Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental Study of Solar-Powered Underfloor Heating in a Defined Space

1 Technical College of Engineering, Duhok Polytechnic University, Duhok, 42001, Iraq

2 Engineering College, Sustainable Energy, Mosul University, Mosul, 41003, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Firas Mahmood Younis. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Energy Resources and Their Processes, Systems, Materials and Policies for Affordable Energy Sustainability)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(2), 19 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.073483

Received 18 September 2025; Accepted 05 December 2025; Issue published 27 January 2026

Abstract

This paper presents an experimental analysis of a solar-assisted powered underfloor heating system, designed primarily to boost energy efficiency and achieve reliable desired steady-state temperature in buildings. We thoroughly tested the system’s thermal and operational features by subjecting it to three distinct scenarios that mimicked diverse solar irradiance and environmental conditions. Our findings reveal a strong correlation between variations in solar input and overall system performance. The Solar Fraction (SF), our key energy efficiency metric, varied significantly across the cases, ranging from 63.1% up to 88.7%. This high reliance on renewables resulted in a substantial reduction in backup power; consequently, the auxiliary electric heater was only required to supply between 1.82 and 3.00 kWh over the test periods. The circulation pump operated on a precise control logic, engaging below 20°C and disengaging at 21°C. Crucially, the experiments verified the system’s ability not only to meet the air temperature setpoint but also to ensure the floor surface temperature stayed within required international comfort criteria. These robust results directly support the study’s main objective. For practical application, we advise increasing the total length of the embedded pipe network. This crucial adjustment would allow for a reduction in the required circulating water temperature, which in turn maximizes the utilization of low-grade solar heat and optimizes radiant heat delivery toward achieving the desired steady-state temperature. Ultimately, the study confirms that solar-assisted underfloor heating offers a technically viable, sustainable, and energy-efficient solution with the potential to significantly cut fossil fuel consumption.Keywords

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description |

| Q | Heat transfer rate, W |

| Mass flow rate, kg/s | |

| Cp | Specific heat capacity, J/kg·K |

| T | Temperature, K |

| ∆T | Air temperature difference, K |

| ∆Tw | Water temperature difference, K |

| A | Surface area, m2 |

| V | Volume, m3 |

| U | Overall heat transfer coefficient, W/m2·K |

| ACH | Air change per hour |

Space heating is an essential element in the building sector, accounting for 33% of total final energy consumption, making it the largest energy demand compared to other end-uses. Energy-efficient insulation techniques and sustainable heating solutions are powerful methods for improving building energy efficiency, significantly reducing energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions [1]. Traditional heating systems, such as gas boilers and electric heaters, contribute significantly to carbon emissions and fossil fuel dependency [2]. With climate change emerging as a crucial issue, there is a growing shift toward renewable energy sources such as solar thermal energy, which is considered a sustainable and energy-efficient heating solution.

Underfloor heating systems are more energy-efficient and widely used in residential and other facilities due to their ability to circulate warm water through embedded pipes, providing comfortable heating. Unlike conventional radiators, these systems operate at lower temperatures, making them highly compatible with renewable energy sources such as solar thermal collectors [3]. The impact of traditional, expensive heating systems on the environment cannot be overlooked, as they depend on fossil fuels. Conversely, solar energy, being a clean and renewable source, offers a viable alternative for heating applications [4]. Solar water heating systems are widely adopted for their simplicity, efficiency, and suitability for low-temperature applications. They are generally classified into direct (open-loop) systems and indirect (closed-loop) systems. Based on the circulation method, they are further divided into passive systems and active systems [5]. These systems typically comprise a solar collector, a heat transfer mechanism, and a storage tank. It is worth mentioning that solar energy is one of the most abundant renewable resources, with an average global potential of around 1000 W/m2 under ideal conditions [6]. The collector absorbs solar radiation and transfers the absorbed heat to a circulating fluid (water, antifreeze), which can be used immediately or stored. In this context, flat plate solar collectors (FPSC) are commonly used due to their low cost, ease of manufacturing, minimal maintenance, and ability to capture both diffuse and direct radiation [7].

The integration of solar energy into underfloor heating systems has gained increasing attention in recent years due to its potential for improving energy efficiency and sustainability. In their theoretical study, Amir et al. [8] identified several advantages associated with underfloor heating systems. They concluded that these systems provide better thermal comfort conditions than conventional systems, as more than 60% of the heat transfer occurs through radiation. Not only that, but also their ability to operate on various energy sources, including fossil fuels, electricity, and renewable energy. Liu et al. [9] examined two types of heating systems: split air conditioning and underfloor heating. They found that underfloor heating, due to its relatively low heat loss and higher comfort level, can achieve the same thermal comfort at a lower temperature than the air conditioning system. This characteristic not only reduces energy consumption but also helps prevent overheating in practical applications. The numerical study performed by Anigrou and Zouini [10] highlights the importance of pipe configuration in underfloor heating systems, demonstrating that spiral coil layouts provide more uniform heat distribution compared to parallel configurations.

Hassan [11] focuses on flat plate solar collectors, the principles of heat transfer and thermal efficiency discussed in the study can be applied to underfloor heating systems. Both systems rely on efficient heat distribution to maintain consistent temperatures, making them suitable for integration with solar energy. On the other hand, Karimi et al. [12] highlighted that underfloor heating systems distribute heat more evenly compared to conventional radiators, requiring lower water temperatures, around 40°C–50°C, and thus reducing energy consumption. This makes underfloor heating systems particularly suitable for integration with solar energy. Furthermore, the solar fraction for Tehran and Tabriz was found to be 53% and 47%, respectively, indicating that solar thermal systems can meet nearly half of the heating demand in these regions.

Underfloor heating systems are widely adopted in European countries like France, Germany, and Sweden. Underfloor heating has demonstrated clear benefits in reducing energy consumption and improving indoor air quality [13]. Izquierdo and de Agustín-Camacho [14] explored a lightweight radiant floor heating (LRFH) configuration that incorporates pipes within aluminium foil layers instead of traditional concrete. Their study combined a theoretical heat transfer model with experimental validation, revealing that the LRFH system offers faster thermal response, minimal structural load, and a lower installation profile. These features make it especially suitable for retrofitting or buildings with strict design constraints. The results support the integration of such systems in sustainable building designs, where maintaining comfort with reduced energy input is a key priority. Abdelmaksoud [15] conducted a study on the performance of a flat-plate solar collector integrated with an underfloor heating system. The results indicated an average efficiency of 51% during the winter, with peak efficiency reaching up to 62% during periods of intense solar radiation. These outcomes support the adoption of solar-powered heating systems, especially in areas with abundant sunlight.

Simou et al. [16], through their numerical study on a heating system for an office building, concluded that the optimal mass flow rates for the solar collector and the underfloor system are 180 and 410 kg/h, respectively. These values were found to maximize heat transfer while minimizing heat losses. They also noted that reducing the floor’s thermal resistance, such as by decreasing its thickness, can lower energy consumption. Furthermore, the total solar fraction achieved in their system reached an impressive 93.72%. Mahmoud et al. [17] highlight that solar heating systems, when coupled with thermal storage, can effectively provide sustainable heating solutions with minimal environmental impact. The study further demonstrates that solar water heating can reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 250.4 kg per year for specific setups in Brazil, emphasizing the global applicability of solar-based systems. The study suggests that proper storage solutions are essential to overcome the intermittent nature of solar radiation, ensuring consistent heating performance. Nolan and Taylor [18] evaluated the performance of a solar combisystem in the Australian climate, which combines solar thermal energy with hydronic underfloor heating and domestic hot water systems. Their study highlighted the potential of solar combisystems to reduce auxiliary energy consumption by optimizing the system design and control strategies. Their findings suggest that by lowering the set temperature of the storage tank and reducing the volume of auxiliary energy used, the system’s efficiency can be significantly improved.

Zeghib and Chaker [19] investigated the efficiency of a solar hydronic space heating system under the Algerian climate. Their study demonstrated that solar energy could cover 20.8% of the total energy demand for heating in a single-family house, with the remaining energy supplied by an auxiliary gas boiler. The system utilized flat-plate solar collectors and a stratified storage tank to provide low-temperature heating through radiators. The authors highlighted that the integration of solar thermal systems with conventional heating systems could significantly reduce auxiliary energy consumption while maintaining thermal comfort at 22°C. Raisul et al. [20] provided a comprehensive review of various solar water heating systems. Their study highlighted the advantages of solar heating systems, such as reduced energy costs and lower environmental impact. Khalil et al. [21] demonstrated that increasing the collector area led to a reduction in auxiliary heater energy consumption, with an optimal collector area of 24 m2 and a storage tank volume of 1.0 m3.

Solar-assisted underfloor heating systems have shown potential for energy efficiency. However, their performance quantification under dynamically varying real environmental conditions, which makes it challenging to isolate system performance metrics remains underexplored. In particular, cold regions, like Duhok city in the north of Iraq, would highly benefit from solar-assisted heating due to the interrupted electric power supply and its high cost. Despite considerable research on solar water heating and underfloor heating systems, few experimental studies have examined their combined performance using a methodology that allows for the precise, controlled assessment of solar contribution ratios within lightweight sandwich-panel structures.

The objective of this research is to experimentally investigate the thermal performance and energy efficiency of a solar-assisted underfloor heating system installed within a defined space in Duhok City, Iraq, with the goal of evaluating its potential for maintaining indoor thermal comfort under variable climatic loads. Distinct from prior research, this work utilizes a hybrid methodology where controlled artificial solar input is applied to the solar collector for standardized thermal gain, while the heating load of the test room remains fully subjected to realistic, uncontrolled external climatic fluctuations. The investigation provides a real-time experimental analysis using a fully instrumented sandwich panel room to deliver quantifiable performance metrics for energy displacement and thermal comfort.

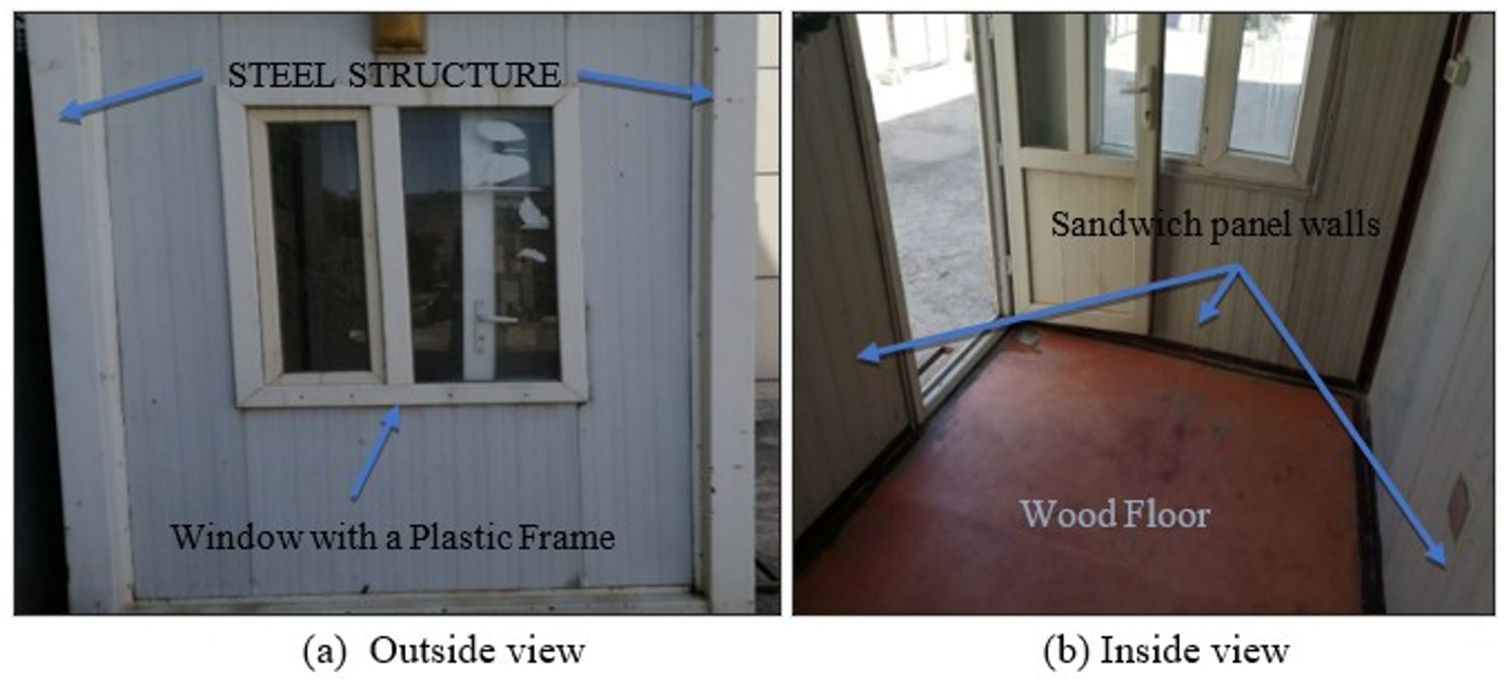

The experimental study was conducted using the GUNT HL320 Solar Thermal and Heat Pump Modular System, located in the energy laboratory at Duhok Polytechnic University. Fig. 1a,b shows the actual test room, a custom-built sandwich panel room, which was installed outside the laboratory, where it was exposed to uncontrolled environmental conditions. This setup allowed the evaluation of a solar-powered underfloor heating system under realistic weather variations, such as fluctuating temperatures and solar radiation levels.

Figure 1: Actual views of the test room used in the experimental study

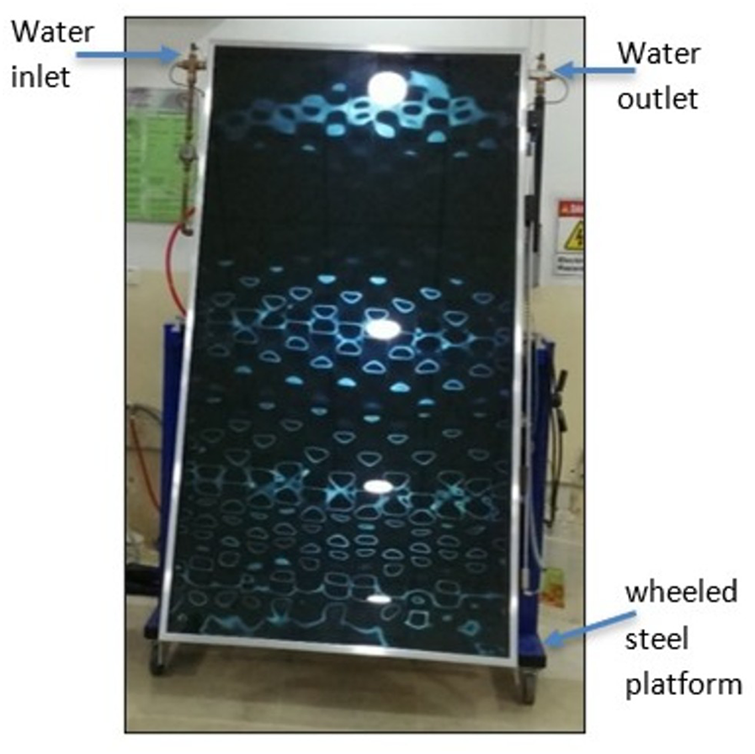

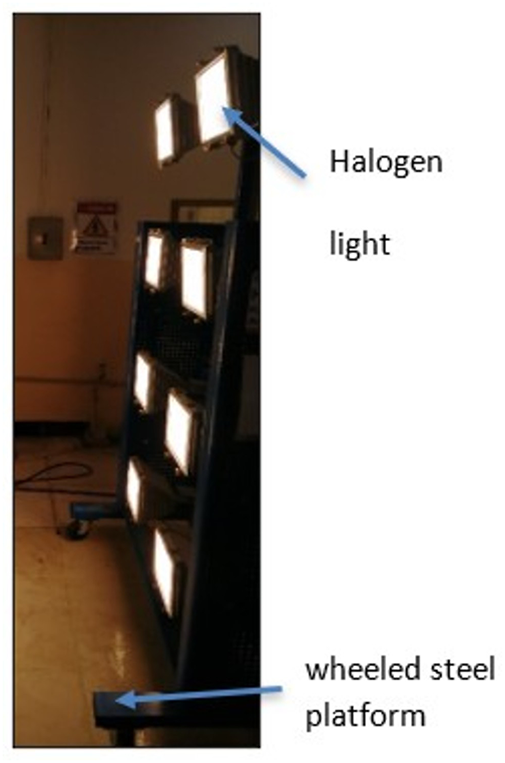

The heating system utilizes flat-plate solar collectors that are part of the GUNT HL320 system, with a 2.5 m2 absorber surface area (Fig. 2). The system simulates solar energy using artificial light sources to heat water in a controlled environment, as shown in Fig. 3. This heated water is then circulated through an underfloor network to supply radiant heat to the room.

Figure 2: GUNT HL 320.03 flat plate collector module used in the experimental system

Figure 3: Artificial light simulation setup within the GUNT HL320 system used to control solar energy input

The underfloor network was constructed using PEX-Al-PEX pipes arranged in a selected concentric layout above an insulation layer of 5 cm thickness, as shown in Fig. 4. The tiles of porcelain were the flooring layer without any screed layer. To complete the system, a circulating pump and a 2 kW auxiliary electric heater were incorporated to circulate the warm water and supply supplemental heating during periods of insufficient thermal energy, respectively.

Figure 4: Concentric layout of the underfloor heating system

2.2 Heating System Configuration

The heating system was developed using the commercial test bench, namely GUNT HL320 Solar Thermal and Heat Pump Modular System. To ensure the practical relevance of our findings, this commercial unit was modified and integrated with an external, realistic underfloor heating system loop, which utilized the defined test room as the actual thermal load. This integration was necessary because the standard GUNT unit does not include a realistic, dedicated underfloor heating component suitable for studying heat transfer dynamics in a building structure.

The system includes:

– The HL 320.03 flat-plate solar collector module simulates solar energy using artificial light sources rather than direct sunlight. Although the system does not rely on actual solar radiation, a tilt angle of 50° was used in irradiance calculations to represent the optimal solar collector orientation for Duhok’s latitude during the winter period, particularly in the month of February, when the experimental tests were conducted. This angle corresponds to the sun’s lower position in the sky during winter, maximizing potential solar energy captured under real environmental conditions.

– The HL 320.05 module accumulates thermal energy generated by the collector into a water storage tank following the module. The stored heat is later circulated through the underfloor heating system.

– The HL 320.02 Conventional Heating module. A 2 kW electric heater provides supplemental heating when simulated solar energy is insufficient. This ensures reliable temperature control and indoor thermal comfort during testing.

Furthermore, an insulated closed-loop system with a constant-speed circulating pump delivers hot water from the storage tank to the underfloor pipe network, with the flow rate manually adjustable and maintained consistently during operation to meet the desired conditions.

To determine the required thermal energy needed to maintain a comfortable indoor temperature in the test room, the heating load was calculated. This calculation is crucial to assess whether the solar-powered underfloor heating system could meet the room’s heating demands under varying environmental conditions.

The following factors were considered for the heating load calculation:

• Room Dimensions: The test room dimensions are 2.75 × 1.75 × 2.38 m3, providing a manageable space for evaluation.

• Room Insulation: The sandwich panels used in the construction of the room provided low thermal conductivity, ensuring that heat losses were minimized. This feature was essential for maintaining internal temperature stability and evaluating the system’s performance accurately.

• Indoor Setpoint Temperature: The target temperature was set at 21°C for optimal comfort.

• External Temperature: Temperature variations outside the test room were monitored to determine the heating load required to counteract the heat losses due to temperature differences between the indoor and outdoor environments.

• Heat transfer: Two approaches were employed to assess the heating demand. First, the heat added to the space was determined empirically using the energy balance equation.

Cp is the specific heat capacity (4186 J/kg∙K), and

ΔTW is the temperature difference between the inlet and outlet of the worm water (K).

Second, the theoretical heat loss was estimated based on convective heat transfer across the experimental space.

where,

U is the overall heat transfer coefficient (W/m2·K),

A is the heat surface area (m2), and

ΔT is the temperature difference between indoor and outdoor conditions (K).

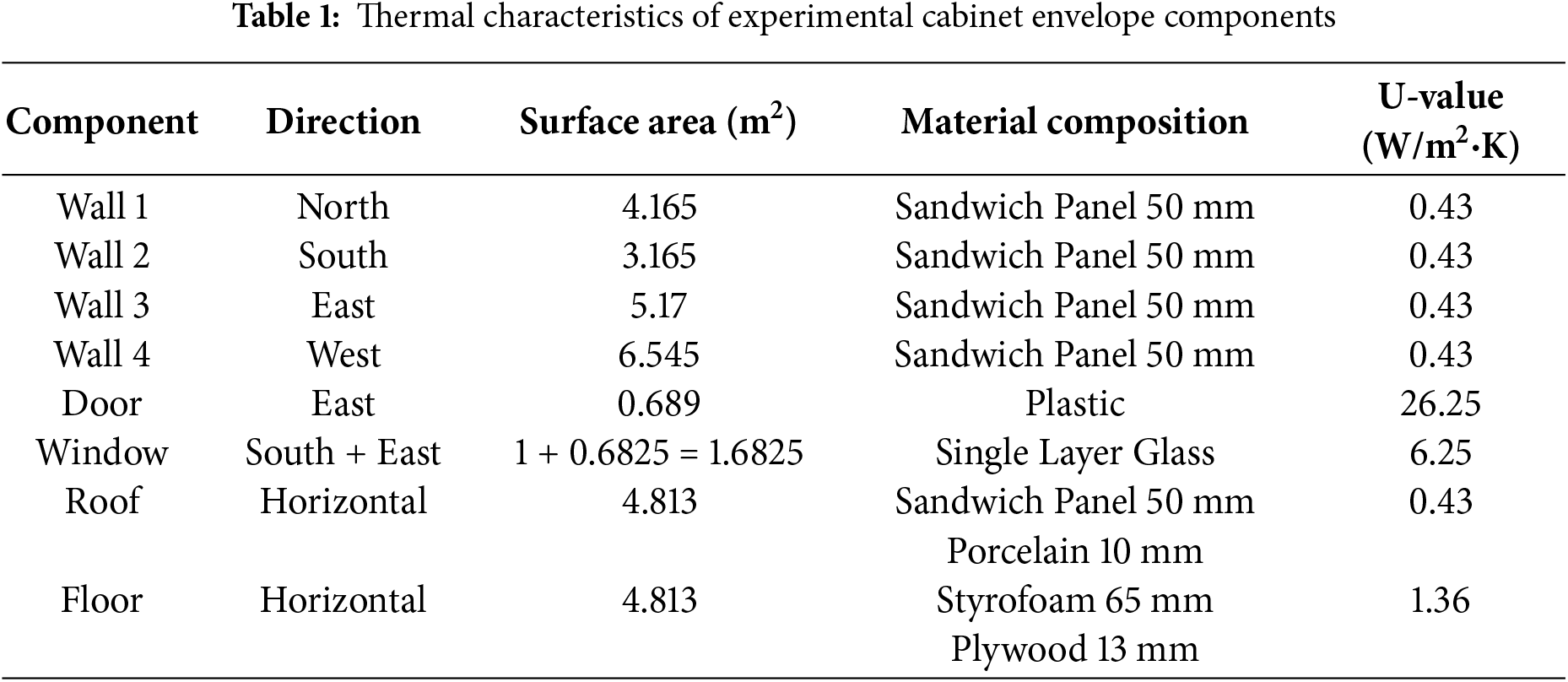

These methods provided a comprehensive understanding of the system’s ability to meet the heating demand. To perform the theoretical heat loss calculations, the thermal properties of the test room’s envelope components were analyzed. Table 1 presents the surface areas, material composition, and corresponding U-values used in the analysis.

In addition to conductive heat losses, air infiltration through gaps and openings was considered. Since the structure resembles older construction with basic sealing, an infiltration rate of 1 Air Change per Hour (ACH) was assumed.

The infiltration heat loss, Qinf, was calculated using:

where V is internal volume of the room (m3).

2.4 Experimental Procedure and Data Collection

The experimental study was conducted in a custom-built sandwich panel room designed specifically for evaluating the performance of a solar-powered underfloor heating system. The room was installed outside the laboratory to ensure exposure to real environmental conditions, providing a more accurate representation of system behavior under natural influences. Constructed using low-thermal-conductivity sandwich panels, the test room minimized external heat interference while maintaining internal heat retention.

To monitor the system’s performance during operation, a variety of instrumentation tools were employed and integrated with the GUNT HL320 data acquisition system:

Room Temperature: Thirteen thermocouples type K were used in the experimental setup, all of which were positioned carefully to map the air temperature profile, five sensors were positioned vertically in the middle of the room, with two more sensors placed close to the floor. Two sensors took readings of the temperature just above and below the floor surface. Two sensors on the surfaces of the inlet and outlet pipes monitored the delivery of heat. Lastly, two sensors took measurements of the outside ambient temperature and the interior window surface temperature.

Hot Water Flow Rate: Monitored using the built-in flow sensors within the HL320 system. Alhough the circulating pump operated at a constant speed, the flow rate could be manually adjusted to achieve the desired operational conditions.

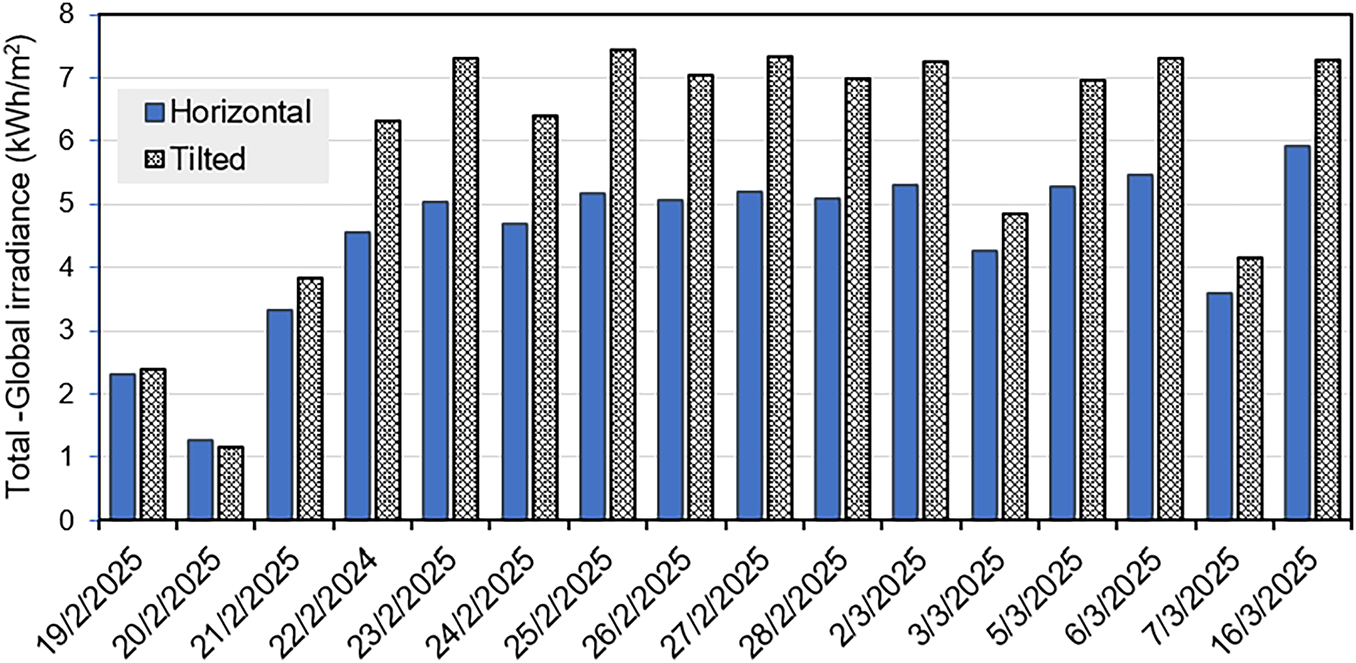

Solar Irradiance: Measured by a pyranometer placed on both horizontal and 50° tilted surfaces. These measurements were essential for quantifying the solar energy potentially available in Duhok City, Iraq, during the experimental period -particularly in February.

The experimental procedure involved operating the system continuously over several hours on the same day under naturally fluctuating weather conditions.

During testing:

• All key parameters, including temperature and operational status, were continuously logged electronically at a fixed interval of 30 s.

• Automatic activation of the auxiliary heater when the storage tank temperature drops below 60°C, ensuring uninterrupted heat delivery.

This methodology framework ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the thermal behavior and efficiency of the solar-powered underfloor heating system under realistic conditions.

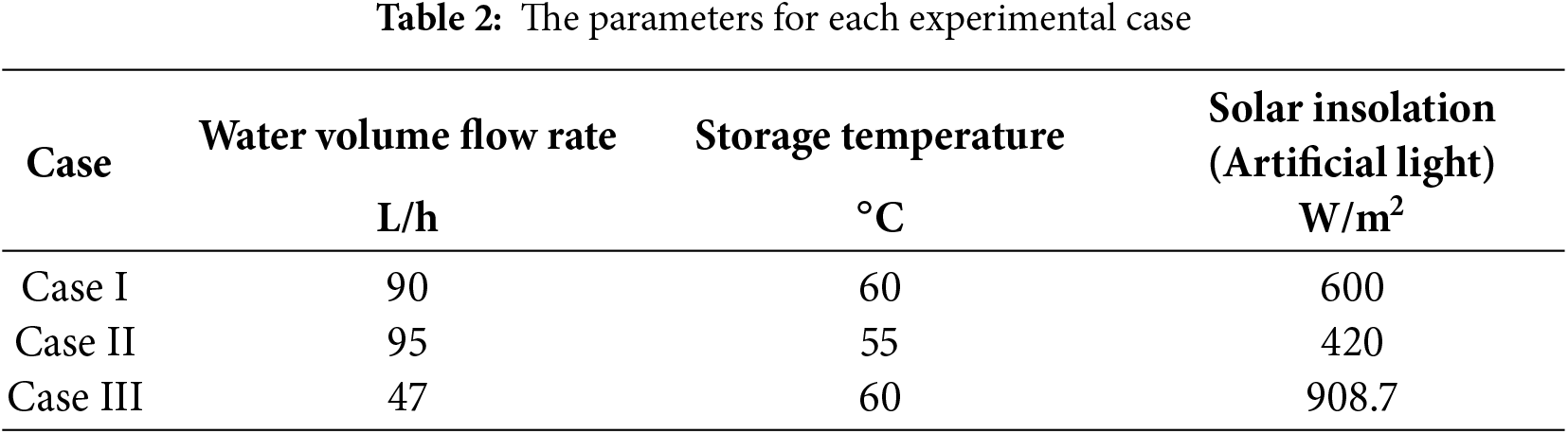

Table 2 summarizes the key operational parameters for each experimental case, demonstrating the significant variation in solar insolation across the three scenarios.

To ensure the highest standard of English readability, the ChatGPT (OpenAI) was employed solely as a language editing and polishing tool during the manuscript preparation phase. The authors emphasize that the model was not used for data analysis, idea generation, or conclusion formulation, and they assume full responsibility for the scientific content and accuracy of the results presented.

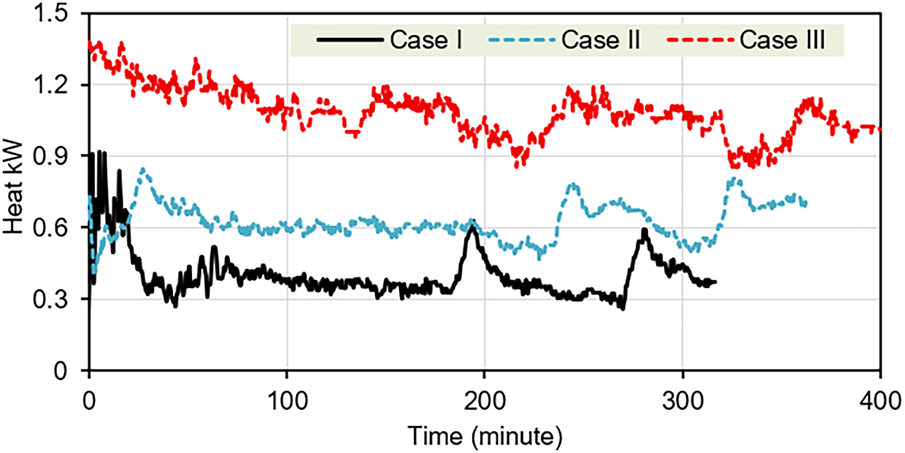

Three experimental tests were conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness and contribution of solar energy in underfloor heating. The three cases reflect different solar energy availability conditions, including clear and cloudy weather. The experiments were carried out under varying conditions but with approximately similar operation durations. The contribution of the electric heater in the three cases was 2.91, 3.00, and 1.82 kWh, respectively. Fig. 5 shows the variation of solar heat added into the buffer tank heating water for three cases.

Figure 5: Variation of solar heat added to the buffer tank in three operating cases

Fig. 6 illustrates the total global solar irradiance (kWh/m2) recorded for Duhok city of Iraq (36.86° Latitude and 42.98° Longitude), where the site of experiments, over selected days between February 19, 2024, and March 16, 2025, for two surface orientations: horizontal and tilted. A collector tilt angle of 50° was used, as this angle enhances solar energy capture, particularly in winter months when solar angles are low. The data clearly indicate that the tilted surface consistently received higher levels of solar irradiance compared to the horizontal surface across nearly all days. From the figure, it is evident that the solar energy received by the inclined collector surface ranges from 1 kWh/m2 on cloudy days to 7 kWh/m2 on clear days. The amount of usable energy will depend on the efficiency of the solar collector. Enhancing efficiency requires minimizing heat losses, which can be achieved using high-quality thermal insulation and secure mounting.

Figure 6: Total global irradiance for horizontal and 50-degree Tilted surface

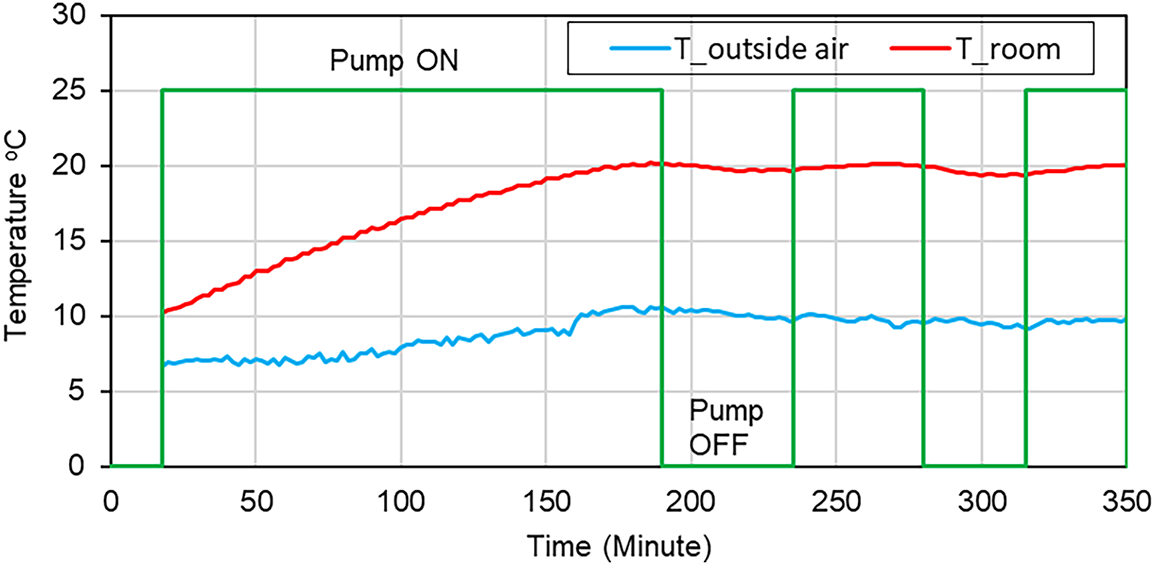

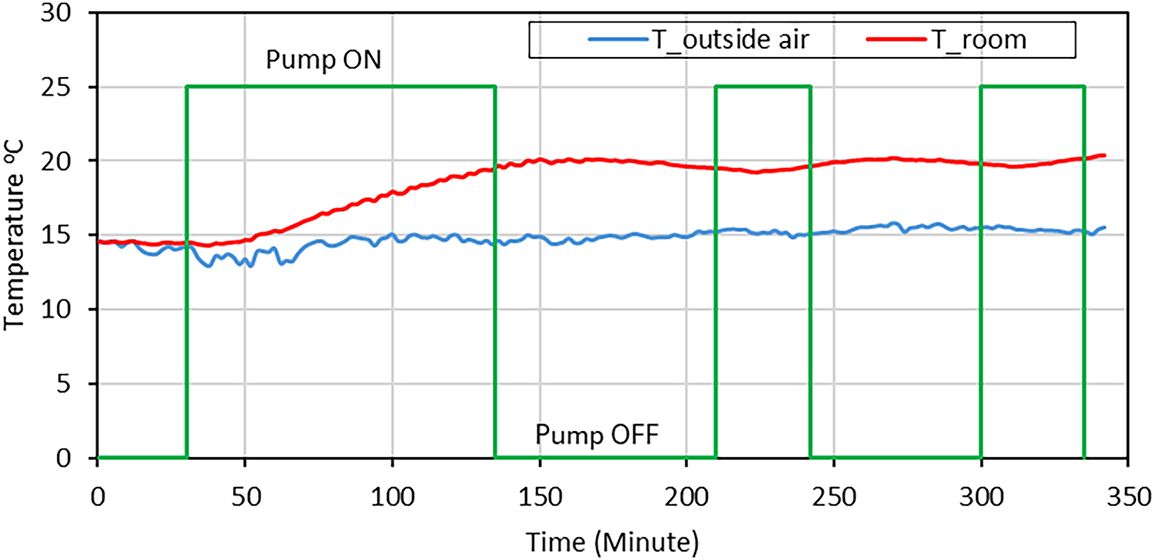

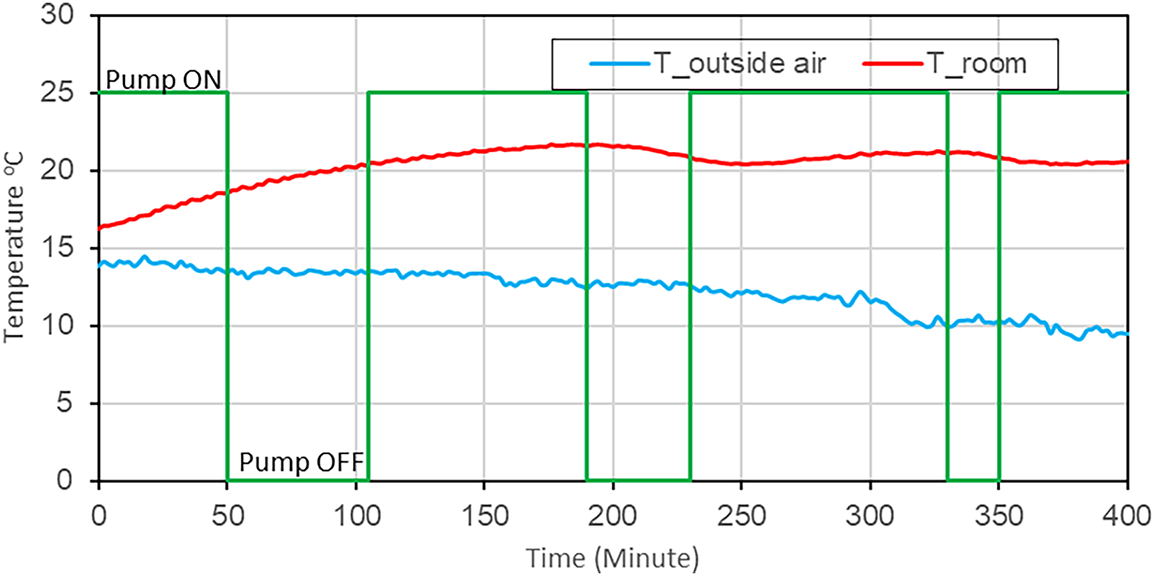

Figs. 7–9 illustrate the variations in both outdoor air temperature and indoor room air temperature, as well as the operational status of the heating circulation pump (ON/OFF) throughout the experiment duration. The pump ceases operation when the room temperature reaches 21°C and resumes operation when the room temperature falls below 20°C. The duration of each experiment was performance-based, requiring the test to continue until two full thermal cycles (pump deactivation and reactivation) were successfully completed to ensure data stability.

Figure 7: Variation of temperature and volume flow rate of underfloor heating water (Case I)

Figure 8: Variation of temperature and volume flow rate of underfloor heating water (Case II)

Figure 9: Variation of temperature and volume flow rate of underfloor heating water (case III)

In the first case, shown in Fig. 7, the outdoor air temperature ranged between 7°C–10°C, and the water flow rate averaged approximately 90 L/h during a pump operation period of about 260 min within a total heating period of 340 min.

In the second case, illustrated in Fig. 8, the outdoor air temperature ranged from 14–16°C, and the average volumetric flow rate was around 95 L/h for an operational period of 160 min during a heating duration of 350 min.

In the third case, depicted in Fig. 9, the outdoor air temperature ranged between 9°C–13°C, and the average water flow rate was approximately 47 L/h during an operational period of 280 min within a total heating duration of 400 min.

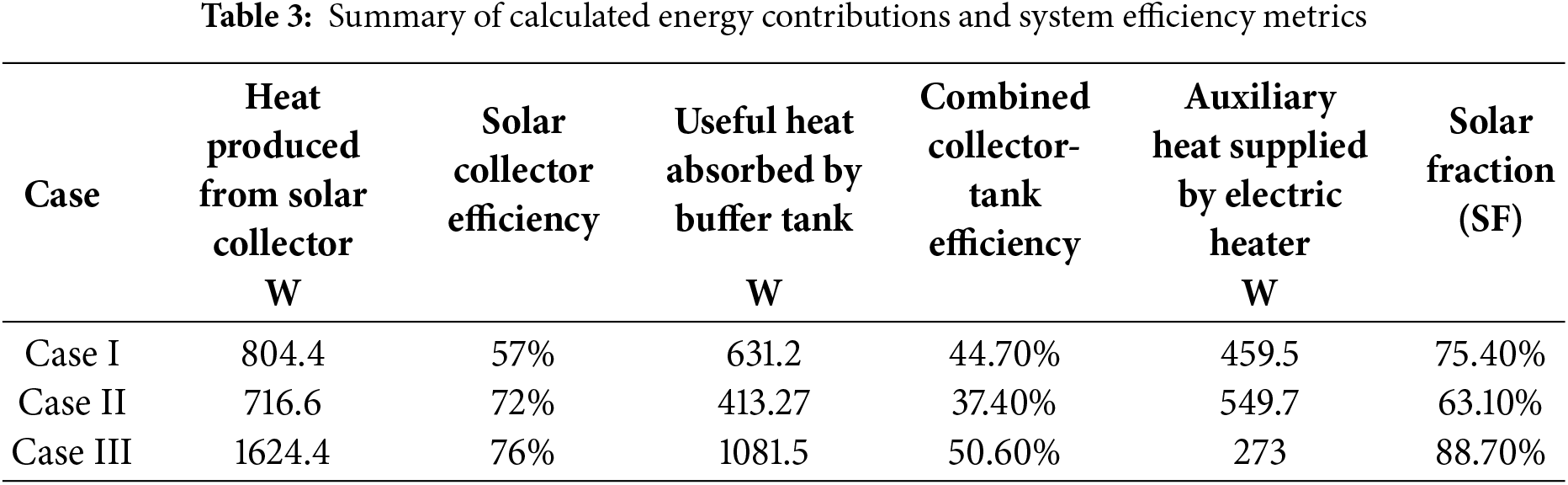

The main energy flow computations and efficiency indicators for the three different operational scenarios are compiled in Table 3. With an emphasis on the Solar Fraction (SF), this data offers the fundamental quantitative evidence for the study’s objective. With the SF ranging from 63.1% to a maximum of 88.7% in Case III, the results clearly show the system’s high efficiency. This high percentage confirms the study’s potential for significant electrical load displacement and quantifies the system’s capacity to maximise the use of renewable energy. Under ideal operating conditions, Case III successfully reduced the dependence on external power sources by achieving this high SF while the auxiliary electric heat drastically decreased to just 273 W. This comparative analysis, which links adjusted flow rates and simulated input to resulting efficiency, is essential for identifying optimal operational strategies.

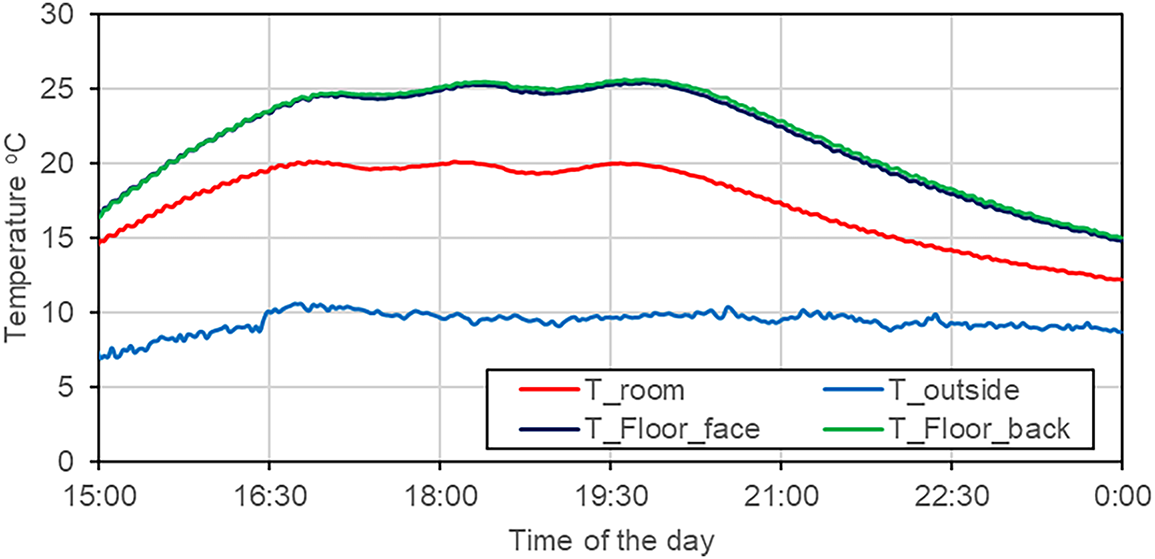

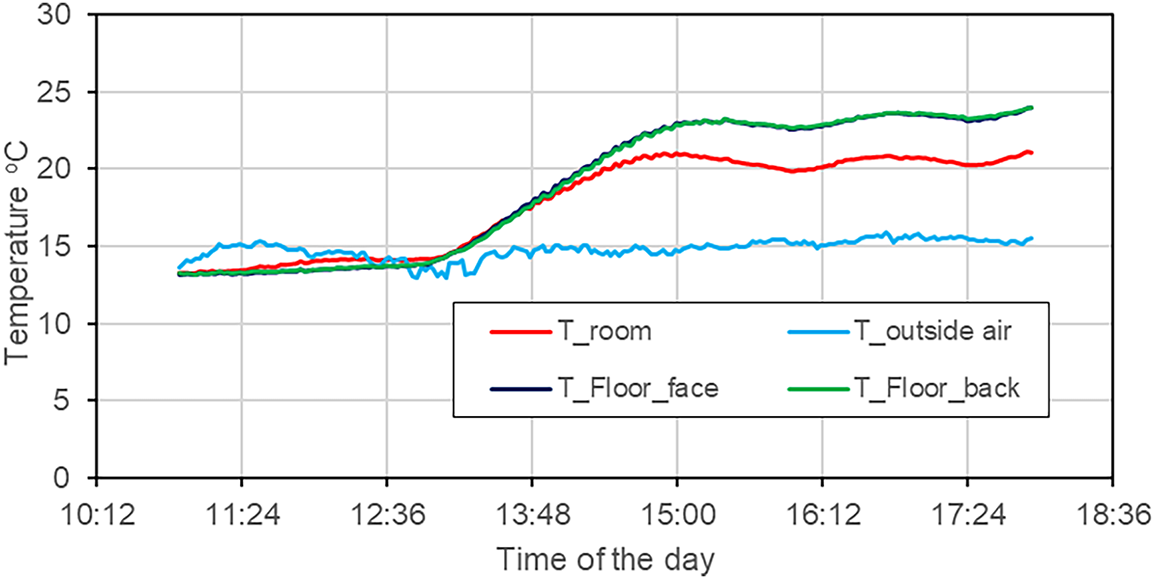

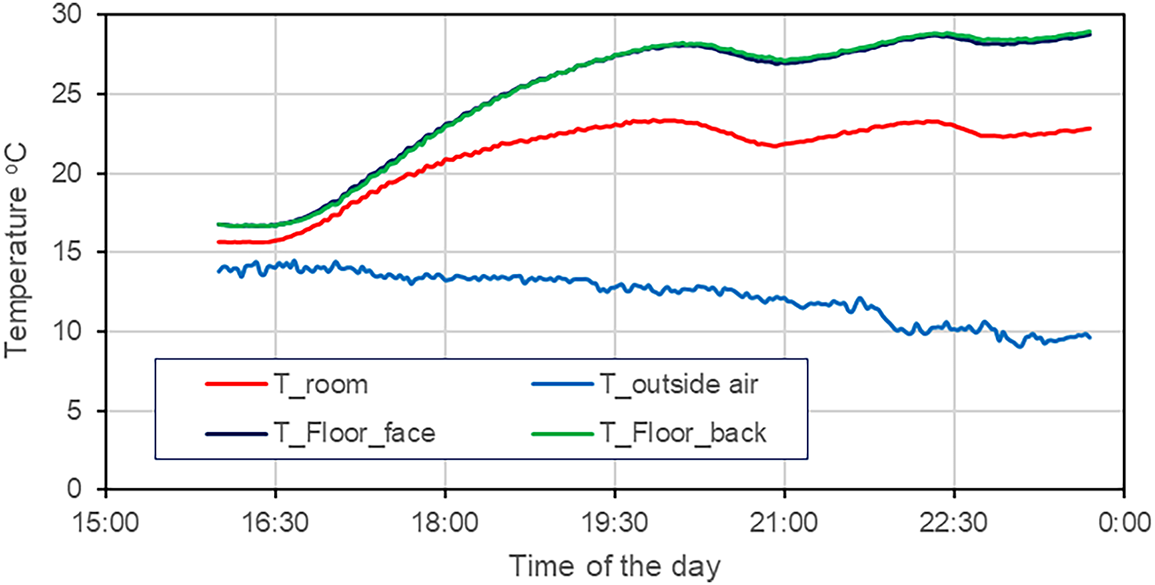

Figs. 10–12 illustrate the variations in both the air temperature and the floor surface temperature inside the room. Here, the x-axis represents the actual time of the experiment, where high heating demand is required. this analysis is critical for thermal comfort validation. For instance, Case I (Fig. 10) demonstrates that despite achieving the air setpoint, the floor temperature experienced a transient drop (from 25°C to 20°C) due to high thermal losses, indicating a need for design adjustments. Crucially, in all operational cases, the figures collectively validate the system’s ability to maintain the floor surface temperature within the required international comfort criteria (typically 25°C to 29°C). This confirmed achievement of satisfactory radiant heat delivery across the floor validates the solar system’s success in providing high-quality thermal comfort.

Figure 10: Room temperature variation over time under the influence of solar collector and heater (Case I)

Figure 11: Room temperature variation over time under the influence of solar collector and heater (Case II)

Figure 12: Room temperature variation over time under the influence of solar collector and heater (Case III)

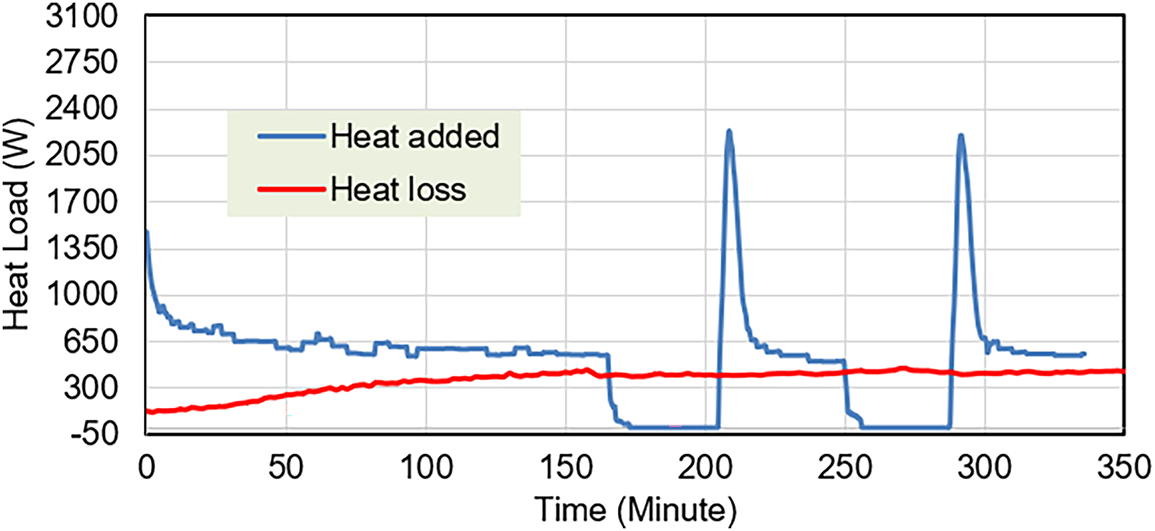

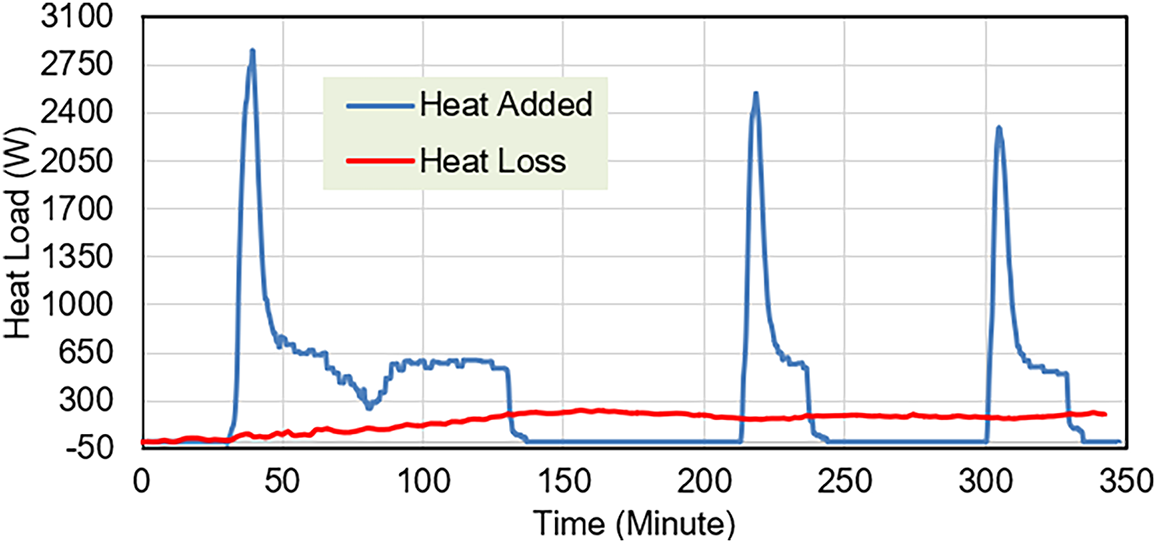

Fig. 13, corresponding to case I, shows that the average heat added during the heating process was approximately 520 W, whereas the heat loss from the room ranged between 100 and 400 W. This variation is attributed to outdoor air temperatures ranging between 6°C and 11°C.

Figure 13: Variation of heating load (Case I)

In case II, depicted in Fig. 14, the average heat added was around 475 W, while heat loss varied from 0 to 250 W. This is because the outdoor air temperature initially was relatively high and close to the indoor temperature (around 15°C).

Figure 14: Variation of heating load (Case II)

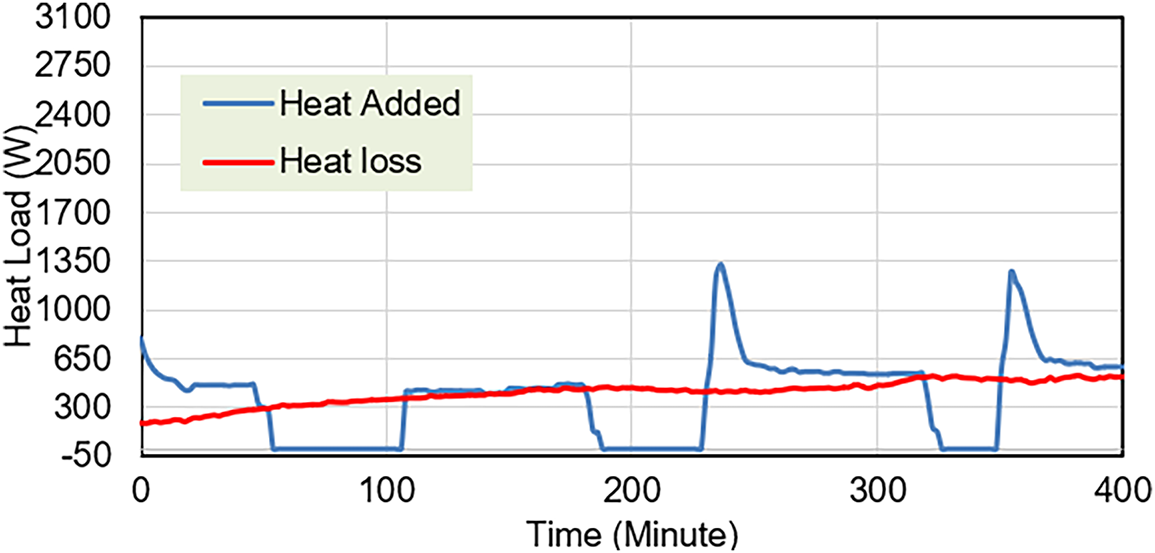

Fig. 15 shows that in case III, the average heat added during the operation of the circulation pump was 500 W. A significant increase in heat loss was observed, ranging from 200 to 500 W, due to the drop in outdoor air temperature to below 10°C.

Figure 15: Variation of heating load (Case III)

The experiments conducted in this study, performed under two types of conditions one controlled within a laboratory environment consisting of a solar collector and a thermal storage tank, and the other under real-world conditions in a test room where thermal comfort was controlled for the air and floor temperatures conclusively confirmed the high potential of the solar-assisted underfloor heating system in enhancing energy efficiency and ensuring reliable thermal comfort. Results showed that a clear correlation between variations in solar irradiance and system performance. The most compelling results came from the solar fraction, the key performance indicator, which varied significantly across the three scenarios, ranging from 63.1% to 88.7%. This high reliance on renewable energy dramatically minimized the need for backup power; consequently, the auxiliary electric heater support was reduced, contributing only 1.82 and 3.00 kWh across the cases.

The system successfully kept the indoor air temperature at its setpoint and, most importantly, maintained the floor surface temperature within accepted world comfort limits. One of the important practical suggestions is to increase the total length of the embedded pipe network. This adjustment would increase the average floor surface temperature, and thereby permit a decrease in the necessary circulating water temperature. This latter aspect is key to the efficiency performance and the sustained delivery of radiant heat flow, leveraging low-grade solar heat as fully as possible.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to the Department of Energy Engineering, Duhok Polytechnic University, for providing the facilities and academic environment essential for conducting this work. Also, the authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the ChatGPT (OpenAI) for its assistance in language refinement and enhancing the overall clarity of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the work as follows: Firas Mahmood Younis: Conceptualization, methodology, experimental work, data collection, formal analysis, and writing—original draft. Omar Mohammed Hamdoon: Data curation, validation, and writing—review & editing. Ayad Younis Abdulla: Supervision, methodology, and writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this study.

References

1. Aste N, Del Pero C, Leonforte F. Toward building sector energy transition. In: Handbook of energy transitions. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2022. p. 127–50. doi:10.1201/9781003315353-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ürge-Vorsatz D, Khosla R, Bernhardt R, Chan YC, Vérez D, Hu S, et al. Advances toward a net-zero global building sector. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2020;45(1):227–69. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-045843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang D, Cai N, Wang Z. Experimental and numerical analysis of lightweight radiant floor heating system. Energy Build. 2013;61:260–6. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.02.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Obaid MJ. Numerical and experimental study of solar water heater in heating a space [master’s thesis]. Najaf, Iraq: Al Furat Al Awsat Technical University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

5. Kalogirou SA. Solar energy engineering: processes and systems. London, UK: Academic Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

6. Duffie JA, Beckman WA. Solar engineering of thermal processes. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013. doi:10.1002/9781118671603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nagar S, Sreenivasa S. Thermal performance investigations of flat plate solar collectors: a holistic and comprehensive review. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2025;150(10):7289–333. doi:10.1007/s10973-025-14084-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mamouri A, Darodi MA, Sherafati S. Floor heating, benefits and solutions to increase system efficiency. J Eng Appl Res. 2024;1(2):199–211. doi:10.48301/JEAR.2024.462443.1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liu Q, Liu Y, Qian F, Xu T, Meng H, Yao Y, et al. Demand response in buildings: comparative study on energy flexibility potential of underfloor heating and air conditioning systems. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;274(3):126801. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.126801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Anigrou Y, Zouini M. Comparative numerical study of floor heating systems using parallel and spiral coil. Sci Afr. 2024;24(11):e02188. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2024.e02188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hassan ZF. Thermal performance analysis of a flat plate solar collector system for heating green-house using nano-fluid [master’s thesis]. Erbil, Iraq: Erbil Polytechnic University; 2022. [Google Scholar]

12. Karimi MS, Fazelpour F, Rosen MA, Shams M. Comparative study of solar-powered underfloor heating system performance in distinctive climates. Renew Energy. 2019;130:524–35. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.06.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Saagoto MS, Sobhan Chowdhury A. A review of solar flat plate thermal collector [technical report]. Gazipur, Bangladesh: Islamic University of Technology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

14. Izquierdo M, de Agustín-Camacho P. Solar heating by radiant floor: experimental results and emission reduction obtained with a micro photovoltaic-heat pump system. Appl Energy. 2015;147:297–307. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Abdelmaksoud WA. Solar energy utilization for underfloor heating system in residential buildings. Energy Rep. 2024;12:979–87. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2024.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Simou Z, Hamdaoui S, Oubenmoh S, El Afou Y, Babaharra O, Mahdaoui M, et al. Thermal evaluation and optimization of a building heating system: radiant floor coupled with a solar system. J Build Pathol Rehabil. 2024;9(1):24. doi:10.1007/s41024-023-00375-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mahmoud M, Ramadan M, Naher S, Pullen K, Olabi AG. The impacts of different heating systems on the environment: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2021;766(25):142625. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Nolan T, Taylor R. Evaluating the performance, design and optimisation of a solar combisystem in the Australian climate. In: Proceedings of the 2015 Asia-Pacific, Solar Research Conference; 2025 Dec 8–10; Queensland, Australia. [Google Scholar]

19. Zeghib I, Chaker A. Efficiency of a solar hydronic space heating system under the Algerian climate. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2016;6(6):1274–9. doi:10.48084/etasr.875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Raisul Islam M, Sumathy K, Khan SU. Solar water heating systems and their market trends. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2013;17(3):1–25. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Khalil SQ, Hamdoon OM, Almakhyoul ZM. Energy consumption enhancement of a solar under floor heating system in a small family house located in Mosul City, Iraq. Al Rafidain Eng J AREJ. 2024;29(1):144–53. doi:10.33899/arej.2024.143521.1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools