Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Maximizing Wind Farm Power Output through Site-Specific Wake Model Calibration and Yaw Optimization

1 Power Dispatch Control Center, Guangdong Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, 510000, China

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

* Corresponding Author: Lifu Ding. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrated Technology Development and Application of Wind Power Systems)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4365-4384. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068712

Received 04 June 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

Wake effects in large-scale wind farms significantly reduce energy capture efficiency. Active Wake Control (AWC), particularly through intentional yaw misalignment of upstream turbines, has emerged as a promising strategy to mitigate these losses by redirecting wakes away from downstream turbines. However, the effectiveness of yaw-based AWC is highly dependent on the accuracy of the underlying wake prediction models, which often require site-specific adjustments to reflect local atmospheric conditions and turbine characteristics. This paper presents an integrated, data-driven framework to maximize wind farm power output. The methodology consists of three key stages. First, a practical simulation-assisted matching method is developed to estimate the True North Alignment (TNA) of each turbine using historical Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) data, resolving a common source of operational uncertainty. Second, key wake expansion parameters of the Floris engineering wake model are calibrated using site-specific SCADA power data, tailoring the model to the Jibei Wind Farm in China. Finally, using this calibrated model, the derivative-free solver NOMAD is employed to determine the optimal yaw angle settings for an 11-turbine cluster under various wind conditions. Simulation studies, based on real operational scenarios, demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework. The optimized yaw control strategies achieved total power output gains of up to 5.4% compared to the baseline zero-yaw operation under specific wake-inducing conditions. Crucially, the analysis reveals that using the site-specific calibrated model for optimization yields substantially better results than using a model with generic parameters, providing an additional power gain of up to 1.43% in tested scenarios. These findings underscore the critical importance of TNA estimation and site-specific model calibration for developing effective AWC strategies. The proposed integrated approach provides a robust and practical workflow for designing and pre-validating yaw control settings, offering a valuable tool for enhancing the economic performance of wind farms.Keywords

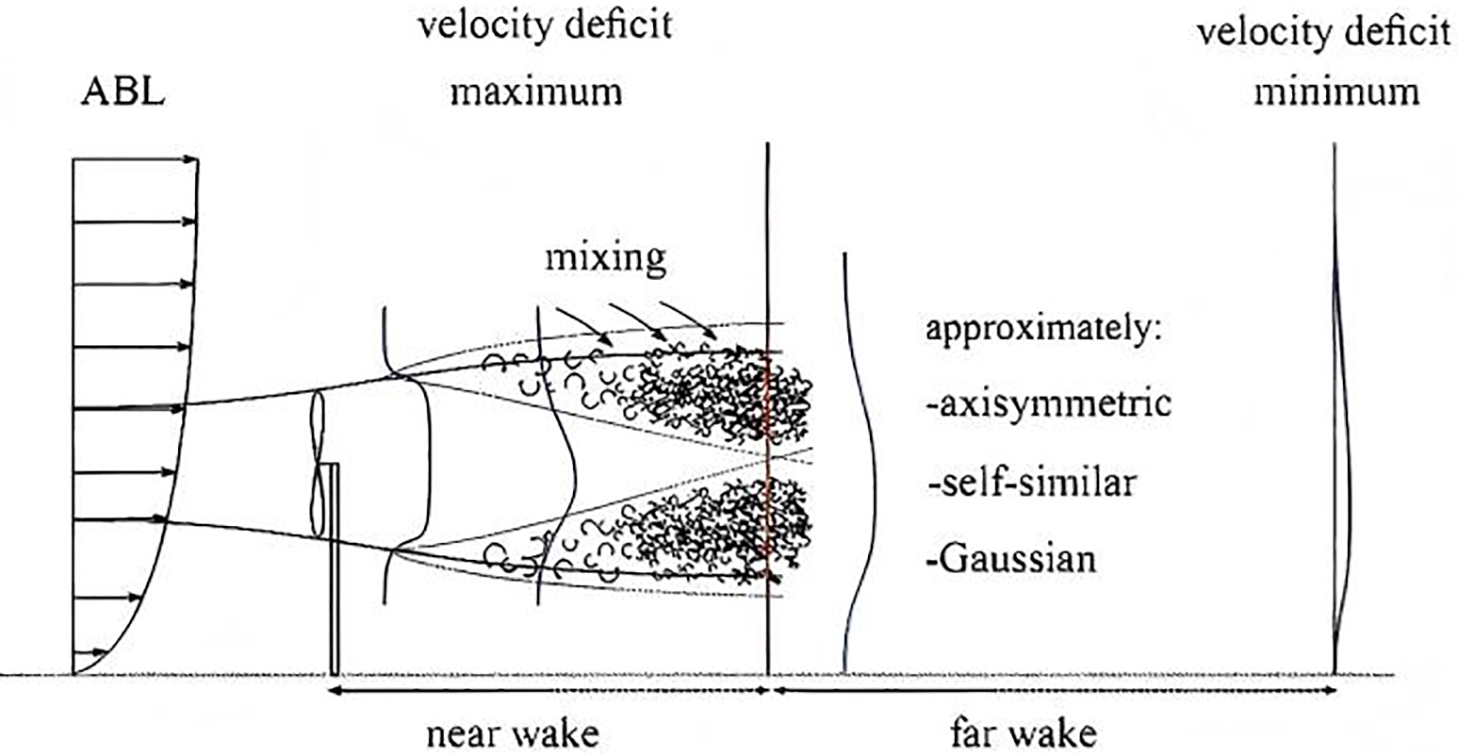

In the global transition to sustainable energy systems, wind power has become a key component due to its environmental benefits and declining costs [1]. China, with its abundant wind resources, has actively promoted the development of the wind power industry, leading to a rapid increase in installed capacity [2,3]. However, as wind farms expand in scale and density, the aerodynamic interactions between wind turbines, known as wake effects, are a major factor limiting overall energy output [4]. The wake generated by upstream turbines is characterized by reduced wind speed and increased turbulence, which not only negatively impacts the power output of downstream turbines but also increases their fatigue load, where the basic form of the wake is illustrated in Fig. 1 [5]. It is estimated that the power loss caused by the wake can reach 10–20% of the total potential power generation [4], significantly affecting the economic viability of wind power projects. Therefore, effectively mitigating wake losses is crucial for maximizing energy capture and enhancing the economic benefits of wind farms. Accurate modeling and simulation are essential for understanding this complex natural phenomenon and finding solutions.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of wind turbine wake

To address wake loss, the Active Wake Control (AWC) strategy has gained significant attention [6,7]. Among AWC technologies, which include axial induction control, wake redirection, and enhanced wake mixing, yaw-based control strategies have shown great potential [8]. This strategy intentionally creates a certain angle between the upstream wind turbine and the incoming wind. By yawing, the wake is laterally deflected, potentially reducing the direct impact on downstream turbines, thereby enhancing the overall power output of the wind farm [9]. To effectively design, analyze, and optimize this method, it is essential to rely on precise modeling and high-performance simulation tools.

The successful implementation of yaw-type AWC depends on several key factors. First, it is essential to accurately predict wake behavior, including the distribution of speed loss and wake deflection trajectories under yaw conditions. To achieve this, researchers have developed various wake models, ranging from classical analytical models like the Jensen model [10,11] and Gaussian model [12] to computationally intensive numerical simulation methods such as large eddy simulation (LES) [13,14]. Parametric models, such as the Floris (FLOw Redirection and Induction in Steady-state) model [15,16], offer a good balance between computational efficiency and simulation accuracy, making them suitable for developing control strategies. The Floris model can explicitly simulate wake deflection and the superposition effect of multiple wakes, often using Gaussian functions to describe speed loss [17].

Second, general wake models often require site-specific calibration to account for local topography, atmospheric conditions, and the characteristics of the wind turbines [16]. The key parameters determining wake expansion and deflection can vary significantly across different sites. Third, practical applications also face challenges related to the quality and availability of data from supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems. For example, the true north alignment (TNA) information, which serves as a reference for yaw angle measurements, may be inaccurate or missing, hindering the accurate interpretation of wind direction and yaw settings [18]. Finally, finding the optimal yaw angle combination for all wind turbines within a wind farm is a complex optimization problem, with objectives that are high-dimensional, nonlinear, and typically non-convex [19]. To address such complex issues, advanced modeling, simulation, and optimization techniques are required, taking into account various factors in the natural environment.

This paper addresses the interconnected challenges by proposing an integrated approach to optimize wind farm power output through yaw control, using a wind farm in northern Hebei, China, as a specific application. The method integrates practical data preprocessing techniques for TNA estimation, site-specific calibration of the Floris wake model, and robust optimization simulations based on the derivative-free NOMAD solver. This approach aims to enhance the energy capture of wind farms and can serve as a reference for constructing high-precision virtual wind farm environments.

Research on wind farm optimization, considering wake effects, has made significant progress. Early work primarily focused on static layout optimization [20]. With the development of active wake control (AWC) technology, particularly yaw control, the focus shifted to operational strategy optimization [21]. The Floris model [22], developed by NREL and its collaborators, has become a commonly used tool in AWC research due to its ability to effectively simulate wake deflection and high computational efficiency [17]. Subsequent extended models, such as FLORIDyn, further incorporate dynamic effects [23]. The effective application of these models requires a deep understanding and precise modeling of the wind farm’s natural environment. Optimization algorithms for yaw control range from gradient-based methods (which require analytical or adjoint gradients [19]) to heuristic algorithms and derivative-free methods [24]. Derivative-free methods, such as the Mesh Adaptive Direct Search (MADS) [25] algorithm (implemented in solvers like NOMAD [26]), are particularly suitable for handling complex, simulation-based ‘black box’ objective functions or noisy data, which are common in wind farm optimization problems. Such simulation optimization techniques are valuable for exploring and testing control strategies in virtual environments.

Despite significant progress, there are still shortcomings in integrating actual data processing, site-specific model calibration, and robust optimization simulation into a unified method validated by site data. Although the TNA error issue has been recognized [18], systematic estimation of TNA using operational data remains to be explored in the AWC context. Similarly, while the importance of model calibration is widely acknowledged, research on practical iterative calibration using data from Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems and integrating it into an optimization framework for validation needs to be enhanced. This study aims to address these gaps and contribute to the development of a more accurate wind farm virtual environment.

This article aims to fill these gaps through the following contributions:

1. A practical simulation-assisted matching method based on normal distribution fitting has been developed and applied to estimate missing or uncertain true north alignment data of wind turbines from SCADA measurement data. This method leverages the consistency between simulated wake patterns and actual SCADA wind conditions/power data, identifying data segments that match specific simulation conditions to achieve a robust estimation of TNA.

2. An iterative estimation method was designed to calibrate the key parameters of the Floris wake model (which affects the wake expansion rate) using the SCADA power data of the target power station (Jibei Wind Farm), so as to improve the prediction accuracy of the model for this specific site. This process also explored the dependence of the calibrated parameters on wind speed and wind turbines.

3. The gradient-free NOMAD solver is applied and analyzed to determine the optimal yaw angle that can maximize the total power of a wind farm under specific wind conditions based on the calibrated Floris model.

Through a simulation case study based on the real operational data of an 11-turbine cluster at the Jibei Wind Farm, the advantages of the integrated method are demonstrated and quantified. The study clearly demonstrates that using site-specific model calibration in simulations can enhance yaw optimization performance. By selecting actual operational scenarios and calibrating with measured data, the study provides a solid simulation foundation for subsequent on-site verification.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed explanation of the problem formulation and mathematical background, including the definition of angles and the structure of the wake model. Section 3 describes the proposed integrated method, which includes TNA estimation, Floris model calibration, and yaw angle optimization. Section 4 presents a case study using data from the Jibei Wind Farm and analyzes the simulation results. Section 5 summarizes the paper, highlighting the main findings and discussing future research directions, particularly the necessity of field validation.

2 Problem Formulation and Mathematical Background

This section formally defines the problem of wind farm yaw optimization and introduces the relevant mathematical concepts and models.

2.1 System Definition and Symbols

Consider a wind farm consisting of

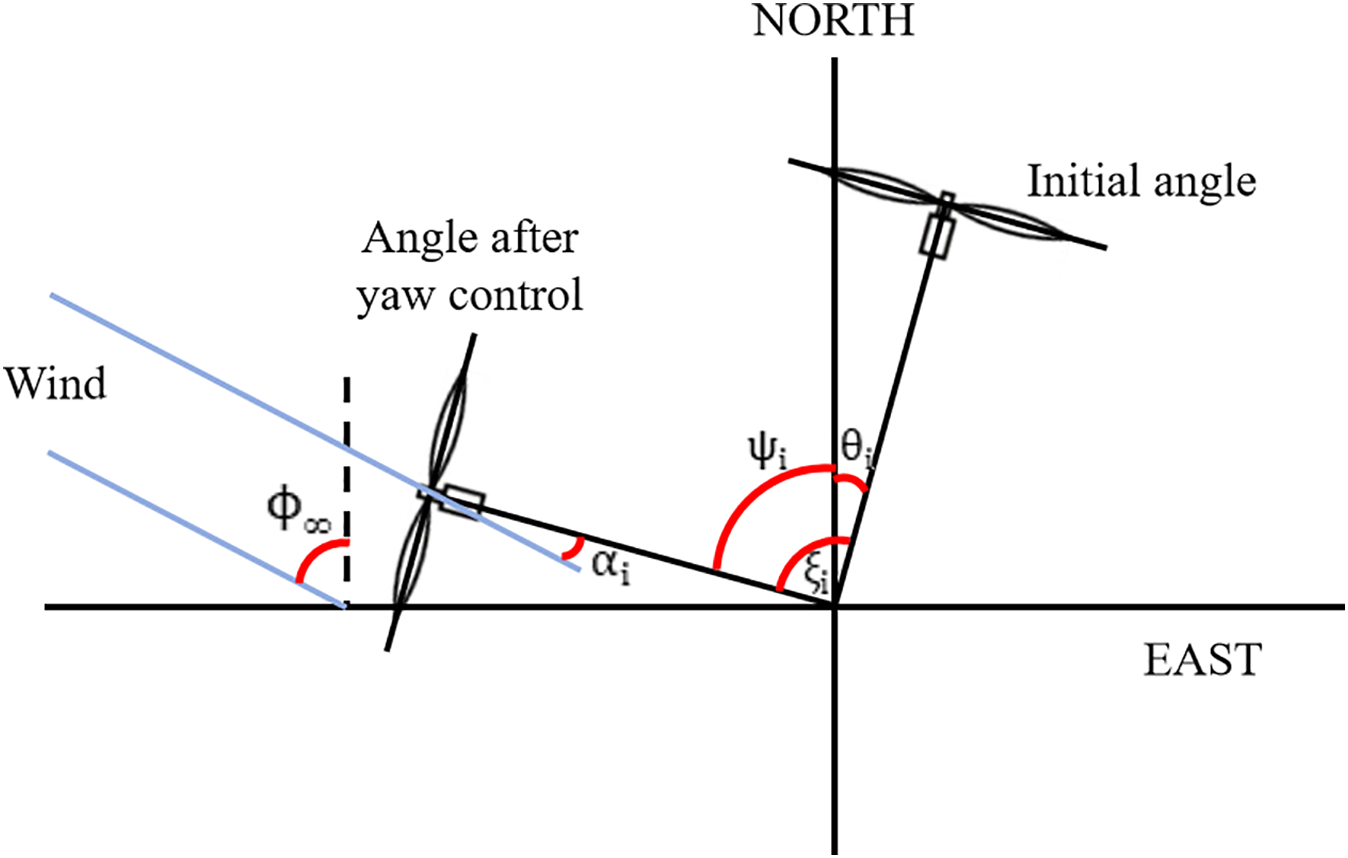

Precise definition of the angle is critical for wake modeling and control. The key angles are defined below and illustrated schematically in Fig. 2. The following definitions are adopted.

Figure 2: Schematic of angle definitions

Fig. 2 presents a simplified schematic for conceptual clarity. The yaw misalignment

The Floris model [16,21] is used to predict wind fields within a wind farm. It calculates the speed loss and deflection caused by each wind turbine, and combines these effects to determine the local wind conditions

The radial width

The cross-sectional and vertical wake widths (

where

The Floris model ultimately provides the following functions:

where

2.3 Power and Thrust Model of Wind Turbine

The power

In yaw conditions, the power coefficient is usually related to the coefficient at zero yaw

where

Similarly, the thrust coefficient

where

Calculating local conditions (

The main objective is to find the yaw angle deviation vector

where the above formula is implicitly used by

Optimization is subject to the operational constraints of allowable yaw angle deviation for each wind turbine:

In this study, a typical restriction was applied as

The optimization problem defined by the above formula shows the following characteristics:

• Nonlinear: The objective function

• Non-convex: The objective function is usually non-convex due to complex wake interactions and potential trade-offs, which may have multiple local optima.

• High dimension: The number of decision variables is the number of wind turbines

• Coupling: The yaw angle

• Black box evaluation: The evaluation of the total power output

These features, especially the non-convexity of the problem and the black box nature of the problem, lead to the use of derivative-free optimization (Derivative-Free Optimization, DFO) algorithms, such as MADS (implemented by the NOMAD solver).

3 Problem Formulation and Mathematical Background

This section details the integrated workflow developed to address the yaw optimization challenges of wind farms. It includes data preprocessing for true north alignment estimation, on-site calibration of the Floris wake model, and the optimization process itself. The workflow integrates real-world operational data from natural environments with simulation models from virtual environments, aiming to enhance the power generation performance of wind farms in complex conditions through precisely calibrated model-driven optimization.

3.1 True North Alignment Angle Estimation

Accurate determination of the true north alignment angle

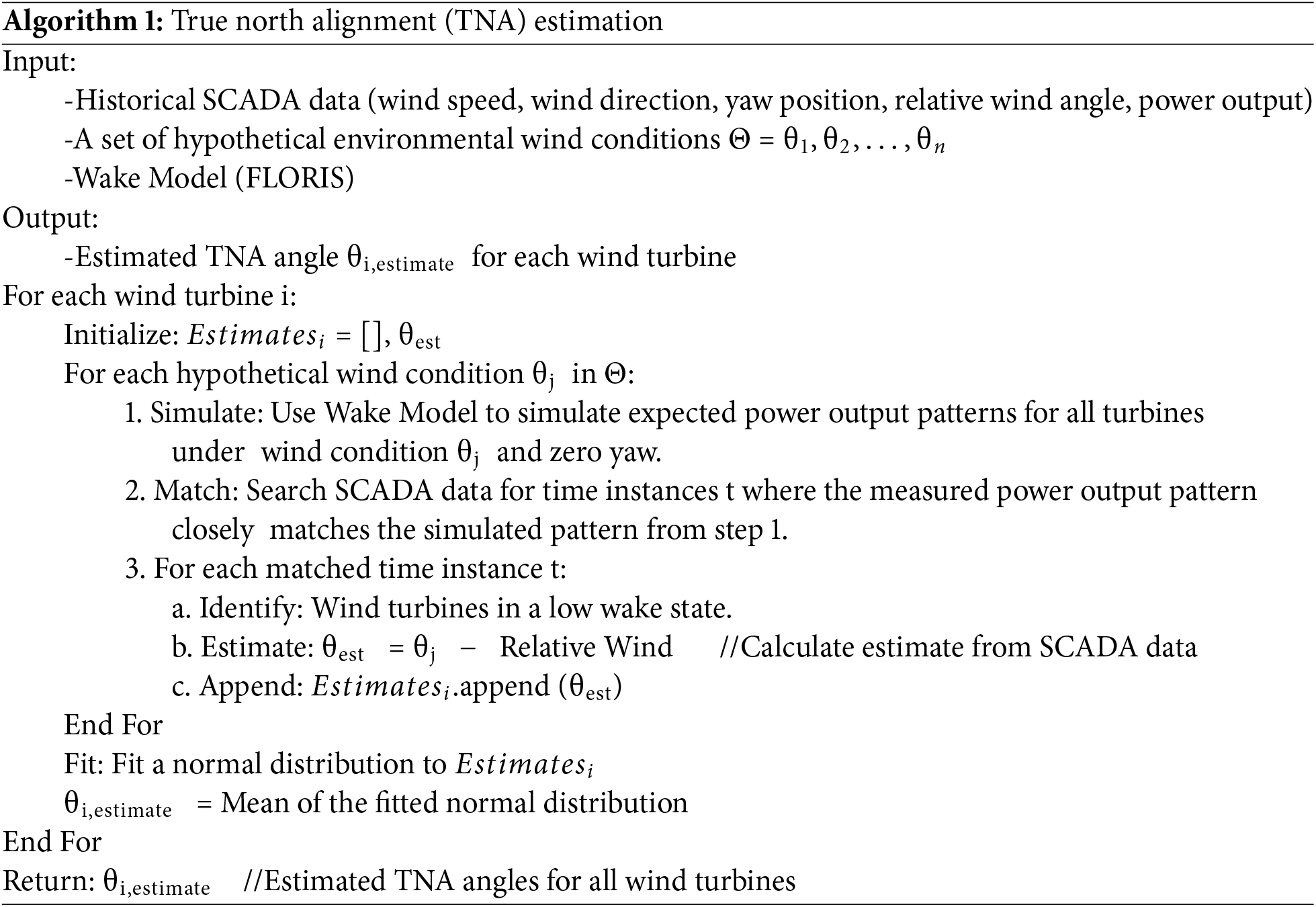

A data-driven simulation-assisted matching method has been proposed, utilizing historical SCADA data for estimating

If the ambient wind direction

However, directly obtaining the instantaneous environmental wind direction at each wind turbine is challenging. Therefore, a simulation-assisted pattern matching method was adopted, which uses more detailed wake simulation models (such as FLORIDyn [22]) to generate expected spatial patterns, thereby combining natural environment observation data with virtual environment simulation results:

1. Select a representative set of environmental wind conditions (

2. For each assumed environmental condition (

3. In the historical SCADA data, time instances

4. For each matched time instance

5. Repeat steps 1–4 for multiple hypothetical environmental conditions (

6. The estimated values of each wind turbine are fitted to a normal distribution. The mean of the fitted distribution

This method leverages the patterns of multiple wind turbines and time instances to provide robust estimates

3.2 Calibration of Parameters of Floris Wake Model

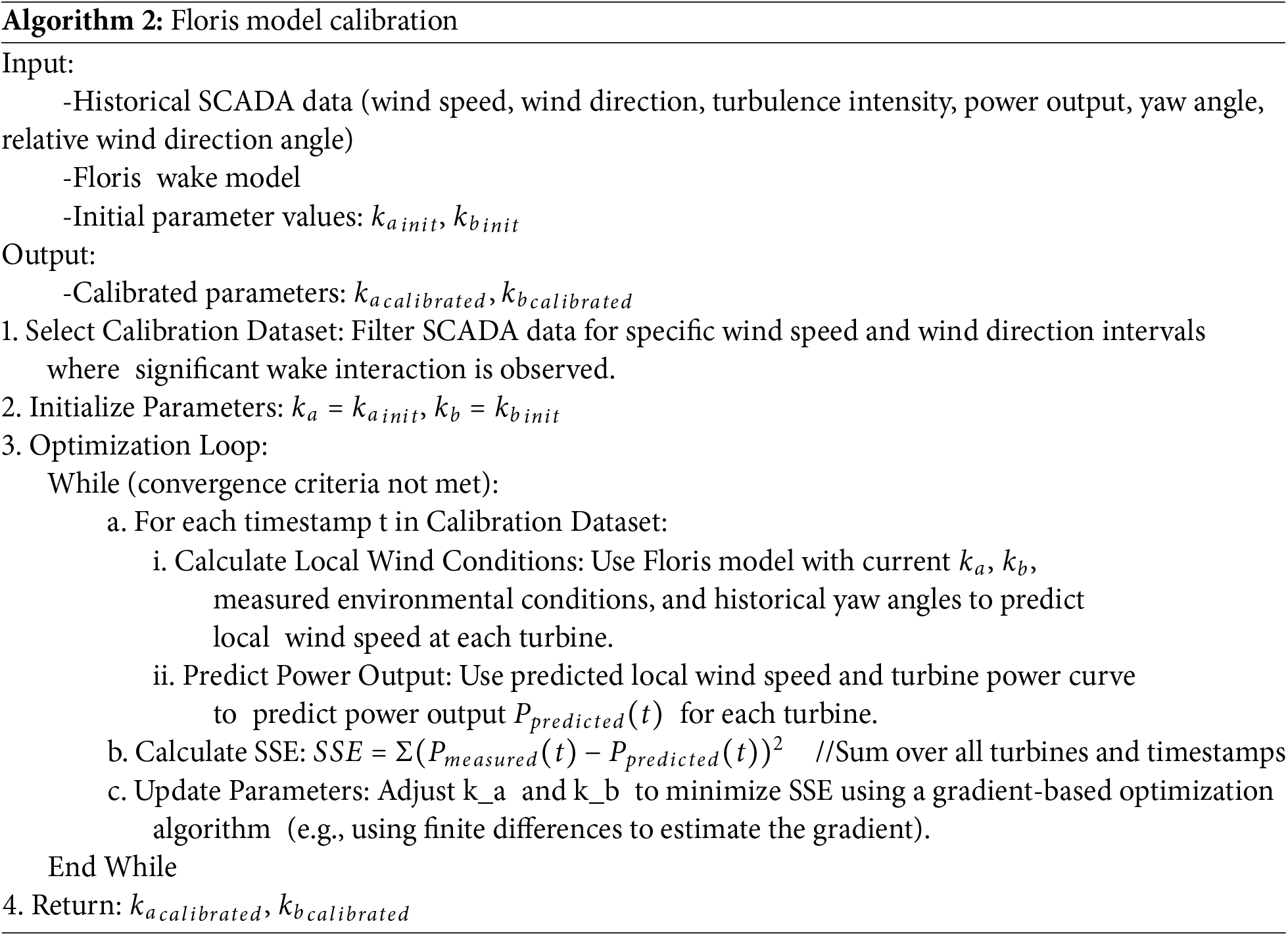

The Floris model includes parameters that influence its predictions, particularly the wake expansion rate controlled by

To enhance the accuracy of the Floris model in predicting wind power at the Jibei Wind Farm, historical SCADA data was used for calibration of

The iterative estimation method adopted is based on the optimization approach to minimize the SSE objective function (11):

1. Select a calibration dataset from the SCADA system, which includes timestamps

2. Initialize parameters

3. The optimization algorithm is used to iteratively adjust

(1) For the current parameter values (

(2) The total SSE is calculated according to Formula (11).

(3) Update the parameters (

4. The iteration is terminated when the convergence criteria are met (e.g., SSE or relative improvement of parameter values is negligible, below the threshold, or maximum number of iterations is reached).

This process generates a set of calibration parameters

3.3 Use NOMAD to Optimize Yaw Angle

Using the calibrated Floris model

As discussed in Section 2.4, this is a nonlinear, non-convex, and high-dimensional optimization problem. While standard wake modeling tools often include built-in, gradient-based optimizers that are suitable for many applications, the specific formulation in this study presents unique challenges. The objective function is evaluated via a complex simulation chain that incorporates the site-specific, data-driven calibrated parameters. This process creates a “black-box” objective function with a complex landscape that can be challenging for gradient-based methods, which are often sensitive to numerical noise and may converge prematurely to a poor local optimum.

For this reason, the NOMAD (Nonlinear Optimization by Mesh Adaptive Direct Search) solver [27] was selected. NOMAD implements the MADS algorithm [28], a derivative-free method specifically designed for its robustness in solving such black-box problems. This choice prioritizes solution quality and reliability, as the algorithm does not require gradient information and uses dynamically refined grids to effectively explore the search space.

MADS is a derivative-free optimization method designed for black-box problems where gradients are unavailable or unreliable. The algorithm operates iteratively through two main steps: a Search step and a Poll step. In each iteration, it explores a set of points on a dynamically adjusted grid, or ‘mesh’, centered around the current best solution. The optional Search step allows for flexible exploration of the solution space using various heuristics. The mandatory Poll step, which guarantees the algorithm’s convergence properties, systematically generates a set of trial points on the mesh in specific directions. If a trial point yields a better objective function value, the iteration is deemed successful, the new point becomes the current best solution, and the mesh may be expanded. If no improvement is found in the Poll step, the iteration is unsuccessful, and the mesh is refined (i.e., its size is reduced) to focus the search more locally in the subsequent iteration. This adaptive process of exploring and refining the search space makes MADS robust and well-suited for complex, simulation-based optimization tasks like wind farm yaw control.

The implementation process involves defining a black-box function interface for the NOMAD call. This function takes a yaw angle deviation vector

4 Case Study and Result Analysis

This section introduces the application of the proposed method to a cluster of 11 wind turbines at the Jibei Wind Farm, and analyzes the simulation performance of the yaw optimization strategy. The case study uses real natural environment data (SCADA records) to define the simulation scenario and calibrate the virtual simulation model (Floris), thereby evaluating the optimization effects under both real operational conditions and the virtual simulation environment.

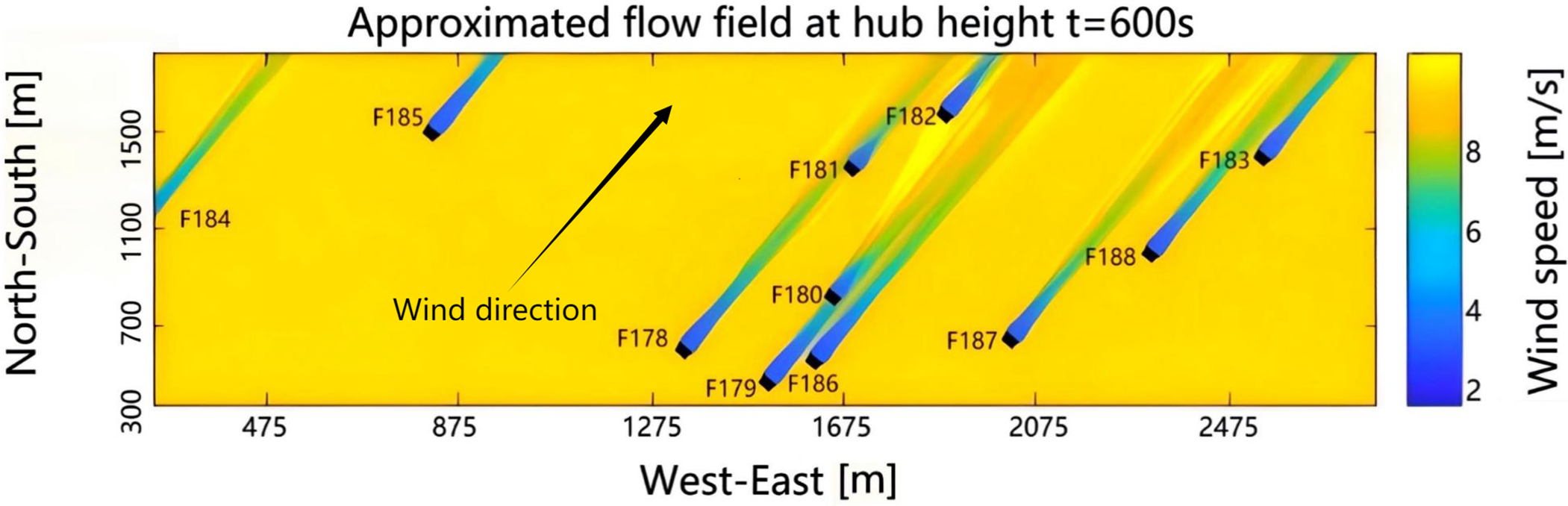

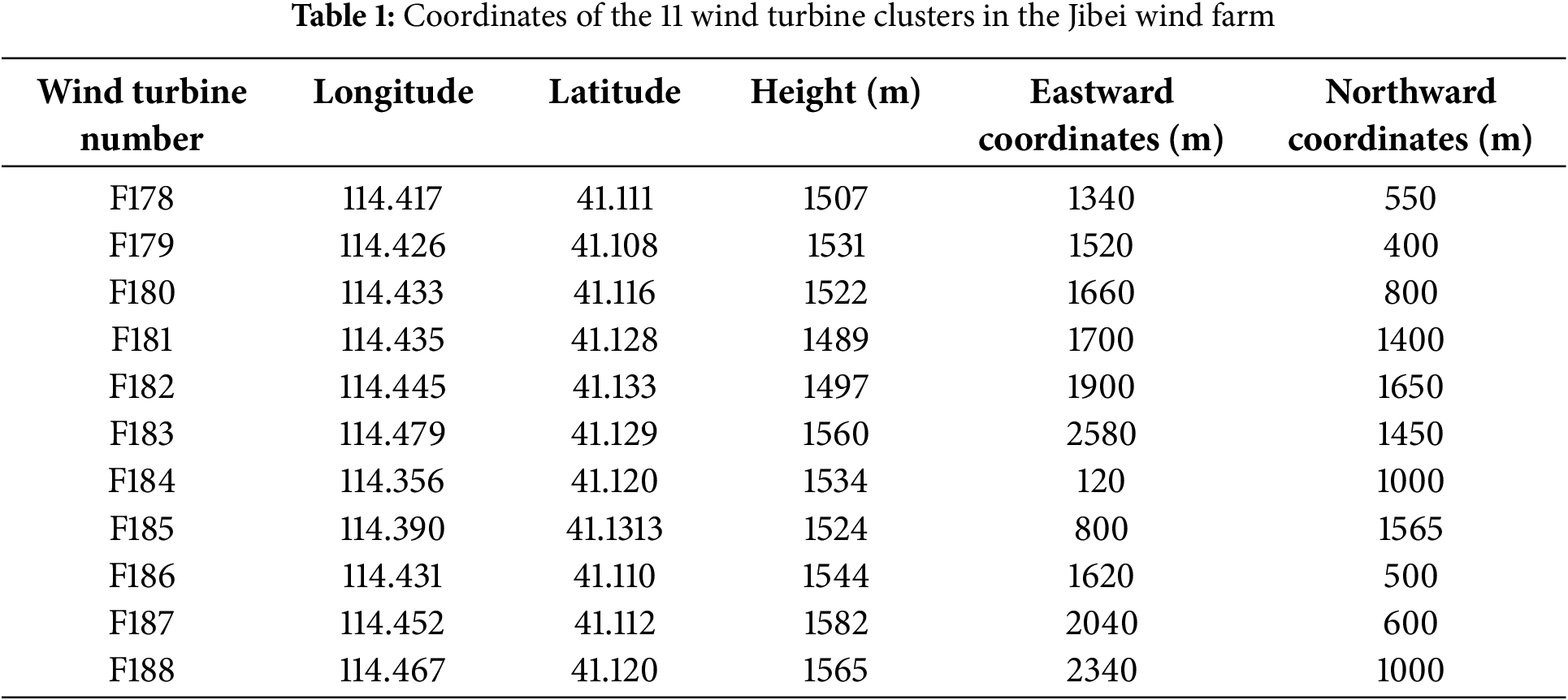

The study focuses on 11 wind turbines (numbered F178–F188) located at the Jibei Wind Farm near Zhangjiakou City, Hebei Province, China. The schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 3 and the geographical coordinates are shown in Table 1.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of 11 wind turbine units in Jibei Wind Farm

The TNA estimates and model calibration were performed using SCADA data collected from the wind farm. Specifically, a six-month dataset, spanning from 01 January 2022, to 30 June 2022, was utilized. This dataset provided 10-min average values for each wind turbine, including wind speed, relative wind direction, yaw position, relative wind angle, and power output. The environmental turbulence intensity was also derived from this SCADA data. The true north alignment angle was estimated using the method described in Section 2.1, which was applied to this comprehensive dataset. Similar values were also obtained for other wind turbines. These estimated TNA values were used to derive historical yaw angle deviations from the SCADA data for calibration and optimization in the Floris simulation.

4.1.2 Wake Model and Calibration

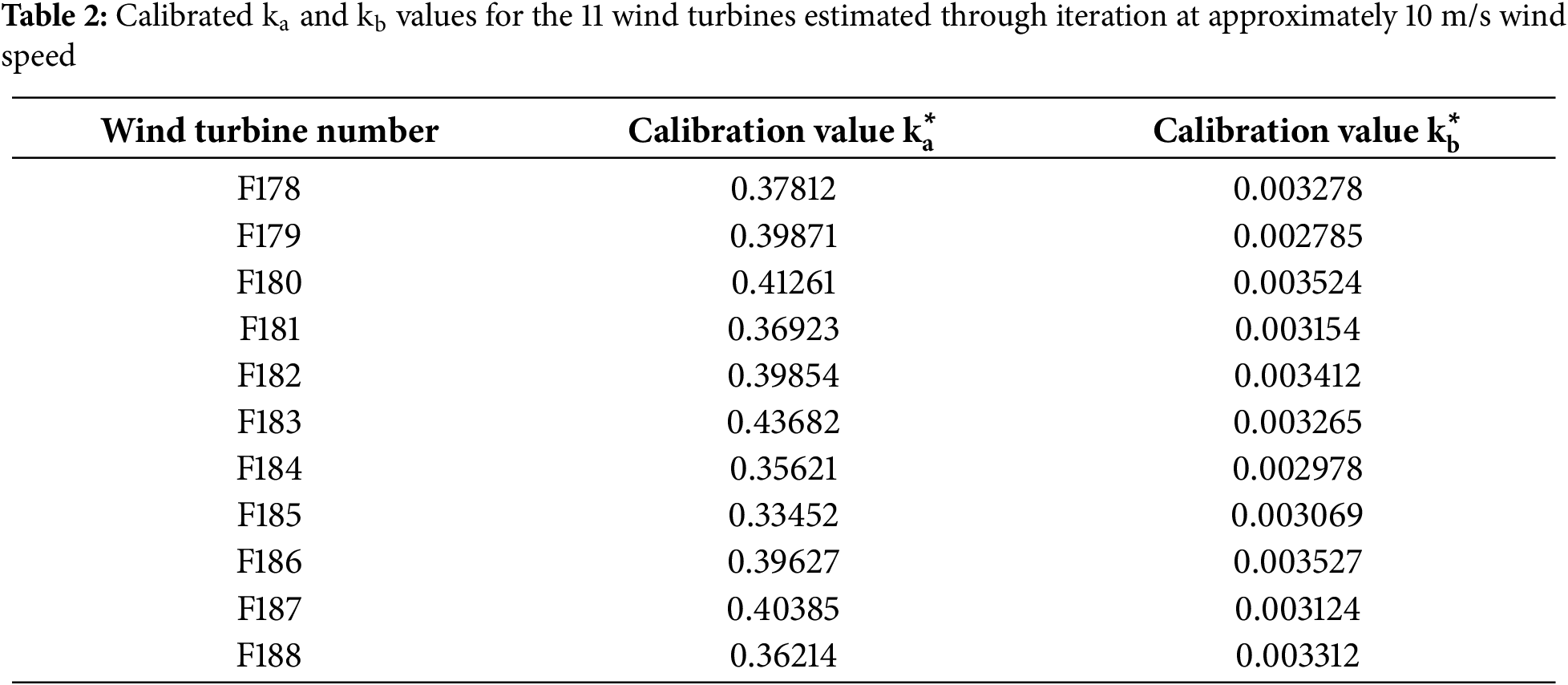

The Floris wake model is implemented based on the modeling methods described in Section 2, including the dependence of the wake expansion slope on

The value range for comparison, the optimization also uses a generic Floris parameter set that represents typical sites. These generic values are the default parameters for Floris:

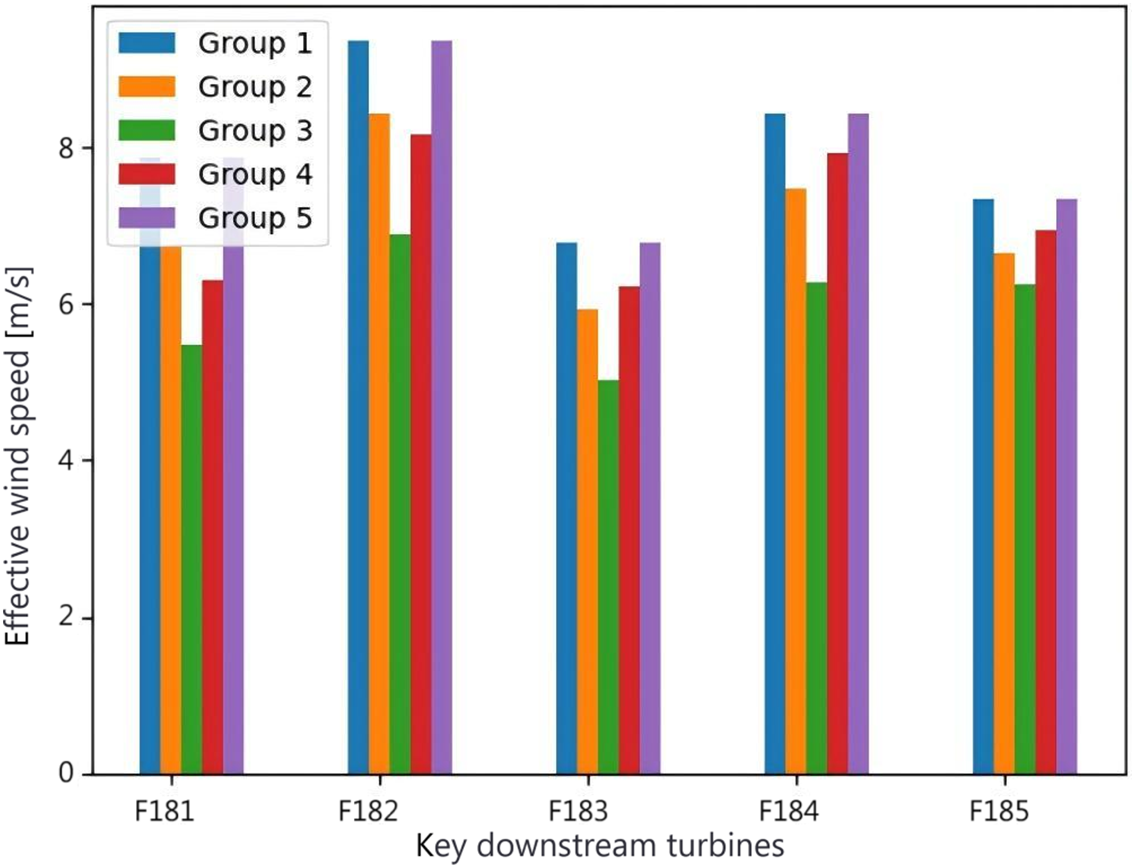

To validate the model’s accuracy, Fig. 4 provides a step-by-step comparison for a representative wake-inducing scenario, evaluating predictions against measured SCADA data for five key downstream turbines (F181–F185). The analysis breaks down the contributions of the proposed methodology. Five groups systematically build up the comparison to show how each component contributes to improving accuracy:

Figure 4: Comparison of predicted effective wind speeds for key downstream turbines, evaluating different model calibration stages against measured SCADA data

• Group 1: “Measured SCADA Data”.

• Group 2: “Generic Model” (Default TNA & Parameters).

• Group 3: “TNA Correction Only”.

• Group 4: “Parameter Calibration Only”.

• Group 5: “Fully Calibrated Model” (TNA + Parameters), which is the proposed method.

The “Generic Model” (using default TNA and parameters) serves as the initial benchmark and exhibits a significant error. Interestingly, applying the “TNA Correction Only” makes the mismatch between the model and data larger for some turbines. Similarly, applying only “Parameter Calibration Only” results in a larger mismatch for the first two turbines (F181 and F182) and only slightly improves the model-to-data match for the other turbines. In contrast, the “Fully Calibrated Model”, which integrates both TNA estimation and site-specific parameter calibration, demonstrates the highest fidelity, aligning most closely with the measured data. This tiered comparison validates that the synergistic combination of both components in the integrated framework is essential for achieving a highly accurate predictive model.

The NOMAD solver (version 3.9.1, invoked through PyNomad) was used to optimize the yaw angles of the 11 wind turbines. The objective function is the total power output of the 11 wind turbines, calculated using the Floris model with either general or site-specific calibration parameters. The decision variables are the yaw angle deviations

A standard NOMAD configuration was employed, and the process was limited to 1000 function evaluations to balance solution quality with computational cost. Each optimization run was executed on a desktop computer with an Intel Core i7-10700 CPU and 32 GB of RAM, and typically completed in 15–20 min.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of yaw optimization, several specific environmental wind conditions were selected based on the analysis of SCADA data and wind turbine layout to identify scenarios with significant wake interaction. These scenarios were obtained by averaging SCADA data points falling within a narrow range of wind speed and wind direction:

• Scenario 1: Wind direction

• Scenario 2: Wind direction

• Scenario 3: Wind direction

• Scenario 4: Wind direction ≈ 275° (interval

• Scenario 5: Wind direction

• Scenario 6: Wind direction

For each scenario, the total simulated power output under three scenarios is calculated, which is consistent with the workflow evaluation framework:

• Baseline: All wind turbines operate with zero yaw deviation (

• Optimization (General Model): The optimal yaw angle deviation

• Optimization (Calibration Model): The optimal yaw angle deviation

Comparisons 1 and 3 show the total simulation gain obtained using the full proposed workflow and calibration model. Comparisons 2 and 3 show the additional simulation gain specifically attributed to the use of the calibration model in optimization, assuming that the calibration model better represents the physical characteristics of the site.

4.2 Simulation Results and Discussion

4.2.1 Simulation Effects of Yaw Optimization (General Model)

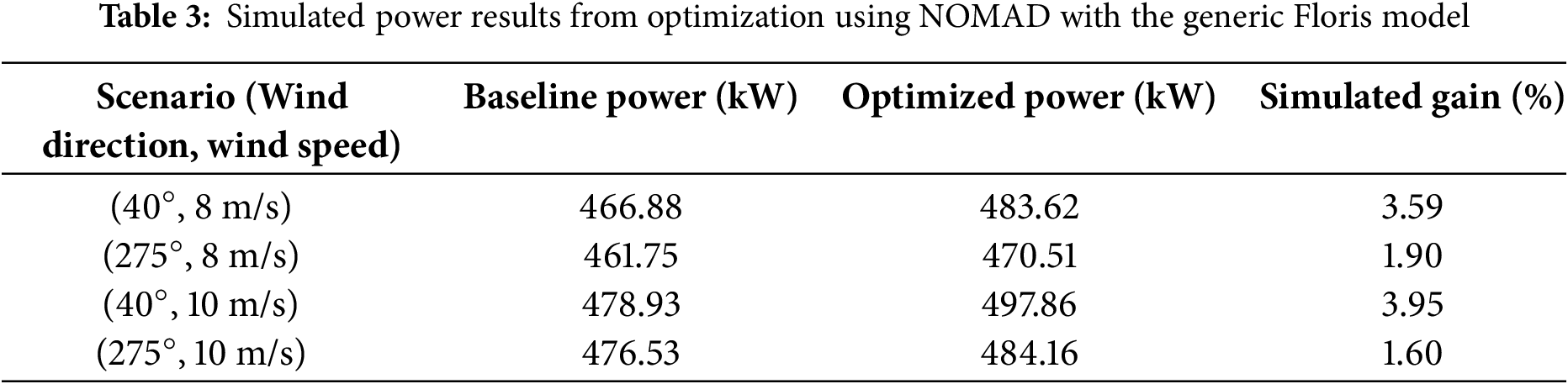

Table 3 summarizes the simulated power gain achieved by using the Floris model with default parameters for yaw optimization in scenarios 1–4, which is relative to the zero yaw baseline (calculated using the calibration model).

The results indicate that, when using a calibrated model for evaluation, the general Floris model simulating yaw optimization can enhance total power output compared to the zero yaw baseline. The simulation gain ranges from 1.60% to 3.95%, depending on the wind conditions. The higher gains observed at a 40° wind direction may be due to more direct wind turbine alignment, leading to stronger wake interactions, which offer greater potential for mitigation through wake guidance.

4.2.2 Model Calibration for Optimizing Simulation Benefits

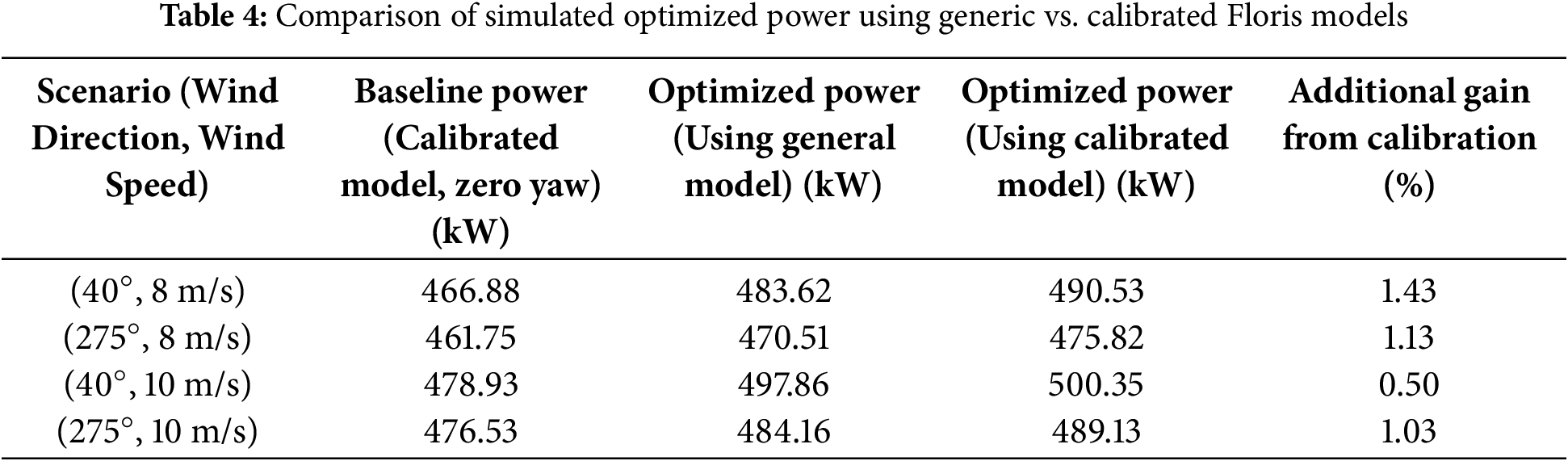

To quantify the benefit of using a site-specific calibrated model, this study compares the outcomes of three distinct simulation scenarios. All scenarios are evaluated using the calibrated model to represent the physical reality of the site, ensuring a fair comparison:

• Baseline Power: The power output with zero yaw deviation, calculated using the calibrated model. This represents the best estimate of the farm’s performance without active wake steering.

• Optimized Power (General Model): The power output achieved using yaw angles that were optimized with generic FLORIS parameters. This shows the benefit of applying a non-site-specific control strategy.

• Optimized Power (Calibrated Model): The power output achieved using yaw angles optimized with the site-specific calibrated parameters. This represents the full potential of the proposed method.

Table 4 presents the results of this comparison for scenarios 1–4. The “Additional Gain from Calibration” column isolates the performance improvement that is solely due to using the calibrated model during the optimization process, demonstrating the practical value of site-specific tuning.

When both outcomes are evaluated using the calibrated model, using site-specific calibrated Floris model parameters

4.2.3 Simulation Results of Representative Scenarios

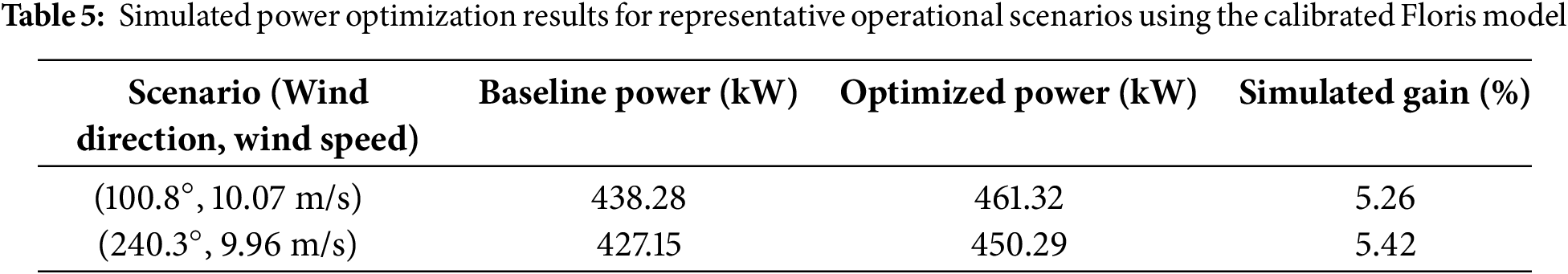

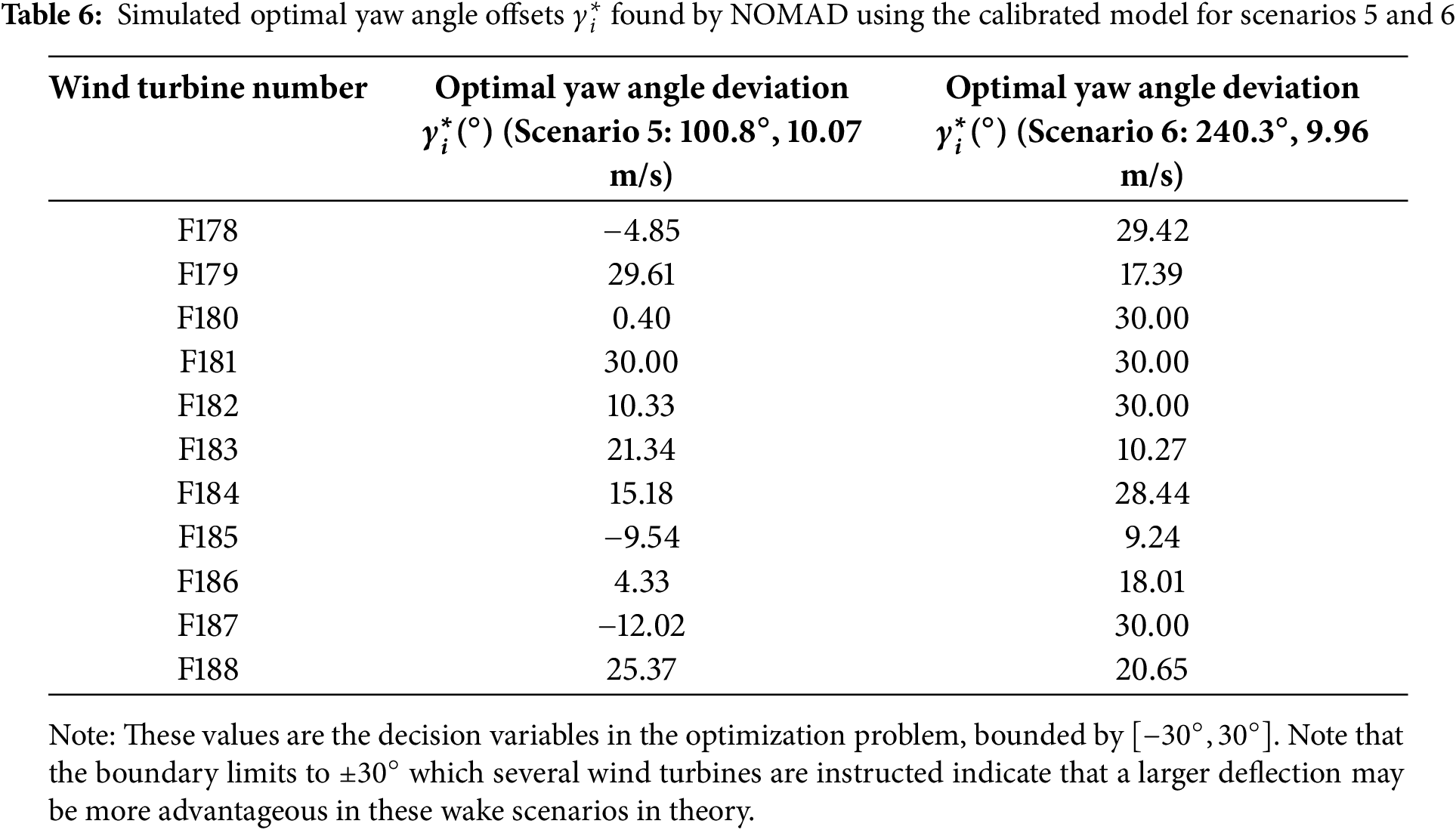

Table 5 shows the simulation optimization results using the calibrated model in two other representative operating scenarios (Scenario 5 and Scenario 6). The optimal yaw angle deviation found by NOMAD for these cases is shown in Table 6.

In these representative operational scenarios, the yaw optimization strategy using the calibration model achieved a significant simulation power gain of 5.26% and 5.42%, compared to the zero yaw baseline. Compared to scenarios 1–4, these higher gains may be due to the particularly strong and direct wake interactions within the cluster of 11 wind turbines caused by specific wind directions, offering greater potential for wake guidance improvements. The optimal yaw angle deviation (Table 6) indicates that different wind turbines are assigned different yaw angles, with upstream turbines typically yawing significantly (reaching the constraint

The simulation case study using the data of Jibei Wind Farm shows the following simulation results within the framework of within the framework of a calibrated Floris model:

Compared with the baseline operation, using Floris model and NOMAD solver for yaw angle optimization in the simulation can effectively improve the total power output of wind turbine cluster.

Site-specific calibration of the Floris wake model parameters

The proposed overall method process, combined with TNA estimation, model calibration and robust optimization, provides a practical way to develop effective AWC strategy. The simulation results are promising and lay a solid foundation for future field verification.

These results validate the proposed method and highlight the importance of accurate, site-specific modeling when active wake control is used to maximize energy capture in a simulation.

This paper uses real operational data to define scenarios and calibrate models, with the simulation case study results clearly demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in a simulation environment. Compared to baseline zero yaw operation, yaw angle optimization significantly boosts simulation power gain. Using site-specific calibration model parameters during the optimization process yields notably better simulation optimization results compared to using default parameters. When using the calibration model, the total simulation power gain observed under specific wake-induced wind conditions can reach up to 5.4%, highlighting the potential practical value of this integrated process after successful on-site implementation. This study confirms that accurate TNA estimation and site-specific model calibration are essential prerequisites for developing effective active wake control strategies based on wake models. The entire study demonstrates the value of integrating natural environmental data with virtual reality simulations in addressing complex engineering problems. Although this study provides valuable insights through simulations, it is based on steady-state assumptions and does not analyze the dynamic evolution of turbulence or the resulting structural loads. The true potential of active wake control can only be realized through a more holistic approach. To that end, our future work is focused on the development of a multi-objective Model Predictive Control (MPC) framework. This advanced strategy will incorporate wind condition forecasting and is designed to co-optimize for two competing goals: maximizing farm-level energy capture while simultaneously minimizing the fatigue loads on individual turbines. The findings in the present paper, particularly the validated, site-specific calibrated model, serve as a crucial foundation for this next-generation controller.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to China South Power Grid Co., Ltd. for the generous support and funding provided for this research.

Funding Statement: This paper is supported by the Science and Technology Project of China South Power Grid Co., Ltd. under Grant No. 036000KK52222044 (GDKJXM20222430).

Author Contributions: Yang Liu: Data analysis, technical discussions. Lifu Ding: Algorithm design, manuscript writing, technical discussions. Zhenfan Yu: Technical discussions, experimental validation. Tannan Xiao: Code development, experimental testing. Qiuyu Lu: Data analysis, experimental validation. Ying Chen: Conceptual framework, project supervision. Weihua Wang: Technical discussions, experimental validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. McCoy A, Musial W, Hammond R, Mulas Hernando D, Duffy P, Beiter P, et al. Offshore wind market report. 2024 edition. Golden, CO, USA: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL); 2024. Report No.: NREL/TP-5000-90525. doi: 10.2172/2434294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xu G, Yang M, Li S, Jiang M, Rehman H. Evaluating the effect of renewable energy investment on renewable energy development in China with panel threshold model. Energy Policy. 2024;187(12):114029. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ahmad S, Raihan A, Ridwan M. Role of economy, technology, and renewable energy toward carbon neutrality in China. J Econ Technol. 2024;2(1):138–54. doi:10.1016/j.ject.2024.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Barthelmie RJ, Hansen K, Frandsen ST, Rathmann O, Schepers JG, Schlez W, et al. Quantifying the impact of wind turbine wakes on power output at offshore wind farms. J Atmos Ocean Technol. 2009;26(9):1848–61. doi:10.1175/2010JTECHA1398.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang K, Kwak G, Cho K, Huh J. Wind farm layout optimization for wake effect uniformity. Energy. 2019;183:983–95. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Knudsen T, Bak T, Svenstrup M. Survey of wind farm control-power and fatigue optimization. Wind Energy. 2015;18(8):1333–51. doi:10.1002/we.1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fleming P, King J, Dykes K, Simley E, Roadman J, Scholbrock A, et al. Initial results from a field campaign of wake steering applied at a commercial wind farm—part 1. Wind Energy Sci. 2019;4(2):273–85. doi:10.5194/wes-4-273-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Houck DR. Review of wake management techniques for wind turbines. Wind Energy. 2022;25(2):195–220. doi:10.1002/we.2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zong H, Sun E. Review of active wake control for horizontal axis wind turbines. Acta Aerodyn Sin. 2022;40(4):51–68. doi:10.7638/kqdlxxb-2021.0249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jiménez Á., Crespo A, Migoya E. Application of a LES technique to characterize the wake deflection of a wind turbine in yaw. Wind Energy. 2010;13(6):559–72. doi:10.1002/we.380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Howland MF, Lele SK, Dabiri JO. Wind farm power optimization through wake steering. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(29):14495–500. doi:10.1073/pnas.1903680116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jensen NO. A note on wind generator interaction. Roskilde, Denmark: Risø National Laboratory; 1983. Report No.: Risø-M-2411. [Google Scholar]

13. Katic I, Højstrup J, Jensen NO. A simple model for cluster efficiency. In: European Wind Energy Association Conference and Exhibition; 1986 Oct 7–9; Rome, Italy. p. 407–10. [Google Scholar]

14. Bastankhah M, Porté-Agel F. A new analytical model for wind-turbine wakes. Renew Energy. 2014;70(10):116–23. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2014.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Porté-Agel F, Wu YT, Lu H, Conzemius RJ. Large-eddy simulation of atmospheric boundary layer flow through wind turbines and wind farms. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn. 2011;99(4):154–68. doi:10.1016/j.jweia.2011.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Göing J, Bartl J, Sætran L. A detached-eddy-simulation study: proper-orthogonal-decomposition of the wake flow behind a model wind turbine. J Phys Conf Ser. 2018;1049(1):012011. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1104/1/012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bastankhah M, Porté-Agel F. Experimental and theoretical study of wind turbine wakes in yawed conditions. J Fluid Mech. 2016;806:506–41. doi:10.1017/jfm.2016.595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Farrell A, King J, Draxl C, Mudafort R, Hamilton N, Bay CJ, et al. Design and analysis of a wake model for spatially heterogeneous flow. Wind Energy Sci. 2021;6(3):737–58. doi:10.5194/wes-6-737-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Schreiber J, Bottasso CL, Bertelè M. Field testing of a local wind inflow estimator and wake detector. Wind Energy Sci Discuss. 2020;2020(3):1–24. doi:10.5194/wes-5-867-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Annoni J, Seiler P, Johnson K, Fleming P, Gebraad P. Evaluating wake models for wind farm control. In: American Control Conference; 2014 Jun 4–6; Portland, OR, USA; 2014. p. 2517–23. doi:10.1109/acc.2014.6858970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mosetti G, Poloni C, Diviacco B. Optimization of wind turbine positioning in large windfarms by means of a genetic algorithm. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn. 1994;51(1):105–16. doi:10.1016/0167-6105(94)90080-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Simley E, Fleming P, Girard N, Alloin L, Godefroy E, Duc T. Results from a wake-steering experiment at a commercial wind plant: investigating the wind speed dependence of wake-steering performance. Wind Energy Sci. 2021;6(6):1427–53. doi:10.5194/wes-6-1427-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. NREL. FLORIS—FLOw redirection and induction in steady state. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://github.com/NREL/floris. [Google Scholar]

24. Doekemeijer BM, van der Hoek D, van Wingerden JW. Closed-loop model-based wind farm control using FLORIS under time-varying inflow conditions. Renew Energy. 2020;156(4):719–30. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Becker M, Ritter B, Doekemeijer B, van der Hoek D, Konigorski U, Allaerts D, et al. The revised FLORIDyn model: implementation of heterogeneous flow and the Gaussian wake. Wind Energy Sci. 2022;7(6):2163–79. doi:10.5194/wes-7-2163-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Simley E, Fleming P, King J. Design and analysis of a wake steering controller with FLORIS. Wind Energy Sci. 2021;6(1):91–114. doi:10.5194/wes-5-451-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Audet C, Dennis JEJr. Mesh adaptive direct search algorithms for constrained optimization. SIAM J Optim. 2006;17(1):188–217. doi:10.1137/040603371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Le Digabel S. Algorithm 909: nOMAD: nonlinear optimization with the MADS algorithm. ACM Trans Math Softw. 2011;37(4):1–15. doi:10.1145/1916461.1916468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools