Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Explainable Transformer-Based Approach for Dental Disease Prediction

Department of Natural, Engineering and Technology Sciences, Faculty of Graduate Studies, Arab American University, Ramallah, P.O. Box 240, Palestine

* Corresponding Author: Ahmad Hasasneh. Email:

Computer Systems Science and Engineering 2025, 49, 481-497. https://doi.org/10.32604/csse.2025.068616

Received 02 June 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 10 October 2025

Abstract

Diagnosing dental disorders using routine photographs can significantly reduce chair-side workload and expand access to care. However, most AI-based image analysis systems suffer from limited interpretability and are trained on class-imbalanced datasets. In this study, we developed a balanced, transformer-based pipeline to detect three common dental disorders: tooth discoloration, calculus, and hypodontia, from standard color images. After applying a color-standardized preprocessing pipeline and performing stratified data splitting, the proposed vision transformer model was fine-tuned and subsequently evaluated using standard classification benchmarks. The model achieved an impressive accuracy of 98.94%, with precision, recall and F1 scores all greater than or equal to 98% for the three classes. To ensure interpretability, three complementary saliency methods, attention roll-out, layer-wise relevance propagation, and LIME, verified that predictions rely on clinically meaningful cues such as stained enamel, supragingival deposits, and edentulous gaps. The proposed method addresses class imbalance through dataset balancing, enhances interpretability using multiple explanation methods, and demonstrates the effectiveness of transformers over CNNs in dental imaging. This method offers a transparent, real-time screening tool suitable for both clinical and tele-dentistry frameworks, providing accessible, clarity-guided care pathways.Keywords

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1], dental diseases are among the most widespread health issues globally, affecting approximately 3.5 billion people. The most common condition is the untreated dental caries, which impacts over 2.5 billion individuals [1]. Other disorders, such as periodontal disease and tooth loss, also significantly contribute to the global health burden, causing pain, discomfort, and a reduced quality of life. These conditions are not only highly prevalent, but also costly to treat, especially when diagnosed at advanced or later stages [2]. Therefore, there is a growing interest in improving diagnostic tools aimed at increasing surgical precision, accuracy and efficiency, particularly through advanced data processing technologies that support early dental intervention.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI), and especially deep learning technologies, is transforming diagnostic imaging in healthcare and dentistry. AI systems in dentistry have been developed for various functions in dentistry, including detecting dental caries and periodontal disease on radiographs, identifying supernumerary teeth, assessing bone age, and even performing forensic identification [3,4]. Many recent deep learning models match, and even exceed, skilled clinicians in diagnostic accuracy. The study in [5] has noted that expert dentists were outperformed by state-of-the-art convolutional neural network (CNN) and U-Net models in caries-lesion detection and periodontal bone-loss identification. In some complex diagnostic situations, AI is approaching perfect performance, where one group reported that a YOLO-based model achieved 98.2% accuracy in detecting odontogenic sinusitis in panoramic X-rays [6]. These developments strengthen the evidence supporting AI’s ability to transform dentistry by enhancing accuracy in data capture, integrated workflow systems, early diagnosis, tailored treatment strategies, and overall clinical outcomes [5].

Despite attaining these milestones, significant obstacles continue to persist. In critical areas such as medicine, where clinical acceptance hinges on transparency, the “black box” nature of artificial intelligence’s decision-making poses a major issue [7]. Diagnoses and treatment plans generated by AI systems must be unquestioningly accepted by both patients and healthcare providers. In healthcare, a lack of explainability erodes trust and leads to significant medicolegal risks [7]. In response to these issues, an increasing number of scholars are adopting Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) algorithms in order to improve the interpretability of model predictions for clinicians [8]. Meanwhile, some scholars have also noted the emergence of new deep learning models, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs), which overcome the limitation of traditional CNN in modelling global image context [9,10]. Ongoing medical imaging research focuses on applying ViTs and hybrid CNN-Transformer models to enhance performance and generalization [11].

However, the majority of dental imaging research continues to use CNN backbones and incorporates ViT models with rigorous Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) validation only occasionally, which creates a noticeable methodological and clinical void. Therefore, this paper aims to address this issue by: (1) constructing a balanced pipeline based on ViTs to classify three prevalent dental conditions, (2) applying clinician-centered explanations using layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP), attention, and local inter-pretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME), and (3) evaluating this method against CNNs using the latest curated dataset. Specifically, the key contributions of this research work include: (i) creating a balanced subset of a publicly available dental dataset to mitigate bias from class imbalance, (ii) integrating three complementary interpretability techniques (attention rollout, LRP, and LIME) to enhance clinical relevance and explainability, and (iii) providing empirical evidence that a single ViT backbone surpasses traditional CNN-based methods in both performance and interpretability for dental image classification.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature and discusses recent advancements in dental diagnosis and classification. Section 3 outlines the methods and materials used, including a description of the datasets used in this study, the preprocessing steps taken, and an introduction to the ViTs and XAI methods. Section 4 presents the results, comparing the performance of a deep learning model (U-Net) and ViTs, followed by a presentation and discussion of the XAI results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and highlights potential directions for future research.

Recent research indicates that deep learning is integrating rapidly into dental diagnostics, often achieving accuracy comparable to seasoned dental professionals. AI algorithms have been implemented to evaluate intra-oral photos, radiographs, and 3-D scans for numerous processes. For example, in pediatric dentistry, AI is applied for proactive caries diagnostics, identifying impacted or supernumerary teeth, estimating the dental age, and more [4]. Ref. [5] conducted a comprehensive assessment on emerging technologies and deep learning in dental diagnostics, and AI systems, in several cases, demonstrated considerable promise and even excelled practitioners in specific tasks. In one instance, a DenseNet-121 and a no-new-U-Net (nnU-Net) model detected and classified caries on panoramic films better than expert diagnosticians [5]. Similarly, a CNN-based approach for cone beam Computed Tomography (CT) images exhibited high accuracy and F1-scores for caries detection [5], confirming that AI has the potential to augment human diagnostic abilities.

Certain deep learning models have been developed for specific types of dental images. For instance, Ref. [12] implemented an ensemble of CNN classifiers on intra-oral camera images for dental caries detection and reached an AUROC of 0.94 with their best ensemble configuration. Interestingly, as noted in [12], they also tried a model with visualizations of its decision regions, which produced lower accuracy (AUROC ≈ 0.91). This suggests that simpler models may be more interpretable but at a trade-off in performance. In another work, Ref. [13] reported an AI system with several pre-trained CNNs—Visual Geometry Group networks (VGG16/19), Residual Network (ResNet50), and Densely Connected Convolutional Network (DenseNet121/169)—that achieved high precision and sensitivity for detecting vertical-root fractures in periapical radiographs using a voting ensemble. The most significant finding from their study was that VGG16, as the best component of the ensemble, attained remarkable specificity along with approximately 0.93 positive predictive value for identifying fractures [13]. So far, it appears that ensemble learning improves robustness in dental-image analysis.

Deep learning is gaining traction in specialized diagnostic areas like pathology and surgical workup. An AI algorithm designed to assess periodontal bone loss and stage periodontitis on panoramic X-rays performed automatic segmentation of the anatomical structures and staged the disease as a periodontist would [14]. In clinical evaluations, the system achieved an accuracy of 94.4% in diagnosing periodontitis, which was slightly better than the periodontist’s 91.1% [14]. However, the system had lower specificity, suggesting a propensity for over-diagnosis and a threshold adjustment requiring clinician feedback. A different team created a multi-stage workflow for the analysis of impacted third molars. Impacted molars were detected on panoramic radiographs by a VGG16 CNN with 93.5% accuracy. Then, a YOLOv7 localized the teeth, and finally their angulation was determined by a ResNet50 classifier with 92.1% accuracy [15]. The effectiveness demonstrated in these steps shows that deep learning is capable of reliably automating intricate dental diagnostic processes of detection and classification, achieving performance on par with expert evaluations.

Additionally, diagnostic AI capabilities expand vertically beyond just image interpretation. In oral oncology, scholars are studying the application of deep learning for cancer cytology as a more refined alternative to deep tissue biopsies. The authors in [16] suggested a multiple-instance learning paradigm to batch-class malignant cells in oral-cytology slides to improve interpretability by determining which cells in a slide suggest neoplasia and have cancer. As presented in her thesis, a conventional single-instance CNN was able to detect oral cancer from patient-level labels with accuracy comparable to a sophisticated MIL model [16]. Both methods gave explanations of how the abnormal cells in the slides were highlighted and, in addition, showed the regions of interest, which provided visual reasoning for the cytotechnologists.

As a whole, the most recent studies noted that deep learning dramatically increases the speed and accuracy of diagnostic processes in dentistry. AI algorithms have shown mastery in a wide range of applications, from detecting caries on X-rays to spotting rare diseases. Some researchers suggest AI has a greater sensitivity toward certain diseases [5,14], leading to the hopeful notion that these technologies may enhance dentists’ clinical decision-making capabilities. All the same, there is a growing appeal for reliability and validation, which cannot be overlooked. Clinicians have shared divergent views regarding the trustworthiness of AI: while a good number accept the possibility of AI-enhanced radiographs assisting in patient education and diagnosing, others take a more cautious stance and doubt the reliability of AI for interpreting images [17]. This highlights the increasing demand for transparency when integrating AI tools into dentistry.

The ViTs have become another deep learning model with increasing use in the analysis of medical images. Unlike CNNs that use convolution filters to extract local features, ViTs use self-attention mechanisms to capture dependencies over long ranges in images [9]. The ability to model global context is vital in medical imaging, as the nuanced details which may be critically important diagnostically often span across an image. Even U-Net variants are unable to go beyond the limitations of local receptive fields, and so traditional CNNs are bound to this locality [9]. On the other hand, ViTs focus on all image regions, thus attending to a far greater field of view and integrating information from everywhere.

The medical field has mostly avoided pure transformer models due to the expensive computational cost and the need for vast training datasets—an issue relevant in fields such as medicine where data is sparse [18]. One survey focused on medical segmentation still pointed out small sample sizes as a drawback for transformers, although there is some relief when pretrained ViTs are used on biomedical data [18]. Thus, there is a growing focus on designs that integrate CNN and Transformer elements. The Authors in [11] discussed radiology’s hybrid ViT-CNN models and emphasized the advantage that these hybrids have over the stand-alone architectures. They are able to harness additional complementary capabilities, which in many cases results in better performance than either architecture used individually.

Transformers continue to make a mark in medical imaging. A transformer was first implemented on the MedMNIST benchmark [19], who showed its effectiveness by reporting surpassed state-of-the-art accuracy on many subsets, like achieving 97.9% accuracy on BloodMNIST. While the use of transformers in dental imaging still has a long way to go, progress is being made. In [10] authors surveyed transformers in stomatological imaging and noted that early attempts to automate the segmentation of oral anatomical structures are exceptionally accurate, although there is much more that can be explored [20,21]. A relevant recent study emphasizes the interpretability advantages of ViTs over CNNs in medical imaging, confirming their potential for diagnostic tasks [22].

It is equally crucial to consider practical aspects while moderating excitement around transformers. In certain dental procedures with scant datasets, CNNs may outperform current transformer models. In [23], U-Net and Swin-Unet were compared on three segmentation tasks involving dental radiographs, and it was observed that CNNs significantly outperformed both pure transformer and hybrid methods in all instances [18]. To solve issues posed by limited datasets, many neural network models utilize inductive biases or incorporate convolutional tokens. SwinUNETR merges Swin-Transformer blocks with U-Net, achieving remarkable accuracy in 3-D medical segmentation, although this comes with longer training periods [23]. Some attention layers in MetaSwin are substituted with efficient spatial pooling, resulting in a reduction in training time, although accuracy remains unchanged [23].

Developing medicine-specific transformers is one of the active research areas. Evolutionary algorithms that are a part of EATFormer apply to ViT models to optimize its parts [24]. Compared to the baseline models, the modified EATFormer improves classification speed and accuracy, particularly in the chest X-ray datasets [24]. Composite models like YoCoNet, which integrate a YOLOv5 detector with a ConvNeXt transformer-based classifier, have been utilized to segment teeth and identify periapical lesions in jaw radiographs with over 90% accuracy and precision [15]. These studies highlight the increasing use—and often hybridization—of vision transformers in medical image analysis.

As AI becomes better at diagnosing medical problems, the need for XAI increases, particularly in medicine where the rationale behind a decision can be equally critical as the decision itself [7,21,25]. Lack of transparency can result in a lack of trust, with clinicians unable to validate or make sense of the AI’s actions, which can endanger safety.

Despite recent progress on dental disease prediction, current approaches still exhibit significant limitations. First, many dental AI models lack sufficient interpretability, which undermines their clinical applicability and the trust of dental practitioners. Second, ViT-based methods remain largely underexplored in dental diagnostics, particularly in conjunction with XAI techniques. Third, existing research often relies on unbalanced or poorly curated datasets, limiting the generalizability and reliability of the results in real-world applications. Consequently, this study aims to address these gaps by proposing a ViT-based classification framework enhanced with XAI, evaluated on a well-curated and balanced dataset.

The study follows the five-stage pipeline outlined in Fig. 1. The first step involves obtaining clinically annotated intra-oral photographs from an open-access repository. Next, each image undergoes a uniform preprocessing routine that improves comparative homogeneity in resolution and overall appearance (with augmentation applied only to the training portion). Then, the pre-processed tensors are transferred to a Vision Transformer (ViT-Base/16) model, which has been previously fine-tuned on similar tasks. In the third step, the prediction results are evaluated on a patient-independent test split using common classification metrics. Lastly, attention roll-out, LRP (Layer-wise Relevance Propagation), and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) are used to generate complementary explanations and to visualize, on a pixel level, the regions influencing predictions.

Figure 1: The workflow of the proposed Vision Transformer model incorporates Explainable AI techniques. The five sequential stages (dataset selection, preprocessing, ViT fine-tuning, performance evaluation, and three-way explainability) are shown from left to right. Abbreviations: ViT, Vision Transformer; LRP, Layer-wise Relevance Propagation; LIME, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations

All the images are obtained from the Oral Diseases dataset available on Kaggle [26], which contains high-resolution Red–Green–Blue (RGB) images labeled for five dental conditions. To avoid the negative effects of extreme class imbalance, only the three most populous categories—Tooth Discoloration, Calculus, and Hypodontia—were kept. The original distribution of the selected classes was as follows: Tooth Discoloration (1834 images), Calculus (1296 images), and Hypodontia (1251 images). To ensure a balanced training set and prevent classifier bias, each category was down-sampled to match the size of the smallest class (1251 images). Alternative balancing methods such as synthetic oversampling and data augmentation were preliminarily explored. However, these methods introduced synthetic bias and reduced validation accuracy. Therefore, random down-sampling was ultimately selected, as shown in Fig. 2. The dataset was split into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets on a patient-independent basis. Due to constraints in the size of the dataset, k-fold cross-validation was not employed in this study. However, future work will incorporate cross-validation to verify the stability and robustness of the classification metrics.

Figure 2: Balanced three-class subset used for model development

All images are resized to 224 × 224 px, transformed into a floating-point tensor, and normalized per channel to the mean and standard deviation of the ImageNet pretraining corpus. Only during training, stochastic geometric and color perturbations including horizontal flips, slight rotations, and mild intensity jitter increase variability within the class. Validation and test samples are not altered, ensuring that each observation is standardized and identical when presented to the classifier.

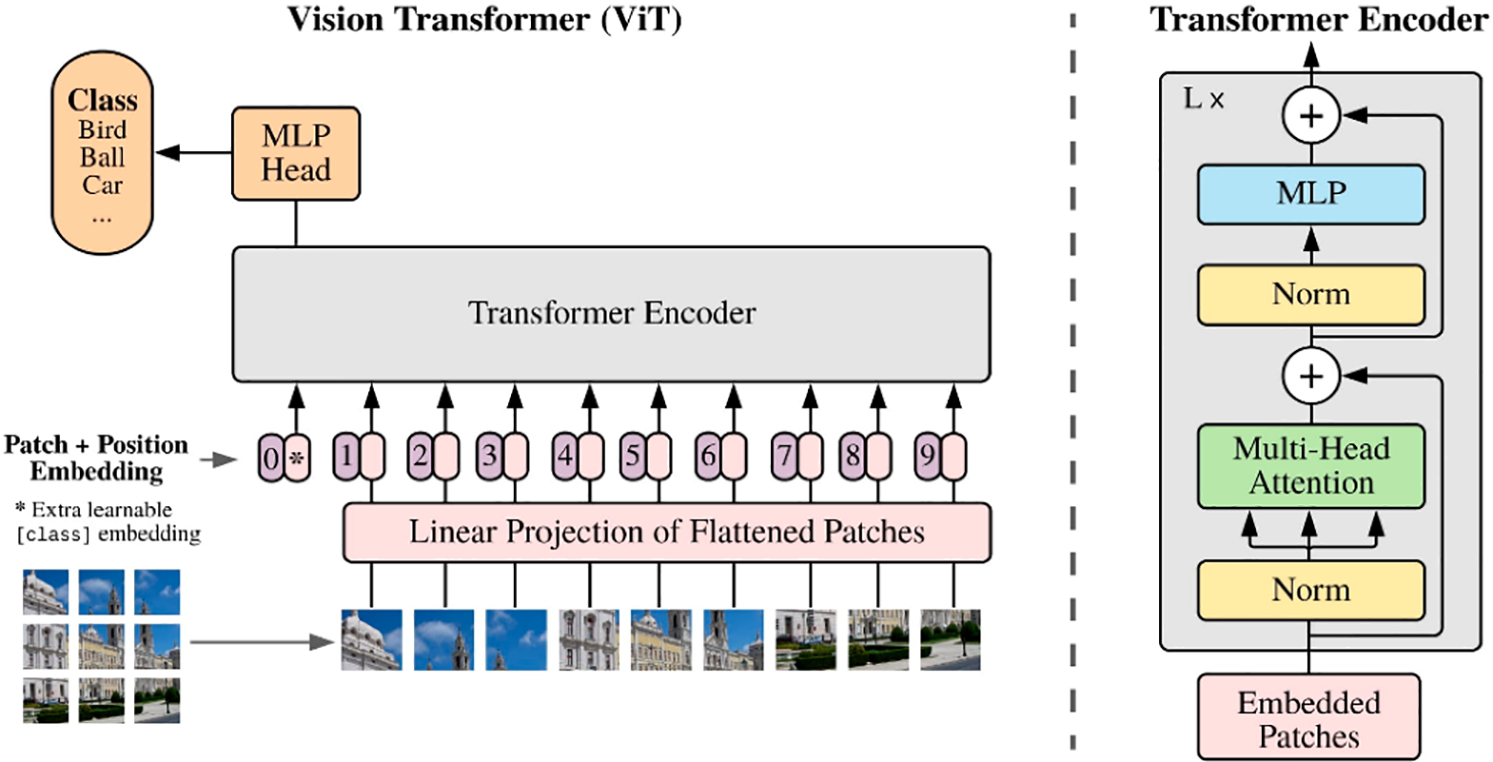

The ViT changes the perception of an image by treating it as a sequence of patches—fixed, non-overlapping, and handled like word tokens in natural language processing (NLP) [27]. Each patch is flattened and transformed into an embedding vector through linear projection. After adding positional encodings and a learnable class token, the sequence is passed through a deep stack of multi-head self-attention layers, where long-range spatial dependencies are captured. The terminal hidden state derived from the class token is fed into a small multilayer perceptron (MLP) that outputs class probabilities. A schematic overview of the base ViT architecture employed is provided in Fig. 3 and Table 1.

Figure 3: Vision transformer (ViT) architecture [27]

A batch size of 32 was chosen because it comfortably fits within a 24 GB GPU, yielding stable gradient estimates without exhausting the memory. This value and other parameters were determined through empirical testing on the validation set. In this testing, combinations of batch sizes (16, 32, and 64) were evaluated for convergence speed, memory usage, and accuracy. AdamW was selected because its adaptive updates and decoupled weight decay have proven effective for transformer fine-tuning. After experimenting with both Adam and AdamW, we found that AdamW yielded better generalization performance. A relatively low initial learning rate prevents divergence during the transfer of weights from large-scale pretraining. The specified weight decay term prevents overfitting to the modest-sized dental corpus. The one-cycle learning rate schedule accelerates convergence by combining precooling with a warm-up phase. The number of epochs (10) was determined using early stopping criteria based on validation loss. Accumulating the gradient to 128 increases the effective batch size without exceeding the hardware capacity. Accuracy preservation was maintained through the combined use of automatic mixed precision. Due to the known risk of overfitting associated with limited dataset size, we employed multiple regularization and augmentation strategies. These strategies included horizontal flips, random rotations (±10°), color jittering, transfer learning from ImageNet-21k, and weight decay (6 × 10−3). We followed best practices from recent transformer applications on small-scale medical datasets. These strategies are shown in Table 2.

The effectiveness of the proposed Vision-Transformer was evaluated using the standard measures of accuracy, recall, precision and the harmonic-mean F1 score. All these indices together capture complementary facets of classification behavior because they consider correct recognitions as well as all possible error types. In addition, class-wise statistics were provided in order to reveal any potential inequity amongst the three diagnostic groups.

where TP denotes true positives, TN true negatives, FP false positives, and FN false negatives.

The overall (macro-averaged) results provide a consistent assessment of all three disordered states of teeth: tooth discolouration, calculus, and hypodontia. However, these per-class results reveal deficiencies which are masked by the averaged performance. These combined assessments strengthen the evaluation of the model across all levels of trust and robustness throughout the entire diagnostic range of the intra-oral photographic dataset.

Attention roll-out, which extends Layer-wise Relevance Propagation to transformers. Attention roll-out recursively multiplies the self-attention matrices across layers and thus projects the influence of all image patches onto the class token. The resulting influence map illustrates, albeit in a coarse manner, an architecture-intrinsic visualization of the regions driving the prediction.

LRP assigns relevance to input pixels based on layer-specific reconstruction rules. A conserved amount of relevance is redistributed from the output neuron to the input pixels. Each pixel is assigned a signed relevance score proportional to the prediction’s class value. Here, the ε-rule is used to stabilize the computations in LRP [28].

LIME describes its approach as generating local explanations from perturbations near the original image. It explains individual predictions by sampling numerous super-pixel perturbations around an image and fitting a sparse linear model to approximate the classifier’s predictions in that area. The coefficients of the fitted model are then used as importance weights. In this work, each image resulted in 1000 perturbations to encapsulate high-fidelity local explanations [29].

These methods combined enrich understanding far beyond what global patch-level attention, fine-grained pixel attribution, or local surrogate interpretability alone can offer, providing a comprehensive explanation of the Vision Transformer’s decisions—a necessity for domain experts to assess clinical plausibility.

4.1 Evaluation of ViT Model Performance

4.1.1 Training and Validation Loss Analysis

Optimization progress is summarized in Fig. 4, which shows the plots for each of the training and validation losses as well as validation accuracy score over ten epochs of fine-tuning. Training loss exhibited a steep decrease during the first two epochs, after which it taper-continued its climb towards convergence until epoch 10. Validation loss showed a brief overshoot at epoch 4 but quickly recovered due to the One Cycle learning rate schedule, which indicates that the network was able to respond positively to augmented data without overfitting to the data. At the same time, validation accuracy climbed from 97% to a stable flat line just below 100%. Minor fluctuations in validation loss suggest potential slight overfitting due to the limited number of training epochs and the small size of the dataset. Future work will explore extending the training duration, increasing the dataset size, and applying additional regularization methods (e.g., stochastic depth, label smoothing) to further improve generalization.

Figure 4: Training and validation loss and accuracy across ten epochs

In Table 3, we highlight the quantitative metrics of the best-performing model on the held-out test split. The Vision Transformer achieved a remarkable accuracy of 98.94%, with precision, recall, F1 score, and per-class recall metrics no lower than 0.98% for every class. The macro- and weighted-average metrics converge to 0.99%, indicating the intended balanced class distribution, while the low-test loss of 0.0608 further confirms the network’s generalization ability.

In Fig. 5, the confusion matrix for the three-class test split is shown. Out of 376 test images, only four were classified incorrectly: two hypodontia were classified as calculus, while one instance each of calculus and tooth discolouration were interchanged with adjacent classes. The matrix vivid strong diagonal dominance and uniform high recalls in the matrix confirm that the ViT differentiates the three pathologies with almost perfect certainty.

Figure 5: Confusion matrix illustrating class-wise performance on the held-out test dataset

4.2 Explainable Artificial Intelligence

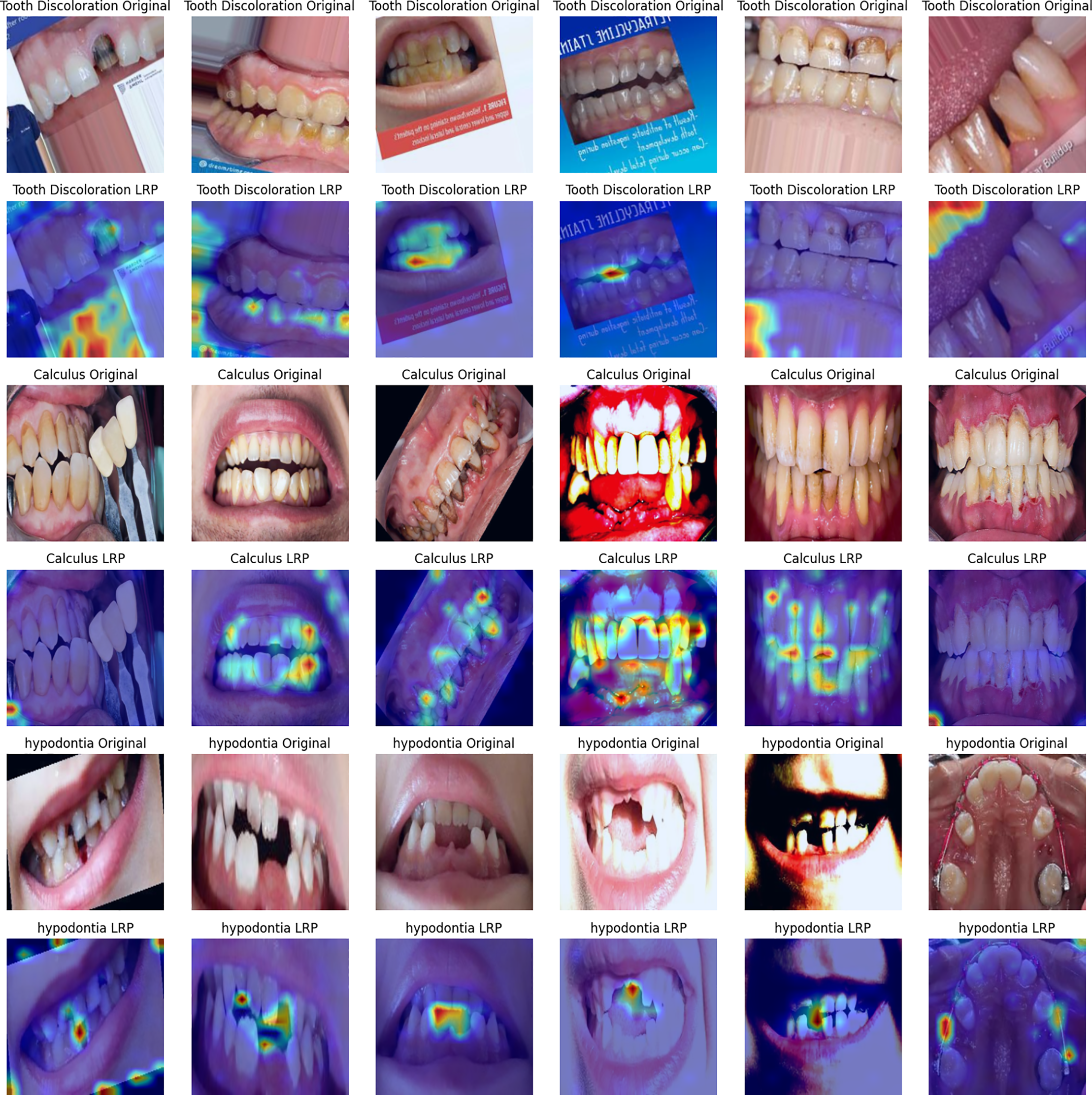

We implemented a tri-modal interpretable AI suite composed of attention roll-out, LRP, and LIME on every correctly classified test image. The qualitative results are summarized in Fig. 6, with extended galleries for LIME and LRP appearing in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively.

Figure 6: Side-by-side comparison of attention roll-out, LRP and LIME explanations for one exemplar per class

Figure 7: LIME super-pixel importance overlays for multiple cases of tooth discolouration, calculus and hypodontia

Figure 8: Layer-wise relevance propagation heat maps corresponding to the image set in Fig. 7

Attention roll-out does not simply use the last layer’s self-attention but aggregates the transformer’s self-attention weights across layers to capture global context. As demonstrated in the rightmost panels of Fig. 6, the maps focus on coarse processes that define each diagnosis, such as stained enamel surfaces for tooth discoloration, edentulous gaps for hypodontia, and supragingival deposit caps for calculus. These regions correspond to the order of inspection a dentist would follow.

LRP works as follows: it heuristically back-propagates a relevance score associated with a given output all the way down to the pixel level. The resulting heatmaps, shown in the second column of Fig. 6 and the panels in Fig. 8, contain hypodontic evidence of chromatic irregularity concentration on singular teeth, the vacant alveolar ridge, and granular textural evidence of tartar in calculus. Such precise attribution validates that the model does not depend on background artifacts or soft tissue colorations.

LIME locally approximates a classifier by fitting a sparse linear model while perturbing an image at the super-pixel level. The super-pixels displayed in the third column of Fig. 6 and the overlays of Fig. 7 consistently highlight regions specific to pathology, which further supports the clinical reasoning of the automated predictions.

In terms of differences, one can see that LRP provides fine-grained, pixel-level relevance; LIME highlights interpretable, super-pixel segments; and Attention offers a high-level view of the model’s global focus. Despite their methodological differences, all three techniques commonly highlight clinically relevant areas and demonstrate consistent interpretation patterns. This coherent agreement demonstrates that the ViT bases its decisions on visually meaningful and medically relevant structures rather than on spurious correlations.

The latest developments in AI-based scanning and photography of oral diseases can be classified into three categories: (i) custom or ensemble convolutional networks, (ii) hybrid CNN–Transformer models, and (iii) pure segmentation models with state-space or attention block augmentations.

Vision Transformers have clear advantages over traditional CNN architectures, particularly due to their self-attention mechanism, which captures global context, and effectively models long-range dependencies that CNN local kernels usually overlook. This capability enhances the model’s scalability to process higher-resolution images and intrinsically improves interpretability through attention-based visualization.

Nevertheless, the proposed study has limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the relatively small size of the test set (10%) may result in overly optimistic performance estimates. Thus, future work should employ larger independent test sets or robust evaluation strategies such as k-fold cross-validation. Second, this research was conducted under controlled imaging and lighting conditions. Therefore, comprehensive external validation across different imaging devices, varied lighting environments, and diverse patient populations is required to ensure real-world generalizability and clinical applicability.

An outright comparison (Table 4) indicates the proposed ViT outstrips performance metrics of contemporary CNNs and hybrid ensembles with a far lower component requirement during inference. As opposed to the custom ResNet-50 of [30], which yielded a calculus accuracy of 86.9% and a severe sensitivity drop due to under-represented gingivitis, our strictly balanced training approach affords consistent sharp precision and recall (98%–100%) for every class. In contrast to Hussain et al.’s weighted three-network ensemble, accuracy is improved by the ViT to 98.9% from 97% with a single forward pass, streamlining maintenance and deployment. Oral-Mamba [31] provides useful lesion-level masks, but its per-image diagnostic accuracy of less than 84% diagnostics lags significantly behind that of the ViT’s, which positions it for a supplementary role: the transformer could perform fast triage and route cases meriting detailed analysis to more complex segmentation models for extensive strategizing.

Equally critical is the area of interpretability. Both Refs. [30,32] use one Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM)-style overlay for each model, while Oral-Mamba visualizes only with pixel masks. On the other hand, this research uses attention roll-out, LRP, and LIME and provides corroborative explanations at different granularities such as patch, pixel, and super-pixel granularity. The layered transparency that this work provides not only complies with emerging clinical-AI regulatory frameworks but reveals that the ViT indeed focuses on clinically pertinent structures: stained enamel in tooth discoloration, gingival-margin deposits for calculus, and the markedly edentulous spaces characteristic of hypodontia, instead of irrelevant background artefacts.

Lastly, the three crucial design decisions underpinning the ViT’s performance are as follows: (1) coarse transfer from ImageNet-21k via transfer learning, which provides strong low-level vision primitives; (2) rigorous class balance, which eliminates the sensitivity gaps from prior work featuring Kaggle datasets [26]; (3) standardisation of data colour during the preprocessing phase, which addresses CNN illumination variance cited as a failure mode for deep learning models. These factors together introduce a novel standard in the setting of deployable vision systems—proximity to perfect accuracy, class-balanced reliability, layer-wise multi-scale dependability, and interpretability.

This study demonstrates that a class-balanced ViT framework can meet modern standards of explainability and transparency while ensuring diagnostic accuracy in dental imaging. Fine-tuning a single ViT model on a well-curated, balanced set of intraoral photographs resulted in remarkable accuracy of 98.94%. This achieved a macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-score of 99%, which closes the gap in class-convex performance disparity prevailing among many CNN benchmarks. The use of three complementary explanation modalities—attention rollout, LRP, and LIME—yielded patch-, pixel-, and region-level explanations that converged on the same pathognomonic features, such as chromatic aberration of enamel, supragingival calculus, and edentulous gaps. This proves that the transformer focuses on salient clinical structures rather than irrelevant details, enhancing trust and medicolegal defensibility. Overall, the novel design of the balanced data, transformer self-attention, and multi-scale interpretability sets a new standard for performance and transparency in automated photographic screening. This demonstrates that lightweight ViT architectures can be trusted as decision support systems in chairside and teledentistry scenarios.

The present findings suggest multiple potential directions for further research. First, the diagnostic bandwidth will expand to include additional oral pathologies, such as dental caries and gingival inflammation. This will enable more thorough chair-side examinations of commonly encountered dental conditions. Second, multi-center prospective data collection projects are envisioned to evaluate cross-device imaging, ethnic groups, and lighting conditions. These studies will use federated learning frameworks to maintain privacy while expanding the training corpus. Third, the applicability of real-time, resource-limited handheld intraoral and mobile devices will be analyzed for low-power, real-time, extensible mobile vision transformers, such as Swin-Tiny, MobileViT, and Mamba-Lite. Fourth, direct comparative baselines will be implemented using k-fold cross-validation to provide a head-to-head performance and interpretability benchmark against the ViT on the identical balanced dataset, comparing it with widely used CNN architectures (e.g., ResNet-50, Dense-Net-121) and hybrid CNN-Transformer models. Fifth, we will investigate multitask extensibility by integrating the current classification head with a transformer-based decoder for segmentation. This allows for concurrent lesion marking and severity annotation. Lastly, extensive human-centered automated loops will be conducted to measure the effect of the proposed multilevel rationales for explanation and annotation on clinician trust, performance, time to diagnosis, and time to decision-making. This will support regulatory compliance and the incorporation of our methods into standard care.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Sari Masri and Ahmad Hasasneh; methodology, Sari Masri; software, Sari Masri; validation, Sari Masri and Ahmad Hasasneh; formal analysis, Sari Masri; investigation, Sari Masri; resources, Sari Masri; data curation, Sari Masri; writing—original draft preparation, Sari Masri; writing—review and editing, Sari Masri and Ahmad Hasasneh; visualization, Sari Masri and Ahmad Hasasneh; supervision, Ahmad Hasasneh; project administration, Sari Masri; funding acquisition, Sari Masri and Ahmad Hasasneh. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Kaggle at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/salmansajid05/oral-diseases (accessed on 22 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization. Oral health [Internet]. [cited on 22 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health. [Google Scholar]

2. Peres MA, MacPherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Shujaat S. Automated machine learning in dentistry: a narrative review of applications, challenges, and future directions. Diagnostics. 2025;15(3):273. doi:10.3390/diagnostics15030273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Rajinikanth SB, Rajkumar DSR, Rajinikanth A, Anandhapandian PA, Bhuvaneswarri J. An overview of artificial intelligence based automated diagnosis in paediatric dentistry. Front Oral Health. 2024;5:1482334. doi:10.3389/froh.2024.1482334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Alanazi MQ. Deep learning models and dental diagnosis: a review. J Clin Med Images Case Rep. 2024;4(4):1720. [Google Scholar]

6. Wu PY, Lin YJ, Chang YJ, Wei ST, Chen CA, Li KC, et al. Deep learning-assisted diagnostic system: apices and odontogenic sinus floor level analysis in dental panoramic radiographs. Bioengineering. 2025;12(2):134. doi:10.3390/bioengineering12020134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Muhammad D, Bendechache M. Unveiling the black box: a systematic review of explainable artificial intelligence in medical image analysis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;24(2):542–60. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2024.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Khoury ZH, Ferguson A, Price JB, Sultan AS, Wang R. Responsible artificial intelligence for addressing equity in oral healthcare. Front Oral Health. 2024;5:1408867. doi:10.3389/froh.2024.1408867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Pu Q, Xi Z, Yin S, Zhao Z, Zhao L. Advantages of transformer and its application for medical image segmentation: a survey. Biomed Eng Online. 2024;23(1):14. doi:10.1186/s12938-024-01212-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Gao Y, Zhang P, Xie Y, Han J, Zeng L, Ning N, et al. Application of transformers in stomatological imaging: a review. Digit Med. 2024;10(3):e24-00001. doi:10.1097/dm-2024-00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kim JW, Khan AU, Banerjee I. Systematic review of hybrid vision transformer architectures for radiological image analysis. J Imag Inform Med. 2025;42(5):1. doi:10.1007/s10278-024-01322-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kang S, Shon B, Park EY, Jeong S, Kim EK. Diagnostic accuracy of dental caries detection using ensemble techniques in deep learning with intraoral camera images. PLoS One. 2024;19(9):e0310004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0310004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Abdelazim R, Fouad EM. Artificial intelligent-driven decision-making for automating root fracture detection in periapical radiographs. Br Dent J Open. 2024;10(1):76. doi:10.1038/s41405-024-00260-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jundaeng J, Chamchong R, Nithikathkul C. Artificial intelligence-powered innovations in periodontal diagnosis: a new era in dental healthcare. Front Med Technol. 2025;6:1469852. doi:10.3389/fmedt.2024.1469852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Veerabhadrappa SK, Vengusamy S, Padarha S, Iyer K, Yadav S. Fully automated deep learning framework for detection and classification of impacted mandibular third molars in panoramic radiographs. J Oral Med Oral Surg. 2025;31(1):7. doi:10.1051/mbcb/2025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Koriakina N, Sladoje N, Bašić V, Lindblad J. Deep multiple instance learning versus conventional deep single instance learning for interpretable oral cancer detection. PLoS One. 2024;19(4):e0302169. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0302169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Slashcheva LD, Schroeder K, Heaton LJ, Cheung HJ, Prosa B, Ferrian N, et al. Artificial intelligence-produced radiographic enhancements in dental clinical care: provider and patient perspectives. Front Oral Health. 2025;6:1473877. doi:10.3389/froh.2025.1473877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Schneider L, Krasowski A, Pitchika V, Bombeck L, Schwendicke F, Büttner M. Assessment of CNNs, transformers, and hybrid architectures in dental image segmentation. J Dent. 2025;156:105668. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2025.105668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Halder A, Gharami S, Sadhu P, Singh PK, Woźniak M, Ijaz MF. Implementing vision transformer for classifying 2D biomedical images. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):12567. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-63094-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tami M, Masri S, Hasasneh A, Tadj C. Transformer-based approach to pathology diagnosis using audio spectrogram. Information. 2024;15(5):253. doi:10.3390/info15050253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Masri S, Hasasneh A, Tami M, Tadj C. Exploring the impact of image-based audio representations in classification tasks using vision transformers and explainable AI techniques. Information. 2024;15(12):751. doi:10.3390/info15120751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mir AN, Rizvi DR, Ahmad MR. Enhancing histopathological image analysis: an explainable vision transformer approach with comprehensive interpretation methods and evaluation of explanation quality. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;149:110519. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lee S, Lee M. MetaSwin: a unified meta vision transformer model for medical image segmentation. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10:e1762. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Shisu Y, Mingwin S, Wanwag Y, Chenso Z, Huing S. Improved EATFormer: a vision transformer for medical image classification. arXiv:2403.13167. 2024. [Google Scholar]

25. Qushtom H, Hasasneh A, Masri S. Enhanced wheat disease detection using deep learning and explainable AI techniques. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(1):1379–95. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sajid S. Oral diseases [Internet]. [cited on 22 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/salmansajid05/oral-diseases. [Google Scholar]

27. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. arXiv:1706.03762. 2017. [Google Scholar]

28. Samek W, Müller KR. Towards explainable artificial intelligence. In: Samek W, Montavon G, Vedaldi A, Hansen LK, Müller KR, editors. Explainable AI: interpreting, explaining and visualizing deep learning. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. p. 5–22. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-28954-6_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C. Why should I trust you? In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016 Aug 13–17; New York, NY, USA. doi:10.1145/2939672.2939778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pericherla ASV, Kalidindi M. A custom Convolutional Neural Network to streamline oral disease detection and screening. J High Sch Sci. 2024;8(3):227–40. doi:10.64336/001c.122214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu Y, Cheng Y, Song Y, Cai D, Zhang N. Oral screening of dental calculus, gingivitis and dental caries through segmentation on intraoral photographic images using deep learning. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):1287. doi:10.1186/s12903-024-05072-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hussain SM, Ali Zaidi S, Hyder A, Movania MM. Integrating ensemble learning into remote health monitoring for accurate prediction of oral and maxillofacial diseases. In: Proceedings of the 2023 25th International Multitopic Conference (INMIC); 2023 Nov 17–18; Lahore, Pakistan. doi:10.1109/INMIC60434.2023.10465788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools