capability for precise temporal localization. Moreover, compared to state-of-the-art methods such as AdaTAD [14] and TriDet [16], DyLoRA-TAD achieves an average mAP of 39.52% across the entire tIoU range, surpassing all baselines and further emphasizing its superior performance.

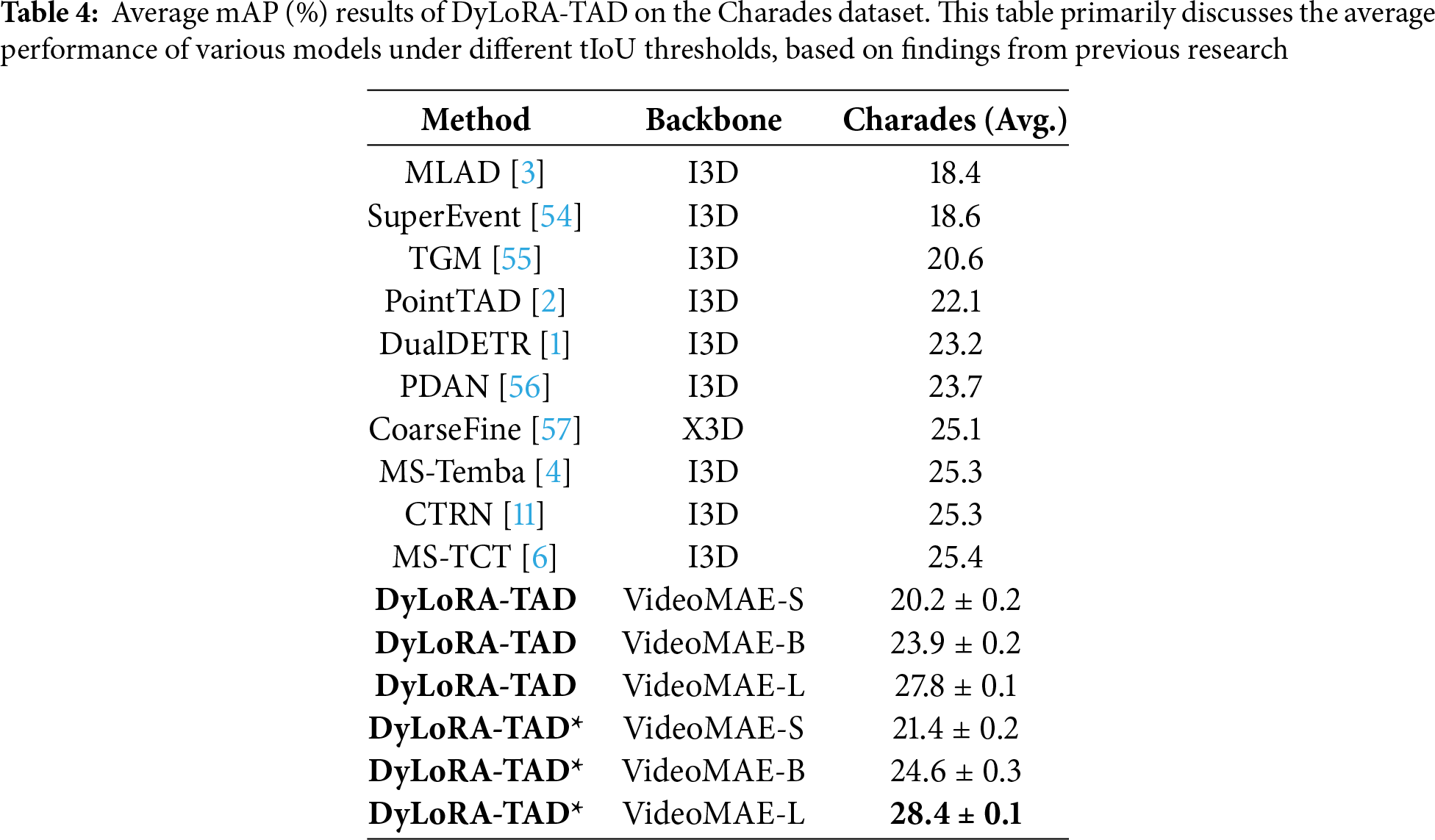

We also present the performance of DyLoRA-TAD on the Charades dataset (see Table 4). When using VideoMAE-L [21] as the backbone network, the model achieved an average mAP of 27.8%, demonstrating its efficient performance in action detection. Additionally, we conducted experiments with the DyLoRA-TAD* variant on the Charades dataset. The results showed that the model achieved an average mAP of 28.4%, further confirming that the Temporal DyLoRA Fuser effectively optimizes the DyLoRA-TAD model.

Overall, as model complexity and video processing improve, average mAP increases, highlighting the importance of choosing suitable architectures and backbones for TAD. While DyLoRA-TAD performs strongly, it still has limitations: on THUMOS14, short-duration actions are hard to localize precisely; on ActivityNet-1.3, distinguishing long, semantically similar actions is challenging, causing drops at high tIoU; and on Charades, overlapping actions and complex scenes lead to category confusion and missed detections. Future work should enhance temporal modeling and context awareness to improve robustness in complex scenarios.

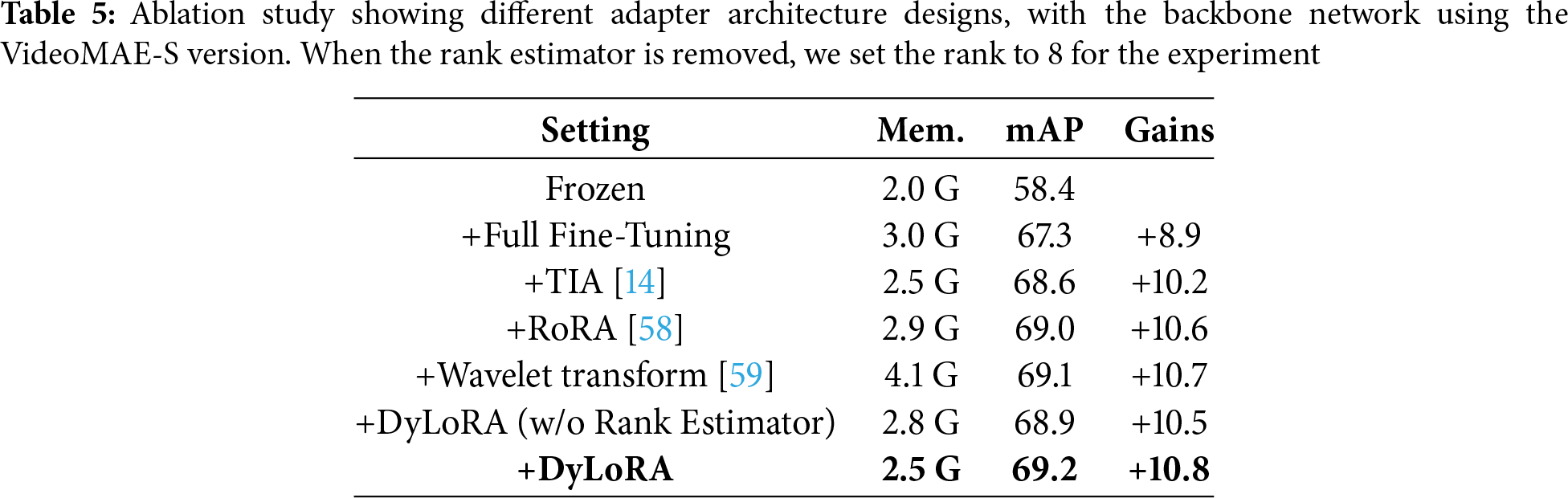

In this section, we further evaluate the proposed DyLoRA-TAD method through ablation studies and validate the advantages of LoRA fine-tuning in improving TAD performance and reducing memory consumption. All of our ablation experiments are conducted on the THUMOS14 dataset.

The ablation study on adapter design (see Table 5) compares different architecture designs. The baseline model with a frozen backbone achieved a mAP of 58.4%, while our DyLoRA-TAD method reached 69.2%, representing a 10.8% improvement. Compared to TIA [14], DyLoRA achieves higher mAP with similar memory consumption, highlighting its significance in TAD tasks. Additionally, RaRA [58] and the Wavelet transform [59] achieve performance close to DyLoRA but with significantly higher memory usage. Removing the rank estimator in DyLoRA results in a 0.3% performance drop and increased memory consumption, indicating the critical role of the rank estimator in maintaining both performance and efficiency. Regarding the computational overhead of dynamic rank prediction, our quantitative experiments show that the extra cost is negligible: memory usage slightly decreases (2.8 G → 2.5 G) while mAP improves (68.9 → 69.2). This indicates that dynamic rank prediction does not offset DyLoRA’s lightweight advantage, and its initialization and update strategies further optimize both performance and memory efficiency.

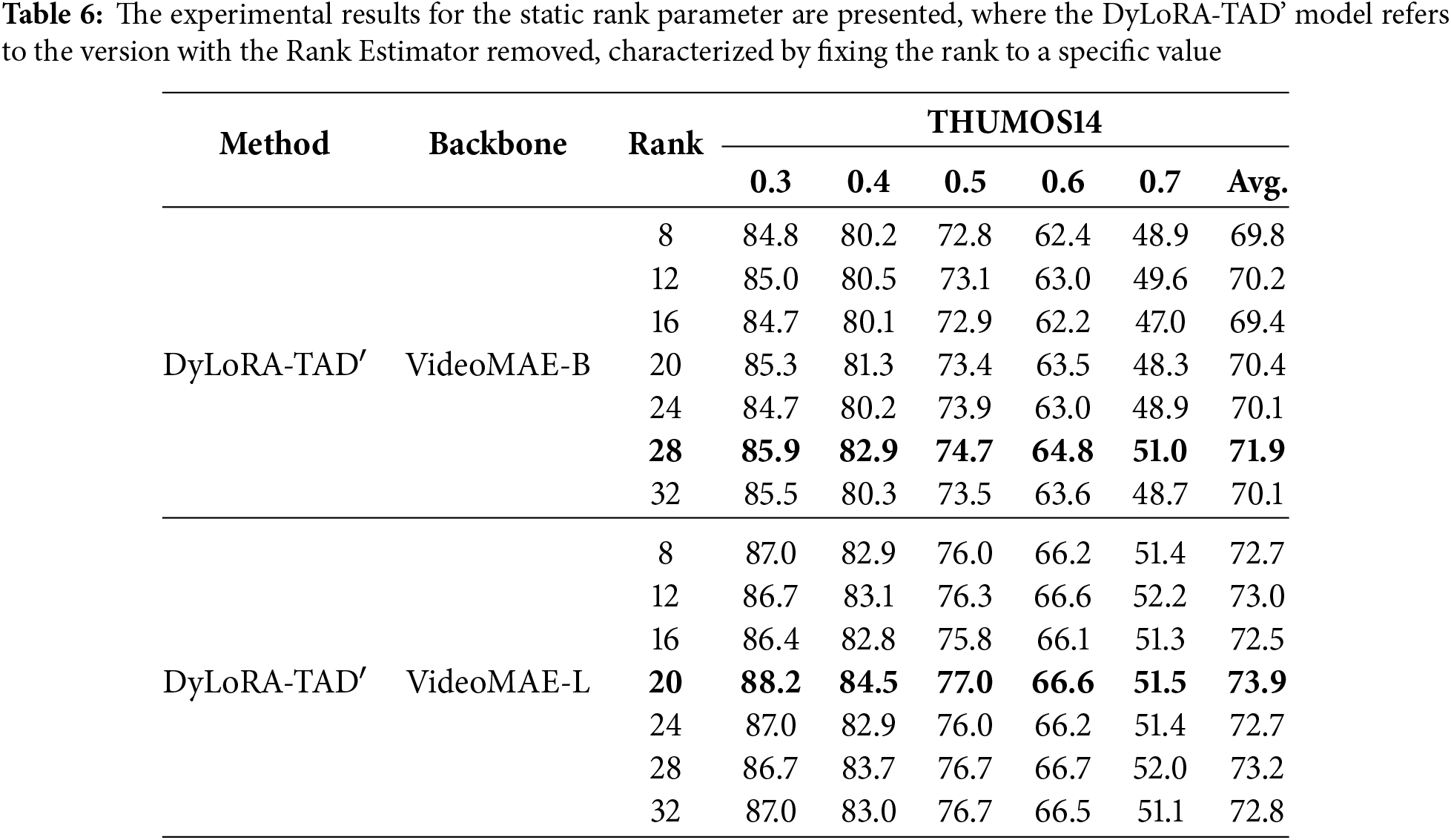

Based on the ablation study of the Rank Estimator in Section 4.4, we further investigate the impact of setting a fixed rank value on model performance. Detailed experimental data can be found in Table 6, where the rank value is set in the range of 8 to 32 with a step size of 4. The results show that when using VideoMAE-B as the backbone network, setting the rank to 28 yields the best model performance with an accuracy of 71.9%. When the backbone network is extended from the VideoMAE-B version to the VideoMAE-L version, setting the rank to 20 achieves performance comparable to that of the original DyLoRA-TAD.

Although setting a fixed rank can achieve performance close to that of dynamic rank adaptation, we observe that this approach significantly increases memory overhead. For example, the ablation study in Table 5 shows that using the Rank Estimator reduces GPU memory usage from 2.8 GB to 2.5 GB, significantly alleviating the resource consumption issue. This also demonstrates from another perspective that DyLoRA not only effectively improves model performance but also makes more efficient use of resources.

This study proposes the DyLoRA-TAD framework to address the high computational cost and small-sample overfitting issues faced during fine-tuning large-scale pre-trained video models for TAD. We design a dynamic low-rank adaptive adapter, DyLoRA, which introduces low-rank matrix decomposition techniques to efficiently fine-tune the critical layers of pre-trained models. This approach significantly reduces training parameters and memory consumption while effectively alleviating overfitting. Specifically, DyLoRA enhances the model’s ability to capture temporal dependencies, addressing the inadequacies of traditional pre-trained models in temporal feature representation. Furthermore, we explore the performance improvement brought by the multi-scale temporal feature fusion module, Temporal DyLoRA Fuser. DyLoRA-TAD, through end-to-end training and task-oriented efficient fine-tuning, enhances the model’s generalization ability and stability, achieving breakthroughs in detection accuracy and providing a lightweight, efficient, and practical solution for real-world applications such as video anomaly detection. We believe that DyLoRA, as a lightweight and efficient fine-tuning solution, demonstrates significant potential in the field of temporal action detection and offers important insights and references for the future development of TAD methods.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Major Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Province, and the Scientific Research Fund of the Yunnan Provincial Department of Education.

Funding Statement: This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62266054), the Major Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Province (Grant No. 202402AD080002), and the Scientific Research Fund of the Yunnan Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. 2025Y0302).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jixin Wu and Mingtao Zhou; methodology, Jixin Wu and Mingtao Zhou; software, Jixin Wu; validation, Jixin Wu, Mingtao Zhou and Di Wu; formal analysis, Jixin Wu; investigation, Jixin Wu and Mingtao Zhou; resources, Wenqi Ren and Jiatian Mei; data curation, Jixin Wu; writing—original draft preparation, Jixin Wu; writing—review and editing, Jixin Wu, Mingtao Zhou and Shu Zhang; visualization, Jixin Wu; supervision, Shu Zhang; project administration, Shu Zhang; funding acquisition, Shu Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the OpenTAD GitHub repository at https://github.com/sming256/OpenTAD (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhu Y, Zhang G, Tan J, Wu G, Wang L. Dual DETRs for multi-label temporal action detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 18559–69. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tan J, Zhao X, Shi X, Kang S, Wang L, Sun Y, et al. PointTAD: multi-label temporal action detection with learnable query points. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:15268–80. [Google Scholar]

3. Tirupattur P, Duarte K, Rawat YS, Shah M. Modeling multi-label action dependencies for temporal action localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 1460–70. [Google Scholar]

4. Sinha A, Raj MS, Wang P, Helmy A, Das S. MS-temba: multi-scale temporal mamba for efficient temporal action detection. arXiv:2501.06138. 2025. [Google Scholar]

5. Dai R, Das S, Bremond F. CTRN: class-temporal relational network for action detection. arXiv:2110.13473. 2021. [Google Scholar]

6. Dai R, Das S, Kahatapitiya K, Ryoo MS, Brémond F. MS-TCT: multi-scale temporal ConvTransformer for action detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–4; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 20009–19. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lysova T. Intersecting perspectives: video surveillance in urban spaces through surveillance society and security state frameworks. Cities. 2025;156(1):105544. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2024.105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wu J, Mou S, Zhou M, Wu D, Zou S, Zhang S. The student classroom behavior recognition based on feature enhancement. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th International Conference on Vision, Image and Signal Processing (ICVISP); 2024 Dec 27–29; Kunming, China. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/ICVISP64524.2024.10959424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang M, Chen G, Zheng YD, Lu T, Wang L. BasicTAD: an astounding RGB-only baseline for temporal action detection. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2023;232(1):103692. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2023.103692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cheng F, Bertasius G. TallFormer: temporal action localization with a long-memory transformer. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 503–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19830-4_29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao C, Liu S, Mangalam K, Ghanem B. Re2TAL: rewiring pretrained video backbones for reversible temporal action localization. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 10637–47. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xin Y, Yang J, Luo S, Du Y, Qin Q, Cen K, et al. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for pre-trained vision models: a survey and benchmark. arXiv:2402.02242. 2024. [Google Scholar]

13. Bai H, LeCun Y, Levine S, Lin Z, Ma Y, Pan J, et al. Fine-tuning large vision-language models as decision-making agents via reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 110935–71. doi:10.52202/079017-3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu S, Zhang CL, Zhao C, Ghanem B. End-to-end temporal action detection with 1B parameters across 1000 frames. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 18591–601. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Piergiovanni AJ, Ryoo M. Temporal gaussian mixture layer for videos. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 5152–61. [Google Scholar]

16. Shi D, Zhong Y, Cao Q, Ma L, Lit J, Tao D. TriDet: temporal action detection with relative boundary modeling. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 18857–66. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lin T, Liu X, Li X, Ding E, Wen S. BMN: boundary-matching network for temporal action proposal generation. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 3888–97. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang CL, Wu J, Li Y. ActionFormer: localizing moments of actions with transformers. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 492–510. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19772-7_29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2021 Jul 18–24; Online. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

20. Yang T, Zhu Y, Xie Y, Zhang A, Chen C, Li M. AIM: adapting image models for efficient video action recognition. arXiv:2302.03024. 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Tong Z, Song Y, Wang J, Wang L. VideoMAE: masked autoencoders are data-efficient learners for self-supervised video pre-training. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 10078–93. [Google Scholar]

22. Patro BN, Namboodiri VP, Agneeswaran VS. SpectFormer: frequency and attention is what you need in a vision transformer. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2025 Feb 26–Mar 6; Tucson, AZ, USA. p. 9543–54. doi:10.1109/WACV61041.2025.00924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, Allen-Zhu Z, Li Y, Wang S, et al. LoRA: low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv:2106.09685. 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. Li W, Yao D, Gong C, Chu X, Jing Q, Zhou X, et al. CausalTAD: causal implicit generative model for debiased online trajectory anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2024 May 13–16; Utrecht, The Netherlands. p. 4477–90. doi:10.1109/ICDE60146.2024.00341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu M, Zhao C, Rojas DS, Thabet A, Ghanem B. G-TAD: sub-graph localization for temporal action detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 10153–62. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xia K, Wang L, Zhou S, Zheng N, Tang W. Learning to refactor action and co-occurrence features for temporal action localization. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 13874–83. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Qing Z, Su H, Gan W, Wang D, Wu W, Wang X, et al. Temporal context aggregation network for temporal action proposal refinement. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 485–94. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhao Z, Wang D, Zhao X. Movement enhancement toward multi-scale video feature representation for temporal action detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 13509–18. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.01247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu X, Wang Q, Hu Y, Tang X, Zhang S, Bai S, et al. End-to-end temporal action detection with transformer. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2022;31:5427–41. doi:10.1109/TIP.2022.3195321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Shi D, Zhong Y, Cao Q, Zhang J, Ma L, Li J, et al. ReAct: temporal action detection with relational queries. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 105–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-20080-9_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Han K, Xiao A, Wu E, Guo J, Xu C, Wang Y. Transformer in transformer. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021); 2021 Dec 6–14; Online. p. 15908–19. [Google Scholar]

32. Han K, Wang Y, Chen H, Chen X, Guo J, Liu Z, et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(1):87–110. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3152247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Lin C, Xu C, Luo D, Wang Y, Tai Y, Wang C, et al. Learning salient boundary feature for anchor-free temporal action localization. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 3319–28. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.00333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang C, Cai H, Zou Y, Xiong Y. RGB stream is enough for temporal action detection. arXiv:2107.04362. 2021. [Google Scholar]

35. Liu X, Bai S, Bai X. An empirical study of end-to-end temporal action detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 19978–87. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dai P, Li Z, Zhang Y, Liu S, Zeng B. PBR-net: imitating physically based rendering using deep neural network. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2020;29:5980–92. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.2987169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Li P, Cao J, Ye X. Prototype contrastive learning for point-supervised temporal action detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213:118965. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ding N, Qin Y, Yang G, Wei F, Yang Z, Su Y, et al. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large-scale pre-trained language models. Nat Mach Intell. 2023;5(3):220–35. doi:10.1038/s42256-023-00626-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fu Z, Yang H, So AM, Lam W, Bing L, Collier N. On the effectiveness of parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(11):12799–807. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i11.26505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Han Z, Gao C, Liu J, Zhang J, Zhang SQ. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: a comprehensive survey. arXiv:2403.14608. 2024. [Google Scholar]

41. Gu J, Yuan J, Cai J, Zhou X, Fan L. La-LoRA: parameter-efficient fine-tuning with layer-wise adaptive low-rank adaptation. Neural Netw. 2025;194(10):108095. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2025.108095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang R, Han J, Liu C, Gao P, Zhou A, Hu X, et al. LLaMA-adapter: efficient fine-tuning of language models with zero-init attention. arXiv:2303.16199. 2023. [Google Scholar]

43. Jia M, Tang L, Chen BC, Cardie C, Belongie S, Hariharan B, et al. Visual prompt tuning. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 709–27. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19827-4_41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li XL, Liang P. Prefix-tuning: optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv:2101.00190. 2021. [Google Scholar]

45. Zhang Y, Zhang T, Wu C, Tao R. Multi-scale spatiotemporal feature fusion network for video saliency prediction. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2024;26:4183–93. doi:10.1109/TMM.2023.3321394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jiang YG, Liu J, Zamir AR, Laptev I. THUMOS Challenge 2015 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: http://www.thumos.info/. [Google Scholar]

47. Heilbron FC, Escorcia V, Ghanem B, Niebles JC. ActivityNet: a large-scale video benchmark for human activity understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 961–70. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sigurdsson GA, Varol G, Wang X, Farhadi A, Laptev I, Gupta A. Hollywood in homes: crowdsourcing data collection for activity understanding. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 510–26. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Melo MA. Accelerate model training with PyTorch 2.X: build more accurate models by boosting the model training process. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Limited; 2024. doi:10.0000/9781805121916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. MMAction2 Contributors. Openmmlab’s next generation video understanding toolbox and benchmark [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://github.com/open-mmlab/mmaction2. [Google Scholar]

51. Shao J, Wang X, Quan R, Zheng J, Yang J, Yang Y. Action sensitivity learning for temporal action localization. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 13411–23. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.01238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Yang L, Zheng Z, Han Y, Cheng H, Song S, Huang G, et al. DyFADet: dynamic feature aggregation for temporal action detection. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. p. 305–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72952-2_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zhu X, Zhu Y, Chen T, Wu W, Dang Y. FDDet: frequency-decoupling for boundary refinement in temporal action detection. arXiv:2504.00647. 2025. [Google Scholar]

54. Piergiovanni A, Ryoo MS. Learning latent super-events to detect multiple activities in videos. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 5304–13. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Liu S, Xu M, Zhao C, Zhao X, Ghanem B. ETAD: training action detection end to end on a laptop. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 4525–34. doi:10.1109/cvprw59228.2023.00476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Dai R, Das S, Minciullo L, Garattoni L, Francesca G, Bremond F. PDAN: pyramid dilated attention network for action detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 2969–78. doi:10.1109/wacv48630.2021.00301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Kahatapitiya K, Ryoo MS. Coarse-fine networks for temporal activity detection in videos. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 8381–90. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Liu J, Kong Z, Dong P, Yang C, Shen X, Zhao P, et al. RoRA: efficient fine-tuning of LLM with reliability optimization for rank adaptation. arXiv:2501.04315. 2025. [Google Scholar]

59. Zhang D. Wavelet transform. In: Fundamentals of image data mining. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 35–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-17989-2_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools