Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Thermo-Hydrodynamic Characteristics of Hybrid Nanofluids for Chip-Level Liquid Cooling in Data Centers: A Review of Numerical Investigations

1 School of Energy and Safety Engineering, Tianjin Chengjian University, Tianjin, 300384, China

2 School of Computer Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi'an, 710126, China

3 Department of Applied Physics and Electronics, Umeå University, Umeå, SE-901 87, Sweden

* Corresponding Authors: Zhihan Lyu. Email: ; Bin Yang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Energy Efficiency and Thermal Management for Data Center)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(9), 3525-3553. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067902

Received 15 May 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 26 August 2025

Abstract

The growth of computing power in data centers (DCs) leads to an increase in energy consumption and noise pollution of air cooling systems. Chip-level cooling with high-efficiency coolant is one of the promising methods to address the cooling challenge for high-power devices in DCs. Hybrid nanofluid (HNF) has the advantages of high thermal conductivity and good rheological properties. This study summarizes the numerical investigations of HNFs in mini/micro heat sinks, including the numerical methods, hydrothermal characteristics, and enhanced heat transfer technologies. The innovations of this paper include: (1) the characteristics, applicable conditions, and scenarios of each theoretical method and numerical method are clarified; (2) the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation can reveal the synergy effect, micro motion, and agglomeration morphology of different nanoparticles. Machine learning (ML) presents a feasible method for parameter prediction, which provides the opportunity for the intelligent regulation of the thermal performance of HNFs; (3) the HNFs flow boiling and the synergy of passive and active technologies may further improve the overall efficiency of liquid cooling systems in DCs. This review provides valuable insights and references for exploring the multi-phase flow and heat transport mechanisms of HNFs, and promoting the practical application of HNFs in chip-level liquid cooling in DCs.Keywords

The rapid evolution of information technologies has put forward higher requirements for the intelligent computing power of data centers (DCs), resulting in an increase in electricity consumption at a rate of more than 10% annually [1]. The cooling system’s energy consumption accounts for nearly 40% of total energy consumption [2]. The exponential growth in the number of transistors on the electronic chips makes the heat production achieve 103–104 W/cm2. This causes uneven temperature distribution and local overtemperature in limited space [3]. The heat generated by different electronic components inside the servers in the DCs is uneven with a transient variation. The specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity of the air are relatively small, leading to a low cooling efficiency. Decreasing the supply air temperature or increasing the supply air volume to eliminate local hotspots will cause overcooling and additional energy consumption [4,5]. Forced air convection heat transfer can only meet the cooling demand below 120 kW/m2, while the liquid cooling technology can meet the heat flux up to 1000 kW/m2 [6]. Traditional air cooling cannot remove the high heat production and respond to the variation of heat flux of micro chips timely. While chip-level liquid cooling can directly take the heat away from the micro chips, which has the advantages of high cooling capacity and low noise, attracting the attention of many scholars [7]. The microchannel heat sink (MCHS) is suitable for chip-level cooling in DCs because of its efficient heat transport, easy integration, and small size [8]. However, traditional pure liquid cannot deal with the heat removal problem of large-power chips and devices for DCs [9,10]. It is urgent to develop novel cooling mediums to heighten the cooling efficiency.

The concept of nanofluids proposed by Choi et al. points the way to enhance the energy transport rate of coolant [11]. Metal, metal oxides, or non-metallic oxide nanoparticles with a diameter of less than 100 nm are uniformly dispersed in the base fluid to produce the nanofluid coolants. A lot of research on traditional mono-nanofluids, i.e., nanofluids with single components, has been carried out [12–15]. Compared with the pure liquid, the thermal conductivity of the mono-nanofluids is heightened, thus improving the heat dissipation capability of the liquid cooling system. Due to the micro convection and disturbance on the boundary layer, mono-nanofluids with high thermal performance have been widely used in electronic component cooling, refrigeration systems, energy storage systems, and other high-tech fields [16,17]. Results showed that the heat transfer capacity of the traditional coolants had been enhanced along with an acceptable pressure drop by adding nanoparticles. At present, mono-nanofluids have been applied in some real scenarios. Micali et al. [18] improved the performance of the air conditioning system by using Al2O3-water nanofluid instead of water in air-cooled chillers. Results manifested that the average coefficient of performance (COP) could be increased by 9.1%, achieving energy savings with low cooling costs and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Wang et al. [19] confirmed the high stability and heat dissipation rate of mono-nanofluid in liquid cooling of DCs. The average specific heat capacity of the supramolecular modified TiO2-nanofluid was 3.15 times higher than that of air cooling based on the experimental results. This proves the feasibility of nanofluids for improving the cooling efficiency of DCs. Gasmi et al. [20] discussed the thermal performance of a motile-microorganism within the nanofluid flow. The solar radiation mechanism, thermophoresis, Brownian motion, and temperature gradient features were explored thoroughly.

The hybrid nanofluid (HNF) contains more than two different particles, which have higher thermal conductivity and superior cooling efficiency than mono-nanofluids [21,22]. The complex interaction between different particles and liquid molecules affects the motion and aggregation of the nanoparticles, thus changing the thermal properties of the coolants. Therefore, revealing the heat transport and hydrodynamic mechanisms of nanoparticles from a microscopic perspective can provide an opportunity for controlling the thermo-hydraulic features of HNFs. The practical applications of the HNFs have proved their good heat transfer performance. Shaalan et al. [23] argued that the electrical efficiency of the photovoltaic (PV) panels could be improved by 12.1% by employing HNFs compared to air cooling. Kanti et al. [24] found that the HNFs could reduce the average temperature of lithium-ion batteries (LIB) by 30.3%, ensuring the temperature uniformity of batteries when the discharge rate was 1C. Nowadays, there are fewer practical applications of HNFs in DCs. Chip-level liquid cooling using HNFs as working media is a potential heat dissipation mode, which should be further investigated numerically and experimentally.

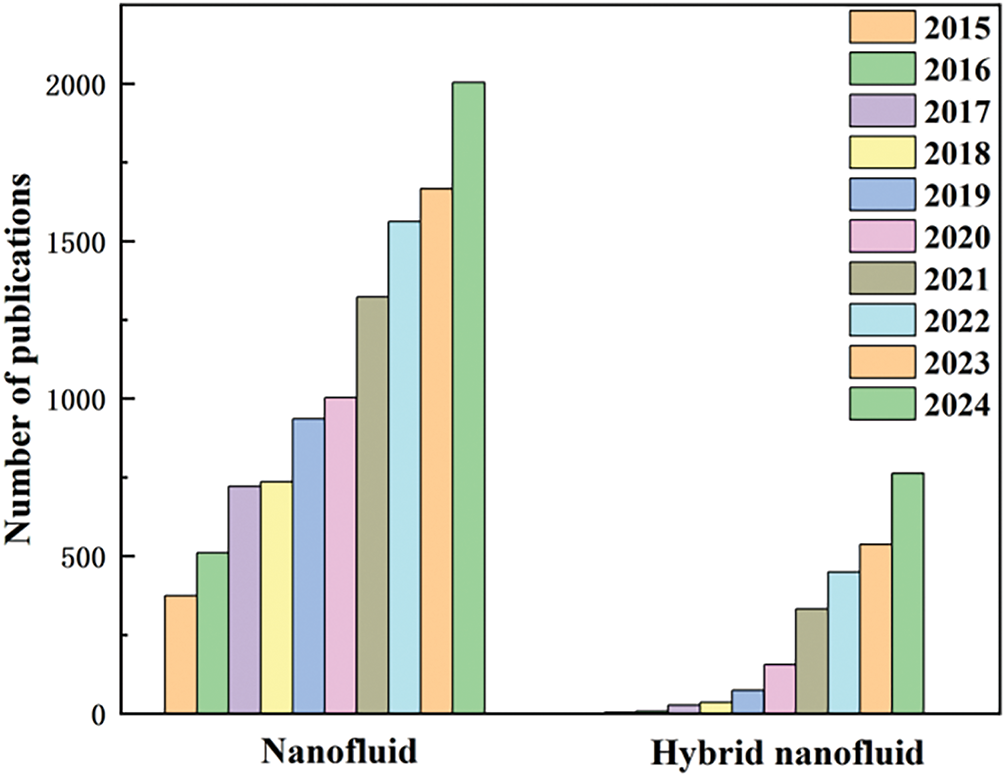

As depicted in Fig. 1, the numerical research on nanofluids has increased markedly over the past decade. There are 2003 papers of numerical studies on nanofluids being published in 2024. Compared to the traditional mono-nanofluids, there are still few numerical studies on HNFs. However, the growth rate of the investigations about HNFs has increased. In recent years, the effects of base fluid, concentration, and other parameters of HNFs on their stability, thermophysical properties, and energy transport characteristics have been discussed by experiments [25,26]. However, the Brownian motion, aggregation effect, and thermophoresis of multi-component nanoparticles will affect their hydrothermal performance. The motion and morphology of nanoparticles are difficult to measure experimentally [27]. Therefore, a growing number of investigators are devoted to numerical simulation. The main aim is to establish the relationship between micro morphology and macro thermo-hydraulic characteristics, revealing the essence of enhanced energy transport [28,29].

Figure 1: Number of numerical research on nanofluids over the past decade

Nowadays, there are some reviews of experimental studies on nanofluids. However, there is a lack of summary, classification, and discussion of numerical studies on HNFs. The research on HNFs has the following deficiencies. (1) The applicable conditions and application scenarios of various theoretical models and numerical methods are not divided; (2) The variation trends of heat transfer coefficient (HTC), pressure drop, and Nusselt number (Nu) have been obtained by numerical simulations and experiments. However, there is a lack of microscopic mechanism explanations for the nature of the phenomena; (3) Most studies only discuss the preparation method and the influence of various parameters on the stability and thermophysical properties of HNFs without practical application data.

Therefore, this paper reviews the progress of numerical investigations of HNFs in recent years, summarizes the existing numerical methods, and identifies future research directions and opportunities. The innovations of this paper include the following aspects. (1) The advantages and disadvantages, applicable conditions, and scenarios of theoretical models and numerical methods are clarified and compared; (2) The energy transport features and thermal performance of HNFs are analyzed and illustrated. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is recommended for the analysis of microscopic motion and behavior of nanoparticles; (3) The limitations, opportunities, and future perspectives are discovered from the aspects of intelligence algorithm, mechanism exploration, and synergy effect of various modification methods.

Firstly, the theoretical models and numerical methods of flow and heat transfer for HNFs were introduced in Section 2. The single-phase model, two-phase model, and thermophysical parameter correlations were elaborated in detail. The characteristics and procedures of the finite element method, finite volume method, and MD simulation were compared. Secondly, the energy transport characteristics of HNFs were analyzed in Section 3, including the thermal conductivity, dynamic viscosity, and HTC. Thirdly, the combination of HNFs and other heat transfer improvement methods was discussed thoroughly in Section 4, including the passive and active methods. Finally, the opportunities and future perspectives for high-efficiency energy transport were proposed in Section 5. The limitations of the current study mainly include the lack of control methods for the thermophysical properties of nanofluids and the practical application in cooling systems of DCs. Therefore, it needs to be further studied in the aspects of configuration modification and optimization, synergy and regulation of multi-nanoparticles, and the combined methods for heat transfer improvement. This review provides feasible methods for revealing the microscopic mechanism of thermal improvement of nanoparticles, thus regulating the thermo-hydraulic performance of HNFs. It promotes the practical applications of HNFs in chip-level liquid cooling of DCs, battery thermal management, renewable energy utilization, etc.

2 Model Description and Methodology

The experimental study on the HNFs can only analyze the thermal and hydraulic performances from the macro-level. While the numerical simulations can clarify the variation of multi-physical fields and explain the heat transport mechanism and flow resistance features at the micro-level. Moreover, the numerical method has low cost and high efficiency, which provides a sufficient theoretical basis for the experiments.

Considering the extremely small volume of nanoparticles, for the low concentration of less than 5%, some researchers defined the HNFs as homogeneous fluids and established a homogeneous model under laminar flow, i.e., single-phase model, to characterize the thermo-hydrodynamic features [30–32]. The following hypotheses are proposed [33]. The nanoparticles are assumed to move at the same velocity as the base fluid without a velocity slip. Nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed in the base fluid. Both the liquid phase and solid phase are in hydrodynamic and thermodynamic equilibrium states. The velocity difference and heat transfer between the solid particles and the fluid are ignored.

The continuity, momentum, and energy equations are summarized as follows [32]:

Continuity equation [32]:

where ρ and

Momentum equation [32]:

where p is the pressure, and μ denotes the viscosity of nanofluids.

Energy equation [32]:

where λ is the thermal conductivity, Cp is the heat capacity, and T is the temperature.

The effects of gravity, the friction between fluid and solid particles, and Brownian force on the nanoparticles will affect the thermo-hydraulic features of the nanofluids. Therefore, some scholars proposed a two-phase model to analyze heat and mass transports considering the HNFs as solid-liquid mixtures [32,34–36]. The assumptions for the numerical simulations include: The nanoparticles are in thermal equilibrium with the base fluid; The thermophysical properties of both nanoparticles and base fluid are considered temperature-dependent; The buoyancy density is assumed a Boussinesq approximation; The radiation, viscous dissipation, and external forces are ignored; There is no chemical reaction; The slip velocity of nanoparticles is introduced considering the different velocity for each phase.

Thus, the continuity, momentum, and energy equations are expressed as:

Continuity equation [37]:

where ρHNF and

Momentum equation [37]:

where, μHNF and

Energy equation [32]:

where φk is the volume fraction of the phase k.

The density and viscosity of HNFs is calculated by [37,38]:

The shear stress of HNFs τHNF and the total shear stress τ are defined as [37]:

In conclusion, the single-phase model ignores the movement of nanoparticles in the base liquid. The two-phase model considers the velocity slip of nanoparticles leading to an additional computational load. Therefore, it is necessary to balance the relationship between computational cost and accuracy. At low Reynolds number (Re), the errors of the single-phase model and the two-phase model are relatively small. With the increase of the Re, the results obtained by the two-phase model have higher accuracy [32]. When the concentration of the nanofluid is low, the convective heat transfer process can well conform to the single-phase assumption [39]. With the increase of the nanoparticle volume fraction (>4%), Moraveji et al. [40] indicated that the gap between the single-phase and two-phase models was 4%–10%. Although the two-phase model has higher accuracy, if the error is within the acceptable range, the single-phase model can be used. Ding et al. [41] pointed out that the single-phase model was inaccurate when the Peclet number exceeds 10, due to the significantly uneven particle distribution. Nevertheless, many researchers choose the single-phase model considering the additional computational cost of the two-phase model. Therefore, the model accuracy and computational efficiency need to be balanced according to specific working conditions for engineering applications.

2.1.3 Thermophysical Parameter Correlations

The heat capacity cp can be written as [42]:

The volume fraction of HNFs is calculated by [42]

The Einstein model is usually used to calculate the effective viscosity of dilute nanofluids, defined as [43]:

With the increase of concentration, the classical Brinkmann model is widely used to calculate the dynamic viscosity μHNF of HNFs [44], shown as

For specific nanoparticles, some scholars have used the following formulas and compared them with the experimental data. When the volume fraction is 0.0625%–1% and the temperature is 25°C–50°C, the dynamic viscosity of Al2O3-MWCNT/SAE40 oil could be predicted by Eq. (16) [45]. The maximum deviation between the experimental data and the predicted data was 2%.

Selvarajoo et al. [46] studied the viscosity of MWCNT-A2O3 at a ratio of 20:80 when the volume concentration ranged from 0.01% to 0.2%, and obtained the following formula. For the volume concentration of 0.25%–1.0% and the temperature of 30°C–50°C, the error of viscosity between the predicted data and experimental data was less than 1.1%.

For the temperature ranging from 20°C to 60°C and the concentration of 0.005, the dynamic viscosity of Al2O3-TiO2/Water can be calculated by [32]:

The thermal conductivity of two-component heterogeneous mixtures can be calculated by the Hamilton-Crosser model considering the empirical shape factor n [47,48].

where n = 3/ψ, ψ is the ratio between the sphere area and real area with equal volumes.

For different types of nanoparticles, Eq. (20) can be rewritten as [49]:

Spherical Al2O3:

Cylindrical MWCNT:

Platelet graphene:

To improve the correlation accuracy, some models take the temperature and particle size into account, as follows [50]:

where Pr and Re are the Prandtl and Reynolds numbers, respectively. dnp is the nanoparticle diameter, and dbf is molecular diameter of the base fluid. For Al2O3-water nanofluids: a = 0.7460, b = 0.3690, c = 0.7476, d = 0.9955 and e = 1.2321. The subscript nf represents the nanofluid.

Then, a function of thermal conductivity is proposed based on “static” and “dynamic” (considering the Brownian motion) [51]:

Considering both static and dynamic, for Co-Ag-Zn ternary-nanofluid, the above formula can be written as [52]

where KB is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 × 10−23), Tref is the reference temperature of nanofluid (293 K), and dp represents the nanoparticle size.

The finite element method (FEM) is usually applied to solve the approximate solutions for partial differential equations. The characteristic of this method is that there is no restriction on the shape of the solution region. The accurate solutions of the differential equations are approximated piecewise. It is suitable for situations with complex boundary domains. FEM is performed to the entire region discretization, and each sub-region becomes a finite element. The specified boundary conditions are embedded into the algebraic equations of each element. The slip, Joule heating, and viscous dissipation are ignored. There are four common methods, namely the Galerkin method, the Collocation method, the Sobdomain Method, and the least square method. Among them, the Galerkin method is used in HNFs more frequently.

Some investigators examined the thermo-hydraulic features of HNFs by FEM. The results indicated that the heat transport rate of binary-nanofluids was higher than that of traditional mono-nanofluids [53–55]. For instance, Ain et al. [54] explored the energy transport characteristics of binary-nanofluids by Comsol software. An artificial neural network (ANN) model was trained to predict various parameters, i.e., Rayleigh number (Ra), Hartmann number (Ha), and concentration. The new approach was proved to be feasible in predicting the thermal features of HNFs. Madkhali et al. [56] and Nawaz et al. [57] compared the thermal and hydraulic characteristics of mono-nanofluid and HNFs. They concluded that the heat transport rate of ternary-nanofluid was higher than that of mono-nanofluid and binary-nanofluid.

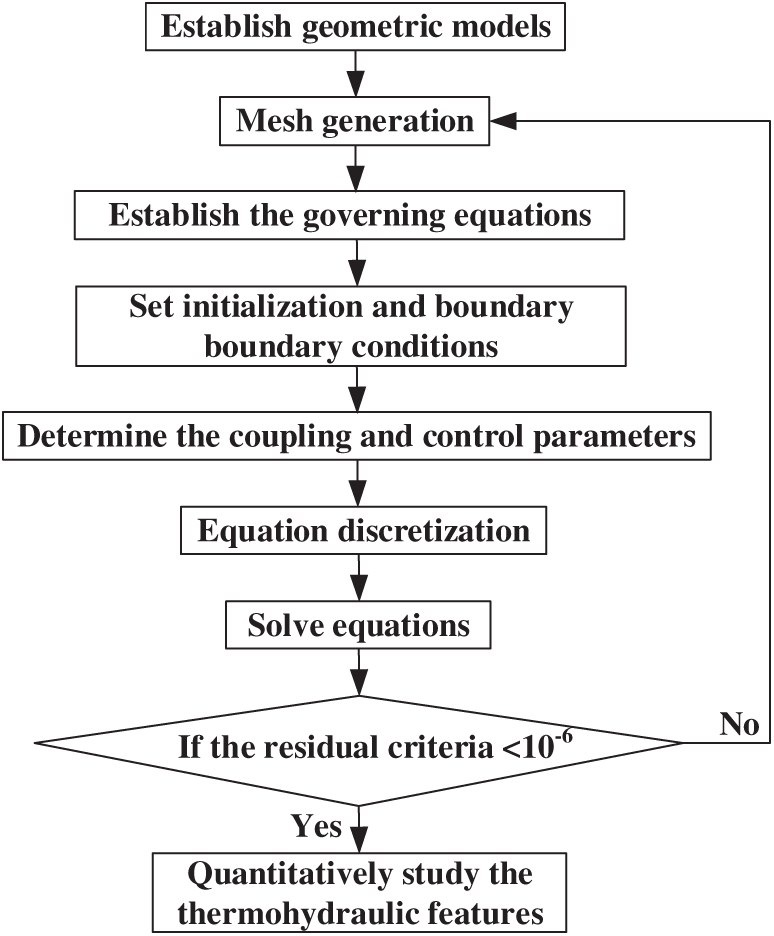

The finite volume method (FVM) divides the computing domain into several non-overlapping control volumes. The governing equations are solved for each control volume. The interpolation functions are only used to calculate the integral of the control volumes. The different interpolation functions can be adopted for corresponding terms in the differential equations. Some investigators explored the thermo-hydraulic features of HNFs in MCHSs by ANSYS Fluent software. The models of steady laminar flow and conjugate heat transfer are usually employed without thermal energy sources. The HNFs are considered incompressible and the thermophysical properties depend on the temperature. The gravity, radiation, and heat loss are ignored. The numerical calculation process is depicted in Fig. 2. A geometric model and computational grid are established firstly by ANSYS Fluent software, CFD software, CFX software, etc. Then, the governing equations are derived based on specific assumptions, and the initialization and boundary conditions (velocity, pressure, constant heat flux, or constant wall temperature) are set. The equations are discretized with second-order upwind. If the residual criteria are less than 10−6, the results are output. Otherwise, the rationality of the mesh should be checked before recalculation.

Figure 2: Numerical calculation for the hydrothermal features of HNFs in micro heat sinks by FVM

The FVM has high efficiency and good convergence, which are adopted to explore the energy transport features of HNFs [28,34,58,59]. Jamshidmofid et al. [28] investigated the cooling capacity and pressure drop of Ag-Al2O3/water nanofluid within left-right and up-down wavy microchannels by FVM. The combination of wavy configuration and HNF mitigated the temperature maldistribution without excessive pressure drop. Jasim et al. [34] employed the FVM to study the thermal performance of Al2O3-Cu/water nanofluid in a vented cavity. The impacts of particle concentration and operating parameters on the thermal features were discussed. The cooling capability was heightened by high concentration and the counter-clockwise rotation of the cylinder.

2.2.3 Molecular Dynamics Simulation

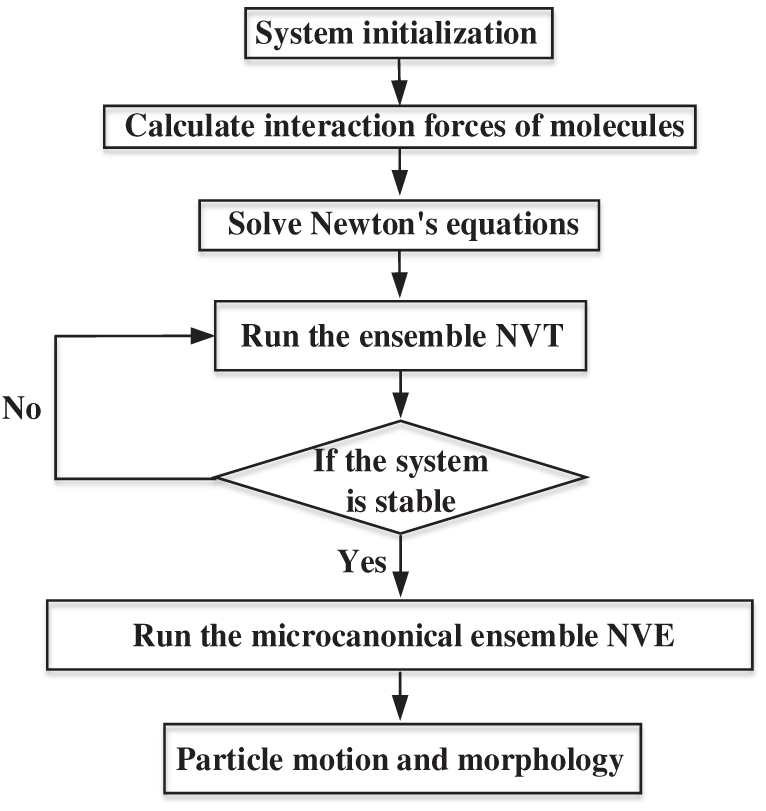

MD simulation can be used to study the structures and properties of atoms or molecules at the nano-scale. According to the principle of statistical mechanics, the physical properties of the molecular system can be obtained from the motion of a single molecule, i.e., the trajectory, speed, and position of the molecule. Different potential functions (e.g., EAM, Lennard-Jones (L-J)) are selected to analyze the impact of particle type, particle size, and other factors on the motion trajectory, number density, and distribution function of molecules. The specific flow chart of MD simulation is provided in Fig. 3. Firstly, the simulation domain, physical parameters of the particles, and the solution equations should be established and determined. The temperature of the entire system is controlled at a setting value by the Langevin thermostat. The canonical ensemble NVT (N is atomic number, V is volume, and T is temperature) ensures the model to a quasi-steady state and prevents errors in subsequent calculations. After that, the numerical simulations are performed in a micro canonical ensemble NVE (E denotes energy). The dynamic behavior of individual particles (position, velocity, etc.) can be obtained by solving the particle motion equations. Thus, the thermal and hydrodynamic performances and other information of the whole system can be derived based on the statistical calculation of the particle motion rules.

Figure 3: Flow chart of MD simulation

The resultant force Fij on the i particle is the vector sum of the forces between the i and j particles, expressed as [60]:

The gradient of the potential function Eij can be calculated by [61]:

where r is the distance between particles i and j. rc is the cutoff radius (r < rc). ε is the potential energy, given by [62]:

where subscripts 1 and 2 represent the different nanoparticles. α is the energy coefficient.

The difference in density and surface charge for different particles in HNFs is relatively large. This will lead to an aggregation effect and threaten the coolant stability. Hou et al. [62] introduced the concept of “degree of looseness” to assess the aggregation patterns of nanoparticles. With the increase of looseness, the thermal conductivity of Janus nanofluid rose first and then decreased. Wang et al. [63] found that the nanoparticles presented a completely aggregated form, a mixed form, and a completely dispersed form respectively when the quantity of charges was low, medium, and high. Some researchers have adopted MD simulation to study the particle collision, Brownian movement, and thermophoresis effect [64–66]. Results illustrated that the micro motion and morphology of nanoparticles determined the thermal properties of novel coolants. Chen et al. [64] revealed the effect of included angle and particle arrangement on the thermal conductivity of Cu-Ar nanofluids. A denser interfacial layer around particles, i.e., a compact heat flux passage, could be created to transfer more heat by optimizing the angle and arrangement of particles. Wang et al. [66] conducted an MD simulation to explore the boiling heat transfer performance on wall surfaces with different nanoparticles. The surface with hybrid nanoparticles presented superior wettability. The early boiling initiation and high heat flux were achieved due to the better matching between the solid and liquid atoms.

In conclusion, the morphology and aggregation of particles at the micro-level are the fundamental factors affecting the stability and thermal properties of nanofluids. The particle combination, preparation method, operating condition, and base fluid play important roles in the morphology and motion of aggregations. The motion and morphology of solid-liquid atoms cannot be obtained by traditional experiments. MD simulation can directly reflect the microscopic features of particles, and explain the energy transport mechanism from the micro-level. However, there are few MD studies on the cooling capability and flow resistance features of HNFs in mini/micro heat sinks, which need to be further carried out.

3 Energy Transport Characteristics of Hybrid Nanofluids

The thermal conductivity of the cooling medium greatly affects the heat transfer rate. A large number of studies have manifested that adding nanoparticles can heighten the thermal conductivity of the coolant. A lot of efforts have been conducted to discover the important degree of operating factors on the thermal conductivity of nanofluids, including the temperature and volume fraction [67,68], pH level [69,70], surface modification [19,71] and dispersant [72,73]. Results demonstrated that the high temperature, large volume fraction, high PH level, and surface modification could heighten the thermal conductivity due to the variation of agglomeration degree. Some studies have shown that the addition of dispersants could improve the thermal conductivity of nanofluids, but other studies have obtained the opposite conclusion.

There is a disagreement on whether HNFs can improve thermal conductivity compared with traditional mono-nanofluids. Some experimental studies indicated that the synergy effect of multi-particles could improve thermal conductivity [74–76]. Nevertheless, other researchers have found that some particle combinations reduced the thermal conductivity compared to the corresponding mono-nanofluids [77,78]. The high temperature and large concentration were helpful in heightening the thermal conductivity because of more intense Brownian motion, micro convection, and particle collisions [79,80]. In addition, some researchers employed neural network algorithms to predict the thermal conductivity of HNFs. They found that the volume fraction was the most important parameter [81,82].

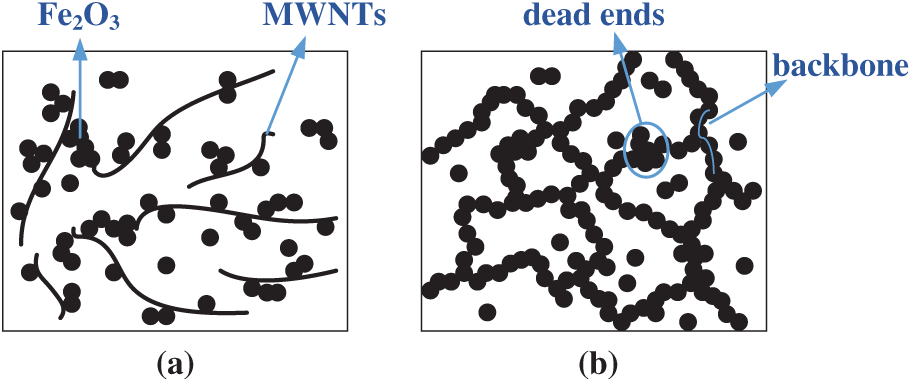

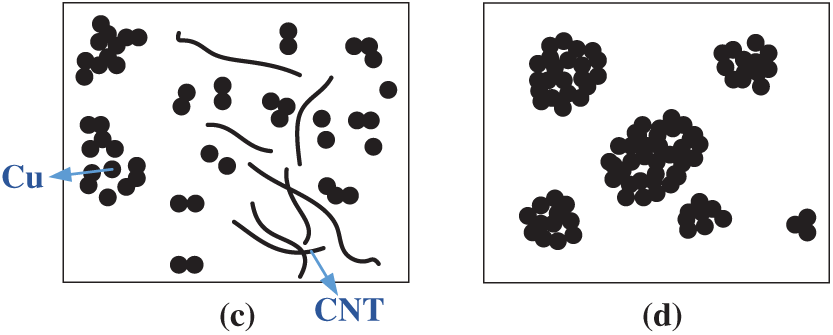

The main reason for the different thermal conductivity properties can be attributed to the various particle combinations, as plotted in Fig. 4. We can observe that the Fe2O3 nanoparticles are mainly concentrated at the contact points between neighboured nanotubes or bridging nanotubes (Fig. 4a). A homogeneous network was formed by Multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWNT) and Fe2O3 nanoparticles, which established effective conductive pathways to heighten the thermal conductivity [76]. The nanoparticles formed the dendritic aggregations, which constructed an efficient energy transport channel. The linear chains spanned the whole cluster (called backbone), while some particles did not run through the entire cluster (called dead ends) [83]. The backbone was mainly responsible for the improvement of thermal conductivity. Therefore, when there were more backbones and fewer dead ends, the thermal conductivity would be improved [84] (Fig. 4b). As depicted in Fig. 4c, there was no good contact between the nanoparticles of Cu and CNT. Thus, no thermal conductivity path was formed. The weakened synergy effect between Cu and CNT nanoparticles resulted in a larger interfacial thermal resistance, leading to no obvious variation in thermal conductivity [77]. The nanoparticle agglomeration built an efficient heat path, which was beneficial to heighten thermal conductivity [85] (Fig. 4d). There was an optimal diameter of the agglomeration structure. When the aggregations exceeded a certain diameter, a further increase in the mass of aggregations would reduce the Brownian motion. In consequence, the thermal conductivity performance would be weakened.

Figure 4: Schematic for synergy effect of different nanoparticles, (a) network pattern; (b) dispersion pattern; (c) branch pattern; (d) agglomeration pattern

We can observe that the numerical studies on the thermal conductivity of HNFs are less than that of traditional nanofluids. The effects of dispersants, PH level, and surface modification on the heat conductivity of HNFs are lacking. The applicability and transferability of intelligent algorithms to predict thermal conductivity need to be further improved. The synergy mechanism of different nanoparticles is still unclear and needs to be further explained by MD simulation.

The large viscosity of the cooling medium will increase the flow resistance and pump power, which reduces the economy of the liquid cooling system in DCs. For traditional mono-nanofluids, the dynamic viscosity will be increased with the augmentation of particle concentration [86]. However, there are conflicting conclusions about the variation tendency of dynamic viscosity with the dispersant concentration [87–89]. This may be related to the various particle types, particle sizes, and preparation methods, which need to be comprehensively analyzed. Moreover, some investigators established neural network models to predict the dynamic viscosity of traditional nanofluids. Results demonstrated that the neural network showed better prediction performance for more data samples. The prediction accuracy was related to the input parameters [90,91].

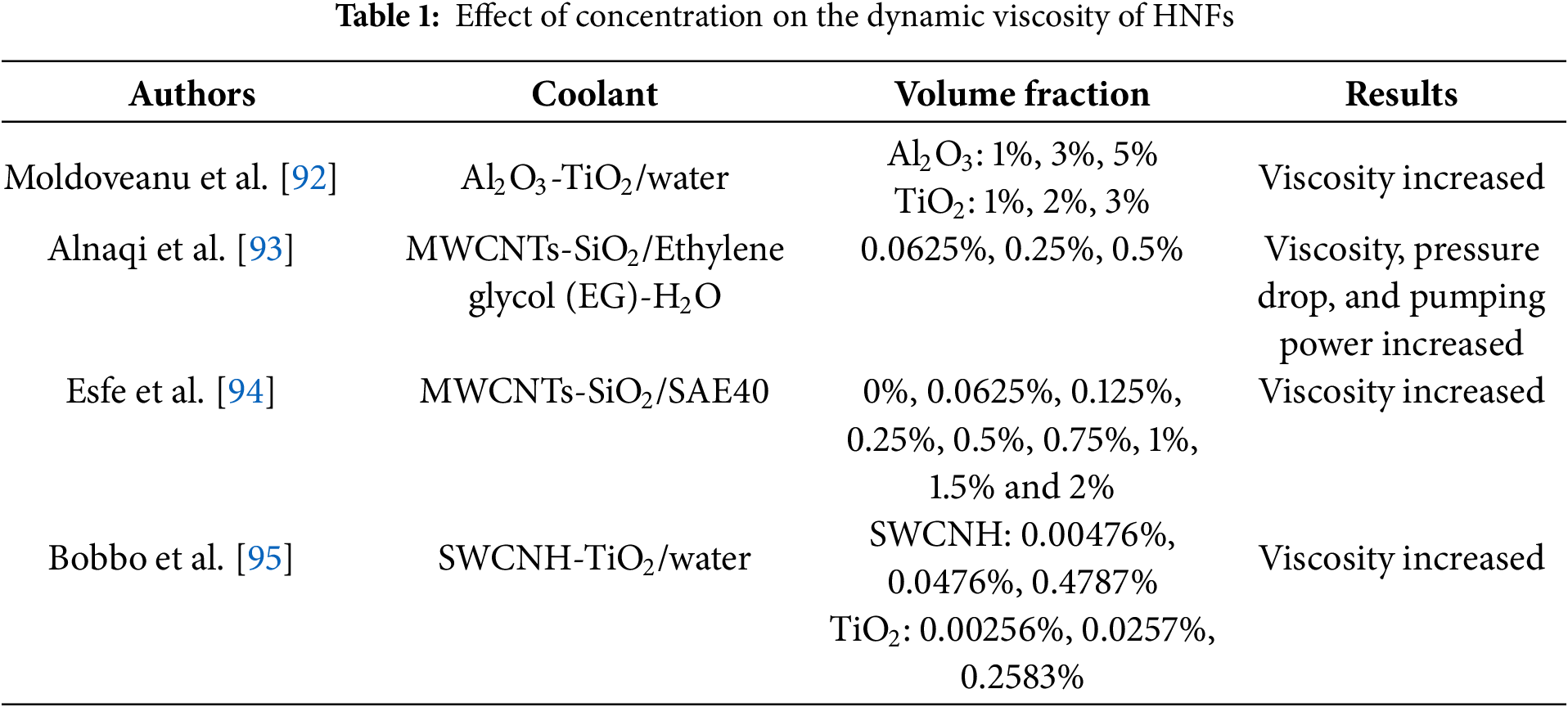

Nowadays, there are few reports about the dynamic viscosity of HNFs in the open literature, especially the numerical studies, as demonstrated in Table 1. Moldoveanu et al. [92] conducted experiments on the energy transport features of HNF and argued that the dynamic viscosity was higher than the corresponding mono-nanofluid. Alnaqi et al. [93] concluded that the increase in concentration led to a considerable increment in viscosity, which dramatically increased the pump energy consumption. Some experiments revealed that the high temperature and low concentration were beneficial in reducing viscosity [94,95]. As the volume fraction of hybrid nanoparticles increases, the viscosity of coolant will be increased. This phenomenon may be related to the aggregation of nanoparticles for high concentration. When aggregations are formed within the nanofluid, higher viscosity, greater pressure drop, and larger pump power consumption are observed. Compared with traditional mono-nanofluids, HNFs have more complex interactions between various particles and base fluid. It is necessary to further study their rheological properties for reducing pump power. Intelligent algorithms, such as machine learning (ML), provide a new way to predict the thermophysical properties of HNFs and regulate the thermal and hydraulic properties. However, there are few related reports.

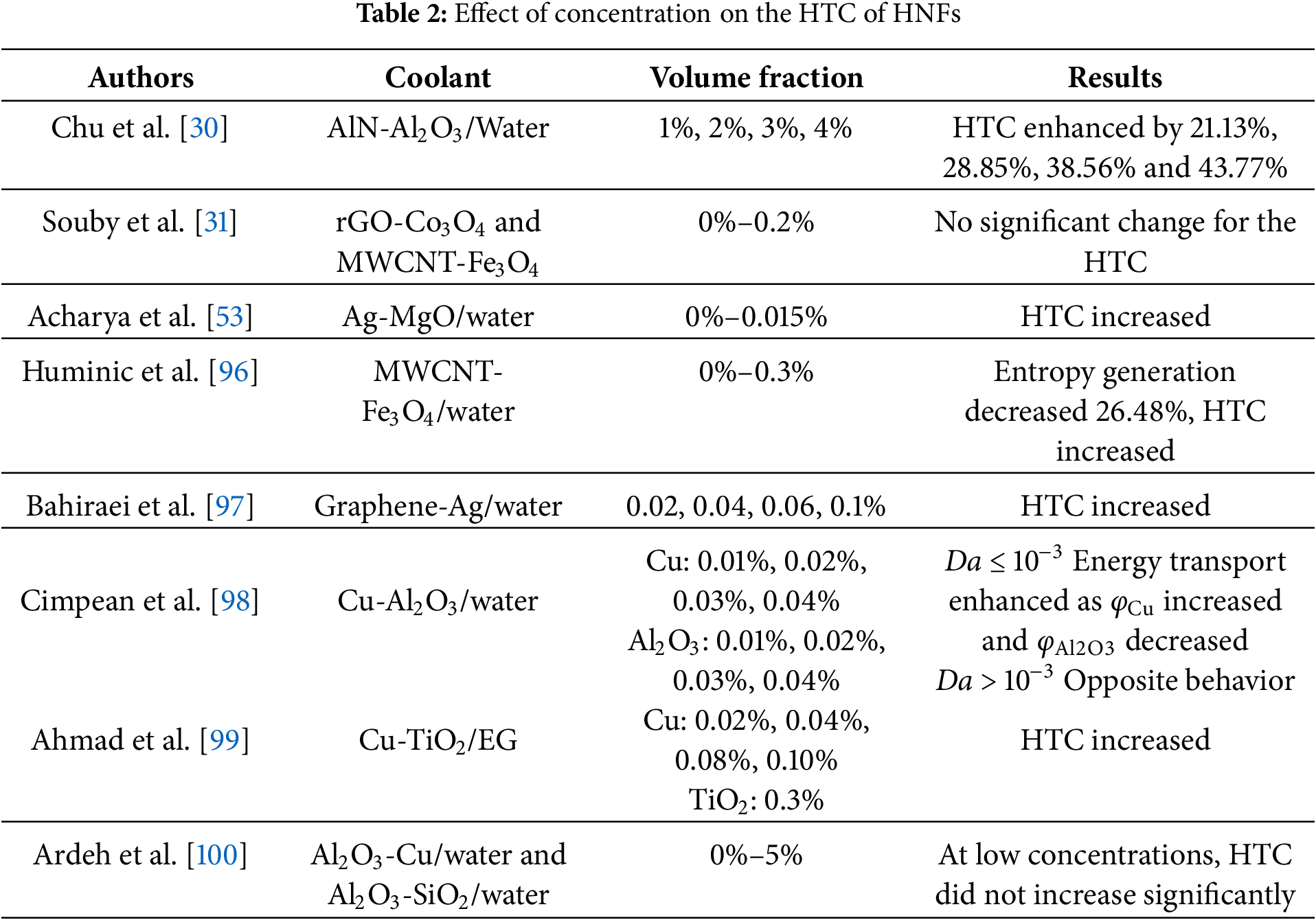

The synergy effect of multi-nanoparticles has a significant impact on the activation energy and aggregation morphology. The interaction between different particles induces complicated micro convection and motion, which influences the thermophysical properties and heat transport characteristics. Particle type, size, concentration, and other parameters have an obvious effect on the HTC of HNFs. Most studies indicated that appropriate particle combinations and relatively large concentrations could achieve a superior heat transport capability [96–100]. The main results are summarized in Table 2.

For instance, Huminic et al. [96] found that the increase in heat conductivity and HTC could be attributed to the combined network of nanoparticles and the delayed development of the boundary layer. Ahmad et al. [99] also believed that the increase in heat transfer was caused by the enlargement of particle volume fraction. In summary, compared with pure coolants, HNFs exhibit a higher HTC. This is mainly because the nanoparticles have high thermal conductivity and Brownian motion characteristics. The particle movement thins the thermal boundary layer and enhances the HTC. However, some existing literature reported that high concentration was not conducive to enhancing heat transfer. Souby et al. [31] and Ardeh et al. [100] assessed the thermal-hydraulic characteristics of HNFs by different evaluation indexes. Results indicated that when the Re was constant, the HTC was improved by HNFs. However, the HTC did not change significantly for a constant flow rate. At low concentrations and low flow rates, there is no obvious difference in HTC between the nanofluids and the pure coolants. Moreover, the nanofluids cause an increase in cooling cost due to the increased pump energy consumption. Thus, evaluating the thermal features by Re may be inaccurate, because the Re is related to the physical properties of the HNFs. The HNFs induce larger pump power and pressure drop, which can not be ignored. The pump power and economy of the liquid cooling system using HNFs need to be considered comprehensively.

According to the open literature, the researches on heat transport characteristics of HNFs are mainly based on experiments. There is a lack of numerical research to reveal the mechanism of particle motion and energy transport at the micro-level. There are opposite conclusions about the effect of dispersants on thermal conductivity and viscosity, which need to be further explored. Increasing the concentration of HNFs can increase the thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity. However, the upper limit of concentration for enhancing HTC has not been clearly explained. The effect of surface modification and PH level on the thermal performance of HNFs is still unclear. The synergy mechanism of different nanoparticles on thermo-hydraulic performance has not been uncovered.

4 Combination of Hybrid Nanofluid and Other Heat Transfer Improvement Methods

Because of the excellent heat transfer potential, nanofluids are widely used in the convective heat transfer process of various heat exchangers. Effective convective heat transfer is essential for high energy efficiency in fields of high-power electronic component cooling in DCs. Heat transfer improvement technologies can be divided into passive and active methods according to the external energy. The passive methods without external energy mainly include surface modification and configuration optimization, etc. The heat transport efficiency can be greatly heightened by increasing the heat transfer area, modifying flow distribution, destroying the boundary layer, and inducing flow disturbance. The active methods require external energy, such as pulsating flow, electric field, magnetic field, etc. The existing literature shows that the HNFs coupled with other heat transfer improvement methods can further heighten the overall performance of the liquid cooling system.

4.1 Passive Method for Heat Transfer Improvement

Some researchers have conducted numerical simulations on the thermo-hydraulic characteristics of the HNFs in complex MCHSs. The combined effect of configuration modification and novel coolant was analyzed and revealed.

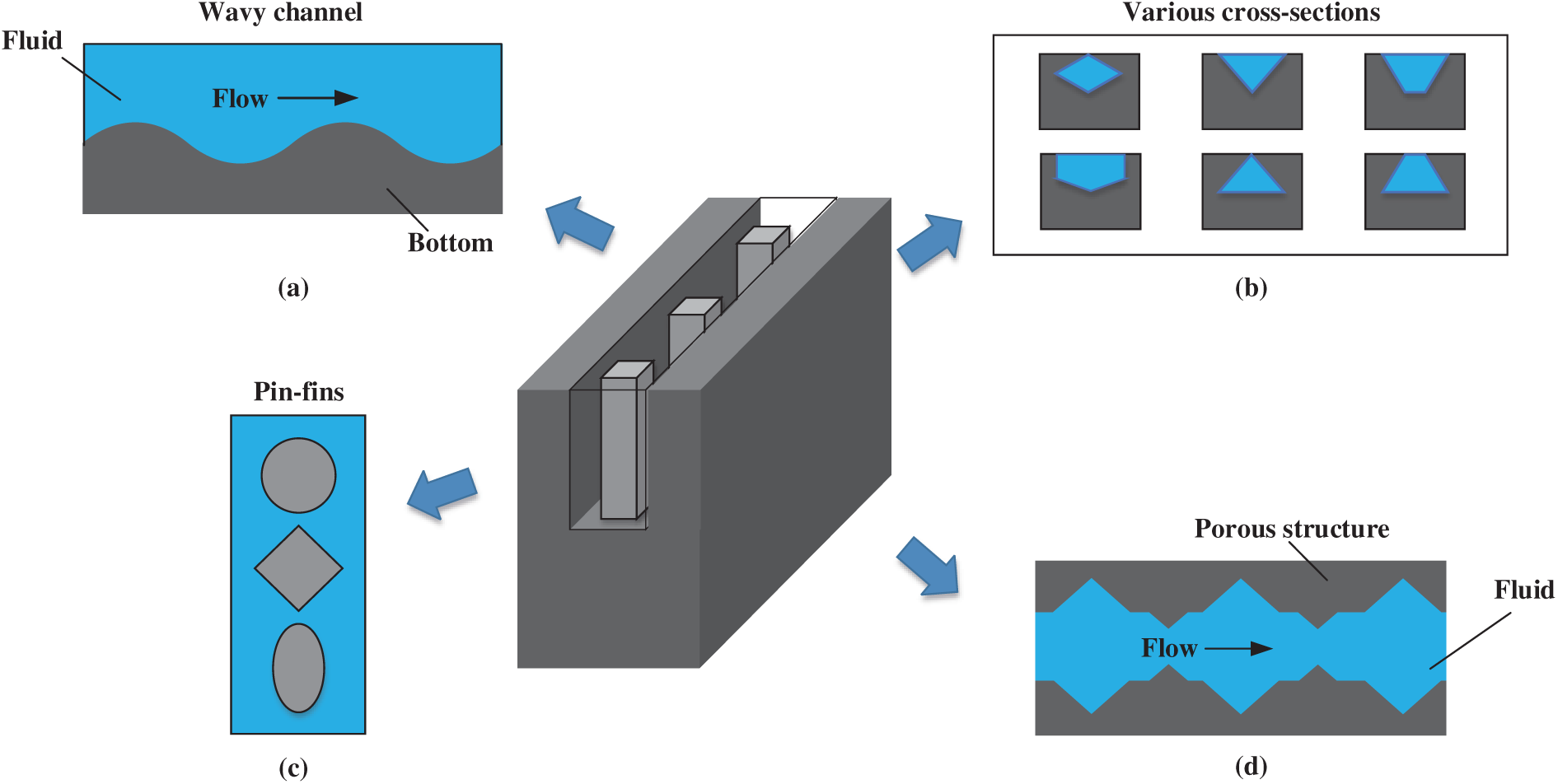

Fig. 5 demonstrates some typical configurations for efficient cooling in open literature. Some efforts have been made to investigate the hydrothermal features of HNFs in MCHSs with corrugated or wavy walls (Fig. 5a). The coupling of wavy configuration and nanoparticles had a favorable effect on heat dissipation [29,101]. The optimal structural parameters for the best thermal performance were obtained. The excessive amplitude of the wavy or corrugated configurations would weaken the cooling effect. Akhtari et al. [102] investigated the synergy impact of the double-layered microchannel and HNF on cooling performance. The Cu 3%-Al2O3 1%-water nanofluid obtained an increased Nu with 10%, and a 17.97°C decrement of peak temperature. The cross-section shape of the channel and the shape of the particle had obvious impacts on the hydrothermal characteristics (Fig. 5b). Results illustrated that the rhombus cross-section tended to achieve the best hydrothermal performance, and the trapezoidal one led to the optimal temperature distribution. The effective contact area had a great impact on the heat dissipation rate. The lamina-shaped nanoparticle with a relatively high concentration presented a larger HTC compared to the spherical nanoparticle for TiO2-MgO-GO ternary-nanofluid [103].

Figure 5: Schematic of different micro structures for enhancing heat transfer of HNFs, (a) wavy channel; (b) various cross-sections; (c) micro pin-fins; (d) porous channel with variable cross-sections

Some research focused on the combination of pin-fin configurations and HNFs (Fig. 5c). The pin-fin configurations were optimized to balance the heat transfer rate and friction losses [104–106]. In addition, the influence of nanoparticle shape and slip mechanisms were also explored. Adopting the shear-thinning fluids as base fluid could prevent the dramatic increase of pressure drop owing to the reduction of viscosity, compared to the water. Aguirre et al. [107] concluded that the micro heat sink with pin-fins and vortex generators increased the HTC with an obvious increment of flow resistance for Newtonian fluid. However, the shear-thinning fluids with multi-nanoparticles reduced the pump energy consumption by 20%. Therefore, the addition of nanoparticles did not ensure an improvement in the overall efficiency of the cooling system. Excessive pump power would reduce the energy efficiency of the liquid cooling system.

The combination of nanofluids and porous media can enhance heat transfer, and reduce pump power due to the high thermal conductivity and permeability (Fig. 5d). Zhai et al. [32] established analytical methods considering the thermodynamic characteristics and nanoparticle migration to reveal the essence of energy transport improvement. The thermophoresis of nanoparticles in the convective heat transfer process at the micro-scale was more obvious than that at the macro-scale. The reason could be attributed to the high particle concentration near the wall and the full mixing in the porous region.

Many investigations have been carried out to heighten the cooling capability of MCHSs by complex configurations and HNFs. However, the modified structures often increase the flow resistance and require additional pump power consumption. Too complex configurations have the defects of machining cost and system economy. It is imperative to explore more efficient and reasonable optimization methods. In addition, more accurate and quantitative indexes are needed to evaluate the temperature uniformity of MCHSs.

A large number of studies have shown that nanofluids have a better cooling effect than pure fluid. However, some results have indicated that the increment of heat transport was less than the increase of pressure drop, resulting in a decrement in overall performance [108]. These contrary conclusions can be attributed to the difference between the particle parameters and the heat sink structures. Therefore, the synergy mechanisms of HNFs and micro structures need to be revealed.

4.2 Active Method for Heat Transfer Improvement

Many studies have shown that pulsating flow can improve the cooling capability and inhibit nanoparticle deposition in the channel. The periodic change of fluid velocity produces the vortexes, enhances the fluid mixing, and destroys the boundary layer [109–111]. Xu et al. [112] employed the combination of pulsating flow and graphene nanofluids to heighten the heat transport. The optimal pulsation frequency was not affected by the nanofluid concentration. The inhibiting effect of pulsating flow on the nanoparticle deposition was proved by image processing technology.

However, the pulsating flow consumes a greater pump power consumption than the constant flow. Inversely, some researchers concluded that the pulsation flow did not provide high HTC. Based on the existing research, the cooling capability of pulsating flow was related to Re and pulsation parameters [113,114]. For different heat exchangers, there was an optimal pulsation frequency/amplitude, and a suitable Re for the best heat transport.

The mechanism of enhanced heat transfer can be explained from the perspective of real-time variation of velocity field obtained by particle image velocimetry (PIV) technology. However, the micro motion and scale effect of nanoparticles will affect the velocity, concentration, and temperature fields, which are difficult to measure experimentally, especially for HNFs.

Many researchers have found that the electric field could enhance the cooling capability of the HNFs [115,116]. The electric field mitigated the nanoparticle deposition to a certain extent. The electrophoretic force, dielectrophoresis force, and electrostriction force were very important for enhancing energy transport [117]. In addition, the Marangoni number, particle concentration, and particle size were also important factors affecting the cooling capability of nanofluids [59].

Some scholars have made a preliminary exploration of the micro motion of nanoparticles under an electric field by MD simulation. Zhao et al. [118] established the MD model to discover the impact of an electric field on the heat transport process of nanofluid. They found that the electric field could reduce the interfacial thermal resistance, disturb the movement of water molecules, and weaken the bond between particles, thus enhancing energy efficiency. Wang et al. [119] found the collision of Cu particles and water molecules could be suppressed by an electric field. The aggregation of nanoparticles was weakened as the electric field intensity increased.

The effect of the magnetic field on the thermophysical properties of nanofluids was studied. The results demonstrated that the magnetic field had a prominent impact on both HTC and friction factor. The magnetic field had a positive contribution to the increase of Nu by adjusting the movement and aggregation of nanoparticles [120,121]. The nanofluids with smaller particles were more suitable for energy transport improvement under the applied magnetic field. However, some studies have shown that the magnetic field increased the temperature of the boundary layer, resulting in a weak energy transport rate [122,123].

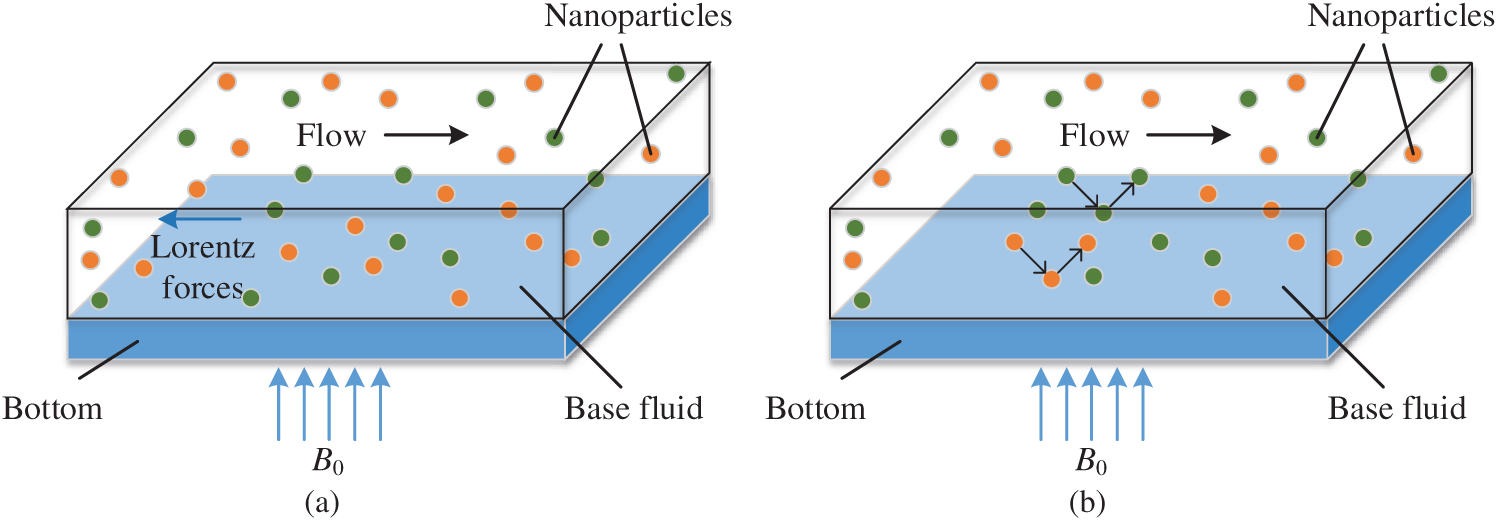

The magnetic field also has a noteworthy impact on the flow characteristics of nanofluids. Babu et al. [124] studied the flow features of ZrO2-MgO/propylene glycol water nanofluid. They found that the flow velocity was increased by the magnetic field, which led to an increment of flow friction. However, the opposite conclusion was obtained by Azhar et al. [125]. They argued that the increment of magnetic field intensity would decrease the friction factor for SiO2-GO-TiO2/water nanofluid. In addition, some researchers discovered that the Lorentz force impeded the flow of nanofluids, causing the reduction of fluid velocity and the increase of fluid temperature [54,126–128].

The impact of the magnetic field on the thermo-hydraulic features of HNFs can be summed up in two conditions, as described in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6a, the increase in magnetic field intensity will lead to a decrease in the flow rate of nanofluids. It can be found that the opposite Lorentz force will be generated under this condition, which hinders the nanofluid flow and deteriorates heat transfer. Nevertheless, when the magnetic metal nanoparticles move toward the heating surface under the magnetic field, the boundary layer will be destroyed and the heat transfer can be strengthened, as depicted in Fig. 6b.

Figure 6: Effect of magnetic field on the nanoparticles, (a) horizontal motion; (b) downward motion

5 Opportunities and Future Perspectives for High-Efficiency Energy Transport

In summary, the existing investigations on the stability, thermophysical properties, and thermo-hydraulic characteristics of HNFs are mainly limited to specific conditions. The research mainly focuses on the sensitivity of preparation parameters, particle parameters, and operating parameters to the thermal performance of the novel coolants. There is a lack of active control methods for enhancing the stability and thermal conductivity of HNFs. The existing results indicate that the HNFs are expected to solve the cooling problem of high-power chips in DCs. However, existing studies do not consider the layout of actual cooling systems in DCs. The wear of the cooling systems caused by the nanoparticles is not analyzed. Therefore, the combination and optimization of MCHSs and HNFs, the microscopic motion of nanoparticles, and the synergy effect of multi-physics fields need to be further studied.

5.1 Solutions for Configuration Modification and Optimization

The complex configurations in the open literature induce higher HTC accompanied by larger pump power. Balancing thermal efficiency and pump power consumption by further optimizing the heat sink and HNFs is critical for the practical application of microchannel liquid cooling in DCs. Most literature has studied the variation of thermal and hydraulic performances with single parameters. The importance degree and internal relations of the different factors have not been elucidated quantitatively.

Some researchers have tried to optimize the structural parameters of heat sinks by intelligent algorithms to improve the HTC and decrease the pump power. Rabiei et al. [129] performed multi-objective optimization by genetic algorithm. The impact of heat sink configuration and nanofluid concentration on heat transfer and pump power was revealed. Results showed that the pump power was mainly affected by the nanofluid concentration, while the cooling performance was mainly affected by the heat sink configuration. Tang et al. [130] constructed a numerical model to explore the thermo-hydraulic features of HNFs in a heat sink with jet-impinging and micro ribs. The intelligent algorithm was adopted to obtain the optimal configuration for multiple targets. The field synergy principle was employed to elucidate the inherent law of thermal enhancement of HNFs.

At present, the response surface method (RSM) and genetic algorithm are the main methods for multi-objective optimization of MCHSs. However, the optimized results are only applicable to specific conditions. The applicability of the optimal configurations of heat sinks should be improved by comprehensive parameter sensitivity analysis and ML. The interaction of micro-scale structures and multi-nanoparticles has not been fully revealed. It is crucial to use intelligent algorithms to optimize the cooling capability and flow resistance of HNFs.

5.2 Solutions of the Synergy and Regulation of Multi-Nanoparticles

Compared to the traditional nanofluids, the thermal and hydrodynamic features of the HNFs are more complicated because of the interaction between various particles. The impact of concentration, dispersant, PH level, and surface modification on the thermo-hydraulic features of HNFs should be analyzed thoroughly.

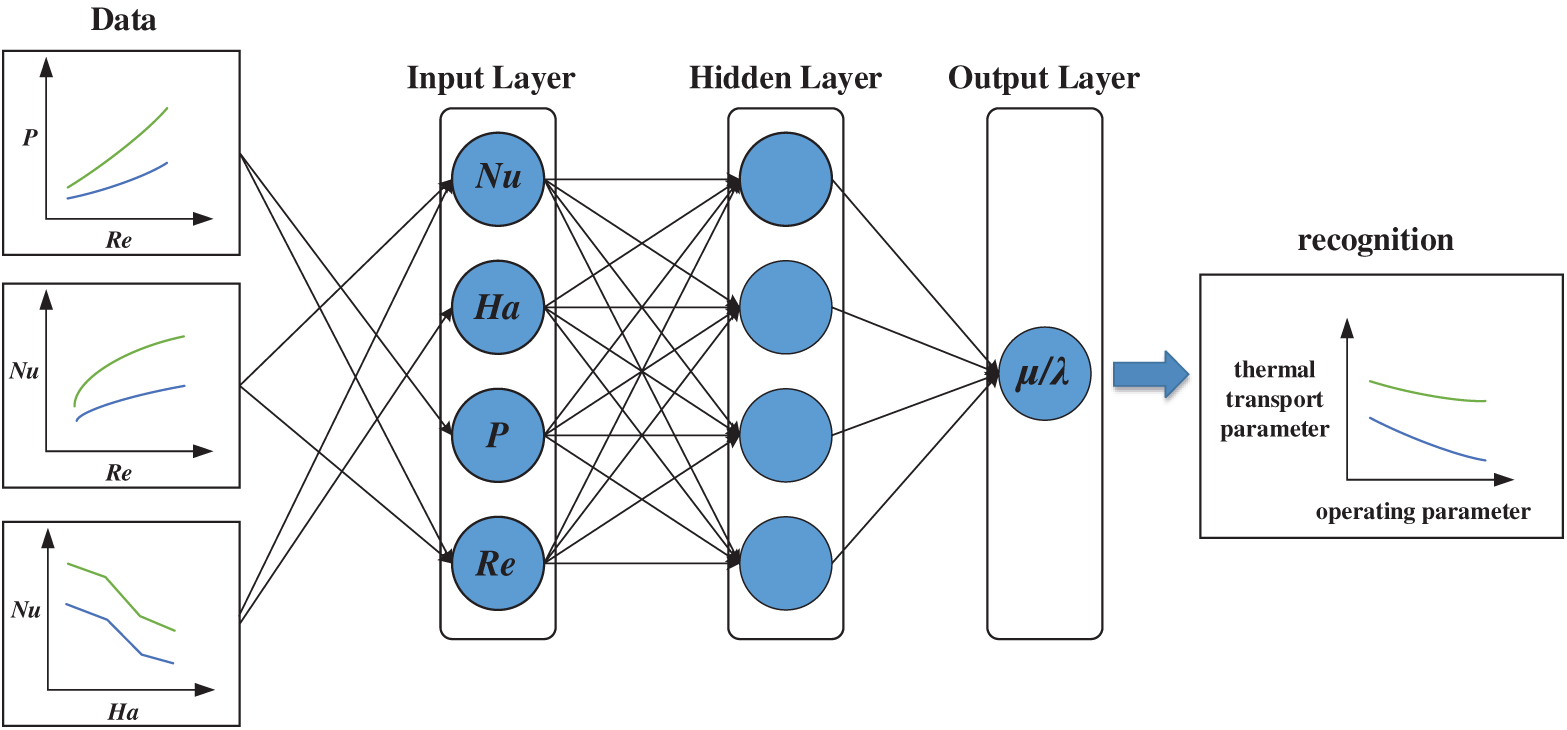

Some scholars have provided prediction models for energy transport parameters for specific ranges. ML with self-learning ability can provide an effective approach for the nonlinear prediction of thermophysical properties of HNFs. The thermal conductivity, viscosity, and surface tension are expected to be fast predicted by a data-driven model. Based on the numerical or experimental samples, a database can be established. The flow and heat transfer characteristics will be classified. The intrinsic interaction of specific parameters and thermo-hydraulic properties can be discovered by intelligence algorithms. The parameter prediction correlations with wide applicability can be obtained, as plotted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Flow chart of ANN prediction for thermophysical properties of nanofluids

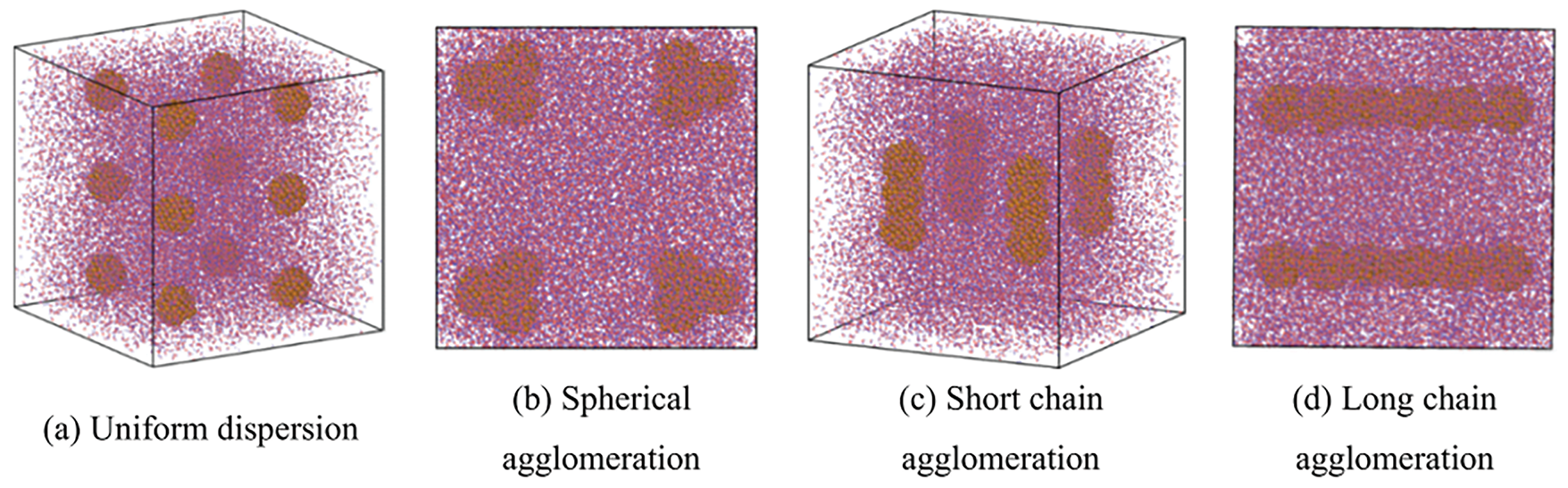

Besides, the synergy effect and micro morphology of different nanoparticles are not completely clear, which is directly related to the stability and thermal properties of novel coolants. The MD simulation provides a solution for discovering the particle motion and aggregation at the micro-level. Li et al. [131,132] conducted a series of MD simulations to illustrate the impact of agglomeration morphology on the heat transport features of traditional mono-nanofluids. By adjusting the distance between nanoparticles, different aggregation morphology will be formed under Van der Waals forces as displayed in Fig. 8. The smaller particle size and lower fractal dimension resulted in higher thermal conductivity and viscosity. The agglomeration morphology directly affected the energy transport characteristics.

Figure 8: Schematic of different aggregation morphology for Cu nanoparticles [132]

Based on the heat transport models of traditional mono-nanofluids, the more complex MD models for HNFs can be established. The impact of concentration, particle type, size and shape, and other operating parameters on the nanolayer thickness, motion trajectory, and distribution function can be clarified. Thereby, the relationship between the particle morphology and energy transport properties of the coolant can be revealed. By adjusting the type and size of the nanoparticles, the optimal combination of different nanoparticles will be obtained, and the heat and mass transport essences can be uncovered.

5.3 Solutions of Combined Method for Heat Transfer Improvement

The boiling heat transfer can obtain higher cooling efficiency accompanied by acceptable pump energy consumption compared to single-phase heat transfer. The combination of flow boiling and HNFs is expected to achieve better heat transfer capability. There is a lack of numerical study to illustrate the interaction of gas-liquid-solid. The traditional numerical simulation can not reveal the influence of the particle motion on the hydrothermal characteristics in depth. Yin et al. [133,134] explored the effects of nanoparticle motion on flow boiling features by MD simulation under two conditions: suspension and deposition.

The heat transport mechanism and the flow boiling pattern of HNFs are closely linked. The bubble behavior and flow evolution for the boiling process of HNFs need to be further explored. The coupling of flow and temperature fields, solid particles, and gas-liquid interactions make bubble growth and flow patterns more complicated, which produces different heat transport mechanisms.

The different particles have different surface tension and wettability, thus affecting the liquid film evaporation. The micro-scale effect and multi-phase flow lead to a nonlinear transient flow field in MCHSs. The HNFs will enhance the randomness of bubble motion and cause the variation of flow pattern. In recent years, the rapid developments of artificial intelligence (AI), computer vision (CV), and ML have provided new ways for extracting bubble dynamics parameters, measuring transient physical fields, and recognizing flow patterns. The effects of particle migration, mixing ratio, and other parameters on bubble growth, flow pattern, and heat transfer can be explained by combining the MD simulation and image processing techniques.

Moreover, the combination of passive and active technologies may further improve the comprehensive performance of the liquid cooling system in DCs. The coupling effect of multi-physics fields, such as electric field, magnetic field, ultrasound, etc., on fluid morphology and energy transport can be fully revealed by the MD model and ML. It is of great significance for the enrichment and development of the theory of micro-scale flow and heat transfer, as well as the practical applications of HNFs in the advanced liquid cooling systems for DCs.

The hybrid nanofluid (HNF) is able to heighten the heat dissipation potential of the chip-level liquid cooling system in data centers (DCs). In this paper, the latest numerical studies on HNFs are introduced and analyzed. The theoretical models, numerical methods, thermophysical parameters, and thermo-hydrodynamic characteristics are outlined. The characteristics, applicable conditions, and scenarios of each method are elucidated. The limitations, opportunities, and future perspectives are provided. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is recommended to analyze the nanoparticle motion and morphology. Intelligent algorithms can be used to predict the physical parameters of nanofluids to regulate their thermal performance. The boiling heat transfer of HNFs and the synergy effect of multi-physical fields are expected to further improve the overall performance of liquid cooling systems. The key findings are as follows:

(1) The aggregation morphology and particle motion can not be captured by traditional visualization experiments and numerical simulation. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation provides a novel perspective to explain the synergy mechanism of different particles and reveal the essence of enhanced heat transport from the micro-level.

(2) The existing parameter prediction models are only suitable for a specific parameter range. The robustness and transferability need to be improved. Intelligent algorithms, such as machine learning (ML), present feasible solutions for fast prediction and optimization, which also provides an opportunity for the intelligent control of heat transport and flow resistance features of HNFs.

(3) There is a lack of numerical investigation on the flow boiling features of HNFs. The effects of particle migration, mixing ratio, and other parameters on bubble growth, flow pattern, and heat transfer are expected to be elucidated by the combination of MD simulation and computer vision (CV). The synergy of passive and active technologies may realize the control of the aggregation morphology and particle motion of HNFs, thus further improving the overall efficiency of cooling systems in DCs.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their helpful suggestions, which significantly enhanced the quality and presentation of this paper.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of Tianjin (No. 24YDTPJC00680), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52406191).

Author Contributions: Yifan Li: Investigation, writing—original manuscript. Congzhe Zhu: writing—original manuscript, writing—review and editing. Zhihan Lyu: methodology. Bin Yang: supervision. Thomas Olofsson: conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| cp | Specific heat capacity (J/kg·K) |

| d | Diameter (m) |

| E | Potential function (eV) |

| F | Resultant force (N) |

| g | Gravitational acceleration (m/s2) |

| Ha | Hartmann number |

| KB | Boltzmann constant |

| m | Mass (kg) |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| P | Pressure (Pa) |

| Pr | Prandtl number |

| rc | Cutoff radius (Å) |

| Ra | Rayleigh number |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| t | Time (s) |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| Velocity vector (m/s) | |

| Greek symbols | |

| α | Energy coefficient |

| ε | Potential energy (eV) |

| λ | Thermal conductivity (W/mK) |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity (Pa·s) |

| ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| σ | Scale parameter |

| τ | Shear stress (N/m2) |

| φ | Volume fraction |

| ψ | Ratio between the sphere area and the real area with equal volumes |

| Subscript | |

| bf | Base fluid |

| dr | Drift |

| k | Phase k |

| np | Nanoparticle |

| nf | Nanofluid |

| ref | Reference |

| Abbreviations | |

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| CV | Computer vision |

| DC | Data center |

| EAM | Embedded atom model |

| EG | Ethylene glycol |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| FVM | Finite volume method |

| HNF | Hybrid nanofluid |

| HTC | Heat transfer coefficient |

| LIB | Lithium-ion batteries |

| MCHS | Microchannel heat sink |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MWNT | Multi-walled carbon nanotube |

| PIV | Particle image velocimetry |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RSM | Response surface method |

References

1. Li XM, Li MY, Zhang YB, Han ZW, Wang SW. Rack-level cooling technologies for data centers—a comprehensive review. J Build Eng. 2024;90:109535. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pambudi N, Sarifudin A, Firdaus R, Ulfa D, Gandidi I, Romadhon R. The immersion cooling technology: current and future development in energy saving. Alexandria Eng J. 2022;61(12):9509–27. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.02.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ding B, Zhang ZH, Gong L, Xu MH, Huang ZQ. A novel thermal management scheme for 3D-IC chips with multi-cores and high power density. Appl Therm Eng. 2020;168:114832. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu ZJ, Zhang GY, Lu SA, Leng PF, Yu Y, Deng J, et al. A comprehensive review of cold plate liquid cooling technology for data centers. Chem Eng Sci. 2025;310(1):121525. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2025.121525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Z, Kandlikar SG. Current status and future trends in data-center cooling technologies. Heat Transfer Eng. 2015;36(6):523–38. doi:10.1080/01457632.2014.939032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Murshed SMS, Castro CAND. A critical review of traditional and emerging techniques and fluids for electronics cooling. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2017;78(1):821–33. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.04.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li ZY, Lu HL, Jiang YG, Liu HC, Xu L, Cao KY, et al. Comprehensive review and future prospects on chip-scale thermal management: core of data center’s thermal management. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;251:123612. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. He ZQ, Yan YF, Zhang ZE. Thermal management and temperature uniformity enhancement of electronic devices by micro heat sinks: a review. Energy. 2020;216(1):119223. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.119223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chethana GD, Gowda BS. Thermal management of air and liquid cooled data centres: a review. Mater Today Proc. 2021;45:145–9. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kong R, Zhang HN, Tang MS, Zou HM, Tian CQ, Ding T. Enhancing data center cooling efficiency and ability: a comprehensive review of direct liquid cooling technologies. Energy. 2024;308(11):132846. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.132846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Choi SUS, Eastman JA. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. In: Proceedings of the 1995 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exhibition; 1995 Nov 12–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

12. Cong TN, Roy G, Gauthier C, Galanis N. Heat transfer enhancement using Al2O3-water nanofluid for an electronic liquid cooling system. Appl Therm Eng. 2007;27(8–9):1501–6. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2006.09.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Vanaki SM, Ganesan P, Mohammed HA. Numerical study of convective heat transfer of nanofluids: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2016;54:1212–39. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang H, Qing S, Gui QH, Zhang XH, Zhang A. Effects of surface modification and surfactants on stability and thermophysical properties of TiO2/water nanofluids. J Mol Liq. 2022;349(3):118098. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2021.118098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sheikholeslami M, Ganji DD. Nanofluid convective heat transfer using semi analytical and numerical approaches: a review. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2016;65(2–3):43–77. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.05.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Khan WA, Kazi SN, Chowdhury ZZ, Zubir MNM, Wong YH, Shaikh K, et al. Application of carbon nanofluids in non-concentrating solar thermal collectors: a critical review of experimental investigations. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells. 2024;276:113046. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2024.113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Behera US, Sangwai JS, Byun HS. A comprehensive review on the recent advances in applications of nanofluids for effective utilization of renewable energy. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2025;207(14):114901. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Micali F, Milanese M, Colangelo G, Risi AD. Reducing CO2 emissions by improving HVAC system efficiency of data centers through nanofluids: a case study. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;275(6481):126889. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.126889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang YX, Zou CJ, Li WJ, Zou YD, Huang HX. Improving stability and thermal properties of TiO2 nanofluids by supramolecular modification: high energy efficiency heat transfer medium for data center cooling system. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;156:119735. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.119735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gasmi H, Obalalu AM, Akindele AO, Salaudeen SA, Khan U, Ishak A, et al. Thermal performance of a motile-microorganism within the two-phase nanofluid flow for the distinct non-Newtonian models on static and moving surfaces. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;58:104392. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nayak MK, Pasha AA, Kamilla BS, Thatoi DN, Juhany K, Kouki M, et al. Synthesis, stability, and heat transfer applications of ternary composite nanofluids—a review over the last decade. Results Eng. 2025;25(9):104284. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Smrity AMA, Yin P. Bridging computational and experimental boundaries: a review of theoretical modeling and experimental validation of hybrid nanofluids in heat transfer applications. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2025;115:109873. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2025.109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shaalan ZA, Hussein AM, Abdullah MZ, Alsayah AM, Alshukri MJ, Khaled M. Enhanced photovoltaic cooling using ZnO/TiO2 hybrid nanofluids: numerical and experimental analysis. Int J Thermofluids. 2025;27(3):101222. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2025.101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kanti PK, Yang ESJ, Wanatasanappan VV, Sharma P, Said NM. Impact of hybrid and mono nanofluids on the cooling performance of lithium-ion batteries: experimental and machine learning insights. J Energy Storage. 2024;101(1):113613. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.113613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bhattad A, Atgur V, Rao BN, Banapurmath NR, Khan TMY, Vadlamudi C, et al. Review on mono and hybrid nanofluids: preparation, properties, investigation, and applications in IC engines and heat transfer. Energies. 2023;16(7):3189. doi:10.3390/en16073189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Rabby MII, Uddin MW, Hassan NMS, Nur MA, Uddin R, Istiaque S, et al. Recent progresses in tri-hybrid nanofluids: a comprehensive review on preparation, stability, thermo-hydraulic properties, and applications. J Mol Liq. 2024;408(1):125257. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Prasher R, Phelan PE, Bhattacharya P. Effect of aggregation kinetics on the thermal conductivity of nanoscale colloidal solutions (nanofluids). Nano Lett. 2006;6(7):1529–34. doi:10.1021/nl060992s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Abbas M, Okasha MM, Abduvalieva D, Akgül A, Hassani MK, Ali AH, et al. Numerical simulation of higher order chemical reactive flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid across an extending cylinder with heat generation and induction effects. Int J Thermofluids. 2025;14(15):101330. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2025.101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Azman A, Mukhtar A, Yusoff MZ, Gunnasegaran P, Ching NK, Yasir ASHM. Numerical investigation of flow characteristics and heat transfer efficiency in sawtooth corrugated pipes with Al2O3-CuO/Water hybrid nanofluid. Results Phys. 2023;53(8):106974. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2023.106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chu YM, Farooq U, Mishra NK, Ahmad Z, Zulfiqar F, Yasmin S, et al. CFD analysis of hybrid nanofluid-based microchannel heat sink for electronic chips cooling: applications in nano-energy thermal devices. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;44(25):102818. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.102818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Souby MM, Salman M, Prabakaran R, Kim SC. Hydrothermal characteristics and irreversibility behavior of microchannel heat sink operated with hybrid nanofluids: a critical assessment. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;49(2):103387. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhai YL, Yao PY, Shen X, Wang H. Thermodynamic evaluation and particle migration of hybrid nanofluids flowing through a complex microchannel with porous fins. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;135:106118. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Eshgarf H, Nadooshan AA, Raisi A. A review of multi-phase and single-phase models in the numerical simulation of nanofluid flow in heat exchangers. Eng Anal Bound Elem. 2023;146(1):910–27. doi:10.1016/j.enganabound.2022.10.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Jasim LM, Hamzah H, Canpolat C, Sahin B. Mixed convection flow of hybrid nanofluid through a vented enclosure with an inner rotating cylinder. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2021;121:105086. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mahmud T, Nag P, Molla M, Saha SC. Convective heat transfer efficacy of an experimentally observed non-Newtonian MWCNT-Fe3O4-EG hybrid nanofluid in a driven enclosure with a heated cylinder. Int J Therm Sci. 2024;204(10):109203. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2024.109203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ahmed SE, Mansour MA, Arafa AAM, Bakier MAY, Mohamed EF. Finite element analyses for hybrid nanofluid flow between two circular cylinders with multiple heat-conducting obstacles using thermal. Alexandria Eng J. 2024;108(8):676–93. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.09.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lotfi R, Saboohi Y, Rashidi AM. Numerical study of forced convective heat transfer of nanofluids: comparison of different approaches. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2010;37(1):74–8. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2009.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ebrahimi A, Rikhtegar F, Sabaghan A, Roohi E. Heat transfer and entropy generation in a microchannel with longitudinal vortex generators using nanofluids. Energy. 2016;101(5):190–201. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2016.01.102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ying ZP, He BS, He D, Kuang YC, Ren J, Song B. Comparisons of single-phase and two-phase models for numerical predictions of Al2O3/water nanofluids convective heat transfer. Adv Powder Technol. 2020;31(7):3050–61. doi:10.1016/j.apt.2020.05.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Moraveji MK, Esmaeili E. Comparison between single-phase and two-phases CFD modeling of laminar forced convection flow of nanofluids in a circular tube under constant heat flux. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2012;39(8):1297–302. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2012.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ding YL, Wen DS. Particle migration in a flow of nanoparticle suspensions. Powder Technol. 2005;149(2–3):84–92. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2004.11.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sahar G, Masih S, Alireza O, Golab E, Karimipour A. Nanoparticles migration due to thermophoresis and Brownian motion and its impact on Ag-MgO/water hybrid nanofluid natural convection. Powder Technol. 2020;375(19):493–503. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2020.07.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kumar DH, Patel HE, Kumar VRR, Sundararajan T, Pradeep T, Das SK. Model for heat conduction in nanofluids. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93(14):144301. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.144301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Brinkman HC. The viscosity of concentrated suspensions and solutions. J Chem Phys. 1952;20(4):571–81. doi:10.1063/1.1700493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Dardan E, Afrand M, Isfahani AHM. Effect of suspending hybrid nanoadditives on rheological behavior of engine oil and pumping power. Appl Therm Eng. 2016;109:524–34. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.08.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Selvarajoo K, Wanatasanappan VV, Luon NY. Experimental measurement of thermal conductivity and viscosity of Al2O3-GO (80: 20) hybrid and mono nanofluids: a new correlation. Diam Relat Mater. 2024;144:111018. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2024.111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Hamilton RL, Crosser OK. Thermal conductivity of heterogeneous two-component systems. Ind Eng Chem Fundam. 1962;3(3):187–91. doi:10.1021/i160003a005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Timofeeva EV, Routbort JL, Singh D. Particle shape effects on thermophysical properties of alumina nanofluids. J Appl Phys. 2009;106(1):014304. doi:10.1063/1.3155999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ahmed SE, Raizah Z, Arafa AAM, Hussein SA. FEM treatments for MHD highly mixed convection flow within partially heated double-lid driven odd-shaped enclosures using ternary composition nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2023;145(2):106854. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2023.106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Chon CH, Kihm KD, Lee SP, Choi SUS. Empirical correlation finding the role of temperature and particle size for nanofluid (Al2O3) thermal conductivity enhancement. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;87(15):1–3. doi:10.1063/1.2093936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Koo J, Kleinstreuer C. A new thermal conductivity model for nanofluids. J Nanopar Res. 2004;6(6):577–88. doi:10.1007/s11051-004-3170-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zahan I, Nasrin R, Khatun S. Thermal performance of ternary-hybrid nanofluids through a convergent-divergent nozzle using distilled water-ethylene glycol mixtures. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;137(11):106254. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Acharya N. Buoyancy driven magnetohydrodynamic hybrid nanofluid flow within a circular enclosure fitted with fins. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;133(2):105980. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.105980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Ain QU, Shaha IA, Alzahrani SM. Enhanced heat transfer in novel star-shaped enclosure with hybrid nanofluids: a neural network-assisted study. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;61(12):105065. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.105065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Said LB, Khan SA, Farooq U, Liu HH, Imran M, Muhammad T, et al. Application of Box-Behnken design with RSM to predict the heat transfer performance of thermo-magnetic convection of hybrid nanofluid inside a novel oval-shaped annulus enclosure. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;61(6):105010. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Madkhali HA. Numerical study on thermal and concentration relaxation time in tri, hybrid and mono nano-Sutterby magnetohydrodynamic fluid under generalized diffusion conditions. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;139(5):106394. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Nawaz M, Gulzar R, Alharbi SO, Alqahtani AS, Malik MY, El-Shafay AS. Numerical study on generalized heat and mass transfer in cross-rheological fluid in the presence of multi-nanoscale particles: a Galerkin finite element approach. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2024;154(5):107413. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Azizi ZH, Shokri V, Karouei SHH. Hydrothermal behaviour of hybrid nanofluid flow in a shell-and conical coil tube heat exchanger; numerical approach. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;58(10):104435. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Hassen W, Safra I, Ghachem K, Alshammari BM, Maatki C, Albalawi H, et al. EHD flow and heat transfer of hybrid nanofluid in a free surface cavity fitted with an internal hot obstacle. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;53(22):103916. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Wang RJ, Qian S, Zhang ZQ. Investigation of the aggregation morphology of nanoparticle on the thermal conductivity of nanofluid by molecular dynamics simulations. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;127(1–2):1138–46. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.08.117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Sun CZ, Lu WQ, Liu J, Bai BF. Molecular dynamics simulation of nanofluid’s effective thermal conductivity in high-shear-rate Couette flow. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2011;54(11–12):2560–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2011.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Hou JM, Shao C, Huang LZ, Du JY, Wang RJ. Why is the thermal conductivity of Janus nanofluid larger?—from the perspective of aggregation morphology. Powder Technol. 2023;430(17):119005. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2023.119005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Wang RJ, Feng C, Zhang Z, Shao C, Du JY. What quantity of charge on the nanoparticle can result in a hybrid morphology of the nanofluid and a higher thermal conductivity? Powder Technol. 2023;422(4):118443. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2023.118443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Chen WZ, Zhai YL, Guo WJ, Shen X, Wang H. A molecular dynamic simulation of the influence of linear aggregations on heat flux direction on the thermal conductivity of nanofluids. Powder Technol. 2023;413(4):118052. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2022.118052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Yu YX, Du JY, Hou JM, Jin X, Wang RJ. Investigation into the underlying mechanisms of the improvement of thermal conductivity of the hybrid nanofluids. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;226(20):125468. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wang Z, Tian ZF. Mechanism of enhanced boiling heat transfer by hydrophilic and hydrophobic hybrid deposited nanoparticles: a molecular dynamics simulation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;231(43):125893. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Li YJ, Zhou JE, Tung S, Schneider E, Xi SQ. A review on development of nanofluid preparation and characterization. Powder Technol. 2009;196(2):89–101. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2009.07.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Ghadimi A, Saidur R, Metselaar HSC. A review of nanofluid stability properties and characterization in stationary conditions. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2011;54(17–18):4051–68. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2011.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Wang XJ, Zhu DS, Yang S. Investigation of pH and SDBS on enhancement of thermal conductivity in nanofluids. Chem Phys Lett. 2009;470(1–3):107–11. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2009.01.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Azizian R, Doroodchi E, Moghtaderi B. Influence of controlled aggregation on thermal conductivity of nanofluids. J Heat Transfer. 2016;138(2):021301. doi:10.1115/1.4031730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Esmaeilzadeh A, Silakhori M, Ghazali NNN, Metselaar HSC, Mamat AB, Sanjani MSN, et al. Thermal performance and numerical simulation of the 1-pyrene carboxylic-acid functionalized graphene nanofluids in a sintered wick heat pipe. Energies. 2020;13(24):6542. doi:10.3390/en13246542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Almitani KH, Abu-Hamdeh NH, Etedali S, Abdollahi A, Goldanlou AS, Golmohammadzadeh A. Effects of surfactant on thermal conductivity of aqueous silica nanofluids. J Mol Liq. 2020;327:114883. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Mostafizur RM, Rasul MG, Nabi MN. Effect of surfactant on stability, thermal conductivity,and viscosity of aluminium oxide-methanol nanofluids for heat transfer applications. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2022;31(3):101302. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2022.101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Munkhbayar B, Tanshen MR, Jeoun J, Chung H, Jeong H. Surfactant-free dispersion of silver nanoparticles into MWCNT-aqueous nanofluids prepared by one-step technique and their thermal characteristics. Ceram Int. 2013;39(6):6415–25. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.01.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Aravind SSJ, Ramaprabhu S. Graphene-multiwalled carbon nanotube-based nanofluids for improved heat dissipation. RSC Adv. 2013;3(13):4199–206. doi:10.1039/C3RA22653K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Chen LF, Cheng M, Yang DJ, Yang L. Enhanced thermal conductivity of nanofluid by synergistic effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Appl Mech Mater. 2014;548–549:118–23. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.548-549.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Jana S, Khojin AS, Zhong WH. Enhancement of fluid thermal conductivity by the addition of single and hybrid nano-additives. Thermochim Acta. 2007;462(1–2):45–55. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2007.06.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Baghbanzadeh M, Rashidi A, Rashtchian D, Lotfi R, Amrollahi A. Synthesis of spherical silica/multiwall carbon nanotubes hybrid nanostructures and investigation of thermal conductivity of related nanofluids. Thermochim Acta. 2012;549:87–94. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2012.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Shilpa B, Leela V, Badruddin IA, Kamangar S, Bashir MN, Ali MN. Integrated neural network based simulation of thermo solutal radiative double-diffusive convection of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow in an inclined annulus with thermophoretic particle deposition. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;62(3):105158. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.105158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Shahsavar A, Bahiraei M. Experimental investigation and modeling of thermal conductivity and viscosity for non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid containing coated CNT/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Powder Technol. 2017;318:441–50. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2017.06.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]