Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ISTIRDA: An Efficient Data Availability Sampling Scheme for Lightweight Nodes in Blockchain

1 School of Computer Science, School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Engineering Research Center of Digital Forensics, Ministry of Education, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

2 School of Software, Shandong University, No. 1500, Shunhua Road, High-Tech Industrial Development Zone, Jinan, 250101, China

3 College of Computer Science and Technology, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, No. 169, Sheng Tai West Road, Nanjing, 210016, China

* Corresponding Author: Shan Ji. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances in Blockchain Technology and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 25 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073237

Received 13 September 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Lightweight nodes are crucial for blockchain scalability, but verifying the availability of complete block data puts significant strain on bandwidth and latency. Existing data availability sampling (DAS) schemes either require trusted setups or suffer from high communication overhead and low verification efficiency. This paper presents ISTIRDA, a DAS scheme that lets light clients certify availability by sampling small random codeword symbols. Built on ISTIR, an improved Reed–Solomon interactive oracle proof of proximity, ISTIRDA combines adaptive folding with dynamic code rate adjustment to preserve soundness while lowering communication. This paper formalizes opening consistency and prove security with bounded error in the random oracle model, giving polylogarithmic verifier queries and no trusted setup. In a prototype compared with FRIDA under equal soundness, ISTIRDA reduces communication by 40.65% to 80%. For data larger than 16 MB, ISTIRDA verifies faster and the advantage widens; at 128 MB, proofs are about 60% smaller and verification time is roughly 25% shorter, while prover overhead remains modest. In peer-to-peer emulation under injected latency and loss, ISTIRDA reaches confidence more quickly and is less sensitive to packet loss and load. These results indicate that ISTIRDA is a scalable and provably secure DAS scheme suitable for high-throughput, large-block public blockchains, substantially easing bandwidth and latency pressure on lightweight nodes.Keywords

Blockchain’s decentralization, immutability, transparency, and traceability have driven impact across finance [1–3], supply chains [4–6], healthcare [7–9], and digital identity [10–13], enabling more efficient, secure, and auditable systems [14]. Nevertheless, scalability remains a primary barrier [15]: Ethereum processes about 60 transactions per second [16], whereas conventional payment rails sustain roughly 1700 TPS and peak near 24,000. The proliferation of decentralized applications (dApps) aggravates congestion and confirmation delays [17,18], reinforcing the urgency of scalable designs for broad adoption.

The use of lightweight nodes [19,20] is key to blockchain scalability. By storing only block headers, they cut storage and computation costs, lowering the participation barrier and promoting decentralization [21]. But without full block data, they cannot directly verify transactions and thus rely on a secure data-availability mechanism. We focus on public blockchains, where full and lightweight nodes coexist and decentralization hinges on the participation of resource-constrained clients. We assume an open, adversarial peer-to-peer setting (e.g., Ethereum-like networks), where lightweight nodes cannot trust arbitrary relays and instead depend on cryptographic data-availability guarantees. This defines our threat model and performance goals, and differentiates our work from permissioned or consortium settings.

Data availability sampling (DAS) [22] is a core cryptographic technique used to resolve the security and performance trade-off in blockchain. This technique allows light nodes to efficiently verify the availability of all data by randomly sampling a small amount of data. This enables light nodes to ensure network security while maintaining low resource consumption.

However, existing DAS designs face various deployment and performance limitations. Hall-Andersen et al. proposed two constructions of DAS schemes [23]. One construction uses vector commitments combined with succinct non-interactive arguments of knowledge (SNARKs), which is sound but computationally expensive and relies on strong cryptographic assumptions. Another, adopted by Ethereum, uses two-dimensional Reed–Solomon (RS) codes [24] with Kate–Zaverucha–Goldberg (KZG) polynomial commitment scheme [25], offering good performance at the expense of a heavy trusted setup. More recently, Hall-Andersen et al. introduced a DAS scheme called FRIDA [26], which is built on FRI [27], a Fast Reed–Solomon interactive oracle proof of proximity (IOPP). FRIDA does not require trusted setup, but still incurs high constant factor communication costs and uses a fixed code rate that does not adapt well to different data scales [28].

To overcome these limitations, we turn to improvements at the IOPP layer. In particular, our work is inspired by the Shift-to-Improve-Rate (STIR) protocol [29]. STIR improves efficiency by reducing the polynomial degree and code rate through recursion. However, its fixed folding ratio and code rate can lead to redundancy or premature shrinking of the query domain. We therefore develop ISTIR, an improved RS IOPP with adaptive folding and dynamic code-rate adjustment. Building on ISTIR, we design ISTIRDA, a DAS scheme tailored for high-frequency and large-data settings. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• This paper presents a DAS that couples recursive RS degree reduction with dynamic code-rate adjustment, restructuring the IOPP to cut communication and accelerate verification—effects most pronounced at large data scales, easing lightweight-node bandwidth pressure.

• This paper proposes an adaptive folding method that selects the folding ratio and adjusts the code rate of each round based on the data size and security requirements, thereby maintaining efficiency and avoiding redundant communication. After 16 MB, ISTIRDA is faster than FRIDA in verification speed, and the gap will become larger and larger as the data size increases.

• This paper provides formal security under standard assumptions and a prototype evaluation: at D = 128 MB, the proof size of ISTIRDA is 60% smaller and the verification time 25% shorter than FRIDA, with the query complexity, the verification time, and proof size reported.

2.1 Data Availability and Origin of DAS

Data availability refers to the ability of all participants in a blockchain network to access the data needed to verify transactions and blocks. This characteristic is crucial for maintaining the network’s decentralization and trustlessness, enabling nodes to independently verify the blockchain’s history and state. DAS is a method for verifying data availability without downloading the complete dataset, and is particularly suitable for lightweight nodes with limited storage capacity.

The concept of DAS was first introduced by Al-Bassam et al. [22]. In a DAS scheme, a potentially malicious block proposer encodes the block’s contents into a short commitment

To improve the efficiency of DAS in practice, Hall-Andersen et al. developed the FRIDA [26], which applies the FRI protocol to data availability. FRIDA avoids a trusted setup and achieves communication complexity that grows polylogarithmically with the block size. It was among the first schemes to explicitly integrate an IOPP into a DAS design, demonstrating that the FRI protocol can be adapted for checking data availability.

In parallel, Wagner et al. [33] presented PeerDAS, a scheme intended for integration into Ethereum. PeerDAS uses RS codes in combination with KZG polynomial commitments to enable sampling-based data availability checks for light clients. Their work describes optimizations for selecting random sample columns and verifying the corresponding commitments efficiently.

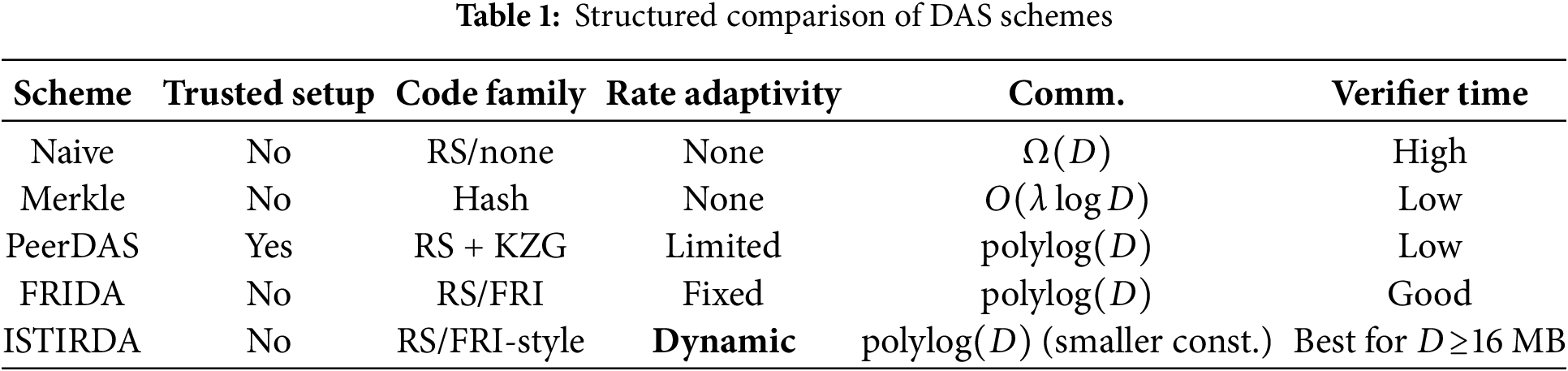

Despite these advances, existing DAS protocols still face scalability challenges. Even schemes with polylogarithmic complexity (such as FRIDA and PeerDAS) incur substantial communication and verification costs when block sizes become very large. Moreover, static choices of code rate or sampling density may be suboptimal under changing network conditions or adaptive adversaries. These limitations motivate ISTIRDA. ISTIRDA introduces adaptive folding and dynamic rate adjustment to tune the coding and sampling process for the data scale and threat model. In effect, ISTIRDA retains the security guarantees of IOPP-based DAS while significantly lowering communication and verification overhead in high-throughput, large-block settings. To highlight the advantages of our proposed scheme, Table 1 presents a comparison of existing schemes.

3.1 Interactive Oracle Proofs of Proximity

Key parameters. Let

Completeness. If

Soundness. If

Query complexity.

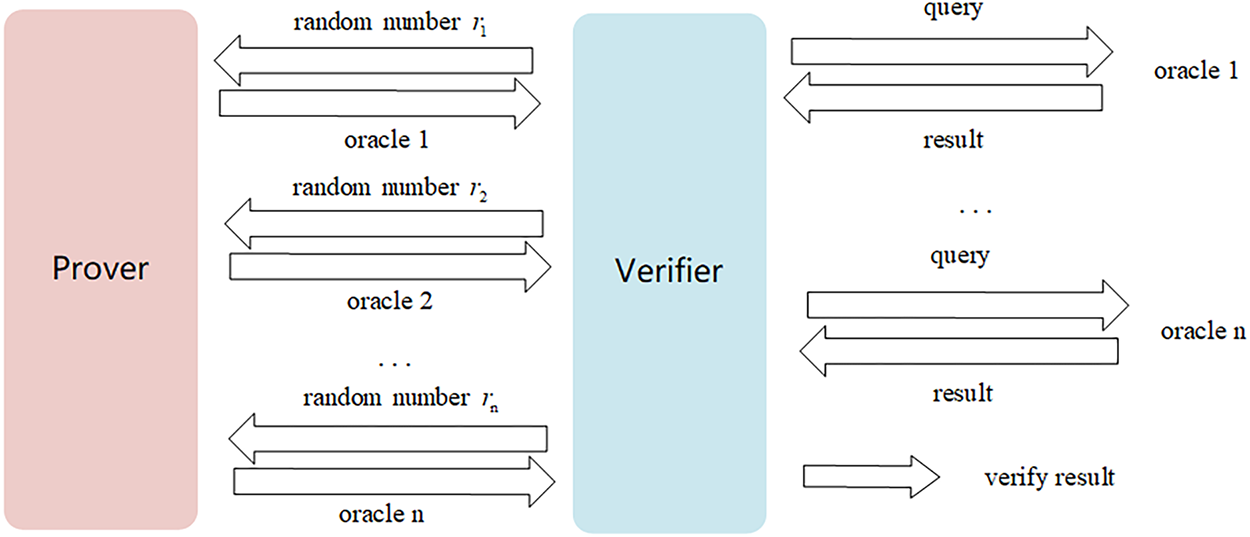

Fig. 1 depicts the workflow of an IOPP. IOPP is an interactive protocol between a prover P and a verifier V that certifies

Figure 1: Workflow of an interactive oracle proofs of proximity

In this paper, the sequence

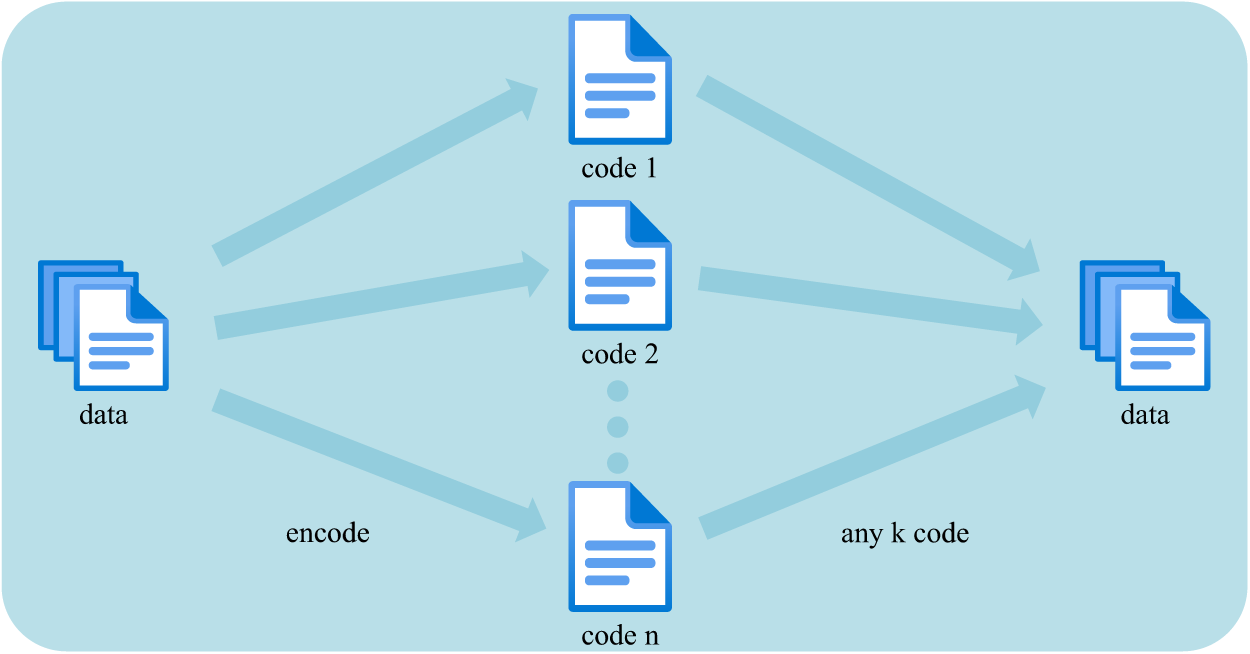

As visualized in Fig. 2, a message polynomial of degree strictly less than

Figure 2: Illustration of RS codes

Let

For illustration, take

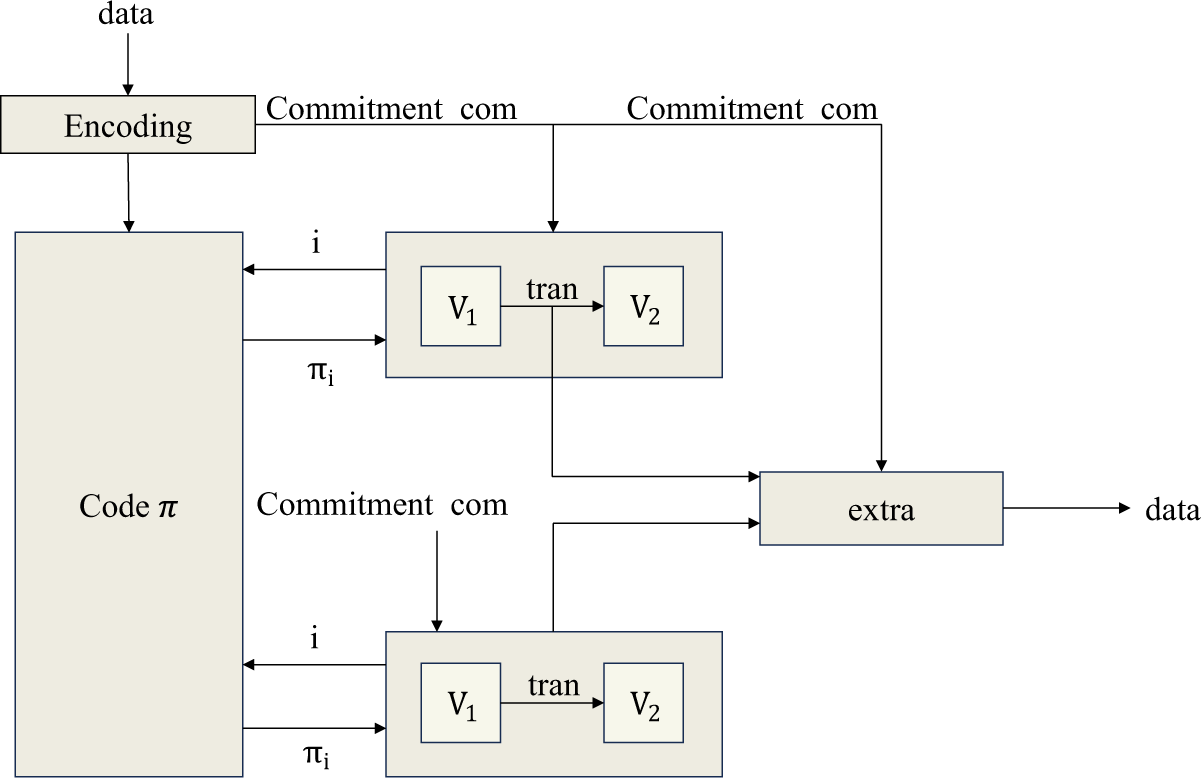

Fig. 3 illustrates the end-to-end flow of the proposed protocol: The original data is first Reed-Solomon encoded to obtain the codeword

Figure 3: Flow of the data availability scheme

In what follows, we refine STIR [29] by removing redundant steps and introducing two mechanisms: adaptive folding and dynamic code-rate adjustment. Unlike STIR’s fixed folding schedule, ISTIR selects the folding ratio per round based on the remaining evaluation domain, residual polynomial degree, and security/redundancy targets, thereby avoiding late-round over-redundancy and premature domain contraction; this reduces both evaluation points and communication, especially at large data scales. The dynamic code-rate rule re-optimizes the rate at each recursion rather than letting it decay on a fixed schedule, balancing early-round bandwidth savings with stronger late-round soundness. We then analyze the resulting complexity parameters, which serve as performance indicators for ISTIRDA.

We further prove that ISTIR satisfies opening consistency under our model, ensuring transcripts remain well-structured across rounds, either close to a valid codeword or rejected, thus precluding attacks that exploit recursive folding. This security foundation enables the standard transformation from ISTIR to an erasure-code commitment and, following FRIDA’s framework [26], to a complete DAS scheme, which we call ISTIRDA.

4.2 Construction of Our Protocol

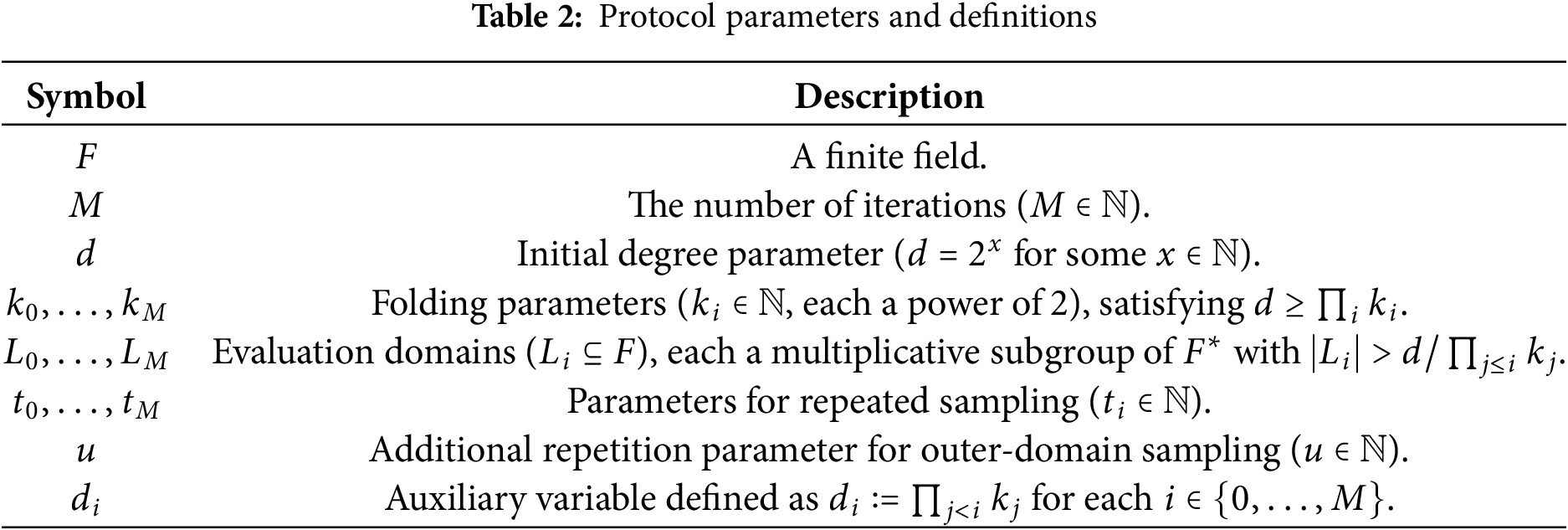

Table 2 lists the protocol parameters and definitions. The specific protocol execution steps are as follows.

Initialization. Define function

Initial Folding Step. The verifier randomly selects a folding scalar

Interactive Protocol Rounds. For round index

(a) Prover Polynomial Folding Transmission: The prover computes and submits the folded function

(b) The verifier selects random points:

(c) For these out-of-domain queries: The verifier receives responses

(d) ISTIR-specific Communication: The verifier sends a random scalar

(e) The prover transmits a prediction message, denoted

Final Round. At this stage, the prover outputs a polynomial

Verifier Decision Phase. The verifier executes the following verification steps:

(a) Iterative Verification Procedure: For

i. For each

ii. Construct the query set

iii. Define a virtual oracle function

(b) Consistency Check for the Final Folding Step:

i. Randomly select evaluation points

ii. For each

iii. Cross-validate with

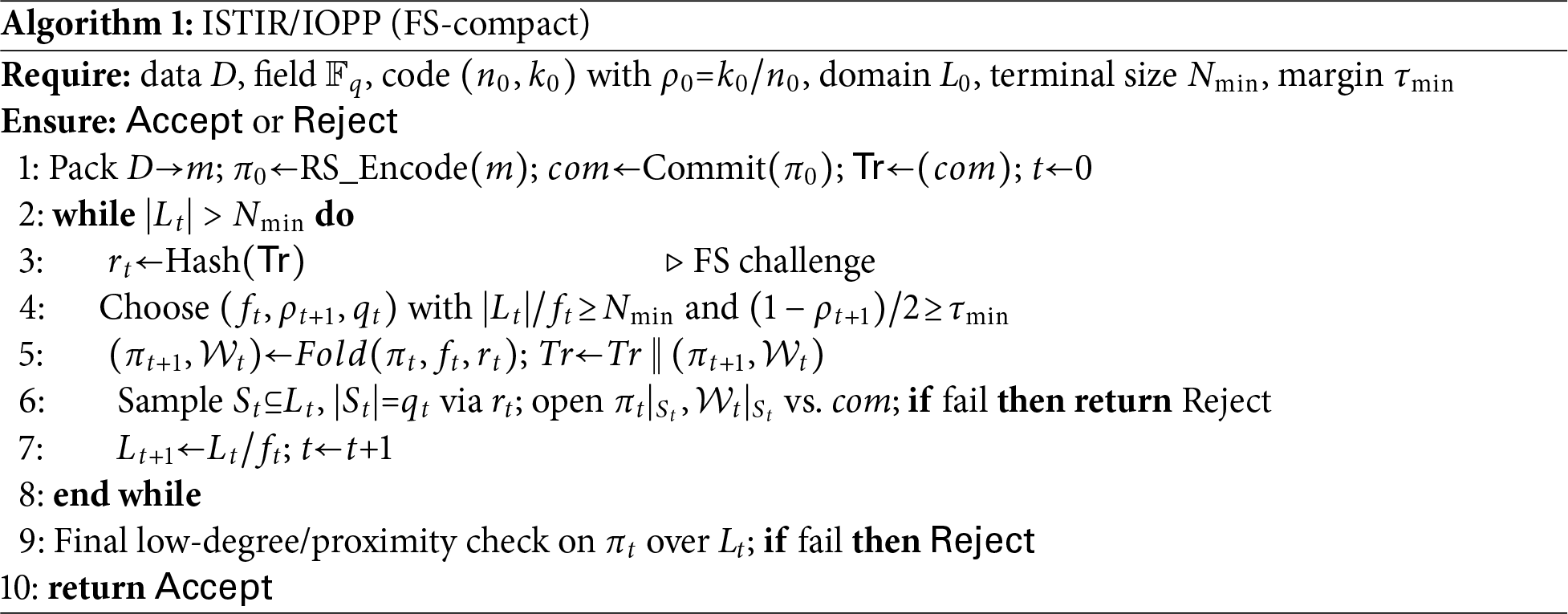

Algorithm 1 gives the Fiat-Shamir compact form of the interactive protocol described above, where the challenge is derived in the random oracle model via

Complexity Parameters.

The protocol involves a total of

In the final stage, the prover additionally sends

In addition, the verifier may submit up to

4.3.1 Defining the Suitable Transcript Set

In an interactive ISTIR protocol, a partial transcript is any prefix of the interaction between the prover and the verifier.

The lucky set consists of partial prover transcripts that satisfy algebraic collision and proximity conditions. In round

Formally, the lucky set contains all partial transcripts for which either

Definition 1 (Lucky Set for ISTIR). Define the unique decoding radius as

A partial transcript of the form

(a) The symbol vector

(b) There exists some element

Furthermore, a partial transcript

The definition of the bad set is relative to the lucky set. A partial transcript is considered part of the bad set if it is not contained in the lucky set and satisfies certain specific “bad” conditions. These conditions include: the prover’s final oracle message does not match the intended codeword; or in some round, the oracle deviates from its expected codeword; or the oracle is closer to an incorrect codeword and fails to preserve the folding structure.

Definition 2 (Bad Set in ISTIR). The unique decoding radius is given by

(a)

(b) there exists some

(c) for every

4.3.2 Four Fundamental Properties of Opening Consistency

No Luck. We need to show that for every

During every round of interaction, the verifier selects a random challenge, and the prover replies based on that challenge. By analyzing the folding of functions, hash operations, and codeword distances within the ISTIR protocol, we can compute the probability that a transcript is extended into the lucky set under certain conditions. For example, given

Lemma 1 (No Luck). ISTIR satisfies the No Luck property, and

Proof. Fix

In what follows, fix an arbitrary

Define

Bad is Rejected. Suppose

If a transcript T lies in the bad set, then by the definition of

Lemma 2 (Bad is Rejected). ISTIR satisfies the property that any transcript labeled as “Bad” will be rejected by the verifier during the opening consistency process.

Proof. Consider

Now consider the case where

Suitability is Close. Let

According to the definitions of suitable transcripts, as well as those of

Lemma 3 (Suitable is Close). ISTIR satisfies the “suitability is close” of opening consistency.

Proof. Suppose

Inconsisteny is Rejected. Suppose

Lemma 4 (Inconsistency is Rejected). ISTIR satisfies the property of inconsistency rejection for opening consistency.

Proof. Recall that suitability implies

Now, there must exist a query location

Moreover, since there exists a query

By the definition of the minimal index

We formally state the opening consistency property of ISTIR in the next theorem.

Theorem 1 (Opening Consistency of ISTIR). ISTIR satisfies opening consistency relative to the formal definitions of

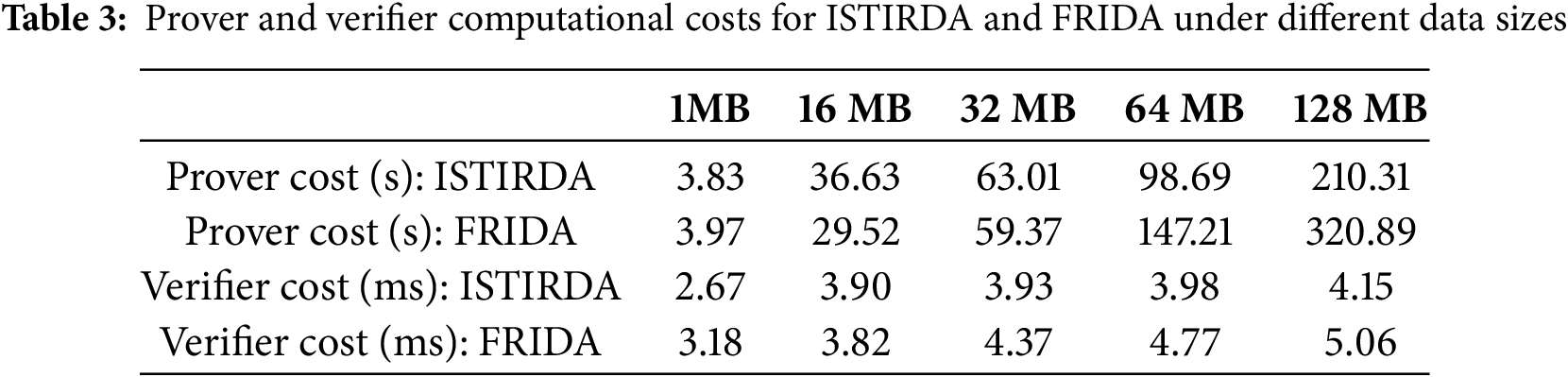

In this section, we conduct a detailed performance evaluation of ISTIRDA. Our evaluation metrics include communication cost, verification time and Time-to-Confidence (TTC). For communication cost and verification time, the schemes compared include Naive, Merkle, FRIDA, and ISTIRDA. Naive and Merkle are used as baseline schemes. Our experimental environment is built on a single machine, equipped with an Intel Core i7-9750H CPU running at 2.6 GHz, 16 GB of RAM, and a 64-bit Ubuntu 14.04 LTS operating system. We use Python 3.8 for implementation. This setup ensures reliable and accurate results. To illustrate system-level behavior, we measure TTC and compare only FRIDA and ISTIRDA. Because ISTIRDA targets permissionless public blockchains, we evaluate it in a controlled peer-to-peer emulation rather than a live network. One proposer process and 10–460 light-client processes run on a single physical host, and we inject latency and packet loss via Linux tc/netem to approximate wide-area blockchain conditions. This preserves the protocol’s logical one-to-many dissemination while giving us strict control over network parameters. We report TTC, defined as the wall-clock time for a light client to reach the target availability confidence. TTC is measured under fixed protocol and network parameters (block size, sampling rate

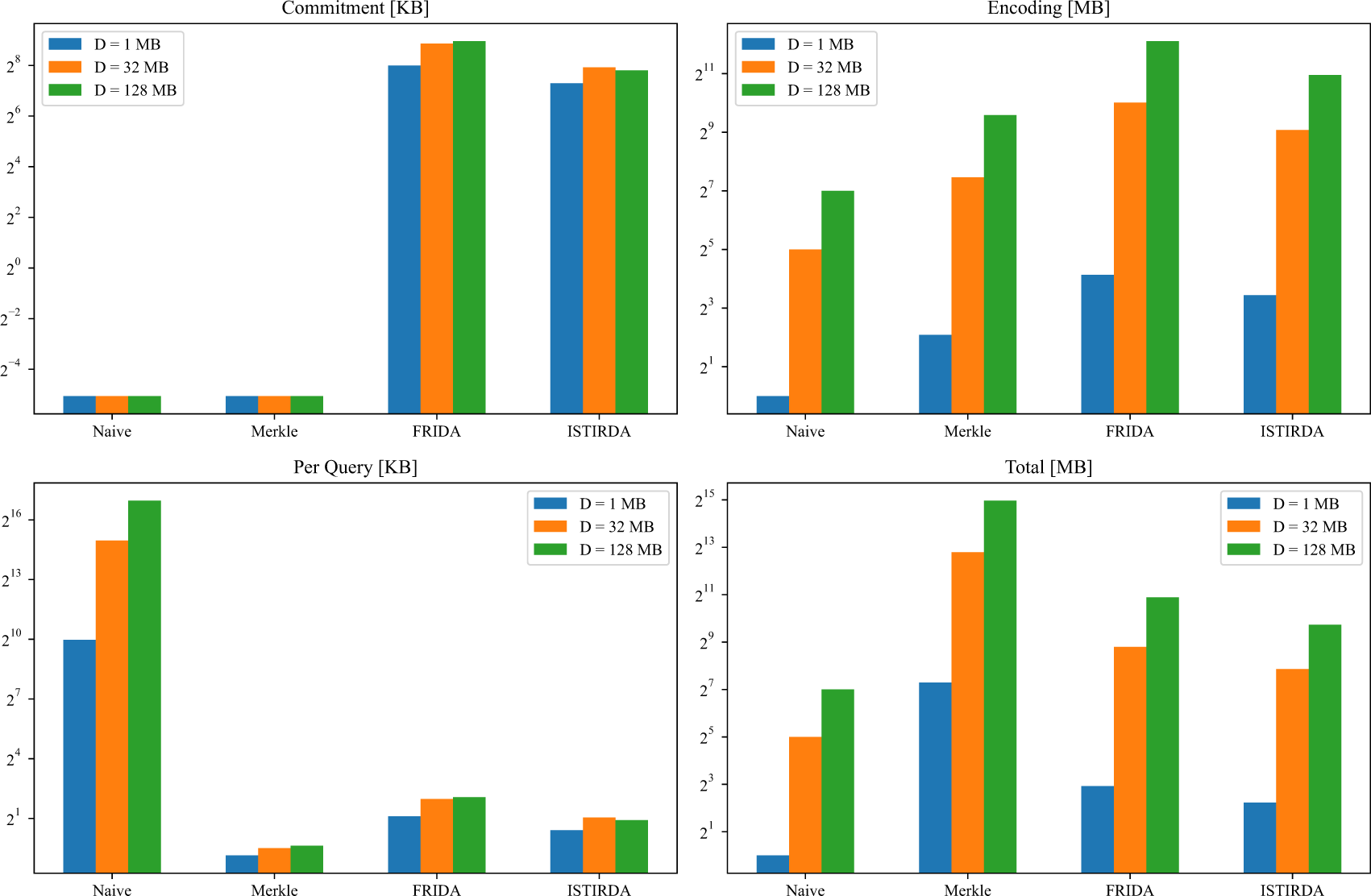

For different encoded data sizes

Fig. 4 presents a performance comparison among ISTIRDA, FRIDA, and other baseline schemes (Naive, Merkle) under different data sizes (

Figure 4: Performance comparison of data availability schemes across multiple metrics and data sizes

Prover computational time. In our tested dataset, the prover’s computational time for ISTIRDA is slightly longer compared to FRIDA. According to measurements, its slowdown ranges from approximately

Verifier computational time. The data shows that when the data size

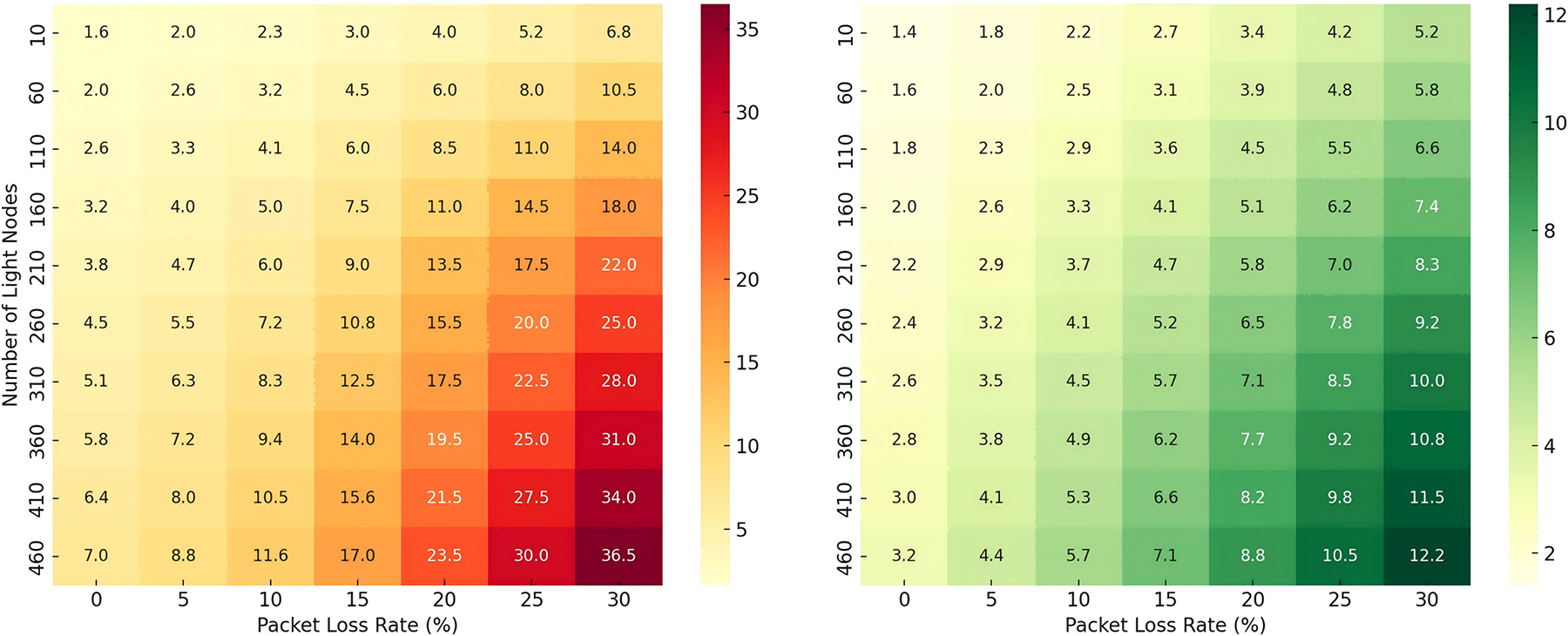

Fig. 5 shows how the time to reach a confident decision varies with node count and packet loss. We observe that as node count and packet loss increase, FRIDA’s TTC rises sharply, indicating that it becomes increasingly sensitive to load concentration. In contrast, ISTIRDA’s TTC curve is much flatter, indicating that its distributed P2P collaborative architecture shares the load and maintains relatively fast convergence to confidence. Thus, under large-scale or degraded network conditions, ISTIRDA exhibits a clear robustness advantage over FRIDA.

Figure 5: Heatmaps of TTC. The x-axis represents node count, the y-axis represents packet loss rate, and the color gradient indicates the time to reach a confident inference. (a) FRIDA; (b) ISTIRDA

ISTIRDA improves upon DAS through rate-adaptive RS-IOPP (ISTIR), reducing the evaluation scope without sacrificing reliability. Experiments demonstrate that ISTIRDA significantly reduces communication and verifier time compared to Naive, Merkle, and FRIDA, especially for large data sizes (e.g., >16 MB), while only adding a small amount of prover overhead. TTC results demonstrate that, under matched reliability and typical bandwidth/loss conditions, ISTIRDA reaches the target availability confidence level faster, and its advantage increases with increasing block size or deteriorating network conditions. This makes ISTIRDA a reliable, scalable, and secure choice for lightweight clients.

This work demonstrates both the theoretical soundness and the practical feasibility of ISTIRDA for public blockchains using a controlled peer-to-peer emulation. Future efforts will move beyond single-machine tc/netem simulations toward physical multi-node testbeds and public testnets instrumented for heterogeneous latency, churn, and loss. A prototype light client integrated into an existing blockchain client (e.g., Geth or Nethermind) will enable end-to-end measurements of bandwidth, CPU/memory footprint, TTC, and failure modes under live consensus dynamics. The comparative scope will expand to emerging data availability designs, including 2D erasure-coded DA chains and ML-guided adaptive sampling to dynamically optimize parameters like folding ratio in response to network conditions, thereby maximizing efficiency while preserving soundness. These evaluations will stress-test scalability and robustness across data scales and adversarial conditions. Finally, compatibility with Layer-2 systems will be explored by sampling published batch data and exposing a lightweight API for provers and light clients, with experiments mapping batch size, sampling rate, and security margins to L1/L2 throughput and latency.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the Key Lab of Education Blockchain and Intelligent Technology, Ministry of Education for supporting this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Research Fund of Key Lab of Education Blockchain and Intelligent Technology, Ministry of Education (EBME25-F-08).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jiaxi Wang; methodology, Jiaxi Wang; validation, Jiaxi Wang; investigation, Wenbo Sun; resources, Ziyuan Zhou; writing—original draft preparation, Jiaxi Wang; writing—review and editing, Shihua Wu; visualization, Jiaxi Wang; supervision, Shan Ji; project administration, Jiang Xu; funding acquisition, Shan Ji. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chang V, Baudier P, Zhang H, Xu Q, Zhang J, Arami M. How Blockchain can impact financial services—the overview, challenges and recommendations from expert interviewees. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2020;158(6):120166. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Patel R, Migliavacca M, Oriani ME. Blockchain in banking and finance: a bibliometric review. Res Int Bus Finance. 2022;62(4–5):101718. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kowalski M, Lee ZWY, Chan TKH. Blockchain technology and trust relationships in trade finance. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;166:120641. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Han Y, Fang X. Systematic review of adopting blockchain in supply chain management: bibliometric analysis and theme discussion. Intl J Prod Res. 2024;62(3):991–1016. doi:10.1080/00207543.2023.2236241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Surucu-Balci E, Iris Ç, Balci G. Digital information in maritime supply chains with blockchain and cloud platforms: supply chain capabilities, barriers, and research opportunities. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2024;198(16):122978. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ren Y, Leng Y, Qi J, Sharma PK, Wang J, Almakhadmeh Z, et al. Multiple cloud storage mechanism based on blockchain in smart homes. Fut Gener Comput Syst. 2021;115(3):304–13. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Miao J, Wang Z, Wu Z, Ning X, Tiwari P. A blockchain-enabled privacy-preserving authentication management protocol for Internet of Medical Things. Exp Syst Appl. 2024;237(1):121329. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Samadhiya A, Kumar A, Arturo Garza-Reyes J, Luthra S, del Olmo García F. Unlock the potential: unveiling the untapped possibilities of blockchain technology in revolutionizing Internet of medical things-based environments through systematic review and future research propositions. Inf Sci. 2024;661(14):120140. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou X, Huang W, Liang W, Yan Z, Ma J, Pan Y, et al. Federated distillation and blockchain empowered secure knowledge sharing for Internet of medical Things. Inf Sci. 2024;662(4):120217. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yan Z, Zhao X, Liu YA, Luo XR. Blockchain-driven decentralized identity management: an interdisciplinary review and research agenda. Inf Manag. 2024;61(7):104026. [Google Scholar]

11. Al Sibahee MA, Abduljabbar ZA, Ngueilbaye A, Luo C, Li J, Huang Y, et al. Blockchain-based authentication schemes in smart environments: a systematic literature review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(21):34774–96. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3422678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shen H, Wang T, Chen J, Tao Y, Chen F. Blockchain-based batch authentication scheme for internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(6):7866–79. doi:10.1109/tvt.2024.3355711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang C, Wang C, Shen J, Vasilakos AV, Wang B, Wang W. Efficient batch verification and privacy-preserving data aggregation scheme in V2G networks. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2025;74(8):12029–12041. doi:10.1109/tvt.2025.3552494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sun L, Wang Y, Ren Y, Xia F. Path signature-based XAI-enabled network time series classification. Sci China Inform Sci. 2024;67(7):170305. doi:10.1007/s11432-023-3978-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rebello GAF, Camilo GF, de Souza LAC, Potop-Butucaru M, de Amorim MD, Campista MEM, et al. A survey on blockchain scalability: from hardware to layer-two protocols. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2024;26(4):2411–58. [Google Scholar]

16. Yaish A, Qin K, Zhou L, Zohar A, Gervais A. Speculative denial-of-service attacks in ethereum. In: 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24). Philadelphia, PA, USA: USENIX Association; 2024. p. 3531–48. [Google Scholar]

17. Ren Y, Lv Z, Xiong NN, Wang J. HCNCT: a cross-chain interaction scheme for the blockchain-based metaverse. ACM Trans Multimed Comput Commun Appl. 2024;20(7):1–23. doi:10.1145/3594542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sheng X, Wang C, Shen J, Sattamuthu H, Radhakrishnan N. Verifiable private data access control in consumer electronics for smart cities. IEEE Consumer Electron Magaz. 2025;14(6):100–6. doi:10.1109/mce.2024.3524750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chatzigiannis P, Baldimtsi F, Chalkias K. SoK: blockchain light clients. In: Eyal I, Garay J, editors. Financial cryptography and data security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 615–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-18283-9_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zong J, Wang C, Shen J, Su C, Wang W. ReLAC: revocable and lightweight access control with blockchain for smart consumer electronics. IEEE Trans Consumer Electron. 2024;70(1):3994–4004. doi:10.1109/tce.2023.3279652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zamyatin A, Avarikioti Z, Perez D, Knottenbelt WJ. TxChain: efficient cryptocurrency light clients via contingent transaction aggregation. In: Garcia-Alfaro J, Navarro-Arribas G, Herrera-Joancomarti J, editors. Data privacy management, cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 269–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-66172-4_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Al-Bassam M, Sonnino A, Buterin V, Khoffi I. Fraud and data availability proofs: detecting invalid blocks in light clients. In: Borisov N, Diaz C, editors. Financial cryptography and data security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 279–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-64331-0_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hall-Andersen M, Simkin M, Wagner B. Foundations of data availability sampling. IACR Commun Cryptol. 2023;1(4):79. doi:10.62056/a09qudhdj. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Reed IS, Solomon G. Polynomial codes over certain finite fields. J Soc Ind Appl Math. 1960;8(2):300–4. doi:10.1137/0108018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kate A, Zaverucha GM, Goldberg I. Constant-size commitments to polynomials and their applications. In: Abe M, editor. ASIACRYPT 2010: Advances in Cryptology. Vol. 6477. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. p. 177–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17373-8_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hall-Andersen M, Simkin M, Wagner B. FRIDA: data availability sampling from FRI. In: Reyzin L, Stebila D, editors. Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 289–324 doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-68391-6_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ben-Sasson E, Bentov I, Horesh Y, Riabzev M. Fast reed-solomon interactive oracle proofs of proximity. In: Chatzigiannakis I, Kaklamanis C, Marx D, Sannella D, editors. 45th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming (ICALP 2018). Vol. 107. Dagstuhl, Germany: Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik; 2018. p. 14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

28. Ben-Sasson E, Carmon D, Ishai Y, Kopparty S, Saraf S. Proximity gaps for reed-solomon codes. In: 2020 IEEE 61st Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 900–9. [Google Scholar]

29. Arnon G, Chiesa A, Fenzi G, Yogev E. STIR: reed-solomon proximity testing with fewer queries. In: Reyzin L, Stebila D, editors. Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 380–413. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-68403-6_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yu M, Sahraei S, Li S, Avestimehr S, Kannan S, Viswanath P. Coded merkle tree: solving data availability attacks in blockchains. In: Bonneau J, Heninger N, editors. Financial cryptography and data security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 114–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-51280-4_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sheng P, Xue B, Kannan S, Viswanath P. ACeD: scalable data availability oracle. In: Borisov N, Diaz C, editors. Financial cryptography and data security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 299–318. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-64331-0_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nazirkhanova K, Neu J, Tse D. Information dispersal with provable retrievability for rollups. In: Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies, AFT ’22. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 180–97. doi:10.1145/3558535.3559778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wagner B, Zapico A. A documentation of Ethereum’s PeerDAS. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2024. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools