Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

IoT-Assisted Cloud Data Sharing with Revocation and Equality Test under Identity-Based Proxy Re-Encryption

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, 202301, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Tung-Tso Tsai. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 14 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073234

Received 13 September 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Cloud services, favored by many enterprises due to their high flexibility and easy operation, are widely used for data storage and processing. However, the high latency, together with transmission overheads of the cloud architecture, makes it difficult to quickly respond to the demands of IoT applications and local computation. To make up for these deficiencies in the cloud, fog computing has emerged as a critical role in the IoT applications. It decentralizes the computing power to various lower nodes close to data sources, so as to achieve the goal of low latency and distributed processing. With the data being frequently exchanged and shared between multiple nodes, it becomes a challenge to authorize data securely and efficiently while protecting user privacy. To address this challenge, proxy re-encryption (PRE) schemes provide a feasible way allowing an intermediary proxy node to re-encrypt ciphertext designated for different authorized data requesters without compromising any plaintext information. Since the proxy is viewed as a semi-trusted party, it should be taken to prevent malicious behaviors and reduce the risk of data leakage when implementing PRE schemes. This paper proposes a new fog-assisted identity-based PRE scheme supporting anonymous key generation, equality test, and user revocation to fulfill various IoT application requirements. Specifically, in a traditional identity-based public key architecture, the key escrow problem and the necessity of a secure channel are major security concerns. We utilize an anonymous key generation technique to solve these problems. The equality test functionality further enables a cloud server to inspect whether two candidate trapdoors contain an identical keyword. In particular, the proposed scheme realizes fine-grained user-level authorization while maintaining strong key confidentiality. To revoke an invalid user identity, we add a revocation list to the system flows to restrict access privileges without increasing additional computation cost. To ensure security, it is shown that our system meets the security notion of IND-PrID-CCA and OW-ID-CCA under the Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) assumption.Keywords

Up to the present, Cloud Computing [1–3] has become a significant technology in our daily lives. It provides various computational resources and services, enabling users to remotely compute, access, and manipulate data without actually building and managing physical hardware. The high flexibility and scalability of cloud computing enable users to access applications and data anytime, anywhere, and dynamically allocate appropriate resources based on actual needs, so as to save costs.

However, with the fast advancement of new technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT) [4,5], a great number of edge devices (e.g., sensors, cameras) have emerged, leading to an explosive increase in the quantity of data. Many IoT applications, such as autonomous vehicles [6], smart cities [7], and intelligent healthcare systems [8], have urgent requirements for real-time data processing. Such a challenge boosts the coming and development of Fog Computing [9–11]. Essentially, fog computing utilizes devices in the edge network for computation instead of solely relying on remote data centers. Since some computational tasks will be processed within fogs, the bandwidth and resources will thus be effectively saved. Nevertheless, how to achieve secure and flexible data sharing in such a collaborative cloud-fog architecture has become a critical issue to be solved.

Proxy Re-Encryption (PRE) schemes are frequently employed mechanisms for secure delegation in distributed environments. In 1998, Blaze et al. [12] introduced the first PRE mechanism allowing the delegation of decryption or signing right. The only restriction is that the authorized proxy cannot further delegate these rights. However, their scheme suffers from collusion attacks, i.e., if the proxy colludes with either user, the other one’s private key could be derived. In 2006, Ateniese et al. [13] pointed out several important traits of PRE schemes, like unidirectional, non-interactive and collusion-safe, establishing a well-defined framework for subsequent research.

In 2010, Wang and Zhong [14] proposed an Identity-Based Proxy Re-encryption (IB-PRE) scheme in which a private key generator (PKG) is responsible for generating users’ private keys. Specifically, a proxy with an authorized re-encryption key is able to convert a ciphertext of A’s identity to another one that could be decrypted by B’s private key. Subsequently, several researchers devoted themselves to the enhancement of security and efficiency of PRE mechanisms. For instance, Zhang et al. [15] came up with a scheme with CCA security that does not use bilinear pairings while Chow et al. [16] also presented another pairing-free approach on the basis of the CDH assumption.

Searching encrypted data in the cloud without decryption is a valuable yet challenging topic. To meet the requirement, the so-called Public Key Encryption with Keyword Search (PEKS) [17] is applicable. In 2020, Lin et al. [18] proposed a Public Key Encryption with Equality Test (PKEET) for cloud storage. Their scheme enables an authorized tester to inspect whether two ciphertexts are in relation to the same plaintext. Compared to the method of PEKS, a PKEET mechanism takes the ciphertext itself as the input for testing rather than utilizing a keyword, thus removing the test restriction of using an identical public key. Thereafter, several variants with keyword search or equality test were introduced, such as the PRE with keyword search [19,20] and the PRE with equality test (PREET) [21,22]. To verify whether the re-encrypted ciphertext generated by the proxy is correct or not, Chen et al. [23] introduced a fair and verifiable identity-based broadcast PRE system with designated sender (FV-IBBPRE-DS). They present the formal definition of FV-IBBPRE-DS schemes and show that their system can be applied to resource-constrained devices.

To deal with the scalability and trust issue of IoT systems, Manzoor et al. [24] proposed a blockchain-based PRE scheme implemented in an Ethereum testbed. The major advantage of using blockchain mechanisms is that financial transactions are automatically managed through smart contracts without manual verification of payments. In 2021, Chen et al. [25] combined the PRE mechanism with an equality test to propose a blockchain-based PRE scheme with equality test (PREET) suitable for vehicular communication systems. In 2024, Han et al. [26] introduced a pairing-free PREET scheme for IoT applications. Their scheme is proved secure in the random oracle model assuming the intractability of the Gap Computational Diffie-Hellman problem. Li et al. [27] also considered the computational benefits of pairing-free techniques and proposed a pairing-free broadcast IB-PRE scheme. Yet, their scheme does not have the functionality of an equality test.

In recent years, some researchers devote themselves to IB-PRE schemes for fog computing environments. Using the collaborative cloud-fog architecture, an IB-PRE scheme with anonymous key generation was developed by Zhang et al. [28] in 2020. Although they employed an anonymous key technique to avoid the key escrow problem inherited in identity-based cryptosystems, their scheme has several security flaws discovered by Lin et al. [29]. In 2023, Lin et al. [30] further came up with an improved IB-PRE scheme with better efficiency, while preserving the feature of anonymous key generation for fog-assisted cloud environments. Nevertheless, neither the keyword search nor the equality test is considered in their work.

Motivated by these studies, we incorporate the functionality of the equality test with the collaborative cloud-fog architecture to propose a secure and revocable IoT data sharing scheme using IB-PRE with equality test. Unlike existing schemes that directly treats one of the two private keys as a trapdoor to achieve user-level authorization, our scheme incorporates a random number into the trapdoor generation process, effectively preventing trapdoor reuse and enhancing key confidentiality. Based on the data request workflow of [30], we also use a revocation list to achieve user revocation without incurring extra computational costs. Furthermore, to ensure both practicality and security, a performance evaluation along with the CCA-level security proof for the proposed system will be presented in a later section.

In this section, the authors first review the definition of bilinear pairing and then state the computational assumption used in the proposed scheme.

Bilinear Pairing

We use the notations of G1 and GT to express two multiplicative groups and both have the same prime order p. The symbol g is a chosen generator from the group G1. We thus denote e: G1 × G1 → GT as a symmetric bilinear pairing that shall satisfy the following three properties:

1. Bilinearity: For all scalars s, t ∈ Zp, the equality e(gs, gt) = e(g, g)st holds.

2. Non-degeneracy: The inequality e(g, g) ≠ 1 holds for some generator g ∈ G1.

3. Computability: For any elements ga, gb ∈ G1, the value e(ga, gb) can be efficiently calculated by a polynomial-time algorithm.

Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) Problem

For a problem instance (g, gx, gy, gz, Q) where Q ∈ GT, it is to determine if Q = e(g, g)xyz.

Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) Assumption

This assumption describes that the advantage of any probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary to successfully solve the DBDH problem is negligible.

This section elaborates the system architecture, algorithmic definitions and security model of the proposed system.

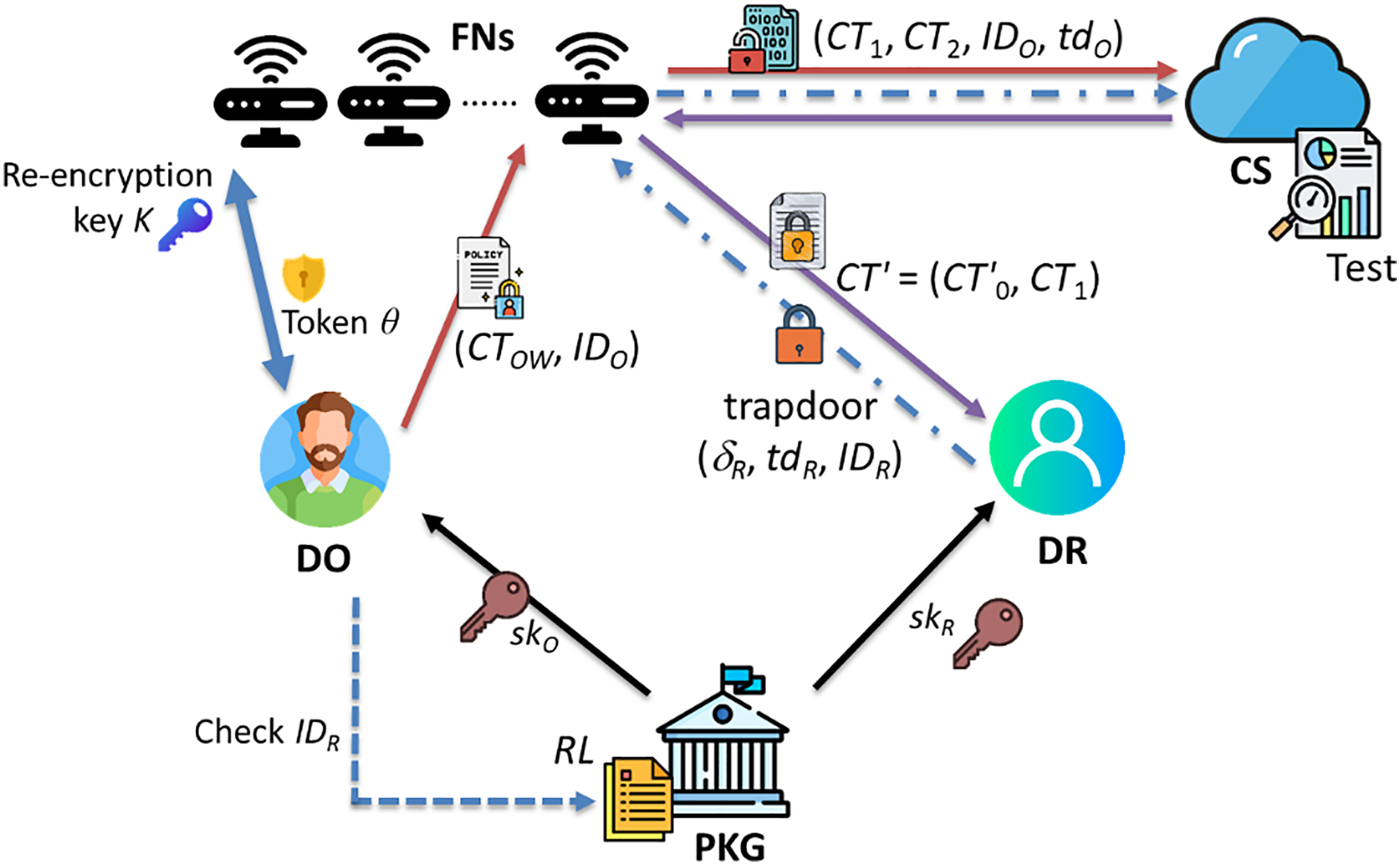

The proposed system has five participating roles:

1. Private Key Generator (PKG): The PKG serves as a trusted third party (TTP) in the system, in charge of system initialization and private key generation of users. For system-wide operations, the PKG is initialized with a pair of master keys, i.e., a Master Secret Key (Msk) as well as a Master Public Key (Mpk), and it is required to store a Revocation List (RL). During the key generation phase, the PKG generates a temporal private key for a user, which is then sent to the user for independent computation to derive their genuine private key. Through this step, the PKG cannot ascertain the user’s genuine private key, thus achieving the effect of an anonymous private key.

2. Data Owner (DO): In this system, the DO encrypts his data utilizing his own private key and uploads the ciphertext to the nearby Fog Nodes (FNs). The ciphertext includes a trapdoor and several partial ciphertext components. The FNs store one partial ciphertext and then upload remaining data to the cloud. If a data requester successfully queries the data, the DO will verify if the data requester is kept on the RL. As long as the DR is on the RL, the DO will not process the request. Otherwise, the DO will compute the corresponding re-encryption key and send it to the FNs.

3. Data Requester (DR): In this system, the DR also encryptes the keyword they wish to query and uploads it to the cloud. The DR can send a data query request to the FNs by using their private key to compute a trapdoor, which is then delivered to the cloud server via FNs.

4. Cloud Server (CS): The CS utilizes trapdoors to test the encrypted keyword of the DO and that of the DR. The result is forwarded to the FNs which in turn convey the result to the data owner, enabling the DO to begin generating the re-encryption key.

5. Fog Nodes (FNs): The FNs are considered semi-trusted entities in this system. They assist in data transmission but may also be curious about the data. The FNs help the DR with data requests and use a re-encryption key created by the data owner to transform the ciphertext requested by the DR. The transformed ciphertext is then delivered to the DR for decryption. FNs can also be seen as proxies for the CS, helping to decrease the computational loads on the cloud.

The following are the definitions of the algorithms used in this paper:

1. Setup: This algorithm processes a security parameter ζ to produce public parameters (Pm) and the Msk for the system.

2. UserKeyGen: This algorithm processes Pm, the Msk, and an identity (IDu) to produce the corresponding private key (sku).

3. Encryption: The DO takes Pm, a keyword (KwO), a symmetric key (J), a plaintext (M), a private key (skO), and his identity (IDO) as the input and then returns a corresponding ciphertext (CT).

4. Trapdoor: The DR takes their identity (IDR), a private key (skR), and the desired keyword (KwR) as input and then returns a trapdoor (tdR).

5. Test: The CS takes two trapdoors (tdR, tdO) along with two ciphertexts (δ, CT2) as input. If the test result shows that the two ciphertexts are associated with the same keyword, the CS will return 1 and send the associated ciphertext CT1 to the FN which also in turn delivers the token (θ) to the DO. If not, the CS outputs 0 and does not inform the FN.

6. ReKeyGen: After the DO verifies the identity of DR, it will take Pm, the token (θ), and its private key (skO) as input, and then return the re-encryption key (K).

7. Re-Encryption: The FNs take Pm, the requester’s identity (IDR), the re-encryption key (K) computed by the DO, and the ciphertext (CT1, CT2) as input, and output a transformed ciphertext.

8. Decryption: This algorithm can be performed in two ways, i.e., decryption by the data owner themselves, or decryption by a data requester. It will take Pm, a private key (sku), and either a ciphertext (CT) or a re-encrypted ciphertext (CT′) as input. It computes the symmetric key (J) and then uses J to decrypt the ciphertext to obtain the plaintext (M).

9. Revocation: The identity (IDrv) of a specific user to be revoked is added to the RL.

This subsection describes IND-PrID-CCA and OW-ID-CCA security models for the proposed system.

Definition 1: (IND-PrID-CCA):

The proposed scheme is proven to satisfy indistinguishability against adaptively chosen identity and chosen ciphertext attacks (IND-PrID-CCA) if no PPT adversary 𝓐 can win the following game against a challenger 𝓑 with a non-negligible advantage:

Initialization: The challenger 𝓑 initializes Setup(1ζ) to generate Pm as well as the Msk. It then forwards Pm to the adversary 𝓐.

Phase 1: 𝓐 adaptively performs the queries below:

1. Private Key Queries: 𝓐 selects a user’s identity ID and sends it to 𝓑. Upon receiving it, 𝓑 runs the UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, ID) algorithm to acquire the private key skID and sends it back to 𝓐.

2. Trapdoor Queries: 𝓐 selects an identity ID along with a keyword KwID and sends them to 𝓑 who will return the corresponding trapdoor (δID, tdID) to 𝓐.

3. Re-encryption Key Queries: 𝓐 selects two non-revoked, legitimate user identities (IDO, IDR) and a keyword Kw and then sends them to 𝓑. 𝓑 runs UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, ID) to obtain skO and skR. It then runs Trapdoor(IDR, skR, Kw) to get the token θ, and finally runs ReKeyGen(Pm, θ, skO) to obtain the re-encryption key K which is returned to 𝓐.

4. Decryption Queries: 𝓐 selects a non-revoked, legitimate identity (ID) with a chosen ciphertext CT′ and then sends them to 𝓑. 𝓑 runs UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, ID) to obtain skID. It then runs Decryption(CT′, skID) to get the result and provide 𝓐 with it.

5. Test Queries: 𝓐 selects two trapdoors (tdR, tdO) along with two ciphertexts (δ, CT) and then sends them to 𝓑. 𝓑 runs Test(CT2, tdO, δ, tdR) and returns 1 if the associated keywords are the same. Otherwise, 𝓑 returns 0 indicating the keywords are different.

6. Revoke Queries: 𝓐 selects a user identity (IDrv) and then sends it to 𝓑. 𝓑 adds IDrv to the maintained revocation list RL.

Challenge: 𝓐 selects ID* as the target identity, a keyword Kw*, a plaintext M* composed of (M1*, M2*, …, Mz*), and a pair of symmetric keys, (J0, J1), with identical lengths. The challenger 𝓑 randomly chooses μ ∈ {0, 1}, takes (Pm, Kw*, Jμ, M*, ID*) as input to calculate a ciphertext CT* together with its trapdoor td* as the challenge for 𝓐.

Phase 2: Upon obtaining it, 𝓐 continues to submit queries the same as Phase 1, subject to the limits below:

1. Querying the private key of ID* is forbidden.

2. Making re-encryption key queries involving (ID*, IDR) or (IDO, ID*) is forbidden.

3. Making trapdoor queries involving (ID*, Kw*) is forbidden.

4. Making decryption queries involving (CT′, skID*) is forbidden.

5. The query bound must not exceed the maximum number of private key queries (qpk), trapdoor queries (qtd), decryption queries (qde), re-encryption key queries (qrk), test queries (qte), and revoke queries (qrv).

Guess: When finishing Phase 2, 𝓐 returns a bit μ′. The adversary 𝓐 is considered successful if μ′ = μ, with its advantage in this game being defined by the formula Adv(𝓐) = |Pr[μ′ = μ] − 1/2|.

Definition 2: (OW-ID-CCA):

The proposed scheme is proven to satisfy one-wayness against adaptively chosen identity and chosen ciphertext attacks (OW-ID-CCA) as long as no PPT adversary 𝓐 can win the following game against a challenger 𝓑 with a non-negligible advantage:

Initialization: The challenger 𝓑 runs the Setup(1ζ) to generate Pm and the Msk. It then forwards Pm to the adversary 𝓐.

Phase 1: 𝓐 adaptively performs the queries below:

1. Private Key Queries: 𝓐 selects a user’s identity ID and sends it to 𝓑. Upon receiving it, 𝓑 runs the UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, ID) algorithm to acquire the private key skID and sends it back to 𝓐.

2. Trapdoor Queries: 𝓐 selects a user’s identity ID along with a keyword KwID and sends them to 𝓑 who will return the corresponding trapdoor (δID, tdID) to 𝓐.

3. Re-encryption Key Queries: 𝓐 selects two non-revoked, legitimate user identities (IDO, IDR) and a keyword Kw and then sends them to 𝓑. 𝓑 runs UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, ID) to obtain skO and skR. It then runs Trapdoor(IDR, skR, Kw) to get the token θ, and finally runs ReKeyGen(Pm, θ, skO) to obtain the re-encryption key K which is returned to 𝓐.

4. Decryption Queries: 𝓐 selects a non-revoked, legitimate identity (ID) and a chosen ciphertext CT′ and then sends them to 𝓑. 𝓑 runs UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, ID) to obtain skID. It then runs Decryption(CT′, skID) to get the result and provide 𝓐 with it.

5. Test Queries: 𝓐 selects two trapdoors (tdR, tdO) along with two ciphertexts (δ, CT) and then sends them to 𝓑. 𝓑 runs Test(CT2, tdO, δ, tdR) and returns 1 if the associated keywords are the same. Otherwise, 𝓑 returns 0 indicating the keywords are different.

6. Revoke Queries: 𝓐 chooses a user identity (IDrv) and then submits it to 𝓑. 𝓑 adds IDrv to the maintained revocation list RL.

Challenge: 𝓐 selects ID* as the target identity, and then 𝓑 randomly generates a keyword Kw*, a plaintext M* composed of (M1*, M2*, …, Mz*), and a symmetric key J* to calculate a ciphertext CT* together with a trapdoor td* as the challenge for 𝓐.

Phase 2: Upon obtaining it, 𝓐 continues to submit queries as in Phase 1, but with the limits below:

1. Querying the private key of ID* is forbidden.

2. Making re-encryption key queries involving (ID*, IDR) or (IDO, ID*) is forbidden.

3. Making decryption queries involving (CT′, skID*) is forbidden.

4. The query bound must not exceed the maximum number of private key queries (qpk), trapdoor queries (qtd), decryption queries (qde), re-encryption key queries (qrk), test queries (qte), and revoke queries (qrv).

Guess: When finishing Phase 2, 𝓐 returns a message M′. The adversary 𝓐 is considered successful if M′ = M*, with its advantage in this game being defined by the formula Adv(𝓐) = Pr[M′ = M*].

This subsection elaborates on the concrete algorithms that constitute our proposed scheme. The system structure is illustrated as Fig. 1.

1. Setup(1 ζ) → (Pm, Msk)

The PKG takes a security parameter ζ as input to generate Pm along with the Msk = α ∈RZp. Pm consists of (e, G1, GT, g, p, H1~3, Mpk, SE, SD), where the parameters are defined below:

(a) G1 and GT are two multiplicative cyclic groups of prime order p. g is a generator of G1. e is a symmetric bilinear pairing that satisfies e: G1 × G1 → GT.

(b) H1~3 are one-way collision-resistant hash functions. H1 and H2 take inputs of arbitrary length and output an element in G1. H3 accepts an input from GT and outputs an element in G1.

(c) Mpk is the master public key and computed as N = gα.

(d) SE and SD are the respective encryption and decryption algorithms of a symmetric cipher.

2. UserKeyGen(Pm, Msk, IDu) → (sku)

The anonymous key generation process is as follows:

(a) A user of identity IDu first chooses random numbers ru, bu ∈R Zp. The user computes Yu = gbu, R′u = YuH1(IDu || ru) and sends (IDu, R′u) to the PKG.

(b) The PKG computes sk′u = (R′uH2(IDu || IDPKG))α and returns (sk′u) to IDu.

(c) The user uses the initially chosen bu to compute their private key (sku1, sku2) = (sk′u/gbu, ru).

(d) The key validity could be confirmed by inspecting whether

3. Encryption(Pm, Kwo, J, M, IDu) → CT

The encryption process of a message M = (M1, M2, …, Mz) and a keyword KwO ∈ G1 is as follows:

(a) The DO, with identity IDO, picks a symmetric key J and random numbers h, v ∈ Zp to compute

(b) Set the partial ciphertext CT0 = (EO,1, EO,2) and CT2 = (EO,3, EO,4).

(c) Let the full ciphertext CTOW = (CT0, CT1, CT2) and the trapdoor be tdO.

(d) The DO sends (CTOW, tdO, IDO) to the FNs.

(e) The FNs store (CT0, IDO) and forward (CT1, CT2, IDO, tdO) to the CS.

4. Trapdoor(IDR, skR2, KwR) → (δR, tdR, IDR)

The trapdoor process of a keyword KwR ∈ G1 is as follows:

(a) The DR, with identity IDR, selects random numbers l, d ∈ Zp and computes:

(b) The DR sends (L, δR, tdR, IDR) to a nearby FN.

(c) The FN generates a token θ = (L, IDR) and forwards the trapdoor (δR, tdR, IDR) to the CS.

5. Test(CT2, tdO, δ, tdR) → 1 or 0

The test process of a ciphertext-trapdoor pair (δ, tdR) and (CT2, tdO) is as follows:

(a) The CS first computes

(b) Then, the CS checks whether e(EO,4, Fj) = e(ER,4, Fi) holds or not.

(c) If it holds, the keywords match. The CS delivers the corresponding ciphertext CT1 to FNs, which in turn forward the token θ to the DO.

(d) Otherwise, no further action is taken.

6. ReKeyGen(Pm, θ, skO) → K

The ReKeyGen process is as follows:

(a) The DO first confirms with the PKG whether the DR’s identity IDR is in the RL.

(b) If it is, the algorithm will output ⊥ and terminate.

(c) Else, the DO selects random numbers x, t ∈ Zp and computes

(d) Finally, the re-encryption key K = (K1, K2, K3) is transmitted to the FNs.

7. Re-encryption(Pm, IDR, K, CT1, CT2) → CT′

Upon receiving the re-encryption key K from the DO, the FNs begin to re-encrypt the ciphertext:

The FNs send CT′ = (CT′0, CT1) to the DR, where CT′0 = (E′1, E′2, E′3, E′4).

8. Decryption(CT, sku) → ( M1, M2, …, Mz)

Decryption is mainly divided into two scenarios:

(a) Decryption by the DO

(b) Decryption by the DR

Then DU can recover Mi with Eq. (23). Correctness derivation for J:

9. Revocation(IDrv, RL) → RL

To revoke a user IDrv, the PKG inputs IDrv and renews the RL as RL ∪ IDrv.

Figure 1: Illustration of system structure for the proposed scheme

4 Security Proof and Comparison

This section provides security proofs for the designed system, which is based on the Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) hardness assumption. Some comparisons with previous works are also given.

In this subsection, we first prove that the proposed system achieves IND-PrID-CCA and OW-ID-CCA security in random oracle models under the DBDH assumption. Then, we analyze that the proposed system is also resistant to collusion attacks involving a malicious PKG, proxy servers, and data users.

Theorem 1: (Proof of IND-PrID-CCA)

Let H1 and H2 be random oracles. Our system achieves the IND-PrID-CCA security based on the DBDH assumption. If there exists any PPT adversary 𝓐 that can break the IND-PrID-CCA security of our scheme with a non-negligible advantage ε, subject to a maximum of qpk private key queries, qtd trapdoor queries, qde decryption queries and qrk re-encryption key queries, an algorithm 𝓑 is able to solve the DBDH problem with a non-negligible advantage ε′ where

and e is the base of the natural logarithm.

Proof: Let (g, ga, gb, gc, z) be an instance of the DBDH problem given to a challenger 𝓑 (i.e., algorithm 𝓑), where a, b, c ∈ Zp and z ∈ GT. 𝓑 will leverage the capabilities of adversary 𝓐 to solve the problem of whether z = e(g, g)abc.

Initialization: First, the challenger 𝓑 performs Setup(1ζ), generating Pm = (e, G1, GT, g, p, H3, Mpk, SE, SD) with Mpk = N = ga. The challenger 𝓑 however, does not know the Msk = a. The parameters Pm are then forwarded to the adversary 𝓐.

Phase 1: 𝓐 can adaptively ask queries below:

1. H1 Random Oracle: For every query of H1(IDi || ri), the challenger 𝓑 searches a list H1-table (denoted as HT1) using (IDi, ri) as the index. If the search yields no result, 𝓑 flips a coin bt1 such that Pr[bt1 = 1] = Ψ. If bt1 = 0, 𝓑 computes Ho1 =

2. H2 Random Oracle: For every query of H2(IDi || IDPKG), the challenger 𝓑 searches a list H2-table (denoted as HT2) using (IDi, IDPKG) as the index. If the search yields no result, 𝓑 computes Ho2 =

3. Private Key Query: For a private key query on IDi, 𝓑 searches HT1 and HT2 using IDi as the index to find (IDi, ri, bt1, b1, Ho1) and (IDi, IDPKG, b2, Ho2). If they do not exist, 𝓑 queries the corresponding oracles of (H1, H2) in the name of 𝓐. If bt1 = 0, the simulation aborts. Or else, 𝓑 sets ski1 =

4. Trapdoor Queries: For a trapdoor query of (IDi, Kwi), 𝓑 searches HT1 using IDi as the index to find (IDi, ri, bt1, b1, Ho1). If it does not exist, 𝓑 queries the corresponding oracles of H1 in the name of 𝓐 using a random ri ∈R Zp. Then, 𝓑 runs Trapdoor(IDi, ri, Kwi) to return (δi, tdi) to 𝓐.

5. Re-encryption Key Query: For every query of (IDO, IDR, Kw) in which IDO ≠ IDR and IDR is a valid user, 𝓑 gets skO through a private key query and stores the related information in HT1. Whenever bt1 = 0 for this identity, the simulation aborts. Otherwise, 𝓑 picks random l, x, t ∈ Zp and computes L = gl, K1 = Nx, K2 =

6. Decryption Query: For every decryption query of (IDu, CT′) where IDu has not been revoked,

7. Test Queries: For every test query of (tdR, tdO, δ, CT), 𝓑 performs the algorithm of Test(CT2, tdO, δ, tdR) and forwards 1 to 𝓐 if the associated keywords are the same. Otherwise, 𝓑 returns 0.

8. Revoke Queries: For every revoke query of (IDrv), 𝓑 performs the algorithm of Revocation(IDrv, RL).

Challenge: 𝓐 selects ID* as the target identity, a keyword Kw*, a plaintext M* composed of (M1*, M2*, …, Mz*), and a pair of symmetric keys, (J0, J1), with identical lengths. The challenger 𝓑 proceeds as follows, taking (Pm, M*, Kw*, Jμ, ID*) as input, where μ ∈R {0, 1} to generate the challenge ciphertext CT* = (CT0*, CT1*, CT2*, td*) intended for 𝓐:

(a) Without loss of generality, we assume that 𝓐 has already queried oracles H1 and H2 for the corresponding ID*. If bt1* = 1 for this query, the challenger 𝓑 aborts.

(b) Otherwise, 𝓑 can utilize (b1, b2) obtained from (HT1, HT2) and h ∈R Zp to compute

(c) Set CT0* = (E1*, E2*) and CT2* = (E3*, E4*).

(d) Finally, 𝓑 returns the challenge ciphertext CT* = (CT0*, CT1*, CT2*) and trapdoor td* to 𝓐.

Phase 2: When receiving the challenge from 𝓑, 𝓐 will continue to submit queries the same as Phase 1, subject to the limits defined in Definition 1.

Guess: At the conclusion of Phase 2, 𝓐 outputs its guess μ′. The challenger 𝓑 then outputs 1 if the guess is correct (μ′ = μ), corresponding to the conclusion that z = e(g, g)abc, and outputs 0 otherwise.

Analysis: Considering the construction in the challenge phase, when e(g, g)abc = z, the ciphertext CT* is properly formed. It follows that the adversary 𝓐 can succeed in breaking the scheme with a non-negligible advantage, i.e., Adv(𝓐) = |Pr[μ′ = μ]

The calculation of Pr[Perfect] requires an analysis of the abortion probabilities. Specifically, we evaluate the likelihood that the challenger 𝓑 terminates the simulation unsuccessfully during the query phases. These probability events are defined as follows:

¬PkQ: All private key queries are executed successfully without abortion.

¬RkQ: All re-encryption key queries are executed successfully without abortion.

¬DeQ: All decryption queries are executed successfully without abortion.

¬Ch: The challenge phase is executed successfully without abortion.

As these events are independent, Pr[Perfect] can be written as Pr[Perfect] = Pr[¬PkQ]·Pr[¬RkQ]·Pr[¬DeQ]·Pr[¬Ch]. It can be seen that in a private key query, 𝓑 terminates if bt1 = 0 for the required ID, i.e., Pr[¬PkQ] ≤

By calculation, when

Theorem 2: (Proof of OW-ID-CCA)

Let H1 and H2 be random oracles. Our system achieves the OW-ID-CCA security under the DBDH assumption. If there exists a PPT adversary 𝓐 that can break the OW-ID-CCA security of the proposed system with a non-negligible advantage ε, subject to a maximum of qpk private key queries, qtd trapdoor queries, qde decryption queries and qrk re-encryption key queries, an algorithm 𝓑 is able to solve the DBDH problem with a non-negligible advantage ε′ where

and e is the base of the natural logarithm.

Proof: Let (g, ga, gb, gc, z) be an instance of the DBDH problem given to a challenger 𝓑 (i.e., algorithm 𝓑), where a, b, c ∈ Zp and z ∈ GT. 𝓑 will leverage the capabilities of adversary 𝓐 to solve the problem of whether z = e(g, g)abc.

Initialization: First, the challenger 𝓑 performs Setup(1λ), generating Pm = (e, G1, GT, g, p, H3, Mpk, SE, SD) with Mpk = N = ga. The challenger 𝓑 however, does not know the Msk = a. The parameters Pm are then forwarded to the adversary 𝓐.

Phase 1: 𝓐 can adaptively ask queries stated in Definition 2 and 𝓑 responds as those in Theorem 1.

Challenge: 𝓐 selects ID* as the target identity, and then 𝓑 randomly generates a keyword Kw*, a plaintext M* composed of (M1*, M2*, …, Mz*), and a symmetric key J* to generate the challenge ciphertext CT* = (CT0*, CT1*, CT2*) along with a trapdoor td* intended for 𝓐:

(a) Without loss of generality, we assume that 𝓐 has already queried the oracle H1 and H2 for the corresponding ID*. If bt1* = 1 for this query, the challenger 𝓑 aborts.

(b) Otherwise, 𝓑 utilizes the information (b1, b2) obtained from (HT1, HT2) and h ∈ Zp to compute

(c) Set CT0* = (E1*, E2*) and CT2* = (E3*, E4*).

(d) Finally, 𝓑 returns the challenge ciphertext CT* = (CT0*, CT1*, CT2*) and trapdoor td* to 𝓐.

Phase 2: When receiving the challenge from 𝓑, 𝓐 will continue to submit queries the same as Phase 1, subject to the limits defined in Definition 1.

Guess: At the conclusion of Phase 2, 𝓐 outputs its guess M′. The challenger 𝓑 then outputs 1 if the guess is correct (M′ = M*), corresponding to the conclusion that z = e(g, g)abc, and outputs 0 otherwise.

Analysis: Considering the construction in the challenge phase, when e(g, g)abc = z, the ciphertext CT* is properly formed. It follows that the adversary 𝓐 can succeed in breaking the scheme with a non-negligible advantage, i.e., Adv(𝓐) = Pr[M′ = M*] ≥ ε. Conversely, if z ≠ e (g, g)abc, CT* is an invalid ciphertext, and 𝓐 has no advantage, meaning Pr[M′ = M*] =

The calculation of Pr[Perfect] requires an analysis of the abortion probabilities. Specifically, we evaluate the likelihood that the challenger 𝓑 terminates the simulation unsuccessfully during the query phases. These probability events are defined as follows:

¬PkQ: All private key queries are executed successfully without abortion.

¬RkQ: All re-encryption key queries are executed successfully without abortion.

¬DeQ: All decryption queries are executed successfully without abortion.

¬Ch: The challenge phase is executed successfully without abortion.

As these events are independent, Pr[Perfect] can be written as Pr[Perfect] = Pr[¬PkQ]·Pr[¬RkQ]·Pr[¬DeQ]·Pr[¬Ch]. It can be seen that in a private key query, 𝓑 terminates if bt1 = 0 for the required ID, i.e., Pr[¬PkQ] ≤

By calculation, when

Consider the leakage of metadata, including search and access pattern leakages, in the proposed system. We believe that it is an acceptable trade-off within our “honest-but-curious” threat model, because its primary security goal is to protect the confidentiality of the plaintext, which is ensured by our IND-PrID-CCA proof. Although a cloud server can infer linkage graphs over time, such an approach is still regarded as a better alternative to avoid significant computational overheads of using privacy-enhancing technologies like oblivious RAM (ORAM) for resource-constrained IoT devices. In many practical applications, like a hospital system, knowing which doctor is accessing which patient’s file is an acceptable operational condition, as long as the confidentiality of file is strictly maintained. Therefore, we argue that the metadata information leakage is acceptable in our threat model for obtaining a better IoT-assisted cloud data sharing solution.

Regarding the security against a semi-honest server, consider the Test and ReKeyGen phases. The semi-honest Proxy must wait for the DO to calculate and send the re-encryption key K. The structure of K incorporates the private key skO of data owner. The Proxy needs to obtain random numbers rO and bO chosen by the DO during their key computation to deduce the complete key. Besides, without the private key of the data requester DR, the Proxy cannot decrypt the re-encrypted ciphertext CT′ to obtain the plaintext.

Furthermore, a malicious PKG, without knowing the corresponding private keys, cannot discover the content of plaintext by attempting to access ciphertexts on the cloud. During the UserKeyGen phase, the user’s private key is generated using an anonymous key generation technique. In spite of the temporal private key, sk′O is computed by the PKG, the genuine one still requires random numbers rO and bO chosen by the user. Therefore, without knowing the user’s genuine private key skO, one cannot decrypt the original ciphertext or perform re-encryption related operations.

Finally, any revoked user attempting to masquerade as a legal user cannot discern the plaintext content without the corresponding private key. If a revoked user impersonates a non-revoked legitimate user IDu, even if they pass the Test phase and choose a random number l to compute L =

Our proposed scheme employs a revocation list (RL) managed by the PKG to handle user revocation. Assuming there are nr revoked users in the system, the storage cost at the PKG is O(nr). This is a linear and manageable cost, because the number of revoked users is typically a fraction of the total user base. The computational cost to perform a revocation check involves a lookup operation on the RL. With a hash table implementation, this cost is O(1) on average, which is efficient. To retrieve the latest RL from the PKG requires a one-time communication cost for each data sharing request. The size of the transmitted data is proportional to the number of revoked users, i.e., O(nr). As for the synchronization and update frequency, our mechanism employs an on-demand synchronization model. The DO queries the PKG for the latest RL only when a data sharing request is authorized. This ensures that the revocation check is always current at the time of access. Although a per-request communication overhead is required, it guarantees immediate and accurate revocation enforcement. Moreover, the primary propagation delay in our revocation process comes from the network latency between the query of DO and PKG. This is an inherent characteristic of any distributed system which requires a central authority for status verification. For many IoT applications, this one-time latency is an acceptable trade-off for ensuring that access control is strictly enforced.

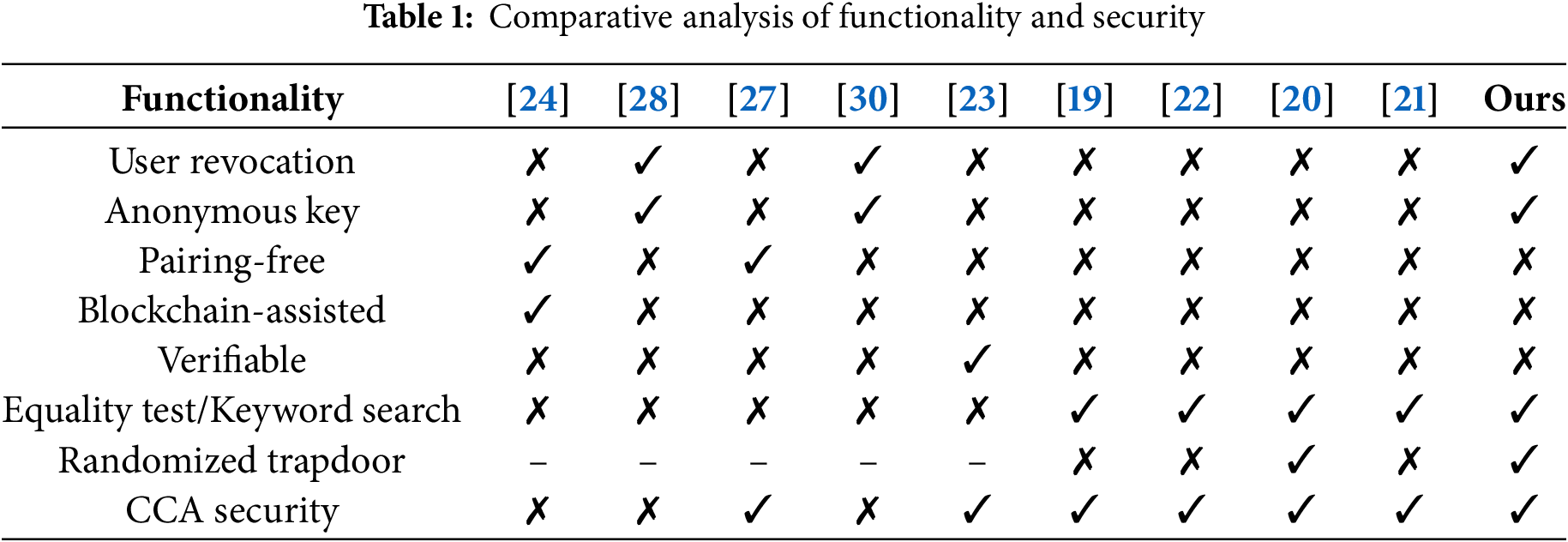

We present an efficiency analysis and functional comparison with previous PRE studies, including the works without equality test [23,24,27,28,30] and those with equality test or keyword search [19–22]. As can be inferred from Table 1, our scheme is the only one to simultaneously provide user revocation, anonymous key generation, an equality test, a randomized trapdoor and CCA security. Although schemes [28,30] support user revocation and anonymous key generation, they lack the functionality for equality test or keyword search. In contrast, schemes [19,22,23] with equality test or keyword search cannot support user revocation and anonymous key generation. Moreover, our scheme adopts a randomized trapdoor to enhance security, which is not provided by [19,22]. Although our system does not incorporate pairing-free, blockchain-assisted or verifiable techniques, this reflects a trade-off aimed at providing a more comprehensive and secure solution based on the proposed IoT-assisted cloud data sharing framework.

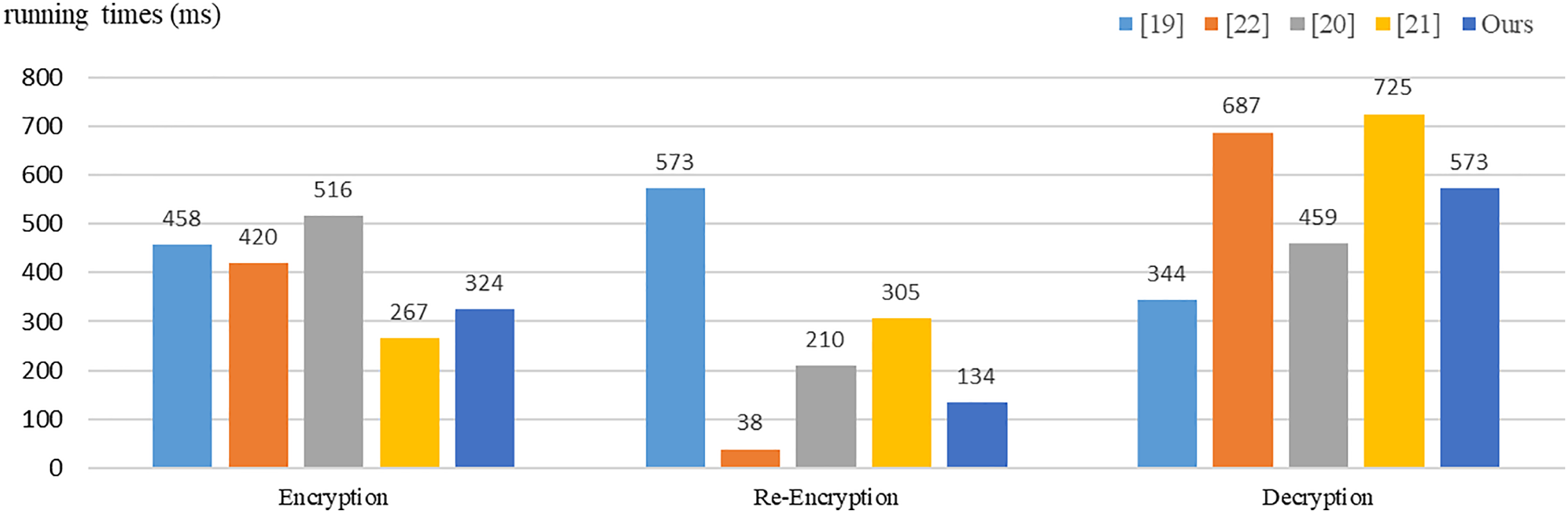

In Fig. 2, we demonstrate a performance analysis of our scheme and previous ones [19–22] that also provide the functionality of equality test or keyword search. The evaluated computations include bilinear pairing operations and exponentiation operations in G1 and GT, respectively. The approximate running time of these three computations are separately 133.663 ms, 38.108 ms, and 38.339 ms based on an experimental environment of Raspberry Pi Zero @ 1.0 GHz CPU with the 512 MB memory size. We focus on the major algorithms: encryption, re-encryption, and decryption by both the data owner and the data user. This result reveals that in the encryption process, scheme [21] has the best efficiency at 267 ms, while the proposed scheme, with a running time of 324 ms, is faster than [19,20,22]. As for the re-encryption process, scheme [22] outperforms all other compared scheme with a time of 38 ms. Although our scheme requires 134 ms, it is still more efficient than schemes [19–21]. In the decryption process, our scheme exhibits a moderate performance level at 573 ms, which is faster than both [21,22]. To sum up, the proposed system demonstrates a well-balanced and competitive performance across the different processes.

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of efficiency [19–22]

With the popularity of IoT applications, fog computing is becoming increasingly important due to its advantages in low latency, rapid response, and support for distributed architectures. In a distributed data sharing environment, how to securely share ciphertext among different data requesters and compare if two ciphertexts correspond to the same plaintext are critical challenges. In this paper, the authors addressed these challenges by presenting a fog-assisted secure and revocable IoT data sharing system using identity-based proxy re-encryption with an equality test. To avoid the problem of key escrow and using secure channels, we utilize an anonymous key generation technique in the proposed system. Also, our designed data request workflow restricts a revoked user from further requesting any ciphertext by employing a simple revocation list without increasing extra computational costs. The equality test feature benefits the cloud server to determine the relation between two candidate ciphertexts. Moreover, the comparison results and the formal security proof clearly reveal that the proposed system offers both better functionalities and security strength.

Although this paper establishes a secure and functional theoretical framework, some practical challenges related to large-scale IoT deployments require further investigation as future work. For instance, handling multi-user concurrent queries to prevent performance bottlenecks at the cloud server and fog nodes would require designing strategies like load balancing and batch processing for equality tests. Furthermore, enhancing applicability for cross-domain data sharing in multi-organizational systems requires extending the current single-PKG model to a hierarchical or federated identity-based framework. Finally, another important practical consideration is developing an efficient dynamic key update mechanism to allow for periodic key renewal for users without requiring full revocation.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under the contract numbers NSTC 114-2221-E-019-055-MY2 and NSTC 114-2221-E-019-069.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Han-Yu Lin and Yi-Chuan Wang; methodology, Yi-Chuan Wang; validation, Han-Yu Lin, Tung-Tso Tsai and Yi-Chuan Wang; formal analysis, Yi-Chuan Wang; resources, Tung-Tso Tsai; data curation, Yi-Chuan Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Han-Yu Lin; writing—review and editing, Tung-Tso Tsai; supervision, Han-Yu Lin; funding acquisition, Han-Yu Lin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lertpongrujikorn P, Salehi MA. Tutorial: object as a service (OaaS) serverless cloud computing paradigm. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 44th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops (ICDCSW); 2024 Jul 23–23; Jersey City, NJ, USA. p. 5–8. doi:10.1109/ICDCSW63686.2024.00006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mell P, Grance T. The NIST definition of cloud computing. Natl Inst Stand Technol. 2011;53:1–7. [Google Scholar]

3. Nam DH. A comparative study of mobile cloud computing, mobile edge computing, and mobile edge cloud computing. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE); 2023 Jul 24–27; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 1219–24. doi:10.1109/CSCE60160.2023.00204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sharbaf MS. IoT driving new business model, and IoT security, privacy, and awareness challenges. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 8th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT); 2022 Oct 26–Nov 11; Yokohama, Japan. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/WF-IoT54382.2022.10152044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Obaid S, Sharma A, Balaji SM, Mangaiyarkarasi V, Chythanya NK, CP. Leveraging blockchain for secure IoT device communication in smart cities. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology (ICICAT); 2024 Nov 23–24; Gorakhpur, India. p. 1398–402. doi:10.1109/ICICAT62666.2024.10923020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Luo Z, Ou D, Lin T, Lin X. Research on wireless dynamic magnetic resonance charging technology for autonomous vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer (EIECT); 2024 Nov 15–17; Shenzhen, China. p. 774–7. doi:10.1109/EIECT64462.2024.10866083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Santosa I, Supangkat SH, Akhmad Arman A. People-centric smart city services measurement using garuda smart city framework. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Mediterranean Smart Cities Conference (MSCC); 2024 May 2–4; Martil-Tetuan, Morocco. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/MSCC62288.2024.10696991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Delsi Robinsha S, Amutha B. IoT revolutionizing healthcare: a survey of smart healthcare system architectures. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Research Methodologies in Knowledge Management, Artificial Intelligence and Telecommunication Engineering (RMKMATE); 2023 Nov 1–2; Chennai, India. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/RMKMATE59243.2023.10369980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tran-Dang H, Bhardwaj S, Rahim T, Musaddiq A, Kim DS. Reinforcement learning based resource management for fog computing environment: literature review, challenges, and open issues. J Commun Netw. 2022;24(1):83–98. doi:10.23919/JCN.2021.000041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Abdali TN, Hassan R, Aman AHM, Nguyen QN. Fog computing advancement: concept, architecture, applications, advantages, and open issues. IEEE Access. 2021;9:75961–80. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3081770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lal R, Singla S, Samal N. Navigating the cloud and fog: an extensive comparative analysis of cloud computing and fog computing architectures. In: Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing, Communication, Power and Embedded System (SCOPES); 2024 Dec 19–21; Odisha, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/SCOPES64467.2024.10991096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Blaze M, Bleumer G, Strauss M. Divertible protocols and atomic proxy cryptography. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 1998 May 31–Jun 4; Espoo, Finland. p. 127–44. doi:10.1007/BFb0054122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ateniese G, Fu K, Green M, Hohenberger S. Improved proxy re-encryption schemes with applications to secure distributed storage. ACM Trans Inf Syst Secur. 2006;9(1):1–30. doi:10.1145/1127345.1127346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang XA, Zhong W. A new identity based proxy re-encryption scheme. In: Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Computer Science; 2010 Apr 23–25; Wuhan, China. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ICBECS.2010.5462448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang L, Wang XA, Wang W. Toward CCA-secure bidirectional proxy re-encryption without pairing nor random oracle. In: Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing Systems; 2010 Jul 5–7; Dalian, China. p. 599–602. doi:10.1109/ICSPS.2010.5555516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chow SSM, Weng J, Yang Y, Deng RH. Efficient unidirectional proxy re-encryption. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Cryptology in Africa; 2010 May 3–6; Stellenbosch, South Africa. p. 316–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12678-9_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lu Y, Li J. Privacy-preserving and forward public key encryption with field-free multi-keyword search for cloud encrypted data. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(4):3619–30. doi:10.1109/TCC.2023.3305370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lin H, Zhao Z, Gao F, Susilo W, Wen Q, Guo F, et al. Lightweight public key encryption with equality test supporting partial authorization in cloud storage. Comput J. 2021;64(8):1226–38. doi:10.1093/comjnl/bxaa144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shao J, Cao Z, Liang X, Lin H. Proxy re-encryption with keyword search. Inf Sci. 2010;180(13):2576–87. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2010.03.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fang L, Susilo W, Ge C, Wang J. Chosen-ciphertext secure anonymous conditional proxy re-encryption with keyword search. Theor Comput Sci. 2012;462(2):39–58. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2012.08.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang CC, Tso R, Liu ZY, Hsu JC, Tseng YF. Improved proxy re-encryption scheme with equality test. In: Proceedings of the 2021 16th Asia Joint Conference on Information Security (Asia JCIS); 2021 Aug 19–20; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 37–44. doi:10.1109/AsiaJCIS53848.2021.00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Elhabob R, Eltayieb N, Xiong H, Kumari S. Equality test on identity-based encryption with cryptographic reverse firewalls for telemedicine systems. IEEE Int Things J. 2025;12(2):2106–21. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3466958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chen L, Chen S, Zhang H, Weng J. Fair and verifiable identity-based broadcast proxy re-encryption with designated sender feasible for medical internet of things. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2025;20(3):6033–45. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2025.3578925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Manzoor A, Liyanage M, Braeke A, Kanhere SS, Ylianttila M. Blockchain based proxy re-encryption scheme for secure IoT data sharing. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC); 2019 May 14–17; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 99–103. doi:10.1109/bloc.2019.8751336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen B, He D, Kumar N, Wang H, Choo KR. A blockchain-based proxy re-encryption with equality test for vehicular communication systems. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2021;8(3):2048–59. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2020.2999551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Han G, Li L, Qin B, Zheng D. Pairing-free proxy re-encryption scheme with equality test for data security of IoT. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(6):102105. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li B, Deng L, Mou Y. A pairing-free identity-based broadcast proxy re-encryption scheme for the cloud. In: Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME); 2024 Sep 13–15; Guiyang, China. p. 521–8. doi:10.1109/ITME63426.2024.00109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang J, Bai W, Wang X. Identity-based data storage scheme with anonymous key generation in fog computing. Soft Comput. 2020;24(8):5561–71. doi:10.1007/s00500-018-3593-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lin HY, Tsai TT, Ting PY, Chen CC. An improved ID-based data storage scheme for fog-enabled IoT environments. Sensors. 2022;22(11):4223. doi:10.3390/s22114223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lin HY, Tsai TT, Ting PY, Fan YR. Identity-based proxy re-encryption scheme using fog computing and anonymous key generation. Sensors. 2023;23(5):2706. doi:10.3390/s23052706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools