Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental and Neural Network Modeling of the Thermal Behavior of an Agricultural Greenhouse Integrated with a Phase Change Material (CaCl2·6H2O)

1 Unité de Recherche Appliquée en Energies Renouvelables, URAER, Centre de Développement des Energies Renouvelables, CDER, Ghardaïa, 47133, Algeria

2 Laboratoire d’Instrumentation, Faculté de Génie Electrique, Université des Sciences et de la Technologie Houari Boumediene, BP 32, El-Alia, Bab-Ezzouar, Alger, 16111, Algeria

3 Department of Energy and Power Engineering, School of Mechanical Engineering, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, 100081, China

4 Solar Energy Research Institute, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

5 Zhengzhou Research Institute, Beijing Institute of Technology, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

* Corresponding Author: Abdelouahab Benseddik. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advance and Development in Solar Energy)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 5021-5037. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.072991

Received 08 September 2025; Accepted 17 October 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

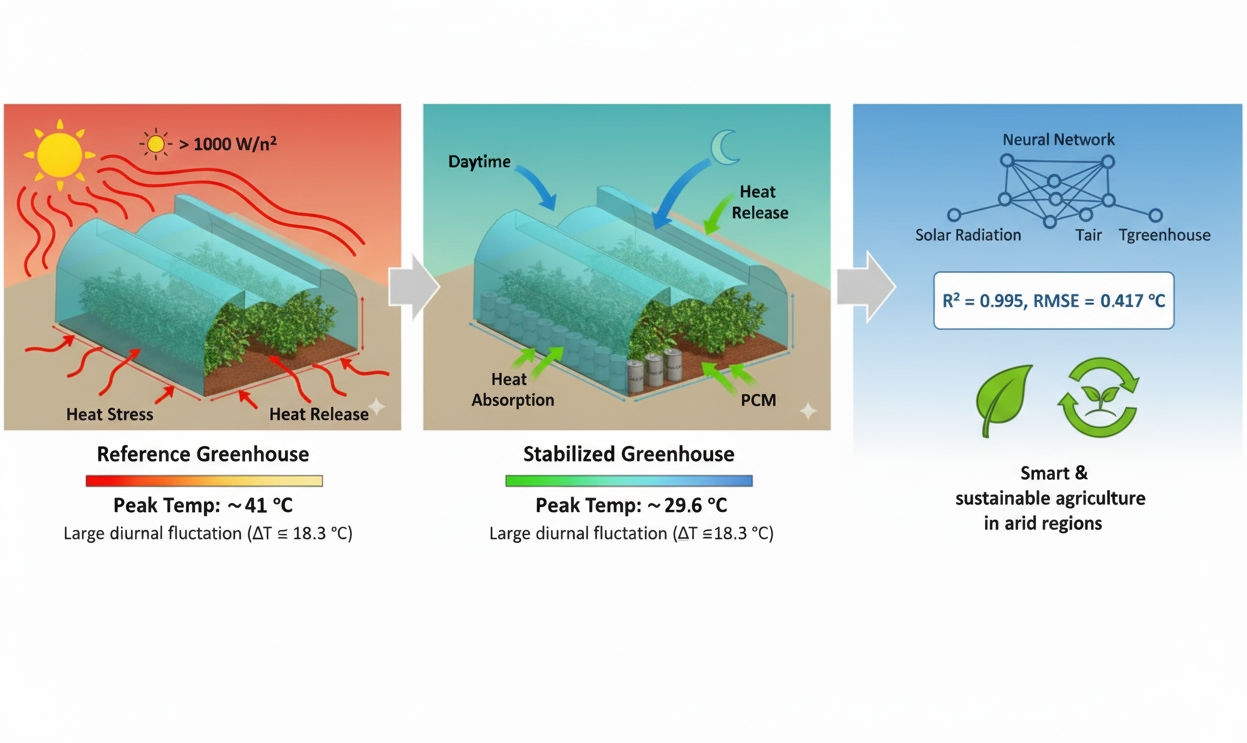

In Saharan climates, greenhouses face extreme diurnal temperature fluctuations that generate thermal stress, reduce crop productivity, and hinder sustainable agricultural practices. Passive thermal storage using Phase Change Materials (PCM) is a promising solution to stabilize microclimatic conditions. This study aims to evaluate experimentally and numerically the effectiveness of PCM integration for moderating greenhouse temperature fluctuations under Saharan climatic conditions. Two identical greenhouse prototypes were constructed in Ghardaïa, Algeria: a reference greenhouse and a PCM-integrated greenhouse using calcium chloride hexahydrate (CaCl2·6H2O). Thermal performance was assessed during a five-day experimental period (7–11 May 2025) under severe ambient conditions. To complement this, a Nonlinear Auto-Regressive with eXogenous inputs (NARX) neural network model was developed and trained using a larger dataset (7–25 May 2025) to predict greenhouse thermal dynamics. The PCM greenhouse reduced peak daytime air temperature by an average of 8.14°C and decreased the diurnal temperature amplitude by 53.6% compared to the reference greenhouse. The NARX model achieved high predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.990, RMSE = 0.425°C, MAE = 0.223°C, MBE = 0.008°C), capturing both sensible and latent heat transfer mechanisms, including PCM melting and solidification. The combined experimental and predictive modeling results confirm the potential of PCM integration as an effective passive thermal regulation strategy for greenhouses in arid regions. This approach enhances microclimatic stability, improves energy efficiency, and supports the sustainability of protected agriculture under extreme climatic conditions.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Agricultural greenhouses play a crucial role in extending growing seasons, improving crop yields, and enhancing food security. However, one of the major challenges in greenhouse cultivation is maintaining a stable internal microclimate, particularly in regions with strong temperature fluctuations between day and night. Conventional approaches to greenhouse climate control often rely on active heating or cooling systems, which are energy-intensive and costly. This has encouraged the exploration of alternative solutions such as latent heat thermal storage using Phase Change Materials (PCMs), which can absorb, store, and release large amounts of energy during phase transitions, thereby buffering indoor temperature fluctuations [1,2].

Over the past two decades, numerous studies have investigated the integration of PCMs into greenhouses, demonstrating their ability to mitigate excessive daytime heat and to release stored thermal energy during the night. For example, Kumari et al. [1] and Claudio and Stoppiello [3] were among the first to analyze the potential use of PCMs for passive thermal heating of greenhouses. Later, Benli [2] proposed a latent heat storage system integrated into solar collectors for greenhouse heating, showing a significant reduction in heating demand. Similarly, Berroug et al. [4] studied a greenhouse with a PCM north wall, confirming the potential of latent storage to improve thermal performance. More recently, Zhang et al. [5], Badji et al. [6], and Xiao et al. [7] have shown that PCM-enhanced systems can effectively reduce temperature peaks inside solar greenhouses under diverse climatic conditions.

Various PCM configurations have been tested, including PCM-filled building materials such as hollow concrete blocks [8], PCM integrated into wall collectors or air heat exchangers [9], and PCM packed beds for hydroponic greenhouses [10]. Other approaches include the preparation of composite or shape-stabilized PCMs for improved thermal reliability in greenhouse applications [11,12]. These investigations demonstrate that PCMs not only stabilize indoor air temperature but also contribute to reducing energy consumption and ensuring optimal crop growth conditions.

Despite these advances, several limitations remain. Many experimental studies have focused on cold or temperate climates [7,10], where PCMs are primarily used to store daytime solar energy and release it at night for heating purposes. Recent studies illustrate this approach, such as Ismail et al. [13], who showed that PCM north walls could extend growing seasons by nearly two months in cold regions, and Chen and Zhou [14], who developed a synergistic PCM system for Chinese solar greenhouses in winter. Similarly, Yan et al. [15] experimentally demonstrated that PCM-enhanced heat recovery systems in conventional greenhouses reduced fuel consumption by up to 23.7%.

By contrast, relatively few investigations have examined PCM use in hot arid or Saharan climates, where the challenge is overheating during the day and large diurnal fluctuations that generate thermal stress for crops. In such conditions, PCMs can serve as cooling buffers by absorbing excess heat during peak daytime hours and releasing it during cooler nighttime periods. Recent work by Badji et al. [6,16] and our research team has contributed to this direction, demonstrating experimentally that PCMs can attenuate diurnal temperature amplitude in semi-arid Algerian greenhouses and that machine learning algorithms, including NARX models, offer high predictive accuracy (R2 > 0.99) for thermal dynamics under real climatic conditions.

Furthermore, while conventional thermal models have been used to evaluate PCM performance, the application of advanced data-driven techniques in greenhouse studies remains relatively limited. Recent reviews highlight the growing role of AI in sustainable agriculture [17], but few studies combine PCM integration with nonlinear autoregressive neural network modeling (NARX) for predictive control of greenhouse thermal environments. This dual approach is particularly promising for ensuring reliable performance in climates characterized by sharp diurnal variations.

In this context, the present work investigates the integration of calcium chloride hexahydrate (CaCl2·6H2O) as a PCM in a double-span greenhouse prototype, with the PCM encapsulated in aluminum beverage cans for practical use. The study combines an experimental campaign carried out under real climatic conditions with data-driven modeling based on NARX neural networks to simulate and predict the greenhouse thermal environment. The main objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of PCM integration in attenuating temperature fluctuations and enhancing nighttime thermal stability in hot regions, arid regions, while also validating predictive modeling approaches with high accuracy.

The experimental study was conducted in the Ghardaïa region of Algeria (32°29′ N, 3°40′ E), which is characterized by a hot desert climate with long, hot summers and short, mild winters. The experimental campaign was carried out from 07 May to 25 May 2025, at the Applied Research Unit for Renewable Energies (URAER).

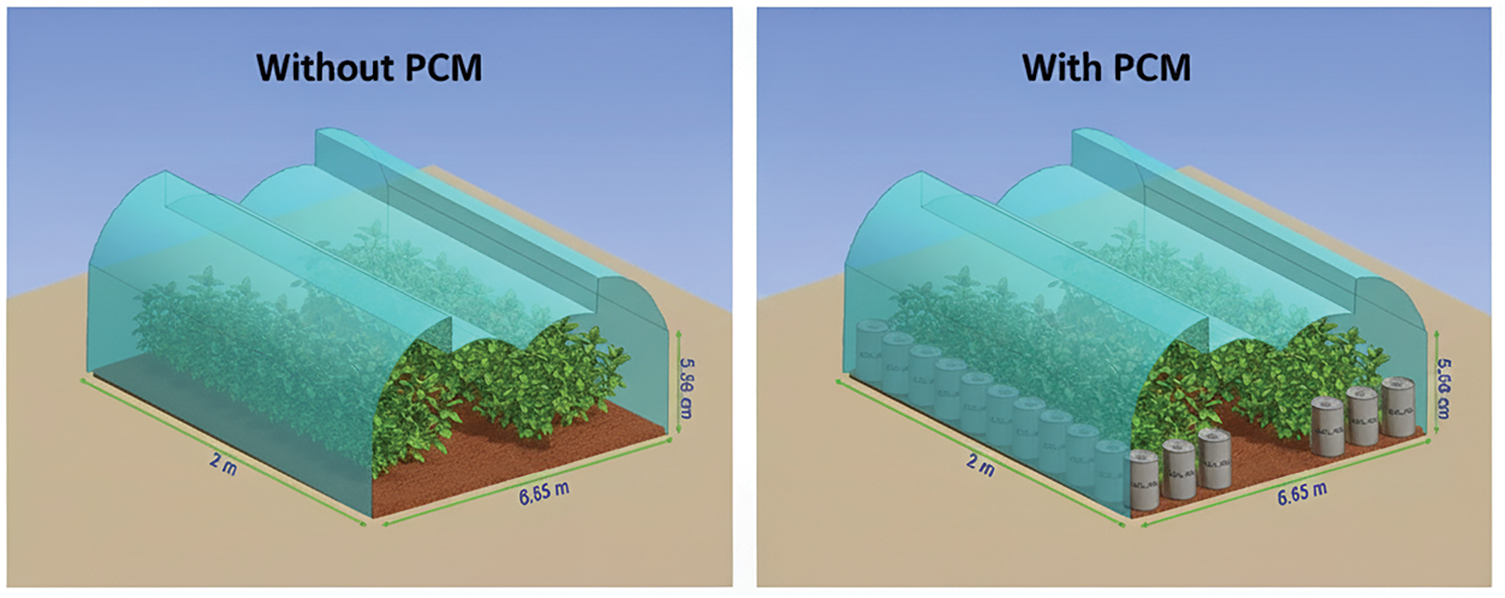

2.2 Prototype Double-Span Plastic Greenhouses

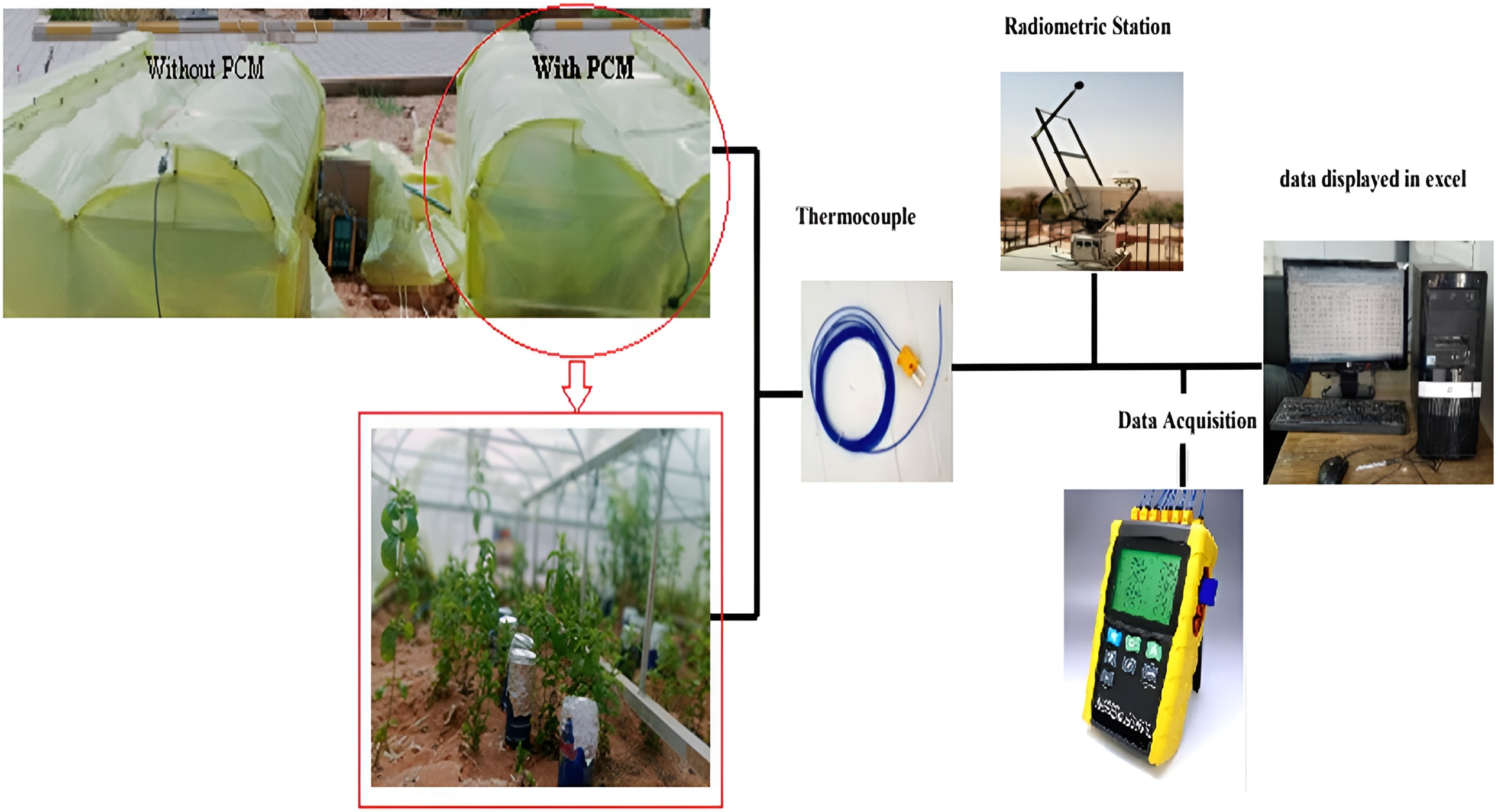

Two identical prototype double-span plastic greenhouses with a North–South orientation. Each greenhouse had a floor area of 3.2 m2 (width = 1.6 m, length = 2 m) and a central height of 0.65 m. The prototypes were designed to enable comparative studies under controlled and natural conditions. Several climatic parameters were recorded both inside and outside the greenhouses, including air temperature, relative humidity, and solar irradiance, in order to evaluate the thermal behavior of the system. The overall view of the two prototypes, showing one without Phase Change Material (PCM) and one with PCM, is presented below (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Reference and modified prototypes

Reference greenhouse: operated without thermal storage.

Modified greenhouse: integrated with a latent heat thermal energy storage system based on calcium chloride hexahydrate (CaCl2·6H2O).

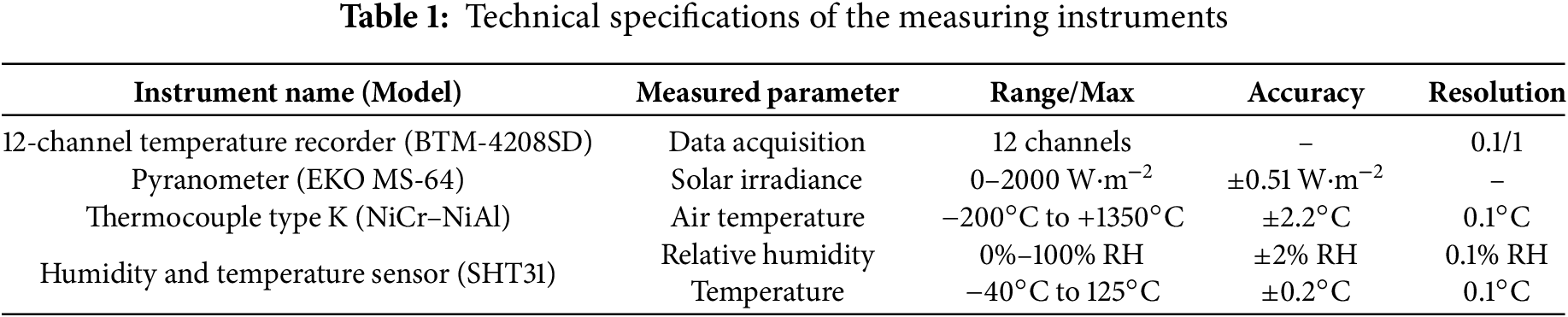

To ensure accurate monitoring of the thermal and environmental conditions inside and outside the experimental greenhouses, a set of calibrated instruments was deployed. Table 1 summarizes the technical specifications of the main sensors and devices used during the experimental campaign.

All thermocouples were connected to the 12-channel recorder to allow simultaneous multi-point measurements, with data acquisition set at 1 min intervals. The pyranometer (EKO MS-64) was installed outside the greenhouses in an unobstructed position to ensure precise recording of incident solar radiation. The SHT31 sensors were deployed both inside and outside the greenhouses to monitor variations in air temperature and relative humidity. This combination of instruments provided a reliable dataset for evaluating the thermal and climatic performance of the greenhouse prototypes.

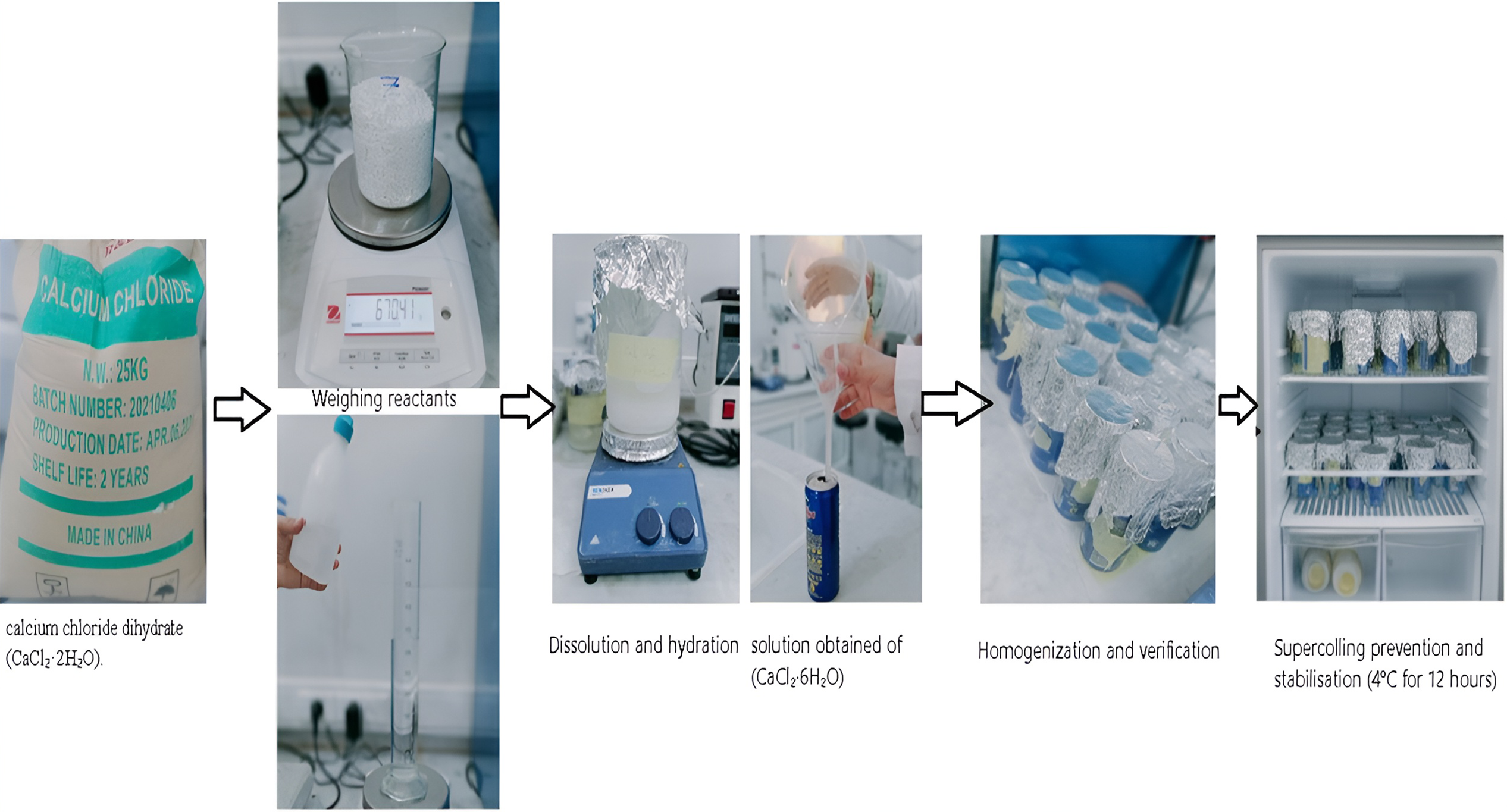

2.4 Preparation of CaCl2·6H2O Storage Material

In order to develop a phase change material (PCM) suitable for the thermal conditions encountered in agricultural greenhouses, we prepared calcium chloride hexahydrate (CaCl2·6H2O) from calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2·2H2O). This choice was based on the advantageous thermophysical properties of this hydrated salt, including its phase transition temperature (≈27°C–29°C), its high thermal storage capacity, and its low-cost local availability.

The preparation followed a rigorous multi-step protocol (Fig. 2): (i) A precise mass of calcium chloride dihydrate was weighed. To prepare one mole of CaCl2·6H2O, we used 670.41 g of CaCl2·2H2O. A volume of 328.68 mL of distilled water was slowly added to the solid salt under continuous stirring. This step is critical because the dissolution of CaCl2·2H2O is highly exothermic; rapid addition would cause a sudden rise in temperature and unwanted evaporation of water. During hydration, the temperature of the solution increased rapidly. To limit evaporation losses and maintain the exact stoichiometry of the final product, the beaker was covered with a layer of aluminum foil. This device also reduced the risk of contamination by atmospheric moisture, as CaCl2 is very hygroscopic. After complete dissolution and homogenization, the solution obtained corresponds to the hexahydrate form of calcium chloride (CaCl2·6H2O). The quality of the product was visually verified by the absence of precipitates and the clarity of the solution. The prepared PCM was transferred into airtight metal cans serving as thermal storage modules. To avoid supercooling (subcooling), which could delay crystallization and alter the melting/solidification cycles, the cans were placed in a refrigerator at 4°C for 12 h. This step ensures controlled nucleation and stabilizes the crystalline structure of CaCl2·6H2O. The cans filled with the stabilized PCM were then installed in the multi-span greenhouse prototype, where they served as buffer elements to regulate internal temperature fluctuations.

Figure 2: Preparation of CaCl2·6H2O thermal storage material

The experimental campaign was conducted over a period of 19 consecutive days (07–25 May 2025) at the Applied Research Unit in Renewable Energies (URAER), Ghardaïa, Algeria. During this period, both greenhouse prototypes were monitored under identical outdoor climatic conditions to allow for a direct comparison of their thermal behavior (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Experimental setup and instrumentation

Measurements were performed according to the following procedure: All sensors (thermocouples, pyranometer, and SHT31 modules) were installed and calibrated before the start of the experiments. The data acquisition system (BTM-4208SD recorder, Lutron, Coopersburg, PA, USA) was configured to log measurements at 1 min intervals throughout the experiment. Multiple thermocouples (Type K) were positioned inside each greenhouse to record air temperature at different heights (near the floor, mid-height, and roof level).

All signals were continuously logged by the 12-channel data recorder.

No artificial heating or cooling was applied; the greenhouses operated solely under natural ventilation and solar heating, representative of real operating conditions in Saharan regions.

The comparison between the two greenhouses was made on the basis of internal air temperature.

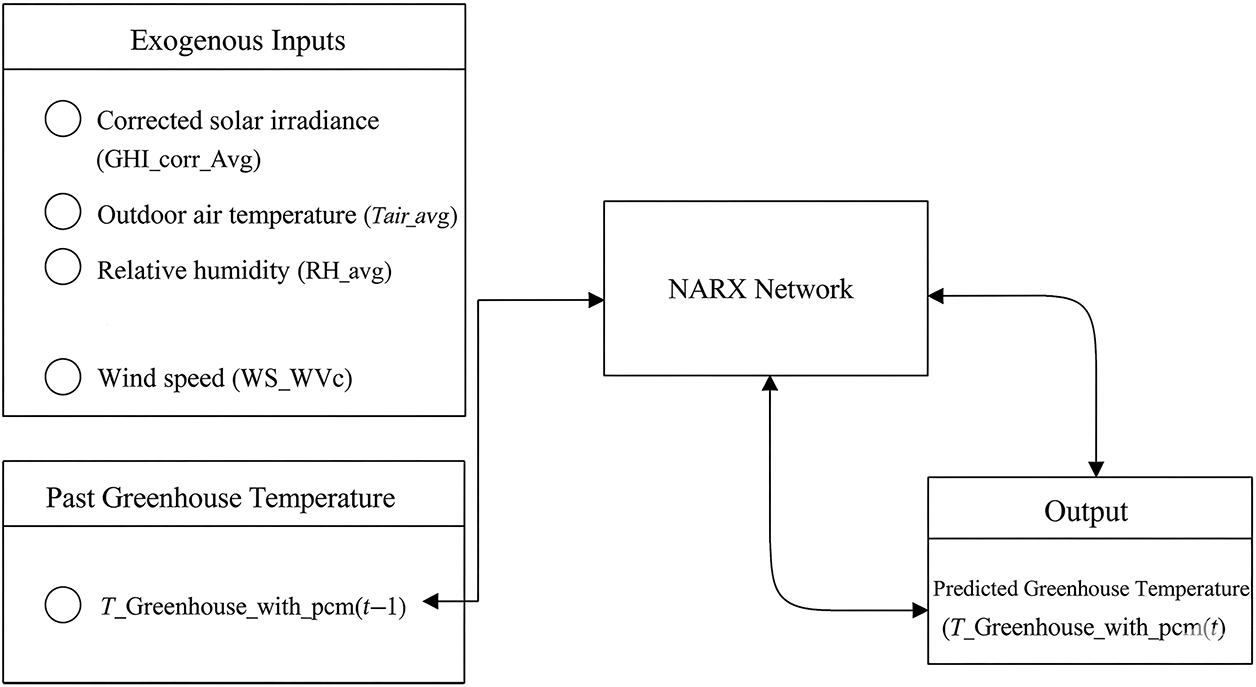

Mathematical modeling is a key tool in energy engineering, as it enables accurate prediction and optimization of dynamic thermal behavior in systems integrating renewable energy and thermal storage technologies. In this study, the nonlinear dynamics of a PCM-equipped greenhouse were modeled using a NARX (Nonlinear AutoRegressive Network with eXogenous Inputs) approach.

2.6.1 Data Collection and Preparation

Experimental data were obtained from the PCM-integrated greenhouse to train and validate the model. Input variables included corrected global solar irradiance (GHI_corr_Avg, W/m2), outdoor air temperature (Tair_Avg, °C), relative humidity (RH_Avg, %), and wind speed (WS_WVc, m/s). The target variable was the internal air temperature (T_Greenhouse_with_pcm, °C).

Data preprocessing involved filtering, removal of duplicates, and linear interpolation of missing values. The final dataset comprised 2737 time-series records, processed and converted to digital format using MATLAB R2020b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

The NARX model, a recurrent neural network architecture, is particularly well suited for nonlinear and dynamic energy systems. It predicts the greenhouse temperature

where

In this formulation:

•

•

•

The conceptual structure of the NARX model is illustrated in Fig. 4, which shows the integration of exogenous climatic inputs, autoregressive feedback, and predicted output.

Figure 4: Conceptual diagram of the NARX model applied to the PCM-equipped greenhouse, showing the flow of exogenous inputs, autoregressive temperature feedback, and predicted output

2.6.3 Advantages and Justification

The choice of the NARX model was motivated by its ability to handle nonlinear and dynamic systems with memory effects, which are particularly relevant for greenhouse thermal processes. Previous work by our team (Badji et al., 2024) [16] demonstrated the comparative advantages of NARX over FFN and RNN models for temperature forecasting in a PCM-integrated greenhouse. In the present study, we extend this approach by applying and validating the NARX model on a new greenhouse prototype tested in May 2025 under different climatic and design conditions. Compared to classical regression or feed-forward neural networks, NARX provides superior predictive accuracy by exploiting past values of both inputs (solar radiation, ambient temperature, humidity) and outputs (internal greenhouse temperature).

2.6.4 Implementation and Training Procedure

The NARX model was implemented in R2020b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) following a structured workflow consisting of five stages:

1. Data preprocessing: Experimental time-series inputs (solar irradiance, ambient air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed) were converted, cleaned, and interpolated to align with greenhouse internal temperature measurements.

2. Network architecture: A dynamic NARX network with input delays (1–2 steps), feedback delays (1–2 steps), and a hidden layer of 15 neurons was employed. The hidden layer used a hyperbolic tangent sigmoid activation, while the output layer used a linear transfer function.

3. Training: The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm was applied with mean square error (MSE) as the cost function. Training typically converged within a few hundred epochs.

4. Validation: Predictions were compared against experimental measurements using multiple statistical indicators: coefficient of determination (R2), and root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean bias error (MBE), and reduced chi-squared (χ2_red).

5. Diagnostics and export: Performance curves, regression plots, and residual analyses were generated to ensure robustness. Predicted and measured datasets were exported into Excel files for reproducibility.

2.6.5 Model Validation and Diagnostic Analysis

The NARX predictions were benchmarked against the experimental greenhouse temperature dataset. Validation plots showed close alignment between measured and predicted values, with residuals distributed symmetrically around zero, indicating no significant bias. Performance indicators confirmed the predictive ability of the model: high R2 values (>0.95) and low RMSE (<1.5°C) across the dataset.

In addition, regression plots between target and network outputs demonstrated slopes close to unity and intercepts near zero, further validating the model. The reduced chi-squared statistic (χ2_red ≈ 1) indicated good consistency with the expected measurement uncertainty (±1°C). Overall, these results confirm that the NARX model is a robust and accurate tool for capturing the nonlinear thermal dynamics of PCM-equipped greenhouses, making it suitable for both performance evaluation and predictive climate control strategies.

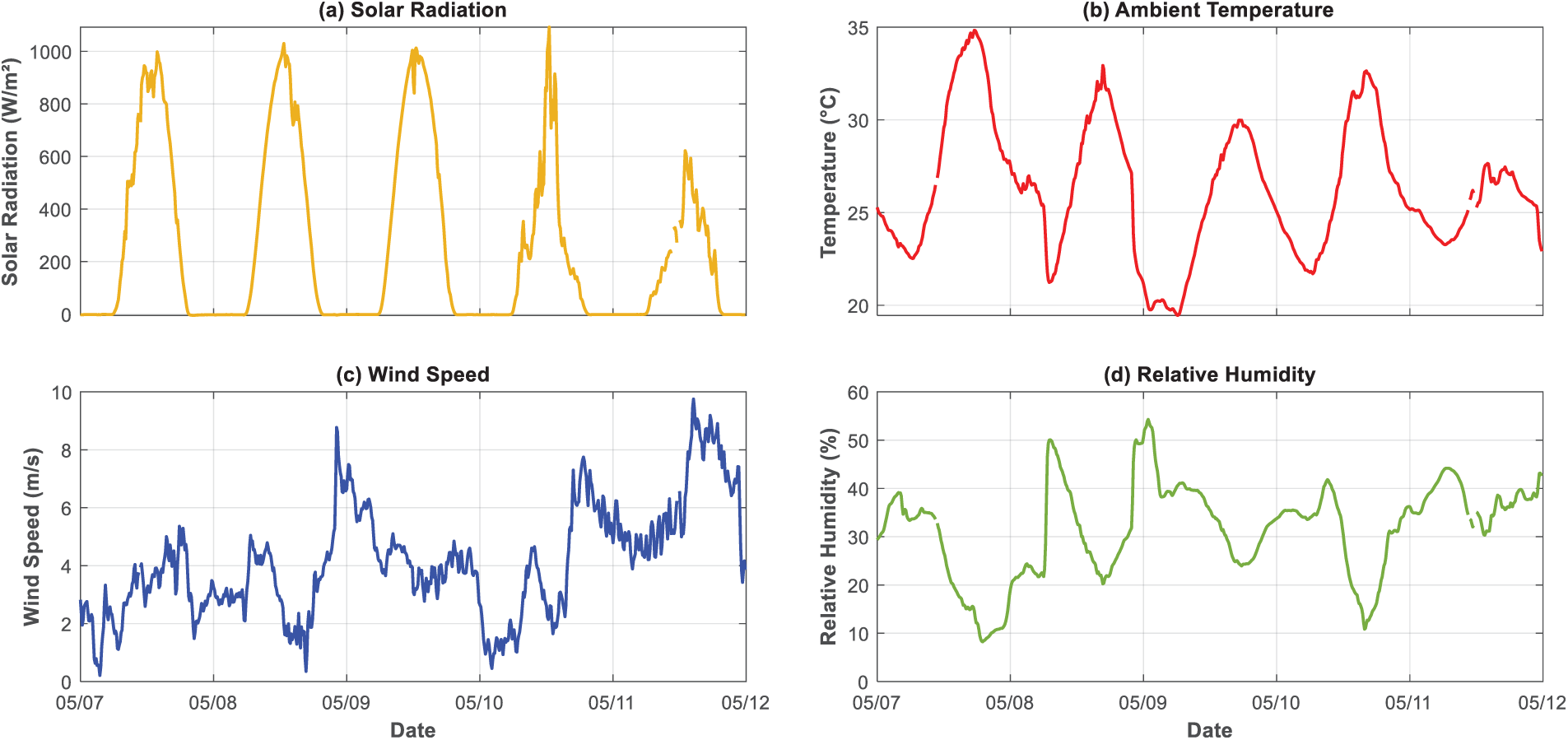

3.1 Climatic Conditions during Experiments

Fig. 5 presents the evolution of the main outdoor climatic parameters (solar radiation, ambient temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity) recorded during the experimental campaign from 7th May to 11th May 2025. As expected for the Saharan climate of Ghardaïa, high solar radiation levels were observed, consistently exceeding 1000 W/m2 at midday, with a peak value of ~1126 W/m2 recorded on 10th May. Ambient temperatures exhibited a strong diurnal pattern, reaching daily maxima between 32.5°C and 34.4°C, with the highest peak of 34.4°C observed on 7th May.

Figure 5: Outdoor climatic conditions during the experimental campaign (07 May to 11 May 2025)

The data reveals a strong inverse correlation between solar radiation/ambient temperature and relative humidity. During peak insolation hours, relative humidity dropped drastically to very low values, often falling below 20% and reaching a minimum of ~9%. Conversely, relative humidity increased during the night, frequently exceeding 50% in the early morning hours following the night of 8th May.

Wind speed was another significant factor, showing considerable variability. While generally moderate during the day, wind speeds occasionally reached high values, with a maximum of ~9.9 m/s recorded on the afternoon of 11th May. These severe and fluctuating conditions of intense solar loading, high temperatures, low humidity, and significant wind stress highlight the challenging environment for agricultural storage and the critical need for effective passive cooling and thermal regulation strategies in in agricultural greenhouses.

3.2 Thermal Performance of the Reference Greenhouse

The thermal behavior of the reference greenhouse without thermal storage was analyzed to establish a baseline for comparison. Fig. 6 presents the temporal evolution of the inside air temperature, compared with the ambient temperature and global horizontal irradiance during the representative day of 07 May 2025.

Figure 6: Evolution of internal air temperature for the reference greenhouse, ambient temperature, and solar radiation on 07 May 2025

The results indicate that the internal air temperature in the reference greenhouse was highly sensitive to solar radiation, exhibiting significant diurnal amplification. Over the five-day experimental period, the reference structure consistently reached high peak temperatures, with a maximum of 40.91°C recorded on 10 May and a five-day average maximum of 37.77 ± 4.32°C (mean ± standard deviation). This temperature rise is attributed to the greenhouse effect, where shortwave solar radiation penetrates the glazing and is absorbed by internal surfaces, leading to substantial heat accumulation.

Conversely, during the nighttime, the internal air temperature dropped rapidly due to radiative and convective losses through the cover. The average minimum temperature was 19.48 ± 1.65°C, with the largest diurnal amplitude reaching 23.11°C on 10 May. Consequently, the reference greenhouse exhibited extreme thermal fluctuations with an average diurnal amplitude of 18.29 ± 5.26°C. Such pronounced variations are known to induce thermal stress in most high-value crops, highlighting a critical limitation of conventional greenhouse designs in arid climates.

Overall, the performance of the reference greenhouse underscores the necessity of integrating passive thermal storage to dampen temperature fluctuations and mitigate nocturnal energy losses.

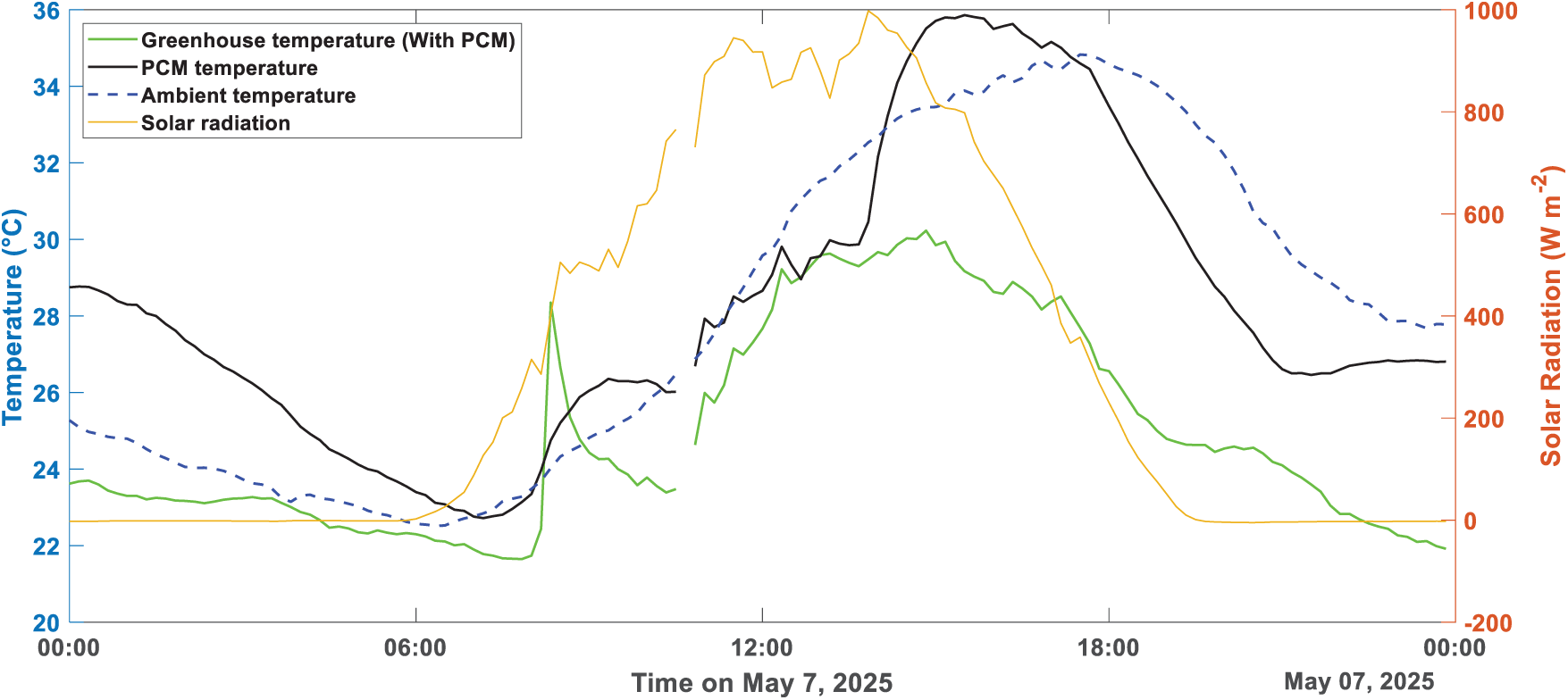

3.3 Thermal Performance of the Greenhouse Equipped with PCM

To evaluate the effect of latent heat storage, the second prototype was equipped with a CaCl2·6H2O-based PCM. Fig. 7 illustrates the evolution of the inside air temperature, the PCM temperature, and the ambient temperature for 07 May 2025.

Figure 7: Evolution of internal air temperature for the PCM-equipped greenhouse, PCM temperature, and ambient air temperature on 07 May 2025

The data presented in Fig. 7 demonstrates the pronounced moderating influence of the PCM. During the daytime, the PCM system effectively absorbed excess solar energy, significantly attenuating peak temperatures. The maximum temperature in the PCM-equipped greenhouse averaged 29.63 ± 3.07°C over the five days, representing an average reduction of 8.14°C compared to the reference greenhouse. This attenuation is visually evidenced by the plateau in the T_pcm curve, which indicates the phase change period where latent heat is stored. The most significant benefit was observed during the nighttime, where the PCM released its stored latent energy through solidification. As a result, the internal air temperature was stabilized. The average minimum temperature in the PCM greenhouse was 21.14 ± 0.57°C, which was 1.66°C higher on average than the reference.

Crucially, the diurnal temperature amplitude was drastically reduced to an average of 8.49 ± 3.28°C, representing a 53.6% reduction in thermal fluctuation compared to the reference case.

These results confirm that the PCM integration effectively decouples the indoor climate from the external conditions, smoothing the thermal profile by absorbing excess energy during the day and releasing it during the night.

It should also be noted that PCM materials such as CaCl2·6H2O may exhibit challenges related to supercooling, incongruent melting, or long-term phase separation, which could affect the repeatability of the thermal buffering effect. While these issues were not dominant in the present short-term experimental campaign, they may become more critical in long-term applications and should be considered in future work.

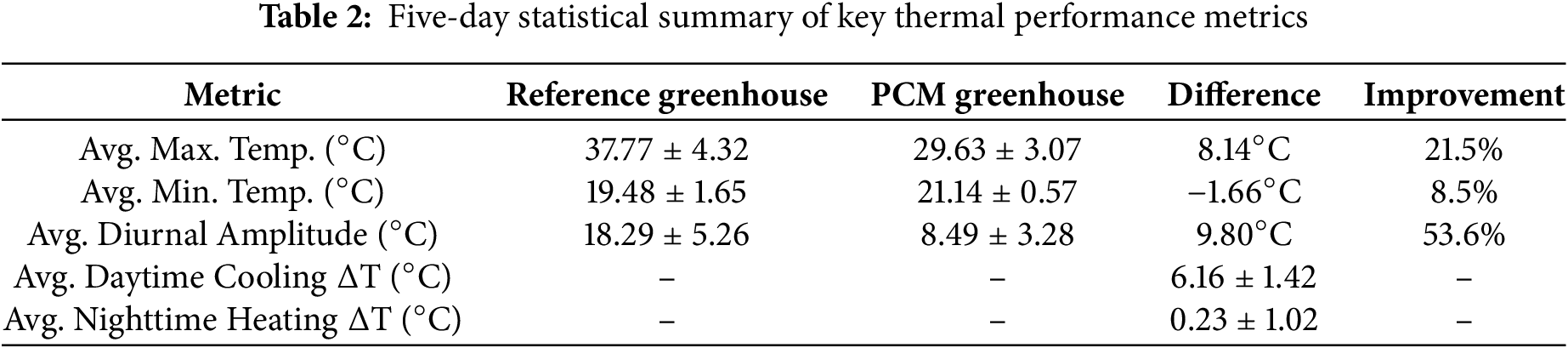

3.4 Comparative Analysis and Statistical Evaluation

A direct comparative analysis was conducted to quantify the impact of PCM integration over the entire five-day period from 07 May to 11 May 2025. Fig. 8 provides a direct comparison of both internal temperatures on 07 May, while Fig. 9 shows the time series for the entire experimental duration, clearly illustrating the consistent performance across different days.

Figure 8: Comparative evolution of internal air temperatures for both greenhouses and ambient air temperature on 07 May 2025

Figure 9: Internal air temperatures of both greenhouse prototypes and ambient temperature from 07 May to 11 May 2025

The multi-day analysis, summarized in Table 2, reveals the system’s robustness. The PCM’s performance was not isolated to a single day but was consistent throughout the experiment, despite variations in daily weather conditions. The average daytime temperature differential (T_ref–T_pcm) was 6.16 ± 1.42°C, with a peak cooling effect of 12.29 ± 3.87°C observed during the hours of highest solar load.

The nighttime performance (Avg. Nighttime Heating ΔT) showed a positive but more variable effect (0.23 ± 1.02°C), indicating that the PCM discharge was sometimes insufficient to fully offset nighttime losses, particularly on cooler nights (e.g., 08 and 11 May). This suggests potential for optimizing PCM mass or its integration for even greater nighttime benefits.

Overall, the integration of the CaCl2·6H2O-based PCM contributed to:

✓ Substantially reducing peak daytime temperatures by an average of 8.14°C.

✓ Elevating and stabilizing minimum nighttime temperatures.

✓ Drastically stabilizing diurnal temperature variations, reducing the amplitude by 53.6%.

✓ Creating a more favorable and consistent microclimate across varying weather conditions.

These findings highlight the significant potential of passive PCM thermal storage to enhance the thermal performance of greenhouses in arid regions. By effectively mitigating the extreme temperatures that characterize conventional structures, PCM integration can extend cropping seasons, improve plant growth rates and quality, and reduce the energy footprint of protected agriculture in climate-sensitive regions like the Sahara. The consistency of results over five days confirms the reliability of this passive solar solution.

Although direct crop trials were not conducted within this study, the observed 53.6% reduction in diurnal temperature amplitude strongly suggests tangible agricultural and economic benefits. Stabilizing greenhouse microclimates is expected to reduce plant stress, enhance crop growth rates and quality, and lower the reliance on auxiliary heating and cooling systems. Future investigations should explicitly quantify these agricultural outcomes, including energy savings and yield improvements, to strengthen the link between thermal stabilization and practical farming benefits.

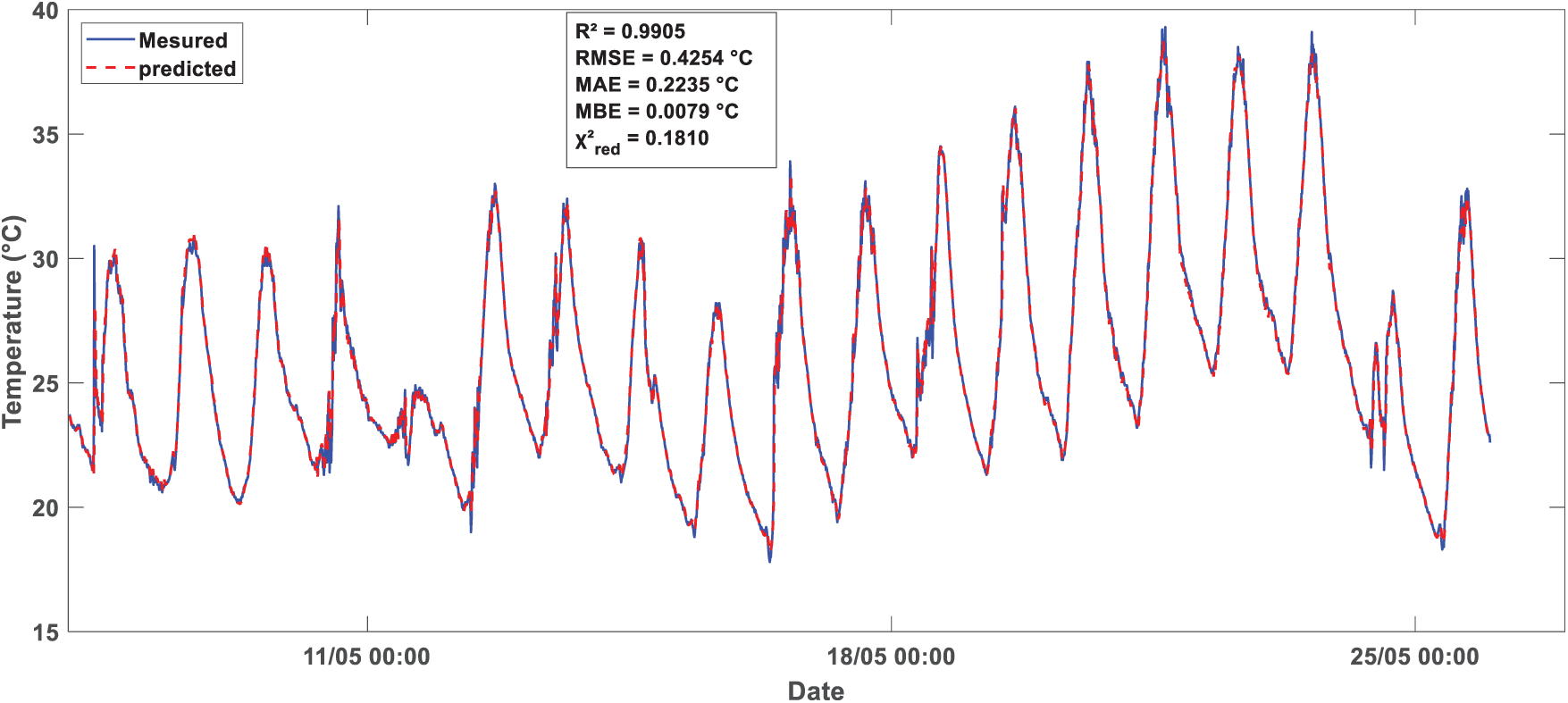

3.5 NARX Modeling and Prediction of Greenhouse Temperature

To complement the experimental analysis and quantitatively validate the efficacy of the Phase Change Material (PCM) for thermal regulation, a predictive model based on a Nonlinear Auto-Regressive with eXogenous inputs (NARX) neural network was developed. This data-driven approach was selected for its proven capability to model complex, non-linear, and dynamic systems, such as the thermal behavior of a greenhouse. The model was trained on experimental data measured from the PCM-equipped greenhouse. The exogenous input variables included ambient temperature and solar irradiance, while the auto-regressive component and the target output were the internal greenhouse temperature. The architecture and hyperparameters (e.g., number of hidden neurons, time delays) were optimized to capture the underlying thermodynamics of the system, including the latent heat effects of the PCM.

3.5.1 Model Performance and Validation

The performance of the trained NARX model is presented in Fig. 10, which shows a comparison between the measured and predicted internal temperatures for the PCM-equipped greenhouse. The results demonstrate an excellent agreement between the simulated and experimental values throughout the entire testing period. The model accurately replicates the key thermal dynamics, including the daily cycles, the rapid temperature rise due to solar gains, and crucially, the thermal plateaus during the PCM’s melting phase and the stabilization during its nighttime solidification. This high fidelity confirms the model’s validity and its ability to learn the complex relationships between external climatic forces and the internal thermal state moderated by the PCM.

Figure 10: Comparison between measured and NARX-predicted internal temperatures in the PCM-equipped greenhouse from 07 May to 25 May 2025

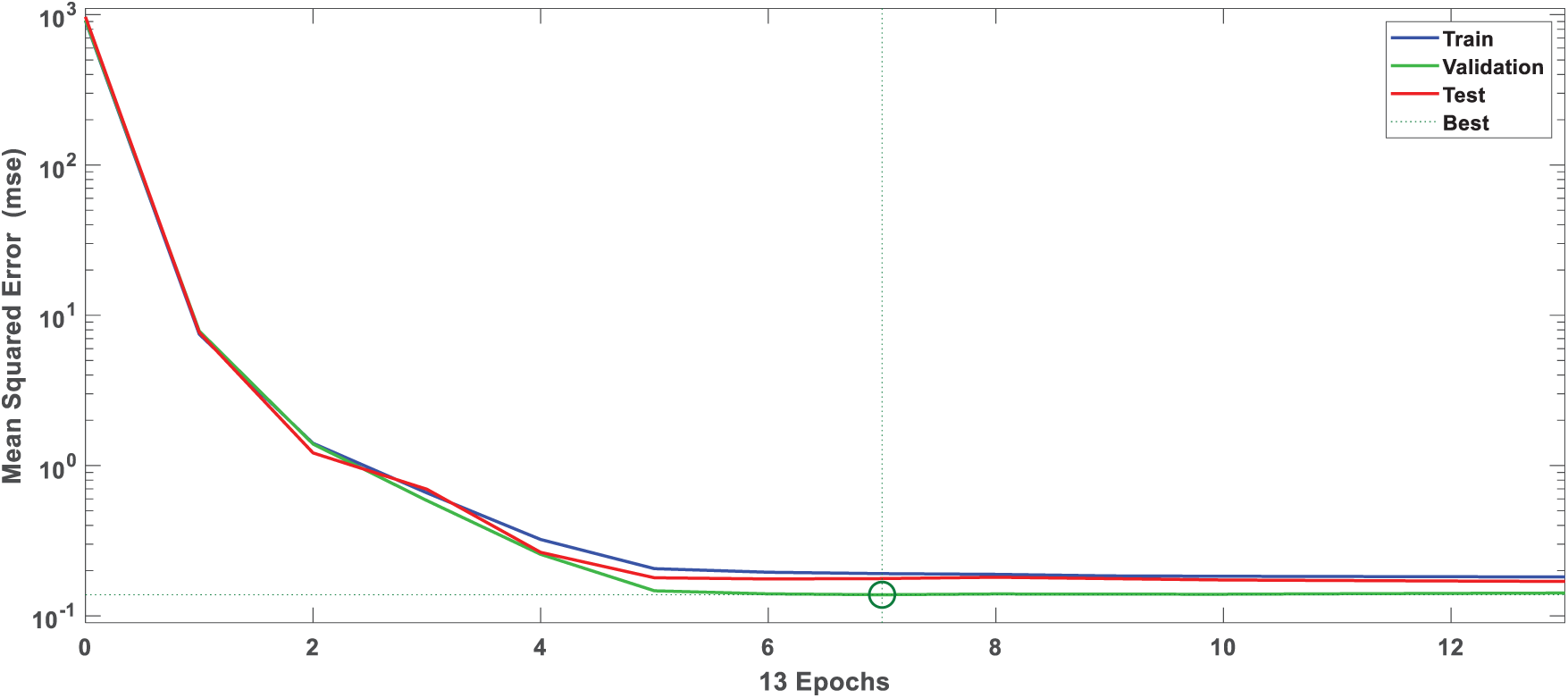

The training convergence of the model is illustrated in Fig. 11, which plots the evolution of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) cost function against training epochs. The observed progressive decrease in error until a stable plateau is reached indicates successful network convergence and effective learning without overfitting. This confirms the model’s robustness and its capacity to generalize the complex dynamic relationships observed experimentally.

Figure 11: Training convergence of the NARX model showing MSE vs. epochs

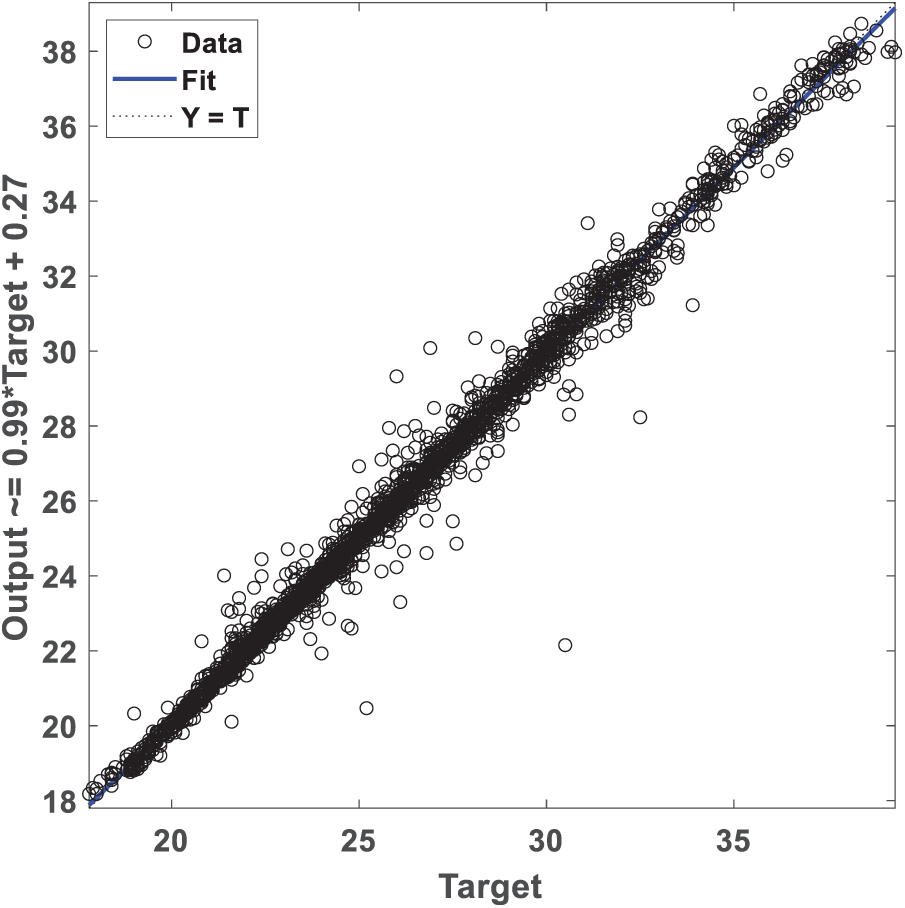

3.5.2 Regression Analysis and Statistical Evaluation

A quantitative analysis was performed to rigorously evaluate the predictive accuracy of the NARX model. The regression plot between all predicted and experimental values is shown in Fig. 12. The data points are tightly clustered along the line of perfect agreement (y = x), which has a slope very close to unity. The exceptionally high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.990) attests to a very strong correlation and explains nearly all the variance in the experimental data.

Figure 12: Regression analysis between predicted and experimental greenhouse temperatures

Furthermore, key statistical indicators were calculated on the independent validation dataset:

✓ Coefficient of Determination (R2): 0.990

✓ Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): 0.425°C

✓ Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 0.223°C

✓ Mean Bias Error (MBE): 0.008°C

The extremely low values of RMSE and MAE indicate a high predictive precision, with an average error of less than half a degree Celsius. The near-zero MBE confirms that the model is unbiased, with no systematic overestimation or underestimation of the temperature.

These comprehensive results validate the NARX model as a highly robust and reliable digital tool. It is capable of not only reproducing the observed thermal cycles with great accuracy but also of predicting the internal temperature of a PCM-equipped greenhouse based solely on external weather data. This opens avenues for its use in predictive climate control systems and for further scenario analysis and optimization studies without the need for costly and time-consuming experimental campaigns.

To strengthen the evaluation, we compared the performance of the NARX model with other commonly used approaches such as multiple linear regression and multilayer perceptrons (MLPs). The NARX model consistently achieved higher R2 values (>0.98) and lower RMSE than these alternatives, confirming its robustness for predicting greenhouse thermal behavior in the presence of PCM.

However, it is important to note that the current NARX model was trained on short-term experimental data, assuming consistent PCM behavior. In practice, degradation mechanisms such as supercooling and phase separation may gradually alter the thermal response of CaCl2·6H2O over repeated thermal cycles. These changes could affect long-term predictive accuracy if not addressed. To mitigate this, future applications should incorporate periodic retraining with updated datasets and consider adaptive learning algorithms to maintain predictive reliability in multi-seasonal greenhouse operations.

From a practical standpoint, the combined experimental–AI framework offers actionable insights for agricultural practice: by predicting and stabilizing greenhouse temperatures, farmers can reduce reliance on auxiliary heating and cooling, thereby decreasing energy costs and improving crop yield stability in Saharan and semi-arid regions.

3.6 Comparative Performance with Other Machine Learning Models

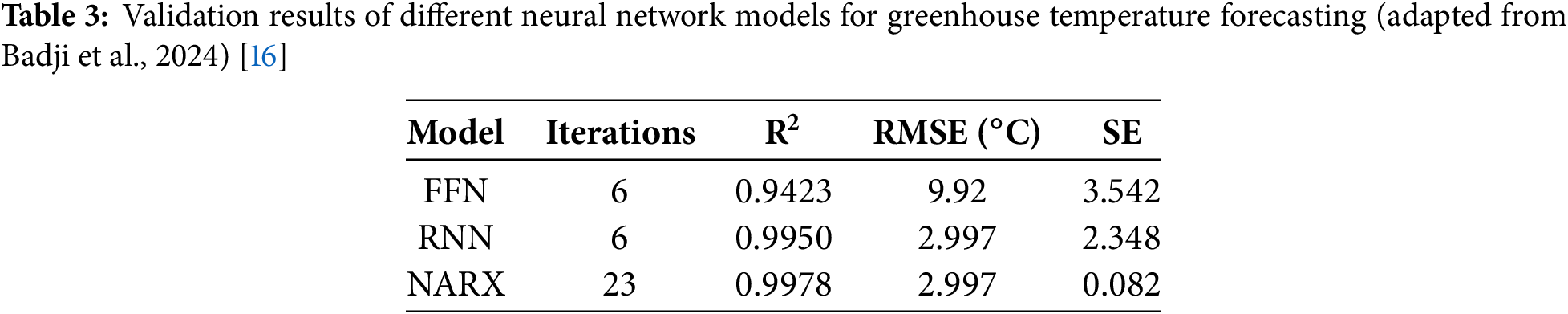

To contextualize the present results, we compared the performance of the NARX model with other machine learning approaches evaluated in our earlier study (Badji et al., 2024 [16]). While that work analyzed a different PCM greenhouse prototype, the comparative trends remain relevant for benchmarking. Three architectures—FFN, RNN-LSTM, and NARX—were trained and tested using climatic data from Ghardaia, Algeria.

The validation results, summarized in Table 3, highlight the superior performance of the NARX model. While FFN exhibited the lowest accuracy (R2 = 0.94, RMSE ≈ 9.9°C), both RNN and NARX achieved high predictive fidelity (R2 > 0.99). However, NARX consistently outperformed the other models in terms of stability and error reduction, achieving the lowest standard error (SE = 0.082) and the most precise predictions.

These results demonstrate that although both RNN-LSTM and NARX provide robust predictions, the NARX model offers a better balance between predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and stability. Its ability to integrate past output feedback with exogenous climatic inputs makes it particularly well suited for greenhouse temperature prediction and justified its use in the present study.

Despite the encouraging results, this study has some limitations. First, the experiments were conducted over a relatively short monitoring period and with a single PCM type and concentration. Second, the greenhouse scale was limited, which may restrict the generalizability of the results. Future studies should extend the monitoring period across different seasons, test other PCM materials, and apply the approach to larger-scale greenhouses to further validate the model.

This study investigated the integration of a CaCl2·6H2O-based phase change material (PCM) as a passive thermal storage solution for agricultural greenhouses in the Saharan climate of Ghardaïa, Algeria. The results highlight the potential of PCM technology to mitigate excessive thermal fluctuations in conventional greenhouse designs.

The reference greenhouse, devoid of thermal mass, experienced extreme diurnal variations with amplitudes averaging 18.29°C, often exceeding 40°C—conditions unsuitable for crop cultivation and post-harvest storage. By contrast, the PCM-equipped greenhouse showed markedly improved performance, lowering daytime peaks by an average of 8.14°C, slightly elevating nighttime minima by 1.66°C, and reducing the overall temperature amplitude by 53.6% to 8.49°C. These improvements confirm the PCM’s ability to stabilize the internal microclimate and decouple it from harsh external conditions.

The NARX neural network model developed and validated in this work proved highly effective in predicting the dynamic thermal behavior of the PCM-greenhouse system, achieving R2 = 0.990, RMSE = 0.425°C, MAE = 0.223°C, and MBE = 0.008°C. Its accuracy demonstrates the model’s capacity to capture nonlinear thermal dynamics, including latent heat effects, and underscores its potential use as a digital twin for future design optimization and predictive climate control.

In conclusion, CaCl2·6H2O PCM integration provides a sustainable, passive solution for greenhouse climate regulation in arid regions, enhancing energy efficiency without operational carbon costs. Future work should focus on economic analysis, optimal PCM design, and scaling strategies, while the NARX model offers promising opportunities for smart, real-time control systems. Beyond scientific validation, the findings provide a practical pathway for farmers to improve crop yield and quality while reducing energy reliance, ultimately strengthening food security in vulnerable environments.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support staff of the URAER experimental platform for their valuable assistance in the fabrication of prototypes used in this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Abdelouahab Benseddik, Ahmed Badji, Hocine Bensaha; Data collection: Abdelouahab Benseddik, Djamel Daoud; Analysis and interpretation of results: Abdelouahab Benseddik, Tarik Hadibi, Yunfeng Wang, Li Ming; Draft manuscript preparation: Abdelouahab Benseddik. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Abdelouahab Benseddik, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kumari N, Tiwari GN, Sodha MS. Effect of phase change material on passive thermal heating of a greenhouse. Int J Energy Res. 2006;30:221–36. doi:10.1002/er.1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Benli H. Performance analysis of a latent heat storage system with phase change material for new designed solar collectors in greenhouse heating. Sol Energy. 2009;83:2109–19. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2009.07.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Claudio C, Stoppiello G. Potential use of phase change materials in greenhouse heating: comparison with a traditional system. J Agric Eng. 2009;3:25–32. doi:10.4081/jae.2009.3.25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Berroug F, Lakhal EK, Omari ME, Faraji M, Qarnia HE. Thermal performance of a greenhouse with a phase change material north wall. Energy Build. 2011;43:3027–35. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.07.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang B, Zhu Y, Zhao H, Yuan Y, Wang G. Preparation and properties of sodium sulfate decahydrate shape-stabilized composite phase change material for solar greenhouse. J Energy Storage. 2025;24:111422. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Badji A, Benseddik A, Bensaha H, Boukhelifa A, Bouhoun S, Nettari C, et al. Experimental assessment of a greenhouse with and without PCM thermal storage energy and prediction of their thermal behavior using machine learning algorithms. J Energy Storage. 2023;71:108133. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.108133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xiao Q, Sun J, Tang H, Zhang L, Diao N, Li H. Preparation and energy-saving effects of disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate composite phase-change material applied in greenhouse cooling. Energy Storage Sci Technol. 2023;12(12):3635. doi:10.19799/j.cnki.2095-4239.2023.0483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Y, Zou Z, Li J, Hu X. Preparation of the small concrete hollow block with PCM and its efficacy in greenhouses. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2010;26:263–7. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2010.02.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liang H, Yang Q, Alejandro L. Development of a wall collector unit and phase change material (PCM) air heat exchanger for heating application in greenhouses. Energy Env Res. 2013;3(1):24–32. doi:10.5539/eer.v3n1p24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Baddadi S, Bobadilla S, Guizani A. Beneficial use of two packed beds of latent storage energy for the heating of a hydroponic greenhouse. Energy Proc. 2019;162:156–63. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2019.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bao L, Hou Q, Wang K, Jiang Z. Preparation and application of inorganic composite phase change materials for solar greenhouses. J Inorg Chem Ind. 2022;54:61–9. [Google Scholar]

12. Lengsfeld K, Walter M, Krus M, Pappert S, Teicht C. Innovative development of programmable phase change materials and their exemplary application. Energies. 2021;14:3440. doi:10.3390/en14123440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ismail MM, Dincer I, Bicer Y, Saghir MZ. Effect of using phase change materials on thermal performance of passive solar greenhouses in cold climates. Int J Thermofluids. 2023;19:100380. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2023.100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen W, Zhou G. Experimental investigation on heating performance of long-and short-term PCM storage in Chinese solar greenhouse. J Energy Storage. 2024;99:113466. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.113466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yan S, Fazilati MA, Toghraie D, Khalili M, Karimipour A. Energy cost and efficiency analysis of greenhouse heating system enhancement using phase change material. Renew Energy. 2021;170:133–40. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.01.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Badji A, Benseddik A, Boukhelifa A, Bensaha H, Erregani RM, Bendriss A, et al. Solar air heater with underground latent heat storage system for greenhouse heating: performance analysis and machine learning prediction. J Energy Storage. 2023;74:109548. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.109548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hoseinzadeh S, Garcia DA. AI-driven innovations in greenhouse agriculture: reanalysis of sustainability and energy efficiency impacts. Energy Convers Manag X. 2024;24:100701. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools