Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Two-Layer Energy Management Strategy for Fuel Cell Ships Considering the Performance Consistency of Fuel Cells

1 Key Laboratory of Transport Industry of Marine Technology and Control Engineering, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, 201306, China

2 Institut d’Électronique et des Technologies du numéRique, UMR CNRS 6164, Nantes Université, Nantes, 44000, France

3 China Classification Society Wuhan Rules & Research Institute, Wuhan, 430010, China

* Corresponding Author: Diju Gao. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(9), 3681-3702. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068656

Received 03 June 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 26 August 2025

Abstract

Hydrogen fuel cell ships are one of the key solutions to achieving zero carbon emissions in shipping. Multi-fuel cell stacks (MFCS) systems are frequently employed to fulfill the power requirements of high-load power equipment on ships. Compared to single-stack system, MFCS may be difficult to apply traditional energy management strategies (EMS) due to their complex structure. In this paper, a two-layer power allocation strategy for MFCS of a hydrogen fuel cell ship is proposed to reduce the complexity of the allocation task by splitting it into each layer of the EMS. The first layer of the EMS is centered on the Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC). The Northern Goshawk Optimization (NGO) algorithm is used to solve the nonlinear optimization problem in NMPC, and the local fine search is performed using sequential quadratic programming (SQP). Based on the power allocation results of the first layer, the second layer is centered on a fuzzy rule-based adaptive power allocation strategy (AP-Fuzzy). The membership function bounds of the fuzzy controller are related to the aging level of the MFCS. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is used to optimize the parameters of the residual membership function to improve the performance of the proposed strategy. The effectiveness of the proposed EMS is verified by comparing it with the traditional EMS. The experimental results show that the EMS proposed in this paper can ensure reasonable hydrogen consumption, slow down the FC aging and equalize its performance, effectively extend the system life, and ensure that the ship has good endurance after completing the mission.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Hydrogen energy is considered the clean energy source with the greatest development scope and application potential in the 21st century [1]. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has adopted a more rigorous stance in recent years regarding energy efficiency and emission targets for ships [2]. The application of clean energy on ships has increasingly become a focal point of research within the field of shipping. The application of hydrogen fuel cells on ships has become a potential solution to achieve zero carbon emissions and to meet the goals of ship maneuverability, durability, efficiency, and low noise [3].

Due to technical and material limitations, high-power fuel cells suffer from high cost and short lifetimes [4,5]. The direct replacement of high-power fuel cells with MFCS may be a more reasonable option. It can not only share the power demand, reduce the burden of FC, and reduce the risk of failure but also improve the stability and safety of the system, avoiding the problems caused by a single high-power FC. However, although multi-fuel cell hybrid ships show many advantages in applications, existing research still has limitations. On the one hand, for the energy management of multi-fuel cell hybrid ships, most of the existing strategies are based on a single reactor system. It’s difficult to be directly applied to the more complex multi-stack scenarios and to realize the best performance. On the other hand, there is inconsistency in the performance of each stack, power generation output, and service life. This increases the complexity of MFCS power allocation, and most existing strategies are inadequate to address these issues.

Efficient energy management technology is one of the necessary prerequisites for hydrogen fuel cell-powered ships to realize zero emissions. The existing energy management strategies for fuel cell-powered ships are typically classified into two main categories: rule-based and optimization-based [6]. For example, an energy management approach based on load prediction and real-time optimization is proposed in [7] to optimize real-time energy allocation through current operating conditions to meet system constraints and maintain battery SOC at a healthy level to minimize operating cost consumption. In [8], an energy management strategy based on fuzzy logic control is proposed to adaptively manage the power allocation between the fuel cell and the energy storage system and reduce the system’s hydrogen consumption. In [9], a dual adaptive EMS is proposed. It uses an adaptive low-pass filter to divide the load current into high-frequency and low-frequency components and generates an adaptive battery current in real time based on the charging state of the supercapacitor. Accordingly, the filter cutoff frequency is dynamically adjusted to ensure that the battery only accepts low-frequency current, while the supercapacitor absorbs high-frequency peaks. This method compresses the range of cutoff frequency changes into a narrower interval, significantly reducing the battery’s peak current and stress, thereby extending battery life. In [10], an energy management strategy for hydrogen fuel cell ships based on an improved dynamic programming algorithm (DP) is proposed to effectively reduce hydrogen fuel consumption and significantly decrease the solution time. In addition, in recent years, deep learning technology has been increasingly applied in the field of energy management. It has gradually become a mainstream research direction. Different from energy management strategies based on rules and optimization algorithms, deep learning-based energy management strategies learn autonomously. They do this by inputting a large amount of historical and real-time ship driving data. It is able to recognize the complex nonlinear relationships and patterns of ships. This is done under different operating conditions. Thus, it realizes accurate and adaptive energy management decisions. For example, in [11], an EMS uses deep Q-learning to optimize the objectives of ship operating cost, fuel cell life, and battery SOC. Meanwhile, the complexity of the reward function is simplified by designing the action space to improve the control effect and convergence of the algorithm. In [12], a data enhancement method combining long- and short-term memory (LSTM) with a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) algorithm is proposed. By utilizing LSTM to enhance the data, the diversity and richness of the data are increased. This operation enables the DRL strategy to better adapt and respond under unknown navigation conditions. The method effectively improves the generalization ability of the DRL strategy and reduces the FC operational stress and hydrogen consumption. Enhance its ability to adapt to changes in the real environment. These strategies offer satisfactory results when applied to a single FC system. But they are not optimal in a ship with MFCS due to the inherent complexity of the system structure and the challenges associated with power allocation across FC. In addition, when the performance of each FC is inconsistent, they will have different power generation efficiencies and lifetimes, which will increase the complexity of power allocation in MFCS. Consequently, these strategies require further optimization and adaptation to effectively address these issues.

Currently, there is limited research on MFCS, and most of the existing studies focus on optimizing for system hydrogen consumption. For example, in [13], a constrained optimization algorithm based on Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions is proposed to optimize the efficiency and system hydrogen consumption for MFCS. In [14], a control strategy, in conjunction with a designed DC/DC converter, is proposed to maintain the fuel cell stack in the MFCS at the maximum power point, with the objective of reducing the system’s hydrogen consumption. In [15], a degradation power allocation strategy is proposed for MFCS, which better optimizes the low power output while satisfying the load power demand. In [16], a two-layer energy management strategy is proposed to dynamically adjust the power allocation through real-time load information and the previous day’s power generation schedule to adapt to the ship’s load fluctuations in actual operation and reduce the system’s fuel consumption. Although existing studies have been effective in optimizing some of the metrics, most of them have neglected the impact of the degradation of the performance of each fuel cell in the MFCS and its differences on the studied metrics. Most of the current studies assume that the performance of the stacks will not degrade and that there is no aging difference between the stacks. However, in long-term operation, the active area of the stack catalyst decreases, the membrane electrode impedance increases, and the performance changes over time due to factors such as operating environment and load fluctuations [17]. Therefore, the development of effective energy management strategies to slow the aging rate of the FC is a necessary condition to ensure the long-term stable operation of the MFCS [18]. For example, in [19], a novel multi-time scale EMS approach for a hybrid FC/battery propulsion system is proposed in this paper. The EMS takes into account battery and FC degradation losses and fuel consumption costs based on actual ship power requirements. It also makes an effective trade-off between time complexity and system optimization by exploring different time scales. The method has a good display of reference significance. In addition, the consistent performance degradation across the MFCS is also important, which not only reduces the number of maintenance visits but also allows users to better predict the current state and lifetime of the MFCS. Currently, three mainstream power allocation strategies are applied to MFCS systems: equal, sequential, and independent allocation strategies [20]. Scholars have compared these three types of strategies [21,22] and improved them [23,24] so that these strategies can equalize the level of performance degradation across FC [25] or ensure the SOC consistency of the storage system [26]. In [27], the research results show that the longer the operating time of the stack under load fluctuation, the faster its aging rate. Therefore, the output power fluctuation rate of the fuel cell stack should be made as small as possible during its operation [28]. Furthermore, it is also necessary to establish a corresponding fuel cell stack aging model, with the help of which the performance degradation of the FC during operation can be monitored in real time [29].

In order to solve the above problems and provide new ideas and methods for energy management of multi-fuel cell hybrid ships. A two-layer energy management strategy for multi-fuel cell hybrid ships is proposed in this paper. It can effectively cope with problems such as inconsistent performance of electric stacks in multi-fuel cell systems and improve the ship’s energy utilization efficiency and operational performance by optimizing the power allocation. Among them, the first layer EMS of the strategy is based on NMPC to realize the optimization of hydrogen consumption, aging increment of batteries, and ship’s range capability during ship’s operation, and to generate the demand power of the MFCS and batteries. The MFCS demand power will be used as the input of the second layer EMS. The second layer EMS is based on the fuzzy rule algorithm (fuzzy) for power allocation, and its goal is to improve the lifetime of the MFCS while maintaining the aging consistency of the MFCS system or reducing the aging differences of each FC.

2 System Structure and Power System Modeling

2.1 Hybrid Ship Design Parameters

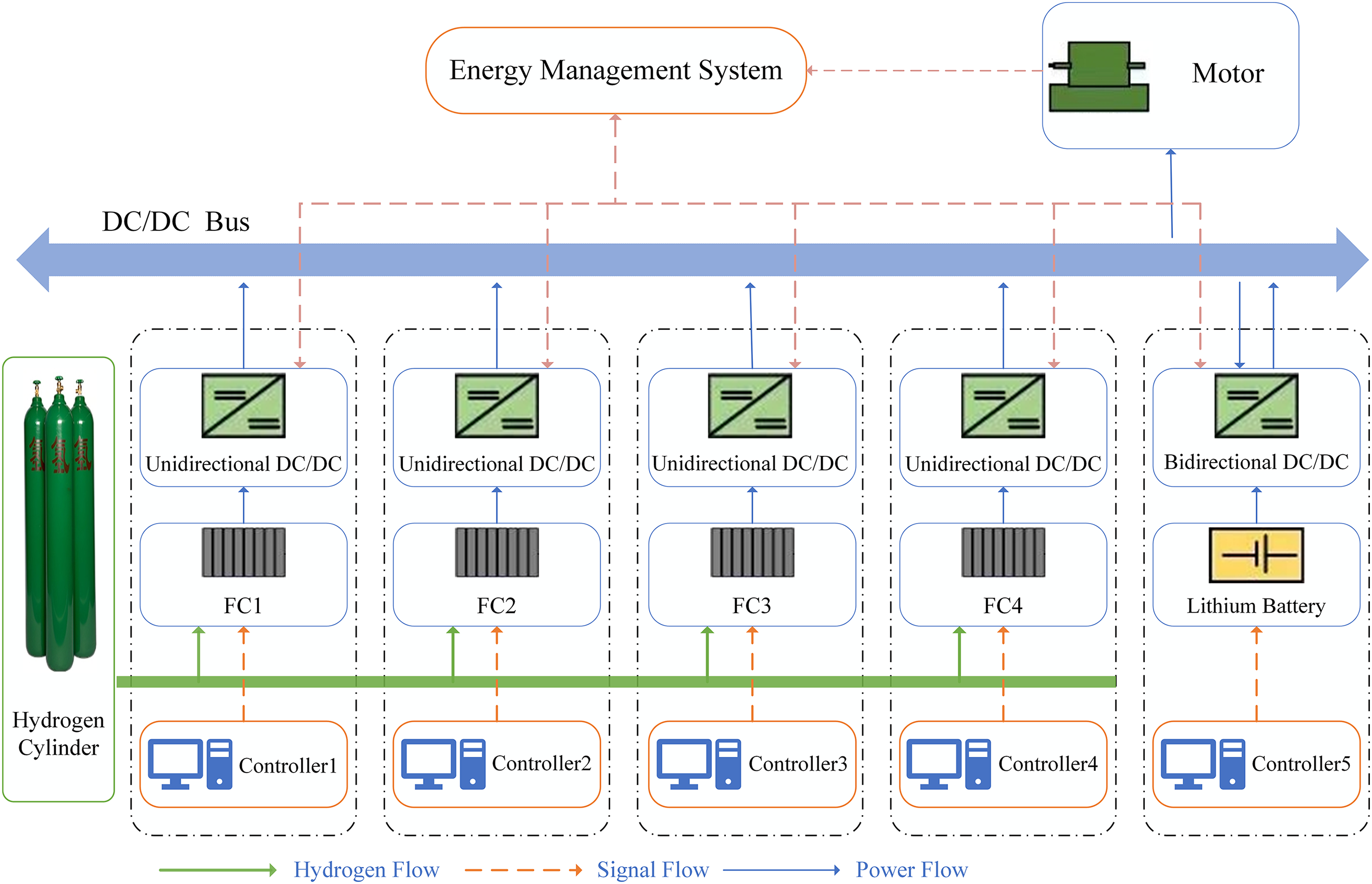

The energy topology used in this study is designed using the energy topology of the “Three Gorges Hydrogen Ship No. 1” [30] as a reference, assuming a ship speed of 20 km/h and a hydrogen storage capacity of 240 kg. A simplified energy transfer diagram of the ship power system is shown in Fig. 1. The system comprises electric motors, fuel cells, and auxiliary energy storage devices, which are connected to the shipboard equipment through rectifiers or inverters.

Figure 1: Ship energy conduction diagram

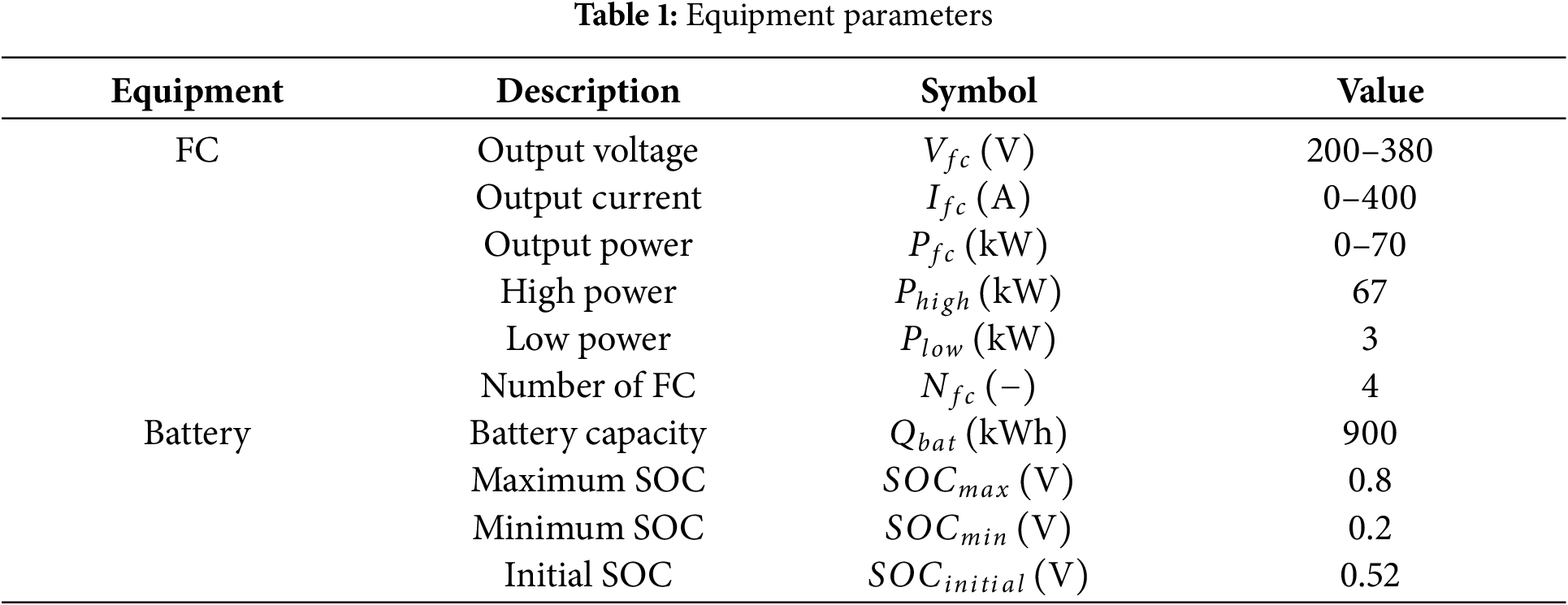

The timely adjustment of the output power distribution of each stack when multiple stacks are put into operation simultaneously can effectively enhance the durability, service life, and system stability of the power stacks [15]. MFCS topology is divided into series and parallel. This paper adopts the parallel structure, the advantage is to improve the stability of the system and make it easy to maintain. The main parameters of the stacks are presented in Table 1.

2.3.1 Fuel Cell Hydrogen Consumption Model

In this paper, a fuel cell hydrogen consumption model is used to describe the numerical relationship between the output power, hydrogen consumption rate, and fuel efficiency. The mathematical model is shown in the following equation:

where

where

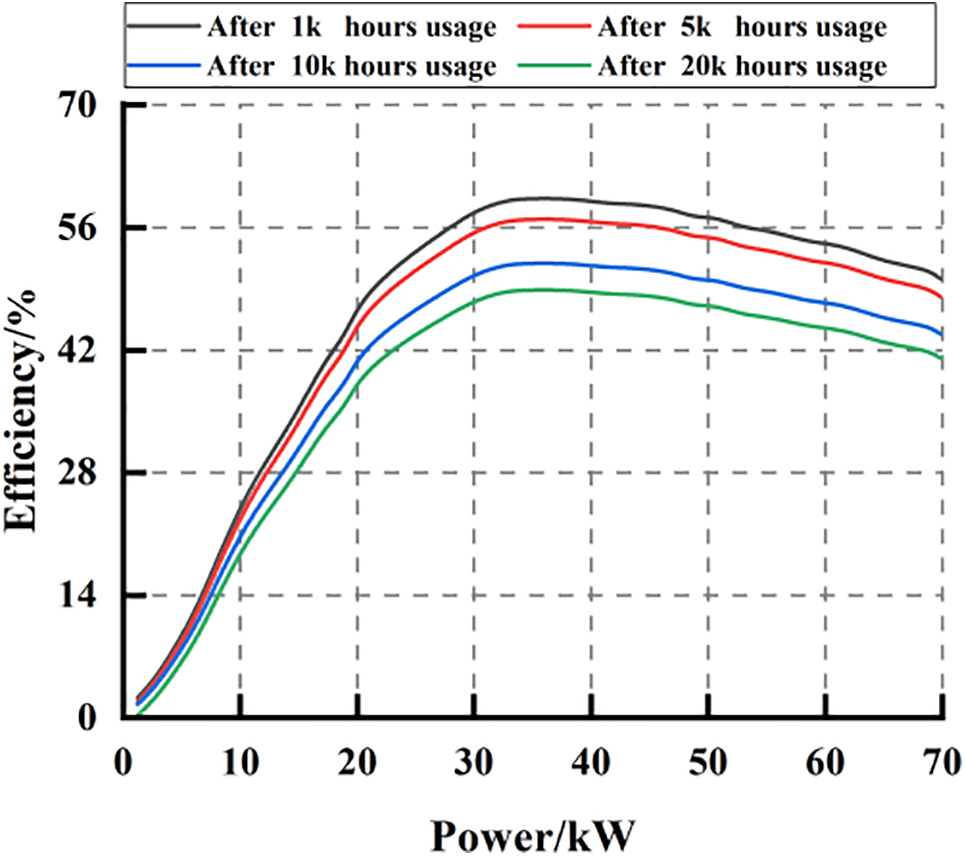

Figure 2: Fuel cell efficiency curves at different degradation levels

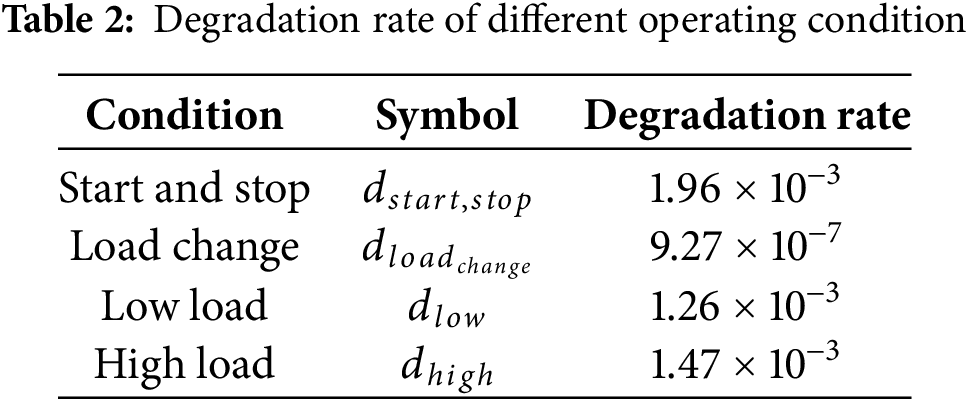

The aging of fuel cells depends on numerous factors, but currently, scholars believe that its aging is primarily caused by four factors: load power fluctuation, start-stop, low-power load, and high-power load. To ensure the validity and accuracy of the construction strategy, a discrete degradation model for the fuel cell was established as follows [31]:

where

2.3.3 Endurance of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Ships Model

The endurance of hydrogen fuel cell ships is a main performance indicator for ship design. Based on the ship endurance evaluation model [32], the endurance evaluation model of the hydrogen fuel cell hybrid ship is established as:

where

To simplify the analysis process, this paper adopts the Rint circuit model to model the battery. The relationship between voltage

where current

where

The SOC expression is as follows:

where

2.4.1 Battery Equivalent Hydrogen Consumption Model

The operating state of a battery is complex and difficult to determine in real time. To simplify the calculation, this paper adopts the average operating state to calculate the equivalent hydrogen consumption. The equivalent hydrogen consumption of battery

where

δ can be calculated as:

where

where

2.4.2 Battery Degradation Model

The battery degradation model used in this paper is an empirical model. Based on the research result [33], the degradation model of batteries is established as:

where D, E, F, G, H, and J are the fitting parameters, T is the temperature (K), and

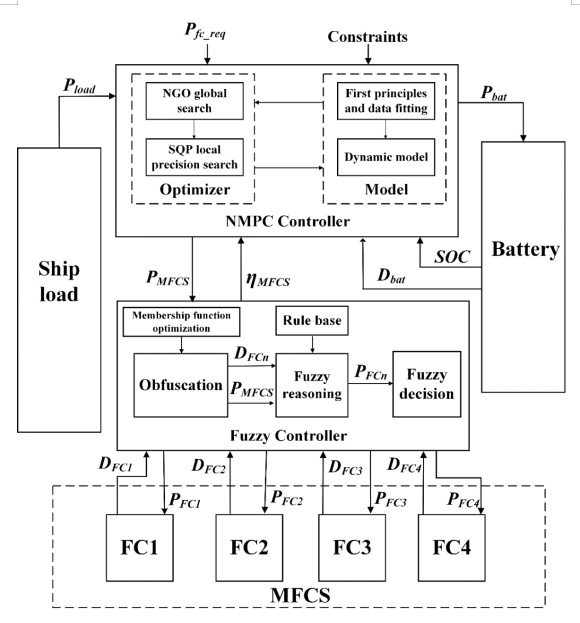

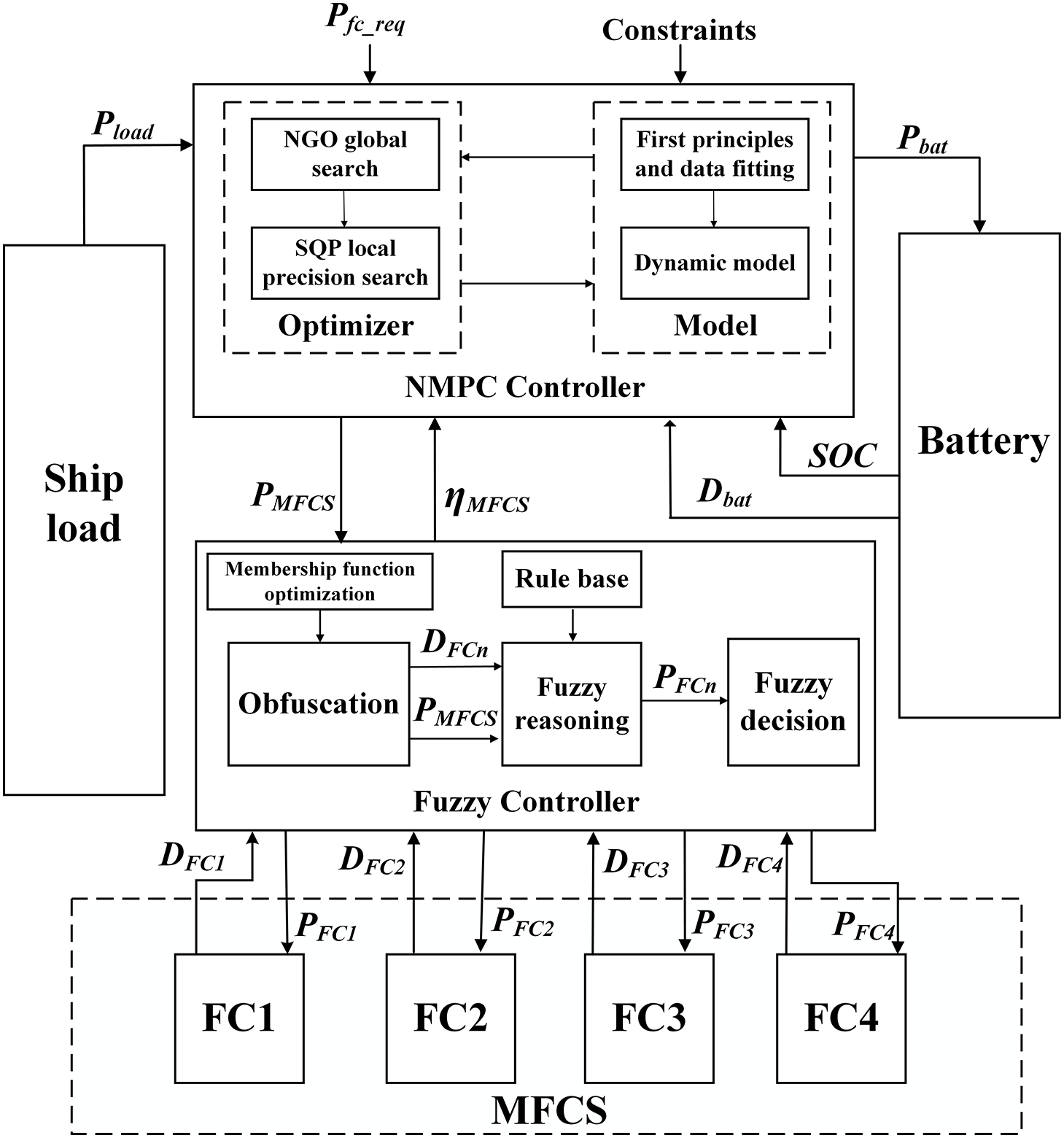

The essence of the energy management for MFCS ships is to meet the ship’s power demand through two energy allocations. The first allocation is the power allocation between the MFCS and the energy storage system, and the second allocation is the power allocation between the FC in the MFCS. The block diagram of the energy management strategy is shown in Fig. 3, where SOC,

Figure 3: Energy management strategy block diagram

As shown in Fig. 3, compared with the existing EMS, the NMPC-NGO + AP-Fuzzy architecture constructed in this paper is more comprehensive in optimizing the ship’s key operation parameters. The architecture innovatively combines NMPC-NGO and AP-Fuzzy. This retains the control accuracy and robustness of the optimization algorithm and the efficiency of the rule-based strategy. The architecture enables the algorithm in this paper to maintain superior performance when dealing with multi-objective optimization tasks. In terms of implementation, this architecture can reasonably allocate several different optimization objectives, thus reducing the computational complexity of the algorithm. In addition, the two-layer EMS designed in this paper fully utilizes the power generation characteristics of Li-ion batteries and fuel cells. At the same time, it takes into account the performance differences of fuel cells in the MFCS. According to these differences, a targeted power allocation strategy is formulated, which greatly reduces the design difficulty of the EMS. The design method is versatile and has unique novelty and high efficiency.

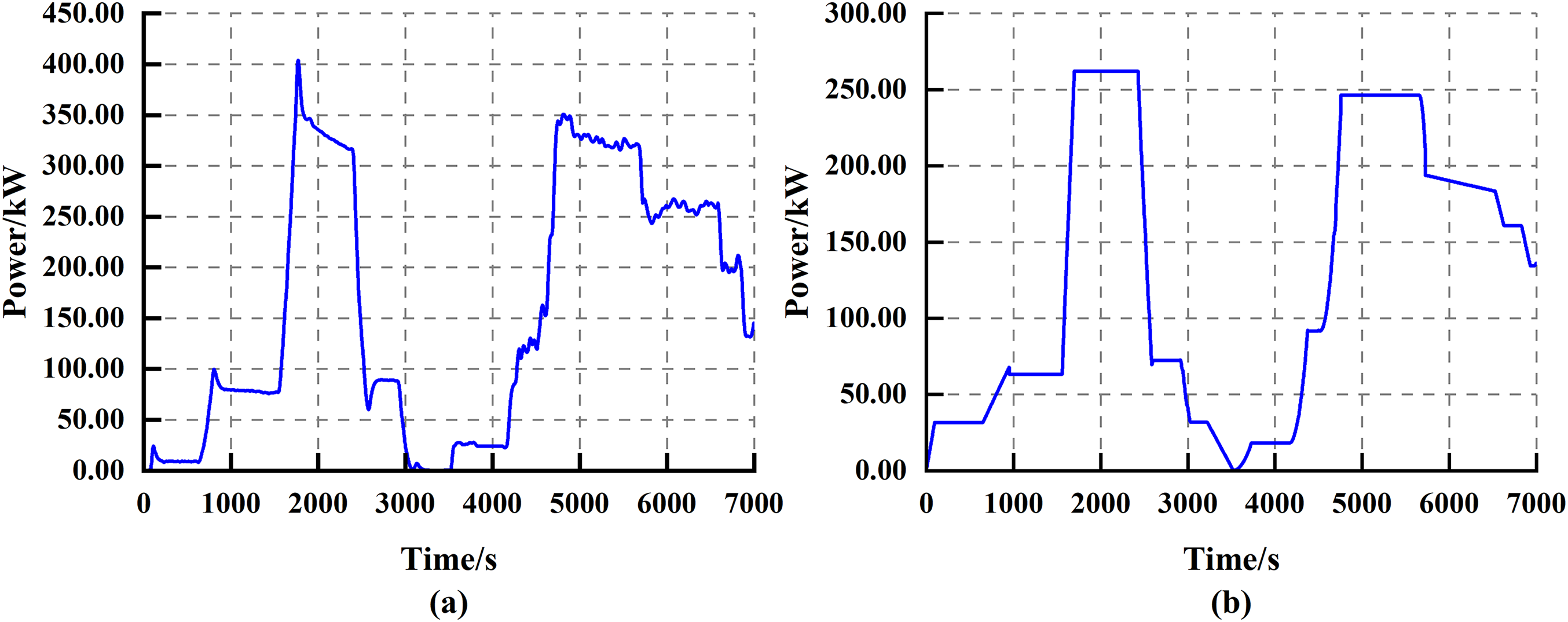

To ensure the effectiveness of the energy management strategy, all the data used in this experiment come from the experimental test platform. The platform is established on the basis of the experimental platform of Wuhan University of Technology. Where the ship load power is shown in Fig. 4a and the fuel cell reference power is shown in Fig. 4b.

Figure 4: (a) Ship load power and (b) MFCS reference power

As shown in Fig. 4a, the ship load power covers a wide range of operating conditions, which can effectively characterize the different working conditions that may be encountered in ship operation and ensure the validity and representativeness of the test results. As shown in Fig. 4b, the reference power setting of MFCS enables the fuel cell to take up most of the output power and respond smoothly to load changes, thus alleviating the accelerated aging problem of FC due to load fluctuations.

3.1 NMPC-NGO Based Energy Management Strategy

Fuel cell energy management is a typical decision-making process for multi-stage optimization problems and thus is suitable for the NMPC algorithm. However, the traditional NMPC algorithm has a greater dependence on the selection of initial values when solving using the SQP algorithm. Improper selection of initial values may lead to falling into local optimal solutions or even failing to find feasible solutions. To solve this problem, the NGO algorithm is introduced into the optimization process in this paper. By transforming the single SQP search into a combination of NGO global search and SQP local accurate search, the problem of improper selection of initial value is avoided, and the stability and tracking performance of the algorithm are improved.

Compared with traditional population optimization algorithms, the NGO algorithm has a stronger ability to find the optimal value and a faster convergence rate [34], and the algorithm primarily encompasses two processes of prey recognition: pursuit and escape [35]. The initial stage, random selection and fast approximation, is described by the following equation:

where

The second stage, the escape and pursuit stage, is described by the following equation:

where

In this simulation, to improve the prediction accuracy, the sampling time is set to 1 s, and both the control time domain

where

In order to reduce the difficulty of obtaining the NMPC control parameters, the sensitivity of the controller is analyzed in this paper in conjunction with the parameter adjustment process in the experiment. It is found that the sensitivity of the controller to parameter changes is closely related to the priority of the optimization objective and the rate of change. When the optimization objective (e.g., reference power tracking error) varies greatly with time steps, parameter changes can disturb the optimization sequence and lead to controller failure. In addition, a change in the weighting factor of a high-priority objective (e.g., system hydrogen consumption) can have a significant impact on its optimization effect. Once the corresponding weighting parameters are adjusted, the overall performance of the controller is also greatly affected.

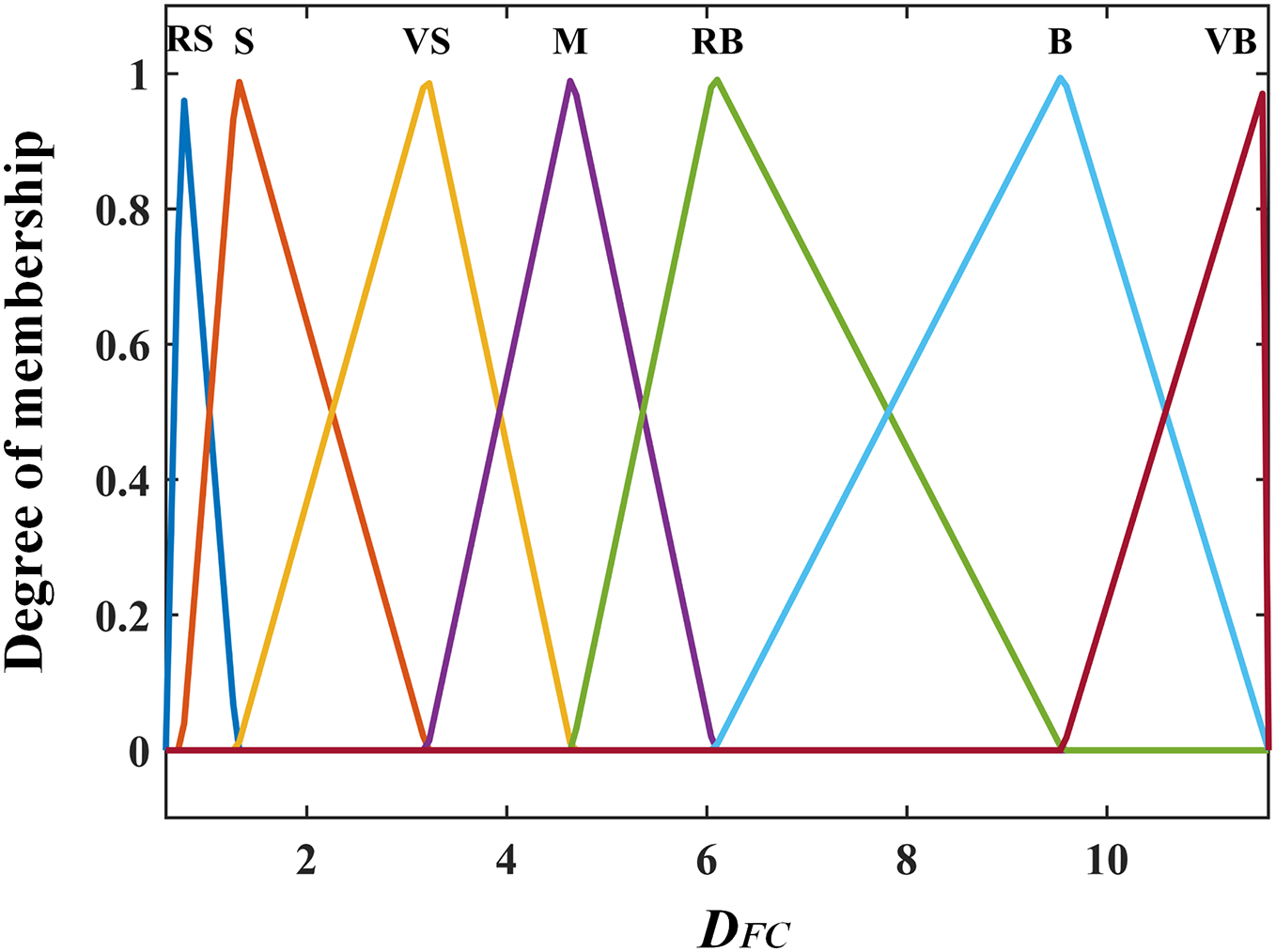

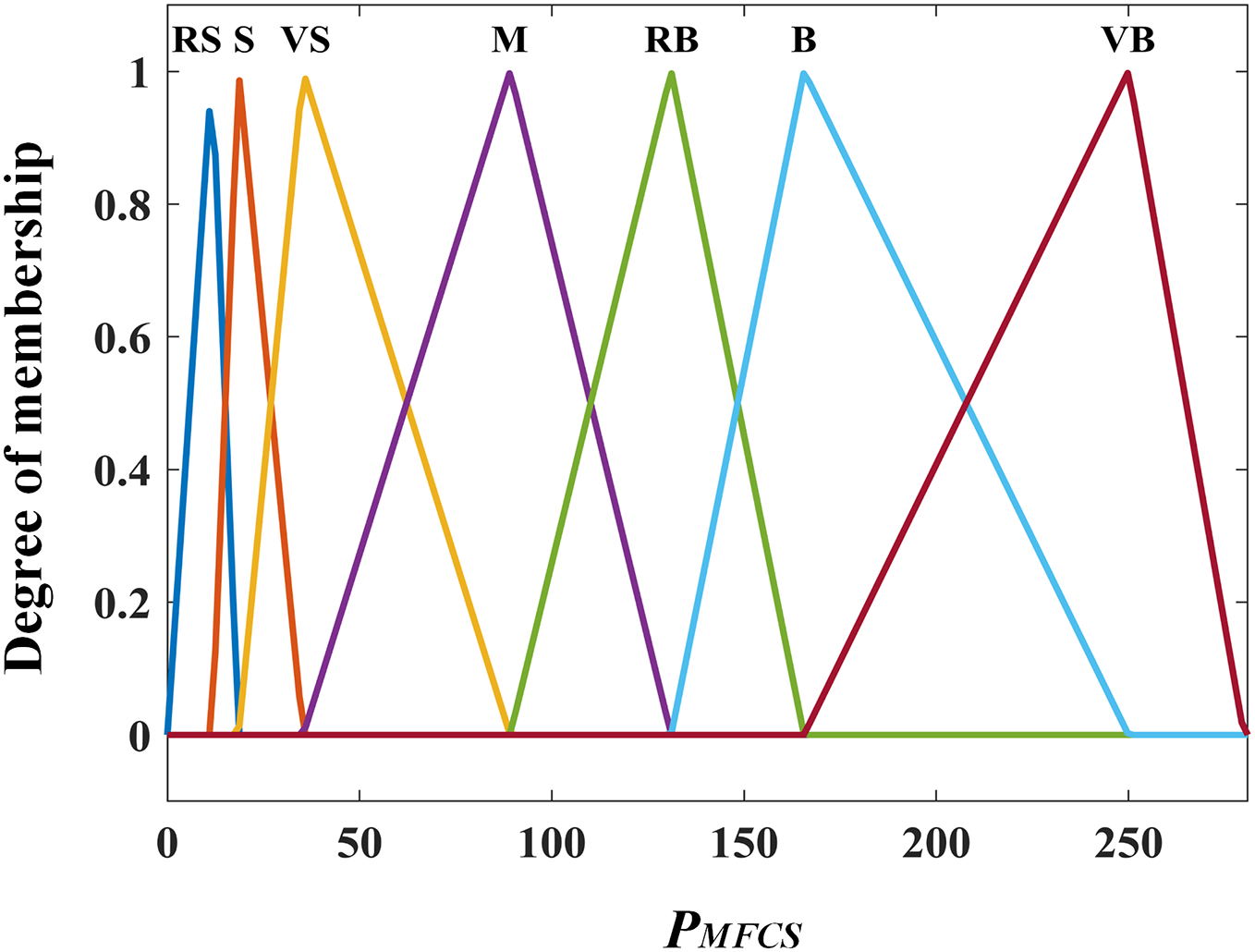

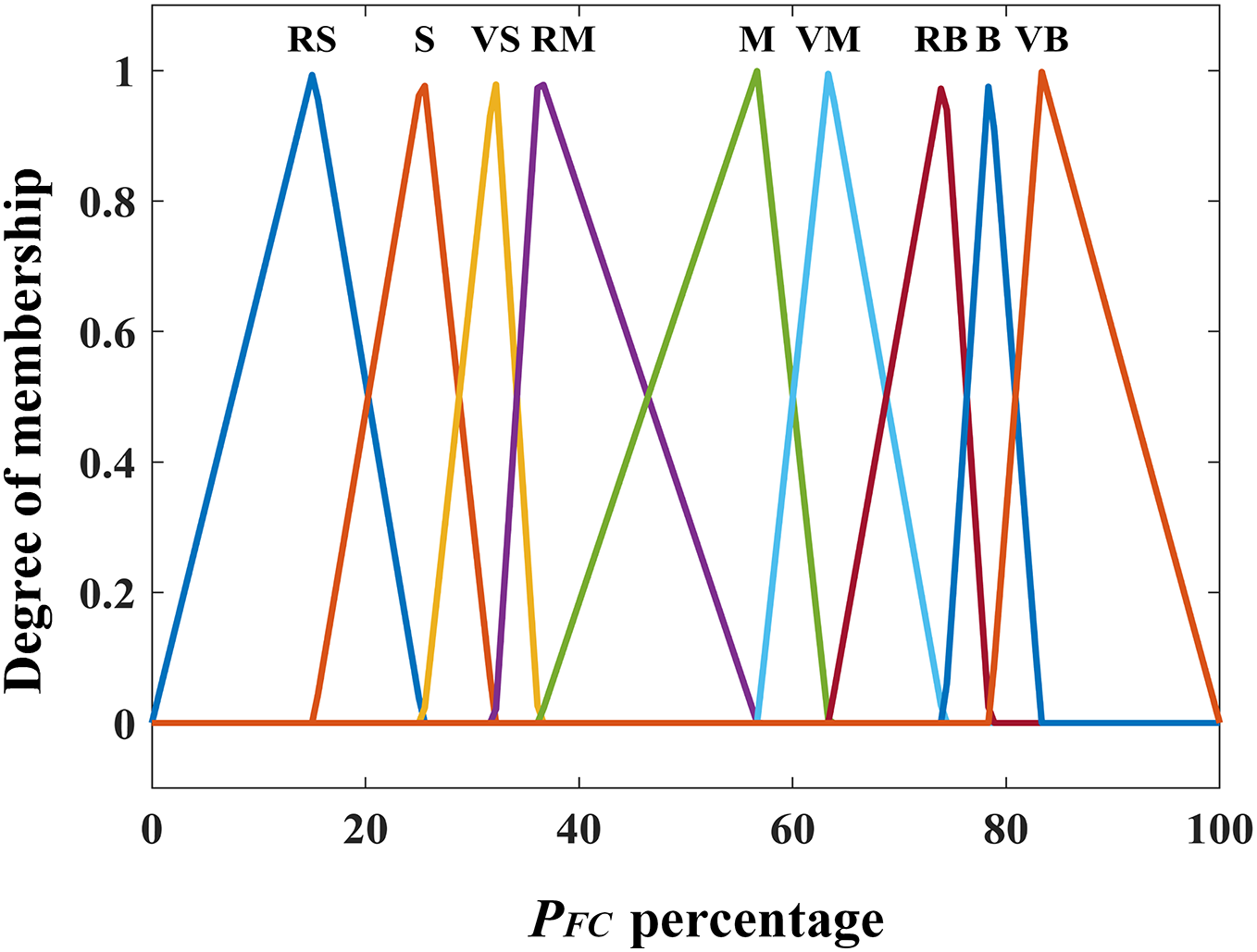

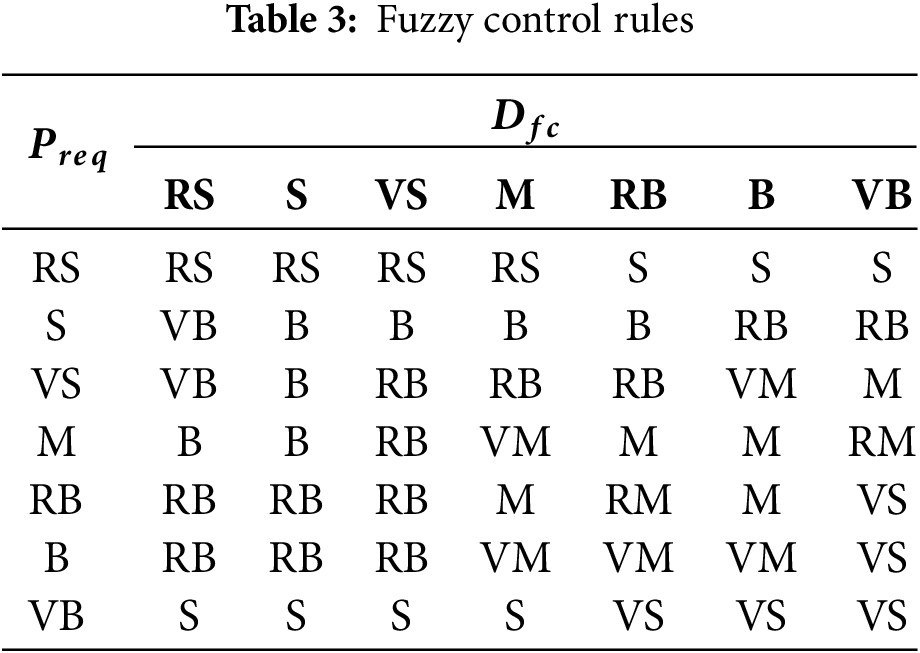

3.2 Fuzzy Rule-Based Adaptive Power Allocation Strategy

In MFCS, the system’s performance will be constrained by the output power of the FC exhibiting the poorest performance [36]. To enhance the lifespan, and performance of the MFCS and reduce the performance degradation of each FC, a fuzzy rule-based adaptive power allocation strategy is proposed in the section. The strategy is dynamically adjusted by linking the membership function boundaries to the aging degree of the MFCS, ensuring that the fuzzy control rules remain effective despite the gradual convergence of aging differences among the FC. In comparison to the conventional fuzzy control strategy, the AP-Fuzzy is capable of accurately tracking the degradation trend of the MFCS performance. The convergence threshold is set to prevent the issue of fluctuating final values and failure to converge due to excessive optimization.

In addition, the membership functions and rules of fuzzy controllers rely on expert experience and are subjective, making it difficult to achieve optimal results. To address this limitation, the PSO algorithm is used to optimize the parameters of the residual membership function to improve the efficiency and performance of the proposed strategy.

The steps of algorithm improvement are briefly described below:

Step 1: Calculate the aging degree of each FC:

Step 2: Identify the FCs with the largest and smallest performance degradation and record their aging values:

Step 3: Calculate the current MFCS aging degree of discrepancy:

Step 4: Set the convergence threshold for the aging difference degree and update the actual values corresponding to the upper and lower limits of the domain of the membership function:

Step 5: Use the optimization algorithm to optimize the remaining parameters of the membership function:

where

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

The domain of fuel cell stack degradation

4 Experimentation and Analysis

In this section, the effectiveness of the proposed energy management strategy is verified by conducting simulation studies and comparing and analyzing the data obtained from the experiments. The experimental environment is configured with MATLAB R2022a and an Intel Core i5-12400f CPU at 2.50 GHz. The project code is available here: https://gitcode.com/qq_64948492/NMPC_NGO_and_AP_Fuzzy (accessed on 22 July 2025).

4.1 Analysis of Optimization Effect Based on NMPC-NGO Algorithm

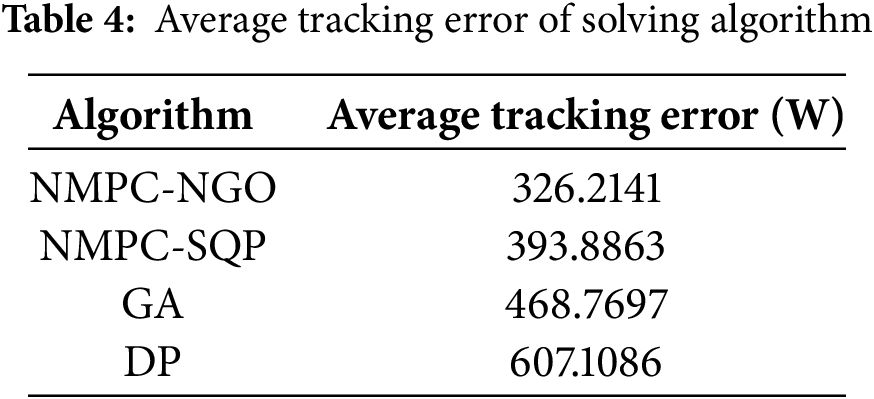

The effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in this paper is verified by comparing it with the three algorithms NMPC-SQP, GA, and DP. The optimization objectives mainly include power tracking performance, system hydrogen consumption, battery aging increment, and algorithm runtime. The average power tracking error of the fuel cell output power is shown in Table 4.

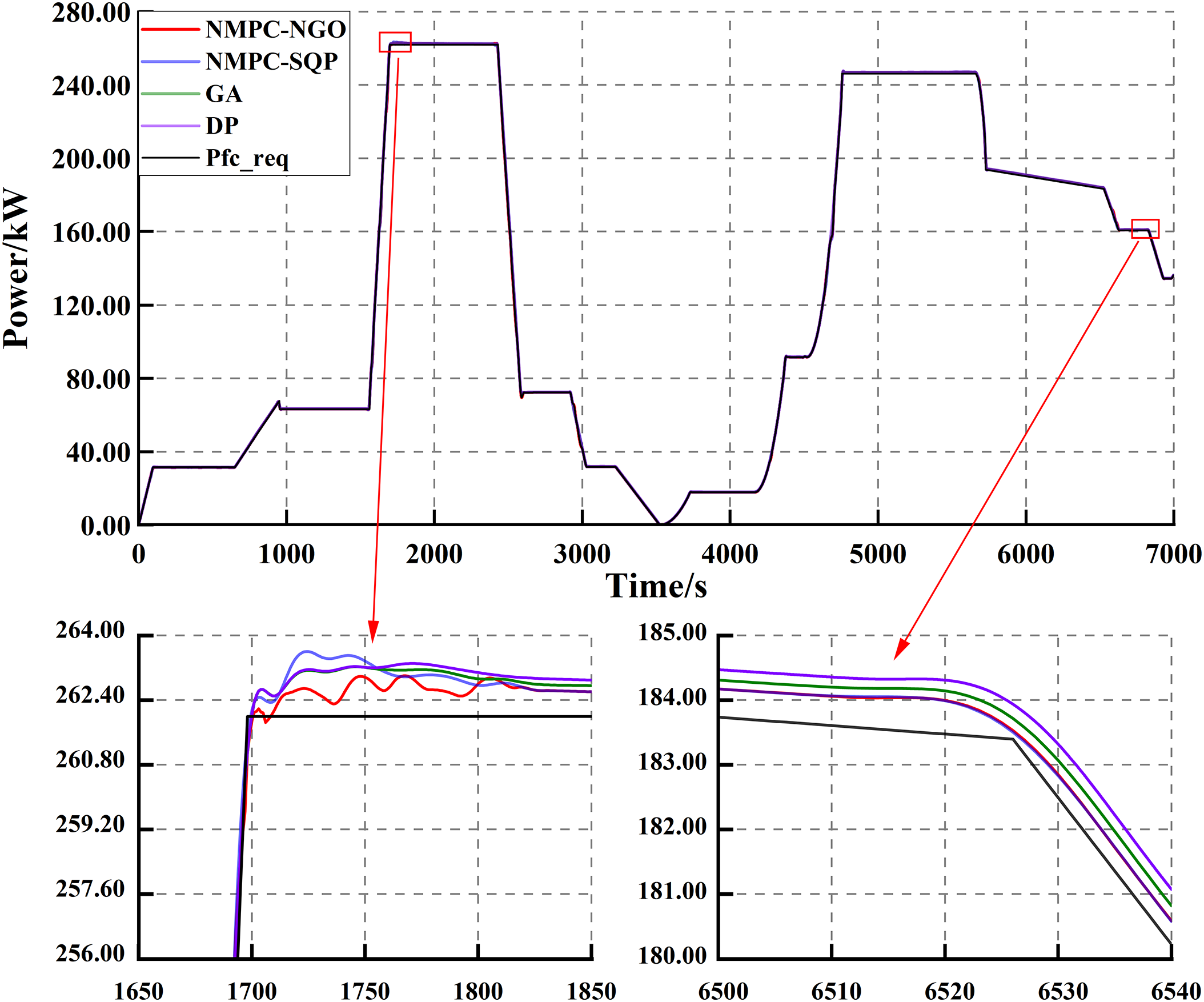

The tracking effect of each algorithm is shown in Fig. 8. Combining Fig. 8 and Table 4, and it can be observed that all four control algorithms can effectively follow the reference output power. Compared with the other three algorithms, the proposed NMPC-NGO algorithm has a smaller average tracking error.

Figure 8: Output power tracking

Moreover, the NMPC-NGO algorithm can respond fast and track the reference trajectory when it changes abruptly. Therefore, the proposed NMPC-NGO strategy outperforms the other three algorithms in terms of tracking.

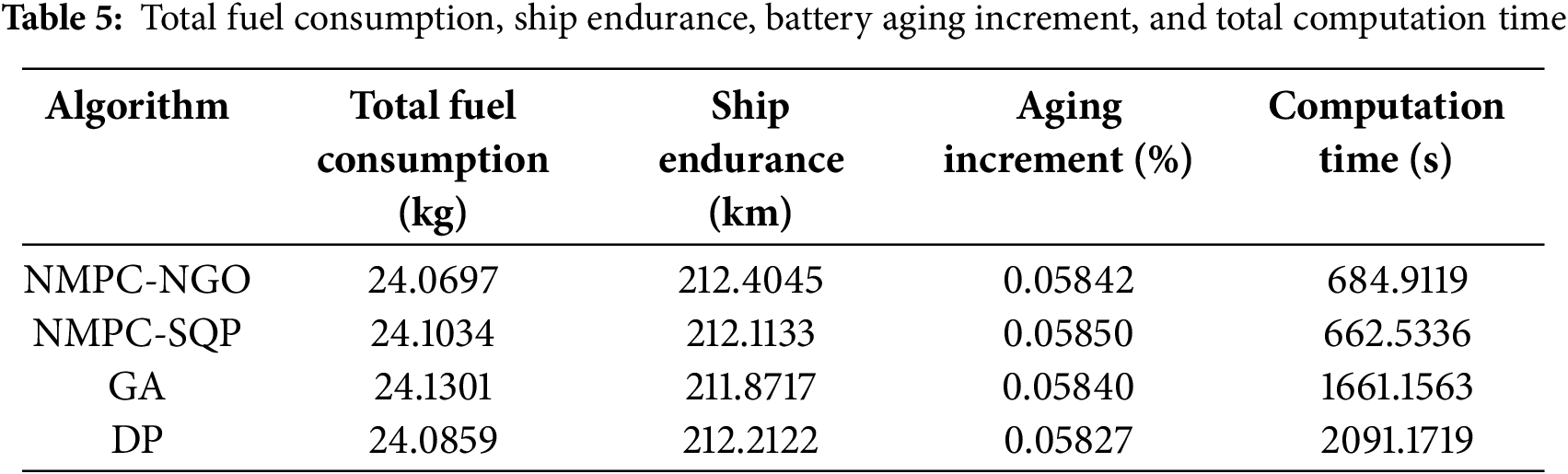

In order to compare the performance of the four algorithms more intuitively and accurately, the total fuel consumption, ship endurance, battery aging increment, and total computation time of the four algorithms during the optimization process are shown in Table 5.

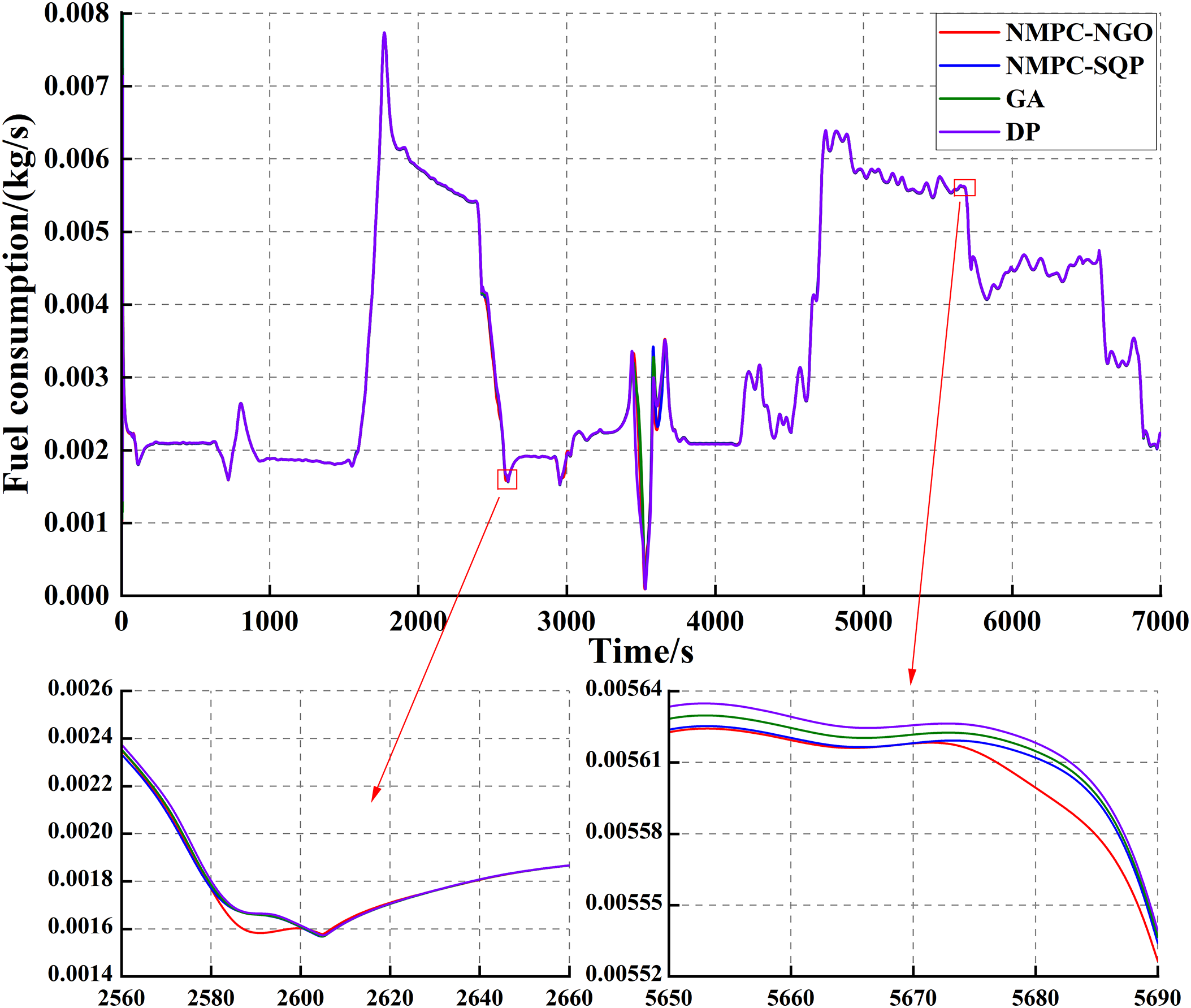

The hydrogen consumption of the four compared algorithms at each step is shown in Fig. 9. As shown in Fig. 9, the hydrogen consumption profile of NMPC-NGO is lower than the hydrogen consumption profiles of the other methods. According to Table 5, the NMPC-NGO algorithm has the lowest total hydrogen consumption, and the longest duration compared to the other three algorithms. Based on each time step with the system hydrogen consumption, NMPC-NGO is at a low hydrogen consumption level most of the time. Therefore, it can be concluded that NMPC-NGO has a more obvious and stable energy-saving effect.

Figure 9: System hydrogen consumption

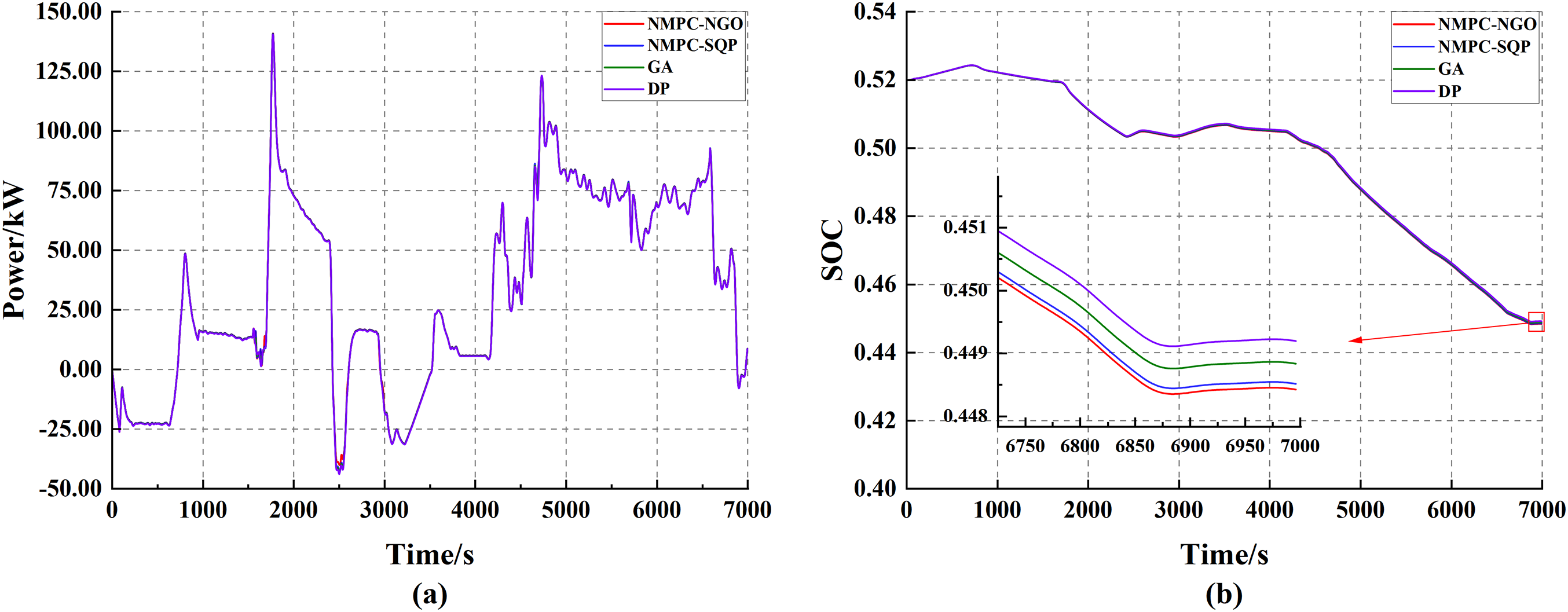

The output power and SOC of the battery of the four compared algorithms are shown in Fig. 10. Combining Fig. 10 and Table 5, it finds that all four algorithms can effectively utilize the batteries to adapt to the load power fluctuations. With the NMPC-NGO algorithm, the battery residual SOC is minimized. This indicates its ability to fully utilize the battery to balance the load power fluctuation to reduce the output power fluctuation of the MFCS system. The NMPC-NGO algorithm has the third highest inhibition capability of battery degradation among the four algorithms, which is only higher than that of the NMPC-SQP algorithm. However, it can be judged from the values of battery aging increment that the four algorithms have a small difference in inhibiting battery performance degradation.

Figure 10: (a) Battery power changes and (b) Battery SOC

Although the NMPC-NGO algorithm is slightly less capable of suppressing the degradation of battery performance compared to the DP and GA algorithms, the length of computation time consumed is also one of the important evaluation indexes for evaluating the optimization algorithms. The computation times of the NMPC-NGO, NMPC-SQP, GA, and DP algorithms are shown in Table 5.

According to Table 5, compared with GA and DP algorithms, NMPC-NGO and NMPC-SQP algorithms can better meet the real-time requirements of ships. Although the computation time of the NMPC-NGO algorithm is higher than that of the NMPC-SQP algorithm, the comparison of the optimization parameters above shows that the comprehensive performance of the NGO-SQP algorithm is not as good as the NMPC-NGO algorithm.

4.2 Fuzzy Rule-Based Adaptive Power Allocation Strategy’ Effectiveness Analysis

Different power allocations will affect the aging speed rate of the FC. The effectiveness of the proposed allocation strategy is verified by comparing it with Fuzzy, Average and Independent allocation strategies. The principles of the Average allocation strategy and the Independent allocation strategy are as follows:

Independent allocation: the on/off state and output power of each FC in the MFCS can be controlled independently and decided by the optimization algorithm.

Average allocation: the MFCS demand power is evenly distributed to each FC.

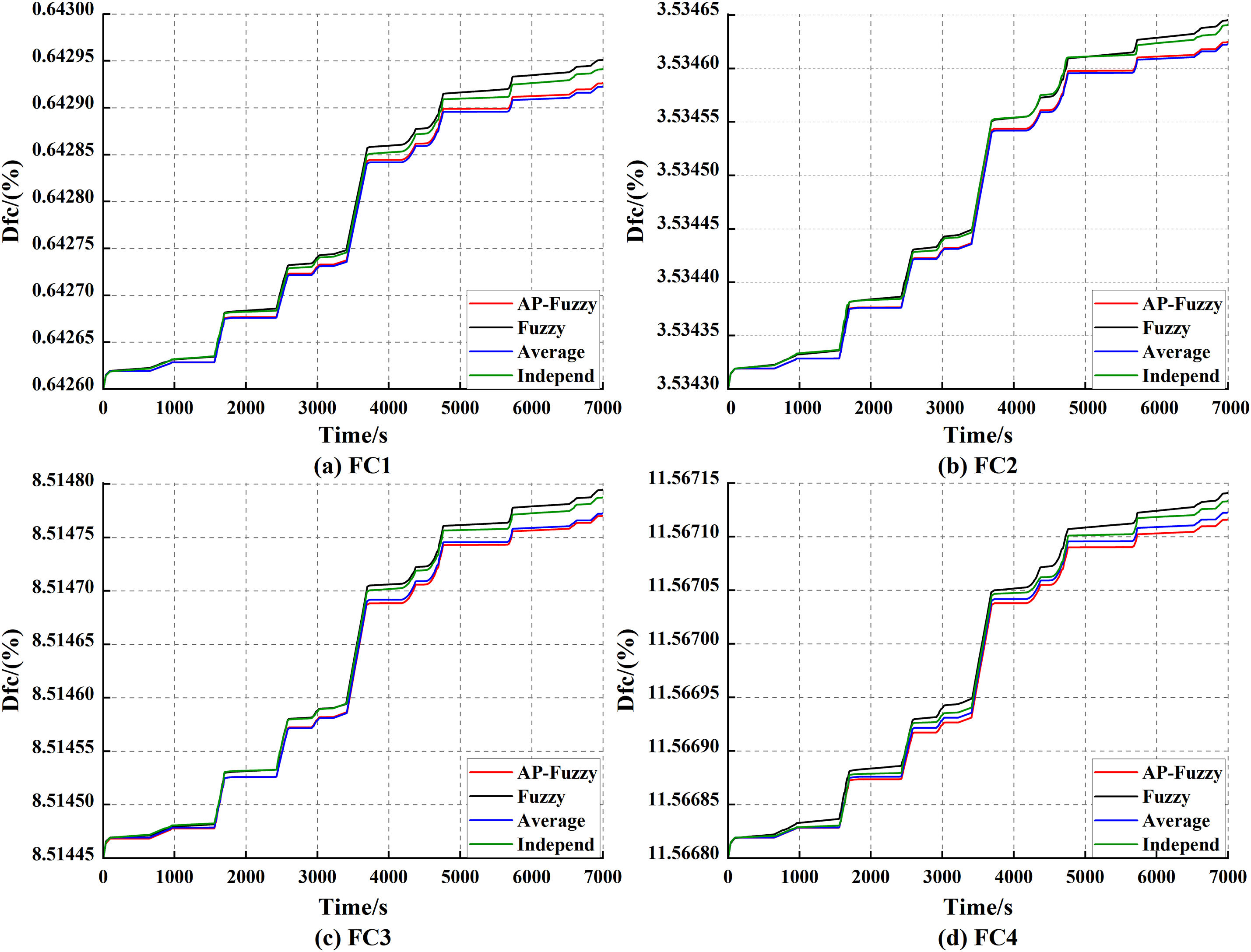

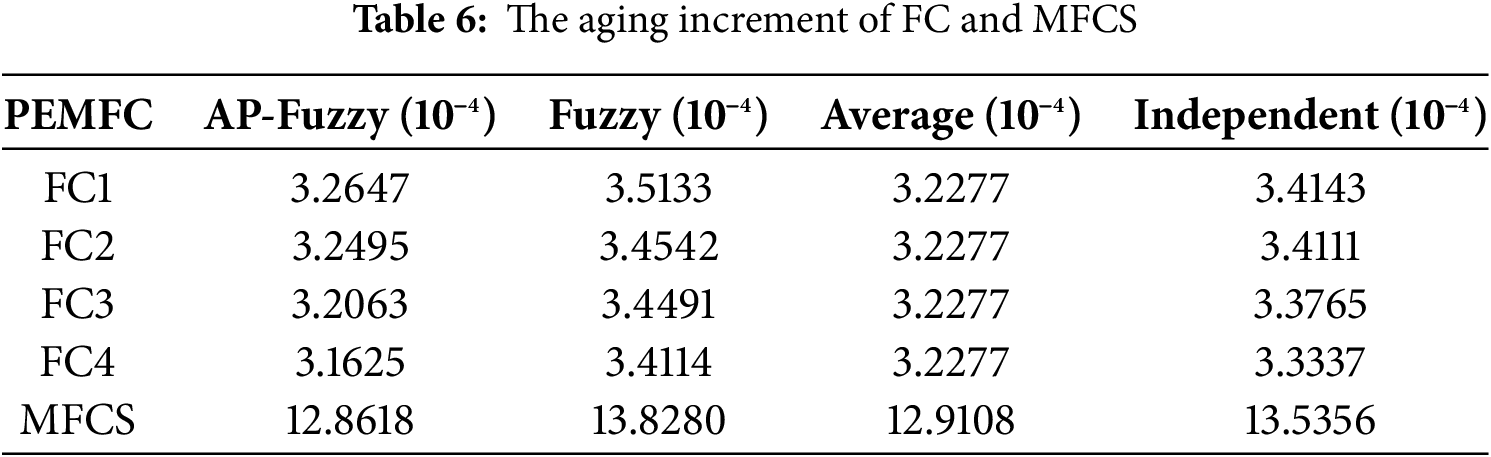

The performance variation of each FC is shown in Fig. 11. The aging of FC and MFCS under the four strategies is shown in Table 6. According to Fig. 11, the FC aging profiles of the AP-Fuzzy and Average strategies are always lower than those of the Fuzzy and Independent strategies during the optimization time period. Further, with the AP-Fuzzy strategy, the aging of FC1 and FC2 is greater than that of the Average strategy, while the aging of FC3 and FC4 is less than that of the Average strategy, but the overall aging of MFCS is the smallest. This indicates that the AP-Fuzzy strategy performs well in suppressing FC performance degradation.

Figure 11: Performance degradation of the MFCS

However, the ability to inhibit FC aging alone does not allow for a comprehensive assessment of the strategy. To effectively extend the service life of MFCS, it is also necessary to consider whether the allocation strategy can narrow the performance gap among FCs. According to Table 6, it finds that with the three strategies other than the Average strategy, the performance degradation of FC1, FC2, FC3, and FC4 shows a decreasing pattern from large to small. This indicates that the difference in the performance degradation between the FCs will be gradually narrowed with the long-term operation of the MFCS, which further illustrates the effectiveness of the AP-Fuzzy strategy. In addition, compared with the other three allocation methods, NMPC-NGO fully considers the performance differences of each FC. It can dynamically adjust the load to avoid overloading the inefficient FCs while allowing the efficient FCs to undertake reasonable tasks, thus reducing the loss and equalizing the performance decay at the global level. It not only promotes the consistency of the performance attenuation of each stack in the MFCS but also suppresses the performance attenuation of the MFCS more significantly, with smaller performance attenuation of each stack and the MFCS, and the service life of the energy system can be effectively extended by utilizing the method proposed in this paper.

Compared with the other three allocation strategies, the AP-Fuzzy strategy not only reduces the degree of difference in performance degradation among the FCs but also minimizes the overall performance degradation of the MFCS, better protects the FCs with poorer performance, and thus is more advantageous in maintaining the system performance and prolonging the service life of the MFCS.

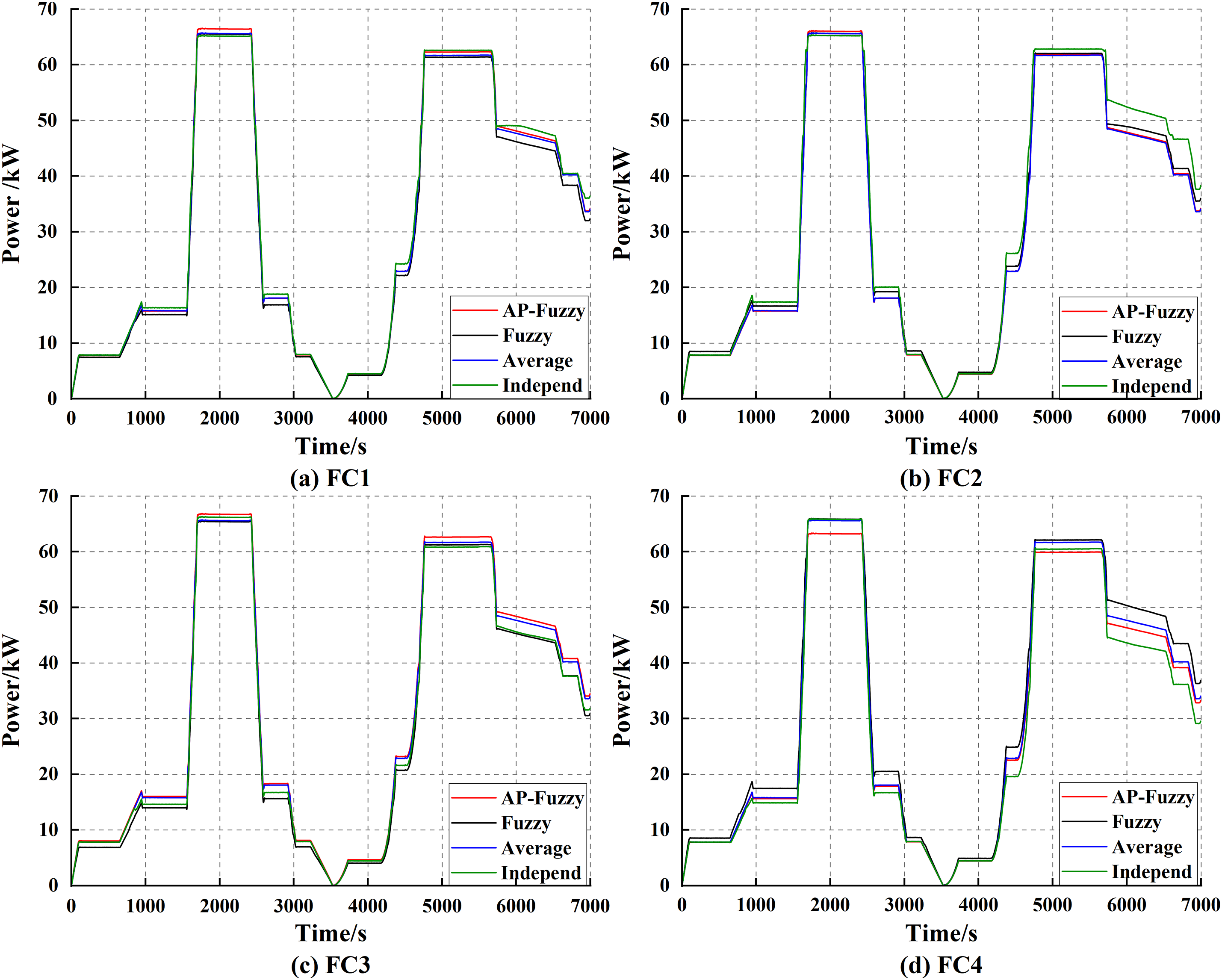

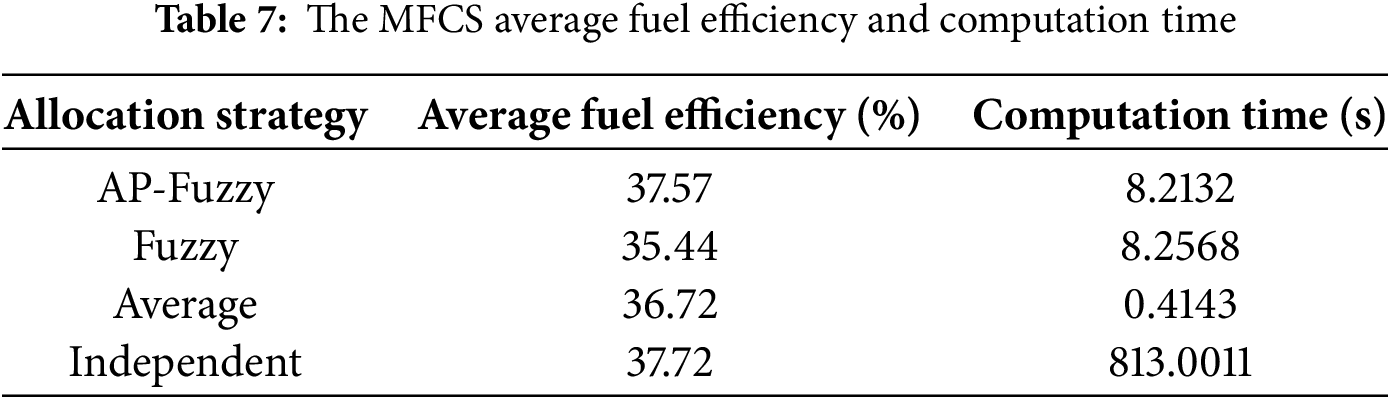

Fuel efficiency and strategy calculation time are also important in the evaluation of power allocation strategies. The power generated by each FC with the four power allocation strategies is illustrated in Fig. 12. The results of the comparative analysis of the four strategies are presented in Table 7, which includes the MFCS fuel efficiency with the calculation time.

Figure 12: MFCS power load power of each FC

As shown in Table 7, in terms of the average fuel efficiency of the MFCS, the average fuel efficiency of the MFCS under the AP-Fuzzy allocation strategy is ranked second among the four compared allocation strategies, slightly lower than that of the independent allocation strategy. In terms of calculation time, although the average allocation strategy has the shortest calculation time, it cannot effectively extend the service life of the MFCS. Although the independent allocation strategy is better than the AP-Fuzzy allocation strategy in improving the efficiency of the MFCS, its longer computation time is not conducive to the real-time control of the ship. Compared with the fuzzy strategy, AP-fuzzy has an improvement in average fuel efficiency, and the computation time is almost the same. Although AP-Fuzzy is not optimal in terms of algorithm computation time and fuel efficiency, its overall performance is well balanced. Therefore, AP-Fuzzy is more suitable as the EMS for fuel cell ship propulsion systems. It guarantees high fuel efficiency while the computation time is well controlled, which shows better adaptability and practicability. In addition, in order to further illustrate the effectiveness of the AP-Fuzzy strategy, the output power profiles of each FC during the optimized time period are shown in Fig. 12.

According to Fig. 12, except for the Average allocation strategy, the other three allocation strategies can achieve the preset power allocation targets. Among them, the effect of AP-Fuzzy is the most obvious, and the output power curve of FC4 is obviously lower than that of FC1, FC2 and FC3, while that of FC1 is higher than that of FC2, FC3 and FC4. During the optimization period, each stack performed its function effectively. Among them, the sum of the output power of FC2 and FC3 is always close to half of the load power, which balances the variation of the load power of the MFCS and avoids too large a difference in the output power or load fluctuation endured by each stack. On this basis, FC1 and FC4 distribute power according to preset requirements and avoid shifting to a high or low load state due to load changes during power distribution. Due to the large performance gap between FC1 and FC4, FC1 bears more output power and load fluctuation than FC4, which effectively mitigates further aging of FC4 and improves the MFCS efficiency.

In addition, the AP-Fuzzy allocation strategy is based on the continuity and high efficiency of the fuzzy controller, and its output power is more in line with the requirements of power stability and real-time performance of real fuel cells.

In this paper, we have proposed a two-layer energy management strategy for fuel cell ships that considers the consistency of fuel cell stack performance degradation. The initial layer of the proposed strategy is based on NMPC, and the NGO algorithm is used for global search and the SQP algorithm for local exact search, ensuring the optimality of the initial power allocation. The second layer of the power allocation strategy is based on fuzzy rule control, and the PSO algorithm is used to optimize the parameters of the membership function with the fuzzy rules. Furthermore, the convergence domain value is defined, and the controller membership function limits are correlated with the degree of aging of the MFCS to guarantee the efficacy of the second power allocation. To enhance the authenticity of the experiment, the ship load power is obtained from the experimental platform, and the power system of the “Three Gorges Hydrogen 1 Ship” is used as a reference to construct the ship power system model.

The results of the theoretical analysis and simulation show that the proposed energy management strategy shows better performance than other compared strategies. The NMPC-NGO algorithm has slightly larger battery aging increments compared to the DP algorithm and the GA algorithm. Compared with the NMPC-SQP algorithm, the NMPC-NGO algorithm is slightly more time-consuming. Although the NMPC-NGO algorithm is slightly less optimized than other conventional algorithms for some parameter values, its comprehensive performance is the best. The performance of AP-Fuzzy is better at promoting MFCS performance degradation consistency and prolonging MFCS lifetime compared to Average, Independent, and Fuzzy allocation. Compared to independent allocation, AP-Fuzzy is slightly less effective in improving fuel efficiency, but its computational time is much shorter and better meets the real-time requirement of ships. In addition, although the computational time of AP-Fuzzy is greater than that of Average allocation, the Average allocation does not have a control function by itself. Therefore, the proposed two-layer energy management strategy can effectively allocate ship energy and provide a viable solution for the energy management of multi-fuel cell stack ships.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The research work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4301403). The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for suggesting valuable improvements to the paper.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Diju Gao, Yi Zhang, Zhaoxia Huang; data collection: Diju Gao, Yide Wang, Yi Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Diju Gao, Yide Wang, Yi Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Yi Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Diju Gao, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bin Jumah A. A comprehensive review of production, applications, and the path to a sustainable energy future with hydrogen. RSC Adv. 2024;14(36):26400–23. doi:10.1039/d4ra04559a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sáez Álvarez P. From maritime salvage to IMO, 2020 strategy: two actions to protect the environment. Mar Pollut Bull. 2021;170(12):112590. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Stark C, Xu Y, Zhang M, Yuan Z, Tao L, Shi W. Study on applicability of energy-saving devices to hydrogen fuel cell-powered ships. J Mar Sci Eng. 2022;10(3):388. doi:10.3390/jmse10030388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Y, Chen W, Li Q, Han Y, Guo A, Wang T. Coordinated optimal power distribution strategy based on maximum efficiency range of multi-stack fuel cell system for high altitude. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;50:374–87. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.08.177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Qasem NAA. A recent overview of proton exchange membrane fuel cells: fundamentals, applications, and advances. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;252:123746. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao D, Chen L, Wang Y. An energy trade-off management strategy for hybrid ships based on event-triggered model predictive control. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2024;162(2):110312. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2024.110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jiang J, Zou L, Liu X, Pang S, Zhang L. An energy management method for combined load forecasting of fuel cell ships. J Phys Conf Ser. 2024;2876(1):012052. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2876/1/012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nivolianiti E, Karnavas YL, Charpentier JF. Fuzzy logic-based energy management strategy for hybrid fuel cell electric ship power and propulsion system. J Mar Sci Eng. 2024;12(10):1813. doi:10.3390/jmse12101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Çorapsız MR, Kahveci H. Double adaptive power allocation strategy in electric vehicles with battery/supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system. Int J Energy Res. 2022;46(13):18819–38. doi:10.1002/er.8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xu C, Fan L, Jiang Z, Shen C, Li H. Investigation on energy management strategy of gas-electric marine hybrid propulsion system with improved dynamic programing algorithm. Int J Engine Res. 2024;25(1):140–55. doi:10.1177/14680874231195279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu L, Liu Y, Zeng Y, Guo H, Ma K, Liu S, et al. Energy management strategy for fuel cell hybrid ships based on deep reinforcement learning with multi-optimization objectives. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;93(2):1258–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.10.192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fan A, Liu H, Wu P, Yang L, Guan C, Li T, et al. LSTM-augmented DRL for generalisable energy management of hydrogen-hybrid ship propulsion systems. eTransportation. 2025;25:100442. doi:10.1016/j.etran.2025.100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liang Y, Liang Q, Zhao J, Li M, Hu J, Chen Y. Online identification of optimal efficiency of multi-stack fuel cells (MFCS). Energy Rep. 2022;8(1):979–89. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.01.243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kelouwani S, Adegnon K, Agbossou K, Dube Y. Online system identification and adaptive control for PEM fuel cell maximum efficiency tracking. IEEE Trans Energy Convers. 2012;27(3):580–92. doi:10.1109/TEC.2012.2194496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liang Y, Liang Q, Zhao J, He J. Downgrade power allocation for multi-fuel cell system (MFCS) based on minimum hydrogen consumption. Energy Rep. 2022;8(5):15574–83. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.11.126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xie P, Asgharian H, Guerrero JM, Vasquez JC, Araya SS, Liso V. A two-layer energy management system for a hybrid electrical passenger ship with multi-PEM fuel cell stack. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;50(1):1005–19. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.09.297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ren P, Pei P, Li Y, Wu Z, Chen D, Huang S. Degradation mechanisms of proton exchange membrane fuel cell under typical automotive operating conditions. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2020;80:100859. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Macias Fernandez A, Kandidayeni M, Boulon L, Chaoui H. An adaptive state machine based energy management strategy for a multi-stack fuel cell hybrid electric vehicle. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2019;69(1):220–34. doi:10.1109/TVT.2019.2950558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shi J, Jiang S, Flø Aarsnes UJ, Nærhcim D, Moura S. Multiple time scale energy management for a fuel cell ship propulsion system. In: Proceedings of the 2024 European Control Conference (ECC); 2024 Jun 25–28; Stockholm, Sweden. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 192–9. [Google Scholar]

20. Kang T, Ham S, Kim M. Performance analysis of multi-stack fuel cell systems for large buildings using electricity and heat. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;87(79):389–400. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.09.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li X, Shang Z, Peng F, Li L, Zhao Y, Liu Z. Increment-oriented online power distribution strategy for multi-stack proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems aimed at collaborative performance enhancement. J Power Sources. 2021;512(45):230512. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Macias A, Kandidayeni M, Boulon L, Chaoui H. A novel online energy management strategy for multi fuel cell systems. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2018 Feb 20–22; Lyon, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 2043–8. doi:10.1109/ICIT.2018.8352503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Garcia JE, Herrera DF, Boulon L, Sicard P, Hernandez A. Power sharing for efficiency optimisation into a multi fuel cell system. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE); 2014 Jun 1–4; Istanbul, Türkiye. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2014. p. 218–23. doi:10.1109/ISIE.2014.6864614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Han X, Li F, Zhang T, Zhang T, Song K. Economic energy management strategy design and simulation for a dual-stack fuel cell electric vehicle. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(16):11584–95. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou S, Zhang G, Fan L, Gao J, Pei F. Scenario-oriented stacks allocation optimization for multi-stack fuel cell systems. Appl Energy. 2022;308(5):118328. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Han Y, Li Q, Wang T, Chen W, Ma L. Multisource coordination energy management strategy based on SOC consensus for a PEMFC–battery–supercapacitor hybrid tramway. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2018;67(1):296–305. doi:10.1109/TVT.2017.2747135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hua Z, Zheng Z, Gao F, Péra MC. Challenges of the remaining useful life prediction for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. In: Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2019 Oct 14–17; Lisbon, Portugal. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 6382–7. doi:10.1109/IECON.2019.8927288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Marx N, Cardozo J, Boulon L, Gustin F, Hissel D, Agbossou K. Comparison of the series and parallel architectures for hybrid multi-stack fuel cell—battery systems. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC); 2015 Oct 19–22; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/VPPC.2015.7352915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tian Z, Wei Z, Wang J, Wang Y, Lei Y, Hu P, et al. Research progress on aging prediction methods for fuel cells: mechanism, methods, and evaluation criteria. Energies. 2023;16(23):7750. doi:10.3390/en16237750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Guan W, Chen L, Wang Z, Chen J, Ye Q, Fan H. A 500 kW hydrogen fuel cell-powered vessel: from concept to sailing. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;89:1466–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.09.418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Song K, Huang X, Cai Z, Huang P, Li F. Research on energy management strategy of fuel-cell vehicles based on nonlinear model predictive control. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;50(106276):1604–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.07.304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen CH, Yu WN. Study on energy balance and driving range of solar electric sightseeing boat. Ship Eng. 2016;38(1):64–6,91. (In Chinese). doi:10.13788/J.Cnki.Cbgc.2016.01.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhu QW, Yu XL, Wu QC, Xu YD, Chen FF, Huang R. Semi-empirical degradation model of lithium-ion battery with high energy density. Energy Storage Sci Technol. 2022;11(7):2324–31. (In Chinese). doi:10.19799/j.cnki.2095-4239.2021.0725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu H, Xiao J, Yao Y, Zhu S, Chen Y, Zhou R, et al. A multi-strategy improved northern goshawk optimization algorithm for optimizing engineering problems. Biomimetics. 2024;9(9):561. doi:10.3390/biomimetics9090561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Dehghani M, Hubálovský Š, Trojovský P. Northern goshawk optimization: a new swarm-based algorithm for solving optimization problems. IEEE Access. 2021;9:162059–80. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3133286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang T, Li Q, Wang X, Chen W, Breaz E, Gao F. A power allocation method for multistack PEMFC system considering fuel cell performance consistency. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2020;56(5):5340–51. doi:10.1109/TIA.2020.3001254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools