Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Artificial Neural Networks and Taguchi Methods for Energy Systems Optimization: A Comprehensive Review

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Payame Noor University, Tehran, P.O. Box 19395-3697, Iran

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Babol Noshirvani University of Technology, Babol, P.O. Box 47148-71167, Iran

* Corresponding Author: Homayoun Boodaghi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI and Advanced Computational Techniques for Sustainable Renewable Energy Systems)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4385-4474. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.070668

Received 21 July 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

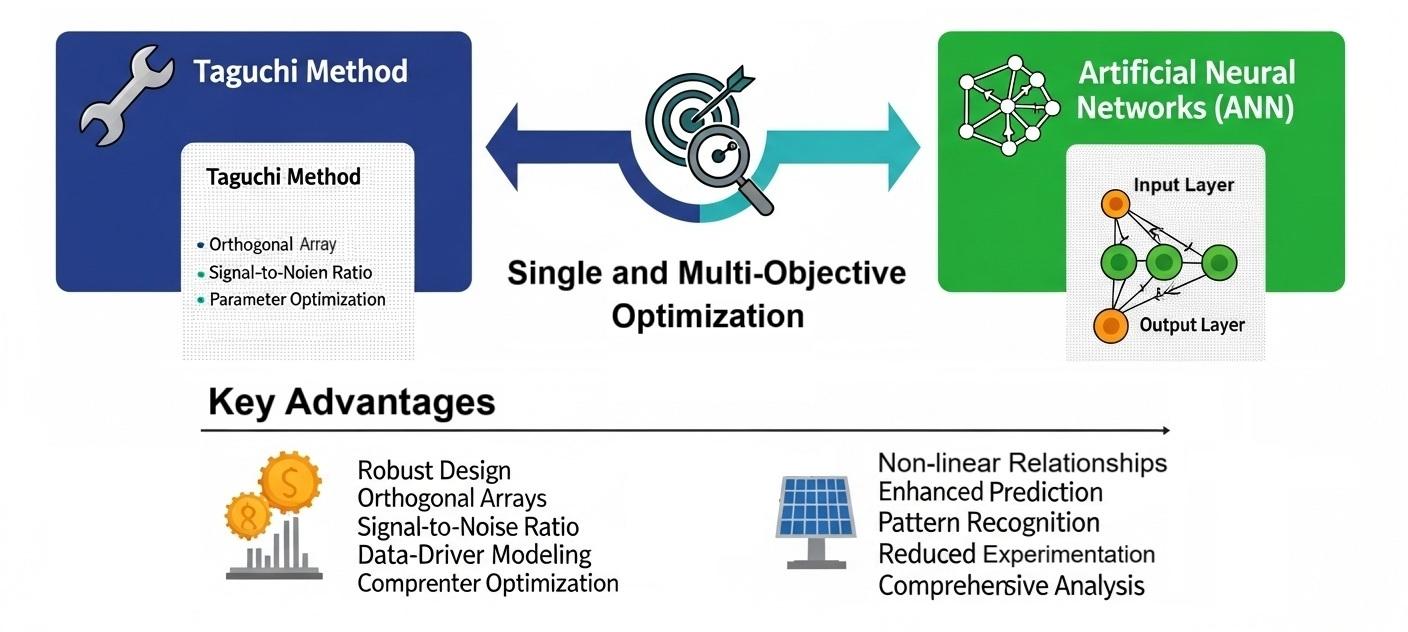

Energy system optimization has become crucial for enhancing efficiency and environmental sustainability. This comprehensive review examines the synergistic application of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Taguchi methods in optimizing diverse energy systems. While previous reviews have focused on these methods separately, this paper presents the first integrated analysis of both approaches across multiple energy applications. We systematically analyze their implementation in: Internal combustion engines, Thermal energy storage systems, Solar energy systems, Wind and tidal turbines, Heat exchangers, and hybrid energy systems. Our findings reveal that ANN models consistently achieve prediction accuracies exceeding 90% when compared to experimental data, while Taguchi-based methods combined with Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) or TOPSIS can improve system performance by up to 20%–30% in multi-objective optimization scenarios. The review introduces novel frameworks for combining these methods and provides critical insights into their complementary strengths. Key statistical metrics, including determination coefficients and error analyses, validate the superior performance of integrated approaches. This work serves as a foundational reference for researchers and practitioners in energy system optimization, offering structured methodologies and future research directions.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

1.1 Background and Significance of Energy System Optimization

The Industrial Revolution in the 18th century marked a significant turning point, initiating a dramatic increase in energy consumption and its applications. This period witnessed a remarkable surge in global energy demand, resulting in substantial growth in manufacturing output, population, and economic development [1]. Consequently, energy and its uses garnered considerable attention.

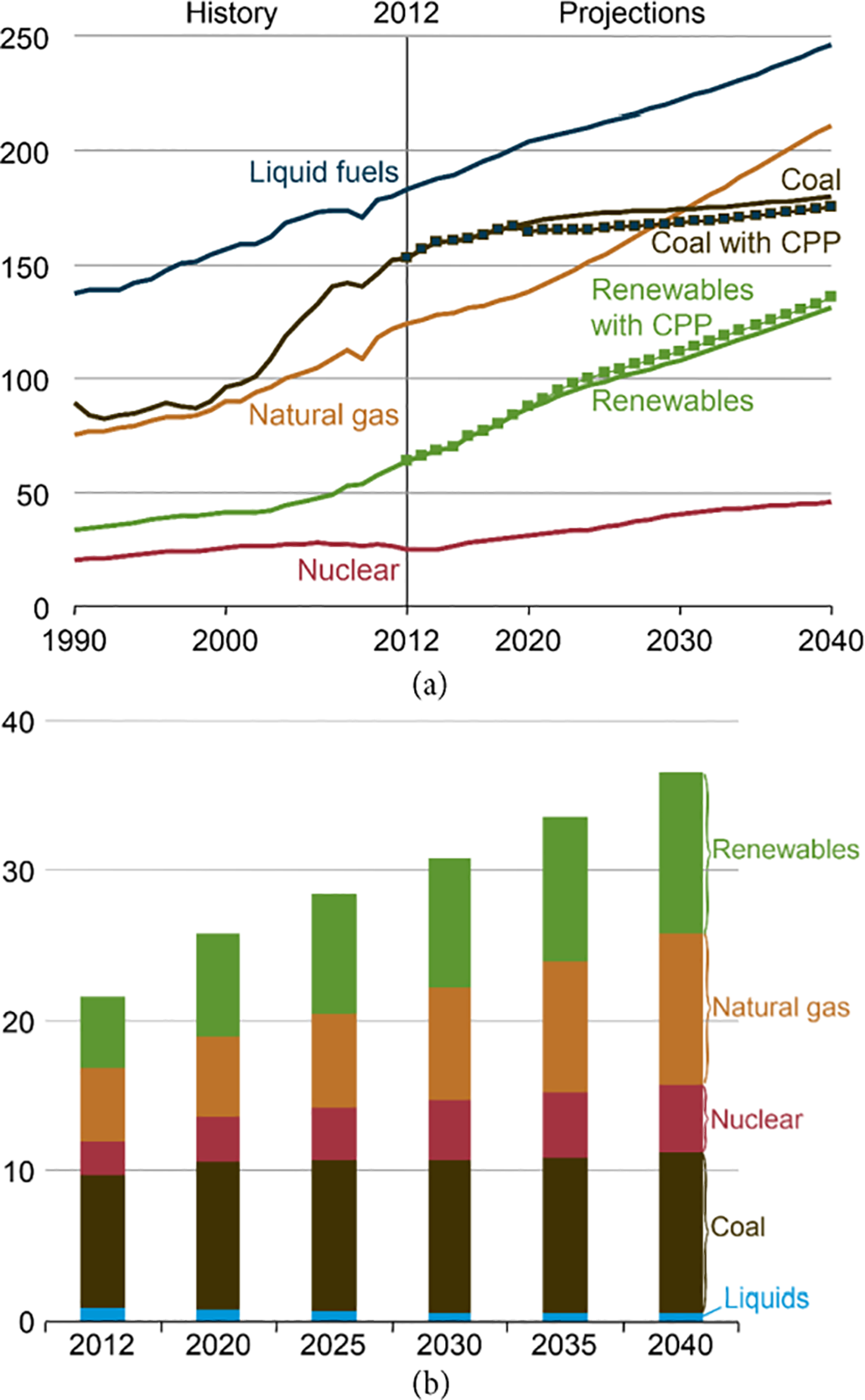

According to the IEO 2016 projection shown in Fig. 1a, global consumption of marketed energy from all fuel sources is expected to increase through 2040. Renewable energy sources are projected to be the fastest-expanding energy source globally over this period, with consumption increasing by an average of 2.6% annually between 2012 and 2040. Following renewables, nuclear power is identified as the world’s second-fastest-growing energy source, with its consumption anticipated to increase by 2.3% per year during the same timeframe. Fig. 1b illustrates the total global net electricity generation by different fuel types through 2040. Renewables are also expected to be the fastest-expanding energy source for electricity generation, experiencing an average annual growth of 2.9% from 2012 to 2040. After renewables, natural gas and nuclear power are projected to be the fastest-growing sources of electricity generation. From 2012 to 2040, electricity generation from natural gas is estimated to increase by 2.7% annually, while nuclear power generation is expected to rise by approximately 2.4% per year.

Figure 1: (a) Total world energy consumption by energy source, 1990–2040 (Quadrillion Btu). Dotted lines for coal and renewables show the projected effects of the U.S. Clean Power Plan (CPP). (b) World net electricity generation by fuel, 2012–40 (trillion kilowatt-hours) [2]

Energy systems encompass all components involved in the production, conversion, distribution, and utilization of energy. They can vary in scope, ranging from local to global, depending on the specific case under study [3]. Properly designed energy systems aim to optimize energy consumption, enhance process efficiency, and recover waste energy [4,5]. Developing countries often face the challenge of reducing their heavy reliance on conventional energy systems, which predominantly use non-renewable fossil fuels. These traditional systems are inefficient and contribute to environmental problems, including global warming.

A long-term goal for global society is the transition to completely sustainable and clean energy systems [6–8]. In the short term, improving the performance of existing energy systems is a crucial solution. This pursuit fosters economic, environmental, technical, and social development, alongside promoting efficient energy use.

Optimizing energy systems requires substantial data and a range of tools. To minimize energy losses, a thorough analysis of diverse subjects is essential [9–11]. In energy systems, objective functions such as quality, performance, and cost can be optimized to achieve optimal results. This involves determining the optimal combination of input variables that influence the objective function and quality characteristics. Furthermore, it is necessary to statistically calculate the impact weight and sensitivity analysis of output parameters relative to input variables.

1.2 Overview of Optimization Techniques: Taguchi and ANN

The Taguchi optimization approach is an increasingly vital and widely used technique for solving various energy system problems [12–14]. Taguchi-based methods offer robust and resource-efficient experimental designs, effectively managing variations in input parameters. These methods excel at systematically identifying influential factors, thereby facilitating multivariate optimization across diverse applications. However, their assumption of linearity and sensitivity to initial estimates can limit their effectiveness with continuous variables. Furthermore, their capacity to explore interaction effects is limited, making them more suitable for specific contexts, such as manufacturing or engineering design. Optimal application requires careful consideration of these strengths and limitations to ensure their appropriateness for the problem domain. Consequently, numerous scholars have employed Taguchi-based methodologies in energy conversion applications to optimize the performance of both single and multi-response objective problems, including turbine [15], PV [16], hydrogen generation [17], desalination [18], thermoelectric generator [19], fuel cell [20], Diesel engine [21], wave energy [22], PVT [23], integrated energy system [24], etc.

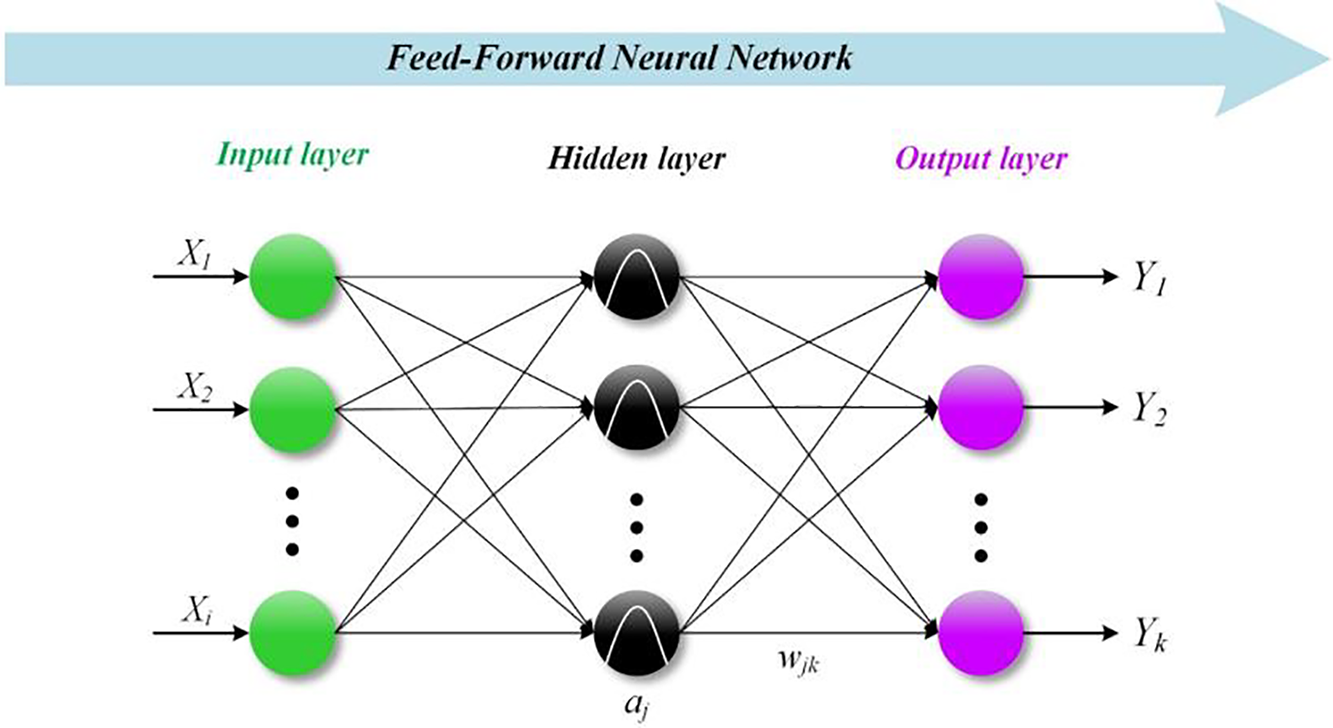

1.2.2 Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

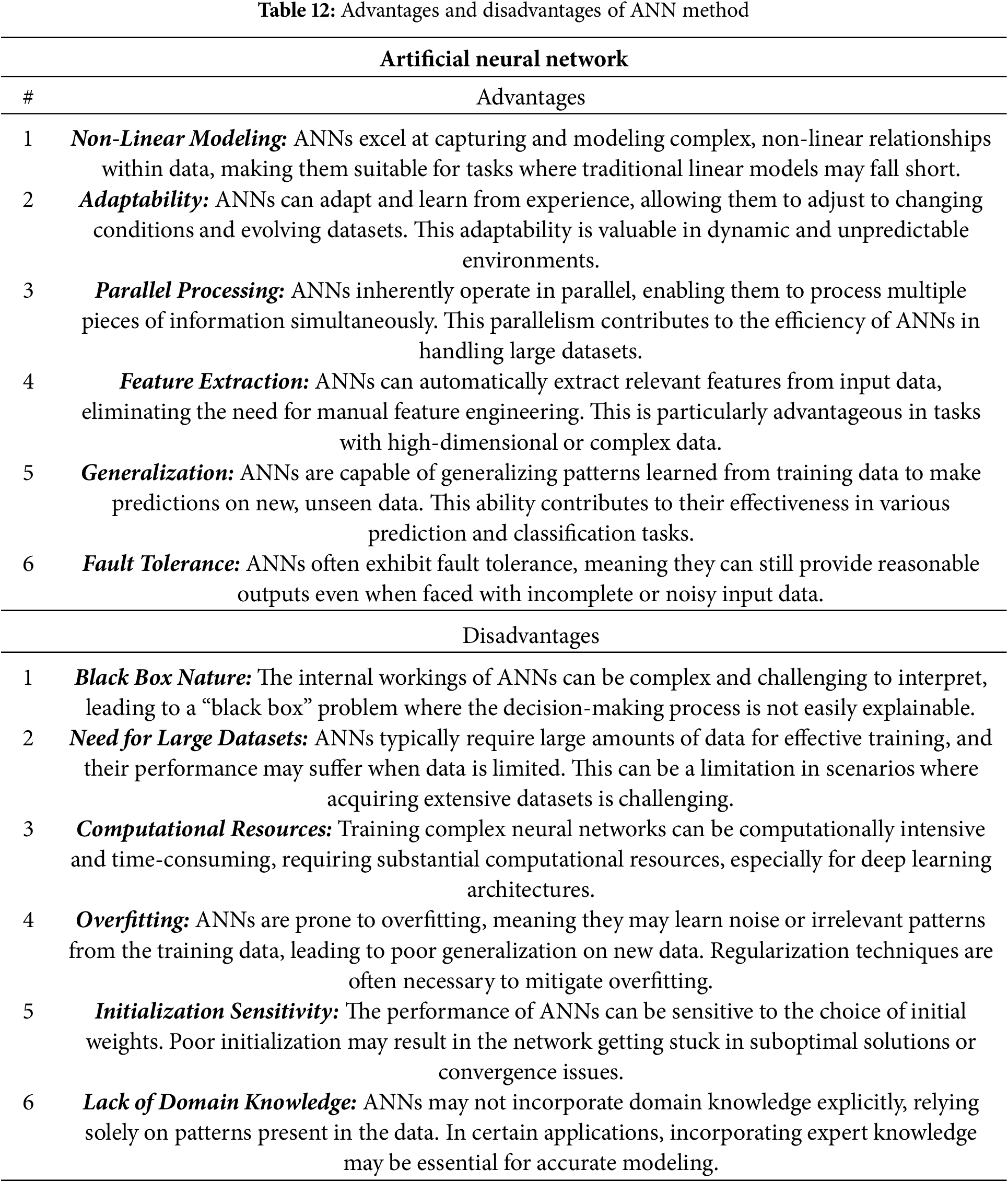

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), inspired by the human brain, are computational models adept at modelling complex, nonlinear relationships between input and output variables. This makes them powerful tools for optimization, simulation, and prediction across various applications. ANNs consist of interconnected neurons organized into layers, where each neuron processes input and transmits results to subsequent layers. Training involves adjusting connection weights to minimize prediction errors, enabling the network to learn from data [25,26]. Over the past decade, ANNs have been extensively employed for optimization in a broad spectrum of energy applications, such as refrigeration [27], PV [28], fuel cell [29], Diesel engine [30], building [31], electrolyzer [32], heat pump [33], hybrid energy system [34], heat exchanger and thermal storage [35], PTC-driven power plant [36], etc. Moreover, ANN techniques have received favorable reviews in diverse engineering and other domains, such as building electrical energy [37], nanofluid applications [38], pharmaceutical [39], solar collectors [40], and HVAC systems [41].

While ANNs offer unparalleled flexibility and accuracy, they do have limitations. Their “black-box” nature makes it challenging to interpret the underlying relationships between variables. Additionally, ANNs require large datasets for training, which may not always be available in energy system applications. Despite these challenges, ANNs have proven invaluable in addressing the complexities of modern energy systems.

1.3 Rationale for Focusing on Taguchi and ANN Methods

While numerous optimization techniques exist, this review explicitly examines the integration of the Taguchi method and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for optimization, given their distinct advantages. The Taguchi method is more than just a DOE technique; it’s a robust design philosophy aimed at minimizing the impact of uncontrollable “noise” factors, which are common in real-world energy systems with fluctuating conditions. Unlike full factorial designs, which are impractical for numerous parameters, Taguchi’s orthogonal arrays provide a resource-efficient method for identifying key factors. While methods like Central Composite Design (CCD) are effective for response surface modelling and precise optimization, the Taguchi method excels in achieving robustness during the initial design and optimization phases, making it highly suitable for engineering applications.

ANNs are chosen for their superior ability to model the complex, non-linear relationships prevalent in most energy systems, a limitation for statistically linear models like Taguchi. Although more advanced deep learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and ensemble methods like Random Forests exist, foundational architectures like the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) are most frequently combined with Taguchi-based DOE in the literature. Therefore, this review focuses on this established pairing to understand its combined strengths and limitations before exploring more complex hybrid models.

Although the Taguchi method and ANNs have been extensively studied in isolation, a significant research gap persists in the literature: a comprehensive review that explores their synergistic and integrated application in energy system optimization. Previous reviews tend to focus on one method or a single energy application, failing to analyze the complementary nature of these two powerful but philosophically distinct approaches. The Taguchi method provides a structured, robust framework for experimentation, while ANNs offer unparalleled capability in modelling the resulting nonlinear system behaviors. This review aims to fill this gap by:

1. Few studies have comprehensively compared the effectiveness of different statistical optimization methods.

2. Providing a systematic analysis of the combined application of Taguchi and ANN methods across diverse energy systems.

3. Highlighting their complementary strengths and limitations.

4. Offering a framework for their implementation in multi-objective optimization problems.

By addressing these gaps, this review aims to enhance the understanding of optimization techniques in energy systems and offer practical insights for researchers and practitioners. Moreover, the primary objectives of this review are to: 1-Analyze the principles and methodologies of the Taguchi method and ANNs. 2-Evaluate their application in various energy systems, including internal combustion engines, thermal energy storage, solar energy, wind turbines, and hybrid systems. 3-Compare their effectiveness in addressing single-objective and multi-objective optimization problems. 4-Identify challenges, limitations, and future research directions for their combined application.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

• Section 2: Provides an in-depth analysis of the Taguchi method, including its key concepts, applications, and limitations.

• Section 3: Discusses the principles and applications of ANNs in energy system optimization.

• Section 4: Explores the combined application of Taguchi and ANN methods across various energy systems.

• Section 5: Compares the performance of these methods and discusses their complementary strengths.

• Section 6: Summarizes the key findings and concludes the review.

2.1 Single-Objective Optimization

Dr. Genichi Taguchi has developed a strategy based on orthogonal array (OA) experiments which presents much more decreased variance for the issues with optimum control variable settings. Accordingly, the combination of the design of experiments (DoE) by optimization of control variables in order to receive the best outcomes is acquired by using this strategy. As yet, there are numerous literatures have published on the detailed methodology, principles, and fundamentals of the Taguchi optimization approach. Nevertheless, this section characterizes an introduction to the notion of this method for single-objective problems. This optimization approach presents a simple and well-organized procedure to optimize the objective function [42]. It is also known as a prevalent utilized statistical technique to acquire importance ranking for various input parameters against the corresponding output responses [43]. The method is employed in various types of study, such as numerical, theoretical, and experimental [44–47]. Generally, the Taguchi OA design and signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio are the two main tools utilized in this strategy. By applying the S/N ratio and OA, this technique allows for determining the optimum combination of design variables with fewer experiments [48].

2.1.1 Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N)

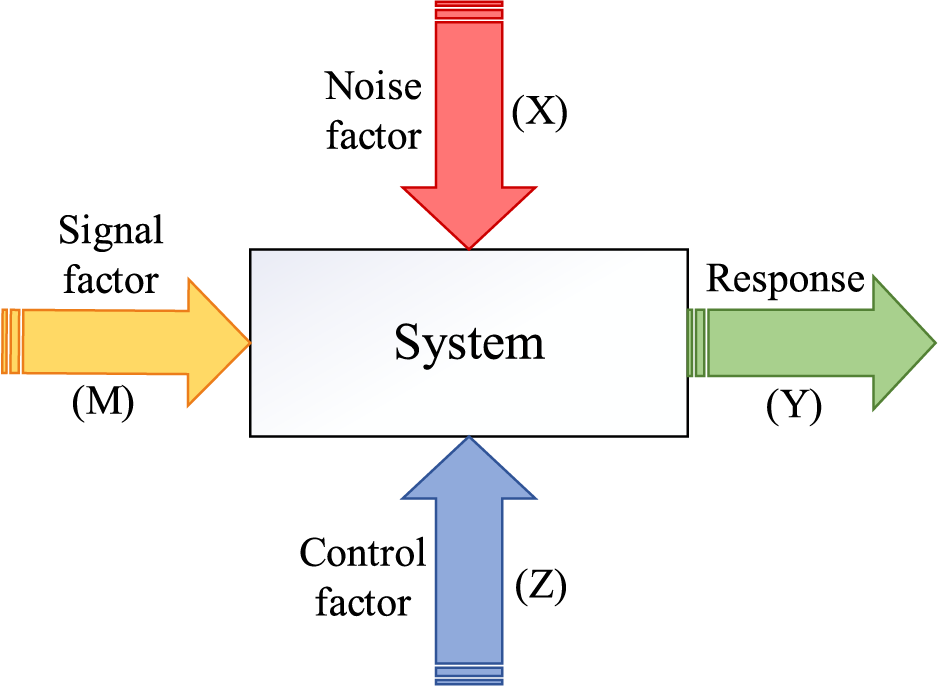

The deviation between the experimental results and desired values can be determined by using the Taguchi quality loss function, which is also known as the S/N ratio. This parameter is employed as a criterion of the ability regarding a process, system or product to perform adequately against the noises. In other words, S/N ratio characterizes how close system’s performance is to the ideal situation. The signal factors describe the desired quantity and could be arranged to meet a particular output value. The undesirable design parameters which are uncontrollable through the process, are called noise factors. The main objective of the Taguchi optimization method is cutting down the noises’ effects on the output [49]. The mentioned concept is illustrated in Fig. 2 called Parameter Diagram (P-Diagram).

Figure 2: The P-Diagram showing the Taguchi method concept

More than 40 different types of S/N ratios have introduced by Taguchi. Three types of the most crucial being is defined by following responses [50,51]:

Smaller the better: A smaller the better (lower the better) response is one that does not take on negative values, and has the target value of zero. The S/N ratio for those characteristics in which the main objective is set to be minimized, is represented by Eq. (2):

Larger the better: This type of response in which the most favorable value is infinity is named the larger-the-better (higher the better). It also does not bear negative values, and there is no pre-arranged objective value. Thus, the larger the characteristic’s value, the better it is. The S/N ratio for this response is as follows, here number of experiments, and experimental response are defined by n, and y, respectively:

Nominal the best: When a particular value is the most desirable, a nominal-the-best response is employed. In other words, either a lower or a higher value for this output response kind is undesirable. It is demonstrated by Eq. (3):

here

To illustrate, consider a simple experiment to optimize a solar PV system’s power output. If four experimental runs with different parameter settings yield power outputs (yi) of 150, 155, 148, and 160 W, the S/N ratio for this ‘Larger the better’ characteristic is calculated as:

This dB value provides a robust measure of performance that can be compared across different experimental settings to identify the optimal combination of factors.

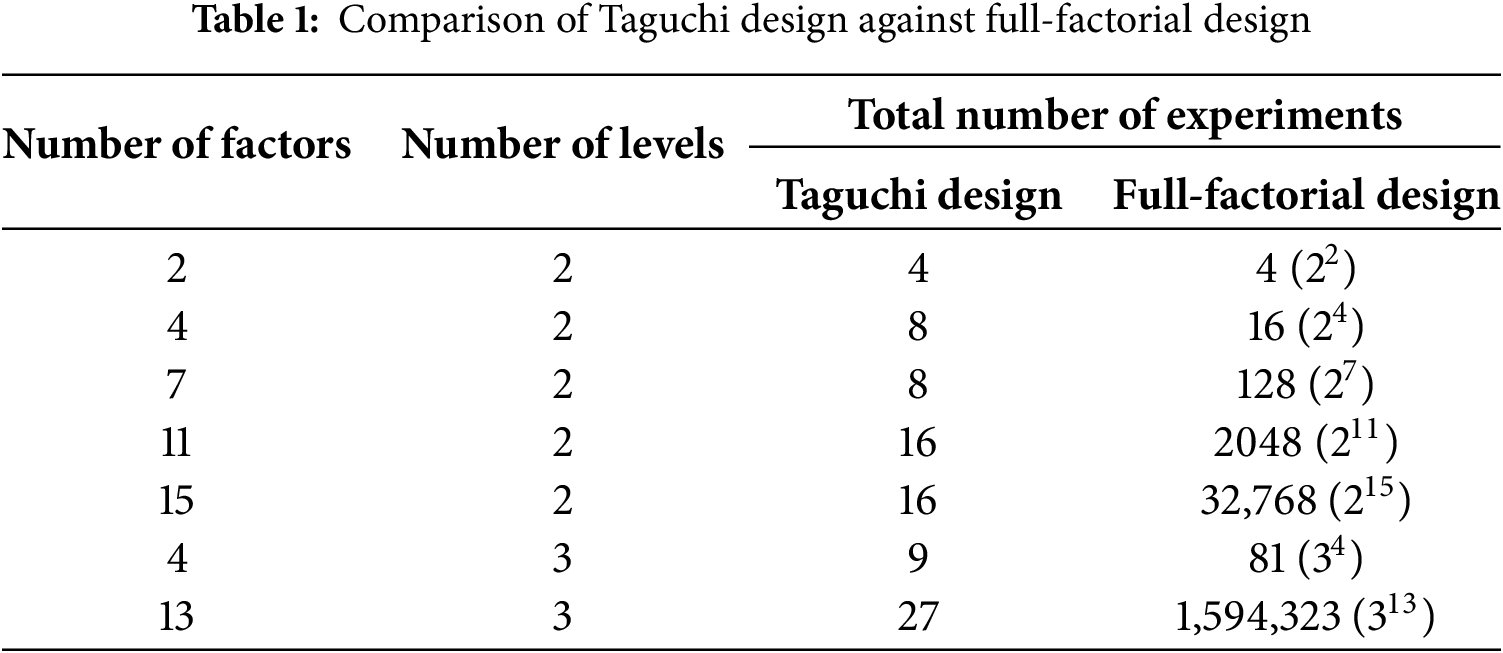

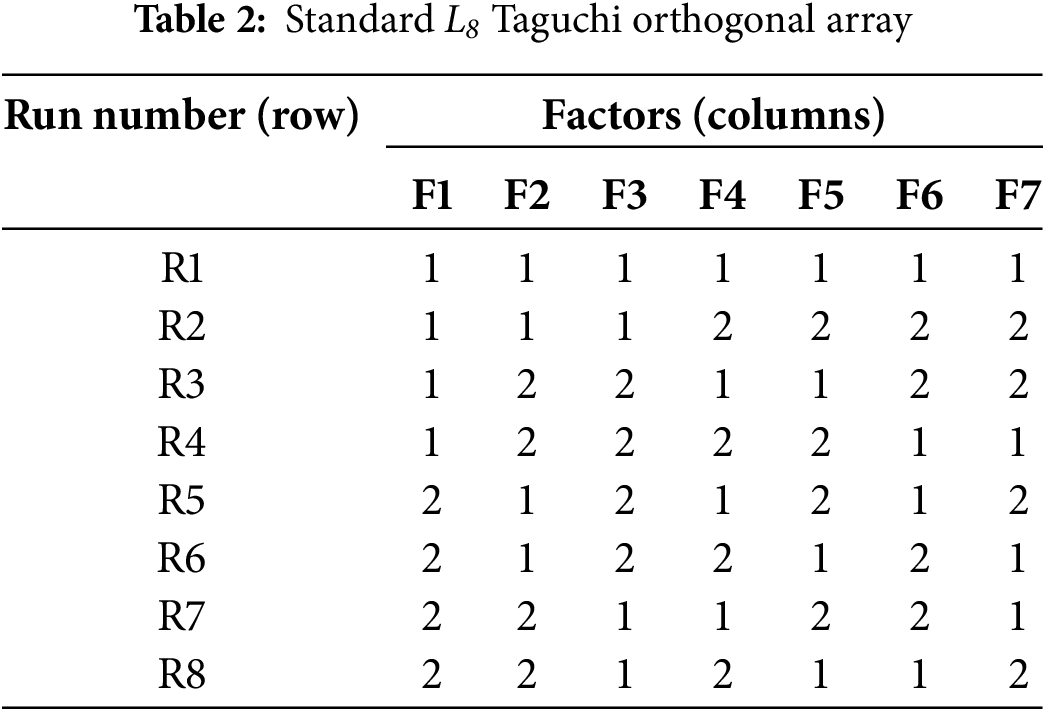

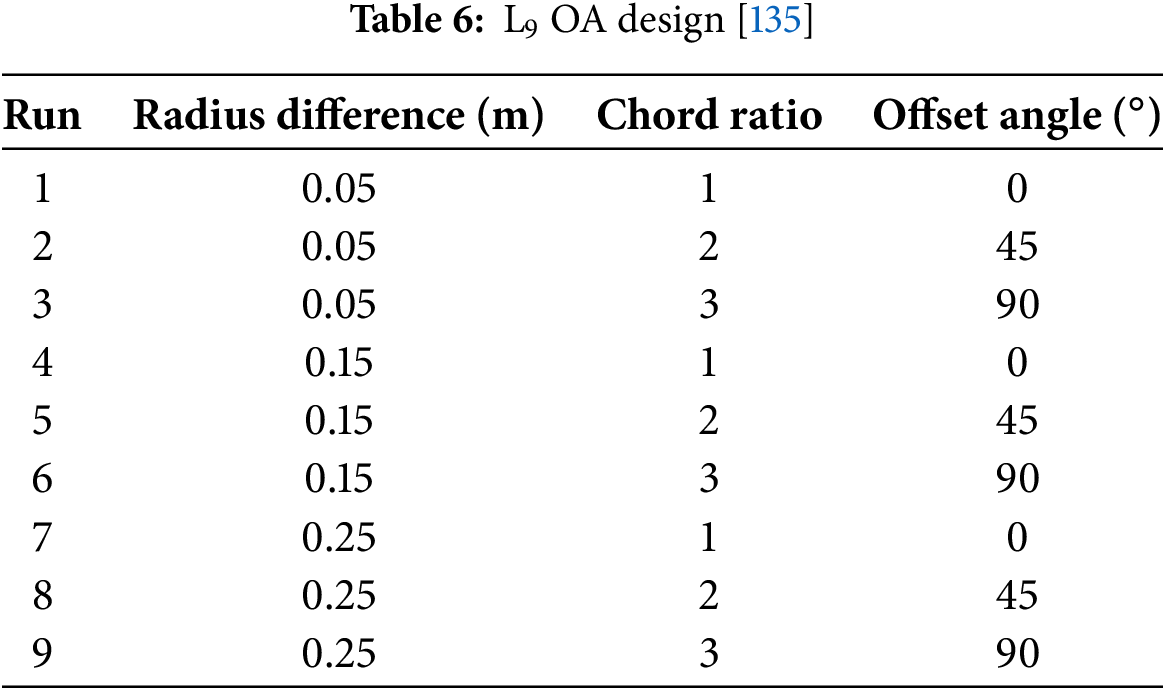

The Taguchi orthogonal array (OA) is defined as a set of matrices for performing the design of experiments that require the least of the full experimental combinations. In order to specify the optimum setting of the control parameters influencing the response, employing the orthogonal array leads to improving the measurement of output response and reducing its variability [52]. The OA trials carry the pairwise balancing feature. This feature makes variables possible to be explored simultaneously so that the effect of none of the variables is neglected. Thus, involving the OA design effectively downsizes the number of experiments [53]. Accordingly, the Taguchi design against the full-factorial design is compared in Table 1. In this table, the total experiments available for various numbers of factors with levels of 2 and 3 proposed by Taguchi’s design and full-factorial design is given. The total number of experiments suggested by Taguchi design is significantly fewer than the full-factorial design. Hence, the advantage of the Taguchi design is well evident in order to the DoE for high-number factor studies.

In DoE process, it is significant to consider the proper OA type. The OA table determination depends on computing the overall degree of freedom (DOF). It is an important parameter for analysis and is acquired via the summation of each factor’s DOF. Generally, the OA is specified by following equation:

where L is Latin square, a is the number of experiments (rows), b is the number of levels, and c is the number of factors (columns). Additionally, to determine the OA and DOF of the process, the following relations are considered:

For instance,

In Table 2, there are eight experimental runs from R1 to R8. The low and high level of each factor is indicated by the 1s and 2s in the matrix, respectively. Each column contains a same number of 1s and 2s. In addition, only four combinations (2, 2), (2, 1), (1, 2), and (1, 1) are employed in each pair of columns, presenting the orthogonal array concept.

2.1.3 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is an examination tool used in statistics that helps to find an observed aggregate variability inside a data set. In the Taguchi optimization approach, the insignificant and significant input factors affecting the performance characteristics of the system are determined by using the ANOVA. The main items which are employed in an ANOVA table are as follows [54,55]:

1) Degree of freedom (DOF): The DOF is defined as the amount of information your data provides that you can spend to estimate the values of unknown population parameters, as well as calculate the variability of these estimates. It is calculated as the level of each input factor minus one. The total DOF is specified as the sum of the singular DOF of factors.

2) Sum of squares (SS): The sum of squares denotes a measurement of deviation or variation from the mean. It is computed as a summation of the squares of the differences from the mean. In the ANOVA table, the total sum of squares enables the presentation of the total variation attributed to different factors. It includes the treatment sum of squares (SST) plus the sum of squares of the residual error (SSE).

3) Experimental error: The various experimental results under a similar set of conditions are defined as the experimental error. To increase the precision of the experimental design, the experimental error should be minimized.

4) Contribution: The contribution percentage represents the proportion of the SS for each input factor. Besides, the ratio of total quality loss generated by the deviation of the factor is defined by contribution.

5) F-value (F): The F-value is defined as the mean square divided by the mean square error. It is employed to specify whether the impact of the factor on the experimental results is significant. It means that the larger the F-value of the factor, the more significant the impact of the factor regarding the objective function.

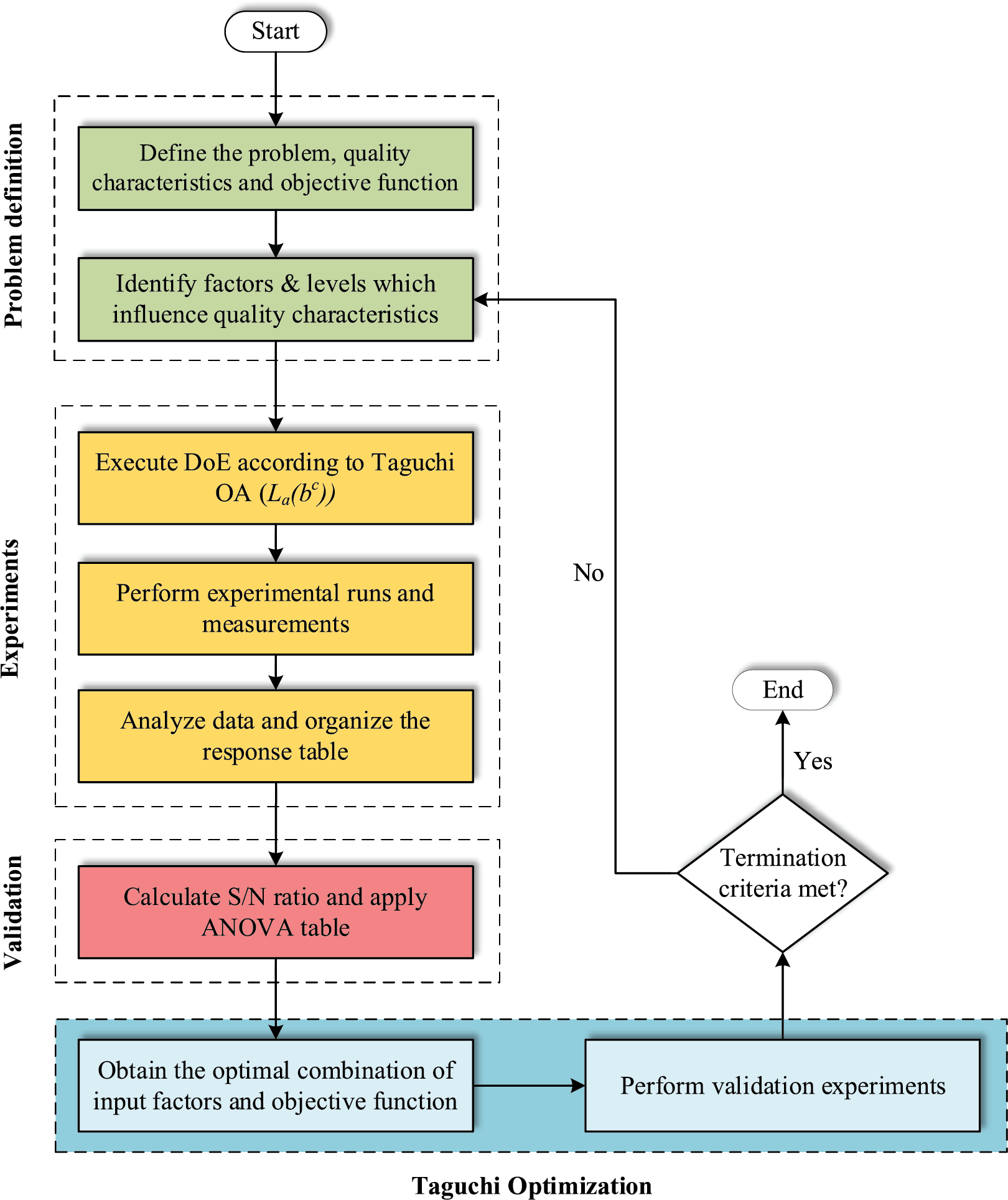

The framework of the Taguchi optimization approach is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The framework for the Taguchi optimization method

2.2 Multi-Objective Optimization

Using the Taguchi technique solitary is not sufficient for describing the effect of input parameters for multi-objective problems. Hence, the Taguchi coupled with Grey relational analysis (GRA), and technique of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) could be employed in optimization of multi-response problems. The Taguchi-based TOPSIS and Taguchi-based GRA are easy to perform, adaptable, and uncomplicated methods compared to the other multi-objective optimization techniques. Accordingly, these techniques are the most widespread optimization methods combined with Taguchi that have been scrutinized in this study.

2.2.1 Grey Relational Analysis (GRA)

The grey relational analysis (GRA) was first proposed by Deng [56]. If we display the utterly known and clear information of a given system in white color and the entirely unknown information of a system in black color, then the information related to most of the systems in the world is not white (entirely known), or black (entirely unknown) information. Rather, they are a combination of the two, i.e., grey. Such systems are called gray systems, whose main characteristics are the incompleteness of information related to that system. According to the GRA, when the data distribution and variation in a sequence are large, the measurement unit of the sequences is not the same. So, data pre-processing is needed. Data pre-processing is a method of converting original numeric sequences into comparable numeric sequences. Hence, the data should be normalized and scaled so that there would be a comparison between sequences. Accordingly, each output response specified by the experimentations is normalized through the 0 to 1 range. It is known as the grey relational generation.

Generally, the normalization can be conducted in three kinds of approaches, and the original sequence could be normalized by following Equations [57]:

I. The smaller the better:

II. The larger the better:

III. The nominal the best:

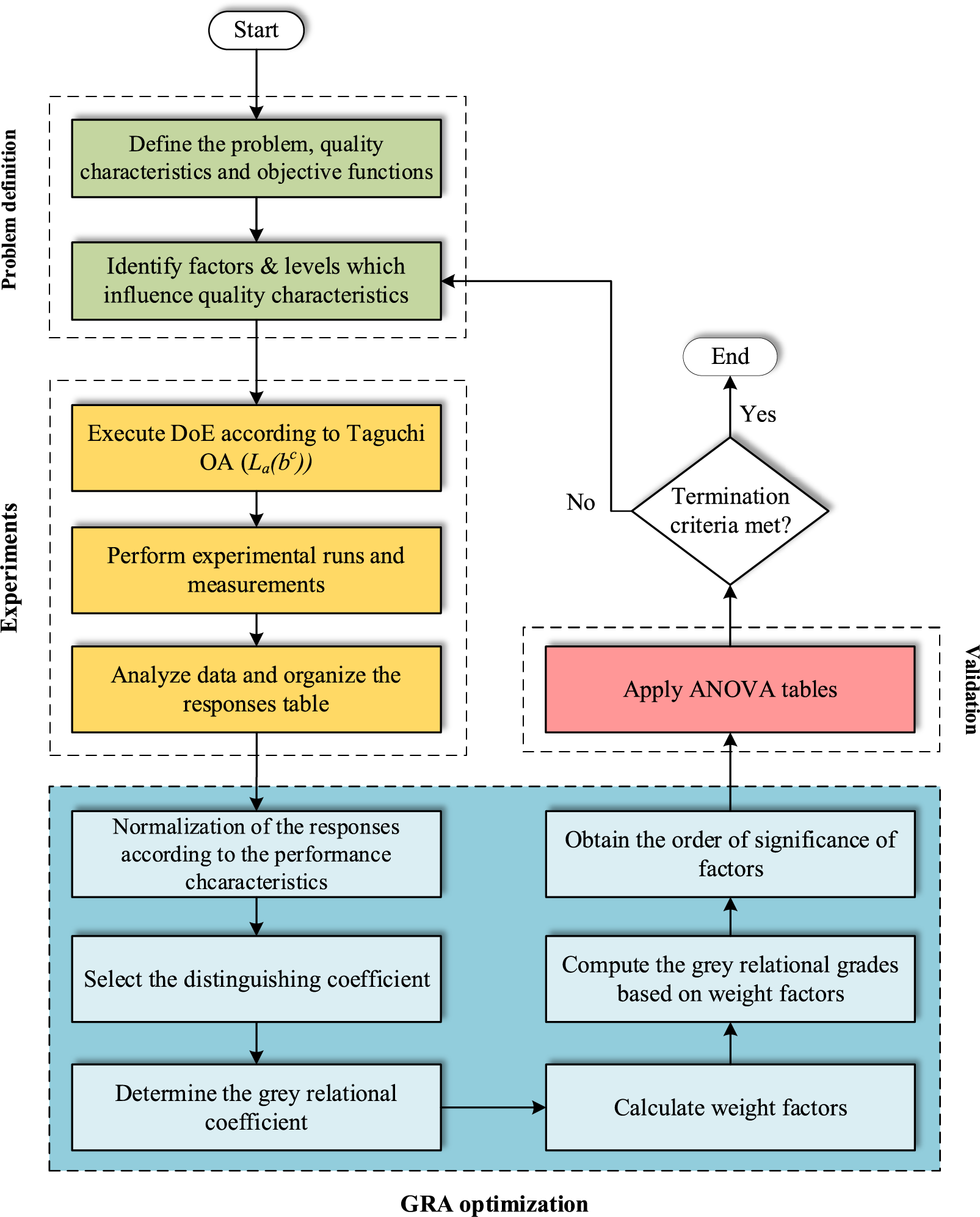

Here, delta means S/N ratio range, p is the number of input parameters, and m is the number of output responses. The framework of the Taguchi-based GRA optimization method is represented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The framework of the Taguchi-based GRA optimization method

2.2.2 Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)

Same as the GRA, this technique is employed to convert a multi-objective optimization problem into a single-objective one. Generally speaking, this technique is applied to incorporate all performance attributes of the system into a single attribute. The Taguchi-based TOPSIS method contains the concept of a multi-objective robust design technique to work out the given multi-objective optimization problem. The robust design indicates an efficient method to specify the optimum combination of the control parameters such it stands robust to the noise factors, and also arises a high performance. The concept of quality loss is practical to the investigation when the performance characteristics are transformed into the (S/N) ratios [63]. As mentioned before, the S/N ratio (

1) Creating the decision matrix by using the number of experimentations and determined S/N ratios for each response as presented in Eq. (17):

2) Calculation of normalized ratings via the vector normalization:

3) Calculation of weighted normalized decision matrix (V):

4) Exploration of positive ideal solution

Here,

5) Determination of separation measures: The distance from each alternative (experimental number) to the positive ideal solution,

and the distance from the negative ideal solution,

6) Determine similarities to the ideal solution by calculation of ranking score (

It should be noted

7) Rank preference order: Choose experimentation with maximum

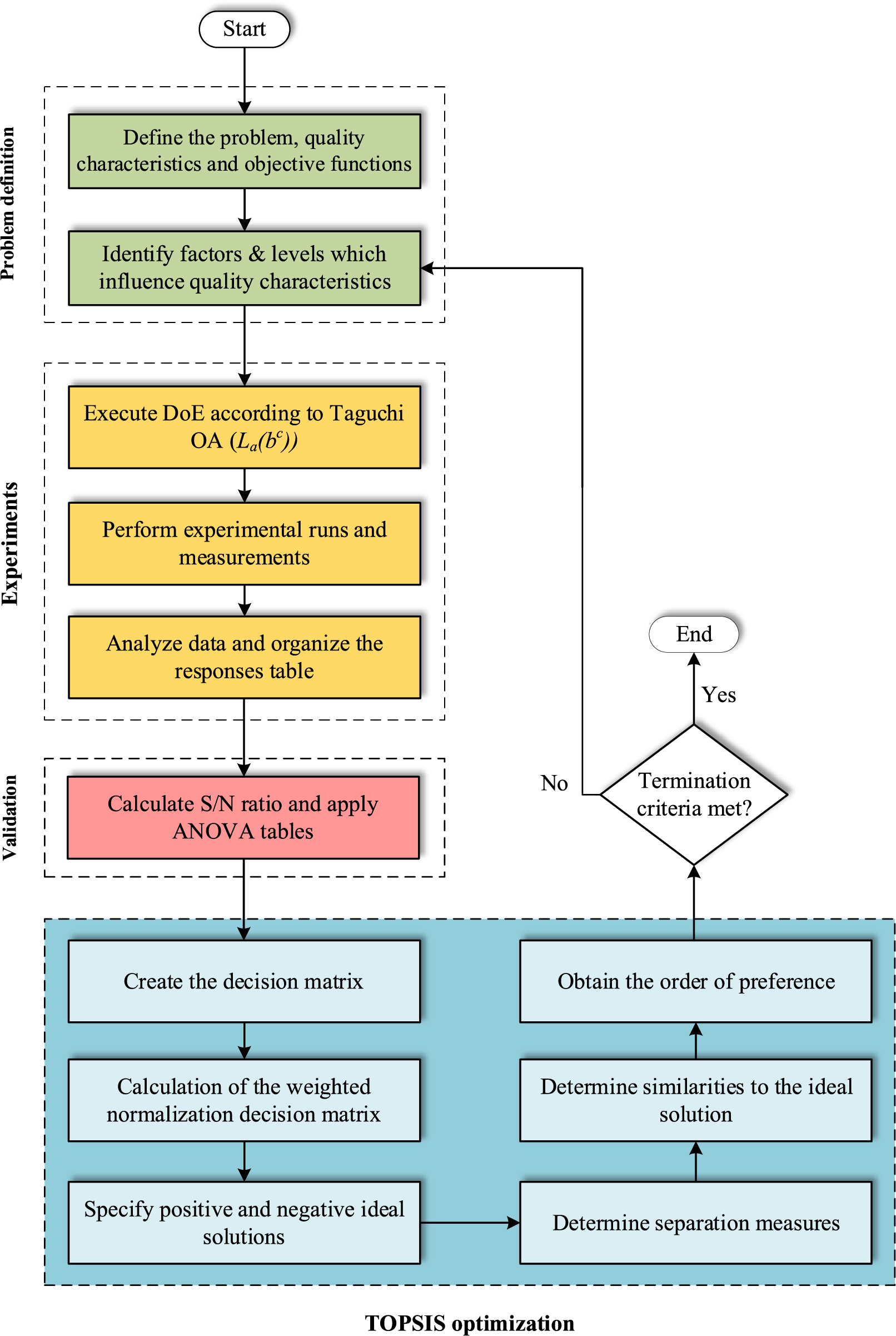

The framework of the Taguchi-based TOPSIS optimization method is provided in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The framework of the Taguchi-based TOPSIS optimization method

3 Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

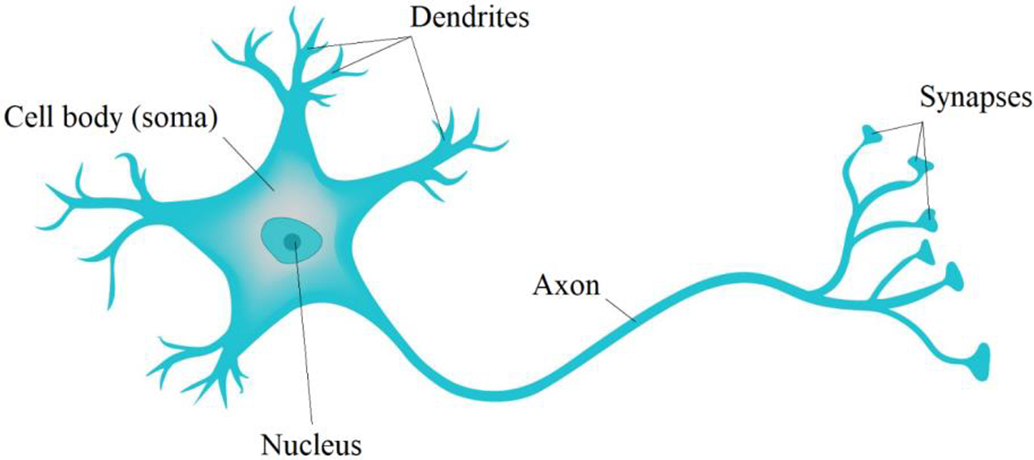

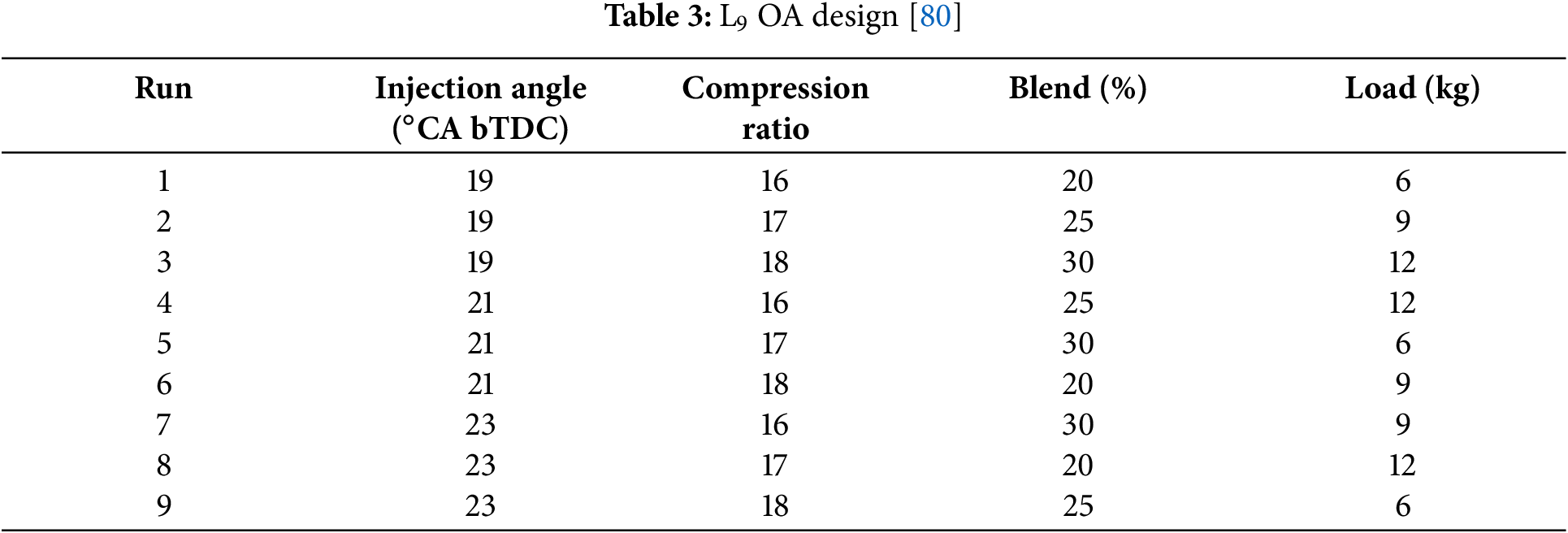

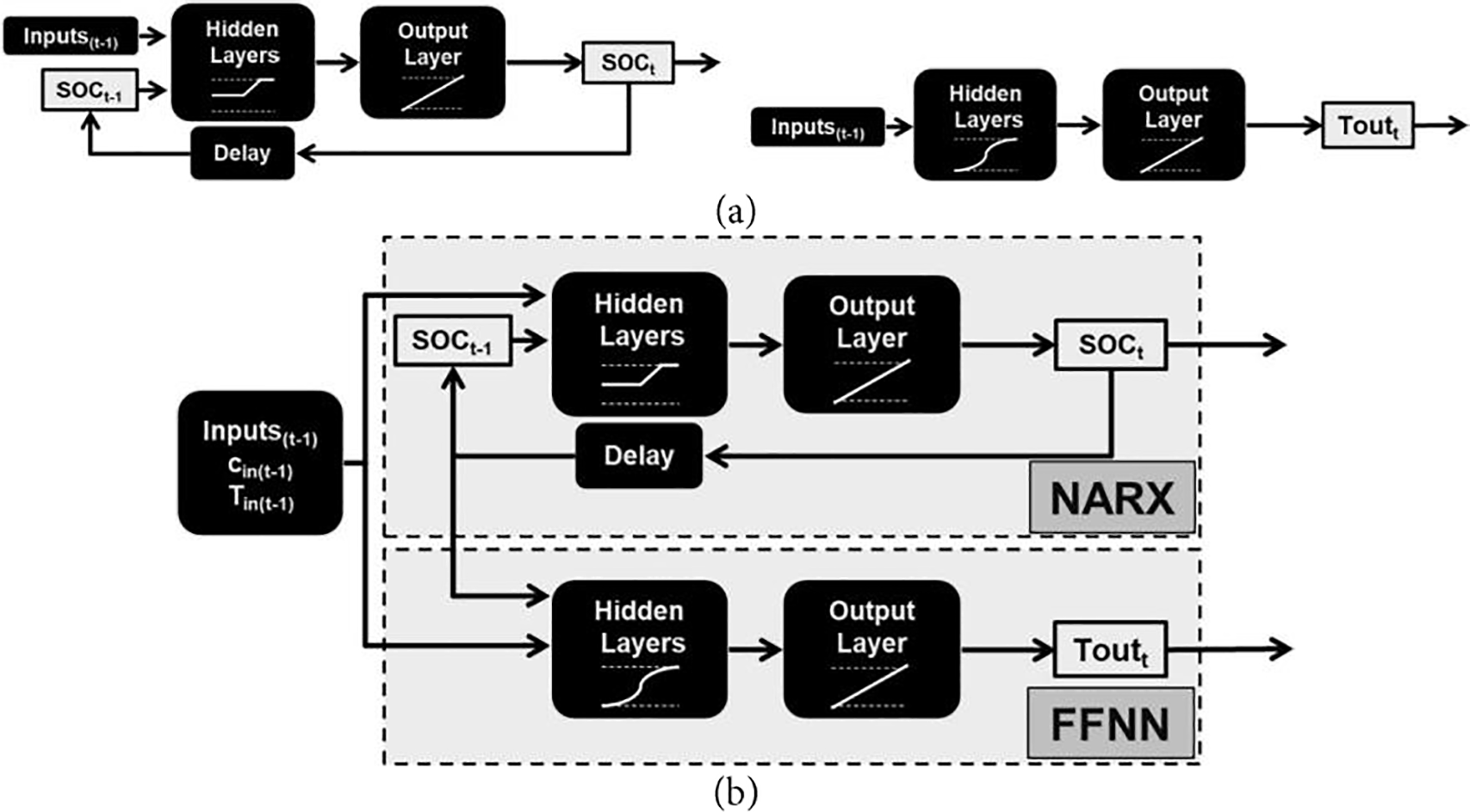

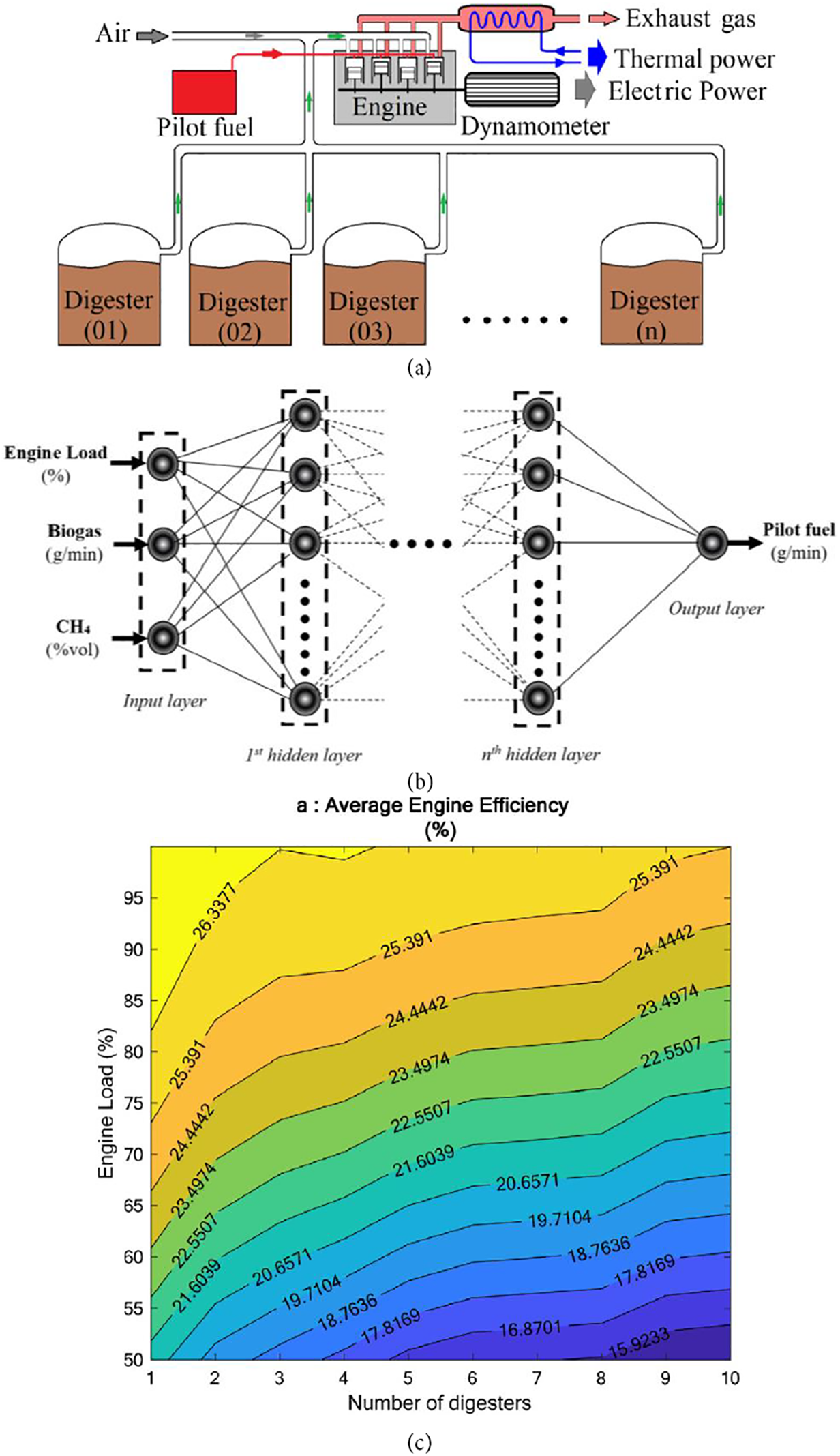

The utilization of ANN techniques extends to modeling, optimization, simulation, and performance prediction of systems. Over the past two decades, its popularity has surged due to its enhanced processing speed and heightened accuracy. Functioning akin to the data processing systems of the human brain, artificial neural networks are composed of neurons, analogous to the fundamental elements regarding biological networks. These neurons comprise components like dendrites (which receive input signals), the cell body or soma (which functions as a processor), synapses (serving as links), and axons (providing exiting signals toward neighboring neurons and executing nonlinear processes) [65]. Fig. 6 illustrates a typical biological human brain’s neuron. The ANN model consists of numerous operating components known as neurons, operating akin to the human brain, it learns and stores knowledge through interconnected links known as weights. Influenced by connection weights, every neuron gains different input signals from neighboring neurons, employs a non-linear activation function, and produces a singular output-signal. This output may then proceed to other neurons, with the neurons collectively processing and forwarding input data to subsequent layers within the network.

Figure 6: Biological neuron of human brain

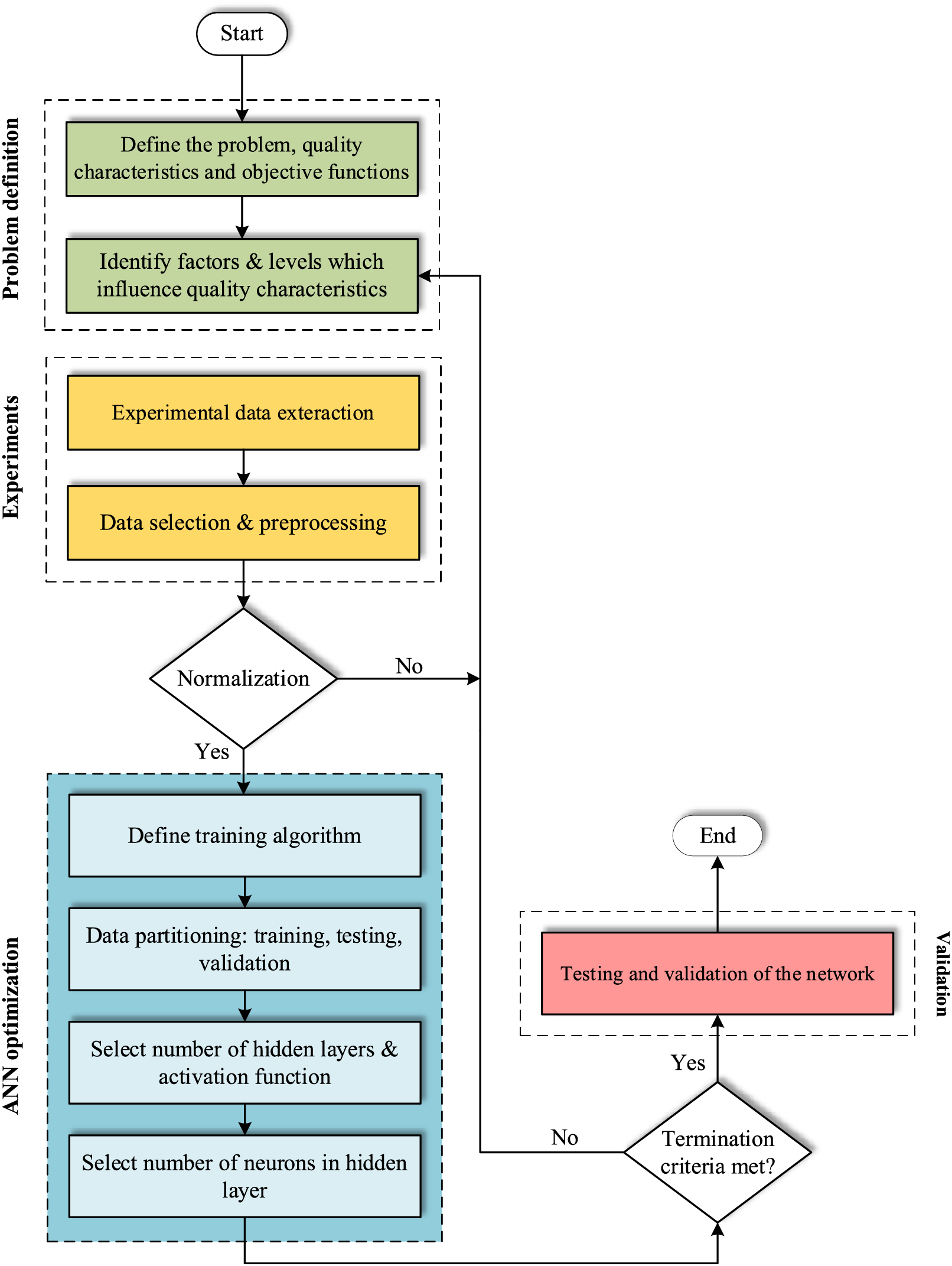

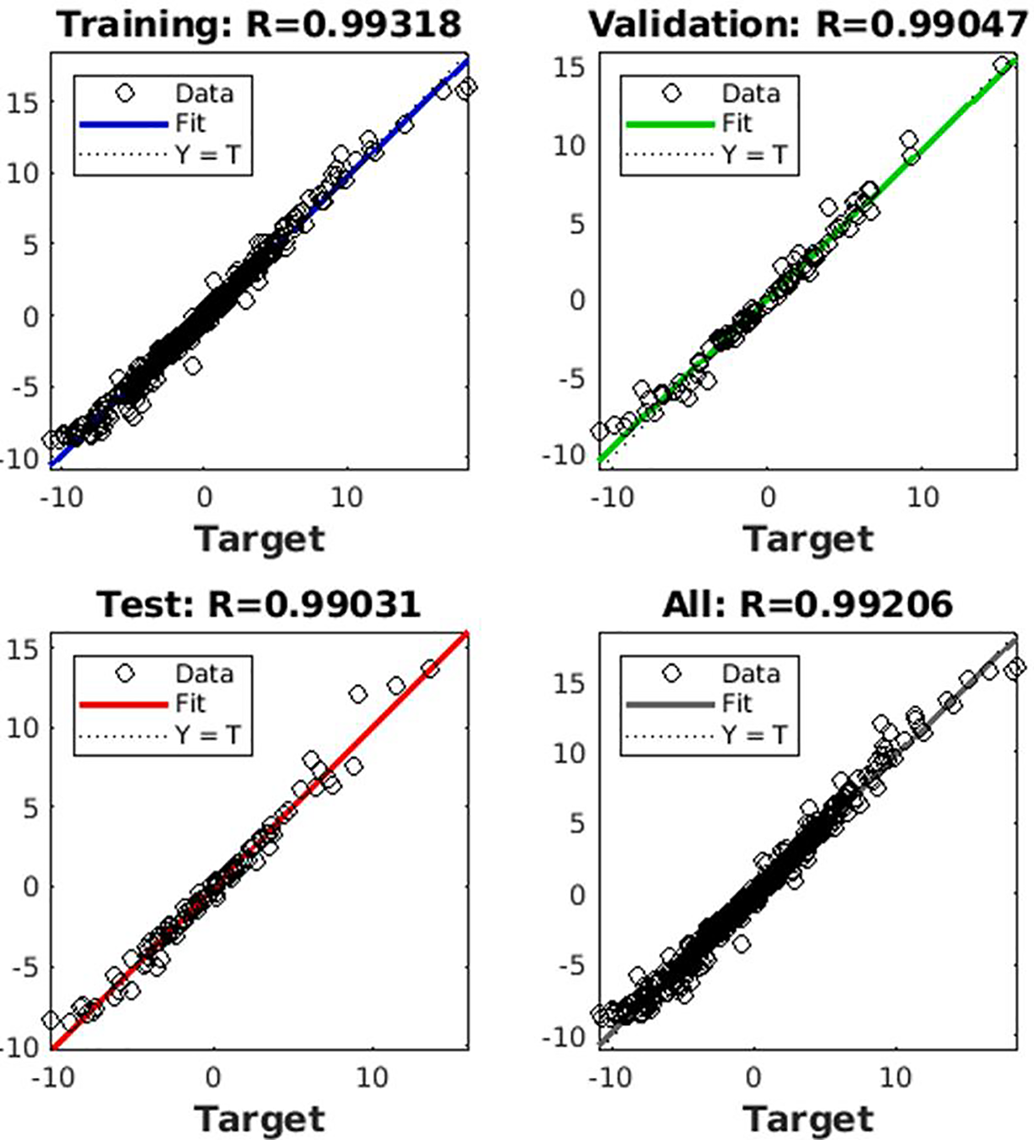

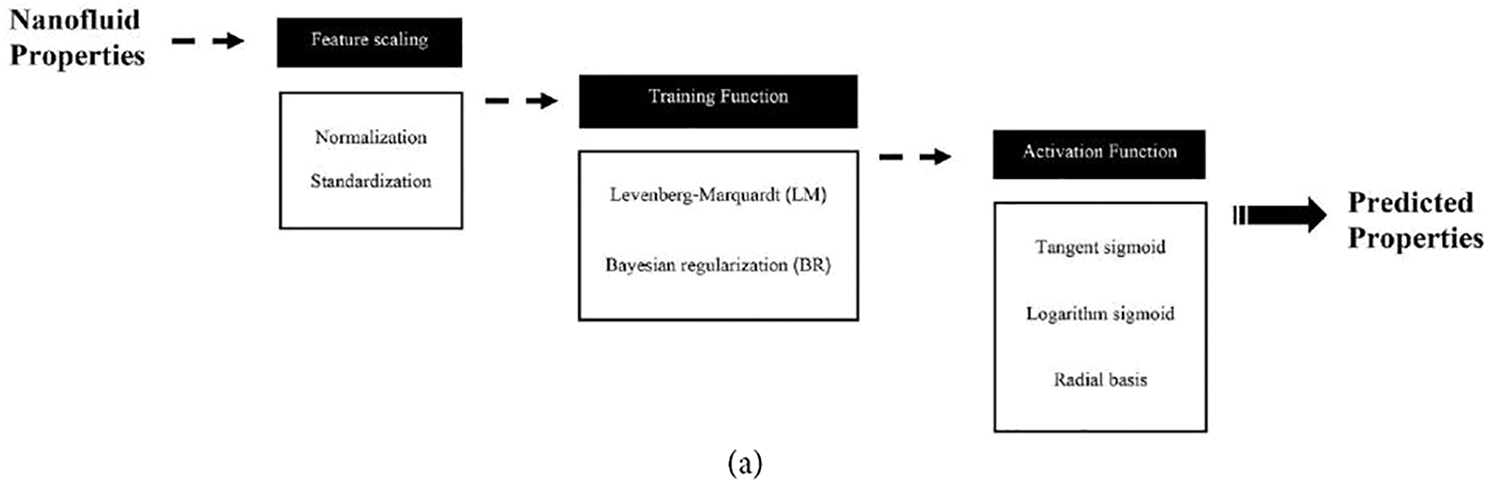

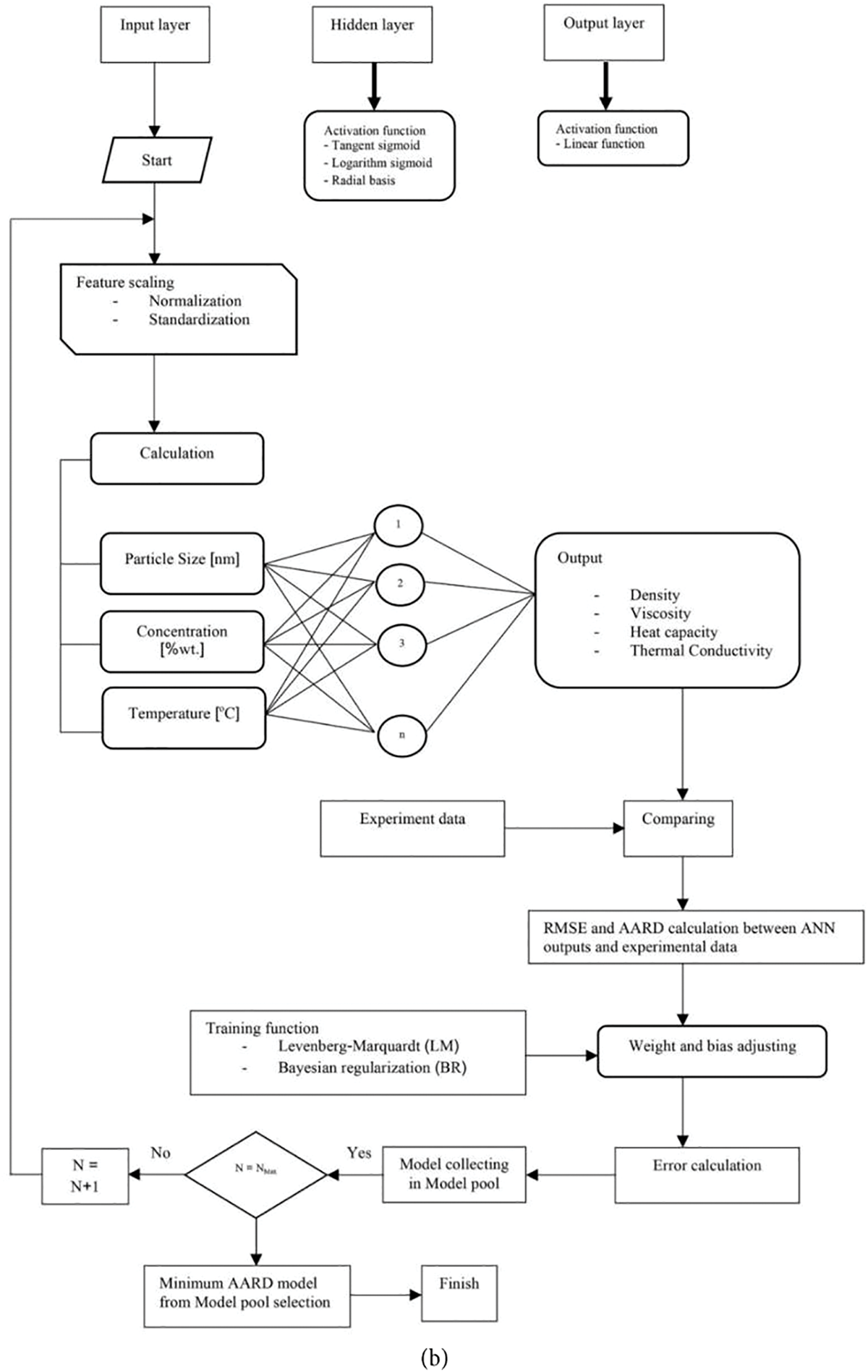

Evaluation of the comprehensive applications of ANNs is feasible by considering factors such as fault tolerance, processing performance, latency, speed, scalability, and convergence accuracy [66]. The substantial potential of ANNs, particularly their fast-speed operating in a massively parallel execution, underscores the necessity for further exploration in this realm. ANN models have demonstrated significant adaptability, nonlinearity, and self-learning capabilities advancements in input-to-output mapping, leading to their widespread use in various functions. Presently, owing to these attributes, ANNs are prominently employed for global method approximation across various numerical paradigms, indicating their effectiveness, efficiency, and success in addressing both simple and complex issues across diverse real-life challenges [67]. ANN can consist of numerous layers, broadly categorized into the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer. The input layer encompasses all input parameters, followed by data computation in the hidden layer, and at the end, the computation of the output vector in the output layer. The implementation of an ANN involves three primary stages: (1) the inputs and outputs selection, (2) the training, and (3) testing. Typically, input and output data are normalized within a specific range, although some studies utilize the data in its raw form without scaling. Subsequently, the data is randomly divided for training, testing, and validation purposes. Essential pre-analysis parameters for ANN include the activation function, input and output selection, the number of neurons in hidden layers, the count of hidden layers, and the training algorithms [68]. Notably, ANN is classified as supervised learning, undergoing training based on input variables and outputs. The learning algorithm’s primary role is to adjust network variables, namely biases and weights, to ensure accurate predictions within acceptable error limits. Commonly known as the cost function, signifies the error signal, which is propagated backward until reaching the minimum signal over numerous training iterations (or epochs). After the training phase concludes, the testing and validation stage assesses the performance of advanced ANN prediction models. Accuracy is gauged using correlation coefficients (R) and coefficients of determination (R2) for training, validation, and testing. Validation involves presenting the new set of inputs to the network, and additional statistical analyses may be conducted to assess the efficiency of predicted responses. The algorithm of ANN method is provided in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The framework of the ANN method

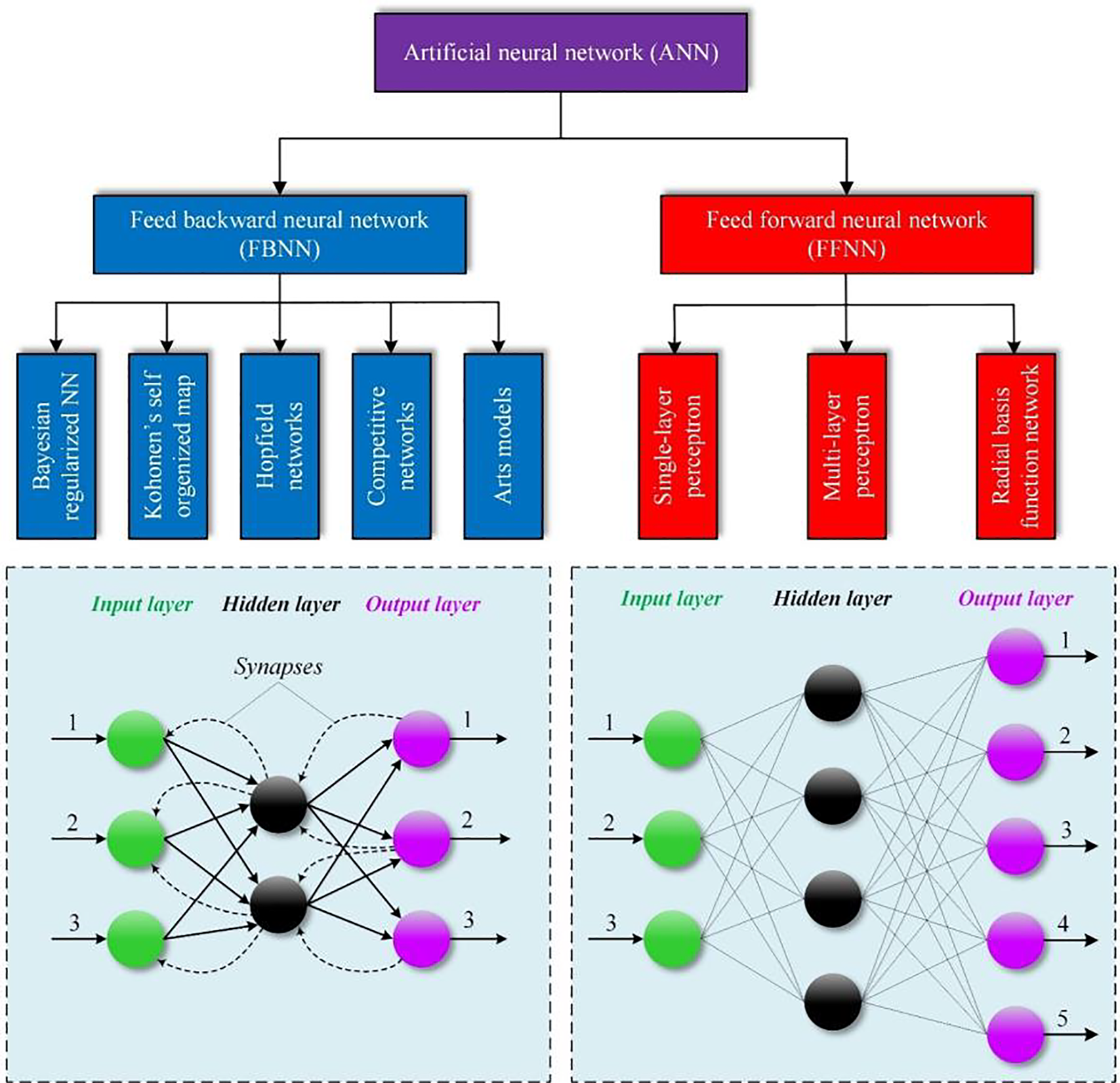

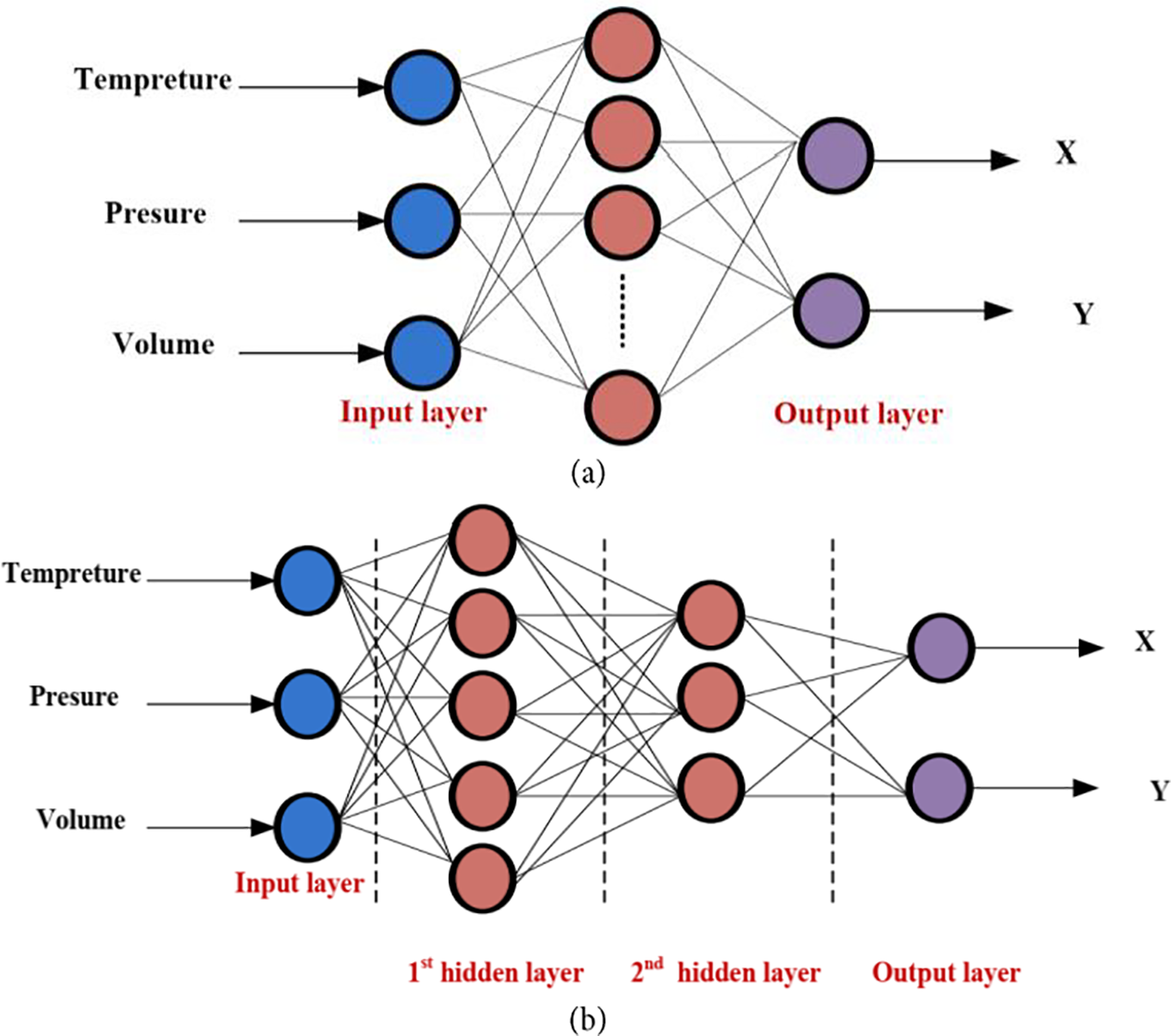

ANNs constitute a potent category of machine-learning models inspired by the neural architecture of the human brain. In the realm of classification, ANNs demonstrate exceptional proficiency in capturing intricate patterns and relationships present in data, enabling them to learn and generalize from examples. ANNs are broadly categorized into feedforward and recurrent architectures. Feedforward networks, with their layered structure, process information sequentially from input to output layers. They are commonly employed in tasks where data exhibits a clear input-output mapping. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), on the other hand, incorporate feedback loops, allowing them to capture temporal dependencies in sequential data. This makes RNNs well-suited for tasks that involve natural language processing and time-series analysis. Hybrid models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for image classification, showcase the versatility of ANNs by integrating specialized layers for extracting hierarchical features [69,70]. As ANNs continue to evolve, their adaptability across diverse domains positions them as a key player in advancing the capabilities of automated classification systems. In Fig. 8, the classification of ANNs is illustrated, focusing on the feedforward neural network (FFNN) as a prominent machine learning classification algorithm. The FFNN structure is characterized by organized layers resembling neuron processing units in the human brain. Each unit within the layers is interconnected, and the strength or weight of these connections varies. The network’s knowledge capacity is determined by the weights of these connections. In a typical FFNN operation, information processing occurs unidirectionally from input units through hidden layers to output units, establishing the network as a classifier. Unlike recurrent networks, FFNNs lack feedback connections between layers. In FFNNs, the information flow is unidirectional, highlighting the progression from input through hidden nodes and ultimately to output nodes [71]. Single-layer and multilayer perceptions are exemplary FFNNs, as depicted in Fig. 8 (right), showcasing a 2-layered FFNN with 3 units in input layer, 4 units in hidden layer, and 5 units in output layer. Notably, input units are determined as the virtual layer with 0 layers, while the hidden layer is distinct from both input and output layers. FFNN applications are categorized into two groups, encompassing conventional machine learning methods and dynamical systems’ control. Networks with at least two hidden layers are acknowledged as deep networks, signifying increased complexity [72].

Figure 8: ANN classification

A single-layer FFNN comprises only input and output layers, with the input layer not involved in computations and therefore not considered. In this setup, the relationship between the output layer and input nodes is strictly one-way. The key feature of a multi-layer FFNN, as opposed to its single-layer counterpart, is the inclusion of at least two hidden neuron layers. In multi-layer FFNNs containing computational neurons, input signals undergo processing within the initial hidden layer. The weighted output parameters in the first layer serve as inputs for the subsequent layer of neurons. Particularly, studies have shown that increasing the quantity of hidden layers improves the network’s capacity to capture non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs, particularly when the quantity of input units of the network is great [73].

Feed backward Neural Networks (FBNN) represent a crucial class of artificial neural networks designed for efficient information processing in a unidirectional manner. These networks find extensive applications in diverse fields because of their capacity to apprehend intricate relationships within data. The architecture involves layers of interconnected neurons, with data flowing from the input layer through hidden layers to the output layer, lacking feedback loops. This unidirectional flow makes FBNNs adept at tasks like pattern recognition, classification, and regression [74]. In this extended discussion, we delve into the classification of FBNNs, including variations like Bayesian Regularized NN, Kohonen’s Self-Organized Map, Hopfield Networks, competitive networks, and ART models. Bayesian Regularized Neural Networks integrate Bayesian principles into the network’s architecture, providing a probabilistic framework for handling uncertainties in the data. This enables more robust decision-making and enhanced generalization capabilities, making them suitable for scenarios with limited data or noisy inputs. Kohonen’s SOM, also known as a self-organizing map or Kohonen map, is an unsupervised learning algorithm within the FBNN category. It is particularly adept at clustering and visualizing high-dimensional data, offering a topological representation of input patterns, making it valuable in tasks such as data mining and dimensionality reduction. Hopfield Networks are a type of recurrent FBNN that serve as content-addressable memory systems. They are well-suited for pattern recognition and associative memory tasks. Hopfield Networks exhibit stable states where specific patterns can be retrieved even when presented with incomplete or noisy input. Competitive networks, also known as winner-take-all networks, involve neurons competing for activation based on input patterns. These networks are often employed in clustering and pattern recognition tasks, where the strongest neuron (winner) represents the recognized pattern. Adaptive Resonance Theory (ART) models, a family of FBNNs, are designed to self-organize in response to varying input patterns [75]. These models exhibit dynamic learning and stability, making them suitable pattern recognition and classification in changing environments.

While FBNNs and FFNNs share the fundamental structure of layered neural networks, their operational distinctions are noteworthy. FBNNs, with their unidirectional flow, are well-suited for tasks requiring the processing of static input data, such as image recognition and classification. In contrast, FFNNs, with their feedforward and feedback connections, excel in capturing temporal dependencies and sequential patterns, making them ideal for tasks like natural language processing and time-series analysis. The choice between FBNNs and FFNNs relays on the particular conditions of the given task, emphasizing the importance of understanding their respective strengths and limitations in the context of the application (see Fig. 8). It’s important to note that overfitting poses a significant challenge in ANN training, where the system may accurately predict outcomes using known datasets but may fail to perform well when presented with new data [76].

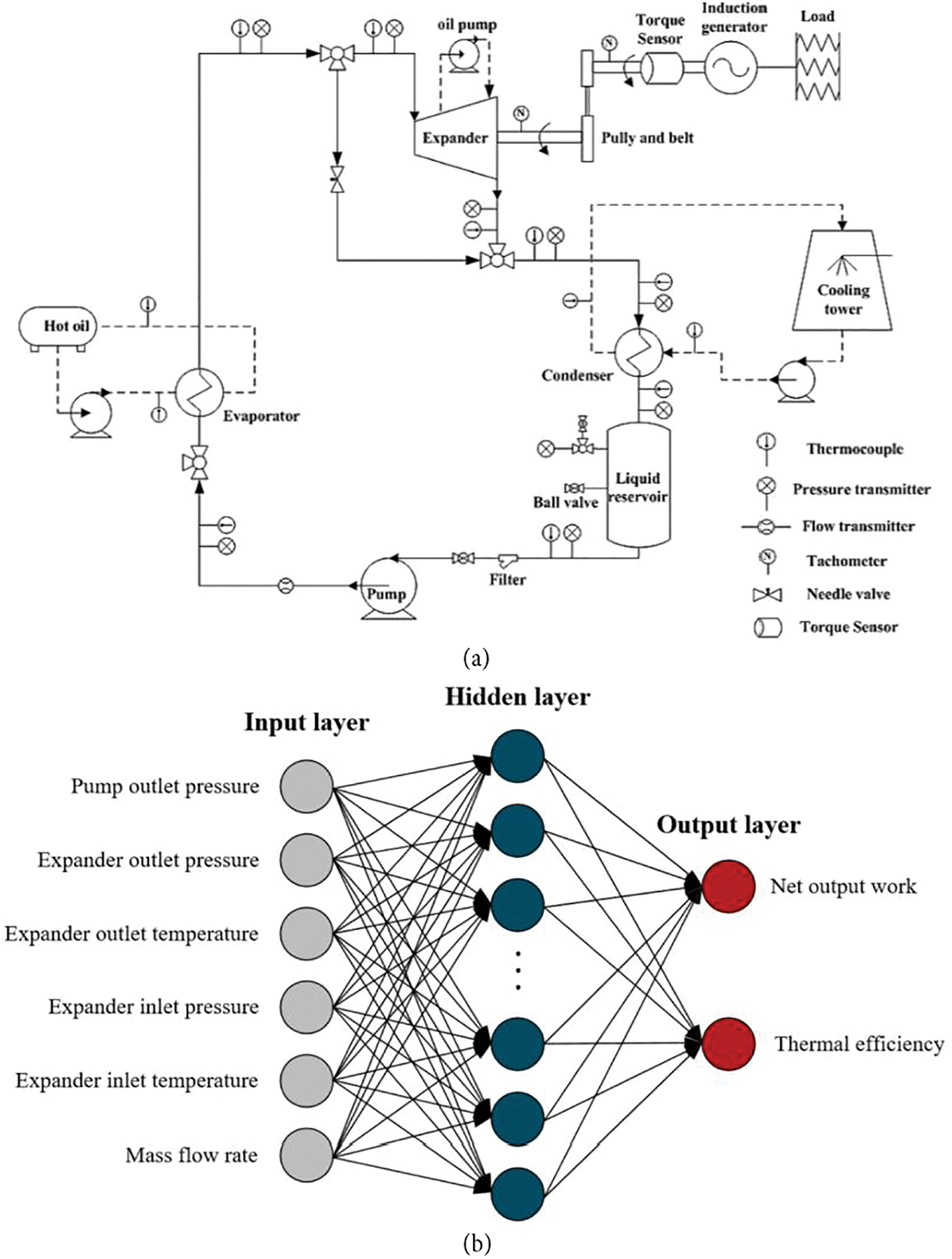

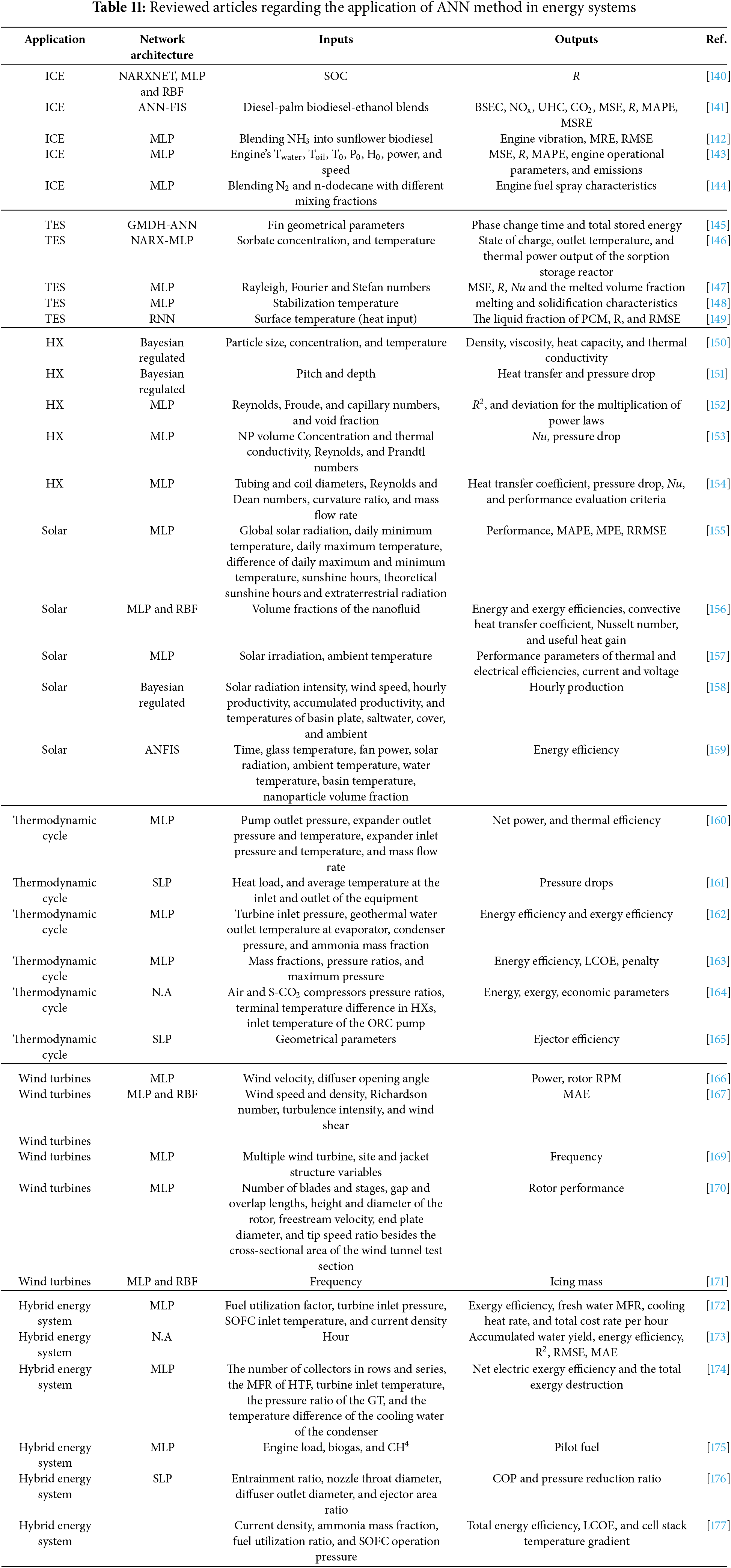

In the realm of energy systems, the predominant ANN models employed are as follows:

(1) Multi-layer perceptron (MLP) FFNN

(2) Radial basis function (RBF) FFNN

The details of these architectural structures are outlined below.

3.2.1 Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) FFNN

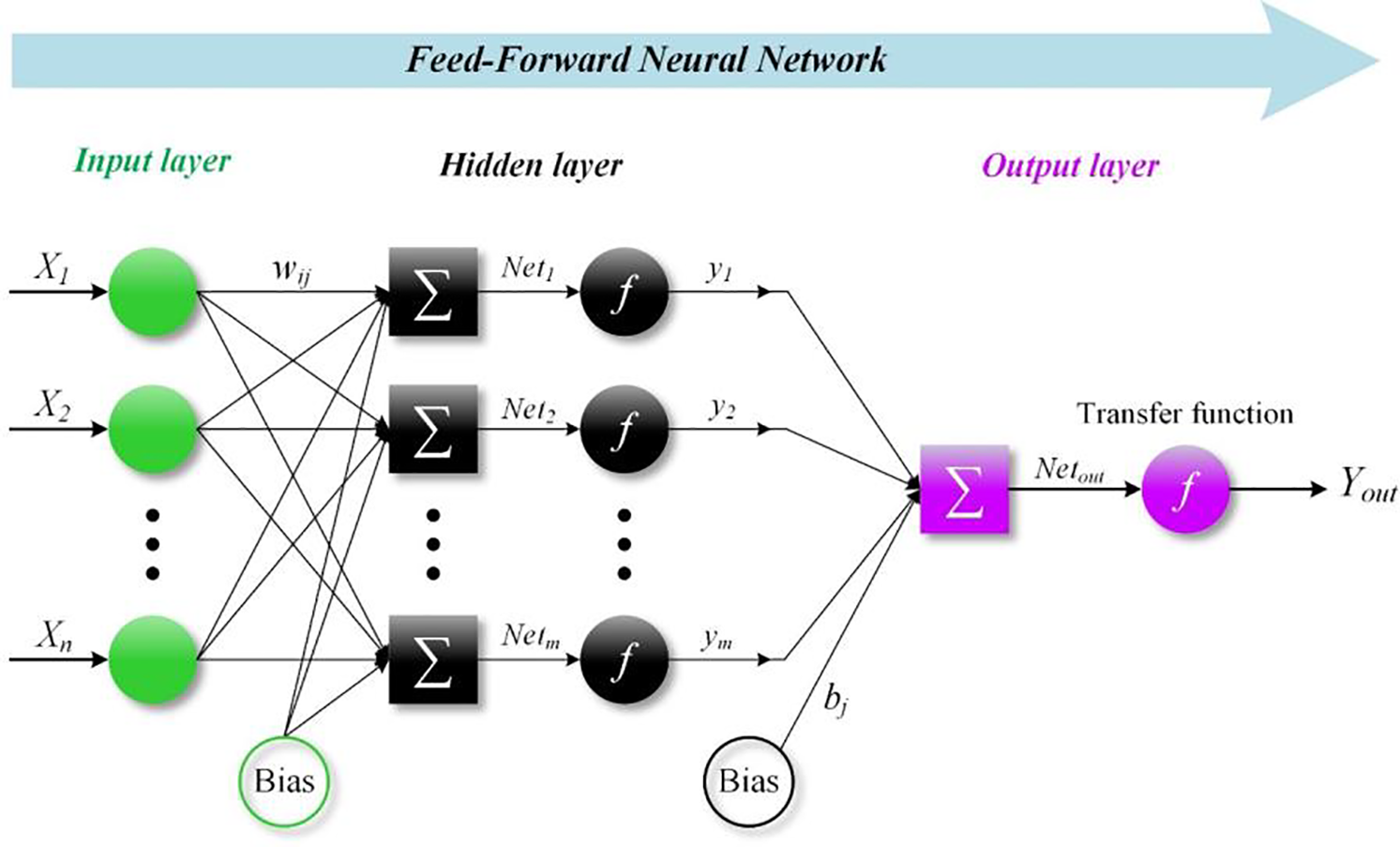

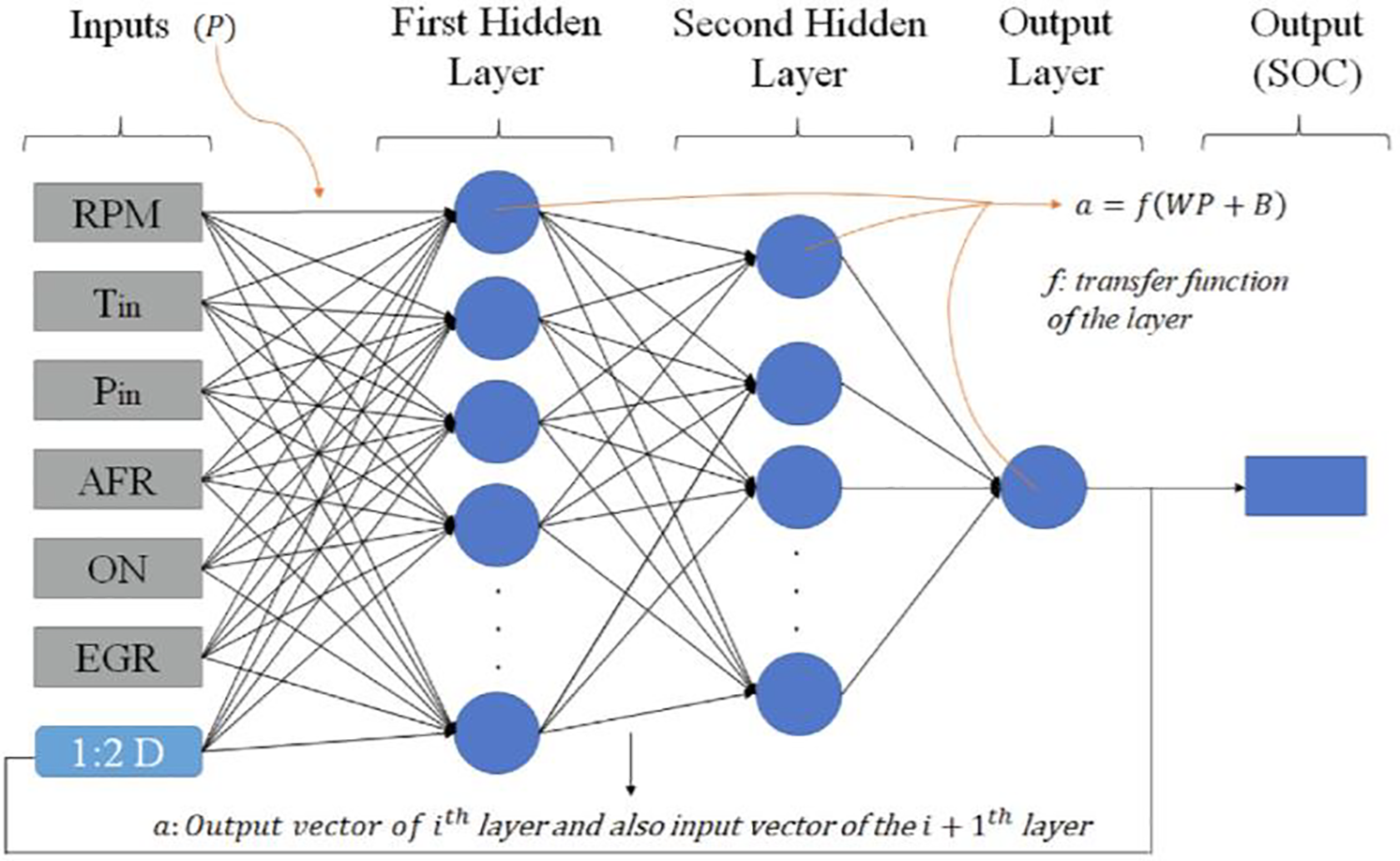

The MLP architecture is composed of three fundamental layers: the input layer, several hidden layers, and the output layer. Within this architecture, neurons receive input information from neighboring neurons, pass within hidden layers, and eventually reach the output layer. Neurons, serving as interconnected processing nodes, collectively form the ANN. Each neuron’s output is determined by a weighted set of inputs. The basic configuration of MLP is provided in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Basic structure of multi-layer perceptron FFNN

Based on the MLP modeling, the collective sum of weighted input units, formed by neurons, is expressed as follows:

In this context, i represents the index of input data (i = 0, 1, 2, ..., n), while wij refers to the weights connecting to the input data ai. Moreover, bj denotes the bias related to the neuron. The configuration of connection weights and biases encodes the information. A transfer function F is utilized to handle the sum of weighted input units in combination with the bias. The output is determined by Eq. (28):

Typically, both output and hidden layers feature an activation function. It can be either non-linear or linear. Various learning algorithms are accessible for establishing connections between inputs and outputs, with the FF back-propagation learning algorithm being the most prevalent. The sigmoid function, is a commonly employed non-linear activation function, characterized by an outcome range spanning from 0 to 1:

If negative values are encountered in the output or input layer, a transfer function called tansig is employed:

The model undergoes training with a specified number of neurons in the hidden layer, transfer function, learning rate, and momentum factor. The MLP stands out as the most prevalent neural model to forecast the efficiency of multiple types of energy systems.

3.2.2 Radial Basis Function (RBF) FFNN

The model shares a 3-layer structure with the MLP model, including the input layer, the hidden layer, and the output layer. Both models operate as feedforward neural networks. Considering the RBF, inputs gathered at the input layer and then transmitted to the second layer, known as the hidden layer. As demonstrated in Fig. 10, after processing in the hidden layer, the signals proceed to the output layer, where the final output data is generated. In the RBF hidden layer, a radial basis activation function is utilized, whereas a linear function is employed at the output layer.

Figure 10: Basic structure of radial basis function FFNN

Typically, the transfer function in the RBF hidden layer is the Gaussian function:

Here,

In this notation,

4 Application of Taguchi and ANN in Energy Systems

Over the past years, most studies in energy applications have highlighted the benefits of the Taguchi optimization method as an examination tool to achieve the maximum amount of information for a given experimental dataset. By utilizing Taguchi-based optimization techniques, factors influencing energy production, transmission, and consumption can be fine-tuned to achieve optimal performance levels regarding both the single-objective and multi-objective problems. This section extensively examines the utilization of Taguchi-based methodologies across a broad range of energy systems, encompassing internal combustion engines (ICEs), thermal energy storage systems (TESs), solar energy installations, thermodynamic cycles, heat exchangers (HXs), as well as wind and tidal turbines.

4.1.1 Internal Combustion Engines (ICEs)

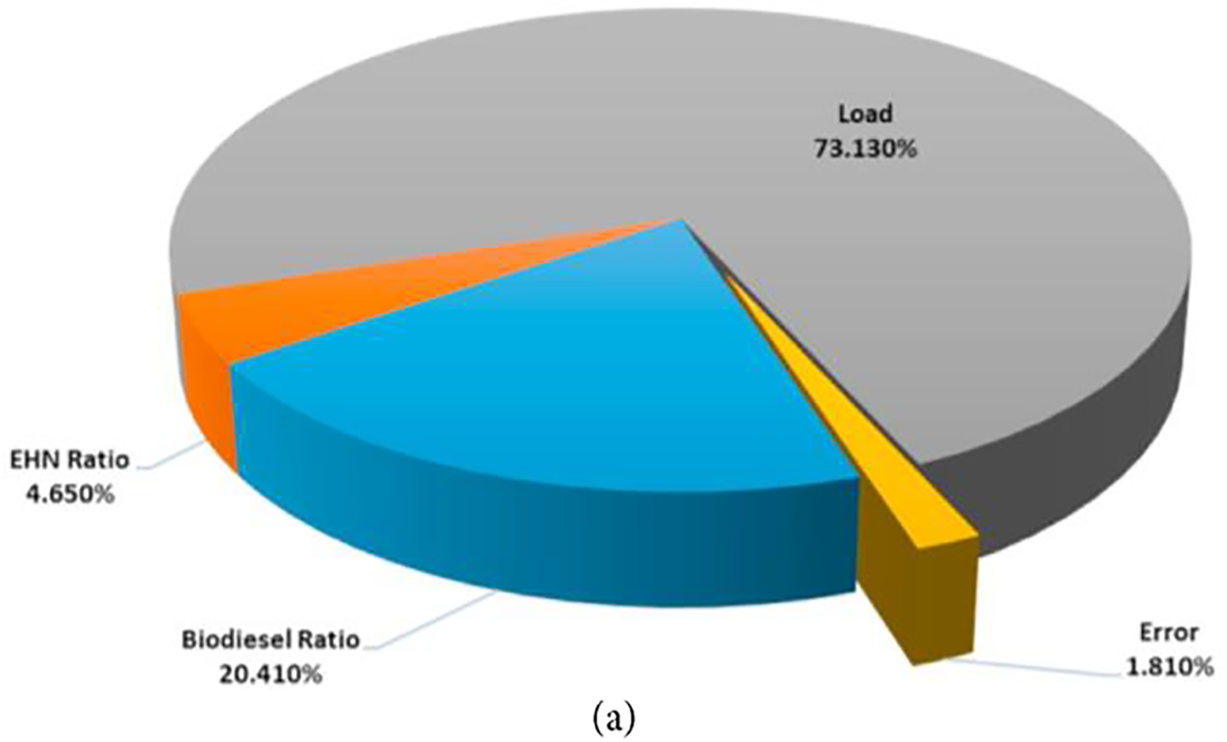

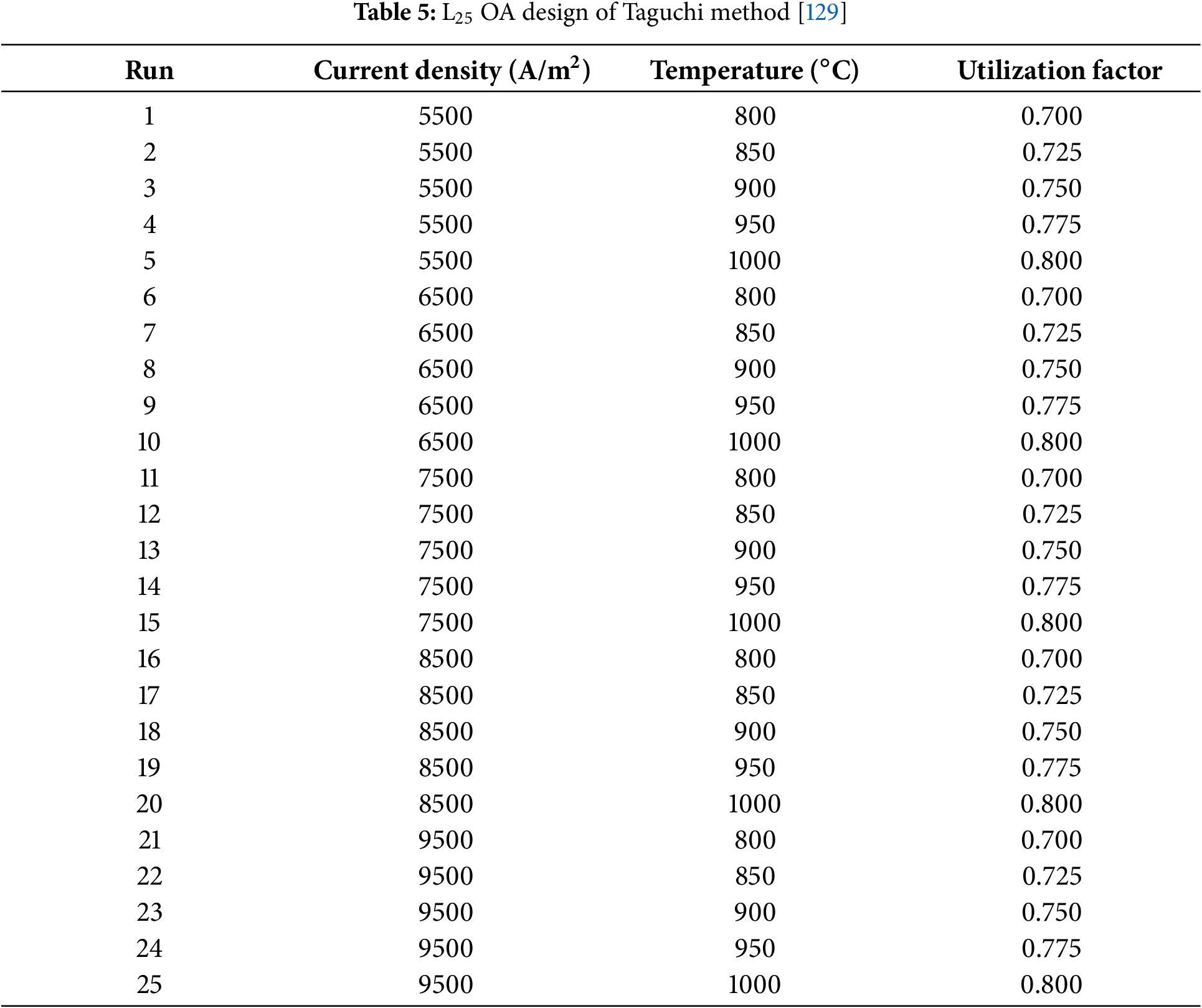

Subramani and Govindasamy [77] optimized the design and fuel factors of a direct injection compression ignition engine in order to lower the NOx and emissions as well as enhance the engine brake thermal efficiency (BTE). The effects of eight input factors, including percentage of biodiesel/diesel blend, butanol, pentanol and propanol, together with injection timing, EGR percentage, piston geometry, and injection pressure, were investigated. The best combination of input factor levels against the objective responses was obtained by using Taguchi OA and the S/N ratio. It was concluded that the effects of the percentage of biodiesel in the diesel/biodiesel blend and the percentage of EGR were negligible. Additionally, compared to other alcohols, propanol has the lowest effect on output responses. Simsek et al. [78] examined the performance and emission characteristics of diesel engine in terms of effects of several proportions of biodiesel fuel mixtures and 2-Ethylhexyl nitrate (EHN) at various engine loads. The percentage blend of EHN, the engine load, and percentage blend of biodiesel fuel mixtures by three levels of each, were considered as control factors (Fig. 11). Hence, the experimental runs were arranged by using L27 OA. The optimization was accomplished to achieve the optimum combination of input control factors and output responses, namely BTE, carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), hydrocarbons (HC), BSFC, and smoke emission. Optimization results showed that a load of 2300 W, and a biodiesel/EHN ratio of around 99/1%, were defined as the optimum combination of control factors. The suggested Taguchi design had the ability to map engine output paradigms with excellent accuracy.

Figure 11: Effect of engine variables on (a) BTE and (b) BSFC [78]

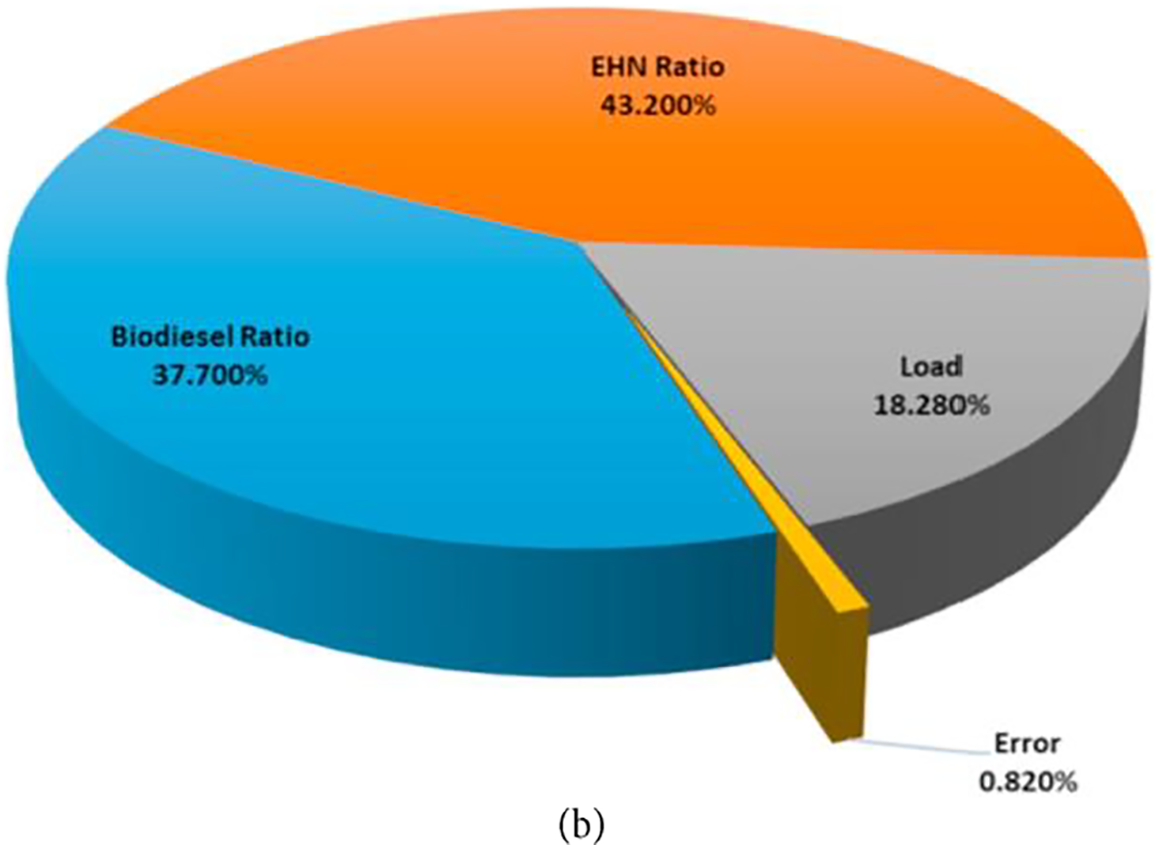

The impacts of engine load, compression ratio (CR), engine speed and, EGR as the control parameters of a port fuel injection SI engine modified from a CI engine fueled by methanol were investigated by Zhou et al. [79]. The thermal efficiency, NOx emissions, and BSFC were as target responses. By employing the Taguchi method and ANOVA, it was revealed that higher amounts of EGR rate and lower CR leads to lower NOx emissions. On the other hand, higher CR was suitable for reducing the BSFC. Additionally, 17:1 was found to be the optimal CR for the investigated engine. Moreover, it was concluded that with an increase in the rate of EGR, flame propagation was decreased, as well as the pressure rise rate and the heat release rate were reduced. The influences of biodiesel, ethanol, and diesel blending on engine performance, combustion, and emissions were explored by Shrivastava et al. [80]. Experimental observations were performed on a CI engine at a constant speed of 1500 rpm and the injection pressure of 210 bar. The four input parameters—injection angle, compression ratio (CR), fuel blend percentage, and engine load—are adjusted to achieve optimal objective responses such as BTE, BSFC, CO2, CO, NOx, HC emissions, and exhaust gas temperature. In order to obtain the optimal combination of the input factors and objective responses, Taguchi L9 OA was applied (Table 3). Furthermore, the ANOVA was operated to specify the contribution of input factor. Injection angle of 19°CA bTDC, CR of 18, fuel blend of 30%, and 50% of the load was calculated as the optimum combination of inputs. By applying the optimum combination, the responses displayed a marginal decrease of BTE by around 2%, BSFC increased by 3%, exhaust gases temperature increased by 3%, CO2 raised by 0.86%, HC reduced by 12 PPM, CO and NOx decreased by up to around 0.029% and 8%, respectively.

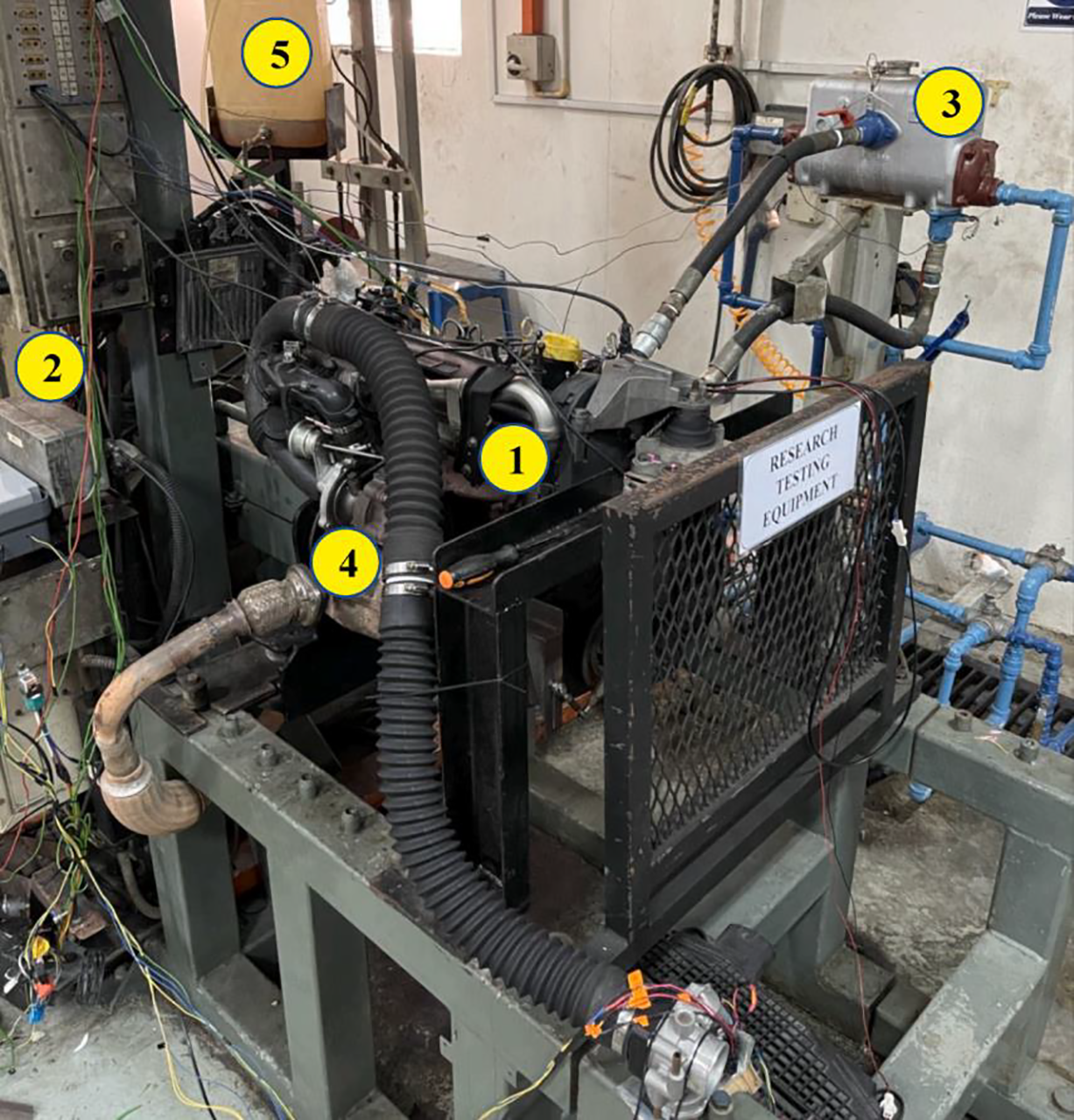

Performance characteristics examination and optimization of a CI engine running dual biodiesel fuel using the Taguchi method were conducted by Pandey et al. [81]. The impacts of several input factors, including CR, percentage of biodiesel blend, and fuel injection pressure against the operating variables such as BTE, BSFC, and emissions, were characterized. According to the experimental design of Taguchi L16 OA, the trials were accomplished for the single-cylinder CI engine operating by the dual biodiesel blends of Soyabean and Karana. To achieve a better performance and exhaust emission features, the best combination of input factors and output responses was calculated. Hence, the Taguchi optimization results indicated that the best combination of input factors to meet the maximum values of BTE had been observed as a biodiesel blend of 20%, CR of 16:1, and fuel injection pressure of 230 bar. A small number of studies have operated the Taguchi-GRA in order to perform multi-response optimization of coconut oil-diesel fuel blends by using different input variables. Hence, Heng Teoh et al. [82] experimentally (Fig. 12) focused on discovering the best combination of biodiesel blend ratio, engine load, and speed under various conditions using the Taguchi-GRA method. The Taguchi method with an L16 OA was employed for DOE. For calculating the optimal variables, the S/N ratio and GRA grade were applied. Moreover, the ANOVA table was utilized to examine the importance of the three engine inputs against the objective responses. The outcomes revealed that considering the combustion features, exhaust emissions, and performance of the CI engine, the following factors were the optimum combination of inputs: a 30% blend ratio, an engine speed of 3850 RPM, and an engine load of 25%. As a comparison to traditional diesel fuel, employing the optimal engine conditions increases TC boost air pressure, CO emissions, O2 levels, and smoke emissions by approximately 0.44%, 12.9%, 1.15%, and 14.97%, respectively.

Figure 12: The arrangement for the experimental setup; (1) test engine, (2) eddy current dynamometer, (3) engine coolant heat exchanger, (4) turbocharger, and (5) fuel supply tank [82]

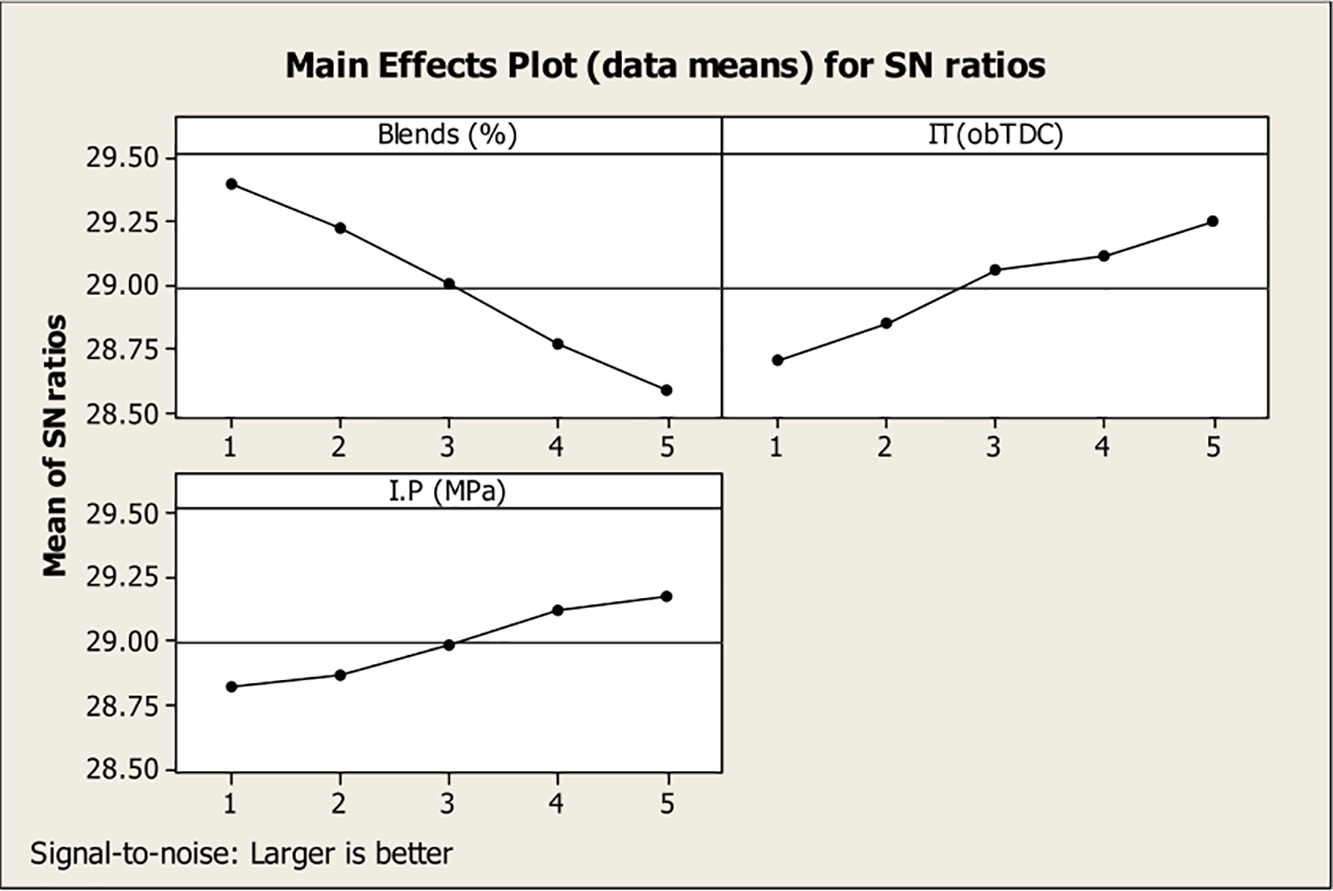

The emission characteristics and combustion performance of a 4-stroke 1-cylinder engine operating canola oil combined diesel with Al2O3 NPs through single and multi-objective optimization techniques were improved by Ramesh et al. [83]. To maximize BTE, and minimize NOx emission along with the fuel cost, the Taguchi S/N ratio, GRA, as well as RSM techniques were utilized. Percentage of the canola oil blend, NPs concentration, injection timing and pressure were considered as the practical input variables. Accordingly, considering Taguchi-GRA integrated with RSM, the optimum combination of inputs was determined as follows: canola oil blend percentage of around 19%, 30 ppm for the concentration of NPs, 220 bar for injection pressure, and fuel injection timing of 21° bTDC. The mentioned combination improves the BTE by up to 16%, together with a reduction of NOx by about 3% in comparison to diesel fuel. By using Taguchi-based GRA, a multi-factor optimization mechanism for combustion efficiency of a hydrogen-fueled micro-cylindrical combustor was explored by Zuo et al. [84]. Taguchi L25 OA was provided according to six input factors, namely inlet velocity, hydrogen/air equivalence ratio, convective heat transfer coefficient (h), inlet temperature, wall emissivity, and wall thermal conductivity. Further, GRA and ANOVA were utilized to assess the impact of these input variables on combustion efficiency, ranking them from highest to lowest effectiveness. Hence, inlet temperature, inlet velocity, and hydrogen/air equivalence ratio were specified as the most influential factors in the combustion efficiency, respectively. To discover the best engine running variables against the optimum engine responses, the Taguchi optimization method was applied by Uslu et al. [85]. They scrutinized the influences of diethyl ether ratio, palm oil ratio, engine load, and injection advance on the performance and emission of the diesel engine. Examinations were configured according to Taguchi L27 OA, considering factors and responses such as BTE, BSFC, exhaust gases temperature, HC, CO, NOx, and smoke. The influential engine input variables on output responses were specified by using ANOVA. The results showed that the largest S/N ratios for BSFC, BTE, and exhaust gas temperature were detected by the lower diethyl ether ratio ratios, lower advance in injection variables, and intermediate engine load values. Moreover, the largest S/N ratio for smoke and CO were observed when using a 20% palm oil blend. Conversely, the maximum S/N ratio for other outputs were attained when using a 0% palm oil blend. Sharma et al. [86] conducted research to investigate and optimize the input variables of a diesel engine operating at full load, fueled with a blend of Pongamia biodiesel. To find the optimum results, a hybrid utility theory-Taguchi optimization method was employed. Experimentation was conducted concerning the combination of utility theory and Taguchi optimization methods. Hence, for multiple input variables, namely fuel injection timing, blends of Pongamia biodiesel, fuel injection pressure, and responses such as NOx, BTE, and smoke, the optimization was carried out (Fig. 13). It was concluded that the 10% of blending for Pongamia biodiesel with injection timing of 23° bTDC, and injection pressure of 22 MPa was discovered as the best engine factors vs. output responses.

Figure 13: Main effect plot of the S/N ratio for BTE [86]

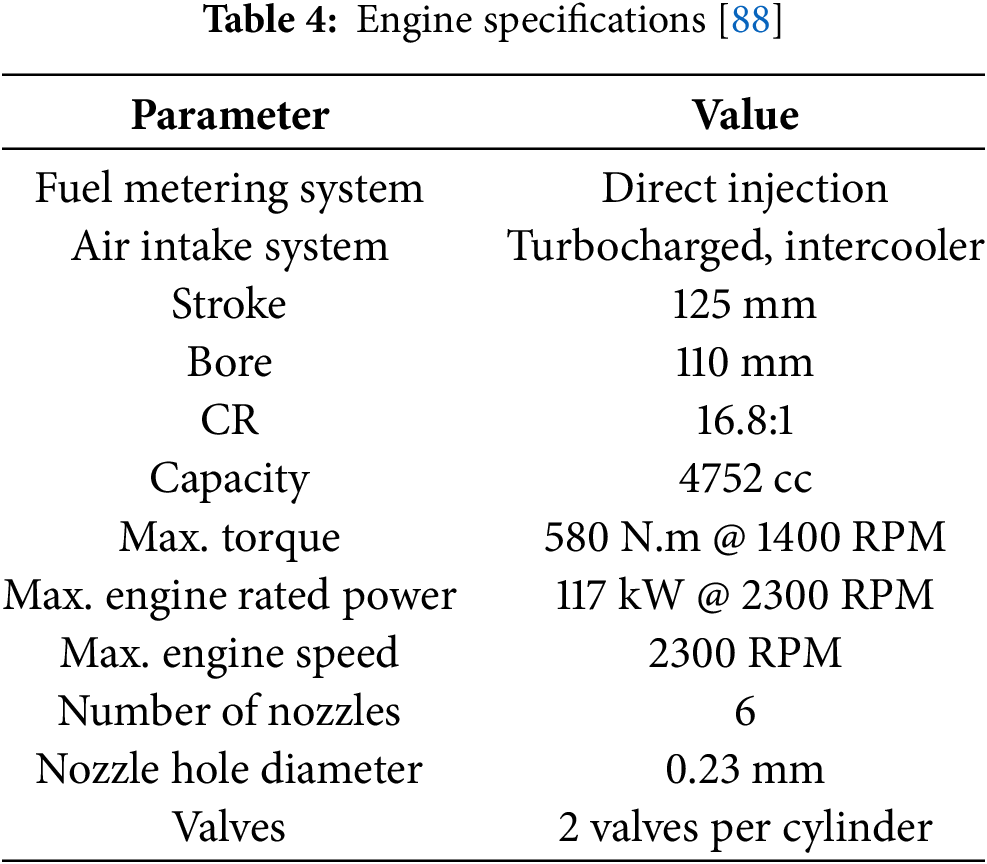

Multi-response optimization of an engine operating by various fuel types, including additives, by using the Taguchi-based GRA technique was conducted by Çelik et al. [87]. Two types of biodiesel fuel called rapeseed oil biodiesel and cottonseed oil biodiesel were considered for this single-cylinder diesel engine. Additionally, n-hexane and n-hexadecane were utilized as additives. Based on input factors and levels, the Taguchi L18 OA was considered, and three levels of 4%, 8%, and 12% were allocated to the additives. Comparing between rapeseed and cottonseed, the outcomes exhibited that rapeseed oil depicted the optimum system responses. Moreover, utilizing the hexadecane offered a better result compared to the hexane additive. ANOVA also indicated that blend and type of fuel were selected as the predominant operating factor influencing the GRA grade in terms of optimization of engine emissions and performance. The optimization outcomes also demonstrated that the best condition of the diesel engine arises by operating rapeseed oil biodiesel including 12% hexadecane as the additive. Taguchi-based GRA and ANN-based optimization to achieve the best performance by low-emission diesel engine fueled with biodiesel was investigated by Gul et al. [88]. The engine’s operational characteristics are indicated in Table 4. The Taguchi L9 OA was applied to acquire the best combination of practical input factors, including the fuel nature, as well as the DI-diesel engine speed and load. The diesel engine was alternatively fueled by waste cooking oil based on pure biodiesel and the 20% blend of biodiesel with regular diesel. The main objective functions were defined to decrease NOx and smoke emissions as well as to enhance in-cylinder pressure, heat release rate, the BSFC, and brake power at different loads. The GRA result determined the best input factors as follows: full engine load, pure biodiesel as the fuel, 2300 RPM for engine speed. Further, the ANOVA revealed that the fuel type was considered the main prominent variable with around 44% influence on the output responses.

Fuzzy logic-based Taguchi method optimization of two input factors called CR and fuel injection timing of a constant-speed diesel engine fueled with oxygenated blends, was studied by Kumar Chidambaram et al. [89]. The examinations involved three types of blends labeled as DEE6 (6% diethyl ether with 94% diesel), DEE8 (8% diethyl ether with 92% diesel), and DEE10 (10% diethyl ether with 90% diesel). The findings revealed an improvement in engine performance when utilizing a compression ratio (CR) of 19:1 for the blends. Among the emissions, NOx emission was noted to be the highest, while CO, unburned HC, and smoke emissions were minimized. The engine performance operating DEE8 with CR of 19:1 and 21°bTDC leads to a 6% improvement in BTE, and a reduction in smoke, HC, and CO up to around 14%, 25%, and 21%, respectively. The fuzzy logic-based Taguchi approach outcomes depicted that the optimum combination of considered input factors was 21°bTDC for fuel injection timing and a 19:1 CR.

Jain et al. [90] focused on producing biodiesel from Water Hyacinth and testing it in a diesel engine to address the twin challenges of the fossil fuel crisis and increasing pollution. A 3.5 kW single-cylinder research engine was used with varied injection timings and engine loads. Results showed the maximum BTE at 80% load, 20° bTDC injection timing, and a compression ratio of 17.5. The L16 OA, S/N ratios, and ANOVA were employed for efficient testing and data analysis. RSM-based desirability optimization yielded reliable predictive models, indicating engine load’s significant impact on brake thermal efficiency and emissions. The optimized output of 24.44% BTE, 51.2 bar PCP, 29.6 ppm CO, 1.51 vol% CO2, 176 ppm NOx, and 23.66 ppm HC was achieved at 78% load and 20° injection advance. The modeling residuals were below 6% in the validation test, affirming the accuracy of the developed correlations. In a similar investigation, the influence of the design and control parameters on the performance and emissions features of a single-cylinder boosted GDI SI engine, was investigated experimentally using the Taguchi method by Atis et al. [91]. The Taguchi L18 OA design has been applied to examine the input factors: intake valve closing (IVC), EGR rate, fuel injection timing, CR, intake port tumble design, piston bowl design, injector spray pattern, and fuel injection pressure. It was concluded that computation of the S/N ratios caused an understanding of the +/− effects of each input factor at three speed-load conditions of the engine. Furthermore, in terms of specified factors, IVC timing, CR, intake port design, EGR rate, and fuel injection timing were determined as more effective factors for the responses.

Taguchi-based optimization strategy and investigation for combined effects of EGR rate, supercharging pressure, biodiesel blends, and ethanol injection through the intake manifold of a DI diesel was accomplished by Ayhan et al. [92]. Experimental runs were performed according to the Taguchi L16 OA design. The appropriate engine operational parameters were specified through the Taguchi optimization method in terms of responses such as engine brake-specific heat consumption, NO, HC, smoke, CO2, and CO emissions. The results revealed that the optimum smoke, HC and CO emissions were achieved in 40% of engine load, biodiesel fuel blend of 50%, without ethanol injection, without EGR, at an engine speed of 1600 RPM, and supercharging pressure of 2.1 bar. Further, the optimized NO emission was observed at engine load of 40%, pure diesel fuel, without ethanol, EGR rate of 20%, the engine speed of 2400 RPM, and supercharging pressure of 2.1 bar.

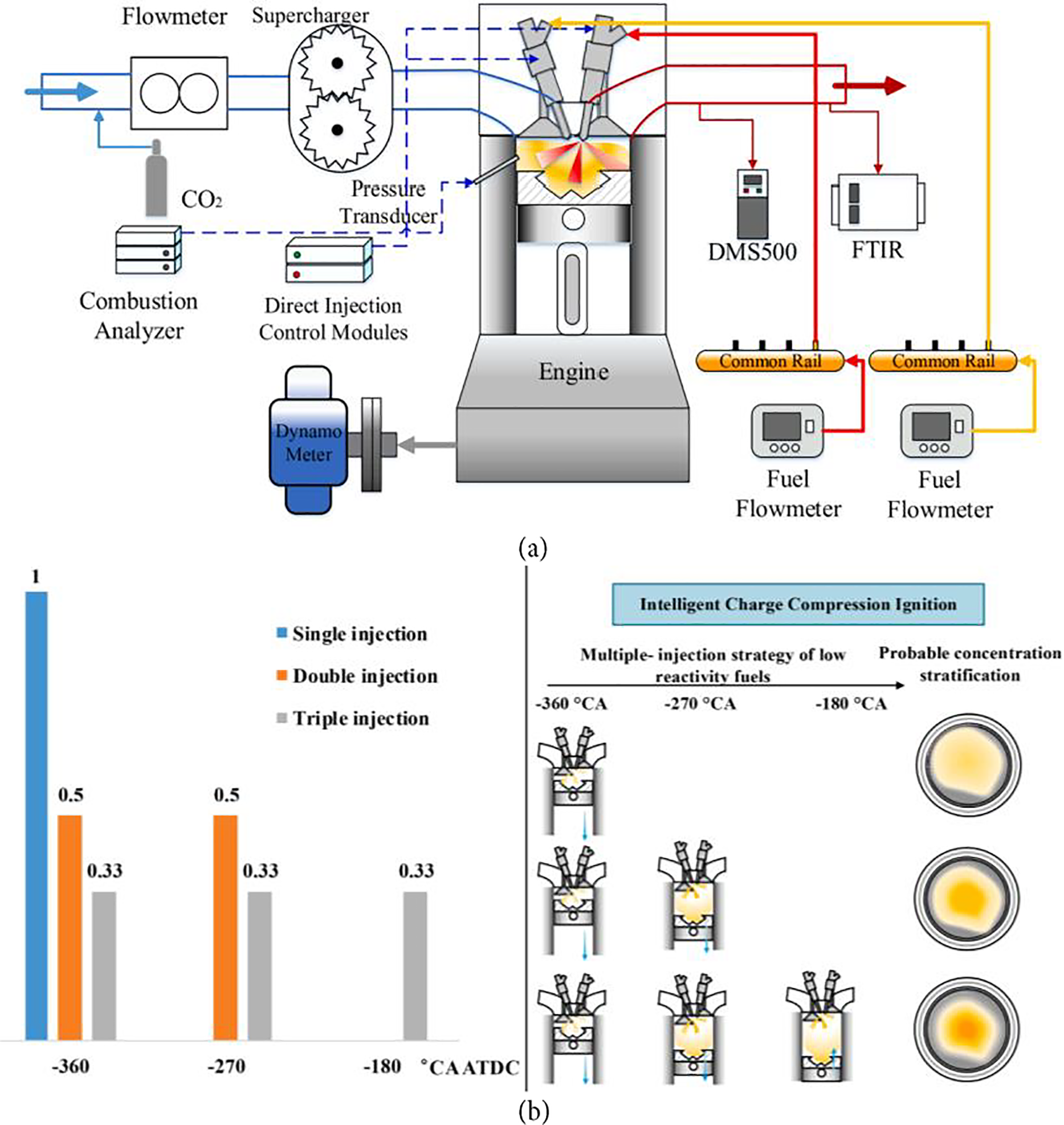

Manigandan et al. [93] employed the Taguchi technique to examine the influence of blends of multiwall carbon nanotubes (MCNs) and hydrogen on the efficiency and emissions of the diesel engine. The Taguchi L16 OA was employed to investigate the effects of the following input parameters: MCNs of 30, 50, and 80 ppm by various fuel blend features, as well as hydrogen of 10%, 20%, and 30%, at various engine loads of 25%–100%. Additionally, the ignition pressure and timing were evaluated at four levels of 180–240 bar and 210–310 CA bTDC, respectively. Results indicated that in a comparison to pure diesel, the hydrogen and MCNs additions reduce the emission accompanied by an increase in the BTE value. The importance of the optimal input parameters was also dissected using the ANOVA table. Hence, it was noticeable that the addition of hydrogen and MCNs led to an improvement in the performance and emission features. Furthermore, results revealed that at the full engine load conditions, brake power was enhanced by up to 13%, and BSFC was decreased by up to 8%. Zhang et al. [94] studied optimizing control parameters for an ICCI type engine, which incorporates an additional DI system (Fig. 14). Taguchi design of experiment, utilizing an L18 orthogonal array, simplified the optimization process. The impacts of factors such as excess air ratio, engine speed and load, premixed strategies, and the fuel energy ratio of E85 (comprising 15% gasoline and 85% ethanol) were examined by using the S/N ratio and the ANOVA regarding their influence on particle number (PN), indicated thermal efficiency (ITE), and gaseous emissions. The Taguchi method provided optimized control rules for ICCI across various operating conditions. Engine load and speed were found to have significant influences on ITE, whereas E85 energy ratio, premixed strategies, and excess air ratio exhibited contrasting degrees of impact on emission characteristics. The optimized strategy achieved an 80% E85 substitution ratio led to a reduction in CO2 emissions to below 500 g/kWh in most conditions, with the ICCI combustion load reaching 75% of the original diesel engine load.

Figure 14: (a) Schematic of the experimental setup system (b) Multiple-injection strategy description [94]

4.1.2 Thermal Energy Storages (TESs)

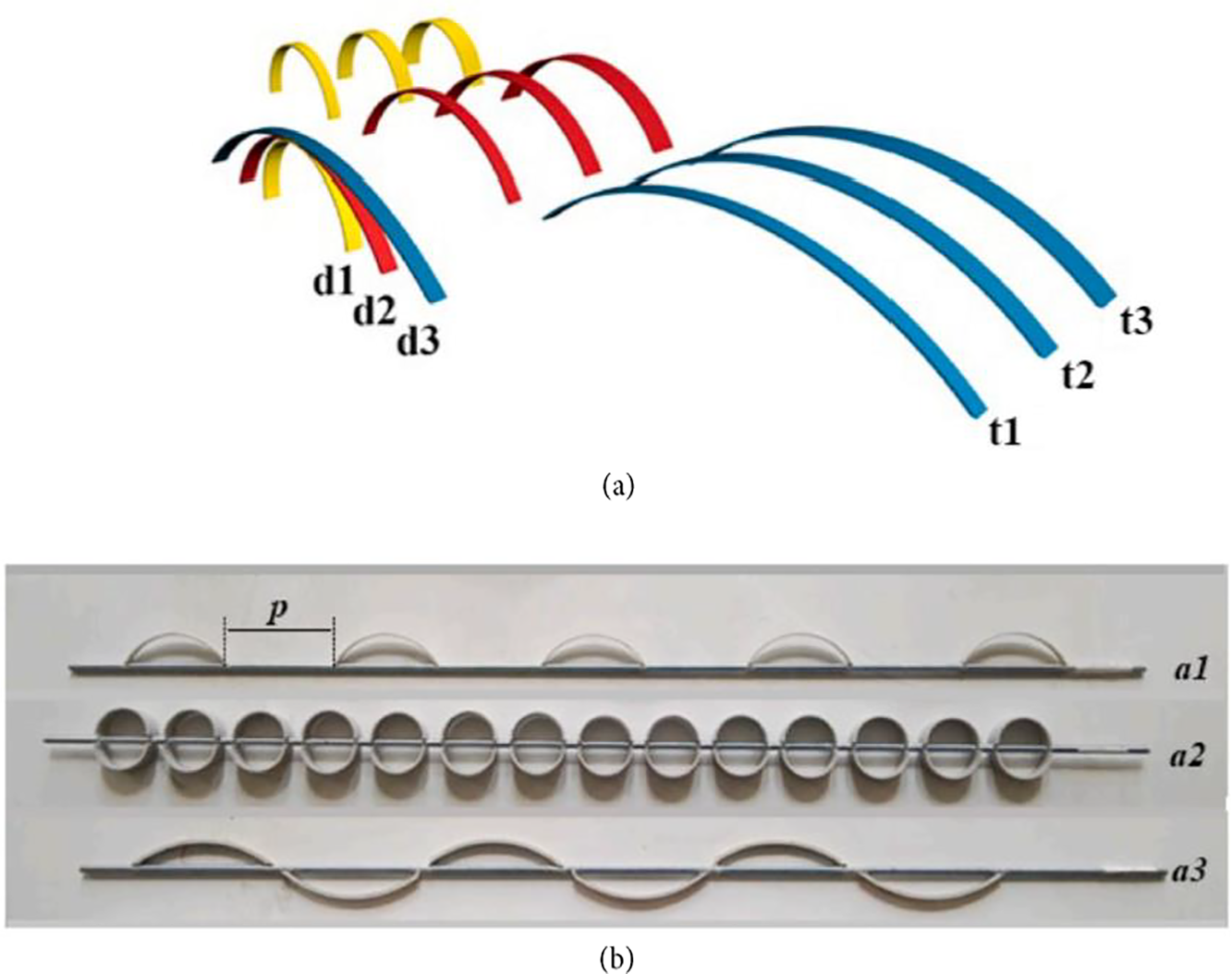

The experimental investigation and Taguchi-based optimization of phase change material (PCM) layer as insulation wall for TES system were conducted by Kurnia et al. [95]. The impacts of main geometric and operating variables such as inlet volumetric flow rate and temperature of the HTF and the ratio of PCM volume to HTF volume were assessed against the efficiency characteristics of the hybrid TES. The results indicated that the hybrid TES system with a PCM wall layer presents a better insulation performance. This arises a higher retained temperature within the storage compared to conventional TES. The capacity of TES heat storing was improved by employing the PCM wall. Moreover, among the input variables, HTF inlet temperature was found to be the most influential parameter on the performance of the Hybrid TES system. By using the Taguchi-based GRA, Çinici et al. [96] experimentally examined the optimum factors affecting the melting time of solar TES unit, including a spring-type heat transfer enhancer of thermal energy storage unit (Fig. 15). Considering the Taguchi L9 OA, the impacts of various input factors including spring diameter, spring pitch, and wire diameter vs. the characteristics of time-dependent enhancement ratio and melting time of latent heat TES unit were scrutinized. The ANOVA tables were utilized to find out the most significant input parameter against the melting time and time-dependent enhancement ratio. Performing the GRA simplifies the optimization process into a single-objective problem rather than a multi-objective one. As a result, the optimal levels were determined to be the highest levels of spring pitch and wire diameter, along with the minimum level of spring diameter.

Figure 15: Experimental arrangement of different copper springs in the PCM storage [96]

The solidification behavior of nano-enhanced PCMs in triplex-tube and shell-and-tube TES units was investigated through the Taguchi optimization approach by Khatibi et al. [97]. The solidification process, as well as thermophysical features of PCM incorporating various metal oxide NPs such as ZnO, SiO2, Al2O3, and CuO inside a triplex tube, was evaluated. To specify the best performance of the system, a comparative study for various HTF temperatures and tube diameters among three typical TES units was conducted. Therefore, triplex-tube plus shell-and-tube with inner and outer cooling by the similar volume for the storage unit were determined. According to the Taguchi analysis, compared to the other NP-PCMs, the Al2O3-PCM indicates a higher rate of solidification at the volume fraction of 2%. In addition, dispersing nanoparticles in PCM is found to be the less effective parameter. As a comparison to other units, the triplex tube presents a better solidification time at any level of input parameters.

The characteristics of the petal-shaped pipes in a shell-and-tube TES unit, were numerically investigated and optimized using the Taguchi method by Ghalambaz et al. [98]. The effects of applying two types of NPs-additives called copper (Cu) and graphene oxide (GO) for heat transfer enhancement, together with the geometrical characteristics of the petal pipe vs. the thermal performance of the TES unit were analyzed. The Taguchi optimization results revealed that compared to a typical design, the optimized tube design could enhance the energy storage capacity for Cu and GO by up to around 23% and 22%, respectively. In comparison to a circular tube without using NP, the optimal design in which Cu operates as NP enhances the heat transfer by around 45%. According to the ANOVA table results, the operating range of petal shaped-tube could impact the energy storage by a contribution ratio of almost 41%, while the NPs share was calculated at about 6%.

The Taguchi-based optimization of melting heat transfer rate in terms of using capric acid PCM in a channel shape TES unit was numerically explored by Mehryan et al. [99]. A mixture of Cu NPs and copper foam was applied to improve the melting heat transfer rate and to enhance the thermal conductivity further. Considering the Taguchi optimization approach, input parameters, including the shape and the porosity of the copper foam layer, plus the volume fraction of NPs, were optimized in order to attain minimum charging time. The outcomes showed that the higher the porosity and volume fraction of NPs leads to the lower charging time of TES. Additionally, simultaneous utilizing the mixture of copper-foam and Cu NPs together with the optimum design of the porous layer decreased the melting time by up to 300%. Besides, it was found that the foam layer porosity was the most effective variable in the heat transfer.

Taguchi optimization and evaluation of the transient thermal performance of PCM outfitted walls were conducted by Zhang and Deng [100]. The effective input parameters considered are as follows: the phase change temperature deviation of PCMs from ambient ones, total latent heat and location of PCMs, along with the thermal conductivity of the wall. Considering the importance of input parameters, the criteria for high thermal performance were acquired. Additionally, a comparison table including three values of synthesis score, thermal index value, and thermal performance level was considered to classify the walls’ performance. Multi-objective optimization, together with experimental research of a TES using PCMs for solar air systems were introduced by Lin et al. [101]. Two conflicting objective functions called effective PCM charging time along with the average heat transfer effectiveness were considered as output responses. The Taguchi L9 OA was proposed for effective input parameters, namely inlet air temperature of the TES unit, charging air flow rate, number of PCM bricks along the TES unit, and number of air channels. Besides, the experimental exploration revealed the impacts of critical parameters on the performance of the air-based PCM-TES system. It was concluded that the system’s average heat transfer effectiveness could be enhanced by up to 15%. At the same time, the effective PCM charging time is raised by up to about 1.5 h.

The experimental study and Taguchi optimization of various control parameters, including plate inclination angle, HTF velocity, and HTF temperature for a plate-type TES unit using PCMs, were accomplished by Sun et al. [102]. The energy charging rate was determined as the objective function of the optimization. According to the optimization results, 55°C for the HTF temperature, the plate inclination of 75°, and the HTF velocity of 5 m/s were defined as the optimum values for input parameters. Applying the mentioned optimum values for input parameters, the optimal energy charging rate was determined to be 760 W, resulting in a 23% improvement. Furthermore, it was observed that the most significant parameters were the HTF temperature followed by the HTF velocity for the melting process. Optimizing the plate inclination angle proved to be an effective method for enhancing the melting process without requiring additional energy or materials.

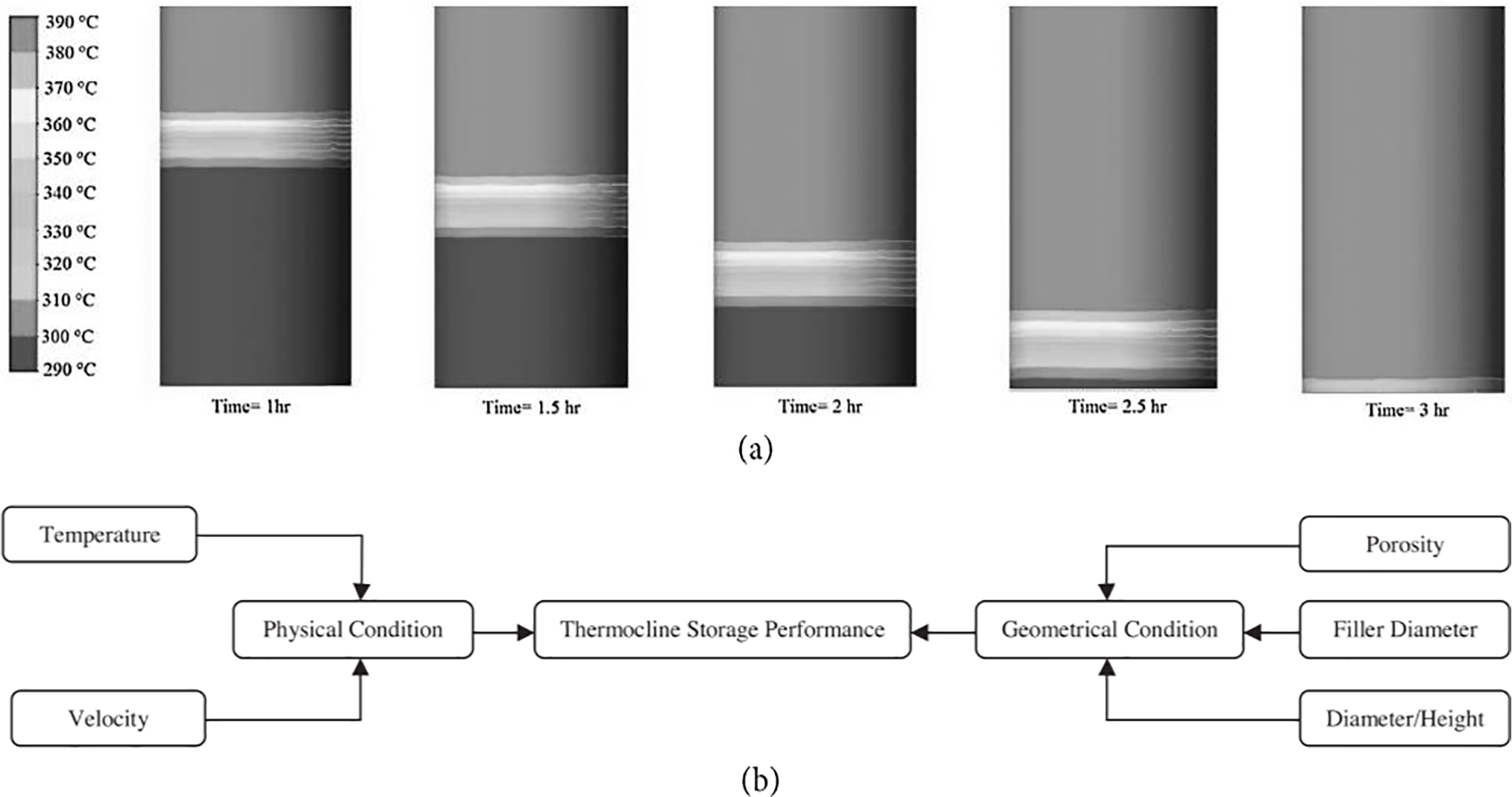

A 3-dimensional CFD numerical modeling and evaluation of dual medium thermocline TES was conducted by Nandi et al. [103]. The thermal performance and characteristics of the proposed system were explored under various working conditions to evaluate the charging and discharging processes of a 50 MWh fixed-size TES (Fig. 16) The 3-dimensional CFD model was developed according to a macroscopic version of the k–epsilon equation for turbulent flow conditions. Besides, the Taguchi optimization approach was employed to optimize design factors related to the thermocline TES system. Hence, the influence of the design factors, namely the inlet fluid Re number, aspect ratio, porosity, and filler size, on the TES performance was assessed. The research outcomes demonstrated that the porosity and aspect ratio were the most significant design factors for thermocline TES, respectively.

Figure 16: (a) Thermocline thermal storage tank temperature distributions at a different charging time (b) Parameters influence thermocline thermal storage performance [103]

The efficiency of the coaxial HX with semicircular striped turbulators was examined by Turgut and Yardımcı [104], considering Taguchi-based GRA (Fig. 17). Control factors were Re number, thickness, pitch, arrangement style, and diameter. As well, the Nu number, thermal performance factor, and friction factor were considered as responses. The Taguchi OA design was considered to find the optimum control parameter levels for maximum heat transfer and minimum friction factor. Considering the GRA, the multi-objective optimization of performance features was calculated, and the impacts of input variables on the pressure loss and the heat transfer were assessed. Based on the ANOVA outcomes, the most influential variable against the Nu number was the Re number with 31% of the contribution. In contrast, the least effective factor was the pitch with about 2%. In addition, results indicated that the Re number was specified as the most critical factor in respect of the total performance characteristics of the HX. Moein Darbari et al. [105] conducted a study to evaluate the performance of a HX by performing a sensitivity evaluation of nanofluid flow through various flat tubes confined between two parallel plates. by utilizing the Taguchi method and ANOVA. The nanofluid, including NPs of AlO by various flat tubes with axial ratios of 1.5–2.5, volume fractions of 0%–8%, and square sections tubes in comparison with circular were employed as input factors. The Taguchi L25 OA design and ANOVA were considered to analyze the sensitivity of pressure drop and heat transfer features of the HX. The conclusion drawn was that by adjusting the further flattening and cross-section, the pressure drop and heat transfer were reduced together. On the other hand, by raising the NPs volume fraction, the heat transfer and flow pressure drop were incremented.

Figure 17: (a) schematic view and (b) photo of turbulators [104]

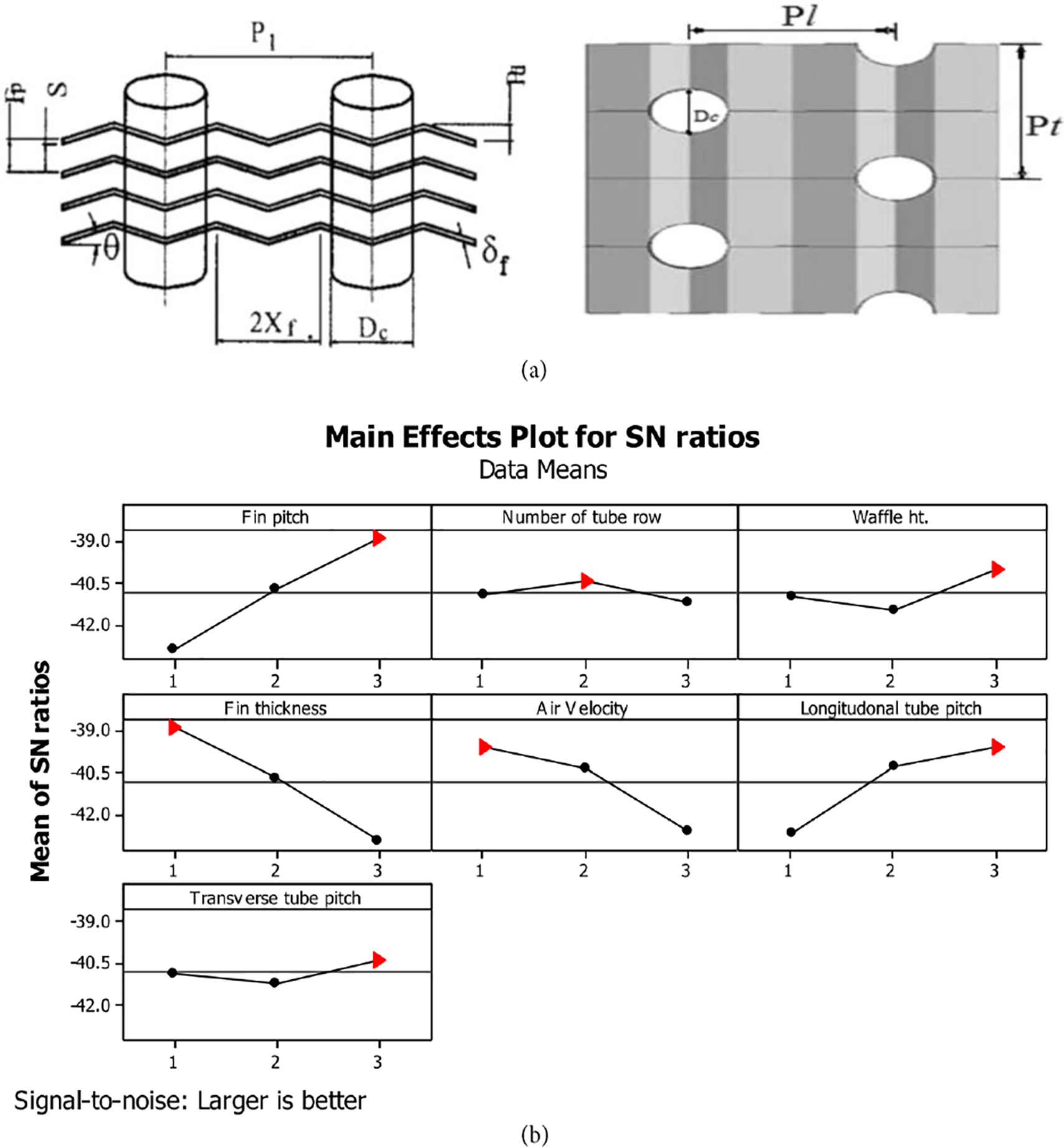

A parametric optimization study of a wavy fin and tube air HX by using the Taguchi-based GRA was accomplished by Kumar and Sahoo [106] (Fig. 18). The HX parametric study for the air-side was considered in terms of heat transfer and friction factor characteristics. Thus, experimental runs were performed for the Taguchi L27 OA design. Examination results exposed the highest contribution ratio against outputs by 47% for fin pitch, followed by 25% for air velocity, and 24% for fin thickness. The output responses were friction factor, heat transfer coefficient, and Colburn factor. The optimum input factors determined by GRA were as follows: air velocity of 5 m/s, 1.8 mm for the waffle height, 6 mm for the tube of fin pitch, 0.12 mm for fin thickness, and 6 for the tube row number. In a comprehensive study conducted by Razak Kaladgi et al. [107], the impacts of various input variables on the thermal characteristics of a car radiator were analyzed and optimized by employing the integrated Taguchi-GRA along with the response surface methodology (RSM). Additionally, the artificial neural network (ANN) modeling was applied to find a more acceptable projection of the non-linear formation of critical data. The Re number, air velocity, and nanofluid concentration were considered as inputs, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) nanofluids comprising NPs of ZnO by different volume concentrations (0.2%–0.6%) were operated. Considering the Taguchi OA and calculating the weighted GRA grade, the following thermal characteristics were optimized: Nusselt number, convection heat transfer coefficient, pressure drop, and the pumping power. The main finding of the study was that heat transfer improvement arises in radiators working with nanofluids at the expense of the pressure drop as well as pumping power.

Figure 18: (a) The geometrical design of a wavy fin and tube radiator of staggered arrangement and (b) effect of design parameters on Colburn factor [106]

Multi-response optimization and numerical investigation for dimples variables affecting the thermal and hydraulic features of a dimpled HX tube employing the Taguchi-based GRA and the RSM were performed by Dagdevir [108]. Dimple diameter of 3–7 mm, dimple pitch length of 10–30 mm, and dimple height of 1.0–1.4 mm were defined as the geometrical input parameters. Accordingly, the maximum value of, h, and the lowest pressure drop were established as the objective functions (Fig. 19). Experimental trials were conducted considering the Taguchi L25 OA design. Hence, the Taguchi analysis and GRA were operated for the single-response and multi-response optimization, respectively. It was found that the dimple pitch length has a higher impact on the pressure drop and convective heat transfer coefficient concurrently. It is followed by the other variables, dimple height and dimple diameter. Additionally, the results demonstrated that the optimum configuration for dimple with a diameter of 7 mm, pitch length of 30 mm, and height of 1.0 mm leads to the maximum h and minimum pressure drop. Taguchi optimization and numerical investigation of the heat transfer characteristics of a spirally corrugated tube was executed by Yang et al. [109]. A 3-dimensional numerical model was developed employing ANSYS FLUENT commercial software. The geometric parameters such as corrugation depth and corrugation spacing were analyzed vs. the heat transfer features. The results represented that heat transfer was improved by generating the secondary flow around the spirally corrugated tube wall. The ANOVA tables exhibited that the contributions of the corrugation spacing and depth against to heat transfer coefficient were around 90%. Increasing the corrugation spacing leads to a reduction of the mean heat transfer coefficient by up to 5%. It was enhanced almost by up to 36% when corrugation depth was augmented from 1–3 mm. Moreover, the optimal combination of inputs, including 3 mm for corrugation depth and 9 mm for corrugation spacing with Re of 30,000, improved the heat transfer by up to 15.0%. Mallik et al. [110] investigated the CFD modeling and optimization of utilizing the Taguchi approach, a cylindrical reactor was created with longitudinal finned cooling tubes that bifurcate, intended to function as a HX for an large-scale metal hydride reactor system. The optimization process was conducted for seven different control parameters using the Taguchi L18 OA design. The 3-dimensional modeling was executed by COMSOL Multiphysics, and the absorption features were examined by considering the variation of pressure and HTF temperature. The results revealed that number of fins, the number of cooling tubes, and the fin length were found to be the most significant variables in optimizing absorption time. Additionally, at an inlet pressure of 20 bar, a cooling fluid temperature of 20°C in a 50 kg system with eight bifurcating finned cooling tubes, a hydrogen storage capacity of 1.21% was acquired in 700 s.

Figure 19: (a) a view of the grid structure for the dimpled tube and (b) effect of dimple diameter on the ℎ and the ΔP [108]

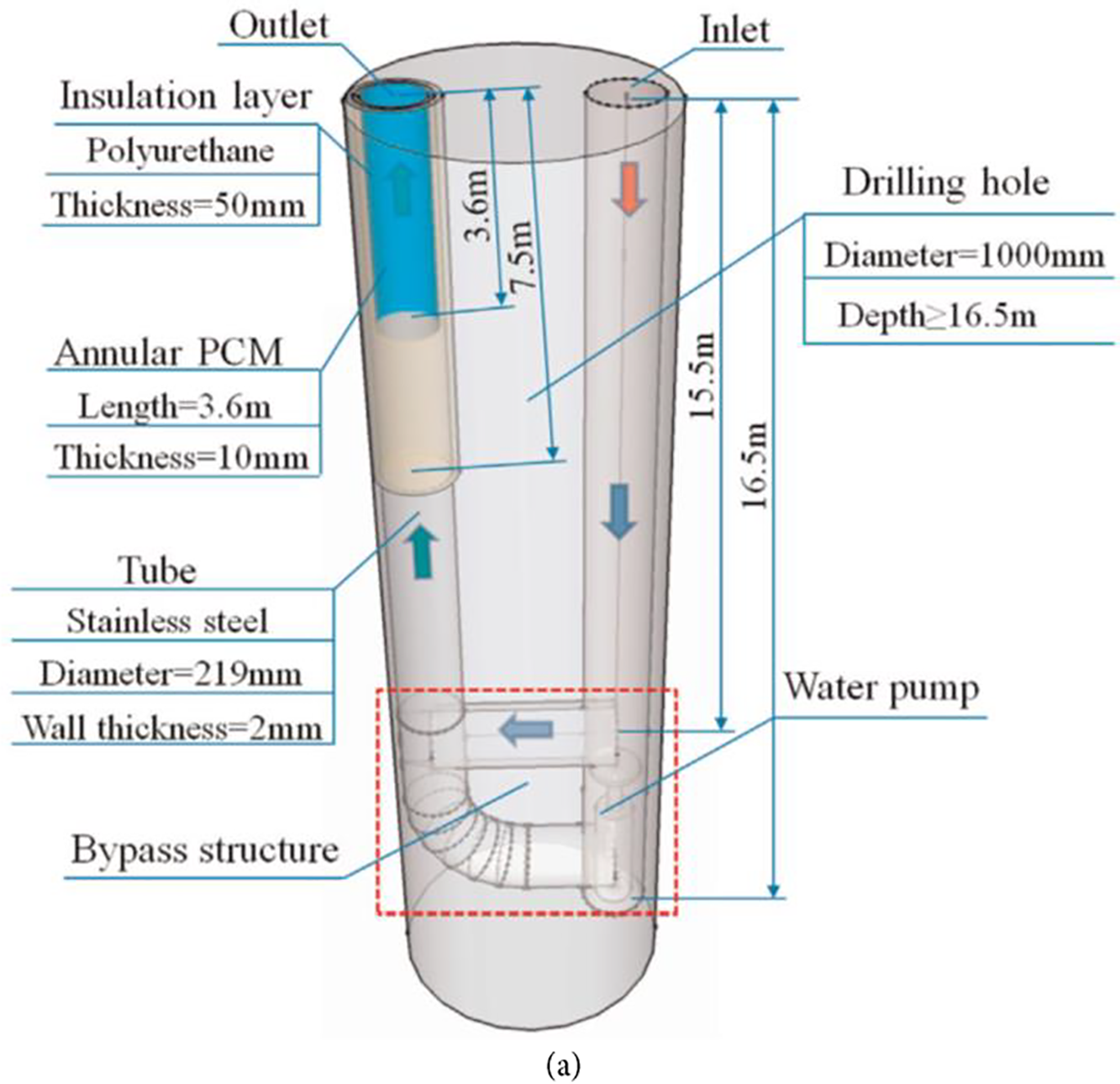

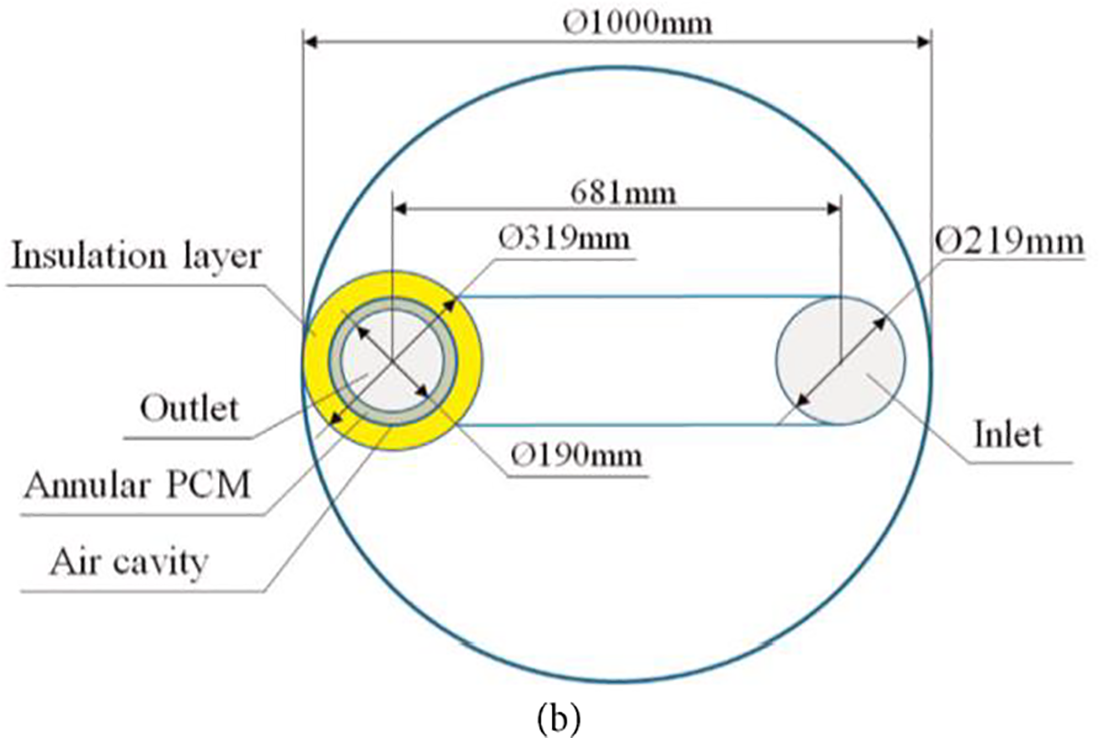

Optimization and sensitivity investigation of an experimental vertical earth-to-air HX system combining the annular PCM using the Taguchi approach were conducted by Liu et al. [111] (Fig. 20). The examination of thermophysical parameters of PCM was executed corresponded to cooling capacity and outlet air temperature fluctuation. Results revealed that fusion temperature of PCM, as well as latent heat of PCM were the most critical parameters corresponding to the cooling capacity, with contribution ratios of almost 38% and 29%, respectively. Whereas melting temperature and thickness of PCM were specified as the most influential parameters corresponding to the temperature fluctuation with contribution ratios of about 26% and 31%, respectively. The energy and exergy study of the heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics of helically corrugated coiled tube HX using the Taguchi approach, was executed by Heydari et al. [112]. To dissect the hydrothermal features of HX, various control factors called inlet fluid flow rate, corrugation pitch, corrugation depth, and the number of rounds were considered. The results demonstrated that when the corrugation depth, inlet fluid flow rate on the coil side, and the number of rounds were increased, the pressure drop and heat transfer were raised concurrently. Furthermore, the most significant variables related to the thermal efficiency of the HX were determined to be the fluid flow rate on the coil side and corrugation depth, respectively. As well, considering the HX hydrodynamic characteristics, the fluid flow rate on the coil side and corrugation pitch were calculated as the most critical parameters, respectively.

Figure 20: (a) The system configuration and (b) its detailed dimensions [111]

To enhance the performance of the helically grooved shell and tube HX, the energy, and exergy investigation of the HX by utilizing the Taguchi optimization method was conducted by Miansari et al. [113]. Considering the Taguchi design, various levels for control parameters called cold fluid rate, groove height, and cold inlet temperature were considered in the survey. According to their findings, the groove boosts the heat transfer rate by up to 5% and was approximately ineffective in the pressure drop. Further, it was revealed that the thermal efficiency of HX varies from 23%–49% in terms of different conditions. The flow rate, together with the inlet temperature had the same influence on the exergy losses. Moreover, the optimum value of groove height was 10 mm. The Taguchi optimization approach was applied by Biçer et al. [114] regarding a shell-and-tube HX operating by a novel three-zonal baffle. CFD analysis was employed to visualize the 3D turbulent flow domain (Fig. 21). The Taguchi technique was operated to define optimum design configurations. The Taguchi L16 OA was applied for different control factors, namely distance between baffles, the ratio of outer diameter to the inner diameter, the rotation angle of the baffle, the ratio of openness to closure, and angle of openness to center. In comparison to the standard baffled shell-and-tube HX, the thermal characteristics of the HX with three-zonal baffles were enhanced moderately. Additionally, the shell-side pressure drop was decreased dramatically. The pressure drop of the shell side was reduced by up to 49% together with a raise in the shell side ΔT by up to around 7%. Furthermore, the three-zonal baffles enhanced the shell-and-tube HX total performance regarding heat transfer rate and pressure drop.

Figure 21: Pressure distributions in the heat exchanger at a mass flow rate of 0.5 kg/s [114]

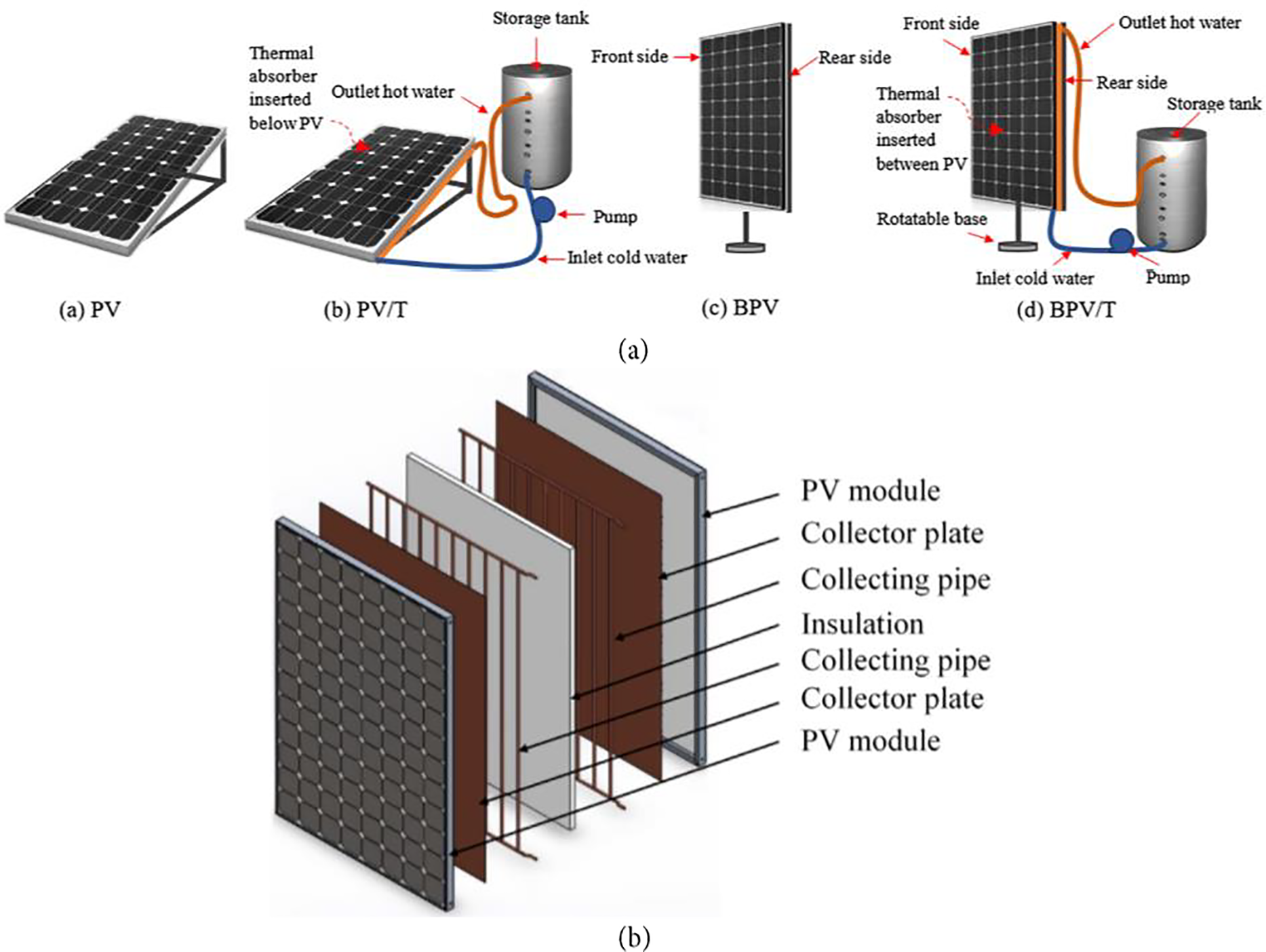

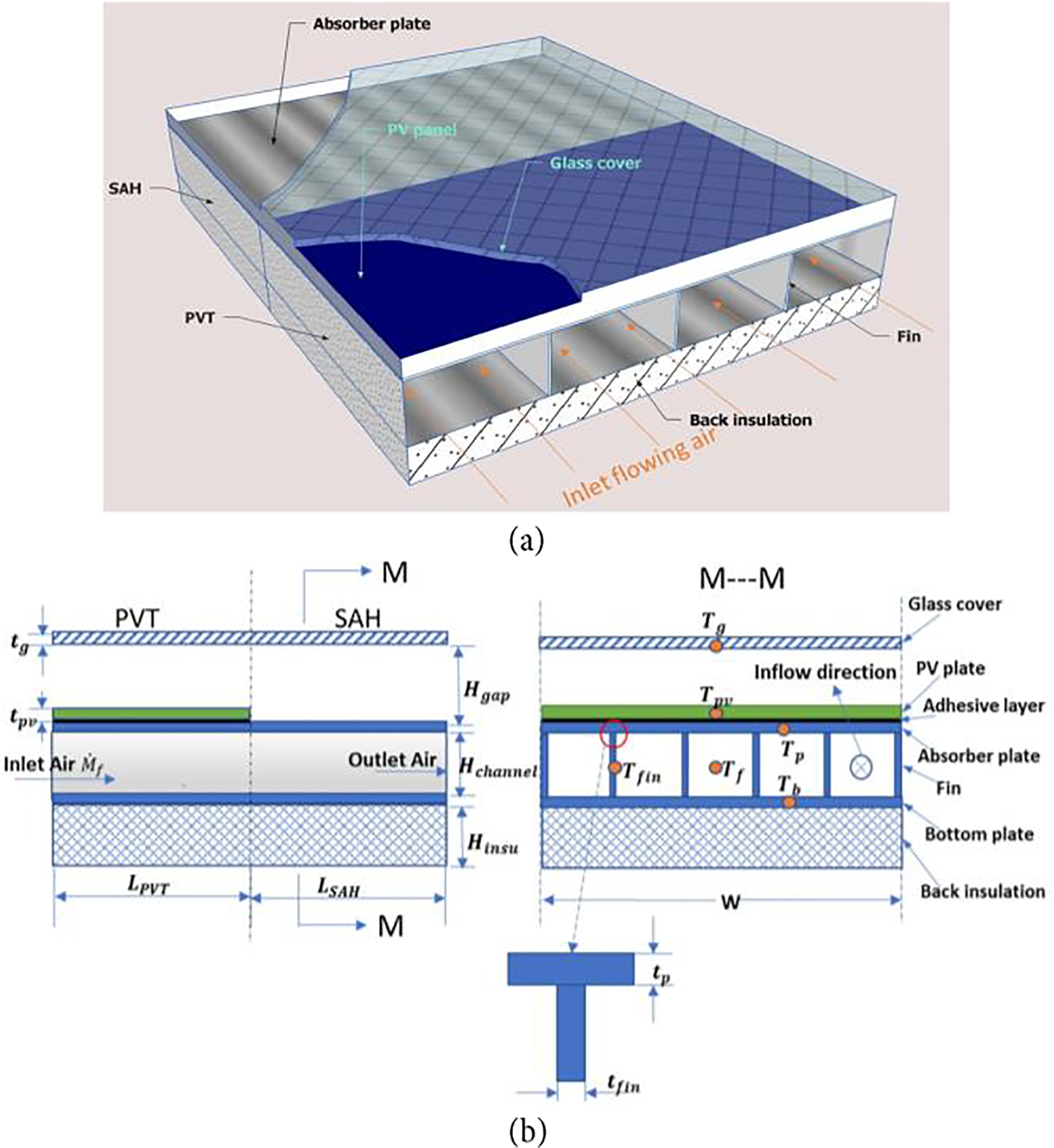

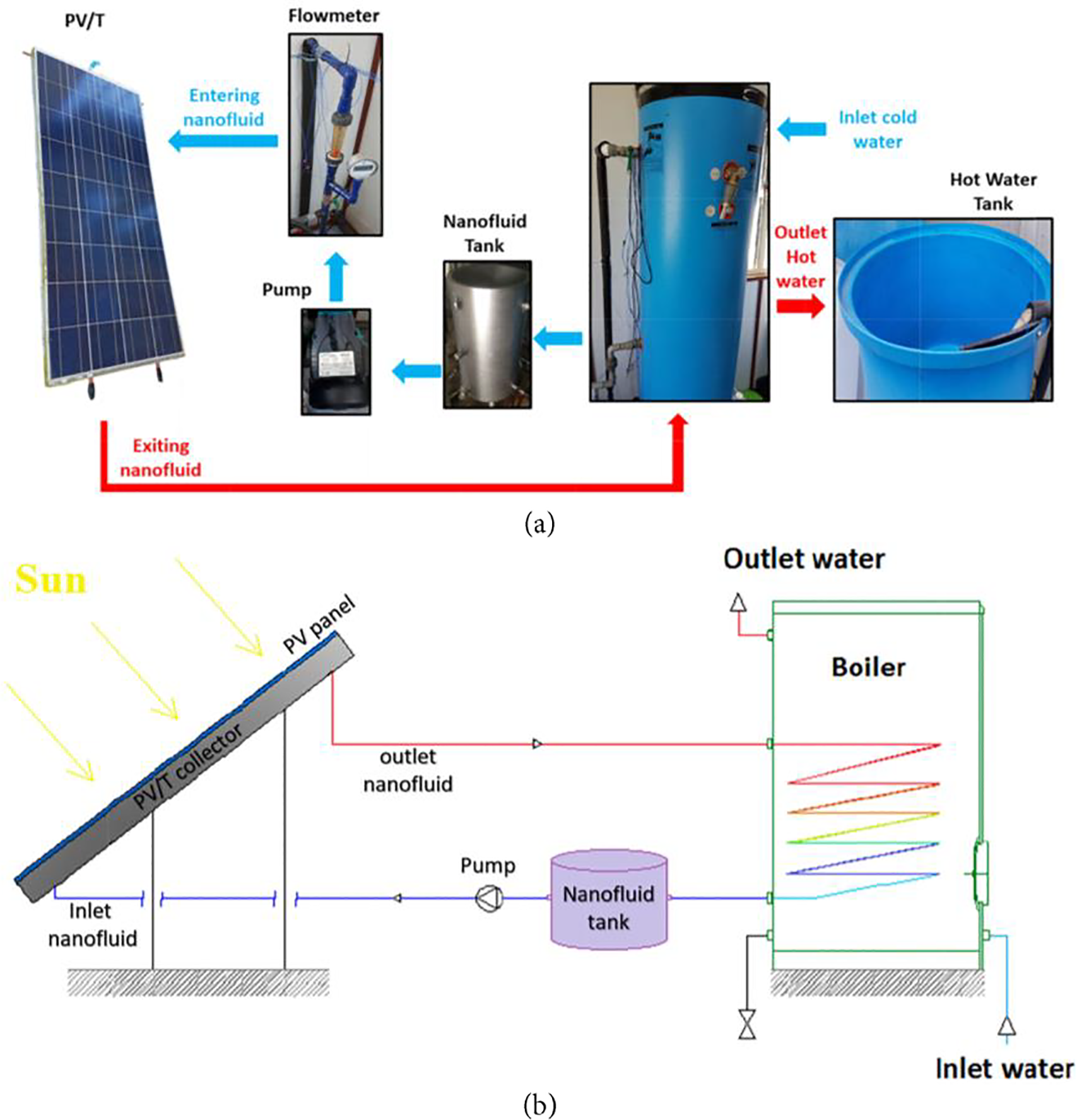

Considering the Taguchi optimization strategy, Raina et al. [115] investigated the optimum orientation of the bifacial photovoltaic (PV) module in India. The main control parameters affecting the power generation and performance characteristics of the PV were: the elevation of the module above the ground, tilt angle, azimuth angle, and the albedo of the location. According to the Taguchi optimization results, an elevation of 0.8 m, an azimuth angle of 22.5°, and a tilt angle of 40° were determined as the best mixtures of control factors to maximize the output response. Further, the adequacy of the Taguchi analysis was calculated via ANOVA tables. Moreover, it was concluded that for modules installed at optimum orientation, boosting the value of albedo leads to improving the performance. In a similar investigation, a bifacial photovoltaic thermal (PVT) system design, as well as parameter optimization, was explored by Kuo et al. [116] (Fig. 22). The input variables, namely the number of collectors, collector material, diameter, mass flow rate (MFR), the ratio of storage tank volume to the surface area, azimuth angle, and cycle temperature, were considered effective control parameters of the design. The electrical and energy efficiencies of the system were defined as the quality characteristics of the study. The outcomes represented that according to the 20-year warranty of the PV module, the bifacial PVT system economic benefit was enhanced by up to 18% and 460% compared to the PVT and PV systems, respectively. Additionally, the overall energy output per unit of area for the bifacial PVT system was higher by up to 20% and 210% compared to the PVT and PV systems, respectively.

Figure 22: (a) Illustrations of PV, PV/T, BPV, BPV/T and (b) Anatomy of the BPV/T module [116]

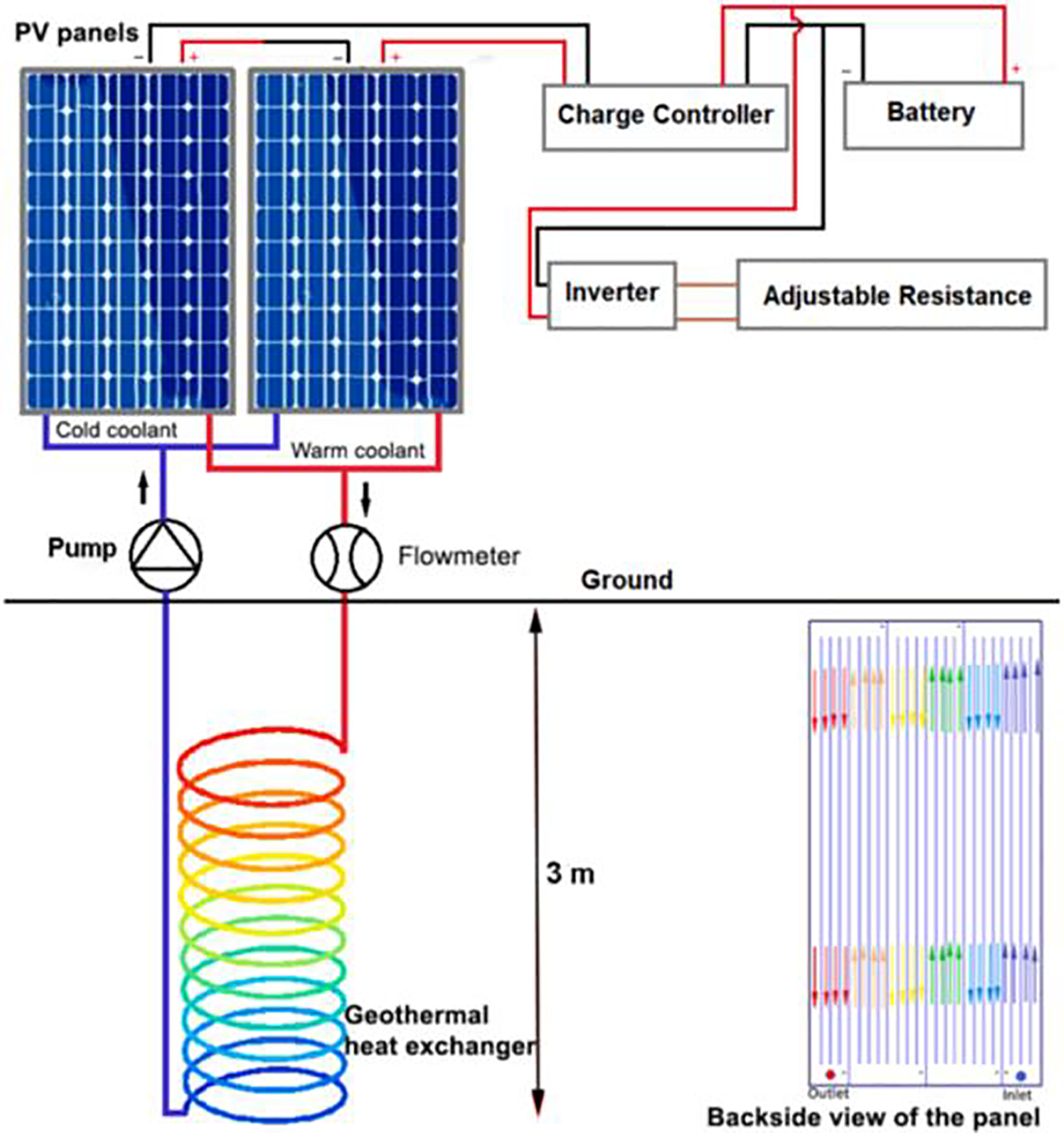

Jafari [117] optimized the energy of a geothermal HX in order to cooling of a PV panel by using the Taguchi optimization approach (Fig. 23). The considered coolant was a combination of ethylene glycol and water, which circulated between two HXs. The mini channel HX was bounded to the PV cells, and the geothermal HX was utilized to remove the PV cells’ heat to the ground. The Taguchi L27 OA design was considered for six control factors, including pipe thickness, pipe length, pipe’s inner diameter, coolant flow rate, soil thermal conductivity, and adjacent coil distance. The results indicated that compared to the conventional PV panel, the mean net electricity generation of the PV panel with a cooling system was improved up to about 10%. Further, the optimal setting of the geothermal cooling system had the potential to improve the net electricity generation of the twin cooled panels by around 12%. For the case study of a 30 kW PV solar plant, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) of the optimized system was determined as 0.089 €/kWh against the ordinary panel of 0.102 €/kWh. An innovative combined system designed by associating a PVT module with a solar thermal (ST) collector in series was investigated through the Taguchi-based GRA multi-objective optimization approach [118]. Considering the Taguchi L25 OA design, the impacts of various control factors such as MFR, coolant inlet temperature, ambient temperature, wind speed, and absorbed solar radiation vs. performance of the system were examined. Thermal efficiency, as well as electrical efficiency of the PVT-ST system, were considered as the output responses of the system. The optimization results showed that solar radiation was found to be the most dominant parameter, with a contribution ratio of about 55% to the proposed system. Whereas an almost contribution ratio of 9% for MFR indicated that approximately this parameter was the most ineffective one. Furthermore, exploiting the optimum combination of the control factors based on the Taguchi-based GRA method enhanced the thermal and electrical efficiencies of the system by up to about 36% and 24%, respectively.

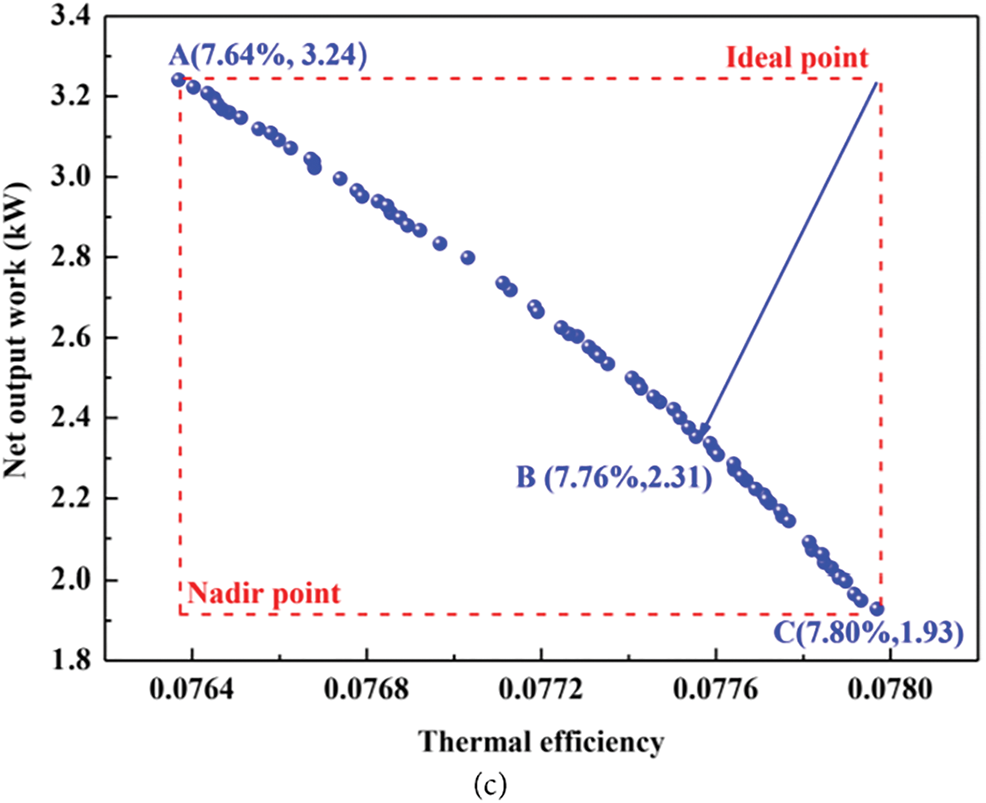

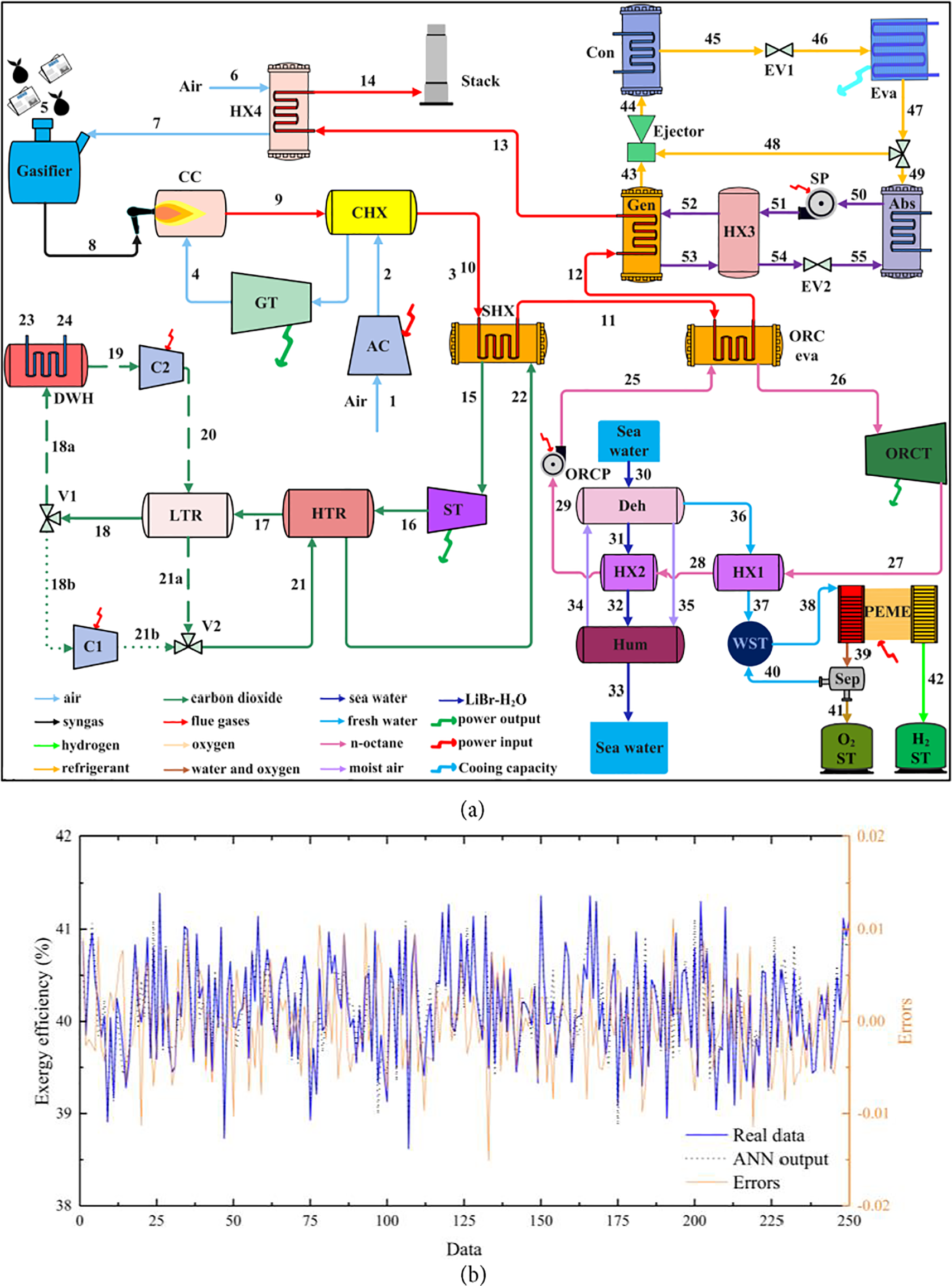

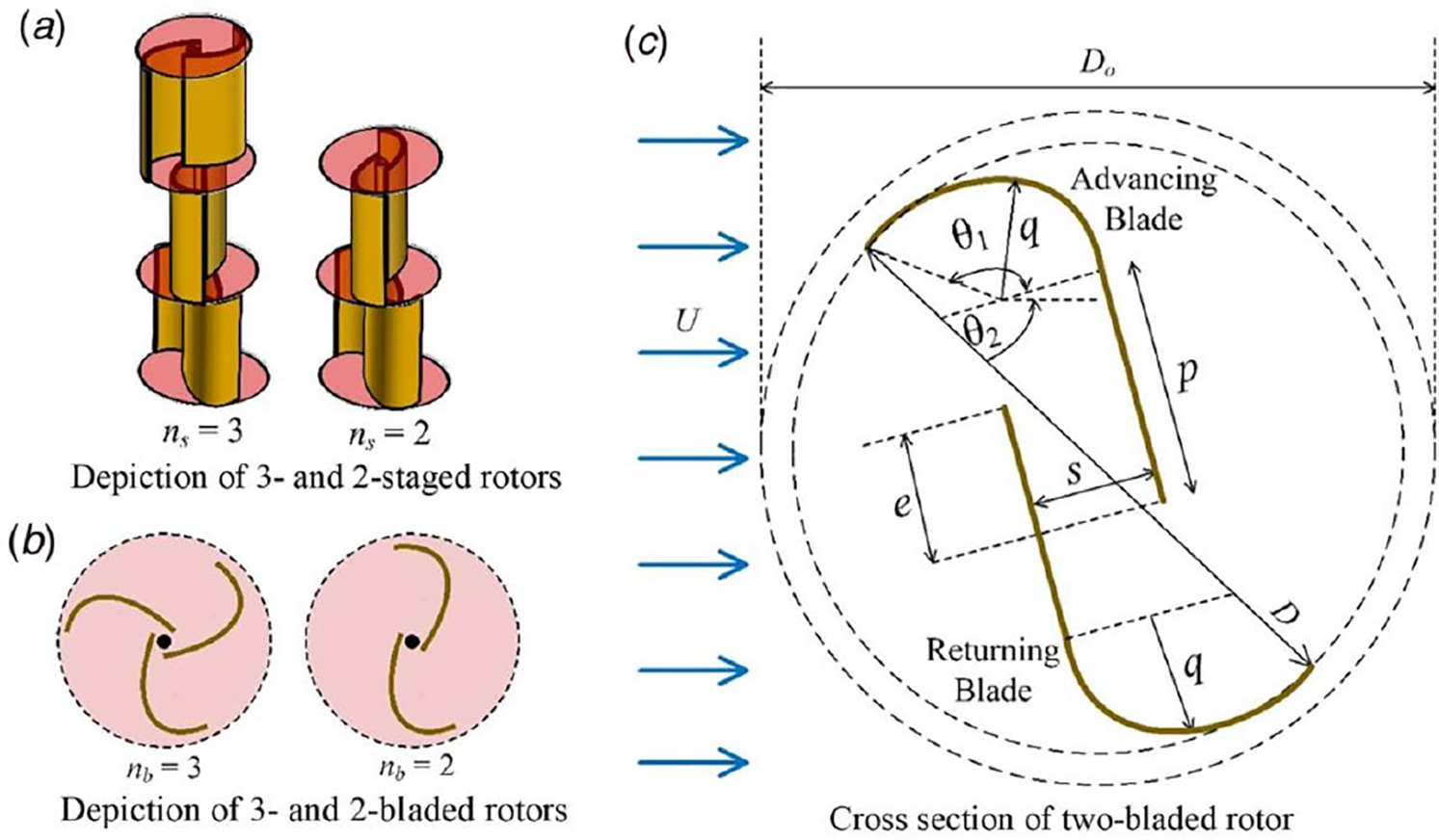

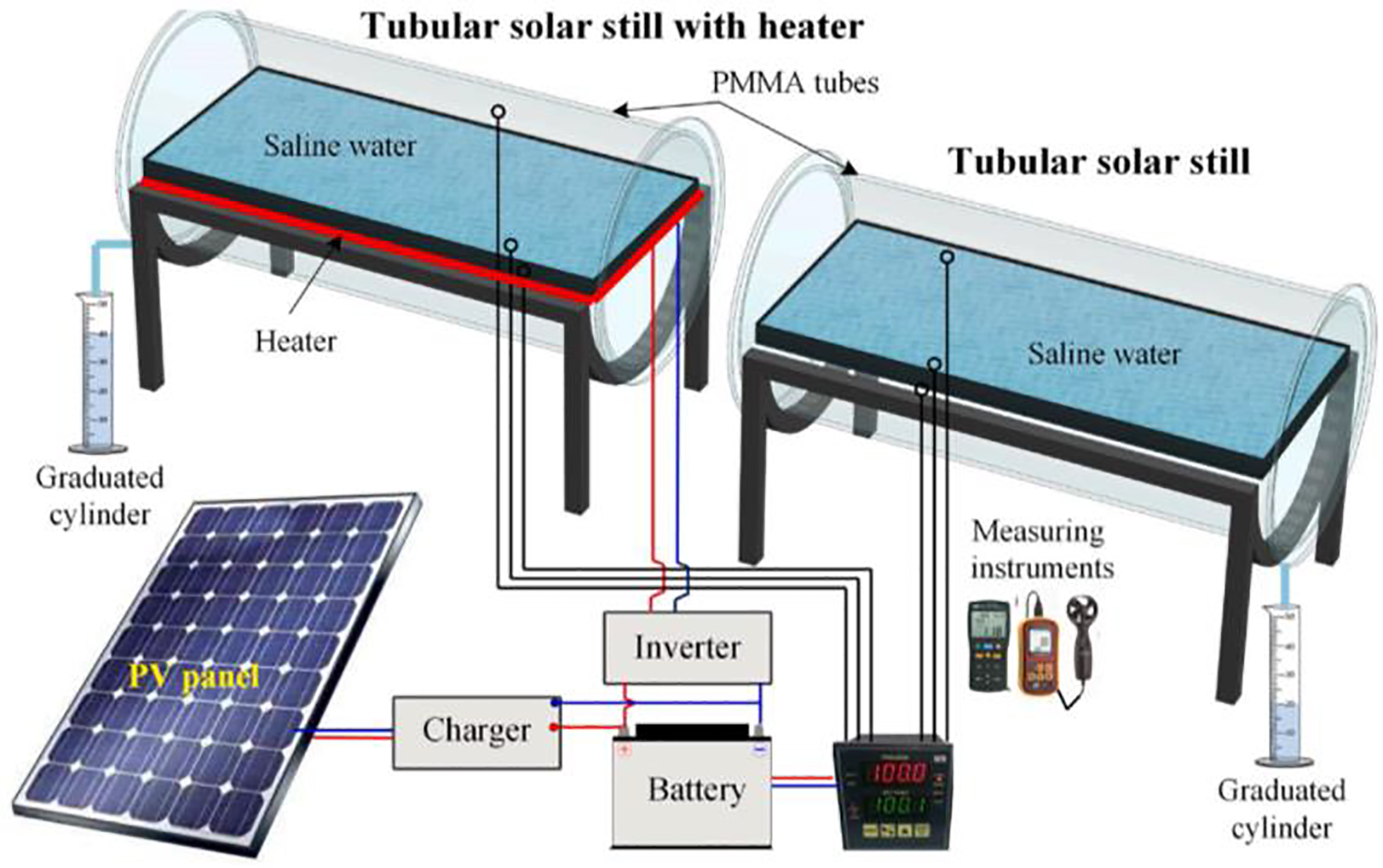

Figure 23: Schematic connections of the designed PV panel with cooling system [117]