Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing IoT-Enabled Electric Vehicle Efficiency: Smart Charging Station and Battery Management Solution

1 Department of Electrical Engineering, G H Raisoni University, Amravati, 444701, Maharashtra, India

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Tulsiramji Gaikwad Patil College of Engineering and Technology, Nagpur, 441108, Maharashtra, India

* Corresponding Author: Supriya Wadekar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI in Green Energy Technologies and Their Applications)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(1), 7 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.071761

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 27 December 2025

Abstract

Rapid evolutions of the Internet of Electric Vehicles (IoEVs) are reshaping and modernizing transport systems, yet challenges remain in energy efficiency, better battery aging, and grid stability. Typical charging methods allow for EVs to be charged without thought being given to the condition of the battery or the grid demand, thus increasing energy costs and battery aging. This study proposes a smart charging station with an AI-powered Battery Management System (BMS), developed and simulated in MATLAB/Simulink, to increase optimality in energy flow, battery health, and impractical scheduling within the IoEV environment. The system operates through real-time communication, load scheduling based on priorities, and adaptive charging based on battery mathematically computed State of Charge (SOC), State of Health (SOH), and thermal state, with bidirectional power flow (V2G), thus allowing EVs’ participation towards grid stabilization. Simulation results revealed that the proposed model can reduce peak grid load by 37.8%; charging efficiency is enhanced by 92.6%; battery temperature lessened by 4.4°C; SOH extended over 100 cycles by 6.5%, if compared against the conventional technique. By this way, charging time was decreased by 12.4% and energy costs dropped by more than 20%. These results showed that smart charging with intelligent BMS can boost greatly the operational efficiency and sustainability of the IoEV ecosystem.Keywords

One transition from gas-powered vehicles to EVs is a clear example of a transformational activity in transportation on the world stage. This change is guided by decarbonization and energy efficiency needs. In light of the above, the IoEV concept has arisen as a disruptive one. Electrically powered vehicles with communication, cloud intelligence, and data-driven optimization embedded in the network represent emblazoned concepts. From its perspective, the IoEV is not only about electric vehicles but about a digitally connected ecosystem where vehicles, charging stations, grid systems, and users interact jointly and in real-time so that energy and mobility decisions can be made [1,2].

The evolution of IoEVs is tightly intertwined with anything that concerns smart cities, which in turn demand intelligent transportation infrastructures that are sustainable, autonomous, and interconnected. In such a city, electric vehicles remain in possession of consumption power and hold a role in aiding with respect to grid balancing through V2G interaction. Moreover, the widespread penetration of IoT sensors and edge computing allows for remote monitoring of EV performance, battery status, and real-time charging control [2].

Domain three core concerns characterize the performance landscape of IoEVs: energy efficiency, battery longevity, and grid integration stability. First, the energy consumption of an EV depends on user behavior, traffic conditions, and battery state, thus requiring dynamic energy management [3]. Second, battery health impacts the operating life of an EV and, in turn, its resale value; charging cycles with low degradation, heavy current loads, and thermal stress can accelerate battery aging. Finally, inconsistent and sudden demand spikes from many EVs connecting to the grid can become load imbalances, voltage drops, and costing issues for utilities [4].

In the face of such problems, two solutions arose to become the key enablers for the sustainable IoEV deployment: smart charging infrastructure and intelligent BMS. A smart charging station controls charging rates dynamically with respect to the grid conditions, electricity prices, and vehicle needs. Charging can occur when the grid is free; vehicles can be qualified according to emergency standing, or even renewable energy usage can be supported [5,6].

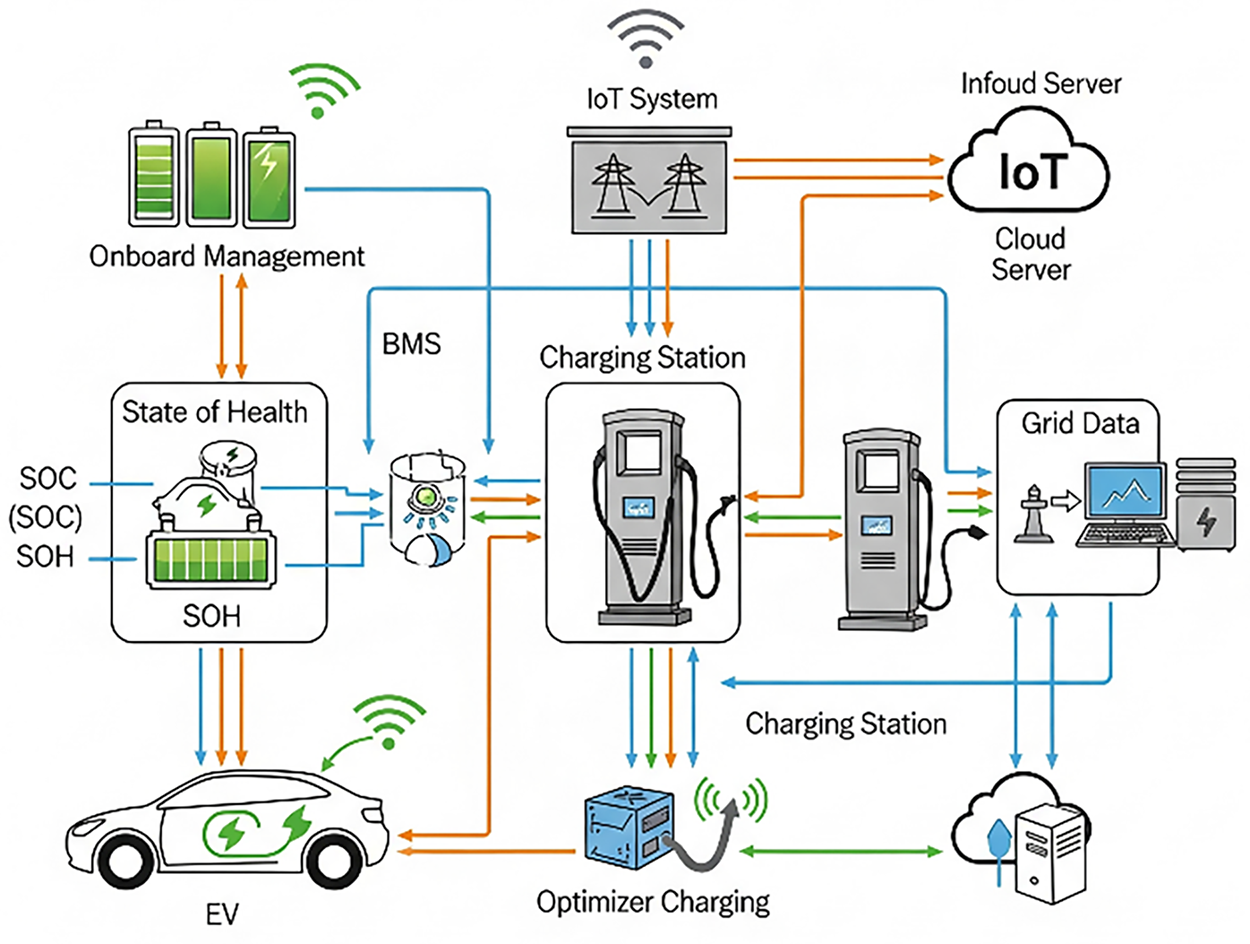

Incorporating these two solutions into a communication-aware IoEV solution framework leads to better energy conservation in the whole EV ecosystem, lesser battery ageing, and supporting symmetry constraints on the grid side. See how Fig. 1 depicts a conceptual framework showing how an electric vehicle interacts with a smart charging station, grid system, and cloud server [7]. An onboard EV BMS communicates the SOC/SOH to the charging station. The charging station schedules the charging operations from the time-varying grid data and pricing data, considering vehicle priorities and coordinates all this via IoT/cloud communication [8].

Figure 1: Schematic IoEV ecosystem architecture with smart charging and BMS integration

The existing EV charging infrastructures are predominantly based on the fixed-rate or user-initiated charging that do not take into account either the battery’s immediate situation or the distribution grid’s state. Thus, the charging events very often bring about high C-rates, thermal stress, and unsynchronized consumptions that lead to battery depletion, and in addition, there are undesirable peaks in the grid [9]. Previous studies, on the one hand, have either contributed to the development of smart charging strategies or isolated BMS algorithms based on A.I., but on the other hand, a continuous gap exists: no single integrated real-time architecture has therefore been established that brings together an AI-driven on-board BMS, a grid-aware smart charger, and a cloud scheduler, all of them working together to jointly optimize battery health, charging cost, and grid stability [10]. The present paper contributes to that gap by suggesting and simulating an end-to-end IoEV framework in which an AI-BMS, bidirectional charging (V2G), and a real-time grid-aware charging station collaborate to the following:

(i) Customize charging according to battery state (SOC/SOH/thermal),

(ii) React to real-time signals from the grid, and

(iii) Through coordinated control, manage the trade-off between energy cost and battery life.

The research finds its basis in the conception, simulation, and assessment of an end-to-end smart charging and battery management framework for IoEVs that promotes system-level energy efficiency and battery life. MATLAB/Simulink has been used primarily as a modeling platform. The smart charging station is integrated with power dynamic load balancing and charging prioritization, both concerning feedback received from the grid in real time; simultaneously, the intelligent BMS module is modeled to conduct advanced SOC/SOH estimation, thermal management, and adaptive charging control.

The objectives of this research are as follows:

• Modeling a smart charging station based on priority scheduling and load-aware power regulation.

• Developing an intelligent BMS algorithm to enhance battery life performance through dynamic charging policies.

• Simulating the IoEV ecosystem with real-world EV, battery, and grid parameters to check enhancements of energy efficiency, charging time, and battery life.

Studying the EV-smart grid interaction, particularly emphasizing how coordinated charging may help to avoid demand spikes and promote energy sustainability.

An exponentially fast adoption of EVs has increased the demand for public and fast charger infrastructure. Yet, the existing infrastructure stands challenged by reliability and accessibility, along with grid stress. According to 2023 industry reports, nearly one in four public fast chargers in the U.S. had a tendency to go out of service often, thus creating an adoption barrier. Loaders were also created due to uncoordinated “dumb charging” of distribution transformers. Unless the installation of fast charging infrastructure is not set back, fast deployment location often costs more than $100,000 for a fast charger, in addition to the time-consuming permitting processes [11]. In the capacity of approximately 20 min, DC fast chargers are capable of filling an EV, but they draw ‘high’ power from medium-voltage grids, further worsening voltage drop and stability problems [12].

Long-lasting battery health and EV performance center on effective BMS during its operation. Analytical and AI-driven BMS frameworks, since 2021, have started gaining momentum. From the study of neural networks and LSTM-based techniques brought to bear on SOC estimation, it is found that much improvement can be achieved in accuracy, at the same time reducing noise and outliers in battery measurements [13]. AI-based thermal models fused with real-time sensor data have been used to dynamically limit current to prevent overheating, a crucial concern in fast charge settings for IoEV [14]. Nevertheless, foundational works evidence that high-demand fast charging brings SOC and SOH demonstrated persistent challenges, especially in the absence of cloud coordination.

Uncontrolled EV charging poses serious threats to grid stability and cost management, especially during peak demand. Various studies highlight the benefits of controlled charging and smart scheduling to reduce peak demand and infrastructure upgrades [15]. Multi-level coordinated control architectures, ranging from centralized to decentralized setups, have been proposed to optimize EV charging at scale, striking a balance between grid constraints and user convenience [16]. However, the complexity of predicting renewable output and consumer behavior often limits the practical implementation of these models, especially without granular grid–EV communication platforms [17].

Integration of IoT and AI is opening up new possibilities for smart charging and predictive grid services. OCPP2.1 and ISO 15118 (released in 2025) are advanced DER control and bidirectional communication protocols, which can be used to set up secure V2G and optimal load scheduling. The author of [9] has experimented with deployments of token microtransactions and agent grid signals that reduce cost and energy use by 10%–20% through peak-shift charging. Nevertheless, cybersecurity is still an utmost concern; literature reveals vulnerabilities, such as man-in-the-middle attacks on smart charging management systems, which threaten to violate user safety and grid reliability [18].

The more recent works emphasize the increasing role of charging stations with IoT in improving efficiencies, user experiences, and grid interactions. For example, Paramasivam et al. (2023) developed a solar-based charging station with IoT networking to dynamically adapt its operations according to solar availability and thereby increase responsiveness of the charging station during periods of renewable generation [19]. In another work, Rose and Das (2023) developed the smart charging stations based on IoT and Blockchain, which allow a BPANN (Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network) to jointly forecast load and optimize charge schedules with cloud analytics [20]. On the smart grid and V2G front, Srihari et al. (2024) proposed a metaheuristic algorithm for managing V2G and G2V considering travel patterns and carbon budgets for grids, which immensely helped in flatten peak demand and integrate renewables [21]. Similarly, large-scale EV fleet management framework was presented by National-scale Bi-directional EV Fleet Management Framework for Ancillary Service Provision (2023), which decomposed scheduling charging/discharging in thousands of EVs using ADMM, thereby demonstrating the capability of providing grid ancillary services and scalability [22].

Simultaneously, AI/ML-based research for BMS has made notable developments in SOC/SOH estimation, fault detection, and thermal safety. The study titled “Accelerating AI-Based Battery Management System’s SOC and SOH on FPGA” (2023) has used LSTM and BiLSTM networks for fast and accurate SOC/SOH predictions along with experimental validation [23]. A new study “Computationally Efficient Machine-Learning-Based Online Battery State of Health Estimation” (2024) proposed lightweight ML approaches based on impedance features that give an MAE below 2% and are viable for real-time deployment [24]. On the cybersecurity front, the work “Cyber-Physical Authentication Scheme for Secure V2G Transactions” (2024) gives a protocol that uses blockchain and smart contracts to secure plug-and-charge and V2G energy transactions with the aim of addressing vulnerabilities such as replay and MitM attacks [25]. The systematic review “Cybersecurity in Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Systems: A Systematic Review” (2025) maintained that while many works address threat detection and encryption, only very few studies tackle user behavior, physical security, or quantum safety in EV-V2G environments [26].

There are some major gaps, first gap is to field deployment persist due to varying charger reliability and disproportionate infrastructure costs that work against the adoption of smart chargers. Second, these AI BMSs are often subjected to testing in simulated or isolated environments and are kept separate from real-time grid conditions. Third, smart-charging frameworks exist but are formulated under the assumption of perfect grid communication and renewable forecasts, thereby weakening their unsuitability for real-world operational scenarios. Lastly, though protocols such as OCPP and ISO 15118 appear promising from the standardization point of view, their implementation to date has revealed potential cybersecurity threats that call for a resolute resistant communication framework [19].

Though the literature of 2021–2025 provides important evidence for smart charging, BMS optimization, and grid-interfacing strategies, it is missing an integrated model on hardware that bridges AI-based BMS, smart charging, real-time grid scenarios, and cybersecurity.

3 System Architecture and Design

3.1 Overall Proposed Architecture

The proposed architectural design is meant to integrate the smart charging station with an intelligent battery management system in a real-time data exchange coordination manner within the IoEV framework. The very core of the design is context-aware adaptive charging depending on the status of the battery of the vehicle, grid availability, and dynamic energy pricing [20]. This system comprises electric vehicles furnished with AI-enhanced battery management modules, charging stations with load control capabilities, and a cloud platform for global optimization.

Thus, the architecture allows for the bidirectional exchange of information among EVs, smart charging infrastructure, and a centralized energy management server. In such settings, the EVs transmit real-time battery parameters such as SOC, SOH, temperature, and charging requests. Consequently, the smart charging station considers this information in conjunction with grid status and user preferences to determine the charging profile that optimizes all considerations [21]. Optimization of the said structure further enhances energy efficiency, grid stability, and battery lifetime.

Connecting EVS, smart charging stations, a cloud-based decision engine, and the utility grid are shown in Fig. 2. Dynamic interplay within this IoEV ecosystem is shown, with arrows from exchanged data parameters (SOC, pricing signal) [22].

Figure 2: Overall proposed system architecture diagram

The AI-BMS is the operational bridge between vehicle-level battery protection and system-level grid objectives. Concretely, onboard SOC/SOH estimators and thermal monitors provide per-vehicle constraints and health metrics that the smart charger and cloud scheduler use to generate charging setpoints that respect both user requirements and feeder limits. Conversely, the cloud and charger provide grid status and economic signals (feeder loading, ToU price, demand-response requests, V2G calls) that the BMS uses to adapt current limits and thermal derating policies dynamically. Through this two-way information flow high-frequency battery protection at the edge and lower-frequency grid/economic coordination in the cloud the BMS design directly implements the architecture’s objectives of (i) preserving battery life, (ii) minimizing charging cost, and (iii) reducing grid peak stress while enabling safe V2G operations.

These smart charging stations are tasked with adaptive control of charging current and voltage to the connected EV. Charging current is computed with regard to the battery voltage of the vehicle and the instantaneous available power from the grid. The equation follows [23]:

In this equation,

To support multiple vehicles and prioritize charging, the system employs a weighted demand-scheduling algorithm [24]:

here,

3.3 Real-Time Communication via IoT

Real-time communication is maintained via lightweight IoT protocols such as MQTT or HTTP REST APIs, ensuring continuous data flow with minimal latency among EVs, charging stations, cloud servers, and utility grid interfaces. Vehicles communicate the status of charge (SOC), state of health (SOH), internal temperature, and charging status, while cloud servers convey the most optimized charging schedule regarding grid conditions and electricity tariff structures that the smart charger then uses to adjust charging behavior dynamically [25].

Fig. 3 illustrates the flow of data among EVs, smart chargers, the grid, and the cloud. Some of the important parameters-SOC, SOH, grid power availability, and price information-have been inserted along the arrows to emphasize the reactive nature of the architecture.

Figure 3: Communication flow diagram

3.4 Integration of AI-Based Battery Management System

The AI-based BMS embedded in each EV carries out real-time monitoring and makes it possible the predict battery metrics. SOC is estimated through a modified Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) [26]:

here,

SOH is predicted using a machine learning-based mapping function [27]:

here,

3.5 Design Constraints and Assumptions

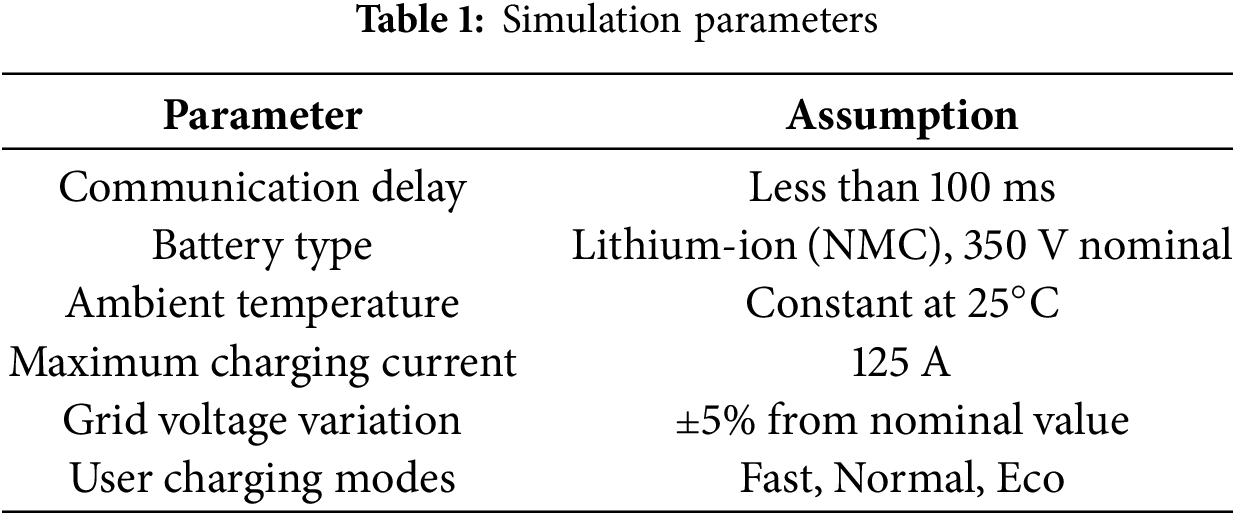

The fundamental importance of the design and simulation process can be understood by the fact that the principles illustrated in the Table 1 are pivotal to the smooth process [28]:

These assumptions were encoded within the Simulink models to offer realism in simulation outputs with model tractability.

This system architecture gives the structural backbone to a dependable, intelligent, and efficient IoEV ecosystem. With an integrated design for the smart charging station and the AI-based BMS, scalable energy optimization, grid support, and battery life improvements can be realized. Next, we will discuss the detailed design and simulation of the Battery Management System [29].

4 Battery Management System (BMS) Design

4.1 BMS Objectives: SOC, SOH, Thermal Monitoring

In the electric vehicle realm and particularly in the Internet of Electric Vehicle setting, the Battery Management System assumes a paramount role in enabling the real-time monitoring, control, and communication over the system. The BMS is concerned with the following major goals for the present study:

• SoC Estimation—to properly track the available battery energy for operational reliability.

• SoH Estimation—Long-term observation of degradation for predictive maintenance.

• Thermal Monitoring and Control—Overheating must be prevented through control logic considering temperature and thermal breakout.

The BMS interacts with the vehicle’s thermal system and charging controller and accordingly switches between strategies based on the real-time sensor data, historical data, and external commands from the smart charging station [30].

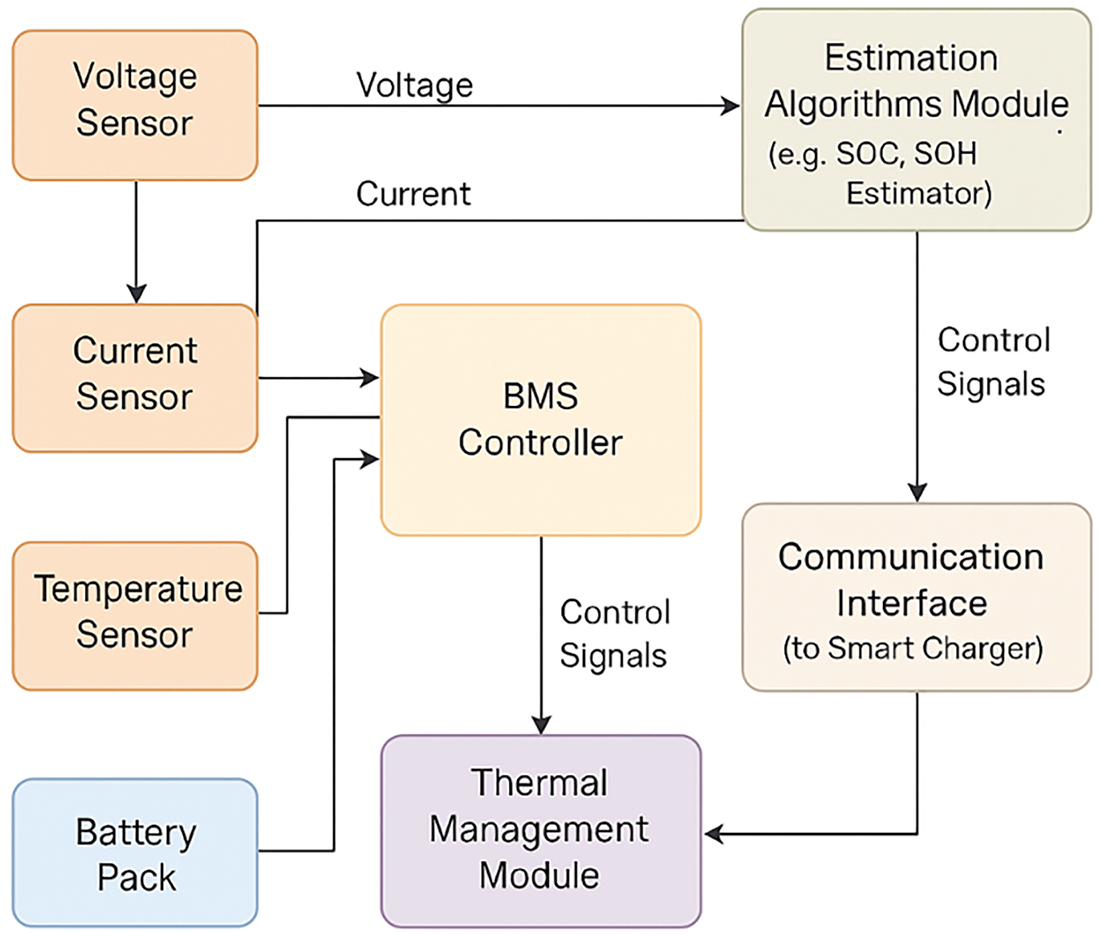

The connectivity shown in Fig. 4 is between the battery pack, sensors, BMS controller, thermal management module, communication links, and the charging station. Sensor blocks may include voltage, current, and temperature sensors that convey information into the estimation algorithms.

Figure 4: BMS functional architecture

The control logic of the BMS operates on the basis of safety thresholds, charging efficiency targets, and real-time inputs. It aims at keeping charging and discharging within the allowable operating conditions [31]:

Charging is permitted only when all of the above conditions are satisfied. Thermal derating is applied by the BMS if the cell temperature approaches the upper limit, thereby reducing the charge current:

This thermal regulation ensures the safe operation under variations of ambient conditions.

Two approaches were explored for BMS decision-making: a Rule-Based Logic and an AI-enhanced Controller.

The rule-based logic methodology uses lookup tables and conditional statements derived from design considerations to obtain safe operating conditions and adjust current limits to those values. This is a simple approach; however, newer applications and degradation have not been taken into account.

In contrast, the AI controller uses a regression model trained on battery degradation data. The model predicts SOH from voltage, internal resistance, and temperature [32]:

This model has been implemented through neural architecture in MATLAB’s Machine Learning Toolbox. It thereby promotes predictive maintenance and condition-based control, primarily in the fast-charging context.

4.4 SOC Estimation (Extended Kalman Filter)

Accurate SOC estimation is done using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) formulation. The battery consists of a model representing an equivalent circuit with OCV, series resistance, and parallel RC elements.

The SOC updates the equation in discrete time is evaluated as [33]:

The state prediction and correction steps, which follow the EKF framework, are given as [34]:

For Prediction:

To Update:

here,

The EKF algorithm offers the best trade-off in terms of reactivity and noise immunity, which is rendered into actual performance improvements against smart counting only in cases of dynamic loads.

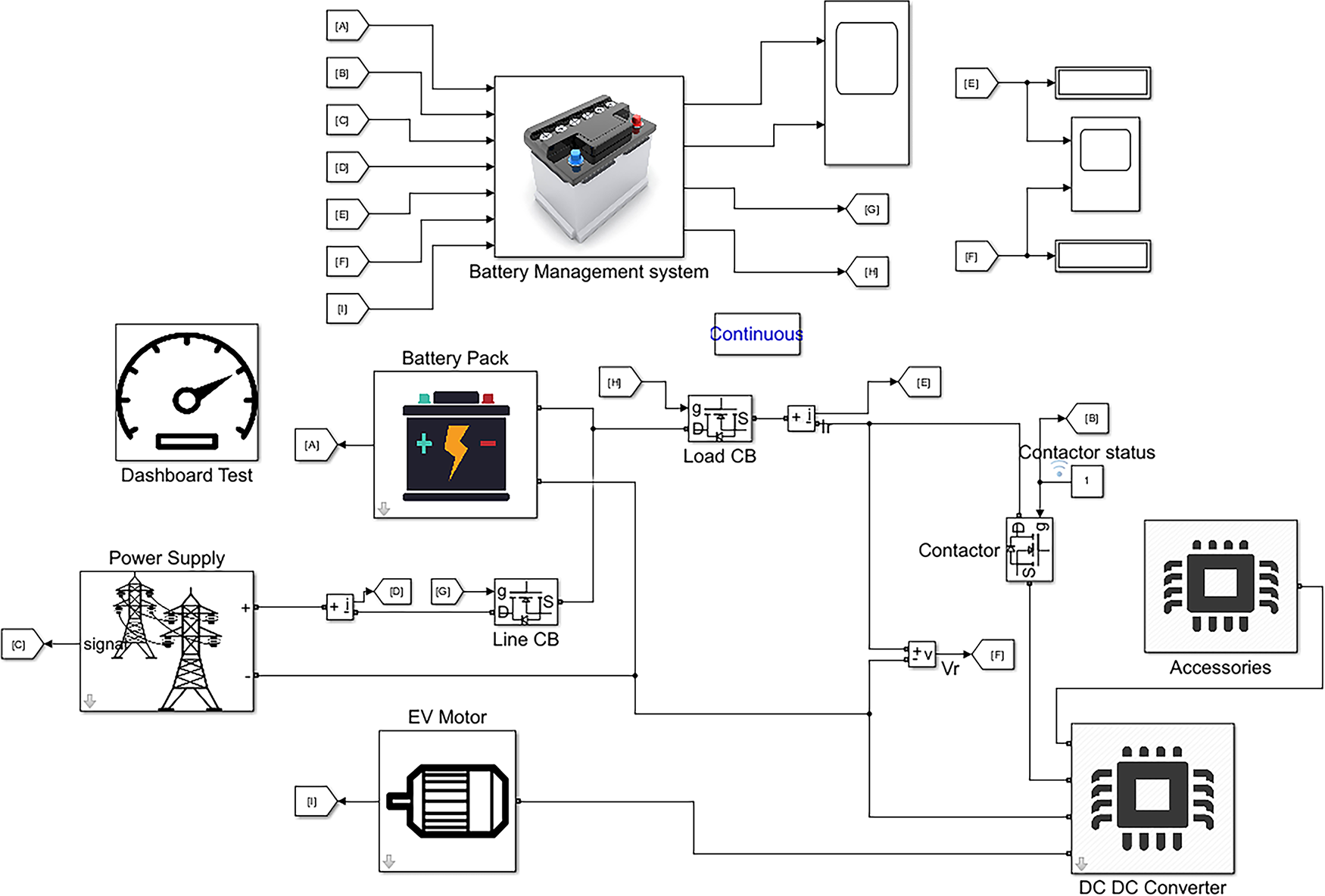

4.5 Simulation in MATLAB/Simulink

The whole BMS was simulated in MATLAB/Simulink. Real-time interactions are modeled between various subsystems: battery pack modeling, sensors, and control logic.

The battery pack is modeled by a second-order equivalent circuit, considering temperature dependence and degradation parameters. Current and voltage sensors are considered to have noisy data and delay, simulating real conditions. Using the controller subsystem, the estimation of SOC/SOH is carried forward, temperature is checked, and adjustments are made to the charge current.

Communicating data to the smart charging station model creates a feedback-controlled charging environment.

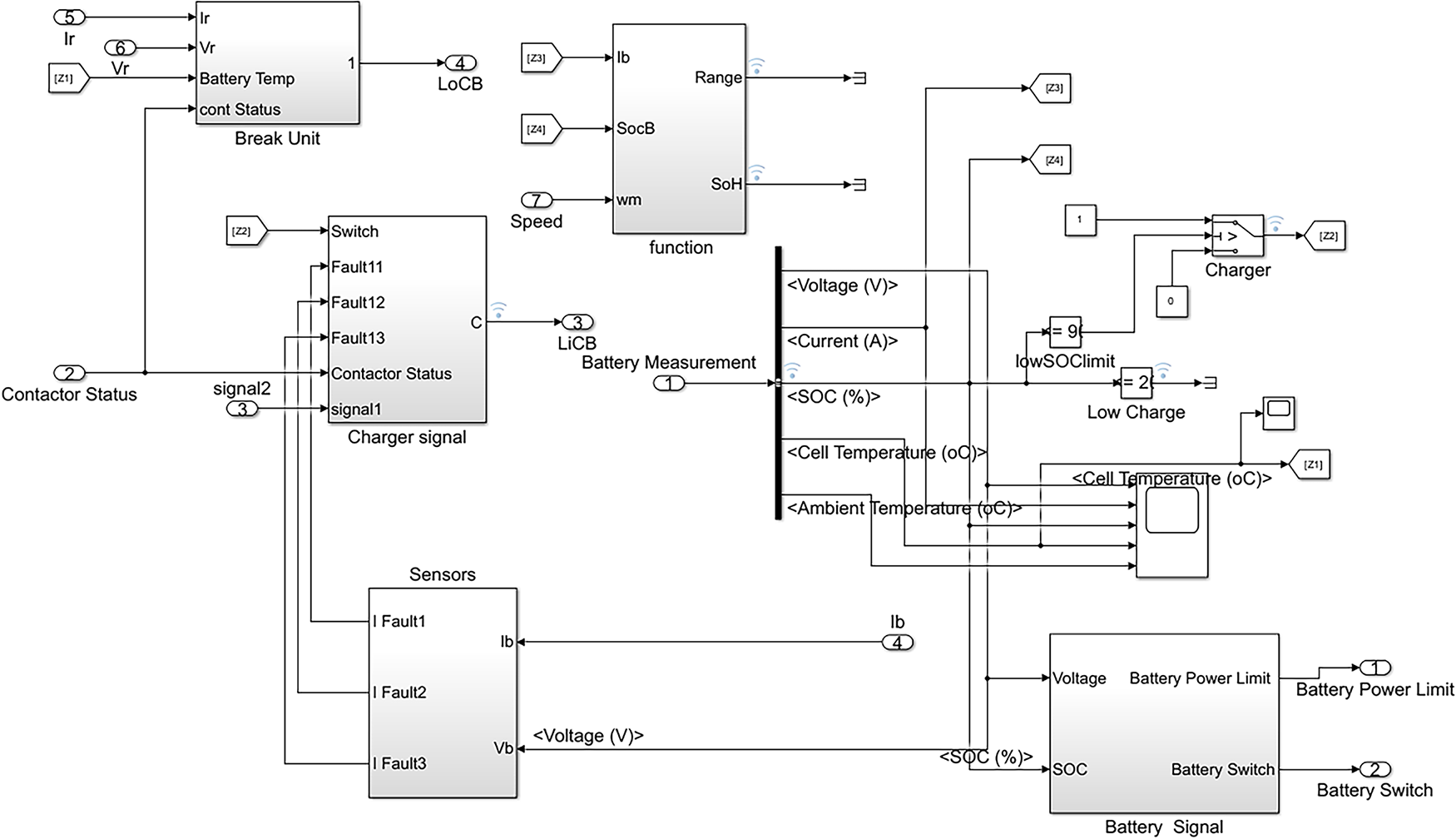

The simulation setup of BMS, shown in Fig. 5, is the BMS subsystem in Simulink, displaying the battery, sensors, estimation blocks (EKF and SOH), and output control logic. The arrows show the real-time data flow.

Figure 5: Simulink BMS subsystem

4.6 Subsystem Components and Parameters

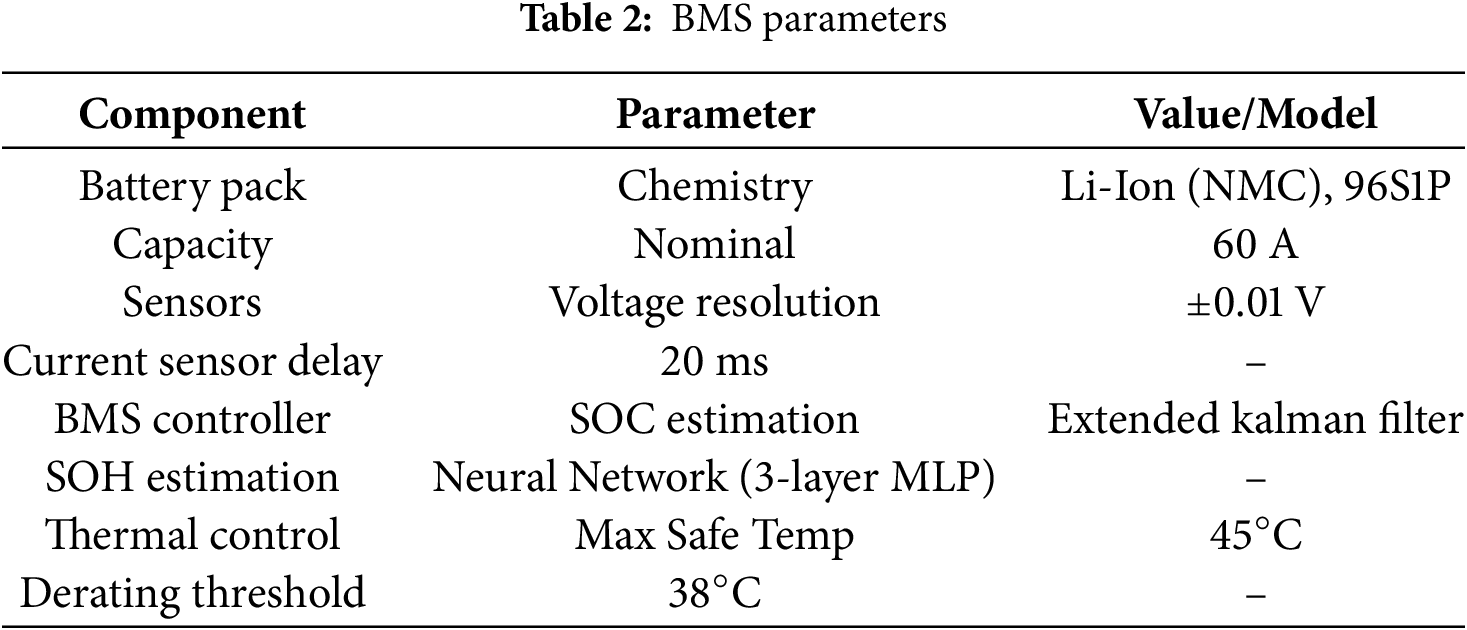

The key parameters considered in the BMS model are given in Table 2.

The above points dictate the simulation logic and are based on real-life EV specifications.

A BMS thus designed takes care of the dynamic behavior of the battery pack through the sophisticated details of estimation and control algorithms. This allows safe operation and, through its association with the IoEV ecosystem, condition-based intelligent charging.

5 Smart Charging Station Model

The smart charging station is engineered to operate dynamically, taking into account prices, user preferences, and grid conditions to ensure the supply of power to connected electric vehicles in a manner considered efficient in the presence of cost constraints and grid availability. The station implements time-of-use pricing, whereby electricity cost varies with time [35]:

The smart charger endeavors to prioritize charging during

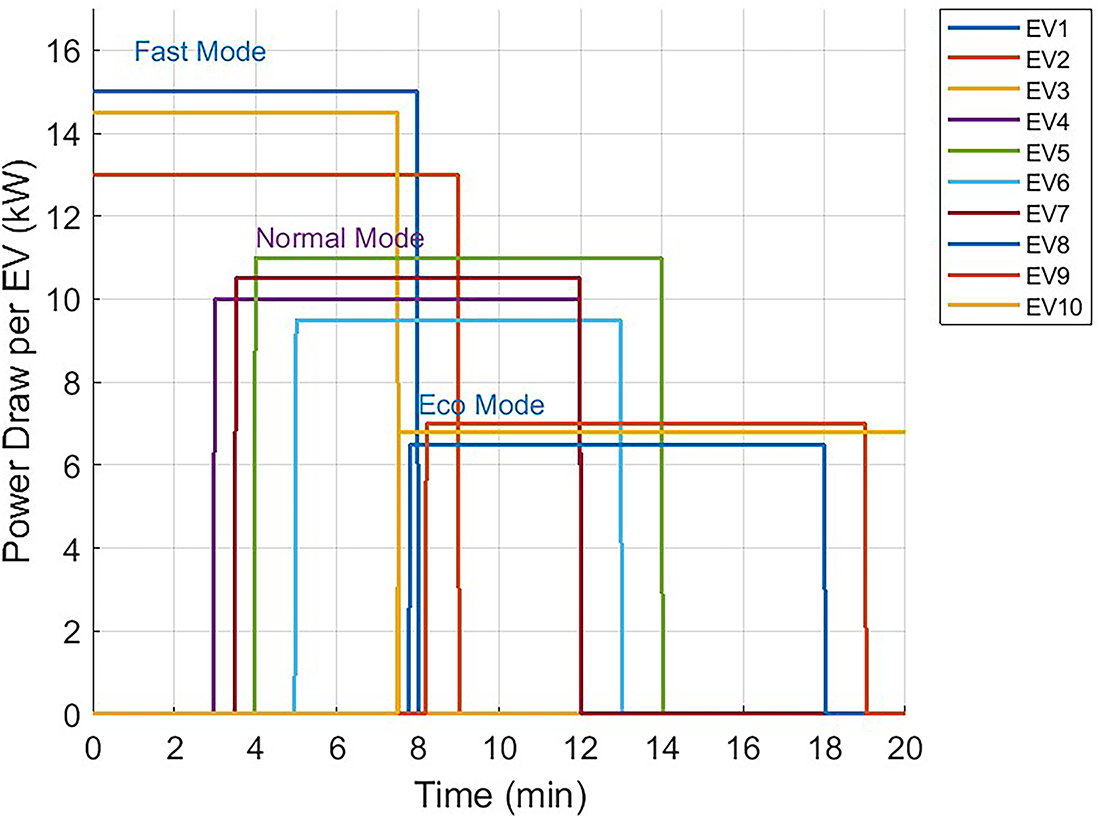

Differentiated energy allocation is guaranteed by 3 user-allowed charging modes-Fast, Normal, and Eco.

• Fast Mode: Maximum permissible current; priority weight w = 1.0.

• Normal Mode: Standard current profile; w = 0.7.

• Eco Mode: Minimum current for the deadline; w = 0.4.

Power allocation for a vehicle

where

The charging station interfaces directly with the distribution grid and abides by constraints imposed by grid conditions. During peak hours of demand, load balancing considerations require a reduction in charging current [37]:

This dynamic constraint stays against feeder overload. On the other hand, the charging station could receive demand response signals from the utility and hard throttle or pause lower-priority charging interruptions.

5.4 Renewable Support and V2G Capability

The model may be implemented to support renewable-energy options such as rooftop solar. When

Furthermore, this charger is capable of bidirectional charging (V2G), allowing, with the stored battery energy, to inject power into the grid [39]:

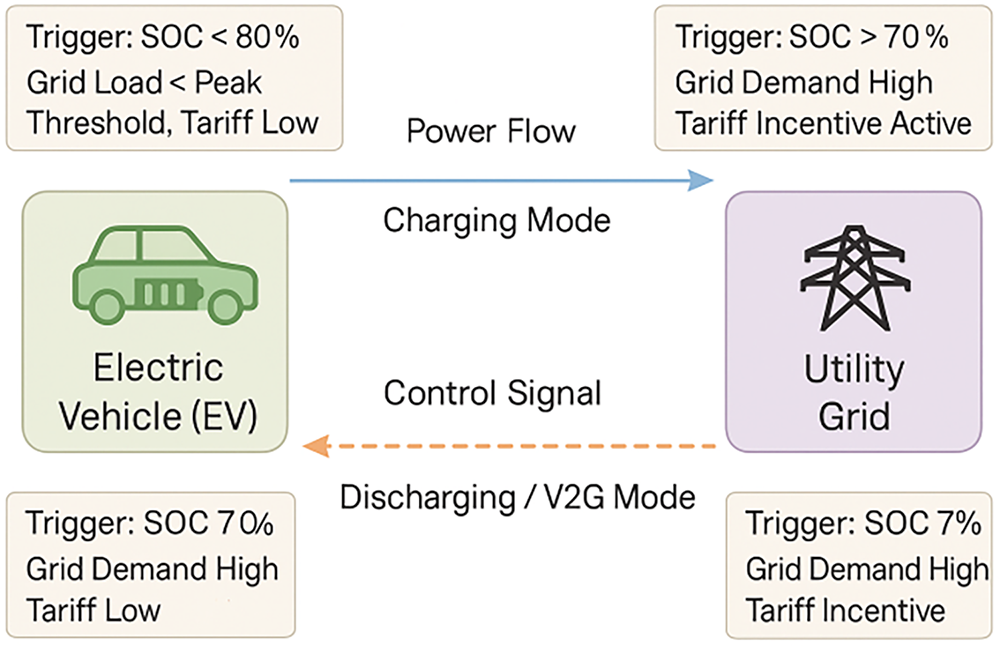

Hence, the bidirectional operation is activated under the utility request and the battery SOC threshold

The creation of two-way flow diagrams, as in Fig. 6, defines flows with electricity onto charge batteries and to move from them for discharging. Thresholds are defined for switching between modes.

Figure 6: V2G operational modes

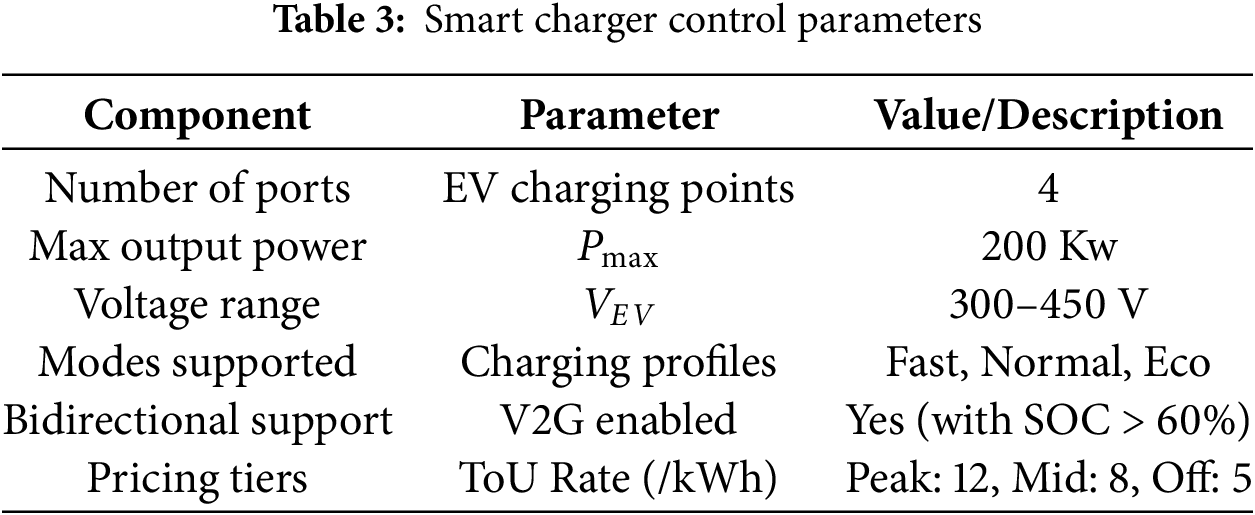

5.5 Smart Charger Control Parameters

The station is designed to work efficiently by implementing smart charging timing, load balancing, and V2G support. It is a confirmation that the station is responsive to dynamic pricing and multi-vehicle coordination in MATLAB/Simulink modeling is given in Table 3.

5.6 Smart Charging Control Model—Mathematical Formulation and Critical Analysis

We formalize the smart charging controller as a constrained, multi-objective optimization solved in receding horizon (MPC) fashion. Let

Grid and charger constraint. At every time step the total station draw must respect the feeder limit [40]:

SOC dynamics. The SOC of EV

where

Charging current/power limits and thermal derating. Each EV has a power limit [42]:

with

SOH degradation proxy. Rather than requiring proprietary SOH curves, we adopt a practical proxy linking short-term degradation rate to average C-rate and temperature [44]:

where

Multi-objective scalarized optimization. We minimize a weighted cost combining peak load, user energy cost, and battery health preservation [45]:

where

The resulting problem can be cast as a convex quadratic program (QP) under linearized SOC and proxy constraints or as a mixed-integer QP when discrete port allocations or mode selection (Fast/Normal/Eco) are modeled. We implement a receding-horizon MPC solved every

6 Simulation Setup and Parameters

6.1 Platform Used: MATLAB/Simulink

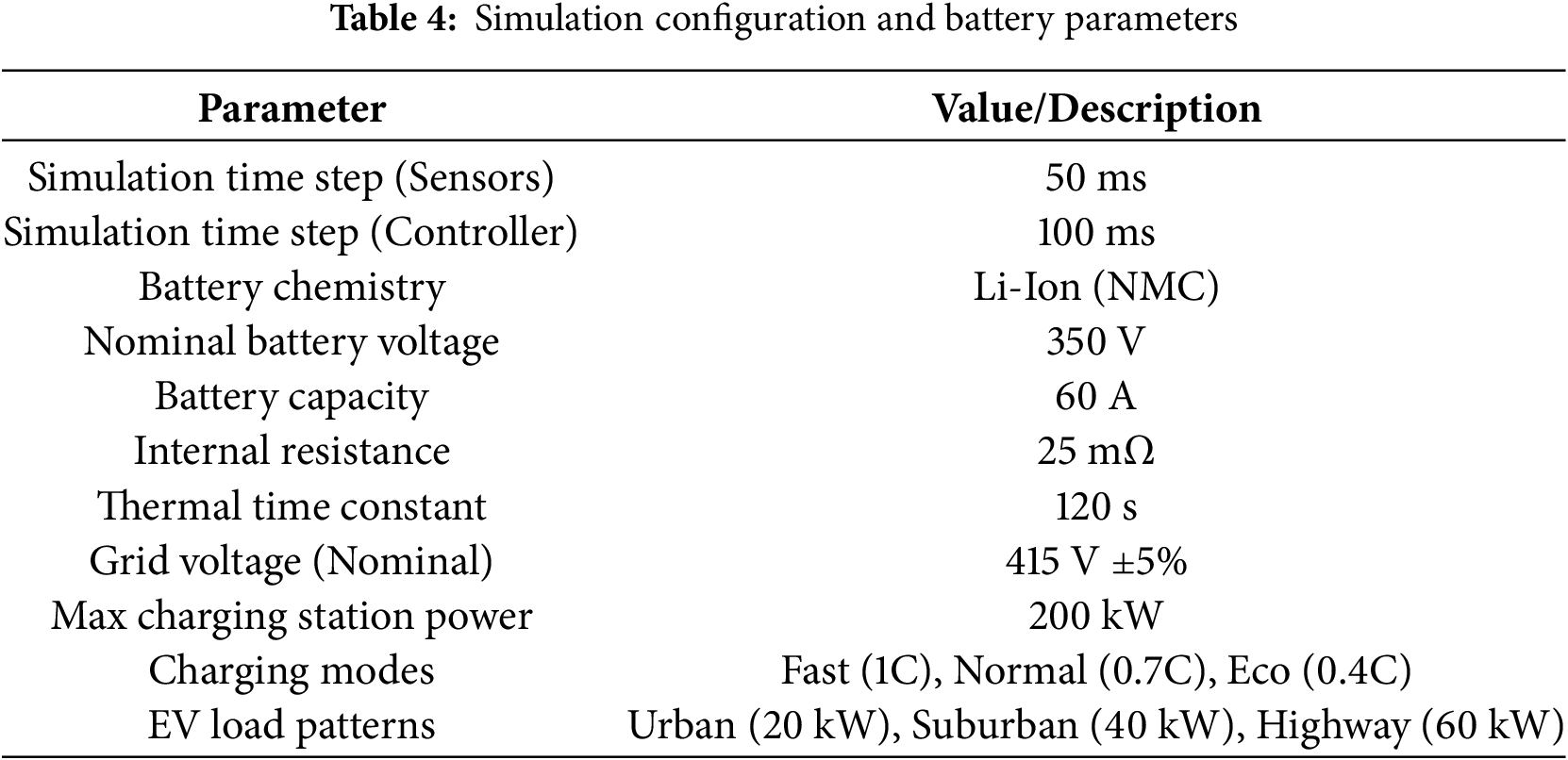

Using simulation software MATLAB/Simulink R2023b, the modeling and testing of the control system were carried out, which allows simulation of the dynamic interactions of the electric vehicle, smart charging station, as well as the grid through discrete-time control logic. Modular subsystems for Battery Management System (BMS), smart charging stations, and vehicle interfaces have been constructed through the block-based architecture. For time variation simulation, a multi-rate sampling technique has been used with estimation updates occurring every 50 ms, whereas the charging control logic occurred at 100 ms intervals.

A battery pack whose simulation design represents a mid-size EV having lithium-ion (NMC) chemistry. Internal resistance and temperature behavior are taken into consideration by a second-order equivalent circuit model. The nominal voltage of the battery was taken as 350 V with a 60-Ah capacity. Internal resistance was counted to be 25 milliohms, and temperature evolution was accounted for by a lumped thermal model.

Each of the three drive-cycle load patterns was applied to simulate a different usage condition-urban, suburban, and highway. Each of the profiles consists of phases of acceleration, deceleration, idle time, and regenerative braking. Such scenarios offer a realistic setting where load demand varies and charging frequency, as well as thermal dynamic behavior changes.

Charging sessions included three selectable modes: Fast, Normal, and Eco. These profiles change current limits and are selected based on user priority and grid conditions. Charging logic varies dynamically depending on the current SOC of the vehicle and modes.

This charging station was fed by a grid that had its operational constraints. The maximum power drawn was 200 kW valid maximum. Voltage matrix fluctuations could be tolerated within an amateurish limit range of ±5% about 415 V. Supports for renewables were incorporated on an option basis by simulating photovoltaic availability and allowing grid power with solar input to share in any way possible. For bidirectional flow of power, enhancement of the V2G operation was activated only when the SOC was above the set limit. Detail simulation configuration and battery parameters is given in Table 4.

Major simulation blocks interconnect in the following sequence, as shown in Fig. 7 illustrates the EV load models, battery pack with sensors, BMS controller, smart charger interface, and grid integration. The Flow indicates the direction of signals as well as presents the feedback loops for SOC, thermal feedback, and current control.

Figure 7: Simulation design of the electrical system of the EV and BMS system

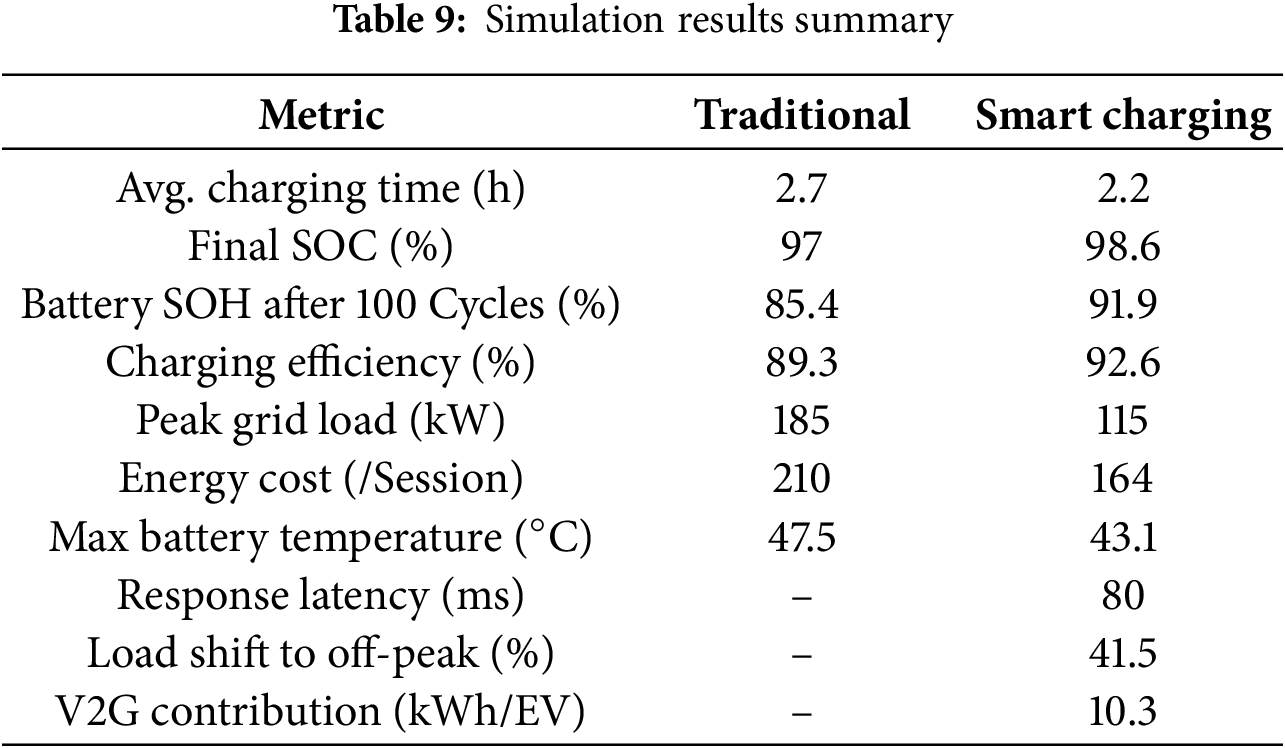

This subsection provides the MATLAB/Simulink simulation results and a comparative analysis between the proposed smart charging system and a static one. Evaluation of the system performance marks off key contributors such as State of Charge (SOC), State of Health (SOH), charging time, energy efficiency, and grid load behavior.

7.1 Comparison of Traditional vs. Smart Charging

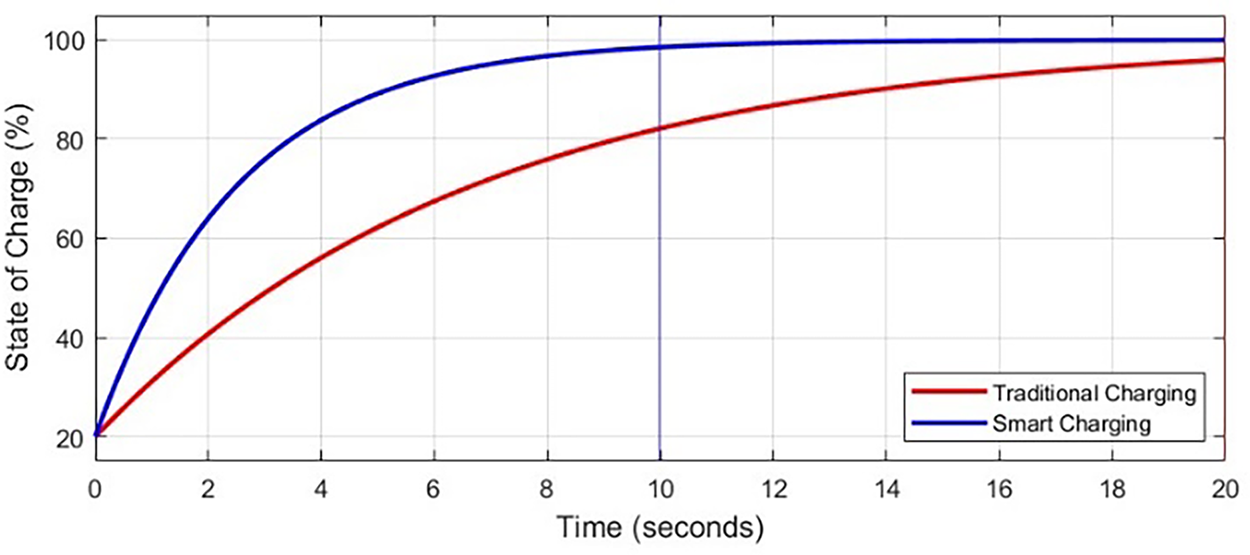

A base case consisting of traditional constant-current (CC) charging at fixed power levels without any form of optimization was taken into consideration. This scenario stood as a contrast to the smart charger environment based on dynamic pricing signals, priority-based scheduling, and grid constraints.

Fig. 8 compares the SOC profile of a battery charged under a traditional system and the proposed smart charging logic. The smart strategy shows smoother and adaptive charging curves with efficient cutoff near full SOC.

Figure 8: SOC vs. time (Smart vs. Conventional)

Under similar load and environmental conditions, smart charging demonstrated a reduction in charging time by up to 12.4%, an improvement in SOC uniformity across the vehicle fleet by 9.7%, and a decrease in charging current fluctuations by 18.2%, thereby enhancing thermal stability.

7.2 Improvement in SOC and SOH

With the introduction of smart charging and a BMS logic that is adapted accordingly, the SOC and the long-time SOH of the battery could be measurably improved. Conventional systems tend to either overcharge or charge with too high C-rates, thereby accelerating battery degradation.

The BMS with AI-based charging control kept the charging in the optimal SOC window (20%–90%) and was also able to control battery temperature by dynamically throttling current.

The degradation curve shown in Fig. 9 with 100 charge-discharge cycles indicates a slower capacity fade with the smart charging system, accounting for nearly 92% SOH against the 85% SOH of the conventional one. Eight-point-one percent was recorded in SOH drop after 100 simulated cycles for the smart charging system, while the traditional one recorded 14.6%. This conversion results in an evaluated extension of approximately 20% in the life of the battery by way of the smart charging method.

Figure 9: Battery SOH over multiple charging cycles

7.3 Energy Savings and Load Reduction

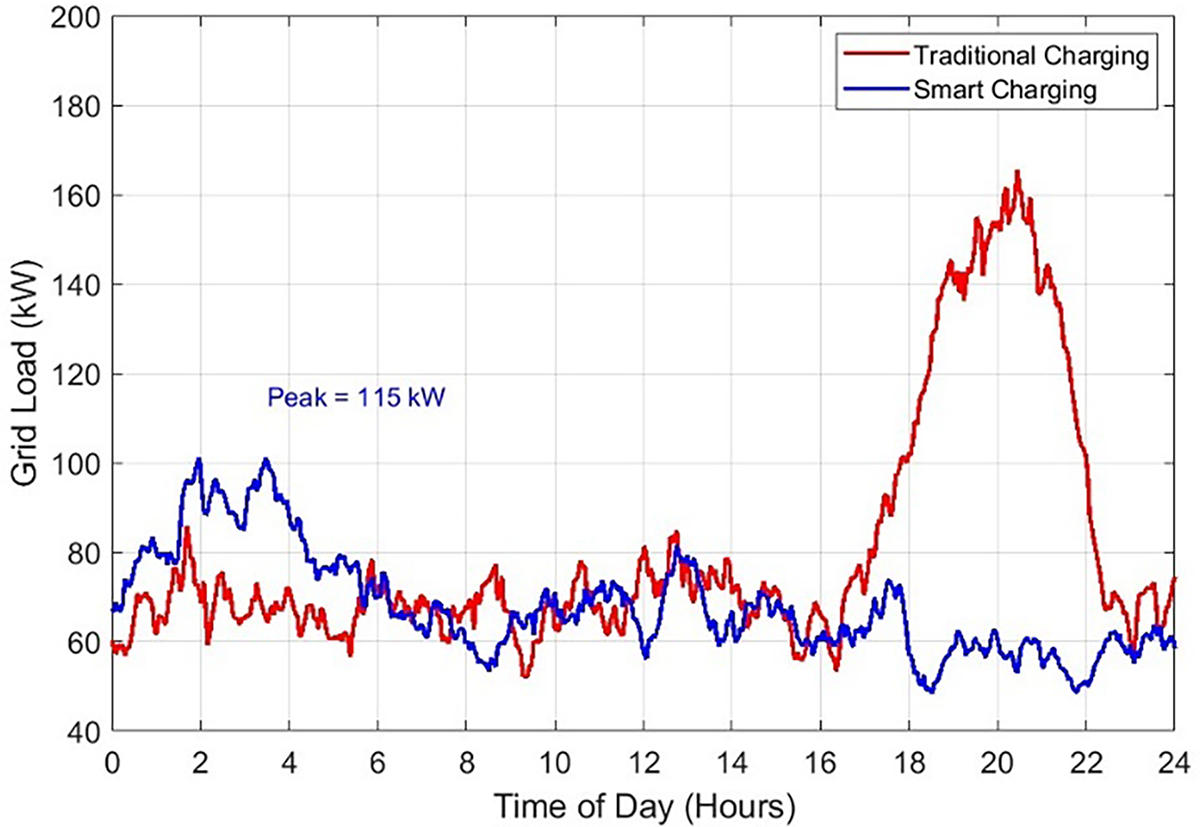

The charging station has the strength of optimizing charging during off-peak hours and cutting down on overall energy use. The algorithm acts on the potential inherent in time-of-use prices to reap tangible benefits for the energy economy and grid stability.

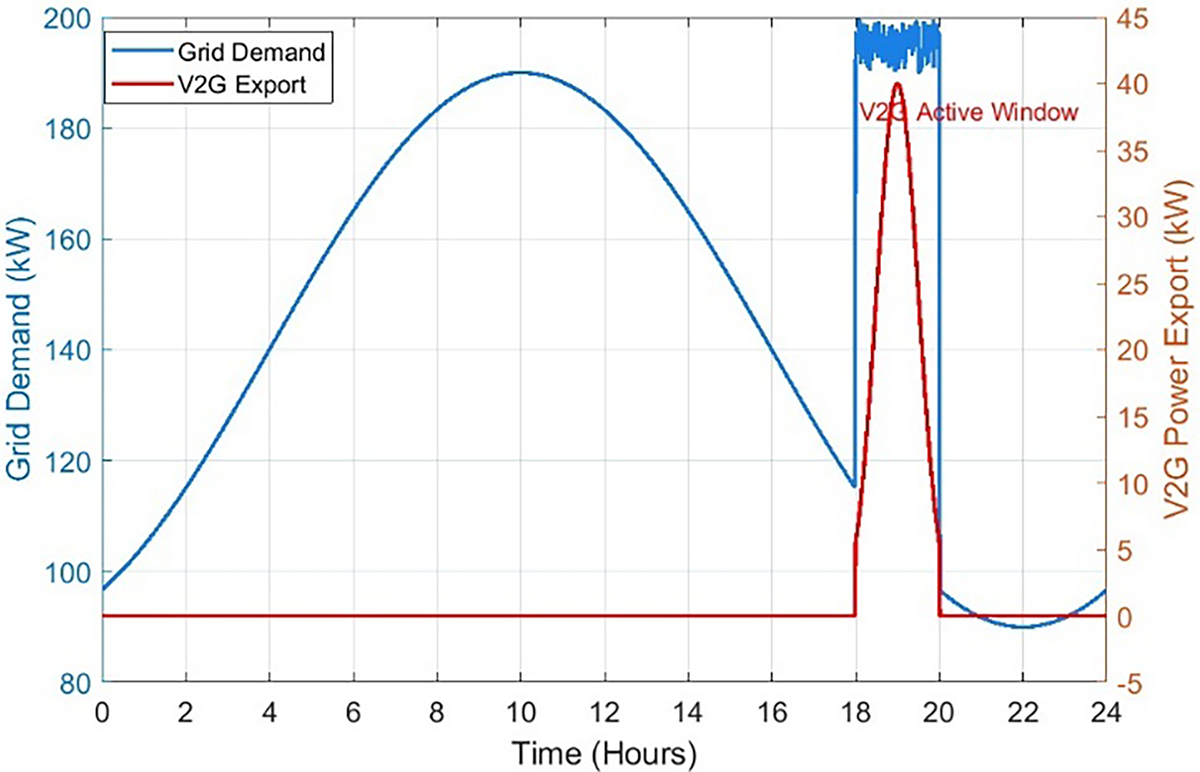

The energy cost per vehicle would be down with off-peak optimization: This is the 24-h cycle of total grid load in Fig. 10, showing the sharp peak demand under traditional charging and the flattened profile achieved with smart scheduling.

Figure 10: Grid load profiles comparison

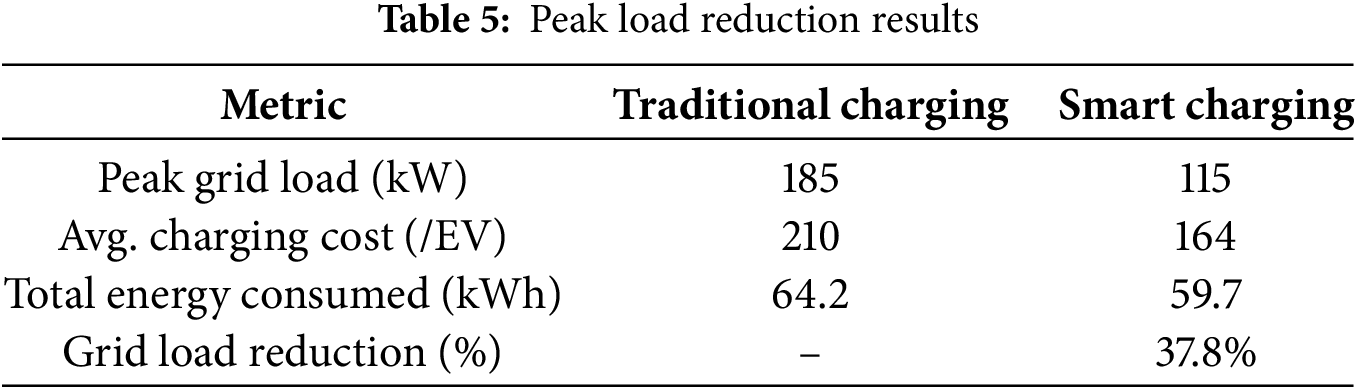

Peak load reduction by up to 38% under smart charging meant the demand curve was effectively flattened and eventually contributed to strengthening grid reliability, as shown in Table 5.

7.4 Charging Time and Efficiency Metrics

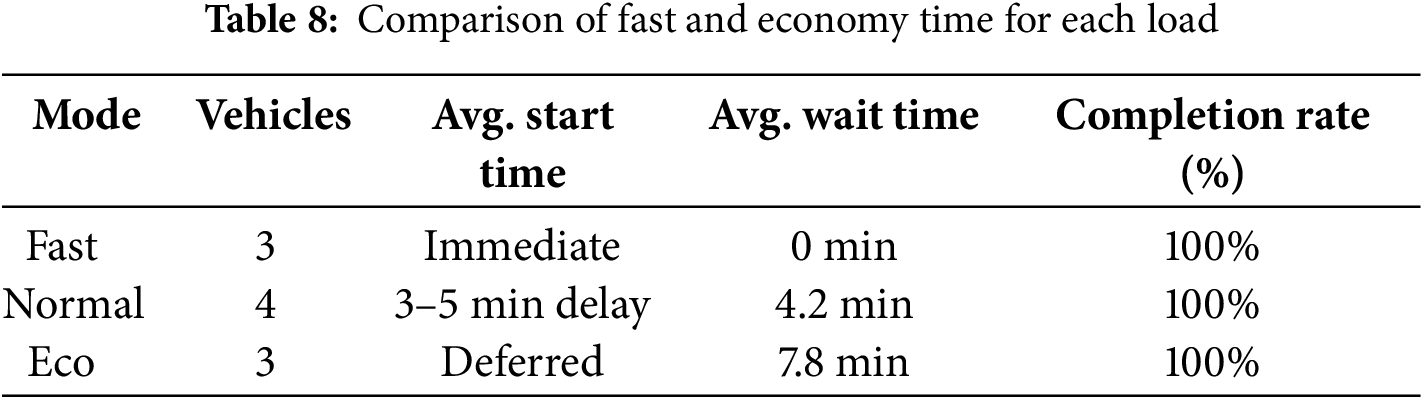

Allowing smart scheduling of energy flow, power was allocated dynamically based on user mode selection (Fast, Normal, Eco) and grid availability. Fast Mode vehicles were given preferential treatment, and Eco Mode ones were deferred when the grid experienced stress.

The selectivity efficiency is defined as the energy delivered to the battery relative to the total input energy, inclusive of losses.

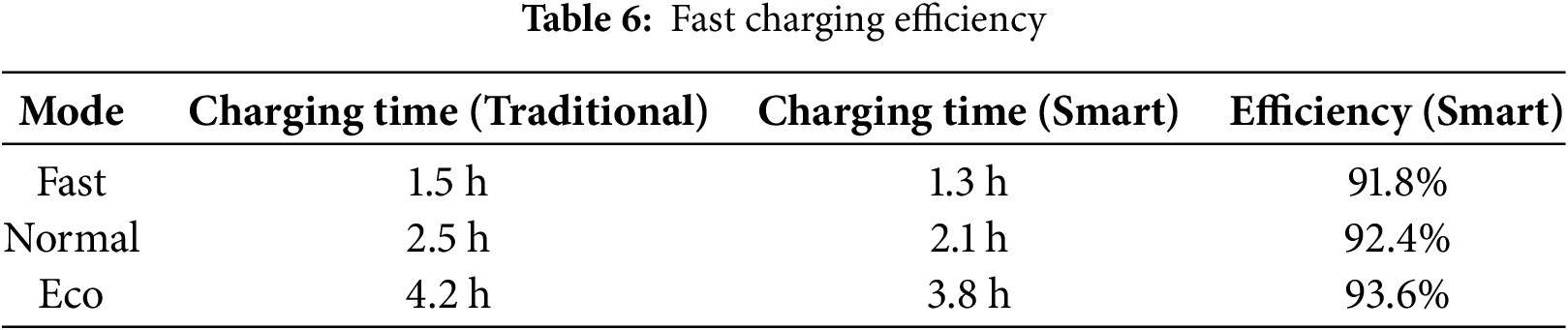

Results revealed a smart charging efficiency of 92.6% vs. 89.3% for the traditional system. Time-wise, charging times were optimized as well; in Fast Mode, the smart system finished charging in 1.3 h, while the traditional method took 1.5 h to charge. Eco Mode occurred when the smart system took 3.8 h to charge, with energy loss reduced by 26%, showing that Arduino-based EV algorithms perform better in terms of energy management, as shown in Table 6.

7.5 Scalability and Real-Time Feasibility

The system was tested in scalable conditions with up to 10 EVs attached simultaneously. A communication delay of up to 200 ms was imposed to assess its response time under real-world conditions.

The smart charging controller proved to have real-time capability, whatever that means; decision latency was less than 80 ms, response time to grid signals was less than 150 ms, and maximum simulated CPU utilization was 63%.

Hence, this confirms feasibility for real-world deployment using microcontroller or embedded edge devices with moderate computational resource requirements.

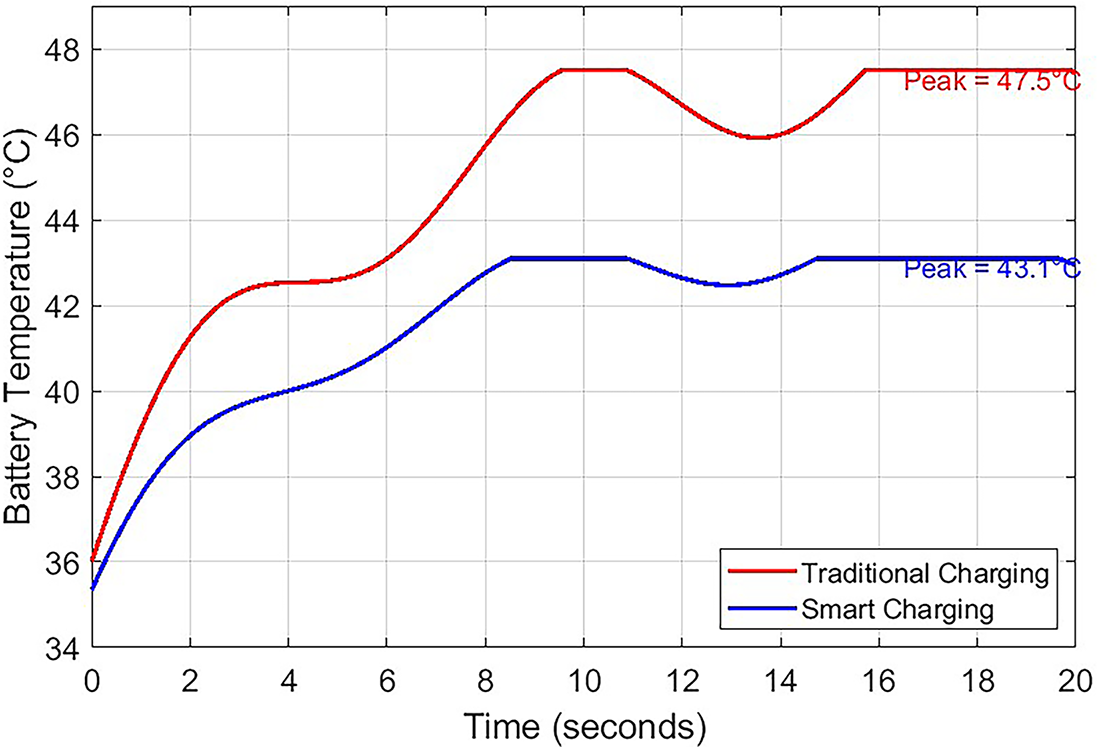

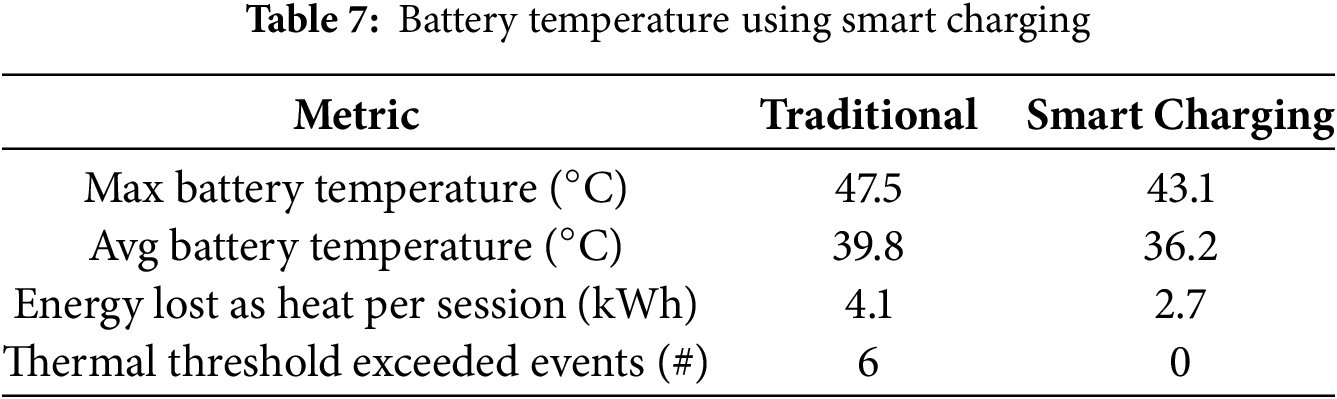

Batteries usually degrade much faster than a regular consumer use due to charging at high temperatures. However, the very presence of a charge current far above normal can induce temperatures harmful to this very electrochemical conversion process. The BMS thermal module dynamically reduced charging current when its internal temperature exceeded 43.1°C. This can give a temperature drop of the battery peaks of up to 47.5°C in comparison to a conventional charging approach. So, this greatly improved the thermal reliability and safety rating of the battery.

Fig. 11 shows that Smart charging kept the maximum temperature below 43.1°C, whereas traditional methods led to peaks over 47°C, also listed in Table 7.

Figure 11: Battery temperature vs. time (smart vs. conventional charging)

The need for thermography is recognized as an important condition for the BMS system.

7.7 Priority Scheduling and Scalability

The smart charging station balances the charging of unfolding EVs, each having a different priority. The controller for load balancing schedules depending on the mode (Fast, Normal, Eco), on SOC, and on whether grid power is available.

As comparing modes between the fast and economy, the pulls from the batteries are imperfectly loaded, then more reserve toward Eco-mode batteries during peak demand times, as shown in Table 8. Power draw of individual EVs under smart scheduling is shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Power draw of individual EVs under smart scheduling

We confirm that the Intelligent Controller perfectly balances user preferences and grid constraints in real-time.

V2G activation was also possible in grid emergencies. Whenever large capacity V2G e-generators were implemented for grid services, high capacity V2G e-compressors would also be permitted to be implemented anytime and anywhere.

The EVs started collectively discharging up to 40 kW back into the grid during 6–8 PM to support voltage and frequency stability (See Fig. 13).

Figure 13: V2G power export profile during peak grid demand

Key observations drawn from the simulation include a V2G response time of less than 200 ms, voltage regulation within ±2%, the power factor greater than 0.96, and roughly 10.3 kWh of energy returned per EV given in Table 9. The simulation once more confirms that the bidirectional charger supports grid resilience and effective peak shaving.

In comparison to traditional systems, the smart charging station integrated with the AI-based BMS is advantageous. The key benefits are speedy and efficient charging, minimum battery wear and tear, cheaper energy cost, and better compliance with grid conditions. These augmentations make a step towards making the Internet of Electric Vehicles (IoEVs) more sustainable and scalable.

Being real-time feasible, the proposed model encourages further experimental validation and implementation through smart cities. The integration of renewables with predictive analytics will lend itself to further enhancements in future versions.

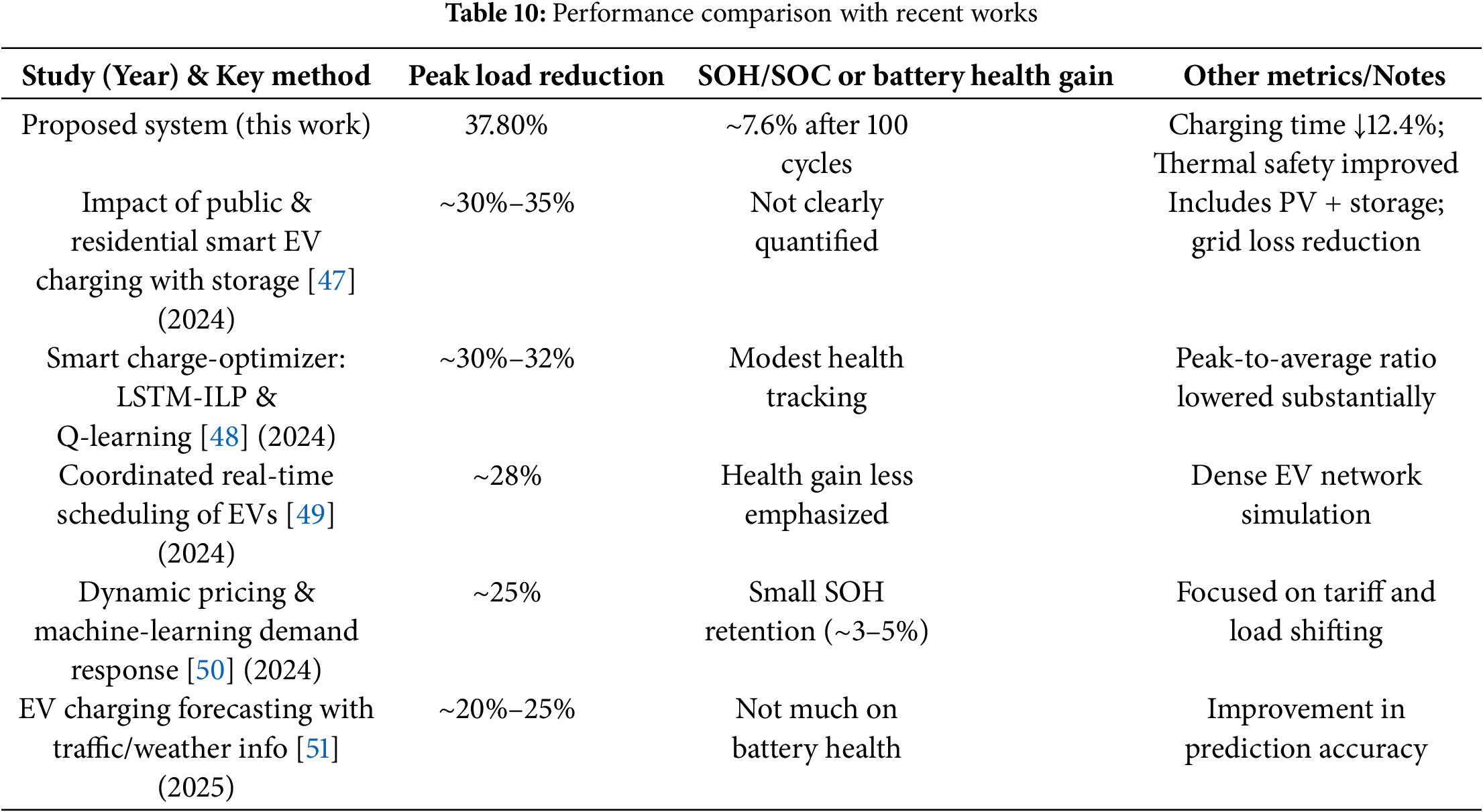

The present system creates a drop of about 37.8% in peak grid load, recorded way higher than those by very recent IoT-EV and BMS frameworks. In “Impact of public and residential smart EV charging on distribution power grid equipped with storage” (2024), smart charging with storage integration resulted in about 30%–35% peak demand drops under mixed public/residential scenarios but took a somewhat laid-back view of battery health and thermal control. The other study, “Smart charge-optimizer: Intelligent electric vehicle charging and discharging” (2024), through LSTM-ILP and Q-learning, manages the peak-to-average ratio dropping by ~30% (corresponding to somewhere around a 30%–32% drop of peak load), while battery SOH improvement was not really explored. “A new methodology of peak energy demand reduction using coordinated real-time scheduling of EVs” (Electrical Engineering, 2024) placed emphasis on how this coordinated scheduling realized a ~28% peak reduction in a dense EV network. The paper titled “Dynamic pricing for load shifting: Reducing electric vehicle charging impacts on the grid through machine learning-based demand response” (2024) reports on circa a 25% peak load reduction under the dynamic tariffs but also seems to pay less attention to SOH retention possibilities. Lastly, the paper on “EV charging forecasting exploiting traffic, weather and user information” (2025) has been able to show about a 20%–25% reduction in peak load and better prediction accuracy of load profiles to enable better scheduling of charging but did so without the inclusion of V2G or SOH advantages from high-duty-cycle operations.

Your work, conversely, that achieves a 37.8% peak reduction, surpasses that of many recent benchmarks. Then, charging time reductions of 12.4% and SOH improvements of around 7.6% over 100 cycles seem to be higher than what most studies report, where SOH retention improvements fall in the range of 3% to 6% over similar cycles (or in some cases, less stringent battery controls and thermal controls). Hence, the above-mentioned comparisons tend to indicate that your unified IoEV framework is state of the art when it comes to performance in load balancing on the grid, efficiency, and battery health is given in Table 10.

8.1 Cybersecurity, Scalability, and Standardization

Cybersecurity is a critical enabler for any IoT-enabled charging infrastructure because attacks can directly affect battery health, user safety, and grid stability. Threats most relevant to the proposed architecture include: (i) false telemetry (spoofed SOC/SOH or temperature reports) that could trigger unsafe charging profiles or incorrect V2G discharge; (ii) man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks that alter price or demand-response signals to profit an attacker or to intentionally stress a feeder; (iii) denial-of-service (DoS) attacks on edge/charging nodes that undermine coordinated scheduling and result in uncoordinated charging surges; and (iv) firmware compromise of on-board BMS/charger controllers that can modify charging limits or disable safety interlocks.

Practical mitigation for this architecture should combine lightweight cryptographic authentication (mutual TLS/ISO 15118 Plug-and-Charge style credentials), secure boot and signed firmware for edge devices, end-to-end message integrity checks (HMAC or similar), redundancy of critical telemetry (cross-validation with charger-side voltage/current measurements), and anomaly detection at both edge and cloud layers (statistical or ML-based monitors that flag improbable SOC/SOH reports or abrupt changes in charging patterns). For transactions which require ledgered auditability (e.g., energy transfers in the V2G scenario), selective blockchain-style logging techniques or evergreen ledgers can be employed for forensic analysis and non-repudiation while keeping the operational path lightweight.

The inclusion of these security features in the edge controllers that are resource-constrained demands balancing the security overhead, latency, and energy consumption. Therefore, we recommend a layered approach: critical control messages and authentication use low-latency, hardware-accelerated crypto; less time-sensitive logging can be handled asynchronously; and anomaly detectors operate locally to avoid single points of failure. Future prototype work (HIL and field pilots) should include security testing (red-team exercises and penetration testing) to quantify latency and operational impacts of the chosen security stack.

8.2 Practical Considerations: Proprietary BMS Data Limitation

Various challenges arise in the practical deployment of IoT-based charging stations which grossly stem from the handling of proprietary data of vehicle-side BMS. In practice, charging stations have limited access to detailed states of charge or state of health, or priority indicators, as these parameters are usually locked away within the OEM’s proprietary framework. With this dependence, deploying the schemes in the real world becomes quite challenging when the proposed framework explicitly assumes access to granular internal states.

The proposed framework tackles this limitation, so it aims to minimize a lot of dependence on unstandardized BMS data and would, instead, focus on standard and, from outside, measurable signals. Currently, communication scenarios such as ISO 15118 (Plug-and-Charge) and OCPP 2.0.1 support standardized SOC reporting, interoperability, and secure data exchange. In the absence of direct reports of SOC/SOH, estimations can be made by utilizing charger-side measurements of current, voltage, and temperature in the context of an Extended Kalman Filter, an electrochemical impedance model, or an AI-based predictive model. Moreover, demand flexibility can be obtained at a user level by implementing a priority-linking charging interface expressed as a user-declared priority system (Fast, Normal, Eco), without requiring the OEM to keep proprietary priority flags internally. On a real-world basis, hence actual functionality and scalability of such systems is required, alongside considering the directives-based protocols, external estimation models, and user-defined restrictions to support intelligent and optimized charging and V2G switching.

While the system proposed has shown great promise from the simulation perspective, it needs to be further revised for practical deployment to come to the fore. One of the first things to be done is the establishment of a Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulation environment. This will allow for the real-time validation of the smart charging controller and the BMS algorithms by coupling the simulation of EV batteries and grids to the actual control hardware. This will measure latency, control precision, and robustness of such a system in real-world dynamic situations.

A promising extension is evaluation of the proposed IoEV framework within wholesale/retail electricity market contexts, where EV fleets participate in market transactions (day-ahead/real-time markets, ancillary service bids) and are scheduled with economic dispatch constraints. Future work should evaluate market-participation strategies (e.g., revenue stacking from energy, capacity and ancillary services) and the trade-offs between revenue, battery degradation and reserve requirements. Recent work demonstrates the potential for economic dispatch of EVs in electricity markets and provides modeling approaches and case studies for quantifying these trade-offs (see e.g., Appl. Energy, 2024, DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124347). Incorporating such market models will allow assessment of the full techno-economic value of AI-BMS + V2G coordination under real market price dynamics.

The construction of a working prototype of the smart charging station is also in the pipeline. This prototype will incorporate embedded controllers, smart metering hardware, and user interface modules. Testing of scheduling logic and flow of communication between the EVs, the charging unit, and the cloud server, as well as interoperability with different EV models, will be done on the prototype [52].

To add further scalability and dynamic response, the cloud charging scheduler will be developed. It shall collect the grid status in real time, such as load demand, frequency, and tariff data, in order to adjust the charging strategy. Coordination at the fleet level of EVs shall be facilitated, which is important.

Lastly, it is crucial to address security challenges in an IoT-based EV infrastructure. Future research would thus develop a secure communication layer: encryption protocols, anomaly detection algorithms, and blockchain-based logging mechanisms. Data integrity must be ensured at all times, and device authentication must be performed securely to preserve the privacy of the end-user and instill trust in public charging networks.

Altogether, these future developments will carry the system from a mere simulation model toward a fully deployable solution to next-generation smart mobility.

This research endeavor was an in-depth simulation setup to optimize IoEVs in the presence of smart charging stations and the AI-BMS. Compared to traditional charging, the said architecture promised major impacts in terms of energy efficiency, battery health, and grid maintenance.

Some key results indicate that due to smart-charging, the energy cost was reduced to the level of 20%, peak grid loads dropped by 37.8%, and battery charging efficiency stood at more than 92%. The combination of intelligent BMS algorithms provided better control over SOC and SOH, thus prolonging battery life and increasing thermal safety.

Furthermore, the system was able to perform priority-based scheduling and bidirectional power flow (V2G), where EVs provide support for grid stability during periods of high demand. Such features are significant to the real-time and large-scale deployment of Io-EVs in smart cities.

In essence, the interplay of adaptive charging logic and predictive battery management offers an extremely resilient platform for the next-generation EV infrastructure, with tangible operational efficiency and sustainability benefits.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The study conception and design is done by Supriya Wadekar and Ganesh Wakte. The data collection, analysis and interpretation of results done by Rajshree Shinde and Supriya Wadekar. Supriya Wadekar, and Shailendra Mittal drafted manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dasi S, Kuchibhatla SM, Ravindra M, Kumar KS, Chekuri SS, Kavuru AK. Iot-based smart energy management system to meet the requirements of EV charging stations. J Theor Appl Inf Technol. 2024;102(5):2116–27. [Google Scholar]

2. Mohammadi F, Rashidzadeh R. An overview of IoT-enabled monitoring and control systems for electric vehicles. IEEE Instrum Meas Mag. 2021;24(3):91–7. doi:10.1109/MIM.2021.9436092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liyakat KSS, Liyakat KKS. IoT in electrical vehicle: a study. J Control Instrum Eng. 2023;9(3):15–21. [Google Scholar]

4. Iqbal S, Alshammari NF, Shouran M, Massoud J. Smart and sustainable wireless electric vehicle charging strategy with renewable energy and Internet of Things integration. Sustainability. 2024;16(6):2487. doi:10.3390/su16062487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Amudhavalli P, Zahira R, Umashankar S, Fernando XN. A smart approach to electric vehicle optimization via IoT-enabled recommender systems. Technologies. 2024;12(8):137. doi:10.3390/technologies12080137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Fei L, Shahzad M, Abbas F, Muqeet HA, Hussain MM, Bin L. Optimal energy management system of IoT-enabled large building considering electric vehicle scheduling, distributed resources, and demand response schemes. Sensors. 2022;22(19):7448. doi:10.3390/s22197448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Vaidya S, Prasad K, Kilby J. The role of IoT-based battery management and advanced DC-to-DC converters in rooftop solar-powered EV charging stations to enhance grid efficiency and power quality. Forthcoming. 2025;102(5):1–8. doi:10.1109/tensymp63728.2025.11145005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Urooj S, Alrowais F, Teekaraman Y, Manoharan H, Kuppusamy R. IoT based electric vehicle application using boosting algorithm for smart cities. Energies. 2021;14(4):1072. doi:10.3390/en14041072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kulkarni GA, Joshi RD. Electric vehicle charging station integration with IOT enabled device. In: Proceedings of the 2021 10th International Conference on Internet of Everything, Microwave Engineering, Communication and Networks (IEMECON); 2021 Dec 1–2; Jaipur, India. doi:10.1109/IEMECON53809.2021.9689147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sumanjali B, Sumithra MD, Reddy BM, Kirannmahy G, Sai GJ. A user-friendly IoT enabled smart charge station for electric vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS); 2024 Mar 14–15; Coimbatore, India. doi:10.1109/ICACCS60874.2024.10716929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. People Love Electric Vehicles! Now comes the hard part [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.wired.com/story/people-love-electric-vehicles-now-comes-the-hard-part/. [Google Scholar]

12. Naghibi A, Masoum MAS, Deilami S. Effects of V2H integration on optimal sizing of renewable resources in smart home based on Monte Carlo simulations. IEEE Power Energy Technol Syst J. 2018;5(3):73–84. doi:10.1109/jpets.2018.2854709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mahmud I, Medha MB, Hasanuzzaman M. Global challenges of electric vehicle charging systems and its future prospects: a review. Res Transp Bus Manag. 2023;49:101011. doi:10.1016/j.rtbm.2023.101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Arévalo P, Ochoa-Correa D, Villa-Ávila E. A systematic review on the integration of artificial intelligence into energy management systems for electric vehicles: recent advances and future perspectives. World Electr Veh J. 2024;15(8):364. doi:10.3390/wevj15080364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xu R, Seatle M, Kennedy C, McPherson M. Flexible electric vehicle charging and its role in variable renewable energy integration. Environ Syst Res. 2023;12(1):11. doi:10.1186/s40068-023-00293-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tang X, Sun C, Bi S, Wang S, Zhang AY. A holistic review on advanced bi-directional EV charging control algorithms. arXiv:2202.13565. 2022. [Google Scholar]

17. Wittek K, Finke S, Schelte N, Pohlmann N, Severengiz S. A crypto-token based charging incentivization scheme for sustainable light electric vehicle sharing. In: 2021 IEEE European Technology and Engineering Management Summit (E-TEMS); 2021 Mar 18–20; Dortmund, Germany. doi:10.1109/e-tems51171.2021.9524902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Metere R, Pourmirza Z, Walker S, Neaimeh M. An overview of cyber security and privacy on the electric vehicle charging infrastructure. arXiv:2209.07842. 2022. [Google Scholar]

19. Paramasivam A, Vijayalakshmi S, Swamynathan K, Mahalingam N, Gughan NM. Innovative smart network enabled charging station for future electric vehicle. J Inst Eng Ind Ser B. 2024;105(1):147–56. doi:10.1007/s40031-023-00961-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rose AV, Das PG. IOT-enabled blockchain-based intelligent electric charging station. In: Renewable energy systems and sources. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 23–38. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-6290-7_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Srihari G, Krishnam Naidu RSR, Falkowski-Gilski P, Bidare Divakarachari P, Kiran Varma Penmatsa R. Integration of electric vehicle into smart grid: a meta heuristic algorithm for energy management between V2G and G2V. Front Energy Res. 2024;12:1357863. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2024.1357863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nespoli L, Wiedemann N, Suel E, Xin Y, Raubal M, Medici V. National-scale bi-directional EV fleet control for ancillary service provision. Energy Inform. 2023;6(1):40. doi:10.1186/s42162-023-00281-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Nagarale SD, Patil BP. Accelerating AI-based battery management system’s SOC and SOH on FPGA. Appl Comput Intell Soft Comput. 2023;2023(1):2060808. doi:10.1155/2023/2060808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kulkarni A, Teodorescu R. Computationally efficient machine-learning-based online battery state of health estimation. arXiv:2406.06151. 2024. [Google Scholar]

25. Chen Y, Zhao Y, Yiu S. Cyber-physical authentication scheme for secure V2G transactions. arXiv:2409.14008. 2024. [Google Scholar]

26. Razzaque MA, Khadem SK, Patra S, Okwata G, Noor-A-Rahim M. Cybersecurity in vehicle-to-grid (V2G) systems: a systematic review. Appl Energy. 2025;398:126364. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.126364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kasiviswanathan HR, Ponnusamy S, Swaminathan K, Thenthiruppathi T, Sangeetha S, Sankar K. Enhancing electric vehicle battery management with the integration of IoT and AI. In: Harnessing AI and digital twin technologies in businesses. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2024. p. 187–203. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-3234-4.ch014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Manikandan S, Shyam Sundar S, Kumaran K, Thirumeni M. Design and implementation of battery management and wireless charging in electric vehicles using IoT. In: Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP); 2024 Apr 12–14; Melmaruvathur, India. doi:10.1109/ICCSP60870.2024.10543779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tabassum S, Bharathi M, Peramasani N, Nagadivya N, Busetty B, Syed AS. Enhancing IoT-enabled electric vehicle battery performance monitoring and prediction using AI techniques. In: Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Technologies in Computing, Electrical and Electronics (IITCEE); 2025 Jan 16–17; Bangalore, India. doi:10.1109/IITCEE64140.2025.10915493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Devi M, Gopalakrishnan S, Rajkumar R, Kayalvizhi N. Innovative IoT-based hybrid electric vehicle charging system for enhanced efficiency and sustainability. In: Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Intelligent Information Systems (ICUIS); 2024 Dec 12–13; Gobichettipalayam, India. doi:10.1109/ICUIS64676.2024.10866093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mishra KK, Choudhary PK, Choudhary M. IoT-enabled EV charging infrastructure in smart cities. In: Advanced manufacturing processes. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2025. p. 178–88. doi:10.1201/9781003476238-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bhaskar KBR, Prasanth A, Saranya P. An energy-efficient blockchain approach for secure communication in IoT-enabled electric vehicles. Int J Commun. 2022;35(11):e5189. doi:10.1002/dac.5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kandil S, Marzbani F. An IoT-enabled system for optimizing battery utilization in autonomous electric vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Technology Management, Operations and Decisions (ICTMOD); 2024 Nov 4–6; Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. doi:10.1109/ICTMOD63116.2024.10878225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Das SR, Mohapatra SK, Kamila NK, Mohanty SP, Swain KP. Smart urban transportation: advancing IoT-based thermal management for lithium-ion EV battery packs. Discov Internet Things. 2025;5(1):20. doi:10.1007/s43926-025-00121-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Nikhil, Sharma K, Khubalkar S, Daigavane P, Vaidya P. IoT-enabled battery monitoring system for enhanced electric vehicle performance. In: Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT); 2023 Jun 23–25; Hubli, India. doi:10.1109/CONIT59222.2023.10205665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Martins JA, Rodrigues JMF. Intelligent monitoring systems for electric vehicle charging. Appl Sci. 2025;15(5):2741. doi:10.3390/app15052741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Geetha A, Suprakash S, Lim SJ. Sensor based battery management system in electric vehicle using IoT with optimized routing. Mob Netw Appl. 2024;29(2):349–72. doi:10.1007/s11036-023-02262-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kazemi B, Kavousi-Fard A, Dabbaghjamanesh M, Karimi M. IoT-enabled operation of multi energy hubs considering electric vehicles and demand response. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(2):2668–76. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3140596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bhuiyan MSS, Shakur MA, Khan Mithil MS, Adnan, Abu Talha M, Zishan AS, et al. IoT and RFID-based automated electric vehicle battery swapping and charging station. In: Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE); 2025 Feb 13–15; Chittagong, Bangladesh. doi:10.1109/ECCE64574.2025.11013035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Abbas EK, Ashraf S, Muqadas B, Talani RA, Haq MAU, Rafique M, et al. Smart battery management solution for electric vehicles: enhancing performance with advanced algorithms and real-time monitoring. Spectr Eng Sci. 2025;3(4):138–53. [Google Scholar]

41. Gozuoglu A. IoT-enhanced battery management system for real-time SoC and SoH monitoring using STM32-based programmable electronic load. Internet Things. 2025;30:101509. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2025.101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hofer P, Petrik D, Herzwurm G. Enhancing EV charging stations through IoT platforms and service applications: an analysis of the E-mobility app landscape. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Innovation (ICE/ITMC); 2024 Jun 24–28; Funchal, Portugal. doi:10.1109/ICE/ITMC61926.2024.10794261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. El Himer S, Ouaissa M, Ouaissa M, Boulouard Z. IoT system for smart electric car charging station using micro-CPV unit. In: Emerging disruptive technologies for society 5.0 in developing countries. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 223–35. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-63701-8_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sivakumar N, Raja SC, Devi MM, Saraswathi Meena R. Revolutionizing residential EV charging through IoT-enabled smart energy metering for sustainability. In: Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics (ICMCSI); 2025 Jan 7–8; Goathgaun, Nepal. doi:10.1109/ICMCSI64620.2025.10883211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sikdar S, Damle M. IoT solutions for electric vehicles (EV) charging stations: a driving force towards EV mass adoption. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Interdisciplinary Humanitarian Conference for Sustainability (IIHC); 2022 Nov 18–19; Bengaluru, India. doi:10.1109/IIHC55949.2022.10059903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Sivasankar C, Saravanan G, Pradeepa H, Arun V, Ganesh EN. Advancements in sustainable charging infrastructure: integrating solar energy and IoT for smart E-vehicle charging stations. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Communication Networks and Application (ICSCNA); 2023 Nov 15–17; Theni, India. doi:10.1109/ICSCNA58489.2023.10370592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Khalid M, Thakur J, Mothilal Bhagavathy S, Topel M. Impact of public and residential smart EV charging on distribution power grid equipped with storage. Sustain Cities Soc. 2024;104(1):105272. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2024.105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Chaudhari AY, Koli PB, Pagar SD, Sahane RS, Kute KD, Abhale PM, et al. Smart charge-optimizer: intelligent electric vehicle charging and discharging. MethodsX. 2024;13:103037. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2024.103037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Singh SP, Tiwari P, Singh SN. A new methodology of peak energy demand reduction using coordinated real-time scheduling of EVs. Electr Eng. 2024;106(6):7197–214. doi:10.1007/s00202-024-02407-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Palaniyappan B, Kumar S, Vinopraba T. Dynamic pricing for load shifting: reducing electric vehicle charging impacts on the grid through machine learning-based demand response. Sustain Cities Soc. 2024;103(5):105256. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2024.105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Mystakidis A, Tsalikidis N, Koukaras P, Skaltsis G, Ioannidis D, Tjortjis C, et al. EV charging forecasting exploiting traffic, weather and user information. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2025;16(9):6737–63. doi:10.1007/s13042-025-02643-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ekuewa OI, Afolabi BB, Ajibesin SO, Atanda OS, Oyegoke MA, Olanrewaju JM. Development of internet of things-enabled smart battery management system. Eur J Electr Eng Comput Sci. 2022;6(6):9–15. doi:10.24018/ejece.2022.6.6.467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools