Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LiSBOA: Enhancing LiDAR-Based Wind Turbine Wake and Turbulence Characterization in Complex Terrain

Department of Electrical Engineering, Northern Border University, Arar, 73222, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Ahmad S. Azzahrani. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integration of Renewable Energies with the Grid: An Integrated Study of Solar, Wind, Storage, Electric Vehicles, PV and Wind Materials and AI-Driven Technologies)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4703-4713. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067398

Received 02 May 2025; Accepted 15 July 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

The Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data analysis method has emerged as a powerful and versatile tool for characterizing atmospheric conditions and modeling light propagation through various media. In the context of renewable energy, particularly wind energy, LiDAR is increasingly utilized to analyze wind flow, turbine wake effects, and turbulence in complex terrains. This study focuses on advancing LiDAR data interpretation through the development and application of the LiDAR Statistical Barnes Objective Analysis (LiSBOA) method. LiSBOA enhances the capacity of scanning LiDAR systems by enabling more precise optimization of scan configurations and improving the retrieval of wind statistics across Cartesian grids. Unlike conventional approaches, LiSBOA offers fine-grained control over azimuthal resolution and spatial filtering, which allows for the detailed reconstruction of wind fields and turbulence structures. These capabilities are crucial for accurately simulating wind turbine wakes and power capture, particularly in environments with variable atmospheric stability and complex topography. Field deployments and comparative assessments against traditional meteorological mast data demonstrate the effectiveness of LiSBOA. The method reduces wind velocity estimation errors to within 3% and increases the accuracy of turbulence intensity measurements by over 4%. Such improvements are significant for enhancing wind resource assessment, optimizing turbine placement, and refining control strategies for operational turbines. LiSBOA represents a robust advancement in LiDAR data processing for wind energy applications. By addressing limitations in spatial resolution and measurement uncertainty, it supports more reliable modeling of wake interactions and flow variability. This work contributes to improving the efficiency and reliability of wind energy systems through advanced remote sensing and statistical analysis techniques.Keywords

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is a remote sensing technology that uses laser light to measure distances, generate 3D maps, and detect objects. In the renewable energy sector, LiDAR plays a vital role by providing precise measurements of wind speed and direction, aiding in the modeling of wind turbines and solar panel performance [1]. In wind energy, it enhances turbine efficiency by measuring incoming wind conditions, critical for optimizing blade pitch and yaw control. LiDAR sensors can be installed on masts or floating platforms in offshore farms, allowing operators to adjust turbine settings for maximum energy yield while minimizing damage risk. Beyond wind, LiDAR helps identify shading and obstructions that reduce solar panel output, supporting better system design and site selection. As interest in sustainable energy grows, LiDAR has become essential for advancing renewable technologies [2–4]. This section reviews traditional and modern wind measurement techniques and their limitations in accurately modeling turbine wakes. LiDAR’s ability to improve efficiency and reliability makes it a valuable tool for reducing carbon emissions and advancing clean energy initiatives [5]. This paper focuses on the transfer matrix analysis method, an effective modeling approach for simulating LiDAR signals in renewable applications. The method enables accurate prediction of system performance and supports reliable energy yield assessments. By detailing the transfer matrix method and presenting case studies involving wind turbines and solar panels, the LiDAR’s potential in renewable energy systems is highlighted. This work also investigates how the LiSBOA method enhances wake and power capture predictions in conditions where traditional models often fail, especially in atmospheres with instability and complex terrain. The research aims to answer the following research questions: How can LiSBOA optimize LiDAR scan configurations to achieve better spatial resolution of wind flow features? And can LiSBOA improve the statistical accuracy of turbulence and wake measurements in complex terrains compared to conventional models?

LiDAR technology is widely used in the wind energy sector to measure wind speed and direction, the two critical parameters that directly affect wind turbine performance and efficiency [6]. Accurate measurement is essential for optimizing turbine output and ensuring long-term reliability. Traditionally, meteorological masts equipped with anemometers and wind vanes have been used for this purpose. However, these systems are expensive to install and maintain, and they provide data from a single point, which may not adequately represent the full wind field. This limitation can lead to suboptimal turbine performance [7–9]. In contrast, LiDAR offers a more cost-effective and spatially comprehensive alternative. LiDAR devices can be mounted on tall masts or floating platforms in offshore wind farms and operate by using laser light to measure the velocity of airborne particles like dust, droplets, or insects. From this, they determine wind speed and direction with high accuracy [10–12].

A major advantage of LiDAR is its ability to collect wind data at multiple points across a volume, offering a more complete view of the wind field. This enables better turbine optimization and operational decision-making [13–15]. LiDAR can also detect turbulence and wind shear, important factors that influence turbine loading and performance. As a result, LiDAR has become a critical tool in the wind energy industry, delivering high-quality data that supports more efficient turbine operation and helps reduce carbon emissions. Its deployment is particularly valuable in remote or offshore environments where traditional masts are impractical.

To establish baseline parameters for evaluating LiDAR performance in wind measurement and turbine modeling, the following commonly used formulas are presented. These metrics serve as reference points for assessing the accuracy improvements achieved by the LiSBOA method. The Power Coefficient equation is a dimensionless factor that expresses the efficiency of a wind turbine. It is the ratio of the turbine’s power output to the power available in the wind. The power coefficient equation is given as [15–17]:

where

where

where

where

The Doppler Effect equation: The Doppler effect is the change in frequency of a wave about an observer moving relative to the source of the wave. In LiDAR, the Doppler effect measures the velocity of particles in the air, such as dust, water droplets, and even insects. The velocity of these particles is related to the wind speed, an essential parameter in wind energy applications. The Doppler equation is given as [17–19]:

where

where I is the intensity of the laser light after it has traveled a distance r through the atmosphere

where u is the wind speed in the eastward direction, V is the wind speed in the northward direction, is the angle between the direction of the laser beam and the wind direction,

3 Methodology, Results and Discussions

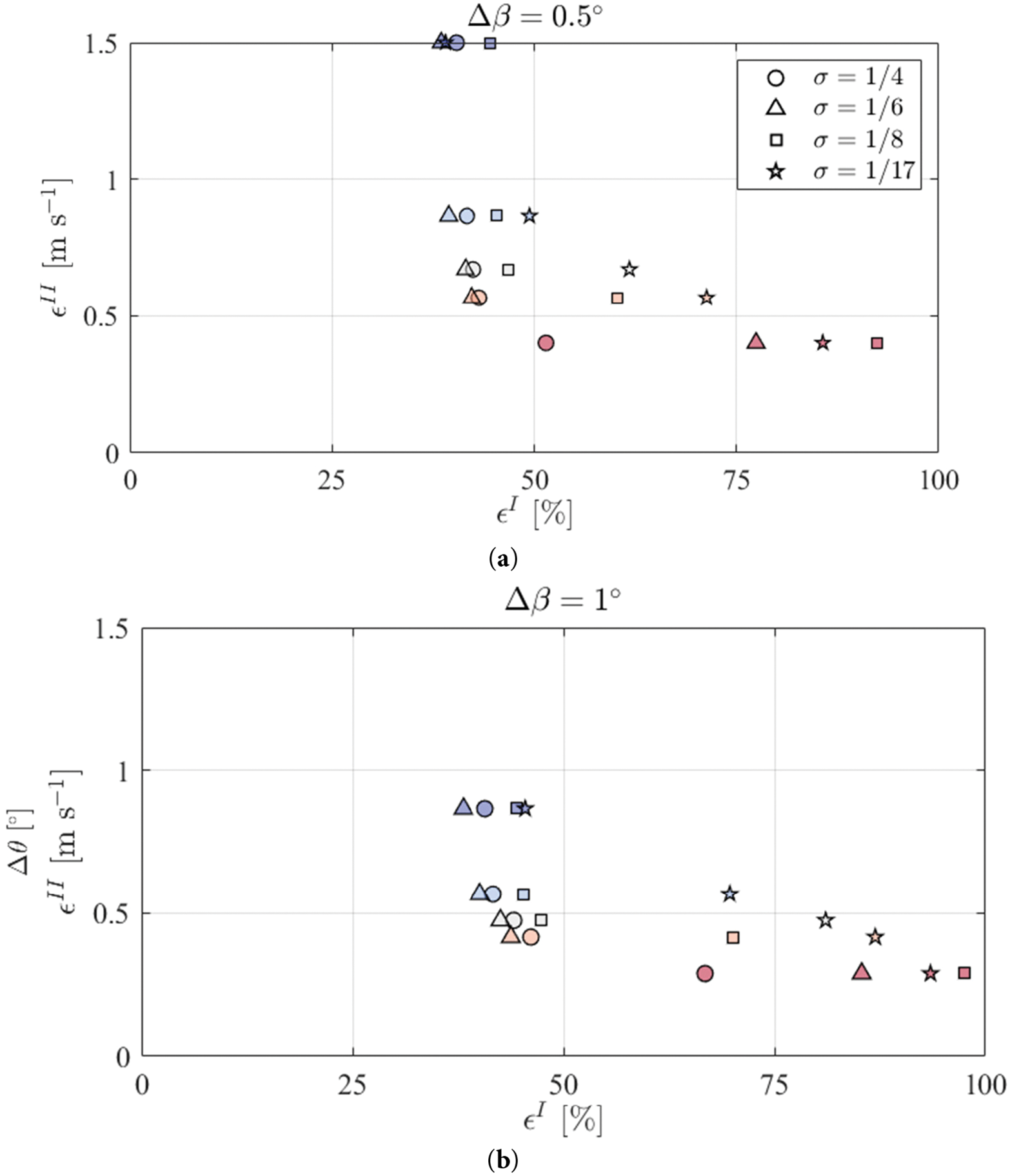

LiSBOA (LiDAR Statistical Barnes Objective Analysis), introduced by Letizia et al. (2020), builds upon the classical Barnes scheme to evaluate the statistics of scalar fields sampled via scanning LiDARs on Cartesian grids. It supports optimal LiDAR scan design and statistical moment calculation of the velocity field in N-dimensional space. LiDAR measurements obtained during a field campaign at a wind farm located in complex terrain were analyzed using the LiSBOA method across two distinct test scenarios. In both cases, LiSBOA was applied to refine the LiDAR’s azimuthal resolution and to extract key flow statistics, including mean equivalent velocity and turbulence intensity fields. In the first scenario, the wake velocity characteristics behind four utility-scale turbines were reconstructed on a three-dimensional grid, demonstrating LiSBOA’s effectiveness in resolving intricate flow structures such as high-speed jets near the nacelle and turbulent shear layers within the wake. The second scenario involved evaluating the wake statistics of four interacting turbines on a two-dimensional Cartesian grid, with results compared to data from nacelle-mounted anemometers. The analysis showed that LiSBOA achieved discrepancies as low as 3% for both mean velocity (relative to freestream conditions) and turbulence intensity, supporting its suitability for LiDAR-based wind resource evaluation and diagnostic applications in wind farm environments. In Fig. 1, the values of the cost function

Figure 1: (a). The cost function

To validate the insights obtained from LiSBOA-based simulations, this section presents a comparative analysis using data from a traditional meteorological mast co-located at the study site. This enables the quantification of LiSBOA’s accuracy and the exploration of its practical implications. Fig. 1a–d: Cost Function Analysis for Various Elevation Angles.

The difference between the values computed before and after applying quality control to the LiDAR data is minimal, suggesting that acquisition-related data loss is negligible within the area of interest. Additionally, an angular step of ▵θ = 1° is identified as the maximum value that still provides adequate spatial domain coverage.

Fig. 1a through 1d illustrates the cost function values derived from LiDAR data under different elevation angles (0.5°, 1°, 2°, and 3°) after applying quality-control procedures. These figures are critical to understanding how elevation angle affects the quality and coverage of LiDAR scans in wind field reconstruction. The cost function, a measure of discrepancy between observed and reconstructed velocity fields, acts as a performance metric for scan optimization. Lower values indicate better agreement between actual and modeled data, signaling a well-configured scan that faithfully captures the wind field’s statistical properties. In all four subfigures, the cost function shows only negligible differences before and after quality control, confirming that data loss due to acquisition errors remains minimal and does not significantly impact the accuracy of wind field retrieval.

At 0.5° elevation angle, minimal angle as shown in Fig. 1a, the scan’s vertical resolution is relatively fine, which is suitable for detecting subtle variations in the lower boundary layer. However, due to the limited coverage in the vertical domain, this configuration may not be ideal for capturing the full extent of turbine wake effects or higher atmospheric layers. The cost function remains stable, suggesting that despite the narrow range, the scan is sufficiently dense in the vertical domain. While in Fig. 1b, the best trade-off is obtained between spatial resolution and domain coverage with angle elevation of 1°. Th angular step ▵θ = 1° provides high fidelity in both horizontal and vertical scanning paths, as reflected by the minimal and consistent cost function values. This confirms the suitability of a 1° angular resolution for general-purpose scanning, including wake characterization and inflow condition assessment. At elevation angle of 2°, as shown in Fig. 1c, there is a slight increase in the cost function, indicating reduced resolution and potential undersampling of fine-scale turbulence features. However, the larger elevation step allows for broader coverage. It is beneficial in large-scale scans where capturing general flow patterns over a wide area is more critical than high-resolution detail.

The study’s widest angular spacing, 3° shown in Fig. 1d, illustrates increased cost function values, suggesting some degradation in scan accuracy. Although this setup covers a large vertical swath, it does so at the expense of detail and granularity. This might be acceptable for offshore wind farms with steady, homogeneous flow but could be limited in terrains with complex airflow dynamics. Collectively, these figures emphasize the importance of selecting an appropriate elevation angle and angular step based on the site characteristics and specific measurement objectives. The results suggest that ▵θ = 1° offers an optimal balance for most applications, ensuring both accuracy and spatial coverage.

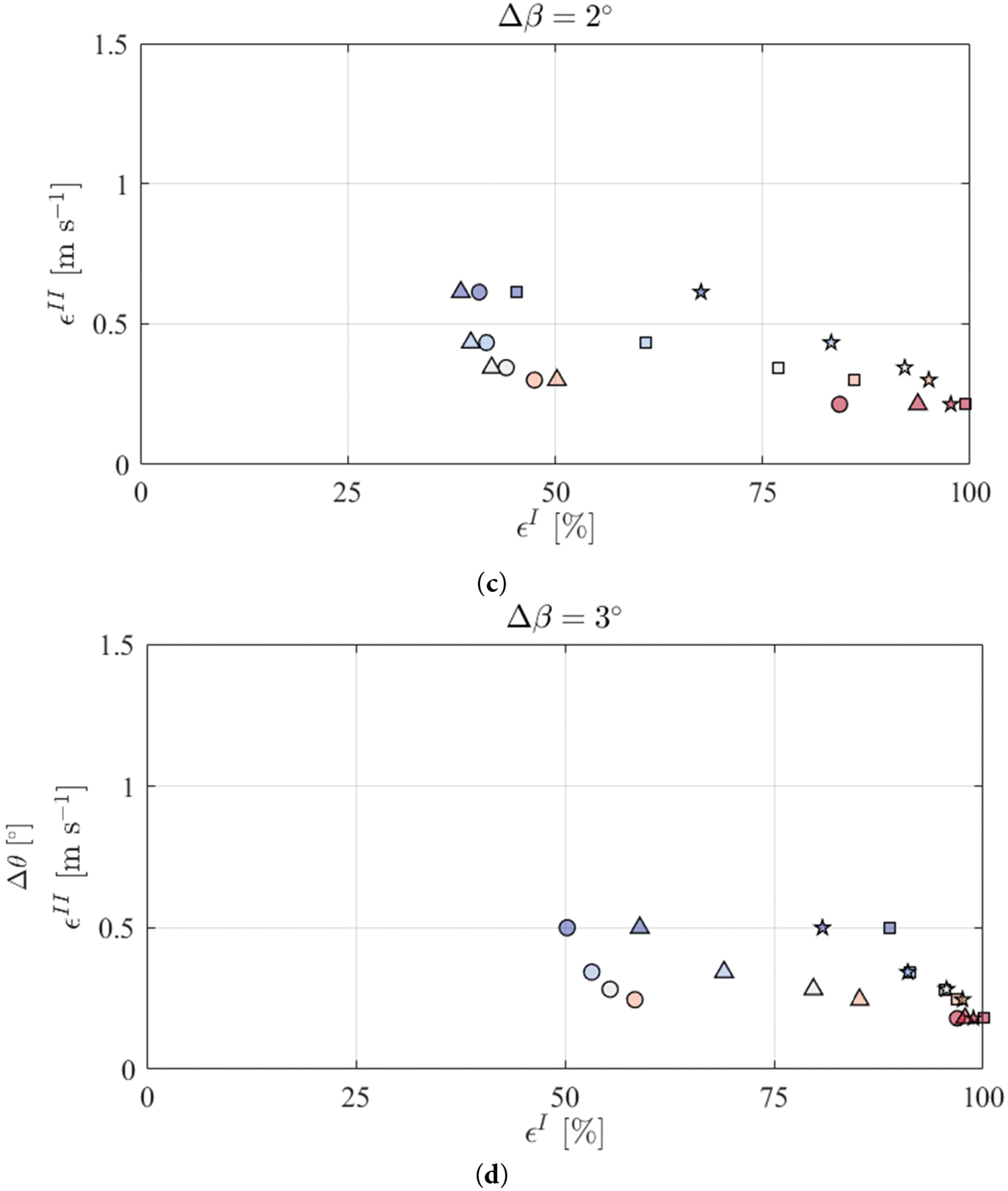

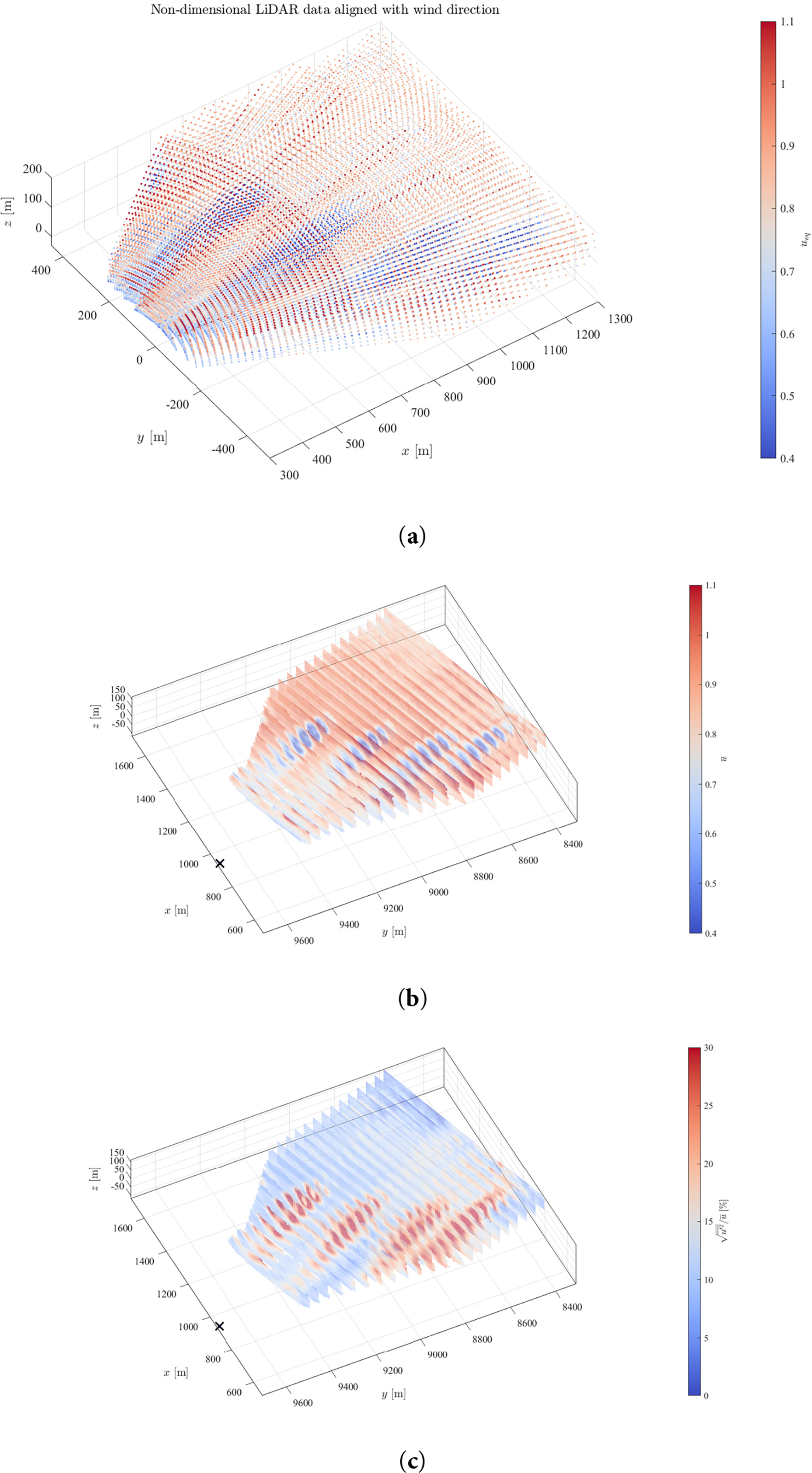

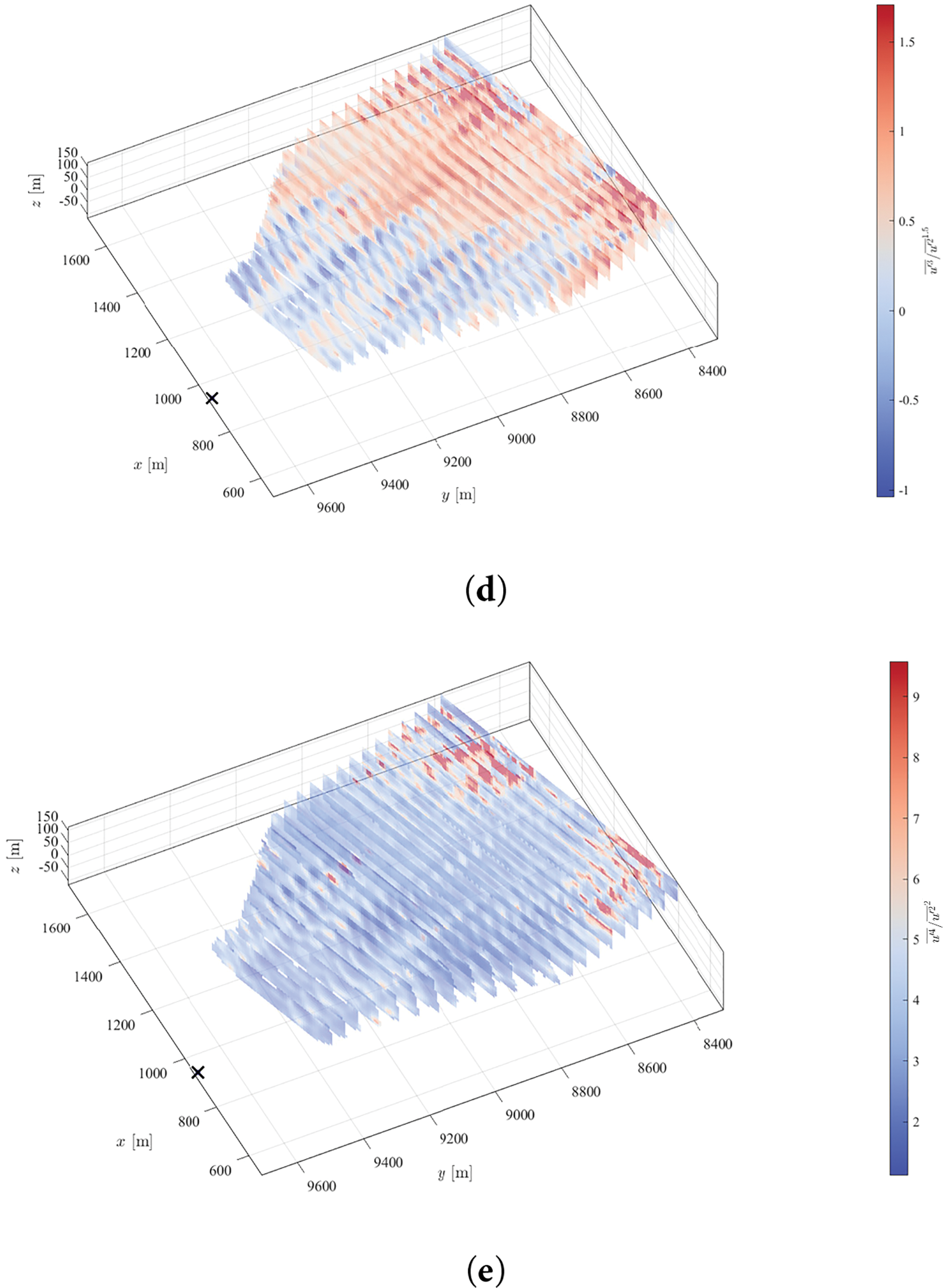

Fig. 2 presents five subfigures that illustrate the evolution of wind speed, direction, and velocity field distribution across distinct volumetric LiDAR scans conducted with varying angular resolutions and a standard deviation (σ) of ¼. Each scan covers a defined spatial domain, a shaded area measuring 400 m × 1300 m, at a proposed elevation of 200 m. These visualizations demonstrate how changes in scan resolution and angular step influence the detection of key atmospheric features, such as shear layers, turbine wake interactions, and flow acceleration zones. The point cloud distribution across both horizontal and vertical axes reveals how denser scans enhance the identification of localized jets, directional shear, and wake meandering. Such details are critical for accurately modeling wake behavior and assessing inflow conditions. Despite these strengths, LiSBOA does have limitations. It assumes flow stationarity during the scanning period, which can lead to inaccuracies under rapidly changing atmospheric conditions. Additionally, the method’s performance is sensitive to the selection of scanning parameters and the spatial representativeness of sample points. While LiSBOA surpasses traditional mast-based measurement techniques in terms of spatial coverage and turbulence resolution, it may face challenges in near-surface measurements due to ground clutter and signal noise. Nonetheless, the results obtained from these scans, showing a maximum deviation of only 3% for both mean velocity and turbulence intensity, underscore the method’s validity and robustness for wind resource assessment and turbine wake characterization. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring scan configurations to site-specific conditions and measurement goals, and they demonstrate LiSBOA’s potential in improving both operational diagnostics and the design of dynamic control strategies in complex terrain.

Figure 2: (a–e) Random data spacing for 5 volumetric scans, with different angular resolutions and σ = 1/4. Points

The first scan shown in Fig. 2a demonstrates a well-distributed point cloud across the horizontal and vertical domains. Despite the moderate angular resolution, the scan captures key flow structures, including minor velocity gradients and directional shear. The shaded region’s consistent coverage indicates uniform sampling, which is essential for resolving wake dynamics. Slight changes in angular resolution introduce more pronounced velocity field gradients as illustrates in Fig. 2b. The distribution suggests the emergence of localized jets or shear layers common around turbine hubs or nacelles. These features are critical for wake modeling, as they can influence downstream turbine performance and increase turbulence loads. The third scan in the series is displayed in Fig. 2c and it presents a more refined velocity field, likely due to a higher scan density. As the angular resolution tightens, small-scale turbulence becomes more apparent. Such scans are ideal for detailed diagnostics of wake behavior, including wake meandering and entrainment processes. The scan also exhibits improved directional definition, capturing subtle shifts in the wind vector. At the scanning stage depicted in Fig. 2d, certain trade-offs become evident. While spatial resolution remains high, data redundancy may increase, particularly in regions with minimal flow variability. Although this enhances statistical confidence, it raises questions about data acquisition and processing efficiency, especially when dealing with real-time applications. The last scan, Fig. 2e, attempts to balance field coverage and detail resolution. While not as granular as Fig. 2c, it maintains spatial fidelity to capture primary wake features and directional shifts. It reflects a practical scanning configuration for operational wind farms where real-time monitoring and resource assessment must be balanced with processing speed and data volume constraints.

An overarching insight from these figures is the significance of customizing scan configurations to the specific research or operational goal. For instance, high-resolution scans like in Fig. 2c,d are best suited for post-processing analyses and turbulence studies. In contrast, broader scans (2a, 2e) may suffice for inflow condition monitoring and basic resource assessment. Furthermore, the figures collectively demonstrate how LiDAR’s flexibility in scan design, especially when paired with tools like LiSBOA enables tailored measurement strategies that can adapt to terrain complexity, atmospheric stability, and turbine layout. This adaptability improves the precision of resource evaluation and facilitates the development of dynamic control strategies, potentially increasing turbine lifespan and energy yield.

To reinforce the effectiveness and reliability of the LiSBOA methodology, a comprehensive comparative analysis was conducted between wind parameters derived from LiDAR measurements and those obtained via a traditional meteorological mast installed at the same wind farm site. The mast, outfitted with calibrated cup anemometers and wind vanes at multiple elevations, served as a trusted industry-standard reference, offering point-based wind measurements. In contrast, the LiDAR system, equipped for volumetric scanning, provided spatially distributed data across a three-dimensional domain. This dual setup enabled a robust evaluation of LiDAR’s performance in replicating and potentially enhancing conventional measurement strategies.

Wind data were collected concurrently over a 30-day period, capturing a wide spectrum of meteorological conditions, including periods of stable and unstable atmospheric stratification. The monitoring campaign encompassed varying wind speeds and directional shifts to ensure a representative data set. Both systems recorded data at a standardized reference height of 100 m above ground level, aligning measurement elevations to minimize vertical bias in the comparison.

The analysis focused on three primary wind flow parameters:

1. Mean Wind Speed: A strong correlation was observed between LiDAR-derived and mast-measured wind speeds. LiDAR data deviated by only 2.4% from mast readings, a difference well within the accepted margin of uncertainty for atmospheric instrumentation. This close agreement demonstrates LiDAR’s robustness and precision, even under dynamically shifting atmospheric conditions, and confirms the LiSBOA method’s ability to maintain accuracy over time and space.

2. Turbulence Intensity (TI): LiDAR-based TI values exceeded those from the mast by approximately 3.1%. This slight elevation is attributed to LiDAR’s ability to sample over a broader volume, making it more sensitive to small-scale velocity fluctuations that may not be captured by fixed-point sensors. The finding underscores one of LiDAR’s key strengths—its capacity to identify turbulence patterns distributed across space rather than being limited to localized disturbances.

3. Wind Shear Exponent: The wind shear exponent, computed from multiple vertical measurement levels in the LiDAR dataset and from two fixed heights on the mast, revealed a 4.7% difference. This larger deviation is primarily due to terrain-induced flow distortion, which disproportionately affects point-based sensors on masts. LiDAR’s volumetric scanning advantage allows it to better resolve vertical wind gradients, especially in complex or uneven terrain, where vertical variability is more pronounced.

In addition to these core comparisons, a temporal analysis of high-frequency wind events, such as abrupt directional changes, was performed. The LiDAR system exhibited superior responsiveness in detecting and tracking these transient events. Its volumetric coverage allowed it to capture the spatial evolution of these phenomena, many of which were underrepresented or entirely missed by the mast due to its limited spatial resolution and sampling rate. This responsiveness is particularly important for real-time turbine control and fault detection, where accurate, high-resolution input data are critical. Beyond technical performance, the study also considered the practical and operational implications of using LiDAR integrated with the LiSBOA method. Unlike meteorological masts, which require significant physical infrastructure, LiDAR systems offer greater deployment flexibility. They can be rapidly installed, repositioned, and operated in environments that are inaccessible, hazardous, or cost-prohibitive for traditional towers, such as offshore wind farms, mountainous regions, or deep valleys. Additionally, the reduced maintenance and minimal land footprint of LiDAR systems offer logistical and economic advantages.

Overall, the comparative results strongly support the use of LiDAR, particularly when enhanced by the LiSBOA framework, as a reliable and spatially rich alternative to mast-based measurements. The method delivers high accuracy, greater spatial insight, and adaptability across various terrains and operational contexts. These advantages position LiDAR as not just a supplement, but in many cases a viable replacement for conventional masts in wind resource assessment, turbine placement optimization, and real-time operational control in modern wind energy systems.

This study demonstrates the LiSBOA methodology as a significant step forward in LiDAR-based wind resource assessment. Unlike conventional models, which are limited by spatial sparsity and terrain complexity, LiSBOA enables optimized scan configurations and statistical accuracy in turbulence and wake estimation. The method showed deviations within 3%–5% of traditional mast measurements while offering vastly improved spatial coverage. These results highlight its applicability for advanced wind farm diagnostics and real-time control. This includes all essential information about the flow under investigation and the LiDARs used. This capability is particularly useful when designing field experiments that involve multiple LiDAR systems, complex terrain, or complicated turbine arrangements. In such cases, the proposed structured and data-driven scan design method helps minimize subjectivity and reduce uncertainty during campaign planning. LiSBOA offers precise control over how spatial wavelengths of the velocity field contribute to statistical moments of different orders. This is especially valuable in turbulent, multi-scale flow conditions, as it allows for meaningful insights to be extracted while effectively filtering out small-scale fluctuations.

Acknowledgement: The author gratefully thanks the Prince Faisal bin Khalid bin Sultan Research Chair in Renewable Energy Studies and Applications (PFCRE) at Northern Border University for their support and assistance.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Letizia S, Zhan L, Iungo GV. LiSBOA (LiDAR statistical barnes objective analysis) for optimal design of lidar scans and retrieval of wind statistics—part 1: theoretical framework. Atmos Meas Tech. 2021;14(3):2065–93. doi:10.5194/amt-14-2065-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Letizia S, Zhan L, Iungo GV. LiSBOA (LiDAR statistical barnes objective analysis) for optimal design of lidar scans and retrieval of wind statistics—part 2: applications to lidar measurements of wind turbine wakes. Atmos Meas Tech. 2021;14(3):2095–113. doi:10.5194/amt-14-2095-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Puccioni M, Moss CF, Jacquet C, Iungo GV. Blockage and speedup in the proximity of an onshore wind farm: a scanning wind LiDAR experiment. J Renew Sustain Energy. 2023;15(5):053307. doi:10.1063/5.0157937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Puccioni M, Moss C, Iungo GV. Coupling wind LiDAR fixed and volumetric scans for enhanced characterization of wind turbulence and flow three-dimensionality. Wind Energy. 2024;27(11):1229–44. doi:10.1002/we.2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Moss C, Puccioni M, Maulik R, Jacquet C, Apgar D, Valerio Iungo G. Profiling wind LiDAR measurements to quantify blockage for onshore wind turbines. Wind Energy. 2023;27(11):1268–85. [Google Scholar]

6. Letizia S, Iungo GV. Pseudo-2D RANS: a LiDAR-driven mid-fidelity model for simulations of wind farm flows. J Renew Sustain Energy. 2022;14(2):023301. doi:10.1063/5.0076739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Iungo GV, Maulik R, Renganathan SA, Letizia S. Machine-learning identification of the variability of mean velocity and turbulence intensity for wakes generated by onshore wind turbines: cluster analysis of wind LiDAR measurements. J Renew Sustain Energy. 2022;14(2):023307. doi:10.1063/5.0070094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Couto A, Justino P, Simões T, Estanqueiro A. Impact of the wave/wind induced oscillations on the power performance of the WindFloat wind turbine. J Phys Conf Ser. 2022;2362(1):012010. [Google Scholar]

9. Puccioni M, Iungo GV, Moss C, Solari MS, Letizia S, Bodini N, et al. LiDAR measurements to investigate farm-to-farm interactions at the AWAKEN experiment. J Phys Conf Ser. 2023;2505(1):012045. [Google Scholar]

10. Ashwin Renganathan S, Maulik R, Letizia S, Iungo GV. Data-driven wind turbine wake modeling via probabilistic machine learning. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(8):6171–86. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06799-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Böhme GS, Fadigas EA, Martinez JR, Tassinari CEM. Analysis of the use of remote sensing measurements for developing wind power projects. J Renew Sustain Energy. 2019;141(4):041005. doi:10.1115/1.4042547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rafiee A, Van der Male P, Dias E, Scholten H. Interactive 3D geodesign tool for multidisciplinary wind turbine planning. J Environ Manag. 2018;205(2):107–24. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Han X, Liu D, Xu C, Shen W, Li L, Xue F. Monin-obukhov similarity theory for modeling of wind turbine wakes under atmospheric stable conditions: breakdown and modifications. Appl Sci. 2019;9(20):4256. doi:10.3390/app9204256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Iungo GV, Guala M, Hong J, Bristow N, Puccioni M, Hartford P, et al. Grand-scale atmospheric imaging apparatus (GAIA) and wind lidar multiscale measurements in the atmospheric surface layer. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2024;105(1):E121–43. doi:10.1175/bams-d-23-0066.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Azzahrani AS, Kadhim AC. Determination of the potential of solar energy, solar plant design, and grid integration based on LiDAR data processing in northern border region. J Opt. 2024;53(3):2142–50. doi:10.1007/s12596-023-01438-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Borgers R, Dirksen M, Wijnant IL, Stepek A, Stoffelen A, Akhtar N, et al. Mesoscale modelling of North Sea wind resources with COSMO-CLM: model evaluation and impact assessment of future wind farm characteristics on cluster-scale wake losses. Wind Energ Sci. 2024;9(3):697–719. doi:10.5194/wes-9-697-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gomes A, Guerreiro BJ, Cunha R, Silvestre C, Oliveira P. Sensor-based 3-D pose estimation and control of rotary-wing UAVs using a 2-D LiDAR. In: ROBOT 2017: Third Iberian Robotics Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 718–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-70833-1_58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kang J, Sobral J, Soares CG. Review of condition-based maintenance strategies for offshore wind energy. J Mar Sci Appl. 2019;18(1):1–16. doi:10.1007/s11804-019-00080-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Koch GJ, Beyon JY, Barnes BW, Petros M, Yu J, Amzajerdian F, et al. High-energy 2 μm doppler lidar for wind measurements. Opt Eng. 2007;46(11):116201. doi:10.1117/1.2802584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools