Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

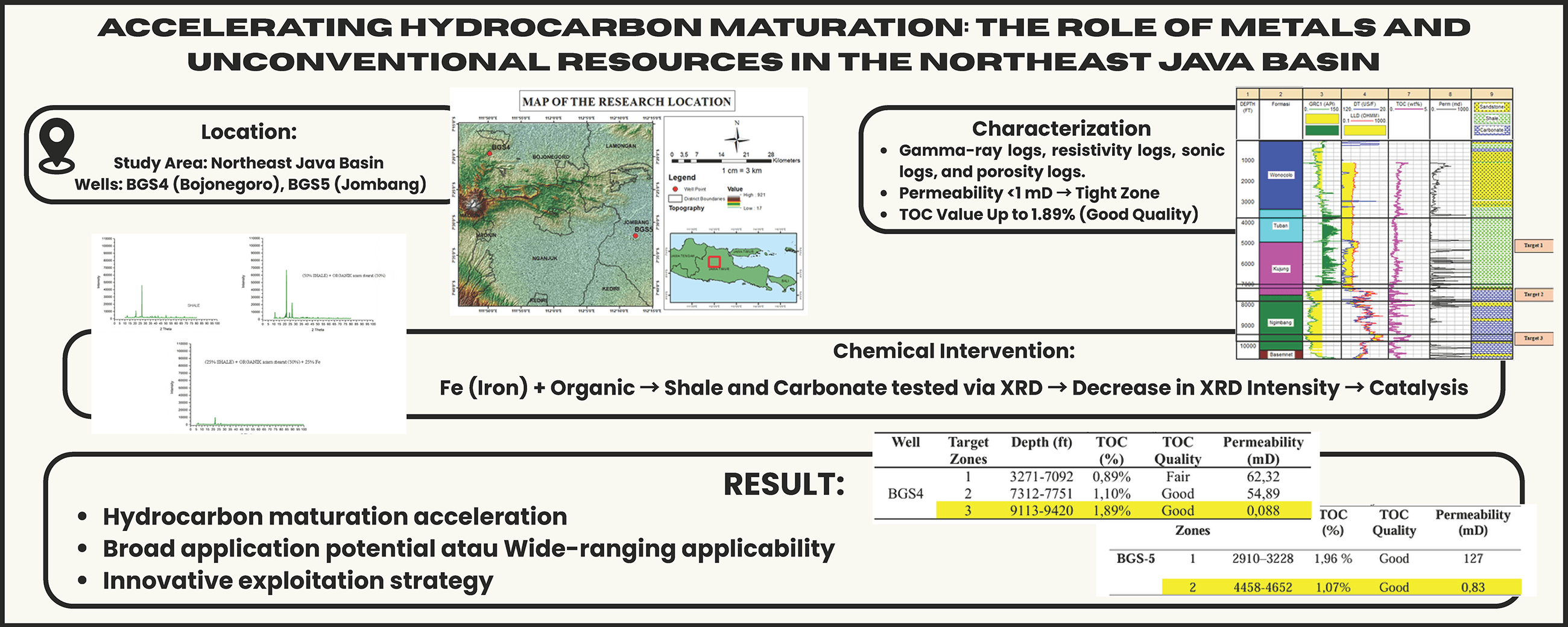

Accelerating Hydrocarbon Maturation: The Role of Metals and Unconventional Resources in the Northeast Java Basin

1 Department of Geophysical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Lampung, Bandar Lampung, 35145, Indonesia

2 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Lampung, Bandar Lampung, 35145, Indonesia

3 Center for Geological Survey, Geological Agency, Bandung, 40122, Indonesia

4 Energy Conversion and Conservation Laboratory, Department of Chemical Engineering, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, 40154, Indonesia

* Corresponding Authors: Bagus Sapto Mulyatno. Email: ; Indra Mamad Gandidi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrated Geology-Engineering Simulation and Optimizationfor Unconventional Oil and Gas Reservoirs)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(8), 3099-3116. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.064336

Received 12 February 2025; Accepted 14 May 2025; Issue published 24 July 2025

Abstract

Rising global energy needs have intensified the search for unconventional hydrocarbon sources, especially in under-selected areas like the Northeast Java Basin. This region harbors promising unconventional hydrocarbon reserves, where source rocks function as dual-phase systems for both hydrocarbon generation and storage. This research investigates how metal-based catalysts, particularly iron (Fe), can expedite hydrocarbon maturation in such reservoirs. Combining well logging, geochemical assessments, seismic data, and advanced lab techniques, including X-ray Diffraction (XRD), we pinpoint optimal zones for exploration. Results indicate that the Tuban, Kujung, and Ngimbang formations contain economically viable unconventional deposits, exhibiting tight reservoir properties (permeability: 0.01–1 md) and moderate to good Total Organic Carbon (TOC) levels (1%–2%). Spatial analysis reveals elevated density concentrations in the northern sector, indicative of high-viscosity hydrocarbons typical of unconventional plays. Crucially, Fe additives were found to markedly enhance organic matter conversion, shortening maturation periods and boosting hydrocarbon yield. XRD data confirms that Fe alters crystalline configurations, increasing reactivity and speeding up thermal breakdown (shifting immature organic compounds toward maturity at an accelerated rate). These findings contribute to the evolving discourse on unconventional resource exploitation by proposing an innovative recovery enhancement strategy. The study also sets a precedent for investigating metal-assisted hydrocarbon conversion in geologically comparable basins globally.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The increasing global energy demand has necessitated exploring unconventional hydrocarbon resources as a viable alternative to conventional reserves. In the Northeast Java Basin, these resources remain underexplored, particularly regarding the acceleration of hydrocarbon maturation processes. This study examines the catalytic role of metals in enhancing maturation rates, offering innovative insights into optimizing hydrocarbon recovery from unconventional sources in the region.

Research on unconventional hydrocarbons has been conducted by several scholars [1–5]. According to Abdelfattah et al., the identification of unconventional hydrocarbons is characterized by impermeable zones, low effective porosity, and lithology predominantly composed of shale, with permeability values below 1 millidarcy (md) [6]. Shale rich in organic minerals will be anisotropic due to its laminated structure and chemical properties [7]. Ahmed & Meehan, further elaborate that while shale typically serves as a source rock in conventional hydrocarbon systems, it acts as both the source and reservoir rock in unconventional hydrocarbon systems [8]. The conceptual framework distinguishing conventional and unconventional hydrocarbon systems is derived from the research of Zendehboudi & Bahadori [9].

Katz et al. define unconventional hydrocarbons as those primarily produced from shale or carbonate formations with extremely low permeability. These hydrocarbons accumulate in poor-quality reservoirs, typically within formations exhibiting effective porosity below 10% [10]. Kingsley, Umeji and Klokov et al. investigated formation evaluation techniques to assess unconventional hydrocarbon prospects, while other researchers have focused on characterizing shale and carbonate formations in unconventional settings [11–15]. Organic-rich shales have made a significant contribution to gas production in the US [16]. In Indonesia, one of the most promising unconventional hydrocarbon resources is located in the Northeast Java Basin, which contains an estimated 42 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of shale gas [17,18]. The East Java Basin, recognized as one of Indonesia’s most productive basins, has been a site of hydrocarbon production since the late 19th century. The region’s complex geological structure, influenced by stratigraphic variations and structural dynamics, further supports its hydrocarbon potential [19]. Among the 128 basins in Indonesia, the Northeast Java Basin holds substantial hydrocarbon reserves, with an estimated 53.7 million stock tank barrels (MMSTB) of oil and condensate, alongside 480.1 billion standard cubic feet (BSCF) of gas reserves [20]. Previous studies by Fadlilah and Sekarsari, have identified unconventional reservoirs within the X field of the Northeast Java Basin, based on permeability, mobility, and transmissibility assessments. Their findings indicate that the Tuban, Kujung, and Ngimbang formations—targeted as unconventional hydrocarbon zones—exhibit significantly low permeability, mobility, and transmissibility values [21,22].

Unconventional hydrocarbons often display immature to early mature stages of thermal maturity, necessitating interventions to accelerate the maturation process within source rocks. Experimental research conducted by Dewanto et al., demonstrated that the addition of iron (Fe) as a catalytic metal enhances the rate of organic matter transformation reactions. This experiment utilized Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to examine particle size variations within clay, carbonate, clay-carbonate, carbonate-organic, and shale materials treated with Fe metal [23]. The SEM-Edax analysis provided insights into the morphological characteristics and elemental composition of these materials [24]. Recent studies in nanocatalysis have revealed that metal oxide-supported multielement nanoparticles exhibit outstanding catalytic performance, combining high efficiency with cost-effectiveness while allowing for nearly limitless compositional variations [25]. Among these, the CuAgNiFeCoRuMn@MgO-P3000 catalyst displayed exceptional efficacy in selectively hydrogenating nitro compounds, highlighting its potential for industrial applications. These findings confirm that transition metals, including iron (Fe), serve as highly effective catalytic agents in facilitating diverse chemical reactions.

This study aims to determine the target zones for unconventional hydrocarbon exploration in wells within the Northeast Java Basin, providing critical information on hydrocarbon source potential. The research integrates well-log data, geochemical analysis, and seismic data to characterize unconventional hydrocarbon-bearing formations. Additionally, SEM and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analyses were conducted with the incorporation of organic compounds, specifically salicylic acid (Asl) and iron (Fe) metal, to evaluate their impact on accelerating organic matter transformation and hydrocarbon maturation. The significance of this study lies in addressing the urgent need for unconventional hydrocarbon production to meet domestic energy demands. The findings will contribute to the identification of viable and non-viable unconventional reservoir zones based on permeability assessments. Furthermore, this research will provide valuable insights into the quality and prospectivity of unconventional hydrocarbon zones by evaluating permeability distribution and density variations. The results of metal additive analysis on source rocks will also inform strategies for enhancing hydrocarbon maturation processes, thereby improving unconventional hydrocarbon recovery potential.

2.1 Regional Geology and Physiography of the Northeast Java Basin

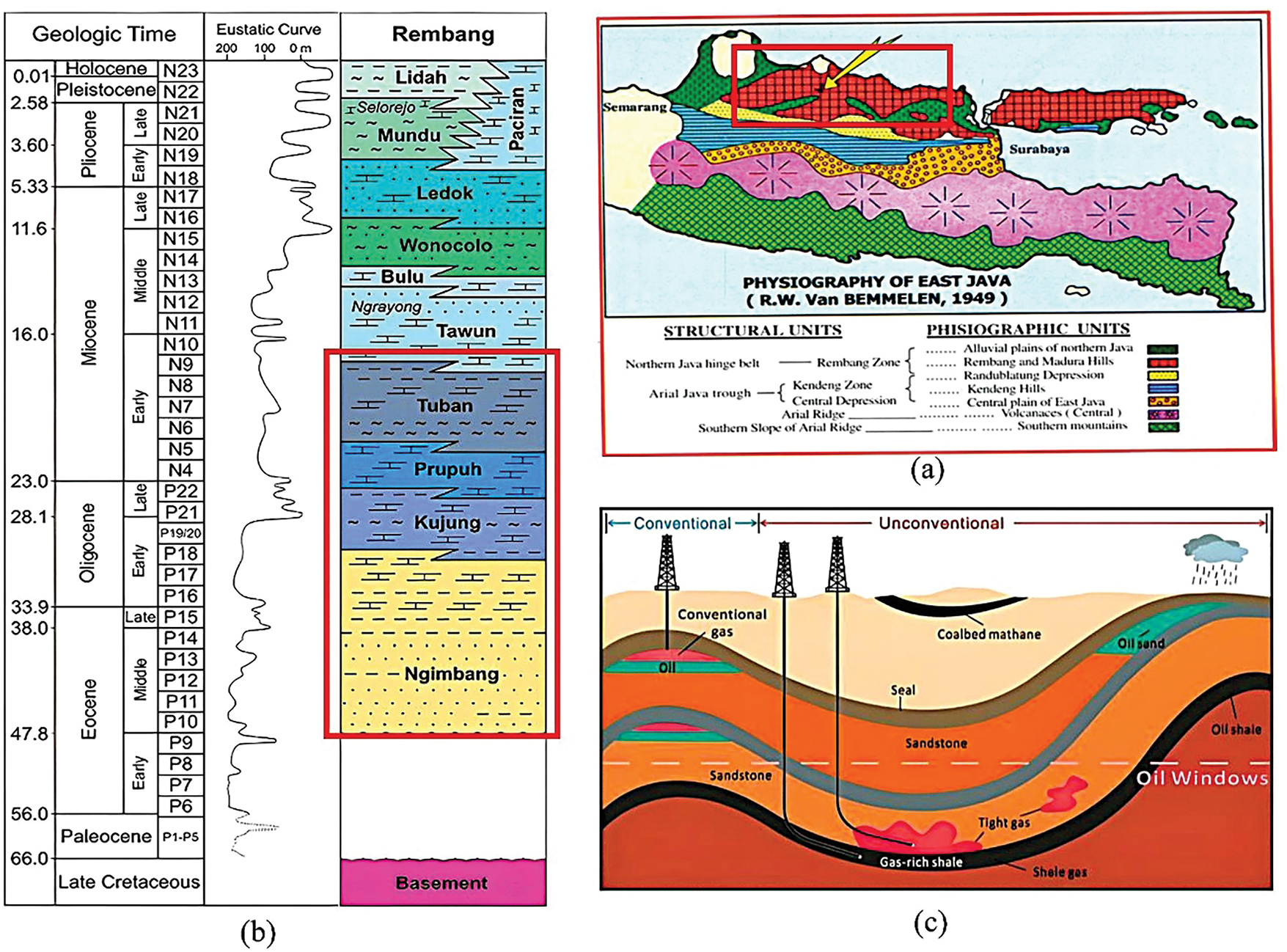

The formation of the East Java Basin is attributed to complex geological processes involving uplift, variations in sea level subsidence, and tectonic plate movements. Structurally, the basin is characterized by a series of normal faults, reverse faults, strike-slip faults, and fold systems oriented predominantly in the west-east direction. These structural features are largely influenced by compressional forces exerted from the north-south axis. The most recent tectonic configuration of this region is primarily driven by the interaction between the Australian and Sunda Plates. Over time, regional structural variations have evolved in response to continuous geodynamic changes [26].

The Northeast Java Basin, a prominent Tertiary Basin in western Indonesia, is a product of the complex interplay of three major tectonic plates. This basin has been a significant source of hydrocarbon reserves, particularly oil and natural gas. However, the evolution and structural development of the Northeast Java Basin remains a subject of ongoing scientific debate [27].

Physiographically, the Northeast Java Basin is subdivided into three primary zones: the Kendeng Zone, the Randublatung Zone, and the Rembang Zone [28]. The study area in this research is situated within the Rembang Zone, a distinct physiographic unit characterized by a series of anticlinorial hills extending in an east-west orientation along the northern part of Java Island. This zone stretches from the northern Purwodadi region to Madura Island, with structural folds displaying an elongated axis in the east-west direction. These folds vary in length, ranging from a few kilometers up to approximately 100 km, as exemplified by the Dokoro Anticline north of Grobogan [29]. A detailed representation of the physiographic configuration of the study area within the Northeast Java Basin is illustrated in Fig. 1a.

Figure 1: (a) Physiographic cross-section of the Northeast Java Basin Basin [29]; (b) Stratigraphy of the Northeast Java Basin [33]; (c) Conventional and unconventional petroleum systems [9]

2.2 Stratigraphy of the Northeast Java Basin

The stratigraphic framework of the Northeast Java Basin is characterized by pre-Tertiary bedrock formations, comprising igneous rocks, ophiolites, metasedimentary sequences, and metamorphic assemblages. These lithological units are structurally segmented by northeast-southwest trending elevations [30]. Regionally, the study area is situated within the Rembang Zone, an integral part of the East Java sedimentary basin [29]. Based on the lithostratigraphic classification proposed by Pringgoprawiro, the stratigraphic succession in the Rembang Zone progresses from the oldest to the youngest as follows: the Ngimbang Formation, the Kujung Formation, the Prupuh Formation, the Tuban Formation, the Ledok Formation, the Mundu Formation, the Paciran Formation, and the Tongue Formation [28]. The Ngimbang Formation, which represents the oldest stratigraphic unit in this succession, rests upon the basin’s basement and is estimated to have been deposited from the Eocene to the Late Miocene [31,32]. A detailed lithostratigraphic depiction of the Rembang Zone, as outlined by Husein [33], is presented in Fig. 1b.

2.3 Unconventional Hydrocarbon Petroleum System of the Northeast Java Basin

The Northeast Java Basin is recognized as the most structurally and stratigraphically complex back-arc basin in Indonesia, making it a highly prospective region for petroleum systems [34]. Unconventional hydrocarbons, as described by Zhang et al., typically accumulate in reservoirs of exceptionally poor quality due to their occurrence within shale formations or adjacent low-permeability lithologies [35].

These reservoirs are characterized by non-interconnected pore networks, resulting in extremely low permeability. The primary source rock of unconventional hydrocarbons consists predominantly of shale interlaminated with tight siltstone or sandstone, leading to the classification of these deposits as hydrocarbon shale formations [36]. In such systems, shale functions not only as the source rock but also as a natural seal due to its impermeable nature. When all five essential elements of a conventional petroleum system—source, reservoir, seal, trap, and migration—coexist within the same stratigraphic unit, the accumulation can be categorized as an unconventional hydrocarbon resource. A schematic representation of the unconventional petroleum system is illustrated in Fig. 1c.

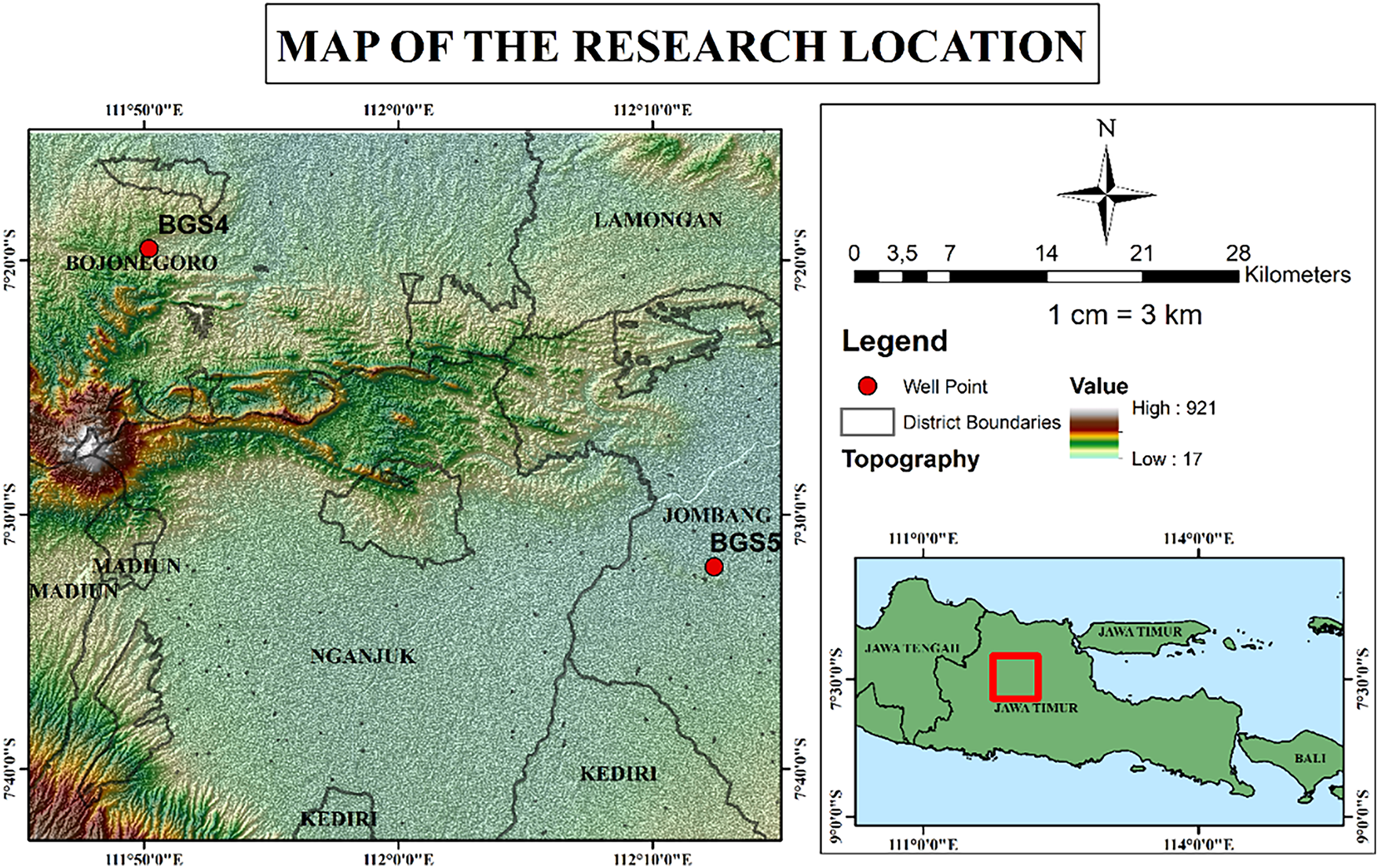

The location of the research area is in East Java Province, including the BGS4 well in Bojonegoro Regency and the BGS5 well in Jombang Regency. The two research wells are included in the North East Java Basin, geographically located at 007°19′33.014″ S and 111°50′11.609″ E. The map of the research area’s location is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Map of the location of the research area

This research was conducted at the Laboratory of Geophysical Engineering, University of Lampung, employing a multi-disciplinary approach to assess the unconventional hydrocarbon potential of the Northeast Java Basin. A comprehensive dataset, encompassing well logs, geochemical analyses, seismic data, checkshot surveys, and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) measurements, formed the foundation of this study. Advanced software tools, including Interactive Petrophysics, Schlumberger Petrel, Hampson Russell Suite, and specialized XRD software, were utilized for data processing, integration, and interpretation. The geochemical analysis focused on vitrinite reflectance (Ro) and total organic carbon (TOC) from core samples, providing critical insights into the basin’s source rock maturity and hydrocarbon potential.

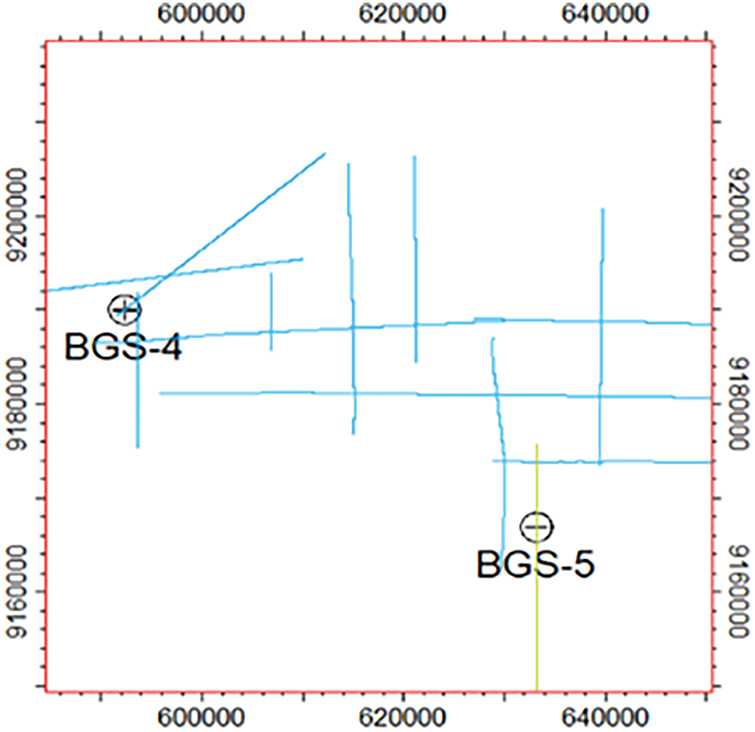

Checkshot data played a pivotal role in establishing the depth-time relationship essential for seismic interpretation. Of the seven wells analyzed, checkshot data were available for two (BGS4 and BGS5), facilitating the accurate conversion of depth-based measurements to time-domain seismic data. This correlation enhances the reliability of seismic interpretation and well-log integration, ultimately improving the accuracy of subsurface characterization.

The geological marker data provide crucial information about the depths of rock layers or formations present within the research area. These marker data are instrumental in identifying and correlating different rock units. In this context, lithological markers were defined by the top shale (Tsh) and bottom shale (Bsh) of each formation under research. The Tsh and Bsh of the BGS4 Well in Tuban Formation are located at 3201–4422 ft, Kujung Formation at 4860–6567 ft, and Ngimbang Formation at 7809–9300 ft. Meanwhile, the Tsh and Bsh of BGS5 Well are located in the Tuban Formation at 3819–4497 ft. In addition, the seismic data used in this study is 2D seismic data in *.segy format, comprising 13 seismic line profiles. Two seismic line profiles intersect with the wells in the research area (BGS4 and BGS5) that are being utilized, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Seismic line cross-section and well location in the research area

3.2 Determination of Unconventional Hydrocarbon Target Zones

In this study, the determination of the target zone is primarily based on the quality of the source rock. A qualitative approach to identifying the target zone of source rock involves analyzing the response of various log curves. The types of well logs utilized in this research include gamma-ray logs, resistivity logs, sonic logs, and porosity logs. Beyond qualitative assessment, the identification of unconventional hydrocarbon target zones also requires a quantitative approach, which involves evaluating key physical parameters of the rock—one of the most crucial being permeability. Permeability refers to the ability of a rock to transmit fluids, including hydrocarbons. These parameters serve as validation criteria to ensure that the selected target zone is not only suitable as a source rock but also viable as an unconventional hydrocarbon reservoir.

The permeability values in this study are calculated using the Timur method, which employs a constant coefficient with parameters a = 0.136, b = 4.4, and c = 2 [37]. Unconventional hydrocarbons are characterized by extremely low permeability values. In addition to serving as a key criterion for reservoir identification, permeability also plays a role in fluid type estimation. According to the findings of Abdelfattah et al., gaseous hydrocarbons typically exhibit permeability values below 0.1 md, whereas liquid hydrocarbons, such as oil, generally have permeability values below 1 md [6]. Furthermore, based on the qualitative classification proposed by Koesoemadinata, rocks with permeability values below 10.5 md are considered tight, those within the 11–15 md range are classified as poor, 15–50 md as fair, 50–250 md as good, 250–1000 md as very good, and values exceeding 1000 md are categorized as excellent [38].

This study also employs the Passey method (ΔlogR) to identify potential zones with high organic content, as indicated by the Total Organic Carbon (TOC) value. The TOC value serves as an essential indicator of the quantity of organic matter within a rock, which is a critical factor for unconventional hydrocarbon accumulation. The presence of a high TOC value directly influences hydrocarbon generation and production potential within a target zone. Based on the classification by Peters & Cassa, TOC values can be categorized as follows: <0.5% (poor quality), 0.5%–1% (fair quality), 1%–2% (good quality), 2%–4% (very good quality), and >4% (excellent quality) [39]. These classifications provide a fundamental reference for evaluating the organic richness of potential source rocks in unconventional hydrocarbon exploration.

3.3 The Addition of Metals to Accelerate Reaction Rates

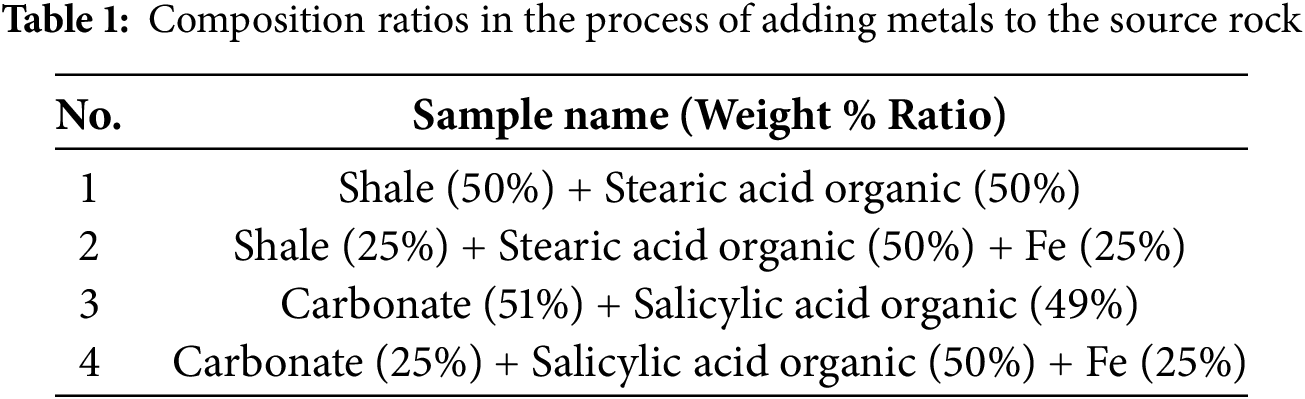

The natural clay (kaolinite/illite) and natural carbonate (calcite CaCO3), both materials possessing characteristics as organic containers according to the research objective, were obtained from coring at specific depths in area X. Organic materials including a cyclic compound group in the form of salicylic acid (C7H6O2), an aliphatic organic compound in the form of stearic acid (C17H35COOH), and iron (Fe) metal, were added as an additive to modify shale material. The addition of metals to the source rock was performed with a specific compositional ratio, as indicated in Table 1.

The catalytic enhancement of rock samples through metal integration starts with selecting appropriate materials, including shale or carbonate cores, organic components (salicylic acid), and a transition metal catalyst (iron). The rock samples, acquired via controlled drilling and coring procedures, undergo thorough purification to eliminate any residual fluid contaminants. Three sample categories are then systematically prepared: (i) pristine rock matrices, (ii) hybrid rock-organic blends (shale/salicylic acid and carbonate/salicylic acid), and (iii) ternary systems combining rock, organic matter, and iron (shale/salicylic acid/Fe and carbonate/salicylic acid/Fe), with concentrations adjusted per Table 1. Advanced material characterization techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), are employed to analyze crystallographic properties, phase composition, and structural features. Additionally, the synergistic effects between mineral substrates and organic additives are evaluated by measuring activation energies and spectral intensities across the sample series.

4.1 Analysis of Unconventional Hydrocarbon Parameters Based on Permeability Value and Calculation of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Value in BGS4 Well

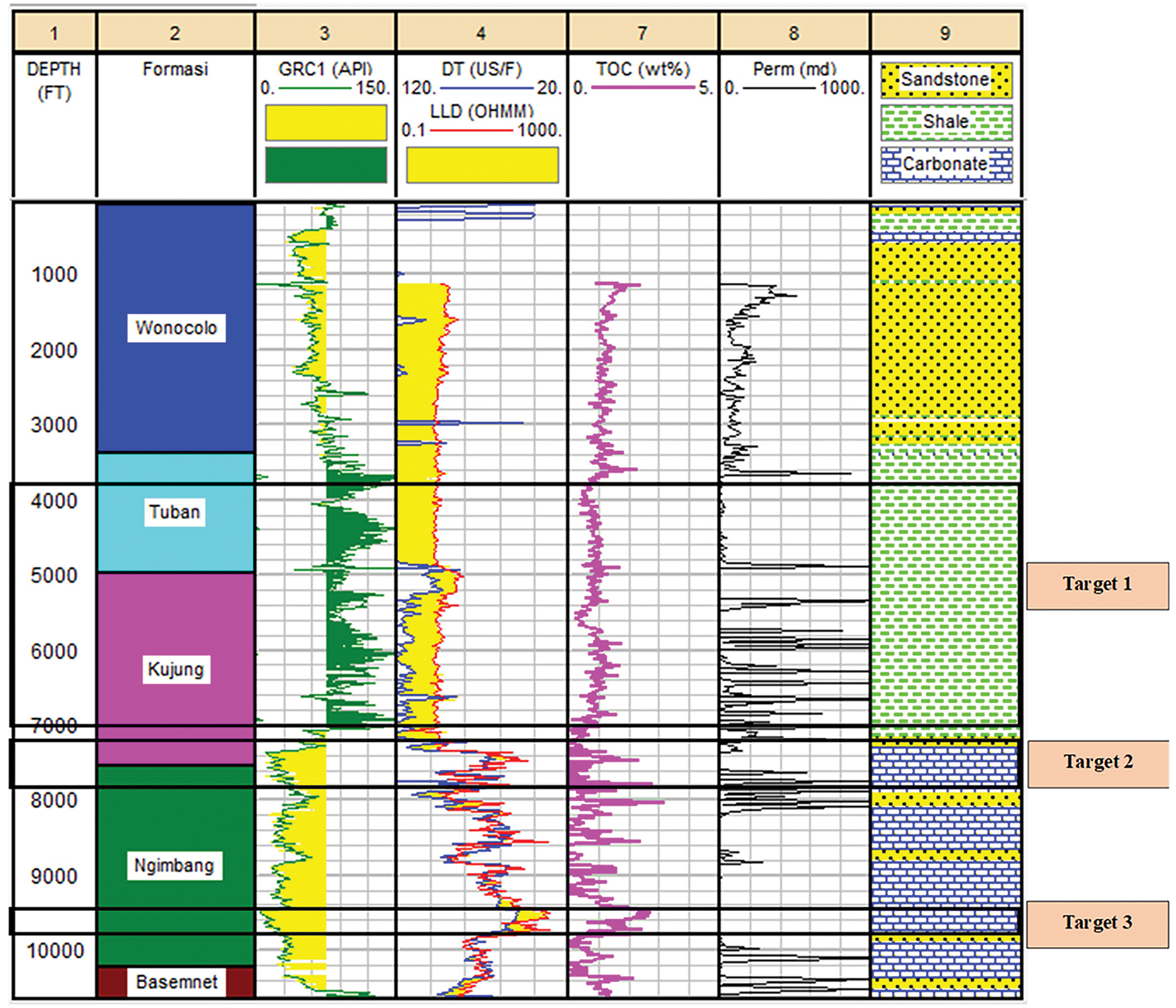

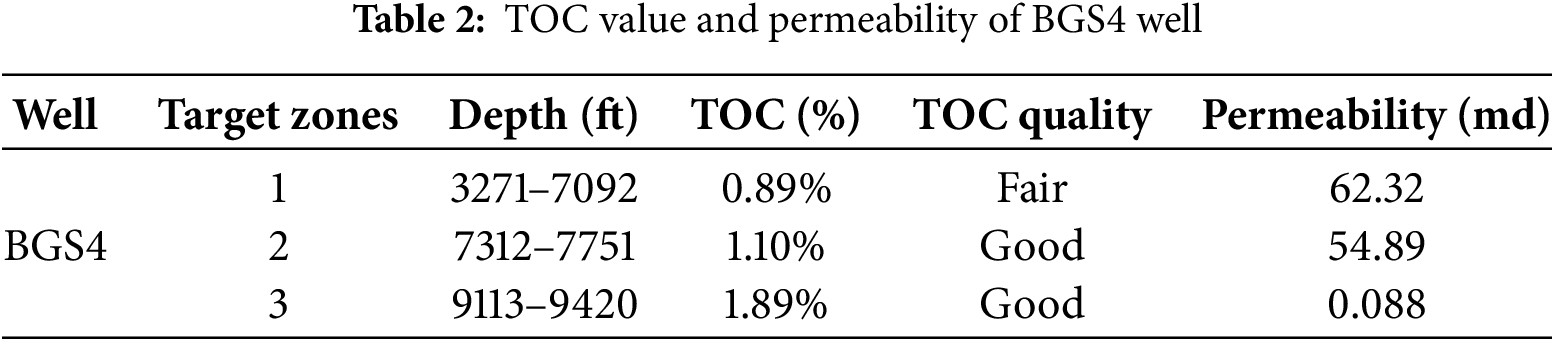

The BGS-4 well extends to a depth of 60–1070 ft, penetrating several key stratigraphic units of the Northeast Java Basin, including the Wonocolo Formation, Tuban Formation, Kujung Formation, Ngimbang Formation, and the Basement. Comprehensive analysis has identified multiple target zones for source rock layers and unconventional hydrocarbon reservoirs. These zones are characterized by distinct geophysical log responses, where high gamma-ray values indicate shale lithology, while low gamma-ray values correspond to carbonate rock lithology. Additionally, the presence of a crossover between the deep resistivity log (LLD) and sonic log (DT) further supports the identification of potential hydrocarbon-bearing formations. Three primary source rock target zones have been delineated within the BGS-4 well, as illustrated in Fig. 4 and detailed in Table 2.

Figure 4: Identification of the source rock layer of the BGS4 well

Among the three identified target zones, Zone 3 emerges as the most promising source rock interval. This conclusion is supported by its carbonate rock lithology, which exhibits a significant organic content. The total organic carbon (TOC) analysis reveals that Zone 3 has the highest TOC concentration, exceeding 1%, which aligns with the criteria established by Tissot & Welte. Their study suggests that hydrocarbon generation is feasible when TOC values exceed 0.5% for shale or non-carbonate lithologies and 0.3% for carbonate rocks [40]. Furthermore, permeability calculations indicate that Zone 3 has a permeability of <0.1 md, classifying it as a tight reservoir with the potential to contain hydrocarbon gas. These characteristics suggest that Zone 3 holds strong potential as an unconventional hydrocarbon reservoir.

Conversely, Target Zones 1 and 2 exhibit higher permeability values (>1 md), indicative of good reservoir quality but predominantly containing water-bearing fluids. The absence of significant hydrocarbon accumulations in these zones diminishes their prospectivity as unconventional hydrocarbon reservoirs. Thus, while Zones 1 and 2 may not be viable for unconventional hydrocarbon extraction, Zone 3 presents a compelling target for further exploration and potential resource development.

Target Zone 3 in the BGS4 well is located at a depth of 9113–9420 feet and is characterized by carbonate lithology. This interpretation aligns with the gamma-ray log response in the zone, which exhibits a leftward deflection or low values, indicative of carbonate rock or limestone. Such characteristics are attributed to the naturally low radioactive element content in carbonate formations. This observation is further supported by the stratigraphy of the study area, where Target Zone 3 lies within the Ngimbang Formation, known for its limestone lithology, particularly in its upper layers. Additionally, Target Zone 3 exhibits a distinct crossover or separation between the resistivity log (LLD) and sonic log (DT), both showing significantly high values. A strong sonic log response suggests the presence of a compact and dense carbonate rock layer with well-interlocked constituent materials, resulting in low permeability and porosity. Meanwhile, high resistivity values indicate the potential presence of hydrocarbon fluids.

Quantitative analysis of permeability in Target Zone 3 revealed a permeability value of 0.088 md. According to Koesoemadinata’s research, this value classifies the rock as tight, implying that fluid flow within the formation is highly restricted. Furthermore, research by Abdelfattah et al., categorizes Target Zone 3 as an unconventional hydrocarbon reservoir, containing gaseous hydrocarbons, as indicated by its extremely low permeability values (typically <0.1 md). Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analysis was also conducted to evaluate the organic richness of the source rock in Target Zone 3. The results indicate an average TOC value of 1.89%. Based on the TOC quality classification by Peters & Cassa, this value suggests that Target Zone 3 in the BGS4 well has good TOC quality, making it a promising candidate for hydrocarbon generation within the petroleum system.

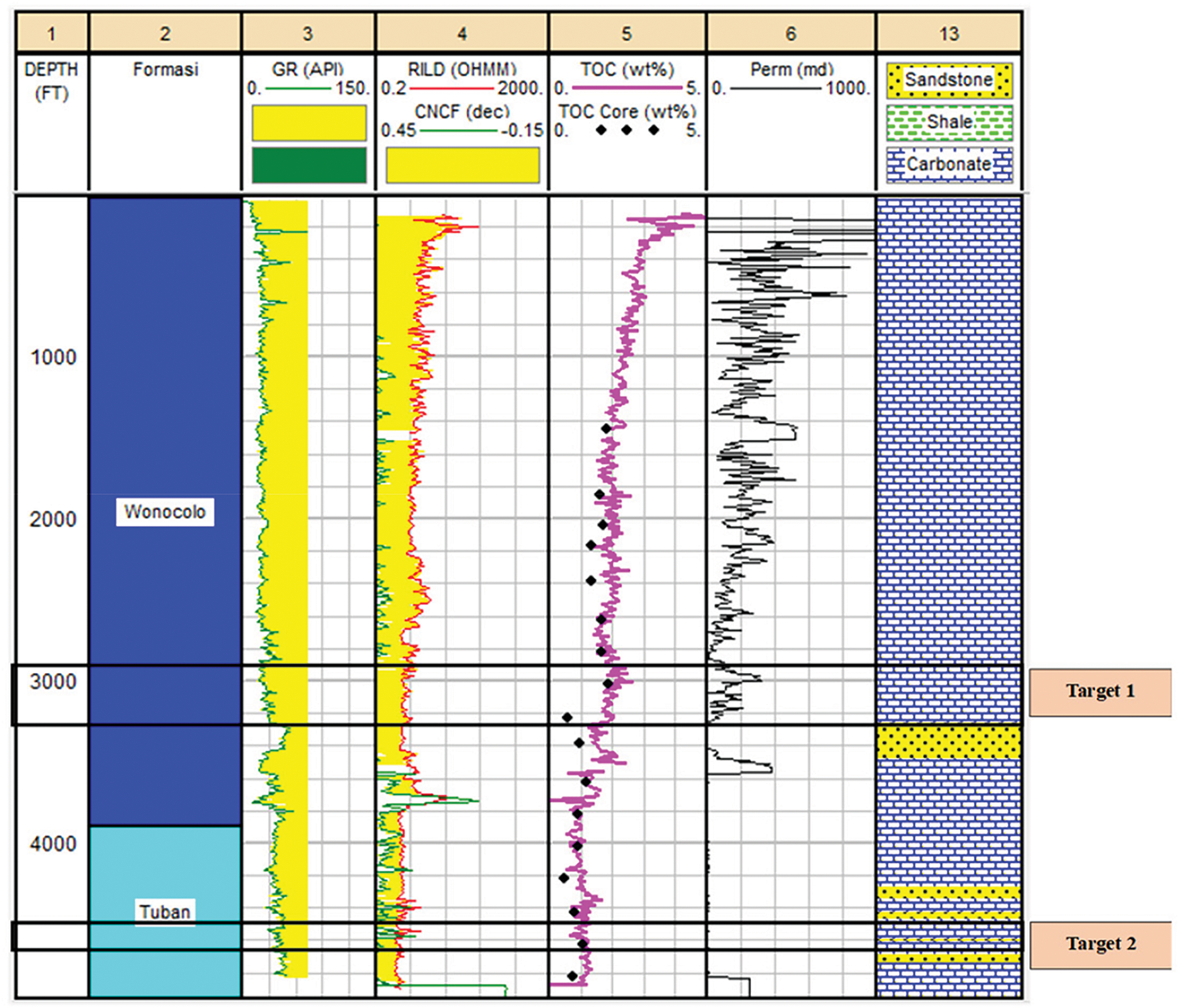

4.2 Analysis of Unconventional Hydrocarbon Parameters Based on Permeability Value and Calculation of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Value in BGS5 Well

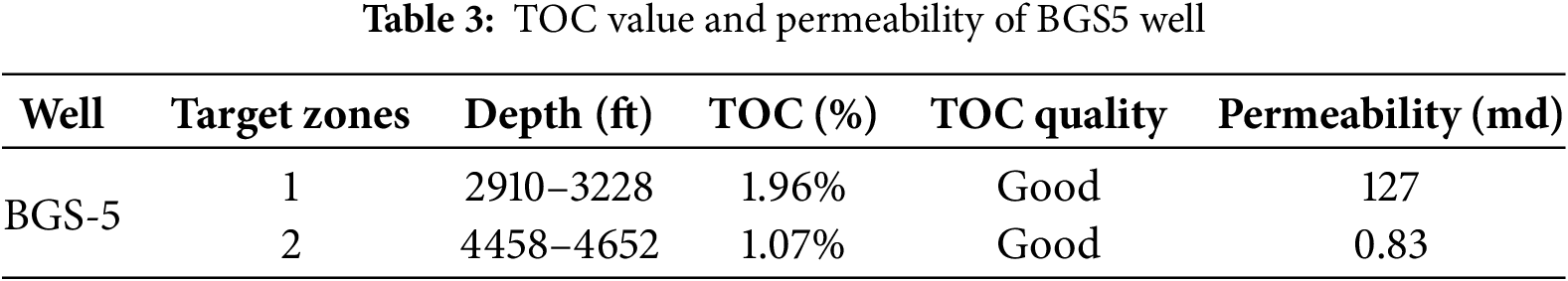

The BGS5 well has a depth of 20–4960 ft. According to the stratigraphy of the North East Java Basin, it comprises the Wonocolo Formation and the Tuban Formation. Based on the analysis that has been carried out, there are several target areas of the source rock layer that can be identified with layers that have a high gamma ray value response as shale lithology or a low gamma ray value response as carbonate lithology and there is a crossover between log resistivity (RILD) and neutron log (CNCF). In the BGS5 well, there are 2 target zones of the source rock layer which can be seen in Fig. 5 and Table 3 below. Based on the analysis of the two target zones in the BGS5 Well, it can be known that Target Zone 2 is a good source rock target zone because it has a carbonate rock lithology that is rich in organic elements, with a value of more than 1% which has good quality and in accordance with research conducted by Tissot & Welte, stating that the TOC content that is sufficient to produce hydrocarbons is around 0.5% for shale or non-carbonate materials and 0.3% for carbonate rocks [40]. Additionally, the results of the permeability value calculation in target zone 2 have a permeability value of <1 md with tight quality and have an oil fluid type hydrocarbon fluid. Based on this, Target Zone 2 has the prospect of being an unconventional hydrocarbon target zone. Meanwhile, Target Zone 1 has a permeability value of >1 md with good quality and has a water-type fluid, so it is not a prospect as an unconventional hydrocarbon target zone.

Figure 5: Identification of the source rock layer of the BGS4 well

Target zone 2 in the BGS5 well has a depth of 4458–4652 ft with a lithology of carbonate rocks. This is in accordance with the response of the gamma ray log in Target Zone 2, which shows a curve deflection to the left or a small value that can be identified as a lithology of carbonate rocks or limestone because carbonate rocks have a low content of radioactive elements. This is also in accordance with the stratigraphy of the study area where the Target Zone 2 is located in the Tuban Formation where the formation has limestone lithology. In addition, in Target Zone 2 there is a crossover or separation between the resistivity log (RILD) and the neutron log (CNCF) of equal magnitude. A large neutron log response can be identified as a compact (hard) carbonate rock because denser (compact) rocks will have more interactions between neutrons and atoms in the rock, which can also increase the probability of neutron throttling and produce a large response. A high resistivity log response is identified by the presence of hydrocarbon fluids.

Quantitatively, in the Target Zone 2, the permeability value was calculated and a permeability value of 0.83 md was obtained. According to Koesoemadinata’s research, it can be seen that the permeability value in the Target Zone 2 is included in the strict quality or can be interpreted as difficult to drain the fluid. According to the research of Abdelfattah et al., it can be seen that Target Zone 2 is an unconventional hydrocarbon target zone that has a type of fluid, namely oil fluid because of the permeability value which generally has a value of <1 md. In Target Zone 2, the TOC value is also calculated which is used to determine the level of organic mineral wealth contained in the source rock. Based on the calculation results, it can be seen that Target Zone 2 has an average TOC value of 1.07%. According to the quality classification of TOC values by Paters & Cassa, the BGS5 well in Target Zone 2 has good TOC quality.

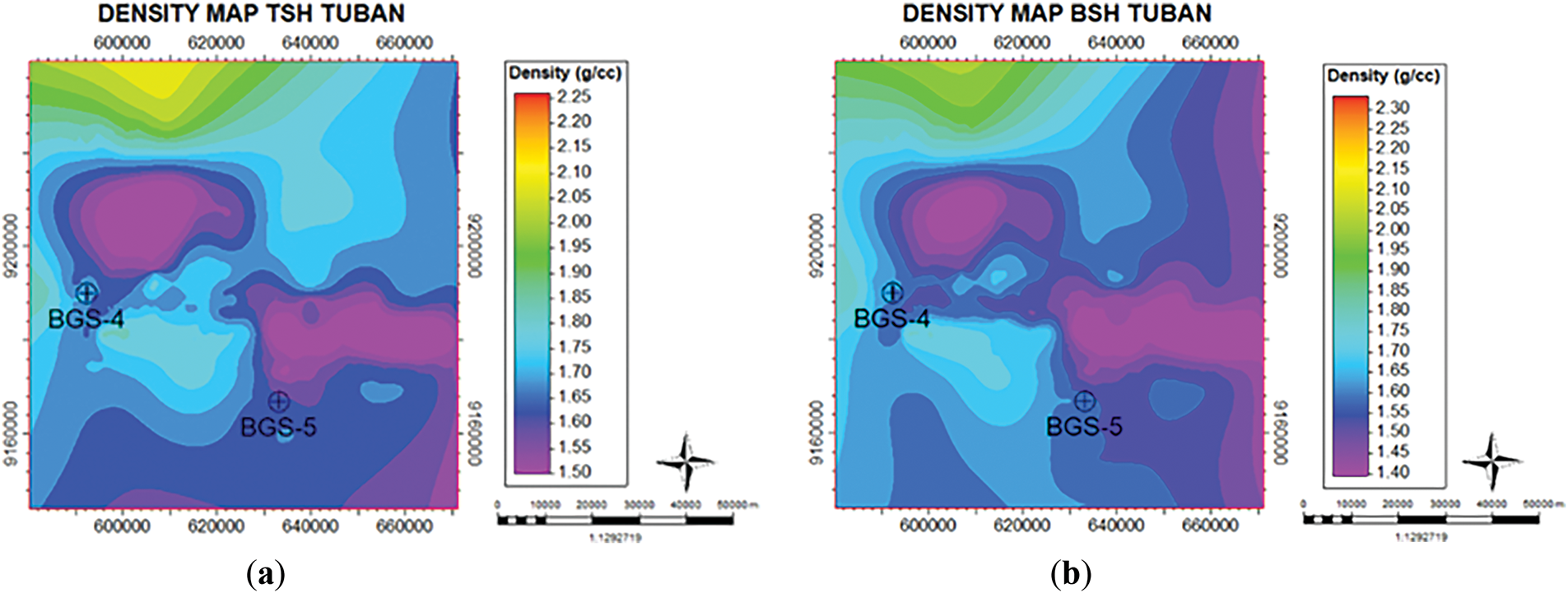

4.3 Distribution of Density Values

Based on Fig. 6a, which illustrates the density distribution on the top shale (TSh) horizon of the Tuban Formation, a clear trend can be observed: regions with higher density values (>2.25 g/cc) predominantly extend towards the northern direction, as indicated by color gradients ranging from yellow to red. Conversely, areas with lower density values (<2.25 g/cc) are oriented towards the southern region, represented by shades of blue to purple. Similarly, Fig. 6b, depicting the density distribution on the bottom shale (BSh) horizon of the Tuban Formation, reveals a comparable pattern, with higher density values (>2.20 g/cc) concentrated in the northern direction and lower density values (<2.20 g/cc) extending towards the south.

Figure 6: (a) Distribution of density values in top shale (TSh) Tuban; (b) Distribution of density values in bottom shale (BSh) Tuban

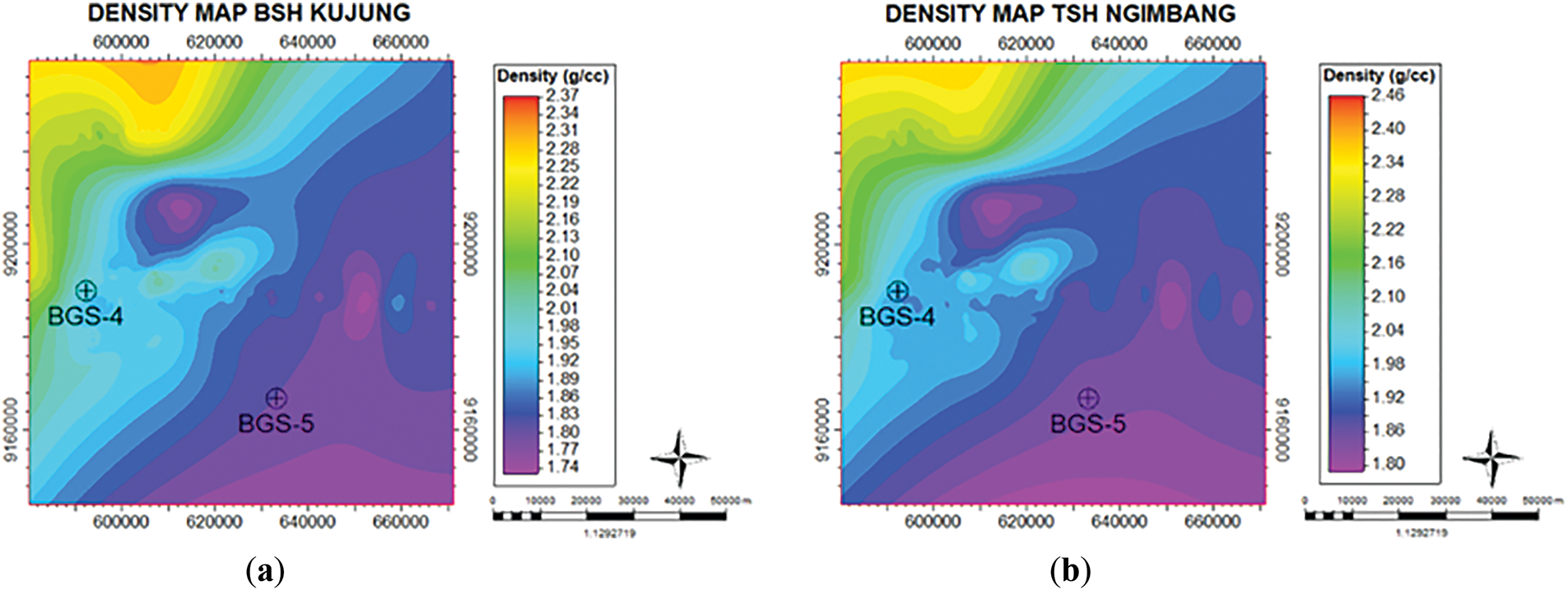

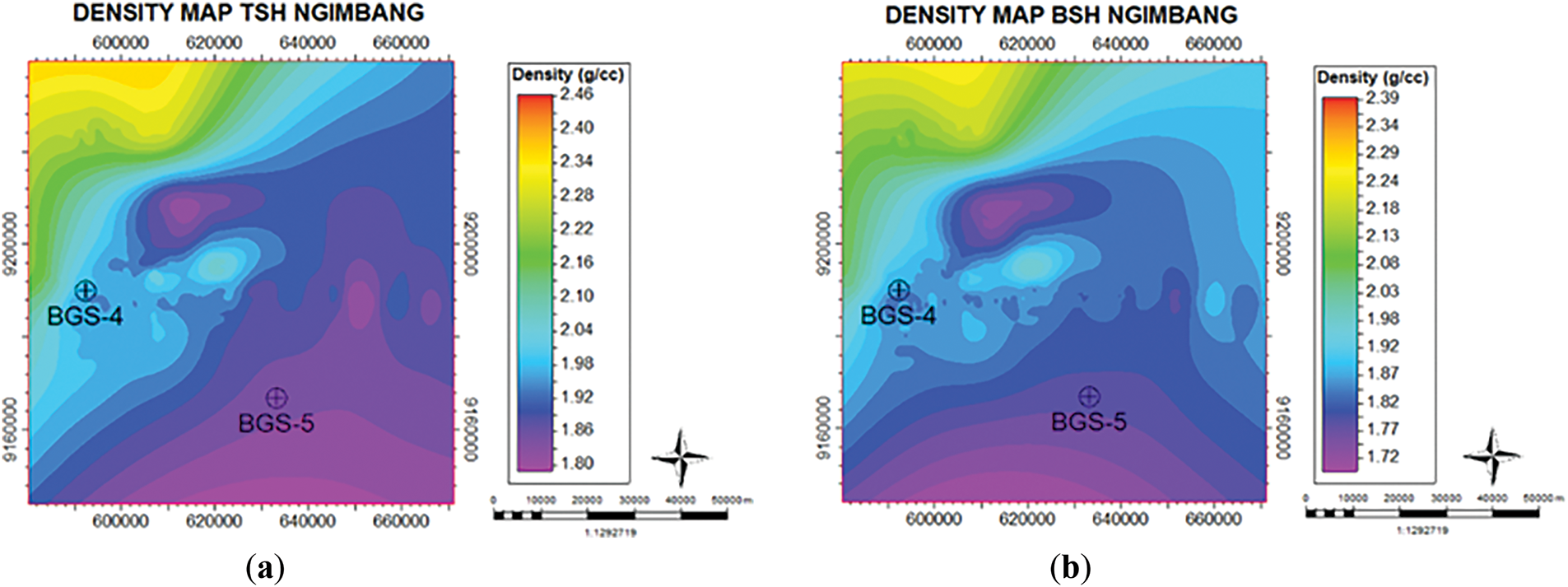

A similar density distribution pattern is observed in the Kujung Formation. As shown in Fig. 7a, the density distribution on the top shale (TSh) horizon indicates that regions with higher density values (>2.28 g/cc) are oriented towards the north, with corresponding color variations from yellow to red. In contrast, lower density values (<2.28 g/cc) are predominantly found in the southern region, illustrated by blue to purple shades. Fig. 7b further supports this observation, showing that on the bottom shale (BSh) horizon of the Kujung Formation, higher density values (>2.31 g/cc) are concentrated in the north, while lower values (<2.31 g/cc) extend towards the south. The Ngimbang Formation follows the same trend. Fig. 8a, which portrays the density distribution on the top shale (TSh) horizon, demonstrates that regions with density values exceeding 2.34 g/cc are primarily located in the northern part of the study area, whereas areas with density values below 2.34 g/cc are concentrated towards the south. This pattern is further reinforced by Fig. 8b, depicting the density distribution on the bottom shale (BSh) horizon, which also shows a predominance of higher density values (>2.34 g/cc) in the north and lower values (<2.34 g/cc) in the south.

Figure 7: (a) Distribution of density values in bottom shale (BSh) Kujung; (b) Distribution of density values in top shale (TSh) Ngimbang

Figure 8: (a) Distribution of density values in top shale (TSh) Ngimbang; (b) Distribution of density values in bottom shale (BSh) Ngimbang

An overall assessment of the density distribution across the Tuban, Kujung, and Ngimbang Formations indicates a consistent trend: higher density values are predominantly oriented toward the north, while lower values extend toward the south. This significant variation in density suggests the potential presence of unconventional hydrocarbons. High-density hydrocarbons typically exhibit greater viscosity, rendering them less mobile and more challenging to extract. This characteristic aligns with the general properties of unconventional hydrocarbons, which tend to have elevated viscosity levels, thus requiring specialized extraction techniques.

4.4 X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Testing on the Addition of Metals

4.4.1 X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Testing on the Addition of Metals to Shale Source Rock

The occurrence of intricate combinations of organic substances and metals within shale specimens can be likened to a crucial element for understanding the level of thermal alteration in source rocks, particularly those geological units primarily composed of this thinly bedded rock type. This intervention intends to accelerate the process by which trapped hydrocarbon compounds reach maturity, functioning by decreasing the energy threshold that must be overcome for reactions and increasing the pace of chemical changes that naturally progress at a glacial pace over geological epochs. To illustrate, the incorporation of organic compounds chemically linked with iron (Fe) can trigger the disruption of the carbon frameworks that constitute hydrocarbons, consequently speeding up the achievement of the desired level of maturity in the source rock.

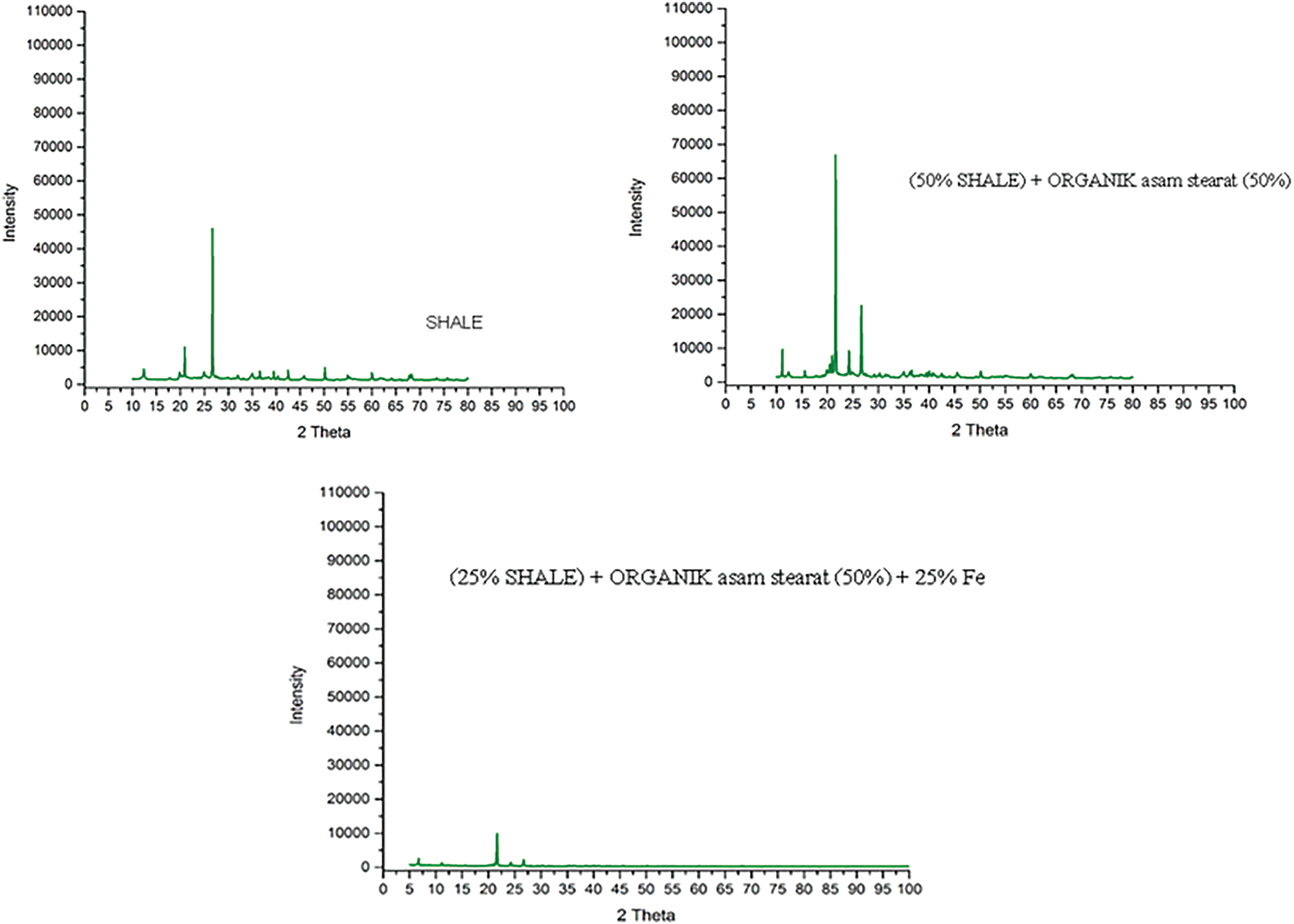

The source rock core in the target area was taken to the laboratory, and metals with a predetermined composition (shale/carbonate, organic, metal) were added. The results of research that have been carried out with each composition are shown in Fig. 9. It shows the XRD graph of clay material, which results from XRD testing on clay at high angles (10°–80°). When observed using the High Score Plus (HSP) software, it is evident that the dominant compound identified in the XRD graph for kaolinite is SiO2 (Silicon Dioxide). The XRD characterization results of the two samples, shale and organic material (as stearic acid), can be observed in Fig. 9. We can identify the two highest peaks at different 2 theta angles for analysis from both graphs. In both materials, no reaction occurs, but the intensity values increase with the addition of organic matter or the organic material composition. If we increase the amount of clay material compared to the organic material, the intensity value becomes lower or slightly approaches that of the clay material.

Figure 9: Composition comparison in adding metal to shale source rock

Since no reaction occurs, the addition of organic material results in the occurrence of the preferred orientation on specific crystal planes. It leads to these planes having higher intensities compared to before. However, there is no change in the 2 theta angle and hkl planes. Based on the Figure, we can understand that the intensity of X-rays absorbed by the detector differs for each sample. The height and depth of the X-ray intensity captured by the X-ray detector are influenced by the level of the regular arrangement of atoms in the crystal as diffracted by the X-ray. The more regularly arranged atoms, the higher the intensity the detector captures.

After analyzing the addition of organic material, adding iron (Fe) to the mixture of shale-organic-Fe (with a composition of 25% shale, 50% stearic acid, and 25% Fe) was carried out. It also resulted in a reaction due to the differences or changes in compounds and hkl planes at the same 2 theta angle while adding Fe. The intensity values dramatically decreased. It can be attributed to the level of regular arrangement of atoms within the crystal, as diffracted by X-rays. In this case, numerous atoms are irregularly arranged, causing the captured intensity to decrease further. A diminishing intensity signifies that the sample has a greater degree of crystal disorder, with more atoms in the layers being irregularly arranged. The formation of the X-ray diffraction pattern occurs due to the scattering of atoms situated on a specific hkl plane within the crystal. The results of the XRD characterization for the shale material (clay-organic) with the addition of Fe can be observed in Fig. 9. Consequently, adding iron to the source rock with shale lithology can have triggered reactions within the shale source rock. Fig. 9 demonstrates that introducing organic minerals and iron (Fe) into shale samples extracted from source rocks markedly diminishes reaction intensity. This observation implies a catalytic mechanism, where such additives could effectively reduce the activation energy required for the reaction, thus enhancing the rate of hydrocarbon generation during thermal maturation in source rocks.

4.4.2 X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Testing on Metal Addition to Carbonate Source Rock

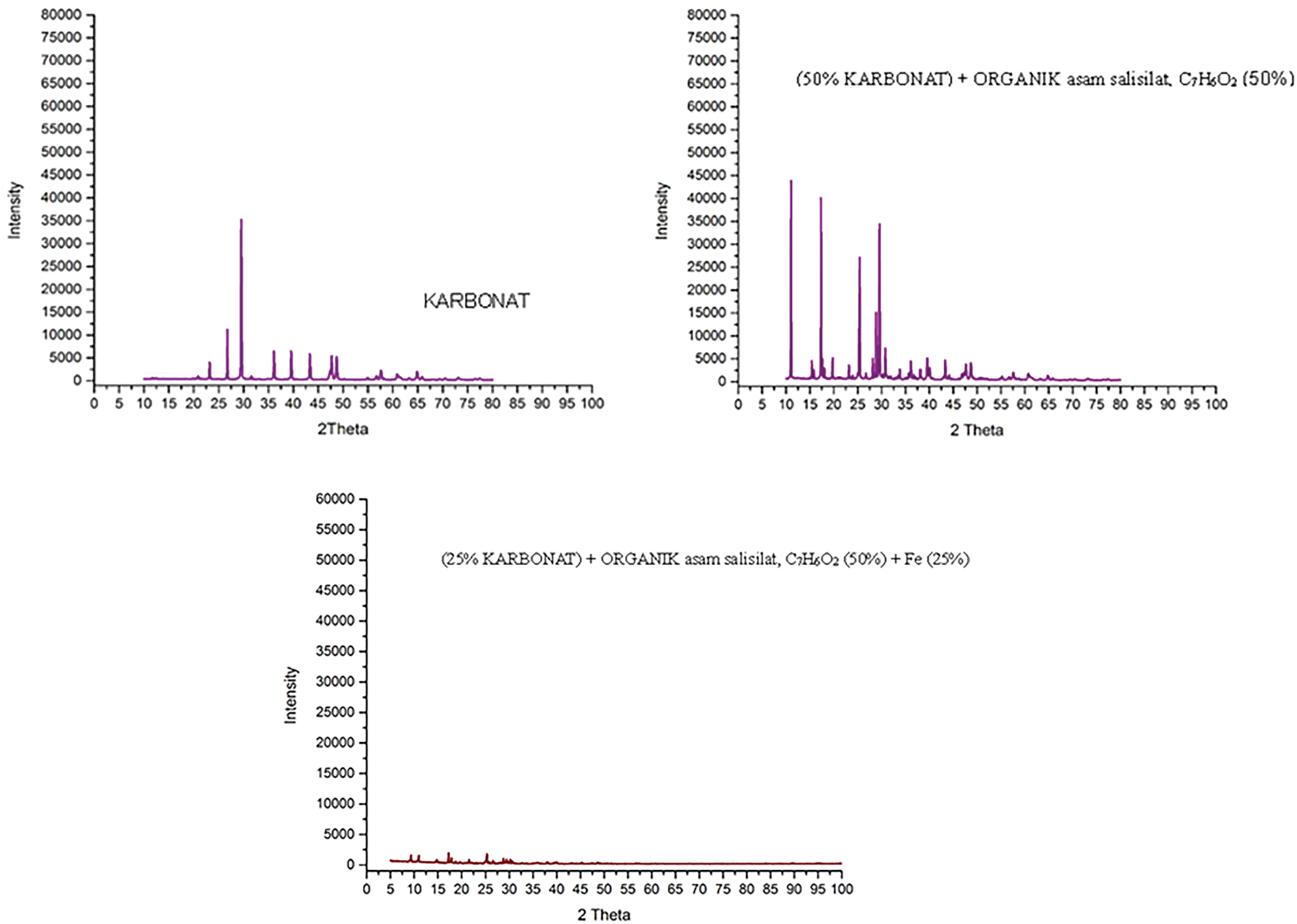

Like shale rocks, carbonate formations can also benefit from the addition of organic minerals and certain metals, particularly iron (Fe) to assess source rock maturity. These additives act as natural catalysts, lowering the energy barrier required for hydrocarbon generation and speeding up reaction rates. In nature, the maturation of hydrocarbons is an extremely slow process, but the presence of organic minerals and Fe facilitates the breakdown of complex hydrocarbon chains, significantly accelerating thermal maturation. This method provides valuable insights into the hydrocarbon generation potential of carbonate-rich source rocks under controlled conditions, offering a practical tool for researchers studying petroleum systems.

Iron (Fe) with a composition of 25% carbonate, 50% salicylic acid, and 25% Fe was added. Similar to the previous cases, when Fe was added, a reaction occurred due to differences or changes in compounds and hkl planes at the same 2 theta angle during the addition of Fe. It resulted in a significant decrease in intensity values. This phenomenon can be attributed to the level of the regular arrangement of atoms within the crystal, as diffracted by X-rays. In this scenario, numerous atoms are irregularly arranged, leading to a further decrease in captured intensity. Diminishing intensity indicates that the sample has a greater degree of crystal disorder, with more atoms in the layers being irregularly arranged.

The formation of the X-ray diffraction pattern is a consequence of the scattering of atoms situated on a specific hkl plane within the crystal. The results of the XRD characterization for the carbonate material, salicylic acid, with the addition of Fe, can be seen in Fig. 10. Consequently, adding iron to the source rock with carbonate lithology can be concluded to have triggered reactions within the carbonate source rock. Fig. 10 demonstrates that introducing organic minerals and iron (Fe) into carbonate samples extracted from source rocks leads to a measurable decrease in reaction intensity. This observation implies a catalytic role, where these additives may facilitate a reduction in activation energy, subsequently enhancing the reaction rate of hydrocarbon generation in source rocks.

Figure 10: Composition ratios in metal addition to carbonate source rock

This study advances the understanding of unconventional hydrocarbon maturation in the Northeast Java Basin by examining the role of metal additives, particularly iron (Fe), in accelerating organic matter transformation. The integration of well log data, geochemical characterization, and seismic interpretation enabled the identification of promising unconventional hydrocarbon reservoirs within the Tuban, Kujung, and Ngimbang formations. Target zones were defined based on permeability and TOC values, with carbonate-rich lithologies exhibiting the highest potential for hydrocarbon generation. The experimental addition of Fe demonstrated a significant enhancement in hydrocarbon maturation rates, as evidenced by XRD analysis, which revealed structural modifications in source rock minerals. This catalytic effect suggests a promising avenue for improving hydrocarbon recovery from low-permeability reservoirs. However, practical implementation requires further optimization to determine the ideal concentration of metal additives, assess potential side reactions, and evaluate the environmental implications of large-scale deployment.

The findings of this study contribute to the broader discourse on unconventional hydrocarbon extraction by offering a novel methodology that combines geophysical assessments with chemical interventions. This integrated approach provides a more comprehensive framework for evaluating and enhancing hydrocarbon maturation in complex geological settings. Future research should focus on refining metal-catalyzed maturation processes, assessing their long-term impact on reservoir integrity, and exploring alternative catalysts to improve efficiency. Additionally, economic feasibility studies should be conducted to determine the viability of scaling these techniques for commercial hydrocarbon production. The successful application of this methodology could significantly enhance energy security by unlocking unconventional hydrocarbon reserves that were previously deemed uneconomical. This research underscores the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches in advancing hydrocarbon exploration and production. By bridging geophysics, geochemistry, and engineering, this study lays the foundation for further innovation in unconventional resource development, with potential implications for global energy sustainability.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their gratitude to the Head of Geological Survey Center (PSG) of KESDM Bandung for granting permission to use data and facilities, which enabled the completion of this research.

Funding Statement: The source of funding for this research comes purely from the author’s funds.

Author Contributions: Bagus Sapto Mulyatno: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Data Analysis, Manuscript Writing, and Editing. Suharso: Supervision and Manuscript Review. Muh Sarkowi: Supervision and Manuscript Review. Ordas Dewanto: Supervision, Data Analysis, and Manuscript Review. Andy Setyo Wibowo: Data Collection and Data Analysis. Asep Irawan: Conceptualization, Data Analysis, Manuscript Writing, and Editing. Indra Mamad Gandidi: Manuscript Writing and Manuscript Review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that were used is confidential.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jia C, Pang X, Song Y. The mechanism of unconventional hydrocarbon formation: hydrocarbon self-sealing and intermolecular forces. Pet Explor Dev. 2021;48(3):507–26. doi:10.1016/s1876-3804(21)60042-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lai J, Wang G, Fan Q, Pang X, Li H, Zhao F, et al. Geophysical well-log evaluation in the era of unconventional hydrocarbon resources: a review on current status and prospects. Surv Geophys. 2022;43(3):913–57. doi:10.1007/s10712-022-09705-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Muther T, Qureshi HA, Syed FI, Aziz H, Siyal A, Dahaghi AK, et al. Unconventional hydrocarbon resources: geological statistics, petrophysical characterization, and field development strategies. J Pet Explor Prod Technol. 2022;12(6):1463–88. doi:10.1007/s13202-021-01404-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Song Y, Li Z, Jiang L, Hong F. The concept and the accumulation characteristics of unconventional hydrocarbon resources. Pet Sci. 2015;12(4):563–72. doi:10.1007/s12182-015-0060-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zou C, Qiu Z, Zhang J, Li Z, Wei H, Liu B, et al. Unconventional petroleum sedimentology: a key to understanding unconventional hydrocarbon accumulation. Engineering. 2022;18(1):62–78. doi:10.1016/j.eng.2022.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdelfattah MH, Abdelalim AM, Yassin MHA. Unconventional reservoar: definitions, types, and Egypt’s potential. Fac Pet Min Eng Suez Univ J. 2015. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3846.0880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zheng D, Miska S, Ziaja M, Zhang J. Study of anisotropic strength properties of shale. AGH Drill Oil Gas. 2019;36(1):93–112. doi:10.7494/drill.2019.36.1.93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmed U, Meehan DN. Unconventional oil and gas resources: exploitation and development. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2016. 894 p. [Google Scholar]

9. Zendehboudi S, Bahadori A. Shale oil: fundamentals, definitions, and applications. In: Zendehboudi S, Bahadori A, editors. Shale oil and gas handbook. Houston, TX, USA: Gulf Professional Publishing; 2017. p. 161–217. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-802100-2.00006-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Katz B, Gao L, Little J, Zhao YR. Geology still matters—unconventional petroleum system disappointments and failures. Unconv Resour. 2021;1(14):18–38. doi:10.1016/j.uncres.2021.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kingsley OK, Umeji OP. Oil shale prospects of Imo Formation Niger Delta Basin, southeastern Nigeria: palynofacies, organic thermal maturation and source rock perspective. J Geol Soc India. 2018;92(4):498–506. doi:10.1007/s12594-018-1048-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Klokov A, Repnik A, Bochkarev V, Bochkarev A. Integrated evaluation of Roseneath-Epsilon-Murteree formations, cooper basin, Australia to develop an optimal approach for sweet spot determination. In: Proceedings of the SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference; 2017 Jul 24–26; Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

13. Kamruzzaman A, Prasad M, Sonnenberg S. Petrophysical rock typing in unconventional shale plays: the Niobrara Formation case study. Interpretation. 2019;7(4):SJ7–22. doi:10.1190/int-2018-0231.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Phaye DK, Bhattacharya B, Chakrabarty S. Heterogeneity characterization from sequence stratigraphic analysis of Paleocene-Early Eocene Cambay Shale formation in Jambusar-Broach area, Cambay Basin. India Mar Pet Geol. 2021;128(3):104986. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Slatt RM, Abousleiman Y. Merging sequence stratigraphy and geomechanics for unconventional gas shales. Lead Edge. 2011;30(3):274–82. doi:10.1190/1.3567258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zheng D, Ozbayoglu E, Miska S, Zhang J. Experimental study of anisotropic strength properties of shale. In: Proceedings of the 57th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium; 2023 Jun 25–28; Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

17. Agustiyar F. Indications of the potential of shale gas for unconventional energy sources in Indonesia. Tadulako Sci Technol J. 2021;2(1):17–25. doi:10.22487/sciencetech.v2i1.15553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jumiati W, Maurich D, Wibowo AS, Nurdiana I. The development of unconventional oil and gas in Indonesia case study on hydrocarbon shale. J Earth Energy Eng. 2020;9(1):11–6. doi:10.25299/jeee.2020.4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Juventa J. Karekteristik reservoar karbonat menggunakan inversi impedansi akustik blok ‘X’ formasi tuban, cekungan Jawa timur. J Geosaintek. 2022;8(1):173–80. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

20. Migas SKK. Annual Report 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 6]. Available from: https://www.skkmigas.go.id/publication?tab=laporan%20tahunan. [Google Scholar]

21. Fadlilah MR. Identification of unconventional reservoirs in The X field of the north east Java Basin based on permeability, mobility and transmissibility [master’s thesis]. Lampung, Indonesia: University of Lampung; 2023. [Google Scholar]

22. Sekarsari NF. Characterization of shale and carbonate as unconventional reservoar in the north east Java Basin [master’s thesis]. Lampung, Indonesia: University of Lampung; 2022. [Google Scholar]

23. Dewanto O, Ferucha I, Darsono D, Rizky S. Conversion of oil shale to liquid hydrocarbons as a new energy resources using iron (Fe)-pillared clay (kaolinite) catalyst. Indones J Appl Phys. 2022;12(2):197–216. doi:10.13057/ijap.v12i2.58414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dewanto O. Comparison of organic maturation levels in CaCO3 and Fe addition, by determination of activation energy using thermogravimetry and pyrolysis analysis methods [dissertation]. Jawa Barat, Indonesia: University of Indonesia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

25. Al Zoubi W, Leoni S, Assfour B, Allaf AW, Kang JH, Ko YG. Continuous synthesis of metaloxide-supported high-entropy alloy nanoparticles with remarkable durability and catalytic activity in the hydrogen reduction reaction. InfoMat. 2025;7(2):e12617. doi:10.1002/inf2.12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Satyana AH. Oligo-Miocene carbonates of Java, Indonesia: tectonic, volcanic setting and petroleum implications. In: Proceedings of the Indonesian Petroleum Association, 30th Annual Convention & Exhibition. Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia: Indonesian Petroleum Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

27. Sribudiyani MN, Ryacudu R, Kunto T, Astono P, Prasetya I, Sapiie B, et al. The collision of the East Java microplate and its implication for hydrocarbon occurrences in the East Java Basin. In: Proceedings of the Indonesian Petroleum Association, 30th Annual Convention & Exhibition. Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia: Indonesian Petroleum Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

28. Pringgoprawiro H. Stratigrafi cekungan Jawa Timur Utara dan Paleogeografinya: sebuah pendekatan baru [dissertation]. Jawa Barat, Indonesia: Bandung Institute of Technology; 1983. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

29. van Bemmelen RW. The geology of Indonesia. The Hague, The Netherlands: Government Printing Office; 1948. 996 p. [Google Scholar]

30. Wijaya PH, Noeradi D. 3D properties modelling to support reservoar characteristic of W-ITB Field in Madura Strait area. Bull Mar Geol. 2010;25(2):77–87. doi:10.32693/bomg.25.2.2010.27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Doust H, Noble RA. Petroleum systems of Indonesia. Mar Pet Geol. 2008;25:103–29. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2007.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bintarto B, Swadesi B, Choiriah SU, Kaesti EY. Pemetaan singkapan di Indonesia berdasarkan pada karakteristik reservoar migas studi kasus Cekungan Jawa Timur Utara [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 6]. Available from: http://eprints.upnyk.ac.id/25021/. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

33. Husein S. Fieldtrip geologi cekungan Jawa timur utara [master’s thesis]. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Gadjah Mada University; 2016. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

34. Satyana AH. Petroleum geology of Indonesia. In: IAGI Professional Courses; 2009 Dec 7–11; Bali, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

35. Zhang XS, Wang HJ, Ma F, Sun XC. Classification and characteristics of tight oil plays. Pet Sci. 2016;13(1):18–33. doi:10.1007/s12182-015-0075-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. LEMIGAS. Strategi percepatan eksplorasi & eksploitasi MNK Shale HC melalui implementasi sumur pilot multi stage fracturing horizontal well (MSFHW). Jakarta, Indonesia: LEMIGAS; 2020. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

37. Timur A. An investigation of permeability, porosity, and residual water saturation relationships for Sandstone Reservoirs. In: Proceedings of the SPWLA 9th Annual Logging Symposium; 1968 Jun 23–26; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

38. Koesoemadinata RP. Geologi minyak dan gas bumi. Bandung, Indonesia: Bandung Institute of Technology; 1978. 172 p. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

39. Peters KE, Cassa MR. Applied source rock geochemistry. In: Magoon LB, Dow WG, editors. The petroleum system—from source to trap. Tulsa, OK, USA: American Association of Petroleum Geologists; 1994. [Google Scholar]

40. Tissot BP, Welte DH. Petroleum formation and occurrence. 2nd ed. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1984. 702 p. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools