Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Objective Enhanced Cheetah Optimizer for Joint Optimization of Computation Offloading and Task Scheduling in Fog Computing

1 Department of Electronic, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, 25000, Pakistan

2 Department of Computer Science, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan, 23200, Pakistan

3 School of Digital Technologies, Narxoz University, Almaty, 050035, Kazakhstan

4 Department of Clinical Laboratories Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif, 21944, Saudi Arabia

5 School of Computing, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

6 Department of Software Engineering, University of Science and Technology, Bannu, 28100, Pakistan

7 Department of Health Information Management and Technology, College of Public Health, Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University, Dammam, 31441, Saudi Arabia

8 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Ateeq Ur Rehman. Email: ; Hend Khalid Alkahtani. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 66 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073818

Received 26 September 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The cloud-fog computing paradigm has emerged as a novel hybrid computing model that integrates computational resources at both fog nodes and cloud servers to address the challenges posed by dynamic and heterogeneous computing networks. Finding an optimal computational resource for task offloading and then executing efficiently is a critical issue to achieve a trade-off between energy consumption and transmission delay. In this network, the task processed at fog nodes reduces transmission delay. Still, it increases energy consumption, while routing tasks to the cloud server saves energy at the cost of higher communication delay. Moreover, the order in which offloaded tasks are executed affects the system’s efficiency. For instance, executing lower-priority tasks before higher-priority jobs can disturb the reliability and stability of the system. Therefore, an efficient strategy of optimal computation offloading and task scheduling is required for operational efficacy. In this paper, we introduced a multi-objective and enhanced version of Cheeta Optimizer (CO), namely (MoECO), to jointly optimize the computation offloading and task scheduling in cloud-fog networks to minimize two competing objectives, i.e., energy consumption and communication delay. MoECO first assigns tasks to the optimal computational nodes and then the allocated tasks are scheduled for processing based on the task priority. The mathematical modelling of CO needs improvement in computation time and convergence speed. Therefore, MoECO is proposed to increase the search capability of agents by controlling the search strategy based on a leader’s location. The adaptive step length operator is adjusted to diversify the solution and thus improves the exploration phase, i.e., global search strategy. Consequently, this prevents the algorithm from getting trapped in the local optimal solution. Moreover, the interaction factor during the exploitation phase is also adjusted based on the location of the prey instead of the adjacent Cheetah. This increases the exploitation capability of agents, i.e., local search capability. Furthermore, MoECO employs a multi-objective Pareto-optimal front to simultaneously minimize designated objectives. Comprehensive simulations in MATLAB demonstrate that the proposed algorithm obtains multiple solutions via a Pareto-optimal front and achieves an efficient trade-off between optimization objectives compared to baseline methods.Keywords

Cloud computing has become an essential component of advanced computing technology. It allows individuals and businesses to access an extensive range of computing resources, like storage, processing power, and computational power [1,2]. Nevertheless, it faces difficulties meeting the demand for delay-sensitive and data-intensive IoT tools [3,4]. To address these challenges, cloud-fog computing has developed as the best tool to handle different types of user requests, which may vary in their needs for low latency, delay, cost-effectiveness, makespan, bandwidth utilization, and energy efficiency [5,6]. This method involved the joint utilization of cloud computing with node computing fixed near data sources, facilitating efficient energy consumption, bandwidth execution, and minimizing delay. However, network latency, data management, limited wireless resources, and complex environments pose numerous challenges to computation offloading and task scheduling in edge computing, demanding the development of efficient techniques [7].

In cloud computing, computation offloading ensures tasks are allocated to suitable computational nodes for efficient and timely processing, while task scheduling determines the optimal execution order of offloaded jobs to enhance performance metrics like resource utilization, energy consumption, and communication delay, etc. The effectiveness of scheduling techniques in fog computing relies on the seamless integration of task allocation and orderly task execution. However, most existing scheduling algorithms focus solely on either task allocation or execution, leading to resource bottlenecks, increased communication delays, and reduced system stability and reliability. A joint optimization of computation offloading and task scheduling is essential to improve bandwidth utilization, maintain energy efficiency, reduce latency, mitigate resource bottlenecks, and enhance overall system stability and reliability [8–10].

Moreover, maintaining an efficient trade-off between computation offloading and task scheduling in cloud-fog computing is also necessary because directing jobs to the cloud servers can reduce energy but increases communication cost and latency, while processing tasks at fog nodes can reduce communication latency but increases energy consumption. Moreover, if the order of execution based on priorities is not taken into account in scheduling, then it will negatively affect the reliability and stability. For example, in a smart city traffic management system, if there is a delay in traffic control based on data received from IoT devices, it can increase the risk of congestion and accidents on the roads. Especially when the system is busy with unnecessary jobs and cannot process important traffic tasks on time. Therefore, optimizing both computing offloading and task scheduling is crucial to achieve the best balance between energy savings and low latency, which is essential for the smooth operation of a system.

Computation offloading and task scheduling in fog computing possess a Nondeterministic polynomial-time complete (NP-complete) optimization problem, requiring an efficient solution to allocate resources effectively [11–13]. Many state-of-the-art techniques exist to seek an ideal solution. Some basic approaches, like brute force techniques and dynamic programming, often lack effectiveness in terms of latency and bandwidth. The brute force technique is impractical in large scenarios owing to the comprehensive search required to map available task resources, which increases in computational complexity. Recent Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) algorithms are powerful methods to solve decision-making problems. However, they require substantial offline training and careful reward function design, making them inefficient for solving multi-objective optimization problems [14]. In contrast, a multi-objective meta-heuristic algorithm efficiently optimizes the conflicting objectives via Pareto-optimal front generation without requiring an extensive training phase. Moreover, they are generally more sample-efficient, easier to reproduce, and simpler to implement in heterogeneous cloud-fog environments.

Recently, several meta-heuristic techniques have been applied to tackle the issues of task scheduling in cloud computing, including particle swarm optimization (PSO) [15], ant colony optimization (ACO) [16], genetic algorithm (GA) [17], and Gray wolf optimization (GWO) [18], among others. The goal of these algorithms is to efficiently tackle the issue of task scheduling to meet the user’s requirement in terms of Quality of service. However, challenges, such as low convergence rates, imbalanced exploration and exploitation phases, limited stochastic operators, focus on a single objective, and the existence of multiple search spaces, can potentially lead to local stagnation, consequently diminishing system efficiency [16].

To address the limitation of existing scheduling techniques, we proposed a Multi-objective Enhanced Cheetah Optimizer (MoECO) to jointly optimize computation offloading and task scheduling in a cloud fog computing environment. MoECO obtains a set of solutions via the Pareto-optimal front. Cheetah Optimizer (CO) is a new meta-heuristic algorithm inspired by the hunting behavior of Cheetahs. The special hunting strategy of Cheetahs comprises three phases, i.e., searching, sitting, waiting, and attacking [19,20].

The CO is well regarded as a strong method for solving many optimization problems. However, the mathematical modelling of the searching and attaching phase could affect the exploration and exploitation capability of agents. Consequently, the CO algorithm reduces convergence speed and increases computation time. To overcome these shortcomings, we modified the CO algorithm, which can improve the local and global search capability of agents while requiring fewer computational resources. The global search capability is improved based on the leader position instead of the Cheetah’s previous position. The step length parameter is modified that contribute to the diversity of solutions and hence increase the exploration capability of agents. Furthermore, the interaction factor during the exploitation phase (i.e., local search) is also adjusted based on the location of a prey instead of the adjacent Cheetah. This adjustment can enable the algorithm to find the near-optimal solution. Thus, local search capability (exploitation) is also enhanced. Attributed to its fast convergence rate, avoiding local optimization, and low computation time, the proposed algorithm efficiently optimizes the task scheduling in fog computing.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to use the MoECO for computation offloading and task scheduling. The innovative aspect of our approach lies in leveraging a multi-objective enhanced cheetah algorithm to jointly optimize computation offloading and task scheduling within a cloud-fog computing environment. We improved the search strategy of agents based on the leader position to escalate the convergence stability and improve the exploration-exploitation balance. To simultaneously minimize the energy consumption and communication latency, we generate a multi-objective Pareto-optimal front while maintaining diverse trade-offs between competing objectives. In our algorithm, each cheetah serves as a candidate solution, encoding a unique task offloading and scheduling strategy. MoECO efficiently allocates resource-intensive tasks to cloud servers and delays sensitive jobs to fog nodes, achieving an optimal trade-off between minimum energy consumption and communication delay. Moreover, the MoECO processes higher priority jobs before lower priority tasks, mitigating resource bottlenecks and escalating system reliability and stability. We simulate MoECO in MATLAB and compare it against the state-of-the-art algorithms. Simulation results show that our scheme outperforms other schemes in minimizing communication delay and energy consumption, while improving task completion rate and fairness index. Furthermore, due to its distinct position updating mechanism, high convergence speed, low computation time, and equal distribution of workload, MoECO strengthens network stability and enables efficient handling of diverse requests originating from heterogeneous IoT devices.

The main contributions of our article are as follows:

• The global and local search capability of CO is improved by adjusting the step length operator and the interaction factor during the attaching phase, respectively.

• A new multi-objective mathematical model for task offloading and scheduling in cloud-fog computing is designed to efficiently offload tasks to the optimal computation node and then schedule the tasks based on the tasks’ priorities.

• The proposed solution is compared with the baseline methods and benchmarks to ensure its efficiency in saving energy, minimizing transmission delay, and reducing network load. The analysis demonstrates that the developed algorithm consistently delivers better performance compared to existing methods.

Unlike benchmark algorithms, which overlook resource diversity and workload distribution, the proposed algorithm effectively addresses these challenges. Additionally, existing algorithms focus solely on either energy consumption or delay, disregarding the impact of other performance metrics. In contrast, the proposed solution evaluates system performance by considering energy consumption and delay, task completion rate, and fairness index, providing a more realistic and comprehensive assessment.

In this section, we review the different work done by other authors in the field of cloud-fog Computing. Wang et al. [21] proposed a task scheduling solution known as Deep Reinforcement Learning-based IoT application Scheduling algorithm (DRLIS), which is significant due to the growing need for low-latency applications in the Internet of Things (IoT) environments. These environments are highly dynamic and often change unpredictably. The DRLIS method has been shown to achieve lower optimization costs and shorter scheduling times compared to Q-Learning, Deep Q-Network (DQN), Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), and NSGA-III. To further enhance the quality of service in fog networks, the authors proposed additional task scheduling methodologies, including Fuzzy Golden Eagle Load Balancing (FGELB) and Golden Eagle Optimization algorithm (GEOA) [22]. These approaches involve three main stages: sorting tasks based on fuzzy logic, ranking and allocating resources using GEOA, and managing power consumption based on the availability and current status of tasks and resources. The FGELB approach was compared against other methods in terms of communication overhead, computation cost, latency, energy consumption, and failure rate, demonstrating its effectiveness.

A time-dependent scheduling mechanism was formulated, exemplifying the use of time-sensitive data modelled by neural networks [23]. A benchmark dataset from authors and consumers was utilized to evaluate energy consumption and response time. The mechanism was implemented using iFogSim, and experiments were conducted against baseline approaches. The results demonstrated that Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HIRO) achieved significantly lower energy consumption compared to current conventional methods.

A method known as the Adaptive Multi-objective Optimization Task Scheduling Method for fog computing (FOG-AMOSM) was designed in [24], focusing on resource cost and task execution as key parameters. To clarify, it was proposed as a multi-objective methodology utilizing a heuristic approach. Furthermore, it outperformed the Round Robin (RR) algorithm in effectively addressing the aforementioned parameters. Siyadatzadeh et al. [25] developed a task scheduler aimed at enhancing reliability and improving the ability to schedule tasks on fog computing (FC) nodes. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Real-Time Task Assignment Strategy in Emerging Fault-Tolerant Fog Computing is proposed, named as ReLIEF and compared with state-of-the-art techniques using the iFogSim simulator. The results demonstrated that ReLIEF effectively reduced delays while balancing workloads across the network.

Jain and Kumar in [26] conducted a survey that included a scheduler designed to address Quality of Service (QoS) challenges in the cloud-fog environment. This scheduler was modelled using the Markov Decision Process, focusing on energy consumption in relation to execution time. The approach was implemented in SimPy and tested against DQN and RR algorithms, demonstrating its effectiveness in optimizing performance. Chandrashekar et al. [27] developed a workflow specifically for assigning tasks to individual processors in the cloud computing paradigm. The proposed technique aimed to minimize both cost and time during project implementation. To evaluate the model, several baseline algorithms were used for comparison, including Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), a UAV-based nighttime arrangement optimization model, and First-Come-First-Served (FCFS). The focus on cost-aware job scheduling for cloud instances has been explored in the work of Cheng et al. [28], where the use of advanced reinforcement learning methods is emphasized. This research highlights the critical importance of cost efficiency in cloud computing environments. Deep reinforcement learning is proposed as a solution to enhance job scheduling by improving both execution time and cost efficiency.

The study highlights the growing significance of cost-conscious strategies in cloud computing and demonstrates how deep reinforcement learning can improve task scheduling practices within cloud instances. It emphasizes the ongoing pursuit of innovative approaches to reducing operational costs while maximizing resource utilization. Additionally, it introduces the concept of an effective cloud computing economy, which is increasingly vital in today’s context. Topics related to cluster computing have also been discussed, with relevant factors outlined to address key challenges in this domain.

Chen et al. [29] proposed a decentralized architecture for an Intelligent Video Surveillance System (IVSS) capable of performing real-time data analysis using fog computing. In this framework, edge computing collaborates with cloud computing to act as a converged computing system. Artificial intelligence (AI) is employed to collect media data from customer-distributed edge network devices. Subsequently, AI enables the distributed storage of information and manages access to this data through distributed accessory equipment, facilitating automatic video telepresence in real time. Rafique et al. [30] introduced a novel task scheduling algorithm that combines Social Problem-Solving Optimization and Cat Swarm Optimization techniques. The primary focus of this study was to reduce response time by efficiently assigning tasks to appropriate fog nodes. This approach emphasizes achieving an optimal level of resource utilization while ensuring tasks are scheduled effectively within the fog computing environment.

Ghobaei-Arani et al. [31] explored the potential of the Moth-Flame Optimization (MFO) algorithm for resource allocation in fog computing. They proposed a taxonomy based on an optimization-driven approach for task execution, where tasks are optimally mapped to computational resources to meet QoS demands while minimizing computational and transmission time. However, the proposed algorithm does not account for the energy cost associated with using the corresponding fog device or node, which could ultimately degrade the overall performance of the system.

An improved discrete NSGA is proposed in [32] to minimize makespan, computation costs, and communication costs. The objective is to automate the scheduling process, thereby reducing the effort required to allocate tasks among personnel. The algorithm dynamically selects fog nodes or cloud servers for processing to ensure efficient load balancing and optimize overall system performance. Multi-objective Gray Wolf Optimization (MGWO), presented by Saif et al. [33], leverages the predatory chase behavior of grey wolves to enhance the performance of the proposed ACO algorithm for task scheduling in a cloud–fog computing network. Energy consumption and transmission delay are considered as optimization objectives. MGWO is implemented on the fog controller, which determines the distribution of the workload to computing assets. The decision is made after accurately assessing and evaluating the nature of the tasks being offered.

Tang and Wong [34] have developed a deep reinforcement learning-based task offloading model in fog computing. The study focuses on addressing issues related to computation offloading and service insertion in fog computing, intending to minimize latency, migration costs, and energy consumption. To achieve this, the optimization problem is framed as a multidimensional Markov decision process.

Razaq et al. [35] propose a fragmentation-based probabilistic Q-learning approach for offloading fragmented tasks to fog computing environments. The concept of software computing is introduced, with the goal of offloading tasks to computational nodes while ensuring load balancing. IoT jobs that arrive are split into segments based on factors such as privacy, completion time, and other real-time constraints. These segments are then delegated to several fog nodes for processing.

The authors in [36] proposed a framework that integrates federated learning with deep reinforcement learning to enable decentralized scheduling, allowing fog nodes to train local DQN models on their own data and aggregate knowledge into a shared global model without exchanging sensitive information. The framework improves task prioritization by classifying workloads based on execution time and deadlines, ensuring that high-priority tasks meet their service level agreements (SLAs). In [37], the authors proposed a hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) named PSO + WOA, a paradigm to address the challenges of job scheduling in large-scale, dynamic, and heterogeneous cloud-fog environments. The hybrid framework combines the exploration capabilities of PSO with the exploitation strengths of WOA. The proposed framework effectively balances exploration and exploitation, thereby improving convergence toward optimal task scheduling. In [38], the authors proposed a Multi-Objective Workflow Scheduling using a Deep Reinforcement Learning approach that integrates DQN-based scheduling with a priority-driven task mapping mechanism. Job priorities are computed based on task dependencies, while the priorities of computational nodes (e.g., virtual machine) are derived from datacenter electricity cost, enabling the DQN-based task scheduler to adaptively assign tasks that jointly minimize makespan and energy consumption.

In [39], the authors proposed a low delay scheduling algorithm for fog computing workflows with energy constraints. The algorithm focuses on minimizing workflow completion time while adhering energy consumption limit. Additionally, the algorithm also improves the system reliability in mobile fog computing under the same energy constraints. A hybrid bio-inspired algorithm for task scheduling in edge computing is proposed in [40]. The authors combine the Slime Model Algorithm and the optimized Harris Hawks Optimizer to improve the convergence accuracy, communication latency, and energy efficiency. Based on the requirements of each task, K-medoids clustering is employed to divide the tasks into computationally intensive, data-intensive, and integrated groups. This is particularly useful in meeting the requirements of each task.

This part presents the architecture of cloud–fog computing, along with the workflow of our proposed task scheduling algorithm.

3.1 Cloud-Fog Computing Architecture

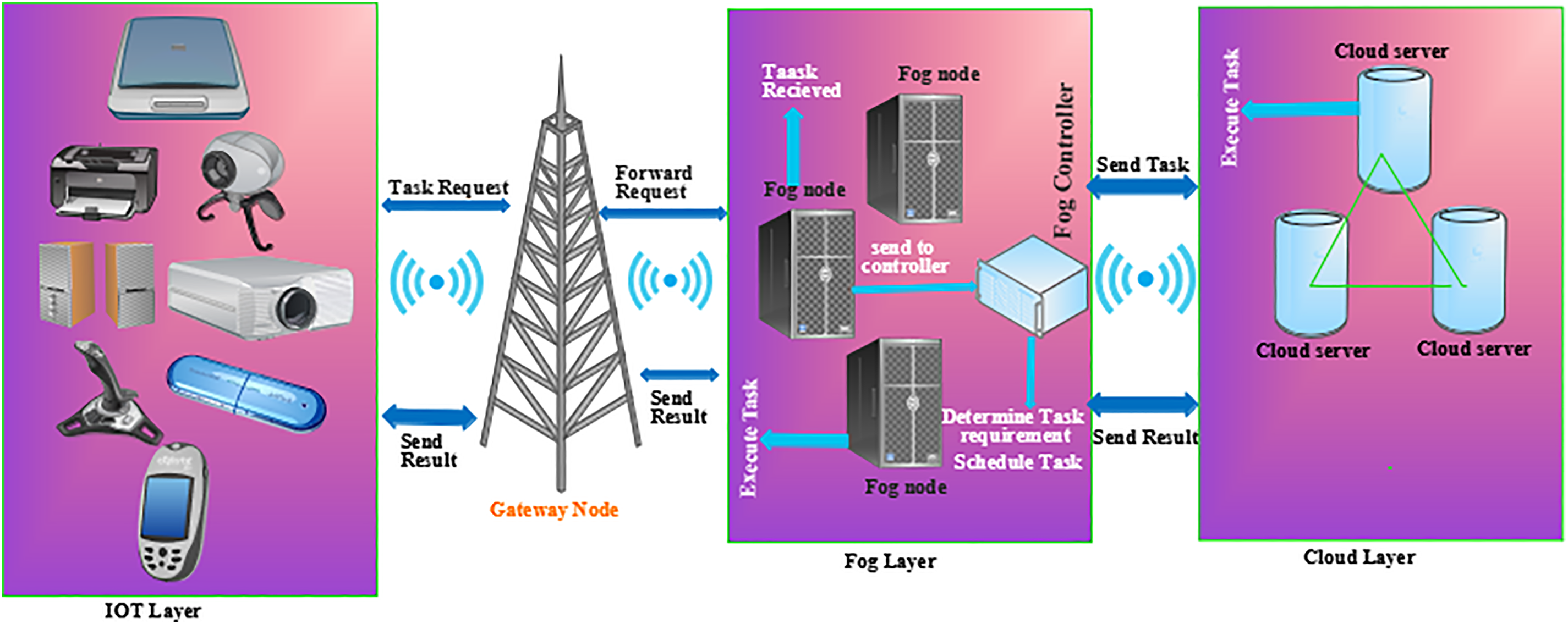

Cloud-fog computing consists of three layers: (1) the IoT layer, (2) the fog layer, and (3) the cloud layer. These three layers are interconnected through wireless devices such as LoRa, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi. The first layer contains the IoT devices, enabling them to send data to the other layers for processing. IoT devices can also communicate with each other, generating crucial information needed for quick responses. Once data is generated by the first layer, it is passed to the second layer, which contains two nodes: the task receiver and the task controller, also referred to as the fog node and fog analyzer. Fog nodes have limited computational power and storage capacity, which helps reduce transmission latency and network overhead. However, certain tasks require additional computational power and storage capacity, prompting the fog node to transmit the data to the cloud server for processing. In each scenario, the task is received by the task receiver (fog node) and directly forwarded to the controller. When the fog node receives a task, it further divides it into subsets for estimation analysis and task scheduling, depending on the task requirements. The fog layer (fog controller) incorporates the proposed algorithm to make optimal task scheduling decisions, considering objectives such as energy consumption and delay. The third layer consists of computational servers with significant computational power. This layer is responsible for processing the tasks and sending them back to the fog layer after completion. The working operation of the proposed task scheduling algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Working operation of the proposed algorithm

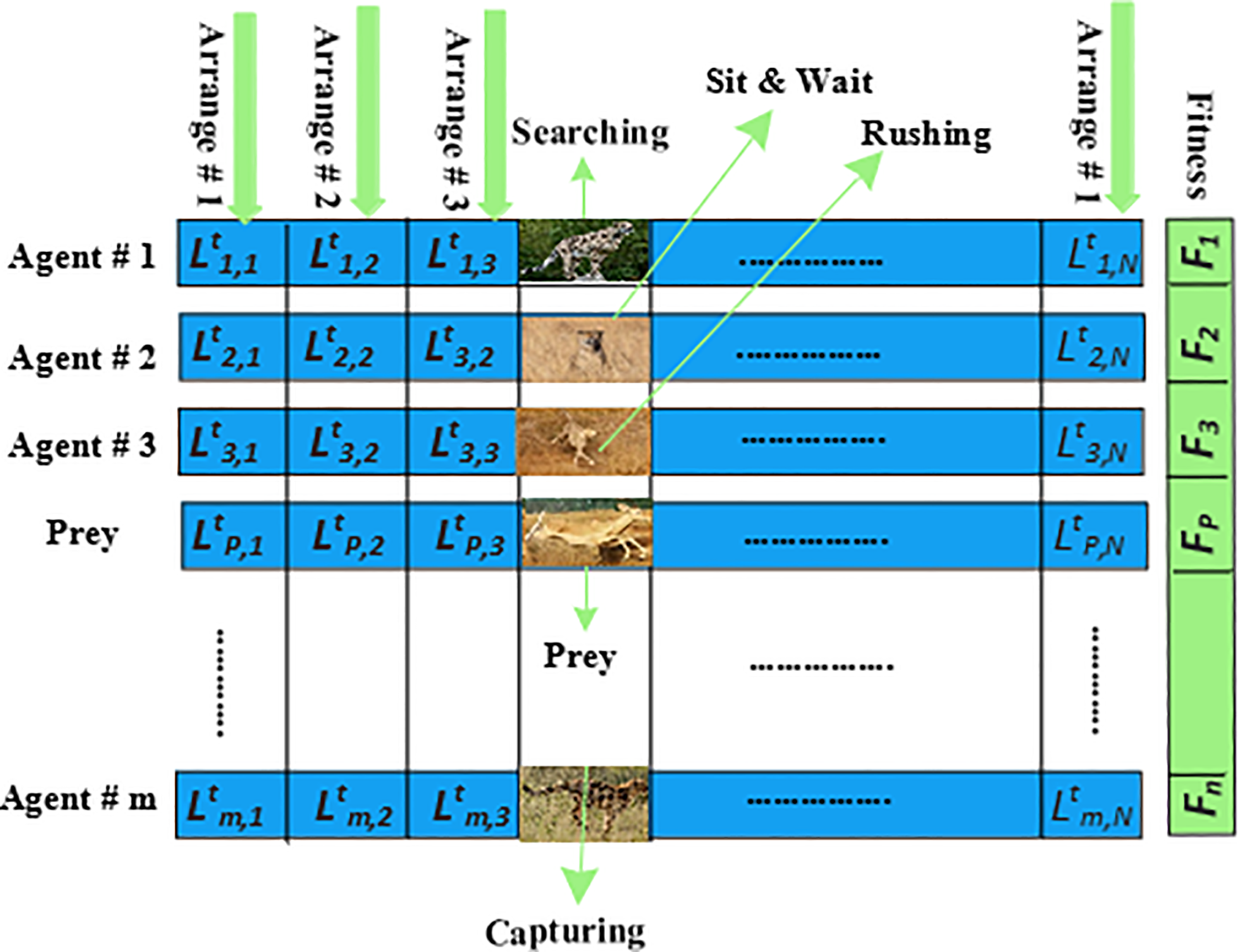

3.2 Cheetah Optimizer (CO) and Multi-Objective CO

CO algorithm is a new meta-heuristic optimization algorithm, inspired by the hunting behavior of Cheetahs. It is primarily designed for tackling complex real-world optimization problems, not only in the field of computer science, but also in other fields like electronics [41], engineering [42], and medical science [43], etc. It is one of the fastest land animals that can run at a speed of 120 km/h. A cheetah is capable of detecting prey upon patrolling its surroundings. When prey is detected, the Cheetah tries to hide himself or on small breaches or hills. In this case, Cheetah does not directly attack the prey, but instead it sits and waits for the prey to come close as much as possible. Cheetah tries to maintain this minimum distance, and once it is within the range, Cheetah attempts to attack the prey. Overall, the hunting strategy of CO is divided into three phases, i.e., (i) search strategy (ii). sit and wait strategy and (iii) attacking strategy. Fig. 2 presents the arrangements of the Cheetah population according to these strategies. Each arrangement of Cheetah in the swarm indicates a solution to the problem. For example, in our case, each arrangement represents a unique task scheduling strategy. Each arrangement is further evaluated to compute the fitness value. Among the population, the best location is considered as the prey, i.e., the best solution. Cheetahs arrange their locations according to the location of the prey. The description of each strategy is given below:

Search phase: In the search phase, Cheetah scans the surrounding area in search of the prey. The searching can be done either sitting or standing, or actively patrolling the environment.

Sit and wait phase: The movement of the Cheetah can lead to the escape of the prey. Therefore, Cheetah needs to be very careful while approaching the prey. To avoid being caught, Cheetahs hide themselves from the prey and sit in a hidden place and wait for the prey to come nearer.

Attack phase: In this phase, there are two important steps (i) Rushing (ii) capturing. Rushing is when Cheetahs decide to attack the prey; they quickly run towards the prey with maximum speed. In capturing, the Cheetahs used flexibility to capture the prey by approaching the prey with maximum speed. The mathematical modelling of each phase of the CO algorithm is given in (19).

Figure 2: Representation of CO algorithm

Mult-objective Cheetah Optimizer (MoCO) is extension of the CO, designed to solve multi-objective optimization problems which encompasses two or more competing objectives that are to be solved simultaneously. Unlike single-objective optimizers, multi-objective optimization problems generate multiple solutions because of multiple conflicting objectives. Mathematically, it is represented as below:

where S is the population size with n number of solutions, with d is the dimension. The objective function F is applied on multiple solutions, i.e., F(S), and multiple Z objective values are generated.

The solutions can either dominate or be non-dominant over one another based on specific conditions.

• Two solutions s1 and s2 are non-dominating over each other if they have the same fitness values, and any fitness value of s1 is either better than s2 or worse than s2.

• Alternatively, s1 dominates s2, if all fitness values of s1 is better than s2 or s2 has some fitness values that is worse than s1.

All the non-dominating solutions are stored in an external archive and arranged in a population and ranked based on dominance. The first rank consists of the best non-dominating solutions. The subsequent rank contains solutions dominated by higher-ranked ones. All the solutions in the archive are called Pareto-optimal solutions and form the Pareto-optimal front. When a new solution dominates the existing one in the archive, then the existing solution is replaced by the new solution, ensuring the archive maintains only the most optimal solutions.

In this section, we introduce the proposed algorithm for tackling the multi-objective optimization problem using the multi-objective enhanced Cheetah Optimizer. The main aim of the proposed algorithm is to offload and schedule N independent tasks with different computing resource needs within cloud computing environments. The algorithm initially offloads each task to an appropriate computational node based on its requirements. For example, energy-intensive tasks are assigned to cloud servers, while delay-sensitive tasks are assigned to fog nodes. The offloaded tasks are then executed considering their deadlines and energy usage. The goal is to minimize total processing time and energy consumption while ensuring all tasks meet their deadlines, thus preventing overloads on any node. Specifically, the algorithm seeks to optimize two key metrics: reducing overall task completion time and decreasing energy consumption.

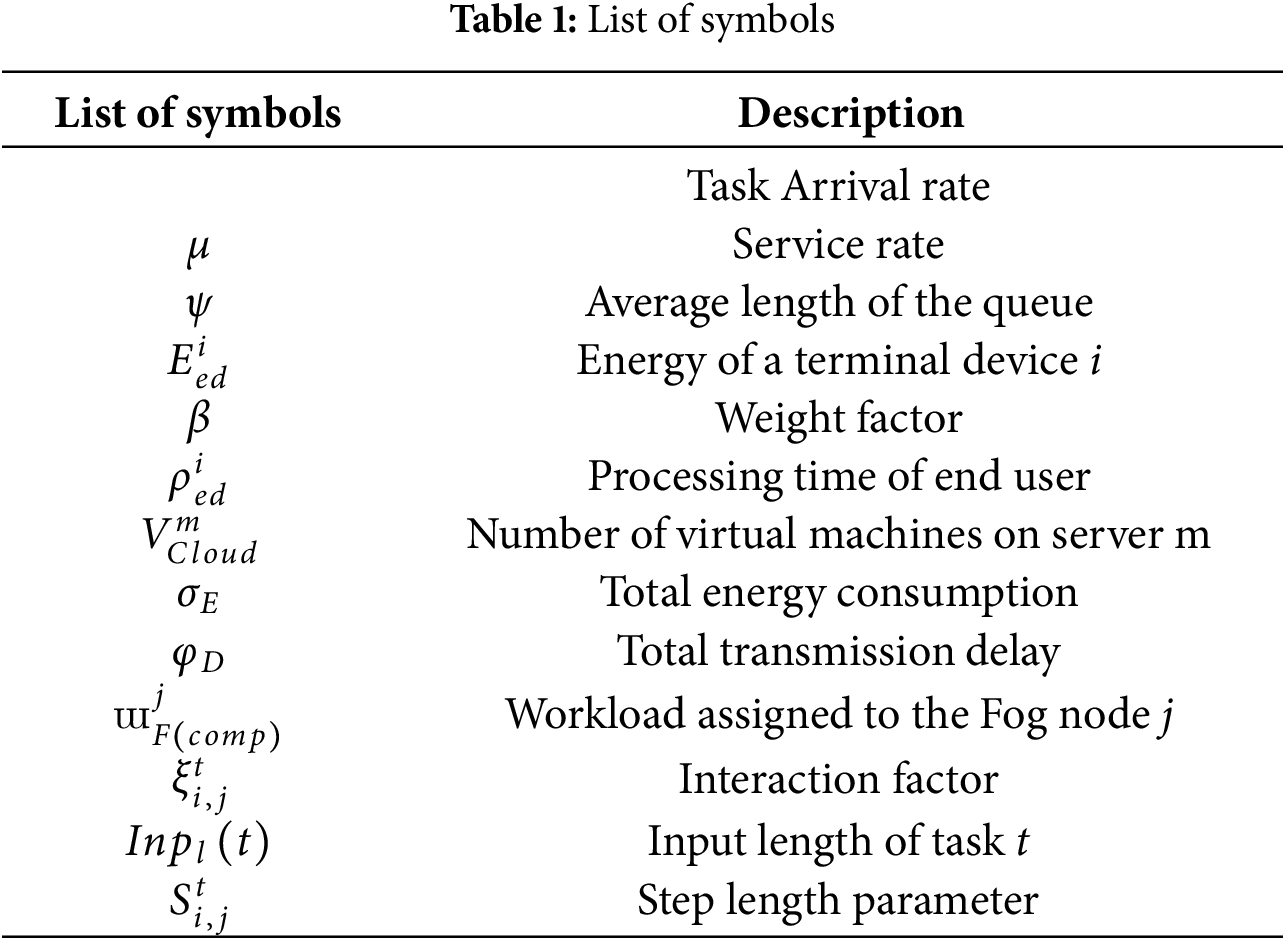

An overview of the proposed algorithm involves six phases. In the first phase, we create the search space with the necessary dimensions and variables, randomly initializing all agents to find the optimal solution. The second phase involves constructing the solution by first offloading tasks to suitable computational nodes, such as fog nodes or cloud servers, and then scheduling these tasks based on their priority. In the third phase, we mutate the solution to increase diversity. The fourth phase evaluates each solution using the objective function and selects the best one with the lowest energy use and transmission latency. Next, we add the solution to the list of non-dominated solutions. The final phase updates the agents’ positions to move closer to the most optimal solutions. Table 1 presents the list of symbols used in equations and the algorithm.

In the context of the fog computing, the system model encompasses fog devices FD = {FD1, FD2, FD3, ... FDn}, set of heterogenous cloud servers represented as Cs = {Cs1, Cs2, Cs3, ... Csm}, the number of IoT end nodes denoted as EN = {EN1, EN2, EN3, ... ENl} and the set of search agents represented as SA = {SA1, SA2, SA3, ... SAh}. Here, we make an assumption that the capacity of cloud computational resources is more than the computation capacity of fog nodes and IoT devices. Similarly, the energy consumption of cloud computational resources is more than that of fog nodes and IoT devices. The scheduling of each incoming task is performed by the fog broker. In the system model, the search agents play the role of candidate solutions that contain a set of tasks, offloaded to various computational resources (fog node or cloud server). The evaluation of solutions is performed by the fitness function that determines the best candidate solution. Afterward, other candidate solution repositions themselves to get closer to the best solution.

In this phase, all the candidate solutions, i.e., Cheetahs, are randomly populated within the search space along with the initialization of fog nodes, cloud servers, and devices. The search space allows the candidate solution to cooperatively search for the potential optimal solution, i.e., optimal task allocation.

In our solution, each candidate solution can be represented by an RxT binary matrix, where R is the number of available computing nodes and T is the number of tasks to be scheduled. In the matrix, if

• Each task is allocated to only one computational node

• The distribution of tasks among the computational nodes must be balanced.

• Tasks must be successfully processed within the deadline

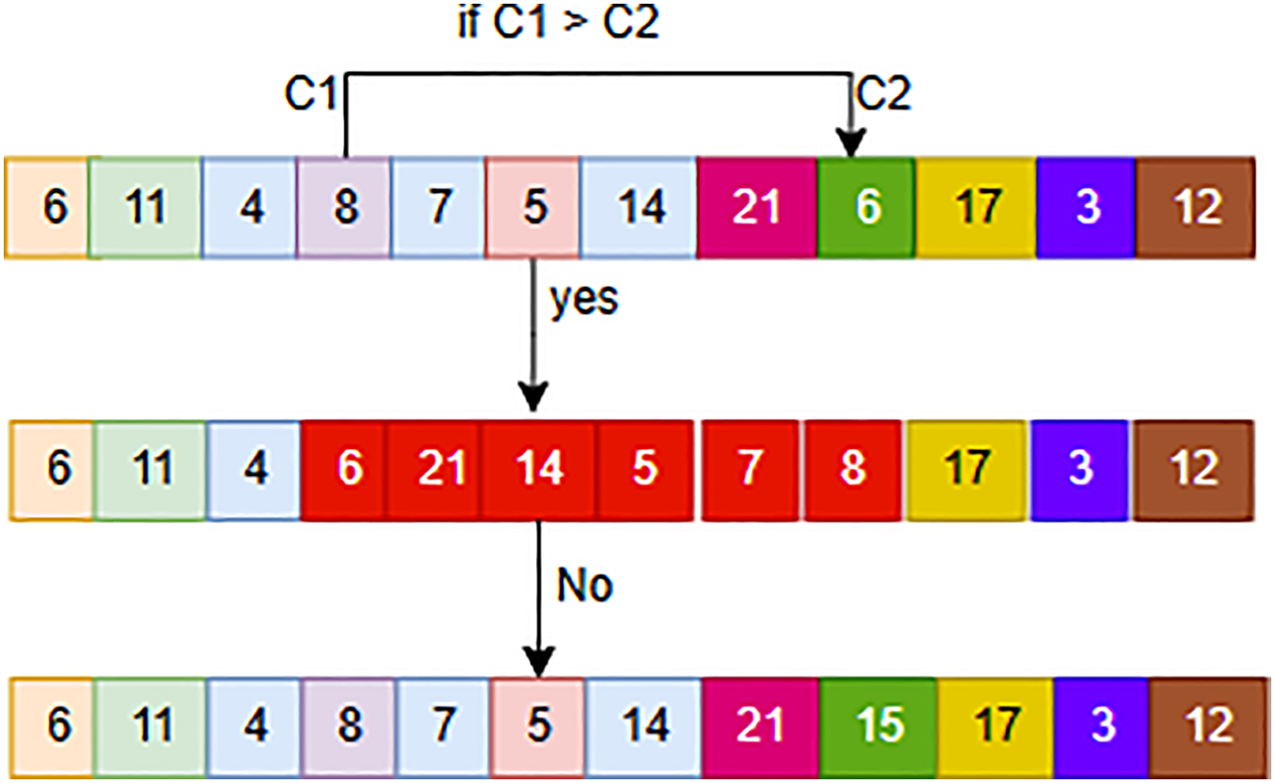

Solution mutation performs a critical role in enhancing the diversity of the solution. To this end, we used the Inverse Mutation Technique (IMT) in which the position of two candidate solutions (i.e., task schedules) is interchanged with each other upon meeting the specified criteria. In Mutation, the solution is selected randomly; for instance, if C1 and C2 are selected, their position is swapped if C1 is greater than C2. Otherwise, no swapping occurs. This procedure is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Inverse mutation technique

The fitness function provides a means of evaluating the search agents’ solutions, which represent the allocation of tasks to the computing nodes. This fitness function computes fitness values of all search agent solutions and it is based on the delay and energy consumption. The fitness function determines the optimal computing node for a task based on the optimal objective values. The fitness function for evaluating each search agent solution is given below:

where

In this section, the total energy consumption of each computational node at various levels is calculated. The energy consumption of a terminal device is calculated by the product of computation time and energy consumption of a terminal device. Mathematically, it is represented as below:

where

The energy consumption at fog node is determined by the computation amount of the workload. The energy consumption of a fog node is directly proportional to the amount of workload; this means that the energy consumption of a node increases with the increase in the workload. It is stated mathematically as below:

where

where

In this subsection, we explain the calculation of the latency of devices at different levels. Each terminal device generates tasks as per the Poisson process. Moreover, each device has an input task queue of M/M/1 with the defined service rate. Mathematically, the delay at the terminal device is calculated as below:

where

The fog device j is assumed to have M/M/C input task queue. Since the middle layer nodes are responsible for task computation, therefore we can compute the delay in this layer as the sum of the communication latency and computation latency. Mathematically, it is represented as below:

where

where

Cloud servers are assumed to have M/M/∞ input queue. It is assumed that cloud server has an infinite computational capacity. Thus, computation delay at the cloud server is negligible. To compute the latency at the cloud server, only communication delay is taken into account. Mathematically, it is expressed as below:

where

For efficient optimization, it is desirable to achieve the minimum value of optimization objectives, i.e., delay and energy consumption. If we have 100 search agents in the search space, then there will be 100 different solutions containing unique task offloading and scheduling strategies. In that case, the solution with the minimum value of objective parameters is considered as the optimal solution.

Non-dominated solutions are called Pareto-optimal solutions, which are stored in a repository whose size is equal to the number of candidate solutions. MoCO uses non-dominating sorting to arrange the solution in a repository found in each iteration. In some cases, the repository may contain the same ranked non-dominated solution, so it is necessary to replace the solution with the new non-dominated solution. This can lead to reducing the exhaustive search and increasing the diversity of the solutions. To replace the solution, we used a predetermined crowding distance value, which is also used to determine the number of neighboring solutions. Mathematically, it is calculated as below:

where

4.7 Enhanced Cheetah Optimizer Algorithm

Cheeta Optimizer has shown its effectiveness in solving various complex, large-scale real-world optimization problems. However, CO suffers from premature convergence and computation time. To address these shortcomings, CO is modified, namely Enhanced Cheeta Optimizer (ECO) to improve convergence speed and reduce computation time. The attacking strategy of ECO encompasses three phases, i.e., search phase, sit and wait phase, and attack phase.

In this phase, Cheetah searches for the optimal solution (prey) based on its surrounding conditions. In the CO, search agents (Cheeta’s) update their location by following their previous position. This leads the algorithm toward local stagnation and reduces convergence speed. In MCO, the searching procedure of search agents is modified by updating positions of search agents based on the position of the leader of the group, i.e., the second-best solution. This reduces randomness and accelerates convergence speed. Mathematically, it is expressed as below:

where

where

Cheetahs are quick chasers that require much energy. In this phase, Cheetahs sit and wait until the prey is close enough to attack. Consequently, this increases the chance of hunting success. Mathematically, it is modelled as below:

Speed and flexibility are two important considerations leveraged by the search agents during the attacking phase. In the previous phase, search agent positions themselves as close as possible to the prey. When prey notice the attack, it changes their direction and run away from the search agent. In response, the search agents adjust their direction and use their high flexibility to catch the prey in unstable conditions and successfully execute the attack. Mathematically, it is modelled as follows:

where

4.7.4 Update Position Criteria

CO uses the hunting factor along with the random parameters to update the location of agents. To update the location using either strategy (search strategy or attacking strategy), a hunting factor (H-factor) is used. The H-factor decreases over the course of iteration, and it is modelled as below:

where t and T are the current and maximum iteration, respectively, rand is a random value between [0, 1].

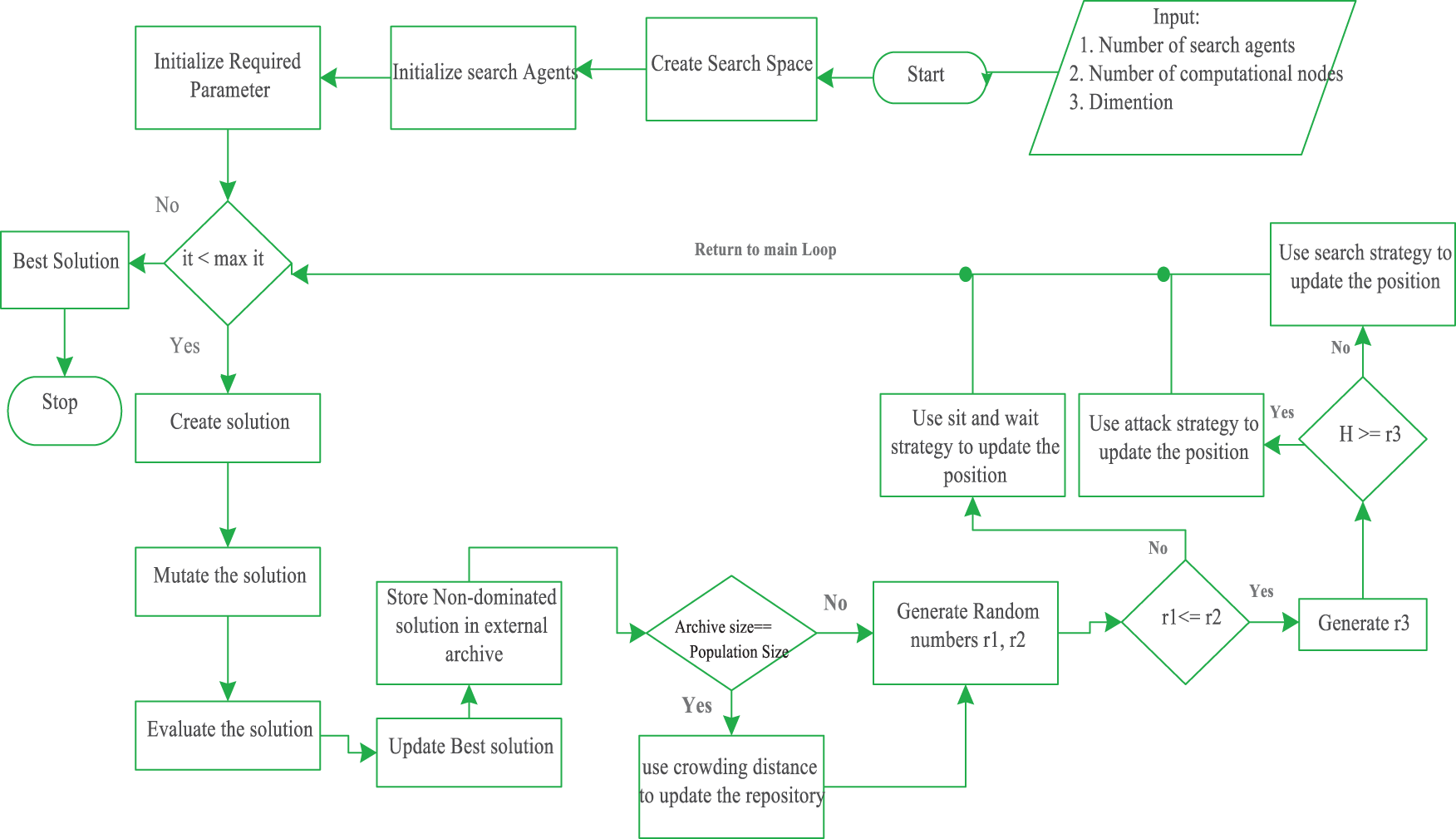

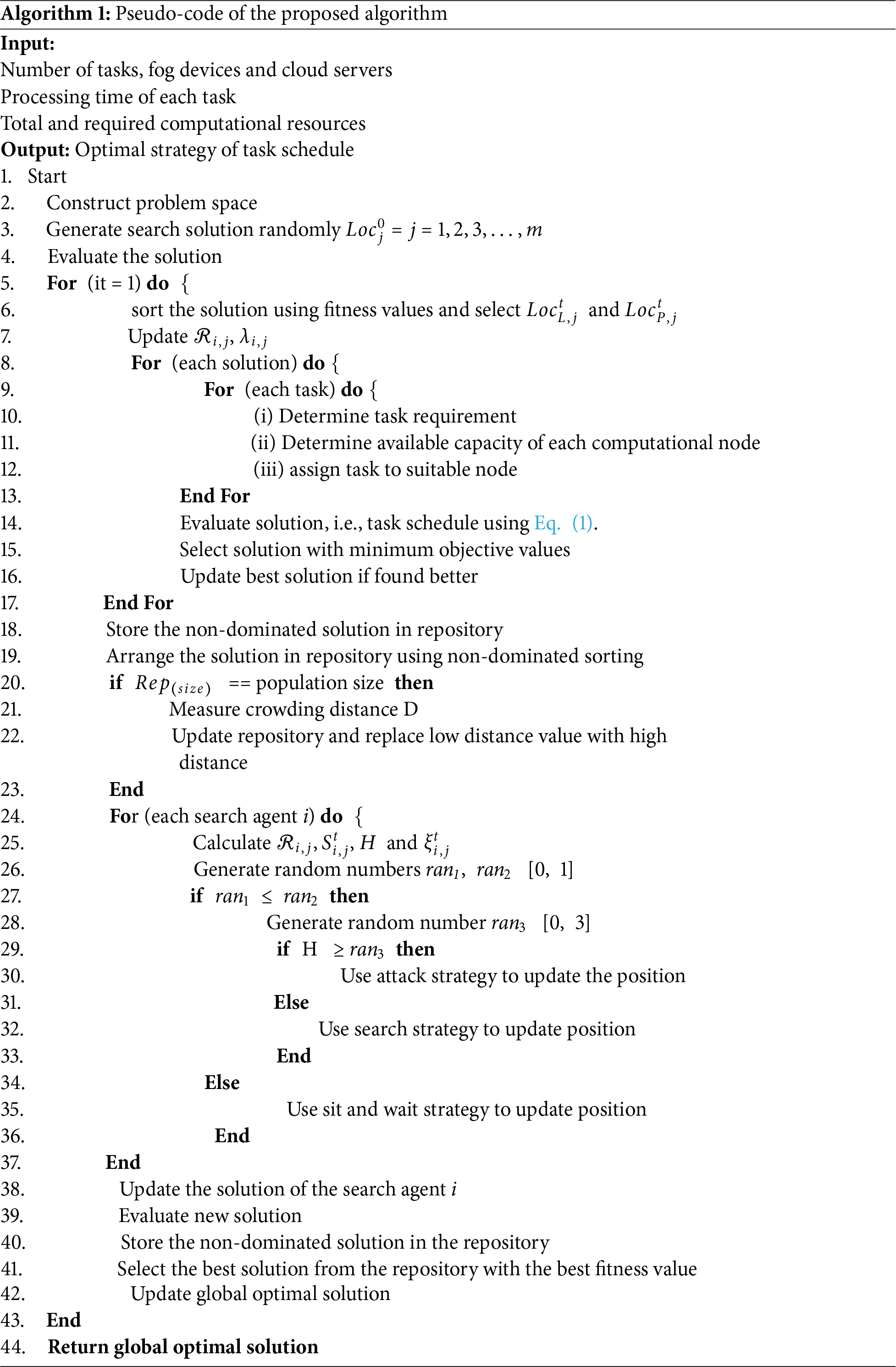

Algorithm 1 contains the pseudo-code of the proposed algorithm. The process begins by initializing essential system parameters, including several fog nodes, end devices, cloud servers, task count, required and available computational resources, etc. In lines # 1–4, the algorithm initializes the search space by randomly populating it with search agents. Each search agent constructs a solution by scheduling N heterogeneous tasks to various computational nodes. Subsequently, the algorithm evaluates each solution using a fitness function. Lines # 6–7 involve sorting the solution by the search agent based on its fitness value. The second-best solution is designated as the leader’s location, while the optimal solution is defined as the prey’s location. Lines # 8–17 are a nested loop in which each search agent creates a new solution by allocating each task to the appropriate computational nodes and then scheduling the offloaded task based on task priorities. Each solution is evaluated using a fitness function, and a solution with the minimum fitness value is selected as the best solution. In line 16, the best solution is updated if it outperforms the previous one. Lines # 18–19, store the non-dominated solution in the external repository and arranges the solution using non-dominated sorting. Lines # 20–23, check the size of the repository; if it is equal to the number of search agents, then the solution with the low crowding distance measure is replaced with the high crowding distance measure. Lines # 24–27 implement a loop in which the location of each search agent is updated as per the search and attack strategy defined by the proposed ECO algorithm. In Lines # 38–42, new solutions are formed after the repositioning of search agents, which are then re-evaluated using the objective function. Line # 40, stores the non-dominated solution in the repository after re-evaluation. The solution with the best objective value from the repository is selected as the best and global optimal solution. In Line # 44, the global optimal solution is returned, which contains a binary matrix of the best computation offloading and task scheduling strategy. The flowchart of the proposed scheduling framework is given in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Flowchart of proposed algorithm

4.9 Implementation of the Proposed Algorithm in a Cloud-Fog Computing Environment

The implementation of the proposed algorithm requires terminal nodes, fog nodes, communication links, and cloud servers. Each terminal node generates either energy-intensive or delay-intensive tasks. The number of tasks generated by a terminal node varies with the computational demands of the device. Each task is analyzed at the fog controller to determine its resource requirements and execution constraints. Based on this analysis, the fog controller constructs a matrix representing joint task offloading and scheduling strategies. Each strategy is treated as a potential candidate solution (search agent) and evaluated using the defined objective function. Afterward, the mathematical model of MoECO is applied to identify the best offloading and scheduling strategy that minimizes both the energy consumption and transmission latency. The computing network then process according to the selected optimal strategy.

4.10 Computational Complexity of the Proposed Algorithm

We compute the computational complexity of each phase and then represent the cumulative complexity of the entire algorithm.

Initialization: The computational complexity of initializing the search space mainly depends on population size. If m search agents are initialized within the search space with the problem dimension D, then the initialization phase takes O (m × D).

Task assignment phase: In this phase, the tasks are offloaded to the suitable computing nodes, either fog device (FDn) or cloud server (Csm) by determining task requirements and availability of computational resources. If Tk represents the total number of tasks, then task assignment phase takes O (m × Tk × (FDn × Csm)).

Fitness evaluation and sorting phase: Each iteration performs fitness computation for

Position update phase: Each search agent updates its position based on adaptive operators (attack, search, sit-and-wait) that involve a constant number of arithmetic operations. The computational complexity of this phase is O(m).

Iterative process: The above phases (2–4) are repeated for T iterations. So, the computational complexity of all the important steps with iterations T is O (T × (m × Tk × (FDn × Csm) + m × Cf (B+ m log m)).

Total computational complexity: The simplified total computational complexity of the proposed algorithm for T iterations and m search agents is O (T × (m × D + m × Tk × (FDn × Csm) + m × Cf (B+ m log m))), which collapses to O (T (m2 log m + m (DTk × Cf FDn × Csm).

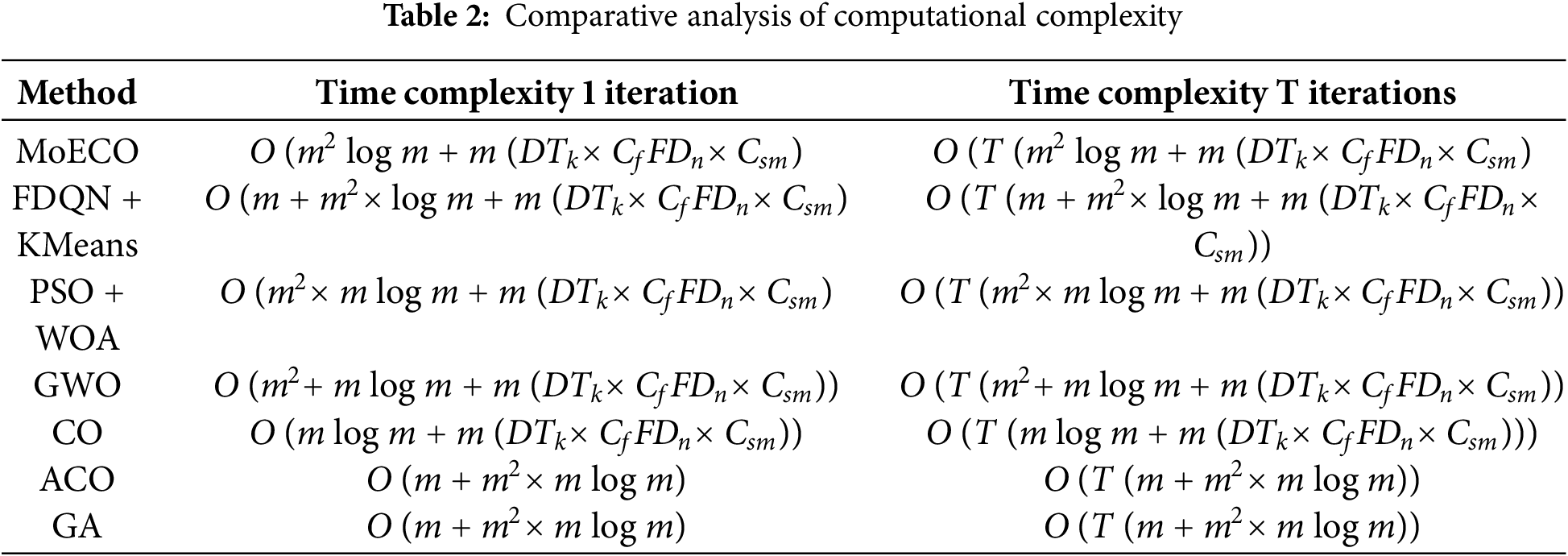

Table 2 unfolds the computational complexities of the proposed and other baseline methods. This analysis demonstrates that the proposed algorithm is capable of solving multi-objective optimization problems effectively, as it provides a better balance between different and mutually exclusive factors such as energy, delay, fairness index, and throughput. Although the computational complexity of this algorithm is slightly higher, this increase is due to the archive non-dominated sorting process, which can affect the performance to some extent in large networks. The computational complexity of ACO and GA algorithms is similar and they are mostly suitable for single-objective optimization. Nevertheless, they require relatively more iterations to reach the optimal solution.

On the other hand, the time complexity of the GWO algorithm is quadratic, which is effective for single-objective problems such as energy consumption or delay, but it often suffers from the problem of premature convergence.

5 Experimental Setup and Results Discussion

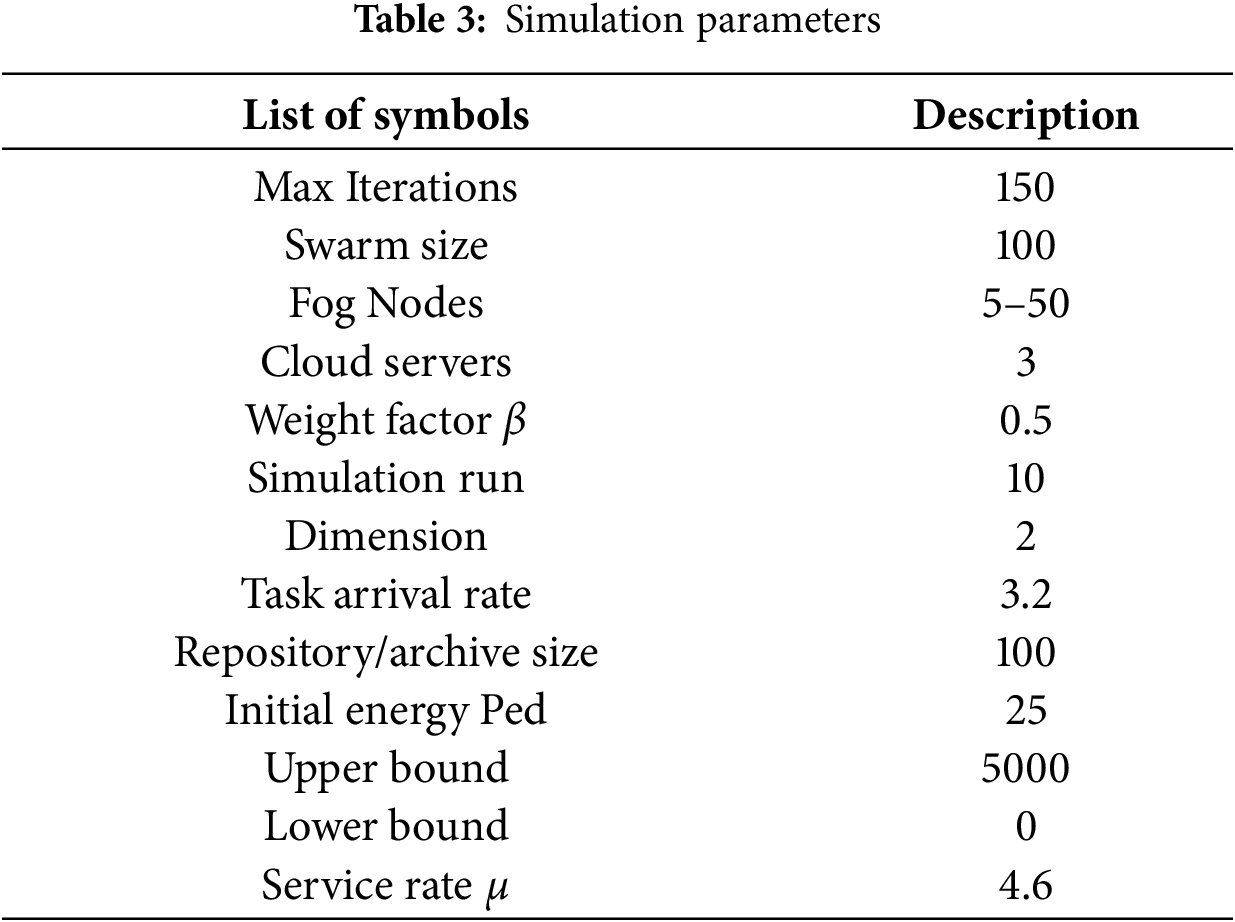

The proposed MoECO scheduling algorithm was implemented in MATLAB 2023a on a laptop with 2.8 GHZ core i9 Intel processor and 16 GB RAM. The simulation environment devices. The proposed algorithm was compared with the baseline methods, namely Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Cheetah Optimizer (CO), and Genetic Algorithm (GA). The analysis with the benchmark schemes was performed using the same simulation parameters as given in Table 3. To ensure the reliability and robustness of the experimental results, each algorithm was executed 10 times. The mean and standard deviation values were computed for all the performance metrics. Moreover, a pairwise student’s t-test (p < 0.005) was applied to analyze the statistical significance of the performance differences between the proposed algorithm and the benchmark algorithms. Furthermore, 95% confidence intervals were computed for each metric to demonstrate the consistency and stability of MoECO across multiple executions. The simulation results demonstrate that our proposed solution efficiently minimizes the energy consumption and communication latency while maximizing task completion rate and fairness index. Efficient joint optimization of computation offloading and task scheduling not only improves network lifetime but also escalates its scalability, reliability, and stability. Simulations prove that our solution effectively handles a large, diverse set of tasks coming from different IoT devices. The simulation was performed using four performance metrics by varying different simulation parameters: (i) energy consumption, (ii) transmission delay, (iii) task completion rate, and (iv) fairness index.

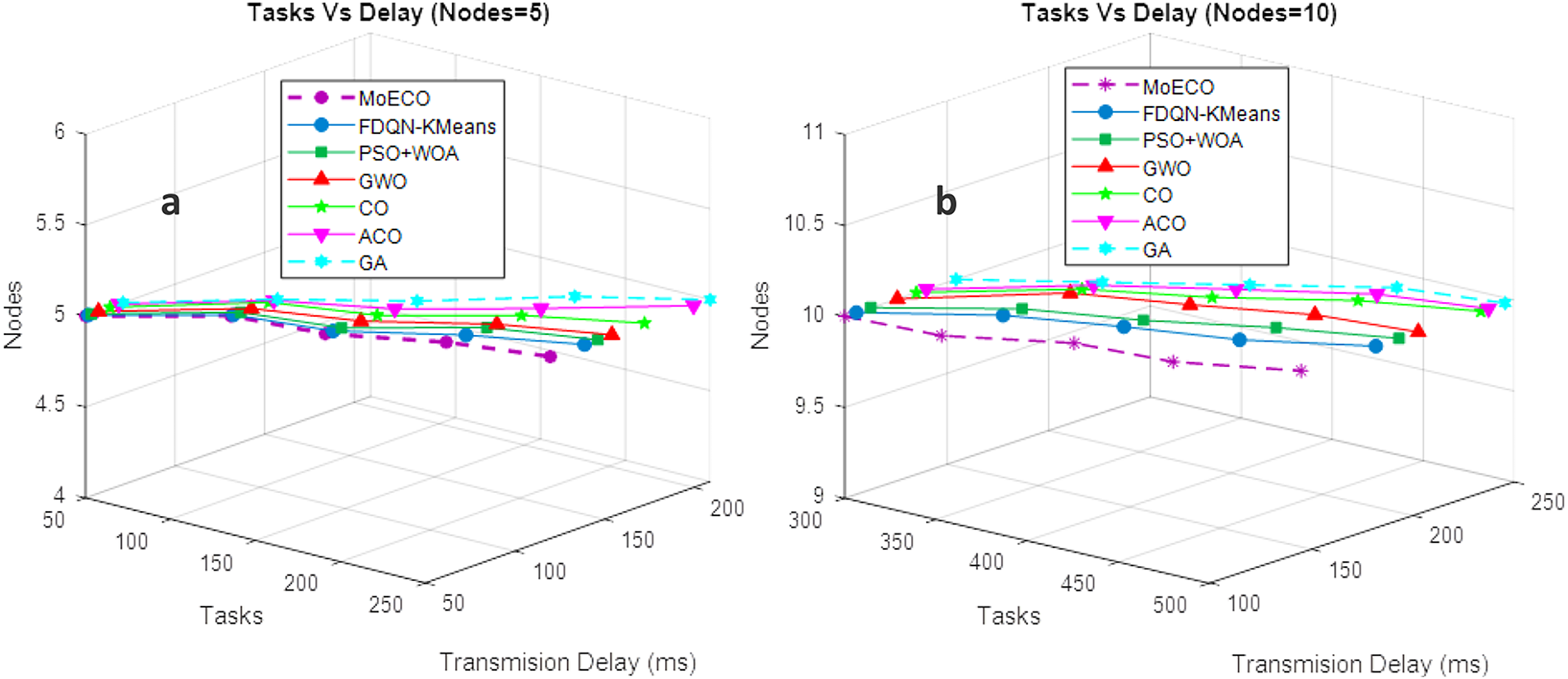

In the first setup, we evaluated the proposed algorithm to measure the total delay of each processed task at levels 50–250, while keeping the number of fog nodes fixed at 5. The performance of the proposed task scheduling algorithm was compared with the original CO and other baseline methods, which improves the searching capability of both exploration and exploitation search phases by adjusting various variables, e.g., step length and interaction factor. This improves the computation time and convergence speed of the proposed algorithm. Consequently, the total transmission delay of the system is minimized through smart resource utilization. The proposed approach dynamically offloads tasks to either fog nodes or cloud servers based on the capacity, bandwidth, and task requirements (e.g., delay sensitive or computation sensitive). Additionally, the proposed algorithm reduces total delay by prioritizing task scheduling based on task completion deadline and energy utilization, implementing load balancing to prevent workload bottlenecks. The results in Fig. 5a demonstrate that our proposed solution exhibits linear behavior against the increasing number of IoT tasks. This signifies that our scheme is stable and efficient when the workload on the system is high.

Figure 5: Transmission Delay (ms) vs. Tasks under different fog node settings: (a) 5 nodes, (b) 10 nodes

Fig. 5b illustrates the analysis of the same experimental setup with different simulation parameters, i.e., we increase the number of tasks from 300 to 500 while the computation nodes, i.e., fog nodes, increase to 10. Here, the proposed algorithm also performs efficiently compared to the state-of-the-art baseline methods in terms of achieving minimum transmission delay. From the results (Fig. 5a,b), we can conclude that our proposed MoECO scheduling algorithm is ideal for a real-time environment where task needs an immediate response, like the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT).

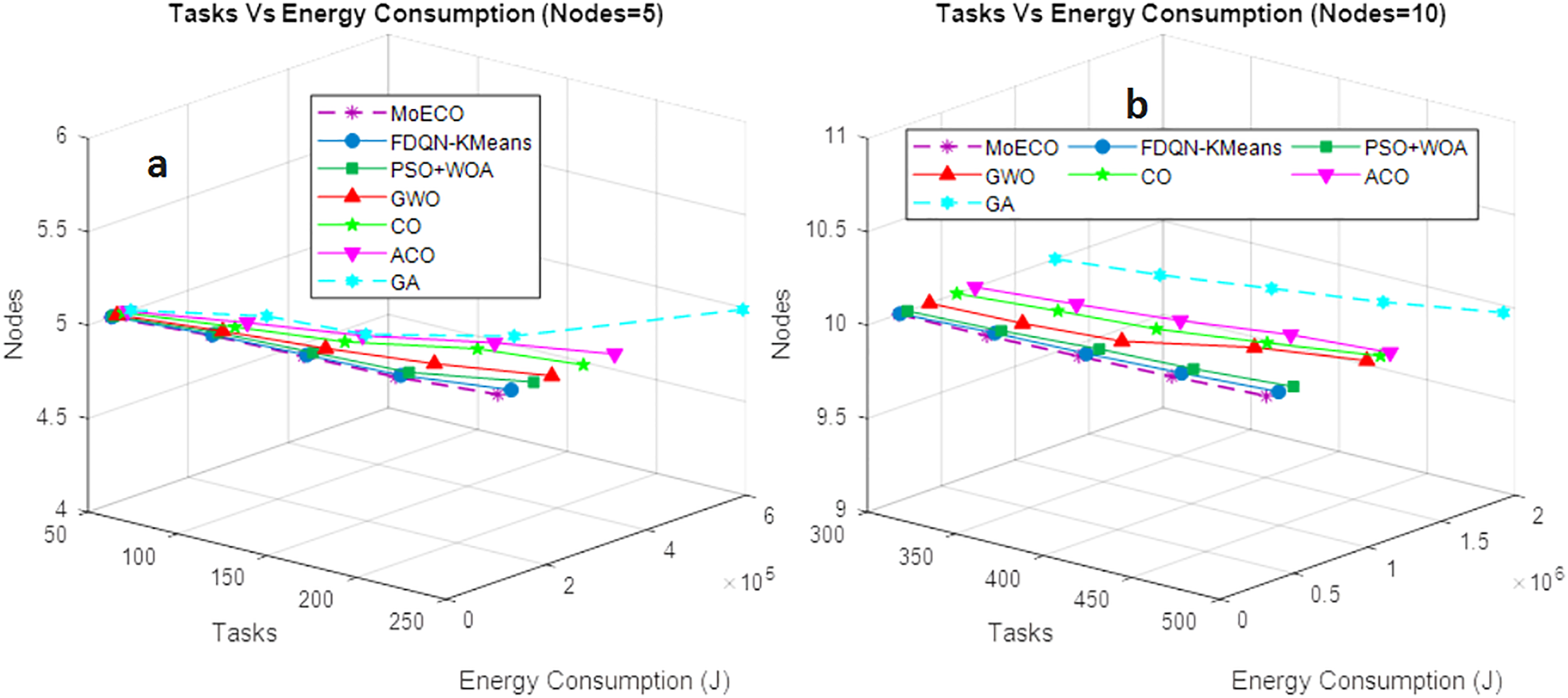

5.2 Number of Tasks vs. Energy Consumption

In this experimental setup, we evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm by analyzing its energy consumption under varying workloads (50–500). The network bandwidth and CPU frequency of a computing node contribute to the energy consumption of a device. The results depicted in Fig. 6a,b demonstrate that the proposed task scheduling algorithm consumes less energy than other approaches, while also extending the lifetime and resource utilization of the network. Compared to the state-of-the-art benchmark schemes, our proposed solution reveals better energy utilization in a complex dynamic fog computing. Unlike baseline methods, which involve higher computational time and low convergence speed to achieve an optimal solution, the proposed ECO scheduling algorithm has high convergence speed, low network overhead, and low computation time. This minimizes the number of iterations to reach the optimal solution, reducing energy consumption.

Figure 6: Energy consumption (J) vs. Tasks under different fog node settings: (a) 5 nodes, (b) 10 nodes

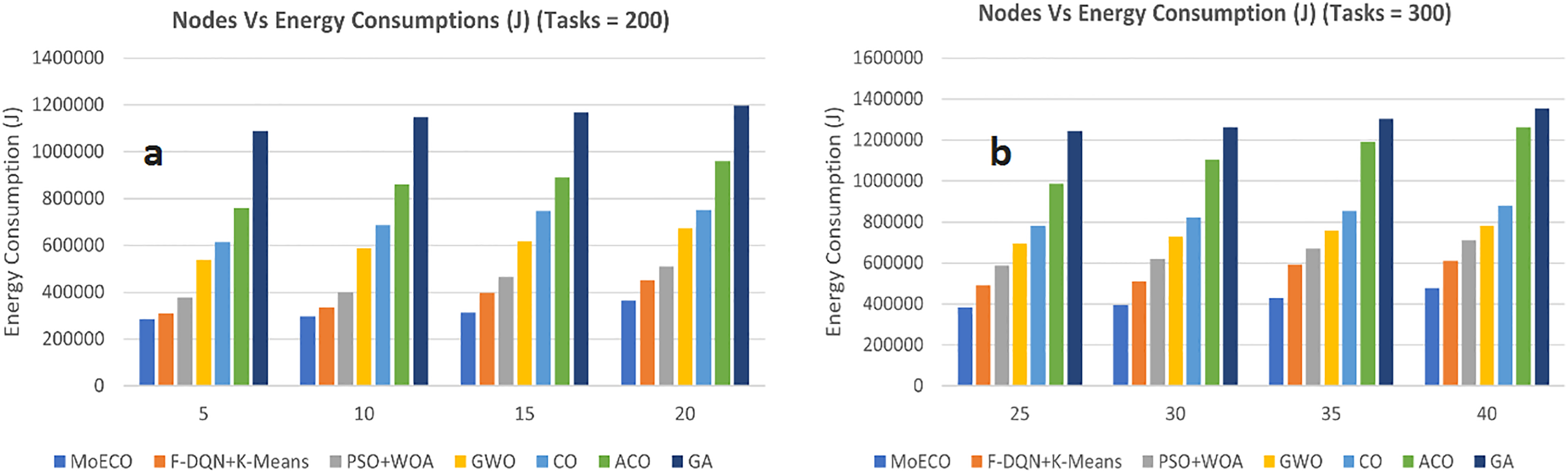

5.3 Number of Fog Nodes vs. Energy Consumption

In this experimental setup, we evaluate the energy consumption at each tier of the architecture across varying numbers of fog nodes (5–50) under the workload of 200 and 300 tasks. It is observed that an increase in the number of fog nodes results in higher energy consumption due to the operational, communication, and data transmission demands of computational nodes. However, an effective resource allocation and scheduling technique can significantly optimize the overall network’s energy consumption. The outcomes, as illustrated in Fig. 7a,b, demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves superior energy optimization compared to the baseline algorithms. The proposed scheme dynamically and intelligently identifies the computational requirements of tasks, ensuring that only computationally intensive tasks are offloaded to the cloud server, while others are processed locally on fog nodes. This strategic approach reduces unnecessary data transmission and leverages local processing capabilities, leading to significant energy savings.

Figure 7: Energy consumption (J) vs. Nodes under different task settings: (a) 200 tasks, (b) 300 tasks

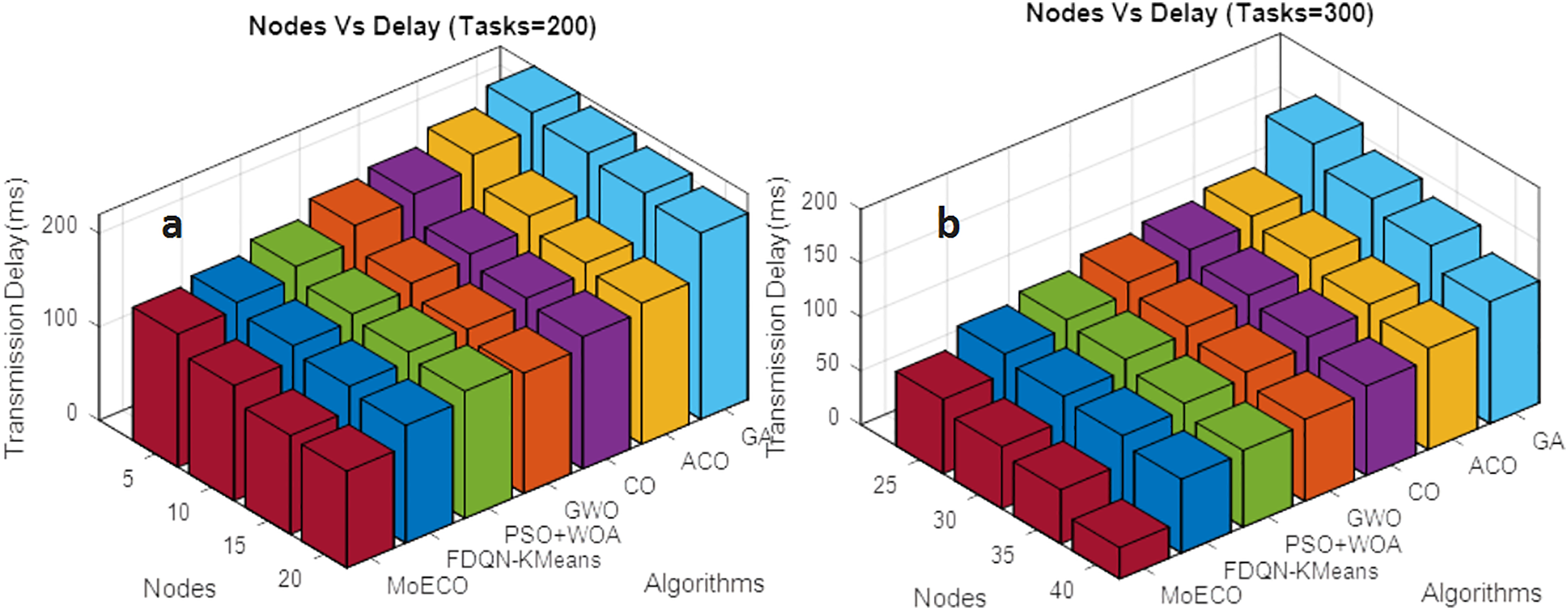

5.4 No of Fog Nodes vs. Transmission Delay

The simulation is performed to evaluate the performance of the proposed scheduling algorithm in terms of transmission delay against the number of nodes under the workload fixed at 200 and 300 tasks. Generally, an increase in fog nodes leads to improved processing capabilities but can also introduce challenges related to task allocation and communication overhead. Effective scheduling techniques are essential to minimize delay and ensure the timely processing of tasks. The simulation results, in Fig. 8a,b, reveal the operational efficacy of our proposed algorithm in reducing transmission delay. By leveraging its efficient convergence speed and computation time, the workloads are effectively distributed among computation nodes, escalating response time and thereby minimizing total transmission delay. In contrast, baseline methods exhibit higher delays due to their comparatively slower convergence and less adaptive resource allocation mechanisms. The efficient results of the proposed algorithm demonstrate the effectiveness in achieving low latency, making it an ideal choice for delay-sensitive applications in fog-cloud computing environments.

Figure 8: Transmission delay (ms) vs. Nodes under different task settings: (a) 200 tasks, (b) 300 tasks

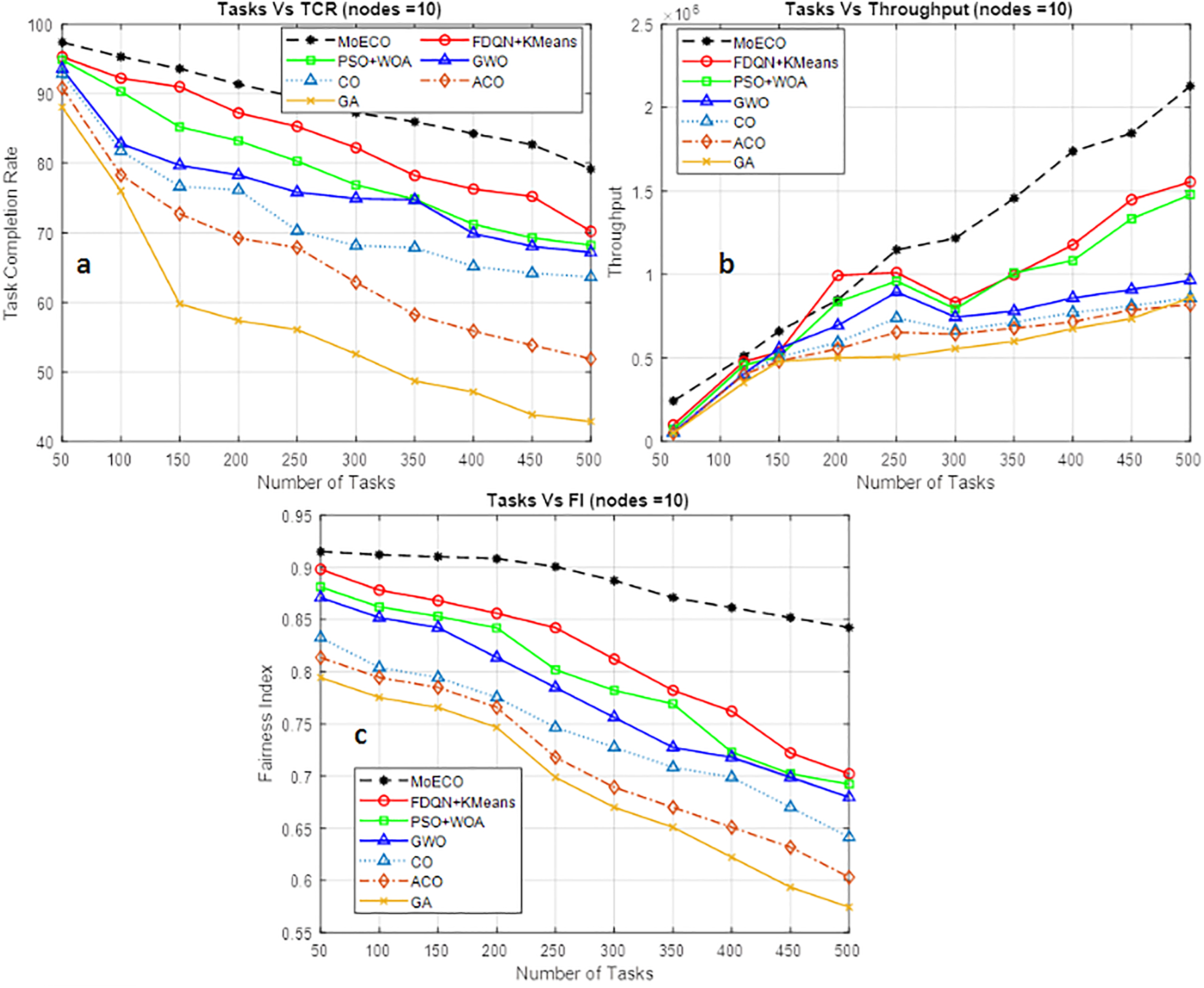

5.5 Task Completion Rate (TCR) and Throughput

TCR indicates the percentage of successfully processed tasks within a given deadline relative to the total number of tasks. In this experimental setup, we calculate the TCR against the number of tasks. The number of tasks varies from 50–500 while the computational nodes are kept constant. The simulation results in Fig. 9a, reflect the efficiency and reliability of the task scheduling algorithm in terms of achieving high TCR compared to the state-of-the-art similar benchmark algorithms. As observed, TCR decreases with the increase in the workload, this trend is expected because with the increase in the workload, the scheduling complexity increases. Moreover, resource contention and deadline violation also affect the task completion rate. The efficient performance of the ECO scheduling algorithm is attributed to high convergence speed, low computation time, and efficient investigation of local and global search capabilities.

Figure 9: Tasks vs. Task completion rate (a), Throughput (b), and Fairness index (c) (Nodes = 10)

Throughput measures how many tasks are completed per unit of time. It assesses the speed and efficiency of the system, i.e., how fast the system can process tasks. In this simulation, we compute the throughput of the proposed MoECO against the number of tasks varying from 60–500. The simulation results in Fig. 9b demonstrate the efficient performance of the proposed algorithm in terms of obtaining high throughput compared to the baseline methods. The results were normalized by a scaling constant to facilitate comparative visualization. A higher throughput value indicates faster task processing capability and improved scalability under increased workloads.

The fairness index assesses how fairly tasks are distributed among computational nodes (i.e., fog nodes and cloud servers). The allocation of resources among tasks must be fair and in accordance with the policy to prevent resource starvation of low-priority tasks. The imbalanced utilization of resources can lead to task drop-offs and reduce system performance. Eq. (23) is used to calculate the fairness index.

where

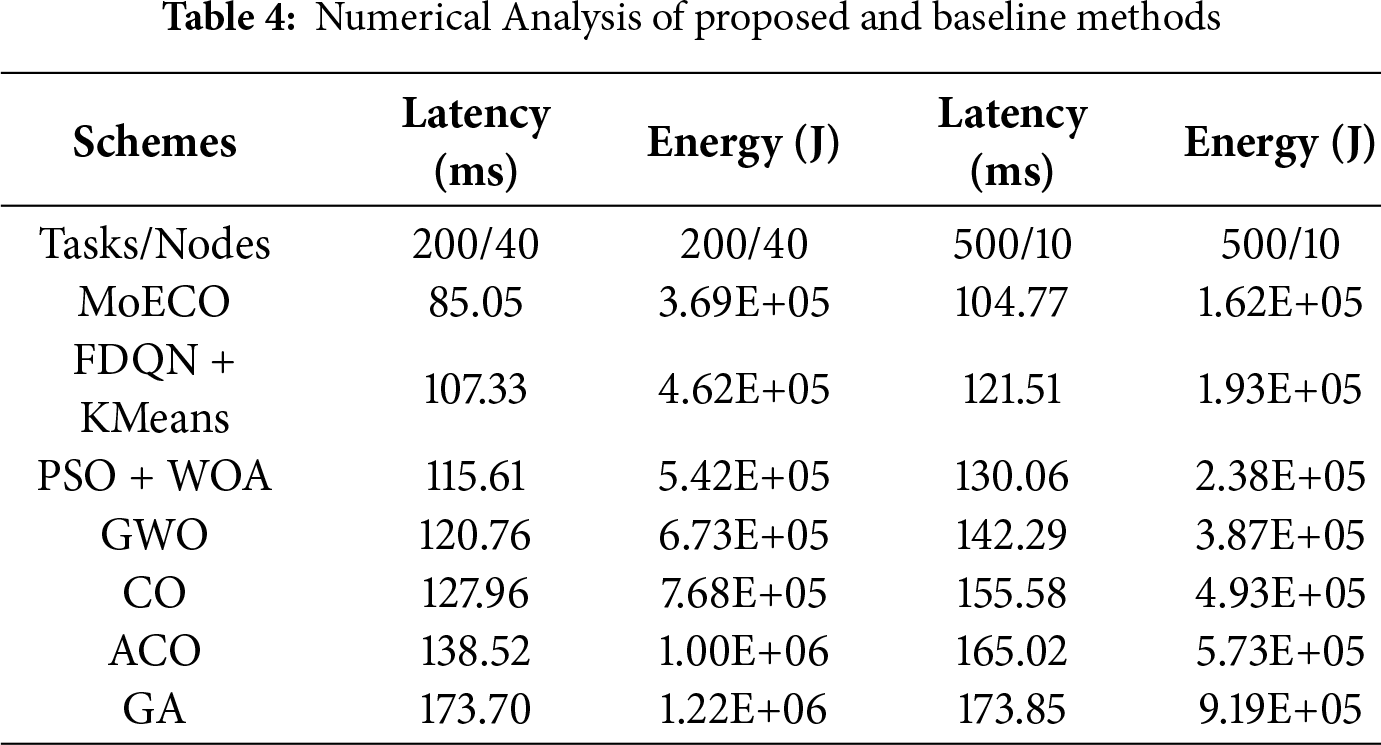

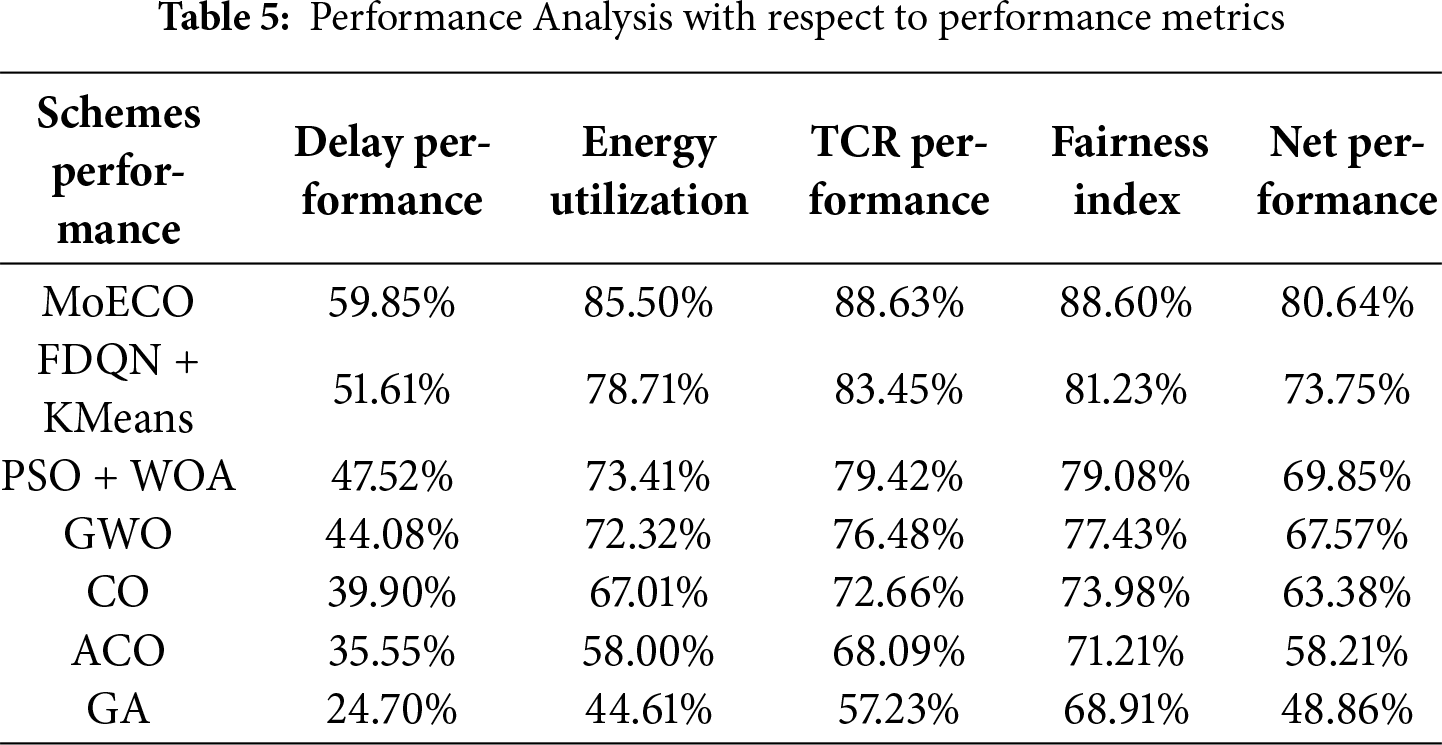

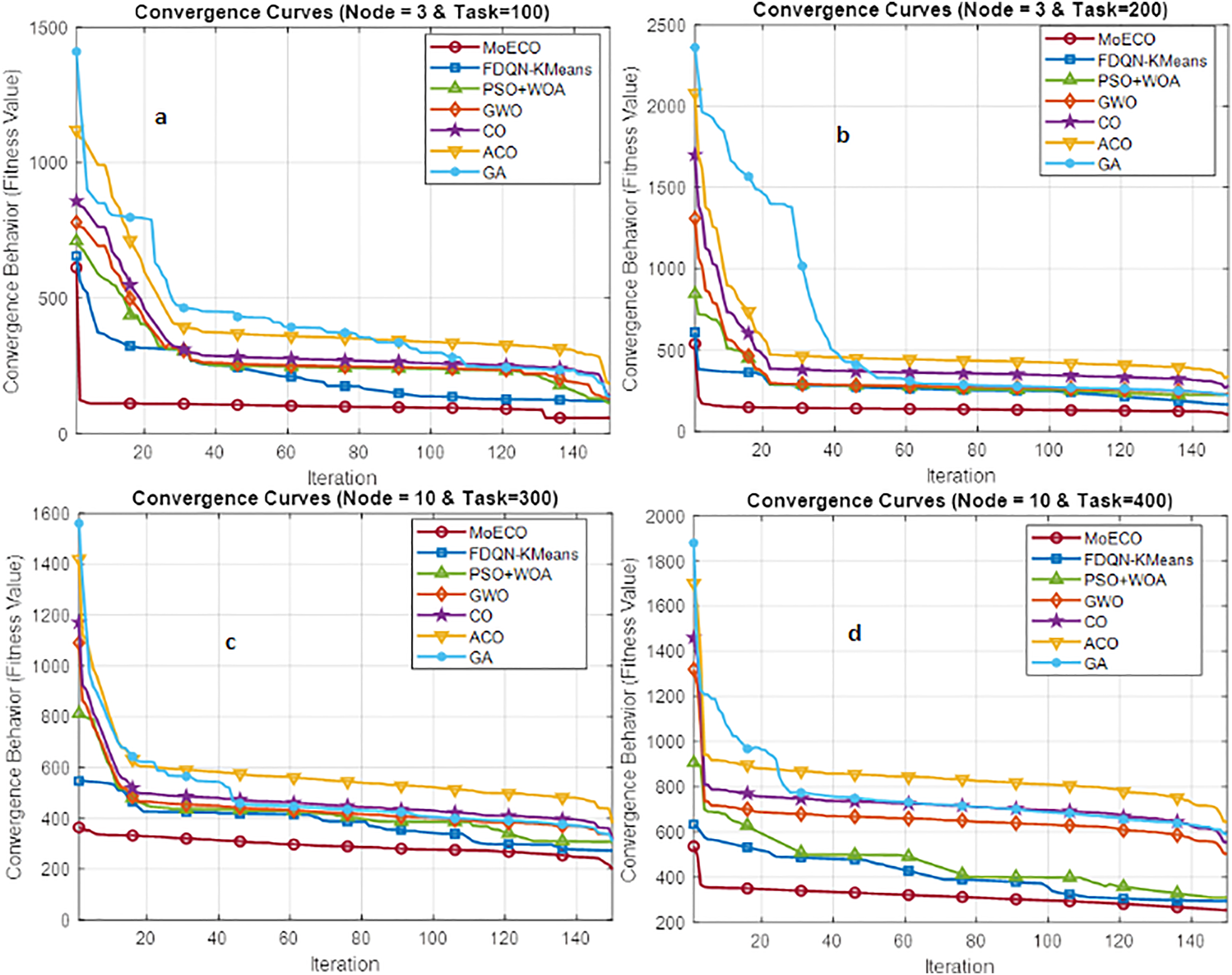

Tables 4 and 5 unfold the comparative and performance analysis of MoECO and similar benchmark algorithms, respectively. The numerical data reveals that the proposed algorithm performs well, with improvements of up to 20% in terms of transmission latency, energy consumption, task completion rate, and fairness index. In Fig. 10, the convergence behavior of MoECO and baseline scheduling algorithms is presented. The results show that our proposed scheduling algorithm exhibits fast, stable, and reliable convergence behavior while reaching the best fitness value (optimal solution). Particularly, the MoECO algorithm obtains the optimal fitness value much faster than the competitors. This implies that our proposed solution has a high convergence speed compared to other algorithms.

Figure 10: Convergence behavior vs. Iterations under different fog node and task settings: (a) 3 nodes & 100 tasks, (b) 3 nodes and 200 tasks, (c) 10 nodes & 300 tasks, (d) 10 nodes & 400 tasks

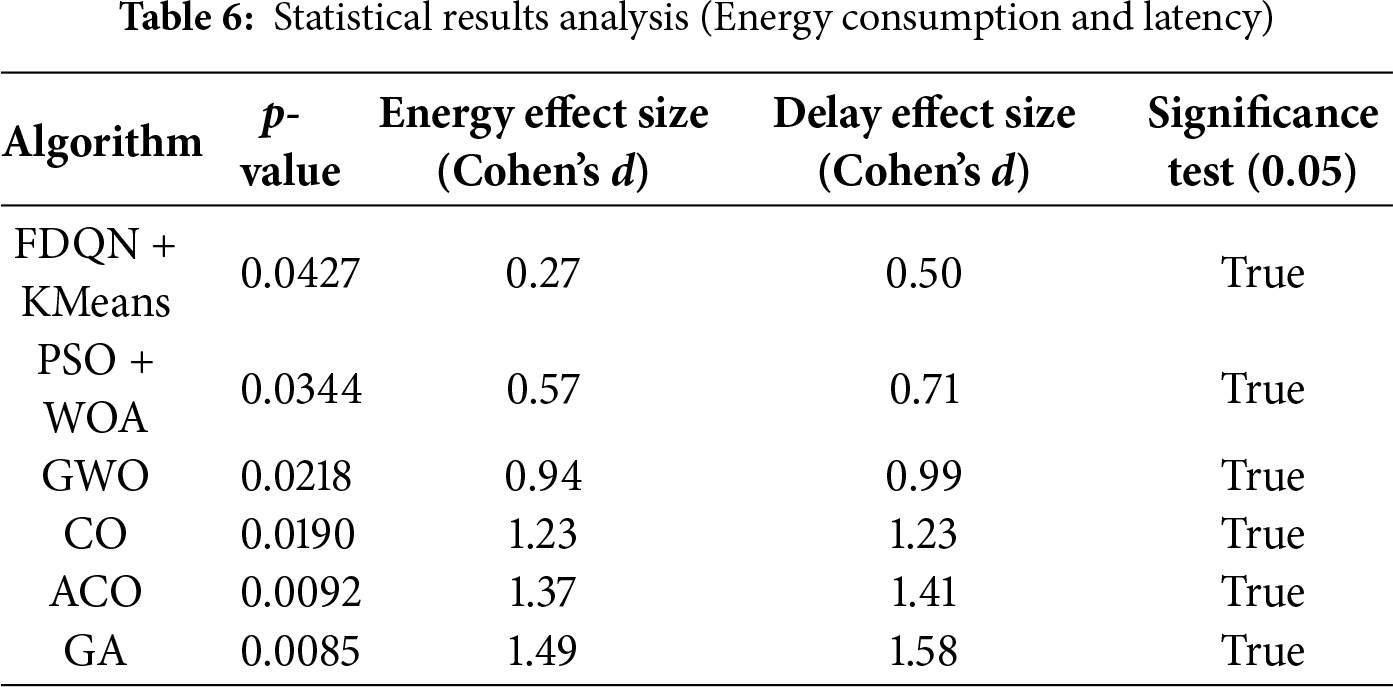

To validate the reliability of the observed performance improvements, Table 6 demonstrates the statistical significance test result between proposed scheme and other baseline methods across two performance metrics, i.e., energy consumption and transmission latency. We employed an MANOVA test to jointly evaluate the differences in both performance metrics, while Cohen’s d was used to measure the magnitude of improvement (effect size). The p-values indicate that MoECO demonstrates statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05) over all compared algorithm. The effect size (Cohen’s d) values complement these results by quantifying the magnitude of improvement. Overall, both statistical significance and effect size analyses confirm that MoECO achieves statistically reliable and practically meaningful improvements over benchmark methods.

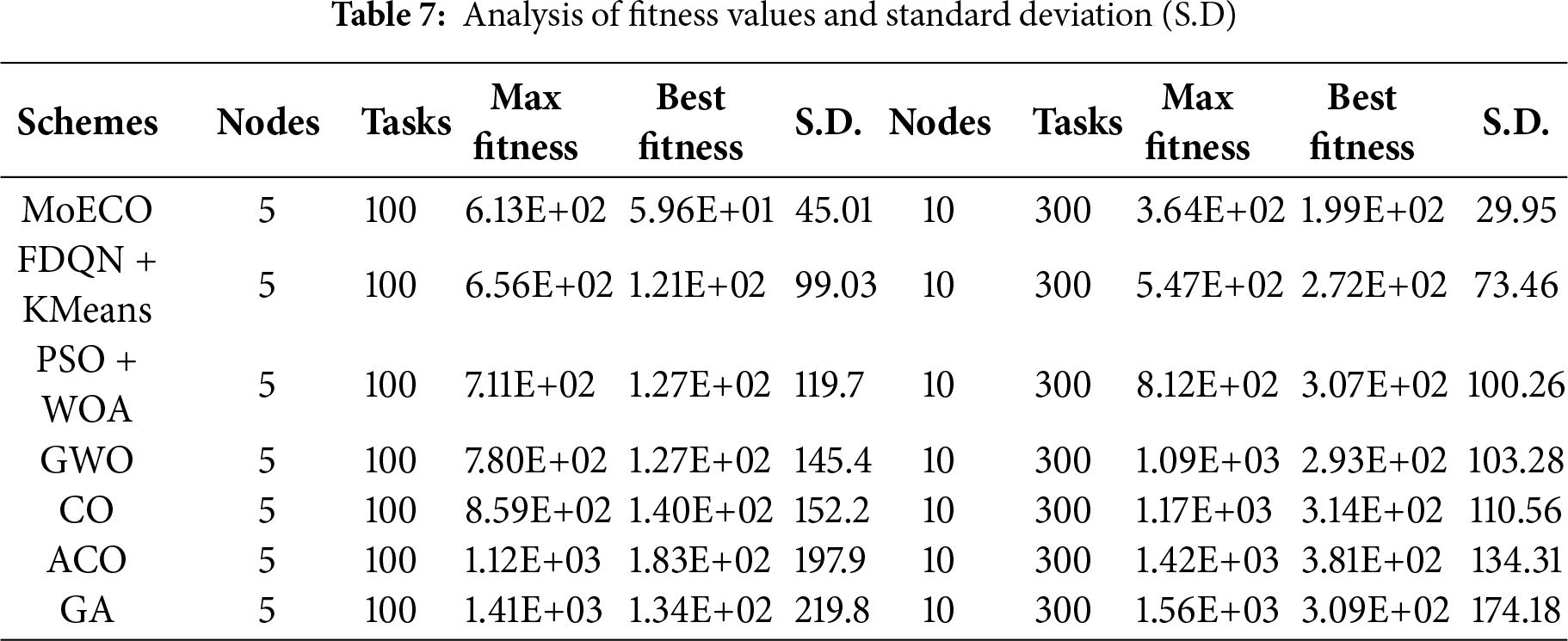

Table 7 presents the convergence behavior of the proposed and baseline methods. In this table, we record the most important parameters of convergence behavior, i.e., minimum fitness value (columns 4th and 8th), maximum fitness value (columns 3rd and 7th), and standard deviation (columns 5th and 9th). These values are recorded for 5 and 10 computational nodes under a workload of 100 and 300 tasks. The convergence behavior of the algorithm indicates the reliability and stability of its performance, where a decrease in standard deviation is an argument that our proposed solution consistently and quickly converges to the optimal solution across different iterations. These features are crucial for task scheduling in fog computing environments, where consistent and reliable performance is required to optimize resource allocation and workload balancing.

These capabilities of the presented algorithm make it an efficient and robust solution for solving complex scheduling in a dynamic computing environment.

To measure the scalability of the proposed scheduling algorithm, both the number of computational nodes and tasks are progressively increased within the cloud-fog hierarchy. Based on the results, as the workloads increased exponentially (50–500), the proposed algorithm maintained a monotonically increasing behavior with a gradual increase in energy consumption and transmission latency. Upon increasing the workloads, MoECO manage such increase via multi-objective decomposition and parallel execution mechanism. This enables the algorithm to compute the objective values one by one instead of computing altogether in one massive problem. The comparative baseline methods demonstrate a sharp rise in energy consumption and delay after 300 tasks, while MoECO scales in a linear-fashion, sustain convergence stability and ensures consistent task distribution across all the computational nodes. This is attributed to the adaptive step-length control and leader–follower coordination mechanism, which prevent premature convergence and ensure balanced exploration across distributed search agents. For large scale IoT networks, this characteristic is particularly valuable because IoT environments often experience bursty workloads, the proposed algorithm can efficiently manage such variation without the loss of convergence stability.

From the results, we conclude that our proposed algorithm efficiently addressed the NP-hard optimization problem, i.e., task scheduling in fog computing. Its success is due to the high convergence speed, low computation time, and diversity in local and global search capabilities. This helps the algorithm to provide the global optimal solution. Given the efficient results of the proposed algorithm, we can successfully apply it to real-world problems. For instance, we can employ the algorithm (after required modifications) in the IoMT environment, where tasks need an immediate response and must be completed within the required deadline. As our proposed solution provides minimum delay and a higher task completion rate, we can efficiently utilize the algorithm in the medical environment for patient monitoring.

In this study, we present a multi-objective and enhanced version of Cheeta Optimizer (CO) for energy-efficient task scheduling specifically tailored for cloud–fog computing environments. The proposed algorithm effectively addresses the critical challenge of optimizing computation offloading and task scheduling in dynamic and heterogeneous networks. By integrating the proposed scheme into the fog controller, our approach enables accurate task estimation, analysis, allocation to appropriate computing nodes and orderly execution of offloaded task, ensuring efficient resource utilization. Extensive evaluations in MATLAB demonstrated the superior performance of our algorithm in terms of designated optimization objectives (i.e., energy consumption and transmission delay) compared to CO and other state-of-the-art methodologies. The ECO efficiently increases the local and global search capabilities by adjusting step length and interaction factors variables of the CO, respectively. This significantly improves the convergence speed and computation time, thereby minimizing transmission delay and energy consumption while maximizing task completion rate and fairness index. Additionally, the algorithm exhibits scalability, maintaining robust performance even under increased workloads.

In the future, we will address the security and privacy of the tasks by employing Federated Learning (FL) and Blockchain technology. FL will enable fog nodes to collaboratively train local offloading model without sharing sensitive information, thus preserving the privacy of the user and reducing the communication cost associated with the centralized data collection. Simultaneously, Blockchain can be employed to provide temper-proof and transparent ledger for verifying offloading records and resource utilization. This combination will ensure data integrity, trustworthiness and secure model aggregation across decentralized nodes. We can explore other new bio-inspired methods like Henry Gas Solubility Optimization (HGSO) Algorithm and Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm (AHA). These advancements will further enhance the reliability and adaptability of cloud–fog computing systems in addressing the growing demands of modern IoT applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this research.

Funding Statement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R384), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Ahmad Zia and Nazia Azim; methodology, Ahmad Zia and Bekarystankyzy Akbayan; software, Nazia Azim and Nouf Al-Kahtani; validation, Ateeq Ur Rehman, Faheem Ullah Khan and Khalid J. Alzahrani; formal analysis, Nouf Al-Kahtani and Ateeq Ur Rehman; investigation, Khalid J. Alzahrani; data curation, Bekarystankyzy Akbayan, Hend Khalid Alkahtani and Faheem Ullah Khan; writing—original draft preparation, Ahmad Zia, Ateeq Ur Rehman and Hend Khalid Alkahtani; writing—review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition, Hend Khalid Alkahtani. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data are present within the article.

Ethics Approval: This research did not involve human participants, animals, or any personally identifiable information.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sun G, Liao D, Zhao D, Xu Z, Yu H. Live migration for multiple correlated virtual machines in cloud-based data centers. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2015;11(2):279–91. doi:10.1109/tsc.2015.2477825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ali A, Azim N, Othman MTB, Rehman AU, Alajmi M, Al-Adhaileh MH, et al. Joint optimization of computation offloading and task scheduling using multi-objective arithmetic optimization algorithm in cloud-fog computing. IEEE Access. 2024;12(7):184158–8. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3512191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kumar M, Gupta P, Kumar A. Performance analysis of a fog computing-based vehicular communication. Int J Veh Inf Commun Syst. 2024;9(2):115–34. doi:10.1504/ijvics.2024.137761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Huang S, Sun C, Pompili D. Meta-ETI: meta-reinforcement learning with explicit task inference for UAV-IoT coverage. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(13):23852–65. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3553808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ali A, Shah SAA, Shloul TA, Assam M, Ghadi YY, Lim S, et al. Multi-objective Harris hawks optimization based task scheduling in cloud-fog computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(13):24334–52. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3391024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dai X, Xiao Z, Jiang H, Alazab M, Lui JC, Min G, et al. Task offloading for cloud-assisted fog computing with dynamic service caching in enterprise management systems. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;19(1):662–72. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3186641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang S. Feature-aware task offloading and scheduling mechanism in vehicle edge computing environment. Int J Veh Inf Commun Syst. 2024;9(4):415–33. doi:10.1504/ijvics.2024.142101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sudhakar RV, Dastagiraiah C, Pattem S, Bhukya S. Multi-objective reinforcement learning based algorithm for dynamic workflow scheduling in cloud computing. Indones J Electr Eng Inform. 2024;12(3):640–9. [Google Scholar]

9. Li Z, Gu W, Shang H, Zhang G, Zhou G. Research on dynamic job shop scheduling problem with AGV based on DQN. Clust Comput. 2025;28(4):236. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04970-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang B, Sang H, Lu C, Meng L, Song Y, Jiang X. Integrated heterogeneous graph and reinforcement learning enabled efficient scheduling for surface mount technology workshop. Inf Sci. 2025;708(3):122023. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2025.122023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wei M, Yang S, Wu W, Sun B. A multi-objective fuzzy optimization model for multi-type aircraft flight scheduling problem. Transport. 2024;39(4):313–22. doi:10.3846/transport.2024.20536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Huang W, Li T, Cao Y, Lyu Z, Liang Y, Yu L, et al. Safe-NORA: safe reinforcement learning-based mobile network resource allocation for diverse user demands. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM 2023); 2023 Oct 21–25; Birmingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

13. Naik BB, Priyanka B, Ansari MSA. Energy-efficient task offloading and efficient resource allocation for edge computing: a quantum inspired particle swarm optimization approach. Clust Comput. 2025;28(3):155. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04833-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Gawali MB, Shinde SK. Task scheduling and resource allocation in cloud computing using a heuristic approach. J Cloud Comput. 2018;7(1):1–16. doi:10.1186/s13677-018-0105-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Nabi S, Ahmad M, Ibrahim M, Hamam H. AdPSO: adaptive PSO-based task scheduling approach for cloud computing. Sensors. 2022;22(3):920. doi:10.3390/s22030920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Sharma N, Garg P. Ant colony based optimization model for QoS-Based task scheduling in cloud computing environment. Meas Sens. 2022;24(1):100531. doi:10.1016/j.measen.2022.100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Peng Z, Pirozmand P, Motevalli M, Esmaeili A. Genetic algorithm-based task scheduling in cloud computing using Mapreduce framework. Math Probl Eng. 2022;2022(1):4290382. doi:10.1155/2022/4290382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mangalampalli S, Karri GR, Kumar M. Multi objective task scheduling algorithm in cloud computing using grey wolf optimization. Clust Comput. 2023;26(6):3803–22. doi:10.1007/s10586-022-03786-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Akbari MA, Zare M, Azizipanah-Abarghooee R, Mirjalili S, Deriche M. The cheetah optimizer: a nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for large-scale optimization problems. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):10953. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-14338-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Memon ZA, Akbari MA, Zare M. An improved cheetah optimizer for accurate and reliable estimation of unknown parameters in photovoltaic cell and module models. Appl Sci. 2023;13(18):9997. doi:10.3390/app13189997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang Z, Goudarzi M, Gong M, Buyya R. Deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling for optimizing system load and response time in edge and fog computing environments. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;152(6):55–69. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.10.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Singh SP. Effective load balancing strategy using fuzzy golden eagle optimization in fog computing environment. Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2022;35(2):100766. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2022.100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Archana R. Multilevel scheduling mechanism for a stochastic fog computing environment using the HIRO model and RNN. Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2023;39(8):100887. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2023.100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang M, Ma H, Wei S, Zeng Y, Chen Y, Hu Y. A multi-objective task scheduling method for fog computing in cyber-physical-social services. IEEE Access. 2020;8:65085–95. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2983742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Siyadatzadeh R, Mehrafrooz F, Ansari M, Safaei B, Shafique M, Henkel J, et al. Relief: a reinforcement-learning-based real-time task assignment strategy in emerging fault-tolerant fog computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(12):10752–63. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3240007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jain V, Kumar B. QoS-aware task offloading in fog environment using multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. J Netw Syst Manag. 2023;31(1):7. doi:10.1007/s10922-022-09696-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chandrashekar C, Krishnadoss P, Kedalu Poornachary V, Ananthakrishnan B, Rangasamy K. HWACOA scheduler: hybrid weighted ant colony optimization algorithm for task scheduling in cloud computing. Appl Sci. 2023;13(6):3433. doi:10.3390/app13063433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Cheng F, Huang Y, Tanpure B, Sawalani P, Cheng L, Liu C. Cost-aware job scheduling for cloud instances using deep reinforcement learning. Clust Comput. 2022;25(1):619–31. doi:10.1007/s10586-021-03436-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen Y, Lin Y, Hu Y, Hsia C, Lian Y, Jhong S. Distributed real-time object detection based on edge-cloud collaboration for smart video surveillance applications. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):93745–59. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3203053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rafique H, Shah MA, Islam SU, Maqsood T, Khan S, Maple C. A novel bio-inspired hybrid algorithm (NBIHA) for efficient resource management in fog computing. IEEE Access. 2019;7:115760–73. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2924958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ghobaei-Arani M, Souri A, Safara F, Norouzi M. An efficient task scheduling approach using moth-flame optimization algorithm for cyber-physical system applications in fog computing. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2020;31(2):e3770. doi:10.1002/ett.3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ali IM, Sallam KM, Moustafa N, Chakraborty R, Ryan M, Choo K-KR. An automated task scheduling model using non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II for fog-cloud systems. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2020;10(4):2294–308. doi:10.1109/tcc.2020.3032386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Saif FA, Latip R, Hanapi ZM, Shafinah K. Multi-objective grey wolf optimizer algorithm for task scheduling in cloud-fog computing. IEEE Access. 2023;11:20635–46. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3241240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tang M, Wong VW. Deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in mobile edge computing systems. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2020;21(6):1985–97. doi:10.1109/tmc.2020.3036871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Razaq MM, Rahim S, Tak B, Peng L. Fragmented task scheduling for load-balanced fog computing based on Q-learning. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2022;2022(1):4218696. doi:10.1155/2022/4218696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Choppara P, Mangalampalli SS. Adaptive task scheduling in fog computing using federated DQN and K-means clustering. IEEE Access. 2025;13(1):75466–92. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3563487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bansal S, Aggarwal H. A multiobjective optimization of task workflow scheduling using hybridization of PSO and WOA algorithms in cloud-fog computing. Clust Comput. 2024;27(8):10921–52. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04522-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mangalampalli S, Hashmi SS, Gupta A, Karri GR, Rajkumar KV, Chakrabarti T, et al. Multi objective prioritized workflow scheduling using deep reinforcement based learning in cloud computing. IEEE Access. 2024;12:5373–92. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3350741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li H, Zhang X, Li H, Duan X, Xu C. SLA-based task offloading for energy consumption constrained workflows in fog computing. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;156(5):64–76. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li H, Liu L, Duan X, Li H, Zheng P, Tang L. Energy-efficient offloading based on hybrid bio-inspired algorithm for edge-cloud integrated computation. Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2024;42(11):100972. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2024.100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Maurya A, Pandey A. Cheetah optimization for optimal power management in standalone solar PV systems with EV integration. Eng Res Express. 2025;7(2):025319. doi:10.1088/2631-8695/adc900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sharma S, Kumar V. Grid-based multi-objective cheetah optimization for engineering applications. Clust Comput. 2025;28(4):266. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04907-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sivasakthivel R, Rajagopal M, Anitha G, Loganathan K, Abbas M, Ksibi A, et al. Simulating online and offline tasks using hybrid cheetah optimization algorithm for patients affected by neurodegenerative diseases. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):8951. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93047-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools