Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Fuel-Minimization-Oriented Power Distribution Strategy of Diesel Power Generation-Energy Storage Parallel Power Supply Architecture

1 State Grid Taixing County Electric Power Supply Company, Taixing, 225300, China

2 College of Automation Engineering, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, 211106, China

3 State Grid Taizhou Electric Power Supply Company, Taizhou, 225300, China

4 Electric Power Research Institute, State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 211103, China

* Corresponding Author: Feilong Jiang. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4873-4897. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.069071

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

To enhance power supply reliability and reduce customer outage time, Mobile Emergency Power Supply Vehicles (MEPSVs), including Mobile Diesel Generator Vehicles (MDGVs) and Mobile Energy Storage Vehicles (MESVs), have become indispensable sources for grid maintenance and disaster response. However, in practice, relying solely on MESVs is constrained by battery capacity, making it difficult to meet long-duration power demands. Conversely, using only MDGVs often results in low efficiency and high fuel consumption under fluctuating load conditions, posing challenges to achieving economical and efficient power supply. To address these issues, this paper investigates the parallel power supply architecture of MDGV and MESV, and develops control models for diesel generator and energy storage converter. A fuel-minimization-oriented power distribution strategy is proposed for coordinated operation, aiming to minimize fuel consumption while maintaining the energy storage state of charge (SOC) within a reasonable range. Furthermore, a voltage–frequency control strategy is employed for the energy storage converter, while active power control is applied to the diesel generator. Through adaptive operation mode switching, the proposed strategy enables efficient and cost-effective parallel operation of MDGV and MESV, ensuring long-duration power supply across a wide load range. This approach overcomes the limitations of conventional single-source power supply methods and provides an effective control solution for the intelligent and efficient operation of emergency power supply systems. Finally, the feasibility of the proposed strategy is verified through simulation and further demonstrated by experiments on a hardware platform.Keywords

As modern society becomes more reliant on power systems, ensuring a continuous supply of electricity is now essential for maintaining the steady functioning of various industries and supporting the smooth progression of economic activities [1–3]. Moreover, guaranteeing stable and adaptable operation of electrical grids has emerged as a core concern for both power enterprises and consumers, especially in scenarios such as emergency power supply in disaster situations, daily maintenance, non-stop operation, and power supply guarantee for important places [4–8]. In these cases, the fast response power supply mode is particularly critical. At present, Mobile Emergency Power Supply Vehicles (MEPSV) are widely used due to their high mobility and large output power, including Mobile Diesel Generator Vehicles (MDGV) and Mobile Energy Storage Vehicles (MESV) [9–12]. Unlike hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), which coordinate energy sources primarily for propulsion purposes [13], MEPSVs are designed specifically to deliver power to external loads.

Most traditional emergency power supply schemes rely on power vehicles equipped with diesel generators. With its maneuverability and independent power supply capability, MDGV can be quickly deployed to power places in emergency situations to provide temporary power supply for loads. Current research on MDGV mainly focuses on dispatch optimization to enhance emergency power supply capabilities following natural disasters or accidents. In the context of improving emergency power supply after extreme weather events, reference [14] proposes an optimization strategy for the pre-allocation and dispatch of mobile power sources, including MDGVs, within a power-transportation coupled network, enhancing load recovery efficiency and emergency response effectiveness. Ref. [15] establishes a three-stage stochastic optimization model, covering planning, preventive response, and emergency response, while incorporating non-anticipativity constraints to better manage uncertainties in emergency power supply and improve distribution network resilience. To enhance power grid reliability, some researchers have explored the use of existing MDGV resources and proposed optimal allocation strategies to mitigate system vulnerabilities and improve supply stability [16]. Ref. [17] integrates network reconfiguration with MDGV scheduling, developing a distributed optimization framework for rapid post-disaster recovery. In [18], an energy-sharing strategy based on power vehicles is studied to support self-sustaining operation in islanded microgrids, enabling autonomous recovery in the event of large-scale power outages. Recently, scholars have investigated distributed restoration strategies that coordinate MDGVs with repair crews to accelerate power grid restoration and enhance overall supply reliability [19]. Additionally, coordinated island partition and scheduling strategies have been proposed to ensure minimum sustainable supply duration in active distribution networks [20]. Overall, current research on MDGV is gradually expanding from single dispatch optimization to comprehensive scheduling, network reconfiguration, and multi-agent coordinated control, aiming to further improve grid resilience and emergency response capabilities.

MDGV are highly effective for emergency power supply due to their rapid deployment and autonomy. However, they have notable drawbacks. Diesel generators are inefficient at low loads, leading to high fuel consumption and increased generation costs [21]. Their response to load fluctuations is slow, causing fuel waste and reduced efficiency, especially in long-term use [22]. Additionally, diesel generators produce noise and emissions, which are problematic in urban and sensitive areas [23–25]. To address voltage unbalance in such scenarios, recent studies have proposed negative sequence current compensation strategies to enhance power quality and capacity utilization in MDGV applications [26]. While much research has focused on MDGV scheduling and dispatch, studies addressing these inherent issues are limited.

MEPSV include not only MDGV but also MESV equipped with storage media, primarily batteries. Compared to MDGVs, MESVs offer higher efficiency, lower emissions, and quieter operation, making them particularly suitable for rapid emergency power supply. However, research on MESVs is still evolving, primarily focusing on scheduling optimization, system integration, and application strategies. In [27], researchers proposed a bi-level pre-positioning method for mobile energy storage in distribution networks, coupled with transportation networks, to enhance system resilience against typhoon disasters. In [28], a coordinated network reconfiguration and mobile energy storage system fleets dispatching model was proposed to enhance the resilience of active distribution networks under forecast uncertainty. Addressing voltage control in active distribution networks, Ref. [29] proposed a coordinated strategy integrating photovoltaics and MESVs to improve voltage quality. The study in [30] explored optimal MESV configuration and scheduling strategies to enhance adaptability in high-renewable penetration scenarios. For MESV applications in large-scale power outages, Ref. [31] demonstrated their capability to shorten restoration time and enhance system resilience. A multi-objective optimization scheduling model was introduced in [32], achieving improvements in cost, energy efficiency, and system stability. To enhance the resilience of distribution networks, Ref. [33] proposed an optimized scheduling strategy for mobile power sources. A recent study further proposed a scheduling method for MESV cluster with consideration of emergency power supply and economic efficiency [34]. In response to deployment challenges in high-renewable energy environments, Ref. [35] introduced a risk-based distributed optimization method, improving scheduling efficiency and routing planning. An adaptive robust load restoration strategy was presented in [36], enhancing system recovery by coordinating distribution network reconfiguration and MESV dispatch. Further advancing MESV scheduling, Ref. [37] developed an online expansion method for multiple MESVs, enabling autonomous operation without communication and increasing emergency power supply flexibility.

Similar to MDGV, MESV research has gradually expanded from single scheduling optimization to comprehensive scheduling, renewable energy integration, and emergency recovery strategies, further enhancing their application value in power grid disaster recovery and dynamic grid operation.

MESVs leverage battery storage to offer fast response, flexible dispatch, noise-free operation, and zero emissions, effectively compensating for the inefficiencies of diesel generators in low-efficiency zones. Their high-power density and rapid charge/discharge capability help smooth load fluctuations, stabilize frequency and voltage, and are particularly suitable for short-term power supply needs, reducing diesel engine operation and fuel consumption. However, limited battery capacity restricts MESVs from sustaining long-term, high-load independent power supply [38–40], making them unsuitable for prolonged repair scenarios, thereby affecting supply reliability. Therefore, relying solely on MDGVs or MESVs cannot fully meet practical requirements. Optimizing power distribution and intelligent dispatch by integrating both technologies is a valuable research direction for achieving efficient power supply.

Currently, there is little specific research on the operating conditions and power distribution of parallel operation between MDGV and MESV. Existing literature mainly focuses on DC microgrid architectures or the overall scheduling optimization of MESV, but in-depth studies on AC parallel operation and power distribution strategies have not yet been conducted. The study in [41] addresses the issue of fault recovery in distributed power grids by proposing a coordinated optimization method that integrates mobile power sources with the distribution network structure to enhance disaster resilience. However, it primarily focuses on the global scheduling optimization of mobile power sources and does not involve specific power distribution strategies for the parallel operation of MDGVs and MESVs. In [42], researchers explore the scheduling of MESV systems and propose an optimization strategy incorporating MDGVs and fuel supply to enhance distribution system resilience. However, this study mainly emphasizes overall resource deployment optimization and does not conduct an in-depth analysis of the parallel operation between MESVs and MDGVs, particularly lacking consideration of power distribution mechanisms in an AC parallel operation mode. A diesel-energy storage parallel power supply strategy based on a DC microgrid is presented in [43], utilizing a diesel rectifier generator and a hybrid energy storage system for energy management. However, since this approach relies on multi-stage converters to couple with the AC main grid, it results in high equipment redundancy and lagging dynamic response, making it difficult to directly apply to the AC parallel operation of MDGVs and MESVs.

In this paper, a fuel-minimization-oriented power distribution strategy for diesel generator–energy storage cooperative power supply is proposed. By integrating the MDGV with the MESV the two can complement each other in power supply tasks. This approach not only leverages the rapid response capability of the MESV under load fluctuations but also ensures continuous power support through the long-term power supply characteristics of the MDGV. When the load is small, the MESV can take on most or all of the power supply tasks, preventing the diesel generator from operating inefficiently and thereby reducing unnecessary fuel consumption. Conversely, when the load is high, the MDGV provides the base power output, while the MESV handles load regulation to maintain system stability and economic efficiency. Furthermore, in scenarios with rapid load changes, the MESV can swiftly adjust to meet demand, avoiding frequent start-ups and shutdowns of the diesel generator, which helps lower operational costs and equipment wear. Additionally, the strategy considers the state of charge (SOC) of the energy storage system, ensuring that the battery remains within an optimal range. Maintaining the SOC at a reasonable level not only prevents excessive degradation but also extends battery lifespan, further enhancing the reliability and sustainability of the power supply system. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

(1) This work proposes a coordinated power allocation strategy that ensures the MDGV operates within its high-efficiency range while leveraging the MESV’s fast response for dynamic load adjustment.

(2) Through real-time power coordination, the system’s adaptability to wide-range load variations is significantly enhanced.

(3) Furthermore, the control design integrates voltage-frequency control for the MESV and active power control for the MDGV to achieve stable and efficient emergency power supply.

2 Diesel Power Generation-Energy Storage Parallel Power Supply Architecture

The parallel power supply architecture of MDGV-MESV studied in this paper is illustrated in Fig. 1. Both MDGVs and MESVs can output 400 V electric energy to power low-voltage distribution stations or other occasions requiring emergency power supply. MDGV can provide a continuous power supply to the load, while the MESV, utilizing batteries as the storage medium, interfaces with the AC bus via an energy storage converter.

Figure 1: Parallel power supply architecture

The advantage of this architecture is that it is different from the traditional MDGV cluster and the MESV cluster. It mitigates the excessive fuel expenses resulting from the inefficient performance of diesel generators under low-load conditions and addresses the limitation of traditional energy storage in sustaining long-term power supply.

3 System Modelling and Analysis

MDGV and MESV each possess an independent control system at the underlying level. To facilitate the subsequent control system design and power distribution strategy development, it is necessary to establish mathematical models for both vehicles. Specifically, for the MDGV, the core active power control target is the diesel engine’s speed governor, while the MESV is centered on the control of the energy storage converter. The following sections will provide a detailed modelling analysis of these key control components.

The diesel generator mainly realizes the adjustment of power output through the diesel engine. Its working principle is based on the thermodynamic cycle of compression ignition, also known as diesel cycle. It increases its temperature by compressed air, and then injects diesel oil into the compressed air, so that the diesel oil burns itself, producing high-temperature and high-pressure gas to push the piston to do work.

The main function of the diesel engine speed control system is to maintain a constant speed of the diesel engine, thereby ensuring a stable AC output from the generator. During the adjustment process, when the load increases, the resistance torque increases, causing a decrease in speed. The system compensates by reducing the speed and increasing fuel supply to regulate the engine. When the load decreases, the resistance torque decreases, and the speed increases. The system adjusts by increasing the speed and reducing the fuel supply. When the load remains constant, the resistance torque and the driving torque reach a balance, and the fuel supply remains steady. Through these adjustment mechanisms, the engine can adapt to load changes, ensuring stable operation of the generator.

The structure of diesel engine is shown in the Fig. 2, including electronic governor, throttle executor, diesel engine and generator. The electronic governor converts the input speed difference signal into a given fuel signal output through the speed control algorithm [44–47]. The throttle executor controls the throttle action under the drive of the given fuel signal, and injects fuel into the diesel engine cylinder in the form of gas flow. The diesel engine outputs the power torque to drive the generator to rotate.

Figure 2: Diesel generator structure

The electronic governor consists of a prime mover speed sensor and a speed controller. The rotational speed sensor can be measured by sensors such as rotary transformer. During the measurement process, the actual measured rotational speed signal may not immediately follow the real rotational speed change due to the dynamic response of the sensor or the influence of the filter. To model the hysteresis effect of the measurement system, it can be approximated using a first-order inertial link. The speed controller mostly adopts the traditional PID control. Therefore, the governor is modelled by transfer function as Eq. (1).

T1 is the sampling time constant, Kp, Ki, Kd are PID parameters. The throttle executor issues commands for the oil output of the speed controller and regulates the oil supply via throttle operation to achieve engine acceleration/deceleration. The throttle executor operates through a rotating electromagnet, where the electromagnet generates a magnetic field when current flows through it. This magnetic field causes the armature, a movable part of the system, to rotate. The rotation of the armature is proportional to the displacement of a sliding sleeve, which is the part that regulates the fuel flow. As the armature rotates, it adjusts the position of the sliding sleeve, thus controlling the amount of fuel injected into the engine. This mechanism enables precise control of the fuel injection, allowing the engine to maintain the desired speed and load conditions, ultimately ensuring efficient and stable engine performance. The motion increment equation is shown in Eq. (2).

In the formula, l is the displacement distance, m is the mass of the armature, k is the stiffness of the reset spring, B is the damping coefficient, F is the electromagnetic force increment. The transfer function G2(s) of throttle actuator is obtained by Laplace transform of Eq. (2) like Eq. (3).

The throttle output acts on the diesel engine, and the final result is the engine’s output torque. The output torque of a diesel engine is proportional to the fuel supply amount of the throttle actuator. Specifically, as the displacement of the throttle actuator increases, the fuel injection volume increases accordingly, leading to a higher output torque of the diesel engine. Under small variations, the change in engine output torque dT is approximately linearly proportional to the change in throttle opening dl, expressed as Eq. (4).

where K is the proportional coefficient, representing the influence of throttle opening on output torque. Additionally, due to the combustion process and the inertia of the mechanical transmission system, the engine output torque exhibits a dynamic response delay with respect to throttle opening changes, denoted as Td. In the complex frequency domain, could get Eq. (5).

where s is the differential operator. By Taylor expansion of the delay link, could get Eq. (6):

Since the engine delay time constant Td is small, the quadratic and higher order terms in the denominator are ignored, and an approximate first-order linear link is obtained:

In the frequency domain, let dT(s) represent the variation in engine output torque and dl(s) represent the variation in throttle opening. Based on Eqs. (5) and (7), the transfer function G3(s) of the diesel engine can be obtained as follows Eq. (8):

This equation indicates that the torque response of the diesel engine is not instantaneous but undergoes a dynamic adjustment process characterized by the time constant Td.

Finally, the diesel engine’s output torque is compared with the generator’s electromagnetic torque. Through the torque equation, the actual speed is obtained, which is then used as feedback for speed adjustment, creating a closed-loop control system. Based on the above modelling analysis, the mathematical model of diesel engine is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Mathematical model of diesel engine

3.2 Energy Storage Converter Modelling

Currently, MESV primarily utilizes batteries as its energy storage medium. Among them, lithium-ion batteries have gained widespread adoption due to their high energy density, long cycle life, high specific power, fast response, and strong environmental adaptability. These advantages make lithium-ion batteries particularly suitable for applications such as emergency power supply, peak shaving, and backup power.

To accurately reflect the electrical characteristics of batteries, equivalent circuit modeling methods are commonly used in research. Among them, the second-order Thevenin model is widely applied for lithium battery modeling because of its high accuracy, clear physical meaning of parameters, and moderate computational complexity. This model incorporates an open-circuit voltage source, series resistance, and two parallel RC networks to effectively capture the static voltage, dynamic response, and polarization effects of the battery. The structure is shown in the Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Second-order Thevenin model

In this model, R0 represents the ohmic internal resistance, and the two RC branches (R1, C1) and (R2, C2) model the battery’s polarization effects. This structure can effectively reflect voltage jumps caused by internal resistance and the relaxation characteristics due to polarization.

The basic KVL, KCL calculation formula for electronic circuits is as follows:

EMF represents the open-circuit voltage, Vh is the hysteresis voltage, and SOC denotes the state of charge of the battery. In this battery model design, the ampere-hour integration method is used to estimate the battery SOC. By integrating the current of the battery during operation over a period of time, the amount of charge Qt charged and discharged during the period is calculated, and then based on the battery charge at the initial moment, the remaining charge is calculated:

Q refers to the total electric quantity released by the battery under standard discharge conditions; Qt + Qt0 represents the electric charge input during the battery’s charging operation; and Qt − Qt0 stands for the electric charge released when the battery is in the discharge operation.

The second-order RC equivalent circuit can represent the fundamental electrical characteristics of most lithium-ion batteries and is widely used in power dispatch studies [48,49]. Since this paper focuses on power coordination based on electrical behavior, detailed electrochemical differences between battery chemistries are not considered.

The MESV is mainly based on the battery-based energy storage converter architecture. In this paper, a two-level three-phase voltage-type inverter is selected as the energy storage converter. For the convenience of analysis, the battery is simplified as a voltage source, and the voltage source SPWM inverter circuit in power electronics technology is used for theoretical analysis. The PWM wave generated by the inverter after the inverter is filtered by the LC filter to filter out the high-order harmonics, and the standard AC sine wave can be output on the grid side. The circuit of the three-phase voltage-type inverter is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Energy storage converter topology

The constant voltage DC power supply voltage is set to E, T1–T6 is the power switching device of the inverter, VD1–VD6 is the diode in parallel on the corresponding power switch, which provides a channel for the freewheeling current. The three-phase equivalent resistance of the inverter AC side output is R, the three-phase filter inductance is L, and the three-phase filter capacitance is C. ua, ub, and uc are the three output voltages of the inverter AC side, respectively. ia, ib, and ic are the output current of the inverter AC side. uga, ugb, and ugc are the three output voltages of the grid side. iga, igb, and igc are the output current of the grid side. The mathematical model of energy storage converter in abc three-phase static coordinate system can be derived as Eqs. (13)–(15).

For the design of the subsequent energy storage converter control, a mathematical model of the converter in the dq coordinate system is derived through coordinate transformation.

ω is the dq axis rotation angular velocity. The next chapter will design a control strategy based on the mathematical model of the inverter.

4 Fuel-Minimization-Oriented Power Distribution Strategy

4.1 Specific Research Scenarios

MEPSVs are primarily deployed for emergency power supply during disasters or power accidents, for temporary support during scheduled maintenance of grid infrastructure, and for electricity assurance during planned outdoor activities or inspections. Based on varying operational scenarios and the criticality of power loads, a differentiated load classification and control strategy is essential.

Power demand can be classified according to two primary criteria:

1. Load Importance: This includes critical loads, such as hospitals, emergency command centers, and key communication facilities, which require uninterrupted and high-quality power supply. In contrast, non-critical loads refer to general usage scenarios, such as field lighting, inspection equipment, or temporary service stations, where power quality and continuity requirements are relatively relaxed;

2. Scenario Type: This includes sudden emergency scenarios, such as natural disasters or unexpected equipment failures that lead to abrupt power outages and demand immediate supply restoration. It also covers planned scenarios, where power demand is anticipated in advance, such as scheduled grid maintenance, pre-approved public events, or routine mobile power support.

The corresponding control strategies are summarized in Table 1.

For critical loads such as hospitals and command centers, the MDGV operates continuously to avoid risks associated with battery depletion or switching delays.

This paper focuses on power distribution under non-critical load scenarios, aiming to enhance supply efficiency through coordinated control of the MDGV and MESV.

4.2 Design of Distribution Rule

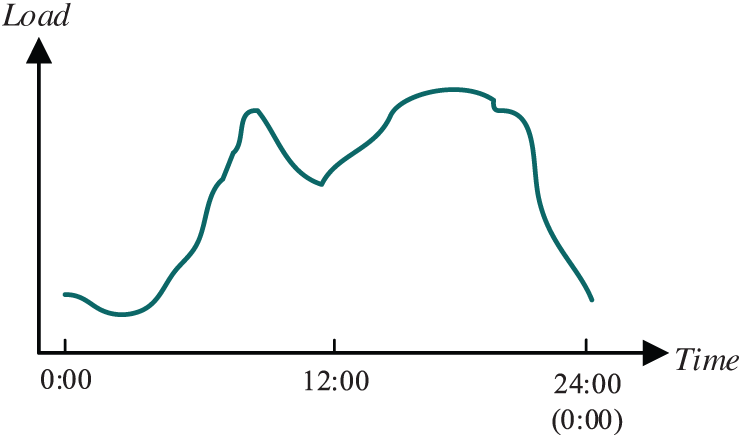

In the actual power generation operation, the load demand is different in different periods. Taking the daily load curve as an example, as shown in the Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Daily load curve

The daily load curve is influenced by various factors, including time, weather, season, and user type. It typically exhibits distinct peaks and troughs, with significant load fluctuations across different periods. Therefore, the power distribution strategy of diesel generator and energy storage converter can be designed for different power levels of load demand.

From the perspective of operating cost and considering the varying fuel consumption of diesel generators at different output levels, this paper develops a diesel-storage power allocation strategy aimed at minimizing fuel loss. The efficiency of diesel generator is not constant under different power output. The correlation between diesel generator fuel consumption and output power is illustrated in Fig. 7, where mf represents the fuel loss rate, and PN represents the generator’s rated power. At low loads, the efficiency of diesel generators is usually low. This is because at low loads, the combustion efficiency of diesel engines is low, and some fuels cannot be completely burned, resulting in increased energy loss, thereby reducing the efficiency of the generator. At the same time, under low load, the mechanical loss of the generator is also relatively high, which will also affect the efficiency of the generator. As the output power of the diesel generator gradually increases, the minimum fuel consumption is achieved within 70%–80% of the rated power, which represents its optimal operating range. If the diesel engine can be maintained in this range, the fuel consumption can be greatly reduced.

Figure 7: Fuel loss curve of diesel generator

In the Diesel Power Generation-Energy Storage Parallel Power Supply Architecture, in addition to paying attention to the fuel loss of diesel generators and ensuring that they operate in the high-efficiency range to reduce fuel costs, it is also necessary to comprehensively consider the SOC of the energy storage system to avoid the impact of overcharging or over-discharging on the life of the energy storage battery. In addition, the dynamic changes of power load should be fully considered during system operation, and the surplus power generation capacity should be reasonably used to charge the energy storage system at low loads, so as to provide support during the subsequent possible peak power consumption period, reduce the load fluctuation of diesel generators, and improve the economy and reliability of the overall power supply system. Based on the above analysis, the starting operating threshold of the diesel generator can be set to 60% of the rated power. Therefore, the power distribution strategy can be designed as Table 2:

This power supply strategy dynamically coordinates the collaborative operation of the generator and energy storage system to achieve an optimized balance between system efficiency and equipment longevity. The core of this strategy lies in matching energy distribution methods under different load conditions: under medium to low loads, energy storage is used to regulate the total load, keeping the generator operating steadily within 70%–80% of its rated power range, thereby improving fuel economy and reducing mechanical wear; under high loads, energy storage provides short-term peak power support to prevent generator overload and enhance system stability. This configuration also allows the MESV to act as a power extender, effectively increasing the maximum available output capacity of the hybrid system during peak conditions. Additionally, the strategy adopts a layered SOC management approach (20%–90%) to limit deep charging and discharging, extending battery lifespan while ensuring sufficient emergency response capability in the event of sudden load fluctuations.

4.3 Design of Control Architecture

Considering that the diesel generator needs to start and stop at any time according to the load size, the MESV is used to provide voltage and frequency support, and the diesel generator is mainly responsible for the output power.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the energy storage converter utilizes a dual closed-loop control strategy for both voltage and current, implemented in the dq coordinate system. The outer loop takes the d-axis voltage given

Figure 8: VF control architecture

The inner loop samples the actual inductor currents id and iq, then compares them with the reference currents

Finally, the target voltage components in the dq axis are transformed into the three-phase stationary coordinate system, and a drive signal is generated using SPWM to regulate the power switch of the energy storage converter, ensuring precise control of the output voltage and current.

This control method effectively achieves independent control of voltage and current, featuring a rapid dynamic response and high steady-state precision. At the same time, decoupling compensation minimizes system coupling interference, thereby enhancing the operational performance and stability of the energy storage converter.

For diesel generator, this paper proposes a power-speed control architecture based on diesel engines, as shown in Fig. 9. Based on the traditional diesel engine speed controller, a power controller is added to adjust the mechanical output power of the diesel engine, thereby controlling the electrical output power of the generator.

Figure 9: Diesel generator control architecture

The power regulator compares the given power Pref of the generator with the actual output power PG and generates a speed correction signal dn through a PI controller. This signal is then applied to the input of the electronic speed governor. The speed governor outputs the throttle control quantity, which adjusts the throttle control to modify the fuel injection amount and thus controls the diesel engine speed. By fine-tuning the engine speed, the mechanical input power is adjusted, and the generator’s output power is regulated to meet the expected power output. The essence of this process is to achieve power regulation by adjusting the speed. Fine-tuning the engine speed allows for precise control of the generator’s power output, ensuring it stays within the desired range to accommodate load changes.

The power-speed double-loop control can stably adjust the engine speed when the power changes, maintain the power stability and response flexibility of the parallel operation of the diesel generator and the energy storage converter, and optimize the diesel consumption.

To verify the feasibility of the proposed control strategy, a system simulation model is developed using Matlab/Simulink. The rated power of the diesel generator and energy storage is set at 30 kW, with the diesel generator’s optimal operating range defined between 70% and 80%, and its starting operating point set at 60%. The detailed parameters are provided in Table 3.

Note that short-duration simulations are adopted in this paper to reflect system behavior under dynamic events, which occur over long-time scales. This approach ensures functional verification while balancing simulation complexity and computational efficiency.

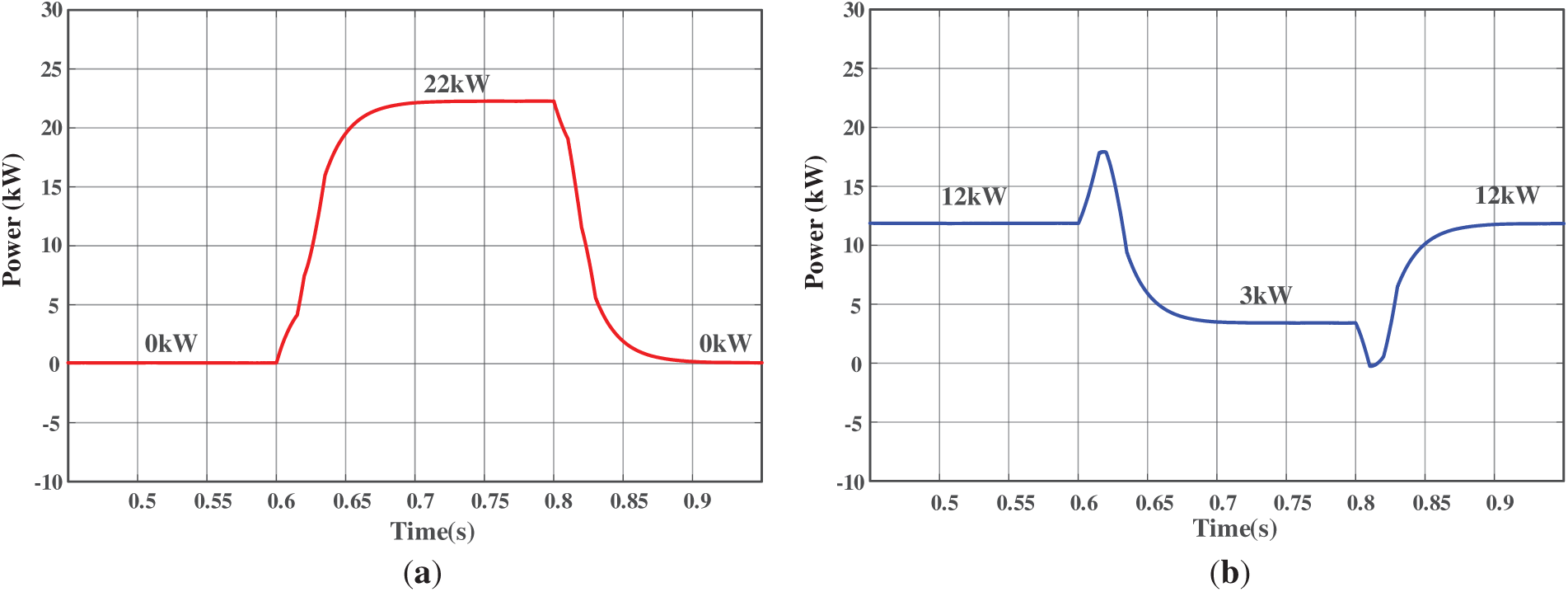

Simulation tests are performed to simulate the load mutation scenario during a grid fault disconnection. Due to the consideration of long-duration power supply scenarios, the startup time of the diesel generator is moderately reduced. The simulation results are presented in Figs. 10–12. The initial load demand is set to 12 kW, which is below the diesel generator’s minimum stable operating point. Therefore, the load is initially powered solely by the MESV, and the MDGV remains idle.

Figure 10: Output phase voltage: (a) RMS voltage wave; (b) Fast fourier transform results of the output voltage

Figure 11: Total output power

Figure 12: Output power: (a) Output power of MDGV; (b) Output power of MESV

At 0.6 s, a sudden 13 kW load is added to the system, resulting in a total demand of 25 kW. In response, the MDGV is started. However, due to its relatively slow dynamic response, the MESV promptly compensates for the sudden load increase. The output power of the MESV peaks at approximately 18 kW, ensuring voltage and frequency stability. As the generator ramps up, its output gradually increases and stabilizes at 22 kW, entering its optimal efficiency operating range. Simultaneously, the MESV output decreases to around 3 kW to match the total power demand.

At 0.8 s, the load demand drops back to 12 kW. The MDGV begins to reduce its output gradually to avoid oversupply, while the MESV is decreased to 0 kW, ensuring smooth voltage recovery and preventing frequency fluctuations. Eventually, the system returns to its initial operating condition, with the MESV supplying the load and the MDGV in standby. Throughout the transition, voltage deviations remain minimal, demonstrating the effectiveness of the coordinated control strategy.

During operation, the system’s output voltage remains stable, with minimal fluctuations and rapid recovery when the load changes suddenly. Additionally, the voltage distortion rate stays below 3%, ensuring high power supply quality.

A simulation is carried out to analyze the coordinated charging behavior of the MDGV and the MESV. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 13. At the beginning of the simulation, the MESV supplies 10 kW to the load, while the MDGV remains inactive to improve fuel economy during low-load conditions.

Figure 13: Charging experiment waveform: (a) Output power of MDGV; (b) Output power of MESV; (c) Total output power; (d) SOC of battery

At 0.6 s, the MDGV is started and quickly ramps up to its optimal operating point of 22 kW. Out of the total generated power, 10 kW continues to supply the load, while the remaining 12 kW is directed to charge the MESV. This charging process ensures efficient utilization of the generator’s output capacity, helping to maintain the system’s overall energy balance.

The coordinated control strategy allows the generator to operate within its high-efficiency range, while simultaneously enabling energy storage replenishment for future transient compensation needs. Throughout the simulation, system voltage and frequency remain stable, indicating the effectiveness of the energy management approach.

5.3 Daily Power Generation Operation Simulation

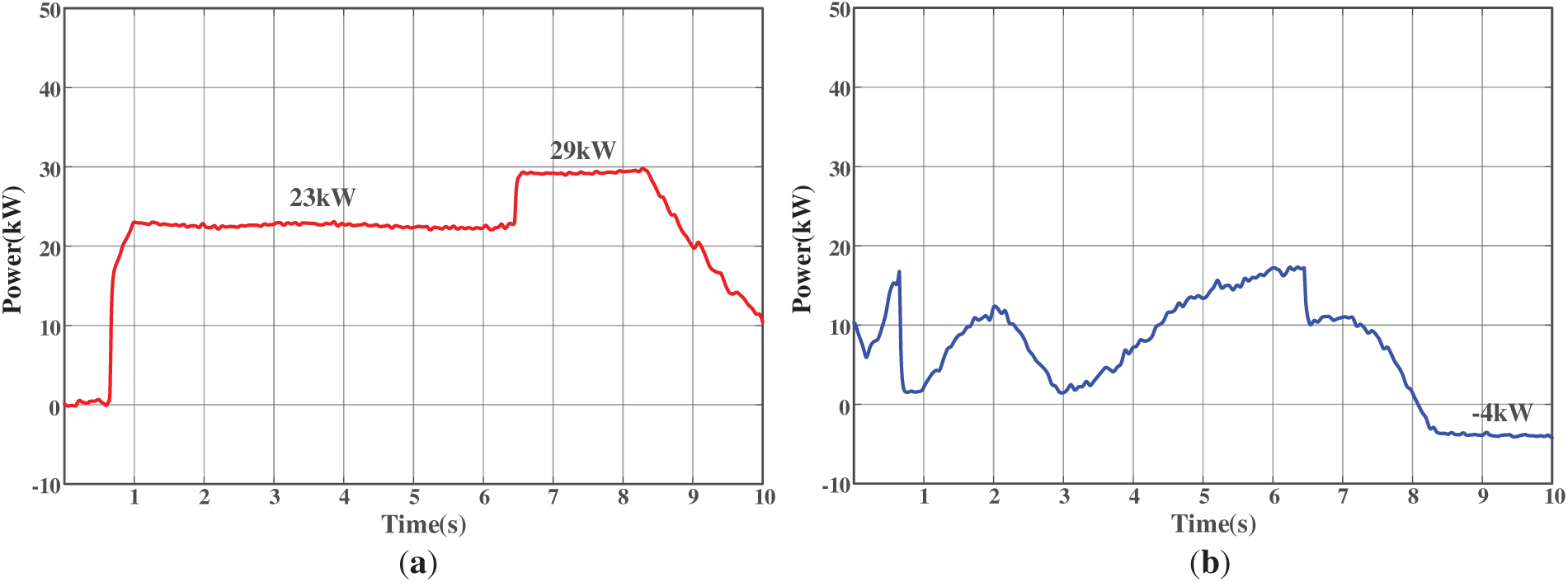

To better validate the performance of the proposed solution in emergency power supply scenarios with long durations and wide load fluctuations, a Simulink simulation was conducted based on typical daily load curve variations. In the simulation, both the operation time and the SOC of the MESV are proportionally scaled, compressing 24 h of load variations into a 10-s simulation window. The load trend includes: low demand from 0–2 s (morning), the first peak from 2–4 s (noon), a higher second peak from 5–8 s (afternoon), and a drop in demand from 8–10 s (night).

As shown in Figs. 14–16, when the load power is below 50% of the MDGV’s rated capacity (i.e., below 23 kW), the MESV operates alone to supply power, preventing the MDGV from running in a low-efficiency zone. Once the load exceeds 23 kW, the MDGV starts operating and maintains a stable output at 75% of its rated capacity (approximately 23 kW) to ensure optimal efficiency. After 8 s, due to insufficient energy in the MESV, the MDGV begins to supply power to both the load and to recharge the MESV. Throughout the entire process, the MDGV maintains stable output, while rapid power fluctuations are handled by the fast-responding MESV, thereby enhancing system stability and ensuring smooth and efficient operation.

Figure 14: Total output power

Figure 15: Output power: (a) Output power of diesel generator; (b) Output power of battery

Figure 16: SOC of MESV

To verify the economic advantage of the proposed scheme, a comparative analysis is conducted with the traditional single power vehicle supply scheme. Since a single MESV has limited discharge duration and cannot independently meet the continuous load demand of this experiment, a single MDGV is used as the comparison scheme. Specifically, the cost of a single power vehicle continuously supplying the load shown in Fig. 14 for 24 h is compared with the total cost under the proposed dual-vehicle parallel scheme with energy management strategy.

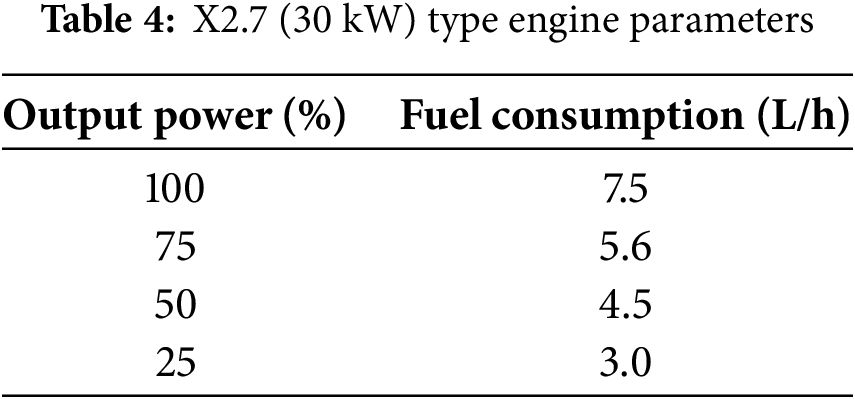

In the proposed scheme, the rated power of the generator vehicle is 30 kW, while the single-vehicle supply requires a generator vehicle with a rated power of 40 kW. Based on a survey of Cummins diesel generator products, two diesel generators with rated powers of 30 and 40 kW are selected for comparison. Their fuel consumption data under different load ratios are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

For a unified comparison, the fuel price is set at 7 RMB/L and the energy price for the energy storage system is set at 0.5 RMB/kWh. Based on these settings, the simulation results are shown in the Fig. 17: the total cost of the conventional MDGV with a rated power of 40 kW operating alone is 1168 RMB, whereas the proposed MESV (Mobile Energy Storage Vehicle, rated power 20 kW)–MDGV (rated power 30 kW) parallel architecture, combined with an optimized power allocation strategy, reduces the total cost to 1041 RMB, achieving a cost reduction of approximately 10.87%.

Figure 17: Cost curve

This demonstrates that the proposed parallel power supply architecture of MDGV-MESV can effectively reduce the specific fuel consumption of the diesel generator under low-load conditions, significantly lowering fuel costs and thereby reducing the overall power generation cost. These results validate the economic advantages of the proposed strategy.

To verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed coordinated power supply strategy between the MDGV and the MESV, an experimental platform was constructed to simulate the hybrid power supply scenario under emergency conditions. As shown in Fig. 18, the platform consists of a programmable DC power source emulating the output characteristics of the energy storage battery, an energy storage converter, and a diesel generator simulation platform based on a 1500 rpm motor-generator set. The system controller is built on a TMS320F28377S digital signal processor, which enables real-time control of power distribution and dynamic coordination between the two energy sources. Control commands are transmitted to the motor-side variable-frequency drive via the Modbus communication protocol to implement precise control of the generator’s mechanical input.

Figure 18: Experimental platform

To verify the output stability and dynamic response of the system under sudden load changes, a load step response test was conducted. In this experiment, A 200 Ω symmetrical three-phase resistive load was suddenly applied to the three-phase output of the system, and the corresponding voltage and current waveforms were recorded.

As shown in Fig. 19a,b, the full process of load application and removal is captured. Upon load application, the output current increased accordingly, while the output voltage remained almost unchanged, exhibiting excellent voltage stability even during the transition. When the load was removed, the voltage and current returned to their no-load levels without noticeable overshoot or oscillation.

Figure 19: Experiment waveform: (a) Output voltage; (b) Output Current

The steady-state performance is illustrated in Fig. 20a,b. After the load is connected, the output voltage remains stable at 400 V, and the output current stabilizes at the expected value according to Ohm’s law. The waveforms demonstrate that the power supply system maintains voltage regulation and load-following ability under sudden load changes, indicating reliable dynamic and steady-state performance.

Figure 20: Steady-State waveform: (a) Output voltage; (b) Output Current

6.2 Joint Power Supply Experiment

In this experiment, the coordinated power supply capability of the diesel generator and energy storage system was evaluated. The energy storage converter was first adjusted to supply 500 W and then increased to 1000 W. After reaching the target output, the energy storage converter power was held constant. Subsequently, the generator output was increased through the governor mechanism, enabling the diesel generator to output an additional 500 W.

As illustrated in Fig. 21, the output voltage remained stable throughout the process, demonstrating the voltage regulation performance of the system under dynamic power redistribution. Fig. 22a displays the current waveform of the energy storage converter, and Fig. 22b shows the load current waveform. From approximately 12 s onward, the load current gradually increased in response to the generator’s rising output, while the energy storage converter output current remained essentially unchanged. This experiment confirms the system’s ability to realize coordinated parallel power supply, with power-sharing behavior consistent with that of a hybrid MESV–MDGV configuration. The results verify that the proposed system can support collaborative operation under hybrid emergency power supply conditions.

Figure 21: Output voltage

Figure 22: Experiment result: (a) Energy storage converter current; (b) Load current

This paper proposes a parallel power supply architecture of MDGV-MESV, which enables stable 400 V AC output with total harmonic distortion (THD) maintained within 5%. Based on this architecture, a fuel-minimization-oriented power distribution strategy is developed to prioritize the use of the MESV for rapid response to load fluctuations, ensuring that the MDGV operates within its high-efficiency range. This not only reduces fuel consumption but also enhances the overall economic performance of the system. Specifically, the MDGV is maintained at above 50% of its rated power output, and can operate near the 75% high-efficiency zone for most of the time. By dynamically allocating power between the two vehicles, the system can flexibly meet varying load demands.

Meanwhile, this strategy effectively improves system performance by maintaining optimal operational efficiency and prolonging the maintenance intervals of the diesel generator. By controlling the MESV’s discharge depth and frequency, the aging effects on the battery are mitigated and the SOC can be maintained above 20%, thus extending the lifespan of the storage system. Furthermore, the adaptive power allocation mechanism enables seamless transitions between power sources, enhancing grid stability during load fluctuations. The tiered SOC management creates a balance between immediate power needs and long-term battery life, resulting in a highly efficient and reliable operation.

At present, this study focuses on the control strategy for coordinated power distribution between a single MDGV and MESV, and verifies its effectiveness through simulation and experimental validation under representative load scenarios. Future work will develop a more comprehensive cost model considering full life-cycle factors and conduct thorough evaluations against other commercial methods and strategies in similar scenarios to better assess the advantages of the proposed approach.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. The author expresses sincere gratitude to all those who participated in this study.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. (Project No. J2024136).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jian Wang, Feifei Bu; methodology, Feilong Jiang; software, Hui Qi; validation, Biao Jiang, Yajun Zhao; formal analysis, Lingyi Ji; investigation, Jian Wang; resources, Tiankui Sun; writing—original draft preparation, Feilong Jiang; writing—review and editing, Yajun Zhao; supervision, Feifei Bu; project administration, Jian Wang, Tiankui Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data used in this study are available on request. Data supporting this study are included in the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| MEPSV | Mobile Emergency Power Supply Vehicle |

| MDGV | Mobile Diesel Generator Vehicle |

| MESV | Mobile Energy Storage Vehicle |

| SOC | State of Charge |

References

1. Panteli M, Mancarella P. The grid: stronger, bigger, smarter?: presenting a conceptual framework of power system resilience. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2015;13(3):58–66. doi:10.1109/MPE.2015.2397334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jasiūnas J, Lund PD, Mikkola J. Energy system resilience—a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;150:111476. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Singh C, Jirutitijaroen P, Mitra J. Introduction to power system reliability. In: Electric power grid reliability evaluation: models and methods. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2019. p. 185–91. doi:10.1002/9781119536772.ch7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen C, Wang J, Ton D. Modernizing distribution system restoration to achieve grid resiliency against extreme weather events: an integrated solution. Proc IEEE. 2017;105(7):1267–88. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2017.2684780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mohamed MA, Chen T, Su W, Jin T. Proactive resilience of power systems against natural disasters: a literature review. IEEE Access. 2019;7:163778–95. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2952362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li J, Lei A, Yu C, Gao Y, Tao W, Li T. An overview of post-event power emergency resource dispatch for coping with extreme weather. In: 2024 Boao New Power System International Forum—Power System and New Energy Technology Innovation Forum (NPSIF); 2024 Dec 8–10; Qionghai, China. doi:10.1109/NPSIF64134.2024.10883258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li Y, Yuan J, Liu C, Yang M, Li M, Pan M. Research on the construction and practice of the technical support system for power supply guarantee in major events. In: 2015 7th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES); 2025 Mar 28–31; Chengdu, China. doi:10.1109/AEEES64634.2025.11019822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tian H, Alhaji A, Long Z, Chow MY. Microgrids for post-disaster power restoration application. In: 2024 IEEE 33rd International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE); 2024 Jun 18–21; Ulsan, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/ISIE54533.2024.10595777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shi W, Liang H, Bittner M. Stochastic planning for power distribution system resilience enhancement against earthquakes considering mobile energy resources. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2024;15(1):414–28. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2023.3296063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xu Y, Wang Y, He J, Su M, Ni P. Resilience-oriented distribution system restoration considering mobile emergency resource dispatch in transportation system. IEEE Access. 2019;7:73899–912. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2921017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang Z, Dehghanian P, Nazemi M. Enhancing seismic resilience of electric power distribution systems with mobile power sources. In: 2019 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting; 2019 Sep 29–Oct 3; Baltimore, MD, USA. doi:10.1109/ias.2019.8912010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Z, Shi Q, Fan K, Han H, Liu W, Li F. Analytical modeling of disaster-induced load loss for preventive allocation of mobile power sources in urban power networks. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy. 2024;12(4):1063–73. doi:10.35833/MPCE.2023.000591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chandra Tella V, Alzayed M, Chaoui H. A comprehensive review of energy management strategies in hybrid electric vehicles: comparative analysis and challenges. IEEE Access. 2024;12:181858–78. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3509737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fan G, Du Z, Lin X, Chen N. Mobile power sources pre-allocation and dispatch strategy in power-transportation coupled network under extreme weather. IET Renew Power Gener. 2024;18(7):1129–48. doi:10.1049/rpg2.12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang G, Zhang F, Zhang X, Wang Z, Meng K, Dong ZY. Mobile emergency generator planning in resilient distribution systems: a three-stage stochastic model with nonanticipativity constraints. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2020;11(6):4847–59. doi:10.1109/TSG.2020.3003595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rodrigues FM, Araujo LR, Penido DRR. A method to improve distribution system reliability using available mobile generators. IEEE Syst J. 2020;15(3):4635–43. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2020.3015154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sun K, Liu J, Zhou X, Jiang R, Xu X, Chen X. A post-event distribution network restoration approach considering network reconfiguration and mobile emergency generator. In: 2024 IEEE 25th China Conference on System Simulation Technology and its Application (CCSSTA); 2024 Jul 21–23; Tianjin, China. doi:10.1109/CCSSTA62096.2024.10691817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sui Q, Zhang L. Self-sustaining of critical park microgrids integrating mobile emergency generators subjective to major outage. CSEE J Power Energy Syst. 2024;10(4):1441–53. doi:10.17775/cseejpes.2023.01670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wu H, Xie Y, Deconinck G, Yu C, Hou K, Sun J, et al. Distributed coordinated restoration of transmission and distribution systems with repair crews and mobile emergency generators. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2024;40(1):4–17. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2024.3394455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sun L, Wang H, Huang Z, Wen F, Ding M. Coordinated islanding partition and scheduling strategy for service restoration of active distribution networks considering minimum sustainable duration. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2024;15(6):5539–54. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3433603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rangel N, Li H, Aristidou P. An optimisation tool for minimising fuel consumption, costs and emissions from Diesel-PV-Battery hybrid microgrids. Appl Energy. 2023;335:120748. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.120748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lee J, Craparo E, Oriti G, Krener A. Optimizing fuel efficiency on an islanded microgrid under varying loads. Energies. 2022;15(21):7943. doi:10.3390/en15217943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Babamohammadi S, Birss AR, Pouran H, Pandhal J, Borhani TN. Emission control and carbon capture from diesel generators and engines: a decade-long perspective. Carbon Capture Sci Technol. 2025;14(3):100379. doi:10.1016/j.ccst.2025.100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pham Minh T, Nguyen Manh D, Tran Quang V, The Luong N, Nguyen The T, Tien ND, et al. The pollutant reduction potential of old generation diesel engine retrofitting after-treatment system. In: The AUN/SEED-Net Joint Regional Conference in Transportation, Energy, and Mechanical Manufacturing Engineering; 2021 Dec 10–12; Hanoi, Vietnam. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-1968-8_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ribeiro PJG, Dias G, Mendes JFG. Public transport decarbonization: an exploratory approach to bus electrification. World Electr Veh J. 2024;15(3):81. doi:10.3390/wevj15030081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Huang Z, Li H, Tang Y, Liang C, Ma M, Xu Y, et al. Technologies for protection and efficient capacity utilization of emergency power supply vehicles based on multi-mode negative sequence compensation control. In: 2024 21st International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP); 2024 Oct 15–18; Chengdu, China. doi:10.1109/ICHQP61174.2024.10768735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou K, Jin Q, Feng B, Wu L. A bi-level mobile energy storage pre-positioning method for distribution network coupled with transportation network against typhoon disaster. IET Renew Power Gener. 2024;18(16):3776–87. doi:10.1049/rpg2.12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu Y, Zhao M, Wu H, Xiang S, Yuan Y. Coordination of network reconfiguration and mobile energy storage system fleets to facilitate active distribution network restoration under forecast uncertainty. Front Energy Res. 2023;10:1024282. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2022.1024282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sun X, Qiu J, Yi Y, Tao Y. Cost-effective coordinated voltage control in active distribution networks with photovoltaics and mobile energy storage systems. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2021;13(1):501–13. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2021.3118404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ahmed HMA, Sindi HF, Azzouz MA, Awad ASA. Optimal sizing and scheduling of mobile energy storage toward high penetration levels of renewable energy and fast charging stations. IEEE Trans Energy Convers. 2022;37(2):1075–86. doi:10.1109/TEC.2021.3116234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang D, Lei J, Zhuang J. Analysis of mobile energy storage to improve the resilience of distribution network for large-scale outage events. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Smart Grid and Energy Internet (SGEI); 2024 Dec 13–15; Shenyang, China. doi:10.1109/SGEI63936.2024.10914177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu J, Lin S, He S, Liu W, Liu M. Multiobjective optimal dispatch of mobile energy storage vehicles in active distribution networks. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(1):804–15. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2022.3220825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lei S, Chen C, Zhou H, Hou Y. Routing and scheduling of mobile power sources for distribution system resilience enhancement. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2019;10(5):5650–62. doi:10.1109/TSG.2018.2889347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao P, Miao J, Chen Y, Wang Z, He R. Optimization scheduling method for mobile energy storage considering economic efficiency and emergency power supply scenarios. In: 2024 11th International Forum on Electrical; 2024 Nov 15–17; Qingdao, China. doi:10.1109/ifeea64237.2024.10878595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lu Z, Xu X, Yan Z, Shahidehpour M, Sun W, Han D. Distributionally robust chance constrained optimization method for risk-based routing and scheduling of shared mobile energy storage system with variable renewable energy. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2024;15(4):2594–608. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2024.3429310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xu R, Zhang C, Zhang D, Dong ZY, Yip C. Adaptive robust load restoration via coordinating distribution network reconfiguration and mobile energy storage. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2024;15(6):5485–99. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3404776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang X, Yi H, Wang Z, Wen Y, Jiang X, Zhuo F. Online expansion of multiple mobile emergency energy storage vehicles without communication. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2024;71(8):8915–26. doi:10.1109/TIE.2023.3331146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Liu X, Zhao F, Hao H, Liu Z. Opportunities, challenges and strategies for developing electric vehicle energy storage systems under the carbon neutrality goal. World Electr Veh J. 2023;14(7):170. doi:10.3390/wevj14070170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Foles A, Fialho L, Horta P, Collares-Pereira M. Economic and energetic assessment of a hybrid vanadium redox flow and lithium-ion batteries considering power sharing strategies impact. arXiv:2301.02535. 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. Psarros GN, Dratsas PA, Papathanassiou SA. A comprehensive review of electricity storage applications in island systems. arXiv:2401.14712. 2024. [Google Scholar]

41. Li C, Xi Y, Lu Y, Liu N, Chen L, Ju L, et al. Resilient outage recovery of a distribution system: co-optimizing mobile power sources with network structure. Prot Control Mod Power Syst. 2022;7(1):32. doi:10.1186/s41601-022-00256-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang W, Xiong X, He Y, Hu J, Chen H. Scheduling of separable mobile energy storage systems with mobile generators and fuel tankers to boost distribution system resilience. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2022;13(1):443–57. doi:10.1109/TSG.2021.3114303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hang M, Wang Y, Sun S, Yu P. Research on power supply strategy of DC microgrid with diesel rectifier generator and hybrid energy storage system. In: 2023 IEEE 7th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2); 2023 Dec 15–18; Hangzhou, China. doi:10.1109/EI259745.2023.10513044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. McGowan DJ, Morrow DJ, Fox B. Integrated governor control for a diesel-generating set. IEEE Trans Energy Convers. 2006;21(2):476–83. doi:10.1109/TEC.2006.874247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Shah C, Wies RW, Hansen TM, Tonkoski R, Shirazi M, Cicilio P. High-fidelity model of stand-alone diesel electric generator with hybrid turbine-governor configuration for microgrid studies. IEEE Access. 2022;10(3):110537–47. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3211300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Long Q, Yu H, Xie F, Lu N, Lubkeman D. Diesel generator model parameterization for microgrid simulation using hybrid box-constrained levenberg-marquardt algorithm. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2021;12(2):943–52. doi:10.1109/TSG.2020.3026617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Shojaee M, Azizi SM. Decentralized robust control of a coupled wind turbine and diesel engine generator system. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2023;38(1):807–17. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2022.3167627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang RP, Shi XG, Wei DC, Wang YQ, Yin W, Cheng Y. Multistage variable current pulse charging strategy based on polarization characteristics of lithium-ion battery. IEEE Trans Energy Convers. 2024;40(1):422–36. doi:10.1109/TEC.2024.3446168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Bhatt HN, Gairola S, Panda MK. Analysis of electric vehicle battery charging time involving its second-order RC equivalent model. In: 2024 IEEE 5th India Council International Subsections Conference (INDISCON); 2024 Aug 22–24; Chandigarh, India. doi:10.1109/INDISCON62179.2024.10744257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools