Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Feasibility Study of Renewable Energy Generation from Palm Oil Waste in Malaysia

1 Department of Computing and Mathematics, South East Technological University, Waterford, X91 K0EK, Ireland

2 Faculty of Engineering, Computing and Science, Swinburne University of Technology Sarawak Campus, Kuching, 93350, Malaysia

3 Faculty of Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, B4 7BD, UK

4 Department of Computing Sciences, AFG College with the University of Aberdeen, Doha, P.O. Box 10805, Qatar

* Corresponding Author: Mujahid Tabassum. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Renewable Energy Systems: Integrating Machine Learning for Enhanced Efficiency and Optimization)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(9), 3433-3457. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.065955

Received 26 March 2025; Accepted 15 July 2025; Issue published 26 August 2025

Abstract

Malaysia, as one of the highest producers of palm oil globally and one of the largest exporters, has a huge potential to use palm oil waste to generate electricity since an abundance of waste is produced during the palm oil extraction process. In this paper, we have first examined and compared the use of palm oil waste as biomass for electricity generation in different countries with reference to Malaysia. Some areas with default accessibility in rural areas, like those in Sabah and Sarawak, require a cheap and reliable source of electricity. Palm oil waste possesses the potential to be the source. Therefore, this research examines the cost-effective comparison between electricity generated from palm oil waste and standalone diesel electric generation in Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia. This research aims to investigate the potential electricity generation using palm oil waste and the feasibility of implementing the technology in rural areas. To implement and analyze the feasibility, a case study has been carried out in a rural area in Sarawak, Malaysia. The finding shows the electricity cost calculation of small towns like Long Lama, Long Miri, and Long Atip, with ten nearby schools, and suggests that using EFB from palm oil waste is cheaper and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. The study also points out the need to conduct further research on power systems, such as energy storage and microgrids, to better understand the future of power systems. By collecting data through questionnaires and surveys, an analysis has been carried out to determine the approximate cost and quantity of palm oil waste to generate cheaper renewable energy. We concluded that electricity generation from palm oil waste is cost-effective and beneficial. The infrastructure can be a microgrid connected to the main grid.Keywords

The rising global energy demand, driven by population growth and industrialization, has intensified the need to shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy due to the environmental harm caused by carbon emissions. In Malaysia, while palm oil production is economically significant, it produces large amounts of biomass waste such as empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm kernel shells, and palm oil mill effluent (POME) which pose serious environmental threats if not properly managed.

In rural areas of Sarawak, such as Marudi, access to stable electricity remains a challenge due to remote locations and high diesel fuel costs. Utilising renewable energy, particularly from palm oil waste, offers a sustainable solution. Biomass sources like EFB and POME can be converted into electricity through biogas and combustion technologies. This approach not only reduces reliance on diesel generators but also addresses waste management and lowers greenhouse gas emissions. Implementing local biomass energy systems can improve energy access, cut operational costs, and promote environmental sustainability in remote communities.

Global energy demand continues to rise annually due to rapid population growth and industrial development. Although fossil fuels have historically been the dominant source of energy due to their established infrastructure and lower upfront costs, their environmental impact is becoming increasingly unsustainable [1,2]. The growing awareness of climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, and rising sea levels has intensified the shift toward renewable energy sources [3]. Fossil fuel combustion, especially from coal, oil, and natural gas, contributes significantly to carbon emissions, necessitating urgent transition strategies toward clean energy alternatives [4].

In the Malaysian context, palm oil production remains a cornerstone of the economy. However, it also generates large volumes of biomass waste, including empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm kernel shells, and POME. These by-products, if improperly managed, are often discarded into landfills, water sources, or used as low-grade fertilizers, posing serious environmental hazards [5]. Recent research highlights the untapped potential of converting this biomass waste into renewable energy through anaerobic digestion, gasification, and combustion technologies [6]. Utilizing palm oil waste not only addresses waste management challenges but also supports rural electrification, especially in underserved regions like Marudi, Sarawak. Malaysia is one of the potential and favourite countries to use the technology as Malaysia is among the countries that produce a large amount of palm oil. Since the amount of waste from palm oil mills is high all over the country, the scope of the research is based on the transportation cost compared with the total diesel fuel used in the rural area and the waste used as the source for biomass energy generation. In addition, palm oil mills are usually located away from the city where there is a palm oil plantation; therefore, the proposed biogas plant should be at a nearby location [7].

This study investigates the viability of using palm oil mill waste as a renewable energy source to generate electricity for rural communities. It draws on current literature comparing the effectiveness of biomass energy utilization in both developed and developing nations. Renewable energy from biomass has the potential to reduce dependency on diesel generators, lower energy costs, and provide a more stable, sustainable electricity supply in rural Malaysia. Thus, the objective of this paper is to assess the feasibility and impact of deploying palm oil waste-based energy systems for rural electrification. In this article, the analysis of using palm oil waste as the energy source has been performed based on the data gathered from available resources and manual calculation was carried out to investigate the potential of applying the technology to build a biogas plant. This biogas plant will have a supply of biomass waste that is collected from the nearby palm oil mills. Therefore, by comparing and analyzing data from developing countries that have already implemented this technology, this paper aims to provide core insights for future researchers to investigate more into implementing this technology. This study explores the potential of converting palm oil waste into renewable energy, particularly for rural electrification in underserved areas like Marudi, Sarawak. Technologies such as anaerobic digestion, gasification, and combustion are highlighted as effective means for converting biomass into electricity. The research evaluates the feasibility of deploying biogas plants near palm oil mills, emphasizing reduced transportation costs and sustainable energy supply compared to diesel generators. Furthermore, this study draws on literature and comparative case studies from both developed and developing countries to assess the practicality and impact of palm oil waste-to-energy systems. Ultimately, it aims to offer valuable insights for future researchers and policymakers interested in expanding Malaysia’s renewable energy capacity through palm biomass utilization.

In the last few decades, oil palm production has been increasing due to high global demand. Several countries, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Colombia, Nigeria, and India, are major players in this sector. As the demand for oils and fats continues to rise, so does the production rate for palm oil. However, this elevated production inevitably leads to the generation of significant palm oil waste, a byproduct typically produced after palm oil is processed in mills. The increasing demand for palm oil from a country like Malaysia, as well as Indonesia, has generated problems for the environment due to the waste produced like EFB, palm oil trunks, palm oil kernel, POME and palm oil shell [8,9]. Therefore, the solution for this problem has been identified whereby palm oil waste is used as an energy source. Since this waste is produced as an agricultural by-product, it is renewable.

The conversion of palm oil biomass into electricity is gaining global attention as a sustainable approach to meet rising energy demands while addressing waste management and environmental concerns. In a typical biomass-to-electricity system, palm oil residues such as EFB, mesocarp fibre, and palm kernel shells (PKS) are combusted to produce high-pressure steam. This steam drives a steam turbine generator, converting thermal energy into mechanical and then electrical energy. Alternative technologies such as gasification or anaerobic digestion are also employed, offering cleaner and more efficient generation pathways.

The growing energy demand in Malaysia is met by both non-renewable and renewable sources [10]. For a country like Malaysia, energy resource is a critical factor in a developing nation since it is one of the main driving forces for the economy [10]. However, heavy dependence on fossil fuels for power generation leads to an increase in pollution in Malaysia. Realizing this fact, the implementation of renewable resources for energy production has become increasingly important due to increasing concern about the environmental problem issue. Renewable energy, such as biomass energy, comes from about 51% of palm oil by-products from the palm oil industry [7]. Malaysia has been classified as among the producers of palm oil that has a big potential in using energy from biomass, especially from palm oil waste, since there is a large amount of waste generated. The waste that is created from the palm oil industry, such as EFB and POME, can be used for generating energy, such as electricity, cooking gas and heating. The vast amount of waste that is created from palm oil mills shows the potential of using waste as an energy resource. One of the wastes, like POME, can be processed through a ponding system since it is a low-cost method [11]. This POME uses a system that needs aerobic ponds, anaerobic ponds, de-oiling tanks and acidification ponds [11]. After being treated and processed, the generated biogas can be used for electricity generation. Based on an analysis of the Biogas Project at Felda, Serting Hilir, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, the estimated cost for a biogas plant is divided into two phases such as Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) 7,647,000 million for phase 1 while the development cost is MYR 2000. MYR 498,594 is needed for other costs. Meanwhile, for the capital investment of phase 2, an investment of MYR 1,638,000 million is required. This investment is required from the estimation of cash for outflow and inflow, where the consideration is made based on the capital, set up and annual operating cost [7]. Besides, since Malaysia produces tonnes of palm oil waste, it is economically viable to produce biomass energy, where an estimated United States Dollars (USD) 7.1 million is needed for a power plant with 5 MW power [7]. Other than that, several companies that provide biogas technology have made an investment of USD 2.24 million for a digesting tank along with a covered lagoon for USD 1.96 million for biogas production [12,13]. This biogas capture and utilization is based on 60 t palm oil mill, and the cost is taken into consideration along with the system design, materials used, durability of the system installed, the location and capacity of the mill and even the efficiency of the digesters. Thus, the investment cost varies from USD 2.24 million to USD 2.80 million per MW [11].

Indonesia is the largest producer of palm oil apart from Malaysia after overtaking Malaysia as the number one producer in 2006 [11]. The increase in energy demand due to strong economic growth in Indonesia has led to energy production that grew 2.8 times and energy consumption that grew almost five times [11]. In Indonesia, the potential of biomass energy is large, considering the transformation in using modern technology like gasification and pyrolysis from traditional direct burning [14]. The residue from agricultural waste, like palm oil residues, can be used for electricity generation apart from municipal waste based on national studies [11]. In Indonesia, a city in Java called Yogyakarta has the potential to use biogas and biomass as renewable energy [15]. Based on the analysis, the agricultural waste that is produced annually is 982,623.78 t/year. This waste can be used as a source to generate biogas energy to help the locals in their daily life [12]. However, the use of biogas and biomass as renewable sources is still low since most electricity generation in Indonesia still uses diesel and coal. Moreover, the energy currently being used in the rural area of Indonesia is mostly for cooking purposes in households and for local entrepreneurs’ usage. The installation of the biogas digester reactor, which can help in generating energy, has a capacity volume of four to five cubic meters with a cost of Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) 5.7 million [15].

India is one of the countries with the largest population in the world, and the increasing demand for energy supply shows the growing need of its people. Since the abundance of biomass resources is high, India has the potential to use this biomass energy based to generate 18 GW from 120–150 million metric tonnes of biomass per year [16]. However, nearly 700 million rural population failed to get the energy supply even though India has traditional biomass, centralized grid electricity and petroleum products [17]. One of the potential locations for biomass energy technology is the Tumkur District in the state of Karnataka, India. The cost of a biomass gasifier includes investment costs and operational costs for a suitable power system technology. The investment cost of the power system includes energy consumption biogas software, gasifier-engine-generator set, building and accessories. The operational cost includes biogas, wood, operator’s wages, repair, and maintenance. There are three estimated costs based on three levels of biomass productivity which are low, medium, and high biomass productivity. The cost for low biomass productivity is Indian Rupees (INR) 4023 million, for medium productivity is INR 2844 million and for high productivity is INR 2081 million [17].

A similar picture can be seen across south America as well. Rural villages in Colombia need renewable energy systems to be installed since electricity generation for households is in high demand [18]. The potential for the power plant to be installed is for the provinces with the largest energy consumption, like Choco, Meta and Putumayo. The demand for energy is 147.15 kWh/month with a 24-h supply. The biomass cost of the technologies that are proposed includes the carburettor, generator, and gas purification system. The biomass cost is free since each village has biomass waste. The proposed system is biomass gasification, where the capital cost to build a 1 MW plant is USD 1,033,021 million. In contrast, another system using biomass combustion needs an investment with a capital cost of USD 5,364,450, and it produces the same amount of power as the biomass gasification system. However, the investment cost is five times more than the biomass gasification system [18].

Other than Colombia, the country that is also famous for its palm oil production is Thailand. The economic development of this country largely depends on the crude palm oil industry [19]. Based on the economic data, it is estimated that palm oil constitutes up to 70% of the vegetable oil market in Thailand, which is equivalent to Thai Baht (THB) 40,000 per annum of market value. Due to the high demand for palm oil, production causes a lot of by-products in the form of solid waste and wastewater from the process. For the wet process of palm oil, the water consumption for the process of Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFB) leads to the production of POME, for which 50%–79% water is used. Later, this wastewater is used for the generation of electricity through anaerobic treatment, where a closed anaerobic tank and gas-engine generators with a capacity of 300–400 kW are used. Therefore, the electricity generation that comes from the production of biogas will come with an estimated cost of THB 19 million [19,20].

Lastly, the potential for a biomass plant for electricity generation is high since the requirement for capital cost is low compared with a coal plant. Apart from that, the waste from this palm oil industry which can be used for biomass energy, has consistent supplies as the production of palm oil is high, especially in a country like Malaysia [20]. In addition, greenhouse gas emissions will decrease because of using POME, which contributes a significant amount of waste as wastewater in palm oil mills. Even though this technology involves a high investment cost, the payback period shows that the investment cost can be recovered within eight years based on the annual profit from 6.2 GWh per year of the electricity sale [21]. Since this paper focusses on applying the technology in Sarawak, the potential is high considering enough palm biomass supply according to the surveys [22]. Moreover, the state government encourages major developers to install the latest technology in their mills, whereby EFB can be used as boiler fuel considering that most of the mills are under the management of major developers [23]. Therefore, a biomass gasifier technology for generating electricity would help the economic activities of rural people and their lifestyles [24].

In Malaysia, the total electricity demand was approximately 168 TWh in 2023, with coal and natural gas accounting for over 70% of the power generation mix [25]. Renewable energy represents around 22%, including hydropower and a growing share from biomass, particularly in Sabah and Sarawak, where palm oil plantations are dense. In Sarawak, the renewable energy share is higher than the national average due to hydroelectric dams, but rural electrification gaps persist, especially in areas like Marudi, making localized biomass solutions highly relevant.

In Indonesia, total electricity demand reached 289 TWh in 2023, with over 85% supplied by fossil fuels. The government aims to raise the renewable energy share to 23% by 2025, with biomass energy identified as a strategic contributor due to its availability from agricultural and palm oil residues [25].

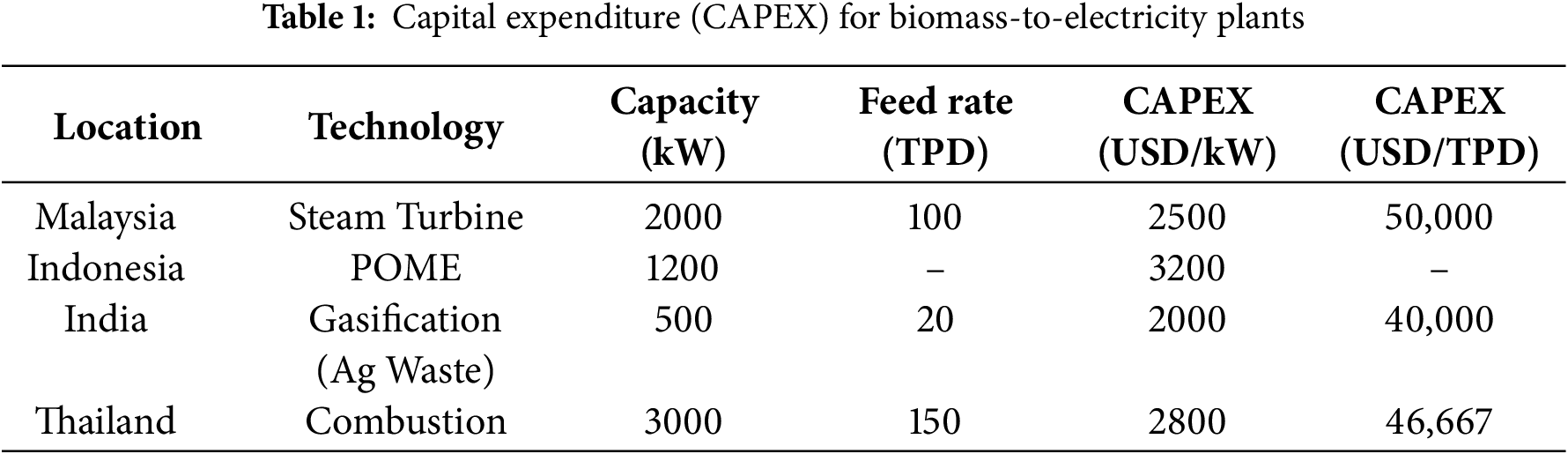

Table 1 presents a structured summary of capital cost estimates from various studies for biomass power plants using palm oil or similar agricultural waste. The capital cost is presented as both per kW installed capacity and per tonne of feedstock per day, converted to USD for comparison across regions [6,26–28].

These figures serve as a basis for scenario development in cost-effective design tailored to rural Malaysian conditions. In Marudi, proximity to palm oil mills reduces transportation costs, further improving project feasibility.

Operating costs (OPEX) include maintenance, labour, transportation of feedstock, ash disposal, and fuel handling systems. The following research [6], estimate an OPEX of USD 30–50/MWh for a typical 2 MW biomass plant in Malaysia. Factors such as local labour costs, equipment availability, and feedstock drying significantly impact on operating expenses. Proper estimation of OPEX is essential to projecting the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) and the long-term sustainability of the system.

The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for biomass power generation ranges from USD 0.07 to 0.12 per kWh, depending on plant size, efficiency, technology type, and location (IRENA, 2024). In rural areas where diesel-based generation can cost over USD 0.25 per kWh, biomass-based electricity offers a cost-competitive and cleaner alternative. Additionally, carbon credit mechanisms or feed-in tariff incentives (such as SEDA Malaysia’s FiT) can enhance financial viability.

2.2 Advantages and Disadvantages

When it comes to the production of palm oil and its products, the demand increases rapidly as the economy grows, especially in developing countries such as China, India and Southeast Asian countries [24]. In Malaysia, an average of 53 million tonnes of residues is generated yearly from the palm oil industry [29]. High demand for palm oil in developing countries leads to a massive expansion of palm plantations causing environmental problems and generating waste [24]. Moreover, it affects biodiversity and the ecosystem of that area as well [30]. Among the ecosystem and environmental issues that are occurring due to plantations and milling in the oil palm industry are deforestation, habitat loss, forest fragmentation, biodiversity loss, food chain disruption, change in soil properties, water and air pollution, peatlands and arable lands conversion, increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, forest fires as well as the incidence of natural disasters [30]. Furthermore, palm oil industry wastes are increasing—oil palm solid wastes of 80 million tonnes of dry biomass in 2010 rose to 100 million dry tonnes by the year 2020 [29]. Although palm oil plantations and mills bring a lot of negative impacts on the ecosystem and environment, energy-related problems are still occurring. Among energy-related problems are the oil crisis and the rapid growth in electricity demand around the globe. Fossil fuels used in electric power generation are decreasing rapidly as well. Therefore, since there is an abundance of available oil palm biomass residues [31], these residues can be used as an alternative resource to generate energy, mainly electricity and help overcome the energy crisis [31]. Even though the electricity generated by using biomass is expected to be less than that from fossil fuels, biomass should be considered as it reduces greenhouse gases, generates considerable income and decreases waste of palm oil plantations and millings. Additionally, the conversion of biomass into electric power is inevitable for developing countries as concerns towards the environment and securing energy are increasing [32]. However, depending on the biomass type, the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) can increase depending on the condition and setups of the conversion process. The following research [33] shows that the combustion process for converting chicken/poultry waste into energy increased CO, NOx and SOx gases depending on the condition applied [33].

There are two factors of energy sustainability—sustainable energy sources and the use of sustainable energy in energy systems [34]. As the studies of various parties, from engineers to environmentalists, regarding the generation of electricity by using oil palm biomass advance, the advantages and drawbacks of using palm oil biomass to generate electricity have been recognized. One of the advantages of using oil palm biomass to generate electricity is a reduction in fossil fuel consumption. An analysis of combustion characteristics of kernel shell, mesocarp fibre and empty fruit bunches, as well as coal/biomass blends via Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), illustrates that co-firing of palm oil wastes and coal can decrease the consumption of coal. Furthermore, the possibility of using oil palm waste to generate electricity can improve fossil fuel energy problems [30]. There will also be an increase in energy productivity as palm oil mills are in rural and remote areas. Most palm oil mill locations are more than a 5-h drive from the nearest town [24]. Moreover, the rural and remote areas have poor electricity supply. Thus, generating power from palm oil mill waste will improve the electric supply and access to electricity for surrounding areas [29].

Environmental issues can also be tackled by using palm oil waste, as POME are one of the major contributors to the pollution of terrestrial and aquatic systems and the release of GHG [30]. POME is a major contribution to water and air pollution due to its massive production of POME [10]. Additionally, worldwide, there are over 190 million tonnes of both solid and liquid residues currently generated by palm oil industries [35]. Malaysia is now concerned with the maximization of resource recovery and sustainable bio-economy development since an abundance of biomass feedstock is available [11]. Thus, using this technology will reduce carbon emissions by electrical power generation sectors in Malaysia. This will also encourage the realization within the country that the commitment to cutting carbon emissions is a serious matter to help reduce the global warming trend and thus mitigate climate change. Using palm oil waste to generate electricity can be a sustainable source of energy and thus address energy demand issues and reduce GHG to lessen global warming [36]. Furthermore, when excess heat from palm oil mills is used for EFB pre-treatment, including the installation of Cogeneration (CHP) plants at palm oil mills, higher carbon credits can be acquired [37].

However, there are also various drawbacks when using palm oil waste for generating electricity in terms of technology, finance, governance and grid connectivity [10]. The goal of generating electricity by using palm oil wastes will be impossible if the excess power is not fed into the main grid [20]. In Sarawak, grid infrastructure developments, legal implications, and tariff considerations vary as compared to Peninsular Malaysia [38]. Constructing transmission line infrastructure requires extremely high capital costs from industry and Government [22]. Sarawak’s transmission gridlines and infrastructures for feed-in excess power from palm oil mills into the main power grid in the state are very lacking. Also, the extra capacity from the burning of biomass is meant to cater for their daily operational needs rather than exporting to the grid made the industry reluctant to replace their current inefficient machinery [38].

Furthermore, the industry is discouraged from switching to low-carbon technology due to the extremely high upfront costs and the corresponding long period of payback [36]. It would cost about MYR 10 million per mill order to set up a biogas plant which is a heavy burden for the mill developers due to the long payback period and uncertainty of recovering investment costs [22]. There are also issues regarding storage for palm biomass that requires large space. On average, sustaining periods for EFB, palm kernel shell, and mesocarp fibre are 12 days, one month and two days, respectively [22]. Another drawback of using palm oil biomass to generate electricity is the lack of interest of the stakeholders involved. The Government’s target is to implement biogas trapping from POME. However, the public-private engagement framework to create a conducive environment for biogas business endeavours is lacking and has not lived up to expectations. The longevity of technology depends on the continuous supply of palm biomass that will sustain the power generation from palm biomass [22]. The probability of a shortage of palm kernel shell and mesocarp fibre is relatively low, as major mill developers usually have high-quality feedstock for their plants [24]. Malaysia has introduced biomass as the fifth fuel resource after petroleum, gas, coal and hydro [18]. Additionally, palm tree plantations in Malaysia are increasing due to the Malaysian Government’s strategies for palm oil-based biodiesel production [18]. Therefore, the by-products of palm oil will be in abundance throughout the year [39]. Furthermore, the palm oil industry is best known as the main sector that generates an abundance of biomass as renewable sources, which includes empty fruit bunches (EFB), mesocarp fibre (MF), palm shell (PS), oil palm fronds (OPF) and oil palm trunks (OPT) [36]. As for Sarawak, there is a demand for research to be done to know the suitability of Empty Fruit Bunches as a power resource to generate power on a large scale [20]. Developing a technology of using POME to generate electricity will boost the renewable energy industry in Malaysia. Since the palm oil industry is one of the main contributors to the national income of Malaysia, the use of POME to generate electricity in a sustainable way will be more reliable and later increase the renewable energy share of energy generation in Malaysia [11].

2.3 Comparison of Electricity Generation in Malaysia with Other Countries

Energy is a basic need for economic growth [40]. Conventional energy, like fossil fuels, is becoming scarce as days pass and will eventually be depleted. Due to the ever-rising demand for energy, the world is forced to come up with efficient and renewable energy to satisfy the human species. Renewable energy is a type of energy that comes out of sources that are not exhausted or depleted when used. Palm oil is regarded as one of the most important oils in the world. Due to the shortage of electricity, the waste of palm oil is considered an option for generating power [41]. The wastes in palm oil are categorized into solid and liquid wastes. EFB, Palm Kernel Shells (PKS) and Mesocarp Fiber (MF) are examples of solid waste. Liquid waste includes POME [42]. CO2 can be captured if electricity is generated through biomass. As of 2010, about 2% of the palm oil produced globally is used in electricity generation [43].

3 Generating Renewable Energy from Palm Oil Wastes in Malaysia

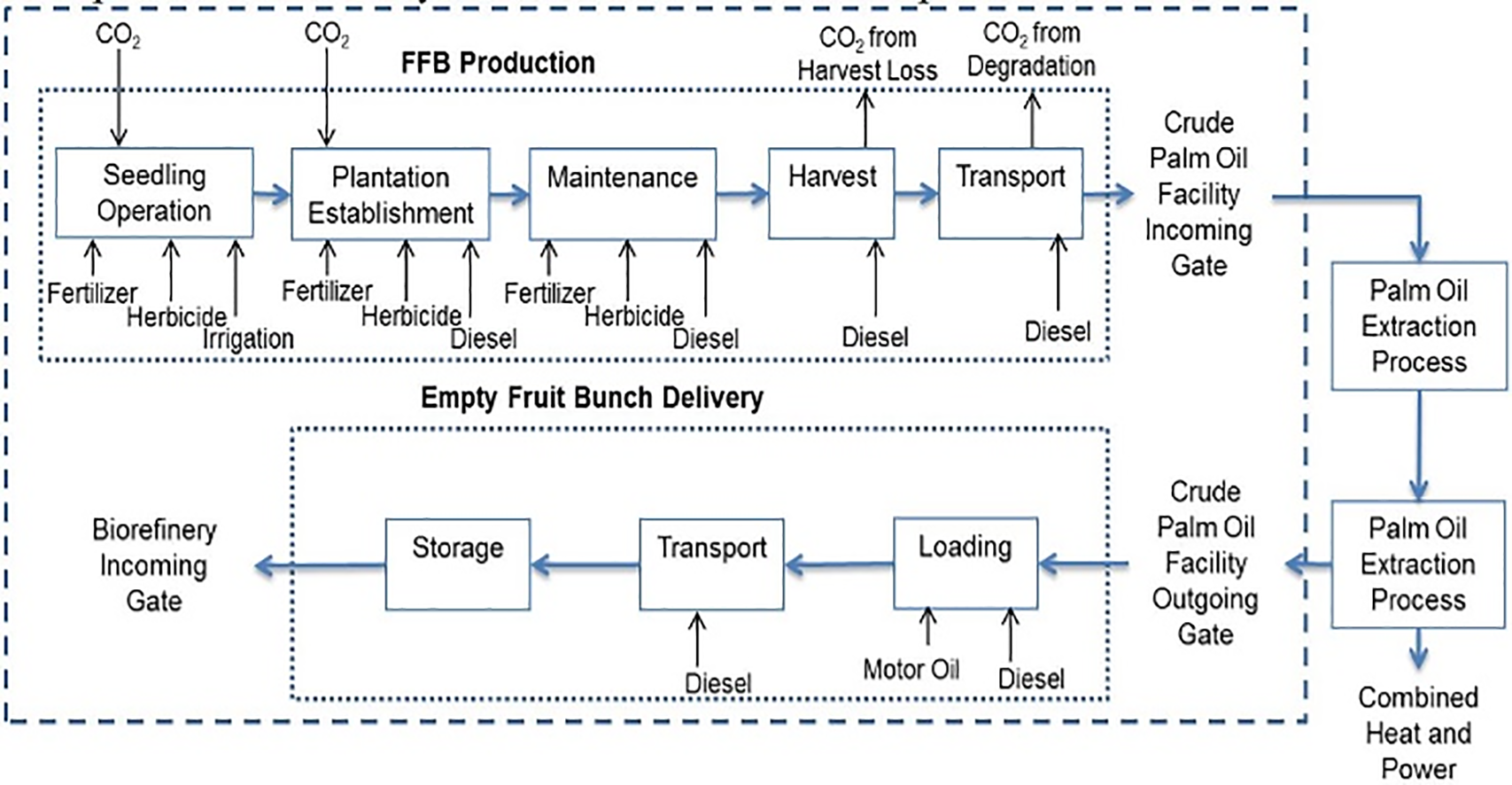

Renewable energy is the primary source of energy for the future. Malaysia has plenty of supply of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) and produces the highest level of emission among ASEAN countries (like Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand) [40]. It also has access to renewable sources of energy (biomass and solar), and the demand for those sources is very high compared to most developed countries [41]. The projection of the demand for maximum energy is estimated at 40,515 MW by 2020. In the past, curbing the use of energy in Malaysia was not seen as a necessity because the increase in energy usage was seen as a measure of development. Recently, measures were put in place to minimize the cost of energy as part of industrialization objectives for “Vision 2020” [42–44]. Fig. 1 shows the complete process of FFB production process [45].

Figure 1: Phases through processes in palm oil life cycle and waste production for possible renewable energy sources [45]

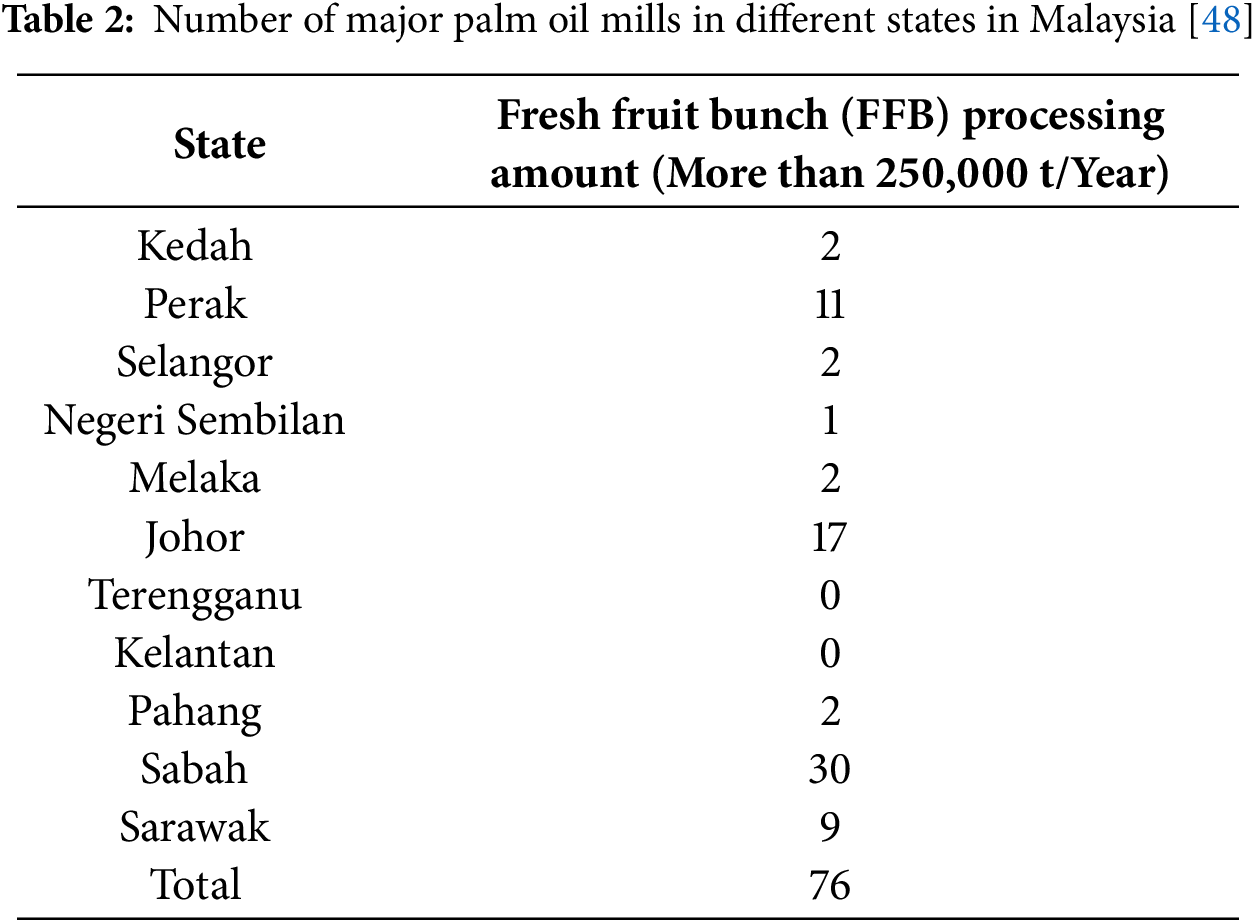

In 2011, MYR 83 billion worth of palm oil was exported worldwide by palm oil-producing nations [46]. Malaysia contributed to 20.2 and 21.25 million metric tons of world palm oil production in 2013 and 2014, respectively [47]. The Malaysian Government recognized that the availability and stability of energy have the utmost significance in stimulating the growth of the economy. It is for this reason that it introduced a four-fuel strategy, namely, coal, natural gas, hydropower, and petroleum, in the early 1980s to reduce petroleum dependency. Recently renewable energy sources were incorporated as the fifth fuel and therefore made it an option or alternative to other sources [46]. Malaysia’s palm oil plantation increased exponentially from 54,000 to 5 million hectares between 1960 and 2011. Table 2 gives a list of palm oil mills in Malaysia [48].

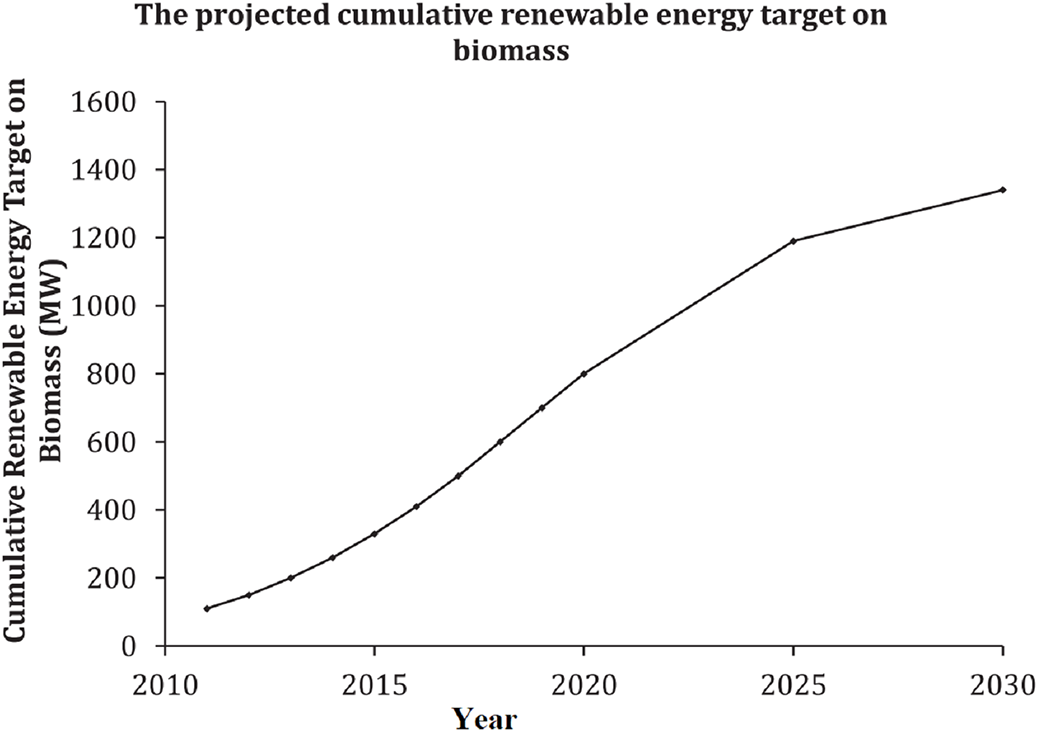

The Government, through the Ministry of Energy in conjunction with Green Technology and Water, is targeting 800 MW of biomass power to be generated by 2020 out of which 500 MW should from palm biomass [49]. Fig. 2 shows the projections.

Figure 2: Projected target for biomass production up until 2030 from various sources for electricity generation, excerpted from [49,50]

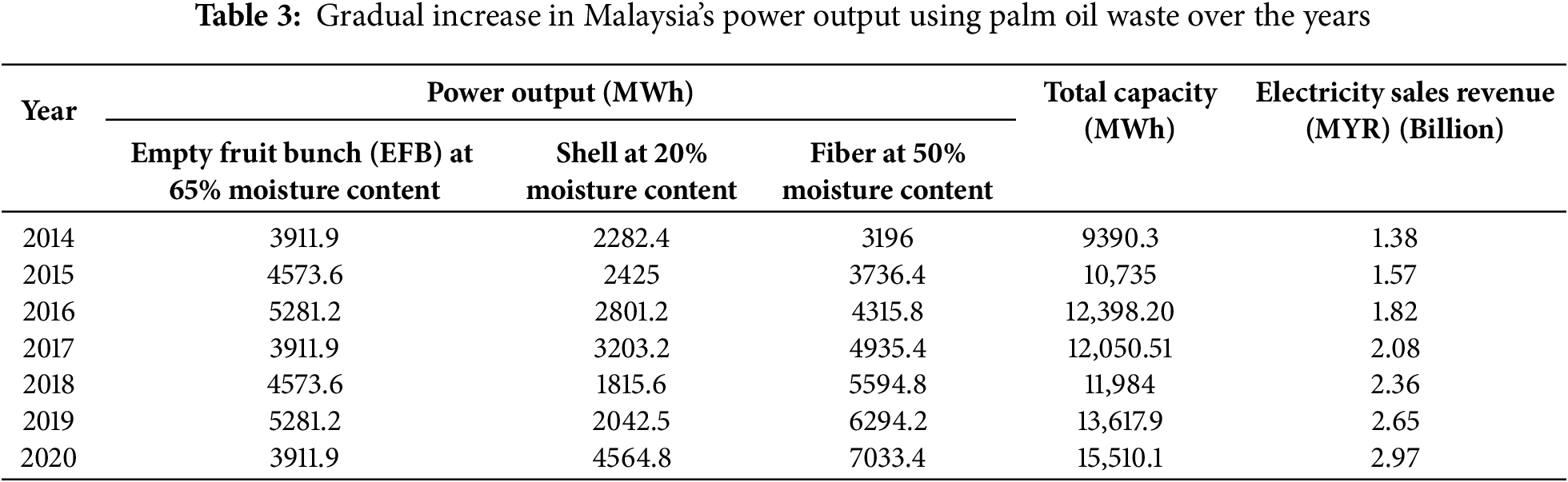

Table 3 shows the amount of electricity generated by Malaysia from palm oil wastes since 2014 [31,34,36,51].

3.1 Rest of the World’s Production of Palm Oil

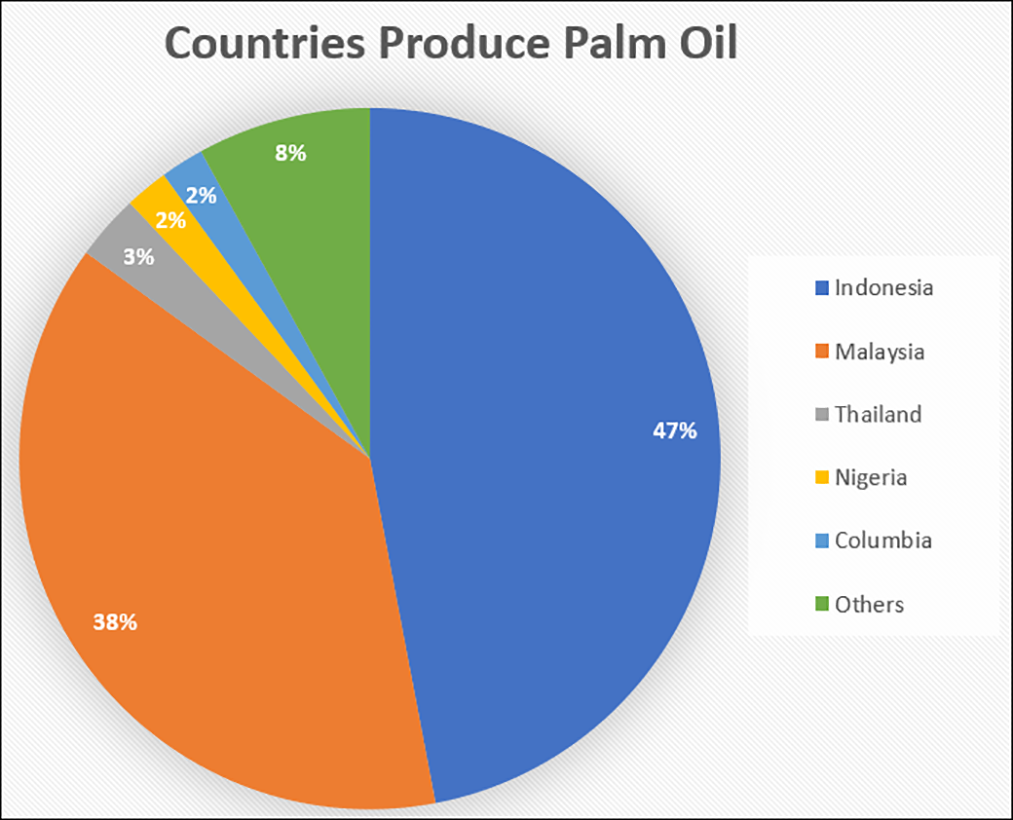

Apart from Malaysia, many other countries produce palm oil. They include Thailand, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Colombia, among others. Fig. 3 shows the percentage of palm oil produced by different countries. In the following section, we have focused on the amount of electricity generated from palm oil wastes by the three largest palm oil-producing countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand) [52].

Figure 3: The share of palm oil production by different countries [55]

Indonesia is rich in renewable energy sources like solar, wind, hydro and the most practical one, which is biomass. Palm oil is an example of biomass that can generate energy. In 2009, Indonesia produced 20.9 million tons of palm oil, thereby becoming the world’s largest producer. Due to its wide availability, palm oil waste was used as an alternative renewable energy source and was therefore used in the production of heat and power [53]. The industry generated different types of palm residues, like Empty Fruit Bunches (EFP), Palm Mesocarp fibers (PMF), and Palm Kernel Shells (PKS), at palm oil mills [40]. In general, palm oil trees have 90% biomass and 10% oil. Torrefaction is among the technologies of utilizing residues of biomass, making it an efficient renewable supply of energy. Torrefied biomass is advantageous in terms of energy production because it possesses Less moisture concentration, High density and reduced oxygen-to-carbon ratio, which increases the heating value.

Torrefaction technology is a better choice when it comes to sustainability and environmentally friendly than other options. The research was conducted on different parts of palm oil residues to find out the best part for torrefaction. The result showed that mesocarp fiber and kernel shell are best suited as feedstocks because of their combustion quality [54]. An oil palm factory in Indonesia, in fact, uses 220,000 t of empty fruit bunches (EFB) per year to generate 10.3 MW of electricity with a steam turbogenerator [44].

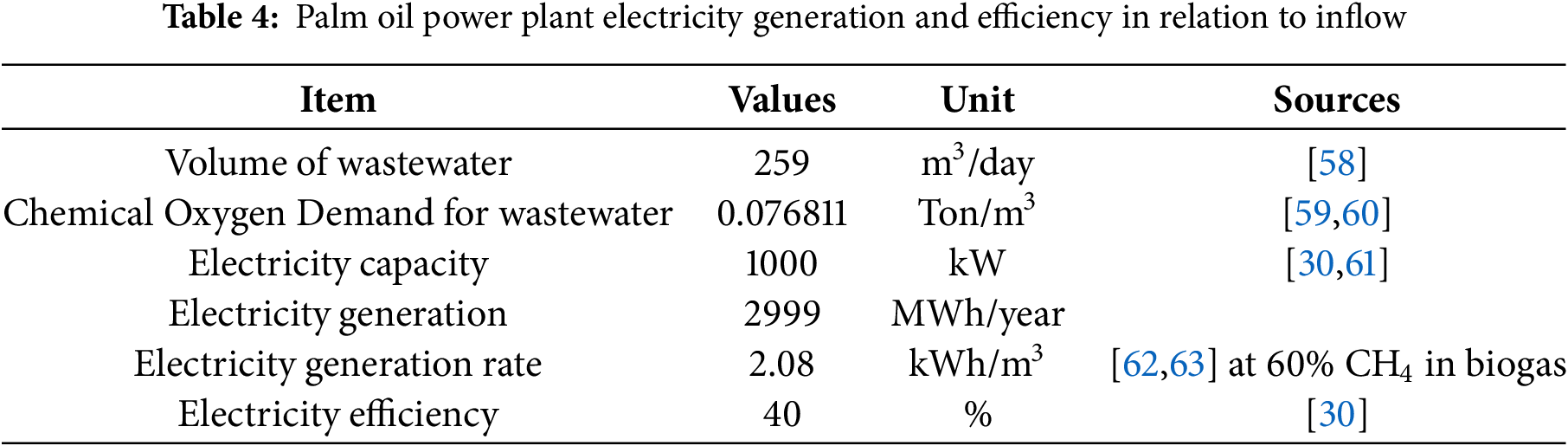

Thailand is ranked as the world’s third-highest producer of palm oil [31]. The palm oil industry in Thailand is continuously expanding due to the consumption of edible oil and the production of biodiesel. In 2009, Thailand produced 1.35 metric tons of palm oil. This was estimated to be 3.06% of total production in the world [52]. During the past decades, the cultivation of oil palm in Thailand has tripled. Since 2000 the deforestation rate has gone high for palm oil plantations [55]. The Government encourages the production of biofuel out of palm oil. This process comes with some drawbacks, like biodiversity loss and pollution brought about by the emission of greenhouse gases. To curb the above environmental setbacks, the Government introduced several options to reduce greenhouse gas emissions [56]. They include the production of biogas from the effluent that comes out of palm oil mills, power generation from empty fruit bunches (EFB) combustion and converting EFB to bio composts. To reduce the environmental effect, the emission of acidifying compounds should be drastically reduced. Combustion of EFB helps to reduce the emission of acidic compounds like methane by converting EFB to electricity. This electricity partially replaces the electricity from the grid [31]. Thailand produces 2999 MWh per year from palm oil waste, as shown in Table 4 [57].

Irresponsible disposal of Palm oil waste is causing an unavoidable economic burden on the societies and industries that deal with oil palm production. Studies suggest that one ton of palm oil fresh fruit bunch generates around 50%–70% of its weight in Palm oil mill effluent [49]. The waste treatment solutions do demand monetary input which is seen as a liability. Therefore, most of the palm oil industry invests little to nothing in their wastewater management. As practice becomes common, it renders the waste that is eventually discharged to be improperly treated, and this trend is increasingly becoming common in developing countries. These activities cannot be fully eradicated as companies will be less diligent in investing in something they deem a loss. An incentive must be placed to entice industries to adopt sustainable waste disposal. A solution that bridges the industries’ economic concerns and the sustainable need for the environment secretly lies in the palm oil waste itself. The waste from palm oil has been known to contain a high level of organic content. This makes it a suitable candidate to produce biogas [11]. Most palm oil mills endorse the open pond waste treatment system (OPWTS) [64]. The government over-watch strategy regulates the treatment process in countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, where it is reported that around 70%–85% of the mills have adopted OPWTS. Although it can be assumed that these regulations are observed due to government enforcement [11], in Malaysia, the Government has started to incentivize the utilization of biogas, and this creates a win-win situation for both the palm oil industry and the Government [65].

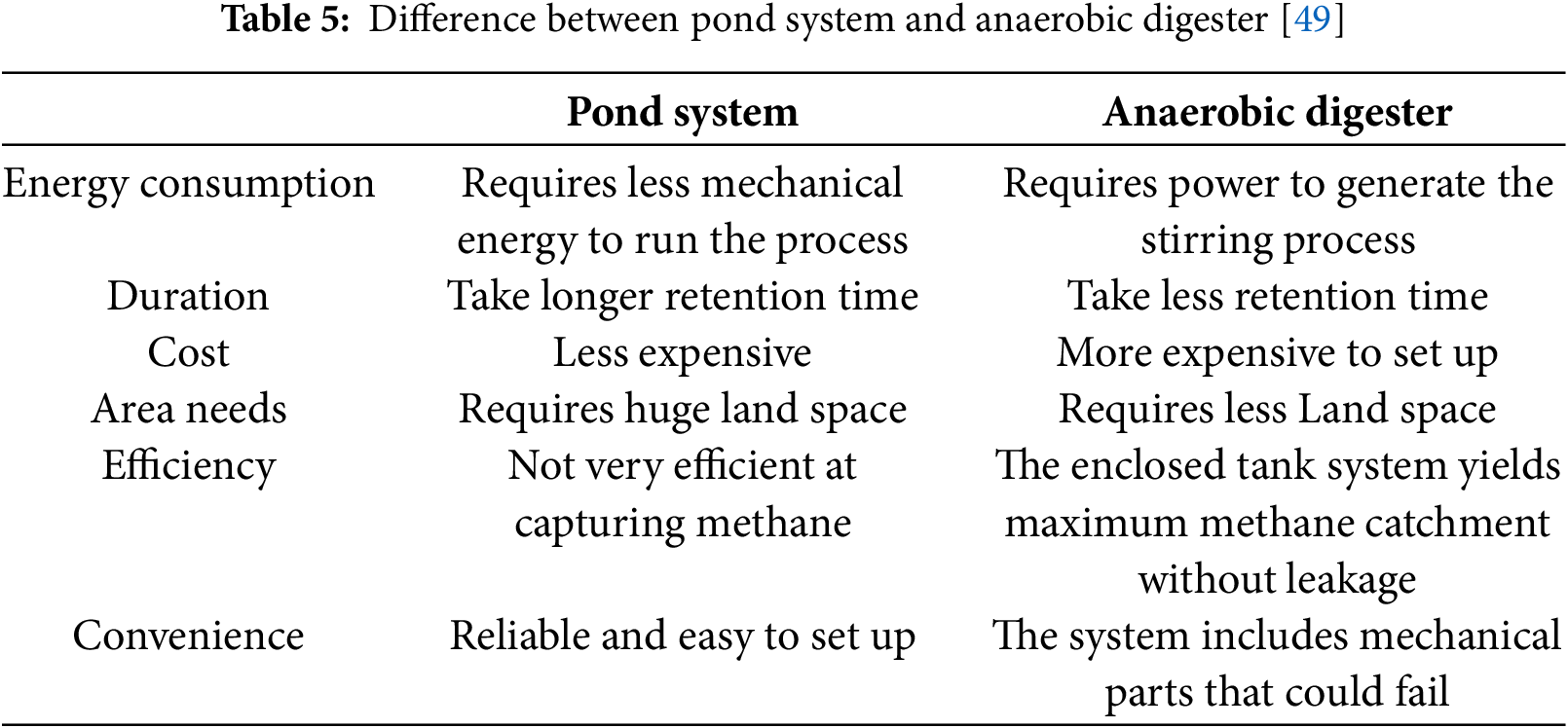

OPWTS as a biological treatment is preferred due to its low cost and its less reliance on mechanical inputs [66]. The system includes ponds that allow the palm oil waste to undergo anaerobic disintegration, which helps to decompose the harmful compounds in the solution. Biogas is produced as a by-product of the slow reaction, and this presents a solution to the economic disadvantages that are normally associated with POME waste discharge [49]. The digestive process in the pond happens in a series of stages. It starts with the anaerobic stage, where bacterial action helps to disintegrate the organic and inorganic contents of the waste. This reduces both the biological and chemical oxygen demand (BOD and COD) of the effluent [65]. Afterwards, the waste is transferred to aerobic and facultative ponds to further reduce the harmful compounds and make the effluent reach the standard quality for discharged waste. Although both processes are often integrated into one system, both have pros and cons, which are outlined in Table 5.

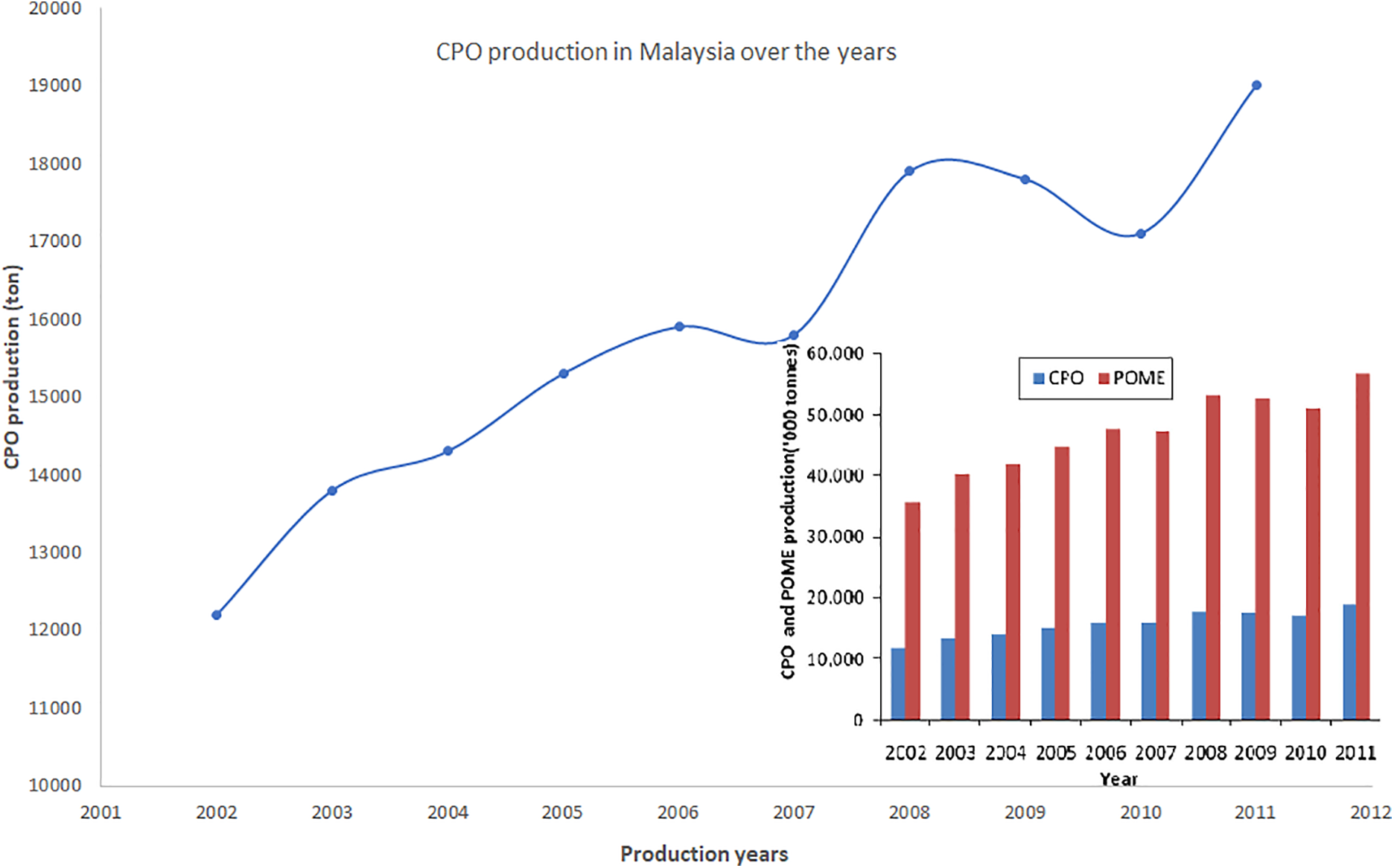

Utilization of biogas for the pond system is done by sealing the ponds with an airtight fabric material which helps trap all the methane produced during the anaerobic process [49]. Other methods that are more effective but not very common include the more expensive POME anaerobic digester, which includes a mechanized stirring feature that speeds up the anaerobic process and efficiently traps the methane gas produced [67]. Throughout the oil extraction process, ample effort is put into oil reclamation from the effluent with the use of a separator to ensure maximum oil yield from the raw bunches. But after all the processing, the oil constitutes only 22.5% of the overall matter of the palms, and the remainder 77.5% makes up the palm bio-matter waste [68]. The ratio of POME generation to CPO production can be estimated from a simple illustration given in Fig. 4 which indicates that the ratio is often more than 3:1.

Figure 4: Relationship between crude palm oil (CPO) production and POME generation in Malaysia [11]

Palm oil production has garnered a bad reputation regarding the sustainability of the process and is one of the leading causes of deforestation and the destruction of biodiversity. Many concerned regulatory boards, such as the ones in the European Union, have become influenced to draw strict regulations on palm oil grown on land that was occupied by forests, putting much emphasis on energy regeneration from the POME waste [69]. Biogas, which is rich in methane content, is not properly utilized in most mills; the wastage contributes to the Global increase in GHG [70]. To combat this problem, the biogas captured will be utilized in electricity generation or as an alternative boiler fuel to replace palm kernel shells which are less efficient. Either way, this will greatly improve overall palm oil production [71]. Highly processed biogas from POME has about 80%–90% of methane content, which is comparable to methane content in conventional natural gas and thus makes it a viable option to be directly streamed into the national gas supply grid to reduce the dependency on fossil-derived gases [72]. Methane capturing helps to reduce GHG, and by this method, about 20–60 kWh of energy/ton FFB can be captured, which contributes to reducing GHG of about 110–170 kg carbon dioxide equ/ton FFB. The energy obtained from the POME biogas retention process, when used to generate electricity, subsidizes the energy consumed by the production facility. A mill that produces around 40 t of FFB per hour will have a potential capacity to produce around 0.1–1.5 megawatts of electricity. Therefore, we can conclude that when effluent palm oil mills are utilized in a sustainable way, it results in a yield of renewable energy which can be used to satisfy the power needs of a mill and make the process sustainable. It is forecasted that in Malaysia, around 500 t of methane could be produced if all the palm oil mills practice biogas catchment. This methane could produce energy that is equivalent to the energy produced by around 800 million litres of diesel [11]. The potential electrical power expected from this peak yield is estimated at 3.2 million MWh. This power can be used to support around 700,000 homes. Consequently, the advent of sustainable POME biogas generation will boost the country’s plan to reduce the national grid’s dependency on fossil fuels [11].

Most conventional palm oil mills have, in one way or another, adopted self-sufficient practices. It is very common for mills to combust residual oil palm fibres and shells to generate fuel for the boilers [64]. It can be argued that from the energy yield listed in the paragraph above, mills stand to gain a lot more economically when they adopt energy generation from biogas. This trend is slowly picking up among palm oil mills in Malaysia thanks to Green Technology Financing Scheme (GTFS), an initiative by the Malaysian Government to reward and encourage industries that contribute to sustainable technologies [65]. Such incentives include tax reliefs, removal of import duties and discounted machinery sales for participants. The utilization of POME for renewable energy generation helps reduce the contamination of rivers and forest drainage paths, leading to the conservation of threatened wildlife [72]. The energy generated can bring economic advantages to the palm oil industry by promising a subsidy on the energy demand of a mill [21]. This will especially assist local and small-time farmers. The aboriginal communities residing around many palm oil plantations will also benefit as the energy generated can supply their rural communities and improve their standards of living. This will solve the long-standing dispute between corporations and forest communities [73].

5 Feasibility of Oil Palm Waste Management

The palm oil industry has been the user of a major and efficient oilseed crop around the world. The two main powerhouses for palm oil production are Malaysia and Indonesia. These major powerhouses alone produced a revenue of USD 40 billion in 2012 [21]. In Malaysia, palm oil wastes are one of the major industrial solid wastes. There are challenges associated with the palm oil industry in Malaysia in terms of waste management. However, these challenges also provide a window of opportunities to utilize these wastes for renewable energy, thus saving costs and increasing the total profit earned in palm oil industries. As the energy consumption in Malaysia increases by 8.1% annually, more energy resources are needed for the increasing demand [21]. Moreover, the challenges also open job opportunities for the Malaysian population. Yet the challenge remains of managing the surplus waste from increased production; oil palm mills must adopt a sustainable waste management technique. But then again, the question remains, do these mills have access to proper waste management methods?

The oil palm industry produces tonnes of waste every year. In Malaysia alone, 19.7 million tonnes of crude palm oil (CPO) have been produced [68]. While this is an impressive figure, what about the waste? In the oil palm industry, there are numerous types of waste produced in the making of oil palm, such as EFB, Oil Palm Shell (OPSh), Mesocarp Fibers, POME, Palm Oil Fuel Ash (POFA), Palm Kernel Cake (PKC), and Decanter Cake (DC). These wastes can be utilized for different purposes. Most of these wastes are organic wastes. So, burying them is not the best option because burying organic waste will produce methane gas. Methane gas is known to be 20 times more potent than greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. However, these wastes can be reused as a source of renewable energy for multiple applications. As for waste management, oil palm waste can be categorized into two uses—agricultural use and non-agricultural use [57,74]. The Empty Fruit Bunches (EFB) can be brought back to the plantation area to be utilized as mulch [72]. It can be applied directly to the land [37]. Empty Fruit Bunches can also be dewatered and utilized to generate electricity or used as organic diesel. Mesocarp Fibers can be utilized as a blend of animal feed. POME contains carotene, which can be utilized in pharmaceuticals. The biogas emitted from POME can be used to generate electricity. Palm Kernel Cake (PKC) is a substance with a texture of greyish white colour. It is produced when extraction of kernel oil production occurs [36]. Since it is rich in carbohydrates, it can be used as feedstock. Decanter Cake (DC) is a palm oil side product that is produced during the extraction phase [32]. The majority of Decanter Cake (DC) can be used as fertilizer or soil cover materials. The utilization of Decanter Cake (DC) as fertilizer is brilliant as it enhances crop nutrient uptake [75]. For non-agricultural use, Empty Fruit Bunches can be used as paper-making pulp. In Japan, Empty Fruit Bunches are used to generate electricity through biomass power plants. In Malaysia, a biomass-fired steam generator plant was used to replace fuel oil with oil palm biomass [76]. The Oil Palm Shell (OPSh) can be used as fuel for boilers. The combustion of OPSh produces oil palm ash which is rich in minerals that can be utilized for various uses. Palm Oil Fuel Ash (POFA) is also a by-product of solid waste used as fuel to generate electricity. Thus, the waste from the palm oil industry can be used for multiple applications. The management of palm oil waste is not a very big issue. But the amount of waste produced is massive.

As for feasibility, these wastes can be managed if the right steps are executed. Although the waste is massive, they can still be turned into proper renewable energy [75]. These wastes are to be collected and transported to biomass plants to be put to good use. For this to occur, the biomass plant should be placed in a suitable location, as transportation costs might increase if the plant is in an improper area [6]. The main aim of using this renewable energy is to reduce spending on fuel. Thus, increasing the transportation cost defeats the purpose of the whole idea. As for rural areas, the biomass plant location must be chosen even more carefully since there may not be a proper route to access certain parts of these areas. For things to become easier, the biomass plant should be placed nearest to the mills and the roads [77].

The study evaluates the feasibility of energy projects that use palm oil waste by considering technical, economic, environmental, and socio-regional factors. Key criteria include resource availability, technological suitability, economic feasibility, environmental impact, socioeconomic benefits, and policy and regulatory support. The research focuses on regions with high production potential, such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and parts of Africa, and identifies areas with high production potential. It also assesses the economic feasibility of the project, analysing factors like initial capital costs, payback periods, government incentives, and fuel cost savings. The study also highlights the socioeconomic benefits of palm oil waste-to-energy projects, particularly in rural areas, and the readiness of regions or industries to adopt them.

The study examines palm oil waste generated during production and its potential for renewable energy generation. It categorises waste as solid and liquid biomass, each with specific energy applications. EFB are fibrous residues rich in lignocellulosic material, suitable for direct combustion, gasification, or pellet production. Palm Kernel Shells (PKS) are hard shells from palm kernels, used in industrial boilers and biochar production. POME is a liquid waste with organic compounds suitable for anaerobic digestion, producing biogas (methane) for on-site electricity or heat. Mesocarp fibre, extracted from fruit pulp, is used as boiler fuel in palm oil mills to support self-sufficient energy systems.

6 Case Study and Cost-Effective Comparison

This case study focuses on a cost-effective comparison between electricity generated by palm oil waste and electricity generated from a standalone diesel electric generation. The research area covered for this analysis is the rural area of Marudi, Sarawak. The location of this research area is 145 km away from the nearest city, Miri, Sarawak and roughly 2 h and 20 min of the journey using the road. Since the research area covers small towns like Long Lama, Long Miri, Long Atip and their surrounding areas, ten schools located nearby are considered for this analysis. The entire town can be reached either by using 4 Wheel Drive on land or by boat as there is no road connected to all the towns. The tarred roads link only up to the Long Lama Ferry Point. The road that is usually used by 4 Wheel Drive is through the logging roads. The journey can be challenging, with the possibility of rough rides in some places. One of the towns known as Long Lama has a ferry point that is called Long Lama Ferry Point. This ferry point is the one that helps vehicles to cross the Baram River to Long Lama town. This research area has trouble with electricity generation since the only way for electricity to be generated is by using diesel fuel, for which the consumption is high and costly. The analysis is done on the possibility of using the waste from palm oil as the source of electricity generation for all the towns nearby. This is because there are several palm oil mills located in the surrounding area, and there are palm oil plantations as well on the outskirts. Thus, the high amount of waste that is produced by all the mills is considered a source for the biogas plant to generate electricity. Fig. 5 shows the investigated research area of Sarawak, Malaysia.

Figure 5: The research area

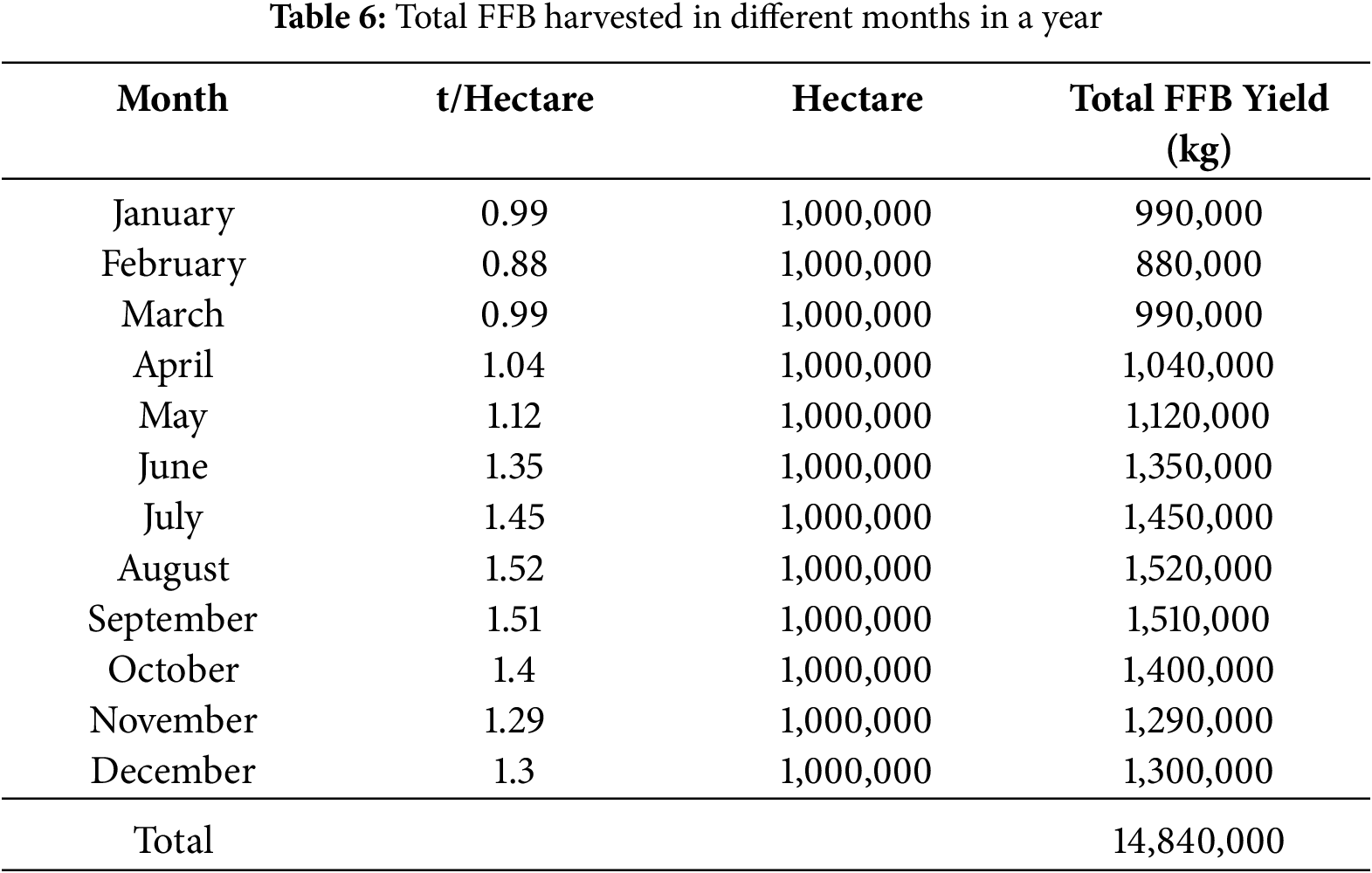

According to the Malaysian Palm Oil Board, Sarawak has 1,268,942 million hectares of mature palm oil plantations [75]. However, for convenience in calculations of oil yield per hectare, the total land for oil palm plantations in Sarawak can be 1 million hectares, which was used by the previous researcher [64]. Table 6 shows the total yield of fresh fruit bunches for the year 2016 [75].

The research was conducted based on google maps together with an online survey. It was found that Sarawak has 65 palm oil mills all around the state [75]. To calculate the total fresh fruit bunches, the total fresh fruit bunch yield was divided by 65 mills. It gives information that each mill produces 22,8307,693 kg of fresh fruit bunch for a year. Since the empty fruit bunch was in the calculations to generate electricity, the amount of empty fruit bunch produced per mill was calculated [27]. Empty fruit bunch is 22%–23% of fresh fruit bunch [61]. Taking the maximum percentage of 23% shows that 52,510,770 kg of empty fruit bunches are produced per mill. There are a total of 10 villages in our research area. Three thousand people, on average, reside in each of these villages. Moreover, there are also ten schools in the area.

In the Malaysian electricity consumption data, 4646 kWh of electricity is consumed per person per year in Sarawak [78], while schools consume 60,520 kWh per year in Sarawak [79]. Therefore, multiplying 30,000 people per year by 4646 kWh and adding the total electricity consumption for schools per year gives a total of 139,985,200 kWh. This value denotes the total electricity consumed for the whole year by 30,000 people and ten schools. Considering that the generator efficiency at the biomass plant to generate electricity would be 38%, the total actual power needed would be 368,382,106 kWh. Taking 1 kJ equals 0.000277778 kWh, the total energy needed to generate 368,382,106 kWh of power would be 1.32617 × 1012 kJ. According to the Sarawak Energy Research and Development department, the calorific value of an empty fruit bunch would be 6028 kJ per kilogram [80]. So, the total amount of empty bunches needed for one whole year to provide sufficient electricity to the research area would be 220,002,409 kg. Dividing it by 365 days gives a value of 602,747 kg of empty fruit bunch per day. This value depicts that waste from 5 mills is needed every day to meet the demands of electricity usage in the research area.

6.2 Cost of Diesel for Electric Generation

To understand the monthly power costs, we visited the schools in the related area and interviewed the management to acquire basic information related to the current electricity and fuel prices. The expenses of a school for electricity usage are MYR 6000 per month. This shows that schools need to spend MYR 200 on electricity daily. Hence, ten schools in the research area spend MYR 2000 per day on electricity alone. For the residents, 30,000 people in 10 villages use up to 140 MW of electricity per year. By obtaining values through journals and websites, if a diesel generator is used for the residents to generate electricity, 1 L of diesel can generate about 4 kW of electricity. So, simple math shows that for 140 MW electricity generation, 35,000 L of diesel are needed. Currently, diesel pricing is MYR 2.08 per liter. Multiplying it by 35,000 L gives a total of MYR 72,800 needed for the whole year and MYR 200 per day for 30,000 people. The total cost of electricity per day for ten schools and ten villages would be MYR 2200.

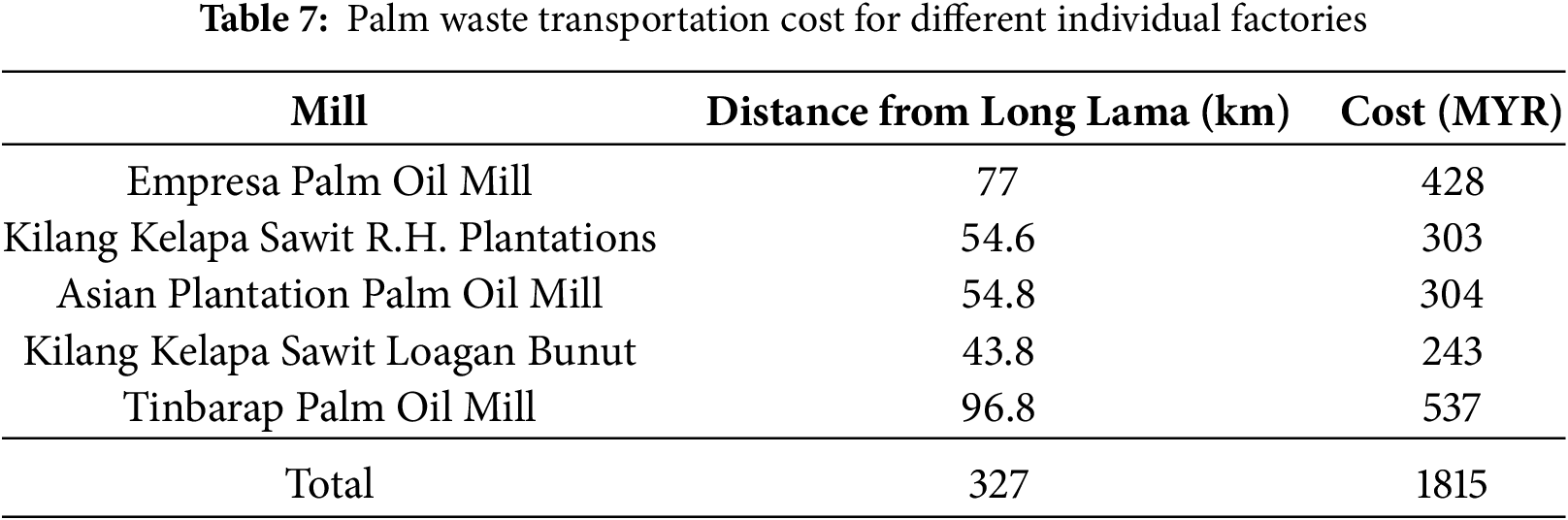

6.3 Cost of Transporting Palm Oil Waste

Since empty fruit bunches are used to generate electricity, transportation costs must be considered for delivering the empty fruit bunch to the self-sustaining biomass plant. The chosen location for the biomass plant would be Long Lama. So, to meet the daily electricity demands, an empty fruit bunch from 5 mills is needed every day. Considering that the transportation lorry has a maximum cargo weight of 18,000 kg, a total of 8 lorries are needed at each mill to transport the empty fruit bunch to the biomass plant. Mills nearest to Long Lama were chosen. Table 7 shows the transportation cost.

Since, on average, a lorry runs about 3 km per liter of diesel, the diesel required by a lorry is (distance from Long Lama/3) liters. The price of diesel per liter is taken to be MYR 2.08. Then, the Total Cost = Distance from Long Lama/3 ∗ No. of Lorries per mill ∗ Diesel cost per liter. The total cost is rounded to the nearest 1.

The total cost shows that it will only take MYR 1815 to power up ten schools and 30,000 people per day. Compared to using diesel, using EFB to generate electricity saves costs and promotes the usage of renewable energy.

6.5 Palm Biomass Compatibility

Various types of biomasses have been studied over the past years to investigate their potential to be an alternative source of renewable energy. Biomass, unlike most other sources, however, depends on its origin and operational conditions in generating output. So, the heating value, emission characteristics, combustion dynamics, etc., are usually varied with the technology and condition applied for harnessing the energy. Investigating the data from published sources shows that palm biomass provides a higher heating value (HHV) than other similar sources, provided that the biomass is conditioned and processed. A study compiled by [49] the HHV of biomasses from a wide range of sources reported to be from 7 to 21 MJ/kg [49]. Although this value is subjective to the process and techniques, palm biomass is always found to have a high HHV among others. In fact, raw palm biomass can provide up to 23 MJ/kg of HHV, whereas torrefied palm biomass was reported to generate 25.6 MJ/kg of biomass [63]. However, conditioning the palm biomass to biochar with normal particle size (100–150 mm) can yield up to 24.5 MJ/kg of HHV [81]. Comparing this value to that of abundant and common agricultural waste biomass, such as rice husk, wheat straw, rice straw and corn stalk, it is found that biomass from these waste produces about 14–21 MJ/kg of HHV, which is considerably lower than palm biomass HHV. Besides, given the fact that a huge amount of biomass can be obtained per unit area of palm plantation, it is obvious that investing in this technology’s practical implementation is more economically feasible [33].

It is understood that palm biomass is used for heat energy like other biomasses, but concrete evidence of generating electricity from this resource alone is rather scarce. It was projected through a preliminary study that about 46,436 GWh per annum of electricity could be potentially generated from EFFB [82]. Total electricity production from palm biomass is subject to argument as the result depends on many related variables. Part of the variables is the setup of new and special facilities, which has discouraged most of the mill owners from shifting from the existing facility to a new one at their premises. In fact, over 50% of the palm mill owners were found reluctant, and 26% said negatively about shifting toward a palm biomass-based electricity generation facility due to the inflicting cost and their scepticism about that technology; however, 58% of them agreed to supply the waste to third party facility for serving the same purpose [51]. Certainly, much is to be done to create awareness among the first users of the biomasses with the fact that such usages help to establish sustainable and circular economic growth. It is important to note that Palm biomass doesn’t emit SOx or HCl during combustion, and since the combustion temperature is well below that of fossil fuel, NOx in flue gas is significantly lower. In comparison, poultry waste biomass can significantly increase these gases in flue gas [59,83].

Biomass, including palm biomass, has been studied as an alternative source of renewable energy. However, the heating value, emission characteristics, and combustion dynamics vary depending on the technology and conditions used. Palm biomass provides a higher heating value (HHV) than other sources, provided it is conditioned and processed. Raw palm biomass can provide up to 23 MJ/kg of HHV, while torrefied palm biomass can generate 25.6 MJ/kg. Conditioning palm biomass to biochar can yield up to 24.5 MJ/kg of HHV. Compared to common agricultural waste biomass, palm biomass produces 14–21 MJ/kg of HHV. Despite its potential, concrete evidence of generating electricity from palm biomass is scarce. Over 50% of palm mill owners are reluctant to switch to a palm biomass-based electricity generation facility due to cost and skepticism. Awareness about sustainable and circular economic growth is needed.

Palm oil waste, particularly EFB and POME, presents a promising renewable energy source in countries like Malaysia and Indonesia. However, several technical, environmental, economic, and policy challenges need to be addressed to make it a sustainable and scalable solution. These include high moisture content in biomass; collection, transport, and logistics; technological limitations; emissions and environmental issues; financial and investment barriers; policy and regulatory gaps; and competing uses of biomass waste.

High moisture content in biomass reduces combustion efficiency and energy output, increasing drying costs and lowering calorific value. Solutions include using drying technologies, co-firing, or anaerobic digestion that work well with wet biomass.

Limited access to appropriate technologies can hinder efficient energy conversion, leading to inconsistent energy generation and higher maintenance. Hybrid systems, technology transfer, and capacity building can help address these issues.

Financial and investment barriers, policy and regulatory gaps, and competing uses of biomass waste can also impact the sustainability and scalability of biomass energy production.

Palm oil waste can be used to generate energy, offering economic and environmental benefits. It provides a low-cost, locally available resource, reduces dependence on imported fossil fuels, supports rural development, lowers energy costs for remote communities, and creates new employment opportunities. This renewable approach also helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions by capturing methane from POME and avoiding CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion. It also addresses agricultural waste management issues and aligns circular economic goals and global climate commitments.

Palm oil waste can be converted into renewable energy through various technologies. Anaerobic digestion, which breaks down organic matter in oxygen-free conditions, reduces methane emissions and provides clean energy for electricity or heat generation. Combustion and co-firing, which burns solid biomass waste like Empty Fruit Bunches and Palm Kernel Shells, offers moderate efficiency but may require emission controls. Gasification converts palm biomass into syngas at high temperatures with limited oxygen, offering cleaner, more controllable energy output. Pyrolysis, which heats palm biomass without oxygen, produces bio-oil, gas, and biochar, contributing to energy sustainability and agricultural productivity. These technologies support a circular economy and strengthen the sustainability of the palm oil industry, especially when decentralized and tailored to local needs.

Palm oil waste can be used for electricity generation, reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Traditional palm oil production produces large volumes of waste, including empty fruit bunches, palm kernel shells, and palm oil mill effluent. These wastes can be converted into energy using methods like anaerobic digestion, combustion, or gasification, reducing harmful emissions. Anaerobic digestion captures methane for biogas, preventing methane emissions over 25 times more potent than CO2. Palm biomass as a renewable energy source reduces reliance on fossil fuels, supporting carbon neutrality and improving air quality. This makes it an environmentally sustainable solution for energy production in palm oil-producing regions.

The implementation of palm oil waste-to-energy technology faces several challenges, including infrastructure limitations, high initial investment costs, limited access to funding, and logistical challenges. Infrastructure limitations are common in rural or developing regions, where modern facilities and waste-processing equipment are lacking. The high initial investment costs can deter private investors or small-scale producers. Limited access to funding and financing is also a challenge, as potential project developers face risks, long payback periods, and regulatory uncertainty. Additionally, transporting bulky biomass over long distances without proper infrastructure can increase costs and reduce efficiency. To overcome these challenges, government support, public-private partnerships, and the development of cost-effective, decentralized energy systems are needed.

Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand are the top global producers of palm oil, each adopting different strategies for managing waste and promoting renewable energy generation. Malaysia has a proactive approach, promoting palm oil biomass and biogas for power generation through initiatives led by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) and national policies like the National Renewable Energy Policy and Action Plan (NREPAP). The government also offers feed-in tariffs under the Sustainable Energy Development Authority (SEDA) to encourage renewable energy investment. Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer, faces challenges in policy enforcement, infrastructure, and environmental regulation. However, progress is being made with increased investment in biogas plants and collaboration with international agencies. Thailand has made notable progress in integrating palm oil waste into its renewable energy mix, particularly in community-based bioenergy projects. All three countries share the opportunity to further develop sustainable bioenergy systems by learning from each other’s strengths.

One of the primary motivations of this study is to mitigate the environmental harm caused by indiscriminate dumping of palm oil waste into water bodies or open land. Improper disposal leads to water pollution, eutrophication, and methane emissions from anaerobic decomposition. An alternative is energy recovery through controlled combustion or thermochemical conversion. However, it is important to assess how hydrocarbon emissions from palm oil biomass combustion compare to conventional fossil fuels.

Studies indicate that while burning palm biomass emits carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter (PM), the total hydrocarbon emissions especially unburnt hydrocarbons are significantly lower than those from coal or diesel combustion. Furthermore, because biomass is considered carbon-neutral over its lifecycle, the net CO2 emissions are substantially reduced. For instance, steam combustion of empty fruit bunches produces approximately 30%–40% lower CO2 emissions per kWh generated compared to coal, and emits negligible sulfur oxides (SOx), reducing acid rain potential.

Therefore, converting palm oil waste into electricity not only recovers energy but also reduces dependency on high-emission fossil fuels, contributing to climate mitigation strategies in Malaysia and beyond.

In this paper, we have reviewed and compared the state of electricity generation from biomass in various palm oil-producing countries. The advantages and disadvantages of using palm oil waste for the generation of electricity have been discussed. We then reported on our study of electricity generation from palm oil waste in a rural area of Marudi, Sarawak. In this area, 30,000 people, as well as 10 schools, are currently using diesel to generate electricity. This costs MYR 2000 per day. It is shown that using EFB from palm oil waste to generate electricity is cheaper in comparison. Biowaste is a renewable resource—its use in electricity generation also reduces GHG. More case studies like ours can be carried out in other rural areas of East Malaysia. Similar studies should be conducted in countries that produce palm oil. Future work may consider capital and running costs for the power plant. The reader might note that we have not done studies on the power system. For example, will energy storage be employed, and if so, what should be the optimum size of such storage? One also needs to study the interaction of the microgrid connected to the main grid. The future of power systems is a smart grid; as such, a grid can handle decentralized power generation from renewables. There are many aspects of research on smart grids. Although some studies have been reported on the integration of solar and wind power in a Borneo-wide grid, little work seems to have been reported on the integration of electricity generated from palm oil waste.

Converting palm oil waste into renewable electricity represents a sustainable and economically viable pathway for addressing both energy needs and environmental challenges in palm oil-producing regions. While the energy potential of palm biomass is substantial, realizing its full value requires overcoming infrastructural, financial, and policy-related obstacles. Targeted strategies such as government incentives, investment in decentralized technologies, public-private partnerships, and community-based energy systems can significantly enhance adoption. Furthermore, raising awareness and promoting technology transfer can support rural development, reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and mitigate climate change impacts. As Malaysia and its regional counterparts continue to lead in palm oil production, leveraging palm oil waste for electricity generation offers a strategic opportunity to transition toward a low-carbon, sustainable energy future.

Acknowledgement: The authors are thankful to the facility provided by the Swinburne University of Technology Sarawak Campus for conducting this research. We are also very thankful for the invaluable input given to this article by Dr. Manas Kumar Halder, who sadly passed away during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Overall research topic and supervision: Mujahid Tabassum, Saad Bin Abdul Kashem. Calculation, tables and figures adjustments: Md. Bazlul Mobin Siddique, Hadi Nabipour Afrouzi. Draft manuscript writing: Mujahid Tabassum, Md. Bazlul Mobin Siddique, Hadi Nabipour Afrouzi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors ensure the authenticity and validity of the materials and data in the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Afrouzi HN, Hassan A, Wimalaratna YP, Ahmed J, Mehranzamir K, Liew SC, et al. Sizing and economic analysis of stand-alone hybrid photovoltaic-wind system for rural electrification: a case study Lundu. Sarawak Clean Eng Technol. 2021;4(3):100191. doi:10.1016/j.clet.2021.100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. International Energy Agency. World energy outlook 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023. [Google Scholar]

3. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change 2023: Synthesis report [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/. [Google Scholar]

4. IRENA. Global renewables outlook 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.irena.org/publications/2024/Jan/Global-Renewables-Outlook-2024. [Google Scholar]

5. Shaikh PH, Bin Mohd Nor N, Ali Sahito A, Nallagownden P, Elamvazuthi I, Shaikh MS. Building energy for sustainable development in Malaysia: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;75(1):1392–403. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rahman A, Farrok O, Haque MM. Environmental impact of renewable energy source based electrical power plants: solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, tidal, ocean, and osmotic. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;161(3):112279. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Begum S, Saad MFM. Techno-economic analysis of electricity generation from biogas using palm oil waste. Asian J Sci Res. 2013;6(2):290–8. doi:10.3923/ajsr.2013.290.298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kashem SBA, Chowdhury ME, Khandakar A, Tabassum M, Ashraf A, Ahmed J. A comprehensive investigation of suitable biomass raw materials and biomass conversion technology in Sarawak. Malaysia Int J Tech. 2020;1(2):75–105. [Google Scholar]

9. Kashem SBA, Chowdhury ME, Tabassum M, Molla ME, Ashraf A, Khandakar A. A comprehensive study on biomass power plant and comparison between sugarcane and palm oil waste. Int J Innov Com Sci Eng. 2020;1(1):26–32. [Google Scholar]

10. Maaji SS, Khan DFS, Haldar MK, Tabassum M, Karunakaran P. Integration of solar and wind power to a Borneo-wide power grid. Int J Environ Sci Dev. 2013;2013:681–7. doi:10.7763/ijesd.2013.v4.438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mohammad S, Baidurah S, Kobayashi T, Ismail N, Leh CP. Palm oil mill effluent treatment processes—a review. Processes. 2021;9(5):739. doi:10.3390/pr9050739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ab Aziz IF. Lignocellulosic biomass-derived biogas: a review on sustainable energy in Malaysia. J Oil Palm Res. 2024;37(1):16–43. doi:10.21894/jopr.2024.0021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tabassum M, Kashem SBA, Mathew K. Distributed energy generation—is it the way of the future? In: Garg A, Bhoi AK, Sanjeevikumar P, Kamani KK, editors. Advances in power systems and energy management. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2017. p. 627–36. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-4394-9_61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Loh SK, Nasrin AB, Mohamad Azri S, Nurul Adela B, Muzzammil N, Daryl Jay T, et al. First report on Malaysia’s experiences and development in biogas capture and utilization from palm oil mill effluent under the Economic Transformation Programme: current and future perspectives. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;74(3):1257–74. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.02.066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pambudi NA, Firdaus RA, Rizkiana R, Ulfa DK, Salsabila MS, Suharno, et al. Renewable energy in Indonesia: current status, potential, and future development. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):2342. doi:10.3390/su15032342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mujiyanto S, Tiess G. Secure energy supply in 2025: indonesia’s need for an energy policy strategy. Energy Policy. 2013;61:31–41. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rosyidi SAP, Bole-Rentel T, Lesmana SB, Ikhsan J. Lessons learnt from the energy needs assessment carried out for the biogas program for rural development in Yogyakarta. Indonesia Procedia Environ Sci. 2014;20:20–9. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Singh J. Management of the agricultural biomass on decentralized basis for producing sustainable power in India. J Clean Prod. 2017;142(6):3985–4000. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chauhan K, Pratap Singh V. Prospect of biomass to bioenergy in India: an overview. Mater Today Proc. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.01.419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cerón AR, Weingärtner S, Kafarov V. Generation of electricity by plant biomass in villages of the Colombian Provinces: chocó, Meta and Putumayo. Chem Eng. 2015;43:577–82. doi:10.3303/CET1543097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Behrens P, Bosker T, Ehrhardt D. How is food production related to biodiversity loss? In: Behrens P, Bosker T, Ehrhardt D, editors. Food and sustainiability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2020. p. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

22. Kennedy Smith R, Hobbs BF. Biomass combustion for electric power: allocation and plant siting using non-linear modeling and mixed integer optimization. J Renewable Sustainable Energy. 2013;5(5):053118. doi:10.1063/1.4819493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kannan R, Ramalingam S, Sampath S, Nedunchezhiyan M, Dillikannan D, Jayabal R. Optimization and synthesis process of biodiesel production from coconut oil using central composite rotatable design of response surface methodology. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part E J Process Mech Eng. 2024;52(133323):09544089241230251. doi:10.1177/09544089241230251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yoshizaki T, Shirai Y, Ali Hassan M, Baharuddin AS, Raja Abdullah NM, Sulaiman A, et al. Improved economic viability of integrated biogas energy and compost production for sustainable palm oil mill management. J Clean Prod. 2013;44:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. International Energy Agency. World energy outlook 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024. [Google Scholar]

26. Pattanayak S, Hauchhum L, Loha C, Sailo L. Feasibility study of biomass gasification for power generation in Northeast India. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2023;13(2):999–1011. doi:10.1007/s13399-021-01419-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Martsri A, Yodpijit N, Jongprasithporn M, Junsupasen S. Energy, economic and environmental (3E) analysis for sustainable development: a case study of a 9.9 MW biomass power plant in Thailand. Appl Sci Eng Prog. 2021;14(3):378–86. doi:10.1109/ieem.2017.8290087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sodri A, Septriana FE. Biogas power generation from palm oil mill effluent (POMEtechno-economic and environmental impact evaluation. Energies. 2022;15(19):7265. doi:10.3390/en15197265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Abul SB, Muhammad EH, Tabassum M, Muscat O, Molla ME, Ashraf A, et al. Feasibility study of solar power system in residential area. Int J Inn Com Sci Eng. 2020;1(1):10–7. [Google Scholar]

30. Aghamohammadi N, Reginald S, Shamiri A, Zinatizadeh A, Wong L, Nik Sulaiman N. An investigation of sustainable power generation from oil palm biomass: a case study in Sarawak. Sustainability. 2016;8(5):416. doi:10.3390/su8050416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Aziz M, Kurniawan T, Oda T, Kashiwagi T. Advanced power generation using biomass wastes from palm oil mills. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;114:1378–86. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.11.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Umar HA, Sulaiman SA, Meor Said MA, Gungor A, Shahbaz M, Inayat M, et al. Assessing the implementation levels of oil palm waste conversion methods in Malaysia and the challenges of commercialisation: towards sustainable energy production. Biomass Bioenergy. 2021;151(2):106179. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2021.106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Qian X, Lee S, Chandrasekaran R, Yang Y, Caballes M, Alamu O, et al. Electricity evaluation and emission characteristics of poultry litter co-combustion process. Appl Sci. 2019;9(19):4116. doi:10.3390/app9194116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Khatun R, Reza MIH, Moniruzzaman M, Yaakob Z. Sustainable oil palm industry: the possibilities. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;76:608–19. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Phuang ZX, Lin Z, Liew PY, Hanafiah MM, Woon KS. The dilemma in energy transition in Malaysia: a comparative life cycle assessment of large scale solar and biodiesel production from palm oil. J Clean Prod. 2022;350:131475. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Angeline AA, Jayakumar J, Asirvatham LG, Marshal JJ, Wongwises S. Power generation enhancement with hybrid thermoelectric generator using biomass waste heat energy. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2017;85(11):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2017.02.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]