Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Curtain Wall Systems as Climate-Adaptive Energy Infrastructures: A Critical Review of Their Role in Sustainable Building Performance

1 Department of Architecture, ST.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2 Energy and Environment Research Center, ShK.C., Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran

* Corresponding Author: Mehdi Jahangiri. Email:

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.070089

Received 08 July 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 27 December 2025

Abstract

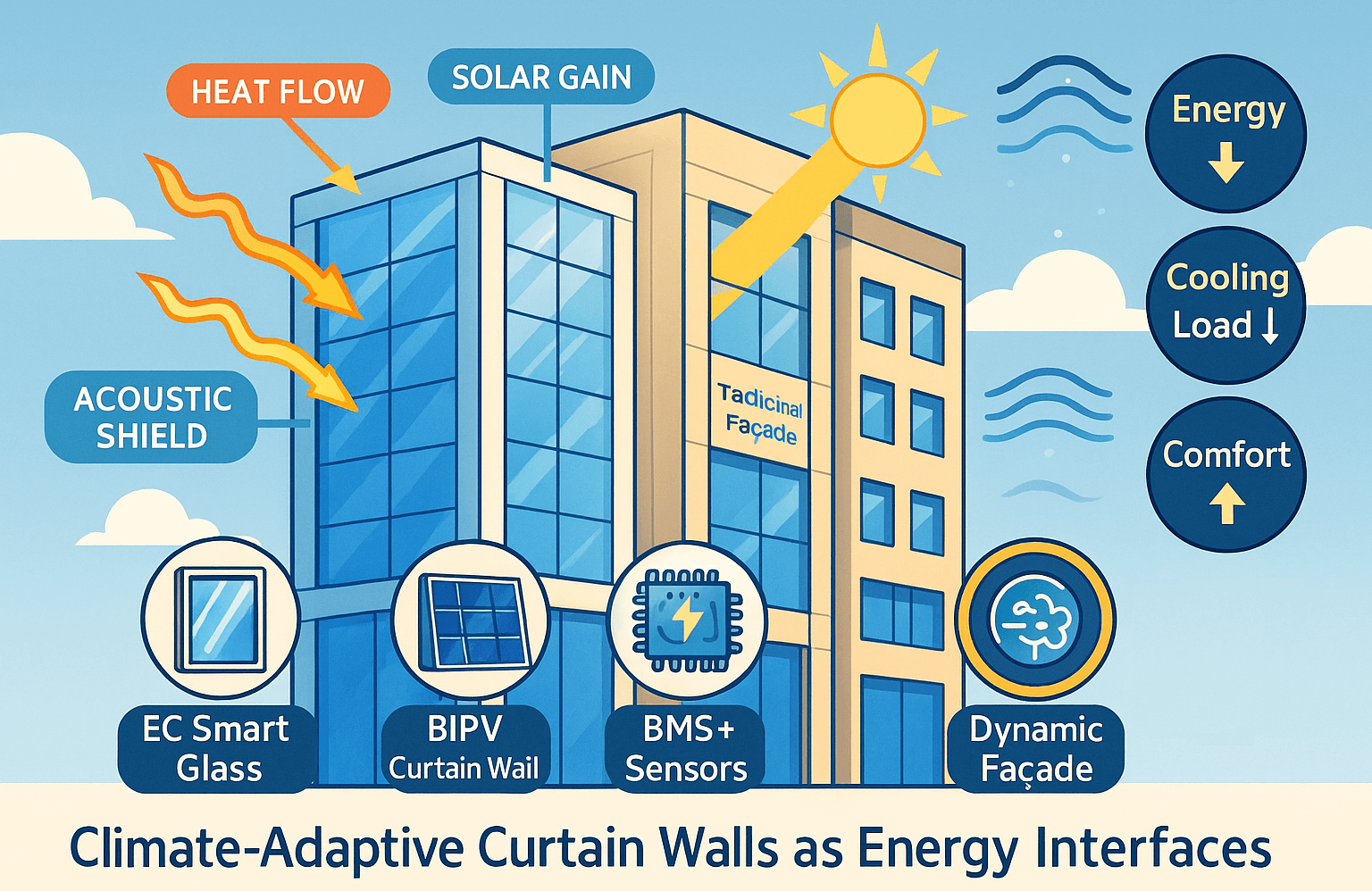

Curtain wall systems have evolved from aesthetic façade elements into multifunctional building envelopes that actively contribute to energy efficiency and climate responsiveness. This review presents a comprehensive examination of curtain walls from an energy-engineering perspective, highlighting their structural typologies (Stick and Unitized), material configurations, and integration with smart technologies such as electrochromic glazing, parametric design algorithms, and Building Management Systems (BMS). The study explores the thermal, acoustic, and solar performance of curtain walls across various climatic zones, supported by comparative analyses and iconic case studies including Apple Park, Burj Khalifa, and Milad Tower. Key challenges—including installation complexity, high maintenance costs, and climate sensitivity—are critically assessed alongside proposed solutions. A central innovation of this work lies in framing curtain walls not only as passive architectural elements but as dynamic interfaces that modulate energy flows, reduce HVAC loads, and enhance occupant comfort. The reviewed data indicate that optimized curtain wall configurations—especially those integrating electrochromic glazing and BIPV modules—can achieve annual energy consumption reductions ranging from approximately 5% to 27%, depending on climate, control strategy, and façade typology. The findings offer a valuable reference for architects, energy engineers, and decision-makers seeking to integrate high-performance façades into future-ready building designs.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

A curtain wall refers to a structurally independent façade system installed on the exterior of a building, functioning as a lightweight cladding layer attached to the structural frame—whether concrete or steel [1]. Its primary function is to separate the interior space from the external environment without bearing any of the building’s gravity loads. This system only carries its own weight and lateral forces such as wind pressure or seismic loads, which it transfers to the main structural framework [2,3]. Curtain walls are typically constructed using lightweight materials such as aluminum and glass, metal panels, engineered stone, or composites [4–6].

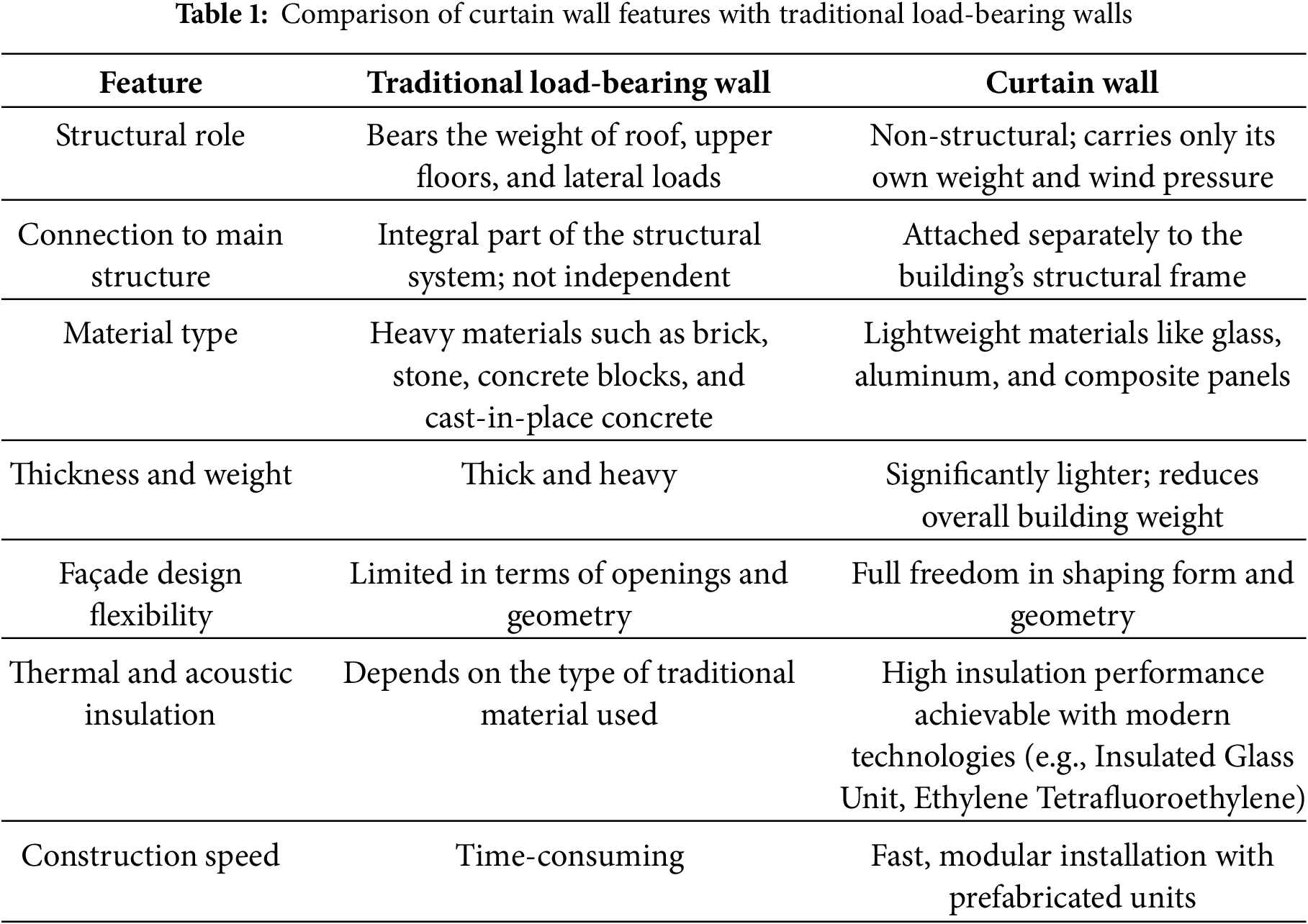

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of the key differences between Curtain Wall systems and traditional load-bearing walls, highlighting their respective roles, materials, and performance characteristics. This comparison is essential for understanding the fundamental shift in modern façade engineering—from heavy, structurally integrated walls to lightweight, non-load-bearing systems (façade structure independent of the building’s primary load-bearing frame) that prioritize design flexibility, energy efficiency, and construction speed [7,8]. As shown in Table 1, curtain walls offer significant advantages in terms of reduced structural load, architectural freedom, and thermal-acoustic performance, making them a preferred choice in contemporary high-rise and sustainable architecture [9–12].

As shown clearly in Fig. 1, curtain walls have evolved over time—from their early forms in modern architecture (such as those seen in the Bauhaus movement) to today’s advanced and large-scale systems. However, across all these examples, their role as structurally detached façade elements has remained constant. The design of these façades has consistently been based on the principles of structural independence, along with the enhancement of aesthetics, transparency, and energy performance [13].

Figure 1: Various examples of curtain wall façades

The earliest examples of glass use in building façades date back to the 19th century. In 1864, the Oriel Chambers building in Liverpool (Fig. 2a), designed by Peter Ellis, is recognized as the first structure featuring a metal-and-glass curtain wall. Utilizing iron frames and large windows, this building maximized natural light and is considered a precursor to modern architecture [14,15].

Figure 2: Evolution of curtain walls in modern architecture: from early examples to contemporary glass skyscrapers

In the early 20th century, the use of glass in façades expanded. In 1909, the Boley Clothing Company building in Kansas City (Fig. 2b), designed by Louis Curtiss, employed glass curtain walls. Similarly, the Hallidie Building in San Francisco (Fig. 2c), designed by Willis Polk in 1918, is known as one of the earliest examples of a suspended glass curtain wall [16,17].

During the 1930s, with industrial advancements and the increasing use of aluminum in the aerospace and automotive industries, this lightweight and durable metal was introduced into construction. Aluminum frames for curtain walls significantly reduced structural weight and accelerated installation.

After World War II, the growing demand for commercial and office buildings led to the widespread adoption of metal-and-glass curtain walls. One of the earliest office buildings with a fully glazed façade is the Lever House in New York (Fig. 2d), designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1952 [18].

In the 1950s, the development of the float glass process by Pilkington enabled the production of large, high-quality glass sheets. This innovation greatly expanded the application of glass in façades. Moreover, the advancement of insulated glazing units improved thermal and acoustic insulation, playing a key role in enhancing building energy performance [2,19,20].

The evolution of curtain wall systems in the 20th century was driven by industrial progress, the invention of new materials such as aluminum and double-glazed glass, and the need for high-energy-efficiency buildings [21–23]. These systems—by offering a modern appearance, enhancing daylight penetration, and reducing structural loads—have become one of the defining elements of contemporary architecture [7,9,24].

Despite extensive research on building envelopes and smart façades, there remains a notable gap in systematically understanding curtain walls as active components of the building’s energy infrastructure—integrating not only architectural and aesthetic considerations but also lifecycle energy and economic performance. The present review specifically addresses this gap by consolidating evidence on (1) energy and environmental metrics, (2) lifecycle cost trade-offs, and (3) comparative insights between Stick and Unitized systems under diverse climatic and operational contexts.

Unlike previous narrative reviews that have predominantly cataloged façade technologies, this work provides a critical synthesis that evaluates empirical evidence, compares conflicting findings, and identifies methodological limitations across studies. For instance, while multiple sources claim energy reduction through adaptive glazing, our review contrasts these results with field-validated outcomes, thus advancing the discourse by distinguishing theoretical potential from real-world performance.

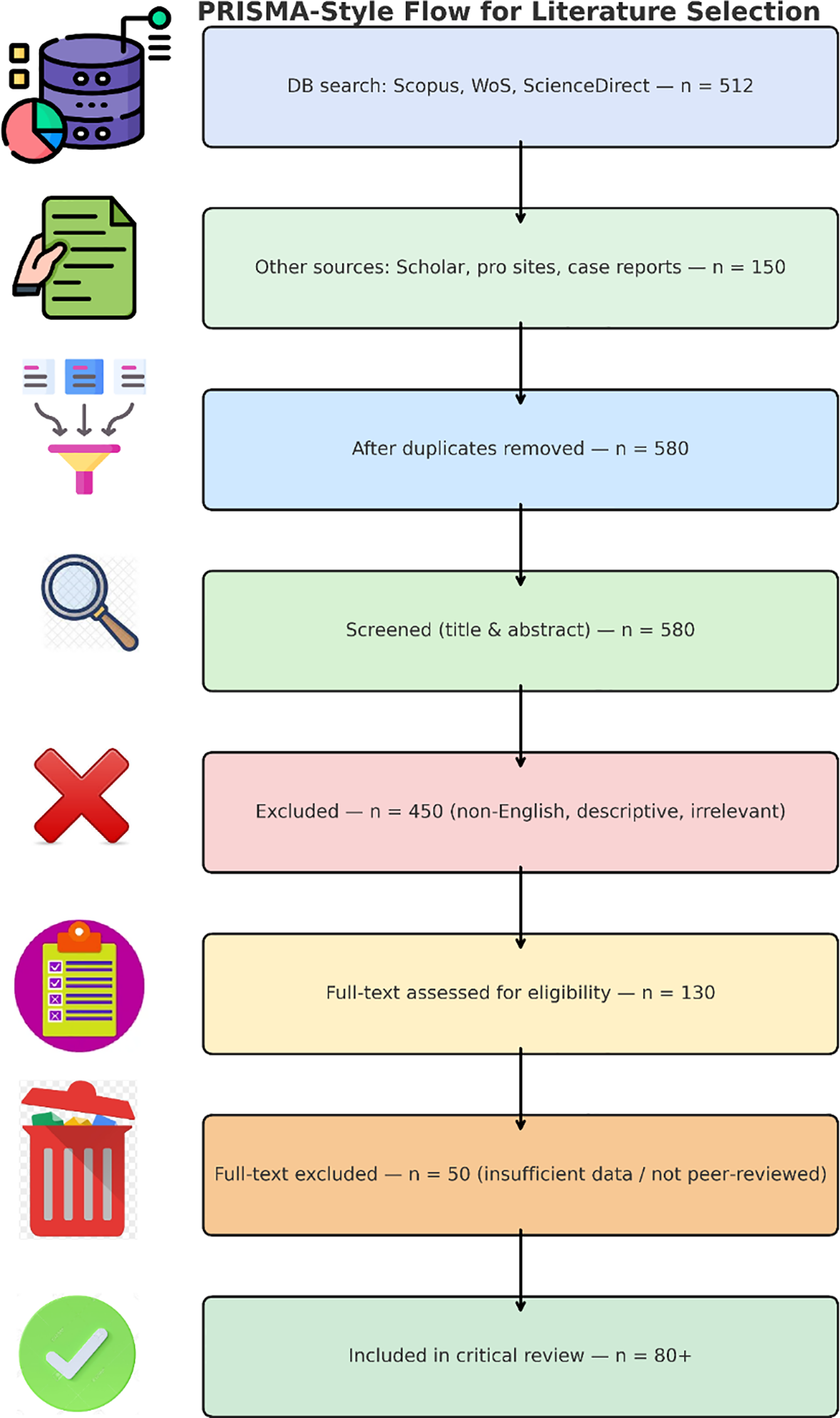

To ensure methodological rigor, this review adopted a structured literature selection process inspired by the PRISMA framework. Searches were conducted across major academic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect) and complemented with targeted queries in Google Scholar, professional websites, and industry case reports. Search strings included terms such as “curtain wall system”, “unitized curtain wall”, “stick curtain wall”, “intelligent façades”, “sustainable building envelopes”, and related keywords. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to capture broader combinations.

The review covered the period 2000–2024, with earlier works included selectively for historical insights. Screening was conducted in two phases: (i) title and abstract evaluation for relevance and English language, followed by (ii) full-text assessment for methodological quality and data sufficiency. Exclusion criteria included non-English works, descriptive reports lacking empirical rigor, and non–peer-reviewed publications.

In total, more than 660 initial records were identified. After removal of duplicates and exclusions, over 80 high-quality sources were included in the critical review. The overall process is summarized in the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Fig. 3), which provides a transparent overview of the scoping and selection strategy.

Figure 3: PRISMA flow diagram of the literature selection process

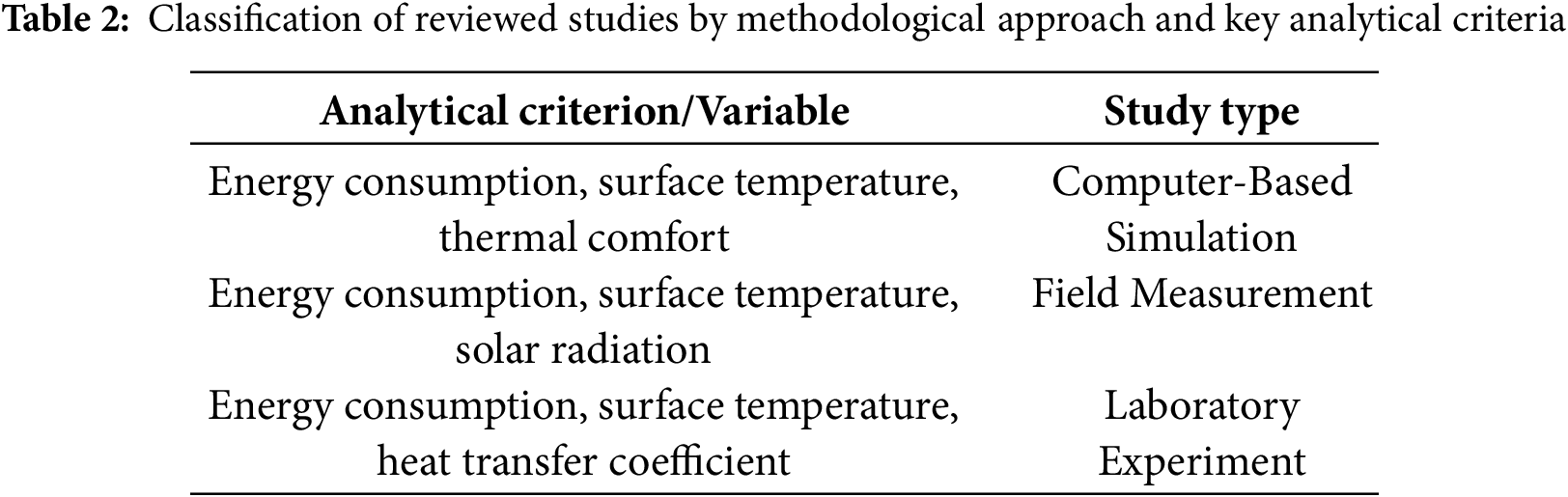

The reviewed studies (over 80 in total) were systematically categorized and analyzed according to a structured methodological framework. Specifically, each study was classified based on its research approach—computer-based simulation, field measurement, or controlled laboratory experiment—and the corresponding analytical variables were extracted (e.g., energy consumption, surface temperature, thermal comfort indices, and other key parameters). This classification allowed methodologically similar studies to be grouped together and their results synthesized in an integrated manner.

In terms of prioritization, the credibility of data and methodological rigor served as the primary criteria. Field measurement studies were emphasized because they provide the most realistic and reliable data under actual operating conditions. Laboratory-based experiments were also given high weight due to their precise control of environmental variables and their essential role in validating simulation models. Simulation studies, while valuable for exploring a wide range of scenarios, were primarily used to extend analytical coverage and their outcomes were systematically compared with empirical findings to ensure robustness.

Additionally, the quality of the studies was evaluated using complementary indicators such as the scientific impact of the publication venue (e.g., Impact Factor, Scientific journal rankings) and the recency of the research (year of publication). These measures ensured that both methodological reliability and the state-of-the-art nature of the findings were adequately reflected in the synthesis.

A summary of the categorization of the reviewed studies and their main analytical variables is provided in the Table 2.

3 Types of Curtain Wall Systems

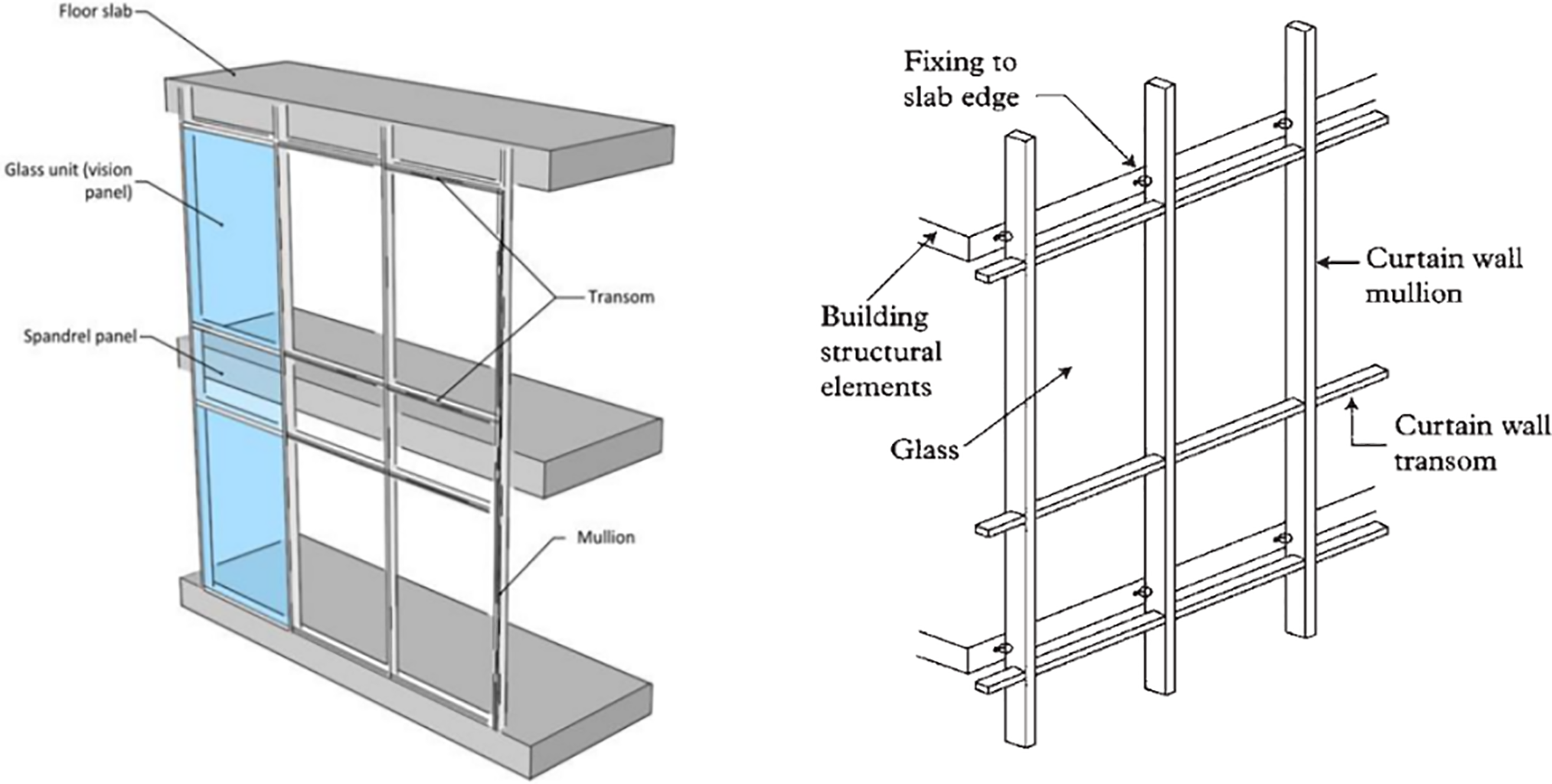

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the Stick System is one of the most common and traditional methods for installing curtain walls [25]. In this system, the structural components of the façade—including vertical mullions and horizontal transoms—are individually assembled and installed on-site [26–28].

Figure 4: Building featuring the Stick System type curtain wall

The aluminum or metal frames are first attached to the main structural skeleton of the building (whether concrete or steel), after which infill panels such as glass, stone, or composite materials are inserted separately into the frame [29,30].

Although this method is more time-consuming and weather-dependent compared to prefabricated systems (such as the Unitized System), it offers advantages in design flexibility and lower initial cost [25,31]. Key features of the Stick System include ease of maintenance, suitability for small- to medium-scale projects, and the ability to make precise adjustments during on-site installation [25,32,33].

Despite its longer installation period, the Stick System remains widely used in office and commercial buildings around the world, particularly in locations where transporting large prefabricated panels is not feasible [21,34,35].

In stick systems, thermal-air sealing performance and façade durability are directly dependent on the qualifications of the workforce during the stages of cutting, alignment, anchoring, sealing, and glazing. Adherence to installation tolerances, proper preparation of joint substrates, application of adhesives/sealants in accordance with manufacturer guidelines, torque control of connections, and execution of QA/QC inspections (ranging from on-site sampling to field tests for air/water leakage) are decisive quality factors. The learning curve and skill gap can affect scheduling, installation cost, and final performance; therefore, in real projects, it is recommended to establish a job competency matrix (frame installer, sealant applicator, crane operator, inspector) and define contractor training and qualification programs prior to implementation. Although quantifying the effect of workforce skill level is beyond the scope of the present work, it is explicitly stated in the present version that adequate training and construction supervision are prerequisites for achieving the designed performance in stick façades.

As shown in Fig. 5, the Unitized System (also known as the modular prefabricated system) is one of the most advanced and industrialized methods of curtain wall construction [36,37]. In this approach, all façade components—including aluminum frames, glass panels, weather seals, insulation, and connectors—are fully pre-assembled in a factory [38]. These pre-fabricated units, or modules, are then transported to the construction site and directly installed onto the structural frame using cranes or lifting equipment [28].

Figure 5: Building façade constructed with the Unitized System

This method offers very high installation speed, uniform and controlled manufacturing quality, reduced human error, and excellent performance against air and water infiltration [39]. It is particularly suitable for high-rise buildings (skyscrapers) where façade access is limited and weather conditions can vary significantly [2,40]. In such cases, the Unitized System provides optimal safety, precision, and efficiency [41–43].

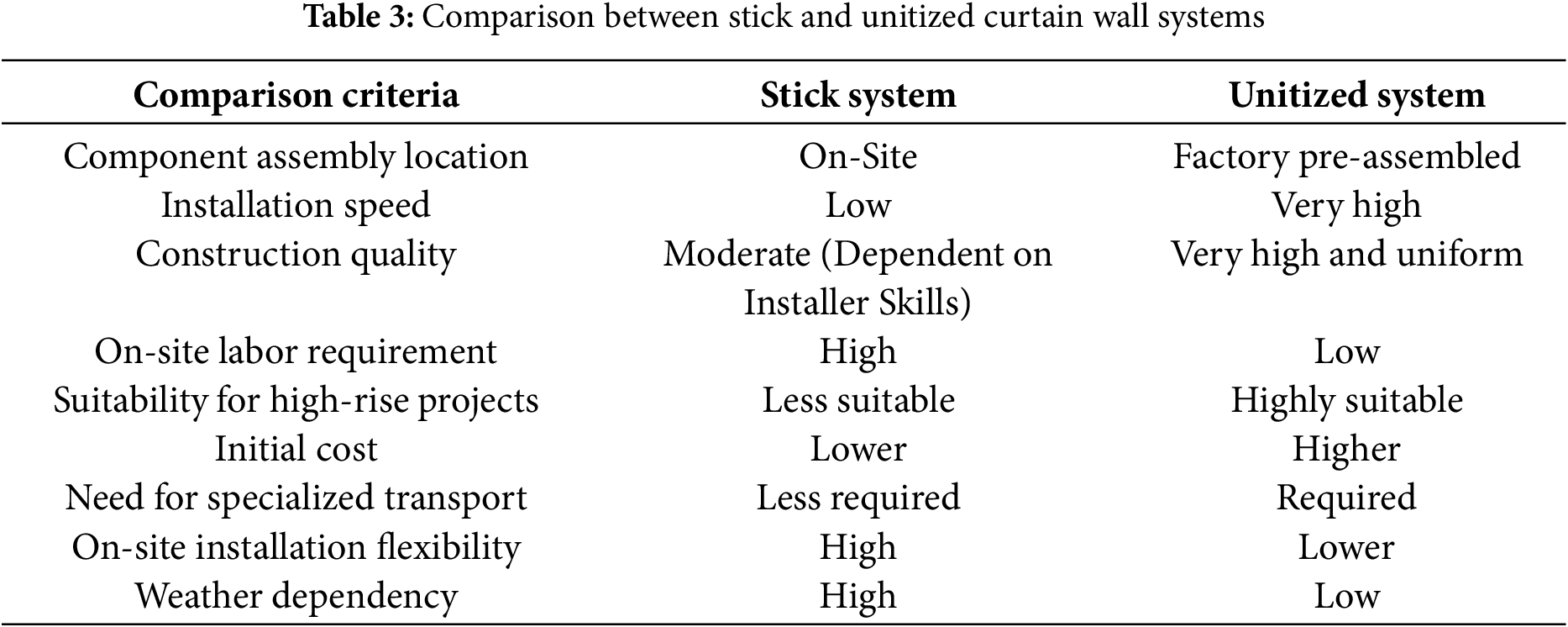

However, it is important to note that this system requires meticulous planning, higher initial costs, specialized transportation, and tight coordination between design and factory production [44,45]. Therefore, the Unitized System is typically used in large-scale, complex projects with distinctive architectural designs. A brief comparison between the two main curtain wall types is provided in Table 3. While Table 3 presents a descriptive comparison, the trade-offs can be better understood through lifecycle cost (LCC) reasoning. Unitized systems, despite 10%–20% higher initial capital cost [46,47], become economically justified in large-scale or high-rise projects where labor efficiency, installation time, and façade precision directly translate into reduced maintenance costs and improved long-term thermal performance. In contrast, Stick systems remain cost-effective for small to medium-scale projects with simpler geometries and limited logistical constraints. This differentiation aligns with payback periods reported in recent façade/BIPV literature, which typically fall in the ~5–15-year range under standard tariff assumptions, and can be as short as ~7 years in demonstrated façade retrofit systems [48–50].

4 Components of a Curtain Wall System

In a curtain wall system, the main components operate in a coordinated and structured manner to create a transparent, lightweight, and non-load-bearing façade [51]. The mullions are vertical members that typically span from floor to ceiling and are responsible for transferring lateral loads—such as wind pressure—to the building’s primary structure [52]. These vertical profiles play a central role in forming the structural frame of the façade.

Complementing them are the transoms, which are horizontal elements placed between mullions. Transoms support glass or opaque panels and play a critical role in load distribution and mechanical attachment of the panels to the frame [53,54].

The panels themselves serve as the outer skin of the building. They can be made of transparent materials like glass (vision panels) or opaque materials such as metal, ceramic, or engineered stone (spandrel panels). These panels act as barriers against environmental elements while enabling natural light to enter the building’s interior.

Finally, the anchors are metallic components or assemblies that connect the curtain wall system to concrete slab edges or the metal framework of the building. Anchors are designed to transfer façade loads to the main structure and must be carefully engineered to accommodate thermal movements, differential settlements, and lateral displacements without damaging the façade. The configuration and interaction of these components are illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Main components of a curtain wall system [55]

Curtain wall systems offer a wide range of advantages in the design and construction of modern buildings due to their unique characteristics [56]. One of their most prominent advantages is the aesthetic appeal they bring to building façades [7]. Through the use of large glazed surfaces, clean lines, and advanced materials, these systems allow architects to align the appearance of buildings with contemporary aesthetic standards. In the building life-cycle assessment literature, authoritative reviews indicate that the share of embodied energy/carbon is typically reported in the quantitative range of 10%–20% of the total life cycle [46,47]. Therefore, to avoid overstatement and in view of the heterogeneity of climate, use type, and material technologies, the present work refers to a conservative range of 5%–15% as a conceptual approximation for the balance between embodied energy and operational savings. This conceptual approximation is subsequently reinforced through the lifecycle cost discussion (Sections 5 and 6), where reported payback periods validate this energy–cost equilibrium.

Additionally, the increased penetration of natural light through transparent glass panels enhances occupants’ quality of life and productivity while reducing energy demand for artificial lighting [57,58]. From an engineering perspective, the use of lightweight materials such as aluminum and glass reduces the dead load on the building structure. This not only optimizes the design of foundations and structural frames but also leads to significant cost savings, especially in high-rise construction projects [59].

Moreover, when panels, seals, and multi-layered assemblies are properly designed, curtain walls can deliver high thermal efficiency. The use of double-glazed glass with Low-E coatings and air or inert gas layers helps to minimize heat and sound transmission, thereby improving the overall energy efficiency of the building [60,61].

6 Disadvantages and Challenges

Despite their many advantages, curtain wall systems also present significant technical and operational challenges that must be carefully addressed during design, installation, and maintenance phases. One of the foremost challenges is the high cost of construction, installation, and maintenance [44]. The use of premium materials such as double-glazed glass, coated aluminum frames, specialized sealants, and precision-engineered metal joints, combined with the need for installation equipment and skilled labor, leads to significantly higher initial costs compared to conventional cladding systems such as stone, brick, or composite panels [62].

In the long term, maintenance and repair costs are also considerable. Glass units, mechanical connections, and seals are vulnerable to thermal cycling, sun exposure, rain, and seasonal expansion/contraction, requiring periodic inspection and replacement [2,63].

Although extensive evidence highlights the energy and thermal comfort benefits of advanced curtain wall systems—particularly when incorporating Low-E glazing, double-skin façades, and electrochromic glass—their economic and practical drawbacks must also be considered. Lifecycle assessment (LCA) and LCC analyses indicate that the environmental and financial burdens of materials and manufacturing can offset much of the reported 15%–25% operational energy savings unless service life, maintenance strategies, and end-of-life scenarios are explicitly addressed. Field data further reveal that sealant deterioration, coating degradation, and electrical failures in smart glazing can reduce real-world performance; therefore, operational–economic analysis, including payback periods, annual maintenance costs per square meter, and sensitivity to failure rates, is essential for reliable decision-making [5]. It is noteworthy that the durability and operational stability of smart glazing systems over their service life depend on various factors, including the quality of the coating layers, climatic conditions, switching cycles, and maintenance practices. Laboratory cycling tests have shown that certain electrochromic samples exhibit only minor reductions in optical contrast or slight increases in response time after thousands of cycles, whereas others demonstrate high stability up to approximately 10,000 cycles [64]. Therefore, applying a uniform annual degradation rate without product-specific data is not recommended.

From a maintenance perspective, the complex structure of curtain walls requires periodic cleaning and replacement of components such as gaskets, sealants, and moving parts, leading to significant operational expenses. LCA results emphasize that in long-life buildings, elements such as insulation, doors, and windows play a decisive role in cumulative impacts; thus, the assumption of “low-maintenance systems” is often overly simplistic and may result in hidden costs and long-term efficiency losses [48,65]. Within a life-cycle assessment framework, reference studies indicate that over a 30-year horizon, the share of operating and maintenance costs for the whole building is typically estimated at around 6% of total life-cycle cost (compared to about 2% for initial costs and about 92% for personnel costs) [66]. It is evident that cleaning and repair costs of glazed façades are a subset of this category and depend on height, access method (BMU/platform), climate, and service contracts; therefore, they should be calculated locally and on the basis of unit area/window rates in project-based estimates.

In terms of climatic sensitivity, performance is highly dependent on environmental conditions. In hot-humid regions, elevated humidity and heavy rainfall can accelerate metal corrosion and water infiltration, progressively diminishing insulation performance and increasing risks of mold or decay. Similarly, storms and high wind loads place considerable stress on glazing panels, raising the likelihood of breakage or detachment. Material selection and design details (e.g., drainage and slope control) must therefore be tailored to local climatic conditions to mitigate vulnerabilities [67,68].

Finally, limitations of modeling must be acknowledged: most studies rely on computational simulations with limited real-world validation. In practice, glass insulation quality declines over time, and protective coatings gradually fail—factors rarely incorporated into initial models. As a result, simulations often underestimate energy consumption, whereas empirical studies suggest that performance degradation over the building lifecycle can increase energy use by 20%–30% [69]. It should be noted that the energy-saving estimations in the present work are based on simulation models calibrated using standard climatic reference files (TMY/TRY) and conventional assumptions regarding occupancy profiles, ventilation rates, thermal boundary conditions, and idealized control strategies. Accordingly, several performance-degrading factors observed in real operation—such as uncertainties in occupant behavior and manual overrides of control systems, sensor errors and BMS setting drifts, gradual component efficiency deterioration and surface contamination/aging of materials, construction non-uniformities like local thermal bridges and unmeasured air leakage, as well as maintenance or accessibility constraints—have been conservatively reflected in the uncertainty margin of the results. It is explicitly stated that the reported figures represent the technical potential under reference conditions and should be adjusted for project-specific applications through energy auditing, post-occupancy data collection, and calibration based on field measurements.

Overall, long-term deterioration of key elements such as double-glazed units and Low-E coatings leads to increased thermal and air infiltration, reinforcing the need to integrate durability and maintenance considerations into sustainability assessments.

Another critical challenge is the need for meticulous design to prevent air and water infiltration [4]. All components—including frames, glazing, sealants, and joints—must be engineered to resist wind pressure, heavy rainfall, and even structural vibrations. Any defect in drainage systems, weatherproofing, or installation can lead to moisture ingress and air leakage, which may damage interior finishes, decrease occupant comfort, and significantly compromise operational energy efficiency. This is particularly important in high-rise buildings and climate-sensitive regions, where thorough climatic and structural analyses are essential during the design phase [70].

Finally, periodic cleaning and façade maintenance present operational challenges [71]. The extensive glazed surfaces, often located at high elevations, are exposed to environmental pollutants, dust, acid rain, and fingerprints. To maintain optical clarity and aesthetic quality, these surfaces must be regularly cleaned using specialized access equipment (e.g., suspended platforms or façade lifts). Neglecting this can lead to visual degradation, reduced natural lighting, and even decreased solar and thermal performance of the windows [72]. Thus, during the design and operational planning of curtain wall systems, these issues must be considered as critical challenges and addressed through appropriate technical and management solutions.

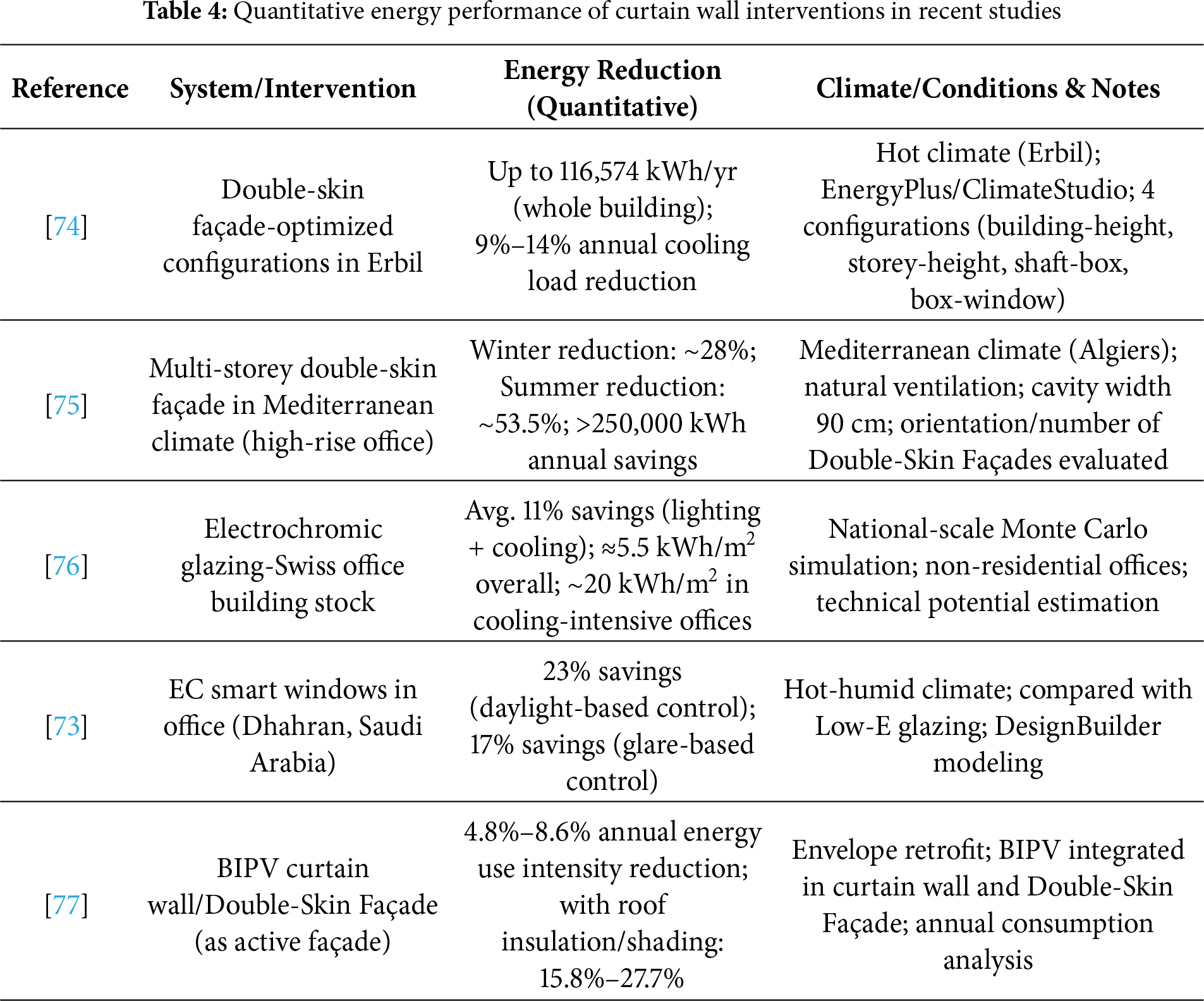

Across the reviewed literature, the reported LCC data converge toward a 5%–15% balance between embodied energy penalties and operational energy savings. However, this ratio varies significantly with façade technology maturity and local energy tariffs. To consolidate these insights, Table 4 reports operational energy reductions ranging from approximately 4.8% to 27.7%, depending on façade type and control strategy—spanning electrochromic glazing, double-skin façades, and BIPV curtain walls [73–77]. When these performance gains are interpreted within lifecycle cost frameworks, they generally correspond to payback periods of about 7–15 years [51,52], particularly in projects integrating smart control systems or BIPV elements. Such synthesis clarifies that the long-term economic justification of high-performance curtain walls depends on both local energy pricing and maintenance frequency.

The examples presented in the present work (such as Milad Tower, Burj Khalifa, and other iconic international projects) were chosen to showcase the range of technologies, structural systems, and implementation strategies in modern façades. It is evident that, due to their large scale, substantial budgets, use of specialized technologies, and unique climatic contexts, these projects do not necessarily represent the economic, technical, and climatic conditions of typical buildings. Accordingly, it is stated that the results from these examples are offered solely as exemplars of advanced technology and design, and that direct generalization of the findings to public, office, or residential buildings should be undertaken with caution and through adaptation to local conditions, capital costs, local climate, and national construction standards. This distinction between “demonstrative studies” and “typical applications” is essential to avoid over-interpretation of the findings at the implementation level.

The Burj Khalifa in Dubai (Fig. 7) [78], as the tallest building in the world, represents one of the most iconic uses of curtain wall systems in modern architecture. Its façade is constructed from a combination of glass, aluminum, stainless steel, and spandrel panels, forming a full-scale curtain wall system that covers more than 130,000 square meters of surface area.

Figure 7: Burj Khalifa, Dubai

This modular system was precisely engineered for high-elevation performance, addressing challenges such as strong wind pressures, extreme desert climate fluctuations, and thermal expansion/contraction of the structure. To achieve optimal thermal and acoustic insulation, double-glazed Low-E coated glass units with solar-resistant layers were used [79].

Fig. 7 illustrates the schematic view of the Burj Khalifa’s curtain wall system, showing its main components such as mullions, transoms, glass panels, and anchorage systems. The façade is designed with a multi-tiered vertical layout, enabling relative movement between façade components and the primary structure, thereby ensuring structural integrity and long-term performance of the system.

Apple Park, located in Cupertino, California, is considered one of the most advanced examples of sustainable and minimalist architecture of the 21st century, featuring a highly sophisticated curtain wall system [80]. The ring-shaped façade of the building, with a diameter of approximately 460 m, is entirely clad with large, curved glass panels forming a transparent, non-load-bearing curtain wall around the central structure.

Each of these glass panels measures about 14 m in height and is made of double-glazed Low-E glass, specially manufactured in Germany to ensure superior thermal insulation and solar radiation control. The curtain wall system of Apple Park is constructed with concealed aluminum frames and precision-engineered anchorage systems connecting to the central structure. This integration provides not only exceptional visual transparency and aesthetic beauty, but also supports natural ventilation, daylight harvesting, and resistance to seismic activity and strong winds.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the schematic view of Apple Park’s curtain wall system demonstrates the harmonious fusion of industrial design with façade engineering. The entire system is designed in a continuous, infinite ring form, serving as a benchmark of the highest level of curtain wall technology used in sustainable building practices.

Figure 8: Apple Park building

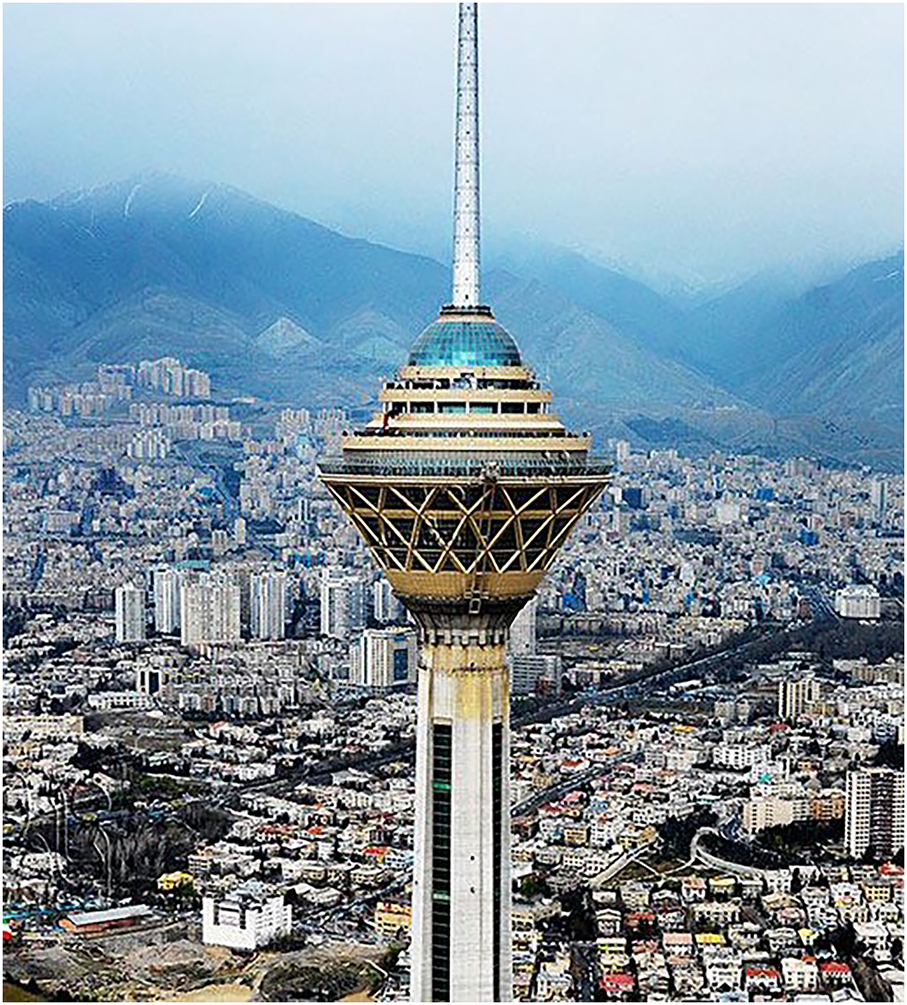

Milad Tower in Tehran, ranked as the sixth tallest telecommunication tower in the world, stands as one of the most prominent landmarks of contemporary Iranian architecture. As shown in Fig. 9, curtain wall systems have been employed extensively in the design of its façade, particularly in the upper and spherical sections of the structure [81]. The primary application of this system is concentrated in the pod section of the tower, which includes the revolving restaurant, observation deck, sky dome, and ICT centers.

Figure 9: Milad Tower, Tehran

In this area, curved and flat glass panels, acting as non-load-bearing elements, are connected to the main steel structure using reinforced aluminum frames. This configuration provides a modern and transparent appearance, allowing for natural daylight penetration, 360-degree panoramic views, and passive ventilation of interior spaces.

Given Tehran’s variable and occasionally harsh climate, the curtain wall system of Milad Tower incorporates multi-glazed panels equipped with solar control coatings and designed to withstand wind loads and seismic activity. The joints and seals are precisely engineered to resist rain and dust infiltration while maintaining excellent thermal and acoustic insulation performance. The application of such advanced façade technology at considerable height and within a complex geometric form necessitated high-precision execution and advanced technical supervision, making Milad Tower a remarkable example of the localization of curtain wall technology in a national-scale architectural project.

In the present work, the primary aim of the analysis was to illustrate how façade design adapts to the specific climatic conditions of Tehran—particularly dust storms, intense solar radiation, and temperature fluctuations—rather than to provide quantitative field monitoring of performance. Given the limitations of available data from dust ingress tests and full-scale wind pressure tests, the current assessment has been conducted on the basis of design documentation, material specifications, and mid-term climatic data for the city of Tehran. Accordingly, it is clarified that this section is descriptive-analytical in nature, and that numerical data concerning watertightness performance, reduction in glass transparency, or dust deposition on the façade surface require field monitoring and real-world performance testing, which can be pursued in future research. Nevertheless, the selection of silicone sealing systems and anti-static coatings in the design of Milad Tower indicates the designers’ awareness of critical climatic conditions and their efforts to mitigate the effects of dust during the operational phase.

8 Application of Curtain Wall Systems in Different Climates

Curtain wall systems require climate-specific design and material selection to ensure optimal thermal performance, structural stability, and energy efficiency. In hot and arid climates—such as the Middle East—controlling solar heat gain is particularly critical. In these regions, the use of Low-E coated glass, double-glazed units filled with argon gas, and heat-reflective coatings can significantly reduce solar radiation and minimize cooling loads on HVAC systems [82]. Additionally, fixed external shading and insulated frames help maintain indoor comfort [67]. According to [83], these strategies directly contribute to energy load reduction in glass-façade buildings.

In cold climates—such as mountainous regions or high latitudes—the primary objective is to prevent heat loss and retain interior warmth. In these cases, triple-glazed units with infrared-reflective coatings, thermal break frames, and elimination of thermal bridges at junctions play a crucial role. A study by Oak Ridge National Laboratory [84] found that insulated frames can reduce energy loss by more than 30% and help prevent condensation on the interior glass surfaces. One of the major sources of energy loss in unitized systems is the presence of thermal bridges at panel junctions, aluminum frames, and structural anchorage points; due to metallic continuity and direct contact with exterior components, these areas can increase heat flux and reduce the overall façade performance (overall U-value). In optimal design, the use of thermal-break profiles, insulating separation strips, interruption of metallic continuity at junctions, and precise control of perimeter joints are effective strategies for reducing the linear thermal transmittance ψ. It should be noted that although a detailed numerical analysis of these effects is beyond the scope of this research, in real projects the contribution of thermal bridges to the building’s total energy loss must be assessed separately and incorporated into thermal performance simulations.

In humid climates where high moisture levels and the risk of condensation are prevalent, effective vapor control and ventilation become essential [85]. In such environments, moisture-resistant interlayers, properly installed seals, and either natural or mechanical back-ventilation behind the glass façade help prevent mold growth, fungal damage, and moisture-related deterioration [86]. Reference [87] emphasizes the importance of selecting appropriate frames and ensuring airtight installation in curtain wall systems designed for humid conditions.

Ultimately, regardless of climate, the key factor is the optimized design of curtain wall systems to minimize energy consumption [88]. This requires a comprehensive assessment of solar exposure, heat transfer dynamics, wind patterns, and geographic context. The incorporation of advanced technologies such as smart glass, Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) systems, and energy modeling software can further minimize energy usage. As stated in [89], well-configured curtain wall systems can significantly impact the overall energy performance of a building and result in substantial annual energy savings.

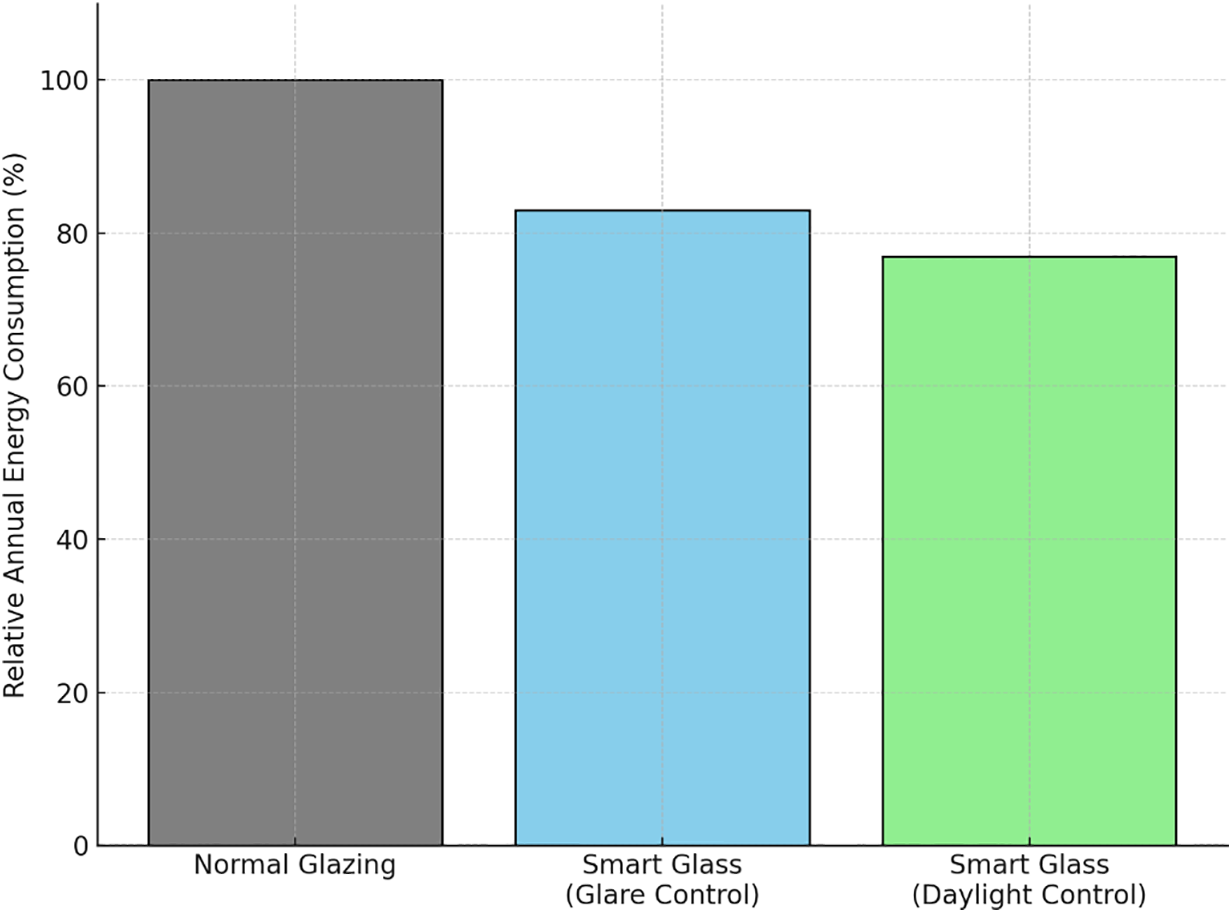

Fig. 10 presents a comparative illustration of the relative annual energy consumption of HVAC systems under three different conditions: conventional glazing, electrochromic smart glass with glare control, and the same smart glass with daylighting control [73]. As the results clearly indicate, employing electrochromic smart glass technology can lead to a significant reduction in building thermal loads, resulting in 17% to 23% savings in annual energy consumption. In the case of conventional glazing, direct solar radiation penetrates the interior, thereby increasing the cooling load on HVAC systems and elevating energy consumption to its highest level. Under the second scenario, the use of smart glass with glare control filters part of the intense solar radiation, resulting in a noticeable decrease in energy usage. In the third and most optimized condition, an intelligent controller adjusts the transmission of daylight based on indoor lighting needs while simultaneously blocking unwanted heat gains; this approach reduces both artificial lighting demand and cooling requirements, yielding the highest level of energy savings.

Figure 10: Comparative annual HVAC energy consumption using conventional glazing and electrochromic smart glass with different control strategies

What makes this figure particularly significant within the context of this study is its direct relevance to the performance of curtain wall systems. Curtain walls—especially unitized types that cover large portions of the building façade with glass panels—play a critical role in mediating heat and solar radiation transfer into the building. Integrating smart glass into curtain wall assemblies transforms the façade from a passive protective layer into a responsive and dynamic environmental interface. This integration, especially when coupled with BMS, enables real-time regulation of the building’s thermal and optical conditions, substantially enhancing the overall energy performance of the envelope. Therefore, the data illustrated in Fig. 10 clearly demonstrate that incorporating smart glass technology into curtain wall designs offers an effective strategy for reducing energy consumption, improving thermal comfort, and achieving the goals of climate-responsive design and sustainable architecture.

In summary, considering local climate conditions, building function, and cutting-edge technologies in curtain wall design not only enhances thermal performance but also contributes to system durability, occupant comfort, and environmental sustainability.

Table 4 provides a consolidated summary of recent studies reporting quantitative energy savings from advanced curtain wall and façade interventions. For Double-Skin Façades, optimized shaft-box and box-window configurations in Erbil (hot climate) achieved total annual reductions of up to 116,574 kWh, alongside cooling load savings of 9%–14% for specific designs [74]. Comparable results have been documented in Mediterranean climates, where multi-storey double-skin façade systems reduced winter energy demand by approximately 28% and summer demand by 53.5%, corresponding to annual savings exceeding 250,000 kWh under optimal orientations [75]. For electrochromic glazing, both building- and national-scale studies demonstrate consistent performance improvements. A Monte Carlo simulation across Swiss office buildings reported an average 11% reduction in electricity demand, equivalent to ≈5.5 kWh/m2 annually, with cooling-intensive offices benefiting from nearly 20 kWh/m2 reductions [76]. Similarly, in a hot-humid climate (Dhahran, Saudi Arabia), electrochromic smart windows delivered total energy savings of 17%–23%, depending on whether the control strategy was daylight- or glare-based [73]. In addition, BIPV curtain walls combined with DSF configurations have shown annual energy intensity reductions of 4.8%–8.6%, which can increase to 15.8%–27.7% when complemented with roof insulation and shading measures [77]. Overall, the evidence summarized in Table 4 highlights that advanced curtain wall technologies consistently deliver 5%–27% reductions in annual building energy consumption, contingent on design typology, control strategy, and climatic context. These findings reinforce the central argument of this review: curtain wall systems should be reframed as dynamic, climate-adaptive energy infrastructures, capable of significantly reducing operational energy demand while supporting the transition toward net-zero building targets.

9 Comparison with Other Building Façade Systems

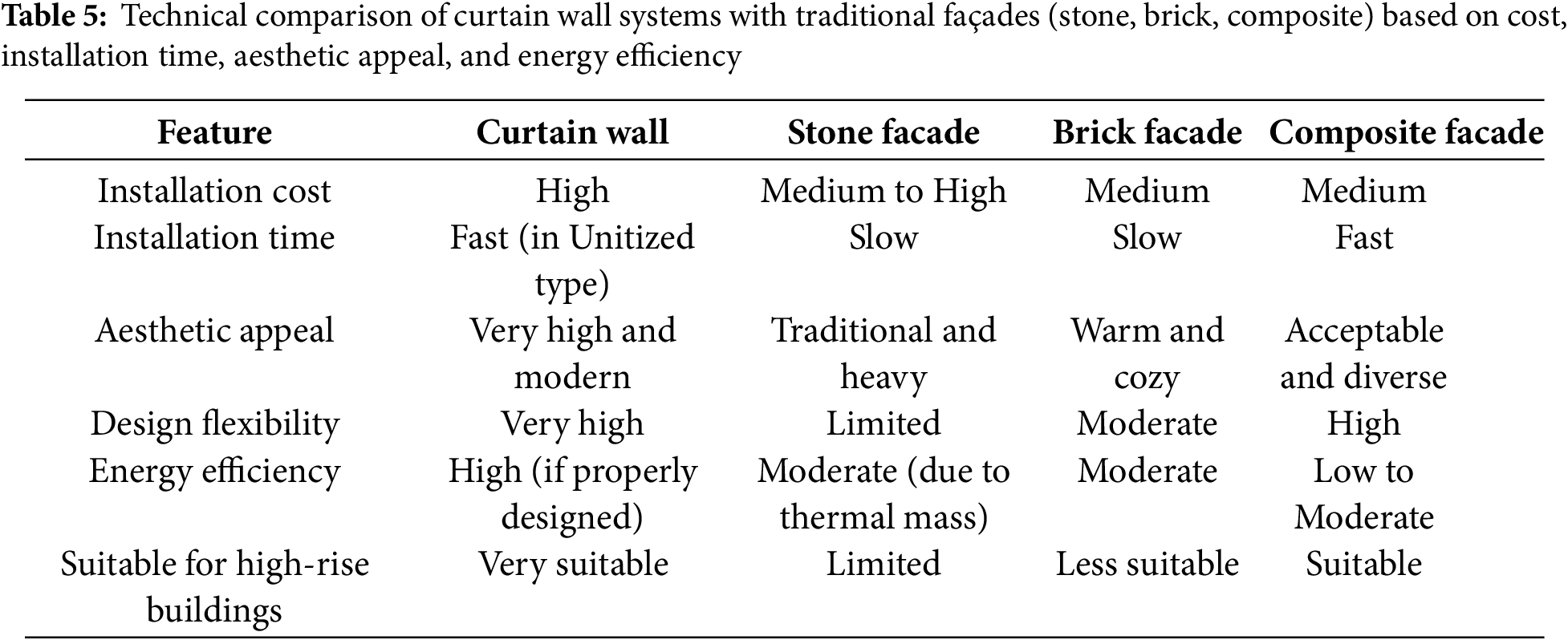

As shown in Table 5, curtain wall systems offer significant advantages over traditional façade types—such as stone, brick, and composite panels—in terms of visual appeal, installation speed (particularly for unitized systems), and energy efficiency, especially when incorporating Low-E glazing and insulated frames [90]. While the initial cost of curtain wall systems is generally higher than conventional façades, their exceptional design flexibility and suitability for high-rise buildings make them a superior solution for modern and sustainable architecture [19].

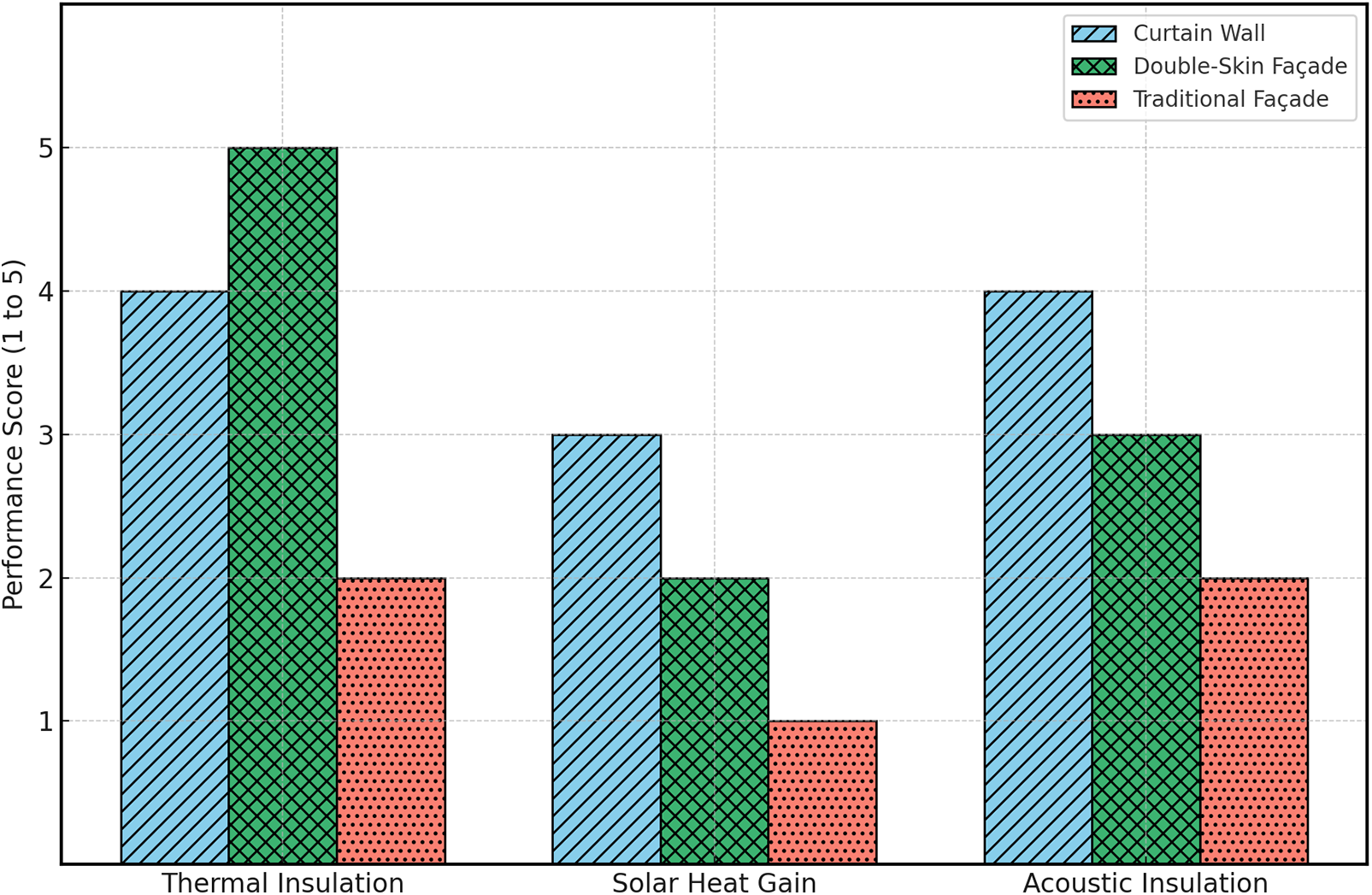

Fig. 11 presents a comparative evaluation of three major building façade systems—namely, the Curtain Wall, Double-Skin Façade, and Traditional Façade—based on three key performance criteria: thermal insulation, solar heat gain control, and acoustic insulation. The data underlying this comparison have been compiled from authoritative prior studies and peer-reviewed open-access scientific sources.

Figure 11: Comparative performance assessment of Curtain Wall, Double-Skin Façade, and Traditional Façade systems across thermal, solar, and acoustic criteria

In terms of thermal insulation, the Double-Skin Façade receives the highest performance rating. By incorporating an intermediate air cavity between two glass layers, this system functions as a dynamic thermal barrier that significantly limits heat exchange with the external environment. According to [31], implementing a double-skin façade can reduce heating and cooling energy demand by up to 40%. The Curtain Wall, when designed using double-glazed units and thermally broken frames, also delivers high thermal performance, although it ranks slightly lower than the double-skin alternative [60]. By contrast, Traditional Façades, due to inconsistent insulation layers and thermal bridging at construction joints, generally fail to provide effective thermal resistance, particularly in climates with extreme heat or cold [59].

With respect to solar heat gain control, the Curtain Wall exhibits moderate yet superior performance compared to the other two systems. The use of low-emissivity (Low-E), reflective, or electrochromic glazing can significantly reduce direct solar radiation and enhance overall energy efficiency [91]. The Double-Skin Façade provides partial control of solar gain through natural ventilation within the cavity; however, in the absence of active shading systems or intelligent controls, it may lead to excessive interior heat accumulation during summer months [83]. Traditional Façades, which lack integrated solar management technologies, typically offer minimal effectiveness in regulating solar exposure [62].

In terms of acoustic insulation, the Curtain Wall system—when equipped with multilayer glazing, sealed framing systems, and precisely engineered joints—can achieve substantial noise reduction. As demonstrated in the study by [11], this system, when properly executed, is capable of reducing ambient noise transmission by up to 40 decibels. The Double-Skin Façade also performs well acoustically due to its dual-glass structure and interstitial air gap, though it requires meticulous installation and airtight detailing to prevent sound leakage [38]. In contrast, Traditional Façades, despite their inherent mass, typically lack specialized construction details for soundproofing and therefore exhibit weaker performance against external noise pollution [85].

This performance-based comparison can assist architects and decision-makers in selecting appropriate façade types for various building applications—particularly in the context of sustainable projects or climate-sensitive environments. Specifically, for high-rise or office buildings, systems such as the Curtain Wall and Double-Skin Façade, which combine architectural aesthetics with energy-oriented functionality and modern technologies, represent more effective and future-ready solutions.

Although numerous studies have highlighted the significant potential of smart glazing for energy savings, fundamental challenges still hinder its widespread adoption. The U.S. Department of Energy (2022) [92] has reported that high upfront costs remain one of the primary barriers to the market acceptance of this technology. In this regard, Villa et al. (2024) [93] observed that the average price of commercial electrochromic glazing is approximately USD 61 per ft2 or higher, which is considerably more expensive compared to conventional windows. From an economic standpoint, precise calculation of the payback period and net present value requires access to detailed data on initial material costs, installation costs, periodic maintenance costs, and the actual rate of energy savings over the service life. Since these parameters depend on the project’s geographic location, energy tariffs, and financial policies, present work provides only a comparative and conceptual analysis based on industry-average data. Nevertheless, it can be stated that the higher upfront investment in advanced façades is typically offset by substantial reductions in cooling and heating loads, and many similar studies report a medium-range payback period (5 to 10 years) [94]. Accordingly, the results of this research are presented primarily to elucidate generalizable technical and economic trends, rather than to provide project-specific numerical estimates.

Beyond the economic dimension, concerns such as performance degradation caused by prolonged UV exposure and the instability of electrochromic layers continue to raise doubts about long-term durability and reliability. Sbar et al. (2012) [95] also emphasized the importance of ensuring stability under diverse climatic conditions. From an environmental perspective, the life-cycle assessment conducted by Papaefthimiou et al. (2006) [96] demonstrated that the embodied energy consumed in the manufacturing of electrochromic windows can be offset within less than one year of use.

Nevertheless, the comprehensive review by Selkowitz et al. (1994) [97] identified factors such as high initial investment, visual comfort concerns, and the need for advanced predictive control strategies as critical obstacles to broader market penetration. In addition, user acceptance remains a decisive factor; in many projects, it has been reported that occupants often deactivate automated control systems, thereby eliminating a significant portion of the anticipated energy savings.

In the current analysis, the performance of building control and automation systems was modeled under ideal conditions and based on self-regulating algorithms. Nevertheless, it should be noted that user behavior and manual interventions (Manual Override) can have a considerable impact on the actual performance of such systems. Post-occupancy studies have shown that occupants—due to thermal comfort preferences, visual perception, or personal habits—sometimes alter the automatic operation of blinds, smart glazing, or ventilation systems, thereby reducing the actual level of energy savings. Therefore, it is explicitly stated that the results of this research represent the technical potential under standard operating conditions, whereas in practice, user behavior, as a critical behavioral variable, may cause deviations from calculated values. Hence, control system design should incorporate user-friendly interfaces, visual feedback mechanisms, and limited ranges of manual adjustments to ensure stability in energy performance.

Finally, the modeling study by Teixeira et al. (2024) [98] pointed out that neglecting thermal and visual comfort aspects in simulations can lead to unrealistic and exaggerated estimates of actual performance.

A review of smart window technologies shows that current solutions still face significant barriers, including very high capital costs (540–1080 USD/m2) [99], long switching times, and limited durability. These limitations, along with issues such as unwanted color shifts, have restricted their market penetration. Nonetheless, experiments indicate that, under proper daylight control, users generally prefer electrochromic windows over fixed glazing and value glare reduction [100]. Thus, adoption decisions require not only modeling studies but also consideration of production cost, operational durability, and user acceptance. Although electrochromic glazing enables adaptive control of solar radiation and potential energy savings, critical evaluations highlight a persistent gap between simulated and real-world performance. For example, a calibrated simulation reported cooling energy savings of about 36%, but also a marked increase in artificial lighting demand due to reduced daylight availability [98]. Economically, electrochromic glazing remains two to three times more expensive than conventional glass, with extended payback periods, while maintenance is complicated by separate wiring and control units that create additional failure points. Early applications further reported issues such as color instability, non-uniform tinting, and limited service life, leading to concerns among owners. Beyond technical and financial aspects, user acceptance also remains uncertain. Some occupants prefer manual transparency control (e.g., with curtains), and automatic switching has sometimes led to dissatisfaction [101]. Although manufacturers now offer user-friendly controls (e.g., mobile apps, wall switches), ensuring trust and alignment with user habits requires further development. Overall, while smart glazing offers notable potential for energy efficiency and comfort, widespread adoption depends on rigorous cost–benefit assessment, long-term durability, and user-centered design.

Overall, this body of evidence demonstrates that a comprehensive and realistic evaluation of electrochromic glazing must simultaneously account for technical performance, economic feasibility, environmental implications, and user behavior.

10 Installation and Execution Considerations

The installation of curtain walls is one of the most critical and technical stages in the construction of modern buildings, requiring precise coordination between the design team, contractors, and safety supervisors [102]. Initially, site preparation is vital—this includes checking level surfaces, verifying the underlying structure, and accurately placing anchors and connection plates to the main frame [30].

Next, the vertical members of the façade, known as mullions, are installed and attached to the primary structure. These must withstand lateral loads such as wind while allowing for thermal expansion and contraction. Horizontal components, or transoms, are then inserted between mullions to form the structural grid of the curtain wall [12,103].

After that, glass or opaque panels are fitted into the frames. These panels must be sealed using high-quality gaskets and waterproofing tapes to prevent the infiltration of water, air, and dust. Final sealing, waterproofing of joints, and installation of finishing covers for the frames are crucial for ensuring the system’s thermal, acoustic, and moisture performance. Upon completion, performance tests such as high-pressure water penetration tests or mechanical stress tests are typically conducted to ensure the system complies with design standards.

Installation at height demands strict adherence to safety protocols. This includes the use of safety gear such as helmets, harnesses, stable scaffolding or building maintenance units, and comprehensive training for installers. Glass panels must be stored and transported vertically in controlled conditions to prevent breakage or exposure to direct sunlight. It is also important to avoid installation during adverse weather conditions, such as strong winds or rain, as they may lead to misalignment or risk of panel fall. All steps must be supervised by experienced engineers to ensure the curtain wall system is not only visually pleasing and functional but also safe, stable, and durable.

11 Modern Technologies in Curtain Wall Systems

Today, curtain wall systems, empowered by modern technologies, have evolved from being mere protective skins into intelligent, adaptive, and energy-efficient infrastructures. These innovations not only improve technical and aesthetic performance but also play a key role in lowering operational energy demand and enhancing the building’s environmental interaction [31].

One of the most prominent technologies is smart glass [73]. These glasses can change their optical properties in response to environmental conditions or electronic commands. For instance, electrochromic glass adjusts its light and heat transmission when voltage is applied [91]. This feature allows curtain walls to automatically reduce glare, unwanted heat, or UV radiation, thus decreasing cooling energy demands and enhancing indoor thermal and visual comfort. Some smart glasses can also function as displays, switchable privacy screens, or even solar energy collectors [104].

Another fundamental advancement is parametric façade design, which is widely used in curtain wall systems [105]. In this approach, the geometry and pattern of the façade panels are algorithmically adapted based on environmental data such as sunlight intensity, wind speed, solar trajectory, and optimal viewing angles. As a result, the façade becomes a dynamic, non-uniform structure responsive to climatic performance. This type of design is implemented using software like Rhino/Grasshopper or Revit and leads to panels with varying dimensions and angles—offering both striking beauty and optimized functionality. In many cutting-edge projects, such façades are integrated with active ventilation systems or movable shading devices.

Finally, integrating curtain wall systems with BMS is a prerequisite for sustainable and smart architecture [82]. Sensors embedded in the façade collect data on surface temperature, light intensity, humidity, and air quality, and relay it to the BMS [26,106]. The system analyzes this data and executes commands such as adjusting ventilation openings, changing the state of smart glass, or controlling automated blinds. This two-way interaction enables the building to respond to climatic conditions, reduces energy usage, increases material lifespan, and enhances occupant comfort.

Field studies and calibrated simulations indicate that the performance of smart glazing often diverges from modeled expectations. For example, Ko et al. (2020) showed that while Suspended Particle Device (SPD) windows reduced cooling demand by up to 29.1%, heating demand increased by 15.8%, leading to a modest 4.1% annual energy reduction [107]. This suggests that simulation models can predict overall performance trends, but actual energy outcomes are strongly influenced by climatic context. Similarly, Yang et al. (2025) [108] reported energy savings of up to 33% for residential buildings in hot-humid climates, whereas Budaiwi and Fasi (2023) [73] documented more moderate reductions of 17%–23% under various glare and daylight control strategies. Similarly, experimental investigations by Piccolo (2010) [109] confirmed that thermal modeling can reasonably capture the general trends of dynamic glazing but highlighted discrepancies in the real-time switching response and solar heat gain modulation. Complementing these findings, operational reports from the U.S. Department of Energy [92] across government buildings demonstrated HVAC energy savings of 10%–20%, with some pilot projects achieving daily reductions between 29% and 65% depending on occupancy and climate. Collectively, these results underscore the trade-off between the optimistic projections of simulation models and the constraints imposed by real-world factors such as durability, long-term maintenance, user acceptance, and climate sensitivity.

The recommendations for humid climates have been formulated based on building physics principles and design standards such as ASTM C920 and EN 12150 regarding sealant selection, back-ventilation of the cavity, and vapor-condensation control; it should be recalled that these results are not grounded in new experimental data but are derived from established guidelines and technical evidence available in the façade industry. Accordingly, empirical evaluation of sealant durability and biotic resistance to mold and mildew can be pursued as part of future field studies.

Although the primary focus of this research was on physical metrics of daylighting and reducing energy consumption, it should be noted that optimizing natural light is always accompanied by a risk of increased glare, and a comprehensive evaluation of light quality requires simultaneous assessment of quantitative and perceptual aspects. Indices such as Unified Glare Rating, Daylight Glare Probability, and Cylindrical Illuminance are standard tools for evaluating users’ visual comfort, which were not included in the present work due to the focus on energy performance. Nevertheless, it is stated that future analyses should consider the combination of energy metrics and luminous comfort, and that users’ visual satisfaction should be complemented through Post-Occupancy Evaluation so that the interactions among daylighting, glare, and perceptual comfort can be examined more comprehensively in the design of smart façades.

In the analysis presented, the operation of integrated BMS and façade-connected sensors was assumed to be under stable, error-free conditions. However, in real operation, factors such as sensor failure rate, calibration drift over time, and controller response delay can lead to deviations from the designed performance. Moreover, with the increasing connectivity of control systems to the Internet, cybersecurity risks and digital intrusions have emerged as new challenges in smart buildings. Therefore, it is stated that the actual effectiveness of BMS systems depends on continuous monitoring strategies, data redundancy, periodic sensor calibration, and layered security protocols (such as data encryption, two-factor authentication, and the segregation of control and user networks). Quantitative assessment of system reliability and cybersecurity risks lies beyond the scope of the present study, but it is proposed as a focus for future research to enable a more comprehensive understanding of the resilience and operational stability of intelligent façade systems.

Curtain wall systems have become a defining feature of contemporary architecture, not only for their aesthetic and structural qualities but also for their potential role in achieving sustainable and energy-efficient buildings. Yet, their performance, costs, and long-term durability remain subjects of debate, requiring systematic analysis. To address this gap, this study conducted a structured review of more than 80 peer-reviewed studies, following PRISMA guidelines, and categorized them based on simulation, field measurement, and experimental approaches. Analytical criteria included energy consumption, thermal and acoustic comfort, surface temperature, and environmental impacts. This multi-dimensional synthesis enabled a balanced evaluation of both the advantages and limitations of curtain wall systems.

• Findings: Curtain walls have evolved from lightweight skins into adaptive infrastructures that actively regulate heat transfer, reduce HVAC loads, and enhance indoor environmental quality. Comparative analyses confirm that system type (Stick vs. Unitized) and installation quality are decisive factors for energy and acoustic efficiency. The integration of advanced technologies—such as electrochromic glazing, BIPV, and real-time BMS controls—has delivered measurable energy savings of 15%–25% across diverse climatic contexts. Case studies including Apple Park, Burj Khalifa, and Milad Tower illustrate how context-specific design, material innovation, and technological intelligence enable façades to function as energy infrastructures rather than passive boundaries.

• Implications: Curtain wall systems should not be regarded solely as aesthetic or structural choices, but as strategic instruments for achieving net-zero energy targets. While their initial costs are higher than conventional façades, lifecycle assessments demonstrate that Low-E glazing, thermally broken frames, and adaptive shading reduce long-term operational costs while improving occupant comfort and environmental performance. For policymakers and investors, these results indicate that the long-term financial and sustainability benefits justify the investment, particularly under stricter energy codes and urban climate goals. Operational monitoring and structured maintenance (e.g., sealant inspections, coating durability, and the reliability of smart-glass electronics) must also be embedded in design and contractual frameworks to ensure sustained performance.

• Research Gaps: Despite technological advances, long-term empirical monitoring of curtain wall performance across varied climates remains limited. The integration of lifecycle cost-benefit analysis with technical energy simulations has not yet reached maturity. This review fills a critical knowledge gap by reframing curtain walls as part of the building’s energy infrastructure and by synthesizing lifecycle and technical data to guide future sustainable façade design decisions. Furthermore, social dimensions—including visual comfort, acoustic quality, and health-related outcomes—are often neglected in energy-centric façade research. This gap highlights the need to combine technical, economic, and human-centered perspectives in future assessments.

• Future Directions: Future research should focus on developing integrated frameworks that combine lifecycle economic evaluation with simulation-based design for thermal, daylight, and acoustic performance. Emerging tools such as AI-driven parametric design and Digital Twin technologies offer significant potential for real-time monitoring, predictive control, and adaptive optimization. At the same time, policy frameworks and incentive mechanisms should be established to accelerate the adoption of high-performance curtain wall systems at the urban scale.

• Final Result: By reframing curtain walls as dynamic, energy-modulating infrastructures, this study outlines a clear roadmap for both academic inquiry and professional practice. Through the integration of advanced materials, intelligent control systems, and climate-responsive strategies, curtain walls can serve as climate-adaptive infrastructures—supporting the transition toward sustainable, resilient, and future-ready buildings.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge the academic and institutional support provided by Islamic Azad University, which created the conditions necessary for conducting this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Samira Rastbod: Literature collection, initial draft writing and visualization. Mehdi Jahangiri: Conceptualization, supervision, methodology and final review. Behrang Moradi: Data organization, preparation of tables and figures. Haleh Nazari: Editing, formatting, references verification and initial draft writing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that all data and materials used in this study are openly available and have been appropriately referenced in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: No ethical approval was needed for this study, as it is based entirely on publicly available literature and involves no original experiments or personal data.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hamida H, Alshibani A. A multi-criteria decision-making model for selecting curtain wall systems in office buildings. J Eng Des Technol. 2021;19(4):904–31. doi:10.1108/jedt-04-2020-0154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Feng C, Ma F, Wang R, Zhang L, Wu G. The operation characteristics analysis of a novel glass curtain wall system by using simulation and test. J Build Eng. 2022;51:104311. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ji X, Zhuang Y, Lim W, Qu Z. Seismic behavior of a fully tempered insulating glass curtain wall system under various loading protocols. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn. 2024;53(1):68–88. doi:10.1002/eqe.4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Schwartz TA. Glass and metal curtain-wall fundamentals. APT Bull. 2001;32(1):37. doi:10.2307/1504691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kim KH. A comparative life cycle assessment of a transparent composite façade system and a glass curtain wall system. Energy Build. 2011;43(12):3436–45. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Spasari I, Conato F, Bayera Madessa H. Glass curtain wall: a systematic review. In: Facade engineering-concepts, materials, techniques and principles of construction. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2025. doi:10.5772/intechopen.1010593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Momeni M, Bedon C. Review on glass curtain walls under different dynamic mechanical loads: regulations, experimental methods and numerical tools. In: Façade design-challenges and future perspective. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2024. doi:10.5772/intechopen.113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kassem M, Dawood N, Mitchell D. A decision support system for the selection of curtain wall systems at the design development stage. Constr Manag Econ. 2012;30(12):1039–53. doi:10.1080/01446193.2012.725940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lee AD, Shepherd P, Evernden MC, Metcalfe D. Optimizing the architectural layouts and technical specifications of curtain walls to minimize use of aluminium. Structures. 2018;13(2):8–25. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2017.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Engelmann M, Kübler A, Hirsch F. Stone-glass curtain wall: designing an outstanding facade in New York City. Glass Struct Eng. 2021;6(3):339–52. doi:10.1007/s40940-020-00141-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Secchi S, Cellai G, Fausti P, Santoni A, Martello NZ. Sound transmission between rooms with curtain wall façades: a case study. Build Acoust. 2015;22(3–4):193–207. doi:10.1260/1351-010x.22.3-4.193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Luo H, Li Z. On wind-induced fatigue of curtain wall supporting structure of a high-rise building. Appl Sci. 2022;12(5):2547. doi:10.3390/app12052547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kim G, Lim HS, Schaefer L, Kim JT. Overall environmental modelling of newly designed curtain wall façade configurations. Indoor Built Environ. 2013;22(1):168–79. doi:10.1177/1420326x12470281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ross BL. Charles B. Clarke’s fagin building: aberration or innovation? Arris. 2009;20(1):64–85. doi:10.1353/arr.2009.0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yeomans D. The pre-history of the curtain wall. Constr Hist. 1998;14:59–82. [Google Scholar]

16. Carpenter J, Colebrook B. Transparency: the substance of light in the design concept. In: The routledge companion for architecture design and practice. 1st ed. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2015. p. 169–83. [Google Scholar]

17. Jabar M. The impact of wind loads on curtain wall design. Seri Iskandar, Malaysia: Universiti Teknologi Petronas; 2010. [Google Scholar]

18. Leslie T, Panchaseelan S, Barron S, Orlando P. Deep space, thin walls: environmental and material precursors to the postwar skyscraper. J Soc Archit Hist. 2018;77(1):77–96. doi:10.1525/jsah.2018.77.1.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Richman RC, Pressnail KD. A more sustainable curtain wall system: analytical modeling of the solar dynamic buffer zone (SDBZ) curtain wall. Build Environ. 2009;44(1):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2008.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kelley SJ. 20th century curtain walls-loss of redundancy and increase in complexity. In: Structural analysis of historic construction: preserving safety and significance, two volume set. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2008. p. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

21. Wu Y, Flemmer C. Glass curtain wall technology and sustainability in commercial buildings in Auckland, New Zealand. Int J Built Environ Sustain. 2020;7(2):57–65. doi:10.11113/ijbes.v7.n2.495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Choi WK, Lee SY, Kim SH, Kim SB, Kim YT, Kim JH. A study on the core design principle of high insulation curtain-wall. Land Hous Rev. 2021;12(1):139–48. [Google Scholar]

23. Nam J, Ryou HS, Kim DJ, Kim SW, Nam JS, Cho S. Experimental and numerical studies on the failure of curtain wall double glazed for radiation effect. Fire Sci Eng. 2015;29(6):40–4. doi:10.7731/kifse.2015.29.6.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hachem C, Athienitis A, Fazio P. Design of curtain wall facades for improved solar potential and daylight distribution. Energy Proc. 2014;57:1815–24. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.10.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yalaz ET, Tavil AU, Celik OC. Lifetime performance evaluation of stick and panel curtain wall systems by full-scale testing. Constr Build Mater. 2018;170:254–71. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Johns B, Arashpour M, Abdi E. Curtain wall installation for high-rise buildings: critical review of current automation solutions and opportunities. Proc Int Symp Autom Robot Constr. 2020;37:393–400. doi:10.22260/isarc2020/0056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Han CS, Lee SY, Lee KY, Park BS. A multidegree-of-freedom manipulator for curtain-wall installation. J Field Robot. 2006;23(5):347–60. doi:10.1002/rob.20122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Orlowski K, Shanaka K, Mendis P. Design and development of weatherproof seals for prefabricated construction: a methodological approach. Buildings. 2018;8(9):117. doi:10.3390/buildings8090117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Song YW, Park JC, Chung MH, Choi BD, Park JH. Thermal performance evaluation of curtain wall frame types. J Asian Archit Build Eng. 2013;12(1):157–63. doi:10.3130/jaabe.12.157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Nam Y, Yeol L, Soo H, Young L, Heon L. Development of the curtain wall installation robot: performance and efficiency tests at a construction site. Auton Rob. 2007;22(3):281–91. doi:10.1007/s10514-006-9019-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Feng C, Ma F, Wang R, Xu Z, Zhang L, Zhao M. An experimental study on the performance of new glass curtain wall system in different seasons. Build Environ. 2022;219(8):109222. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hwang DW, Yoo SH, Park SY, Choi YK. Process improvement method of unitized curtain wall installation for high-rise building-through transform of CYCLONE modeling method. J Archit Inst Korea Struct Constr. 2017;33(3):29–40. doi:10.5659/jaik_sc.2017.33.3.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bustamante V, Cedrón JP, Del Savio AA. VDC framework proposal for curtain wall construction process optimization. In: ECPPM 2022-eWork and eBusiness in architecture, engineering and construction 2022. London, UK: CRC Press; 2023. p. 165–72. doi:10.1201/9781003354222-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gargallo M, Cordero B, Garcia-Santos A. Material selection and characterization for a novel frame-integrated curtain wall. Materials. 2021;14(8):1896. doi:10.3390/ma14081896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen K, Lu W. Design for manufacture and assembly oriented design approach to a curtain wall system: a case study of a commercial building in Wuhan. China Sustainability. 2018;10(7):2211. doi:10.3390/su10072211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ilter E, Tavil A, Celik OC. Full-scale performance testing and evaluation of unitized curtain walls. J Facade Des Eng. 2015;3(1):39–47. doi:10.3233/fde-150028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chen T, Tai KF, Raharjo GP, Heng CK, Leow SW. A novel design approach to prefabricated BIPV walls for multi-storey buildings. J Build Eng. 2023;63:105469. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mjörnell K. Experience from using prefabricated elements for adding insulation and upgrading of external façades. In: Case studies of building pathology in cultural heritage. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2016. p. 95–113. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0639-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hopps ER, Burhoe AM. Considerations for unitized building enclosure systems: selecting, designing, installing, and testing unitized building enclosure systems. In: Building science and the physics of building enclosure performance. Vol. 2. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2022. p. 133–43. doi:10.1520/stp163520210047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. van Roosmalen M, Herrmann A, Kumar A. A review of prefabricated self-sufficient facades with integrated decentralised HVAC and renewable energy generation and storage. Energy Build. 2021;248:111107. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lee H, Oh M, Seo J, Kim W. Seismic and energy performance evaluation of large-scale curtain walls subjected to displacement control fasteners. Appl Sci. 2021;11(15):6725. doi:10.3390/app11156725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Bianchi S, Lori G, Hayez V, Manara G, Schipper R, Pampanin S, et al. Seismic testing and performance evaluation of unitized curtain walls. Earthq Engng Struct Dyn. 2025;54(12):3090–107. doi:10.1002/eqe.70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yuan Y, Zhou Y, Wang L, Wu Z, Liu W, Chen J. Coupled deformation behavior analysis for the glass panel in unitized hidden-frame supported glass curtain wall system. Eng Struct. 2021;244:112782. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu L, Wang L, Guo Z, Luo Z. Cost-oriented design optimization of single building curtain wall. Buildings. 2023;13(3):730. doi:10.3390/buildings13030730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Leśniak A, Górka M. Evaluation of selected lightweight curtain wall solutions using multi criteria analysis. AIP Conf Proc. 2018;1978:240003. doi:10.1063/1.5043864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ramesh T, Prakash R, Shukla KK. Life cycle energy analysis of buildings: an overview. Energy Build. 2010;42(10):1592–600. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2010.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sartori I, Hestnes AG. Energy use in the life cycle of conventional and low-energy buildings: a review article. Energy Build. 2007;39(3):249–57. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2006.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Smith AR, Ghamari M, Velusamy S, Sundaram S. Thin-film technologies for sustainable building-integrated photovoltaics. Energies. 2024;17(24):6363. doi:10.3390/en17246363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. European Commission. Multifunctional energy efficient façade system for building retrofitting (MeeFS)—project reporting [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/285411/reporting. [Google Scholar]

50. A2PBEER Project Consortium. A2PBEER final report—affordable and adaptable public buildings through energy efficient retrofitting 2018 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/609/609060/final1-a2pbeer-finalreport-total.pdf. [Google Scholar]

51. Eom J, Kang Y. Curtain wall construction: issues and different perspectives among project stakeholders. J Manage Eng. 2022;38(5):04022054. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0001085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Naqash MT, Formisano A. Assessment of cantilevered curtain wall system supported by tension rods for an enclosed circular building. Structures. 2024;68:107133. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2024.107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wan Z, Schling E. Structural principles of an asymptotic lamella curtain wall. Thin Walled Struct. 2022;180:109772. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2022.109772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Schling E, Wan Z. A geometry-based design approach and structural behaviour for an asymptotic curtain wall system. J Build Eng. 2022;52:104432. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Sam K. Impact of energy and atmosphere. In: Handbook of green building design and construction. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2012. p. 385–492. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-385128-4.00009-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Oh J, Yoo H, Kim S. Evaluation of strategies to improve the thermal performance of steel frames in curtain wall systems. Energies. 2016;9(12):1055. doi:10.3390/en9121055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Sarmadi H, Mahdavinejad M. A designerly approach to Algae-based large open office curtain wall façades to integrated visual comfort and daylight efficiency. Sol Energy. 2023;251(3):350–65. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2023.01.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Rigone P, Giussani P. Integration of solar technologies in facades: performances and applications for curtain walling. In: Advanced materials in smart building skins for sustainability. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 167–88. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-09695-2_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Zhang Y, Huang L, Zhou Y. Analysis of indoor thermal comfort of test model building installing double-glazed window with curtains based on CFD. Procedia Eng. 2015;121:1990–7. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2015.09.197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Cheong CY, Brambilla A, Gasparri E, Kuru A, Sangiorgio A. Life cycle assessment of curtain wall facades: a screening study on end-of-life scenarios. J Build Eng. 2024;84:108600. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Lighten up your design: the benefits of glass curtain wall systems [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://tfire.com.au/passive-fire-blog/lighten-up-your-design-the-benefits-of-glass-curtain-wall-systems/. [Google Scholar]