Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modelling and Analysis of Enhanced Power Generation by Recovering Waste Heat from Fallujah White Cement Factory for Clean Energy Sustainability

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Karabük University, Karabük, 78050, Türkiye

2 Mechanical Engineering Department, University of Technology-Iraq, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq

3 Training and Workshop Center, University of Technology-Iraq, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq

4 Energy and Renewable Energies Technology Center, University of Technology-Iraq, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Hasanain A. Abdul Wahhab. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Energy Resources and Their Processes, Systems, Materials and Policies for Affordable Energy Sustainability)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(2), 22 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.073702

Received 23 September 2025; Accepted 20 November 2025; Issue published 27 January 2026

Abstract

Improving energy efficiency and lowering negative environmental impact through waste heat recovery (WHR) is a critical step toward sustainable cement manufacturing. This study analyzes advanced cogeneration systems for recovering waste heat from the Fallujah White Cement Plant in Iraq. The novelty of this work lies in its direct application and comparative thermodynamic analysis of three distinct cogeneration cycles—the Organic Rankine Cycle, the Single-Flash Steam Cycle, and the Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle—within the Iraqi cement industry, a context that has not been widely studied. The main objective is to evaluate and compare these models to determine the most effective approach for enhancing energy and exergy efficiencies. The methodology involved detailed thermodynamic and exergy analyses of each system, supported by mathematical modelling and simulation using data from plant operations. The results reveal that the Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle emerged as the most effective system, delivering 13.76 MW of net power with a thermal efficiency of 32.8% and an exergy efficiency of 51%. This significantly outperformed the baseline Organic Rankine Cycle (8.18 MW, 18.8% thermal efficiency, 30.7% exergy efficiency). These findings confirm that multi-pressure steam cycles offer a robust and practical solution for the Fallujah plant. This application provides a clear, high-impact pathway to enhance national industrial energy efficiency, significantly reduce CO2 emissions, and promote clean energy sustainability in Iraq. Future work should consider economic feasibility and potential integration with renewable energy sources to further enhance sustainability.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| AQC | Air quenching cooler |

| SP | Suspension preheater |

| RC | Rankine cycle |

| CDM | Clean development mechanism |

| CDT | Clean development techniqe |

| EES | Engineering equation solver |

| ORC | Organic rankine cycle |

| ORT | Organic rankine turbine |

| Symbols | |

| P | Pressure (MPa) |

| T | Temperature (°C) |

| h | Enthalpy (kJ/kg) |

| s | Entropy (kJ/kg·K) |

| ηth | Thermal efficiency (%) |

| ηex | Exergy efficiency (%) |

| m | Mass flow rate (kg/s) |

| Turbine work (kW) | |

| Pump work (kW) | |

| Net output power (kW) | |

| Heat input (kW) | |

| Heat rejected (kW) | |

| Ex | Exergy (kW) |

| ΔT | Temperature difference (°C) |

| ΔP | Pressure difference (MPa) |

| x | Dryness fraction (–) |

| V | Specific volume (m3/kg) |

Cement production stands as one of the most energy-intensive industrial processes, with energy costs representing a substantial portion of operational expenses. Energy consumption accounts for 40%–60% of manufacturing costs in cement plants [1], while surveys indicate that cement manufacturing plants spend approximately 40% of their capital on energy resources and fossil fuels [2,3]. The most energy-intensive stage occurs during clinker formation in the rotary kiln, which consumes 85% of the total energy in typical dry processes [4]. The clinker production sub-process alone uses three-quarters of the total energy input as combustion heat [5,6].

A significant portion of this energy input is lost as waste heat through various pathways. Studies indicate that 35%–40% of the total heat input is dissipated as waste heat [7,8]. The primary sources of waste heat include radiated and convective heat losses from kiln surfaces (approximately 15.11% of total energy loss), exhaust flue gas and hot air from kiln and cooler stacks (around 24.76% of total energy loss), suspension preheater flue gas, and clinker cooler hot air [9,10]. These flue gases, which contain high amounts of thermal energy and are emitted at temperatures in the hundreds of degrees Celsius, represent the most significant opportunity for waste heat recovery [11]. The recovery of this waste heat presents considerable potential for economic, environmental, and social benefits when integrated into existing power generation systems [11]. Heat recovery systems can increase energy efficiency by nearly 20% while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and helping combat global warming [12]. For cement plants with daily production capacities of up to 6000 t, waste heat recovery systems can potentially generate 5.9 MW of electrical energy, save 82.5 t of fuel oil consumption per day, and reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 99.12 t per day [5,13].

Multiple technologies have been developed and implemented for waste heat recovery in cement manufacturing, each suited to different temperature ranges and operational requirements [8]. Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) systems represent one of the most suitable options for cement plant applications, particularly effective for flue gas temperatures in the 200°C–300°C range from suspension preheaters and air-quenching coolers (AQC) [13]. Ahmed et al. [8] discussed the design and application of an ORC system that converts low- and medium-temperature heat sources (80°C–300°C) into power using organic fluids instead of water. The study uses actual data from a cement factory and selects R134a as the working fluid due to its suitability for the given conditions. Basheer et al. [14] investigated the possibility of delivering hybrid energy to Pakistani cement plants. Five cement plants were selected, and the feasibility of implementing four off-grid hybrid energy models (HEMs) for these plants was evaluated using HOMER Pro. Mossie et al. [15] presented a case study in the Ethiopian cement industry, identifying the steam Rankine cycle as the most feasible waste heat recovery option. This option is capable of producing 8.9 MW of power, covering 18% of the plant’s electricity demand. Hamdan et al. [16] studied a new waste heat recovery system, designed to preheat clinker, which is projected to reduce a cement factory’s petroleum coke consumption by 22,005 t per year, cutting the annual carbon footprint by 68,905 t of CO2. Turakulov et al. [17] conducted a techno-economic analysis of a cement plant in Uzbekistan and found that implementing waste heat recovery could reduce clinker production costs by 3.81%, decrease indirect CO2 emissions by 63.26%, and lower the levelized cost of clinker by 7.49%. Fergani et al. [18] investigated the application of an ORC system for waste heat recovery in the cement industry using three working fluids: cyclohexane, benzene, and toluene. Results from simulation and optimization highlight the potential of ORC for efficient and sustainable power generation in industrial applications. Pili et al. [19] evaluated the potential of ORC technology for generating electricity from industrial waste heat in Germany, focusing on steel, cement, and glass manufacturing. Results show that while only 10–15% of the theoretical waste heat potential can be practically converted, the economic potential remains significant, with annual electricity savings of 2.0–3.8 TWh and an ORC capacity of 227–435 MWe. The steel industry shows the highest potential (1.3–2.3 TWh/year), followed by cement (0.7–1.3 TWh/year) and glass (0.1–0.4 TWh/year). Moreira and Arrieta [20] evaluated the thermodynamic and economic performance of simple and regenerative ORCs for waste heat recovery in Brazilian cement factories. Using optimization with the genetic algorithm method, the best-performing working fluids were identified as R141b, R11, and R123, offering high net power output, thermal efficiency, and exergy efficiency. Results indicate that ORCs could generate between 4000–9000 kW (~80 MW), avoid around 221,069 kg CO2/year, and achieve payback periods of less than two years, with internal rates of return exceeding 80%/year.

Advanced cycle configurations have also been explored for enhanced performance. Júnior et al. [21] evaluated the Kalina cycle for electricity generation from exhaust gases in a Brazilian cement factory with a production capacity of 2100 t of clinker per day. The Kalina cycle achieved a power output of about 2429 kW, with thermal and exergetic efficiencies of 0.233 and 0.478, respectively. Mirolli [22] highlighted the potential of the Kalina Cycle as an efficient and eco-friendly solution for waste heat recovery in cement production. By utilizing hot gases from cement processes, the Kalina Cycle can improve thermal efficiency by 20–40% compared to conventional systems, generating electricity without additional fuel consumption. Steam-organic combined cycle optimization studies have identified optimal operating parameters for maximum efficiency and economic performance. Chen et al. [10] proposed a novel waste heat recovery system (WHRS) for cement plants, integrated with the heat regeneration process of a coal-fired power plant. By channeling exhaust heat from cement production into the steam cycle of the coal plant, the system significantly enhances waste heat utilization. Results show that the new WHRS generates 6.75 MW more net power compared to conventional systems, with improvements of 18.11% in power generation efficiency and 8.11% in net thermal efficiency. Khater et al. [13] explored waste heat recovery in white cement plants using different Rankine cycles. Spiro-pentane showed the best performance, but cyclopentane was recommended for its low cost and availability. The steam-organic combined Rankine cycle was found to be most efficient, offering higher power output and lower capital costs than the conventional steam Rankine cycle. Amiri Rad and Mohammadi [23] examined waste heat recovery at the Sabzevar cement factory using a steam cycle. Results showed that boiler pressure strongly influenced energy and exergy performance. Maximum exergy absorption was achieved at 891.8 kPa, while the highest net power output and efficiencies occurred at 1398 kPa. Aboelwafa et al. [24] investigated Rankine cycles for power generation in cement plants using waste heat from three temperature ranges. Six organic fluids plus water were tested, focusing on efficiency and suitability. Methanol showed the best performance, achieving the highest net power output, efficiency, and lowest irreversibility, along with the shortest payback period of 4 years. Thus, methanol is recommended as the optimal working fluid for waste heat recovery in cement industries.

Although many studies have explored waste heat recovery in cement plants worldwide, few have addressed the specific conditions of Iraqi factories such as the Fallujah White Cement Plant, where energy losses remain high and utilization technologies are underdeveloped. The novelty of this study lies in applying comparative energy and exergy analyses of three cogeneration cycles, organic Rankine, single steam flash, and dual-pressure steam, to identify the most effective solution under local operational constraints.

The objective is to evaluate the technical and thermodynamic performance of these cycles and determine their feasibility for clean energy sustainability. The methodology involves modeling and simulation of heat recovery systems using actual plant data, followed by performance analysis of thermal efficiency, exergy efficiency, and power output. The importance of this research stems from its potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve plant efficiency, and provide practical recommendations for the Iraqi cement industry. Limitations include reliance on plant-specific data and assumptions in modeling, which may restrict the generalizability of findings to other contexts.

Cement production is one of the most energy-intensive industrial processes, with thermal energy consumption accounting for nearly half of its total production cost and contributing significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions. Improving energy efficiency through waste heat recovery (WHR) is therefore a critical step toward sustainable cement manufacturing. This work presents a novel thermal waste recovery analysis, making a significant contribution to the field by demonstrating a clear path to large-scale energy savings and environmental sustainability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the methodology, presenting the system configurations for the Organic Rankine Cycle, Single-Flash Steam Cycle, and Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle, along with the thermodynamic and exergy models used for the analysis. Section 3 presents and critically discusses the performance results, comparing the net power output, thermal efficiency, and exergy efficiency of the three cycles. Finally, Section 4 provides the main conclusions of the study, offering specific recommendations for implementation based on the findings.

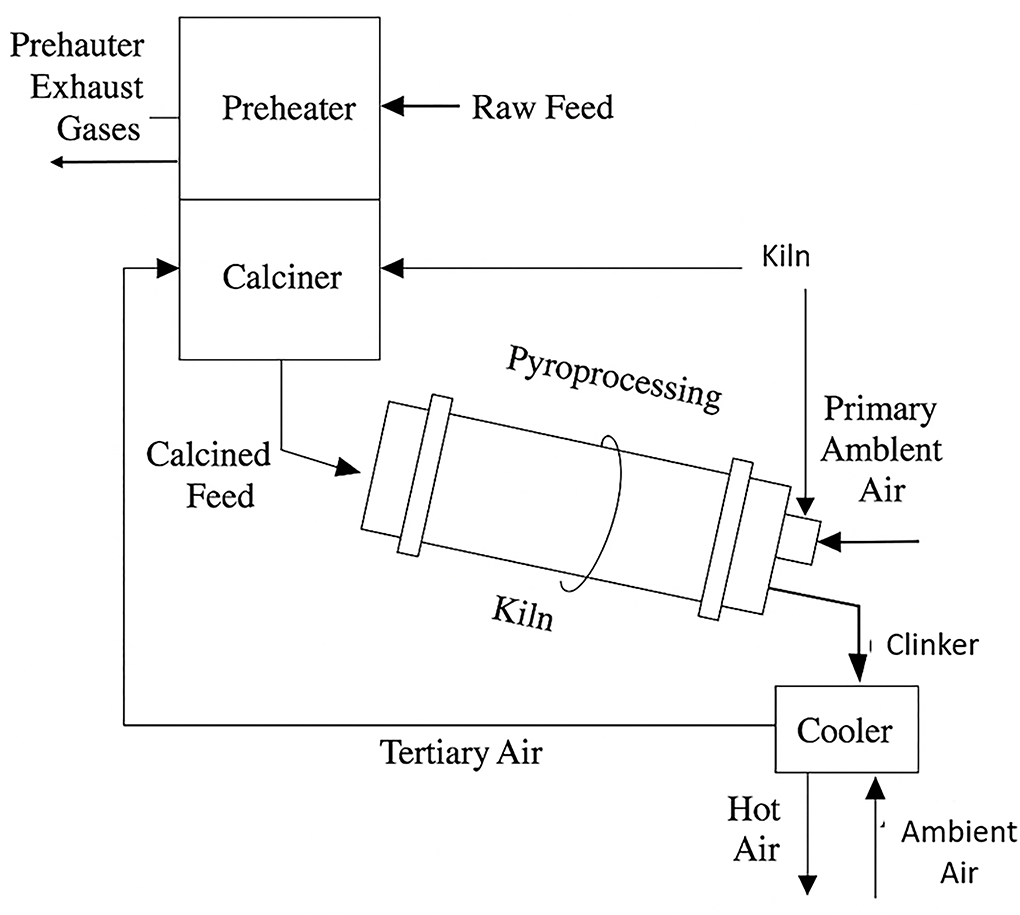

Fig. 1 illustrates a schematic of the dry-process cement line. The two primary sources of high-temperature waste heat suitable for recovery are the suspension preheater (SP) exhaust and the clinker cooler (AQC) exhaust. As hot flue gases exit the preheater (approximately 379°C for this plant) and hot air exits the clinker cooler (approximately 349°C), they carry away a significant amount of thermal energy. These two streams represent the main opportunity for implementing the waste heat recovery systems analyzed in this paper.

Figure 1: Schematic of a dry-process cement plant identifying the main waste heat recovery sources (Suspension Preheater Exhaust and Clinker Cooler Exhaust)

All simulations for this study were performed using the Engineering Equation Solver (EES) software. To simulate the system’s net power and performance, the following thermodynamic assumptions were applied:

• The entire system is modeled as operating at a steady state.

• Changes in kinetic and potential energy across all components are considered negligible.

• Major components (turbines, pumps) are assumed to be adiabatic, with no heat loss to the surroundings.

• Pressure drops in the boilers, condenser, and all connecting pipes are neglected. Heat addition and rejection are modeled as isobaric (constant pressure) processes.

• The working fluid at the condenser outlet is a saturated liquid.

• For the exergy analysis, the environment (dead state) conditions are defined as T0 = 25°C and P0 = 101.325 kPa.

This study applies a thermodynamic and exergy-based methodology to assess the potential of WHR at the Fallujah White Cement Plant in Iraq. Three cogeneration models: the ORC, the Single Flash Steam Cycle, and the Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle, were developed and analyzed under actual plant operating conditions.

2.1 Organic Rankine Cycle for Waste Heat Recovery

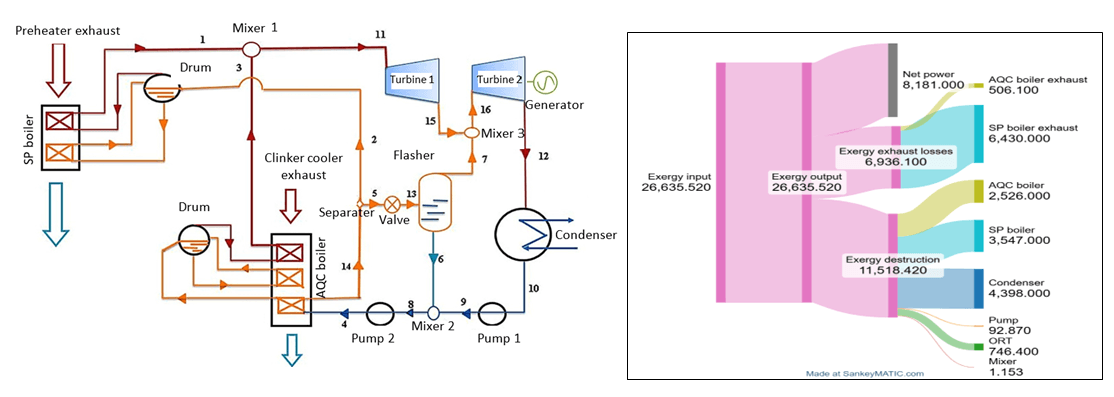

The ORC is considered one of the most effective methods for utilizing waste heat. Fig. 2 illustrates the ORC applied at the Fallujah White Cement Plant for WHR. The ORC is particularly suitable for low- to medium-temperature heat sources, making it effective for cement plant applications where large amounts of waste heat are available.

Figure 2: Process flow diagram of the organic rankine cycle (ORC) for waste heat recovery from preheater and clinker cooler exhausts at the Fallujah white cement plant

The system utilizes exhaust gases from both the preheater and the clinker cooler to generate thermal energy in the SP boiler and AQC boiler. The organic working fluid is pressurized by a pump, heated in the boilers, and then expanded in a turbine to generate power, while the condenser ensures fluid recirculation.

In the ORC configuration, R245fa was selected as the working fluid due to its favorable thermophysical properties for low- to medium-grade heat recovery. It offers a low boiling point, good thermal stability, and compatibility with the temperature range of the waste heat streams from the cement plant.

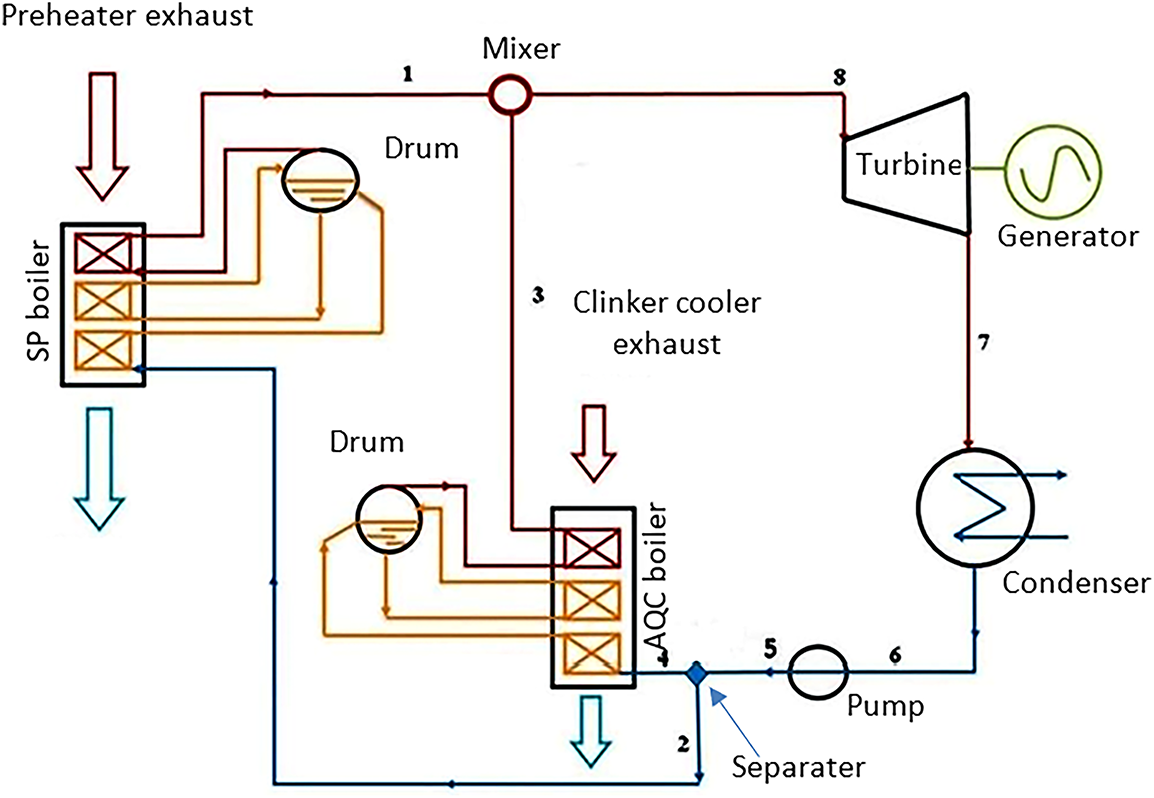

2.2 Single Flash Steam Cycle for Waste Heat Recovery

Fig. 3 illustrates a Single Flash Steam Cycle (SFSC) for WHR at the Fallujah White Cement Plant. The system is designed to capture waste heat from cement production exhaust gases (preheater exhaust and clinker cooler exhaust) and convert it into useful power through steam turbines. Preheater exhaust and clinker cooler exhaust are the main sources of waste heat in cement production. The gases pass through the SP boiler and AQC boiler, where their heat is recovered to generate steam. The recovered heat produces steam in both boilers, which is collected in drums. A steam and water mixture flows into a separator, where steam is separated from liquid water. The separated steam is directed towards the turbine system, while the water is recirculated with the help of pumps. Steam first enters Turbine 1, where it expands and generates power (point 11 → 15). Partially expanded steam is then directed through a flasher and mixers, where additional flash steam is produced from the hot water. His secondary steam is routed into Turbine 2 (point 16 → 12), providing an extra stage of power generation. Exhaust steam from Turbine 2 flows to the condenser (point 12 → 10), where it is cooled back into liquid form. The condensed water is then pressurized by pumps 1 and 2, passed through mixers, and recirculated into the cycle to repeat the process. Mixers combine different streams of steam or water to optimize energy use. Flasher generates additional steam by flashing high-pressure water into low-pressure steam, increasing cycle efficiency. Pumps maintain circulation and pressure for the working fluid.

Figure 3: Process flow diagram of the single-flash steam cycle for waste heat recovery from preheater and clinker cooler exhausts at the Fallujah white cement plant

The SFSC system utilizes both preheater and clinker cooler exhaust gases, maximizing waste heat recovery, and increases power generation efficiency by employing two turbines and a flash system. At the same time, it reduces cement plant energy consumption and reliance on grid electricity, and is environmentally beneficial, as it lowers CO2 emissions by recycling waste heat.

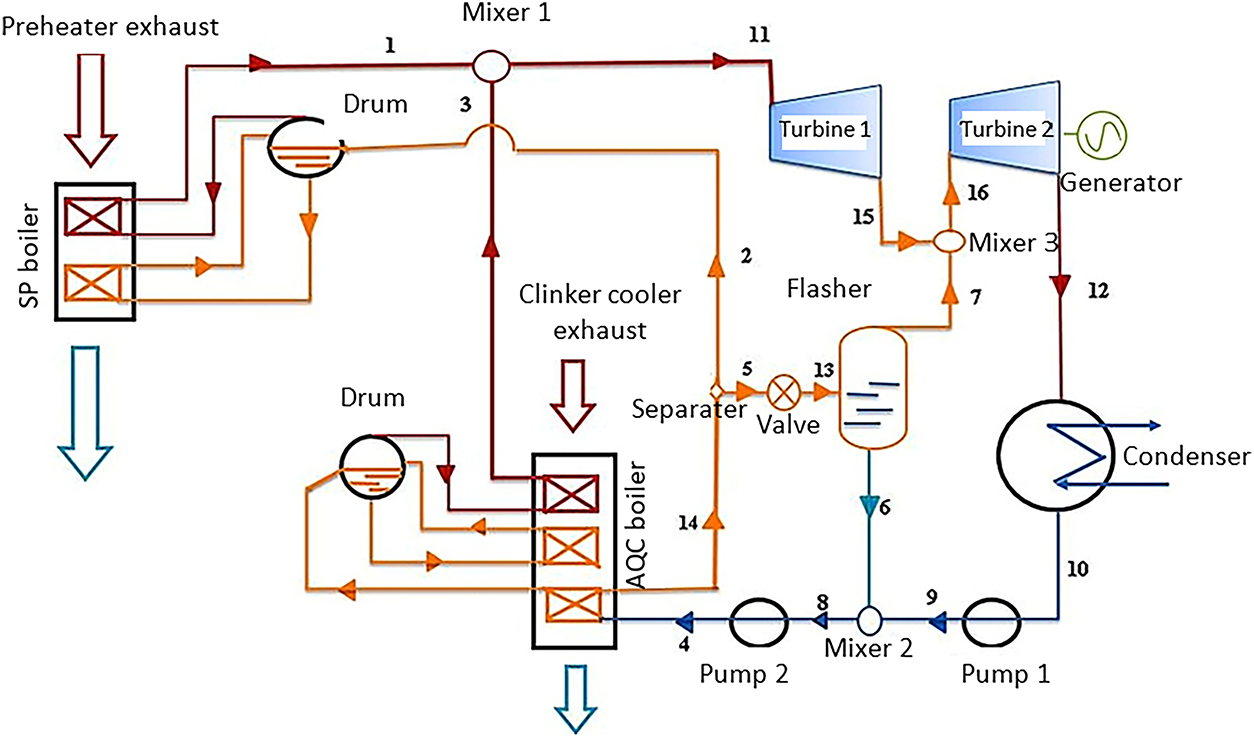

2.3 Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle for Enhanced Waste Heat Utilization

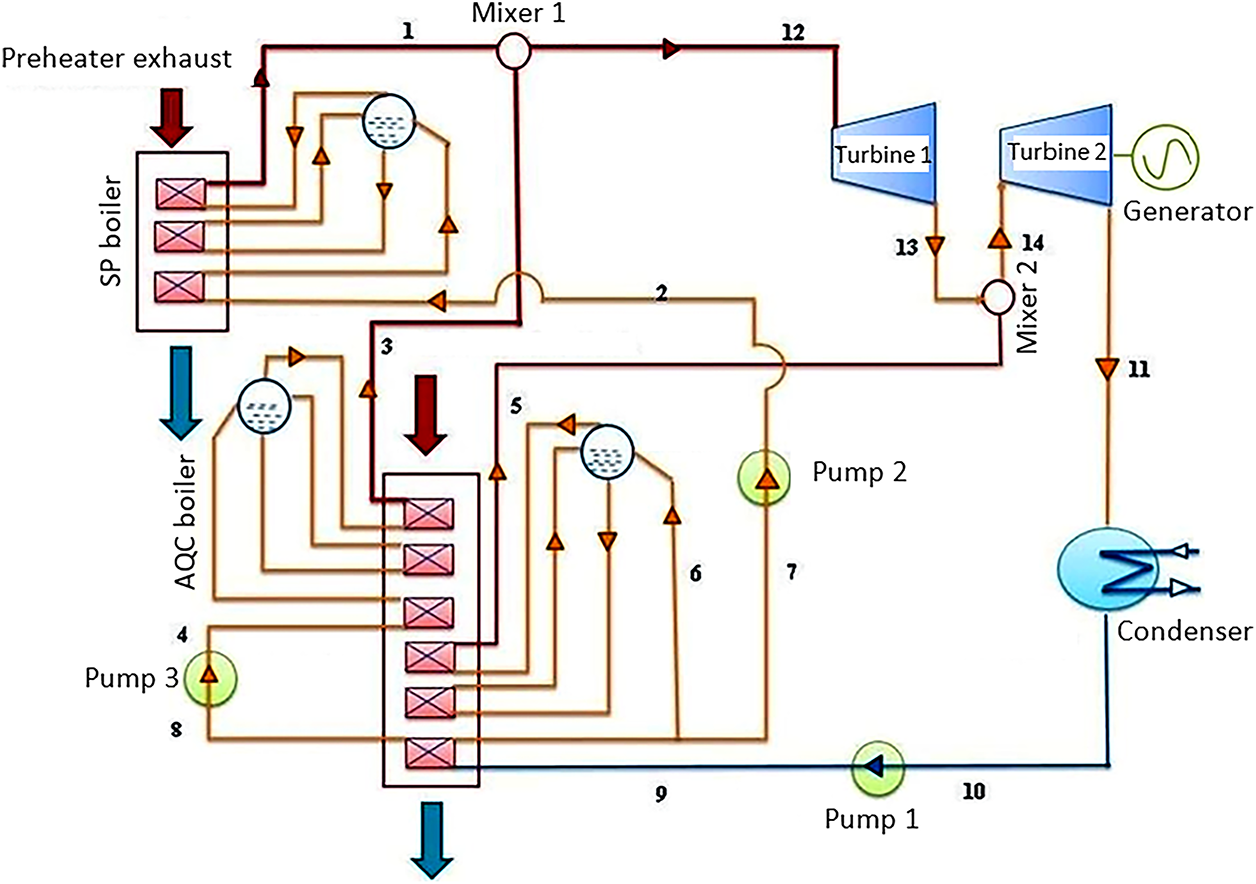

Fig. 4 presents a Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle (DPSC) for WHR at the Fallujah White Cement Plant. The DPSC has higher efficiency than the single-flash cycle, since it captures heat at multiple temperature levels, and it reduces waste heat losses by using both high- and low-pressure steam streams. Also, it increases total power output, making it suitable for large-scale cement plants with high exhaust flow, and improves plant economics by reducing electricity purchase and lowering CO2 emissions. Unlike the single-flash steam cycle, this system operates with two pressure levels to better utilize the available waste heat from the cement production process. Also, preheater exhaust and clinker cooler exhaust gases are the main waste heat sources, and these gases pass through boilers. The SP boiler utilizes hot gases from the preheater. The AQC boiler uses waste heat from clinker cooling. The drum system collects a steam-water mixture and separates it. High-pressure steam is generated from the hotter sections of the SP boiler and AQC boiler. Low-pressure steam is simultaneously produced in other boiler sections where exhaust gases are cooler. This dual-level generation ensures maximum recovery of heat from gases with varying temperatures. High-pressure steam is directed to Turbine 1 (line 12 → 13), where it expands and generates power. After expansion, the exhaust steam is mixed with the low-pressure steam (from the AQC boiler and drum) at Mix 2. The combined flow then enters Turbine 2 (line 14 → 11), where additional expansion occurs, producing more power. The steam leaving Turbine 2 passes into the Condenser (line 11 → 10), where it is cooled and converted back to water. Pumps pressurize the condensed water and circulate it back to the SP and AQC boilers. This maintains a closed-loop cycle, continuously recovering waste heat and producing power.

Figure 4: Process flow diagram of the Dual-pressure steam cycle for waste heat recovery from preheater and clinker cooler exhausts at the Fallujah white cement plant

Energy analysis is vital for assessing system performance and guiding design. Using the first law of thermodynamics, this study evaluates the energy efficiency of the developed system, with the following equations showing energy conservation for each component [25,26].

The developed model’s first law efficiency is calculated as [27]:

Exergy analysis is a powerful tool for improving energy efficiency, as it quantifies a system’s potential for useful work. It is widely used to model and predict thermal behavior, with the overall balance for each component expressed as [28]:

The exergy of each state point can be considered as:

The exergy destruction of each part will be calculated using the exergy balance equation as follows [29]:

The stream exergy rate is obtained by the following relations [30,31]:

The developed model’s second law efficiency is calculated as [27]:

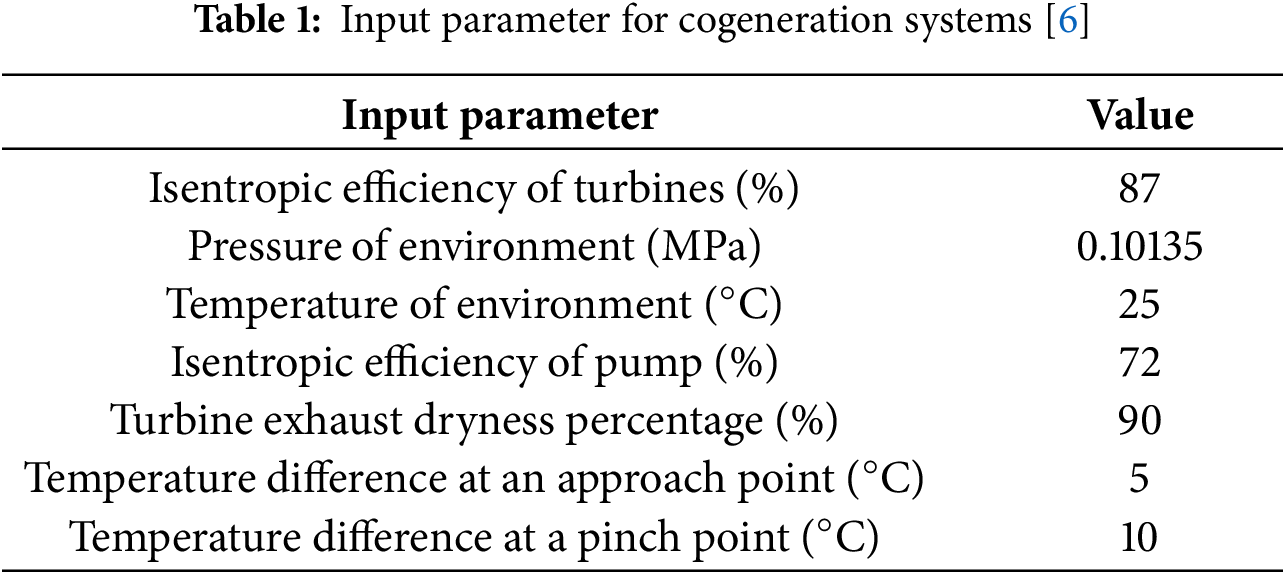

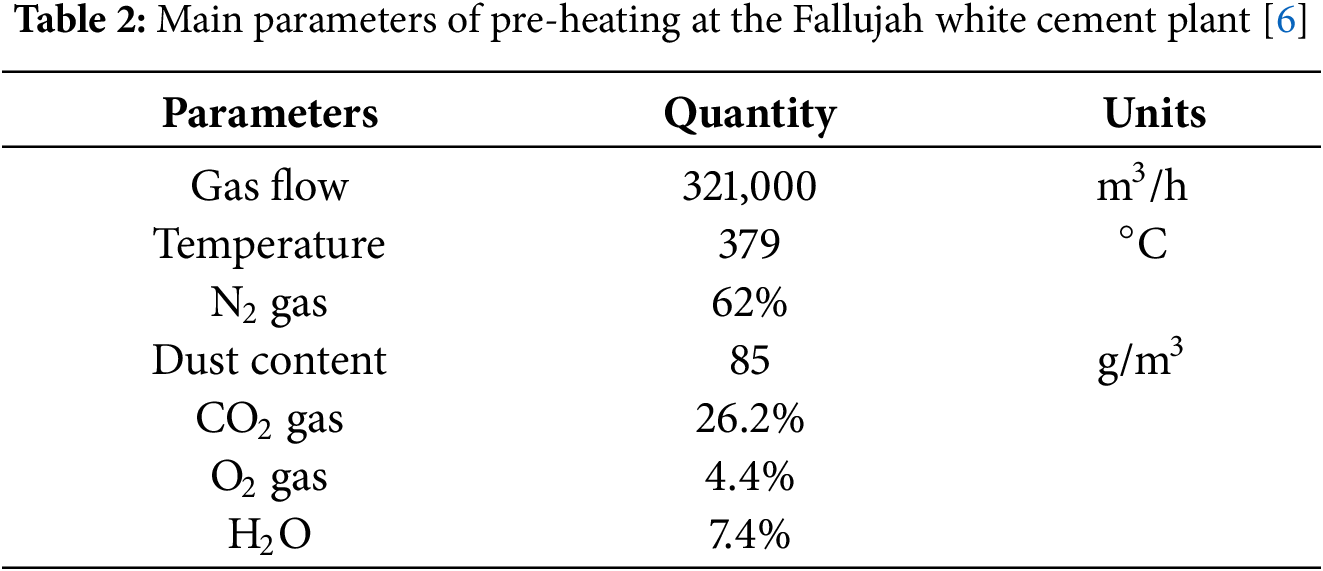

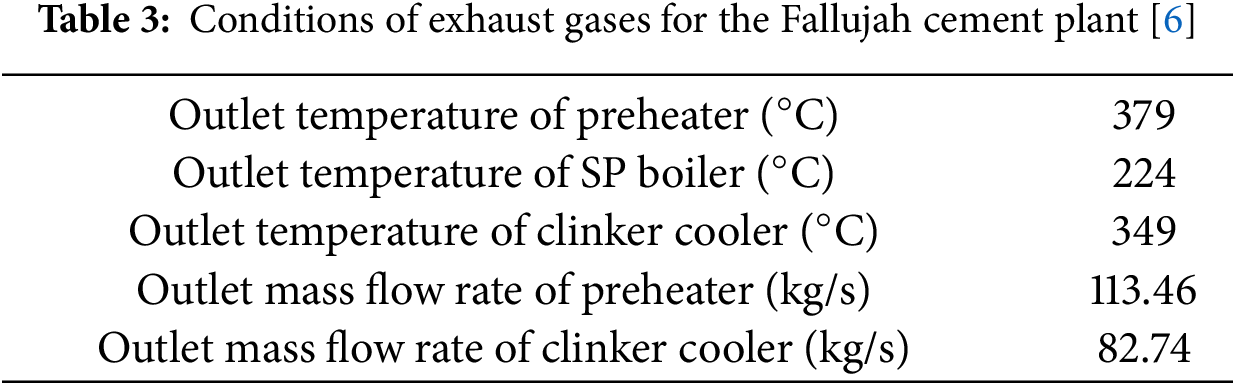

2.5 Cogeneration Systems Input Parameters

The input parameters used for the cogeneration system modeling were obtained from operational data of the Fallujah White Cement Plant, design specifications of the existing equipment, and standard thermodynamic property tables. Plant data include average mass flow rates, gas compositions, and temperature profiles of exhaust gases from the suspension preheater and clinker cooler. Material and thermal properties such as specific heats and enthalpies were derived from standard references. These parameters formed the basis for the mathematical modeling of the organic Rankine cycle, single-steam flash cycle, and dual-pressure steam cycle. Table 1 presents the general input parameters of the cogeneration systems, including gas flow rates, chemical composition, and baseline thermal conditions. These values were derived from actual plant measurements and standard references, serving as the foundation for the subsequent simulations.

Table 2 lists the design specifications of the suspension preheater and clinker cooler, highlighting their thermal and operational characteristics. These parameters were used to define the boundary conditions for waste heat recovery and to evaluate the potential of integrating cogeneration cycles.

Table 3 provides the thermodynamic properties of the working fluids and gases relevant to the cogeneration analysis. Specific heat, enthalpy, and entropy values were obtained from property tables and applied to calculate energy and exergy balances across the system.

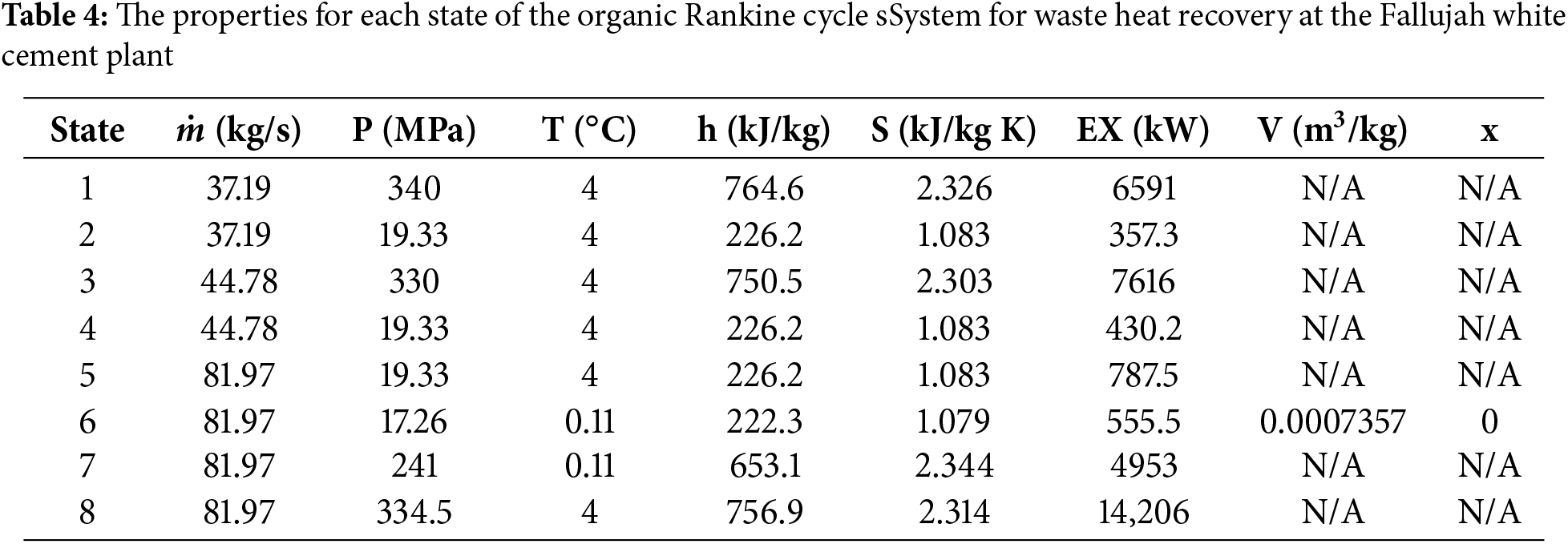

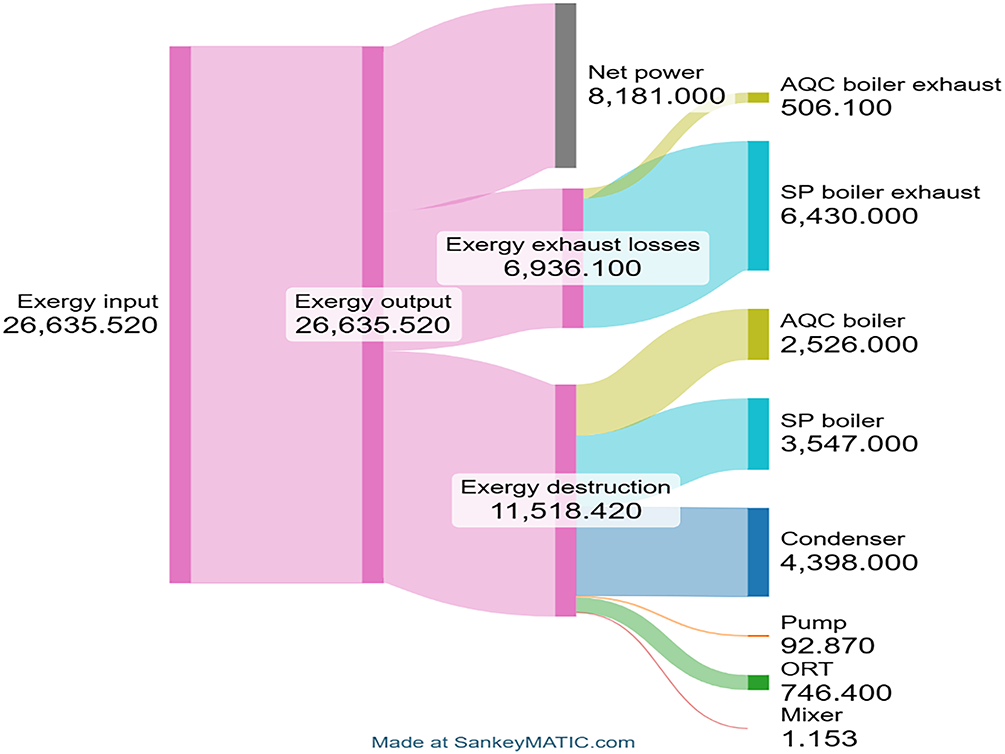

The ORC analysis results are summarized in Tables 4–6. Table 4 lists the thermodynamic properties at each state of the ORC system and summarizes the key performance indicators of the ORC implemented at the Fallujah White Cement Plant. The turbine generates 8506 kW of power, which is the primary contributor to the net output. The pump work is relatively small (324.9 kW). The exhaust temperature of the AQC boiler is maintained at 70°C, ensuring safe operation, preventing condensation, and minimizing thermal losses. The heat input is divided between the AQC boiler (23,480 kW) and the suspension preheater (SP) boiler (20,022 kW), giving a total input of 43,502 kW. The net power output of the cycle is 8181 kW, indicating strong potential for energy recovery from existing waste streams. From an exergetic perspective, the efficiency is 30.72%, suggesting that a significant portion of the available work potential is converted into useful power. The thermal efficiency of 18.81% is typical for ORC systems operating with low- to medium-grade waste heat sources. Overall, these results highlight the viability of the ORC system in enhancing plant energy efficiency, reducing dependence on external electricity, and contributing to CO2 emissions reduction.

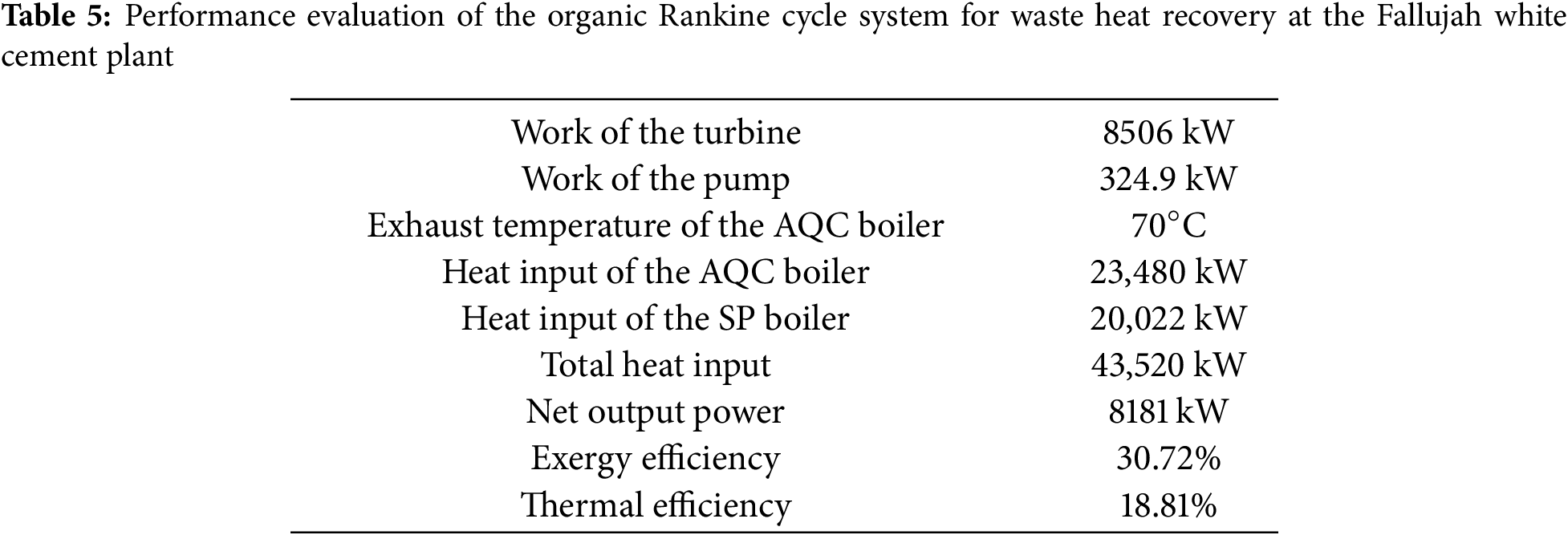

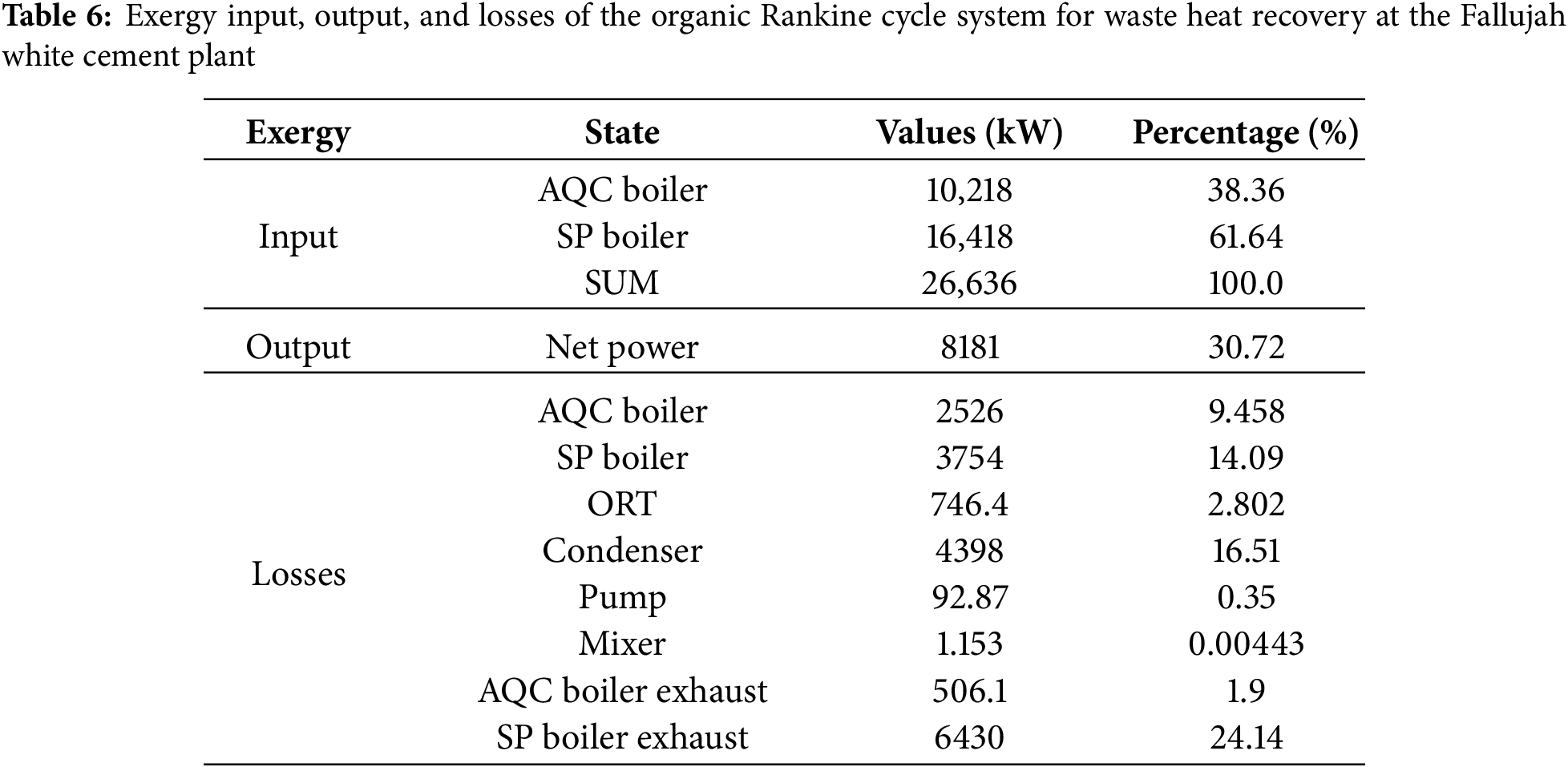

Fig. 5 and Table 6 present a comprehensive view of the exergy performance of the ORC system designed for waste heat recovery at the Fallujah White Cement Plant. The total exergy input to the system is 26,636 kW, primarily supplied by the SP boiler (16,418 kW, 61.64%) and the AQC boiler (10,218 kW, 38.36%). This indicates that the SP boiler is the dominant contributor of thermal energy in the plant, consistent with the operational characteristics of cement manufacturing.

Figure 5: Sankey diagram of exergy flow in the organic Rankine cycle waste heat recovery system at Fallujah white cement plant

The system delivers a net power output of 8181 kW, which corresponds to 30.72% of the total exergy input, showcasing the effectiveness of the ORC process in converting otherwise wasted heat into useful electricity. The largest share of exergy destruction is observed in the SP boiler (3754 kW, 14.09%), followed by the AQC boiler (2526 kW, 9.46%) and the condenser (4398 kW, 16.51%). Together, these three components account for more than 40% of the total exergy input, making them the critical areas where optimization could yield substantial performance improvements. The ORT (746.4 kW, 2.80%), pump (92.87 kW, 0.35%), and mixer (1.15 kW, 0.0044%) represent relatively minor contributions to overall losses. Exergy exhaust losses are also considerable, particularly from the SP boiler exhaust (6430 kW, 24.14%), with a smaller contribution from the AQC boiler exhaust (506.1 kW, 1.9%).

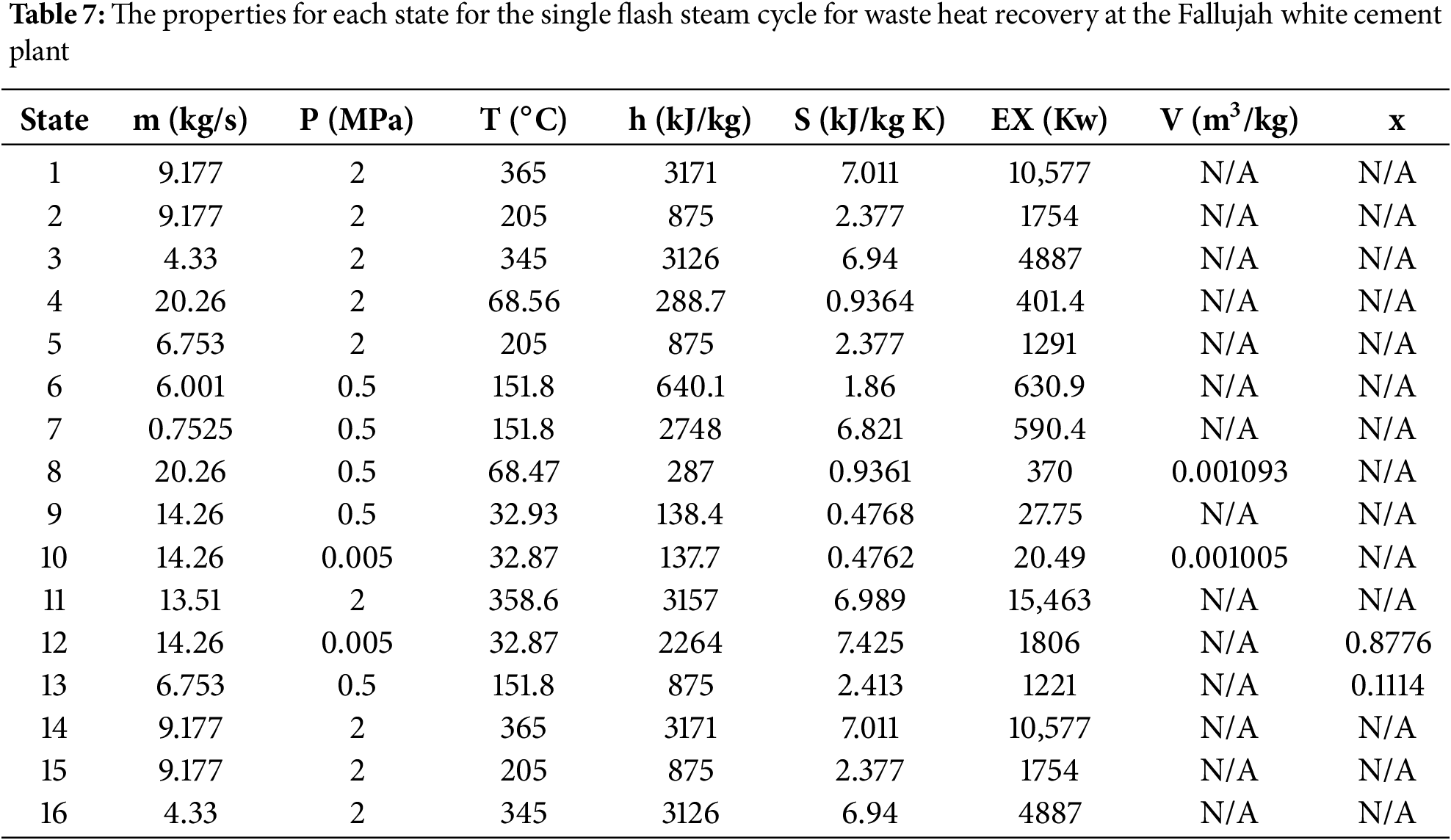

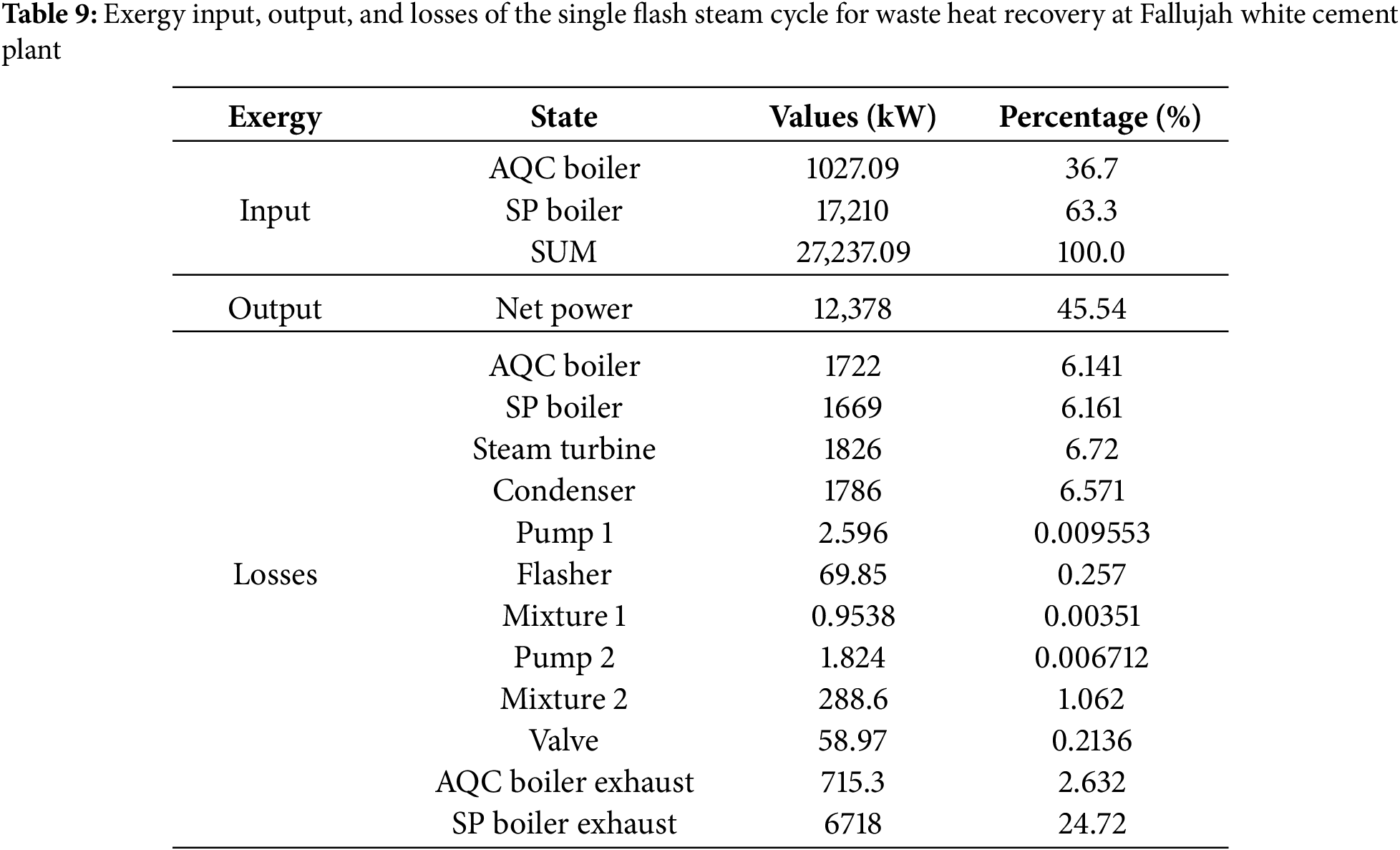

Table 7 summarizes the thermodynamic properties at each state for a single-flash steam cycle for waste heat recovery at the Fallujah white cement plant.

Table 8 presents the single-flash configuration delivers 12,378 kW of net power from a total heat input of 42,698 kW, yielding a thermal efficiency of ≈29% (12,378/42,698). Turbine work totals 12,441 kW, while pump consumption is only 43.05 kW. Heat input is well balanced between sources: AQC 21,628 kW (≈50.7%) and SP 21,070 kW (≈49.3%), which helps match the cycle’s single pressure level to a broad temperature range. The AQC exhaust at 94°C indicates deep recovery from clinker-cooler gases.

From the second-law perspective, the exergy efficiency is 45.54%, meaning just under half of the available work potential is converted into electricity; the remainder is destroyed mainly by finite temperature differences in the boilers and by heat rejection in the condenser.

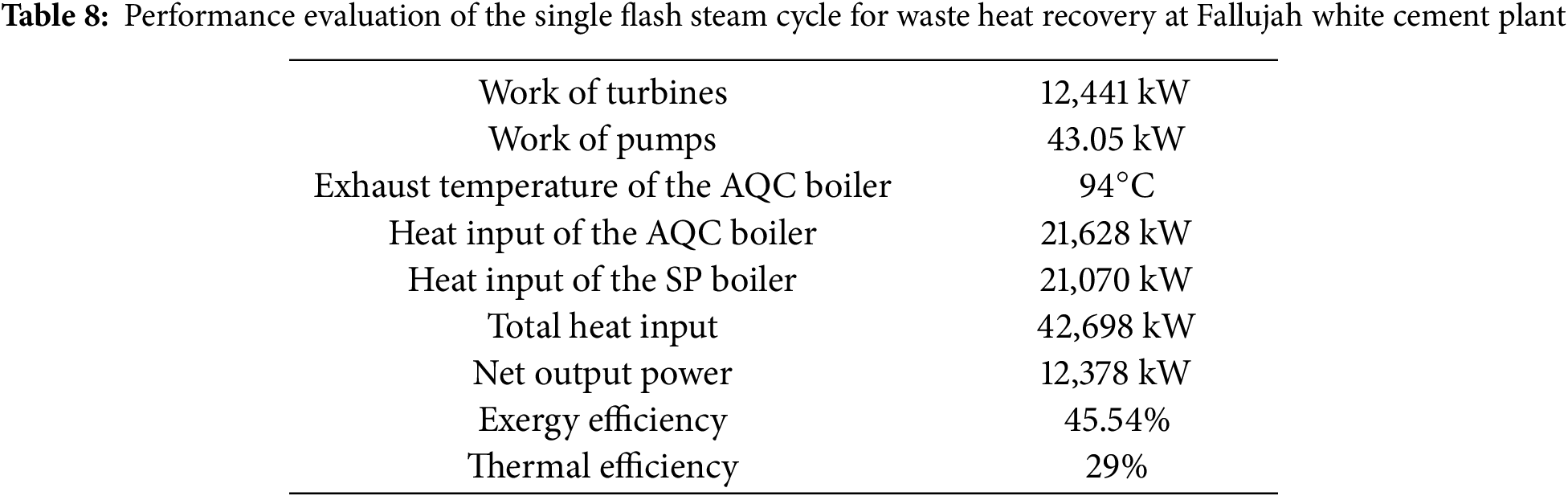

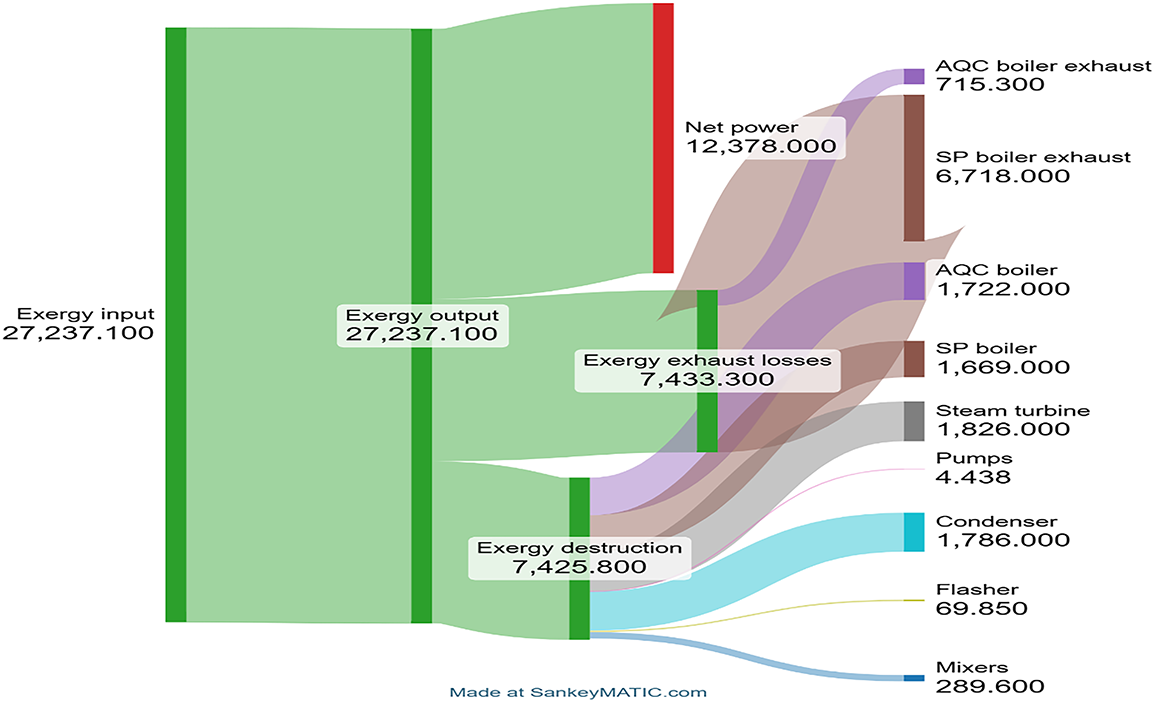

Table 9 and Fig. 6 illustrate the exergy performance and distribution of the single-flash steam cycle used for WHR at the Fallujah White Cement Plant. The system receives a total exergy input of 27,237 kW, of which the SP boiler provides the majority share (63.3%) compared to the AQC boiler (36.7%).

Figure 6: Sankey diagram of exergy flow in the single flash steam cycle waste heat recovery at Fallujah white cement plant

The cycle delivers 12,378 kW as net power, corresponding to an exergy efficiency of 45.54%. However, this also indicates that more than half of the available exergy is degraded due to irreversibilities and exhaust losses. Within the losses, SP boiler exhaust emerges as the largest contributor (6718 kW, 24.7%). In contrast, the AQC boiler exhaust is relatively minor at 715 kW (2.6%).

Exergy destruction is also significant in the steam turbine (1826 kW, 6.72%), condenser (1786 kW, 6.57%), and both boilers (AQC 1722 kW, 6.14%; SP 1669 kW, 6.16%). Smaller but notable contributions come from the flasher (69.9 kW), valve (59.0 kW), and mixers (289.6 kW combined). Pumps are negligible in comparison (<0.01%).

The Sankey diagram, shown in Fig. 6, vividly illustrates these flows: the green inflow (exergy input) is split into useful net power (~46%) and various destruction pathways, where the SP boiler exhaust stream visually dominates. The condenser’s branch is also substantial, showing wasted low-grade heat that could potentially be recovered through cogeneration or district heating applications.

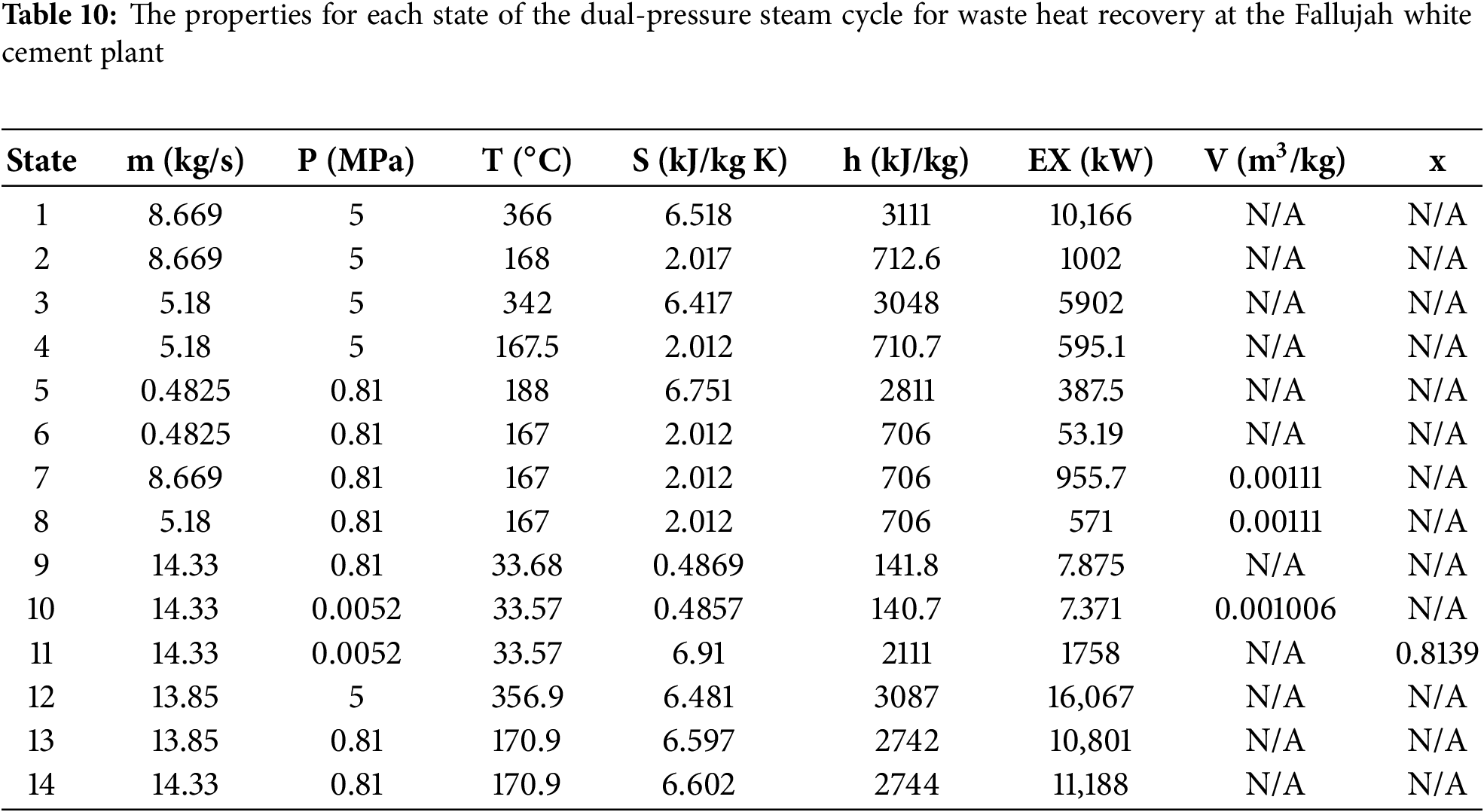

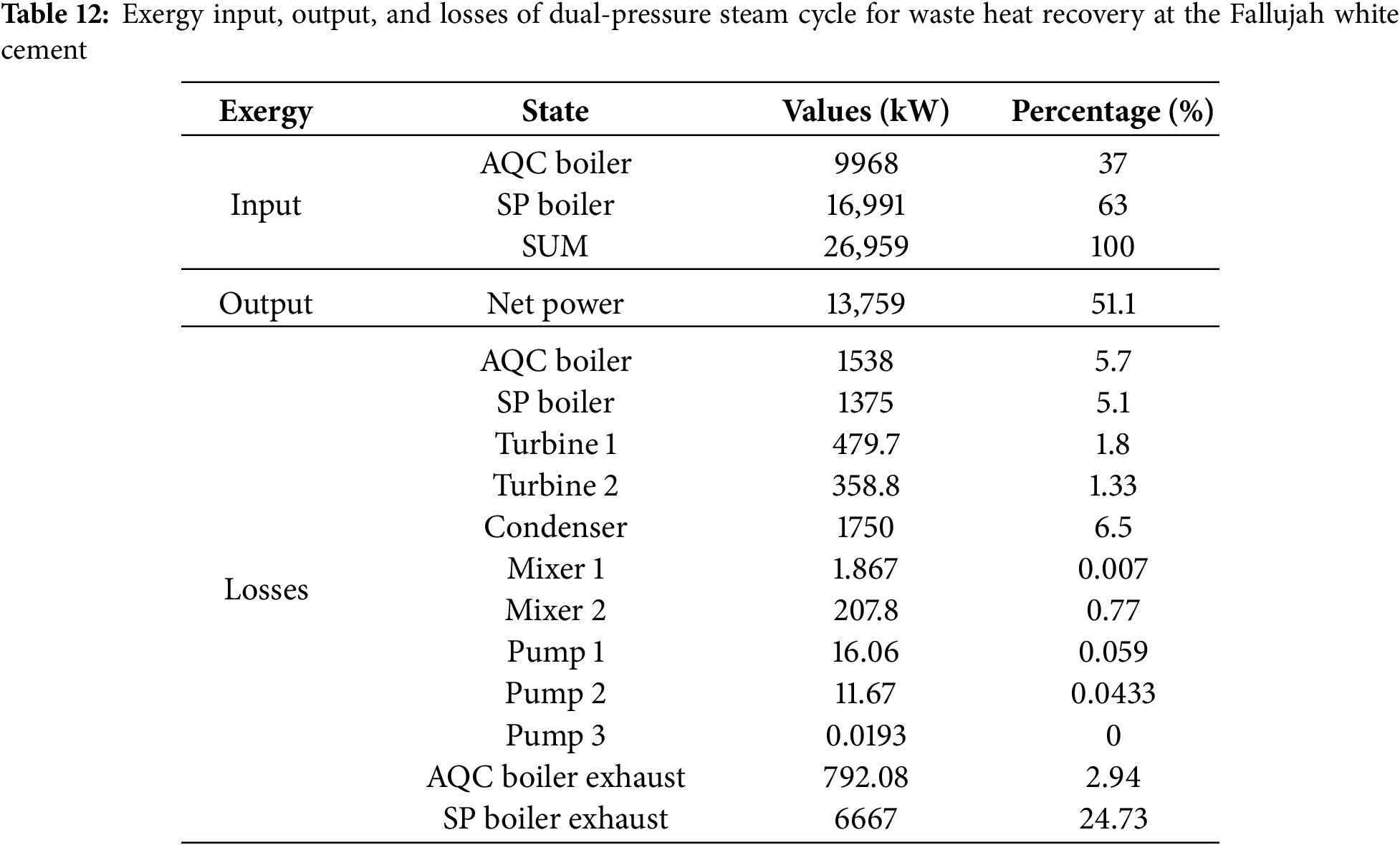

Table 10 summarizes the thermodynamic properties at each state point of the dual-pressure steam cycle for WHR at the Fallujah white cement. These properties, including temperature, pressure, enthalpy, and entropy, provide a complete description of the working fluid’s condition throughout the system.

Table 11 presents the key performance indicators of the dual-pressure steam cycle applied in the Fallujah white cement plant. The dual-pressure configuration converts 13,759 kW of electricity from 42,002 kW of recovered heat, i.e., a thermal efficiency of 32.76%. Turbine power is 13,858 kW; subtracting 98.23 kW of pumping. Heat input is almost evenly split: AQC 21,208 kW (50.5%) and SP 20,794 kW (49.5%), which is together with two pressure levels-improves temperature matching to the exhaust streams and reduces pinch losses compared with single-pressure layouts.

From the second-law view, the exergy efficiency is 51.04%, meaning just over half of the available work potential becomes electricity. Relative to the single-flash case (12,378 kW, 29.0%, 45.54%), the dual-pressure cycle delivers +11.2% more net power and gains +3.76 percentage points in thermal efficiency and +5.5 points in exergy efficiency. The ORC improvements are larger (net power +68% and exergy efficiency +~16 points), reflecting better utilization of medium-temperature sources by steam at two pressure levels.

Overall, Table 12 confirms the dual-pressure system as the best-performing option, combining higher output with materially lower second-law losses under the Fallujah plant’s conditions. The overall net output power achieved is 14,095 kW, showing a significant improvement over single-pressure configurations. Moreover, the cycle exhibits a high exergy efficiency of 51.17% and a thermal efficiency of 33.18%.

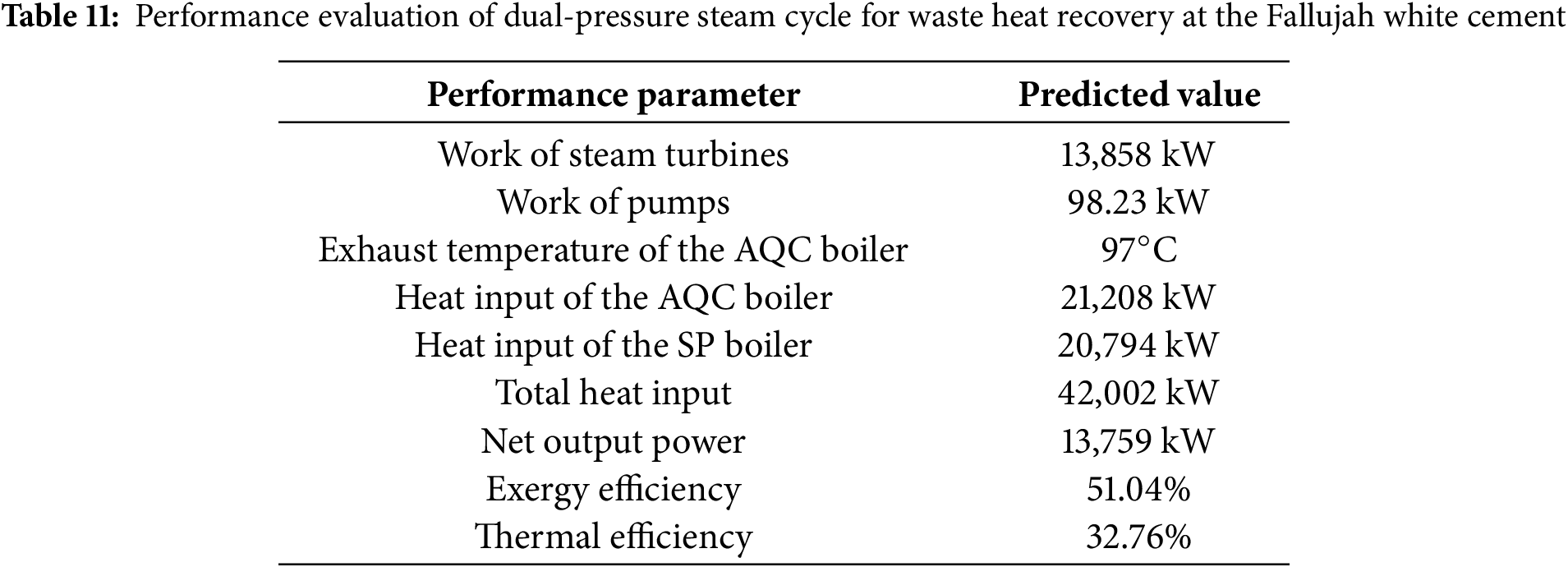

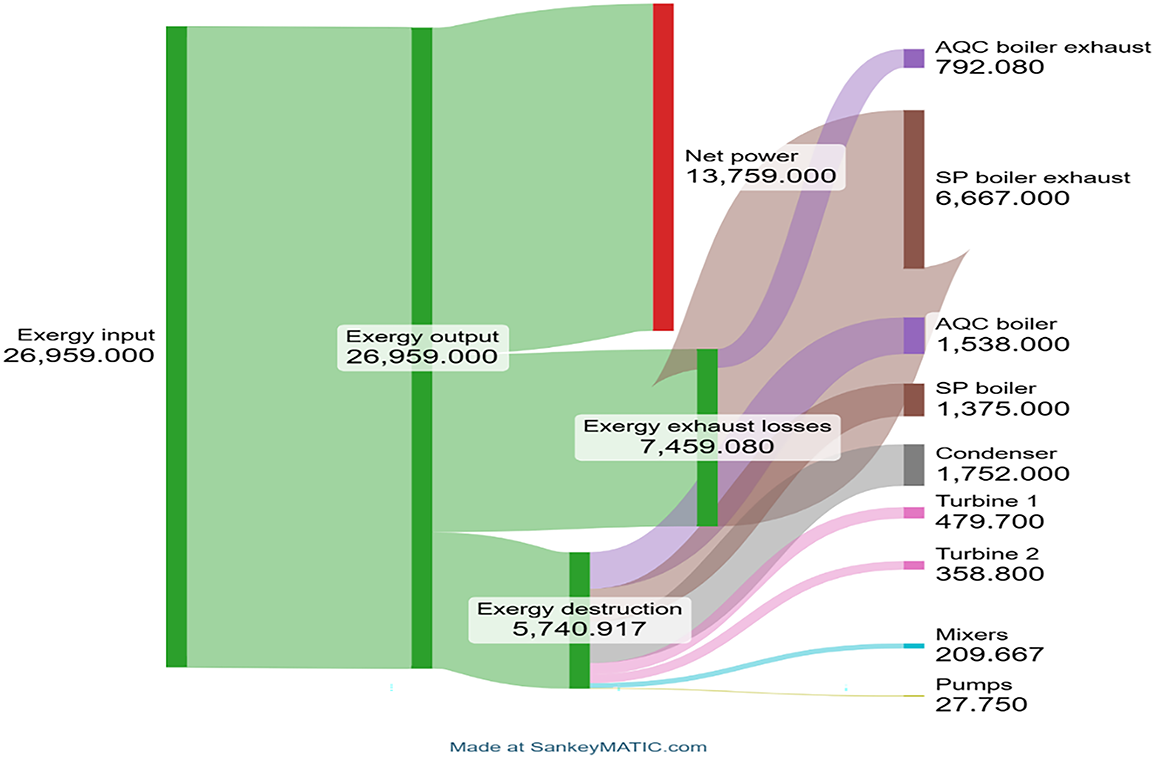

Table 12 and Fig. 7 present a detailed exergy balance of the dual-pressure steam cycle applied in the Fallujah white cement plant. The total exergy input to the system is 26,959 kW, derived mainly from the SP boiler (63%) and the AQC boiler (37%). This indicates that the SP boiler plays a more dominant role in supplying waste heat energy, consistent with its larger thermal capacity in the cement production line. The system achieves a net power output of 13,759 kW, representing 51.1% of the total exergy input. This is a relatively high utilization rate compared to single-pressure or ORC systems.

Figure 7: Sankey diagram of exergy flow in the dual-pressure steam cycle for waste heat recovery at the Fallujah white cement

The AQC boiler and SP boiler contribute exergy losses and destruction of 1538 kW, which is 5.7% and 1375 kW, which is 5.1%, respectively. The steam turbines, Turbine 1 and Turbine 2, show smaller destruction rates at 1.8% and 1.33%, respectively, due to irreversibilities in expansion. The condenser contributes 1750 kW, which is 6.5%, reflecting unavoidable thermal rejection to the environment. Minor losses occur in pumps, 1, 2, and 3 are 0.059% + 0.043% + negligible, respectively, and mixers (0.77% total), which are insignificant compared to major components.

The SP boiler exhaust is the largest contributor, with 6667 kW, which is 24.73%, confirming that a large portion of usable exergy still leaves with the flue gases. The AQC boiler exhaust is smaller, at 792 kW, which is 2.94%, showing that heat recovery in this section is relatively more effective.

The Sankey diagram shown in Fig. 6 illustrates the flow of exergy from input to useful output and losses. The thick stream toward net power of 13,759 kW highlights the significant share of exergy converted into work, confirming the high efficiency of this cycle. The exergy destruction flow 5740.9 kW is distributed mainly across the condenser, boilers, and turbines, while the exergy exhaust losses of 7459 kW steam primarily from the SP boiler exhaust. The relative thinness of streams associated with pumps and mixers emphasizes their negligible contribution to overall irreversibilities.

Compared to the single-flash steam cycle, the dual-pressure cycle demonstrates: higher net power efficiency (51.1% vs. 45.5%), and better distribution of exergy destruction across boilers and turbines, reducing localized inefficiencies. However, the SP boiler exhaust remains a persistent challenge, suggesting the need for further waste heat recovery technologies (e.g., economizers or additional bottoming cycles).

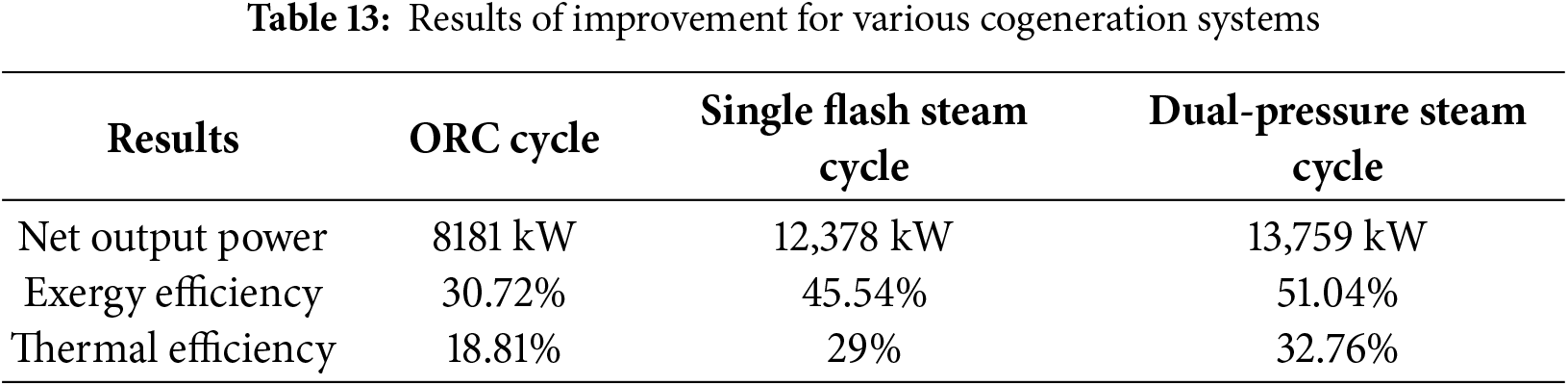

Table 13 highlights the progressive improvements achieved when moving from the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) to the Single Flash Steam Cycle and finally to the Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle. The findings present that the ORC is simpler and suitable for low-grade waste heat, but its performance is modest. Single Flash provides a significant boost in both power and efficiency, making it a more attractive option. Dual-Pressure emerges as the optimal choice, offering the best balance between output power, exergy efficiency, and thermal efficiency, making it the most promising system for large-scale waste heat recovery at the Fallujah White Cement Plant.

The ORC cycle generates 8181 kW, while the Single Flash Steam Cycle significantly improves the output to 12,378 kW (about 51% higher). The Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle achieves the highest output at 13,759 kW, marking an increase of nearly 68% compared to ORC, showing its superior ability to harness waste heat.

ORC shows the lowest exergy efficiency (30.72%), mainly due to irreversibilities in the working fluid and condenser. Single Flash improves efficiency to 45.54%, indicating better utilization of available exergy in the steam cycle. Dual-Pressure achieves 51.04%, the highest efficiency, by reducing exergy destruction through staged pressure levels and better thermal matching.

While the dual-pressure system offers the highest net power (13,759 kW) and efficiency (32.76%), it is also the most complex. It requires a larger footprint, more sophisticated control systems to manage two pressure levels, and a higher initial capital investment. The single-flash steam cycle represents a robust compromise, generating significant power (12,378 kW) with less complexity and cost than the dual-pressure system. The ORC remains an attractive option despite its lower performance (8181 kW, 18.81% efficiency). Its key advantages are operational simplicity and lower maintenance. It operates at much lower pressures than steam cycles, reducing mechanical stress and safety concerns. The organic working fluids are often non-corrosive and self-lubricating, which simplifies maintenance. This makes ORC a viable, lower-risk choice, especially for plants prioritizing reliability and ease of operation over maximum power generation.

The performance of the proposed ORCe, with a thermal efficiency of 18.81%, compares more favourably with the thermal efficiency reported by Fierro et al. [32], which is 15.96%. Furthermore, while the Kalina cycle is often cited as an advanced alternative, Júnior et al. [21] reported thermal and exergetic efficiencies of 23.3% and 47.8%, respectively, for that cycle. This suggests the proposed Dual-Pressure steam model not only outperforms the Single-Flash (29% thermal efficiency) and ORC (18.81% thermal efficiency) baselines but is also highly competitive with other advanced cycles discussed in the literature.

This study examined waste heat recovery (WHR) opportunities at the Fallujah White Cement Plant by evaluating three cogeneration models: the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), the Single-Flash Steam Cycle, and the Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle. The analyses confirmed that the Dual-Pressure Steam Cycle is the most effective configuration, producing the highest net output power (13.76 MW) and achieving superior thermal (32.76%) and exergy (51.04%) efficiencies.

Based on these findings, this study offers a specific recommendation: the dual-pressure steam cycle should be prioritized for implementation in large-scale Iraqi cement factories, such as the Fallujah plant. Conversely, the simpler ORC system may be a more suitable option for smaller plants or those with lower-temperature waste heat sources where operational simplicity is a key consideration.

The implementation of an effective WHR system provides critical environmental benefits. By generating up to 13.76 MW of electricity from waste heat, the plant can dramatically reduce its reliance on the electrical grid. This results in substantial fossil fuel savings and a significant reduction in CO2 emissions, directly contributing to Iraq’s clean energy and environmental sustainability objectives.

While thermodynamically promising, this study acknowledges several limitations, particularly the severe risk of dust fouling and challenges associated with integrating the Iraqi grid. Therefore, future research must move beyond this comparative analysis to include a comprehensive techno-economic analysis to confirm financial viability. Following this, a pilot-scale demonstration is recommended to validate performance under real operational conditions. Finally, assessing integration with renewable energy sources (hybridization) will be essential to provide a complete and robust roadmap for sustainable cement production in Iraq.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge Karabuk University for supporting the research and producing this paper.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Abdulrazzak Akroot and Kayser Aziz Ameen; methodology, Hussein Ali Mutlag, and Hasanain A. Abdul Wahhab; software, Abdulrazzak Akroot and Amer Kalash; validation, Abdulrazzak Akroot and Kayser Aziz Ameen; formal analysis, Miqdam T. Chaichan; investigation, Miqdam T. Chaichan and Hussein Ali Mutlag; resources, Hasanain A. Abdul Wahhab and Hussein Ali Mutlag; data curation, Abdulrazzak Akroot and Kayser Aziz Ameen; writing—original draft preparation, Miqdam T. Chaichan; writing—review and editing, Abdulrazzak Akroot; visualization, Haitham M. Ibrahim; supervision, Miqdam T. Chaichan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Hasanain A. Abdul Wahhab, upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang Y, Xu Y, Qiu Y, Ning S. Thermodynamics, economy and environment analyses and optimization of series, parallel, dual-loop Kalina cycles for double-source heat recovery in cement industry. PLoS One. 2025;20(2):e0315972. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0315972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ohunakin OS, Leramo OR, Abidakun OA, Odunfa MK, Bafuwa OB. Energy and cost analysis of cement production using the wet and dry processes in Nigeria. Energy Power Eng. 2013;5(9):537–50. doi:10.4236/epe.2013.59059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Amiri A, Vaseghi MR. Waste heat recovery power generation systems for cement production process. IEEE Trans Ind Applicat. 2015;51(1):13–9. doi:10.1109/tia.2014.2347196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Han Y, Guo J, Zheng W, Ding J, Zhu L, Che Y, et al. Evaluation of a novel waste heat recovery system for the cement industry using multi-criteria analysis (MCA) approach. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Global on Renewable Energy and Development (IGRED 2017); 2017 Dec 22–25; Singapore. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2017. p. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

5. Salum AH, Ismail BH, Sadik SH. Opting of an organic rankine cycle based on waste heat recovery system to produce electric energy in cement plant. Iraqi J Ind Res. 2022;9(2):91–9. doi:10.53523/ijoirvol9i2id194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mutlag HA. Process modeling of waste heat recovery systems to generate power in Fallujah white cement plant [master’s thesis]. Karabük, Türkiye: Karabuk Universit; 2021. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

7. Roy JP, Mishra MK, Misra A. Parametric optimization and performance analysis of a waste heat recovery system using organic Rankine cycle. Energy. 2010;35(12):5049–62. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2010.08.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmed A, Esmaeil KK, Irfan MA, Al-Mufadi FA. Design methodology of organic Rankine cycle for waste heat recovery in cement plants. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;129(111703):421–30. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.10.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao Y, Chen H, Zhang Y, Jin Z, Pan P, Zhang G. A novel waste heat power generation system based on the integration of Carnot battery and waste heat recovery in a cement plant. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;280:128159. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.128159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen H, Wang Y, An L, Xu G, Zhu X, Liu W, et al. Performance evaluation of a novel design for the waste heat recovery of a cement plant incorporating a coal-fired power plant. Energy. 2022;246:123420. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.123420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cho KC, Shin KY, Shim J, Bae SS, Kwon OD. Performance analysis of a waste heat recovery system for a biogas engine using waste resources in an industrial complex. Energies. 2024;17(3):727. doi:10.3390/en17030727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cuce PM, Riffat S. A comprehensive review of heat recovery systems for building applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;47(7):665–82. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khater AM, Soliman A, Ahmed TS, Ismail IM. Power generation in white cement plants from waste heat recovery using steam-organic combined Rankine cycle. Case Stud Chem Environ Eng. 2021;4(1):100138. doi:10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Basheer Y, Waqar A, Qaisar SM, Ahmed T, Ullah N, Alotaibi S. Analyzing the prospect of hybrid energy in the cement industry of Pakistan, using HOMER pro. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12440. doi:10.3390/su141912440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mossie AT, Khatiwada D, Palm B, Bekele G. Techno-economic analysis of waste heat recovery power plants in cement industry—a case study in Ethiopia. Next Energy. 2025;8(1):100339. doi:10.1016/j.nxener.2025.100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hamdan M, Al-Kasasbeh T, Qawasmeh B, Al Assaf A. Waste heat recovery to improve the carbon footprint a case study: cement industry in Jordan. Int Rev Civ Eng IRECE. 2023;14(2):144. doi:10.15866/irece.v14i2.21938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Turakulov Z, Kamolov A, Norkobilov A, Variny M, Fallanza M. Enhancing sustainability and energy savings in cement production via waste heat recovery. Eng Proc. 2024;67(1):11. doi:10.3390/engproc2024067011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fergani Z, Touil D, Morosuk T. Multi-criteria exergy based optimization of an organic Rankine cycle for waste heat recovery in the cement industry. Energy Convers Manag. 2016;112:81–90. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2015.12.083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pili R, García Martínez L, Wieland C, Spliethoff H. Techno-economic potential of waste heat recovery from German energy-intensive industry with organic Rankine cycle technology. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020;134(9):110324. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Moreira LF, Arrieta FRP. Thermal and economic assessment of organic Rankine cycles for waste heat recovery in cement plants. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2019;114:109315. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.109315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Júnior EPB, Arrieta MDP, Arrieta FRP, Silva CHF. Assessment of a Kalina cycle for waste heat recovery in the cement industry. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;147(1):421–37. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.10.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mirolli MD. The Kalina cycle for cement kiln waste heat recovery power plants. In: Proceedings of the Conference Record Cement Industry Technical Conference; 2005 May 15–20; Kansas City, MO, USA. p. 330–6. [Google Scholar]

23. Amiri Rad E, Mohammadi S. Energetic and exergetic optimized Rankine cycle for waste heat recovery in a cement factory. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;132:410–22. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.12.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Aboelwafa O, Ahmed TS, Soliman AF, Ismail IM. Organic Rankine cycle and steam Rankine cycle for waste heat recovery in a cement plant in Egypt: a comparative case study. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2020;1:19–42. [Google Scholar]

25. Akroot A. Thermodynamic and environmental performance analysis of the marib integrated power and cooling cycle. Black Sea J Eng Sci. 2025;8(3):814–23. doi:10.34248/bsengineering.1627614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Akroot A, Al Shammre AS. Techno-economic and environmental impact analysis of a 50 MW solar-powered Rankine cycle system. Processes. 2024;12(6):1059. doi:10.3390/pr12061059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Soltani S, Mahmoudi SMS, Yari M, Morosuk T, Rosen MA, Zare V. A comparative exergoeconomic analysis of two biomass and co-firing combined power plants. Energy Convers Manag. 2013;76(6):83–91. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2013.07.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Aghaziarati Z, Aghdam AH. Thermoeconomic analysis of a novel combined cooling, heating and power system based on solar organic Rankine cycle and cascade refrigeration cycle. Renew Energy. 2021;164(1):1267–83. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.10.106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Akroot A, Namli L. Performance assessment of an electrolyte-supported and anode-supported planar solid oxide fuel cells hybrid system. J Ther Eng. 2021;7:1921–35. doi:10.14744/jten.2021.0006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Talal W, Akroot A. Exergoeconomic analysis of an integrated solar combined cycle in the Al-qayara power plant in Iraq. Processes. 2023;11(3):656. doi:10.3390/pr11030656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Akroot A, Refaei M. Thermodynamic and exergoeconomic assessment of a solar-assisted combined cooling, heating, and power system in Antalya, Turkey. Gazi Üniversitesi Fen Bilim Derg Part C Tasarım Ve Teknol. 2025;13(1):231–44. doi:10.29109/gujsc.1591445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fierro JJ, Escudero-Atehortua A, Nieto-Londoño C, Giraldo M, Jouhara H, Wrobel LC. Evaluation of waste heat recovery technologies for the cement industry. Int J Thermofluids. 2020;7–8(4):100040. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2020.100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools