Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimal Working Fluid Selection and Performance Enhancement of ORC Systems for Diesel Engine Waste Heat Recovery

Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Automation, Huaiyin Institute of Technology, Huaiyin, 223002, China

* Corresponding Author: Jie Ji. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Analytics on Energy Systems)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(2), 23 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068106

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 09 July 2025; Issue published 27 January 2026

Abstract

In the quest to enhance energy efficiency and reduce environmental impact in the transportation sector, the recovery of waste heat from diesel engines has become a critical area of focus. This study provided an exhaustive thermodynamic analysis optimizing Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) systems for waste heat recovery from diesel engines. The study assessed the performance of five candidate working fluids—R11, R123, R113, R245fa, and R141b—under a range of operating conditions, specifically varying overheat temperatures and evaporation pressures. The results indicated that the choice of working fluid substantially influences the system’s exergetic efficiency, net output power, and thermal efficiency. R245fa showed an outstanding net output power of 30.39 kW at high overheat conditions, outperforming R11, which is significant for high-temperature waste heat recovery. At lower temperatures, R11 and R113 demonstrated higher exergetic efficiencies, with R11 reaching a peak exergetic efficiency of 7.4% at an evaporation pressure of 10 bar and an overheat of 10°C. The study also revealed that controlling the overheat and optimizing the evaporation pressure are crucial for enhancing the net output power of the ORC system. Specifically, at an evaporation pressure of 30 bar and an overheat of 0°C, R113 exhibited the lowest exergetic destruction of 544.5 kJ/kg, making it a suitable choice for minimizing irreversible losses. These findings are instrumental for understanding the performance of ORC systems in waste heat recovery applications and offer valuable insights for the design and operation of more efficient and environmentally friendly diesel engine systems.Keywords

The background of waste heat recovery from vehicle diesel engines is becoming increasingly prominent. Under the dual pressures of global energy scarcity and intensifying environmental pollution, enhancing energy utilization efficiency and reducing energy consumption have emerged as pressing issues within the automotive industry [1,2]. Diesel engines, serving as a primary power source, generate a substantial amount of exhaust waste heat during operation, which has traditionally been directly emitted into the environment, leading to significant energy wastage [3]. To tap into this potential, waste heat recovery technologies for vehicle diesel engines have been developed, aiming to efficiently recover and transform this waste heat into a cleaner and more efficient energy utilization solution for vehicles [4]. It is estimated that light-duty vehicles powered by internal combustion engines lose approximately 60% of their fuel energy in the form of waste heat to the environment, with half of this energy lost in exhaust gases and the other half in engine coolant [5]. The development of waste heat recovery (WHR) systems seeks to harness this significant energy resource, thereby improving the efficiency of the powertrain and reducing fuel consumption for vehicles [6]. The utilization of vehicle waste heat based on Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) technology, while highly promising, faces multiple challenges that require careful consideration in terms of compact space design, thermal source stability management, system lightweighting, efficient cooling, and energy optimization configuration [7]. Specifically, this technology aims to convert the low-grade thermal energy of vehicles into high-value electrical or mechanical energy, thereby enhancing energy utilization efficiency and promoting energy conservation and emission reduction. However, due to the constraints of vehicle interior space, there is a demand for systems that are both compact and efficient [8]. Additionally, it is necessary to address the fluctuations in heat emission from diesel engines and optimize the exhaust system to minimize back pressure impacts [9]. Furthermore, there is a need to balance system performance with weight, design efficient cooling mechanisms, and flexibly configure recovered energy to meet the actual needs of vehicles, thus maximizing energy utilization through technological innovation and system optimization [10]. Currently, vehicles fueled by petroleum still constitute the majority of the vehicle fleet, and their thermal efficiency is relatively low, with a significant proportion of the total energy from fuel combustion being lost through exhaust gases [11]. Organic Rankine Cycle technology, as a means of recovering waste heat from vehicle engine exhaust, can effectively improve energy utilization rates and achieve the goal of energy conservation and emission reduction [12,13]. However, vehicles operate under transient conditions on roads, and how the engine-ORC system can work synergistically to maximize energy-saving potential is a hot topic in this field of research [14].

In order to improve the fuel utilization efficiency of internal combustion engine, especially diesel engine, the waste heat recovery efficiency of organic Rankine cycle (ORC) technology is selected as for different working conditions [15]. Researchers [16] have conducted an analysis and optimization of the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system driven by industrial low-temperature waste heat, exploring the integration of ORC with the Absorption Refrigeration Cycle (ARC) and the Ejector Refrigeration Cycle (ERC) for the recovery of low-temperature waste heat. The study assessed the impact of various operational parameters on system performance and compared the performance of the systems before and after coupling. The results indicated that, under non-coupled conditions, when the evaporation temperature of the ORC exceeds a certain value, the net power output, refrigeration capacity, and exergy efficiency of the ORC-ARC system are all higher than those of the ORC-ERC system. A model integrating an automotive engine with an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system was constructed in [17], and its validity was confirmed through data from various driving cycles. The ORC system, typically employed in stationary applications, has been demonstrated to be viable when integrated with powertrain systems within road traffic power systems. In [18], the ORC system for natural gas-powered buses was investigated, with real-world driving tests conducted to measure exhaust mass flow rate and temperature, enabling the calculation of recoverable thermal power within the ORC unit. The performance of the ORC system, in terms of actual cycle efficiency and power generation, was calculated assuming n-pentane as the working fluid. Ref. [19] offers a complete thermodynamic analysis, cycle configuration, system sizing, and working fluid selection for a standalone engine coolant recovery based on the organic Rankine cycle. The study examines the system’s performance under fluctuating flow conditions of cooling water with varying engine speeds and loads, taking into account the impact of thermal source mass flow rate changes on heat input. The research indicates that R245fa exhibits superior performance, achieving a cycle efficiency of 4.72% and a work output of 0.97 kW in a double expander configuration. Literature [20] investigates the impact of working fluids on the performance of engine-ORC systems under various operating conditions. Based on a static ORC model, the selection of working fluids, structure, and process parameters was analyzed. For vehicle diesel engine applications, a single-cycle ORC configuration is proposed due to its ability to utilize multiple waste heat sources and address issues related to weight, space, and cost. In contrast, stationary diesel engine applications are more suited to a dual-loop ORC configuration, which is less constrained by weight and space limitations Literature [21] introduces an innovative parallel dual-expander Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system and develops four operational modes tailored to different heat sources. After experimental validation under 16 sets of varying heat source conditions, the ORC system and its operational strategies have demonstrated excellent adaptability to heat sources. Based on engine efficiency, the system efficiently recovers waste heat under variable conditions by making rational use of the surplus heat from cooling water. Despite some research on the selection of working fluids for the ORC system under different operating conditions, such as using R123, n-pentane, R245a, and other fluids, challenges remain in terms of the limitations of working fluid selection and the complexity of system configuration. Furthermore, the optimal working fluid selection for vehicle diesel engines under specific operating conditions requires more in-depth research and experimental validation, considering system configurations that take into account factors such as weight, space, and cost. There is a lack of analysis on the thermodynamic parameters of different organic working fluids for the ORC and their impact on overall system performance under various operating conditions.

Scholars have recently developed a series of efficient cyclic systems to more effectively harness waste heat and energy from engine coolant water. A parallel dual-expander Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system operating under various conditions has been proposed in literature [22], with experimental exploration leading to the formulation of corresponding operational strategies. The experimental results indicate that the system’s heat source conditions are expanded, enabling efficient utilization of cooling water waste heat. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (S-CO2) Brayton cycles [23] serve as an effective technology for recovering waste heat from Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) engines, and the selection of cycle configuration is crucial for enhancing recovery efficiency. Literature [24] is dedicated to exploring the application potential of S-CO2, Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), and Thermoelectric Generator (TEG) systems in Waste Heat Recovery from Exhaust Gases (WHRE) in automotive applications, with a particular focus on heavy-duty diesel engines such as those used in ships, trucks, and locomotives. A turbine power generation system designed to recover this wasted energy has been studied and simulated in literature [25]. The application of ORC waste heat recovery systems in hybrid electric vehicles has been modeled and tested using GT-SUITE software in literature [26], revealing that the ORC system achieved a maximum cycle efficiency of 5.4% and a recovered power of 2.02 kW, with subsequent economic analysis and comparison of different waste heat recovery technologies. An ORC waste heat recovery system model has been established in literature [27], discovering that ethanol systems perform best over a wide operating range with efficiencies reaching up to 24.1%, which can be further enhanced to 9.0% with the addition of a conditioner; cyclopentane is suitable for low-temperature exhaust waste heat recovery with efficiencies as high as 27.6%; and R1233ZD systems outperform R245fa, making them suitable for low-quality waste heat recovery. Dual-pressure ORC has been widely applied in engine waste heat recovery, and optimal dual-pressure ORC systems have been designed and parameter-optimized for different engine waste heat source conditions. Research [28] proposed a method for constructing a system selection chart, with results showing that compared to the dual-pressure ORC system with the lowest net output power and thermal efficiency, the optimal system can increase net output power by 8.34% to 28.52% and thermal efficiency by 8.43% to 32.38%. In summary, although the models of diesel engine ORC waste heat recovery systems have been innovatively improved to varying degrees, the research on diesel engines is not deep enough. However, models are often limited to a single dimension, failing to comprehensively consider multiple evaluation indicators such as thermodynamic, economic, and environmental performance, as well as the impact of working fluid thermodynamic parameters on the system.

To systematically investigate the thermodynamic performance of Dual-Loop Organic Rankine Cycle (DORC) systems, a comparative analysis of traditional and advanced exergy analyses was conducted in literature [29], utilizing a straight-six, four-stroke turbocharged diesel engine. The study contrasted the outcomes of conventional exergy analysis with those of advanced exergy analysis. Sensitivity analysis was also implemented to further explore the impact of operational parameters on avoidable endogenous exergy losses. In literature [30], the focus was on the energy and exergy characteristics of a dual-loop Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) integrated with heavy-duty diesel engines. The results indicated that increases in both engine parameters and cycle parameters enhance system output power, with engine variable changes having a more significant impact. Variations in engine speed and fuel injection timing had a relatively minor effect on system thermal efficiency. To achieve maximum exergy efficiency and minimum electricity production cost (EPC) for a specific ORC system, researchers [31] developed a multi-objective optimization model and employed Genetic Algorithms (GA) for solution. In this model, evaporation temperature and condensation temperature were selected as decision variables. Initially, working fluids such as R245fa, R245ca, R600, R600a, R601, and R601a were studied for variations in exergy efficiency and EPC with respect to evaporation and condensation temperatures. Subsequent multi-objective optimizations yielded Rankine parameters for different working fluids. The findings suggested that R245fa outperforms other working fluids in the specific ORC system. This research provides deeper insights into the operational characteristics of ORC systems and offers valuable guidance for achieving more efficient and economical waste heat recovery. Literature [32] addressed the underutilization of thermal energy in ORC systems by constructing a system model and conducting an in-depth sensitivity analysis based on heat exchanger performance variations. Additionally, to counteract heat source temperature fluctuations, modeling calculations and adjustment schemes were proposed to ensure stable power generation. Preliminary results revealed the significant impact of key system parameters such as evaporation pressure and condensation temperature on performance, providing valuable references for the design and practical application of ORC systems. In literature [33], energy and exergy analyses were conducted on five different dry working fluids for ORC, namely R600a, R600, R245fa, R123, and R113. The performance parameters of ORC were evaluated under various evaporation temperatures and waste heat fluid inlet temperatures. The study demonstrated that R600a performed best in terms of thermal efficiency, exergy efficiency, net power output, and reduction in total irreversibility when increasing evaporation temperature and waste heat fluid inlet temperature. Since diesel engine operation energy is closely related to engine conditions and ORC system selection parameters, the available exhaust energy of the diesel engine fluctuates with changes in ORC system component parameters. Furthermore, the study did not consider the impact of different engine speeds and torques on the system. While energy and exergy analyses of ORC waste heat recovery were conducted at different evaporation temperatures, for automotive diesel engines, it is essential to consider the impact of equipment selection and steam and cooling water consumption under different conditions on the engine. The study did not account for the influence of steam and cooling water on the diesel engine, and different parameters can lead to variations in the available energy of the automotive diesel engine, indicating an incomplete consideration of ORC system parameter studies.

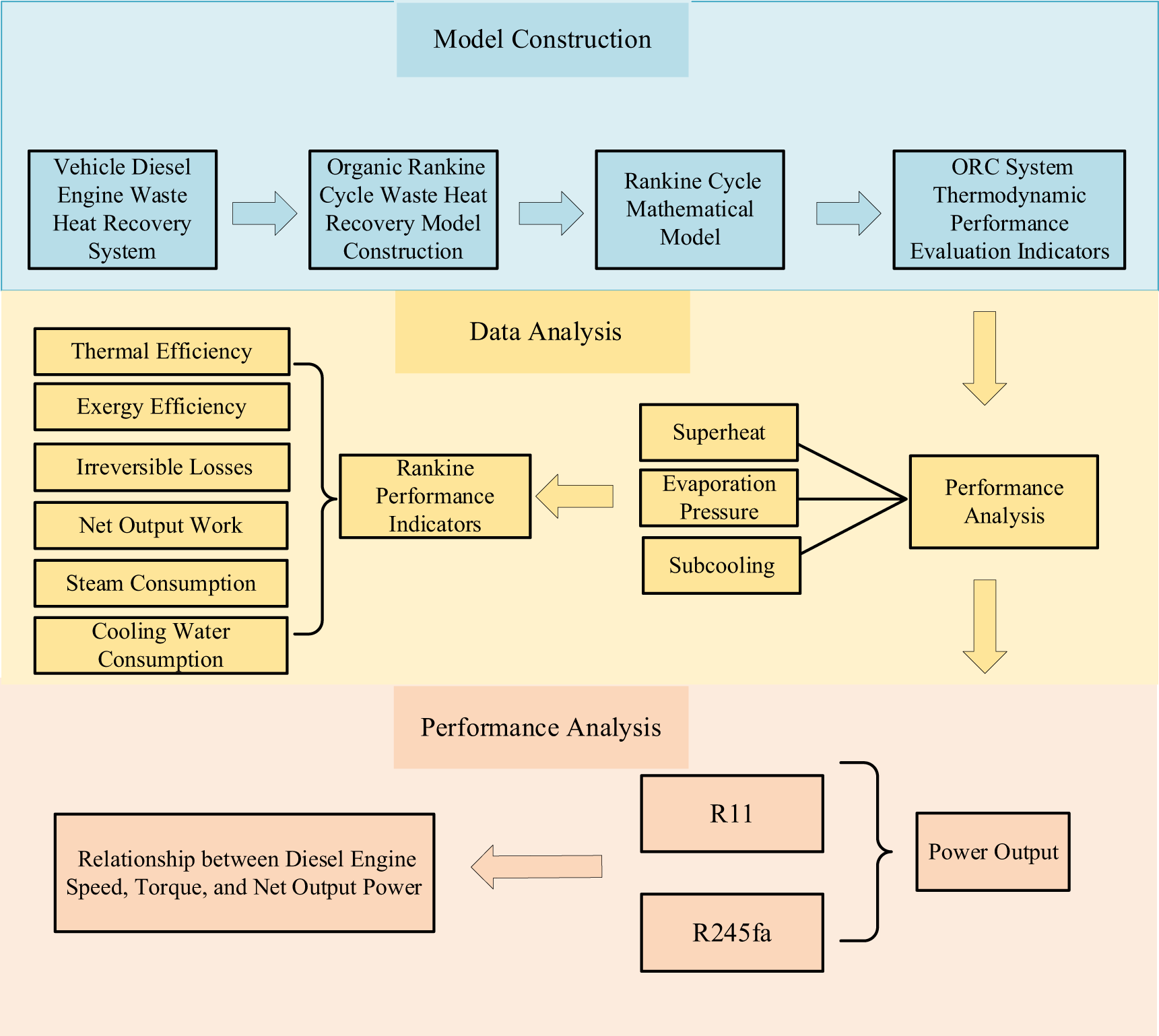

Against the backdrop of waste heat recovery from vehicular diesel engines using Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) technology, the selection of working fluids is constrained, necessitating in-depth research and experimental validation to identify the optimal working fluid under various operating conditions. While model structure innovation is continuously advancing, it is often limited to a single dimension, lacking a comprehensive consideration of thermodynamic, economic, and environmental performance. Furthermore, existing studies on waste heat recovery performance under specific conditions do not sufficiently analyze system parameters and actual influencing factors, such as steam and cooling water data. Therefore, this study addresses the limitations in working fluid selection for ORC waste heat recovery under different operating conditions by comparing the impact of the evaporation pressure of five working fluids on the thermodynamic parameters of the ORC system, thereby identifying the most suitable optimal working fluid for different conditions. Concurrently, an ORC waste heat recovery model is constructed, taking into account multiple thermodynamic evaluation indicators. The study comprehensively assesses the impact of working fluids on the thermodynamic parameters of the Organic Rankine Cycle system. Additionally, for waste heat recovery performance under specific conditions, the research conducts a thorough analysis of system parameters and actual influencing factors, such as steam and cooling water data, to more accurately evaluate the performance of ORC systems in waste heat recovery for hybrid trucks. Finally, an analysis of the available energy of diesel engines at different speeds and torques is conducted, with a detailed analysis of the net output power for R11 and R245fa. As depicted in Fig. 1, the overall schematic of the system is presented.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of a vehicle diesel engine

2 Diesel Engine ORC Waste Heat Recovery Systems in Vehicles

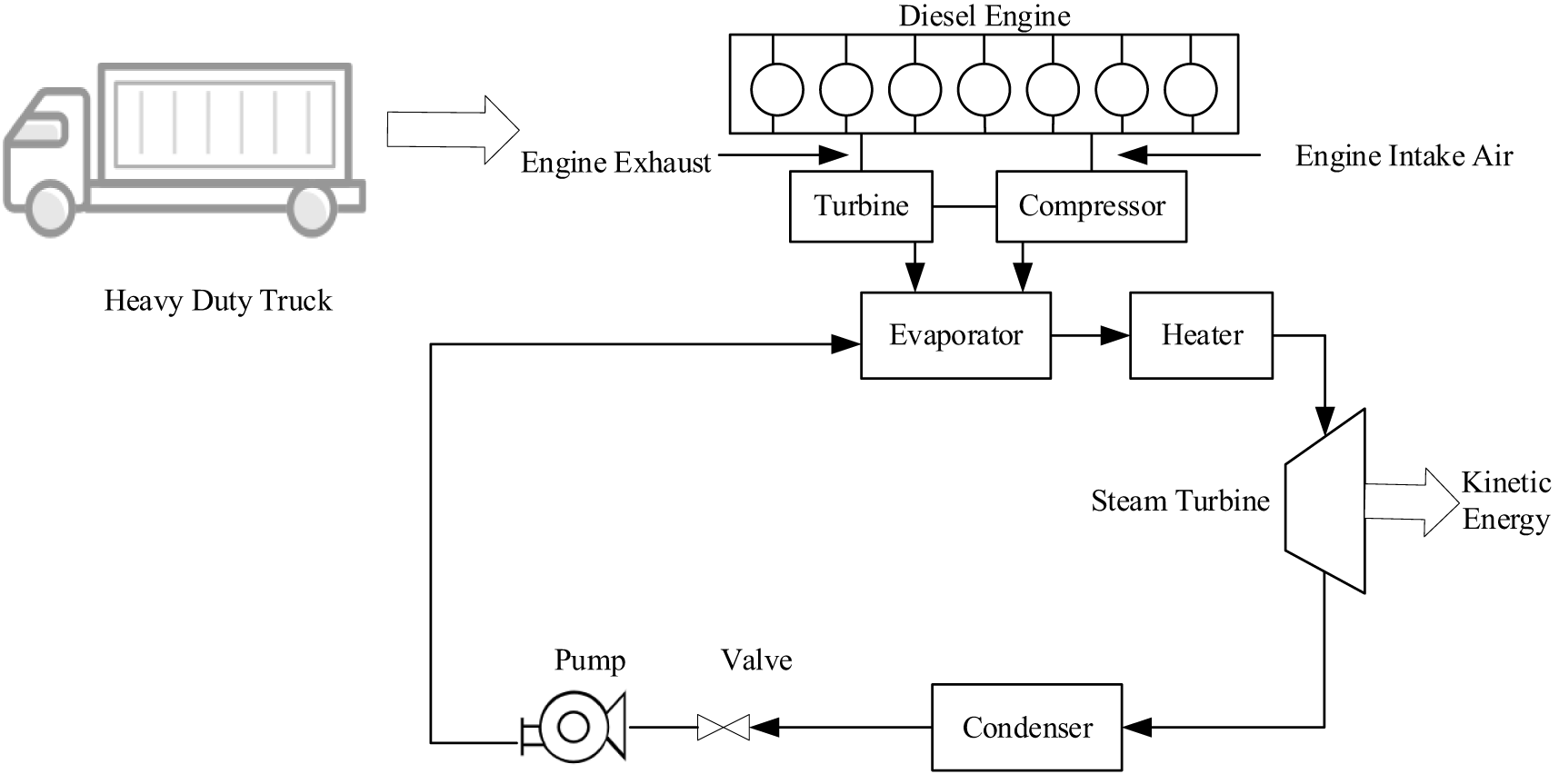

The Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system employs an organic working fluid as a medium for energy transfer, capturing waste heat from the high-temperature exhaust gases emitted by diesel engines. This heat is absorbed in the evaporator, causing the working fluid to vaporize into high-temperature, high-pressure vapor. The vapor then drives a turbine, converting thermal energy into mechanical energy. After expansion, the working fluid enters the condenser, where it is cooled and liquefied before returning to the storage tank, thus completing the cycle. Throughout this process, the ORC system efficiently recovers and utilizes low-temperature thermal energy. Fig. 2 illustrates the integrated setup of a vehicular diesel engine with an ORC waste heat recovery unit.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of a vehicle diesel engine with ORC waste heat recovery system

2.1 Construction of ORC Waste Heat Recovery Models

This article addresses the vehicular diesel engine’s cascade waste heat recovery system, optimizing the system structure and parameter configuration to analyze the optimal selection of exergy efficiency, thermal efficiency, and irreversible losses in diesel engine waste heat recovery. This has led to the efficient recovery and utilization of diesel engine waste heat. The system not only enhances energy utilization efficiency but also reduces energy consumption and emissions, offering significant economic and environmental benefits. Future research may further explore the application of novel working fluids, optimization of system dynamic characteristics, and integration strategies with other vehicular systems to further improve overall system performance and reliability.

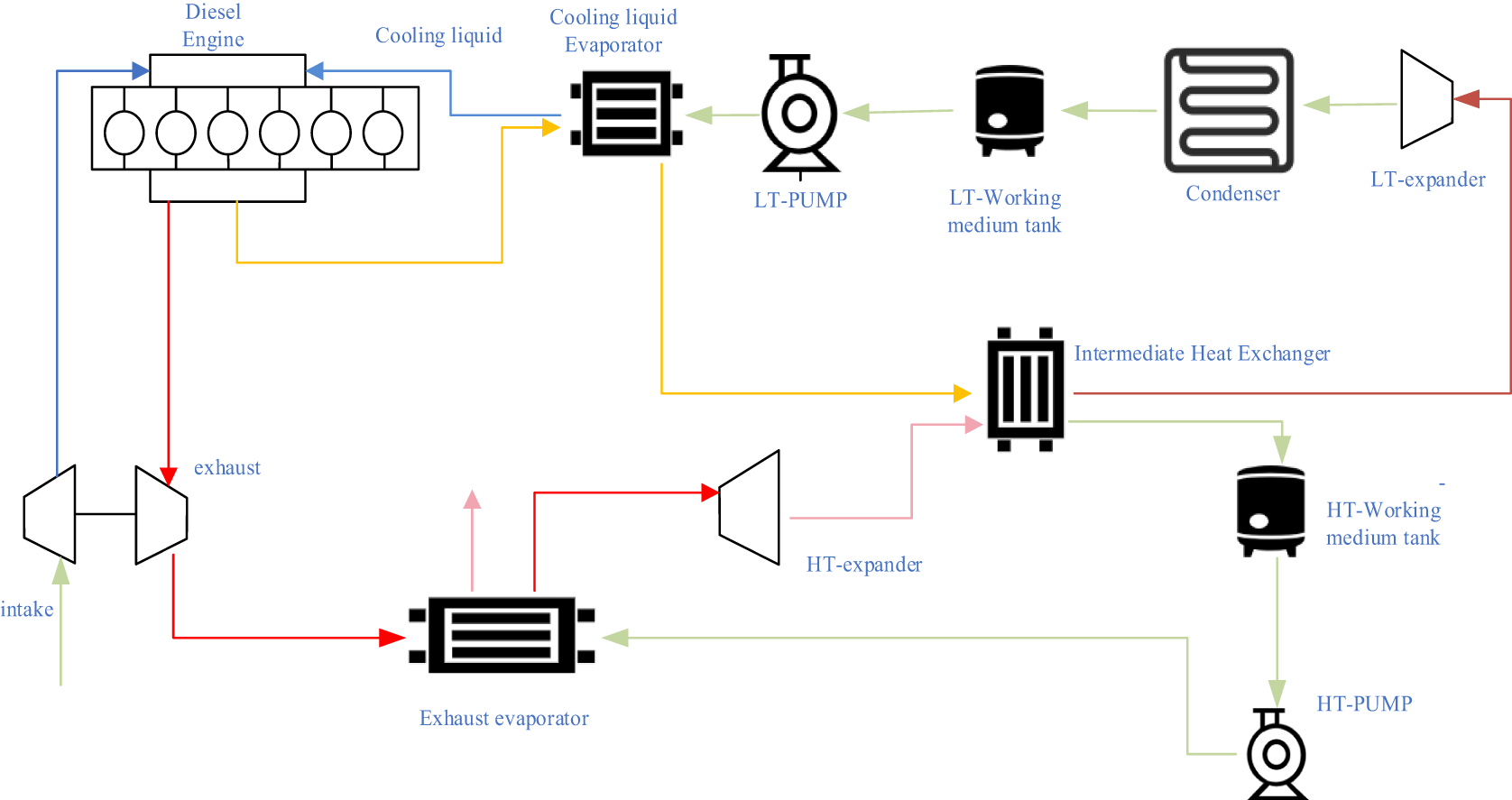

In the waste heat recovery system of diesel engines, the high-temperature exhaust gases emitted by the engine serve as a valuable heat source, efficiently recovered and utilized through a series of meticulously designed processes. Specifically, the exhaust gases generated during the diesel engine’s operation are significantly hotter than ambient temperatures, containing a substantial amount of thermal energy. These high-temperature exhaust gases are first guided to the evaporator module of the ORC (Organic Rankine Cycle) system via specially designed gas pipelines. Within the evaporator, the low-temperature, low-pressure organic working fluid undergoes an indirect heat exchange with the high-temperature exhaust gases, absorbing the heat and undergoing a phase change, gradually vaporizing from a liquid to a high-temperature, high-pressure vapor. This high-temperature, high-pressure vapor is then sent to the turbine or expander, where its internal energy is converted into mechanical energy through expansion, driving the generator to rotate and thereby converting mechanical energy into electrical energy. This process not only achieves the transformation of thermal energy into electrical energy but also significantly reduces the temperature of exhaust gas emissions, which is beneficial for reducing thermal pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. After completing work, the vapor enters the condenser, releases the remaining heat under the action of the cooling medium, and condenses back into a liquid state. The condensed liquid organic working fluid, after being pressurized by a pump, re-enters the evaporator for the next cycle, thus achieving the closed-loop operation of the entire waste heat recovery system. In summary, the waste heat recovery process from diesel engine exhaust gases, facilitated by the ORC system, achieves an efficient conversion of thermal energy into electrical energy, enhancing energy utilization efficiency and reducing environmental pollution, marking it as a significant technological breakthrough in the field of energy conservation and emission reduction. Fig. 3 illustrates the organic Rankine cascade waste heat recovery model.

Figure 3: Schematic representation of the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) cascade waste heat recovery model

2.2 Rankine Cycle Mathematical Models

In the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system, the working fluid undergoes compression within the working fluid pump, consuming electrical energy in the process. The power consumed can be quantified as follows:

The heat absorbed by the liquid working fluid in the evaporator from the waste heat of the diesel engine exhaust, which is then heated is obarically to become high-temperature and high-pressure working fluid vapor, can be described as follows:

In the formula, h2 represents the specific enthalpy of the working fluid at the outlet of the evaporator, in kJ/kg.

Expansion process output power:

In the formula,

The net output power of the system is given by the formula:

The heat released by the working fluid during the condensation process:

The power consumption factor is an important indicator for evaluating the functional efficiency of a pump, referring to the pump work consumed to produce a unit of net output work. The calculation formula is:

The exergy at any point

In the formula:

The exergy efficiency of the system is:

In the formula:

The thermal efficiency of the system is:

2.3 Organic Rankine Cycle Thermodynamic Indicators Include

In an ORC system, the expander is the component that outputs work, and the working fluid pump is the component that consumes energy. Starting from the first law of thermodynamics and analyzing based on the law of energy conservation, the net output work obtained by the system is the output shaft work of the expander minus the work consumed by the working fluid pump. The calculation formula is expressed as Eq. (9).

2.3.2 Thermal Efficiency of the Cycle

From thermodynamic analysis, it can be concluded that the thermal efficiency of the ORC system’s cycle is the ratio of “benefit” to “cost”, where “benefit” refers to the system’s net output work, and “cost” refers to the heat absorbed by the working fluid in the evaporator.

In the ORC system, the valuable benefit exergy only includes the net output work. For the exergy input at the evaporator inlet being exhaust waste heat, the total exergy loss of the system is:

The system’s exergy efficiency is the ratio of the net output work of the working fluid to the exergy of the heat absorbed by the working fluid in the evaporator.

2.3.5 Overall Thermal Recovery Efficiency and Total Exergy Recovery Efficiency

After passing through the evaporator heat exchange, the exhaust waste heat generally has a higher temperature than the ambient temperature at the outlet, possessing a certain ability to do work, and becomes the external heat loss emitted into the atmospheric environment. To measure the energy conversion effect of waste heat recovery by taking this into account, the overall thermal recovery efficiency and the total exergy recovery efficiency are introduced, which are calculated as follows:

3 Selection and Performance Analysis of Working Fluids

3.1 Selection of Working Fluids

The primary sources of waste heat in engines include exhaust gases and cooling water. Among these, the exhaust gases account for approximately 30% of the heat generated by combustion, exhibit the highest temperature, and possess the highest quality of thermal energy, making them a focal point for heat recovery efforts.

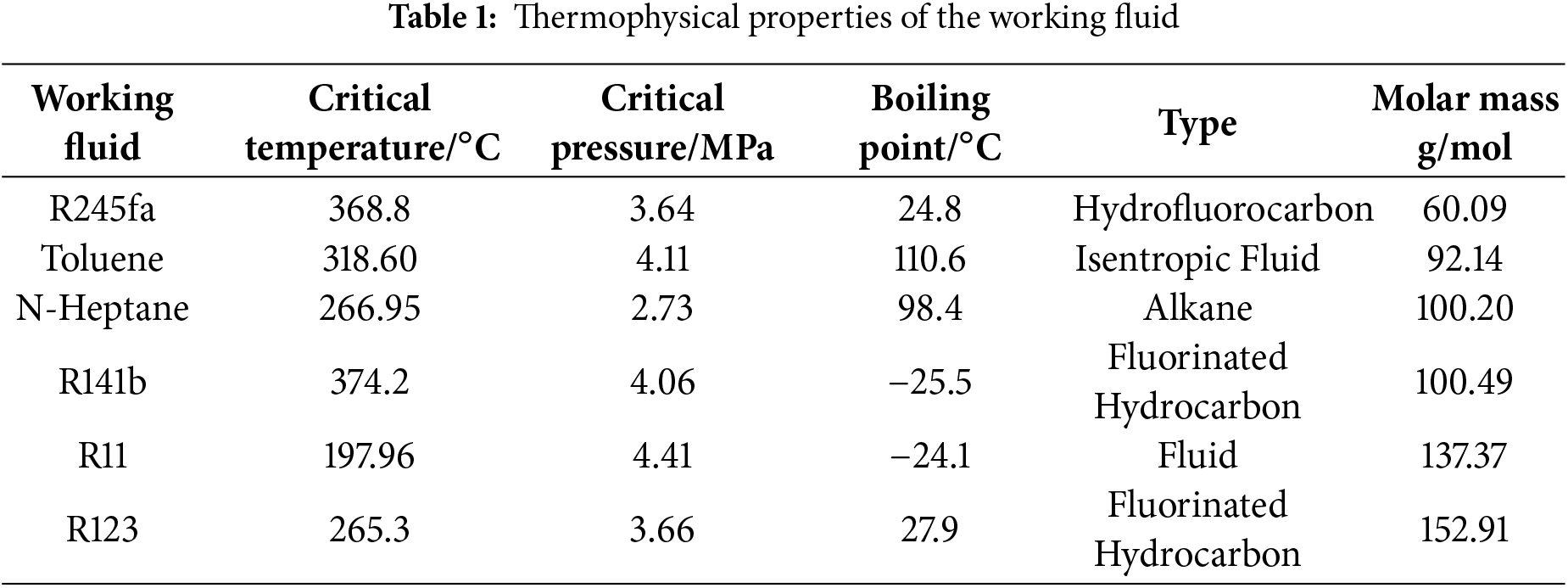

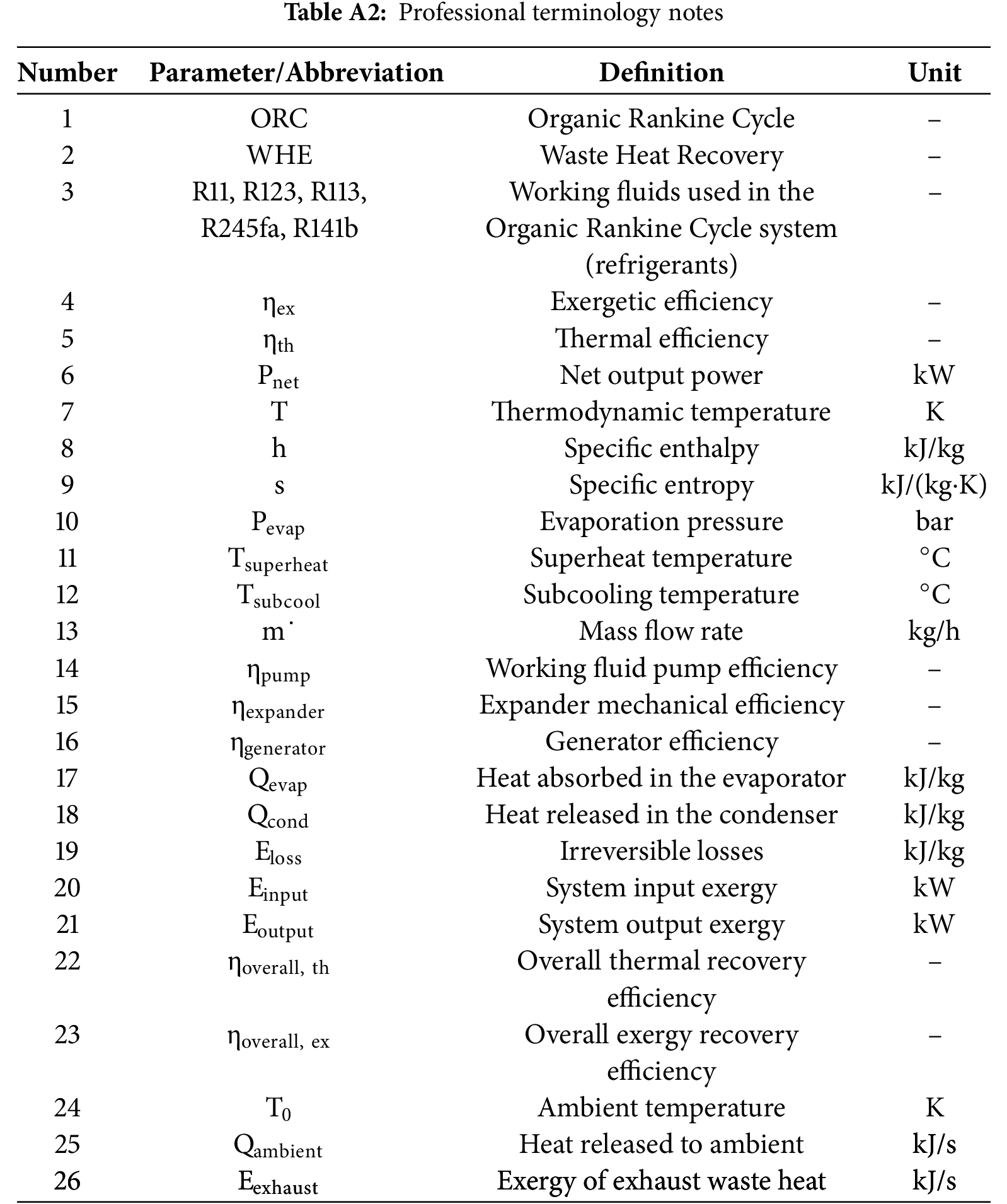

Organic working fluids are one of the critical factors affecting the performance of organic Rankine cycle (ORC) waste heat recovery systems. In ORC systems, the selection of an organic working fluid requires a careful balance between boiling points. Utilizing a working fluid with a boiling point that is excessively high may lead to an increase in the evaporation temperature of the system, enhancing the difficulty of energy conversion, reducing overall thermal efficiency, and necessitating higher system pressures and more complex equipment design, thereby increasing operational costs and safety hazards. Conversely, selecting a working fluid with a boiling point that is too low may result in inadequate waste heat recovery, especially under conditions of low-temperature waste heat sources, leading to a decline in system performance and a decrease in thermal recovery efficiency. Therefore, comprehensively considering the boiling point factor and choosing an organic working fluid that is moderate and compatible with the system conditions is essential for ensuring the system operates efficiently, safely, and stably. In the selection of organic working fluids, it is imperative to consider not only their operational performance but also their safety and environmental impact. Table 1 presents the thermophysical properties of several working fluids, including their critical temperature, critical pressure, boiling point, type, and molar mass.

3.2 The Impact of Working Fluids on ORC Waste Heat Recovery Performance

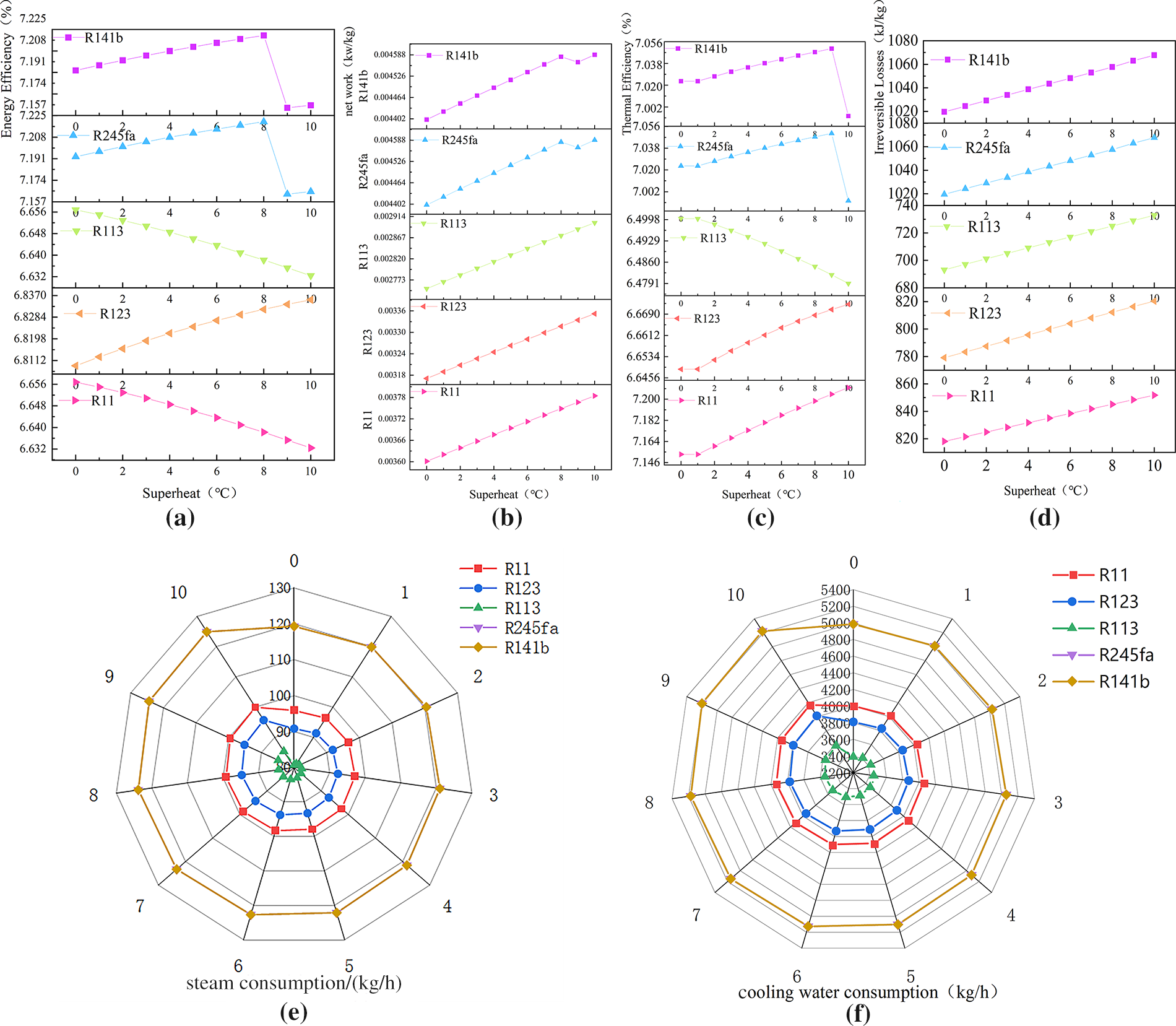

Fig. 4a–f comprehensively compares the multidimensional impacts of five types of working fluids (R141b, R245fa, R113, R11, R123) on the waste heat recovery performance of an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) through scatter plots and radar charts. Specifically, Fig. 4a–d presents, in the form of line graphs, the changing trends of exergy efficiency, net output power, thermal efficiency, and irreversible losses for different working fluids under varying superheat degrees (0°C–10°C). In Fig. 4a, it can be clearly seen that as the superheat degree increases, the exergy efficiencies of the working fluids exhibit different trends. Among them, R123 achieves an exergy efficiency of 6.815% at a superheat degree of 2°C and reaches its highest exergy efficiency of 6.837% at 10°C. Fig. 4b illustrates the relationship between net output power and superheat degree, with R245fa demonstrating a significant advantage in net output power at high superheat degrees, reaching a maximum of 0.00584 kW/kg at 8°C. The thermal efficiency curves in Fig. 4c further reveal the efficiency differences among the working fluids during the energy conversion process. R11 has a thermal efficiency of 7.200% at a superheat degree of 2°C and reaches its highest thermal efficiency of 7.182% at 6°C. Fig. 4d reflects the loss situations of different working fluids during the energy transfer process through the trend of irreversible losses, with R113 achieving the lowest irreversible loss of approximately 544.5 kJ/kg at a specific evaporation pressure and a subcooling degree of 0°C. Furthermore, Fig. 4e,f visually compares the performance of the working fluids in terms of steam consumption (0–130 kg/h) and cooling water consumption (0–5400 kg/h) through radar charts. These radar charts not only display the numerical performance of each working fluid on a single resource consumption indicator, such as R11’s steam consumption being as low as 10 kg/h under certain conditions and relatively low cooling water consumption; they also intuitively reflect the advantages and disadvantages of each working fluid in terms of comprehensive resource consumption through the shape and area of the polygons. These charts provide detailed data support for a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of different working fluids in an ORC system.

Figure 4: Thermodynamic performance parameter analysis. (a) The impact of superheat variation on exergetic efficiency of five working fluids, (b) The impact of superheat variation on net work for five working fluids, (c) The effect of superheat variation on thermal efficiency for five working fluids, (d) The influence of superheat on irreversible losses for five working fluids, (e) The influence of superheat on steam consumption for five working fluids, (f) The influence of superheat on cooling water consumption for five working fluids

This study delves into the performance of five organic working fluids in an ORC waste heat recovery system through multidimensional performance parameter analysis. The research results indicate that the different working fluids exhibit significant differences in exergy efficiency, net output power, thermal efficiency, irreversible losses, and resource consumption. These differences are not only reflected in single performance indicators, such as R123’s exergy efficiency advantage at specific superheat degrees and R245fa’s net output power advantage at high superheat degrees; they are also reflected in the comprehensive performance of multiple indicators, such as the comprehensive performance of steam consumption and cooling water consumption displayed in the radar charts. Therefore, in practical applications, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the performance characteristics of each working fluid and make an optimized selection based on specific requirements and system conditions. For example, in scenarios pursuing high net output power, R245fa can be given priority; while in situations with strict restrictions on resource consumption, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the performance of each working fluid in terms of steam consumption and cooling water consumption and choose a working fluid with lower resource consumption, such as R11. This study not only provides a scientific basis for the selection of working fluids in ORC systems but also offers important references for subsequent system design and optimization, contributing to the widespread application and development of ORC technology in the field of waste heat recovery.

3.3 Performance of Working Fluids at Varying Pressures and Subcooling

To further delve into the performance analysis between working fluids and subcooling, the impact of five organic working fluids under evaporation pressures ranging from 10 to 30 bar, with a constant superheat of 10°C and subcooling degrees between 0°C and 5°C, on system irreversibilities, thermal efficiency, and exergy efficiency was investigated.

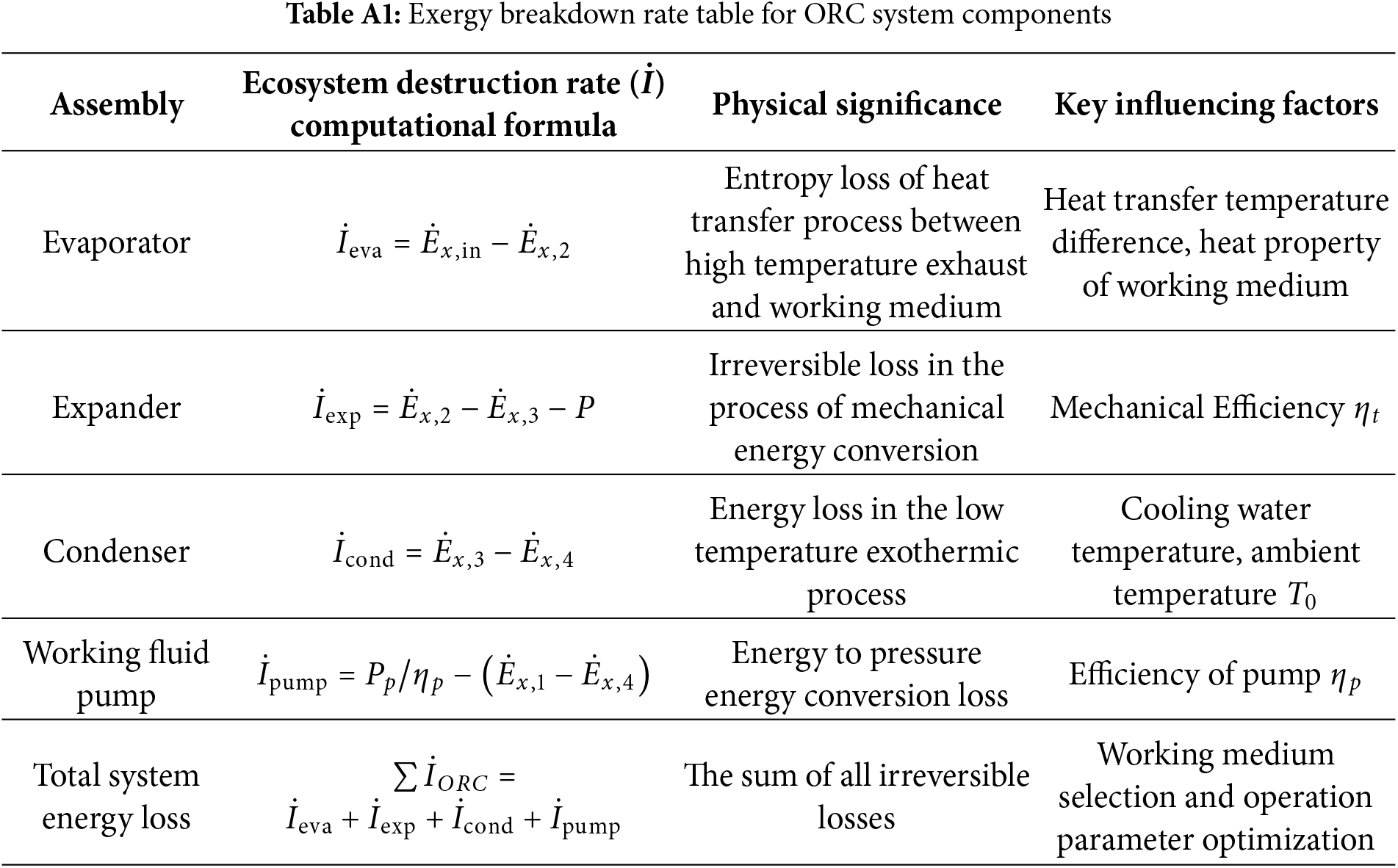

3.3.1 Influence of Working Fluids at Varying Pressures and Subcooling on System Irreversibilities Losses

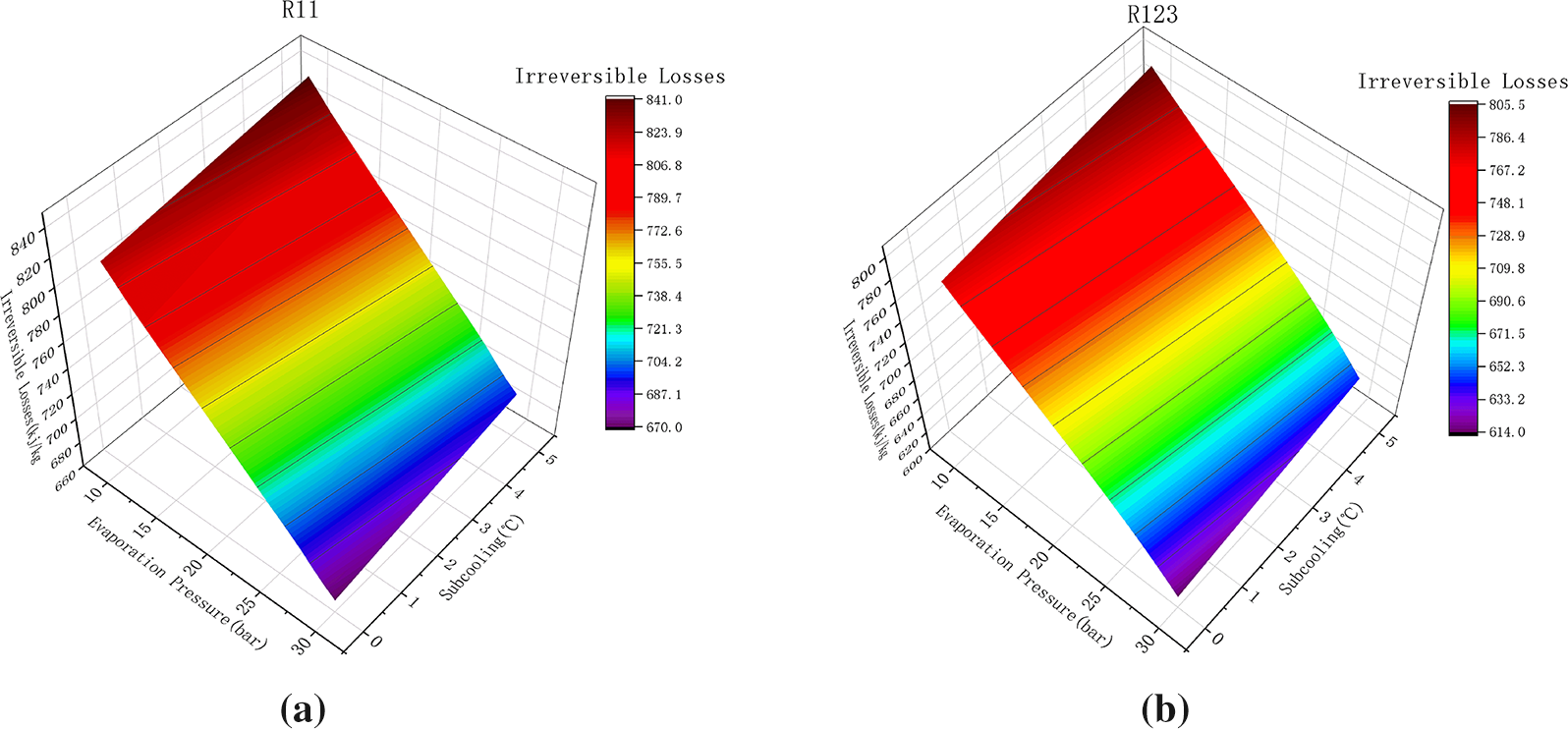

Fig. 5a–e presents an in-depth exploration of the impact of five organic working fluids (R11, R123, R113, R245fa, R141b) on the irreversible losses in an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system under varying evaporation pressures and subcooling degrees. Through systematic analysis, it has been found that as the evaporation pressure increases, the irreversible losses of all working fluids exhibit a downward trend, whereas with an increase in subcooling degree, the irreversible losses correspondingly rise. Specifically, R11 and R123 demonstrate lower irreversible losses at higher evaporation pressures and lower subcooling degrees. However, under certain conditions, R113 exhibits even more outstanding performance. Notably, at an evaporation pressure of 30 bar and a subcooling degree of 0°C, R113 achieves the lowest irreversible loss of just 544.5 kJ/kg, significantly lower than the other fluids. In contrast, R245fa and R141b exhibit higher irreversible losses under the same conditions, indicating an adverse effect on system performance.

Figure 5: Sensitivity analysis of irreversible losses. (a) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling variations on irreversible losses for R11 working fluid, (b) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on irreversible losses for R123 working fluid, (c) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on irreversible losses for R113 working fluid, (d) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on irreversible losses for R245fa working fluid, (e) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on irreversible losses for R141b working fluid

A comprehensive analysis reveals that, with the objective of minimizing irreversible losses, R113 performs best under the conditions of 30 bar evaporation pressure and 0°C subcooling degree, making it the most efficient choice for waste heat recovery among the working fluids examined. This finding provides an important reference for the selection of working fluids in practical applications of ORC systems, particularly in scenarios where efficient waste heat recovery is essential. Therefore, when designing ORC systems, priority should be given to working fluids that can minimize irreversible losses under given operating conditions, such as R113, to achieve more efficient waste heat recovery and energy utilization.

This study systematically investigates the thermodynamic mechanisms underlying the increased irreversible losses in Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) systems with rising evaporation pressure and subcooling degree. The results reveal three primary contributing factors: (1) Elevated evaporation pressure significantly increases working fluid pump power consumption while reducing expander isentropic efficiency, leading to irreversible losses during energy conversion; (2) Increased subcooling exacerbates heat transfer temperature differences in the condenser and elevates pump cavitation risk, further degrading system efficiency; (3) Distinct thermodynamic properties of different working fluids result in markedly varied responses to operational parameters, as evidenced by R113 demonstrating optimal performance at 30 bar/0°C (minimum exergy losses: 544.5 kJ/kg) compared to R245fa’s maximum losses at 10 bar/5°C (1098 kJ/kg). To mitigate irreversible losses, the evaporation pressure should be maintained within 10–20 bar and subcooling controlled at 0°C–3°C, with working fluid selection tailored to operating conditions (R113 for low-temperature applications, R245fa for high-temperature scenarios). These findings provide crucial theoretical foundations for ORC system optimization and offer significant guidance for enhancing waste heat recovery efficiency.

3.3.2 Influence of Working Fluids at Varying Pressures and Subcooling on Thermal Efficiency

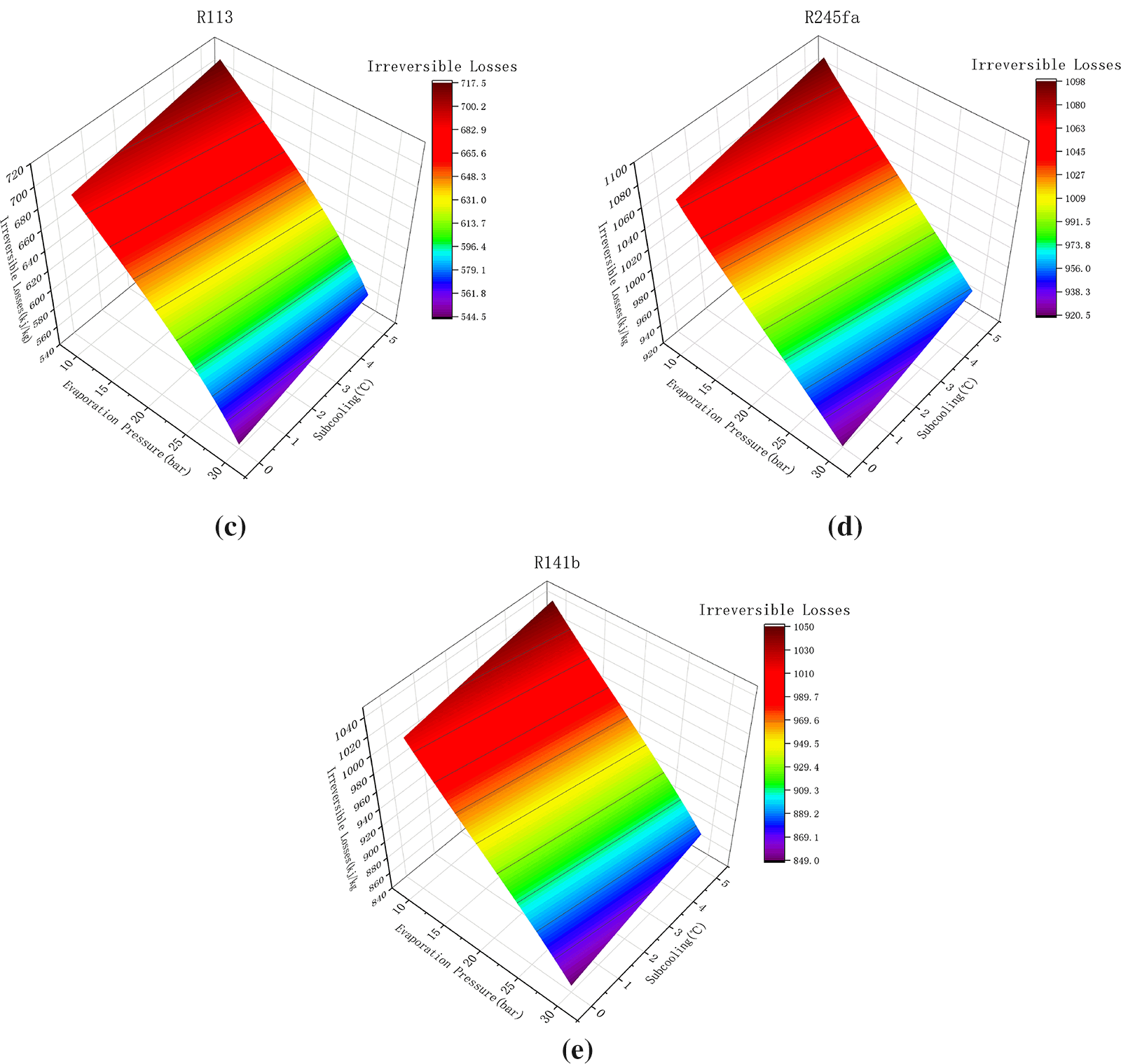

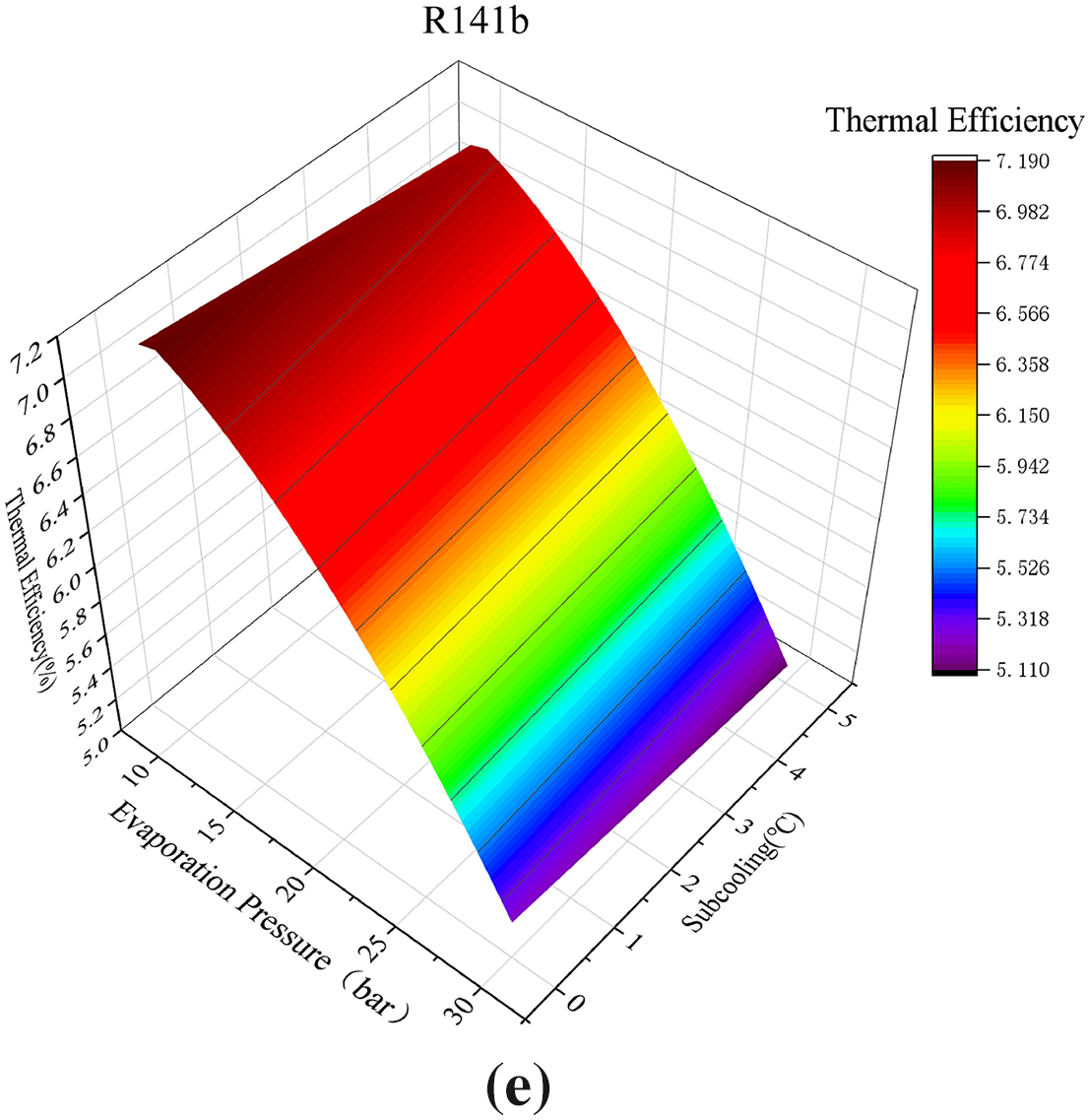

Fig. 6a–e demonstrates the impact of five types of working fluids (R141b, R245fa, R113, R11, R123) on the thermal efficiency of an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system under varying evaporation pressures and subcooling degrees. Through these three-dimensional surface plots, it is observable how evaporation pressure and subcooling degree jointly influence the system’s thermal efficiency. As depicted in the figures, for all working fluids, the thermal efficiency exhibits a certain trend with the increase of evaporation pressure, while changes in subcooling degree also have a significant impact on thermal efficiency. The thermal efficiency performance of each working fluid varies under different combinations of pressure and subcooling degree, providing abundant data support for optimizing the performance of the ORC system.

Figure 6: Sensitivity analysis of thermal efficiency (a) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on thermal efficiency for R11 working fluid, (b) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcoolingt on thermal efficiency for R123 working fluid, (c) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on thermal efficiency for R113 working fluid, (d) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on thermal efficiency for R245fa working fluid, (e) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on thermal efficiency for R141b working fluid

A comprehensive analysis reveals that different working fluids exhibit distinct thermal efficiency performances under specific evaporation pressures and subcooling degrees. When selecting a suitable working fluid, it is essential to comprehensively consider the operating pressure range of the system and the required subcooling degree. For instance, in certain high-pressure application scenarios, R11 and R123 may demonstrate higher thermal efficiency, whereas in low-pressure applications or those requiring specific subcooling degrees, R141b or R245fa may be more appropriate. Therefore, in practical applications, the working fluid that maximizes thermal efficiency should be selected based on specific system requirements and operating conditions to achieve optimal performance of the ORC system.

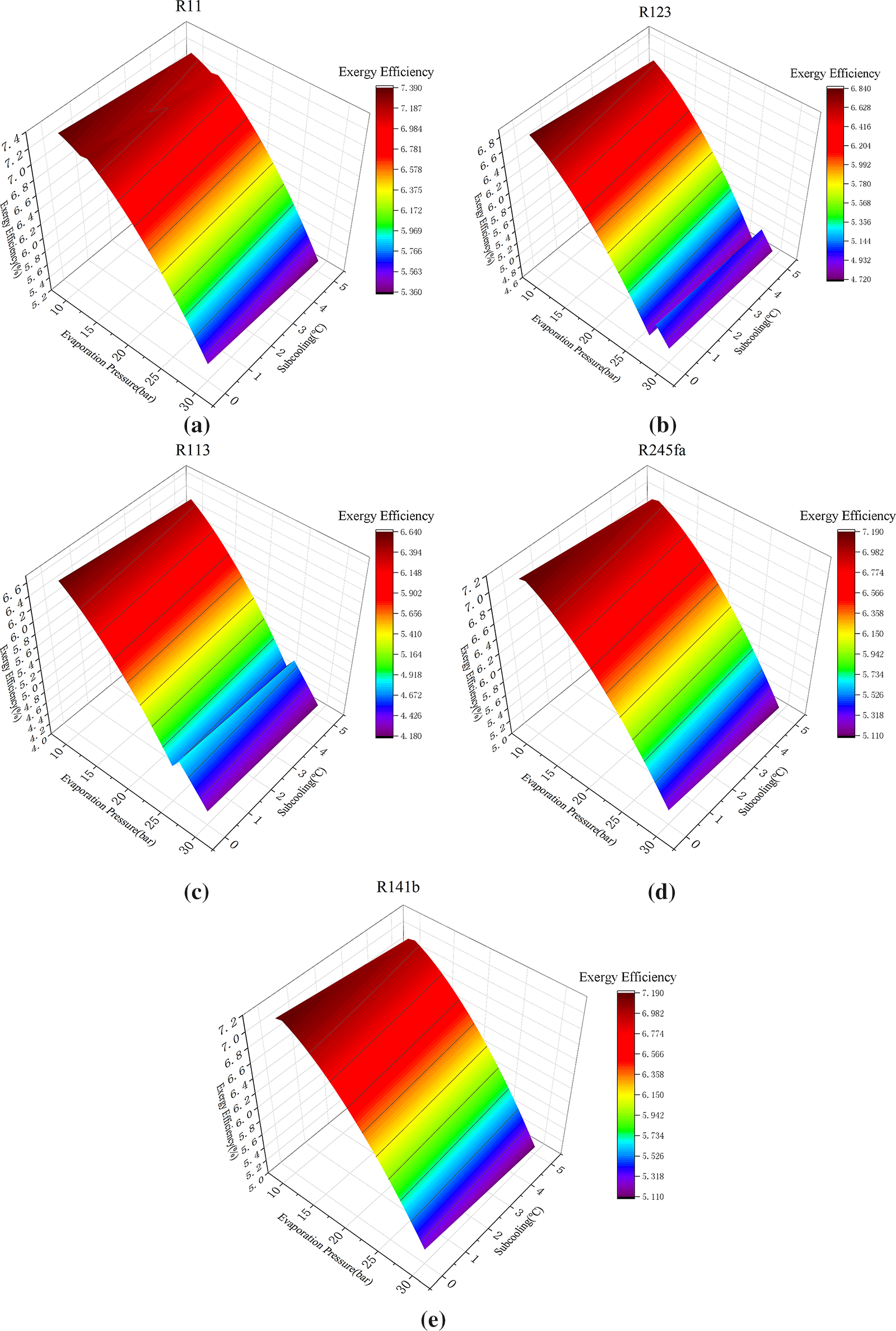

3.3.3 Influence of Working Fluids at Varying Pressures and Subcooling on Exergy Efficiency

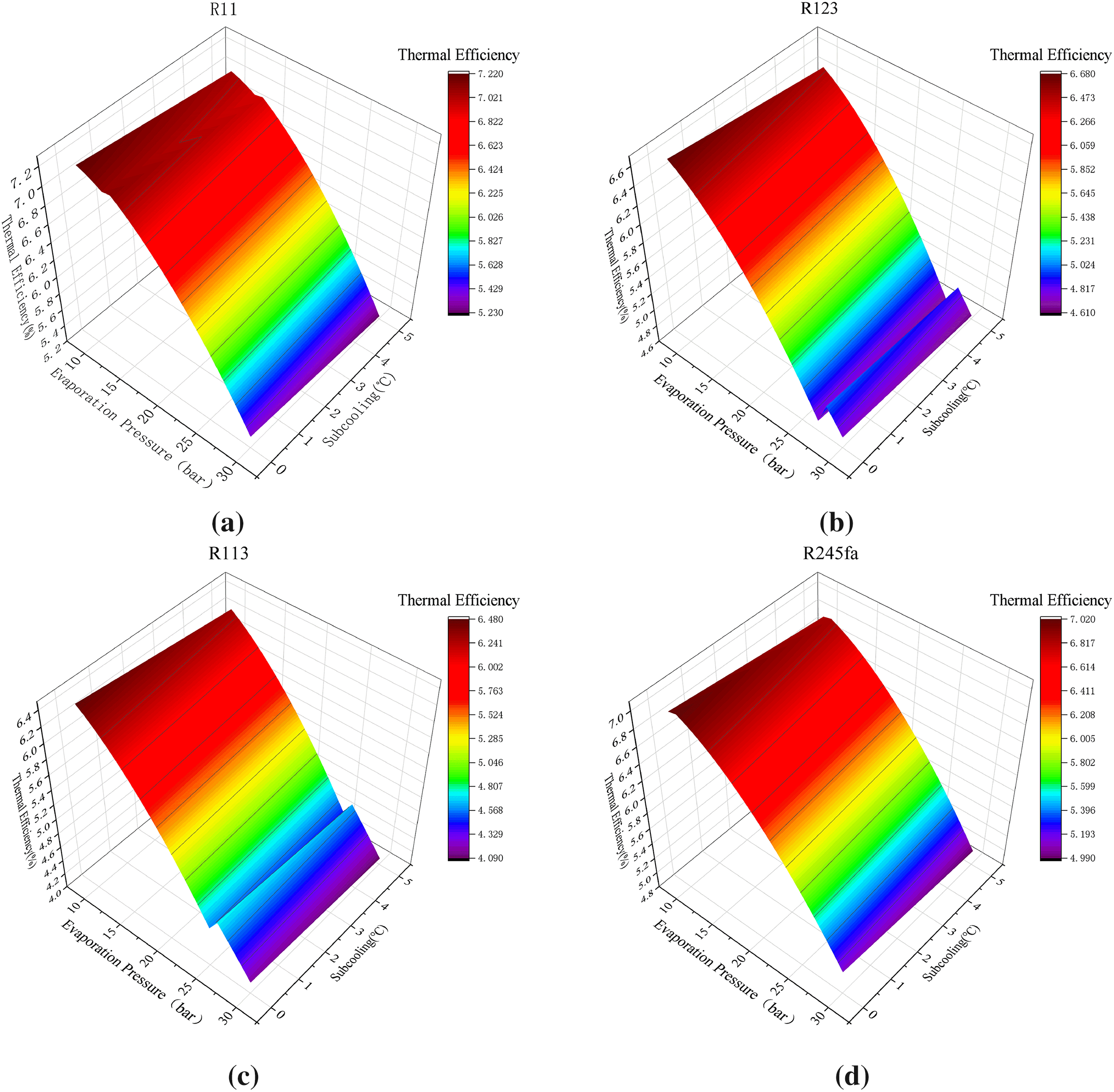

As illustrated in Table A1, the exergy destruction rates across various components of the ORC system provide critical insights into the system’s energy efficiency. Table A2, found in Appendix A, offers a comprehensive glossary of terms related to the ORC system. This study provides a detailed analysis of the specific impact of five types of organic working fluids (R141b, R245fa, R113, R11, R123) on the exergy efficiency of an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system under varying evaporation pressures and subcooling degrees through Fig. 7a–e. The analysis reveals significant differences in exergy efficiency among the working fluids under identical operating conditions. Notably, the R113 working fluid exhibits higher exergy efficiency in most scenarios, enabling more effective reduction of irreversible losses during the energy conversion process. Furthermore, evaporation pressure and subcooling degree, as key operating parameters, have a non-negligible impact on exergy efficiency. Generally, an increase in evaporation pressure is conducive to improving exergy efficiency, whereas an increase in subcooling degree may reduce it. It is evident that under the specific conditions of 30 bar evaporation pressure and 0°C subcooling degree, the R113 working fluid achieves the lowest irreversible loss and, consequently, the highest exergy efficiency. This finding provides crucial experimental evidence for the optimal design of ORC systems.

Figure 7: Sensitivity analysis of exergy efficiency (a) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on exergy efficiency for R11 working fluid, (b) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on exergy efficiency for R123 working fluid, (c) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on exergy efficiency for working fluid R113, (d) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on exergy efficiency for working fluid R245fa, (e) The impact of evaporation pressure and subcooling on exergy efficiency for working fluid R141b

In summary, this study uncovers the pivotal influence of working fluid selection and operating conditions on the exergy efficiency of an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system. With the goal of pursuing high exergy efficiency, the R113 working fluid emerges as the preferred choice for ORC systems due to its outstanding thermophysical properties and exceptional performance under specific operating conditions. Particularly under the conditions of 30 bar evaporation pressure and 0°C subcooling degree, the R113 working fluid demonstrates unparalleled exergy efficiency advantages, providing valuable guidance for the practical application of ORC systems. Therefore, we recommend prioritizing the use of the R113 working fluid in actual engineering applications and maximizing the exergy efficiency of ORC systems by precisely controlling key operating parameters such as evaporation pressure and subcooling degree, thereby achieving efficient energy recovery and utilization. This research finding not only holds significant value for enhancing the performance of ORC technology but also contributes new scientific evidence to promote sustainable development in the field of energy recovery and utilization.

(1) The selection of organic working fluids significantly impacts the performance of the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system.

The selection of organic working fluids has a pronounced effect on the performance of Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) systems. Under varying degrees of superheat, the impact on the exergetic efficiency, net output work, and thermal efficiency of ORC systems is distinct for fluids such as R11, R123, R113, R245fa, and R141b. For instance, at lower temperatures, R11 and R113 exhibit higher exergetic efficiencies, while R123 demonstrates superior performance at higher temperatures. Consequently, the judicious selection of an organic working fluid tailored to specific operating conditions can significantly enhance the overall performance of ORC systems.

(2) As the degree of superheat increases, the net output work of ORC systems utilizing various working fluids initially ascends, reaching a peak at a specific superheat level. For instance, R141b and R245fa achieve their maximum net output work at a superheat of 10°C. This phenomenon underscores the critical role of superheat control in the optimization of ORC system performance. Under conditions where the evaporation pressure varies from 10 to 30 bar and the superheat is held constant, the irreversible losses of the system employing R11 exhibit a roughly linear increase with the rise in subcooling. The minimum irreversible losses, recorded at 670 kJ/kg, occur at an evaporation pressure of 30 bar and a subcooling of 0°C. These findings highlight the importance of managing evaporation pressure and subcooling to minimize inefficiencies and enhance the overall performance of ORC systems.

(3) An increase in evaporation pressure and subcooling leads to an escalation in irreversible losses within the system, resulting in a degradation of both thermal efficiency and exergetic efficiency, which is detrimental to the operation of the system and the recovery of waste heat.

(4) In summary, factors such as the compactness of the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system, thermal management strategies, control algorithms, and exhaust backpressure control technologies will significantly impact system performance in future research and applications. Through the analysis of working fluid parameters, this paper demonstrates that different environmental conditions and working fluids can be configured based on specific requirements. By reasonably selecting organic working fluids, controlling superheat, optimizing the operating conditions of diesel engines, and refining system design and optimization, the exergetic efficiency, thermal efficiency, and net output power of waste heat recovery from diesel engines can be enhanced, thereby achieving efficient waste heat recovery and utilization. This is of great significance for promoting energy conservation, emission reduction, and efficient energy utilization in the automotive industry.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the following individuals and organizations for their valuable contributions and support during the preparation of this manuscript: Huaiyin Institute of Technology: For providing the necessary facilities and resources that enabled the successful completion of this research. Institute of Smart Energy: For their financial support and encouragement, which were crucial for the development of this study. All participating researchers: For their dedication and hard work in conducting the experiments and analyzing the data. Anonymous reviewers: For their insightful comments and suggestions that greatly improved the quality of this manuscript. Technical staff: For their assistance in maintaining the laboratory equipment and ensuring the smooth operation of all experiments. We also acknowledge the support from [any other specific grants or funding bodies] that contributed to the research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Huaiyin Institute of Technology—Institute of Smart Energy.

Author Contributions: Zujun Ding: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. Shuaichao Wu: Software, Validation. Chenliang Ji: Data Curation, Visualization. Xinyu Feng: Review, Editing. Yuanyuan Shi: Investigation, Resources. Baolian Liu: Writing—Review & Editing. Wan Chen: Investigation, Project Administration. Qiuchan Bai: Funding Acquisition, Resources. Hengrui Zhou: Methodology. Hui Huang: Formal Analysis. Jie Ji: Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author—Prof. Jie Ji upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Feng J, Tang Y, Zhu S, Deng K, Bai S, Li S. Design of a combined organic Rankine cycle and turbo-compounding system recovering multigrade waste heat from a marine two-stroke engine. Energy. 2024;309:133151. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.133151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang X, Wang X, Yuan P, Ling Z, Bian X, Wang J, et al. Experimental study on the comparative performance of R1233zd(E) and R123 for organic Rankine cycle for engine waste heat recovery. Int J Green Energy. 2024;21(14):3305–12. doi:10.1080/15435075.2024.2376734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ouyang T, Pan M, Tan X, Li L, Huang Y, Mo C. Power prediction and packed bed heat storage control for marine diesel engine waste heat recovery. Appl Energy. 2024;357:122520. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sprouse CE III, Depcik C. Review of organic Rankine cycles for internal combustion engine exhaust waste heat recovery. Appl Therm Eng. 2013;51(1–2):711–22. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2012.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bhakta S, Kundu B. A review of thermoelectric generators in automobile waste heat recovery systems for improving energy utilization. Energies. 2024;17(5):1016. doi:10.3390/en17051016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yuan M, Vad Mathiesen B, Schneider N, Xia J, Zheng W, Sorknæs P, et al. Renewable energy and waste heat recovery in district heating systems in China: a systematic review. Energy. 2024;294:130788. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.130788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ding Y, Liu Y, Wang M, Du W, Qian F. Heat integration, simultaneous structure and parameter optimisation, and techno-economic evaluation of waste heat recovery systems for petrochemical industry. Energy. 2024;296:131083. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wu X, Qin J, Chen J, Wang Y. Efficient predictive control method for ORC waste heat recovery system based on recurrent neural network. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;257:124352. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.124352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liu H, Lu B, Xu Y, Ju X, Wang W, Zhang Z, et al. Experimental investigation of a splitting organic Rankine cycle for dual waste heat recovery. Energy Convers Manag. 2024;320:119005. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.119005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Raheli Kaleibar M, Khoshbakhti Saray R, Pourgol M. Comprehensive assumption-free dynamic simulation of an organic Rankine cycle using moving-boundary method. Energy. 2024;307:132584. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.132584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Baldinelli A, Francesconi M, Antonelli M. Hydrogen, E-fuels, biofuels: what is the most viable alternative to diesel for heavy-duty internal combustion engine vehicles? Energies. 2024;17(18):4728. doi:10.3390/en17184728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chatzopoulou MA, Markides CN. Thermodynamic optimisation of a high-electrical efficiency integrated internal combustion engine—organic Rankine cycle combined heat and power system. Appl Energy. 2018;226(1):1229–51. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.06.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu H, Zhang H, Yang F, Hou X, Yu F, Song S. Multi-objective optimization of fin-and-tube evaporator for a diesel engine-organic Rankine cycle (ORC) combined system using particle swarm optimization algorithm. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;151:147–57. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.08.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao R, Zhang H, Song S, Tian Y, Yang Y, Liu Y. Integrated simulation and control strategy of the diesel engine-organic Rankine cycle (ORC) combined system. Energy Convers Manag. 2018;156(2):639–54. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.11.078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Corigliano O, Algieri A, Fragiacomo P. Turning data center waste heat into energy: a guide to organic Rankine cycle system design and performance evaluation. Appl Sci. 2024;14(14):6046. doi:10.3390/app14146046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sun W, Yue X, Wang Y. Exergy efficiency analysis of ORC (Organic Rankine Cycle) and ORC-based combined cycles driven by low-temperature waste heat. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;135:63–73. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2016.12.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ping X, Yang F, Zhang H, Xing C, Yu M, Wang Y. Investigation and multi-objective optimization of vehicle engine-organic Rankine cycle (ORC) combined system in different driving conditions. Energy. 2023;263:125672. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.125672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang R, Zhao J, Zhu L, Kuang G. Multi-objective optimization of organic Rankine cycle for low-grade waste heat recovery. E3S Web Conf. 2019;118:03053. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/201911803053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Boodaghi H, Etghani MM, Sedighi K. Performance analysis of a dual-loop bottoming organic Rankine cycle (ORC) for waste heat recovery of a heavy-duty diesel engine, part I: thermodynamic analysis. Energy Convers Manag. 2021;241:113830. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.113830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ahamed M, Pesyridis A, Ahbabi Saray J, Mahmoudzadeh Andwari A, Gharehghani A, Rajoo S. Comparative assessment of sCO2 cycles, optimal ORC, and thermoelectric generators for exhaust waste heat recovery applications from heavy-duty diesel engines. Energies. 2023;16(11):4339. doi:10.3390/en16114339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lan S, Li Q, Guo X, Wang S, Chen R. Fuel saving potential analysis of bifunctional vehicular waste heat recovery system using thermoelectric generator and organic Rankine cycle. Energy. 2023;263:125717. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.125717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang X, Wang X, Cai J, Wang R, Bian X, He Z, et al. Operation strategy of a multi-mode organic Rankine cycle system for waste heat recovery from engine cooling water. Energy. 2023;263:125934. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.125934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yu M, Yang F, Zhang H, Yan Y, Ping X, Pan Y, et al. Thermoeconomic performance of supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycle systems for CNG engine waste heat recovery. Energy. 2024;289:129972. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.129972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Varshil P, Deshmukh D. A comprehensive review of waste heat recovery from a diesel engine using organic Rankine cycle. Energy Rep. 2021;7:3951–70. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.06.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu Y, Cui Y, Wang Y, Wang P. Simulation study on exhaust turbine power generation for waste heat recovery from exhaust of a diesel engine. Energy Rep. 2021;7:8378–89. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.09.083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mariani A, Morrone B, Prati MV, Unich A. Waste heat recovery from a heavy-duty natural gas engine by Organic Rankine Cycle. E3S Web Conf. 2020;197:06023. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202019706023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li D, Sun Q, Sun K, Zhang G, Bai S, Li G. Diesel engine waste heat recovery system comprehensive optimization based on system and heat exchanger simulation. Open Phys. 2021;19(1):331–40. doi:10.1515/phys-2021-0039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang X, Wang X, Cai J, Wang R, Bian X, Wang J, et al. Selection maps of dual-pressure organic Rankine cycle configurations for engine waste heat recovery applications. Appl Therm Eng. 2023;228:120478. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang Z, Hu Y, Xia X. Comparison of conventional and advanced exergy analysis for dual-loop organic Rankine cycle used in engine waste heat recovery. J Therm Sci. 2021;30(1):177–90. doi:10.1007/s11630-020-1299-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Singh I, Kumar P, Dhar A. Low-temperature waste heat recovery from internal combustion engines and power output improvement through dual-expander organic Rankine cycle technology. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part D J Automob Eng. 2023;237(14):3432–47. doi:10.1177/09544070221144156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Özdemir E, Kılıç M. Energy and exergy analysis of an organic Rankine cycle using different working fluids from waste heat recovery. Int J Environ Trends. 2017;1(1):32–45. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1234567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ji L, Wang X, He Z, Xing Z. Design of a steady-state adjustment method and sensitivity analysis for an ORC system with plate heat exchangers. Appl Sci. 2024;14(19):8728. doi:10.3390/app14198728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bin Wan Ramli WR, Pesyridis A, Gohil D, Alshammari F. Organic Rankine cycle waste heat recovery for passenger hybrid electric vehicles. Energies. 2020;13(17):4532. doi:10.3390/en13174532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools