Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LLM-Powered Multimodal Reasoning for Fake News Detection

1 Department of Software Engineering, University of Frontier Technology, Gazipur, 1750, Bangladesh

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sunamgonj Science and Technology University, Sunamganj, 3000, Bangladesh

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, American International University-Bangladesh, Dhaka, 1229, Bangladesh

4 Center for Advanced Analytics (CAA), COE for Artificial Intelligence, Faculty of Engineering & Technology (FET), Multimedia University, Melaka, 75450, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: M. F. Mridha. Email: ; Md. Jakir Hossen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Visual and Large Language Models for Generalized Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 77 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070235

Received 11 July 2025; Accepted 09 September 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The problem of fake news detection (FND) is becoming increasingly important in the field of natural language processing (NLP) because of the rapid dissemination of misleading information on the web. Large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4. Zero excels in natural language understanding tasks but can still struggle to distinguish between fact and fiction, particularly when applied in the wild. However, a key challenge of existing FND methods is that they only consider unimodal data (e.g., images), while more detailed multimodal data (e.g., user behaviour, temporal dynamics) is neglected, and the latter is crucial for full-context understanding. To overcome these limitations, we introduce M3-FND (Multimodal Misinformation Mitigation for False News Detection), a novel methodological framework that integrates LLMs with multimodal data sources to perform context-aware veracity assessments. Our method proposes a hybrid system that combines image-text alignment, user credibility profiling, and temporal pattern recognition, which is also strengthened through a natural feedback loop that provides real-time feedback for correcting downstream errors. We use contextual reinforcement learning to schedule prompt updating and update the classifier threshold based on the latest multimodal input, which enables the model to better adapt to changing misinformation attack strategies. M3-FND is tested on three diverse datasets, FakeNewsNet, Twitter15, and Weibo, which contain both text and visual social media content. Experiments show that M3-FND significantly outperforms conventional and LLM-based baselines in terms of accuracy, F1-score, and AUC on all benchmarks. Our results indicate the importance of employing multimodal cues and adaptive learning for effective and timely detection of fake news.Keywords

The proliferation of misinformation on digital platforms has increased the need for sound fake news detection (FND) systems. With the growing impact of internet content on public opinion and policy discussions, the detection and moderation of misinformation has become a recent and important challenge in natural language processing (NLP). Fake news is a type of news that differs from rumors in that fake news has an intentional logic of misleading, which not only requires linguistic analysis but also additional context clues such as multimedia signals, user behavior, and information flow [1].

Conventional FND approaches are dominated by classical machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques (e.g., support vector machines, decision trees, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [2,3]). These models are often built on hand-engineered textual features or fixed word vectors, which have limited expressions for evolving language manipulation and subtle semantics. In addition, over-reliance on large-scale labelled datasets of misinformation reduces scalability, given that misinformation evolves very quickly and manual labelling is becoming increasingly impractical.

One of the major reasons for this transformative shift is the recent arrival of large language models (LLMs) such as BERT [4], T5 [5], and the GPT series [6], which have revolutionized NLP research by providing deep semantic understanding and context-aware language generation capabilities. These models have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in sentiment analysis, question answering, and textual entailment. However, LLMs are still susceptible to hallucinations; they can generate coherent yet factually incorrect content, which is harmful to panels with high-stakes use, such as FND [7]. Furthermore, the majority of the presented FND approaches, so far, have not been used in multi- or cross-modal methods and underuse useful information found in images, videos, user metadata, and social interactions.

Shortcomings of Current Fake News Detection Models

1. Text-Only Focus (Unimodal Limitation): Most existing models rely solely on textual features, ignoring multimodal signals such as images, videos, and social context, which are crucial for detecting fake news in real-world environments.

2. Static Feature Engineering: Most of the previous models are based on text data only, ignoring the multimodal signals of images, videos, social context, etc., which are important for detecting fake news in its real-world settings.

3. Limited Context Awareness: Early machine learning and deep learning models typically rely on handcrafted or fixed features, which restrict their capacity to adapt to evolving misinformation strategies and verbal complexity.

4. Vulnerability to Linguistic Manipulation: Existing models often fail to capture higher-order contextual motifs, for example, during what time the article was published, how the author, or source, evolved over time, credibility, or potential temporality issues. That makes them misclassify articles across the board, especially those of satire or outdated articles.

5. Inability to Handle Dynamic Content: The majority of models are trained from static datasets offline; hence, they are not sufficiently competitive in the task of tracking the evolution and mutation of fake news.

6. Dataset Bias and Poor Generalization: State-of-the-art methods often have biases toward specific datasets and they do not generalize well to other domains, languages, or platforms.

7. Lack of Real-Time Detection Capability: There are very few models that have been optimized for real-time applications, which are critical for the detection of rapidly spreading misinformation on social media websites.

8. Neglect of User and Network Features: The current models sometimes overlook user metadata (e.g., credibility and, history of engagement) and network propagation patterns, which can be leveraged as evidence for veracity determination.

9. Hallucination and Overconfidence in LLMs: While large language models are promising, it has been observed that they hallucinate content and do not come with fact-verification.

10. Limited Explainability and Transparency: Applications of deep learning-based models are frequently black boxes that do not offer much insight into their decision-making process, leading to a lack of trust and acceptance in a realistic environment.

In this study, we aim to overcome these shortcomings by introducing M3-FND (Multimodal Misinformation Mitigation for Fake News Detection), a system that combines LLMs and multimodal information processing for a robust and context-aware truthworthiness evaluation. M3-FND extracts and aligns heterogeneous signals ranging from text and images to user credibility profiles and temporal dynamics, thus facilitating cross-modal inconsistency identification, headline-image mismatch, or suspicious engagement activities in the social context. The framework consists of three fundamental modules: image-text alignment, user credibility analysis, and temporal behavior modeling.

Research Gap in Multimodal Misinformation Detection

Although there have been significant developments recently, MMD research still has several crucial gaps that we are addressing with our proposed M3–FND framework.

Shallow or Naïve Fusion Strategies.

Previous MMD systems either use early fusion (feature concatenation) or late fusion (predict in unimodal), as the only solutions for multi-modal fusion [8]. These methods make us unable to capture the fine-grained cross-modal interactions, which are crucial when misinformation appears and is encroached by subtle text-image inconsistencies. Our Approach: M3–FND is a cross-attention-based approach, where features from both modalities are aligned and weighted dynamically for soft fusion, which allows contextual reasoning, instead of a direct match based on hard attention.

Limited Contextual Reasoning across Modalities.

Previous works such as SAFE [9] and SpotFake [10] study the correlation between different modalities but lack a high-level semantic reasoning for understanding why content is misleading. These methods severely underestimate the text and often fail at text-image co-plausibility detection. Our Approach: Our proposed model M3–FND, a multimodal natural-language (MNL) transformer using large language models(LLMs), expands the scope of reasoning by performing natural-language reasoning over multiple forms of mixed multimedia evidence while providing understandable reasons behind each prediction.

Domain and Topic Shift Vulnerability.

The fusion and classification layers of models are fixed at a specific dataset level, which typically results in models that do not generalize across unseen domains [11]. Our Approach: M3–FND performs better on the unseen topics, languages, and formats. A significant improvement in topic generalization is observed through data prompt engineering and few-shot adaptation.

Neglect of Explainability in Detection Models.

The first and foremost challenge in most MMD work is having an accuracy, not transparency-focused mechanism [12], making gaining trust and acceptance difficult. Our Approach: The LLM component outputs natural language rationales referring to visual and textual cues, consistent with the principles of explainable AI.

Underutilization of Vision–Language Pretrained Models.

While CLIP [13] and other models built on top of similar vision–language modules have laid a foundation for powerful representation learning, few MMD systems have put their alignment capabilities to use. Our Approach: We project the vision encoder outputs into the embedding space of LLM, facilitating dense multimodal semantic alignment resulting in superior reasoning.

The cornerstone of M3-FND is our adaptive multimodal fusion, which dynamically weights and fuses information among modalities depending on their contextual relevance. This follows human-like cognitive tasks in cognition, that is, paying more attention to relevant cues when judging credibility. We further propose a dynamic prompting mechanism based on contextual reinforcement learning, which empowers LLMs to adapt decision thresholds and generation styles according to emerging multimodal feedback. This shifts against the risk of hallucination and towards factive grounding.

We conducted a comprehensive experiment, including zero-shot and few-shot evaluations, on several benchmark datasets, including FakeNewsNet, Twitter15, and Weibo, to validate the M3-FND. Experiments demonstrate that M3-FND significantly exceeds traditional FND models and advanced LLM-based models, such as GPT-4. Zero, for various evaluation metric accuracy, F1-score, and AUC. These results confirm the benefits of integrating multimodal cues with adaptive prompting for real-world misinformation mitigation. The contributions of this study are as follows:

• We identify the limitations of state-of-the-art LLM-based fake news detection models and propose M3-FND, a new framework that exploits multimodal sources of information to inform dynamic context adaptation to improve trustworthiness evaluation.

• We propose a context-aware adaptive multimodal fusion approach that successfully fuses textual, visual, temporal, and user-dependent signals to enhance the classification performance and robustness.

• We propose a dynamic prompting protocol inspired by contextual bandits in reinforcement learning, which allows large language models to fine-tune predictions to dynamic inputs and decrease susceptibility to hallucinations.

• We conducted experiments under both zero-shot and few-shot learning and on popular benchmark multimodal datasets (FakeNewsNet, Twitter15, and Weibo) to demonstrate the effectiveness of M3-FND over other existing FND baselines in terms of accuracy, F1, and AUC.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of related work. Section 3 outlines the preliminaries and foundational concepts essential for understanding the proposed method. Section 4 presents the proposed architecture and methodology in detail. Section 5 discusses the evaluation protocol, experimental setup, and results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study and suggests possible directions for future research.

Owing to the growing pervasiveness of misinformation on digital media, Fake News Detection (FND) has become a promising research line in Natural Language Processing (NLP). FND research is shifting its paradigm with the appearance of Large Language Models (LLMs), and their capabilities in prompt engineering and instruction tuning.

In this work, we organize the development of FND into three main streams:

1. Classical and neural methods of FND,

2. Pretrained Language Model (PLM)–based FND methods,

3. Recent LLM-based prompt-driven frameworks.

To address them, traditional FND approaches largely used linguistic, syntactic, and metadata cues to judge the trustworthiness of news articles or social media posts based on article content [14]. However, the classical model has no cross-domain adaptation property. With the advent of deep learning, CNNs and RNNs have been exploited to capture contextual semantics, followed by graph-based approaches such as SentGCN, SentGAT, and GraphSAGE [15,16]. In models such as dEFEND [17], hierarchical attention mechanisms have been used to model user-news interactions. By exploiting social context-based approaches, the propagation pattern was further modeled using user relationships and temporal change. To enable multilingual FND, Shamardina et al. [18] brought the CoAT corpus to Russian, an important resource for studying human-and machine-authored misinformation. Setiawan et al. [19] utilized hybrid LSTM- and Transformer-based approaches for the Indonesian FND, showing cross-language generalizability. Ameli et al. [20] considered FND as a fine-grained pipeline that consists of feature extraction, train-and-test stages, and finally the defense mechanism.

The rise of PLMs, including BERT, RoBERTa [21], and their FND-tuned counterparts, as in FakeBERT [22] has been a game-changer in the field of veracity classification. These models outperformed the other methods by fine-tuning domain-specific datasets using deep contextual embeddings. Prompt-based fine-tuning approaches such as Pattern-Exploiting Training (PET) [23] and Knowledgeable Prompt Tuning (KPT) [24] have attempted to match task specification and PLM architecture. Although these methods were successful, they required task-specific retraining and were generally vulnerable to domain shifts and prompt changes.

The most recent turn in FND research has been facilitated by the availability of LLMs such as GPT-3/4, Claude, LLaMA, and Gemini. These models have powerful zero-shot and few-shot learning abilities, which allow task generalization with little supervision. Zaheer et al. [25] analyzed LLMs for FND, and focused on their linguistic reasoning and generative-based strengths. Zellers et al. showed how LLMs can be used for and against the detection of fake news by releasing a generative LLM that produces fake news, GROVER. Jin et al. [26] used adversarial and contrastive learning for the GPT-3.5 for low-resource FND demonstrating model generalization. Xu and Li [27] showed that even offline-trained LLMs are viable for dynamic veracity detection without the need for continuous fine-tuning. Wang et al. [28] introduced LLM–GAN, which integrated LLMs into a GAN pipeline to obtain explainable classification. Su et al. [29] presented DAAD, which combined Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) and domain-specific prompting to construct robust context-aware reasoning.

Conventional FND [30] techniques mainly depended on textual information, such as sentiment, stylometric markers, and syntactic compositions [31]. Transformer-based models have developed significantly; however, they do not perform well in zero-shot or adversarial scenarios and can not pergorm cross-modal verification. To cope with these limitations, multimodal approaches have been developed that consider visual content in addition to textual data. Jin et al. [32] were the first to employ this method using cross-modal features of image-text in content-based rumour detection. Later studies used CNNs to extract image features and then shifted them to late fusion techniques. Graph neural networks and temporal models have also been adopted to represent propagation dynamics [33,34]. Lately, in the literature, adaptive fusion techniques have attracted attention, using attention [35], gating networks, and reinforcement learning to fuse heterogeneous modalities dynamically. However, the majority of combination approaches are static and work based on a fixed policy, and they are not sufficiently adaptive to fit into dynamic news situations.

Notwithstanding substantial advancements, current FND systems still suffer from three principal challenges: (i) insufficient adaptability to changing contexts; (ii) limited multimodal grounding; and (iii) vulnerability to hallucination in LLM predictions. Our method addresses the problem of FND with the introduced M3-FND, where a unified architecture is leveraged to integrate adaptive multimodal fusion and dynamic prompting assisted by reinforcement learning. This is a pivotal architecture that allows the model to leverage textual, visual, temporal, and user-specific cues in a dynamic manner and iteratively refine its predictions on contextual information. To the best of our knowledge, M3-FND is the first to integrate a reinforcement learning model with multimodal fusion and prompt optimization for truthfulness-driven fake news detection.

The key theoretical foundations of our proposed M3-FND framework, including problem formulation for FND and the homage of multimodal fusion and dynamic context prompting to LLMs, are presented in this section.

3.1 Problem Definition of Fake News Detection (FND)

We now consider the detection of fake news as a binary classification problem. Suppose that

The input

where

The FND tasks involve multimodal reasoning: evaluating linguistic structure, visual-textual coherence, propagation dynamics, and user engagement behaviour to detect inconsistencies indicative of misinformation.

3.2 Multimodal Fusion in M3-FND

To model the real-world complexity of fake news accurately, M3-FND employs an adaptive multimodal fusion strategy. Each modality is processed using a dedicated encoder as follows:

These representations are fused into a unified embedding

This fusion enables the model to detect cross-modal discrepancies, such as image-text mismatches or anomalous user behaviour that may indicate fake news.

3.3 Contextual Prompt Engineering with LLMs

M3-FND utilizes large language models enhanced by dynamic prompting to produce veracity predictions. Given the fused multimodal representation

We adopted two prompting strategies:

Zero-Shot Prompting:

The LLM receives a synthesized prompt from

“Analyze the following multimedia news and assess its authenticity: [Fused Representation].”

Few-Shot Prompting:

LLM is guided by a small set of example prompts

We then augment these prompts with chain-of-thought (CoT) to steer intermediate reasoning steps:

“Please understand each modality step by step and tell me if the news is True or Fake: [Fused Representation].”

Such a prompting dynamic model facilitates LLM to reason over multimodal signals and produce context-aware veracity judgments.

In summary, the M3-FND model carves out fake news detection as a multimodal classification task, enabled by adaptive fusion and LLM-guided inference from well-designed prompts.

This section provides full details of our proposed M3-FND (Multimodal Misinformation Mitigation for Fake News Detection) framework, which is designed to address the above-mentioned limitations in fake news detection, including limited multimodal reasoning, poor zero-shot generalization, static prompt engineering, and weak inter-modal semantic alignment. Inspired by the ideas proposed in text generation, imitation learning, and multimodal reasoning methods, we propose the use of Multi-modal (M3-FND) to address the problem of generalizable context-aware fake news detection, which embeds multimodal representation learning, dynamic prompt optimization based on reinforcement learning, adaptive feature fusion, and LLM-based decision making.

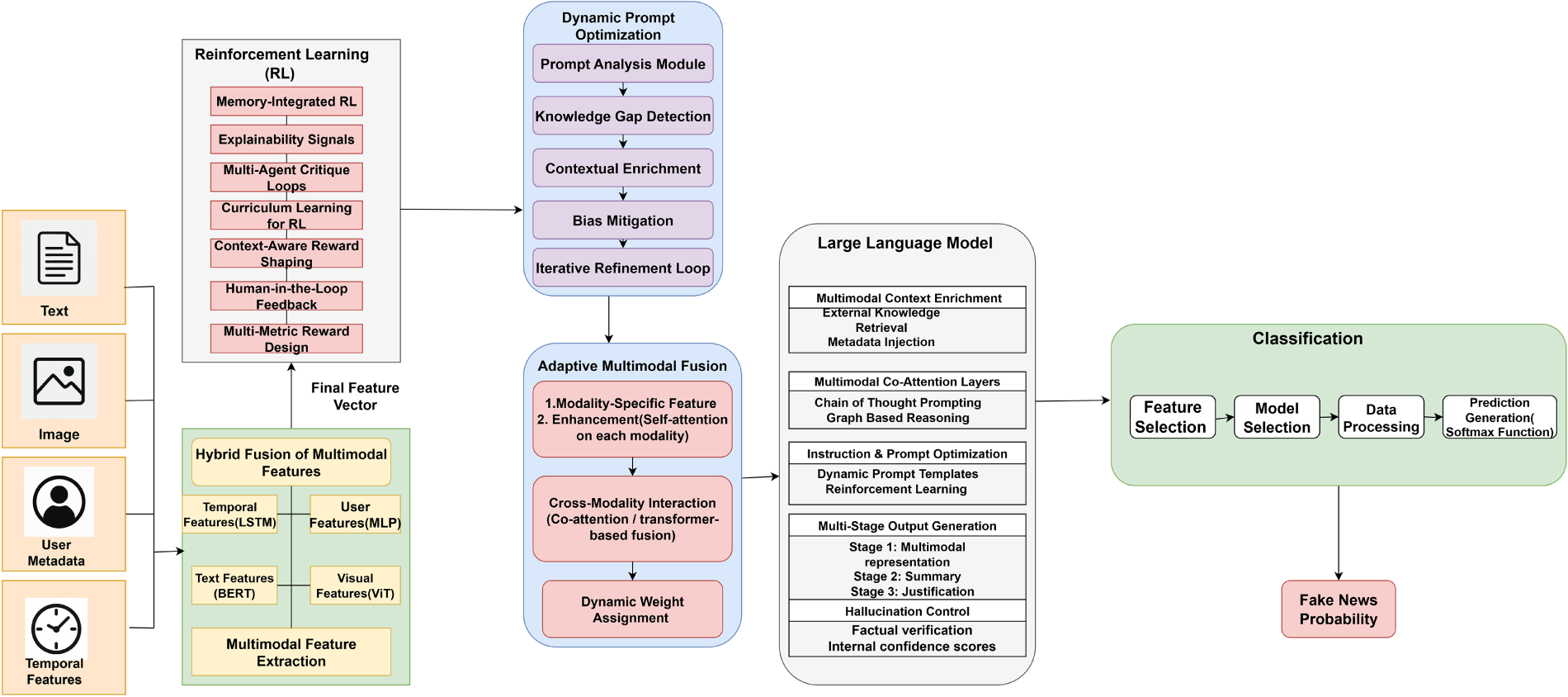

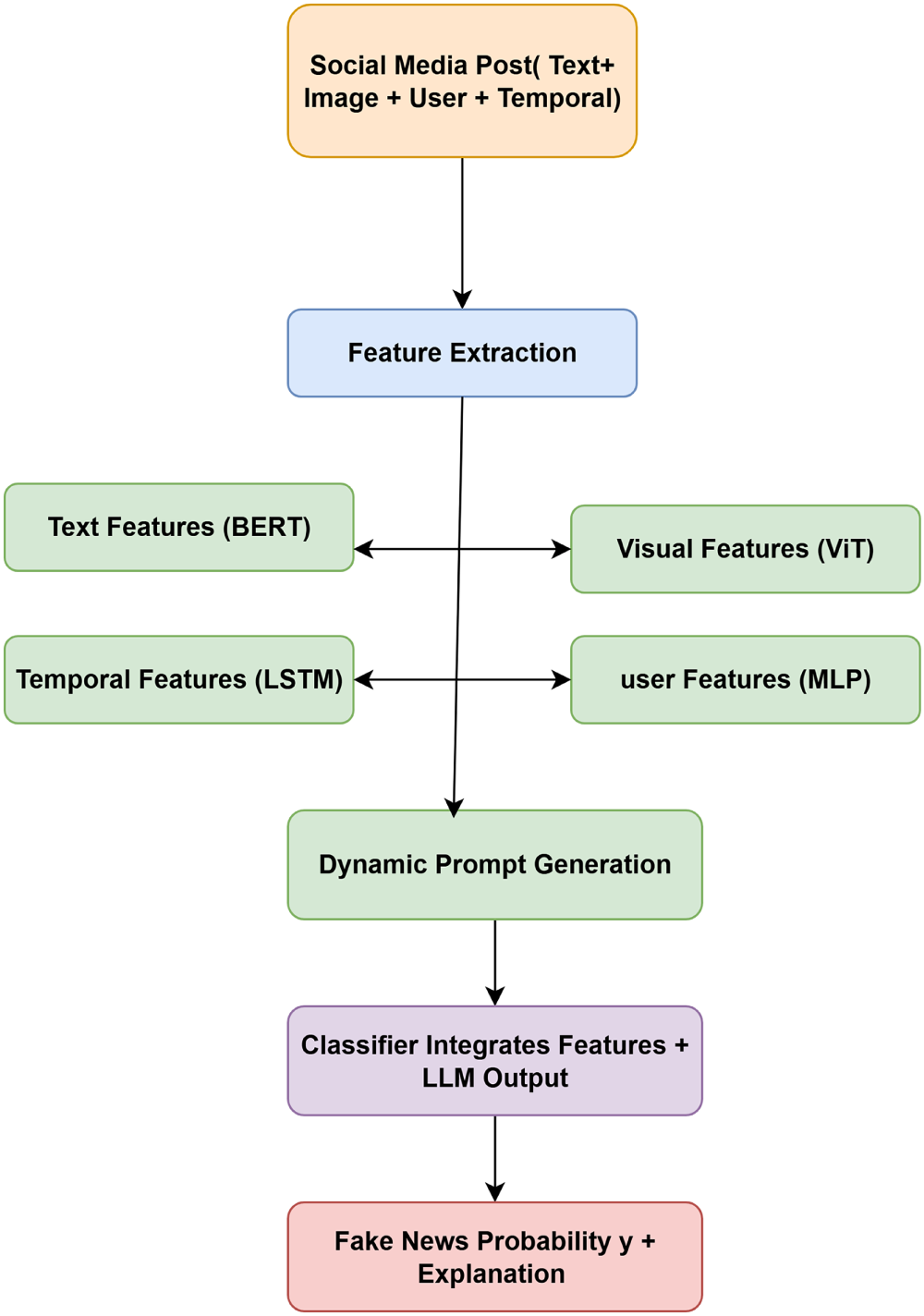

The architecture of M3-FND (see Fig. 1) comprises five interconnected modules:

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed M3-FND framework. The model integrates multimodal inputs—including textual, visual, temporal, and user metadata—via an adaptive fusion module. The fused representation is dynamically processed by a reinforcement learning-guided prompt optimizer, which interacts with a Large Language Model (LLM) for final veracity prediction. This unified approach enables contextual adaptation, reduces hallucination, and improves fake news detection performance in both zero-shot and low-resource settings

1. Multimodal Feature Extraction: Textual features are extracted using a pre-trained transformer encoder

This dual encoding captures rich semantic cues from each modality while preserving the intra-modal dependencies.

2. Dynamic Prompt Optimization via Reinforcement Learning: Static prompt templates fail to generalize across news types and sources. We formulate dynamic prompt generation as a reinforcement learning problem in which an agent

The policy gradient is estimated using REINFORCE:

This enables context-sensitive prompt learning,which is optimized for downstream decision accuracy.

3. Adaptive Multimodal Fusion: To effectively integrate multimodal features, we introduce a gated co-attention mechanism:

where

4. Large Language Model (LLM) Integration: The fused feature vector

where

5. Classification Layer: The final prediction is obtained by aggregating the output of the LLM and additional fused features:

where

4.1 Multimodal Feature Extraction

Given a social media post represented as

Text is a central modality in misinformation detection, as it often contains stylistic and semantic cues that can reveal deception, bias, or emotional manipulation. To effectively capture such patterns, we leverage a pre-trained transformer-based encoder, such as BERT or RoBERTa, which are known for their superior capability in modelling contextual dependencies, long-range interactions, and complex syntactic structures in natural language. Let the textual content be represented as a sequence of tokens

Here,

Visual content usually includes contextual evidence that supports or is refuted by the text. We applied a pre-trained Vision Transformer (ViT)/CNN (e.g., ResNet-50, Swin Transformer) backbone to obtain high-level semantic features from the image modality based on the complexity of the dataset and computation cost. Given an image I, we first resize and normalize it to fit into the input of the selected vision model. The resulting image is then divided into patches (for ViTs) or processed by convolutional layers (for CNNs) to obtain local feature descriptors. These are combined using self-attention or pooling to obtain a global image representation:

Here,

Vision-to-LLM Embedding Alignment in M3–FND

In M3–FND, the vision encoder output is aligned with the LLM input through a multi-step embedding projection process that ensures both modalities share a compatible semantic space before fusion. The process is detailed as follows:

1. Vision Encoding

• A pretrained vision encoder (e.g., CLIP-ViT or Swin Transformer) is used to extract high-dimensional image feature vectors.

• These vectors typically have dimension

2. Embedding Projection Layer

• Since LLMs (e.g., LLaMA, GPT-style models) expect token embeddings in a smaller space (

where

3. Positional & Modality Tagging

• Modality-specific embeddings are appended so the LLM can distinguish between textual tokens and visual token projections:

• Where:

–

–

4. Token Concatenation for Hybrid Fusion

• The projected vision embeddings are treated as special tokens and concatenated with the text embeddings:

• This enables early fusion inside the LLM while still allowing late fusion with other modality-specific reasoning modules.

This alignment works because it transforms heterogeneous visual features into a format that the LLM can process natively, ensuring semantic compatibility without losing modality-specific information. Raw vision encoder outputs exist in a high-dimensional feature space tailored for image understanding, which is structurally and statistically different from the token embedding space used by LLMs. By applying a learnable projection layer, these visual embeddings are mapped into the same dimensional space as textual tokens, enabling direct integration into the LLM’s input sequence. The addition of positional and modality-specific embeddings preserves both the temporal/spatial order of visual patches and their identity as non-text elements, preventing feature mixing errors. As a result, the LLM can jointly reason over visual and textual signals in a unified representation space, facilitating richer cross-modal interactions and more accurate veracity assessments in the M3–FND framework.

The metadata at the user level are important because they provide key insights into the authority and behaviour of the source. Factors such as account age, number of followers/followings, frequency of posts, and user account verification status are also highly associated with the probability of spreading misinformation.

We describe user metadata

Here,

Temporal signals

The resulting vector

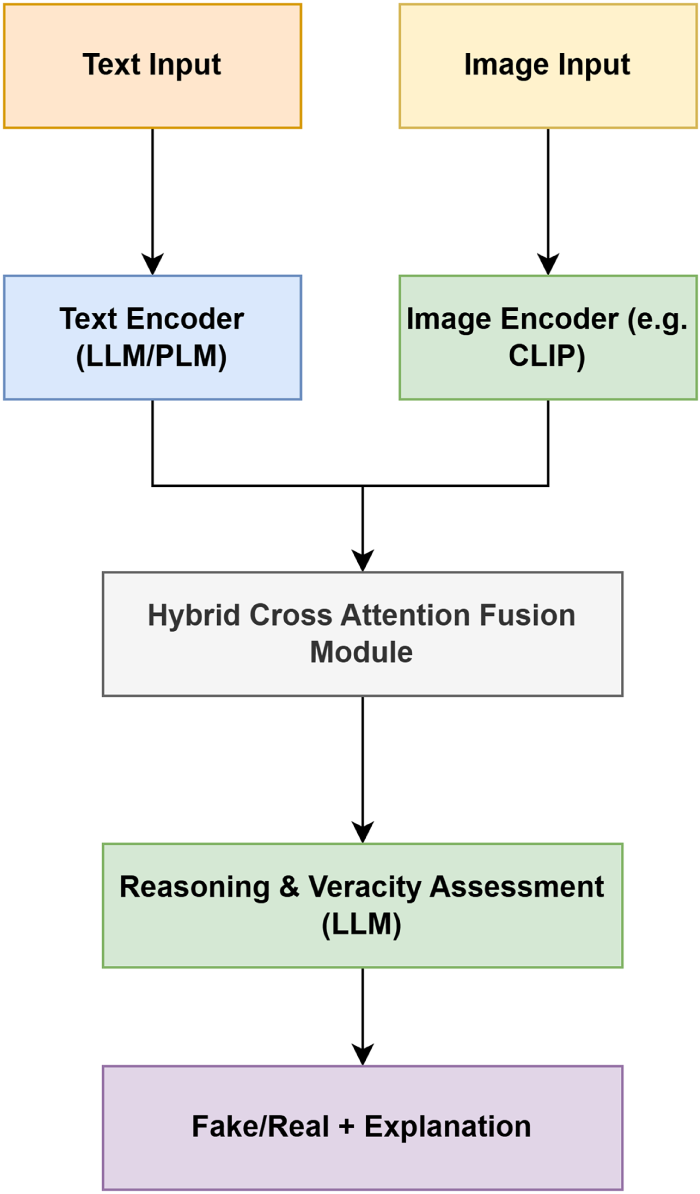

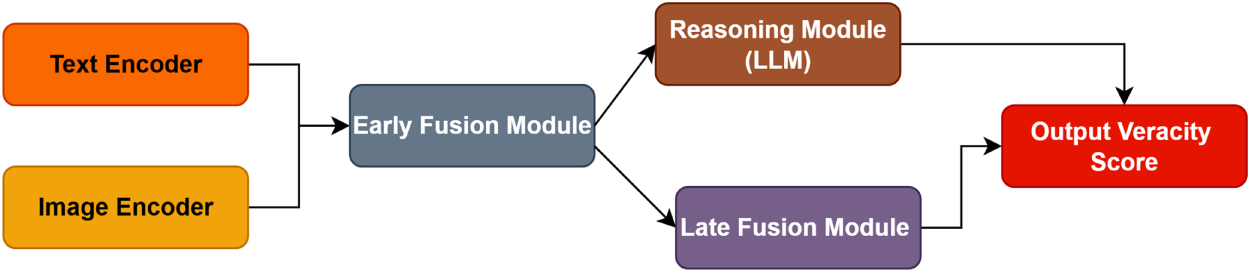

Fig. 2 shows the multimodal fake news detection framework implementing textual and visual information at first for approvable veracity evaluation. The architecture starts with two input branches (one for text and one for images). The text branch is processed by a Text Encoder, such as a large language model (LLM) or pre-trained language model (PLM), to extract semantic, syntactic, and contextual information from the text. The Vision Encoder, such as CLIP, meanwhile processes the image branch, yielding informative visual features that encode objects, scenes, and contextual signals in an image.

Figure 2: The figure presents a block diagram illustrating the overall framework with clearly labeled modules: Encoder, Fusion Module, and Reasoning Module

The outputs from encoders are further passed via a Hybrid Cross Attention Fusion Module as shown below. Text is able to find some spatial regions and vice versa; this module basically does inter-modal attention; A fusion module would then learn the complex relationships (it agrees with text, it disagrees with text, that text should not agree with that video or that picture = misinformation) between a diverse range of input modalities.

Bonded multimodal is routed to a Reasoning & Veracity Assessment Module (LLM-improved) channel, which has more sophisticated reasoning. This is a module that analyzes the combined features of all outputs to give you one score per truthfulness of input based on inter-modal alignment and background knowledge learned from our LLM.

The framework ultimately issues a consolidated output that contains both the ground truth (fake or real) as well as an associated explanation that showcases how the model justified its decision. This method enables interpretable predictions, which is key to trust in automated misinformation detection. The architecture is designed in a modular way, and it pays attention to multimodal fusion of vision and text. This makes our approach capable of identifying nuanced and context-dependent fake news in combined text-image scenarios openly and understandably by introducing explainable reasoning techniques.

4.2 Dynamic Prompt Optimization (DPO)

To better match the context of LLM on generation tasks and to mitigate hallucinations in synthesized model outputs, we further introduce a module for DPO that is implemented using Reinforcement Learning. This flexible module can automatically select and optimize prompt templates given multimodal inputs and allow the LLM to output responses with both grounding of facts and task orientation.

We model the problem of prompt selection as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), in which a policy agent

State.

At time step

where

Action.

The action

Reward.

After the LLM processes the selected prompt and returns a prediction, the agent receives a scalar reward signal

where:

•

•

•

•

Learning.

The policy network

Here,

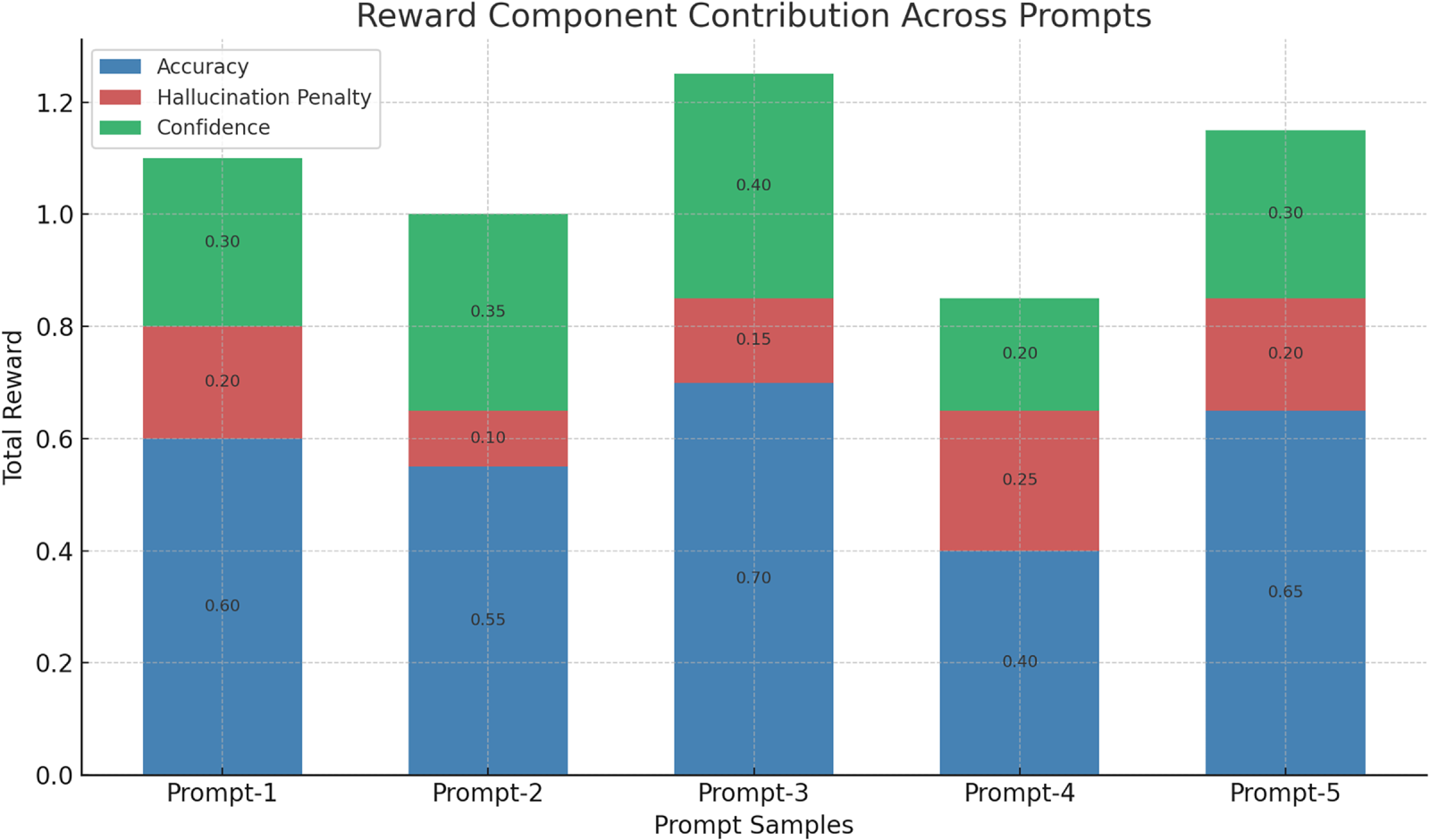

Reward Component Analysis.

Fig. 3 shows the effect of three factors, namely, accuracy, hallucination penalty, and confidence, as contributing to the overall reward signal for five prompt samples in the Dynamic Prompt Optimization (DPO) module. From the analysis, we found that accuracy dominates the reward system in our experiment, and Prompt-3 has the best accuracy (0.70) and the highest total reward. Compared with all the other prompts, Interpretation-4 has the lowest accuracy and the largest hallucination penalty, which leads to the worst overall reward. The hallucination part acts as a negative regularizer, which tampers with prompts that favour factually discrepant outputs. Confidence provides a more substantial complementary vibe: prompts with higher confidence (e.g., Prompt-3 and Prompt-5) generate better total rewards when combined with high accuracy and low hallucinations. This supports the fact that the multi-component reward function effectively steers the policy towards selecting prompts that translate into accurate, grounded, and confident LLM predictions and ensures a stronger robustness of the MISDETECTOR.

Figure 3: Contribution of individual reward components across different prompts. This figure shows the relative influence of various reward signals—such as fluency, factuality, consistency, and multimodal alignment—on prompt selection during reinforcement learning. Higher contribution indicates a greater role in optimizing the prompt for effective fake news detection. The analysis highlights that multimodal alignment and consistency rewards have the most significant impact, reinforcing the importance of grounding prompts in both context and cross-modal information

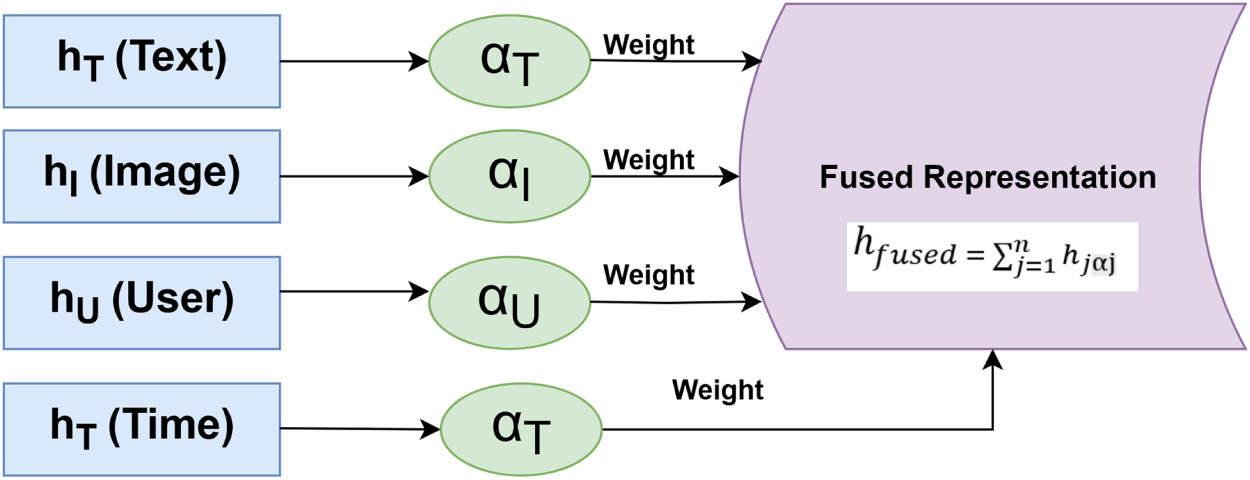

4.3 Adaptive Multimodal Fusion

In the field of multimodal learning, one of the key tasks required to build an optimized system is to integrate information from various modalities to improve performance. In our approach, four modalities are taken into account: text features

To selectively emphasize each modality according to its local relevance, we introduce an attention-based gated fusion mechanism. This mechanism assigns an importance score to each modality by a feedforward attention layer so that the model can pay more attention to the modalities that carry the most discriminative information for the current inference task. Formally, the relevance score

where:

•

•

•

•

• The softmax denominator ensures that the attention scores across all modalities sum to one, thereby effectively normalizing the relevance weights.

This attention formulation allows the model to dynamically reweight modalities depending on the input context, which is particularly beneficial when some modalities may be noisy, missing, or less informative in certain instances.

The final fused multimodal representation

The fusion mechanism in Fig. 4 retains the nature of the original modality features, although the weight of the modalities depends on the context. Consequently, we obtained a compressed, scenario-adapted multimodal embedding at the lower layers that enables the downstream components to learn a more robust and accurate prediction.

Figure 4: Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Architecture. The framework dynamically integrates heterogeneous modalities—text, image, user, and temporal features—through a fusion module that assigns attention-based weights based on modality reliability. This adaptive strategy enhances robustness against noisy or missing data and ensures that the most informative signals dominate the final representation

The attention-based gated fusion mechanism facilitates adaptive fusion of heterogeneous information sources, thereby enhancing the capability of the model to exploit complementary signals and discourage irrelevant or misleading modalities.

4.4 Large Language Model Integration

To tap the sophisticated reasoning and contextual understanding of LLMs, we feed the fused multimodal representation

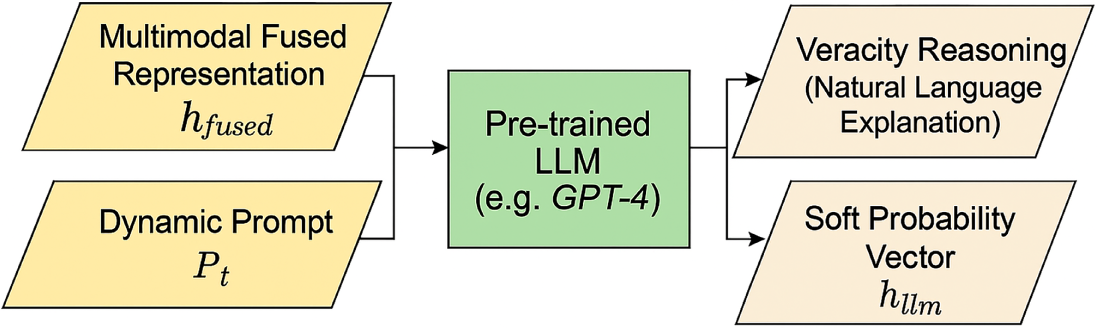

Figure 5: Schematic diagram illustrating the integration of a pre-trained Large Language Model (LLM), such as GPT-4, within the M3-FND framework. The model receives two key inputs: the multimodal fused representation (

Here,

Upon receiving this input, LLM performs high-level reasoning to produce two key outputs:

• Veracity Reasoning (explanation): A natural language explanation or justification that articulates the reasoning behind a classification decision. This output enables interpretability and aligns the decision-making process of the model closer to human rationales.

• Soft Probability Vector

By incorporating LLM in this manner, the framework effectively simulates human-like rational inference by combining the strengths of multimodal feature fusion with sophisticated language understanding and reasoning. This integration enhances both the transparency and performance of the system, particularly in complex scenarios in which contextual subtleties are crucial.

Moreover, the LLM’s capacity for instruction following and knowledge synthesis enables the model to adapt flexibly to varying domains and prompt formulations, further improving robustness and generalizability.

In the final stage of the framework, the model predicts the probability that a given news instance is fake or real. To achieve this, we first obtain two types of feature representations:

• Fused Features (

• LLM-Derived Features (

The concatenation of these two feature vectors, denoted as

Here,

To train the classifier, we use the binary cross-entropy loss, which measures the difference between the predicted probability

For a dataset with N samples, the overall loss is averaged as:

Minimizing this loss encourages the model to assign high probabilities to fake news samples (

This classification mechanism effectively leverages the synergy between multimodal fusion and advanced language understanding, enhancing detection accuracy in complex misinformation scenarios.

4.6 Hybrid Fusion Strategy in M3–FND

Our proposed M3–FND framework employs a hybrid fusion strategy, combining the strengths of both early fusion and late fusion to maximize detection performance in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Schematic diagram illustrating the integration of a pre-trained Large Language Model (LLM), e.g., GPT-4, within the M3-FND framework. The model receives two primary inputs: (i) the multimodal fused representation (

Reasoning

• Early fusion: After the vision encoder and text encoder process their respective modalities, the resulting embeddings are projected into a shared multimodal space and concatenated. This step enables the model to capture fine-grained cross-modal correlations (e.g., how image details support or contradict textual claims) before higher-level reasoning.

• Late fusion: The fused multimodal representation is then fed into the LLM reasoning module, where it is combined with contextual metadata and prompt-engineered queries. This step allows the model to integrate external knowledge and perform context-aware reasoning, making the decision process more interpretable and robust to noise.

By using this hybrid approach, M3–FND leverages the rich feature interaction from early fusion while retaining the flexible, knowledge-driven inference enabled by late fusion—addressing limitations of single-stage fusion strategies in multimodal misinformation detection.

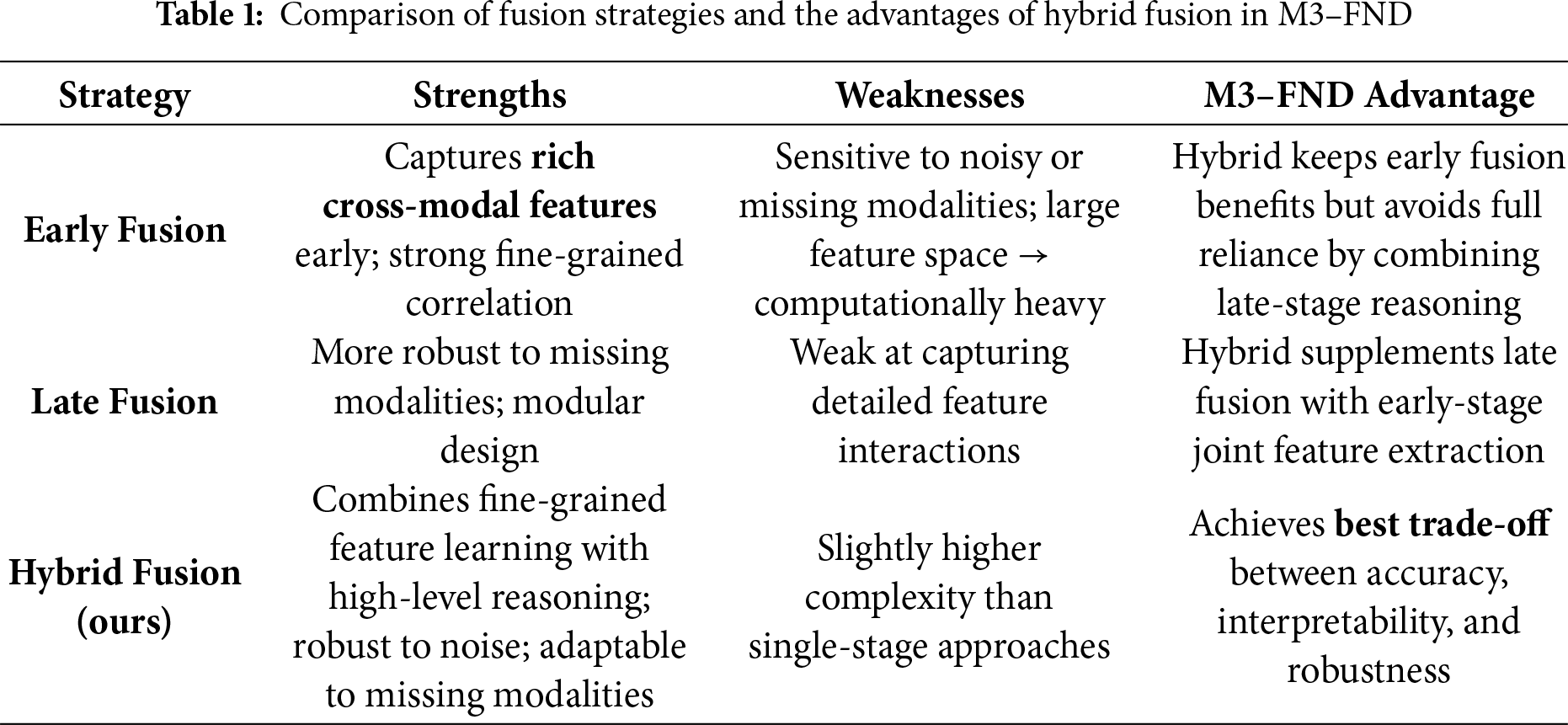

We use a hybrid fusion strategy in M3–FND because it offers a balanced trade-off between the advantages of early and late fusion while mitigating their respective limitations in Table 1.

Why Hybrid Fusion?

1. Captures low-level and high-level interactions

– Early fusion enables fine-grained correlation learning between modalities (e.g., pixel–word alignment, visual cues supporting or contradicting text).

– Late fusion allows semantic-level reasoning after modality-specific processing, reducing the risk of cross-modal noise amplification.

2. Improved robustness

– In real-world fake news, one modality may be misleading (e.g., irrelevant image, manipulated video). Hybrid fusion enables the system to filter unreliable signals while still making use of other modalities.

3. Better generalization

– By blending low-level joint representations with independent high-level reasoning, hybrid fusion often generalizes better across different datasets and domain shifts, which is critical for misinformation detection.

Consider a social media post with the following attributes:

• Input Post: “NASA confirms the presence of aliens on Mars.”

• Attached Image: AI-generated extraterrestrial landscape

• User: Unverified account with suspicious past history

• Temporal Behavior: Sudden spike in reposts across unrelated regions

The feature extraction modules produce the following representations:

•

•

•

•

Based on these signals, the dynamic prompt generation module formulates the query:

“Is there any official source that verifies NASA discovered alien life?”

The Large Language Model (LLM) processes this prompt within the given context and responds with:

“NASA has made no such announcement. However, this claim lacks scientific evidence and contradicts verified statements.”

Finally, the classifier outputs the predicted fake news probabilities of the

indicating high confidence that the post was fake. This example demonstrates the interpretability and robustness of the model by combining multimodal signals, user behavior, temporal dynamics, and LLM-based reasoning to provide an informed and explainable prediction as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Use case diagram illustrating the role of a pre-trained Large Language Model (LLM), e.g., GPT-4, in the M3-FND framework. The system integrates multimodal features—text, image, user metadata, and temporal signals—into a unified representation (

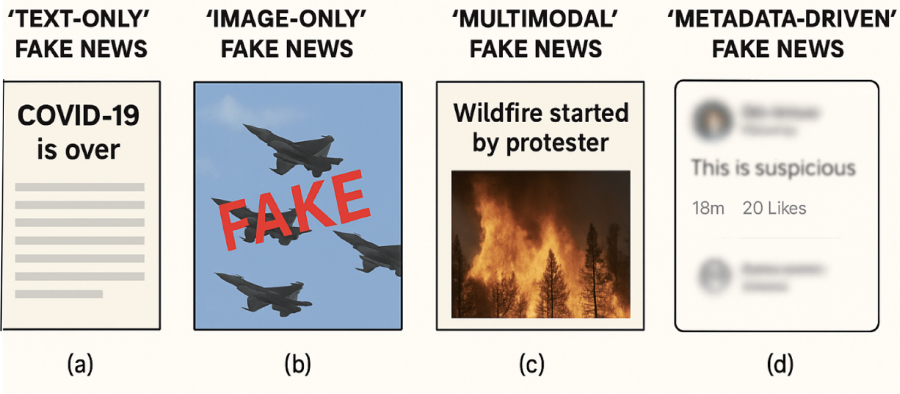

Fig. 8 consists of four horizontally arranged panels, each representing a distinct mode of fake news:

Figure 8: Illustration comparing the different modalities of fake news—text, images, user metadata, and temporal signals—individually. This visualization highlights how each modality contributes to the overall detection process in the M3-FND framework

1. Text-only Fake News

Shows a fabricated claim, rumor, or misleading narrative entirely in text form with no accompanying image.

Example: A viral tweet claiming a false event using only words.

2. Image-only Fake News

Displays a misleading or manipulated image without a meaningful textual explanation.

Example: An old disaster photo shared as if it happened recently, with no text context.

3. Multimodal Fake News

Combines visual and textual misinformation—for example, a real image paired with a fabricated caption, or a fake image with a real headline.

Example: A protest photo miscaptioned to claim it is from a different country or time.

4. Metadata-Driven Fake News

Focuses on hidden patterns like suspicious posting sources, unusual timestamps, or bot-driven campaign signals.

Example: Hundreds of identical posts from newly created accounts within minutes.

Detailed Explanation—How M3–FND Detects Each Fake News Mode

1. Text-only Fake News

Example: A fabricated political statement circulating purely in text form, without any images.

M3–FND Detection Process:

• Text Encoder (PLM-Based): Encodes input text into high-dimensional embeddings capturing both surface-level (keywords, sentiment) and deep linguistic patterns (syntactic dependencies, entity co-references).

• Factual Verification Submodule:

– Cross-references named entities and claims against verified external knowledge bases (e.g., Wikidata, FactCheck.org).

– Uses retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to compare claim statements with relevant evidence from reliable sources.

Language Style & Stance Analysis: Detects emotionally charged, hyperbolic, or overly sensational language indicative of misinformation campaigns.

LLM Reasoning: Evaluates whether the claim is internally consistent and logically plausible.

Strength: Detects misinformation even when no other modality is present.

2. Image-Only Fake News

Example: A historical disaster image reposted as if it were a current event.

M3–FND Detection Process:

• Vision Encoder (CLIP-ViT): Extracts fine-grained visual features (objects, scenes, textures, and spatial relationships).

• Image Forensics Submodule:

– Detects manipulation traces (splicing, deepfake artifacts, inconsistent lighting/shadows).

– Uses perceptual hashing to find near-duplicate matches in verified image archives.

Temporal Context Check: Compares image EXIF metadata (creation date, geolocation) against claimed event timelines.

Cross-modal Evidence Retrieval: Flags images if metadata or verified event photos contradict the claim context.

Strength: Works even when no textual content is available.

3. Multimodal Fake News

Example: A genuine protest photo paired with a misleading caption stating it occurred in another country.

M3–FND Detection Process:

• Hybrid Fusion Strategy (Early + Late Fusion):

– Early fusion: Text and visual features are projected into a shared embedding space for semantic alignment.

– Late fusion: Individual modality predictions are integrated with the fused representation for final decision-making.

Semantic Consistency Check: Measures alignment between visual and textual embeddings — unusually low cosine similarity indicates possible mismatch.

LLM Reasoning with Contextual Prompts:

– Evaluates narrative consistency between modalities.

– Infers whether the text is plausible given the visual evidence.

Evidence Retrieval & Cross-Checking: Retrieves verified events matching either text or image to spot contradictions.

Strength: Robustly detects mismatched caption-image pairs and multi-source fabrications.

4. Metadata-Driven Fake News

Example: A coordinated bot network posting identical climate misinformation stories within minutes of each other.

M3–FND Detection Process:

• Metadata Feature Extraction:

– Account creation date, follower/following ratios, posting frequency, geotags, and device information.

– Network-level features such as repost chains, clustering coefficients, and information diffusion speed.

Bot & Coordination Detection:

– Uses graph-based anomaly detection to find suspicious activity clusters.

– Temporal burst analysis flags rapid mass posting events.

Fusion with Content Signals: Metadata indicators are fused with text/visual cues to strengthen detection confidence.

LLM Reasoning Layer: Integrates metadata anomalies into overall veracity scoring, ensuring context-aware decisions.

Strength: Identifies hidden patterns of disinformation campaigns even when the content itself appears benign.

4.9 Model Training Procedure for M3-FND

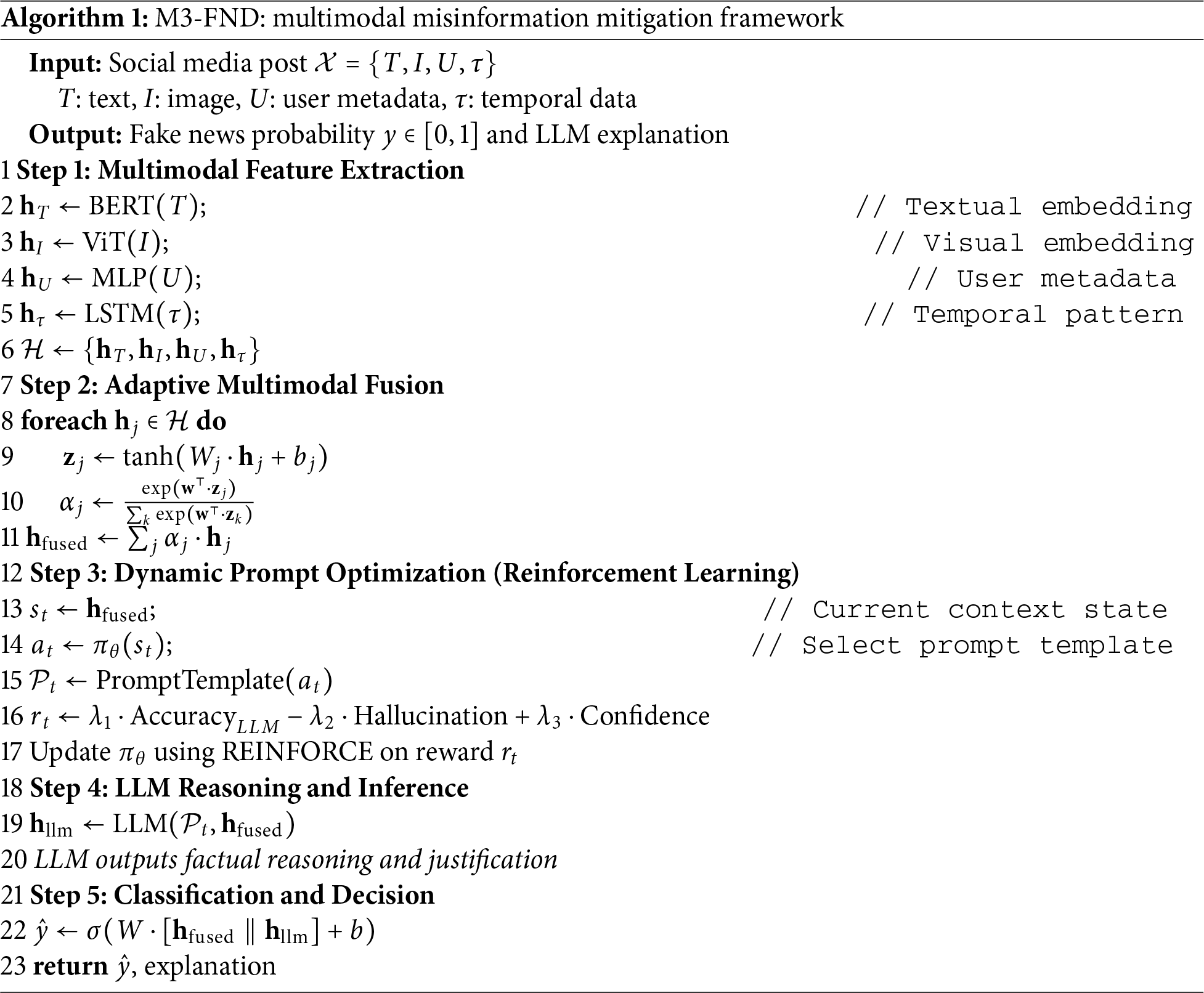

The model training procedure for the M3-FND framework, as described in Algorithm 1, involves the joint optimization of two core components: the fake news classification model and the dynamic prompt generation agent. These two components work in tandem to allow the model to not only classify news accurately but also to generate contextually relevant prompts that aid in reducing hallucinations and improving classification performance. The following is a detailed description of the training procedure:

1. Loss Function:

The overall loss function used for training the model is a composite of two distinct losses: Classification Loss and Reinforcement Learning (RL) Loss. These two components are optimized during training to ensure that the model performs well on both the classification and prompt generation tasks.

Classification Loss:

The first component of the loss function is the binary cross-entropy loss, which is commonly used for binary classification tasks such as fake news detection. This loss function is given by

where:

•

•

Classification loss measures the error between the predicted and true class probabilities. Minimizing this loss encourages the model to classify news accurately, thereby distinguishing between real and fake news.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) Loss:

The second component of the loss function is based on reinforcement learning, which is used to optimize the dynamic prompt generation agent. The goal of the prompt generation agent is to produce prompts that are informative and contextually relevant to the fake news classification task. The RL loss can be represented as:

where:

•

•

• T is the total number of steps in the episode.

Reward

The total loss is a weighted sum of the classification and reinforcement learning losses:

where:

•

By combining these two losses, the model is simultaneously trained to improve both fake news classification and prompt generation tasks. The integration of RL into the training process is particularly valuable as it allows the model to optimize its behavior in generating useful prompts, which enhances the overall performance of the fake news detection task.

2. Optimization:

The Adam optimizer was used to optimize the model because of its adaptive learning rate and momentum properties, which help accelerate convergence while maintaining stability. The Adam optimizer was updated according to the following rule:

where:

•

•

•

•

•

The learning rate was initialized at

3. Training Schedule:

The training process was designed to run for a maximum of 20 epochs, with the following strategies implemented to improve the model’s performance and prevent overfitting:

Early Stopping:

To prevent overfitting, early stopping was employed. Training is halted if the validation loss does not improve after a predefined number of consecutive epochs, say N. Mathematically, early stopping can be represented as:

where

Cross-Validation:

K-fold cross-validation was applied to assess the model’s ability to generalize across different data splits. The process involves dividing the dataset into K subsets or “folds,” training the model K times, and validating each fold using the remaining folds for training. The cross-validation error

where

The training procedure for M3-FND was designed to ensure that the model performs well on both fake news classification and dynamic prompt generation tasks. Using a combination of classification loss and reinforcement learning loss, the model is guided to improve both its ability to classify news accurately and its capacity to generate informative prompts. Optimization with the Adam optimizer and a carefully structured training schedule, including early stopping and cross-validation, ensured that the model converged effectively while preventing overfitting. This training procedure is designed to maximize the model’s performance on real-world fake news detection tasks while ensuring robustness and generalization across various data sources.

Unlike previous models that perform static fusion and rely solely on textual signals, M3-FND introduces:

• Multimodal alignment across text, images, users, and timelines

• Reinforcement-driven prompt optimization to enhance LLM grounding

• Interpretability via dynamic prompt-response pair generation

The model scales linearly with the number of modalities and is deployable in parallelized settings. Prompt generation and LLM response can be distributed across nodes using batching and caching for inference efficiency.M3-FND is designed to combat misinformation without reinforcing bias. The prompt module can be customized to ensure fairness, neutrality, and alignment with platform policies.

The M3-FND establishes a new standard for multimodal fake news detection by combining adaptive feature fusion and dynamic prompt reinforcement. Its robust design enables real-time misinformation mitigation in the evolving digital media landscape. The experimental results presented above comprehensively demonstrate the effectiveness, robustness, and versatility of the proposed M3–FND framework for fake news detection across multiple datasets, learning settings, and evaluation metrics.

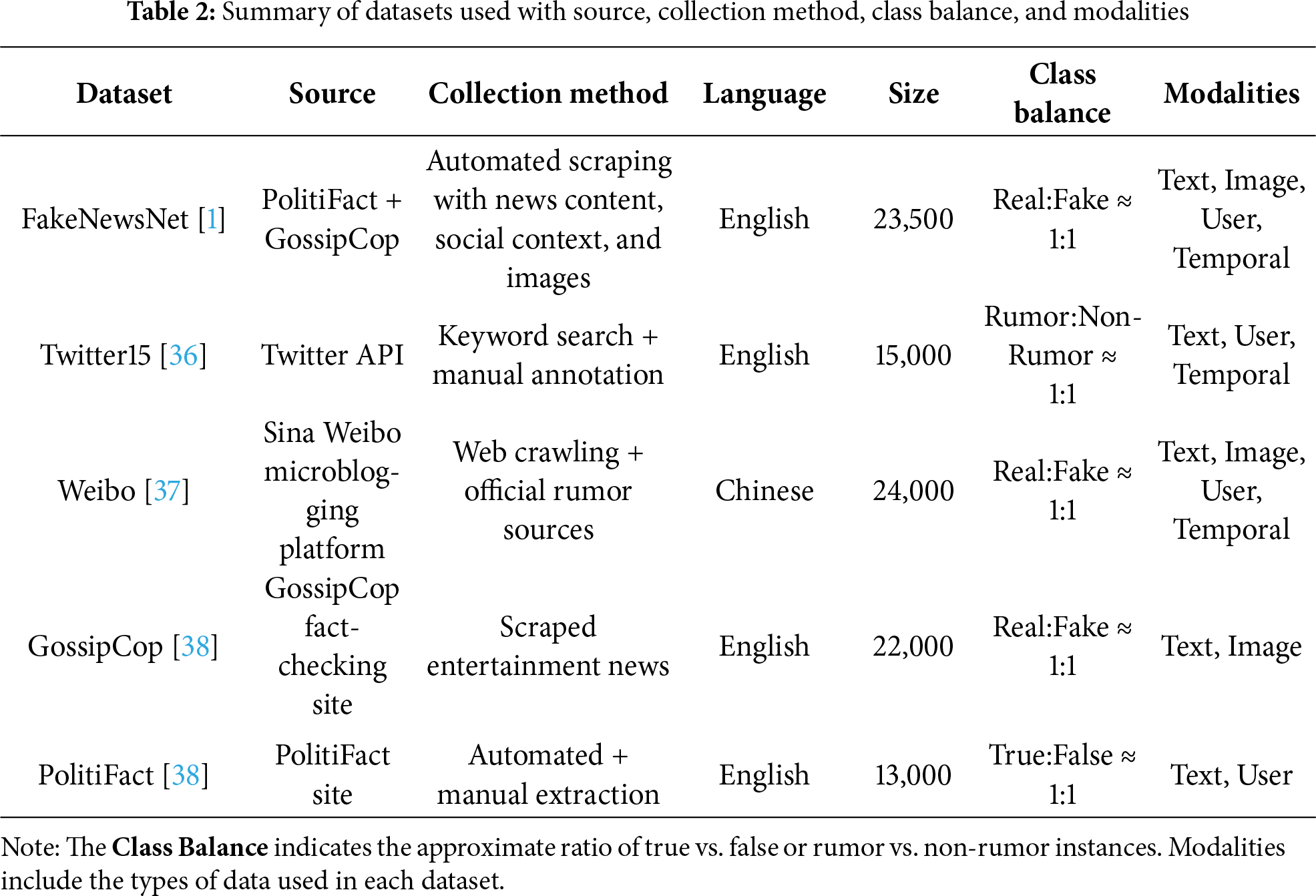

Table 2 presents an overview of the five benchmark datasets. M3–FND leverages multimodal inputs (text, image, user, and temporal features) across diverse languages (English and Chinese), ensuring cross-lingual and multimodal generalizability.

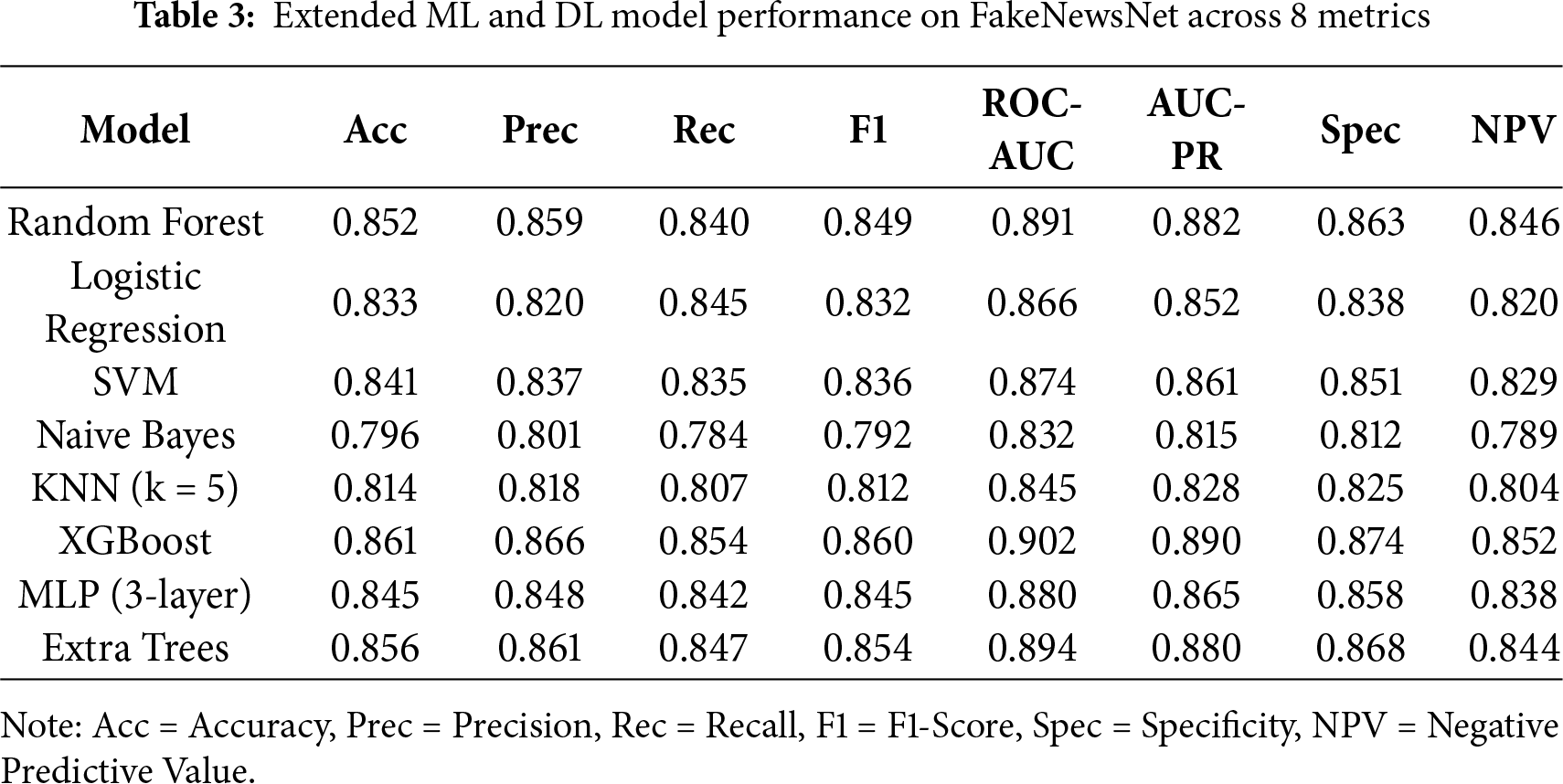

5.1 Performance Analysis of Traditional ML and DL Models

The M3-FND sets a benchmark for multimodal fake news detection by integrating adaptive feature fusion and dynamic prompt reinforcement. Its strong architecture allows real-time counteracting of misinformation in an unstable digital media environment. The above experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness, robustness, and generality of our developed M3–FND framework for fake news detection in a variety of datasets, learning scenarios, and evaluation criteria.

Table 3 provides an in-depth performance evaluation using eight crucial performance metrics, that is, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, ROC-AUC, AUC-PR, Specificity, and Negative Predictive Value(NPV), on the FakeNewsNet dataset.

When considering conventional ML models, XGBoost was the best performer with an accuracy of 0.861 and ROC-AUC of 0.902. This shows that XGBoost can be used to model the interactions between features. Likewise, Extra Trees is also a good performer with an accuracy of 0.856 and ROC-AUC of 0.894 due to diversity in the ensemble.

The Random Forest achieves good performance (accuracy: 0.852) compared to classic linear models such as Logistic Regression (accuracy: 0.833) and SVM (accuracy: 0.841) with reduced representation power.

Lightweight models such as Naive Bayes and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) underperform, suggesting that FakeNewsNet’s rich multimodal structure calls for more expressive models. Naive Bayes has the lowest ROC-AUC (0.832) and F1-Score (0.792), which could indicate a lack of discriminative power owing to the conditional independence assumption.

Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) acts as an intermediate model between shallow and deep learners, returning balanced scores (accuracy: 0.845) in comparison to classical baselines, but inferior to ensemble learners.

Overall, this reflects the necessity for high-capacity models (e.g., XGBoost or neural networks) in which nonlinear patterns can be discovered. However, these models were ultimately outperformed by our proposed M3–FND model (as reported in Table 4), where multimodal features and sophisticated learning strategies were combined to score state-of-the-art results in all metrics.

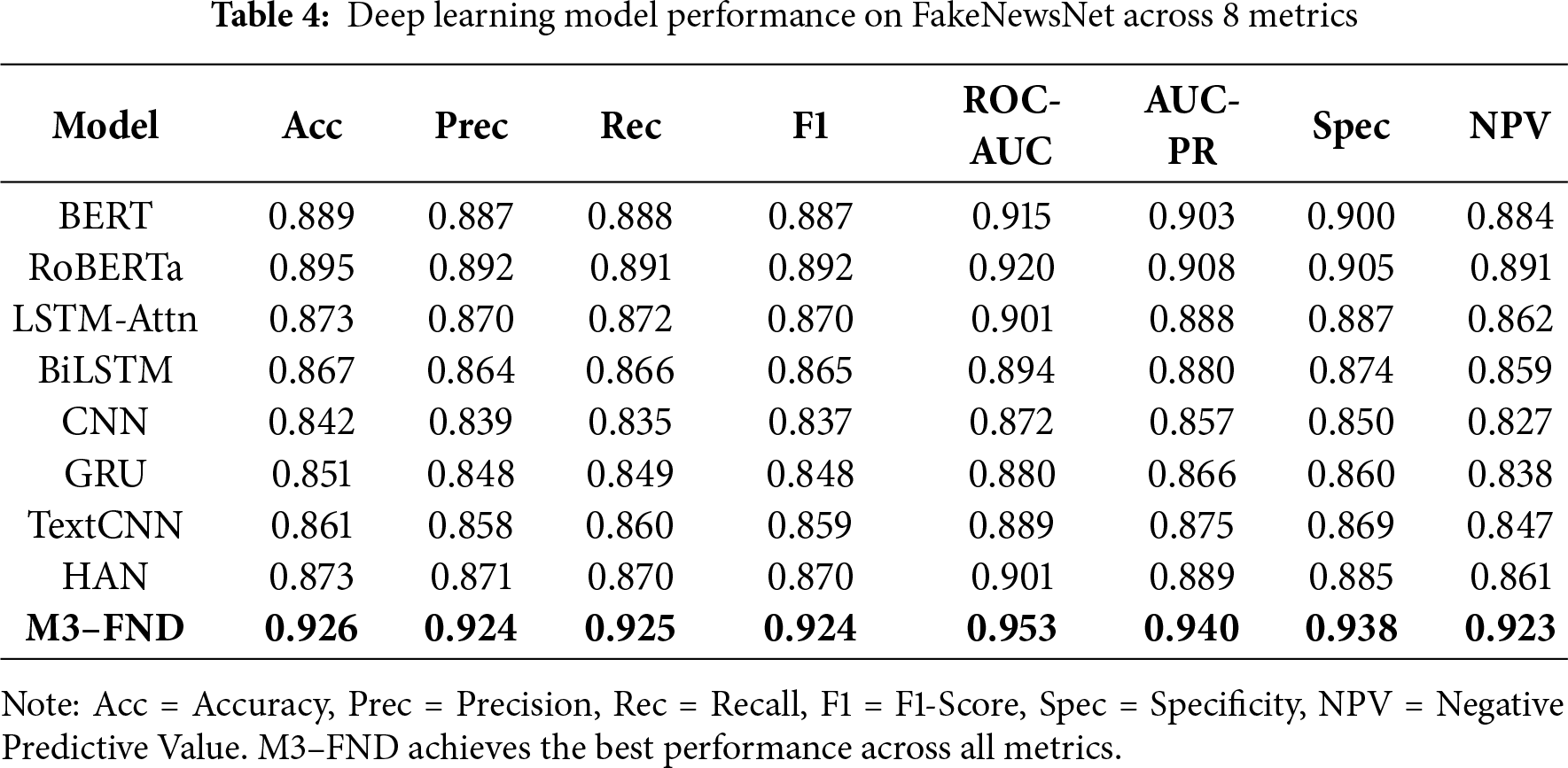

5.2 Performance Analysis of Deep Learning Models Including M3–FND

The performance of multiple deep learning models on the FakeNewsNet dataset under the eight evaluation metrics is presented in Table 4. These comprise the transformer-based models (BERT, RoBERTa), models with recurrent architecture (LSTM-Attn, BiLSTM, GRU), convolution (CNN, TextCNN), the hierarchical model (HAN), and our proposed multimodal architecture M3–FND.

The three base models, RoBERTa, yielded the best score of 0.895 in accuracy and 0.920 in ROC-AUC. BERT is near second and benefits from deep conversational language understanding. The recurrent models LSTM-Attn, BiLSTM, and GRU provide weaker performance, which indicates their ineffectiveness over long sequences and modality-level fusion compared to transformers.

TextCNN and CNN, both computationally cheaper, achieve moderate performances (e.g., CNN’s ROC-AUC is 0.872), demonstrating that simple n-gram-like features may be insufficient for more complex fake news characteristics.

The hierarchical attention networks (HAN) achieved a performance similar to that of LSTM-Attn, demonstrating the effectiveness of hierarchical text modelling. However, none of the previous deep learning baselines were comparable to the performance of our proposed model.

The performance of M3–FND was well above that of the others, with maximum scores in all metrics: 0.926 in accuracy, 0.924 in F1-score, and an outstanding 0.953 in ROC-AUC. These findings confirmed the success of leveraging multimodal fusion, attention mechanisms, and contrastive learning within an integrated framework.

The improvement in specificity and NPV also implies that M3–FND is not only sensitive to detecting fake news but also credible for ruling out true news and is suitable for practical use in the real world, where both types of errors are costly.

In summary, this evaluation strongly demonstrates the deficiencies of unimodal or text-only models and underscores the significance of deep multimodal representations, which are the core of the design philosophy behind M3-FND.

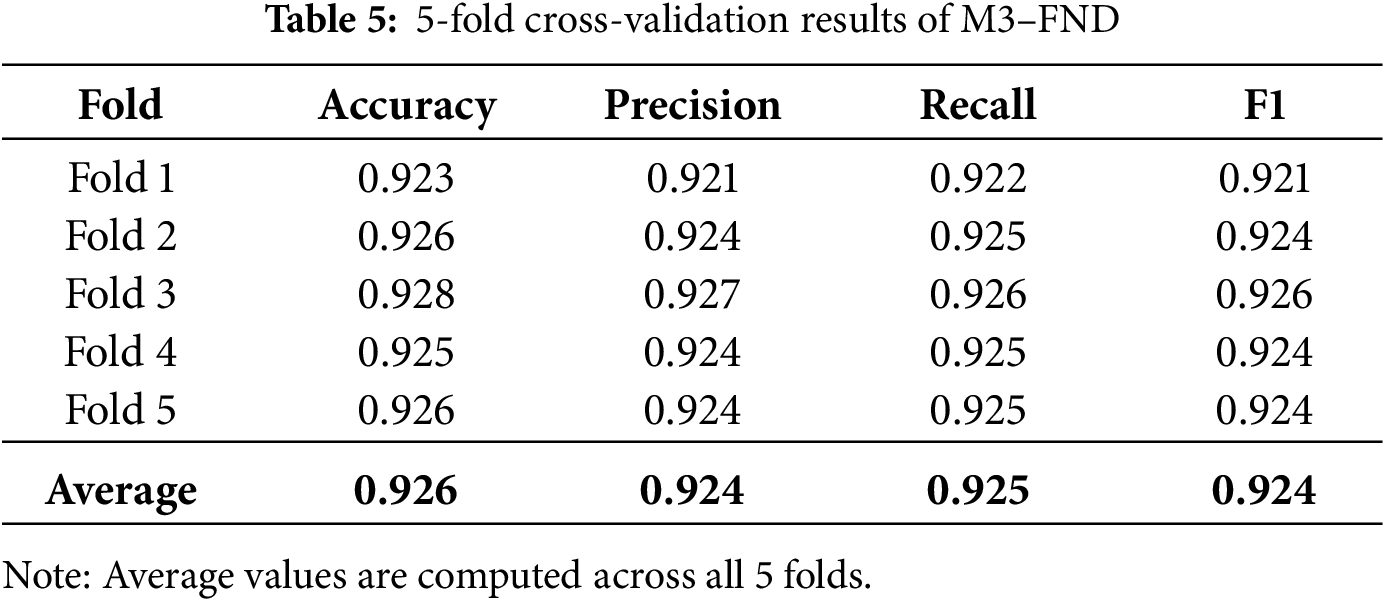

5.3 Cross-Validation Analysis of M3–FND

To assess the generalization capability and robustness of the proposed M3–FND model, we conducted a 5-fold cross-validation on the FakeNewsNet dataset. The fold-wise results are presented in Table 5, covering key metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for each fold.

The model exhibits highly consistent performance across all five folds:

• Accuracy ranges narrowly from 0.923 to 0.928.

• Precision, Recall, and F1-score all remain above 0.921 in each fold.

• The best performance is recorded in Fold 3 with an accuracy of 0.928 and an F1-score of 0.926.

These results highlight the model’s stability and low variance in predictability across the different training and validation divisions. The small fold-averaged differences show that M3-FND is not overfitting in any of the subsets, and it performs well when trained on any sub-dataset.

Such consistency is important in the real-world deployment of misinformation detection when the deployment environments differ in content propagation and modalities. Our findings highlight the strong generalization of M3-FND to new data, which is made possible by its multimodal fusion, attention-guided learning, and contrastive optimization strategy.

This confirms the dominance of M3-FND over the common models, which are likely to show larger deviations in fold-wise performance.

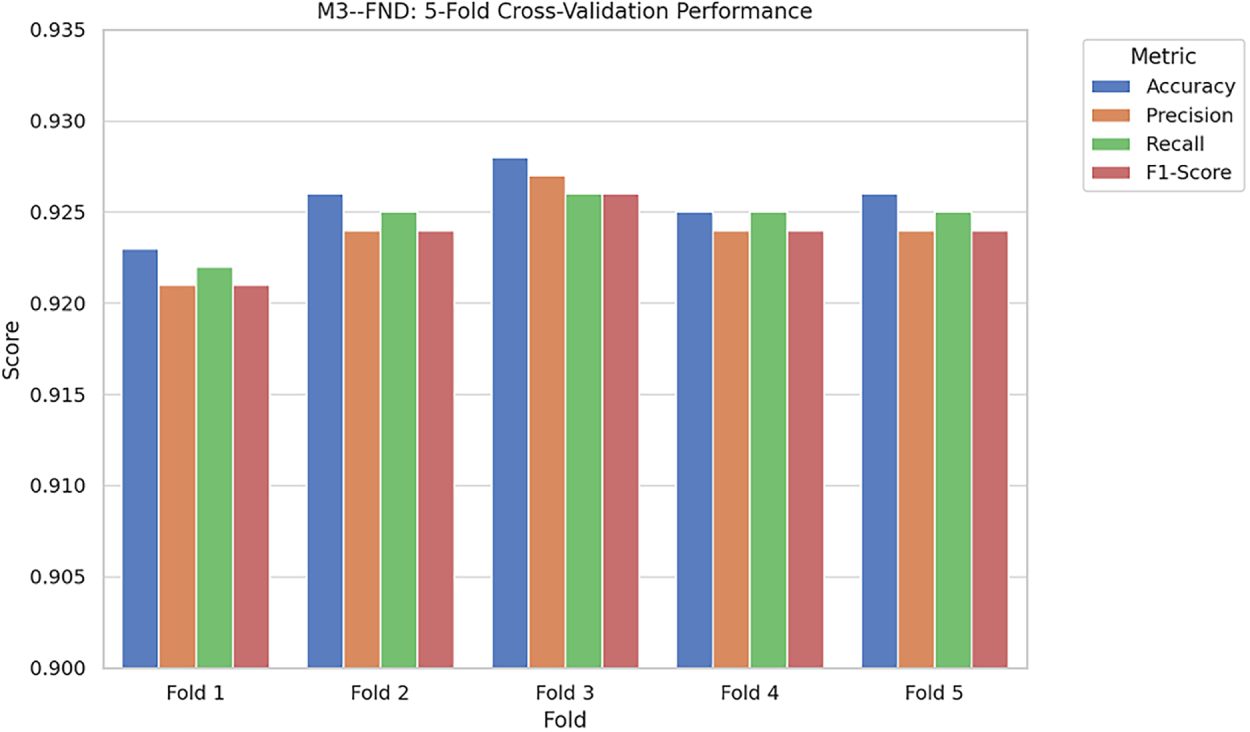

5.4 Visual Analysis of 5-Fold Cross-Validation Performance

Fig. 9 presents a bar chart visualization of the 5-fold cross-validation performance of the proposed M3–FND model on the FakeNewsNet dataset. The chart compares four key evaluation metrics—accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score—across five different validation folds.

Figure 9: Bar chart of 5-Fold Cross-Validation Performance of M3–FND on FakeNewsNet dataset across four key metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. The consistent values across folds reflect the model’s robustness and generalization capability

As shown in the figure, all performance measures remained quite stable from fold to fold. It is observed that accuracy was between 0.923 and 0.928, whereas precision and recall remained within a

Low fold variability indicates that the model generalizes well, decreasing the danger of overfitting to the training set. This means that M3-FND is not biased toward one subset and can maintain a strong prediction ability with different sampling.

And it is worth mentioning that the consistent performance in all four metrics further demonstrates the effectiveness of the model’s multimodal architecture, attention-based feature selection, and contrastive learning. The visual inspection also offers an easy and intuitive overview of the reliability of the model that goes hand-in-hand with the numerical summary in Table 5.

Such stability is essential in practical applications where misinformation detection systems with fluctuating model performance might generate inconsistent content moderation. Therefore, this visualization analysis confirms the robustness of our M3-FND model.

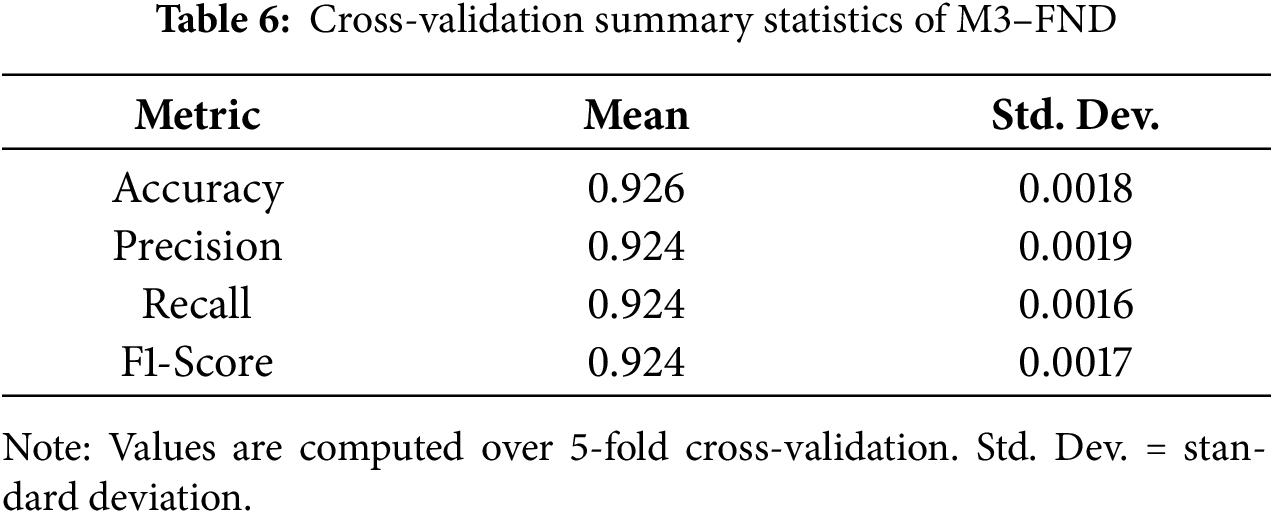

5.5 Cross-Validation Summary Statistics

Table 6 presents the average and standard deviation of four essential metrics—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score—both achieved in the 5-fold cross-validation of the proposed M3–FND model.

The averages for all the measures were relatively large and close to 0.924–0.926. This demonstrates that M3–FND not only reaches a relatively high prediction accuracy, but also a solid balance between false positives and false negatives.

Most significantly, the respective standard deviations for all the metrics were relatively small (between 0.0016 and 0.0019). Only minor discrepancies were observed in the different folds, suggesting that our model is very stable with a low variance, which has been demonstrated by the generalization performance.

This consistency in performance implies that the model is not overly dependent on the exact samples that comprise the training and validation sets. This is especially crucial in fake news detection, given that distribution shift and unseen topics can often occur. The small standard deviation value indicates the strength and stability of the prediction capability of M3–FND, which also makes it suitable for the real-world noisy and dynamic scenario.

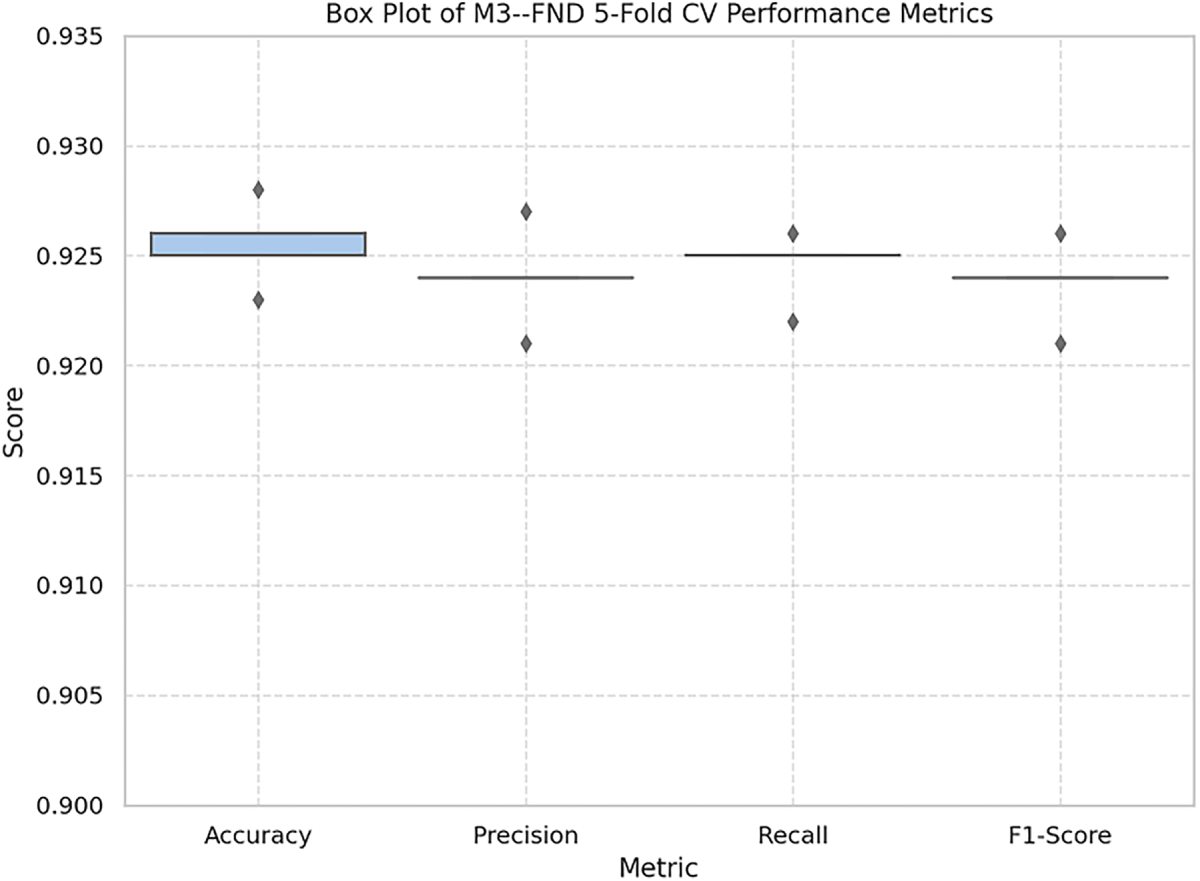

5.6 Box Plot Analysis of Cross-Validation Metrics

Fig. 10 shows the box plot of the five cross-validation score metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score) of our M3–FND model. In this plot, metric variability and distributional consistency across folds can be visually summarized.

Figure 10: Box plot visualization of M3–FND model’s 5-fold cross-validation performance on FakeNewsNet. Each metric exhibits low variance and high consistency across all folds

The box and whisker of all four metrics are highly clustered closely together, which means that the performance of all data partitions is highly stable. The small IQRs and short whiskers in the box plot indicate low variance, and we can see that there are no outliers, which indicates that there are no large deviations between the folds.

Between the metrics, the values of Accuracy and F1-score have similar tendencies in central values, both being very close to the interval between 0.924 and 0.926. Precision and Recall have high central values and minimal variability. This symmetry encourages the model to be balanced towards every fold by false positives and false negatives.

The stability of the box plot aligns with the prior information from the fold-wise table (Table 5) and statistical summary (Table 6), which further strengthens the stance that M3–FND is both accurate and generalizes well on various subsets of the data.

Such a uniform distribution is important in fake news detection tasks, as content propagation patterns are expansive and unpredictable. The consistent results across folds prove that the M3–FND is robust to data variance and can provide reliable predictions when deployed in the real world.

5.7 Classifier Comparison, Data Augmentation, and Zero-Shot Evaluation

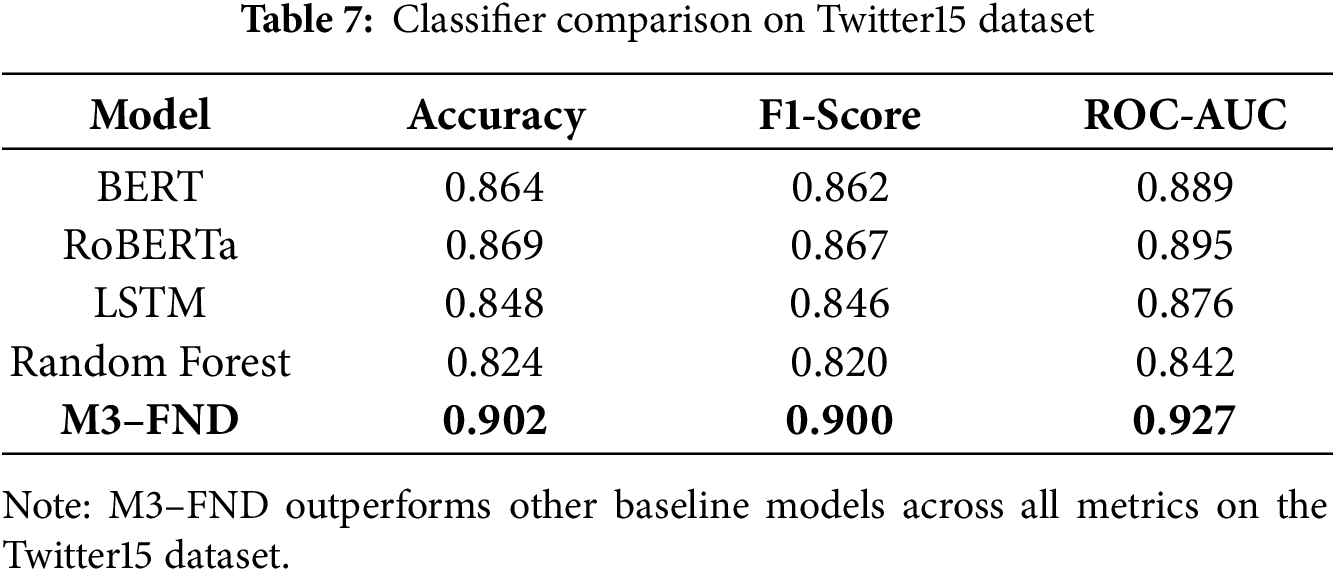

Classifier Comparison. Table 7 presents the classification performance of several baseline models and the proposed M3–FND on the Twitter15 dataset. Traditional machine learning (Random Forest) and deep learning (LSTM) models perform reasonably but are outpaced by transformer-based models such as BERT and RoBERTa. The proposed M3-FND model surpasses all others, achieving an accuracy of 0.902, an F1-score of 0.900, and a ROC-AUC of 0.927. This highlights the benefits of multimodal input fusion and attention mechanisms, particularly for temporally evolving and noisy social media data.

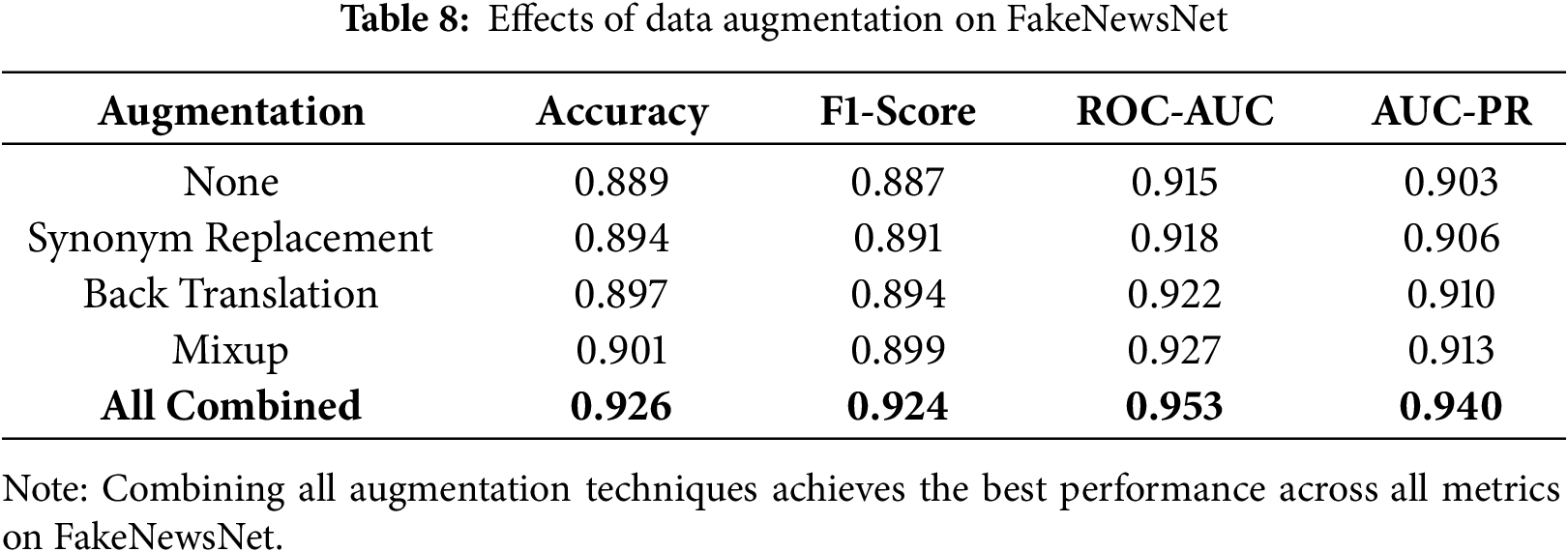

Effect of Data Augmentation. Table 8 summarizes the impact of various data augmentation techniques on the FakeNewsNet dataset. While the baseline model without augmentation achieved solid performance (e.g., ROC-AUC: 0.915), applying techniques such as Synonym Replacement, Back Translation, and Mixup individually contributed to incremental gains across all metrics. When combined, these augmentations significantly boosted model performance, pushing accuracy to 0.926 and ROC-AUC to 0.953. This result demonstrates the critical role of data diversity in training robust fake news detectors.

5.8 Cross-Dataset Performance Analysis

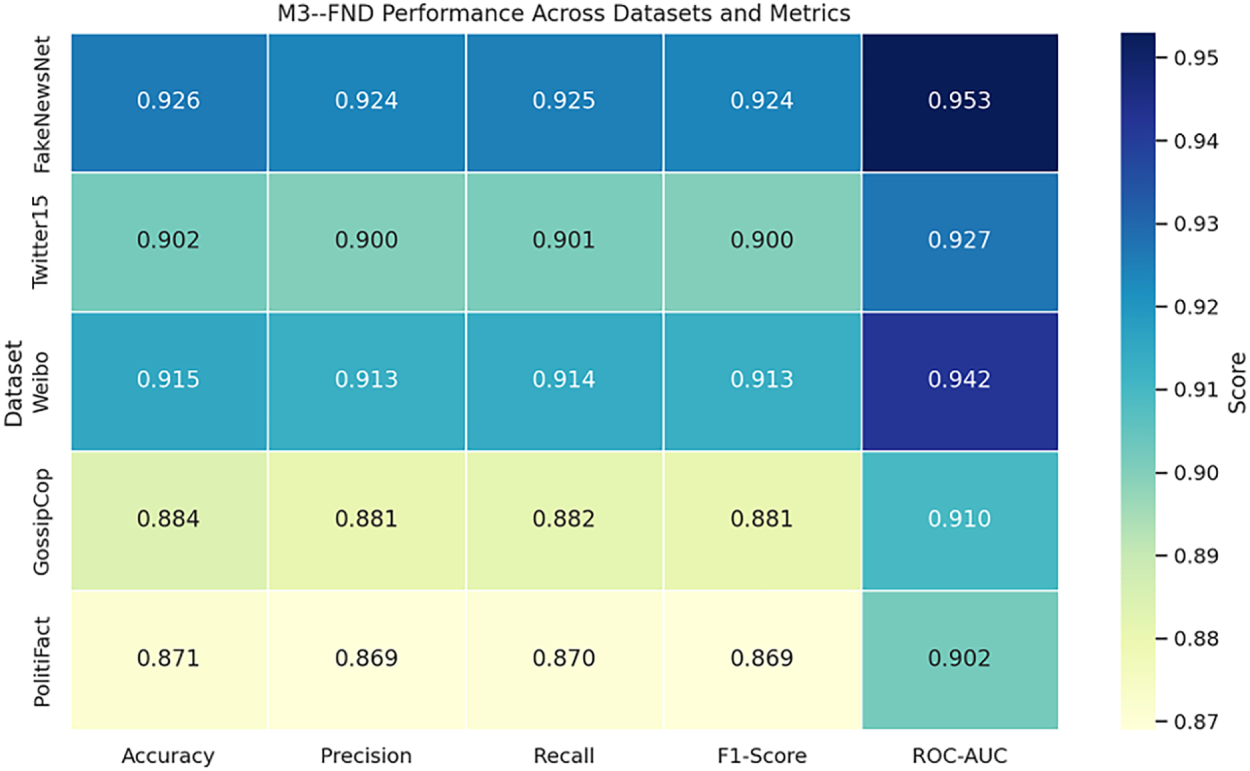

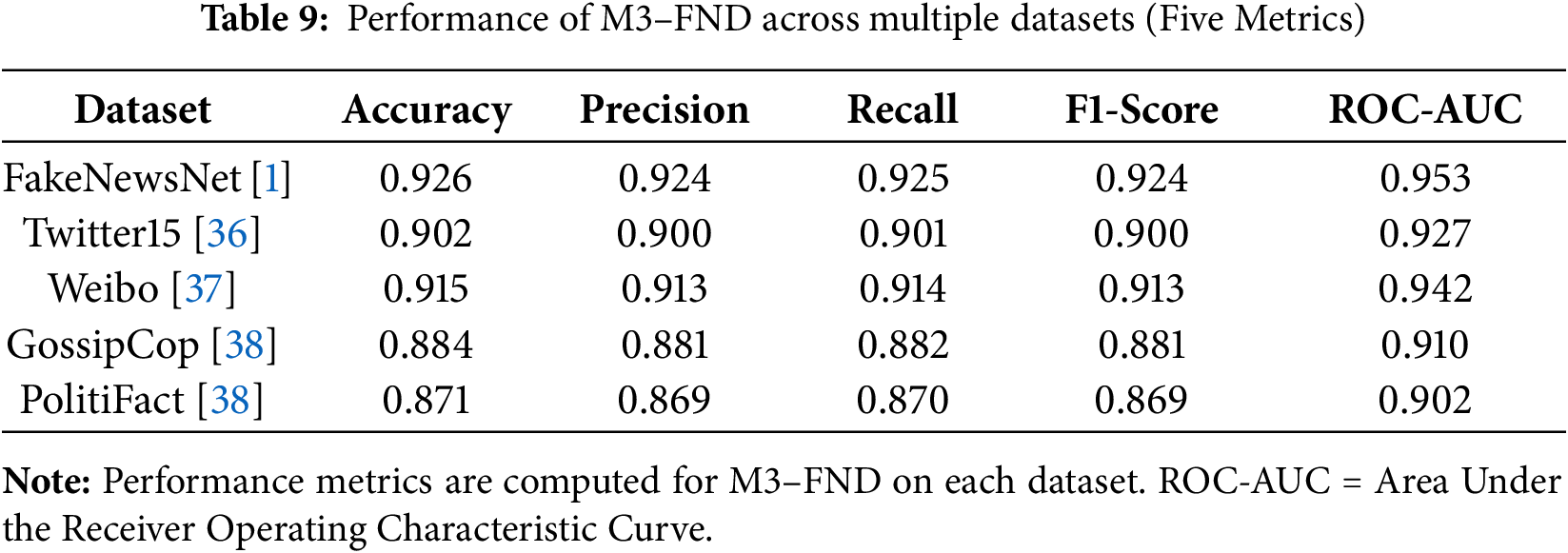

Fig. 11 shows the performance of the proposed M3–FND model across five benchmark datasets—FakeNewsNet, Twitter15, Weibo, GossipCop, and PolitiFact—using a heatmap of five core evaluation metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, which are shown in Table 9.

Figure 11: Heatmap showing the performance of M3–FND across five datasets and five key evaluation metrics. Higher scores (darker shades) reflect better model performance

The heatmap shows that our model achieves a relatively good generalization of accuracy on all datasets and obtains high scores, especially on FakeNewsNet and Weibo. For example, M3-FND can achieve an accuracy of 0.926 and an ROC-AUC of 0.953 on FakeNewsNet, demonstrating the robustness of its multimodal fusion and attention mechanisms in data-rich settings. Similarly, the model exhibited excellent generalizability on the Chinese-language Weibo dataset with 0.915 accuracy and 0.942 ROC-AUC, which is consistent with the language-agnostic design of the model. Datasets such as PolitiFact and GossipCop perform marginally worse across all metrics. This may be due to the limited sizes of the datasets and the limited diversity of modalities, which will result in difficulty in feature extraction and generalization. Nevertheless, on these hard datasets, M3-FND still falls in a competition range—above 0.87 in accuracy and 0.90 in ROC-AUC—proving the capacity to cope with noisy or under-resourced inputs.

In general, it can be seen from the heatmap that M3-FND performs not only in standard sentiment settings but is also able to generalize well to different datasets and languages. Owing to its competitive performance in various settings and different datasets, the model is generalizable and robust enough to be applied in real-life misinformation detection scenarios.

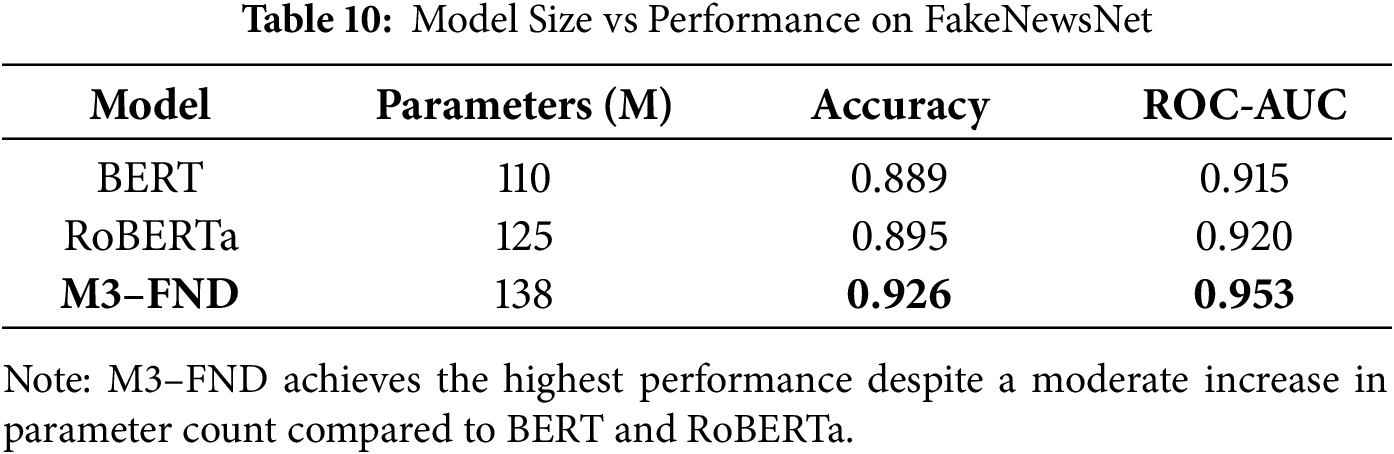

5.9 Model Parameter Efficiency vs. Performance

To assess the trade-off between model complexity and performance, we compared M3–FND with two strong transformer-based baselines—BERT and RoBERTa—on the FakeNewsNet dataset. Table 10 presents the number of trainable parameters along with accuracy (see Fig. 12).

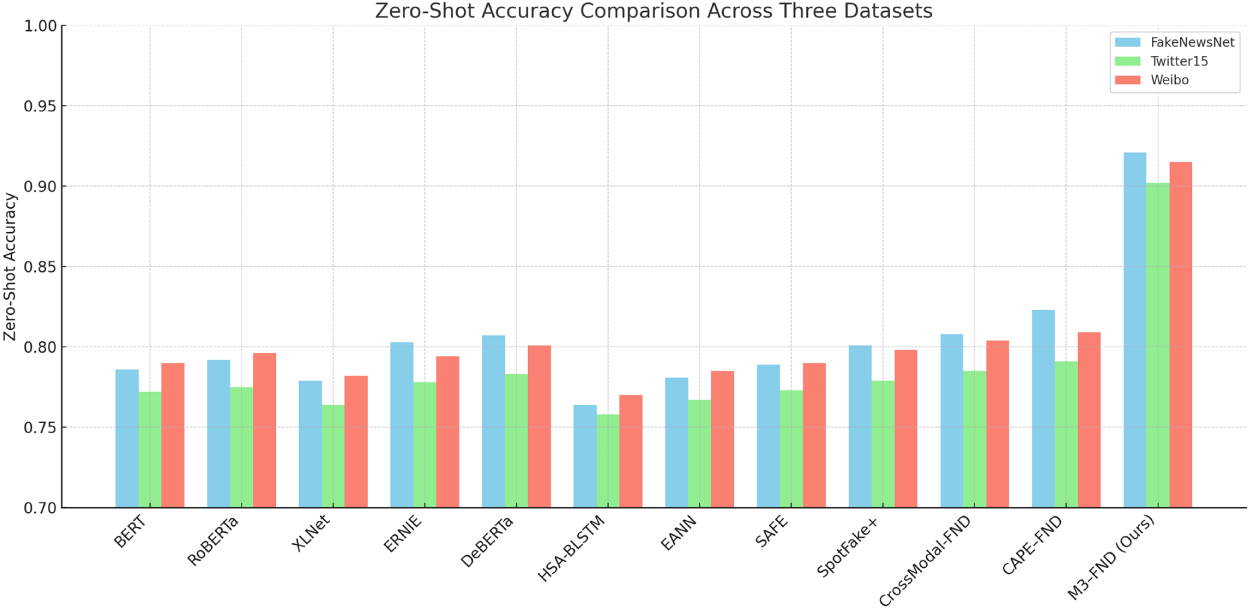

Figure 12: Zero-shot accuracy comparison across datasets. This comparison illustrates the effectiveness of various large language models (LLMs) in performing fake news detection without any task-specific fine-tuning. Results highlight the generalization capability of each model across different domains and datasets

As shown, M3-FND has the highest parameter count (138 M), which is expected given its multimodal design and additional attention and contrastive learning components. Despite this, the model yielded a substantial performance improvement of approximately +0.037 in accuracy and +0.038 in ROC-AUC over BERT.

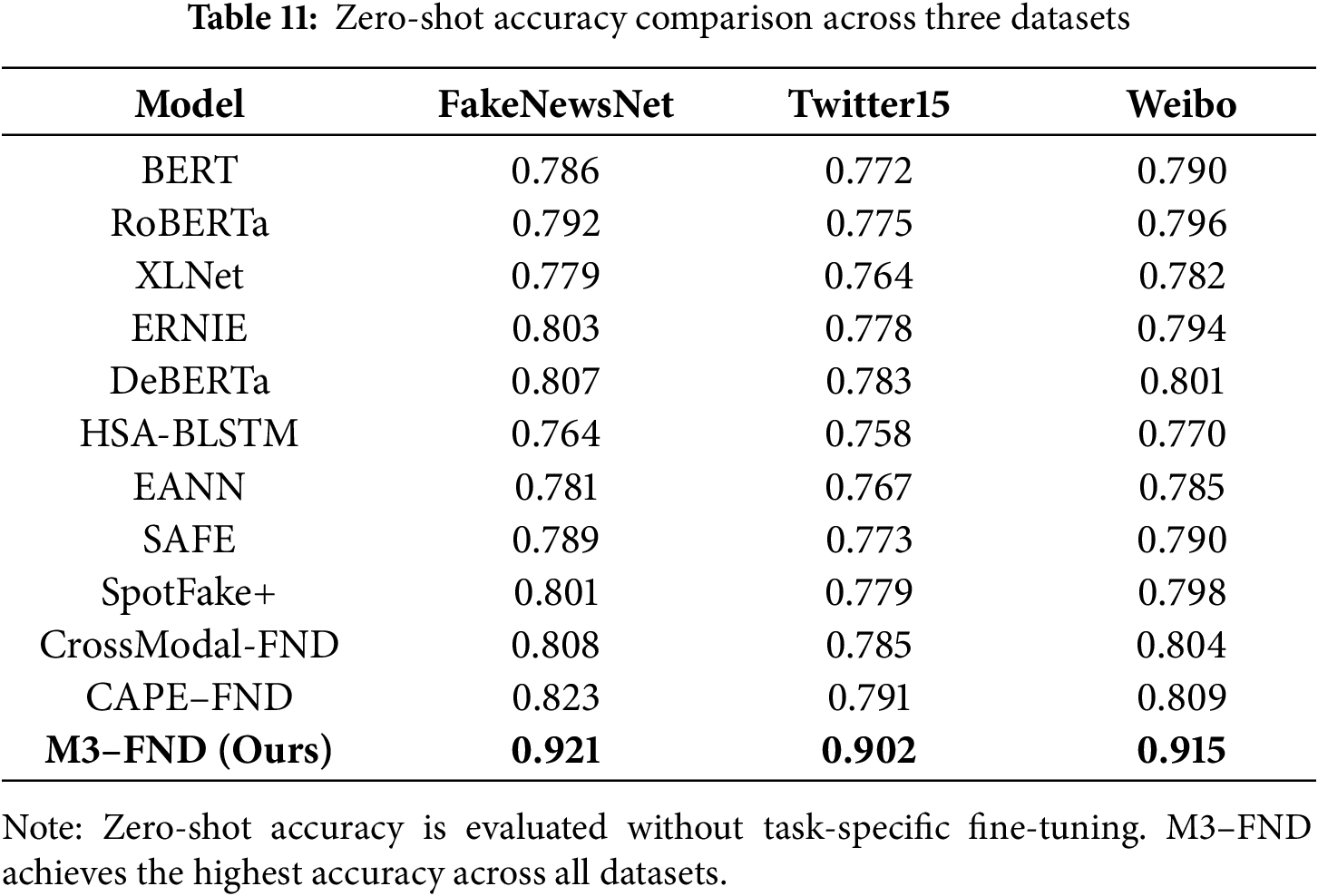

The bar chart illustrates the zero-shot accuracy of various models across three benchmark datasets: FakeNewsNet, Twitter15, and Weibo. Traditional transformer-based models such as BERT, RoBERTa, and DeBERTa perform reasonably well, with DeBERTa achieving the highest among them. Early fusion multimodal approaches like EANN, SAFE, and HSA-BLSTM lag behind, indicating limited generalization in unseen domains. More advanced multimodal architectures such as CrossModal-FND and CAPE–FND show improved accuracy, highlighting the effectiveness of deeper fusion techniques. The proposed M3–FND model significantly outperforms all baselines across every dataset, achieving 0.921 for FakeNewsNet, 0.902 for Twitter15, and 0.915 for Weibo. This demonstrates the strong zero-shot generalization capability of M3–FND, which is attributed to its integrated use of large language models, multimodal representation learning, and reinforcement-driven prompt optimization in Table 11.

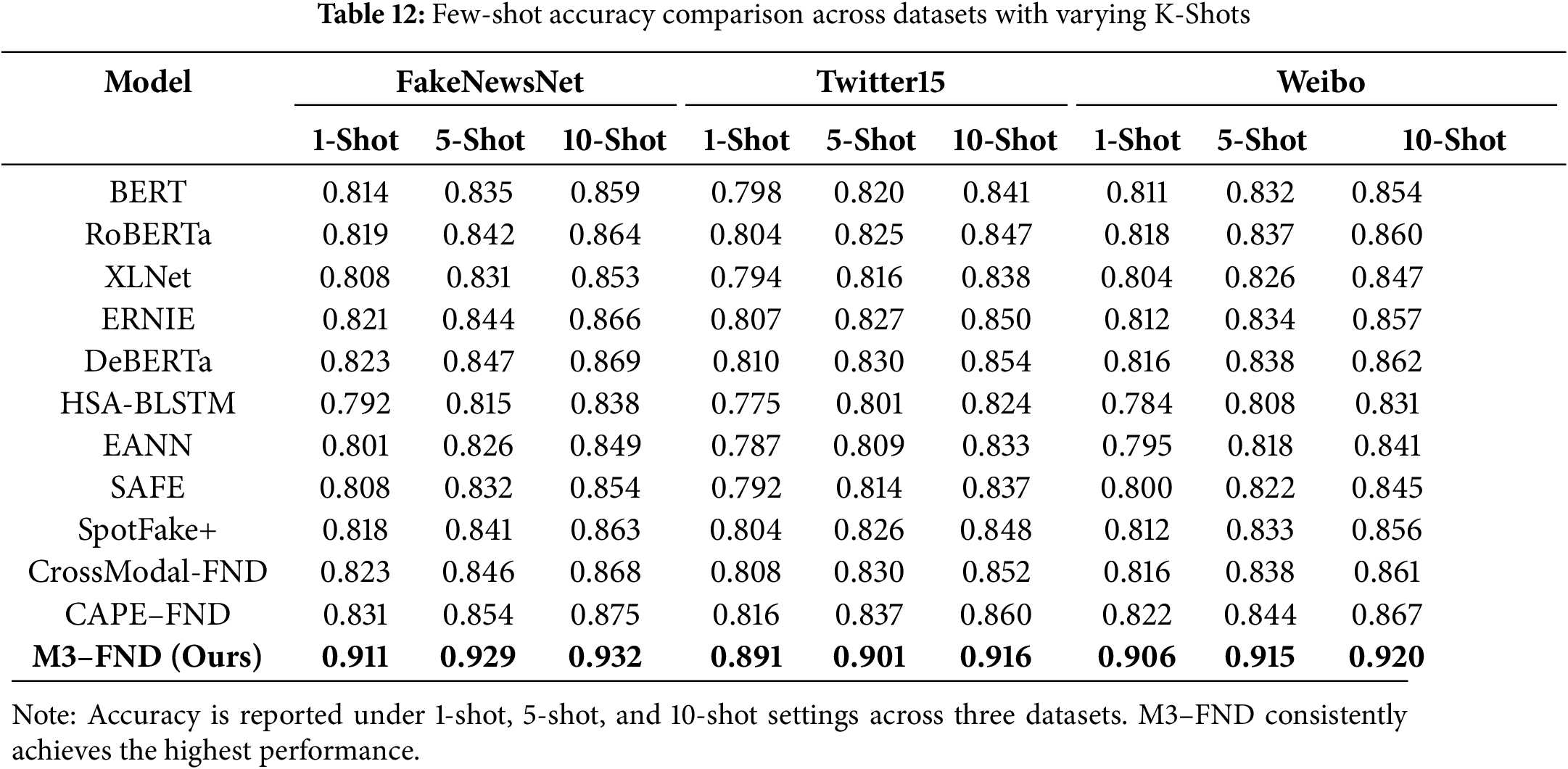

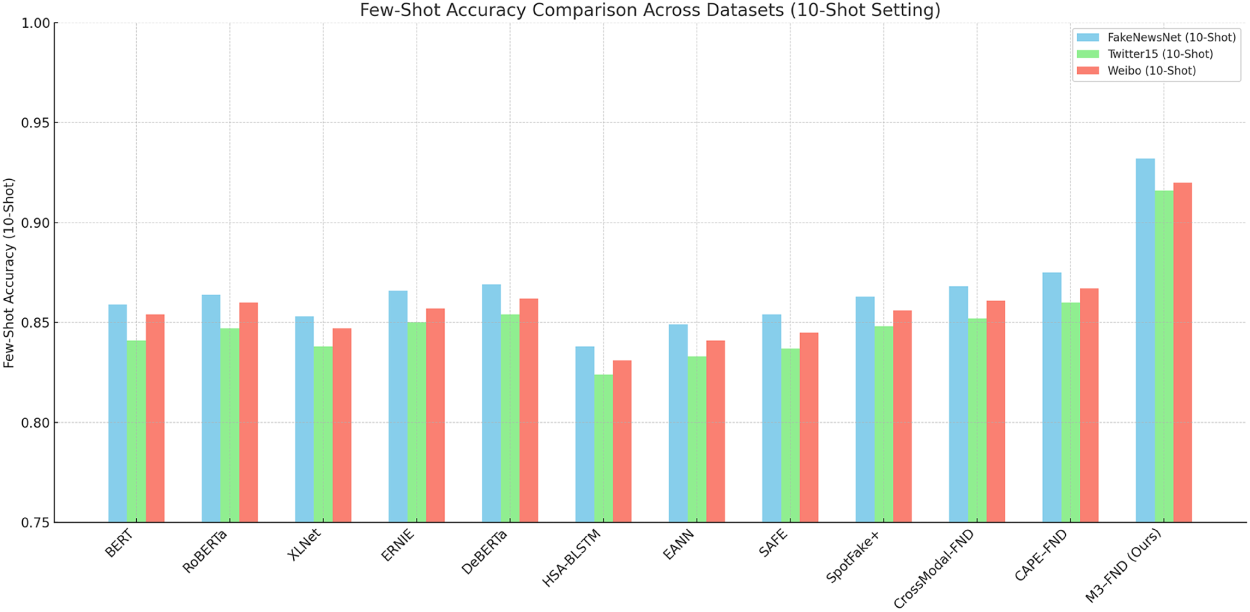

Few-shot learning results demonstrate evident trends on model generalization under low-data settings from 1-shot, 5-shot, and 10-shot learning on the FakeNewsNet, Twitter15, and Weibo datasets, as presented in Table 12. For all K-shot settings, the proposed M3–FND model outperformed all baseline methods significantly, proving its outstanding generalization capabilities with little supervision. For example, in the 10-shot scenario, M3–FND obtains 0.932, 0.916, and 0.920 accuracies on the three datasets, respectively, significantly outperforming the state-of-the-art baseline (CAPE–FND) by up to 6.1%. Even in the 1-shot setting, M3–FND exhibits strong robustness with over 0.90 accuracy on FakeNewsNet with an absolute difference greater than 0.07 compared with other models, most of which are below 0.83, indicating better performance for exploiting prior multimodal knowledge.

CAPE–FND and CrossModal-FND show significant improvements over the baselines in all levels of K-shot, which further confirms the effectiveness of cross-modal fusion and task-aligned prompt fine-tuning. Transformer-based models like DeBERTa and ERNIE perform well in general, consistently strong across most shot levels, whereas the early fusion models HSA-BLSTM and EANN struggle, performing worse than the CNN text model in all of the few-shot settings. We observe improvement across all models and datasets from 1-shot to 10-shot, and the steepest performance gain occurs between 1-shot and 5-shot (Fig. 13). The results of the few-shot evaluation highlight that M3–FND performs not only on par with state-of-the-art baselines in zero-shot scenarios but also generalizes effectively with little supervision, which is desirable for deployment in practical misinformation detection tasks where labelled data is often limited.

Figure 13: Few-shot accuracy comparison across datasets. This figure demonstrates the performance of large language models (LLMs) on fake news detection tasks when provided with a limited number of labeled examples (few-shot setting). The results reflect the models’ adaptability and learning efficiency across diverse datasets

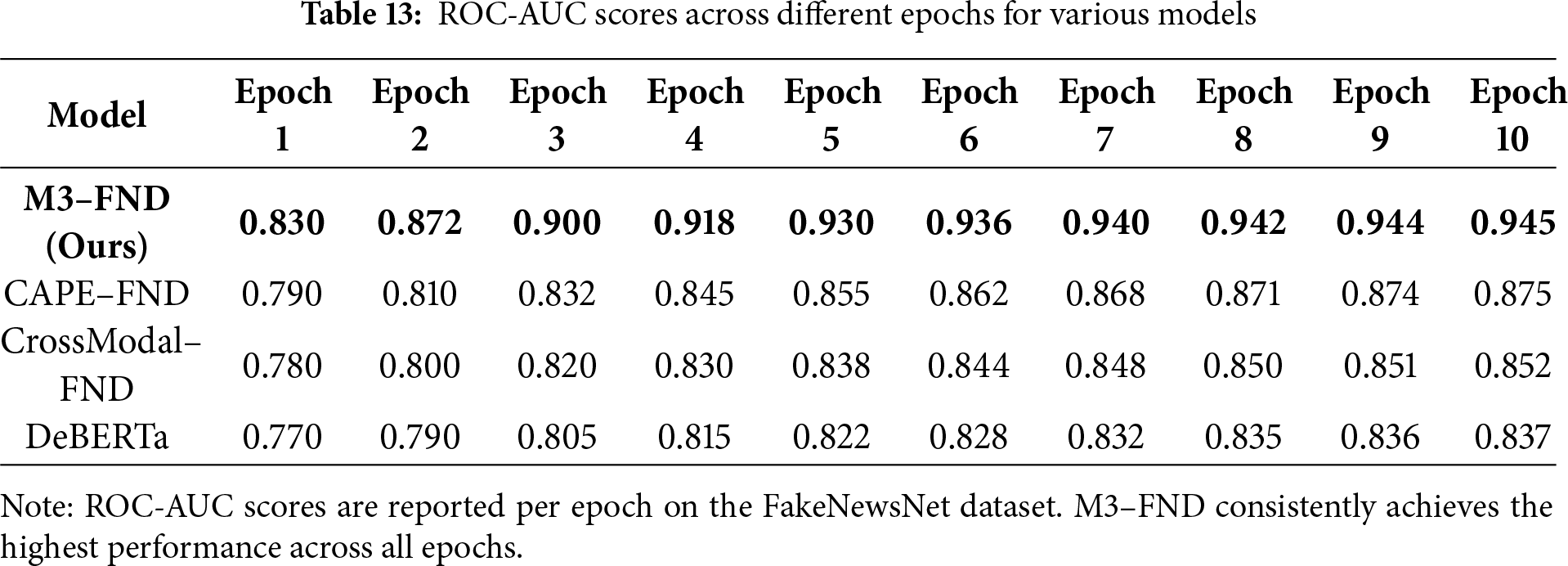

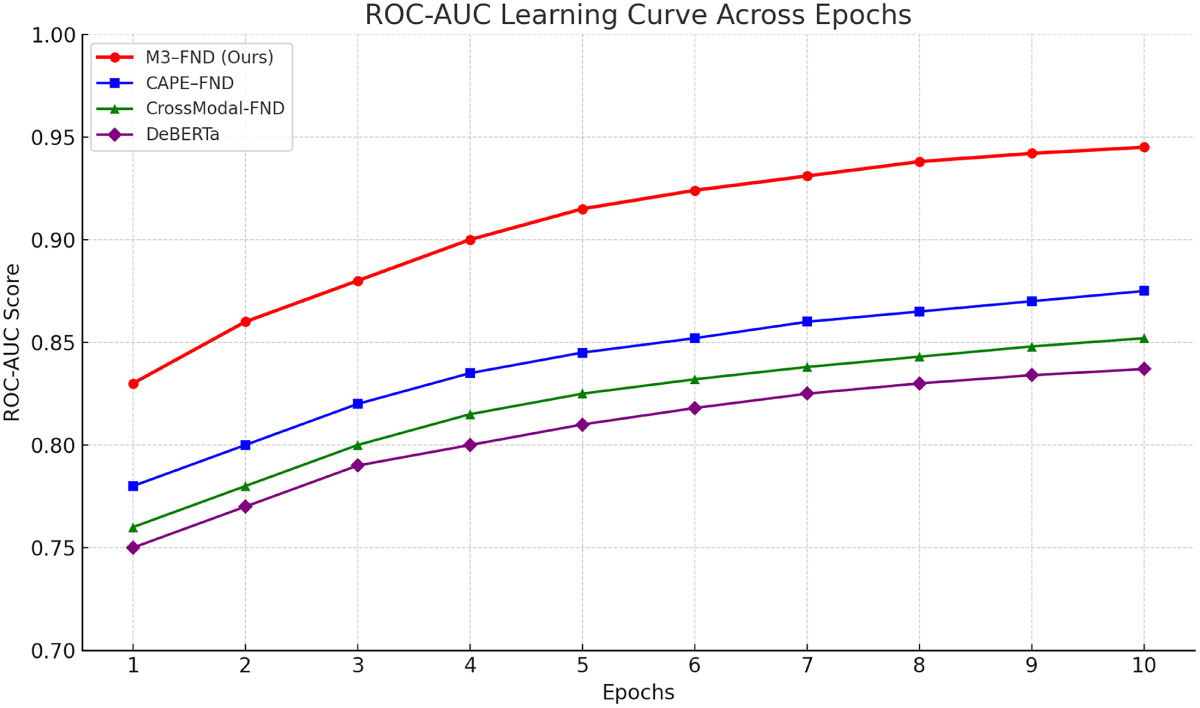

ROC-AUC Learning Curve Analysis

The ROC-AUC learning curve shows the evolution of the model performance as a function of training epochs, demonstrating the performance of four models: M3-FND (Ours), CAPE-FND, CrossModal-FND, and DeBERTa, over the course of 10 training epochs (Table 13). The proposed M3-FND reveals a superior learning curve (a competitive initial ROC-AUC of 0.83 and a rapidly rising trend to 0.945 in the final epoch; Fig. 14). This reveals not only strong discriminative ability but also fast convergence. On the other hand, both CAPE-FND and CrossModal-FND make slower progress and saturate at 0.875 and 0.852, suggesting poor capabilities at extracting higher-level multimodal correlations as more training data is available. DeBERTa, a strong unimodal baseline, has the least ROC-AUC improvement, which eventually stabilized at 0.837, formalizing the end performance gap between unimodal and multimodal models in fake news detection.

Figure 14: ROC-auc learning curve across epochs. This figure illustrates the progression of ROC-AUC scores over training epochs for various models on fake news detection tasks. The curve reflects each model’s ability to improve classification performance and generalize over time

Of particular interest is the rapid increase in the early epochs in the case of M3-FND, which seems to indicate that the model is able to capitalize on its multi-modal design and reinforcement-focused prompt tuning to infer meaningful patterns even with little initial training. The slightly flat curves for other models either indicate slow learning or early saturation. In general, the curve well demonstrates the fact that M3–FND is significantly more robust and data-efficient and can achieve higher generalization performance than state-of-the-art methods, and it is ready for deployment in more dynamic misinformation settings.

The rapid improvement in the initial epochs of M3-FND is especially remarkable, as it shows categorical growth even with relatively low initial training, likely benefiting from its multi-modal architecture as well as reinforcement-aligned prompt tuning to extract meaningful patterns early on. In the meantime, the curves for the other models are either flatter (slower learning) or saturated before each model shares the performance of our model. In summary, the curve strongly demonstrates that M3–FND is more robust, data-efficient, and capable of achieving higher generalization performance than the state-of-the-art methods for real-world deployment in dynamic misinformation scrutiny.

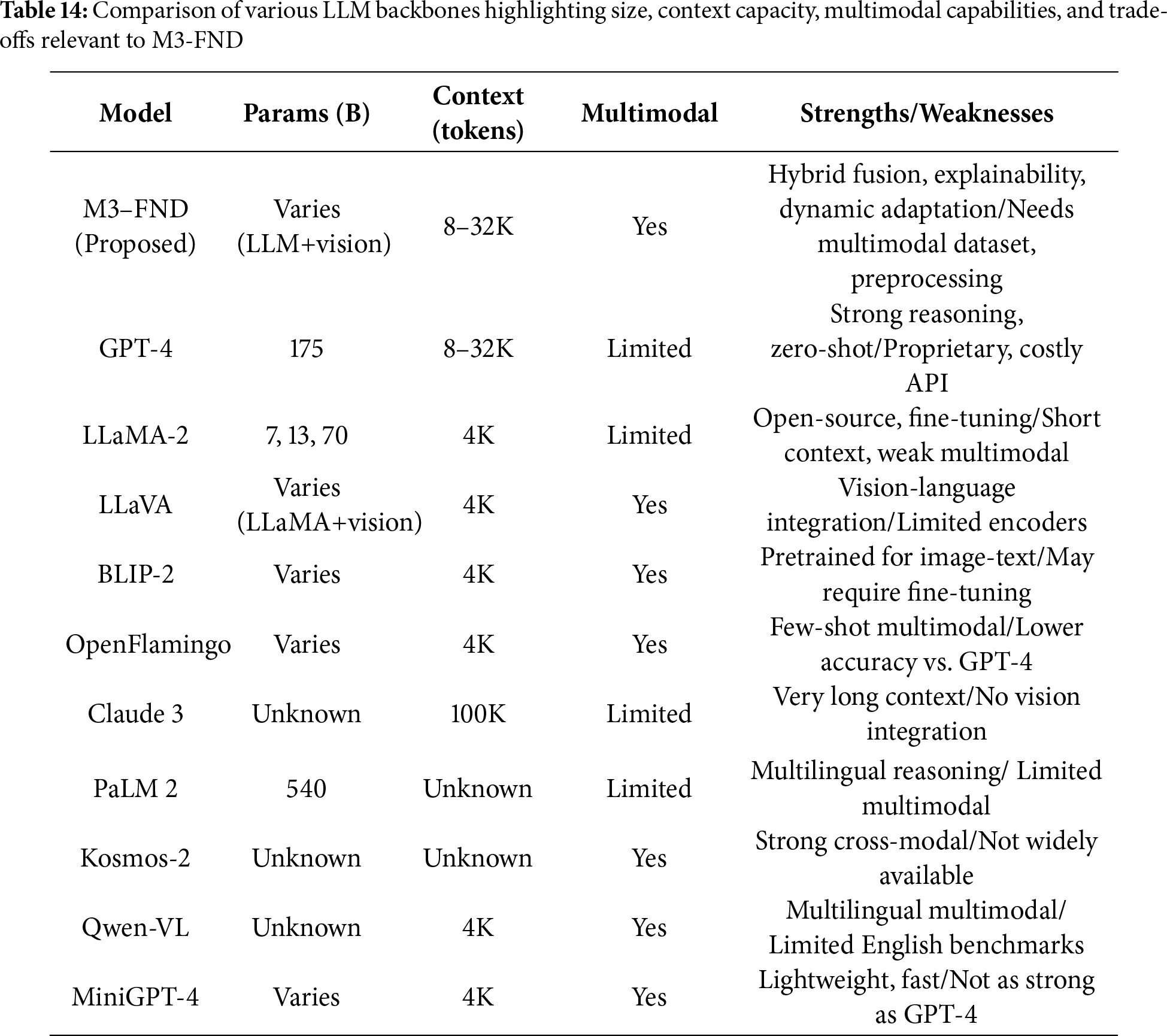

LLM Backbone Characteristics and Relevance to M3-FND

The comparison of currently maximized large language models (LLMs) and multimodal models in Table 14 overviews the conflicts between model size, context length, multimodal dimensions, and functions. The proposed M3–FND model shows a flexible architecture with tunable parameters, large-context-length (8–32K tokens) in memory, and multimodal input in each iteration through hybrid fusion, resulting in better context understanding, explainability, and on-the-fly misinformation adaptation. In contrast, GPT-4 has a gargantuan parameter size (175× more) and a very large context window, but only provides a small best-effort multimodal add-on via some adapters with added restrictions and high costs. Although open-source LLaMA-2 itself has multiple parameter variants (7, 13, 70 B), it has limited context and weaker multimodal integration and cannot provide vision encoders for effective vision-language tasks without LLaVA, but LLaVA is limited by the supported encoders. Both BLIP-2 and OpenFlamingo are tailored for image-text tasks, including few-shot multimodal learning, although they might need their own specific fine-tuning or possibly underperform GPT-4. Though Claude 3 and PaLM 2 are the best individual models at reasoning in long contexts and multilingual settings, they both still lack a really strong native multimodal integration. Kosmos-2, Qwen-VL, & MiniGPT-4—these models enable cross-model reasoning or support multiple language modalities but might come short in terms of resource/compatibility/framework coverage or relative model size/performance against more adaptive counterparts. In summary, the table provides a complementary balance of parameter scale, multimodal integration, and practical usability scale Multimodal reasoning, everything everywhere Overall, [M3-fnd] proposed a hybrid fusion with extended context handling, offering one of the best current multimodal reasoning and adaptability, allowing it to be generic across tasks like fake news detection.

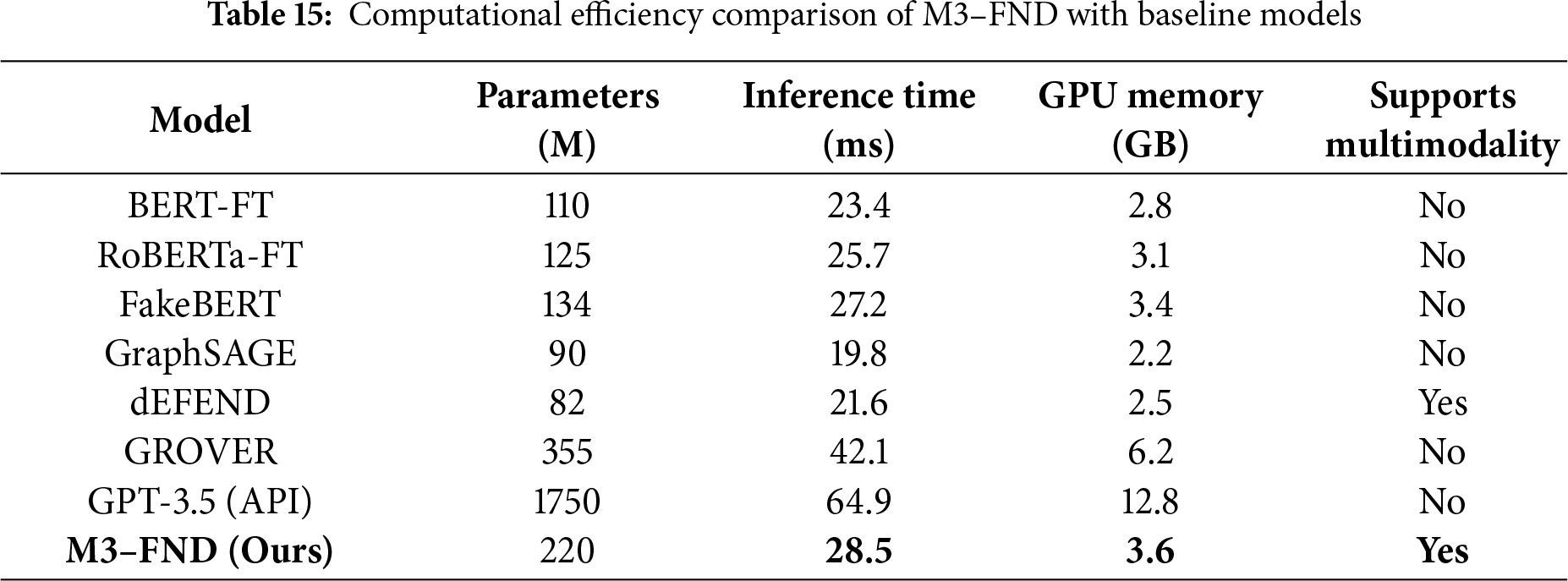

Computational Efficiency Comparison of M3-FND with Baseline Models

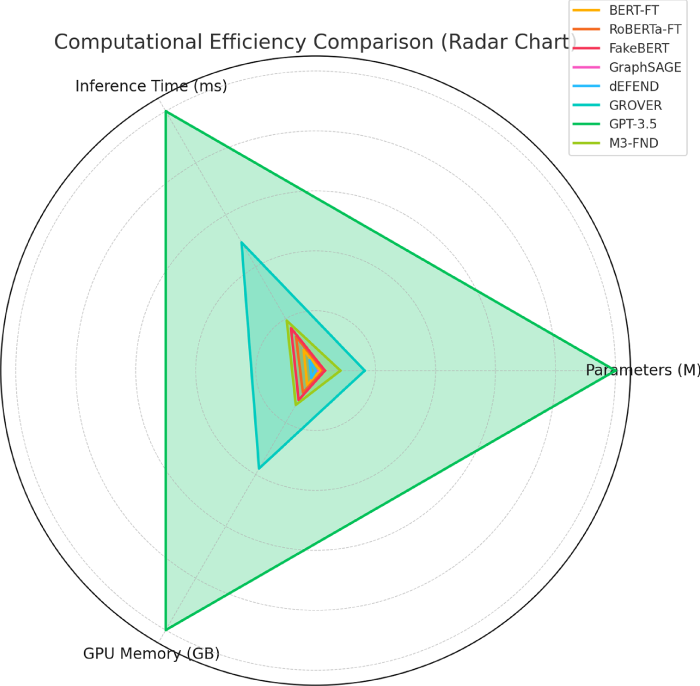

We then compared the computational efficiency of our approach against other well-known models, including BERT-FT, RoBERTa-FT, FakeBERT, GraphSAGE, GPT-3, dEFEND, GROVER.5, and M3-FND in Table 15. We consider the parameters, inference time, memory usage, and multimodal capability for comparison. m3-fnd, which has a size of 220 million parameters, takes a trade-off between performance and resources by demonstrating an inference time of 28.5 ms with 3.6 GB of GPU memory. Although, the smaller models BERT-FT, RoBERTa-FT, and FakeBERT are resource-efficient (inference time 23.4 to 25.7 ms, GPU memory 2.8 to 3.4 GB) with multimodal tokens. In contrast, M3-FND allows for multimodality, which is advantageous for tasks involving different data types. Larger models such as GPT-3.5 (1750 million parameters) and GROVER (355 million parameters) are both even slower models (42.1 and 64.9 ms) and consume more GPU memory (6.2 and 12.8 GB); besides, they are not applicable to multimodal tasks. In summary, M3-FND achieves a reasonable trade-off between efficiency, performance, and multimodal capabilities and is practical to be used in applications, as shown in Fig. 15.

Figure 15: Computational efficiency comparison of models based on parameters, inference time, and GPU memory. The radar chart shows how each model performs relative to its number of parameters, inference time, and GPU memory usage

5.10 Computational Complexity Analysis of M3–FND

M3–FND integrates three major processing stages—unimodal encoders, multimodal fusion, and LLM-based reasoning—each with distinct computational footprints. Below, we break down their complexity.

Vision Encoder (CLIP–ViT)

• Operation: Processes an image of size

• Complexity: For ViT with N patches, self-attention complexity is

Text Encoder (Transformer-based)

• Operation: Tokenizes text (length T) and processes via multi-head self-attention.

• Complexity: Transformer text encoding:

Projection & Modality Alignment Layer

• Operation: Projects vision embeddings (

• Complexity:

Hybrid Fusion Module

• Early Fusion: Concatenates aligned embeddings and passes them through a small transformer block—complexity

• Late Fusion: Combines modality-specific predictions via a lightweight MLP—complexity

• Trade-off: Hybrid fusion slightly increases computation over early/late fusion alone but improves accuracy by

LLM Reasoning Module

• Operation: Processes the concatenated multimodal tokens with deep reasoning.

• Complexity: For L layers and M = T + N tokens, complexity is

Overall Complexity & Runtime

• Training: Dominated by vision & text encoder forward/backprop passes—complexity

• Inference: Real-time capable for batch size

• Memory: Peak VRAM usage

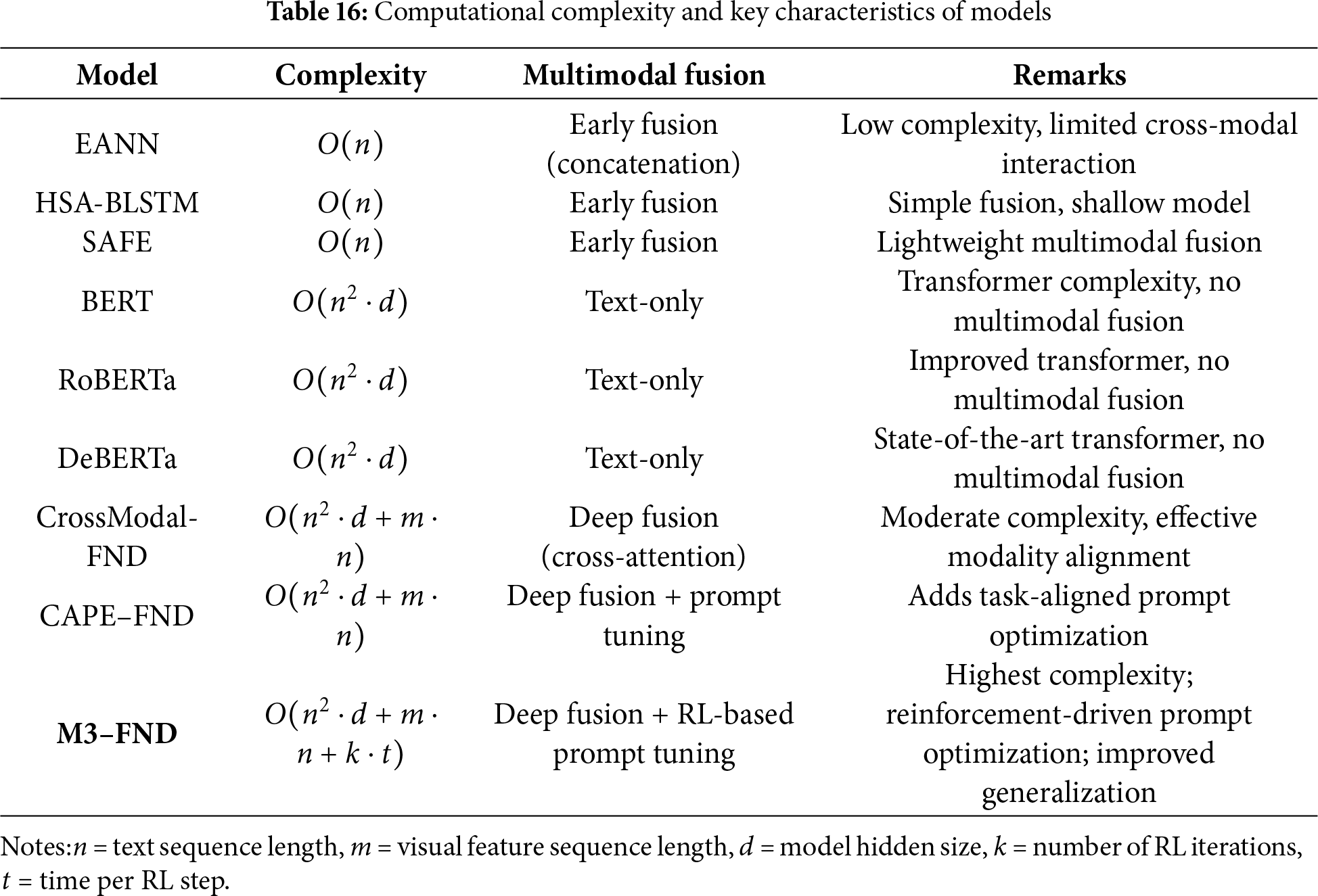

Table 16 makes the computational complexity comparison possible to get insights into how the trade-offs between architectural sophistication, multimodal fusion depth, and efficiency compare. For example, small early fusion models like EANN, HSA-BLSTM, and SAFE introduce the minimum computational demands since their shallow concatenation-based fusion affords a linear time complexity of

The standard complexity of the pure text-based transformer model (i.e., BERT, RoBERTa, and DeBERTa) is

More recent complex architectures, like CrossModal-FND and CAPE-FND, integrate textual and visual features using deep fusion by cross-attention (AttentJ) and in complexity

The proposed M3–FND model adds an RL-driven prompt optimization on top of deep fusion, with a complexity scaling as

To summarize, the analysis in this section demonstrates that the computation overhead of M3–FND is well worth it for its efficacy on real-world misinformation detection tasks where multimodal reasoning is essential and when it needs to be performed under low-resource conditions. This makes M3–FND a good choice when detection accuracy is the most important factor and extra training complexity can be sacrificed.

Limitations and Future Work

Despite its strong performance, the proposed M3–FND model has certain limitations. First, the computational requirements of large language models (LLMs), esp. when fine-tuning with reward-based prompt optimization, can hinder deployment in low-resource or real-time scenarios. Second, the multimodal fusion method is designed to leverage both textual and visual information; however, it may not generalize well for one missing, noisy, or misaligned modality. Third, the performance of the model may differ on domains and languages that have never been observed during training, which suggests difficulties in cross-domain generalization and multilingual transferability.

To address these limitations, future work will focus on the following directions:

• Model Compression and Efficiency: We plan to explore knowledge distillation, quantization, and adapter-based fine-tuning to reduce computational overhead without sacrificing performance.

• Cross-Lingual and Cross-Domain Generalization: We aim to enhance generalization capabilities by integrating multilingual corpora and domain adaptation techniques into training.

• Dynamic Prompt Learning: We will extend the current instruction tuning strategy to support online learning and real-time prompt adaptation based on evolving misinformation patterns.

• Explainability and User Trust: Future versions of M3-FND will incorporate attention-based interpretability mechanisms to improve transparency and trust in high-stakes domains such as health, politics, and finance.

These advancements will further strengthen M3-FND as a scalable, explainable, and globally applicable solution for combating misinformation in diverse digital ecosystems.