Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Peltier Water Cooling System with Solar Energy and IoT Technology Demonstration Set

Faculty of Technical Education, King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok, Bangkok, 10800, Thailand

* Corresponding Authors: Prasongsuk Songsree. Email: ; Chaiyapon Thongchaisuratkrul. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI in Green Energy Technologies and Their Applications)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4541-4559. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068448

Received 29 May 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

The purpose of this research is to design and develop a demonstration Set of a water cooling system using a Peltier with solar energy and technology, and IoT (Internet of Things), and test and measure the performance of the Peltier Plate Water Cooling System Demonstration Set under different environmental conditions. To be used as a model for clean energy systems and experimental learning materials. The prototype system consists of a 100-W solar panel, a 12 V 20 Ah battery, a Peltier plate, a DS18B20 sensor, and a NodeMCU microcontroller. The system performance is determined by analyzing the energy drawn from the water (Q) compared to the electrical energy supplied to the plate (Q2) and calculating the coefficient of performance (COP) value to evaluate the performance of the system, as well as testing the operation under different light conditions (morning, noon, evening) with real-time temperature data and control behavior recorded via IoT (Internet of Things). The results showed that the system can reduce the water temperature by an average of 4°C–7.5°C within 60–90 min, with an average COP (COEFFICIENT OF PERFORMANCE) in the range of 0.3–0.4 during unstable solar energy periods. The system can respond to commands via the Blynk application in under 2 s and can also operate continuously on battery backup power during low-light hours.Keywords

Currently, there is a growing demand for cooling systems that are chemical-free and can be used in remote areas. Peltier modules are a promising technology in this field because they do not use refrigerants. They have no moving parts and can work with solar energy efficiently when integrated with IoT (Internet of Things) technology. It can also be applied as a demonstration set for learning in underprivileged areas. It helps learners understand the principles of cooling, energy management, and intelligent system control concretely. Based on these considerations, the researcher proposes the idea of developing a Demonstration series of water cooling systems with Peltier plates, solar energy, and IoT (Internet of Things) to be used as both a prototype of a clean energy system and an experimental learning material in the context of modern education. While the core technologies applied in this study—Peltier cooling, solar energy, and IoT (Internet of Things) control—are not novel individually, their integration into a self-contained, low-cost, educationally oriented system represents a unique contribution. This framework is designed specifically for energy-constrained environments and aims to enhance real-world STEM learning while supporting practical off-grid cooling solutions.

The primary objective of this research is to design and develop a demonstration set of a water cooling system that integrates a thermoelectric Peltier plate with solar energy and Internet of Things (IoT) technology. This initiative responds to the increasing demand for chemical-free cooling systems that are applicable in energy-constrained or off-grid environments, especially in rural or underdeveloped areas. The integration of solar power with smart control via IoT (Internet of Things) aims to reduce reliance on traditional electricity sources while offering hands-on learning materials for STEM education. In addition, the study seeks to evaluate the performance of the developed prototype under varying environmental conditions. By observing the system’s behavior across different light intensities and temperature ranges, and analyzing the cooling efficiency through the coefficient of performance (COP), the research highlights both technical feasibility and real-world application potential. The dual aim is to contribute not only to technological advancement but also to the development of pedagogical tools in energy and environmental engineering.

The design and development of a water cooling system using Peltier plates in combination with solar energy and Internet of Things (IoT) technology requires knowledge from various fields, including physics, energy engineering, information systems, and automation. Recent studies have explored similar integrations of thermoelectric cooling and renewable power. Ref. [1] proposed a solar-powered Peltier refrigeration unit for remote environments and implemented IoT (Internet of Things) based thermal control using Peltier modules in electric vehicle battery systems. These studies highlight both the potential and current limitations of smart thermoelectric cooling under variable energy conditions [2].

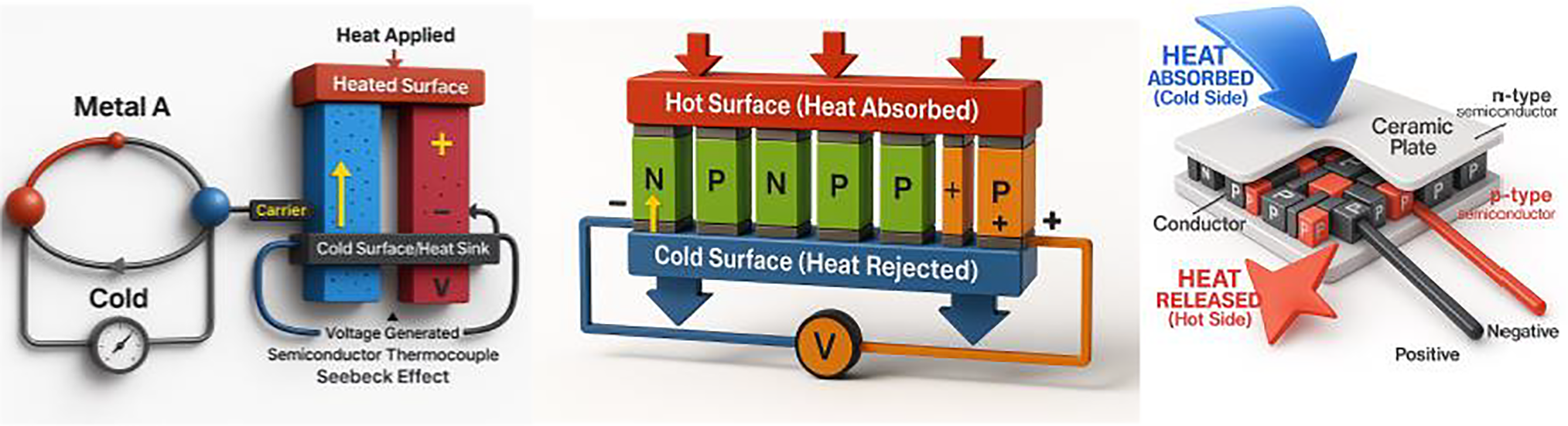

The basic phenomenon of energy transformation from the difference in heating and cooling temperature on a conductor to electrical energy was first discovered by [3], a German physicist, who discovered that when the ends of two types of conductors are connected, there is a difference in temperature at the junction of the conductors. As shown in Fig. 1, the diagram shows the Seebeck Effect thermoelectric principle and the structure of the thermoelectric module, drawing on information from an article published on the website of the Thai Physical Association that shows the physical basis of the phenomenon. It also describes the engineering structures of thermoelectric devices, both 2D and 3D, to facilitate the mechanism of converting thermal energy into electrical energy in a systematic manner. The leftmost image shows a fundamental experiment on the Seebeck Effect, the basis of thermoelectrics, using two metal A wires joined together and with different temperatures at both ends. When there is a temperature difference between the two ends, electrons move from the hot side to the cold side. This movement causes a voltage or current in the circuit. The hot spot emits electrons. The cold spot receives electrons. This principle shows that heat can be directly converted into electrical energy, which is at the heart of thermoelectric generators. The middle image shows a diagram of a 2D thermoelectric module, which shows the arrangement of P-type (orange) and N-type (green) semiconductor materials alternately in pairs, connected between the hot surface and the cold surface. When heat passes through semiconductor materials, the movement of electrical carriers (electrons and holes) occurs, resulting in a voltage between the negative and positive electrodes. This electricity can be continued through an external electrical circuit, with a voltmeter displaying. This type of structure is commonly used in engineering applications.

Figure 1: Diagram illustrating the thermoelectric Seebeck Effect and the structure of a Peltier module, created by the authors based on conceptual information from the Thai Physical Society [4]

3.1 Application in Peltier Module Systems

In the context of this research, thermoelectric theory, especially the Peltier effect, is of direct importance because the Peltier plates used in refrigeration systems operate on this principle. As a result, one side is cooler (cold side) and the other side is hotter (hot side). A heat sink or cooling system will be able to create an efficient, small cooling system without the use of refrigerants. Prior to discussing component advantages, it is essential to recognize that recent implementations of Peltier modules in embedded environments, such as the work in [2], emphasize the need for real-time thermal feedback, optimized power delivery, and stability under fluctuating load conditions. These insights inform the design direction of the present study [5].

3.2 Theoretical Concept of Solar Energy

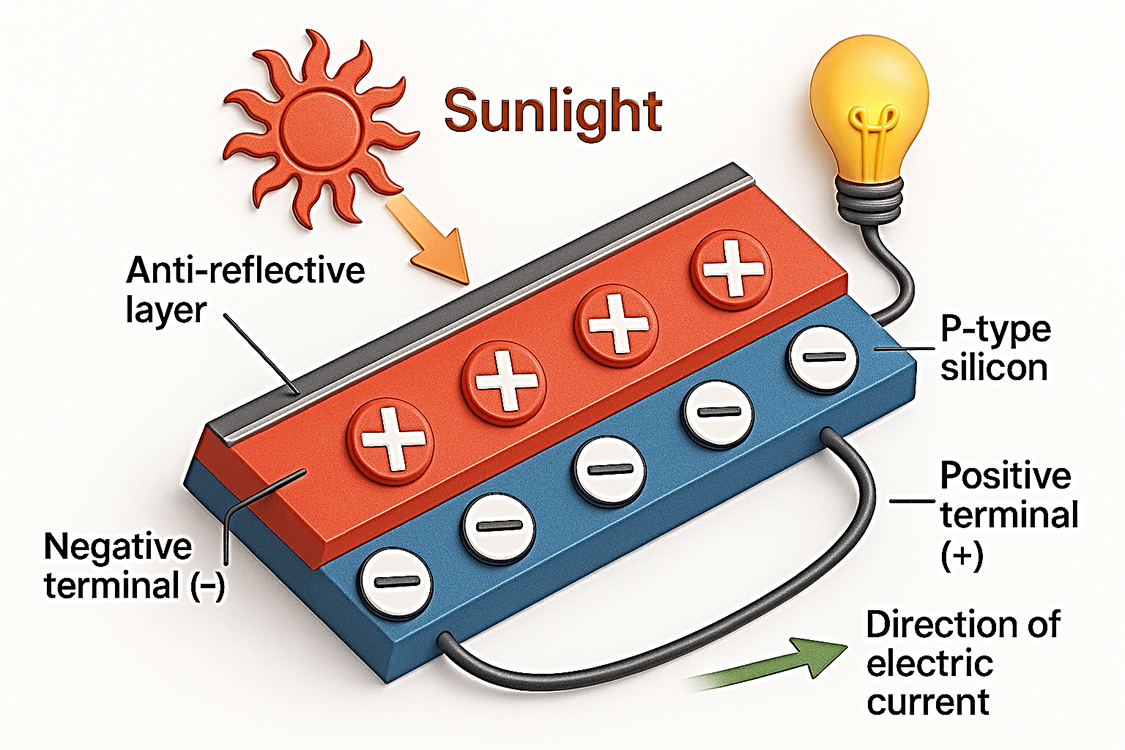

Solar energy is one of the core components of the future renewable energy system, based on the theory of the Photovoltaic Effect and the ever-evolving solar cell technology. The photovoltaic effect was discovered during experimentation with electrodes in solution, and found that light can stimulate the generation of electricity. One of the key processes of converting solar energy into electrical energy is the photovoltaic effect, as reported in [6]. Solar cell technology is responsible for converting solar energy into electrical energy directly through a physical process called the Photovoltaic Effect. The diagram presented illustrates the principle of operation of solar cells in a three-dimensional manner that is easy to understand and realistic. As shown in Fig. 2. Starting with sunlight, which falls on the surface of the photovoltaic cells coated with an anti-reflective layer to increase the efficiency of light absorption. When photons from sunlight hit the cell layer, the electrons in the atoms of the material break out of their bonds and move freely. When an electron is excited by light and breaks away from an atom in the P-type layer, it is pushed by an internal electric force to move to the N-type layer, causing a potential difference between the two poles, thereby generating electricity [6].

Figure 2: Principle of solar cell operation: photovoltaic phenomenon in semiconductor layer, created by the authors

3.3 IoT (Internet of Things) Theory Concept

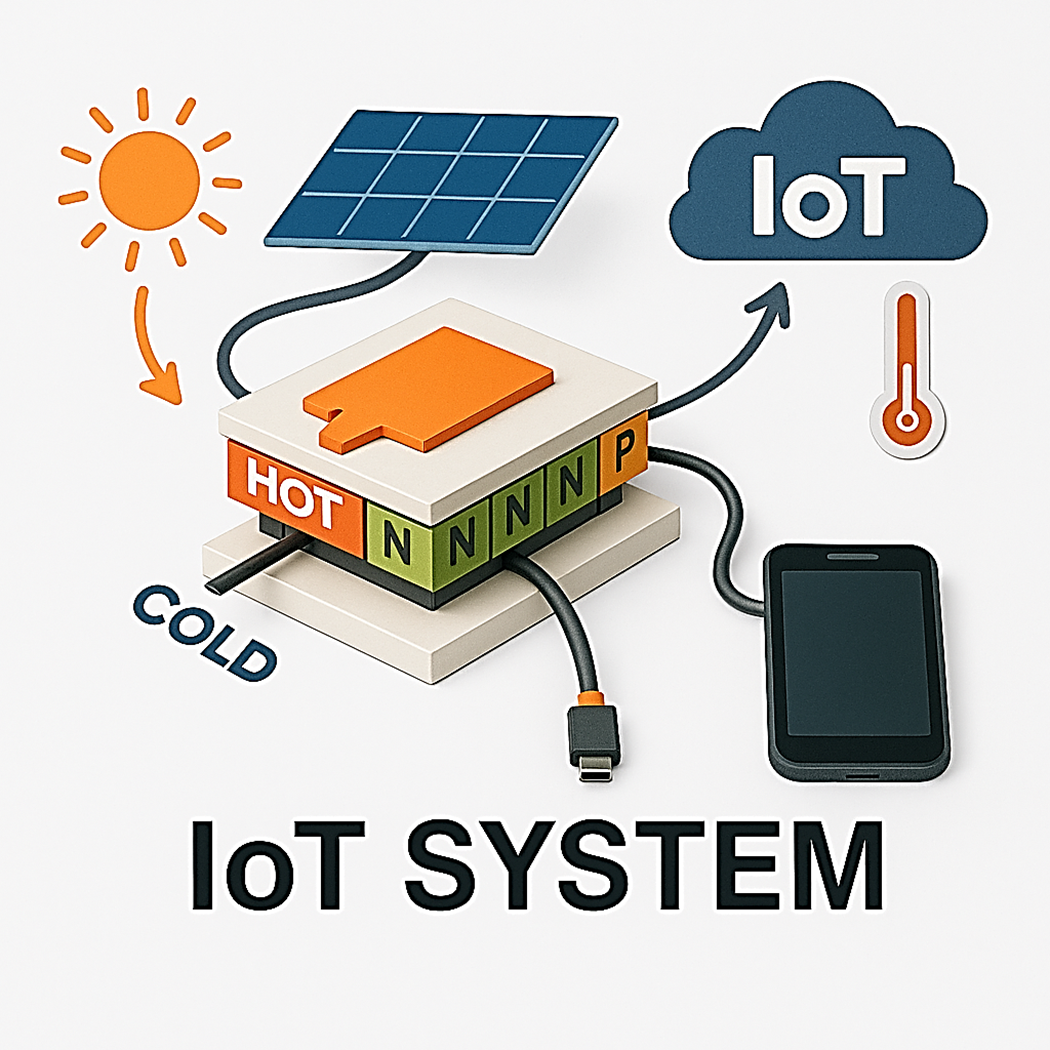

While many recent cooling systems incorporate IoT (Internet of Things) for basic automation, several studies have noted shortcomings in their ability to adapt to fluctuating power supply and thermal load. Real-time responsiveness and energy-aware control remain critical challenges that this study aims to address. The concept originated from [7], which explained that IoT is the interconnection of devices that can communicate with each other through a network without relying directly on human commands. Researchers have proposed IoT (Internet of Things) technology as a medium for real-time monitoring and control [8]. As shown in Fig. 3. The status of the module and the power consumption via a smartphone or remote control device. In addition, the system can respond automatically through sensors connected to the Internet, enabling efficient energy management, reducing losses, and increasing ease of use.

Figure 3: Principles of IoT (Internet of Things) technology, created by the authors

3.4 Technology Performance Evaluation Concept

After the development of the prototype system, its performance this value is used to indicate how efficiently the system is able to harness energy to achieve thermal results. Despite the established thermodynamic foundation, recent literature indicates that achieving high COP (coefficient of performance) in practical thermoelectric systems remains a challenge. Most studies focus on fixed-load scenarios without accounting for variable solar input or adaptive control strategies. This research fills that gap by integrating IoT-based power regulation with solar-powered cooling, enabling autonomous operation in off-grid or resource-constrained environments.

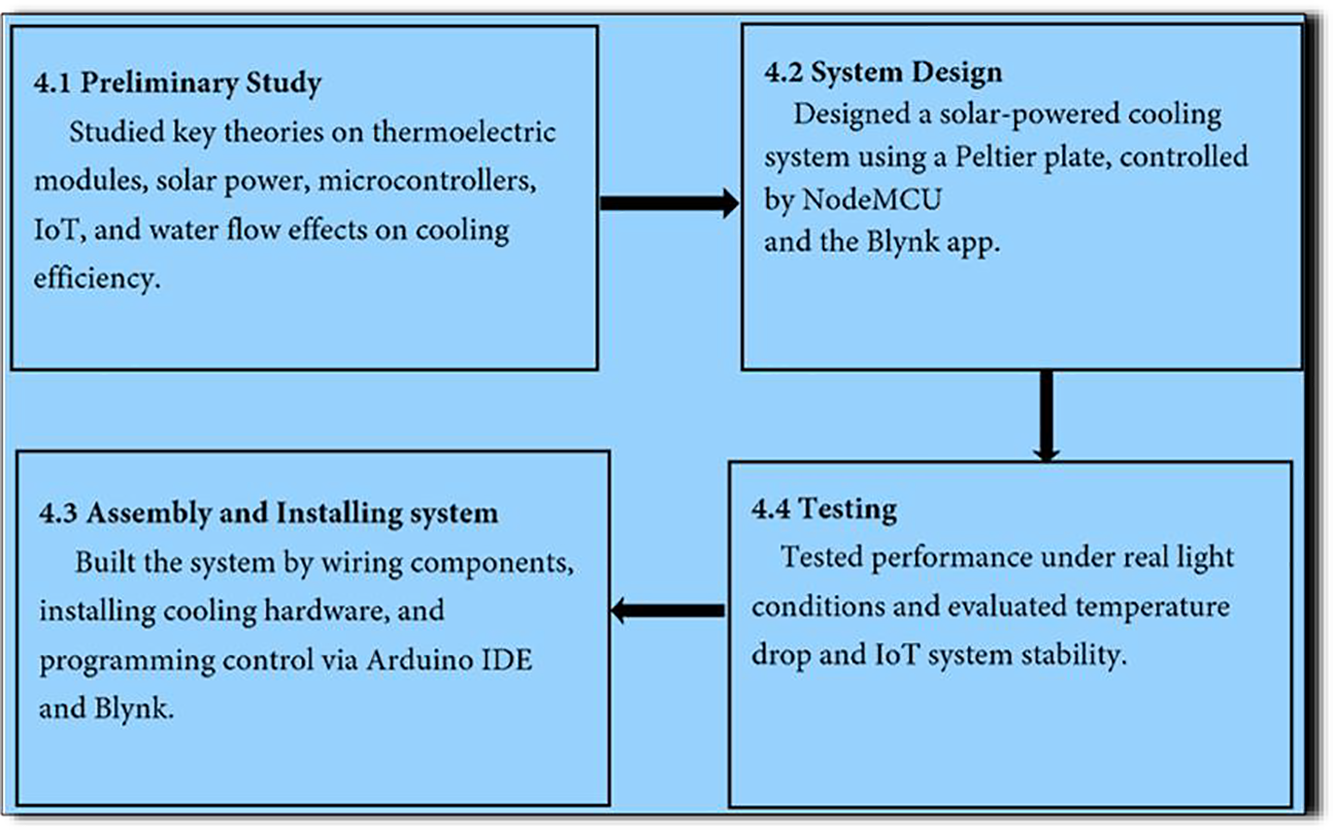

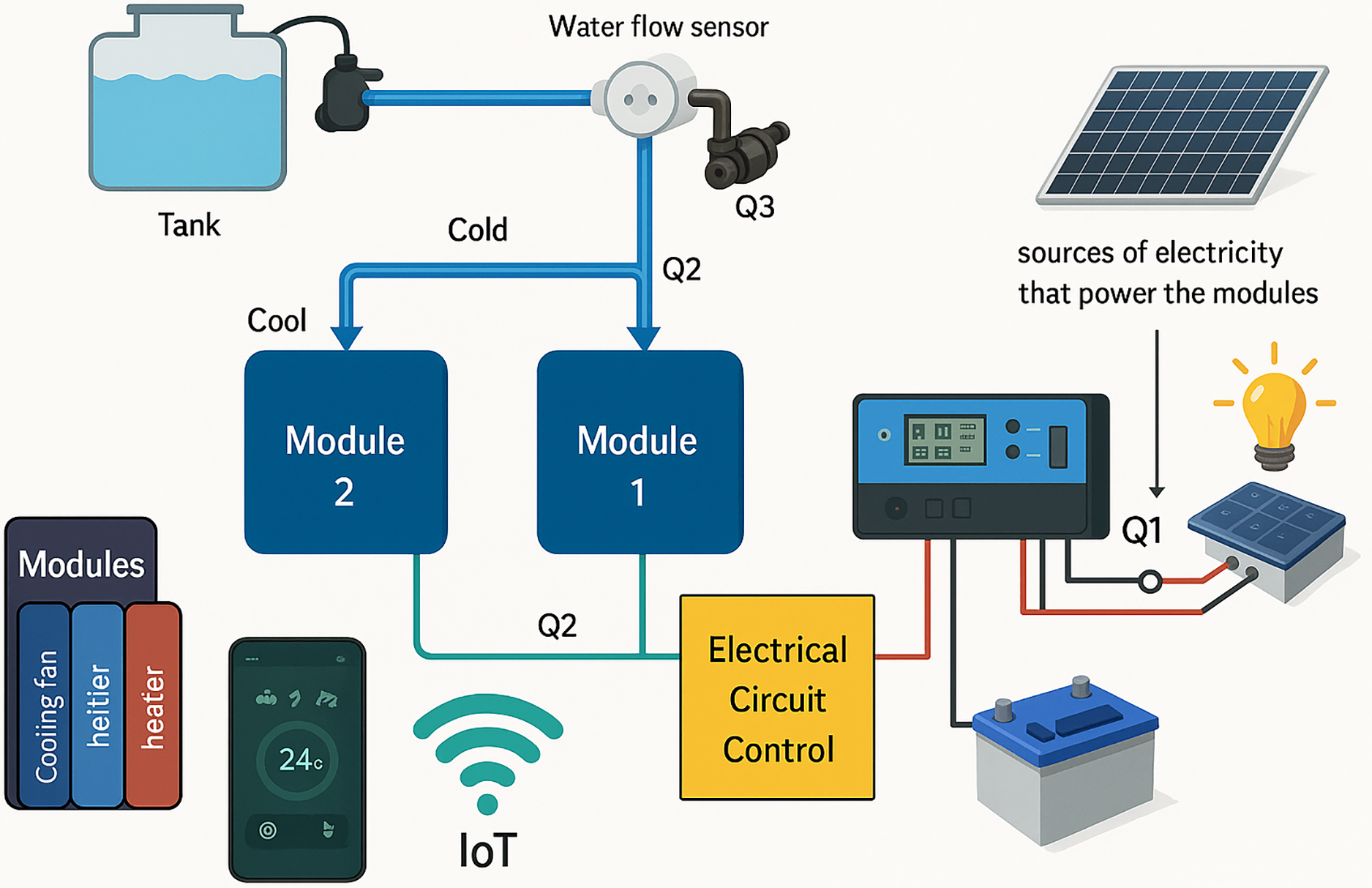

This research is experimental in nature and aims to design and develop a solar-powered water cooling system using Peltier technology, integrated with IoT (Internet of Things)-based control and monitoring. To achieve this, the research methodology was divided into several key phases. The process begins with a comprehensive theoretical study to establish the foundation for system design, as detailed in Sections 4.1–4.4. As shown in Fig. 4. This preliminary study supports the subsequent phases, including system design, hardware assembly, and performance evaluation under real-world conditions.

Figure 4: Research framework

The researcher studied relevant theoretical data to support the system design. This included

(1) The Seebeck and Peltier effects, which explain the thermal-to-electric and electric-to-thermal energy conversion in TEC1-12706 thermoelectric modules, forming the core operating principle of the cooling system

(2) The photovoltaic effect, which governs solar energy harvesting and conversion into electrical energy used by the system

(3) The microcontroller-based control logic implemented via NodeMCU ESP8266, which processes real-time input from temperature sensors and manages the switching behavior of the Peltier plate

(4) Fundamental IoT (Internet of Things) communication protocols, which allow real-time data transmission and control through the Blynk platform

(5) The influence of fluid dynamics, including flow rate, water volume, and thermal mass, which directly affect heat exchange efficiency and cooling duration. These theoretical foundations were used to guide both the hardware design and experimental testing.

The system was designed as a closed-loop solar-powered water cooling unit, incorporating energy harvesting, thermal exchange, control, and monitoring layers. The experimental platform configuration included solar input, a charge controller, battery storage, a NodeMCU-based control module, temperature sensors, and the water tank integrated with Peltier plates. This structured layout improves understanding of the system interactions between hardware and control logic.

4.3 Assembling and Installing the System

The hardware setup followed a step-by-step integration process, starting with the solar charging circuit, followed by the connection of the Peltier plates with heatsinks and fans, and then installation of the DS18B20 temperature sensors. The microcontroller (NodeMCU ESP8266) was programmed using the Arduino IDE and mounted on a custom PCB board detailing component interaction and wiring logic [5].

To ensure consistency and replicability, the experimental protocol was structured as follows:

1. System initialization and baseline temperature logging

The system was powered on and allowed to stabilize. The initial water temperature was recorded before any cooling began [9].

2. Exposure to designated light conditions (morning/noon/evening)

The system was tested under natural light in three time intervals to simulate varying irradiance:

3. Morning (08:00–10:00)

4. Noon (11:00–14:00)

Evening (16:00–18:00)

Real-time data acquisition via the Blynk dashboard

The NodeMCU controller transmitted temperature and voltage data through Wi-Fi. These were displayed and logged on the Blynk IoT (Internet of Things) platform in real time [10].

Automatic activation/deactivation of the Peltier module based on sensor thresholds

The system turned the Peltier plate ON when the temperature exceeded 25°C and OFF when the temperature dropped below 18°C, following predefined thresholds.

Data recording for ΔT, power consumption, and system latency

All changes in tank water temperature (ΔT), voltage/current draw, and control response time were recorded for performance evaluation.

The results of the design and development of a water cooling system using Peltier plates and IoT (Internet of Things) technology show that the system can operate efficiently. The design and development of a water cooling demonstration system using solar-powered Peltier plates, in combination with an IoT-based control system, was effective. The key results are detailed as follows.

5.1 Design and Development Results of Water Cooling System Using Peltier Plates with Solar Energy and IoT (Internet of Things) Technology

It was found that the system can produce cooling using solar energy. The solar panel supplied enough power to operate the Peltier plates and the entire control circuit during the day. The system can effectively reduce the water temperature in the tank. Details are as follows.

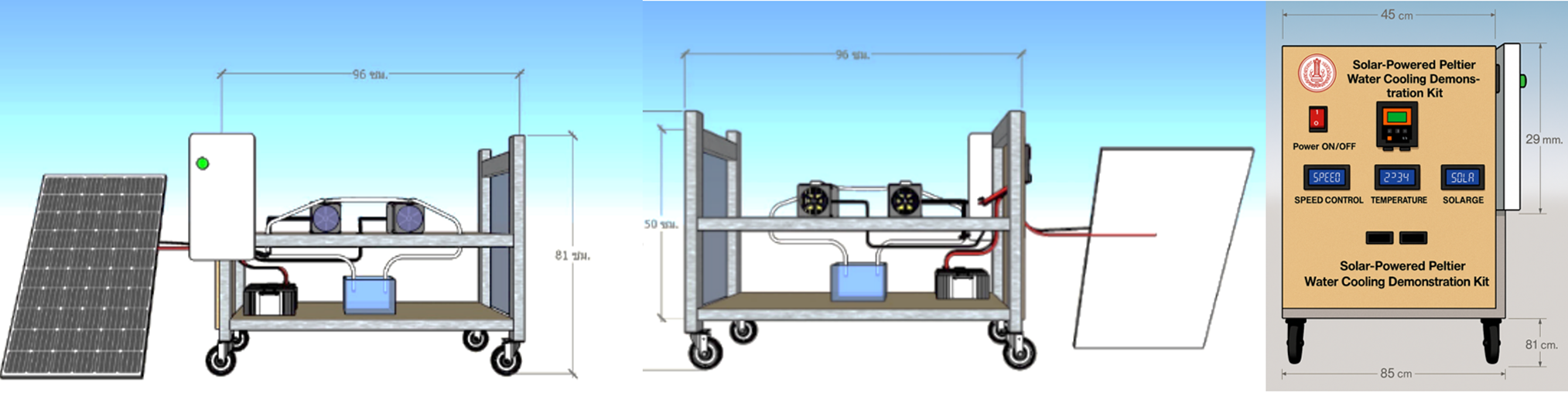

5.1.1 Laying a Water Cooling System Using Solar Plate Tiers

The system’s modular design enabled temperature reduction through two sequential Peltier cooling stages. Under average noon irradiance (700–850 W/m2), the first stage achieved a ΔT of 2.3°C, while the second stage provided an additional 2.5°C drop, leading to a total cooling of 4.8°C within 60 min. This staged approach allowed greater efficiency than single-plate systems reported in [11] achieved only a 3.1°C drop under similar conditions. The solar-powered configuration sustained operation without requiring grid input, validating the system’s suitability for off-grid use. As shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Simulation of a demonstration set of water cooling using Peltier plates with solar energy and IoT (Internet of Things) technology, created by the authors

From the picture, you can see that the cooling system and IoT (Internet of Things) plate are installed between the two sides of the heat sink. On the hot side, there is a fan to help cool it. While the cold side is in contact with the insulated water tank. It is connected to the NodeMCU ESP8266 to transmit data to the Blynk platform via Wi-Fi and automatically control the on-off of the system according to the specified values [9]. The core of the system is the Peltier plate, which is responsible for creating the temperature difference between the two surfaces when electricity is supplied. The hot side is installed in conjunction with a heat sink and cooling fan to help efficiently transfer heat away from the Peltier plate, whereas the cold side is placed in direct contact with the wall of the water tank, which is insulated with polyurethane (PU) foam. The purpose is to transfer cold water into the tank and maintain the water temperature within a certain range. To measure and control the temperature of water in the system, DS18B20 series digital sensors are used, which have high accuracy in measuring the temperature of liquids and can be directly connected to the NodeMCU ESP8266 board [8]. The NodeMCU board acts as an intermediary to receive temperature data from sensors and then relay it to the Blynk platform via Wi-Fi, allowing users to track the temperature values of the water in the tank in real-time through a smartphone or other mobile device connected to the Internet. A 12 V or higher solar panel should be installed on a surface that receives the most sunlight. Connect the wire from the panel to the Solar Charge Controller, which controls the current sent to the battery to prevent overcharging or over-discharging [9]. Connect the cable from the Solar Charge Controller to the 12 V battery (Deep Cycle) to store energy. Check the voltage supplied to the system with a multimeter to ensure that the system is stable and safe before connecting to another circuit.

5.1.2 Installation of the Refrigeration Unit, Plate, Heat Sink, Fan, and Water Tank

The researchers installed Peltier (TEC1-12706) plates and applied thermal paste to both sides of the plate to increase heat transfer efficiency. An aluminum heatsink was installed on the hot side, and a cooling fan was used. On the cold side of the Peltier plate, it was attached to the wall of a 5-L water tank, which was made of plastic or stainless steel and was insulated with Polyurethane foam (PU Foam) to protect against external heat. The structure was fixed using a base made from acrylic or MDF wooden panels to hold the components securely. All parts were installed either vertically or horizontally according to the design to ensure efficient heat transfer and safe wiring. The signal from the DS18B20 sensor was routed to the NodeMCU board. The waterproof DS18B20 sensor was installed in water or on the tank wall, with the sensor head in direct contact with the liquid to ensure accurate measurement. The sensor’s 3 wires (VCC, GND, DATA) were connected, with a 4.7 kΩ pull-up resistor between the DATA line and VCC to provide stable digital communication to the NodeMCU ESP8266 board, which functions as a microcontroller with Wi-Fi capability [4].

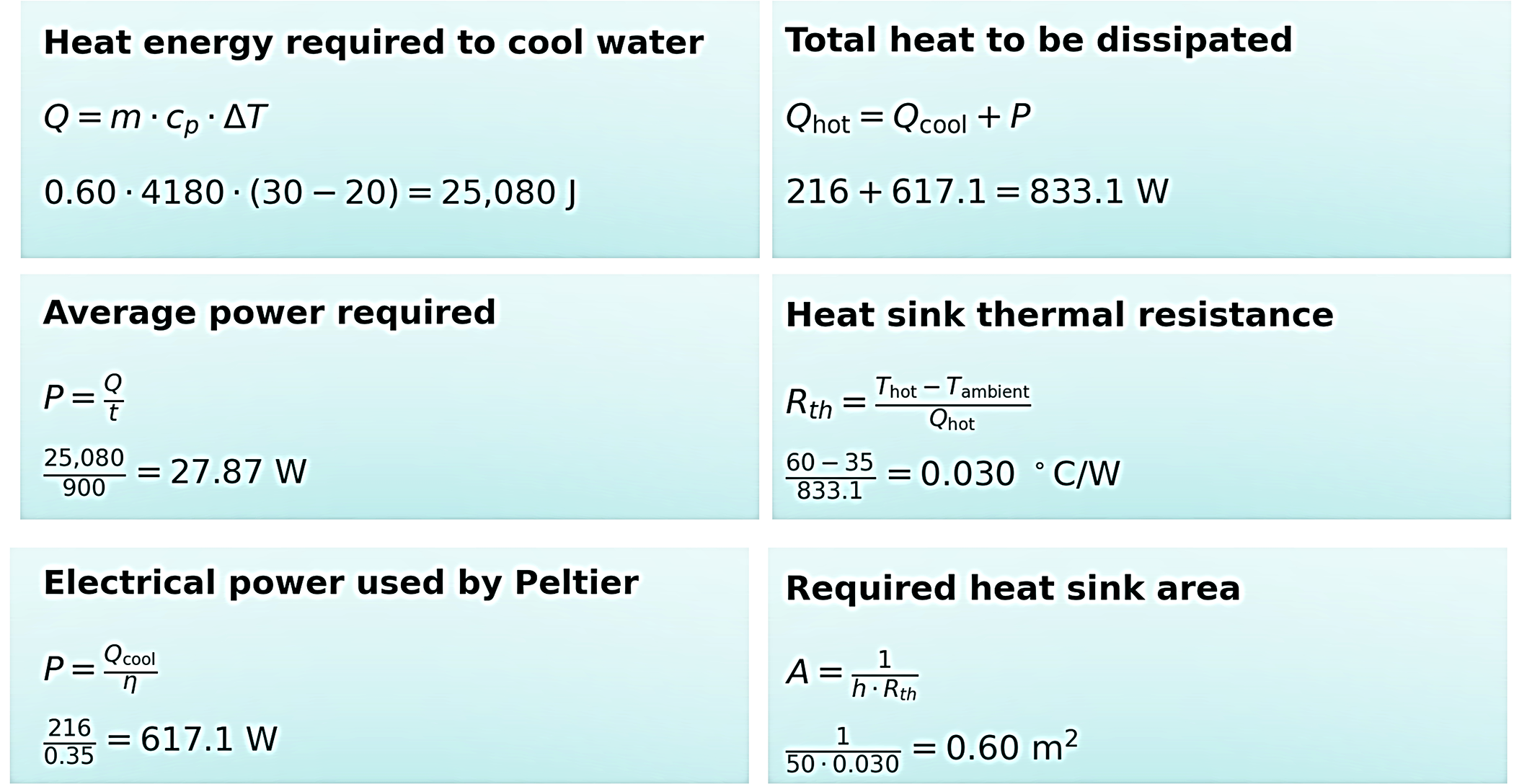

5.1.3 Calculation of a Cooling System with a Thermoelectric Plate (Peltier)

To assess the cooling capability and energy efficiency of the system, the researcher performed a series of theoretical calculations based on thermodynamic principles. These calculations include the amount of heat energy required to reduce the water temperature, the average power input, the electrical power consumption of the Peltier module, and the thermal dissipation requirement. Additionally, the thermal resistance and surface area of the heat sink were determined to ensure the system’s stability under continuous operation. The results of these calculations are summarized in Fig. 6, which presents step-by-step equations, substituted values, and outcomes that were used to guide the design and optimization of the thermoelectric cooling system.

Figure 6: Simulation results of the design of a thermoelectric plate cooling system to reduce water temperature

The researchers applied the basic principles of heat transfer and energy consumption in refrigeration systems. They used physics and engineering equations to analyze and design simulations of the thermoelectric plate refrigeration system. The goal was to reduce the water temperature and to evaluate the performance of the equipment from quantitative data.

1. The energy required to cool the water was calculated using the equation Q = m × cp × ΔT. With 600 mL (or 0.6 kg) of water cooled from 30°C to 20°C, the system needed to transfer 25,080 J of thermal energy, establishing the system’s cooling load [10].

2. The average power over 15 min (900 s) was found to be 27.87 W, a critical figure for power supply design.

3. Considering the Peltier plate’s efficiency at 35% (COP (coefficient of performance) = 0.35), achieving 216 W of cooling power requires 617.1 W of input power, indicating system losses and the importance of selecting efficient components.

4. The total thermal load including cooling and electrical power was 833.1 W, which must be dissipated from the hot side to avoid system inefficiencies.

5. The required heat sink thermal resistance was calculated as 0.030°C/W, a low value demanding high-performance cooling equipment.

6. Given the heat dissipation of 833.1 W and a convection coefficient of 50 W/m2·K, the necessary heat sink surface area was determined to be at least 0.6 m².

5.1.4 Refrigeration System Assembly Results with IoT (Internet of Things) Technology for Real-Time Control and Monitoring

The researcher applied embedded electronic devices (embedded systems) and Internet of Things (IoT) technology to enable automatic control and real-time monitoring of system status. Key findings include:

The real-time monitoring system showed high reliability, with temperature readings updated every 2 s and IoT (Internet of Things) command response delay averaging 1.3 s under full load. This update interval is appropriate given the nature of thermoelectric cooling and the specifications of the DS18B20 digital sensor, which operates optimally at sampling intervals of 750 ms to 1 s depending on resolution. Since temperature change in water-based systems occurs relatively slowly, a 2-s interval is technically sufficient for accurate monitoring without unnecessary processing [4]. During evening operation, where supply voltage dropped to 11.2–11.6 V, response latency increased slightly to 1.8–2.1 s. Nonetheless, the system maintained accuracy within ±0.5°C, confirming the robustness of the NodeMCU-Blynk integration in low-power environments. Compared to similar PV-based IoT (Internet of Things) systems reported [3] which had delays of 3–5 s, this implementation provided faster and more stable real-time performance.

5.2 Results of Hardware Application and Driver Writing with Arduino IDE

The researcher developed the system using the Arduino IDE platform as the primary tool for programming and uploading to the NodeMCU (ESP8266), which functions as the microcontroller for the entire system.

In the first step, the necessary libraries were installed to ensure compatibility with devices, including OneWire and Dallas Temperature for communicating with the DS18B20 temperature sensor, and BlynkSimpleEsp8266.h for connecting the NodeMCU to the Blynk platform [9]. This Setup enables real-time data control and display through the Blynk smartphone application. When the water temperature exceeds 25°C, the system triggers the Peltier plate to turn on, and when the temperature drops below 18°C, it turns off via the NodeMCU’s Digital Output pin.

During development, a major obstacle encountered was the unstable Wi-Fi connection of the NodeMCU in certain test environments, causing the Blynk app to lose functionality or real-time display. Additionally, DS18B20 sensors occasionally returned null values or −127°C due to data contact errors. Unstable power supply from the solar source sometimes caused the system to restart due to voltage drops.

To address these issues, the researcher implemented a Wi-Fi status check routine every 5 s with automatic reconnection. Filtering conditions were added to exclude abnormal sensor values if the reading was outside the 0°C–50°C range, the system would wait for a valid input. Capacitor circuits and voltage filters were also added to the NodeMCU to stabilize operation under fluctuating solar voltage. The final system code was uploaded to the NodeMCU via USB, setting the appropriate port in the Arduino IDE.

For remote control, the Blynk application was used to build a control interface that included a temperature display widget, an LED indicator for operation status, and button/slider widgets for control preSets. The authentication token (Auth Token) generated by the Blynk app was embedded into the Arduino code, allowing for secure and real-time communication with the IoT (Internet of Things) platform.

5.3 To Test and Evaluate the Performance of the Water Cooling System from the Plate under Different Environmental Conditions

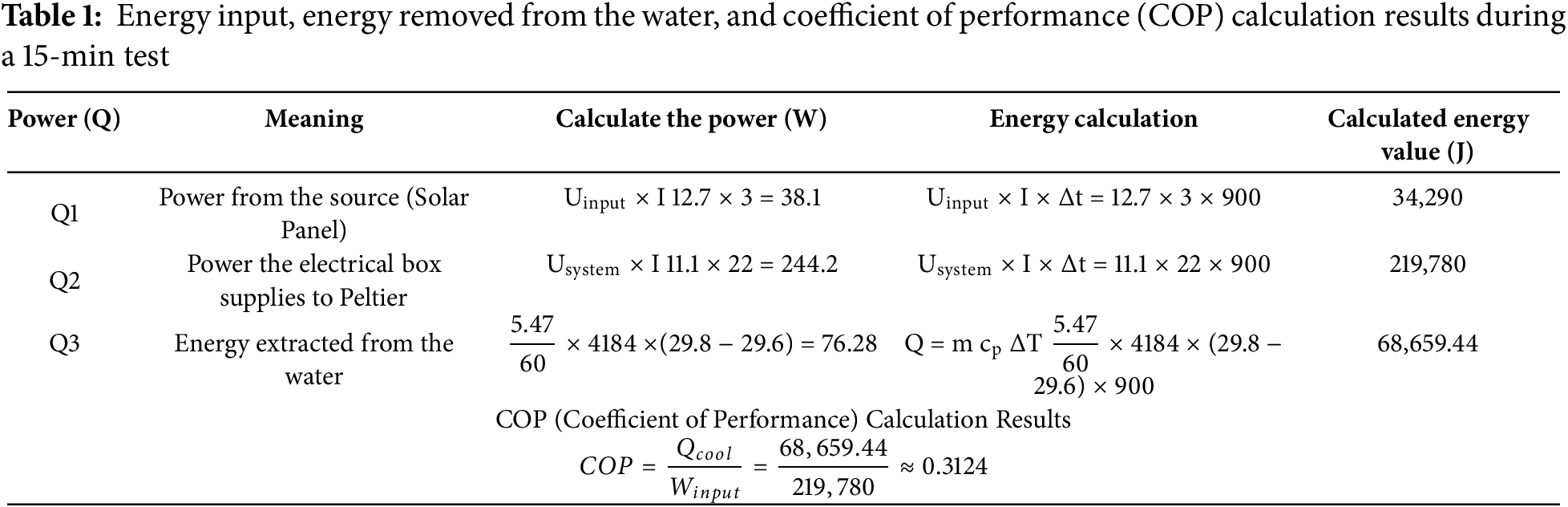

5.3.1 Energy Efficiency Used to Test for over 15 min

This Table 1 summarizes the power inputs and thermal energy transferred during a 15-min test of the system. Q1 represents the power sourced from the solar panel, calculated using voltage and current input values and found to deliver 34,290 J of energy. Q2 reflects the energy supplied from the system to the Peltier plate, calculated to be 219,780 J, based on operating voltage and current. Q3 measures the thermal energy extracted from the water, computed at 68,659.44 J using the standard equation Q = m × cp × ΔT [3]. The efficiency of the system, expressed as Coefficient of Performance (COP), was calculated as: COP (COEFFICIENT OF PERFORMANCE) = Q_cool/W_input = 68,659.44/219,780 ≈ 0.3124.

To demonstrate dynamic behavior, temperature values were recorded at 2-s intervals over the course of 60–90 min. The system exhibited a consistent thermal response under varying irradiance levels. The water temperature decreased steadily from 30.0°C to 22.5°C within 60 min at peak sunlight, with control switching events triggered precisely at 25°C and 18°C. The Peltier plate activation and deactivation correlated well with sensor readings and predefined thresholds, confirming the responsiveness of the control logic in real-time conditions.

5.3.2 Analysis of Performance Calculation Results: COP (Coefficient of Performance) of Peltier Plate Refrigeration System

The performance calculation results for the coefficient of performance (COP) of the Peltier Plate Cooling System were based on both experimental data and energy calculations. The prototype cooling system was powered by energy from an external supply.

Power from the solar panel (Q1). The system received power equivalent to 38.1 W over 15 min (900 s), totaling 34,290 J. This is considered the source energy value for the entire system.

Power supplied to the Peltier plate (Q2). The distribution box provided 244.2 W to the thermoelectric plate over the same 900-s period, resulting in a total energy input of 219,780 J. This figure represents the main electrical energy consumption used to drive the cooling system.

Energy absorbed from the water (Q3): The system successfully transferred 68,659.44 J of heat energy from the water. This was calculated based on the mass of water, its specific heat capacity, and a temperature drop (ΔT) of approximately 0.2°C over the 900-s operation.

The accuracy of temperature measurement was a critical consideration, given that thermal changes in this study often occurred within a narrow range (ΔT = 3–7.5°C). All temperature data were recorded using the DS18B20 sensor, which has a typical accuracy of ±0.5°C and a resolution of 0.0625°C. To improve reliability, each reported value represents the average of at least three measurements taken over the same time interval.

Solar irradiance data were obtained using a handheld digital lux meter and converted approximately to W/m² using standard conversion factors, which may introduce an uncertainty margin of ±10%–15%, depending on ambient light conditions. While these values are sufficient for general analysis and trend comparison, they represent a potential source of deviation in coefficient of performance (COP) estimation.

Future work may incorporate calibrated pyranometers and multi-point thermal sensors to reduce measurement uncertainty and enhance reproducibility.

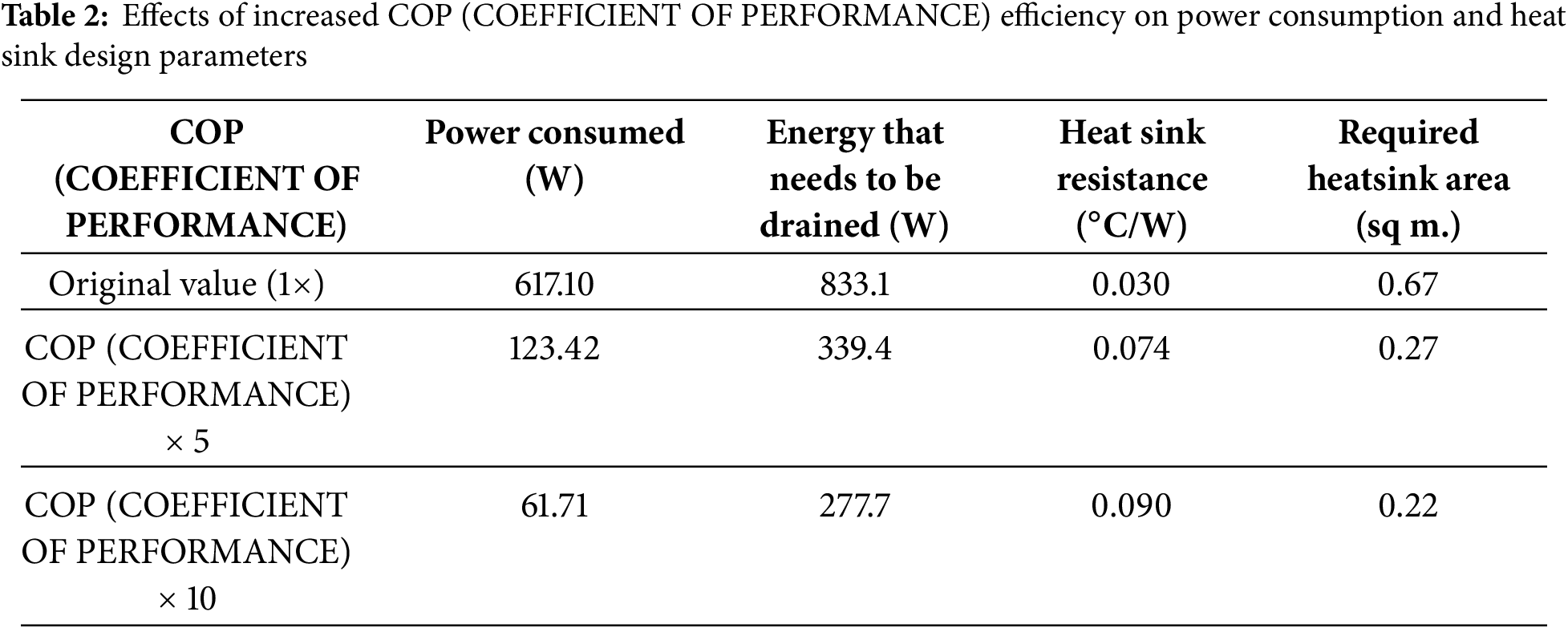

5.3.3 Effects of COP (Coefficient of Performance) Efficiency on Power and Heat Sink Design

Table 2 shows The coefficient of performance (COP) efficiency observed is low to medium, which is characteristic of Peltier modules compared to vapor compression cooling systems. The calculated COP indicates that the system consumes approximately 3.2 times more electricity than the amount of cooling energy generated. This low efficiency is likely due to insufficient heat dissipation from the hot side of the Peltier module, a low temperature differential (ΔT), power loss in the supply circuit, and poor thermal interfaces between the plate and water tank.

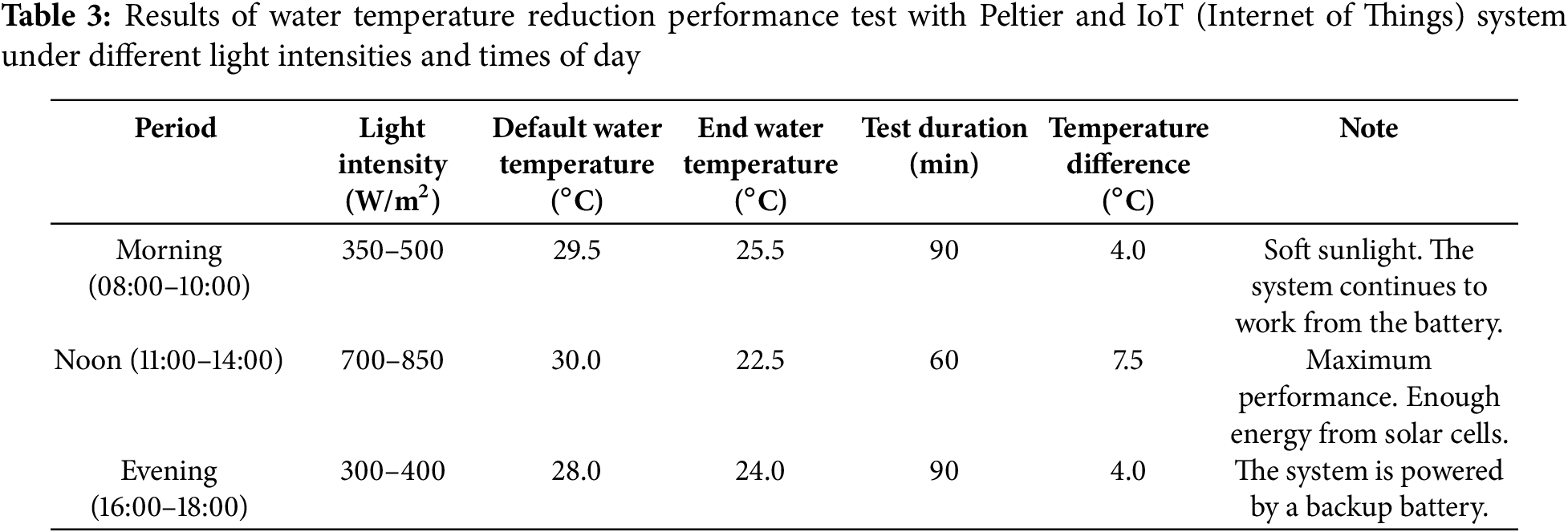

Enhancements such as using high-quality heat sinks and fans, applying PWM control to minimize average current, selecting Peltier models with higher COP values, and improving the ΔT range could significantly improve efficiency. Table 3 illustrates that improving COP not only reduces power consumption and cooling demand but also lowers heat sink size and performance requirements. Therefore, performance optimization is crucial when higher efficiency is desired.

The results from Sections 5.1.1 to 5.3.3 show that the solar-powered Peltier water cooling system was capable of reducing water temperature by an average of 4°C–7.5°C, depending on solar intensity and time of day. The system responded to IoT (Internet of Things) commands with a latency of less than 2 s and operated automatically through real-time thresholds, fulfilling the goal of autonomous, off-grid thermal control [1]. While traditional solar Peltier designs require grid backup under low irradiance, this system maintained continuous operation using a 12 V/20 Ah battery, performing reliably even under 300–400 W/m2 sunlight. In terms of system response, the reported control latency was between 3–5 s, whereas this system maintained faster and more stable performance. While the system’s Coefficient of Performance (COP) remains modest at 0.31–0.40, the combination of dual-stage cooling, solar-battery integration, and IoT-based automation represents a novel step forward in compact, deployable refrigeration systems. This performance level is promising for real-world applications in rural health, agricultural cooling, and STEM-based education kits. Limitations of the current system include dependence on solar input stability for continuous operation. Occasional sensor faults (null or −127°C readings) from DS18B20 during unstable voltage. NodeMCU Wi-Fi fluctuations in low-signal areas [11].

5.3.4 COP (Coefficient of Performance)-Based System Optimization and Heat Sink Design Considerations

The researchers conducted calculations to evaluate the performance of the Peltier plates in producing effective cooling. The analysis considered key variables including power consumption, heat dissipation requirements, heat sink resistance, and the required surface area of the heat sink to efficiently manage heat accumulation in the system.

Under controlled cooling output, system efficiency (coefficient of performance, COP) was varied from a baseline (1×) up to 15×. As shown in Table 3, when COP was at the baseline level, the system consumed 617.10 W and generated 833.1 W of heat to be dissipated. This required a heat sink area of approximately 0.67 m2 and a low heat resistance of 0.030°C/W to prevent heat accumulation.

When the COP increased fivefold, the power demand dropped significantly to 123.42 W, and the thermal dissipation load decreased to 339.4 W. Accordingly, the required heat sink area was reduced to 0.27 m2, and the allowed heat resistance increased to 0.074°C/W. At 10× and 15× COP levels, further reductions in power and heat sink specifications were achieved, making the system increasingly compact and energy-efficient.

These results demonstrate the potential for optimized design through COP enhancement, which would lead to more space-saving and sustainable systems. Additionally, due to the system’s reliance on solar power, performance is affected by daylight and weather variations. Hence, researchers also tested performance under various light conditions, as illustrated in the next table (Table 3).

5.3.5 Testing the System at Different Times and Lighting Conditions

Table 3 shows the results of the water temperature reduction performance test under different light intensities and times of day. As shown in Fig. 7. The analysis is as follows:

Figure 7: Graph showing the efficiency of reducing water temperature with the Peltier system and IoT (Internet of Things) under different light intensities, created by the authors

Morning (08:00–10:00) Light intensity ranged from 350–500 W/m2, classified as relatively low. During this period, the system reduced the water temperature from 29.5°C to 25.5°C within 90 min, a 4.0°C drop while operating primarily from battery backup.

Noon (11:00–14:00) This time yielded the best performance due to the highest light intensity (700–850 W/m2). The system achieved a temperature reduction from 30.0°C to 22.5°C in just 60 min, a 7.5°C drop, indicating optimal use of direct solar energy.

Evening (16:00–18:00) Even with lower light levels (300–400 W/m2), the system successfully reduced water temperature from 28.0°C to 24.0°C within 90 min (4.0°C reduction), again supported by the battery during reduced sunlight conditions.

The graphical results from the system test confirm that the cooling system is most effective during midday (11:00–14:00), when sunlight intensity reaches its peak around 700–850 W/m2. During this time, the system reduced water temperature by 7.5°C within just 60 min.

In the morning and evening periods, despite significantly lower irradiance levels (300–500 W/m2), the system still achieved a 4.0°C temperature drop, though over a longer duration of 90 min. This indicates that while solar irradiance enhances system performance, the use of a backup battery allows for continuous operation even in lower-light conditions.

These results highlight the reliability and autonomy of the off-grid system, making it highly suitable for use in remote areas without access to the main electrical grid. The combination of solar energy, IoT (Internet of Things) technology, and efficient thermal components makes the system adaptable and sustainable for continuous, all-day cooling applications.

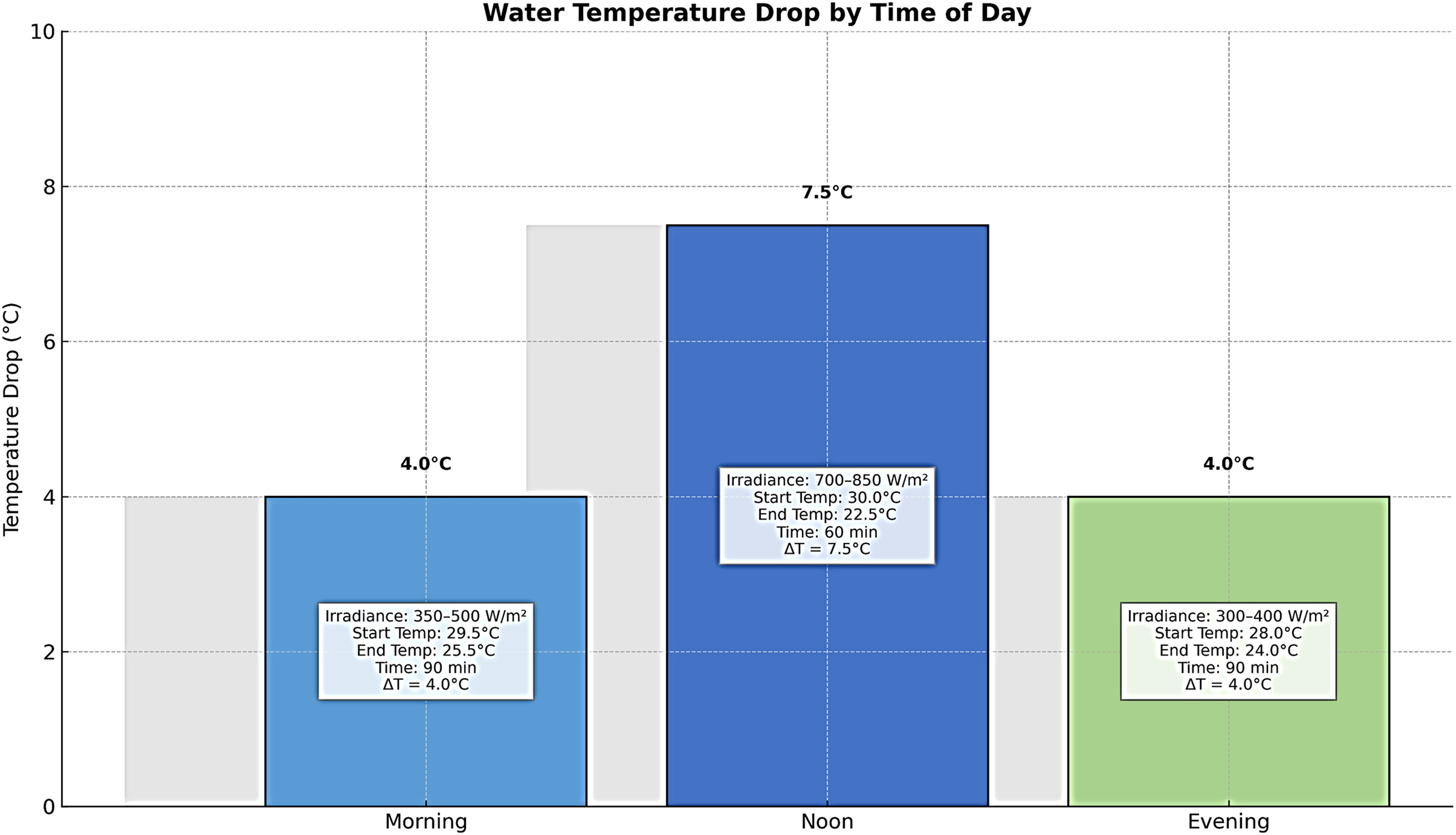

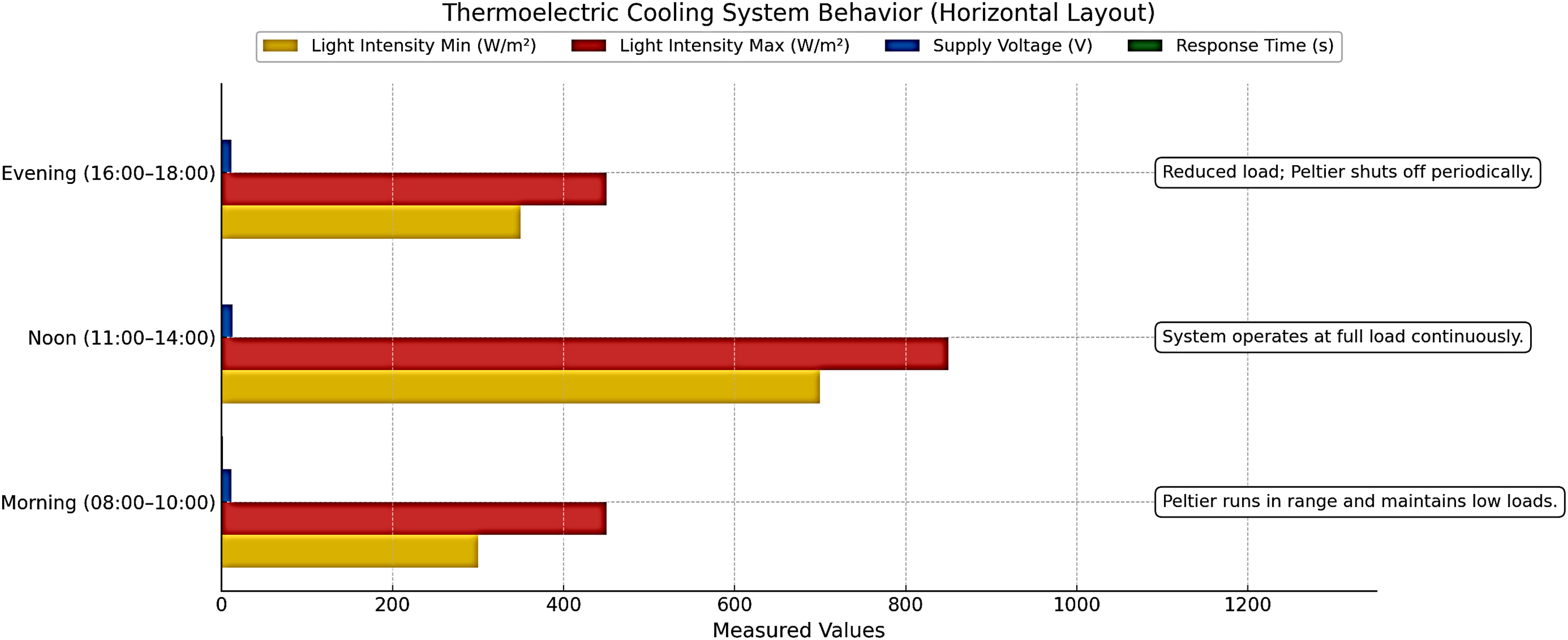

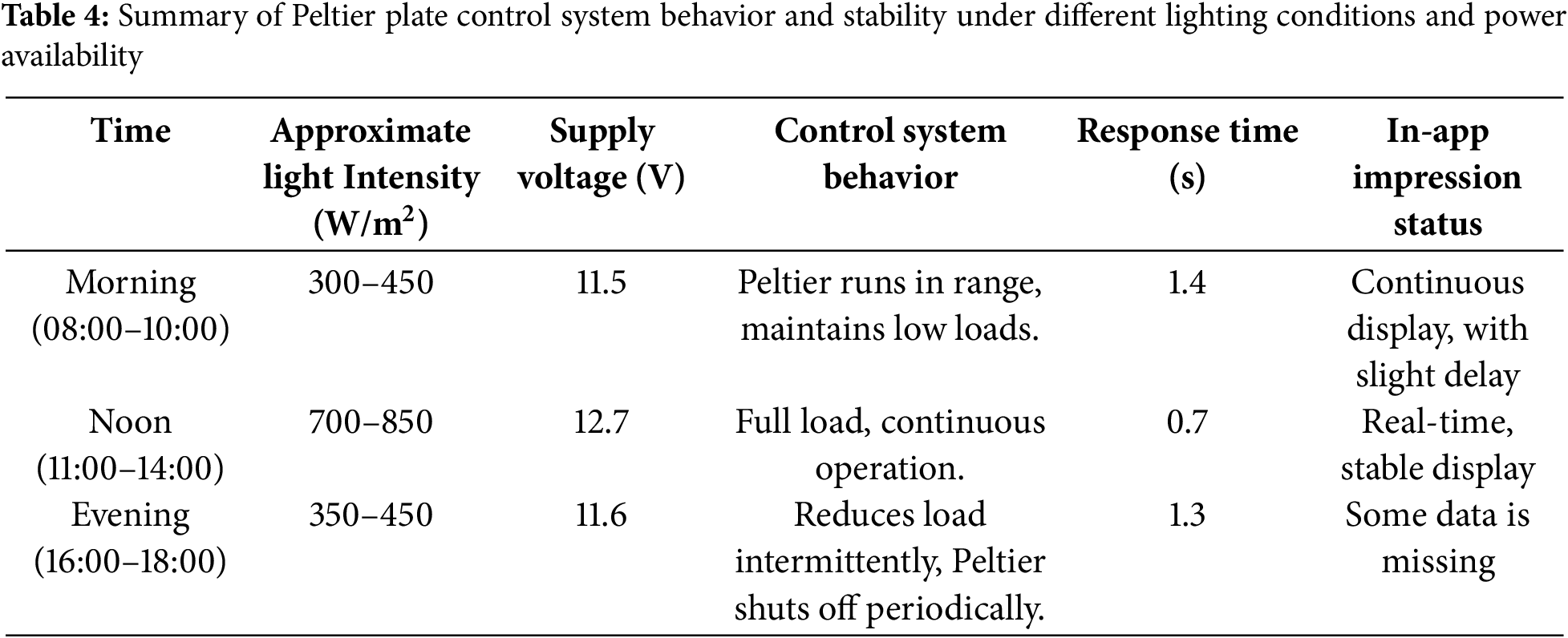

5.3.6 Stability Analysis of Plate Load Control System

The thermoelectric cooling system, which utilizes Peltier modules for temperature control, exhibits varying behaviors depending on the time of day. This horizontal bar graph visually presents the system’s performance through four key metrics: minimum and maximum light intensity (W/m2), supply voltage (V), and response time (s). The graph is segmented into three operational periods: Morning (08:00–10:00), Noon (11:00–14:00), and Evening (16:00–18:00) to analyze system dynamics under different environmental conditions. As shown in Fig. 8. Table 4 summarizes the Peltier plate control system behavior and stability under different lighting conditions and power availability.

Figure 8: Thermoelectric cooling system behavior using Peltier plates under different time intervals and light intensities, created by the authors

Morning, the system receives relatively low solar radiation (300–450 W/m2), operates at 11.5 V, and has a delayed 1.4-s response time. It runs in a limited capacity to maintain low loads, showing energy efficiency but reduced cooling performance.

Noon Peak conditions (700–850 W/m2, 12.7 V) lead to full-load operation with the best response time of 0.7 s. The system demonstrates optimal efficiency and control precision.

Evening, with lower light (350–450 W/m2) and 11.6 V supply, response time increases to 1.3 s. The control strategy adapts by intermittently shutting off the Peltier module to conserve energy.

Overall, the graph illustrates the system’s capacity to adjust to varying solar input through adaptive voltage and thermal load management, ensuring functional cooling throughout the day.

6 Demonstration and Deployment

The completed system was demonstrated in both indoor laboratory conditions and outdoor field settings. In the lab, the system responded reliably to temperature thresholds, displaying real-time sensor values on the Blynk platform and executing automatic control logic. As shown in Figs. 9–11. The cooling cycle was observable, with an average temperature drop of 4°C–6°C within 60–90 min. In field demonstrations, such as in rural school workshops and simulated off-grid environments, the system remained operational under sunlight intensity ranging from 300–850 W/m2. Observers were able to monitor sensor data and control the system via mobile interface, highlighting the system’s potential for STEM education, clean energy training, and agricultural cooling scenarios. Feedback from demonstration participants indicated high interest in the system’s portability and its ability to operate without a power grid. Teachers noted its usefulness in explaining thermodynamics and real-world IoT (Internet of Things) applications to students. The system was also seen as promising for adaptation into small-scale vaccine coolers or smart farming modules with environmental control.

Figure 9: Design and development of a demonstration Set of a water cooling system using a plate-tier with solar energy and IoT (Internet of Things) technology, created by the authors

Figure 10: Demonstration of a water cooling system using Peltier plates with solar energy and IoT (Internet of Things) technology in action, created by the authors

Figure 11: Demonstration Set of water cooling system tested with solar energy in lab and outdoor Settings with different water levels, created by the authors

Beyond functional performance, the system’s true value lies in its ability to bring applied science and technology to rural communities, under-resourced schools, and off-grid scenarios. It serves as a platform that bridges theory and practice, and facilitates the teaching of thermodynamics, energy management, and IoT (Internet of Things) in a tangible way. The system can be replicated using accessible components, making it ideal for hands-on education and grassroots deployment in energy-limited regions.

The purpose of this research is to design and develop a demonstration Set of chilled water systems using solar plate powered by solar energy and controlled through IoT (Internet of Things) technology.

Results of system design and development indicate that the designed system can effectively cool using solar panels as a direct power source. Peltier plates reduced the internal temperature of the cooling chamber by 6°C–10°C within 60–90 min under moderate to high sunlight conditions. The use of a non-refrigerant system provides high safety and is suitable for portable use or applications in remote locations. Efficiency, however, decreases in cold or cloudy weather without a backup battery. However, the efficiency decreases in cold or cloudy weather without a backup battery. These results are consistent with the work of Kumar et al. [12], who developed an air-cooling system using Peltier modules and IoT control that can operate efficiently in remote areas, as well as with the work of BimaJaya et al. [13], which showed that using a water-cooling system combined with IoT can help improve the performance of solar panels, resulting in greater stability and higher overall system efficiency. These findings are consistent with the suggestion that thermoelectric plates are promising for solar-powered refrigeration if heat management is properly designed, leading to substantial performance gains [14].

This aligns focused on solar-powered Peltier-based systems tailored for remote regions, emphasizing portability and educational applications. The current research complements this by offering a practical demonstration Set for experimental learning using low-cost equipment and clean energy [1].

Although this study utilizes the Blynk platform for system monitoring and control, the primary contribution does not lie in the specific tool used, but in the generalizable IoT (Internet of Things) control framework that can be applied across multiple platforms and contexts [9]. The value of the proposed framework stems from its modularity, low-power compatibility, and adaptability to energy-constrained environments. It integrates sensor-actuator-control logic, enables threshold-based automation, supports energy-aware load management, and provides real-time feedback. This structure is platform-agnostic and may be implemented via alternatives such as MQTT or Node-RED, depending on scale and connectivity. Importantly, the framework is designed for deployment in under-resourced or off-grid areas. By demonstrating that an inexpensive, educationally oriented thermoelectric cooling system can be managed through a lightweight IoT interface-even under fluctuating solar, this study offers a scalable model for applications in environmental sensing, agriculture, vaccine storage, and STEM education. Delays in command response do not exceed 2 s. The NodeMCU and DS18B20 temperature sensor exhibited stable performance with a measurement tolerance of ±0.5°C. These outcomes are consistent with findings [3]. Emphasized the enhancement of control and energy efficiency in solar-dependent systems through IoT integration. Moreover, the use of environmental sensors and IoT (Internet of Things) for smart solar systems has been demonstrated in recent research [15], A real-time thermal management system for electric vehicle batteries using Peltier plates and IoT platforms, showing the potential of adaptive control and alert systems. These examples reinforce the practical applicability of the presented research in both educational and energy-sensitive environments [2].

This research demonstrates the feasibility of a compact, solar-powered Peltier water cooling system integrated with IoT control. The system successfully reduced water temperature by 4°C–7.5°C under varying solar irradiance, and maintained real-time responsiveness through the Blynk platform with a delay of less than 2 s [9].

While the system’s coefficient of performance (COP) remains moderate (0.31–0.40), its ability to operate autonomously using solar and battery power confirms its applicability in off-grid environments such as rural areas, agricultural use, and educational contexts.

Despite certain limitations-such as sensitivity to solar stability and occasional sensor the project provides a foundation for future development in low-power cooling, smart energy management, and real-time environmental monitoring using affordable, open-source technologies.

Although this study does not introduce a new scientific theory, it contributes a replicable and scalable integration model of solar-powered thermoelectric cooling with IoT automation. Its significance lies in practical applicability, affordability, and educational accessibility-factors often overlooked in industrial implementations. This aligns with global efforts toward inclusive technology, clean energy access, and STEM outreach.

One of the practical challenges in designing solar-powered cooling systems is the intermittent nature of solar irradiance, which leads to fluctuating energy availability. In the current prototype, the system simply turns off the Peltier module when power is low or when the water reaches its target temperature. However, this control logic does not fully utilize the available PV power during periods of moderate or declining sunlight. A more efficient approach would be to implement thermal storage strategies, such as pre-cooling a water reservoir during peak sunlight hours and using it as a passive cold sink during low irradiance periods. This would allow the system to maintain cooling performance without additional power draw. Future work could explore intelligent power routing, battery-supercapacitor hybrids, or variable-speed operation of the Peltier module to better match the available energy curve. By addressing this challenge, the system’s efficiency, autonomy, and sustainability could be significantly improved.

1. The optimization of Peltier plates should be studied by using a switching power circuit design to fine-tune the cooling rate and reduce energy loss.

2. The COP values in different lighting conditions should be continuously analyzed to better reflect the system operation under real conditions.

3. The use of multi-point sensing allows for more accurate temperature control, especially in tanks with a large water capacity or that need constant cooling.

4. The system should be tested in a variety of seasons and climates to ensure that the system can be applied in real-world areas with unstable sunlight, such as the rainy season or mountainous regions.

5. IoT (Internet of Things) interfaces should be developed with an automated notification and data logging system for retrospective analysis and long-term planning.

6. The system can be applied in field applications such as smart farms, rural areas, or locations without access to electricity, using solar energy in combination with IoT control.

7. It can be used as a learning demonstration, Set at the high school or vocational level for teaching physics and renewable energy concepts, helping students understand systemic connections.

8. In terms of commercial development, this system has potential for expansion into portable vaccine storage boxes, food pantries in remote areas, or field-deployed electronics cooling units.

9. Government organizations or educational agencies promoting learning in remote areas can adopt this demonstration Set to foster awareness of clean technology and sustainable energy practices.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the Advisor for his valuable guidance, technical advice, and continuous support throughout the research on the Peltier Water Cooling System with Solar Energy and IoT Technology. His contributions played a vital role in the successful completion of this study. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for language refinement and Grammarly for grammar checking during the preparation of this manuscript. All outputs generated were carefully reviewed and verified by the authors.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive direct financial support; however, it was supported in kind through resources, technical consultation, and laboratory access generously provided by Chaiyapon Thongchaisuratkrul and relevant institutions.

Author Contributions: Prasongsuk Songsree was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, project administration, system design, experiment setup, and data collection. Chaiyapon Thongchaisuratkrul served as a technical advisor, guiding the experimental process and technical aspects. Both authors contributed to data analysis, manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and by institutional guidelines.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

1. Singh RP, Patel D, Rajput RS. Solar-powered Peltier refrigeration system: design, applications, and limitations. International [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/103798194/Solar_Powered_Peltier_Refrigeration_System_Design_Applications_and_Limitations. [Google Scholar]

2. Gunasekar N, Abishek H, Bharath NS, Gokul G. (2025). The Internet of Things enabled an automatic battery cooling system using the Peltier effect. Warrendale, PA, USA: SAE Technical Paper; 2025. Report No.: 2025-01-5004. doi:10.4271/2025-01-5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Arjun KG, Pruthviraj BG, Rashmi P. Design and implementation of based solar-powered portable refrigeration unit. Paper Presented at: The IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research; 2017 May 19–20; Bangalore, India. [Google Scholar]

4. Maxim Integrated. DS18B20 programmable resolution 1-wire digital thermometer [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/data-sheets/DS18B20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

5. Thai Physics Society. Study of the material scope of thermoelectrics [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.thaiphysoc.org/article/313/. [Google Scholar]

6. Becquerel AE. Mémoire sur les effets électriques produits sous l’influence des rayons solaires, Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://scispace.com/papers/memoire-sur-les-effets-electriques-produits-sous-l-influence-ixfuhld9o5. (In French). [Google Scholar]

7. Ashton K. That ‘Internet of Things’ thing. RFID Journal [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.rfidjournal.com/expert-views/that-internet-of-things-thing/73881/. [Google Scholar]

8. Gubbi J, Buyya R, Marusic S, Palaniswami M. Internet of Things (IoTa vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2013;29(7):1645–60. doi:10.1016/j.future.2013.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Çengel YA, Boles MA. Thermodynamics: an engineering approach. 8th ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015. [Google Scholar]

10. Blynk Inc. Blynk documentation [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://docs.blynk.io. [Google Scholar]

11. Uzair M, Al-Kafrawi S, Al-Janadi K, Al-Bulushi I. A low-cost, real-time rooftop IoT-based photovoltaic (PV) system for energy management and home automation. Energ Eng. 2022;119(1):83–101. doi:10.32604/ee.2022.016411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kumar V, Arun A, Kaarthik A, Dharan G. Solar air cooler with peltier device using IoT. Int Res J Mod Eng Technol Sci. 2024;6(10):4231–4. [Google Scholar]

13. BimaJaya A, Permana AD, Devitra H. Solar panel efficiency enhancement through water cooling with IoT integration. J Power Energy Control. 2025;2(1):67–80. doi:10.62777/pec.v2i1.53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang J, Lu L, Jiao K. Solar- and/or radiative cooling-driven thermoelectric generators: a critical review. Energ Eng. 2024;121(10):2681–718. doi:10.32604/ee.2024.051051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lavanya L. Design of an intelligent solar cooling system with IoT (Internet of Things) monitoring. In: Paulose K, Dhanalakshmi M, editors. Lecture notes in electrical engineering. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 221–30. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-3090-2_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools