Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Solar Thermal Drying Kinetics of Faecal Sludge: Effect of Convection Air Stream Conditions and Type of Sludge

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Research & Development Centre (WASH R&D Centre), University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Campus, Durban, 4041, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Santiago Septien. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advance and Development in Solar Energy)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(8), 3177-3199. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.063898

Received 27 January 2025; Accepted 05 June 2025; Issue published 24 July 2025

Abstract

Onsite sanitation offers a sustainable alternative to centralized wastewater treatment; however, effective faecal sludge management is crucial for safe disposal and resource recovery. Among emerging treatment solutions, solar thermal drying holds significant promise to reduce sludge moisture content and enhance handling. Despite this potential, its application remains limited, with important knowledge gaps, particularly concerning the drying kinetics under different environmental and operational conditions. This study aims to fill these gaps by investigating the solar thermal drying behaviour of faecal sludge from ventilated improved pit latrines (VIPs) and urine-diverting dry toilets (UDs), with a specific focus on how air temperature and velocity influence drying performance. A bench-scale solar drying apparatus was used to investigate thin-layer sludge drying kinetics under controlled airflow conditions. The drying experiments were conducted at varying air temperatures (ambient, 40°C, and 80°C) and velocities (0, 0.5, and 1 m/s), where heated air was supplied via an electric resistance heater. Key drying parameters—including drying rate, critical moisture content, effective moisture diffusivity, and activation energy—were determined. Results showed that drying proceeded through a constant-rate period followed by a falling-rate period, with the critical moisture content ranging from 1.41 to 1.78 g/g db. Higher temperatures and airflow reduced the duration of the constant-rate phase, increased drying rates (0.31–0.99 g/g·min·m2), and enhanced moisture diffusivity (4.56 × 10−9 to 1.52 × 10−8 m2/s). Activation energy decreased with increased airflow, suggesting reduced temperature sensitivity. Thermal efficiency ranged from 14.6% to 35.1%, with solar energy contributing 73%–95% of total input. VIP sludge dried faster than UD sludge, which showed signs of surface crusting that limited moisture transfer. This research offers valuable insights into solar drying design and operation, providing scientific evidence to improve faecal sludge treatment strategies in decentralized sanitation systems.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileFaecal Sludge Management (FSM) is essential to ensure safe sanitation in areas that rely on onsite sanitation systems and where conventional sewerage infrastructure is unavailable. Effective FSM minimizes environmental pollution, reduces public health risks, and supports resource recovery. Faecal sludge offers potential for reuse in multiple applications, including fertilizer, soil conditioner, biofuel, animal protein, and building material [1]. Among the available treatment methods, drying is particularly important as it significantly reduces the moisture content, thereby lowering mass and volume, which in turn decreases transportation and storage costs [2]. Moreover, thermal drying can lead to pathogen inactivation, making the sludge safer for handling and reuse [3]. Drying can serve as either a final treatment step to reuse or a pre-treatment before further processing [4].

Drying processes, which remove moisture through evaporation, are particularly challenging and energy-intensive when applied to faecal sludge due to its high moisture-binding capacity. Conventional drying beds, although widely adopted, require large land areas and extended drying times. Thermal dryers accelerate the process but are often limited by their high energy demands. The use of solar energy, an abundant and renewable resource, offers a promising alternative, enabling lower operational costs while maintaining drying efficiency.

Solar thermal drying has been extensively applied in the agricultural sector to preserve food and agricultural products [5,6]. However, sludge drying differs fundamentally from agricultural product drying because of material characteristics. While food and agricultural items are typically hygroscopic solids, faecal sludge behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid with viscoelastic properties. Consequently, the design of solar dryers must account for these specific properties, requiring adaptations tailored to sludge rather than directly replicating agricultural dryer designs.

For wastewater treatment sludge, large-scale solar thermal drying has been implemented, primarily through greenhouse-based systems such as those in Managua, Nicaragua, and Mallorca, Spain [7,8]. The Mallorca solar plant, with an area of 17,260 m2, is among the largest in the world, while the Managua facility, at 8760 m2, is the largest in the Americas. Both plants treat approximately 30,000 t of sludge per year, reducing moisture content from 70%–80% to 20%–40%. Their reported drying rates are 1–1.7 t/year/m2 for Mallorca and 4.3 t/year/m2 for Managua. Importantly, the specific energy consumption for both systems is less than 60 kWh per ton of evaporated moisture, substantially lower than conventional thermal drying systems, which typically consume 800 to 1000 kWh/ton.

Recent research efforts have focused on optimizing solar dryer performance and innovating new system designs. For instance, Sorrenti et al. [9] developed a closed-static solar greenhouse at pilot scale that utilized forced ventilation with aerothermal flat solar panels to supply hot air directly for sludge drying, where the airflow was introduced underneath the sludge bed and flowed through it. This system achieved a reduction in moisture content from 95% to 5% over 25 days in winter, with a specific energy consumption of 450 kWh/ton. Similarly, Khanlari et al. [10] modified a conventional solar drying chamber by adding a transparent glass cover, which experimental and modeling results demonstrated could decrease drying time by approximately 40%. Poblete et al. [11] investigated the integration of a rock bed inside a tank for solar thermal energy storage, resulting in improved efficiency (37.8%) compared to the system without thermal storage (22.2%). Wang et al. [12] introduced a sandwich-like drying chamber designed for rooftop installation, achieving a drying rate of 6.72 g/h with an optimal sludge layer thickness of 5 mm, reducing moisture content from 79% to 5% within 11 h under a solar irradiance of 500 W/m2. Masmoudi et al. [13] further demonstrated the superior performance of draining solar thermal systems compared to traditional open-air drying beds and highlighted that the system operating under forced convection conditions yielded better results than relying solely on natural convection.

Beyond system design, several studies have evaluated the quality of sludge after solar drying to assess its safe disposal and reuse potential. Works by An-Nori et al. [14–16] examined pathogen removal, heavy metal content, micropollutant behavior, and agronomic value after drying. Solar drying significantly reduces pathogen content without negatively impacting nutrient concentrations, while it also reduces the mobility of heavy metals, even though their total concentrations remain unchanged. However, further research is needed to fully understand micropollutant dynamics during the drying process. A broader review by Gomes et al. [17] assessed the suitability of solar thermal drying systems for wastewater treatment plants, using a SWOT analysis framework (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) to aid in the selection and deployment of appropriate technologies.

Despite these advancements, solar thermal drying specifically for faecal sludge from onsite sanitation systems remains largely underexplored. In many regions with pressing sanitation needs, solar irradiation is abundant, making solar drying an especially attractive option. Yet, only limited studies have investigated solar drying for faecal sludge. Muspratt et al. [18] used a transparent plastic roof installed at a 15° angle over conventional drying beds for drying faecal sludge from pit latrines and septic tanks in Accra, Ghana. In their study, faecal sludge at all three tested depths (6, 8, and 10 cm) achieved nearly 60% total solids within 15 days, which was faster than results observed in a conventional drying bed tests achieving 45% total solids after 34 days of drying with an initial sludge depth of less than 30 cm. Similarly, Seck et al. [19] tested greenhouses built over drying beds in Dakar, Senegal, examining passive vs. active ventilation. Their findings indicated that active ventilation significantly enhanced performance, while passive systems faced condensation on the walls of the greenhouse. Compared to uncovered beds, the greenhouses accelerated drying during the rainy season (reducing moisture content to 10% within 20–27 days, compared to 40% in uncovered beds). However, during dry seasons, the performance difference between covered and uncovered systems was negligible, suggesting that greenhouses primarily helped mitigate moisture uptake during rainfall rather than substantially increasing evaporation rates.

There is a critical need to develop sludge-specific solar dryer designs that enhance heat and mass transfer, optimize drying kinetics, account for the heterogeneity of faecal sludge properties, and address the specific challenges posed by decentralized sanitation systems. In response to these needs, this study aimed to investigate and characterize solar thermal drying processes for faecal sludge, with the goal of providing fundamental knowledge and critical insights to support the development of energy-efficient solar drying systems tailored to faecal sludge management. A forced convection solar thermal dryer configuration was selected for investigation, as this design has demonstrated superior performance compared to open-air and passive ventilation systems. The work was conducted using a novel solar thermobalance specifically designed for this study, enabling precise characterization of drying kinetics under controlled solar thermal conditions. The study focused on analyzing drying kinetics under different operational parameters, quantifying heat and mass transfer characteristics, and evaluating thermal efficiency.

This study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee from the University of KwaZulu-Natal under ethical clearance BREC/00000203/2019.

Faecal sludge from ventilated improved pit (VIP) and urine diversion (UD) toilets was used for this study, as these sanitation systems are prevalent within the local municipality (eThekwini) and generate a significant portion of sanitation waste. Solar drying presents a viable treatment solution for this sludge, offering an environmentally sustainable approach to mitigate the municipality’s disposal challenges while enabling resource recovery.

Samples were collected from a faecal sludge treatment plant (FSTP) located in Isipingo, KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. The sludge originated from routine pit emptying activities within the eThekwini Municipality (Durban metropolis). Pit emptying is typically carried out manually using hand tools such as shovels for digging and pitchforks for removing larger solid waste. No water was added during the emptying process.

At the FSTP, sludge from different toilet types was combined into a single pile. Since the samples were taken from this mixed sludge, they were considered representative of the faecal sludge composition from various toilets across the municipality. Approximately 20 kg of each sample type was placed in sealed plastic containers and transported to the laboratory. The sludge was screened using a 5 mm sieve to remove non-biodegradable materials commonly disposed of in pits, a frequent practice in the Durban region. Samples were then stored in a laboratory cold room at 4°C to prevent biological degradation and maintain sludge properties until testing.

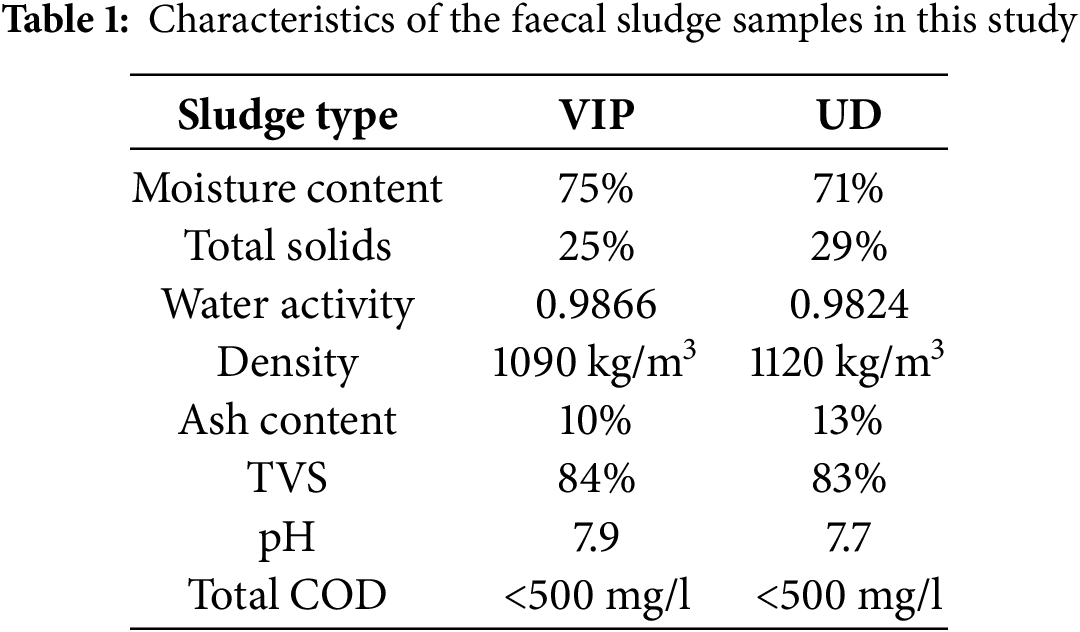

Prior to experimentation, the initial physicochemical properties of the sludge were analyzed. These analyses included moisture content, total solids, water activity, density, total volatile solids (TVS), ash content, chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH, and electrical conductivity. All tests were conducted following standard procedures for faecal sludge analysis as outlined by Velkushanova et al. [20].

Table 1 presents the results of the physicochemical analyses of the sludge samples. The measured values were comparable to those reported in the literature for typical faecal sludge [21–23]. The average recorded moisture content was 73% for VIP sludge and 71% for UD sludge. The initial water activity values, 0.9866 for VIP and 0.9824 for UD, were close to 1, suggesting a significant proportion of loosely bound moisture.

2.2 Description of the Laboratory-Scale Solar Thermal Drying System

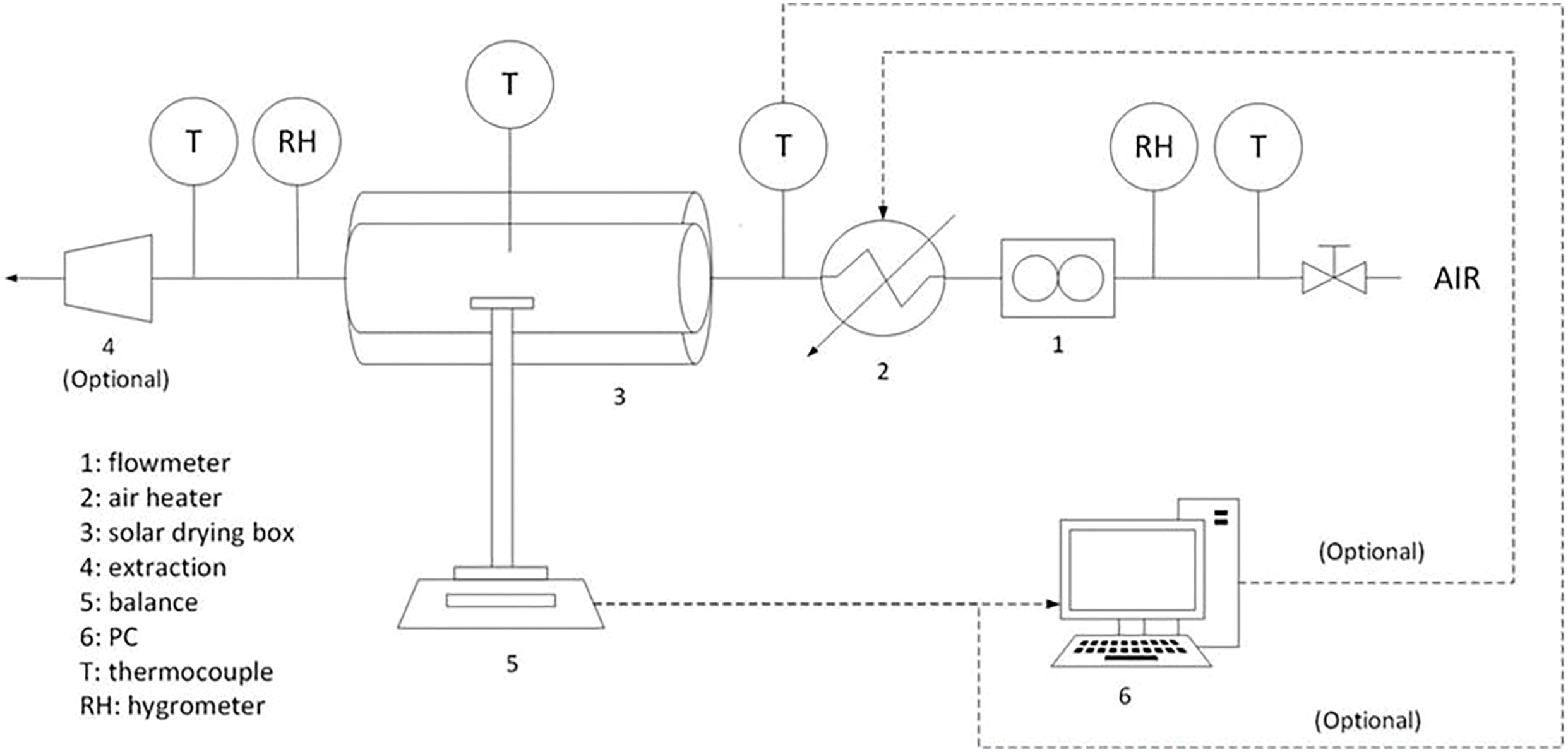

Experiments were conducted using a laboratory-scale solar thermal drying rig (Fig. 1), which was designed and constructed in-house to enable real-time measurement of drying kinetics during solar thermal drying, functioning similarly to a thermobalance, and previously used in earlier studies [24].

Figure 1: Schematic layout of the solar thermal drying rig setup

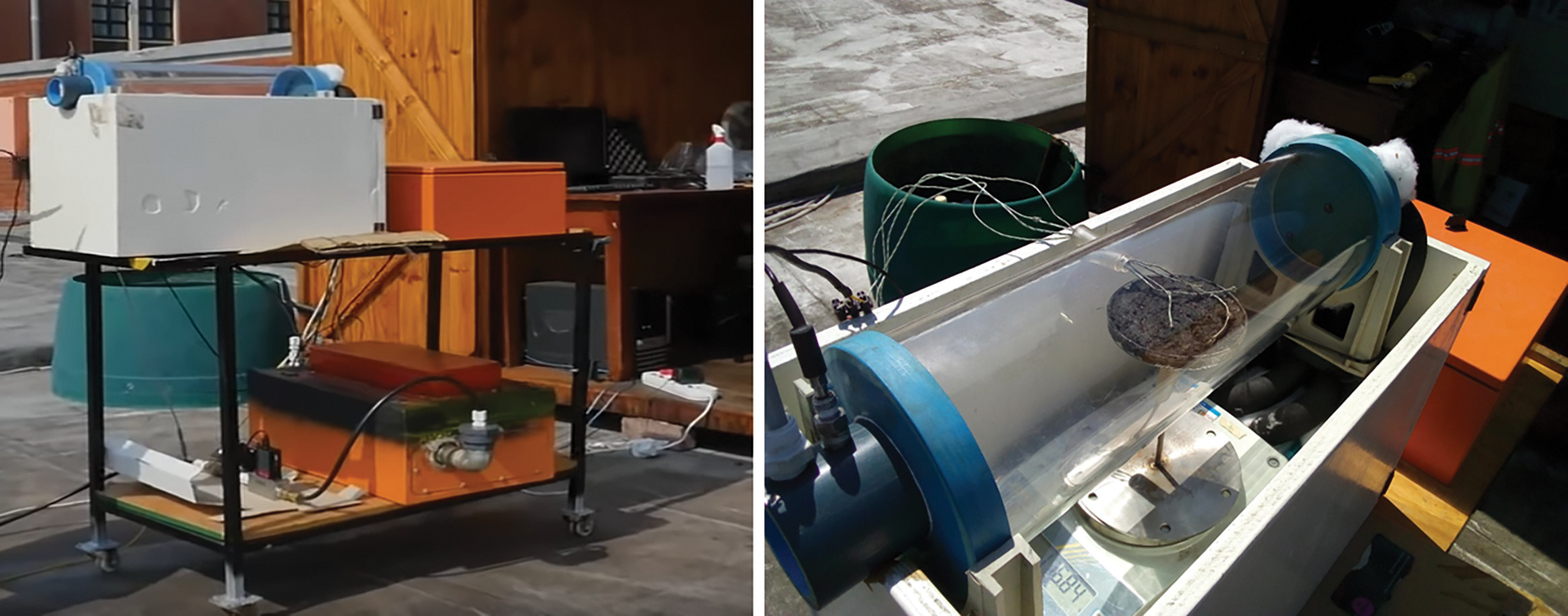

The drying rig was installed on the roof of the Chemical Engineering building at the Howard College campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa (latitude: 29°52′08.1″ S; longitude: 30°58′46.6″ E). The experiments were performed in an open space to ensure unobstructed exposure to sunlight throughout the day. Fig. 2 presents photographs of the apparatus and solar drying chamber during one of the experiments.

Figure 2: Photographs of the experimental setup

The key components of the solar thermal convection drying setup are described below:

(a) Drying chamber: The drying chamber was constructed from acrylic in a cylindrical shape, with a length of 500 mm and an internal diameter of 140 mm. It was fitted with two centrally located ports, each 20 mm in diameter, to allow connections for the balance and temperature sensors. The chamber material had an estimated transmittance of 80%.

(b) Airflow system: Compressed air was supplied from the Chemical Engineering building’s air line at a maximum pressure of 4 bar, sufficient to achieve the desired airflow rates. The air was introduced into the drying chamber through a multi-entry inlet, ensuring uniform air velocity distribution across the chamber cross-section.

(c) Mass balance: A digital balance (Model ACB 3000, Adam Equipment, UK) with an accuracy of ±0.01 g was used to measure sample mass. The balance was enclosed in a wooden box to protect measurements from external disturbances such as wind and overheating due to solar radiation exposure.

(d) Air heater: Before entering the drying chamber, the airstream could be preheated using a homemade 20 A electric air heater. The heater was connected to a data interface, allowing precise control of the air temperature.

(e) Temperature measurement: Type-K thermocouples (0.3 mm diameter) were used to measure the temperatures of sludge samples and air within the drying chamber. To minimize heat loss and ensure accurate readings, the thermocouple wires were insulated with glass fiber. Additionally, PT100 temperature sensors were installed at both the inlet and outlet of the drying chamber to monitor air temperatures entering and leaving the chamber.

(f) Humidity measurement: Humidity probes (model HPP809A031, TE Connectivity, Switzerland; model HP474ACR, Delta Ohm, Italy) were used to measure air humidity at both the inlet and outlet of the drying chamber.

(g) Flowrate measurement: The air flowrate was varied by a proportional 2-way solenoid valve (Burker, Germany) with a flow controller (Burkert 8605, Burkert, Germany) and the flow measured by mass flowmeter (Alicat M-1000SPLM-D/10V, Alicat Scientific, USA) that was connected in series to the flow controller.

(h) Air velocity measurement: The airflow velocity at the chamber outlet was monitored at hourly intervals using a hot-wire anemometer (model ET-961, Everbest Technologies, China).

(i) Irradiance measurement: Solar irradiance near the drying chamber was measured using a second-class silicon photoelectric pyranometer (model CMP3, Kipp & Zonen, Netherlands) with an accuracy of ±15 W/m2.

(j) Sample crucible: Samples were placed on a cylindrical acrylic crucible with dimensions 110 mm in diameter and 10 mm in thickness.

(k) Data interface: A data acquisition system, developed in-house, was designed using LabVIEW software, enabling real-time communication between the measuring instruments and a computer. Measurements from the balance, thermocouples, temperature sensors, humidity meters, and pyranometer were transmitted to the computer via data loggers. All data loggers were housed within a dedicated data acquisition box, which also contained the power supply and control system for the air heater.

Drying experiments were conducted daily for five hours, from 10:00 to 15:00, under sunny conditions. The tests took place during two seasonal periods: October and November 2019 (spring) and January to March 2020 (summer). During these experiments, solar irradiance levels typically ranged between 800 and 1350 W/m2 under clear sky conditions.

Before each experiment, sludge samples were taken from the cold room and left in an open shed for 30 min to reach ambient temperature. Prior to the experiment, a sludge sample was spread to a uniform thickness of 5 mm on the crucible and placed inside the transparent cylindrical chamber, where it was exposed to solar radiation. To ensure stable operating conditions, the drying rig was preheated for 15 min before introducing the sample, allowing the air temperature and flow rate to stabilize. The crucible was linked to a mass balance, which recorded mass changes every 60 s to track the drying kinetics in real-time.

All experiments were conducted under a low relative humidity close to 0%, corresponding to the humidity level of the compressed air supply. The operational parameters were as follows:

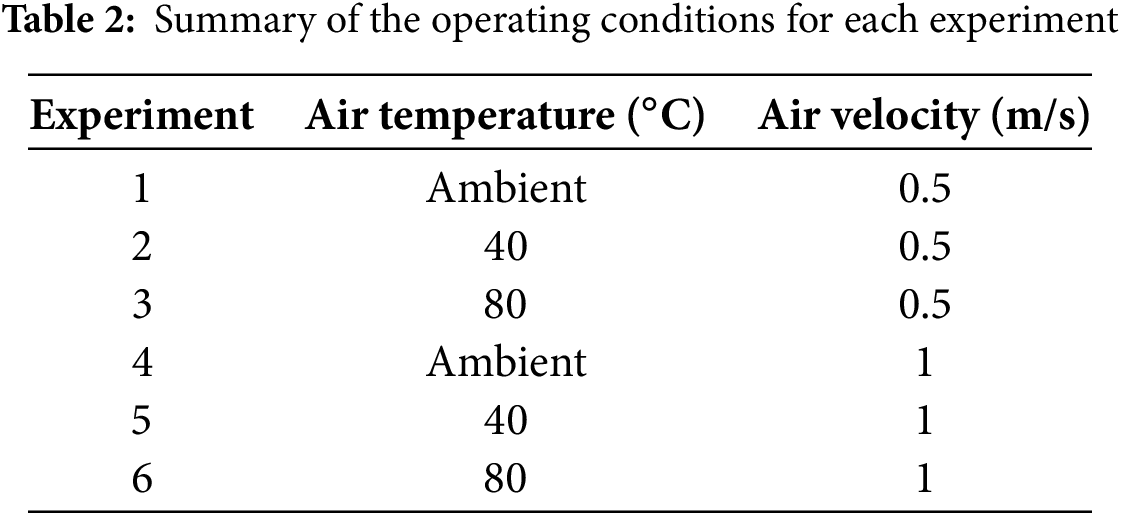

• Air velocity: Two air velocities were tested: 0.5 and 1 m/s. These velocities were achieved by adjusting the flow control valve to a half-open position for 0.5 m/s and fully open for 1 m/s, corresponding to airflow rates of 4.2 and 8.4 m3/min, respectively.

• Air temperature: Experiments were performed at three temperature levels: ambient temperature, 40°C, and 80°C. The desired air temperature was set via the data interface, and dry air was preheated in the air heater box before entering the drying chamber.

Table 2 provides a summary of the experimental plan. To ensure repeatability, each experiment was conducted twice under identical operating conditions. The average ambient air temperature during the tests was approximately 23°C.

The airflow regime during experiments at 0.5 m/s was classified as transitional, representing an intermediate state between laminar and turbulent flow, with hydraulic Reynolds numbers ranging between 2000 and 5000. For experiments conducted at 1 m/s, the airflow regime was identified as turbulent, as all Reynolds number values exceeded 5000. The Reynolds number calculations can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

The temperature evolution of the sludge during drying exhibited an initial rapid increase as the air reached steady-state conditions and the sludge approached the wet-bulb temperature, followed by a phase where the temperature remained relatively constant. The temperature evolution of sludge during the drying process can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Throughout the solar drying experiments, mass, temperature, relative humidity, and solar irradiance were continuously monitored over time. This section outlines the data processing methods employed to analyze key process parameters and achieve the study’s objectives.

2.4.1 Moisture Content and Moisture Ratio

Moisture content is defined as the amount of moisture present in the sludge samples at any given time of the drying process. From the recorded sample mass reading, the moisture content on wet basis, Mwb,t [g/g total mass], and on dry basis, Mdb,t [g/g db], were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

where

Moisture ratio

where

Equilibrium moisture content

2.4.2 Drying Rate and Critical Moisture Content

The drying rate

where

Before calculating the drying rate, the experimental drying curves (moisture content vs. time) were smoothed using Microsoft Excel trendlines. The drying curve was segmented into two phases: an initial linear section, followed by a nonlinear section. A linear regression model was applied to the first segment, while an exponential regression model was used for the second. The coefficient of determination R2 for these regression fits ranged from 0.984 to 0.999. The transition between the linear and exponential phases was identified through visual inspection. The constant rate period was represented by the equation derived from the linear segment, whereas the falling rate period was described by the equation from the exponential segment. The critical moisture content was calculated using a linear interpolation formula, as presented in Eq. (5).

where

2.4.3 Moisture Diffusivity and Activation Energy

Moisture diffusivity was determined from the falling rate period of the drying curve (i.e., the exponential phase). The analytical solution for a flat slab geometry was employed to estimate effective diffusivity, as it offers simplicity compared to other geometries and aligns well with the shape of the sludge samples. The analysis was conducted at temperatures of 23°C (ambient), 40°C, and 80°C, with the airstream maintained at constant velocities of 0.5 and 1 m/s.

The following assumptions were made for this analysis [25]:

• Moisture transport within the sludge occurs solely through diffusion.

• The diffusion coefficient and sludge temperature remain constant.

• The sludge is homogeneous, resulting in a uniform initial moisture distribution.

• Shrinkage effects are negligible.

The analytical solution of Fick’s second law was derived for an infinite plate of a specified thickness, resulting in Eq. (6) [26].

where

Considering that, for extended drying periods, only the first term of the series remains significant, the solution from Eq. (6) simplifies to Eq. (7) [25,26]. Eq. (7) can be then re-arranged as Eq. (8).

By applying Eq. (8) a graph of

where

The activation energy quantifies the relationship between moisture diffusivity and temperature, following the Arrhenius equation, as expressed in Eq. (10).

where

Using Eq. (10), a graph of

The drying system was powered by two energy sources: solar radiation (radiative heat power) and the heated airflow (convective heat power).

The convective power

where

The radiative solar power

where

The total power of the system,

The efficiency

It was assumed that all the energy absorbed by the sludge

where

For each set of replicate experiments conducted under identical conditions, the mean value of each measured parameter was calculated. The variability among replicates was quantified by computing the standard deviation, providing an estimate of the measurement uncertainty. This approach ensures that the reported results accurately reflect both the central tendency and the dispersion inherent in the experimental data.

This section presents the results obtained under varying air temperature and air velocity conditions. Each experiment was conducted twice under identical settings (run 1 and run 2).

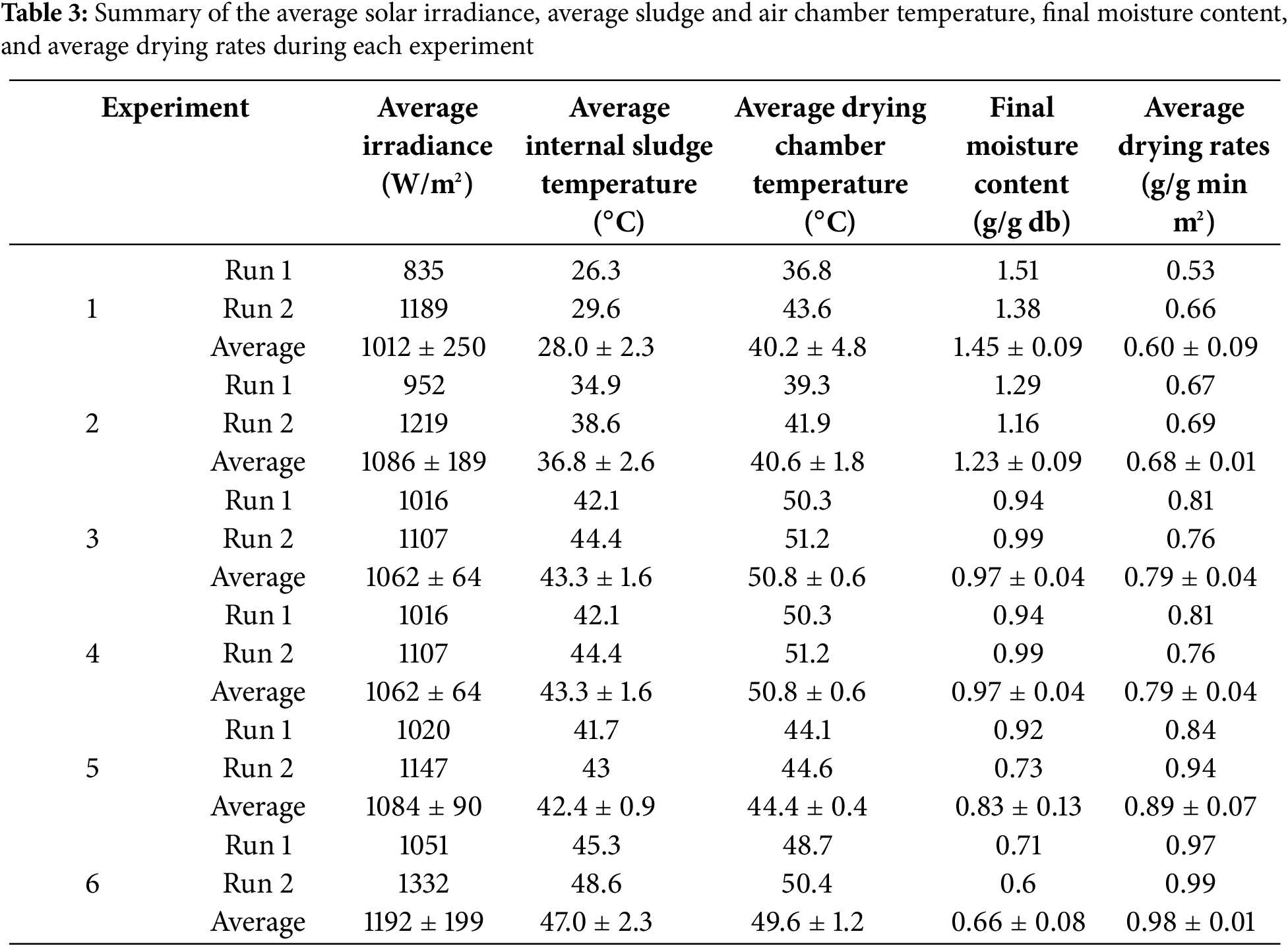

Table 3 provides a summary of key experimental parameters, including solar irradiance, sludge and drying chamber temperatures, drying rates, and final moisture content at the end of the drying process. The solar irradiance and temperature values shown represent the average measurements recorded during each experiment.

Note that the relative humidity at the outlet of the drying chamber is not indicated in the table. This is because its value remained nearly constant throughout the tests, around 10%. This stability can be attributed to the significantly larger volume of the drying chamber compared to the sample size, allowing the evaporated moisture to be rapidly diluted.

The operating conditions for each of the experiments, i.e., experiments 1 to 6, were as presented in Table 2.

3.1 Effect of Air Velocity and Temperature

The influence of air temperature on faecal sludge solar drying was examined using VIP sludge samples under different airflow temperatures: ambient (23°C), 40°C, and 80°C, while maintaining a constant air velocity of either 0.5 or 1 m/s. The variation in air temperature was designed to simulate both direct and indirect solar drying conditions, where the drying material is exposed to solar radiation while the carrier air inside the drying chamber can be preheated.

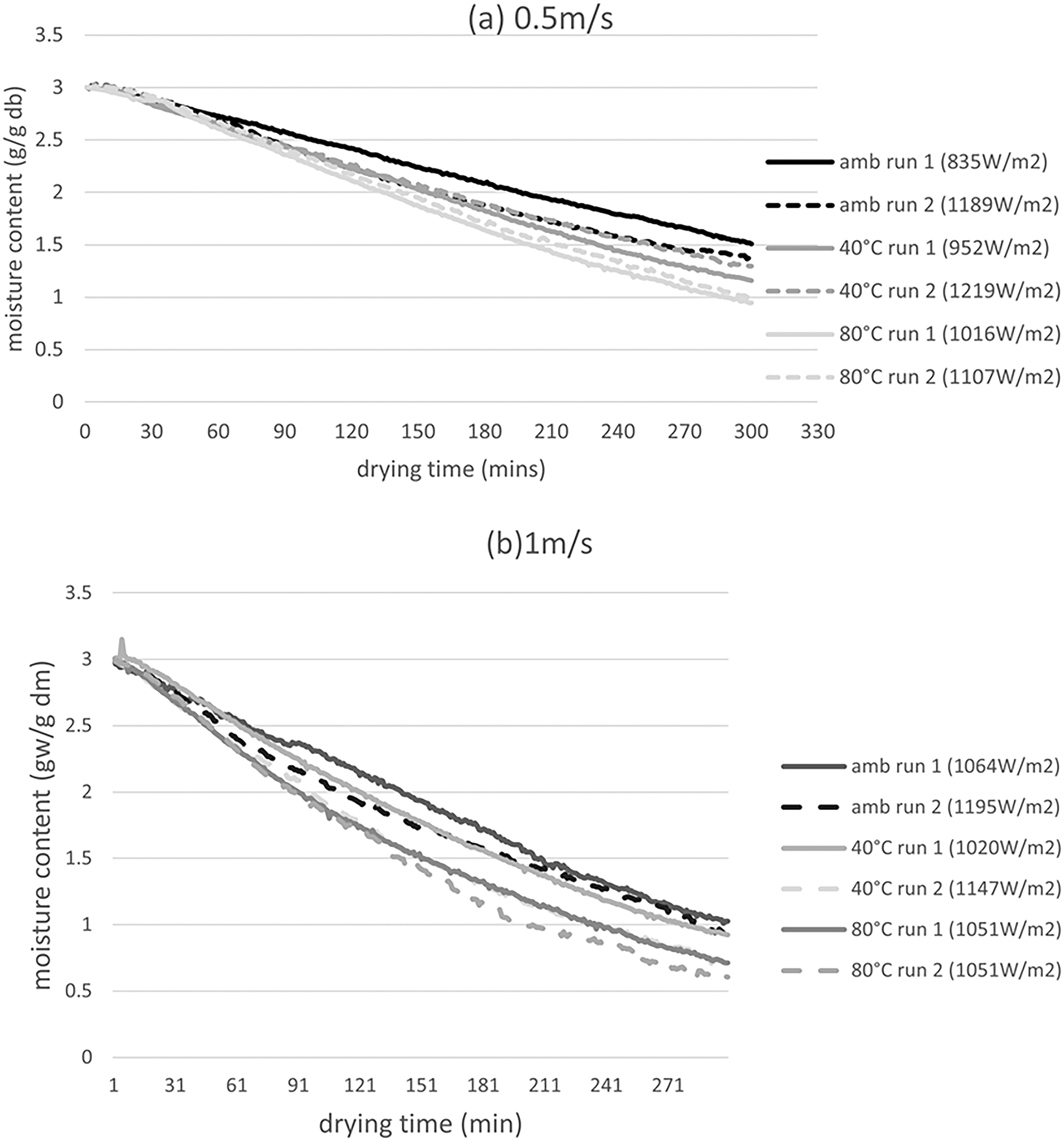

Fig. 3 illustrates the drying curves, showing the moisture content evolution over time at airflow velocities of 0.5 and 1 m/s. After 5 h of drying, the moisture content at 0.5 m/s air velocity (Fig. 3a) averaged 1.47 g/g db at ambient temperature, 1.23 g/g db at 40°C, and 0.97 g/g db at 80°C. At 1 m/s air velocity (Fig. 3b), the final recorded moisture contents were lower, averaging 0.98 g/g db at ambient conditions, 0.83 g/g db at 40°C, and 0.66 g/g db at 80°C.

Figure 3: Drying curves at varying air temperature (ambient 23°C, 40°C, and 80°C) for VIP sludge at 0.5 m/s (a) and 1 m/s (b) air velocity

Hence, an increase in air temperature led to a greater reduction in drying time and, consequently, a lower final moisture content. Indeed, higher air temperatures accelerated the drying process by increasing vapor pressure within the sludge and enhancing heat and mass transfer rates, thereby facilitating faster moisture removal. This trend aligns with findings reported by Ameri et al. [27] for solar drying of sewage sludge.

In Fig. 3a, the drying rate remained similar between the experiments conducted at ambient temperature (run 2) and 40°C (run 1). This can be attributed to the significantly higher solar irradiance at ambient air temperature (1189 W/m2) compared to 40°C (958 W/m2). These results indicate that, in a system combining both direct and indirect solar drying, both solar irradiance and air temperature influence drying kinetics.

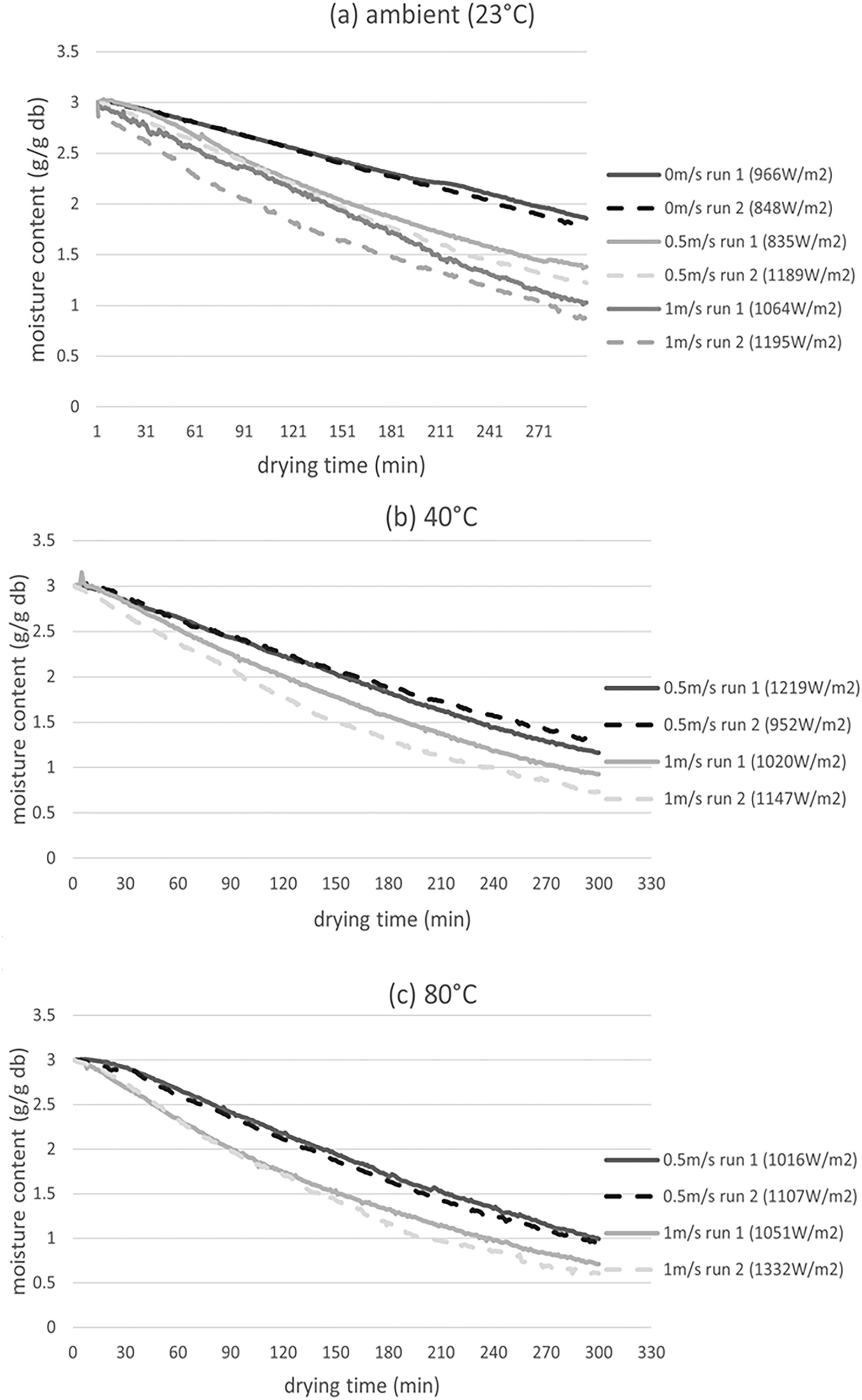

The effect of air velocity on faecal sludge solar drying was evaluated by conducting experiments with VIP sludge at a constant air temperature while varying air velocity at 0, 0.5, and 1 m/s. Fig. 4 presents the drying curves corresponding to different air velocities at ambient temperature, 40°C, and 80°C. Experiments without airflow (i.e., at zero air velocity) were performed only at ambient conditions, as airflow was necessary for higher temperature experiments.

Figure 4: Drying curves at varying air velocity (0, 0.5, 1 m/s) for VIP sludge at ambient air temperature (a) ambient temperature (23°C), (b) 40°C, and (c) 80°C

At ambient temperature (Fig. 4a), the final moisture content averaged 1.82 g/g db at 0 m/s, 1.47 g/g db at 0.5 m/s, and 0.98 g/g db at 1 m/s. At 40°C (Fig. 4b), the final moisture contents were 1.23 g/g db at 0.5 m/s and 0.83 g/g db at 1 m/s. At 80°C (Fig. 4c), moisture content further decreased to 0.97 g/g db at 0.5 m/s and 0.66 g/g db at 1 m/s. The results indicate that higher air velocities resulted in lower final moisture content across all temperature conditions, with the fastest drying observed at 1 m/s, followed by 0.5 m/s, and the slowest at 0 m/s. This suggests that increasing air velocity enhances the drying rate. The acceleration in drying can be attributed to a reduction in boundary layer thickness at the sludge surface, which improves heat and mass transfer rates. Consequently, moisture migrates more efficiently from the sludge to the airstream, and heating is more effective, particularly when preheated air is used [28].

The positive influence of temperature and airflow velocity on drying performance aligns with theoretical expectations and is consistent with findings in the literature. Celma et al. [29] and Ali et al. [30] investigated the impact of air temperature (ranging from 20°C to 90°C) on the drying of thin-layer sludge from oil extraction and sewage sludge, respectively, within an indirect solar dryer. Both studies reported a faster reduction in moisture content with increasing air temperature. Similarly, Parlak et al. [31] conducted solar drying experiments on thin-layer poultry abattoir sludge and observed that aeration significantly accelerated moisture loss compared to tests conducted without airflow.

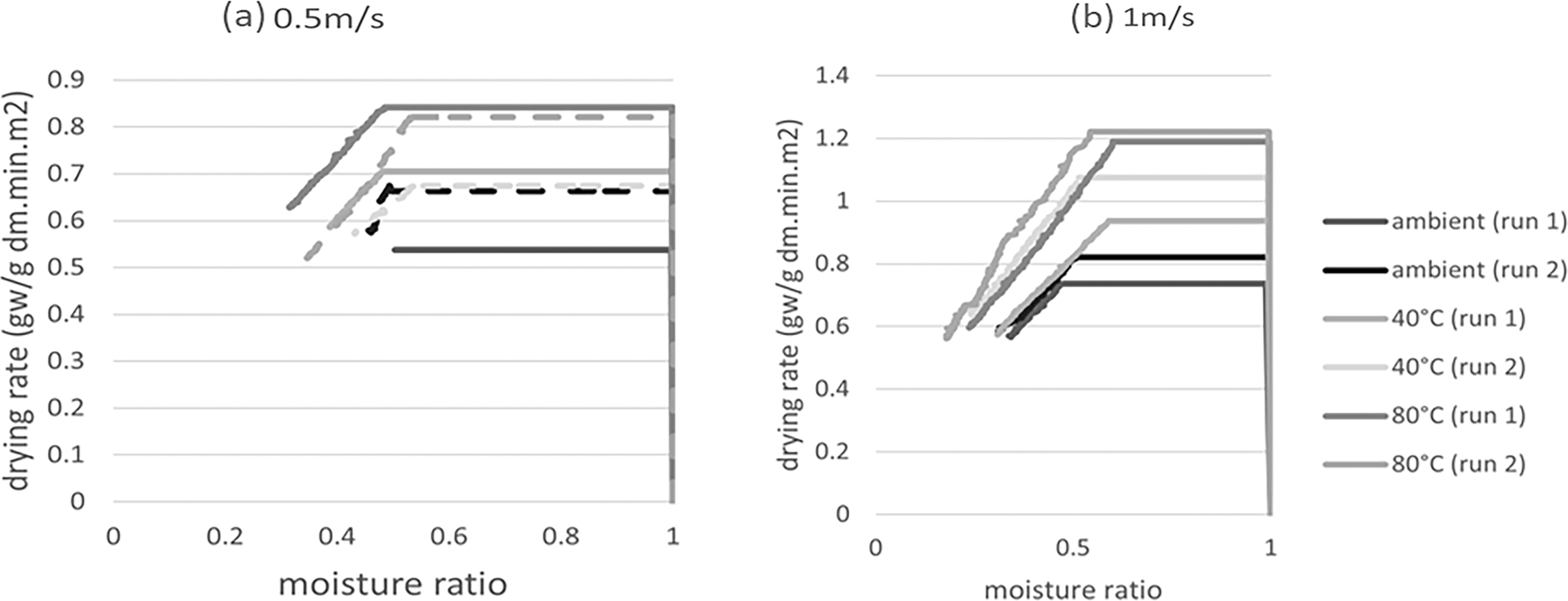

Fig. 5 illustrates the variation of drying rates with moisture ratio (Krischer curves) for VIP sludge at air velocities of 0.5 and 1 m/s, under different air temperatures (ambient, 40°C, and 80°C). The results indicate that drying rates remained constant initially and then declined after a certain period. Drying followed a typical pattern, occurring in the constant rate period until the critical moisture ratio was reached, after which the falling rate period began. An exception to this trend was observed in the ‘ambient (run 1)’ experiment, where the drying rate remained constant, suggesting that the critical moisture ratio was not reached.

Figure 5: Drying rate curves for VIP sludge at air velocity of 0.5 m/s (a) and 1 m/s (b), at varying air temperature (ambient, 40°C and 80°C)

According to drying theory, the constant rate period occurs when the entire surface of the sludge remains saturated with moisture, allowing continuous evaporation that is immediately replenished by moisture migration from within the sample. Once the critical moisture ratio is reached, the moisture on the surface evaporates more rapidly than it can be replaced from the interior, leading to a decline in the overall drying rate and marking the onset of the falling rate period.

It was also observed that drying rates in Fig. 5b (1 m/s) were consistently higher than those in Fig. 5a (0.5 m/s), with the highest drying rates occurring at 80°C and the lowest at ambient temperature. As expected, drying rates increased with both air velocity and temperature. Furthermore, the convective mass transfer coefficients increased from 7.47 × 10−3 to 9.49 × 10−3 m/s at 0.5 m/s air velocity and from 1.04 × 10−2 to 1.34 × 10−2 m/s at 1 m/s air velocity as the air temperature increased. Similarly, the convective heat transfer coefficients were approximately 8 W/m2·K at 0.5 m/s and 11.5 W/m2·K at 1 m/s. These trends in heat and mass transfer coefficients explain the observed increase in drying rates, as higher heat and mass transfer rates facilitate faster moisture removal from the sludge. Detailed calculations of the heat and mass transfer coefficients are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

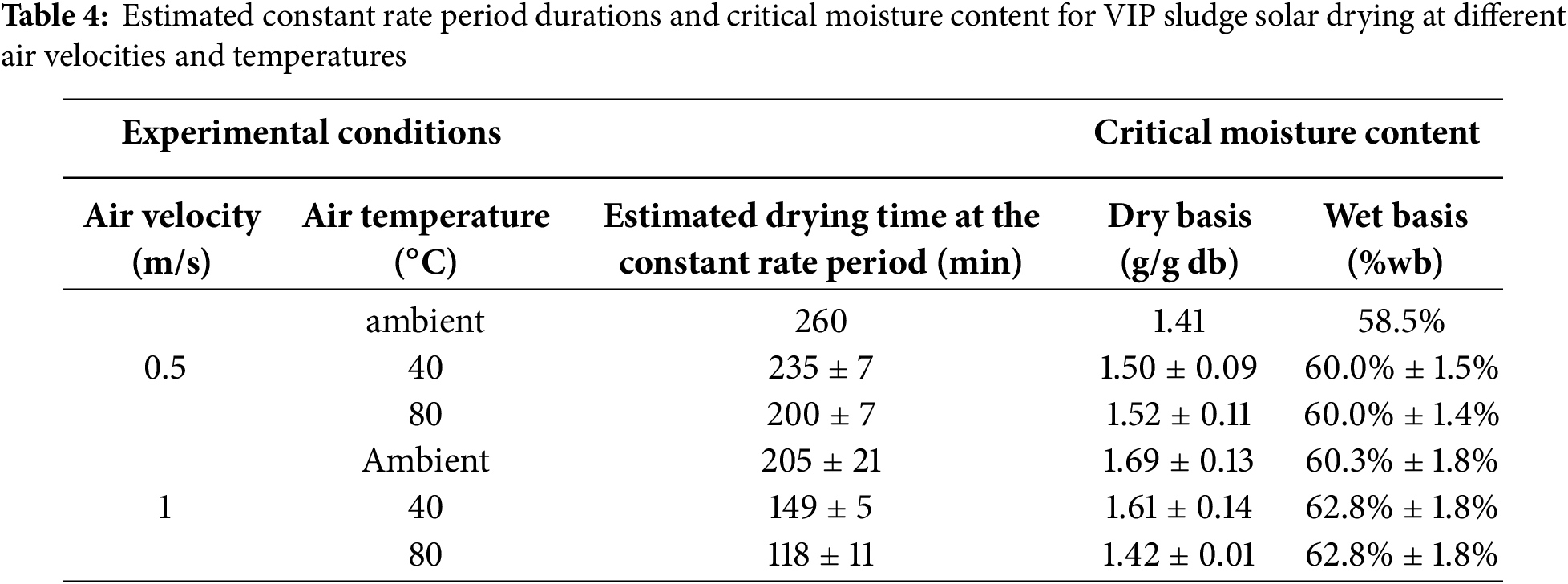

Table 4 presents the estimated duration of the constant rate period and the critical moisture content at different air velocities and temperatures. These parameters were identified at the point on the drying curve where the moisture content transitions from a linear to a nonlinear decrease.

Table 4 shows that the duration of the constant rate period decreased with increasing air temperature and velocity. This can be attributed to the higher moisture removal rates at elevated temperatures and airflow speeds, which accelerate the depletion of surface moisture, leading to a quicker transition to the falling rate period. The critical moisture content ranged between 1.4 and 1.7 g/g on a dry basis (58%–64% on a wet basis) but did not exhibit a consistent trend across different conditions. Variations in critical moisture content may be attributed to experimental uncertainties.

Compared to literature data, the drying rates observed in this study—ranging from 0.55 g/g db/min/m2 at ambient temperature to 1.2 g/g db/min/m2 at 80°C—were generally higher than those reported for the solar drying (direct or indirect) of thin layers of sewage or poultry abattoir sludge. Specifically, previous studies reported drying rates of 0.06 g/g db/min/m2 at 65°C [27,32], 0.09 g/g db/min/m2 at >55°C [31], 0.13 g/g db/min/m2 at 65°C [12], and significantly lower values of 0.009, 0.006, and 0.002 g/g db/min/m2 at 80°C, 60°C, and 40°C, respectively [29]. In contrast, the drying rates found by Ali et al. [30], which ranged from 1.8 to 0.7 g/g db/min/m2 between 90°C and 50°C, were within the same range as those obtained in this study.

Regarding critical moisture content, the values obtained in this work (approximately 1.5 g/g db) were lower than those reported for sewage and poultry abattoir sludge, which ranged between 2 and 3 g/g db [27,30–32]. In contrast, they were higher than the critical moisture content reported for olive oil extraction sludge [29]. Additionally, literature data indicate that no constant rate period was observed at temperatures above 80°C, which differs from the drying behavior observed in this study.

3.1.3 Effective Diffusivity and Activation Energy

The experimental drying rate curves in this study revealed both constant and falling rate periods in nearly all experiments. The falling rate period was analyzed using Fick’s second law to describe the drying behavior. This analysis was conducted for VIP sludge under solar drying conditions at air velocities of 0.5 and 1 m/s, across different air temperatures.

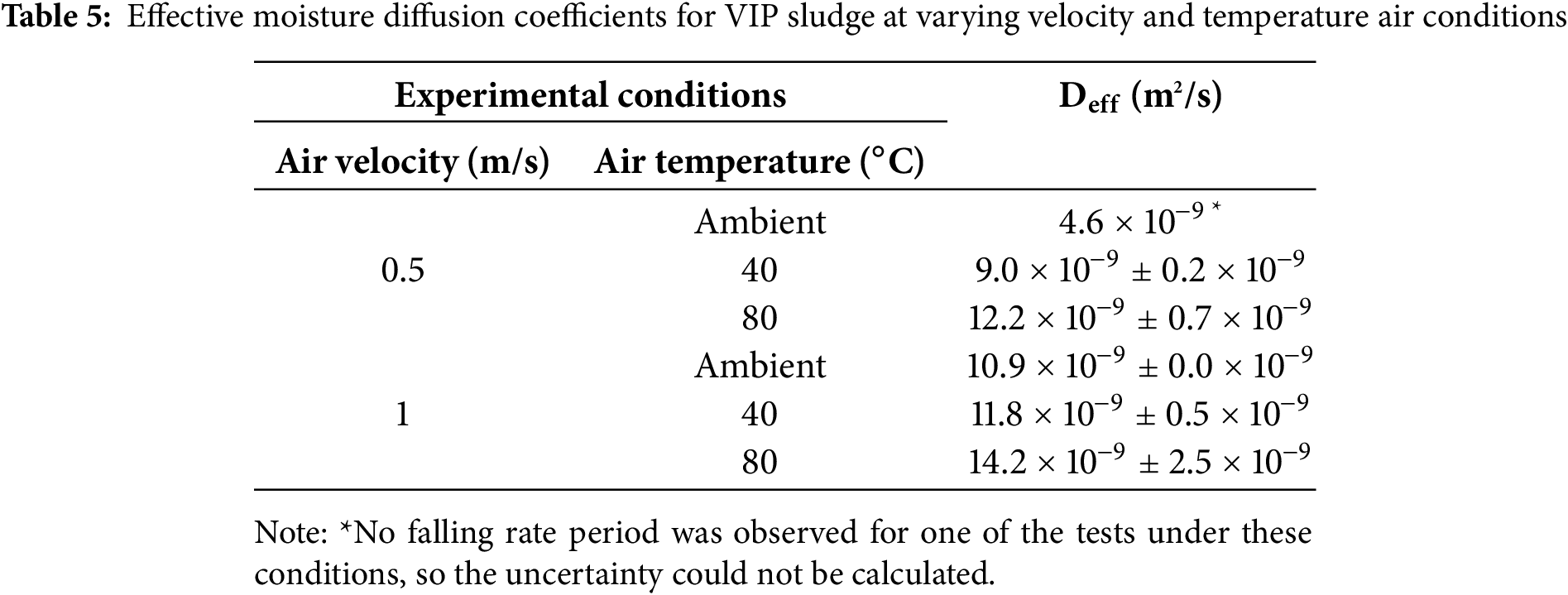

Table 5 presents the effective moisture diffusivity

As shown in Table 5, the effective moisture diffusivity

Table 5 also shows that increasing air velocity from 0.5 to 1 m/s led to a corresponding increase in

The

The effective diffusivity values obtained in this study are lower than those reported by Ameri et al. [32] and Masmoudi et al. [13] for sewage sludge, in the order of 10−8 m2/s. In contrast, they are higher than the values documented by Wang et al. [12] for sewage sludge, Parlak et al. [31] for poultry abattoir sludge, and Celma et al. [29] for olive oil extraction sludge, which are generally in the order of 10−10 or 10−11 m2/s. These findings suggest that faecal sludge has an intermediary moisture mobility than other sludge types during solar drying.

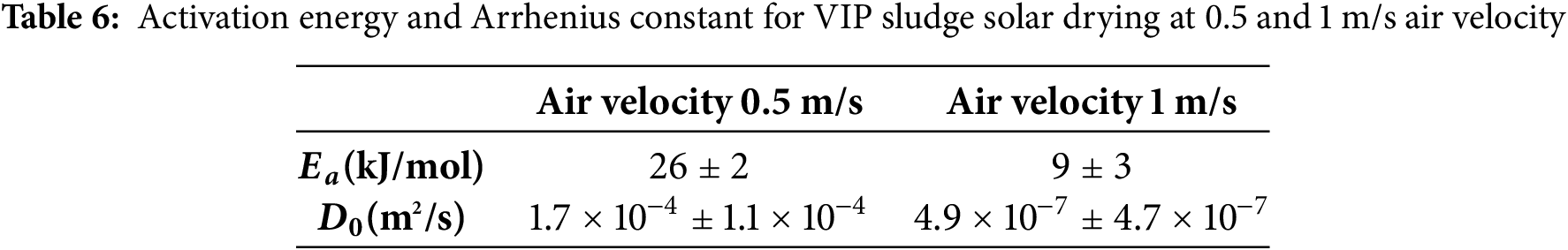

Table 6 presents the activation energy values for sludge under different air velocity conditions, averaged over duplicate experiments.

The results in Table 6 indicate that activation energy

The activation energy at 0.5 m/s falls within the range reported in the literature for faecal sludge thermal drying, which varies from 23 to 36 kJ/mol [33,34], and is comparable to the activation energy of approximately 32 kJ/mol reported for sewage sludge solar drying by Ameri et al. [32], while it is higher than the activation energy of 16 kJ/mol reported for the solar drying of olive oil extraction sludge [29]. The activation energy at 1 m/s air velocity is the lowest among all the cases mentioned, indicating that this experimental case exhibited the least temperature dependency.

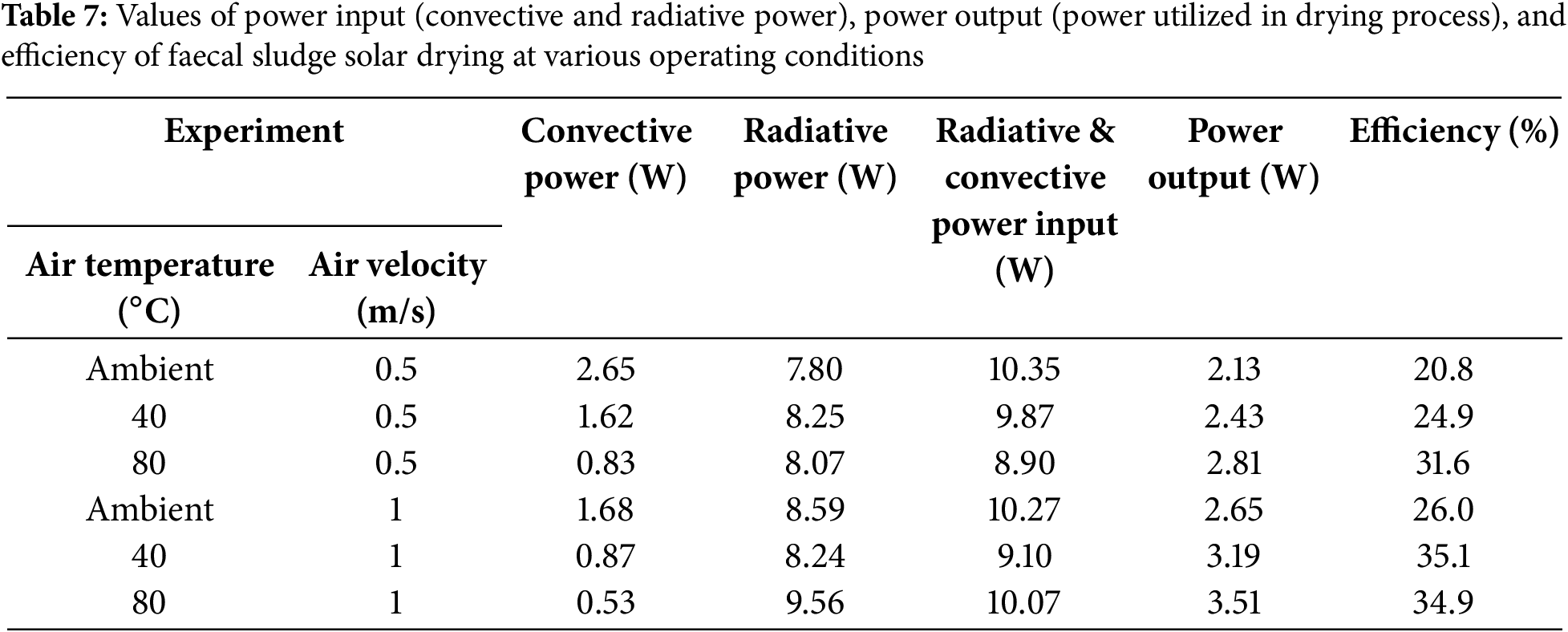

In this study, the performance of the drying system was evaluated based on power and thermal efficiency calculations. Power was determined by calculating the energy transferred to the sludge through heated airflow and solar radiation. This energy was categorized into radiative power

Experimental results indicated positive convective power values, confirming that the sludge temperature remained lower than the surrounding air temperature. This suggests that the sludge absorbed thermal energy from the surrounding air to facilitate moisture evaporation. Additionally, convective power decreased as air temperature increased, due to the reduction in the temperature difference between the sludge and the surrounding air.

The results in Table 6 indicate that solar radiation was the primary source of thermal energy for drying, contributing significantly more than convective heat input. The proportion of solar thermal energy to convective thermal energy ranged from 73% to 95%, confirming that solar energy was the dominant contributor to the drying process in the solar thermal drying system in this work.

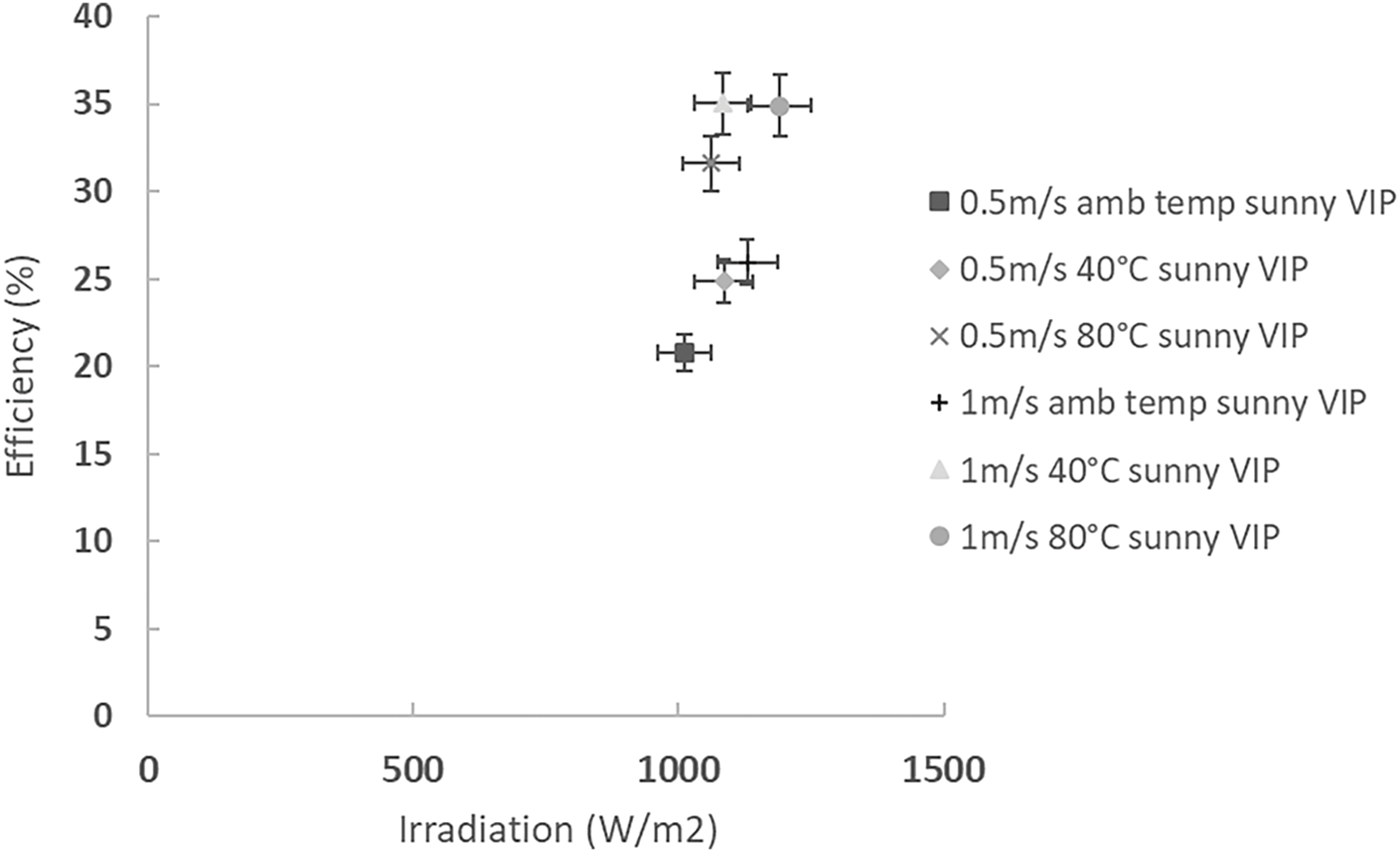

The drying system’s efficiency across all experiments ranged between 20.8% and 35.1%, aligning with reported values for solar thermal drying efficiency for sludge [11,12]. As shown in Fig. 6, no clear correlation was observed between efficiency and solar irradiance. This can be attributed to the fact that all experiments were conducted under similar sunny conditions, resulting in minimal variation in solar irradiance. However, a noticeable increase in thermal efficiency was observed with rising air temperature and air velocity, suggesting that these factors played a more significant role in enhancing drying performance.

Figure 6: Efficiency as a function of solar irradiance for solar drying of VIP sludge at varying conditions of air temperature and velocity

3.2 Effect of the Type of Faecal Sludge

To assess variations in drying behavior between different types of faecal sludge, additional experiments were conducted using UD sludge samples under the same operating conditions as those used for VIP sludge.

3.2.1 Drying Curves for UD and VIP Sludge

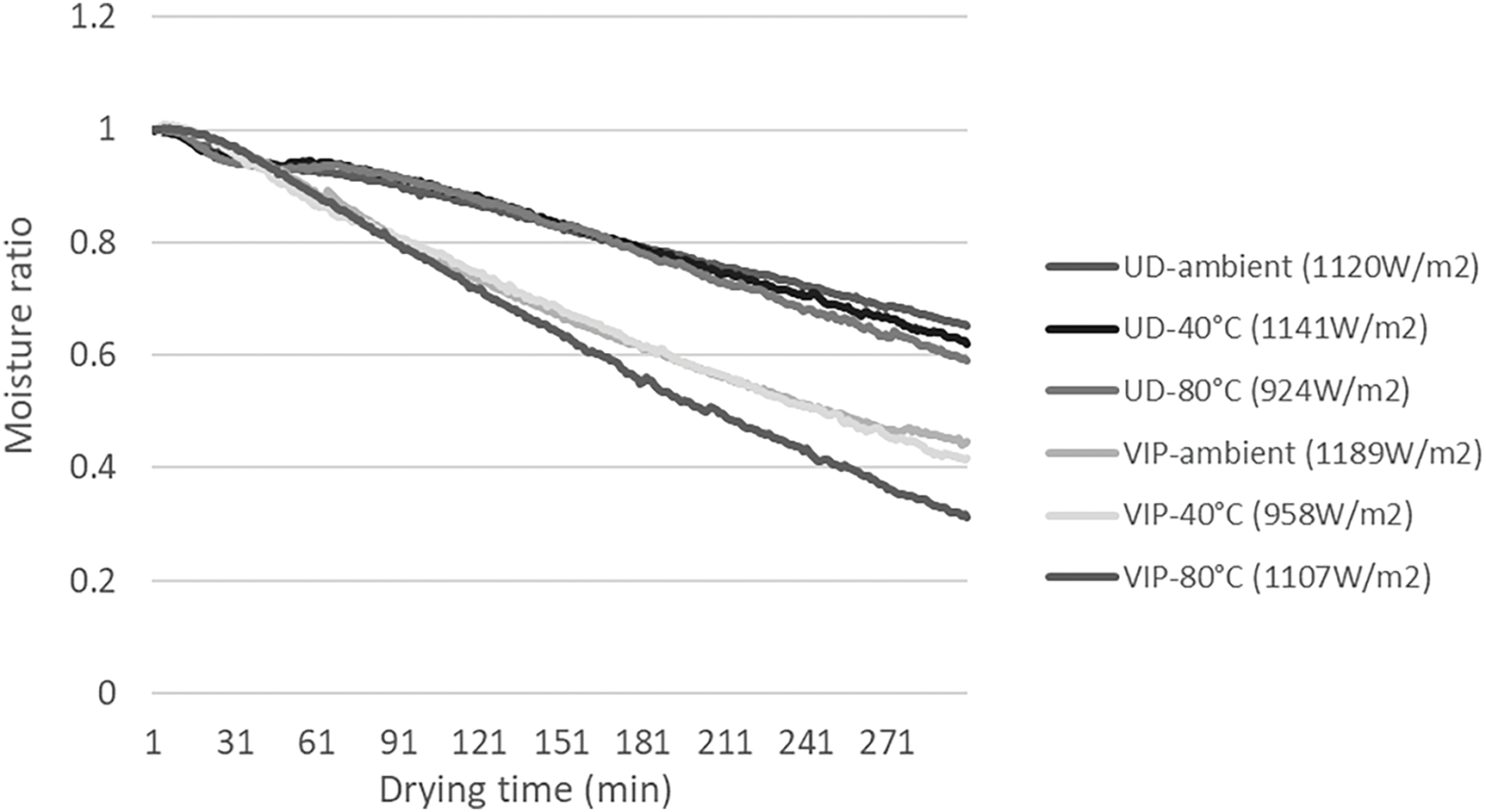

Fig. 7 presents the drying curves for UD and VIP sludge samples at a constant air velocity (0.5 m/s) and varying air temperatures (ambient, 40°C, and 80°C). Initially, both UD and VIP sludge exhibited similar moisture reduction rates. However, after approximately 30 min of drying, the moisture loss in UD sludge slowed significantly compared to VIP sludge.

Figure 7: Drying curves at 0.5 m/s air velocity for both UD and VIP sludge at ambient temperature, 40°C and 80°C

At the end of the 5-h drying period, the final moisture ratios recorded at ambient, 40°C, and 80°C were 0.65, 0.62, and 0.59 for UD sludge, corresponding to final moisture contents of 1.59, 1.50, and 1.44 g/g db, respectively. In contrast, VIP sludge exhibited lower final moisture ratios of 0.45, 0.42, and 0.31, corresponding to final moisture contents of 1.45, 1.23, and 0.97 g/g db, respectively.

The slower drying rate of UD sludge can probably be attributed to the formation of a denser and harder crust layer on its surface during the early stages of drying, whereas the crust formed on VIP sludge remained significantly softer. The relative hardness of the crust was estimated by measuring the force required by the experimenter to pierce the top surface with a pin at the end of the experiment. The harder crust in UD sludge may have acted as a barrier, trapping moisture inside and restricting mass transfer to the surrounding environment. Additionally, this dense crust layer could have increased resistance to heat penetration into the UD sludge core, further limiting moisture evaporation [35].

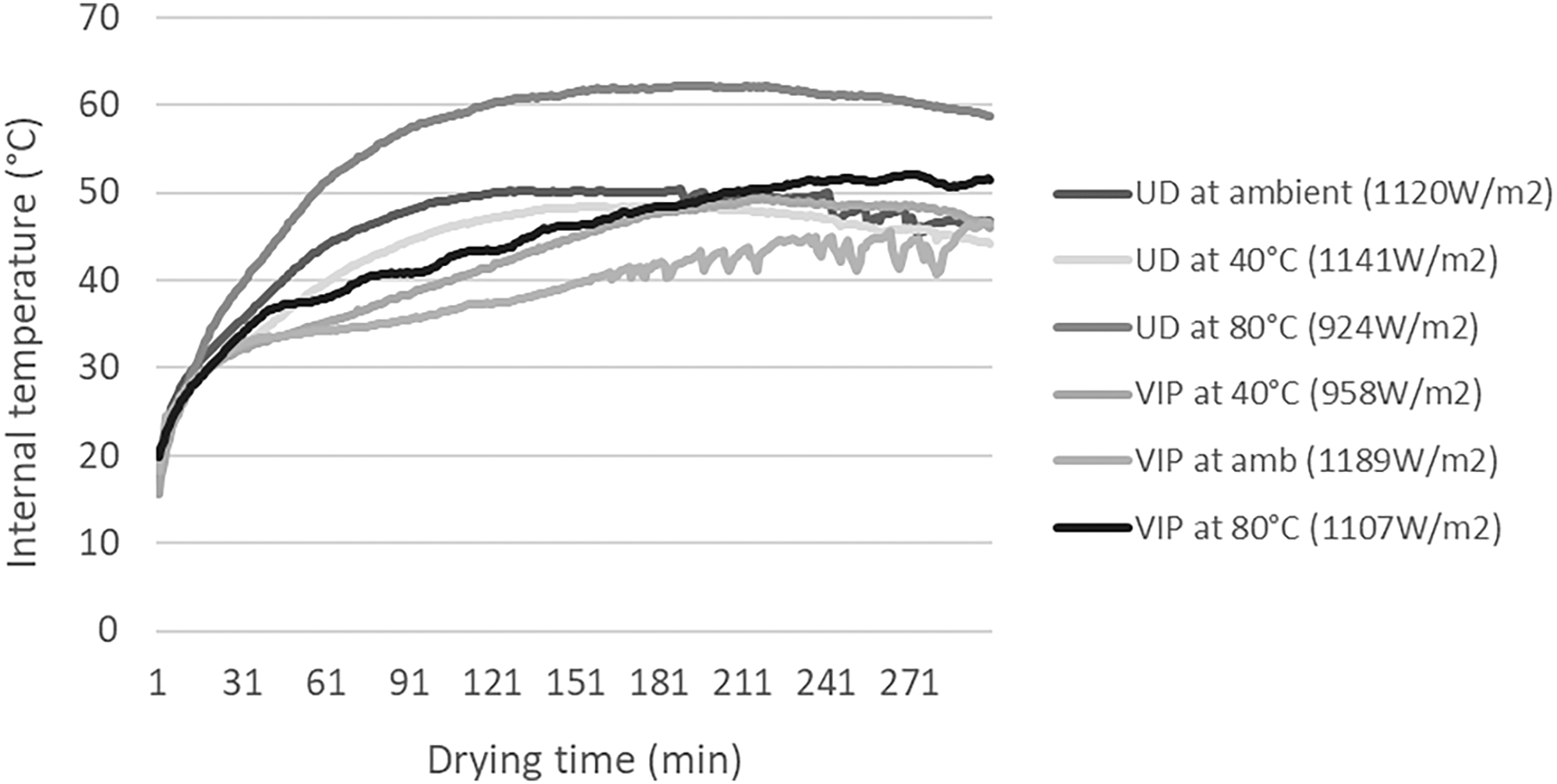

Fig. 8 illustrates the variation in internal temperature for VIP and UD sludge during drying. The results indicate that the internal temperature of UD sludge samples rose more rapidly and reached a higher value at the beginning of the drying process compared to VIP sludge. This suggests that UD samples attained the drying temperature (i.e., the wet-bulb temperature) more quickly than VIP sludge.

Figure 8: Internal temperature for UD and VIP sludge during drying at ambient temperature, 40°C, and 80°C, and at 0.5 m/s air velocity

The higher initial temperature observed in UD sludge may have contributed to the early formation of a crust, as reported in previous studies [36,37].

This study characterized the kinetics of faecal sludge solar thermal drying to provide a deeper understanding of the process. The findings from this research in terms of drying kinetics and energy efficiency can support the design, implementation, and upscaling of solar thermal technologies for faecal sludge treatment, a cost-effective and sustainable solution, particularly in regions with abundant solar resources such as South Africa.

The solar thermal drying of a thin layer of faecal sludge over 5 h resulted in a reduction of moisture content from 2.6–3.0 g/g db to 1.6–0.5 g/g db, depending on the operating conditions. This corresponded to moisture removal between 40% and 85%, with drying rates ranging from 0.55 to 1.2 g/g db/min/m2. Drying initially occurred in the constant rate period, followed by a transition to the falling rate period once the critical moisture content was reached, which varied between 1.41 and 1.78 g/g db without a distinct trend related to operating conditions. The effective diffusivity ranged from 6.6 × 10−9 to 14.2 × 10−9 m2/s, with activation energy values between 9 and 26 kJ/mol.

The results demonstrated that air temperature and velocity significantly influenced the drying kinetics. Higher air temperatures and velocities enhanced drying rates due to increased heat and mass transfer and greater effective diffusivity. Additionally, activation energy decreased with increasing air velocity, suggesting that higher airflow reduced the temperature dependency of the drying process. VIP sludge exhibited greater moisture reduction compared to UD sludge, likely due to the formation of a hard crust layer on UD sludge during the early stages of drying, which restricted moisture migration.

Solar radiation was the primary source of heat input in the drying system, contributing between 73% and 95% of the total energy input on sunny days. The overall thermal efficiency of the process ranged from 14.6% to 35.1%, with a noticeable increase in efficiency as air temperature and velocity increased.

This study highlights the importance of proper ventilation in solar thermal faecal sludge drying systems. Higher air velocities and preheating of the incoming airstream can improve drying kinetics, shorten drying times, and enhance overall efficiency. Additionally, the drying behavior of faecal sludge can vary depending on its origin, with surface crust formation potentially hindering moisture migration from the sludge core to the environment. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms and impact of crust formation during the drying process, as well as an environmental analysis to assess the sustainability of the process.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely acknowledge to the eThekwini Municipality for facilitating sample collection and to the technical and administrative staff of the WASH R&D Centre for their invaluable assistance in ensuring the smooth execution of this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Water Research Commission through the grant K5/2582 and the Gates Foundation through the grant OPP1170678.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Martin Nyanzi Mawejje, Jon Pocock, Santiago Septien; Data collection: Martin Nyanzi Mawejje; Analysis and interpretation of results: Martin Nyanzi Mawejje, Jon Pocock, Santiago Septien; Draft manuscript preparation: Martin Nyanzi Mawejje, Jon Pocock, Santiago Septien. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Santiago Septien (septiens@ukzn.ac.za), upon request. An important part of the data is also available at the “Addendum of data related to drying of faecal sludge from on-site sanitation facilities and fresh faeces” (link: https://gatesopenresearch.org/documents/4-188, accessed on 30 May 2025).

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee from the University of KwaZulu-Natal under ethical clearance BREC/00000203/2019.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| FSM | Faecal sludge management |

| FSTP | Faecal sludge treatment plant |

| TVS | Total volatile solids |

| UD | Urine-diverting |

| VIP | Ventilated improved pit |

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ee.2025.063898/s1.

References

1. Diener S, Semiyaga S, Niwagaba CB, Muspratt AM, Gning JB, Mbéguéré M, et al. A value proposition: resource recovery from faecal sludge—can it be the driver for improved sanitation? Resour Conserv Recycl. 2014;88(12):32–8. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Léonard A, Blacher S, Marchot P, Pirard JP, Crine M. Measurement of shrinkage and cracks associated to convective drying of soft materials by X-ray microtomography. Dry Technol. 2004;22(7):1695–708. doi:10.1081/drt-200025629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen G, Lock Yue P, Mujumdar AS. Sludge dewatering and drying. Dry Technol. 2002;20(4–5):883–916. doi:10.1081/drt-120003768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Shanahan EF, Roiko A, Tindale NW, Thomas MP, Walpole R, Kurtböke DI. Evaluation of pathogen removal in a solar sludge drying facility using microbial indicators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(2):565–82. doi:10.3390/ijerph7020565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Simo-Tagne M, Tagne Tagne A, Ndukwu MC, Bennamoun L, Obounou Akong MB, El Marouani M, et al. Numerical study of the drying of cassava root chips using an indirect solar dryer in natural convection. AgriEngineering. 2021;3(1):138–57. doi:10.3390/agriengineering3010009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Suraparaju SK, Elangovan E, Muthuvairavan G, Samykano M, Elumalai PV, Natarajan SK, et al. Assessing thermal and economic performance of solar dryers in sustainable strategies for bottle gourd and tomato preservation. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27755. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-78147-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Meyer-Schärenberg U, Pöppke M. Large-scale solar sludge drying in Managua/Nicaragua. Wasser Und Abfall. 2010;12(3):26. [Google Scholar]

8. Kurt M, Aksoy A, Sanin FD. Evaluation of solar sludge drying alternatives by costs and area requirements. Water Res. 2015;82(1):47–57. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.04.043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sorrenti A, Corsino SF, Traina F, Viviani G, Torregrossa M. Enhanced sewage sludge drying with a modified solar greenhouse. Clean Technol. 2022;4(2):407–19. doi:10.3390/cleantechnol4020026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Khanlari A, Tuncer AD, Sözen A, Şirin C, Gungor A. Energetic, environmental and economic analysis of drying municipal sewage sludge with a modified sustainable solar drying system. Sol Energy. 2020;208(1):787–99. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2020.08.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Poblete R, Painemal O. Improvement of the solar drying process of sludge using thermal storage. J Environ Manage. 2020;255:109883. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang P, Mohammed D, Zhou P, Lou Z, Qian P, Zhou Q. Roof solar drying processes for sewage sludge within sandwich-like chamber bed. Renew Energy. 2019;136:1071–81. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.09.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Masmoudi A, Ben Sik Ali A, Dhaouadi H, Mhiri H. Comparison between two solar drying techniques of sewage sludge: draining solar drying and drying bed. Waste Biomass Valori. 2021;12(7):4089–102. doi:10.1007/s12649-020-01293-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. An-nori A, El Fels L, Ezzariai A, El Gharous M, El Mejahed K, Hafidi M. Effects of solar drying on heavy metals availability and phytotoxicity in municipal sewage sludge under semi-arid climate. Environ Technol Innov. 2020;19(7):101039. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2020.101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. An-Nori A, El Fels L, Ezzariai A, El Hayani B, El Mejahed K, El Gharous M, et al. Effectiveness of helminth egg reduction by solar drying and liming of sewage sludge. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(11):14080–91. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-11619-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. An-nori A, Ezzariai A, El Mejahed K, El Fels L, El Gharous M, Hafidi M. Solar drying as an eco-friendly technology for sewage sludge stabilization: assessment of micropollutant behavior, pathogen removal, and agronomic value. Front Environ Sci. 2022;10:814590. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.814590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gomes LACN, Gonçalves RF, Martins MF, Sogari CN. Assessing the suitability of solar dryers applied to wastewater plants: a review. J Environ Manage. 2023;326(Pt A):116640. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Muspratt AM, Nakato T, Niwagaba C, Dione H, Kang J, Stupin L, et al. Fuel potential of faecal sludge: calorific value results from Uganda, Ghana and Senegal. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev. 2014;4(2):223–30. doi:10.2166/washdev.2013.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Seck A, Gold M, Niang S, Mbéguéré M, Diop C, Strande L. Faecal sludge drying beds: increasing drying rates for fuel resource recovery in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev. 2015;5(1):72–80. doi:10.2166/washdev.2014.213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Velkushanova K, Strande L, Ronteltap M, Koottatep T, Brdjanovic D, Buckley C. Methods for faecal sludge analysis. London, UK: IWA Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

21. Strande L, Schoebitz L, Bischoff F, Ddiba D, Okello F, Englund M, et al. Methods to reliably estimate faecal sludge quantities and qualities for the design of treatment technologies and management solutions. J Environ Manage. 2018;223:898–907. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Brouckaert CJ, Foxon KM, Wood K. Modelling the filling rate of pit latrines. Water SA. 2013;39(4):555–62. doi:10.4314/wsa.v39i4.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rose C, Parker A, Jefferson B, Cartmell E. The characterization of feces and urine: a review of the literature to inform advanced treatment technology. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2015;45(17):1827–79. doi:10.1080/10643389.2014.1000761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Septien S, Mugauri TR, Singh A, Inambao F. Drying of faecal sludge using solar thermal energy. Lynnwood Manor, Pretoria: Water Research Commission; 2017. Report No.: 2582/1/18. [Google Scholar]

25. Koukouch A, Idlimam A, Asbik M, Sarh B, Izrar B, Bostyn S, et al. Experimental determination of the effective moisture diffusivity and activation energy during convective solar drying of olive pomace waste. Renew Energy. 2017;101(6):565–74. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mghazli S, Ouhammou M, Hidar N, Lahnine L, Idlimam A, Mahrouz M. Drying characteristics and kinetics solar drying of Moroccan rosemary leaves. Renew Energy. 2017;108(9–10):303–10. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2017.02.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ameri B, Hanini S, Benhamou A, Chibane D. Comparative approach to the performance of direct and indirect solar drying of sludge from sewage plants, experimental and theoretical evaluation. Sol Energy. 2018;159(2):722–32. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2017.11.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Aral S, Beşe AV. Convective drying of hawthorn fruit (Crataegus spp.effect of experimental parameters on drying kinetics, color, shrinkage, and rehydration capacity. Food Chem. 2016;210(1):577–84. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.04.128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Celma AR, Rojas S, López F, Montero I, Miranda T. Thin-layer drying behaviour of sludge of olive oil extraction. J Food Eng. 2007;80(4):1261–71. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.09.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ali I, Abdelkader L, El Houssayne B, Mohamed K, El Khadir L. Solar convective drying in thin layers and modeling of municipal waste at three temperatures. Appl Therm Eng. 2016;108(12):41–7. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.07.098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Parlak N, Ozdemir S, Yetilmezsoy K, Bahramian M. Mathematical modeling of thin-layer solar drying of poultry abattoir sludge. Int J Environ Res. 2021;15(1):177–90. doi:10.1007/s41742-020-00308-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ameri B, Hanini S, Boumahdi M. Influence of drying methods on the thermodynamic parameters, effective moisture diffusion and drying rate of wastewater sewage sludge. Renew Energy. 2020;147(4):1107–19. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.09.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Somorin T, Getahun S, Septien S, Mabbet I, Kolios A, Buckley C. Isothermal drying characteristics and kinetics of human faecal sludges. Gates Open Res. 2021;4:67. doi:10.12688/gatesopenres.13137.2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Pocock J, Septien S, Makununika BN, Velkushanova KV, Buckley CA. Convective drying kinetics of faecal sludge from VIP latrines. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):e09221. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sharma A, Chen CR, Vu Lan N. Solar-energy drying systems: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2009;13(6–7):1185–210. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2008.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lu T, Shen S, Liu X. Numerical and experimental investigation of heat and mass transfer in unsaturated porous media with low convective drying intensity. Heat Transf. 2008;37(5):290–312. doi:10.1002/htj.20205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Siebert T, Zuber M, Engelhardt S, Baumbach T, Karbstein HP, Gaukel V. Visualization of crust formation during hot-air-drying via micro-CT. Dry Technol. 2019;37(15):1881–90. doi:10.1080/07373937.2018.1539746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools