Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Multi-Scale Graph Neural Networks Ensemble Approach for Enhanced DDoS Detection

1 Faculty of Nursing, Babylon University, Hilla, 11001, Iraq

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, 91369, Iran

3 Computer Engineering Department, Hakim Sabzevari University (HSU), Sabzevar, 91369, Iran

4 Intelligent Medical Systems Department, College of Sciences, Al-Mustaqbal University, Hilla, 51001, Babylon, Iraq

5 College of Information Technology, University of Babylon, Hilla, 51001, Babylon, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Seyed Amin Hosseini Seno. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 49 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073236

Received 13 September 2025; Accepted 26 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are one of the severe threats to network infrastructure, sometimes bypassing traditional diagnosis algorithms because of their evolving complexity. Present Machine Learning (ML) techniques for DDoS attack diagnosis normally apply network traffic statistical features such as packet sizes and inter-arrival times. However, such techniques sometimes fail to capture complicated relations among various traffic flows. In this paper, we present a new multi-scale ensemble strategy given the Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for improving DDoS detection. Our technique divides traffic into macro- and micro-level elements, letting various GNN models to get the two corase-scale anomalies and subtle, stealthy attack models. Through modeling network traffic as graph-structured data, GNNs efficiently learn intricate relations among network entities. The proposed ensemble learning algorithm combines the results of several GNNs to improve generalization, robustness, and scalability. Extensive experiments on three benchmark datasets—UNSW-NB15, CICIDS2017, and CICDDoS2019—show that our approach outperforms traditional machine learning and deep learning models in detecting both high-rate and low-rate (stealthy) DDoS attacks, with significant improvements in accuracy and recall. These findings demonstrate the suggested method’s applicability and robustness for real-world implementation in contexts where several DDoS patterns coexist.Keywords

In the last few years, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks have appeared as one of the most disruptive as well as dangerous cyber threats, aiming at crucial online services and infrastructures of the network [1]. DDoS attacks are now applied by hackers and they are complicated to guard against. This is the technology of attack obtained from the Denial of Service (DoS) attack. These types of attacks are launched by coordinated botnets that are shared and remotely controlled [2]. DDoS attack integrates several computer devices to send a huge number of consecutive attacks. Such attacks maliciously originate from several systems, making it not possible for the sources of computer/network to present services to their established customers. Normally, this is stated as a service that interrupts/suspends connections to the Internet, therefore decreasing network performance. So, this could make the network paralyzed [3]. Such attacks that flood networks with bad traffic could cause financial losses, strict service downtime, and ruin an organization’s reputation. Traditional DDoS diagnosis techniques, like methods based on signature and anomaly, sometimes struggle to control such attacks’ significant and ever-evolving aspects, especially when met with low-rate/stealthy traffic models [4].

The general system of diagnosis is important for diagnosing and mitigating DDoS attacks efficiently. Such a system must be able to analyze the two aggregated traffic models and particular traffic flows for recognizing anomalies that might show an attack. Analyzing aggregated traffic presents perspectives into the whole network, while checking particular flows of traffic aids in recognizing suspicious activity between 2 endpoints. Integrating such insights allows a flexible diagnosis system to differentiate between legal traffic and bad attacks [5]. The DDoS diagnosis system should achieve a trade-off among (i) the delay caused by the large amount of traffic under analysis (to provide sufficient overview for controlling potential malicious models), and (ii) the reactivity required to implement accurate mitigation and security policies before consequential damage occurs. Such attacks target exhausting target systems’ resources through overwhelming them with huge traffic volumes/exploiting subtle vulnerabilities via stealthy, low-rate models. Traditional DDoS diagnosis techniques that basically depend on strategies based on signature/statistical, sometimes deal with adapting to the attack strategies’ evolving aspect, especially while coping with micro-level (low-rate) attacks, which mimic legal traffic/large-scale (macro) attacks, which are quickly shared over several resources [6]. So, conventional ML methods generally operate on flat feature representations, failing to get complicated structural and relational models in network traffic [7]. Such restrictions hinder their capability in diagnosing coordinated/anomalous manners that span over various network temporal and spatial levels [8].

With the emergence of ML and DL methods, some researchers have examined their ability for DDoS diagnosis. ML models like Support Vector Machines (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Random Forest (RF) were used for classifying network traffic given the statistical attributes; however, such techniques sometimes deal with complicated interactions among network entities. More recently, DL models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) illustrated satisfactory outcomes, leveraging their capability for automatically learn high-level features from raw data. Although such models generally treat the data, they overlook the inherent relations among nodes of the network [9].

Strategies based on graphs have appeared as an efficient solution to overcome the traditional techniques’ restrictions. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have obtained attention because of their capability to model complicated, relational data. In the DDoS diagnosis context, GNNs could get relations between different network nodes (like users, servers, routers) and also learn hidden relations which traditional ML models might overlook. Some research presented GNNs’ usage for network traffic analysis, illustrating that GNNs perform better than conventional methods through getting more intricate dependencies in data [10].

To address the challenges in accurately detecting DDoS attacks and improving scalability, we present a new strategy based on multi-scale feature extraction using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). Our main opinion is to divide network traffic into macro-level and micro-level parts, with every part showing various models of attack. Macro-level models get large-scale, high-volume traffic spikes normal to DDoS attacks, while micro-level models concentrate on diagnosing more subtle and low-rate attacks, which might be hard to recognize using traditional techniques. By leveraging GNNs’ power to model network traffic as graph-structured data, our technique could efficiently learn the two large-scale traffic models and hidden relations among network nodes, which are important for recognizing attacks.

Also, we develop an ensemble learning approach, integrating several models of GNN for developing a robust and accurate NIDS. The proposed ensemble strategy integrates the strengths of multiple GNN models by aggregating their multi-scale extracted features, which enhances detection accuracy while reducing the risk of overfitting. This makes it particularly effective for handling large-scale network traffic and diverse DDoS attack patterns.

For assessing our presented technique’s efficiency, we perform tests on a broadly applied benchmark set of data: UNSW-NB15. Our outcomes show that the presented multi-scale GNN ensemble strategy importantly performs better than traditional ML and DL models in terms of recall, accuracy, and capability in diagnosing the two high-rate and low-rate DDoS attacks. The capability of controlling the two macro- and micro-level attack models makes our technique highly flexible and appropriate for real-life development in active network areas.

The present study makes the following main contributions:

• We present a new strategy that divides network traffic into macro- and micro-level models, making the system able to efficiently detect the two large-scale and stealthy DDoS attacks. Macro-level attributes target broad and high-volume attack models, while micro-level features concentrate on subtle, low-rate anomalies that sometimes evade traditional diagnosis systems.

• Our model leverages various Graph Neural Network (GNN) architectures—Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN), Graph Attention Networks (GAT), and GraphSAGE—each used at various levels (global, local, intermediate). The model lets general traffic manners’ learning, from immediate node interactions to wider network-wide models.

• We transform raw traffic data into graph structures where nodes show entities (like IP addresses/sessions) and edges show communication links. The representation gets the complicated network traffic relational aspect and presents rich context to diagnose anomalous behavior.

• We combine several GNNs’ predictions by applying ensemble learning methods like stacking, voting, and weighted averaging. Such an approach increases robustness, decreases overfitting, and develops the model’s generalization capability over various DDoS attacks.

• Against traditional models that are biased to high-volume attacks, our strategy can recognize the two huge botnet-based floods and stealthy, low-rate DDoS models, developing real-life applicability in active network areas.

This study is organized as follows: In Section 2, we review related work in DDoS detection. Section 3 presents the details of the proposed multi-scale GNN ensemble approach. Section 4 discusses the experimental setup and datasets used. Section 5 presents the results and analysis of our experiments. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

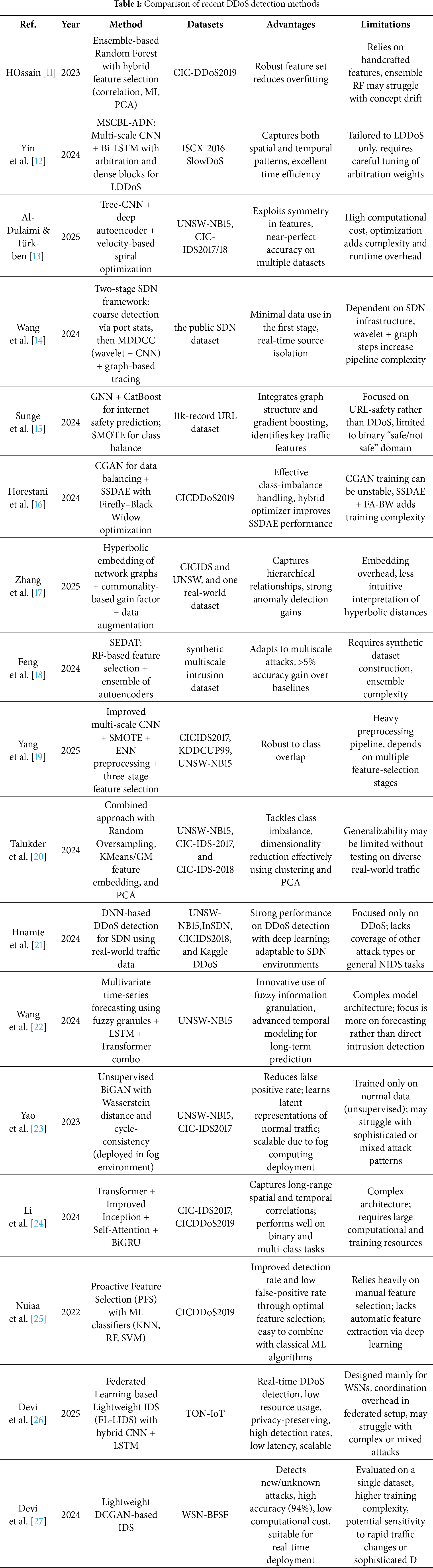

DDoS diagnosis has been a crucial study domain for many years, and different methods have been presented for recognizing and mitigating the attacks. Traditionally, DDoS diagnosis techniques could be largely grouped into anomaly and signature-based, as well as hybrid strategies. Methods based on signature depend on predefined attack models and are highly efficient for familiar attack kinds; however, they fail to diagnose new/evolving attack approaches. On one hand, anomaly-based methods concentrate on recognizing deviations from normal network behavior, making them more appropriate to diagnose unfamiliar attacks. Although they sometimes suffer from high false-positive rates, particularly in active network areas. Hossain [11] presented the strategy based on an ensemble for DDoS diagnosis, applying an RF classifier integrated with a new feature selection technique. His work considers the main restrictions in background DDoS diagnosis systems, like high false positive rates and traditional classifiers’ inability to model complicated models of traffic. For developing performance, Hossain provided a hybrid feature selection approach that combines principal component analysis (PCA), correlation analysis, and mutual information. His study bolsters ensemble learning and robust feature selection efficiency in developing DDoS diagnosis abilities. Yin et al. [12] presented a new model known as MSCBL-ADN to diagnose low-rate distributed denial-of-service (LDDoS) attacks, which are especially problematic because of their stealthy aspect and minimal traffic footprint. Their strategy combines multi-scale CNNs and bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) networks for considering restrictions in diagnosis accuracy and computational effectiveness in present techniques. Particularly, CNNs are applied for extracting spatial features, while Bi-LSTMs get temporal dependencies. The arbitration algorithm is developed for re-weighting extracted features’ significance, pursued by a 2-block dense connection network for the last classification. Al-Dulaimi et al. [13] defined multiple frameworks to diagnose Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks by leveraging symmetrical models in network traffic and feature shares. Their technique integrates Tree Convolutional Neural Network (Tree-CNN) to get hierarchical symmetrical dependencies with a deep autoencoder, which decreases noise while preserving latent structural symmetries. Also, they presented a Leader-Guided Velocity-Based Spiral Optimization mechanism for optimizing the two autoencoder and Tree-CNN parameters, striking an efficient balance among exploration and exploitation in optimization. Wang et al. [14] presented a 2-step diagnosis and mitigation framework for DDoS attacks in Software Defined Networking (SDN) areas, considering issues of high computational cost, ineffective use of features, and usage of bandwidth in traditional strategies. Their technique starts with coarse-grained diagnosis applying traffic statistics from SDN switch ports, followed by a refined diagnosis step applying a Multi-Dimensional Deep Convolutional Classifier (MDDCC). MDDCC leverages wavelet decomposition and CNNs for extracting detailed multi-dimensional features from traffic data. Such features are used for accurate potential attack traffic classification. Also, the strategy incorporates graph-theoretic methods and restrictive policies to trace and isolate attacks’ sources of attacks in the network. Sunge et al. [15] concentrated on developing internet security via predictive models’ improvement, being able to recognize high-risk online behavior and influential security features. Identifying generic models, restrictions, and challenges of class imbalance prevalent in internet security prediction, they presented developed ML methods’ usage—Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost). The research used a dataset including 11,055 records with 30 features and binary classification labels (safe vs. not safe). To consider the imbalance in class share, they developed the SMOTE method before model training. Their work boldly combines feature selection and advanced classification models, which is significant for developing internet security prediction systems, precision, and reliability. Ref. [16] presented a DL-driven intrusion detection architecture especially aimed at recognizing Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks in cloud computing and network areas. Their strategy contains basic steps: data preprocessing and balancing, applying a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN) for handling class imbalance and classification, by applying a Stacked Sparse Denoising Autoencoder (SSDAE) optimized with a Firefly-Black Widow (FA-BW) multiple mechanism. This work concentrates on the effectiveness of integrating DL with hybrid optimization methods to enhance cybersecurity in against DDoS attacks. Zhang et al. [17] defined a hyperbolic-embedding strategy for network anomaly diagnosis on graph-structured data. They embed network graphs into hyperbolic space where hierarchical and relational structures are naturally obtained, and also define the new gain agent given the commonality metrics for preserving relative distances while calculating edge weights. For dealing with labeled anomalies, they develop methods of data augmentation. Their tests show that optimizing edge-weight features in this hyperbolic embedding shows considerably better gains in anomaly diagnosis performance than concentrating on node features alone, making the technique robust and scalable for complicated areas of the network. Feng et al. [18] improved the stacked ensemble learning architecture known as Stacked Ensemble Learning-Based Detection Model for Multiscale Network Attacks (SEDAT) to diagnose highly concealed, multiscale network intrusions. Firstly, they made a new multiscale intrusion manner dataset featuring 3 attack scales and 2 probabilistic attack models. Their SEDAT model applies an RF-driven feature selection stage pursued by several autoencoder-based learners to get and show differing attack manner scales. By integrating such autoencoders in an ensemble, SEDAT adapts to complicated, multiscale traffic models that single models normally miss. Yang et al. [19] presented a developed IDS and developed a multi-scale CNN framework for capturing network traffic features at differing resolutions. Their technique defines multi-step preprocessing pipeline which integrates SMOTE and Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN) for addressing class imbalance and sample overlap with a 3-step feature selection approach—RF significance scoring, Recursive Feature Elimination, Information Gain—for optimizing performance and decreasing complexity. Talukder et al. [20] presented a new strategy for network IDS through integrating different methods for considering issues of dimension decrease, imbalanced data, and feature embedding. Our model leverages the Random Oversampling (RO) technique for dealing with data imbalance, uses feature embedding via K-means and GM clustering outcomes, and develops Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimension decrease. We assessed our model’s performance with 4 prominent ML mechanisms, XGB, RF, DT, and ET, for binary and multilabel classification research. Hnamte et al. [21] defined an innovative strategy for the diagnosis of DDoS leveraging a DNN framework rooted in DL rules. The presented model shows a scalable and adaptable architecture, making meticulous network traffic data analysis able to discern intricate models indicative of DDoS attacks. To confirm our method’s effectiveness, rigorous assessments were performed applying authentic real-life traffic data. Outcomes unequivocally demonstrate our DNN-driven strategy superiority across traditional DDoS diagnosis methods. The present study keeps considerable promise to bolster network security, especially in the active software-defined network (SDN) areas’ landscape. Ref. [22] modeled long-term multivariate time-series predicting modeling architecture in Gaussian fuzzy information granules light. The model contains under multivariate time series’ granulation technique and a neural network model, which integrates a backpropagation neural network, a long short-term memory neural network, and a transformer for long-term prediction, where a fuzzy information granule segmentation technique exists with polynomials as the main line and a novel representation technique for fuzzy info granules. Yao et al. [23] presented the unsupervised anomaly detection system that uses a Bidirectional Generative Adversarial Network (BiGAN) and learns latent representations of typical IoT data using the Wasserstein distance and cycle-consistency. This method relies only on standard data for training and may have trouble identifying more complex or mixed attack patterns, even while it lowers the false positive rate and increases scalability through fog computing deployment. Li et al. [24] uses a Transformer-based architecture that enhances temporal dependencies by combining self-attention and an enhanced Inception module for multi-scale spatial feature extraction with a BiGRU. This approach’s primary benefit is its capacity to capture temporal and spatial correlations, which results in excellent performance in binary and multi-class classification tasks. Nevertheless, this is accomplished at the expense of increased computing and training resources as well as architectural complexity. Nuiaa et al. [25] present a proactive feature selection (PFS) model that is based on an optimization technique inspired by nature. They test the model using a number of machine learning classifiers on the CICDDoS2019 dataset. Through optimal feature selection, their approach increases detection rate and decreases false positive rate; nevertheless, it is mostly dependent on the quality of the input characteristics chosen and does not have automatic feature extraction. Devi et al. [26] suggested a Federated Learning-based Lightweight IDS (FL-LIDS) for Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) that uses a hybrid CNN + LSTM to identify DDoS attacks in real-time while preserving privacy and consuming minimal resources. The approach is appropriate for contexts with limited resources since it delivers high detection rates and minimal latency. However, it is primarily intended for WSNs, adds overhead for coordination, and could not be as effective against really sophisticated assaults. Devi et al. [27] introduced a lightweight DCGAN-based intrusion detection system (IDS) for WSNs was presented. It was trained using the WSN-BFSF dataset and improved the identification of unknown and novel threats while keeping computational costs low. It achieves real-time applicability and great accuracy (94%). Evaluation on a single dataset, increased training complexity, and possible susceptibility to complicated or quickly evolving DDoS attacks are some of the limitations. Recent techniques, such as SEDAT [18] and MSCBL-ADN [12], use multiscale strategies to increase intrusion detection. SEDAT uses stacked ensemble autoencoders with RF-based feature selection on handmade data to address multiscale attack behaviors, but lacks relational modeling. MSCBL-ADN combines CNNs and Bi-LSTM layers to process spatial-temporal patterns, which are excellent for LDDoS attacks but rely on sequence data. In contrast, our method employs a graph-based architecture to explicitly describe interactions between network components, with a multi-scale GNN ensemble used to discover both structural and temporal anomalies. Furthermore, our model’s heterogeneous combination of GCN and GAT addresses both global and local attention processes, increasing adaptability and scalability in a wide range of DDoS scenarios. In spite of progress made in DDoS diagnosis, some issues exist for controlling attacks variety and complexity in real-life areas. Multi-scale and graph-driven strategies integrated with ensemble learning represent a promising avenue for improving the performance and scalability of DDoS diagnosis systems. Such observations motivate our presented multi-scale GNN ensemble strategy that looks for: (1) modeling network traffic as hierarchical graphs at hybrid scales, (2) integrating light GNNs (GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE, GIN) via effective ensemble approaches, (3) maintaining real-time feasibility, high accuracy, and low false positives in production network areas. Table 1 presents recent DDoS diagnosis methods comparative overview, highlighting main advantages and limitations.

3 Background on Graph Neural Networks

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are DL models designed for operating on graph-structured data. A graph includes nodes (vertices) and edges (connections among nodes), which could show broad relational data. GNNs are especially efficient for tasks where data shows natural graph structure, like recommendation systems, social networks, and molecular structures, as in our case, analyzing network traffic for DDoS diagnosis.

The main opinion behind GNNs is learning every node representation in a graph by aggregating information from its neighbors. It is performed via message-passing stages, where every node updates its state by taking features of its neighboring nodes and the edges connecting them into consideration. The process lets GNN get local and global graph structures that are important for tasks like graph classification, node classification, and link prediction.

The GNN framework normally includes elements:

• Node Representation: Every node in the graph is shown by a vector of features that encodes its features. In a network traffic context, such attributes contain flow characteristics, packet statistics, and temporal info on traffic.

• Message Passing: The Basic operation in GNNs is message passing, where every node aggregates info from its neighbors. The aggregation could be done by applying various tasks like sum, mean/max, followed by a transformation via a neural network layer.

• Graph Convolution: Like convolutions in CNNs, graph convolutions are used for aggregating neighborhood info. The graph convolution function is modelled for controlling graph neighborhoods’ variable size and structure, making it appropriate for irregularly structured data.

• Aggregation and Update: After the message is conveyed, the node’s feature vector is updated given the aggregated info. Such an update is normally done by applying layer of neural network (like a completely connected layer) followed by a non-linear activation function.

• Readout/Pooling: After some message passing layers, the last node representations are aggregated to achieve a global graph representation. It could be applied for graph-level functions like classification/regression/for downstream functions such as DDoS attack diagnosis.

GNN Variants

During the years, some GNN variations were presented to consider various issues and improve their performance:

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) [26]: One of the most popular GNN variants, GCNs define a graph convolution term that uses convolutions to graph data. In GCNs, every node’s representation is updated by aggregating its neighbors’ features in localized behavior. GCNs illustrated success in node classification functions.

Equations below define the GCN layer update principle:

That H(l) and H(l+1) are GCN layer input and output feature matrices, in turn;

That

Graph Attention Networks (GAT) [27]: GATs define the attention mechanism in GNNs, letting the model determine various weights to various neighbors in the aggregation process. It aids GATs to concentrate on the most informative nodes and has been illustrated for developing performance in graph-driven tasks.

The equation below defines the GAT layer update principle:

That

GraphSAGE (Graph Sample and Aggregation) [28]: Against traditional GNNs, which apply whole neighbors in the graph, GraphSAGE defines sampling a fixed-size neighborhood term for every node to develop scalability in huge graphs. The aggregated info from the sampled neighborhood is applied to update the node’s representation.

GraphSAGE conducts local neighborhood sampling and aggregation to create the sampled nodes’ embeddings. The stage of sampling presents advantages in that the computational and memory complexity is constant, considering the graph size. As the target node, v ∈ V, is assigned, a stable neighborhood set, uk, is sampled as:

That Aν is the neighboring nodes set of ν, and Nk is the sample size at depth k. S(Aν, Nk) is a sampler from a unique share U(1, deg(v)) as a default setting. So, the receptive single node domain increases considering layers’ number, K, size of

The basic node embeddings,

The mean concat aggregator averages embeddings,

That

Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) [29]: GINs are modelled for developing expressive GNNs’ power. Through applying a simple but highly expressive aggregation task, GINs could differentiate among various graph structures more efficiently, making them appropriate for functions needing fine-grained graph comparisons.

Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) is one of the most promising GNN variations; the discriminative/representational power is the same as the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) graph isomorphism test power. GIN could be updated based on the formula below:

That

That v, G are in turn a node and a graph. CONCAT(·) shows concatenate function. This was shown theoretically and experimentally that GIN has more discriminative/representational graph structures power than the last GNN models.

We propose a multi-scale ensemble strategy based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for DDoS detection, aiming to handle both large-scale and stealthy low-rate attacks effectively. In this strategy, network traffic data is partitioned into macro- and micro-level subsets, where macro-level data corresponds to large traffic surges typical of flood-based attacks, while micro-level data focuses on subtle traffic variations seen in stealthy or low-rate attacks. Each subset is processed by a dedicated GNN model that learns the relational structures within its respective scale.

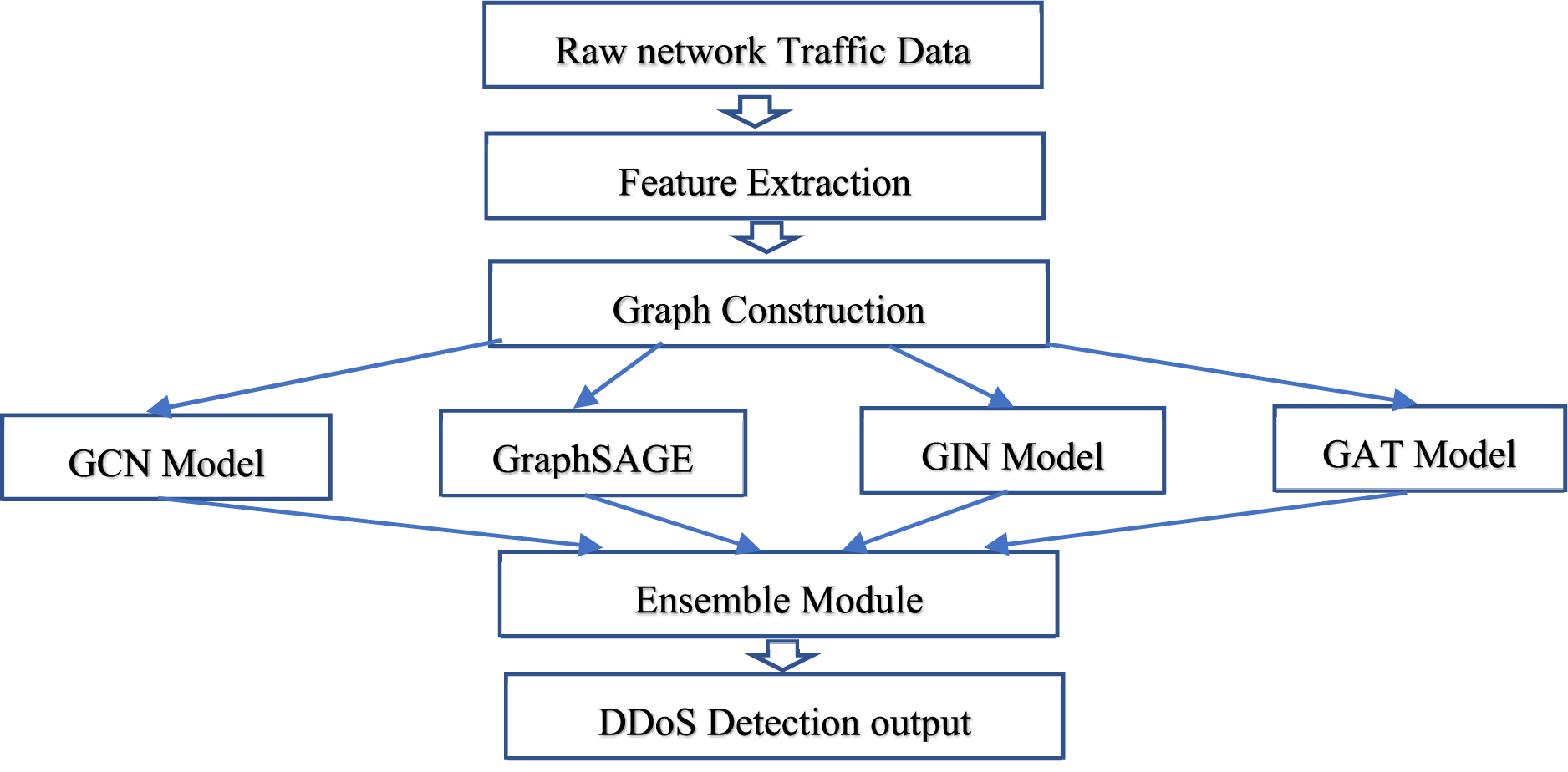

Following the feature extraction phase, ensemble learning techniques such as bagging or boosting are employed to combine the outputs of these GNN models, leveraging the strengths of individual models while reducing the risk of overfitting. This approach allows the system to capture complex dependencies in network traffic data that traditional threshold-based or signature-based detection methods often overlook. By integrating multi-scale analysis and ensemble learning, the proposed method improves detection accuracy and scalability while maintaining adaptability to evolving DDoS attack strategies in large-scale network environments as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Block diagram of the proposed method

The presented system framework for DDoS attack diagnosis is given the graph network traffic representation that nodes and edges are related to entities in the network and their interactions, in turn. The graph-driven modeling lets the system to efficiently get structural and temporal dependencies inherent in network communications. Every node might show a host, IP address, and a session based on analysis. Edges’ granularity reflects communication among nodes and are weighted applying metrics like packet counts, byte volumes/session durations. The representation transforms traditional tabular network data into a rich structure that makes deeper perspectives able into potential anomalies.

Where A is traffic graph adjacency matrix that every entry Aij equals the observed communication weight wij (e.g., packet count/byte volume) among node i and node j, zero when no direct link presents. The matrix X gathers d-dimensional feature of whole N nodes’ vectors.

4.2 Multi-Scale GNN Framework for Micro and Macro Attack Detection

The main issue in diagnosing DDoS is the ability to recognize the two big-scale (macro) and stealthy (micro) attacks. Macro attacks are characterized by high-volume traffic from several resources aiming single victim, sometimes causing noticeable spikes in traffic and connectivity models. Against, micro attacks are low-rate and stealthy by nature, often flying under the radar by mimicking legitimate traffic patterns. These attacks might manifest as abnormal short-duration sessions/small traffic bursts from a single host which are hard to diagnose with traditional techniques.

For considering such issues, we present multi-scale Graph Neural Network (GNN) architecture that analyzes graph of network at various locality levels. It contains every node’s local (1-hop) neighborhood of every node to get fine-grained manners related to micro attacks, intermediate (2-hop) neighborhood to discover shared models, and global scale to recognize coordinated attack models over the whole network graph. By checking various levels of node connectivity and interaction, the model is able to diagnose the two subtle and big-scale anomalies.

In order to capture both local and global dependencies within network traffic, the proposed multi-scale decomposition splits the traffic graph into representations at the macro and micro levels. Theoretically, there are two main levels of granularity at which DDoS traffic behavior naturally happens. While the micro-level records specific temporal and packet-level correlations linked to stealthy or low-rate attacks, the macro-level represents aggregate patterns like overall flow intensity and burst behavior. According to exploratory analyses, the addition of a second decomposition scale increases model complexity while producing little gain in detection accuracy. Therefore, the two-scale arrangement provides a useful trade-off between model efficiency and representation richness.

Various GNN frameworks are developed over such scales. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) are applied for aggregating information from immediate neighbors by averaging node attributes, making them efficient for local and intermediate model learning. Graph Attention Networks (GAT) incorporate attention algorithms for determining various weights to neighboring nodes, allowing model to concentrate on more informative connections that is especially effective for recognizing micro-level anomalies. GraphSAGE is developed for its scalability and sampling-driven aggregation approach, making effective learning able over big graphs. Optionally, Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) are combined for their robust ability to differentiate graph structures, making them well-suited to diagnose complicated topological variations indicative of stealthy/shared attacks.

In every GNN layer l, node i updates its representation

After processing with different GNN models (e.g., GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE, GIN), an ensemble learning method such as soft voting or averaging is applied to combine predictions, leveraging the strengths of each model while reducing variance in detection results. Windows are labeled as benign or DDoS based on the ensemble output against a defined threshold, and detected events can be logged for real-time monitoring or integrated with mitigation modules in operational environments.

This integrated pipeline, from traffic preprocessing and graph construction to multi-scale GNN learning and ensemble-based detection, ensures that the proposed method is fully executable for scalable and accurate DDoS diagnosis in real network environments.

In order to give a comprehensive algorithmic explanation of the suggested architecture, we clearly specify the scale partitioning at the macro and micro levels. The micro-level collects flows below this threshold, which frequently display subtle, covert attack patterns, while the macro-level contains flows that surpass a threshold based on average packet count and inter-arrival intervals. The following parameters are set for each GNN model: dropout = 0.3, learning rate = 0.001, hidden units = 64, and number of layers = 3. On the basis of validation results, additional hyperparameters were chosen.

The weighted ensemble approach is used to aggregate the outputs of the macro- and micro-level GNNs. To improve robustness and generalization, predictions are fused using a weighted voting process, and weights are allocated according to each model’s validation accuracy.

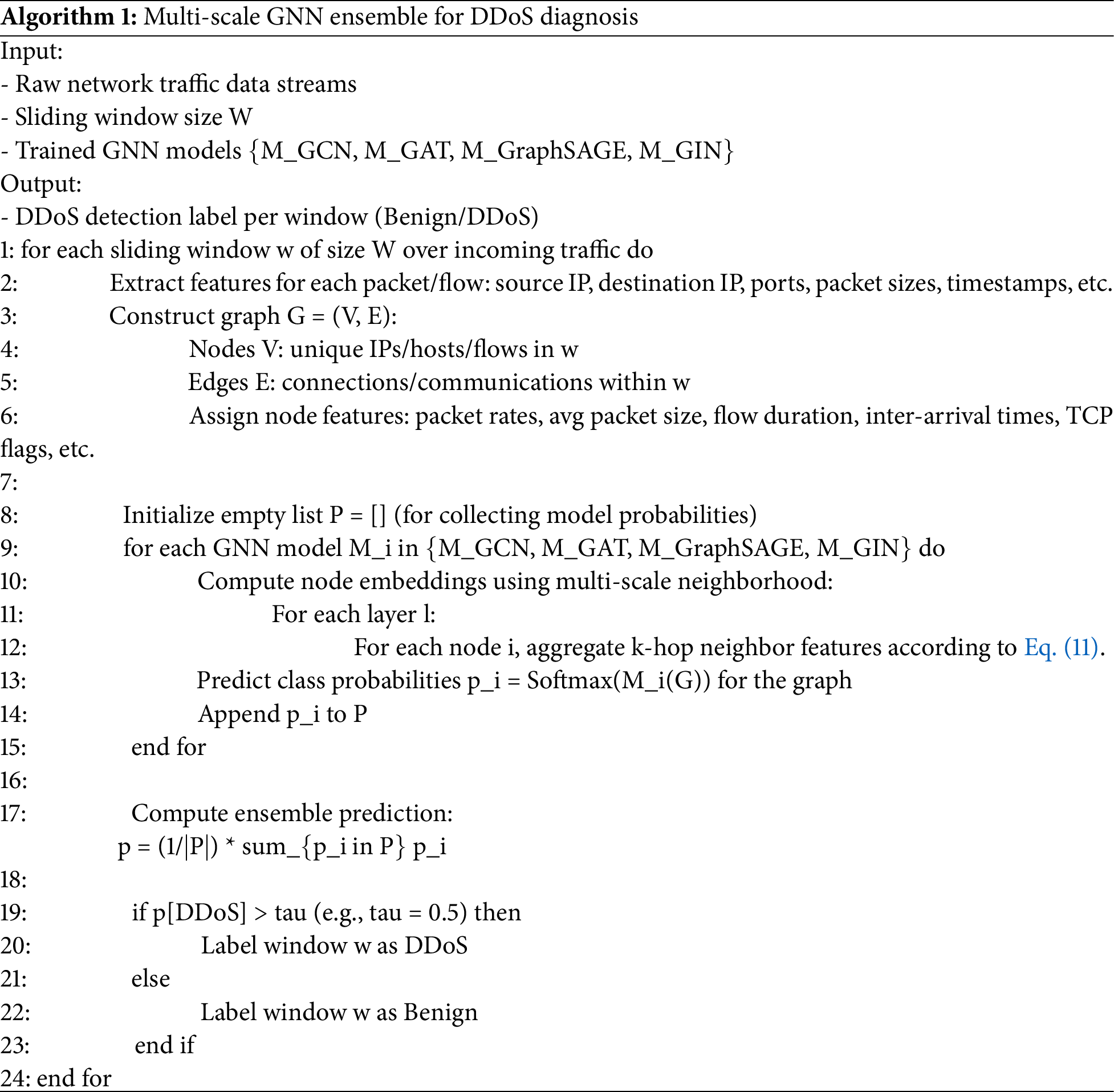

Algorithm 1 illustrates the proposed multi-scale GNN ensemble framework for DDoS detection. In this method, network traffic data is first segmented into sliding windows, and features such as source and destination IPs, ports, packet sizes, and timestamps are extracted to construct a graph where nodes represent hosts or flows and edges represent their connections. Node features like packet rate, average packet size, and inter-arrival times are assigned to capture traffic behaviors. Multiple GNN models, including GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE, and GIN, are applied in parallel on this graph to extract multi-scale neighborhood information, enabling the detection of both macro-scale (large, high-volume attacks) and micro-scale (low-rate, stealthy attacks) patterns. During this process, node representations are updated according to Eq. (11), ensuring consistent feature propagation across different neighborhood scales. Each GNN model outputs a class probability indicating the likelihood of a DDoS attack, and these probabilities are combined using an ensemble approach to form the final prediction. If the probability exceeds a defined threshold, the window is labeled as a DDoS attack; otherwise, it is labeled as benign. This algorithm enhances detection accuracy while maintaining scalability and robustness in real-world environments, allowing the system to effectively capture complex and subtle attack behaviors across different traffic granularities.

4.3 Selection of GNN Architectures

Network flows or hosts are represented as nodes in each dataset, while edges record node-to-node communication or similarity associations. The relevant nodes and edges are given tabular information, such as packet sizes, inter-arrival periods, and flow properties, after they have been normalized. GNNs can efficiently simulate intricate relationships and interactions in network traffic for DDoS detection because to this graph representation.

In this paper, we offer a multi-scale ensemble framework that improves DDoS attack detection by leveraging four distinct Graph Neural Network (GNN) architectures: Graph Attention Networks (GAT), Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN), GraphSAGE, and Graph Isomorphism Networks. Each of these architectures brings unique strengths: Each of these architectures brings unique strengths: GCN accurately captures local neighborhood patterns by aggregating characteristics from immediate neighbors, which is critical for finding common structural irregularities in network traffic. GAT incorporates attention techniques that assign different weights to neighbors, allowing the model to concentrate on highly informative nodes and subtle attack signals. GraphSAGE enhances scalability by sampling fixed-size neighborhoods, allowing it to handle vast and dynamic network graphs. Meanwhile, GIN offers higher expressive capacity via a highly discriminative aggregation function and multilayer perceptrons, which aid in identifying complicated graph structures. By merging these models into an ensemble, our framework gains multi-scale and heterogeneous feature extraction, resulting in increased robustness and generalization over a wide range of DDoS scenarios.

Our detection process works with sliding panes of network traffic data, converting each window into a graph with network entities as nodes and their interactions as edges. Node features include flow-level information, including packet rates, average packet size, flow duration, and temporal metrics. Each trained GNN model processes the graph individually, aggregating multi-hop neighborhoods to learn complete node embeddings. The output probabilities from all models are then combined using an average ensemble technique to get the final classification decision. This strategy not only leverages the complementary characteristics of each GNN variant but also enhances overall detection accuracy and reduces the risk of overfitting compared to single-model methods.

Compared to previous efforts that mostly rely on single GNN architectures, our multi-scale ensemble outperforms them in identifying both volumetric and stealthy DDoS attacks. While GCN-based models are effective at capturing local graph structures, and GATs enhance focus on relevant nodes through attention, their isolation can hinder flexibility to various assault patterns. Our model achieves improved discriminative power and scalability by combining various GNN types, as evidenced by our study of multiple benchmark datasets. This ensemble technique creates a more durable and accurate detection system, tackling the issues faced by complex and dynamic DDoS threats.

Dynamic Graph Generation from Network Traffic Logs

To dynamically create graph representations, raw network traffic logs from datasets like UNSW-NB15 [30], CICDDoS2019 [31], and CICIDS2017 [32] are processed in sliding time periods. While edges show communication or resemblance relationships between nodes, each node represents a network flow or host. From the logs, features like flow statistics, packet size, and inter-arrival time are taken out, normalized, and allocated to nodes and edges. This dynamic graph representation enhances real-time detection capabilities and enables GNN models to effectively capture changing patterns of DDoS attacks.

By constructing each micro-level graph within fixed-size time periods and restricting the amount of network flows included, we are able to manage the size and density of these graphs. Nodes and edges are also filtered; minor or redundant edges are removed, while only flows with high activity or strong similarity are kept. This approach strikes a balance between structural fidelity and computing efficiency, making micro-level graphs comprehensible while still identifying key DDoS attack trends.

4.4 Ensemble Learning for Robust Prediction

For increasing system accuracy, robustness, and generalization, we develop an approach of ensemble learning that integrates several GNN-driven results trained at various scales/applying various frameworks. Such fusion leverages every model’s uniform strengths for presenting more general data understanding.

Three ensemble methods are taken into consideration. Firstly, majority voting integrates the whole model’s predictions, choosing a label that gets the most votes. Such a technique is simple but efficient in decreasing individual model errors. Under majority voting, every M base models casts a predicted label

Secondly, we apply weighted averaging, where every model’s prediction is multiplied by a weight proportional to the performance (e.g., F1-score on validation set), and the last prediction is assigned given the aggregated weighted scores. In weighted averaging, every model’s probability output p(m) is scaled by weight αm, proportional to the validation performance wm; the last score

At last, a more important stacking strategy is performed where base models’ predictions are applied as input features for a meta-learner (for example, logistic regression/shallow neural network). Such a meta-model learns to integrate predictions in a way that optimally decreases error given the learned models on validation data. In stacking, we feed concatenated probability vectors {p(m)} from whole MMM base models into a meta-learner fmeta (like logistic regression) that learns how to best integrate them into the last prediction

The ensemble approach proposes some advantages. This mitigates individual model’ variance, develops the two macro and micro attacks’ diagnosis, also guarantees that the last decision is less sensitive to the weaknesses of each unique model. In addition, the strategy causes higher stability and better adaptability in active areas of the network.

A weighted fusion technique is used to merge the predictions of the macro-scale and micro-scale GNN models. The weight of each model is automatically established depending on its F1-score on the validation set. The weighted total of the GNN predictions is the final ensemble output, which is then thresholded to provide the binary DDoS detection decision. This method increases overall resilience, performance, and reproducibility without requiring manual adjustment and makes use of the complementing advantages of both GNN models.

The presented model is trained applying a cross-entropy loss task appropriate for binary classification (attack vs. normal). We apply Adam optimizer because of its adaptive learning rate algorithm, that convergence speed and stability. For avoiding overfitting, regularization methods like dropout are used, and early stopping is applied given the validation loss. We train the network by reducing binary cross-entropy loss where yi ∈ {0, 1}is the true label of sample i,

Model is assessed by applying hybrid metrics of performance, such as F1-Score, Accuracy, Recall, and Precision, that present the general classifier’s performance view. Also, the AUC-ROC metric is applied for assessing the capability of the model for differentiating between usual and bad traffic under imbalanced data situations. Such assessments are performed over various kinds and under differing network load classes to guarantee the diagnosis system’s generalizability and robustness.

This part shows the DDoS diagnosis system experimental outcomes applying Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and model ensemble approaches. The tests were done on a dataset: UNSW-NB15. Such tests aim to assess the presented model performance of the proposed model in detecting DDoS attacks at different scales (macro and micro). We evaluate the model’s performance by applying different metrics: F1-score, Accuracy, Recall, and Precision.

The main datasets used to initiate the framework are UNSW-NB15 [30], CICDDoS2019 [31], and CICIDS2017 [32]. Such sets of data were carefully chosen to reflect the broad real-life security scenarios.

UNSW-NB15: Improved by the Cybersecurity Laboratory at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), this dataset is particularly modelled to assess network IDSs. Made by IXIA, PerfectStorm means this simulates novel network traffic and different network attacks, including nearly 2,540,044 records. UNSW-NB15 attributes both traditional attacks (like scanning, DoS, fuzzing) and more developed anomalies, like shellcode and backdoor attacks that exploit vulnerabilities in subtle and sophisticated ways. Such developed attacks are sometimes hard to diagnose without accurate feature extraction and representation.

CICDDoS2019 dataset: It contains different DDoS attacks that could be performed through TCP/UDP app layer protocols. Attack taxonomy in a set of data is performed in the case of assaults based on exploitation and reflection. More than 80 stream attributes are contained in a set of data. A Set of data was collected over two different days to analyze the test and train. Dataset assaults contain DDoS attacks applying LDAP, DNS, NTP, MSSQL, NetBIOS, SYN, SNMP, and UDP-Lag.

CICIDS2017 dataset: The CICIDS2017 dataset includes Brute Force SSH, DoS, Heartbleed, Web Attack, Infiltration, DDoS, Brute Force FTP, and Botnet. The CICFlowMeter tool extracted 80+ features for each flow from traffic data. This dataset contains 2,830,743 records, including 557,646 malicious records and 2,273,097 benign records. The performance of the proposed model was evaluated using the CICIDS2017 dataset, specifically the Friday Working Hours Afternoon DDoS subset.

The presented model includes two basic elements: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to extract the two macro and micro-scale features, and an approach to include model predictions. In the tests, we applied GCN (Graph Convolutional Network) and GraphSAGE models for processing features based on a graph. The ensemble approach included applying methods of Voting and Weighted Averaging.

• Optimizers: The Adam optimizer was applied for training the model.

• Loss Function: The Cross-Entropy loss function was developed for classification.

• Regularization: Dropout with a rate of 0.5 was applied to avoid overfitting.

In assessing classification models’ performance, especially in binary classification, some main metrics have been developed for presenting a general model’s efficiency analysis. Such metrics contain F1 Score, Precision, and Recall, each proposing uniform perspectives on various models’ predictive abilities.

• TP (True Positives): Accurately predicted positive samples.

• TN (True Negatives): Accurately predicted negative samples.

• FP (False Positives): Inaccurately predicted positive samples.

• FN (False Negatives): Inaccurately predicted negative samples.

The cases’ ratio which are accurately grouped into whole samples describes accuracy. Accuracy shows how efficiently the model could distinguish between legal and bad traffic in the DDoS attack diagnosis context. The mathematical formula for accuracy is:

Precision assesses the model’s positive predictions’ accuracy. A higher precision shows that the model has a lower false positive rate, showing its ability to accurately recognize positive samples with min error.

Recall (sensitivity) evaluates the capability of the model for accurately recognizing whole positive log entries. This is computed as the true positive predictions’ rate to the total sum of positive log entries in the dataset. A high recall score shows that the model efficiently gets most of the true positive cases.

F1 score shows harmonic precision and recall mean. This presents a balanced model’s performance assessment by taking the two false positives and false negatives into consideration at the same time. A higher F1 score shows better balance between precision and recall.

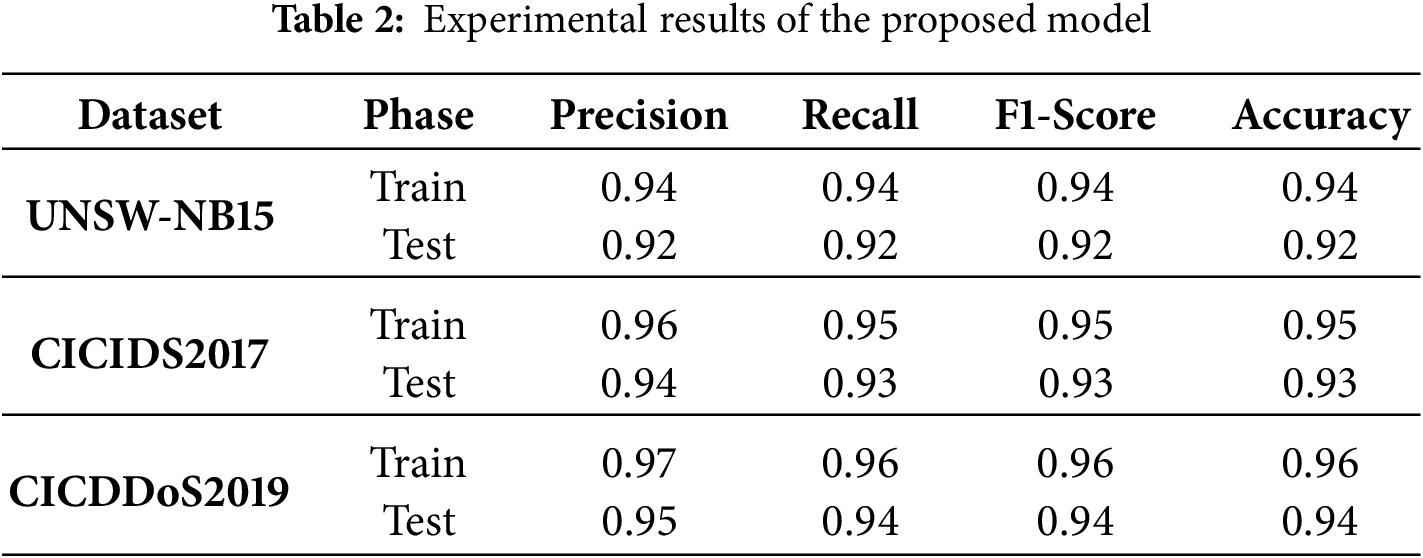

This part shows the detailed performance outcomes of the presented model and compares it with other new techniques in Table 2.

The proposed ensemble model based on stacking Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) performs consistently well in categorizing normal and attack traffic across numerous benchmark datasets, including UNSW-NB15, CICIDS2017, and CICDDoS2019. Preliminary tests with an additional scale did not yield significant improvement, confirming the efficiency of the two-scale configuration.

The model achieved a training accuracy of 94% on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, with good class-wise metrics such as precision of 0.95 and recall of 0.95 for the attack class (label 1), demonstrating its robust ability to detect malicious behavior with few false negatives. The model also had good precision (0.92) and recall (0.90) for regular traffic (label 0), with F1-scores of 0.91 (class 0) and 0.95 (class 1). Macro and weighted averages were within 0.93–0.94, demonstrating balanced performance across both classes.

During testing, the model maintained its outstanding generalization performance, with an accuracy of 92%. It achieved a precision of 0.93 and recall of 0.94 for the attack class, and 0.90 precision and 0.87 recall for regular traffic, yielding F1-scores of 0.88 and 0.93, respectively. These findings confirm the model’s ability to identify previously unknown harmful patterns with minimal loss of accuracy. On the CICIDS2017 dataset, the model improved even further, achieving 95% training accuracy and 93% testing accuracy. The F1-score for the attack class stayed at 0.94 or better, demonstrating its ability to detect stealthy attacks in complicated traffic circumstances.

The performance on CICDDoS2019 was the most robust, with training accuracy of 96% and testing accuracy of 94%, as well as precision and recall exceeding 0.95 in the assault class. These numbers demonstrate the model’s great scalability and adaptability to evolving DDoS patterns. Overall, the GNN-based stacking ensemble not only retains high accuracy and F1-score across all three datasets, but it also demonstrates outstanding generalizability and robust detection of low-rate and high-volume attacks, making it a suitable candidate for real-world intrusion detection systems (IDS).

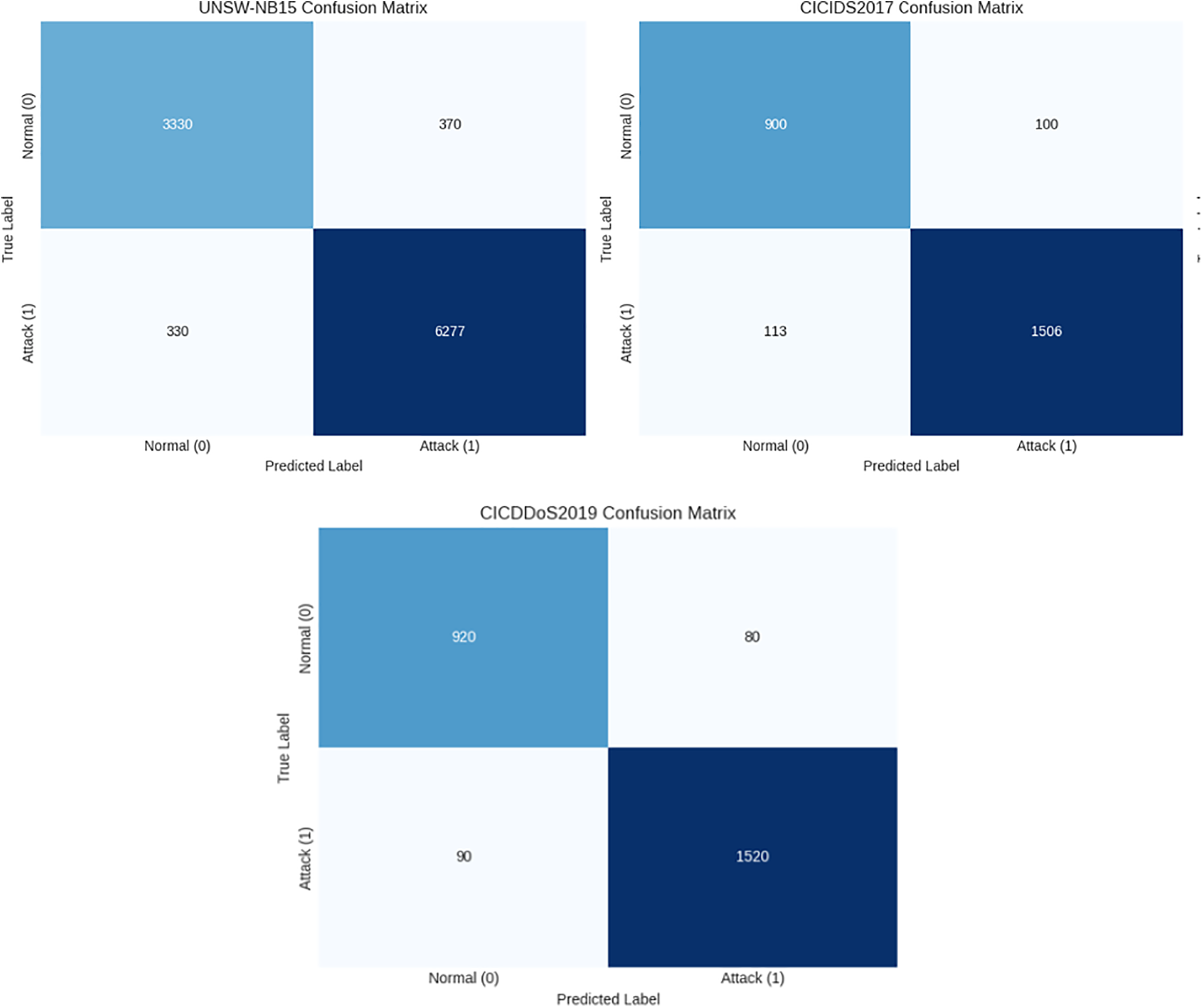

A comparison of the confusion matrices from three datasets—UNSW-NB15, CICIDS2017, and CICDDoS2019—in Fig. 2, shows that the proposed model performs well and consistently in DDoS detection. The confusion matrix shows that the model accurately classified 3330 cases of class 0 as true negatives and 6277 examples of class 1 as true positives. Meanwhile, 370 cases of class 0 were improperly classified as class 1 (false positives), whereas 330 instances of class 1 were misclassified as class 0 (false negatives).

Figure 2: Test the confusion matrix of the proposed method

The relatively high proportion of true positives over false negatives illustrates the model’s good recall for class 1, which efficiently detects DDoS attack samples. Similarly, the false positive count remains within a reasonable range, which contributes to a favorable Type I error rate. This balance between correctly recognizing attack traffic and reducing false alarms is a crucial contributor to the model’s high accuracy and F1-score.

The confusion matrix shows that the model correctly classified 900 cases of class 0 as true negatives and 1506 instances of class 1 as true positives. A total of 100 class 0 cases were inaccurately identified as class 1 (false positives), and 113 class 1 instances were incorrectly forecasted as class 0 (false negatives). Given the significant number of true positives over false negatives, these findings demonstrate the model’s excellent efficiency in detecting attack traffic (class 1). Furthermore, the comparatively low frequency of false positives shows that the model retains acceptable precision while avoiding excessive false alarms. Overall, the matrix demonstrates well-balanced classification performance, particularly given the complexity of DDoS patterns in CICIDS2017.

As illustrated in the confusion matrix, the model accurately classified 920 cases of class 0 (normal) and 1520 instances of class 1 (DDoS). It misidentified 80 class 0 instances as class 1 (false positives) and 90 class 1 instances as class 0 (false negatives). This distribution. The low number of false positives adds to improved precision, whereas the small number of false negatives supports strong recall for class 1. On the CICDDoS2019 dataset, the model performs similarly in both classes.

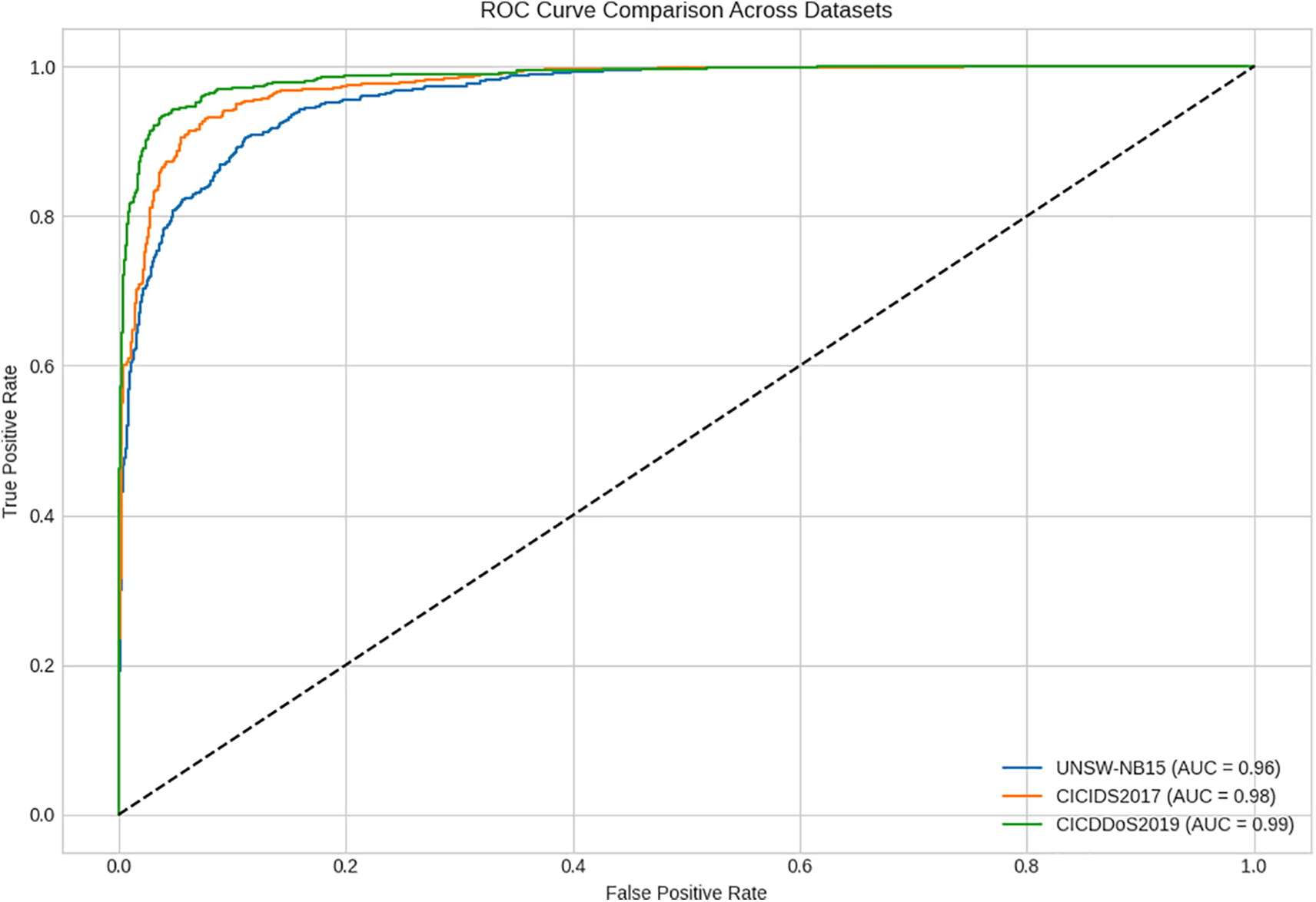

The ROC curves for the training and test sets show excellent classification performance in Fig. 3, with AUC values of about 0.99 and 0.98, respectively. Furthermore, examination on benchmark datasets validates the model’s resilience, with AUC values of ~0.96 on UNSW-NB15, ~0.98 on CICIDS2017, and ~0.99 on CICDDoS2019. These continuously high AUC scores demonstrate the model’s ability to distinguish between benign and malicious network data at various classification levels.

Figure 3: The ROC curve for the testing set

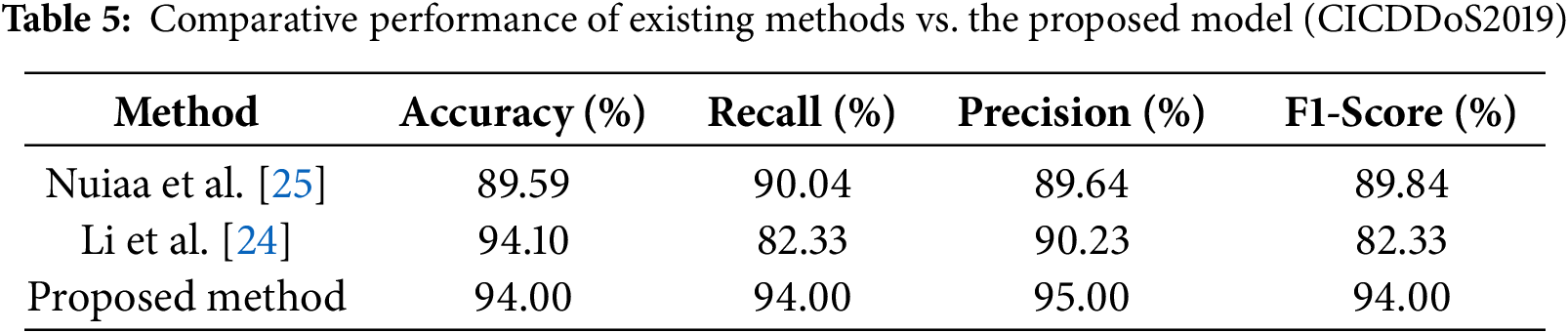

This good result demonstrates the suggested stacking-based ensemble model’s extraordinary discriminative capability, which is achieved by leveraging Graph Neural Networks (GNN) for improved feature extraction and the strength of ensemble learning at the decision level. This architecture enables the model to capture the intricate correlations found in network traffic data while preserving strong generalization to previously unseen samples. Furthermore, the high AUC values imply that the model is good at correctly detecting positive situations while avoiding false positives. This achievement is due to precise hyperparameter tuning, clever training approaches to prevent overfitting, and careful treatment of class imbalance issues. For assessing the presented technique’s efficiency, we compared its performance with other well-known DDoS diagnosis methods. The outcomes illustrated that the presented model performs better than other techniques in terms of F1-score, accuracy, and recall. We contrast three new deep learning IDS techniques with the suggested multi-scale GNN ensemble. For unsupervised anomaly detection, Yao et al. [23] employ a BiGAN, which increases scalability but has trouble with intricate attack patterns. The Transformer-BiGRU architecture used by Li et al. [24] efficiently captures temporal and spatial correlations, but it comes at a significant computational cost. An optimization-based feature selection strategy that enhances detection but depends on manually chosen features is put forth by Nuiaa et al. [25]. In contrast to current techniques, our method uses both macro- and micro-scale ensemble learning to model network traffic as graph-structured data, resulting in more balanced and robust detection of both low- and high-rate DDoS attacks (Tables 3–5).

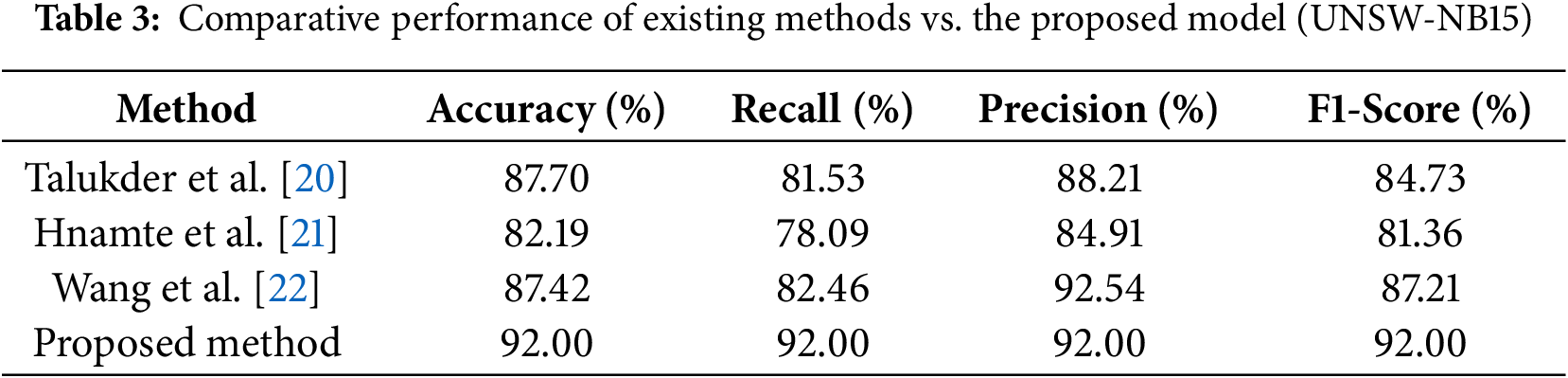

The performance metrics comparative analysis over present techniques and the presented strategy shows the proposed IDS’s efficiency and superiority. Among the last works, Wang et al. [22] obtained the highest F1-score (87.21%) and precision (92.54%), showing robust predictive balance and a low rate of false positives. Talukder et al. [20] outperformed well with a respectable accuracy of 87.70% and precision of 88.21%; however, their recall (81.53%) was considerably lower, indicating that several samples of attack remained undiagnosed. Hnamte et al. [21] reported the lowest values over the whole metrics, with an F1-score of 81.36%, showing space for development in the two sensitivity and specificity.

Unlike the presented technique performs better than whole baselines with an F1-score of 92%, accuracy of 92%, recall of 92%, and precision of 92%. The stable and balanced performance over the whole metrics signifies the technique’s robust capability for diagnosing bad traffic with the two high sensitivities (recall) and precision, reducing the two false negatives and positives. The development across present techniques could be attributed to the developed modeling methods, combination as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), in a Stacking ensemble architecture that increases feature representation and decision strength. Totally, the presented model not only surpasses the previous techniques in every unique metric but also obtains the most balanced and reliable IDS performance.

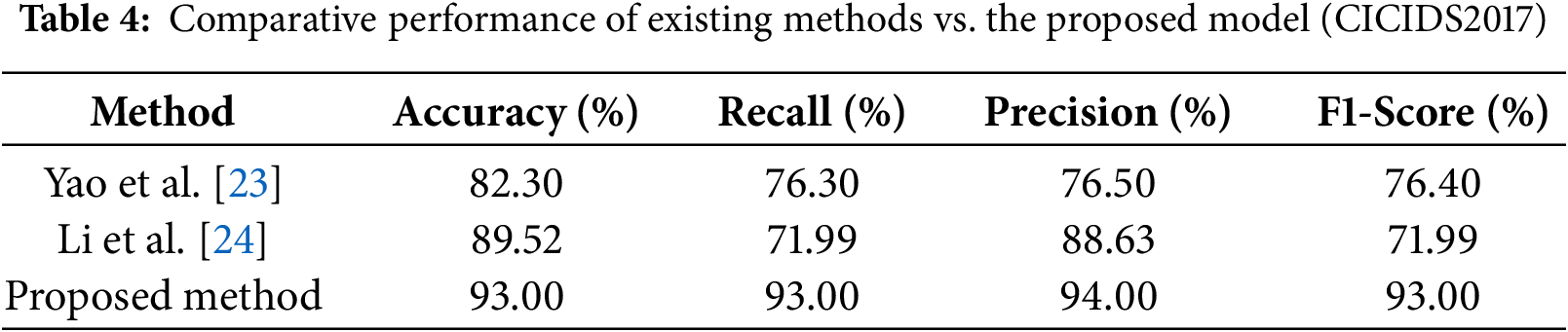

On the CICIDS2017 dataset, the results in Table 3 unequivocally show how much better the suggested strategy is than the current techniques. Specifically, the accuracy of the suggested model is 93%, a significant improvement above that of Li et al. (89.52%) and Yao et al. (82.30%). More significantly, the recall rises sharply to 93%, whereas the recall values of the two earlier approaches are lower (76.30% and 71.99%, respectively), suggesting that the suggested model is far more successful in accurately detecting assault cases. Similar to this, the suggested method’s precision (94%) surpasses that of Li et al. (88.63%) and Yao et al. (76.50%), indicating that it can detect malicious traffic with fewer false alarms. As a result, the suggested model’s F1-score (93%) is much higher than the baselines, indicating a balanced improvement in recall and precision. Overall, these figures show that by attaining thorough performance gains across all assessment criteria, the suggested strategy provides a more robust and dependable detection capability than current approaches.

The results shown in Table 4 demonstrate that, when tested on the CICDDoS2019 dataset, the suggested approach retains a significant generalization capability. A considerable amount of attack traffic goes unnoticed, as evidenced by the very low recall (82.33%) of Li et al. and Nuiaa et al., despite their balanced performance (accuracy of 89.59% and F1-score of 89.84%) and somewhat higher accuracy (94.10%). On the other hand, the suggested model regularly demonstrates strong recall (94%) and precision (95%), in addition to achieving a high accuracy (94%), resulting in a superior F1-score of 94%. These findings demonstrate that the suggested approach can both lower false positives and catch a higher percentage of assault occurrences. As a result, it provides more consistent and dependable detection performance on all assessment parameters on CICDDoS2019 when compared to the current methods as shown in Table 5.

High detection performance is the main goal of the suggested multi-scale GNN ensemble, although interpretability is crucial for real-world implementation. Explainable AI methods like GNNExplainer or SHAP, which enable the identification of significant nodes, edges, or traffic factors influencing predictions, can be used to understand the model’s choices. Investigating these techniques can improve confidence in practical applications and yield further insights into the behavior of the model.

Even if the suggested multi-scale GNN ensemble is tested on a number of benchmark datasets, thorough robustness testing is still a crucial area that needs more research. Future research will examine how well the model handles concept drift in dynamic network contexts, how resilient it is to adversarial attacks, and how well it performs when dealing with noisy or missing traffic data. Deeper understanding of the model’s dependability and suitability for practical implementations will be possible thanks to these assessments.

High detection performance is attained by the suggested multi-scale GNN ensemble while preserving useful processing economy. The system can process about 30,000 packets per second on a computer with 8 CPU cores, 32 GB RAM, and 8 GB GPU VRAM because graph generation takes about 5–10 ms per sample, training takes about 2–3 h per dataset on an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU, and inference latency is about 3 ms per sample. About 8 GB of GPU and 32 GB of RAM are used for training and inference. These findings suggest that the model can be used for edge deployment and is practical for real-time DDoS detection. In large-scale networks, further optimizations like model trimming or quantization may lower resource usage and increase deployment effectiveness.

5.5 Limitations of the Proposed Model

There are a number of drawbacks to the suggested multi-scale GNN ensemble, despite its excellent detection performance. Particularly for ensemble processing and micro-level graph creation, there are significant memory and computational demands. Despite being tested on three benchmark datasets, there may not be any applicability to new attack types or network settings. It may be difficult to install in real-time in very big networks. Furthermore, it is challenging to explain individual forecasts due to the inherent interpretability restrictions of GNN-based models. Lastly, the model’s resilience to concept drift and adversarial attacks has not been thoroughly evaluated, offering suggestions for further study.

Here, we presented the new DDoS diagnosis system given the multi-scale Graph Neural Network (GNN) ensemble strategy, efficiently getting the two big-scale and subtle, low-rate DDoS attacks. Through sharing network traffic into macro- and micro-level features, our system could model the two big traffic spikes and stealthy attack models, proposing important developments in diagnosis accuracy. Also, the ensemble strategy we developed integrated the strengths of hybrid GNN models, later increasing system robustness and performance. The experimental findings on the UNSW-NB15, CICIDS2017, and CICDDoS2019 datasets show that our suggested strategy is effective, with high F1-scores, precision, recall, and accuracy that consistently exceed traditional methods and other deep learning models. Despite these promising results, various avenues for future research and optimization remain open. One main domain is developing scalability and real-time detection capabilities of the system, ensuring it can handle large-scale networks effectively. In addition, considering the issue of diagnosing novel and evolving DDoS attack models via methods such as transfer learning and meta-learning would aid the model to adapt to new kinds of attacks. Future attempts would concentrate on combining systems into the present network security infrastructures, presenting a general solution to DDoS threats. To develop model performance, we plan to explore data augmentation and synthetic data generation methods for controlling rare attack scenarios more efficiently. Also, increasing model explainability via explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP and LIME would develop trust in the system’s decisions. At last, exploring the model’s resilience to adversarial attacks and fortifying it in contrast to these threats would be critical in guaranteeing its robustness in real-life scenarios. By considering such issues, we aim to considerably increase the DDoS diagnosis abilities of our system and guarantee its efficiency in large-scale, real-time network areas

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder, Mehdi Ebady Manaa; methodology, Hamid Noori, Davood Zabihzadeh; software, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; validation, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; formal analysis, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; investigation, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; resources, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; data curation, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; writing—original draft preparation, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; writing—review and editing, Seyed Amin Hosseini Seno; visualization, Seyed Amin Hosseini Seno; supervision, Seyed Amin Hosseini Seno; project administration, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder; funding acquisition, Noor Mueen Mohammed Ali Hayder. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This research employed publicly accessible CICIDS2017 dataset. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chethuhn/network-intrusion-dataset (accessed on 24 February 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| DDoS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| GNNs | Graph Neural Networks |

References

1. Qasim SS, Nsaif SM. Advancements in time series-based detection systems for distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks: a comprehensive review. Babylon J Netw. 2024;2024:9–17. doi:10.58496/bjn/2024/002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cheng J, Liu Y, Tang X, Sheng VS, Li M, Li J. DDoS attack detection via multi-scale convolutional neural network. Comput Mater Contin. 2020;62(3):1317–33. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.06177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zolfagharipour L, Kadhim MH, Mandeel TH. Enhance the security of access to IoT-based equipment in fog. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Al-Sadiq International Conference on Communication and Information Technology (AICCIT); 2023 Jul 4–6; Al-Muthana, Iraq. p. 142–6. doi:10.1109/AICCIT57614.2023.10218280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Alitbi ZK, Hosseini Seno SA, Ghaemi Bafghi A, Zabihzadeh D. A generalized and real-time network intrusion detection system through incremental feature encoding and similarity embedding learning. Sensors. 2025;25(16):4961. doi:10.3390/s25164961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bakar RA, De Marinis L, Cugini F, Paolucci F. FTG-Net-E: a hierarchical ensemble graph neural network for DDoS attack detection. Comput Netw. 2024;250:110508. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hayder NMM, Seno SAH, Noori H, Zabihzadeh D, Manaa ME. Improved DDoS attack detection-based feature selection by using graph convolutional network-transformer model. Oper Res Eng Sci Theory Appl. 2025;8(2):22–46. [Google Scholar]

7. Wang S, Yu PS. Graph neural networks in anomaly detection. In: Graph neural networks: foundations, frontiers, and applications. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 557–78. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6054-2_26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Le HD, Park M. Enhancing multi-class attack detection in graph neural network through feature rearrangement. Electronics. 2024;13(12):2404. doi:10.3390/electronics13122404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Barsellotti L, De Marinis L, Cugini F, Paolucci F. FTG-net: hierarchical flow-to-traffic graph neural network for DDoS attack detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 24th International Conference on High Performance Switching and Routing (HPSR); 2023 Jun 5–7; Albuquerque, NM, USA. p. 173–8. doi:10.1109/HPSR57248.2023.10147929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Khemani B, Patil S, Kotecha K, Tanwar S. A review of graph neural networks: concepts, architectures, techniques, challenges, datasets, applications, and future directions. J Big Data. 2024;11(1):18. doi:10.1186/s40537-023-00876-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hossain MA. Enhanced ensemble-based distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack detection with novel feature selection: a robust cybersecurity approach. Artif Intell Evol. 2023;4(2):165–86. doi:10.37256/aie.4220233337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yin X, Fang W, Liu Z, Liu D. A novel multi-scale CNN and Bi-LSTM arbitration dense network model for low-rate DDoS attack detection. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5111. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-55814-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Al-Dulaimi RTA, Türkben AK. A hybrid tree convolutional neural network with leader-guided spiral optimization for detecting symmetric patterns in network anomalies. Symmetry. 2025;17(3):421. doi:10.3390/sym17030421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang K, Fu Y, Duan X, Liu T. Detection and mitigation of DDoS attacks based on multi-dimensional characteristics in SDN. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):16421. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-66907-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sunge AS, Hendric SW, Pramudito DK. Using graph neural networks and catboost for internet security prediction with SMOTE. J Ilm Tek Elektro Komput Dan Inform. 2024;10(4):747–62. [Google Scholar]

16. Horestani SJ, Soltani S, Seno SAH. A deep neural network architecture for intrusion detection in software-defined networks. Comput Knowl Eng. 2022;5(2):31–44. doi:10.22067/CKE.2022.75815.1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang H, Zhou Y, Xu H, Shi J, Lin X, Gao Y. Graph neural network approach with spatial structure to anomaly detection of network data. J Big Data. 2025;12(1):105. doi:10.1186/s40537-025-01149-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Feng Y, Yang Z, Sun Q, Liu Y. SEDAT: a stacked ensemble learning-based detection model for multiscale network attacks. Electronics. 2024;13(15):2953. doi:10.3390/electronics13152953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang H, Yu J, Zhai R. High-precision intrusion detection for cybersecurity communications based on multi-scale convolutional neural networks. J Supercomput. 2024;81(1):277. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06737-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Talukder MA, Islam MM, Uddin MA, Hasan KF, Sharmin S, Alyami SA, et al. Machine learning-based network intrusion detection for big and imbalanced data using oversampling, stacking feature embedding and feature extraction. J Big Data. 2024;11(1):33. doi:10.1186/s40537-024-00886-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hnamte V, Ahmad Najar A, Nhung-Nguyen H, Hussain J, Sugali MN. DDoS attack detection and mitigation using deep neural network in SDN environment. Comput Secur. 2024;138:103661. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang W, Liu W, Chen H. Information granules-based BP neural network for long-term prediction of time series. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2021;29(10):2975–87. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2020.3009764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yao W, Shi H, Zhao H. Scalable anomaly-based intrusion detection for secure internet of things using generative adversarial networks in fog environment. J Netw Comput Appl. 2023;214:103622. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2023.103622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li N, Gao Z, Ye J, Tang W, Che X, Chen Y. A novel and efficient multi-scale spatio-temporal residual network for multi-class intrusion detection. In: Machine learning for cyber security. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 271–83. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-4566-4_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Nuiaa RR, Manickam S, Alsaeedi AH, Alomari ES. A new proactive feature selection model based on the enhanced optimization algorithms to detect DRDoS attacks. Int J Electr Comput Eng. 2022;12(2):1869. doi:10.11591/ijece.v12i2.pp1869-1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Devi M, Nandal P, Sehrawat H. Federated learning-enabled lightweight intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks: a cybersecurity approach against DDoS attacks in smart city environments. Intell Syst Appl. 2025;27:200553. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2025.200553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Devi M, Nandal P, Sehrawat H. A lightweight approach for intrusion detection in WSNs based on DCGAN. Int J Inf Technol. 2025;17(2):951–7. doi:10.1007/s41870-024-02347-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Oh J, Cho K, Bruna J. Advancing GraphSAGE with a data-driven node sampling. arXiv:1904.12935. 2019. [Google Scholar]

29. Li J, Liu Y, Gu L. DDoS attack detection based on neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Symposium on Aware Computing; 2010 Nov 1–4; Tainan, Taiwan. p. 196–9. doi:10.1109/ISAC.2010.5670479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Moustafa N, Slay J. UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In: Proceedings of the 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS); 2015 Nov 10–12; Canberra, Australia. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/MilCIS.2015.7348942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. CICDDoS2019 Dataset [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dhoogla/cicddos2019. [Google Scholar]

32. CICIDS2017 Dataset [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chethuhn/network-intrusion-dataset. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools