Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design of a Patrol and Security Robot with Semantic Mapping and Obstacle Avoidance System Using RGB-D Camera and LiDAR

Department of Electrical Engineering, Ming Chuan University, No. 5 De Ming Rd., Gui Shan District, Taoyuan, 333, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Shu-Yin Chiang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 72 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074528

Received 13 October 2025; Accepted 10 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

This paper presents an intelligent patrol and security robot integrating 2D LiDAR and RGB-D vision sensors to achieve semantic simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), real-time object recognition, and dynamic obstacle avoidance. The system employs the YOLOv7 deep-learning framework for semantic detection and SLAM for localization and mapping, fusing geometric and visual data to build a high-fidelity 2D semantic map. This map enables the robot to identify and project object information for improved situational awareness. Experimental results show that object recognition reached 95.4% mAP@0.5. Semantic completeness increased from 68.7% (single view) to 94.1% (multi-view) with an average position error of 3.1 cm. During navigation, the robot achieved 98.0% reliability, avoided moving obstacles in 90.0% of encounters, and replanned paths in 0.42 s on average. The integration of LiDAR-based SLAM with deep-learning–driven semantic perception establishes a robust foundation for intelligent, adaptive, and safe robotic navigation in dynamic environments.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of intelligent robotics and artificial intelligence (AI), supporting traditional industries through digital transformation has become an important direction in modern research. In the security sector—where personnel are responsible for anti-theft patrols, disaster prevention, and facility monitoring—the growing challenges of labor shortages and aging populations make automated assistance increasingly valuable. Security tasks typically require long working hours and frequent night patrols, placing significant physical and cognitive strain on human workers. Introducing AI-driven robotic systems can alleviate workload, enhance operational efficiency, and modernize traditional security services.

Despite progress in robotics, certain security operations—such as physically responding to intruders—remain difficult to automate fully. Therefore, this study focuses on developing an intelligent security robot designed to patrol, detect, record, and report events, thereby augmenting rather than replacing human guards. Commercial systems such as the Knightscope K5, Sharp INTELLOS, and Rover-S5 have demonstrated the feasibility of automated surveillance using wheeled mobile platforms and LiDAR-based perception.

In academic research, security robots generally fall into categories including single-robot patrol, multi-robot collaboration, and human–robot cooperative systems. Jullie Josephine et al. [1] developed a mobile patrol robot for human–intruder recognition, while Aggravi et al. [2] proposed a human-supervised multi-robot surveillance framework. Other works have applied patrol robots to equipment inspection [3], gas-leak detection [4], and irregular patrol scheduling [5]. Additional studies explored night-vision systems [6], optimized path planning [7], depth-based obstacle avoidance [8], neural-network-enhanced localization [9], and CNN-based distributed patrol systems [10].

Further innovations include multi-sensor fusion for safer navigation. Sawano et al. [11] integrated GNSS, LiDAR, infrared sensors, and Bluetooth for personnel tracking, while Khalid et al. [12] employed GPS and AI cameras for anomaly detection. Deep-learning-based perception also plays a significant role, demonstrated by systems that combine segmentation with depth sensing [13], hierarchical multi-robot coordination with 3D SLAM [14], and reinforcement learning for improved exploration [15]. For navigation, Dijkstra’s algorithm [16] and A* [17] remain fundamental choices, with A* combining the strengths of best-first search [18] and Dijkstra’s algorithm through a heuristic function f(n) = g(n) + h(n), where g(n) is the travel cost and h(n) is the estimated distance to the goal, enabling efficient optimal-path computation.

Recent developments in semantic SLAM have further advanced robotic perception. Yang and Wang [19] proposed robust semantic SLAM for dynamic outdoor environments, while lightweight semantic mapping architectures have been introduced for low-power platforms [20,21]. Li et al. presented two influential systems in 2024: SD-SLAM [22], capable of distinguishing static and dynamic objects using LiDAR semantics, and Hi-SLAM [23], which integrates hierarchical semantic representations into 3D Gaussian splatting. More recent frameworks [24,25] focus on open-world perception and multimodal semantic fusion, highlighting the growing trend toward unified deep semantic mapping capable of operating reliably in complex environments.

Motivated by these developments, this study proposes a LiDAR + RGB-D fusion SLAM system featuring real-time semantic integration, multi-view fusion, and predictive dynamic obstacle avoidance tailored for indoor security patrol. The system combines machine vision, object recognition, night-vision enhancement, and LiDAR-based geometric mapping to generate a semantically rich representation of the environment. The goal is to enable an intelligent patrol robot capable of autonomous navigation, semantic mapping, event detection, and safe obstacle avoidance, thereby enhancing operational efficiency and reducing the burden on human personnel. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the materials and methods, Section 3 describes experimental results and comparative evaluations, and Section 4 concludes the study and discusses future extensions.

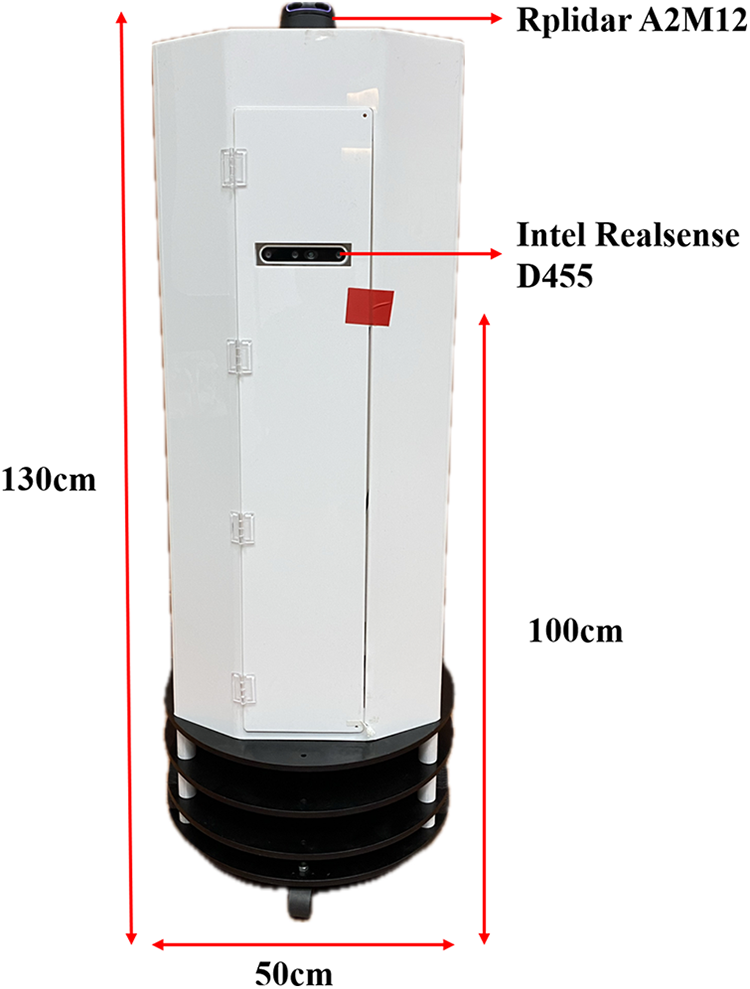

The security robot developed in this study measures approximately 130 cm in height and 50 cm in width. It adopts a differential-drive chassis, powered by two DYNAMIXEL XM540 servo motors that independently control the left and right wheels, enabling precise linear and rotational motion. The robot is equipped with two primary perception sensors: an RPLIDAR A2M12 laser scanner and an Intel RealSense D455 RGB-D camera, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hardware architecture of the proposed security robot integrating LiDAR and RGB-D camera

The RPLIDAR A2M12, mounted on the upper section of the robot and vertically aligned with the depth camera, performs 2D LiDAR-based SLAM, generating a real-time occupancy grid map used for localization and navigation. The Intel RealSense D455, positioned approximately 100 cm above the ground within the robot’s torso, captures synchronized RGB and depth frames, enabling semantic perception and distance estimation. The RGB images are processed using the YOLOv7 deep-learning framework for object detection, while the depth data provide metric information for spatial positioning. The fusion of LiDAR geometry and RGB-D semantics establishes a robust multi-sensor perception framework suitable for complex indoor environments.

All experiments were conducted using ROS 1 (Noetic Ninjemys) running on an ASUS ROG Zephyrus G14 (2021) laptop equipped with an AMD Ryzen 9-4900HS (8 cores, 3.0–4.3 GHz), an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU (6 GB GDDR6), and 32 GB RAM, operating under Ubuntu 20.04 LTS. The perception and control modules were implemented in Python 3.8 within the ROS Noetic middleware, enabling modular integration of mapping, detection, and navigation functions.

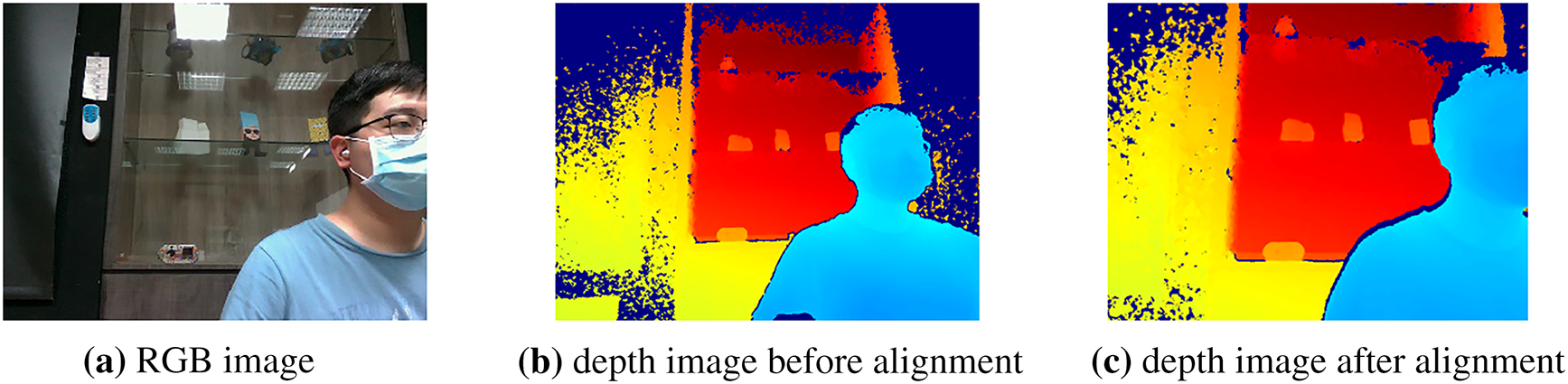

This study focuses on constructing an environmental semantic map and an obstacle avoidance system through the fusion of RGB and depth information. Because the object recognition pipeline depends on pixel-level correspondence between color and depth frames, accurate alignment between the RGB and depth images of the Intel RealSense D455 is essential. Although both streams are captured at a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels, the physical baseline and intrinsic differences between the RGB and depth sensors cause noticeable spatial displacement. Therefore, an image alignment step must be performed prior to data fusion [26].

As shown in Fig. 2, 2a presents the RGB image, Fig. 2b shows the raw depth image before alignment, and Fig. 2c displays the corrected result. Without alignment, depth values sampled at a given pixel location may correspond to a different point in space, producing incorrect distance measurements and degraded semantic mapping. To visualize the disparity, the depth frames in Fig. 2b,c are stored as 16-bit integers and normalized to a 0–255 color scale.

Figure 2: Differences before and after alignment of RGB images and depth image

The alignment process is implemented using the align_to() function provided by the Intel RealSense SDK, which performs an intrinsic-aware affine projection from the depth coordinate system to the RGB optical frame. The transformation can be expressed in (1) as:

where

After alignment, each depth pixel is mapped to the corresponding RGB location, enabling accurate pixel-wise fusion for object detection and semantic labeling. The aligned depth images are then used to segment RGB regions of interest and estimate object distance, significantly improving the reliability of the semantic map. Additionally, precise depth–RGB alignment is crucial for the downstream multi-view semantic fusion process. Since semantic labels from different viewpoints are re-projected into a global LiDAR frame, misalignment at the sensor level would accumulate and cause semantic drift or fragmented object masks. By ensuring consistent pixel correspondence, the aligned RGB-D data provide a reliable foundation for robust multi-sensor fusion, improving object consistency across multiple views.

2.2 Construction of Environmental Semantic Map

The RPLIDAR A2M12 mounted on the top of the robot first generates a 2D occupancy grid map of the surrounding environment, which serves as the geometric foundation for navigation. To enrich the geometric map with contextual information, the robot performs semantic object recognition using the Mask R-CNN framework (Fig. 3), which extracts pixel-level object masks and assigns distinct semantic labels.

Figure 3: Semantic object recognition using mask r-cnn

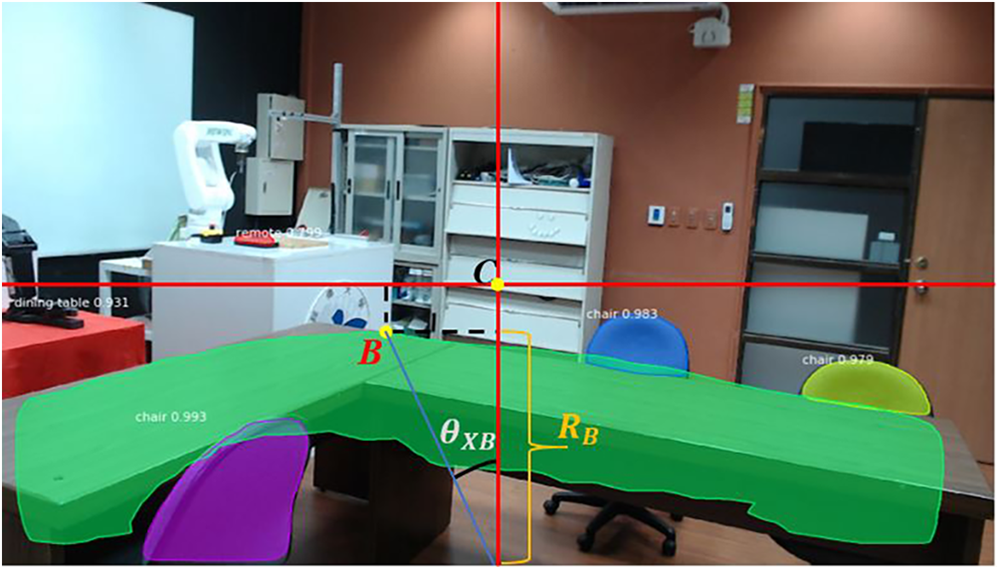

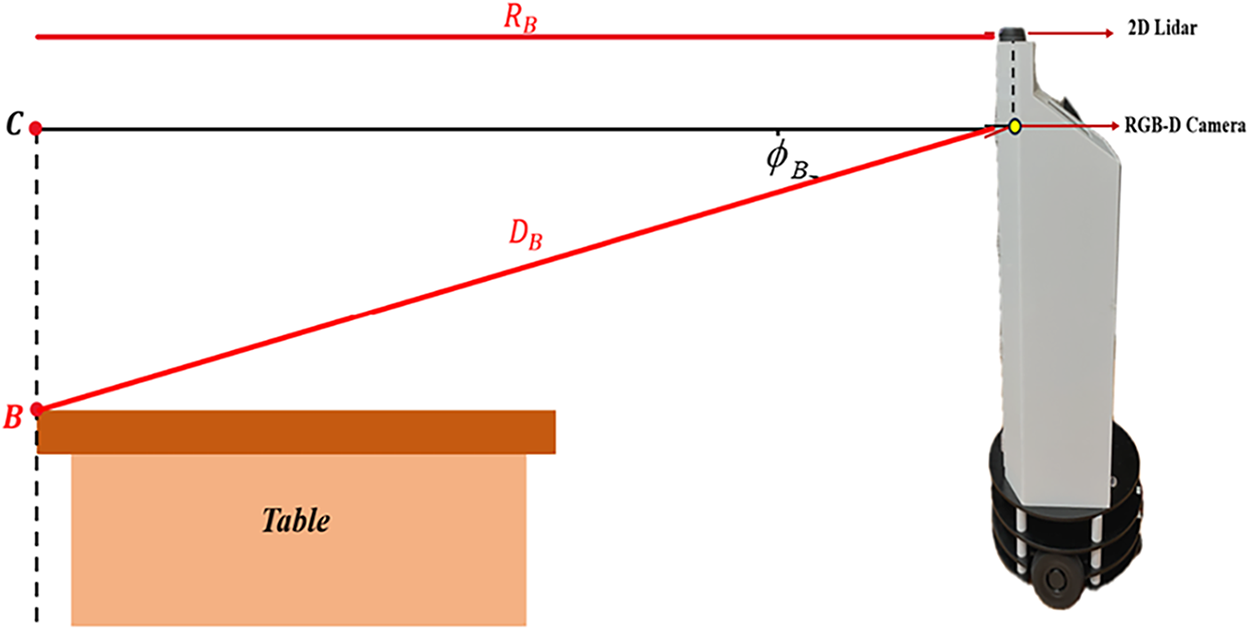

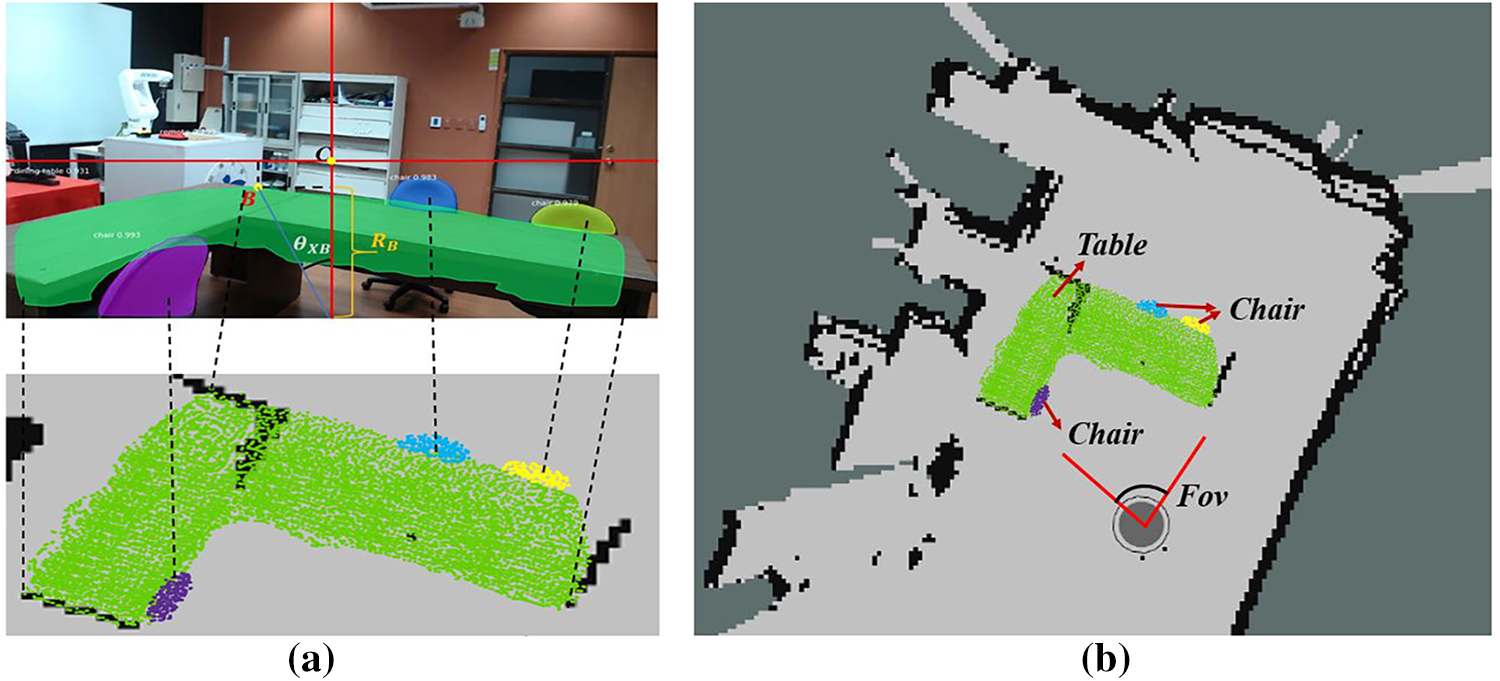

To determine the spatial position of each detected object, the system combines the semantic mask with the depth information from the Intel RealSense D455 RGB-D camera. As shown in Fig. 4, the spatial relationship of an object point B is computed by converting its pixel coordinates to angular offsets and depth-based radial distance.

Figure 4: Distance and angle estimation from RGB-D image perspective

2.2.1 Camera Geometry and Pixel-to-Angle Conversion

The D455 camera has a horizontal field of view (FOV) of 70° and a vertical FOV of 43°, corresponding to focal parameters FX, and FY. The RGB image resolution is 1920 × 1080, with pixel dimensions IX, and IY. As shown in Fig. 5, the image center, C located at (PXC, PYC) serves as the reference for determining the angle and distance of any pixel point, B at (PXB, PYB).

Figure 5: Mask R-CNN object projection and SLAM mapping

The angular resolution per pixel is computed in (2) and (3). The horizontal and vertical angular offsets for point B are then obtained by (4) and (5). Using the depth value DB captured at pixel B, the radial distance to the object is determined using (6), which compensates for the camera’s vertical viewing angle.

2.2.2 Projection of Semantic Objects onto the SLAM Map

Each object point is mapped from the camera frame to the 2D SLAM reference frame through its polar coordinate representation in (7). Similarly, for any pixel N belonging to an object mask, its mapping coordinate is shown in (8). All pixels within the Mask R-CNN segmentation mask are thus projected onto the 2D LiDAR map, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. This process enriches the geometric map with semantic labels, producing a 2D semantic map in Fig. 5b.

As the robot moves through the environment, the system continuously integrates semantic labels, depth geometry, and LiDAR-based SLAM updates, enabling both structural understanding and contextual awareness. This fusion allows the robot to perform semantically informed navigation, such as avoiding identified objects or prioritizing specific target categories during patrol operations.

During robot operation, the RPLIDAR A2M12 continuously performs 2D LiDAR-based SLAM to construct an occupancy grid map of the environment. Simultaneously, the Intel RealSense D455 RGB-D camera captures synchronized color and depth images, which are processed using the YOLOv7 framework for object detection and semantic classification. Once an object is identified, the corresponding depth value is extracted at the detected pixel coordinates, allowing the system to compute the object’s distance and angular position. The resulting spatial information is then transformed into the LiDAR coordinate frame and projected onto the 2D grid map, forming a semantic-enhanced map that incorporates both geometric and contextual cues. This semantic map provides the input for the A* algorithm for global route planning and serves as the basis for real-time obstacle avoidance.

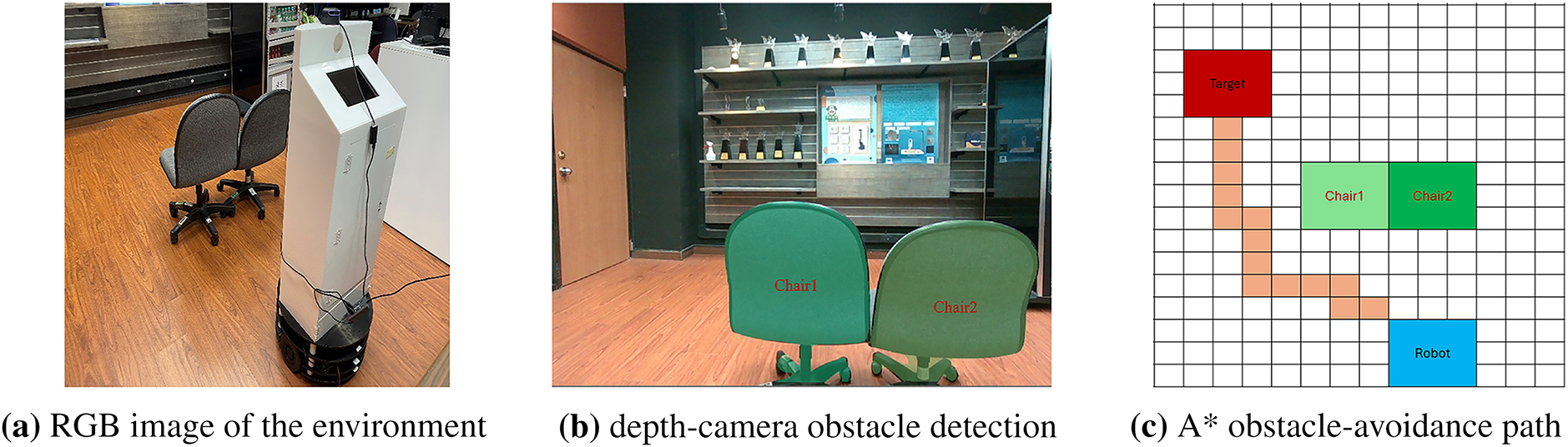

2.3.1 A*-Based Obstacle Avoidance System

The A* algorithm is employed to compute an optimal path through the 2D SLAM map. Fig. 6a shows the initial environment, while Fig. 6b,c illustrates the detection and mapping of static obstacles. The D455 camera identifies the contours and semantic labels of static objects, which are converted into obstacle nodes within the grid map.

Figure 6: RGB view, depth detection, and A* avoidance path

During planning, the A* algorithm evaluates each node using: f(n) = g(n) + h(n), where g(n) is cost accumulated from start to node, and h(n) is heuristic estimate (Euclidean distance) from node n to goal. Nodes corresponding to obstacles (from LiDAR or RGB-D masks) are removed from the traversable set. The algorithm then computes the shortest collision-free path, shown as the orange trajectory in Fig. 6c. This path is passed to the motion controller for precise navigation.

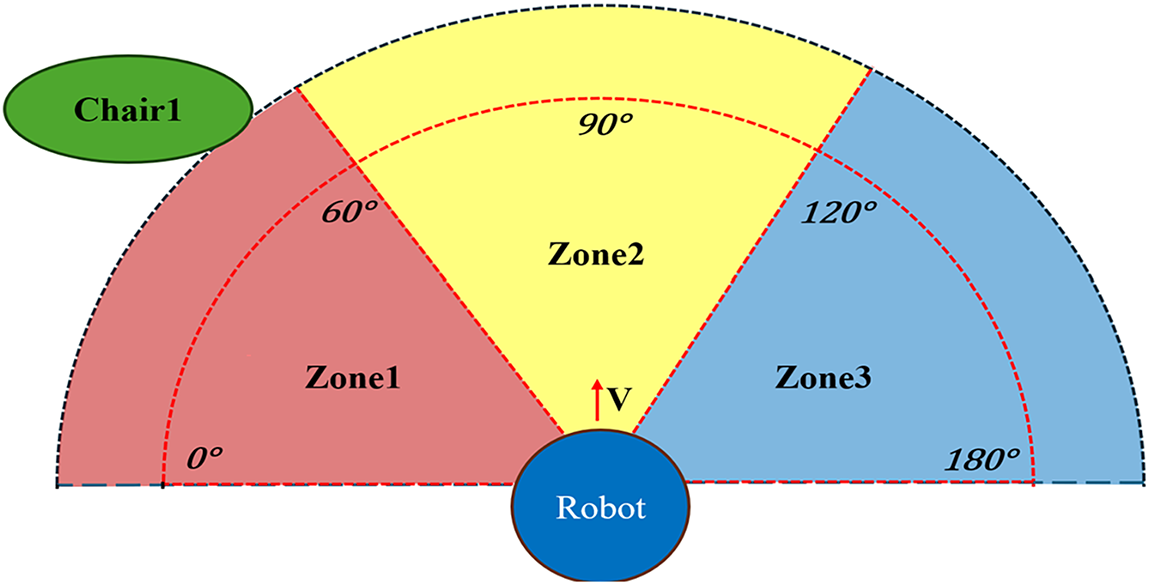

2.3.2 Real-Time Visual Obstacle Avoidance System

During navigation, the robot may encounter unknown obstacles not present in the static map. To ensure safe operation, the RGB-D camera continuously scans a 180° semicircular region in front of the robot. As shown in Fig. 7, this region is divided into three angular zones in (9).

Figure 7: Definition of obstacle angles and zones

(1) Obstacle Localization

The 3D position of an obstacle point is determined using the pinhole camera model in (10).

where (xp, yp, zp) is the point in 3D camera coordinates, and (xc, yc, zc) is the optical center.

(2) Input Fuzzy Variables

Two fuzzy variables are used to guide the motor control behavior. The first variable is the Obstacle Distance D, which is represented by three fuzzy membership sets—Near, Medium, and Far. This relationship can be expressed as in (11). The second variable is the Obstacle Angle θ, which is also divided into three fuzzy membership sets—Left, Center, and Right. Its fuzzy representation is given by (12).

(3) Output Fuzzy Variables

The fuzzy output variables correspond to velocity adjustments for the left and right wheels, as defined in (13):

where

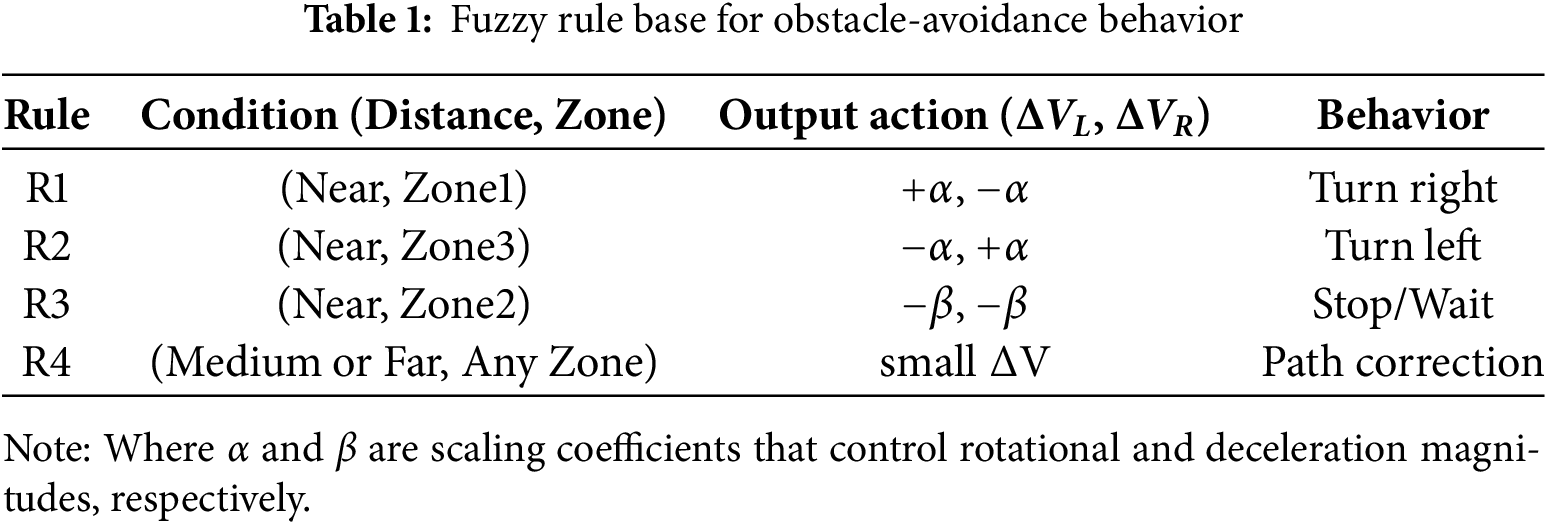

(4) Fuzzy Inference Rules

The robot’s obstacle-avoidance decisions are determined by a fuzzy rule base, as summarized in Table 1.

(5) Defuzzification

The final wheel speed adjustments are obtained using the Center of Gravity (COG) method as shown in (14). This process converts fuzzy control outputs into precise motor commands, ensuring smooth and continuous motion.

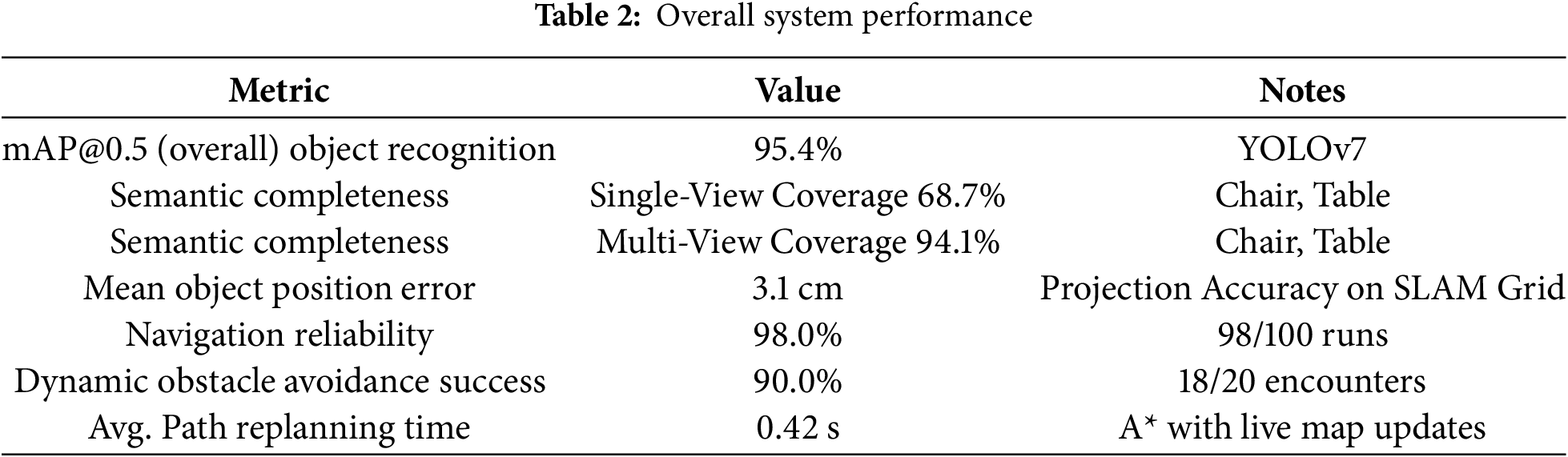

2.3.3 Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance System

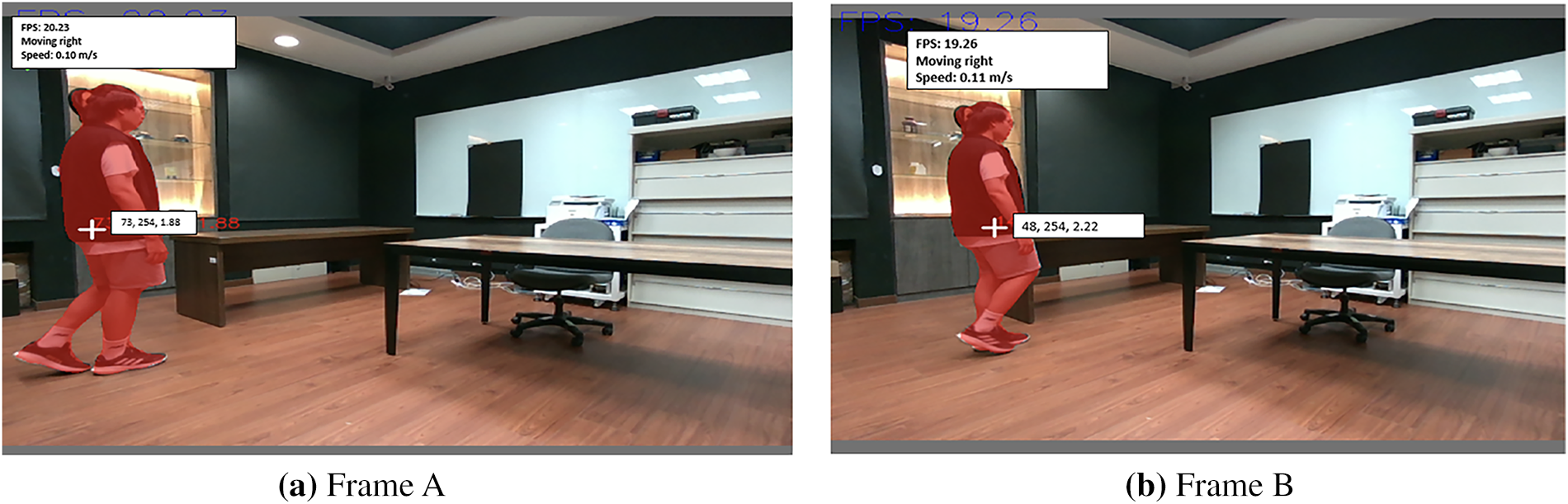

In dynamic environments, moving objects such as pedestrians may appear unpredictably in front of the robot. To ensure safe navigation, the proposed dynamic obstacle avoidance system integrates pixel-motion analysis, depth-based spatial estimation, and predictive trajectory modeling. As illustrated in Fig. 8, a moving person is detected across two consecutive frames, Frame A and Frame B, where the YOLOv7 model identifies the object and extracts its center pixel coordinates. The horizontal and vertical pixel displacements between the frames are computed using (15) and (16), respectively. These pixel shifts represent the apparent motion of the obstacle in the image plane.

Figure 8: Moving person detection and velocity calculation

To convert these pixel displacements into real-world spatial motion, the camera’s intrinsic parameters and the measured depth D are applied. The corresponding metric displacements along the X- and Y-axes are obtained using (17) and (18). Based on these values, the total movement distance of the object is calculated using (19), and its real-world velocity is derived by dividing this displacement by the frame interval Δt, as shown in (20).

To obtain a stable estimate of the object’s future motion, a lightweight Kalman filter is applied. The state vector, which consists of the object’s planar position and velocity, is defined in (21), and its temporal evolution follows the constant-velocity model in (22), where

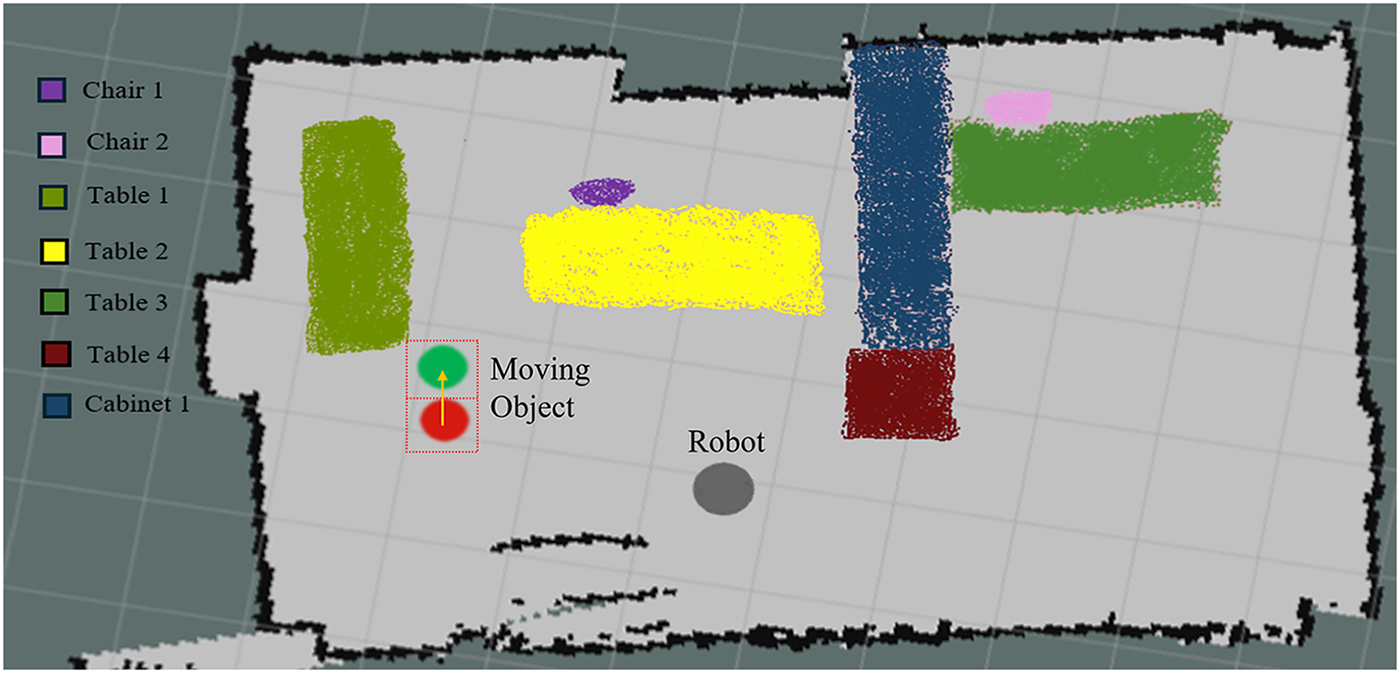

The Kalman filter smooths noisy observations and provides a reliable prediction of the obstacle’s future position. As shown in Fig. 9, the red marker denotes the current detected position of the moving person, while the green marker indicates the predicted future position generated by the Kalman filter. When the predicted point lies on or near the robot’s A* path, the navigation controller proactively adjusts the wheel speeds to steer away from the anticipated collision location or temporarily reduces forward velocity. This predictive strategy enables smooth, anticipatory avoidance behavior and ensures safe robot operation in indoor environments where humans or objects may be in motion.

Figure 9: 2D Semantic map for predicted moving object positions

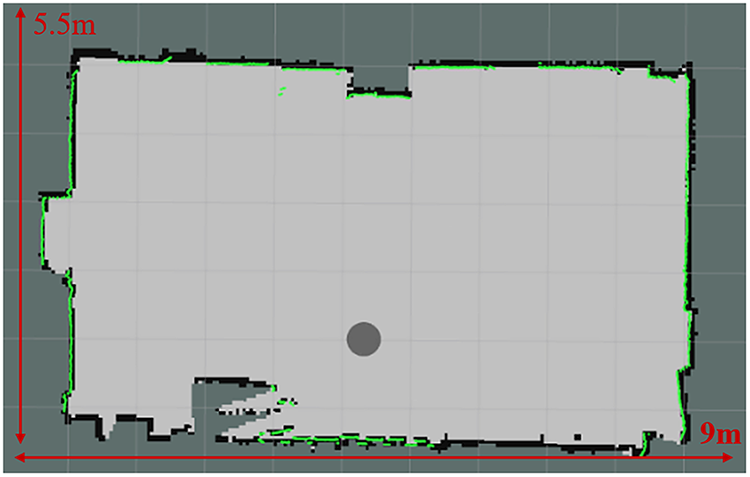

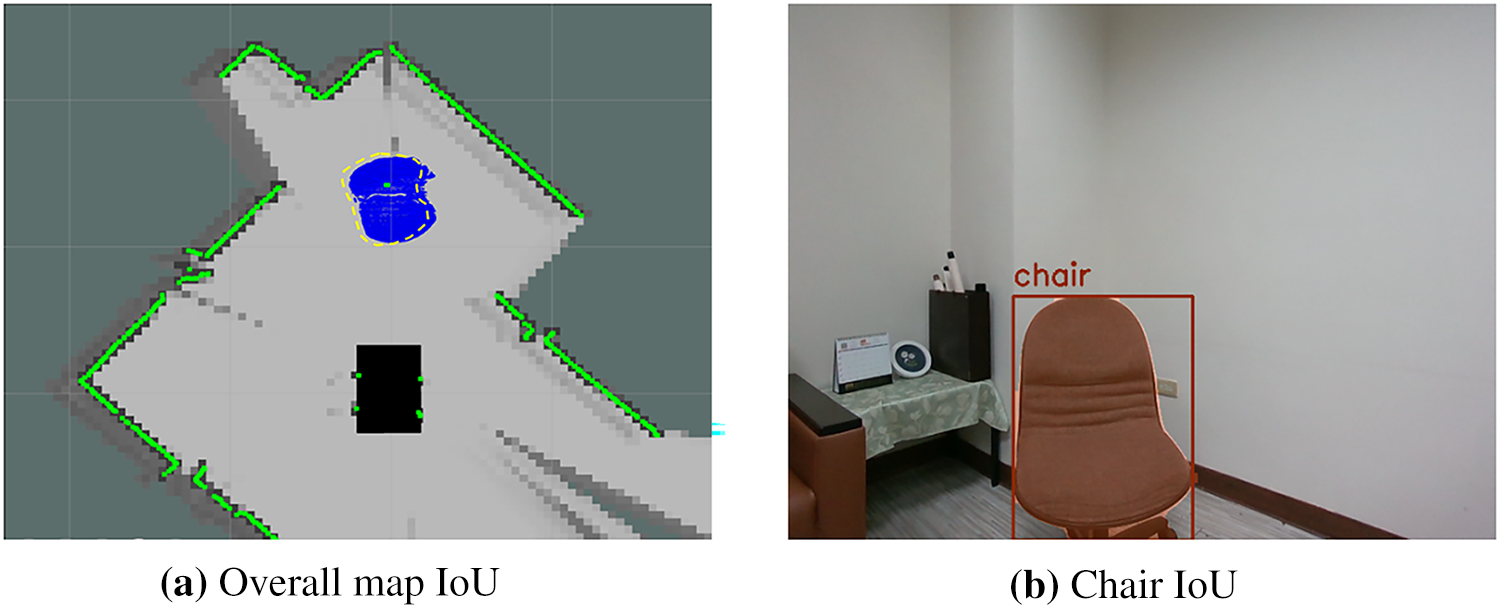

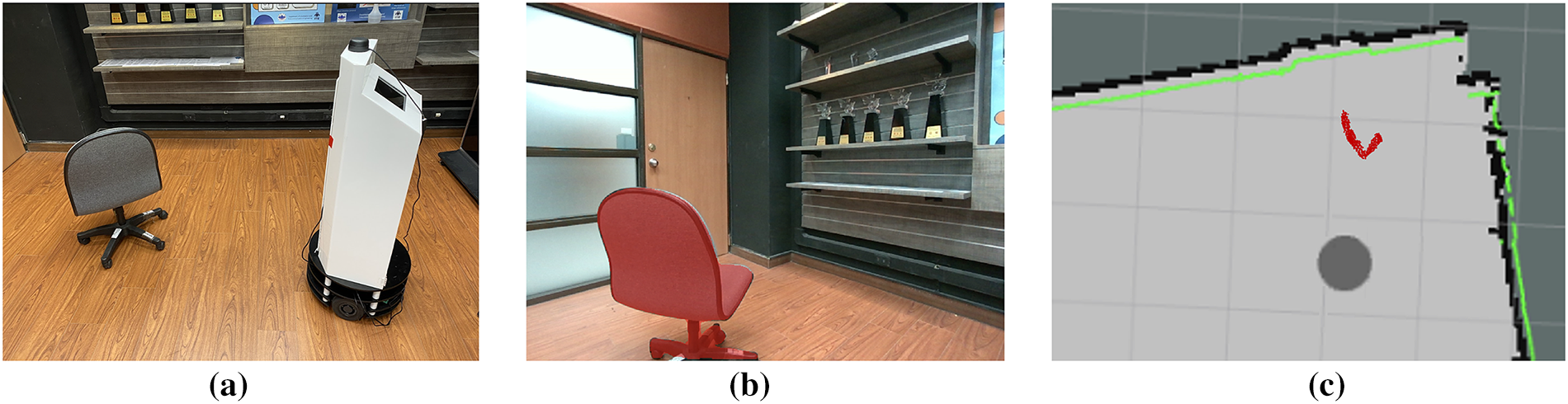

The first indoor classroom environment, measuring approximately 9 by 5.5 m, was used to construct the baseline geometric map using the 2D LiDAR-based SLAM system. The resulting occupancy grid map is shown in Fig. 10, where gray regions represent free and navigable space, black cells denote walls and fixed obstacles, and green points correspond to real-time LiDAR reflections. Each grid cell measures 1 m × 1 m, and the reconstructed structure accurately reflects the physical dimensions of the classroom, providing a reliable geometric foundation for subsequent semantic mapping experiments.

Figure 10: 2D grid map of the experimental environment

To evaluate the contribution of different sensing modalities, a second indoor classroom environment—shown in Fig. 11—was used for a multi-sensor ablation study. The LiDAR-only map in Fig. 12 demonstrates globally stable geometry but lacks any semantic information. The RGB-D–only map in Fig. 13 contains semantic cues but exhibits incomplete contours and localized inconsistencies caused by occlusion, depth noise, and limited field of view. In contrast, the fused LiDAR + RGB-D semantic map in Fig. 14 combines LiDAR-based structural accuracy with RGB-D semantic perception, resulting in a more complete and context-rich reconstruction.

Figure 11: Real-world experimental environment

Figure 12: 2D LiDAR-based SLAM map

Figure 13: RGB-D–only mapping result

Figure 14: LiDAR + RGB-D fused semantic map

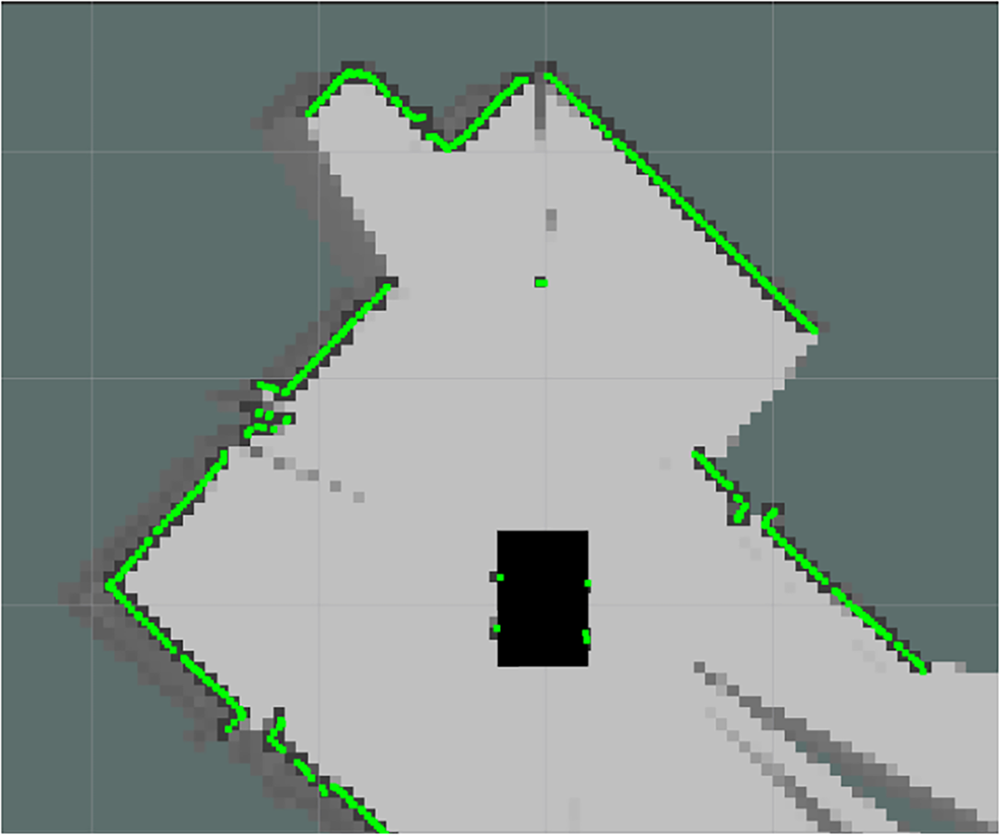

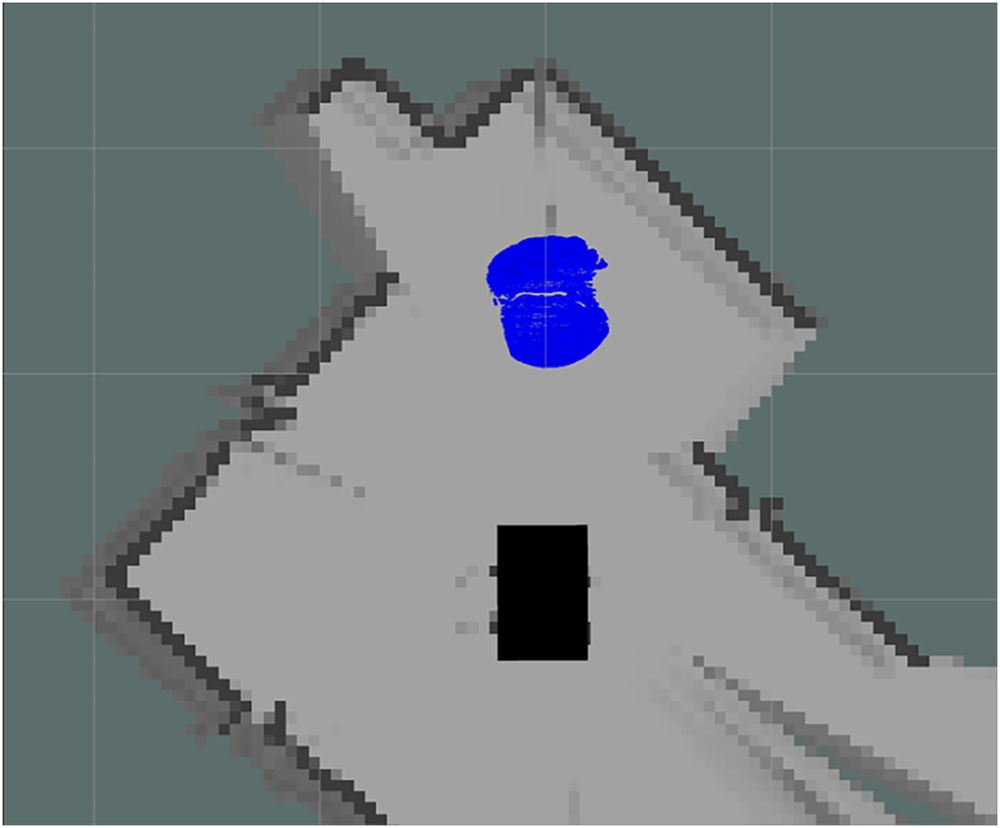

Mapping performance was quantitatively assessed using the Intersection over Union (IoU) metric. For the global map evaluation, IoU is defined in (23). Using the fused LiDAR + RGB-D mapping result, the global map IoU shown in Fig. 15a is calculated in (24). It demonstrating strong agreement between the fused reconstruction and the ground-truth reference layout. Similarly, object-level IoU was computed for a chair to evaluate semantic contour accuracy. The object IoU of corresponding value measured from Fig. 15b is calculated in (25). These quantitative results confirm that the fused LiDAR + RGB-D mapping significantly improves both global map completeness and object-level contour reconstruction compared with single-modality methods.

Figure 15: IoU comparison

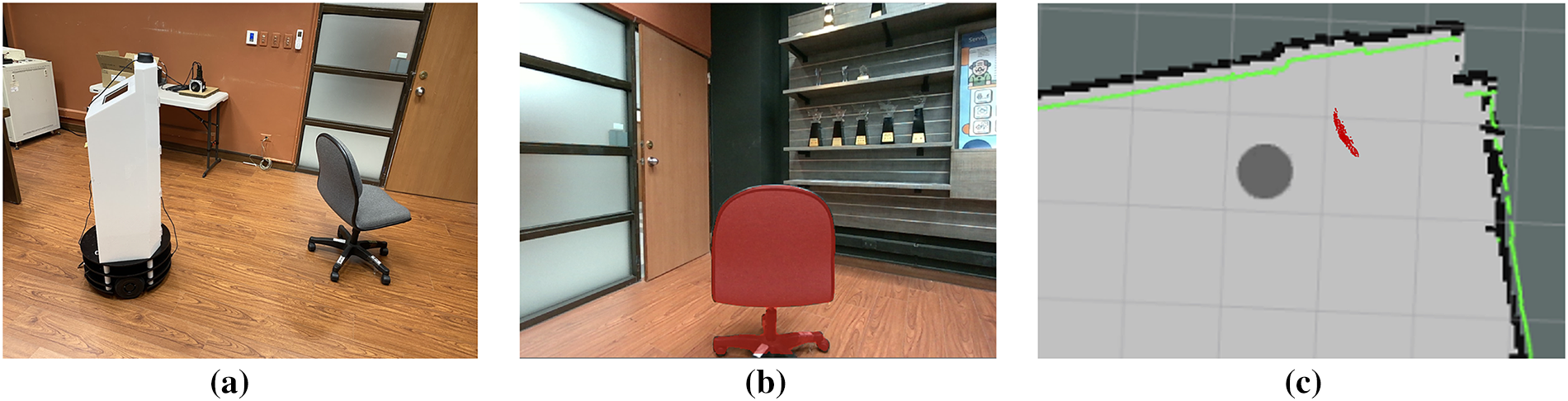

Beyond multi-sensor fusion, the system further enhances semantic completeness through multi-view observation. Figs. 16–18 illustrate how object contours are progressively reconstructed when the robot observes a chair from different viewpoints within the 9 m × 5.5 m classroom. When the robot faces the back of the chair (Fig. 16a), the visible region is limited, and the segmentation result (Fig. 16b) captures only the rear surface. Consequently, the semantic projection onto the SLAM map (Fig. 16c) shows only the chair’s width, with no information about its thickness. This incomplete representation is expected since only a single, restricted viewpoint is available. As the robot moves to an oblique rear angle (Fig. 17a), additional structural features of the chair come into view. The recognition output (Fig. 17b) now includes part of the side panel, and the corresponding semantic projection (Fig. 17c) begins to recover the object’s depth and partial thickness. Although the contour remains incomplete, the accumulated information contributes to a more accurate representation. Finally, when positioned at the side view (Fig. 18a), nearly the entire geometry of the chair becomes visible. The segmentation mask (Fig. 18b) captures the full outline, and the semantic projection (Fig. 18c) reveals a complete and correct reconstruction of both width and thickness. This demonstrates how repeated observations from diverse viewpoints reduce occlusion effects and compensate for missing information in earlier frames.

Figure 16: Semantic map constructed when the robot faces the back of the chair

Figure 17: Semantic map constructed when the robot is positioned at the oblique rear of the chair

Figure 18: Semantic map constructed when the robot is positioned at the side of the chair

Through this iterative multi-view process, semantic evidence from multiple viewpoints is aggregated over time, enabling the system to construct more complete object contours and produce a richer semantic map. This capability is essential for robust navigation, as it allows the robot to understand its environment beyond simple obstacle presence, capturing object shape, orientation, and spatial relationships.

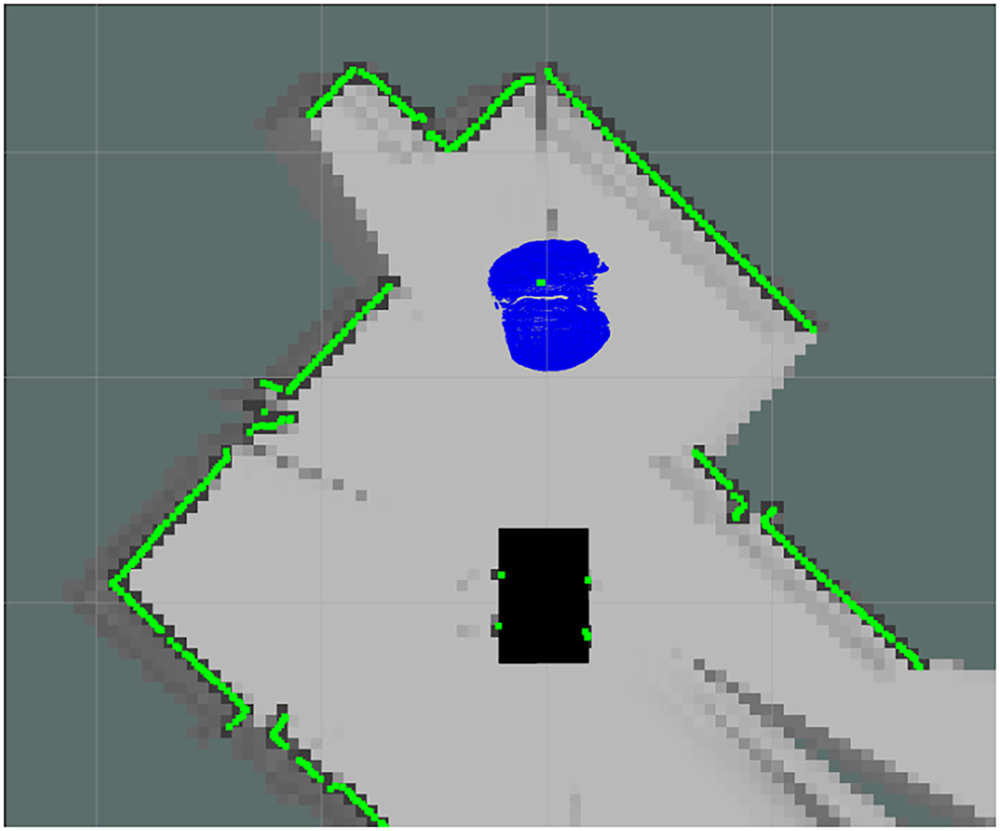

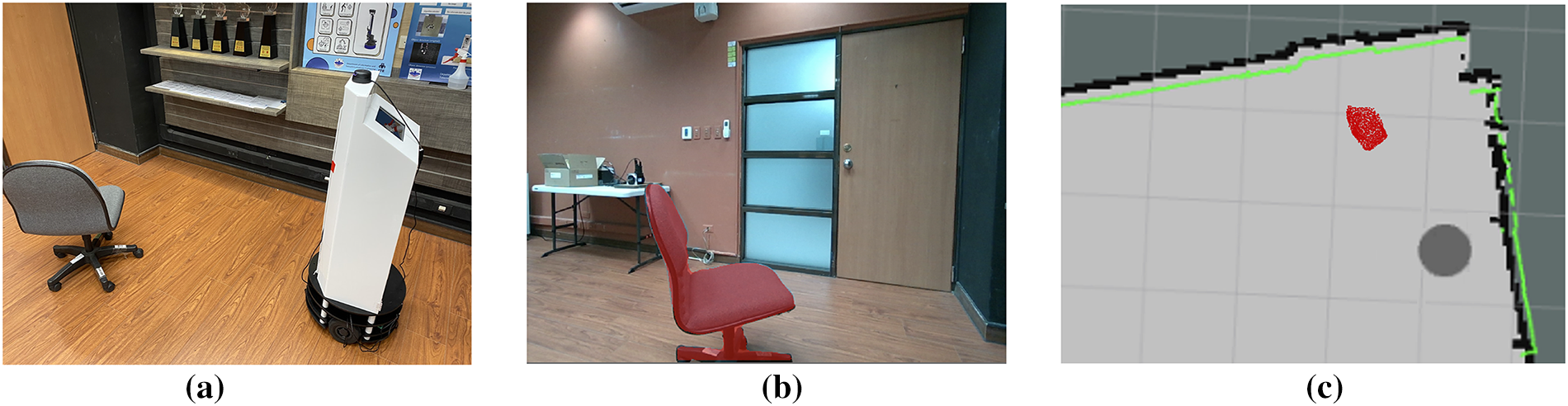

3.2 Dynamic Object Avoidance System

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed perception and dynamic obstacle avoidance framework, a moving pedestrian was introduced into the robot’s navigation path. The complete replanning process is illustrated in Fig. 19. As the pedestrian walks from right to left in front of the robot (Fig. 19a), the integrated YOLOv7 module detects the person in the RGB-D image stream, and the center point of the detected bounding box is projected onto the semantic map as shown by the red marker. Using the depth measurement and pixel-motion estimation described earlier, the system predicts the pedestrian’s likely position one second ahead; this predicted location is indicated by a green marker in Fig. 19b. As the pedestrian continues to move (Fig. 19c), the predictive model updates the estimated position based on the temporal displacement between consecutive frames. Even before the pedestrian enters the robot’s physical path, the predicted point in Fig. 19d indicates that a potential collision may occur. When this predicted obstacle node intersects with the robot’s planned A* route, the corresponding grid cells are flagged as non-traversable (shown in red), prompting the robot to pause or adjust its trajectory until the path is safe. After the pedestrian leaves the robot’s travel corridor (Fig. 19e), the system updates the semantic map and computes a new optimal route using A* in Fig. 19f.

Figure 19: Path planning process for a moving object

Unlike conventional rule-based systems that only react to the current obstacle position, the proposed framework incorporates short-term motion prediction, using both instantaneous pixel displacement and the Kalman-filter–smoothed velocity estimate. This anticipatory behavior allows the robot to respond proactively to moving objects rather than relying solely on reactive avoidance, thereby improving safety and navigation smoothness. Although the motion prediction assumes near-constant velocity over short intervals—an approximation that is valid for human walking speeds—the additional Kalman filtering reduces noise and stabilizes the prediction, addressing the reviewer’s concern regarding reliability of pure linear extrapolation.

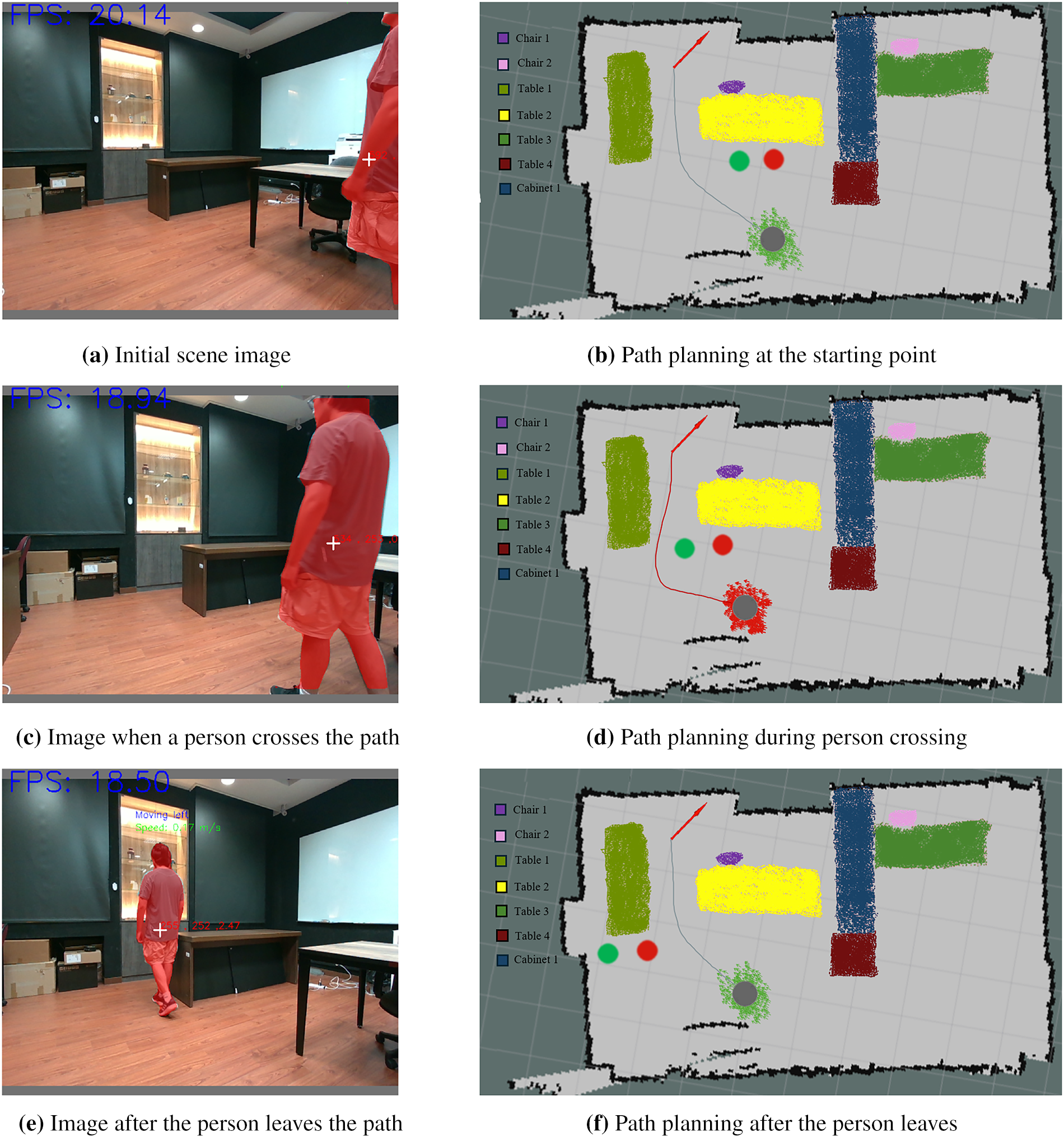

By continuously updating the semantic map and replanning in real time, the robot successfully avoids dynamic obstacles and maintains safe navigation. Quantitative performance metrics summarizing the system’s capabilities are listed in Table 2. The proposed method achieved a 95.4% mAP@0.5 for object recognition, and semantic completeness increased from 68.7% (single-view) to 94.1% (multi-view). The mean object position error, after projection onto the SLAM map, was 3.1 cm. During navigation trials, the robot demonstrated 98.0% reliability, successfully avoided moving obstacles in 90.0% of encounters, and achieved an average replanning time of 0.42 s. These results confirm that the integration of semantic perception, multi-view fusion, and predictive obstacle avoidance enables accurate, efficient, and robust autonomous navigation in dynamic indoor environments.

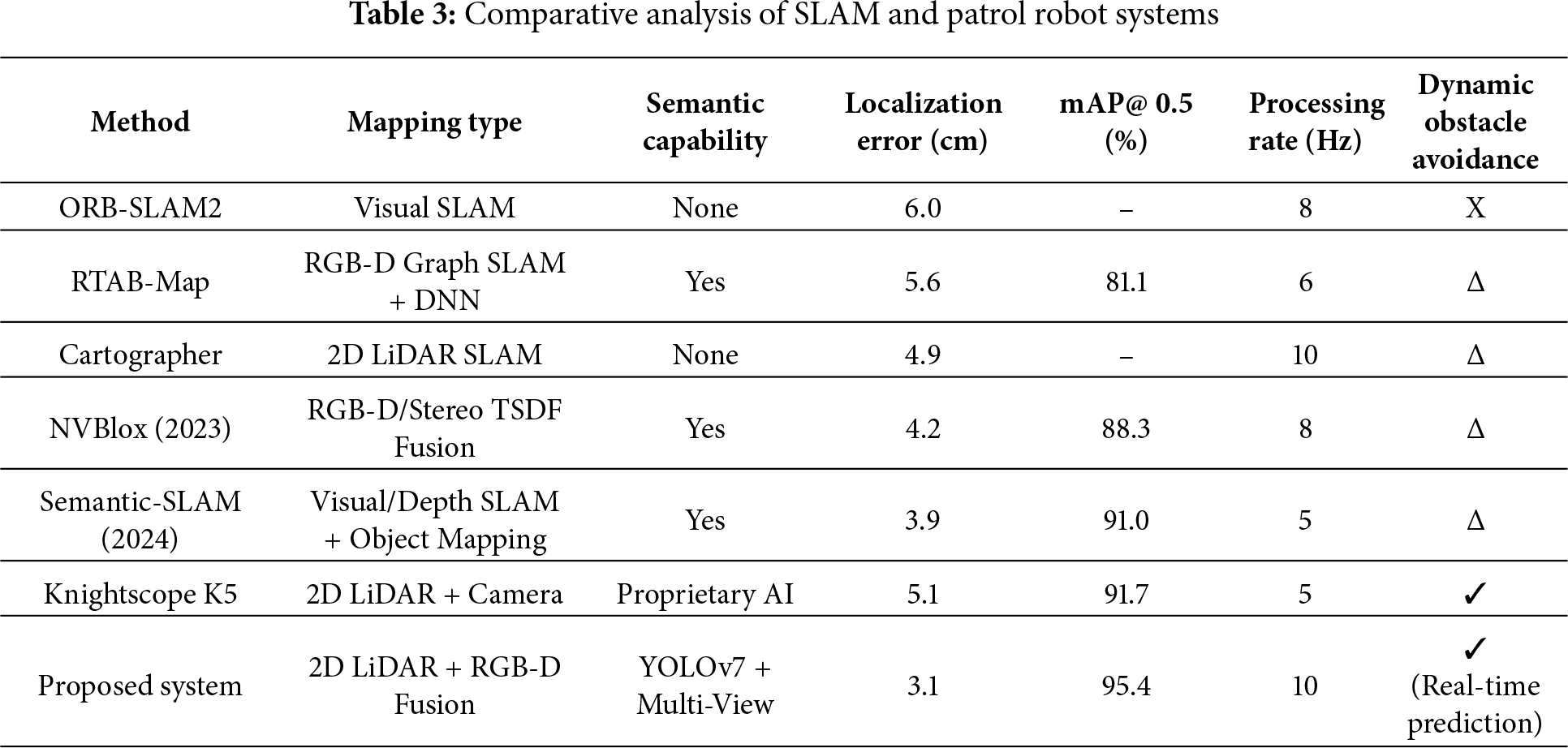

3.3 Comparison with Existing Systems

A comprehensive comparison between the proposed system and representative SLAM-based patrol and navigation frameworks is presented in Table 3. Traditional geometric SLAM methods such as ORB-SLAM2 and Cartographer provide accurate localization but lack semantic perception, limiting their ability to recognize objects or handle dynamic human movement. Systems such as RTAB-Map (semantic mode) and NVBlox incorporate semantic segmentation, yet they require higher computational resources and are primarily optimized for dense 3D reconstruction rather than lightweight real-time patrol tasks. Commercial patrol robots like Knightscope K5 integrate multiple sensors but rely on closed-source software, restricting flexibility for research or adaptation.

The proposed 2D LiDAR + RGB-D fusion SLAM system achieves a localization error of 3.1 cm and high-quality semantic mapping through multi-view fusion. The integration of YOLOv7 enables accurate object recognition and supports prediction-based dynamic obstacle avoidance, offering capabilities beyond those of purely geometric SLAM systems. Despite using a portable computing platform, the system maintains real-time performance at 10 Hz, demonstrating efficiency suitable for indoor patrol and monitoring applications.

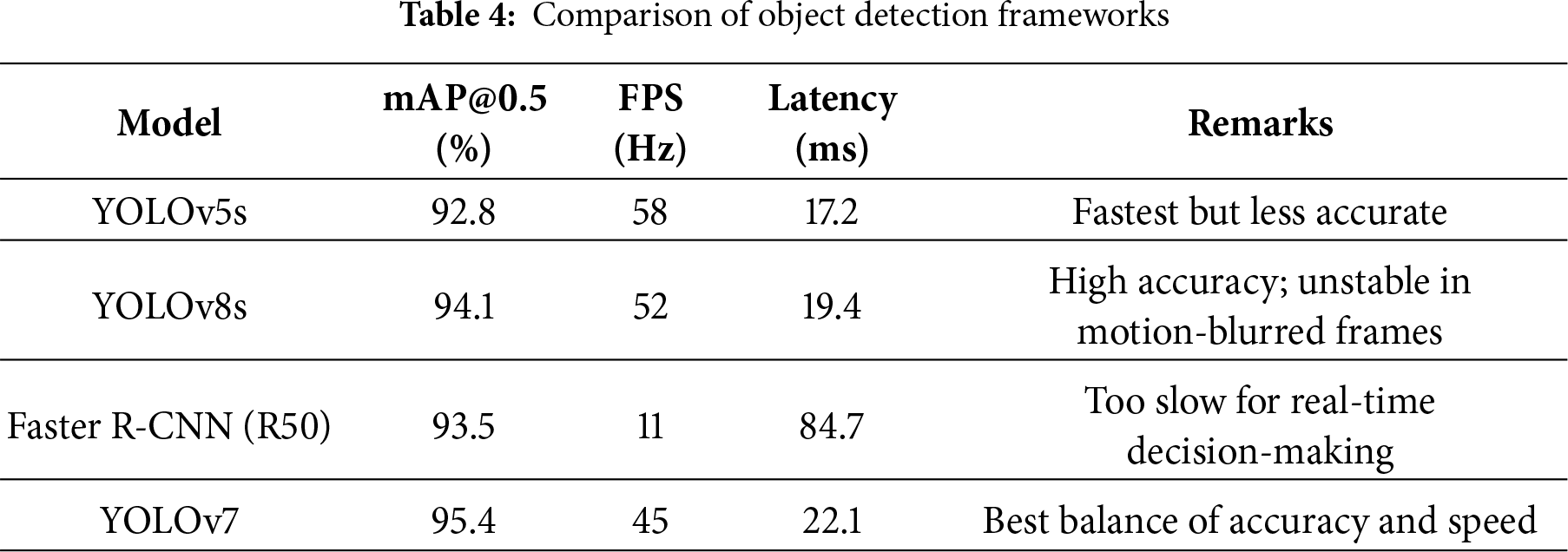

To further evaluate the detection backbone, YOLOv7 was compared against widely adopted models including YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and Faster R-CNN under identical hardware and dataset conditions. As summarized in Table 4, YOLOv7 achieved the highest overall accuracy while maintaining real-time inference speed, making it well suited for onboard robotic perception. Although YOLOv8 achieves high benchmark results in general datasets, its performance degraded in indoor patrol scenes due to motion blur and low-contrast lighting. Faster R-CNN produced competitive accuracy but was not suitable for real-time navigation given its significantly lower frame rate.

This study presents an integrated 2D LiDAR and RGB-D fusion system for autonomous indoor patrol, capable of generating accurate semantic maps, detecting objects in real time, and performing predictive dynamic obstacle avoidance. By combining LiDAR-based SLAM with multi-view semantic fusion, the system overcomes the limitations of single-modality perception, achieving a localization error of 3.1 cm and significantly improving semantic completeness from 68.7% (single view) to 94.1% (multi-view). The fusion-based mapping method also demonstrated the highest overall IoU (97%) and object-level IoU (97.3%) among the evaluated approaches.

The integration of YOLOv7 provides robust object detection (mAP@0.5 = 95.4%) and outperforms YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and Faster R-CNN in both accuracy and real-time suitability for robotic navigation. The proposed prediction-enhanced dynamic obstacle avoidance framework further enables the robot to anticipate pedestrian motion, update the semantic map continuously, and perform real-time path replanning with an average latency of 0.42 s. During navigation trials, the robot achieved 98.0% reliability and successfully avoided moving obstacles in 90.0% of encounters, demonstrating its adaptability in dynamic indoor environments.

Overall, the proposed system provides a modular, computationally efficient, and extensible framework that bridges geometric SLAM with semantic understanding and predictive behavior. These characteristics make it well suited for indoor security patrol, monitoring, and other autonomous service-robot applications. Future work will explore reinforcement learning–based local planners, multi-floor semantic mapping, and large-language-model–driven interaction to further enhance the robot’s decision-making and environmental understanding.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their gratitude to Li-Chieh Chang, a senior student in the Department of Electrical Engineering at Ming Chuan University, for his assistance with experimental testing.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under Grant NSTC 114-2221-E-130-007.

Author Contributions: Shu-Yin Chiang, as the corresponding author, conceived the study, contributed to its investigation, development, and coordination, and wrote the original draft. Shin-En Huang conducted data analysis and implemented experimental techniques in the study. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jullie Josephine DC, Gracia Nisi P, Frank S, Manikandan A, Bhavaneskumar S, Sakthivel T. Night patrol robot for detecting and tracking of human motions using proximity sensor. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Edge Computing and Applications (ICECAA); 2022 Oct 13–15; Tamilnadu, India. p. 912–5. doi:10.1109/icecaa55415.2022.9936381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Aggravi M, Sirignano G, Giordano PR, Pacchierotti C. Decentralized control of a heterogeneous human–robot team for exploration and patrolling. IEEE Trans Automat Sci Eng. 2022;19(4):3109–25. doi:10.1109/tase.2021.3106386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao X, Peng Z, Zhao S. Substation electric power equipment detection based on patrol robots. Artif Life Robot. 2020;25(3):482–7. doi:10.1007/s10015-020-00604-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yousif T, El-Medany W. Development and hardware implementation of IoT-based patrol robot for remote gas leak inspection. Int J Electr Comput Eng Syst (Online). 2022;13(4):279–92. doi:10.32985/ijeces.13.4.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Huang L, Zhou M, Hao K, Hou E. A survey of multi-robot regular and adversarial patrolling. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sinica. 2019;6(4):894–903. doi:10.1109/jas.2019.1911537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Manasa P, Harsha KS, Deepak DM, Karthik R, Naveen O. Night vision patrolling robot. J Xi’an Univ Archit Technol. 2020;8(5):172–87. [Google Scholar]

7. Chen Z, Wu H, Chen Y, Cheng L, Zhang B. Patrol robot path planning in nuclear power plant using an interval multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm. Appl Soft Comput. 2022;116:108192. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jiang Z, Zhao Q, Tomioka Y. Depth image-based obstacle avoidance for an in-door patrol robot. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC); 2019 Jul 7–10; Kobe, Japan. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/icmlc48188.2019.8949186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dong L, Lv J. Research on indoor patrol robot location based on BP neural network. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2020;546(5):052035. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/546/5/052035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yan D, Cao H, Wang T, Chen R, Xue S. Graph-based knowledge acquisition with convolutional networks for distribution network patrol robots. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2021;2(5):384–93. doi:10.1109/tai.2021.3087116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sawano Y, Watanabe T, Terashima Y, Kiyohara R. Localization method for SLAM using an autonomous cart as a guard robot. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 46th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); 2022 Jun 27–Jul 1; Los Alamitos, CA, USA. p. 1193–8. doi:10.1109/compsac54236.2022.00188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Khalid F, Albab IH, Roy D, Asif AP, Shikder K. Night patrolling robot. In: 2021 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST); 2021 Jan 5–7; Dhaka, Bangladesh. p. 377–82. doi:10.1109/icrest51555.2021.9331198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xu H, Chen T, Zhang Q, Lu J, Yang Z. A deep learning and depth image based obstacle detection and distance measurement method for substation patrol robot. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Advanced Electrical and Energy Systems; 2020 Aug 18–21; Osaka, Japan. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

14. Freda L, Gianni M, Pirri F, Gawel A, Dubé R, Siegwart R, et al. 3D multi-robot patrolling with a two-level coordination strategy. Auton Rob. 2019;43(7):1747–79. doi:10.1007/s10514-018-09822-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zheng J, Mao S, Wu Z, Kong P, Qiang H. Improved path planning for indoor patrol robot based on deep reinforcement learning. Symmetry. 2022;14(1):132. doi:10.3390/sym14010132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dijkstra EW. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. In: Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 287–90. doi:10.1145/3544585.3544600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chabini I, Lan S. Adaptations of the A* algorithm for the computation of fastest paths in deterministic discrete-time dynamic networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2002;3(1):60–74. doi:10.1109/6979.994796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hart P, Nilsson N, Raphael B. A formal basis for the heuristic determination of minimum cost paths. IEEE Trans Syst Sci Cyber. 1968;4(2):100–7. doi:10.1109/tssc.1968.300136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang L, Wang L. A semantic SLAM-based dense mapping approach for large-scale dynamic outdoor environment. Measurement. 2022;204:112001. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.112001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Alhmiedat T, Alia OM. Utilizing a deep neural network for robot semantic classification in indoor environments. Sci Rep. 2025;15:21937. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-07921-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang J, Tarrio J, Agapito L, Alcantarilla PF, Vakhitov A. SeMLaPS: real-time semantic mapping with latent prior networks and quasi-planar segmentation. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023;8(12):7954–61. doi:10.1109/lra.2023.3322647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li F, Fu C, Sun D, Li J, Wang J. SD-SLAM: a semantic SLAM approach for dynamic scenes based on LiDAR point clouds. Big Data Res. 2024;36:100463. doi:10.1016/j.bdr.2024.100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li J, Firkat E, Zhu J, Zhu B, Zhu J, Hamdulla A. HI-SLAM: hierarchical implicit neural representation for SLAM. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;271:126487. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Miao L, Liu W, Deng Z. A frontier review of semantic SLAM technologies applied to the open world. Sensors. 2025;25(16):4994. doi:10.3390/s25164994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu S, Zhuang Y, Zhang C, Li Q, Hou J. Sem-SLAM: semantic-integrated SLAM approach for 3D reconstruction. Appl Sci. 2025;15(14):7881. doi:10.3390/app15147881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chiang SY, Lin TY. Low-brightness object recognition based on deep learning. Comput Mater Continua. 2024;79(2):1757–73. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.049477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools