Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Probabilistic Graphical Model-Based Operational Reliability-Centric Design of Offshore Wind Farm Feeder Layouts

1 Power Dispatch Control Center, Guangdong Power Grid Company Ltd., Gaungzhou, 510000, China

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

3 State Key Laboratory of Power System Operation and Control, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

* Corresponding Author: Ying Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Grid Integration and Electrical Engineering of Wind Energy Systems: Innovations, Challenges, and Applications)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4799-4814. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.069131

Received 15 June 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

The rapid expansion of offshore wind energy necessitates robust and cost-effective electrical collector system (ECS) designs that prioritize lifetime operational reliability. Traditional optimization approaches often simplify reliability considerations or fail to holistically integrate them with economic and technical constraints. This paper introduces a novel, two-stage optimization framework for offshore wind farm (OWF) ECS planning that systematically incorporates reliability. The first stage employs Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) to determine an optimal radial network topology, considering linearized reliability approximations and geographical constraints. The second stage enhances this design by strategically placing tie-lines using a Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Program (MIQCP). This stage leverages a dynamic-aware adaptation of Multi-Source Multi-Terminal Network Reliability (MSMT-NR) assessment, with its inherent nonlinear equations successfully transformed into a solvable MIQCP form for loopy networks. A benchmark case study demonstrates the framework’s efficacy, illustrating how increasing the emphasis on reliability leads to more distributed and interconnected network topologies, effectively balancing investment costs against enhanced system resilience.Keywords

The global energy landscape is undergoing a transformative shift towards renewable sources to mitigate climate change and reduce dependence on fossil fuels [1]. Within this transition, wind energy, particularly offshore wind, has emerged as a critical component, recognized for its potential to generate substantial electric power with lower environmental impact compared to traditional sources [2]. The offshore wind sector is experiencing unprecedented growth and falling costs [3]. As of December 2023, global installed offshore wind capacity reached 75.2 GW, with projections indicating a substantial increase to 138 GW by 2028. This expansion is evident in various regions, including established markets and emerging areas like Vietnam, which aims for 10 GW by 2030 [4], and Taiwan, targeting 5.7 GW by 2025 [5]. The increasing integration of offshore wind into national grids, especially in European nations, highlights the need for robust infrastructure [6].

A crucial aspect of designing and operating cost-effective and efficient offshore wind farms (OWFs) lies in optimizing the internal electrical infrastructure, specifically the feeder layout [7]. This optimization is a key challenge in the global design process for modern offshore wind farms [8]. Efficient feeder layouts are essential for maximizing power output while minimizing energy losses [1], and they also play a vital role in ensuring system reliability and reducing overall project costs [9].

However, optimizing these layouts is a complex task due to the need to balance numerous, often conflicting, objectives [10]. This complexity is amplified by the broader challenges inherent in large-scale offshore wind development [11]. The problem involves a range of electrical considerations, from fundamental aspects like power transfer capacities and voltage rise [9] to ensuring high power quality [12]. A primary concern is designing for fault tolerance [13], which can be enhanced with modern solutions such as smart switch configurations to improve system reliability [14]. Economic factors like cable installation costs, the cost of lost energy production, and operational expenditures are also significant drivers. Furthermore, technical challenges are posed by harsh marine environments, especially concerning the dynamic cable requirements for floating turbines [15]. Finally, grid integration issues and the sheer complexity of managing large-scale systems with numerous components must be considered, requiring robust frameworks to ensure reliability [16].

Existing research has addressed various aspects of wind farm optimization, including wind turbine placement to maximize power output and minimize wake effects [17], and cable routing primarily focused on cost and reliability for onshore farms using methods like Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) [9]. Optimization studies for offshore cable layouts have utilized mathematical programming like MILP, focusing on objectives such as minimizing cost and power losses, or balancing cost and network robustness. Other multi-objective approaches have been applied to related problems such as site selection considering conflicting criteria [4] and grid integration including energy storage sizing and control co-design. While these studies provide valuable insights into specific challenges and objectives, there is a notable gap in comprehensive, integrated frameworks that simultaneously consider the diverse range of electrical, economic, environmental, technical, and potentially social factors relevant to offshore wind farm feeder layout optimization within a unified approach. The complexity arises from the need to optimize multiple, often conflicting objectives, which requires advanced modeling and solution methods [18].

Constraints in MILP models for feeder layout ensure the feasibility and operational integrity of the electrical network. These constraints can incorporate various factors vital for network design, such as ensuring a feasible electrical network topology, accounting for power transfer capacities, and considering power quality issues. In broader energy system contexts, MILP constraints also include meeting demand, respecting operational limits of generators, and transmission capacity limits [18]. Reliability considerations can also be integrated into the MILP formulation for cable routing optimization. Beyond layout, MILP has been applied to optimize system configurations for economic profit based on factors like electricity price profiles and costs [6].

Recent research has begun to address this gap more directly, though limitations remain. A notable contribution [19] by proposed an ECS planning method that incorporates network reconfiguration following faults, utilizing a two-stage stochastic programming approach to optimize network reliability under N-1 contingency scenarios. While this was a significant step towards reliability-aware design, its methodology lacks effective consideration of higher-order contingencies. Such cascading or concurrent failures, though less frequent, can have a disproportionately large impact on lifetime energy production and financial viability. This limitation highlights the need for a planning framework capable of optimizing the ECS topology based on a more comprehensive and nuanced assessment of network reliability under a wider range of failure scenarios.

Therefore, the primary objective of this paper is to develop and validate a reliability-centered collector network planning framework that comprehensively accounts for the varying reliability levels of different network topologies. To achieve this, we proposed a novel, two-stage optimization framework for OWF electrical collector system design that fully integrates lifetime operational reliability. The key contributions of this work are threefold:

(1) We adapted a Multi-Source Multi-Terminal Network Reliability (MSMT-NR) assessment for the planning stage, where the complex issue of network reliability can be incorporated into the optimization problem during the planning stage.

(2) A bifurcated optimization strategy is proposed. The first stage determines an optimal radial network topology through Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) considering linearized reliability constraints and geographical constraints. Subsequently, this design is enhanced by strategically placing tie-lines using a Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Program (MIQCP) that incorporates the more complex, nonlinear MSMT-NR equations for loopy networks.

(3) The proposed framework is benchmarked through a case study that demonstrates how varying the emphasis on reliability impacts the resulting network topology, leading to more distributed and interconnected designs as reliability becomes paramount.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the problem description of the reliability-centered ECS system design. Section 3 develops a detailed mathematical model and proposes corresponding solution methods for the complex nonlinear optimization problem. Section 4 presents case studies, while Section 5 discusses the extension method and limitations of the proposed method. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Reliability-Centric Feeder Layout Design

2.1 Feeder Layout Design Problem Description

The planning of a wind farm is typically carried out in two stages. In the first stage, the optimal layout of wind turbines is determined based on local meteorological conditions, using simulation and analysis methods such as flow field dynamics modeling. Once the specific locations of the turbines have been established, the second stage involves planning the wind farm’s collector network. This paper focuses solely on the network planning problem under the premise that the turbine locations have already been determined. The design of the electrical collector system (ECS) for an offshore wind farm (OWF) is a critical and complex optimization task. It involves determining the optimal layout of inter-array cables connecting individual wind turbines (WTs) to one or more offshore substations (OSSs). The primary goal is to ensure efficient power transmission while minimizing overall lifetime costs and maximizing system reliability. This problem is inherently NP-hard due to the vast combinatorial search space of potential cable connections, especially for large-scale OWFs. The challenge lies in striking a balance between the significant capital expenditure (CAPEX) for submarine cables and their installation, operational expenditure (OPEX), and the economic impact of energy losses or curtailment due to cable failures.

Traditional ECS designs often adhere to predefined structures like radial or ring configurations. Radial layouts are cost-effective in terms of initial investment but offer low reliability, as a single cable fault can disconnect multiple turbines. Loopy layouts enhance reliability by providing alternative power flow paths but incur higher cabling costs. Therefore, it is necessary to balance the following two objectives through optimization methods.

1. Investment Cost (

2. Reliability Cost (

In summary, the general form of the topology optimization problem can be formulated as follows:

2.2 Reliability Evaluation of ECS

ECS are critical infrastructure responsible for aggregating the power generated by individual wind turbine generators (WTGs) and transmitting it to an OSS or directly to export cables. The reliability of this network significantly impacts the overall availability and economic performance of the OWF. These networks can feature various topologies, such as radial strings, star configurations, or increasingly, looped or meshed designs to enhance redundancy against component failures (e.g., subsea cables, switchgear). Drawing upon the probabilistic assessment frameworks like the one proposed by [20] for urban distribution grids, a rigorous approach to quantify collector network reliability is essential.

2.2.1 Risk-Based Reliability Metrics

To evaluate the reliability of an OWF collector network, system-level risk metrics are crucial. Similar to urban grids, metrics such as Loss of Load Probability (LOLP) and Expected Energy Not Served (EENS) are highly relevant. For a collector network, LOLP can be interpreted as the probability that the power from a specific WTG or a group of WTGs cannot reach the designated collection point (e.g., the OSS high-voltage busbar). The EENS quantifies the expected amount of energy that fails to be delivered due to failures within the collector system over a given period. Adapting the formulation from [20], the discretized EENS for an OWF considering potential generation from WTGs can be expressed as:

where

2.2.2 Multi-Source Multi-Terminal Network Reliability (MSMT-NR) Modeling

The collector network can be modeled as a probabilistic graph

given that component

2.2.3 Analytical Inference and Decomposition for Complex Topologies

For simple radial or tree-like collector strings, the LOLP for each WTG connection might be expressed analytically. For instance, if WTG

where

However, such a recursive decomposition approach cannot be incorporated into optimization problems involving topology planning. This is because any change in topology necessitates re-decomposition, which alters the problem structure. For solver-based optimization algorithms, this is impractical, as it results in frequent changes of constraints. Therefore, traditional network reliability assessment methods are difficult to integrate effectively with accurate optimization algorithms.

The optimization of ECS topology presents unique challenges due to the complexity of simultaneously addressing reliability requirements, geographical constraints, and cost considerations. To manage this complexity effectively, we propose a two-stage approach to the topology planning problem.

In this approach, the first stage focuses on determining an optimal radial topology that serves as the primary operational structure of the wind farm. Radial topologies are preferred during normal operation for their simplicity, lower cost, and reduced protection requirements. The second stage identifies strategic tie-line placements that enhance system reliability by providing alternative power flow paths during contingencies.

This decomposition offers significant computational advantages by addressing the more tractable radial network design first, before incorporating the nonlinear reliability constraints associated with loopy networks. Additionally, it mirrors the actual operational paradigm of offshore wind farms, where the network primarily functions in a radial configuration but can reconfigure to utilize tie-lines during fault conditions.

The following sections detail the mathematical formulation for each stage, beginning with the constraints that ensure radiality and reliability in the first stage, followed by the more complex reliability modeling required for networks with tie-lines in the second stage.

3.1 First Stage: Optimal Radial Topology Design

In order to ensure the radial operation of the offshore wind farm collection network, topological constraints need to be considered. To reduce the number of binary variables in the model and thus enhance computational efficiency, reference [21] introduced a compact set of constraints for radial network formulation. These constraints simultaneously reduce both the number of variables and constraints, thereby improving the solution efficiency of the first stage problem. The mathematical expression for these constraints is as follows:

where

In radial systems, the path from a node to the OSS node is unique. The power flow on each branch is directed, as shown in Fig. 1. Thus, the series reliability equation can be adopted. Specifically, the reliability

where

Figure 1: Radial network with directed branches (S is OSS Node)

Under ideal numerical precision, the aforementioned constraints can precisely express the reliability relationship. However, even established commercial optimization solvers may encounter numerical issues, leading to problem structures that are difficult to solve. Therefore, it is imperative to employ the big-M method to relax the unique equality constraint at each node. Instead, a series of inequality constraints should be used to express the reliability assessment embodied in Eq. (10).

When

3.1.3 Network Capacity Constraints

Each feeder is subject to a certain capacity limit, beyond which power transmission is not permitted. Therefore, it is necessary to impose overall network capacity constraints during the planning process to prevent the occurrence of excessively long feeder lines.

The network flow constraints utilize several variables:

3.1.4 Geographical Constraints

Since submarine cables are laid on the seabed surface, it is generally necessary to avoid cable crossings. Therefore, the following constraint must be satisfied [19]:

where

Here,

Thus, the overall problem for the first stage is:

Here,

3.2 Second Stage: Optimal Tie-Line Placement

3.2.1 Loopy Network Reliability Constraints

In networks with tie-lines, the direction cannot be determined due to the topology reconfiguration. The MSMT-NR method proposed in [20] enables reliability analysis for scenarios involving multiple OSSs. However, the “deletion-contraction decomposition” approach adopted by this method is not suitable for exact solutions to optimization problems. Therefore, this paper simplifies the calculation process of branch variables in MSMT-NR, making it amenable to exact optimization via mathematical solvers. The constraints of simplified MSMT-NR equations are as follows:

where

3.2.2 Overestimation of Nodal Reliabilities

The MSMT-NR algorithm requires deletion-contraction decomposition, which is infeasible for MIP algorithms to implement. The above constraints may lead to overestimation for reliabilities. However, the overestimation of most topologies does not significantly affect reliability-oriented planning (because although reliability is overestimated, the resulting structure is still reliable). However, one triangular structure will cause a significant (or problematic) overestimation of reliability, as shown in Fig. 2 below.

Figure 2: Triangular structure in network design

While triangular topologies are mathematically common, they are seldom encountered in engineering practice. Therefore, in this study, we eliminate triangular topologies from the final network planning results, which effectively reduces the overall structural complexity and improves the efficiency of subsequent reliability assessments. When

3.3 MIQCP Transformation for the MSMT-NR Equations

Even the simplified MSMT-NR equations still contain complex multiplicative relationships. Such general nonlinear constraints are not suitable for direct solution by solvers. We consider constraints of the form:

where

Additionally, we enforce:

The transformation introduces

3.4 Overall Algorithmic Framework

The proposed optimization framework systematically designs the OWF feeder layout in a two-stage process. The first stage establishes a cost-effective and operationally simple radial network by solving a Mixed-Integer Linear Program (MILP). This stage approximates reliability and enforces geographical and capacity constraints. The second stage takes this radial design as a baseline and enhances its resilience by strategically adding tie-lines. This is achieved by solving a Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Program (MIQCP), which employs a more sophisticated loopy network reliability model. The complete procedure is detailed in Algorithm 1.

The geographical information of the wind turbines is based on the WT30 wind power case study presented in [19]. It is assumed that the capacity of each line in the network is 10 p.u., and the power output requirement of a single wind turbine is 2 p.u. And the branch reliability

All experiments were conducted on a server equipped with an EPYC 48-core processor and 256 GB of memory, utilizing Gurobi 12.0 as the solver. Furthermore, to accelerate the identification of feasible solutions, the “No relaxation heuristics” option was enabled during the experiments, and sufficient lazy constraints were added prior to the start of the solving process.

4.2 Optimal Radial Network Design

Under different reliability coefficients

Figure 3: Topology design results of WT30 case at

Figure 4: Topology design results of WT30 case at

Figure 5: Topology design results of WT30 case at

4.3 Optimal Tie-Line Placement

The design results of the tie-lines are shown in Figs. 3–5 with dashed lines. When the reliability requirements are low, the system adds three tie-lines almost exclusively at locations that are both close in proximity and most effective in enhancing reliability. However, as the reliability requirements of the system increase, the basic topology can already provide a relatively reliable network structure. When

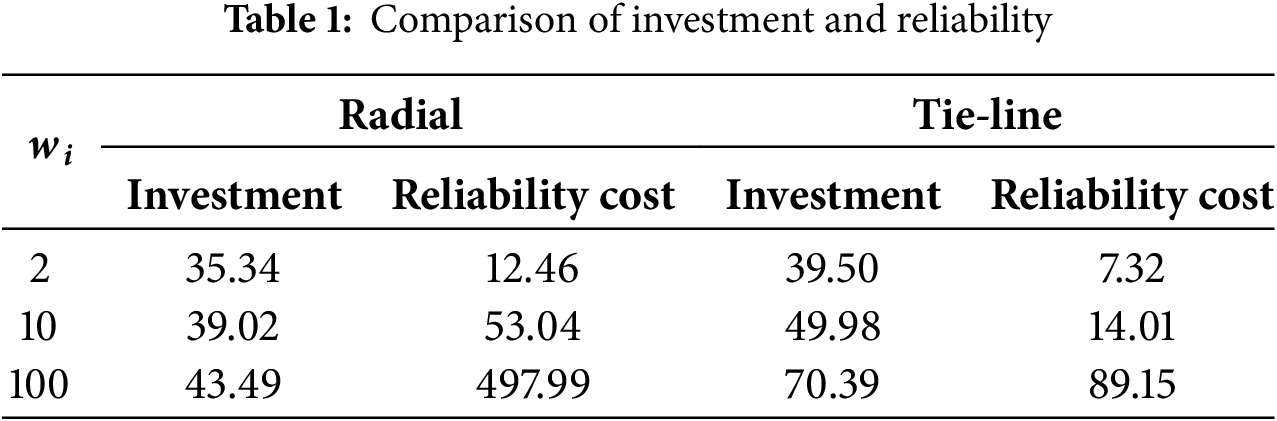

Reliability and investment cost results are shown in Table 1. The WT30 case provides additional evidence that when reliability requirements are stringent (e.g.,

4.4 Performance Validation of the Two Stage Formulation

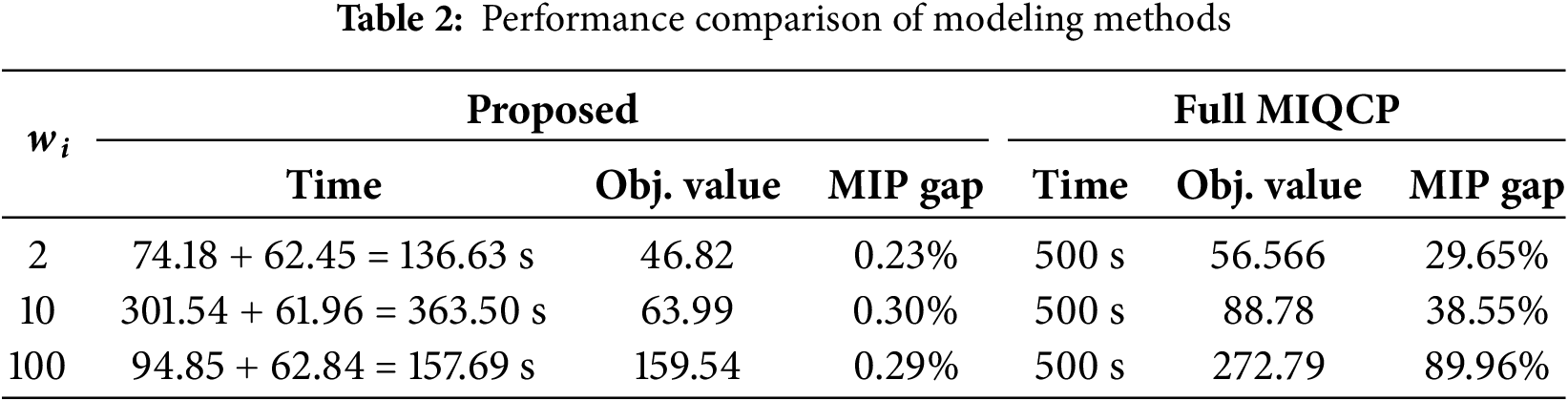

In this section, we shall undertake a comparative analysis of the computational efficiency of the proposed methods. Given the challenging nature of solving nonlinear and non-convex MIQCP, we have set a maximum resolution time of 500 s for all problems, with heuristic feasible solution algorithms constrained to 60 s. For comparison, we denote the complete second-stage model as Full-MIQCP, which implies that it is not initialized with the radial topology planning results from the first stage. Table 2 presents the results of the computation time (The time taken by the proposed method is expressed as the sum of stage 1 and stage 2):

It is apparent that within the 500-s limit, the Full MIQCP method struggles to provide optimal solutions, resulting in a substantial MIP Gap, which indicates inadequate exploration of the entire solution space. On the other hand, ECS typically operates in a radial topology, and the proposed method ensures that the selected lines can form the most reliable radial network, something that Full-MIQCP cannot guarantee. It is important to note that, due to the complexity of integer programming, the results clearly indicate that achieving radial topology planning when the reliability weight (

5.1 The Impact of Variable Reliability on the Planning Stage

In engineering practice, submarine cables of the same model are often used for lines at different locations. When the marine environmental conditions are similar, the failure rates of these lines are typically comparable. Therefore, it is appropriate to characterize their reliability using the same parameters during the planning stage. If the reliabilities of the various edges in the system differ, a stochastic programming approach can be employed for optimization. First, representative failure probability scenarios can be generated based on meteorological and seabed data around the wind farm. Subsequently, stochastic programming based on these scenarios can be used to optimize the sum of the expected system-wide failure risk and investment cost. This approach will substantially increase the scale of the optimization problem.

Common mode failure refers to the simultaneous failure of multiple lines due to the same underlying cause. Such occurrences are relatively rare in the stable environment of the seabed. When common-cause failures need to be taken into account, conventional series network reliability models become inapplicable. Instead, probabilistic graphical models that support joint distributions, such as Bayesian networks, should be employed. Further research is required regarding the translation of these models into mixed-integer programming frameworks.

5.3 Extension to Large Scale Cases

In practical engineering scenarios, a single OSS rarely serves more than 50 wind turbines, making the 30-node scale both reasonable and representative. For larger-scale wind farms, a partitioning approach is typically adopted, whereby wind turbines located in close proximity are grouped and assigned to a specific OSS. Therefore, in practical applications, the proposed method can be implemented by first optimizing the topology for a single OSS, followed by coordinated design among multiple OSSs to reduce system complexity. This approach facilitates the extension of the methodology to larger-scale wind farm systems. Therefore, in future research, we will adopt advanced wind turbine partitioning methods for optimization planning, which will enable the efficient handling of larger-scale optimization problems.

This paper presented a novel two-stage optimization framework for designing offshore wind farm (OWF) electrical collector systems (ECS) with a central focus on lifetime operational reliability. Addressing the limitations of existing methods, our approach offers a more comprehensive and integrated solution. Key contributions include: (1) the adaptation of a Multi-Source Multi-Terminal Network Reliability (MSMT-NR) assessment parameterized with expected lifetime component behaviors for the planning stage; (2) a bifurcated optimization strategy that first establishes an optimal radial topology via Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) with linearized reliability, and subsequently enhances it with tie-lines determined by a Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Program (MIQCP) incorporating full MSMT-NR for loopy networks; (3) the successful transformation of the nonlinear MSMT-NR equations into a tractable MIQCP formulation; and (4) a demonstration, via a benchmark WT30 case study, of how varying the emphasis on reliability directly influences the resulting network topology.

Future research could extend this framework in several promising directions. For increasingly large-scale OWFs, exploring advanced heuristic or metaheuristic algorithms, or hybrid approaches, to manage computational complexity while maintaining solution quality is crucial. Furthermore, additional optimization factors can be introduced, such as integrating the selection of cable types into the optimization model.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to China South Power Grid Co., Ltd. for the generous support and funding provided for this research.

Funding Statement: This paper is supported by the Science and Technology Project of China South Power Grid Co., Ltd., Grant Nos. 036000KK52222044, GDKJXM20222430.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Qiuyu Lu and Ying Chen; methodology, Qiuyu Lu and Ying Chen; software, Qiuyu Lu and Yunqi Yan; validation, Yang Liu, Yinguo Yang and Tannan Xiao; formal analysis, Qiuyu Lu and Ying Chen; investigation, Qiuyu Lu and Yang Liu; resources, Yunqi Yan and Ying Chen; data curation, Qiuyu Lu and Yunqi Yan; writing—original draft preparation, Qiuyu Lu, Yunqi Yan and Tannan Xiao; writing—review and editing, Yang Liu, Ying Chen and Guobing Wu; supervision, Ying Chen; project administration, Ying Chen; funding acquisition, Ying Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Paul K, Jyothi B, Kumar RS, Singh AR, Bajaj M, Hemanth Kumar B, et al. Optimizing sustainable energy management in grid connected microgrids using quantum particle swarm optimization for cost and emission reduction. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):5843. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-90040-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sharma H, Wang W, Huang B, Ramachandran T, Adetola V. Multi-objective control co-design using graph-based optimization for offshore wind farm grid integration. In: 2024 American Control Conference (ACC); 2024 Jul 10–12; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 2580–5. [Google Scholar]

3. Warder SC, Piggott MD. Mapping global offshore wind wake losses, layout optimisation potential, and climate change effects. arXiv:2408.15028. 2025. [Google Scholar]

4. Wang CN, Nguyen NAT, Dang TT. Offshore wind power station (OWPS) site selection using a two-stage MCDM-based spherical fuzzy set approach. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4260. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08257-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lee TY, Wu YT, Kueh MT, Lin CY, Lin YY, Sheng YF. Impacts of offshore wind farms on the atmospheric environment over taiwan strait during an extreme weather typhoon event. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):823. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-842008/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wiegner JF, Ossentjuk IM, Nienhuis RM, Vakis AI, Gibescu M, Gazzani M. Harvesting the wind-assessment of offshore electricity storage systems. Comput Aided Chem Eng. 2024;53(12):2185–90. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-28824-1.50365-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Christie LA, Sahin A, Ogunsemi A, Zăvoianu AC, McCall JAW. On the multi-objective optimization of wind farm cable layouts with regard to cost and robustness. In: Parallel problem solving from nature—PPSN XVIII: 18th international conference, PPSN 2024. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2024. p. 367–82. [Google Scholar]

8. Pérez-Rúa JA, Das K, Stolpe M, Cutululis NA. Global optimization of offshore wind farm collection systems. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2020;35(3):2256–67. doi:10.1109/tpwrs.2019.2957312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. žarkovic SD, Shayesteh E, Hilber P. Onshore wind farm-reliability centered cable routing. Elect Power Syst Res. 2021;196(2):107201. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2021.107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rodrigues S, Bauer P, Bosman PAN. Multi-objective optimization of wind farm layouts–complexity, constraint handling and scalability. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;65(2):587–609. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.07.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Offshore wind development in the Great Lakes: challenges, resources and technical solutions | ocean dynamics [Internet]. [cited 29 Jul 2025]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10236-025-01666-7. [Google Scholar]

12. Yousaf MZ, Singh AR, Khalid S, Bajaj M, Kumar BH, Zaitsev I. Bayesian-optimized LSTM-DWT approach for reliable fault detection in MMC-based HVDC systems. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):17968. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-68985-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Vedachalam N, Umapathy A, Ramadass GA. Fault-tolerant design approach for reliable offshore multi-megawatt variable frequency converters. J Ocean Eng Sci. 2016;1(3):226–37. doi:10.1016/j.joes.2016.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Smart switch configuration and reliability assessment method for electrical collector systems in offshore wind farms [Internet]. [cited 29 Jul 2025]. Available from: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/xddlxtyqjnyxb-e202406007. [Google Scholar]

15. Rentschler MUT, Adam F, Chainho P, Krügel K, Vicente PC. Parametric study of dynamic inter-array cable systems for floating offshore wind turbines. Mar Syst Ocean Technol. 2020;15(1):16–25. doi:10.1007/s40868-020-00071-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ivanhoe RO, Wang L, Kolios A. Generic framework for reliability assessment of offshore wind turbine jacket support structures under stochastic and time dependent variables. Ocean Eng. 2020;216:107691. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2020.107691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nguyen KD, Tran TT, Vo DN. Optimal turbine placement in wind power plants using search algorithms. J Electr Eng Technol. 2025;20(4):2107–19. [Google Scholar]

18. Yu S, You L, Zhou S. A review of optimization modeling and solution methods in renewable energy systems. Front Eng Manag. 2023;10(4):640–71. doi:10.1007/s42524-023-0271-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ding X, Du Y, Shen X, Wu Q, Zhang X, Hatziargyriou ND. Reliability-based planning of cable layout for offshore wind farm electrical collector system considering post-fault network reconfiguration. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2025;16(1):419–33. doi:10.1109/tste.2024.3462476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yan Y, Chen Y, Cui Z, Xiao T. Probabilistic resilience assessment of urban distribution power grids by fast inference of multi-source multi-terminal network reliability. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2025;261:111077. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2025.111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sun S, Li G, Chen C, Bian Y, Bie Z. A novel formulation of radiality constraints for resilient reconfiguration of distribution systems. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2023;14(2):1337–40. doi:10.1109/tsg.2022.3220054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei W, Wang J. Modeling and optimization of interdependent energy infrastructures. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

23. Aguayo MM, Sarin SC, Sherali HD. Solving the single and multiple asymmetric traveling salesmen problems by generating subtour elimination constraints from integer solutions. IISE Trans. 2018;50(1):45–53. doi:10.1080/24725854.2017.1374580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools