Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Research Advances in the Application of Non-Nickel-Based Perovskite Materials for Biogas Reforming

1 State Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Reservoir Geology and Exploitation, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, 610500, China

2 School of New Energy and Materials, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, 610500, China

* Corresponding Author: Zeai Huang. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4331-4347. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.070226

Received 11 July 2025; Accepted 09 September 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

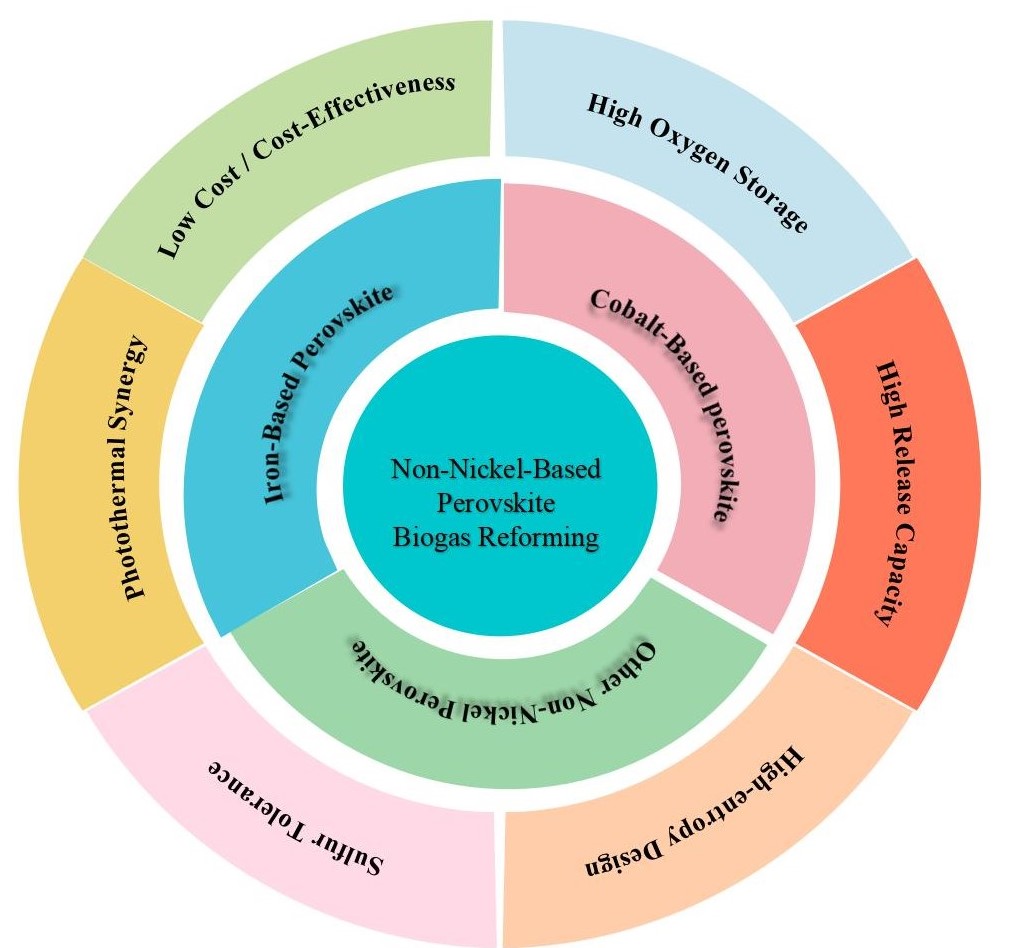

Under the driving goal of carbon neutrality, biogas reforming technology has garnered significant attention due to its ability to convert greenhouse gases (CH4/CO2) into syngas (H2/CO). Conventional nickel-based catalysts suffer from issues such as carbon deposition, sintering and sulfur poisoning. Non-nickel-based perovskite materials, with their tunable crystal structure, dynamic oxygen vacancy characteristics, and excellent anti-coking/anti-sulfur performance, have emerged as a promising alternative. This review systematically summarizes the design for non-nickel-based perovskite materials, including optimizing lattice oxygen migration ability and active site stability by A/B site doping, defect engineering and heterojunction construction. The enhancing the conversion rate of CH4/CO2 by using the carbon oxidation mechanism mediated by oxygen vacancies, and maintaining good durability in complex biogas environments containing H2S, NH3, etc. The photo-thermal synergistic catalysis further improves the reaction efficiency through energy coupling. However, challenges such as long-term operational stability (high-temperature lattice reconstruction), the cost of large-scale preparation and the synergistic poisoning effect of sulfur and water are still challenges for practical application. In the future, it is necessary to combine high-throughput computation, in situ characterization and multi-technology coupling to promote the leap of non-nickel-based perovskites materials from laboratory to industrial biogas reforming units.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

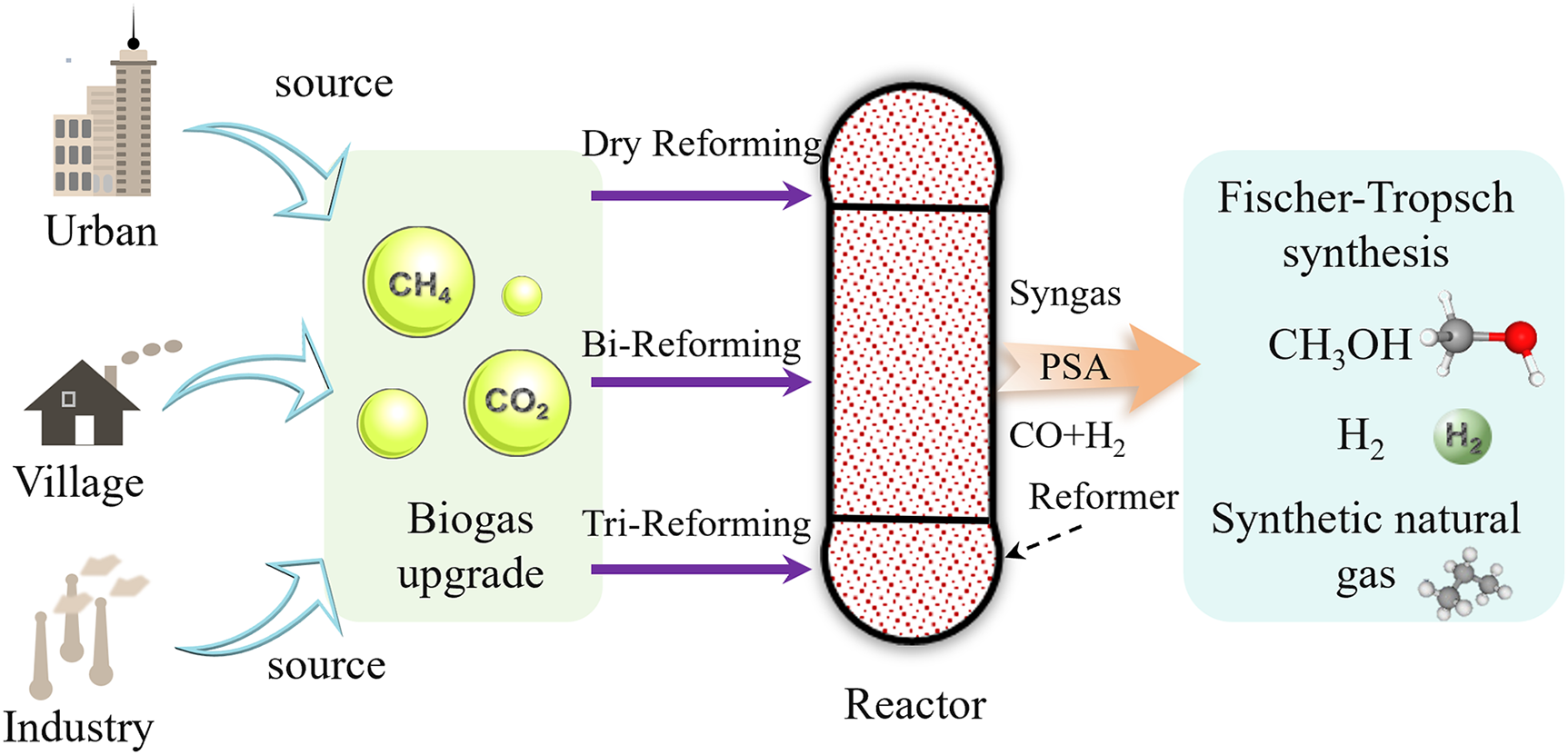

Driven by the goal of carbon neutrality, biogas, as a renewable resource rich in CH4 (45%–70%) and CO2 (25%–45%), plays a crucial role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions [1–3]. Methane has a global warming potential (GWP) 28–36 times greater than that of CO2, and its direct emission can exacerbate the climate crisis. However, the direct utilization of biogas faces multiple challenges, including its low heating value (15–25 MJ/m3, only 50% of that of natural gas), the presence of sulfur and H2O components (such as H2S) that can poison catalysts, and carbon deposition [4]. To improve utilization efficiency, catalytic reforming technology converts CH4 and CO2 into syngas (H2/CO), thereby avoiding the cost associated with CO2 separation and enabling production high-value-added chemicals (e.g., methanol, liquid fuels) [5–7]. Dry reforming of methane (DRM) directly utilizes the inherent CO2 in biogas, but its highly endothermic nature requires high temperatures (>800°C) to drive the reaction, which can easily lead to carbon deposition [8]. Steam-assisted dual reforming suppresses carbon deposition by introducing H2O and increases the H2/CO ratio to 1.1–2.7, but it requires precise control of steam addition [9–11]. Tri-reforming, which integrates DRM, steam reforming, and partial oxidation, utilizes exothermic reaction involving O2 to balance energy consumption and stabilizes the H2/CO ratio at 1.5–2.2. However, it faces challenges related to competing reaction pathways and operational complexity [12–15]. Therefore, the development of highly efficient and stable catalysts is the core bottleneck for the industrialization of biogas reforming technology. Fig. 1 illustrates the upgrading and utilization process of biogas.

Figure 1: Overview of biogas upgrading and syngas production technologies, as well as syngas applications

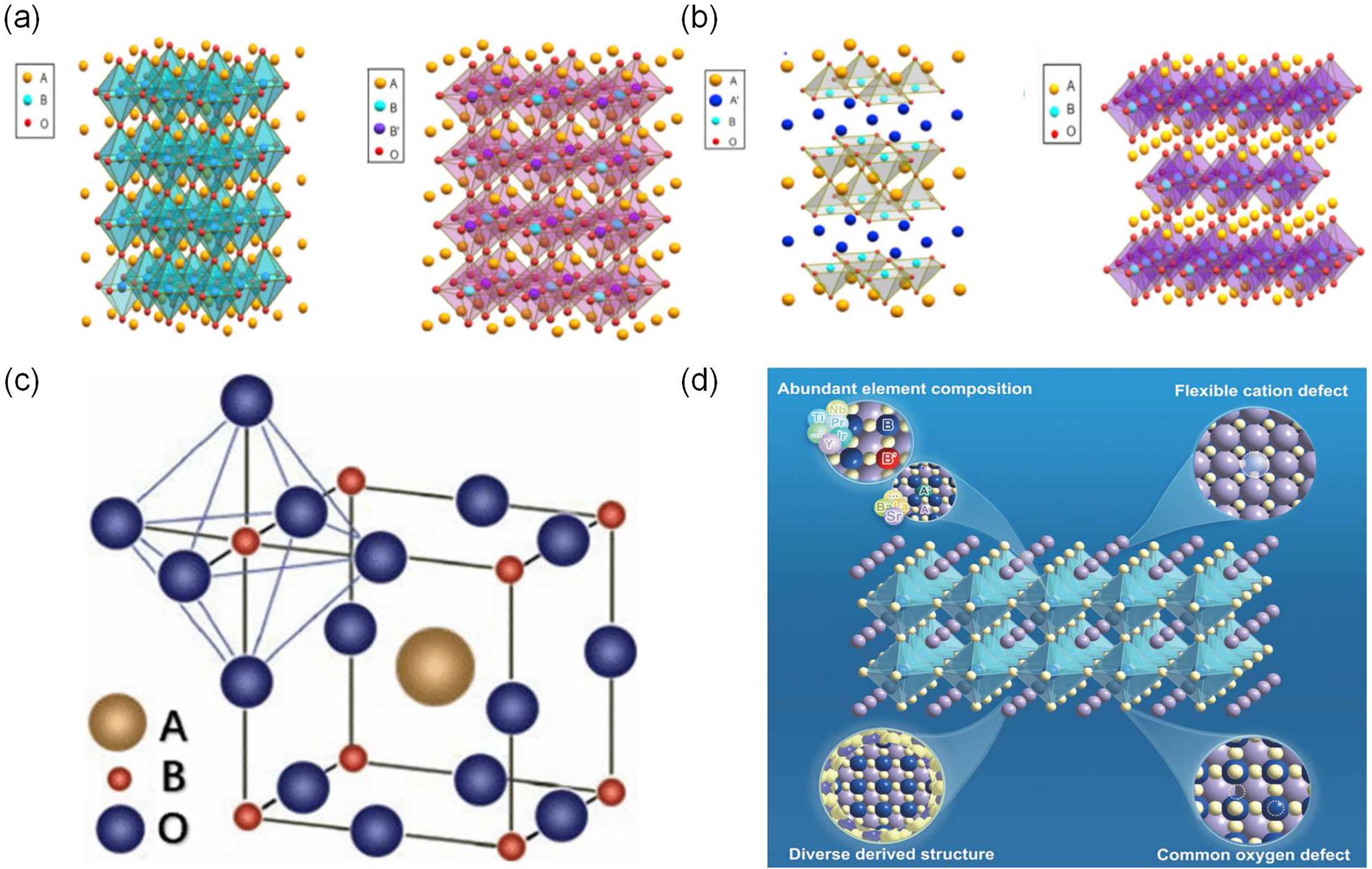

Perovskite materials have attracted considerable attention in the field of catalysis due to their unique ABO3 perovskite structure. The A-site cations (such as La3+, Sr2+, etc.) occupy dodecahedral centers, while the B-site transition metals (such as Co, Mn, Fe, etc.) are located at the center of the oxygen octahedra, collectively forming a stable three-dimensional network framework [16–18], as illustrated in Fig. 2c,d. This structure endows the materials with excellent thermal stability and tunable oxygen vacancy concentrations. The B-site serves as the catalytic center involved in redox reactions, while the A-site regulates the electronic structure through lattice distortion [19,20]. Additionally, perovskite materials possess a rich array of structural derivatives, including single perovskites, double perovskites, layered perovskites, and defective perovskites, as depicted in Fig. 2a,b. Diverse performance optimizations can be achieved through different structural designs [21,22]. The dynamic oxygen vacancies in perovskites effectively promotes the oxidation of carbon species, thereby significantly improves CH4 and CO2 conversion rates. Moreover, they exhibit good stability in complex biogas compositions (such as those containing H2S, NH3), demonstrating great potential to replace traditional nickel-based catalysts. Research indicates that perovskite catalysts can effectively adsorb and activate the main components of biogas, CH4 and CO2, promoting oxygen transport and storage through oxygen vacancies and oxygen storage capacity, thereby enhancing reaction activity [23]. For instance, perovskite catalysts like LaFeO3 significantly enhance oxygen mobility through the tilting of FeO6 octahedra, leading to improved catalyst activity [24].

Figure 2: Different perovskite lattice structures: (a) Single perovskite and double perovskite; (b) Layered double perovskite and Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite structure [35]; (c) Schematic diagram of perovskite structure [17]; (d) Schematic diagram of the compositional diversity of perovskite oxides [18]. Adapted with permission from reference [17,18,35]. (a,b) Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (c) Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (d) Copyright 2023, Elsevier

Furthermore, material performance can be further enhanced through A/B-site doping and bimetallic synergistic effects. For instance, in LaCoO3 catalysts, A-site Sr doping induces lattice expansion, reduces the formation energy of oxygen vacancies, while B-site doping forms alloys, enhancing catalyst activity and stability [25,26]. The dynamic regulation of active sites also enables the material to adapt to varying reaction conditions. For example, the layered perovskite PrBaFeCoO5+δ achieves dynamic control of active site via the reversible precipitation/dissolution of Co-Fe nanoparticles, maintaining stability and low coking during long-term CH4 conversion tests [27]. Additionally, notable progress has been made in the composite structure design of perovskite catalysts with other materials. Combinations with other porous carrier materials prevent the aggregation of active species, enhancing the active phases and stability on the catalyst surface [27–29]. The preparation of core–shell structures also markedly suppresses the sintering and deactivation of active metals [30–33]. Owing to their excellent optoelectronic properties, perovskite materials also show great potential in photocatalysis. By forming heterojunction structures with other photocatalysts, their catalytic performance is further enhanced [34]. These research advancements indicate that perovskite catalysts hold broad application prospects in biogas reforming and are poised to become an ideal alternative to conventional nickel-based catalysts.

Nickel-based catalysts and their perovskite-derived counterparts have been extensively discussed by Chava et al. [36] and Manfro and Souza [37]. Owing to their unique physicochemical properties and economic advantages, nickel-based catalysts and nickel-based perovskites hold an important positions and are widely used in the field of catalysis, particularly in CH4 reforming and CO2 reforming reactions. Nickel’s high activity and abundant resources make it an ideal catalytic material [38], while the thermal stability and oxygen storage capacity of the perovskite structure further enhance the performance of nickel-based catalysts. However, nickel-based catalysts face critical challenges in practical applications, including carbon deposition, sintering, and sulfur poisoning, which severely compromise their stability and service life [19,39,40]. For example, in a typical biogas CO2 reforming reaction, LaNiO3-based catalysts exhibit a carbon deposition rate as high as 70% when operated at 850°C, leading to rapid deactivation within a short period [37]. This rapid deactivation not only limits their operation lifespan in industrial applications but also increases the cost and complexity of industrial production, becoming a major bottleneck that restricts its large-scale commercial application. Although metal doping and support modification can partially improve catalyst properties, the inherent coking tendency due to nickel’s high activity, the sintering tendency at high temperatures, and the sensitivity to impurities make these issues difficult to fundamentally resolve. They remain the key focuses and ongoing challenges in current research.

This review focus on non-nickel-based perovskite catalysts, which have achieved significant breakthrough in the field of biogas reforming, particularly in terms of structural design, performance optimization, and sustainability. Compared with traditional nickel-based catalysts, non-nickel-based perovskite materials have significantly enhance catalytic performance due to their tunable crystal structures and dynamic oxygen vacancy characteristics. For example, iron-based perovskite catalysts improve lattice oxygen migration and anti-coking properties through A/B site doping and defect engineering strategies [41,42]. Studies have shown that B-site doping with metals such as Mn can significantly enhances the mobility of lattice oxygen, thereby inhibiting coke formation and improving gasification performance [43]. Moreover, cobalt-based perovskite catalysts demonstrated excellent oxygen storage and release capabilities by optimizing the coordination environment of B-site metals and rare-earth elements, effectively promoting CO2 activation and oxidation of carbon deposits, and significantly improving the stability and anti-coking properties of the catalyst [44]. By incorporating Ce into perovskite-type oxides, researchers have optimized specific surface area and oxygen storage capacity, achieving high CH4 and CO2 conversion rates at 800°C while significantly inhibiting coke formation [45].

The structural and functional design of these non-nickel-based catalysts not only enhances catalytic performance but also offers significant sustainable value. For example, perovskite materials can exhibit good stability in complex biogas components (such as containing H2S, NH3) and significantly improve the conversion rates of CH4 and CO2 through oxygen vacancy-mediated carbon oxidation and dynamic active site regulation [46]. Moreover, photo-thermal synergistic catalysis, as an emerging strategy, combines the input of light and heat energy to further improve the efficiency and sustainability of non-nickel-based perovskite materials in biogas conversion [47]. A notable example is the development of an Ag–LaFeO3/TiO2 Z-scheme photocatalyst, which achieves CO2 reduction and CH4 oxidation under plasmonic effects, leading to significantly enhanced conversion rates [34].

Against this background, this review highlights recent research progress and challenges of non-nickel-based perovskite materials in biogas reforming, providing a systematic summary of the latest advances in the structural design and performance optimization of iron-based, cobalt-based, and other types of perovskites. In contrast to previous reviews, this work not only discusses the adaptability of perovskite catalysts in complex biogas environments but also emphasizes the role of emerging strategies—such as photo-thermal synergistic catalysis—in enhancing catalytic efficiency and sustainability. Moreover, by analyzing current technological pathways and future development directions, this review clarifies the potential and challenges of non-nickel-based perovskite materials in practical applications, offering theoretical guidance and technical references to facilitate the transition from laboratory research to industrial-scale implementation, which holds considerable practical significance.

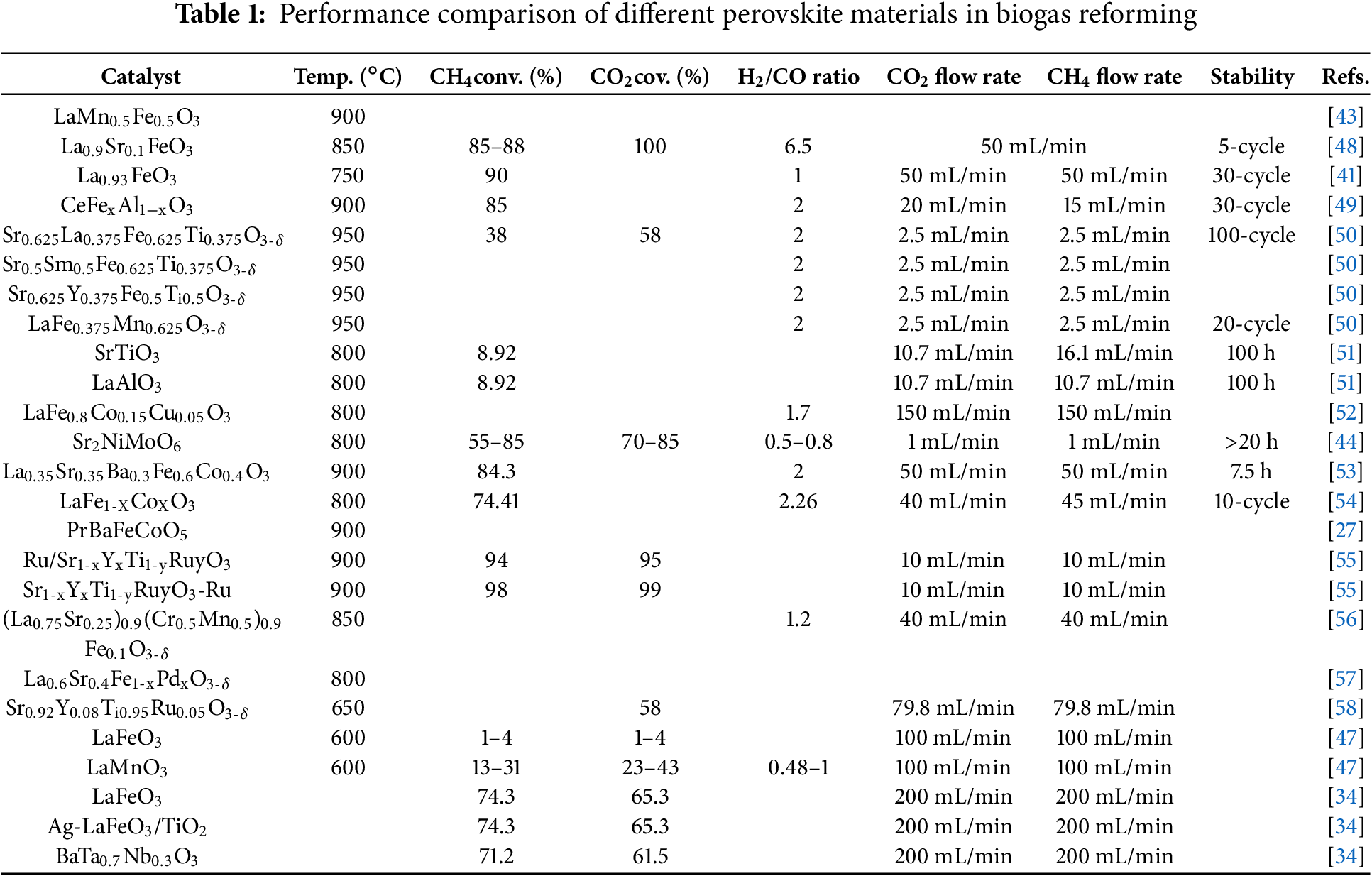

To enable intuitive comparison of the performance of various perovskite materials in biogas reforming, Table 1 summarizes key performance parameters of different perovskite catalysts reported in recent studies. These data not only reflect the behavior of various materials under reaction conditions but also provide valuable references for subsequent catalyst design and optimization

2 Design and Classification of Non-Nickel-Based Perovskite Catalytic Systems

Iron-based perovskite materials have demonstrated considerable potential in biogas conversion and syngas production owing to their tunable crystal structures and excellent redox activity. Researchers have systematically optimized the catalytic performance and stability of iron-based perovskites through strategies such as A/B-site doping, defect engineering, and structural compositing, providing new ideas for the breakthrough of DRM and Chemical Looping Dry Reforming (CL-DRM) technologies. Compared with nickel-based and cerium-based oxygen carriers, iron-based oxygen carriers, which are more environmentally and health-compatible and competitively priced, are more worthy of further research. Unlike cerium-based oxygen carriers, which have unsatisfactory conversion rates, iron-based oxygen carriers are more prone to deep reduction to form CO [59].

Researchers have successfully optimized lattice oxygen mobility and anti-coking properties doping strategies. For instance, Chen et al. [43] synthesized LaFeO3 (LF)-based perovskite and investigated the effects of partial doping of B-site metal Mn and other elements on gasification performance. The experimental results showed that the oxygen carrier after doping exhibited a significant increase in gasification activity in chemical looping steam gasification (CLSG), with total gas yield and hydrogen selectivity increasing by 64.7% and 45.7%, respectively. This improvement was primarily attributed to the effective enhancement of lattice oxygen mobility by Mn and other dopants, which promoted the migration of bulk oxygen to the surface, thereby suppressing carbon deposition. Furthermore, the synergistic effect between the dopants and Fe further improved oxygen carrier mobility, indicating that the selection of B-site dopants is critical for the material’s anti-coking performance. In the field of CL-DRM, Yang et al. [60] prepared a Sr0.98Fe0.7Co0.3O3-δ perovskite oxygen carrier through B-site doping. Testing at 850°C show that the oxygen carrier achieved a methane conversion rate of 87%, a carbon monoxide selectivity of 94%, a synthesis gas yield of 8.5 mmol/g, and a CO yield of 4.2 mmol/g. It was evident that B-site doping with cobalt enhanced the oxygen mobility and the activation ability of CH4 and CO2. Similarly, Jiang et al. [61] systematically evaluated the performance of LaFeO3, SrFeO3, and their doped derivatives. Experiments found that the doped oxygen carriers exhibited excellent anti-coking properties in the temperature range of 750°C–850°C, which was attributed to the enhanced redox activity of the oxygen carriers, promoting the dynamic replenishment of surface oxygen species. Similarly, Sayyed and Vaidya [62] designed an iron-based perovskite with Ce doping to reduce carbon deposition, achieving a hydrogen yield of 79% at 850°C, with excellent cycling stability. The introduction of carrier materials further enhanced the performance. Wei et al. [63] promoted the reducibility and oxygen transport of perovskites through cerium doping. After reduction, the conversion rate of CH4/CO2 remained above 90% at 750°C for 50 h without coking. Tian et al. [59] found that the pyrolysis of methane on Fe0 sites invariably results in carbon deposition. By designing a core–shell structure to encapsulate Fe0, they provided an effective strategy to prevent direct contact between methane and Fe0, thereby inhibiting coking without relying solely on controlling metal particle size.

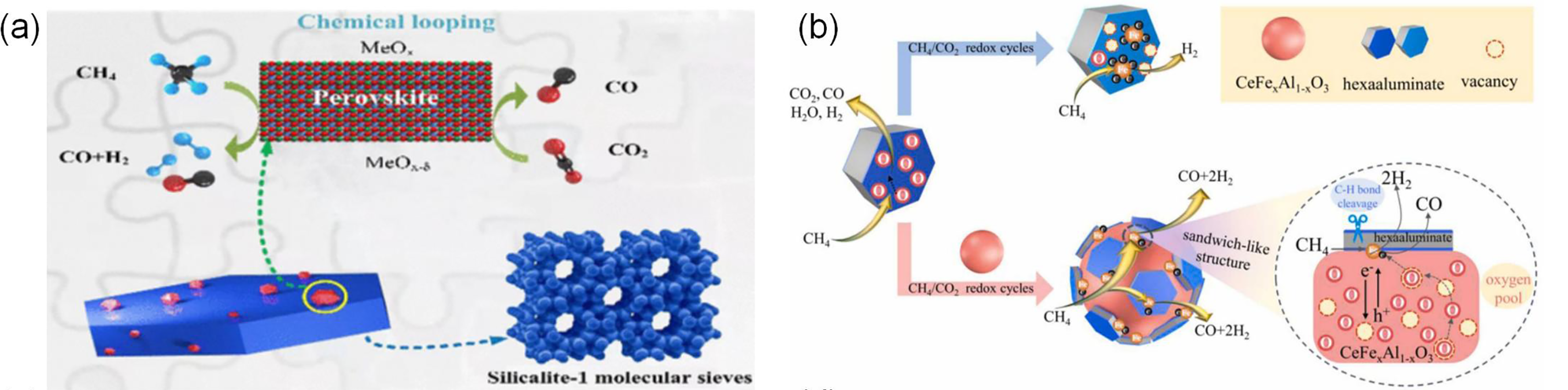

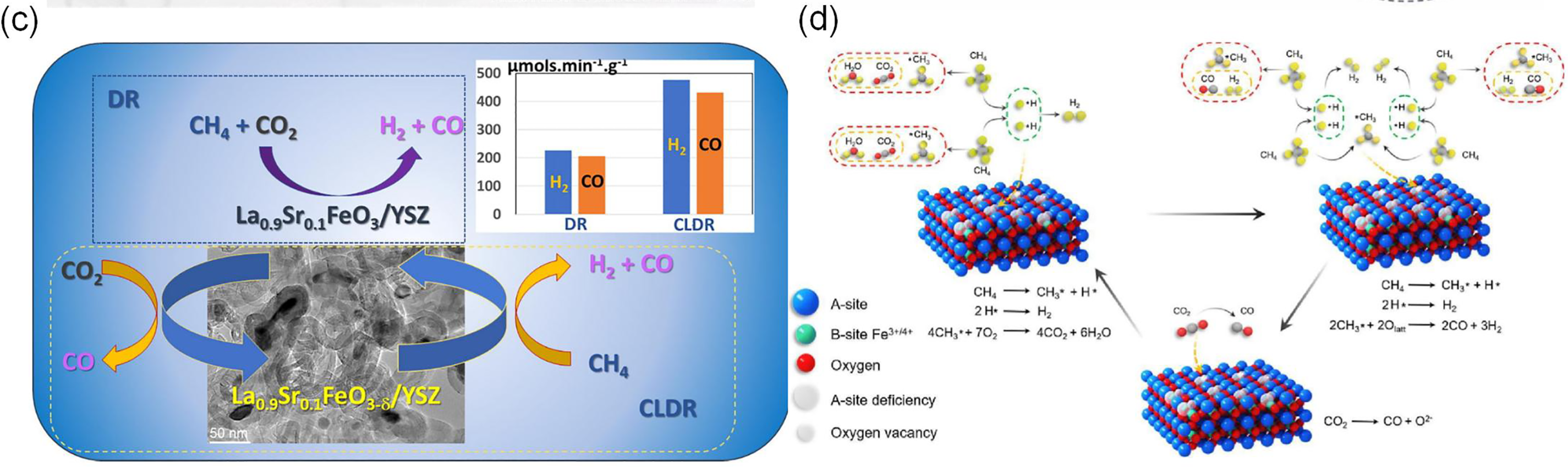

Several studies have enhanced lattice oxygen mobility and the regulation mechanism of surface active oxygen through unique composite structures and the introduction of A-site cation vacancies. Yuan et al. [52] loaded LaFe0.8Co0.15Cu0.05O3 onto Silicalite-1, which significantly increased the methane reaction rate. The porous structure not only optimized oxygen transport but also inhibited coking through interfacial effects. The composite structure and reaction mechanism are shown in Fig. 3a. Sastre et al. [48] found that multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the surface of La0.9Sr0.1FeO3/YSZ composite materials could promote CO generation through the reaction CO2 + C → 2CO. The structure and reaction mechanism are shown in Fig. 3c, although long-term stability still needs to be verified. Chen et al. [41] designed a La0.93FeO3-δ oxygen carrier through A-site cation vacancy engineering and found that the oxygen vacancies on its surface played a key role in CH4 adsorption and activation. The introduction of A-site cation vacancies increased the amount of Fe4+, exposed more Fe-O bonds, and thus promoted CH4 adsorption and C-H bond breaking. CO2 was produced after the consumption of active oxygen species, followed by the outward diffusion of bulk lattice oxygen to replenish the lattice oxygen consumed during the CH4 oxidation stage, generating a large amount of syngas. This oxygen cycling mechanism not only increased the CH4 conversion rate but also significantly enhanced anti-coking properties.

Figure 3: (a) Oxygen carrier of LaFe0.8Co0.15Cu0.05O3/S-1 (Silicalite-1) [52]; (b) Reaction mechanism of BF3 and CeO2-BF3 redox catalysts [49]; (c) La0.9Sr0.1FeO3 supported on YSZ and its catalytic reaction mechanism [48]; (d) A-site cation vacancy and reaction mechanism in LaFeO3 [41]. Adapted with permission from reference [41,48,49,52]. (a) Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (b) Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (c) Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (d) Copyright 2023, Elsevier

Iron-based perovskites can be effectively enhanced through B-site doping to improve catalytic performance, with the reaction process illustrated in Fig. 3d. Yang et al. [49] studied the in situ formation of perovskite-type CeFexAl1−xO3 induced by the interaction between CeO2 and hexaaluminate and found that the doping of Fe ions significantly weakened the strength of Ce-O and Fe-O bonds, reduced the formation energy of oxygen vacancies, and thus formed a large number of oxygen vacancies. Under continuous CO2 supply, it cycled stably, thereby enhancing the supply capacity of lattice oxygen. As shown in Fig. 3b, the close contact of CeFexAl1−xO3 with the metal Fe0 forms a unique hexaluminate/Fe0/CeFexAl1−xO3 sandwich structure, which ensures the timely supply of oxygen to Fe0, and the material exhibits excellent carbon resistance and high CH4 conversion rate (~90%), and the material exhibits better thermal stability compared to traditional nickel-based catalysts—maintaining structural integrity at 800°C without significant sintering. At the same time, the carbon accumulation was only 0.03 mg, which was much lower than the common >1 mg in nickel-based systems. Additionally, The LaFexCo1-xO3 perovskite formed by Fe doping of LaCoO3, with its random macroporous structure formed by nanoparticle stacking, effectively promotes the formation of oxygen vacancies, thereby enhancing the adsorption capacity for H2S and further strengthening sulfur resistance [64].

Photothermal synergistic catalysis, as an emerging strategy, significantly enhances the efficiency and sustainability of iron-based perovskite materials in biogas conversion by combining photonic and thermal energy inputs. For example, Chung and Chang [34] coupled Ag nanoparticle-modified LaFeO3 with TiO2 to form an Ag-LaFeO3/TiO2 (ALFTO) Z-scheme photocatalyst. ALFTO showed thermal stability in the process of biogas conversion to syngas. Under the action of plasmons, ALFTO achieved the reduction of CO2 and the oxidation of CH4 through the separation and transfer of photogenerated electrons and holes, with conversion rates of CH4 and CO2 reaching 78.5% and 72.3%, respectively. The high-energy electrons provided by plasmons can excite the photocatalyst, promoting the migration of electrons from the conduction band to the valence band, thereby accelerating the reaction rate. In terms of sulfur resistance, introducing other metal elements or forming composite structures can significantly enhance sulfur resistance. In LaFeO3, forming a Z-scheme photocatalytic system with BaTa0.7Nb0.3O3 can effectively oxidize H2S to SO2, which is then converted into other sulfur compounds, reducing the deposition of sulfides on the catalyst surface and thereby improving sulfur resistance. In addition, the redox cycle of Ce3+/Ce4+ in La0.5Ce0.5FeO3 can capture H2S to form Ce2O2S or Ce(SO4)2, reducing the coverage of sulfur species on active metals. Even in biogas with a sulfur concentration as high as 220 ppm, it can still maintain a CH4 conversion rate of over 80% [65].

Cobalt-based perovskites share many similarities with iron-based perovskites in biogas conversion, which are mainly reflected in their unique structures and properties. These materials exhibit excellent oxygen storage and release capacity, which effectively promotes CO2 activation and carbon deposit oxidation, thereby enhancing catalyst stability and anti-coking performance. Furthermore, their high specific surface area and porous structure contribute to improved dispersion of active metals and an increased number of active sites, leading to enhanced catalytic activity. Good thermal stability and mechanical strength allow them to maintain structural integrity under the high-temperature conditions required for biogas reforming, reducing catalyst sintering and deactivation. Additionally, cobalt-based perovskites demonstrate high tunability; by modifying metal ions at the A/B sites, the electronic structure and surface properties of the catalyst can be precisely adjusted, thereby optimizing its adsorption and activation capabilities toward the main components of biogas. These comprehensive advantages make cobalt-based perovskites a highly promising catalytic material for biogas reforming.

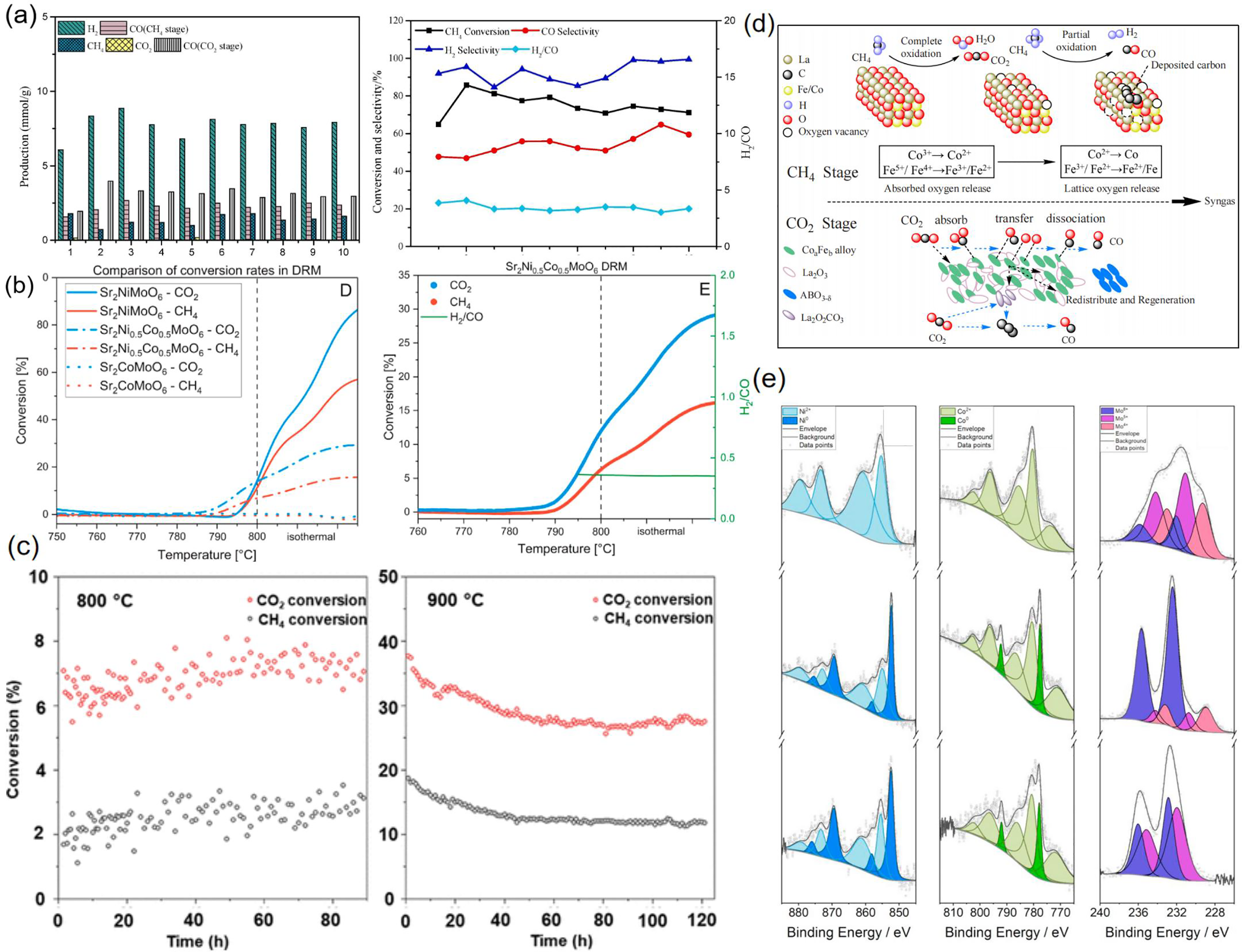

By optimizing the coordination environment of B-site metals and rare-earth elements, a balance between activity and stability can be achieved. For example, Sheshko et al. [66] and Bai et al. [45] investigated the performance of GdCoO3 and LaCeCoO4 in dry reforming of methane, respectively. GdCoO3 achieved 100% CH4 conversion and 60% CO2 conversion at 750°C, with an H2/CO ratio close to 1. Its high activity is attributed to the synergistic effect of the strong oxygen affinity of Gd3+ and the reducibility of Co3+. LaCeCoO4 exhibited CH4 and CO2 conversion rates of 90.1% and 84.8% at 800°C, respectively. The doping of cerium optimized the specific surface area and oxygen storage capacity, thereby significantly suppressing coking. Jiang et al. [67] systematically studied the oxygen storage and release behavior of single perovskites LaBO3 (B = Co, Cu, Mn, V) and found that LaCoO3, due to the high activity of the Co3+/Co2+ redox pair, demonstrated the best oxygen release capability in the low-temperature range of 250°C–550°C. Its lattice oxygen migration rate was significantly higher than that of LaNiO3 and LaMnO3. However, single perovskites have limitations in structural stability at high temperatures. For example, the specific surface area of LaCoO3 decreased after several hours of reaction at 800°C. In contrast, the double perovskite Sr2Ni0.5Co0.5MoO6 designed by Winterstein et al. [44] exhibited significant advantages in high-temperature anti-sintering, as shown in Fig. 4a,e. This performance difference originates from the high thermal stability of the Mo-O bonds in the double perovskite structure, which enhances the lattice distortion energy compared to single perovskites, effectively suppressing the migration and agglomeration of active metals such as Co and Ni. To further optimize catalytic activity and anti-coking properties, the synergistic effect of dual metals was further validated in the study by Shen et al. [54]. In LaFe0.5Co0.5O3, Fe3+ preferentially participates in CH4 dissociation, while Co2+ accelerates CO2 decomposition. Fig. 4d illustrates the spatially separated dual-functional mechanism, which enables the catalyst to maintain a 74.3% CH4 conversion rate over 10 cycles with minimal carbon deposition.

Figure 4: (a) Gas yields, CH4 conversion, selectivity of H2 and CO, and H2/CO ratio obtained during the cyclic reactions of LaFe0.5Co0.5O3 [54]; (b) CH4 reforming and H2/CO ratio for Sr2NixCo1-xMoO6 [44]; (c) Long-term stability test of CO2/CH4 conversion rates at 800°C and 900°C [27]; (d) The process in which Fe3+ and Co2+ play different roles during the CH4 oxidation stage and the CO2 oxidation stage [54]; (e) XPS spectra of Ni2p, Co2p3/2, and Mo3d for Sr2Ni0.5Co0.5MoO6 in the calcined state, H2-reduced state, and after DRM (from top to bottom), with Ni2p, Co2p, and Mo3d spectra shown from left to right. Adapted with permission from reference [27,44,54]. (a,d) Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (b,e) Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (c) Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society

In the aspect of dynamic redox regulation, Yang et al. [53] designed the La0.35Sr0.35Ba0.3Fe0.6Co0.4O3 (LSBFC64) oxygen carrier. By doping with Co, the concentration of oxygen vacancies was increased. In the CL-DRM process, lattice oxygen preferentially participated in the partial oxidation of CH4 to generate syngas. Meanwhile, CO2 acted as a soft oxidant to regenerate the oxygen vacancies, thereby maintaining the concentration of syngas at a relatively high level. In comparison, Managutti et al. [27] developed the PrBaFeCoO5+δ layered perovskite. The dynamic active site regulation was realized through the reversible precipitation/dissolution of Co-Fe nanoparticles (NPs). Under the reduction condition at 800°C, the NPs were precipitated from the perovskite matrix, exposing highly active metal sites to facilitate the activation of CH4. The stability of this process could be sustained for about 100 h. Under the oxidation condition, the NPs were re-dissolved into the lattice, which inhibited the sintering deactivation, as shown in Fig. 4c.

The improvement of anti-sintering and anti-coking properties relies on the microstructure design of the materials and the optimization of surface chemical properties. Vecino-Mantilla and Lo Faro [68] reported that the layered perovskite La1.5Sr1.5Co1.5Ni0.5O7±δ, through co-doping with multiple elements (La, Sr, Co, Ni), induces lattice distortion, which suppresses the migration of metal particles. In the dry biogas test at 800°C, the size of the Co-Ni alloy particles remains stable at the nanoscale. This structural stability is complementary to the oxygen vacancy gradient distribution strategy proposed by Long et al. [69]: in CeNi0.5Co0.5O3, the surface Co content is significantly higher than that in the bulk, forming an oxygen vacancy concentration gradient. The oxygen vacancies enriched on the surface preferentially oxidize the coking intermediates. Temperature-Programmed Oxidation (TPO) tests show that the coking oxidation onset temperature is reduced to 320°C (compared to 450°C for traditional catalysts), and the coking rate is low. In addition, in La0.6Sr0.4Co0.4Ni0.6O3, the strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) between the NiCo alloy and the La-Sr-O matrix, through charge transfer, promotes the rate of coking gasification reactions.

The performance comparison of different catalytic systems reveals the applicability boundaries of material design strategies: at temperatures <600°C, LaCoO3 and CeNi0.5Co0.5O3, due to their high oxygen mobility and bimetallic synergistic effects, achieve CH4 conversion rates of 68.5% and 94.6%, respectively. However, at temperatures above 800°C, Sr2Ni0.5Co0.5MoO6 and PrBaFeCoO5+δ, with their structural rigidity and dynamic active site regulation, not only maintain the CH4 conversion rate but also further control the coking rate. It should be noted that although the layered and double perovskite systems show outstanding high-temperature stability, their synthesis complexity and cost are about 30%–50% higher than those of single perovskites. This can be addressed by large-scale manufacturing processes (such as spray pyrolysis and tape casting) to reduce costs. Future research needs to further combine in situ characterization, such as environmental Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), synchrotron X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) with machine learning-assisted design to reveal the dynamic evolution mechanisms at the nanoscale and explore the adaptability of cobalt-based perovskites in complex systems such as sulfur-rich biogas, in order to promote their practical application in industrial-scale biogas conversion devices.

2.3 Other Non-Nickel Perovskite Systems

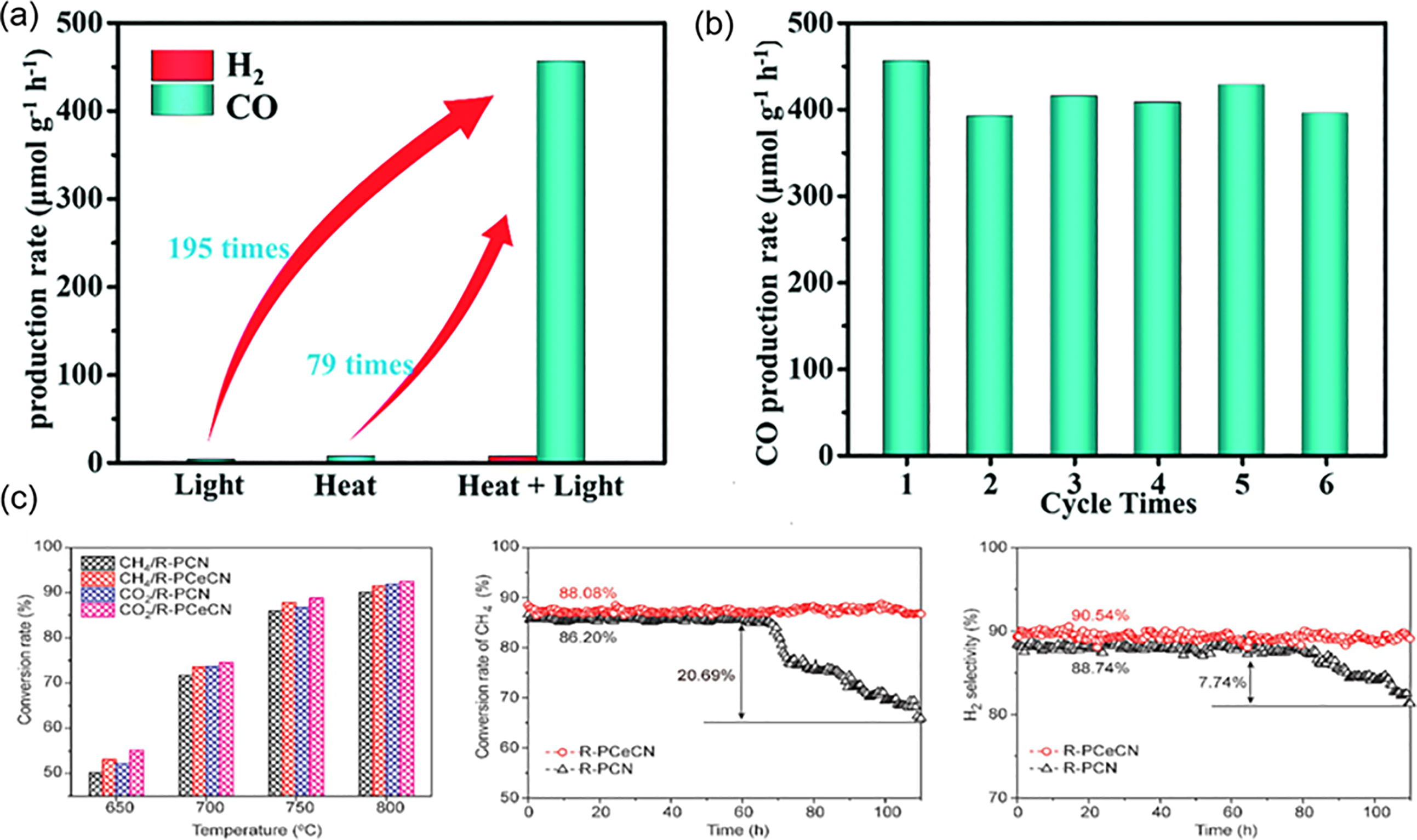

In the development of other perovskite catalysts, researchers have significantly expanded the performance boundaries of biogas reforming catalysts through strategies of compositional diversification, structural engineering, and interface regulation. The Ce-doped LaMnO3 system proposed by Wei et al. [63] revealed the mechanism by which rare-earth elements regulate the redox kinetics and oxygen vacancy formation ability of perovskites. By substituting 5% of La3+ with Ce3+, the concentration of oxygen vacancies formed during the reduction process of LaMnO3 was increased compared to the undoped system, and it also induced the uniform precipitation of nanoparticles from the perovskite lattice. Under the conditions of 750°C and CH4/CO2 = 1:1, the CH4 conversion rate of this catalyst was stably above 90% with no coking, while LaMnO3 suffered from structural collapse due to excessive reduction of Mn3+, leading to a decline in activity within 6 h. Similarly, the Ce-doped PrCrO3-δ developed by Peng et al. [70] reduced the formation energy of oxygen vacancies, achieving high CH4 conversion rates at 750°C and improved anti-coking properties with 110 h of stability compared to the undoped system, as shown in Fig. 5c. In addition, synergistic photo-thermal effects can also be utilized, such as the Ag/AgBr/CsPbBr3 composite system developed by the Gao P team [71], which exhibited a unique interfacial charge transfer mechanism. This structural design achieved a CO yield of 456.15 µmol g−1 h−1 at 200°C, which is two orders of magnitude higher than that of traditional thermal catalysis. It is worth noting that the system, through the design of matching thermal expansion coefficients, effectively alleviated the interfacial stress during the thermal cycling process, resulting in no significant decline in catalyst activity after six cycles, as shown in Fig. 5a,b.

Figure 5: (a) Catalytic activity of Ag/AgBr/CsPbBr3 for photocatalysis, thermal catalysis (200°C), and photo-thermal catalysis (200°C) [71]; (b) Stability of Ag/AgBr/CsPbBr3 in terms of CO yield [71]; (c) Reaction performance and stability of Ce-doped PrCrO3-δ catalyst for CH4/CO2 reforming [70]. adapted with permission from reference [70,71]. (a,b) Copyright 2022, Royal Society Chemistry. (c) Copyright 2022, Elsevier

The photothermal synergistic catalysis strategy demonstrates remarkable advantages over conventional catalytic approaches by integrating photoenergy and thermal energy inputs to achieve synergistic optimization of reaction pathways. Compared with traditional thermal catalysis (typically requiring 700°C–900°C), this strategy significantly reduces temperature requirements, as evidenced by the Ag/AgBr/CsPbBr3 system exhibiting 79-fold higher CO yield under 200°C photothermal conditions than pure thermal catalysis. In contrast to pure photocatalysis limited by carrier recombination, photothermal synergy enhances charge separation through thermal effects, boosting the activity of identical catalysts by up to 195 times. When compared with plasmonic catalysis, the construction of Z-scheme heterostructures (e.g., Ag-LaFeO3/TiO2) not only elevates syngas production to 20.2 mol/kWh but also substantially improves sulfur resistance [34].

Perovskite materials derived from metal-organic framework (MOF) precursors, with their controllable porous structures and high specific surface areas, have become a breakthrough in anti-coking design. Muñoz et al. [26] synthesized an aluminum-based perovskite via the MOF gel method, achieving 75% CH4 conversion and 80% CO2 conversion in dry reforming reactions at 700°C. The hierarchical porous structure and high surface hydroxyl density of this material significantly enhanced CO2 adsorption capacity, thereby suppressing the formation of coking precursors. High-resolution TEM revealed that nanoparticles were embedded in the perovskite lattice through a “substrate growth” mode, with interface binding energies higher than those obtained by other methods, resulting in improved performance compared to catalysts prepared by traditional impregnation methods. Similarly, Lee [72] developed a CaTiO3 catalyst through the topological transformation of MOF precursors to form perovskite-metal interfaces. This catalyst showed increased H2 yield in CH4/CO2 conversion, with its anti-coking properties attributed to the high oxygen mobility of Ca2+ and the promotion of the water-gas shift reaction by Ti4+.

Layered perovskites and high-entropy designs have further expanded the adaptability of catalysts. Chava et al. [42] developed Ba-doped La0.84Ba0.06Al0.85Ni0.15O3 (LB6AN-15), which achieved 60% CH4 conversion and 93% CO2 conversion under CH4/CO2 = 1.5 conditions. The introduction of Ba2+ enhanced the A-site defect concentration and surface basicity, reducing the equilibrium constant value of the Boudouard reaction and lowering the coking rate compared to the undoped system. Double perovskites, such as La1.5Sr1.5Co1.5Ni0.5O7±δ, through the synergistic effect of multiple elements and lattice distortion, showed a performance drop of about 2% in long-term stability tests at 800°C with dry biogas (reaction atmosphere: CH4, 60 mol%, and CO2, 40 mol%) and demonstrated resistance to carbon deposition [68].

Moreover, comparative studies in biogas and fuel cells revealed that the thermal expansion coefficient of the layered system La1.5Sr1.5Co1.5Nb0.5O7.55 matched better with the YSZ electrolyte than that of single perovskite systems, reducing interfacial contact resistance. Despite significant progress in activity and stability, the industrial application of multi-element perovskite systems still faces challenges such as high synthesis costs and poor controllability of complex compositions. For example, the Sr0.92Y0.08Ti0.95Ru0.05O3-δ catalyst [58] (SYTRu5), although showing excellent anti-sulfur and anti-coking properties, has a material cost more than 50% higher than that of traditional Ni-based systems due to its noble metal content. Regarding sulfur tolerance in other types of perovskites, the double perovskite Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6-δ (SFMO), through theoretical calculations constructing phase diagrams of surface interactions with sulfur, found that surfaces with higher molybdenum content were more sulfur-resistant, while FeO2 terminated surfaces were more susceptible to sulfur poisoning. Therefore, by doping Ti into the B-site of Sr2FeMoO6-δ, a more stable Sr2TiFe0.5Mo0.5O6 [73] was obtained when supplied with sulfur-containing syngas. This material exhibited excellent phase stability at 750°C in a H2S-containing environment, with its cubic crystal structure showing no significant distortion after sulfur exposure, attributed to the stabilizing effect of Mo6+ on the lattice. In addition, core-shell structures, such as catalysts with an alloy core and superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 shell, demonstrated high catalytic activity in the presence of 30 ppm H2S. The alloy promoted the reforming reaction, while the γ-Fe2O3 shell interacted with H2S and decomposed it into elemental sulfur, thereby enhancing sulfur resistance [74]. Future research also needs to focus on the substitution of low-cost elements, in situ characterization techniques to reveal dynamic reaction mechanisms, and the development of large-scale manufacturing processes to promote the transition of non-Ni-based perovskite catalysts from the laboratory to practical applications.

This review systematically summarizes recent advancements in the performance optimization of iron-based, cobalt-based, and other non-nickel perovskite materials, highlighting the significant differences between iron-based and cobalt-based systems in terms of redox kinetics, structural stability, active site modulation, and photothermal response characteristics. Through precise structural engineering strategies such as A/B-site doping, defect engineering, and heterostructure construction, these materials exhibit exceptional lattice oxygen mobility (e.g., La0.93FeO3-δ achieves 90% CH4 conversion at 750°C) and superior anti-coking properties (carbon accumulation <0.03 mg, significantly lower than >1 mg in nickel-based catalysts). The oxygen vacancy-mediated carbon oxidation mechanism, as demonstrated by CeFexAl1-xO3 and LaFe0.5Co0.5O3, enables sustained production of syngas with tunable H2/CO ratios ranging from 0.5 to 2.7, effectively addressing the core limitations of traditional nickel-based catalysts in sintering and sulfur poisoning.

Emerging photothermal synergistic catalysis technology further breaks through the energy barriers of conventional thermal catalytic processes. For instance, Ag-LaFeO3/TiO2 achieves 78.5% CH4 conversion at 200°C, with an efficiency 79 times higher than that of pure thermal catalysis. Such innovations, combined with dynamic active site regulation in layered perovskites (e.g., PrBaFeCoO5+δ maintains 100-h stability through reversible nanoparticle exsolution), highlight the adaptability of these materials in complex biogas environments containing H2S (tolerance up to 220 ppm).

It is particularly noteworthy that the oxygen vacancy-mediated carbon oxidation mechanism significantly enhances CH4/CO2 conversion efficiency, while emerging technological pathways such as photothermal synergistic catalysis further broken through the energy efficiency limitations of conventional thermal catalysis.

4 Challenges and Future Perspectives

Although non-nickel-based perovskite materials demonstrate remarkable advantages in biogas reforming applications, their practical implementation still faces multiple challenges. Critical issues remain unresolved, including structural stability against lattice reconstruction under long-term high-temperature conditions, scalable production cost control, and synergistic poisoning effects from complex biogas components (e.g., combined H2S and H2O contamination).

Future research should focus on the following directions: integrating high-throughput computational screening with in-situ characterization techniques to develop perovskite systems with optimized tolerance factors; elucidating the dynamic evolution mechanisms of active sites; and designing self-healing gradient oxygen vacancy materials.

Through multidisciplinary integration (e.g., coupling chemical looping reforming with photothermal catalysis) and atomic-scale manufacturing process optimization, we anticipate achieving the leap from laboratory-scale research to industrial biogas conversion systems using non-nickel perovskite catalysts. This development pathway will provide critical technological support for green energy conversion under carbon neutrality goals, requiring not only continuous breakthroughs in fundamental research but also deep industry-academia collaboration to bridge material design with engineering applications.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work has been financially supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2023ZDZX0005).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to this article as follows: Funding acquisition, guidance, and research conception: Zeai Huang; Investigation, data collection, and writing: Hao Tan; Original draft and editing: Hao Tan and Runxian Gong; Manuscript preparation: Hao Tan, Zeai Huang, Junming Mei, Tianyu Yan, Kejie Wu, Daoquan Zhu, Zhibin Zhang and Ruiyang Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Park MJ, Kim HM, Gu YJ, Jeong DW. Optimization of biogas-reforming conditions considering carbon formation, hydrogen production, and energy efficiencies. Energy. 2023;265(440):126273. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.126273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zabochnicka M, Wolny L, Zawieja I, Lozano Sanchez FD. Biogas production from waste food as an element of circular bioeconomy in the context of water protection. Desalin Water Treat. 2023;301:289–95. doi:10.5004/dwt.2023.29792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gkotsis P, Kougias P, Mitrakas M, Zouboulis A. Biogas upgrading technologies-recent advances in membrane-based processes. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(10):3965–93. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.10.228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Capa A, García R, Chen D, Rubiera F, Pevida C, Gil MV. On the effect of biogas composition on the H2 production by sorption enhanced steam reforming (SESR). Renew Energy. 2020;160(Part A):575–83. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.06.122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Deng R, Wu J, Huang Z, Feng Z, Hu W, Tang Y, et al. Biogas to chemicals: a review of the state-of-the-art conversion processes. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2025;15(10):14653–73. doi:10.1007/s13399-024-06343-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hernandez B, Martin M. Optimization for biogas to chemicals via tri-reforming. Analysis of Fischer-Tropsch fuels from biogas. Energy Convers Manag. 2018;174(27):998–1013. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.08.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Alipour Z, Babu Borugadda V, Wang H, Dalai AK. Syngas production through dry reforming: a review on catalysts and their materials, preparation methods and reactor type. Chem Eng J. 2023;452(2019):139416. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.139416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hu W, Wu J, Huang Z, Tan H, Tang Y, Feng Z, et al. Catalyst development for biogas dry reforming: a review of recent progress. Catalysts. 2024;14(8):494. doi:10.3390/catal14080494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lin W, Huang X, Qin Z, Han B, Chen J, Yan K, et al. Bi-reforming of biogas to metgas (CO-2H2) over β-cyclodextrin modified hydrotalcite derived oxides supported robust Ni nanocatalysts. Sep Purif Technol. 2025;360:130848. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2024.130848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li W, Zhao G, Zhong J, Xie J. Upgrading renewable biogas into syngas via bi-reforming over high-entropy spinel-type catalysts derived from layered double hydroxides. Fuel. 2024;358(46):130155. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Huang X, Lin W, Zhong J, Xie J, Chen Y. Bi-reforming of model biogas to syngas over ultrasmall Ru/MgO nano-catalysts prepared via soft template-assisted mechanochemical method. Sep Purif Technol. 2025;354:129301. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2024.129301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao X, Joseph B, Kuhn J, Ozcan S. Biogas reforming to syngas: a review. iScience. 2020;23(5):101082. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kumar R, Kumar A. Recent advances of biogas reforming for hydrogen production: methods, purification, utility and techno-economics analysis. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;76(11):108–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.02.143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jung S, Lee J, Moon DH, Kim KH, Kwon EE. Upgrading biogas into syngas through dry reforming. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;143:110949. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Shen Y, Liu Y, Yu H. Enhancement of the quality of syngas from catalytic steam gasification of biomass by the addition of methane/model biogas. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43(45):20428–37. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.09.068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang Q, Liu G, Liu Y. Perovskite-type oxides as the catalyst precursors for preparing supported metallic nanocatalysts: a review. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2018;57(1):1–17. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.7b03251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu C, Park J, De Santiago HA, Xu B, Li W, Zhang D, et al. Perovskite oxide materials for solar thermochemical hydrogen production from water splitting through chemical looping. ACS Catal. 2024;14(19):14974–5013. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c03357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Y, Wang L, Zhang K, Xu J, Wu Q, Xie Z, et al. Electrocatalytic water splitting over perovskite oxide catalysts. Chin J Catal. 2023;50:109–25. doi:10.1016/S1872-2067(23)64452-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bhattar S, Abedin MA, Kanitkar S, Spivey JJ. A review on dry reforming of methane over perovskite derived catalysts. Catal Today. 2021;365:2–23. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2020.10.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Humayun M, Li Z, Israr M, Khan A, Luo W, Wang C, et al. Perovskite type ABO3 oxides in photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and solid oxide fuel cells: state of the art and future prospects. Chem Rev. 2025;125(6):3165–241. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.4c00553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Bilal Hanif M, Motola M, Qayyum S, Rauf S, Khalid A, Li CJ, et al. Recent advancements, doping strategies and the future perspective of perovskite-based solid oxide fuel cells for energy conversion. Chem Eng J. 2022;428(2):132603. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.132603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Alam M, Naeem N, Khoja AH, Khan UM, Towfiq Partho A, Kaushal N, et al. Recent advancements in perovskite materials and their DFT exploration for dry reforming of methane to syngas production. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;87(44):1288–326. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.09.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Oh J, Joo S, Lim C, Kim HJ, Ciucci F, Wang JQ, et al. Precise modulation of triple-phase boundaries towards a highly functional exsolved catalyst for dry reforming of methane under a dilution-free system. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61(33):e202204990. doi:10.1002/anie.202204990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, Pei C, Chang X, Chen S, Liu R, Zhao ZJ, et al. FeO6 octahedral distortion activates lattice oxygen in perovskite ferrite for methane partial oxidation coupled with CO2 splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(26):11540–9. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c04643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sun Y, Zhang Y, Yin X, Zhang C, Li Y, Bai J. Recent advances in the design of high-performance cobalt-based catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Green Chem. 2024;26(9):5103–26. doi:10.1039/D3GC05136F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Muñoz HJ, Korili SA, Gil A. Facile synthesis of an Ni/LaAlO3–perovskite via an MOF gel precursor for the dry reforming of methane. Catal Today. 2024;429:114487. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2023.114487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Managutti PB, Yu H, Hernandez O, Prestipino C, Dorcet V, Wang H, et al. Exsolution of Co-Fe alloy nanoparticles on the PrBaFeCoO5+δ layered perovskite monitored by neutron powder diffraction and catalytic effect on dry reforming of methane. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(19):23040–50. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c22239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bahari MB, Mamat CR, Jalil AA, Hassan NS, Hatta AH, Alhassan M, et al. Mitigating deactivation in dry methane reforming by lanthanum catalysts for enhanced hydrogen production: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;104:426–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.06.122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bian Z, Wang Z, Jiang B, Hongmanorom P, Zhong W, Kawi S. A review on perovskite catalysts for reforming of methane to hydrogen production. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020;134(38):110291. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang L, Lian J, Li L, Peng C, Liu W, Xu X, et al. LaNiO3 nanocube embedded in mesoporous silica for dry reforming of methane with enhanced coking resistance. Micropor Mesopor Mater. 2018;266:189–97. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.02.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li M, Liu W, Mao Y, Liu K, Zhang L, Cao Z, et al. Design dual confinement Ni@S-1@SiO2 catalyst with enhanced carbon resistance for methane dry reforming. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;83:79–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.08.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kaviani M, Rezaei M, Alavi SM, Akbari E. Biogas dry reforming over nickel-silica sandwiched core-shell catalysts with various shell thicknesses. Fuel. 2024;355:129533. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang W, Qu J, Zhao B, Yang G, Shao Z. Core-shell structured Li0.33La0.56TiO3 perovskite as a highly efficient and sulfur-tolerant anode for solid-oxide fuel cells. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3(16):8545–51. doi:10.1039/C5TA01213A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chung WC, Chang MB. Synergistic effects of plasma Z-scheme photocatalysis process for biogas conversion. J CO2 Util. 2020;40:101190. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2020.101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zainon AN, Somalu MR, Kamarul Bahrain AM, Muchtar A, Baharuddin NA, Muhammed Ali SA, et al. Challenges in using perovskite-based anode materials for solid oxide fuel cells with various fuels: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(53):20441–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.12.192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chava R, D BAV, Roy B, Appari S. Recent advances and perspectives of perovskite-derived Ni-based catalysts for CO2 reforming of biogas. J CO2 Util. 2022;65:102206. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2022.102206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Manfro RL, Souza MMVM. Overview of Ni-based catalysts for hydrogen production from biogas reforming. Catalysts. 2023;13(9):1296. doi:10.3390/catal13091296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang Z, Bi G, Han B, Liu L, Zhong J, Xie J. Upgrading biogas into syngas via bi-reforming of model biogas over ruthenium-based nano-catalysts synthesized via mechanochemical method. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(45):16958–70. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.01.202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Georgiadis AG, Charisiou ND, Goula MA. A mini-review on lanthanum-nickel-based perovskite-derived catalysts for hydrogen production via the dry reforming of methane (DRM). Catalysts. 2023;13(10):1357. doi:10.3390/catal13101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Gupta A, Kumar R, Sharma JP, Ahmadi MH, Najser J, Blazek V, et al. The role of catalyst in hydrogen production: a critical review. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2024;149(24):14517–34. doi:10.1007/s10973-024-13753-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen Z, Zhang J, Li D, Li K, Wang H, Zhu T, et al. Enhanced performance of La1-xFeO3-δ oxygen carrier via a-site cation defect engineering for chemical looping dry reforming of methane. Fuel Process Technol. 2023;248:107820. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2023.107820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chava R, Seriyala AK, Varma DBA, Yeluvu K, Roy B, Appari S. Investigation of Ba doping in a-site deficient perovskite Ni-exsolved catalysts for biogas dry reforming. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(71):27652–70. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.03.464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Chen J, Wang X, Gai D, Wang J. B-site semi-doped LaFeO3 perovskite oxygen carrier for biomass chemical looping steam gasification to produce hydrogen-rich syngas. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;103:446–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.01.190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Winterstein TF, Malleier C, Klötzer B, Kahlenberg V, Hejny C, Bekheet MF, et al. Molybdate-based double perovskite materials in methane dry reforming. Mater Today Chem. 2024;41(11):102255. doi:10.1016/j.mtchem.2024.102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bai Y, Wang Y, Yuan W, Sun W, Zhang G, Zheng L, et al. Catalytic performance of perovskite-like oxide doped cerium (La2 − x Cex CoO4 ± y) as catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Chin J Chem Eng. 2019;27(2):379–85. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2018.05.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Nirmal Kumar S, Appari S, Kuncharam BVR. Techniques for overcoming sulfur poisoning of catalyst employed in hydrocarbon reforming. Catal Surv Asia. 2021;25(4):362–88. doi:10.1007/s10563-021-09340-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Osti A, Costa S, Rizzato L, Senoner B, Glisenti A. Photothermal activation of methane dry reforming on perovskite-supported Ni-catalysts: impact of support composition and Ni loading method. Catal Today. 2025;449:115200. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2025.115200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sastre D, Galván CÁ, Pizarro P, Coronado JM. Enhanced performance of CH4 dry reforming over La0.9Sr0.1FeO3/YSZ under chemical looping conditions. Fuel. 2022;309(5):122122. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yang Q, Chen L, Jin N, Zhu Y, He J, Zhao P, et al. Boosted carbon resistance of ceria-hexaaluminate by in situ formed CeFexAl1−xO3 as oxygen pool for chemical looping dry reforming of methane. Appl Catal B Environ. 2023;330:122636. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Iftikhar S, Martin W, Wang X, Liu J, Gao Y, Li F. Ru-promoted perovskites as effective redox catalysts for CO2 splitting and methane partial oxidation in a cyclic redox scheme. Nanoscale. 2022;14(48):18094–105. doi:10.1039/D2NR04437D. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Gu S, Choi JW, Suh DJ, Park YK, Choi J, Ha JM. Upgrading of sulfur-containing biogas into high quality fuel via oxidative coupling of methane. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(13):19363–77. doi:10.1002/er.7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Yuan K, Wang Y, Li K, Zhu X, Wang H, Jiang L, et al. LaFe0.8Co0.15Cu0.05O3 supported on silicalite-1 as a durable oxygen carrier for chemical looping reforming of CH4 coupled with CO2 reduction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(34):39004–13. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c12700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yang L, Zhang J, Wei J. Highly active La0.35Sr0.35Ba0.3Fe1-xCoxO3 oxygen carriers with the anchored nanoparticles for chemical looping dry reforming of methane. Fuel. 2023;349(10):128771. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Shen X, Sun Y, Wu Y, Wang J, Jiang E, Xu X, et al. The coupling of CH4 partial oxidation and CO2 splitting for syngas production via double perovskite-type oxides LaFexCo1−xO3. Fuel. 2020;268(22):117381. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Kim HS, Jeon Y, Kim JH, Jang GY, Yoon SP, Yun JW. Characteristics of Sr1−xYxTi1−yRuyO3+/−δ and Ru-impregnated Sr1−xYxTiO3+/−δ perovskite catalysts as SOFC anode for methane dry reforming. Appl Surf Sci. 2020;510(1996):145450. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zhang X, Song Y, Guan F, Zhou Y, Lv H, Liu Q, et al. (La0.75Sr0.25)0.95(Cr0.5Mn0.5)O3-δ-Ce0.8Gd0.2O1.9 scaffolded composite cathode for high temperature CO2 electroreduction in solid oxide electrolysis cell. J Power Sources. 2018;400:104–13. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.08.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Choi HJ, Kwak M, Kim TW, Seo DW, Woo SK, Kim SD. Redox stability of La0.6Sr0.4Fe1-xScxO3-δ for tubular solid oxide cells interconnector. Ceram Int. 2017;43(10):7929–34. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.03.120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Jun YB, Park JH, Kim HS, Jung KS, Yoon SP, Lee CW. A simulation model for ruthenium-catalyzed dry reforming of methane (DRM) at different temperatures and gas compositions. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;49(17):786–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.07.199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Tian M, Wang C, Han Y, Wang X. Recent advances of oxygen carriers for chemical looping reforming of methane. ChemCatChem. 2021;13(7):1615–37. doi:10.1002/cctc.202001481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Yang L, Zhao Z, Cui C, Zhang J, Wei J. Effect of nickel and cobalt doping on the redox performance of SrFeO3–δ toward chemical looping dry reforming of methane. Energy Fuels. 2023;37(16):12045–57. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c01149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Jiang Q, Xin Y, Xing J, Sun X, Long Y, Hong H, et al. Performance of iron-based perovskite-type oxides for chemical looping dry reforming of methane. Energy Fuels. 2024;38(21):21189–203. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c01480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Sayyed SZ, Vaidya PD. Chemical looping-steam reforming of biogas and methane over lanthanum-based perovskite for improved production of syngas and hydrogen. Energy Fuels. 2023;37(23):19082–91. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c02769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Wei T, Pan X, Wang S, Qiu P, Du X, Liu B, et al. Ce-enhanced LaMnO3 perovskite catalyst with exsolved Ni particles for H2 production from CH4 dry reforming. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2021;5(21):5481–9. doi:10.1039/D1SE01111A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Zheng X, Li B, Shen L, Cao Y, Zhan Y, Zheng S, et al. Oxygen vacancies engineering of Fe doped LaCoO3 perovskite catalysts for efficient H2S selective oxidation. Appl Catal B Environ. 2023;329:122526. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Wang S, Kasarapu SSK, Clough PT. High-throughput screening of sulfur-resistant catalysts for steam methane reforming using machine learning and microkinetic modeling. ACS Omega. 2024;9(10):12184–94. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c00119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Sheshko TF, Kryuchkova TA, Yafarova LV, Borodina EM, Serov YM, Zvereva IA, et al. Gd-Co-Fe perovskite mixed oxides as catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2022;30(3):100897. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2022.100897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Jiang Y, Li Z, Zhu T, Li D, Wang H, Zhu X. Oxygen storage characteristics and redox behaviors of lanthanum perovskite oxides with transition metals in the B-sites. Energy Fuels. 2023;37(13):9419–33. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c00569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Vecino-Mantilla S, Lo Faro M. A doped cobaltite for enhanced SOFCs fed with dry biogas. Electrochim Acta. 2023;464:142927. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2023.142927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Long DB, Nguyen T, Phan HP. Facilely synthesized CeNi1-xCoxO3 perovskite catalyst for combined steam and CO2 reforming of methane. Arab J Sci Eng. 2025;50(6):4351–66. doi:10.1007/s13369-024-09764-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Peng W, Li Z, Liu B, Qiu P, Yan D, Jia L, et al. Enhanced activity and stability of Ce-doped PrCrO3-supported nickel catalyst for dry reforming of methane. Sep Purif Technol. 2022;303(1):122245. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Gao P, Wang P, Liu X, Cui Z, Wu Y, Zhang X, et al. Photothermal synergy for efficient dry reforming of CH4 by an Ag/AgBr/CsPbBr3 composite. Catal Sci Technol. 2022;12(5):1628–36. doi:10.1039/D1CY02281D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Lee JG. Use of A-site metal exsolution from a hydrated perovskite titanate for combined steam and CO2 reforming of methane. Inorg Chem. 2023;62(14):5831–5. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c00470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Walker E, Ammal SC, Suthirakun S, Chen F, Terejanu GA, Heyden A. Mechanism of sulfur poisoning of Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6-δPerovskite anode under solid oxide fuel cell conditions. J Phys Chem C. 2014;118(41):23545–52. doi:10.1021/jp507593k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Sun J, Du X, Li Z, Yu H, Hong Y, Pan M, et al. Rational design of poisoning-resistant catalyst based on γ-Al2O3 for hydrolysis of carbonyl sulfide. Chem Eng Sci. 2024;295:120150. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2024.120150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools