Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Variable Integral Parameter Control Strategy for Secondary Frequency Regulation with Multiple Energy Storage Units

Key Laboratory of Modern Power System Simulation and Control & Renewable Energy Technology, Ministry of Education (Northeast Electric Power University), Jilin, 132012, China

* Corresponding Author: Jinyu Guo. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(10), 3961-3983. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067811

Received 13 May 2025; Accepted 16 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

In high-renewable-energy power systems, the demand for fast-responding capabilities is growing. To address the limitations of conventional closed-loop frequency control, where the integral coefficient cannot dynamically adjust the frequency regulation command based on the state of charge (SoC) of energy storage units, this paper proposes a secondary frequency regulation control strategy based on variable integral coefficients for multiple energy storage units. First, a power-uniform controller is designed to ensure that thermal power units gradually take on more regulation power during the frequency regulation process. Next, a control framework based on variable integral coefficients is proposed within the secondary frequency regulation model, along with an objective function that simultaneously considers both Automatic Generation Control (AGC) command tracking performance and SoC recovery requirements of energy storage units. Finally, a gradient descent optimization method is used to dynamically adjust the gain of the energy storage integral controller, allowing multiple energy storage units to respond in real-time to AGC instructions and SoC variations. Simulation results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method. Compared to traditional strategies, the proposed approach takes into account the SoC discrepancies among multiple energy storage units and the duration of system net power imbalances. It successfully implements secondary frequency regulation while achieving dynamic power allocation among the units.Keywords

With the increasing penetration of renewable energy into power grids, system inertia has gradually declined, and uncertain power fluctuations have become more frequent [1,2]. At the same time, the conventional frequency regulation capabilities of power grids are deteriorating, placing growing pressure on frequency control [3]. Due to their inherently high inertia, thermal power units exhibit limited performance in mitigating high-frequency fluctuations. Therefore, it has become particularly important to investigate new optimization control strategies to meet the frequency regulation requirements of power systems.

With the advancement of energy storage technologies and supportive government policies, energy storage systems (ESS) have emerged as vital contributors to grid frequency regulation, complementing conventional generation units [4,5]. ESS offer rapid response capabilities, especially in secondary frequency regulation (SFR), by promptly compensating for frequency deviations and balancing power. However, their regulation capabilities are constrained by their state of charge (SoC). Under sustained high-load operation, SoC may approach its upper or lower limits, weakening the system’s regulation capacity [6–8]. Therefore, strategies that can coordinate thermal and storage resources, enhance ESS longevity, and improve the overall economic efficiency of frequency regulation warrant further investigation [9,10].

In recent years, both domestic and international scholars have conducted in-depth research on the power allocation problem of secondary frequency regulation in power systems. Recent advances have particularly emphasized the integration of energy storage systems with conventional power sources, aiming to improve system flexibility and frequency stability.

Among them, model predictive control (MPC) and distributed optimization methods have been widely explored. Reference [11] systematically reviewed MPC-based control frameworks in energy systems, demonstrating that while MPC provides high accuracy in prediction and constraint handling, it often suffers from large computational burdens, posing challenges for real-time implementation. Reference [12] optimally allocates the real-time master scheduling instructions of AGC to different AGC units based on real-time prediction information. However, this method heavily depends on the accuracy of forecasting models and requires substantial computational resources, limiting its real-time applicability. Reference [13] proposed a two-layer optimization strategy for frequency regulation power of fire-multi-storage systems based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition and multi-objective genetic algorithm. Despite its theoretical advantages, this approach suffers from high computational complexity and inadequate responsiveness in practical grid conditions. Reference [14] proposed a two-level frequency regulation strategy based on model predictive control. By scheduling isolated microgrids containing a large number of heterogeneous distributed resources, frequency stability and economic performance optimization were achieved. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of distributed resources increases system modeling difficulty and control overhead. These methods are effective in enhancing control precision, but often lack the lightweight, adaptive capabilities required in real-world applications.

Another line of research focuses on multi-scale coordinated control and thermal-storage synergy modeling. Reference [15] proposed the thermal power—energy storage modeling and multi-scale collaborative rolling optimization control method in the frequency regulation scenario, further reducing the frequency regulation deviation of the power grid. However, the scalability and real-time coordination across multiple subsystems remain challenging. Reference [16] designed a hybrid scheduling control for wind farms and battery systems to accelerate nominal charge recovery and meet enhanced frequency response service requirements, which enhances SoC management but introduces control complexity. Reference [17] proposes a coordinated frequency regulation control strategy for wind, fire and storage based on multi-scale decomposition, and presents a multi-scale decomposition method for frequency difference instructions based on wavelet packet decomposition. However, this method faces limitations in high-frequency fluctuation response and increases the complexity of multi-unit coordination. Reference [18] aims at minimizing the total frequency regulation cost and SoC penalty, and adopts the method of quadratic programming to solve and optimize the output of each energy storage power station. Nevertheless, the method lacks an explicit mechanism to resolve trade-offs between conflicting objectives and does not include adaptive strategies for real-time system adjustments. Overall, these strategies offer improved coordination but still struggle with system scalability and dynamic adaptability.

Beyond real-time optimization, recent studies have also addressed SoC state management and dynamic withdrawal mechanisms to maintain long-term regulation capabilities. Reference [19] reviewed battery energy storage applications in grid frequency services and emphasized the importance of dynamic SoC control, degradation-aware scheduling, and adaptive threshold mechanisms to ensure sustained regulation performance. Reference [20] proposed an adaptive optimization and exit mechanism design method for energy storage frequency regulation control parameters. This adaptive feedback strategy improves regulation flexibility but may still struggle with tuning parameters under diverse grid conditions. Reference [21] explored a ramp-up-margin-based exit strategy for ESS during the frequency recovery stage, allowing smooth system handover. However, its applicability under varying load profiles still requires empirical validation. Reference [22] divided the state intervals between the energy storage SoC and the system frequency regulation requirements, proposed the switching strategy between the intervals, and carried out the adaptive recovery of the SoC according to the energy storage state. The method’s accuracy depends heavily on precise SoC-state partitioning, which can be challenging under dynamic operating conditions. Reference [23] presented a distributed fixed-time control strategy that improves AGC responsiveness by balancing power deviations. Although the scheme improves responsiveness, it may increase communication and computational overhead, posing challenges for large-scale deployment.

In summary, although existing research provides a range of control strategies for SFR in thermal–storage systems, limitations remain in terms of real-time adaptability, multi-unit coordination, and long-term SoC robustness, motivating further exploration of lightweight, adaptive control frameworks.

1.3 Research Gaps and Contributions

Despite the aforementioned progress, several research gaps remain:

(1) For the distribution of AGC signals, optimization algorithms or decomposition techniques are mostly adopted. But when dealing with the high-frequency fluctuations of complex power grids, the response speed lags behind and cannot meet the real-time frequency regulation requirements of the power grid;

(2) The lack of a dynamic release mechanism for fast-response units is not conducive to maintaining the long-term rapid regulation capacity of the power grid, resulting in the failure of fast-response units to fully release their regulation capacity during the high-frequency fluctuation regulation process.

(3) To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel secondary frequency regulation control strategy for thermal–energy storage systems based on a variable integral coefficient.

The proposed method introduces the following key innovations:

(1) Dynamic integral gain adjustment using a lightweight gradient descent algorithm, which enables more efficient control without the need for complex optimization routines;

(2) Dual feedback design, where the gain tuning simultaneously responds to AGC signal variations and SoC trajectories, enhancing responsiveness and SoC balance;

(3) Coordinated power allocation among multiple energy storage units, which accounts for their individual regulation capabilities and SoC levels, enabling real-time, state-aware task distribution and improving overall system efficiency;

(4) A time-sequenced regulation mechanism that enables thermal power units to progressively assume frequency regulation tasks as energy storage units withdraw, ensuring sustainable long-term regulation capability and system stability.

The proposed method dynamically adjusts the integral gain of the energy storage controller using gradient descent, enabling real-time responsiveness to AGC signals and SoC variations. Furthermore, it improves power allocation efficiency among multiple energy storage units, ensuring sustained regulation performance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a secondary frequency regulation model incorporating the proposed variable integral parameter control strategy. Section 3 introduces the control strategy for multiple ESS based on variable integral coefficients. Section 4 provides case studies and performance evaluations. Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2 Modeling of TP–ES Frequency Regulation with VPCS

2.1 Modeling of Secondary FR in Regional Power Grids with ES

2.1.1 The Framework of Frequency Regulation

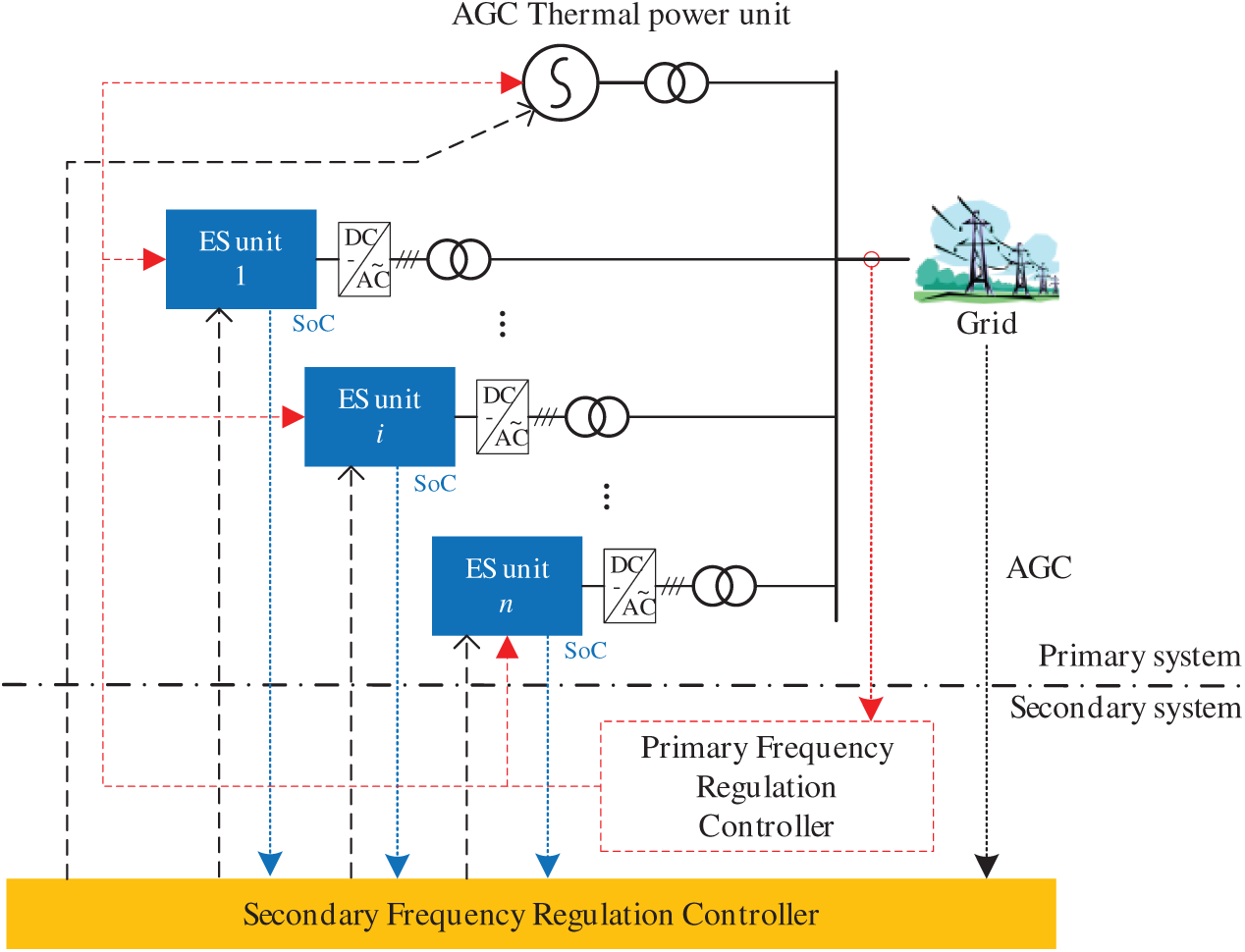

This study constructs a closed-loop frequency regulation system incorporating energy storage units, based on a system frequency response model, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The model primarily consists of a thermal power unit model, an energy storage system model, a generator-load model, and a secondary frequency regulation power controller [24]. In this configuration, AGC units and energy storage systems allocate Area Control Error (ACE) signals based on predefined participation factors, while non-AGC units perform primary frequency regulation under governor control. The modeling of regional secondary frequency regulation adopts thermal power unit models and parameters as referenced in [25–28].

Figure 1: Closed-loop secondary frequency regulation model for regional power grids with energy storage

The secondary frequency regulation power controller designed in this paper controls the secondary frequency regulation power distribution among multiple units based on the AGC signal of the power grid and the SoC conditions of multiple ES units.

2.1.2 Power System Frequency Response Model

In power systems, the system frequency deviation can be calculated by Eq. (1).

In the equation, H denotes the system inertia constant; D is the system damping coefficient, and

2.1.3 Thermal Power Unit Model

Usually, considering the governor system, turbine, and reheater of thermal power units, the transfer function between the frequency regulation power command and the actual output of the unit is given in Eq. (2).

In the equation,

Typically, the parameters are set as

2.1.4 Energy Storage System Model

For energy storage systems, when the capacity constraint is not considered, the transfer function between the frequency regulation power command and the actual output is given in Eq. (4).

In this paper, the parameter

2.2 Secondary FR Control Scheme for TP and ES

2.2.1 Primary Frequency Regulation in TP-ES Hybrid Systems

While the power distribution for secondary frequency regulation in the thermal storage system is being implemented, the primary frequency regulation is also active. When the system frequency deviation exceeds the dead zone range of primary frequency regulation, both thermal power units and energy storage participate in primary frequency regulation. Both the energy storage system and the thermal power unit adopt the droop control strategy. For thermal power units, their primary frequency regulation command

In the formula,

For the ES, its primary frequency regulation command is given by Eq. (6).

2.2.2 AGC Distribution between TP and ES

When the frequency deviation of the system exceeds the set dead zone range, the primary frequency regulation resources of the power grid start to participate in the primary frequency regulation autonomously, without control from the dispatching center. If the dispatching center detects a prolonged frequency offset, it immediately issues dispatch instructions to the secondary frequency regulation resources based on the extent of the frequency deviation, gradually reducing the system frequency offset.

For AGC units, the AGC instructions issued by the system are equal to the product of the integral of the regional power deviation and the allocation factor, as shown in Eq. (7).

In the Eq. (6), Kx,i represents the participation factor of the AGC unit (When x takes G, it refers to the thermal power unit, whereas when x is S, it denotes the energy storage unit). K is the frequency deviation factor,

2.2.3 AGC Uniformity Controller of Thermal Power Units

Due to the rapid power regulation capabilities of energy storage, it assumes a larger portion of the frequency regulation power at the initial stage to accelerate the recovery of the system frequency. As the regulation proceeds, thermal power units with continuous output capacity should assume more frequency regulation responsibilities to release the frequency regulation capacity of energy storage. For this purpose, a multi-unit power uniformity controller was designed. The power setting value of the thermal power unit is:

In the formula,

In the formula,

Furthermore, two operators are defined in Eq. (8), as shown in Eqs. (10) and (11), respectively.

In the formula,

In the formula, zmax represents the maximum value of z and zmin represents the minimum value of z.

2.2.4 Output Constraints of ES

To prevent the energy storage system from responding to power instructions without limit, avoid the SoC from approaching the limit excessively, and protect the battery life, this study designs a Logistic regression-based constraint module. This module accounts for both the real-time SoC and demand power of the energy storage system, and regulates the maximum charging and discharging power accordingly. The function expression is as follows:

In the formula: Pmax represents the maximum technical output of energy storage;

Therefore, the power constraints of energy storage are shown as Eq. (14).

3 Secondary FR Control for Multiple ES Units Based on VPCS

Under the traditional control strategy, the integral coefficient remains constant. As a result, once the secondary frequency regulation process is completed, the output of each unit remains unchanged. Although this approach enhances system responsiveness, the continued involvement of energy storage after frequency restoration leads to deviations in its state of charge (SoC). This not only results in inefficient use of fast-regulating resources but also reduces the operating margin of conventional generation units.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a secondary frequency regulation strategy with variable integral coefficients for multiple energy storage (ES) units, leveraging the power–energy coupling characteristics of ES and considering the system’s demand for rapid frequency regulation. The structure of the proposed controller is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Framework diagram of VPCS

At the initial stage of secondary frequency regulation, the AGC tracking component dominates, allowing ES units to assume a portion of the AGC power. Once the frequency is largely stabilized, the SoC recovery component takes over. It first reallocates the power from ES units with significant SoC deviations to those with more margin, and eventually shifts the ES regulation burden to thermal power units.

Notably, during the power transfer process, system frequency may fluctuate again. In such cases, the AGC command dynamically adjusts based on the frequency deviation. The AGC tracking component moderates the speed of SoC recovery, thereby limiting frequency oscillations caused by power redistribution between ES units and thermal units.

3.2 The Objective Function for Controlling ES

During the frequency regulation process of the storage-containing system, the regulation objective is defined as a weighted sum of SoC deviation and AGC tracking deviation, as expressed in Eq. (15):

In the formula:

Considering that the state of charge of energy storage and the output power of energy storage have the relationship as shown in Eq. (16).

In the formula, ESmax represents the maximum capacity of the energy storage,

Since in the frequency modulation time scale, energy storage usually can only operate in a unique working state, thus Eq. (17) holds:

In addition, during the frequency regulation process of energy storage, its output power

In the formula, kp,i represents the proportional control coefficient of energy storage i,

Substituting Eqs. (13) and (14) into Eq. (11) gives Eq. (19).

3.3 The Implementation of Gradient Descent Control Algorithm

For Eq. (19), the partial derivatives of Ks,i are obtained as shown in Eq. (20).

For the integral control coefficients kS,i of energy storage, while conducting closed-loop control of the system frequency, they are corrected in the direction of gradient descent. Each correction of the integral control coefficient is a single-step gradient descent optimization process, as shown in Eq. (21).

In the formula, is the iterative speed coefficient, and the iterative speed coefficient matrix is defined as

As the frequency regulation process progresses, the system frequency gradually stabilizes, and the SoC of the energy storage units also tends toward a steady state. Consequently, the gradient descent optimization process evolves into the optimization of a deterministic objective function. This leads to the convergence of the integral control coefficient toward a value that minimizes the objective function and maintains relative stability.

3.4 Integration Feasibility with Existing AGC Framework

The proposed control strategy maintains compatibility with existing communication links and SCADA systems. Instead of altering the centralized AGC instruction structure, the strategy modifies how energy storage units interpret these instructions—shifting from direct power dispatch to the use of integral gain coefficients that are computed locally. To support this, each energy storage unit needs to incorporate a lightweight software module that performs real-time frequency deviation integration and dynamically adjusts its response based on the computed gain. For thermal power units, the AGC control logic and interface remain unchanged, ensuring seamless integration without hardware modifications. This architecture enables centralized calculation of coordination parameters while allowing distributed, adaptive power response from storage units based on local frequency and SoC states, thereby preserving centralized dispatch coordination and improving system flexibility.

3.5 Computational Complexity and Convergence Speed Analysis

The proposed control strategy uses a gradient descent algorithm to update integral coefficients in real time at each control cycle, enabling simultaneous optimization and operation. By focusing only on the integral coefficients, it avoids complex high-dimensional nonlinear optimization, greatly reducing computational complexity. Each cycle computes gradients from current system feedback (frequency deviation and energy storage state) and updates the coefficients, which are applied in the next cycle. This lightweight calculation typically completes within milliseconds, meeting real-time power system requirements. Continuous online adjustment allows fast adaptation to system changes, maintaining near-optimal control parameters and improving frequency regulation sensitivity and stability. Overall, the strategy balances low computation with high real-time performance, enhancing energy storage participation efficiency and reliability.

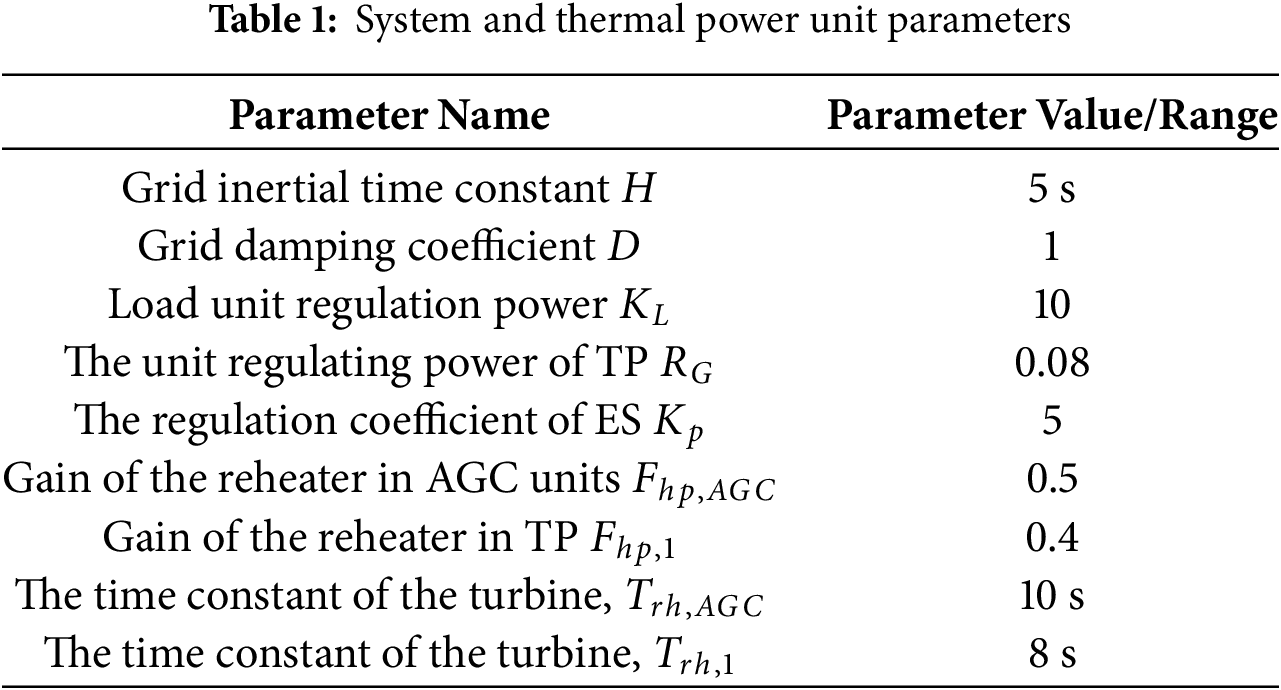

To verify the effectiveness of the control strategy proposed in this paper, a simulation was developed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment. In this simulation, a total of 2 AGC units, 4 non-AGC units, and 2 energy storage units that respond to AGC instructions were configured. All units participated in primary frequency regulation, with two AGC units and two energy storage units tracking the ACE instructions through an integration loop.

The frequency deviation signal was proportionally amplified into an ACE signal, which was then distributed to the two AGC units and two energy storage units according to their participation factors through a low-pass filtering mechanism. Additionally, to verify the effect of the SoC recovery strategy proposed in this paper, two energy storage devices with different states of charge (SoCs) were set up. The simulation parameters are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

4.2 Case Study Result Analysis

4.2.1 System Frequency Response under Closed-Loop Control

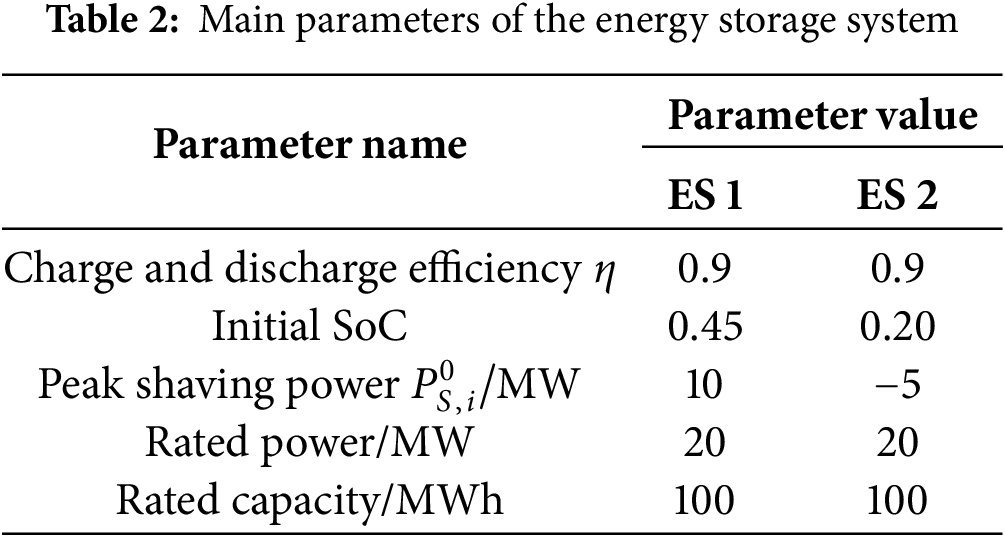

In order to comparatively analyze the regulation capacity of the system frequency closed-loop controller in the control system under conditions such as whether energy storage is added, the addition of energy storage to the control strategy in this paper, and the adoption of the constant coefficient integral control strategy, Select the long-term net power deficit (step signal), short-term net power deficit (window-opening signal), long-term net power deficit (continuous signal), and short-term net power deficit (continuous signal) as the net power deficit signals; The waveforms of the four signals are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Four types of net power deficit signals

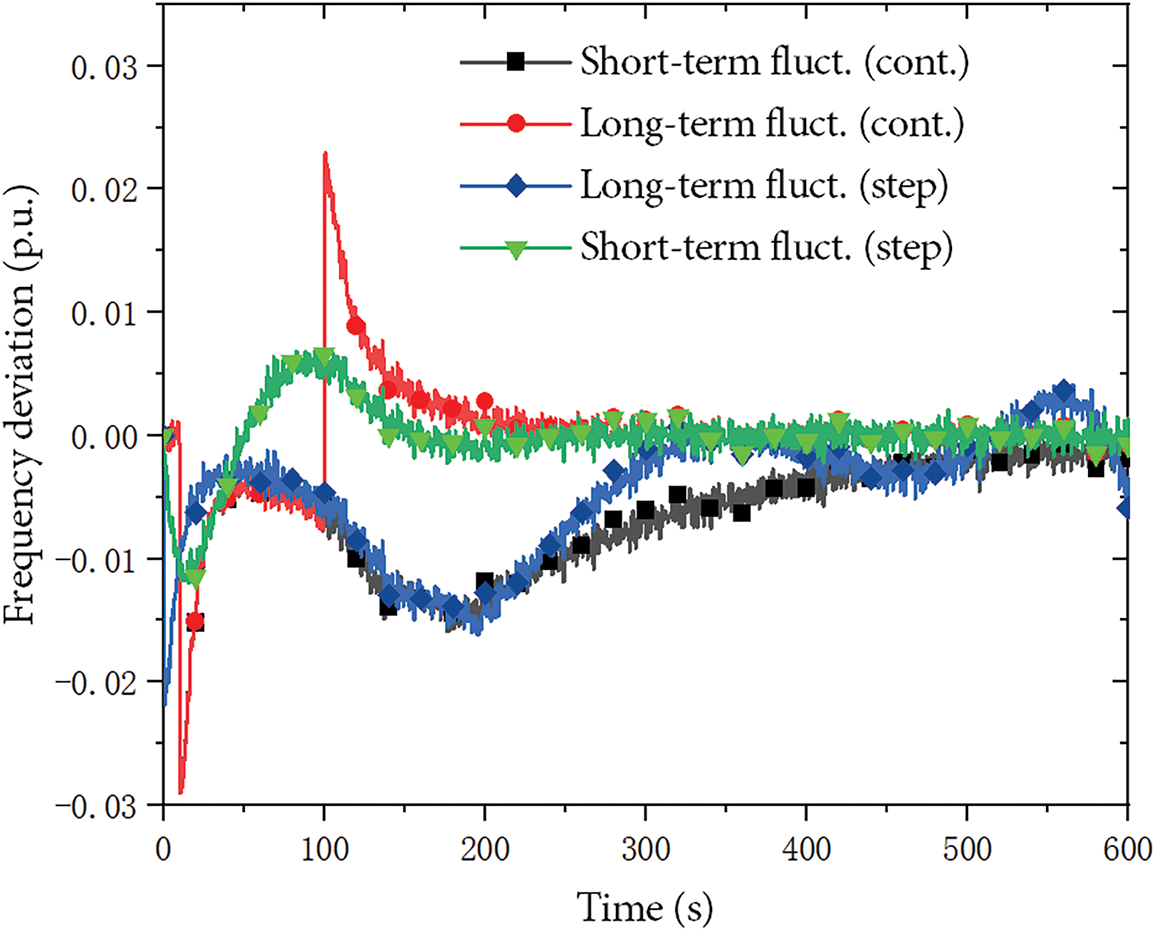

The frequency response under four different net power deficit signals is shown in Fig. 4 using the proposed variable integral coefficient strategy. The simulation results indicate that, despite the differences in the duration of the net power deficit, the system’s frequency response remains in the primary frequency regulation stage during the early phase of frequency closed-loop control, and the role of secondary frequency regulation is not yet noticeable. As time progresses and the net power deficit gradually dissipates, the system’s frequency returns to the steady-state value after a brief adjustment. The system experiences a slight frequency increase around 100–300 s under a long-term power deficit, with a peak of approximately 0.015 p.u. after two types of net power deficit signals are applied. This frequency increase is likely caused by the control strategy’s emphasis on SoC balancing, which reallocates power between ES and thermal units during the stabilization period. Ultimately, the system completes the frequency regulation process to some extent and enters steady-state operation.

Figure 4: Frequency response under four typical scenarios using the proposed variable integral coefficient control strategy (

By comparing Figs. 4 and 5, from around 50 s to around 400 s, compared with the constant integration coefficient control strategy, the variable integration coefficient control strategy caused a slight increase in frequency during this period, while the latter ended the frequency regulation process and entered the steady-state operation within the range of about 50 to 100 s.

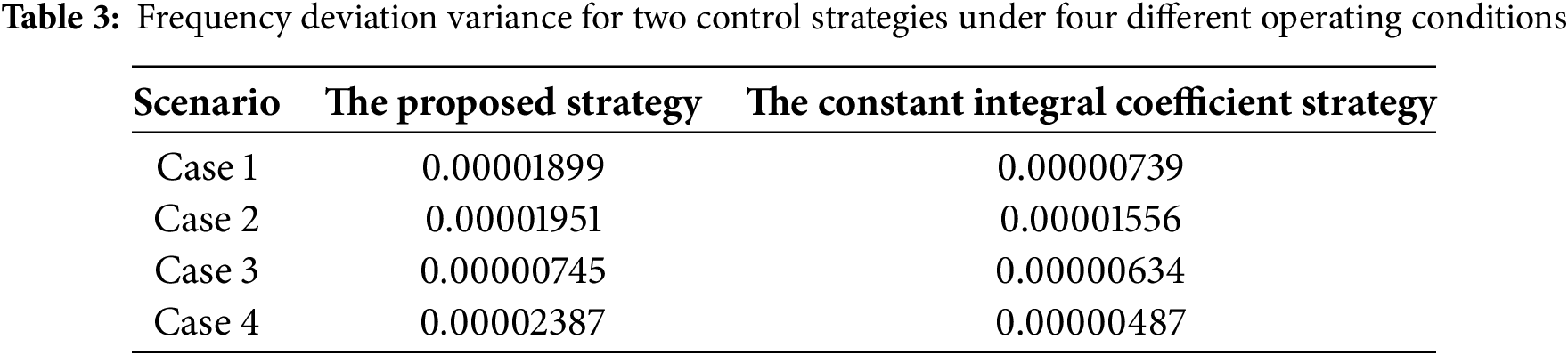

Figure 5: Frequency response under four typical scenarios using the constant integral coefficient strategy (

As shown in Table 3, the variance of frequency deviation under the proposed strategy is generally slightly higher than that of the constant integral coefficient strategy across all four scenarios, with more noticeable differences observed in Case 1 and Case 4. Specifically, the proposed strategy yields variance values of 0.00001899 and 0.00002387 in Case 1 and Case 4, respectively, while the corresponding values under the constant strategy are only 0.00000739 and 0.00000487. In Case 2 and Case 3, the performance of the two strategies is relatively similar.

4.2.2 Coordination of Frequency Regulation Power between TP and ES

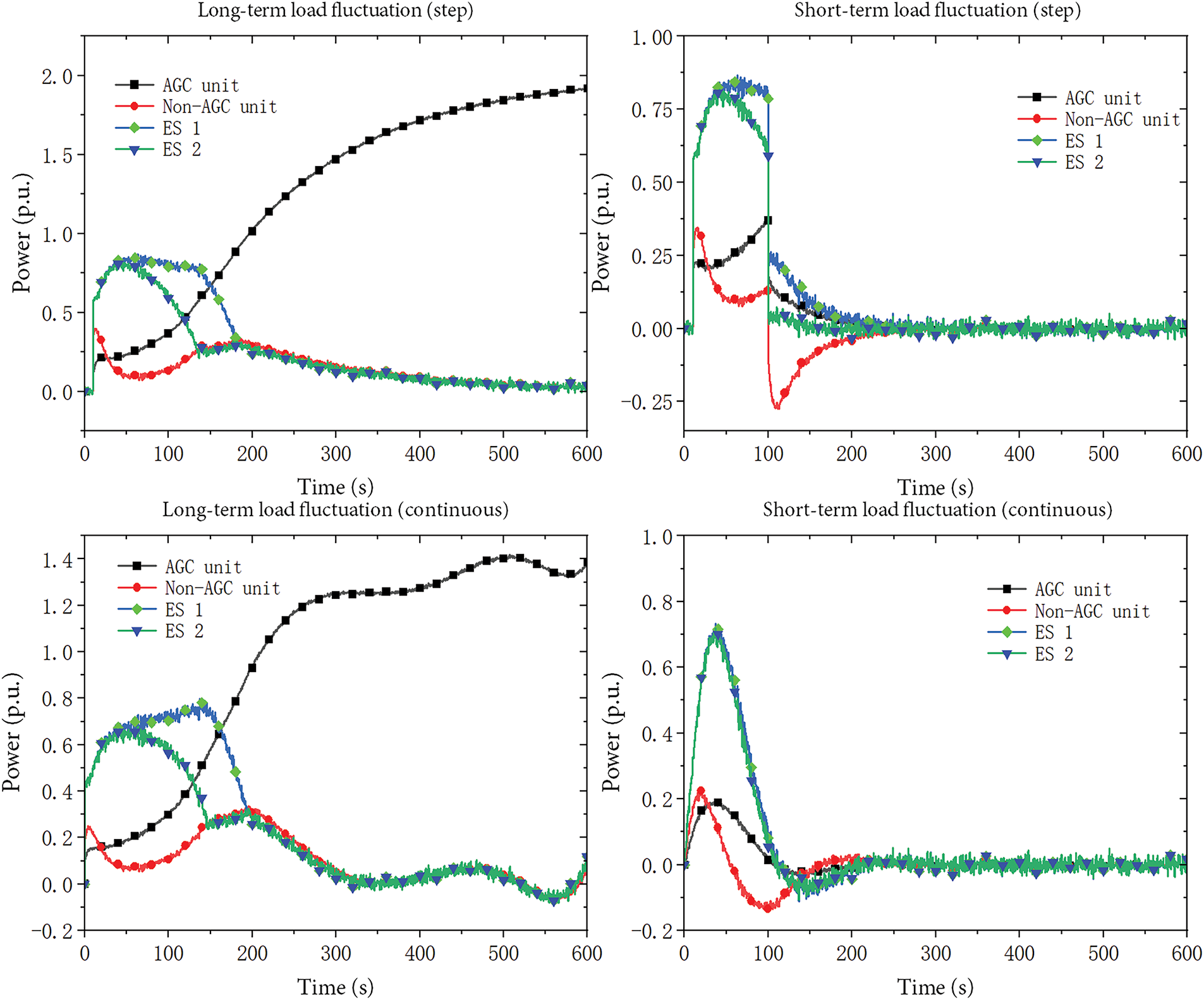

The simulation in Fig. 6 shows the process of frequency modulation power transfer in response to four types of net power deficit signals. When the system encounters a long-term net power deficit, it enters the frequency modulation power transfer process around 50 s. During this process, SoC recovery significantly affects the power allocation between storage units. The SoC of energy storage 1 is closer to 0.5 compared to energy storage 2.

Figure 6: Time-series secondary frequency regulation power of each unit under four typical disturbance scenarios using the proposed variable integral coefficient control strategy (

Therefore, the output power of energy storage 2 is transferred first, followed by the transfer of the output power of energy storage 1. During the frequency modulation power transfer process, due to the relatively slow change in the output power of the thermal power unit and the relatively fast change in the output power of the energy storage system, the system frequency slightly rises at this point, triggering the action of the primary frequency regulation unit. As the power transfer progresses, the system’s frequency deviation gradually activates the secondary frequency regulation output of the thermal power AGC unit, gradually increasing until the frequency deviation is eliminated.

When comparing the system’s response to long-term net power deficits (step signals) and short-term net power deficits (step signals), once the net power deficit disappears, the power transfer process can quickly conclude and transition into a new frequency adjustment process.

By comparing Figs. 6 and 7, the transfer of frequency modulation power cannot be achieved by using the constant integral coefficient control strategy. Regardless of the duration of the net power shortfall, the secondary frequency regulation task is undertaken by the energy storage system. Furthermore, throughout the entire frequency regulation process, although the two energy storage units have different SoCs, they both undertake the same frequency regulation responsibility.

Figure 7: Time-series secondary frequency regulation power of each unit under four typical disturbance scenarios using the constant integral coefficient strategy (

By comparing the strategy in this paper with the constant integration coefficient control strategy, the strategy in this paper can, after basically stabilizing the system frequency, control the energy storage to exit operation in the order of SoC state, and ultimately achieve the transfer of energy storage frequency regulation power to thermal power (that is, the transfer of frequency regulation responsibility from rapid support units to long-term support units). During the power transfer process, the frequency rises slightly but is basically controlled within a relatively reasonable range.

Furthermore, when the system has a short-term frequency modulation requirement, the control strategy proposed in this paper can also identify the system status and promptly suspend the power transfer process. When the frequency gradually recovers, the strategy in this paper can continue to work to a certain extent and take the lead in causing the units whose SoC deviates more from the ideal SoC to exit operation. However, it cannot be denied that the control strategy in this paper, to a certain extent, prolongs the recovery time of the frequency when dealing with the short-term frequency modulation demand.

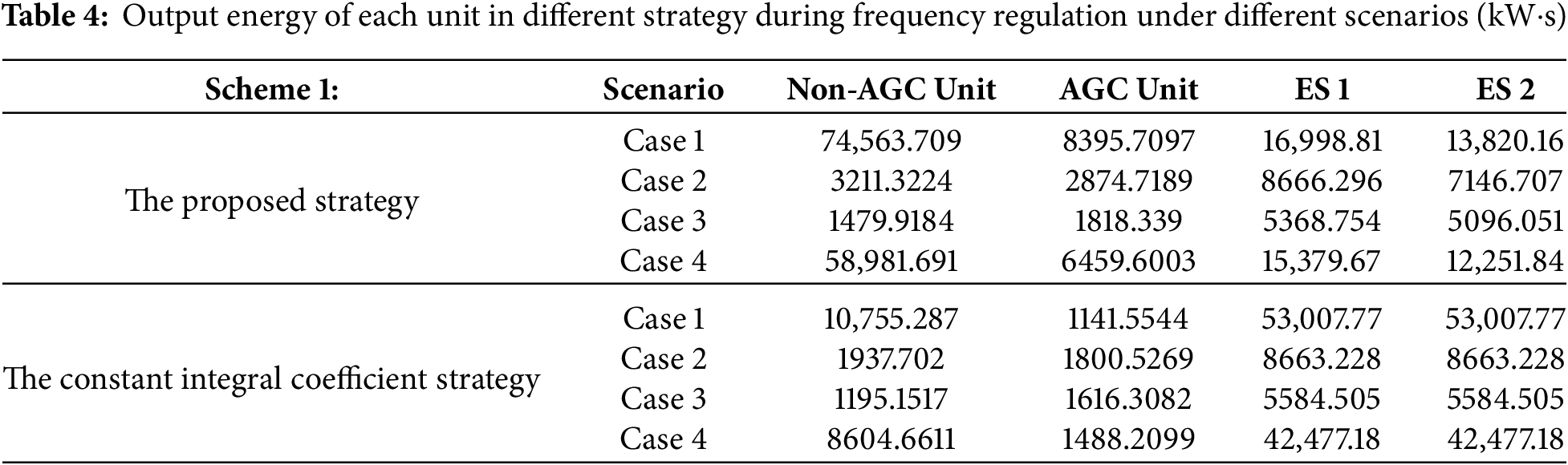

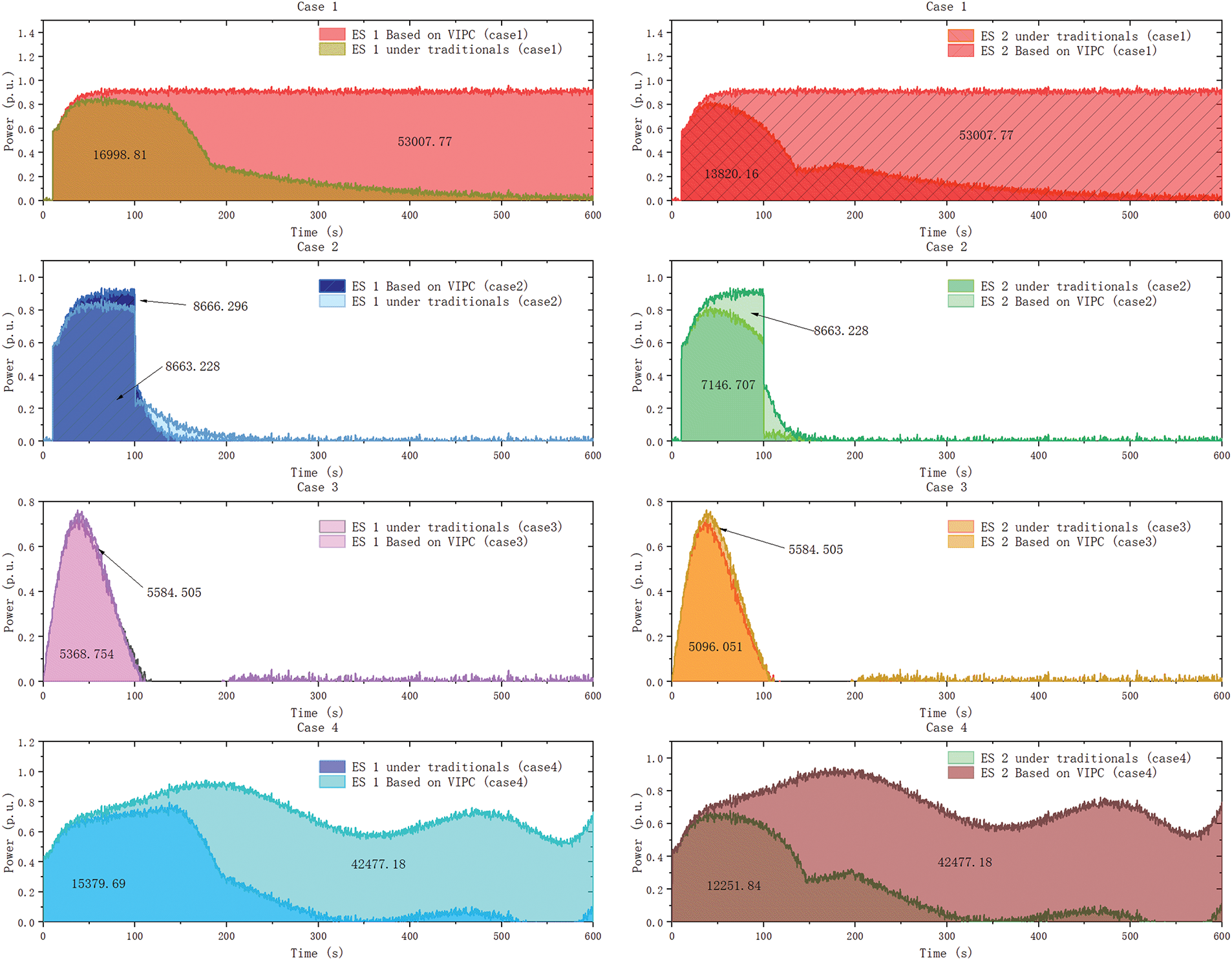

Meanwhile, the data in Table 4 represent the energy output (in kW·s) of each unit during frequency regulation across different scenarios. As shown in the table, the energy storage systems (ES 1 and ES 2), especially Storage 2, consistently deliver the largest share of regulation energy under the proposed strategy, confirming their pivotal role in rapid-response regulation.

In short-term load fluctuation scenarios (Case 2 and Case 4), the proposed strategy significantly enhances the contribution of energy storage systems. For instance, in Case 2, Storage 2 outputs 7146.71 kW·s, compared to 8663.23 kW·s under the constant coefficient strategy. In Case 4, Storage 2 under the proposed strategy reaches 12,251.84 kW·s, substantially higher than the 42,477.18 kW·s shared equally by both storages in the baseline strategy, which implies a more differentiated and responsive allocation. Notably, Storage 1 also demonstrates increased output (15,379.67 kW·s) under the proposed scheme. The corresponding power and energy trajectories of the two storage systems under the four strategies are illustrated in Fig. 8, which clearly shows the dynamic regulation effect and differentiated contributions under various operating modes.

Figure 8: The output power and energy of the two energy storage systems under the four strategies in both the classic control strategy and the conventional control strategy (

In contrast, for long-term load fluctuation scenarios (Case 1 and Case 3), the regulation burden under the proposed strategy shifts more toward conventional thermal AGC units. Specifically, AGC units deliver 8395.71 kW·s in Case 1 and 1818.34 kW·s in Case 3—both higher than the corresponding values in the constant coefficient strategy. This indicates that the proposed approach dynamically allocates regulation responsibility based on the duration and nature of the fluctuation, with thermal units taking a leading role in sustained response tasks.

4.2.3 Real-Time Integral Coefficient Adjustment Based on Gradient Descent

As shown in Fig. 9, the control coefficient of the energy storage integration link starts to gradually decrease under the action of the single-step gradient descent method. This has led to the secondary frequency regulation power undertaken by energy storage beginning to shift to thermal power units.

Figure 9: Control coefficient for the integral component under long-term net power deficit (step signal) input

As the power transfer progresses, the integration control coefficients of the two energy storage units begin to decline at varying rates, influenced by their respective SoC levels. The unit with an SoC further from the target value shows a faster decline in its integration control coefficient compared to the other unit. After about 200 s, the coefficient of the energy storage integration control link approaches zero. After that, the energy storage participates in the primary frequency regulation control of the power grid.

4.2.4 Effect of Objective Function Coefficients on System Control Performance

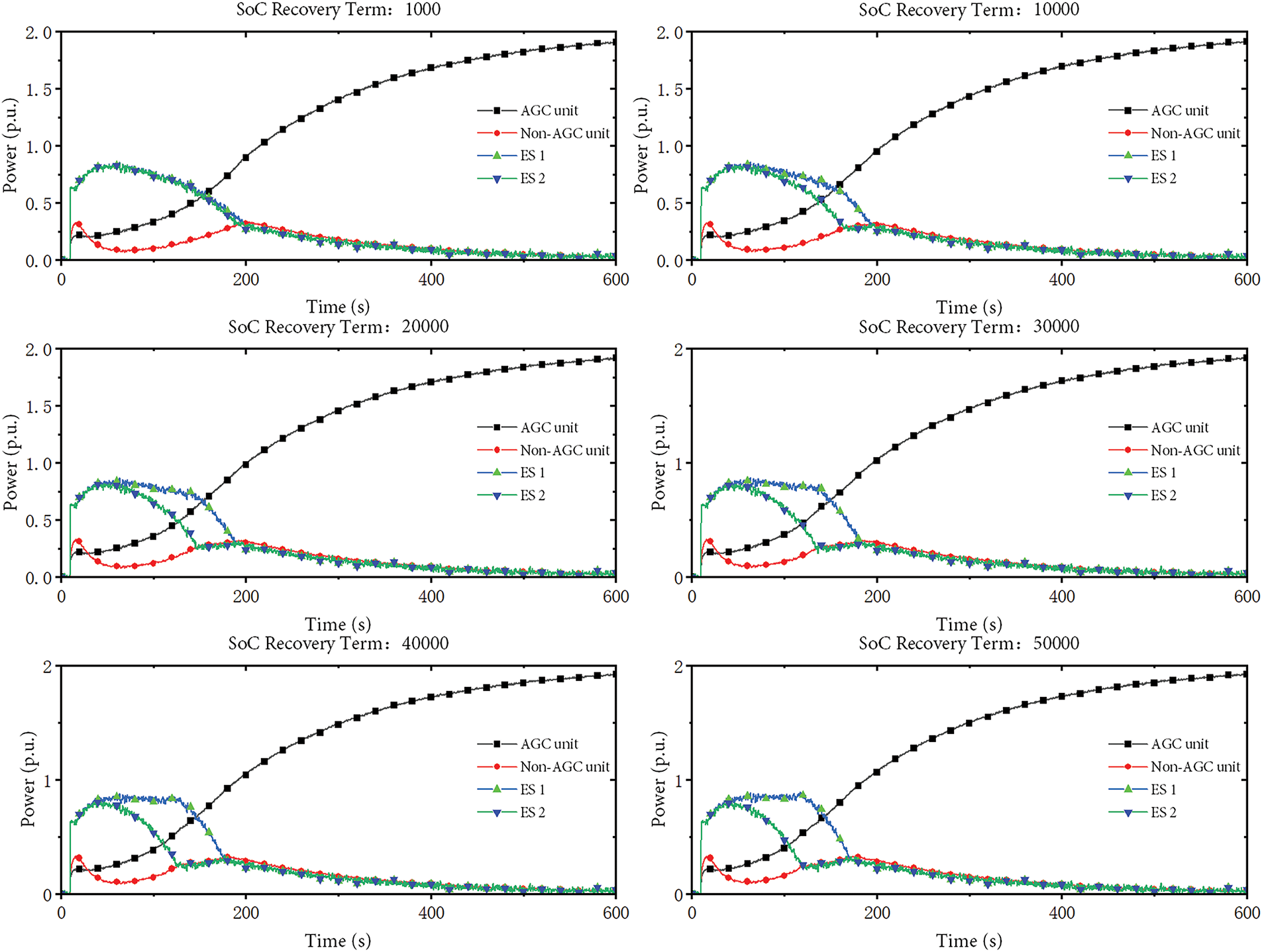

As shown in Fig. 10 presents the influence of the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term on the system frequency response. In the simulation, the AGC following coefficient is set to, and the weight coefficients of the SoC recovery term are set to 1000, 10,000, 20,000, 30,000, 40,000 and 50,000, respectively. As shown in the figure, the SoC recovery coefficient basically does not affect the frequency response of the system; The magnitude of the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term shows a positive correlation with the occurrence of power transfer.

Figure 10: Influence of the weight coefficient for the SoC recovery term on system frequency response in Case 1 (

As shown in Fig. 11 shows the influence of the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term on power transfer; With the continuous increase of the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term, the degree to which the differences of energy storage SoCs are reflected in the power transfer process becomes more and more obvious. When the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term exceeds 29,999, the leading degree of withdrawal from operation for the units whose SoC deviates from the ideal SoC than those whose SoC is closer does not increase due to the increase of the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term.

Figure 11: Influence of the weight coefficient for the SoC recovery term on power distribution between units in Case 1 (

Under six parameters, the output curves of thermal power units are basically similar. In other words, the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term has a significant impact on the power transfer between energy storage, but has no significant impact on the allocation between energy storage and thermal power.

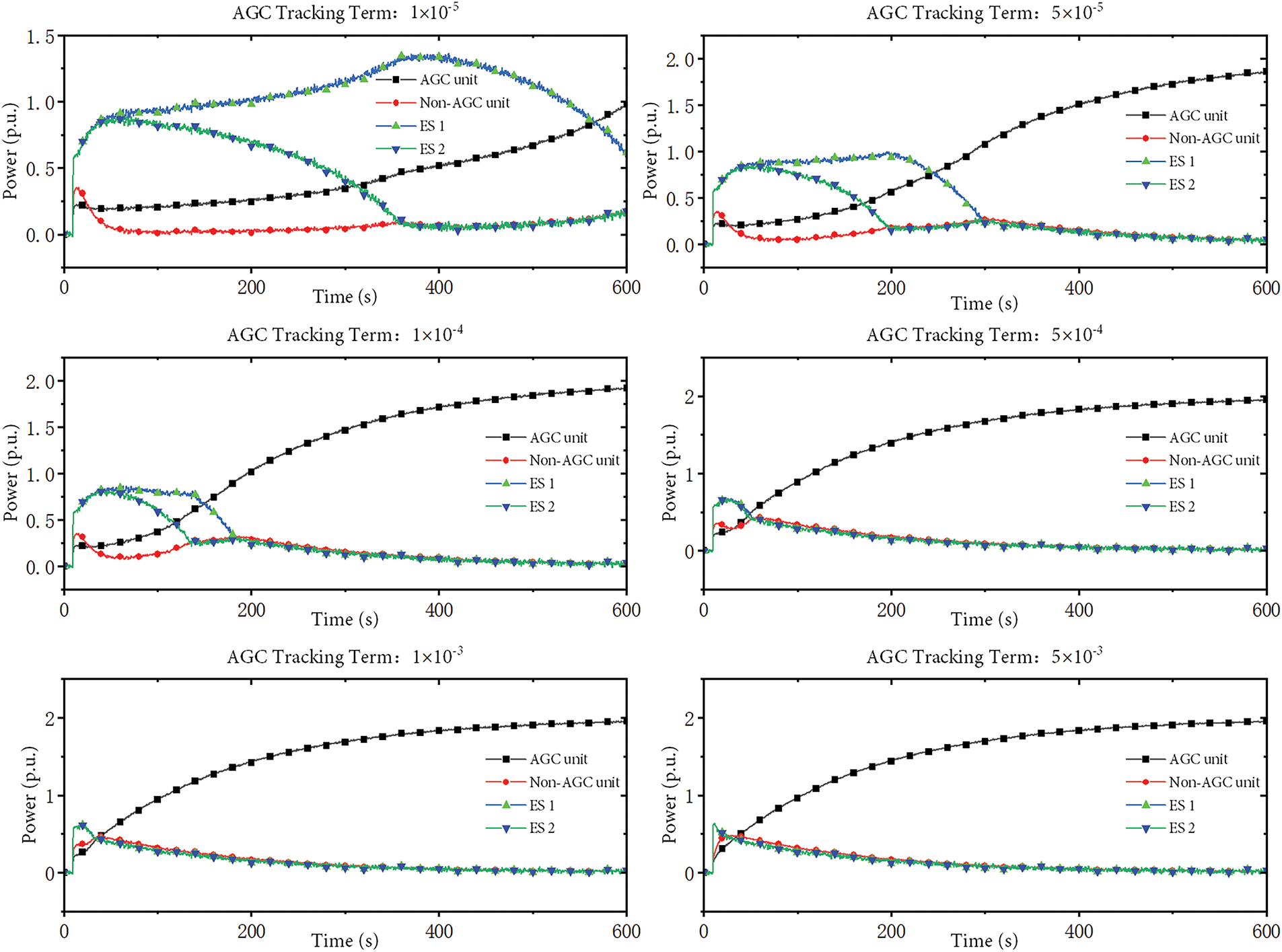

When conducting the influence of the weight coefficient of the AGC following term on the system control performance, the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term is taken as 29,999. AGC follows the term weight coefficient to take 6 values such as

As shown in Fig. 12, it is the influence of the weight coefficient of the AGC following term on the frequency response of the system; Compared with Fig. 10, the influence of the weight coefficient of the AGC following term on the system frequency response is very obvious. The larger the weight coefficient of the AGC following term is, the further forward the maximum amplitude point of the secondary fluctuation of the system frequency is, and the greater the maximum amplitude of the fluctuation is. The maximum fluctuation amplitude reaches 0.03 (p.u.).

Figure 12: Influence of the weight coefficient for the AGC tracking term on system frequency response in Case 1 (

As shown in Fig. 13, the larger the weight coefficient of the AGC following term is, the earlier the energy storage system will transfer power to the thermal power unit. When the weight coefficients of the AGC recovery term are at the three values of

Figure 13: Influence of the weight coefficient for the AGC tracking term on power distribution between units in Case 1 (

By comparing the influence of the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term and the weight coefficient of the AGC following term on the frequency response of the system and the power transfer process between units, the weight coefficient of the SoC recovery term can enable the energy storage units whose SoC deviates far from the ideal SoC to exit preferentially, and most of the power in this exit part is borne by other energy storage units. The AGC follower term weight coefficient can control the power transfer process between the energy storage unit and the thermal power unit. Furthermore, the power transfer process between energy storage units always takes precedence over that between energy storage and thermal power units.

This paper, aiming at the problem of the increasing occurrence frequency of uncertain power shortage time in the power system and the current situation of the continuous connection of energy storage systems to the power system, proposes a novel secondary frequency regulation strategy for thermal-energy storage hybrid systems, featuring dynamic gain adjustment and multi-level coordination among storage units and thermal power units. Finally, simulation verification and analysis were carried out, and the conclusions are as follows:

(1) The proposed control framework effectively separates the frequency regulation tasks: energy storage systems rapidly respond to high-frequency AGC signals, while thermal units handle the low-frequency components. This helps improve frequency regulation performance and mitigate SoC swings and rotor fatigue under test scenarios

(2) Simulation results demonstrate that under small-scale frequency fluctuations, the proposed strategy can reduce unnecessary response from small thermal power units, mitigating mechanical wear. Notably, the method maintains compatibility with existing AGC control frameworks, avoiding extensive retrofitting of control systems.

(3) A dual-feedback mechanism, combining SoC trajectories and AGC signal variation, allows for real-time dynamic gain adjustment via lightweight gradient descent. This enhances adaptability and ensures that units with depleted SoC exit appropriately, improving sustainability and regulation continuity.

(4) The proposed multi-machine power coordination mechanism enables thermal power units to gradually take over regulation duties from energy storage, forming a time-sequenced dynamic transition. This extends the effectiveness of fast-response resources and improves long-term grid frequency stability.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the Key Laboratory of Modern Power System Simulation and Control & Renewable Energy Technology, Ministry of Education (Northeast Electric Power University). Thank them for their contributions, which are crucial to achieving the goals of this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception, task division, content planning, model development, simulation validation, and draft manuscript preparation: Jinyu Guo, Xingxu Zhu and Zezhong Liu; supervision, methodology guidance, result interpretation: Cuiping Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AGC | Automatic Generation Control |

| ACE | Area Control Error |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| ES | Energy Storage |

| TP | Thermal power unit |

| VPCS | Variable integral parameter control strategy |

| FR | Frequency Regulation |

References

1. Yong P, Zhang N, Liu Y, Hou Q, Li Y, Kang C. Exploring the cellular base station dispatch potential towards power system frequency regulation. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2022;37(1):820–3. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2021.3124141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang M, Mu Y, Shi Q, Jia H, Li F. Electric vehicle aggregator modeling and control for frequency regulation considering progressive state recovery. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2020;11(5):4176–89. doi:10.1109/TSG.2020.2981843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang YJA, Zhao C, Tang W, Low SH. Profit-maximizing planning and control of battery energy storage systems for primary frequency control. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2018;9(2):712–23. doi:10.1109/TSG.2016.2562672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhu Y, Huang L, Zhang Q. Sparse measurement-based dynamic modeling for power system frequency response. Electr Power Syst Res. 2021;198:107245. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2021.107245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xue S, Zeng S, Song Y, Hu X, Liang J, Qing H. Adaptive secondary frequency regulation strategy for energy storage based on dynamic primary frequency regulation. IEEE Trans Power Deliv. 2024;39(6):3503–13. doi:10.1109/TPWRD.2024.3485121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qi T, Ye C, Hui H, Zhao Y. Fast frequency regulation utilizing non-aggregate thermostatically controlled loads based on edge intelligent terminals. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2024;15(4):3571–84. doi:10.1109/TSG.2023.3346467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. International Energy Agency (IEA). Global hydrogen review 2023 [Internet]. Paris, France: IEA; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2023. [Google Scholar]

8. Meng L, Dragicevic T, Vasquez JC, Guerrero JM. Review on control of energy storage systems for frequency regulation in renewable energy-based microgrids. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;72(41):895–906. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hao L, Chen L, Huang Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhang H. Challenges and prospects of primary frequency regulation for coal-fired units in new power systems. Autom Electr Power Syst. 2024;48(8):14–29. (In Chinese). doi:10.7500/AEPS20230822001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhao Y, Liu M, Wang J, Li F. Flexible coal-fired power and battery storage synergy for peak regulation: a techno-economic study. Appl Energy. 2023;335:120753. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Minchala-Ávila C, Arévalo P, Ochoa-Correa D, Pauta-Díaz C, Beltrán T, Vázquez-Rodríguez C, et al. A systematic review of model predictive control for robust and efficient energy management in electric vehicle integration and V2G applications. Modelling. 2025;6(1):20. doi:10.3390/modelling6010020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dai R, Dou X, Yu J, Wang H, Zhang M, Liu Q. Stochastic model predictive control strategy for secondary frequency regulation of virtual power plant with PV-storage-charging. Power Syst Technol. 2024;48(8):3228–37. (In Chinese). doi:10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2023.2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li Z, Bai N, Cheng Z. Distributed collaborative AGC method for heterogeneous frequency regulation units in new power systems. Power Syst Technol. 2024;48(6):2327–35. (In Chinese). doi:10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2023.1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhu Q, Li Y, Zhang M, Liu W, Chen X, Sun J. Optimization control and economic evaluation of energy storage for frequency regulation. Energy. 2022;256:124553. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rehman A, Bo R. Sizing battery—PV system in extreme fast charging station: uncertainties and frequency regulation participation. Appl Energy. 2022;313:118845. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.118845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen P, Wang W, Yang J. Coordinated frequency regulation control strategy of wind-thermal-storage system based on multi-scale decomposition. Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica. 2024;45(3):428–35. (In Chinese). doi:10.19912/j.0254-0096.tynxb.2022-1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang S, Yuan B, Xu Q. Optimization control strategy for secondary frequency regulation of power grid with large-scale energy storage participation. Electr Power Autom Equip. 2019;39(5):82–8,95. (In Chinese). doi:10.16081/j.epae.201905014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fu Y, Wan Y, Zhang X. Active support and frequency regulation state transition control of energy storage virtual inertia. Proc CSEE. 2024;44(7):2628–41. doi:10.13334/j.0258-8013.pcsee.230267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhao C, Andersen PB, Træholt C, Hashemi S, Zhang L, You S, et al. Grid-connected battery energy storage system: a review on application and integration. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2023;182(6):113400. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Faraji M, Mahdavi MS, Nurmanova V, Gharehpetian GB, Bagheri M. Coordinated control of flywheel and battery energy storage systems for frequency regulation in diesel generator-based microgrid. IEEE Access. 2025;13:65980–96. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3559722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shen W, Li M, Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhao P, Qiu Y. Hybrid energy storage capacity allocation based on EEMD-EMD and grey relational analysis. Front Energy Res. 2023;10:1021189. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2022.1021189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yi Z, Xu Y, Gu W. Distributed model predictive control based secondary frequency regulation for a microgrid with massive distributed resources. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2021;12(2):1078–89. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2020.3023722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Boyle J, Littler T, Foley A. Battery energy storage system state-of-charge management to ensure availability of frequency regulating services from wind farms. Renew Energy. 2020;160:1119–35. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.06.157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li P, Wu Q, Yang M. Distributed distributionally robust dispatch for integrated transmission-distribution systems. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2021;36(2):1193–205. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2020.3016704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu Y, Parisio A, Li Z. Optimization-based ramping reserve allocation of BESS for AGC enhancement. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2024;39(2):2491–505. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2023.3291023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Knap V, Kazmi H, Edl R, Sossan F, Marechal F, Bacher P. Robust secondary frequency control under deregulated two-area power systems: application of fuzzy-PID control. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2021;133(6):107230. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. He L, Tan Z, Li Y, Cao Y, Chen C. A coordinated consensus control strategy for distributed battery energy storages considering different frequency control demands. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2023;15(1):304–15. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2023.3283972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wiley A, Sun H, Thomas J, Rees M, Wu Y. A refined steam turbine model for primary frequency regulation with real-time adaptability. Energy Sci Eng. 2022;10(2):234–45. doi:10.1002/ese3.1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools