Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring Efficiency of Silicon Carbide for Next Generation of Alkali & Alkaline Earth Metals-Ion Batteries Using Quantum Mechanic Method

1 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Kastamonu University, Kastamonu, 37150, Turkey

2 Department of Chemical Engineering, CT.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, 1496969191, Iran

* Corresponding Author: Fatemeh Mollaamin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Analytics on Energy Systems)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4971-4986. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.069945

Received 03 July 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Delving alternative high-performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries have always attracted scientist attention. A wide-bandgap semiconductor with excellent mechanical properties, “silicon carbide (SiC)”, has been introduced as the anode electrode. Two-dimensional SiC has special hybridization which can build it as an appropriate substitution for graphene. Energy storage technologies are keys in the extension and function of electric devices. To keep up with steady innovations in saving energy technologies, it is essential to progress corresponding practical strategies. In this research article, SiC has been designed and characterized as an anode electrode for lithium (Li), sodium (Na), beryllium (Be), and magnesium (Mg) ion batteries, forming SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C, and SiMg2C nanoclusters. A comprehensive study of energy-saving by SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C, and SiMg2C complexes was conducted using computational methods, accompanied by analysis of charge density differences (CDD), total density of states (TDOS), and localized orbital locator (LOL) for hybrid clusters of SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C, and SiMg2C. Functionalizing lithium, sodium, beryllium, and magnesium can shift the negative charge distribution of carbon toward electron-acceptor states in SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C, and SiMg2C nanoclusters. Higher Si/C content can increase battery capacity via SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C, and SiMg2C nanoclusters during the energy storage process and improve rate performance by enhancing electrical conductivity. Besides, silicon carbide anode material may improve cycling consistency by mitigating electrode degradation, and it augments capacity owing to higher surface capacitance.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Seeking alternative high-performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries was emphasized. A wide-bandgap semiconductor with excellent mechanical properties, “silicon carbide”, has been pursued as the anode electrode. A significant volume change during charge-discharge of Si-based nanostructures as anode electrodes for high-energy lithium-ion batteries has been considered the most serious obstacle to their commercial use [1–4].

In addition to the low diffusion barrier, moderate open-circuit voltage, and excellent electronic conductivity during sodiation, the researchers proposed that the SiC structure is a promising anode material for Na-ion batteries. More importantly, they found that the intercalation strength of Na ions into C-based multilayer materials could be enhanced by increasing the number of covalent bonds of “Na–C”, which could be realized via doping by atoms (Li, Be, B, Al, Si or P) with lower electronegativity than that of the C atom [5–9].

The novel structure of a SiC monolayer was investigated for sodium and potassium storage using DFT. It was revealed that SiC exhibits negative adsorption energies for K/Na adsorption on its surface. Furthermore, the SiC monolayer can efficiently achieve a high content of Na/K loading on both sides of its surface. Additionally, it is demonstrated that the semiconducting SiC monolayer transforms into a metallic state with excellent conductivity upon Na/K adsorption. These findings underscore the potential of the SiC monolayer as a promising anode candidate for both sodium-and potassium-ion batteries [10].

Anode materials based on silicon carbide and III-nitride nanosheets are investigated for magnesium-ion batteries (MIBs) as a possible alternative to lithium-and sodium-ion batteries. The results from density functional theory calculations reveal higher values of the internal energy change and cell voltage for MIBs with silicon carbide, boron nitride, aluminum nitride, and gallium nitride anode materials than for previously reported carbon nanomaterials [11].

Whereas the polarizability of the Si atom is more than that of the C atom, it is assumed that the Si-C/C/Si nanosurface may contribute more intensely to the compositions in the hybrid to the pure C-nanostructures [12–14]. The previous investigations of energy-saving devices through H-adsorption have been tailored owing to DFT calculations with a semiconductor group of Si/Ge/Sn/Pb nano-carbides [15], Mg-Al nanoalloy [16] and Al/C/Si doping of BN nanocomposite [17]. Nanomaterials with distinctive structures are being investigated for their potential in electrocatalysis, fuel cells, and energy-saving applications [18].

Recently, investigations have been done by outlining the electrochemical reaction mechanisms and challenges associated with Si-based anodes in alkali metal-ion batteries, and then they have presented various approaches, including the architectural engineering of Si, the surface engineering of Si-based materials, and the construction of Si-based composites to improve the battery performance. Therefore, the anticipated challenges and opportunities in developing silicon-based anode materials for alkali-metal-ion batteries can be explored [19].

In another study, Dong et al. used titanium silicon carbide (Ti3SiC2, TSC) to prepare the Si-based anode composite (Si/TSC) to improve the performance of the LIB. TSC was used as a mechanical strengthening and highly conductive matrix for the Si-based anode [20]. Following in-depth characterization, samples were measured to assess, for the first time, their performance correlated with chemical composition variations in Li-, Na-, Be-, or Mg-batteries.

2 Theoretical Backgrounds, Materials and Methods

Development of the applied Density Functional Theory (DFT) methodology only became notable after Kohn and Sham released their reputable series of equations which are introduced as Kohn-Sham (KS) equations [21,22]:

By representing the single particle orbitals

Finally, the total energy could be measured by the KS method due to the Eq. (4):

Therefore, the precise exchange energy functional is described by the Kohn–Sham orbitals in lieu of the density which is cited as the indirect density functional. This research has employed the penetration of the hybrid functional of three-parameter basis set of “B3LYP (Becke, Lee, Yang, Parr)” within the conception of DFT upon theoretical computations [23,24]. The popular B3LYP (Becke, three-parameter, Lee–Yang–Parr) and the exchange-correlation functional become as Eq. (5) [23–25]:

Calculations with spin polarization were performed within DFT [26]. The exchange correlation potentials were treated by the “Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)” parameterization within the “general gradient approximation (GGA)” [27,28]. Fig. 1a–d has shown alkali metals and alkaline earth metals-based nanoclusters of SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C.

Figure 1: Adding Li, Na, Be, Mg to SiC nanocluster and formation of (a) SiLi2C, (b) SiNa2C, (c) SiBe2C and (d) SiMg2C complexes towards saving energy in novel batteries

The analysis of Bader charge parameter [29] has been illustrated for energy storage by hybrid clusters of SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C (Fig. 1a–d) accompanying the Gaussian 16 revision C.01 computational software [30] and the GaussView 6.1 graphical program [31].

One of the most significant advantages of applying SiC nanocluster as the anode material in Li-, Na-, Be-or Mg-batteries is increasing energy storage utility due to enhancing the electrical conductivity between Si/C and surface area. In this investigation, homogenously distributed silicon or carbon elements can be immobilized in the SiC matrix, which prevents their tendency to form the agglomeration under battery cycling. The Li/Na/Be/Mg insertion might also result the cleavage of some C–Li, C–Na, C–Be or C–Mg bonds in the SiC anode material and the expansion of favorable sites for the subsequent ion insertion in the network (Fig. 1a–d).

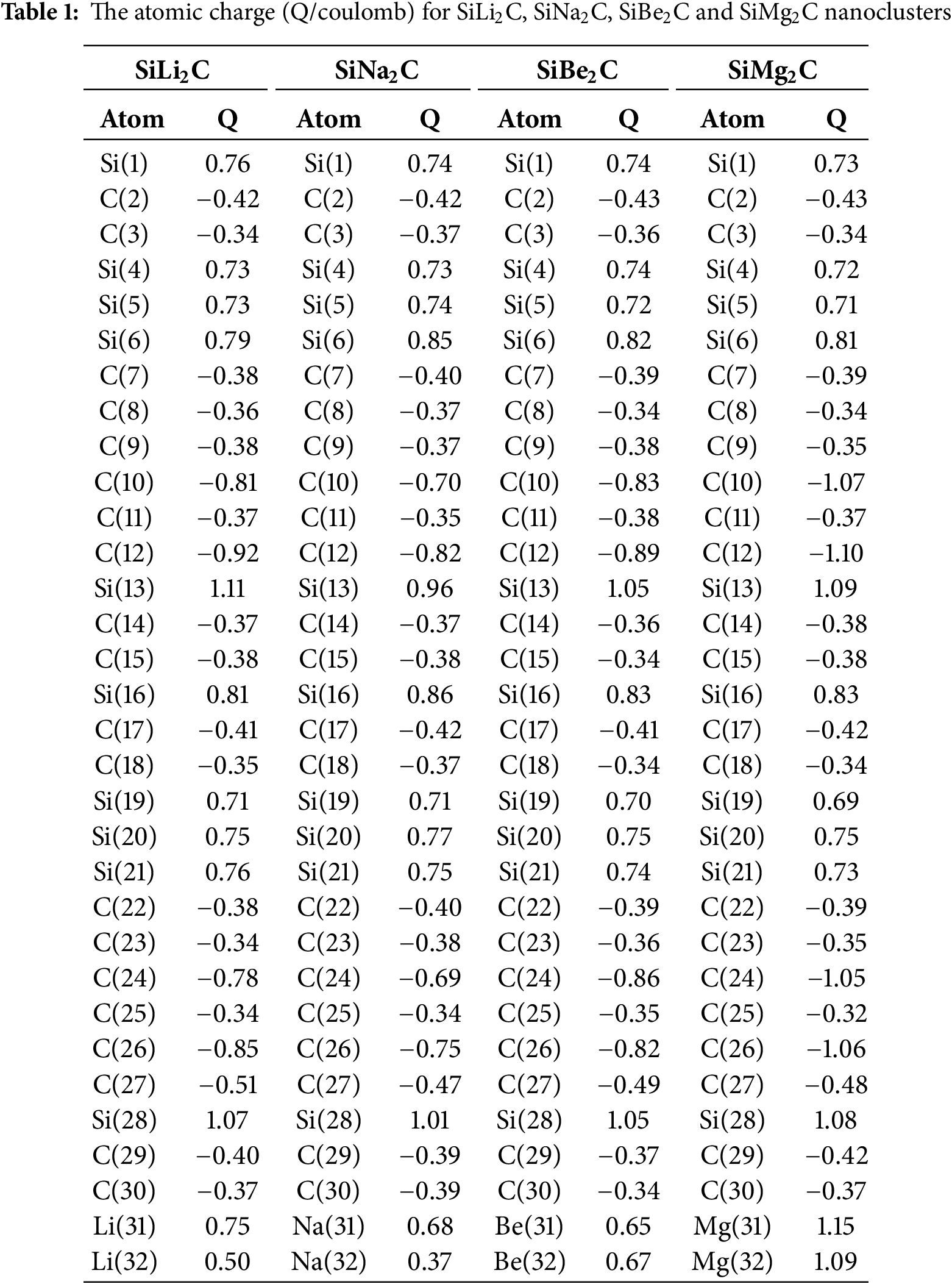

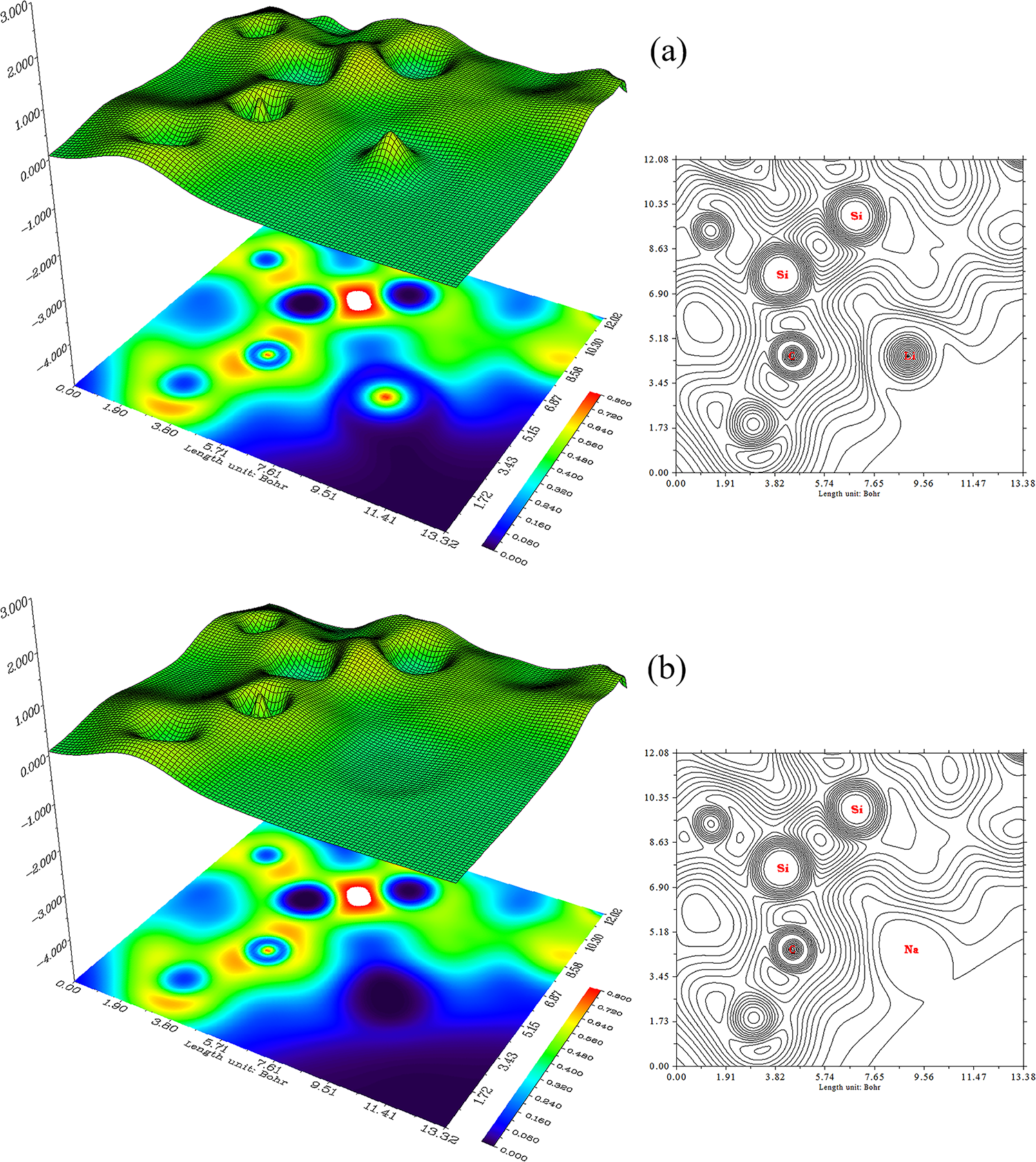

3.1 Charge Density Differences Analysis

In Fig. 2a–d, charge density differences (CDD) [32] have been shown for SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters with the vibration in the district about −12 to +9 Bohr through co-interaction between alkali metals of Li(31)–Li(32), Na(31)–Na(32) and alkaline earth metals of Be(31)–Be(32), Mg(31)–Mg(32).

Figure 2: The CDD graphs for (a) SiLi2C, (b) SiNa2C, (c) SiBe2C and (d) SiMg2C nanoclusters

Moreover, the elements of C(2), C(3), C(7)–C(12), C(14), C(15), C(17), C(18), C(22)–C(27), C(29), C(30) from SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters have displayed the vibration about −12 to +9 Bohr (Table 1 and Fig. 2a,d).

The charge distribution has been illustrated during alkali and alkaline earth metals captured by SiC nanostructure towards formation of SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters, respectively (Table 1). Functionalizing of Li, Na, Be, Mg atoms can augment the negative atomic charge of C(2), C(3), C(7)–C(12), C(14), C(15), C(17), C(18), C(22)–C(27), C(29), C(30) as electron acceptors in SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters (Fig. 3a–d).

Figure 3: The changes of charge distribution for (a) SiLi2C, (b) SiNa2C, (c) SiBe2C and (d) SiMg2C nanoclusters

In isolated system (such as molecule), the energy levels are discrete, the concept of “density of states (DOS)” is supposed to be completely valueless in this situation. Therefore, the “original total DOS (TDOS)” of an isolated system can be written as [33]:

The normalized Gaussian function is defined as:

“FWHM (full width at half maximum)” is an adjustable parameter in “Multiwfn” [34,35]. Furthermore, the curve map of “broadened partial DOS (PDOS)” and “overlap DOS (OPDOS)” are valuable for visualizing the orbital composition analysis, that “PDOS function of fragment A” is defined as:

where “

where “

Regarding energy storage by SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters, TDOS has been evaluated. This factor can demonstrate the existence of important chemical interactions on the “convex side” (Fig. 4a–d).

Figure 4: The TDOS graphs of (a) SiLi2C, (b) SiNa2C, (c) SiBe2C and (d) SiMg2C nanoclusters

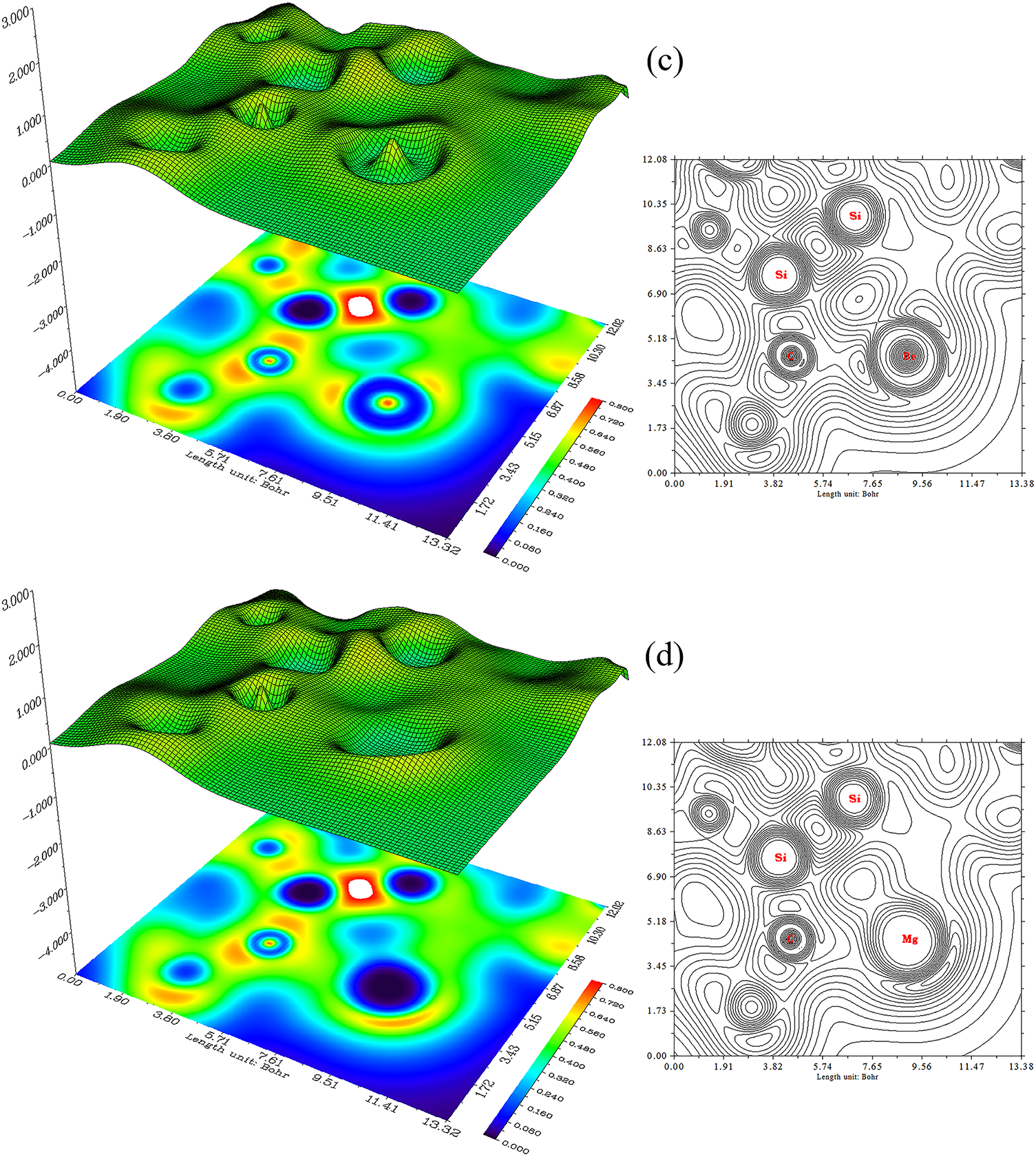

3.3 Localized Orbital Locator Analysis

Localized orbital locator (LOL) has a similar expression compared to “electron localization function (ELF)” [36].

“Multiwfn” [34,35] also supports the approximate version of “LOL” defined by “Tsirelson and Stash” [37,38], namely the actual kinetic energy term in “LOL” is replaced by “second-order gradient expansion like ELF” which may demonstrate a broad span of bonding samples. This “Tsirelson’s version of LOL” can be activated by setting “ELFLOL_type to 1. For special reason”, if “ELFLOL_type in settings.ini is changed from 0 to 2”, another formalism will be used:

If the parameter “ELFLOL_cut in settings.ini is set to x”, then “LOL will be zero where LOL is less than x”.

Trapping of Li, Na, Be, Mg atoms by SiC nanostructure (Fig. 5a–d) has concluded SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters (Fig. 5a–d).

Figure 5: The counter (right side) and shaded (left side) maps of LOL graphs for (a) SiLi2C, (b) SiNa2C, (c) SiBe2C and (d) SiMg2C nanoclusters

SiLi2C (Fig. 5a), SiNa2C (Fig. 5b), SiBe2C (Fig. 5c) and SiMg2C (Fig. 5d) have demonstrated the electron delocalization through an isosurface map with labeling atoms of C(10), C(12), Si(13), C(24), C(26), Si(28), X(31)/X(32) (X = Li, Na, Be, Mg). In fact, the counter map of LOL can confirm that SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters may augment the efficiency of energy storage (Fig. 5a–d and Table 2).

Moreover, intermolecular orbital overlap integral is important in discussions of intermolecular charge transfer which can calculate HOMO-HOMO and LUMO-LUMO overlap integrals between the alkali/alkaline earth metals and silicon carbide (Table 2).

In addition, the amount of “Mayer bond order” [39] is generally according to empirical bond order for the single bond is nearly 1.0. “Mulliken bond order” [40] with a small accord with empirical bond order is not appropriate for quantifying bonding strength, for which Mayer bond order always performs better. However, “Mulliken bond order” is a good qualitative indicator for “positive amount” of bonding and “negative amount” of antibonding which are evacuated and localized, respectively (Table 3).

As it is seen in Table 3, “Laplacian bond order” [41] has a straight cohesion with bond polarity, bond dissociation energy and bond vibrational frequency. The low value of Laplacian bond order might demonstrate that it is insensitive to the calculation degree applied for producing electron density. Generally, the value of “Fuzzy bond order” is near Mayer bond order, especially for low-polar bonds, but much more stable with respect to the change in basis-set. Computation of “Fuzzy bond order” demands running “Becke’s DFT” numerical integration, owing to which calculation value is larger than assessment of “Mayer bond order” and it can concede more precisely [42].

Alkali/Alkaline earth metals captured by silicon carbide towards the formation of SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C and SiMg2C nanoclusters were studied by DFT computational methods. Changes in charge density indicate a notable charge transfer in the SiLi2C, SiNa2C, SiBe2C, and SiMg2C heteroclusters. Due to the semiconducting nature of SiC, it is usually composited with C for better ionic and electronic conductivities. It is well established that increasing Li, Na, Be, or Mg in cell batteries can enhance energy efficiency.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to Kastamonu University for completing this paper and its research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fatemeh Mollaamin; data collection: Fatemeh Mollaamin and Majid Monajjemi; analysis and interpretation of results: Fatemeh Mollaamin and Majid Monajjemi; draft manuscript preparation: Fatemeh Mollaamin and Majid Monajjemi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Fan X, Deng D, Li Y, Wu QH. Recent progress in SiC nanostructures as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Curr Mater Sci. 2023;16(1):18–29. doi:10.2174/2666145415666220822120615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao X, Lehto VP. Challenges and prospects of nanosized silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Nanotechnology. 2021;32(4):042002. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/abb850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wen Q, Qu F, Yu Z, Graczyk-Zajac M, Xiong X, Riedel R. Si-based polymer-derived ceramics for energy conversion and storage. J Adv Ceram. 2022;11(2):197–246. doi:10.1007/s40145-021-0562-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ge M, Cao C, Biesold GM, Sewell CD, Hao SM, Huang J, et al. Silicon anodes: recent advances in silicon-based electrodes: from fundamental research toward practical applications. Adv Mater. 2021;33(16):2004577. doi:10.1002/adma.202170124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shao G, Hanaor DA, Wang J, Kober D, Li S, Wang X, et al. Polymer-derived SiOC integrated with a graphene aerogel as a highly stable Li-ion battery anode. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(41):46045–56. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c12376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Mollaamin F. Anchoring of 2D layered materials of Ge5Si5O20 for (Li/Na/K)-(Rb/Cs) batteries towards eco-friendly energy storage. BMC Chem. 2025;19(1):233. doi:10.1186/s13065-025-01593-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wilamowska-Zawlocka M, Puczkarski P, Grabowska Z, Kaspar J, Graczyk-Zajac M, Riedel R, et al. Silicon oxycarbide ceramics as anodes for lithium ion batteries: influence of carbon content on lithium storage capacity. Rsc Adv. 2016;6(106):104597–607. doi:10.1039/C6RA24539K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Pradeep VS, Ayana DG, Graczyk-Zajac M, Soraru GD, Riedel R. High rate capability of SiOC ceramic aerogels with tailored porosity as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim Acta. 2015;157:41–5. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2015.01.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liu Q, Fu C, Xiao B, Li Y, Cheng J, Liu Z, et al. Graphitic SiC: a potential anode material for Na-ion battery with extremely high storage capacity. Int J Quantum Chem. 2021;121(10):e26608. doi:10.1002/qua.26608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Peng Q, Rehman J, Ullah M, Tighezza AM, Hanif MB, Shibl MF, et al. Anchoring of K and Na on the surface of a novel SiC monolayer: first-principles predictions. J Energy Storage. 2024;104(13):114435. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.114435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Khan AA, Ahmad R, Ahmad I. Silicon carbide and III-Nitrides nanosheets: promising anodes for Mg-ion batteries. Mater Chem Phys. 2021;257(45):123785. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.123785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yodsin N, Sakagami H, Udagawa T, Ishimoto T, Jungsuttiwong S, Tachikawa M. Metal-doped carbon nanocones as highly efficient catalysts for hydrogen storage: nuclear quantum effect on hydrogen spillover mechanism. Mol Catal. 2021;504:111486. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2021.111486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Taha HO, El Mahdy AM, El Shemy FES, Hassan MM. Hydrogen storage in SiC, GeC, and SnC nanocones functionalized with nickel, density functional theory—study. Int J Quantum Chem. 2023;123(3):e27023. doi:10.1002/qua.27023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wei T, Zhou Y, Sun C, Guo X, Xu S, Chen D, et al. An intermittent lithium deposition model based on CuMn-bimetallic MOF derivatives for composite lithium anode with ultrahigh areal capacity and current densities. Nano Res. 2024;17(4):2763–9. doi:10.1007/s12274-023-6187-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mollaamin F, Monajjemi M. Nanomaterials for sustainable energy in hydrogen-fuel cell: functionalization and characterization of carbon nano-semiconductors with silicon, germanium, tin or lead through density functional theory study. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2024;18(2):607–23. doi:10.1134/s1990793124020271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mollaamin F, Shahriari S, Monajjemi M. Influence of transition metals for emergence of energy storage in fuel cells through hydrogen adsorption on the MgAl surface. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2024;18(2):398–418. doi:10.1134/s199079312402026x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mollaamin F, Monajjemi M. Electric and magnetic evaluation of aluminum-magnesium nanoalloy decorated with germanium through heterocyclic carbenes adsorption: a density functional theory study. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2023;17(3):658–72. doi:10.1134/s1990793123030223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mollaamin F, Monajjemi M. Adsorption ability of Ga5N10 nanomaterial for removing metal ions contamination from drinking water by DFT. Int J Quantum Chem. 2024;124(2):e27348. doi:10.1002/qua.27348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tareq FK, Rudra S. Enhancing the performance of silicon-based anode materials for alkali metal (Li, Na, K) ion battery: a review on advanced strategies. Mater Today Commun. 2024;39:108653. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dong Z, Gu H, Du W, Feng Z, Zhang C, Jiang Y, et al. Si/Ti3SiC2 composite anode with enhanced elastic modulus and high electronic conductivity for lithium-ion batteries. J Power Sources. 2019;431:55–62. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.05.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kohn W, Sham LJ. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys Rev. 1965;140(4A):A1133–8. doi:10.1103/physrev.140.a1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hohenberg P, Kohn W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys Rev. 1964;136(3B):B864–71. doi:10.1103/physrev.136.b864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98(7):5648–52. doi:10.1063/1.464913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B. 1988;37(2):785–9. doi:10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Vosko SH, Wilk L, Nusair M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: a critical analysis. Can J Phys. 1980;58(8):1200–11. doi:10.1139/p80-159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Grimme S, Antony J, Ehrlich S, Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J Chem Phys. 2010;132(15):154104. doi:10.1063/1.3382344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865–8. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Mollaamin F. Investigating the treatment of transition metals for ameliorating the ability of boron nitride for gas sensing & removing: a molecular characterization by DFT framework. Prot Met Phys Chem Surf. 2024;60(6):1050–63. doi:10.1134/s2070205124702502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Henkelman G, Arnaldsson A, Jónsson H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput Mater Sci. 2006;36(3):354–60. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2005.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, et al. Gaussian 16, revision C.01. Wallingford, CT, USA: Gaussian, Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

31. Dennington R, Keith TA, Millam JM. GaussView, version 6.06.16. Shawnee Mission, KS, USA: Semichem Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

32. Xu Z, Qin C, Yu Y, Jiang G, Zhao L. First-principles study of adsorption, dissociation, and diffusion of hydrogen on α-U (110) surface. AIP Adv. 2024;14(5):055114. doi:10.1063/5.0208082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mollaamin F. Alkali metals doped on tin-silicon and germanium-silicon oxides for energy storage in hybrid biofuel cells: a first-principles study. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2025;19(3):722–36. doi:10.1134/s1990793125700393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lu T, Chen F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J Comput Chem. 2012;33(5):580–92. doi:10.1002/jcc.22885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Lu T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn J Chem Phys. 2024;161(8):082503. doi:10.1063/5.0216272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Schmider HL, Becke AD. Chemical content of the kinetic energy density. J Mol Struct THEOCHEM. 2000;527(1–3):51–61. doi:10.1016/s0166-1280(00)00477-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tsirelson V, Stash A. Analyzing experimental electron density with the localized-orbital locator. Struct Sci. 2002;58(5):780–5. doi:10.1107/s0108768102012338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Matta CF, Ayers PW, Cook R. The physics of electron localization and delocalization. In: Electron localization-delocalization matrices. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 7–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-51434-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mayer I. Improved definition of bond orders for correlated wave functions. Chem Phys Lett. 2012;544:83–6. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2012.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mollaamin F, Monajjemi M. Doping of graphene nanostructure with iron, nickel and zinc as selective detector for the toxic gas removal: a density functional theory study. J Carbon Res. 2023;9(1):20. doi:10.3390/c9010020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lu T, Chen F. Bond order analysis based on the Laplacian of electron density in fuzzy overlap space. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117(14):3100–8. doi:10.1021/jp4010345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang X, Zhang X, Pedrycz W, Yang SH, Boutat D. Consensus of T-S fuzzy fractional-order, singular perturbation, multi-agent systems. Fractal Fract. 2024;8(9):523. doi:10.3390/fractalfract8090523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools