Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Feasibility of Micro-Hydro Power for Rural Electrification in Bangladesh: A Case Study from the Chittagong Hill Tracts

1 School of Engineering, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chittagong University of Engineering & Technology, Chittagong, 4349, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Ratan Kumar Das. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Analytics on Energy Systems)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4815-4835. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.071727

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Bangladesh has achieved notable progress in expanding electricity access nationwide. Nonetheless, remote and topographically challenging regions such as the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) continue to face coverage gaps due to grid extension difficulties. This research investigates the technical feasibility of micro-hydro power (MHP) systems as viable off-grid solutions for rural electrification in CHT. Field surveys conducted across various sites assessed available head and flow rates using GPS-based elevation measurements and portable flow meters. Seasonal fluctuations were factored into the analysis to ensure year-round operational viability. The study involved estimating power output, selecting appropriate turbine types based on head-flow data, and proposing preliminary plant configurations. Results identify multiple locations with adequate head (2.5 to 10.4 m) and flow rates (0.10 to 0.35 m3/s), capable of generating between 1.5 and 16.5 kW, sufficient for essential rural applications. Based on site-specific head and discharge characteristics, Kaplan and Francis turbines were identified as the most suitable configurations, offering high efficiency for the medium-flow, low-to-medium head environments typical of the studied regions. Despite inherent technical potential, challenges such as seasonal variability, infrastructure complexities, and policy deficiencies remain. This investigation addresses a critical knowledge gap in local renewable energy planning. It offers a data-driven foundation for pilot projects and community-scale electrification initiatives in Bangladesh’s remote mountainous areas.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

1.1 Global Energy Transition and the Role of Hydropower

The global energy system is undergoing a transformative shift, driven by the urgent need to mitigate climate change, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and ensure long-term energy security. Hydropower, one of the oldest forms of renewable energy, has played a pivotal role in electricity generation for over a century, with early developments dating back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries [1]. While the initial focus of hydropower was on large-scale installations, recent decades have witnessed a diversification of the technology, with increased attention on small and micro-hydro systems.

Globally, hydropower accounted for approximately 16% of electricity generation in 2022, making it the most significant single renewable energy contributor [2]. The role of hydropower varies significantly by region: in Asia, for example, countries like China, India, and Nepal have invested heavily in hydropower as part of their renewable energy expansion, while in Europe, Norway derives nearly all its electricity from hydro sources [3]. Despite its widespread use, global hydropower potential remains underutilized, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Southeast Asia, where untapped river systems could support both large and small-scale projects [4].

As the global energy transition accelerates, hydropower’s role is being redefined within a broader strategy of decentralization and grid independence. Small-scale and micro-hydropower systems, which typically range from a few kilowatts to under 100 kW, are increasingly seen as essential tools for rural electrification and community empowerment [5]. These systems provide clean, stable, and locally managed power, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and enhancing resilience against energy supply disruptions.

To illustrate the distribution of global electricity generation sources, Fig. 1 presents the latest global electricity mix, highlighting the contribution of hydropower relative to other renewables and fossil fuels.

Figure 1: Global electricity generation by source [2]

1.2 Bangladesh’s Energy Scenario

Bangladesh has undergone a remarkable transformation in its electricity generation capacity over the past two decades, increasing from under 5000 MW in the early 2000s to over 28,000 MW by 2023 [6]. This expansion has helped the country achieve near-universal access to electricity, with over 97% of the population reportedly connected to the grid [7]. However, this rapid growth has come with a heavy reliance on fossil fuels, which currently dominate the national energy mix [8].

Natural gas remains the backbone of Bangladesh’s power sector, contributing approximately 54.83% of total electricity generation [9]. This is followed by furnace oil (21.83%) and coal (20.45%) [10,11]. In stark contrast, renewable energy sources—including solar and hydropower—account for less than 3% of the country’s total installed capacity [12]. This imbalance not only raises concerns about energy security and long-term sustainability but also exposes the economy to volatility in global fuel prices and contributes to rising greenhouse gas emissions [13].

Recognizing these challenges, the Government of Bangladesh has introduced several policy measures aimed at increasing the share of renewable energy. The Renewable Energy Policy of 2008 set an initial target of achieving 10% of electricity from renewables by 2020—a goal that remains unmet but continues to guide current strategies. More recently, the Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan (2021) has articulated a vision for transitioning towards a greener economy, including net-zero emissions aspirations by mid-century [13].

Despite these policy intentions, significant disparities persist in energy access, particularly in rural and geographically isolated regions such as the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the Chars (riverine islands), and coastal areas [14]. Many of these regions remain either underserved or entirely off-grid, relying on diesel generators or traditional biomass for their energy needs, both of which are expensive, environmentally damaging, and unreliable.

In this context, decentralized renewable energy solutions such as micro-hydropower present a practical and sustainable alternative. These systems can not only enhance energy access in remote regions but also contribute to reducing the country’s dependence on fossil fuels and lowering carbon emissions. The current breakdown of Bangladesh’s electricity generation is illustrated in Fig. 2, highlighting the significant underrepresentation of renewable energy in the national portfolio [15].

Figure 2: Bangladesh electricity generation by source (BPDB, 2023) [15]

1.3 The Need for Rural Electrification

Access to reliable electricity is widely acknowledged as a fundamental driver of socioeconomic development. In rural Bangladesh, however, energy poverty continues to impede progress in key areas such as education, healthcare, communication, and small-scale industrial development. Despite significant strides in national electrification, millions of people living in remote, hilly, or geographically isolated areas remain either completely off-grid or experience frequent and prolonged power outages [16].

The consequences of inadequate electrification are multifaceted. Educational outcomes suffer as children are unable to study after dark; healthcare services remain limited without the ability to power essential medical equipment; and economic opportunities are constrained, particularly for small businesses and agricultural processing, which increasingly require mechanization. Furthermore, the reliance on traditional biomass fuels such as firewood, charcoal, and kerosene not only contributes to indoor air pollution and adverse health outcomes but also exacerbates environmental degradation through deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions [17].

Globally, numerous countries have successfully demonstrated the transformative potential of rural electrification through decentralized renewable energy systems. In Nepal, for instance, over 3000 micro-hydro plants have been installed, providing electricity to more than 1.5 million people and fostering economic growth in remote mountain communities. Similarly, micro-grid solar and micro-hydro projects in India and Kenya have significantly improved energy access, resilience, and quality of life in rural settings [2,18].

For Bangladesh, achieving universal energy access is a central tenet of the government’s Vision 2041 strategy, which aims to transform the country into an upper-middle-income economy [19]. Moreover, expanding clean energy access directly supports Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7), which seeks to ensure affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. In this context, micro-hydropower presents a compelling solution that can bridge the energy divide, fostering inclusive development while minimizing environmental impacts [18].

1.4 Micro-Hydropower: A Sustainable Solution

Over the past two decades, a significant body of research has emerged evaluating the technical, economic, and environmental aspects of micro-hydropower systems. Globally, studies have highlighted the adaptability of micro-hydro systems in diverse terrains—from mountainous regions in Nepal and Peru to rain-fed hill tracts in Southeast Asia. Micro-hydropower is increasingly recognized as a practical, sustainable, and community-oriented solution for off-grid electrification, particularly in rural and mountainous regions where extending conventional grid infrastructure is technically challenging and economically unviable [20]. Unlike large hydropower projects, which often require significant capital investment, land acquisition, and environmental clearance, micro-hydropower systems are designed to operate on a small scale, making them ideal for decentralized energy generation with minimal ecological impact [21].

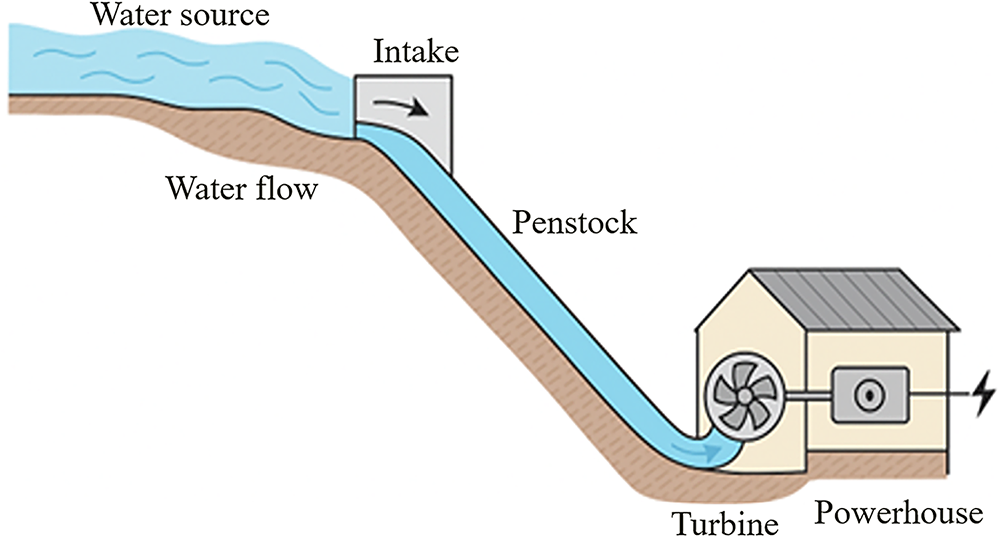

A typical micro-hydropower system harnesses the kinetic and potential energy of flowing water from rivers, streams, or waterfalls. These systems consist of four main components: an intake to capture water, a penstock to convey water to the turbine, the turbine itself to convert water flow into mechanical energy, and a generator to produce electricity. The electricity generated can be supplied directly to households, small industries, schools, and health centres or integrated into isolated micro-grids serving entire communities.

Several types of turbines are employed in micro-hydro applications depending on site-specific conditions. For high-head, low-flow situations, Pelton turbines are common, while crossflow and Turgo turbines are suitable for medium-head and flow ranges. Kaplan and Francis turbines, on the other hand, are often used in low-head, high-flow environments, which are characteristic of many sites in Bangladesh’s hilly regions. Recent technological advancements have led to the development of modular micro-hydro systems that are easier to install, require less maintenance, and offer improved energy conversion efficiency.

Material selection plays a vital role in the longevity and performance of micro-hydropower installations. The use of stainless steel for turbine components, for example, enhances resistance to corrosion, wear, and sediment abrasion, particularly in rivers with high mineral content or fluctuating flow conditions.

Globally, micro-hydropower has delivered impressive results in supporting rural electrification and socioeconomic development. In Nepal, micro-hydro projects have been instrumental in transforming rural economies, creating jobs, and improving education and healthcare [22,23]. Similar outcomes have been documented in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and parts of East Africa, where micro-hydro systems have empowered local communities and reduced dependence on expensive diesel generators. While the global literature strongly supports micro-hydro as a viable rural energy solution, context-specific feasibility studies and implementation frameworks remain underexplored in Bangladesh.

For Bangladesh, micro-hydropower offers a significant opportunity to improve energy access in regions such as the Chittagong Hill Tracts, where conventional grid extension is impractical [24]. It aligns with the country’s renewable energy ambitions and provides an environmentally friendly solution that can be operated and maintained locally, fostering resilience and self-sufficiency [25].

A simplified schematic of a typical micro-hydro power system configuration is presented in Fig. 3, visually summarizing the key components and flow of energy within such systems.

Figure 3: Schematic of a typical micro hydro power system, adapted from [14]

1.5 Objectives and Unique Contribution of the Study

Previous studies in Bangladesh have focused primarily on solar home systems, biomass, or large hydro potential, with limited empirical investigation into site-specific micro-hydro feasibility in off-grid hill tracts. Additionally, there is a noticeable gap in integrating geospatial field data with hydrological assessments and turbine matching in this unique terrain.

The overarching aim of this study is to assess the feasibility of micro-hydro power plants (MHPPs) as a sustainable and context-appropriate solution for enhancing rural electrification in Bangladesh, particularly in remote and underserved regions such as the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Unlike previous studies that have predominantly focused on large-scale hydropower or grid-based solutions, this research emphasizes site-specific analysis and the technical, environmental, and socio-economic viability of small-scale hydropower systems.

This study aims to address these gaps by conducting a detailed feasibility assessment of potential micro-hydro sites across multiple locations in the CHT region. Key objectives include:

• On-site measurement of flow rate and head using accessible field methods

• Estimation of site-wise power generation potential

• Turbine selection based on specific speed analysis

• Preliminary financial viability and policy implications

• The unique contributions of this manuscript lie in:

• Providing one of the first ground-truthed, multi-site micro-hydro assessments in Bangladesh’s CHT

• Presenting site-calibrated turbine selection for head-flow matching

• Highlighting cost ranges, LCOE, and local implementation barriers

• Offering a context-specific foundation for micro-hydro integration into Bangladesh’s off-grid rural electrification strategy

This section describes the methodological framework for identifying, assessing, and analyzing the technical feasibility of micro-hydro power sites in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. The approach involved site reconnaissance, field measurements, hydrological calculations, component design, and power output estimation.

2.1 Site Selection and Field Survey

Potential sites were identified based on geographical elevation, stream flow availability, and accessibility. A field survey was conducted at six locations: Sapchari Waterfall (Khagrachori), Chotokumira Canal (Chittagong), Mahamaya Char (Mirsarai), Ruangchori Canal (Bandarban), Sailopropat Spring (Bandarban), and Kodala Chara (Rangunia). Basic measurements such as water head (height difference) and stream width/depth were taken onsite.

2.2 Measurement of Flow Velocity

Flow velocity was determined using the float method, where a floating object is released along a marked distance of the stream, and the time taken to travel that distance is recorded. The velocity is then estimated using:

where:

v: velocity (m/s)

L: measured length (m)

t: time (s)

An average of three trials was taken to minimize measurement errors.

The float method, though widely used for preliminary hydrological assessments, is subject to measurement errors, particularly in shallow, turbulent, or irregular channels. This method approximates surface velocity, which is typically higher than the average cross-sectional flow velocity. To correct this, we applied a standard empirical correction factor ranging from 0.6 to 0.8, depending on observed channel conditions, as suggested by field hydrology handbooks [26]. Measurement uncertainty also stems from human reaction time during float tracking, variable channel roughness, and possible velocity gradients across the width of the stream.

Based on sensitivity analysis from similar field studies, the overall error margin of the float method is estimated to range between ±10% to ±25% of the actual discharge, depending on channel uniformity and observation consistency [27]. Due to limited access to current meters or Doppler flow sensors in the remote hill tracts, and given the reconnaissance nature of this study, the float method was deemed acceptable for preliminary site feasibility screening. Future implementation studies will incorporate more accurate methods like velocity–area gauging with current meters or ultrasonic sensors, along with long-term seasonal monitoring to refine flow profiles.

2.3 Discharge and Cross-Sectional Area Estimation

To estimate the volumetric flow rate (discharge Q), the cross-sectional area A of the stream was approximated based on depth and width measurements. The equation used:

where:

Q: discharge (m3/s)

A: cross-sectional area (m2)

v: velocity (m/s)

Fig. 4 below illustrates the float method used for measuring velocity.

Figure 4: Schematic of the float method for flow measurement, adapted from [28]

Given logistical and time constraints, only two seasonal measurements (dry and wet) were collected. While this limits the ability to capture interannual variability, the measurements align with regional patterns observed in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. According to the BWDB hydrological bulletins [29] and studies by IUCN (2016) [30], rivers in this region typically exhibit 2–4× variation in flow between wet and dry seasons, driven by monsoon intensity. The flow rates recorded in this study fall within those bounds, suggesting that the selected seasonal snapshots are reasonably representative for initial technical assessments. Nevertheless, long-term discharge monitoring is recommended for final design decisions.

The vertical drop or head H of each site was measured using GPS elevation data and topographical inspection. In some sites, direct elevation differences were recorded. It is acknowledged that standard handheld GPS devices have vertical error margins of ±1–2 m, which can influence accuracy at low-head sites. For example, at Kodalachara, where the measured head is approximately 2.5 m, this uncertainty could potentially represent a significant portion of the total head. Although site accessibility limited the use of more precise surveying instruments such as differential GPS (DGPS) or total station, future feasibility assessments and detailed project design phases should incorporate such tools to ensure reliable head estimation and economic viability.

The theoretical power output at each site was calculated using:

where:

P: Power (Watts)

η: Turbine efficiency (estimated between 80%–95% based on turbine type)

ρ: water density (1000 kg/m3)

g: Gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s2)

Q: Discharge (m3/s)

H: Net head (m)

Efficiency values were chosen according to turbine characteristics sourced from empirical charts.

Although micro-hydro turbines are theoretically capable of efficiencies in the range of 80%–95% under ideal conditions, actual efficiencies in rural and off-grid contexts are often lower due to factors such as sediment buildup, partial load operation, simplified civil works, and locally fabricated turbine runners. For community-scale schemes, a more realistic operating efficiency range is 60%–75%, as supported by prior rural deployment studies [31].

2.6 Turbine Type and Dimensional Estimation

The specific speed (Ns) was used for turbine selection:

where:

N: Design speed (rpm, taken as 150 rpm)

Q: Discharge (m3/s)

H: Net head (m)

Based on Ns values, turbines were selected from standard charts (e.g., Kaplan, Pelton, or Francis).

Runner diameters were estimated using:

For the specific speed analysis, a nominal speed of 150 rpm was assumed to estimate the Ns values across all sites. This value serves as a typical representation for small-scale micro-hydro turbines in rural applications, enabling comparative screening between turbine types. However, this fixed-speed assumption does not reflect the full complexity of real-world turbine-generator matching, which may involve belt transmission, gearboxes, or direct-drive systems operating at site-specific speeds. In practice, final turbine selection and speed design should be refined through detailed electromechanical modeling, accounting for generator efficiency curves and local load requirements.

Fig. 5 shows a typical turbine selection chart.

Figure 5: Turbine selection chart based on specific speed and head

The micro-hydro system includes an intake structure, a penstock, a turbine-generator unit, and a tailrace. Components were modeled using simplified CAD and verified against field-scale dimensions.

Fig. 6 summarizes the full methodological workflow.

Figure 6: Methodological flowchart for site feasibility and system assessment

While the study conducted seasonal field measurements to approximate dry and wet season conditions, it is acknowledged that long-term hydrological variability (e.g., multi-year trends or climate-induced changes) was not captured. Continuous flow monitoring and basin-level hydrological modeling would be essential in future work to ensure design robustness under extreme seasonal fluctuations.

This section provides a detailed analysis of the viability of micro-hydropower installations at six pre-selected sites within the Chittagong Hill Tracts, based solely on verified field measurements conducted during the fieldwork campaign outlined in this study. Each subsection examines a different element of the assessment, starting with site characteristics and progressing to power estimation, seasonal variation, turbine selection, infrastructure, and overall feasibility.

3.1 Overview of Selected Sites

The six sites selected for analysis include Sapchari, Chotokumira, Mahamaya, Ruangchari, Sailopropat, and Kodalachara. These sites were identified based on their topographical features, proximity to load centers, and the presence of perennial streams with visible heads.

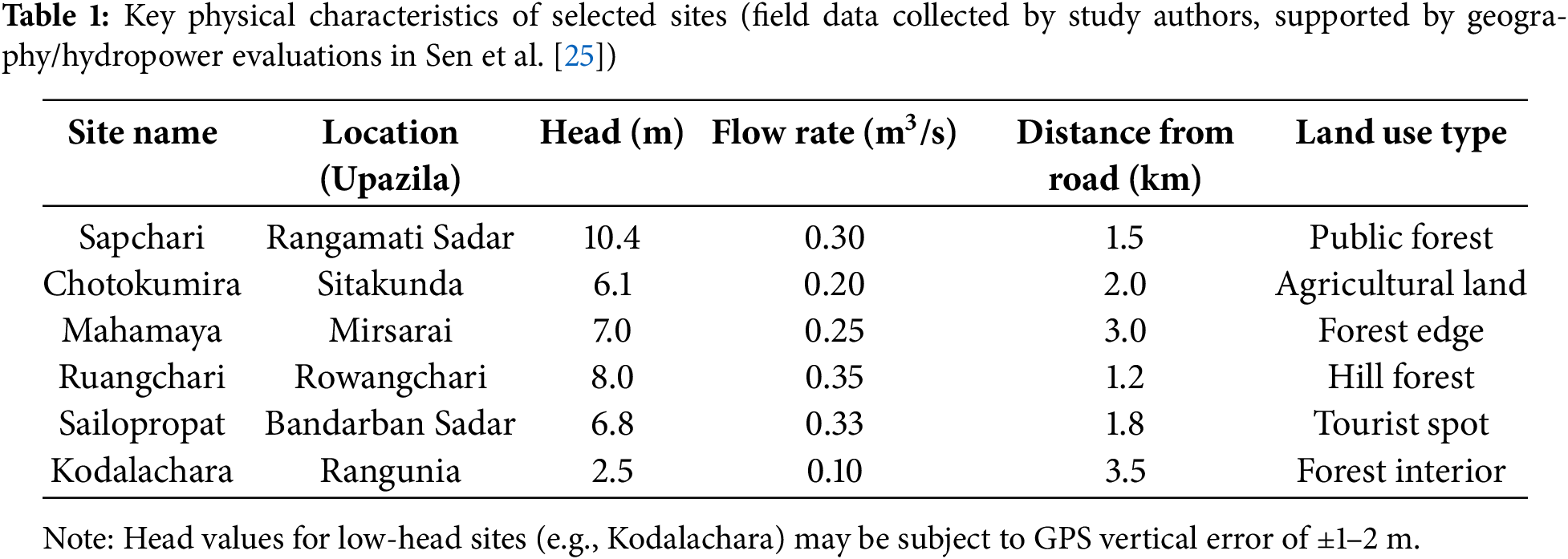

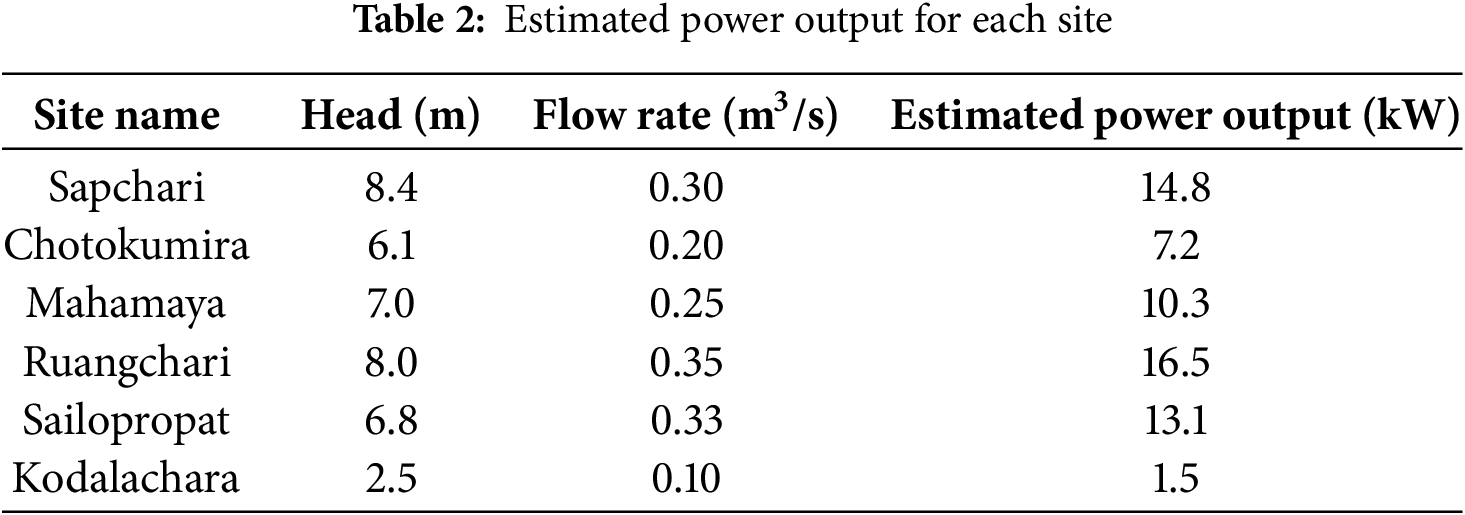

From Table 1, it is evident that Sapchari and Ruangchari possess the most favorable combination of head and discharge. Kodalachara has limited hydrological potential due to both low head and flow, which constrains its feasibility without hybridization.

The spatial distribution of the sites across Bandarban District illustrates the strategic selection of locations with diverse geographic and hydrological characteristics. The elevation gradient is particularly prominent in Sapchari and Ruangchari, both of which are in high-slope terrains—ideal for gravity-fed micro-hydro systems.

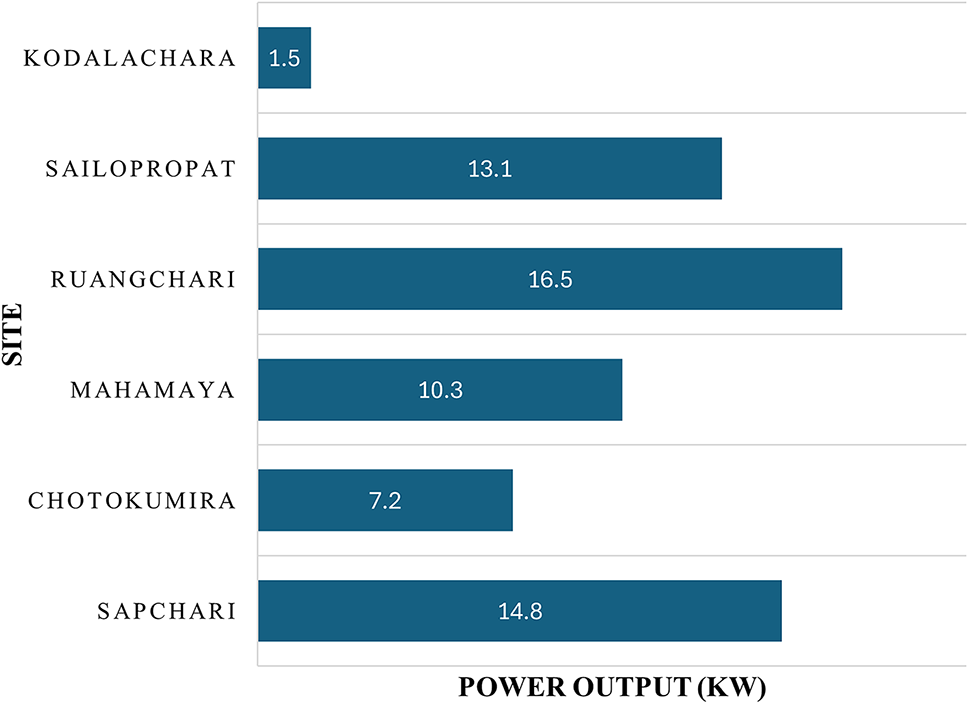

The theoretical power output of each site was calculated based on the standard hydropower Eq. (3). The resulting power outputs for each site are presented in Table 2.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, Ruangchari achieves the highest estimated power output because of its advantageous mix of high head and substantial discharge. Sapchari and Sailopropat also demonstrate strong potential, with outputs exceeding 13 kW. Conversely, Kodalachara performs marginally, indicating that hybrid systems or alternative site options might be required for economic feasibility. The outputs validate the practical potential of decentralized micro-hydro plants in the region. Sites with power output above 10 kW are ideal for standalone community electrification or microgrid integration.

Figure 7: Bar chart of site-wise power output estimation

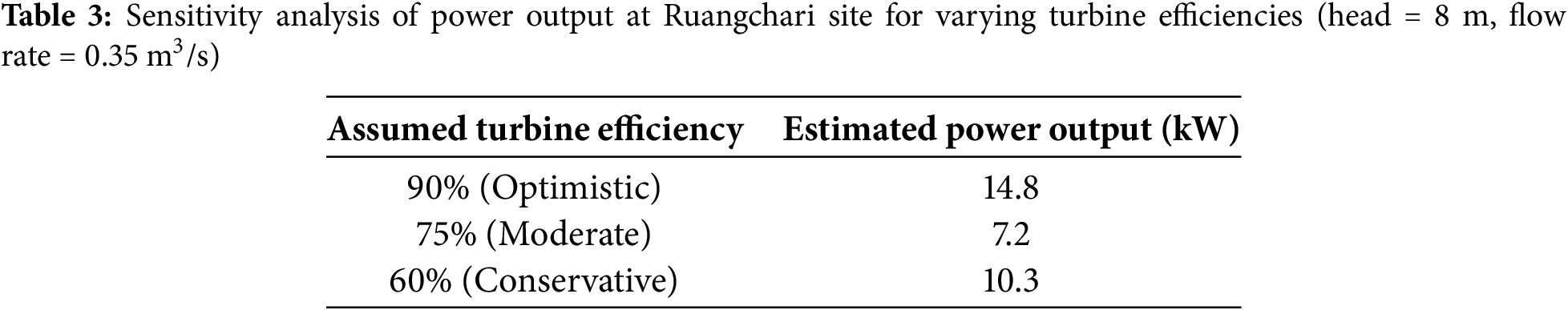

To assess the impact of turbine efficiency on potential output, a sensitivity analysis was conducted for Ruangchari (head = 8 m, flow rate = 0.35 m3/s). As shown in Table 3, estimated power output varies substantially with efficiency assumptions, from 16.5 kW (conservative, 60%) to 24.7 kW (optimistic, 90%). This reinforces the need for cautious design assumptions and efforts to reduce hydraulic losses and optimize fabrication quality in local deployments.

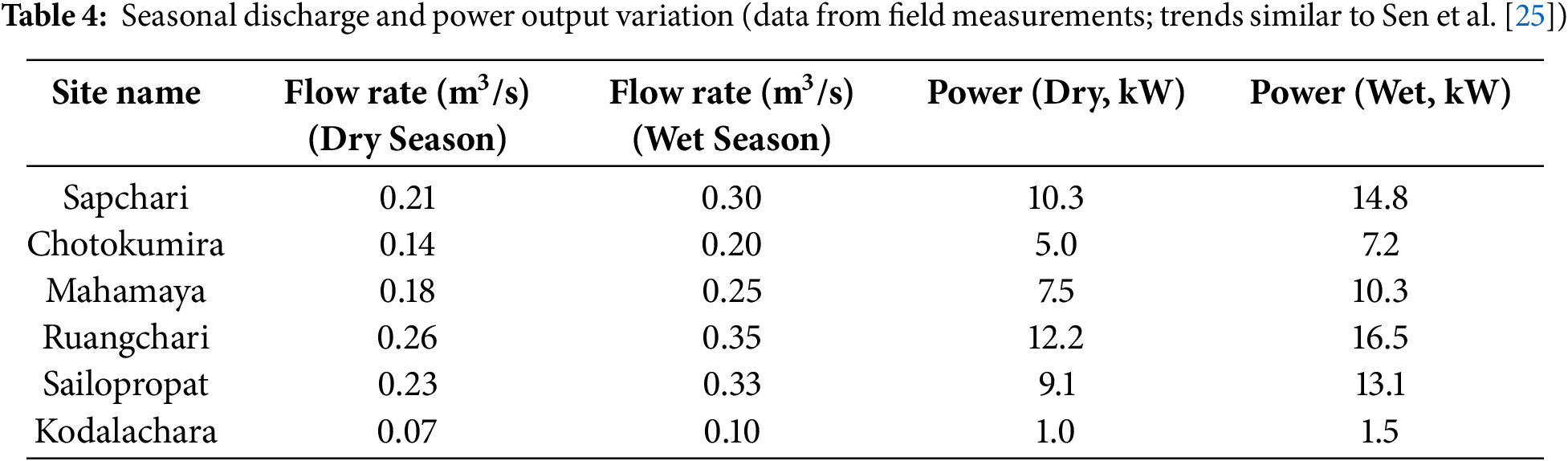

3.3 Seasonal Flow and Power Variation

To understand the year-round feasibility of the proposed micro-hydro sites, seasonal variation in stream discharge was assessed for both dry and wet seasons. Field data were collected using float method flow measurements during two distinct periods—March (dry season) and August (wet season), which are summarized in Table 4. This allowed for a practical comparison of seasonal resource availability and its effect on power generation.

The seasonal analysis shows a steady decline of 20%–30% in power output across all sites during the dry season (Fig. 8). Ruangchari, Sapchari, and Sailopropat still deliver reasonable outputs above 9 kW even in dry months, suggesting potential for continuous operation with slight load adjustments. Conversely, Kodalachara approaches infeasibility during dry periods. This highlights the need for multi-seasonal design strategies, such as flow regulation reservoirs or hybrid systems with solar PV, to maintain system reliability throughout the year.

Figure 8: Seasonal flow and power output

3.4 Preliminary Financial Assessment

While the primary objective of this study is to evaluate the technical feasibility of micro-hydro installations, a preliminary understanding of financial viability is critical to inform deployment strategies. Regional case studies indicate capital costs for micro-hydro systems in South and Southeast Asia typically range from USD 1500 to 3500 per installed kW, varying by site conditions and local manufacturing involvement [32,33].

For power outputs between 1.5 and 16.5 kW (as identified in this study), total system costs are estimated to be between USD 3750 and 41,250 per site. Assuming minimal maintenance over 15 years and a 30%–45% capacity factor, the LCOE is estimated at USD 0.10–0.25/kWh—comparable to diesel and solar + battery systems in remote areas [34].

Furthermore, in areas where community labor reduces civil and installation costs, the payback period may fall between 5 and 8 years, especially when replacing costly diesel generators. However, site-specific financial modeling (including operation and maintenance costs, subsidies, and tariff structure) should be undertaken in future pilot implementations.

3.5 Turbine Selection Suitability

Selecting the appropriate turbine for each micro-hydro site is essential to achieving optimal system performance and cost-effectiveness. Turbine selection depends primarily on the available head and discharge, with consideration given to efficiency, part-load performance, and ease of maintenance. For this assessment, a customized turbine selection chart was developed based on the head and flow rate characteristics of the six surveyed sites.

As seen in Fig. 9, the chart focuses on three practical turbine types applicable to the studied sites:

Figure 9: Turbine selection chart based on head and discharge (based on head vs. flow, adapted from [35])

• Kaplan turbines are ideal for low-head (below 10 m) and high-discharge conditions. This makes them suitable for Kodalachara, Chotokumira, and Sailopropat, which exhibit relatively lower heads but moderate to high flow availability, especially in the wet season.

• Francis turbines operate efficiently within medium-head (5–25 m) and moderate-flow regions. Sites such as Sapchari, Ruangchari, and Mahamaya, with heads ranging from 7–10.4 m and substantial flow rates, fall well within this category.

• Pelton turbines, typically used for high-head (>40 m), low-discharge applications, are excluded from consideration, as none of the selected sites meet the high-head requirement.

This selection approach aligns the hydrological profile of each site with the most efficient and cost-effective turbine category, ensuring reliable performance and longevity in remote and rugged terrains. It also helps reduce the mismatch losses, enabling better load management and improved capacity utilization throughout the year.

Seasonal Considerations in Turbine Sizing.

In order to account for seasonal hydrological variability, both dry-season and wet-season flow measurements were collected at each site. These represent the two operational extremes encountered annually. Turbine sizing was performed based on the mean dry season flow rate, ensuring that the system remains operational during periods of low water availability. Oversizing turbines for peak monsoon flows was avoided, as it would compromise efficiency and increase capital costs during most of the year.

Peak flood conditions were considered through intake design and spillway provisions, but not factored into power generation capacity, as those flows are infrequent and short-lived. The adopted approach ensures year-round viability while avoiding part-load inefficiencies. A detailed hydrological simulation over multiple years was beyond the scope of this study, but is recommended for future site development stages.

Furthermore, in regions with particularly steep seasonal gradients, modular turbine arrangements (e.g., dual nozzles or flow bypass valves) may be incorporated in future pilot projects to accommodate a broader range of flow rates.

3.6 Civil Infrastructure Considerations

The feasibility of a micro-hydropower system extends beyond just hydrological parameters—it is critically dependent on the practicality, simplicity, and site adaptability of civil infrastructure. Key civil components, such as intake structures, canals, forebays, penstocks, powerhouse placement, and tailraces, must be optimized to suit the site’s topography and hydrodynamic behavior. Based on field reconnaissance and report chapters, two sites—Sapchari and Ruangchari—emerged as the most promising and are discussed in terms of their civil layout requirements (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: Schematic layouts of civil infrastructure for Sapchari and Ruangchari

Sapchari Site Layout:

• Intake and Canal: Located near a high-gradient stream segment, a small diversion intake with coarse screening is proposed, channeling water into a short open canal.

• Forebay Tank: A masonry forebay with trash rack and desilting chamber is essential due to seasonal sediment influx. It acts as the transition point before pressurized flow into the penstock.

• Penstock: Given the moderate head (10.4 m), a mild steel or HDPE pipe can suffice, running approximately 50–70 m down a slope to the powerhouse.

• Powerhouse Configuration: A split/double powerhouse was considered based on terrain constraints. This allows better alignment with flow direction and land gradient.

• Tailrace: The used water is discharged back into the stream via a short open channel—tailrace—with minimal erosion risk.

Ruangchari Site Layout:

• Intake Structure: Similar to Sapchari, but less complex due to cleaner upstream conditions. Debris screening is still necessary.

• No Forebay: Unlike Sapchari, Ruangchari’s natural terrain allows for a direct penstock feed, minimizing infrastructure cost and visual impact.

• Penstock: A longer but less steep run (~80 m) due to a gradual slope. Anchoring and thrust blocks are critical for structural stability.

• Powerhouse: A compact single-unit housing is sufficient, due to accessible land near the stream confluence.

• Tailrace: Present and visible, enabling smooth return of water post-turbine operation, with potential for minor irrigation reuse downstream.

Both sites offer cost-effective layouts that align with community-scale hydropower needs. While Sapchari requires more structural intervention (forebay, split powerhouse), it also offers slightly better protection against dry season variability. Ruangchari’s natural alignment supports a simplified setup, lowering construction time and cost.

These layout differences highlight the importance of site-specific customization in micro-hydro system design, even among sites with similar power potentials.

3.7 Overall Feasibility Assessment

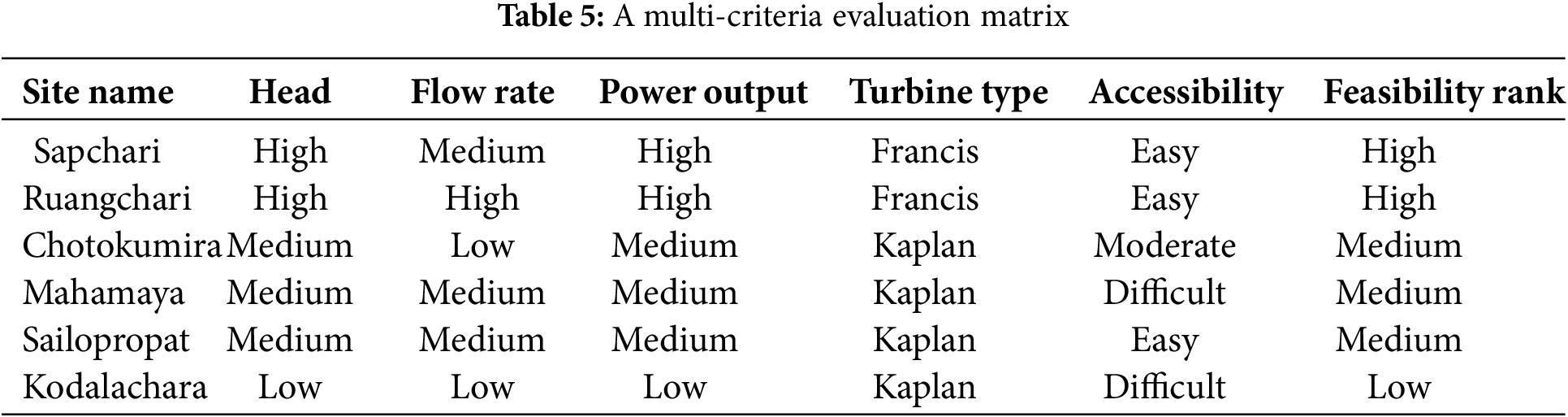

To conclude the feasibility assessment, a multi-criteria evaluation was conducted, incorporating technical parameters such as head, discharge, power output, and turbine compatibility. Additional considerations like site accessibility and land type were also factored in to assess the practicality of installation. Based on a scoring system that assigns qualitative rankings (High, Medium, Low) to each criterion, the six sites were evaluated holistically.

Table 5 summarizes the composite feasibility classification. Sapchari and Ruangchari scored highest in terms of both hydrological parameters and logistical ease, marking them as prime candidates for micro-hydro deployment. Chotokumira and Mahamaya fell in the medium category due to lower discharge and/or more complex access conditions. Kodalachara, with its low head and flow, presents minimal technical viability.

This matrix provides a clear guideline for prioritizing investment and technical studies, focusing on high-ranking sites for immediate pilot implementation.

Comparative studies from similar topographies such as Nepal, Bhutan, and Northeast India reveal that successful micro-hydro installations in remote mountainous communities have operated with heads as low as 2–3 m and flow rates of 0.1–0.4 m3/s, yielding outputs in the range of 2–20 kW [36,37]. The estimated power ranges and head-flow combinations from this study align well with these regional precedents, suggesting that the CHT region holds comparable potential for micro-hydro deployment. Moreover, lessons from community-driven schemes in Nepal and Northeast India—particularly regarding local fabrication, sediment control, and decentralized management—offer valuable parallels for implementation in Bangladesh.

4 Socio-Economic, Environmental Impact Analysis, and Policy Implications

This section evaluates the potential socio-economic and environmental impacts of installing micro-hydropower systems in the selected sites within the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The analysis is based on field observations, local stakeholder input during data collection, and established literature on rural electrification impacts.

Implementation of micro-hydro systems in Sapchari, Ruangchari, and other promising locations is expected to generate a transformative impact on the livelihood and well-being of the local communities.

• Access to Electricity: At present, several villages in these remote areas rely on kerosene lamps or battery-powered lighting. A micro-hydro system generating 10 to 16 kW can power LED lighting, charge mobile devices, and support basic household appliances for 20–30 households.

• Improved Quality of Life: Electrification will enable extended hours for education and productivity. Schools, health centers, and community halls could benefit from lighting and cooling.

• Economic Opportunities: The availability of power will support micro-enterprises such as rice mills, sewing workshops, or refrigeration for food preservation. Employment opportunities will arise during construction (e.g., civil works) and operation (e.g., system monitoring and maintenance).

• Capacity Building: Local youths can be trained in maintaining the turbines, control systems, and penstock infrastructure, promoting skill development and reducing dependence on external technicians.

Matching Estimated Supply to Community Demand

The estimated power outputs (1.5–16.5 kW) were evaluated against typical rural energy demand profiles in Bangladesh. Based on reports from IDCOL and local NGO-led rural electrification projects, essential household needs such as LED lighting, phone charging, fans, and small appliances require approximately 100–200 W per household. Community infrastructure (e.g., schools, clinics) and small businesses (e.g., tailoring shops, tea stalls) add incremental loads ranging from 0.5–2 kW depending on usage patterns. For example, a 5 kW micro-hydro system can typically support 25–40 households, along with one or two community-scale services like irrigation pumps (1–1.5 kW), depending on load management and operating hours. In higher-potential sites (e.g., Ruangchari, 16.5 kW), the system could support 100+ households, several community loads, and still maintain redundancy during peak hours. Demand-side matching was not simulated in detail but was cross-referenced with practical deployment experiences of similar-scale MHP systems in Nepal and India. Future pilot projects should involve load surveys and community participation to refine system sizing, prioritization of critical loads, and day-night load balancing.

Micro-hydro systems, especially those using run-of-river schemes as considered in this study, have a minimal environmental footprint compared to large hydro or fossil-based alternatives.

• Minimal Displacement: None of the selected sites requires damming or significant diversion of water, avoiding displacement or submergence of settlements or farmland.

• Preservation of Natural Flow: The systems operate on residual flow principles, ensuring aquatic ecosystems downstream maintain continuity.

• Low Emissions: Micro-hydro plants produce no direct greenhouse gas emissions, helping reduce reliance on diesel generators or biomass burning.

• Construction Footprint: Environmental disruption during construction is limited to small-scale civil works such as intake weirs, forebay tanks, and powerhouse excavation. Use of local materials and manual labor can further reduce this impact.

4.3 Site-Specific Observations

• Sapchari: The area lies within a forest boundary but has existing trails and access paths. No tree cutting or significant alteration is required for penstock or turbine housing.

• Ruangchari: The powerhouse can be located near the stream without affecting agricultural land. The use of natural slope minimizes excavation, and community participation during site surveys suggests strong social acceptance.

4.4 Community Engagement and Governance Considerations

Although this study primarily focuses on technical and physical feasibility, the success of micro-hydro systems in rural contexts critically depends on community ownership, maintenance culture, and institutional frameworks. Effective governance models—such as community co-operatives, public-private partnerships, or hybrid models involving local NGOs—should be explored during implementation phases. Participatory planning and capacity-building are also vital to ensure long-term sustainability. These socio-institutional aspects were outside the current study’s scope but are recommended for deeper assessment in future deployments.

While solar PV has dominated off-grid electrification efforts in Bangladesh, the integration of micro-hydro power (MHP) within national rural energy policies remains limited. The existing Renewable Energy Policy (2008) sets a broad target for 10% renewable energy, yet lacks micro-hydro-specific strategies, incentives, or financing models. Institutional efforts, such as those by the Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL), have focused heavily on solar home systems, with negligible investment in hydro-based mini-grids. However, in mountainous regions like the Chittagong Hill Tracts, MHP offers unique locational advantages over solar due to topographic head availability and seasonal streamflow. A structured roadmap for micro-hydro—including guidelines for licensing, grid integration (where feasible), and community ownership models—could enhance deployment. Drawing on experiences from Nepal and Sri Lanka, Bangladesh could benefit from decentralized planning frameworks, capacity-building in local governance, and public-private partnerships to promote community-scale MHP systems. Institutional inclusion of MHP in the national electrification policy would provide long-term direction and unlock donor and government funding streams.

5 Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Study

This study offers a detailed techno-socio-economic feasibility analysis for deploying micro-hydropower systems in remote hill regions of Bangladesh, focusing on sites like Sapchari and Ruangchari. Through extensive field surveys, hydrological assessments, turbine choice evaluations, civil infrastructure planning, and community observations during site visits, viable sites with the best site capable of producing up to 16.5 kW of clean, renewable energy.

Seasonal flow data and head measurements confirmed the potential for year-round power generation at both sites, with seasonal changes properly accounted for in system design. The turbine selection chart, which considers head and discharge, supports using Kaplan or Francis turbines depending on site conditions. Infrastructure layouts were customised to the topography and environment of each location. Additionally, socio-economic studies highlighted benefits such as enhanced living standards, local employment, and environmental sustainability. Key findings include:

• Ruanachari and Sapchari are the most technically and socially viable micro-hydro sites.

• Seasonal flow variation is moderate, enabling consistent energy production, especially during monsoon and post-monsoon periods.

• Local communities show strong support and interest, particularly when community-managed operation and maintenance are proposed.

• Environmental impact is minimal thanks to run-of-river designs and the lack of major civil structures.

• Future work could expand on this study by:

• Piloting a micro-hydro project at a site such as Sapchari to test the proposed design and turbine choice in real-world conditions.

• Creating a hybrid renewable energy model that combines micro-hydro with solar PV to improve year-round dependability.

• Performing a financial analysis that includes capital costs, levelised cost of electricity (LCOE), and possible funding options.

• Extending the survey to nearby hill tracts to repeat this feasibility mapping approach and develop a regional electrification strategy.

In conclusion, micro-hydropower emerges as a highly promising and context-specific solution for enhancing energy access in the remote hill regions of Bangladesh. Through effective implementation and active community engagement, this decentralized strategy can significantly contribute to rural development, resilience, and energy equity.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the local authorities and communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts region for facilitating field access and site data collection. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for assisting with language editing and improving manuscript structure.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: Ratan Kumar Das: Conceptualization, Data Collection, Methodology, Drafting of Manuscript, Supervision. Hamed Hassan: Field Survey, Data Processing, Initial Drafting. Abhijit Date: Supervision, Review, and Editing. Harun Chowdhury: Methodology, Review, and Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This article does not contain any studies involving human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Amin SB. The energy transition in Bangladesh: pathway to future energy security [Internet]. Dhaka, Bangladesh: TBS News; 2025 Feb 3 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.tbsnews.net/supplement/energy-transition-bangladesh-pathway-future-energy-security-1059401. [Google Scholar]

2. IEA. Hydropower has a crucial role in accelerating clean energy transitions to achieve countries’ climate ambitions securely [Internet]. Paris, France: International Energy Agency (IEA); 2021 Jun 30 [cited 2024 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/news/hydropower-has-a-crucial-role-in-accelerating-clean-energy-transitions-to-achieve-countries-climate-ambitions-securely. [Google Scholar]

3. Othman ME, Sidek LM, Basri H, El-Shafie A, Ahmed AN. Climate challenges for sustainable hydropower development and operational resilience: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2025;209:115108. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ramião JP, Carvalho-Santos C, Pinto R, Pascoal C. Hydropower contribution to the renewable energy transition under climate change. Water Resour Manag. 2023;37(1):175–91. doi:10.1007/s11269-022-03361-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. ICSHP UND. Small Hydropower and Climate Change [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO); 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 10]. Available from: www.unido.org/WSHPDR. [Google Scholar]

6. Mahbub T. Energy in Bangladesh: from scarcity to universal access. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024;54(4):101490. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2024.101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lowcarbonpower.org. Electricity in Bangladesh in 2024 [Internet]. Berkeley, CA, USA: Lowcarbonpower.org; 2024 Jun 12 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://lowcarbonpower.org/region/Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

8. Bagdadee AH, Zhang L. Sustainable rural development by hybrid power generation: a case study of kuakata. Bangladesh Results Eng. 2024;24(1):103005. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Das NK, Chakrabartty J, Dey M, Gupta AS, Matin MA. Present energy scenario and future energy mix of Bangladesh. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020;32:100576. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2020.100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Energy HU, Bangladesh MRD. Energy scenario of Bangladesh 2023–24 [Internet]. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Hydrocarbon Unit, Energy and Mineral Resources Division; 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://hcu.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/hcu.portal.gov.bd/publications/ae775b7e_b63d_491d_81e4_b317ff8e11ca/2024-07-15-09-11-d13a3451b969fb9a3c5c74e9130c9f6c.pdf. [Google Scholar]

11. Miskat MI, Ahmed A, Rahman MS, Chowdhury H, Chowdhury T, Chowdhury P, et al. An overview of the hydropower production potential in Bangladesh to meet the energy requirements. Environ Eng Res. 2021;26(6):200514. doi:10.4491/eer.2020.514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alam S. Charting an electricity sector transition pathway for Bangladesh [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA: Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA); 2023 Apr [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://ieefa.org/resources/charting-electricity-sector-transition-pathway-bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

13. SREDA. National energy balance of Bangladesh [Internet]. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority (SREDA); 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://sreda.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/sreda.portal.gov.bd/page/639366d4_9e29_4fcd_975a_b0f345a49cff/2024-04-30-06-11-1eefba07ac5af703bac17abc09d72a42.pdf. [Google Scholar]

14. Razan JI, Islam RS, Hasan R, Hasan S, Islam F. A comprehensive study of micro-hydropower plant and its potential in Bangladesh. Int Sch Res Not. 2012;2012(1):635396. doi:10.5402/2012/635396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. BPDB (Bangladesh Power Development Board). Annual report 2022–23 [Internet]. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Power Development Board; 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://bpdb.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bpdb.portal.gov.bd/page/771c9a89_a06c_4c2f_9b8c_699d17ed769a/2024-01-03-06-02-dda85c69e3462d6de89b6486edd08779.pdf. [Google Scholar]

16. World Bank. Lighting up rural communities in Bangladesh: the second rural electrification and renewable energy development project [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Group; 2021 Mar 13 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2021/03/13/lighting-up-rural-communities-in-bangladesh-the-second-rural-electrification-and-renewable-energy-development-project. [Google Scholar]

17. Rani J, Kumari JR, Chand SK, Chand S. Climate change and renewable energy. In: Tripathi G, Shakya A, Kanga S, Singh SK, Rai PK, editors. Big data, artificial intelligence, and data analytics in climate change research: for sustainable development goals. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 153–71. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-1685-2_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chakma ND. Sustainable Energy for all: Making a case for community-scale micro-hydro as the solution [Internet]. Berkeley, CA, USA: International Rivers; 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: www.internationalrivers.org. [Google Scholar]

19. Mollik S, Rashid MM, Hasanuzzaman M, Karim ME, Hosenuzzaman M. Prospects, progress, policies, and effects of rural electrification in Bangladesh. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;65:553–67. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.06.091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Berga L. The role of hydropower in climate change mitigation and adaptation: a review. Engineering. 2016;2(3):313–8. doi:10.1016/J.Eng.2016.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Das HS, Yatim AH, Tan CW, Lau KY. Proposition of a PV/tidal powered micro-hydro and diesel hybrid system: a southern Bangladesh focus. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;53:1137–48. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Butchers J, Williamson S, Booker J. Micro-hydropower in Nepal: analysing the project process to understand drivers that strengthen and weaken sustainability. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1582. doi:10.3390/su13031582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bhandari R, Saptalena LG, Kusch W. Sustainability assessment of a micro hydropower plant in Nepal. Energy Sustain Soc. 2018;8(1):3. doi:10.1186/s13705-018-0147-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Islam MS, Gupta SD, Masum MS, Karim SA, Rahman MG. A case study of the notion and model of micro hydro power plant using the kinetic energy of flowing water of Burinadi and Meghna river of Bangladesh. Eng J. 2013;17(4):47–60. doi:10.4186/ej.2013.17.4.47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sen SK, Al Nafi Khan AH, Dutta S, Mortuza AA, Sumaiya U. Hydropower potentials in Bangladesh in context of current exploitation of energy sources: a comprehensive review. Int J Energy Water Resour. 2022;6(3):413–35. doi:10.1007/s42108-021-00176-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gordon ND, McMahon TA, Finlayson BL, Gippel CJ, Nathan RJ. Stream hydrology: an introduction for ecologists. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

27. Shaw EM. Hydrology in practice. 3rd ed. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 1993. 569 p. [Google Scholar]

28. ESHA (European Small Hydropower Association). ESHA guide on how to develop a small hydropower plant [Internet]. Brussels, Belgium: European Small Hydropower Association (ESHA); 2004 [cited 2024 Jan 10]. Available from: https://docslib.org/doc/12566833/esha-guide-on-how-to-develop-a-small-hydropower-plant. [Google Scholar]

29. BWDB (Bangladesh Water Development Board). Annual hydrological report [Internet]. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB); [cited 2025 Sep 9]. Available from: http://hims.bwdb.gov.bd/hydrology/index.php?pagetitle=journals&id=57. [Google Scholar]

30. IUCN Bangladesh. Hydrological assessment of the chittagong hill tracts region [Internet]. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature; 2016 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://iucn.org/resources/publications. [Google Scholar]

31. Williams AA, Simpson R. Pico hydro—reducing technical risks for rural electrification. Renew Energy. 2009;34(8):1986–91. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2008.12.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Paish O. Small hydro power: technology and current status. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2002;6(6):537–56. doi:10.1016/S1364-0321(02)00006-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ferroukhi R, Nagpal D, Lopez-Pena A, Hodges T, Mohtar RH, Daher B, et al. Renewable energy in the water, energy & food nexus. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA); 2015. 125 p. [Google Scholar]

34. Khennas S, Barnett A. Micro-hydro power: an option for socio-economic development. In: Proceedings of the World Renewable Energy Congress VI. Oxford, UK: Pergamon; 2000. p. 1511–17. [Google Scholar]

35. IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency). Renewable energy technologies: cost analysis series. volume 1: power sector issue 3/5-hydropower [Internet]. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA); 2012 Jun [cited 2025 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2012/Jun/Renewable-Energy-Cost-Analysis–-Hydropower?utm_. [Google Scholar]

36. Palit D, Sarangi GK. Renewable energy based mini-grids for enhancing electricity access: experiences and lessons from India. In: Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Green Energy for Sustainable Development (ICUE); 2014 Mar 19; Piscataway, NJ, USA: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE); 2014. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

37. Hussain A, Sarangi GK, Pandit A, Ishaq S, Mamnun N, Ahmad B, et al. Hydropower development in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region: issues, policies and opportunities. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2019;107:446–61. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools